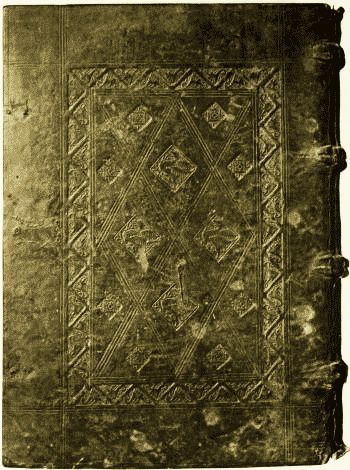

BINDING WITH CAXTON'S DIES

(Frontispiece, and see page 85)]

The Publication Committee of the Caxton Club certifies that this is one of an edition of two hundred and fifty-two copies printed on American hand-made paper, of which two hundred and forty are for sale, and three copies printed on Japanese vellum. The printing was done from type which has been distributed.

This is also one of one hundred and forty-eight copies into which has been incorporated a leaf from an imperfect copy of the first edition of Chaucer's "Canterbury Tales," printed by William Caxton, and formerly in Lord Ashburnham's library, having been purchased for this purpose by the Caxton Club. The copies so treated comprise the three Japanese vellum copies and one hundred and forty-five of the American hand-made paper copies; all of the latter are for sale.

BY

E. GORDON DUFF, M. A. OXON.

SANDARS READER IN BIBLIOGRAPHY IN THE

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

CHICAGO

THE CAXTON CLUB

MCMV

COPYRIGHT BY THE CAXTON CLUB

NINETEEN HUNDRED AND FIVE

| chapter | page | |

| Preface | 11 | |

| I. | Caxton's Early Life | 13 |

| II. | Caxton's Press at Bruges | 22 |

| III. | The Early Westminster Press | 33 |

| IV. | 1480-1483 | 47 |

| V. | 1483-1487 | 56 |

| VI. | 1487-1491 | 70 |

| VII. | Caxton's Death | 86 |

| Appendix | 91 | |

| Index | 99 |

| plate | page | |

| Binding with Caxton's Dies

[From the cover of a book in the library of Corpus Christi College, Oxford.] |

Frontispiece | |

| I. | Prologue from the Bartholomaeus This contains the verse relating to Caxton's first learning to print. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] (Erratum: Read Prologue for Epilogue on Plate I.) |

22 |

| II. | The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye Printed in Caxton's Type 1. Leaf 253, the first of the third book. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

28 |

| III. | Epilogue to Boethius Printed in Caxton's Type 3. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

36 |

| IV. | The Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres Printed in Caxton's Type 2. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

38 |

| V. | Caxton's Advertisement Printed in Caxton's Type 3. Intended as an advertisement for the Pica or Directorium ad usum Sarum. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

42 |

| VI. | The Mirrour of the World Printed in Caxton's Type 2*. The woodcuts in this book are the first used in England. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

50 |

| VII. | The Mirrour of the World Printed in Caxton's Type 2*. This shows a diagram with the explanations filled in in MS. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] [pg 8] |

50 |

| VIII. | The Game and Playe of the Chesse Printed in Caxton's Type 2*. The wood-cut represents the philosopher who invented the game. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

52 |

| IX. | Liber Festivalis Printed in Caxton's Type 4*. The colophon to the second part of the book entitled "Quattuor Sermones." [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

56 |

| X. | Chaucer's Canterbury Tales Printed in Caxton's Type 4*. This is the second edition printed by Caxton, but the first with illustrations. [From the copy in the British Museum.] |

58 |

| XI. | The Fables of Esope Printed in Caxton's Type 4*. These two cuts show the ordinary type of work throughout the book. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

60 |

| XII. | The Fables of Esope The wood-cut here shewn is engraved in an entirely different manner from the rest. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

60 |

| XIII. | The Fables of Esope Shewing the only ornamental initial letter used by Caxton. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

62 |

| XIV. | The Image of Pity [From the unique wood-cut in the British Museum.] |

66 |

| XV. | Speculum Vitæ Christi Printed in Caxton's Type 5. The wood-cut depicts the visit of Christ to Mary and Martha. [From the copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

66 |

| XVI. | Caxton's Device [From an example in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

70 |

| XVII. | Legenda ad usum Sarum Printed at Paris by W. Maynyal, probably for Caxton. The book is known only from fragments. [From a leaf in the University Library, Cambridge.] |

70 |

| XVIII. | The Indulgence of 1489[pg 9] Printed in Caxton's Type 7. This type is not mentioned by Blades in his Life of Caxton. [From a copy in the British Museum.] |

72 |

| XIX. | The Boke of Eneydos Printed in Caxton's Type 6. This page gives Caxton's curious story about the variations in the English language. [From the copy in the British Museum.] |

76 |

| XX. | Ars Moriendi Printed in Caxton's Type 6 [text] and 8 [heading]. [From the unique copy in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

76 |

| XXI. | Servitium de Transfiguratione Jesu Christi Printed in Caxton's Type 5. [From the unique copy in the British Museum.] |

78 |

| XXII. | The Crucifixion Used by Caxton in the Fifteen Oes, and frequently afterwards by Wynkyn de Worde. [From an example in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.] |

78 |

| XXIII. | The Lyf of Saint Katherin Printed by W. de Worde with a modification of Caxton's Type 4*. The large initials serve to distinguish de Worde's work from Caxton's. [From the copy in the British Museum.] |

80 |

| XXIV. and XXV. | The Metamorphoses of Ovid Two leaves, one with the colophon, from a manuscript prepared by Caxton for the press, and perhaps in his own hand. [From the MS. in the Pepysian Library, Magdalene College, Cambridge.] |

82 |

A life of Caxton must of necessity be little more than an account of his work. As in the case of the great inventor Gutenberg, nothing but a few documents are connected with his name. In those days of tedious communication and imperfect learning, the new art was considered as merely a means of mechanically producing manuscripts, which the general public must have looked on with apathy. By the time that its vast importance was fully perceived, the personal history of the pioneers was lost.

Caxton, however, indulged now and then in little pieces of personal expression in his prefaces, which, if they tell us little of his life, throw a certain amount of pleasant light on his character.

In the present book I have tried to avoid as far as possible the merely mechanical bibliographical detail, which has been relegated in an abridged form to an appendix, and have confined myself to a more general description of the books, especially of those not hitherto correctly or fully described.

Since William Blades compiled his great work, The Life and Typography of William Caxton, some discoveries have been made and some errors corrected, but his book must always remain the main authority on the subject, the solid foundation for the history of our first printer.

Where I have pointed out mistakes in his book or filled up omissions, it is in no spirit of fault-finding, but rather the desire of a worker in the same field to add a few stones to the great monument he has built.

Chain Bridge, Berwyn, May, 1902.

Amongst those men to whom belongs the honour of having introduced the art of printing into the various countries of Europe, none holds a more marked or a more important position than William Caxton. This is not the place to discuss the vexed questions, when, where, or by whom the art was really discovered; but the general opinion may be accepted, that in Germany, before the year 1450, Gutenberg had thought out the invention of movable type and the use of the printing-press, and that before the end of the year 1454 a dated piece of printing had been issued. From town to town down the waterways of Germany the art spread, and the German printers passed from their own to other countries,—to Italy, to Switzerland, and to France; but in none of these countries did the press in any way reflect the native learning or the popular literature. Germany produced nothing but theology or law,—bibles, psalters, and works of Aquinas and Jerome, Clement or Justinian. Italy, full of zeal for the new revival of letters, would have nothing but classics; and as in Italy so in France, where the press was at work under the shadow of the University.

