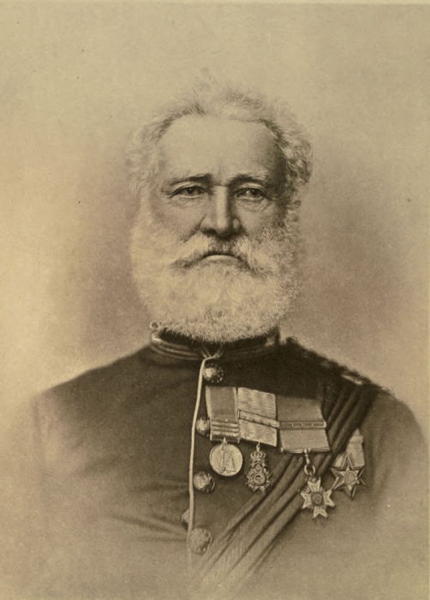

Lt. Col. Joseph Anderson, C. B.

THE following pages have been selected from the autobiography of my grandfather, the late Colonel Joseph Anderson, who was born in Sutherlandshire, Scotland, on June 1, 1790, and died on July 18, 1877. It should be stated that this narrative was written only for his own family. He had never kept a diary—nor even any notes of his adventures and travels—and only began to write his reminiscences of the long-past years when he was seventy-four, in the quiet of his beautiful home near Melbourne, Australia. His memory was perfectly amazing; but if any slight inaccuracies should be discovered, the reader is asked to excuse them, on account of his age. He was a “grand old man” in every sense, and lived in excellent health of mind and body until his eighty-eighth year. To the very last he was always keenly interested in military matters, and never failed to attend, in uniform, all the important volunteer reviews held in Melbourne, where his upright, soldierly figure attracted universal admiration. His son, the late Colonel Acland Anderson, C.M.G., was for many years the Colonel-Commandant of the Military Forces of H.M. Government in Victoria, which appointment he held till his death in January, 1882. He was the founder of the Volunteer Organization, as in 1855 he raised a Rifle Corps in Melbourne, which was not only the first in Victoria but probably the first in Australia.

September, 1913.

Born in Scotland—At fifteen years old appointed to the 78th Regiment—First visit to London—Join regiment at Shorncliffe—Embark for Gibraltar—Put under arrest—Lieutenant James Mackay

Expedition to Calabria—In General Acland’s brigade—Battle of Maida—Sergeant McCrae and the wounded Frenchman—Reggio—Capture of Catrone—Taormina—Syracuse

Expedition to Egypt—We take possession of Alexandria—Entrapped by the enemy at Rosetta—A trying retreat

Colonel McLeod’s death and losses of his detachment—Captain Mackay honoured by Turkish Pasha—Return to Sicily—78th goes to England—Attack of ophthalmia

Gazetted to lieutenancy in 24th Regiment—Embarked for Portugal—Battle of Talavera—Wounded—Soldiers seize Spanish pigs

Army kindly received in Portugal—Much fighting with French army under Massena—Lord Wellington’s retreat on the Lines of Torres Vedras—Battle of Busaco

Continued fighting—General Beresford knighted—English and French officers spend evenings together at theatres, etc., with consent of their commanders—Massena retires to Santarem

Story of the lost regimental books and the honesty of the soldiers

Much fighting—We drive the enemy across the Mondego at Coimbra—Battle of Fuentes d’Onoro—I go into the French lines to take away the body of a friend

On sick-leave in England—In Scotland—Journey of seventy miles in twenty-four hours on foot after a ball—Appointed to assist at brigade office, 1813—Appointed captain and brigade-major in the York Chasseurs

Portsmouth—Guernsey—Sail for Barbados—Honest Henry—Frightful storm—Adventure at Funchal

Life in Barbados—I am appointed acting-paymaster—President of a court-martial—Deputy judge-advocate—At St. Vincent—Expedition to Guadeloupe—Appointed deputy-assistant quartermaster-general and sent to Guadeloupe

Sent to Dominica—A fatal foot-race—I give up appointment and rejoin my regiment at St. Vincent—An awful voyage

Jamaica—Return to England—York Chasseurs disbanded—Trip to France—An amusing duel

Appointed captain in the 50th Regiment—Embark for Jamaica—A terrible storm and a drunken captain—Return to port—Sail again with another captain—Ship chased by a pirate—Jamaica once more

Appointed deputy judge-advocate—Sir John Keane—An interesting court-martial—Sent with a small detachment to Port Maria—Awful outbreak of yellow fever

Invalided to England—Ship injured on coral rock—Dangerous voyage—Married on 25th November, 1826—Portsmouth—The Duke of Clarence—Ireland—Complimented by Sir Hussey Vivian on execution of difficult manœuvres.

Dr. Doyle’s sermon—Ordered to New South Wales—Sail for Sydney with three hundred convicts—Mutiny at Norfolk Island—Appointed colonel-commandant there

Life at Norfolk Island—Trial of the mutineers—A fresh conspiracy—Execution of thirteen mutineers

Sunday Services at Norfolk Island in 4 I appoint two convicts (who had been educated for the Church) to officiate—Find about a hundred ex-soldiers among the convicts—Separate them from the others, with great success

Life at Norfolk Island in 4 Solitary case of misconduct among the soldier gang—I get many pardoned and many sentences shortened—Theatricals and other amusements—Visit from my brother—Mr. MacLeod

Wreck of the Friendship—I am attacked by Captain Harrison and MacLeod—I receive the Royal Guelphic Order of Knighthood—Secure the sheep and cattle station of “Mangalore” in Port Phillip with my brother—Leave Norfolk Island—Visit to Mangalore

Court of inquiry as to my management of Norfolk Island—Major Bunbury reprimanded by Commander-in-Chief at the Horse Guards for his unfounded charges

50th Regiment ordered to India—Sudden death of one of my boys—Voyage to India—First experiences of Calcutta

Magnificent entertainments at Calcutta—Dost Mahomet—Wreck of the Ferguson—Preparations for Burmese campaign—Special favour shown to soldiers of the 50th Regiment

Great welcome to Moulmein—No fighting after all—The Madras native regiments

Return to Calcutta—Much illness in regiment—Boat journey of three months to Cawnpore—Incidents of the voyage—Death of Daniel Shean

Life at Cawnpore—Quarrel between Mowatt and Burke—Court-martial

Expedition to Gwalior—In command of the regiment—Brigadier Black—His accident—I am appointed to the command of the brigade—Battle of Punniar—In General Gray’s absence I order a charge on the enemy’s guns—Severely wounded

“My brigade had carried all before it”—Painful return to camp—General Gray’s dispatch

Slow recovery from my wound—Painful journey by palanquin to Cawnpore—Am created a C.B.—Other honours and promotions

Riding accident at Cawnpore—Foot seriously injured—Get two years’ leave of absence—Voyage to Cape Town—On to Australia—A strange cabin

Sydney once more—Visit Mangalore—Select land for house near Melbourne—My War Medal

Sail for India—Dangers of Torres Straits—Copang—Arrival at Calcutta—My son appointed to the 50th Regiment

Violent gale at Loodhiana—Two hundred men, women, and children buried—By river steamer to Allahabad—Rejoin the regiment at Cawnpore—Return voyage down the Ganges

The guns captured in the Sutlej campaign—Lord Hardinge’s compliments to the regiment—I secure compensation for the regiment’s losses at Loodhiana—Voyage to Cape Town

Return to England—Continued in command of the regiment

Decide to retire—Return to Australia

“Expedition to Calabria, including the battle of Maida, and subsequent operations, and capture of the fortress of Catrone; expedition to Egypt in 1807; Peninsular War from April, 1809, to January, 1812, including the battles of Talavera (wounded) and Busaco; retreat to the Lines of Torres Vedras and various affairs there; with the advance at Espinhal, battle of Fuentes d’Onoro, and many other affairs and skirmishes. (War Medal with four clasps.) Served at the capture of Guadeloupe in 1815. Commanded a brigade at the battle of Punniar (medal), and was severely wounded at its head when in the act of charging the enemy’s guns.”—Hart’s Army List.

