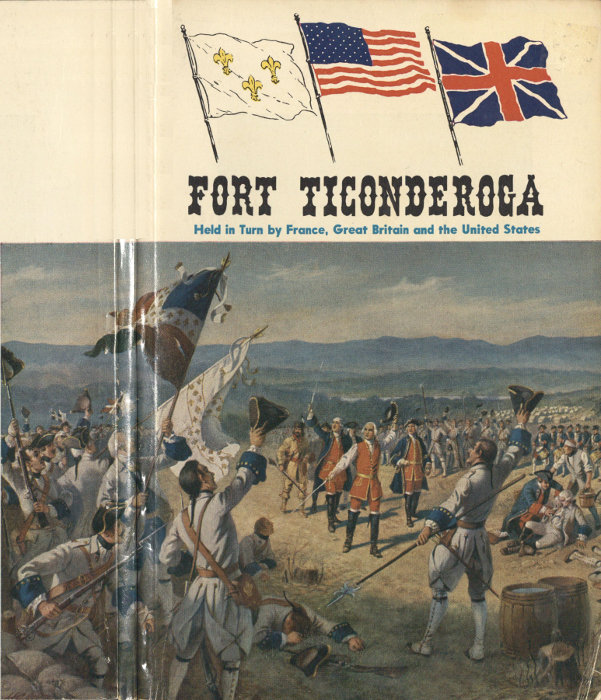

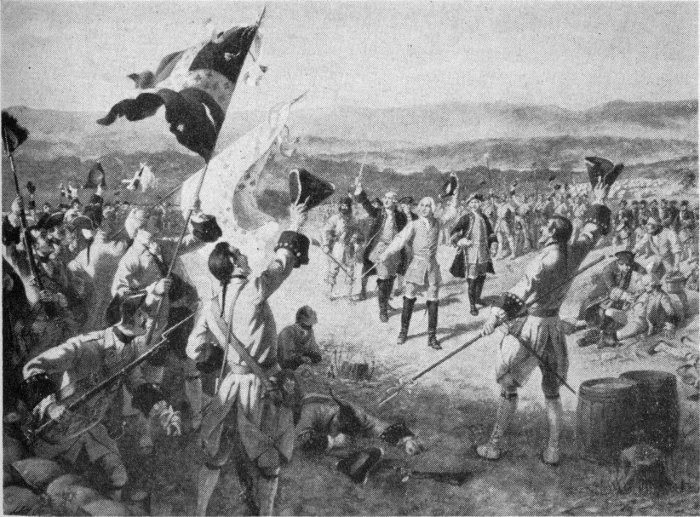

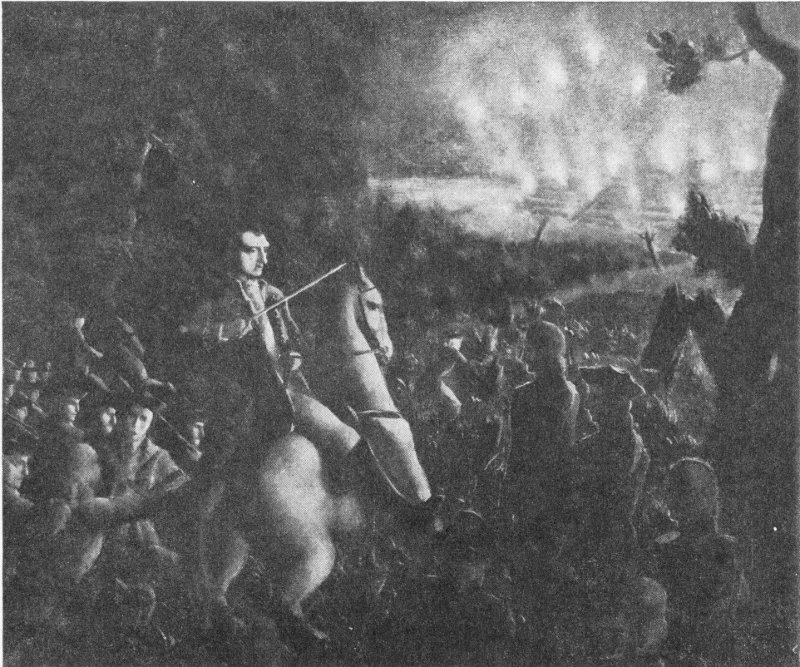

Cover: Montcalm Congratulating His Victorious Troops,

Battle of Carillon, Fort Ticonderoga, July 8, 1758.

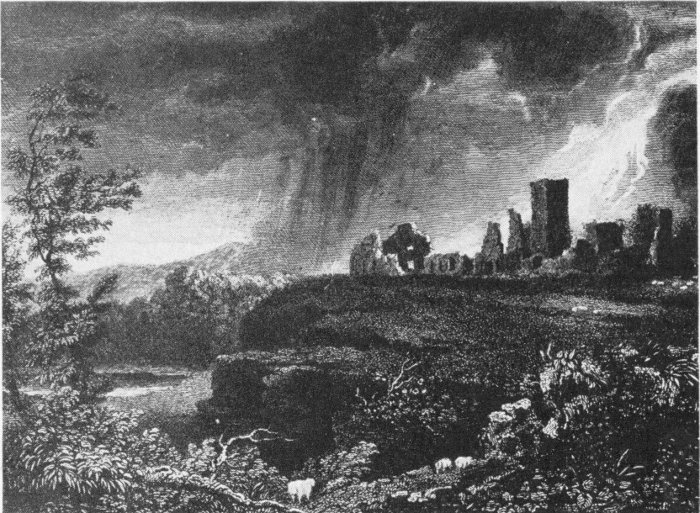

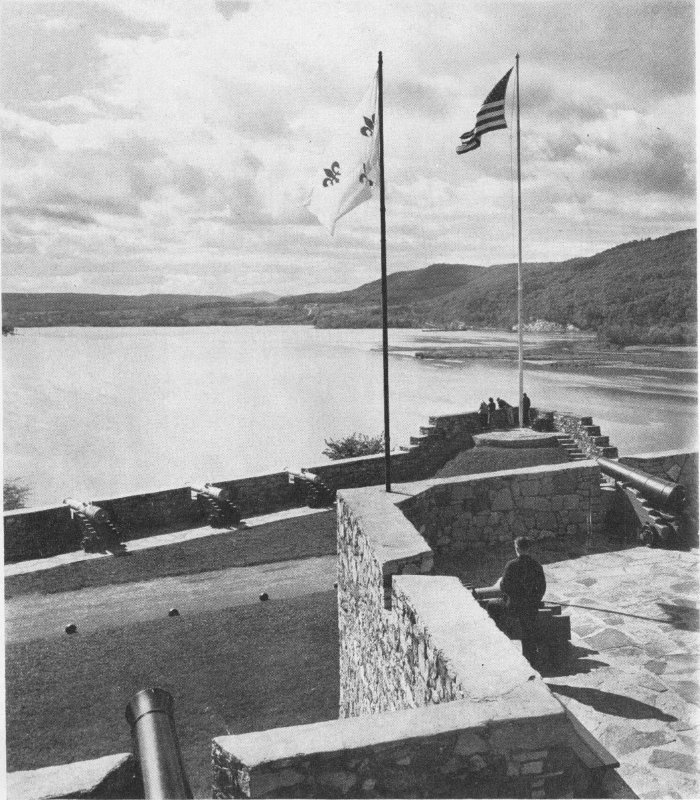

Fort Ticonderoga: Looking South, Up Lake Champlain

Compiled from Contemporary Sources

By S. H. P. Pell

Profusely Illustrated

Reprinted for the Fort Ticonderoga Museum

1966

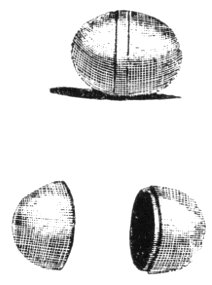

“The little bronze flint and tinder box illustrated, was found in 1888 by the present Museum Director, then a small boy. His brother dislodged a stone while they were climbing around the fort. Under the stone was this box with flint and tinder in it. Bronze and of French design, it must have belonged to some important officer, probably Montcalm de Levis, Bougainville or Bourlamacque. The busts represent Cupid and Psyche; the faces are extraordinarily beautiful and expressive. The box measures 2¼ by 1¼ inches.

I consider this box and the back plate for the suit of half-armor (found a few years ago) the most interesting of the thousands of articles found at the Fort.

This little box stimulated the Director’s interest. Even as a small boy he hoped some day to preserve and perhaps restore Fort Ticonderoga. Many a year was to pass before this dream could become a reality.”

Flint and Tinder Box Which Started the Fort Ticonderoga Collection (Found by S. H. P. Pell, when a small boy)

(Drawing by Herbert Sherlock of North Canton, Ohio)

BUSTS in CENTER of TOP and BOTTOM of CASE

BOX OPEN SHOWING INTERIOR

DETAIL of FLOWER DESIGN

and BORDER

REAR of HINGE

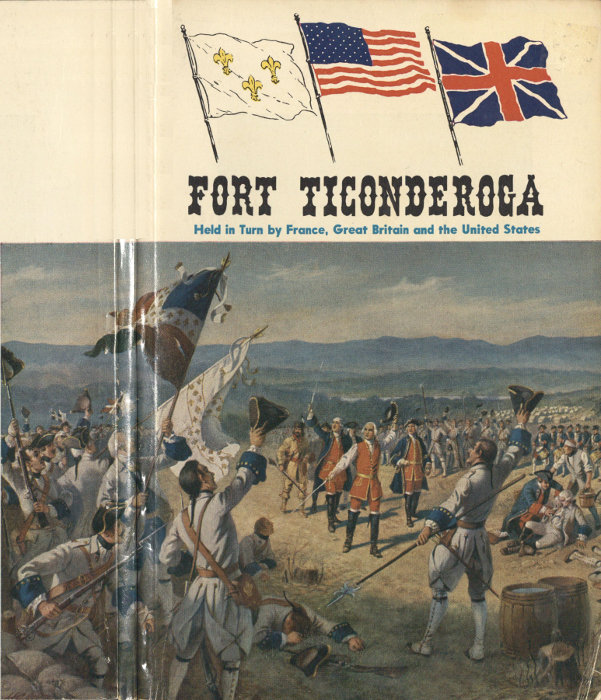

Major Robert Rogers and An Indian Chief

Airview of Fort Ticonderoga Showing Strategic Location of Mount Defiance, Beyond Which Is Lake George

Indian Costumes, From Lafitau. 1, Iroquois; 2, Algonquin

When Columbus was landing in the West Indies, and discovering America, the Champlain Valley was thickly populated. There are signs of Indian village sites all along the shores and the thousands of stone implements, arrow and spear points, scrapers, hatchets, pestles and mortars that are turned up each year indicate an occupation of hundreds, probably thousands, of years. But when the first white man arrived all was silence and desolation. The fierce Iroquois from the south had not long before slaughtered the peaceful Algonquin Indians and driven the survivors back into the mountains, where they were living a hand to mouth existence. In fact so degenerate had they become that the Iroquois referred to them as “Adirondacks” or “Bark-eaters,” because of their necessity of depending on the bark of trees during the winter when game was scarce. Remains of these people are so many that for a hundred years arrow heads and other stone implements have been found on the shore of the lake under the walls of the Fort and yet each rain and wind storm discloses new ones. These Indians were a partly agricultural people as shown by the many bits of pottery and hoes that are found, but little is definitely known of them or their habits.

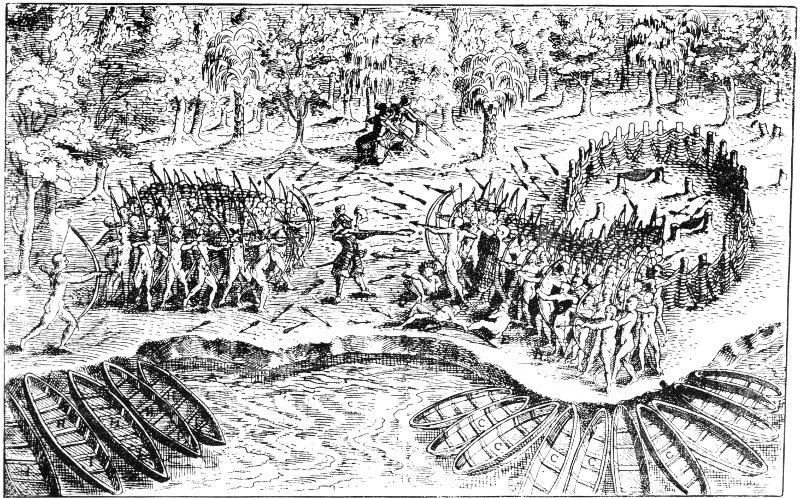

Champlain and the Iroquois Near Ticonderoga, July 30, 1609 From “Champlain’s Life and Travels, 1613”

In May, 1609, the same year that Hendrick Hudson discovered and named Hudson’s River, Samuel de Champlain with a contingent of eleven Frenchmen, a small body of Montagnais Indians and between two and three hundred Hurons left Quebec on an exploring expedition to the south.

At the rapids of the Richelieu, Champlain quarreled with his Indians, who had assured him that there was smooth water from the St. Lawrence to the great lake to the south. Three-quarters of them went home and with them he sent all but two of his white companions. His force now consisted of three Frenchmen and sixty Montagnais and Hurons.

They traveled in twenty-four canoes and soon entered Lake Champlain, and, as they now were approaching the Iroquois country, they traveled by night and hid in the woods by day.

Champlain’s own description of his discovery and the battle at Ticonderoga from his “Voyages and Discoveries” published in Paris, 1613 ... reads as follows:

“We left next day, continuing our route along the river as far as the mouth of the Lake. Here are a number of beautiful, but low islands filled with very fine woods and prairies, a quantity of game and wild animals, such as stags, deer, fawns, roe-bucks, bears and other sorts of animals that come from the main land to the said islands. We caught a quantity of them. There is also quite a number of beavers, as well in the river as in several other streams which fall into it. These parts, though agreeable, are not inhabited by any Indians, in consequence of their wars. They retire from the rivers as far as possible, deep into the country, in order not to be so soon discovered.

