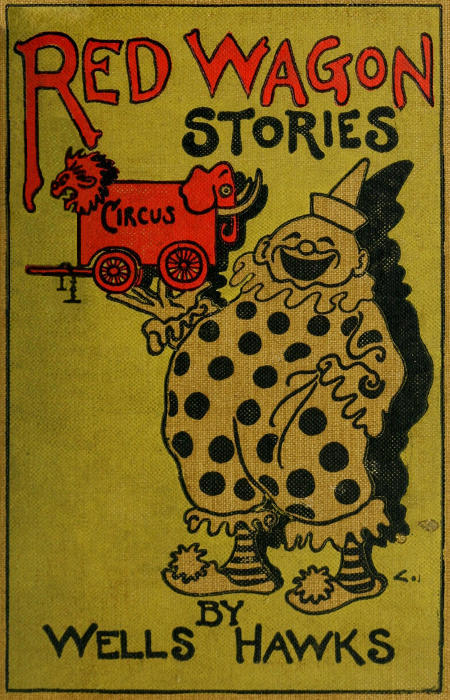

Red Wagon Stories

or

Tales Told Under the Tent

BY

WELLS HAWKS

I. & M. OTTENHEIMER

PUBLISHERS

No. 321 West Baltimore Street

Baltimore, Md.

BY

WELLS HAWKS

I. & M. OTTENHEIMER

PUBLISHERS

No. 321 West Baltimore Street

Baltimore, Md.

Cover Design by

J. R. CROSSLEY.

Copyrighted 1904.

I. & M. OTTENHEIMER.

BALTIMORE, MD.

Between the shows there were seven of the circus outfit who would sit around the ring bank and on the carpet pads just to talk. Here are some of the tales told under the big round top when the tent was empty.

And to those happy days of bread and preserves, when we bare-footed kids sneaked out of the backyard gate to the circus lot and led the spotted ponies to water, these little yarns are affectionately dedicated:—

| PAGE. | |

| The Press Agent’s Story | 7 |

| The Old Grafter’s Lament | 14 |

| The Bill Poster’s Visit | 21 |

| The Candy Butcher’s Dream of Love | 30 |

| The Boss Canvasman’s Yarn | 33 |

| The Side Show Spieler Speaks | 48 |

| The Band Master’s Solo | 54 |

| The Candy Butcher Talks About a Love Affair and His Encounter With the Buckwheat Man | 59 |

| The Concert Manager Gets Reminiscent | 70 |

| The Hands at the Window | 75 |

| The Concert Manager Tells the Boys an Elephant Story | 83 |

The Press Agent of the Big Show had formerly been dramatic editor of the leading daily in Council Bluffs. It was his star boast that he was the only critic in the Middle West that ever had the nerve to roast Joe Jefferson, and he said he did it in the interest of art.

“Art,” says he, “must be preserved, an’ the only way to do it is by knockin’.”

The Press Agent wore his hair long, had a smooth face, and looked like a police reporter out on a three-column story with the facts coming in slowly. He hadn’t much baggage, but he always carried about a ream of adjective hit paper, two lead pencils, and a pass-pad. No man ever heard him talk without wondering what kind of stuff he beat out on a typewriter.

The saw dust spreader was smoothing out the ring for the night acts and the rest of the gang were sitting around roasting[8] the route when the Press Agent came through the red curtains at the dressing tent entrance picking his teeth with a straw. He sat down on the box where the Greaser Knife Thrower kept his keen steels, and filling his pipe waited for a break in the conversation. Then he asked the gasoline man for a match. After he got the fire he saw there were no words loose from the ring-bankers, so he starts his skein.

“Well, lads, we hit ’em up hard at the mat today, 12,000 on the blue boards an’ the ticket wagon window down before the harness is on for the entree. S’pose them laddy-bucks in No. 2 car will say it was a good billin’, but I’m tellin’ you people that this is a readin’ community, an’ it was the press work that had the coin hittin’ the window this date, an’ that’s no cold cream con, either. The Gov’nor knows it, for he gives me a good word an’ a back pat jus’ as the parade was startin’ for the main highway.

“I’m given youse the real word, an’ it’s this—when you can get ’em readin’ about the Big Show you’ve already got ’em feelin’ for change to buy, an’ that’s as true as ticker talk. The old man sees[9] in the paper that the Big Show will soon be on the lot, an’ when he gets home to daily bread he tells it to the old woman; the kids get next and there’s no let up on papa ’till he promises to buy in for the whole family. An’ workin’ one is workin’ all—that’s my motto. It’s the press work that gets ’em talkin’, an’ it’s the talkin’ that’ll make ’em give up even when wheat is down to 48 an’ interest on mortgages is starin’ ’em in the face. Get the paper talk an’ the money is so sure that you can be plannin’ new acts for next season before the first pasteboard hits the bottom of the red box on the gate.

“But, say, it ain’t no children’s game to get this paper talk. The good old days when you could blow into the newspaper offices with a loud vest and a tiger claw hangin’ on your watch guard is done. Them times the old agent would lay down a cigar on the editor’s desk, spread a lot of salve about the greatest yet and the only one in captivity story, and then work the gag ‘write me somethin’, old man.’ But them days is strictly past. It’s a new make up now, an’ a new line of talk that wins ’em. You want to enter quiet like just as if you were one[10] of them Sunday school boys with a write-up on a rally in the church basement. The editor gives you the size-up for this, an’ when you says ‘I’m ahead of the Big Show comin’ 25th and 26th,’ he’s so surprised that he’s glad to see you, an’ it’s once aroun’ the track before the bunch sees the flag that he asks you out to drink before you spring your pass-pad. And, if you don’t believe me, ask soft talking Jim Jay Brady and have it passed off for gospel.

“It’s the approach that makes the center shot this new century. Go in easy, be skimp with your talk, don’t spread the salve too thick, an’ give ’em clean copy—that’s the game; be you ahead of Henry Irving with ten carloads of stuff, a dinky little farce comedy with a society dame doin’ the lead, a melodrama with a real convict a-cracking the safe, or one of them Broadway big ones—no matter, it’s the same, an’ what goes for them goes for the Big Show, whether you’ve got 68 cars on the sidin’, or you have slipped in after night with rubber boots on—and that’s no Tody Hamilton catch line.

“But you don’t want to be too certain; you can get your chances in this line just[11] as easy as in the shootin’ gallery when its bullets against clay pipes. Some of the boys that handles the copy for the Eastern press can put up a frost that would keep Chicago beef around the world in a sailin’ ship. But you can melt ’em if you make good. Remember hittin’ Boston las’ season an’ runnin’ up against one of these heady boys with a foldin’ forehead. I give it to ’em easy, an’ when I says circus he looks at me through his windows an’ says so haughty:

“‘Ah, the circus! Quite a diverting entertainment. Originated with the Greeks.’

“Now wouldn’t that make you itch? Me mind gets to chasin’ ’roun’ for a proper come-back, an’ I tries to recollect the names of some of them old guys what went paddlin’ ’roun’ in a sheet an’ sandals spittin’ out wise words that no one has forgot. An’ mem’ry lands me at the right dock, so I han’s this to the college boy:

“‘Yes,’ sez I, ‘I believe it was Aristophanes who wrote an epic on the circus to be read at one of Nero’s spring openin’s.’

“The words is hardly out of me mouth when he gives me one of those looks that would have made Peary thought he had found the pole. So I lays me copy on the desk and gives five bells to back water an’ I’m in the elevator. An’ so help me Bob, I hardly reaches the pavement before I sees sheets of paper flutterin’ in the air an’ me copy falls on the asphalt. The college boy had lifted it. Now you would think that it was a sheet that roasted us. Not at all, not at all. He gives us a two-column write-up and three half tones that had me up to the bar an’ dizzy for a day. The worst will fool you.

“An’, say, that reminds me. Remember when we was playin’ the week’s run in Chicago las’ July? Well, I’d been skatin’ roun’ to the papers an’ buyin’ drinks for the press boys, an’ it was joggin’ along to three on the dials when I remembers I have a bed at the hotel. It was out near the lot, an’ I starts out to walk. I’m crossin’ the railroad tracks when a weary steps out an’ asks me for a match. I gives up, when another comes into the talk an’ says, ‘Give us money.’ Say, I didn’t have but thirty cents, an’ I gave up. But the[13] highwaymen thought I was lyin’, an’ was going to tap me when I says, ‘Now, boys, let’s argue this out.’ So I takes them two Jesse Jameses under a lamp post an’ gives them a josh talk on the Big Show that has ’em serfy.”

“Well,” said the Boss Canvasman, who was always interested when there was any fight talk, “what happened, what happened?”

“What happened?” says the Press Agent. “Hear me! I takes out me pass-pad an’ writes passes for them robbers until a policeman comes, when I turns ’em over. An’ that ain’t all; I gets a column story in each of the afternoon sheets on how the Press Agent of the Big Show captures two bold boys, an’ the Gov’nor gives me the good word and a double X, an’ I says thankee an’ repeats me motto, ‘An’ workin’ one is workin’ all,’ to every barkeeper that was sellin’ after midnight that evenin’.”