1. “Military Order of the Bath,” founded by King George I, 25th May, 1725.

2. “The Guelphic Order” (Hanoverian), founded by King George IV, when Prince Regent, in the name of his father, George III, on 12th August, 1815.

3. “The War Medal,” granted by the Queen, 1st June, 1847, for services in the Peninsular War (4 clasps):—

The War Medal has on the obverse the head of the Queen, with the date, 1848; and on the reverse Her Majesty, as the representative of the country or people, is in the act of crowning with a laurel wreath the Duke of Wellington, in a kneeling attitude, as emblematic of the army.

4. Mahratta Campaign of 1843: “Indian Star of Bronze,” made from the captured guns. Battle of Punniar, 29th December, 1843.

“About four o’clock in the afternoon the enemy was observed to have taken up a strong position on a chain of lofty hills four miles eastward of the camp.... The Second Infantry Brigade, under Brigadier Anderson, of the 50th, arrived in time to put a finish to the action; forming on the crest of a hill, he, by a gallant and judicious movement, attacked the enemy’s left, and completely defeated him, taking the remainder of his guns.... Major White took the Second Infantry Brigade out of action upon Brigadier Anderson being wounded.”—Carter’s “Medals of the British Army.”

Born in Scotland—At fifteen years old appointed to the 78th Regiment—First visit to London—Join regiment at Shorncliffe—Embark for Gibraltar—Put under arrest—Lieutenant James Mackay

I SUDDENLY and most unexpectedly got my commission as an ensign in the 78th Regiment (27th June, 1805) through the influence of my brother William, a captain in the same corps, being then only within a few days of my fifteenth year. But before I go any further I must mention an amusing incident which took place before I left Banff Academy to join my regiment, and as in the present day it may not appear much to my credit, I beg my dear ones who may read this to remember I was still a boy, and with less experience of the world than most of the youths of the present day. Out of my pocket money I managed to save six shillings, with which I purchased an old gun to amuse myself, and to shoot sparrows during our play hours; and this being contrary to all rules and positive standing-orders, I kept my dangerous weapon at an old woman’s house a little way from town. A few chosen companions knew of my secret and accompanied me one evening to enjoy our sport, but there was one amongst them to whom I refused a shot, so next day he reported me and my gun to the second master. I was called up and questioned on his evidence, when I stoutly and boldly denied every word he said. The good master, Mr. Simpson, then said, “You have told a lie, sir, and I must punish you; so down with your breeches.” I at once resisted, and said, “I am an officer and won’t submit.” He then called two or three boys to assist him in clearing for action, but I still resisted, and kicked and thumped them all round, until the noise became so loud that the good old rector came in from his room and said, “What is all this?” On his being told, and also my reasons for resisting, he laughed most heartily and said, “I will not disgrace you, sir; you are an officer, and I will not disgrace you.” So I was allowed to escape and to go back to my seat. Many years afterwards I returned to Banff, and the rector and I had many laughs over this frolic, and at the same time I met Mr. Simpson, but found it difficult to convince him of my continued good will, and that I never forgot the good and salutary lesson he gave me.

Six weeks after this I received a letter from my brother ordering me to join my regiment, then stationed at Shorncliffe barracks in Kent, and directing me at the same time to go in the first instance to my uncle, Dr. Anderson, at Peterhead, to receive an outfit, and then, without being allowed to go home to see my father, I was shipped off for London in one of the trading sloops of that day, and consigned to another friend of ours, Mr. Tod, who was married to my only aunt. They received me most kindly, and here I found a number of young ladies, my cousins, who were about my own age, and with whom I soon became happy and intimate. I remained with them for a fortnight, and during that time Mr. Tod took me to his tailor, who furnished me with all my necessary regimentals, and not a little proud was I on finding myself for the first time dressed out in scarlet and gold. Mr. Tod took me also to many of the public places and streets of London, and to this day I cannot forget how the good old man laughed at my surprise and remarks about all the pretty women who unblushingly stared at me.

On the 18th August, 1805, I took my leave, and by coach proceeded to join my regiment at Shorncliffe barracks. My brother William received me on my arrival, and then took me to the colonel to introduce me, and afterwards to the adjutant to report my arrival, and then to my future home for a time, his own house at Sandgate; and with him I remained for two months, until we marched for Portsmouth to embark for Gibraltar. In the meantime I attended all daily parades, morning and evening, and was drilled and instructed in a squad with the men.

But before I go any further I must mention that soon after joining the regiment my brother told me I was never regularly gazetted to my ensigncy. That appointment had been given to my brother John, who at the same time got a cadetship in the Madras Army, which my father considered the best appointment of the two, and consequently wrote to my brother William to use his interest with General McKenzie Fraser, the full colonel of the 78th (from whom the ensigncy was procured), to say that his brother John was provided for, but that he had another brother, Joseph, to whom he hoped he would kindly transfer the commission; and this the general at once consented to do, and so I was ordered to join, and for nearly two years after my name appeared “... Anderson” in the Army List. Such chances do not happen nowadays.

We arrived at Portsmouth at the beginning of October, and embarked on the following day for Gibraltar. The transports of those days were wretched, and their provisions were even worse, and in the miserable tub Neptune, to which I was doomed, we were so crowded that I, as the youngest subaltern, had neither berth nor cot allowed me, and I was obliged to double up with another young ensign, and to make the best I could of it. Yet we were very jolly, and all went on well until we got off Lisbon, about the 19th of October, when the commodore of all the other ships-of-war in charge of the convoy made the signal, “An enemy in sight, put in to port in view,” and this was immediately answered by every ship in the convoy. The whole fleet then went about and steered direct for Lisbon, and so we continued with every sail set, until on the same evening, and following day, we were all safely at anchor in the Tagus. We heard soon after, that the enemy we discovered in time was part of the French fleet then making for Trafalgar, and in a few days more we had the great and glorious news of Nelson’s splendid and complete victory over the combined fleets of France and Spain off Cape Trafalgar, on the 21st October, 1805, and of their almost complete capture and destruction. But, alas! how great was the price of this national success, for Nelson fell, and many gallant officers, soldiers, and sailors with him.

A few days after receiving this great news we again sailed from Lisbon for Gibraltar, and beyond Cape Trafalgar we came up with our own partly dismasted and disabled ships, and all which could be safely brought away of the enemy’s captured vessels, the former proudly distinguished by their English tattered flags, and the latter humbled by the British ensign flying triumphantly over the national emblems of France and Spain. This was indeed a proud sight, and a lasting day of triumph and renown to old England, for from that time to the present hour the might of the Spanish navy was crushed and the French navy never appeared formidable to us again. We soon passed our noble heroes and their prizes, and our fleet reached Gibraltar a few days afterwards.

The regiment landed next day, and occupied Windmill Hill and Europa Point barracks. There were no less than four other regiments there when we arrived, and I liked that gay station very much. But there for the first and only time of my military life I was put in arrest, and became so alarmed that I cried bitterly, and thought I was going to be hanged at least! The other ensigns of the regiment were all many years older than I, and one of them in particular used to bully and annoy me constantly, so that on one of these occasions I made use of most insulting and ungentlemanlike language to him. Our kind and parental colonel (Macleod of Guinnes) was then in the habit of inviting all the young officers to breakfast with him, and on the following morning I went as usual in full dress to his house, about a mile from our barracks, and there on entering I found Cameron seated with others. The colonel soon appeared, and wished all good morning in his accustomed kind manner and asked us to take our seats. Breakfast passed over as usual. As soon as the table was cleared Colonel Macleod stood up and called us all to him, and then, addressing me, said, “Mr. Anderson, Mr. Cameron has reported to me that you have been making use of most improper language to him, and as you seem to forget you are no longer a schoolboy, but an officer, I must put you under arrest, and send you home in disgrace to your family. Leave your sword there, sir [on the table], and go to your barracks immediately.” Poor me! I at once showed I was still but a schoolboy, for I cried and sobbed fearfully, and returned to my barracks with a broken heart.

