| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/ourtowncivicduty00fryeuoft |

YOUNG AMERICAN READERS

BY

JANE EAYRE FRYER

AUTHOR OF “THE MARY FRANCES STORY-INSTRUCTION BOOKS”

ILLUSTRATIONS BY CHARLES HOLLOWAY, JANE ALLEN BOYER AND FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

In these vital tasks of acquiring a broader view of human possibilities the common school must have a large part. I urge that teachers and other school officers increase materially the time and attention devoted to instruction bearing directly on the problems of community and national life.—Woodrow Wilson.

THE JOHN C. WINSTON COMPANY, Publishers

PHILADELPHIACHICAGO

Copyright, 1920, by

The John C. Winston Co.

Copyright, 1918, by

The John C. Winston Co.

All Rights Reserved

It will be seen at a glance that Part I of this reader contains material emphasizing the civic virtues of courage, self-control, thrift, perseverance and kindness to animals. Since these virtues are so essential to the good citizen, the lesson periods devoted to the teaching of them are among the most profitable in the course in Civics for the Elementary Grades.

In the earlier Young American Reader, “Our Home and Personal Duty,” the children learned about their dependence upon the people who serve by contributing to their physical needs—the people connected with home life. In this volume, “Our Town and Civic Duty,” the idea of service is still the dominant note.

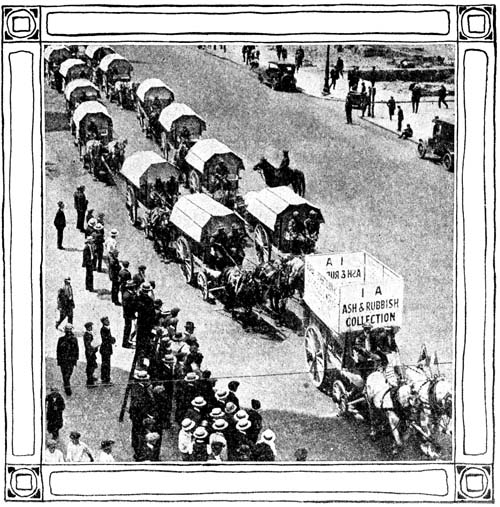

The work herein differs from that of the earlier volume, however, in that the people who are being studied render a service which is primarily civic. Therefore, in Part II a study is made of public servants, both those who are directly in the employ of the community and those who, although employed by private individuals, are, through contract, engaged in public service. Among these are the policeman, the postman, the fireman, the street cleaner, the garbage collector, and the ash and rubbish collector. In the study of these various people the threefold idea of dependence, interdependence and co-operation through community agencies finds ample illustration.

Of course, it should always be kept in mind that the purpose is to understand the nature of the service rendered, and that the acquiring of information is but incidental. The work should be so treated as to arouse in the children[Pg iv] an interest in these public servants, a friendly feeling toward them, and a desire to aid them in the services they are rendering.

In Part III, the nation-wide movement for Safety First finds expression. The aim is two-fold; to point out the sources of danger, and to teach habits of carefulness and caution.

The study and work of the Junior Red Cross, which form the subject matter of Part IV, are admirably adapted to bring the pupil into direct contact with one of the most inspiring aspects of our national life as exemplified in the humane and patriotic activities of the American Red Cross.

Suggestions as to the Method of Teaching. It is well known that children learn best by doing. Therefore, teachers are more and more appreciating the value of dramatization, or story acting.

Whenever the stories in the reader are suitable, their dramatization is a simple matter. The children are assigned the various parts, which they enact just as they remember the story. In no case should the words be memorized. The children enter eagerly into the spirit of the story, and the point of the lesson is thus deeply impressed on their minds. They should be encouraged to talk about the various topics in the book, and to describe their own experiences.

It should always be borne in mind that when children begin to realize that the good of all depends upon the thorough and conscientious work of the individual, the foundation of good citizenship is being laid.

This reader is not intended to be exhaustive in any sense, but rather suggestive, so that the teacher may use any original ideas which add to the interest of the lessons.

In his introduction to the previous volume, Doctor[Pg v] J. Lynn Barnard emphasizes this point when he says: “Like all texts or other helps in education, these civic readers cannot teach themselves or take the place of a live teacher. But it is believed that they can be of great assistance to sympathetic, civically minded instructors of youth who feel that the training of our children in the ideals and practices of good citizenship is the most imperative duty and, at the same time, the highest privilege that can come to any teacher.”

Special thanks are due to Doctor J. Lynn Barnard of the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy, for valuable suggestions and helpful criticism in the making of this reader; also to Miss Isabel Jean Galbraith, a demonstration teacher of the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy, for assistance in preparing the questions on the lessons.

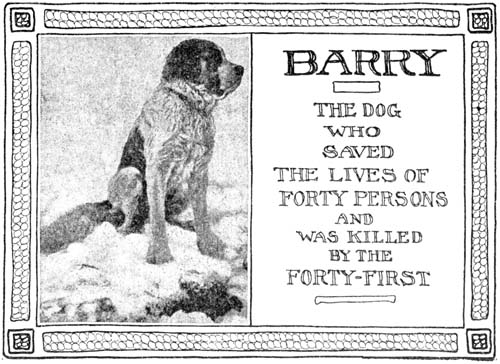

For kind permission to use copyrighted and other material acknowledgments are due to the following: Cassell & Co. for “Better Not, Bob!” from Little Folks; The Bobbs-Merrill Company for “The Knights of the Silver Shield,” from Why the Chimes Rang, by Raymond M. Alden, Copyright 1908; The American Humane Education Society for “The Story of Barry,” selections by George T. Angell, and other material; Wilmer Atkinson Company for the story of “Nellie’s Dog;” Miss H. H. Jacobs for two selections; The Animal Rescue League of Boston and The Ohio Humane Society for selections; and to The Macmillan Company for “How the Mail is Delivered,” from How We Travel, by James F. Chamberlain; to The Red Cross Magazine for several photographs; to the F. A. Owen Publishing Company for the “Red Cross Emblem,” “Plain Buttons,” “The American Flag,” and other material from Normal Instructor and Primary Plans.

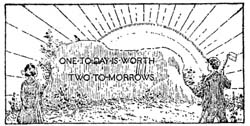

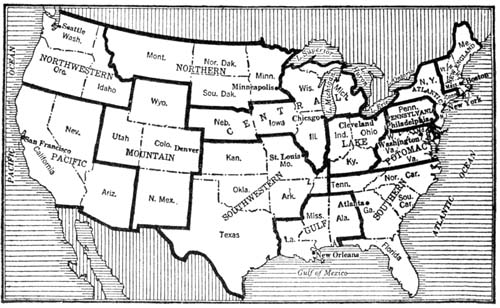

A bird’s-eye view of the plan of the young american readers

It may be said that a child’s life and experience move forward in ever widening circles, beginning with the closest intimate home relations, and broadening out into knowledge of community, of city, and finally of national life.

A glance at the above diagram will show the working plan of the Young American Readers. This plan follows the natural growth and development of the child’s mind, and aims by teaching the civic virtues and simplest community relations to lay the foundations of good citizenship. See Outline of Work.

| PART I | ||

| CIVIC VIRTUES | ||

| Stories Teaching Courage, Self-control, Thrift, Perseverance, Patriotism, Kindness to Animals. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Courage (Physical) | ||

