THE AUTHOR.

DAY BY DAY WITH

THE RUSSIAN ARMY

1914-15

BY

BERNARD PARES

Official British Observer with the Russian Armies in the Field

WITH MAPS

LONDON

CONSTABLE & COMPANY Ltd.

1915

TO

NICHOLAS AND MARY HOMYAKOV

For the last ten years or more I have paid long visits to Russia, being interested in anything that might conduce to closer relations between the two countries. During this time the whole course of Russia's public life has brought her far nearer to England—in particular, the creation of new legislative institutions, the wonderful economic development of the country, and the first real acquaintance which England has made with Russian culture. I always travelled to Russia through Germany, whose people had an inborn unintelligence and contempt for all things Russian, and whose Government has done what it could to hold England and Russia at arm's length from each other. I often used to wonder which of us Germany would fight first.

When Germany declared war on Russia, I volunteered for service, and was arranging to start for Russia when we, too, were involved in the war. I arrived there some two weeks afterwards, and after a stay in Petrograd and Moscow was asked to take up the duty of official correspondent with the Russian army. It was some time before I was able to go to the army, and at first only in company of some twelve others with officers of the General Staff who were not yet permitted to take us to the actual front. We, however, visited Galicia and Warsaw, and saw a good deal of the army. After these[Pg x] journeys I was allowed to join the Red Cross organisation with the Third Army as an attaché of an old friend, Mr. Michael Stakhovich, who was at the head of this organisation; and there General Radko Dmitriev, whom I had known earlier, kindly gave me a written permit to visit any part of the firing line; my Red Cross work was in transport and the forward hospitals. My instructions did not include telegraphing, and my diary notes, though dispatched by special messengers, necessarily took a month or more to reach England; but I had the great satisfaction of sharing in the life of the army, where I was entertained with the kindest hospitality and invited to see and take part in anything that was doing.

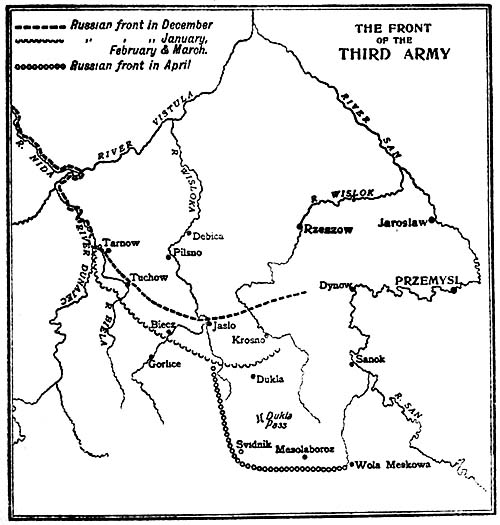

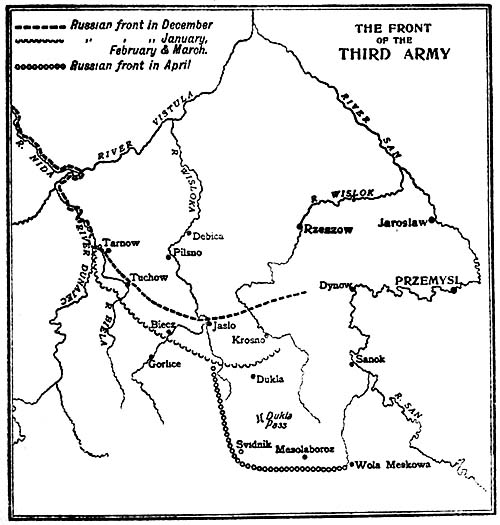

The Third Army was at the main curve in the Russian front, the point where the German and Austrian forces joined hands. It was engaged in the conquest of Galicia, and on its fortunes, more perhaps than on those of any other army on either front, might depend the issue of the whole campaign. We were the advance guard of the liberation of the Slavs, and to us was falling the rôle of separating Austria from Germany, or, what is the same thing in more precise terms, separating Hungary from Prussia. I had the good fortune to have many old friends in this area. My work in hospitals and the permission to interrogate prisoners at the front gave me the best view that one could have of the process of political and military disintegration which was and is at work in the Austrian empire. I took part in the advanced transport work of the Red Cross, visited in detail the left and right flanks of the army, and went to the centre just at the moment when the enemy fell with overwhelming[Pg xi] force of artillery on this part. I retreated with the army to the San and to the province of Lublin. My visits to the actual front had in each case a given object—usually to form a judgment on some question on which depended the immediate course of the campaign.

I am now authorised to publish my more public communications, including my diary notes with the Third Army. I am also obliged to the Liverpool Daily Post and Mercury for leave to reprint my note of September 1914 on Moscow. I think it will be seen that if we lost Galicia we lost it well, and that the moral superiority remained and remains on our side throughout. We were driven out by sheer weight of metal, but our troops turned at every point to show that the old relations of man to man were unchanged. The diary of an Austrian officer who was several times opposite to me will, I think, make this clear. When Russia has half the enemy's material equipment we know, and he does, that we shall be travelling in the opposite direction.

It was a delight to be with these splendid men. I never saw anything base all the while that I was with the army. There was no drunkenness; every one was at his best, and it was the simplest and noblest atmosphere in which I have ever lived.

Bernard Pares.

July-August 1914.

While the war cloud was breaking, I was close to my birthplace at Dorking with my father, whom I was not to see again. Though eighty-one years old he was in his full vigour of heart, mind and body, and we were motoring every day among the beautiful Surrey hills. He had had a great life of work for others, born just after the first Reform Bill which his own father had helped to carry through the House of Commons, and stamped with the robust faith and vigour of the great generation of the Old Liberals. Like every other interest of his children, he had always followed with the fullest participation my own work in Russia, and I had everything packed for my yearly visit there. In London I had had short visits from Mr. Protopopov, a liberal Russian publicist, and later from the eminent leader of Polish public life, Mr. Dmowski, than whom I know no better political head in Europe. Both had expected war for years past, but neither had any idea how close it was. Mr. Protopopov was absorbed in a study of English town planning and Mr. Dmowski was correcting the proofs of his last article for my Russian Review, which he ended with the words, "The time is not yet." He[Pg 2] came down and motored with us through what he called "the paradise of trees"—and Poland itself has some of the finest trees in Europe; and my father was keenly interested in his hopes for the future of Poland. He was going to the English seaside when events called him back to an adventurous journey across Europe, in the course of which he was twice arrested in Germany, the second time in company of his old political opponent, the reactionary Russian Minister of Education, the late Mr. Kasso. To them a German Polish sentry said that as a Pole he wished for the victory of Russia, for "though the Russian made himself unpleasant, the Schwab (Swabian or German) was far more dangerous."

When I read Austria's demands on Serbia, I felt that it must mean a European war, and that we should have to take part in it. I remember the ordinary traveller in a London hotel explaining to me how infinitely more important the Ulster question was than the Serbian. It was clear that the really mischievous factor was the simultaneous official and public support of Germany, who claimed to draw an imaginary line around the Austro-Serbian conflict and threatened war to any one who interfered in the war. I had long realised the humbug of pretending that Austria was anything distinct from or independent of Germany; and the claim of the two to settle in their own favour one of the most thorny questions in Europe could never be tolerated by Russia. The Bosnian withdrawal of 1909 would, I knew, never be repeated, least of all by the Russian Emperor. The line had been crossed; it was "mailed fist" once too often.

[Pg 3]Serbia's reply showed the extreme calm and circumspection both of Serbia and of Russia. Then came in quick succession the great days, when every one's political horizon was daily forced wider, when all the home squabbles of the different countries—the Caillaux case, the Russian labour troubles, and the Irish conflict, on which Germany had counted so much—were hurrying back as fast as possible into their proper background. There was a significant catch when the Austro-Russian conversations were renewed, and Germany, who had now come out in her true leadership, went forward to the forcing of war. The absurd inconsequences of German diplomacy reached their extraordinary culmination in the actual declaration to Russia. To make sure of war, the German ambassador in St. Petersburg received for delivery a formal declaration with alternative wordings suitable to any answer which Russia might give to the German ultimatum; and this genial diplomatist delivered the draft with both alternative wordings to the Russian Foreign Minister, Mr. Sazonov. It is the last communication printed in the Russian Orange Book.