The same evening a dear friend of my family, Captain John Mackay of Bighouse, called on me (no doubt at the request of the colonel), and frightened me more than ever, for he told me again that I would be brought to a general court-martial and deprived of my commission. I now cried more than ever, and I told him all that had passed between me and Cameron, and the constant insults and liberties he attempted to take with me in the presence of the other officers. I was glad to see from my friend’s remarks that he began to think Cameron was more to blame than I was, yet he still told me I must prepare for the worst, and so he left me to my own misery. I shall never forget my sufferings that night. However, next day I was ordered to attend at the colonel’s quarters, and there found most of the officers assembled, Cameron amongst them. The colonel then addressed us, and said, “Mr. Anderson, I have been inquiring into your conduct, and find that you, Mr. Cameron, most grossly insulted this young gentleman, and by your daring, unwarrantable, and most unofficerlike conduct provoked a young boy to forget himself. You, sir, are many years older and ought to know better; I consider you therefore far more culpable and blameable in every respect than Mr. Anderson. You have both acted very improperly, but for the present I shall take no further notice of your conduct than with this reprimand to warn you both to be more careful and correct for the future; and now, Mr. Anderson, you are released from your arrest, and will return to your duty.” Off I went in joy to my barracks, thankful indeed for this proper support and friendly admonition, and from that day I enjoyed myself and felt happy with my brother-officers.

I was at this time attached to a company commanded by an old and experienced officer, Lieutenant James Mackay, a most studious man, and an acknowledged scholar, whose pride, next to his profession, was in his books. His instruction and care did me more good than any previous or subsequent opportunities I ever had for study. I was quartered with him at Europa Point, and he made me rise early and visit our men’s barracks at Windmill Hill, two miles distant, every morning. I then returned to breakfast with him, after which we went to our public parade, which was no sooner over than we got home, and then he made me sit down to certain books and studies which he gave me. This he made me continue daily while we remained at Gibraltar, although (at the instigation of the other officers) I often tricked him, and tried hard to get off from such control and (as I then thought) drudgery. Being a perfect master of the French language, he was one of the British officers sent with Napoleon Bonaparte to the island of St. Helena, and afterwards recalled by our Government on the suspicion of being too intimate with the ex-Emperor.

Expedition to Calabria—In General Acland’s brigade—Battle of Maida—Sergeant McCrae and the wounded Frenchman—Reggio—Capture of Catrone—Taormina—Syracuse

EARLY in 1806 our regiment left Gibraltar for Messina, where we continued some months, and then marched for Milazzo, where we camped until we embarked, in June of the same year, as a part of the expedition under Lieut.-General Sir John Stuart for Calabria, landing with the other troops in the gulf of St. Euphemia on the morning of the 1st of July. The object of this force was to attack the French General Regnier, then in that part of Italy with a considerable army. Our landing was but slightly opposed, because our convoy, the Endymion frigate (Captain Hoste), took up her position as near the shore as possible, and by her fire soon cleared the beach and drove the enemy far beyond our first footing. He made a partial stand, however, on a rising ground inland; but as our troops advanced, and after a skirmish, we soon forced him to retreat on his supports and finally on his main body. We then halted for the day, and the enemy left advanced posts and videttes to watch our movements. We soon bivouacked for the night about 6 miles from the beach, with, of course, the same precautions. During that evening and the following day we were busily engaged in landing our heavy stores of provisions. On the 3rd July we advanced a few miles to reconnoitre and to gain information of the enemy’s force and main position, and on the memorable and beautiful morning of the 4th July we finally advanced in columns, and soon found ourselves on the unusually clear and extensive plain of Maida, the enemy showing in mass on the distant hills and woods, about three miles from us, with a river in front which greatly strengthened their position.

As soon as we got half across the plain, our columns were halted, and the troops deployed into two lines, the one to support the other, with our skirmishers thrown out in front to cover us. We were then directed to “order arms and stand at ease”; thus formed, we offered a fair field to the enemy. Our brigade, consisting of the 58th, 78th, and 81st Regiments, under General Acland, formed our front line, and in this position we remained at least half an hour gazing at our enemy; by this time the French were seen in full view debouching from the hills and woods, and, crossing the river, they advanced with all confidence towards us. As soon as they had cleared the river their advance halted, and the whole then formed into two columns, in which order they steadily advanced with drums playing and colours flying. We remained quiet and steady, but impatient, on our ground, and had a full view of our foes, as they boldly and confidently advanced, evidently expecting that they could, and would, walk over us; and so they ought to have done, for we afterwards ascertained they numbered upwards of nine thousand of their best troops, while our force did not much exceed six thousand men! Their cavalry was also more numerous, for we had only one squadron of the 23rd Light Dragoons; but ours was so admirably managed that it kept the others in check during the whole day.

As soon as these formidable French columns came sufficiently near, and not till then, our lines were called to “attention” and ordered to “shoulder arms.” Then commenced in earnest the glorious battle of Maida, first with a volley from our brigade into the enemy’s columns and from our artillery at each flank without ceasing, followed by independent file firing as fast as our men could load; and well they did their work! Nor were the enemy idle; they returned our fire without ceasing, then in part commenced to deploy into line. The independent file firing was still continued with more vigour than ever for at least a quarter of an hour, when many brave men fell on both sides. Our brigade was then ordered to charge, supported by our second line, and this they did lustily and with endless hearty cheers, the French at the same moment following our example and advancing towards us at a steady charge of bayonets, the rolling of drums, and endless loud cheers. Both armies were equally determined to carry all before them; it was not till we got within five or six paces of each other that the enemy wavered, broke their ranks, and gave way, turning away to a man and scampering off, most of them throwing away their arms at the same time; but our men continued their cheers and got up with some of them, and numbers were either bayoneted, shot, or taken prisoners. The enemy was then fairly driven over the bridge by which they had advanced, or forced into the river, where numbers were captured or drowned.

Our loss was comparatively small. The brave 78th had about a dozen men killed and many wounded. The 20th Regiment landed during the action, and by an able and hurried manœuvre managed to get on the enemy’s right flank, and contributed much to the success of the day. Captain McLean, of that regiment, was the only officer killed in the battle. I shall never forget my horror when I beheld numbers of gallant French soldiers weltering in their blood and groaning in agony from the most fearful wounds. And here I must mention an incident to the honour and credit of one of our Highland sergeants of grenadiers, Farquhar McCrae, who could not speak one word of English nor of French. He was wounded after we had passed over the first line of dead and dying Frenchmen, and while passing through the heap of wounded one of them made him a sign that he wanted a drink, on which McCrae immediately turned round and made towards the river; but he had no sooner done so, than his ungrateful enemy levelled his musket and wounded him slightly in the arm. McCrae looked back, saw from whom the shot came, and going up to the man he seized his firelock, and after a struggle soon got it away from him; then, taking it by the muzzle, raised the butt over the Frenchman’s head and said, with a terrible Gaelic oath, “I’ll knock your brains out!” But a more generous impulse seized him; he actually went back to the river and brought the wretched man some water!

I have heard that in Lieut.-General Sir John Stewart’s official dispatch concerning the battle of Maida it is stated that the bayonets of the contending forces actually crossed during the charge. They may have done so, in some parts of the line—but so far as I could see they did not do so, and I have never heard any one who was in the action say that “the bayonets actually crossed.”