Fortunately for England, the German printers never reached her shores, nor had the new learning crossed the Channel when Caxton set up his press at Westminster, so that, unique amongst the nations of Europe, England's first printer was one of her own people, and the first products of her press books in her own language. Many writers, such as Gibbon and Isaac Disraeli, have seen fit to disparage the [pg 14] work of Caxton, and have levelled sneers, tinged with their typical inaccuracy, at the printer and his books. Gibbon laments that Caxton "was reduced to comply with the vicious taste of his readers; to gratify the nobles with treatises on heraldry, hawking, and the game of chess [Caxton printed neither of the first two]; and to amuse the popular credulity with romances of fabulous knights and legends of more fabulous saints." "The world," he continues, "is not indebted to England for one first edition of a classic author." Disraeli, following Gibbon, writes: "As a printer without erudition, Caxton would naturally accommodate himself to the tastes of his age, and it was therefore a consequence that no great author appears among the Caxtons." And again: "Caxton, mindful of his commercial interests and the taste of his readers, left the glory of restoring the classical writers of antiquity, which he could not read, to the learned printers of Italy."

It is idle to argue with men of this attitude of mind. Of what use would it have been to us, or profit to our printer, to reprint editions of the classics which were pouring forth from foreign presses, and even there, where most in demand, were becoming unsaleable? Those who wanted classics could easily and did easily obtain them from the foreign stationers. Caxton's work was infinitely more valuable. He printed all the English poetry of any moment then in existence. Chaucer he printed at the commencement of his career, and issued a new edition when a purer text offered itself. Lidgate and Gower soon followed. He printed the available English chronicles, those of Brut and Higden, and the great romances, such as the History of Jason and the Morte d'Arthur. While other printers employed their presses on the dead languages he worked at the living. He gave to the people the classics of their own land, and at a time when the character of our literary tongue was being [pg 15] settled did more than any other man before or since has done to establish the English language.

Caxton's personal history is unfortunately surrounded by considerable obscurity. Apart from the glimpses which we catch here and there in the curious and interesting prefaces which he added to many of the books he printed, we know scarcely anything of him. Thus the story of his life wants that variety of incident which appeals so forcibly to human sympathy and communicates to a biography its chief and deepest interest. The first fact of his life we learn from the preface of the first book he printed. "I was born and lerned myn Englissh in Kente in the Weeld where I doubte not is spoken as brode and rude Englissh as is in ony place of Englond."

This is the only reference to his birthplace, and such as it is, is remarkably vague, for the extent or limits of the Weald of Kent were never clearly defined. William Lambarde, in his Perambulation of Kent, writes thus of it: "For it is manifest by the auncient Saxon chronicles, by Asserus Menevensis, Henrie of Huntingdon, and almost all others of latter time, that beginning at Winchelsea in Sussex it reacheth in length a hundred and twenty miles toward the West and stretched thirty miles in breadth toward the North." The name Caxton, Cauxton, or Causton, as it is variously spelt, was not an uncommon one in England, but there was one family of that name specially connected with that part of the country who owned the manor of Caustons, near Hadlow, in the Weald of Kent. Though the property had passed into other hands before the time of the printer's birth, some families of the name remained in the neighbourhood, and one at least retained the name of the old home, for there is still in existence a will dated 1490 of John Cawston of Hadlow Hall, Essex.

The Weald was largely inhabited by the descendants of the Flemish families who had been induced by Edward III. to settle there and carry on the manufacture of cloth. Privileged by the king, the trade rapidly grew, and in the fifteenth century was one of great importance. This mixture of Flemish blood may account in certain ways for the "brode and rude Englissh," just as the Flemish trade influenced Caxton's future career.

In the prologue to Charles the Great, Caxton thanks his parents for having given him a good education, whereby he was enabled to earn an honest living, but unfortunately does not tell us where the education was obtained, though it would probably be at home, and not in London, as some have suggested. After leaving school Caxton was apprenticed to a London merchant of high position in the year 1438. This is the first actual date in his life which we possess, and one from which it is possible to arrive with some reasonable accuracy at his age.

Although then, as now, it was customary for a man to attain his majority at the age of twenty-one, there was also a rule, at any rate in the city of London, that none could attain his civic majority, or be admitted to the freedom of the city, until he had reached the age of twenty-four. The period for which a lad was bound apprentice was based on this fact, for it was always so arranged that he should issue from his apprenticeship on attaining his civic majority. The length of servitude varied from seven to fourteen years, so it is easy to calculate that the time of Caxton's birth must lie between the years 1421 and 1428. When we consider also that by 1449 he was not only out of his apprenticeship, but evidently a man of means and position, we are justified in supposing that he served the shortest time possible, and was born in 1421 or very little later.

The master to whom he was bound, Robert Large, was one of the [pg 17] most wealthy and important merchants in the city of London, and a leading member of the Mercers' Company. In 1427 he was Warden of his Company, in 1430 he was made a Sheriff of London, and in 1439-40 rose to the highest dignity in the city, and became Lord Mayor. His house, "sometime a Jew's synagogue, since a house of friars, then a nobleman's house, after that a merchant's house, wherein mayoralties have been kept, but now a wine tavern (1594)," stood at the north end of the Old Jewry. Here Caxton had plenty of company,—Robert Large and his wife, four sons, two daughters, two assistants, and eight apprentices. Only three years, however, were passed with this household, for Large did not long survive his mayoralty, dying on the 4th of April, 1441. Amongst the many bequests in his will the apprentices were not forgotten, and the youngest, William Caxton, received a legacy of twenty marks.

On the death of Robert Large, in April, 1441, Caxton was still an apprentice, and not released from his indentures. If no specific transfer to a new master had been made under the will of the old, the executors were bound to supply the apprentices with the means of continuing their service. That Caxton served his full time we know to have been the case, since he was admitted a few years later to the Livery of the Mercers' Company, but it is clear that he did not remain in England. In the prologue to the Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, written in 1471, he says: "I have contynued by the space of xxx yere for the most part in the contres of Braband, Flandres, Holand, and Zeland"; and this would infer that he finished his time of apprenticeship abroad.

About 1445 or 1446 Caxton had served his time, and he became a merchant trading on his own account, and apparently with considerable success, a result naturally to be expected from his conspicuous energy. By 1450 he was settled at Bruges, and there exists in the [pg 18] town archives the report of a lawsuit in which he was concerned in that year. Caxton and another merchant, John Selle, had become sureties for the sum of £110 owed by John Granton, a merchant of the Staple of Calais, to William Craes, another merchant. As Granton had left Bruges without paying his debt, Craes had caused the arrest of the sureties. These admitted their liability, but pleaded that Craes should wait the return of Granton, who was a very rich man, and had perhaps already repaid the debt. The verdict went against Caxton and his friend, who were compelled to give security for the sum demanded; but it was also decreed that should Granton, on his return to Bruges, be able to prove that the money had been paid before his departure, the complainant should be fined an amount double that of the sum claimed.

In 1453 Caxton paid a short visit to England in company with two fellow-traders, when all three were admitted to the Livery of the Mercers' Company.

For the next ten years we can only conjecture what Caxton's life may have been, as no authentic information has been preserved. All that can be said is, that he must have succeeded in his business and have become prosperous and influential, for when the next reference to him occurs, in the books of the Mercers' Company for 1463, he was acting as governor of that powerful corporation, the Merchant Adventurers.

This Company, which had existed from very early times, had been formed to protect the interests of merchants trading abroad, and though many guilds were represented, the Mercers were so much the most important, both in numbers and wealth, that they took the chief control, and it was in their books that the transactions of the Adventurers were entered.

In 1462 the Company obtained from Edward IV. a larger charter, [pg 19] and in it a certain William Obray was appointed "Governor of the English Merchants" at Bruges. This post, however, he did not fill for long, for in the year following we find that his duties were being performed by Caxton. Up to at least as late as May, 1469, he continued to hold this high position. His work at this period must have been most onerous, for the Duke of Burgundy set his face against the importation of foreign goods, and decreed the exclusion of all English-made cloth from his dominions. As a natural result, the Parliament of England passed an act prohibiting the sale of Flemish goods at home, so that the trade of the foreign merchants was for a time paralyzed. With the death of Philip in 1467, and the succession of his son Charles the Bold, matters were entirely changed. The marriage of Charles with the Princess Margaret, sister of Edward IV., cemented the friendship of the two countries, and friendly business relations were again established. The various negotiations entailed by these changes, in all of which Caxton must have played an important part, perhaps impaired his health, and were responsible for his complaint of a few years later, that age was daily creeping upon him and enfeebling his body.

