The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. Variations in hyphenation have been standardised but all other spelling and punctuation remains unchanged.

Titles from the Contents, "Casualty List" and "Miscellaneous" have been added to Pages 81 and 85 respectively.

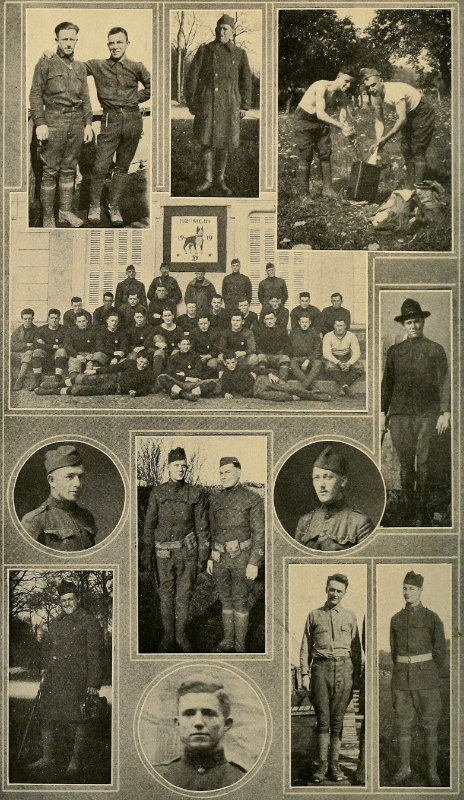

CAPTAIN JOHN ALLAN PATON, U. S. A.

Killed in Action

October 27, 1918.

EDITED BY

A MEMBER OF THE COMPANY

FROM DIARIES AND OFFICIAL

RECORDS

Copyright, 1919, by Robert John McCarthy

All Rights Reserved

| Page | |

| Chapter I—Before the War | 1 |

| Chapter II—Mobilization | 10 |

| Chapter III—Preparation | 14 |

| Chapter IV—Going Over | 19 |

| Chapter V—Training | 24 |

| Chapter VI—Chemin des Dames | 34 |

| Chapter VII—Toul Sector | 42 |

| Chapter VIII—Chateau Thierry | 51 |

| Chapter IX—St. Mihiel | 59 |

| Chapter X—North of Verdun | 66 |

| Chapter XI—After the Armistice | 73 |

| Casualty List | 81 |

| Miscellaneous | 85 |

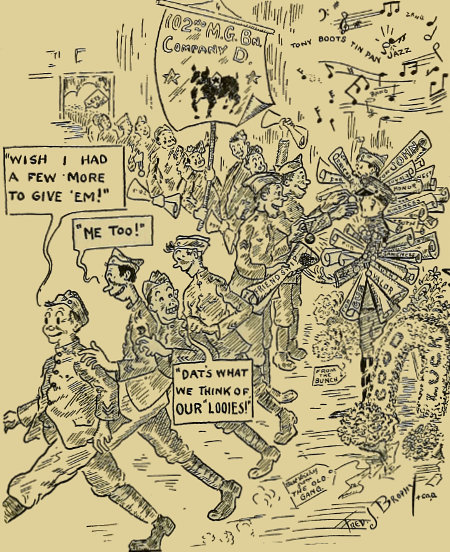

It is hoped that this book will serve as a reminder to all D Company men and their descendants of the serious and frivolous, sad and happy moments of an experience which alone could be obtained in a great conflict. From the time of the first call to service to the final muster-out of the Company, theirs were the thrills of the silent secrecy of war-time movements, the glorious reception at home when the task was completed, the joy of seeing their comrades honored, the sorrow at their loss, and for those who remain, the satisfaction of knowing they accomplished the end toward which they were turned when the declaration of war against Germany was proclaimed.

To the nobility of sacrifice shown by all those who remain in the hallowed fields of France this work is dedicated, as well as to that of the one who was singled out as a concrete example of the best D Company could produce. Not the smallest measure of honor is taken from the names of Rogers, Parmalee, Kennedy, Kapitzke, Butler, Callahan, Donth, McAviney, Meickle, Wickwire, Rosenkind and Wilfore by selecting that of their commander, for in him lived the same spirit which guided them, and their memory will last as long as free men battle for the right and champion the cause of justice.

R. J. M.

Westville, Conn., Nov. 30, 1919.

From the dash and romance of cavalry to the plodding machine-gunner of the Great War, from the gilt-bedecked uniforms of a parade organization to the grim olive drab of the American army, and from citizen soldiery who took drilling once each week as a recreation, to mud-spattered, cootie-infested veterans, was the path of evolution followed by Troop "A," Cavalry, Connecticut National Guard. It was brought into existence by act of the General Assembly of Connecticut on the second Thursday of October, 1808, which authorized the formation of a company of cavalry to be known as the "Second Company of the Governor's Horse Guards ... to attend upon and escort him in times of peace and war," and by accepting this obligation and supplying its own equipment and uniforms to be exempted "from every other kind of military duty."

As a social organization, the Company continued to enlist the élite of New Haven and the surrounding towns for nearly a hundred years, appearing in parades as escort for distinguished visitors and vieing with similar organizations in Connecticut and neighboring states in making the social seasons a round of gayety for its members and friends. During its early history, while the seat of the state government was located in New Haven, the occasions were numerous when it was called upon to perform its chosen duty of parading. However, with the advent of the day when men who formerly had fine saddle horses were provided with automobiles, and with the shifting of the state capitol to Hartford, interest in the Horse Guards relaxed slightly, and it was unkindly remarked by envious infantrymen that the mounts used by the Company had become so accustomed to making their daily rounds with the milk wagons they attempted to stop at familiar houses along the route of march.

An amendment to the original charter was passed by the General Assembly in 1861, increasing the strength of the Company from sixty to one hundred and twenty enlisted men, with one2 major, one captain, four lieutenants, eight sergeants and eight corporals completing the roster of officers and non-commissioned officers where there had been but one captain, two lieutenants, three sergeants and four corporals under the first charter.

While the company of Horse Guards took no active part as a unit in the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Civil War and the Spanish-American War, men from the organization had left the Company to take important parts in all four conflicts.

A second amendment to the charter, approved June 17, 1901, provided that upon application "either or both companies of the Governor's Horse Guards" could be organized as a troop of cavalry in the Connecticut National Guard with a personnel of "one captain, one first lieutenant, one second lieutenant, one first sergeant, one quartermaster sergeant, six sergeants, six corporals, two farriers, one saddler, two trumpeters and not more than forty nor less than thirty-five privates." Seeing in this act an opportunity to become a military unit, the organization promptly presented a petition, and an order was issued by Adjutant General Cole July 5, 1901, authorizing the immediate formation of the troop, to be designated as Troop "A," Connecticut National Guard. This was followed by the election of Luzerne C. Ludington to the office of captain of the Troop. William J. Bradnack was chosen first lieutenant and Robert J. Woodruff second lieutenant, with John Hugo first sergeant and the following members:—

Shortly after receiving recognition as a militia unit, the Troop was called together and it was decided that the Second Regiment armory on Meadow Street was unfitted for cavalry drill, so a committee was appointed to obtain a site for a new armory. Generous contributions on the part of prominent citizens enabled the erection of a wooden structure on the lot at 839 Orange Street. This building was barely completed when, in January 1905, it was burned to the ground.

Undaunted by this reverse, it was immediately decided to rebuild, and plans were made to put up a fire-proof structure. Once more men interested in the success of the Troop aided the building project by purchasing bonds, and the armory as it now stands was opened with appropriate ceremony in the Spring of 1906.

When the State bought the armory from the Troop it was suggested to men who held bonds covering the indebtedness on the building that the Troop should own a certain number of horses. Release from the payment of many obligations allowed the purchase of twenty horses in the Fall of 1909, and these were installed in the stables in the rear of the armory.

Funds to furnish the club rooms and pay interest on the building bonds were obtained through the willingness of the men to turn into the treasury the pay they received for the time spent in camp each year with the other militia units. These were added to from time to time by receipts from very popular and successful horse shows held in the winters of 1907, 1908, 1909 and 1910. These shows attracted exhibits from the best known fanciers in the East, and were famed as society events.4 Features of these shows were the crack drill exhibitions given by squads selected from the Troop's best riders. A military tournament, which included all competition that could be arranged for mounted men, followed when horse shows reached the point of exclusiveness they attained as the automobile came into common use.