The Old Grafter had corns on his knuckles from holding greenbacks between his fingers.

He looked a trifle seedy about the costume, but his moustache was waxed—the moustache, too, was dyed and you saw the reason when he took his hat off. The Old Grafter wore a celluloid collar and a polka dotted dickey, and when his vest was opened it showed up the shyness of his linen.

The Concert Manager was springing gossip about the principal clown who was having trouble with his wife who did the iron jaw swing. He saw the Old Grafter coming across the ring and he stopped, for it was pretty well known that old-timer wouldn’t stand for scandal. The Old Grafter bit off enough tobacco from the canvasman’s plug to make a comfortable quid and then sat down on the snake box. He was looking sad and there was silence. Presently he sent a splash of[15] juice up against the center pole and after shifting the quid he opened up.

“Say fellers, I’ve been cuttin’ the cards since John Robinson had money in tent shows an’ I’ve come to the verdict, it’s this—when you’ve got the green in your pocket an’ the suckers is tipped off they’ll crowd you as thick as flies on the popcorn pile, but when there ain’t no coin to jingle you kin get so lonesome that you’ll go to bed with a hot water bot’l for company.”

This bit of wisdom impressed the gang, for no one spoke, and the Old Grafter threw his reversing bar and chinned out this—

“The old days is gone an’ they’s left the circus graft on a weedy sidin’ with no roun’ trips back to the lan’ of promise. Them was the one ring days an’ in them times there was allus fodder for the hogs. Today it’s one ring, two rings, three rings and a stage—the biggest tent on earth, but for the grafter—nothin’, nothin’. Me, what use to turn the shank of the week with a bigger wad than the principal bareback gets, me makes today a dirty twenty on percentage an’ sellin’ reserved seats. I’m ashamed to look the[16] old days in the face. Why say in them days many a time the proprietor of the Big Show was touchin’ the grafter for cash when business was bad an’ today so diff’rent, so diff’rent—if I gets into a poker play on the train an’ the ante’s a nickel I’ve got to reach twice to find the coin. If I’d had the good sense what’s in Bill McGinnis head I’d a bought a little road tavern like he did twenty years ago an’ I’d a-had a bank book roostin’ back of the bar. But I thinks there’s still somethin’ doin’ my end an’ I waits an’ loses—and what do I get—a couple of treasuries and some change at the pay off durin’ the season with crackers and cheese for me an’ the old woman in the winter. It’s the diff’rence ’tween horse radish an’ saw dust an’ its got me slippin’ back.

“I’ll tell you fellers somethin’ ’bout the old days. ’Twas ’bout ’76 an’ we was graftin’ with a one ring outfit. We struck good crops and sunny weather in the one nighters in the Ohio valley. The farmers had money an’ there was peaches in the orchard for every boy with the troup that had a bag of tricks. Everybody was standin’ in on the graft an’ we had a fixer two days ahead so there’d be no call. We[17] was carryin’ a car with the lay out an’ four tin horns that was science on faro and turnin’ the wheel. The big game was invited to the car an’ there was allus a set out an’ sumthin’ to drink. The little fish was worked on the lot an’ there was days, many days when the graft was mor’n the ticket wagon count up, an’ the rake off was loafin’ ’bout par, continuous. Good days them, me boys, for ev’ry body from the boss of the outfit down to the stake driver. Money was comin’ easy an’ when there was any protestin’ on the part of the patrons an’ it got to fists, or gun play we passed along the Hey Rube an’ there was Gettysburg till mornin’ if they was lookin’ for battle.

“The best burg we hit was a lit’l settlement where we had a two mile haul up the pike from track to lot. Everything was ripe for graftin’ an’ we was ready for harvest. Seems like a reform committee had to hit down all the games and the folks was hungry for gamlin’. The posters in No. 1 car piped us off on conditions an’ it was said that them paste spreaders traveled off with a roll from stud polker in the car after the bills was on the stands.

“They wuz on the lots waitin’ for us when the boss landed to lay off the pitch for the round top, we wuz only usin’ one then an’ had no an’mals to speak of. The fakirs got in the game early an’ transparent cards from gay Paree was the first bait and bitin’ was good. ’Fore the parade started all hands was busy on the lot takin’ care of the games an’ say the farmers had it with ’em in rolls. The foxy boy in the ticket wagon has all his bad coin ready and the constable with the badge has been fixed with a ten to see there’s no argument when short change is handed out.

“Oh! we worked systematic them days.

“Well, say, before the band had struck up the grand march for the entree gold bricks wuz sellin’ like cod fish cakes at a nigger camp meetin’ an’ the boys what was workin’ the shells had to lay off to get the stiffness out’er their fingers.

“I hates to tell it, I hates to tell it in the days there’s nothing’ doin’.

“You see I was cappin’ for the boss of the show an’ say that day keeps me busier than a man drivin’ sheep. The outfit was gettin’ thirty-five per cent. of the graft an’ if the partic’lar grafter who was gettin’[19] the coin failed to come up we se’ed that he was prop’ly turned over to the off’cers of the law an’ we did the prosecutin’ on the groun’ that we was runnin’ a strictly moral show. Say, while I was watchin’, a farmer with a bunch of weeds under his chin an’ a face like a quince comes up to me an’ makes a holler. Somebody had touched him for his wad ’fore he could get to the games an’ he was dead sore. I se’ed that he was goin’ to make trouble so I remembers that his wagon is standin’ in the dirt road by the lot. I gives a stakeman the tip he kicks the off bay in the flanks an’ there’s a runaway. The corn cutter chases after his team an’ forgits that he ever had a roll.

“An’ say at night down in the car the air was hot. The tin horns was busy and coin was droppin’ like rotten apples in a mill race. The boys what was dealin’ the faro had monkeyed with the deck an’ it was far to the bad for the spenders. ’Bout time to start haulin’ for the cars two burly boys begins to talk fight an’ it looks like Hey Rube all aroun’. One sticks his knuckles into me face an’ I says to him sort’er fierce like.

“Say, young fellow, if youse lookin’ for fight I’ll git one of the boys to stick his teeth in your neck an’ you’ll change your mind.

“There was no gun playin’ but there was a lot of chinnin’ and cussin’ but we finally gets the tin horns out an’ starts ’em up the road to the first section. The gang is hot after us an’ there was only one thing saved us. Jes’ as the crowd was closin’ in I sees the tiger den with the two blacks pullin’ it comin’ over the hill. I chases forward to the trainer an’ when the cage gits up close we jes’ shoves them two tin horn dealers in the den with the tigers an’ saves their lives.”

“Never could make a return date there, could you, Bill?” asked the Boss Canvasman as he made one of the spotted coach dogs take a jump through his hands.

“Return date, well I should reckon. Went back there in two months an’ still foun’ ’em ripe. But there was only one way to do it. The Boss had to paint over all the cars an’ wagons an’ change the name of the show. The hay boys thought it was a new outfit.”

The Bill Poster was a stranger to most every one in the outfit. He traveled a month ahead of the show on Advertising Car No. 2, and while he hung around during the run in New York he never got well enough acquainted to mix in with the ring bank squatters. While the outfit had great respect for him, and especially for his work, he wasn’t generally understood, and this did not keep his popularity up to par. He always seemed solid with the business staff and called the assistant treasurer by his first name, and these two conditions were known to the sawdust boys. They always took off their hats to anybody on the staff, and the man in the ticket wagon was only known at the pay-off. Then, too, he dressed well and wore a diamond, that is, a real one, and altogether his financial condition was too good.

But for some reason or other the Bill Poster did happen back on the show one[22] afternoon. Just after the matinee, when the gang sat down on the bank for the spiel, he was seen walking across the track, and the boys at once began to speculate on what brought the paste spreader back to home. Some of them thought it was for a call-down, and the concert manager declared that was the cause, for, said he, “I never seen a town billed so rotten as this un.” But the gasoline man, who was a close observer, thought different. He knew that there was a little fairy working in the Fall of Rome ballet that was sweet on the paste boy, and he put the rest of the crowd wise before the conversation got too far from the shore.

“Cert’nly,” he said. “Didn’t I see the guy in his plaid rags ev’ry night when he was playin’ the Garden, gittin’ the little lady at the dressin’ room door and blowin’ her off to butter cakes an’ coffee before she chases to the bridge an’ home.”

The gasoline man was getting real gabby on the love affair, when the Bill Poster came through the red curtains over the dressing tent entrance and walked across the ring to where the gang sat in the shadows. He had a sassy little “Howdy”[23] for everybody and then passed around a box of Turkish cigarettes. Everybody passed it up, and the Boss Canvasman bit off a two-by-three chew from his plug and looked sour.

“Slipped back to see the Boss,” said the Bill Poster, as he lighted one of the Turkish boys with a match he took out of a sterling box that had a beer ad. on it. “Ain’t no secret; I want a transfer. I’m good an’ tired of the slow work on No. 2 car, an’ so I gets a day off an’ runs back to see if the Boss won’t put me with the opposition crew.”