The question was, how soon we should all see it. The news of the German declaration was in the English Sunday papers. Many English clergymen see virtue in not reading Sunday papers. I went to church. The clergyman began his sermon: "They tell me that the Sunday papers assert that Germany has declared war on Russia." Not a very promising beginning, but England was there the next minute. "If this is true," he went on, "and if we come into it, as we shall have to, we stand at the end of the long period when we have[Pg 4] been spoiling ourselves with riches and comfort and forgetting what it is to make sacrifices"; and there followed an impromptu but very clear forecast of what was to be asked of us.

No one will forget the great days of probation, when each great country in turn was called on to stand and give whatever it had of the best. Russia was what one had felt sure that she would be. The Emperor's pledge not to make peace while a German soldier was in Russia, was an exact repetition of the words of Alexander I, but given this time at the very beginning of the war. The wonderful scene before the Winter Palace showed sovereign and people at one; and the wrecking of the German Embassy was an answer of the Russian workmen to an active propaganda of discontent that had issued from its walls. Next came France's turn, her remarkable coolness and discretion, and the outburst of patriotic devotion which the President of the Chamber voiced in the words, "Lift up your hearts" (Haut les cœurs). Then the turn of the Belgians, king and people, and their splendid and simple devotion. And now it was for us to speak.

I believed that we were sure to come into the war, but it was three days of waiting and the invasion of Belgium that gave us a united England. The Germans did our job for us. It was a quick conversion for those who hesitated; one day, neutrality to be saved; the next, neutrality past saving; the next, war, and war to the end. When we were waiting before the post office for Sir Edward Grey's speech, every one was asking, "Have they done the right thing?" This was[Pg 5] the atmosphere of the London streets on the night that we declared war. We all lived on a few very simple thoughts. It was clear that there must be endless losses and many cruel inventions, but just as clear not only that we had to win but that, if we were not failing to ourselves, we were sure to.

I was in London before our declaration to ask what I could do, and was now making my last preparations for starting. The squalor of the great city had taken the aspect of a dingy ironclad at work. At the Bank of England, where payment could still be claimed in gold, I was asked the object of my journey. No one seemed to know about routes except Cook & Son. In the country the mobilisation passed us silent and unnoticed, except for the aeroplanes which we saw streaming southwards. I saw my father in his garden for the last time, went to London, and there, in a confusion of little things and big, with a taxi piled in haste with parcels of the most various nature and ownership, hurried to King's Cross, bundled into a full third-class carriage and started for Russia.

August 21.

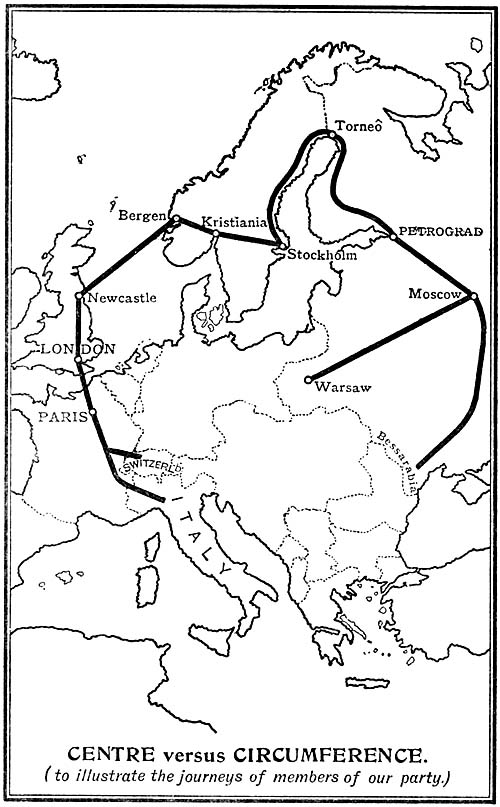

At King's Cross I was already almost in Russia. The sixty or so Russians who had come to the Dental Congress in London, after one sitting had been caught by the war. Their English hosts looked after them splendidly, and they themselves pooled the supplies of money which they happened to have on them. There were also several members of the Russian ballet, and other Russians on their way from Italy, Switzerland and France, going[Pg 6] via Norway and Sweden to St. Petersburg. Our route of itself was a striking illustration of the great military advantage possessed by Germany and Austria. With its interior lines of communication, the great German[Pg 7] punching machine could measure its forces to any blow which it wished to deal on either side, while for any contact with each other the Allies had to crawl right round the circumference. For this military advantage, however, the aggressors had sacrificed in the most evident way all political considerations. In a quarrel which Austria had picked with Serbia, Germany forced war on Russia for daring to mobilise. Germany made an ultimatum to France at the same time, so as to make war with both countries simultaneously and give herself time to crush France before Russia could help her. For greater speed against France, she invaded neutral Belgium, thus making England an enemy and Italy a neutral. The absurdity became apparent when, with all this done, we were still waiting for the completion of the Russian mobilisation which was the nominal cause of the European War. Hence the union of so many peoples; but for all that the military advantage remained. It was as if Europe had the stomach ache, with shooting pains in all directions.

I asked a friend in the train what might be the state of mind of the Emperor William. He replied by quoting the answer of an Irishman: "He's probably thinking, Is there any one that I've left out?"

At Newcastle, the Norwegian steamer had booked at least forty more passengers than it could berth. I only got on to the boat by a special claim and had to sleep in a passage with my things scattered round me. All the corridors were taken up in this way. The Russians are admirable fellow-passengers: they had organised themselves informally under a natural leader into a[Pg 8] great family. One corridor was set apart for a night nursery. The women received special consideration, and any one who had a berth was ready to give it up to them. One Russian, thinking I was ill, offered me his. I was ensconced with my back to the wall at the head of a staircase, and they would stop to chat as they went up or down. They had been greatly impressed by the spirit in England: the Englishman they regarded as a civil fellow who had better not be provoked, for if he was he would get to business at once and not look back till it was finished. They spoke very simply of themselves and of their little failings, and said that for this reason it was the greatest comfort to have England with them. What had impressed them most was the calm and vigour with which we had faced our financial crisis. They had seen some of our territorial troops, whom they classed very high for physique and spirit. They had much to tell one of France and Italy, and also of insults offered to them or their friends when leaving Germany. There were outbursts of sheer hooliganism marked with a sort of brutal contempt for Russians, and one lady, they said, had the earrings torn out of her ears. Their humanity was shocked by all this. They had nothing but condemnation for anything of the kind, from whatever side it came, and they were quite ready to criticise their own people or ours wherever there was any ground for doing so.

The captain said to me, "We sail under the protection of England." We were stopped once by an English warship, but only for a few minutes. At Bergen I found new fellow-passengers, and after an evening which was a succession of fiords, lakes, rocky heights and[Pg 9] white villages, we passed by a wonderfully engineered railway over the snow level and down to Kristiania. The Norwegians were friendly and sympathetic, the Swedes courteous but reserved. There had recently been unveiled a frontier monument showing two brothers shaking hands; and one felt that the one country would not move without the other.

Between Kristiania and Stockholm I wrote an article on the Poles, and directly afterwards, puzzling out a Swedish newspaper, I read the manifesto of the Grand Duke Nicholas. We had with us Poles who were travelling right round to Warsaw. From Stockholm the more apprehensive members of our party went northward for the long land journey by Torneô. The rest of us risked the voyage across the Gulf of Bothnia. In the beautiful Skerries, we were at one point sent back by a Swedish gunboat and piloted past a mine field. I was on a Finnish boat, which was fair prize; so I had an interest in any ship that showed itself on this hostile sea. When we reached Raumo, a little improvised port in Finland, there was an outburst of relief for those who had come so far and were home again at last. All classes joined and enjoyed the home-coming together. The train picked up detachments of Russian troops on their way to the war. I had no seat, and went and slept or drowsed for an hour or two in a carriage full of soldiers. As I lay on a wooden bench I listened to a young peasant recruit with a bright clear face who was talking to his mother. It seemed to be a kind of fairy tale that he was telling her, and the clearly spoken words mingled with the movement of the train: "And he went again to the[Pg 10] lake, and there he found the girl, and there was the golden ring, the ring of parting."

Petrograd.

I shall not dwell on the six weeks or so that I spent in St. Petersburg. My time was taken up with a number of details and with arrangements for getting to the front. I had volunteered for the Red Cross when I was asked to serve as official correspondent.