“Next day we entered the lake, which is of considerable extent; some 50 or 60 leagues in length, where I saw 4 beautiful islands, 10, 12 and 15 leagues in length formerly inhabited, as well as the Iroquois river, by Indians, but abandoned since they have been at war the one with the other.

“Several rivers, also, discharge into the lake, surrounded by a number of fine trees similar to those we have in France, with a quantity of vines handsomer than any I ever saw; a great many chestnuts, and I have not yet seen except the margin of the lake, where there is a large abundance of fish of divers species. Among the rest there is one called by the Indians of the country Chaousarou, the divers lengths. The largest I was informed by the people, are of eight to ten feet. I saw one of 5, as thick as a thigh, with a head as big as two fists, with jaws two feet and a half long, and a double set of very sharp and dangerous teeth. The form of the body resembles that of the pike, and it is armed with scales that a thrust of a poniard cannot pierce; and is of a silver grey colour. The point of the snout is like that of a hog. This fish makes war on all others in the lakes and rivers and possesses, as those people assure me, a wonderful instinct; which is, that when it wants to catch any birds, it goes among the rushes or reeds, bordering the lake in many places, keeping the beak out of the water without budging, so that when the birds perch on his beak, imagining it a limb of a tree, it is so subtle that closing the jaws which it keeps half open, it draws the birds under water by the feet. The Indians gave me a head of it, which they prize highly, saying, when they have a headache they let blood with the teeth of this fish at the seat of the pain which immediately goes away.

“Continuing our route along the west side of the lake, contemplating the country, I saw on the east side very high mountains capped with snow. I asked the Indians if those parts were inhabited? They answered me, Yes, and that they were Iroquois, and that there were in those parts beautiful valleys, and fields fertile in corn as good as I had ever eaten 13 in the country, with an infinitude of other fruits, and that the lake extended close to the mountains, which were, according to my judgment, 15 leagues from us. I saw others, to the South, not less high than the former; only, that they were without snow. The Indians told me it was there we were to go to meet their enemies, and that they were thickly inhabited, and that we must pass by a waterfall which I afterwards saw, and thence enter another lake three or four leagues, long, and having arrived at its head, there were 4 leagues overland to be traveled to pass to a river which flows toward the coast of the Almouchiquois, tending towards that of the Almouchiquois, and that they were only two days going there in their canoes, as I understood since from some prisoners we took, who, by means of some Algonquin interpreters, who were acquainted with the Iroquois language, conversed freely with me about all they had noticed.

“Now, on coming within about two or three days journey of the enemy’s quarters, we traveled only by night and rested by day. Nevertheless, they never omitted their usual superstitions to ascertain whether their enterprise would be successful, and often asked me whether I had dreamed and seen their enemies. I answered no; and encouraged them and gave them good hopes. Night fell, and we continued our journey until morning when we withdrew into the picket fort to pass the remainder of the day there. About ten or eleven o’clock I lay down after having walked some time around our quarters, and falling asleep, I thought I beheld our enemies, the Iroquois, drowning within sight of us in the Lake near a mountain; and being desirous to save them, that our savage allies told me that I must let them all perish as they were good for nothing. On awakening, they did not omit, as usual to ask me, if I had any dream, I did tell them, in fact, what I had dreamed. It gained such credit among them that they no longer doubted but they should meet with success.

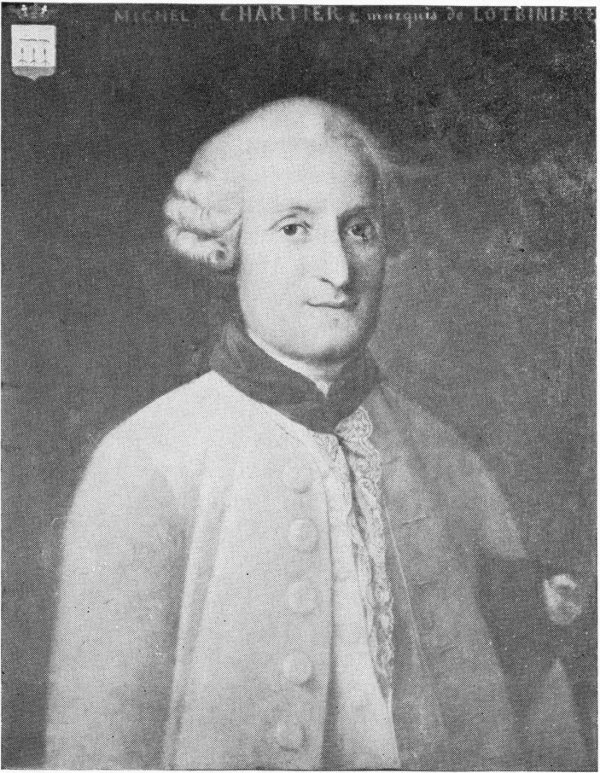

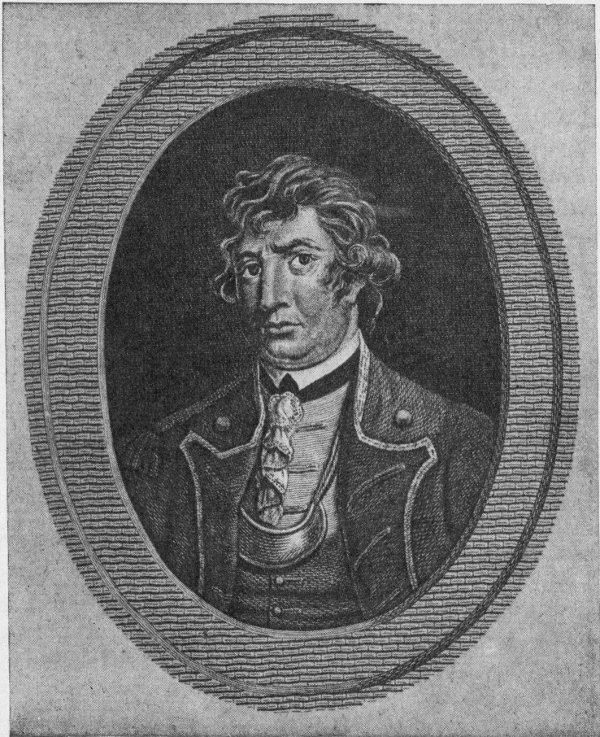

Marquis de Lotbiniere

“At nightfall we embarked in our canoes to continue our journey, and as we advanced very softly and noiselessly, we encountered a war party of Iroquois, on the twenty-ninth of the month, about ten o’clock, at night, at the point of a cape which juts into the lake on the west side. They and we began to shout, each seizing his arms. We withdrew towards the water and the Iroquois repaired on shore, and arranged all their canoes, the one beside the other, and began to hew down trees with villainous axes, which they sometimes got in war, and others of stone, and fortified themselves very securely.

“Our party, likewise, kept their canoes arranged the one alongside the other, tied to poles so as not to run adrift, in order to fight all together should need be. We were on the water about an arrow-shot from their barricades.

“When they were armed and in order, they sent two canoes from the fleet to know if their enemies wished to fight, who answered they desired nothing else; but that just then, there was not much light, and that we must wait for day to distinguish each other, and that they would give us battle at sun rise. This was agreed to by our party. Meanwhile the whole night was spent in dancing and singing, as well on one side as on the other, mingled with an infinitude of insults and other taunts, such as the little courage we had; how powerless our resistance against their arms, and that when day would break we should experience this to our ruin. Ours, likewise, did not fail in repartee; telling them they should witness the effects of arms they had never seen before; and a multitude of other speeches, as is usual at a siege of a town. After the one and the other had sung, danced and parliamented enough, day broke. My companions and I were always concealed, for fear the enemy should see us preparing our arms the best we could, being however separated, each in one of the canoes belonging to the savage Montagnais. After being equipped with light armour we took each an arquebus and went ashore. I saw 16 the enemy leave their barricade; they were about 200 men, of strong and robust appearance, who were coming slowly towards us, with a gravity and assurance which greatly pleased me, led on by three Chiefs. Our’s were marching in similar order, and told me that those who bore three lofty plumes were the Chiefs, and that there were but these three and they were to be recognized by those plumes, and that I must do all I could to kill them. I promised to do what I could, and that I was very sorry they could not clearly understand me, so as to give them the order and plan of attacking their enemies, as we should indubitably defeat them all; but there was no help for that; that I was very glad to encourage them and to manifest to them my good will when we should be engaged.

“The moment we landed they began to run about two hundred paces toward their enemies who stood firm, and had not yet perceived my companions, who went into the bush with some savages. Our’s commenced calling me in a loud voice, and making way for me, opened in two parts, and placed me at their head, marching about 20 paces in advance, until I was within 30 paces of the enemy. The moment they saw me, they halted, gazing at me and I at them. When I saw them preparing to shoot at us, I raised my arquebus, and aiming directly at one of the three Chiefs, two of them fell to the ground by this shot and one of their companions received a wound of which he died afterwards. I had put 4 balls in my arquebus. Our’s on witnessing a shot so favorable for them, set up such tremendous shouts that thunder could not have been heard; and yet, there was no lack of arrows on one side and the other. The Iroquois were greatly astonished seeing two men killed so instantaneously, notwithstanding they were provided with arrow-proof armour woven of cotton-thread and wood; this frightened them very much. Whilst I was reloading, one of my companions in the bush fired a shot, which so astonished them anew, seeing their Chiefs slain, that they lost courage, took flight and abandoned the field and their fort, hiding 17 themselves in the depths of the forest, whither pursuing them, I killed some others. Our savages also killed several of them and took ten or twelve prisoners. The rest carried off the wounded. Fifteen or sixteen of ours were wounded by arrows; they were promptly cured.

“After having gained the victory, they amused themselves plundering Indian corn and meal from the enemy; also their arms which they had thrown away in order to run the better. And having feasted, danced and sung, we returned three hours afterwards with the prisoners.

“The place where this battle was fought is in 43 degrees some minutes latitude, and I named it Lake Champlain.”

Historians agree that this fight took place on the low ground, northeast of the Fort at Ticonderoga. It was the Iroquois’ first introduction to firearms and forever alienated that great fighting confederation from the French.

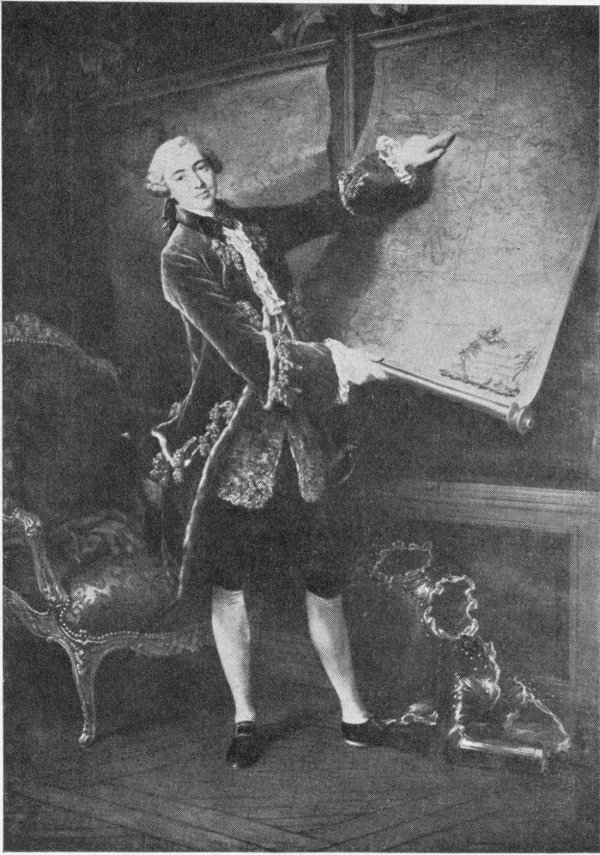

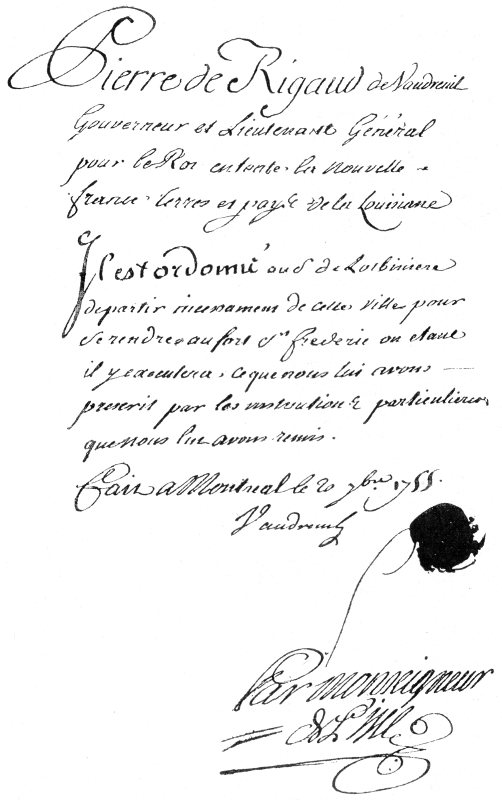

Marquis de Vaudreuil

From 1609 to 1755 nothing of great interest happened at Ticonderoga. War parties, explorers and traders passed up and down the lake in a steady stream, but few left records. The English pushed north as far as the south end of Lake George and built Fort William Henry; the French, as far south as Crown Point and built Fort St. Frederic. All between was a wild country, claimed by both France and Great Britain.

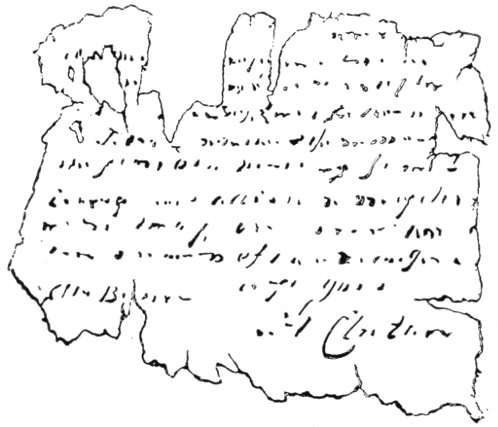

In 1755 Michel Chartier, afterwards Marquis de Lotbiniere, under instruction from the Marquis de Vaudreuil, Governor-General of New France, came down from Crown Point to select a site for a new fort. His aide-memoire from de Vaudreuil is in the Fort Library. In October he started cutting the great trees and leveling the ground to build the stone fortress which he first called Fort Vaudreuil, but which was afterwards given the name of Carillon, “A Chime of Bells,” named from the sound of the falls where the water from Lake George runs into Lake Champlain. He employed the garrison from Crown Point and at one time as many as 2,000 men were at work and made extraordinary progress, considering that he was erecting a fort in the wilderness.