The defeat was perfect, and the victory glorious beyond all praise. We remained on the field of battle burying our dead and attending the wounded and embarking our prisoners; then we marched for Reggio, the castle of which was then besieged by some others of our troops from Sicily, who now joined our force, except the 78th Regiment, which was at once embarked under convoy of the Endymion frigate and destined for the capture of the fortress of Catrone, on the east coast of Italy. We arrived and anchored off that place. About a week afterwards the Endymion took up her position within range of the fort, and all were ordered to be in readiness for an immediate landing. Major Macdonnell was sent on shore with a flag of truce and proposals to the governor of the fort to surrender. He returned to say that the terms were accepted. Some companies of the 78th were then landed near the fort, when the whole French garrison marched out as prisoners of war and laid down their arms in front of our line, being allowed to retain only their personal baggage, and the officers their swords. They were at once embarked and divided amongst our transports. The fort was dismantled and the guns spiked. We re-embarked, and our little fleet sailed in triumph back to Messina; but on landing we were ordered to Syracuse, and sent detachments to Augusta and to Taormina. I was with the latter, and had not been long there before I fancied myself in love with the daughter of a widow, who did all she could to encourage me and tempt me to a marriage by constantly parading a quantity of silver plate and jewels as a part of my portion; but this chance of my imaginary good luck was soon put an end to, for I was suddenly called back to headquarters, Syracuse, and there forgot my love affair.

Expedition to Egypt—We take possession of Alexandria—Entrapped by the enemy at Rosetta—A trying retreat

IN March, 1807, we embarked as part of an expedition from Sicily under General McKenzie Fraser, destined for Egypt. We sailed from Syracuse on the 7th, arrived at Aboukir Bay about the middle of the same month, and found there a large fleet of our men-of-war and a numerous fleet of transports with the other troops of our expedition. The object of our force was to create a diversion in favour of Russia against the Turkish army in that country.

On the following morning all our light men-of-war and gunboats took up their stations as near the landing-place as the depth of the water would permit. The first division of our troops were at the same time ordered into the different ships’ launches and towed by the smaller boats to the shore, a distance of at least four miles; but the weather was unusually fine. A considerable body of the enemy appeared on the sand-hill above the landing-place, but our gun-brig and gunboats soon dispersed them, and we landed without difficulty, except a good wetting as far as the knee, for the water was shallow and our boats could not get nearer than a few yards from the beach. The remainder of the troops followed in the course of the day, and landed with the same success and safety, and next morning the stores, camp equipage, and guns were landed without accident. The usual advance guard was pushed forward, and the remainder of the troops followed in divisions, the enemy’s advanced posts retiring before us, and that evening we camped, without any covering, on the dry sand, about six miles inland. Some of the enemy’s cavalry were visible, but only in small numbers to watch our movements.

Next day we commenced our march for Alexandria, with very little interruption, beyond occasionally seeing large detachments of Turkish cavalry, with which our advanced guards and videttes exchanged shots and some volleys occasionally. Our advance to Alexandria continued much in the same way for a few days; we had fine weather and hot sands for our beds, with which we covered ourselves over. We felt well and slept very comfortably, and it was not till we arrived before the walls of the town that the enemy appeared in force and attempted to dispute our advance, but after a partial action and the loss of a few men killed and wounded we soon drove them before us and forced them to take shelter behind the walls of the town, and soon after the firing ceased on both sides for that day. We camped as before, beyond the walls of the old town, with our advanced piquets posted, and all other necessary precautions. It was found next morning that the enemy had evacuated the city of Alexandria during the night, and we then took formal possession, keeping most of our troops still in camp.

A force of about twelve hundred men was now told off and detached under Brigadier-General Wauchope to proceed against the town of Rosetta, on the Nile. They arrived before that place in twelve days, in safety. The general marched his men right into the centre of the town without any opposition, not even seeing an enemy, but then, being entrapped, a heavy fire was opened upon him from the tops of the houses and windows, without even the power of returning a shot. Death and confusion followed. General Wauchope was amongst the first who fell dead, and in a few minutes nearly all his detachment were either killed or wounded, and those who escaped for the moment were made prisoners and with the wounded put to death, so that only a few escaped altogether, and these found their way back to Alexandria to tell the sad and murderous tale.

This barbarous and butchering defeat required to be avenged, and a second force of about eighteen hundred men, under Major-General Sir W. Stewart, was told off for this service, in which my regiment, the 78th, was included. We marched from Alexandria late in March and arrived before Rosetta on the 7th of April, and on getting into position before the town the first thing we saw was the dead and mutilated bodies of hundreds of the former force. They were, of course, at once buried, and vengeance was the prevailing cry and feeling of the living. The late Field-Marshal Sir John Burgoyne was then a captain and our chief engineer. He at once began to throw up breastworks and other temporary defences for our guns and for the troops, these being partly completed by the next day. Some of our heavy ordnance were in battery, and commenced at once to shell the town; at the same time the enemy opened a heavy fire of artillery upon us, which was continued by both sides until dark. Rosetta is a walled town, known then to be strongly fortified. Our works were continued day and night, and additional guns got into position, until all were mounted and brought to bear on the town. The only visible good effect our cannonade produced was the cutting in two and upsetting of many lofty minarets of the mosques; we never heard the extent of their losses, but as Rosetta was full of troops and inhabitants, their casualties must have been very considerable. All our efforts failed to make any practicable breach in the walls, therefore no regular assault was attempted. Almost every evening the enemy sallied forth in large detachments of cavalry and infantry to attack our advance posts and picquets, but our troops of dragoons (ever on the watch) soon met them, and generally dispersed them; but they never gave us a fair chance, for they usually galloped off and got back to their stronghold just as we had an opportunity of destroying them.

Ten days after we commenced this siege, our good, gallant Colonel McLeod, of the 78th, was detached with five hundred men for El-Hamed, some 50 miles higher up the Nile, to check any reinforcements or surprise by additional troops coming down the Nile from Cairo to Rosetta, and our own main body continued the siege much in the same daily routine for a fortnight longer, but still unfortunately without any success in making a practicable breach in the outer walls so as to give us a fair chance of assault. All this time we were losing many brave men. It was then finally determined to raise the siege as hopeless, and to return to Alexandria. Orders to this effect were sent to Colonel McLeod, with instructions to meet us on a given day and hour at Lake Etcho; therefore, during the night of the 20th of April our batteries were dismantled and all our heavy guns spiked and buried deeply in the sand.

On the morning of the 21st our troops were under arms and formed into a hollow square, with a few pieces of light artillery and ammunition and stores in the centre. In this way we commenced our retreat for Lake Etcho. We had scarcely moved off when our square was surrounded by thousands of Turkish cavalry and infantry, howling, screaming, and galloping like savages around us, at the same time firing at us from their long muskets, but fortunately with comparatively little loss to us. We occasionally halted our square, wheeled back a section, and gave them a few rounds of shot and shell from our artillery, then moved on in the same good order. This was a long and trying day, and the only retreat in square I ever saw. It occupied us nearly twelve hours, from five in the morning till the same hour in the evening. The enemy, with fearful shouts, followed us, firing the whole of that time, but they never showed any positive determination to charge or to break our square. We were not so delicate with them, for we gave them many rounds from our guns, and when they ventured sufficiently near they were sure of more volleys than one, and we had the satisfaction of seeing numbers of them fall. We had few men killed, who were unavoidably left behind, but we were able to carry away our wounded.

Colonel McLeod’s death and losses of his detachment—Captain Mackay honoured by Turkish Pasha—Return to Sicily—78th goes to England—Attack of ophthalmia

WE had soon another trial awaiting us. When we got to Etcho there was no appearance of Colonel McLeod or his detachment, nor any message from him. It was therefore at once determined to march back to El-Hamet, to ascertain his fate; and there we received information that Colonel McLeod had been attacked that morning by a large force of Turks in boats from Cairo, and the whole of his detachment destroyed, and he, that good and promising soldier, was amongst the first who fell. After a short council of war we again wheeled about and marched back to Etcho, where we camped for the night. Next day we continued our retreat to Alexandria, where we arrived without any further molestation.

