Besides the higher-grade deities, whose worship is

enjoined and treated of in the Shāstras and Purānas, numerous

other minor deities, none of whom however find a place in the

Scriptures, are worshipped by the lower classes. The principle

underlying the whole fabric of the worship of these minor deities, who

for the most part are the spirits of dead ancestors or heroes, has more

in it of fear for their power of harming than of love for their divine

nature. All untoward occurrences in domestic affairs, all bodily

ailments and unusual natural phenomena, inexplicable to the simple mind

of the villager, are attributed to the malignant action of these

nameless and numerous spirits, hovering over and haunting the

habitations of men.1 The latent dread of receiving injuries from these evil

spirits results in the worship by the low-class people of a number of

devas and mātās, as they are called. The poor

villager, surrounded on all sides by hosts of hovering spirits, ready

to take offence, or even to possess him, on the smallest pretext,

requires some tangible protector to save him from such malign

influences.1 He sets up and

enshrines the spirit that he believes to have been beneficent to him,

and so deserving of worship, and makes vows in its honour, often

becoming himself the officiating priest. Each such deity has its own

particular thānak (sthāna) or locality. Thus

there is hardly a village which has not a particular deity of its own.

But in addition to this deity, others in far off villages are generally

held in high esteem.1

There are a number of ways in which these lower-class deities can be

installed. Their images are made either of wood, stone, or

metal.2 No temples or shrines are erected in their

honour.3 An ordinary way of representing them is by drawing a

trident, (trishūl, a weapon peculiar to god Shiva) in

red-lead and oil on an upright slab of stone

on a public road, on any dead wall, on the confines of a village, or a

mountain side, or a hill top, in an underground cellar, or on the bank

of a stream.4 Some people paint tridents in their own houses. The

trishūl, or trident, may also be made of wood, in which

case its three points are plastered with red-lead and oil and covered

with a thin coating of tin.5 Sometimes carved wooden images in human

shape, daubed over with red-lead and oil, are placed in a small wooden

chariot or in a recess about a foot square. In some shrines two brooms

or whisks of peacock’s feathers are placed on either side of the

image.6 A slight difficulty overcome or a disease remedied by

a vow in honour of any of these deities offers the occasion for an

installation, and in all future emergencies of the same kind similar

vows are observed. A mātā installed to protect a

fortress or a street is called a Gadheri Mātā, and the

worshippers of a fortress, or street, mother are known as

Pothias.7 At the time of installation flags are hoisted near the

dedicated places. A troop of dancers with jingling anklets recite holy

verses, while the bhuva, exorcist-priest, performs the

ceremonies. Generally installations are frequent during the

[16]Navarātra8 holidays when, if no human-shaped

image is set up, a trishūl at least is drawn in red-lead

and oil.9 Some of these evil deities require, at the time of

their installation, the balidān (sacrifice or oblation) of

a goat or a he-buffalo. Also, when a spirit is to be exorcised, the

symbol of the familiar spirit of the exorcist is set up and invoked by

him.9 After the

installation, no systematic form of worship is followed in connection

with them.10 Regular forms are prescribed for the real gods

of the Purānas. But upon these the low-caste people are not

authorised to attend.

Still, in practice there are two forms of worship: ordinary or

sāmānya-pūjā and special or

vishesha-pūjā.11 Ordinary worship is performed by

bathing the deity—which can be done by sprinkling a few drops of

water over it—burning a ghi, or an oil, lamp before it, and by

offering a cocoanut and a pice or a half-anna piece. The last is taken

away by the bhuva, or priest, who returns generally half or

three-quarters of the cocoanut as a prasād of the god.

There are no particular days prescribed for such worship, but

Sundays and Tuesdays would seem to be the most favoured.12 On such

days, offerings are made for the fulfilment of a vow recorded in order

to avoid a bādhā, or impending evil. In the observance

of this vow the devotee abstains from certain things, such as ghi,

butter, milk, rice, juvar, betelnut till the period of the vow expires.

When a vow is thus discharged, the devotee offers flowers, garlands,

incense, food or drink according to the terms of his vow.12 The dhūpa,

i.e., burning incense of gūgal (balsamodendron) is

one of the commonest methods of worship.

The days for special worship are the Navarātra holidays, the

second day of the bright half of Āshādh, the ninth month of

the Hindu Calendar,13 Divāsā14 or the fifteenth day of the dark

half of Āshādh, and Kālī-chaudas15 or the fourteenth

day of the dark half of Āshvin, the last month; besides other

extraordinary occasions when a spirit has to be exorcised out of a sick

person.

The Navarātra days are said to be the most auspicious days for

devī-worship. People believing in the power of the mātās

observe fast on these days. Most of them at least fast on the eighth

day of the Navarātra known as Mātā-ashtamī, taking

only a light meal which consists of roots, as a rule, especially the

suran (Amorphophallus campanulatus), and of

dates and milk.16 On the Navarātra days red-lead and oil are

applied to the images of the devis, and a number of oblations, such as

loaves, cooked rice, lāpsi17, vadān18 and

bāklā19 are offered.20 The utmost ceremonial cleanliness

is observed in the preparation of these viands. The corn is sifted,

cleaned, ground or pounded, cooked, treated with frankincense, offered

to the gods and lastly partaken of before sunset, and all these

operations must be performed on the same day; for the offerings must

not see lamp-light.21 Girls are not allowed to partake of these

offerings. All ceremonies should be conducted with much earnestness and

reverence; otherwise the offerings will fail to prove acceptable to the

mātās or devis.21

On Mātā-ashtamī and Kālī-chaudas devotees

sometimes offer rams, goats or buffaloes as victims to the devis or

devas in addition to the usual offerings of lāpsi,

vadān and bāklā.21 The night of Kālī-chaudas is believed

to be so favourable for the efficacious [17]recitation

(sādhana) of certain mantras, mysterious

incantations possessing sway over spirits, that bhuvas

(exorcists) leave the village and sit up performing certain rites in

cemeteries, on burning-ghats, and in other

equally suitable places where spirits are supposed to

congregate.22

On Divāsā, the last day of Āshādh, the ninth

month, low-caste people bathe their gods with water and milk, besmear

them with red-lead and oil, and make offerings of cocoanuts,

lāpsi, bāklā of adād

(Phaseoleus radiatus) or

kansār23. Particular offerings are believed to be favoured by

particular deities: for instance, khichdo (rice and pulse boiled

together) and oil, or tavo (flat unleavened loaves) are favoured

by the goddess Meldi, boiled rice by Shikotar and lāpsi by

the goddess Gātrād.24

On these holidays, as well as on the second day of the bright half

of Āshādh the devotees hoist flags in honour of the spirits,

and play on certain musical instruments producing discordant sounds.

Meanwhile bhuvas, believed to be interpreters of the wills of

evil spirits, undergo self-torture, with the firm conviction that the

spirits have entered their persons. Sometimes they lash themselves with

iron chains or cotton braided scourges.25 At times a bhuva places a

pan-full of sweet oil over a fire till it boils. He then fries cakes in

it, and takes them out with his unprotected hands, sprinkling the

boiling oil over his hair. He further dips thick cotton wicks into the

oil, lights them and puts them into his mouth and throws red-hot

bullets into his mouth, seemingly without any injury.26 This process secures

the confidence of the sevakas or followers, and is very often

used by bhuvas when exorcising spirits from persons whose

confidence the bhuvas wish to gain. A bowl-full of water is then

passed round the head of the ailing person (or animal) to be charmed,

and the contents are swallowed by the exorcist to show that he has

swallowed in the water all the ills the flesh of the patient is heir

to.26

In the cure of certain diseases by exorcising the process known as

utār is sometimes gone through. An utār is a

sacrificial offering of the nature of a scapegoat, and consists of a

black earthen vessel, open and broad at the top, and containing

lāpsi, vadān, bāklā, a yard of

atlas (dark-red silk fabric), one rupee and four annas in cash,

pieces of charcoal, red-lead, sorro (or surmo-lead ore used as

eye-powder), an iron-nail and three cocoanuts.26 Very often a trident is drawn in red-lead and oil

on the outer sides of the black earthen vessel.27 The bhuva

carries the utār in his hands with a drawn sword in a

procession, to the noise of the jingling of the anklets of his

companions, the beating of drums and the rattling of cymbals. After

placing the utār in the cemetery the procession returns

with tumultuous shouts of joy and much jingling of anklets.28

Sometimes bhuvas are summoned for two or three nights

preceding the day of the utār ceremony, and a ceremony

known as Dānklān-beswān or the installation of

the dānklā29 is performed. (A

dānklā30 is a special spirit instrument in the shape of a

small kettle-drum producing, when beaten by a stick, a most discordant,

and, by long association, a melancholy, gruesome and ghastly

sound—K. B. Fazlullah).

