*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 55776 ***

Footnotes have been collected at the end of the text, and are

linked for ease of reference. The numbering of footnotes began at ‘1’ for

each chapter. In this version, footnotes have been re-sequenced

across the text for uniqueness of reference. There are also several instances

of footnotes appearing as glosses on other footnotes, identified

in all instances as ‘a’. These have been numbered ‘Na’, where ‘N’

is the number of the note.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

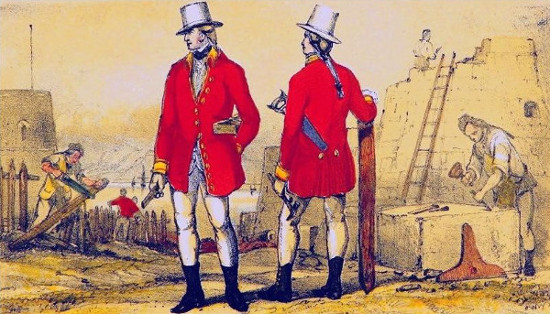

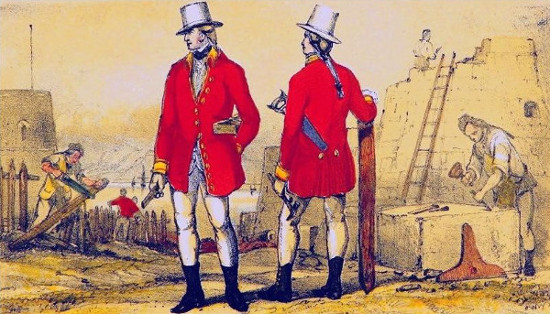

SOLDIER ARTIFICER COMPANY

Plate I.

UNIFORM 1786

Printed by M & N Hanhart.

I

FROM THE FORMATION OF THE CORPS IN MARCH 1772, TO THE DATE

WHEN ITS DESIGNATION WAS CHANGED TO THAT OF

ROYAL ENGINEERS,

IN OCTOBER 1856.

BY

T. W. J. CONNOLLY,

QUARTERMASTER OF THE ROYAL ENGINEERS.

“Of most disastrous chances,

Of moving accidents, by flood and field;

Of hair-breadth scapes i' the imminent deadly breach.”—Shakspeare.

“There is a corps which is often about him, unseen and unsuspected, and which is labouring

as hard for him in peace as others do in war.”—The Times.

With Seventeen Coloured Illustrations.

SECOND EDITION, WITH CONSIDERABLE ADDITIONS.

IN TWO VOLUMES.—VOL. I.

LONDON:

LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, LONGMANS, AND ROBERTS.

1857.

LONDON: PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

iii

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

The First Edition of the Work has long been out of print, and

the Second would have been published earlier, only that an

expected change in the designation of the corps delayed its

appearance. That change having occurred, the volumes are

republished, recording the services of the corps to the date it

continued to bear its old title.

Revised in many places, with verbal inaccuracies corrected,

aided moreover by journals and official memoranda placed at

my disposal to modify or enlarge certain incidents and services,

the work is as complete as it would seem to be possible at

present to produce it.

The concluding Chapters record the services of the corps in

the Aland Islands, in Turkey, Bulgaria, Circassia, Wallachia,

and the Crimea. The siege of Sebastopol and the destruction

of the memorable docks have been given with the fulness which

the industry and gallantry of the sappers merited; and in

order that the many adventures and enterprises recorded in the

final years of the history should not fail in interest and accuracy,

Colonel Sandham, the Director of the Royal Engineer

Establishment, with the permission of General Sir John Burgoyne,

kindly lent me the assistance of the Engineers’ Diary

of the Siege, as well as several collateral reports concerning

ivits progress and the demolition of the docks. At the

same time I think it right to say, that no attempt has been

made in these pages to offer a history of the Crimean operations.

So much only of the details has been worked into the

narrative as was necessary to preserve unbroken the thread of

sapper services in connexion with particular works and undertakings.

It should also be borne in mind, that these volumes are

devoted to the affairs of the Royal Sappers and Miners; and,

consequently, that care has been taken to touch as lightly as

practicable on the services of other regiments. Hence the

officers of the Royal Engineers have only been named when

it was desirable to identify them with parties of Sappers, whom

on certain occasions they commanded.

I feel a loyal pride in being able to state that the work has

been honoured with the munificent patronage of Her Majesty

the Queen, and of His Royal Highness the Prince Albert;

than which nothing could be more acceptable to me, either as

an author or a subject.

In closing I beg to express my deep obligations to General

Sir John Burgoyne, Bart., G.C.B., the officers of the corps

generally, my personal friends, and the public, for the patronage

with which I have been favoured; and also to the Press, for

the handsome manner in which it has noticed and commended

my labours.

Brompton Barracks,

March 1857.

v

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

In 1836, soon after Lieutenant Robert Dashwood, R.E., was

appointed Acting Adjutant of the Royal Sappers and Miners

at Woolwich, he was directed by Brigade-Major, now Colonel

Matson, to prepare a list of officers of the Royal Engineers who

had commanded, from time to time, the different companies of

the corps. I assisted him in the duty; but while he was in the

midst of his work, he was prematurely cut off by death, and the

task of completing the statement devolved on me. It now

forms a referential record at the head-quarter office.

Led in its progress to consult old documents and returns, I

conceived the idea of making myself acquainted with the whole

history of the corps. With this view, after daily fulfilling the

routine duty of the office, I spent all my leisure intervals in

bringing to light old books and papers, which for years had

been buried in disused depositories and stores.

Whilst thus engaged, two Acting Adjutants, Lieutenants

F. A. Yorke and T. Webb, R.E., were successively appointed

to the corps at Woolwich. Both officers entered with some

spirit into the attempt to trace a history of its services; but

before they had proceeded to any great length, were interrupted

in their labours by removal to other stations in consequence of

promotion. Adjutant Yorke, however, succeeded so far, that

he drew up a brief account of the formation of the sappers,

vicommencing with the Gibraltar company in 1772, and detailed

its subsequent augmentations and reductions. This statement

also forms a permanent record in the office; and Captain Webb

made fair progress with an outline account of its active services.

To both officers it was my good fortune to afford such aid as

they required, in the collection of information for their respective

efforts.

In 1847, when medals were granted to the veterans of the

last war, Brigade-Major, now Colonel Sandham, observed the

readiness with which I spoke of historical events in which the

corps was concerned, and of the services of particular individuals

who had belonged to it. He also saw the facility with

which I supplied the information required to establish the

claims of the several applicants for medals and clasps. This

induced him, after some little conversation on the subject, to

direct me to prepare for publication a history of the corps.

Much fragmentary matter I had already accumulated, for

twelve years had been consumed by me in wading through

books and documents in quest of dates and occurrences.

Nevertheless, it was not without serious misgivings that I set

myself officially to the task, and the researches and labours

embodied in the following pages are the result.

In the intervals of important and onerous public duty, the

materials for the memoir have been collected and the work

methodized and written. Necessarily severe was the application

required under such circumstances; but by steady perseverance,

even at times when my health was scarcely able to bear

up against the exertion it needed, I have succeeded, without

omitting any service that I know of, in completing the history to

the siege of Sebastopol.

The work certainly is one of no pretension, and on this score

may be regarded as having cost but little toil in its preparation;

viibut I may observe, that from the absence of many particular

records, the unaccountable neglect in furnishing others, and

the striking imperfections in many of the remaining papers,

arising from complexity, vagueness, obliteration, or decay,

more than ordinary difficulty, research, and trouble were experienced,

in gathering the materials essential to give anything

like a reasonable delineation of the events narrated in the

Memoir. Paucity of detail in numbers, want of description

with reference to particular occurrences, and gaps in many

years from the loss of muster-rolls and official documents, run

through a period of nearly half a century, from 1772 to 1815:

and strange as it may appear, even the casualties in action so

carefully reported in other corps, have, from some inexplicable

cause, either been omitted altogether in the war despatches or

given inaccurately. In later years, however, the connexion

between the officers of the Royal Engineers and the soldiers of

the Royal Sappers and Miners has been so fully established,

that attention to these important minutiæ forms a decided

feature in the improved command of the corps.

In employments of a purely civil character in which the

Royal Sappers and Miners have shared, care has been taken to

explain, as fully as the records and collateral evidence would

admit, the nature of its duties; and, likewise, to multiply

authorities to prove the estimation in which it was held for

its services and conduct. This has been mainly done, to offer

a practical reply to an association, incorporated within the last

twelve years, which, in the course of a futile agitation, endeavoured

by injurious statements to lessen the corps in public

esteem.