Somewhere about 1469 Caxton's business position and manner of life appear to have undergone a considerable change, though we have now no clue as to what occasioned it. He gave up his position as Governor of the Adventurers and entered the service of the Duchess of Burgundy, but in what capacity is not known. In the greater leisure which the change afforded, he was able to pursue his literary tastes, and began the translation of the book which was destined to be the first he printed, Le Recueil des Histoires de Troyes. But there is perhaps another reason which prevailed with him to alter his mode of life. He was no doubt a wealthy man and able to retire from business, and it seems fairly certain that about this time he [pg 20] married. In 1496 his daughter Elizabeth was divorced from her husband, Gerard Croppe, owing apparently to some quarrels about bequests; and assuming Caxton to have been married in 1469 the daughter would have been twenty-one at the time of his death. The rules of the various companies of merchants trading abroad were extremely strict on the subject of celibacy, a necessary result of their method of living. Each nation had its house, where its merchants lived together on an almost monastic system. Each had his own little bed-chamber in a large dormitory, but meals were all taken together in a common room.

Caxton's duties in the service of the Duchess had most probably to do with affairs of trade, in which at that time even the highest nobility often engaged. The Duchess obtained from her brother Edward IV. special privileges and exemptions in regard to her own private trading in English wool, and she would naturally require some one with competent knowledge to manage her affairs. This, with her interest in Caxton's literary work, probably determined her choice, and under her protection and patronage Caxton recommenced his work of translation. In 1471 he finished and presented to the Duchess the translation of Le Recueil des Histoires de Troyes, which had been begun in Bruges in March, 1469, continued in Ghent, and ended in Cologne in September, 1471.

The completion of this manuscript was no doubt the turning-point in Caxton's career, as we may judge from his words in the epilogue to the printed book. "Thus ende I this book whyche I have translated after myn Auctor as nyghe as god hath gyven me connyng to whom be gyven the laude and preysyng. And for as moche as in the wrytyng of the same my penne is worn, myn hande wery and not stedfast, myn eyen dimmed with overmoche lokyng on the whit paper, and my corage not so prone and redy to laboure [pg 21] as hit hath ben, and that age crepeth on me dayly and febleth all the bodye, and also because I have promysid to dyverce gentilmen and to my frendes to addresse to hem as hastely as I myght this sayd book. Therefore I have practysed and lerned at my grete charge and dispense to ordeyne this said booke in prynte after the maner and forme as ye may here see. And it is not wreton with penne and ynke as other bokes ben to thende that every man may have them attones. For all the bookes of this storye named the recule of the historyes of troyes thus enprynted as ye here see were begonne in oon day, and also fynysshed in oon day."

The trouble of multiplying copies with a pen was too great to be undertaken, and the aid of the new art was called in. Caxton ceased to be a scribe and became a printer.

In what city and from what printer Caxton received his earliest training in the art of printing has been a much debated question amongst bibliographers. The only direct assertion on the point is to be found in the lines which form part of the prologue written by Wynkyn de Worde, and added to the translation of the De proprietatibus rerum of Bartholomaeus Anglicus, issued about 1495.

"And also of your charyte call to remembraunce,

The soule of William Caxton, the fyrste prynter of this book,

In Laten tongue at Coleyn, hymself to avaunce,

That every well disposed man may thereon look."

As Wynkyn de Worde was for long associated with Caxton in business and became after his death his successor, it seems impossible to put aside his very plain statement as entirely inaccurate. William Blades, in his Life of Caxton, utterly denies the whole story. "Are we to understand," he writes, "that the editio princeps of Bartholomaeus proceeded from Caxton's press, or that he only printed the first Cologne edition? that he issued a translation of his own, which is the only way in which the production of the work could advance him in the Latin tongue? or that he printed in Latin to advance his own interests? The last seems the most probable reading. But though the words will bear many constructions, they are evidently intended to mean that Caxton printed Bartholomaeus at Cologne. Now, this seems to be merely a careless statement of Wynkyn de Worde; for if Caxton did really print Bartholomaeus in that city, it must have been with his own types and presses, as the workmanship of his early volumes proves that he had no connexion with the Cologne printers, whose practices were entirely different."

The meaning which Mr. Blades has read into the lines seems hardly a reasonable one. Surely, the expression "hymself to avaunce" cannot apply to the advancement of his own interests, but rather to knowledge; nor can we imagine a sensible person who wished to learn Latin entering a printing-office for that purpose. It must rather apply to the printing itself, and point to the fact that when at Cologne he printed or assisted to print an edition of the Bartholomaeus in Latin in order to learn the practical details of the art.

It must also be borne in mind that in 1471, when Caxton paid his visit to Cologne, printing had been introduced into few towns. Printed books were spread far and wide, and some of Schoeffer's editions have inscriptions showing that they had been bought at an early date, within a year of their issue, at Bruges; but Cologne was the nearest town where the press was actually at work, and where already a number of printers were settled.

Blades adds as another argument the fact that no edition of a Bartholomaeus has been found printed in Caxton's type, but when starting as a mere learner in another person's office he could hardly be expected to have type of his own. But there is an edition of the Bartholomaeus, which, though without date or name of place or printer, was certainly printed at Cologne about the time of Caxton's visit. It is a large folio of 248 leaves, with two columns to the page and 55 lines to a column. It is described by Dibdin in his Bibliotheca Spenceriana (Vol. III., p. 180), though with his usual inaccuracy he gives the number of leaves as 238. There is little doubt that the words of Wynkyn de Worde refer to this edition.

Cologne, as might be expected from its advantageous position on the Rhine, was one of the earliest towns to which the art of printing spread from Mainz. Ulric Zel, its first printer, was settled there some time before 1466, when he issued his first dated book, and by 1470 several others were at work. The study of early Cologne printing is extremely complex, for the majority of books which were produced there contain no indication of printer, place of printing, or date. Some printers issued many volumes, and their names are still unknown, so that they can only be referred to under the name of some special book which they printed; as, the "Printer of Dictys," the "Printer of Dares," and so on.

M. Madden, the French writer on early printing, who had a genius for obtaining from plausible premisses the most utterly preposterous conclusions, was possessed with the idea that the monastery of Weidenbach, near Cologne, was a vast school of typography, where printers of all nations and tongues learned their art. He ends up his article on Caxton, as he ended up those on other early printers, "Je finis cette lettre en vous promettant de revenir, tôt ou tard, s'il plaît à Dieu, sur William Caxton se faisant initier à la typographie, non pas à Bruges, par Colard Mansion, comme le veut M. W. Blades, mais à Weidenbach, par les frères de la vie commune."

As we know from Caxton's own statements, he had when at Cologne considerable leisure, which was partly employed in writing out his translation of Le Recueil, and like all literary persons, must have felt great interest in the new art. It was no longer a secret one, and there would be little difficulty for a rich and important man like Caxton to obtain access to a printing-office, where he might learn the practical working and master the necessary details.

The mechanical part of the work was not at that time a complicated [pg 25] process, and would certainly not have taken long to master. Caxton no doubt learned from observation the method of cutting and the mechanism of casting type, and by a little practical work the setting up of type, the inking, and the pulling off the impression.

At the close of 1471 Caxton returned to Bruges, and presented to the Duchess of Burgundy the manuscript of the Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, which he had finished while at Cologne. This work, which had been undertaken at the request of the Duchess, proved to be exceedingly popular at the court. Caxton was importuned to set to work on other copies for rich noblemen. The length of time which the production of these copies would take reminded him of the excellent invention which he had seen at work at Cologne, that art of writing by mechanical means, "ars artificialiter scribendi," as the earliest printers called it, by which numerous copies could be produced at one and the same time.