Many sects have special deities of their own, attended upon by a

bhuva of the same order.31 The bhuva holds a high position

in the society of his caste-fellows. He believes himself to be

possessed by the devi or mātā whose attendant he is, and

declares, [18]while possessed by her, the will of the

mātā, replying for her to such questions as may be put to

him.32 The devis are supposed to appear in specially

favoured bhuvas and to endow them with prophetic

powers.33

The following is a list of some of the inferior local deities of

Gujarat and Kathiawar:—

(1) Suro-pūro.—This is generally the spirit of some brave

ancestor who died a heroic death, and is worshipped by his descendants

as a family-god at his birthplace as well as at the scene of his death,

where a pillar (pālio) is erected to his memory.34

(2) Vachhro, otherwise known by the name of Dādā

(sire).—This is said to have been a Rajput, killed in rescuing

the cowherds of some Chārans, who invoked his aid, from a party of

free-booters.35 He is considered to be the family-god of the Ahirs of

Solanki descent, and is the sole village-deity in Okha and Baradi

Districts.36 Other places dedicated to this god are

Padānā, Aniālā, Taluka Mengani,37 Khajurdi,

Khirasarā and Anida.38 He is represented by a stone horse, and

Chārans perform priestly duties in front of him.39 Submission to, and

vows in honour of, this god, are believed to cure

rabid-dog-bites.40

(3) Sarmālio commands worship in Gondal, Khokhāri and many

other places. Newly-married couples of many castes loosen the knots

tied in their marriage-scarves as a mark of respect for him.41 Persons

bitten by a snake wear round their necks a piece of thread dedicated to

this god.40

(4) Shitalā is a goddess known for

the cure of small-pox.—Persons attacked by this disease observe

vows in her honour. Kālāvad and Syādlā are places

dedicated to her.40

(5) Ganāgor.—Virgins who are anxious to secure suitable

husbands and comfortable establishments worship this goddess and

observe vows in her honour.40

(6) Todāliā.—She has neither an idol nor a temple set

up in her honour, but is represented by a heap of stones lying on the

village boundary—Pādal or Jāmpā. All marriage

processions, before entering the village (Sānkā) or passing

by the heap, pay homage to this deity and offer a cocoanut, failure to

do which is believed to arouse her wrath. She does not command daily

adoration, but on occasions the attendant, who is a Chumvāliā

Koli, and who appropriates all the presents to this deity, burns

frankincense of gugal (balsamodendron) and lights a lamp before

her.42

(7) Buttāya also is represented by a heap of stones on a

hillock in the vicinity of Sānkā. Her worshipper is a

Talabdia Koli. A long season of drought leads to her propitiation by

feasting Brāhmans, for which purpose four pounds of corn are taken

in her name from each threshing floor in the village.42

(8) Surdhan.—This seems to have been some brave Kshatriya

warrior who died on a battlefield. A temple is erected to his memory,

containing an image of Shiva. The attending priest is an Atit.42

(9) Ghogho.—This is a cobra-god worshipped in the village of

Bikhijada having a Bajana (tumbler) for his attending priest.42

(10) Pir.—This is a Musalman saint, in whose honour no tomb is

erected, the special site alone being worshipped by a devotee.42

(11) Raneki is represented by a heap of stones, and is attended upon

by chamārs (tanners). Her favourite resort is near the

Dhedvādā (i.e., a quarter inhabited by sweepers). A

childless Girasia is said to [19]have observed a vow in

her honour for a son, and a son being born to him, he dedicated certain

lands to her; but they are no longer in the possession of the

attendants.43

(12) Hanuman.—On a mound of earth there is an old worn-out

image of this god. People sometimes light a lamp there, offer cocoanuts

and plaster the image with red-lead and oil. A sādhu of the

Māragi sect, a Koli by birth, acts as pujari.43

(13) Shaktā (or shakti).—This is a Girasia goddess

attended upon by a Chumvāliā Koli. On the Navarātra

days, as well as on the following day, Girasias worship this goddess,

and if necessary observe vows in her name.43

(14) Harsidh.—Gāndhavi in Bardā and Ujjain are the

places dedicated to this goddess. There is a tradition connected with

her that her image stood in a place of worship facing the sea on Mount

Koyalo in Gandhavi. She was believed to sink or swallow all the vessels

that sailed by. A Bania named Jagadusā, knowing this, propitiated

her by the performance of religious austerities. On being asked what

boon he wanted from her, he requested her to descend from her

mountain-seat. She agreed on the Bania promising to offer a living

victim for every footstep she took in descending. Thus he sacrificed

one victim after another until the number of victims he had brought was

exhausted. He then first offered his four or five children, then his

wife and lastly himself. In reward for his self-devotion the goddess

faced towards Miani and no mishaps are believed to take place in the

village.44

(15) Hinglaj.—This goddess has a place of worship a hundred

and fifty miles from Karachi in Sind, to which her devotees and

believers make pilgrimage.44

In the village of Jāsdān, in Kathiawar, there is an

ancient shrine of Kālu-Pīr in whose memory there are two

sepulchres covered with costly fabrics, and a large flag floats over

the building. Both Hindus and Musalmans believe45 in this saint, and

offer cocoanuts, sweetmeats and money to his soul. A part of the

offering being passed through the smoke of frankincense, burning in a

brazier near the saint’s grave in the shrine, the rest is

returned to the offerer. Every morning and evening a big kettle-drum is

beaten in the Pīr’s honour.46

Other minor deities are Shikotār, believed by sailors to be

able to protect them from the dangers of the deep;47 Charmathvati, the

goddess of the Rabarīs;48 Macho, the god of the

shepherds;48 Meldi, in whom

Vaghries (bird-catchers) believe;49 Pithād, the favourite god of

Dheds;50 Dhavdi, who is worshipped by a hajām

(barber);51 Khodiar;52 Géla,52 Dādamo,52 Kshetrapāl,52 Chāvad,53 Mongal,53 Avad,53

Pālan,53 Vir

[20]Vaital,54 Jālio,54 Gadio,54 Paino,54

Parolio,54 Sevalio,54 Andhario,54 Fulio,54

Bhoravo,54

Ragantio,54 Chod,55

Gātrad,55 Mammai and

Verai.56 There are frequent additions to the number, as any

new disease or unusual and untoward incident may bring a new spirit

into existence. The installation of such deities is not a costly

concern,57 and thus there is no serious check on their

recognition.

The sun, the beneficent night-dispelling, light-bestowing great

luminary, is believed to be the visible manifestation of the Almighty

God,58 and inspires the human mind with a feeling of

grateful reverence which finds expression in titles like

Savitā, Life-Producer, the nourisher and generator of all

life and activity59.

He is the chief rain-sender60; there is a couplet used in Gujarat

illustrative of this belief. It runs:—“Oblations are cast

into the Fire: the smoke carries the prayers to the sun; the Divine

Luminary, propitiated, responds in sending down gentle showers.”

“The sacred smoke, rising from the sacrificial offerings, ascends

through the ethereal regions to the Sun. He transforms it into the

rain-giving clouds, the rains produce food, and food produces the

powers of generation and multiplication and plenty. Thus, the sun, as

the propagator of animal life, is believed to be the highest

deity.60”

It is pretty generally believed that vows in honour of the sun are

highly efficacious in curing eye-diseases and strengthening the

eyesight. Mr. Damodar Karsonji Pandya quotes from the

Bhagvadgītā the saying of Krishna:

“I am the very light of the sun and the

moon.61” Being the embodiment or the fountain of light,

the sun imparts his lustre either to the bodies or to the eyes of his

devotees. It is said that a Rajput woman of Gomātā in Gondal

and a Brahman of Rajkot were cured of white leprosy by vows in honour

of the sun.62 Similar vows are made to this day for the cure of the

same disease. Persons in Kathiawar suffering from ophthalmic disorders,

venereal affections, leucoderma and white leprosy are known to observe

vows in honour of the sun.63

The Parmār Rajputs believe in the efficacy of vows in honour of

the sun deity of Māndavrāj, in curing hydrophobia.64

Women believe that a vow or a vrat made to the sun is the

sure means of attaining their desires. Chiefly their vows are made with

the object of securing a son. On the fulfilment of this desire, in

gratitude to the Great Luminary, the child is often called after him,

and given such a name as Suraj-Rām, Bhānu-Shankar,

Ravi-Shankar, Adit-Rām.65

Many cradles are received as presents at the temple of

Māndavrāj, indicating that the barren women who had made vows

to the deity have been satisfied in their desire for a son, the vows

being fulfilled by the present of such toy-cradles to the sun. In the

case of rich donors, these cradles are made of precious metal.66

At Mandvara, in the Muli District of Kathiawar, the Parmār

Rajputs, as well as the Kāthis, bow to the image of the sun, on

their marriage-day, in company with their newly-married

brides.66 After the birth

of [21]a son to a Rajputani, the hair on the

boy’s head is shaved for the first time in the presence of the

Māndavrāj deity,67 and a suit of rich clothes is presented

to the image by the maternal uncle of the child.68

The sun is सर्वसाक्षी

the observer of all things and nothing can escape his notice.69 His eye is

believed to possess the lustre of the three Vedic lores, viz.,

Rigveda, Yajurveda and Sāmaveda, and is therefore known by the

name of वेदत्रयी.

