*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 56167 ***

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

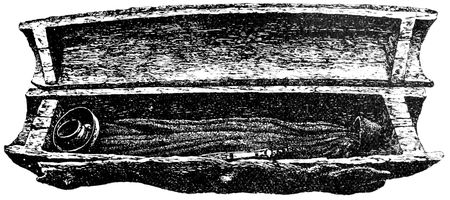

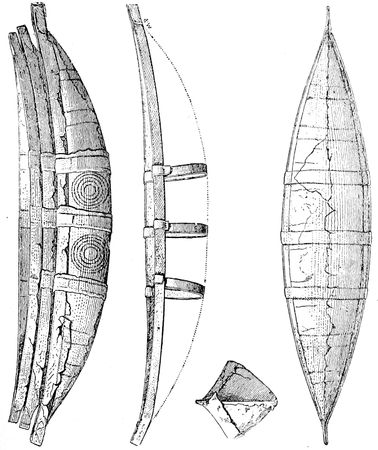

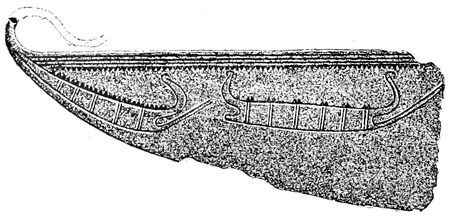

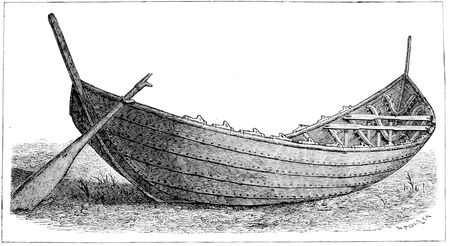

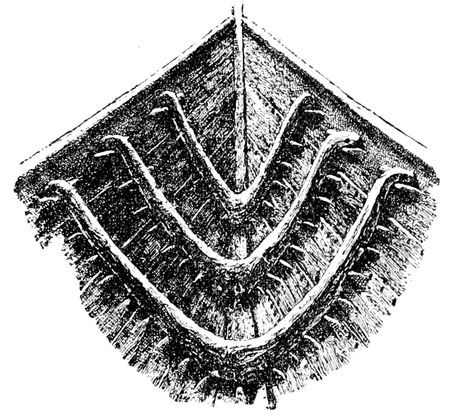

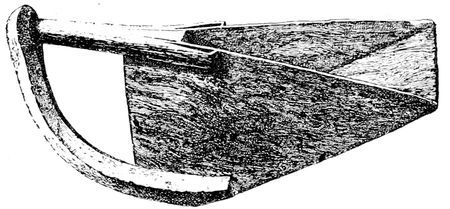

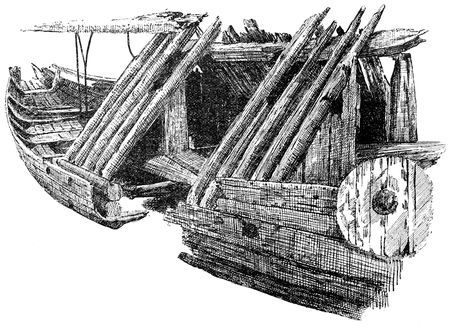

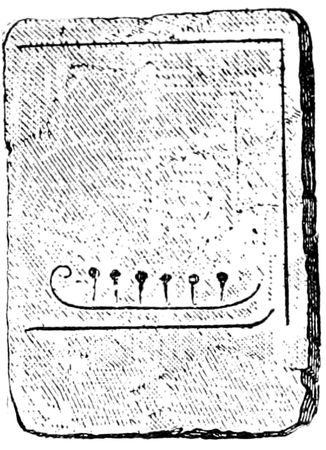

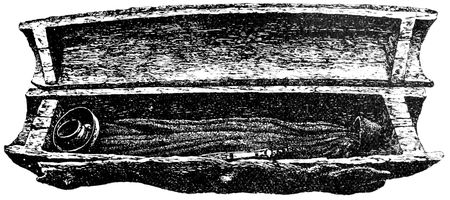

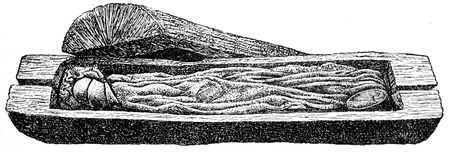

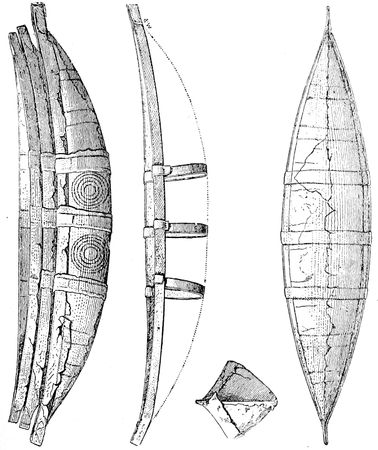

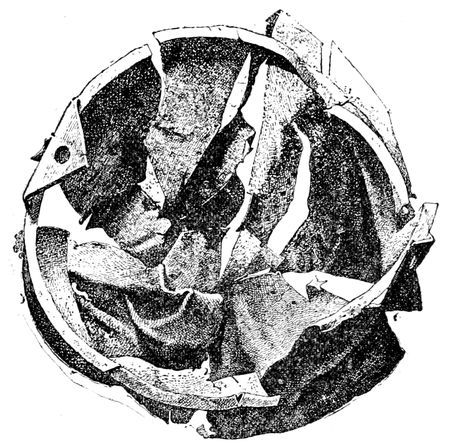

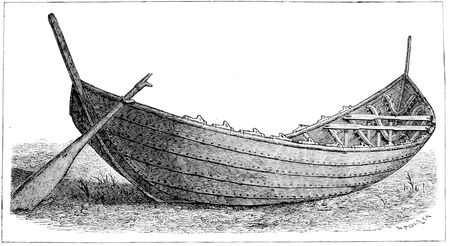

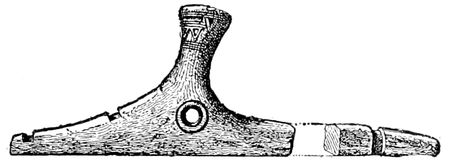

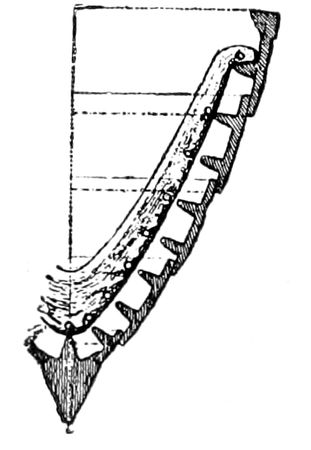

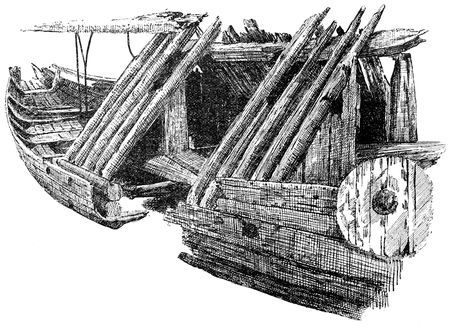

VIKING SHIP, USED FOR BURIAL (GOKSTAD, NORWAY).

(Length of keel, 60 feet; total length, 75 feet; broadest part, 15½ feet; depth from the upper part of bulwark to bottom of keel, 3½ feet.)

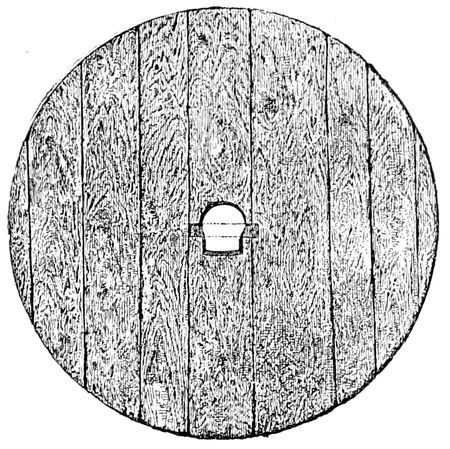

Judging from the number of holes seen, which were about 18 inches below the gunwale, it carried sixteen oars, and was consequently a sixteen-seater. Its preservation is due to the blue clay in which it was partly embedded, the upper part being eaten away owing to the clay being mixed with sand, thus allowing the rain and air to penetrate. It is entirely of oak, clinker built, calked with cows’ hair spun in a sort of cord.

THE VIKING AGE

THE EARLY HISTORY MANNERS, AND CUSTOMS OF THE ANCESTORS OF THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING NATIONS

ILLUSTRATED FROM

THE ANTIQUITIES DISCOVERED IN MOUNDS, CAIRNS, AND BOGS AS WELL AS FROM THE ANCIENT SAGAS AND EDDAS

BY

PAUL B. DU CHAILLU

AUTHOR OF “EXPLORATIONS IN EQUATORIAL AFRICA,” “LAND OF THE MIDNIGHT SUN,” ETC.

WITH 1366 ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAP

IN TWO VOLUMES.—Vol. I

NEW YORK:

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS.

1889.

Copyright, 1889, by

PAUL B. DU CHAILLU.

Press of J. J. Little & Co.,

Astor Place, New York.

TO

GEORGE C. TAYLOR, Esq.,

OF NEW YORK.

To you, my dear Taylor, who, like myself, have travelled over many

lands, and led the same adventurous life in days gone by, I dedicate

“The Viking Age,” in remembrance of years of friendship, of the

many pleasant days we have spent together, and especially of our

wanderings in the Land of the Midnight Sun, in the home of the old

Vikings, while I was engaged on the present work.

New York, September, 1889.

vii

PREFACE.

While studying the progress made in the colonisation of

different parts of the world by European nations, I have

often asked myself the following questions:—

How is it that over every region of the globe the spread of

the English-speaking people and of their language far exceeds

that of all the other European nations combined?

Why is it that, wherever the English-speaking people have

settled, or are at this day found, even in small numbers, they

are far more energetic, daring, adventurous, and prosperous,

and understand the art of self-government and of ruling alien

peoples far better than other colonising nations?

Whence do the English-speaking communities derive the

remarkable energy they possess; for the people of Britain

when invaded by the Romans did not show any such quality?

What are the causes which have made the English such a

pre-eminently seafaring people? for without such a characteristic

they could not have been the founders of so many

states and colonies speaking the English tongue!

In studying the history of the world we find that all the

nations which have risen to high power and widespread dominion

have been founded by men endowed with great, I may say

terrible, energy; extreme bravery and the love of conquest

being the most prominent traits of their character. The

mighty sword with all its evils has thus far always proved a

great engine of civilisation.

To get a satisfactory answer to the above questions we must

go far back, and study the history of the race who settled

in Britain during and after the Roman occupation. We

viiishall thus find why their descendants are to-day so brave, successful,

energetic and prosperous in the lands which they

have colonised; and why they are so pre-eminently skilled in

the art of self-government.

We find that a long stretch of coast is not sufficient, though

necessary, to make the population of a country a seafaring

nation. When the Romans invaded Britain, the Brits had no

fleet to oppose them. We do not until a later period meet

with that love of the sea which is so characteristically

English:—not before the gradual absorption of the earlier

inhabitants by a blue-eyed and yellow-haired seafaring people

who succeeded in planting themselves and their language in

the country.

To the numerous warlike and ocean-loving tribes of the

North, the ancestors of the English-speaking people, we must

look for the transformation that took place in Britain. In

their descendants we recognise to this day many of the very

same traits of character which these old Northmen possessed,

as will be seen on the perusal of this work.

Britain, after a continuous immigration which lasted several

hundred years, became the most powerful colony of the

Northern tribes, several of the chiefs of the latter claiming to

own a great part of England in the seventh and eighth centuries.

At last the time came when the land of the emigrants

waxed more powerful, more populous than the mother-country,

and asserted her independence; and to-day the people of

England, as they look over the broad Atlantic, may discern a

similar process which is taking place in the New World.

The impartial mind which rises above the prejudice of

nationality must acknowledge that no country will leave a

more glorious impress upon the history of the world than

England. Her work cannot be undone; should she to-day

sink beneath the seas which bathe her shores, her record will

for ever stand brilliantly illuminated on the page of history.

The great states which she has founded, which have inherited

her tongue, and which are destined to play a most important

part in the future of civilisation, will be witnesses of the

mighty work she has accomplished. They will look back with

pride to the progenitors of their race who lived in the glorious

ixand never-to-be-forgotten countries of the North, the birthplace

of a new epoch in the history of mankind.