All mention of the Royal Engineers in this memoir has been

studiously suppressed, except when such was unavoidable to

give identity to the different duties and services of the Royal

viiiSappers and Miners, and also, when their direct and particular

connexion with the corps in certain situations, rendered allusion

to them justifiable. This course was suggested to me by an

officer of high rank, for the obvious reason that, as the Royal

Engineers is a body entirely distinct from the Sappers and

Miners, and possesses its own annals, any reference to, or particularization

of, its services in a work professedly confined to

the corps, would not only be extraneous, but tend to lessen its

value, and weaken its interest with those for whose information

it was especially written.

Here, however, it should be observed, that the Royal Sappers

and Miners, though a separate and integral body of itself,

is nevertheless, and has been from the commencement, officered

by the Royal Engineers; and whatever excellence or advancement

is traced in its career and public usefulness, whether as

soldiers or mechanics, is fairly, in a great degree, attributable

to the officers; for, in every circumstance of service and situation,

they have liberally opened up for them new channels of

employment to engage their faculties and energies, and have

afforded them at all times scope and facilities to develop their

mental and physical resources, and to fit them to perform with

credit, not only the circumscribed duties of soldiers, but the

more extended requirements of sappers, artizans, and professional

men.

By the omission of all but special reference to the officers,

room has thus been given for mentioning many non-commissioned

officers and privates, who have attracted public attention

and gained encomium for their meritorious services; some for

their skill and ingenuity; others for their integrity and devotion;

and others for their acquirements, their vigorous exertions

and labours; their ardour, their endurance, and their valour.

While the recognition of such examples cannot fail to incite

ixothers to emulate the military virtues of their more distinguished

predecessors and comrades, it is earnestly hoped, that

every member of the corps will be led to feel a personal interest

in its reputation and honour, and a pride in its discipline and

loyalty; its usefulness and efficiency in peace; its heroism and

achievements in war.

The drawings were executed on stone by George B. Campion,

Esq., master of landscape drawing at the Royal Military

Academy, Woolwich. In illustrations like those in the present

volumes, it was scarcely possible to delineate with exactness

the complicated ornament which make up the ensemble of a

soldier’s uniform. Notwithstanding this disadvantage, the

costume has been well defined, and much interest given to the

embellishments, by the introduction of accessories, characteristic

of the duties and employments of the corps.

My respectful acknowledgments are due to Sir John Burgoyne,

the Inspector-General of Fortifications, for making the

subject of my exertions known in a circular from his own hand,

to the officers of the Royal Engineers; and in offering him the

expression of my gratitude, I think it right with a feeling of

sincere thankfulness to mention, that the success which has

attended that kind appeal, has been more, perhaps, than I

could reasonably expect. Several of the officers have afforded

me much encouragement in the work, as well by suggestion

and advice, as by the liberality of their contributions; but,

wanting the liberty to publish their names, I am precluded

from making a record, to which it would have been my pride to

give publicity.

To my own corps I am also indebted for many pleasing

proofs of concern, as evinced in their anxiety to see the undertaking

prosper. Nearly 200 copies have been demanded by

the non-commissioned officers, including a few of the privates,

xand when the price of the work is considered, the generosity of

my patrons is as striking as noble.

To S. W. Fullom, Esq., I here offer the expression of my

grateful thanks for his amiable and disinterested counsel, cheerfully

accorded on the many occasions I had to seek it; and for

kindly assisting me in looking over the sheets as the work

passed through the press.

I now submit the volumes to my corps and the profession,

and am not without hope that they may also be acceptable to

a portion of the public. As far as the sources of my information

and research have extended, the memoir will be found

truthful and impartial. It was my aim to execute it with an

integrity that would place me beyond impeachment: I therefore

feel some confidence that indulgence will be shown for its

defects, and also for whatever errors, through inadvertency,

may have crept into the work.

THOMAS CONNOLLY.

Royal Sappers and Miners’ Barracks,

Woolwich, March 1855.

xi

CONTENTS OF VOL. I.

| |

| 1772-1779. |

| |

PAGE |

| |

| Origin of Corps—Its establishment and pay—Engineers to command it—Its designation—Working pay—Recruiting—Dismissal of civil artificers—Names of officers—Non-commissioned officers—First augmentation—Consequent promotions—Names of other officers joined—King’s Bastion—Second augmentation |

1 |

| |

| 1779-1782. |

| |

| Jealousy of Spain—Declares war with England—Strength of the garrison at Gibraltar—Preparations for defence and employment of the company—Siege commenced—Privations of the garrison—Grand sortie and conduct of the company—Its subsequent exertions—Origin of the subterranean galleries—Their extraordinary prosecution—Princess Anne’s battery—Third augmentation—Names of non-commissioned officers |

10 |

| |

| |

| 1782-1783. |

| |

| Siege continued—Magnitude of the works—Chevaux-de-frise from Landport-Glacis across the inundation—Précis of other works—Firing red-hot shot—Damage done to the works of the garrison, and exertions of the company in restoring them—Grand attack, and burning of the battering flotilla—Reluctance of the enemy to quit the contest—Kilns for heating shot—Orange bastion—Subterranean galleries—Discovery of the enemy mining under the Rock—Ulterior dependence of the enemy—Peace—Conduct of the company during the siege—Casualties |

22 |

| |

| |

| 1783. |

| |

| Duc de Crillon’s compliments respecting the works—Subterranean galleries—Their supposed inefficiency—Henry Ince—Quickness of sight of two boys of the company—Employment of the boys during the siege—Thomas Richmond and John Brand—Models constructed by them |

29 |

| |

| |

| xii1783. |

| |

| State of the fortress—Execution of the works depended upon the company—Casualties filled up by transfers from the line—Composition—Recruiting—Relieved from all duties, garrison and regimental—Anniversary of the destruction of the Spanish battering flotilla |

39 |

| |

| |

| 1786-1787. |

| |

| Company divided into two—Numerous discharges—Cause of the men becoming so soon ineffective—Fourth augmentation—Labourers—Recruiting, reinforcements—Dismissal of foreign artificers—Wreck of brig ‘Mercury’—Uniform dress—Working ditto—Names of officers—Privileges—Cave under the signal-house |

43 |

| |

| |

| 1779-1788. |

| |

| Colonel Debbieg’s proposal for organizing a corps of artificers—Rejected—Employment of artillerymen on the works at home—Duke of Richmond’s “Extensive plans of fortification”—Formation of corps ordered—Singular silence of the House of Commons on the subject—Mr. Sheridan calls attention to it—Insertion of corps for first time in the Mutiny Bill—Debate upon it in both Houses of Parliament |

53 |

| |

| |

| 1787-1788. |

| |

| Constitution of corps—Master artificers—Officers—Rank and post of the corps—Captains of companies; stations—Allowance to captains; adjutants—Recruiting—Labourers—“Richmond’s whims”—Progress of recruiting—Articles of agreement—Corps not to do garrison duty—Sergeant-Majors—John Drew—Alexander Spence—Uniform dress—Working dress—Hearts o' pipe-clay—“The Queen’s bounty”—Arms, &c.—Distinction of ranks—Jews’ wish |

64 |

| |

| |

| 1789-1792. |

| |

| Appointment of Quartermaster and Colonel-Commandant—Distribution of corps, Captains of companies—Jealousy and ill-feeling of the civil artificers—Riot at Plymouth—Its casualties—Recruits wrecked on passage to Gibraltar—Song, “Bay of Biscay, O!”—Defence of the Tower of London against the Jacobins—Bagshot-heath encampment—Alterations in the uniform and working dress |

72 |

| |

| |

| 1793. |

| |

| War with France—Artificers demanded for foreign service—Consequent effects—Detachment to West Indies—Fever at Antigua—Detachment to Flanders—Siege of Valenciennes—Waterdown Camp—Reinforcement to Flanders—Siege of Dunkirk—Nieuport—Another reinforcement to Flanders—Toulon—Private Samuel Myers at Fort Mulgrave—Formation of four companies for service abroad—Establishment and strength of corps |

81 |

| |

| |

| xiii1794-1795. |

| |

| Working dress—Company sails for West Indies—Martinique—Spirited conduct of detachment there—Guadaloupe—Mortality—Toulon—Flanders—Reinforcement to company there—Return of the company—Works at Gravesend—Irregularities in the corps—Causes—Redeeming qualities—Appointment of Regimental Adjutant and Sergeant-major—Consequences—Woolwich becomes the head-quarters—Alteration in working dress |