The attestation of a document in his name as

Sūrya-Nārāyana-Sākshi is believed to be ample

security for the sincerity and good faith of the parties.70 Oaths in

the name of the sun are considered so binding that persons swearing in

his name are held to be pledged to the strictest truth.71

Virgin girls observe a vrat, or vow, called the

‘tili-vrat’ in the sun’s honour, for attaining

अखंड

सौभाग्य—eternal

exemption from widowhood. In making this vrat, or vow, the

votary, having bathed and worshipped the sun, sprinkles wet red-lac

drops before him.72

According to Forbes’s Rāsmālā, the sun revealed

to the Kāthis the plan of regaining their lost kingdom, and thus

commanded their devout worship and reverence. The temple named

Suraj-deval, near Thān, was set up by the Kāthis in

recognition of this favour. In it both the visible resplendent disc of

the sun and his image are adored.73

People whose horoscopes declare them to have been born under the

Sūrya-dashā, or solar influence, have from time to

time to observe vows prescribed by Hindu astrology.74

Cultivators are said to observe vows in honour of the sun for the

safety of their cattle.75

The following are some of the standard books on

sun-worship:—

(1) Aditya-hridaya—literally, the Heart of the Sun. It treats

of the glory of the sun and the mode of worshipping him.

(2) Brihadāranyakopanishad and Mandula-Brahmans—portions

of Yajurveda recited by Vedic Brahmans with a

view to tender symbolic as well as mental prayers to the sun.

(3) Bibhrād—the fourth chapter of the Rudri.

(4) A passage in Brāhman—a portion of the Vedas,

beginning with the words स्वयंभूरसि

Thou art self-existent—is entirely devoted to

Sun-worship.76

(5) Sūrya-Purāna—A treatise relating a number of

stories in glorification of the sun.

(6) Sūrya-kavacha.77

(7) Sūrya-gīta.

(8) Sūrya-Sahasranama—a list of one thousand names of

Sūrya.78

It is customary among Hindus to cleanse their teeth every morning

with a wooden stick, known as dātan79 and then to offer

salutations to the sun in the form of a verse which means: “Oh

God, the dātans are torn asunder and the sins disappear. Oh

the penetrator of the innermost parts, forgive us our sins. Do good

unto the benevolent and unto our neighbours.” This prayer is

common in the mouths of the vulgar laity.80

Better educated people recite a shloka, which runs: “Bow unto

Savitri, the sun, the observer of this world and its quarters, the eye

of the universe, the inspirer of all energy, the holder of a three-fold

personality [22](being an embodiment of the forms of the

three gods of the Hindu Trinity, Brahma, Vishnu and

Maheshvar)—the embodiment of the three Vedas, the giver of

happiness and the abode of God.81

After his toilet a high-caste Hindu should take a bath and offer

morning prayers and arghyas to the sun.82 The

Trikāla-Sandhyā is enjoined by the Shāstras on

every Brahman, i.e., every Brahman should perform the

Sandhyā thrice during the day: in the morning, at mid-day

and in the evening. The Sandhyā is the prayer a Brahman

offers, sitting in divine meditation, when he offers three

arghyas to the sun and recites the Gāyatrī mantra 108

times.83

The arghya is an offering of water in a spoon half filled

with barley seeds, sesamum seeds, sandal ointment, rice, and white

flowers. In offering the arghya the right foot is folded below

the left, the spoon is lifted to the forehead and is emptied towards

the sun after reciting the Gāyatrī mantra.84 If water is not

available for offering the arghyas, sand may serve the purpose.

But the sun must not be deprived of his arghyas.85

The Gāyatrī is the most sacred mantra in honour of the

sun, containing, as it does, the highest laudations of him.85 A Brahman ought to recite this

mantra 324 times every day. Otherwise he incurs a sin as great as the

slaughter of a cow.86 Accordingly a Rudrākshmālā, or a

rosary of 108 Rudrāksh beads, is used in connecting the number of

Gāyatrīs recited.87 It is exclusively the right of the

twice-born to recite the Gāyatrī. None else is authorised to

recite or even to hear a word of it. Neither females nor Shūdras

ought to catch an echo of even a single syllable of the

Gāyatrī mantra88.

A ceremony, called Sūryopasthān, in which a man has to

stand facing the sun with his hands stretched upwards at an angle

towards the sun, is performed as a part of the

sandhyā.89

Of the days of the week, Ravivar, or Sunday is the most suitable for

Sun worship90. Persons wishing to secure wealth, good-health and a

happy progeny, especially people suffering from disorders caused by

heat and from diseases of the eyes, barren women, and men anxious for

victory on the battlefield, weekly observe vows in honour of the sun,

and the day on which the vow is to be kept is Sunday.91 It is left to the

devotee to fix the number of Sundays on which he will observe the

vrat, and he may choose to observe all the Sundays of the

year.92 On such days the devotees undergo ceremonial

purifications by means of baths and the putting on of clean garments,

occupy a reserved clean seat, light a ghi-lamp and recite the

Aditya-hridaya-pātha, which is the prescribed mantra for Sun

worship.93 Then follows the Nyāsa, (न्यास) in the recitation of

which the devotee has to make certain gestures (or to perform physical

ceremonials). First the tips of all the four fingers are made to touch

the thumb as is done in counting. Then the tips of the fingers are made

to touch the palm of the other hand. Then one hand is laid over the

other. Then the fingers are made to touch the heart, the head, the

eyes, and the hair in regular order. The right hand is then put round

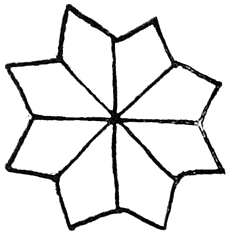

the head and made to smite the left.93 An ashtadala or eight-cornered figure is drawn

in gulal, [23](red powder) and

frankincense, red ointment and red flowers are offered to the

sun.94 Durvā grass is also commonly used in the process

of Sun-worship.95

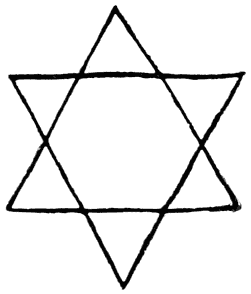

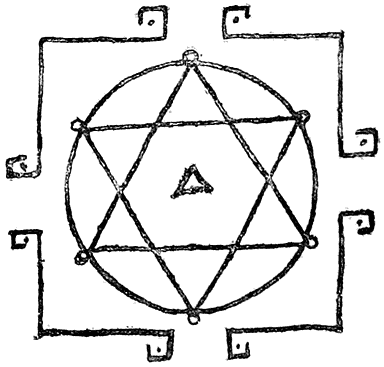

Sometimes a hexangular figure is drawn instead of the

ashtadal, a copper disc is placed over it and the sun is

worshipped by Panchopachar or the five-fold ceremonials.96 Of all

ceremonials a namaskār is especially dear to the sun.97 It is

said:—

नमस्कारप्रियो

भानुर्जलधाराप्रियः

शिवः ।

परोपकारप्रियो

विष्णुर्ब्राह्मणो

भोजनप्रियः

॥

A namaskār or bow is dear to the sun; a stream of

water (pouring water in a small stream over Shiva’s idol) is dear

to Shiva: benevolence to Vishnu and a good dinner to a

Brahman.97

In observing vows in the sun’s honour on Sundays, the

following special foods are prescribed in particular months:98—

(1) In Kārtika, the first month, the devotee is to take only

three leaves of the Tulsi or the holy basil plant.

(2) In Mārgashīrsha, the devotee may only lick a few

pieces of candied sugar.

(3) In Pausha, the devotee may chew three stalks of green darbha

grass.

(4) In Māgha, a few seeds of sesamum and sugar mixed together

may be swallowed.

(5) In Phālguna, a consecrated draught of curds and sugar may

be drunk.

(6) In Chaitra, people should break their fasts with a little ghi

and molasses.