As ages roll on, England, the mother of nations, cannot

escape the fate that awaits all; for on the scroll of time this

everlasting truth is written—birth, growth, maturity, decay;—and

how difficult for us to realise the fact when in the fulness

of power, strength, and pride! Where is or where has been

the nation that can or could exclaim, “This saying does not

apply to me; I was born great from the beginning; I am so

now, and will continue to be powerful to the end of time.”

The ruined and deserted cities; the scanty records of history,

which tell us of dead civilisations, the fragmentary traditions

of religious beliefs, the wrecks of empires, and the forgotten

graves, are the pathetic and silent witnesses of the great past,

and a sad suggestion of the inevitable fate in store for all.

The materials used in these volumes, in describing the

cosmogony and mythology, the life, religion, laws and customs

of the ancestors of the English-speaking nations of to-day, are

mainly derived from records found in Iceland. These parchments,

upon which the history of the North is written, and

which are begrimed by the smoke of the Icelandic cabin, and

worn by the centuries which have passed over them, recount

to us the history and the glorious deeds of the race.

No land has bequeathed to us a literature, giving so minute

and comprehensive an account of the life of a people. These

Sagas (or “say”) record the leading events of a man’s life, or

family history, and date from a period even anterior to the first

settlement of Iceland (about 870 A.D.).

Some Sagas bear evident traces of having been derived, or

even copied, from earlier documents now lost: in some cases

definite quotations are given; others are evidently of a fabulous

character, and have to be treated with great caution; but even

these may be used as illustrating the customs of the times at

which they were written. Occasionally great confusion is

caused by the blending of the similar names of persons living

at different periods.

My method of putting together the series of descriptions

which will be found in the ‘Viking Age’ has been as

follows:—

xBy reading carefully every Saga—and there are hundreds

of them—dealing with the events of a man’s life from his

birth to his death, I was able to select the passages bearing

on the various customs. When in one Saga the bare fact of

a birth, or a marriage, or a burial, or a feast, etc., etc., was

mentioned, in others full details of the ceremonies connected

with them were found. After thus collecting my material,

which was of the most superabundant character, I went over

it and selected what seemed to me to be the best accounts of

the various customs with which I deal in these volumes. I

have not been content with the translations of other persons,

but have in every case gone to the original documents and

adopted my own rendering of them.

Some extracts from the Frankish Chronicles are given in

the Appendix, as showing the power of the Northmen, and

bearing strong testimony to the truthfulness of the Sagas. If

I had not been afraid of being tedious, I could also have

given extracts from Arabic, Russian, and other annals to the

same effect.

The testimony of archæology as corroborating the Sagas

forms one of the most important links in the chain of my

argument; parchments and written records form but a portion

of the material from which I have derived my account of the

‘Viking Age.’ During the last fifty years the History of the

Northmen has been unearthed as it were—like that of the

Egyptians, Assyrians, and Romans—by the discovery of almost

every kind of implement, weapon, and ornament produced by

that accomplished race.

The Museums of Denmark, Sweden, Norway, England,

France, Germany, Russia, are as richly stored with such objects

as are the British Museum, the Louvre, the Museums of Naples

and Boulak with the treasures of Egypt and Pompeii.

