Handbook 144

By David Lavender

Produced by the

Division of Publications

National Park Service

U.S. Department of the Interior

Washington, D.C.

American history begins not with the English at Jamestown or the Pilgrims at Plymouth but with Spanish exploration of the border country from Florida to California in the 16th century. This handbook describes the expeditions of three intrepid explorers—De Soto, Coronado, and Cabrillo—their adventures, their encounters with native inhabitants, and the consequences, good and ill, of their journeys. This little-known story is related by David Lavender, author of many books on the American West. His work gives perspective to the several national parks that commemorate the first Spanish explorations.

National Park Handbooks, compact introductions to the natural and historical places administered by the National Park Service, are designed to promote public understanding and enjoyment of the parks. These handbooks are intended to be informative reading and useful guides. More than 100 titles are in print. They are sold at parks and by mail from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402.

This 16th-century woodcut, the product of an artist with a fertile imagination but little information, epitomizes the contemporary view that European discoverers were bringing civilization to the grateful natives of the New World.

A magic date: 1492. The year began with Christopher Columbus watching the Moors surrender the city of Granada, their last stronghold in Spain, to the joint monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. He reminded them of the triumph in a summation he wrote later of what he too had accomplished that year. “I saw the banners of your Highnesses raised on the towers of the Alhambra in the city of Granada, and I saw the Moorish king go out of the gate of the city and kiss the hands of your Highnesses and of my lord the Prince.” Shortly after the victory, he added, “your Highnesses ... determined to send me, Christopher Columbus to the countries of India, so that I might see what they were like, the lands and the people, and might seek out and know the nature of everything that is there....”

This remarkable coincidence—the expulsion of the Moors from Spain and Columbus’s almost simultaneous discovery of the “Indies”—resulted in a burst of explosive expansionism. The following year, 1493, Columbus established Spain’s first colony in the New World on the island of Hispaniola, occupied now by Haiti and the Dominican Republic. By 1515 Cuba had been conquered and its cities of Santiago and Havana established as bases for further exploration. In 1519 Hernán Cortés swept out of Cuba into Mexico and found a new source of wealth for his country, his followers, and himself by looting the Aztec empire of stores of gold and silver the Indians had been accumulating for centuries. A decade later Francisco Pizarro began his dogged and even more lucrative conquest of the Incas of Peru.

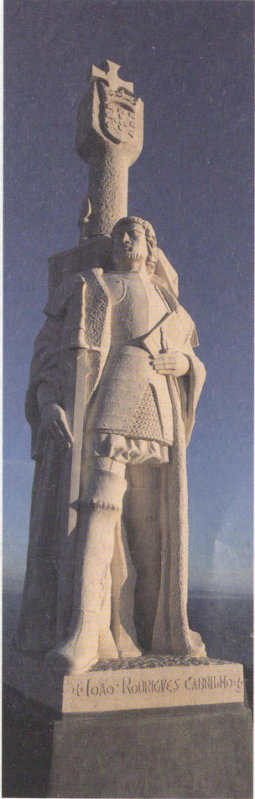

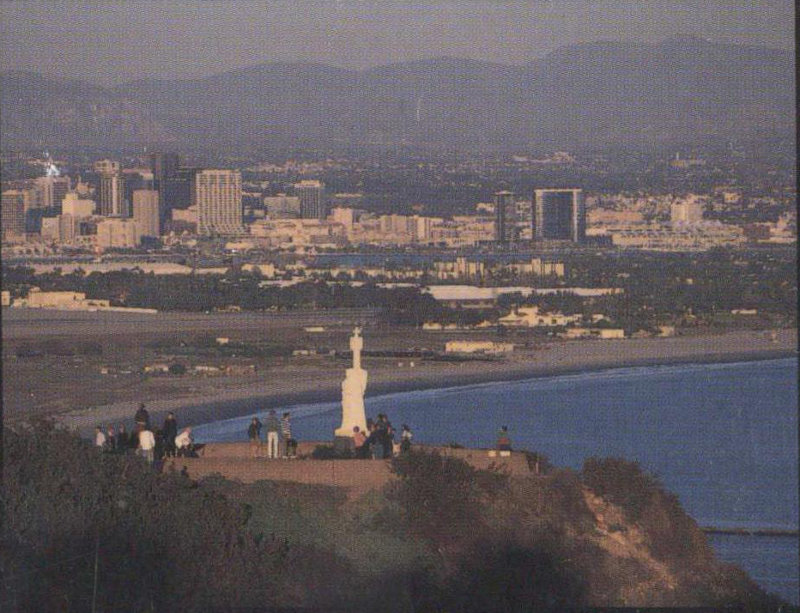

Meanwhile, what of the Northern Mystery, as historian Herbert E. Bolton aptly named the unknown lands above Mexico? Was it not logical that similar treasures awaited discovery there? And so the fever for adventure and riches drew three more distance-defying explorers—Hernando de Soto, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, and Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo—into three different parts of what is now the United States. Each reached as far as he did because inside him burned the awesome, often contradictory, but always steel-bright fires of medieval Spain.

Our tangible connection to this age of pathfinding and discovery is a scattering of historic places stretching from Florida to California. They are evidence of Spanish life and color in the old borderlands. This book draws into a whole the stories of several such places. Here are the beginnings of Spanish North America.