During this period the men were being perfected in field work by road marches and manœuvers. In many of these they were placed under the command of regular army officers and rode beside troopers from the regular army, with due credit to their militia training.

In 1909 Sergeant Harry Denton was detailed by the War Department to instruct the Troop in the arts of war. The coming of this excellent soldier marked the advent of a new era for the unit. Riding classes were organized for ladies and large squads turned out every week for "monkey drill." Monkey drill taught the men the rudiments of trick riding and many of them became very well versed in handling their mounts and themselves in the difficult manœuvers. One of the best squads developed in the Troop included George Condren and John Paton, who later commanded the Company in France, Frank E. Wolf, who led the Company to its training area on the other side, George Wallace and Harold W. Herrick, who were commissioned officers during the great War, and others who were prominent in home activities during the period of hostilities.

Always ready for any action, the Troop was not called upon to aid the State authorities until June 4, 1911, when rioting in Middletown by striking employees of the Russell Brothers' mills resulted in a call received at the Troop armory at 1:30 in the afternoon on that date. The first platoon, comprised of two officers and thirty-two men, was loaded on a special train and arrived on the scene of the trouble three hours later, fully equipped and ready for any eventuality. However, the presence of the Troop and the businesslike deportment of the men proved sufficient to prevent further outbreaks, and after four days of duty the Troopers were ordered home.

For nearly nine years the original officers remained on the active roster. In 1910 Second Lieutenant Robert J. Woodruff found it necessary to resign because of his duties in the courts,5 and Frank E. Wolf was chosen by the men to take his place. The retirement of First Lieutenant William J. Bradnack three years later caused the advancement of Lieutenant Wolf to that rank and then to captain in 1915, when Captain Luzerne C. Ludington left the service after more than thirty years as an officer in the old Horse Guards and the Troop.

When Lieutenant Wolf became captain, his junior officers were First Lieutenant F. T. Maroney and Second Lieutenant William H. Welch. It was these three men who headed the remodeled Troop which left Niantic, Conn., their summer manœuvering grounds, for the Mexican border on June 29, 1916, when National Guard units of the different states were answering the call to mobilization in order to quell the vicious raids being made upon American lives and property along the Mexican border line.

Sergeant Harry Homers, who had relieved Sergeant Denton6 as instructor to the Troop and afterward obtained his discharge from the regular army to enter business, was one of the men to appear for enlistment when word was sent out that a number were needed to bring the Troop up to its war strength of one hundred and five men. Men on reserve were called back, and within four days Sergeant Condren, in charge of the recruiting, announced that no more were needed. Called out June 19, the Troop remained at the Armory until June 25, when extra men and equipment were loaded onto a special train and sent to the state camp at Niantic, while those with riding experience rode the Troop mounts overland.

Physical examinations in camp reduced the number of men on the roster, but the required strength was ready for muster into the federal service and the subsequent trip to Nogales, Arizona. Troop trains carrying horses move slowly, and nine days passed before the men detrained at the little border town in the far southwest. The intense heat of the sun in that climate proved trying for men accustomed to the climate of the seacoast, so within a few weeks numerous discharges were granted following persistent examinations by the medical department.

Camped at the top of a hill not far from Nogales, the majority of the men had their first experience in soldiering and considered the treatment they received in the light of hardship until they looked back on this trip as a picnic from the battlefields of Europe. Here they learned to ride, shoot, mount guard and do kitchen police according to the steel-bound regulations of the army. They learned something of the value and meaning of discipline, learned how to care for themselves and their horses, and for the first time, as soldiers, carried loaded ammunition in their belts when they walked guard in the streets of the little border town, always in sight of the squalid, sneaky-looking Mexican sentries just across that narrow strip of neutral territory on the boundary line.

New horses were issued by the government so that each man had a mount to care for and call his own, and when, during the latter part of August, the Troop was called upon to take part in manœuvers, they rode like veterans, drawing commendation for both officers and men.

One of the most serious blows to the morale of the organization7 was felt by the Troop not long after it reached Nogales. The carefully selected cook, who enlisted for the tour of duty, proved better at handling cards than he did at conjuring food out of army rations. Instructor Sergeant Arthur J. Fisher, assigned to the Troop a couple of years previously when Sergeant Homers left the army, stepped into the breach, however, and gave the men the benefit of his years of experience in regular army kitchens. Under his direction Arthur Parmalee and Francis Foley gained expert knowledge and the Troop kitchen became as efficient as any in the district.

Assigned to relieve a troop of the regular cavalry doing patrol duty near the custom house at Lochiel, twenty-eight miles east of Nogales, the Troop spent a month there patrolling and perfecting the prescribed drills. The surroundings of the new camp were ideal for out-door life and the twenty miles that intervened between the men and the nearest army post tended to foster organization spirit. Card games, letter writing and rides over the hills occupied the spare time the men found on their hands at rare intervals. It was only the persistent rumors and chilly nights which came with fall weather that made the men anxious to leave for home.

There being no further necessity of maintaining such a large force of men at the border, the Troop was named as one of the units to start the homeward trip. Returning to Nogales September 30, Troop A occupied, as barracks, mess halls of the type they had built when they first arrived. There they worked on the problems of turning over horses and equipment to the authorities, only thirty-two horses and equipment for that number being allotted to the Troop by the War Department, and entrained, bound for home, October 10.

A long trip through the mountainous section of the southwest and the prairie region of the west with only short daily stops to water and feed the horses, found the Troopers willing to take the first chance that offered to relieve the monotony of the journey. When the train stopped at Kansas City for a short time many of the men visited the city. Supplies were purchased from the Troop fund to add to the issued rations of corned beef hash and beans and the train pulled out with a happy crowd of soldiers.

Mysterious bottles made their appearance from under coats and inside shirts to add their share to the celebration. There was no sleep in the Pullmans that night. Making friends with the guard at the door of the kitchen car was easy, for he was Irish and inclined to be friendly, so a case of fresh eggs was soon in the hands of the men nearest the door. These they used with great abandon to the discomfort of the porter and members of the guard. The next morning omelets were dripping from the lighting fixtures and walls and formed a thick film over hats and shoes exposed to the attack. The violent character of the barrage prevented investigation during the battle and when the affair had quieted down it was judged by First Sergeant Herrick that the entire car-load was at fault so all were pressed into service to police the car.

The rest of the trip home was long and tedious. Innumerable delays were experienced, for, with the emergency at an end, the railroads shifted troop trains aside at the least excuse. The journey was brightened, however, by a trip to Niagara Falls for the men who took advantage of a stop at Buffalo. New Haven people lined the streets in an unprecedented outpouring of welcome when the train pulled into the home station October 22.

Parades followed during the next week, with a city banquet for all returned men, and the Troop was mustered out of the federal service, November 4, 1916, after four months experience in the field. Early the following week the members of the organization were fêted by the hustling organization of Troop A veterans and prominent New Haven men paid tribute to the spirit the unit had shown in its first attempt at regular soldiering.

The winter which followed was filled with preparation for eventualities. The shadow of war spreading irresistibly from the European battlefields grew more ominous over the country until unrestricted submarine warfare brought to a focus the indignities the United States had suffered from Germany since the sinking of the Lusitania. After the declaration of war April 6, 1917, an order was issued causing four troops of cavalry to be formed, from the two then in existence in the State, to make up the Third Separate Squadron of Militia Cavalry.

The nucleus for M Troop, formed in New Haven, was taken from among the non-commissioned officers and privates of Troop9 A. Lieutenant William H. Welch, who had been made first lieutenant upon the resignation of Lieutenant Maroney, became captain of the new troop. First Sergeant Herrick was made first lieutenant and Stable Sergeant George M. Wallace was advanced to the rank of second lieutenant. This change resulted in the appointment of Sergeant George D. Condren as first lieutenant of Troop A and Supply Sergeant John A. Paton was commissioned second lieutenant.