The gang was silent. Nobody had asked for the why, so nobody commented on it. The fact that he was going to have nerve enough to ask to get in the opposition crew filled the concert manager with disgust, for he knew something about bill posting, and also knew that it took a triple-plated crackerjack to hold a place with this crowd of rush pasters of a three-ring outfit.

“There’s nothin’ to it,” continued the Bill Poster, “gettin’ into a town where ev’rything is dead ready, all the boards up, and nothing to do but paste. I want a little excitement. I allus gets it in the[24] winter, when I’m billin’ a hall show. Many a time I’ve laid me bundle of lithos under a doorstep to punch some guy who was tearin’ down my stuff in saloons where I’d spent up me money, and then hangin’ his stuff in the window. I tell you the opposition crew is the crowd to have the ginger. When your car is hangin’ up on a grassy sidin’ an’ you gits a wire that the other show is routin’ three days ahead of your own bookin’s, it makes you jump. The boss wires the head of the gang to jump for the town and beat ’em up. Beat ’em out, but on the level, legitimate—but beat ’em up. Don’t tear down none of their billin’, but kill it if you have to buy the side of the Presbyterian meetin’ house to git a showin’ for them nine-colored twenty-eight sheet stands.”

As far as the gang on the bank was concerned, the Bill Poster was talking Greek, and he had ’em wingin’. The Concert Manager thought he was “next,” but his coupling broke before his understanding left the city limits. Just then the Press Agent of the Big Show happened in and the talk hadn’t gone three lengths before the Bill Poster and the[25] newspaper man crossed bayonets. Both were doing the publicity gag, and both had a well set and riveted idea that each one and not the other was bringing the people into the tent and giving the show a good gate to send back on the statement to the high hat boys in the city who were doing the financing.

“Let me tell you something,” said the Press Agent, as serious as if he was arguing to get a half column write-up on fourteen dollars’ worth of advertising in the only daily in the town. “Let me tell you. These days the people who are spending money for amusements reads the papers, and it’s the paper talk that lands the coin at the window. I know what I’m talkin’ about. Bill posting is all right, but it’s the newspaper work that does the real singin’.”

“Come off!” said the Bill Poster. “You’re only pluggin’ your own job. You don’t mean to tell me that the boss of this outfit would keep all the printin’ shops in Cincinnatty goin’ night an’ day to git out the wall stuff if they didn’t think it was some good. An’ say, they wouldn’t be runnin’ three billin’ cars ahead of this here show if there wasn’t[26] some come-back to the money they was blowin’. Why, say, what do you think they are? Your press work is all right, an’ my bill postin’ is all right, an’ you’ve got to have both.”

“Well, maybe you’re right,” said the Press Agent; “I guess they use the billing to emphasize my work.”

“I don’t know so sure what you means, partner,” said the Bill Poster, “but the Boss of our car figgers it out this way: He says that the readin’ in the papers about the big show makes ’em look at the pictures on the wall. And, says he, the pictures on the wall makes ’em read what is in the papers. An’, say, he’s been pastin’ since the John Robinson days.”

“Guess he’s right,” said the Press Agent.

This last statement hit the gang as real good sense, and they half agreed that the Bill Poster knew something about his business.

“I tell you, boys,” continued the Bill Poster, as he took a seat on the sawdust pile and lighted another one of the Sultan’s dreams, “in me dull moments, when we is travelin’ an’ there’s nothin’ to do but layin’ out paper an’ gittin’ the buckets[27] ready, I figgers it out this way: You can git ’em with the paper talk all right; but there’s one thing you can do with good bill postin’ and litho work, an’ it’s this, you can’t make ’em read the papers, but bless me, you can make ’em see bill postin’. Say, me an’ the gang I work with in New York have sniped the subway fence so hard with red-on-yellows that you would think there was nothing else on Broadway. Did you see ’em? Well, you bet. There was so much color stickin’ along the ditch that it hurt your eyes when you rode by in a car. That’s what I claims for proper billin’. You can git it where they’ve got to see it.

“Say, to prove what I says is right, I’ll tell you a little experience I has. I was doin’ the litho work for a cheap price house that was playin’ the old favorites with a stock. They puts on ‘The White Squadron.’ The boss comes to me and says, ‘Look here, Jim, I wants you to do your best with this piece; its costin’ us a lot of money to get it on, and we wants to get it back. There’s a diamond stud coming to you if you gets what I calls a good showin’.’ Say, I would ’a’ done it anyhow for them kind words, but I says[28] I’ll git that diamond if I puts bills all over the trees in Central Park an’ goes up in stripes for ten years for doin’ it. I was thinkin’ all the time some new gag to work, when one mornin’ comin’ down I reads that there’s a yacht race in Harlem river that afternoon. You know, boys, ‘The White Squadron’ is one of them naval pieces, an’ has a lot of ships in it. Well, the Sunday before I’d pasted up a lot of one an’ a half sheet boards with type an’ litho stuff, an’ I has it loaded in a wagon ready to git out on the street some night and sit the boards in doorways. But no, says I. Me partner an’ I drives the team out to the Harlem River bridge. The river is so thick with tugs and launches full of people to see the boat race that you can hardly find the water. We waits until the race starts, an’ then we clumps them boards into the river, carefully like, so they will fall with the picture side up. They hits the current and starts floatin’ down. They all seems to cling together, and make a big raft, an’ all you can see is ‘White Squadron.’ Everybody on the bridge and the boats is a readin’ and laughin’, and we knows it’s the showin’ of our lives. And say, the[29] boards keeps on driftin’ wid the current an’ gits so thick that when the guys in the paper boats hits that part of the river they gits stuck and the race has to be called off.”

“Well,” said the Press Agent, coolly, “did the show do any business?”

“Business!” replies the Bill Poster; “you’d a thought there was a fire in the neighborhood ev’ry night, the crowd was there so thick fightin’ to git in. An’ say, the guys what got broke up in the boat race is so stuck on the joke that they gives a theatre party an’ the papers is full of it.”

“Yes,” said the Press Agent, “and it took the press agent to get that in the papers.”

“But the bill posters got ’em in the house,” retorted the Bill Poster, with the air of a man who had knocked the local welterweight over the ropes.

It was generally conceded that the Candy Butcher was the handsomest man in the outfit. To be sure, the gent who did the sixty-one horse act in Ring Three was a Charlie boy for good looks, but it was only when he was in the red coat and working. When he left the dressing tent and went red light hunting in a one night stand he looked like a canvasman on a visit home to his people, but he was a hot card when he had the dicer on in the horse act. It was so different with the Candy Butcher—he was always dressed up and he never looked like he felt it.

No one ever saw the Candy Butcher wear a coat, but his checked trousers were always creased whether the big show was playing a one night in Keokuk or doing a run in the Madison Square Garden over in the hot city. And he always wore a vest, but it was never buttoned and there was a red striped shirt with one of those[31] Montana boys screwed in the bosom right under the dickey dot of a bow. The vest was something to speak about—it had the band wagon way to the bad on the distribution of colors and looked like page 89 in a wall paper drummer’s sample book. There was a shiny chain with an elk’s tooth and a tiger’s claw and in one vest pocket was a date book with a tooth brush and a blue pencil doing a duet on the other side of the rainbow. The Candy Butcher always wore pink underwear and had his sleeves rolls up to his elbows. And you don’t want to forget the little miniature of “blondy” that he had pinned right over his blood pump.

And as a matter of detail the Candy Butcher always had this get up the whole season and no grease spots ever scored—he was just the same whether it was back of the tub and the peanuts giving the “five tonight good people” gag, selling concert tickets during the run-offs in the hippodrome or Sunday afternoon in the ladies’ coach, section three, telling the big blonde who did the cloud swing in the round top rigging that of all the girls she was the onliest.

The gang was sitting on a carpet roll under the big top when the Candy Butcher came across the track and sat down on the ring bank. He was looking sad, but his pants were creased and the Montana boy was shining like a frozen hunk of Kennebec water. He rolled himself a cigarette and the gang being silent he edged in with this bunch of talk:

“I’m bluer this evenin’ than the paste boards they’re passin’ out of the ticket wagon an’ if it wasn’t for gettin’ the dock at the pay off I’d be up against some boozery workin’ the syphon like an engine at a tenement fire. I ain’t got no life in me ’t all an’ I won’t have until we leaves the east an’ strikes the west country. B’lieve me, me boys, the east is all right for business, for I can pass out the sour juice at five a throw right here as well as any where, but it’s myself an’ not the place. It was too much of a feather bed las’ season an’ I was fool enough not to remember that I had to wake up. There ain’t no use talkin’, whenever a guy gets a good dream in this here life some sucker has got to give him the alarm clock finish an’ he wakes up with a yell.