On my arrival I saw Mr. Sazonov, who spoke very simply about the overdoing of the mailed fist; he was as quiet and natural as he always is. He was very pleased with the mobilisation, which he told me had been so enthusiastic as to gain many hours on the schedule. This was the account that I heard everywhere. Mr. N. N. Lvov, of Saratov on the Volga, one of the most respected public men in Russia, was at his estate at the time. When the news of war came, the peasants, who were harvesting, went straight off to the recruiting depot and thence to the church, where all who were starting took the communion; there was no shouting, no drinking, though the abstinence edict had not then been issued; and every man who was called up, except one who was away on a visit, was in his place at the railway station that same evening. In other parts the peasants went round and collected money for the soldiers' families, and even in small villages quite large sums were given. The abstinence edict answered to a desire that had been expressed very generally among the peasants for some years. It was thoroughly enforced both in the country and in the towns. In the country the savings banks[Pg 11] at once began steadily to fill, and the peasants, who would speak very naïvely of their former drunkenness, hoped that the edict would be permanent. In the towns some few restaurants were for a time still allowed to supply beer, but this ceased later. In all this time I only saw one drunken man.

The whole country was at once at its very best. After a mean and confused period every one saw his road to sacrifice. The difference between the Russians and us was that while this feeling, often so acute with us, could often find no road, in Russia, with her conscription and her huge Red Cross organisation, the path was easy. All the life of the country streamed straight into the war; age limits did not act as with us; and the rear, including the capital, was depleted of nearly every one. This made one feel that no good work could be done here without access to the army. Nearly all my friends were gone off, and I was anxious to join them.

The interval was filled with different lesser interests. The question of communications between the Allies was engaging a great deal of attention. I was a member of a committee at the Russo-British Chamber of Commerce, which was working out arrangements for trade routes. My English friends and I also tried to plan an exchange of articles, asking leading Russians and Englishmen to write respectively in English and Russian papers. But, though this was felt to be important, we broke down on the Russian side, because those who wished to write for us were swept away to war work at the front. In the rear the most important work was the relief of the families left behind. This engaged a number of devoted[Pg 12] workers and was soon brought into very good order both at St. Petersburg and at Moscow, but it was in the main a task for women.

At the outset of the war the aged Premier, Mr. Goremykin, whose political record was that of a benevolent Conservative, at once saw the need of engaging the full co-operation of the nation as a whole. After consultation with public leaders the Duma was summoned. A few representative speeches were expected, but with a remarkable spontaneity not only every section of political opinion, but every race in the vast Russian empire took its part in a striking series of declarations of loyalty and devotion. Each man spoke plainly the feelings of himself and those for whom he spoke. Perhaps no speeches left a greater impression than those of the Lithuanians and of the Jews; these last found a noble spokesman in Mr. Friedmann. The speeches in the Duma, which were circulated all over the country, were a revelation to the public and to the Duma itself; and the war thus had from the first a national character; it was a great act in the national life of Russia.

In particular it was found that the Red Cross work could not possibly be organised on any basis of suspicion of public initiative. In the Japanese War Zemstva were still suspect to the Government, because they represented the elective principle. The Zemstva created a large Red Cross organisation under the admirable Prince George Lvov, but it worked under great difficulties. Now Mr. Goremykin confided the main work of the Red Cross to Prince Lvov and the Zemstva; and almost every one prominent in Zemstvo or Duma life engaged in this[Pg 13] work, which gave splendid results. The later attempt of the reactionary Minister of the Interior, Mr. Maklakov, to close this organisation ended in his resignation.

Red Cross Zemstvo work meant the nationalisation of Russian public life, which had so long been under the strong control of reactionary German influences. The liberation from these influences was sealed by the re-naming of the capital. The German name, St. Petersburg, was exchanged for the Russian Petrograd. This was no fad. It was the fitting end to a long struggle of the Russian people as a whole, under a national sovereign, to develop itself independently of any mailed fist, to manage its own affairs as Russian instincts should direct.

In Moscow in 1812 the Emperor met his people after the beginning of the war. Gentry offered their lives; merchants, with clenched fists and streaming eyes, offered one-third of all their substance. In 1914 the Emperor again went to pray with his people in Moscow, and the growth of a still greater Russia has only augmented those proportions, deepened the reach of that historic example of patriotic self-sacrifice.

"Russia," said one of the best Russians to me, Mr. N. N. Lvov, "was lost in a confusion of petty quarrels and intrigues; and suddenly we see that the real Russia is there."

The pleasant streets of this great country city, so far more homelike than those of the capital, we found even more country-like than ever; a notable absence everywhere of young men; the feeling that all those who were left were at work somewhere together.

In the town hall, which I have always found so[Pg 14] thronged and busy, none of the chief public men were to be seen; the work of all seemed to have passed to the new department opened close by for the town organisation in connection with the Red Cross. There, after a long wait while numberless applicants for service passed us, we received an admirably short and clear explanation of the work for the wounded. In the same building was organised the care for the poor, strongly developed in recent years at twenty-nine local branches, and now working wholesale and with splendid effect for the homes of those who have gone to the war.

At the Zemstvo League there was the atmosphere of all the years of missionary work for the people that has been carried on in camping conditions for so many years by the Zemstvo in all sorts of country corners of Russia. Every one was moving quietly and quickly about his share of the common business. At the big green baize table every seat was occupied—here a woman of the poorer class volunteering as a Red Cross sister, there a medical student asking for service. Small conferences of fellow-workers going on in all the side rooms; and in the evening a common discussion of how the Zemstvo work could be carried further to the economic support of the population; an appeal is being drawn up to go to every one in Russia. Here I found the excellent "twin" secretaries of the President of the Duma, Mr. Shchepkin and Mr. Alexeyev, who have done so much for friendship with England, and the head of the whole Zemstvo League, Prince Lvov, who in a few simple words gave all the objects of the work for the wounded, who were expected to number 750,000.

[Pg 15]Next we were taken to the chief depots. Princess Gagarin has given her beautiful house for one, and now lives in a corner of it, helping at the work. There are two main departments for paid work and for unpaid. Patterns of all the clothes, pillows, and hospital linen required for the wounded are sent here, and the material cut out is given out to 3,200 women, some of whom stand in a long file in the court outside. Every day the store, which works till midnight, is cleared for a new supply, and the materials prepared are packed in cases of birch bark for the army. In the Government horse-breeding department there is another great depot under the direction of Princess O. Trubetskoy. The workers, rich and poor, all have their simple meals together in one of the working rooms. There is a large store of chemicals, and elsewhere a department for the supply of furniture and implements for the field hospitals.

It would be hard to make those who cannot see it feel how intimately the Russian people now feels itself bound up with the English in a great common effort. The Rector of Moscow University, with whom I was only able to converse by telephone, said to me: "Tell them in England that we have one heart and one soul with them."

Every day great numbers of wounded are brought by train to Moscow. By the admirable arrangements of Countess O. Bobrinsky, a vast number of students, young women, and helpers of all kinds are waiting for them at the Alexandrovsky station to assist in moving them and to supply them with refreshments. An enormous silent crowd surrounds the white station. The owners[Pg 16] of motors are waiting ready with their carriages; all details are in order. Three trains come in between six and ten o'clock. The sight is a terrible one; faces bound up, limbs missing; some few have died on the journey. The wounded are moved quickly and quietly to the private carriages. As they pass through the crowd all hats are off, and the soldiers sometimes reply with a salute. It is all silent; it is the pulse of a great family beating as that of one man.

October 8.

The Emperor's visit to the Vilna was a great success. He rode through the town unguarded. The streets were crowded, the reception most cordial. The upper classes in Vilna are mostly Poles, a kind of Polish "enclave." There are several splendid Catholic churches. On the road to the station are gates with some revered Catholic images, before which all passers by remove their hats. There is a large Jewish trading population often living in extreme poverty: for instance, sometimes in three tiers of cellars one below another. The peasants are mostly Lithuanians. Thus there are not many Russians except officials. At the beginning of war the nearness of the enemy was felt with much anxiety. Now there is an atmosphere of work and assurance. The Grand Hotel and several public buildings are converted into hospitals, where the Polish language is largely used. The Emperor visited all the chief hospitals, and spoke with many wounded, distributing medals in such numbers that the supply ran short. He received a Jewish deputation and spoke with thanks of the sympathetic attitude of the[Pg 17] Jews in this hour so solemn for Russia. The general feeling may be described as like a new page of history. Among Poles, educated or uneducated, enthusiasm is general. This is all the more striking because in no circumstances could Vilna be considered as politically Polish. Vilna shows all the aspects of war conditions, but the country around is being actively cultivated.

October 10.