(7) In Vaishākha, the only satisfaction allowed to those

observing the vrat is to lick their own palms three times.

(8) In Jyeshtha, the fast is observed simply on three anjalis

or palmfuls of pure water.

(9) In Ashādha, three chillies may be eaten.

(10) In Shrāvana, only cow-urine and molasses are tasted.

(11) In Bhādrapada, cow-dung and sugar are partaken of.

(12) In Āshvina, the application of chandan (sandal wood)

either in the form of an ointment or of powder.

Only a few very pious and enthusiastic devotees observe all Sundays

in the above manner. In average cases, the devotee allows himself rice,

ghi, sugar, milk, i.e., white food, the restriction being only

as to colour.98

People observing vows in honour of the sun take food only once

during the day, and that too in bājas or dishes made of

khākhara (or palāsh) leaves. This is considered one of

the conditions of worship, there being some mysterious relation between

Sūrya and the khākhara.99

If the Pushya Nakshatra happens to fall on a Sunday, the worship of

the sun on that day is believed to be most efficacious in fulfilling

the desires of the devotees.100

Of the days of the month, the seventh day of both the bright and the

dark halves of each month101 and the Amāvāsyā day,

i.e., the last day of a Hindu calendar month,102 are set apart for

Sun-worship. The ceremonies of the worship are the same as those on

Sundays. In fact, in almost all the observances in connection with the

sun the same ceremonials are to be gone through. Very often a Brahman

recites the pātha directing [24]his hosts

or hostesses to perform certain ceremonial gestures. On the last of the

number of days which the devotee has decided to observe, the

vrat is celebrated and Brahmans are feasted. This celebration of

the vrat is known as vratujavavun.103

The special occasions for Sun-worship are the Sankrānti days

and the solar eclipses.

In each year there are twelve Sankrānti days on which the sun

moves from one sign of the zodiac to another. Sun-worship is performed

on all these Sankrāntis, but Makara-Sankrānti, which falls on

the 12th or 13th of January, is considered the most important.104 The

Uttarāyana-parvan falls on this day, i.e., the sun now

crosses to his northern course from his southern, and the time of that

Parvan is considered so holy that a person dying then directly attains

salvation.105 On this day, many Hindus go on a pilgrimage to holy

places, offer prayers and sacrifices to the sun, and give alms to

Brahmans in the shape of sesamum seeds, gold, garments and

cows.106 Much secret, as well as open, charity is

dispensed,107 grass and cotton-seeds are given to cows, and

lāpsi108 and loaves to dogs.107 Sweet balls of sesamum seeds and molasses are eaten as

a prasād and given to Brahmans, and dainties such as

lāpsi are partaken of by Hindu households, in company with

a Brahman or two, who are given dakshinā after the meals.109

On solar eclipse days, most of the Hindu sects bathe and offer

prayers to God. During the eclipse the sun is believed to be combating

with the demon Rāhu, prayers being offered for the sun’s

success. When the sun has freed himself from the grasp of the demon and

sheds his full lustre on the earth, the people take ceremonial baths,

offer prayers to God with a concentrated mind, and well-to-do people

give in alms as much as they can afford of all kinds of grain.110

The Chāturmās-vrat, very common in Kathiawar, is a

favourite one with Hindus. The devotee, in performing this vrat,

abstains from food on those days during the monsoons on which, owing to

cloudy weather, the sun is not visible. Even if the sun is concealed by

the clouds for days together, the devout votary keeps fasting till he

sees the deity again.111

Barren women, women whose children die, and especially those who

lose their male children, women whose husbands suffer from diseases

caused by heat, lepers, and persons suffering from ophthalmic ailments

observe the vow of the sun in the following manner.112 The vows are kept

on Sundays and Amāvāsyā days, and the number of such

days is determined by the devotee in accordance with the behests of a

learned Brahman. The woman observes a fast on such days, bathes herself

at noon when the sun reaches the zenith, and dresses herself in clean

garments. Facing the sun, she dips twelve red karan flowers in red or

white sandal ointment and recites the twelve names of Sūrya as she

presents one flower after another to the sun with a bow.113 On each

day of the vrat, she takes food only once, in the shape of

lāpsi, in bajas of khākharā or palāsh

leaves; white food in the form of rice, or rice cooked in milk is

sometimes allowed. She keeps a ghi-lamp burning day and night, offers

frankincense, and sleeps at night on a bed made on the floor.114

People who are declared by the Brahmans to be under the evil

influence (dashā) of Sūrya, observe vows in the sun’s

honour and go through the prescribed rites on Sundays. Such persons

take special kinds of food and engage the services of priests to recite

[25]holy texts in honour of the sun. If all goes

well on Sunday, Brahmans, Sādhus and other pious persons are

entertained at a feast. This feast is known as vrat-ujavavun.

Some persons have the sun’s image (an ashtadal) engraved on a

copper or a golden plate for daily or weekly worship.115

On the twelfth day after the delivery of a child, the sun is

worshipped and the homa sacrifice is performed.116

If at a wedding the sun happens to be in an unfavourable position

according to the bridegroom’s horoscope, an image of the sun is

drawn on gold-leaf and given away in charity. Charity in any other form

is also common on such an occasion.116

A Nāgar bride performs sun-worship for the seven days preceding

her wedding.117

In Hindu funeral ceremonies three arghyas are offered to the

sun, and the following mantra is chanted118:—

आदित्यो

भास्करो

भानू रविः

सूर्यो

दिवाकरः ।

षण्नाम

स्मरेन्नित्यं

महापातकनाशानम्

॥

It means—one should ever recite the six names of

the Sun, Aditya, Bhāskar, Bhānu, Ravi, Surya, Divākar,

which destroy sin.

The sun is also worshipped on the thirteenth day after the death of

a person, when arghyas are offered, and two earthen pots,

containing a handful of raw khichedi—rice and

pulse—and covered with yellow pieces of cotton are placed outside

the house. This ceremony is called gadāso bharvo.118

Rajahs of the solar race always worship the rising sun. They also

keep a golden image of the sun in their palaces, and engage learned

Brahmans to recite verses in his honour. On Sundays they take only one

meal and that of simple rice (for white food is most acceptable to the

sun).119

Circumambulations round images and other holy objects are considered

meritorious and to cause the destruction of sin.120 The subject has been

dwelt on at length in the Dharma-sindhu-grantha, Vratarāja, and

Shodashopachāra among the Dharma-Shāstras of the

Hindus.121

The object round which turns are taken is either the image of a god,

such as of Ganpati, Mahādev or Vishnu122 or the portrait of a

guru, or his footmarks engraved or impressed upon some

substance, or the agni-kunda (the fire-pit),123 or the holy

cow124, or some sacred tree or plant, such as the Vad

(banyan tree), the Pipal (ficus

religiosa),125 the Shami (prosopis

spicegera), the Amba (mango tree), the Asopalava tree

(Polyalthea longifolia),126 or the Tulsi (sweet

basil) plant.

It is said to have been a custom of the Brahmans in ancient times to

complete their daily rites before sunrise every morning, and then to

take turns round temples and holy objects. The practice is much less

common now than formerly.127 Still, visitors to a temple or an

idol, usually are careful to go round it a few times at least

(generally five or seven). The usual procedure at such a time is to

strike gongs or ring bells after the turns, to cast a glance at the

shikhar or the pinnacle of the temple, and then to

return.128

Women observing the chāturmās-vrat, or the monsoon

vow, lasting from the eleventh day of the bright half of Ashādh

(the ninth month) to the eleventh day of the bright half of Kārtik

(the first month) first worship the object, round which they wish to

take turns, with panchāmrit (a mixture of milk, curds,

sugar, ghi and honey). The number of turns may be either 5, 7, 21 or

108. At each turn they keep entwining a fine cotton thread and place a

pendā129 or a bantāsā130 or a betel-leaf or an

almond, a cocoanut, a fig or some [26]other

fruit before the image or the object walked round. These offerings are

claimed by the priest who superintends the ceremony.131 When a sacred tree

is circumambulated, water is poured out at the foot of the tree at each

turn.132

During the month of Shrāvan (the tenth month) and during the

Purushottama (or the intercalatory) month, men and women observe a

number of vows, in respect of which, every morning and evening, they

take turns round holy images and objects.133

People observing the chāturmās-vrat (or monsoon

vow), called Tulsi-vivāha (marriage of Tulsi), worship that plant

and take turns round it on every eleventh day of both the bright and

the dark halves of each of the monsoon months.133 The gautrat-vrat (gau = cow) necessitates