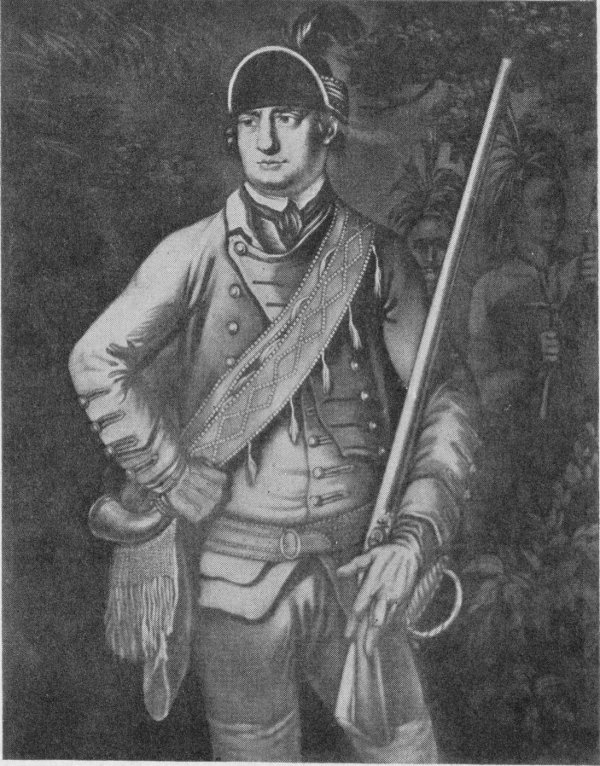

Robert Rogers, the famous ranger, several times during the building of the Fort reconnoitered and reported on the progress of the work. September 9, 1756, he says:

“I was within a mile of Ticonderoga fort where I endeavored to reconnoitre the enemy’s works and strength. They were engaged in raising the walls of the fort and erecting a large blockhouse near the southeast corner of the fort with ports in it for cannon. East from the blockhouse was a battery which I imagined commanded the lake.”

Part of the Original Instructions for de Lotbiniere

to Start Construction of Fort Ticonderoga

(This manuscript is in the Fort Library)

He also reports the French to be building a sawmill at the lower end of the falls. On Christmas Eve, 1757, Rogers got close enough to kill about seventeen head of cattle and set fire to the wood piles of the garrison. To the horns of one of the cattle, he attached a note to the commander of the fort:

“I am obliged to you, sir, for the repose you have allowed me to take. I thank you for the fresh meat you have sent me. I will take care of my prisoners. I request you to present my compliments to the Marquis de Montcalm.

(Signed) “Rogers, Commander of the Independent Companies.”

In 1755, Baron de Dieskau had gone from Crown Point to attack Sir William Johnson at Lake George. Dieskau was wounded, and his defeated army fought their way back to Ticonderoga.

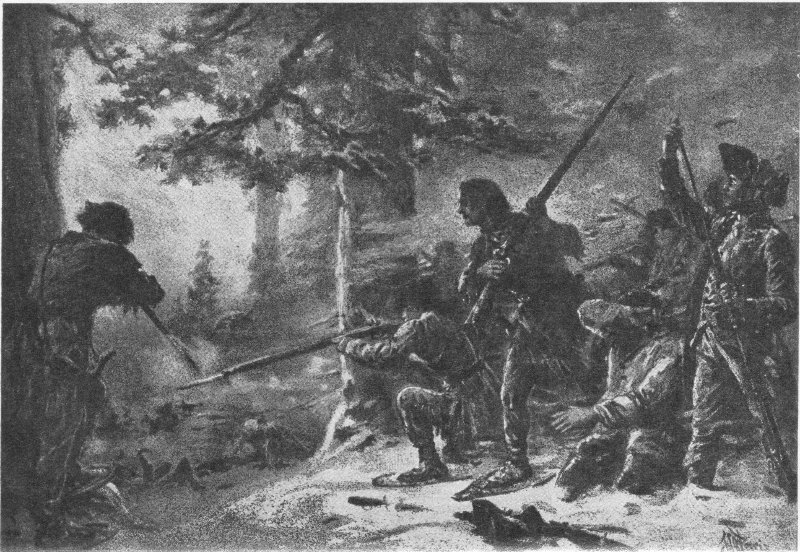

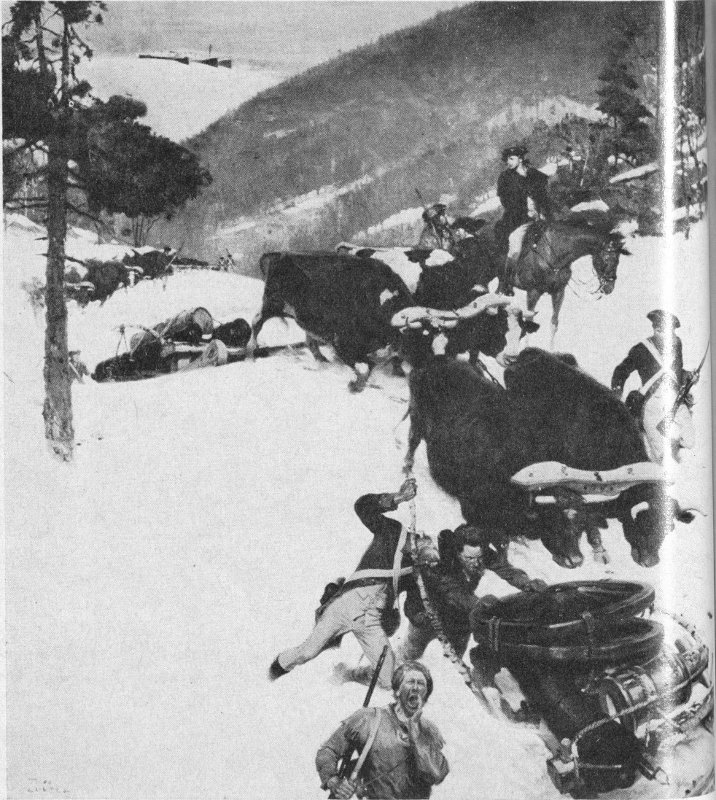

In March, 1758, Rogers’ famous battle on snowshoes was fought a few miles from Ticonderoga when the French under Captain Durentaye, commanding a party of Indians and Canadians, captured and destroyed most of his force.

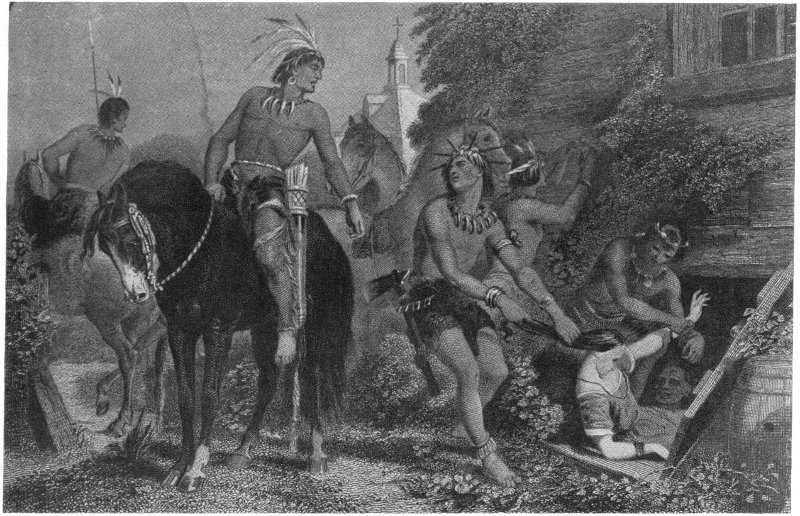

The guns which De Lotbiniere mounted on the Fort were mostly from Crown Point and Montreal but some were brought from Fort William Henry in 1757 when Montcalm captured that fort from Lieut. Col. Munro. It was after Munro’s surrender that the famous massacre of Fort William Henry occurred. The British garrison was marching unarmed to Fort Edward when it was attacked by Montcalm’s Indians. The French officers did their best to protect the garrison but many were slain.

De Lotbiniere wrote to the Minister from Carillon on the 31st October, 1756:

Major Robert Rogers

“My Lord:—

“I was so much occupied last year at the departure of the last ships that it was not possible for me to render you an account of the St. Frederic campaign, which M. de Vaudreuil ordered me to begin immediately after M. de Dieskau’s affair. I left with orders to examine the Carillon Point ... where the waters of the Grande Baye and of Lake St. Sacrement meet. At this point is the head of the navigation of Lake Champlain. M. de Vaudreuil feared with reason that, the enemy gaining possession of it, it would be very difficult for us to dislodge him, and that being solidly established there, [and we] would be exposed to see him appear in the midst of our settlements at the moment we least expected, it being possible for him to make during winter all necessary preparations to operate in the spring.

“I found on my arrival at St. Frederic an intrenchment begun on wrong principles which I felt obliged to continue to be agreeable to the Commandant of the Army who feared the enemy might at any moment attack the Fort. At last, on the 12th October, on the order of M. le Marquis de Vaudreuil, these works ceased and we moved the camp from St. Frederic to Carillon to begin a Fort at the location which I should find to be most suitable for such purpose.

“I decided to establish it on the ridge of rock which runs from the point to the falls of Lake St. Sacrement. As the season did not permit of our hoping to accomplish much work before winter I was obliged to restrict my efforts more than I would have liked so as to at least place the garrison under cover until the spring.

“I contented myself with reserving sufficient ground in the front for a camp of 2,000 to 3,000 men, if need be, covered by the Fort, and although I was obliged to operate in the midst of a wood without being able to see while surveying more than thirty yards ahead of me, I think I was fortunate enough to have made the best use of the ground I was ordered to fortify. We were not prepared to build in stone, having neither the material assembled nor the workmen. We were therefore obliged to line the works in oak which fortunately was plentiful on the spot. I began the parapet of the whole work which I formed in a double row of timbers distant ten feet from one another and bound together by two cross-pieces dovetailed at their extremities, to retain the timbers. This had reached the height of seven feet by the 28th November, date of the departure of the army, which could not remain longer owing to the ice beginning to form.

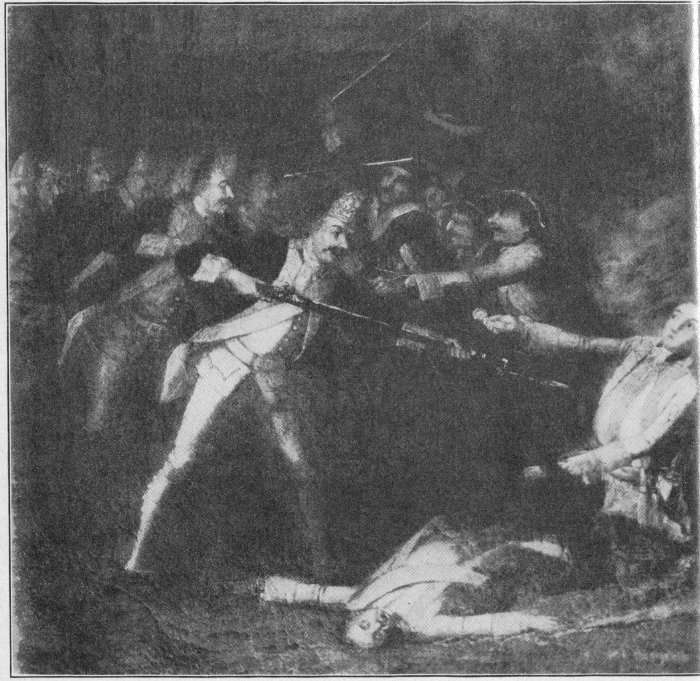

Wounding of Baron Dieskau. From a Painting in the Museum

“I remained until February hoping to be able to use the garrison to advance the works; but finding that it was not possible to make the garrison work, I decided to return to Montreal after the barracks had been finished, to recuperate from the fatigues of the campaign and the unwholesome food I had taken.