“Say, I can call the turn on the folks on the blue boards an’ have ’em all drinkin’ lemon juice and shellin’ peanuts an’ I likes to do it, but me heart ain’t in the work, this season and that’s no lithograph josh either. I’ll tell you and some of youse may give me the grin, but it’s ten to one you’ve had the soft spot yourselves, so I ain’t a-carin’. Remember the Congress of Nations gag they was workin’ las’ season? Well right back of me lay out there was a lot of maidens that was doin’ the gypsy village and fakin’ a lot of beads and fortune tellin’. There was one little fairy in the outfit that had me dead, an’ I don’t mind tellin’ you that she had me soft from the start. She wasn’t none of these city pick ups but a nice little gal that talked quiet and minded her own. She didn’t mix with the rest of the push an’ we got thick the first day the canvass went up. She tells me her story confidential like an’ I give her me sympathy, for her people was dead agin her for troopin’. You see she had been working in a New York hash house, where they had Bible talk on the wall an’ where they gave a splash of beans and a draw for a dime. She gets tired an’ a guy what has[34] been eatin’ at the place gives her a job in a boardin’ house waitin’ on the table. Here she meets the man what has the Congress get up to put on an’ he tells her gilt edge stories about the circus business and to cut the talk down she joins out with the show. Well, say, she was the real thing to me. In two months she had me stoppin’ the booze an sendin’ money home to the folks, an’ it was a center shot to get that out of me. She was allus lookin’ for a chance to do me somethin’ kind an’ one day she did a little turn that I wont forget long after I’ve past the old man’ home.

“We had struck a rough run of one nighters in Ohio and was looking for bright things across the river in the West Virginney townships. I had to do the German Emperor in the parade an’ when we got back to the lot I begins to get me stand ready for the sale. I’d packed up careful on the last stand and thought it was sunny for the next. But when I got me chest open I finds the citric acid jug missing, and the floaters I’d saved to throw on the top of the tub was gone too. I had a cussin’ spell for a brief and then I[35] goes on a still hunt for lemons—the real yellow. But bless me I couldn’t find one in the village an’ there was nothin’ doin’ with the barkeeper what had ’em. Comin’ back I see’s a dago doin’ the shaker across from the lot. He has ’bout a dozen lemons and I offers him a good price, but the brown boy wouldn’t sell an’ I was sorer than a doped lion. I goes into the tent and meets Maggie, that was the name of me fairy, an’ she was sewin’ silvers on her little coat. She sees me sad like an’ I unloads me woes. The gal didn’t say much, but she rubs her hand across me frowner an’ sez, never mind, John, I’ll help ye out, an’ goes ’way. Say, youse may give me the laugh, but durn me if that lass didn’t come back in ’bout an hour carryin’ a bucket an’ I mos’ had a fit when I see’s it full of gooseberries? What’s the game? sez I.

“Watch me?” sez Maggie, “an’ I’ll keep you in the business.”

“Durn me, boys, if that little maiden didn’t mash them berries to a pulp, strain ’em through the Hoochie Coochie gal’s veil and have the tub full of sour juice in seven minutes. I pours in the water,[36] finds me floaters and puts them on the ice bank an’ before the gang is passin’ once ’roun’ I’m sellin’ the juice as if lemons was growin’ on locust trees. Gooseberries too an’ the yaps couldn’t git enough of it. It was better than any graft ever in the one ring days an’ the little gal had done it all. Ain’t no use tellin’ you that I gives her a new shirt waist an’ she gives me a squeeze that makes me top spin like a merry-go-round.

“An’ say I fixed that dago that wouldn’t give up. I tipped off one of the drivers and when the first pole wagon leaves the lot with the eight grays a pullin’ it, the leads shies into the shaker stand an’ gives it the apple cart finish.

“But the little fairy I lost her an’ that’s why I’m sad. It was this way. The gal what did the twistin’ for the Turks had the fever an’ they shipped her home. The guy what had the Congress comes to Maggie, gives her the jersey and the gauzy pants and sez she must do the part. Maggie kicked an’ said she was engaged for the gypsie village. The guy says “not at all” and Maggie pulls off the spangles an’ goes home. An’ say I ain’t been right[37] since, an’ some days I feels like playin’ quits myself.”

The gang looked at the Candy Butcher consolingly, but no one spoke.

“The las’ I hears from her,” she said, “she had gone back to waitin’.” She’s slingin’ hash in a Brooklyn Caf’, but I loves her just as hard.

The Boss Canvasman was always sad. He never talked—he just chewed his tobacco and worked. Like the Candy Butcher, he never wore a coat, but he cut the pink underwear the Lemonade Boy flashed when he had his sleeves rolled up at the tub. Of course, the Boss had a coat, one that had run through a dozen seasons, but he always kept it strapped down under the driver’s cushion on the pole wagon. Whenever he did use it, the coat was doing duty for a pillow when the last section was late pulling out, and he was sleeping on a gondola with the wall poles for a mat.

The Boss Canvasman’s pants were ancient history, and his vest was always open. He wore one of those motorman watches, with a shoestring for a chain. He never looked at the watch except at night, for when it was daytime he could pull off the hour on the second by the[39] slant of the shadows across the big “top.” The Boss never wore a collar. On Sunday he would put a gold button in the shirt band, lean disconsolately against the tongue of the pole wagon, and feel uncomfortable because he was dressed up.

There was no coin and jewel flash about the Boss Canvasman. But he did wear a rusty button in the lapel of his vest—one of those G. A. R. things. Across his face there was a long red scar, and sometimes when he had been drinking he talked about the first Ohio Cavalry—Gettysburg was the answer. He feared nobody nor anything. He had no friends, except probably the Stock Boss, and there was a tie there, because the two had done the wagon show long years back before three rings were dreamed of and farmers were living on their own hog meat and were happy. If he ever did talk, it was when something went wrong, and then his line of words were unfit for publication—even in a Chicago weekly.

It looked like a squall just as the matinee was breaking, and the boys at the cages were hurrying the people along to get the tent clear before the water fell. The Boss Canvasman was hard at it getting[40] the guys tight and throwing in cinders around the big poles, where the dirt was soft. He was taking no chances on a blow. He had been mixed up in several of those wind things down in Texas, where a cyclone struck the lot, and all that was left when the sun got back was the ticket wagon and the elephants that were chained to earth. He knew his game.

After the usual beef stew and the splash of beans had been put away with a cup of black in the meal tent, the gang gathered about the rink bank for a little rest. The Sawdust Spreader and the Gasoline Man were talking scandal, as usual. This time it was the Snake Charmer, who mixed it too strong with the bottles on the last stand, lost the keys to her snake-box and two boas and a black boy starved to death before the feeders could get the rabbits under the fangs.

The gang sat down in silence until the Concert Manager cut in with some weather talk. It looked stormy, and as it was the last night of the stand and a long haul to the cars, everybody was feeling a little sore. With a storm coming up, the[41] tent to watch, and then the haul and an eight-hour jump with a hustle for the march in spangles down the highway the next morning. It had everybody grouchy and thinking about hall shows with a roof and a stove.

“Youse is doing a lot of guff about a rain,” cut in the Side Show Spieler, as he polished up his shiny brim on the corner of the leaping tick, “but youse kin stay inside when its droppin’, but for me—the open and still the same old gab for the dimes.”

The Boss Canvasman came up along the ring bank, and without noticing the crowd on the sawdust began to jamb down the cinders around the net-pole with the heel of his boot. From the distance came a low rumble of thunder. The gang looked at each other. Everybody in the outfit feared a storm; not so much for the storm itself, but for the effect it had on the Boss Canvasman. He never talked, but when the basses under the hills were growling and the lightning was doing a fancy jig against the blue, he let loose a vocabulary that would put a canalboat captain to the blush of shame and send a sea-soaked old jib[42] reefer to flight as a down and out cusser beyond appeal, cards torn up, tables turned over and police at the door. He used the same two-em words, but the way they hit the air would have made holes in a battleship.

The broadcloth boys, who came over in the sailing ships and scared the Indians into religion by telling them how warm it was in perdition, couldn’t touch the Boss Canvasman for a scare when he got on the same topic. He had a way of saying “hell!” that made you want to turn in a fire alarm just for personal comfort.

Presently he came across to the gang, and to the surprise of all the rink-bank squatters loosened up.

“Talkin’ ’bout workin’ in the rain, is you?” he said, with a sneer, and a cross-hook glance at the Side Show Spieler. “You’ve got no kick. Say, you’ll have your head on some Mamie’s shoulder in the last day coach, up an’ away, while me an’ my gang is still workin’ on this lot gittin’ this round top on the wagon without streakin’ her wid mud.”

There was not a reply, for the boys knew he was right. The Side Show Spieler hung around a bit, and, with a[43] typhoid smile, remarked that he guessed he’d bow hisself out, and more than that, he did.

“Speakin’ about storms,” said the Boss Canvasman, as he tied a long, running knot in the guy that held the triple bars, “I guess you fellows ’ceptin’ some of the old boys, dunno what it is for a rain an’ a blow. I dun bin circusin’ it for forty year, and, say, I’ve met some blows an’ lightnin’ that no sailor chap ain’t hit, I don’t care how often he’s bin ’round the Horn.”