perambulations round a cow, and the Vat-Sāvitri-vrat round

the Vad or banyan tree. The banyan tree is also circumambulated on the

Kapilashashthi day (the sixth day of the bright half of

Mārgashīrsha, the second month) and on the

Amāvāsyā or the last day of Bhādrapada (the

eleventh month).134

Women who are anxious to prolong the lives of their husbands take

turns round the Tulsi plant or the banyan tree. At each turn they wind

a fine cotton thread. At the end of the last turn, they throw red lac

and rice over the tree and place a betelnut and a pice or a half-anna

piece before it.135

The Shāstras authorise four pradakshinās (or

perambulations) for Vishnu, three for the goddesses, and a half (or one

and a half)136 for Shiva.137 But the usual number of

pradakshinās is either 5, 7, 21 or 108. In taking turns

round the image of Vishnu, one must take care to keep one’s right

side towards the image, while in the case of Shiva, one must not cross

the jalādhari138 or the small passage for conducting water

poured over the Shiva-linga.137

Sometimes in pradakshinās the votary repeats the name of

the deity round which the turns are taken while the priest recites the

names of the gods in Shlokas.139 Sometimes the following verse is

repeated.140

पापोऽहं

पापकर्माऽहं

पापात्मा

पापसंभवः

।

त्राहि मां

पुण्डरीकाक्ष

सर्वपापहरो

भव ॥

यानि

कानि च

पापानि

जन्मांतरकृतानि

च ।

तानि

तानि

विनश्यन्तु

प्रदक्षिणपदेपदे

॥

‘I am sinful, the doer of sin, a sinful soul and

am born of sin. O lotus-eyed One! protect me and take away all sins

from me. Whatever sins I may have committed now as well as in my former

births, may every one of them perish at each footstep of my

pradakshinā.’

The recitation and the turns are supposed to free the soul from the

pherā of lakh-choryasi141. Alms are given many

times to the poor after pradakshinās.142

The reason why pradakshinās are taken during the day is

that they have to be taken in the presence of the sun, the great

everlasting witness of all human actions.143

[27]

As all seeds and vegetation receive their nourishment from solar and

lunar rays, the latter are believed in the same way to help embryonic

development.144

The heat of the sun causes the trees and plants to give forth new

sprouts, and therefore he is called ‘Savita’ or

Producer.145 Solar and lunar rays are also believed to facilitate

and expedite delivery.146 The medical science of the Hindus declares the

Amāvāsya (new-moon day) and Pūrnima (full-moon day)

days—on both of which days the influence of the sun and the moon

is most powerful—to be so critical for child-bearing women as to

cause, at times, premature delivery.147 Hence, before delivery, women are

made to take turns in the sunlight and also in moonlight, in order to

invigorate the fœtus, thus securing that their delivery may be

easy. [The assistance rendered by solar rays in facilitating the

delivery is said to impart a hot temperament to the child so born, and

that by the lunar rays a cool one.]148 After delivery, a woman should

glance at the sun with her hands clasped, and should offer rice and red

flowers to him.149 Sitting in the sun after delivery is considered

beneficial to women enfeebled by the effort.150 It is a cure for the

paleness due to exhaustion,151 and infuses new vigour.152

The Bhils believe that the exposure of a new-born child to the sun

confers upon the child immunity from injury by cold and heat.153

The practice of making recently delivered women sit in the sun does

not seem to be widespread, nor does it prevail in Kathiawar. In

Kathiawar, on the contrary, women are kept secluded from sunlight in a

dark room at the time of child-birth, and are warmed by artificial

means.154 On the other hand, it is customary in many places

to bring a woman into the sunlight after a certain period has elapsed

since her delivery. The duration of this period varies from four days

to a month and a quarter. Sometimes a woman is not allowed to see

sunlight after child-birth until she presents the child to the sun with

certain ceremonies, either on the fourth or the sixth day from the date

of her delivery.155

A ceremony called the Shashthi-Karma is performed on the sixth day

after the birth of a child, and the Nāmkaran ceremony—the

ceremony of giving a name—on the twelfth day. The mother of the

child is sometimes not allowed to see the sun before the completion of

these ceremonies.156 Occasionally, on the eleventh day after

child-birth, the mother is made to take a bath in the sun.157

Exactly a month and a quarter from the date of delivery a woman is

taken to a neighbouring stream to offer prayers to the sun and to fetch

water thence in an earthen vessel. This ceremony is known as

Zarmāzaryan.158 Seven small betel-nuts are used in the ceremony.

They are carried by the mother, and distributed by her to barren women,

who believe that, by eating the nuts from her hand, they are likely to

conceive.159 [28]

In difficult labour cases, chakrāvā water is

sometimes given to women. The chakrāvā is a figure of

seven cross lines drawn on a bell-metal dish, over which the finest

white dust has been spread. This figure is shown to the woman in

labour: water is then poured into the dish and offered her to

drink.160 The figure is said to be a representation of

Chitrangad.161 It is also believed to be connected with a story in

the Mahābhāarata.162 Subhadrā, the sister of god

Krishna and the wife of Arjuna, one of the five Pāndavas,

conceived a demon, an enemy of Krishna. The demon would not leave the

womb of Subhadrā even twelve months after the date of her

conception, and began to harass the mother. Krishna, the incarnation of

god, knowing of the demon’s presence and the cause of his delay,

took pity on the afflicted condition of his sister and read

chakrāvā, (Chakravyūha) a book consisting of seven

chapters and explaining the method of conquering a labyrinthine fort

with seven cross-lined forts. Krishna completed six chapters, and

promised to teach the demon the seventh, provided he came out. The

demon ceased troubling Subhadrā and emerged from the womb. He was

called Abhimanyu. Krishna never read the seventh chapter for then

Abhimanyu would have been invincible and able to take his life. This

ignorance of the seventh chapter cost Abhimanyu his life on the field

of Kuru-kshetra in conquering the seven cross-lined labyrinthine forts.

As the art of conquering a labyrinthine fort when taught to a demon in

the womb facilitated the delivery of Subhadrā, a belief spread

that drinking in the figure of the seven cross-lined labyrinthine fort

would facilitate the delivery of all women who had difficulties in

child-birth.162

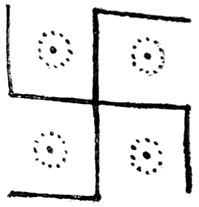

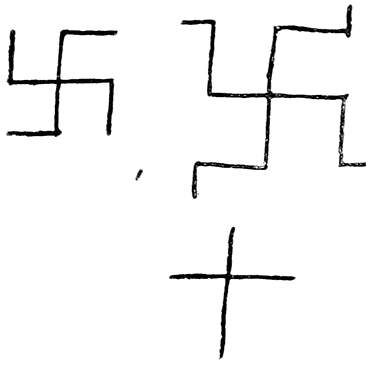

The figure Swastika (literally auspicious), drawn as shown

below, is an auspicious sign, and is believed to be a mark of good luck

and a source of blessings. It is one of the sixteen line-marks on the

sole of the lotus-like feet of the god Ishwar, the Creator of the

Universe.163 The fame of the good effects of the Swastika figure

is said to have been first diffused throughout society by

Nārad-Muni, as instructed by the god Brahma.164

Various conjectures have been made concerning the origin of this

figure. The following explanation is found in a work named

Siddhāntsar. The Eternal Sat or Essence, that has neither

beginning nor end nor any maker, exhibits all the religious principles

in a chakra or a wheel-form. This round shape has no

circumference; but any point in it is a centre; which being specified,

the explanation of the whole universe in a circle is easy. Thus the

figure ☉ indicates the creation of the universe from Sat

or Essence. The centre with the circumference is the womb, the place of

creation of the universe. The centre then expanding into a line, the

diameter thus formed represents the male principle,

linga-rūp, that is the producer, through the medium of

activity in the great womb or mahā-yoni. When the line

assumes the form of a cross, it explains the creation of the universe

by an unprecedented combination of the two distinct natures, animate

and inanimate. The circumference being [29]removed,

the remaining cross represents the creation of the world. The Swastika,

or Sathia, as it is sometimes called, in its winged form (卍)

suggests the possession of creative powers by the opposite natures,

animate and inanimate.165

Another theory is that an image of the eight-leaved lotus, springing

from the navel of Vishnu, one of the Hindu Trinity, was formerly drawn

on auspicious occasions as a sign of good luck. The exact imitation of

the original being difficult, the latter assumed a variety of forms,

one of which is the Swastika.166

Some people see an image of the god Ganpati in the figure. That god

being the master and protector of all auspicious ceremonies has to be

invoked on all such occasions. The incapacity of the devotees to draw a

faithful picture of Ganpati gave rise to a number of forms which came

to be known by the name of Swastika.167

There are more ways than one of drawing the Swastika, as shown

below, but the original form was of the shape of a cross. The first

consonant of the Gujarati alphabet, ka, now drawn thus ક,

was also originally drawn in the form of a cross (+). Some persons

therefore suppose that the Swastika may be nothing more than the letter

ક (ka), written in the old style and standing for the word

kalyān or welfare.168

Though the Swastika is widely regarded as the symbol of the sun,

some people ascribe the figure to different deities, viz., to

Agni,169 to Ganpati,170 to Laxmi,171 to Shiva,172 besides

the sun. It is also said to represent Swasti, the daughter of Brahma,

who received the boon from her father of being worshipped on all

auspicious occasions.173 Most persons, however, regard the Swastika as

the symbol of the sun. It is said that particular figures are

prescribed as suitable for the installation of particular deities: a

triangle for one, a square for another, a pentagon for a third, and the

Swastika for the sun.174 The Swastika is worshipped in the Ratnagiri

district, and regarded as the symbol as well as the seat of the

Sun-god.175 The people of the Thana district believe the

Swastika to be the central point of the helmet of the sun; and a vow,

called the Swastika-vrat, is observed by women in its honour.