| Ida Lewis, the Heroine of Lime Rock Light | 3 | |

| Run! John, Run! | 6 | |

| He Did Not Hesitate | 7 | |

| Down a Manhole | 9 | |

| Courage (Moral) | ||

| The Twelve Points of the Scout Law | 11 | |

| Captain Abraham Lincoln and the Indian | 12 | |

| Daniel in the Lions’ Den | 17 | |

| Self-control | ||

| Better Not, Bob! (adapted), Hartley Richards | 21 | |

| The Knights of the Silver Shield (adapted), Raymond M. Alden | 30 | |

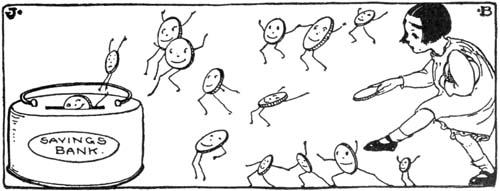

| Thrift | ||

| The Prince and the Crumbs of Dough | 37 | |

| The Tramp | 41 | |

| [Pg viii]Uncle Sam’s Money | 46 | |

| Three Ways to Use Money | 48 | |

| Thrift Day | 50 | |

| How Richard Planted a Dollar | 54 | |

| How to Start a Bank Account | 58 | |

| Perseverance | ||

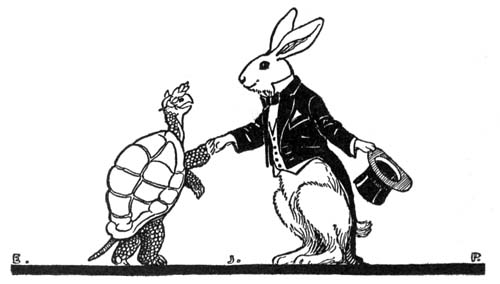

| The Hare and the Tortoise (a play) | 60 | |

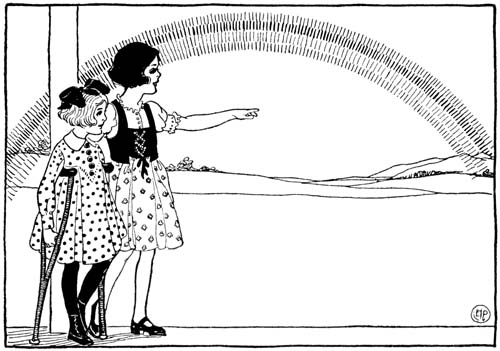

| At the End of the Rainbow | 63 | |

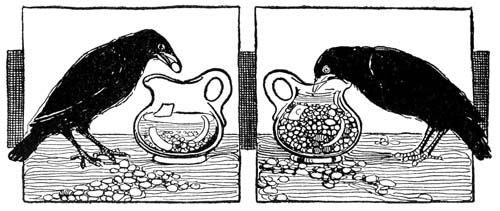

| The Crow and the Pitcher | 74 | |

| Drive the Nail Aright | 76 | |

| Kindness to Animals | ||

| The Arabian Horse | 79 | |

| The Story of Barry | 81 | |

| Bands of Mercy | 84 | |

| Some Things Mr. Angell Told Boys and Girls | 85 | |

| Nellie’s Dog, Robert E. Hewes | 87 | |

| Who Said Rats? H. H. Jacobs | 92 | |

| A Brave Mother, H. H. Jacobs | 93 | |

| About Thoreau | 96 | |

| Fair Play for Our Wild Animals | 96 | |

| The True Story of Pedro | 97 | |

| What Children Can Do | 99 | |

| A Horse’s Petition to His Driver | 100 | |

| The Horse’s Point of View | 101 | |

| A Man Who Knew How | 103 | |

| How to Treat a Horse | 103 | |

| The Horse’s Prayer | 104 | |

| Birds as the Friends of Plants | 108 | |

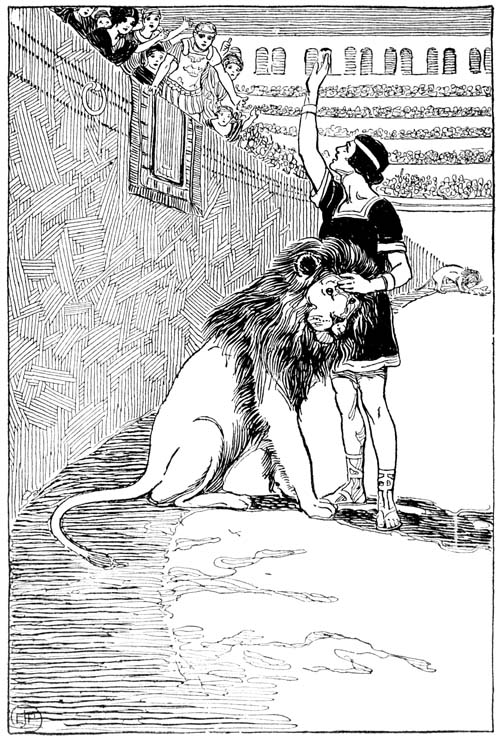

| [Pg ix]Androclus and the Lion | 113 | |

| List of Books about Animals | 117 | |

| PART II | ||

| STORIES ABOUT OUR PUBLIC SERVANTS | ||

| The Policeman | ||

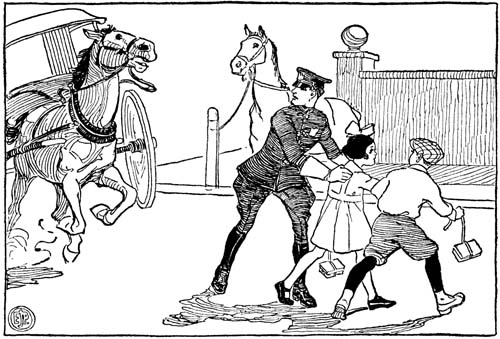

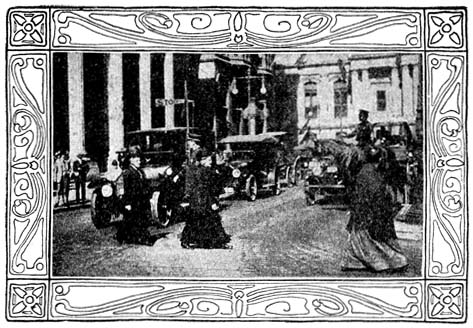

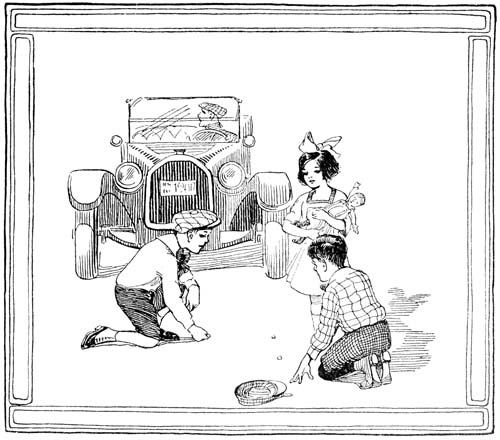

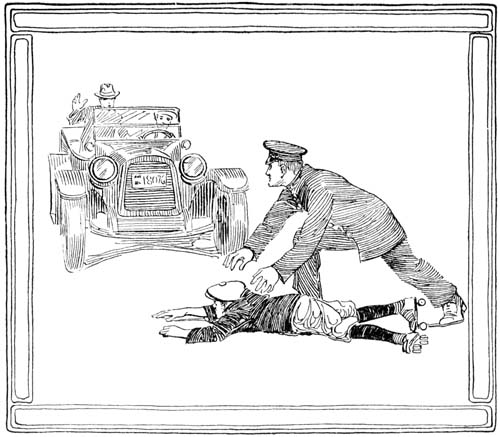

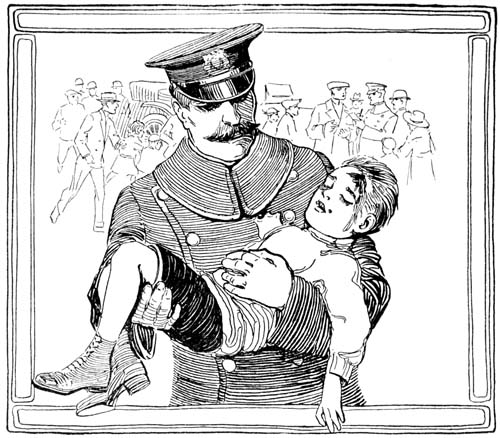

| The Policeman and the Runaway | 122 | |

| Everybody’s Friend | 125 | |

| What the Policeman Does for Us | 126 | |

| How We May Aid the Policeman | 127 | |

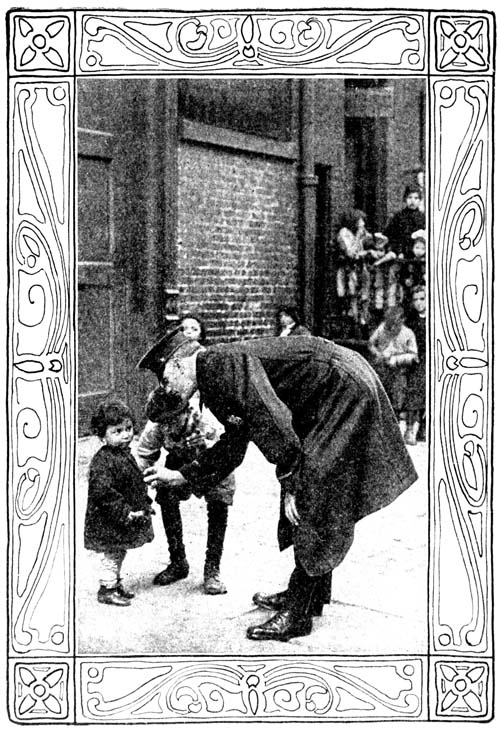

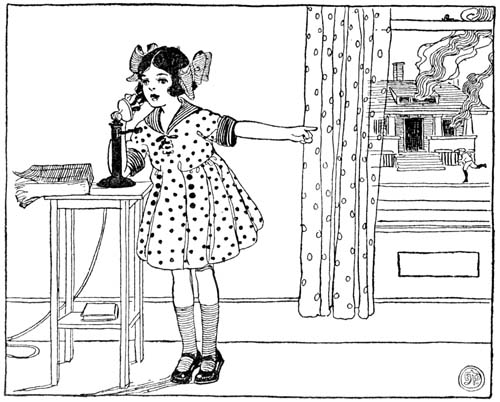

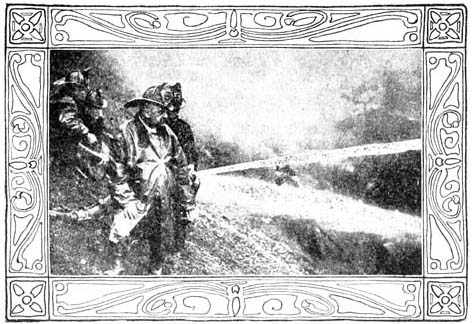

| The Fireman | ||

| Duties of a Fireman | 129 | |

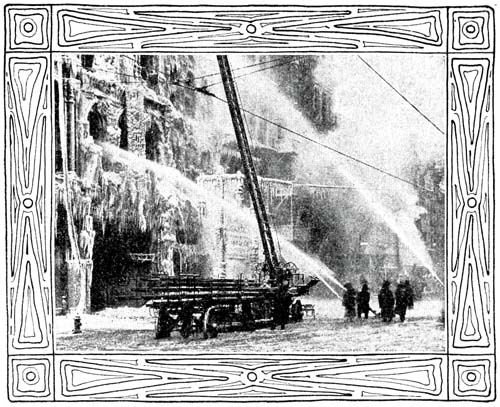

| The Story of a Fire | 130 | |

| I. | Jack Gives the Alarm | 130 |

| II. | At the Fire | 133 |

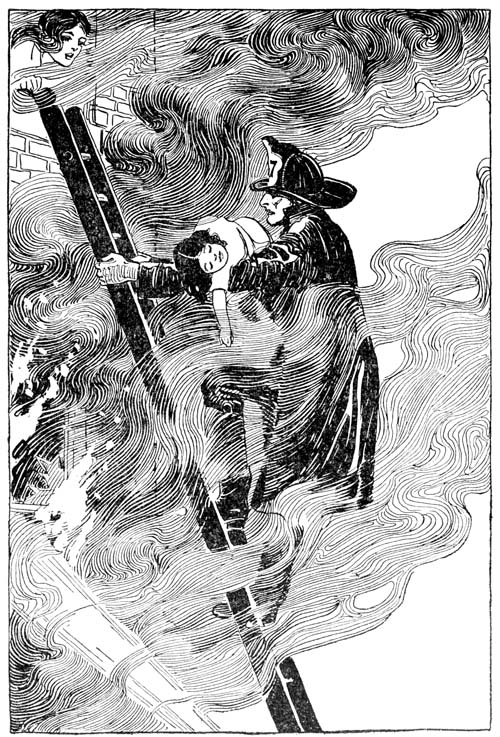

| III. | The Rescue of Shorty | 136 |

| How to Help the Fireman | 141 | |

| Don’ts for Your Own Protection | 143 | |

| The Postman | ||

| How the Mail is Delivered, James F. Chamberlain (adapted) | 145 | |

| I. | Uncle Charles Writes from Alaska | 145 |

| II. | Early Mail Carriers | 148 |

| III. | Postage Stamps | 150 |

| IV. | The Pony Express | 153 |

| V. | The Mails of Today | 154 |

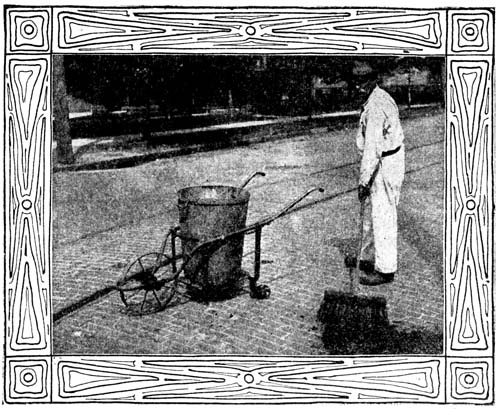

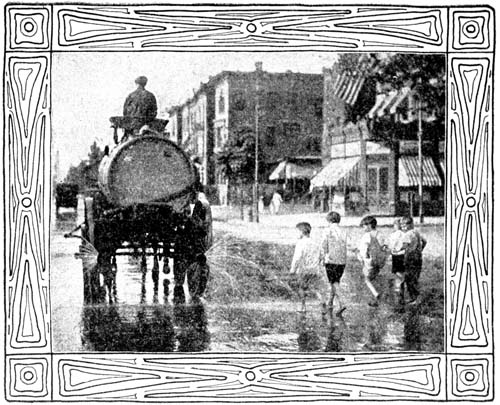

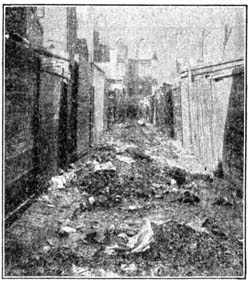

| The Street Cleaner[Pg x] | ||

| Ben Franklin’s Own Story about Philadelphia Streets | 159 | |

| You and Your Streets | 161 | |

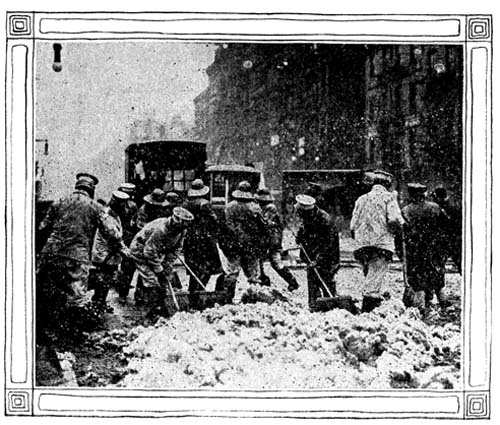

