This cover was produced by the Transcriber

and is in the public domain.

This cover was produced by the Transcriber

and is in the public domain.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Preface by E. Halford Ross, Esq., m.r.c.s., l.r.c.p., &c. | ||

| I. | A Product of Human Insanitation | 1 |

| II. | Identification of the Common House-Fly | 7 |

| III. | Some other Flies and their Diverse Habits | 16 |

| IV. | Myiasis and the Œstridæ | 26 |

| V. | General Life History | 33 |

| VI. | Structure of the House-Fly | 43 |

| VII. | Distribution and Concentration of Flies | 49 |

| VIII. | Natural Enemies of Flies | 53 |

| IX. | Disseminators of Disease | 58 |

| X. | Remedial Measures; Cremation of Refuse | 64 |

| XI. | Control Within the House | 71 |

| XII. | Service and Utility of Flies | 78 |

| XIII. | A Campaign of Effective Warfare, Conclusion | 84 |

| Description of the Wingate Fly Chart | 89 | |

| Table of Wing Cells and Veins | 93 | |

| Glossary Index of Terms used | 94 | |

| Alphabetical List of Sixty Families | 95 | |

| Numbered List of Families with Descriptive Notes and References | 108 | |

| Analytical Table of Families | 113 |

| PAGE | ||

| Fig. 1. | The House-Fly, Female, Enlarged | 6 |

| Fig. 2. | The Lesser House-Fly, Male, Enlarged | 6 |

| Fig. 2a. | The Stable-Fly, Female, Enlarged | 6 |

| Fig. 3. | Wing Patterns contrasted | 12 |

| Fig. 5. | Metamorphosis; Larva, Instar, Imago | 39 |

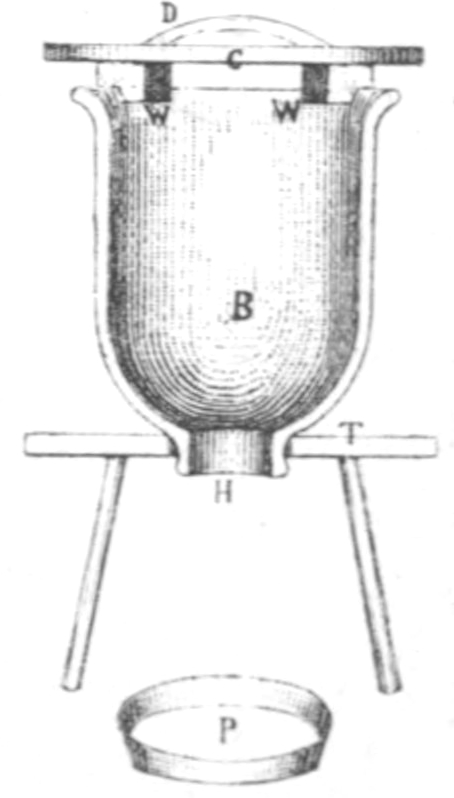

| Fig. 6. | Apparatus for the Breeding of Gentles | 81 |

| THE WINGATE FLY CHART (Appendix) | ||

| Plate I. | External Parts and Characters, named | 88 |

| Plate II. | Antennæ, many-jointed types | 97 |

| Plate III. | Antennæ, three or few-jointed types | 99 |

| Plate IV. | Wings, Type-forms of Nemocera | 101 |

| Plate V. | Wings, other Type-forms | 103 |

| Plate VI. | Details of Special Characteristics, etc. | 105 |

| Plate VII. | Ditto | 107 |

The dangers of house-flies to the health of the community have come into such recent prominence that the appearance of Major Hurlstone Hardy's book should fill a want. It is written lucidly and clearly, yet in that popular style which is so frequently lacking in scientific works. This is a great advantage. Too often scientists are prone to bring out works couched in terms which cannot be understood by an interested public that is not versed in technical terms. Thus matter which is of the greatest general importance is passed unread by many, and is, in consequence, not acted upon.

Major Hardy has a knowledge of these deadly insects which, in my opinion, is unsurpassed, because he has the personal experience of practical experiment combined with the instincts of the naturalist. The result is an account both accurate and interesting which should prove of the greatest value.

The discovery of the transmission of disease by mosquitoes required the passage of a decade before its essentials were grasped by the public mind; that of the prevention of small-pox required a century. But the dangers of house-flies is rapidly becoming known in consequence of the popular literature, which is growing, describing the details of the lives of these loathly creatures. In this way only can such knowledge be spread—a knowledge which must become general before flies and the maladies they convey can be generally and satisfactorily dealt with. It is of little use to make great discoveries and then to hide them on the musty bookshelves of learned societies. Instead, they should be adapted to practical purposes applied for the good of suffering humanity; and the best way to do this is to bring out well-written, interesting, and easily read books of this kind, so that all who run may read and their readings endure. This book should assist much to accomplish this end. Thus we may look forward confidently to the day when house-flies, and the diseases they carry, are things of the past. The "Book of the Fly" must take its place in the history of the events which are to lead up to the winning of that goal.

With the present day zeal for popularising interest in common things (called nature study) there has arisen the demand for knowledge practically useful and thoroughly up-to-date, yet in a form free from much of the technical terminology and treatment which are essential in the student's more fully developed scientific handbook.

The "House-fly" is a fit subject for a simplified study of this kind, and the present booklet is an attempt to afford information very different to that of the "popular" works, which only were accessible to the writer's hands between fifty and sixty years ago; the writers of those old books all followed the lead of the reverend and learned contributors to the famous and monumental "Bridgwater Treatises." "The Wonders of Nature explained," "Humble Creatures" (a study of the earth-worm and the house-fly, in popularised language), "The Treasury of Knowledge," "Simple Lessons for Home Use," were the kind of cheaper works in touch with a past generation; these latter and other later well-intended publications will now be found to be somewhat deficient or even a little misleading entomologically; they abounded in pious sentimentality and mostly attempted an aggravatingly grandiose literary style, but all have rather failed in teaching practical economic utility, in connection with which nature-knowledge can be rendered as interesting as any other kind of instructive literature. The tribe of two-winged flies, in particular, has not even yet received a full and adequate study by scientists. A preference has ever been shown towards those other branches of entomology, which may be more interesting to the cabinet-specimen collector, but which cannot pretend to have an equal hygienic and economic importance to humanity.

The presence of the house-fly in our dwellings is often submitted to as an irritating but an inevitable nuisance; yet very certain remedial measures would almost exterminate the creature, which is a dangerous and filthy peril. To many people it will seem a most incredible exaggeration when told that it is really worse than any one of the less common creatures universally regarded with horror and disgust as pestiferous vermin. The surmise may be true that the disgusting body louse carried bacteria, which spread the "black death"; and, even though the rat's flea has been found to be the carrier transmitting bubonic plague, yet amongst people living now in civilised communities within the temperate zones these parasites cannot be ranked as dangerous equally with the house-fly. The modern crusade against the house-fly is not based on any such new discovery, as is that against the mosquito gnats, which are the means of spreading zymotic diseases mainly in the tropics. The malignity of the fly is recorded in most ancient history and folk-lore, yet not very long ago there prevailed amongst certain classes opinions very different to those of old as well as to those of the present day. A short anecdote will perhaps amuse as well as explain those misplaced sentiments, which have not quite died out.

In the middle of the last century there was a boy, thought to be too delicate to be sent to school, who early earned for himself the character of being a strange child. When barely more than nine years old he visited an Aunt who was a veritable exemplar of genteel breeding and propriety after the early Victorian pattern. There he was seriously reprimanded for the "cruelty" of feeding his secret pets, which were garden spiders, with flies which were, so the Aunt said, "poor innocent creatures made by God for a useful purpose," but, she inconsequentially added,—"Spiders were horrid." The strange child replied that the Devil made the flies, and that God made the spiders to eat them. The astonished Aunt then elicited the fact that the strange child's father had explained, during a Sunday Bible lesson, that Beelzebub (the Devil) meant Lord-of-flies.