The woman draws a figure of the Swastika and worships it daily during

the Chāturmās (the four months of

the rainy season), at the expiration of which she presents a Brahman

with a golden or silver plate with the Swastika drawn upon it.176

A number of other ideas are prevalent about the significance of the

Swastika. Some persons believe that it indicates the four

directions;177 some think that it represents the four

mārgas—courses or objects of human

desires—viz., (1) Dharma, religion; (2) Artha, wealth; (3)

Kām, love; (4) Moksha, salvation.178 Some again take it to be an

image of the ladder [30]leading to the

heavens.179 Others suppose it to be a representation of the

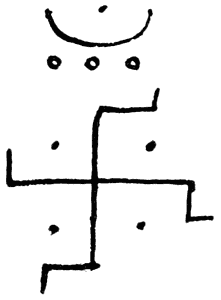

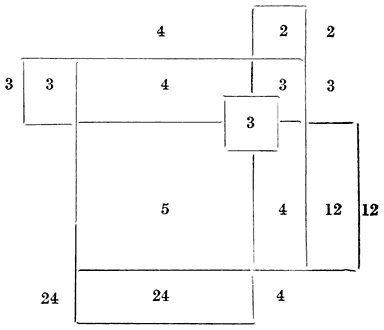

terrestrial globe, and the four piles of corn placed in the figure, as

shown below (p. 16) represent the four mountains, Udayāchala,

Astāchal, Meru and Mandārāchala.180 The Swastika is also

believed to be the foundation-stone of the universe.181

The Swastika is much in favour with the gods as a seat or couch, and

as soon as it is drawn it is immediately occupied by some

deity.182 It is customary therefore to draw the Swastika on

most auspicious and festive occasions, such as marriage and thread

ceremonies, the first pregnancy ceremonies and the Divali

holidays.183 In the Konkan the Swastika is always drawn on the

Antarpāt, or the piece of cloth which is held between the

bride and the bridegroom at the time of a Hindu wedding.184 And at

the time of the Punyāha-wāchan, a ceremony which precedes a

Hindu wedding, the figure is drawn in rice and is worshipped.184 Throughout the

Chāturmās some persons paint the auspicious Swastikas, either

on their thresholds or at their doors, every morning.185

On the sixth day from the date of a child’s birth, a piece of

cloth is marked with a Swastika in red lac, the cloth is stretched on a

bedstead and the child is placed upon it.186 An account of this

ceremony is to be found in the treatises Jayantishastra,

Jātakarma, and Janakālaya.186

Before joining the village-school, little boys are made to worship

Saraswati, the goddess of learning, after having installed her on a

Swastika, in order that the acquisition of learning may be

facilitated.187

A Brahman host, inviting a party of brother-Brahmans to dinner,

marks the figure one (૧) against the names of those who are

eligible for dakshinā, and a Swastika against the names of those

who are not eligible. These latter are the yajamāns or

patrons of the inviting Brahman, who is himself their

pūjya, i.e., deserving to be worshipped by them. A

bindu or dot, in place of the Swastika, is considered

inauspicious.188

The Swastika is used in calculating the number of days taken in

pilgrimage by one’s relations, one figure being painted on the

wall each day from the date of separation.188

It is said that the Swastika when drawn on a wall is the

representation of Jogmāya. Jogmāya is a Natural Power,

bringing about the union of two separated beings.189

The Jains paint the Swastika in the way noted below and explain the

figure in the following manner:—The four projectors indicate four

kinds of souls: viz., (1) Manushya or human, (2) Tiryach or of

lower animals, (3) Deva or divine, (4) Naraki or hellish. The three

circular marks denote the three Ratnas or jewels, viz., (1)

Jnān or knowledge, (2) Darshana or faith, (3) Charita or good

conduct; and the semi-circular curve, at the top of the three circles,

indicates salvation.190

[31]

Every Jain devotee, while visiting the images of his gods, draws a

Sathia (Swastika)191 before them and places a valuable object over it.

The sign is held so sacred that a Jain woman has it embroidered on the

reticule or kothali in which she carries rice to holy

places.192

‘I am the very light of the sun and the moon,’ observes

Lord Krishna in his dialogue with Arjuna,193 and the moon also

receives divine honours like the sun. Moon-worship secures wealth,

augments progeny, and betters the condition of milch-cattle.194 The

suitable days for such worship are the second and the fourth days of

the bright half of every month (Dwitīya or Bīj and Chaturthi

or Choth, respectively) and every full-moon day (Purnima or Punema). On

either of these days the devotees of Chandra (the moon) fast for the

whole of the day and take their food only after the moon has risen and

after they have seen and worshipped her.195 Some dainty dish such

as kansār,196 or plantains and puris,197 is specially cooked

for the occasion.

A sight of the moon on the second day of the bright half of every

month is considered auspicious. After seeing the moon on this day some

people also look at silver and gold coins for luck.198 The belief in the

value of this practice is so strong that, immediately after seeing the

moon, people refrain from beholding any other object. Their idea is

that silver, which looks as bright as the moon, will be obtained in

abundance if they look at a silver piece immediately after seeing the

moon.199 Moon worship on this day is also supposed to

guarantee the safety of persons at sea.200 In the south, milk and sugar is

offered to the moon after the usual worship, and learned Brahmans are

invited to partake of it. What remains after satisfying the Brahmans is

divided among the community.199 On this day, those who keep cattle do not churn whey

nor curd milk nor sell it, but consume the whole supply in feasts to

friends and neighbours.201 The Ahirs and Rabaris especially are very

particular about the use of milk in feasts only: for they believe that

their cattle are thereby preserved in good condition.202

The fourth day of the dark half of every month is the day for the

observance of the chaturthi-vrat (or choth-vrat). This

vrat is observed in honour of the god Ganpati and by men only. The

devotees fast on this day, bathe at night after seeing the moon, light

a ghi lamp, and offer prayers to the moon. They also recite a

pāth containing verses in honour of Ganpati, and, after

worshipping that god, take their food consisting of some specially

prepared dish. This vrat is said to fulfil the dreams of the

devotees.203

The day for the chaturthi-vrat in the month of Bhādrapad

(the 11th month of the Gujarati Hindus) is the fourth day of the bright

half instead of the fourth day of the dark half,204 and on this day

(Ganesh [32]Chaturthi205) the moon is not

worshipped. The very sight of her is regarded as ominous, and is

purposely avoided.206 The story is that once upon a time the gods went out

for a ride in their respective conveyances. It so happened that the god

Ganpati fell off his usual charger, the rat, and this awkward mishap

drew a smile from Chandra (the moon). Ganpati, not relishing the joke,

became angry and cursed Chandra saying that no mortal would care to see

his face on that day (which happened to be the fourth day of the bright

half of Bhādrapad). If any one happens to see the moon even

unwittingly on this day, he may expect trouble very soon.207 There is

one way, however, out of the difficulty, and that is to throw stones on

the houses of neighbours. When the neighbours utter abuse in return,

the abuse atones for the sin of having looked at the moon on the

forbidden night. The day is therefore called (in Gujarat)