Activity preparatory to the mobilization of national guard units began with Troop A early in April when the usual weekly drill was augmented by an extra session later in the week for the non-commissioned officers and ambitious privates who cared to attend. Hikes on Saturday afternoons and several trips to Montgomery's farm in Mt. Carmel were added to the training. This program was filled with interest by the proclamation of President Wilson in May calling all militiamen in the northeastern department into active service on July 25th. Then a period was given over to equipping the men and forming them into units of correct proportions during which there were endless amounts of paper-work to be handled and a large percentage of recruits to be trained.

As the 26th Division never saw a concentration camp, this early training was of such a nature as to physically fit the men for active duty, but at no time tended to increase their knowledge of the particular work they were to do. On responding to the call to report at the Troop A armory in Orange Street on the morning of July 25th the men found that their soldierly duties lay largely in packing equipment to be shipped to camp, a little kitchen police and cleaning out the armory. Considered as necessary evils, these tasks were cared for with good will. However, the departure of Lieutenant Condren with thirty-one men and the Troop's complement of horses on July 27 for Niantic was an appreciated move in the direction of desired activity, and the following day the remainder of the organization experienced the varied emotions of a leave-taking on the Green with Mayor Campner on hand to bid them good-bye in the name of the city, and a cheering crowd lining the streets to the station.

Soft muscles felt the strain of unloading the freight from the special train which bore the unit to Niantic, and with the camp erected, the kitchen operating and a guard posted, the rigors of the first night in camp for many of the men were softened by11 slumber which soon overcame any objection men from offices and factories might have taken to sleeping on cots long since past the stage of usefulness.

In the meantime the men under the command of Lieutenant Condren had arrived at camp, put up picket lines and cared for their horses. They had made the march from New Haven to Niantic by easy stages and had been extensively fêted in the village of Westbrook by one of the residents who had befriended the Troop on former occasions. Thus field conditions obtained for the first time for the new Troop A.

Sunday in camp was its usual delight with visitors from home and Monday was given over to perfecting the camp arrangements. Other units on the state reservation were Troops B, L and M, forming with Troop A the 3d Separate Squadron of Connecticut Cavalry, Troop A, Signal Corps, the 1st Ambulance Company, the Field Hospital, the 1st Separate Company (Infantry), and batteries E and F, 10th Field Artillery, all units of the Connecticut militia. All were placed under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Shuttleworth, U. S. A., for training and organization.

The following week both mounted and dismounted drills were inaugurated and camp routine began with a formal guard mount on July 31, the first few attempts at this ceremony affording great amusement for all except those participating. Social lions in the ranks of the Company were establishing themselves in the hearts of the fair inhabitants of Pine Grove and carrying off the honors at the dance pavilion and under the energetic leadership of Sergeant Rogers a baseball team was being formed. In short, camp was being established with all the formalities attendant upon such an event.

On Saturday, August 3, all organizations were mustered into the Federal service by Lieutenant Colonel Shuttleworth. Thus the men were made soldiers of the United States Army, permitting the War Department to use the various militia units for duty outside the borders of Connecticut. Governor Marcus B. Holcomb reviewed the Squadron on the afternoon of August 7 in its first and last appearance before him as cavalry.

Baseball was taking its proper place on the schedule with games arranged for Saturdays, Sundays and Wednesdays, but12 Troop A fared not so well on the diamond in competition with the rest of the Battalion as it did later on the football field. The proper spirit to win games was never lacking, but talent was scarce until the recruiting drive of the latter part of the month brought several good players into the Company.

Summer's hottest and most sultry days were passed at Niantic with the minimum of discomfort because of the location of the camp almost on the shores of Long Island Sound, where breezes from the water tempered the efforts of the sun down to a point where comfort was possible and the proximity of bathing facilities allowed the men relief after drills.

Evidences of preparation for a prolonged stay and perhaps a lack of knowledge concerning the conditions in store for them created a certain restlessness among the men, whose hearts were all centered on the hope of getting to France.

Endeavors of the ladies of Niantic to promote community spirit and provide the men with the proper kinds of entertainment were ably seconded by Troop members, who were always well represented at social events and took a leading part in contributing excellent talent for all sorts of entertainments. From Scheffler's singing and Culver's type of vaudeville to Parmalee and Hine as boxers, there was an almost endless amount of artistic ability.

In preparation for the journey the men were to take, talks were delivered on hygiene and kindred topics by members of the medical department; and a Red Cross worker who had seen service with the French armies related some of his experiences to crowds which grasped each word with the avidity of a youngster listening to his first tales of achievement. The "Front" was a great mystery and one who had actually seen parts of that ever-changing line of opposing armies was looked up to as an individual upon whom the gods of fortune had smiled.

Another effect of this feeling of impending movements which was growing among the men was an increased desire to take advantage of the proximity to their homes, and many were the exits and entries through the fence while the unsuspecting guard "walking his post in a military manner" was going, according to schedule, in the opposite direction.

Falling as a mixed blessing came the announcement on August13 15 that the horses were to be taken from the Troop and the personnel used in the formation of a machine gun company. To the new men in the ranks it was a relief, but to those who were with the outfit when it enjoyed that happy little picnic on the Mexican Border during the summer of 1916 it meant the loss of their most valued friends. They wasted no time in mourning, however, but gathered up all the available information on machine-gun work and set their minds to become proficient in that branch of the service with the cheerful prospect of becoming members in what the British army called the "suicide club."

The last two weeks of August produced revolutionary changes in the old Troop, recruits were eagerly sought to fill out the ranks of the organization from its cavalry strength of one hundred and five men to the machine-gun requirements of one hundred and eighty, requisitions were entered for the new equipment and clothing prescribed for troops going overseas, and doughboy training, both in close order drill and road hikes, took the place of mounted drill. Batteries E and F of the Field Artillery left camp for a concentration point in Massachusetts, and the First Separate Company entrained for Springfield, where they were scheduled to guard the arsenal, leaving the 101st Machine Gun Battalion, of which Troop A had become Company A, with the Field Hospital the only occupants of the camp.

Vaccination and inoculation, those terrors of all early experiences in the army, held the stage on the afternoon of August 21, with the usual accompaniment of blanched faces and shaky knees. It was at this particularly unfavorable time the announcement was made by Captain Wolf that the ranks were to be brought up to the strength required by the addition of a number of men from the 1st Vermont regiment of infantry. This organization had been split up to complete units forming the 26th Division.

Leaving the impression that he had been called to attend an officers' school, Lieutenant Condren left the following day, and the end of his journey found him in France, one of the first National Guard officers to reach his goal. Within a few days Lieutenant Nelson arrived with the Vermont contingent, and Lieutenants Carroll and Bacharach were assigned to duty with the Company by Major Howard, so that nearly a full complement of officers was available for duties mainly of an ornamental nature.

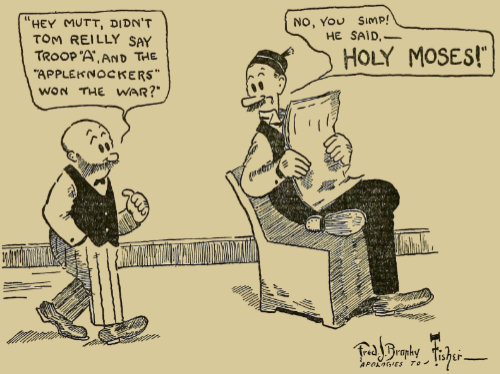

Having been duly welcomed as "Green Mountain Boys," and, in the manner of the Company, christened "Apple Knockers,"15 the Vermont men were received into the fellowship of the organization. Upon their arrival the newcomers occupied a company street of their own, the work of erecting it having been conferred upon A Company, as many similar and equally arduous honors were conferred upon that unit while it remained a member of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion. The apportionment of the men to the different companies completed, forty-six of the Vermonters came to A Company, most of whom held non-commissioned officers' warrants or had attained the dignity accompanying the rank of private first class.

Since the edict had gone forth that an old cavalry organization was to become a "doughboy" outfit, and the yellow hat cord of gallant memory was to be replaced by the blue of the lowly infantry "with the dirt behind their ears," the order had been more or less completely ignored, so that drills had the appearance of a disciplinary formation at a large army post where both arms of the service were represented. This brought out an order which caused all cords to change magically to the endorsed blue color, at least until the men reached a safe distance from camp, where the change could be effected without danger of apprehension, for who would dare return to New Haven wearing the colors he had frowned upon in happier times? Leather leggins were threatened, but the blow never descended and the "doughboys" from Yale Field continued to salute the brilliantly polished puttees of the men from Niantic as they strutted down Church Street.

