*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 56071 ***

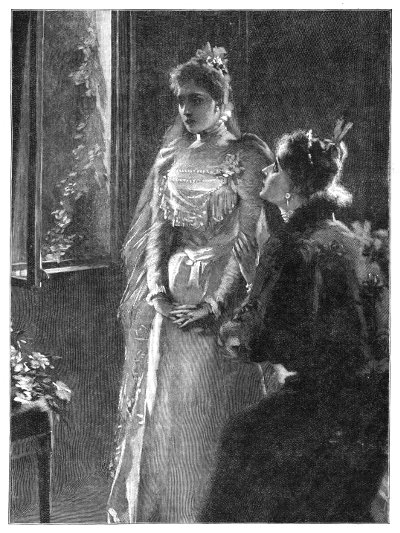

Oh, happy bride!

Heaven’s sunlight wraps thee in a golden gleam,

And in thine eyes the light of love supreme,

And in thy heart the dawning of a dream,

And what beside!

Hopes reaching wide,

Out into the new life unbegun,

Into the untrodden ways thy feet may run

And the dim future only known by One—

The One Who died.

And a sweet pride

That thou art chosen the whole world above,

And girt about with mightiness of love,

Which waits to cherish thee as tend’rest dove

Till death divide.

And there abide

In thy full heart most sweet-sad memories

Of one who smiles on thee from out the skies,

Thy best belovèd, now in Paradise,

Thy earliest guide;

At whose dear side

Thy girlhood’s opening flower sweetly grew,

Till death transplanted her into the blue;

There to watch over thee with love more true

And purified.

In the untried

And varying life which waits thee, rosy-hued,

God speed thee! and give daily grace renewed,

And bless with all His large beatitude

Thy marriage-tide.

Though thou be tried

And troubled oftentimes in this new life,

Christ wall be with thee through the calm and strife,

Help thee to beautify the name of wife,

Oh, happy bride!

All rights reserved.]

{290}

A TALE OF THE FRANCO-ENGLISH WAR NINETY YEARS AGO.

By AGNES GIBERNE, Author of “Sun, Moon and Stars,” “The Girl at the Dower House,” etc.

CHAPTER XIX.

ORDERED TO BITCHE.

Roy forgot everything

except the

affair on hand.

He dashed upstairs

and into

the salon at a

headlong pace,

knocking over a

chair as he entered.

It fell with

a crash, and Roy

stopped short. Denham was on the

sofa, no one else being present except

Lucille, who, with her bonnet on, as if

she were going out, had just taken an

empty cup from his hand.

“Roy, you unkind boy,” she said,

turning with a look of positive anger.

“How you can do it!”

“O I’m sorry. I didn’t remember.

Isn’t Den better?”

“Not remember! But you ought to

remember. So without thought. It is

selfishness.”

For Lucille to be seriously displeased

with Roy was an event so new in

his experience, that Roy gazed with

astonished eyes.

“No matter,” interposed Denham.

“Had a good time, Roy?”

“I’ve seen lots of people. Den, I’m

sorry, really. I didn’t mean——”

“No, of course not. It’s all right.”

“Where is my father?” Roy asked in

a subdued voice.

“Gone out—but ten minutes since,”

said Lucille. “General Cunningham

sent to see him on business. And

Colonel Baron has to go with him somewhere,

and cannot return soon. So

dinner is put off till six.”

“And mamma?”

“Mrs. Baron had a call to pay in the

same direction. Captain Ivor thought

he might get half-an-hour’s sleep. Roy,

be good, I entreat. Do not fidget, and

knock over chairs, and talk, talk, talk,

without ending.”

Roy nodded, and Lucille moved towards

the door, adding, as she went,

“I also have to see someone, but I

shall be back soon.”

Roy sat down in a favourite attitude,

facing the back of a chair, and wondering

what to do next. Would it be right

to tell Denham what had happened?

Would it be wrong to put off telling?

Curtis had enjoined him to speak at

once; but Curtis had not known the

posture of affairs. The matter might

be of consequence, or it might not.

Roy was disquieted, but not seriously

uneasy; and he hesitated to worry

Denham without cause.

“Seen anybody?” asked Ivor.

“Yes; numbers.”

Then a break.

“Found Curtis?”

“Yes. And Carey too. Would you

like to hear all about it?”

“By-and-by, I think. It will keep.”

Silence again, and Roy debated

afresh. What if his action should

mean bringing Curtis into trouble?

That thought had considerable weight.

Three times he formed with his lips

the preliminary “I say, Den!” and

three times he refrained. The third

time some slight sound escaped him, for

Denham asked drowsily, “Anything

you want?”

“Lucille told me not to talk. Does

it matter?”

Ivor did not protest, as Roy had half

hoped. He was evidently dropping off,

and Roy decided that a short delay was

unavoidable. He took up a volume that

lay near; and, being no longer a book-hater,

he became absorbed in its contents.

General Wirion, chips of wood,

the Imperial nose, and irate landladies,

faded out of his mind. The matter was

no doubt a pity, but after all it meant

only—so Roy supposed—a pull upon his

father’s purse. Boys are apt to look

upon parental purses as unlimited in

depth.

Denham was sound asleep, and Roy

kept as motionless as any girl; not that

girls are always quiet. An hour passed;

another half-hour; and he began to

grow restless. Might it be possible to

slip away?

Gruff voices and heavy trampling feet,

in the hall below, broke into the stillness,

and Denham woke up. “This is

lazy work,” he said wearily. “Roy—here

yet! What time is it?”

“Nearly five. Dinner isn’t till six.

Head any better?”

“Yes. I’m wretched company for you

to-day. Different to-morrow, I hope.”

“You can’t help it. You’ve just got

to get rested—that’s all. I say, what a

noise they are making downstairs.

Frenchmen do kick up such a rumpus

about everything.”

The door opened hurriedly, and

Lucille came in, wearing still her bonnet,

as if just returned from a walk.

“I am so sorry,” she said. “I do

not know what it means, but I must tell.

I have no choice. O it surely must

be a mistake, it cannot be truly——”

Lucille startled herself no less than

her listeners by a sharp sob. She

caught Roy’s arm with both hands,

holding him fast. “Roy—Roy—what

is it that you have done? O what have

you done?” she cried.

“Is it that bosh about the cast? O

I know. They want to be paid, I

suppose. Lucille, Den has been asleep,

and I’ve been as quiet as anything—and

then for you to come in like this!

Den, you just keep still, and I’ll go and

speak to them. I’ll settle it all. I

know my father will pay.”

“No, no, no—stay—you must not

go,” panted Lucille. “Stay—it is the

gendarmes! And they come to arrest

you—to take you away!”

The word “gendarmes” acted as an

electric shock, bringing Denham to his

feet in a moment.

“What is it all about? I do not

understand.” He touched Roy on the

shoulder, with an imperative—“Tell

me.”

“It was only—I’d have told you

before, only I didn’t like to bother you.

It was at Curtis’. There was a bust of

Boney on the mantelshelf, and I just

shied bits of wood at it, in fun. And I

said ‘À bas Napoléon,’ or something of

that sort; and then I threw a ball, and

the idiotic thing tumbled down and

broke into pieces. And the landlady—she’s

a regular out-and-out virago—happened

that very moment to come in,

and she saw and heard. And she

vowed she would tell of it. Curtis tried

to explain things away, and I offered to

pay, but she wouldn’t listen. She went

on shrieking at us, and said it was an

insult to the Emperor, and Wirion

should know of it. She’s a Bonapartist—worse

luck! Curtis made me hurry

off, and said I was to tell my father at

once. But he was out, and you—you

know——” with a glance at Lucille,

who wrung her hands, while Ivor said,

“Roy, were you utterly mad?”

“I—don’t know. Was it very stupid?

Will it matter, do you think? I’m

sorry about you—most. I thought they

would wait till to-morrow; but I suppose

they want me to go and pay

directly. Is that it?” looking towards

Lucille.

“No, no, no,” she answered, again

wringing her hands. “It is to take—to

take Roy—to the citadel!”