Dagad-choth, i.e., the Choth of stones.208

On the fourth day of the dark half of Phālgun (the 5th month of

Gujarati Hindus) some villagers fast for the whole of the day and

remain standing from sunset till the moon rises. They break their fast

after seeing the moon. The day is, therefore, called ubhi

(i.e., standing) choth.209

Virgins sometimes observe a vow on Poshi-Punema or the full-moon day

of Pausha (the 3rd month of the Gujarati Hindus). On this day a virgin

prepares her evening meal with her own hands on the upper terrace of

her house. She then bores a hole through the centre of a loaf, and

observes the moon through it, repeating while doing so a verse210 which

means: O Poshi-Punemadi, khichadi (rice and pulse mixed

together) is cooked on the terrace, and the sister of the brother takes

her meal.211 The meal usually consists either of rice and milk or

of rice cooked in milk and sweetened with sugar, or of

kansār. She has to ask the permission of her brother or

brothers before she may take her food; and if the brother refuses his

permission, she has to fast for the whole of the day.212 The whole ceremony

is believed to prolong the lives of her brothers and her future

husband. The moon is also worshipped at the time of

griha-shānti, i.e., the ceremonies performed before

inhabiting a newly-built house.213

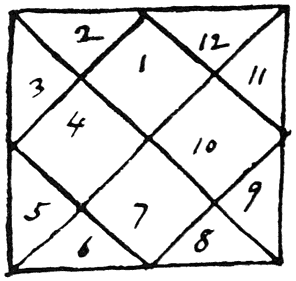

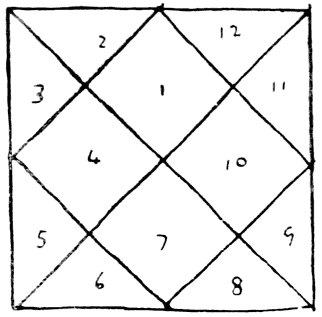

If the moon is unfavourable to a man born under a particular

constellation, on account of his occupying either the 6th, the 8th or

the 12th square in a kundali214 (see below) prayers are offered

to the moon; and if the occasion is a marriage, a bell-metal dish, full

of rice, is presented to Brahmans.215

[33]

The appearance of the moon and the position of the horns of her

crescent at particular times are carefully watched as omens of future

events. Cultivators believe that if the moon is visible on the second

day of the bright half of Āshādh (the 9th month of Gujarati

Hindus), the sesamum crops of that season will be abundant; but if the

moon be hidden from sight on that day, the weather will be cloudy

during the whole of Āshādh, and will prove unfavourable to

vegetable growth.216 If the moon appears reddish on a Bīj day (or

the second day of the bright half of a month), and if the northern horn

of the crescent be high up, prices in the market are believed to rise;

if, on the other hand, it is low, it prognosticates a fall in prices.

If the two horns are on a level, current prices will continue.216

Similarly, the northern horn of the crescent, if it is high up on

the Bīj day of Āshādh, augurs abundant rainfall; if it

is low, it foreshadows a season of drought.217

If the moon presents a greenish aspect on the full-moon day of

Āshādh, excessive rains may be expected in a few days; if on

that day she rises quite clear and reddish, there is very little hope

of good rains; if she is partly covered by clouds when she rises and

then gets clear of the clouds, and then again disappears in the clouds

in three ghadis,218 three pohors,218 or three days, rain is sure to fall.219

If on the 5th day of the bright half of Chaitra, the moon appears to

the west of the Rohini constellation, the prices of cotton are believed

to rise; if to the east, they are said to fall; and if in the same

line, the current rates are believed to be likely to continue.220

The Bīj (2nd day) and the ninth day of Āshādh (the

9th month of the Gujaratis and the 4th month of the Hindus of the

Deccan) falling on a Sunday is a combination that foretells excessive

heat. If they fall on Wednesday, intense cold is said to be the result.

Their occurring on a Tuesday, threatens absence of rains, and on a

Monday, a Thursday or a Friday, foreshadows excessive

rainfall.221

Thunder on Jeth-Sud-Bīj, or the second day of the bright half

of Jyeshtha, is a bad omen and threatens famine.222

The spots on the moon have given rise to numerous beliefs,

mythological as well as fanciful. One of them is that they are the

result of a curse, pronounced by the sage Gautama on Chandra. Indra,

the god of rain, was infatuated with the charms of Ahalyā, the

wife of Gautama, and with the help of Chandra laid a cunning plot to

gain his ignoble object. Accordingly, one night, Chandra set earlier

than usual, when Indra assumed the form of a cock and crowed at

midnight in order to deceive Gautama into the belief that it was dawn,

and therefore his time for going to the Ganges to perform his religious

services. The trick was successful, and the holy sage being thus got

rid of, Indra assumed the form of Gautama himself and approached

Ahalyā, who was surprised to see her husband (as she thought) so

quickly returned. The wily god allayed her suspicions by explaining

that it was not yet time for the morning ceremonies, and thus enjoyed

the favours due to her husband. Gautama, in the meanwhile, finding the

water of the Ganges cool and placid, and discovering that it was not

yet dawn, returned to his hermitage. On reaching home he detected the

treachery of Indra, who tried to escape in the disguise of a tom-cat.

The exasperated sage then cursed Indra, Chandra and his wife: Indra to

have a thousand sores on his person, Ahalyā to turn into a stone,

and Chandra to have a stain on his fair face.223

Another mythological story is that Daksha Prajāpati, the son of

Brahmā, gave all his [34]twenty-seven daughters

in marriage to Chandra, who was inspired with love for one of them

only, named Rohini, the most beautiful of them all. The slighted

twenty-six sisters complained to their father, Daksha, of

Chandra’s preference for Rohini. Daksha in anger cursed Chandra

to be attacked by consumption (which is supposed to be the reason of

the waning of the moon) and his face to be marred by a stain.224

The curse of Gautama and the curse of Daksha are also supposed to be

reasons of the waxing and the waning of the moon.

Another belief regarding the moon-spots is that when the head of

Ganpati was severed by Shiva’s trident, it flew off and fell into

the chariot of the moon. The spots are either the head itself225 or are

due to drops of blood fallen from the flying severed head.226

The spots are also said to be explained by the fact of the image of

god Krishna or Vishnu227 residing in the heart of the moon who, as a

devotee of Vishnu, holds his image dear to his heart.228

The moon is often called mrigānka (lit. deer-marked) and

mriga-lānchhana

(lit.

deer-stained); and a further explanation of the spots in this

connection is that the moon-god took into his lap a strayed deer, out

of compassion, and thus his lap became stained.229 Jains believe that in

the nether parts of the moon’s vimān or vehicle,

there is an image of a deer whose shadow is seen in the spots.230

Some persons declare the spots to be a shami tree

(prosopis spicigera).231 The belief of the masses in Gujarat is

said to be that the spot on the moon’s disc is the seat of an old

woman, who sits spinning her wheel with a goat tethered near

her.232 If the droppings of the goat were to fall on earth,

departed souls would return to the earth.233

It is said that a child and a tree are never seen to grow except

during the night. Such growth is therefore held to be due to lunar

rays.234 As all trees, plants, etc., thrive owing to the

influence of the moon, the moon-god is called the lord of herbs. The

moon is also a reservoir of nectar and is called Sudhākar,

i.e., one having nectarine rays.235 As the lord of

herbs, the moon-god is supposed to have the power of removing all

diseases that are curable by drugs, and of restoring men to

health.236

Persons suffering from white leprosy, black leprosy, consumption and

diseases of the eyes are believed to be cured by the observance of the

Bīj and Punema vows.237 Consumption in its

incipient and latter stages is also said to be cured by exposure to the

rays of the moon.238 Constant glimpses of the moon add to the lustre of

the eyes.239 On the Sharad-Punema, or the 15th day of the

bright half of Ashvin (the last month of the Gujaratis and the 7th

month of the Deccani Hindus), tailors pass a thread through their

needles in the belief that they will thereby gain keener eyesight.240

A cotton-wick is exposed to the moon on Sharad-Punema, and is

afterwards lighted in oil poured over the image of Hanūmān.

