BY

JOHN G. ZIMMERMAN.

With the Life of the Author.

IN TWO PARTS.

NEW-YORK:—C. WELLS.

56, Gold-street.

1840.

| CHAP. | PAGE. | |

| PART I. | ||

| Life of the author | 9 | |

| I. | Introduction, | 15 |

| II. | Influence of solitude upon the mind, | 19 |

| III. | Influence of solitude upon the heart, | 60 |

| IV. | General advantages of retirement, | 109 |

| V. | Advantages of solitude in exile, | 134 |

| VI. | Advantages of solitude in old age and on the bed of death, | 138 |

| PART II. | ||

| I. | Introduction, | 149 |

| II. | Of the motives to solitude, | 157 |

| III. | Disadvantages of solitude, | 185 |

| IV. | Influence of solitude on the imagination, | 200 |

| V. | Effects of solitude on a melancholy mind, | 216 |

| VI. | Influence of solitude on the passions, | 235 |

| VII. | Of the danger of idleness in solitude, | 274 |

| VIII. | Conclusion, | 279 |

Weak and delicate minds may, perhaps, be alarmed by the title of this work. The word solitude, may possibly engender melancholy ideas; but they have only to read a few pages to be undeceived. The author is not one of those extravagant misanthropists who expect that men, formed by nature for the enjoyments of society, and impelled continually towards it by a multitude of powerful and invincible propensities, should seek refuge in forests, and inhabit the dreary cave or lonely cell; he is a friend to the species, a rational philosopher, and the virtuous citizen, who, encouraged by the esteem of his sovereign, endeavors to enlighten the minds of his fellow creatures upon a subject of infinite importance to them, the attainment of true felicity.

No writer appears more completely convinced than M. Zimmerman, that man is born for society, or feels its duties with more refined sensibility.

It is the nature of human society, and its correspondent duties, which he here undertakes to examine. The important characters of father, husband, son, and citizen, impose on man a variety of obligations, which are always dear to virtuous minds, and establish between him, his country, his family, and his friends, relations too necessary and attractive to be disregarded.

But it is not amidst tumultuous joys and noisy pleasures; in the chimeras of ambition, or the illusions of self-love; in the indulgence of feeling, or the gratification of desire, that men must expect to feel the charms of those mutual ties which link them so firmly to society. It is not in such enjoyments that men can feel the dignity of those duties, the performance of which nature has rendered productive of so many pleasures, or hope to taste that true felicity which results from an independent mind and a contented heart: a felicity seldom sought after, only because it is so little known, but which every individual may find within his own bosom. Who, alas! does not constantly experience the necessity of entering into that sacred asylum to search for consolation under the real or imaginary misfortunes of life, or to alleviate indeed more frequently the fatigue of its painful pleasures? Yes, all men, from the mercenary trader, who sinks under the anxiety of his daily task, to the proud statesman, intoxicated by the incense of popular applause, experience the desire of terminating their arduous career. Every bosom feels an anxiety for repose, and fondly wishes to steal from the vortex of a busy and perturbed life, to enjoy the tranquillity of solitude.

It is under the peaceful shades of solitude that the mind regenerates and acquires fresh force; it is there alone that the happy can enjoy the fulness of felicity, or the miserable forget their wo; it is there that the bosom of sensibility experiences its most delicious emotions; it is there that creative genius frees itself from the thraldom of society, and surrenders itself to the impetuous rays of an ardent imagination. To this desired goal all our ideas and desires perpetually tend.[7] “There is,” says Dr. Johnson, “scarcely any writer, who has not celebrated the happiness of rural privacy, and delighted himself and his readers with the melody of birds, the whisper of groves, and the murmurs of rivulets; nor any man eminent for extent of capacity, or greatness of exploits, that has not left behind him some memorials of lonely wisdom and silent dignity.”

The original work from which the following pages are selected, consists of four large volumes, which have acquired the universal approbation of the German empire, and obtained the suffrages of an empress celebrated for the superior brilliancy of her mind, and who has signified her approbation in the most flattering manner.

On the 26th of January, 1785, a courier, dispatched by the Russian envoy at Hamburg, presented M. Zimmerman with a small casket, in the name of her majesty the empress of Russia. The casket contained a ring set round with diamonds of an extraordinary size and lustre; and a gold medal bearing on one side the portrait of the empress, and on the other the date of the happy reformation of the Russian empire. This present the empress accompanied with a letter, written with her own hand, containing these remarkable words:—“To M. Zimmerman, counsellor of state, and physician to his Britannic majesty, to thank him for the excellent precepts he has given to mankind in his treatise upon solitude.”

John George Zimmerman was born on the 8th day of December, 1728, at Brugg, a small town in the canton of Berne.

His father, John Zimmerman, was eminently distinguished as an able and eloquent member of the provincial council. His mother, who was equally respected and beloved for her good sense, easy manners, and modest virtues, was the daughter of the celebrated Pache, whose extraordinary learning and great abilities, had contributed to advance him to a seat in the parliament of Paris.

The father of Zimmerman undertook the arduous task of superintending his education, and, by the assistance of able preceptors, instructed him in the rudiments of all the useful and ornamental sciences, until he had attained the age of fourteen years, when he sent him to the university of Berne, where, under Kirchberger, the historian and professor of rhetoric, and Altman, the celebrated Greek professor, he studied, for three years, philology and the belles lettres, with unremitting assiduity and attention.

Having passed nearly five years at the university, he began to think of applying the stores of information he had acquired to the purposes of active life; and after mentioning the subject cursorily to a few relations, he immediately resolved to follow the practice of physic. The extraordinary fame of Haller, who had recently been promoted by king George II. to a professorship in the university of Gottingen, resounded at this time throughout Europe: and Zimmerman determined to prosecute his studies in physic under the auspices of this great and celebrated master. He was admitted[10] into the university on the 12th of September, 1747, and obtained his degree on the 14th of August, 1751. To relax his mind from severer studies, he cultivated a complete knowledge of the English language, and became so great a proficient in the polite and elegant literature of this country, that the British poets, particularly Shakspeare, Pope, and Thomson, were as familiar to him as his favorite authors, Homer and Virgil. Every moment, in short, of the four years he passed at Gottingen, was employed in the improvement of his mind; and so early as the year 1751, he produced a work in which he discovered the dawnings of that extraordinary genius which afterwards spread abroad with so much effulgence.[1]

During the early part of his residence at Berne, he published many excellent essays on various subjects in the Helvetic Journal; particularly a work on the talents and erudition of Haller. This grateful tribute, to the just merits of his friend and benefactor, he afterwards enlarged into a complete history of his life and writings, as a scholar, a philosopher, a physician, and a man.

The health of Haller, which had suffered greatly by the severity of study, seemed to decline in proportion as his fame increased; and, obtaining permission to leave Gottingen, he repaired to Berne, to try, by the advice and assistance of Zimmerman, to restore, if possible, his decayed constitution. The benefits he experienced in a short time were so great, that he determined to relinquish his professorship, and to pass the remainder of his days in that city. In the family of Haller, lived a young lady, nearly related to him, whose maiden name was Mely, and whose husband, M. Stek, had been sometime dead. Zimmerman became deeply enamored of her charms: he offered her his hand in marriage; and they were united at the altar in the bands of mutual affection.

Soon after his union with this amiable woman, the situation of physician to the town of Brugg became vacant, which he was invited by the inhabitants to fill; and he accordingly relinquished the pleasures and advantages he enjoyed at Berne and returned to the place of his nativity, with a view to settle himself there for life. His time, however, was not so entirely engrossed[11] by the duties of his profession, as to prevent him from indulging his mind in the pursuits of literature; and he read almost every work of reputed merit, whether of physic, or moral philosophy, belles lettres, history, voyages, or even novels and romances, which the various presses of Europe from time to time produced. The novels and romances of England, in particular, gave him great delight.