This strange child was taken a walk over Doncaster Heath by the Aunt's maid. There a dead rabbit was seen from which maggots were crawling, and the maid explained that it was fly-blown. Next they both stroked and patted a patient donkey, and the strange child observed maggots rolling out of the donkey's nostril[1] on to the ground; he wondered much that live animals should be fly-blown. He also saw with pity some cows, around whose eyes flies clustered.

Pondering on these matters, one day he confided to the Aunt his confirmed opinion in these words—"It seems, Aunt, to me that people who won't kill flies deserve to be fly-blown." Doubtless, it would have been better if he had expressed himself thus—People who will not kill fleas deserve to be flea-bitten; and people who will not wage war against flies deserve to be fly-tormented. However, the horrified Aunt mistook the observation for insult and impudent rebellion, and what ensued need not be related as pointing no useful moral. The strange child was merely a genuine early nature student ahead of the times by some fifty or sixty years. In due course he learnt a more orthodox account of "Creation," and the existence of mysteries in facts physiological and spiritual, which can only be imperfectly comprehended in this world.

His craving for nature study was not satisfied with the reading of most of the cheap books then published for the diffusion of knowledge. Collecting butterflies and moths sufficed for some of his schoolfellows in later years, but, not then having access to really good handbooks, he became an original investigator in wide fields of nature study, and thus learnt that many statements and opinions, which ordinarily even at the present day pass current as facts, are erroneous and misleading. Accordingly, the reader need not be surprised at some statements in the following pages at variance with what may be met with elsewhere.

1. Stevens' Book of the Farm and many other publications describe the similar affliction of sheep by Œstrus ovis but omit to notice the case of the donkey, which I have witnessed several times, but have never seen a horse or pony thus afflicted. There is a fly termed Œstrus nasalis, of which the victimised host is uncertain, for Linnæus was mistaken in stating that the larvæ are found in the fauces of "horses, asses, mules, stags, and goats," entering by the nostril.

The old fanciful dogma that everything existing was actually created "in the beginning," and "for a purpose," was once ardently championed as controverting aggressive Voltairean atheism, but it must be now recognised as an unwarranted assumption, deduced from an orthodox doctrine of "design," which in itself seems acceptably agreeable with the idea of unity, consistency, and perfection in Creation and The Creator. In fact the said "fanciful" dogma never really was an integral part of Christian Catholic doctrine. The house-fly, as we know it, is absolutely the developed product of human insanitation; scientifically and practically it is a new "species" of an old "genus" established by a long course of breeding in man-made environments.

Fig. 2. The Lesser House-Fly, Male, Enlarged.

Fig. 2a. The Stable-Fly, Female, Enlarged.

Although there are several other kinds of flies which occasionally visit the dwellings of mankind, there is one super-abundant species, Musca domestica, to which the name of "house-fly" pre-eminently belongs. In the scientist's discriminating judgment, when viewed microscopically, it differs substantially from others; but it differs very little in general appearance from certain outdoor flies and from one not uncommon indoor smaller companion, Fannia canicularis, which is not classified amongst the Muscidæ but amongst the Anthomyidæ. This latter has been fitly termed the "lesser House-fly;" it has the same habit of delighting to pester man as much as or more than cattle outdoors. Both these flies join with several others in frequenting stables and cow-sheds.

These two flies and the familiar "blue-bottle" (again it seems that we are liable to confuse two species) are the special subject of our present study; but it will be as well to take passing notice of some few other members of the tribe classified by scientists as belonging to the order Diptera. The species of this order native to Great Britain are said to number nearly three thousand, of which quite two hundred of largish sizes are exceedingly common and widely distributed. This order is characterised by the fact that all the species are furnished with one pair of wings only:— dis = double, pteron = wing; they all undergo a metamorphosis analogous to that of four-winged insects.

The dipterid flies are apt to be popularly recognised as flies (with fat bodies) and gnats (with slim bodies); but they may be more intelligently classified (with a few anomalous exceptions) as flies (a) having a trunk-like mouth or proboscis (miscalled a tongue), terminating with bilobed suctorial lips, and as flies (b) having a bayonet-like trunk, or a sheaf-like tubular spike with skin-piercing lancets. No two-winged flies have stings; the tail of the female, which terminates with the ovipositor and is retractile in a telescopic manner, is very soft and quite unlike the sting of the ichneumon or the ovipositor of the "saw-fly," both of which possess two pairs of wings like bees and wasps, and therefore are classified with the insect race called Hymenopteræ.

Omitting Aphides (green-flies, plant-lice, and the like) which are an "order" by themselves, and excluding gnats of slim form, mosquitoes, and midges, which are mainly crepuscular, nocturnal, or shade frequenting, we might try unscientifically to sub-divide the more conspicuously sunshine-loving and day-flying flies into:—(1) flower and honey seeking flies; (2) cattle pestering sweat-flies; (3) skin-piercing, blood-sucking flies; (4) insectivorous flies; (5) fungus flies; (6) carrion and filth flies; and to these must be added another small group (7) which comprises those of the wondrous family of the Œstridæ, the most horrible though not the most injurious of the animal persecuting and torturing flies; this last group, strange to say, are absolutely destitute of any mouth and feed only in the maggot stage. In many cases, however, it happens that the males and the females differ in feeding habits as well as in colours and markings, whilst only their patterns of wing-veins and some less prominently apparent features are constant in the two sexes. These circumstances discountenance the above grouping.

Again, if we tried to group our flies with adequate regard to their very diverse habits of life, in the larval stage as well as to their subsequent metamorphoses, we should find that these are details which are obscure and in many cases unknown or imperfectly recorded. However, after much study and many revisions, a scientific classification has been contrived based upon the minutely differentiated characteristics which are technically explained in the Appendix to this booklet.

Whilst the notorious house-frequenting flies above-mentioned and the blue-bottle are remarkably omnivorous in their feeding, the great majority of outdoor flies are quite otherwise inclined, and do not find much attraction in anything but their own individual preferences. Indeed, the breeze-flies, and many others, avoid human habitations; even the grey blow-fly, unlike the blue-bottle, rather seems shy of the house. In the above grouping, according to feeding habits, the house-fly must be preferably consorted with (2) sweat-flies, but the blue-bottle with (6) carrion flies; however, the house-fly and the blue-bottle are very near akin, and by reason of similarity of wing-pattern both are included in the family of the Muscidæ.

In the entomological systematist's classification the primary separation of flies into two sub-divisions starts with a difficulty, for it is based upon circumstances often obscure and in some cases at least imperfectly known.

The first sub-division, Diptera Orthorrhapha, comprises those flies which in the stage of the pupa or chrysalid disclose the outline of the perfect insect; in the other sub-division, Diptera Cyclorrhapha, there are grouped together all those flies of which the larvæ make for themselves a puparium or barrel-like case out of their larval skin.

The first mentioned sub-division comprises all the gnats, midges, and most of the slender flies which are outside the scope of the present work, but it also includes a few kinds of more stoutly built flies, to which some allusion will be made in the following pages, as for example, the breeze-flies, Tabanidæ.

The second sub-division comprises many families, including the muscid-like flies, of which the house-fly is the type. The flies of this type are to be found in the families of Muscida, Anthomyida, Tachinida, and Cordylurida, comprising nearly 700 British species, of which many rather closely resemble one another when superficially observed.

The approved classification of flies is to some extent dependent upon the formation of the antennæ, but the unique feature of the systematic differentiation is based upon a very intricate method of scrutinising, identifying, and numbering the vein-like strengthening ribs called veins, nervures, or nerve-lines, which, starting from the shoulder, mark with characteristic patterns the transparent tissue of the wing. We are rather compelled to follow something like this plan (simplified) for the purpose of clearly distinguishing the "lesser house-fly" from the common "house-fly."

In the accompanying illustrations rather similar patterns of wings are shown; these are typical of the Muscidæ and Anthomyidæ, which, taken together, comprise amongst others all the cattle and human pestering "sweat-flies"; only a few really blood-sucking flies are included amongst the Muscidæ.