“To the citadel!” Roy opened his

eyes. “O I say, what a farce! For

knocking down a wretched little image,

not worth fifty sous!”

“For breaking a bust of the Emperor,

and for shouting—‘À bas——’”

Lucille could not finish.

“You mean—that they will keep him

there to-night?” Denham said.

She looked at him with eyes that were

almost wild with fear. “Oui—oui—the

citadel to-night! And to-morrow—they

say—to Bitche.”

“To—Bitche!” whispered Roy. He

grew white, for that word was a sound

of terror in the ears of English prisoners,

and his glance went in appeal to

Ivor.

“Stay here, Roy. I will speak to

them.”

Ivor crossed the room with his rapid

resolute stride, and went out, meeting

the gendarmes half-way downstairs.

Lucille clutched Roy’s arm again, half

in reproach, half in protection. “Ah,

my poor boy! mon pauvre garçon! how

could you? Ah, such folly! As if there

were not already trouble enough! Ah,

my unhappy Roy!”

“Shut up, Lucille! You needn’t jaw

a fellow like that! It can’t mean anything

really, you know. Wirion just

thinks he can screw a lot of money out

of my father. And that’s the worst of

it,” declared Roy, in an undertone. “I

hate to have done such a stupid thing—and{291}

I hate the worry of it for Den, just

now when he’s like this. But you know

they couldn’t really send me to Bitche

only for smashing a paltry image. It

would be ridiculous.”

“Ah, Roy! even you little know—you—what

it means to be under a despot,

such as—but one may not dare to

speak.”

Lucille’s tears came fast. They

stood listening. From the staircase

rose loud rough voices, alternating with

Ivor’s not loud but masterful tones.

That he was prisoner, and that they

had power to arrest him too, if they

chose, made not a grain of difference

in his bearing. It was not defiant or

excited, but undoubtedly it was haughty;

and Lucille, just able to see him from

where she stood, found herself wondering—did

he wish to go to prison with Roy?

She could almost have believed it.

“Eh bien, messieurs. Since l’Empéreur

sees fit to war with schoolboys,

so be it,” she heard him say sternly in

his polished French. “To me, as an

Englishman, it appears that his Majesty

might find a foe more worthy of his

prowess.”

“But, ah, why make them angry?”

murmured Lucille.

A few more words, and Denham came

back. One look at his face made

questions almost needless.

“Then I am to go, Den?”

“I fear—no help for it. The men

have authority. You will have to spend

to-night in the citadel. But I am coming

with you, and I shall insist upon seeing

Wirion himself.”

“But you—you cannot! You are

ill!” remonstrated Lucille. “Will not

Colonel Baron go? Not you.”

He put aside the objection as unimportant.

“Roy must take a few things with

him—not more than he can carry himself.

I hope it may be only for the one

night. They allow us twenty minutes—not

longer. That is a concession.”

“I will put his things together for

him,” Lucille said quickly.

“One moment. May I beg a kindness?”

“Anything in the world.”

“If Colonel Baron does not return

before we start—and he will not—would

you, if possible, find him, and beg him

to come at once to the citadel? Then,

Mrs. Baron——”

Ivor’s set features yielded slightly;

for the thought of Roy’s mother without

her boy was hard to face. Lucille

watched him with grieved eyes.

“I will tell her, but not everything—not

yet as to Bitche, for that may be

averted. I will stay with her—comfort

her—do all that I am able. Is this what

you would ask?”

“God bless you!” he said huskily,

and she hurried away.

“Den, must I go with those fellows

really?” asked Roy, beginning to understand

what he had brought upon himself.

“I never thought of that. Can’t you

manage to get me off? Won’t they

let me wait—till my father comes

back?”

“They will consent to no delay. He

will follow us soon. And, Roy, I must

urge you to be careful what you say.

Any word that you may let slip without

thinking will be used against you. I

hoped that you had learnt that lesson.”

A listener, overhearing Denham with

the gendarmes, might have questioned

whether he had learnt it himself; but

Roy was in no condition of mind to be

critical. Dismay grew in his face.

“And if you can’t get me off—— If

I am sent to Bitche——” with widening

gaze.

“If you are”—with much more of an

effort than Roy could imagine—“then

you will meet it like a man. Whatever

comes, you must be brave and true

through all. Keep up heart, and

remember that it is only for a time.

And, my boy, never let yourself say or

do what you would be ashamed to tell

your father.”

“Or—you”—with a catch of his

breath.

“Or me!”—steadily. “Remember

always that you are an Englishman—that

you are your father’s son—that you

are my friend—and that your duty to

God comes first. For your mother’s

sake, bear patiently. Don’t make

matters worse by useless anger. And—think

how she will be praying for

you!”

Denham could hardly say the words.

Roy’s lips quivered.

“Yes, I will! Only, if you could get

me off!”

“My dear boy, if they would take me

in your stead——”

“Den, I’m so sorry! I’m not

frightened, you know—only it’s horrid

to have to go! Just when you’ve come

and all! And it would have been so

jolly! And it’s such a bother for you,

too! I do wish I hadn’t done it!”

Ten minutes later the two started—Roy

under the gendarme-escort, Ivor

keeping pace with them.

Lucille then hastened away on her

sorrowful mission, leaving a message

with old M. Courant, in case either

Colonel or Mrs. Baron should return

during her absence—not the same

message for Mrs. Baron as for the

Colonel.

Half-an-hour’s search brought her

into contact with the latter, and she

poured forth a breathless tale. Heavier

and heavier grew the cloud upon his

face. He knew too well the uses that

might be made of Roy’s boyish escapade.

At the sound of that dread word—“Bitche”—a

grey shadow came.

“Captain Ivor went with Roy to the

citadel. He ought not—he has been so

suffering all day—but he would not let

Roy go alone. And he asked, would

you follow them as soon as possible?

For me, I will find Mrs. Baron, and

will stay with her.”

The Colonel muttered words of thanks,

and went off at his best speed.

Would he and Captain Ivor be able

to do anything? Would they even be

admitted to the presence of the autocratic

commandant? Denham might

talk of insisting; but prisoners had no

power to insist. If he did, he might

only be thrown into prison himself!

Was that what he wanted—to go with

the boy?

“Ah, j’espère que non!” Lucille

muttered fervently.

And if they were admitted, what

then? Would money purchase Roy’s

immunity from punishment? General

Wirion’s known cupidity gave some

ground for hope. Yet, would he neglect

such an opportunity for displaying

Imperialist zeal?

Lucille put these questions to herself

as she flew homeward. On the way she

met little Mrs. Curtis, and for one

moment stopped in response to the

other’s gesture.

“Is it true?” Mrs. Curtis asked, with

a scared look. “They tell me Roy has

been arrested. Is it so? My husband

could do nothing. The landlady was

off before he could speak to her again.

He thought that Roy and the Colonel

would be coming round directly, and so

he waited in. But they did not come.

And now two gendarmes are quartered

in our lodgings, and Hugh may not stir

without their leave. It is horrid! But—Roy?”

“I cannot wait! Roy is taken

to the citadel! I have to see to

his mother! Do not keep me,

Madame.” And again Lucille sped

homeward.

As she had half hoped, half dreaded,

she found Mrs. Baron indoors before

herself, alone in the salon, and uneasy

at Captain Ivor’s absence.

“He ought not to have gone out,”

she said. “He will be seriously ill if

he does not let himself rest. It is Roy’s

doing, I suppose—so thoughtless of

Roy! I must tell Denham that I will

not have him spoil my boy in this way.

It is not good for Roy, and Denham

will suffer for it. You do not know

where he is gone?”

“Oui!” faltered Lucille, and Mrs.

Baron looked at her.

“You have been crying! What is

it?”

As gently as might be, Lucille broke

the news of what had happened; and

Mrs. Baron seemed stunned. Roy—her

Roy—in the hands of the pitiless

gendarmes! Roy imprisoned in the

citadel! Lucille made no mention of

Bitche; but too many prisoners had

been passed on thither for the idea not

to occur to Mrs. Baron.