Mr. Blades, in common with almost every writer, assumes that printing was introduced into Bruges at a very much earlier date than there is any warrant for supposing. He speaks of Colard Mansion as having "established a press shortly after 1470 at Bruges." Other writers put back the date as much as three years earlier, confusing, as is often the case, the date of the writing of a book with the date of its printing. Colard Mansion's name does not occur in a dated colophon before 1476, in his edition of the French translation of a work of Boccaccio, and we have no reason to suppose that he began to work more than two years at the outside before this date. In the guild-books at Bruges he is entered as a writer and illuminator of manuscripts from 1454 to 1473, so that we are certainly justified in considering that he did not commence to print until after the latter date. Other writers have brought forward a mysterious and little known printer, Jean Brito, as [pg 26] having not only introduced the art into Bruges, but as being the inventor of printing. An ambiguous statement in one of his imprints, where he says that he learned to print by himself with no one to teach him, refers more probably to some method of casting type, and not to an independent discovery, and his method of work and other details point almost certainly to a date about 1480. Some of his type is interesting as being almost identical with a fount used a few years later in London.

Now, there is one very important point in this controversy which appears to have been quite overlooked. Caxton, we may suppose, learned the art of printing about 1471 at Cologne, the nearest place to Bruges where the printing-press was then at work. But, say the opponents of this theory, his type bears no resemblance to Cologne type, so that the theory is absurd. It must, however, be remembered that in the interval between Caxton's learning the art and beginning to practice it printers had begun to work in Utrecht, Alost, and Louvain. If he required any practical assistance in the cutting or casting of type or the preparation of a press, he would naturally turn to the printers nearest to him,—Thierry Martens, with John of Westphalia at Alost, or to John Veldener or John of Westphalia (who had moved from Alost in 1474) at Louvain.

Caxton's preparations for setting up a printing-press on his own account were most probably made in 1474. His assistant or partner, Colard Mansion, by profession a writer and illuminator of manuscripts, is entered as such in the books of the Guild of St. John from 1454 to 1473, when his connexion with the guild ceases. This may point to two things: he had either left Bruges, perhaps in search of printing material, or had changed his profession; and the former seems the most probable explanation.

If Caxton was assisted by any outside printer in the preparation [pg 27] of his type, there can be little doubt that that printer was John Veldener of Louvain. Veldener was matriculated at Louvain in the faculty of medicine, July 30, 1473. In August, 1474, in an edition of the Consolatio peccatorum of Jacobus de Theramo, printed by him, there is a prefatory letter addressed "Johanni Veldener, artis impressoriae magistro," showing that he was by that time a printer. He was also, as he himself tells us, a type-founder, and in 1475 he made use of a type in many respects identical with one used by Caxton.

In body they are precisely the same, and in most of the letters they are to all appearance identical; and the fact of their making their appearance about the same time in the Lectura super institutionibus of Angelus de Aretio, printed at Louvain by Veldener, and in the Quatre derrenieres choses, printed at Bruges by Caxton, would certainly appear to point to some connexion between the two printers.

Furnished with a press and two founts of type, both of the West Flanders kind and cut in imitation of the ordinary book-hand, William Caxton and Colard Mansion started on their career as printers.

Unlike all other early printers, Caxton looked to his own country and his own language for a model, and although in a foreign country, issued as his first work the first printed book in the English language. Other countries had been content to be ruled by the new laws forced upon them by the revival of learning. Caxton then, as through his life, spent his best energies in the service of our English tongue. The Recuyell of the Hystoryes of Troye, a translation by Caxton from the French of Raoul Le Fevre, who in his turn had adapted it from earlier writers on the Trojan war, was the first book to be issued.

The prologue to the first part and the epilogues to the second and third contain a few interesting details of Caxton's life. That to the third contains some remarks about the printing. "Therefore I have practysed and lerned at my grete charge and dispense to ordeyne this said booke in prynte after the maner and forme as ye may here see, and it is not wreton with penne and ynke as other bokes ben to thende that every man may have them attones. For all the bookes of this storye named the recule of the historyes of troyes thus enprynted as ye here see were begonne in oon day, and also fynysshed in oon day."

The wording of this sentence, which is perhaps slightly ambiguous, has caused several writers to fall into a curious error in supposing that Caxton meant to assert that the printed books were begun and finished in one day. His real meaning, of course, was, that while in written books the whole of a volume was finished before another was begun, in printed books the beginnings of all the copies of which the edition was to consist were printed off in one day, so also the last sheet of all the copies would be printed off in one day, and the whole edition finished simultaneously.

The Recuyell is a small folio of 352 leaves, the first being blank, and each page contains 31 lines, spaced out in a very uneven manner. The second leaf, on which the book begins, contains Caxton's prologue, printed in red ink. The book is without signatures, headlines, numbers to the pages, or catchwords.

Although a considerable number of copies—some twenty in all—are still in existence, almost every one is imperfect. The very interesting copy bought by the Duke of Devonshire at the Roxburghe sale in 1812 for £1,060 10s. which had at one time belonged to Elizabeth, wife of Edward IV., wanted the last leaf; Lord Spencer's wanted the introduction. Blades, it should be noticed, in his lists of existing copies of Caxton's books, uses the word "perfect" in a misleading way, often taking no notice of the blank leaves being missing, which are essential to a perfect copy, and often also omitting to distinguish between a made-up copy and one in genuine original condition.

The finest copy is probably that formerly in the library of the Earl of Jersey, which was sold in 1885. It was described as perfect, and possessed the blank leaf at the beginning. Valued in 1756, when Bryan Fairfax's library was bought by Lord Jersey's ancestor, Mr. Child, at £8 8s., it produced the high price of £1,820.

The next book to appear from the Bruges press was the Game and playe of the Chess, "In which I fynde," as Caxton says in his prologue, "thauctorites, dictees, and stories of auncient doctours philosophres poetes and of other wyse men whiche been recounted and applied unto the moralite of the publique wele as well of the nobles as of the comyn peple after the game and playe of the chesse."

The original of the work was the Liber de ludo scacchorum of Jacobus de Cessolis, which had been translated into French by Jean Faron and Jean de Vignay, both belonging to the order of preaching friars, but who worked quite independently of each other. Caxton appears to have made use of both versions, part of his book being translated from one and part from the other.

It is a considerably shorter book than the Recuyell, containing only 74 leaves, of which the first and last were blank. Like the last, it is a folio, with 31 lines to the page. It is not a very scarce book, as about twelve copies are known, but of these almost every one is imperfect. The best copy known is probably that belonging to Colonel Holford, of Dorchester House, which still remains in its old binding, and another beautiful copy was obtained [pg 30] by Lord Spencer from the library of Lincoln Minster, the source of many rarities in the Spencer collection. The story has often been told how Dibdin, the well-known writer of romantic bibliography, persuaded the lax Dean and Chapter of Lincoln to part with their Caxtons to Lord Spencer. We must, however, give even Dibdin his due, and point out that he was quite ignorant of the transaction, which was carried out by Edwards, the bookseller. The letter from Lord Spencer to Dibdin is still in existence, in which he describes the new Caxtons he had acquired, carefully omitting to say through whom or from what source. This, however, Dibdin found out for himself some time after, and raided Lincoln on his own account. He issued a small catalogue of his purchases, under the title of A Lincoln Nosegay, and a few were bought by Lord Spencer, the remainder finding their way into the libraries of Heber and other collectors.

The last book printed by Caxton and Mansion in partnership at Bruges was the Quatre derrenieres choses, a treatise on the four last things, Death and Judgment, Heaven and Hell, commonly known under the Latin titles of De quattuor novissimis or Memorare novissima, and later issued in English by Caxton as the Cordyale.

In this book first appears Caxton's type No. 2, which bears so strong a resemblance to the fount used by Veldener. The book is a folio of 74 leaves (not 72, as stated by Blades), and has 28 lines to the page. There is a certain amount of printing in red, which was produced in a peculiar way. It was not done by a separate pull of the press, as was the general custom, but the whole page having been set up and inked, the ink was wiped off from the portions to be printed in red, and the red colour applied to them by hand, and the whole printed at one pull.