90 |

| |

| |

| 1795-1796. |

| |

| Companies to St. Domingo and the Caribbee Islands—Reduction of St. Lucia—Conduct of company there—Gallantry in forming lodgment and converting it into a battery—Attack on Bombarde—Distribution and conduct of St. Domingo company—Mortality in the West Indies—Detachment to Halifax, Nova Scotia—Dougal Hamilton—Detachments to Calshot Castle and St. Marcou |

101 |

| |

| |

| 1797. |

| |

| Detachments to Portugal—To Dover—Transfers to the Artillery-Enlistment of artificers only—Incorporation of Gibraltar companies with the corps—Capture of Trinidad—Draft to West Indies—Failure at Porto Rico—Fording the lagoon, by private D. Sinclair—Private W. Rogers at the bridge St. Julien—Saves his officer—Casualties by fever in Caribbean company—Filling up company at St. Domingo with negroes—Mutinies in the fleet at Portsmouth—Conduct of Plymouth company—Emeute in the Royal Artillery, Woolwich—Increase of pay—Marquis Cornwallis’s approbation of the corps—Mutiny at the Nore—Consequent removal of detachment to Gravesend—Alterations in dress |

105 |

| |

| |

| 1798-1799. |

| |

| Contribution of corps to the State—Detachment with expedition to maritime Flanders—Destruction of the Bruges canal—Battle near Ostend—Draft to West Indies—Capture of Surinam—St. Domingo evacuated—Expedition to Minorca—Conduct of detachment while serving there—Composition of detachments for foreign service—Parties to Sevenoaks and Harwich—Mission to Turkey—Its movements and services—Special detachment to Gibraltar to construct a cistern for the Navy—Detachment with the expedition to Holland—Its services—Origin of the Royal Staff Corps |

116 |

| |

| |

| 1800. |

| |

| Mortality in the West Indies—Blockade of Malta—Capture of a transport on passage from Nova Scotia—Movements and services of detachments in Turkey; attacked with fever—Anecdote of private Thomas Taylor at Constantinople—Cruise of expedition to Cadiz—Attack on the city abandoned—Subsequent movements of the expedition; Malta; and re-embarkation for Egypt—Statistics of companies at Gibraltar |

126 |

| |

| xiv1801-1802. |

| |

| Distribution of corps—Dispersion of West India company—Statistics—Detachment to St. Marcou—Capture of Danish settlements—Casualties in West India company—Compared with mortality in Gibraltar companies—Working dress—Services, &c., of detachment at Gibraltar—Conduct of Sergeant W. Shirres—Concession to the companies by the Duke of Kent—Cocked hat superseded by the chaco |

132 |

| |

| |

| 1803-1805. |

| |

| Party to Ceylon—The treaty of Amiens broken—State of West India company—Capture of St. Lucia—Tobago—Demerara, Essequibo, and Berbice—Works at Spike Island—Capture of Surinam—Conduct of private George Mitchell—Batavian soldiers join West India company—Fever at Gibraltar—Consequent mortality—Humane and intrepid conduct of three privates—Invasion of England—Works at Dover—Jersey—Chelmsford—Martello towers at Eastbourne—Bomb tenders at Woolwich—Recruiting—Volunteers from the Line and Militia—Treaty of St. Petersburg—Party to Naples—Ditto to Hanover |

141 |

| |

| |

| 1806. |

| |

| First detachment to Cape of Good Hope—Misfortunes at Buenos Ayres—Reinforcements to Gibraltar—Services at Calabria—Formation of Maltese military artificers—Increase of pay to royal military artificers—Augmentation to the corps and reorganization of the companies—Establishment and annual expense—Working pay—Sub-Lieutenants introduced—Indiscipline and character of the corps |

153 |

| |

| |

| 1807. |

| |

| Appointments of Adjutant and Quartermaster—Captain John T. Jones—Disasters at Buenos Ayres—Egypt—Reinforcement to Messina—Detachment of Maltese military artificers to Sicily—Newfoundland—Copenhagen—Captures in the Caribbean Sea—Madeira—Danish Islands in the West Indies—Hythe |

161 |

| |

| |

| 1808. |

| |

| War in the Peninsula—Expedition thither—Detachments to the seat of war, with Captains Landmann, Elphinstone, Squire, Burgoyne, and Smyth—Captain John T. Jones—Reinforcement to Newfoundland—Discipline at Halifax—Services at Messina—Parties temporarily detached to different places—The queue |

165 |

| |

| |

| 1809. |

| |

| xvRetreat to Coruña—Miserable state of the detachment on reaching England—Hardships of the stragglers—Capture of Martinique—Skill of George Mitchell at the siege—Fever in the West Indies—Reduction of the Saintes—Detachment to Portugal—Battles of Oporto and Talavera—Casualties in the retreat, and distribution of the party—Naples—Zante and the Ionian Islands—Term of service of the Maltese military artificers—Siege of Flushing—Services of the military artificers there—Gallantry, in the batteries, of John Millar, Thomas Wild, and Thomas Letts—Conduct of corps at the siege—Casualties by the Walcheren fever—Skilful conduct of Corporal T. Stevens in the demolitions at Flushing—Captain John T. Jones—Servants—Incidental detachments |

168 |

| |

| |

| 1810. |

| |

| Capture of Guadaloupe—Of St. Martin’s and St. Eustatius—Torres Vedras—Anecdote of Corporal William Wilson at the Lines—Almeida and Busaco—Detachments to Cadiz—Puntales and La Isla—Destruction of Forts Barbara and St. Felipe, near Gibraltar—Santa Maura—Occasional detachments |

175 |

| |

| |

| 1811. |

| |

| Mortality in the West Indies—Strength and distribution of detachments in the Peninsula—Recapture of Olivenza—Field instruction prior to siege of Badajoz—Conduct of corps at the siege—Conduct of Sergeant Rogers in reconnoitring—Reinforcement to Portugal and duties of the detachment—Its distribution and services—Battle of Barrosa; gallant conduct of Sergeant John Cameron—Tarragona—Defence of Tarifa—Augmentation to corps and reconstruction of companies—Annual expense of corps—Command of the companies—Their stationary character—The wealthy corporal—New distribution of corps—Commissions to Sub-Lieutenants, and ingenious inventions of Lieutenant Munro |

178 |

| |

| |

| 1812. |

| |

| Plymouth company instructed in field duties—Engineer establishment at Chatham—Major Pasley appointed its director—Discipline and drill of corps—Its character—Sir John Sinclair ex-private—Title of corps changed—Captain G. Buchanan—A sergeant acrobat—Cuidad Rodrigo—Exertions of a company on the march to the siege—Repairs to the fortress—Siege of Badajoz—Difficulties in removing the stores to the park—Duties of the sappers in the operation—Gallant behaviour of Patrick Rooney and William Harry—Also of a party at Fort Picurina, and of Patrick Burke and Robert Miller—Hazardous attempt to blow down the batardeau in the ditch of the lunette, and conduct of corporal Stack—Bravery of a party in mining under the bridge of the inundation—Distribution of the Peninsular companies and their services—Bridges of Yecla and Serrada—Reinforcement to Spain—Salamanca—Burgos, and boldness of Patrick Burke and Andrew Alexander at the siege—Bridge of Alba—Carthagena—Reinforcement to Cadiz; action at Seville—Reinforcement to the Peninsula and distribution of the sappers—Green Island—Tarragona—First detachment to Bermuda |

187 |

| |

| |

| xvi1813. |

| |

| Designation of corps modified—Uniform—Working dress—Arms—Mode of promoting non-commissioned officers—Rank of colour-sergeant created—Company to Canada—Reinforcement to Bermuda—Sub-Lieutenant Mackenzie appointed Town-Major there—Sickness at Gibraltar—Services of company in East Catalonia—Malha da Sorda—Services on the advance to Vittoria—Bridge at Toro—Blockade of Pampeluna—Pyrenees—Stockades near Roncesvalles—San Sebastian and services of the corps at the siege—Valour of sergeants Powis and Davis—Of private Borland; and of corporal Evans—Casualties in the siege—Restoration of the fortifications—Pontoon train—Bidassoa—Bridge across it, and conduct of privates Owen Connor and Nowlan—Vera—Nivelle, and behaviour of corporal Councill—Bridge over that river—Bridges over the Nive, and daring exertions of private Dowling—Fording the Nive, and posts of honour accorded to corporal Jamieson and private Braid—Strength and distribution of corps in the Peninsula—Recruiting |