Day by day several rumours reached us about our lost detachment and the gallant defence they made, but nothing positive or upon which we could rely, until the sudden appearance, six weeks afterwards, at Alexandria of Lieutenant Mathieson, who was one of the survivors, who now came to us in a Turkish dress with some proposals from the Turks at Cairo. From him we learnt that they were attacked most unexpectedly on the morning of the 21st April by a large Turkish force, who came down the Nile in boats from Cairo, on their way to Rosetta, and after gallantly resisting until more than two-thirds of their number were either killed or wounded, and the last rounds of ammunition expended, the remnant were overpowered and obliged to surrender. He also described their position at El-Hamet. Colonel McLeod and the main force were stationed on the top of a hill, and detachments of fifty, thirty, and twenty men were posted round the base, in the strongest possible places, with orders to fall back on the main body if attacked. While so posted and before daylight, the enemy landed from their boats, surrounded the hill, and at once commenced the attack. Our men fought desperately, for they expected no quarter, and numbers fell. Captain Colin Mackay with his grenadier company commanded one of the outposts, and, like all the others, fought heroically; but his two subalterns, McCrae and Christie, and nearly half his men were soon killed. He himself received a fearful sabre cut in the neck (from which, although he lived for many years, he never completely recovered) and also a severe musket wound in the thigh, both of which rendered him at once prostrate. But Mackay’s spirit was not gone, for he then ordered his few remaining men to leave him to die there, and to make the best of their retreat to the headquarters; but this they would not do, declaring to a man that they would sooner die with him, than leave him. Two of his remaining sergeants then got their captain on their shoulders and succeeded under a heavy fire in carrying him off in safety to the top of the hill, and there learnt that their Colonel was already amongst the slain.

The command then devolved upon a Major Vogalson (a German); he at once wished to surrender, fixing his white handkerchief on the top of his sword, as a sign of truce to the enemy. Colin Mackay lay under a gun bleeding and suffering severely from his wound, but he happily still retained his senses, and being told that Major Vogalson wished to surrender he cried out, “Soldiers, never, never while we have a round left!” upon which they cheered him again and again, and set Major Vogalson’s authority completely aside; thus they actually continued to fight until the very last round of their ammunition was gone. The enemy pressed in upon them, and after a desperate struggle they were overpowered and obliged to surrender. The Turkish Pasha who commanded, then rode up and inquired, “Where is the brave man who has so long and so ably resisted me?” Colin Mackay, the hero of the day, was pointed out to him lying still in agony under a gun, on which Ali Pasha dismounted and, creeping near Mackay, took the sword off his own neck and shoulders and placed it gracefully on Mackay, saying, “You are indeed a brave man, and you deserve to wear my sword.” From that time and long afterwards (although still a prisoner) he received the most marked attentions from the Pasha.

The few prisoners who survived were then secured, the dead were decapitated (and I fear many of the wounded also), and their living comrades were forced to carry their heads in sacks to the boats, and poor Colonel McLeod’s conspicuous amongst the number. Most of the enemy then embarked with their prisoners and their trophies and returned in triumph to Cairo. There the heads of the dead were exhibited on poles for some weeks round the principal palaces of the authorities. The survivors were committed to confinement, and the officers were allowed at large on their paroles and treated well, especially Captain Mackay, who continued to receive the most marked attentions from every one. In this state they remained nearly eight months, when, after a variety of negotiations, they were exchanged and sent back to join us at Alexandria.

In another month the whole of our force left Egypt and returned to Sicily, far from proud of the result of our unfortunate and badly managed expedition. The 78th went to Messina, and, without landing, were ordered to Gibraltar, and on arrival there were sent direct to England.

Here I must mention that during the last eight months of our inactive life in Egypt our troops suffered much from ophthalmia. I was for many months laid up from that fearful malady, from which I suffer to this day, as I have partially lost the sight of my right eye; many of our men lost one, some both eyes, and became totally blind. From that period until now I have been subject to occasional attacks of inflammation of the eyes, so bad in 1821 and 1822 that I was recommended by my medical attendants to apply for a pension. This I did through Lord Palmerston, then Secretary of War, on which I was ordered for treatment and report to Fort Pitt at Chatham, where for six weeks I was exposed to all kinds of pains and penalties. In consequence, I received a letter from Lord Palmerston saying that His Majesty was pleased to grant me the pension of an ensign, that being the rank I held when I received the injury to my sight. I wrote back to thank his lordship, but saying that, as the regulations for pensions had been changed, the amount now being allowed to increase with the rank of the individual so favoured, I still hoped, as I was now a captain, I should not be made a solitary exception to the rule. To this I received a reply ordering me again to Fort Pitt for treatment there. I remained under similar torture for another month. Soon after, I had a third reply, informing me that on the second report of the medical board His Majesty was pleased to grant me the pension of a lieutenant. I was then quartered in the Isle of Wight, so got leave of absence and went to London, determined in so good a cause to see Lord Palmerston in person. I was admitted, and then renewed my application and entreated his lordship to reconsider my case, adding that not only one eye was nearly gone but the other suffering much also. He was writing at the time and never took his pen from his paper, yet he was very kind and appeared to listen to me attentively; then, looking up, said, “I must put you on half-pay, sir, if you are so great a sufferer.” I said, “I hope not, my lord, while I am able to do my duty, as I have nothing else to depend upon but my commission.” He then smiled and said, “Well, write to me again, and I shall see what can be done.” I did so, and in due course had the satisfaction to receive a notification stating that under the circumstances of my case His Majesty was graciously pleased to grant me the pension of a captain.

But to return from this long digression to where I left my early history in the brave 78th, I proceed to say that after finally leaving Gibraltar we arrived safely in Portsmouth and marched for Canterbury, a few months after to Chichester, and then to the Isle of Wight, where we detached in companies to all parts of the island. I was sent even further with a small detachment to Selsea barracks in Sussex, to take charge of a large ophthalmic depot of that station.

Gazetted to lieutenancy in 24th Regiment—Embarked for Portugal—Battle of Talavera—Wounded—Soldiers seize Spanish pigs

I WAS not long at Selsea barracks before I wrote to the Horse Guards soliciting promotion, for I was then more than three years an ensign—an unusual period at that time. I received a sharp answer informing me that I ought to make my application through the officer commanding my regiment. This frightened me a little, for I now dreaded his displeasure also, for he was a perfect stranger to me. I had never seen him, having lately been appointed from another regiment. In a few days I regained confidence and made up my mind to write and tell my colonel frankly what I had done in ignorance of the rules of the service, and begging him to renew my application to the Horse Guards. I acted wisely, for a few weeks later I saw myself gazetted to a lieutenancy in the 24th Regiment, and being relieved of my command at Selsea, I joined that corps soon afterwards in Guernsey. This was in October, 1808; after remaining there till April, 1809, we embarked for Portugal to join the army under Sir Arthur Wellesley.

After a prosperous journey I found myself again in Lisbon. The march of the 24th to join the army was by a route along the banks of the Tagus, our principal halting-places being Villafranca, Azambuja, Cartaxo, Santarem, Abrantes, and Portalegre. We halted a month at Santarem, where we were most hospitably treated by the inhabitants. There, at a large convent, the mother abbess paid us great attention, and not only entertained us occasionally with fruits and sweetmeats, but allowed us daily to visit the convent and see the nuns. There was a large hall or reception-room, where visitors assembled, in which, at the far end, there was a large grated window in an unusually thick wall; both sides of the window were barred, but sufficiently open and lighted to enable us to see through the adjoining room. The nuns appeared in twos and threes in the inner room, and in this way we chatted and made love for hours daily, but the gratings between us were so far apart that we could only reach the tips of their fingers. It was during one of these visits that the mother abbess sent a privileged servant to lay out a table with fruit and cakes, and in return for all these favours we sent our band to play under the convent walls every other evening. We left Santarem with much regret.

We joined General John Ronald McKenzie’s brigade, consisting (with the 24th) of the 31st and 45th Regiments; during the months of May and June we joined many other brigades and divisions of the army. Early in July the whole British force was concentrated and reviewed on the plains of Oropesa by the Spanish general, Cuesta, who proved afterwards a worthless man and a bad soldier, and yet he was then, by gross mismanagement and perhaps by the treachery of the Spanish Government, considered senior to Sir Arthur Wellesley. Our whole army in line at that review made a grand and magnificent appearance.