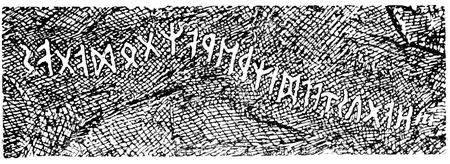

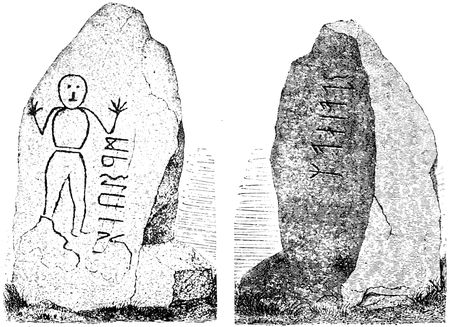

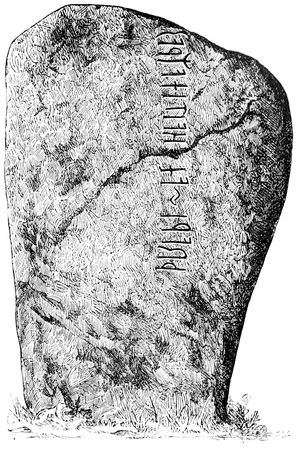

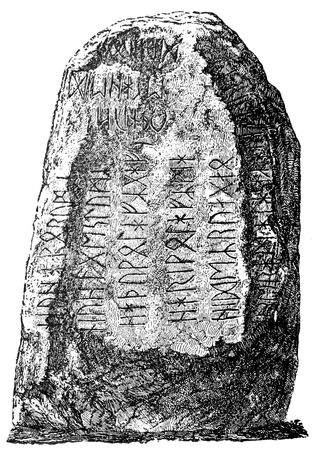

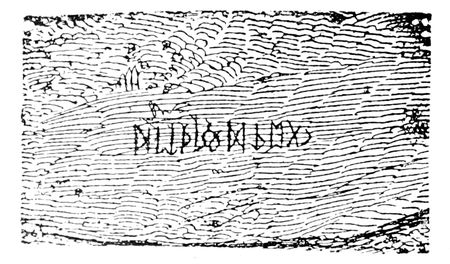

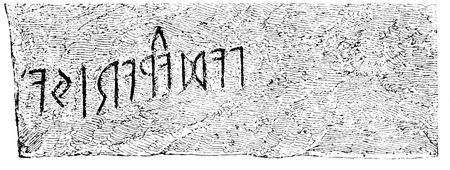

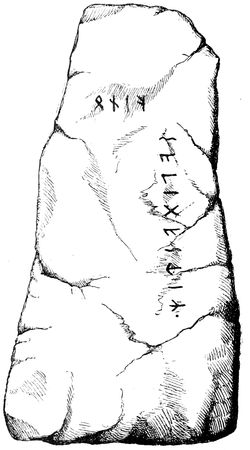

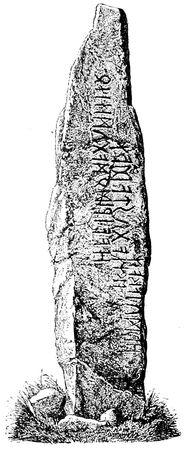

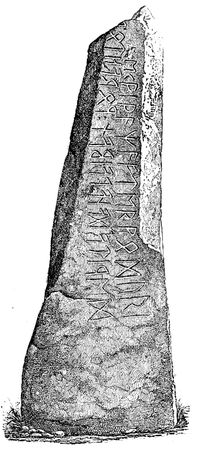

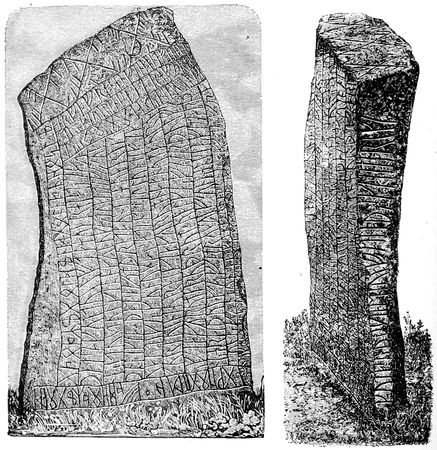

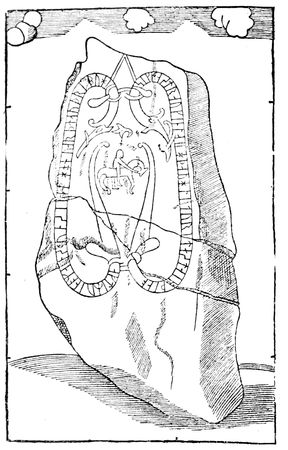

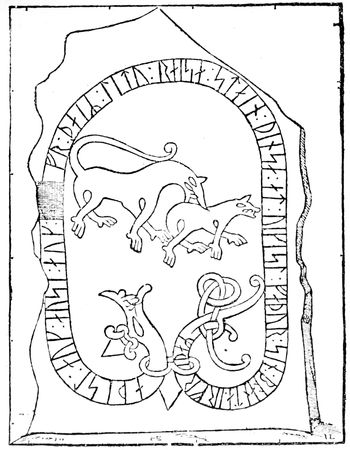

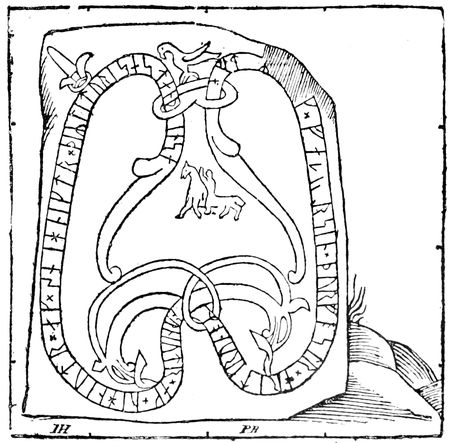

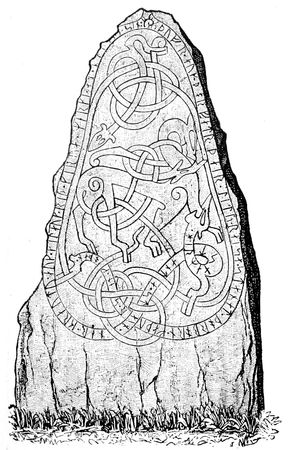

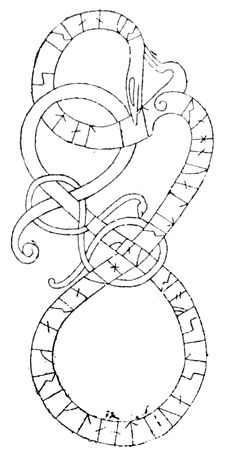

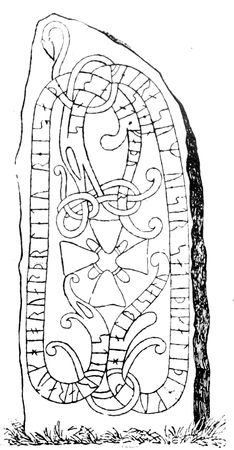

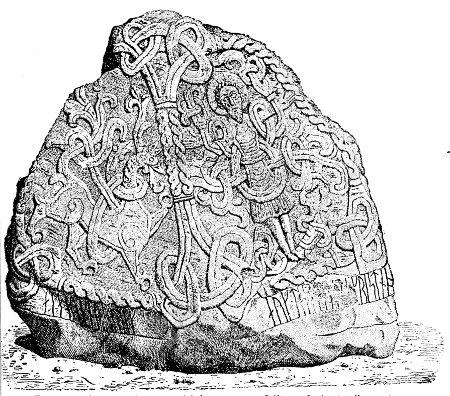

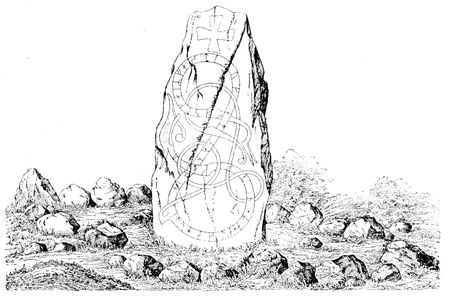

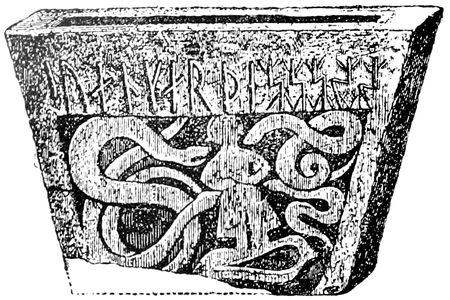

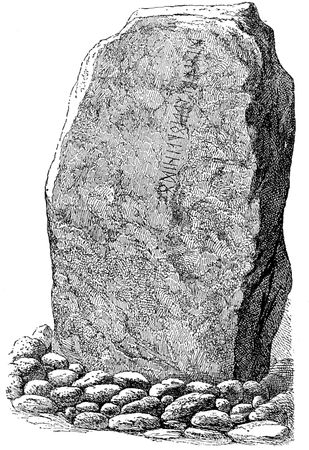

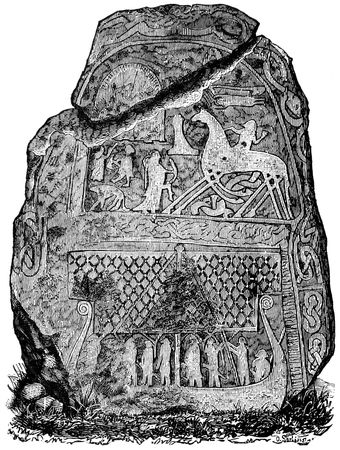

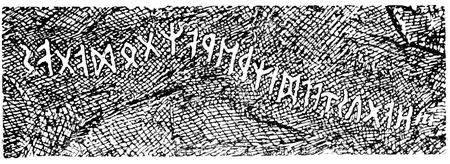

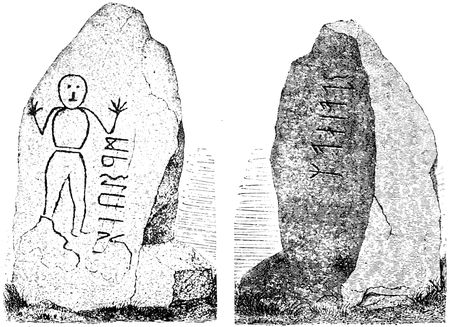

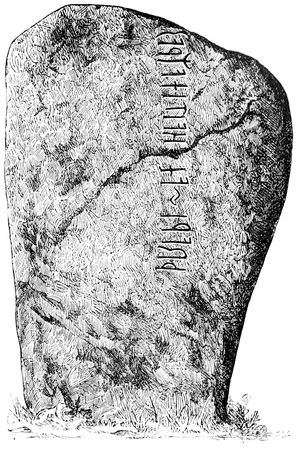

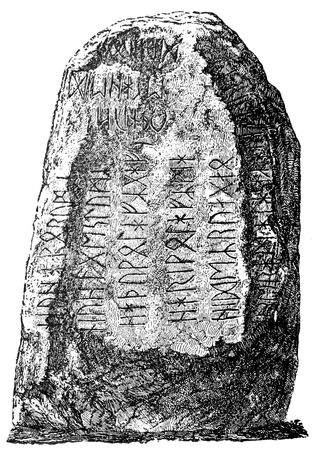

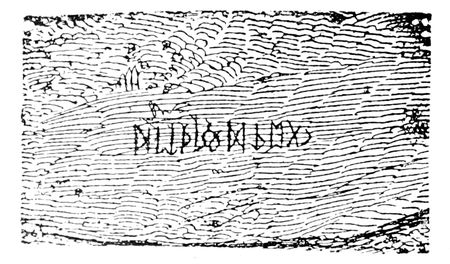

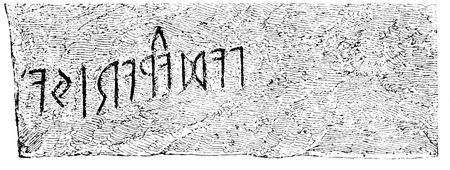

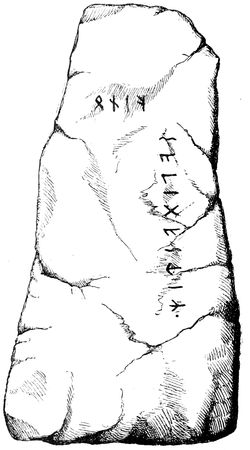

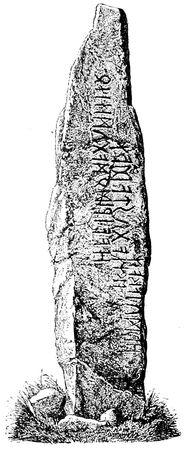

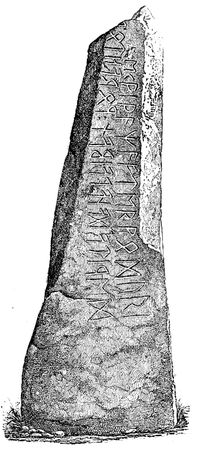

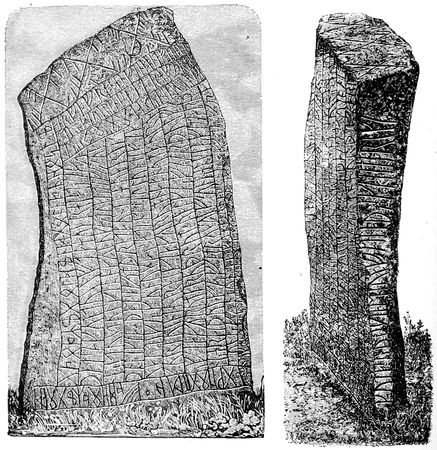

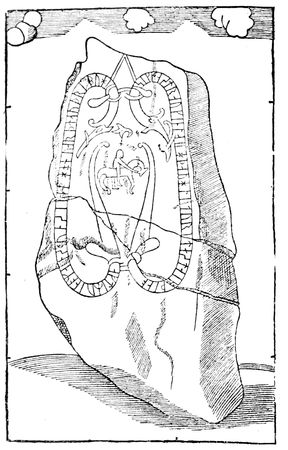

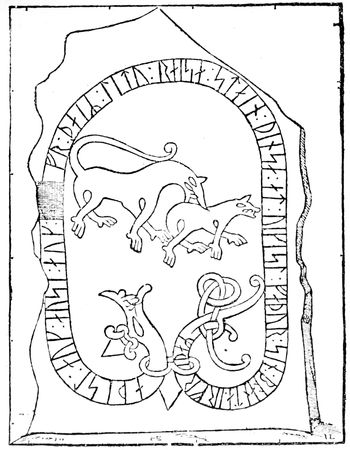

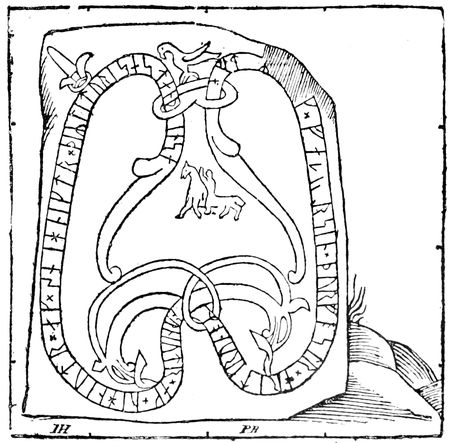

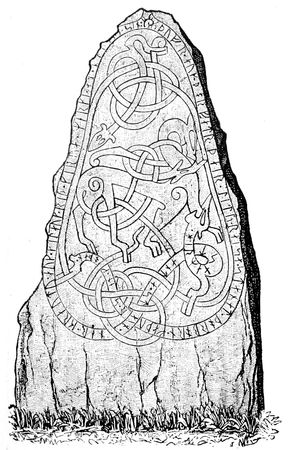

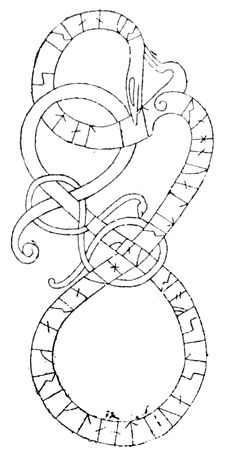

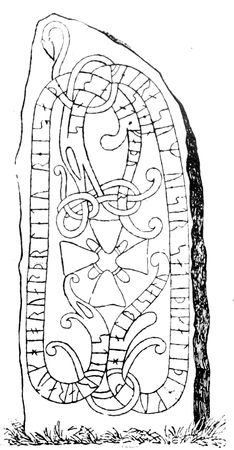

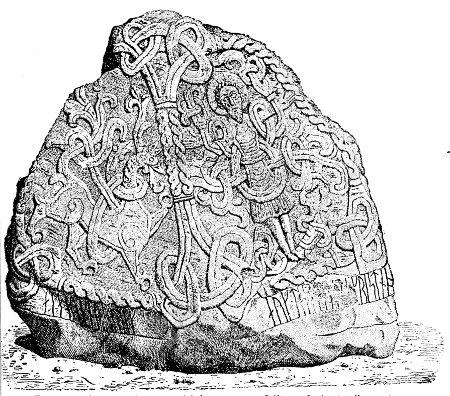

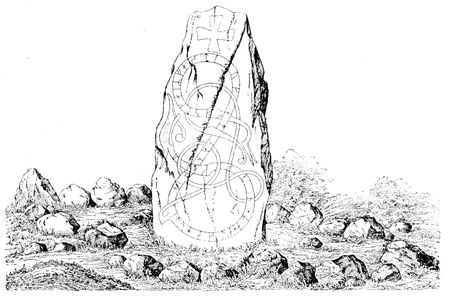

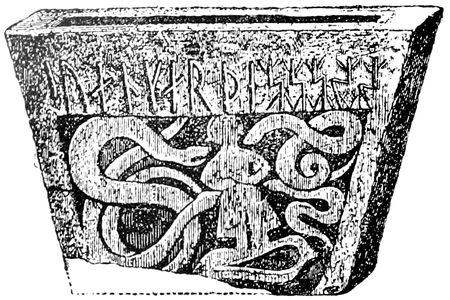

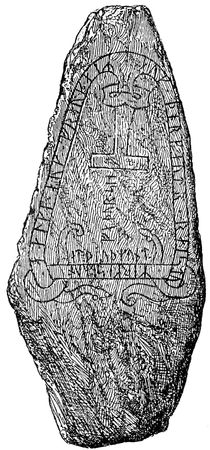

I have myself seen nearly all the objects or graves illustrated

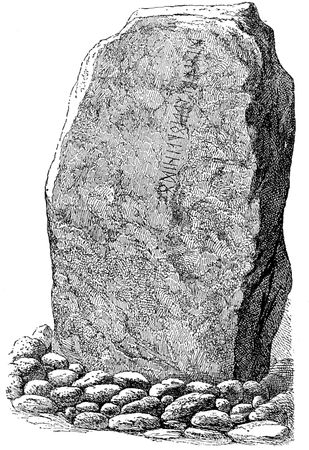

in this book, with the exception of a few Runic stones

which have now disappeared, but are given in an old work of

Jorgensen.

As my materials expanded themselves before me I felt like

one of those mariners of old on a voyage of discovery. To

them new lands were continuously coming into view; to me

xinew materials, new fields of literary and archæological wealth

unfolded themselves incessantly. Thus carried away by

enthusiasm and the love of the task I had undertaken, I have

been able to labour for eight years and a half on the present

work, with some interruptions from exhaustion and impaired

health. May I, then, ask the indulgence of a public, which has

always been kind to me, for all the shortcomings of my work?

I have received valuable assistance from many friends, but

I desire especially to express my thanks to Mr. Bruun, the

Chief Librarian of the Royal Library of Denmark, for his

great kindness in allowing me so many privileges during the

years I have worked in Copenhagen; to Mr. Birket Smith, of

the University Library of Copenhagen; and Mr. Kaalund,

Keeper of the Arna Magnæan Collection of Manuscripts, for

the uniform courtesy they have shown me; among antiquarians,

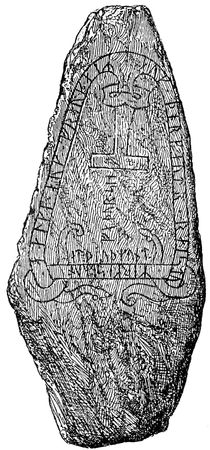

to my friend Professor George Stephens, author of

the magnificent work, ‘Northern Runic Monuments,’ for his

readiness in giving me all the information and help I needed,

which sometimes occupied much of his valuable time (several

illustrations of the runic stones, etc., in these volumes are

taken from his work); to Mr. Vedel, Vice-President of the

Royal Society of Antiquarians; to Messrs. Herbst, Sophus

Müller, and Petersen, of the Royal Museum of Northern

Antiquities, for their great courtesy; I am also indebted to

the works of the following distinguished antiquarians which

have been invaluable to me in my researches and which have

furnished me with many of the illustrations for my book: Ole

Rygh, Bugge, Engelhart, Nicolaysen, Sehested, Steenstrup,

Madsen, Säve, Montelius, Holmberg, Jorgensen, Baltzer, and

Lorange; also to the works of the historians, Keyser, Geijer,

Munch, Rafn, Vigfusson. My sincere thanks are also due to my

young friend Jon Stefánsson, an Icelandic student, for his constant

help in rendering the translations of the Sagas as accurate

and literal as possible; and to my old friend Mr. Rasmus B.

Anderson, late American Minister to Denmark, and translator

of the ‘Later Edda,’ etc.; in England, to Messrs. A. S. Murray,

Franks, and Read, of the British Museum; to Dr. Warre,

the head master of Eton, and to General Pitt Rivers, author

of a valuable work on the excavations in Cranborne Chase,

xiiwhich contains objects strikingly similar to those of Scandinavia;

also to my friends Mr. J. S. Keltie and Mr. Arthur

L. Roberts; to my old friends Messrs. Clowes, who have

taken great pains in carrying out what has proved to be a

very difficult task for the printer, and who have had the work

over two-and-a-half years in type.

I must thank, above all, my esteemed and venerable publisher,

John Murray, for the great interest he has taken in the

present work, which has tried his patience and liberality many

a time, and also for the many years of uninterrupted friendship

and the pleasant business relations (unhampered by any written

agreement whatever), which have existed between us from the

time when I came to him almost a lad, and he first undertook

the publication of ‘Explorations in Equatorial Africa,’ in 1861,

not forgetting my dear friends, his sons, John and Hallam,

the former of whom has assisted me materially in seeing the

work through the press, and my old companion Robert Cooke.