| Equipment of Street Cleaners | 166 | |

| How We May Help Keep the Streets Clean | 167 | |

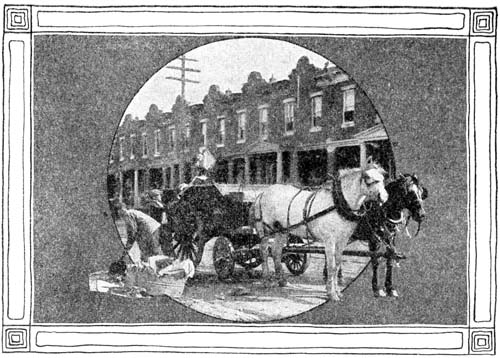

| The Garbage Collector | ||

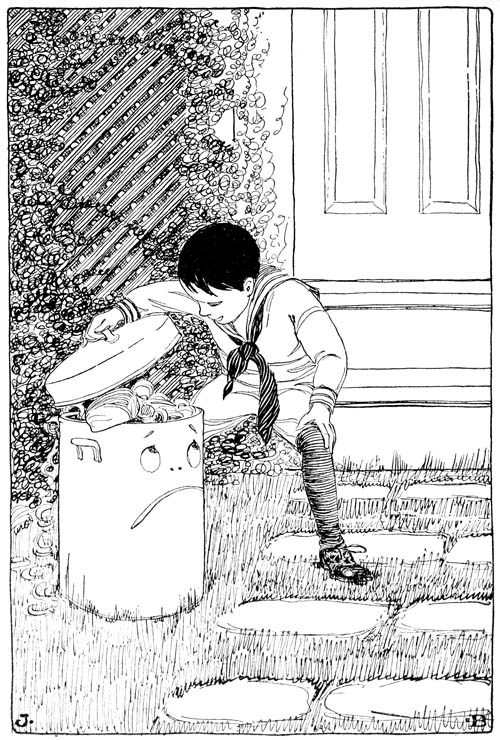

| What the Garbage Can Told Robert | 169 | |

| Two Garbage Collectors | 175 | |

| Robert’s Visit to the Garbage Plant | 179 | |

| The Ash and Rubbish Collector | ||

| The Fire That Started Itself | 180 | |

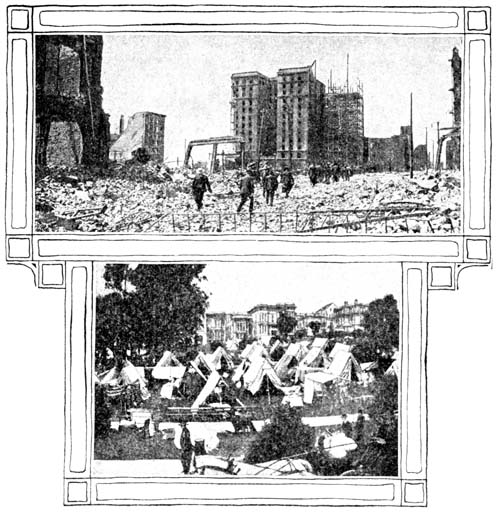

| PART III | ||

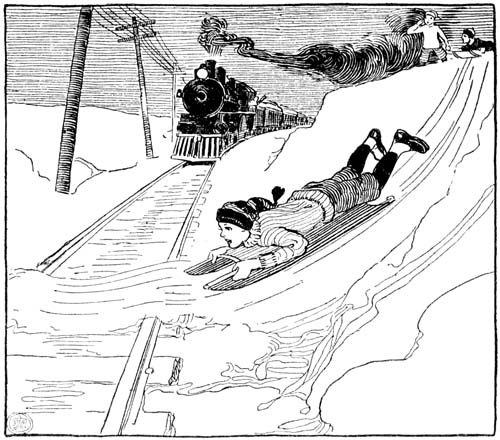

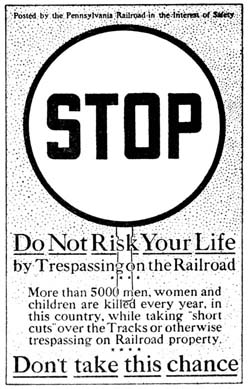

| SAFETY FIRST | ||

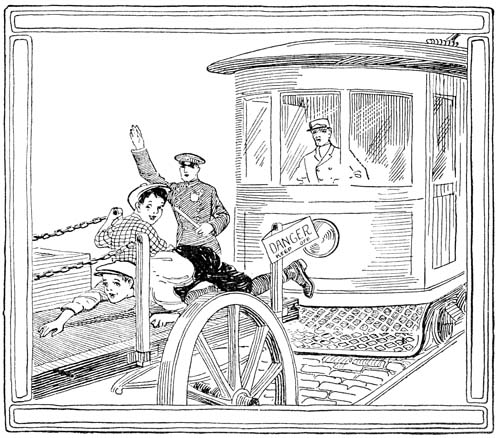

| Who Am I | 187 | |

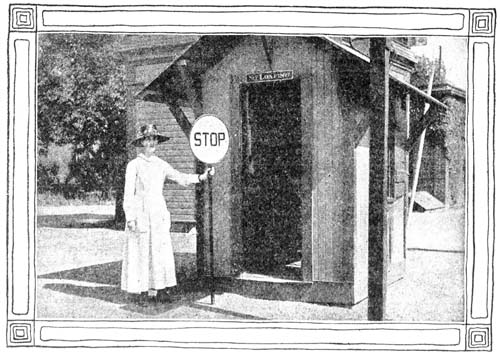

| Our Safety First Men | 189 | |

| Brave Watchman Receives Medal from President Wilson | 193 | |

| Stop! Look! Listen! | 194 | |

| Be on Your Guard | 196 | |

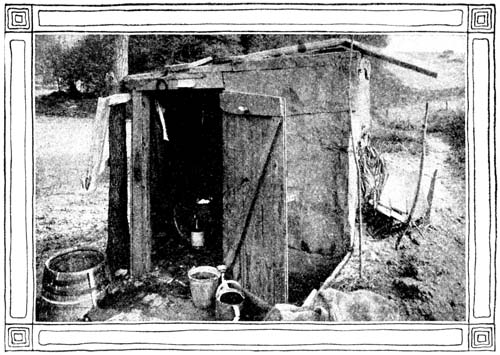

| A Clean City | 201 | |

| Fire-Prevention Day | 202 | |

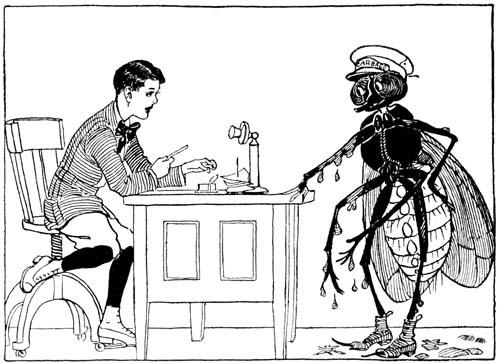

| How to Fight Flies | 204 | |

| How to Fight Mosquitoes | 206 | |

| How to Make a Mosquito Trap | 208 | |

| PART IV[Pg xi] | ||

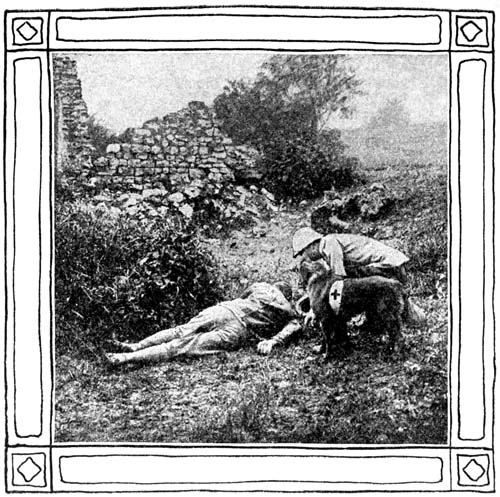

| THE AMERICAN RED CROSS | ||

| Junior Membership and School Activities | ||

| Patriotic Service | ||

| The Junior Red Cross | 213 | |

| The President’s Proclamation | 214 | |

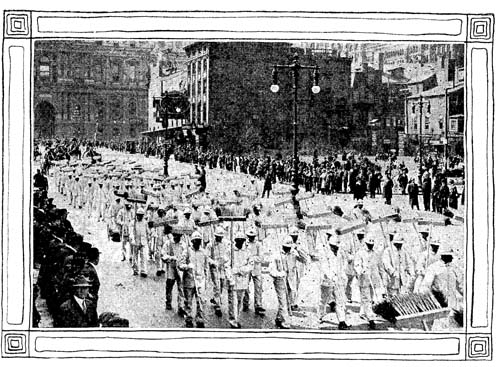

| What the Children Did | 215 | |

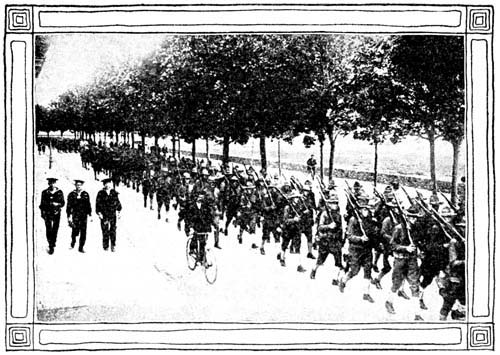

| The Red Cross in War | 216 | |

| The Red Cross in Peace | 216 | |

| The Good Neighbor | 219 | |

| Our Two Flags | 220 | |

| The Red Cross Flag | 220 | |

| Florence Nightingale | 221 | |

| Henri Dunant | 222 | |

| Clara Barton | 222 | |

| I. | The Christmas Baby | 223 |

| II. | The Little Nurse | 223 |

| III. | Clara Grows Up | 224 |

| IV. | The Civil War | 225 |

| V. | The Army Nurse | 226 |

| VI. | Miss Barton Hears of the Red Cross | 226 |

| VII. | The American Red Cross | 227 |

| When There Was No Red Cross | 228 | |

| When the Red Cross Came | 229 | |

| The Red Cross | 231 | |

| How Maplewood Won Sonny | 232 | |

| The Junior Red Cross’ First Birthday | 233 | |

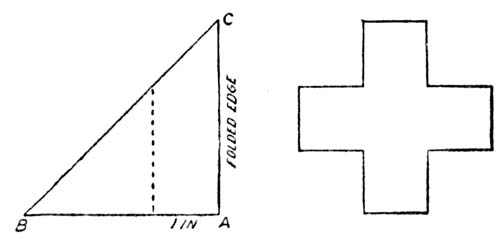

| How to Make a Red Cross Emblem | 234 | |

| I Knew You’d Come | 235 | |

| Patriotism[Pg xii] | ||

| The Debt | 236 | |

| Pledge Of Allegiance To Our Flag | 237 | |

| To the Flag, Edward B. Seymour | 238 | |

| The American Flag | 239 | |

| Plain Buttons—The Man Without a Country (adapted) | 240 | |

| America, My Homeland | 247 | |

| Columbus, Joaquin Miller | 248 | |

| Democracy | 250 | |

| The Future—What Will It Bring? | 251 | |

| ————— | ||

| Outline of Work (For the Teacher) | 253 | |

| How to Obtain Information about the Junior Red Cross | 258 | |

Stories Teaching Courage, Self-Control, Thrift, Perseverance, Patriotism, Kindness to Animals

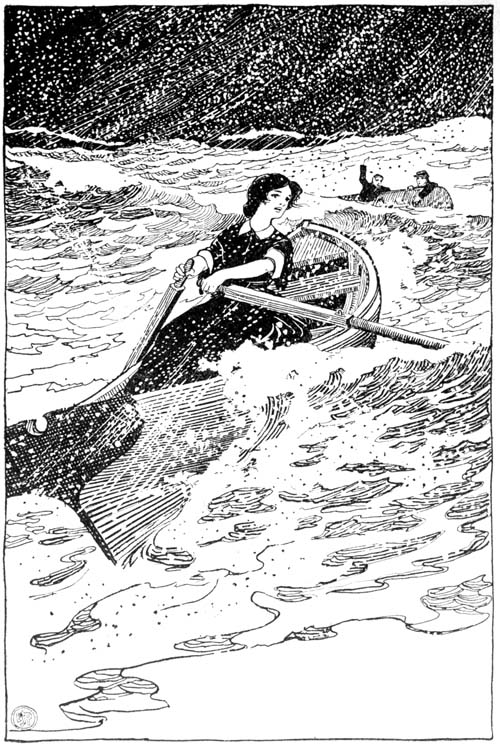

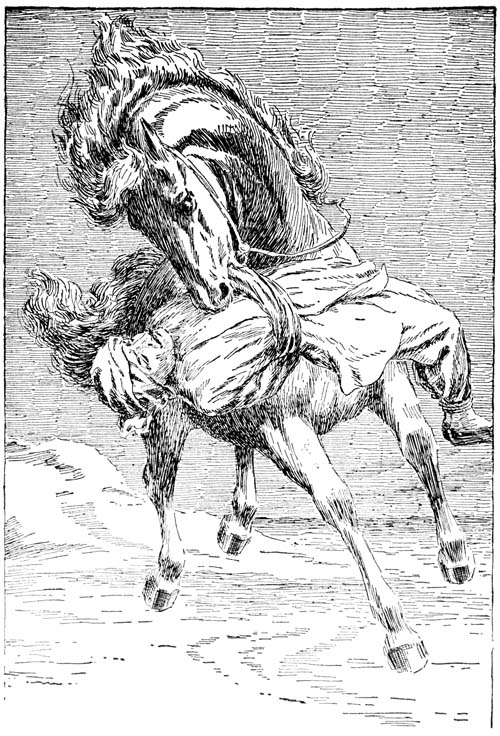

It was a Hard Struggle to Make Headway

This is the story of Ida Lewis, a New England girl who became famous as a lighthouse keeper.

Ida’s father, Captain Lewis, kept the lighthouse on Lime Rock, near Newport in Rhode Island. While Ida was still a young girl, Captain Lewis became a helpless cripple, and the entire care of the light fell upon the daughter.