For long but one copy of this book was known, preserved in the [pg 31] British Museum, and bound up with a copy of the Meditacions sur les sept pseaulmes, to be described shortly. Some years ago, however, another copy wanting two leaves was found, and it is now in a private collection in America.

This was the last book printed abroad with which Caxton had any connexion, and the new type used in it was no doubt specially prepared for him to carry to England. It contained far more distinct types than the first, which had 163, for it began with 217, which were increased on recasting to at least 254.

Supplied with new type and other printing material, Caxton made his preparations to return to his own country. The exact date cannot now be determined, but it was probably early in the year 1476. It is curious that just about this time one of the Cologne presses issued the first edition of the Breviary for the use of the church of Salisbury, the use adopted by all the south of England, and it may be that Caxton, who had had dealings with the Cologne printers, may have been connected in some way with its production and publication in England.

After Caxton had left Bruges his former partner, Colard Mansion, continued to print by himself. In Caxton's first type, which had been left behind at Bruges, he printed three books, Le Recueil des histoires de Troyes, Les fais et prouesses du chevalier Jason, and the Meditacions sur les sept pseaulmes. All three are in folio, with 31 lines to the page. As they are often confused by writers with books really printed by Caxton, and as they are produced from type which was at one time in his possession, they may perhaps merit a short description.

The Recueil contains 286 leaves, of which two are blank. Six copies are known, of which by far the finest was sold at the Watson Taylor sale in 1823 to Lord Spencer. It was then in its original [pg 32] binding and uncut, but Lord Spencer, who, like most collectors of his day, despised old bindings, had it rebound in morocco, and the edges trimmed and gilt. Another very fine copy, probably "conveyed" from some continental library, was purchased from M. Libri by the British Museum in 1844.

The Jason contains 134 leaves, of which the first and last two are blank. A magnificent copy, the only one in England, is in the library of Eton College, and there are two other copies, slightly imperfect, at Paris.

Of the third book, the Meditacions sur les sept pseaulmes, only one copy is known to exist. It is in the British Museum, bound up with a copy of the Quatre derrenieres choses, and is quite perfect. It contains 34 leaves, the last being blank.

Mansion continued for some time onwards to print at Bruges in the workshop which perhaps he had shared with Caxton, over the church porch of St. Donatus, but later in life seems to have been unsuccessful and fallen on evil times. The books which he then printed with such little success are now by the chance of fate the most sought for and valuable amongst the productions of the early continental press.

In 1476 Caxton returned to England and took up his residence in the precincts of Westminster Abbey, at a house with the sign of the "Red Pale" in the "almonesrye." This locality is thus described by Stow: "Now will I speake of the gate-house, and of Totehill streete, stretching from the west part of the close.... The gate towards the west is a Gaile for offenders.... On the South-side of this gate, King Henry the 7. founded an almeshouse.... Near unto this house westward was an old chappel of S. Anne, over against the which, the Lady Margaret, mother to King Henry the 7. erected an Almeshouse for poore women ... the place wherein this chappell and Almeshouse standeth was called the Elemosinary or Almory, now corruptly the Ambry, for that the Almes of the Abbey were there distributed to the poore."

In the account roll of John Estenay, sacrist of Westminster from September 29, 1476, to September 29, 1477, we find, under the heading "Firme terrarum infra Sanctuarium," the entry "De alia shopa ibidem dimissa Willelmo Caxton, per annum Xs." Another account-book, still preserved at Westminster, shows that in 1483 Caxton paid for two shops or houses, and in 1484 besides these for a loft over the gateway of the Almonry, described in 1486 as the room over the road (Camera supra viam), and in 1488 as the room over the road at the entrance to the Almonry (Camera supra viam eundo ad Elemosinariam). This latter was perhaps rented as a place to store the unsold portion of his stock.

The neighbourhood of the Abbey seems to have been a place much favoured by merchants of the Staple and dealers in wool, and this may have had something to do with Caxton's choice. He always continued to be a member of the Mercers' Company, and many of his fellow-members must have formed his acquaintance, or learned to esteem him, while he held his honourable and responsible post of Governor of the English nation in the Low Countries. Like himself, many were members of the Fraternity of our Blessed Lady Assumption and benefactors to the church of St. Margaret. The abbots of Westminster themselves were in the wool trade, and according to Stow had six wool-houses in the Staple granted them by King Henry VI. Some such special causes, or perhaps certain privileges obtained from Margaret, Henry VII.'s mother, who was one of the printer's patrons, must have made Caxton fix his choice on Westminster rather than on London, the great centre for all merchants, and which might have been supposed more suitable for a printer.

The first book with a date issued in England was the Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres, which was finished on the 18th of November, 1477. That Caxton should have allowed more than a year to elapse before issuing any work from his press seems improbable, especially considering the untiring energy with which he worked. On this point a curious piece of evidence is to be found in the prologue to the edition of King Apolyn of Tyre, printed by Wynkyn de Worde in 1510. Robert Copland, an assistant of De Worde and the translator of the book, says: "My worshipful master Wynken de Worde, having a little book of an ancient history of a kyng, sometyme reigning in the countree of Thyre called Appolyn, concernynge his malfortunes and peryllous adventures right espouventables, bryefly compyled and pyteous for to here, the which boke [pg 35] I Robert Coplande have me applyed for to translate out of the Frensshe language into our maternal Englysshe tongue at the exhortacion of my forsayd mayster, accordynge dyrectly to myn auctor, gladly followynge the trace of my mayster Caxton, begynnynge with small storyes and pamfletes and so to other."

Now, taking all the books printed by Caxton before the end of the year 1478, in number twenty-one, and considering that the first dated book was not issued until almost the end of 1477, and that Caxton had then presumably been in England for over a year, there does seem some reasonable ground for believing the statement of Copland, especially as there are amongst these early books a number which exactly answer to the description of "small storyes and pamfletes."

An exactly analogous case occurs in regard to the introduction of printing into Scotland. The first printer, Andrew Myllar, while preparing for the publication of the Aberdeen Breviary, which was issued at Edinburgh in 1509-10, published in 1508 a series of small pamphlets, consisting of stories and poems by Dunbar, Chaucer, and others. As might naturally be expected, such small books were especially liable to destruction, both on account of their size and the popularity of their subjects. It is not surprising to find that the majority have been preserved to us in single copies only. All the ten Edinburgh books are unique, and almost all the early Caxton quartos, so that it is impossible under these conditions to estimate what the output of Caxton's first year's working may have been. In writing of these earliest books, it will be perhaps best to take the folios first, and then the numerous small works, since, as they all agree so exactly as regards printing, they cannot be arranged in any definite order.

The first of the folios issued was most probably the History of [pg 36] Jason, translated by Caxton himself from the French version of Raoul Le Fevre immediately after he had finished those of the Recueil and the Game of Chess. The translation was undertaken under the patronage of Edward IV., with a view to the presentation of the book when finished to the ill-fated Prince of Wales, afterwards Edward V., "to thentent he may begynne to lerne rede Englissh." The book has every appearance of having been one of the very earliest issues of the Westminster press, and at the end of 1476 or beginning of 1477 the young prince would have been about four years old, a very suitable age to begin his education.

The book contains 150 leaves, of which the first and last are blank, and a full page has 29 lines. Like all early Caxtons, it has no signatures, which were not introduced until 1480; no headlines, which were rarely used; no numbers to the pages, which occur still more rarely; and no catch-words, which were never used at all.

As in all other early printed books, spaces were left for the insertion of illuminated initials at the beginnings of the chapters. Now, while in contemporary French, Italian, and Low Country books such spaces were often filled with the most gracefully designed and beautifully illuminated initials, rich in scrollwork and foliage, and ornamented with coats of arms or miniatures, there is not, so far as I know, any early English book in existence containing any attempt at such decoration. As a rule, the spaces were left blank as they came from the printer. In some cases, where the paragraph marks have been filled in by the rubricator, he has roughly daubed in the initial with his brush, making no attempt at ornament, or even neatness in the letter itself.