“And it was I who brought him to

France! It was I who would not let

him be sent home when he might have

gone! O Roy, Roy!” she moaned.

Lucille had hard work to bring any

touch of comfort to her.

Hour after hour crept by. Once a

messenger arrived with a pencil note

from Colonel Baron to his wife—

“Do not sit up if we are late. We

are doing what we can. I cannot

persuade Denham to go back.”

Not sit up! Neither Mrs. Baron nor

Lucille could dream of doing anything

else. This suspense drew them together,

and Lucille found herself to be one with

the Barons in their trouble.

Nine o’clock, ten o’clock, and at

length eleven o’clock. Soon after came

a sound of footsteps. Not of bounding,

boyish steps. No Roy came rushing

gaily into the room. Lucille had found

fault with him that afternoon for his{292}

noisy impulsiveness; but now, from her

very heart, she would have welcomed

his merry rush. Only Colonel Baron

and Ivor entered.

The Colonel’s face was heavily overclouded,

while Denham’s features were

rigid as iron, and entirely without colour.

“Roy?” whispered Mrs. Baron.

Deep silence answered the unspoken

question. Colonel Baron stood with

folded arms, gazing at his wife. Denham

moved two or three paces away,

and rested one arm on the back of a

tall chair, as if scarcely able to keep

himself upright.

“Roy!” repeated Mrs. Baron, her

voice sharpened and thinned. “You

have not brought—Roy!”

A single piercing laugh rang out.

She stopped the sound abruptly with

one quick indrawing of her breath, and

waited.

Colonel Baron tried to speak, and

no sound came. Denham remained

motionless, not even attempting to raise

his eyes.

“Oui!” Lucille said restlessly. “Il

est—il est——”

The Colonel managed a few short

words. There was no possibility of

softening what had to be said.

“To-night—the citadel. To-morrow—to

Bitche!”

“To Bitche!” echoed Lucille.

“Ah-h!”

To Bitche—that terrible fortress-prison,

the nightmare of Verdun

prisoners! Their Roy to be sent to

Bitche! Mrs. Baron swayed slightly

as if on the verge of fainting. Roy,

her petted and idolised darling—her

boy, so tenderly cared for—to be hurried

away to Bitche!

Lucille hardly could have told which

of the two she was watching with the

more intense attention—Mrs. Baron,

stunned and wordless, or Denham, with

his fixed still face of suffering.

“And nothing—nothing—can be

done?” she asked.

“We have tried everything!” the

Colonel answered gloomily.[1]

(To be continued.)

By Mrs. MOLESWORTH.

No true child-lover would

maintain that all children

are equally lovable,

or indeed, in

some—though, I

think, rare instances—lovable

at all.

But in this, speaking

for myself, I detect no

inconsistency, no falsity

to one’s colours.

For the qualities or deficiencies

which make

a child unlovable may

be summed up in one

word; they are such

as make it unchildlike.

And this, not necessarily,

if at all, as regards

a child’s mental

qualities. It is the

moral side of child-nature

that attracts—the

heart, the spirit.

For painful as it is to meet with precocity of

mind in some instances, especially the precocity

of the kind forced upon the children of the

poor not unfrequently, this, unchildlike as it

is, is by no means incompatible with great

sweetness and beauty of the moral character,

great power of affection, delightful candour,

even that most exquisite of childlike possessions—trustfulness.

Yes, the root of a child’s nature, the

essential groundwork of it, to be lovely and

lovable, must be childlike. But a literal

meaning must be given to the pretty adjective.

I would not even altogether eliminate from it

certain qualities which might, strictly speaking,

be perhaps more correctly described as

childish, seeing that if we limited the

word too narrowly, we should lose others of

the great charms of children, their queer,

delightful inconsistencies and exaggerations,

their quaint originality, their grotesque

imaginings, all of which, in more or less

degree, a real child, even a dull or stupid one,

possesses.

Take, for example, the unconscious egoism,

almost amounting, logically speaking, to

“arrogance,” of most children. The world,

nay, the universe, is their own little life and

surroundings; their house and family are the

rules, the proper thing, all others exceptions.

It is not, in most instances, till childhood is

growing into a phase of the past, that the

sense of comparison is really developed, or

that the young creatures take in that other

circumstances or conditions besides their own

may be what should be, that they themselves do

not hold a monopoly of the model existence.

There is something pretty as well as absurd

in this—to my mind, at least, in certain

directions, something almost sacred, which it

would be desecration to touch with hasty or

careless fingers; which, one almost grieves to

know, must pass, like all illusions, however

sweet and innocent, when its day is over.

To recall some recollections of my own

childish beliefs—if the egotism may be

pardoned, on the ground that one’s own

experiences of this nature cannot but be the

most trustworthy. I often smile to myself,

with the smile “akin to tears,” when I look

back to some of the faiths, the first principles,

of my earliest years.

Foremost among these was the belief in the

absolute perfection of my father and mother.

I thought that they could not do wrong, that

they knew everything. I remember feeling

extremely surprised and perplexed on some

occasions when, having involuntarily—for I,

like most children, but seldom expressed or

alluded to my deepest convictions—allowed

this creed of mine to escape me, the subjects of

it—though not without a smile—endeavoured

tenderly to correct my estimate of them.

“There are many, many things I do not

know about, my little girl,” my father would

say, adding once, I remember—for this remark

impressed me greatly—“I only know enough

to begin to see that I am exceedingly

ignorant.” And my mother was even more

emphatic in her deprecation of our nursery

fiat that “mamma was quite, quite good.”

Not that these protestations shook our

faith. In my own case I know that the

unconscious arrogance with regard to family

conditions extended to ludicrous details. I

thought that the Christian names of my parents

were the only correct ones for papas and

mammas; I believed that the order in which

we children stood—there were six of us, boy,

girl, boy, girl, boy, girl—was the appointed

order of nature, that all deviation from these

and other particulars of the kind was abnormal

and incorrect, and I viewed with condescending

pity the playmates whose brothers and

sisters were wrongly arranged, or whose

parents suffered under “not right” names.

Gradually, of course, these queer, childish

“articles of belief” faded—melted away in

the clearer vision of experience and developing

intellect. But they left a something behind

them which I should be sorry to be without;

and they left too, I think, a certain faculty of

penetration into infant inner life, which

circumstances have shown themselves kindly

in preserving and deepening. I have learnt

to feel since that nearly all children have

their own odd and original theories of things,

though many forget, as life advances, to

remember about their own childhood’s beliefs

and imaginings. And this is not unnatural,

when we take into account the rarity and

difficulty of obtaining a child’s full confidence,

for uncommunicated, unexpressed thoughts

are apt to die away from want of word-clothing.

One really learns more about

children from the revelations of grown-up

men and women who “remember,” and have

cherished their remembrances, than from the

children of the moment themselves.

Still, queer ideas crop out to others sometimes.

Not often—if it happened oftener we

should be less struck by their oddity, by their

grotesque originality. A few which, in some

instances, not without difficulty and the

exertion of some amount of diplomacy, I have

succeeded in extracting—no, that is not the

right word for a matter of such fairylike

delicacy—in drawing out, as the bee draws

the honey from the tiny flowers—occur to me

as I write, and may be worth mention.

A small boy of my acquaintance, after a fit

of extreme penitence for some little offence

against his grandmother, whom he was very

fond of, added to his “so very sorry,” “never

do it again, never, never,” the unintelligible

assurance, “I will be always good to you,

dear little granny, always; and when you

have to go round all the houses, I’ll see that

our cook gives you lots and lots of scraps—very

nice ones—and nice old boots and shoes,

and everything you want. I’ll even”—with

a burst of enthusiastic devotion—“I’ll even

go round with you my own self.”

Grandmother expressed her sense of the

intended good offices, but gingerly, with my

assistance, set to work to find out what the

little fellow meant—what in the world he had

got into his head; and it was no easy task, I

can assure you. But at last we succeeded.