197 |

| |

| |

| 1814. |

| |

| Wreck of ‘Queen’ transport; humanity of sergeant Mackenzie; heroic exertions of private M‘Carthy—Quartermaster; Brigade-Major—Santona; useful services of corporal Hay—Bridge of Itzassu near Cambo-Orthes; conduct of sergeant Stephens—Toulouse—Bridge of the Adour; duties of the sappers—Flotilla to form the bridge—Casualties in venturing the bar—Conduct of the corps in its construction—Bayonne—Expedition to North America—Return to England of certain companies from the Peninsula—Company to Holland; its duties; bridge over the Maerk; Tholen; Fort Frederick—March for Antwerp—Action at Merxam—Esprit de corps—Coolness of sergeant Stevens and corporal Milburn—Distribution; bridge-making—Surprise of Bergen-op-Zoom—Conduct of the sappers, and casualties in the operation—A mild Irish-man—Bravery of corporal Creighton and private Lomas—South Beveland—Reinforcement to the Netherlands—Review by the Emperor of Russia—School for companies at Antwerp—Detachments in the Netherlands, company at Tournai—Movements of the company in Italy and Sicily—Expedition to Tuscany; party to Corfu—Canada; distribution of company there, and its active services—Reinforcement to Canada—Washington, Baltimore, New Orleans—Notice of corporal Scrafield—Expedition to the State of Maine |

209 |

| |

| |

| 1815. |

| |

| xviiSiege of Fort Boyer—Alertness of company on passage to New Orleans—Return of the sappers from North America—Services and movements of companies in Canada—Also in Nova Scotia—Captures of Martinique and Guadaloupe—Services and movements of companies in Italy—Maltese sappers disbanded—Pay of Sub-Lieutenants—Ypres—Increase to sappers’ force in Holland; its duties and detachments; notice of sergeant Purcell—Renewal of the war—Strength of the corps sent to the Netherlands—Pontoneers—Battle of Waterloo—Disastrous situation of a company in retreating—General order about the alarm and the stragglers—Sergeant-major Hilton at Brussels—Notice of lance-corporal Donnelly—Exertions of another company in pressing to the field—Organization of the engineer establishment in France—Pontoon train—Magnitude of the engineer establishment; hired drivers; Flemish seamen—Assault of Peronne, valour of Sub-lieutenant Stratton and lance-corporal Councill—Pontoon bridges on the Seine—Conduct of corps during the campaign—Corporal Coombs with the Prussian army—Usefulness of the sappers in attending to the horses, &c., of the department in France—Domiciliary visit to Montmartre |

225 |

| |

| |

| 1816-1818. |

| |

| Movements in France—Return of six companies from thence to England—Strength of those remaining, and detachments from them—St. Helena—Return of company from Italy—Disbandment of the war company of Maltese sappers—Battle of Algiers—Conduct of corps at Valenciennes—Instances in which the want of arms was felt during the war—Arming the corps attributable to accidental circumstances—Training and instruction of the corps in France—Its misconduct—But remarkable efficiency at drill—Municipal thanks to companies at Valenciennes—Dress—Bugles adopted—Reduction in the corps—Sub-lieutenants disbanded—Withdrawal of companies from certain stations—Relief of company at Barbadoes—Repairing damages at St. Lucia; conduct of the old West India company—Corfu—Inspection of corps in France—Epaulettes introduced—Sordid conduct of four men in refusing to wear them—Murder of private Milne, and consequent punishment of corps in France by the Duke of Wellington—Return of the sappers from France |

241 |

| |

| |

| 1819-1824. |

| |

| Reduction in the corps—Distribution—Sergeant Thomas Brown, the modeller—Reinforcement to the Cape, and services of the detachment during the Kaffir war—Epidemic at Bermuda—Damages at Antigua occasioned by a hurricane—Visit to Chatham of the Duke of Clarence—Withdrawal of a detachment from Corfu—A private becomes a peer—Draft to Bermuda—Second visit to Chatham of the Duke of Clarence—Fever at Barbadoes—Death of Napoleon, and withdrawal of company from St. Helena—Notice of private John Bennett—Movements of the company in Canada—Trigonometrical operations under the Board of Longitude—Feversham—Relief of the old Gibraltar company—Breast-plates—St. Nicholas’ Island—Condition of company at Barbadoes when inspected by the Engineer Commission—Scattered state of the detachment at the Cape—Services of the detachment at Corfu—Intelligence and usefulness of sergeant Hall and corporal Lawson—Special services of corporal John Smith—Pontoon trials—Sheerness—Notice of corporal Shorter—Forage-caps and swords |

253 |

| |

| |

| xviii1825-1826. |

| |

| Dress—Curtailment of benefits by the change—Chacos—Survey of Ireland—Formation of the first company for the duty—Establishment of corps; company to Corfu—Second company for the survey—Efforts to complete the companies raised for it—Pontoon trials in presence of the Duke of Wellington—Western Africa—Third company for the survey: additional working pay—Employments and strength of the sappers in Ireland—Drummond Light; Slieve Snacht and Divis—Endurance of private Alexander Smith—Wreck of ‘Shipley’ transport—Berbice; corporal Sirrell at Antigua |

263 |

| |

| |

| 1827-1829. |

| |

| Augmentation—Reinforcement to Bermuda—Companies for Rideau Canal—Reinforcement to the Cape—Monument to the memory of General Wolfe—Increase to the survey companies—Supernumerary promotions—Measurement of Lough Foyle base—Suggestion of sergeant Sim for measuring across the river Roe—Survey companies inspected by Major-General Sir James C. Smith; opinion of their services by Sir Henry Hardinge—Sergeant-major Townsend—Demolition of the Glacière Bastion at Quebec—Banquet to fifth company by Lord Dalhousie—Service of the sappers at the citadel of Quebec—Notice of sergeants Dunnett and John Smith—Works to be executed by contract—Trial of pontoons, and exertions of corporal James Forbes—Epidemic at Gibraltar—Island of Ascension; corporal Beal—Forage-caps—Company withdrawn from Nova Scotia—Party to Sandhurst College, and usefulness of corporal Forbes |

271 |

| |

| |

| 1830-1832. |

| |

| The chaco—Brigade-Major Rice Jones—Island of Ascension—Notice of corporal Beal—Detachment to the Tower of London—Chatham during the Reform agitation—Staff appointments—Sergeant McLaren the first medallist in the corps—Terrific hurricane at Barbadoes; distinguished conduct of colour-sergeant Harris and corporal Muir—Subaqueous destruction of the ‘Arethusa’ at Barbadoes—Return of a detachment to the Tower of London—Rideau canal; services of the sappers in its construction; casualties; and disbandment of the companies—Costume—First detachment to the Mauritius—Notice of corporal Reed—Pendennis Castle |

281 |

| |

| |

| 1833-1836. |

| |

| xixInspection at Chatham by Lord Hill—Pontoon experiments—Withdrawal of companies from the ports—Reduction of the corps, and reorganization of the companies—Recall of companies from abroad—Purfleet—Trigonometrical survey of west coast of England—Draft to the Cape—Review at Chatham by Lord Hill—Motto to the corps—Reinforcement to the Mauritius—Inspection at Woolwich by Sir Frederick Mulcaster—Mortality from cholera; services of corporals Hopkins and Ritchley—Entertainment to the detachment at the Mauritius by Sir William Nicolay—Triangulation of the west coast of Scotland—Kaffir war—Appointments of ten foremen of works—Death of Quartermaster Galloway—Succeeded by sergeant-major Hilton—Sergeant Forbes—Notice of his father—Lieutenant Dashwood—Euphrates expedition—Labours of the party—Sergeant Sim—Generosity of Colonel Chesney, R.A.—Additional smiths to the expedition—Loss of the ‘Tigris’ steamer—Descent of the Euphrates—Sappers with the expedition employed as engineers—Corporal Greenhill—Approbation of the services of the party—Triangulation of west coast of Scotland—Addiscombe—Expedition to Spain—Character of the detachment that accompanied it—Passages; action in front of San Sebastian—Reinforcement to Spain—Final trial of pontoons—Mission to Constantinople |

289 |

| |

| |

| 1837. |

| |

| Change in the dress—Increase of non-commissioned officers—Services of the detachment at Ametza Gaña—Oriamendi—Desierto convent on the Nervion—Fuentarabia—Oyarzun—Aindoin—Miscellaneous employment of the detachment—Trigonometrical survey west coast of Scotland—Inspection at Woolwich by Lord Hill and Sir Hussey Vivian—Staff appointments—Labours of sergeant Lanyon—Staff-sergeants' accoutrements—Expedition to New Holland—Corporal Coles selected as the man Friday of his chief—Exploration from High Bluff Point to Hanover Bay; difficulties and trials of the trip; great thirst—Exertions and critical situation of Coles—His courageous bearing—Touching instance of devotion to his chief—Employments of the party—Exploration into the interior with Coles and private Mustard—Hardships in its prosecution—Threatened attack of the natives; return to the camp |