You couldn’t have looked into the face of that old fellow without believing every word. He was burned brown by every clime, creased and seamed by every frost, and parched and dryed by every wind, and his hands for knots and gnarls had an old oak twice around the track and then past the judges and turf writers, all off and back to the street cars.

“Say, I’m going to tell you fellers sumthin’,” said the Boss, as he sat down and began twisting together a piece of rope that was getting to look like a lion’s tail. The gang was startled, for in the memory of none there never lodged the fact that the Boss Canvasman had been seen to sit[44] down as long as the pole was standing. But he did, and what’s more, he reeled off a yarn.

“Jes, ’fore the war broke out,” he said, “I had enlisted in the First Ohio, I was workin’ down the Valley of Virginia wid a little wagon show doin’ the same kind of work I’se doin’ now, ’cept it was nothin’ but play to this. Funny, too, for six months afore I was down that same valley wid the cavalry cuttin’ into them rebs, an’ I don’t mind telling you they was a cuttin’ us, too, wid Mosby in the woods an’ ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, God knows where.

“Well, we had been doin’ a day an’ a night stand in one of the little towns, an’ had a fourteen mile haul down the pike for the next. We was hopin’ for a moon, not so much to strike by, but for the drive, for the people hadn’t got the roads to right, an’ they was still full of artillery ruts an’ wagon train wrecks. But we pulled off the show, an’ before the last bareback was on I has the menagerie canvas on the wagons, all stakes up and the dens down the road, with the boys leadin’ the elephants and the two camels over the hills. It had been squally like, all night, but I had the round top tightened up so[45] hard that youse could have walked the ropes an’ there was no danger.

“But jes’ as Dutch Andy was playin’ his last piece there was a bust of wind an’ a flash of lightnin’, an’ she began to come down in solid sheets. We gets the people out and gets to work on the tent wall. This peels off in a jiffy, an’ the rain lets up. Then down wid the big top an’ on the wagon. But sumthin’ catches in the riggin’ on the main pole, an’ I sees I has to send me helper up on a climb to get her clear. Everything was gone but the pole wagon and a few side show things, an’ the ’bus we bosses rode in, with four grays pullin’ it. Afore I sends my helper, Jim, a fine boy, what had been a sailor, up the pole, I send four men out to hold her up by hangin’ on the long rope to the far stake. Jim skins up to the top an’ gits her loose, but before he kin git down the gang holdin’ the long guy loses their holt, an’ the pole falls.

“Well, we picks up Jim, an’ he is pretty bad. Ribs in, an’ a lot of cuts. We tried ev’ry house aroun’, but no doctor, though there was one good old lady who gave us some arnicy and strips of bandage she said she’d kept to use on her husband[46] when he got shot up in the Saturday night fights ’bout the tavern. So we piles poor Jim into the ’bus, and drives off easy, while we walks along quiet like an’ sore. Poor Jim, he jes’ groans an’ talks ’bout doin’ his best, an’ I keeps givin’ him liquor to make him forget it.

“But it was all over for Jim, an’ we jes pullin’ out of a clump of woods down by a river when we sees he’s dead. There was no use carryin’ his body long, an’ he didn’t have no people to ship it to, so we decided to give him a decent burial. Two of the stakemen digs the place, an’ we lays poor Jim away under a willow tree. Jes’ then one of the boys speaks up an’ sez:

“‘Say, boys, it don’t seem right to plant Jim without sayin’ sumthin’.’

“But there wasn’t a mother’s son in the crowd knew what to say, though they is all on to what the fellow means. We waits awhile an’ I sez:

“‘Well, there might be a little singin’.’

“An’ I wishes that I had the principal clown there, for he was good on sad songs, ’specially if he’d been boozin’ a little.

“‘Might git the band,’ sez one of the boys.

“‘But the band is way ahead.’ We is all studyin’ like, when over the hills comes the whistling wagon.

“‘Here is the calliope,’ sez one of the stakemen.

“So we stops it, and ‘Reddy’ Cavenaugh, who played the whistles, besides doublin’ for Peter the Great in the street parade, sez he has enough steam on to play a little. We backs the calliope around, an’ three of the boys holds the hosses. Then Reddy played soft like, jes’ as soft as he could, on the whistles, an’ we all lifts our hats.”

“What did he play?” asked the Candy Butcher, as he wiped away a tear with his red cuff.

“Well,” said the Boss Canvasman, “he only knowed two tunes, ‘When Johnny Comes Marchin’ Home’ and ‘The Blue Danube,’ but we planted Jim to both.”

The Side Show Spieler was a tall dark man with a sad face. He was clean shaven, wore his hair slightly long and looked like William Jennings Bryan, after the vote was in and counted and the telegraph operators had gone home. He had a deep baritone voice and a vocabulary that was always It. The Spieler carried more education than any man on the pay-roll and it was said that he was the only man in the outfit that could read the Latin names on the animal cages. It was generally supposed that he was one of the better days’ boys, but he never told the story of his past life to any of the gang.

It had started to rain just after the afternoon performance, and as it was the night to strike and haul, the six squatters on the ring bank were silent and sore. The Spieler came in from the menagerie[49] and joined the layout. He never sat down, so he stood for a while in front of the others. No one spoke and he let a little conversation hit the air.

“What’s the matter with you fellows? Sore ’cause it is raining! Don’t see why, you all are under cover. I’ve got to stand out there in front of the tent and talk for dimes.”

“Yes,” said the Boss Canvasman, “and I’ve got this tent to roll up an’ load.

“Well be happy, be happy,” said the Spieler. Then after a pause. “Say, you fellows can help me out a little. The Boss gives me a talk last night, and says while the spiel for the little show is all right and good he wants a new one for the big stands we strikes next week. I’ve been digging up the old talk I used to tear off on the Midway at the Chicago Show and I’ve about studied her out, if youse don’t care I’ll just unroll here an’ see if its the proper josh.”

There was no objection, so the Spieler mounts one of the red painted stools, the object holders stand on for the little lady to jump the banners. Then he serves his spiel:

“And now good people if you will kindly give me your attention for a few moments I will explain to you the great congress of freaks, oddities of mother nature and strange and curious collection of wonders shown in the tent. Remember you have plenty of time, the Big Show does not commence for fully harf an hour. Surely you will not leave the lot until you have seen all—all good people—all provided for you in this monster entertainment, this caravan of canvas covered world sought wonders. Come a little closer. Please. Thank you. First, let me call your attention to a remarkable group of reindeer. We have not one—three—five—or six of these specimens of the animal kingdom, but a whole herd of them—a herd of them—a herd of reindeer from the land of the midnight sun, where there is but one night, one day—reindeers, my friends, from the icy mountains of far away Norway the greatest group ever exhibited in any colossal enterprise that has ever been organized by mortal man.

“Next you will find the ostrich farm. This strange bird that furnishes plumage for me ladies’ bonnet, and that comes[51] from the sunny sands of Africa. And remember the cool of the evening is the best time to see the ostriches, for it is then you may notice their marked pe-cu-li-ar-i-ties. Listen, good people, reindeer and ostriches—reindeer from the frozen north—ostriches from torrid Africa—specimens from each zone, the most astounding representation of nature’s wonderland ever shown. Reindeer and ostriches—as the poet says:

“And all for a dime, ten cents, will you hesitate? but wait, good people, that is not all. The wonder of wonders is yet to come—Bobo—he eats ’em alive, he eats ’em alive. You must see Bobo. This strange and curious specimen of humanity who exists upon poisonous reptiles, captured in the jungles of the Tasmanian blue gum tree and brought to civilized America, he still lives on snakes—Bobo, the snake eater—Bobo, he eats ’em alive, he eats ’em alive.

“One moment, good people, one moment—this is not all. Listen—Wild Rose—the half girl and half dog. This remarkable freak of nature that has puzzled the scientists of two continents. Queen Mary, the largest fat woman ever shown under canvas or in hall of curios, the marvelous Samson, the giant of today, who bears upon his breast great rocks to be broken with a sledge, and last but not least—Professor Corello and his troupe of performing roaches, the only attempt ever made to develop the hitherto unknown powers of these insects. The greatest, most interesting and educating avalanche of remarkable freaks and strange and curious people ever shown. And all for a dime, two nickels, good people—a dime, but a dime. The performance is about to begin—one dime—the sight of an invested fortune, the greatest stroke of genius of the modern showman—yours for a dime.”

The Spieler took a long breath and then looked at his audience.

“How’s that,” he asked, “how’s that for a furnace talk?”

“It’s all right, Cap,” said the Concert Manager; “it’ll bring ’em.”

“Say,” said the Boss Canvasman, “how do you keep that voice of yours shoutin’ all the time?”

“Boozin’, boozin’ up,” said the Spieler, “boozin’ up.”

The leader of the Big Show’s band wasn’t much on technique, but if there were any notes coming to an E-flat cornet that he had overlooked something was wrong with the whole theory of music.