In critically comparing these four patterns, the chief feature to be observed is the small rib-like nervure called the "discal" "cross-vein," which is situate in the very middle of the wing, and which connects the lowest of a group of longitudinal nerve-lines or veins in the front (or upper) half of the wing to the uppermost of the other group of longitudinal nerve-lines in the hind (or lower) half of the wing. Three "main" longitudinal lines, technically termed "veins," are theoretically recognised as constituting the upper group and four "main" longitudinal lines the lower group; but these "veins" (numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7) will be found to be varied in different families and genera, each often with characteristic diverging branches, whilst some veins may be rather inconspicuous or quite absent. We will here devote our attention only to two such "veins," those respectively termed "vein 3" and "vein 4" which are connected in the very middle of the wing, as above mentioned, by the small but always distinct "discal" "cross-vein." The illustrated patterns herewith show wings divided into about twelve compartments or cells, to all of which learned entomological writers give troublesome technical names, not nearly so intelligible as the nomenclature symbols of the late Rev. W. J. Wingate, explained in the Appendix herewith. For present purposes a simple observation of the (externomedial) vein "V, 4," where it is the lower boundary of the (subapical) cell "O, 42," will suffice.

Fig. 3. Wing patterns contrasted.

The pattern of the first figure illustrates the wing of the common blue-bottle; here "vein 4" does not run at all straight in the last part of its course, but curiously bends very suddenly upwards at an angle and meets the margin very near to "vein 3." In the wing of a large blue-bottle it will be easy to recognise this plan.

The pattern of the second figure is rather similar, for the vein 4 likewise has a sudden bend upwards; it terminates practically contiguous with vein 3 at the margin. This pattern is characteristic of the "house-fly"; thus it will be easy for the reader to identify the common house-fly by the close resemblance of its wing pattern to that of the blue-bottle, with which it is classified in the family of the Muscidæ.

In the pattern of the next figure the vein 4 runs comparatively straight throughout and meets the margin at a spot intermediate between the third and fifth veins; here all the main nerve-lines diverge more evenly and terminate more equi-distantly apart; this latter plan is the wing pattern which will suffice to identify the lesser house-fly, but it is shared with all the Anthomyidæ, and more or less with some others, which are very common outdoor flies.

The pattern of the lowest figure illustrates the wing of the common blood-sucking stable-fly, Stomoxys calcitrans, which only occasionally invades the house. Here the vein 4 is deflected upwards towards the margin ending near the termination of the vein 3, but the bend is a smoothly rounded curve and not a curiously abrupt angle, as in the first and second figures.

If the reader will study the house-fly in captured specimens, he will be able to observe that they slightly differ in their inconspicuous colouration and markings.

The male of the lesser house-fly is sometimes more observable than the male of the commoner house-fly, by reason of his being a most indefatigable dancer with companions in mid air around any central ornament, and also by reason of his possessing pale patches, more or less yellowish grey, on the sides of the abdomen; but such markings are also in some degree observable in other male flies, being very conspicuously of a brighter yellow in the common small outdoor raven-fly, M. corvina. The back of the thorax of the house-fly is marked sometimes distinctly, sometimes indistinctly, with four dark lines on an ash-grey background; the lesser house-fly has three faintly darkish lines only. Quite a number of outdoor flies have similar markings, but these often look like closely adjacent or indistinct spots. The wing pattern is the readiest guide for distinguishing the lesser house-fly, both male and female. The males of the hairy (almost bristly) raven-fly also indulge in the dancing habit, but still more so do those of the latrine-fly, Fannia scalaris, which may be distinguished by its uniformly ashy-grey abdomen.

These common co-inhabitants of our dwellings vary in size according to their nourishment when in the larval stage (maggots); after the perfect insect emerges from the puparium, it swells out and fattens, but does not grow in the real sense of the word. If 1000 house-flies will weigh an ounce, then it may be calculated that 1600 average specimens of the other kind will likewise weigh an ounce.

In representing that the house-fly exceeds the lesser house-fly in numbers in the proportion of twenty or thirty to one, it must be borne in mind that the occurrence of the latter varies widely—casually according to the locality, and temporarily according to the time of the year, being more commonly observed when and where the other kind is scarce.

The lesser house-fly has summer broods at longer intervals than has the common house-fly. Towards the end of the summer its last brood hibernates in the puparium, and emerges as early as the end of March or early in April, whilst the common house-fly is not usually observable until a later date, although it is credited with more generally braving the dangers of attempting to hibernate in the imago stage. My attempts to test the capability of the house-fly by aiding October and November flies to hibernate invariably terminated in the creature's death long before springtime. However, it is very apparent that under the shelter and encouragement of warm winter environments in towns, amidst restaurants, bakeries, large hotels and certain factories, as well as and even more than in mews, adult flies of the latest autumn broods can, to some extent, survive mid-winter with very little or no prolonged hibernation.

Just as the common "house-fly" and the "lesser house-fly" are often in error regarded as the same species with an insignificantly small difference of size, so the identity of each in turn may be confused with several other species which are not uncommon, but they are all normally outdoor flies.

The chief of these is the excessively common stable-fly, Stomoxys calcitrans, whose generic and specific designations are well given, for they mean "sharp-mouth," "kicking," the latter word denoting the action of the tormented horse; it has a long, thin, stiff, skin-piercing, shining black trunk, furnished with two lancets. It is an eager blood sucker. In size and colour it rather resembles the house-fly, but anyone who is keen sighted will recognise it at once by its bayonet-like trunk, held projecting prominently in front of its head. It is much addicted to basking outdoors on sunny walls, but on the approach of darkness or of inclement weather it will occasionally seek shelter indoors. Its wing pattern rather resembles that of the common house-fly, as has been previously explained.

Round about dairy farms Hæmatobia stimulans, a fly slightly smaller than the stable-fly, with a striped thorax and a blood-sucking trunk, will often leave the cattle to assail humanity. A still smaller, somewhat hairy, muscid type of fly, Lyperosia irritans, is also a common aggressor of oxen throughout the summer.

Musca corvina, the raven-fly, is smaller than the house-fly; it has very distinct dark markings; the abdomen of the female is chequered, but that of the male has a black central stripe on a yellowish abdomen. It frequents gardens, parks, and meadows. It is much less prolific than the house-fly, with which it shares the sweat-fly pestering habit.

Cyrtoneura simplex is a little smaller and more common than the species last mentioned; its larvæ are bred in the dung of cows and other animals which it very severely pesters. However, many species of dung-bred flies do not in the least participate in the cattle-pestering habit.

The Anthomyidæ are a family of about 250 small and medium sized garden frequenting and country flies, mainly of flower and honey seeking habits. Nevertheless, some are dung-frequenting; none are blood-sucking, but several are cattle-pestering sweat-flies, which, even more pertinaciously than the house-fly, will circle round one's head and repeatedly buzz against one's face. Of these, the small Hydrotœa irritans and Hy. dentipes are amongst the worst offenders. A few of the Anthomyidæ are vegetarian garden pests; the larvæ of the cabbage-fly, the root-fly, the onion-fly and the celery-fly are, in some seasons, very destructive. The so-called "turnip-fly" is a small striped beetle of the same genus, Phillotreta, as the unstriped "flea-beetle" of the hop-fields. The larvæ of the majority of the species of the family of Anthomyidæ are, more or less, feeders on decadent vegetable matter, but some, like those of the genus Fannia, are preferentially feeders on dung. The female of the latrine fly, Fannia scalaris, so closely resembles the lesser house-fly that only the expert with a magnifying glass, after a careful examination, can tell which is which; the male differs from the male of the lesser house-fly by being without the yellowish patches on the abdomen.

There is a larger and less common muscid fly, with an ashy-grey body, but with reddish legs, named by entomologists Muscina stabulans, which not only in body colour, but also in the pestering habit, resembles the house-fly; its Latin specific name is rather objectionable as too suggestive of the common "stable-fly," which name belongs to Stomoxys calcitrans above-mentioned; its larvæ have been found in cow-dung, but they can also flourish on vegetarian fare.