But the amusements which Brugg afforded were extremely confined: and he fell into a state of nervous langor, or rather into a peevish dejection of spirits, neglecting society, and devoting himself almost entirely to a retired and sedentary life.

Under these circumstances, this excellent and able man passed fourteen years of an uneasy life; but neither his increasing practice, the success of his literary pursuits,[2] the exhortations of his friends, nor the endeavors of his family, were able to remove the melancholy and discontent that preyed continually on his mind. After some fruitless efforts to please him, he was in the beginning of April, 1768, appointed by the interest of Dr. Tissot, and baron Hockstettin, to the post of principal physician to the king of Great Britain, at Hanover; and he departed from Brugg, to take possession of his new office, on the 4th of July, in the same year. Here he was plunged into the deepest affliction by the loss of his amiable wife, who after many years of lingering sufferance, and pious resignation, expired in his arms, on the 23d of June, 1770;[12] an event which he has described in the following work, with eloquent tenderness and sensibility. His children too, were to him additional causes of the keenest anguish and the deepest distress. His daughter had from her earliest infancy, discovered symptoms of consumption, so strong and inveterate as to defy all the powers of medicine, and which, in the summer of 1781, destroyed her life. The character of this amiable girl, and the feelings of her afflicted father on this melancholy event, his own pen has very affectingly described in the following work.

But the state and condition of his son was still more distressing to his feelings than even the death of his beloved daughter. This unhappy youth, who, while he was at the university, discovered the finest fancy and the soundest understanding, either from a malignant and inveterate species of scrofula, with which he had been periodically tortured from his earliest infancy, or from too close an application to study, fell very early in life into a state of bodily infirmity and mental langor, which terminated in the month of December, 1777, in a total derangement of his faculties; and he has now continued, in spite of every endeavor to restore him, a perfect idiot for more than twenty years.

The domestic comforts of Zimmerman were now almost entirely destroyed; till at length, he fixed upon the daughter of M. Berger, the king’s physician at Lunenbourg, and niece to baron de Berger, as a person in every respect qualified to make him happy, and they were united to each other in marriage about the beginning of October, 1782. Zimmerman was nearly thirty years older than his bride: but genius and good sense are always young: and the similarity of their characters obliterated all recollection of disparity of age.

It was at this period that he composed his great and favorite work on solitude, thirty years after the publication of his first essay on the subject. It consists of four volumes in quarto: the two first of which were published in 1784; and the remaining volumes in 1786. “A work,” says Tissot, “which will always be read with as much profit as pleasure, as it contains the most sublime conceptions, the greatest sagacity of observation, and extreme propriety of application, much ability in the choice of examples, and (what I cannot commend too highly, because I can say nothing that does him so much honor, nor give him any praise that would[13] be more gratifying to his own heart) a constant anxiety for the interest of religion, with the sacred and solemn truths of which his mind was most devoutly impressed.”

The king of Prussia, while he was reviewing his troops in Silesia, in the autumn of the year 1785, caught a severe cold, which settled on his lungs and in the course of nine months brought on symptoms of an approaching dropsy. Zimmerman, by two very flattering letters of the 6th and 16th of June, 1786, was solicited by his majesty to attend him, and he arrived at Potzdam on the 23d of the same month; but he immediately discovered that his royal patient had but little hopes of recovery; and, after trying the effect of such medicines as he thought most likely to afford relief, he returned to Hanover on the 11th of July following.[3] But it was not Frederick alone who discovered his abilities. When in the year 1788, the melancholy state of the king of England’s health alarmed the affection of his subjects, and produced an anxiety throughout Europe for his recovery, the government of Hanover dispatched Zimmerman to Holland, that he might be nearer London, in case his presence there became necessary; and he continued at the Hague until all danger was over.

Zimmerman was the first who had the courage to unveil the dangerous principles of the new philosophers, and to exhibit to the eyes of the German princes the risk they ran in neglecting to oppose the progress of so formidable a league. He convinced many of them, and particularly the emperor Leopold II. that the views of these illuminated conspirators were the destruction of Christianity, and the subversion of all regular government. These exertions, while they contributed to lessen the danger which threatened his adopted country, greatly impaired his health.

In the month of November, 1794, he was obliged to have recourse to strong opiates to procure even a short repose: his appetite decreased; his strength failed him; and he became so weak and emaciated, that, in January 1795, he was induced to visit a few particular patients in his carriage, it was painful to him to write a prescription, and he frequently fainted while ascending to the room. These symptoms were followed by[14] a dizziness in his head, which obliged him to relinquish all business. At length the axis of his brain gave way, and reduced him to such a state of mental imbecility, that he was haunted continually by an idea that the enemy was plundering his house, and that he and his family were reduced to a state of misery and want. His medical friends, particularly Dr. Wichman, by whom he was constantly attended, contributed their advice and assistance to restore him to health; and conceiving that a journey and a change of air were the best remedies that could be applied, they sent him to Eutin, in the duchy of Holstein, where he continued three months, and about the month of June, 1795, returned to Hanover greatly recovered. But the fatal dart had infixed itself too deeply to be entirely removed; he soon afterwards relapsed into his former imbecility, and barely existed in lingering sufferance for many months, refusing to take any medicines, and scarcely any food; continually harassed and distressed by the cruel allusion of poverty, which again haunted his imagination. At certain intervals his mind seemed to recover only for the purpose of rendering him sensible of his approaching dissolution; for he frequently said to his physicians, “My death I perceive will be slow and painful;” and, about fourteen hours before he died, he exclaimed, “Leave me to myself; I am dying.” At length his emaciated body and exhausted mind sunk beneath the burden of mortality, and he expired without a groan, on the 7th October, 1795, aged 66 years and ten months.

Solitude is that intellectual state in which the mind voluntarily surrenders itself to its own reflections. The philosopher, therefore, who withdraws his attention from every external object to the contemplation of his own ideas, is not less solitary than he who abandons society, and resigns himself entirely to the calm enjoyments of lonely life.

The word “solitude” does not necessarily import a total retreat from the world and its concerns: the dome of domestic society, a rural village, or the library of a learned friend, may respectively become the seat of solitude, as well as the silent shade of some sequestered spot far removed from all connection with mankind.

A person may be frequently solitary without being alone. The haughty baron, proud of his illustrious descent, is solitary unless he is surrounded by his equals: a profound reasoner is solitary at the tables of the witty and the gay. The mind may be as abstracted amidst a numerous assembly; as much withdrawn from every surrounding object; as retired and concentrated in itself; as solitary, in short, as a monk in his cloister, or a hermit in his cave. Solitude, indeed, may exist amidst the tumultuous intercourse of an agitated city as well as in the peaceful shades of rural retirement; at London and at Paris, as well as on the plains of Thebes and the deserts of Nitria.

The mind, when withdrawn from external objects, adopts, freely and extensively, the dictates of its own ideas, and implicitly follows the taste, the temperament, the inclination, and the genius, of its possessor. Sauntering through the cloisters of the Magdalen convent[16] at Hidelshiem, I could not observe, without a smile, an aviary of canary birds, which had been bred in the cell of a female devotee. A gentleman of Brabant, lived five-and-twenty years without ever going out of his house, entertaining himself during that long period with forming a magnificent cabinet of pictures and paintings. Even unfortunate captives, who are doomed to perpetual imprisonment, may soften the rigors of their fate, by resigning themselves, as far as their situation will permit, to the ruling passion of their souls. Michael Ducret, the Swiss philosopher, while he was confined in the castle of Aarburg, in the canton of Berne, in Swisserland, measured the height of the Alps: and while the mind of baron Trenck, during his imprisonment at Magdebourg, was with incessant anxiety, fabricating projects to effect his escape, general Walrave, the companion of his captivity, contentedly passed his time in feeding chickens.

The human mind, in proportion as it is deprived of external resources, sedulously labors to find within itself the means of happiness, learns to rely with confidence on its own exertions, and gains with greater certainty the power of being happy.