The way he could blow melody out of that piece of polished brass was something that the rest of the outfit never understood. He was a little fellow with a very small moustache that ran largely to waxed ends. He always wore a blue uniform and a cap, and he looked like a messenger boy. The twenty-eight “star soloists” that he directed possessed more wind than a Western cyclone and an Eastern typhoon blown into one, for twice a day they played from one-thirty until the last race in the hippodrome was off, and this was no five finger exercise.

The gang was rather talkative when the leader came across from the band stand, so he sat down on the corner of the[55] elevated stage and hummed to himself. Presently the chorus cut out and he soloed thusly:

“I ain’t no Sousa, boys, an’ there ain’t no brass hangin’ to my pea jacket, but say, if there’s any leader that can get more noise out of them 28 than I can, I’ll eat every bit of sawdust under the tent an’ say thankee when I’m done.”

Nobody disputed this distinction and the leader continued to cadenza:

“It ain’t no snap tossin’ off melody for a show like this. When I’m out with the minstrels in the winter the game’s easy, but the snap is nothin’ but blow, an’ you’ve got a lot of crazy ones in the ring here to take cues from. An’ talkin’ about them 28 of mine, there ain’t no show band in the country that can beat ’em switchin’.”

“Say, you know the night we opened in the Garden? Well, we was playin’ ‘The Holy City’ for the guy in spangles what rolls hissef up the spiral. The music plot was ‘Holy City’ to the top, a little of the shiver while he was makin’ the last turn, an’ then a lot of brass an’ bing-bing when he makes the rush to the ring. Well, the boys were playin’ the ‘Holy City’ fine and[56] daisy when the equestrian director comes across the track an’ whispers:

“‘Here’s Dewey comin’ up by the reserved section.’

“So I knows he wants somethin’ appropriate, an’ I gives the signal for ‘Here Comes a Sailor.’ Well, them twenty-eight switches like a limited on a clear track an’ the crowd on the boards goes wild. But the guy in the tin ball, he’s been kneelin’ it up to ‘The Holy City,’ an’ when the music changes to swift he can’t work his knees fas’ enough an’ he lets go an’ nearly breaks his back. He calls me a Dutch somethin’, I didn’t jes’ catch, an’ it costs him 25 fine off the pay sheet.

“An’ speakin’ about noise, fifteen year ago I leaves home, where I was workin’ in a harness factory and leadin’ the Silver Cornet Band in the evenin’, an’ goes on the road with a medicine show. We has one of them long-haired boys doin’ the fake dentist an’ pullin’ teeth without pain while his wife does the female doctor an’ sells pills. We six brass has to play when Doc an’ his wife is workin’, an’ in the mornin’ go back of the stage an’ roll pills an’ put ’em in fancy boxes what Doc sells with the packages of Australian[57] gold pens, the little joker transparent cards an’ the South American Cyroola Corn Cure what he gives away to each an’ every purchaser of Dr. Sorino’s Death Delayin’ Pellets.

“Well, the game was to git some coon in the crowd to come up on the stage an’ have his tooth pulled for nothin’ an’ without pain. Doc gets the moke in the chair an’ makes his spiel ’bout the great pain killer he has an’ says it won’t hurt the boy on the velvet. The band was all brass except Cooney Watson, who was playin’ a kettle drum an’ workin’ the bass and cymbals with a pedal. While Doc was gittin’ the forceps on the tooth we played soft an’ quiet like an’ as soon as he gives the jerk we lets loose with a march an’ you can’t hear nigger man holler to save your life. It was great, an’ it worked the countries all the times. Cooney would make you think there was a thunder storm comin’ up the way he beat them drums.

“But poor Cooney. Doc picks up six Indians to make the show stronger an’ introduce his famous Indian bitters. The red boys had a new moon an’ asks Cooney to loan ’em the drum to do the Tom Tom.[58] Cooney says no an’ the Big Chief gets good an’ sore, but says nothin’. The next day we has a parade an’ we brass is on top of a wagon with Doc’s ads, painted on the side. The Indians is ridin’ along behind us. Well, say, we had hardly hit the main street when the Indian what was sore on the drummer throws his lariat and lassos poor Cooney off the wagon, drums an’ all, into the middle of a bunch of cows what was gettin’ weighed. He was pretty bad, so we shipped him home.”

“That ain’t Cooney beatin’ the drum with us, is it?” asks the Boss Canvasman as he tied a long running knot in the guy rope to the net under the swings for the brother act.

“No indeed,” says the Leader, “Cooney never joins out again. The las’ I seen of him he was workin’ at his trade out in Indianny—he was paintin’ the roof of the courthouse when we had the parade.”

The Candy Butcher of the Big Show looked like a cut-out in a Sunday supplement. He was the best dressed man in the outfit, and no matter what he was doing and where he was doing it he always looked fixed up, and he felt it.

His pants were always creased whether the show was doing a run in the large city or playing the one-nighters on a single-track jerk-water beyond the Wabash. He never wore his coat when working, and his loud linen would have stopped a limited with one flash from the tower. He was there with the pink underwear, and his stockings had more kinds of color in them than the side of the band wagon when the season was new. The Candy Butcher was always dressed, and when he got behind the counter to pull off the “Five tonight, good people!” gag he[60] would have made the window of an East Side gents’ furnishing store drop the curtain. The Candy Butcher didn’t mix in much with the men in the outfit. He had a chemical moustache that he zephyred with a velvet voice, and he was always aces with the ladies. When Section One was pulling out for a long Sunday jump, be sure of Him for the day coach with the girls. He was good at that, and, while he didn’t always make a landing, he managed generally to get his bowline fast to the pier before the current caught him.

He always wore his coat in the meal tent, but he took it off right after supper and carried it on his arm. The make-up didn’t miss the ulster much, for he had on a vest that was three strikes and out for rainbow colors—one of those rum omelette tinted things that a Philadelphia button buyer puts on for Saturday night when he’s waiting at the stage door for some spotlight Sadie. He was there with the cheap tailors, all right.

The squatters on the ring bank were just settling for the afternoon gab while the equestrian director, sore because he couldn’t get away to keep a date, was rearranging[61] the horse acts with a piece of a pencil on the back of the night’s card. The Candy Butcher came through a crevice in the tent and stopped to talk to the Saw Dust Spreader, who was standing behind the wardrobe basket pulling on his plush pants.

“What you dressin’ for?” said the Candy Butcher.

“Oh, they’re gettin’ cheap,” said the Saw Dust Spreader. “I’ve got to double for an object holder, an’ I’m up for the leaps right after the entree.”

“What do you care,” said the Candy Butcher, “long as peppermint is striped?”

Then he laughed at his own little trade journal joke. He was full of those. He was always reading song books and joke budgets when waiting to get up on the blue boards to sell tickets for the concert after the show. He came across the track and joined the gang.

“Gee!” said the Side Show Spieler, who was always good on the opening line, “youse dressed up for fair tonight! Looks like youse goin’ to a birthday party.”

“Not for me,” replied the Candy Butcher, as he put another piece of gum under the mustache. “Cut out the parties[62] for Willie in the Summer an’ after this in the winter no more front parlor talks for me after ma is in bed an’ the old man is out in the cold switchin’ down in the railroad yard.”

“Sore again,” said the Concert Manager; “you’ve always got your kick comin’ on sumthin’.”

“Well, I wouldn’t,” said the Candy Butcher, “but you fellows is allus runnin’ me in when it comes to any girl talk. Say, I ain’t the masher of this outfit, take it from me. If I could do the look killin’ an’ have ’em runnin’ me like the boy what does the principal bareback—the popcorn and the soft drinks—well, no more for Jamesie.”

The gang sort of warmed up to this talk, so he let her out another notch and began.

“Say,” he continued, “youse fellows is allus lookin’ for sumthin’ soft. Well, say, I’ve got a game for this season that will kill ’em. No more kicks over the lemonade tub for me. I’ve got ’em all skinned on the sour juice game. Say, you may not know it, but it’s a losin’ game when you’r runnin’ to one-nighters and sellin’ lemon juice. It looks good to see[63] me hollerin’ over the chunk of ice an’ takin’ in the half dimes while I’m passin’ out the cold drink an’ the peanuts; but, say, you never thought how many of them nicks it takes to buy a box of lemons. All right, all right in the city, bo’, for the yellow boys, but when you are run out in the meadows it’s diff’rent, diff’rent.

“So, says I, during the winter when I’m managin’ me penny arcade wid the talkin’ machines, says, ’ll get up a scheme that will make the lemons back to the shady groves for you, no more fore me. An’, say, I gits me think tank on it and I invents sumthin’. Say, you’ll laugh, but I pulled it off this afternoon, an’, say, they all fell for once.”

“What is it, Bill?” asked the Old Grafter, always ready for a new shot at the purse.