The common blue-bottle is now named Calliphora erythrocephala (red-head), and it can be recognised by its reddish face and black hairs for a beard, whilst the less common blue-bottle, named Calliphora vomitoria, may be said to have a reddish beard upon a black face; the latter has the blue colour more evenly distributed over the abdomen, whereon the former has dark markings.

Polietes lardaria is a fly sometimes mistaken for the blue-bottle; its specific name is rather too suggestive of resemblance in habit. It may be recognised by its having four black stripes on the thorax, by its large white squamæ, and its tesselated glaucous abdomen; its wing pattern classifies it as belonging to the Anthomyidæ, whilst the true blue-bottles belong to the Muscidæ, and the grey blow-flies to a section (Sarcophagina) of the Tachinidæ.

There are some other outdoor flies which are not very dissimilar to the common blue-bottle, but they are more soberly coloured, ranging from bluish black to speckled and tinted greys; some of these have a pattern on the shiny upper surface of the abdomen which is conspicuously and beautifully chequered. Closely akin to these latter is the large grey blow-fly, or flesh-fly, Sarcophaga carnaria; it is much referred to in entomological books as of marvellous fecundity. The female deposits not eggs in a few hundreds, but already hatched maggots to the number of many thousands. Amongst half-a-dozen rarer kinds of smaller grey blow-flies the females differ in their striped markings, but their respective males seem quite indistinguishable apart.

Notwithstanding the prodigious fecundity of the grey blow-fly, the credit of being a practically useful scavenger of carrion must be given only to the blue-bottle, which is of a more robust habit, and which so promptly monopolises available matter that Sarcophaga carnaria and her congeners are sometimes, perforce, compelled to give their larvæ a mere vegetarian diet.

The yellow cow-dung fly, Scatophaga stercoraria, is inoffensive, and one of the commonest flies observable in the course of a country-side ramble. It and its congeners are distinct in habits and appearance from any of the other flies above-mentioned. In this species the male is larger than the rather more smooth and dull-coloured female. Its body is furry but slender; it has small eyes and head parts. In repose it holds its wings parallel close above the abdomen, more like the "breeze-flies," or true "gad-flies," than the ordinary muscid flies. Although its proboscis does not seem as formidable as that of more insectivorous flies, yet it may sometimes be observed pouncing upon some small fly, which it holds with its powerful legs. This fly does not appear to be very predaceously inclined; perhaps it is only "acting a part," like some other creatures, including the amorous male of the common frog, which, failing to secure a more natural and complacent "partner in the dance," will in springtime seize upon and very persistently cling to an astonished carp.

Amongst many flies with bodies favoured with a brilliant metallic sheen, several species of green-bottle flies (Luciliæ) are notorious. Of these latter L. Cæsar is the most common, but L. Sericata is by far the worst in England, not uncommonly laying eggs upon sheep; many are of a brilliant golden green, but some vary towards a coppery green; all have red eyes and silvery faces. In summer-time these flies seize every opportunity of depositing their eggs upon any sores or skin wounds of animals; their larvæ normally feed on carrion and dung. The green-bottle, like the blue-bottle flies, are fond of both sweets and filth, but they do not pester wholesome animals as do the sweat-flies.

Next to the Muscidæ the most often observed and easily recognisable as a distinct family of flies are the Syrphidæ, which include the "hover-flies," the drone-flies (often mistaken for the male of the hive-bee), and a number of other very common flies of a generally similar full-bodied shape, in most of which colour stripes and bands more or less suggest a comparison with wasps. The numerous species native to Great Britain are widely distributed, and, excepting the rare and very hairy Merodon narcissi, of which the larvæ feed on liliaceous bulbs, none is injurious and some are beneficial. Nearly all the flies of this family frequent flowers. The habit of many to hover for hours about a favoured spot, as if for mere pleasure, is remarkable; but it is not generally recognised that some of these hover-flies (of the genus Syrphus) are hawking for winged aphides and other small insects, which they quickly suck dry and drop whilst still on the wing. Many of the flower-frequenting Syrphidæ are great devourers of pollen; all have strongly developed suctorial mouth parts.

The larvæ of the various syrphid flies differ greatly in appearance and habit; some are terrestrial; some aquatic; some semi-aquatic; some feed on decadent vegetation; some on sewage and filth, and some are insectivorous. Most useful to the horticulturist are those of the genus Syrphus, which feed on green-fly and other aphides. The most curious in shape are the "rat-tail" maggots of the common drone-fly, Eristalis tenax (also others of allied genera), which can extend their long tubular tails and breathe atmospheric air through the same whilst lying under water. The larvæ of the genus Volucella are found dwelling in the nests of bumble-bees and wasps; it is rather uncertain how far they are commensal, or parasitic, or devourers of dead matter. Some of the syrphid flies are single-brooded, but some at least are double or treble-brooded in the year; records are wanting about many, and which, if any other than the common drone-fly, are multi-brooded. Anyhow, none appears to breed in Great Britain as rapidly as do the house-fly, the blue-bottle, and other muscid flies.

The larvæ of Conops flavipes are parasitic in the body of the adult bumble-bee, and they pupate therein.

The small family of the Stratiomyidæ contains a few fairly common species called soldier-flies; these are interesting as linking Orthorrhapha with Cyclorrhapha; their larvæ are some aquatic (the star-tailed maggots), others terrestrial, and some have hard shell-like skins; but they are not so curiously like a creeping marine limpet as are those belonging to the genus Microdon (of the Syrphidæ), which are rare and wonderful dwellers in ants' nests.

There is a curiously shaped race of parasitic flies which cling to the host like a louse, called Hippoboscidæ; these have more than the usual provision of claws to their feet, both in the number (normally two) and size of the claws. The forest or spider-fly attaches itself to some part of the body out of reach of the horse's tongue. The ked, tick, or sheep louse-fly has a similar mode of life, and, after selecting its host, it becomes wingless. These flies, strange to say, nurse and nourish their larvæ within the oviduct, and, when one might think that they were laying their eggs, they are depositing pupæ or larvæ just ready to pupate. There are some species of the family of the louse-flies which infest birds.

The true gad-flies of the family of Tabanida were, and sometimes still are called "blinden breeze-flies," and sometimes dun-flies; by a very easy mistake the countryman's word "blinden" (blind) has got changed by authors in books to "blinding," which is nonsense, and misses a wonderful instance of old-folk knowledge; the females are amongst the most inveterate blood-sucking flies, but the males are mere idle loiterers in summer sunshine on flowers; the eggs are laid on herbage in moist situations; the maggots and pupæ of many of these species are said "to be found in the soil," and some, if not all the larvæ, are predaceous, attacking worms and underground larvæ of various insects. They are more or less midsummer flies and are single-brooded. There are several largeish species (of the genera Tabanus and Therioplectes) found in Great Britain, and they are diversely distributed, being respectively woodland, moorland, lowland, and highland inhabitants. The great ox-gad-fly is as large as a bumble-bee, though more long than broad in body, but the term gad-fly is often wrongly given to the worble-fly, which is really more bee-like, being furry and rounder in body. The genus Hæmatopota comprises three smaller sized extra vicious blood suckers, H. pluvialis, rather common, H. italica, very local, and H. crassicornis, darker in colour and with spotted and dark tinted wings. Several of the large gad-flies have dull-tinted wings. They have large, shallow, brightly shining and curiously banded compound eyes, but no "ocelli"; they all seem to be at least semi-blind, and the females are rather sluggish, except between the hours of 11 a.m. and 5 p.m. in bright midsummer sunshine. The females hunt entirely by scent and are easily captured when attacking human beings; they alight on their victims with a stealthy silent approach. They appear unable to discriminate between clothing and bare skin as suitable spots for feeding. Amongst a band of mountaineering pedestrians, on a sunny day, it was observable that there would be a dozen or more "blinden breeze-flies" settling on the back of one, whilst the rest of the party were only favoured now and then by one or two apiece. It was apparently the smell of the "home-spun" coat which attracted; the colour of the garment did not seem to be the cause of the selection. Sunshine loving flies prefer white and pale colours. If a dog could speak, he would explain the smell of some "finished" cloth, but, for the sake of the fastidious, the secret is not here disclosed.