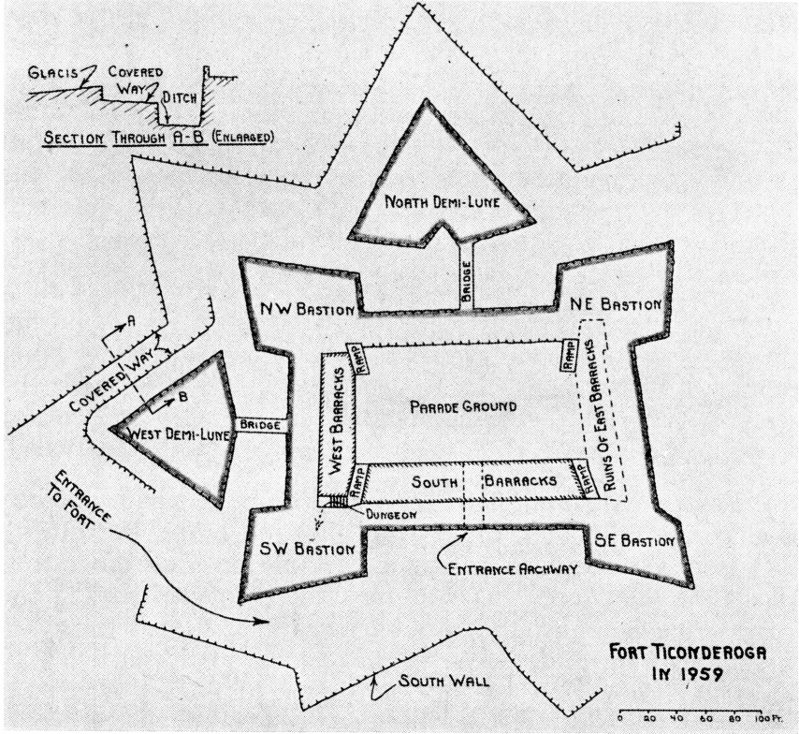

“I left [Montreal] this year [1756] at the end of April and arrived at the Fort the first days of May, when I resumed work which dragged on for nearly a month not having the required workmen. During this campaign we raised all the Fort to the height of the cordon. The earth ramparts were made,—the platforms of the bastions completed, a cover built for each bastion bomb-proof, two stone barracks built, the ditches of the place dug to the rock everywhere, part of the rock even removed on two fronts, the ditches of the two demi-lunes also excavated to the rock, a store-house established outside the Fort as well as a hospital. The parapet was raised on the two fronts exposed to the enemy’s batteries if he undertook to besiege this place, the exterior part of the Fort supported by masonry resting on the solid rock. The next campaign will be devoted to overhauling the main body of the place and building the two demi-lunes proposed, as well as the redoubt at the extreme of the Carillon Point. We will also work at the covered way and the glacis. There will be two barracks to build in stone in the interior of the Fort. As there is but one bastion exposed to attack I think it would be well to protect it by a counter guard. This would constitute an additional obstruction which might discourage the enemy from any attack on that side and, should he do so, I would hope that the place, once completed, he would not succeed. I would be flattered, My Lord, if you gave me 26 your orders to work with more latitude and, if you approve the counter guard which would not be very expensive, I would beg of you to order it by the first ships coming from France in order to embrace at the same time the whole works. M. le Comte de la Galissoniere to whom I communicated the information which I have acquired on this district will not let you ignore how advantageous it is and of what consequence it is to France. I presume to flatter myself, My Lord, that you will consider me for the position occupied heretofore by M. de Lery. I think I have worked in a manner to deserve it.”

It was during the summer of 1757 that De Lotbiniere started to substitute stone for most of the timbers he had used on the outer walls of the Fort.

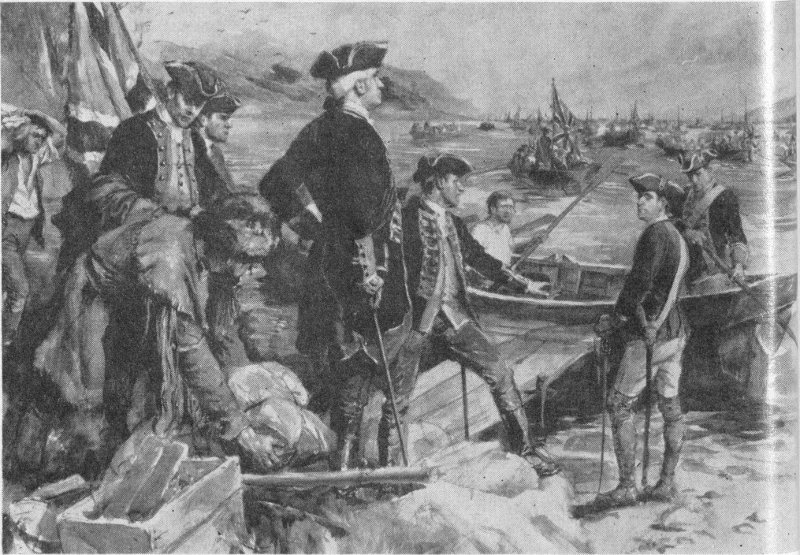

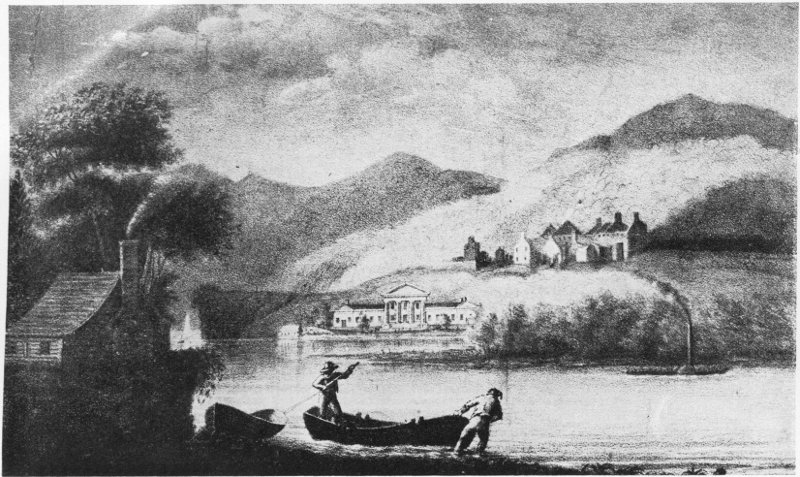

Abercromby’s Expedition Against Fort Ticonderoga

Embarking at Head of Lake George

Courtesy Glens Falls Insurance Company

In 1758 the Fort was almost completed. General James Abercromby had gathered at the head of Lake George the greatest army ever seen on the American continent, almost 15,000 men, of which 6,000 were British regulars and the rest provincials from New England, New York and New Jersey.

In July, 1758, this great army, great for its day and place, left Fort William Henry in hundreds of batteaux and whale boats to attack Fort Carillon. It must have been an extraordinarily beautiful sight, that vast fleet of little boats filled with the Red Coats and the plaids of Highlanders. Early in the morning of July 6th the army landed on what is now known as Howe’s Cove at the northern end of Lake George. The army immediately advanced in three columns but was soon lost in the dense forest which then covered the whole country. An advance party of French under the Sieur de Trepezec had been watching the landing from what the French called Mount Pelee, but which is now called Roger’s Rock. In trying to return to the Fort they had also lost their way and met one of the advancing columns, commanded by George Augustus, Viscount Howe, a grandson of George the First of England. At the first fire Lord Howe was killed and with his death the heart went out of the army. He was the real leader of the expedition. Captain Monypenny, his aide, reported his death in the following letter:

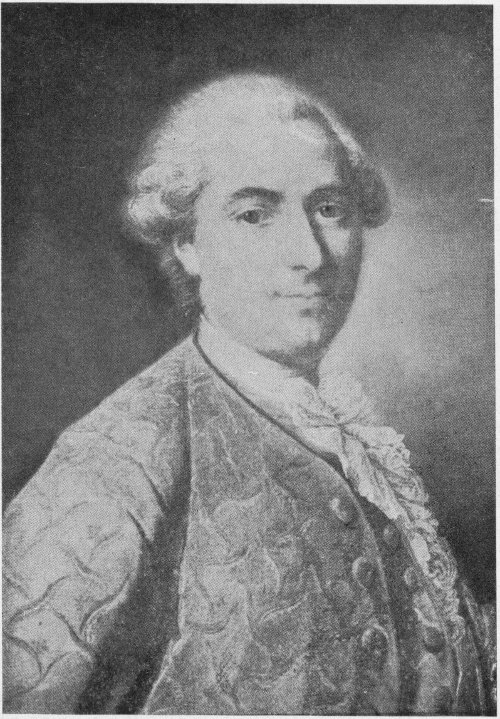

The Marquis de Montcalm

(From a Pastel in the Museum.)

To Mr. Calcraft, dated Camp at Lake George, 11th July, 1758:

“Sir:

“It is with the utmost concern, I write you of the death of Lord Howe. On the 6th the whole army landed without opposition, at the carrying place, about seven miles from Ticonderoga. About two o’clock, they march’d in four columns, to invest the breast work, where the enemy was encamp’d, near the Fort. The Rangers were before the army and the light infantry and marksmen at the heads of the columns. We expected, and met with some opposition near a small river, which we had to cross. When the firing began on the part of the left column, Lord Howe thinking it would be of the greatest consequence, to beat the enemy with the light troops, so as not to stop the march of the main body, went up with them, and had just gained the top of the hill, where the firing was, when he was killed. Never ball had a more deadly direction. It entered his breast on the left side, and (as the surgeans say) pierced his lungs, and heart, and shattered his back bone. I was about six yards from him, he fell on his back and never moved, only his hands quivered an instant.

“The French party was about 400 men, ’tis computed 200 of them were killed, 160, whereof five are officers, are prisoners; their commanding officer, and the partizan who conducted them were killed, by the prisoner’s account, in short, very few, if any, got back.

“The loss our country has sustained in His Lordship is inexpressible, and I’m afraid irreparable. The spirit he inspired in the troops, indefatigable pains he took in forwarding the publick service, the pattern he show’d of every military virtue, can only be believed by those, who were eye witnesses of it. The confidence the army, both regular and provincial, had in his abilities as a general officer, the readiness with which every order of his, or ev’n intimation of what would be agreeable to him, was comply’d with, is almost incredible. When his body was brought into camp scarce an eye was free from tears.

“As his Lordship had chose me to act as an aide de camp to him, when he was to have commanded on the winter expedition, which did not take place, and afterwards on his being made a brigadier general, had got me appointed Brigade Major, and I had constantly lived with him since that time....”

“(Signed) Al. Monypenny.”

Brig. General Lord Howe

The three columns returned to the landing place on the 6th, and on the 7th the army again advanced, this time by way of the bridge over the small stream connecting Lake George with Lake Champlain. The French had destroyed the bridge in retreating but it was soon repaired. On the night of the 7th the whole army lay on their arms, in what is now the Village of Ticonderoga, and on the morning of the 8th advanced again in three columns to attack the Fort. In the meantime Montcalm had elected not to wait until the Fort was invested but to fight in the woods. With almost superhuman energy he threw an earthwork across the whole peninsula of Ticonderoga, about three-quarters of a mile from the Fort. It consisted of a great wall of logs, and an abatis of trees with their branches sharpened, a hundred feet or so from the trenches. He, himself, commanded the 31 center, the Chevalier de Lévis the right, and the Colonel de Bourlamaque the left. Early in the morning the British columns attacked. All through that hot, sultry July day the fight went on. Abercromby had established his headquarters at the French sawmill but had been deceived as to the strength of Montcalm’s defenses. In this fight the 42nd Highlanders, the famous Black Watch, suffered enormously. Many of the Highlanders fought their way through the abatis and some even reached the great log wall, only to be killed by bayonet or bullet. The Royal American, a regiment still in the British army as the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, had losses second only to the Black Watch. And at the end of the day Abercromby’s army was forced to retreat, leaving the French in command of the field. The British and Colonial losses in this fight were almost as great as the whole French defending force.

(Translated from a contemporary French manuscript report in the Museum Library)

“The Marquis de Vaudreuil, uncertain of the movements of the enemy, thought necessary at the beginning of this campaign to distribute his forces. He appointed the Chevalier de Lévis to execute a secret expedition with a picked detachment, of which 400 men were chosen from the land troops. The rest of these troops were sent by order of the Marquis de Montcalm to defend the border of Lake Saint Sacrement [Lake George]. The Marquis de Montcalm arrived at Carillon the 30th of June. The report of prisoners made a few days before left him no doubt that the enemy had gathered, near the ruins of Fort William Henry, an army of 20,000 to 25,000 men and that their intention was to advance immediately upon him.

Duc de Lévis

“He imparted at once this news to the Marquis de Vaudreuil and did not hesitate to take an advanced position which would deceive the enemy, retard his movement and give time for the colonial help to arrive. In consequence, le Sieur de Bourlamaque was ordered to take possession of the portage at the head of Lake Saint Sacrement, with the battalions of La Reine, of Guyenne and of Bearn. The Marquis de Montcalm, with those of La Sarre, of the Royal Roussillon, of the Languedoc Regiment and the 1st battalion of Berry, occupied personally the two banks of the Chute River, thus named because in that spot the Lake St. Sacrement, narrowed by the mountains, pours its bubbling waters into the St. Frederic River and Lake Champlain. The 2nd Berry battalion took charge of the defense and service at the Fort of Carillon.

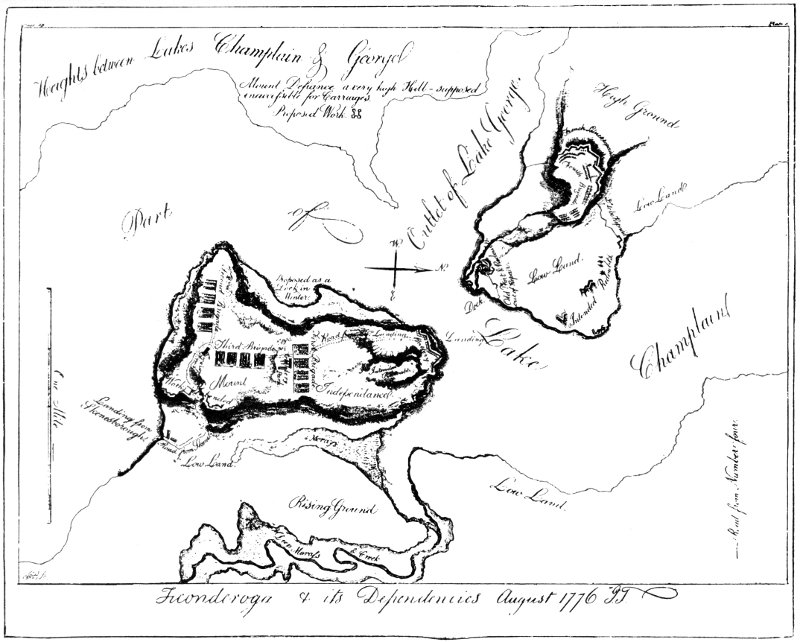

A PLAN of

the TOWN and FORT of

CARILLON

at

TICONDEROGA;

with

the ATTACK made by the

BRITISH ARMY

Commanded by Genl. Abercrombie.

on July 1758

Engraved by

Thos. Jefferys, Geographer to his Royal Highness the

Prince of Wales.

“The Marquis de Montcalm made the Sieurs de Pontleroy and Désandrouins, Engineers, reconnoitre and determine a site for a fortified position which could cover this fort; and as we had only a few Canadians and only 15 savages, he took from the French battalions two troops of volunteers, the command of which was given to the Sieur Bernard, captain in the Bearn Regiment, and Duprat, captain in La Sarre Regiment.