It was now known that the French army under General Marmont was not very far ahead of us, and every one believed we were now concentrated and advancing to the attack. These reports were soon confirmed by facts; after a few days of marching we found ourselves on the 23rd July encamped near the river Alberche, with General Cuesta’s Spanish army on our right, the town and position of Talavera de la Reina a few miles in front on the opposite side of the river, with Marshal Marmont and the whole French army not far distant facing us. It was afterwards well known that Sir Arthur Wellesley fully intended to cross the Alberche on the following morning and attack the enemy, but General Cuesta overruled any such advance on the pretence that the river was not fordable. It was then suspected that the real reason for delay was to allow the enemy time to fall back on his reinforcements. On the 25th, when our advance was ordered and made, we found the water of the river only knee-deep; so we crossed, guns, cavalry, and infantry, without any difficulty, and heard that the French had actually retreated on reinforcements they expected from Madrid under King Joseph. Our main body was now halted, and in course of the day occupied the position of Talavera de la Reina; the whole of the Spanish army went on pretending to watch the movements of the enemy, while at the same time General Donkin’s brigade and ours, consisting of the 87th and 88th Regiments, followed close upon the Spaniards with the intention of watching them! We halted at Santa Olalla, eight or ten miles in front of Talavera, and there took up a strong position. The Spaniards continued their advance and marched farther. On the following noon we were astounded by seeing the whole Spanish army in confused mobs of hundreds retreating past us without any attempt at order or discipline, shouting that the French army was upon us. Our two brigades immediately got under arms and formed in line ready to receive the enemy, without making any attempt to stop the cowardly fugitives, and we soon lost sight of them. We remained firm in line till the French came well in sight; then we gave them a few volleys and retired in echelon of brigades, each halting occasionally and fronting as the ground favoured us, giving the enemy volley after volley.

This order of retreat was continued for some miles through a thickly wooded country. At last we got upon a most extensive plain, keeping the same order till the enemy affronted and opened a heavy fire, but fortunately their guns fell short, and we returned the fire with more success, and soon we saw our own gallant army drawn up in order on the heights and grounds near Talavera. This cheered us, and we continued our retreat and defence in the most perfect order. It was a most splendid sight; on nearing the main position of our army a considerable body of our cavalry advanced to meet us, and our batteries from the heights opened a heavy and destructive fire at the enemy.

Then commenced in earnest the glorious battle of Talavera, on the 27th July, 1809. The enemy made several deployments of their numerous columns during the action, attacking with desperation almost every part of our extended line, but on every occasion they failed and were driven back; yet fresh troops were brought up, the battle raged furiously, and there was much slaughter on both sides. I was slightly wounded in the thigh just as we got into our own lines. On the morning of the 28th a heavy and constant cannonade was commenced, and the battle was renewed with more vigour. The French columns came on boldly and tried again and again to walk over us and break our lines, but we defied them, and at every assault they were driven back with fearful slaughter; then they advanced with fresh troops, cheering and shouting “Vive l’Empereur!” The others, disheartened by our determined resistance, faced about with the altered cry “Sauve qui peut.” The slaughter on both sides was fearful butchering work, and was continued by both armies the whole of that memorable day. Our loss in men was unusually great, and the French loss was said to be greater than ours. When the morning of the 29th dawned, not a Frenchman was to be seen! Their whole army had retired during the night of the 28th! leaving us the victors and masters of the field of battle.

A fearful and most distressing sight that field presented as we went over it, covered with thousands of the enemy’s dead as well as our own, and thousands of wounded, numbers with their clothes entirely or partially burnt off their bodies from the dry grass on which they lay having caught fire from the bursting of shells during the action; there were many of the wounded who could not crawl away and escape. Those who still lived were at once removed, and the dead were buried. We remained on the field of battle three days more, attending to the wounded. Having then received information that Marshal Soult with the French army was at Plasencia and advancing on us, our whole army was put in retreat towards Portugal by Truxhillo, Arzobispo, and Merida, leaving the wounded and many medical officers in hospitals at Talavera. The road taken was across country, and so bad that we were obliged to employ pioneers and strong working parties to enable us to get on. From these unavoidable causes and delays, our marches on many days did not exceed ten miles, and our provisions became very limited. We had much rain, and our men suffered much from sickness, fevers, agues, and dysentery; the latter was much increased by the quantity of raw Indian corn and wild honey which the country produced, and which the soldiers consumed in spite of every threat and order to the contrary.

This retreat lasted three weeks, and I never remember seeing more general suffering and sickness. On crossing the bridge of Arzobispo we met a division of the Spanish army driving before them a herd of many hundreds of swine. Our men broke loose from their ranks as if by instinct, surrounded the pigs, and in defiance of all orders and authority, the men seized each a pig, and cut it up immediately into several pieces; so each secured their mess for that day, then again fell into place in the ranks, as if nothing had happened—this in open defiance of the continued exertions and threats of all their officers, from the general downwards. The Spaniards stood still in amazement, evidently in doubt whether they should attempt to avenge their losses, but they did not do so, and each army continued its march in opposite directions. When we camped for the night our good soldiers sent a liberal portion of their spoil to each of their officers, nor were the generals forgotten! and they, like the youngest of us, were thankful, at that time, for so good a mess. We continued our retreat by Elvas and Badajoz, then halted at various stages, and were quartered in the different towns and villages on the banks of the Guadiana for some months afterwards.

Army kindly received in Portugal—Much fighting with French army under Massena—Lord Wellington’s retreat on the lines of Torres Vedras—Battle of Busaco

WE were now in Portugal, and by the kindness and hospitality of the inhabitants were made truly comfortable. We felt this change, for in Spain we were always received coolly, and got nothing in the way of food from the inhabitants upon whom we were quartered, whereas in Portugal we were received and welcomed with open arms by every one; whether rich or poor, these good people upon whom we were billeted always shared their food with us, and gave us freely of the best of every sort of provisions they had. Towards the end of this year (1809) the army was again in motion for the north of Portugal, and after a variety of marches and changes of quarters my division halted at Vizeu, Mangualde, Anseda, Linhares, and Celorico; at each of these places we had abundance of provisions and supplies and were, by the kindness of the inhabitants, most comfortable. Some time before this, the 31st and 45th Regiments were removed from our brigade and replaced by the 42nd and 61st Regiments.

Our troops remained inactive till about the beginning of July, 1810; then we heard that the French army, greatly reinforced, was advancing upon us under Marshal Massena. They were checked for a time by some hard fighting with our advance light division, under General Crawford, also by continued resistance of the garrisons of Ciudad Rodrigo and Almeida. The former was occupied generally by Spanish troops and some Portuguese militia, the latter fortress by one English regiment and three or four Portuguese regiments, with brave Colonel Cox, of our service, as the governor. Both these forts resisted gallantly and successfully for a short time, but after a siege of a fortnight Ciudad Rodrigo surrendered, and in ten days more the principal magazines and public buildings in Almeida were levelled to the ground by a sudden explosion, killing five hundred troops and inhabitants and destroying the principal works and means of defence; in this state of confusion and terror the brave governor, Colonel Cox, was obliged to capitulate. It was afterwards discovered that this shame and sacrifice was occasioned by the treachery of one of the Portuguese officers, who was actually the lieutenant-governor of the fort, and who openly headed a mutiny of the garrison against the governor, Colonel Cox, aided and assisted by another Portuguese officer, who was the chief of the artillery, and who had been for some time in secret correspondence with France!

The surrender of these two important strongholds encouraged the enemy to renew their advance, so that in the beginning of September Lord Wellington commenced his able and well-devised retreat on the Lines of Torres Vedras, within thirty miles of Lisbon. The Portuguese army under General Beresford and the Spaniards under the Marquis de la Romana, retreating on our flank for the same destination, all believed that we were making the best of our way to our ships for embarkation, and with the full intention of finally quitting the country. So secretly had the works of the Lines of Torres Vedras been carried on, that only rumours of their existence were heard, and those only by very few officers of high rank. It was even said that neither the English nor Portuguese Government knew anything positive about these works nor where they were constructed, and I remember well that most of our officers laughed at the idea of our remaining in Portugal, and heavy bets were daily made, during our retreat, on the chances or the certainty of our embarkation. But different indeed were the results, and all the world soon acknowledged the master-mind of our most noble and gallant commander.