We reached the Russian headquarters as the bugle sounded for evening prayer. The atmosphere here is one of complete simplicity and homeliness. Our small party includes several distinguished journalists from most of the chief Russian papers, also eminent French, American and Japanese representatives of the Press. We found the Grand Ducal train on a side line. It was spacious and comfortable but simply appointed. We were received by the Chief of the General Staff, one of the youngest lieutenant-generals in the Russian army. He is a strongly built man with a powerful head, whose carriage and speech communicate confidence. He spoke very simply of the military conditions, of the common task, and of his assurance of the full co-operation of the public and Press. The Grand Duke then entered, his light step, bright eye and imposing stature well shown up by his easy cavalry uniform. Shaking hands with each of us, both before and after his address, he said: "Gentlemen, I am glad to welcome you to my quarters. I have always thought, and continue to think, that the Press, in competent and worthy hands, can do an enormous[Pg 18] amount of good. I am sure you gentlemen are just the men who by your communications through the papers, telling all that is most keenly interesting, and by your correct exposition of the facts, can do good both to the public and to us. I unfortunately and necessarily cannot show you all I should be perhaps glad to show, as in every war, and particularly in this stupendous one, the observing of military secrecy relative to the plan and all that can reveal it is the pledge of success. I have marked out a road on which you will be able to acquaint yourselves with just what is of most lively interest to all, and what all are anxious to know. Allow me to wish you success and to express to you my confidence that by your work you will do all the good which is expected of you as representatives of the public, and will calm relations and friends and all who are suffering and anxious. I welcome you, gentlemen, and wish you full success." We were invited to join in the lunch and dinner of the General Staff in their restaurant car. There were no formalities—it was simply a number of fellow workers having their meals together, without distinction, just as in the big houses in Moscow where the making of clothes for the army is proceeding. A notice forbids handshaking in the restaurant, under fine of threepence for the wounded. I noticed a street picture of the Cossack Kruchkov in his single-handed combat with eleven German Dragoons, also a map of the front of the Allies in the West, but hardly any other decorations. Among the party there was, in accordance with the temperance edict, no alcohol.

[Pg 19]October 12.

To-day I visited several wounded from the Austrian front, mostly serious cases. The first, an Upper Austrian with a broken leg, spoke cheerily of his wound and his surroundings. He described the Russian artillery fire as particularly formidable. His own corps had run short of ammunition, not of food. Another prisoner, a young German from Bohemia, singularly pleasing and simple, described the fighting at Krasnik, where he was hit in the leg. The battle, he said, was terrible. The Austrian artillery here was uncovered and was crushed. The Russian rifle line took cover so well that he could not descry them from two hundred yards in front of his own skirmishing line, but its firing took great effect. I saw also an Austrian doctor taken prisoner, and now continuing his work salaried by the Russians. All three prisoners evidently felt nothing antagonistic in their surroundings. They struck me as men who had fulfilled a civic duty without either grudge or any distinctive national feeling. I spoke with several Russians who had been badly hit in their first days of fighting, especially at Krasnik. Here a young Jew fell in the firing line on a slope, and saw thence more than half of his company knocked over as they pressed forward. He was picked up next morning. A Russian described how his company charged a small body of Austrians, who retired precipitately to a wood but reappeared supported by three quickfirers which mowed down most of his company. All accounts agreed that the Austrians could never put up resistance to Russian bayonet charges. This was[Pg 20] particularly noticeable in the later fighting. As one sturdy fellow put it, "No, they don't charge us, we charge them, and they clear out." I was most of all impressed by a frail lad of twenty who looked a mere boy. He was not wounded, and was sent back simply because he was worn out by the campaigning. He said, "They are firing on my brother and not on me. That is not right, I ought to be where they all are." One feels it is a great wave rolling forward with one spirit driving it on.

Many of these wounded had only been picked up after lying for some time on the field. I saw one heroic lady, a sister of mercy, who had herself carried a wounded officer from the firing line. Both the hospitals that I visited were strongly staffed. In the second, designed only for serious cases, and admirably equipped with drugs, Roentgen apparatus and operating rooms, the sister of the Emperor, the Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna (who went through the full two years' preparation) is working as a sister of mercy under all the ordinary discipline and conditions of travel and work. Starting at the outbreak of the war, she was in time for the tremendous pressure of the great Austrian battles, when the hospital had to provide for three hundred patients instead of the expected two hundred. All the arrangements in these hospitals, based on fifty years' experience of Russian country hospital work, were carried out under the most difficult conditions and bore the impression of missionary devotion. Here, for instance, all the medicine chests were adapted for frequent transport; the table is also the travelling chest, and so on.

The country aspect was also noticeable in an army[Pg 21] bread factory which I visited. The rye bread is dried to a portable biscuit; the soldier can carry a large supply of this biscuit and has something to eat in the firing line when other provisions run short.

Lvov (Lemberg), October 15.

To-day, on their arrival, the Russian Governor-General of Galicia received the correspondents, and addressed us as follows—

"I am glad, gentlemen, to meet you; I am well aware of the enormous advantage that can be derived from the use of the Press, and am only sorry that you are to be for so short a time in Galicia, for I should like you to have had the opportunity of studying on the spot the difficult questions of administration: you might have communicated to me your impressions and suggestions—for in your capacity of writers you are trained critics. We have to deal in Galicia with various nationalities, and very divergent political views.

"I shall be glad if I can be of any assistance in your study of the country. I have already communicated to various deputations, and to the public, the principles of my attitude toward the problems of administration, and have no alterations to make in my declared views.

"Eastern Galicia should become part of Russia. Western Galicia, when its conquest has been completed, should form part of the kingdom of Poland, within the empire. My policy as to the religious question is very definite. I have no desire to compel any one to join the Orthodox Church. If a two-thirds majority in any[Pg 22] given village desires to conform to the Orthodox Church, then they should be given the parish church. This does not mean that the remaining third should not be free to remain in its former communion. I am avoiding even any suggestion of compulsion. The peasants pass over very easily to Orthodoxy; for them the question is in no way acute, indeed the so-called Uniats consider they are Orthodox already. But it is different for the clergy, for whom the question is a real one. I respect all the priests who have remained in their parishes, and they have not been disturbed. Those who have abandoned their benefices I am not restoring: nor shall I permit the return of any who are associated with any political agitation against Russia.

"A difficult question has arisen relating to Austrian officials in the town of Lvov: from persons of means they have now become paupers requiring assistance. Another question is that of credit: numbers of banks are without their cash, which has all been taken away to Vienna. These banks are sending a deputation to Petrograd to solicit the support of the Bank of Russia.

"There is also the question of the police. I am waiting for trained policemen to be sent from Russia: it is impossible, of course, to use untrained men for administrative work, and meanwhile I contrive to employ the local Austrian police. Some magistrates have fled—we have to put the affairs of justice in order: I am awaiting a representative of the Ministry of Justice, who will examine the question.

"In certain regions around Lvov, Nikolayev, Gorodok and other places where there has been severe fighting,[Pg 23] the population has been left in a state of great distress. In Bukovina, however, there is little distress, except in the towns; and as the crops there are good, we are importing food into Galicia from thence. The relief of distress is being dealt with by committees, including prominent local residents, under the Directors of Districts, and controlled by a central committee, whose chairman is Count Vladimir Bobrinsky. In cases of extreme distress it is being arranged that money may be advanced to the necessitous.

"I have established in Galicia three provinces: Lvov (Lemberg), Tarnopol, and Bukovina. Perhaps we may establish another province, following the line of demarcation of the Russian population, which on maps of Austrian Poland is admitted to include parts of the region about Sanok (in central Galicia)."

October 24.

I have spent some days in the Austrian territory conquered by the Russians. The Russian broad gauge has been carried some distance into Galicia, and the further railway communication with the Austrian gauge and carriages is in working order. The large waiting-rooms were covered with wounded on stretchers with doctors and sisters of mercy in constant attendance. They utter no sound, except in very few cases when under attention. One poor fellow, a bronzed and strapping lad struck through the lungs, I saw dying; he looked so hale and strong; his wide eyes kept moving as he gasped and wrestled silently with death; he seemed so grateful to those who sat with him; he died early in the morning.[Pg 24] I talked with three Hungarian privates, keen-eyed and vigorous. They said their men were very good with the bayonet and seldom surrendered, a statement which was confirmed by a Russian cavalry officer who had just returned from fighting in the passes, though it seems the Hungarians do not consider the war as national beyond the Carpathians, and they fight well because they are warlike and not because they like this war. The prisoners with whom I talked were very energetic in praising their treatment by the Russians, which is indeed beyond praise. Everywhere they met people with tea, sugar, and cigarettes. One said repeatedly, "I can say nothing," and another said, "I cannot but wish that we may do as well by them in Hungary." These were the only Austrian prisoners in whom I have seen a trace of that national enthusiasm for the war which is so evident in all the Russian soldiers. I talked with two Italians, simple, friendly fellows who described their treatment as pulito, or very decent.