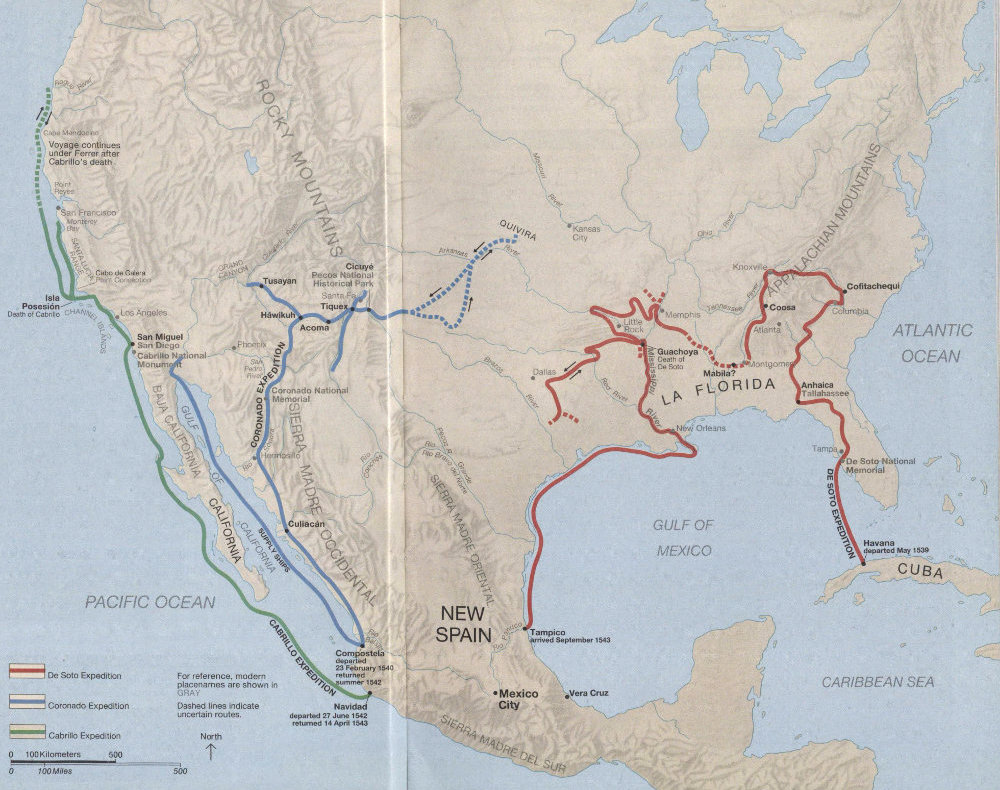

Routes of the Explorers

High-resolution Map

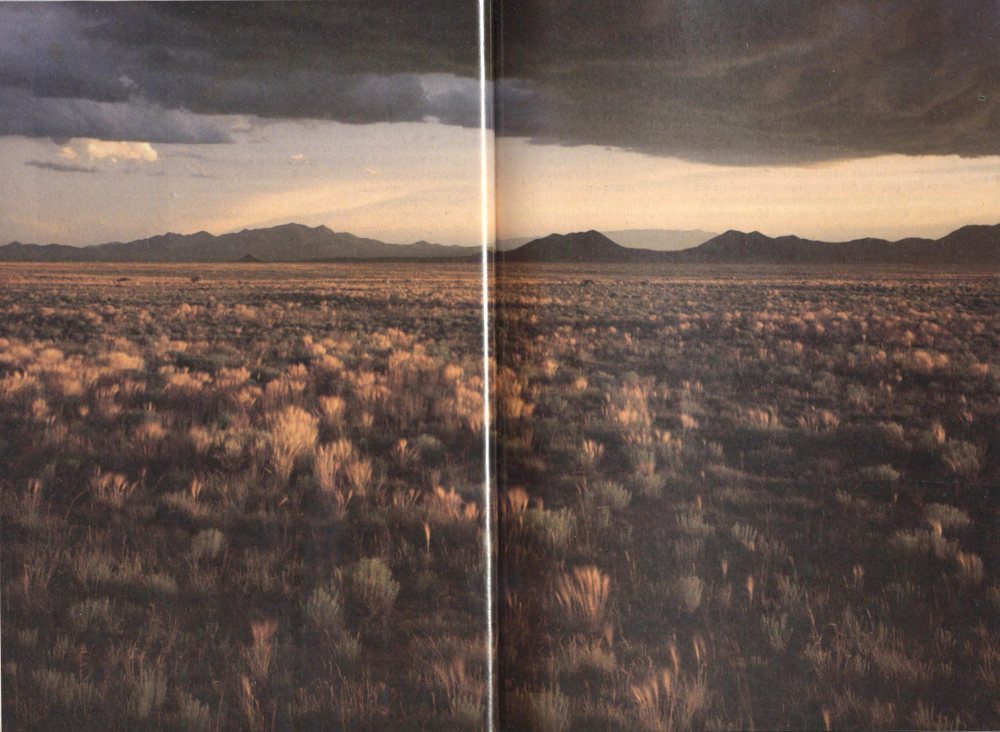

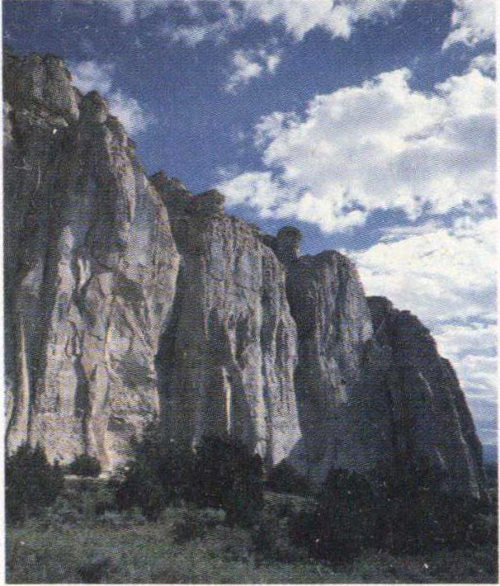

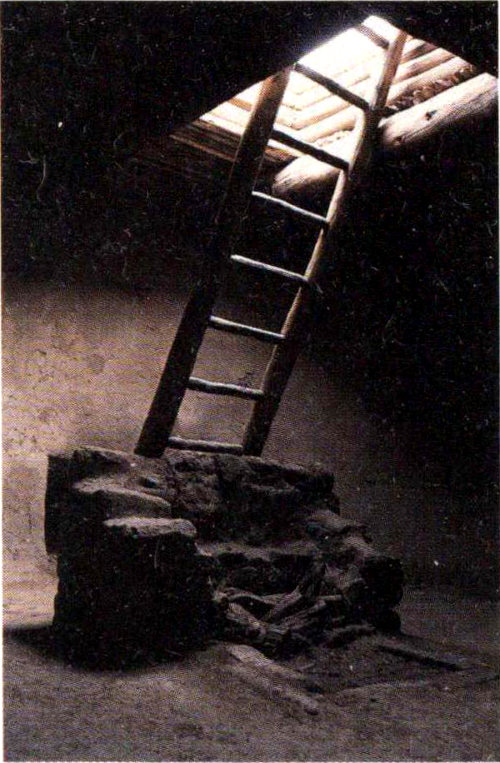

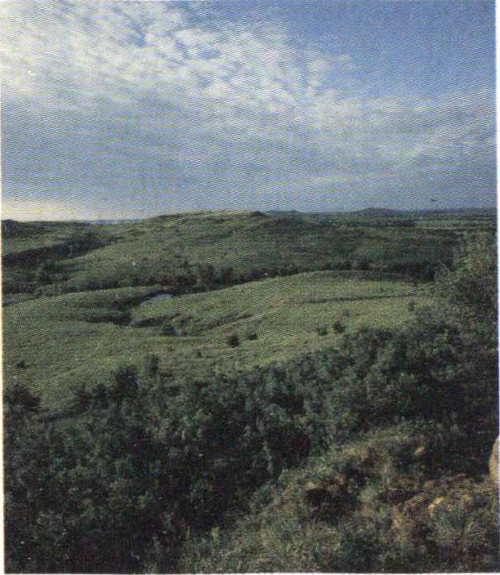

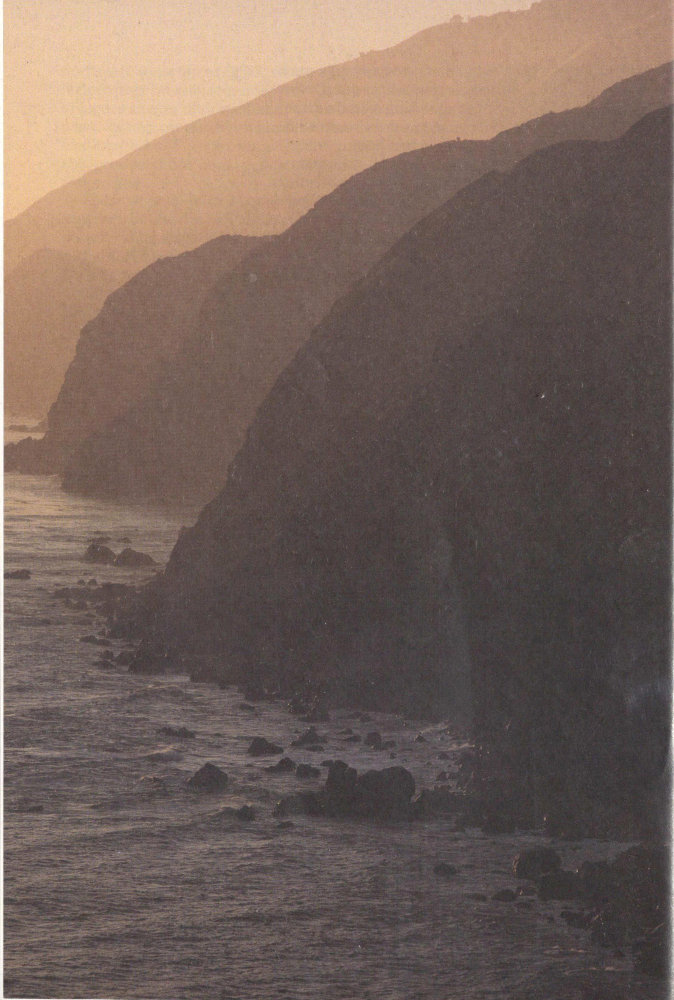

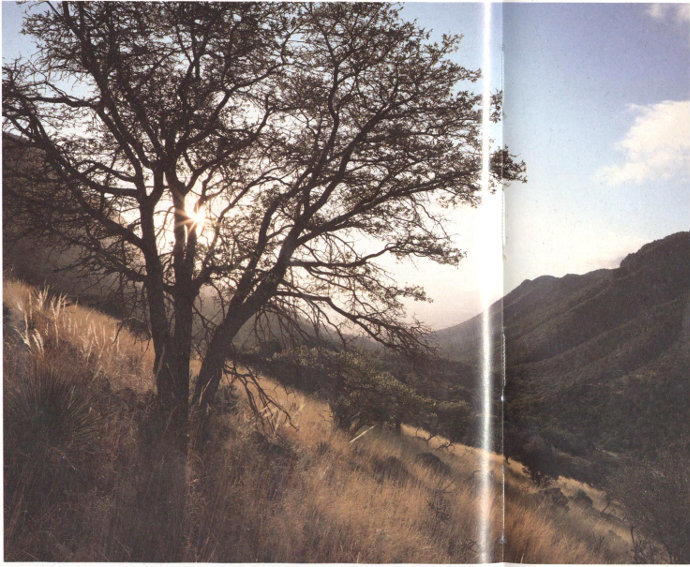

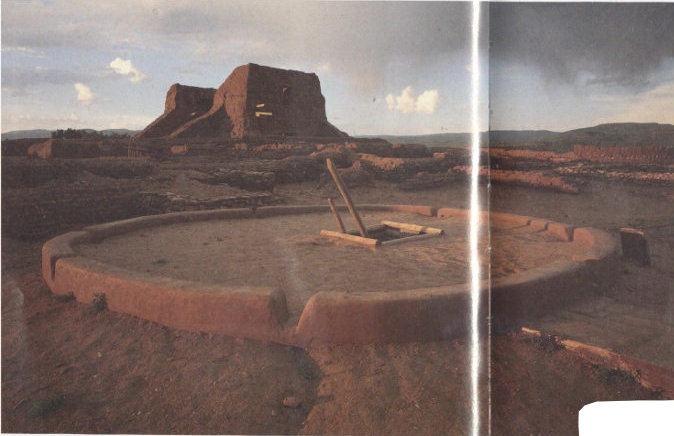

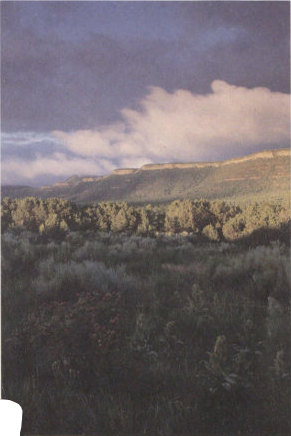

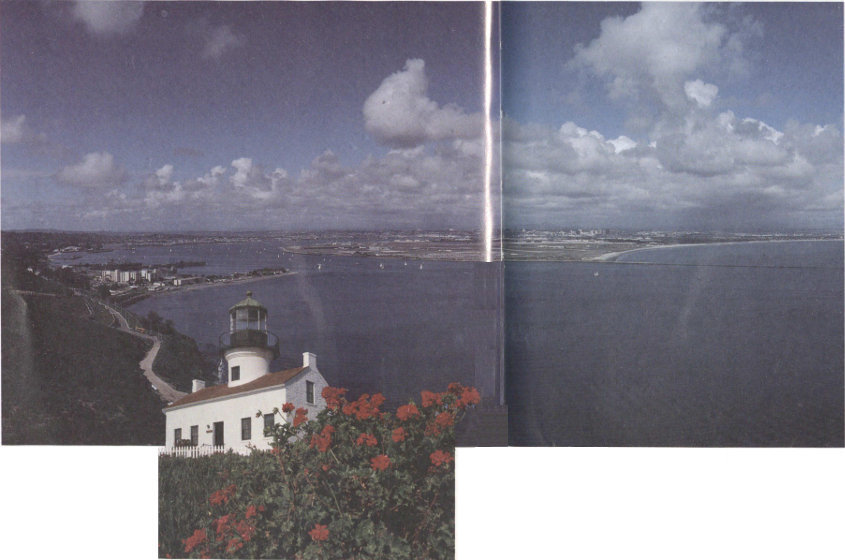

The first Spanish expeditions into the northern borderlands of New Spain sampled the continent’s wondrous diversity. De Soto made his great march across a luxuriant country so stunning and productive that the expedition’s journals are full of admiring description. He encountered complex native societies, which were often organized into powerful chiefdoms—generous in peace but formidable in war. Centuries of settlement has greatly altered this landscape. Not so Coronado’s country. A traveler to the Southwest can still see places evocative of the first Spanish encounters with Indians of the pueblos and Plains. A sailor retracing Cabrillo’s route up the California coast runs past mountains that, in the words of the chronicler, “seem to reach the heavens ... [and are] covered with snow”—mountains he called the Sierra Nevada. They are today’s Santa Lucia range. Cabrillo’s voyage is now best followed in the imagination.

| 1440-60 | The Portuguese explore coast of Africa |

| 1492 | Moors defeated in Spain; Columbus lands in New World |

| 1497 | Vasco da Gama sails to India by way of Africa |

| 1513 | Ponce de León claims Florida for Spain |

| 1519-21 | Magellan’s fleet sails around the world |

| 1521 | Cortés conquers the Aztecs |

| 1528 | Narváez attempts a colony in Florida |

| 1529-36 | The wanderings of Cabeza de Vaca |

| 1532 | Pizarro overthrows the Incas of Peru |

| 1539-43 | De Soto expedition |

| 1540-42 | Coronado expedition |

| 1542-43 | Cabrillo’s voyage |

| 1562 | French Huguenots settle in Florida |

| 1565 | Menendez establishes St. Augustine |

| 1584 | Ralegh plants colony on North Carolina coast |

| 1598 | Oñate expedition into Southwest |

| 1607 | English settle at Jamestown |

| 1620 | Pilgrims settle at Plymouth |

| De Soto | Coronado | Cabrillo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1539 | Lands in Florida in late May; marches through upper Florida; major battle at Napituca; guerilla war with Apalachees; winter camp at Anhaica (Tallahassee) | ||

| 1540 | Following Indian trails, expedition swings in a wide arc through Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Alabama, encountering major chiefdoms. Bloody battle at Mabila (central Alabama) in October | Departs from Compostela with an army of 300 cavalry and infantry, several hundred Indian allies, friars, and a long pack train. Alarcón sails up the Gulf of California with three vessels. Expedition penetrates American Southwest, reaches Háwikuh in July; engages the Zuñi in battle; Coronado wounded. Tovar explores Hopi villages in Arizona. Alarcón reaches mouth of Colorado River. Cárdenas sights the Grand Canyon. Alvarado marches to Acoma, Pecos, and beyond. | Accompanies an exploring expedition up the northwest coast as almirante (second in command). Expedition abandoned after its leader is killed fighting Indians. |

| 1541 | Winters among ancestral Chickasaw Indians of Mississippi and suffers attack by them; crosses Mississippi in May; travels in great loop through Arkansas; discovers buffalo hunters and a people who live in scattered houses and not in villages; endures severe winter at Autiamque | Journeys to Quivira (Kansas). Winters at Tiguex; puts down an Indian revolt. | Gathers a new exploring fleet for Mendoza. |

| 1542 | Reaches the rich chiefdom of Anilco; at nearby Guachoya, De Soto sends out scout parties who find nothing but wilderness; De Soto dies, is succeeded by Moscoso. After fruitless wandering in east Texas, Moscoso retraces route to Anilco | The army departs for home in April, arrives in Mexico City in mid-summer. Coronado reports to Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza on expedition, resumes his governorship of Nueva Galicia. Months later Coronado is tried for mismanagement of expedition but acquitted. | Dispatched by Mendoza to continue exploration of the northwest. June: Sails from Navidad, near Colima, Mexico. September 28: Sights “a sheltered port and a very good one.” This is San Diego Bay, which he names San Miguel. October: Sails through the Channel Islands, suffers fall and injury. November: Reaches the northernmost point of the voyage, perhaps Point Reyes, California, but turns back. |

| 1543 | Winter camp at Aminoya on Mississippi; survivors—half the original number—build boats to float downriver; in September, they reach Pánuco River, in Mexico | January 3: Dies on San Miguel Island (Channel Islands). February: The fleet sails north again, perhaps as far as Oregon before turning back. April: Fleet arrives back at Navidad, nine months after embarking. |

In 1493 on his second voyage Columbus stopped at St. Croix, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands. It was then “a very beautiful and fertile” island cultivated by Carib Indians. A boat he sent ashore met with a canoe full of Caribs. In an ensuing fight, one Indian was killed and several captured—the first serious hostilities with New World natives. Salt River Bay National Historical Park preserves the scene of this fateful encounter.

