The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

A NATIVE OF JAMAICA ISLAND

TO THE PROGRESSIVE PLANTER AND HONEST MILLER OF SPICES, TO THE SCRUPULOUS AND CONSCIENTIOUS WHOLESALE AND RETAIL DEALER, TO THE EARNEST COMMERCIAL MAN, AND TO THE CONSUMER WHO IS PARTICULAR: THIS BOOK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED.

| Introduction, | 5, 6 |

| Early History of Spices, | 7-9 |

| Adulteration of Spices | 10-14 |

| How to Detect Adulterations in Spices—their Formation and Analysis, | 15-34 |

| Potato Starch, | 21 |

| Maranta Starch, | 22 |

| Circuma, | 22 |

| Leguminous Starches, | 23 |

| Nutmeg Starch, | 23 |

| Capsicum Starch, | 23 |

| Pepper Starch, | 23 |

| Cinnamon Starch, | 24 |

| Buckwheat Starch, | 24 |

| Maize or Corn Starch, | 24 |

| Rice Starch, | 24 |

| Wheat Starch, | 24 |

| Barley Starch, | 25 |

| Rye Starch, | 25 |

| Oat Starch, | 25 |

| Reagents and Apparatus, | 30 |

| The Determination, | 32 |

| Black Pepper, | 35-58 |

| White Pepper, | 59-61 |

| Long Pepper, | 62-65 |

| Capsicum, or Cayenne, | 66-74 |

| Pimento, or Allspice, | 75-80 |

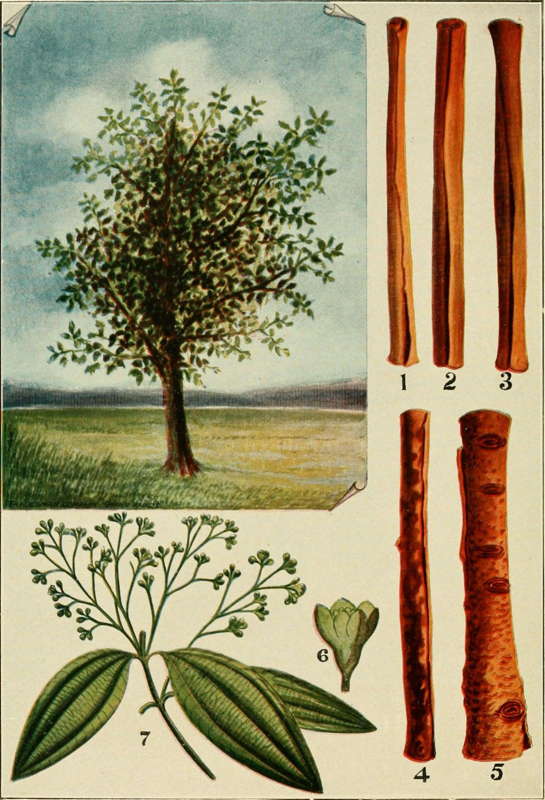

| Cinnamon and Cassia, | 81-107 |

| Chemical Composition of Cassia and Cinnamon, | 107 |

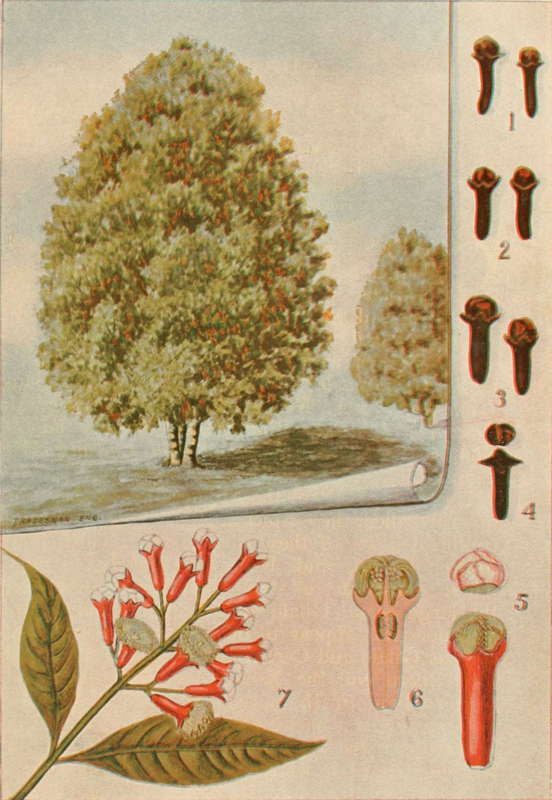

| Cloves, | 108-121 |

| Ginger, | 122-135 |

| Nutmegs, | 136-151 |

| Mace, | 152-156 |

| The Chemical Composition of Mace | 155 |

| Mustard, | 157-168 |

| Wet Mustard or French Mustard | 161 |

| Herbs, | 169-179 |

| Sage, | 169 |

| Marjoram, | 171 |

| Parsley, | 172 |

| Savory, | 173 |

| Thyme, | 174 |

| Seed, | 176 |

| Caraway, | 176 |

| Coriander, | 177 |

| Cardamom, | 178 |

It is with a certain feeling of helplessness and loneliness that I am venturing upon the attempt to trace out the history of spices, as I have not a spice grove or garden to step into for my information; but I must depend upon a far-distant country, where intelligence is but little above what it was five hundred years ago, where may be found the lair of the lion and the jungles of the tiger, where the elephant is used as a beast of burden, where the people file their teeth and color them black because they think natural white teeth too much like dogs’ teeth. The fact that such ignorance is general in the Spice Islands obviously makes my information the more difficult to obtain. Moreover, the camera and its uses are not known among the Malays, and the painter’s art is not among their imaginings. For these reasons, the illustrations I have obtained have been secured only at great cost, but they are as true to nature in color as it is possible for printer’s ink to make them. I hope they will aid me in realizing my purpose of making dealers in spices more familiar with their goods.

It was not until after long and careful consideration of the fact that the mass of people know but little about the condiments which are to be found on almost every table, and of the further fact of the “inhumanity of man to man” in adulterating, that I was bold enough to attempt to write upon a subject never before written upon, except in a meager way. And although I do not expect to interest all who may read my pages, I hope to create a wish in some to know more of the flavors which so tickle the palate, the fruits of that far-distant county, the Straits Settlement, and neighboring regions.

If I succeed in creating a desire among the retail dealers in spices to know the goods better, and to sell only those which are pure and wholesome, I shall feel that my work has not been a failure. In placing the same before the public, I believe it to be the most complete work ever written upon the subject with which it deals.

The Author.

I am much indebted to the United States Department of Agriculture, Bulletin 13, by Clifford Richardson, for information in Chapter 3, on Adulterations and Analysis of Spices. Also to the United States Consulates of the cities of Penang, Singapore, and Colombo, to whom I extend thanks.

THE terms spices and condiments are applied to those articles which, while possessing in themselves no nutritious principles, are added to food to make it more palatable and to stimulate digestion. They are of an exclusively vegetable origin, and occupy an important position in the diet of the human race.

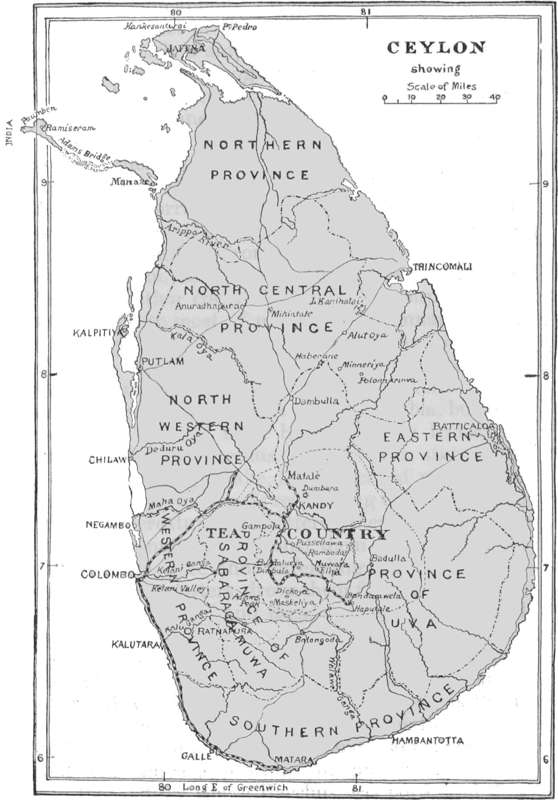

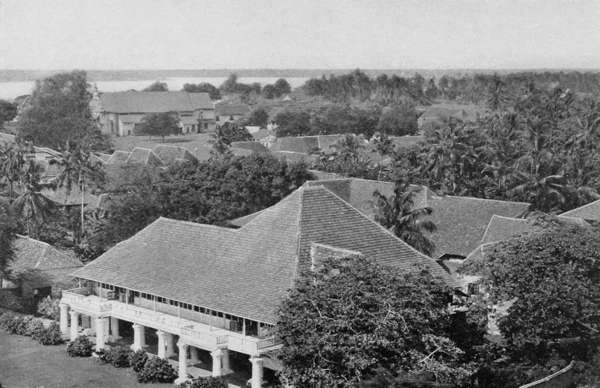

A ride of thirty-five days by ocean steamer from New York City brings us to the city of Singapore, situated on a small island of that name, the principal exporting city and the metropolis and capital of Malaysia, the Straits Settlement, India. The islands that constitute the Straits Settlement are crowned with spice forests. Here the noonday sun is truly vertical twice each year, and for many days it passes so near the zenith that change is scarcely perceptible. Here the grand constellation Orion passes overhead, while the Great Bear and Pole Star lie low down in the horizon. To the south may be seen the Southern Cross, and the planets high in the zenith.

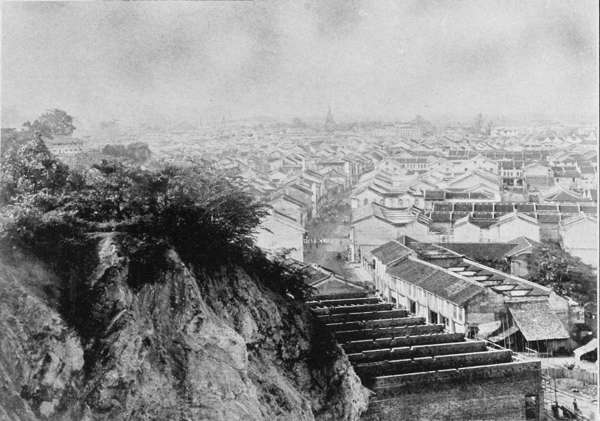

ASIATIC ARCHIPELAGO

No autumn tints, like those of our Northern woods, deck the spice forests. There is no purple and yellow dying foliage which rivals, and even excels, the expiring dolphin in splendor, and the long, cold sleep of winter and the first gentle touch of spring are unknown. But instead, we behold a ceaseless round of active life, which weaves the fair scenery of the tropics into one monotonous whole, the component parts of which exhibit in detail untold variety and beauty; and no one component part impresses us more forcibly than the spice trees. It is said that sailors, several miles at sea, in favorable weather, with a gentle land breeze, can tell they are nearing land long before they come in sight of the islands by the fragrance of the spice gardens. Singapore has a population of only 200,000, and the small island on which it is built contains but 145,000 acres, yet the city does a business of $200,000,000 a year and can count its millionaires by the score. Eighty years ago, the place where it stands was simply a jungle for tigers.