The Slovenes and Bohemians seemed rather in a maze about the whole thing. A Ruthenian soldier of Galicia was quite frank about it. "Of course we had to go," he said, but he expressed pleasure at the Russians winning Galicia, and even regarded it as compensation for his wound.

I saw off a train of Russian wounded. They were most brotherly and thoughtful for each other. An Austrian patient told me he was happy and had made great friends with the Russian next to him. The electric trams are used for ambulances, and the chief buildings are turned into hospitals. The biggest is in the Polytechnicum, and[Pg 25] is served practically by Poles. The big Russian hospital of the Dowager Empress is very well equipped. The Red Cross organisation is in the hands of eminent public men; such as Homyakov, Stakhovich and Lerche, who visited England with the party of Russian Legislators in 1909. Count Vladimir Bobrinsky, another member of that party, is chairman of the relief committee appointed by his cousin the Russian Governor-General of Galicia. The town is old and pleasing, set in undulating country. It is in excellent order. A little sporadic street firing was quickly suppressed. All inhabitants throughout the conquered territory must be at home from ten in the evening till four unless they have special permission. How well this rule is kept one could judge when returning from the station. No one was out except Russian sentries and Austrian policemen, who have been continued on their work. Otherwise one sees no signs of a conquered town.

The day the Russians entered, the Polish paper issued its morning edition under Austrian control and its evening edition under Russian. The electric lighting and tramways continued working and the shops remained open. The fighting, which was most severe, was all outside. But even on the sites of engagements the amount of damage done by artillery is limited to few places and few houses, and cultivation is now going on, without any signs of war, close up to the present front. A general order forbids the leaving about of any refuse. There is no friction between the Little Russian peasants and the troops or the new administrators; but the Jews adopt a waiting attitude. The general position is a great credit to the[Pg 26] Russians, and gives ample proof of their close kinship with the great majority of the conquered population.

October 26.

I have visited some of the battlefields of Galicia. It is much too early to attempt any thorough account of these battles; nor did the conditions of my visits make any complete examination possible.

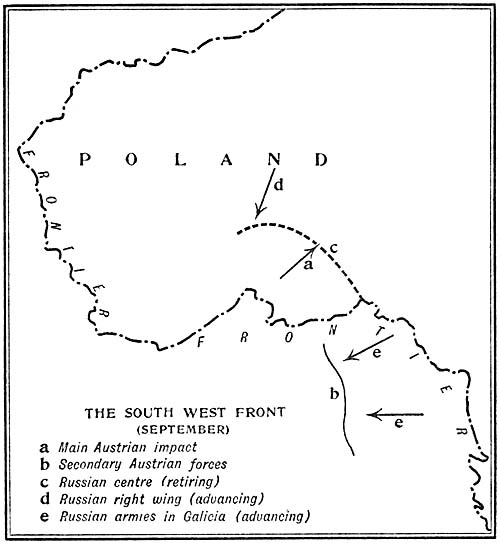

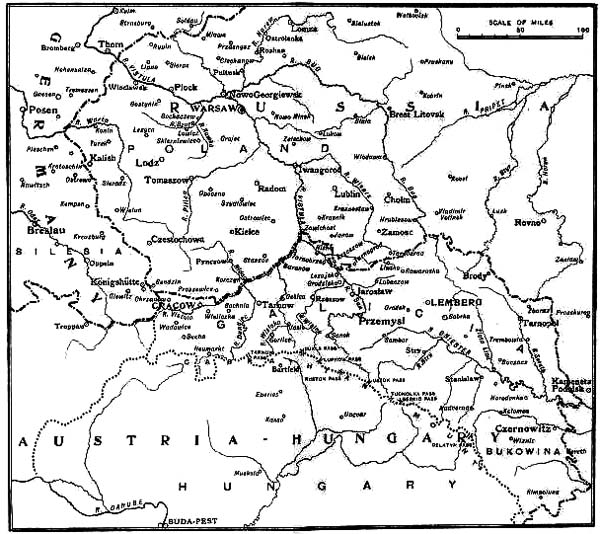

The chief harm which Germany and Austria could inflict in a war against Russia was to conquer Russian Poland, whose frontier made defence extremely difficult. Regarding this protuberance as a head, Germany and Austria could make a simultaneous amputating operation at its neck, attacking the one from East Prussia and the other from Galicia. But the German policy, which had other and more primary objects, precipitated war with France and threw the bulk of the German forces westward. Thus the German army in East Prussia kept the defensive, and Austria was left to make her advance from Galicia without support.

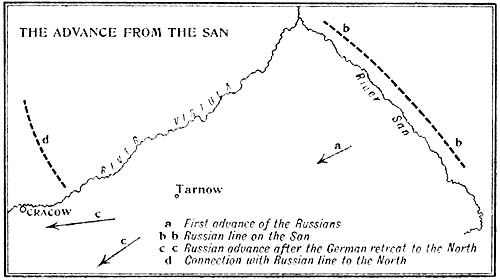

The Austrian forces on this front were at first more numerous than the Russians. The Russians had been prepared to defend the line of the Bug, which would have meant the temporary abandonment of nearly all Poland. But the alliance with France and England made it both possible and desirable to advance, and at the battle of Gnila Lipa the army on the Austrian right was driven back beyond Lvov (Lemberg), the town falling into Russian hands. The next great fighting was for the possession of the line of the river San.

It must be remembered that while the fighting lines ran roughly from north to south, the frontier line here ran from east to west. Thus the left of each force occupied the territory of the other. The first decisive success had been that of the Russian left in Galicia; but the Austrian left and centre were still allowed to advance further into Russian Poland. A double movement was then undertaken against them. While General Brusilov pushed home in southern Galicia the success already obtained on this side, and thus secured the Russian left flank from a counter-offensive, General Ruzsky, the conqueror of Lvov, came in on the Austrian centre at Rava Ruska,[Pg 28] while other Russian armies, detached from the reserves standing between the Russian northern and southern fronts, and making good use of the advantageous railway connexion, arrived to the north of the Austrian left. Seldom has a tactical battle been planned on so large a scale. The Austrians, threatened at this point with outflanking on both sides, after several days' hard defensive fighting, withdrew with a haste that had the character of a rout, and which only saved them from complete annihilation. Their centre, like their already beaten right, retired southwards toward Hungary, while their left, just escaping the peril of being surrounded, fell back rapidly in the direction of Cracow, where it was strengthened by further support from Germany. Two German corps had already joined it, but too late to avert the reverse already described. The success of Brusilov at Gorodok (Grodek) secured to the Russians the line of the river San as far as Peremyshl (Przemysl).

This series of operations, after the Russian evacuation of East Prussia necessitated by the strong German movements on the northern fronts, left Russia with the following line of defence: the Niemen, the Bobr, the Narev, the middle Vistula, the San (to Peremyshl) and the Carpathians. This line includes the larger part of Russian Poland, the city of Warsaw, and western Galicia, with its capital, Lvov. This line is infinitely more satisfactory than that of the Bug. Its security on the south depends in part on the action of Rumania, but a counter-offensive from Hungary has already been repulsed on this side. On the north, attempts of the Germans on Grodno and on Warsaw have been triumphantly repulsed; and[Pg 29] the Russians have since fought with success along almost the whole line; a serious German and Austrian effort is to be anticipated on the middle Vistula and the San.