Very closely allied to the true breeze-flies in habit of life are the species of the genus Chrysops, of which two only are often met with in England, namely Ch. cœcutiens and Ch. relicta; these flies are very keen blood suckers; they are smaller, slightly more slender and brighter coloured than the commoner Tabanidæ; it is characteristic of the genus Chrysops that the antennæ are quite twice the length of the remarkably short horns of the majority of common full-bodied flies; all the species possess beautiful golden glittering eyes (whence the name Chrysops), and their wings are spotted and tinted.

One of the most horribly disgusting but serious facts connected with flies is observable most conspicuously amongst the wondrous family of the Œstrida. These pass the larval stage of life, not on, but inside the bodies of living animals; and the perfect insect, strange to say, is absolutely destitute of a mouth opening. Much misrepresentation has been prevalent, based entirely upon surmise, connecting "myiasis" in mankind, which is various but very rare, with the common infliction of horses and horned cattle with Œstrid maggots. Myiasis is the medical term given to all the various forms of animal infliction by internal parasitic maggots, and this subject is reserved for discussion in the next chapter.

The characteristics and natures of the very numerous tribes and families of other kinds of flies will be found summarised in the Appendix of this booklet.

The family of the Œstridæ is the most curious and horrific of all the different tribes of flies; it is very limited in species, of which five or six are prevalent throughout Great Britain. The worst of these could be almost exterminated with ease, but unfortunately mistaken ideas have prevailed, and graziers commonly believe that though the sheep's nostril fly is conspicuously harmful and dangerous, the horse's bot-fly and its congeners are negligible as regards the practical health of the host. The bot-fly and the worble-flies are all of a largish size, only the sheep's nostril fly and Œstrus hæmorrhoidalis, which latter infests the throat and rectum of the horse, are of a medium size.

It has been known from very ancient times that man himself was not exempt from some fly, which was imagined to resemble the horse's bot-fly, and it has been wrongly surmised that many different creatures and all ruminant animals were more or less subject to the attacks, each one of its own kind, of œstrid fly. It is undeniable that man is sometimes internally afflicted with dipterid larvæ, but it is most certain that the fly to be incriminated is not a congener of the horse's bot-fly.

An old illustrated French encyclopædic work gives coloured pictures of the flies and larvæ of Œstrus bovis (the worble-fly of the ox) and of Œstrus equi (the bot-fly of the horse), but only the larvæ of a so-called Œstrus hominis is figured. Recently, however, new attempts have been made to identify the species causing intestinal myiasis, of which the larvæ are observable from time to time in the course of post-mortem examinations and during anatomical study. Of recent years it has been suggested that the lesser house-fly is addicted to such a manner of breeding; then later that another species of the same genus has been found to be the real culprit. However, the peculiar larvæ of these last-mentioned flies do not in the least resemble the fat round larvæ of the true bot-fly or of the worble-fly, which are correctly represented in the above-mentioned French work, nor the round and rather smooth maggots which were observed in Westminster Hospital nearly fifty years ago, and at other places from time to time both before and since, giving rise to much wonder and discussion, and also to very incredible tales.

Another more credible surmise attributes the offence of human intestinal myiasis to Muscina stabulans; if this be correct, the infliction would be probably due to the subject having eaten damaged and egg-laden plums or similar fruit, for M. stabulans is credited with being normally, though not exclusively, fruitarian or vegetarian.

If any one of the above suppositions be true, it does not exclude any other one, amongst many explanatory surmises, from being possible. Judging from the remarkable attractiveness of the odour of humanity to the common house-fly, and from the fact of the maggots possessing well developed tenter-hooks on their heads (somewhat like those which the bot-fly maggots use for internal attachment), it is just as likely, nay more likely, that this species (as the writer stated for the information of the authorities of Westminster Hospital nearly fifty years ago) is more than any other capable of adopting such a life-cycle existence; these maggots would mature after five or six days feeding and then emerge. If there were a veritable "Œstrus hominis," however rare, the hairy and peculiar female would be conspicuously observable, a persistent hoverer about the person of her victim until she had attached eggs to his body, from which the maggots would not emerge until after nine months. Most of the tropical flies, which are said to similarly attack humanity, may be rather compared to the green-bottle flies which infest sheep, but the latest medical records and reports profess to identify ten or twelve species of very different genera as having myiasic capabilities.

The family of Œstrida has been fitly divided into three sections, namely, the Gastrophilinæ (the larvæ living in the gullet, the stomach, or the intestines), the Hypoderminæ (worble-flies), and the Œstrinæ (nasal or nostril flies); all the species are hairy or furry, and the gravid females fly slowly with loud buzzing, in a characteristic attitude peculiar by the bending downwards of abdomen and tail, with a much extruded ovipositor.

The sheep's nostril-fly, Œstrus ovis, has a chequered abdomen and is less hairy than others; it is the type of the section to which the generic term Cephalomyia is given in some books; species of this section attack deer and other animals.

The section termed Hypoderminæ comprises the "worble" flies or "marble" flies. One may imagine that the latter name indicates in the mind of the cowherd the appearance of the round pustulent boils on the hide of the suffering animal, and that the former name is a corruption of "worm-hole," originating with the tanner, observant of the deterioration of injured hides. A mixing of the terms worm-hole and marble probably originated the name "warble." The maggots live under the skin on the back of oxen, and breathe externally through openings in the boil-like excrescences. The discoloured flesh of infected oxen is called "flecked." Two species of worble-flies are prevalent, one or the other, in many parts of England.

The third section, to which the sub-family termed Gastrophilina is sometimes applied, comprises the "bot-fly," which commonly infects the horse; it is the imperfect knowledge of this latter which has led to erroneous surmises explanatory of the horribly disgusting fact of human intestinal myiasis.

All the species of all the three sections are single-brooded. Although the flies themselves can inflict no immediate pain, at their mere sight all the animals out at grass on the farm are seized with an instinctive terror, conspicuously greater than when attacked and copiously bled by any "blinden" breeze flies, which, however, fly more silently and settle on their victims very furtively. One can understand the violent efforts of the horse to free himself from the exceedingly painful bites of a newly attached forest-fly, but one can only wonder at the frantic galloping of oxen and horses to and fro when a non-biting œstrid fly buzzes about like a harmless fat bumble bee and slowly approaches.

The females of all the worble-flies, the nostril-flies, and the bot-fly are short-lived, appearing on the wing in August, possibly seen a few days earlier. In the act of ovipositing they make themselves very conspicuous; they lay their eggs whilst hovering in the air, their extruded ovipositors attaching glutinous eggs to their victims. The hatching of the eggs of the bot-fly is assisted by the habit of animals to lick themselves and each other, when certainly their warm, moist tongues will convey into their mouths the newly emerged bot-fly's maggots, which many months later are to be found attached to the internal lining of the unwilling host's stomach. When fully grown in June, these maggots loosen their hold, are discharged with the dung, and pupate in the soil.

No satisfactory account has yet been given as to the early stages of the maggots of the worble-flies. The eggs, having been attached to hairs on the host's hide in August, the prominent round pustulent swellings, called worbles, wherein the maggots dwell, do not become conspicuous until the following months of April and May. It is a reasonable surmise that the obscure and long first-period of the maggot's existence may more or less conform to that of some of those flies which are also single-brooded but are predaceous or parasitic on insects. The newly hatched maggot perhaps can crawl, but does not feed until after several moults; at each moulting the strange creature becomes smaller and smaller, but probably at the same time is provided with a new head well suited for the purpose of that period; firstly, with a burrowing or grappling head, and in due time with a feeding suctorial mouth, and then only does practical growth begin. No dipterid flies, at all events, known to be native to Great Britain, possess skin-piercing ovipositors.