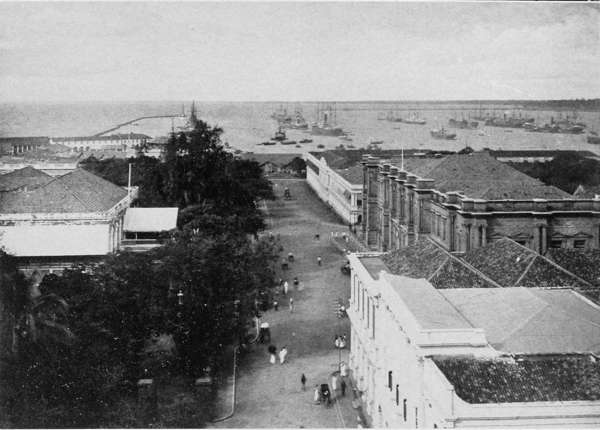

Singapore has ships from every port of the world going in and out of its harbor, and its streets are as lively as those of New York. You can go from it to the continent in a rowboat in one-half hour. Close connections are also made at Singapore for Siam, Borneo, Australia, China, Japan, Sumatra, and Ceylon, and it is the half-way station of the voyage around the world. The Island of Ceylon, with Colombo as its capital and chief city of export, also produces many fine spices. What could India do without her Spice Forests? This is a question which remains unanswered. We might as well ask what the United States could do without its wheat fields.

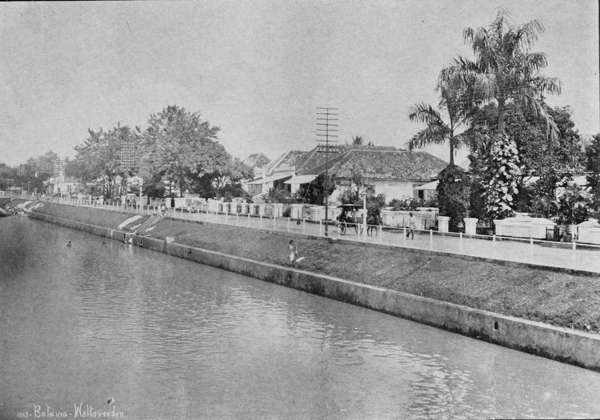

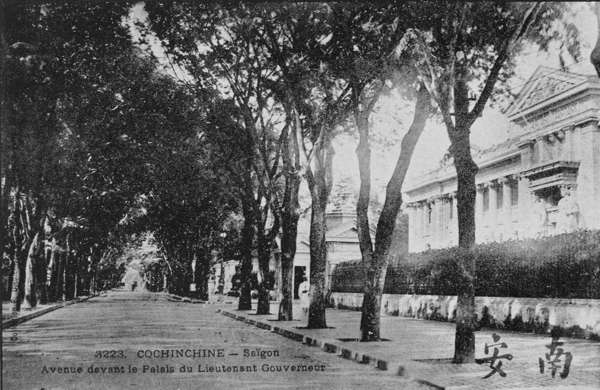

The different grades of spices take their names from the country or city from which they are exported, each different kind having a flavor of its own. Our best grades come mostly from Penang, and are called “Penang Spice,” while spice of nearly as good a quality comes from parts of Malabar. Other chief cities of export are Bombay, Batavia, Calcutta, and Cayenne, South America; but the most important is Singapore, as has been before mentioned.

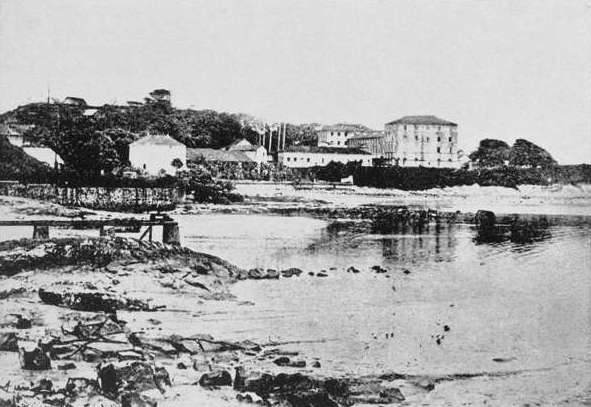

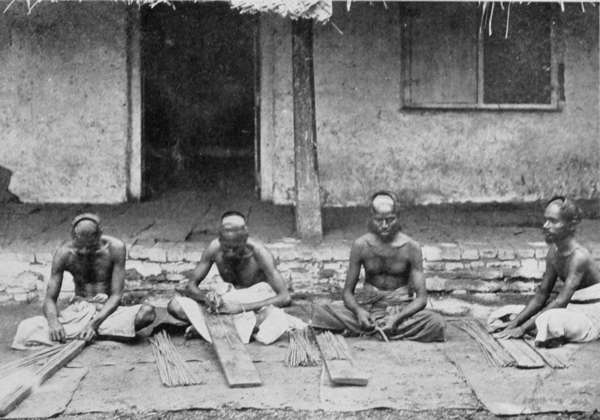

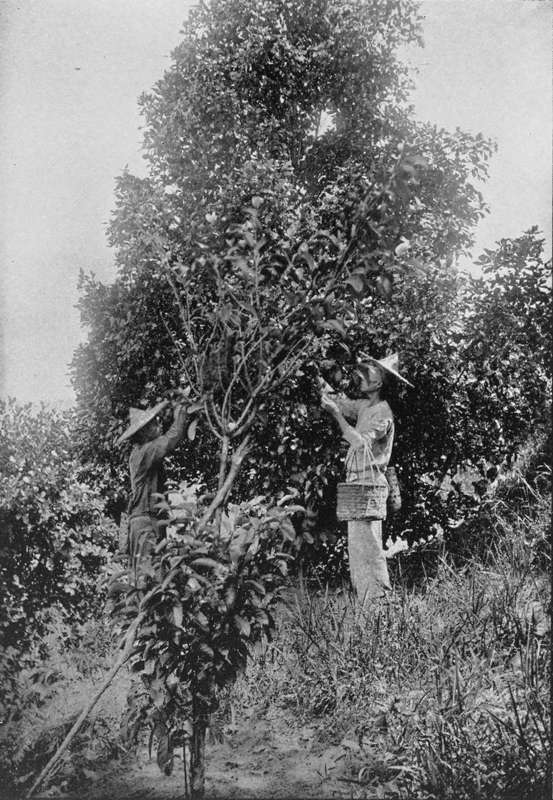

A PLANTATION ON JAMAICA ISLAND

A PLANTATION IN INDIA

The declared value of all spices shipped direct to this country averages about $12,000,000 worth annually. Among the cities that import spices New York stands first, probably receiving more than three-quarters of all importations. In 1898, 5,000,000 pounds of ginger were received at New York—19,000 bags being from Calcutta, 9,010 from Africa, 65,000 from Cochin, 3,608 barrels from Jamaica. There were 6,000,000 pounds of pepper received at New York, and probably nearly as much more at other ports. This may seem a large amount, but when we consider the quantity used in prepared meats and pickles, and the fact that pepper is on every table which can afford a pepper-box or caster, and that pepper enters into some of our food at nearly every meal, the above amount, which gives less than one-sixth of a pound per capita, is not large. A larger sum is paid for pepper than for any other spice. The amount paid for spices in this country annually does not fall much short of one dollar per capita at retail prices.

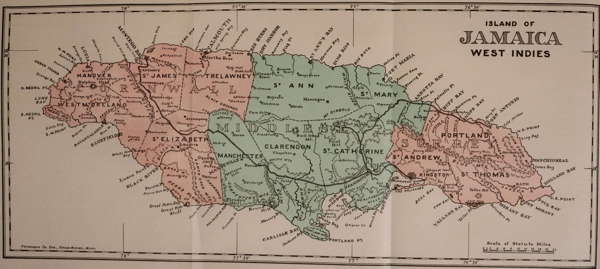

Four and one-half days by ocean steamer from New York brings us to the Island of Jamaica; and this chapter would not be complete if I did not mention that gem of the West Indies, the home of the Pimento and the famous Jamaica Ginger. Xaymaca (the Indian name for Jamaica) is like a huge mountain standing alone in the Caribbean Sea, with its hard, white coral beach and ideal climate. The ride from Kingston, the capital of the island, with its 50,000 population of picturesque folks (Americans, Europeans, West Indies women, gorgeously arrayed, and the coolie women loaded with ornaments), to beautiful Montego Bay and Port Antonio is an experience never to be forgotten.

THE Dutch at one time tried to control much of the spice trade but were frustrated by the birds which carried the seeds and planted them in other countries. We are strongly inclined to look upon the scheming Dutchman with contempt for this selfish act, but there is to-day hovering over spice products a greater evil, which makes one feel almost like shedding tears of shame for the acts of men who adulterate spices. If they would stop in their work long enough to ponder on the following appropriate words, they might receive new light in their attempt to mock Nature:

When the spice grinder will consider how hard it is to hide the spark of Nature, whoever yields reward to him who seeks and loves her best, and when the retail dealer of spices will remember that there is another man on the other side of the counter who is entitled to his money’s worth, then, and not until then, will the evil of the adulteration of spices be done away with. A merchant who will, knowingly, sell to his customer adulterated spices at the value of pure goods is worse than a thief, because he not only robs them of their money but gives them poison for their stomach.

Spice millers should not be counterfeiters! How can they afford to imperil their reputation by advertising “scheme goods”? Let them grind their spices to give Nature’s flavors as they grow in the balmy forests of the East Indies. Let them not mix these spices to suit the price of the retail dealer, but grind them pure, to please the tongue and the palate, and then hang out their sign, as their business would suggest, as spice millers or grinders, instead of “spice manufacturers.” If the retail dealer of adulterated spices trusts a customer who will not pay his indebtedness, he calls the man a rogue, but forgets that the greater rogue is himself; that his customer has the law on his side, and that his best witness is the adulterated goods which were sold him; furthermore, this dealer is teaching to the clerk whom he has taken into his employ, with a promise to teach the young man the trade and good business principles of an honest merchant, the trade of a thief, and as such teaches him to rob his employer. If the merchant breaks his part of the contract, can he expect the clerk to keep his? If the clerk, trained by the dealer in dishonesty, steals from the cash-drawer, would it be right to discharge him with a tarnish on the good name he had when he entered such employ? Let the dealer keep pure goods, and teach his clerk their merit. By so doing, he can be twice armed when he is selling in competition with a dealer of adulterations.