Manifestations of grief at the passing of the yellow hat cords took the form of a funeral procession on the evening of August 30, when, preceded by Corporal Curtiss and Guerrant rendering portions of the "Dead March" on bugle and harmonica, the men as mourners marched with measured tread to the parade ground. They followed a plank which served as a bier for a representative of the deposed cords, and, after a dance symbolical of their grief, the pallbearers laid it to rest, while Shemitz, with the powers characteristic of his race, paid a glowing tribute to the deceased. After hymns had been sung the crowd broke up to hide its tears and console itself in the various ways which have become common to mankind, or were common before prohibition placed its clammy hand on the vitals of the universal consoler.

Muster on the afternoon of August 31 was followed a week later by pay day with a trip to New Haven that night for most of the men and a ride back to camp on the 2:20. This train made several unscheduled stops near the Niantic station because the conductor was adamant toward pleas from the men and would have carried them to New London had they not taken the matter into their own hands and opened the air valves when close to Niantic.

Bill Bell's famous and much maligned whistle made its appearance during this period, for First Sergeant McGeer had departed for the Officers' Training Camp at Plattsburg, and the one long and one short signal was in order for any time of the day or night. Because it was rumored that McGeer would return to the Company if unsuccessful in his quest for a commission, he received the best wishes of all the men and was treated to a shower bath in his bunk the night before he left—an honor accorded to but few men in the Company.

Straw ticks had been issued and they were filled and put to use now to replace the cots, which, in various stages of demolition, had been turned in and, according to the best information, sent to Camp Devens to accommodate the first men of the selective draft to arrive at that cantonment.

Fall weather, with its snappy morning air and delightful days, gradually replaced the warmer days of late summer, enthroning football in the place baseball had occupied. The first game was a heart-breaking affair in which neither A Company nor B Company was able to score, the second was also a tie in which C Company scored seven points equally with A Company, and the third was disastrous for the finances of the old Company, for D Company, formerly M Troop, scored four touchdowns to one for A.

All plans were interrupted on September 23, when orders were sent out from Battalion Headquarters to strike tents and roll packs preparatory to leaving the camp. This accomplished, with a day's cooked rations issued and loaded down with packs which would have taxed the capacity of the staunchest of pack mules and taken prizes for the variety of form and number of bundles and bags hung over them, the column, in command of Captain Wolf, toiled out through the streets of Niantic and17 interminably along the roads leading in the direction of New London. Halts for rest were short and infrequent, and the one called for the noon lunch seemed to be the only event which could have saved from complete collapse many in the long, struggling procession.

There was much speculation on the truth of the rumor that a train was awaiting the men before they finally saw the head of the column turn back toward Niantic. A squad of grinning cooks stood at present arms with brooms and sticks of wood, but this sight did not tend to sweeten the tempers of the returning men who found they must again pitch their tents and rearrange their belongings to the best advantage for a longer stay. Sweetly worded memoranda from Headquarters conveyed the information that the Major was pleased with the showing the men had made in breaking camp, but they failed to explain why orders prohibiting men from riding in any form of conveyance on the march did not apply to a man from C Company who rode by several times while the column was on the march and turned on the men gazes of pitying condescension.

Cosmopolitan elements were added to the Company by the acquisition of several men from the draft contingent and Corporal Charles Nutt was assigned the post of instructor and guide over the new men, all but one of whom were destined to complete the tour of duty with the Company. Conscientious Charlie watched over his men like a hen with a brood of new chicks,—he took them to mess, to the supply tent, answered for them at reveille and retreat, and drilled them during the hours set apart for that purpose.

Politics played its part in the life of the men when on election day, October 2, they were transported to New Haven in automobiles by the Republicans or were given railroad transportation by the Democrats, while the stern non-partisan element travelled by freight or graft. The ardent voters were almost persuaded to remain when word came that pay was ready to be distributed on that day, but the call home was stronger and they returned to get their share of the funds the following morning.

Another method of getting home was discovered shortly after this, and with a special train chartered for team and rooters, most of the Company, with the exception of certain members18 from Vermont who had travelled home for a visit without going through the formalities of asking permission, left for New Haven at noon Saturday, October 7, on a final trip and to play a game of football against the Annex A. C., one of the strongest semi-professional teams in the state. Sunday, the day of the game, was ideal, but the opposing team was too strong for the soldiers and came out on the long end of a 20-0 score.

For some time previous to this, men in the habit of talking to their friends over the telephone in camp found that remarks indicating an expected move in the near future resulted in the loss of their connection and a stern reprimand, so Monday's preparations, while full of interest, were not unexpected. Instructions on the conduct of the troops while travelling were given out and full preparations made for leaving at a moment's notice. There was no freight to be handled for all heavy baggage had been packed and loaded into box cars nearly a month before, leading the way to the port of embarkation.

Profiteering, at least from the point of view of the soldier, had brought disfavor on a man who conducted a small store near the grounds, so the last night in camp was selected by certain bold spirits to have a final settlement with him. They completed their task by earnest demolition of all property they could find belonging to the accused individual. His complaint caused assembly to be blown at headquarters and a strict check taken of all men absent. Well-founded alibis were numerous, however, and nothing came of the incident to reflect on the records of any of the suspected men.

Early on the morning of Wednesday, October 9, orders were again received to break camp. This time preparations gave them a genuine flavor, and at 9:30, in a disagreeable rain, which they were to know better after two winters in France, the men started their journey, cheered on by the hospitable residents of Niantic and full of eagerness to reach its end.

Having but a small percentage of globe-trotters among their number, the ensuing weeks on water and land were full of interest for all the men, even the blasé travellers showing just a hint of excitement during the trip through the submarine danger zone. Although the day was dreary when the train pulled away from the station at Niantic, the weather cleared as the seacoast was left behind, and by the time Springfield was passed the skies had cleared and the beauties of the tree-clad hills of Vermont and New Hampshire adorned in their gorgeously colored autumn foliage presented a glorious farewell to the men as the setting sun added its roseate glow to their final view of the U. S. A.

Travelling at night in a well-filled day coach has its difficulties if one has the desire to snatch a few minutes of sleep, but most of the men, thoroughly tired from their efforts of the past few days and their broken sleep of the preceding nights, managed to court slumber in some of the most amazing positions. At midnight all were aroused at White River Junction, Vermont, to be served coffee, the quality of which ever after was an unfailing object of invectives and a taunt to the Vermont members of the Company.

After circling the city of Montreal, the train arrived at 6 o'clock the following morning on the pier near His Majesty's Ship Megantic, and within an hour the entire Battalion with its baggage had been hurried aboard, A and B Companies to occupy the hold of the ship, with C and D in the second class cabins. At 10 o'clock the ship left the pier and began the journey down the St. Lawrence river. Of course the river was calm, and with a berth ticket and a mess ticket safely in their grasp, most of the men spent their time in exploring the ship as far as was permitted and viewing the pastoral scenery of Quebec and Labrador.

Early in the evening of October 11 the ship passed under Victoria bridge and stopping at the historic city of Quebec took20 aboard two hundred Serbian reservists in their quaint costumes, loaded down with baggage of all descriptions. The following morning the pitching and tossing of the ship produced some doubt in the minds of many as to the wisdom of leaving the blankets. Then followed a day of misery and dejection for all except those few and fortunate ones who were not subject to the attacks of "mal de mer."

To thoroughly appreciate the wonderful land-locked harbor of Halifax one must pass through the rough water the men had experienced and then watch the ship steam into the smoothest of basins, protected as it is from the ocean by a wall of rocks almost large enough to be called mountains. Here the Megantic lay at anchor from Saturday afternoon until Sunday afternoon when, after a hundred Canadian artillerymen had been added to the passengers, the convoy, consisting of the transports Baltic, Scotia, Justicia and Megantic, the tankers Cherryleaf and Cloverleaf, a British auxiliary cruiser and a tramp freighter, steamed out of the harbor. With the entire passenger list assembled at boat drill and standing at attention, bands on the British warships lying in the harbor played "The Star Spangled Banner" as the transports passed by.