A work, therefore, on the subject of solitude, appeared to me likely to facilitate man in his search after true felicity.

Unworthy, however, as the dissipation and pleasures of the world appear to me to be, of the avidity with which they are pursued, I equally disapprove of the extravagant system which inculcates a total dereliction of society; which will be found, when seriously examined, to be equally romantic and impracticable. To be able to live independent of all assistance, except from our own power, is, I acknowledge, a noble effort of the human mind; but it is equally great and dignified to learn the art of enjoying the comforts of society with happiness to ourselves, and with utility to others.

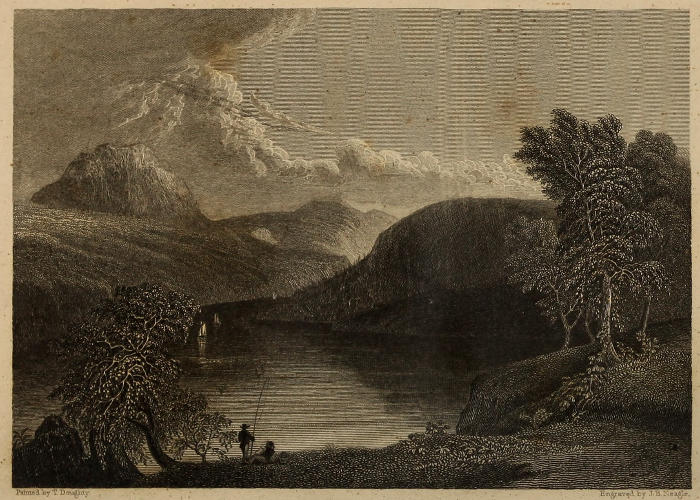

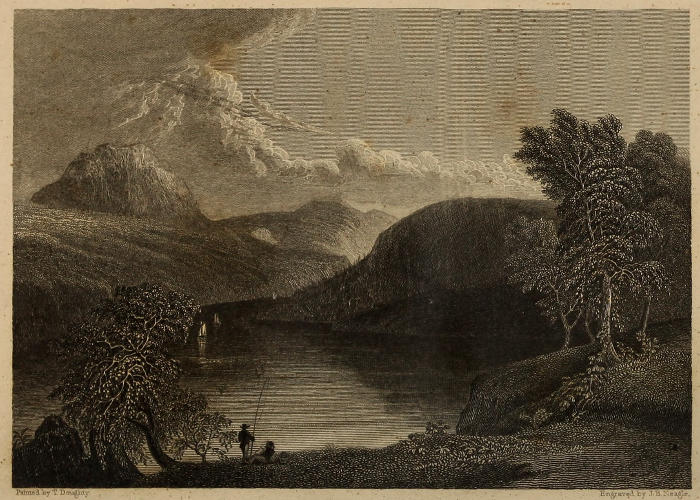

While, therefore, I exhort my readers to listen to the advantages of occasional retirement, I warn them against that dangerous excess into which some of the disciples of this philosophy have fallen; an excess equally repugnant to reason and religion. May I happily steer through all the dangers with which my subject is surrounded; sacrifice nothing to prejudice; offer no violation to truth; and gain the approbation of[17] the judicious and reflecting! If affliction shall feel one ray of comfort, or melancholy, released from a portion of its horrors, raise its down cast head; if I shall convince the lover of rural life, that all the finer springs of pleasure dry up and decay in the intense joys of crowded cities, and that the warmest emotions of the heart become there cold and torpid; if I shall evince the superior pleasures of the country; how many resources rural life affords against the langors of indolence; what purity of sentiment, what peaceful repose, what exalted happiness, is inspired by verdant meads, and the view of lively flocks quitting their rich pastures to seek, with the declining sun, their evening folds: how highly the romantic scenery of a wild and striking country, interspersed with cottages, the habitations of a happy, free, contented race of men, elevates the soul; how far more interesting to the heart are the joyful occupations of rural industry, than the dull and tasteless entertainments of a dissipated city; how much more easily, in short, the most excruciating sorrows are pleasingly subdued on the fragrant border of a peaceful stream, than in the midst of those treacherous delights which occupy the courts of kings—all my wishes will be accomplished, and my happiness complete.

Retirement from the world may prove peculiarly beneficial at two periods of life: in youth, to acquire the rudiments of useful information, to lay the foundation of the character intended to be pursued, and to obtain that train of thought which is to guide us through life; in age, to cast a retrospective view on the course we have run; to reflect on the events we have observed, the vicissitudes we have experienced: to enjoy the flowers we have gathered on the way, and to congratulate ourselves upon the tempests we have survived. Lord Bolingbroke, in his “Idea of a Patriot King,” says, there is not a more profound nor a finer observation in all lord Bacon’s works, than the following: “We must choose betimes such virtuous objects as are proportioned to the means we have of pursuing them, and belong particularly to the stations we are in, and the duties of those stations. We must determine and fix our minds in such manner upon them, that the pursuit of them may become the business, and the attainment of them the end of our whole lives. Thus we shall imitate the great operations of nature,[18] and not the feeble, slow, and imperfect operations of art. We must not proceed in forming the moral character, as a statuary proceeds in forming a statue, who works sometimes on the face, sometimes on one part, and sometimes on an other; but we must proceed, and it is in our power to proceed, as nature does in forming a flower, or any other of her productions; rudimenta partium omnium simul parit et producit: she throws out altogether, and at once, the whole system of every being, and the rudiments of all the parts.”

It is, therefore, more especially to those youthful minds, who still remain susceptible of virtuous impressions, that I here pretend to point out the path which leads to true felicity. And if you acknowledge that I have enlightened your mind, corrected your manners, and tranquillized your heart, I shall congratulate myself on the success of my design, and think my labors richly rewarded.

Believe me, all ye amiable youths, from whose minds the artifices and gayeties of the world have not yet obliterated the precepts of a virtuous education; who are yet uninfected with its inglorious vanities; who, still ignorant of the tricks and blandishments of seduction, have preserved the desire to perform some glorious action, and retained the power to accomplish it; who, in the midst of feasting, dancing, and assemblies, feel an inclination to escape from their unsatisfactory delights; solitude will afford you a safe asylum. Let the voice of experience recommend you to cultivate a fondness for domestic pleasures, to incite and fortify your souls to noble deeds, to acquire that cool judgment and intrepid spirit which enables you to form correct estimates of the characters of mankind, and of the pleasures of society. But to accomplish this high end, you must turn your eyes from those trifling and insignificant examples which a degenerated race of men affords, and study the illustrious characters of the ancient Greeks, the Romans, and the Modern English. In what nation will you find more celebrated instances of human greatness? What people possesses more valor, courage, firmness, and knowledge; where do the arts and sciences shine with greater splendor, or with more useful effect? But do not deceive yourselves by a belief that you will acquire the character of an Englishman by wearing a cropped head of hair; no, you must pluck the roots of vice from your mind, destroy[19] the seeds of weakness in your bosoms, and imitate the great examples of heroic virtue which that nation so frequently affords. It is an ardent love of liberty, undaunted courage, deep penetration, elevated sentiment, and well cultivated understanding, that constitute the British character; and not their cropped heads, half-boots, and round hats. It is virtue alone, and not dress or titles, that can ennoble or adorn the human character. Dress is an object too minute and trifling wholly to occupy a rational mind; and an illustrious descent is only advantageous as it renders the real merits of its immediate possessor more conspicuous. Never, however, lose sight of this important truth, that no one can be truly great until he has gained a knowledge of himself: a knowledge which can only be acquired by occasional retirement.

The true value of liberty can only be conceived by minds that are free: slaves remain indolently contented in captivity. Men who have been long tossed upon the troubled ocean of life, and have learned by severe experience to entertain just notions of the world and its concerns, to examine every object with unclouded and impartial eyes, to walk erect in the strict and thorny paths of virtue, and to find their happiness in the reflections of an honest mind, alone are free.