I have so far visited only Galich (Halicz), the junction of the Stryi (Stryj) and Dniestr, and the battlefield of Rava Ruska. Galich was at the south of the first Austrian line of defence. The Dniestr here presents from the north-eastern side a concave front, defended by extensive wire entanglements and trenches, and, behind the river, by low but jutting hills. The town, which lies on a ledge between these hills and the river, bears the distinctive Russian character and possesses an ancient Russian church, now Uniat, and a remnant of an early Russian tower. There is no doubt of the Russian-ness of Galich; the only inhabitants whom one sees besides the picturesque Little Russians are the numerous Jews. There was nothing to indicate nearness of the enemy, and complete order prevailed, the Russian authorities being evidently chiefly concerned with the newness of their work and the task of organisation. Friendly relations were maintained between the troops here and the inhabitants; and the only violences of which there was local evidence were those committed by Austrian soldiers before the evacuation of the town. In spite of the strength of the position, no serious resistance was offered here. The Russians appeared unexpectedly at a point on the north of the river, taking in reverse the Austrian field works at this point. They shelled the neighbouring township with extraordinary accuracy, destroying only the houses in the middle and leaving standing the two churches and a third spired building, the town hall. The Austrians then retired[Pg 30] rapidly over the bridge, which they blew up, and evacuated Galich.

At the junction of the Dniestr and Stryi we also found deep trenches, some six feet deep and three feet wide. The tower at the bridge head, commanding a wide, flat outlook, had suffered but little. The railway bridge had been blown up. Here, too, there were no signs of serious resistance. At a railway junction in the neighbourhood there were again striking signs of the accuracy of the Russian artillery fire, only a distant portion of the station building having suffered. Close by lay a very handsome French chateau belonging to the Austrian General Desveaux, who was connected with the Polish family of Lubomirski. The interior of this chateau had been systematically wrecked by the Little Russian peasants of the locality, the top torn off the piano, family portraits defaced, sofa and chairs destroyed, and the bare floor covered with a thick litter of valuable sketches and pictures, among which I noticed a map of the Austrian army manœuvres of 1893. I heard here and in other places of the violences committed against the peasants by the Austrian troops on their passage, the inhabitants being often left entirely destitute. The Ruthenian troops in the Austrian army were in a very difficult position: in several cases they fired in the air; and the attacking Russians would sometimes do the same, on which numbers of the Little Russians would come over to them. The Cossacks who preceded the Russian army offered no violence here, I was told, except where villagers told them untruly that the Austrian troops had left the village; with such cases they dealt summarily. They were also sometimes[Pg 31] drastic, though not necessarily violent, with the local Jews, who in Galicia have held the peasants in the severest bondage, leaving only starvation wages to the tenants of their farms and exacting daily humiliations of obeisance.

My examination of these questions could only be very short; but the general picture obtained was, I think, in the main correct, because it was confirmed by much that I have heard from the soldiers of both sides; and it is clear that the Russians considered themselves to be at home among the Ruthenians of Galicia, whose dialect many of them are able to talk with ease. One thing was clear: namely, that there was no friction in the parts which I visited, except with the Jews, and that life was going on as if the war were a thousand miles away instead of almost at one's doors.

Our visit to Rava Ruska presented much greater military interest; we drove round the south, east, and north front of the Russian attack on this little town, and very valuable explanations were given by an able officer of the General Staff. On the southern front, near the station of Kamionka Woloska, where there were lines of trenches, the deep holes made by bursting Russian shells and sometimes filled with water, lay thick together.

The eastern front was more interesting. Here there were many lines of rifle pits, Austrian, Russian, or Austrian converted into Russian. The Austrian rifle pits were much shallower and less finished than the Russian, which were generally squarer, deeper and with higher cover. An officer's rifle pit just behind those of his men showed their care and work for him, as was also indicated in[Pg 32] letters written after the battle. Casques of cuirassiers, many Hungarian knapsacks, broken rifles, fragments of shrapnel, potatoes pulled up, and such oddments as an Austrian picture postcard, were to be found in or near the rifle pits. These wide plains, practically without cover, were reminiscent of Wagram. A high landmark was a crucifix on which one of the arms of the figure was shot away; underneath it was a "brother's grave" containing the bodies of 120 Austrians and 21 Russians. Another cross of fresh-cut wood marked the Russian soldiers tribute to an officer: "God's servant, Gregory." Close to one line of trenches stood a village absolutely untouched, and in the fields between stood a picturesque group of villagers at their field work, one in an Austrian uniform and two boys in Austrian shakos.

The hottest fight had been on the north-eastern front. Here, after a wood and a fall of the ground, there came a gradual bare slope of a mile and a half crowned by two Austrian batteries which lay just behind the crest. This ground had been disputed inch by inch and was seamed with some five or six lines of rifle pits. At one point three Russian shells fired from about due east had fallen plump on three neighbouring rifle pits, and fragments of uniform all round gave evidence of the wholesale devastation which they had worked. All the ground was cut up with deep shell pits, and this place, which was a kind of angle of the defending line, must have become literally untenable. The pits for the Austrian guns still contained a broken wheel and other relics, and close by was a cross made of shrapnel.

The impressions which most defined themselves from[Pg 33] this battlefield were the almost entire absence of cover, the exposed position of the rifle pits, the deadliness of the Russian artillery, the toughness of the resistance offered, and lastly the thunder of cannon from some thirty miles away, which was sounding in our ears all the time of our visit to the field of Rava Ruska.

We did not pursue our journey further along the northern positions. In the market place we saw an angry scramble of a large number of Jews over some sacks of flour; and in a wood outside we passed a strong, masterful old Jew with dignified bearing striding silently with his two sons over his land, a sight which is hardly to be seen in Russia. The Jewish land-leasers here sometimes take ten-elevenths of the profits, as contrasted with the two-thirds which the leaseholder takes in Russia. Distant hills to the north marked the old frontier of Russia.

From narratives of soldiers a few characteristics of all this fighting may be added. The attack was throughout delivered by the Russians, even where their numbers are inferior. The men are full of the finest spirit, and they have the greatest confidence in their artillery, though the proportion of field guns to a unit is less numerous on the Russian side than on the German or Austrian. When given the word to advance, the Russians feel that they are going to drive the Austrians from the field and go forward with an invincible rush. They say that less resort is made to the bayonet by the Austrians and by the Germans. In the rifle fire of their enemies they find, to use the expression of one of them, "nothing striking," the one thing that commands their respect is the heavy artillery, but the Russian field artillery has had a marked[Pg 34] advantage. Small bodies of Austrians have made repeated use of copses to draw advancing Russian companies on to their quick-firing guns, which have sometimes done deadly work. Cavalry has played but an insignificant part in the fighting.

But the most impressive thing of all is the extraordinary endurance of the men in the trenches. It is a common experience for a man to be five to eight days in the trenches in pouring rain, almost, or sometimes altogether without food, then perhaps to rush on the enemy, to fall and see half his comrades fall, but the rest still going forward, to lie perhaps through a night, and then to the hospital to lose a limb: and yet, spite of the reaction, such men are not only patient and affectionate to all who do anything for them, but really cheerful and contented, often literally jovial and always in no doubt of the ultimate issue.

There are no two accounts of the spirit in the Russian army. One feels it as a regiment goes past on foot or packed into a train, with one private tuning up an indefinite number of verses and the rest falling into parts that give all the solemnity of a hymn. It draws everything to it; so that no one seems to feel he is living unless he is getting to the front; the talk of all those who are already at work, whether officers or men, is balanced and confident, and all little comforts are shared simply as among brothers. I saw a little boy of twelve with a busby looking as large as himself, an orphan who performed bicycle tricks in a circus, and had now persuaded a passing regiment to let him come with them, and seemed to have found his family at last.

[Pg 35]All the life of Russia is streaming into the war, and never was the Russian people more visible than it is now in the Russian army.

October 30.

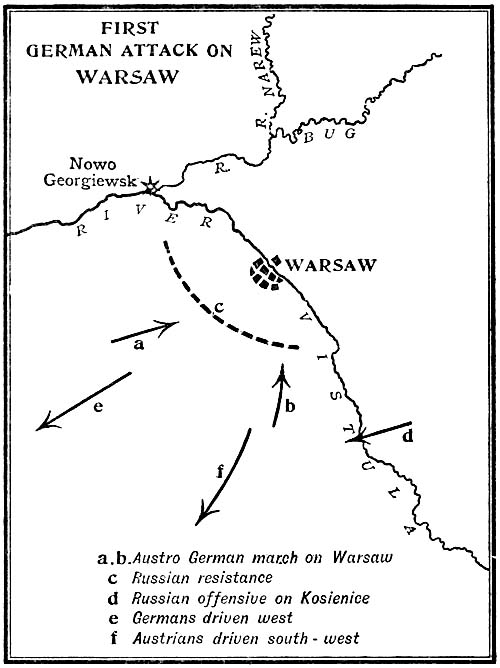

I have spent some days in Warsaw and have examined the scenes of the recent fighting as far out as beyond Skiernewice. The Russian river line of defence ran along the Niemen, Bobr, Narew, middle Vistula and San. The Germans had not previously seriously tested the strength of the centre of this line, and Russian reports issued had so far only spoken of a northern and a southern front.