An estimated 3,000 battles wracked the Iberian Peninsula between AD 711, when Moors from Africa invaded what became Spain, and 1492, when they were finally expelled. Nor were battles against the Moors the only ones. The Christian leaders of the peninsula’s several principalities fought each other and their recalcitrant nobles in a constant quest for power, until finally Ferdinand and Isabella welded together, by marriage, all the units except Portugal.

Centralization of power in the hands of national governments was one of the characteristics that marked the slow emergence in Europe of what history calls the modern world. The reasons are manifold. A central government supported by a rising middle class of merchants and bankers was able to create big armies of professional soldiers and equip them with newly introduced gunpowder, a capability quite beyond the reach of the old feudal nobles. Concurrently, the new governments consolidated economic power, partly through nationwide taxation. New industries were encouraged. Feelings of nationalism swelled; people took pride in considering themselves Spaniards rather than just Castillians.

International trade assumed new importance, especially trade with the Orient, whose extraordinary wealth had been revealed by the adventures of the Venetian family of Polo as recounted by Marco, the youngest of the group. Land caravans to the fabled East were difficult, however, and limited by interruptions and tributes imposed by Moslem middlemen. So why not travel to the Orient by water, either by circling the southern tip of Africa or sailing due west across the Atlantic?

The most logical place in Europe for starting the endeavor was the Iberian Peninsula, which dipped down toward Africa and all but closed off the western end of the Mediterranean Sea. The exploration of Africa was launched during the middle of the 15th century by Prince Henry the Navigator of tiny Portugal. 14 His success and that of the Portuguese rulers who followed him was so astounding that Ferdinand and Isabella at last agreed to support Columbus in a competitive transatlantic attempt. The point is vital. Spain’s feudal nobles probably could not have financed the expedition; the central government of newly unified Spain did.

Prince Henry of Portugal (1394-1460). His attempts at reaching the Indies by outflanking Africa earned for him the title of Navigator, though he himself never went on exploring voyages. His headquarter at Sagres on the western-most promontory of Portugal was a gathering place for cosmographers, astronomers, chartmakers, and ship-builders. Their work inaugurated in the 15th century the great age of discovery that Spain continued in the next century.

Columbus took the risk because he believed, as had the ancient Greeks, that the circumference of the world was much smaller than it actually was. He also believed, as had Marco Polo, that Asia extended farther east than it does. When he found land at approximately the longitude that he expected to, he assumed joyfully that he was close to Cathay (China) and the islands of India. From that misapprehension comes, of course, the name West Indies for the islands of the Caribbean and Indians for their inhabitants, a term that quickly spread throughout the hemisphere.

The islands and the eastern coasts of Central America and the northwestern part of South America that he and Amerigo Vespucci (hence the name America) skirted on separate expeditions during the following decade were disappointing—no teeming cities crowned with exotic architecture, no kings and queens dressed in flowing silk and laden with precious gems, no warehouses bulging with expensive spices. To a less energetic nation than Spain, the failure of expectations might have ended further activity. But emerging Spain saw opportunities in the wilderness. Some gold could be taken from the placer mines on the island of Hispaniola. Plantations worked by enslaved Indians could be developed on Cuba and Puerto Rico. Those Indians—all Indians—had a greater attraction than just as laborers, however. Alone of all European nations, Spain was committed to incorporating the native Americans into the empire as loyal, taxpaying subjects. Priests accompanied exploring expeditions. After the entradas were completed, missionaries settled among the tribes and began the civilizing process, as civilization was defined by the conquerors.

The Spaniards saw themselves as particularly fitted for carrying out this God-given program. Eight centuries of war against the Moors had brought a strong sense of unity to the peninsula’s extraordinary mix of bloodlines—descendants of ancient Greeks, Romans, 15 Carthegenians, and Celts as well as indigenous Iberians. Contests with Muslims and attacks on Jews through the Inquisition (Jews were also expelled from Spain in 1492) had spread a crusading religious fervor throughout the nation. Many a Spaniard felt in his bones what was in fact the truth: Spain was poised in the 16th century for a great leap forward that would, for a time, make her the dominant power in Europe. Supreme confidence generated in many Spaniards a pride that unfriendly nations such as England regarded as arrogance.

One side effect of all this was the creation of a large class of professional soldiers who scorned all other callings. Success in battle brought them a living of sorts; victors, for example, could force Muslims to work patches of ground for them. A man could become an hidalgo, entitled to use the word Don in front of his name and pass it on, generation after generation, to his sons. The first-born of these families picked up the nation’s plums. They were appointed to prestigious places in the army, the church, or the royal bureaucracy. For the rest there was little but their swords and a readiness for adventure.

The New World opened new opportunities for these younger sons and their followers. They could join small private armies that went, with the monarch’s permission, into the Americas to spread the gospel among the “heathens” while simultaneously looting the defeated Indians’ storehouses of treasure and taking their lands. Prime examples of this grasping for treasure are furnished by some of the conquistadores who hailed from the harsh, barren lands of the Extremadura region of Castile—names that still ring triumphantly throughout most of the New World: Hernán Cortés, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, the brothers Pizarro, and Hernando de Soto.

Christopher Columbus, whose 1492 voyage opened a new world to Europeans. Though many artists have attempted portraits of Columbus, none were from life. This portrait is a copy of a painting done in 1525.

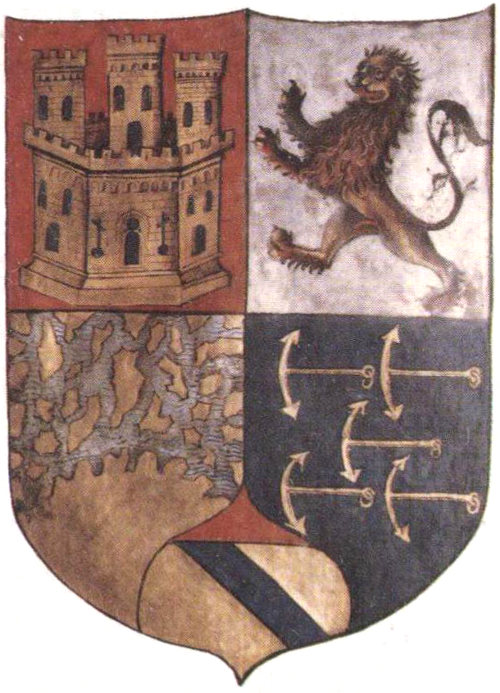

After the First Voyage, the Spanish monarchs granted to Columbus and his descendents this coat of arms. It signified his new place in the nobility. The gold castle and purple lion linked him to the sovereigns. The golden islands in the sea proclaimed his discoveries. The anchors were emblems of his rank as admiral.

The crown gave little except permission and titles—adelantado (“he who leads the way”) and governor—to men such as these. But if the risks were great, so too at times were the rewards. As already indicated, there might be riches to divide after the king had taken his 20 percent share. There were plantations to be founded and tended by Indians who gave their labor, however willingly, in exchange for being taught the ways of Christians. The size of each man’s share in these gains depended partly on his initial investment in the expedition. Money wasn’t all. The contribution 16 could be—and this was a crucial point—energy, ability, intense patriotism, religious zeal, and often ruthlessness.

Each man took with him to the New World what he had. Apparently there were few full suits of armor, though Francisco Vásquez de Coronado did possess one that was handsomely gilded to look like the gold he was searching for.

Partial suits—coats of mail made of small, interlinked rings of metal or cuirasses of plate armor that protected the wearer’s front and sides—were more numerous. Most cuirasses were made with a ridge running down the front and curved in such a way that a lance point striking the metal would, it was hoped, glance off without penetrating. It was hoped, too, that arrows would be similarly deflected. The chronicles tell, however, of Indian bows driving arrows entirely through plate armor and of cane arrows splintering on striking chain mail. The needle-sharp pieces then passed through the metal rings, inflicting puncture wounds that festered. Jackets made of quilted padding or even of tough bullhide were probably as effective against arrows as metal.

Priests accompanied most expeditions of discovery. Like their countrymen, most clergy were poorly equipped to understand and tolerate the new societies they encountered in America. One clergyman who rose far above his time and place was Bartolomé de las Casas, who spoke out against abuse of the Indians but met with great opposition from vested interests.

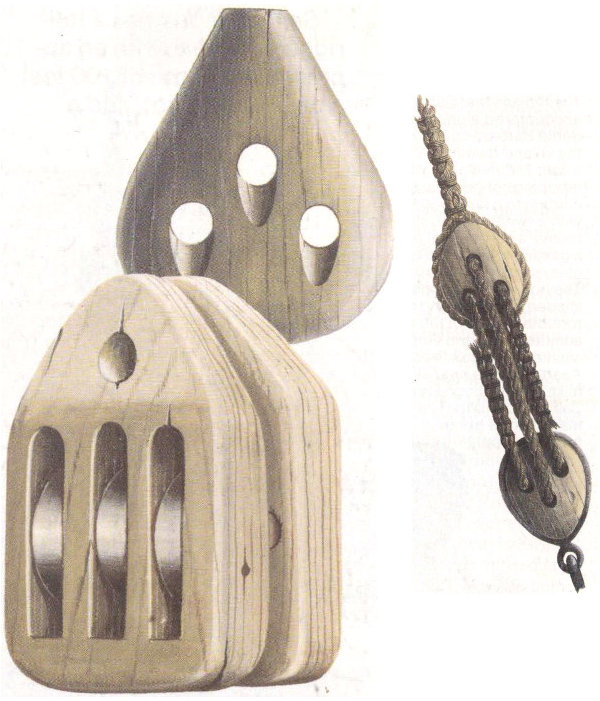

Footmen, who constituted the greater part of every New World expedition, carried pikes or halberds, crossbows or arquebuses, and sometimes maces or battle axes. A crossbow, whose string was pulled tight by a crank, propelled iron darts with great force and accuracy from grooves in the weapon’s stock. An arquebus was a primitive musket about 3 feet in length but lacked accuracy at distances greater than 75 yards or so. Indians, it turned out, could shoot several arrows in the time the handler of a crossbow or arquebus could fire once.

Cavalrymen, the elite of the force, were armed with lances, swords for slashing, and daggers. Long lances were generally couched against the rider’s body, as in tournaments or charges against similarly equipped European adversaries. A lance driven through an Indian’s body, however, would sometimes hang up and pull the rider from his saddle. Accordingly, shorter weapons held in an upraised hand were preferred in the New World. They could be hurled or held and directed at the enemy’s face—an enemy on foot, for the native Americans did not yet have horses.

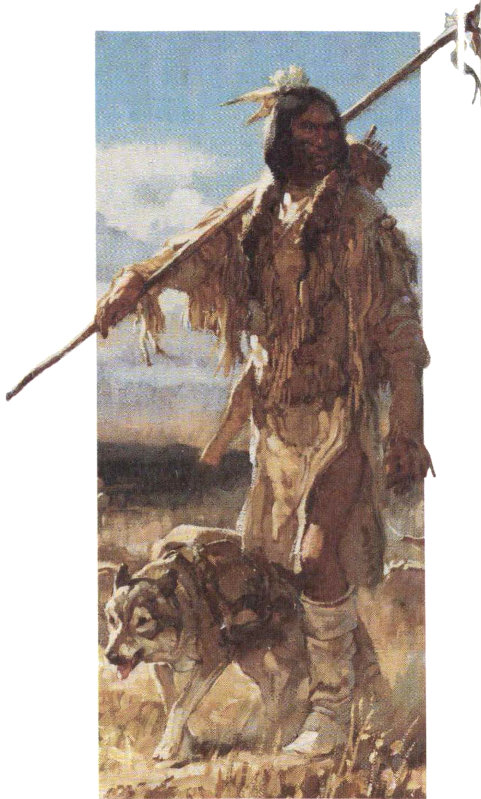

The conquistadores were as superb horsemen as the world has seen. Their animals were loved and 17 pampered. During the early years in the Americas they were relatively rare and expensive (few survived the tempestuous sea journey from Europe to become breeding stock), and just the sight of them terrified Indians. The fearful impact of a cavalry charge, lances flying or thrusting, swords slashing, and wardogs sometimes racing beside the horses, goes far to explain how small groups of Spaniards were able to triumph over great numerical odds. Pedro de Casteñada, one of the historians of the Coronado expedition, put it thus: “after God, we owed the victory to the horses.”