One stormy day, as Ida was looking out over the water, she saw a rowboat capsize. In a moment, she was in the lifeboat rowing to the spot. There, in the high waves, three young men were struggling for their lives. Somehow, Ida got them all safely aboard her boat and rowed them to Lime Rock.

That was the first of her life-saving ventures. Before she was twenty-five years old there were ten rescues to the credit of this brave girl.

Ida did not seem to know fear. She risked her life constantly. Whenever a vessel was wrecked or a life was in danger within sight of her lighthouse, Ida Lewis and her lifeboat were always the first to go to the rescue.

One wintry evening in March, 1869, came the rescue that made Ida famous throughout the land.

She was nursing a severe cold, and sat toasting her stockinged feet in the oven of the kitchen stove. Around her shoulders her mother had thrown a towel for added warmth.

Outside the lighthouse a winter blizzard was blowing,[Pg 4] churning the waters of the harbor and sending heavy rollers crashing against the rock.

Suddenly above the roar of the tempest, Ida heard a familiar sound—the cry of men in distress.

Even a strong man might have thought twice before risking his life on such a night—but not Ida Lewis.

Without shoes or hat, she threw open the kitchen door and ran for the boat.

“Oh, don’t go!” called her mother; “it is too great a risk!”

“I must go, mother!” cried the brave girl, running faster.

“Here’s your coat,” called her mother again.

“I haven’t a moment to spare if I am to reach them in time!” cried Ida, pulling away at the oars.

She had only a single thought. Human life was in danger. Her path of duty led to the open water.

Strong though she was, it was a hard struggle to make headway against those terrible waves. Time and again she was driven back. But she would not give up. At last she guided her boat to the spot where the voices were still crying for help.

There she found two men clinging to the keel of a capsized boat. They were almost exhausted when she helped them to safety in her lifeboat.

The men were soldiers from Fort Adams, across the bay. Returning from Newport at night, they were caught in the gale and their frail boat was upset.

“When I heard those men calling,” said Ida, in telling about it afterwards, “I started right out just as I was, with a towel over my shoulders.

[Pg 5]“I had to whack them on the fingers with an oar to make them let go of the side of my boat, or they would have upset it. My father was an old sailor, and he often told me to take drowning people in over the stern; and I’ve always done so.”

The story of Ida’s heroic deed sent a thrill of admiration across the country. The soldiers of the fort gave her a gold watch and chain. The citizens of Newport, to show their pride in her, presented her with a fine new surfboat. This boat was christened the “Rescue.” The legislature of Rhode Island praised her for bravery; and the humane and life-saving societies sent her gold and silver medals.

Best of all, Congress passed a special act, making her the official keeper of Lime Rock Lighthouse in place of the father who had died some years before.

For over fifty years she held this position. It was her duty to trim the lamps every day, and to keep them burning brightly every night. Not once in all that half century did the light fail to shine and guide ships in safety. When an old lady, Ida Lewis was asked if she was ever afraid.

“I don’t know that I was ever afraid,” she replied; “I just went, and that was all there was to it. I never even thought of danger.

“If there were some people out there who needed help,” she said, pointing across the water, “I would get into my boat and go to them, even if I knew I could not get back. Wouldn’t you?”

Do you wonder that Ida Lewis was called the heroine of Lime Rock Light?

Once there was a boy, John Hart, who lived at the edge of a wood, half a mile from a village. One winter evening his mother said, “John, I want you to go to the village on an errand; are you afraid of the dark?”

“No, indeed, mother, I’m not afraid.”

John set out bravely on the lonely road. Passing a great oak tree, he heard a queer rustling sound. His heart beat fast and fear whispered, “Run! John, run!” His feet began to run, but he said, “I won’t run!” Then he saw that the sound was made by leaves blown about in the wind. “Only leaves,” he said, laughing.

Halfway to the village a dark figure was standing beside the path. Fear whispered, “A robber! Run! John, run!” but he thought, “I won’t run,” and called out as he drew nearer, “Good evening!” Then he saw that the robber was a small fir tree. “Only a fir tree,” he said, and laughed again.

Just outside the village a tall white figure appeared beside a dark hedge. Fear whispered, “A ghost! Run! John, run!” Although shivering, he said, “I will not run!” Then the ghost disappeared, and the rising moon was shining through a break in the hedge. “Only moonshine,” he said, laughing once more.

His errand done, John set out on his return. The ghost was gone, the fir tree was a friendly sentinel, the leaves were still playing in the wind. The next day he cut down the fir tree and set it up as a Christmas tree. Spreading some dry leaves beneath it, he said, “Just suppose, mother, I’d let them scare me.”

In a forest on the banks of the Shenandoah River, in the northern part of Virginia, a party of young surveyors were eating their picnic dinner.

Suddenly they heard the shriek of a woman. “Oh, my boy! my poor little boy is drowning!” rose the cry. The young men sprang to their feet, and rushed toward the river.

A tall youth of eighteen was the first to reach the woman, whom two men were holding back from the water’s edge.

“Oh, sir,” pleaded the woman, as the young man approached; “please help me! My boy is drowning, and these men will not let me go!”

[Pg 8]“It would be madness!” exclaimed one of the men. “She would jump into the river, and be dashed to pieces in the rapids.”

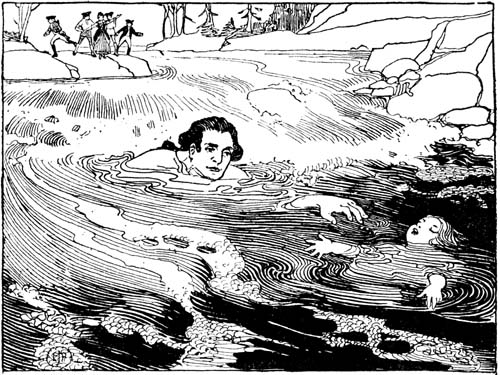

Throwing off his coat, the youth sprang to the edge of the bank. For a moment he scanned the rocks and the whirling currents. Then, as the bright red of the little boy’s dress caught his eye, he plunged into the roaring foam. Everyone watched the struggle, as he battled against the raging waters.

Twice the boy went down; twice he reappeared farther and farther away. The terrible rapids were bearing him on to the most dangerous part of the river. The youth put forth all his strength. Three times the child was almost within his grasp; three times an ever stronger eddy tossed it from him.

On the bank the people waited breathless, almost hopeless. Suddenly, the brave swimmer caught the little body. A shout of joy arose that quickly changed into a cry of horror. The boy and man had shot over the falls and vanished in the seething waters below.

The watchers ran along the bank, peering into the foaming, boiling depths.

“There! There they are!” cried the mother. “See! See, they are safe!” She fell on her knees with a prayer of thanksgiving. Eager, willing arms drew them up from the water—the boy insensible, but alive; the youth well-nigh exhausted.

“God will reward you for this day’s work,” said the grateful woman. “The blessings of thousands will be yours.” She spoke truly; for the youth of whom this story is told was George Washington.—Selected.

If Willie Duncan had played where his mother told him to play, he would not have fallen down a manhole; neither would he have had a narrow escape from losing his life by being buried in the snow.

But Willie was only four years old, and therefore not so much to blame as an older boy would have been.

The street cleaners were dumping the dirty snow from the street into a manhole, which opened into a big drain. This drain carried off the rain in summer and the snow in winter.

While the shovelers were at work, Willie toddled across the street. Before the men near the manhole could stop him, he disappeared into the opening.

“Bring a ladder!” some one shouted. But there were no ladders in that street of crowded houses.

[Pg 10]“Turn in a fire alarm!” some one else cried—and this was quickly done.

The men knew that firemen always bring ladders, and that they perform many other duties besides putting out fires.

While they were waiting for the ladder, Frank Brown came running up. Now, Frank was only twelve years old, but he was a boy of quick wit and great presence of mind. Only the summer before, he had jumped into the river from a pier to rescue a small boy from drowning.

“Let me go down and get him out,” cried Frank to the workmen.

The men tied ropes about the daring boy and lowered him feet first into the manhole.

Meanwhile, they could hear poor Willie crying bitterly down there in the soft, cold snow.

“Where are you?” called Frank.

“Here I am in the snow,” came a wee voice from the darkness.

Frank caught the half-frozen little boy in his arms, and both were quickly pulled to the surface.

Willie was hurried off to the hospital to be treated for exposure; but Frank was none the worse for his adventure.

While all this was happening, an accident befell the fire patrol which was rushing to Willie’s rescue. The patrol motor-truck ran into a bakery wagon. The driver of the wagon was thrown out and hurt. Both the wagon and the patrol truck were damaged.

[Pg 11]Wasn’t it fortunate for Willie that day that Frank Brown knew what to do, and did it?

When the people praised Frank, he said, “Oh, that was nothing. I am glad I could help the poor little chap—but I would have gone down there to save even a kitten, wouldn’t you?”

QUESTIONS

Since it took some time for the fire patrol to reach the manhole after the accident, what would have become of the little boy if Frank had not been a hero?

How would you like to go down into a dark, cold manhole to rescue somebody?

Tell what you know about Hero Medals—those of Andrew Carnegie, and others.

Do you think that Frank was a Boy Scout? Why?

1. A scout is trustworthy.

2. A scout is loyal.

3. A scout is helpful.

4. A scout is friendly.

5. A scout is courteous.

6. A scout is kind.

7. A scout is obedient.

8. A scout is cheerful.

9. A scout is thrifty.

10. A scout is brave.

11. A scout is clean.

12. A scout is reverent.

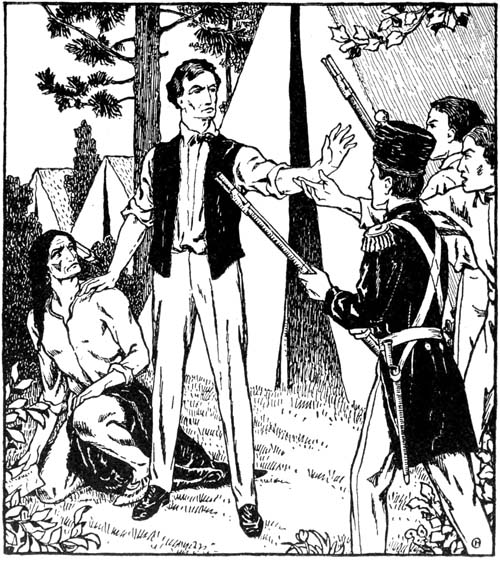

Among the rough young men of the frontier, Abraham Lincoln was famous for his quick wit and great strength. Many stories are told of his courage in[Pg 13] rescuing the weak and helpless from danger, often at the risk of his life.

When Lincoln was serving as captain in the Black Hawk War, there wandered into his camp one day a poor old Indian. The Indian carried no weapon, and he was too old to be dangerous. He was just a forlorn, hungry old man in search of food.

“Injun white man’s friend,” he cried to the soldiers, as he took a paper from his belt and held it out to them.

The paper was a pass from the general in command, saying that the old man was a peaceful, friendly Indian.

But the soldiers were too much excited to pay any attention to the pass.

“Kill him! Scalp him! Shoot him!” they cried, running for their weapons.

They were enlisted to fight Indians, and here was an Indian—perhaps Black Hawk himself. They were not going to let him escape.

“Me good Injun! Big White Chief says so—see talking paper,” protested the Indian, again offering them the paper.

“Get out! You can’t play that game on us. You’re a spy! Shoot him! Shoot him!” the soldiers shouted.

A dozen men leveled their rifles ready to fire. The others handled the old Indian so roughly and made so much noise over their prize that they aroused the captain.

“What is all the trouble about?” he demanded, coming from his tent.

[Pg 14]His glance fell on the frightened Indian, cowering on the ground.

Dashing in among his men, he threw up their weapons, and shouted, “Halt! Hold on, don’t fire! Stop, I tell you!”

Then, placing his hand on the red man’s shoulder, he cried, “Stand back, all of you! You ought to be ashamed of yourselves—pitching into a poor old redskin! What are you thinking of? Would you kill an unarmed man?”

“He’s a spy! He’s a spy!” shouted the soldiers.

“If he’s a spy,” answered Lincoln, “we will prove it, and he shall suffer the penalty. Until then, any man who harms him will have to answer to me.”

The poor old Indian crouched at Lincoln’s feet, recognizing in him his only friend.

“What are you afraid of?” demanded one of the ringleaders, raising his rifle. “We’re not afraid to shoot him, even if you are a coward!”