I cannot close this preface without thanking my old and

ever true friend Robert Winthrop, of New York, descendant

of the celebrated Colonial Governor of Massachusetts, to whom

I dedicated “The Land of the Midnight Sun,” for his unfailing

kindness and sympathy during the years I have been

engaged in the present work.

New York, September, 1889.

xiii

CONTENTS OF VOL. I

| CHAPTER I. |

|

PAGE |

| |

| Civilisation and Antiquities of the North |

1 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER II. |

| |

| Roman and Greek Accounts of the Northmen |

7 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER III. |

| |

| The Settlement of Britain by Northmen |

17 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| |

| The Mythology and Cosmogony of the Norsemen |

27 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER V. |

| |

| Mythology and Cosmogony (continued) |

44 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| |

| Odin of the North |

51 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| |

| The Successors of Odin of the North |

62 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| |

| The Stone Age |

69 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER IX. |

| |

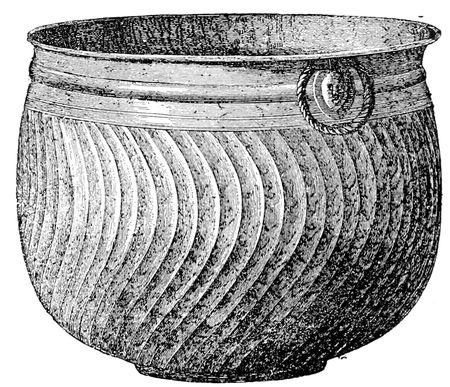

| The Bronze Age |

84 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER X. |

| |

| The Iron Age |

125 |

| |

| |

| xivCHAPTER XI. |

| |

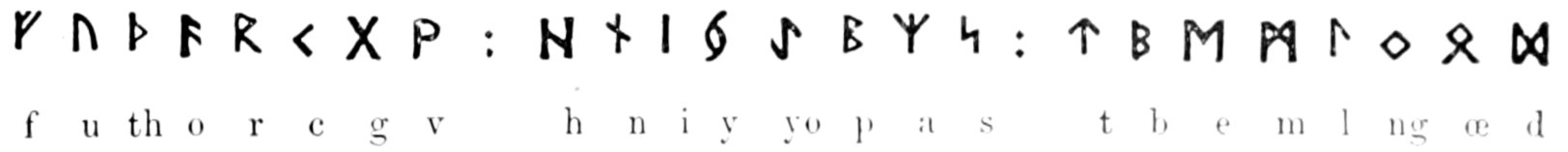

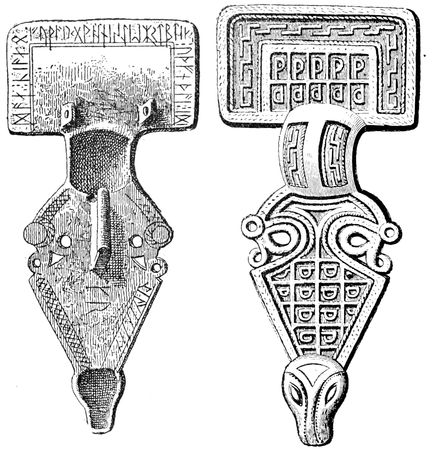

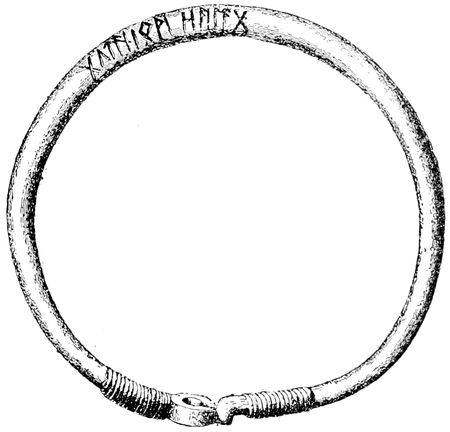

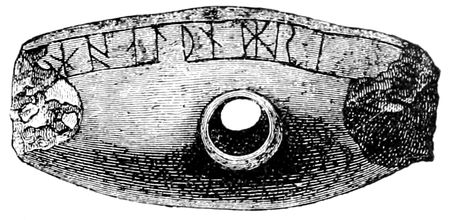

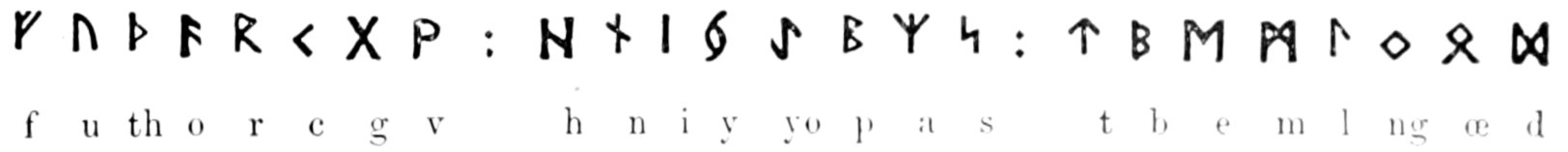

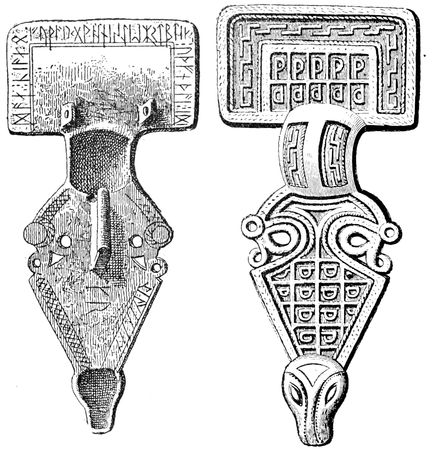

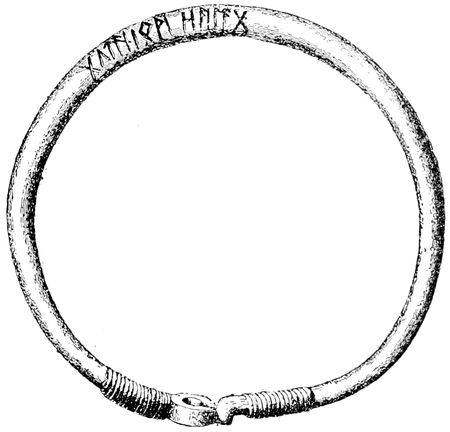

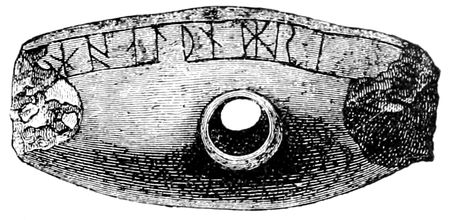

| Runes |

154 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XII. |

| |

| Northern Relics—Bog Finds |

193 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

| |

| Northern Relics—Ground Finds |

235 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XIV. |

| |

| Description of some Remarkable Graves and their Contents |

247 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XV. |

| |

| Greek and Roman Antiquities in the North |

259 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XVI. |

| |

| Glass |

276 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XVII. |

| |

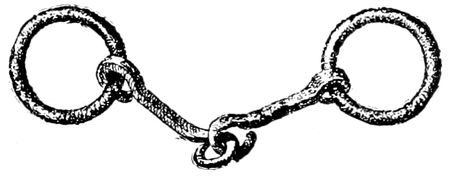

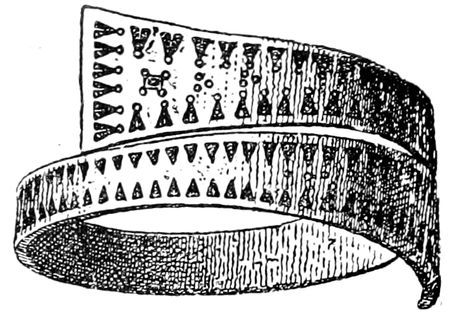

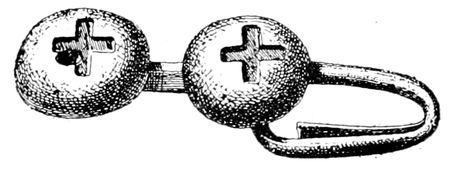

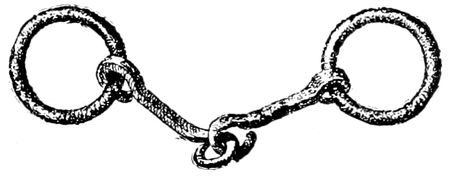

| Horses—Waggons |

285 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XVIII. |

| |

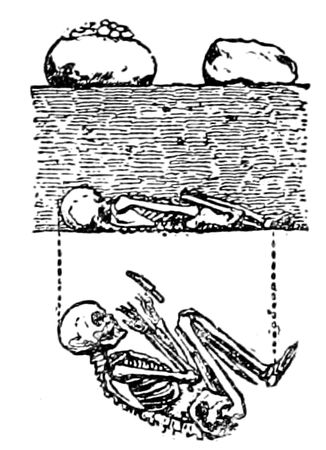

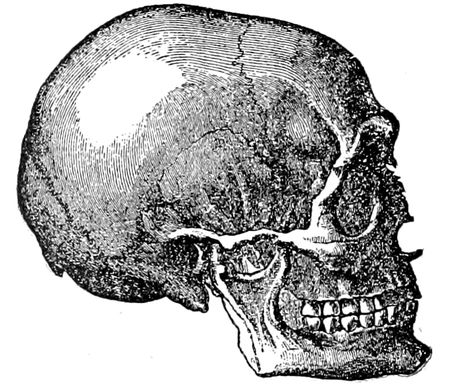

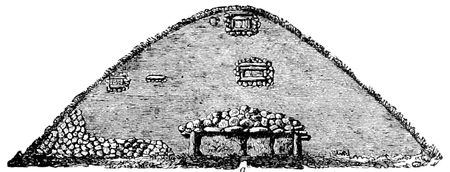

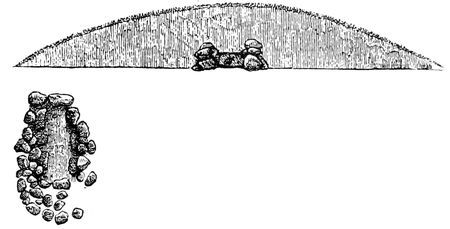

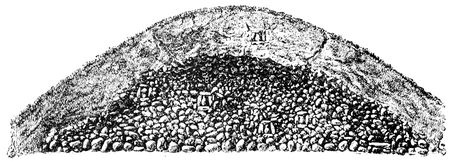

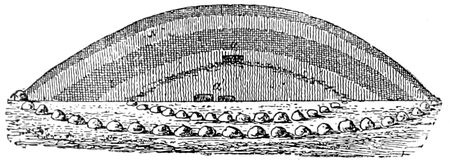

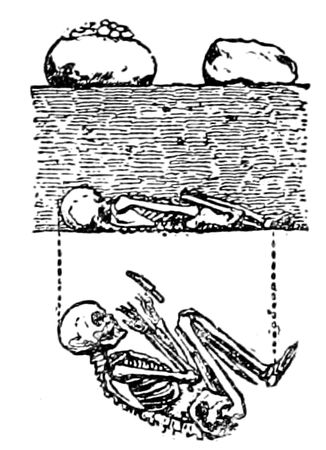

| Various Forms of Graves |

299 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XIX. |

| |

| Burials |

320 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XX. |

| |

| Religion.—Worship, Sacrifices, etc. |

343 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXI. |

| |

| Religion.—Altars, Temples, High-Seat Pillars, etc. |

356 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXII. |

| |

| Religion.—Human Sacrifices |

364 |

| |

| |

| xvCHAPTER XXIII. |

| |

| Religion.—Idols and Worship of Men and Animals, etc. |

375 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXIV. |

| |

| Religion.—The Nornir and Valkyrias |

385 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXV. |

| |

| Religion.—The Volvas |

394 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXVI. |

| |

| Religion.—Ægir and Ran |

403 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXVII. |

| |

| Religion.—Sacrifices to the Alfar, Disir, Fylgja, Hamingja, and Landvœttir |

409 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. |

| |

| Valhöll-valhalla |

420 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXIX. |

| |

| Superstitions.—Shape-Changing |

430 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXX. |

| |

| Superstitions.—Witchcraft |

439 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXXI. |

| |

| Superstitions.—Omens |

450 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXXII. |

| |

| Superstitions.—Dreams |

456 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. |

| |

| The Struggle between Paganism and Christianity |

464 |

| |

| |

| xviCHAPTER XXXIV. |

| |

| The Land |

478 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXXV. |

| |

| Divisions of People into Classes |

486 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. |

| |

| Slavery—Thraldom |

502 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. |

| |

| The Thing |

515 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. |

| |

| The Godi and the Godiship |

525 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. |

| |

| The Laws of the Earlier English Tribes |

532 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XL. |

| |

| Indemnity, Weregild |

544 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XLI. |

| |

| The Oath and Ordeal |

553 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XLII. |

| |

| Duelling |

563 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XLIII. |

| |

| Outlawry |

578 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XLIV. |

| |

| Revenge |

584 |

xvii

A LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL SAGAS

QUOTED IN

THE VIKING AGE,

INCLUDING THE PERIODS WITH WHICH THEY DEAL.