Perhaps that moment might be catalogued as one of the most poignant thrills of a lifetime. The men were leaving behind them the land to which they might never return. They faced first the dangers of the submarines, and if they passed safely through that menace still greater perils awaited them. There were those who covered their emotion well while the bands played the National Anthem, but there was a long silence even after the harbor of Halifax was far to the stern and the ship was reaching out into the first real ground swells which betokened their presence on the boundless Atlantic.

Routine on board ship was rather irksome to men who had been free a good share of the time in camp to follow the dictates of their own desires. Twice daily there were boat drills, and there were calisthenics and even short classes in various subjects during dull hours. One of the most mystifying things about the ship was the seeming regularity with which passageways were opened and closed to traffic. It is related that while "Tempy" Sullivan was on guard at one of the passageways21 Captain Wolf nearly ascended the stairs before that astute person discovered him, whereupon, in spite of all the Captain's pleas, he was forced to descend the way he had come and try another place. "Them's my orders," said Sullivan with stony determination when the Captain explained he was officer of the day.

Ideas of English hospitality were given a set-back by the prices which the stewards aboard ship charged for all commodities. The prices of tobacco were prohibitive and there were no matches to be had within a short time of sailing, and it was whispered that the fruit being sold had been sent to the ship by the Red Cross for free distribution among the soldiers. Beer was on tap at the wet canteen after three days out.

Fair weather favored the ships until they started on a course which was to take them to the north of Ireland, when they met fog, rain and hail in varying quantities until Sunday, October 21, a day before sighting the west coast of Scotland, the weather cleared. On the afternoon of that day an escort of nine British destroyers made its appearance, bobbing on the large waves like corks in a wash-tub and dashing through the convoy, flashing their signals with heliographs by day and blinkers by night.

Wales was sighted on the starboard the morning of October 23 and that night at 7 o'clock, after waiting for some time in the Mersey for a pilot, the troops debarked onto Liverpool's famous floating dock, immediately boarding the queer little English trains, which waited nearby. On the trip following the men had their first sight of Englishwomen engaged in men's work and garbed in the unconventional overalls and jumpers which later became common at home. A short stop was made at Birmingham where coffee almost as bad as the White River Junction brand was handed out. Some of the men survived the crush at the lunch counter to discover later that the patriotic workers there had given them almost half as much as they had bought. At 4:30 the next morning the train stopped at Borden and the Battalion hiked about four miles through the mud in a drizzling rain to Oxley, where watersoaked, leaky tents were assigned while the cooks used all their magic to coax a fair meal out of the available rations.

Tramping around in the mud which was at all times ankle22 deep and often deeper, a Y. M. C. A. hut was discovered with a small stock of food and an American in charge. Here change was made from American to English money and most of the supplies available were purchased. Rest that night was more or less disturbed and wishes were expressed for that dry little bunk in the ship. The rain always found a hole just above the sleepers and there was no way of repairing the leak. At that, the men fared better than the officers, for the tents of the latter were located in a wind-swept area and the high winds of the night levelled them completely.

At 4 o'clock the following morning it was up and going again. This time the train passed down through the sunny green fields of the English countryside (for the rain had abated during the early hours) past farmhands tilling the soil behind neatly trimmed hedges, through cities which hid beneath their appearance of calm a hive of industry, to the port of Southampton, where another rest camp was the prospect. Like that at Borden, this proved to be muddy, but duck-boards helped in this difficulty. Here were American marines doing police duty, German prisoners at work on the roads and the interesting buildings of one of the oldest cities in the country. The stay here lasted until October 29. Long before this, however, cash supplies had dwindled to such an extent that but few of the men continued to patronize the restaurants, although the food served at the kitchen seemed barely sufficient to keep life in the body of a healthy soldier.

Crowded aboard the channel steamer Londonderry with British soldiers from all corners of the world, the trip across the English Channel was begun after a long tedious wait, during which the opportunity was afforded the men of seeing their first example of what a torpedo could do to the side of a ship. The Gloucester Castle lying in dry dock exhibited a wound through which a fair sized motor truck could be driven. Passing out of the harbor, the ship waited for darkness in the shelter of land and then began that leaping, bounding journey of seven hours which landed the Battalion in Le Havre, but first gave most of the men one of their worst tastes of seasickness.

Le Havre offered the troops their first sight of French soil, but it was not as pleasantly impressive as it might have been,23 for toiling uphill four miles with all your belongings on your back will make the most wonderful scenery in the world fade into mediocrity without the added misfortunes of scanty supplies and the same dreary weather which was encountered during the stay in England.

Hydroplanes and dirigibles were sights for the men during the twenty-four hours spent in Le Havre, but the status of "Sunny France" had received its classification along with the "Santa Claus" myth and subsequent months did not tend to disprove this impression. Funds were at the lowest possible level. Most of the spare cash scattered through the Company was made up of the few shillings which were saved from the onslaughts of the English merchants. Coupled with this was the much lamented fact that extra rations supposed to meet the Battalion in England had been side-tracked in some out-of-the-way place, and they only reached the units for which they were intended after they were well established in training camps in the Vosges.

Luckily the station platforms at Le Havre were covered with bales of cotton when the Battalion arrived to entrain at 5:30 on the afternoon of October 31, for these served as excellent beds and they were universally utilized as such until the train was ready to leave at midnight. The following day, with stops at Nantes and Versailles for coffee and various halts all along the line for reasons at no time apparent, after the manner of the French railway systems, the troop train continued its eastward journey, passing through Chateau Thierry and the scene of the first battle of the Marne, through Troyes, where coffee and rum were served by French soldiers, to the destination at Neufchateau, where the headquarters of the 26th Division were located and about which clustered the various units of that organization during the period of training which followed.

At 9 o'clock on the morning of November 2 the Battalion detrained at Neufchateau with hungry, travel-worn men willing to unroll their packs in any place having the slightest appearance of being a stationary camp, but it took all their optimism to greet enthusiastically the mud-surrounded barracks provided for the Company about three and a half miles southeast of Neufchateau near the village of Certilleux, in the department of the Vosges.

Surrounded as it was by hills characteristic of that part of France, and isolated from the other units of its command, A Company developed its community along lines approved by itself. The barracks, of which there were four on the east side of the road and one on the opposite side, all of that temporary type of structure manufactured in sections and reared without much attempt at making them comfortable, were connected with wide stone walks. The material for these walks was brought from the hill near at hand after hours of labor which took the kinks out of unused muscles and increased appetites, which were far from being satisfied because of the addled condition of the supply service then prevailing with the American Expeditionary Forces.

Three of the group of four barracks were adopted for the use of the Company, floors were laid, bunks of heavy green wood which had to be carried from the railroad station nearly a mile distant were gradually put into place, the kitchen was installed in one of the barracks with the mess hall as an adjunct and the orderly room occupying a small space near the end of the latter. Finally the small cylindrical stoves, the only available means of heating the barracks, were installed, three to a building. The single barracks on the west side of the road was fitted up for a guard house and supply room until the horses, mules and gun carts claimed it for their own.

Detail work was plentiful, for water was supplied by a small brook originating in springs near the top of the hill and it was necessary to carry it a hundred yards to the kitchen. Coal for25 the barracks stoves was only obtainable by carrying it from points of distribution, for transportation was scarce early in the fall of 1917. To supply the kitchen with wood, chopping details were sent into areas designated by the French authorities and the sticks were carried to camp by the Company.

Getting settled in the barracks was a comparatively short operation, for the men had been making new homes during the past month under more trying conditions each time, until they considered board floors and more or less dependable roofs downright luxuries. The bunks, most of which were of the "double-deck" variety, that is, one superimposed over another, with staunch wooden posts, were finally arranged in double rows on each side of the barracks, leaving a broad aisle through the center of the building. Sergeants who were fortunate enough found small single bunks which they placed in the middle of the barracks clustered around the stove which occupied the aisle there. These bunks also made seats for the rest of the men when winter nights made the space around the stove a coveted commodity.