Seven copies of the Jason are still extant, the majority imperfect. By far the finest copy known was that sold at the Ashburnham sale in 1897, and which is now in a private collection in America. It is in the original leather binding as it issued from Caxton's workshop, and is quite uncut. This copy has generally been considered the finest Caxton in existence, and its various changes of ownership can be traced back for over two hundred years.

The great admiration which Caxton had for the work of Chaucer would no doubt make him anxious to issue it from his press as soon as possible, and we may therefore ascribe to an early date the publication of the Canterbury Tales and the translation of Boethius. The Canterbury Tales is a small folio of 374 leaves, with 29 lines to the page, and so rare that it is believed that no genuine perfect copy is in existence. Blades, in his account of the book, censures Dibdin for describing the copy at Merton College, Oxford, as imperfect, which, however, in Dibdin's time it certainly was, though through the kindness of Lord Spencer the missing leaves were afterwards supplied. One other copy, complete as regards text, is in the British Museum, having formed part of the library of George III. The Boethius contains 94 leaves, and is a much more common book. One copy is worthy of special mention, as it was the means of bringing to light the existence of three books printed by Caxton which up to that time were unknown. It was found by Mr. Blades in the old grammar-school library at St. Alban's, and he has left us an interesting account of its discovery. "After examining a few interesting books, I pulled out one which was lying flat upon the top of others. It was in a most deplorable state, covered thickly with a damp, sticky dust, and with a considerable portion of the back rotted away by wet. The white decay fell in lumps on the floor as the unappreciated volume was opened. [pg 38] It proved to be Geoffrey Chaucer's English translation of Boecius de Consolatione Philosophiae, printed by Caxton, in the original binding, as issued from Caxton's workshop, and uncut!" "On dissecting the covers they were found to be composed entirely of waste sheets from Caxton's press, two or three being printed on one side only. The two covers yielded no less than fifty-six half-sheets of printed paper, proving the existence of three works from Caxton's press quite unknown before." These fragments came from thirteen different books, and though other examples of one of the unknown works have been found, two, the Sarum Horae and Sarum Pica, are still known from these fragments only.

The Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres, though most probably by no means the first book printed in England, must still hold the important position of being the first with a definite date, November 18, 1477. The book was translated from the French by Lord Rivers, who had borrowed the original while on a voyage to the shrine of St. James of Compostella from a fellow-traveller, the famous knight Lewis de Bretaylles. Having finished his translation, he handed it to Caxton to "oversee" and to print, and the printer himself added a chapter "touchyng women." To this a quaint introduction is prefixed, in which it is pointed out that the gallant Earl had omitted the chapter, perhaps at request of some fair lady, "or ellys for the very affeccyon, love and good wylle that he hath unto alle ladyes and gentyl women." "But," continues Caxton, "for as moche as I am not in certeyn wheder it was in my lordis copye or not, or ellis peradventure that the wynde had blowe over the leef at the tyme of translacion of his booke, I purpose to wryte tho same saynges of that Greke Socrates, whiche wrote of tho women of grece and nothyng of them of this Royame, whom I suppose he never knewe."

It is curious that with one exception no copy of this first edition has a colophon. The copy in which it occurs was in Lord Spencer's library and is now at Manchester, but beyond this small addition, it varies in no way from the other copies. All the examples of the second edition, which was issued a few years later, contain a reprint of this colophon.

The Dictes when perfect contained 78 leaves (not, as stated by Blades, 76), of which the first and last two are blank, and though more than a dozen copies of the book are known, not one is quite perfect. In the library of Lambeth Palace is a manuscript of this work on vellum, copied from Caxton's edition, and dated December 29, 1477. It contains one poor illumination showing Earl Rivers presenting the copy to the Prince of Wales, afterwards Edward V. By the side of the Earl is an ecclesiastic, probably "Haywarde," the writer of the manuscript, and this figure has by some been considered, quite erroneously, to be intended for a portrait of Caxton.

The Dictes or Sayengis was followed shortly by another dated folio, the Morale Proverbes of Cristyne, issued on the 20th of February, 1478. It contains only four printed leaves, and three copies are known. The two verses added at the end of the book tell us of the author, translator, and printer, and are interesting as being the earliest printed specimen of Caxton's poetical attempts.

"Of these sayynges Cristyne was aucteuresse

Whiche in makyng hadde suche Intelligence

That thereof she was mireur and maistresse

Hire werkes testifie thexperience

In frenssh languaige was writen this sentence

And thus Englished dooth hit rehers

Antoin Widevylle therl Ryvers.

[pg 40]"Go thou litil quayer and recommaund me

Unto the good grace of my special lorde

Therle Ryveris, for I have enprinted the

At his commandement, followyng eury worde

His copye, as his secretaire can recorde

At Westmestre, of feuerer the xx daye

And of kynd Edward the xvjj yere vraye."

The author, Christine de Pisan, wife of Étienne Castel, was one of the most famous women of the middle ages. Left early a widow, with but narrow means, she had three children and her own parents to provide for. Being a woman of high attainments and considerable learning, she took up the profession of literature, and for many years worked incessantly. Les proverbes moraulx was written as a supplement to Les enseignemens moraulx, an instructive work addressed to her young son, Jean Castel, who was for some time in England in the service of the Earl of Salisbury.

Another point to be noticed about this book is the date, which here, fortunately, is quite clear. Among the early printers there is very considerable variation as to the day on which the new year began. Putting on one side the foreign and considering only the English printers, the dates narrow themselves to two, January 1st and March 25th, so that any date falling between these two may be in two different years, according to the habit of the printer. For instance, March 1, 1470, will really mean 1470 if the printer began his year on January 1st. If, on the other hand, he did not begin it until March 25th, the real date will be 1471.

Fortunately, Caxton frequently added to his dates the regnal year, which gives at once a definite solution. For instance, his edition of the Cordyale was begun the day after Lord Rivers handed him the manuscript, on February 3, 1478, and finished on March [pg 41] 24th following, in the nineteenth year of Edward IV. Now, the nineteenth year of Edward IV. ran from March 4, 1479, to March 3, 1480, so that Caxton's 1478 was really 1479, and his custom was, therefore, to begin his years on the 25th of March.

As has been said earlier, it is probable that Caxton began his printing in England with small pamphlets, and of these a considerable number have come down to our time, but as the majority are unique, it is impossible to conjecture how many may have utterly perished. The most considerable collection is in the University Library, Cambridge, which owns a series, originally bound in one volume, which was in the collection of Bishop Moore presented to the University in 1715 by George the First. This library was peculiarly rich in early English books; indeed, the great majority of those now at Cambridge formed part of it, and their acquisition was mainly due to the exertions of that much maligned person, John Bagford, whom Moore employed to search for such rarities, and who did so with conspicuous success.

Amongst these priceless volumes one stands out pre-eminent. It was until recently in an old calf binding, lettered on the back, "Old poetry printed by Caxton," and contained eight pieces, the Stans puer ad mensam, the Parvus Catho, The Chorle and the Bird, The Horse, the Shepe and the Goose, The Temple of Glas, The Temple of Brass, The Book of Courtesy, and Anelida and Arcyte. Five of these are absolutely unique; of the others a second copy is known.

These books must have caught the popular taste, for of several we find second editions issued almost at once. A second issue of the Parvus Catho is known from a unique copy belonging to the Duke of Devonshire. York Cathedral possesses the only known copy (with the exception of a few leaves at Cambridge) of the [pg 42] second edition of The Horse, the Shepe and the Goose, and a unique second edition of The Chorle and the Bird.

All these little poetical pieces agree typographically. They contain nothing but the bare text, and are without signatures, headlines, or pagination. Probably they were all issued at intervals of a few days, and not many printed, so that the second editions may have been issued only a few months after the first.

There are three other early quartos to be noticed, which are of quite a different class from those just mentioned. These are the Sarum Ordinale, the Propositio Johannis Russell, and the Infancia Salvatoris.