The path of virtue, indeed, is devious, dark and dreary; but though it leads the traveller over hills of difficulty, it at length brings him into the delightful and extensive plains of permanent happiness and secure repose.

The love of solitude, when cultivated in the morn of life, elevates the mind to a noble independence; but to acquire the advantage which solitude is capable of affording, the mind must not be impelled to it by melancholy and discontent, but by a real distaste to the idle pleasures of the world, a rational contempt for the deceitful joys of life, and just apprehensions of being corrupted and seduced by its insinuating and destructive gayeties.

Many men have acquired and exercised in solitude that transcendent greatness of mind which defies events; and, like the majestic cedar, which braves the fury of the most violent tempest, have resisted, with heroic courage, the severest storms of fate.

Solitude, indeed, sometimes renders the mind in a slight degree arrogant and conceited; but these effects are easily removed by a judicious intercourse with mankind. Misanthropy, contempt of folly, and pride of spirit, are, in noble minds, changed by the maturity of age into dignity of character; and that fear of the opinion of the world which awed the weakness and inexperience of youth, is succeeded by firmness, and a high disdain of those false notions by which it was dismayed: the observations once so dreadful lose all their stings; the mind views objects not as they are, but as they ought to be; and, feeling a contempt for vice, rises into a noble enthusiasm for virtue, gaining from the conflict a rational experience and a compassionate feeling which never decay.

The science of the heart, indeed, with which youth should be familiarized as early as possible, is too frequently neglected. It removes the asperities and polishes the rough surfaces of the mind. This science is founded on that noble philosophy which regulates the characters of men; and operating more by love than by rigid precept, corrects the cold dictates of reason by the warm feelings of the heart; opens to view the dangers to which they are exposed; animates the dormant faculties of the mind, and prompts them to the practice of all the virtues.

Dion was educated in all the turpitude and servility of courts, accustomed to a life of softness and effeminacy, and, what is still worse, tainted by ostentation, luxury, and every species of vicious pleasure; but no sooner did he listen to the divine Plato, and acquire thereby a taste for that sublime philosophy which inculcates the practice of virtue, than his whole soul became deeply enamored of its charms. The same love of virtue with which Plato inspired the mind of Dion, may be silently, and almost imperceptibly infused by every tender mother into the mind of her child. Philosophy, from the lips of a wise and sensible woman, glides quietly, but with strong effect, into the mind through the feelings of the heart. Who is not fond of walking, even through the most rough and difficult[21] paths, when conducted by the hand of love? What species of instruction can be more successful than soft lessons from a female tongue, dictated by a mind profound in understanding, and elevated in sentiment, where the heart feels all the affection that her precepts inspire? Oh! may every mother, so endowed, be blessed with a child who delights to listen in private to her edifying observations; who, with a book in his hand, loves to seek among the rocks some sequestered spot favorable to study; who when walking with his dogs and gun, frequently reclines under the friendly shade of some majestic tree, and contemplates the great and glorious characters which the pages of Plutarch present to his view, instead of toiling through the thickest of the surrounding woods hunting for game.

The wishes of a mother are accomplished when the silence and solitude of the forests seize and animate the mind of her loved child; when he begins to feel that he has seen sufficiently the pleasures of the world; when he begins to perceive that there are greater and more valued characters than noblemen or esquires, than ministers or kings; characters who enjoy a more elevated sense of pleasure than gaming tables and assemblies are capable of affording; who seek, at every interval of leisure, the shades of solitude with rapturous delight; whose minds have been inspired with a love of literature and philosophy from their earliest infancy; whose bosoms have glowed with a love of science through every subsequent period of their lives; and who, amidst the greatest calamities, are capable of banishing, by a secret charm, the deepest melancholy and most profound dejection.

The advantages of solitude to a mind that feels a real disgust at the tiresome intercourses of society, are inconceivable. Freed from the world, the veil which obscured the intellect suddenly falls, the clouds which dimmed the light of reason disappear, the painful burden which oppressed the soul is alleviated; we no longer wrestle with surrounding perils; the apprehension of danger vanishes; the sense of misfortune becomes softened; the dispensations of Providence no longer excite the murmur of discontent; and we enjoy the delightful pleasures of a calm, serene and happy mind. Patience and resignation follow and reside with a contented heart; every corroding care flies away on the wings of gayety; and on every side agreeable and interesting[22] scenes present themselves to our view; the brilliant sun sinking behind the lofty mountains tinging their snow-crowned turrets with golden rays; the feathered choir hastening to seek within their mossy cells a soft, a silent, and secure repose; the shrill crowing of the amorous cock; the solemn and stately march of oxen returning from their daily toil, and the graceful paces of the generous steed. But, amidst the vicious pleasures of a great metropolis, where sense and truth are constantly despised, and integrity and conscience thrown aside as inconvenient and oppressive, the fairest forms of fancy are obscured, and the purest virtues of the heart corrupted.

But the first and most incontestable advantage of solitude is, that it accustoms the mind to think; the imagination becomes more vivid, and the memory more faithful, while the sense remains undisturbed, and no external object agitates the soul. Removed far from the tiresome tumults of public society, where a multitude of heterogeneous objects dance before our eyes and fill the mind with incoherent notions, we learn to fix our attention to a single subject, and to contemplate that alone. An author, whose works I could read with pleasure every hour of my life, says, “It is the power of attention which, in a great measure distinguishes the wise and great from the vulgar and trifling herd of men. The latter are accustomed to think, or rather to dream, without knowing the subject of their thoughts. In their unconnected rovings they pursue no end, they follow no track. Every thing floats loose and disjointed on the surface of their minds, like leaves scattered and blown about on the face of the waters.”

The habit of thinking with steadiness and attention can only be acquired by avoiding the distraction which a multiplicity of objects always create; by turning our observation from external things, and seeking a situation in which our daily occupations are not perpetually shifting their course, and changing their direction.

Idleness and inattention soon destroy all the advantages of retirement; for the most dangerous passions, when the mind is not properly employed, rise into fermentation, and produce a variety of eccentric ideas and irregular desires. It is necessary, also, to elevate our thoughts above the mean consideration of sensual objects; the unincumbered mind then recalls all that[23] it has read; all that has pleased the eye or delighted the ear; and reflecting on every idea which either observation, experience, or discourse, has produced, gains new information by every reflection, and conveys the purest pleasures to the soul. The intellect contemplates all the former scenes of life; views by anticipation those that are yet to come, and blends all ideas of past and future in the actual enjoyment of the present moment. To keep, however, the mental powers in proper tone, it is necessary to direct our attention invariably toward some noble and interesting study.

It may, perhaps, excite a smile, when I assert, that solitude is the only school in which the characters of men can be properly developed; but it must be recollected, that, although the materials of this study must be amassed in society, it is in solitude alone that we can apply them to their proper use. The world is the great scene of our observations; but to apply them with propriety to their respective objects is exclusively the work of solitude. It is admitted that a knowledge of the nature of man is necessary to our happiness; and therefore I cannot conceive how it is possible to call those characters malignant and misanthropic, who while they continue in the world, endeavor to discover even the faults, foibles and imperfections of human kind. The pursuit of this species of knowledge, which can only be gained by observation, is surely laudable, and not deserving the obloquy that has been cast on it. Do I, in my medical character, feel any malignity or hatred to the species, when I study the nature, and explore the secret causes of those weaknesses and disorders which are incidental to the human frame? When I examine the subject with the closest inspection, and point out for the general benefit, I hope, of mankind, as well as for my own satisfaction, all the frail and imperfect parts in the anatomy of the human body?