305 |

| |

| |

| 1838. |

| |

| xxServices of party in New Holland—Start for the interior—Labours of the expedition; corporal Auger—Captain Grey and corporal Coles expect an attack—Attitude of private Auger at the camp against the menace of the natives—Captain Grey and Coles attacked; their critical situation: the chief wounded; devotion of Coles—Usefulness of Auger—Renew the march; Auger finds a singular ford—Discovers a cave with a sculptured face in it—Mustard traces the spoor of a quadruped still unseen in New Holland—A sleep in the trees—Trials of the party—Primitive washing—Auger the van of the adventurers—Humane attention of the Captain to Mustard; reach Hanover Bay; arrive at the Mauritius—Detachment in Spain—Attack on Orio—Usurvil; Oyarzun—Miscellaneous employments of the party—Reinforcement to it; Casa Aquirre—Orio—Secret mission to Muñagorri—Second visit to the same chief—Notice of corporal John Down—Bidassoa—Triangulation of north of Scotland—Also of the Frith of the Clyde—Insurrection in Canada; guard of honour to Lord Durham—Company inspected by the Governor-General on the plains of Abraham—Inspection at Niagara by Sir George Arthur—Services and movements of the company in Canada; attack at Beauharnois—Submarine demolition of wrecks near Gravesend—Expedient to prevent accidents by vessels fouling the diving-bell lighter—Conduct of the sappers in the operations; exertions of sergeant-major Jones—Fatal accident to a diver—Intrepidity of sergeants Ross and Young—Blasting the bow of the brig ‘William,’ by sergeant-major Jones—Withdrawal of the sappers from the canal at Hythe |

315 |

| |

| |

| 1839. |

| |

| Expedition to Western Australia under Captain Grey—Excursion with Auger to the north of Perth—Search for Mr. Ellis—Exploration of shores from Freemantle—Bernier and Dorre Islands; want of water; trials of the party—Water allowance reduced—A lagoon discovered—Privations and hardships of the party—Return to Bernier Island for stores—Its altered appearance—Destruction of the depôt of provisions—Consternation of Coles—Auger’s example under the circumstances—Expedition makes for Swan River—Perilous landing at Gantheaume Bay—Overland journey to Perth; straits of the adventurers—Auger searching for a missing man—Coles observes the natives; arrangements to meet them—Water found by Auger—A spring discovered by Coles at Water Peak—Disaffection about long marches; forced journeys determined upon; the two sappers and a few others accompany the Captain—Desperate hardships and fatigues; the last revolting resource of thirst—Extraordinary exertions of the travellers; their sufferings from thirst; water found—Appalling bivouac—Coles’s agony and fortitude—Struggles of the adventurers; they at last reach Perth—Auger joins two expeditions in search of the slow walkers—Disposal of Coles and Auger |

328 |

| |

| |

| 1839. |

| |

| xxiServices of the detachment in Spain—Last party of the artillery on the survey—Survey of South Australia—Inspection at Limerick by Sir William Macbean—Triangulation of north of Scotland—Also of the Clyde—Pontoons by sergeant Hopkins—Augmentation of the corps—Also of the survey companies—Supernumerary rank annulled—Tithe surveys; quality of work executed on them by discharged sappers; efficient surveys of sergeant Doull—Increase of survey pay—Staff appointments on the survey—Responsibility of quartermaster-sergeant M‘Kay—Colonel Colby’s classes—Based upon particular attainments—Disputed territory in the State of Maine—Movements and services of the party employed in its survey; intrepidity of corporal M‘Queen—Experiments with the diving-bell—Also with the voltaic battery—Improvement in the priming wires by Captain Sandham; sergeant-major Jones’s waterproof composition and imitation fuses—Demolition and removal of the wreck of the ‘Royal George’—Organization of detachment employed in the operation—Emulation of parties—Success of the divers; labours of the sappers—Diving-bell abandoned—Accident to private Brabant—Fearlessness of corporal Harris in unloading gunpowder from the cylinders—Hazardous duty in soldering the loading-hole of the cylinder—First sapper helmet divers—Conduct and exertions of the detachment |

341 |

| |

| |

| 1840. |

| |

| Return of the detachment from Spain—Its conduct during the war—Survey of the northern counties of England—Notice of sergeant Cottingham—Secondary triangulation of the north of Scotland—Increase to survey allowances—Augmentation to the survey companies—Renewal of survey of the disputed boundary in the state of Maine—Corporal Hearnden at Sandhurst—Wreck of the ‘Royal George;’ duties of the sappers in its removal—Exertions of sergeant-major Jones—The divers—An accident—Usefulness of the detachment engaged in the work—Boat adventure at Spithead—Andrew Anderson—Thomas P. Cook—Transfer of detachment from the Mauritius to the Cape—Survey of La Caille’s arc of meridian there—Detachment to Syria—Its active services, including capture of Acre—Reinforcement to Syria |

354 |

| |

| |

| 1841. |

| |

| Syria—Landing at Caiffa; Mount Carmel—Cave of Elijah; epidemic—Colour-sergeant Black—Inspection at Beirout by the Seraskier; return of the detachment to England—Expedition to the Niger—Model farm—Gori—Fever sets in; return of the expedition—Services of the sappers attached to it—Corporal Edmonds and the elephant—and the Princess—Staff-sergeant’s undress—Staff appointments—Wreck of the 'Royal George'—Sergeant March—Sapper-divers—Curiosities—Under-water pay; means used to aid the divers—Speaking under water—Gallantry of private Skelton—Alarming accidents—Constitutional unfitness for diving—Boundary survey in the state of Maine—Augmentation to corps for Bermuda—Sandhurst; corporal Carlin’s services—Quartermaster-sergeant Fraser—Intrepidity of private Entwistle—Colonel Pasley—Efficiency of the corps—Its conduct, and impolicy of reducing its establishment—Sir John Jones’s opinion of the sappers—And also the Rev. G. R. Gleig’s |

365 |

| |

| |

| 1842. |

| |

| xxiiParty to Natal—The march—Action at Congella—Boers attack the camp—Then besiege it—Sortie on the Boers' trenches—Incidents—Privations—Conduct of the detachment; courageous bearing of sergeant Young—Services of the party after hostilities had ceased—Detachment to the Falkland Islands—Landing—Character of the country—Services of the party—Its movements; and amusements—Professor Airy’s opinion of the corps—Fire at Woolwich; its consequences—Wreck of the 'Royal George'—Classification of the divers—Corporal Harris’s exertions in removing the wreck of the ‘Perdita’ mooring lighter—Assists an unsuccessful comrade—Difficulties in recovering the pig-iron ballast—Adventure with Mr. Cussell’s lighter—Isolation of Jones at the bottom—Annoyed by the presence of a human body; Harris, less sensitive, captures it—The keel—Accidents—Conflict between two rival divers—Conduct of the sappers employed in the operation—Demolition of beacons at Blythe Sand, Sheerness—Testimonial to sergeant-major Jones for his services in connection with it |

384 |

| |

| |

| 1842. |

| |

| Draft to Canada—Company recalled from thence—Its services and movements—Its character—Labours of colour-sergeant Lanyon—Increase to Gibraltar—Reduction in the corps—Irish survey completed; force employed in its prosecution—Reasons for conducting it under military rule—Economy of superintendence by sappers—Their employments—Sergeants West, Doull, Spalding, Keville—Corporals George Newman, Andrew Duncan—Staff appointments to the survey companies—Dangers—Hardships—Average strength of sapper force employed—Casualties—Kindness of the Irish—Gradual transfer of sappers for the English survey—Distribution; Southampton |

401 |

| |

| |

| 1843. |

| |

| Falkland Islands; services of the detachment there—Exploration trips—Seat of government changed—Turner’s stream—Bull-fight—Round Down Cliff, near Dover—Boundary line in North America—Sergeant-major Forbes—Operations for removing the wreck of the 'Royal George'—Exertions of the party—Private Girvan—Sagacity of corporal Jones—Success of the divers—Exertions to recover the missing guns—Harris’s nest—His district pardonably invaded—Wreck of the 'Edgar,' and corporal Jones—Power of water to convey sound—Girvan at the ‘Edgar’—An accident—Cessation of the work—Conduct of the detachment employed in it—Sir George Murray’s commendation—Longitude of Valentia—Rebellion in Ireland—Colour-sergeant Lanyon explores the passages under Dublin Castle—Fever at Bermuda—Burning of the ‘Missouri’ steamer at Gibraltar—Hong-Kong—Inspection at Woolwich by the Grand Duke Michael of Russia—Percussion carbine and accoutrements |