The soot, which is thus produced, if used on the Kali-chaudas

day—the fourteenth day of the dark half of Ashvin—is said

to possess much efficacy in strengthening the eyesight and also in

preserving the eyes from any disease during the ensuing year.241

Sweetened milk or water is exposed to moonlight during the whole of

the night of [35]Sharad-punema (the full-moon day of

Ashvin) in order to absorb the nectarine rays of the moon, and is drunk

next morning. Drinking in the rays of the moon in this manner is

believed to cure diseases caused by heat as well as eye-diseases, and

it similarly strengthens the eyesight and improves the

complexion.242 Sugar-candy thus exposed and preserved in an

air-tight jar is partaken of in small quantities every morning to gain

strength and to improve the complexion.243 The absorption of the lunar rays

through the open mouth or eyes is also believed to be of great effect

in achieving these objects.244

Once upon a time the gods and demons, by their united efforts,

churned the ocean and obtained therefrom fourteen ratnas or

precious things.245 These were distributed among them. Lakshmi, the

kaustubha jewel, the Shārnga bow and the conch-shell fell

to the share of Vishnu, and the poison, Halāhal visha, was

disposed of to Shiva. Only two things remained, sudhā, or

nectar, and surā or liquor. To both gods and demons the

nectar was the most important of all the prizes. A hard contest ensuing

between them for the possession of it, the demons, by force, snatched

the bowl of nectar from the gods. In this disaster to the gods, Vishnu

came to their help in the form of Mohini—a most fascinating

woman—and proposed to the demons that the distribution of the

immortalising fluid should be entrusted to her. On their consent,

Vishnu or Mohini, made the gods and the demons sit in opposite rows and

began first to serve the nectar to the gods. The demon Rāhu, the

son of Sinhikā, fearing lest the whole of the nectar might be

exhausted before the turn of the demons came, took the shape of a god

and placed himself amongst them between Chandra (the moon) and

Sūrya (the sun). The nectar was served to him in turn, but on

Chandra and Sūrya detecting the trick, the demon’s head was

cut off by Vishnu’s discus, the sudarshana-chakra.

Rāhu however did not die: for he had tasted the nectar, which had

reached his throat. The head and trunk lived and became immortal, the

former being named Rāhu, and the latter Ketu. Both swore revenge

on Chandra and Sūrya. At times, therefore, they pounce upon

Chandra and Sūrya with the intention of devouring them. In the

fight that ensues, Chandra and Sūrya are successful only after a

long contest, with the assistance of the gods, and by the merit of the

prayers that men offer.246

The reason of the eclipse is either that Chandra and Sūrya

bleed in the fight with Rāhu and their forms get

blackened247; or that the demon Rāhu comes between the two

luminaries and this earth, and thus causes an eclipse248; or because

Rāhu obstructs the sun and the moon in their daily course, and

this intervention causes an eclipse249; or because Rāhu swallows

the sun and the moon, but his throat being open, they escape, their

short disappearance causing an eclipse.250

Besides the mythological story, there is a belief in Gujarat that a

bhangi (scavenger or sweeper), creditor of the sun and the moon,

goes to recover his debts due from them, and that his shadow falling

against either of them causes an eclipse.251 [36]

A third explanation of the eclipse is that the sun and the moon

revolve round the Meru mountain, and the shadow of the mountain falling

upon either of them causes an eclipse.252

It is believed amongst Hindus that eclipses occur when too much sin

accumulates in this world.253 Most Hindus regard an eclipse as

ominous, and consider the eclipse period to be unholy and inauspicious.

The contact of the demon Rāhu with the rays of the sun and the

moon pollutes everything on earth. Great precautions therefore become

necessary to avoid pollution.254 A period of three

pohors255 (prahars) in the case of the moon, and of

four in the case of the sun, before the actual commencement of an

eclipse, is known as vedha, i.e., the time when the

luminaries are already under the influence of the demon. During this

period and during the time of an eclipse people observe a strict fast.

Anyone taking food within the prohibited period is considered

sutaki or ceremonially impure, as if a death had happened in his

family.256 An exception is, however, made in the case of

children, pregnant women and suckling mothers who cannot bear the

privation of a strict fast. From the beginning of an eclipse to its

end, everything in the house is believed to be polluted, if

touched.256

As the sun and the moon are believed to be in trouble during an

eclipse, people offer prayers to God from the beginning of the

vedha for their release. It is the custom to visit some holy

place on an eclipse-day, to take a bath there, and to read holy

passages from the Shāstras. Some people, especially Brahmans, sit

devoutly on river-banks and offer prayers to the sun.256 Much secret as well as open

charity is given at the time of an eclipse. But the receivers of

charity during the actual period of an eclipse are the lowest classes

only, such as bhangis, mahārs and māngs.

When an eclipse is at its full, these people go about the streets

giving vent to such cries as āpó dān

chhuté chānd (give alms for the relief of the

moon!).257

Among the gifts such people receive are cotton clothes, cash, grain

such as sesamum seeds, udad, pulses, and salt.258 The gift of a pair

of shoes is much recommended.259 Sometimes a figure of the eclipsed sun

or moon is drawn in juari seeds and given away to a

bhangi.260

Although the period of an eclipse is considered inauspicious, it is

valued by those who profess the black art. All mantras,

incantations, and prayogas, applications or experiments, which

ordinarily require a long time to take effect, produce the wished for

result without delay if performed during the process of an

eclipse.261

If a man’s wife is pregnant, he may not smoke during the

period of an eclipse lest his child become deformed.262 Ploughing a farm

on a lunar-eclipse day is supposed to cause the birth of

Chāndrā-children, i.e., children afflicted by the

moon.262

After an eclipse Hindus bathe, perform ablution ceremonies, and

dress themselves in clean garments. The houses are cleansed by

cowdunging the floors, vessels are rubbed and cleansed, and clothes are

washed, in order to get rid of the pollution caused by the

eclipse.263 Unwashed clothes of cotton, wool, silk or hemp,

according to popular belief, do not become polluted.263 The placing of darbha

grass on things which are otherwise liable to pollution is also

sufficient to keep them unpolluted.264

Brahmans cannot accept anything during the impious time of an

eclipse, but after it [37]is over, alms are freely

given to them in the shape of such costly articles as fine clothes,

gold, cattle and the like.265

After an eclipse Hindus may not break their fast till they have

again seen the full disc of the released sun or the moon. It sometimes

happens that the sun or the moon sets gherāyalā (while

still eclipsed), and people have then to fast for the whole of the

night or the day after, until the sun or the moon is again fully

visible.266

There is a shloka in the Jyotish-Shāstra to the

effect that Rāhu would surely devour Chandra if the

nakshatra, or constellation of the second day of the dark half

of a preceding month, were to recur on the Purnima (full-moon day) of

the succeeding month. Similarly, in solar eclipses, a similar

catastrophe would occur if the constellation of the second day of the

bright half of a month were to recur on the Amāvāsya (the

last day) of that month.267 The year in which many eclipses occur is

believed to prove a bad year for epidemic diseases.268

The Jains do not believe in the Hindu theory of grahana (or

the eclipse).269 Musalmans do not perform the special ceremonies

beyond the recital of special prayers; and even these are held to be

supererogatory.270

With the exception that some people believe that the stars are the

abodes of the gods,271 the popular belief about the heavenly bodies seems

to be that they are the souls of virtuous and saintly persons,

translated to the heavens for their good deeds and endowed with a

lustre proportionate to their merits.272 And this idea is illustrated in

the traditions that are current about some of the stars. The seven

bright stars of the constellation Saptarshi (or the Great Bear)

are said to be the seven sages, Kashyapa, Atri, Bhāradwāj,

Vishwāmitra, Gautama, Jāmadagni and Vasishtha, who had

mastered several parts of the Vedas, and were considered

specialists in the branches studied by each, and were invested with

divine honours in reward for their proficiency.273 Another story relates

how a certain hunter and his family, who had unconsciously achieved

great religious merit, were installed as the constellation

Saptarshi274 (or the Great Bear). A hunter, it is narrated in the

Shivarātri-māhātmya, was arrested for debt on a

Shivrātri275 day, and while in jail heard by chance the

words ‘Shiva, Shiva’ repeated by some devotees. Without

understanding their meaning, he also began to repeat the same words,

even after he was released in the evening. He had received no food

during the day, and had thus observed a compulsory fast. In order to

obtain food for himself and his family, he stationed himself behind a

Bel276 tree, hoping to shoot a deer or some other animal

that might come to quench its thirst at a neighbouring tank. While

adjusting an arrow to his bowstring, [38]he plucked

some leaves out of the thick foliage of the tree and threw them down.

The leaves, however, chanced to fall on a Shiva-linga which

happened to stand below, and secured for him the merit of having

worshipped god Shiva with Bel-leaves on a Shivrātri day. He

was also all the while repeating the god’s name and had undergone

a fast. The result was that not only were his past sins forgiven, but

he was placed with his family in heaven.277

Similarly, Dhruva, the son of king Uttānapād, attained

divine favour by unflagging devotion, and was given a constant place in

the heavens as the immovable pole-star.278

According to Hindu astrology, there are nine grahas279 or

planets, twelve rāshis280 or signs of the zodiac, and

twenty-seven nakshatras281 or constellations. Books on astrology

explain the distinct forms of the nakshatras. For instance, the

Ashvini constellation consists of two stars and presents the appearance

of a horse. It ascends the zenith at midnight on the purnima

(the 15th day of the bright half) of Ashvin (the first month of the

Gujarati Hindus). The constellation of Mrig consists of seven stars,