“In the evening of the 5th scouts which we had on Lake Saint Sacrement informed us that they had seen large numbers of barges which might be and were, in fact, the vanguard of the enemy’s army. At once the order was given to the troops of the Portage and the Chute camps to take their armaments, to spend the night at the bivouac, and to clear the equipages. The volunteers of Duprat were sent to take position on a creek called the Bernetz which, flowing between the mountains that cover this part of the country, runs into the Chute River. The enemy could pass around us by the back of these mountains. It was essential to be aware of such a movement. 350 men under the command of the Sieur de Trepezec, captain in the Bearn Regiment, were detached to take a position between the Pelee Mountain and the left bank of Lake Saint Sacrement and the volunteers of Bernard occupied another post intermediary between the Pelee Mountain and the Portage camps. Measures were taken also to throw light on a possible disembarkment which the enemy might make on the right bank of the lake.

“The 6th. At four o’clock in the morning, the vanguard of the opponent’s army was located in sight of the portage. At once the Marquis de Montcalm sent orders to 34 the Sieurs de Pontleroy and Désandrouins to lay out, in front of Carillon on the ground already marked, trenches and abatis and to the 2nd Battalion of Berry to work at them with its ensigns.

Major General Israel Putnam

“The enemy began to disembark at nine o’clock; the Sieur de Bourlamaque retreated then in their presence with the 3rd battalion from the portage and in the best of order. He joined the Marquis de Montcalm who was waiting for 35 him, formed for battle, on the heights at the right bank of the Chute, with Roussillon Regiment and the first Berry Battalion; these five battalions passed the river, destroyed the bridge and combined with La Sarre and Languedoc Regiments occupied the heights which edge the left bank. This retreat would have been carried out without the loss of a single man, if the detachment of the Sieur de Trepezec had not lost its way. Abandoned by the few savages that acted as guides, it strayed in those wood-covered mountains and came, after walking 12 hours, upon an English column bound for the Chute River. Of this detachment 6 officers and about 150 soldiers were killed or made prisoners. They defended themselves a long time, but they had to retreat before a superior force. The English made an important loss in the person of Lord Howe, quartermaster general of their army and Colonel of one of the Regiments of old England.

“At six o’clock in the evening, the Sieur Duprat, having announced that the enemy was heading towards the Bernetz Creek with pioneers and that their plan was evidently to throw a bridge over it, the Marquis de Montcalm sent the order to retreat and started his own retreat towards the heights of Carillon, where he arrived at sunset. That same evening a portion of the opponents’ regular troops and Rangers occupied the two banks of the Chute River, going towards the Bernetz Creek and entrenching there. The rest of their army occupied the place of disembarkment and the portage, and entrenched there also.

“The 7th. The French army was all employed working at the abatis which had been started the day before by the 2nd Berry Battalion. The officers were setting the example and the flags were hoisted—the plan of the defences had been laid out on the heights, 650 fathoms from Carillon fort.

“On the left side it was backed up by an embankment 80 fathoms away from the Chute River, the top of which was capped by a wall. This wall was flanked by a gap 36 back of which 6 cannon were to be placed to fire at it as well as to the river. On the right it was also backed by an embankment the slope of which was not as steep as the one on the left; the plain between this hill and Lake Saint Sacrement River was bordered by a branch of the trenches and also by a battery of 4 cannon which were only placed there the day after the battle. Also the guns of the Fort were pointed toward this plain as well as at any other disembarkment which might be effected on the left.

“The center followed the sinuosities of the ground, keeping the top of the height, and all the parts flanked one another reciprocally. Several, to tell the truth, were hit there, as well as on the right and on the left by a cross fire of the enemy, but it was because we didn’t have time to put up traverses. That kind of defence was made by tree trunks put one on top of the other, and had in front of it fallen trees the branches of which, cut and sharpened, gave the effect of a chevaux de frise.

“Between 6 and 8 o’clock in the evening the piquets of our troops, detached by order of the Chevalier de Lévis, arrived at the camp and the Chevalier de Lévis himself went there at night.

“All day our volunteers fired against the Rangers of the enemy. General Abercromby with the main part of the militia and the balance made up of regular troops advanced up to the falls. He had sent there several barges and pontoons mounted with two guns each. These troops built also on the same day several trenches, one in front of the other, of which the nearest one to our abatis was hardly a cannon range away. We spent the night in bivouac along side the trenches.

“The 8th. At dawn we beat the drums so as to let all the troops know their posts for the defense of the entrenchment, following the above arrangement, which was about that in which they worked. The army was composed at the right of battalions of La Reine, La Sarre, Royal Roussillon, 37 Languedoc and Guyenne Regiments and two Berry and the one battalion of the Bearn Regiment and also of 450 Canadians or Marines which brought the total to 3,000 fighting men.

“At the left of the line they posted the Sarre and the Languedoc battalions and the two piquets that had arrived the day before. The volunteers of Bernard and Duprat were guarding the gap on the Chute River.

“The center was occupied by the first Berry Battalion, by one Royal Roussillon and by the rest of the piquets of the Chevalier de Lévis.

“Battalions of La Reine, the Bearn and the Guyenne defended the right and in the plain between the embankment of this right [flank] and the Saint Frederic River they had posted the colonial troops and the Canadians, defended also by abatis. On the whole front of the line each battalion had back of itself a company of grenadiers and a piquet in reserve to support their battalion and also to be able to move where they might be needed. The Chevalier de Lévis took charge of the right, the Sieur de Bourlamaque of the left, the Marquis de Montcalm kept the center for himself.

“This arrangement, fixed and known, the troops at once fell back to work, some of them busy improving the abatis, the rest erecting the two batteries mentioned above and a redoubt to protect the right.

“That day in the morning, Colonel [Sir William] Johnson joined the English army with 300 savages of the Five Nations with ‘Tchactas,’ the Wolf, and Captain Jacob with 140 more. Soon after we saw them, as well as some Rangers, standing on a mountain opposite Carillon on the other side of the Chute River. They even discharged much musketry which interrupted the work. We did not bother answering them.

“At half past twelve, the English army debouched upon us. The company of grenadiers, the volunteers and the 38 advanced guards retreated in good order and joined the line again. At the same movement and at a given signal all the troops took their posts.

“The left was attacked first by two columns, one of which was trying to turn the trenches and found itself under the fire of La Sarre Regiment, the other directed its efforts on a salient between the Languedoc and the Berry battalions. The center, where the Royal Roussillon was, was attacked almost at the same time by a third column; a fourth attacked the right between the Bearn and La Reine battalions. All these columns were intermingled with their Rangers and their best riflemen, covered by the trees, kept up a murderous fire.

“At the beginning of the fight several barges and pontoons coming from the Chute advanced in sight of Carillon. The steadiness of the volunteers of Bernard and Duprat, supported by Sieur de Poulharies at the head of a company of grenadiers and of a piquet of the Royal Roussillon, with a few cannon shots fired from the fort, made them retreat.

“These different attacks were almost all in the afternoon and almost everywhere of the greatest intensity.

“As the Canadians and the colonial troops had not been attacked they directed their fire upon the column which was attacking our right and which from time to time was within their range. This column, made up of English grenadiers and of Scotch Highlanders, charged repeatedly for three hours without either being rebuked or broken up, and several were killed at only fifteen feet from our lines.

“At about five o’clock the column which had attacked vigorously the Royal Roussillon threw itself back on the salient defended by the Regiment of Guyenne and by the left wing of the Bearn, the column which had attacked the right wing drew back also, so that the danger became urgent in those parts. The Chevalier de Lévis moved there with a few troops of the right [wing] at which the enemy was shooting. The Marquis de Montcalm hastened there also 39 with some of the reserves and the enemy met a resistance which slowed up, at last, their ardor.

“The left was still standing up against the firing of two columns which were endeavoring to break through that part. The Sieur de Bourlamaque had been dangerously wounded there at about 4 o’clock and Sieur de Senezeraque and de Privast, Lieutenant Colonels of La Sarre and the Languedoc Regiments were taking his place and giving the best of orders. The Marquis de Montcalm rushed there several times and took pains to have help sent there in all critical moments.

“At 6 o’clock the two columns on the right gave up attacking the Guyenne battalions and made one more attempt against the Royal Roussillon and Berry. At last, after a last effort to the left, at 7 o’clock, the enemy retreated, protected by the shooting of the Rangers, which kept on until night. They abandoned on the battlefield their dead and some of their wounded.

“The darkness of the night, the exhaustion and small number of our troops, the strength of the enemy which, in spite of its defeat, was still in numbers superior to us, the nature of these woods in which one could not, without assistance of the savages, start out against an army which must have had from 400 to 500 of them, several trenches built in echelon from the battlefield up to their camp, those are the obstacles that prevented us following the enemy in its retreat. We even thought that they would attempt to take their revenge and we worked all night to escape attack from the neighboring heights by traverses, to improve the Canadian abatis, and to finish the batteries of the left and of the right [flanks] which had been begun in the morning.

“The 9th. Our volunteers having informed the Marquis de Montcalm that the post of the Chute and of the portage seemed abandoned, he gave orders to the Chevalier de Lévis to go the next day at day break with the grenadiers, the volunteers and the Canadians to reconnoitre what had become of the enemy.

“The Chevalier de Lévis advanced beyond the portage. He found everywhere the vestige of a hurried flight wounded, supplies, abandoned equipage, debris of barges and charred pontoons, unquestionable proofs of the great loss which the enemy had made. We estimate it at about 4,000 men killed or wounded. Were we to believe some of them, and judge by the promptitude of their retreat, it would be still more considerable. They have lost several officers and generals, Lord Howe, Sir Spitall, Major General Commander in Chief of the forces of New York, and several others.

“The savages of the Five Nations remained as spectators at the tail of the column; they were waiting probably to declare themselves after the result of a fight which, to the English, did not seem doubtful.

“The orders which were published in their colonies for the levying and upkeep of this army, announces the general invasion of Canada and the same statements are made in all the commissions of their officers and militia. We must do them justice in saying that they attacked us with the most ardent tenacity. It is not ordinary that trenches have stood seven hours’ attack at a stretch and almost without respite.

“We owe this victory to good manœuvres of our generals before and during the action and to the extraordinary, unbelievable gallantry of our troops. All the officers of the army behaved in a way that each one of them deserves special praise. We have had about 350 men killed and wounded, 38 of which were officers.”

A British account of the fight from “An Historical Journal of the Campaigns in North America,” London, 1759, is as follows:

“A schooner arrived, from Boston, this morning; by this vessel we had the satisfaction to receive a bag of letters, some from Europe, and others from the southward, but none from the eastward; among those which I got was the following one, from my friend in the Commander in Chief’s army, dated Albany, July the 29th, 1758.

‘I scratched a few lines to you, on the 11th instant, from Fort Edward, and, as I wrote in great pain, I think it was scarce legible;—such, as it was, shall be glad to hear it reached you safe: in a few days after I dispatched it to you, my fever abated, and I was judged to be out of danger; for some time, however, it was apprehended I should lose my arm; as all my baggage remained here since last winter, I obtained leave to remove to this place, knowing I could be better accommodated here, than in my confined situation at Fort Edward: in my last, I promised you a particular account of our unhappy storm of the 8th instant; it is a mortifying talk, but you shall be indulged, as I know you are curious after every occurrence. It will be needless to have retrospect to any events preceding the 4th of this month, as there was not any thing remarkable, except preparing for the expedition, and embarking our provisions, stores, and artillery; the latter were mounted on floats or rafts, for the protection of our armament upon the lake, and to cover us at our landing. On the 5th, the whole army, amounting to about sixteen thousand men, embarked likewise; our transports were bateaux and whaleboats, and in such numbers as to cover the lake for a considerable length of way, as may well be supposed; we proceeded soon after in great order, and, as I was in one of the foremost divisions, as soon as we were put in motion, I think I never beheld so delightful a prospect. On the 6th, we arrived early in the morning at the cove, where we were to land: here we expected some opposition; but a party of light troops having got on shore, and finding all clear, the whole army landed without loss of time, formed into columns and marched immediately; upon our approach, an advanced guard of the enemy, consisting of several hundred regulars and savages, who were posted in a strong intrenched camp, retired very precipitately, after setting fire to their camp, and destroying almost every thing they had with them; we continued our march through dark woods and swamps that were almost impassable, till at length, having lost our way, the army being obliged to break their order of march, 42 we were perplexed, thrown into confusion, and fell in upon one another, in a most disorderly manner: it was at this time that Brigadier Lord Howe, being advanced a considerable way ahead of us, with all the light infantry, and one of our columns, came up with the before-mentioned advanced guard of the enemy, who we also suppose to have lost themselves in their retreat, when a smart skirmish ensued, in which we were victors, though with some loss; trifling, however, in comparison to that which the army sustained by his Lordship’s fall, who was killed at the first charge, and is universally regretted both by officers and soldiers; the enemy suffered much in this encounter, being very roughly handled; and we made many men and several officers prisoners. On the morning of the 7th we marched back to the landing-place, in order to give the troops time to rest and refresh themselves, being by this time not a little harrassed, as may well be conceived: here we incamped, got a fresh supply of provisions, and boiled our kettles; we had not been there many hours, when a detachment of the army (to which I belonged) were sent off under Colonel Bradstreet, to dispossess the enemy of a post they had at a saw-mill, about two miles from Ticonderoga; but they did not wait for us; for, upon receiving intelligence, by their scouts of our approach, they destroyed the mill, and a bridge that lay across the river; the latter we soon replaced, and lay, upon our arms until the evening, when we were joined by the remainder of the army. I wish I could throw a veil over what is to follow; for I confess I am at a loss how to proceed:—our army was numerous, we were in good spirits, and, if I may give you my own private opinion, I believe we were one and all infatuated with a notion of carrying every obstacle, with so great a force we had, by a mere Coup de Musqueterie; to such chimerical and romantic ideas I entirely attribute our great disaster on the 8th, in which we were confirmed by the report of our chief engineer, who had reconnoitred the enemy’s works, and determined our fate, by declaring it as his opinion, that it was very practical to carry them by a general storm; accordingly, 43 the army being formed, and every thing in readiness, we proceeded to the attack, which was as well conducted and supported as any bold undertaking ever was;—but alas! we soon found ourselves grossly deceived;—the intrenchments were different from what we had expected, and were made to believe, their breast-works were uncommonly high, and the ground in their front, for a great length of way, was covered with an Abatis de Bois, laid so close and thick, that their works were really rendered impregnable. The troops, by the cool and spirited example of the General, made many eager efforts to no purpose; for we were so intangled in the branches of the felled trees, that we could not possibly advance; the enemy were sensible of this, and remained steady at their breast-works, repeating their fire, which, from their numbers, was very weighty, and, from a conviction of their own safety, was served with great composure. Such was our situation for almost five hours, when, at length, finding our loss considerable, and no prospect of carrying our point, we were ordered to desist, and retire;—the army retreated to the ground we had occupied on the preceding night at the sawmill, and the wounded were sent off to the bateaux without delay, where the remains of our shattered forces joined us early on the ninth, and the whole re-embarked, and continued our retreat to Lake George; there we arrived the same evening and encamped. That place is computed to be about thirty miles from Ticonderoga (though I believe it is more) and fourteen from Fort Edward, whither, as also to this town (from which I now write) all the wounded were sent the next day. Our loss is indeed very considerable, as you will see by the inclosed return. The valiant Colonels Donaldson, Bever, and Major Proby, with many other of our friends, I am heartily sorry to acquaint you, are among the slain. So that what we find so feelingly expressed by the poet is here fatally verified,

‘For, How many mothers shall bewail their sons!