Warsaw lay beyond the defensive river line. A rapid seizure of the city before winter set in would have greatly strengthened the Prussian northern front and have endangered the Russian occupation of Galicia. It would also have created a moral effect on the Poles and might have served as a support to any proposals to negotiate.

The Germans advanced principally from the south-west, a region largely left in their hands. German army corps reached a line south-east of Blonie, and at Pruszkow they were little more than six miles from Warsaw. The cannonade shook the windows in the city. German aeroplanes dropped bombs near the railway bridge, Etat Major and elsewhere, killing over a hundred persons but not achieving any military object. The population were much exasperated, and many went out to the scene of the fighting. The brunt of the defence fell on two Russian corps, especially on one containing Siberian troops which had to oppose three German corps. Splendid work was done at Pruszkow and also by a Siberian regiment[Pg 36] at Rakitna. Here the Germans, covered by woods and gardens, delayed the Russian advance and placed machine guns on the roof of a high church. The inhabitants say that the Siberians long refrained from returning the fire from the church. The regiment lost its colonel and many officers and 275 men, but held good till reinforced. Several Russian corps arrived, and the Russians then drove the Germans back in successive rearguard engagements which lasted for eighteen days. Another regiment specially distinguished itself at Kazimierz and received a telegram from the Commander-in-Chief, congratulating it on a brilliant bayonet attack. Two days ago it drove back the enemy with the bayonet through a wood, inflicting heavy loss. The Germans retired rapidly in the night south-westward. The country up to several miles west and south of Lowicz and Skiernewice has now been recovered.

The Germans in these operations seized provisions and some valuables and committed some minor indignities, but the country has in no way an aspect of devastation. The population is strongly for Russia and offers every service to the Russian soldiers. In Warsaw great enthusiasm prevails, with a very striking difference from the attitude before the war and the Grand Duke's appeal. The Germans during their withdrawal made clean work of bridges, railways, and stores. There was every sign of a deliberate and well-executed retreat. Fewer prisoners were taken than in the case of the Austrians, the wounded being mostly carried away. The Russian artillery worked with great precision and effect, and the Russian infantry, after artillery preparation, attacked throughout.

[Pg 37]There is no sign of any likelihood of a further German aggressive on this side before winter, but there is always the possibility of an early conflict southward, where the Russians need to secure and complete their conquest of Galicia, and the enemy have to guard their base of joint action between Germany and Austria.

October 30.

My visits to the scenes of fighting in the Warsaw area have been of interest. The main scene of the most critical fighting, Pruszkow, we did not visit. The Germans tried to force their way up here from the south, close to the Vistula, and got to within some nine miles from Warsaw. If they had captured the town (about 900,000 inhabitants, of whom 300,000 are Jews), and occupied the Vistula bridges, they would have established an enormous political and military advantage, which could not have been reversed without the greatest difficulty. Though Warsaw was beyond their line of defence, the Russians made every effort to hold it.

We visited a point in the centre of the line of defence, where the Russians held good under heavy losses; their rifle pits were close up to a copse and gardens, and they had tried to secure a footing even closer in. From thence their line ran in a convex curve to Rakitna. Here their artillery had battered in the sides of the lofty and impressive church, leaving standing the woodwork of the roof and two irregular pinnacles. The Germans fired from this church; they had confined several of the inhabitants in the vaults. The buildings near the church were reduced to ruins. Close up against the village lay[Pg 38] graves of the attacking Siberian regiment, marked by lofty well-cut orthodox crosses, the men lying together under a vast regular mound and Colonel Gozhansky and six of his officers under separate crosses at the base, while at the head stood one great cross for all the dead of the regiment. The inscriptions were throughout in almost identical language, ending: "Sleep in peace, hero and sufferer." In a small garden close by, the Germans had buried their dead so rapidly that some of them were still uncovered. On two neighbouring crosses they had paid their tribute to "six brave German warriors" and to "six brave Russian warriors." Through a great hole in the ruined church one caught sight of a crucifix, untouched but surrounded with marks of shot in the wall. In the neighbouring township of Blonie, the town hall had been set on fire.

Blonie, which was the northern point of the line of battle, lies about eighteen miles due west of Warsaw; from thence runs an excellent broad chaussée, embanked and lined with poplars, going straight westward towards the frontier. At Sochaczew the high bridge over the river was broken off clean at both ends and the central supports entirely destroyed, but there were few other marks of war. At Lowicz the bridge had been destroyed and, as at Sochaczew and Skiernewice, had been very rapidly repaired by the pursuing Russians. Lowicz lies in flat country, through which the rivers make deep furrows. It is a clean and picturesque little place, with a symmetrical central square flanked by large buildings and with the fine parish church at the western end. The Poles of this part wear very distinctive[Pg 39] national costumes; the women have skirts in broad and narrow vertical stripes, with orange, or sometimes red, as the foundation of colour, the narrow stripes being usually black, purple and yellow; round their shoulders they wear what look like similar skirts, fastened with ribbons at the neck, and they have variegated aprons, in which the foundation colour of the dress is absent; the general impression in the fields or on the sky line is of a mass of orange. The old men wear grizzled grey overcoats and broad-brimmed hats, and the younger men elaborate and tight-fitting costumes that suggest a groom of the eighteenth century, or loose zouave blouses and trousers of blue or other colours. Houses in the villages are spacious and plastered white, with sometimes a certain amount of decoration, usually in blue. At Lowicz there were some marks of war. My host for the night, an old soldier from Orenburg who had served under Skobelev, spoke with indignation of the recent German occupation; they had taken all the supplies that they could find. But there were no signs of any permanent occupation, and the German requisitions could not have been very thorough, as one saw many geese, pigs and, above all, very fine horses in this part, and the inhabitants had quite settled down again to their ordinary occupations. From such accounts as I have read of the conditions in Germany, I should think that one would see there fewer young and middle-aged men and less field work going on than in this no-man's land that has lain between the two hostile lines of defence and has been traversed by each army in turn.

[Pg 40]From Lowicz to Skiernewice there runs south-westward a chaussée and also a more direct road that passes through an area of sand and mud. Napoleon used to say that in his campaign of Poland (1807) he had discovered a fifth element—mud. There is no other obstacle, the broad undulating plains suggesting parts of the north of France; combining lights and shades, they offer scope for the artist, and the long lines of well-to-do villages have a pleasing effect that is enhanced by the graceful local costumes. The peasants are well built and good featured, often with a military air and carriage; their manners are excellent, and their intercourse with the Russian soldiers is both courteous and cordial. They were at any time ready to come and help in the frequent breakdowns of our motors, and I noticed, to my surprise, after experiences of other years in Warsaw, that they felt no difficulty in understanding Russian and in making themselves intelligible to us. At some points on our road there were marks of rearguard fighting, and as we were told, two or three wounded, but we saw hardly any prisoners, except a body of Landwehr men, and no trophies. At the village of Mokra (which means "damp") the houses still bore the ordinary German chalk marks assigning the billets to given numbers of men. At Skiernewice the coal stores at the station had been fired and were still burning: but the town was comfortably held by the Russians, and we found no difficulty in the matter of supplies and quarters. Skiernewice will be remembered as one of the last stopping places in the Russian empire on the road from Moscow to Berlin, and also as a former meeting place of the three emperors.[Pg 41] It has great preserves for pheasants, which are only touched during the visits of the Sovereign. There is the usual central square of Polish houses, and here, as in Sochaczew, the Jews were in evidence, though they have been removed from some military centres where they have given assistance to the enemy. From Skiernewice we travelled a considerable distance south-westwards, passing over a fine military position carefully prepared by the Germans, and commanding a view of some ten miles to the north-east, but abandoned without any sign of resistance. At every point we met the picturesque-looking peasants returning to their now recovered homes.