Desperation also played a part. The adventurers often found themselves hundreds of miles from any possibility of help. Stamina in the face of hunger and hardship, courage and energy in opposition to attack and fear were the basic elements of salvation. Of necessity the men adopted whatever methods promised to carry them to their goals. Religious fanaticism was another motive. To Cortés’s men, the Aztecs, who regularly offered human sacrifices to a heathen god, were an abomination and deserved to be annihilated, or at least enslaved, if they did not accept the Christian salvation held out to them. This attitude carried over, in somewhat lesser degree, to all Indians, even though Spain’s rulers constantly exhorted gentleness, and missionaries went with every major group to offer heaven to souls lost in darkness. That is, if Indians had souls, which many Europeans of the time sincerely doubted.

Finally, every conquistador was stirred to action by his own credulity. The Church had brought him up to believe implicitly in miracles. A large part of his education consisted of peopling the unknown world with marvels and monsters. A favorite tale, though by no means the only one, dealt with seven Catholic bishops and their congregations who fled from the invading Moors to the island of Antilia. There they burned their ships and diligently built seven glorious cities, for naturally Christian settlements would be more dazzling than pagan ones. Mas allá: there is more beyond. A wondrous dream, Spanish-style. It carried, in succession, Pánfilo Narváez, Hernando de Soto, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, and Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo into what became the United States. There reality at last took command.

- Cavalryman in armor

- Pikeman

- Arquebusier, c. 1540

- Crossbowman arming his weapon

- Wardogs

- Swordsman

With a few thousand soldiers Spain conquered the Americas. Most of the soldiers were unemployed veterans of an army tempered by long campaigns against the Moors in Iberia and the French in North Italy. They came to America, wrote an eyewitness, “to serve God and His Majesty, to give light to those who were in darkness, and to grow rich, as all men desire to do.”

Los conquistadores were tough, disciplined, and as ruthless as circumstances required. Their weapons—evolved in the formal battle of Europe—were the matchlock musket (sometimes called an arquebus), the crossbow, pikes, lances (carried by cavalry), swords, cannon, and above all the horse, which Indians universally regarded as a supernatural being. This weaponry served well against organized armies in Central America and Peru that fought in formations mostly with clubs, spears, and slings. But in North America, the Spaniards faced skilled and elusive archers who could drive an arrow through armor. The crossbow and musket soon proved useless. Far more effective were sword-wielding cavalry and infantry and (for De Soto) wardogs. In the one battle Southeast Indians had a chance of winning (Mabila, 18 October 1540), De Soto against great odds slaughtered his antagonists. Thousands died against only 18 or so Spaniards. Foreshadowing things to come, this battle demonstrated that Indians fighting with Stone Age weapons were no match against European arms and tactics.

19

An infantryman armed his crossbow by pushing the bowspring back with a lever, engaging the trigger catch, and inserting a metal-tipped dart. This weapon was effective in Europe against formations and armor but less useful against a foe who quite sensibly soon learned to fight by stealth and avoid open combat.

- Lever for arming the bow

- Stock

- Trigger

- Bowstring

The Spanish sword at its best was a superb piece of craftsmanship. About 41 inches long, it was double-edged, razor sharp, and flexible. A fine Toledo blade could be bent into a semi-circle and withstand a hard strike against steel. At hand-to-hand combat, Spanish swordsmen were unexcelled in either Europe or the New World.

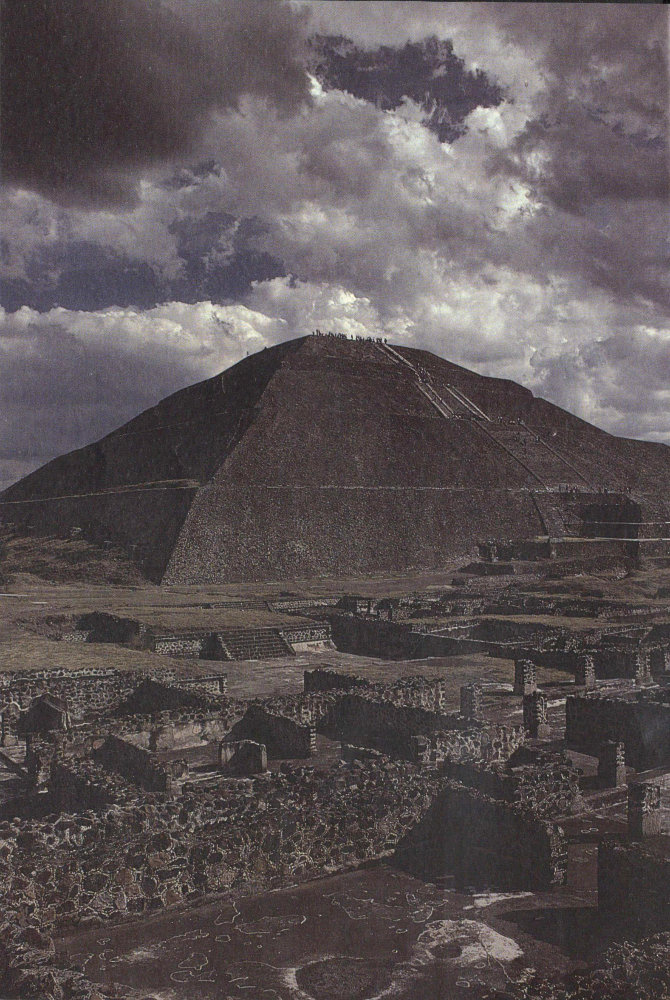

Temple of the Sun, religious center of the Aztec city of Teotihuacán. A priest ascending this immense pyramid seemingly disappeared into the sky.

Redheaded Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca—Cabeza de Vaca translates as Cow’s Head—was a man of considerable pride and, apparently, some wry humor. In 1483, about three years after his birth, its exact date unknown, his paternal grandfather, Pedro de Vera, conquered the Grand Canary Island off the northwest coast of Africa for Spain, a feat that brought a glow, in court circles, to the name de Vera. And then there was his mother’s name, Teresa Cabeza de Vaca. Legend avers that back in 1212 her ancestor, a shepherd, had used the skull of a cow to mark a mountain pass that let a Christian army surprise and defeat its Mohammedan enemy. The shepherd’s sovereign thereupon bestowed the name Cabeza de Vaca on the family. Young Alvar Nuñez must have enjoyed the story, for he adopted his mother’s surname rather than his father’s, a not unusual custom in Spain.

He fought in several battles for Ferdinand and Isabella and for their grandson, Charles V, and was severely wounded at least once. In 1526, when he was about 46, Charles appointed him royal treasurer of a large expedition Pánfilo de Narváez proposed to lead into Florida, a name that then covered a huge region stretching from the peninsula around the dimly known north Gulf Coast to the Rio de las Palmas in northeastern Mexico.[1] If treasure was found—and treasure was Narváez’s goal—it would be up to Cabeza de Vaca to make sure the king received his 20 percent share. Other financial duties were involved, so that altogether it seemed a promising appointment for a middle-aged ex-soldier and able administrator. As events turned out, Vaca could hardly have suffered a greater misfortune.

The problem, which merits a digression, was Pánfilo de Narváez, the expedition’s leader. About the same age as Cabeza de Vaca, he was tall, courtly, and deep voiced, qualities that helped marvelously in advancing his career. He had prospered as a pioneer settler in Jamaica, and between 1511 and 1515 had aided 22 Diego Velásquez in the conquest of Cuba, a feat which had elevated Velásquez to the governorship of the island. Both men added to their riches by using enforced Indian labor to exploit the island’s shallow placer mines and embryonic plantations. And although both could easily have retired to comfortable estates, each wanted more money, a common itch.

Charles, King of Spain, 1516-56, and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, 1519-58. Under his rule, Spain carved out a new empire in the Americas to go with its dominions in Europe.

As chief administrator of Cuba, Velásquez was allowed by the government in Spain to authorize explorations of the Caribbean. In 1517 and 1518 he exercised this right by licensing seafarers to explore and trade along the coasts of Yucatan and Mexico, capture Indian slaves, and scout out the country for booty. In return for the licenses, Velásquez would share in whatever gains resulted.

Of his searchers for new wealth, the one whose name would ring down through history was Hernán Cortés. Cocky, crafty, reckless, and adept with the ladies, Cortés had come to Cuba as Velásquez’s private secretary at the same time Narváez had. He, too, had prospered, but unlike Narváez he had quarreled sharply with his former boss. Though a reconciliation had been effected, it was touchy. Still, Cortés had money and was willing to spend it on risky adventures, and so, in 1518, he was authorized to explore Mexico’s eastern coast. He assembled a fleet of 11 ships, 16 precious horses, and prodigious stores of armaments. People grew so excited about his prospects that he easily recruited 500 or so soldiers and 100 sailors—nearly half of Cuba’s male population.

While he was preparing his expedition, some of Velásquez’s other scouts returned with rumors of a fabulous empire of Aztec Indians and their capital city, Tenochtitlán, built on an island in a shallow lake that filled most of a high mountain valley in Mexico. Growing suddenly nervous about Cortés—how loyal would he be with treasure in front of him and an army at his back?—Velásquez in February 1519 revoked Cortés’s commission. Defying him, Cortés slipped away and disappeared.

One of the world’s most fabulous adventures followed. Landing on the Yucatan coast, Cortés rescued a survivor of one of Velásquez’s earlier expeditions—a man who in his captivity had learned the Mayan language. Employing the one-time prisoner as an interpreter, Cortés turned his fleet northward, probing the coast. Such resistance as developed among the 23 Indians was quickly crushed by the terrifying aspect of the expedition’s few horses. During one of those aborted battles, Cortés rescued yet another captive, a woman named Malinche whom the priest with the expedition baptized and named Marina.

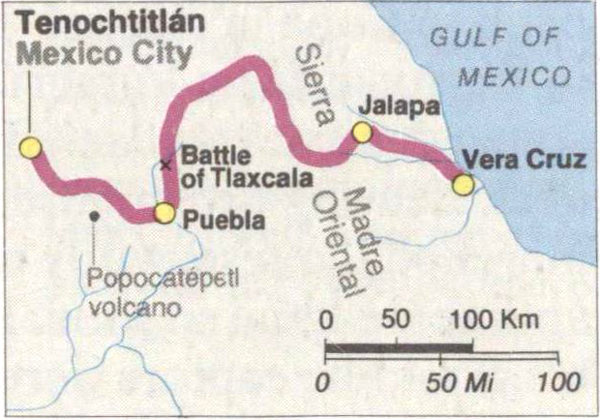

Hernán Cortés with 600 men and 16 horses overthrew the Aztec empire. This illustration of the conquistador was made from life.

The map traces his route from the coast to Tenochtitlán in 1519.

Marina was a Nahua, or Aztec. While in captivity she too had learned the Mayan tongue and could converse with the rescued Spaniard. Through this linguistic conduit, the conquistadores received exciting information about Tenochtitlán, the glittering city of the Aztecs, predecessor of today’s Mexico City. A dazzling prize! And why, Cortés surely wondered, should he share any of it with Diego Velásquez, sitting safely at home in Cuba?

On April 21, 1519, the fleet dropped anchor at the sea end of a trail leading to the city. There Cortés laid the foundations of a port that he named Vera Cruz (today Veracruz). Calling his men together—they, too, were excited about prospects—he prevailed on the majority to elect him captain-general of the expedition, a move that in Cortés’s mind freed him of his obligations to Velásquez and made him answerable only to King Charles V. Simultaneously, he sent emissaries to Moctezuma, emperor of the Aztecs, asking for an audience.

The timing could hardly have been more propitious. The Aztec rule was harsh; subject nations seethed with discontent; Tenochtitlán itself was torn with dissensions. Fearful that the strangers might be able to capitalize on the undercurrents of the rebellion—and fearful, too, that the newcomers might somehow be descendants of the ancient serpent-god, Quetzalcoatl—Moctezuma tried to buy off the Spaniards. Down to Veracruz went five noble diplomats accompanied by 100 porters laden with treasure. All of it was breathtaking, but what really dumbfounded the Spaniards were two metal disks the size of cartwheels. One, representing the Sun God, was of solid gold. The other, dedicated to the Moon, was of silver.