Upon invitation the 102d Regiment Band came to the mess hall the Sunday following the Company's arrival at Certilleux and raised the spirits of the men with a concert. Tuesday a march was made to Neufchateau where steel helmets and full machine gun equipment, as far as the guns and carts were concerned, were drawn from the French ordnance depot there. The equipment was hauled back to camp on a hike memorable for its strenuous character.

Spare time had been curtailed in attempts to make the camp tenable, but now was spent in gaining a first-hand knowledge of the surrounding territory. These walks of exploration were cut short by the announcement, November 10, that Mechanic Curtiss had developed a case of measles and been sent to the hospital. His case was followed by others, so the quarantine, applied immediately, hedged in the Company and prevented it from passing the borders of the little camp for nearly a month. First Sergeant Bell, whose boundless energy was responsible for the improvements made about the camp, took command of the situation and did all within his power to add to the meager pleasures of the men by holding impromptu entertainments in the mess26 hall. The first of these was his trial and conviction by a mock court on serious charges preferred by Dockendorff; the sentence recommended by the jury, of which Captain Wolf was foreman, involved the loss of his whistle. Judge Carroll suspended execution of judgment in view of the accused's early record and Tony Scandore's band completed the program.

Other gatherings of equal interest were arranged, during which the Morning Scratch was presented with its ephemeral owners and contributors and its policy of "charity to none and malice toward all." This remarkable paper not only attracted the attention of the divisional censor, but outlived three editions in which plain fabrication vied with outspoken truth in ferreting out the peculiar qualities of well-known men in the organization. Sergeant McCarthy and Corporal Malone acted as editors of this worthy "sheet" but shielded the names of contributors to the last.

Robinson and Stearns valiantly attacked the "general's march" unceasingly when the word was passed down that General Pershing was coming to inspect the Company on November 11. Clothing and equipment were scrubbed as never before, but the stigma of a quarantine saved the men the nerve-racking experience of an inspection by the General, and the only sight they had of him was when his car flashed past to Landaville where the headquarters of the 102d Regiment was located.

After patiently translating most of the French handbook on the Hotchkiss machine gun which was issued to the Company the previous week, Lieutenants Carroll and Nelson transmitted their information to the rest of the Company officers and the men were called out for the first demonstration. Described as being "air-cooled, gas operated and strip-fed," the gun was extremely heavy but at the same time one of the most dependable machine guns used in the war, and its comparatively simple mechanism soon was well known by most of the men.

All during this time of acclimation "chow" was as scarce as Mike Shea's speeches, kitchen police was a detail for which first class privates strove and methods of adding to the slender rations were many as well as devious. Matches were unheard of things, cigarettes priceless luxuries. There were few men in the Company who would not have pledged at least half of their next month's pay for a satisfying supply of chocolate.

All company officers being quartered in barracks a quarter mile down the road with the exception of Captain Wolf, who enjoyed the distinction of a clean, dry room with one of those slumber-provoking French beds in a house in the village of Certilleux, were relieved from quarantine restrictions, as were Lacaillade and Hobart, who found refuge with the second battalion of the 102d Regiment while measles, or the threats thereof, held the camp in their grasp.

Drills in the handling of machine guns took up the attention of most of the Company during the ensuing weeks, while the headquarters section was trained in signalling and general liaison work. Lieutenant Dolan was assigned to the Company as an instructor and began his work with an interesting lecture on "Gas in Modern Warfare," and the general atmosphere of war was heightened by planes passing over the camp at all hours. Columns of French artillery travelled in seemingly endless procession in the direction of Epinal and the occasional booming of the anti-aircraft guns in the defense of Toul and Nancy far to the north of the camp came in intermittent echoes.

With a concrete floor, constructed by Shea and Delaney, and equipped with a French type of water heater, consisting of a large cauldron set over a very small fire box in which wood was used as fuel, the company bathroom erected in the rear end of barracks No. 222 was opened for general use on November 24. Popular from the first day, this addition to the conveniences of the camp was kept in operation by a company order decreeing that each man must bathe at least once each week or as many more times as he had the opportunity. One man was detailed to keep the water at the right temperature and level in the heater, so facilities for bathing were never lacking.

Arguments on the war, its probable end, the chances for the Company to get to the "Front" and other topics fully as engrossing were discussed about the fires at night until a seeming lack of military knowledge among the men prompted an order which brought about evening schools on "Drill Regulations" and other phases of army life. A study of these tactics was pursued with a thoroughness which would have been impossible to acquire under the more distracting conditions at the camp back in Niantic.

Boundless good fortune struck camp the day before Thanksgiving.28 Turkey and special rations were issued and freight containing cigarettes, tobacco and the company phonograph arrived. Measles had entirely disappeared, so the quarantine was lifted and allowed the men a freedom which had not been theirs since the arrival in France. All night the kitchen police and cooks toiled to make the holiday dinner one to be remembered, and their efforts were rewarded, for they presented the Company with a feast which in amount and variety would have satisfied the wildest wish. Turkey and cranberry sauce reigned supreme, severely crowded for popularity by sweet potatoes and other vegetables, pumpkin pies, coffee and a barrel of beer.

In a program of athletic events arranged for the day, all but necessary duties being suspended, the officers' race showed Lieutenant Nelson to be the fleetest with Lieutenant Bacharach a close second; McLaughlin bested the efforts of the sergeants, with Curtiss but a few feet behind; Poirier grabbed the corporals' contest, as well as the "free-for-all"—and Malone travelled next. Cook Conroy running against the privates first class took first prize and Johnson took second; Nutile, Rourke and Hannon finished in that order when the privates took their turn on the field. Thirty-two points was the total of the third platoon's efforts when men from that group took the gun-squad competition and the relay race. In the team scores they were followed by the first platoon with nineteen to its credit, while headquarters with seven points and the second platoon with five brought up the rear.

Following dinner, which was served at the conventional hour of 6 o'clock and for which the third platoon, in recognition of its prowess on the athletic field, stood first in line, prizes were distributed to all successful contestants. The double quartette which had been under the tutelage of Lieutenant Bacharach for some time made its first appearance, the Morning Scratch was heard through its second edition, and each of the officers gave a short talk. Sergeant Bell bade farewell to the Company because of his impending departure for the Army Candidate School.

A succession of acting first sergeants followed when Sergeant Bell left and Curtiss was finally picked for the permanent position. Automatic weapon schools were patronized by Sergeants29 Cramer, McLoughlin and Reilly and Corporals McKiernan and Viebranz during the following month while the Company was getting first experience in target practice under the guidance of instructors assigned from the French Army.

On December 6 the first letters from home were received, and four days later information was eagerly sought concerning the French monetary system, for Lieutenant Nelson, as Battalion Paymaster, gave out the pay due the Company in francs. For a few days the shops of Neufchateau were deluged with chocolate and souvenir seekers. Meager stores of French were overhauled in the attempt to express needs to the merchants and the services of French-speaking members of the outfit were rewarded with liberal amounts of wine and all the eatables procurable.

Lieutenant Chester C. Thomas was assigned to the Company from C Company of the Battalion. His original organization was the Vermont regiment of which Lieutenant Nelson and various enlisted men in the Company had been members. His addition brought the number of officers in the Company to seven, one in excess of the requirements of the tables of organization and was the preparation for the removal of Captain Wolf, which took place during the following month.

Christmas day brought more festivities. A tree was set up in the mess hall and decorated in the approved manner with candles and tinsel, the hall itself being transformed into a bower of green and red through the efforts of the committee appointed30 to care for the arrangements. Turkey was again issued and the supplies augmented by purchases at the commissary in Neufchateau. Christmas packages from home which had been arriving for some time were distributed by Captain Wolf and every member of the Company was presented with a gift bought from the Company fund. The Company in turn presented its commander with a fur coat to aid him in withstanding the rigors of a winter which was at no time gentle.

The day was enjoyed to the utmost. Buglers were silenced so that the unusual pleasure of lying luxuriously in bunks could be enjoyed for the first time. Much of the day was spent in revelling in the contents of the boxes received from home. No Christmas stocking of childhood ever held half the fascination of those little packages. Everything brought back cherished memories and the enjoyment was doubled by the fact that no duties disturbed the calm of reflections. Following the dinner that night the mess hall was cleared and a stage set up over the serving tables in the kitchen, complete with an artistic backdrop decorated in conventional style by Guerrant, a curtain which would open in the center after sufficient coaxing, and footlights patiently manufactured by Saddler Thompson from tobacco cans and candles.