How many widows weep their husbands slain!’

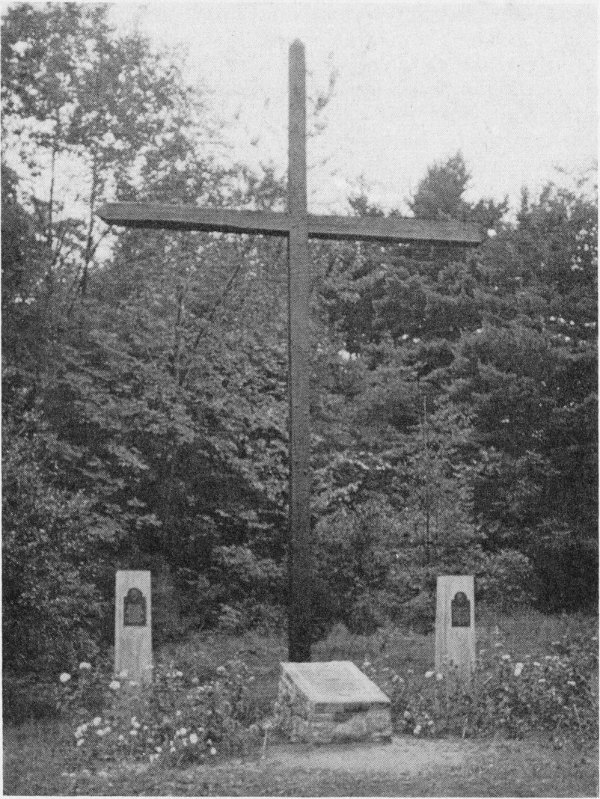

Replica of the Cross Erected by General Montcalm, Commemorating the French Victory at Carillon

What loss the enemy sustained, or if any, it is impossible for us to be able to give the least account of; they did not attempt to pursue us in our retreat.—Let me hear from 45 you upon receipt of this packet, and, if anything should occur in the farther course of this campaign, you shall hear from me again; but, I presume the French general will cut out such work for us, as will oblige our forces to act on the defensive.’”

In August of this year Israel Putnam, while scouting near Fort Miller, was captured by some French and Indians, and, after being stripped of his coat, vest, stockings and shoes, was loaded with the packs of the wounded and marched toward Ticonderoga. During this trip he was stripped naked, tied to a tree, and preparations were made for burning him when a French officer interposed. Reaching Ticonderoga, he was examined by the Marquis de Montcalm and sent to Montreal as a prisoner. Afterwards exchanged, he lived to have a distinguished career in the Revolution.

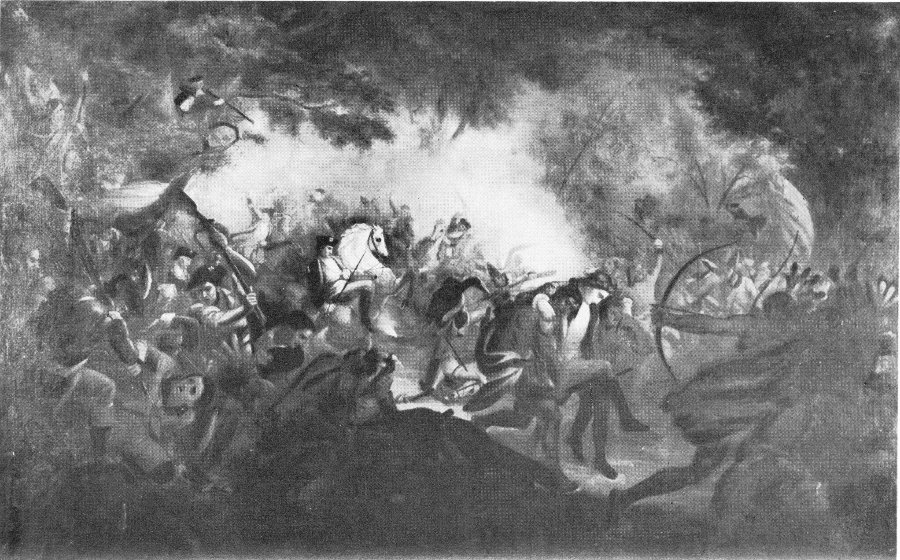

Montcalm Congratulating His Victorious Troops

After the Battle of July 8, 1758

(Painting by Harry A. Ogden in the Fort Ticonderoga Museum)

Major Robert Rogers’ Battle on Snowshoes in 1757

(From a Painting in the Glens Falls Insurance Co. Building)

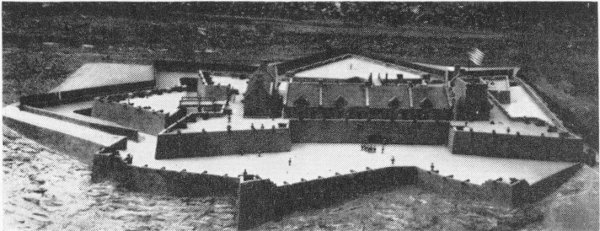

The next year, 1759, General Jeffrey Amherst, who had succeeded General Abercromby, again advanced down Lake George to attack the Fort. On July 21st with 5743 British regulars and about the same number of provincials he left Fort William Henry. In the meantime, the French garrison at Ticonderoga had been much reduced. Montcalm had gone to the defense of Quebec, leaving General Bourlamaque, who had been slightly wounded the year before, in command. Amherst’s army followed Abercromby’s route but instead of attacking proceeded to invest the Fort. Bourlamaque soon realized that he would be starved out and captured within a reasonable time, so, after a few days defense decided to evacuate. He left Captain Hebecourt with 400 of the garrison and with the balance retreated to Crown Point and eventually to Isle aux Noix. Hebecourt kept up a heavy artillery fire as the British advanced through the French lines and threw up counter defenses. Amherst was then within 600 yards of the Fort. He did not know that Bourlamaque had retreated with most of the French Army. On the 3rd night Hebecourt embarked the balance of his force, set fire to the Fort and left a lighted match headed for the powder magazine, which was located in the South East Bastion. The Fort was soon in flames and the magazine blew up with a tremendous explosion. Hebecourt made good his retreat to Isle aux Noix where he joined Bourlamaque.

An excellent description of the taking of the Fort by Amherst is contained in a letter from a Massachusetts soldier, Eli Forbush, in the Museum collection. It follows herewith:

Sir Jeffrey Amherst

Camp at Ticonderoga or Fort Carillon Aug. 4, 1759.

“Very Rev’d & Hon’d Sr.

“Tis an old saying better late than never, therefore I presume (tho too unseasonably) to wait upon you with a line, to tell you what God has done for us the army and his Chh [Church] and people in gen’l. On ye 21 of July ye army imbarked for this place, which consisted of 11756, the Invincible rydau sail’d in ye rear of grenadiers, light infantry and rangers, and in ye front of remaining army and ye sloop Halifax brought up ye rear of ye whole. The fleet reached Sabbath Day Point by day light, then the Invincible came to anchor, and ye whole Fleet lay upon ye ores, till break of day, when ye signal was given for sailing, and the whole landed without opposition, between ye hours of nine and eleven, 22d, the light infantry, rangers, and grenad’rs marched immediately for the mill, where they found the 49 enemy posted, in three advantageous places, but as soon as they saw the dexterity and resolution of our advancing parties, they fled and left ye grounds in our possession and as our people got ye first fire and received only a running fire from them, little execution was done on either side, we obtain 3 prisoners and kild 3 on ye spot, and received only a slight wound or two from them. The whole army marched forward, beside what was necessary to guard the landing place, with ye vessels and stores, some were imployed in persuing the enemy, some in clearing the roads, and ye water course from ye mill, others in taking possession of all ye most advantageous ground near ye Fort—the whole was performed with ye greatest regularity, ye least noise, a noble calmness and intrepid resolution, ye whole army seemed to pertake of ye very soul of ye commander. As ye enemy had not force nor courage to man ye lines yt provd so fatal to our brave troops last year, we took possession of them without much opposition, and before day of ye 23d began to intrench and ye body of ye army incamped behind ye breastwork, which covered them from ye enemies fire, as soon as it was light and ye enemy perceived our disposition, they raised a smart canonade upon us, but without effect, those that were intrenching, between ye Breastwork and ye Fort had by this time covered ymselves, and ye breastwork was a defence to ye camp, they continued to canonade and to throw yr shells, and we continued to intrench, advancing nearer and nearer, the Gen’l ordered yt no fire shd be returned upon ye enemy (except in case of necessary defence) till he had all ye batteries ready to open at once, and as ye trenches were long ye digging bad, the whole could not be compleated till Thursday night ye 26 or rather Fryday morning ye 27. When ye batteries were to be opened at once, the enemy seemed fully sensible of ye fatal consequences of such heavy batteries for a little after midnight between ye 26 & 27. they blew up ye magazine and made off, some by land on ye east side of ye lake and some by water with all yt they could carry (which could be but a little), nineteen of those 50 that went off by land got lost and came into our camp next morning, some of ye light infantry yt were posted on ye left by ye lake side hearing ye enemies boats fire several cannon loaded with grape in among ym which greatly dismad and destresd them,—we found 3 of ye boats adrift loaded with powder and other stores, others broke and sunk.

General Amherst and the Burning Fort

From a painting in the Museum Collection

“Six o’Clock 27. the French flagg was struck and ye English hoisted on ye same staff, but as ye Fort was in flames and cannon loaded and a large number of small armes, which kept a continual fire as ye wood burnt, the 51 Gen’l gave orders yt ye greatest caution shd usd in taking possession, About 8 o’Clock they began to attempt to extinguish ye fire, and to draw ye charges from those cannon yt ye fire had not reached,—We found 13 pieces of cannon mounted, 4 Mortars two 13 Inch, two 9. Other artillery is found since sunk in ye waters, the strength of ye Fort exceeds ye most sanguine imagination, nature and art are Joind to render it impregnable, and had not ye enemy behaved like cowards and traitors they might have held out a long siege. Our loss is very inconsiderable (except Col. Townsend) who was killed with a cannon ball on ye 25th besides him we have lost none of note, the whole according to ye returns yt have been made is 96 killd and wounded, 20 only of which was kild on ye spot—We have had one killed as he stood centry and one Stockbridge Indian, an Ensign, which is all ye loss that we have sustained by ye savages since the Fort was abandoned. It came out in Gen’l Orders that publick thanks shd be given at ye head of every core for ye conquest obtained, ever since we got possession ye whole army has been imploy’d in extinguishing ye fire of ye Fort, repairing ye breeches made by ye explosion, gitting over ye beteaus and boats, provisions, and artilery stores, in rebuilding ye mills and in erecting two more rydaus all whch are near accomplished. August 3. A scout in from Crown-Point and brot certain intelligence that the enemy have destroyed and abandoned that also, upon which ye Gen’l sent a party immediately to take possession, and this morning saild himself with his artilery and ye main body of ye army leaving only such numbers as are necessary to defend ye several posts which he has established and to carry on the works at ye mills and ye Fort, tis supposd yt ye whole army will be ready to cross the Lake Champlain in about ten days. We have two rydaus that carry Six 12 pounders in yr sides and one 24 in ye bowes. four roe galleys yt carry one 18 in each of yr bowes one flat boat and one six pounder and four bay-boats with swivals and a brig in great forwardness, all which we hope will be sufficient against the 3 schooners 52 which ye enemy having cruzing in ye Lake, so yet our success is not only great but ye prospect still clear yt we shl by ye divine aide do ye business we came upon—The health of ye army is very extraordinary in ye two battalions where I am concerned, yr has died but two with sickness and one kild by ye enemy, (ye sentery above mentioned) when I visited the fort which was about 9 o’Clock Friday morning 27th I found many monuments of superstition which would furnish a curious mind with aboundant matter for speculation—one thing I cant omit, near ye breast-work where so many spilt yr blood last year, was a cross erected of 30 feet high, painted red with this inscription in lead on yt side next to ye breastwork ‘Sone Principes eorum Sicut oneb et heb et Zebee et ...’ and under this at ye foot of ye cross was an open grave—on ye opposite side of ye cross next to ye Fort was this inscribed in lead viz ‘Hoc Signum Vincit’—These are the most remarkable, yt has feel within my notice since I wrote last. I hope you will pardon my prolixity and overlook ye many imperfections of my relation, tis a good story tho it is not well told, if you please let Mr. Breek see the contents as I have not time to write particularly to him nor anything new besides to communicate.

“Please to give all proper salutations to all friends on ye river and give me leave to subscribe your most obd’t and affectionate son

Eli Forbush

“Last night I was hon’d with the reception of yr fav’r of ye 16 ulto for which I thank you.”

To the Reverend Mr. Steven Williams in Springfield, Lon Meadow Precinct. [Mass.]