The tall young captain faced his accuser and slowly began to roll up his sleeves.

“Who says I’m a coward?” he demanded.

There was no response to this.

Every man in the company knew the great strength of that brawny arm; some had felt it on more than one occasion.

“Get out, Capt’n,” they said; “that’s not fair! You’re bigger and stronger than we are. Give us a show!”

“I’ll give you all the show you want, boys,” Captain Lincoln replied; “more than you are willing to[Pg 15] give this Indian. Take it out of me, if you can; but you shall not touch him.”

Again, there was no answer.

The Indian showed his pass, which proved him to be one of the friendly Indians from General Cass’ division. Lincoln knew at once that it was genuine.

The young captain ordered one of the men to give the captive food and let him go free. The poor man could not speak his thanks. To show his gratitude, he knelt down and kissed the feet of the young soldier.

The men scattered and the trouble was over. No man in that camp had any desire to try his strength with Captain Abraham Lincoln, who was ready to protect a friendless Indian with his life.

MEMORY GEMS

They Have not Hurt Me, for I Have Done no Wrong

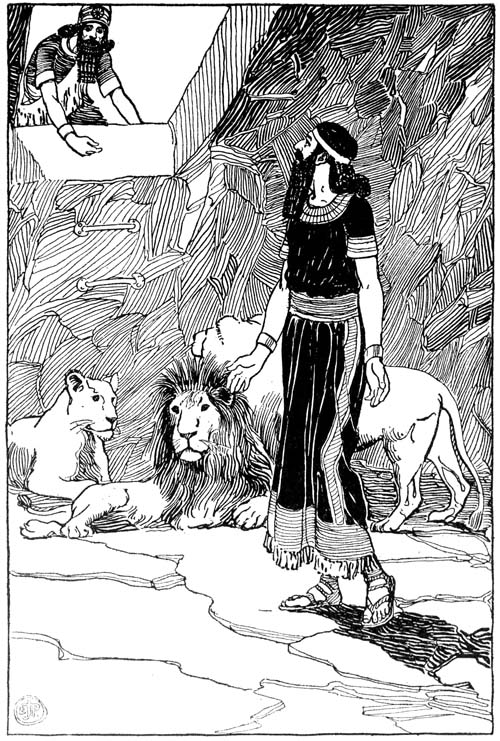

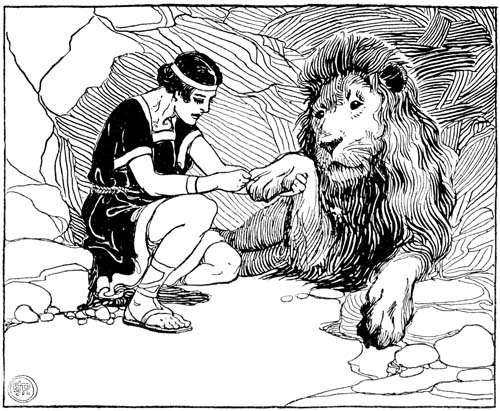

In the days of long ago, when Darius was king, a very brave man lived in Babylon. His name was Daniel. Daniel was just as truthful as he was brave. No one ever knew him to do a mean thing, or to tell a lie.

Now, Daniel was a foreigner. He had been carried to Babylon as a captive when a little boy. But that made no difference to King Darius. The king liked Daniel because he was loyal and faithful, which was more than could be said for some of the king’s servants. So the king made Daniel first ruler in the kingdom—a very high position indeed; but the proud nobles and princes of Babylon were very angry at this.

“He’s only a foreigner,” some said. “We despise him.”

“He was little better than a slave when he came here; now he rules over us,” others said. “We hate him.”

Then they put their heads together and plotted to kill Daniel. “Come,” the plotters said. “Let us search his record and accuse him to the king. He must be dishonest, or a bribe-taker, to succeed like this.”

These men judged Daniel by themselves. They searched high and they searched low, but could not find a single item of wrongdoing. Daniel was true to his trust. His enemies were defeated, but not for long; for they kept on plotting.

“Why didn’t we think of it before?” cried one.[Pg 18] “We’ll put him in a trap. His religion—he won’t give that up even to save his life.”

Now, you must know that the people of Babylon worshipped idols; Daniel worshipped the true God.

This is the trap they laid for Daniel. They went to the king and said:

“King Darius, live forever. All the nobles and princes of the kingdom desire to pass a law that whoever shall pray to any god or man for thirty days, save to thee, O king, shall be thrown into the den of lions. Now, O king, sign the writing that it be not changed, according to the laws of Babylon which alter not.”

This pleased the king’s vanity and he signed the law, not knowing that it was aimed at Daniel.

Then the plotters set spies to catch Daniel.

When Daniel knew that the law was signed, he might have said to himself: “Oh, well, it’s only for thirty days; I won’t pray at all; or I’ll pray in secret; or I’ll go to the king, who is my friend, and explain the plot.”

He did none of these things. This is what he did. He went into his house; up the stairs to his bedroom; opened the window toward the far-off city of his birth; knelt down and prayed to his God. He did this at morning, at noon, at night—three times a day as he had always done.

Daniel did just what his enemies had expected. He walked right into their trap, rather than disobey his[Pg 19] conscience. It took a brave heart to do that. To be thrown into the den of lions meant certain death.

“Ha! ha!” laughed the plotters, “now we have him;” and they came in the morning to report to the king.

“O great king,” they said, “this foreigner, Daniel, pays no regard to the law that thou hast signed, but openly worships his God three times a day.”

Then the king was very angry with himself for having signed the law. All that day he tried to find some way to save Daniel, but could not; for the laws of Babylon, once made, could not be changed.

The same evening, the plotters came again, accusing Daniel. Then the king could wait no longer and sent for Daniel.

“O Daniel,” said the king, “the law must be obeyed. It may be that thy God whom thou servest continually will deliver thee.”

Daniel made no reply.

Then the king sadly ordered the soldiers to take Daniel to the lions.

The den was underground. As the soldiers removed the flat stone from the mouth of the den, the snarling beasts could be heard below.

Quickly they lifted Daniel and threw him in. He made no resistance. They replaced the stone over the mouth of the den, and the king sealed it, so that no one could open the den without his permission.

Then the king went to his palace. He sent away the musicians and refused to eat. All night long he tossed on his bed and could not sleep.

[Pg 20]Meanwhile, Daniel’s enemies were having a merry time, drinking to celebrate their victory.

By daylight, the king was in a fever. Hastily he rose, ran out of his palace to the den, and ordered the guard to remove the stone.

Then he stooped and looked down, fearful of what he was sure had happened. All was quiet.

“O Daniel, Daniel,” he cried. “Is thy God able to deliver thee from the lions?”

Then up from the den rose Daniel’s voice, clear and steady:

“O king, live forever. My God hath sent his angel to shut the lions’ mouths, and they have not hurt me, for I have done no wrong.”

“Lift him out! Lift him out!” cried the king, too happy to wait another moment.

Quickly they lifted Daniel into the daylight. Not a scratch was found on him anywhere.

Then the king ordered the plotters to be brought to the den immediately.

“You laid a trap for my faithful servant, Daniel,” cried the king to them, “and have walked into it yourselves. The fate you intended for him is reserved for you. What have you to say?”

But they could say nothing, save to beg for mercy.

“Away with them to the lions!” ordered the king.

Thud! thud! thud! “Hit him in the eye!” “Knock the pipe out of his mouth!” “Ha! ha! there goes his nose!” “I hit him that time!”

The victim of this piece of cruelty was only a snowman, which the boys of Strappington School had set up in their playground.

But how was Mr. Gregor, who lived next door to the school, to know that it was only a snowman? And what was more natural than that he should peep over the playground wall to see what was going on? And how was little Ralph Ruddy to know that Mr. Gregor was there? And how was he to know that the[Pg 22] snowball which was meant for the snowman’s pipe would land itself on Mr. Gregor’s nose?

Oh, the horror that seized upon the school at that dire event, and the dead silence that reigned in that playground! For those were the good old times of long ago, when anything that went wrong was set right with a birch-rod. Little Ralph Ruddy knew only too well what was coming, when he saw the angry man stalk into the schoolhouse and speak to the schoolmaster.

When the bell rang at four o’clock, the boys came out; and among them was Bob Hardy, the son of a poor farm laborer.

“It’s a shame,” muttered Bob, “to make a row ’bout an accident. Of course the schoolmaster had to take some notice of it. He is talking to little Ralph now. I told him Ralph did not mean to do it. Just the same, I’ll smash old Gregor’s windows for him.”

And Bob meant to do it, too. When all were asleep, he made his way down to the schoolhouse by moonlight, with a pocketful of stones.

He climbed the wall of the playground, and stood there all ready to open fire, when a voice startled him, a sort of shivering whisper. “Better not, Bob! better wait a bit!” said the voice.

Bob dropped the stone and looked about; but there was no one near him except the snowman shining weirdly in the pale moonlight. However, the words set Bob to thinking, and instead of breaking Mr. Gregor’s windows, he went home again and got into bed.

That was in January; and when January was done February came, as happens in most years. February brought good fortune—at least Bob’s mother said so, for she got work at the squire’s for which she was well paid.

But it did not turn out to be such very good fortune, after all; for the butler said she stole a silver spoon, and told the squire so; and if the butler could have proved what he said, the squire would have sent her to prison; but he could not, so she got off; and Bob’s mother declared that she had no doubt the butler took the spoon himself.

“All right,” said Bob to himself, “I’ll try the strength of my new oaken stick across that butler’s back.” And he meant it too, for that very evening he shouldered his cudgel and tramped away to the big house. When he got there the door stood wide open; so in he walked.

Now, there hung in the hall the portrait of a queer old lady in a stiff frill and a long waist and an old-fashioned hoop petticoat; and when Bob entered the house, what should this old lady do but shake her head at him! To be sure, there was only a flickering lamp in the entry, and Bob thought at first it must have been the dim light and his own fancy; so he went striding through the hall with his cudgel in his hand: “Better not, Bob!” said the old lady; “better wait a bit!”

[Pg 24]“Why, they won’t let me do anything!” grumbled Bob; but he went home without thrashing the butler, all the same.

That was in February, you know. Well, when February was done, March came, and with it came greater ill-fortune than ever; for Bob’s father was driving his master’s horse and cart to market, when what should jump out of the ditch but old Nanny Jones’s donkey, an ugly beast at the best of times, and enough to frighten any horse. But what must the brute do on this occasion but set up a terrific braying, which sent Farmer Thornycroft’s new horse nearly out of his wits, so that he backed the cart and all that was in it—including Bob’s father—into the ditch.

A pretty sight they looked there, for the horse was sitting where the driver ought to be, and Bob’s father was seated, much against his wish, in a large basket full of eggs, with his legs sticking out one side and his head the other.

Of course, Farmer Thornycroft did not like to lose his eggs—who would?—for even the most obliging hens cannot be persuaded to lay an extra number in order to make up for those that are broken; but for all that, Farmer Thornycroft had no right to lay all the blame on Bob’s father, and keep two shillings out of his week’s wage.

So Bob’s father protested, and that made Farmer Thornycroft angry; and then, since fire kindles fire, Bob’s father grew angry too, and called the farmer a[Pg 25] cruel brute; so the farmer dismissed him and gave him no wages at all.

We can hardly be surprised that when Bob heard of all this he felt a trifle out of sorts. He went pelting over the fields, and all the way, he muttered to himself, “A cruel shame I call it, but I’ll pay him back; I mean to let his sheep out of the pen, and then I will just go and tell him that I’ve done it.”

Now, the field just before you come to Farmer Thornycroft’s sheep-pen was sown with spring wheat, and they had put up a scarecrow there to frighten the[Pg 26] birds away. The scarecrow was truly sorry to see Bob scouring across the field in such a temper; so just as Bob passed him, he flapped out at him with one sleeve, and the boy turned sharply round to see who it was.

“Only a scarecrow,” said he, “blown about by the wind,” and went on his way. But as he went, strange to say, he thought he heard a voice call after him, “Better not, Bob! better wait a bit!”

So Bob went home again, and never let the sheep astray after all; but he thought it very hard that he might not punish either Mr. Gregor or the butler or the farmer.

Now, the folk that hide behind the shadows thought well of Bob for his self-restraint, and they determined that they would work for him and make all straight again. So when Bob went down to the riverside next day, and took out his knife to cut some reeds for “whistle-pipes,” Father Pan breathed upon the reeds and enchanted them. “What a breeze!” exclaimed Bob; but he knew nothing at all of what had in reality happened.