I have been astonished to read in current literature much about œstrid flies which is not in agreement with my long course of personal observation; for instance, one high authority (F. R. S.) writes that œstrid "flies" appear from May until October, and hints that their egg-laying aggressions upon their victims are not conspicuously observable. I feel confident that the facts are quite otherwise.

That the bot-flies normally (and a few others abnormally, but for short periods only) pass a very long larval stage in the stomach and alimentary canal of herbivorous animals is one of the greatest marvels of insect life. All other growing creatures, which normally breathe in free air, require a certain large amount of breathable oxygen; and they would be stupefied or killed by a much smaller percentage of carbonic dioxide and other fermentive gases of digestion than undoubtedly exist in the strange abode wherein the bot-fly maggots dwell during the entire period of their feeding career. It has been stated that fly maggots artificially ingested into the human system have emerged alive in a normal condition, but the repulsive and objectionable experiment is not stated to have procured well nourished and full grown normally pupating larvæ. Some of the maggots of human intestinal myiasis are not perhaps amenable to artificial culture up to the stage of final metamorphosis; and they do not appear to have developed a breed or new species with a distinct habit of life. All the credible accounts of human intestinal myiasis point towards some fly which is plural-brooded, and of which the larvæ develop rapidly and promptly quit the body all at once; otherwise more than one infection must have occurred. The tales of prolonged continuous breeding, with slow and prodigiously copious emergings at intervals, should be altogether discredited.

It is an amply warranted criticism to say that recently published records by authorities, in an endeavour to comprise every reported instance of myiasic infection, seem to countenance mere coarse Gargantuan jokes. On the other hand, it is painful to read such a "cock-and-bull" story as that of the doctor about his elderly lady patient, up whose nostril a gravid female blue-bottle flew and successfully performed the prolonged and delicate operation of laying therein a large batch of eggs, in spite of all attempts to expel the invader by violent sneezing. Day by day the said doctor observed the terrible injury, and the symptoms accompanying the growth of the feeding maggots, whilst the injection of a spoonful of paraffin would have effected an instantaneous cure.

Whereas the blue-bottle rarely enters the dwellings of mankind, except gravid females led by the sense of smell in search of fish, or flesh meat, and (less eagerly) sweets, both species of house-fly and both sexes seem to delight in the mere odour of humanity; breeding females will seek the larder and the dust-bin, but others will very provokingly pervade all quarters. Although avoiding a dark or deeply shaded room, the house-fly seems to like partial shade; it will be content to remain indoors and to rejoice in a warm kitchen, even on a hot summer's day, whilst all the other kinds of flies are enjoying the outdoor sunshine. It may be said of nearly a dozen other species, occasionally observable crawling on window panes, that they are "outdoor" flies, and that their occurrence indoors is accidental. In fact, they are mostly observed when trying to escape.

Next after human habitations, stables, cow-sheds and pig-sties are the delight of the breeding female house-fly. Round about and in these latter resorts she associates with an immense host of rather small sized flies, and amongst a few others of equal size with the skin-piercing and blood-sucking stable-fly; but many stablemen are ignorant of the difference of the two kinds of flies and of the serious suffering of their horses from the bites of the stable-fly. This lamentable ignorance was shared by the joint authors of "Humble Creatures," published in 1858, when Neo-Darwinism was in vogue, and many books were published for popularising a knowledge of common things and spreading an interest in nature-study; this publication, which is still (1914) in print and very little revised, has probably led some later would-be nature-study teachers to follow suit in confusing the characteristics of the two species. Very often the fly most numerously breeding in the manure heaps of the mews will be Borborus equinus, or some other of the same family, which are characterised by a very simple pattern of wing nervures and by the absence of squamæ or scales behind the wings; also the ankle joints of the feet are most peculiarly short and broad. B. equinus, and a great host of other dung breeding flies of a still smaller size, may be considered beneficial insects; they do not pester cattle, and their larvæ make food more scarce for injurious flies.

The breeding habits of the blue-bottle are very conspicuous by reason of its haste and boldness in taking possession of dead animals. It is incapable of breeding in horse or cow dung, to which latter the green-bottle fly often resorts.

The blue-bottle deposits her eggs, 500 or 600, preferably on dead fish, or flesh, and sometimes on the sores or the flesh of wounded animals, but both the house-flies preferably affect dung, carrion, garbage, and all kinds of fermenting vegetable matter. It has been commonly but not truly said that the principal breeding places of the house-fly are the mews and the farmyards where manure is allowed to accumulate; the house-fly has a preference for horse dung before cow dung, which is preferred by some other kinds of flies; however, near towns, the domestic dust-bins, heaps of market garbage, and deposits of town refuse give rise to a worse plague of house-flies than stables. All these flies deposit batches of white eggs, and are careful to place them as much as possible in crevices and shielded from exposure to strong light, or from draughts.

The two house-flies and the blue-bottle have similar larval stages, but their larvæ, called maggots, differ. The larvæ avoid daylight and cannot withstand dryness. As the larvæ feed, they have the power of ejecting or excreting a juice, which dissolves the food before they imbibe the material; their mouths are suctorial and are destitute of teeth or biting jaws.

The larva of the house-fly is an eyeless and legless maggot, one half inch long when full grown and extended; twelve cylindrical segments may be counted in its body, or even thirteen if we separately distinguish the small head segment, which may be withdrawn, and but little observable; five or six rear segments are of nearly equal stoutness when only half grown; afterwards counting from the three stoutish rear segments, the others taper towards the very small head. The middle and rear segments have pad-like bristly processes underneath, which aid the maggots in creeping, in which action they also make much use of the head segment's grappling hook. The maggots feed voraciously, but they seem, like the larvæ of the honey bee, to pass out very little anal excreta; some have thought that, like what is said of bee larvæ, no excrement is discharged until after the imago has emerged from the puparium; but such conduct seems altogether incredible. In the bee-hive doubtless the assiduous workers ever wash their babies clean and lick up all matter, just like domestic cats and dogs, when nursing their young.

The larva of the blue-bottle, called a gentle, is proportionately larger but very similar, except that the rear segment possesses a ring of tubercles, which may have some useful function in connection with two breathing tracks, which have their orifices at that part of the body.

The larva of the lesser house-fly is very peculiar; all its segments have projecting tubercles; its whole body is rather louse-shaped, having not cylindrical but somewhat flattened segments, of which the middle are the broader, and those near the head and tail the narrower.

The transformations in the case of the blue-bottle are typical of the house-fly and others of closely related families and genera which are many-brooded within the year; these creatures develop very rapidly immediately after emerging from the egg. Some other kinds of dipterid maggots, which are single-brooded, pass a very prolonged and obscure early period of skin-shedding and non-feeding, a preparatory sort of baby-hood metamorphosis; then at last they begin to feed voraciously and to follow the general habits of other maggots. Some maggots curiously refuse to feed except in company; probably some are unable to feed on dung except where other species are providing the necessary dissolving juice.

When the common maggots or gentles have ceased feeding, they burrow into the ground or crawl away, often to a considerable distance, apparently seeking a secluded, a more wholesomely clean, and a dryer spot. During this migrating time, they are palatable food for many birds, which would not eat them in their former food-loaded or unscoured state. Indeed, it is doubtful whether either a vulture or a raven could eat a fly-blown carcase without danger of myiasic punishment. The skin of the larva whilst growing is transparent, but, when about to pupate, it thickens and becomes an opaque creamy white.

The most marvellous part of the metamorphosis of the blue-bottle is concealed, when the gentle becomes the pupa; according to Réaumur the embryonic fly develops most curiously inside the puparium by a procedure not exactly like the change from the caterpillar to the chrysalid in the case of the butterfly. After a pause of a day or two, the front segments of the fully fed maggot contract, so that the body assumes a barrel-like shape; the skin then hardens, and turning a reddish brown it becomes a much contracted shell or case called the puparium. However, the long slender maggot has done something more than merely shrink and shape itself conformably to the case; it has withdrawn its embryonic head, so small as to be hardly distinguishable microscopically, together with its embryonic legs, wings and thorax into its embryonic abdomen! As the development proceeds, and the embryonic members of the future perfect insect acquire their destined shape, the immensely increased head and the thorax with its appendage members slowly emerge, and the partly inverted integument of the abdomen rolls back, disclosing the shape of a fly not before recognisable.