412 |

| |

| |

| 1844. |

| |

| xxiiiRemeasurement of La Caille’s arc at the Cape—Reconnoitring excursion of sergeant Hemming—Falkland Islands—Draft to Bermuda—Inspection at Gibraltar by General Sir Robert Wilson—Final operations against the ‘Royal George’—and the ‘Edgar’—Discovery of the amidships—incident connected with it—Combats with crustacea—Success of corporal Jones—Injury to a diver—Private Skelton drowned—Conduct of the detachment employed in the work—Submarine repairs to the ‘Tay’ steamer at Bermuda by corporal Harris—Widening and deepening the ship channel at St. George’s—Accidents from mining experiments at Chatham—Notice of corporal John Wood—Inspection at Hong-Kong by Major-General D’Aguilar |

431 |

| |

| |

| 1845. |

| |

| Sheerness—Increase to the corps at the Cape—Survey of Windsor—Skill of privates Holland and Hogan as draughtsmen—Etchings by the latter for the Queen and Prince Albert—Unique idea of the use of a bullet—Inspection at Gibraltar by Sir Robert Wilson—Falkland Islands—Discharges on the survey duty during the railway mania |

444 |

| |

| |

| 1846. |

| |

| Boundary surveys in North America—Duties of the party engaged in it—Mode of ascertaining longitudes—Trials of the party; Owen Lonergan—The sixty-four mile line—Official recognition of services of the party—Sergeant James Mulligan—Kaffir war—Corporal B. Castledine—Parties employed at the guns—Graham’s Town—Fort Brown—Patrols—Bridge over the Fish River—Field services with the second division—Dodo’s kraal—Waterloo Bay—Field services with the first division—Patrol under Lieutenant Bourchier—Mutiny of the Swellandam native infantry—Conduct of corps in the campaign—Alterations in the dress—Drainage of Windsor—Detachment to Hudson’s Bay—Its organization—Journey to Fort Garry—Sergeant Philip Clark—Private R. Penton—Corporal T. Macpherson—Lower Fort Garry—Particular services—Return to England |

448 |

| |

| |

| 1846. |

| |

| Exploration survey for a railway in North America—Services of the party employed on it—Personal services of sergeant A. Calder—Augmentation to the corps—Reinforcement to China—Recall of a company from Bermuda—Royal presents to the reading-room at Southampton—Inspection at Gibraltar by Sir Robert Wilson—Third company placed at the disposal of the Board of Works in Ireland—Sergeant J. Baston—Services of the company—Distinguished from the works controlled by the civilians—Gallantry of private G. Windsor—Coolness of private E. West—Intrepid and useful services of private William Baker—Survey of Southampton, and its incomparable map |

465 |

| |

| |

| xxiv1847. |

| |

| Detachments in South Australia—Corporal W. Forrest—Augmentation to the corps—Destruction of the Bogue and other forts—Services of the detachment at Canton—First detachment to New Zealand—Survey of Dover and Winchelsea—Also of Pembroke—Flattering allusion to the corps—Sir John Richardson’s expedition to the Arctic regions—Cedar Lake—Private Geddes’s encounter with the bear—Winter quarters at Cumberland House—Road-making in Zetland—Active services at the Cape—Company to Portsmouth |

478 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| VOL. I. |

| |

| Plate |

|

|

|

|

Page |

| I. |

Uniform |

1786 |

|

To face Title. |

|

| II. |

Working-dress |

1786 |

|

|

49 |

| III. |

Uniform |

1787 |

|

|

69 |

| IV. |

Working-dress |

1787 |

|

|

69 |

| V. |

Uniform |

1792 |

|

|

79 |

| VI. |

Working-dress |

1794 |

|

|

80 |

| VII. |

Working-dress |

1795 |

|

|

100 |

| VIII. |

Uniform |

1797 |

|

|

115 |

| IX. |

Uniform |

1802 |

|

|

140 |

| X. |

Working-dress |

1813 |

|

|

198 |

| XI. |

Uniform |

1813 |

|

|

198 |

| XII. |

Uniform |

1823 |

|

|

258 |

| XIII. |

Uniform and working-dress |

1825 |

|

|

262 |

| XIV. |

Uniform |

1832 |

|

|

287 |

| XV. |

Uniform |

1843 |

|

|

429 |

| |

| VOL. II. |

| |

XVI.

XVII. |

Uniform

Working-dress |

1854

1854 |

} |

To face Title. |

|

1HISTORY

OF THE

ROYAL SAPPERS AND MINERS.

1772—1779.

Origin of Corps—Its establishment and pay—Engineers to command it—Its

designation—Working pay—Recruiting—Dismissal of civil artificers—Names

of officers—Non-commissioned officers—First augmentation—Consequent

promotions—Names of other officers joined—King’s Bastion—Second

augmentation.

Before the year 1772, the works at Gibraltar were mainly

executed by civil mechanics from the Continent and England,

who were not engaged for any term of years, but were hired

like ordinary artificers, and could leave the Rock whenever

they felt disposed. Not being amenable to military discipline,

they were indolent and disorderly, and wholly regardless of

authority. The only means of punishing them was by reprimand,

suspension, or dismissal, and these means were quite

ineffectual to check irregularities. The dismissal of mechanics

and replacing them by others was always attended with considerable

inconvenience and expense, and often failed to secure

an equivalent advantage. Consequently, the works progressed

very slowly, imposing much additional trouble and anxiety upon

the officers. Even the better class of artificers—locally termed

“guinea men” from their high wages—who had something at

stake in their situations, could not be relied upon. It therefore

2became necessary that steps should be taken to put a stop to

the evil, and to secure the services of a sufficient number of

steady, obedient mechanics, upon whom dependence could, at

all times, be placed, for the proper execution of the works.

With this view, Lieutenant-Colonel William Green, the chief

engineer at the fortress, suggested the formation of a company

of military artificers as the only expedient. Of the value of

this suggestion some experience had been derived, from the

occasional occupation on the works, of mechanics belonging to

the different regiments in garrison. Indeed, ever since the

taking of Gibraltar, in 1704, soldiers had so been employed,

particularly artillerymen, whose services to the fortress were

always found to be beneficial. There was every reason, therefore,

to expect that, when the department became entirely military

in its character, corresponding results on a large scale would

ensue. Besides which it was considered, that the employment

of a military company on the works, organized expressly for

the purpose, would produce a great saving of expense to the

public; and also, that the men would be ready to participate

in any military operation for the defence of the place, either

as artificers or soldiers, should our relations with other countries

render it desirable.

Influenced by these considerations, Colonel Green submitted

the suggestion to the Governor and Lieutenant-Governor of

Gibraltar. Too well aware themselves of the disadvantages

of the system of civil labour in carrying on the works of The

fortress, they were favourable to the trial of any experiment

that promised success; and in recommending the plan to the

attention of the Secretary of State, they expressed their decided

opinion that many advantages would certainly arise to the

service and the fortress by its adoption. The royal consent was

accordingly given to the measure in a Warrant, under the sign

manual, dated 6th March, 1772; and thus originated the corps,

whose history is attempted to be traced in these pages.

The Warrant authorized the raising and forming of a

company of artificers to consist of the following numbers and

ranks, with the regimental pay annexed to each rank:—

| 3 |

| |

|

s. |

d. |

|

| 1 |

Sergeant and as adjutant[1] |

3 |

0 |

a-day. |

| 3 |

Sergeants, each |

1 |

6 |

” |

| 3 |

Corporals |

1 |

2 |

” |

| 60 |

Privates, or working men skilled in the following trades:—Stone-cutters, masons, miners, lime-burners, carpenters, smiths, gardeners, or wheelers, each |

0 |

10 |

” |

| 1 |

Drummer |

0 |

10 |

” |

| 68 |

Total. |

|

|

|

And officers of the corps of engineers were appointed to

command this new body, to which was given the name of “The

Soldier-Artificer Company.”[2]

Each non-commissioned officer and man was to receive as a

remuneration for his labour a sum not exceeding two reals[3]

a day in addition to his regimental pay; but this extra allowance

was only to be given for such days as he was actually

employed on the works.

The recruiting for the company was a service of but little

difficulty, as permission was granted to fill it with men from the

4regiments then serving in the garrison; and although the

company was restricted to the taking of properly qualified

mechanics of good character, yet, at the end of the year, after

supplying the places occasioned by casualties, there were only

eighteen rank and file wanting to complete. As vacancies

occurred, such of the soldiers of the garrison as came up to

the established criteria, and wished to be transferred into the

company, were allowed the indulgence; and this mode was the

only one followed, for filling up the soldier-artificers, for many

years after their formation.