I have said that we commenced this retreat early in September, disputing the ground daily as opportunities offered, and as we were covered by our Light Division, these brave men had nearly all the hard work and most of the fighting, but, when necessary, other troops were brought up to their support, and occasionally to relieve them from this constant harassing duty. For a few days the Portuguese militia under Colonel Trant and the Spaniards under the Marquis de la Romana were constantly kept to guard our flanks. In this way the main body, by different roads, retreated in good order for twenty or thirty miles a day, most of the inhabitants leaving their homes and property and falling back in thousands before us, rich and poor, men, women, and children, carrying little with them beyond the clothing on their backs, and halting and bivouacking in the open fields, a short distance before us, whenever the army halted for the night.

A month after we started, our division was suddenly moved off the main line of road, from the crossing of the Mondego River above Coimbra, to the mountain position of the Sierra de Busaco, some miles farther in rear of the above river and city; all the other divisions of the army were directed to the same point. Having scrambled up that mountain as best we could, our whole army was soon formed in order of battle. Below us was an extensive open but thickly wooded country, and there we saw the whole of the French army, under General Massena, advancing in many columns to attack us. The Sierra de Busaco is a very extensive range of mountains, and the main road from Coimbra, passes over the centre of it, to the interior; but in all the other places it is so precipitous and rocky, that our gallant old commander was obliged to be carried up in a blanket by four sergeants, for no horse could ascend there. By two o’clock on the afternoon of the 27th September our whole army was in position, our guns in battery, and our light troops thrown out in front for some distance. These arrangements were not long completed when the French, in different columns, advanced to attack, covered by clouds of their light troops and skirmishers. As soon as they came within range they commenced the battle with continued rounds from their numerous artillery, and our batteries returned the compliment. The skirmishers of both armies opened their fire furiously, and two of their columns pushed forward up the most easy and accessible part of the mountain with drums playing and endless cheers, and appeared as if determined to carry all before them. Our lines stood firm and retained their fire till the enemy came within easy range; they then gave a general volley, followed by a thundering, well-directed independent file firing, covered by our artillery, which soon made the enemy halt, stagger, and hesitate, and in a few minutes they were seen to face about and to retire in very good order. Their loss must have been great, and so was ours. At daylight on the morning of the 28th the battle was again renewed in a more extended and general way by the enemy, for they attacked simultaneously several points of our position; at the same time column after column was seen pressing up the mountain in every direction, and in one place so successfully, that at break of day one of the heaviest and largest of these actually managed to reach within a few yards of our position before it was seen by our troops. They were no sooner seen than received with a volley; yet they gallantly kept their ground, and returned our fire without ceasing for about half an hour; during that time neither of the contending lines advanced, nor gave way one inch. At last our men were ordered to charge; then the enemy retired, and, at the point of the bayonet, were driven down the hill pell-mell, in the greatest confusion, leaving many hundreds of their dead and wounded behind them. Their other minor columns of attack were repulsed in like manner. In course of that day the battle was again renewed, and the French were finally driven back, although they fought ably and with much gallantry. During this day’s battle our invincible and gallant Commander-in-Chief, Lord Wellington, pulled up with all his staff in front of my regiment, and dismounted, directing one of his orderlies to do the same and to hold his horse steady by the bridle. He then placed his field-glass in rest over his saddle, and for some minutes continued coolly and quietly to reconnoitre the enemy, and this under a heavy fire!

On the morning of the 29th there was not a Frenchman to be seen. They had retired during the night, and were soon known to be moving to turn the left of our position, so as to cut off our retreat by Coimbra and the main road. But our “master-mind and head” was equal to the occasion, and in another hour the whole of our army was in retreat by a different route, to cross the Mondego River at and above Coimbra. This we did many hours before the enemy could reach us. For days we kept possession of Coimbra and the neighbouring banks of the Mondego, to give our faithful friends the inhabitants time to destroy, bury, or remove their valuables, and above all their provisions, lest they should fall into the hands of the enemy. These arrangements were made from the commencement of our retreat, and strictly carried out by the inhabitants. They left their homes and accompanied the army, taking with them only a few of their valuables. Before reaching Torres Vedras I remember seeing many of these noble patriots, rich and poor, all barefooted and in rags. When we finally halted they went to Lisbon. These arrangements were more distressing to General Massena than all the fighting and opposition he met with, for he was so sure of driving us into the sea, or forcing us to embark, that he left his principal magazines of provisions behind, confident of finding sufficient supplies in the country through which he passed. In all these hopes and speculations he was indeed sadly disappointed; the consequence was that they were sorely tried, and suffered much from their limited and always uncertain commissariat. We arrived at the Lines of Torres Vedras on the 10th and 11th of October, closely pursued by the enemy, their advance guards and our rear troops constantly skirmishing, and causing some loss to them and to us; but we always found time to bury our dead and carry away the wounded.

We had no sooner taken up our relative positions than we were surprised and amazed at the formidable and strong appearance of the temporary works in which we found ourselves, and which we soon learnt extended in a direct line for thirty miles from Alhandra, on the banks of the Tagus, to Mafra, on the sea coast, thus covering Lisbon completely, from the broad and deep river on one side to the wide ocean on the other, this line forming in most places a continuous chain of rising ground. My division (the 1st) was stationed at headquarters, Sobral, about the centre of the lines. By this happy chance we had an opportunity of seeing Lord Wellington daily, and of sharing his dinners occasionally, in our turn, for he made a point of asking the juniors as well as the senior officers; and dinner then, with good wine, was worth having! Yet upon the whole we fared very well, for we had a good and regular supply from Lisbon.

Continued fighting—General Beresford knighted—English and French officers spend evenings together at theatres, etc. with consent of their commanders—Massena retires to Santarem

THE French were up and in position along our whole line. The next day Marshal Massena massed the strongest of his columns in front of our most formidable works, and desperate attacks were made on various parts of our line, but these, after hours of hard fighting, were always repulsed. The rest of each day was spent in staring at each other and watching the movements of the enemy, and frequently by a heavy cannonade for hours by both armies. Our loss was considerable; and from the French deserters, who were very numerous at this time, we learnt that their killed and wounded far exceeded ours, and that they were suffering much from sickness and want of provisions. In this way we remained constantly on the defensive, and frequently fighting, for upwards of four months, our army keeping our own ground and never attempting to attack the enemy, and always driving them back with much slaughter whenever they advanced to storm or carry away any of our works. During these operations the Marquis de la Romana, with his division of the Spanish army, joined us.

When we had been so employed for about two months, an authority reached Lord Wellington from England to confer the honour of knighthood on General Beresford, then the Commander-in-Chief of the Portuguese army. A general order was issued by Lord Wellington inviting one-third of the combined armies of England, Spain, and Portugal to assemble at the royal palace of Mafra, on a given day, to witness the ceremony of General Beresford being knighted, which stated that the Commander-in-Chief intended to return to his post at an early hour that night, and wished every officer to do the same, and concluded with an expression of his confidence that the remaining generals and officers of the army who were left at their posts would do their duty if attacked by the enemy during his absence. I was one of the happy ones who took advantage of this invitation, and at an early hour on the day named I started for the palace of Mafra, a distance of about fifteen miles. On our arrival there we found not only many hundreds of officers—English, Spanish, and Portuguese—but also a great portion of the Portuguese nobility, all come to do honour to the occasion, Lord Wellington and his brilliant staff amongst them; and, what was more remarkable, large masses of the French army not a quarter of a mile away from us, with their advanced piquets and sentries, were looking quietly and coolly on at our gathering, and although our visitors from Lisbon advanced in crowds as near as possible to look and stare at them in turn, not the slightest attempt was made by our brave enemies to alarm or disturb them. The same consideration and courtesy was continued during the whole of that memorable occasion, so I think to this day that the good feeling and understanding must have been previously arranged between Lord Wellington and General Massena.