Cortés declined to respond as expected. He loaded the treasure onto one of his ships and ordered the captain to sail directly to Spain, where he would use the booty to win the approval of Charles V. The rest of the ships he burned so that none of the men in the command who were still loyal to Velásquez could return to Cuba and stir up trouble there. As for his own men, they too would fight harder if they knew 24 that no ships were waiting to evacuate them if they were defeated.

Xipe Totec, Aztec god of fertility, one of many gods in the Aztec pantheon, redrawn from the original codex. He wears the flayed skin of a sacrificial victim. Ritual killing horrified Spaniards and in their eyes justified the conquest. But to Aztecs the gods and their extravagant costumes were an important part of everyday life, condensations of vital social truths.

In November 1519, Tenochtitlán capitulated after a short, hard fight. Cortés took Moctezuma hostage and then paused to contemplate his enormous prize.

Unknown to the victors, the captain of the ship bound for Spain did pause in Cuba to check on some land he owned there. It was a short stay but long enough for the sailors to talk. Astounded couriers sped the word to Velásquez. The governor was outraged. He was already at work gathering a strong force of 900 men equipped with 80 horses and 13 ships to pursue Cortés and arrest him for defying orders. Doubly furious at what seemed to him Cortés’s latest treachery, he put Pánfilo de Narváez in charge of a punitive force to bring the disloyal conquistador back to Cuba in chains!

Warnings from Veracruz reached Cortés at the Aztec capital. He reacted with characteristic boldness. Leaving two hundred men at Tenochtitlán, he marched the rest swiftly to the coast. No one there anticipated him so soon. Late at night, when most of his would-be captors were asleep, he waded his men across a swollen stream and attacked without warning. During the chaos that followed, a lance point put out one of Narváez’s eyes. By dawn the field was in Cortés’s hands. Most of Narváez’s men, hearing of the riches of Tenochtitlán, deserted their commander and swore fealty to the victor.

While Narváez remained under guard at Veracruz, nursing his wound, Cortés marched back to rejoin the rest of his men at Tenochtitlán. The Aztecs let the returning soldiers reach the palace compound and then attacked in waves of thousands. The hostage emperor, Moctezuma, was stoned to death by his own people while pleading for peace. Trying once again to use the night as cover, Cortés on June 30, 1520, led hundreds of Spaniards and several thousand Indian allies onto one of the stone-and-earth causeways that connected the island city to the mainland. Aztecs swarmed after them in canoes. On that famed noche triste—night of sorrows—850 Spaniards and upwards of 4,000 of their allies died.

Fortune shifted quickly, however. Wheeling around on the plains outside the city and making adroit use of his few horses and guns, Cortés defeated the army pursuing him. Doggedly then he put together a fresh 25 army of Indians who hated the Aztecs and of whites who were dribbling into Mexico to see what was going on. The next year, on August 13, 1521, he recaptured Tenochtitlán, again at heavy cost. By twisting logic only a little, he could have blamed all these troubles on Narváez’s inept interference. He did not. He treated the man kindly and then sent him home to Spain with, so it is said, a bagful of golden artifacts.

“I saw the things which have been brought to the King from the new land of gold, a sun all of gold a whole fathom broad, and a moon all of silver of the same size, also two rooms full of the armour of the people there, and all manner of wondrous weapons of [the Aztecs], harnesses and darts, very strange clothing, beds and all kinds of wonderful objects of human use, much better worth of seeing than prodigies. These things are so precious that they are valued at a hundred thousand florins. All the days of my life I have seen nothing that rejoiced my heart so much as these things, for I saw among them wonderful works of art, and I marvelled at the subtle ingenia of people in foreign lands. Indeed, I cannot express all that I thought there.”—Albrecht Dürer upon seeing the Aztec objects Cortés sent Charles V in 1519.

In Spain Narváez intrigued against the nation’s hero, as Cortés then was, as best he could. He also yearned for a conquest in which he could redeem himself. When the governorship of Florida fell open, he applied for the position and won. His plan was to establish his first colony at Río de las Palmas, north of Pánuco, on Mexico’s northeast coast, where Cortés had already placed a defensive outpost. From there he could put pressure on his enemy, who many of the king’s council thought was growing too big for his boots. He could also search for the treasure that he was sure lay somewhere in the north, in the land from which he supposed the Aztecs had originally come—land where the fabled Seven Cities might lie.

Six hundred soldiers, sailors, and would-be settlers, a few of whom had their wives with them, left Spain aboard five ships in June 1527. One of the adventurers was Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, making his first trip to the New World. It was a hard journey—desertions, groundings, a deadly hurricane, and finally a series of adverse storms that drove the little fleet off its intended course for the Río de las Palmas to a landing on the west coast of the Florida peninsula, probably opposite the head of Tampa Bay.

In view of the peninsula’s nearness to Cuba, remarkably little was known about it. Beginning with Alonso Alvarez de Pineda in 1519, a few sea explorers had groped along its western coast on their way to Mexico. Occasional traders and slave hunters had poked into some of its lovely bays—and had often taken severe trouncings from the Indians for their pains. Juan Ponce de León, the only man to try to establish a colony there, was mortally wounded during the attempt.

Tenochtitlán, predecessor of today’s Mexico City, was one of the most magnificent cities in the world when Cortés and his small army arrived in 1519. The sight of the radiant city in the center of a large lake astonished the Spaniards. “We did not know what to say, or whether what appeared before us was real,” wrote a soldier, “for there were great cities along the shore and many others in the lake, all filled with canoes, and at intervals along the causeways there were many bridges....”

About 250,000 persons lived here and in its sister city Tlatelolco (left). The market place was huge. “Some of the soldiers with us had been in many parts of the world, in Constantinople and all over Italy and Rome, and they said they had never 27 seen a public square so perfectly laid out, so large, so orderly, and so full of people.”

At the center of the city—and the Aztec religion—was the Templo Major, a complex of temples and shrines to the gods of fertility and war—the sources of Aztec power. The surfaces of the temples were richly ornamented in symbols and myths that expressed their complete vision of life. It was this city, which governed a vast empire in central Mexico, that the intrepid Cortés and his band overthrew in 1521. Within a few years a splendid and original civilization lay in ruins.

Narváez must have known of the dangers, but when he saw a yellow object among some fish nets in a village from which the Indians had fled on his approach, he jumped to the conclusion that it was gold. Hopefully, he showed the object to some Indians he lured into camp, they pointed north and said vehemently, “Apalachee! Apalachee!” Straightway Narváez decided to march there overland with the main part of his force, 40 of them mounted on the skin-and-bone horses that had survived the sea journey. The rest of the group, including its women, were directed to sail along the coast to a harbor supposedly known to the expedition’s pilot. There the two groups would come together again.

The Aztecs and kindred people were wonderful artists in gold. The lifesize breastplate is Mixtecan, perhaps the representation of the god of death.

The gold plug is an Aztecan facial ornament. Nobles and military leaders routinely wore plugs as a sign of rank. The plugs were inserted through a hole below the lip or in the cheek.

Cabeza de Vaca protested. They couldn’t be sure they understood the Indians properly. Would the two parties be able to find each other again on the intricate coast? They did not have food enough for exploring. First they should locate their colony in an area suitable for farming and send the ships to Cuba for supplies. Time enough then to search for gold.

Narváez waved him aside. The ships sailed on and the land party headed north, each man carrying two pounds of biscuits and half a pound of bacon. After 15 days of hunger they luckily seized some Indians who led them to a field of maize ripe enough for harvesting. Strengthened somewhat but beset by clouds of insects, they waded on through bogs, built rafts for crossing rivers—a drowned horse fed some of them one night—and then entered a region of enormous trees where piles of fallen timber created an almost impassable maze.

Apalachee, located close to the site of modern Tallahassee, turned out to be a village of 40 small houses roofed with thatch. No gold. Disgruntled, Narváez imprisoned an Apalachee chief and appropriated some of the houses for shelter. The villagers retaliated by setting fire to the buildings, a tactic that became common during later years.

The invaders stayed 25 days, scouting the surrounding country and resting as best they could under constant sniping by displaced inhabitants. They then headed west toward another town of reputed richness, Aute, near present-day St. Marks, on Apalachee Bay. Indians shadowed them, killing or wounding several men with hard-pointed arrows capable of piercing armor. Cabeza de Vaca was one of those nicked.

On the Spaniards’ approach, the inhabitants of Aute burned their huts and fled. There was no gold in the ruins. No silver. No jewels. And no sign of Spanish ships in the bay. As a mysterious fever began felling the men one by one, Narváez said that Pánuco 29 could not be far away. If they could build boats....

How? The men knew nothing about the art of shipbuilding. The only materials they had were what they and their horses wore. Total helplessness—until God’s will, Cabeza de Vaca wrote years later, prompted one anonymous fellow to say he thought he could make a bellows out of deerskin and wooden pipes. With the bellows they could produce heat enough to transform spurs, bridle-bits, crossbow darts, and iron stirrups into nails. Excited by that proposal, a Greek spoke up, saying he knew how to manufacture waterproofing pitch from the resin in the pine trees surrounding them.

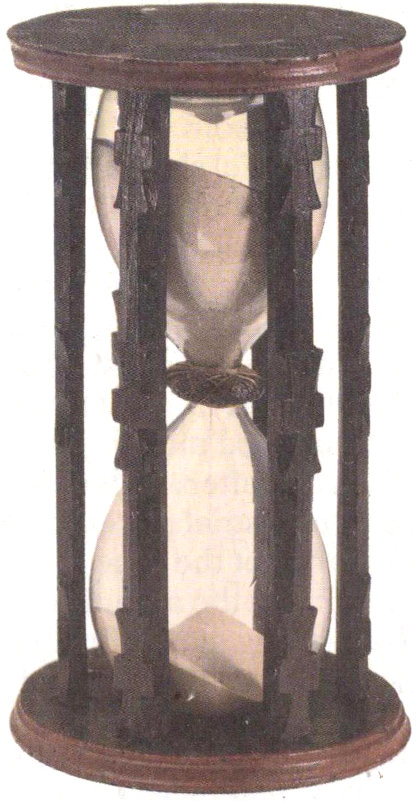

Working with the energy of desperation, the men put together, between August 5 and September 20 five crude boats, each about 33 feet long. They made sails out of their clothing, rope out of horse hair and palmetto fibre, anchors out of stone. Those not involved in the construction used the surviving horses—a diminishing number since they killed one every third day for food—to bring in 640 bushels of corn from the fields at Aute. Several men died from fever or wounds received from the Indians—not altogether an ill wind, since the five boats could not have carried more than the 250 or so persons who overloaded them at sailing time. Narváez, exercising a leader’s prerogative, picked out the best boat and strongest crew for himself.

They crawled along close to the shore, sat out storms behind islands, lost more men to Indian attack, and suffered so terribly from thirst—the water bottles they had made from horsehide soon rotted—that four of them drank salt water in their misery and perished. A more historic moment than any of them would ever realize came toward the end of October 1528, when, as they were edging out past some marshy islands, a powerful current of fresh water swept them far out to sea. They had discovered the mouth of a great river—the Mississippi.

As they worked back toward the coast on the far side of the river mouth, winds and sea currents quickened their pace. Despite strenuous efforts the crews could not keep the boats together. The men with Cabeza de Vaca grew so exhausted that they shouted to Narváez to toss them a rope and help pull them along. Narváez refused. “When the sun sank,” the treasurer recalled later, “all who were in my boat 30 were fallen one on another, so near to death that there were few of them in a state of sensibility.” They lay inert throughout the night. At dawn—it was November 6, 1528—Cabeza de Vaca heard the tumult of breakers but could take no measures to meet the threat. A giant wave lifted the boat out of the water and dropped it with a crash on what was either Galveston Island off the coast of Texas or a nearby stub of a peninsula.

The “hunch-backed cows” that Vaca and his companions saw were the wide-ranging American bison. “They have small horns like the cows of Morocco,” he wrote. “The hair is very long and wooly like a rug. Some are tawny, others are black. In my judgment the flesh is finer and fatter than cows from [Spain].”