| Name of Saga. |

Century with which they deal. |

| The Earlier Edda |

These are Mythical, and no accurate date can be affixed to them. |

| |

| The Later Edda |

| |

|

| Fórnaldarsögur contains:— |

|

| |

Völsunga |

Partly Mythical. |

| |

Hervara |

| |

Thorstein Vikingsson’s (father of Fridthjof) |

| |

Ketil Hæng’s sons |

| |

Grim Lodinkinnis’ |

| |

Fridthjof’s |

| |

|

|

| |

Hrolf Kraki’s |

VI.(?) |

| |

Half’s |

VI.(?) |

| |

Sögubrot |

VI.-VII.(?) |

| |

Ragnar Lodbrok’s |

VIII.(?) |

| |

Ragnar Lodbrok’s Sons’ |

VIII.(?) |

| |

|

|

| |

Norna Gest’s |

No date can be assigned to these. |

| |

Gautrek’s |

| |

Orvar Odd’s |

| |

Herraud and Bosi’s |

| |

Egil and Asmund’s |

| |

Hjalmter and Ölver’s |

| |

Göngu Hrelf’s |

| |

An Bosveigi’s |

| |

| ⁂ The above dates are all more or less conjectural, and the Sagas are chiefly valuable as illustrating manners and customs. |

| |

| |

Egil’s |

Middle of IX. to end of X. |

| |

Njala’s |

End of X. to beginning of XI. |

| |

Laxdæla |

IX.-XI. (886–1030). |

| |

Eyrbyggja |

IX.-XI. (890–1031). |

| |

|

|

| Islandinga Sögur contains:— |

|

| I. |

Hord’s Saga |

X. (950–990). |

| II. |

Hœnsa Thoris’ Saga |

X.-XI.(990–1010). |

| III. |

Gunnlaug Ormstunga’s Saga |

X.-XI. |

| IV. |

Viga Styr’s Saga |

X.-XI. |

| V. |

Kjalnesinga Saga |

IX.-XI. |

| VI. |

Gisli Súrsson |

X. |

| xviii |

|

|

| Droplaugarsona Saga |

X. |

| |

|

|

| Hrafnkel Freysgodi |

X. |

| |

|

|

| Bjorn Hitdæla Kappi |

First half of XI. |

| |

|

|

| Kormak’s |

X. |

| |

|

|

| Fornsögur contains:— |

|

| I. |

Vatnsdæla Saga |

IX.-XI. (c. 870–1000). |

| II. |

Floamanna Saga |

X. (c. 985–990). |

| III. |

Hallfred’s Saga |

End of X. |

| |

|

|

| Gretti’s Saga |

X.-XI. (Grettir died 1031). |

| |

|

|

| Viga Glum |

X. |

| |

|

|

| Vallaljots |

Beginning of XI. |

| |

|

|

| Vapnfirdinga |

IX.-X. |

| |

|

|

| Thorskfirdinga, or Gullthóri’s |

X. (c. 900–930). |

| |

|

|

| Heidar Viga (continuation of Viga Styr’s) |

First half of XI. |

| |

|

|

| Fœreyinga |

X.-XI. (c. 960–1040). |

| |

|

|

| Finnbogi Rami’s |

X. |

| |

|

|

| Eirek the Red |

|

| |

|

|

| Thátt of Styrbjörn (nephew of Eirek the Victorious, who fell at the battle of Fyrisvellir, 983) |

X. |

| |

|

|

| Landnama |

IX.-X. (the colonisation of Iceland). |

| |

|

|

| Islendinga bok |

IX.-XI. (c. 874–1118). |

| |

Ljosvetninga |

990–1050. |

| |

Vemund’s Saga |

End of X. century. |

| |

Svarfdœla |

First half of X. century. |

| |

|

|

| Biskupa Sögur contains:— |

|

| |

Kristni Saga |

X.-XII. (c. 980–1120). |

| |

Sturlunga |

XII.-XIII. (c. 1120–1284). |

| |

|

|

| Fornmanna Sögur contains:— |

|

| I. |

Sagas of Kings of Norway |

|

| II. |

Jomsvikinga Saga |

X. |

| III. |

Knytlinga Saga |

XI.-XII. |

| IV. |

Fagrskinna (short history of Kings of Norway from Halfdan the Black to Sverrir) |

IX.-XII. |

| |

|

|

| Heimskringla Saga contains the Ynglinga Saga, the great work of Snorri Sturluson |

Written in first half of XIII. cent., giving history of the Kings of Norway and Sweden from Odin down to 1177. |

| |

|

|

| Flateyjarbok contains lives of Kings of Norway, etc. |

|

| |

|

|

| Fostbrædra Saga |

XI. (c. 1015–30). |

| |

|

|

| Konung’s Skuggsja |

XIII. |

| |

|

|

| Rimbegla |

XIV. |

| |

|

|

| Orkneyinga |

IX.-XIII. (c. 870–1206). |

xix

A LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL KINGS OF DENMARK, NORWAY, AND SWEDEN,

SOME OF WHOM HAVE SAGAS OF THEIR OWN.

KINGS OF DENMARK.

|

A.D. |

| Gorm |

900–940 |

| Harald Bluetooth |

945–985 |

| Svein Tjuguskegg |

985–1014 |

| Harald |

1014–1018 |

| Knut the Great |

1018–1035 |

| Hörda Knut |

1035–1042 |

| Magnus the Good, ruled over Denmark and Norway |

1042–1047 |

| Svein Ulfsson |

1047–1075 |

KINGS OF NORWAY.

|

|

A.D. |

| Halfdan the Black, died |

|

860 |

| Harald Fairhair, |

reigned |

860–930 |

| Eirik Bloodaxe |

” |

930–934 |

| Hakon the Good |

” |

934–960 |

| Harald Grafeld (greyskin) |

” |

960–965 |

| Hakon Jarl the Great, the hero of the battle of Gomsviking, |

” |

965–995 |

| Olaf Tryggvason |

” |

995–1000 |

| Eirik Jarl |

” |

1000–1015 |

| St Olaf |

” |

1015–1028 |

| Knut the Great |

” |

1028–1035 |

| Magnus the Good |

” |

1035–1047 |

| Harald Hardradi |

” |

1047–1066 |

| Olaf the Quiet |

” |

1066–1093 |

| Magnus Barefoot |

” |

1093–1103 |

| Three sons:—Eystein, Olaf, Sigurd Jórsalafari |

|

1103–1130 |

| Civil war—Harald Gilli, Magnus the Blind, and others |

|

1130–1162 |

| Magnus Erlingsson |

|

1162–1184 |

| Sverrir (Sigurdson) |

|

1184–1202 |

KINGS OF SWEDEN.

(Not mentioned in the Odinic Genealogies, vol. i. p. 67.)

|

A.D. |

| Ivar Vidfadmi |

Kings of Sweden and Denmark. |

| Harald Hilditönn |

| Sigurd Hring |

| Ragnar Lodbrók |

| |

|

| Björn Ironside |

|

| Eirik and Refil |

|

| Eymund and Björn |

800–830 |

| Olaf and Eymund |

c. 850 |

| Eyrik Eymundsson died |

c. 882 |

| Björn Eiriksson and Hring |

900–950 |

| Eirik the Victorious |

c. 950–994 |

| Olaf Skaut-konung |

c. 994–1022 |

| Önund Jakob |

c. 1022–1050 |

| Eymund the Old |

c. 1050–1060 |

| Steinkel Rögnvaldson |

c. 1060–1066 |

Geography and Nomenclature of the Viking Age

1

CHAPTER I.

CIVILISATION AND ANTIQUITIES OF THE NORTH.

Early antiquities of the North—Literature: English and Frankish chronicles—Early

civilisation—Beauty of ornaments, weapons, &c.

A study of the ancient literature and abundant archæology of

the North gives us a true picture of the character and life of

the Norse ancestors of the English-speaking peoples.

We can form a satisfactory idea of their religious, social,

political, and warlike life. We can follow them from their

birth to their grave. We see the infant exposed to die, or

water sprinkled,[1] and a name bestowed upon it; follow the

child in his education, in his sports; the young man in his

practice of arms; the maiden in her domestic duties and

embroidery; the adult in his warlike expeditions; hear the clash

of swords and the songs of the Scald, looking on and inciting

the warriors to greater deeds of daring, or it may be recounting

afterwards the glorious death of the hero. We listen to the

old man giving his advice at the Thing.[2] We learn about

their dress, ornaments, implements, weapons; their expressive

names and complicated relationships; their dwellings and

convivial halls, with their primitive or magnificent furniture;

their temples, sacrifices, gods, and sacred ceremonies; their

personal appearance, even to the hair, eyes, face and limbs.

Their festivals, betrothal and marriage feasts are open to us.

We are present at their athletic games preparatory to the stern

realities of the life of that period, where honour and renown

were won on the battle-field; at the revel and drunken bout;

2behold the dead warrior on his burning ship or on the pyre,

and surrounded by his weapons, horses, slaves, or fallen companions

who are to enter with him into Valhalla;[3] look into

the death chamber, see the mounding and the Arvel, or inheritance

feast.

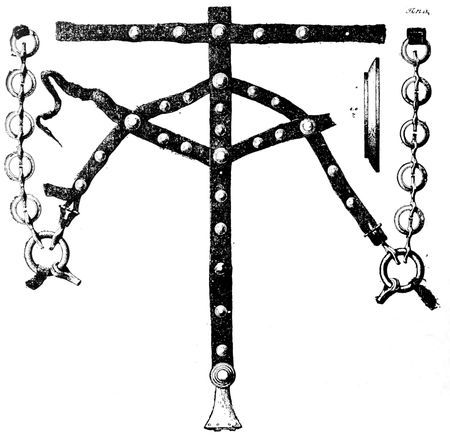

These Norsemen had carriages or chariots, as well as

horses, and the numerous skeletons of this animal in graves or

bogs prove it to have been in common use at a very early

period. Their dress, and the splendour of their riding equipment

for war, the richness of the ornamentation of their

weapons of offence and defence are often carefully described.

Everywhere we see that gold was in the greatest abundance.

The descriptions of such wealth might seem to be very much

exaggerated; but, as will be seen in the course of this work,

the antiquities treasured in the museums of the North bear

witness to the truthfulness of the records. The spade has

developed the history of Scandinavia, as it has done that of

Assyria and Etruria, but in addition the Northmen had the

Saga and Edda literature to perpetuate their deeds.

We are the more astonished as we peruse the Eddas and Sagas

giving the history of the North, and examine the antiquities

found in the country, for we hear hardly anything about the

customs of the people from the Roman writers, and our ideas

regarding them have been thoroughly vitiated by the earlier

Frankish and English chronicles and other monkish writings,

or by the historians who have taken these records as a trustworthy

authority.

Some writers, in order to give more weight to these

chronicles, and to show the great difference that existed

between the invaders and invaded, and how superior the latter

were to the former, paint in a graphic manner, without a

shadow of authority, the contrast between the two peoples.

England is described as being at that time a most beautiful

country, a panegyric which does not apply to fifteen or twenty

centuries ago; while the country of the aggressor is depicted

as one of swamp and forest inhabited by wild and savage men.

It is forgotten that after a while the people of the country

attacked were the same people as those of the North or their

3descendants, who in intelligence, civilisation, and manly virtues

were far superior to the original and effete inhabitants of

the shores they invaded.

The men of the North who settled and conquered part of

Gaul and Britain, whose might the power of Rome could not

destroy, and whose depredations it could not prevent, were not

savages; the Romans did not dare attack these men at home

with their fleet or with their armies. Nay, they even had

allowed these Northmen to settle peacefully in their provinces

of Gaul and Britain.

No, the people who were then spread over a great part of

the present Russia, who overran Germania, who knew the art

of writing, who led their conquering hosts to Spain, into the

Mediterranean, to Italy, Sicily, Greece, the Black Sea, Palestine,

Africa, and even crossed the broad Atlantic to America,

who were undisputed masters of the sea for more than twelve

centuries, were not barbarians. Let those who uphold the contrary

view produce evidence from archæology of an indigenous

British or Gallic civilisation which surpasses that of the North.