Let not the merchant profess to seek after the prosperity of the country; let him wonder not that business is dull; that labor is unemployed; that enterprise is dead, when he is doing all he can to destroy business and commercial prosperity by undermining the public confidence, which is the foundation upon which all commercial enterprise rests. Nothing is more essential to business prosperity than a confidence that prosperous, existing conditions will remain unchanged. He who is helping to destroy that confidence makes himself a stumbling block in the public highway of humanity and, as such, is a detriment to mankind. He is the greatest enemy to self that humanity can produce. He is like a vine which climbs the tree and obtains its life by sucking the life of that to which it clings. No man can be a good citizen who will wrong his fellow man simply because the laws of the country will protect him or, in other words, will not punish him for such wrongdoing. A miller or retail dealer of mixed or adulterated spices is as much a criminal as the man who has ingenuity enough to shape a coin from alloy and stamp it as a legal standard, or as one who counterfeits a bank note, for all are guilty of illegal acts to obtain wealth. The government punishes the counterfeiter of money, but the dealer in adulterated goods is allowed freedom. The government will grant a patent for the latest improvement in machinery for mixing spices, but it will not grant a patent for a die to counterfeit bank notes.

The dealing in adulterations is not confined to the poorer dealers. Among those who are guilty of this wrong we find the wealthy and those professing to be Christians—men who shudder at a dishonest act, but they apparently forget their duty to God and man. Is not such conduct mockery? Is it not offensive to God? If not, where could we find that which would be? Let men dare to do right if they wish to be successful and respected. Let them dare to do right for the sake of their fellow man who is striving for an honest living. Let them dare to do right and not wait for the law to compel them. Let them remember that there is something in an honest name which they cannot afford to lose! To the consumer of spices, this should be said: Be willing your grocer should live and obtain a profit for his work. Do not compel him to handle adulterated goods by quoting him the price of his neighbor dealer who sells the adulterated stock. Spices of high order are more costly, but are cheap to the consumer by reason of excess of flavor and strength. Let your dealer know you can appreciate a good article and, if he handles adulterated goods, remind him “that he may fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all of the time, but he can’t fool all of the people all of the time.” [1]As an illustration of the extent of the adulteration of spices, the fact may be cited that one firm in New York City used and put upon the market in their spices more than 5,000 pounds of cocoanut shells. To show how bold the custom has become, the following quotation is copied from a journal devoted to spices:

“All necessary information for spice manufacturing supplied.”

And the following advertisements appear:

“Manufacturers of spice mixtures and mustard. Goods made to order for wholesale.”

“Grocers’ spice mixtures and cayenne pepper a specialty.”

Another reads:

“Manufacturers of all kinds of spice mixtures. My celebrated brand of P. D. pepper is superior to any made; samples sent on application. Goods shipped to all parts of the United States. Spice mixtures a specialty.”

Out of all samples obtained at random from the miller or retail dealer, one-half to two-thirds have been found to be adulterated. Such a state of affairs is simply barbarous.

1. Since the words on adulterations were written, the pure food laws of the different states have been greatly enforced, which has reduced adulterating almost to an entirety; but enough yet remains to make them of value.

Cloves were prepared with the volatile oil extracted, and with the cloves there were ground clove stems, roasted shells, wheat flour, peas, and minerals. Allspice is ground with burnt shells and crackers, spent clove stems and charcoal and mineral color. Ginger, with corn flour, mustard hulls, coloring, and yellow corn meal.

Mace, with flour buckwheat, wild mace, and corn meal. Cayenne, with rice flour, stale shipstuff, yellow corn meal, tumeric, and mineral red. Cassia, with ground shells and crackers, tumeric, and minerals.

Cinnamon, with cassia, peas, starch, mustard hulls and tumeric, mineral cracker dust, burnt shells, or charcoal. Pepper, with refuse of all kinds, ground crackers, cocoanut shells, cayenne, peas, beans, yellow corn meal, buckwheat hulls, nutmegs, cereal, starch, mustard hulls, rice flour, charcoal, and pepper dust. Mustard, with tumeric for color, and cayenne to tone it up, cereal starch, peas, yellow corn meal, ginger, and gypsum.

By comparing prices in the following table of ground and whole spices, we may see to what extent adulteration is carried on. This adulteration is so largely practiced that it has given rise to a branch of the manufacturing industry of great magnitude, which has for its sole object the manufacture of articles known as “spice mixtures,” or “pepper dust,” which are known to the trade by such technical abbreviations as “P. D.” This is a venerable fraud, which has expanded with rapidity.

| KINDS OF SPICE PRODUCT | GROUND | WHOLE PRICE |

|---|---|---|

| Cassia, Batavia, | 7 to 7½ cents | 10 cents |

| Cassia, China, | 5¼ cents | 42 cents |

| Cassia, Saigon, | 36 to 40 cents | |

| Cloves, Amboyna, | 27 cents | 32 cents |

| Ginger, African, | 5 cents | 8 cents |

| Ginger, Cochin, | 13 cents | 12 cents |

| Mace, | 50 cents | |

| Nutmegs, 110s, | 48 cents | |

| Pepper, black, Singapore, | 18 cents | 18 cents |

| Pepper, black, West Coast, | 16 cents | 15 cents |

| Pepper, white, Penang, | 29 cents | 32 cents |

| Pepper, red, Zanzibar, | 9 cents | 10 cents |

| Pimento, | 5 cents | |

| Mustard, yellow, | 4 cents | 12 cents |

| Mustard, brown, | 5 cents | 12 cents |

Of course, the above prices are standard for the year when the comparison was made, but it is well to examine the figures as given and compare the price of the whole spice with the ground. Such comparison affords good indications of the extent of adulteration, since the meal is sold below the cost of the whole spice. We now find this article put up in barrels, as “P. D. Pepper,” “P. D. Ginger,” “P. D. Cloves,” and so on through the entire aromatic list. Different cities use different material for their pepper dust, using that which is most easily and, therefore, most cheaply obtained in their locality.

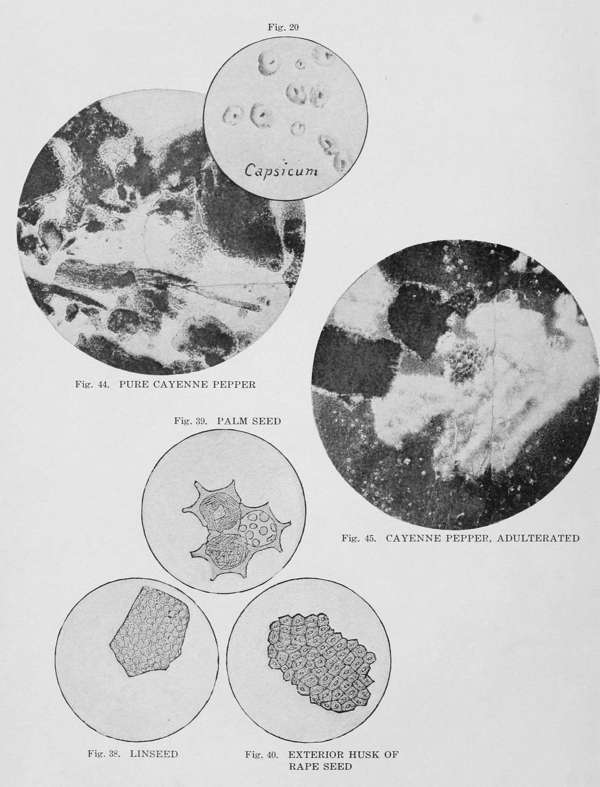

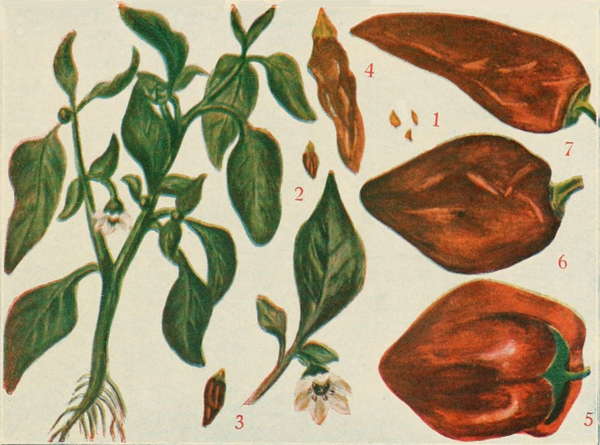

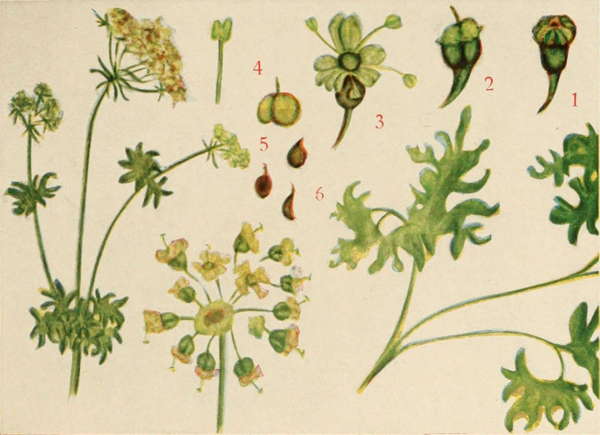

Fig. 20. Capsicum

Fig. 38. LINSEED

Fig. 39. PALM SEED

Fig. 40. EXTERIOR HUSK OF RAPE SEED

Fig. 44. PURE CAYENNE PEPPER

Fig. 45. CAYENNE PEPPER, ADULTERATED

AS far as its practical use to the merchant or consumer of spices is concerned, it would be as well, perhaps, if this chapter remained unwritten, and yet this treatise would be far from complete without it, as much of that which is herein contained is of the utmost importance, could it be put into practice.

In this chapter I attempt to give ways to detect adulterations, but the lamentable fact is that the general merchants have neither the time nor the facilities at hand to discover the foreign substance.

There are two principal ways of detecting adulterations in spices, which depend upon the difference in the structure of the cells between the adulterants and the true spice to which they are added, and also on their proximate composition. The former difference is recognized by the mechanical separation and by the use of the microscope, and the latter by chemical analysis. The adulterations found in spices may be classed in four grades:

First. Integuments of grains of seeds, such as bran of wheat and buckwheat, hulls of mustard seed, flax seed, etc.

Second. Farinaceous substances of low price, as spice damaged in transportation or by long storage, middlings, corn meal, and stale ship bread.

Third. Leguminous seeds, as peas and beans, which contribute largely to the profit of the mixer.

Fourth. Various articles chosen with reference to their suitableness to bring up the mixtures, as nearly as possible, to the required standard color of the genuine article; various shades from light colors to dark brown may be obtained by skillful roasting of the farinaceous and leguminous substances, and a little tumeric goes a long way to give a rich yellow color to real mustard made from pale counterfeit of wheat flour and terra-alba, or the defective paleness of artificial black pepper is brought to the desired tone by judicious sifting in of a finely pulverized charcoal.

From what has been said of the different foreign substances used for adulterations of spices and condiments, the necessity of knowing the structure and formation of the molecules of both principal and foreign elements which constitute the principal tissues of the particular plant-parts used for the adulterations is apparent, while in the chemical examination the principle of proximate analysis must be understood and applied.