After Lieutenant Bacharach's orchestra had played an "overture" and the Company filled mess hall seats, the double quartette occupied the stage and gave a few well-received selections. "Rubber" Callahan furnished the next feature, winning applause by his nimble dancing. Then, with a setting almost theatrical, McCarthy as cub reporter was ordered by Malone, as city editor, to read certain excerpts from the third and final edition of the Morning Scratch. News was plenty for this edition and scandal was related with a true flavor, outdoing previous attempts by so much that serious consequences threatened for a time after the edition appeared in public.

After the quartette had again offered its best to the audience, Poirier, Foster and Hunihan presented a melodramatic sketch in which Poirier played the part of the villain, Foster that of the trusting wife and Hunihan that of the honest young workingman who was tempted but thought better of it and sold the old pistol to buy chocolate for the baby, putting an end to a31 situation which threatened to become painful. Eddie O'Neill entertained with his best steps and then Hobart and Cath appeared on the stage, the former in the garb of a Scotchman (or so it was said to be) and the latter in a combination of attire which surpasses any power of description because of its varied character. After a brief and wholly unnecessary bit of persiflage these ambitious entertainers broke forth in song which would have been passed on mercifully by those present had not Hobart essayed an encore which was more than the audience could stand and they exhibited their disapproval by showering the stage with all movable objects.

Eddie Malone added to the interest of the day by vanquishing three visitors from a neighboring camp in such a manner that they promised revenge, and began a return with augmented forces, but abandoned their enterprise before they reached the camp and returned to their own barracks.

No turkey was repeated for New Year's Day, but a pig was purchased from a nearby farmer and proved a welcome addition to the rations.

British and French gas masks issued the day before Christmas were used constantly in drills. Two long, tiresome days were spent in the drillgrounds of the infantry, where trenches were simulated by paths through the snow and where the inactivity produced severe trouble with frostbitten feet, forcing Ralph Moore to go to the hospital for a considerable stay.

Lieutenant Condren assumed command of the Company when Captain Wolf left to become divisional billeting officer on January 13, inaugurating his reign by confining all members of the Company to camp and advancing the hour of reveille forty-five minutes because of the disappearance of two cans of milk from the kitchen. The mystery of the milk remained unsolved, however, and five days later the regular schedule of calls was resumed. All during the following month Sundays were taken up with drills or fatigue work, not to mention the endless inspections which make the lives of all soldiers miserable.

Major Howard, in command of the Battalion during all this time, graced the company with visits only on two occasions. Orders were received from the headquarters of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion, but it soon became evident that the32 identity of Company A was to be changed, for orders were issued causing that organization to be placed under the command of the major of the 102d Machine Gun Battalion for "instruction and training." These orders were never rescinded and in due time D Company of the 102d Machine Gun Battalion was designated as a permanent title and A Company of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion passed into oblivion, along with Troop A, Connecticut National Guard. In accomplishing this stroke, Major Howard also succeeded in having D Company of his battalion transferred to the 103d Machine Gun Battalion, leaving him in command of the two Hartford companies which now became the divisional reserve, equipped with motor transportation and held out of the line during the greater part of the campaigns which followed.

Final preparation for the first trip to the trenches which the men were told would take place early in February consisted in training the mules issued to the Company to haul the gun-carts, ammunition carts, caissons, rolling kitchens and escort wagons, inspections without number, trips to the machine gun range33 where all the guns in the division were assembled for practice, and the policing ever necessary before an organization could leave a camp it had occupied.

Pay and mail brought more joy to the camp on January 23 and the following nights were spent visiting the nearby cafés or, when opportunity offered, taking the quaint train which conveyed the men to and from Neufchateau at a cost of two cents per trip in real money. The fate of five small pigs dropped from a train in the vicinity of camp was promptly decided by Minor and Parmalee, who captured them and after a night spent by most of the Company trying to keep the porkers in captivity, they were killed and served at mess the following day.

Trips to the machine gun range laid out by one member of the Company in coöperation with a man from Battalion headquarters near Prez sous Lafauche, southwest of Neufchateau, were made by French motor truck. There the men had their first demonstration of barrage fire over the heads of friendly troops, were addressed for the first time by Major General Clarence R. Edwards, commander of the Division, and Colonel Parker, famed throughout the army for his work in connection with the development of the machine gun and at that time the energetic commander of the 102d Infantry Regiment, who, in his direct manner described vividly the part machine guns were intended to play in the war.

Interspersed with machine gun work was instruction in grenade throwing and the final test of the gas masks when the entire Company passed through a chamber filled with chlorine gas.

Farewell was bade the camp which had served as a home for more than three months on February 7, when after a final and extensive policing, the Company slung packs and began the hike over the hill leading to Chatenois and eventually to the trenches.

Early plans of the War Department for training troops in France included a period during which the "Yanks" were brigaded with French or British units to spend a probationary time in the lines, when they received instruction in trench routine, were taken on raiding expeditions by the veteran fighters of the Allies and received their baptism of fire, often very severe when the Hun discovered the presence of green troops on the front. It was on this course of training the Company was bound when just at dusk on February 7 packs were slung and the men began their struggle up the ice-covered hill on the road to Chatenois.

Experience in hiking to the trenches soon taught enlisted men that the primitive life on the front line did not call for various accoutrements thought necessary in the barracks, or at least it was much easier to do without certain articles than it was to carry them. This first trip, however, saw packs, bundles and bags such as had adorned the men when they left Niantic. By the time they reached the top of the hill back of the camp, although many rests had intervened during the climb, resolutions galore were made concerning the amount to be packed on another trip. With very little climbing to do on the rest of the journey, it was made in good time, and under the supervision of Lieutenant Paton the gun carts and wagons were loaded onto the waiting train, after which rations for the trip were drawn for each car and the men made themselves comfortable for the night.

Sleeping on the floor of a box car had no terrors for the men who had spent the past three months on the hard bunks of the barracks, so the bumping, swaying progress of the train leaving early the following morning failed to disturb the rest of most of the sleepers. The next day as the train passed through Epernay, Bar le Duc and Chalons-sur-Marne, wooden crosses on the graves of the first valiant defenders of the Marne and houses wrecked by shell fire and flames brought clearly to their minds the step they were taking toward the completion of a task35 other men had found hard. The naturally light-hearted spirit of the Company prevented any depression and singing could be heard from end to end of the train as it rolled along on the grand line of France through some of the prettiest scenery that land affords. Travelling most of the time through valleys where the tiny villages dotted with white the green of early spring crowning the hills on all sides, "Sunny France" became more of a reality and the spirit of her men, fighting to preserve these peaceful scenes, became more thoroughly appreciated as some of its inspiration dawned upon their brothers in Democracy.