As soon as the whole company had arrived, as many as could be got in were assembled in the principal hall of the palace; then appeared Lord Wellington with General Beresford on his arm, followed by a numerous suite of general officers and Portuguese nobility, and the Commander-in-Chief’s personal staff. A circle was formed in the centre of the hall, into which all the grandees entered. His Majesty’s commands were then read, on which General Beresford knelt down, and Lord Wellington, drawing his sword, waved it over the General’s head, saying, “Arise, Sir William Carr Beresford,” and ended so far the imposing pageant. Then was opened a folding door, displaying many tables laid out with a most recherché dinner and choice wines for at least five hundred people. I was one of the fortunate ones who succeeded in getting early admission. Then dancing was commenced, and kept on without ceasing until daylight. Our popular commander danced without ever resting, and appeared thoroughly to enjoy himself, though he retired at midnight, and many followed his example; but by far the greater number remained till morning, much to the delight of all the lovely and illustrious donnas and señoras of Lisbon. The night was very dark, and many officers going home lost their way and got into the enemy’s lines, but on stating whence they came, were all treated most kindly, and at daylight were allowed with hearty good wishes to proceed to their respective quarters.

For many weeks after this we continued in the Lines of Torres Vedras receiving the enemy’s attacks, and after many hard struggles invariably driving them back in confusion. At last Marshal Massena saw he could neither force our position, nor hope for any lasting success by continuing his efforts, so about the middle of January, 1811, being known to be sorely tried for supplies and provisions, he retreated with his army thirty miles or more, then established his headquarters at Santarem, the approach to which he at once fortified. We followed without delay and fixed our headquarters at Cartaxo, within ten miles of Santarem, with one Light Division in front and in sight of the enemy. The remaining corps were distributed on the various roads to our right and left, following and watching the movements of our foes; and so we continued for two months, without anything important being done. Our Light Division did make some attempt to force the enemy’s advance position in front of Santarem. This was a narrow causeway nearly a quarter of a mile long, built with stone and lime over the centre of an extensive bog or morass, very soft and knee-deep in water, at the enemy’s end being strongly fortified with numerous covering breastworks and guns in battery; but each attack failed with considerable loss to us. For some weeks no further efforts were made in this direction, for after a long reconnaissance it was believed that the storming and carrying of such a place would entail a fearful sacrifice of life. It was then determined to make one more effort, and the three grenadier companies of my brigade were told off to lead the advance of the storming party across the causeway. For this perilous duty we marched off one morning before daylight to a certain rendezvous in a wood near the site of our intended operations. There we found, in considerable numbers, masses of infantry and many guns in battery, ready to support us, and a part of the Light Division prepared to flank our advance, by taking at once the swamps and marshes, and so clearing the way for other troops to follow with the hope of turning both the enemy’s flanks and getting into their rear, while we, the storming party, at the double, with our powerful supports, should pass the causeway and storm and carry the enemy’s stronghold and batteries at the end of it. All was well arranged, and willing and ready were all to make the attempt; but fortunately for many of us, just about the appointed hour for our advance it came on to rain heavily, and so continued without ceasing for some hours after daylight. As we could no longer conceal our movements from the enemy, this attack was given up, and we marched back to our quarters without any loss, but with a good wetting. Had the attack taken place our loss would have been terribly heavy.

The most happy feeling prevailed between our Light Division and the French advanced posts and garrison at Santarem. Many of our officers used to go by special invitation to pass their evenings at the theatre with the French officers at Santarem, and on every such occasion were treated in the most hospitable manner, and always returned well pleased with their visits. Of course, the sanction of the Commanders-in-Chief of both armies was given to this intimacy. The Marquis de la Romana died at Cartaxo while we were there, and was laid in state for many days, and buried with much splendour and all military honours.

While here our “patrone,” the owner of our house, used to visit us very frequently. One morning, while he was present, I was sitting before the fire and poking with the tongs at the back of the chimney, when suddenly it gave way, exposing a tin box, on which “patrone” called out in alarm, “Mio dinhero! mio dinhero!” and at once seized it; but we insisted on seeing the contents, and found a considerable sum of money, the poor man’s all, and of course we restored it to him. When the French were advancing some months before, most of the inhabitants hid their treasures much in the same way.

I was one morning taking an early walk with Lieutenant Hunt, of my regiment, in the immediate neighbourhood of Cartaxo, when we observed in a field a mule and a donkey grazing; not far off was a Portuguese peasant. I called him and asked to whom the animals belonged; he said he did not know, but that he believed they had strayed from the French lines, so I told him to drive them up to my quarters, and that I would give him a few dollars for his trouble.

Story of the lost regimental books and the honesty of the soldiers

I MUST now tell a more creditable story. At this time I commanded a company, and had also unofficially the charge of the accounts and payments of another company, the captain having a great dislike to bookkeeping. In those days the military chest of the army was so low that the troops were frequently two or three months in arrear of pay; but the soldiers’ accounts were regularly made up and balanced every month, and carried forward ready for payment when money was available. I was then sufficiently lucky to have a donkey of my own, although before this I was, like most subalterns, contented to share a donkey or mule with another officer, for the carriage of our limited baggage and spare provision; the Government allowing us forage for one animal between every two subalterns, and one ration of forage to each captain. My good and trusty beast carried two hampers covered with tarpaulin, on which was printed most distinctly my name, “Lieutenant Anderson, 24th Regiment,” and in these I carried not only my few changes of clothes and spare provisions, but also my two companies’ books, ledgers, etc., and at that time about two hundred dollars in cash. We had all native servants at this time; mine, a Portuguese boy, was always in charge of my baggage and donkey. The day we marched into Cartaxo, all the baggage arrived in due course except mine, and for some hours we could hear nothing of my boy nor of my donkey. At last, about dusk, he came up crying, and told me he had lost my all. I waited for many days, still hoping to hear something of my property, but all to no purpose. There were no records kept of the soldiers’ accounts except the company’s ledgers, so I was thus, in consequence of my loss, entirely at the mercy of my men, and had no other course left to me but to parade my own, and then the other company, and explain the situation, and my confidence in them all, and then to take from their own lips the amount of balances, debit or credit, of their respective accounts. I committed their statements at once to paper, but of course I could not say if they were correct or not. I then gave up all hope of ever seeing my lost property again.

I was advised to request the adjutant-general of the army to circulate a memorandum in General Orders, describing my donkey and baggage, and offering a handsome reward for discovery, recovery, or for any information respecting them. A few days afterwards I received a letter from a corporal of the 5th Dragoon Guards, stationed at Azambuja, informing me that on the very evening of my loss he found my donkey feeding in a cornfield near his quarters; soon afterwards, seeing two soldiers of the 24th Regiment, he asked them if they knew Lieutenant Anderson; being told that they did, he asked if they would take charge of the donkey, to which they willingly consented, so he gave all over to them, with directions to be sure to deliver them in safety. This letter I at once took to my commanding officer, who ordered me to go without delay to Azambuja to see the corporal, and ask if he thought he could remember and identify the men. I rode off alone through a wild country, a distance of twenty miles, got to Azambuja in good time that evening, and found the corporal, whose name I cannot now remember. He expressed great surprise at my not having received the things, as more than a month had passed since he had given them over to the two men of the 24th. He said one was a grenadier and the other a battalion man, that he had not noticed them much, but thought he might be able to point them out. On this I went to General Sir Lowry Cole and told him my story; he at once ordered the corporal to accompany me back to Cartaxo. That evening we started under heavy rain, and rode all night. The corporal was a tall and powerful man, and I must confess that I felt a little afraid of him. The night was very dark, and the ride for many miles was through a long wood. I more than once thought that if the corporal was himself the thief he might now dispose of me without any one being the wiser, so I ordered him to ride some distance in front, on pretence of looking for the road, so as to give me time for a bolt should he turn upon me. My fears proved ungenerous and unfounded, for without any accident we arrived at Cartaxo.