From 1759 to 1775 it was peaceful and tranquil at Ticonderoga. There are but few records, though the British maintained a garrison at the Fort and also one at Crown Point. The Fort was used as a storehouse for military supplies, and presumably the garrison did its best to entertain itself in what was then a wilderness. Major Gavin Cochrane commanded for four years, and in 1765 Major Thomas James went down from Ticonderoga to New York to aid in enforcing the Stamp Act. On February 15th, 1767, Lieutenant-Governor Carleton wrote from Montreal to Major General Gage:

“The forts of Crown Point and Ticonderoga are in a very declining condition ... should you approve of keeping up these posts, it will be best to repair them as soon as possible.”

Crown Point caught on fire in April, 1773, and a large part of the barracks was destroyed by an explosion in the magazine. Detachments of the 60th Regiment, the Royal American Regiment of Foot, was stationed here for many years, and Major General Haldimand spent a short time at the Fort. Early in 1775 Major Philip Skene of Skenesborough was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Crown Point and Ticonderoga. However, as he was captured on his return from England the same year and confined as a Loyalist, (though afterwards exchanged and was with Burgoyne in 1777) he could not have done very much Lieutenant-Governoring.

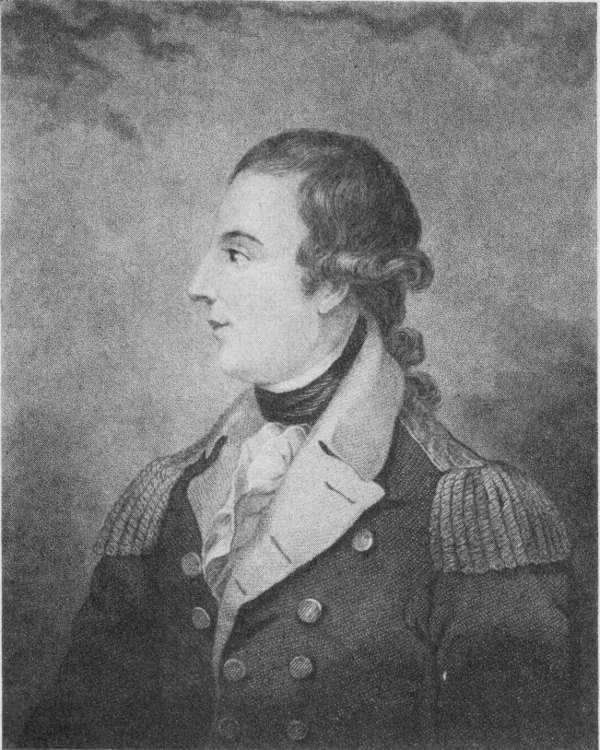

Ethan Allen

In 1775, while the trouble in Boston was brewing, Samuel Holden Parsons, Colonel Samuel Wyllys and Silas Deane, all of Connecticut, and probably at the suggestion of Colonel John Brown of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, conceived the idea of seizing Ticonderoga and capturing the great quantities of military supplies known to be stored in the Fort.

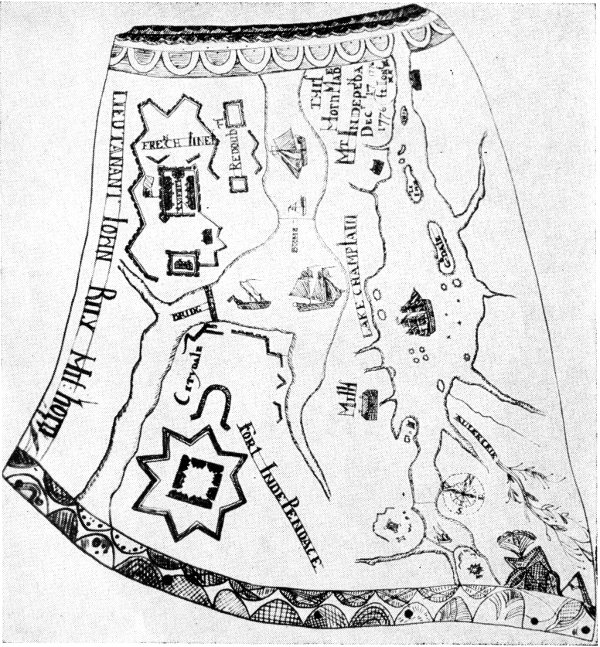

The Colony of Massachusetts voted a considerable sum and Colonel Benedict Arnold was authorized to raise a force and seize the fort. About the same time, however, Ethan Allen, leader of a body of irregular troops known as the Green Mountain Boys, also conceived the idea. Allen and Arnold met in Castleton, Vermont, and both claimed the command. The Green Mountain Boys absolutely refused 55 to serve under anyone but Allen. Eventually a compromise was made and a joint command agreed on. A rendezvous was agreed on in Hand’s Cove on the east side of Lake Champlain about two miles north of the Fort and on the night of May 9th about 350 men had gathered. There was a scarcity of boats, however, and the few obtainable were rowed back and forth all night, landing just north of the present Fort Ticonderoga Ferry. Shortly before daylight only 83 men and a number of officers had reached the west shore. Not daring to postpone the attack, Allen proceeded by the wood road then running across the swamp which formerly existed in what is now the North Field. His own account of the capture is as follows:

“I landed eighty-three men near the garrison, and sent the boats back for the rear guard commanded by Col. Seth Warner; but the day began to dawn, and I found myself under a necessity to attack the fort, before the rear could cross the lake; and, as it was viewed hazardous, I harangued the officers and soldiers in the manner following:

‘Friends and fellow soldiers, you have, for a number of years past, been a scourge and terror to arbitrary power. Your valour has been famed abroad, and acknowledged, as appears by the advice and orders to me (from the general assembly of Connecticut) to surprise and take the garrison now before us. I now propose to advance before you, and in person conduct you through the wicket-gate; for we must this morning either quit our pretensions to valour, or possess ourselves of this fortress in a few minutes; and, in as much as it is a desperate attempt, (which none but the bravest of men dare undertake) I do not urge it on any contrary to his will. You that will undertake voluntarily poise your firelocks.’

“The men being (at this time) drawn up in three ranks, each poised his firelock. I ordered them to face to the right; and, at the head of the centre-file, marched them immediately to the wicket-gate aforesaid, where I found a 56 centry posted, who instantly snapped his fusee at me; I ran immediately toward him, and he retreated through the covered way into the parade within the garrison, gave a halloo, and ran under a bomb-proof. My party who followed me into the fort, I formed on the parade in such a manner as to face the two barracks which faced each other. The garrison being asleep, (except the centries) we gave three huzzas which greatly surprised them. One of the centries made a pass at one of my officers with charged bayonet and slightly wounded him: My first thought was to kill him with my sword; but, in an instant, altered the design and fury of the blow to a slight cut on the side of the head; upon which he dropped his gun, and asked quarter, which I readily granted him, and demanded of him the place where the commanding officer slept; he showed me a pair of stairs in the front of a barrack, on the west part of the garrison, which led up to a second story in said barrack, to which I immediately repaired, and ordered the commander (Capt. Delaplace) to come forth instantly, or I would sacrifice the whole garrison; at which the capt. came immediately to the door with his breeches in his hand, when I ordered him to deliver to me the fort instantly, who asked me by what authority I demanded it; I answered, ‘In the name of the great Jehovah, and the Continental Congress.’ (The authority of the Congress being very little known at that time) he began to speak again; but I interrupted him, and with my drawn sword over his head, again demanded an immediate surrender of the garrison; to which he then complied, and ordered his men to be forthwith paraded without arms, as he had given up the garrison; in the meantime some of my officers had given orders, and in consequence thereof, sundry of the barrack doors were beat down, and about one-third of the garrison imprisoned, which consisted of the said commander, a Lieut. Feltham, a conductor of artillery, a gunner, two serjeants, and forty-four rank and file; about one hundred pieces of cannon, one 13 inch mortar, and a number of swivels. This surprise was carried into execution in the gray of the morning of the 10th day of May, 1775. The sun seemed to rise that morning with a superior lustre; and Ticonderoga and its dependencies smiled on its conquerors, who tossed about the flowing bowl, and wished success to Congress, and liberty and freedom of America.” The flowing bowl evidently had its effect as Allen’s first account of the capture of the Fort reads as follows:

Catamount Tavern in Bennington Where Ethan Allen And the Others Laid Plans To Capture The Fortress of Ticonderoga

To the Massachusetts Council,

“Gentlemen: I have to inform you, with pleasure unfelt before, that on the break of day of the tenth of May, 1775, by the order of the General Assembly of the Colony of Connecticut, I took the fortress of Ticonderoga by storm. The soldiery was composed of about one hundred Green Mountain Boys and nearly fifty veteran soldiers from the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The latter was under command of Colonel James Easton, who behaved with great zeal and fortitude,—not only in council; but in the assault. The soldiery behaved with such resistless fury, that they 58 so terrified the Kings troops, that they durst not fire on their assailants, and our soldiery was agreeably disappointed. The soldiery behaved with uncommon rancour when they leaped into the Fort; and it must be confessed, that the Colonel has greatly contributed to the taking of that fortress, as well as John Brown, Esq., attorney at law, who was also an able counsellor, and was personally in the attack. I expect the Colonies will maintain this fort. As to the cannon and war-like stores, I hope they may serve the cause of liberty instead of tyranny, and I humbly implore your assistance in immediately assisting the Government of Connecticut in establishing a garrison in the reduced premises. Colonel Easton will inform you at large. From, gentlemen, your most obedient, humble servant.

Ethan Allen”

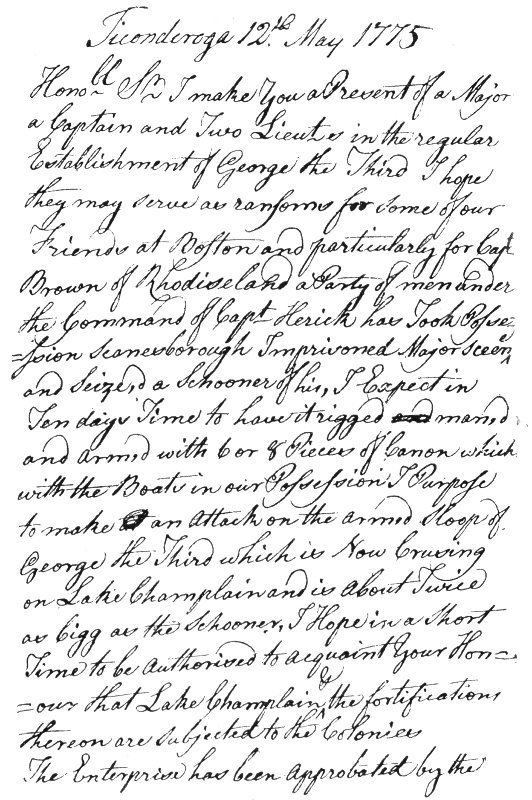

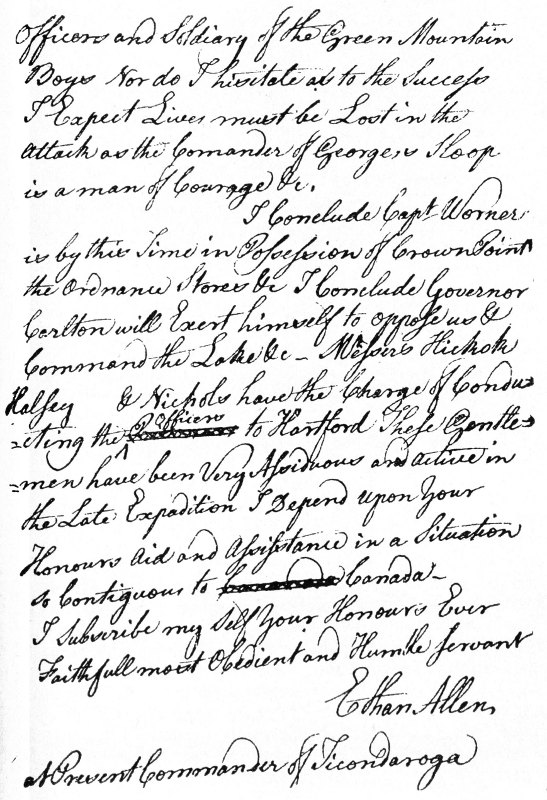

On the 12th, however, he sent a more temperate account to the Governor of Connecticut, the original manuscript of which is now in the Fort Library and reads as follows:

“Hon’ble Sir: I make you a present of a Major, a Captain, and two Lieutenants in the regular Establishment of George the Third. I hope they may serve as ransoms for some of our friends at Boston, and particularly for Captain Brown of Rhode Island. A party of men, under the command of Capt. Herrick, has took possession of Skenesborough, imprisoned Major Skene, and seized a schooner of his. I expect, in ten days time, to have it rigged, manned and armed, with six or eight pieces of cannon, which, with the boats in our possession, I purpose to make an attack on the armed sloop of George the Third, which is now cruising on Lake Champlain, and is about twice as big as the schooner. I hope in a short time to be authorized to acquaint your Honour, that Lake Champlain, and the fortifications thereon, are subject to the Colonies.

“The enterprise has been approbated by the officers and soldiery of the Green Mountains boys, nor do I hesitate as to the success. I expect lives must be lost in the attack, as the commander of George’s sloop is a man of courage, etc.

“Messrs. Hickock, Halsey and Nichols have the charge of conducting the officers to Hartford. These gentlemen have been very assiduous and active in the late expedition.

“I depend upon your Honour’s aid and assistance in a situation so contiguous to Canada.

“I subscribe myself, your Honour’s ever faithful, Most obedient and humble servant.

Ethan Allen

“At present commander at Ticonderoga. To the Hon’ble Johnathan Trumbull, esq., Capt. General and Governor of the Colony of Connecticut.”