Karankawa Indians who had gathered at the spot to dig roots succored them. A little later they joined the crew of another capsized boat that had been commanded by captains Alonso de Castillo and Andrés Dorantes, whose black slave Estéban was with him. The combined group numbered about 80, most of them infirm and next to naked. Numbly, they tried to repair Cabeza de Vaca’s boat so the strongest could sail to Pánuco for help. It sank. Four volunteers then agreed to try to reach Mexico by land. They never returned.

A winter of intense cold, starvation, and fever left only 15 alive, Cabeza de Vaca barely so. In the spring, 13 of the survivors moved off with the greater part of the Indians in search of food, leaving Cabeza de Vaca and a second invalid, Lope de Oviedo, behind with a small band. As soon as Cabeza de Vaca was able to work, the Indians set him to digging roots and carrying firewood. To escape the drudgery he became a trader, traveling far inland with a pack of shells, flints, cane for arrow shafts, sinews and so on for barter. During the wanderings he became the first European known to have seen bison.

His great desire was to walk southwest along the coast until he reached other men of his own kind, and he urged Oviedo to join him. The fellow kept promising he would as soon as he was better. Not wishing to desert a fellow Spaniard, Cabeza de Vaca wasted four years through one postponement after another. At last they started, but then Oviedo caved in with fear and turned back, preferring familiar miseries to the unknown.

Shortly thereafter, in 1532, in the bottomlands of the Colorado River of Texas, where several bands were harvesting walnuts, Cabeza de Vaca stumbled joyously across Castillo, Dorantes, and the vigorous black Estéban. The trio were also ready to strike for Mexico if they could escape from their 31 masters, but they warned against fierce tribes to the southwest. They should try a route farther north.

After two years of interruption and frustrations they made the break. The incredible journey, broken by long stays at various Indian camps, lasted two years. At times they traveled alone. More often they were accompanied by Indians. After they had chanced to pray over an ailing man, who thereupon leaped up and declared himself cured, they became revered as supernatural medicinemen, children of the sun. Their marches, often scouted out for them by Estéban, who also served as interpreter—he learned six languages during those arduous years—became triumphal processions. Sometimes, says Cabeza de Vaca, as many as 4,000 Indians would accompany them from one village to the next, a figure that, as Bernard DeVoto has pointed out, should be taken as a way of saying “quite a few.” Those who escorted them would often loot the first village they reached, whereupon its inhabitants, moving on with the quartet to another village, would recoup their losses by plundering it.

What route did they follow? No one knows. Cabeza de Vaca’s descriptions of Indian customs, rivers, mountains, vegetation, and so on have led some students to suggest that the wanderers may have gone as far north as southern New Mexico and Arizona. Others think they traveled out of west Texas into Chihuahua. But whatever the way, it eventually merged with one of the trade trails that ran between the Pueblo Indian towns of the Southwest and those in the heavily populated, southward trending valleys of Sonora. They reached the Sonora area in the spring of 1536.

What had they seen along the way? Not much, according to a report that the survivors sent to the audiencia in Hispaniola in 1537. Just buffalo robes that had originated in the country of the plains Indians and beautifully woven cotton mantas that their native hosts had obtained by trade with Indians somewhere in the north (probably the Pueblos of the Rio Grande). Bits of coral and turquoise. And miles and miles of desolation, thinly populated by primitive tribes. Writing a memoir of the trip six years later, Cabeza de Vaca improved only slightly on the tales. In Sonora, he related, he was given five emeralds shaped like arrowheads; the donors said the “jewels” had been purchased in the north with parrot feathers and plumes. Sadly, he lost the five artifacts before 32 anyone else saw them. He also told of handling a small bell made of copper and of hearing stories about large cities filled with big houses and surrounded by boundless fields of maize.

Such reports were too vague and understated to create much popular excitement—at first. But as Antonio de Mendoza, New Spain’s first and recently arrived Viceroy, realized, the calm might not last. For a similar story told a few years earlier to the infamous Nuño de Guzmán by an Indian slave named Tejo had stirred up a violent reaction.

At the time Guzmán had been governor of Pánuco on Mexico’s northeast coast and was making a fortune selling slaves to plantations throughout the West Indies. But that wasn’t enough, and his ears pricked up when he listened to Tejo telling about a trip with his father to seven marvelous cities far to the northwest—cities whose streets were lined with the shops of goldsmiths and silversmiths.

The story may well have had an element of truth in it. If a trader kept traveling northwest from Pánuco—and some of Mexico’s early Indian traders were far-ranging—he would eventually reach the impressive pueblo towns of today’s New Mexico. Where the notion of goldsmiths came from is something else, but Guzman believed it because he wanted to.

Instead of taking a direct line to his goal, he put together a strong force, fought his way across the mountains to the west coast, and hewed out, as a base of operations for a thrust along the trade trails leading north, the all-but-independent province of Nueva Galicia. (It embraced the better part of the present-day Mexican states of Nayarit and Sinaloa.) Illness and then his arrest for his slave-dealings put a stop to the northern plans, but the appearance of the Vaca party out of the wilderness might, Mendoza feared, lead the great Cortés to appropriate the idea for himself.

Cortés was ripe for trouble. Because of his insubordination to Diego Velásquez of Cuba, the king had refused to name him Viceroy of New Spain, but then had tried to compensate for the injustice, as Cortés considered it, by naming him the Marquís of the Valley of Oaxaca and giving him the right to explore the South Seas (south of Asia) for new principalities. On their quests some of his ship captains stirred Guzmán’s jealousy by sailing north along the coast 33 of Nueva Galicia. When Guzmán seized one of those ships in the port of Chiametla, the Marquís rushed up with a small army and took it back. He then used that ship to cross what he called the Sea of Cortés (today’s Gulf of California) and claim possession, in the name of the king, of pearl fisheries his mariners had discovered at La Paz in what we call Baja California. The fisheries were not proving lucrative, however, and the least sign that something better existed farther north might tempt him to push on.

It behooved Mendoza, as the king’s representative, to move first, before New Spain’s legitimate northward expansion was halted by one of these semi-autonomous conquistadores. Dutifully reporting each of his moves to Charles V—caution was part of his nature—he asked, in turn, Castillo, Dorantes, and Cabeza de Vaca to lead a small exploring party into the north and learn what was really there. Not surprisingly, in view of their experiences, each refused.

In 1537, Cabeza de Vaca returned to Spain. Skeptics say he wanted to persuade the king to appoint him adelantado of Florida so that he could move independently into the north from that direction. On reaching Madrid, however, he found that Charles had already given the post to Hernando de Soto.

Years later one of De Soto’s Portuguese officers from the town of Elvas—he identified himself only as a hidalgo (gentleman) of Spain—wrote that De Soto offered to take Cabeza de Vaca along as second in command for the sake of his guidance. Again the wanderer declined. But, said the hidalgo, whose accuracy cannot be checked, Vaca did drop hints to his friends and relatives that led them to sell everything they had in order to buy enough equipment to join the expedition. Possibly. But all we really know is that Cabeza de Vaca, the only man to brush against both of the entradas that gave the world its first views of what became the United States, never returned there himself. He was sent to South America instead.

Mendoza of course learned by ship of De Soto’s appointment and of necessity had to assume that one of the new adelantado’s goals would be the Seven Cities. So now he had twin worries, Cortés in the west, De Soto in the east. But before considering the steps he took to checkmate them, it is well to look at De Soto’s adventure, for he is the one who, through sheer luck, had the head start.

- NARVÁEZ EXPEDITION

- Santiago, Cuba

- {west Florida coast}: Narváez Expedition lands April 1526

- Apalachee

- Aute: Expedition builds boats

- CABEZA DE VACA

- {Texas coast}: Expedition wrecks; Cabeza de Vaca continues overland

- Colorado River

- Pecos River

- Gila River

- Rio Sonora

- Corazones

- Culiacán: Cabeza de Vaca arrives 1536

35

Cabeza de Vaca and three companions, sole survivors of the ill-fated Narváez expedition (1527), were the first Europeans to cross the North American continent. They spent 8 years traveling 6,000 miles through the interior of Florida, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and northern Mexico. The journey itself was an incredible feat of human stamina and pluck. Equally remarkable is Cabeza de Vaca’s account of his adventure. La Relación, first published In 1542, revised Spanish conceptions about the size and nature of the continent north of Mexico. The book is also the first detailed description of native Americans. In his wanderings Cabeza de Vaca came to admire Indians, whom he came to see as fellow humans who could be won over only by kindness. His book—which can be considered the beginning of American literature—is a record of both a physical and a spiritual journey.

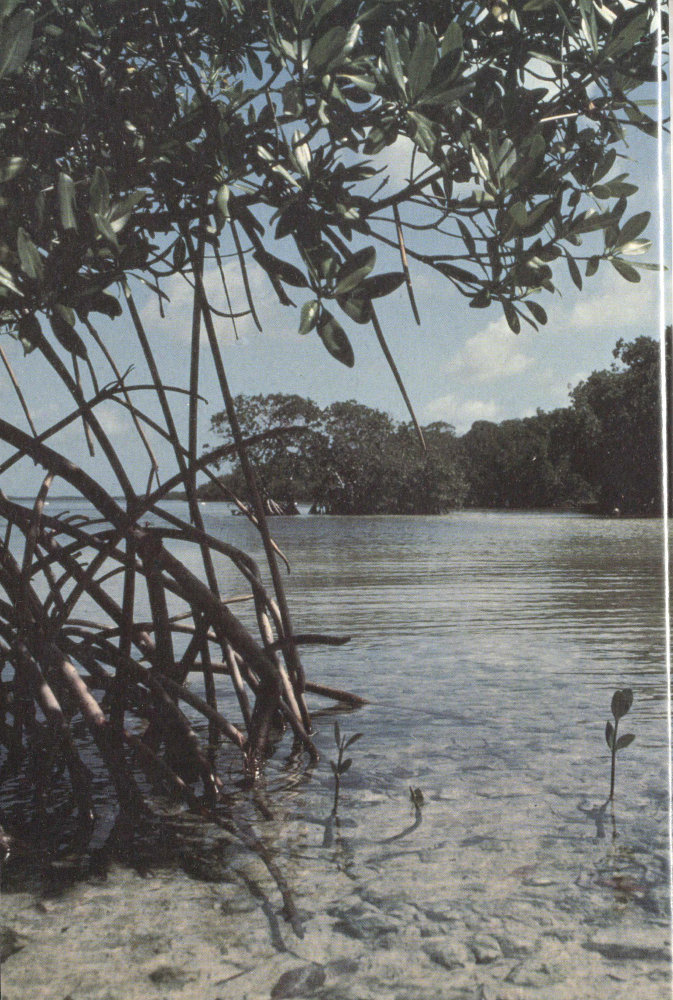

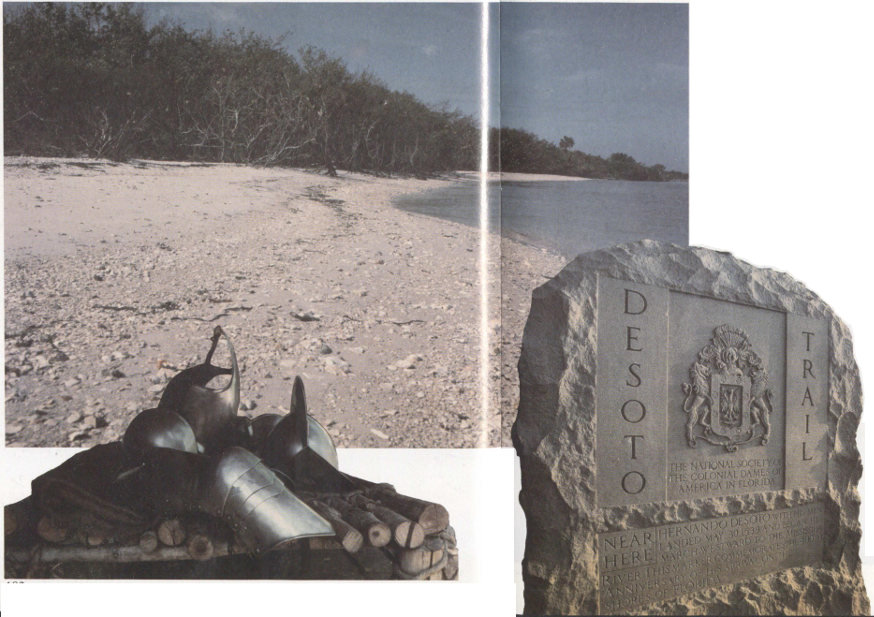

Mangrove near De Soto National Memorial. Thickets of this plant once formed great barriers along the Florida shore.