It is also necessary that the analyst should be thoroughly acquainted with the application of the microscope, to determine the cellular structure, to make determinations of proximate principles in the substances under examination, since a mechanical separation by the microscope is more expeditious and is more at the command of the majority of persons searching for adulterations. For a mechanical analysis of food separations, a powerful microscope of good workmanship is required. It is better if it is supplied with a substance condenser and Nical prisms for the use of polarized light. Objectives of an inch and half inch, and, for some starches, one-fifth inch, equivalent focus, are sufficient. One eye-piece of medium depth, one-fourth to one-sixth, adjusted at 160 degrees is enough, with plenty of good light. The analyst should also have plenty of sieves of 40 to 60 meshes to the inch to be used for separation, which will furnish means of detecting adulterants and selecting particles for investigation, and will often reveal the presence of foreign material without further examination, since many adulterants are not ground so fine as the spices to which they are added, and by passing the mixtures through the sieves the coarser particles remaining will be either recognized at once by an unaided educated eye or with a pocket lens.

In this way, tumeric is readily separated from mustard and yellow corn meal; mustard hulls and cayenne, from low-grade pepper. Where a pocket lens is insufficient, the higher power of the microscope is confirmatory. It is also desirable to be provided with a dissecting microscope for selecting particles for examination from large masses of ground spice, and for this a large Zeiss stand, made for that purpose, is best, but simpler forms, or even a hand lens, will answer the purpose. For smaller apparatus, a few beakers, watch crystals, stirring rods, and specimen tubes, with bottles for reagents, will be sufficient, in addition to the ordinary glass slides and covers for glasses. The reagents required for chemical analysis (if no great amount is used) are as follows:

Balsam in benzol and glycerine jelly are desirable for mounting media, and some wax sheets will be needed for making cells. In addition, the analyst should supply himself with specimens of whole spices, starches, and known adulterants, which may be used to become acquainted with the forms and appearances to be expected; it is easier to begin one’s study in this way on sections prepared with the knife, and afterwards the powdered substance may be taken up.

To study the physiological structure in the spices and their adulterants is quite difficult, as the vegetable tissues which make up the structure of the spices and the materials of a vegetable origin which are added as adulterations consist of cells of different forms and thickness; those which are most prominent and common are the parenchyma, the sclerenchyma fibrous tissue, and the fibro-vascular bundles. Spiral and dotted vessels are also common in several of the adulterants, and in the epidermis are other forms of tissue which it is necessary to be well acquainted with, though not physiologically. The parenchyma is the most abundant tissue in all material of vegetable origin, making up the largest proportion of the main part of the plant. It is composed of thin wall cells which may be recognized in the potato and in the interior of the stems of maize. In the latter plant, also, the fibro-vascular system is well exemplified, running as scattered bundles between the nodes or joints. Fibrous tissue consists of elongated thick-walled cells of fibers which are very common in the vegetable kingdom and are well illustrated in flax, but they are not so commonly used for adulterating purposes. They are optically active, and in the shorter forms they somewhat resemble the cells next described. They are seen in one of the coats of buckwheat hulls and in the outer husks of the cocoanut.

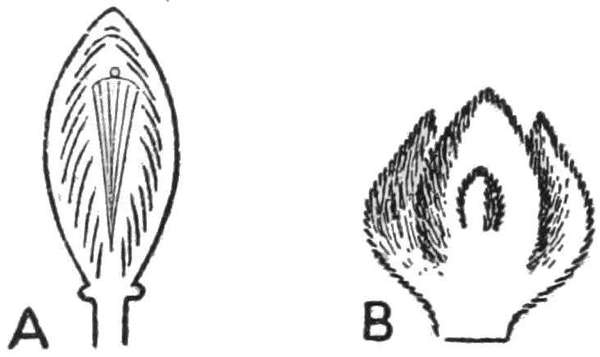

The sclerenchyma is found in the shells of many nuts and in one or two of the spices, the cells being known as stone cells, from the great thickening of their walls. To them is due the hardness of the shell of the cocoanut, the pits of the olive, etc. (See Fig. 1.) Spiral and dotted vessels are common in woody tissue and are readily recognized. All these forms an analyst should make himself familiar with.

In pepper and mustard the parenchyma cells are prominent in the interior of the berry, while those constituting the outer coats are indistinct in the pepper, because of their deep color; but in the mustard are characteristics of this particular species. In fact, in many of the spices, and especially those which are seeds, the forms of the epidermal cells are very striking, and, if no attempt is made to classify them their peculiarities must be carefully noted, as the recognition of the presence of foreign husky matter depends upon a knowledge of the normal appearance in any spice.

The fibro-vascular bundles are most prominent in ginger and in the barks, while in the powdered spices they are found as stringy particles. The sclerenchyma, or stone cells, as shown in Fig. 1, are common in the adulterant, especially in cocoanut shells, where may also be seen numerous spiral cells, and in the exterior coats of fibrous tissue. As to aids to distinguish these structures, the following peculiarities may be cited:

Fig. 1. STONE CELLS

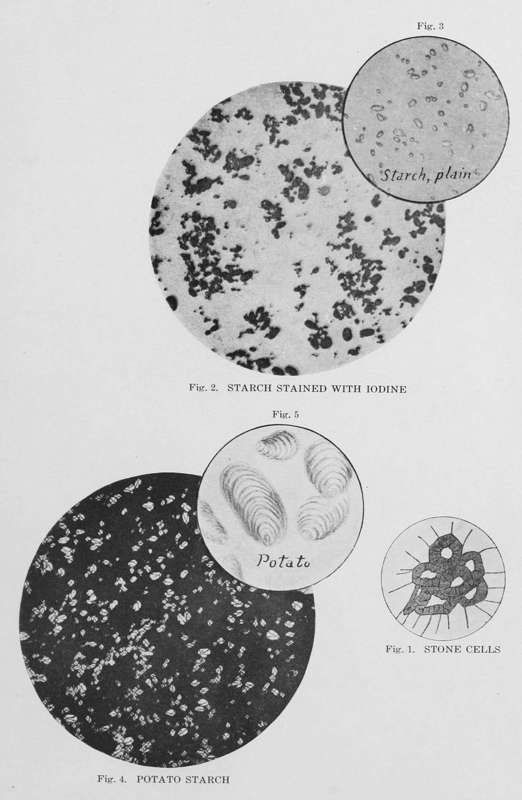

Fig. 2. STARCH STAINED WITH IODINE

Fig. 3. Starch, plain

Fig. 4. POTATO STARCH

Fig. 5. Potato

The stone cells and fibrous tissue are optically active, and are, therefore, readily detected with polarized light, shining out in the dark field of the microscope as silver-white or yellowish bodies.

The fibro-vascular bundles are stained deep orange brown with iodine, owing to the nitrogenous matter which they contain, while parenchyma is not affected by this reagent, aside from the cell contents, nor has it any action on polarized light, remaining quite invisible in the field with crossed prisms.

Next to cellular tissue, starch is the most important element for consideration in the plant, which possesses an organized structure and is distinguished by its reaction with iodine solution, which gives it a deep blue or blackish-blue color, varying somewhat with different kinds of starch and with the strength of the reagent, and its absence is marked by no blue color under the same circumstances.

Heat, however, as in the process of baking, so alters starches, converting them into dextrine and related bodies, that they give a brown color with iodine, instead of a blue-black; they are no longer starch, however; their form, not being essentially changed, permits of their identification, with a study of the size and shape of the granules of the hilum, or central depressions of nucleus, and the prominence and position of the rings. By polarized light and selenite, the starches of tubers showed a more varied play of colors than the cereal and leguminous starches which are produced above ground. The starches we are to consider are those of a limited number to be met with in spices and their adulterants, and one must be able readily to recognize the following:

STARCH NATURAL TO SPICES AND CONDIMENTS

STARCHES OF ADMIXTURES

Maranata and other arrowroots:

No one of these is complete in itself, but from the characters given, and with the aid of illustrations, the starches which commonly occur in substances which are here considered may usually be identified without difficulty.

For the benefit of those who have had no experience with the microscope, I will give the following directions:

Take a small portion of the starch or spice to be examined upon a clean camel’s hair brush and dust it upon a common slide, blow the excess away and moisten that retained with a drop of a mixture of equal parts of glycerine and water, or with glycerine and camphor water, and cover with a glass. It is well to have a small supply of the common starches in a series of tubes which can be mounted at any moment and used for comparison. They may be permanently mounted by making with cork borers, of two sizes, a wax cell ring equal to the diameter of the cover glass and, after cementing the cell to the slide with copal varnish thinned with turpentine and introducing the starch and glycerine mixture, fixing the cover glass on after running some of the cement over the top of the ring. A little experience will enable one to put the right amount of liquid in the cell and to make a preparation that will keep for some time. After several months, however, it is hard to distinguish the rings which mark the development of the granule, and it is better to keep it fresh.

For other purposes, the starches should be mounted in prepared Canada Balsam, or by well-known methods in which they may be preserved indefinitely, but they are scarcely visible with ordinary illumination and must be viewed by polarized light, which will bring out distinctive characters not seen as well, or not at all, in the other mounts. When mounted in the manner described, in glycerine and water, or in water alone, if for temporary use, under a microscope with one objective of equivalent focus of one-half to one-fifth inch, and with means for oblique illumination, the starches will display characteristics which are illustrated in Figs. 2, 3, and 4. The illustrations have been drawn from Nature; Fig. 2 gives starch stained with iodine; Fig. 3 gives shape and size of plain starch, and presence or absence of a nucleus, or hilum, and of the rings and their arrangements which can be made out. The starch is classed in its proper place.

If mounted in balsam, their appearance is scarcely visible under any form of illumination with ordinary light, the index refraction of the granules and the balsam being so similar, but when polarized light is used the effect is a striking one. (See plates of ginger, where it is easy to distinguish all the characteristics, except the rings, the center of the cross being at the nucleus of the granule.)

The principal starches which are met with may be described as follows in connection with illustrations given, beginning with those of the arrowroot class, including potato, ginger, and tumeric.

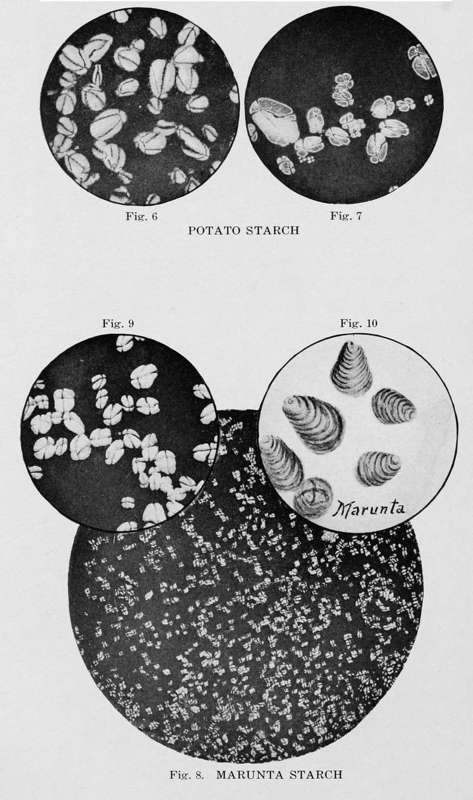

Fig. 6. & Fig. 7. POTATO STARCH

Fig. 8. MARUNTA STARCH

Fig. 9. Fig. 10. MARUNTA

Potato starch grains are very variable in size, being found from .05 to .10 millimeter in length, and in shape from oval and allied forms to irregular, and even round in the smallest; these variations are illustrated in Fig. 4, but the frequency of the smaller granules is not as evident as in Figs. 5 and 6. The layers in some granules are very plain and in others are hardly visible. They are rather more prominent in the starch obtained from a freshly cut surface. The rings are more distinct near the hilum, or nucleus, which in this, as in all tuberous starches, is eccentric, shading off toward the broader or more expanded portion of the granules.