“‘What is it?’ Well, say! You know how them guys is stringin’ you about fake lemonade, ’cause you ain’t got no yellow slices floatin’ on the top of the tub. Well, what is you goin’ to do when lemons is 45 per, an’ even the barkeeps is usin’ the acid for the sour. Well, me, I just has a dozen lemon slices made out of celluloid, an’, say, Bill, you can’t tell ’em from the[64] real, ’pon my word, boy, when they is floatin’ aroun’ in the tub after I has poured in me water, me citric acid and me sugar. Why, say, it looks like one of them things at a Fresh Air give-out, where everything is dun on the level, ’cause the reporters is watchin’. I jes’ works me celluloid slices on the stan’, an’ when biz is dun wipes ’em off, puts ’em in the box, an’ theyse jes’ as good as new, an’ there’s more comin’ to the Dime Savin’ for Will, an’ that’s no song book wit.”

The crowd eyed him in silence with that awe that meets a pack of undergraduates when they first gaze upon the man who discovered some new chemical analysis they never expect to understand.

The Saw Dust Spreader joined the crowd just then looking like a cheap leading man in a ten and twenty “Carmen,” with the red pants and the little coat. It was he for gossip, so he broke in.

“Yes, you’re pretty good,” he said to the Candy Butcher, remembering the laugh he got when he came across the tan bark. “But, say, where was you all last week? No lyin’ now, Willie, ’cause I’m on, dead on.”

“Well, I dunno that it’s any secret,” said the Candy Butcher. “I dun me duty an’ I suffered for it.”

The gang looked like a listening party, so he began to reel:

“Say, it’s pretty tough when a fellow starts out to do the right thing by a little lady and gets the flag. It jes’ shows that whenever you gits to dreamin’ good somebody is goin’ to give you an alarm clock finish an’ let you wake up with a shriek. Remember two seasons ago, when we was workin’ the Congress of Nations gag in the manager’s tent? Well, me it is who meets a little lady who is doin’ the bead stitchin’ in the gypsy village. She’s a pretty little thing an’ quietlike. Well, she seems lonesome like an’ one wet night I carries her across the lot when the mud is up to your knees. She seems to like it an’ we has a long talk in the car.

“It seems that she used to work in a bean place where she is called Number 8. I thinks that is funny, so I allus calls her Number 8.

“Seems like her folks was sore on her for troopin’, an’ she comes to me for sympathy. Well, she had me stoppin’ the booze before we was two weeks out, an’ I[66] was gettin’ quiet in me gab and cuttin’ down on the swear talk. She tells me the way she gets into the circus is that a big guy what was engagin’ people for the Congress used to eat his butter cakes at her table, an’ he keeps on tellin’ her what a fine life it is to be an actress, an’, as he has been readin’ about it in books, she throws up the waitin’ job and joins out. The big guy gets half of her first week for the gettin’ her the job.

“But it seems that when Number 8 pulls out of the bean place that she breaks the heart of the guy with the white cap that cooks the buckwheats in the window. He’s been sweet on her from the first day she hollered the hot cakes an’ he pulls ’em off the griddle an’ looks into her eyes. Well, this guy takes a solemn oath that he’ll kill the bloke that makes his Mamie give up waitin’ an’ go troopin’. He never gets next to the big jay what gave her the job, but when he was doin’ the big city he sees me chasin’ her home every night. He gives me a look I don’t like, an’ I asks Number 8 what it means.

“‘Oh, don’t mind him’ she says, ‘he used to belong to my euchre.’

“Now, if I’d been wise I’d a-known Number 8 was connin’, for what did that little fairy know about euchre parties? I knows now that she was pullin’ off some speech she heard in the theatre where the lady shoots the dook across the card table because he brings the coachman into the parlor to get a drink while the other dook is sayin’ his good-by speech. I is too sweet on the fairy then to know that she’s connin’ me.

“Well, jes’ the last week we was playin’ New York, who does I meet in the park lookin’ at the fish but Number 8. She looks so sweet an’ nice that it all comes back, an’ me up an’ speaks. She says sorter haughty:

“‘Who are you, sir? Whom are you addressin’?

“Say, that hit me like a blast, when all of a sudden I get a welt across the head wid sumthin’ that is iron. Say, I falls, but is up, and though the knock has given me the blood, I see that it’s the guy what cooks the buckwheats in the window who was tryin’ to do the killin’. An’ say, he has run out of his bean place an’ hit me wid the cake turner. I grasps him, an’ it’s catch-as-catch-can, an’ Number 8 screamin’[68] on the bench. I gives him a couple of good ones when in a jiffy it’s rainin’ plates an’ coffee cups, an’ I’m gettin, ’em on the face. Say, his whole gang from the bean shop was out in their white coats, throwin’ the crockery an’ me gettin’ it.

“I knows the show is shut up an’ help is a long way off. Somebody yells, ‘Lick the brute,’ an’ I gets another pie plate in the eye.

“‘What’s he done?’ says a cab driver.

“‘He insulted me wife,’ said the buckwheat cake man.

“I tried to explain, but he gives me another one with the cake-turner an’ I’m on the asphalt.

“I’se gettin’ it good, an’ I sees I must get help or cut the season for the city ward. So I yells ‘Hey, Rube!’

“Well, what do you think? There was a couple of old tramps a-sleepin’ on a bench, an’ when they hears me scream, me on me back wid the buckwheat man sittin’ on me, I sees ’em move, I yells it again, an’ one of them wearies says:

“‘That sounds familiar-like to me.’

“‘Hey, Rube!’ I gives it again, an’, say, they gets in, an’ they put that waiter gang into a pile that looks like a hash brown in a spill.”

“Well, what happened to you?” said the Canvasman, who was always there for the battle tales.

“Me, say, I gets it all. A couple of dinnys pulls me to a box, an’ in the cell all night for me. An’, say, if it hadn’t been for James A., Lord bless his soul, me to the island for winter quarters an’ in stripes.”

“But what becomes of the fairy?” says the Saw Dust Spreader, who always likes to know the finish.

“What becomes of her?” says the Candy Butcher, feeling a couple of scars. “I hears it all later. She had married the guy an’ moves over to Jersey. He’s keepin’ a saloon, an’ she’s cookin’ the oysters. He gives one with every drink.”

The manager of the concert company looked like a Methodist minister going to see the bishop. He wore a high silk hat and a last-winter’s double-breasted coat. Whenever he talked he held the hat in one hand and rubbed it with the other so that it looked like a clipped yearling at a country run off. His voice was a deep bass, and when he did the “remember good people the Big Show is not yet ’arf over” from the elevated stage you could gamble on the words hitting every ear.

He was sitting on the ring bank looking over his touch list when the conversation grew wavy and then dropped to a hush.

“This here tent business is pullin’ down to a theatrical man,” he said as he lighted a choked stogie. “Give me the hall show every time for the cush and comfort an’ I’ll be easy an’ shippin’ in money to the backer if the bookin’s is good. The rep[71] shows is the thing me boys if you can deliver, an’ you can strike territory that ain’t been ploughed to death by a lot of yellows.

“Had out a rep company that was a winner. We was playin’ ‘East Lynne’ and doin’ it good with six people and a band on the balcony at 7 to 8. The way we threw them dramatic chunks into the ten, twenty and thirts was sumthin’ remark’ble. We wasn’t connin’ neither, but givin’ ’em a show that had ’em weepin’ from ring up to las’ curt’n. Say, I had a leadin’ lady that was the genuine. She had been up three times before the school commissioners for declaimin’ an’ her old man thought she was a Mary Anderson. We joshed him along on the Mary Anderson gag an’ the old guy checked in with a five hundred for a starter to get the fit up and the gal’s costumes. Say, she was a blonde with a figure that set the town hall tonight people on the road to ruin with all brakes off. The leadin’ man was a cuff juggler and he wouldn’t settle down, but he doubled in props an’ was all right. The heavy was one of those chesty boys who was alles givin’ me the jab ‘when I was with Booth.’ He started out all right,[72] all right in the first act, but he died out before the curt’n got down; the old man was pretty rotten, thank you, but the way he could play an E flat cornet on the balcony was sumthin’ strictly proper. I’m jes’ tellin’ youse what you can do with a lot of bum players, if you’ve got the goods, an’ youse gets the bookin’s. I was workin’ the crowd on a $300 salary an’ playin’ up into the gross on $750 a week an’ livin’ like the man what owns his lay out. But I let go.

“You see some of the managers down on the coal oil circuit in Central Pennsylvania got the vaudeville bug and was yellin’ for specialties. So I gets the soubrette to do a rag time stunt between the second an’ third, an’ the first night the gal’ry window jumps nine and a half to the good. I says that’s what they wants an’ I keeps the specialty in for good. But the Lady Isabel of the push was getting artistic an’ she says no to the specialty. I says yes, an’ her old man comes on an’ says Mary Anderson didn’t have no gal singin’ and showin’ her legs in her show, so me an’ the old guy plays quits. Well, it was gettin’ warm, so I picks up me little soubrette, gets a privilege at a fair an’[73] starts in to do the black tent. We had a little round top, blacker on the inside than a Bow’ry alley. The game was to get the yaps inside, all lights out, flash the calcium, an’ then do the floatin’ illusion. The little gal would float roun’ the tent an’ hand me out roses, and the gang would go daffy. You see she was rigged up in one of these white gowns an’ was chasin’ round in a back flap stickin’ her head and body through wherever I had a slit. But I has a good lime light man an’ the payin’s never coupled to the con.