But a difference is supposed to exist between the observations which we are permitted to make upon the anatomy of the human body, and those which we assume respecting the philosophy of the mind. The physician, it is said, studies the maladies which are incidental to the human frame, to apply such remedies as particular occasion may require: but it is contended, that the moralist has a different end in view. This distinction, however, is certainly without foundation. A sensible and feeling philosopher views both the moral[24] and physical defects of his fellow creatures with an equal degree of regret. Why do moralists shun mankind, by retiring into solitude, if it be not to avoid the contagion of those vices which they perceive so prevalent in the world, and which are not observed by those who are in the habit of seeing them daily indulged without censure or restraint? The mind, without doubt feels a considerable degree of pleasure in detecting the imperfections of human nature; and where that detection may prove beneficial to mankind, without doing an injury to any individual, to publish them to the world, to point out their qualities, to place them, by a luminous description before the eyes of men, is in my idea, a pleasure so far from being mischievous, that I rather think, and I trust I shall continue to think so even in the hour of death, it is the only real mode of discovering the machinations of the devil, and destroying the effects of his work. Solitude, therefore, as it tends to excite a disposition to think with effect, to direct the attention to proper objects, to strengthen observation, and to increase the natural sagacity of the mind, is the school in which a true knowledge of the human character is most likely to be acquired.

Bonnet, in an affecting passage of the preface to his celebrated work on the Nature of the Soul, relates the manner in which solitude rendered even his defect of sight advantageous to him. “Solitude,” says he, “necessarily leads the mind to meditation. The circumstances in which I have hitherto lived, joined to the sorrows which have attended me for many years, and from which I am not yet released, induced me to seek in reflection those comforts which my unhappy condition rendered necessary; and my mind is now become my constant retreat: from the enjoyments it affords I derive pleasures which, like potent charms, dispel all my afflictions.” At this period the virtuous Bonnet was almost blind. Another excellent character, of a different kind, who devotes his time to the education of youth, Pfeffel, at Colmar, supports himself under the affliction of total blindness in a manner equally noble and affecting, by a lifeless solitary indeed, but by the opportunities of frequent leisure which he employs in the study of philosophy, the recreations of poetry, and the exercises of humanity. There was formerly in Japan a college of blind persons, who, in all probability, were endued with quicker discernment than many[25] members of more enlightened colleges. These sightless academicians devoted their time to the study of history, poetry, and music. The most celebrated traits in the annals of their country became the subject of their muse; and the harmony of their verses could only be excelled by the melody of their music. In reflecting upon the idleness and dissipation in which a number of solitary persons pass their time, we contemplate the conduct of these blind Japanese with the highest pleasure. The mind’s eye opened and afforded them ample compensation for the loss of the corporeal organ. Light, life, and joy, flowed into their minds through surrounding darkness, and blessed them with high enjoyment of tranquil thought and innocent occupation.

Solitude teaches us to think, and thoughts become the principal spring of human actions; for the actions of men, it is truly said, are, nothing more than their thoughts embodied, and brought into substantial existence. The mind, therefore, has only to examine with candor and impartiality the idea which it feels the greatest inclination to pursue, in order to penetrate and expound the mystery of the human character; and he who has not been accustomed to self-examination, will upon such a scrutiny, frequently discover truths of extreme importance to his happiness, which the mists of worldly delusion had concealed totally from his view.

Liberty and leisure are all that an active mind requires in solitude. The moment such a character finds itself alone, all the energies of his soul put themselves into motion, and rise to a height incomparably greater than they could have reached under the impulse of a mind clogged and oppressed by the encumbrances of society. Even plodding authors, who only endeavor to improve the thoughts of others, and aim not at originality for themselves, derive such advantages from solitude, as to render them contented with their humble labors; but to superior minds, how exquisite are the pleasures they feel when solitude inspires the idea and facilitates the execution of works of virtue and public benefit! works which constantly irritate the passions of the foolish, and confound the guilty consciences of the wicked. The exuberance of a fine fertile imagination is chastened by the surrounding tranquility of solitude: all its diverging rays are concentrated to[26] one certain point; and the mind exalted to such powerful energy, that whenever it is inclined to strike, the blow becomes tremendous and irresistible. Conscious of the extent and force of his powers, a character thus collected cannot be dismayed by legions of adversaries; and he waits, with judicious circumspection, to render sooner or later, complete justice to the enemies of virtue. The profligacy of the world, where vice usurps the seat of greatness, hypocrisy assumes the face of candor, and prejudice overpowers the voice of truth, must, indeed, sting his bosom with the keenest sensations of mortification and regret; but cast his philosophic eye over the disordered scene, he will separate what ought to be indulged from what ought not to be endured; and by a happy, well-timed stroke of satire from his pen, will destroy the bloom of vice, disappoint machinations of hipocrisy, and expose the fallacies on which prejudice is founded.

Truth unfolds her charms in solitude with superior splendor. A great and good man; Dr. Blair, of Edinburgh, says, “The great and the worthy, the pious and the virtuous, have ever been addicted to serious retirement. It is the characteristic of little and frivolous minds to be wholly occupied with the vulgar objects of life. These fill up their desires, and supply all the entertainment which their coarse apprehensions can relish. But a more refined and enlarged mind leaves the world behind it, feels a call for higher pleasures, and seeks them in retreat. The man of public spirit has recourse to it in order to reform plans for general good; the man of genius in order to dwell on his favorite themes; the philosopher to pursue his discoveries; and the saint to improve himself in grace.”

Numa, the legislator of Rome, while he was only a private individual, retired on the death of Tatia, his beloved wife, into the deep forests of Aricia and wandered in solitary musings through the thickest groves and most sequestered shades. Superstition imputed his lonely propensity, not to disappointment, discontent, or hatred to mankind, but to a higher cause: a wish silently to communicate with some protecting deity. A rumor was circulated that the goddess Egeria, captivated by his virtues, had united herself to him in the sacred bonds of love, and by enlightening his mind, and storing it with superior wisdom, had led him to divine felicity. The Druids also, who dwelt among the rocks, in the woods,[27] and in the most solitary places, are supposed to have instructed the infant nobility of their respective nations in wisdom and in eloquence, in the phenomena of nature, in astronomy, in the precepts of religion, and the mysteries of eternity. The profound wisdom thus bestowed on the characters of the Druids, although it was, like the story of Numa, the mere effects of imagination, discovers with what enthusiasm every age and country have revered those venerable characters who in the silence of the groves, and in the tranquillity of solitude, have devoted their time and talents to the improvement of the human mind, and the reformation of the species.

Genius frequently brings forth its finest fruit in solitude, merely by the exertion of its own intrinsic powers, unaided by the patronage of the great, the adulation of the multitude, or the hope of mercenary reward. Flanders, amidst all the horrors of civil discord, produced painters as rich in fame as they were poor in circumstances. The celebrated Correggio had so seldom been rewarded during his life, that the paltry payment of ten pistoles of German coin, and which he was obliged to travel as far as Parma, to receive, created in his mind a joy so excessive, that it caused his death. The self-approbation of conscious merit was the only recompense these great artists received; they painted with the hope of immortal fame; and posterity has done them justice.

Profound meditation in solitude and silence frequently exalts the mind above its natural tone, fires the imagination, and produces the most refined and sublime conceptions. The soul then tastes the purest and most refined delight, and almost loses the idea of existence in the intellectual pleasure it receives. The mind on every motion darts through space into eternity; and raised, in his free enjoyment of its powers by its own enthusiasm, strengthens itself in the habitude of contemplating the noblest subjects, and of adopting the most heroic pursuits. It was in a solitary retreat, amidst the shades of a lofty mountain near Byrmont, that the foundation of one of the most extraordinary achievements of the present age was laid. The king of Prussia, while on a visit to Spa, withdrew himself from the company, and walked in silent solitude amongst the most sequestered groves of this beautiful mountain, then adorned in all the rude luxuriance of[28] nature, and to this day distinguished by the appellation of “The Royal Mountain”.[4] On this uninhabited spot, since become the seat of dissipation, the youthful monarch, it is said first formed the plan of conquering Silesia.