The hilum appears as a shadowy depression (Fig. 4) and, with polarized light, its position is well marked by the junction of the arms of the cross. It will be found by comparison of Fig. 6 and Fig. 7, that in the potato it is more often at the smaller end of the granules, and that in the arrowroot it is at the larger. With polarized light and a selenite plate a beautiful play of colors is obtained.

The smaller granules, by their nearly round shape, may be confused with other starches, but their presence at once serves to distinguish them from Maranta or Bermuda arrowroot starch. Rarely, compound granules are found composed of two or three single ones each within its own nucleus.

Of the same type as the potato starch are various arrowroots. The only ones commonly met with in this country are the Bermuda, the starch of the rhizome of Maranta arundinacea, and the starch of tumeric.

The granules are not usually so varied in size or shape as those of the potato, as may be seen in Figs. 8, 9, and 10. They average about .07 millimeters in length. They are about the same size as the average of those of the potato, but are never found as large or as small. This fact, together with the fact that the end at which the nucleus appears is broader in the Maranta and more pointed in the potato, enables one to distinguish the starches without difficulty. With polarized light, the results are similar to those seen with potato starch, and, by this means, the two varieties may be readily distinguished by displaying, in a striking way, the forms of the granule and the position of the hilum, as is illustrated in Figs. 8 and 9.

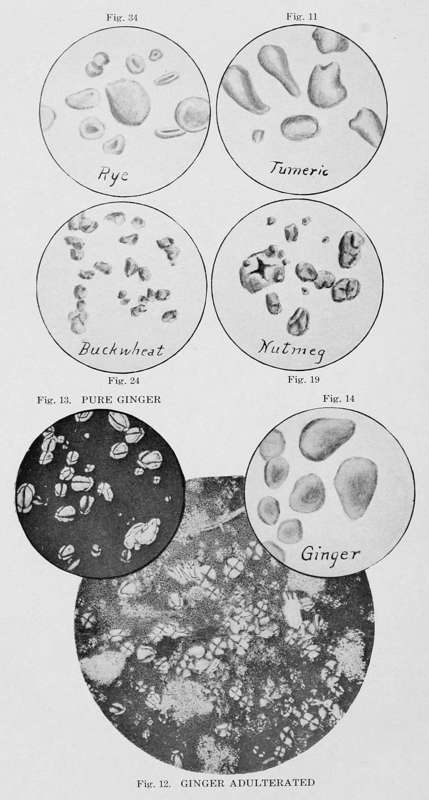

Circuma, or tumeric starch (Fig. 11), though of the arrowroot class, is quite distinct in appearance from these we have described, being most irregular in outline, so that it is impossible to define its shape or to do more than to refer to the illustration. Many of the granules are long and narrow and drawn out to quite a point. The rings are distinct in the larger, and the size is about that of Maranta.

Ginger starch (Figs. 12, 13, and 14) is of the same class as potato and Maranta and several others which are of underground origin. In outline, it is not oval like those named, but is more rectangular, having more obtuse angles in the larger granules and being cylindrical or circular in outline in the smaller; its average size is nearly the same as Maranta starch, but it is much more variable in size and form, the rings being scarcely visible even with most favorable illuminations. Fig. 12 shows ginger adulterated.

Fig. 15. BEANS

Fig. 16. Beans

Fig. 17. PEAS

Fig. 18. Peas.

Fig. 46. CINNAMON ADULTERATED

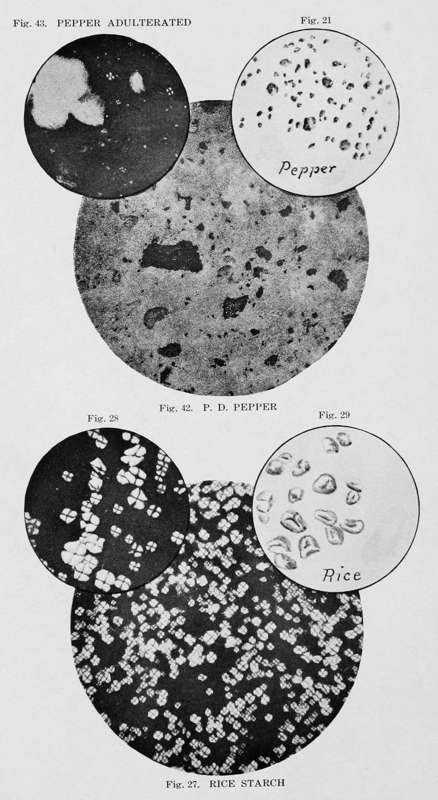

Fig. 21. Pepper

Fig. 27. RICE STARCH

Fig. 28. RICE STARCH

Fig. 29. Rice

Fig 42. P. D. PEPPER

Fig. 43. PEPPER ADULTERATED

Such as those of beans and peas (Figs. 15, 16, 17, and 18), produce but a slight effect under polarized light; the rings are scarcely visible, and the hilum is stellate or much cracked along a median line. This characteristic is more marked in the bean than in the pea. In the latter it resembles fresh dough kneaded again into the center as in making rolls, and in the former the shape assumed by the same after baking. In both it varies in size from .025 to .10 millimeter in length.

Fig. 19 has rings scarcely visible and not iridescent with polarized light. It is smaller in size than the preceding, which it resembles, being at times as long as .05 millimeter down to smaller than .005 millimeter, and of extremely irregular form, having angular depressions and angular outlines. It is distinguished by a budded appearance caused by the adherence of small granules to the larger.

Fig. 20 is nearly circular or rounded polyhedral in forms with scarcely visible rings, and in most cases a depressed hilum, resembling in size and shape corn starch, but having peculiar irregularities which distinguish it, such as rosette-like formation on a flattened granule, or a round depression at one end. It does not polarize as actively as maize starch and can be distinguished from rice by the greater angularity of the latter.

Fig. 21 is the most minute starch which is usually met with, not averaging over .001 millimeter nor exceeding .005. It is irregularly polyhedral and polarizes very well, but requires a high power to discover any detail when a hilum is found. It cannot be confused with other starches.

Figs. 22 and 23 have an extremely irregular polyhedral or distorted granules, often united in groups with smaller granules and adherent to the larger ones. In size, it varies from .001 to .025 millimeter, averaging nearly the latter size. In some granules the hilum can be distinguished, but no rings; it is readily detected with polarized light.

Fig. 24 is very characteristic. It consists of a chain or groups of angular granules with a not very evident circular nucleus and without rings. The outline is strikingly angular and the size not very variable, being about .01 to .015 millimeter.

Figs. 25 and 26 have granules largely of the same size from .02 to .03 millimeter in diameter, with now and then a few which are much smaller; they are mostly circular in shape or, rather, polyhedral with rounded angles. They form very brilliant objects with polarized light, but with ordinary illumination show but the faintest signs of rings and a well-developed hilum, at times star-shaped and at others more like a circular depression.

Figs. 27, 28, and 29, is very similar to corn starch, and is easily confused with it, being about the same size. It is, however, distinguished from it by its polygonal form and its well-defined angles. The hilum is more prominent and more often stellate, or linear, and several grains are at times united.

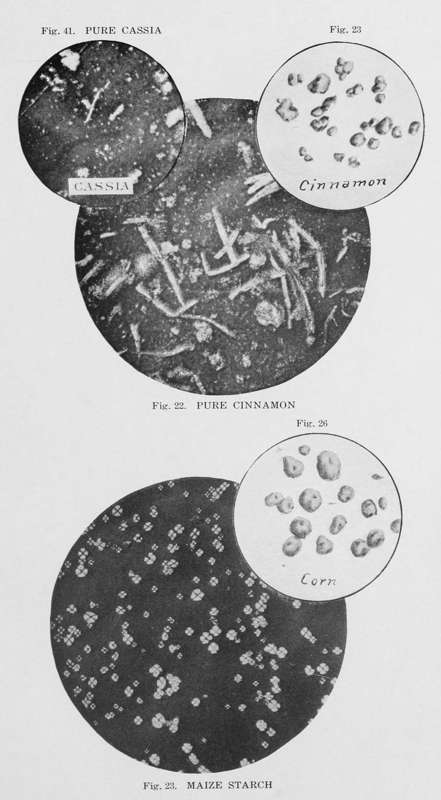

Fig. 22. PURE CINNAMON

Fig. 23 Cinnamon

Fig. 25. MAIZE STARCH

Fig. 26 Corn

Fig. 41. PURE CASSIA

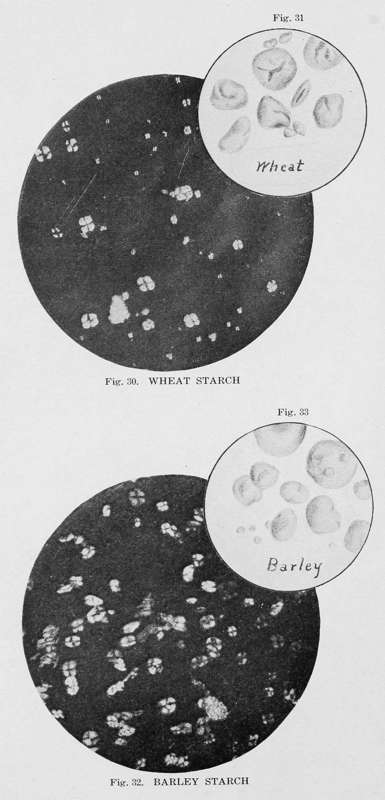

Fig. 30. WHEAT STARCH

Fig. 31 Wheat

Fig. 32. BARLEY STARCH

Fig. 33 Barley

Figs. 30 and 31 are quite variable in size, varying from .05 to .012 millimeter in diameter, and this starch belongs to the same class as barley and rye; the hilum is invisible and the rings are not prominent; the granules are circular disks in form, and there are now and then contorted depressions, resembling those in the pea starch; it is the least regular of the three starches and does not polarize actively.

Figs. 32 and 33 are quite similar to that of wheat, but barley starch does not vary so much in size, averaging .05 millimeter. It has rings more distinct and very small granules adhering to the largest in bud-like forms.

Fig. 34 is more variable in size, many of the granules not exceeding .02 millimeter while the largest reach .06 to .07 millimeter. It lacks distinctive characteristics entirely, and is the most simple in form of all starches described.

Figs. 35 and 36, is unique, being composed of large compound masses of polyhedral granules from .12 to .02 millimeter in length, the single granules averaging .02 to .015 millimeter. It does not polarize actively, as may be seen in the figures, and displays neither rings nor hilum.

The first sign of maize or corn meal as an adulterant is the thin outer coat which becomes detached in milling and is not readily crushed. In yellow corn it has a pinkish color, and simple, longitudinal cells.

Broken rice is sometimes used as a dilutant; it may be recognized by the brilliant appearance of the hard white particles which may be picked out of the spice under a hand lens.