It appeared that the confusion in the boy’s

mind arose from the, in a sense, double

meaning of the word “old.” He associated

it, naturally enough, with the idea of poverty,

material worthlessness, in conjunction with that

of age and long-livedness. Every human being,

he believed, had to descend, “when you gets

very old,” to a state of beggardom; his dear

granny, like everybody else, would have to

wander from door to door with a piteous tale

of want; but from his door she should never{293}

be repulsed; nay indeed, he himself would

take her by the hand and lead her on the

painful round. Nor did he murmur at this

strange order of things; to him it was a

“has-to-be,” accepted like the darkness that

follows the day; like the gradual out-at-toe

condition of his own little worn-out shoes;

and I greatly doubt if our carefully-worded explanation

of his mistake carried real conviction

with it. I strongly suspect that he remained

on the look-out for granny in her new rôle for

a good many months, or even years, to come.

Some other curious childish beliefs recur to

my memory. I knew a little girl who

cherished as an undoubted article of faith a

legend—how originated who can say?—perhaps

suggested by some half poetical talk of her

elders about the aging year, the year about

to bid us farewell and so on, perhaps entirely

evolved out of her own fantastic little brain—that

on the 31st of December the “old year”

took material human form and strolled about

the world in the guise of an aged man, though

unrecognised by the uninitiated crowd. She

had the habit on this day of taking up her

quarters in a corner of the deep, old-fashioned

window-sill of her nursery, and there, in

patient silence, gazing down into the street

till Mr. Old-year should have passed by.

Nor were her hopes disappointed. She

always caught sight of him and nodded her

own farewell, unexpectful of any response.

“He couldn’t say good-bye to everybody;

he wouldn’t have time,” was her explanation

to the little sister to whom she at last confided

her odd fancy, and through whose indiscretion

it leaked out to the rest of the nursery group.

“But how do you know him?” she was

asked. “Is he always dressed the same?”

“Oh, no,” was the reply, “he sometimes

wears a black coat and sometimes a brown;

and one year he had a blue one with brass

buttons. That was the first year I saw him,

and I have never missed him since. He has

always white hair, and he walks slowly,

looking about him. I always know him,

almost as well as you’d know Santa Claus

if he came along the street, though, of course,

he never does. He comes down chimneys,

and I don’t think children ever do see him,

for they’re always asleep.”

The little woman was, wisely I think, left

undisturbed in her innocent fancy. How

many more times she ensconced herself in her

window on the 31st of December I cannot

say. The belief in the poor Old-year’s lonely

wandering interested her for the time and did

her no harm, then gently faded, to be revived

perhaps as a story of “When mother was

a little girl,” when mother came to have

little girls of her own to beg for her childish

reminiscences.

This personification of abstract ideas is a

peculiarity, a speciality of children, as it

was no doubt of the children of the world’s

history—our remote ancestors. And I have

noticed that among abstract ideas that of

time has a particular fascination for imaginative

little people. Many years ago I happened

to be staying in a country house when

a group of children arrived from town to

spend their summer holiday with the uncle

and aunt to whom it belonged. Entering the

room where these little sisters were quartered,

early in the morning after their journey, I was

surprised to find the trio wide awake, each

sitting up in her cot, in absolute silence as if

listening for something.

I too stood silent and still for a minute or

two, till yielding to curiosity I turned to the

nearest bed, which happened to be that of the

youngest, a girl of five or six.

“What is it, Francie?” I inquired. “Are

you trying to hear the church bells”—for

it was Sunday morning—“or what?”

With perfect seriousness she turned to me

as she replied—

“No, auntie dear. We are listening to

time passing. We can always hear it when

we first come to the country. In London

there is too much noise. Meg”—her mature

sister of ten—“taught us about it. So we

always try to wake early the first morning on

purpose to hear it.”

Another friend of mine, now an elderly, if

not quite an old, woman, had a curious fancy

when a very young child, in connection with

which there is a pretty anecdote of the poet

Wordsworth, which may make the story

worth relating. This little girl believed that

during the night before a birthday a miraculous

amount of “growing” was done, and on

the morning on which her elder brother attained

the age of six, she, his junior by two

years, flew into the nursery when he was being

dressed, expecting to see a marvellous transformation.

But—to her immense disappointment—there

stood her dear Jack looking

precisely as he had done when she bade him

good-night the evening before. Maimie’s

feelings were too much for her.

“Oh, Jack,” she cried, bursting into tears,

“why haven’t you growed big? I thought

you’d be kite a big boy this morning.”

Jack and nurse stared at her. I am afraid

they called her a silly girl, but however that

may have been, her disappointment was vivid

enough for the remembrance of it to have

lasted through well nigh half a century, and

her tears flowed on. Just then came a tap

at the door, followed by the entrance of the

cook, a north countrywoman and a great

favourite with the children. A glance at her

showed Maimie that she was weeping, and

when their old friend threw her arms around

the little people, and kissed them, amidst

her sobs Maimie felt certain that the source

of her grief was the same as of her own.

“Is you crying ’cos Jack hasn’t growed for

his birthday?” asked the little girl. But

Hannah shook her head.

“I don’t know what you mean, my sweet

one,” said the old woman. “I’m crying

because I’ve got to leave you. This very

morning I’m going, and I’ve come to say

good-bye.”

This startling announcement checked

Maimie’s tears, or if they flowed again it was

from a different cause.

“Oh, dear Hannah,” the two exclaimed,

“why must you go if it makes you so unhappy?

Doesn’t mamma want you to

stay?”

“Oh, yes, dearie,” was the reply, “but it’s

my duty to go to my old mistress. She’s ill

now and sad, and she thinks Hannah can

nurse her better than anyone else.”

So with tender farewells to the children

she was never to see again, poor Hannah went

her way.

Her “old mistress” was Miss Dorothy

Wordsworth. And though Jack and Maimie

never saw the faithful servant any more, they

heard from, or rather of, her before long. For

only a few weeks had passed when one morning

the postman brought a small parcel

directed to themselves, and a letter to Jack,

Hannah’s particular pet. The letter and the

addresses were in a queer, somewhat shaky

hand-writing, that of Mr. Wordsworth himself,

now an aged man, for it was within a few

years of his death; the parcel contained a

tempting-looking volume, bound in red and

gold—“Selections for the young”—of the

laureate’s poems, with Jack’s name inscribed

therein, and even more gratifying, from the

kindly thoughtfulness it displayed, a little

silk neckerchief in tartan—the children’s

own tartan, for they belonged to a Scotch

clan—for Maimie. And the letter, written to

the old servant’s dictation, for she could not

write herself, told of her consultation with her

master as to the most appropriate presents

to choose for her little favourites.

Almost more touching than the trustfulness

of children is their extraordinary endurance—a

quality often, I fear, carried to a painful and

even dangerous point. It has its root, I suspect,

in their innate trust, their belief that

whatever their elders deem right must be so;

also perhaps, in a certain almost fatalistic

acceptance of things as they are. But on few

subjects connected with childhood have I felt

more strongly than on this. No parent is

justified in “taking for granted” the moral

qualifications, even the suitability of the persons

in charge of their little boys and girls,

however unexceptionable may be the references

and recommendations they bring. It

takes tact and gives trouble, but it is among

the first of the duties of mothers especially to

make sure on such points for themselves. For

besides their trust in their elders and their

natural resignation to the conditions about

them, there is an extreme sense of loyalty in

most children, a horror of “tell-taling,”

such as are often far too slightly appreciated

or taken into account.

As these remarks are professedly a

“ramble” I may be forgiven for reverting to

that beautiful trustfulness, by relating an

incident which, though trivial in the extreme,

has never faded from my memory. We were

returning, late at night, or so at least it

seemed to me, from some kind of juvenile

entertainment at Christmas time. It was a

stormy evening; I was a very little girl, and

since infancy, high wind has always frightened

me, and that night it was blowing fiercely. I

was already trembling, when the carriage

suddenly stopped. My father at once sprang

out, for there was no second man on the box;

there was nothing wrong, only the coachman’s

hat had blown off! He got down and

ran back for it, and my father replaced him

and drove on slowly, for the wind had made

the horse restless.