Solitude teaches with the happiest effect the important value of time, of which the indolent, having no conception, can form no estimate. A man who is ardently bent on employment, who is anxious not to live entirely in vain, never observes the rapid movements of a stop watch, the true image of transitory life, and most striking emblem of the flight of time, without alarm and apprehension. Social intercourse, when it tends to keep the mind and heart in a proper tone, when it contributes to enlarge the sphere of knowledge, or to banish corroding care, cannot, indeed, be considered a sacrifice of time. But where social intercourse, even when attended with these happy effects engages all our attention, turns the calmness of friendship into violence of love, transforms hours into minutes, and drives away all ideas, except those which the object of our affection inspires, year after year will roll unimproved away. Time properly employed never appears tedious; on the contrary, to him who is engaged in usefully discharging the duties of his station, according to the best of his ability, it is light, and pleasantly transitory.

A certain young prince, by the assistance of a number of domestics, seldom employs above five or six minutes in dressing. Of his carriage it would be incorrect to say he goes in it; for it flies. His table is superb and hospitable, but the pleasures of it are short and frugal. Princes, indeed, seem disposed to do every thing with rapidity. This royal youth who possesses extraordinary talents, and uncommon dignity of character, attends in his own person to every application, and affords satisfaction and delight in every interview. His domestic establishment engages his most scrupulous attention; and he employs seven hours every day without exception, throughout the year, in reading the best English, Italian, French, and German authors. It may therefore be truly said, that this prince is well acquainted with the value of time.

The hours which a man of the world throws idly away, are in solitude disposed of with profitable pleasure;[29] and no pleasure can be more profitable than that which results from the judicious use of time. Men have many duties to perform: he, therefore, who wishes to discharge them honorably, will vigilantly seize the earliest opportunity, if he does not wish that any part of the passing moments should be torn like a useless page from the book of life. Useful employment stops the career of time, and prolongs our existence. To think and to work, is to live. Our ideas never flow with more rapidity and abundance, or with greater gayety, than in those hours which useful labor steals from idleness and dissipation. To employ our time with economy, we should frequently reflect how many hours escape from us against our inclination. A celebrated English author says, “When we have deducted all that is absorbed in sleep, all that is inevitably appropriated to the demands of nature, or irresistably engrossed by the tyranny of custom; all that is passed in regulating the superficial decorations of life, or is given up in the reciprocation of civility to the disposal of others; all that is torn from us by the violence of disease, or stolen imperceptibility away by lassitude and langor; we shall find that part of our duration very small of which we can truly call ourselves masters, or which we can spend wholly at our own choice. Many of our hours are lost in a rotation of petty cares, in a constant recurrence of the same employments, many of our provisions for ease or happiness are always exhausted by the present day, and a great part of our existence serves no other purpose than that of enabling us to enjoy the rest.”

Time is never more misspent than while we declaim against the want of it; all our actions are then tinctured with peevishness. The yoke of life is certainly the least oppressive when we carry it with good humor; and in the shades of rural retirement, when we have once acquired a resolution to pass our hours with economy, sorrowful lamentations on the subject of time misspent, and business neglected, never torture the mind.

Solitude, indeed, may prove more dangerous than all the dissipation of the world, if the mind be not properly employed. Every man, from the monarch on the throne to the peasant in the cottage, should have a daily task, which he should feel it his duty to perform without delay. “Carpe diem,” says Horace; and this recommendation[30] will extend with equal propriety to every hour of our lives.

The voluptuous of every description, the votaries of Bacchus and the sons of Anacreon, exhort us to drive away corroding care, to promote incessant gaiety, and to enjoy the fleeting hours as they pass; and these precepts, when rightly understood, and properly applied, are founded in strong sense and sound reason; but they must not be understood or applied in the way these sensualists advise; they must not be consumed in drinking and debauchery; but employed in steadily advancing toward the accomplishment of the task which our respective duties require us to perform. “If,” says Petrarch, “you feel any inclination to serve God, in which consists the highest felicities of our nature; if you are disposed to elevate the mind by the study of letters, which, next to religion, procures us the truest pleasures; if by your sentiments and writings, you are anxious to leave behind you something that will memorize your name with posterity; stop the rapid progress of time, and prolong the course of this uncertain life—fly, ah; fly, I beseech you, from the enjoyment of the world, and pass the few remaining days you have to live in … Solitude.”

Solitude refines the taste, by affording the mind greater opportunities to call and select the beauties of those objects which engage its attention. There it depends entirely upon ourselves to make choice of those employments which afford the highest pleasure; to read those writings, and to encourage those reflections which tend mostly to purify the mind, and store it with the richest variety of images. The false notions which we so easily acquire in the world, by relying upon the sentiments of others, instead of consulting our own, are in solitude easily avoided. To be obliged constantly to say, “I dare not think otherwise,” is insupportable. Why, alas! will not men strive to form opinions of their own, rather than submit to be guided by the arbitrary dictates of others? If a work please me, of what importance is it to me whether the beau monde approve of it or not?—What information do I receive from you, ye cold and miserable critics?—Does your approbation make me feel whatever is truly noble, great and good, with higher relish or more refined delight?—How can I submit to the judgment of men who always examine hastily, and generally determine wrong?

Men of enlightened minds, who are capable of correctly distinguishing beauties from defects, whose bosoms feel the highest pleasure from the works of genius, and the severest pain from dullness and depravity, while they admire with enthusiasm, condemn with judgment and deliberation; and, retiring from the vulgar herd, either alone or in the society of selected friends, resign themselves to the delights of a tranquil intercourse with the illustrious sages of antiquity, and with those writers who have distinguished and adorned succeeding times.

Solitude, by enlarging the sphere of its information, by awakening a more lively curiosity, by relieving fatigue, and by promoting application, renders the mind more active, and multiplies the number of its ideas. A man who is well acquainted with all these advantages, has said, that, “by silent, solitary reflection, we exercise and strengthen all the powers of the mind. The many obstacles which render it difficult to pursue our path disperse and retire, and we return to a busy, social life, with more cheerfulness and content. The sphere of our understanding becomes enlarged by reflection; we have learned to survey more objects, and to behold them more intellectually together; we carry a clearer sight, a juster judgment, and firmer principles with us into the world in which we are to live and act; and are then more able, even in the midst of all its distractions, to preserve our attention, to think with accuracy, to determine with judgment, in a degree proportioned to the preparations we have made in the hours of retirement.” Alas! in the ordinary commerce of the world, the curiosity of a rational mind soon decays, whilst in solitude it hourly augments. The researches of a finite being necessarily proceed by slow degrees. The mind links one proposition to another, joins experience with observation, and from the discovery of one truth proceeds in search of others. The astronomers who first observed the course of the planets, little imagined how important their discoveries would prove to the future interests and happiness of mankind. Attached by the spangled splendor of the firmament, and observing that the stars nightly changed their course, curiosity induced them to explore the cause of this phenomenon, and led them to pursue the road of science. It is thus that the soul, by silent activity, augments its powers; and a contemplative mind advances[32] in knowledge in proportion as it investigates the various causes, the immediate effects, and the remote consequences of an established truth. Reason, indeed, by impeding the wings of the imagination, renders her flight less rapid, but it makes the object of attainment more sure. Drawn aside by the charms of fancy, the mind may construct new worlds; but they immediately burst, like airy bubbles formed of soap and water; while reason examines the materials of its projected fabric, and uses those only which are durable and good.

“The great art to learn much,” says Locke, “is to undertake a little at a time.” Dr. Johnson, the celebrated English writer, has very forcibly observed, that “all the performances of human art, at which we look with praise or wonder, are instances of the resistless force of perseverance: it is by this that the quarry becomes a pyramid, and that distant countries are united by canals. If a man was to compare the effect of a single stroke with the pick-axe, or of one impression of a spade, with the general design and last result, he would be overwhelmed with the sense of their disproportion; yet those petty operations, incessantly continued, in time surmount the greatest difficulties; and mountains are levelled, and oceans bounded by the slender force of human beings. It is therefore of the utmost importance that those who have any intention of deviating from the beaten roads of life, and acquiring a reputation superior to names hourly swept away by time among the refuse of fame, should add to their reason and their spirit the power of persisting in their purposes; acquire the art of sapping what they cannot batter; and the habit of vanquishing obstinate resistance by obstinate attacks.”