The two cereals named (broken rice and maize corn) are the only ones which are commonly met with that introduce starch.

Wheat bran (Fig. 37) is occasionally added, which can be recognized by its distinctive structural character and is better understood from an authentic specimen, which should be soaked in chloral-hydrate.

As modified cereals, we find refuse bread, cracker dust, and stale ship bread, in which the wheat starch is much changed from its original form by the heat and moisture, so that at times it might be confused with leguminous starch, but the softness of the particles and the ease with which they fall to pieces in water reveal their true name. Oil seed, oil cake, and husk (Figs. 38, 39, and 40) are very commonly used and are readily recognized by the peculiar structure of the outer coats of the seed. The particles, which can be usually found and selected with a dissecting microscope, should be examined in alcohol or glycerine, or a mixture of the two, as the outer coats of some seeds, such as mustard, are swollen by water and become indistinct. Many varieties of the cruciferous seeds resemble it very much, so that it is difficult to distinguish them, but it is generally recognized by the outer layer of hexagonal cells and a middle and inner coating, which consists of peculiar angular cells, the latter being much larger than the former, which are the most characteristic feature, and should be compared with seeds of known origin. After soaking in chloral-hydrate, the remaining interior layers are, perhaps, more easily made out, in some cases, after moderate bleaching with nitric acid and chlorate; the interior of this seed is not blued by iodine.

Peanut, or ground nut cake, is recognized by the characteristic structure of the red-brownish coat, which surrounds the seed, and consists of polygonal cells with peculiar saw-toothed thickening of the walls. The seed itself consists of polygonal cells full of oil and starch granules, which are globular in form and not easily confused with pepper starch. The structure of the brown membrane is best made out in chloral-hydrate, which removes the red color and leaves the fragments of a bright yellow.

Linseed cake is distinguished by the fact that its husk is made up of one or two characteristic elements. The outer coat, or epidermis, is colorless and swells up in water, forming a mucilage, like the mustard seed. Beneath this is a layer of thin, round, yellow cells, while the third is very characteristic and consists of narrow and very thick-walled dotted vessels; next to these is an inner layer of compact polygonal cells, with fairly thin, but still thickly dotted, white walls and dark-brown contents containing tumeric. The endogen and embryo are free from starch and will not color yellow by potash, as is the case with mustard and rape seed cake.

Fig. 35. OAT STARCH

Fig. 36. Oats

Fig. 37. WHEAT BRAN

Fig. 46. POWDERED ALLSPICE SHOWING PORT WINE CELLS. (A) STARCH

Cocoanut shells are often used, and have numerous, both long and short, stone cells and spiral vessels from this fibrous tissue; the long stone cells having thinner walls than the shorter cells, all of which are readily seen after bleaching. When the shells are roasted, they refuse to bleach, and it is then only possible to class the particles, on which the reagents do not act, as roasted shells or charcoal, which are frequently used in pepper to give desired color to material rendered too light by white adulterants.

Buckwheat, after bleaching, shows a preponderance of tissue made up of long, slender, and pointed sclerenchyma cells and a smaller amount of reticulated tissue, resembling the cereals somewhat and cayenne pepper. Portions of the interior of the seed are also visible and consist of an agglomeration of small hexagonal cells which originally contained starch. The starch is readily recognized by its peculiar characteristics. The sclerenchyma is, of course, optically active and forms a beautiful and distinctive object with polarized light. Sawdust of various woods may be recognized by the fragments of various spiral and dotted vessels and fibrous material which are not found in spices or in other adulterants.

Rice bran is made up prominently of two series of cells at right angles to each other, which make up the outer coats of grain, the structure being best made out after soaking in chloral-hydrate; the cells of one series are long, small, and thin-walled, and are arranged in parallel bundles; the others have very much thicker walls and are only two or three times as long as they are broad.

Clove stems are distinguished by their peculiar yellow dotted vessels and their large and quite numerous cells, neither of which is seen prominently in the substances which are adulterated. The peculiarities of adulterants should be carefully confirmed and the eye trained by practice so as to become accustomed to recognizing their structure by a study of the actual substance.

Take one gram of powdered spice which will pass a 60-mesh sieve and dry at 150 degrees to 110 degrees C. in an air bath provided with a regulator, until a successive weighing shows a gain, which denotes that oxidization has begun, which takes about 12 hours, or over night; the loss is water, together with the largest part of volatile oil. Deduction of the volatile oil, as determined in the ether extract, will give a close approximation of water. The ash portion is determined by incineration at a very low temperature, such as may be attained in a gas muffle, which is the most convenient arrangement for work of this kind. The proportion of ash insoluble in acid may be determined where there is a reason to believe that sand is present.

To find the amount of volatile oil by ether extract: Two grains of substance are extracted for twenty-four hours in a siphoning extraction apparatus, being first placed in a test tube, which is inserted into a continuous extraction apparatus of the intermittent siphon class, the tube used being an ordinary test tube, the bottom of which has been blown out. A wad of washed cotton of sufficient thickness is put in the lower end of the tubes to prevent any solid particles of the sample from finding their way into the receiving flask; another wad of cotton is packed on top of the sample, and the apparatus is then so adjusted that the condensed ether drops into the tube and percolates through the sample siphons into the receiving flask. In this way the operation is continued the length of time named. The best ether should be used to avoid extracting substances other than oil soluble in alcohol, and to continue the extraction for at least the time named, as piperine and several other proximate principles are not extremely soluble in ether. On stopping the extraction, the extract is washed into a light, weighed, glass dish, and the ether is allowed to evaporate spontaneously, but not too rapidly, for the reason that water, which is difficult to remove, might be condensed into the dish. In a short time the ether will disappear, and the dish is placed in a dessicator with pumice and sulphuric acid, not with chloride of calcium, which has been shown to be useless. It is allowed to remain over night to remove any moisture; the loss of oil by this process is scarcely appreciable. The dish is next weighed and afterward heated to 110 degrees C. for some hours, to drive off the volatile oil, beginning at a low temperature, as the oil is easily oxidized, and then is not volatile oil. The residue is weighed, the difference being calculated to volatile oil and examined as to its composition of purity.

Fig. 11. Tumeric

Fig. 12. GINGER ADULTERATED

Fig. 13. PURE GINGER

Fig. 14. Ginger

Fig. 19. Nutmeg

Fig. 24. Buckwheat

Fig. 34. Rye

Alcohol extract is made in the same manner as the ether extract, using, of course, the substance extracted. The solvent may be either absolute alcohol—that of 95 per cent. by volume, or 80 per cent. by weight, the latter being preferable in most cases, as there is no definite point with the stronger spirit at which the extraction is completed.

The amount of reducing material produced by boiling the spices with dilute acids serves with several as an index of purity. In the case of pepper, which contains a large amount of starch, the addition of fibrous adulterants reduces the equivalent of reducing sugar, which are indicated in the solution after boiling with acid. Tumeric is always found in spices, such as cloves and pimento of good quality.

It has been said that preliminary extractions of the material with the best ether is necessary to remove oil and other substances, not tannin on which permanganate may act; ordinary ether will not answer, as it contains so much alcohol and water as to dissolve some of the tannin.

The substance freed from ether should be extracted with boiling water and the extract made up to such dilution that 10 CC. is equal to about 10 CC. of the thirtieth normal,—permanganate solution used. The titration must be performed slowly to insure accuracy, the permanganate being run in at the rate of not more than a drop in a second, or three drops in two seconds. The eye must become accustomed to the bleaching of the indigo used, and select some one tint of yellow, as the end of reaction is then possible to duplicate. That part of the material analyzed, which is insoluble in acid and alkali of certain strength after treatment for a definite length of time, at a definite temperature, is called crude fiber, and it may be described as follows: Select two grains of substance 200 CC. of 5 per cent. hydrochloric acid; steam bath two hours, raising the liquid to a temperature of 90 degrees to 95 degrees C. filtration on linen cloth, washing back into beaker with 200 CC. 5 per cent. sodic-hydrate; steam bath two hours, filtration on asbestos, washing with hot water, alcohol, and ether, drying at 120 degrees, weighing, ignition and crude fiber from loss in weight.

(1). Hydrochloric acid whose absolute strength has been determined.

(a). By precipitating with silver nitrate and weighing the silver chloride.

(b). By sodium carbonate, as described in Fresenius Quantitative Analysis, second American edition, page 680.

(c). by determining the amount neutralized by the distillate from a weighed quantity of pure ammonium-chloride boiled with an excess of sodium-hydrate.

(2). Standard ammonia whose strength relative to the acid has been accurately determined.

(3). C. P. sulphuric acid specific gravity 1.83, free from nitrates, and also from ammonium sulphates, which are sometimes added in the process of manufacture to destroy oxides of nitrogen.

(4). Mercuric-oxide, HgO, prepared in the wet way. That prepared from mercury nitrate cannot safely be used.

(5). Potassium permanganate tolerably finely pulverized.

(6). Granulated zinc.

(7). A solution of 40 grams of commercial potassium-sulphide in one liter of water.

(8). A saturated solution of sodium-hydrate, free from nitrates which are sometimes added in the process of manufacture to destroy organic matter and improve the color of the product.

(9). Solution of cochineal, prepared according to Fresenius Quantitative Analysis, second American edition, page 679.

(10). Burettes should be calibrated in all cases by the user.

(11). Digestion flasks of hard, and moderately thick, well-annealed glass, which should be about 9 inches long, with a round, pear-shaped bottom, having a maximum diameter of 2½ inches and tapering out gradually in a long neck, which is three-fourths of an inch in diameter at the narrowest part and flared a little at the edge. The total capacity is 225 to 250 cubic centimeters.

(12). Distillation flasks of ordinary shape, 550 cubic centimeters capacity, and fitted with rubber stoppers, and a bulb tube above to prevent the possibility of sodium-hydrate being carried over mechanically during distillation; this is adjusted to the tube of the condenser by a rubber tube.

(13). A condenser with tube of block tin is best, as glass is decomposed by steam and ammonia vapor, and will give up alkali enough to impair accuracy; the tank should be made of copper, supported by wooden frame, so that its bottom is 11 inches above the workbench on which it stands. It should be about 16 inches high, 32 inches long, and 3 inches wide, gradually widening 6 inches toward the top; the water-supply tube should extend to the bottom, and there should be a larger overflow pipe above.

The block tin condensing tubes should be about ⅜ of an inch inner measure and seven in number, entering the tank through holes in the front side of it near the top above the level of the overflow, and pass down perpendicularly through the tank and out through the rubber stoppers, tightly fitted into holes in the bottom; they should project 1½ inches below the bottom of the tank, and connect by short rubber tubes, with glass bulb tubes, of the usual shape, which dip into glass precipitating beakers. These beakers should project about 6½ inches high by 3 inches in diameter below, gradually narrowing above, and should be about 500 cubic centimeters capacity. The titration can be made directly in them. The seven distillation flasks should be supported on a sheet-iron shelf attached to the wooden frame which supports the tank at the front; where each flask is to stand, a circular hole should be cut with three projecting lips to support the wire gauze under the flask, and three other lips to hold the flask in place, and to prevent its moving laterally out of place while distillation is going on. Below the sheet-iron shelf should be a metal tube carrying seven Bunsen burners, each with a stopcock like those of a gas combustion furnace. These burners are of larger diameter at the top, which prevents smoking when covered with fine gauze to prevent the flame from striking back.