“Oh, mamma,” I exclaimed, “I am so

frightened. The coachman has gone away.”

“Yes, darling,” said my mother, “but

don’t you see papa is driving?”

I shall never forget the impression of

absolute comfort and fearlessness that came

over me at her words.

“Papa is driving,” I repeated to myself.

“We are quite, quite safe.”

And all through the many years since that

winter night, the impression has never faded;

often and often it has returned to me as a

suggestion of the essential beauty of trust,

the germ of the “perfect love” towards

which we strive.

Not a propos of the foregoing reminiscences,

yet not, I hope, mal a propos in a

roundabout paper, two anecdotes of a different

kind, of children, recur to me, showing the

odd directions that their cogitations sometimes

take.

A little boy of my acquaintance, partly

perhaps from nervousness, was subject to

violent fits of crying, most irritating and perplexing

to deal with. Once started—often by

some absurdly trivial cause—there was literally

no saying when Charley would leave off. One

day, after an unusually long and exhausting

attack, to his mother’s great relief, the floods

gave signs of abating; she left the room to

fetch him a glass of water. On her return the

sobs had subsided.

“Oh, Charley,” she said, with natural but

ill-advised expression of her feelings, “you

have really worn me out. If ever you have

children of your own, who cry like you, I

hope you will remember your poor mother.”

Forthwith, to her dismay, the wails and

tears burst out again, and it was not till some

time had elapsed that the child would listen

to her repeated inquiries as to what in the

world he was crying for now. At last came

the little looked-for reply.

“It wasn’t because of this morning,”{294}

(what had started the fit I do not remember)

“I’d left off crying about that. It was you

thinking I would bring up my children so

badly.”

Anecdote No. 2 relates to a more exalted

personage than Master Charley.

Several years ago I was gratified by hearing

from a friend then resident in Italy and

acquainted with the Court circle, that one of

my earliest books for children, Carrots,

had found great favour in the eyes of the

young Crown Prince, then a mere boy. His

exact sentiments on the subject were conveyed

to me in a letter written at his request.

The story had amused and interested him at a

moment when he was specially in want of

entertainment, for it was just at the date of

the death of his grandfather, the great Victor

Emanuel, and his little namesake had not been

allowed to go out riding or driving as usual

for several days. He did not know how he

would have passed the time but for

Carrots, he said. He wished Mrs. Molesworth

to know this, and he also wished to

make a request to her. Would she write

another book as soon as possible—(not, as

one might have expected, of further details of

my little hero’s boyhood, but)—to tell how

“Carrots” brought up his own children when

he became a big man and was married!

By JESSIE MANSERGH (Mrs. G. de Horne Vaizey), Author of “Sisters Three,” etc.

CHAPTER XVIII.

“Something has happened!

Something

terrible has

happened to the

child! And she

was left in our

charge. We are responsible.

Oh, if

any harm has happened

to Peggy,

however, ever, ever,

can I bear to live

and send the news

to her parents——”

“My dearest, you

have done your best;

you could not have

been kinder or more

thoughtful. No

blame can attach to

you. Remember

that Peggy is in

higher hands than yours. However far

from us she may be, she can never stray

out of God’s keeping. It all seems very

dark and mysterious, but——”

At this moment a loud rat-tat-tat

sounded on the knocker, and with one

accord the hearers darted into the hall

and stood panting and gasping while

Arthur threw open the door.

“Telegram, sir!” said a sharp,

young voice, and the brown envelope

which causes so much agitation in quiet

households was thrust forward in a

small cold hand. Arthur looked at the

address and handed it to the Vicar.

“It is for you, sir, but it cannot possibly

be anything about——”

Mr. Asplin tore open the envelope,

glanced over the words, and broke into

an exclamation of amazement. “It is!

It is from Peggy herself!—‘Euston

Station. Returning by 10.30 train.

Please meet me at twelve o’clock.—Peggy.’

What in the world does it

mean?” He looked round the group

of anxious faces, only to see his own

expression of bewilderment repeated on

each in turn.

“Euston! Returning! She is in

London. She is coming back from

town!” “She ran away to London,

to-night when she was so happy, when

Arthur had just arrived! Why? Why?

Why?” “She must have caught the

seven o’clock train.” “She must have

left the house almost immediately after

going upstairs to dress for dinner.”

“Oh, father, why should she go to

London?”

“I am quite unable to tell you, my

dear,” replied the Vicar drily. He

looked at his wife’s white, exhausted

face, and his eyes flashed with the

“A-word-with-you-in-my-study” expression,

which argued ill for Miss

Peggy’s reception. Mrs. Asplin, however,

was too thankful to know of the

girl’s safety to have any thought for herself.

She began to smile, with the tears

still running down her face, and to draw

long breaths of relief and satisfaction.

“It’s no use trying to guess at that,

Millie dear. It is enough for me to

know that she is alive and well. We

shall just have to try and compose ourselves

in patience until we hear Peggy’s

own explanation. Let me see! There

is nearly an hour before you need set

out. What can we do to pass the time

as quickly as possible?”

“Have some coffee, I should say!

None of us have had too much dinner,

and a little refreshment would be very

welcome after all this strain,” said

Arthur, promptly, and Mrs. Asplin

eagerly welcomed the suggestion.

“That’s what I call a really practical

proposal! Ring the bell, dear,

and I will order it at once. I am

sure we shall all have thankful hearts

while we drink it.” She looked appealingly

at Mr. Asplin as she spoke,

but there was no answering smile on

his face. The lines down his cheeks

looked deeper and grimmer than ever.

“Oh, goody, goody, goodness, aren’t

I glad I am not Peggy!” sighed

Mellicent to herself, while Arthur

Saville pursed his lips together, and

thought, “Poor little Peg! She’ll

catch it. I’ve never seen the dominie

look so savage. This is a nice sort of

treat for a fellow who has been ordered

away for rest and refreshment! I wish

the next two hours were safely over.”

Wishing unfortunately, however, can

never carry us over the painful crises of

our lives. We have to face them as

best we may, and Arthur needed all

his cheery confidence to sustain him

during the damp walk which followed,

when the Vicar tramped silently by his

side, his shovel hat pulled over his eyes,

his mackintosh coat flapping to and fro

in the wind.

They reached the station in good

time, and punctually to the minute the

lights of the London express were seen

in the distance. The train drew up,

and among the few passengers who

alighted the figure of Peggy, in her

scarlet trimmed hat, was easily

distinguished. She was assisted out of

the carriage by an elderly gentleman, in

a big travelling coat, who stood by her

side as she looked about for her friends.

As Mr. Asplin and Arthur approached,

they only heard his hearty, “Now you

are all right!” and Peggy’s elegant

rejoinder, “Exceedingly indebted to you

for all your kindness!” Then he

stepped back into the carriage, and she

came forward to meet them, half shy, half

smiling, “I—I am afraid that you——”

“We will defer explanations, Mariquita,

if you please, until we reach home. A

fly is waiting. We will return as quickly

as possible,” said the Vicar frigidly,

and the brother and sister lagged behind

as he led the way out of the station,

gesticulating and whispering together

in furtive fashion.

“Oh, you Peggy! Now you have

done it! No end of a row!”

“Couldn’t help it! So sorry. Had

to go. Stick to me, Arthur, whatever

you do!”

“Like a leech! We’ll worry through

somehow. Never say die!” Then the

fly was reached, and they jolted home

in silence.

Mrs. Asplin and the four young folks

were sitting waiting in the drawing-room,

and each one turned an eager,

excited face towards the doorway as

Peggy entered, her cheeks white, but

with shining eyes, and hair ruffled into

little ends beneath the scarlet cap. Mrs.

Asplin would have rushed forward in welcome,

but a look in her husband’s face

restrained her, and there was a deathlike

silence in the room as he took up

his position by the mantelpiece.

“Mariquita,” he said slowly, “you

have caused us to-night some hours of

the most acute and painful anxiety

which we have ever experienced. You

disappeared suddenly from among us,

and until ten o’clock, when your telegram

arrived, we had not the faintest notion

as to where you could be. The most

tragic suspicions came to our minds.