When Hernando de Soto returned to Spain from two decades of adventure in the New World, he must have seemed to those who encountered him, or even heard of him, the embodiment of what a conquistador should be. He carried his tall, hard, handsome body with the unmistakable air of triumph that comes from having won by his own efforts wealth, fame, and a noble bride—all before he was 35 years old. The exact date of his birth is unknown, but it may have coincided with the last year of the 15th century. His birthplace was in the austere province of Extremadura. His father was a Méndez, his mother a de Soto; his elder brother Juan followed the Spanish custom of using both names: Juan Méndez de Soto. Hernando, the second son, chose to be different. According to his biographer, Miguel Albornoz, he was his mother’s favorite. He therefore dropped Méndez from his name and became known to history only as De Soto—an appellation he carried far.

Another native of Extremadura and a neighbor of the De Soto family was Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, the fabled conqueror of Darién (Panama) and discoverer of the Pacific Ocean. Determined to emulate Balboa, who was still alive somewhere in the New World, young Hernando de Soto made his way, aged 14 or so, to Seville. There he found employment as a page in the household of the notorious schemer, 75-year-old Pedro Arias Dávila, better known as Pedrárias. When Pedrárias sailed to Central America in 1514 as a colonial administrator, De Soto went along.

He witnessed the quarrel that sprang up between his patron and Balboa, a quarrel that ended in 1519 when Balboa was convicted of treason through the intrigues of Pedrárias and beheaded. Grieving, De Soto retrieved the headless corpse and with the help of an Indian girl gave it a Christian burial. Yet he remained loyal to Pedrárias and followed him to Nicaragua, where he developed the ice-hard maturity that marked his later career. He mastered the arts of 38 dealing in Indian slaves, looting temples, and ransacking Indian graves for valuable mortuary offerings. By such means he prospered so well that when Pizarro, also a native of Extremadura, needed help on his expedition to Peru, De Soto was able to respond with two ships and 200 men.

De Soto was a leader of experience and resolve. The expedition’s chronicler characterized him as “an inflexible man, and dry of word, who, although he liked to know what the others all thought and had to say, after he once said a thing he did not like to be opposed, and as he ever acted as he thought best, all bent to his will.” This likeness was published in Antonio Herrera y Tordesillas’s Historia General, 1728. No authentic portrait is known to exist.

In the final assault on the Incas, De Soto was generally the one chosen to lead reconnoitering or vanguard parties over the difficult trails of the Andes. After the first great victory was achieved, he saw a sight that ever afterwards burned in his memory. The conquered emperor, Atahualpa (actually one of two brothers contending for the throne), offered, as his ransom, to pile a room 17 feet wide, 22 feet long, and 9 high with golden ornaments, vases, goblets, statuettes. In addition he said, he would fill a somewhat smaller adjoining chamber twice over with silver. In spite of that tremendous gesture, he was then tricked into ordering the death of his brother, for which he himself was executed. The treachery drew angry protests from De Soto.

The next conquest was of mountain-perched Cuzco, less rewarding than anticipated because it had been stripped of treasure during the filling of the rooms. Though De Soto was named lieutenant-governor, the quarrels that broke out between the generals led him to give up the position and return to Spain with his share of the booty. Various estimates of its size have been given, but since there is no satisfactory way of comparing purchasing power then and now, the figures are elusive. Still, it must have been the equivalent of several million of today’s dollars.

He made a point of cutting a fine figure in Spain. Everywhere he went he was accompanied by a dazzling entourage composed mostly of officers who had ridden with him in Panama and Peru. He became a favorite of the King, to whom he loaned money; and he married a daughter of his old patron, Pedrárias. A plush life. But as the lazy days drifted by, De Soto grew restless. He needed activity and he wanted gold. Roomfuls of gold. And fame.

Yielding to his importunities, Charles V made him governor of Cuba and adelantado of Florida, which then stretched from the Atlantic as far north as the Carolinas and on around the Gulf of Mexico to the Río de las Palmas. The usual stipulations about the division of treasure were spelled out in the license. 39 The King was to have one-fifth of all spoils of battle, one-fifth of any revenue derived from mining precious metals, and one-tenth of all loot taken from graves, sepulchres, Indian temples. Once the region had been explored, De Soto was to become the governor of whatever 200 leagues of coastal area he picked out. There he was to found colonies and build three fortified harbors. He was to pacify the Indians and provide the necessary number of priests and friars to convert them. He was to bear the entire costs of the expedition. When it was over, he would receive, in addition to his share of any booty and a grant of land 12 leagues square (about 50,000 acres), a salary of 2,000 ducats a year, roughly $60,000 today.

The expedition, its quota of men more than filled with volunteers who supplied their own armor and arms, landed in Cuba in June 1538 and spent nearly a year there while De Soto attended to administrative duties and organized the entrada. He used far more care than Narváez had. While scouts searched for a good harbor on Florida’s west coast, the commissary department rustled up many loads of hard ship biscuit, 5,000 bushels of maize, quantities of bacon, and a herd of rangy hogs. They also brought with them long, clanking strands of iron chains and collars, portents of things to come.

The chronicles of the expedition give different figures about the numbers involved, but this is a reasonable approximation: close to 700 men, perhaps a hundred camp followers, including a few women, many slaves, eight ecclesiastical persons, and 240 or so horses. Having learned from Cabeza de Vaca about some of Narváez’s mistakes, De Soto included among the soldiers several artisans capable of working with their hands. People, horses, hogs, and big dogs that could be used for attacking Indians, and a confusion of supplies and equipment were loaded aboard five low-waisted, high-pooped, square-rigged ships ranging from 500 to 800 tons burden. Overflow was accommodated, uncomfortably, in two caravels and two small pinnaces.

The fleet spent a week in late May 1539, reaching the southernmost part of what is generally believed to have been Tampa Bay.[2] While the ships were groping over the shoals so that unloading could begin, patrols of both horsemen and footmen, happy to be free of the cramped quarters, dashed off through the 40 undergrowth to learn what lay ahead. They soon discovered that the countryside, though sweet-smelling with flowers, was a maze of bogs, meandering streams, and thick stands of mangroves and oaks. Another tax on travel were small groups of tall, naked Indians, probably Timucuans. The Indians eluded the horsemen by dodging nimbly through swamps and behind trees, now and then letting an arrow flash out from one of their bows. Fortunately one of the few captives the patrols seized was Juan Ortiz, a former member of the ill-fated Narváez expedition.

Ortiz had returned to Cuba with the explorer’s ships after they had failed to make contact with the land party and then had been hired by Narváez’s distraught wife to search for her husband in a pinnace she provided. On visiting Narváez’s initial landing place at Tampa Bay, Ortiz had been captured and had lived ever since with a group that controlled part of the region around the bay. He knew the Timucuans’ language and could speak through interpreters to other Indian groups. But in all that time he had never been far afield and could report only rumors about distant places. Gold? There was none near at hand, but far to the north was a powerful kingdom abounding in maize. Its inhabitants might know of minerals.

A scouting party dispatched to investigate returned with a tantalizing message that would be repeated over and over during the long trek: the gold was somewhere else, this time at a place called Cale, where the warriors wore golden helmets. De Soto nodded complacently. In a region as vast as Florida, he told the Gentleman of Elvas, there were bound to be riches.

Mindful still of the colony he was supposed to found, he left Pedro Calderón near Tampa Bay with three small ships, their sailors, and a hundred soldiers. They had two years’ supply of food and seed for planting. If he found a better place to settle, he would let them know. Meanwhile the other caravel and the five big ships were to return to Havana for fresh supplies and new recruits.

Moving inland farther than Narváez had and marching in divisions, the army moved north. Tough going. Rains were heavy that year. Bogs oozed; lakes and streams rose. The wayfarers waded some streams and bridged others. The men herded the pigs through the mud—the sows had farrowed and there 41 were about 300 now—grooming horses, setting up wet camps and then, tired out, pulverizing, in curved log mortars, the grain they had taken from Indian fields and storage cribs so they could boil it into gruel. Discontent boiled up. There’d better be gold somewhere in this hellhole.

There was none at Cale, but a little farther on.... They straggled through the vicinity of today’s Gainesville and, inclining a little west of north, reached a village called Aguacaliquen. There an advance party captured several women, one of whom was the daughter of the cacique, or chief. The father was told he could not get her back until he had guided the Spaniards into the territory of the next tribe to the west. This he did while several of his villagers followed, playing on bone flutes as a sign of peace and begging that father and daughter be released.

When pleas produced nothing—De Soto feared being left in the wilderness with no guides—the Indians decided to ambush the Spaniards at “a very pleasant village” called Napituca, near today’s Live Oak, Florida. De Soto’s interpreter, Juan Ortiz, discovered the plot and gave warning. Spirits leaped. After two months of being harassed by Indian guerrillas, the Spaniards could at last vent their frustration on a massed army—about 400 Indians, as it turned out. Giving thanks to God, the cavalry charged, lances thrusting, swords slashing. Bellow of arquebuses, zings of crossbow darts, yells of “Santiago!” from pike-wielding foot soldiers. Scores of Indians died; hundreds were captured, including a remnant that fled into two nearby lakes and, by hiding in the cold, night-shrouded waters, evaded capture until morning—a brave stand that won both admiration and kind treatment from the Spanish force.

Not all the captives were handled that generously. Their services were needed. During marches males were linked by chains and iron collars and forced to serve as porters for the army. Women, historian Garcilaso de la Vega wrote after talking to participants in the adventure, served as “domestics,” grinding the rations of maize, cooking the meals, and so on. Rodrigo Ranjel, De Soto’s private secretary, was more specific: the soldiers desired women for “foul use and lewdness.” Whenever the conquerors seized a new village, its cacique was impressed as a hostage and guide and released only after his subjects had 42 served as bearers over the next stretch of the journey. Rebels against the enslavement received punishments designed to warn other recalcitrants. Some had a hand or nose cut off, a few were tied to stakes and burned or shot to death with arrows fired by Indian auxiliaries. Now and then one was torn to pieces by the Spaniard’s war dogs. They accepted the ordeals with a stoicism that won the grudging approval of the expedition’s chroniclers.

In October 1539, De Soto’s army entered the land of the Apalachees. According to Ranjel, they found “much maize and beans and squash and diverse fruits and many deer and a great diversity of birds and fish.” Like Narváez before them, they decided to winter at the fruitful spot, site of today’s Tallahassee.

They evicted the Indians of the main town, Anhaica, and settled down in the log and straw houses. Taking advantage of a high wind, the Indians burned most of the place. Later, the intense cold killed almost all of the despondent Indian slaves captured at the battle of Napituca. In spite of the misfortunes, De Soto decided to use Apalachee as a center for future explorations. He sent Juan de Añasco and 30 cavalrymen south through bogs and sniping Indians to Tampa Bay to bring up Calderón’s hundred soldiers and the three small ships. When the vessels arrived at the very harbor from which Narváez had sailed (as revealed by the remnants of the forge and the grisly piles of horse bones) De Soto dispatched the ships west under Francisco Maldonado to find a protected bay to which the reinforcements waiting in Havana could be brought the following summer.

Meanwhile another distraction arose. Working through a chain of interpreters, Juan Ortiz learned from an Indian captive that a truly rich country, Cofitachequi, lay to the northeast, in the vicinity of what is now Camden, South Carolina. Promptly, De Soto decided to take his regrouped army there.

They left on March 3, 1540. Because most of their captives had died, the men again had to carry their own rations and prepare their own meals. Spring-swollen streams blocked the way; one was so wide the men built a ferry and hauled it back and forth with hawsers. The cacique of Cofitachequi turned out to be a woman. Bedecked in furs, feathers, and the freshwater pearls that were common in the mussels of the southeast, she greeted them warmly. “Be this coming to these shores most happy,” she said according to one chronicler. “My ability can in no way equal my wishes, nor my services [equal] the merits of so great a prince; nevertheless, good wishes are to be valued more than the treasures of the earth without them. With sincerest and purest good will, I tender you my person, my lands, my people, and make you these small gifts.”