(14). The stand for holding the digestion flask should consist of a pan of sheet iron, 29 inches long by 8 inches wide, on the front of which is fastened a shelf of sheet iron as long as the pan, 5 inches wide and 4 inches high. In this are cut six holes 1⅝ inches in diameter. At the back of the pan is a stout wire running lengthwise of the stand, 8 inches high, with a bend or depression opposite each hole in the shelf. The digestion flask rests with its lower part over a hole in the shelf and its neck in one of the depressions in the wire frame, which holds it securely in position, and heat should be supplied with Bunsen burners below the shelf.

One gram of the substance to be analyzed is brought into a digestion flask with approximately 0.7 grams of mercuric-oxide, and 20 cubic centimeters of sulphuric acid, and the flask is placed on the frame described in an inclined position, and heated below the boiling point of the acid for from five to fifteen minutes, or until frothing has ceased. The heat is then raised until it boils briskly. No further attention is required until the contents of the flask have become a clear liquor, which is colorless, or, at least, has only a very pale straw color. The flask is then removed from the flame, held upright, and, while yet hot, potassium permanganate is dropped in carefully and in small quantities at a time until, after shaking, the liquid remains of a green or purple color.

After cooling, the contents of the flask are then transferred to the distilling flask with water, and to this 25 cubic centimeters of potassium-sulphide solution are added, 50 cubic centimeters of the soda solution, or sufficient to make the reaction strongly alkaline, and with a few pieces of granulated zinc.

The flask is at once connected with the condenser and the contents of the flask are distilled until all of the ammonia has passed over into the standard acid contained in the precipitating flask previously described and the concentrated solution can no longer be safely boiled.

This operation usually requires from 20 to 40 minutes. The distillate is then titrated with standard ammonia. The use of the mercuric-oxide in this operation greatly shortens the time necessary for digestion, which is rarely over an hour and a half in the case of substances most difficult to oxidize, and is more commonly less than an hour.

In most cases the use of potassium permanganate is quite unnecessary, but it is believed that in exceptional cases it is required for complete oxidation, and, in view of the uncertainty, it is always used.

Potassium-sulphide removes all mercury from solutions and so prevents the formation of mercuro-ammonium compounds which are not completely decomposed by soda solution.

The addition of zinc gives rise to an evolution of hydrogen and prevents violent bumping. Previous to use, the reagents should be tested by a blank experiment with sugar, which will partially reduce any nitrates that are present which might otherwise escape notice.

This method cannot be used for the determination of nitrogen substances which contain nitrate or certain albumenoids.

These methods of analysis are suitable to all spices and have been used with them. They are but a general process, however, and are dependent for their value on uniformity in the way they are carried out and the manner in which peculiarities of proximate composition in different spices are considered in drawing conclusions; determinations of particular substances, such as piperine, require, however, modifications, which must be described when discussing the analysis of each separate spice.

The chemical composition of olive stones and cocoanut shells is about as follows:

| Water, | 5.63 | 6.15 |

| Ash, | 4.28 | 2.15 |

| Fiber, | 41.33 | 37.15 |

| Albumenoids, | 1.56 | 1.25 |

| Nitrogen, | .25 | .20 |

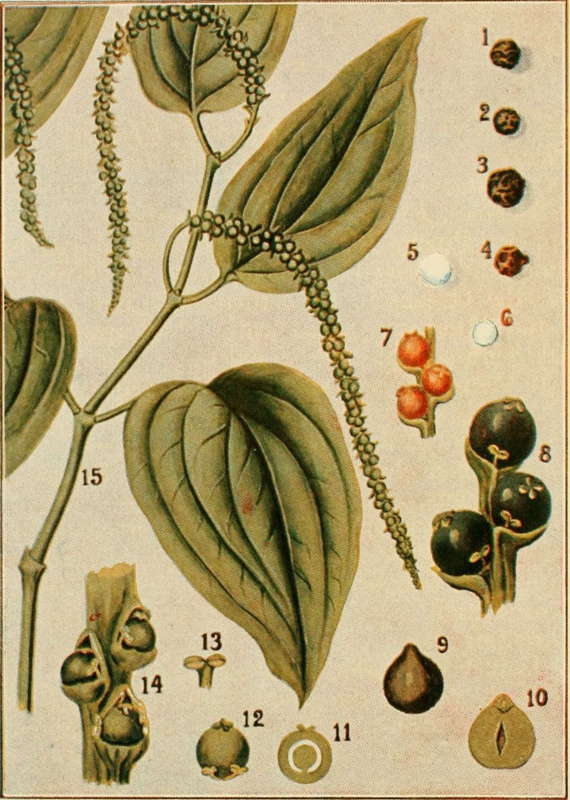

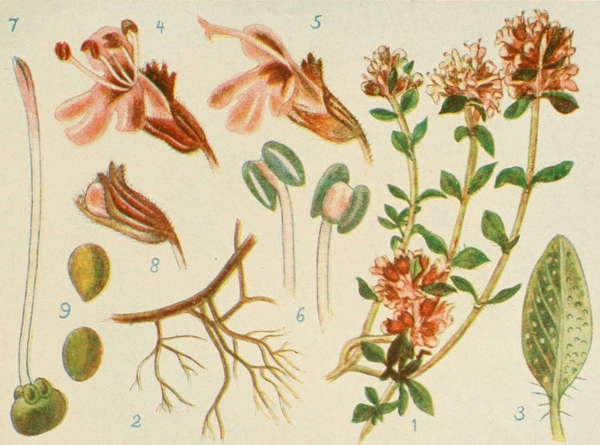

BLACK PEPPER (Piper Nigrum)

1 Malabar

2 Acheen or Sumatra

3 Mangalore

4 Singapore

5 White, from Penang, with all three coats removed

6 White, with one coat removed

7, 8 Parts of spikes

9, 10 Fruit

12 Ovary with stamens

13 Stamens

14 Portion of spike

15 A flowering twig

FRENCH, Poivre; German, Pfeffer; Italian, Pepe Nero; Spanish, Pimienta; Portuguese, Pimenta; Cyngalese, Gammaris; Javanese, Maricha; Persian, Filfll-Seeah; Hindoostanse, Gol-mirch.

Pepper (Piper) Nigrum, a name employed by the Romans, and derived by them from the Greek word peperi; the Greeks in their turn must have derived it from the Hindoos. Botanically it is applied to the typical genus plant of the natural order piperaceae. Of all the varieties of spices used as a condiment, pepper is the only one which grows on a climbing vine, and there is no kind of spice better known or more esteemed or more extensively used than pepper. Its consumption is enormous.

Black pepper is one of the earliest spices known to mankind, being of extreme antiquity. Choice spices and rare gums were among the precious treasures of the kings of Egypt more than two thousand years before the Christian era.

The history of its development from earliest times is well brought out by the account given in the Pharmacopœia. According to Fluckiger and Hanbury the spice was well known as early as the fourth century B. C. Arrian, the author of Periplus of the Frythrean Sea, which was written about A. D. 618, states that pepper was then imported from Barake, the shipping place of Nelkunda localities, which have been identified with points on the Malabar coast. To this spice, Venice, Genoa, and other commercial cities of central Europe are indebted for much of their wealth.

The caravan of trading Midianites, who purchased Joseph from his brethren and sold him into Egypt were bearers of “spices and balm” for the Egyptian market, and when the sons of Jacob were making preparations to visit the land the second time to propitiate the lord of the realm, their father said to them: “Take of the best fruits of the land and carry down a little balm, and a little honey, spice, and myrrh, nuts and almonds.”

During the palmy days of Egypt, when they embalmed all of their distinguished dead, precious gums and fragrant pungent spices were largely called into requisition. Even the Israelites in their ritualistic worship held in such high esteem many of these rare gums and oils that their law forbade their use for any other purpose.

Pepper received mention in the epic poems of the ancient Hindoos. Theophrastus differentiated between round and long pepper, Diascarides mentioned long pepper, white pepper and black pepper, and Pliny, the naturalist, expressed his surprise that it should come into general use considering its want of flavor, and he states that the price of pepper in his time at Rome was nine shillings and four pence per pound, English money. Both he and Diascarides, as well as Hippocrates, write of the medicinal virtues of spices and of their use in medicine. Pepper has been so scarce at times and so expensive that one pound was considered a royal present, and was used like money as a medium of exchange, while at other times its market value has been very low.

In its frequent mention by Roman writers of the Augustan age we are told that it was used by them to pay tribute. One of the articles demanded by Alaric, the daring ruler of the barbaric Visigoths in 410 A. D., of this conquered and greatly humiliated race was 3,000 pounds of pepper. During this dark middle age pepper was so costly that rents were paid in pepper corn, the amount being about one pound at stated times. Even now in places this custom still continues. It is not, therefore, surprising that during the first centuries of the Christian era the common black pepper was prized as highly in the city of Rome as its weight in gold. Black pepper is found in the East Indian Islands, among which may be mentioned the Malay Archipelago, Java, Sumatra, Rhio, Johore. It is also a native of Siam and Cochin China, and it grows wild in the forests of Malabar and Travancore. It is cultivated in some parts of the United States and in the West India Islands.

The early history of the pepper trade is similar to that of other Eastern spices. The Dutch for a long time confined the cultivation of it to the Island of Java. To accomplish this they forced its cultivation with so much earnestness that they defeated their own purpose and a more enlightened system has prevailed for the past thirty years. Since it is no longer under government monopoly, and entire freedom is allowed in the raising of this spice, its cultivation has been greatly increased. The king of Portugal contracted with middlemen in each of his forts on the coast of Malabar for an annual supply of 30,000 quintals of pepper, and bound himself to send five ships every year to export that amount. All risk was held by the middlemen or farmers “who landed it in Portugal.” As a compensation for this risk, the middlemen obtained the price of twelve ducats a quintal and had great and strong privileges: “First, that no man of what estate or condition soever he be, either Portingall or of any place in India, may deale or trade in pepper, but they upon paine of death which is very sharply looked into. And although the pepper were for the king’s own person, yet must the farmers pepper be first laden to whom the Viceroy and other officers and Captains of India must give all assistance, helpe and favour with watching same and all other things whatsoever that shall by said farmers be required for the safetie and benefite of the said pepper.”

In fact, it was because the price of pepper was so high during the Middle Ages that the Portuguese were led to seek a sea route to India. After the passage around the Cape of Good Hope had been discovered, about 1496, there was a considerable reduction in the price of pepper, and when it began to be cultivated in the Islands of the Malay Archipelago, another reduction was made. It, however, remained a monopoly of the Portuguese crown for many years, even as late as the eighteenth century. The earliest reference to a trade in pepper in England is A. D. 978-1016, when it was enacted that traders bringing their ships to Billingsgate should pay at Christmas and Easter, with other tributes, ten pounds of pepper.