We have spent the evening in rushing to

and fro, searching and inquiring in all

directions. Mrs. Asplin has had a

shock from which, I fear, she will be

some time in recovering. Your brother’s

pleasure in his visit has been spoiled.

We await your explanation. I am at a

loss to imagine any reason sufficiently

good to excuse such behaviour; but I

will say no more until I have heard what

you have to say.”

Peggy stood like a prisoner at the bar,

with hanging head and hands clasped{295}

together. As the Vicar spoke of his

wife, she darted a look at Mrs. Asplin,

and a quiver of emotion passed over her

face. When he had finished she drew

a deep breath, raised her head and

looked him full in the face with her

bright, earnest eyes.

“I am sorry,” she said slowly. “I

can’t tell you in words how sorry I am.

I know it will be difficult, but I hope

you will forgive me. I was thinking

what I had better do while I was

coming back in the train, and I decided

that I ought to tell you everything, even

though it is supposed to be a secret.

Robert will forgive me, and it is Robert’s

secret as much as mine. I’ll begin at

the beginning. About five weeks ago

Robert saw an advertisement of a prize

that was offered by a magazine. You

had to make up a calendar with quotations

for every day in the year, and the

person who sent in the best selection

would get thirty pounds. Rob wanted

the money very badly to buy a microscope,

and he asked me to help him. I

was to have ten pounds for myself if we

won, but I didn’t care about that. I

just wanted to help Rob. I said I

would take the money, because I knew

if I didn’t he would not let me work so

hard, and I thought I would spend it

in buying p—p—presents for you all at

Christmas.”—Peggy’s voice faltered at

this point, and she gulped nervously

several times before she could go on

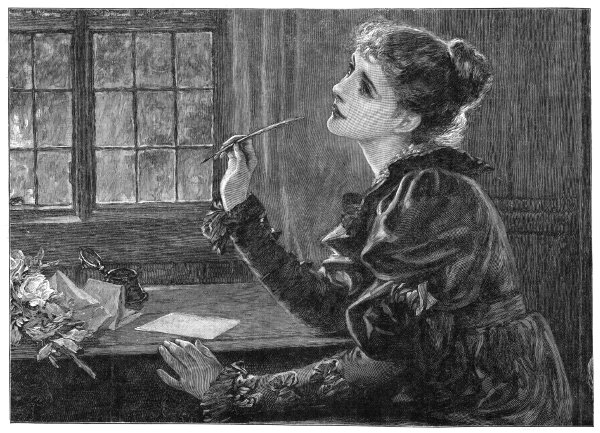

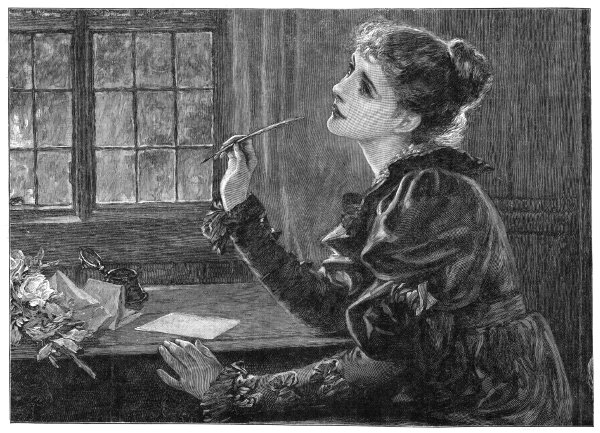

with her story.—“We had to work very

hard, because the time was so short.

Robert had not seen the advertisement

until it had been out some time. I printed

the headings on the cards; that is why I

sat so much in my own room. The last

fortnight I have been writing every

morning before six o’clock. Oh, you

can’t think how difficult it was to get it

finished, but Robert was determined to

go on; he thought our chance was very

good, because he had found some beautiful

extracts, and translated others, and the

pages really looked pretty and dainty.

The MS. had to be in London this morning;

if it missed the post last night

all our work would have been wasted,

and at the very last Lady Darcy took

Rob away with her, and I was left with

everything to finish. I may have slept

a little bit the last two nights; I did lie

down for an hour or two, and I may

have had a doze, but I don’t think so! I

wrote the last word this morning after

the breakfast-bell had rung, and I made

up the parcel at twelve o’clock. I

thought of going out and posting it

then; of course, that is what I should

have done, but”—her voice trembled

once more—“I was so tired! I thought

I would give it to the postman myself,

and that would do just as well. I didn’t

put it with the letters because I was

afraid someone would see the address

and ask questions, and Rob had said

that I was to keep it a secret until we

knew whether we had won. I left the

parcel on my table. Then Arthur came!

I was so happy—there was so much to

talk about—we had tea—it seemed like

five minutes. Everyone was amazed

when we found it was time to dress,

but even then I forgot all about the

calendar. I only remembered that

Arthur was here, and was going to stay

for four days, and all the way upstairs I

was saying to myself, ‘I’m happy, I’m

happy; oh, I am happy!’ because, you

know, though you are so kind, you have

so many relations belonging to you

whom you love better than me, and my

own people are all far away, and sometimes

I’ve been very lonely! I thought

of nothing but Arthur, and then I opened

the door of my room, and there, before

my eyes, was the parcel; Rob’s parcel

that he had trusted to me—that I had

solemnly promised—to post in time——”

She stopped short, and there was a gasp

of interest and commiseration among the

listeners. Peggy caught it; she glanced

sharply at the Vicar’s face, saw its sternness

replaced by a momentary softness,

and was quick to make the most of her

opportunity. Out flew the dramatic little

hand, her eyes flashed, her voice thrilled

with suppressed excitement.

“It lay there before my eyes, and I

stood and looked at it ... I thought of

nothing, but just stood and stared. I

heard you all come upstairs, and the

doors shut, and Arthur’s voice laughing

and talking; but there was only one thing

I could remember—I had forgotten Rob’s

parcel, and he would come back, and I

should have to tell him, and see his

face! I felt as if I were paralysed, and

then suddenly I seized the parcel in my

hands, and flew downstairs. I put on

my cap and cloak and went out into the

garden. I didn’t know what I was

going to do, but I was going to do

something! I ran on and on, through

the village, down towards the station.

I knew it was too late for the post office,

but I had a sort of feeling that if I were

at the station something might be done.

Just as I got there a train came in, and

I heard the porter call out ‘London

express.’ I thought—no! I did not

think at all—I just ran up to a carriage

and took a seat, and the door banged

and away we went. The porter came

and asked for my ticket, and I had a

great deal of trouble to convince him

that I had only really come from here,

and not all the way. There was an old

lady in the carriage, and she told him

that it was quite true, for she had seen

me come in. When we went off again,

she looked at me very hard, and said,

‘Are you in trouble, dear?’ and I said,

‘Yes I am, but oh, please don’t talk to

me! Do please leave me alone!’ for I

had begun to realise what I had done,

and that I couldn’t be back for hours

and hours, and that you would all be so

anxious and unhappy. I think I was

as miserable as you were when I sent off

that telegram. I posted the parcel in

London, and went and sat in the waiting-room.

I had an hour and a half to

wait, and I was wretched, and nervous,

and horribly hungry. I had no money

left but a few coppers, and I was afraid

to spend them and have nothing left.

It seemed like a whole day, but at last

the train came in, and I saw a dear old

gentleman with white hair standing on

the platform. I took a fancy to his

appearance, so I walked up to him, and

bowed and said, ‘Excuse me, sir, I

find myself in a dilemma! Will you

allow me to travel in the same carriage

as yourself?’ He was most agreeable.

He had travelled all over the world, and

talked in the most interesting fashion,

but I could not listen to his conversation.

I was too unhappy. Then we arrived,

and Mr. Asplin called me ‘M—M—Mariquita!’

and w—wouldn’t let you

kiss me——”

Her voice broke helplessly this time,

and she stood silent, with quivering lip

while sighs and sobs of sympathy echoed

from every side. Mrs. Asplin cast a

glance at her husband, half defiant, half

appealing, met a smile of assent, and

rushed impetuously to Peggy’s side.