Bob finished his pan-pipes, and trudged along and whistled on them to his heart’s content. When he got to the village, he was surprised to see a little girl begin to dance to his tune, and then another little girl, and then another. Bob was so astonished that he left off playing, and stood looking at them, open-mouthed, with wonder. But as soon as he left off[Pg 27] playing, the little girls ceased to dance, and begged him not to play again, for the whistle-pipes, they were sure, must be bewitched.

“Ho! ho!” cried Bob, “here’s a pretty game. I’ll just give old Gregor a turn. Come! that will not do him any harm, at any rate!”

Strange to say, at that very moment Mr. Gregor came along the street.

“Toot! toot! toot! tweedle, tweedle, toot!” went the pan-pipes; and away went Mr. Gregor’s legs, cutting such capers as the world never looked upon before. Gaily trudged Bob along the street, and gaily danced Mr. Gregor. The people looked out of their windows, and laughed; and the poor man begged Bob to leave off playing.

“No, no,” answered Bob; “poor little Ralph Ruddy never meant to hit you, and you made him dance with pain. It is your turn now.”

Just then the squire’s butler came down the street. Of course, he was much puzzled to see Mr. Gregor dancing to the sound of a boy’s whistle, but he was presently more surprised to find himself doing the very same thing. He tried with all his might to retain his stately gait; but it was all of no use. His legs flew up in spite of himself, and away he went behind Mr. Gregor following Bob all through the village and dancing for all he was worth.

The best sight was still to come; for the tyrannical Farmer Thornycroft was just then walking home from market in a great heat, with a big sample of corn in each of his side-pockets; and turning suddenly round a corner, he went right into the middle of the strange[Pg 28] procession and began to dance in a moment. Up flew his great fat legs, and away he went, pitching and tossing, and jumping and twirling, and jigging up and down like an elephant in a fit.

How the people laughed, to be sure, standing in their doorways, and viewing this odd trio! Mr. Gregor was nearly fainting, the butler was in despair, and the perspiration poured down the farmer’s face; but that mattered not to Bob; he had promised himself to take them for a dance all round the village, and he did it. At length, when he had completed the tour, he stopped for just one moment, and asked Mr. Gregor whether he would beg Ralph Ruddy’s pardon; and Mr. Gregor said he would, if only Bob would leave off playing.

Then Bob asked the farmer if he would take his father back and pay him his wages, and the farmer[Pg 29] said he would; and, finally, he made the butler promise to tell the squire that his mother had nothing to do with stealing the silver spoon.

Then Bob left off playing. The three poor men went home in a terrible plight; and Mr. Gregor begged little Ralph’s pardon; and the butler cleared the stain from Bob’s mother’s character; and Bob’s father went back to work; and Farmer Thornycroft soon afterwards took Bob on too, and he made the best farm-boy that ever lived.

—Adapted from the story in Little Folks

By Hartley Richards.

QUESTIONS

Did a little voice ever say “Better not” to you?

Did you listen?

Were you glad afterwards?

MEMORY GEMS

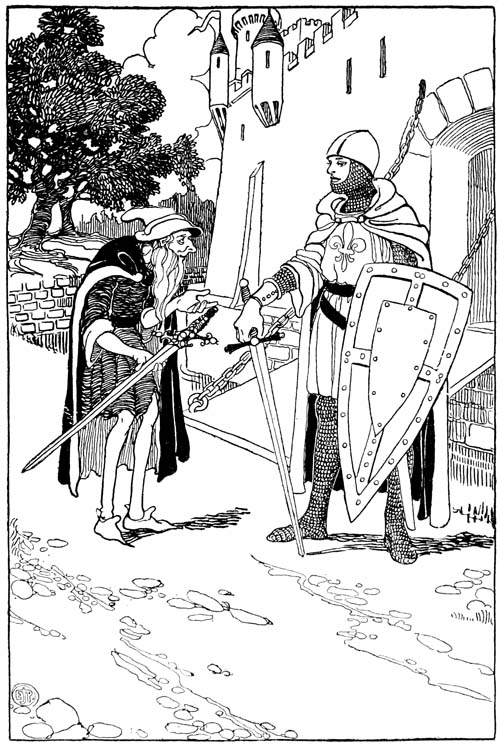

Once upon a time, a long while ago, in a big dark forest there was a great gray castle. It had high stone walls and tall turrets that you could see a long way off over the tree-tops.

Perhaps you are wondering who lived in this castle far off in the woods.

Well, you see there were cruel giants in the forest—so cruel that the king kept a company of knights in the castle to help travelers.

These knights wore the most wonderful suits of armor you ever saw. They had tall helmets on their heads, with long red plumes floating behind. They carried long spears, too; but the most wonderful thing about them was their shields. These had been made by a great magician, and when the knights first got them they were all cloudy; but as their owners did more and more brave deeds, the shields grew brighter and brighter.

Once in a long while, when a knight had fought a terribly hard battle or had done a great many very, very brave deeds, a beautiful golden star would appear in the center of the shield.

One day a messenger came riding up to the castle in great haste. He was terribly excited and he shouted, “The giants are coming! They are all gathered together to fight you!”

You can imagine the commotion that took place in the castle! There was a great hurrying and scurrying[Pg 31] to bolt and bar all the doors and windows, to polish armor, and to get everything ready.

The youngest knight of all, Sir Roland, was so happy that he did not know what to do! You see, he had done many brave deeds already, and he was thinking how much brighter his shield would be now that he had a chance to go into a real battle. He could hardly wait!

By and by, all the knights were ready and the lord of the castle said:

“Somebody must stay here to guard the gate. Sir Roland, you are the youngest; suppose you stay; and remember—don’t let any one in.”

Poor Sir Roland! I wonder if you can imagine how he felt. Why, he just felt as if he wanted to die! To think that he had to stay at home when he wanted to go more than anyone else. But he was a real knight, so he made no reply.

He even tried to smile as he stood at the gate and watched all the other knights ride away with their banners flying and their armor flashing in the sunshine and their red plumes waving in the wind. Oh, how he did want to go! He watched till they had galloped out of sight, and then he went back into the lonely castle.

After a long while, one of the knights came limping back from the battle.

“Oh, it’s a dreadful fight,” he said. “I think you[Pg 32] ought to go and help. I’ve been wounded; but I’ll guard the gate while you go.”

You see, he wasn’t a brave knight and he was glad to get away from the battle. Sir Roland’s face became all happy again, for he thought, “Here is my chance!” And he was just about to go; when, suddenly, he seemed to hear a voice, “You stay to guard the gate; and remember—don’t let any one in.” So instead of going, he said, “I can’t let any one in, not even you. I must stay and guard the gate. Your place is at the battle.”

That sounds easy to say, doesn’t it? But it was very hard to do, when he wanted to go more than anything else in the world.

After the knight had gone, there was nothing for him to do but to wonder how the fight was going and to wish that he was right in the midst of it.

By and by, he saw a little bent old woman coming along the road. Oh, I almost forgot to tell you that all around the castle there was a moat—a sort of ditch, filled with water—and the only way to get to the castle was over a little narrow drawbridge that led to the gate. When the knights didn’t want any one to come in, they could pull the bridge up against the wall.

Well, the little old woman came up and asked Sir Roland if she might come in to get something to eat. Sir Roland said, “Nobody may come in today; but I’ll get you some food.”

[Pg 33]So he called one of the servants; and while she waited the old woman began to talk.

“My, there is a terrible fight in the forest,” she said.

“How is it going?” Sir Roland asked.

“Badly for the knights,” she replied. “It is a wonder to me that you are not out there fighting, instead of standing here doing nothing.”

“I have to stay to guard the gate,” said Sir Roland.

“Hm-m-m,” said the old woman. “I guess you are one of those knights who don’t like to fight. I guess you are glad of an excuse to stay home.” And she laughed at him and made fun of him.

Sir Roland was so angry that he opened his lips to answer; and then he remembered that she was old. So he closed them again, and gave her the food. Then she went away.

Now, he wanted to go more than ever since he knew that the knights were losing the battle. It was pretty hard to be laughed at and called a coward! Oh, how he did want to go!

Soon a queer little old man came up the road. He wore a long black cloak and he called out to Sir Roland, “My, what a lazy knight! Why aren’t you at the fight? See, I have brought you a magic sword.”

He pulled out from under his cloak the most wonderful sword you ever saw. It flashed like diamonds in the sun.

See, I Have Brought You a Magic Sword

“If you take this to the fight you will win for your lord. Nothing can stand before it.”

Sir Roland reached for it, and the little old man stepped on the drawbridge. Suddenly, the knight remembered, and said, “No!” so loudly that the old man stepped back. But still he called out, “Take it! It is the sword of all swords! It is for you!”

Sir Roland wanted it so badly that, for fear he might take it, he called the porters to pull up the drawbridge.

Then, as he watched from the gate, what do you think happened? It was the most wonderful thing you could imagine! The little old man began to grow and grow till he was one of the giants! Then Sir Roland knew that he had almost let one of the enemy into the castle.

For a while, everything was very quiet. Suddenly, he heard a sound, and soon he saw the knights riding toward the castle so happily that he knew that they had won. Soon they were inside, and were talking together about all the brave deeds they had done.

The lord of the castle sat down on his high seat in the main hall with all his knights around him. Sir Roland stepped up to give him the key of the gate. All at once, one of the knights cried, “The shield! Sir Roland’s shield!”

And there, shining in the center, was a beautiful golden star. Sir Roland was holding his shield in front of him, so he could not see it. But the others[Pg 36] looked and wondered; and the lord of the castle asked, “What happened? Did the giants come? Did you fight any alone?”

“No,” said Sir Roland. “Only one came, and soon he went away again.”

Then he told all about the little old woman and the little old man, and the knights still wondered about the star. But the lord of the castle said, “Men make mistakes, but our shields never do. Sir Roland has fought and won the greatest battle of all today.”

—Raymond M. Alden—Adapted.

QUESTIONS

It was much harder for Sir Roland to stay and guard the gate than it would have been for him to go to the fight, wasn’t it?

How many times was he tempted?

What might have happened if he had not guarded the gate?

Which knight gained the greatest victory of all?

Over whom did he gain it?

Can you remember a time when you did the right thing even though you felt very much like doing something else?

MEMORY GEMS

He that ruleth his spirit is better than he that taketh a city.—Bible.

A strong heart may be ruined in fortune, but not in spirit.—Victor Hugo.

Be sure to put your feet in the right place; then stand firm.—Lincoln.

He who cannot control himself cannot control others.

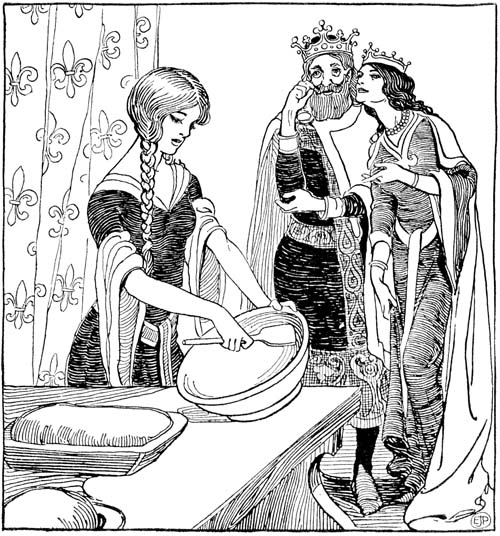

Once upon a time, so an old story says, a certain king was anxious that his son, the prince, should marry the most thrifty maiden to be found in his kingdom.

So he invited to the palace on a certain date all the young women of the country, for that was the custom when a new princess was to be chosen.

[Pg 38]On every side were arranged long tables, at which each girl was given a place.

Upon the tables were the materials and bowls and pans needed in making bread. In the center of the room on a small platform sat the king and queen, the prince, and several courtiers.

When they had all taken their places, the king announced that there would be a contest in bread-mixing; and that a handsome prize would be given to the young woman who, in the judgment of the king and queen, made bread in the best way.

You can imagine how excited all the young women were, and how each one set about her task trembling with nervousness, yet in her secret heart hoping to win the prize.

You can imagine, too, how difficult it was to act as judge; for the king and queen knew there must be several young women there who could make bread equally well.

Every once in a while, the king whispered to the queen, and the queen smiled and shook her head doubtfully, as if to say, “We shall have a hard task to judge with fairness.”