At a low-lying village we saw vedettes riding to and fro, trains of supplies, vans of the Red Cross being loaded with wounded, and in front of the poor thatched cottages a line of deeply hollowed trenches, from which rose a colonel, a simple homely man in workday uniform, to offer us part of the repast. There was the strong family feeling typical of any gathering of Russians. We passed along the line chatting with the men; a young colonel galloped up to invite us to visit his guns; but we turned to a nearer battery, of which the old commander did us the honours. These men were from a military province in the heart of Russia, and their faces passed into a broad friendly grin as they stood to their guns for us, sat to be photographed at their tea-drinking, and told the story of their last fighting. They had been firing for all the last two days. At about half a mile lay a copse on a hill, at first held by the Germans, and behind it a long wooded ridge near which were German rifle pits. The[Pg 42] German artillery put up a cross fire from both sides. Their shells had done very little damage. The Russian infantry charged up the nearer slope and drove the Germans with the bayonet through the copse. Here there were more than three hundred German dead; among them boys of thirteen and fourteen, whose soldiers' pay-books gave their ages. One officer remained standing just as the blow had caught him. In the night the Germans had rapidly withdrawn and were now several miles away.

On a bare slope to the right of the battery stood an infantry regiment, which in eighteen days' fighting had been reduced to about half its strength. As we approached, we saw it drawn up under arms and in a hollow square. A priest was preaching. He was arrayed in rich blue vestments, which showed up in the dull earthen colour of the slope and of the soldiers. His strong handsome features and long hair recalled pictures of Christ. His deep voice carried without effort to the ranks in the rear. As I approached, he was saying, "Never forget that wherever you are and whatever is happening to you the eye of God is on you and watching over you." After the sermon followed prayers, a band of soldiers at his side, led by a tall Red Cross soldier, joining in the beautiful other-world chants of the Eastern Church; they were trained singers and sang just as in church, without any accompaniment and with perfect balance and rhythm, the tall soldier conducting them very quietly with his hand. At one point, the prayers for the Emperor, all crossed themselves. All fell on their knees again at the prayers for the Russian troops,[Pg 43] for the armies of the Allies and that God should give them every success. Once more all knelt at the prayers for their slain comrades, while the beautiful "Eternal memory" was chanted by the little choir. The rest of the service was standing; the men remained firm and motionless, in fixed and silent attention. There were impressive moments when the priest placed a little Gospel, bound in blue velvet, on an improvised lectern of six bayonets crossed in front of him, and when turning to all sides shadowed the men with a little gold cross which he waved slowly with both hands. After the service the Colonel stepped forward and with a quick movement called for the salute to the flag, and every musket was raised with a dull rattle that sounded out over the vast open space under the grey sky. Next he read out in a loud clear voice a message from the Commander-in-Chief congratulating the regiment on the brilliant bayonet attack at Kazimierz, and called out: "For Tsar and country, Hurrah!" This cheer rose like low thunder and died away in distant peals. Some twenty to thirty men had received the cross of St. George for personal bravery, and these, at a word from the Colonel, stepped out and filed by with quick springing step, circling round the priest and the piled bayonets, then stopped in front of him to kiss the Cross which he pressed in turn to the lips of each. Then the whole regiment fell into movement and swung round the open square, the cross movements, carried out slowly and in perfect order, giving the appearance of a labyrinth. One could not tell which way the men would turn, but they swung round with precision and came forward with the strength[Pg 44] of a great river. An officer had asked me to carry a postcard message for him, and while he wrote "I am alive and well" and a short greeting, we were caught in the current, which parted to each side of us at the words of the kneeling writer, "Brothers, don't come over me." As each section passed the saluting point, the officer ordered the salute, the Colonel replied with a word of congratulation, and the men gave a short sharp cry expressing their readiness for work. There was a remarkable regularity and springiness in the march of the men, and their motion was that of an elemental force moving well within its strength, like the flow of the Neva. After the march past the Colonel handed to us a whole bundle of postcards for home.

We passed from the bare grey slope with all this strong life on it and drove forward to the next village, lately held by the Germans and now abandoned. Here we saw a very different spectacle, showing the effectiveness of the Russian artillery. The houses were for the most part long and spacious, built of huge stones with a superstructure of wood and roof of thatch. Some of them still remained intact; but most had only the stone basis standing. Everywhere were groups of the bright orange-coloured peasants, just returned, and in one house stood an old woman making her first examination of her devastated home. We stood in the slush on the dirty lane listening to the last report of a mounted staff officer, and as the Germans were evidently retreating rapidly we turned back to Skiernewice. We had followed the Russian advance some seventy miles from Warsaw.

It is well to recognize the value of these operations.[Pg 45] The Germans would obtain obvious advantages from a rapid seizure of Warsaw. So far western Poland, lying between the two military lines of defence, had been a kind of no-man's land, and as the main operations were to north or to south, the Germans had made here a number of raids and had secured partial and transitory successes. They now, as at Grodno, tasted the actual Russian line of defence. The Russian forces in the centre were much stronger than anticipated, and making a great effort, not only repulsed the attack but made any real success on the German side impossible. The political aspect of the attempt and the character of its failure are illustrated by the following incident. The King of Saxony, whose ancestors were kings of Poland, had sent a court official with presents and decorations for those who should take part in the capture of Warsaw, and this official was himself captured by Cossacks after the repulse. The Germans, on the failure of their attempt, withdrew quickly but in good order, leaving few prisoners and spoils of war. The country was not devastated. There had been, after the repulse, some disgraceful incidents, e.g. they had made a Polish landowner and his servants stand in the Russian line of fire: and clocks and ornaments were taken away. But I have no evidence of any atrocities such as those in Belgium, and these could hardly have escaped observation. The German troops seem to have been partly reservists, with whom excesses are less likely. The signs indicate that the retreat is definitive, and such is the inference from the reported incendiarism at Lodz, which is full of German factories.

[Pg 46]November 4.

Trustworthy eyewitnesses speak with great enthusiasm of the conduct of the Russian troops on the Upper Vistula, where more serious fighting is to be expected. The influence of the Commander-in-Chief has produced the selection of capable commanders everywhere, and the subordinate officers are full of spirit and energy. Here again the German heavy artillery commands respect, but the Russian field guns and howitzers are served with remarkable precision and alertness and meet with great success. The complete confidence of the Russian infantry in the effectiveness of the Russian artillery is a striking and general feature. The men are always keen for bayonet work, which the enemy consistently avoids.

The Russian cavalry has, by different accounts, shown great dash and has been handled with dash and skill. In a raid beyond the river on the enemy's communications, a Russian cavalry division came on Germans in the dusk, and the troopers with the baggage column in the centre left the baggage and, charging, completely routed the enemy. The division several times got into the German forces, taking many prisoners. Large numbers of stragglers have been taken by the Russians. A Hungarian division put up a good resistance for three days and then collapsed.

German officers pay ridiculously small sums for their keep; for example, two marks for two days' keep of three officers, and they appropriate valuables and take all stores. The population in southern Poland is in a state of profound distress, and the Russians are organising extensive[Pg 47] relief work. The Germans compel captured officers to work with the men, spit at them and drive them about bare to the waist.

A competent eyewitness in East Prussia says that the German communications are very good, and that underground telephones are frequently discovered. Large forces are in close contact here, and the Russian counter-stroke has much impressed the enemy. Our men bear fatigue and privations with great endurance.

The Polish population shows the greatest alacrity in assisting the Russian troops both in the country and in the towns. All Poles now readily speak Russian. Yesterday the Warsaw Press entertained the Russian and foreign correspondents. There was a distinguished gathering, and both Russians and Poles spoke with striking frankness and feeling. One eminent Polish leader, Mr. Dmowski, said that all the blood shed between the two nations was drowned in the heavy sacrifices of the present common struggle. Polish politicians are keenly enthusiastic for France and Great Britain, and are studying the development of closer economic and other relations with Great Britain.

The Russian advance is now much more complete in southern Poland and is better lined up with the forces in Galicia. This advance tends to secure the Russian position on the northern frontier, where any German initiative becomes daily more hazardous. The ordinary fresh yearly Russian contingents mean an increase of half a million men. The arrangements for the wounded provide, if necessary, for over a million.

[Pg 48]November 8.

I have just made a journey over the country lying between Warsaw and Cracow, where the Russian advance is now proceeding. My previous communication spoke of the original line of Russian defence along the Bug, and the later and more advanced line along the Vistula and the Narew. Present events are rapidly converting the new advance west of Warsaw from a counterstroke into a general transference of the sphere of operations and a most valuable rectification of the whole Russian line.

In East Prussia the Germans are being slowly driven back by a double turning movement. Further westward the northern frontier of Poland is well secured. The Russians have now occupied and hold firmly Plock, Lodz, Piotrkow, Kielce and Sandomir, as also Jaroslaw and all the other passages of the river San. A glance at the map will show the importance of this line, which is only a stage in the general advance.