It is activity of mind that gives life to the most dreary desert, converts the solitary cell into a social world, gives immortal fame to genius, and produces master-pieces of ingenuity to the artist. The mind feels a pleasure in the exercise of its powers proportioned to the difficulties it meets with, and the obstacles it has to surmount. When Apelles was reproached for having painted so few pictures, and for the incessant anxiety with which he retouched his works, he contented himself with this observation, “I paint for posterity.”

The inactivity of monastic solitude, the sterile tranquillity[33] of the cloister, are ill suited to those who, after a serious preparation in retirement, and an assiduous examination of their own powers, feel a capacity and inclination to perform great and good actions for the benefit of mankind. Princes cannot live the lives of monks; statesmen are no longer sought for in monasteries and convents; generals are no longer chosen from the members of the church. Petrarch, therefore, very pertinently observes, “that solitude must not be inactive, nor leisure uselessly employed. A character indolent, slothful, languid, and detached from the affairs of life, must infallibly become melancholy and miserable. From such a being no good can be expected; he cannot pursue any useful science, or possess the faculties of a great man.”

The rich and luxurious may claim an exclusive right to those pleasures which are capable of being purchased by pelf, in which the mind has no enjoyment, and which only afford a temporary relief to langor, by steeping the senses in forgetfulness; but in the precious pleasures of intellect, so easily accessible by all mankind, the great have no exclusive privilege; for such enjoyments are only to be procured by our own industry, by serious reflection, profound thought, and deep research; exertions which open hidden qualities to the mind, and lead it to the knowledge of truth, and to the contemplation of our physical and moral nature.

A Swiss preacher has in a German pulpit said, “The streams of mental pleasures, of which all men may equally partake, flow from one to the other; and that of which we have most frequently tasted, loses neither its flavor nor its virtues, but frequently acquires new charms, and conveys additional pleasure the oftener it is tasted. The subjects of these pleasures are as unbounded as the reign of truth, as extensive as the world, as unlimited as the divine perfections. Incorporeal pleasures, therefore, are much more durable than all others; they neither disappear with the light of the day, change with the external form of things, nor descend with our bodies to the tomb; but continue with us while we exist; accompany us under all the vicissitudes not only of our natural life, but of that which is to come; secure us in the darkness of the night, and compensate for all the miseries we are doomed to suffer.”

Great and exalted minds, therefore, have always,[34] even in the bustle of gaiety, or amidst the more agitated career of high ambition, preserved a taste for intellectual pleasures. Engaged in affairs of the most important consequence, notwithstanding the variety of objects by which their attention was distracted, they were still faithful to the muses, and fondly devoted their minds to works of genius. They disregarded the false notion, that reading and knowledge are useless to great men; and frequently condescended, without a blush, to become writers themselves.

Philip of Macedon, having invited Dionysius the younger to dine with him at Corinth, attempted to deride the father of his royal guest, because he had blended the characters of prince and poet, and had employed his leisure in writing odes and tragedies. “How could the king find leisure,” said Philip, “to write those trifles?” “In those hours,” answered Dionysius, “which you and I spend in drunkenness and debauchery.”

Alexander who was passionately fond of reading and whilst the world resounded with his victories, whilst blood and carnage marked his progress, whilst he dragged captive monarchs at his chariot wheels, and marched with increasing ardor over smoking towns and desolated provinces in search of new objects of victory, felt during certain intervals, the langors of unemployed time; and lamenting that Asia afforded no books to amuse his leisure, he wrote to Harpalus to send him the works of Philistus, the tragedies of Euripides, Sophocles, Æschylus, and the dithyrambics of Thalestes.

Brutus, the avenger of the violated liberties of Rome, while serving in the army under Pompey, employed among books all the moments he could spare from the duties of his station; and was even thus employed during the awful night which preceded the celebrated battle of Pharsalia, by which the fate of the empire was decided. Oppressed by the excessive heat of the day, and by the preparatory arrangement of the army, which was encamped in the middle of summer on a marshy plain, he sought relief from the bath, and retired to his tent, where, whilst others were locked in the arms of sleep, or contemplating the event of the ensuing day, he employed himself until the morning dawned, in drawing a plan from the History of Polybius.

Cicero, who was more sensible of mental pleasures[35] than any other character, says, in his oration for the poet Archias, “Why should I be ashamed to acknowledge pleasures like these, since for so many years the enjoyment of them has never prevented me from relieving the wants of others, or deprived me of the courage to attack vice and defend virtue? Who can justly blame, who can censure me, if, while others are pursuing the views of interest, gazing at festal shows and idle ceremonies, exploring new pleasures, engaged in midnight revels, in the distraction of gaming, the madness of intemperance, neither reposing the body, nor recreating the mind, I spend the recollective hours in a pleasing review of my past life, in dedicating my time to learning and the muses?”

Pliny the elder, full of the same spirit devoted every moment of his life to learning. A person read to him during his meals; and he never travelled without a book and a portable writing-desk by his side. He made extracts from every work he read; and scarcely conceiving himself alive while his faculties were absorbed in sleep, endeavored by his diligence, to double the duration of his existence.

Pliny the younger, read upon all occasions, whether riding, walking, or sitting, whenever a moment’s leisure afforded him the opportunity; but he made it an invariable rule to prefer the discharge of the duties of his station to those occupations which he followed only as amusement. It was this disposition which so strongly inclined him to solitude and retirement. “Shall I never,” exclaimed he in moments of vexation, “break the fetters by which I am restrained? Are they indissoluble? Alas! I have no hope of being gratified—every day brings new torments. No sooner is one duty performed than another succeeds. The chains of business become every hour more weighty and extensive.”

The mind of Petrarch was always gloomy and dejected, except when he was reading, writing, or resigned to the agreeable illusions of poetry, upon the banks of some inspiring stream, among the romantic rocks and mountains, or the flower-enamelled vallies of the Alps. To avoid the loss of time during his travels, he constantly wrote at every inn where he stopped for refreshment. One of his friends, the bishop of Cavaillon, being alarmed lest the intense application with which he studied at Vaucluse might totally ruin a constitution[36] already much impaired, requested of him one day the key of his library. Petrarch immediately gave it him without asking the reason of his request; when the good bishop, instantly locking up his books and writing-desk, said, “Petrarch, I hereby interdict you from the use of pen, ink, and paper, for the space of ten days.” The sentence was severe; but the offender suppressed his feelings, and submitted to his fate. The first day of his exile from his favorite pursuits was tedious, the second accompanied with incessant headache, and the third brought on symptoms of an approaching fever. The bishop, observing his indisposition, kindly returned him the key, and restored him to his health.

The late earl of Chatham, on his entering into the world, was a cornet in a troop of horse dragoons. The regiment was quartered in a small village in England. The duties of his station were the first objects of his attention; but the moment these were discharged, he retired into solitude during the remainder of the day, and devoted his mind to the study of history. Subject from his infancy to an hereditary gout, he endeavored to eradicate it by regularity and abstinence; and perhaps it was the feeble state of his health which first led him into retirement; but, however that may be, it was certainly in retirement that he had laid the foundation of that glory which he afterwards acquired. Characters of this description, it may be said, are no longer to be found; but in my opinion both the idea and assertion would be erroneous. Was the earl of Chatham inferior in greatness to a Roman? And will his son, who already, in the earliest stage of manhood, thunders forth his eloquence in the senate, like Demosthenes, and captivates like Pericles the hearts of all who hear him: who is now, even in the five-and-twentieth year of his age, dreaded abroad, and beloved at home, as prime minister of the British empire; ever think, or act under any circumstances with less greatness, than his illustrious father? What men have been, man may always be. Europe now produces characters as great as ever adorned a throne or commanded a field. Wisdom and virtue may exist, by proper cultivation, as well in public as in private life; and become as perfect in a crowded palace as in a solitary cottage.