Great Britain derived a duty from it for centuries, and as late as 1623 this duty was five shillings, or about $1.20 per pound. English grocers were known as “Peppers.” Even in 1823 the duty was two shillings and six pence per pound. The pepper alluded to by Pliny at his time in Rome must have been the product of Malabar, the nearest part of India to Europe, and must have cost in Malabar about 2d. per pound. It probably went to Europe by crossing the Indian and Arabian oceans with the easterly monsoon, sailing up the Red Sea, crossing the desert, and then going down the Nile, and making its way along the Mediterranean. This voyage in our time can be made in one month; at that time it probably took eighteen months. Transit and custom duties must have been paid over and over again and there must have been plenty of extortion. These facts will explain how pepper could not be sold in the Roman market under fifty-six times its prime cost. Immediately previous to the discovery of the route to India by the Cape of Good Hope we find that the price of pepper in the market of Europe had fallen to 6s. a pound, or 3s. 4d. less than in the time of Pliny. What probably contributed to this fall in price was the superior skill in navigation of the now converted Mohammedan Arabs, Turks, and Venetians, and the extension of their commerce in the Eastern Archipelago, which abounded in pepper.

Black pepper was then for many years considered a very choice article and, like gold, silver, and precious stones, it was possessed only by persons of wealth, and was for generations found only on royal tables and those of the rich and noble who aspired to rank with the rulers of the realm.

The British gave up the chief pepper ground of the world, which was the grand Island of Sumatra, to the Dutch for the small Dutch colony in Western Africa, which has involved both nations in little wars and has cost the Dutch more lives and money than it is worth; but prestige must also be sustained, and general after general returned with a shattered reputation from the “Atyeh,” as the Dutch called Acheen. When the East India Company first formed a settlement on the coast of Sumatra, it directed its attention to produce large growths of pepper. A stipulation was made with some of the native chiefs, binding them to compel their subjects each to cultivate a certain number of pepper vines, and the whole product was to be delivered to the company’s agents at a price far below the actual cost of cultivation and harvesting. The chiefs for a long time enforced obedience to this arbitrary measure and their success in this was supposed to be permanently assured by granting them an allowance proportionate to the quantity of pepper delivered.

This arbitrary practice was too keenly felt by the natives to be endured, and, the influence of the chiefs soon declining and the people becoming negligent in the cultivation, the annual supply fell off. The chiefs, unable longer to maintain their despotic practice, abandoned to the agents of the company the task of obliging the people to labor that others might reap. Now the rights of the people are more respected and the injustice of the methods formerly used are fully acknowledged; the cultivation of pepper in Sumatra, as well as elsewhere, is free.

Perhaps the earliest writer to describe the extent of the cultivation of pepper was Linschoten. He speaks of its coming from Mala or Malabar, and his friend and commentator of pepper, Paludanus, enters into a long account of its medicinal virtues. “It warmeth the mawe,” he writes, “and consumeth the cold slymenes thereof to ease the payne in the mawe which proceedeth of rawnesse and winde, it is good to eat fyve pepper cornes everie morning. He that hath a bad or thick sight, let him use pepper cornes with annis fennel seed and cloves for there by the mystinesse of the eyes which darken the sight is cleared and driven away.” But in modern medicine it is very little used, being rarely prescribed except indirectly as an ingredient of some compound.

Black pepper is the dried fruit of the piper nigrum, a perennial climbing shrub indigenous to the forests of Travancore, a native state in India, province of Madras, and of Malabar, a province of India, from which it has been introduced into the other countries mentioned.

Two species of piper will be found under drugs, “Cubebs” and a third falls within the range of the articled drugs “Kava-Kava,” and Narcotics; and two others are dealt with under “Narcotics.” There remain then for description as spice, black pepper, white pepper, long pepper, and Ashantee pepper.

In planting a new garden where no wild pepper vines are to be had, level land is selected which borders on a river or small stream without much sloping, but not so low as to be liable to any overflow from the stream, as the land must be kept well drained. Pepper is a hardy plant and will grow on almost any soil, but not on old, worn-out plantations or on poor sandy or clay soil, as more depends on the soil than on the cultivation. It should not be planted on hillsides because the earth will wash from the roots in time of rains. The best soil for pepper culture is a well-drained vegetable loam; swamp lands are very good in a hot climate with heavy rains.

The vine may be propagated either from the seed or by cuttings. When berries are selected for seed they are first soaked for three days, when the outer coat can be removed. The seed is then dried in the shade, after which it is sown by drills in nursery beds, which are made in the usual manner in good moist soil in a shady locality. Frequent watering will be necessary, if it be a dry time, until the plants have four leaves, when they will be ready for planting.

The land to be planted is to be cleared of underbrush. Sometimes large trees are burned by setting fire to their trunks. The tree will then decay and will be attacked by insects and will become a heap of rotten dust. This dust is washed by the rain around the roots of the vines, making a good fertilizer.

The land cleared is next well planted and hoed and is lined out 7 × 7 feet, and holes are dug two feet square and fifteen inches deep, which are filled with good soil or leaf mold if it can be secured. In filling these holes they should not be heaped, as depressions are better for the plant, but care should be taken that all that portion of the plant underground in the nursery should be buried in the garden.

The land is fenced by mud walls made into terraces. The vines need support, for if they are not supported they will spread over the ground with the result that there will be much loss of fruit.

When posts are used, as is the case on the Island of Borneo, they should be twelve feet long and eight inches square, with the lower end tarred for two feet, to prevent decaying in the ground. The plantation will then have the appearance of a hop field. But there are many disadvantages in connection with the post support, as the posts must be reset at intervals (much oftener than the vines) and the removing of the post disturbs the aerial roots of the vine, which cling to them. Even if the vine be trained to its new post, it will take some time for it to attach sufficiently to receive any support or nourishment. As the poles furnish little or no shade, a severe drought will largely ruin the plants. For these reasons the use of posts has not proved a success. Different countries use different growing trees for the support, thus securing shade protection as well. Many kinds of trees are used. One of these is the mango or the bread tree, which will yield the planter one crop of fruit each year in addition to the pepper crop; but the bread tree (artocarpus-incioa), being of slow growth, should not be used for a support until it is twelve years old. The Jack tree (artocarpus-integrifolia) is sometimes used in Malabar as a second choice, but its fruit is diminished in quantity and quality by the pressure of the pepper, and sometimes the monkeys will pull them out or the crickets nip off the tops. The erythrina-Indica (erythrina coroilodendron), a thorn tree called by the natives chingkariang, is much used in Sumatra for an early support. It grows quickly and is easily started by simply sticking a large branch in the ground in the rainy season. It will be capable of supporting the vine in one year, but it will soon be killed by the growing vine, not lasting more than twelve years. For this reason the mango or bread tree is planted beside it and when the erythrina-Indica tree dies out the first choice mango tree (manganifera-Indica) is ready to take its place and will furnish support for the vine for twenty years. Moreover, the fruit of the tree will not be affected by the growing vines. Plantations are set on the tilled land from July to August about twelve paces apart. In February and March the supporting trees are planted forty feet apart. They are kept well watered during the dry season, and when ten feet high are topped and kept trimmed or the leaves are picked off so as not to shade the plant too much. If the pepper garden is small, the vines may be planted near the trees already growing. Plants raised from the seed in nurseries are transplanted in May or June, being placed in the prepared holes five feet apart with their root end from the tree and with the growing perennial vine top directed towards its support. The root should be as far distant as possible from the support. If the plants are of slow growth, manure may be applied to the surface of the ground. In China burnt earth and rotten fish are used. The land must be kept free from weeds and the plants must be kept well watered on alternate days in the dry season.

The pepper vines are trained to their support in October and November. They may begin to bear fruit the first year, but do not yield much until the third or fourth year. The hoeing, training, and fertilizing are kept up twice each year in October and November and July and August. The moist earth should be heaped up and well tramped down about the plant. When the vines are six feet high they will cling to the trees without further training. The vines will bear for about fourteen years and even thirty years sometimes in extra good soil, but when past fourteen years they will usually decline in vigor and fruitfulness. The vine, after topping, is from eight to ten feet long, but if left to grow its full length will be from twenty to thirty feet long and will go to wood and bear less fruit, and the fruit would be difficult to gather. When cuttings are to be used for planting, at least three should be placed in each hole with six inches under ground or four inches above ground, the portion above ground to be directed towards the support. The plantation is next covered with leaves, dried grass, or weeds as a protection from the sun and to keep the earth moist and cool.

The vines grow rapidly if it is wet weather. When they have run up the support two feet, the ends are nipped off so as to cause lateral branches to start out. In some places, when the vines are from a year to eighteen months old and have grown five feet up the support, they are carefully detached and the ends, having been coiled up in a spiral form, are buried in a hole dug in the ground close to its roots, except a small surface of the stem. This process is called letting down. It insures a large crop, producing seven or more vines to one supporting tree. Plants raised from cuttings will only bear from seven to eight years, but the quantity and quality of the pepper is far superior to that raised from the seed.

The planting of the cuttings in baskets is often carried on in the following manner: The cuttings, which are about eighteen inches long, are put half a dozen in a basket; at higher altitudes more are used, sometimes as many as ten or twelve. The basket is then filled with earth and is buried at the foot of the supporting tree, care being taken that they do not touch. In October and November the ground around the baskets is dug up and the vines are manured with cow dung and leaves. The baskets are said to be a great protection to the young vines and they insure much better results. The end of the vine makes the best cutting, as it is a growing terminal bud. Vines growing wild, such as are indigenous to the forests of Malabar and Travancore, are left planted with the forest trees for their support. The surplus shade and underbrush are cut out and the ground is weeded, old vines being replaced by young ones. The product raised in this way is about as good as the cultivated.

A pepper garden is generally planted with plenty of room for roads, so as to secure easy access to all parts of it and with the least possible grade, which should not be more than one foot in twenty. The garden contains anywhere from five to fifteen acres and is divided into plots by hedges of shrubs, each plot containing from five hundred to one thousand plants. The plants are pruned or thinned by hand as they grow bushy at the top, when the flexible stems generally entwine at the top of their support and then bend downward, having their extremities as well as their branches loaded with fruit. It matters not how many stalks grow from the same root until the vine begins to bear fruit, but when fruit bearing begins only one or two stems should be left, as more would weaken the root and it would not, for that reason, bear as abundantly. All suckers and side shoots must be carefully removed. Trenches are cut to the neighbor props where the vines have failed, and through these trenches superfluous shoots are conducted, where they soon ascend around the adjacent tree. By this means the plantation is of a uniform growth, and, since the ground is kept well weeded and is elevated, and since there is an open border of twelve feet wide around each garden, there is given to the plantation an admirable symmetry and neatness of appearance.

HARVESTING OF BLACK PEPPER

COAST NEAR MANGALORE

The pepper vine or climbing shrub is mentioned by Sir John Mandeville in his travels of 1322 to 1356 as follows: “The pepper growethe in manere as doth a wylde vine that is planted fast by the trees of the woodee for to susteynen it by, as doth the vyne and fruyt thereof hangethe in manere as Reysinges; and the tree is so thikke charged that it semethe that it wolde breke, and when it is ripe it is all grene as it were ivy berryes; and then men kytten them as men doe the vynes and then they putten it upon an owven and there it waxeth blak and crisp.”