The whole of the civil mechanics were not discharged from

the department on account of this measure. Such of them were

retained as were considered, from their qualifications and conduct,

to be useful in the fortress, and they were placed under

the superintendence of the non-commissioned officers of the

company, who were appointed foremen of the different trades.

The foreign artificers were, with few exceptions,exceptions, dismissed; and

twenty English “contracted artificers,” or “guinea men,” were

sent home. Previously, however, such of the good men of the

number as were willing to be “entertained” in the company

were permitted the option of enlisting, but none availed themselves

of the offer.

The officers of engineers who were first attached to the

company were the following:—

Lieutenant-Colonel William Green, captain.

Captain John Phipps, Esq.

Capt.-Lieut. and Captain Theophilus Lefance, Esq.

Lieutenant John Evelegh.

And they were desired to take under their command and inspection

the non-commissioned officers and private men of the

company, and to pay particular attention to their good conduct

and regular behaviour.[4]

5On the 30th June, the date on which the company was first

mustered, the non-commissioned officers were—

| Sergeant-major |

Thomas Bridges.[5] |

| Sergeant |

David Young, Carpenter. |

| Sergeant |

Henry Ince, Miner. |

To these were added, on the 31st December—

| Sergeant |

Edward Macdonald. |

| Corporal |

Robert Blair, and |

| Corporal |

Peter Fraser. |

and soon afterwards—

who completed the non-commissioned officers to the full number

authorised by the warrant.

6At the time the soldier-artificers were raised, the extensive

works ordered to be executed by his Majesty in October, 1770,

were in progress, and furnished an excellent opportunity for

testing their capabilities and merits. The advantage of the

change, and the consequent benefits accruing to the fortress,

were soon apparent. Scarcely had the company been in

existence a year, before Major-General Boyd, the Lieutenant-Governor,

impressed with the conviction of its usefulness,

represented, in several communications to Lord Rochford, the

Secretary of State, the expediency of augmenting it; and he

was the more urgent for its sanction as the new works in hand—which

were absolutely essential for the defence of the place—required

to be hastened with all possible despatch. The recommendation,

coming from so high an authority, met with ready

attention, and a Warrant dated 25th March, 1774, was accordingly

issued for adding twenty-five men to the company. Its

establishment was then fixed as follows:—

| Sergeant-major |

1 |

| Sergeants |

4 |

| Corporals |

4 |

| Drummer |

1 |

| Private artificers |

83 |

| Total |

93 |

To the former list of non-commissioned officers were now

added—

Ensign William Skinner joined the company 20th May, and

Ensign William Booth 23rd June.

7No sooner was the company completed to its new establishment

than the engineers proceeded with greater spirit in the

erection of the King’s Bastion, the foundation stone of which

was laid in 1773 by General Boyd.[7] This work, which was of

material consequence for the safety of the fortress, caused the

General much concern, and he employed his best efforts for its

8completion.[8] But, unavoidable delay in some official arrangements

at home, coupled with a little misunderstanding and the

loss of many civil mechanics, greatly retarded the work.

This led General Boyd in 1775 to apply for another augmentation

to the soldier-artificers, which was the more necessary

as three regiments, furnishing a number of mechanics for the

fortifications, were about to leave the Rock; and also as the

foreign artificers—several of whom had been re-engaged since

the pressure of the works—were like birds of passage, abandoning

the fortress when they pleased. This the soldier-artificers

could not do. To their attention and assiduity, therefore,

the progress of the bastion and other works of the garrison

were mainly attributable; and General Boyd, in a letter to

Lord Rochford, dated 5th October, 1775, gave them full credit

for their services. “We can,” wrote the General, “depend

only upon the artificer company for constant work, and on

soldiers occasionally. Had it not been for the artificer company,

we should not have made half the progress in the King’s

Bastion, as well as in the other works of the garrison.”

On the 16th January, 1776, His Majesty sanctioned an addition

to the company of one sergeant, one corporal, one drummer,

and twenty privates, all masons, who were to be reduced again

when the Hanoverian troops should leave the fortress.[9] With

9this increase the company consisted of 116 non-commissioned

officers and men.

Steadily the works advanced; soon the King’s Bastion[10] was

finished, and the fortress was now in such a state of defence

as greatly to alleviate the apprehension, which, a few years

before, caused General Boyd so much anxiety. Though not

exactly all that could be desired to oppose the onslaught of a

determined and daring adversary, it was yet capable of a long

and obstinate resistance; and, from the political phases of the

period, it did not seem at all unlikely that its strength would

soon be tried, and the prowess and fortitude of the garrison

tested.

10

1779-1782.

Jealousy of Spain—Declares war with England—Strength of the garrison at

Gibraltar—Preparations for defence and employment of the company—Siege

commenced—Privations of the garrison—Grand sortie and conduct of the

company—Its subsequent exertions—Origin of the subterranean galleries—Their

extraordinary prosecution—Princess Anne’s battery—Third augmentation—Names

of non-commissioned officers.

Gibraltar, ever since its capture by the English in 1704, had

been a source of much jealousy and uneasiness to Spain, and

her desire to restore it to her dominions was manifested in the

frequent attempts she made with that view. Invariably she was

repelled by the indomitable bravery of the garrison; but a

slave to her purpose, she did not desist from her efforts, and in

the absence of any real occasion for disagreement with England,

scrupled not to create one, in order that she might attack, and

if possible, regain the fortress.

A favourable opportunity for the purpose at length arrived.

Soon after the convention of Saratoga in 1777, the Americans

entered into an alliance with France, which was the cause of a

rupture between the latter nation and Great Britain. Hostilities

had been carried on for six months, when Spain insinuated

herself into the dispute under pacific pretensions. Her

proposals, however, were of such a nature as rendered it impossible

for the British Government to accept them without lessening

the national honour; and being rejected, the refusal was

made the pretext for war. It was accordingly declared by

Spain on the 16th June, and her eager attention was at once

turned to Gibraltar. On the 21st of the same month she took

the first step of a hostile nature, by closing the communication

between Spain and the fortress.

11At this time the garrison consisted of an army of 5,382

officers and men under General Eliott. Lieut.-General Boyd

was second in command. Of this force the engineers and

artificers amounted to the following numbers under Colonel

Green:—

| Officers |

8 |

| Sergeants |

6 |

| Drummers |

2 |

| Rank and File |

106[11] |

| Total |

122 |

No particular demonstration on the part of the Spaniards

immediately followed the closing of the communication; but

General Eliott, anticipating an early attack upon the Rock,

made arrangements to meet it. All was activity and preparation

within the fortress; and the engineers with the artificers

were constantly occupied in strengthening the defences. For

better accomplishing this paramount service, the company was

divided into three portions on the 23rd August, and directed to

instruct the line workmen in the duties required of them. To

prevent misunderstanding with regard to the line non-commissioned

officers—who might under certain circumstances become

litigious—the Chief Engineer issued orders to the effect, that

all such soldiers coming into the king’s works, were to take

directions from the non-commissioned officers of the company in

the execution of their professional duty.[12]

On the 12th September, General Eliott commenced operations

by opening a fire on the enemy, which was so unexpected,

that the latter were surprised and dispersed. On recovering

from the panic, they scarcely ventured, or indeed cared, to retaliate;

for their object obviously was, not to subject themselves

to a costly expenditure of ammunition, shot, &c., but to distress

the garrison by famine, and thereby obtain an easy surrender.

In this, however, they were disappointed; for the enduring

12hardihood of the garrison, and the occasional arrival of relief,

frustrated their object, and compelled the Spaniards to have

recourse to the more expensive and difficult method of besieging

the place.[13]

At this period the privations of the soldiers in the fortress

were of so severe a nature, that many of them were constrained

to seek expedients from unusual resources to supply their

wants; and in this way, thistles, dandelion, and other wild

herbs, the produce of a barren rock, were used to satisfy their

cravings. The following enumeration of some of the necessaries

of life, with their prices affixed, will afford an idea of the extent

of the scarcity:—

| |

s. |

d. |

|

s. |

d. |

|

| Mutton or beef . |

2 |

6 |

to |

3 |

6 |

per lb. sometimes higher. |

| Salt beef or pork |

1 |

0 |

to |

1 |

3 |

per lb. |

| Biscuit crumbs |

0 |

10 |

to |

1 |

0 |

per lb. |

| Milk and water |

|

|

|

1 |

3 |

a pint. |

| Eggs |

|

|

|

0 |

6 |

each. |

| A small cabbage |

|

|

|

1 |

6 |

|

| A small bunch of outward leaves |

0 |

6 |

|

Thus curtailed in their provisions, the wonder is, that the

men were at all capable of supporting life, and keeping their

opponents in check. But notwithstanding this embarrassing

privation, their energy and courage were by no means weakened,

nor their spirit and ardour depressed.