In one corner of the room, working very quietly, was a very pretty young girl. She was so far away from the king and queen, who were a little near-sighted, that they had not observed her as carefully as they had some of the others. But when the prince leaned forward and spoke to them, they raised their hand glasses and turned their eyes in her direction, to watch her every motion.

[Pg 39]“We will examine the loaves as soon as they are placed in the pans,” announced the king presently; and soon he led the queen and the prince around the tables.

They came last to the place where the fair young girl was standing. The king and queen looked not only at the beautiful white loaves in the pans, but at the empty bowl in which the dough had been mixed. They looked at each other, and nodded and smiled; then at the prince, and nodded and smiled.

“What is your name, my dear?” asked the king, turning toward the table once more.

“Hildegarde,” replied the maiden, blushing with shyness.

“Come with us,” said the king and the queen leading the way; and the prince bowed low before her.

“May I escort you, Miss Hildegarde?” he asked, offering his arm, on which she hesitated to place her hand, fearing lest the flour might mark his velvet coat.

Upon this, the prince drew her hand through his arm, and they followed the king and queen.

When they reached the platform, the king took Hildegarde’s hand in his.

“We, the king and queen, judge that this young lady has won the prize because she has made bread in the best way,” he announced. “All of you have made beautiful loaves; but Hildegarde is the only one who has scraped all the dough from the bowl and paddle, wasting nothing. Let the prince present the prize. Kneel, Hildegarde.”

As the maiden knelt on the cushion at the feet of the[Pg 40] king and queen, the prince came forward and placed a sparkling diamond ring on her finger, and raised her to her feet.

“Will you accept it as a betrothal ring, and become my princess?” he whispered; and Hildegarde answered, “Yes.”

“The prince goes with the prize,” said the king; “for he wants to have for his princess the most thrifty maiden in the land.”

All the young women were invited to the wedding of the prince and Hildegarde, and each received as a souvenir a beautiful little gold purse in the form of a loaf of bread.

QUESTIONS

Did the king and queen and prince need the crumbs of dough?

Then why do you think Hildegarde was chosen?

Why does it pay to save little things?

Do you know that the gold dust in the sweepings at the mint amounts to many dollars in a year?

Can you think of something you could save at your house?

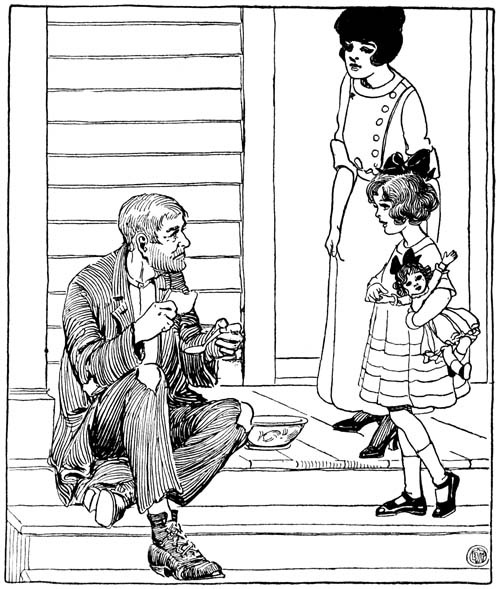

“Oh, mother, I saw such a funny old tramp up the street,” said Stella, as she came running into the house. “The boys were calling him names. ‘Look at old red nose,’ they called. He was so angry; you ought to have seen him shake his stick at them.”

“That was very wrong—to make fun of an old man, even if he was a tramp,” replied Mrs. Clark, looking serious.

“Yes, that is what I thought, mother. He seemed so poor and old. His clothes were shabby, his shoes were full of holes, and his hat was too big for him. He had such a bristly beard and such a red nose, and was so dirty!”

“Poor old man, one can not help feeling sorry for him,” sighed Mrs. Clark.

“But what makes him so poor, mother?”

“It may be misfortune, my dear; but usually tramps will not work, nor will they stay in one place. They prefer to wander from place to place and beg for food. But come, dinner is ready.”

Just as they were seated at the table, they heard a heavy step on the back porch; and a moment later there came a rap on the kitchen door.

The little girl went to open the door. In a moment, she came running back with a frightened look on her face.

“Quick, mother,” she cried, “here is the tramp at our back door.”

“Don’t be frightened, dear. I’ll go to the door,” said Mrs. Clark.

“Please, ma’am, will you give me a bite to eat? I’m hungry. I haven’t had anything to eat to-day,” begged the tramp, touching his old battered hat.

[Pg 43]Mrs. Clark was about to shut the door, but seeing the discouraged look in the tramp’s face, she quickly changed her mind.

“Yes, I’ll give you something,” she said. “Sit down on the porch.”

With a look of grateful relief, the tramp sank down on the step.

In a minute, Mrs. Clark brought him a big bowl of the warm soup she had prepared for dinner, and two thick slices of bread.

Clinging close to her mother, Stella watched the tramp devour the food greedily.

“My, he must have been hungry!” she thought.

After the tramp had eaten most of the food, Mrs. Clark asked, “Where is your home?”

“I have no home, lady.”

“But where do you live?”

“Oh, anywhere I happen to be.”

“Yes, but where do you sleep?”

“Sometimes in the station house; sometimes in barns; anywhere I can.”

“Where are your friends?”

“I haven’t any friends, lady, except kind-hearted people like you, who sometimes take pity on me and give me something to eat.”

“What will become of you?”

“I don’t know, lady; I don’t know, and sometimes I don’t care.”

“I do not mean to be curious, but would you mind[Pg 44] telling me how you came to be in such a plight?” said the kind woman.

“It is a long story,” said the tramp wearily. “I had a good home and was well brought up; but somehow I never seemed to prosper for long. I guess I was slack and careless; everything seemed to come so hard and go so easily. I worked on and off. When I got anything I ate it up, drank it up, or let it get away—didn’t know how to save—and now I am old and have no home and nobody to respect me.” A tear trickled down the old man’s red nose.

Then he stood up and handed back the empty bowl. “But I must not bother you with my troubles,” he said. “Thank you for the food and for speaking kindly to me.” With that, he tipped his hat and hobbled off.

They watched him out of the window as he went down the street. Soon they saw a police officer come around the corner.

He stopped the tramp, spoke to him, and pointed up the road leading out of town.

“What did the officer tell him, mother?” asked the little girl.

“I think he told him to move on,” replied Mrs. Clark sadly. “Come, dear, dinner will be cold.”

A few days later, Aunt Anne came from the next town to visit the family.

Stella eagerly told her about the tramp.

“Why, that must be the poor old man the police found one morning in our park. He was lying on a bench, sick; he had completely given out,” said Aunt Anne.

[Pg 45]“What did they do with him?” asked Stella.

“They put him in the ambulance and took him off to the county poor farm.”

“The poor farm?”

“Yes, that is where tramps and shiftless people generally land.”

“Oh, how dreadful!” exclaimed the little girl. “Aunty, I don’t see why tramps don’t work?”

“Neither do I,” said Aunt Anne, shaking her head.

QUESTIONS

Why is it that no one respects a tramp?

Does a man who works hard often become a tramp?

Name some of the things a tramp wastes that he should save.

What must we do in order to have plenty to eat and wear, and to have a comfortable home to live in?

What must we do with part of the money we earn?

Does a tramp ever have a bank account?

Can a tramp be of help to others? Why not?

There is one thing that Uncle Sam likes to do for his people himself, and that he forbids any one else to do under penalty of the law. He likes to make their money.

One of his first acts when setting up in business was to start a factory, the United States Mint, for the coining of money. There are several mints now, and in them is made all the money that circulates in the United States.

Uncle Sam makes five kinds of money: gold money, silver money, nickel money, copper money, and paper money; and places on each piece the United States stamp.

One peculiar thing about money is that you cannot eat it when hungry, drink it when thirsty, wear it for clothing, or build a house out of it. What kind of cake, or coat, or house would pennies or nickels or silver dollars make?

King Midas—in the story of the Golden Touch—found this out to his sorrow.

There is one thing, however, that money will do a little better than anything else; and it is because it will do this thing that Uncle Sam makes it.

Money enables us to buy food to eat, clothing to wear, and houses to live in. It is of little value in[Pg 47] itself, except as it enables us to purchase the things we need.

Just imagine what would happen if there were no such thing as money. Suppose you are working for a baker. At the end of each week, pay day comes; but there is no money, so the baker offers you three hundred loaves of bread for your week’s work. These loaves of bread you would have to exchange for clothing or other needs. This would be a very troublesome thing to do.

To overcome this trouble, therefore, money was invented. Money represents labor or goods. You are paid for your labor or your goods, not in other labor or goods, but in money, which you can carry in your pocket or keep in the bank. And with this money you can buy whatever you need.

Money enables you to leave in the bakery the three hundred loaves of bread you earned, and to buy a loaf as you need it.

Money, then, takes the place of goods, because it can be exchanged for them. To lose or waste money is the same as losing or wasting the goods that money will buy.

A family would be considered foolish to throw enough money to buy a loaf of bread into the river. Yet what difference is there between this family and the one that wastes a loaf of bread, a slice at a time? To waste money or goods is just as bad as to throw them away.

When we earn money, there are just three ways in which we can use it rightly: save part, spend part, give part away. All three uses are very important.

Money saved should be put in the bank. There it grows by what you add to it from time to time. It also grows by the addition of the interest which the bank pays for the use of money. Money saved is always ready for a rainy day. People who save money always have money to spend.

The spending of money is quite as important as the saving of it. Money should be spent for food to nourish our bodies, for garments to clothe them, and for houses to protect them.

[Pg 49]When buying by the pound, see that you get full weight; when buying by the yard or peck, see that you get full measure. The principal thing in buying is to get all that you pay for. In selling, the principal thing is to give full value for the money that you receive.

Money should also be spent for education. Money spent in educating the mind is money well spent. The great successes in life are made by boys and girls who go to school and learn all they can. Many stories could be told about children who have earned and saved money to go to school, and of parents who have sacrificed many pleasures and comforts to help their children gain an education.

To give money away wisely is quite as important as saving or spending it. Money should be saved, not only to spend, but to give away. Else what will you do when Christmas comes and when birthdays come?

Besides, there are the churches, hospitals, orphanages, the Red Cross, and many other good causes that need our gifts. We give our money to these, not with the idea of what we can get out of them, but for the pleasure of helping to make the world a pleasanter and better place in which to live.

QUESTIONS

Do you know that many people start in life without money, and by saving little sums become prosperous?

When you go to the library, will you ask for books that tell about successful men, and read about how each of them started in life?

Do you know anyone who has earned or saved money in order to go to school?

February third has recently been set aside in many places as Thrift Day.

Thrift means wise management.

A thrifty person never wastes what could be saved by thoughtfulness.

A thrifty person is one who does not waste anything, but gets the full value of everything.

A thrifty person sets traps to catch the waste, and changes it into things worth having.

Those who know, say that American people are the most wasteful of all people in the world.

They tell us that we waste money, food, forests, time, energy, and thousands of the little daily supplies which we might save.

If we all save what we can, it will be a very large amount when added together.

It seems like a little thing to throw away one sheet of paper, doesn’t it?

Suppose you count the number of sheets of paper in your writing pad at school. Let us say there are one hundred sheets, and that each pad costs the Board of Education five cents. If there are forty thousand children who waste one sheet of paper a day, the wasted sheets will amount to four hundred pads a day. At five cents a pad, four hundred pads will cost[Pg 51] twenty dollars a day. There are about two hundred school days a year. Multiply twenty dollars by two hundred and you will find that the wasted sheets would cost four thousand dollars in a school year!

You would never have imagined that, would you? See how much the school boys and girls can save for the taxpayers, and for the children who will come to school later. That is being thrifty.

If there were but ten thousand boxes of matches in our country, think how careful we would be not to waste one match. But few people think about so simple a matter. Yet matches are made from wood; and forests have to be cut down to make the matches we use.

Old rags and old rubber do not seem to be of any value; yet in every city there are men who grow rich by collecting them.

In some schools the children bring old newspapers on a certain day, and you would be surprised to learn how much money one school made in this way for new playground games. That was thrift.

It seems to be a very little thing to play or idle away an evening; yet it was in odd moments that some of our greatest men studied until they were well educated.

Abraham Lincoln never “lost sixty golden minutes somewhere between sunrise and sunset.”

You all know the story of Benjamin Franklin—how he began life as a poor boy, and how by thrift,[Pg 52] he became later in life one of the most useful and wealthy citizens of America.