Other naturalists would have it believed that the true account of the transformation is as follows,—when the maggot has shrunk and freed its body inside its skin which forms the case or puparium, all its pre-existing internal organs become absolutely dissolved; then out of the fluid mass a new growth ensues, constituting the pupa with its recognised shape. This account is the one represented in most modern entomological books, and is based partly upon B. T. Lowne's monographic work on the blow-fly.

The comparative embryologist of our day is inclined to be a hyper-theorist, and so it seems that some have not remained content with either of the above accounts; to them, apparently, the production of the large and complex head of the imago out of a single small anterior segment of the maggot requires a more recondite explanation, and must be brought into harmony with analogous facts. To this end some degree of linked support is found by the investigations of microscopic anatomy, and it has been conjectured that not one or two head segments, but five are lying blended and embryonically hidden in the larvæ, all ready to bud forth. However, for fear of wearying too much with the theories of advanced erudite scientists, the following jeu d'esprit is presented, instead of a more elaborate and sober attempt, to lure the unscientific lay reader to an extreme hypothetical conception of the "essential unity" underlying the apparent diversities of Nature within that vast domain of the Kingdom of Fauna, which is obviously outside the later creation of a vertebrate Animalia.

Fig. 5. Illustrating the debatable continuity of a

12-segmented structure throughout the metamorphosis.

The futurist's dogmatic CREDO of creative progress, "For him who would meritoriously pass his histological examinations, and qualify as a Professor and Doctor of Science, above all it is necessary that he should acknowledge the unicellularity of the primæval OVUM (or egg), whence proceeds the seventeen-segmented boneless ANNELID (or worm), out of which there develops the quadrangular articulated crustacean INSTAR (or shell-encased aurelian), which metamorphosises into the winged IMAGO (the angelic? or diabolic? fly); in the contemplation of this knowledge alone is there supreme Darwinian Modernismal salvation and felicity." Amen.

In view of the prosaic illustration of transmutation, figure 5 above, the futurist disciple will have to accept the seventeenness of segmentation by something like faith without sight.

The quadrangularity of the crustacean stage is based upon the idea that the wings bud out from the two upper corners, whilst the legs develop from the lower corners of the transmuting instar.

Perchance the reader will desire information about the use of this curious word "instar," which has not the honour of notice in Dr. Sir J. Murray's New English Dictionary. One might well feel proud of the opportunity of adding the smallest item to such a stupendous and monumental work, but I fear I am only qualified to venture a fair guess. Virgil, I believe, used this term in allusion to the legendary wooden horse of the Greeks at their siege of Troy. Some time less than one hundred years ago entomologists recognised that the words aurelian, chrysalis, and pupa were none of them an inherently fit term of general application to the stage of insect life to be indicated. After many attempts, this latest proposed substitute seems to be gaining favour.

The fly emerges after bursting apart the first four segments of the puparium; this it does by a curious provision, whereby it can inflate a chamber in its head in a queer, balloon-like fashion, making a bag-like extrusion, which it uses as a punching and pushing machine.

After emerging from the ground, the fly withdraws the bag-like extrusion and cleans itself. Its body soon grows fit and it becomes very active, as long as daylight and warm weather favour it; otherwise it seeks shelter and becomes quiescent; however, artificial light and heat will awaken it to nocturnal activity. Sweets, carrion, and filth are all attractive to the blue-bottle, but the house-fly and the lesser house-fly also find extraordinary attraction in both man and his dwelling.

Considering the superfluity of other flies, and the multitude of other insects ever ready to do duty as devourers of carrion, garbage, and filth, the scavenging services of the larvæ of the house-fly can be well dispensed with.

In civilised communities cremation in a refuse destructor is the only sanitary method of treating town refuse. The economic value of the fly is very little, and consists merely in its food value for certain birds.

In warm weather the scavenging capabilities of all the carrion and filth feeding maggots are very remarkable, and there appears no exaggeration in the statement by Linnæus, that the progeny of three flesh flies can eat up the carcase of a horse sooner than it could be devoured by a lion.

When a batch of eggs has matured in the abdomen of the female, she is most careful in the location and manner of their disposal. Guided by the sense of smell, she will not lay her eggs except in contact with food, or in places securing her progeny access to their intended food. By the use of her soft, slender ovipositor, which is telescopically extensile and flexible, the eggs are deposited in shaded and concealed situations.

The house-fly is credited with laying batches of eggs at intervals, perhaps four or more times, and about 150 on the first occasion, then 100, and less on subsequent occasions. Under favourable circumstances the eggs may hatch within a few hours of their being laid. The maggots of midsummer broods may be full grown and pupate in six days, and the perfect insect may emerge from the puparium in another ten days of warm weather, but in cold weather the pupæ of autumnal broods may remain dormant for several weeks, or even months. When nine or ten days old the mature fly may begin to lay eggs; hence, with such a life-cycle, in a month of very favourable weather the progeny of a single pair may number, say, 500; in two months' time the number may become 250 times 500; and in three months' time many millions!

The house-fly has quite the typical insect form, inasmuch as there are three well defined sections of body—the head, the chest or thorax, and the abdomen; also it has three pairs of legs, each with nine joints, of which five joints constitute what may be called the foot. The twelve segments of the maggot are observable as twelve rings in the puparium, but in the fly the three which form the thorax look like one, whilst the eight which should theoretically exist in the abdomen look like four or five, until the rings of the ovipositor are counted.

The illustration on page 39 will make plain how the permanence of the twelve-segment structure (conspicuous in the larval stage) has been thought to persist throughout the life-cycle, but at the same time will disclose how great is the change in the relative proportions of these segments.

The prominent features of the hemispherical head are the two large compound eyes and the proboscis or trunk-like mouth. The antennæ or horns are very short appendages with three joints; small plume-like projections, called arista, are attached to the third segment; the horns hang down over a hollow in the middle of the face, and are insignificant in size when compared with those of other kinds of insects; but their structure viewed under the microscope is intricate, and they may be efficient organs of sense perception, probably in part auditory. The really unique feature is the retractile and suctorial proboscis, which is often incorrectly regarded as the tongue; it is normally held doubled up and withdrawn towards a hollow under the head, whence it is from time to time extruded. The structure of this member is characteristic of the entire tribe to which the house-fly belongs; it is a fusion or combination of mouth parts, which in other insects are used more or less separately for the various functions of inspecting, biting, masticating, drinking and swallowing. In the house-fly the proboscis is absolutely suctorial, and is not provided with the lancets used by the blood-sucking flies for piercing the skin. Two maxillary palpi are attached to the upper or basal part of the proboscis, which is called the rostrum (a snout); the lower part is called the haustellum (a pump), and it has at the end a pair of soft cushion-like lobes or lips, which, when spread apart, form a heart-shaped pad with an opening in the centre. The maxillary palpi are used for feeling and probably smelling. Each mouth-lobe has a main collecting central channel and thirty subsidiary cross channels of a wonderfully complex character. Imbibed fluids pass from the mouth-lobes to the gullet along a passage in the haustellum and the rostrum.

As with many other flies and other insects, there are on the top of the head very small simple and rather inconspicuous eyes called ocelli, three in number, between the large and prominent compound eyes, which latter are said to possess each four thousand facets. The compound eyes of the male fly are proportionately larger than those of the female; it is quite observable that they approach each other more closely at the top of the head, a feature of sex differentiation which is shared with bees, wasps, and many other insect creatures. It is thought that a single brain image arises from the combined views of the four thousand facets of the compound eyes blending with the view conveyed through the "ocelli." However, it is a most curious fact that it is the inconspicuous ocelli which are of supreme importance visually. The compound eyes have doubtless some special function, but throughout the insect world the size of compound eyes is not a certain indication of keenness of sight. The vision of the fly is good for distinguishing the movement of any broad mass, but it is rather ineffective for observing a thin line, as may be proved by slowly lowering a knife blade, with a steady hand, when its body may be severed before the fly takes alarm. It is a remarkable fact that the family of Tabanida (blood-sucking breeze flies), which are destitute of "ocelli," are the dullest sighted of all flies; in fact, at least semi-blind. Moses Harris observed that a blue-bottle became practically blindfolded when its ocelli were covered with an opaque pigment. Probably this is the case with other insects. Bees, which require long distance sight for home returning, are well provided with ocelli. Butterflies, however, without the use of ocelli have a distinct faculty of daylight vision for a moderate distance. The investigation of sight by blindfolding is very difficult in flies.