“My darling! I’ll kiss you now.

You see we knew nothing of your

trouble, dear, and we were so very, very

anxious. Mr. Asplin is not angry with you

any longer, are you, Austin? You know

now that she had no intention of grieving

us, and that she is truly sorry——”

“I never thought—I never thought—”

sobbed Peggy; and the Vicar gave a

slow, kindly smile.

“Ah, Peggy, that is just what I complain

about. You don’t think, dear, and

that causes all the trouble. No, I am

not angry any longer. I realise that the

circumstances were peculiar, and that

your distress was naturally very great.

At the same time, it was a most mad

and foolish thing for a girl of your age

to rush off by rail, alone, and at nighttime,

to a place like London. You say

that you had only a few coppers left in

your purse. Now suppose there had

been no train back to-night, what would

you have done? It does not bear thinking

of, my dear, or that you should have

waited alone in the station for so long,

or thrown yourself on strangers for protection.

What would your parents have

said to such an escapade?”

Peggy sighed, and cast down her eyes.

“I think they would have been cross

too. I am sure they would have been

anxious, but I know they would forgive

me when I was sorry, and promised that

I really and truly would try to be better

and more thoughtful! They would say,

‘Peggy, dear, you have been sufficiently

punished! Consider yourself

absolved!...’”

The Vicar’s lips twitched, and a

twinkle came into his eye. “Well,

then, I will say the same! I am sure

you have regretted your hastiness by this

time, and it will be a lesson to you in the

future. For Arthur’s sake, as well as

your own, we will say no more on the

subject. It would be a pity if his visit

were spoiled. Just one thing, Peggy, to

show you that, after all, grown-up

people are wiser than young ones, and

that it is just as well to refer to them

now and then, in matters of difficulty!

Has it ever occurred to you that the

mail went up to London by the very

train in which you yourself travelled,

and that by giving your parcel to the

guard it could still have been put in the

bag? Did not that thought never occur

to your wise little brain?”

Peggy made a gesture as of one

heaping dust and ashes on her head.

“I never did,” she said, “not for a

single moment! And I thought I was so

clever! I am covered with confusion!”

(To be continued.)

{296}

THE STORY OF A FRIENDSHIP.

CHAPTER I.

“What a thing friendship is, world without end!”—Browning.

Yes, Linnæa March was the dunce of the

school. She was neither pretty nor attractive,

nor did she seem to wish to be either.

Nobody understood Linnæa. She made

friends with no one, and no one made friends

with her. Even the teachers said she was a

girl nothing could be done with, and concluded

to leave her alone.

One new governess, Miss Golding, had

brought a look of interest to the girl’s face

over a story of Indian life, and had determined

to follow up her advantage and make friends

with this solitary pupil; but her next advance

had been met with such decided coldness that

Miss Golding went over to the opinion of the

other teachers, that “it was best to leave

Linnæa March alone.”

The truth of the matter was that Linnæa

had overheard a remark from the lips of the

wit of the school—“Golding is trying to

cultivate the March hare. Don’t you wish

she may succeed?” This name had been

given her by the same girl, Marion Edwards,

very soon after she came to school. Marion

was not a girl who actually meant to be

unkind, but she had a ready tongue, and,

when she saw a chance to make a witty

remark, did not trouble herself to consider

anyone’s feelings.

How cruel schoolgirls are to each other

without knowing it! And these were not

hard-hearted girls—some of them developed

into the very sweetest and best of women.

Had they known or thought what a lonely

life Linnæa had had, they might have taken

more trouble to approach her; but it was the

fashion of the school to shun her, and she

certainly gave no one any encouragement to

do otherwise.

No one came into Linnæa’s cubicle to

discuss some little bit of gossip before going

to bed; no one gave a playful tap on the

wooden partition, which divided her room

from the next, as was done to everyone else

now and then. Friends kissed each other

when they met in the morning; no one

dreamed of kissing Linnæa, unless it was the

governesses, who did it to all as a matter of

form.

Did she miss it, do you ask?

She said vehemently to herself over and

over again that she did not—she loved none

of them, and wanted nobody’s love. Nobody

knew it, nobody suspected it, but—ah, what

a wealth of love lay dormant in that lonely

heart!—what a hungering after affection that

seemed doomed to be for ever denied!

She nursed and fostered an intense love for

the mother she had never seen, unless in

babyhood. She had been born in India,

where her parents still were, and her mother

had been so ill for a long time after the birth

that it had been deemed wise to send the

delicate baby of eighteen months home to

England to be brought up by a maiden aunt,

as, in any case, she must very soon, like all

Anglo-Indian children, leave the trying climate.

Thus Linnæa could not remember the face of

her mother, but she cherished a photograph

of her, and her letters were the bright spots in

an otherwise colourless life.

Miss March had no love for the child

committed to her care, and made no pretence

of any. Her comfort and training were

strictly looked after—no suspicion of neglect

could be breathed—but the love which is

necessary to the happiness of a child’s life was

a-wanting.

“Such a very unattractive child!” Miss

March described her to her acquaintances,

even at times in the presence of the little girl,

so that she grew up with the idea firmly

rooted in her mind that she was plain, stupid,

and that no one cared for her. Companions

she had none—in fact, was not allowed to

have—for her aunt could not tolerate any

noise or disorder in her well-regulated house.

Mrs. Sedley, the Rector’s wife, had invited

the solitary child to come and have a romp

with her lively boys and girls; but the

invitation had been refused, because Miss

March could not think of having them at her

house in return.

Mrs. Sedley’s motherly heart was glad

when she heard it had been decided that

Linnæa should go to a boarding school.

“She will have companions now, poor child;

and lead a much brighter life than she has

led here.” But the life she led now was little

if any brighter than the other had been.

The first morning after her arrival in school

Linnæa was introduced to her companions by

Miss Elder, the principal.

“This is a new companion for you—Linnæa

March. I hope you will all be friendly to her

as she is a stranger yet.”

Plainly dressed to severity, her face more

forbidding than usual from the fact that she

felt shy but would not show it, Linnæa sat on

a chair near the door, and the other girls did

their duty by staring at her unmercifully.

One governess was in the room and, unfortunately,

not a very judicious one. After a

few minutes had passed, she looked over at

the newcomer and said—

“Now, little girl, don’t look so sulky. You

must put on a nice pleasant face, so that your

companions will like you.”

{297}

It was an unhappy remark. Some of the

more forward girls tittered, and the forlorn,

lonely child felt even more isolated and

friendless than she had felt in her aunt’s

house.

“Come away over here,” said the governess

again, “and tell us how old you are and where

you come from.”

“From the Ark, I should guess!” whispered

one girl, who was supposed to be witty by

some—herself in particular.

Linnæa was forthwith subjected to a string

of small questions, which she answered mostly

in monosyllables. The whispered remark had

been overheard by the sensitive child, and her

heart had begun to harden towards girls and

governess alike.

Some of the pupils made advances at first,

but Linnæa met them all with a suspicion and

distrust that chilled and disappointed. Therefore,

incredible as it may seem, at the age of

sixteen, and after seven years at Meldon Hall,

Linnæa March was utterly without a friend in

the school.

CHAPTER II.

THE “NEW GIRL.”

“And was her grandfather really an earl?”

“And shall we have to call her Lady

Gwendoline when we speak to her?”

“I wonder what she is like; I am dying to

see her!”

“She is coming to-night; but perhaps Miss

Elder won’t trot her out until to-morrow.”

What an excited hubbub was going on in

Meldon Hall schoolroom. The girls had

been told that a new pupil would arrive that

night. This alone, in mid-term, would have

been enough to arouse some interest, but

when it got abroad by some means or another

that the importation was a beauty, an heiress,

and related to an earl, their excitement

knew no bounds.