The Sarum Ordinale, or Pica, was a book giving the rules for the concurrence and occurrence of festivals, containing an explanation for adapting the calendar to the services of each week, in accordance with the thirty-five varieties of the almanac. This book would be in very considerable demand amongst those officiating in services, and would be a good method of attracting the attention of the priests to the new art, so that no sooner had the book been printed than Caxton struck off a little advertisement about it. "If it plese ony man spirituel or temporel to bye ony pyes of two and thre comemoracions of salisburi use enpryntid after the forme of this present lettre whiche ben wel and truly correct, late hym come to westmonester in to the almonesrye at the reed pale and he shal have them good chepe. Supplico stet cedula." The quaint Latin ending, "Pray don't tear down the advertisement," was then perhaps a customary formula attached to notices put up in ecclesiastical or legal precincts, but it might naturally be supposed that those most likely to damage or tear down advertisements would be uneducated people, who would be ignorant of Latin.

When the advertisement first came before the notice of writers on printing, the existence of the Ordinale was unknown, and it is amusing to read the various conjectures as to the buying of "pyes" hazarded by them. One of the most ingenious occurred in a letter from Henry Bradshaw to William Blades, which was that the syllable "co" had dropped out by accident, and that the word should read "copyes," and this appeared all the more probable, as the word "pyes" comes at the end of the first line, which is slightly shorter than the rest. This is the only specimen of an early English book advertisement known, though foreign examples are not uncommon.

The Propositio Johannis Russell is one of the very few pieces printed by Caxton dealing with current affairs or politics. It is the oration delivered at Ghent, early in 1470, on the occasion of the investiture of the Duke of Burgundy with the Order of the Garter. It has often been considered as one of Caxton's very earliest pieces,—perhaps printed at Bruges. Blades writes, rather vaguely: "To me it appears most likely that it was issued at Bruges at no long period after its delivery, and before Caxton's final departure for England. At that town, both with the subjects of the Duke of Burgundy and the 'English nation' there resident, it would secure a good circulation; not so if issued seven years after its delivery in another country."

It could not have been printed anywhere by Caxton before 1475, and everything seems to point to its having been printed at Westminster in 1476-1477, perhaps at the instance of the author himself, then Bishop of Rochester.

It is a little quarto tract of four leaves, and two copies only are known, one belonging to the Earl of Leicester at Holkham, the other, formerly in the Spencer Library, now at Manchester. This latter was originally bound up, apparently by mistake, amongst the [pg 44] blank leaves of a note-book used for miscellaneous manuscript treatises of the fifteenth century, which run on over the first and last blank pages of the tract itself. It appeared, unrecognized, at the Brand sale in 1807, and was described amongst the MSS., "A work on theology and religion, with five leaves at the end a very great curiosity, very early printed on wooden blocks, or type." It was bought by Lord Blandford for forty-five shillings, and purchased at his sale in 1819 by Lord Spencer for £126.

Blades speaks of it as in its original binding, a quite inexplicable mistake, for it was bound between the years 1807 and 1819 in resplendently gilt morocco, double, with gauffered gilt edges! The copy at Holkham, which used to be in an old vellum wrapper, has also been rebound, and the two inner leaves, by some unfortunate mistake, transposed.

Of the Infancia Salvatoris, a version of one of the smaller treatises among the apocryphal books of the New Testament, but one copy is known. It was in the celebrated Harleian Library, which was bought entire by Osborne in 1746. The Caxton collectors of the period seem to have passed it over, for it did not get sold, even at its very modest price, until three years later, when it was bought for the University Library of Göttingen. It is still in its old red morocco Harleian binding, with Osborne's price—15—on the fly-leaf. Another note records, "aus dem Katalogen Thomas Osborne in London d. 12 Maij 1749 (No 4179) erkauft." Blades, in his description of the book, which he had not examined, conjectured that it was made up in three quires, the first of eight leaves, the second and third of six each, making in all twenty leaves, including a blank both at beginning and end. An examination of the water-marks of the paper shows that this was not the case, and that it consisted of two quires, the [pg 45] first of eight leaves, the second of ten, and that there were no blank leaves.

This tract, and the Compassio lamentationis Beate Marie Virginis, are the only two unique Caxtons in libraries outside England.

Some time towards the end of 1478 Caxton recast his fount No. 2, in which almost all the books so far mentioned were printed, and added a few extra types. With this new fount he printed the Margarita Eloquentiae of Laurentius de Saona, Saona being the earlier form of Savona, the birthplace of Columbus, a city not far from Genoa. At the end of the book, which contains neither name of printer nor place, is a notice that the work was completed at Cambridge on the 6th of July, 1478.

In an old catalogue of books bequeathed by Archbishop Parker to the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, the entry occurs, "Rethorica nova impressa Canteb. fo. 1478." Strype, in writing his life of the Archbishop, came across this notice and communicated it to Bagford, who reported it in his turn to Tanner, the antiquary. Ames, from their information, placed it at the head of Cambridge books in his Typographical Antiquities, and Herbert, in his reprint, merely reproduced the account. Dibdin does not mention it, and it was not until 1861 that Henry Bradshaw, coming across it by accident, discovered that it was a genuine production of Caxton's press.

The book is a folio of 124 leaves, and besides the copy at Cambridge, one other is known, now in the University Library at Upsala.

On the 24th of March, 1479, was issued the Cordyale, a translation from the French Quatre derrenieres choses, by Earl Rivers. The translation, as the colophon tells us, was handed to Caxton on the day of the Purification (February 2d), and the printing was [pg 46] begun "the morn after the saide Purification of our blissid Lady, which was the daye of Seint Blase, Bisshop and Martir: And finisshed on the even of the annunciacion of our said bilissid Lady fallyng on the wednesday the 24 daye of Marche."

The Cordyale contains 78 leaves, with a blank at each end, and is not very uncommon. The second edition of the Dictes or Sayengis was issued this year, and is considerably rarer than the first, only four copies being known. Its collation is exactly the same as the first, and Blades has fallen into the same mistake, and gives it two leaves too few.

The year 1480 saw a considerable change in Caxton's methods of printing. Hitherto he had been content to print his books without signatures, although these were generally in use abroad, but their obvious utility appears to have impressed him, and henceforward he always printed them. The earlier books were of course signed, but the signatures were written in by hand, a very laborious process compared with setting them up with the type, and the greater clearness of the printed letter must have been an advantage to the bookbinder. About this time also he began to decorate his books with illustrations, a concession perhaps to popular taste, for his own inclination seems to have led him more to the literary than the artistic side of book production.

Another matter also may have helped to bring about this change, the settlement of a rival printer in London. Two other presses had before this started in England, one at Oxford in 1478, and one at St. Alban's about a year later, but their distance rendered them little dangerous as rivals, while the nature of their productions was mainly scholastic and little suited to the popular taste. But with a press setting up work some two miles away matters were quite different. There was no knowing what it might not print.

John Lettou, this first London printer, came apparently from Rome, bringing with him a small, neat gothic type, which had already been used in that city to print several books. To judge [pg 48] from his name, he was a native of Lithuania, of which Lettou is an old English form. He was certainly a practised workman, and his books are very foreign in appearance, and quite unlike the work of any other early English printer.

Caxton's first piece of work in 1480 was a broadside Indulgence, issued by John Kendale by authority of Sixtus IV., to all persons who would contribute towards the defence of Rhodes, which was being besieged by the Turks. The copy in the British Museum, which is the only one at present known, is filled in with the names of Symon Mountfort and Emma, his wife, and is dated the last day of March. Another example which was in existence about 1790, but has now disappeared, was filled in with the names of Richard and John Catlyn, and dated April 16th. This Indulgence begins with a wood-cut initial letter, the first to be used in England.