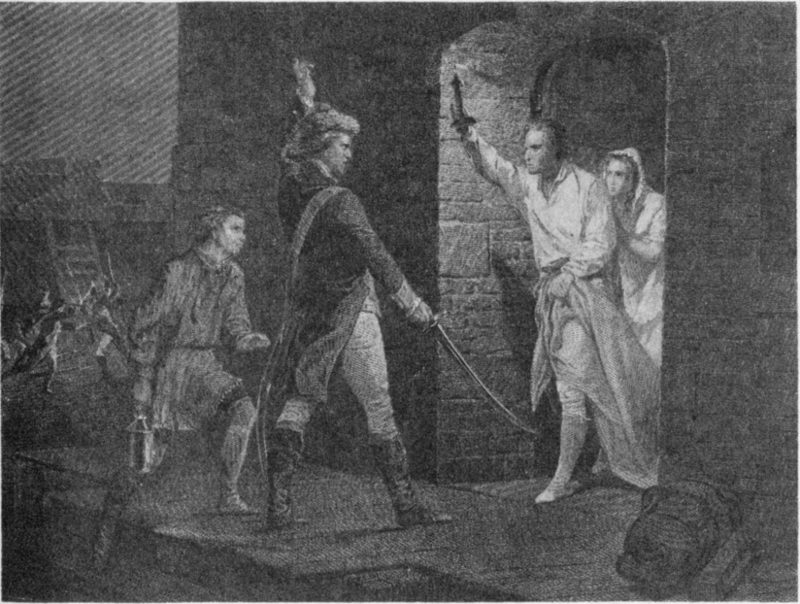

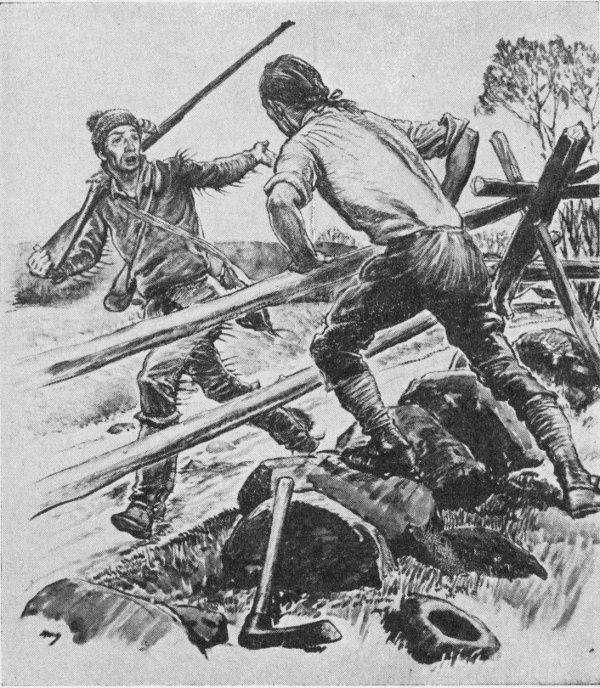

Ethan Allen and Captain Delaplace at The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

It is interesting to note that in neither of Allen’s reports does he mention Arnold, who had a joint command with him. Hard feeling between the two commanders had already developed. Arnold was a commissioned officer in the Connecticut Militia and Allen, an amateur. Professional soldiers and amateurs never have hit it off.

Letter From Ethan Allen, Ticonderoga, May 12, 1775, Manuscript in the Museum Collection

Ticonderoga 12th. May 1775

Honobl Sir I make You a Present of a Major a Captain and Two Lieuts in the regular Establishment of George the Third I hope they may serve as ransoms for some of our Friends at Boston and particularly for Capt Brown of Rhodiseland a Party of men under the Command of Capt Herich has Took Posession Scenesborough Imprisoned Major Sceene and Seized a Schooner of his, I Expect in ten days Time to have it rigged and man’d and armed with 6 or 8 Pieces of Canon which with the Boat in our Possession I Purpose to make an attack on the armed Sloop of George the Third which is Now Cruising on Lake Champlain and is about Twice as bigg as the Schooner. I Hope in a Short Time to be authorized to acquaint your Hoour that Lake Champlain ^& the fortifications thereon are subjected to the Colonies The Enterprise has been approbated by the 61 Officers and Soldiary of the Green Mountain Boys Nor do I hesitate as to the Success I Expect Lives must be Lost in the attack as the Comander of George’s Sloop is a man of Courage &c.

I Conclude Capt Warner is by this time in Possession of Crown Point the Ordnance Stores &c I Conclude Governor Carlton will Exert himself to oppose us & Command the Lake &c—Messers Hickock Halsey & Nichols have the Charge of Conducting the ^Officers{illegible} to Harford These Gentlemen have been Very Assiduous and active in the Late Expedition I depend upon Your Honours Aid and Assistance in a Situation so Contiguous to CanandaigaCanada—I Subscribe my Self Your Honours Ever Faithfull most Obedient and Humble Servant

Ethan Allen,

at Present Commander of Ticonderoga

A few years ago Mr. Allen French discovered the manuscript of Lieutenant Feltham’s report, which reads as follows:

New York, June 11th 1775.

“Sir

“Capt. Delaplace of the 26th regt has given me directions to lay before you in as plain a narrative as I can the manner of the surprizal of the fort of Ticonderoga on 10th May with all the circumstances after it that I thought might be of any service in giving you Exy any light into the affair.

“Allen Needs You at Ti”

(Courtesy National Life Insurance Company of Vermont)

“Capt. Delaplace having in the course of the winter applied to Gen. Carleton for a reinforcement, as he had reason to suspect some attack from some circumstances that happend’d in his neighborhood, Gen Carleton was pleased to order a detachment of a subaltern and 20 men to be sent in two or three separate parties the first party of which was sent as a crew along with Major Dunbar who left Canada about the 12th April, I being the first subaltern on command was ordered down with 10 men in a few days more, to give up to Capt Delaplace with whom Lt Wadman was to remain, having receiv’d orders from the regt some time before to join there. as he was not arrived when I came I had orders to wait until he did. I was 12 days there before he came which was about an hour after the fort was surprised. I had not lain in the fort on my arrival having left the only tolerable rooms there for Mr. Wadman if he arrived with his family, but being unwell, had lain in the fort for two or three nights preceding the 10th May, on which morning about half an hour after three in my sleep I was awaken’d by numbers of shreiks, & the words no quarter, no quarter from a number of arm’d rabble I jump’d up about which time I heard the noise continue in the area of the fort I ran undress’d to knock at Capt. Delaplaces door & to receive his orders or wake him, the door was fast the room I lay in being close to Capt Delaplace I stept back, put on my coat & waist coat & return’d to his room, there being no possibility of getting to the men as there were numbers of the rioters on the bastions of the wing of the fort on which the door of my room and back door of Capt Delaplaces room led, with great difficulty, I got into his room, being pursued, from which there was a door down by stairs in to the area of the fort, I ask’d Capt Delaplace who was by now just up what I should do, & offer’d to force my way if possible to our men, on opening this door the bottom of the stairs was filld with the rioters & many were forcing their way up, knowing the Commg Officer lived there, as they had broke open the lower rooms 64 where the officers live in winter, and could not find them there, from the top of the stairs I endeavour’d to make them hear me, but it was impossible, on making a signal not to come up the stairs, they stop’d, & proclaimd silence among themselves, I then address’d them, but in a stile not agreeable to them I ask’d them a number of questions, expecting to amuse them till our people fired which I must certainly own I thought would have been the case, after asking them the most material questions, I could think viz by what authority they entered his majesties fort who were the leaders and what their intent &c &c I was informd by one Ethan Allen and one Benedict Arnold that they had a joint command, Arnold informing me he came from instructions recd from the congress at Cambridge which he afterwards shew’d me. Mr. Allen told me his orders were from the province of Connecticut & that he must have immediate possession of the fort and all the effects of George the third (those were his words) Mr. Allen insisting on this with a drawn sword over my head & numbers of his followers firelocks presented at me alledging I was commanding officer & to give up the fort, and if it was not comply’d with, or that there was a single gun fired in the fort neither man woman or child should be left alive in the fort. Mr. Arnold begg’d it in a genteel manner but without success, it was owing to him they were prevented getting into Capt Delaplaces room, after they found I did not command. Capt. Delaplace being now dress’d came out, when after talking to him some time, they put me back into the room they placed two sentry’s on me and took Capt Delaplace down stairs they also placed sentrys at the back door, from the beginning of the noise till half an hour after this I never saw a Soldier, tho’ I heard a great noise in their rooms and can not account otherwise than that they must have been seiz’d in their beds before I got on the stairs, or at the first coming in, which must be the case as Allen wounded one of the guard on his struggling with him in the guard room immediately after his entrance into the fort. When I did see our men they were drawn up without arms, 65 which were all put into one room over which they placed sentrys and allotted one to each soldier their strength at first coming that is the number they had ferry’d over in the night amounted to about 90 but from their entrance & shouting they were constantly landing men till about 10 o’clock when I suppose there were about 300, & by the next morning at least another 100 who I suppose were waiting the event & came now to join in the plunder which was most rigidly perform’d as to liquor, provisions, &c whether belonging to his majesty or private property, about noon on the 10th May, our men were sent to the landing at L. George, & sent over next day, then march’d by Albany to Hartford Connecticut where they arrived on the 22d they would not allow an Officer to go with them tho’ I requested it. They sent Capt Delaplace his Lady, family & Lt Wadman & myself by Skenesborough to Hartford where we arrived the 21st.”

Shortly after Allen’s capture of the Fort Congress decided to garrison the place, and what was afterwards called the Northern Army was concentrated there. It consisted mostly of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania troops with the Pennsylvanians the best equipped and organized. General Philip Schuyler of New York was in command through 1775. The Fort was repaired and the old French Lines strengthened and a number of redoubts started.

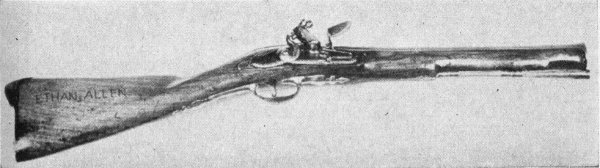

Ethan Allen’s Blunderbuss in the Museum Collection

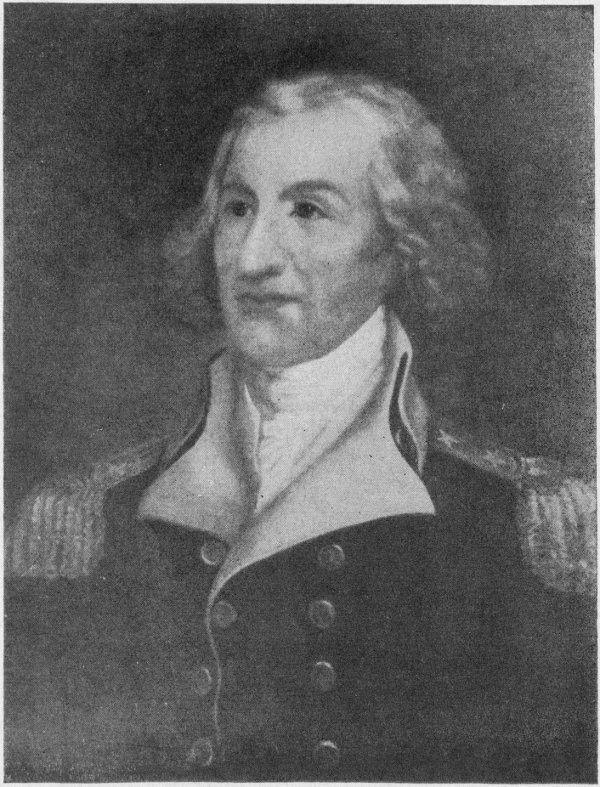

Benedict Arnold

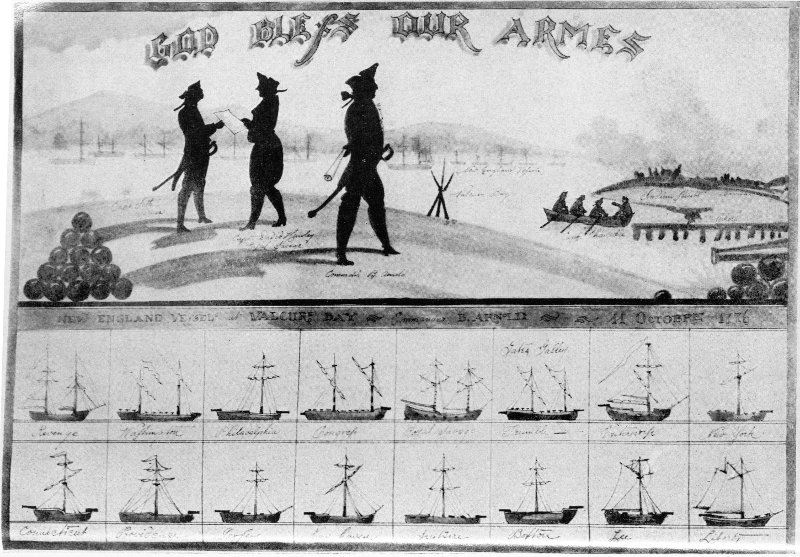

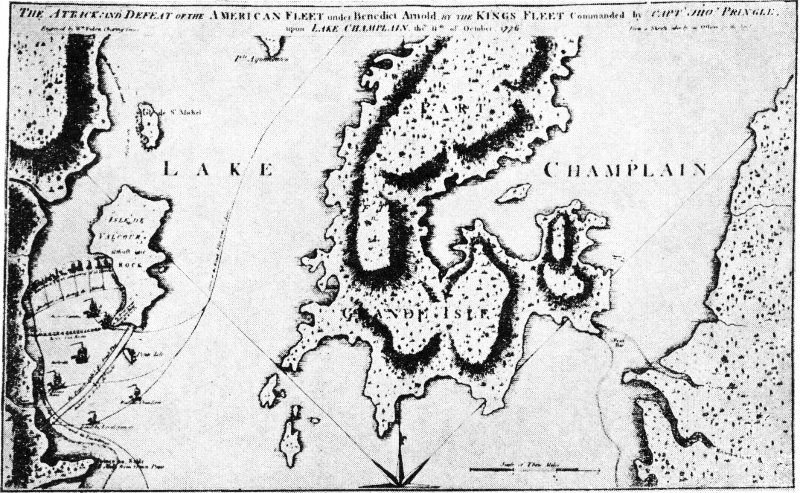

A number of important things happened at Ticonderoga during the American occupation between Allen’s capture, May 10th, 1775, and St. Clair’s evacuation before Burgoyne, July 6, 1777.