“It was good for thirty a day and the privilege was cheap, but say, the finish was tragic. You see the gal had run off from home, where she was makin’ three dollars spinnin’ yarn in a mill an’ payin’ her people two fifty board. She gets stuck on the show business an’ goes out with a rep, where I picks her up. Well, it seems that her old man gets sort o’ dippy ’cause he didn’ do the right thing by the little one an’ started out to fin’ her. Somebody tells the old boy she is dead an’ he falls down for a while. But he gets up and goes wanderin’ ’bout to all the shows lookin’ for the gal. Well, he gets into my show one day an’ when we flashes[74] the illusion there’s a yell an’ the old one says, ‘me daughter, me daughter,’ and the gal flops an’ breaks up the show. She gets sorry an’ goes home with the gray hair an’ I loses the graft and strikes this.”

The Boss Canvasman started in to do a little cussin’ because the round top over the stage was sagging and he broke up the talk.

But the Press Agent wants the finish of the yarn, and he speaks up:

“Well, Pop, what became of the gal?”

“Oh,” says Pop, “the old man goes under the ground an’ the jig stepper goes back to the business. Last season she was doublin’ with the iron chested man doin’ a singin’ specialty in the side show. But they’s both out now. The iron chested man is yellin’ the stations on the Ninth Avenue L, and the Mamie girl is makin’ ten a week posin’ for chromos that you wouldn’t hang over the thermometer, s’ help me.”

The man who sold the red paste-boards at the ticket wagon always dressed better than the man who owned the circus. He ran largely to striped vests and wore shirts that were of the sassiest shade of pink. Like the Candy Butcher, he never wore his coat when he was working, but the vest and the trousers made him a swell enough picture. The rest of the outfit regarded him with the same awe that fills the spirit of a man earning twelve dollars a week who accidentally runs into J. Pierpont Morgan. To be sure, the Ticket Seller never had as much cash as the Wall Street man, but he made a bigger flash. He always carried a roll, and as his accounts never failed to balance and he stood good with the Boss, it was generally presumed that the gold boys he carried in his upper vest pocket were his own.

The gang that talked on the ring bank between the afternoon and the night show[76] had great respect for this member of the outfit. He had a line of talk that sounded big, and that was always inspiring to the crowd. He knew just what the Big Show was taking in, and he liked to talk about it. He talked figures, and the ring bank crowd only knew it by the thousands of people that roosted on the blue boards when the bill was being run off under the main top. In the winter months, when the Big Show had gone to quarters, the Ticket Man managed a burlesque house in Chicago, and it was said that he wore so many diamonds on the pink bosom that it wasn’t necessary to turn on the lobby lights when the night audience was coming in. He was a loud boy, all right, but he backed the noise with coin. When the Ticket Man wasn’t talking about money, he let loose a bunch of racing talk that would have feazed the principal writer on a daily turf sheet. He used words that seldom got farther than the paddock, and he picked winners like a diamond expert getting out the real shines from a pile of glass.

And with both lines of talk he had ’em all faded when it came to the con. He had a line of explanations that would[77] make any man think he threw down a two-spot when he knew that he walked up to the window with a double X.

“Lemme tell you fellows sumthin’” he said, as he came in after supper in the meal tent and sat down for a smoke. “You’se can always hear a lot of knockin’ for the boys what sells in the wagon. Now take it from me, don’t youse believe a word of it till youse gets the other side. You hear a lot of hollerin’ that ev’rybody is gettin’ done, and that the boys in the wagon is buyin’ gov’ment bonds and furnishing flats on the short change graft. But it ain’t so—not altogether. It was in the old days, when I started in the business, but it ain’t now. Graftin’ is dead, take it from me.”

“Yes,” said the Old Grafter, with a deep sigh, “you’re right, Bill, graftin’ is dead, an’ it was a sorry day for me when it died.”

“You’re right, Jim; half way right, but it won’t go these days. But what I’m tellin’ you is right; when you is sellin’ hard tickets to a long line that is rushin’ to get to the tent, youse can’t go out and have a personal interview with every man that runs away an’ leaves his change on[78] the window. An’ say, whose goin’ to take chances givin’ it up when he does come back? Not me, not me; I see me little bank-roll in the Dime Savin’s lookin’ like a busted baloon on the end of the season. Say, don’t make no mistake, ev’ry hand at the window is a hand ag’in’ you. I know what I’m talkin’ about. There ain’t a man in the country who don’t think he’s doin’ a smart trick when he beats a circus man out of money. They’ll all do you when they can. Mark my word. I’ve been passing out hard tickets with this outfit for nine years an’ long before that with a fly-by-night, an’ I knows the game—ev’ry hand that comes up to that window will do you if it can. I’ve had too many Reubs hand me a two-dollar bill an’ say it was a tenner.”

“What do you do then?” asked the Concert Manager.

“Do?” said the Ticket Man. “Do? Why, I’d just look Reuben in the eye an’ say Brush on, haysy, you ain’t got a ten; wait till you sell your wheat an’ come back an’ then I’ll gamble with you.”

“It’s all right now, dead square an’ on the level, but youse know what it was in the graftin’ days,” he continued, as he[79] wiped the dust off his patent leathers with a horse plume. “We turned the season them days with a bunch of money that was all our own, and nobody kickin’. I was out with a little graftin’ show that had more gamblin’ on one lot than a county fair, an’, say, I wasn’t takin’ no chances with them grafters an’ tinhorns! I knowed the countries would buy their tickets before they went at the games, an’ say, I wasn’t overlookin’ my bit.

“Me an’ the fixer stood pat. He travelled three days ahead, an’ had it all squared with the Mayor of the burg and the police so the games could go on an’ no kick. Well, he would get hold of a smart lookin’ constable, take him aroun’ back of the courthouse and give him a talk. The constable likes it bein’ taken into the confidence of a showman, an’ lets ev’rybody see it, ’cause he’s proud.

“Well, the fixer sez, ‘You’re a smart lookin’ young man; you do me a turn when the show comes, an’ if the Boss likes you, he may take you along for Chief Detective!’

“Say, that hits the Reub so hard, that Chief Detective talk, and for three days he’s seein’ visions of hisself flashin’ his[80] tin all along the line. Well, he reports to me, and I gives him instructions and a ten-dollar bill, with promise of a five after the show if he does his work. I posts him in front of the window, and has him fixed to butt in when there’s any kick, an’ say, ‘No arguments; keep movin’, gentlemen!’

“An’ he does it good, and I throws the short change, an’ with the band a goin’ in the tent and the crowd crazy to get at the games, I picks out a little bag of coin before the tinhorns lands on the roll. An’ me helper, who was a bit of a mechanic, he takes the sill of the window in the wagon and tilts it with the slant to the inside. A guy comes along and throws up a dollar bill, and says give me one. With one hand I throw down the ticket, an’ with the other throw up two quarters, or a quarter two tens and a five. They hit the glass, an’ say, with that slant some of it was sure to come back, an’ Mr. Man is in too big a hurry for the Big Show to notice, an’ the constable, who’s to get the five, keeps ’em movin’. At night the constable says he wants to have a private conversation an’ takes me off.

“‘Look a here,’ sez he, ‘that agent ahead of the circus sez if I could do the work I might be made chief detective.’

“Not a word, keep quiet, says I. You’ll spoil it.

“The constable don’t just get next, but it soun’s good. ‘See that man over there?’ sez I. Constable looks aroun’ an’ sees the big boy that allus stood by the gate an’ who wasn’t no more of an officer than me.

“Well, sez I, that man has been watchin’ you. He’s Mr. Pinkerton himself, and as soon as he makes out his official report to Superintendent Byrnes you gets the job. He thanks me an’ I give him the fivespot. He goes home an’ tells ev’rybody for the names I spring was so good he didn’t see through the con. But, of course, I’ve got to give the fixer a bit. An’ say, that’s the trouble with graftin’. You’ve got to fix too many people to keep from gettin’ a holler. But none of it now. I stick to what I says, that ev’ry hand that comes up to the window is a hand ag’in’ you, and will do you if it can. You’re goin’ to get short change, all right, but don’t do no old-fashioned graftin’. I tell you there’s[82] only one way to get it honest, an’ if the band is playin’ while you’re sellin’, it will keep your line movin’ at the window, an’ it’s a poor evenin’ you can’t pick up fifteen at least that was left and nobody hurt. Of course, I calls them back—but I never could holler loud.”

The Ticket Man took out a solid gold watch, with a stop movement, and his initials in diamonds on the back.

“Well, guess I better get at it,” and he left and went to the ticket wagon, where on the inside he sat on a little stool with the tickets in one hand and the change on the other side.

Then the hands began to come up and he was at work again.