Solitude will ultimately render the mind superior to all the vicissitudes and miseries of life. The man[37] whose bosom neither riches, nor luxury, nor grandeur can render happy, may, with a book in his hand, forget all his torments under the friendly shade of every tree, and experience pleasures as infinite as they are varied, as pure as they are lasting, as lively as they are unfading, and as compatible with every public duty as they are contributary to private happiness. The highest public duty, indeed, is that of employing our faculties for the benefit of mankind, and can no where be so advantageously discharged as in solitude. To acquire a true notion of men and things, and boldly to announce our opinions to the world, is an indispensible obligation on every individual. The press is the channel through which writers diffuse the light of truth among the people, and display its radiance to the eyes of the great. Good writers inspire the mind with courage to think for itself; and the free communication of sentiments contributes to the improvement and imperfection of human reason. It is this love of liberty that leads men into solitude, where they may throw off the chains by which they are fettered in the world. It is this disposition to be free, that makes the man who thinks in solitude, boldly speak a language which, in the corrupted intercourse of society, he would not have dared openly to hazard. Courage is the companion of solitude. The man who does not fear to seek his comforts in the peaceful shades of retirement, looks with firmness on the pride and insolence of the great, and tears from the face of despotism the mask by which it is concealed.

His mind, enriched by knowledge, may defy the frowns of fortune, and see unmoved the various vicissitudes of life. When Demetrius had captured the city of Megara, and the property of the inhabitants had been entirely pillaged by the soldiers, he recollected that Stilpo, a philosopher of great reputation, who sought only the retirement and tranquility of a studious life, was among the number. Having sent for him, Demetrius asked him if he had lost any thing during the pillage? “No,” replied the philosopher, “my property is safe, for it exists only in my mind.”

Solitude encourages the disclosure of those sentiments and feelings which the manners of the world compel us to conceal. The mind there unburthens itself with ease and freedom. The pen, indeed, is not always taken up because we are alone; but if we are inclined to write, we ought to be alone. To cultivate[38] philosophy, or court the muse with effect, the mind must be free from all embarrassment. The incessant cries of children, or the frequent intrusion of servants with messages of ceremony and cards of compliment, distract attention. An author, whether walking in the open air, seated in his closet, reclined under the shade of a spreading tree, or stretched upon a sofa, must be free to follow all the impulses of his mind, and indulge every bent and turn of his genius. To compose with success, he must feel an irresistible inclination, and be able to indulge his sentiments and emotions without obstacle or restraint. There are, indeed, minds possessed of a divine inspiration, which is capable of subduing every difficulty, and bearing down all opposition: and an author should suspend his work until he feels this secret call within his bosom, and watch for those propitious moments when the mind pours forth its ideas with energy, and the heart feels the subject with increasing warmth; for

Petrarch felt this sacred impulse when he tore himself from Avignon, the most vicious and corrupted city of the age, to which the pope had recently transferred the papal chair; and although still young, noble, ardent, honored by his holiness, respected by princes, courted by cardinals, he voluntarily quitted the splendid tumults of this brilliant court, and retired to the celebrated solitude of Vaucluse, at the distance of six leagues from Avignon, with only one servant to attend him, and no other possession than an humble cottage and its surrounding garden. Charmed with the natural beauties of this rural retreat, he adorned it with an excellent library, and dwelt, for many years, in wise tranquillity and rational repose, employing his leisure in completing and polishing his works: and producing more original compositions during this period than at any other of his life. But, although he here devoted much time and attention to his writings, it was long before he could be persuaded to make them public.[39] Virgil calls the leisure he enjoyed at Naples, ignoble and obscure; but it was during this leisure that he wrote the Georgics, the most perfect of all his works, and which evince, in almost every line, that he wrote for immortality.

The suffrage of posterity, indeed, is a noble expectation, which every excellent and great writer cherishes with enthusiasm. An inferior mind contents itself with a more humble recompense, and sometimes obtains its due reward. But writers both great and good, must withdraw from the interruptions of society, and seeking the silence of the groves, and the shades, retire into their own minds: for every thing they perform, all that they produce, is the effect of solitude. To accomplish a work capable of existing through future ages, or deserving the approbation of contemporary sages, the love of solitude must entirely occupy their souls; for there the mind reviews and arranges, with the happiest effect, all the ideas and impressions it has gained in its observations in the world: it is there alone that the dart of satire can be truly sharpened against inveterate prejudices and infatuated opinions; it is there alone that the vices and follies of mankind present themselves accurately to the view of the moralist, and excite his ardent endeavors to correct and reform them. The hope of immortality is certainly the highest with which a great writer can possibly flatter his mind; but he must possess the comprehensive genius of a Bacon: think with the acuteness of Voltaire: compose with the ease and elegance of Rousseau; and, like them, produce master-pieces worthy of posterity in order to obtain it.

The love of fame, as well in the cottage as on the throne, or in the camp, stimulates the mind to the performance of those actions which are most likely to survive mortality and live beyond the grave, and which when achieved, render the evening of life as brilliant as its morning. “The praises (says Plutarch,) bestowed upon great and exalted minds, only spur on and rouse their emulation: like a rapid torrent, the glory which they have already acquired, hurries them irresistibly on to every thing that is great and noble.—They never consider themselves sufficiently rewarded. Their present actions are only pledges of what may be expected from them; and they would blush not to live faithful to their glory, and to render it still more illustrious by the noblest actions.”

The ear which would be deaf to servile adulation and insipid compliment, will listen with pleasure to the enthusiasm with which Cicero exclaims, “Why should we dissemble what it is impossible for us to conceal? Why should we not be proud of confessing candidly that we all aspire to fame? The love of praise influences all mankind, and the greatest minds are the most susceptible of it. The philosophers who most preach up a contempt for fame, prefix their names to their works: and the very performances in which they deny ostentation, are evident proofs of their vanity and love of praise. Virtue requires no other reward for all the toils and dangers to which she exposes herself than that of fame and glory. Take away this flattering reward, and what would remain in the narrow career of life to prompt her exertions? If the mind could not launch into the prospect of futurity, or the operations of the soul were to be limited to the space that bounds those of the body, she would not weaken herself by constant fatigues, nor weary herself with continual watchings and anxieties; she would not think even life itself worthy of a struggle: but there lives in the breast of every good man a principle which unceasingly prompts and inspirits him to the pursuit of a fame beyond the present hour; a fame not commensurate to our mortal existence, but co-extensive with the latest posterity. Can we, who every day expose ourselves to dangers for our country, and have never passed one moment of our lives without anxiety or trouble, meanly think that all consciousness shall be buried with us in the grave? If the greatest men have been careful to preserve their busts and their statues, those images, not of their minds, but of their bodies, ought we not rather to transmit to posterity the resemblance of our wisdom and virtue? For my part, at least, I acknowledge, that in all my actions I conceived that I was disseminating and transmitting my fame to the remotest corners and the latest ages of the world. Whether, therefore, my consciousness of this shall cease in the grave, or, as some have thought, shall survive as a property of the soul, is of little importance. Of one thing I am certain, that at this instant I feel from the reflection a flattering hope and a delightful sensation.”

This is the true enthusiasm with which preceptors should inspire the bosoms of their young pupils. Whoever[41] shall be happy enough to light up this generous flame, and increase it by constant application, will see the object of his care voluntarily relinquish the pernicious pleasures of youth, enter with virtuous dignity on the stage of life, and add, by the performance of the noblest actions, new lustre to science, and brighter rays to glory. The desire of extending our fame by noble deeds, and of increasing the good opinion of mankind by a dignified conduct and real greatness of soul, confers advantages which neither illustrious birth, elevated rank, nor great fortune can bestow; and which, even on the throne, are only to be acquired by a life of exemplary virtue, and an anxious attention to the suffrages of posterity.