The antiquities of the North even without its literature

would throw an indirect but valuable light on the history of

the earlier Norse tribes, the so-called barbarians, fiends, devils,

sons of Pluto, &c., of the Frankish and English chronicles.

To the latter we can refer for stories of terrible acts of cruelty

committed by the countrymen of the writers who recount

them with complacency; maiming prisoners or antagonists

and sending multitudes into slavery far away from their homes.

But the greatest of all outrages in the eyes of these monkish

scribes was that the Northmen burned a church or used it for

sheltering their men or stabling their horses.

The writers of the English and Frankish chronicles were

the worst enemies of the Northmen, ignorant and bigoted men

when judged by the standard of our time; through their

writings we hardly know anything of the customs of their

own people. They could see nothing good in a man who had

not a religion identical with their own.

Still allowance must be made for the chroniclers; they wrote

the history of their own period with the bigotry, passions, and

hatreds, of their times.

4The striking fact brought vividly before our mind is that

the people of the North, even before the time when they

carried their warfare into Gaul and Britain, possessed a

degree of civilisation which would be difficult for us to realise

were it not that the antiquities help us in a most remarkable

manner, and in many essential points, to corroborate the

truthfulness of the Eddas and Sagas.

The indisputable fact remains that both the Gauls and the

Britons were conquered by the Romans and afterwards by the

Northern tribes.

This Northern civilisation was peculiar to itself, having

nothing in common with the Roman world. Rome knew

nothing of these people till they began to frequent the coasts

of her North Sea provinces, in the days of Tacitus, and after

his time the Mediterranean. The North was separated from

Rome by the swamps and forests of Germania—a vague term

given to a country north and north-east of Italy, a land

without boundaries, and inhabited by a great number of

warlike, wild, uncivilised tribes. According to the accounts

of Roman writers, these people were very unlike those of the

North, and we must take the description given of them to be

correct, as there is no archæological discovery to prove the

contrary. They were distinct; one was comparatively civilised,

the other was not.

The manly civilisation the Northmen possessed was their

own; from their records, corroborated by finds in Southern

Russia, it seems to have advanced north from about the shores

of the Black Sea, and we shall be able to see in the perusal of

these pages how many Northern customs were like those of the

ancient Greeks.

A view of the past history of the world will show us that

the growth of nations which have become powerful has been

remarkably steady, and has depended upon the superior

intelligence of the conquering people over their neighbours;

just as to-day the nations who have taken possession of

far-off lands and extended their domain, are superior to the

conquered.

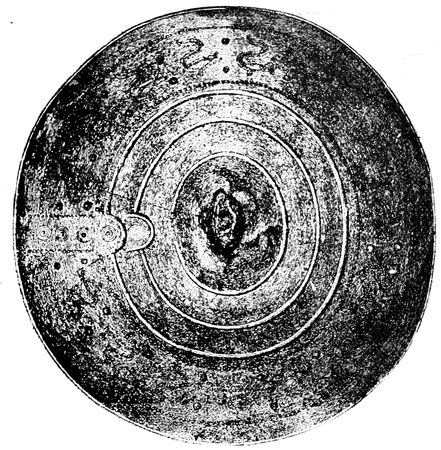

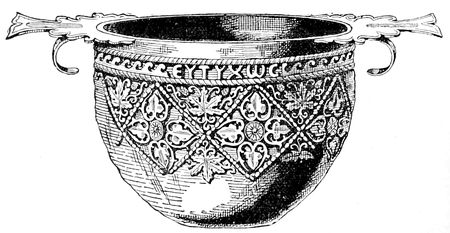

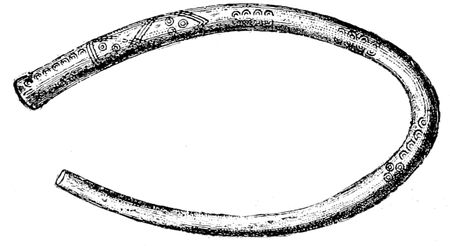

The museums of Copenhagen, Stockholm, Christiania,

Bergen, Lünd, Göteborg, and many smaller ones in the provincial

5towns of the three Scandinavian kingdoms, show a most

wonderful collection of antiquities which stand unrivalled in

Central and Northern Europe for their wealth of weapons and

costly objects of gold and silver, belonging to the bronze and

iron age, and every year additions are made.