Benjamin Franklin learned great wisdom through his experiences, and he was anxious that other people might learn the same lessons; so he printed an almanac and put into it many wise sayings, which he hoped would be remembered.

He called his almanac “Poor Richard’s Almanac.” Here are a few of its wise sayings:

“For age and want, save while you may;

No morning sun lasts all the day.”“But dost thou love life? Then do not squander time, for that is the stuff life is made of.”

“A small leak will sink a ship.”

“Be ashamed to catch yourself idle.”

“Always taking out of a meal-tub and never putting in soon comes to the bottom.”

“One to-day is worth two to-morrows.”

“Many a little makes a mickle.”

“Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; that is, waste nothing.”

“No pains, no gains.”

QUESTIONS

Can you think of some ways in which you can save your clothing?

Have you ever tried forming a Thrift Club in your class to see what and how much you can save?

What might you do with the money?

When vacation time came, Richard went to visit his Uncle Dick on the farm.

He fed the chickens regularly, and he drove the cows and sheep to pasture. Indeed, he worked so hard and helped so much that his uncle promised to pay him.

So one day Uncle Dick handed him a silver dollar. Richard was delighted to think he had earned so much money. He put the dollar first into one pocket, then into another. This seemed to amuse Uncle Dick.

[Pg 55]“What are you going to do with your money?” he asked.

“I don’t know exactly,” Richard replied. “What would you do with it, uncle?”

“I think that I should plant it,” said Uncle Dick.

“Plant it!” exclaimed Richard. “Why, will it grow?”

“Yes,” said Uncle Dick, “it will, if it is planted in the right place.”

Just then some one called him away, and he forgot about Richard and his dollar.

But Richard did not forget. The next morning bright and early, he was out digging in the garden.

“What are you going to plant?” asked Uncle Dick when he saw him.

“My dollar,” answered Richard, pulling the money proudly out of his pocket. Then seeing the smile in his uncle’s face he added, “You know you said it would grow, uncle, if I planted it in the right place. Isn’t this the right place?”

“Did you think I meant that pennies would grow on bushes?” said Uncle Dick. “I didn’t mean that, boy. I’m going to drive over to Bernardsville after breakfast. If you will go with me, I will show you the right place to plant a dollar to make it grow.”

Richard hurried with his breakfast because he was greatly excited by the thought of his ride.

As they drove toward the town, every now and then he put his hand in his pocket to see if his dollar was safe.

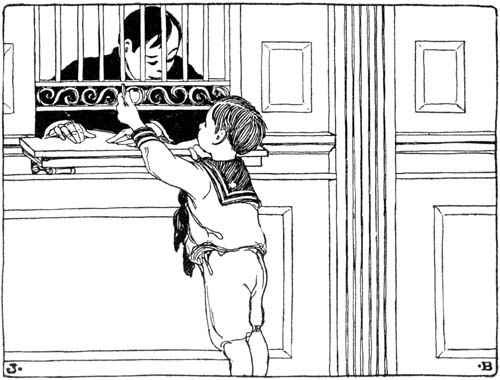

Finally, they reached Bernardsville, and Uncle Dick drew up before a large stone building. “This is a bank, a place where dollars grow,” he explained. “Come inside with me and, if you wish, we will plant your dollar.”

He led the way to a window over a high counter.

“How do you do, Mr. Cashier?” he said. “This young man is my nephew, and he wishes to plant a dollar so that it may start to grow. Will you please show him the right place to plant it?”

“Indeed I shall be glad to,” said the man behind the window. “If your nephew will hand me his dollar, I will plant it for him.”

Richard gravely pulled the money from his pocket and handed it through the window. The man gave him a card and asked him to write his name.

When Richard returned the card, Mr. Cashier took up a neat little book, wrote Richard’s name on the cover and made a note inside the book, which said that Richard had one dollar in the bank. Then he gave him the book, together with a pretty nickel home-safe, such as savings banks keep for children who save pennies, nickels, dimes, quarters, and, sometimes, even dollars.

“This is a home-savings bank,” explained Mr. Cashier. “Your dollar which you handed through the window will grow in two ways. We will make it grow by paying you interest. You may make it grow by adding more money to it. You take this little[Pg 57] nickel safe, and put your pennies and other money into it; when you come again to our bank, bring it with you. See, here is the key I shall use for unlocking it. I will add what is in it to the dollar you already have.”

“Don’t we get the key?” asked Richard in a whisper, as other people came up to the window, and he and his uncle passed on.

“No,” answered his uncle. “If we had it, we might be tempted to open the safe and use the money; then your dollar wouldn’t grow.”

“What did Mr. Cashier mean by saying, ‘we will make your money grow?’” asked Richard when they were once more driving toward home.

“He meant that the bank people will pay you three cents for every dollar you let them use for a year.”

“Isn’t that fine!” exclaimed Richard. Then he opened the box that held his pretty home-safe.

“The next time we take this to bank,” he said, “when I shake it, it will jingle.”

“I believe it will!” said Uncle Dick laughing; “and I believe it will make your first dollar grow big.”

And it did; for Richard worked hard and saved almost all of his money. When the cashier opened it with the key the next time Richard and Uncle Dick went to the bank, even he seemed surprised as he counted the money.

“Well, young man,” he said, “I see you know one way to plant a dollar and make it grow.”

EVERY BOY AND GIRL SHOULD HAVE A BANK ACCOUNT

The first dollar is the hardest to save, but not so hard as it seems.

If you save five cents a week you will have your first dollar in twenty weeks.

If you save ten cents a week you will have your first dollar in half the time, or in ten weeks.

If you are able to save twenty-five cents a week you will have your first dollar in one-fifth of the time, or in four weeks.

When you put this dollar in the savings bank you have started a bank account, which is something to be proud of.

If you save regularly it will not be long before you have another dollar to add to the one already in the bank.

Money is saved a little at a time.

A mile is walked one step at a time.

A house is built one brick at a time, one nail at a time.

If you save at the rate of five cents a week for a year, how much money will you have in the bank?

If at the rate of ten cents a week for a year, how much will you have?

If at the rate of twenty-five cents a week for a year, how much?

Money in the bank keeps on growing because the bank adds interest for the use of your money.

[Pg 59]By and by, you will want a sum of money for some important thing. Then you will be glad that you have a bank account to help you.

Why not begin saving for it today?

INTEREST TABLES

These tables show how money grows when placed at simple interest.

At Three Per Cent

| $1 | $2 | $3 | $4 | $5 | $6 | $7 | $8 | $9 | $10 | $100 | $1000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year 6 mos. 3 mos. |

.03 .01 .00 |

.06 .03 .01 |

.09 .04 .02 |

.12 .06 .03 |

.15 .07 .03 |

.18 .09 .04 |

.21 .10 .05 |

.24 .12 .06 |

.27 .13 .06 |

.30 .15 .07 |

3.00 1.50 .75 |

30.00 15.00 7.50 |

At Five Per Cent

| $1 | $2 | $3 | $4 | $5 | $6 | $7 | $8 | $9 | $10 | $100 | $1000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year 6 mos. 3 mos. |

.05 .02 .01 |

.10 .05 .02 |

.15 .07 .03 |

.20 .10 .05 |

.25 .12 .06 |

.30 .15 .07 |

.35 .17 .08 |

.40 .20 .10 |

.45 .22 .11 |

.50 .25 .12 |

5.00 2.50 1.25 |

50.00 25.00 12.50 |

QUESTIONS

How much will $1.00 amount to in six months? In one year?

How much will $10.00 amount to in six months? In one year?

The Hare (talking to his neighbors): Ho, ho, here comes that slow-poke, Mr. Tortoise! Look at him crawling along! Why, he doesn’t move faster than a snail! I will wish him good day. (He goes toward the tortoise.) Good morning, Mr. Tortoise; you must be tired to travel so slowly!

The Tortoise: Good morning, neighbor. No, I am not tired, and I do move slowly; but if I keep on moving, I get where I am going.

The Hare: Oh, you do, do you? Well, if I moved as slowly as you, I wouldn’t try to get to many places, I am sure.

The Tortoise: Oh, I don’t know about that. I guess if we started out for the same place, I would be there as soon as you.

[Pg 61]The Hare: What a joke! I’ll take that up! Will you race me to the river?

The Tortoise: I will.

The Hare: Are you in earnest! Come on; you will soon see my feet fly when you race with me.

The Tortoise: Very well! I will start right away. (He goes slowly on.)

The Hare (moving toward the neighbors): Listen! Oh, such a joke! The tortoise is going to race with me to the river.

Neighbors: Oh, what fun! Let us be the judges. We will run over to the river to mark a goal. (They go.)

The Hare (yawning): If it isn’t too funny to see the poor old tortoise jogging along. It will not take me ten minutes to get to the goal. I guess I will lie down and take a nap, for I am a little tired. (He lies down, stretches himself out, and goes to sleep.)

The Tortoise (moving slowly): Slow—and—steady—slow—and—steady. One, two, three, four. It is hard work to race, but I will keep on trying. I will keep on trying—just a little way at a time. Just—a—little—at—a—time.

The Hare (waking up and looking about him): Why, I must have overslept! Dear me, I don’t see the tortoise! Why, if that slow fellow should win the race, I should be the laughing-stock of all the neighbors. Maybe I should be written down in a fable! But pshaw! I shall overtake him just around the turn.

The Tortoise (crossing the goal): Slow—and—steady—slow—and—steady.

[Pg 62]Group of Neighbors (clapping their hands): Slow and steady wins the race. You win, Mr. Perseverance.

The Hare (bounding over the goal just a minute too late): Oh, if I had only kept on! If I only had not stopped for a nap! Did the tortoise win?

Neighbors: Ha, ha, ha! just one minute too late! Mr. Tortoise wins!

(The hare and the tortoise shake hands.)

The Hare: You have taught me two lessons, Mr. Tortoise—never give up trying; and, don’t be too sure. I congratulate you upon winning the race.

The Tortoise: Thank you. Sometimes plodders do come out ahead.

Neighbors: “Perseverance wins success.”

QUESTIONS

Why do you suppose the hare decided to take a little nap?

Was it easy for the tortoise to get to the goal?

Did you ever have something hard to do? Did you keep on until you finished?

In your class there are some children like the slow and steady tortoise, and some like the hare who think they can rest once in a while.

Are you like either one?

Once upon a time there was a little girl, named Letty, who had a little crippled sister.

Letty loved her little sister very dearly and wished that she might be cured.

But her father and mother were so poor that they could not afford to send for the great doctor who could make their little girl well.

So, during the summer vacation Letty worked for a neighbor and saved all the money she earned. She hoped that if she kept every penny she would soon have enough to pay the doctor for curing her sister. But her little hoard grew very slowly, because, you see, she earned only fifteen cents a week.

[Pg 64]One day there was a heavy thunder storm; and when the storm was over, a beautiful rainbow appeared in the sky. Letty stood on the neighbor’s porch and watched the rainbow.

“I wonder what is at the end of the rainbow,” she said to herself; but Mrs. Harrison—for that was the neighbor’s name—overheard her.

“Why,” she exclaimed, “don’t you know? There is a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. I have always heard that. If anyone takes it away, another pot of gold comes in its place. But no one is permitted to take more than one pot of gold.”

Letty said nothing, but she began to think very hard. “If I could find that pot of gold,” she thought, “I could use it to have my little sister cured.”

And then and there Letty decided to do a very daring thing. So, early the next morning, just as soon as she could see, she got out of bed and went noiselessly downstairs. She packed a lunch and started out to find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

She remembered quite well where the rainbow had seemed to end—in the forest half way up the distant mountain. In the bright morning sunlight, it appeared to be much nearer than it really was. She was sure she could find the way.

After she had walked a long time, however, she came to a place that she had never seen before.

It was a swampy, marshy meadow; and her feet sank deep into the miry mud as she splashed along.

“Oh, dear!” she thought. “I almost wish I hadn’t come! I shall have to turn back!”

What Do You Suppose Made that Noise?

Then suddenly, she thought of the little lame sister who could not run and play.

“I will go on,” Letty said; “I must!”

Just then, she saw in front of her a grassy little island, or hummock, quite large enough for her two feet. She managed to step on it; and—what do you think? She saw before her a whole row of hummocks all the way across the meadow!

“How nice that will be for any one else who looks for the end of the rainbow,” thought little Letty, as she sat down on the last hummock to rest.

The next minute, she heard a loud Hiss-s-s!

What do you suppose made that noise? Yes, a big black snake.