In November, 1781, the Spaniards were very zealous in completing

their defences; so much so that towards the latter part

of the month their batteries presented an appearance at once

stupendous and formidable. This proud bulwark naturally

arrested the Governor’s attention, and as naturally engendered

the determination to assault and destroy it. On the 26th

November, he desired a selection to be made from the troops

for this purpose. To each of the right and centre columns a

detachment of the company—in all twelve non-commissioned

officers as overseers, and forty privates—was attached, under

13Lieutenants Skinner and Johnson of the Engineers; and 160

working men from the line were directed to assist them. To

the left column a hundred sailors were told off to do the duty

of pioneers. The soldier-artificers were supplied with hammers,

axes, crow-bars, fire-faggots, and other burning materials.

Upon the setting of the moon at three o’clock on the morning

of the 27th November the sortie was made. The moment

Lieut.-Colonel Hugo, who had charge of the right column,

took possession of the parallel, Lieutenant Johnson with the

artificers and pioneers commenced with great promptitude and

dexterity to dismantle the works. Similar daring efforts succeeded

the rush of Lieutenant Skinner’s artificers and workmen

into the St. Carlo’s Battery with the column of Lieut.-Colonel

Dachenhausen; but the number of the soldier-artificers attached

to the sortie, whose ardour and labours were everywhere apparent,

being both inconsiderable and insufficient to effect the

demolition with the expedition required, the Governor sent

back to the garrison for the remainder of the company to come

and assist in the operation.[14] Hurrying to the spot to share in

the struggle, they were soon distributed through the batteries;

and the efficiency of their exertions was sensibly seen, in the

rapidity with which the works were razed and in flames. Only

one of the company was wounded.[15]

General Eliott in his despatch on this sortie, observes, “The

pioneers,” meaning artificers, “and artillerists, made wonderful

exertions, and spread their fire with such amazing rapidity, that

in half an hour, two mortar batteries of ten 13-inch mortars,

and three batteries of six guns each, with all the lines of

approach, communication, traverses, &c. were in flames and

reduced to ashes. Their mortars and cannon were spiked, and

14their beds, carriages, and platforms destroyed. Their magazines

blew up one after another, as the fire approached

them.”[16]

Shortly after the sortie the repairs to the defences at the

north front and other works of the fortress, found full employment

for the company. Leisure could not be permitted, and

the necessary intervals of rest were frequently interrupted by

demands for their assistance, particularly in caissonning the

batteries at Willis’s.[17] Sickness also set in about this time;

nearly 700 of the garrison were in hospital; the working parties

were curtailed; and officers' servants and others, unused to

hard labour and unskilled in the use of tools, were sent to

the works to lessen the fatigue to which their less-favoured

comrades were constantly subjected. Much extra duty and

exertion were thus necessarily thrown upon the company, and

though frequently exposed to imminent danger, they worked,

both by night and day, with cheerfulness and zeal. In the

sickness that prevailed, they did not share so much as might be

supposed from the laborious nature of their duties, sixteen only

being returned sick, leaving eighty-one available for the service

of the works.

On a fine day in May 1782, the Governor, attended by the

Chief Engineer and staff, made an inspection of the batteries at

the north front. Great havoc had been made in some of them

by the enemy’s fire; and for the present they were abandoned

whilst the artificers were restoring them. Meditating for a few

moments over the ruins, he said aloud, “I will give a thousand

dollars to any one who can suggest how I am to get a flanking

fire upon the enemy’s works.” A pause followed the exciting

exclamation, when sergeant-major Ince of the company, who

was in attendance upon the Chief Engineer, stepped forward

and suggested the idea of forming galleries in the rock to effect

15the desired object. The General at once saw the propriety of

the scheme, and directed it to be carried into execution.[18]

Upon orders being issued by the Chief Engineer, twelve good

miners of the company were selected for this novel and difficult

service, and sergeant-major Ince was nominated to take the

executive direction of the work. On the 25th of May, he commenced

to mine a gallery from a place above Farringdon’s

Battery (Willis'), to communicate, through the rock, to the

notch or projection in the scarp under the Royal Battery. The

gallery was to be six feet high and six feet wide. The successful

progress of this preliminary work was followed by a desire

to extend the excavation from the cave at the head of the

King’s lines, to the cave at the end of the Queen’s lines, of the

same dimensions as the former gallery. A body of well-instructed

miners was expressly appointed for the duty,[19] and on

16the 6th July, they began this new subterranean passage. On

the 15th, the first “embrasure was opened in the face of the

rock communicating with the gallery above Farringdon’s.” To

effect this, “the mine was loaded with an unusual quantity of

powder, and the explosion was so amazingly loud, that almost

the whole of the enemy’s camp turned out at the report: but

what,” adds the chronicler, “must their surprise have been,

when they observed whence the smoke issued!”[20] The gallery

was now widened to admit of the placement of a gun with

sufficient room for its recoil, and when finished, a 24-pounder

was mounted in it.[21] Before the ensuing September, five heavy

guns were placed in the gallery; and in little more than twelve

months from the day it was commenced, it was pushed to the

notch, where a battery, as originally proposed, was afterwards

established and distinguished, on account of its extensive

capacity, by the name of “St George’s Hall.”[22]

At Princess Anne’s Battery (Willis'), on the 11th June, a

shell from the enemy fell through one of the magazines, and,

bursting, the powder instantly ignited and blew up. The whole

rock shook with the violence of the explosion, which, tearing

up the magazine, threw its massive fragments to an almost

incredible distance into the sea. Three merlons on the west flank

of the battery, with several men who had run behind them for

shelter, were blown into the Prince’s lines beneath, which, with the

Queen’s lower down the rock, were almost filled with the rubbish

ejected from the upper battery, as also with men dreadfully

scorched and mangled. The loss among the workmen was very

17severe. Fourteen were killed and fifteen wounded.[23] Private

George Brown, a mason of the company, was amongst the

former.

In July the company could only muster ninety-two men of

all ranks, including the wounded and sick, having lost twenty-two

men during the siege by death, six of whom had been

killed. This was the more unfortunate, as the siege was daily

assuming a more serious aspect, the enemy collecting in greater

force, and the effect of the cannonade upon the defences more

telling and ruinous. Naturally the Governor’s attention was

called to the deficiency; and as his chief dependence rested

upon the soldier-artificers for the execution and direction of the

more important works, he was not only anxious for their completion

to the authorized establishment, but convinced of the

desirableness of augmenting them. In this view he was the

more confirmed, by the representations of Major-General Green,

the chief engineer, and Lieutenant-General Boyd. As soon,

therefore, as an opportunity offered, he urgently requested the

Duke of Richmond, then Master-General of the Ordnance, to

fill up the company with mechanics from England, and also to

make a liberal increase to its establishment. His Grace accordingly

submitted the recommendation to His Majesty, and

a Warrant, dated 31st August, 1782, was issued ordering the

company to be increased with 118 men. Its establishment now

amounted to—

| |

1 |

Sergeant-major. |

| |

10 |

Sergeants. |

| |

10 |

Corporals. |

| |

209 |

Working-men. |

| |

4 |

Drummers. |

| Total |

234 |

|

To carry out the wishes of General Eliott, the Duke of

Richmond employed parties in England and Scotland to enlist

the required number, which for the most part consisted of carpenters,

sawyers, and smiths. With great spirit and success the

recruiting was conducted; and in less than a month 141

18mechanics—more than enough to meet both the deficiency and

the authorized increase—were embarked for the Rock on board

the transports which accompanied the relieving fleet under Lord

Hood. Twenty landed on the 15th October; a similar number

next day, and the remaining 101 on the 21st. By this increase

the carpenters were 66 in number, the sawyers 31, and the

smiths 57. The masons at this time were 30 strong.

The non-commissioned officers,[24] as they stood immediately

after this augmentation, were as follows:—

| Sergeant-major—Henry Ince. |

| |

| |

Sergeants:— |

| |

| David Young, carpenter. |

| Edward Macdonald.[25] |

| Robert Blyth,[26] mason. |

| 19Alexander Grigor. |

| James Smith, smith. |

| Thomas Jackson, smith. |

| 20Robert Brand, mason. |

| Robert Daniel. |