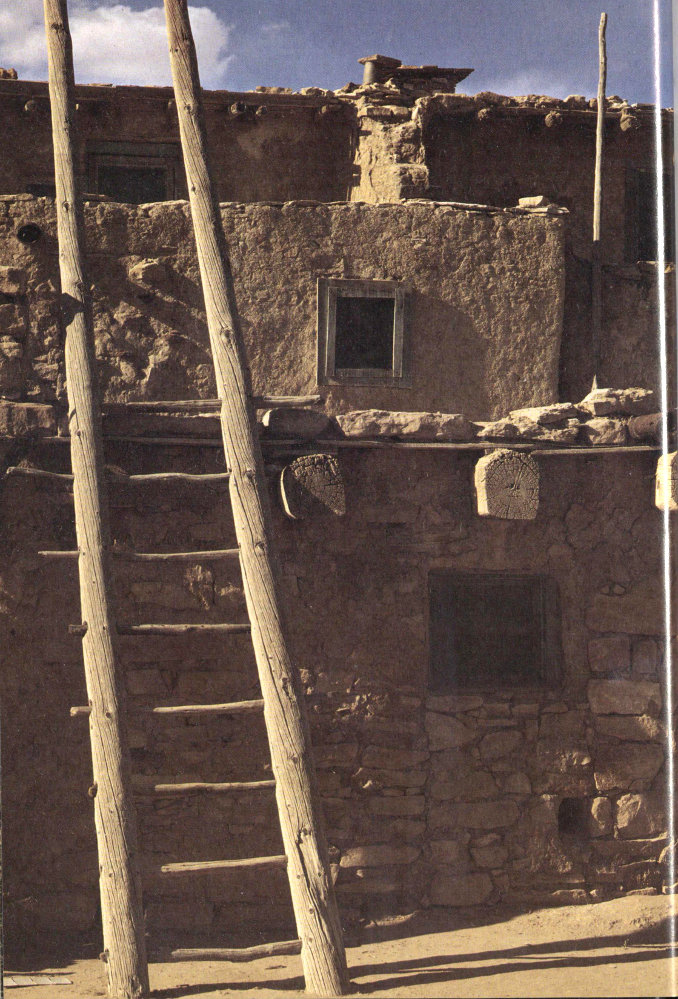

The only site linked with certainty to De Soto is Anhaica, once the principal town of the Apalachee Indians.

This numerous and powerful people resisted the Spaniards’ intrusion into their country in autumn 1539, harassing the march and burning villages to deny food to the army. At Anhaica De Soto found an abandoned town of “250 large and good houses.” The Spaniards settled in and spent five months here. They scoured the countryside for provisions, seizing quantities of maize, pumpkins, beans, and dried persimmons. The Indians raided the town twice and set fires. When the army departed in spring, they carried enough maize to last them across 200 miles of wilderness.

Artifacts from the Tallahassee site: bits of chain mail (top), an arrow point (above); a copper coin minted in Spain between 1505-17; the metal tip of a cross bow dart.

Digging also turned up fragments of olive jars of the type shown at left. The chain mail shirt at right above shows the type of body armor worn by Spaniards in the first decades of the New World conquest. The jar and shirt were not found at the site.

The exact site of Anhaica lay unknown for 450 years. It was discovered by accident in 1987 by archeologist Calvin Jones while searching in downtown Tallahassee, Florida, for a 17th-century Spanish mission. Digging on land planned for development, he and others recovered many 16th-century Spanish artifacts (iron, coins, olive jar fragments, beads, the mandible of a pig) in context with Apalachee pottery. Analysis left no doubt that this was the site of De Soto’s first winter camp.

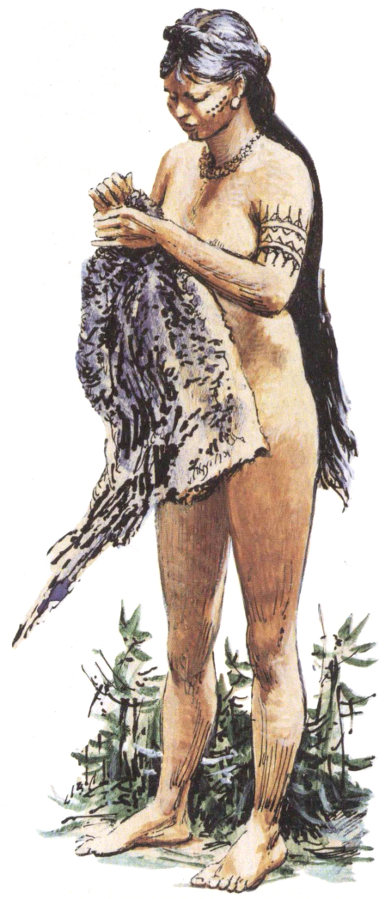

The female cacique of Cofitachequi, apparently a woman of considerable authority, greeted De Soto’s army with ceremony and gifts of food and clothing. Though she had befriended the expedition, she was seized as a hostage and guide but eventually escaped. Artist Louis S. Glanzman illustrates the cacique as she may have appeared at the time of the encounter.

She gave De Soto strands of freshwater pearls and let the men take more from tombs located in mounds raised above the ground. They were not very good pearls and had been discolored by being bored with redhot copper spindles. But they were the closest things to treasure the men had found so far, and De Soto filled a cane chest with 350 pounds of them.

Won by the pearls, the lush countryside, and the navigability of the Wateree-Santee Rivers, which drained southeast into the Atlantic, the men wanted to found a colony there. De Soto refused. There was not enough food at Cofitachequi for the army. Moreover, he was still hoping, in the words of the Gentleman of Elvas, for another windfall “like that of Atabalipa [Atahualpa] of Peru.”

The place to investigate, he heard, was off across the Appalachian Mountains to the northwest. Seizing the cacique who had befriended him, he forced her to enlist a portion of her subjects as porters and domestics for the disgruntled men. They moved rapidly through South Carolina into western North Carolina. By trails that had never before seen a horse, let alone a herd of pigs, they crossed the mountains into the tumbled region of the French Broad and Pigeon Rivers. There the cacique of the pearls managed to escape. As usual, there was no gold.

Hoping, presumably, to meet the ships coming from Havana with supplies and reinforcements, De Soto at last turned south through the land that Creek Indians later occupied in northern Alabama. As they traveled down the Coosa River, they entered a new chiefdom and there laid hold of a tall, disdainful leader named Tascaluza. De Soto demanded women and slaves. With pretended meekness Tascaluza provided the army with a hundred porters and then secretly sent word ahead to his warriors in the stockaded town of Mabila, from which today’s Mobile takes its name, to prepare an ambush. When the town came into sight, De Soto carelessly let the main part of the 45 hungry army disperse to forage. Leaving the fettered bearers outside the entrance, the general and a handful of aides entered the village with Tascaluza. Hot words soon broke out, and the Indians hurled themselves at the enemy. The Spaniards clustered around their leader. Although five were killed and De Soto was knocked down a time or two, they managed to fight their way back outside. During the uproar the porters picked up the food, armaments, and other baggage they had been carrying and rushed inside the stockade with it, to join Tascaluza’s people.

Assembling his soldiers, De Soto launched attacks against all sides of the barricaded town. With axes and fire the yelling Spaniards smashed through the palisades. While the battle raged from house to house, the tinder-box town went up in flames. Realizing they were being defeated, some of the Indians threw themselves into the fire rather than surrender. The last survivor hanged himself with his bowstring. Reports of Spanish losses range from 18 to 22 killed and 148 wounded, including De Soto. Somewhere between 7 and 12 irreplaceable horses perished and 28 were injured. Indian losses were estimated by a chronicler at 2,500.

Since landing at Tampa Bay, the Spaniards had lost 102 men from all causes. The chest of pearls De Soto had hoped to send to Cuba as a lure for replacements had disappeared in the fire, along with most of the army’s spare clothing, weapons, and food. Yet when the interpreter, Juan Ortiz, told De Soto of Indian reports of ships in Mobile Bay a few days away, he ordered him to stay silent. He knew the men would desert if they thought they could reach the ships, and his pride could not tolerate that. Go home empty-handed, beaten, and disgraced? Never.

He rallied the army. For 28 days the healthy doctored the wounded with, said Garcilaso de la Vega, unguents made from the fat of dead Indians. Their commander moved among them, bolstering their spirits, so that when he ordered them to face north again, they obeyed, though they all knew that ships from Havana had been scheduled to meet them somewhere.

They followed the Tombigbee River into northeastern Mississippi to Chicaza, where they wintered (1540-41) among the Chickasaw Indians. When they made their usual request for porters, women, clothing, and food for the spring march, the Chickasaws responded one day at dawn by setting fire to the section of the town in which the invaders were bivouacked. The confusion was total—and perhaps a salvation for the Spaniards. Several terrified horses broke loose and stampeded wildly. Their squeals and the pounding of their hooves, and the sight of De Soto and a few others who had managed to get mounted bearing down on them with lances (before De Soto’s saddle turned and he fell heavily) frightened the Indians into flight.

De Soto was seeking another Peru in Florida. But after three years and thousands of miles, his futile quest ended in a watery grave in the Mississippi. For natives of the Southeast, the entrada was also tragic. The warfare weakened chiefdoms, and Old World diseases ravaged populations. By the time the English and French began their invasions in the a 17th century, the complex mound-building chiefdoms of the region had vanished. They were replaced by the historic tribes whose diminished numbers were no match for westward-expanding Americans.

Route of De Soto

High-resolution Map47In his swing across the Southeast, De Soto’s men traveled over Indian trails and were sustained by Indian supplies. Without native help it is unlikely the expedition could have progressed much beyond the Florida interior. The encounters with native societies—chronicled by several participants—give the expedition significance beyond its own time. The journals combined with archeological and ethnographic data have enabled scholars to map much of the route and to rediscover the lost world of the once mighty chiefdoms of the Apalachee, Ichisi, Ocute, Coosa, Pacaha, and other groups.

This version of the route is based on the work of Professor Charles Hudson and others who have attempted to reconstruct the entire route. There is good scholarly consensus for some segments, but other parts of the route will remain in dispute unless new archeological evidence is forthcoming.

- De Soto Expedition. Dashed line indicates uncertain route.

- *Known site, possibly visited by De Soto

- ·Uncertain Site

- From Havana, Cuba

- De Soto National Monument

- *Ucita

- ·Cale

- *Aguacaliquen

- ·Napituca 15 Sept 1539

- Spaniards route Timacua Indians, take 200 prisoners

- *Auta

- *Anhaica

- Winter camp 1539-40

- ·Toa

- *Ichisi

- Ocmulgee National Monument

- *Cofitachequl

- May 1540 Encounter with female ruler

- ·Xuala

- *Chiaha

- *Coosa

- Political center of an important Indian chiefdom

- ·Itaba

- Etowah Indian Mounds State Historic Site

- *Piachi

- ·Mabila?

- 19 Oct 1540 Major battle with Chief Tasculuza and his allies

- *Apafalaya

- Mound State Monument

- ·Chicaza

- Winter camp 1540-41

- Spaniards beat off Indian attack in spring

- ·Alibamu

- *Quizquiz

- *Aquixo

- *Casqui

- Parkin Archeological State Park

- *Pacaha

- Scouting parties

- *Coligua

- *Calpista

- *Tanico

- ·Tula

- ·Autiempque

- Winter camp 1541-42

- *Anilco

- ·Amihoya

- Winter camp 1542-43

- Spaniards build boats to take them down the Mississippi

- ·Guachoya

- 21 May 1542 Death of De Soto

- Scouting parties

- Expedition continues under Moscoso after De Soto’s death

- *Chaguate

- *Naguatex

- ·Nondacao

- ·Aays

- ·Guasco

- Scouting parties

It was a disaster, nevertheless. Twelve soldiers and a white woman still with the army—she was pregnant—were dead as were several score pigs and 57 horses, the latter mourned as deeply as the men, for they were the army’s true strength. But once again, they rallied, improvised forges for retempering their weapons, replaced the shafts of their lances, and learned to patch their clothing with woven grasses, pounded bark, and pieces of Indian blankets.