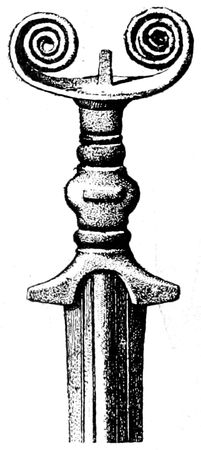

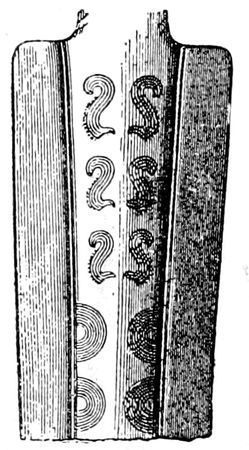

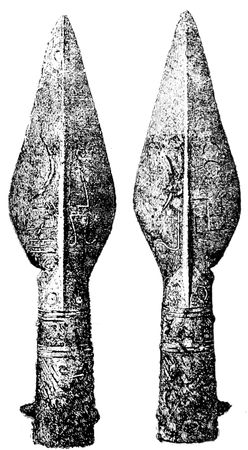

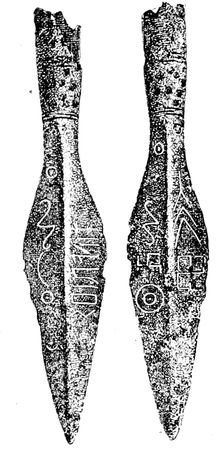

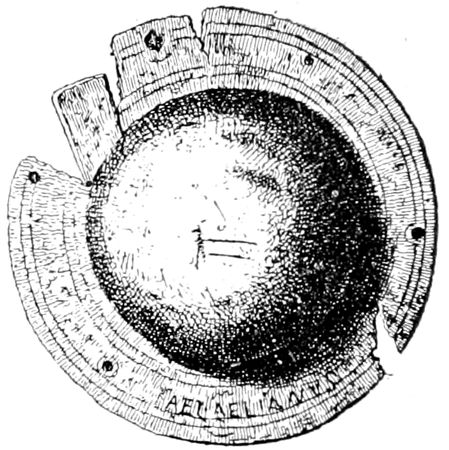

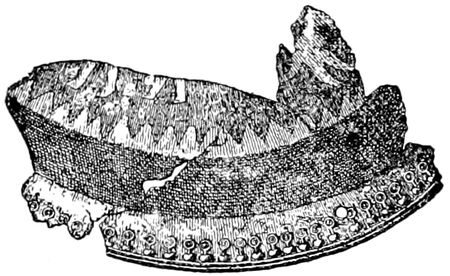

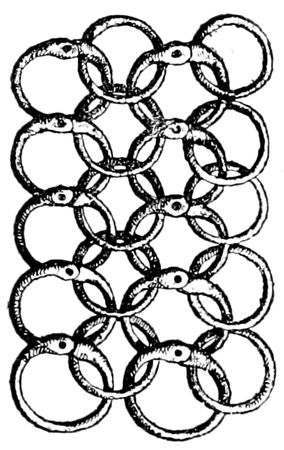

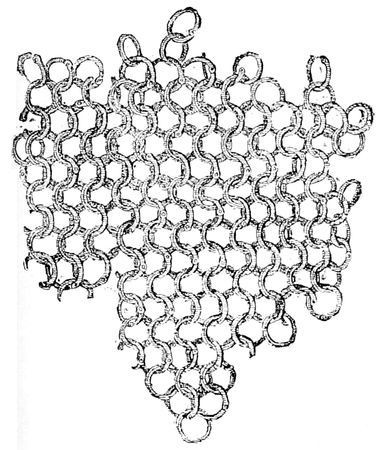

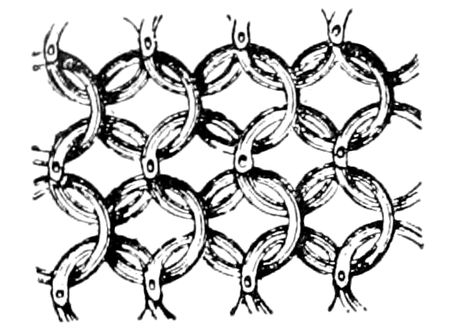

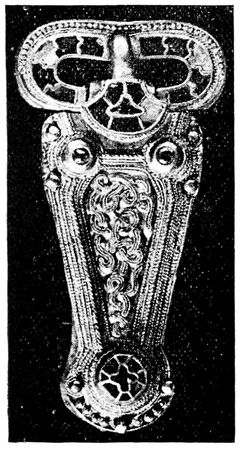

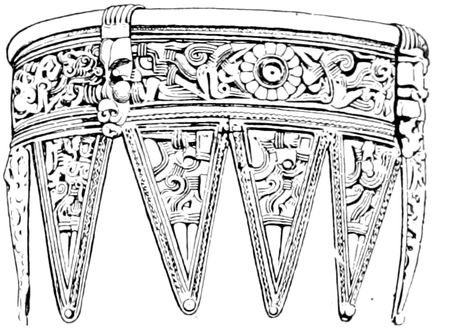

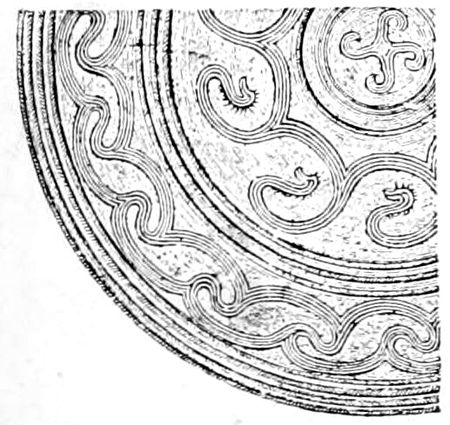

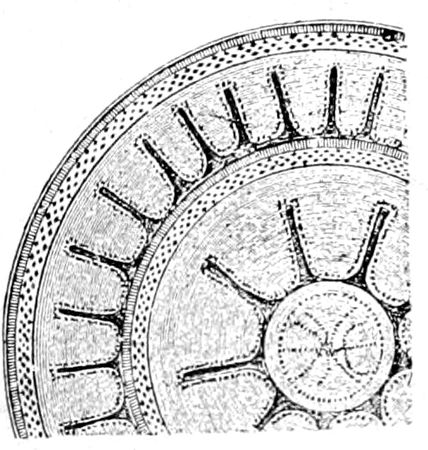

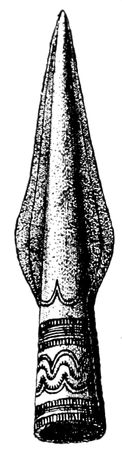

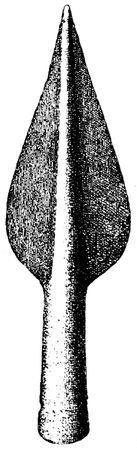

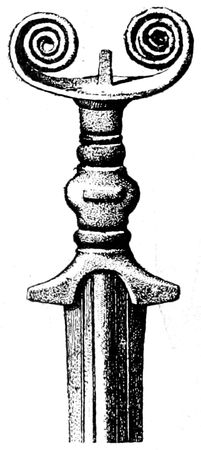

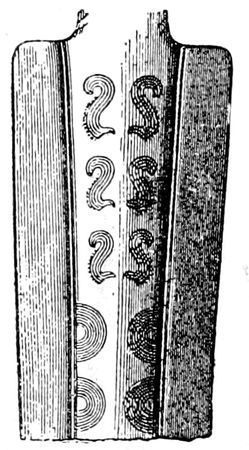

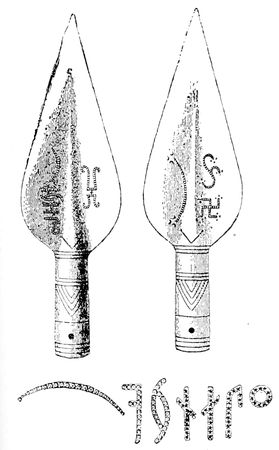

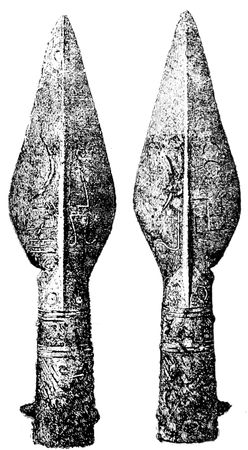

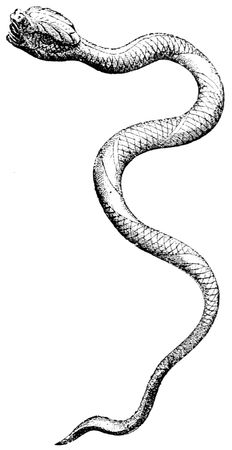

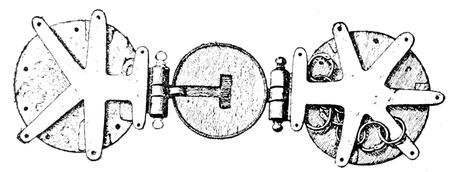

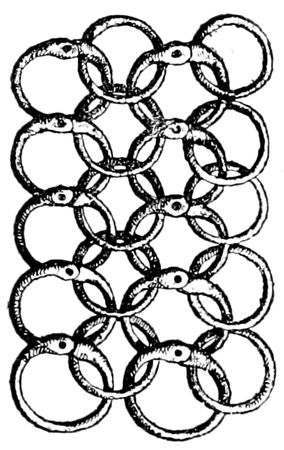

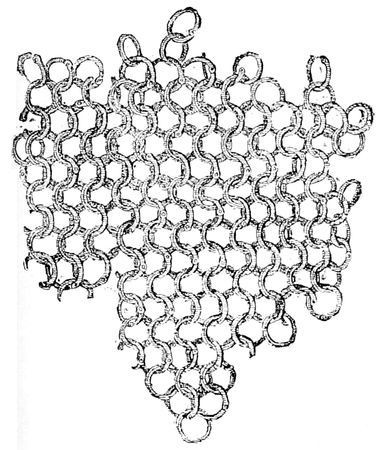

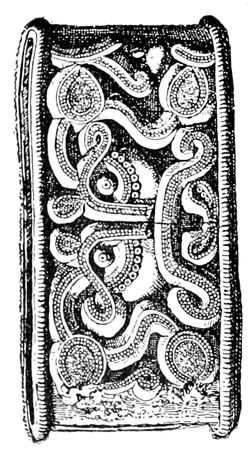

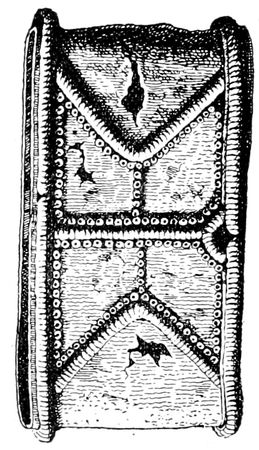

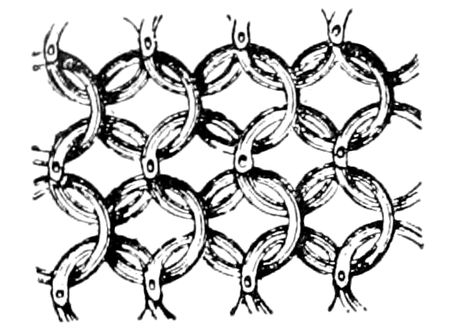

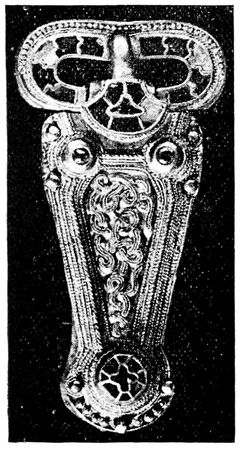

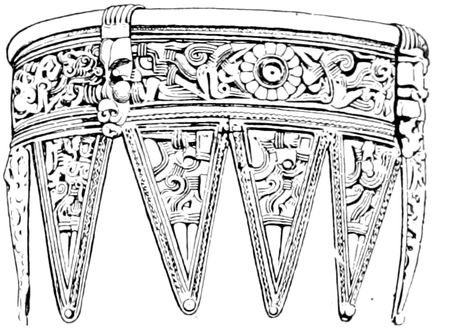

The weapons found with their peculiar northern ornamentation,

and the superb ring coats-of-mail, show the skill of the

people in working iron. A great number of their early swords

and other weapons are damascened even so far back as the

beginning of the Christian era, and show either that this

art was practised in the North long before its introduction

into the rest of Europe from Damascus by the Crusaders, or

that the Norsemen were so far advanced as to be able to

appreciate the artistic manufactures of Southern nations.

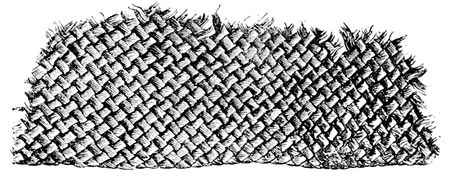

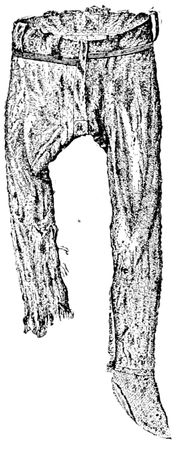

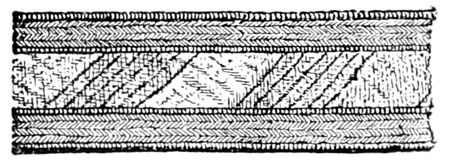

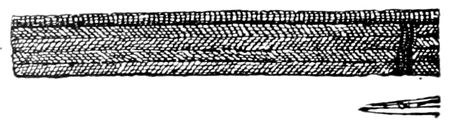

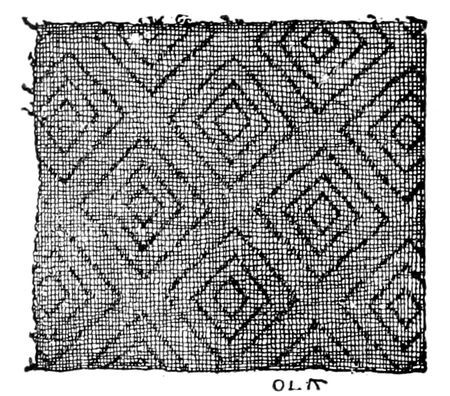

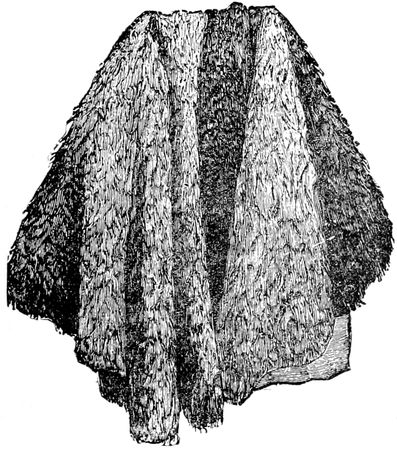

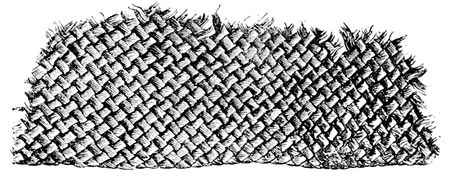

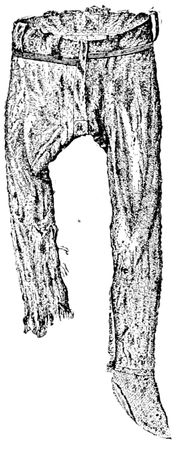

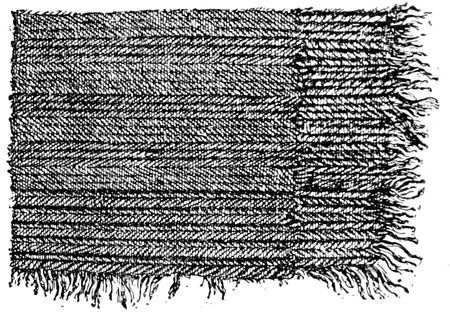

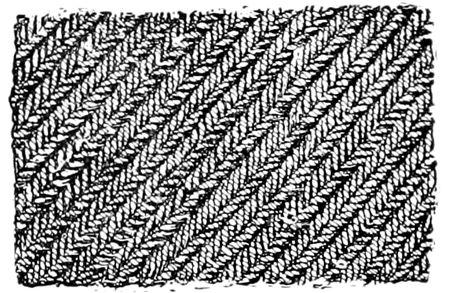

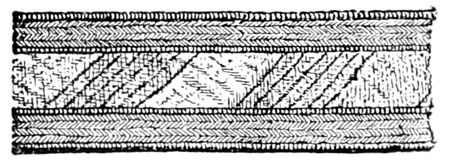

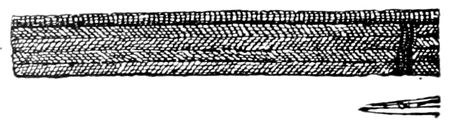

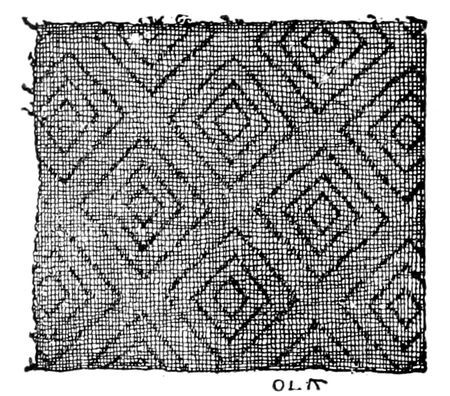

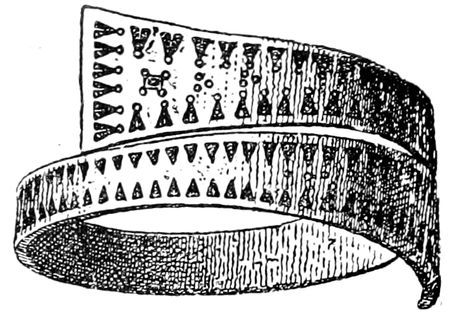

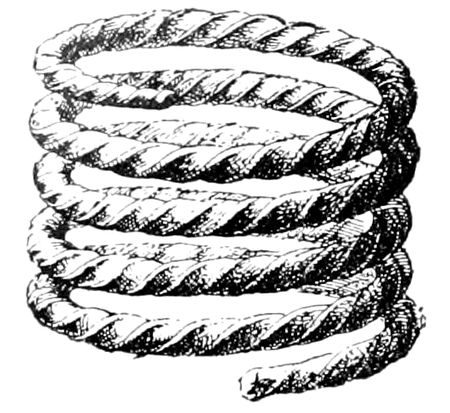

The remnants of articles of clothing with graceful patterns,

interwoven with threads of gold and silver, which have fortunately

escaped entire destruction, show the existence of

great skill in weaving. Entire suits of wearing apparel

remain to tell us how some of the people dressed in the

beginning of our era.

Beautiful vessels of silver and gold also testify to the taste

and luxury of those early times. The knowledge of the art

of writing and of gilding is clearly demonstrated. In some

cases, nearly twenty centuries have not been able to tarnish or

obliterate the splendour of the gilt jewels of the Northmen.

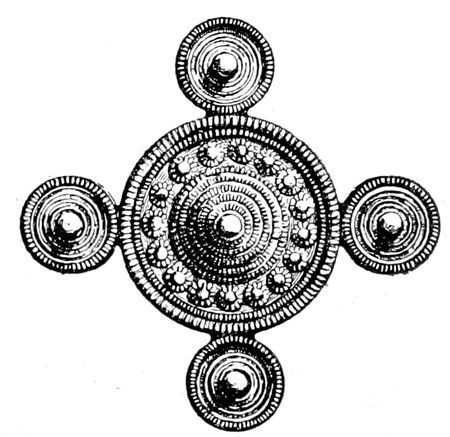

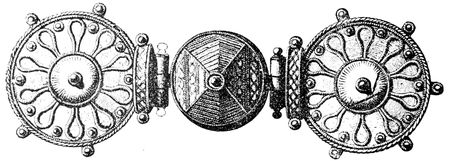

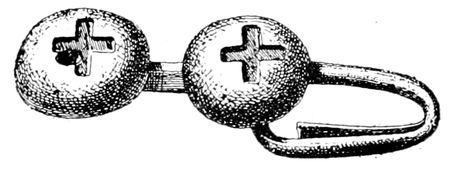

We find among their remains—either of their own manufacture

or imported, perhaps as spoils of war—repoussé work of

gold or silver, bronze, silver, and wood work covered with the

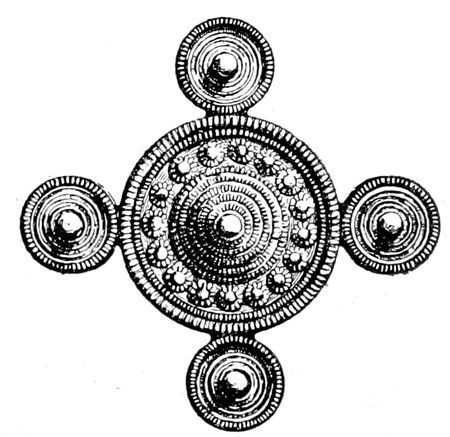

thinnest sheets of gold; the filigree work displays great skill,

and some of it could not be surpassed now. Many objects

are ornamented with niello, and of so thorough a northern

pattern, that they are incontestably of home manufacture.