John Kendale, in the proclamation of Edward IV. of April, 1480, which relates to this appeal for assistance, is styled "Turcopolier of Rhodes and locum tenens of the Grand Master in Italy, England, Flanders, and Ireland," and he was at a later date implicated in a plot against the King's life. He is the subject of the earliest known existing contemporary English medal, which was struck in 1480. No sooner had Caxton issued this Indulgence, which is printed in the large No. 2* type, and very unsuitable for that kind of work, than the rival printer, John Lettou, issued two editions printed in his small, neat type. This attracted Caxton's attention, and he immediately set to work on a new small type, No. 4, which came into use soon afterwards.

Two books only in this new type are without signatures, so that they may presumably be taken to be the earliest; these are a Vocabulary in French and English, and a Servitium de Visitatione Beatae Mariae Virginis. The first is a small folio of 26 leaves, of which [pg 49] the first is blank, and consists of words and short phrases in the two languages, arranged in opposite columns. It is an uninteresting book to look at, but must have been useful, for it was reprinted in the fifteenth century both by Wynkyn de Worde and Richard Pynson, and also in the early sixteenth. Four copies are known, in Bamburgh Castle, Ripon Cathedral, the Rylands Library, and an imperfect copy in the Duke of Devonshire's library.

The second book, the Servitium, has, I think, been always wrongly described. All that now remains of it are seven leaves in the British Museum, the last being blank; and the whole book was considered to have consisted of a quire of eight leaves, the first being wanting. The Servitium was a special service intended to be incorporated into the Breviary and Missal. The Pope had announced it in 1390, but it was not until 1480 that the Archbishop of Canterbury received from the Prolocutor a proposal to order the observance of July 2d as a fixed feast of the Visitation, "sub more duplicis festi secundum usum Sarum, cum pleno servitio." The book would therefore contain the full service for the day itself, the special parts for the week days following (except the fourth which was the octave of SS. Peter and Paul), and the service for the octave. Almost the whole of the principal service, which would have occupied a considerable space, is wanting, so that it may be assumed that the book consisted originally of at least two quires, or sixteen leaves. An edition of the Psalter must have been printed about this time, and is perhaps the first book in which Caxton made use of signatures; it is at any rate the only one, with the exception of Reynard the Fox, in which he went so far wrong as to necessitate the insertion of an extra leaf in one quire. This book, a quarto of 177 leaves, has a handsome appearance, as it is printed throughout with the formal church-type No. 3, the only complete book in [pg 50] which this type alone is used. The only copy known is in the British Museum, to which it came with the Royal Library, having belonged at one time to Queen Mary, whose initials are on the back of the binding.

An edition of the Book of Hours of Salisbury use was printed about the same time in the same type, but nothing remains of it now except two fragments found in the binding of a Caxton Boethius in the Grammar School at St. Alban's, and since purchased by the British Museum. It was a quarto of the same size as the Psalter, and a full page contained 20 lines.

On the 10th of June, 1480, Caxton finished his first edition of the Chronicles of England, a folio of 182 leaves, which, as he says in his preface, "Atte requeste of dyverce gentilmen I have endevourd me to enprinte." Though mainly derived from the ordinary manuscript copies, the history has been brought down to a later date, and this continuation may very well have been written by Caxton himself. In August of the same year, the Description of Britain was issued. It is taken from Higden's Polycronicon, and was clearly intended to form a supplement to the Chronicles, with which it is commonly found bound up. More copies of it appear to have been printed than of the Chronicles, for it is found also with the second edition of the Chronicles, though it was not reprinted.

John Lidgate's poem, Curia Sapientiae, or The Court of Sapience, a poem in seven-line stanzas, containing descriptions of animals, birds, and fishes, with a survey of the arts and sciences, was published about this time. It is a folio of 40 leaves, of which the first and last two are blank. Three copies only are known, all of which are in public libraries.

Early in 1481 Caxton finished his translation of The Mirror of the World, and it must have been printed immediately after. The work was a commission from his friend Hugh Bryce, a fellow-member of the Mercers' Company, and who must often have met Caxton on his official visits to Bruges. In this book for the first time the printer made use of illustrations. These are of two kinds. The first consists of little pictures, rudely designed and coarsely cut, of masters engaged in teaching their pupils various sciences, or of single figures engaged in scientific pursuits. These are original and introduced by Caxton. The second series are diagrams more or less carefully copied from the MSS. In his prologue he says that there are twenty-seven figures, "without whiche it may not lightly be understande." Curiously enough, he himself goes astray, for in the first part, which should contain eight diagrams, he puts the second and third in their wrong places and omits the fourth. The nine diagrams of the second part are wrongly drawn, and in some cases misplaced, owing to the original text having been misunderstood. The diagrams of the third part are most correct, but although ten are mentioned, only nine appear.

An interesting point about these diagrams is, that they have short explanations written in them in ink, and in all copies where these inscriptions are found they are in the same handwriting. Oldys, who first drew attention to this peculiarity, supposed the handwriting to be that of Caxton himself, and though this is not impossible, it is more probable that this simple and monotonous task would be done by one of his assistants.

The History of Reynard the Fox was translated by Caxton in 1481 from the Dutch edition printed at Gouda in 1479 by Gerard Leeu, a printer who later on at Antwerp reprinted some of Caxton's English books. The story of Reynard was extremely popular and widely spread, yet it appears that no manuscripts exist with the story in the form given by Caxton. Five copies of this book are [pg 52] known; one of them, the fine copy which was in the Spencer collection, is part of the spoil obtained from Lincoln Minster. A mistake of the printer necessitated the insertion of a half printed leaf in all copies between leaves 48 and 49.

On the 12th of August, 1481, Caxton issued a translation of two treatises of Cicero, De senectute and De amicitia, and a work of Bonaccursus de Montemagno, entitled De nobilitate. The translation of the first two into French was made by command of Louis, Duke of Bourbon, in 1405, by Laurence de Premierfait, and the last by Jean Mielot. The English translation seems to have been made by Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester, at the desire of Sir John Fastolfe, for whom his son-in-law, Scrope, a kinsman of Tiptoft, had translated the Dictes or Sayengis. Cicero apparently did not appeal so much to the popular taste as such stories as Reynard, so that it is now one of the commonest of Caxton's books, some twenty-five to thirty copies being known.

On the 20th of November, in the same year, appeared another romance, The History of Godfrey of Bologne, or The Conquest of Jerusalem, translated by Caxton from the French. Almost every copy known of this book is imperfect, but there is a beautiful example in the possession of Colonel Holford. It was Edward the Fourth's own copy, and at the end of the fifteenth century had come by some means into the possession of Roger Thorney, a mercer of London and a patron of Caxton's successor, Wynkyn de Worde, who printed, at his request, his edition of the Polycronicon. After various changes of ownership, it came into the possession of a noted collector, Richard Smith, and at his auction in 1682 was bought by the Earl of Peterborough for the not excessive sum of eighteen shillings and two pence.

About this time two more illustrated books were issued, a third edition of Burgh's Cato parvus et magnus, and a second edition of the Game of Chess.

The Cato contains two wood-cuts out of the set made for the Mirror of the World. It is a folio of 28 leaves, of which the first was blank, and is wanting in the two known copies, those in St. John's College, Oxford, and the Spencer collection.

The Game of Chess contains twenty-four illustrations, but the wood-cuts used number only sixteen, for many served their purpose twice. The first cut is of the son of Nebuchadnezzar, named Evilmerodach, described in the text as "a jolly man without justice, who did do hew his father his body into three hundred pieces." Most of the remainder are pictures of the various pieces.

The suggestion which has sometimes been made that Caxton's wood-cuts were engraved abroad is quite without foundation. They are very often copied from those in foreign books, but their very clumsy execution would be well within the capacity of the veriest tyro in wood-engraving. Mr. Linton suggested that they might have been cut in soft metal, but as the blocks when found in later books often have marks clearly showing that they had been injured by worm-holes, this conjecture is untenable.

As with all illustrated books, most of the remaining copies of the Game of Chess are more or less imperfect. The dated books of 1482 are two in number, and both historical; these are Higden's Polycronicon and the second edition of the Chronicles of England.