Marion Edwards, perched on the back of

a chair, gave out what she had heard, and a

little more, to an admiring audience who

took Marion’s words for vastly more than

they were worth. In every school there are one

or two leading spirits, and Meldon Hall had

at present two leaders—Marion Edwards and

Edith Barclay. Edith was the clever,

studious girl of the school; and amongst those

who were inclined to be industrious, she was

looked up to with great reverence. Marion

was handsome, rich, and had an aptitude for

making witty remarks, which made her at once

admired and feared by her “set.” The two

leaders were quite friendly; they were in no

wise rivals of each other, being altogether

different in disposition and aims. Edith loved

study for study’s sake, and had secret thoughts

of entering a profession. Marion cared

nothing for her lessons, but easily managed

to get along in a superficial way; she was an

only daughter and rich, and was looking

forward to entering society after she left

school. Marion’s feelings were divided between

pleasure at the prospect of knowing a

girl whose grandfather was an earl, and a

secret fear that this rich beauty might want to

queen it even over her, and that her set might

forsake her for the greater light.

The only one who was really indifferent to

the new arrival was Linnæa. She had had

her times of hidden excitement over an

expected newcomer, and vague longings that

she might be “nice,” but these feelings were

over and done, with long ago. Successive

disappointments had embittered her, and now

it was a matter of little moment to her who

came and went. This night she had a slight

headache and felt tired of her schoolfellows’

chatter and not inclined to face the introduction

of a new girl, proud and haughty, who

would doubtless criticise her looks and

manners and set her down—as all the others

had done—as hopelessly unattractive. She

therefore slipped quietly away to her room.

“Oh, I do wish Miss Elder would bring

her in to-night!” said one; and, as if in

response to her wish, the door opened and the

principal entered, followed by the new girl.

“This is Miss Gwendoline Rivers,” said

Miss Elder, introducing a few of the girls who

were nearest her by name. “I shall leave

her with you for twenty minutes, but after

that she must go to bed, as she has come a

long way to-day.”

Shyness was not one of the new pupil’s

failings, and she asked more questions than

she answered. Soon she had found out all

the rules and regulations of the school, and

had taken mental note of a few of the

characters around her. Report had been

correct as far as her beauty and wealth were

concerned—her connection with the earl was

a little more remote—she was indeed a lovely

girl. Her dark eyes were large and lustrous,

and her face had an almost southern richness

of colouring. Her appearance was aristocratic

to a degree, and her clothes were expensive

and in the best of taste.

“Are you all here?” she said by-and-by,

looking round on the group.

“All except two. Alice Melrose is in bed

with neuralgia, and Linnæa March has retired

for the night.”

“And, pray, why has Linnæa March retired

for the night? Had she not the curiosity

to wait up and see the newest thing in girls?

I suppose she knew I should arrive to-night,

as you all did, and I know you were all

dying for me to put in an appearance so

that you might deluge me with questions.

But I think I have got more out of you

than you have out of me. I find the only

way to avoid too many questions is to ask

a great many yourself. Tell me about Miss

March, please; I am quite excited. What

an outlandish name, too? She is altogether

very mysterious!”

“There is not much to tell about Linnæa

March, as you will soon know. You will find

the best way is to leave her alone, for, as sure

as fate, she will not trouble herself about you,

any more than she has about the rest of us.”

“But that is precisely what I never do! I

never allow anyone to be indifferent to me;

they may hate me, if they please, but they

shall not be indifferent!”

“You don’t know Linnæa. I don’t believe

she knows what love and hate are—love, at

least; she might manage to hate you,

perhaps!”

“I shall make her love me then!”

The girls laughed. There was something

very fresh and original about this young lady

who spoke as if the world and anything in

it were hers for the asking. It was easily

seen she had not been denied much during

her life, and most of them felt very much

inclined to carry on the spoiling process if

only they might be termed friends of this

beautiful and determined young woman; for

if there is anything young people worship, it

is determination. But to talk of making

Linnæa March love her was a little too absurd.

“How long is it since this unimpressionable

young lady left the company? She won’t be

in bed yet, will she? One of you go up to

her room and tell her the new girl wants to

see her, and bring her down.”

Really, this was most ridiculous! Who

was to go and give this extraordinary message

to Linnæa March? As if to-morrow were

not soon enough to see her! Whoever went

would not get a very great reception.

“Has she a chum here?”

“She has no chum at all.”

“Then do you go!” said the imperious

Miss Rivers, pointing to a pleasant-looking

girl beside her. “Listen to me,” said

Gwendoline, when the messenger had departed;

“I mean to make this Linnæa March

like me; in fact, I mean to make her fall over

head and ears in love with me, and none of you

must say a word to influence her in any way.

I have never yet made up my mind to do a

thing that I have not done, and I shall show

you that I can do this.”

The excitement of the school was aroused,

and the girls awaited with great interest the

development of the comedy to be enacted in

their midst. Would it be a comedy or a

tragedy? If, as she boasted, Gwendoline

Rivers were able to awaken the love which

lay dormant in that sensitive heart, woe to

Linnæa if she should discover the motive

which had called it forth; it would run a

chance of souring her whole after life.

After a few minutes the door opened and

the messenger returned, accompanied by

Linnæa.

“Now, you know, I don’t think it was nice

of you to go off to bed without waiting to see

me!” said Gwendoline, advancing towards

her with a smile and holding out her hand.

Linnæa’s sensitive face flushed.

“I am sorry if I appeared rude,” she said;

“I did not think of it.”

“You will be forgiven this time; but”—looking

serious—“I hope you have not a

headache; if so, I shall be sorry I brought you

down.”

“Oh, no, thank you! I am quite well. I

often go up earlier than the others.”

“Well, I sha’n’t keep you down long, for

I am going to bed myself. I shall go up with

you now and try if I can find my cubicle

again.”

Calling good-night to the others, Gwendoline

slipped her arm through Linnæa’s, and

the two walked away in the direction of the

stairs.

“How strange it is, coming in amongst a

lot of girls one has never seen before! It is

fortunate for me I am not shy, else, I suppose,

I should feel dreadfully put out. How long

have you been here?”

“Seven years.”

“Seven years! Such a long time to be

away from home!”

“My father and mother are out in India.{298}

I shall go there when I am finished with

school.”

“Oh, how splendid! I should love to go

to India. I have a brother who went out last

year, and when I leave school I mean to pay

him a visit. Perhaps we may happen to go

together. Wouldn’t that be nice? Is this

your cubicle? Horrid, bare places, aren’t

they? I was warned about it and brought

some pictures and things with me; but I

sha’n’t unpack them to-night—I am too

sleepy. Shall we say good-night, then? I

somehow think we shall be friends.”

Gwendoline, as she spoke, leant over and

kissed Linnæa on the cheek, then ran away to

find her bedroom.

“Funny, quiet little thing!” said Gwendoline

as she went. “I wonder if I shall

make good my words? She seemed almost

workable to-night. I was prepared to brave

a few snubs to begin with.”

And what about Linnæa? She did not

begin to undress at once as usual. Why was

she so excited to-night? Something had

come over her, and it was nothing more nor

less than a subtle magnetism towards this

beautiful girl who had taken more notice of

her than of any of the others—who had kissed

her when she bade her good-night. Why

had she felt so wooden and stupid? Why

had she not returned the kiss? What must

this girl think of her?

She was in bed at last, but could not sleep.

She seemed to feel the kiss on her cheek and

hear the voice saying they might be friends.

By-and-by, when sleep came, she dreamt that

her father and mother had come to school to

take her home—the time she had looked

forward to through all the seven years—and

she told them she wanted to stay another year

because Gwendoline had come.

(To be continued.)

The letters of a favourite

daughter of George

III., and an aunt of

the Queen, whose life

extended through

the eventful period

1770-1840, make a

book of great interest

and permanent

value. The period

referred to takes in

some of the more momentous events in modern

history—the loss of the American colonies, the

French Revolution, the battle of Waterloo,

and the fall of Napoleon—as well as various

important parliamentary movements at home.

Letter-writing is now generally supposed to be

a lost art; but the Princess Elizabeth, as one

who “ever remained an Englishwoman to the

backbone,” wrote letters of the genuine old-time