There are two cephalic ganglions, which are regarded as the brain; these are situated in the upper part of the head close to the neck. There are also ganglions in the thorax with connections extending into the abdomen.

The thorax is mainly occupied with the powerful muscles which actuate the attached wings, the legs, and the small appendages called halteres or balancers, which are supposed to be obsolete hind wings. There are three unequal segments in the thorax; the pair of front legs belong to the first segment, the wings and the pair of middle legs are attached to the second larger segment, whilst the third is connected with the hind legs and the halteres.

The breathing apparatus of the fly is distributed in portions over the head, thorax, and abdomen; it consists of a number of internal air-sacks with membranous ducts ramifying everywhere; the largest air-sacks are in the abdomen near the waist. There is a pair of external spiracles to each segment of the body, and these lead to the air-sacks.

The lines on the wings of the house-fly called nervures have already been alluded to in Chapter II. These nervures are strengthening ribs to the transparent tissues of the wings. The tissues are double (top and bottom) enclosing the nervures, which are so united to the connections called trachæ of the air-sacks, that the newly emerged fly helps to extend its limp and crumpled wings by a process of inflating the nervures.

The stomach is located partly in the thorax and partly in the abdomen. A passage from the gullet passes through the neck into the lower part of the thorax, where are the entrances to two long capacious chambers, of which the upper one is the true stomach and the lower one a store pouch, which latter may be likened to the honey bag of the bee. The fly habitually regurgitates liquid food stored in this pouch, and, somewhat after the manner of the cow chewing the cud, passes the same back into the true stomach, whence it proceeds onwards through the digestive track.

The abdomen holds all the other ordinary internal organs including that which may be called the heart, and which lies above the stomach; it consists of a long muscular tubular vessel with four contractile chambers.

Although the organ called the brain is located in the head, and although that called the heart is in the abdomen, yet some sense of control over bodily motions curiously exists separately in the ganglions of different parts of the body. This fact seems to make it possible for one extremity of the body to continue performing a pleasurable action (say, the head drinking honey) after the other extremity has endured a painful catastrophe (say, amputation of the abdomen). However, it may be fairly surmised that no creatures of a lower grade than warm-blooded vertebrate animals feel pleasure and pain in any way at least after the manner of mankind.

The most vital part of the fly is not the head but the thorax. A severe squeeze on the thorax will effectually paralyse and kill the creature. Muscular movements of different parts of the fly's body, which continue after severance or other fatal injury, cannot be regarded as visible proof of a slow death and prolonged sensibility.

Possessed of six legs, each with nine joints, the fly exercises a unique capability of walking; the legs are moved three at a time, a front and a hind leg on one side advancing simultaneously with the middle leg on the other side; thus the fly proceeds most securely always poised on three feet, which are so well furnished with pads, claw-like hooks, and hairs, that it can walk over polished glass and can even walk upside-down along comparatively smooth surfaces.

In comparison with the more heavily constructed wasp, with its four wings, the house-fly, with its two wings, is the more alert and active flier. The wasp is more robust than the fly and will be active in weather too inclement for the latter; however, some of the frail and slender gnats will brave cold temperatures impossible for the wasp.

It might be supposed that a strongly developed house haunting proclivity would not be consistent with a disposition to roam far afield from the locality of birth. Many clever experiments have been made with marked flies released and recaptured within measured distances and times. After an immensity of pains taken, very little profitable knowledge has been arrived at thereby. Little of what we really want to know is indicated by such a fact as that, out of hundreds or of thousands of marked flies released, one per cent was recaptured at spots as remote as a mile within two or three days, or by such a fact as that a large percentage should be observed to remain within a more limited home circuit. The variable factors of temperature, wind, sunshine and rain inevitably tend to discredit the reliability of the observed results following any such experiments.

Close observations of the habits of the house-fly reveal the very appurtenant fact that the movements of newly-hatched flies, for their first six or seven days' active life, differ from those of a more mature age, when the breeding instinct has grown strong. The latter are disposed to locate themselves for the rest of their lives in and about one attractive spot, and they are indisposed to fly high above ground or to travel far, unless it be with the object of leaving an unsatisfying locality and discovering a better place. However, the younger flies seem to feel no such restrictive influence, for, as soon as they have become fit and the weather suits, they show an inclination to fly high and thus may travel to very remote places. It is just the same with peacock, red admiral, and tortoise-shell butterflies, which I have often reared and released for adding to the interest and beauty of a flower garden. In sunny weather many or most will soon wander never to return; those which have remained a few days continue residence close round about, especially if nettles, the food plant, grow in the neighbourhood.

It would be of great interest if we could discover how far a plague of flies arising from unsanitory surroundings in one locality is liable to spread to the injury of other localities.

On this subject nothing useful can be said other than can be safely surmised from the known habits of the fly. The female has none of the attachment of the honey-bee to its hive and community; she is not moved by an instinct like that of the wandering bumble-bee in spring to found a colony; she is indeed very solicitous about the disposal of her eggs, but she is not impelled by any desire to place successive deposits in one locality.

The lesser house-fly has proclivities similar to those of the common house-fly, but probably she travels less far afield although a little more inclined to outdoor life.

Very little is known about most of the common outdoor sweat-flies. Some breed in dung, and may be many-brooded and otherwise resemble the house-fly in prolific increase; others are more consistently vegetarian in the larval stage and slower in development; and some are possibly even single-brooded, like certain foreign large sized flies which fortunately appear only for a few weeks of summer weather, for they have a curious semi-blood-sucking habit of feeding after or alongside the skin-piercing flies, and their suctorial mouths are capable of further inflaming wounds and carrying infection from one animal to another.

The robust blue-bottle very closely resembles the house-fly in an inclination to spread the brood. Mature females, however, do sometimes show a slight temporary kind of "homing" instinct; having secured a cosy corner and a well sheltered retreat in a sunny wall, the occupant will battle for its possession, buffeting new comers.

Some of the smaller filth flies and many of the fungus flies have their lives, in the imago stage, influenced and shortened by their extra early sexual maturity; the females are fertilised whilst newly hatched and their wings limp and unfolded. This fact accounts for our seldom seeing some kinds of these flies abroad except females; and these are never seen to indulge in dances, flirtations, and games of chasing and buffeting each other, after the manner of so many kinds of flies. They habitually fly low; nevertheless they travel very great distances, for, though short, their flights are incessant when searching for their special kind of food.

The most disinclined to roam of all common flies is the stable-fly. None other is a more eager seeker of sunshine, but when basking on a sunny wall it seems unwary and sluggish; it is seldom to be seen far from where horses or cattle are stationed or stabled; however, it will make very long journeys hovering about a driven horse or reposing on the car.

A plague of flies of local origin will not take many weeks of summer weather to spread, but it is generally observable that plagues of flies, like many other occurrences, are simultaneous co-incidences distributed over wide areas and at places remote from each other.

Flies, which are such insidious and pertinacious persecutors of man and beast, are themselves the prey of innumerable enemies; many species are much sought for by birds, they are devoured by lizards and toads, and they are equally preyed upon by predaceous insects. Those flies which have bodies with banded colours, and which otherwise somewhat resemble bees and wasps, probably escape being the victims of some birds; but the tribe of flies does not, like the beetles, the lepidopteræ, and some other insects, furnish instances of other common protective devices, such as bearing and voiding offensive secretions, or attempted concealment in repose by mimicry of environment.