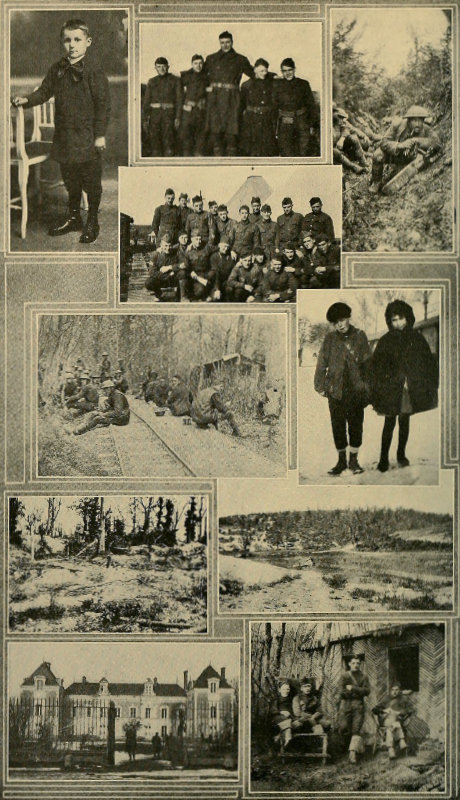

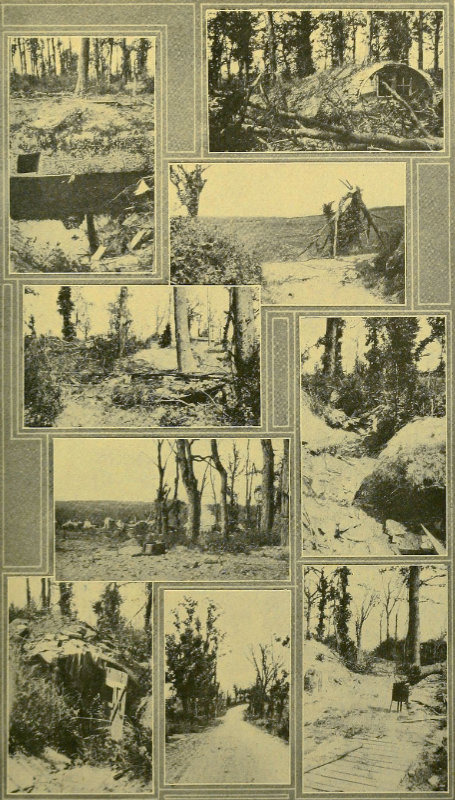

Early evening found the train at Dormans, a short distance east of Chateau-Thierry, and from there a branch line was followed to Braisne, a town less than six months before in the hands of the Hun. War zone rules prevailed here and the unloading was done mainly in darkness but accomplished quickly. At the end of a ten kilometer march the Battalion was billeted in the ruined city of Vailly. To D Company fell a hut of similar type to the ones used as barracks in Certilleux. Sleep was curtailed the next morning by orders to move to the security of dugouts and cellars with which the city was filled. During the balance of the day explorations were in order, for the surrounding country offered limitless opportunities to observe the havoc wrought by war. Twice the opposing armies had battled through this portion of the department of Aisne, so that trenches, observation posts and graves of soldiers of both powers were plentiful.

Airplanes passed time and again on their missions over the lines. Men of the Company saw their first struggle between aviators, viewed breathlessly the feat of a German birdman who destroyed a French observation balloon and the escape of the observer from the basket of the "blimp" in a parachute. The camouflage screens used so extensively during the war were much in evidence here as the roads were open to enemy observation. All other artifices of war as it had been developed since the introduction of trench fighting were to be seen in abundance.

On the night of February 10 C Company of the 102d Machine Gun Battalion entered the line at Froidmont Farm and took positions turned over to them by the French along the slopes of the famous ridge crowned for the distance of about four kilometers36 by the Chemin des Dames, from which the sector took its name.

Packs were rolled on short notice in the afternoon of the 13th and a march of four kilometers to the east took the Company to the ruined village of Chavonne where the wagon train established quarters and above which the Company was billeted in caves called "Les Grenouilles" (the frogs). Here were electric lights and wooden floors and French Army canteens nearby, but luxuries lost their interest when a German aviator and his machine, felled perhaps three months before, were discovered in a shell-pitted field near the cave.

Preparations for the coming trip to the front were continued, the guns polished and oiled to the last degree, carts thoroughly overhauled and personal equipment put in proper order. Aerial activity offered the only distraction from duty. One bright day when the entire Company was viewing a combat between Allied and German planes from the hill above its appointed home, General Peter E. Traub (at that time in command of the 51st Infantry Brigade, of which the Company was a part) made an impromptu visit, resulting in a comprehensive and forceful lecture from that officer on the proper deportment of soldiers when enemy planes came into view.

According to the routine established reconnaissance parties preceded their respective companies into the line by twenty-four hours to allow a relief without endangering the strength of the position. In conformity with this Lieutenant Condren, with a representative from each section, went ahead of the Company. On February 16 Lieutenant Thomas led the balance of the command up through Ostel, where dusk was awaited because of the exposed road to be traversed between that village and Froidmont Farm, the objective of the Company. From there they marched down the road in sections into the cave cut from the soft limestone deposit from which the first and second platoons took positions in the first line, with the third remaining in the cave as a reserve.

One of the wonders of the war, that cave had a capacity of about ten thousand men, most of whom could be furnished with sleeping quarters. It was equipped with electric lights burned only during certain hours of the day, officers' quarters and37 kitchens for a limited number of men and the ever present French canteen with its stock of wine and chocolate.

Passing through the cave, the men designated to take the first shift on the line found travelling difficult when they reached the stairs leading up and out at the front. These were narrow and steep with roof so low that "Duke" Rowley's equipment wedged him in and he was forced to have some of it removed before he could continue. Finally reaching the outside, guides were waiting to conduct the squads to the replacements they were to occupy, and after guns were set up all but a guard for each gun sought the dugouts, which were deep, small and unventilated.

One of the difficulties of duty in this part of the line was the disposal of the kitchen which was finally left near Ostel in a depression which became known as the forerunner of a long line of "Shrapnel Valleys" for the smoke from the fires always presented a fair target to Hun gunners. From here the "grub" was carried to the men in the line in large marmite cans constructed with the idea of keeping food warm and fitted with handles supposed to make them more easily portable. These38 trips accomplished twice each day by details from each section were often fraught with danger, for the Hun insisted on "strafing" the road at the most inopportune times, and hairbreadth escapes were daily topics while the gun squads waited in their dugouts.

Accustomed to activity of a strenuous sort during most of their waking hours, the men found trench warfare irksome, wondering at the businesslike attitude adopted by the doughty French soldiers who took their trips to the trenches much as most Americans take their daily work in peace times. Chaffing under the restraint, McAviney and Parmalee produced life-sized bombardments one night for the benefit of Lieutenants Bacharach and Carroll by throwing hand grenades over the parapet until their tactics were discovered.

Gas alarms and drills, airplanes passing over and one call for a barrage which brought a prompt response from the Company guns broke the monotony of the stay. The main source of amusement, however, was watching the shells from American batteries break in the village of Chevregny, which with Monampteuil occupied the ridge on the opposite side of the valley in the German lines. Through this valley ran the Ailette River, a tributary of the Oise, as did the canal connecting the Oise with the Aisne.

Relieved by C Company February 22, the Company proceeded back to quarters at Chavonne.

Turkey was on the menu for the 24th and arrangements were made with Dr. Johnston, of the Y. M. C. A., so that each man was allowed a limited amount of credit at his canteen, for all were penniless as usual. Added to these luxuries was a bath for everyone obtainable at a station in Vailly loaned by the French authorities.

Soupir, St. Mard and Cys-la-Commune, the latter two south of the Aisne, were visited by the men during the next two days. Some of the officers also made the trip to the neighboring towns. Lieutenants Nelson and Paton, returning from a purchasing expedition and failing to find the road leading across the bridge, commandeered a raft which failed them in mid-stream and their supplies were resting on the bottom of the river when they succeeded in reaching the bank.

On their second trip to the lines, made on the night of the 27th, the Company officers decided it would be necessary to pass through the cave, and after a long struggle through twisted paths, barbed wire, broken trench timbers and mud worse than ordinary because of a recent fall of snow, the men reached their assigned positions.

With the exception of a raid conducted by the French in coöperation with members of the 101st Infantry Regiment, on the left of the Company positions, followed by intermittent bombardments of retaliation by both sides, the second shift in the trenches for the members of old Troop A was uneventful. Routine duties continued until Friday, March 8, when French soldiers relieved them and they returned to billets at Chavonne. The Hun's farewell was enthusiastic, high explosives and gas shells expressing his hatred for the new units in the line. A bombing squadron bound for Paris passed above the men as they trudged back through Ostel and gas shells were so numerous that much of the trip was made with the masks adjusted.

In preparation for eventualities, the French authorities were constructing defensive positions protected by barbed wire for several miles to the rear of the lines they then occupied. It was into some of these just to the rear of American batteries near Ostel that part of D Company was sent on the day following its relief from the front line. Life at these posts was ideal, duties were cut to a minimum, food was brought in plentiful quantities to the doors of the dugouts, and with pay day on the Wednesday following the relief, French canteens were liberally patronized. Excellent weather prevailed during the rest of the stay in this sector and when the Battalion left Chavonne for Braisne March 18 impressions concerning the character of war were of a high nature for the Company had passed through its training period with no casualties and but few real hardships.