The art of enamelling seems also to have been known to the

artificers of the period.

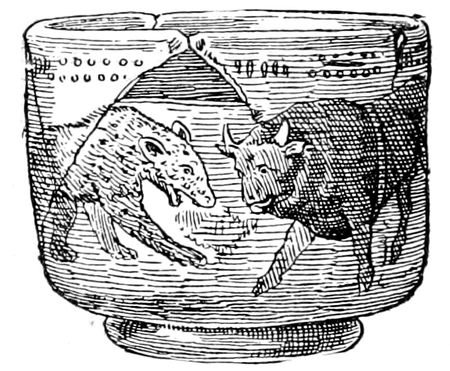

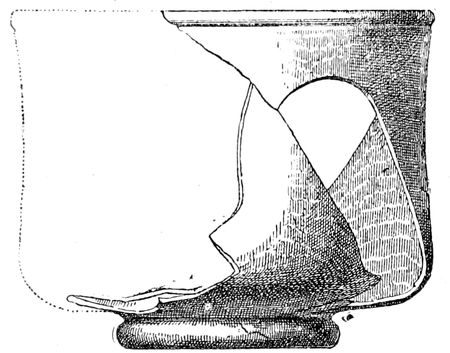

Objects, many of which show much refined taste, such as

superb specimens of glass vessels with exquisite painted

subjects—unrivalled for their beauty of pattern, even in the

museums of Italy and Russia—objects of bronze, &c., make us

pause with astonishment, and musingly ask ourselves from

6what country these came. The names of Etruria, of ancient

Greece, and of Rome, naturally occur to our minds.

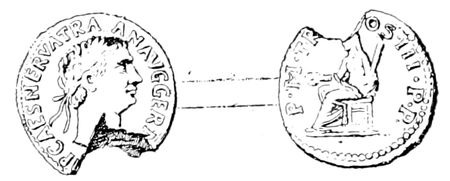

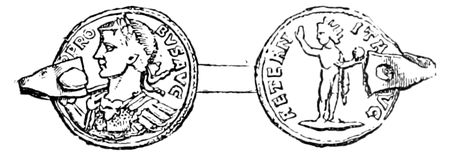

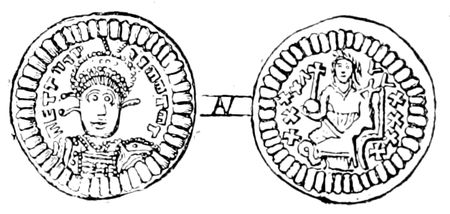

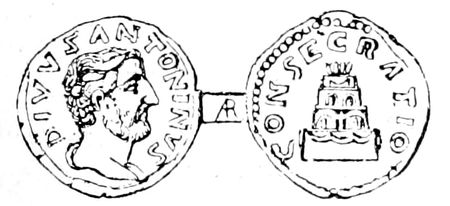

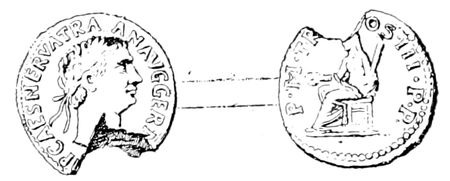

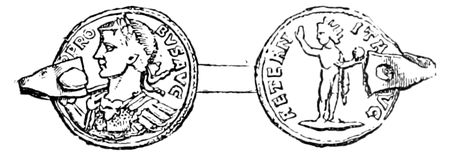

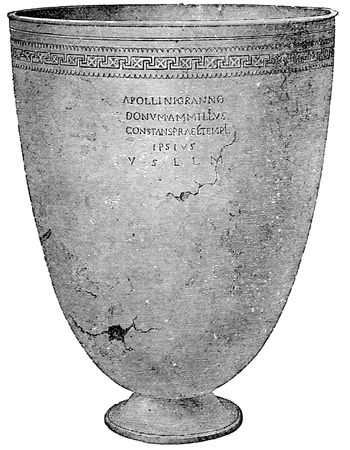

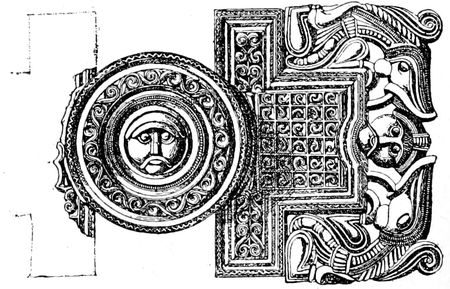

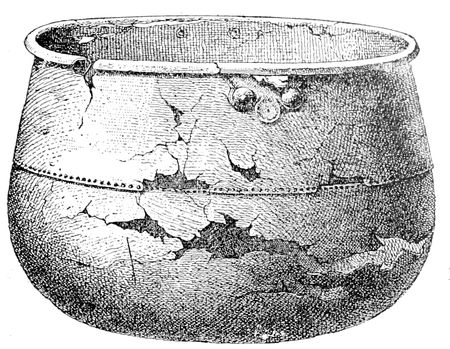

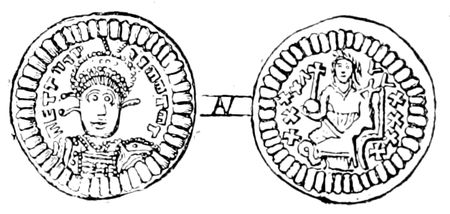

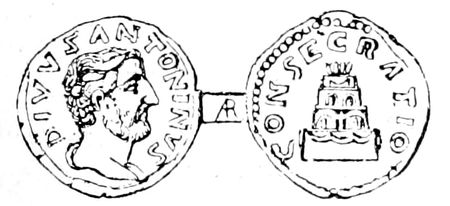

Other objects of unquestionable Roman and Greek manufacture,

and hundreds and thousands of coins, of the first,

second, third and fourth centuries of the Christian era, show

the early intercourse the people of the North had with the

western and eastern Roman empire, and with Frisia, Gaul,

and Britain.

A careful perusal of the Eddas and Sagas will enable us,

with the help of the ancient Greek and Latin writers, and

without any serious break in the chain of events, to make out

a fairly continuous history which throws considerable light on

the progenitors of the English-speaking people, their migrations

northward from their old home on the shores of the

Black Sea, their religion, and the settlement of Scandinavia,

of England, and other countries.

7

CHAPTER II.

ROMAN AND GREEK ACCOUNTS OF THE NORTHMEN.

The three maritime tribes of the North—The fleets of the Sueones—Expeditions

of Saxons and Franks—Home of these tribes—The tribes of

Germania not seafaring—Probable origin of the names Saxons and Franks.

Roman writers give us the names of three maritime tribes of

the North, which were called by them Sueones, Saxones, and

Franci. The first of these, which is the earliest mentioned, is

thus described by Tacitus (circ. 57–117 A.D.):—

“Hence the States of the Sueones, situated in the ocean

itself, are not only powerful on land, but also have mighty

fleets. The shape of their ships is different, in that, having

a prow at each end, they are always ready for running on to

the beach. They are not worked by sails, nor are the oars

fastened to the sides in regular order, but left loose as in

some rivers, so that they can be shifted here or there as

circumstances may require.”[4]

The word Sviar, which is constantly met with in the Sagas

to denote the inhabitants of Svithjod (Sweden), or the country

of which Upsala was the capital, corresponds somewhat to the

name Sueones, and it is highly probable that in Sueones we

have the root of Sviar and of Svithjod. The ships described

by Tacitus are exactly like those which are described in this

work as having been found in the North.

It stands to reason that the maritime power of the Sueones

must have been the growth of centuries before the time of

Tacitus, and from analogy of historical records we know that the

fleets of powerful nations do not remain idle. Hence we must

come to the conclusion that the Sueones navigated the sea long

8before the time of Tacitus, an hypothesis which is implied by

the Eddas and Sagas as well as by the antiquities discovered.

That the Sueones, with such fleets, did not navigate westward

further than Frisia is not credible, the more so that it was

only necessary for them to follow the coast in order to come to

the shores of Gaul, from which they could see Britain, and

such maritime people must have had intercourse with the

inhabitants of that island at that period; indeed, the objects

of the earlier iron age discovered in Britain, which were until

lately classed as Anglo-Roman, are identical with those of the

country from which these people came, i.e., Scandinavia.

The Veneti, a tribe who inhabited Brittany, and whose

power on the sea is described by Cæsar, were in all probability

the advance-guard of the tribes of the North; their ships

were built of oak, with iron nails, just as those of the Northmen;

and the people of the country in which they settled were

not seafaring.[5] Moreover, the similarity of the name to that

of the Venedi, who are conjecturally placed by Tacitus on the

shores of the Baltic, and to the Vends, so frequently mentioned

in the Sagas, can scarcely be regarded as a mere accident.

“The Veneti have a very great number of ships, with which

they have been accustomed to sail to Britain, and excel the

rest of the people in their knowledge and experience of

nautical affairs; and as only a few ports lie scattered along

9that stormy and open sea, of which they are in possession,

they hold as tributaries almost all those who have been

accustomed to traffic in that sea....”

“For their own ships were built and equipped in the following

manner: Their ships were more flat-bottomed than our vessels,

in order that they might be able more easily to guard against

shallows and the ebbing of the tide; the prows were very much

elevated, as also the sterns, so as to encounter heavy waves

and storms. The vessels were built wholly of oak, so as to

bear any violence or shock; the cross-benches, a foot in breadth,

were fastened by iron spikes of the thickness of the thumb;

the anchors were secured to iron chains, instead of to ropes;

raw hides and thinly-dressed skins were used for sails, either

on account of their want of canvas and ignorance of its use,

or for this reason, which is the more likely, that they considered

that such violent ocean storms and such strong winds

could not be resisted, and such heavy vessels could not be

conveniently managed by sails. The attack of our fleet on

these vessels was of such a nature that the only advantage

was in its swiftness and the power of its oars; in everything

else, considering the situation and the fury of the storm, they

had the advantage. For neither could our ships damage them

by ramming (so strongly were they built), nor was a weapon

easily made to reach them, owing to their height, and for the

same reason they were not so easily held by grappling-irons.

To this was added, that when the wind had begun to get

strong, and they had driven before the gale, they could better

weather the storm, and also more safely anchor among shallows,

and, when left by the tide, need in no respect fear rocks and

reefs, the dangers from all which things were greatly to be

dreaded by our vessels.”

Roman writers after the time of Tacitus mention warlike

and maritime expeditions by the Saxons and Franks. Their

names do not occur in Tacitus, but it is not altogether

improbable that these people, whom later writers mention as

ravaging every country which they could enter by sea or land,

are the people whom Tacitus knew as the Sueones.

The maritime power of the Sueones could not have totally

disappeared in a century, a hypothesis which is borne out

by the fact that after a lapse of seven centuries they are

again mentioned in the time of Charlemagne; nor could the

supremacy of the so-called Saxons and Franks on the sea have

10arisen in a day; it must have been the growth of even generations

before the time of Tacitus.

Ptolemy (circ. A.D. 140) is the first writer who mentions the

Saxons as inhabiting a territory north of the Elbe, on the neck

of the Cimbric Chersonesus.[6] They occupied but a small space,

for between them and the Cimbri, at the northern extremity of

the peninsula, he places ten other tribes, among them the Angli.

About a century after the time of Ptolemy, Franks and

Saxons had already widely extended their expeditions at sea.

Some of the former made an expedition from the Euxine,

through the Mediterranean, plundered Syracuse, and returned

without mishap across the great sea (A.D. circ. 280).[7]

“He (Probus) permitted the Bastarnæ, a Scythian race, who

had submitted themselves to him, to settle in certain districts

of Thrace which he allotted to them, and from thenceforth

these people always lived under the laws and institutions of

Rome. And there were certain Franks who had come to the

Emperor, and had asked for land on which to settle. A part

of them, however, revolted, and having obtained a large

number of ships, caused disturbances throughout the whole of

Greece, and having landed in Sicily and made an assault on

Syracuse, they caused much slaughter there. They also landed

in Libya, but were repulsed at the approach of the Carthaginian

forces. Nevertheless, they managed to get back to

their home unscathed.”

“Why should I tell again of the most remote nations of the

Franks (of Francia), which were carried away not from those

regions which the Romans had on a former occasion invaded,

but from their own native territory, and the farthest shores of the

land of the barbarians, and transported to the deserted parts of

Gaul that they might promote the peace of the Roman Empire

by their cultivation and its armies by their recruits?”[8]

11“There came to mind the incredible daring and undeserved

success of a handful of the captive Franks under the Emperor

Probus. For they, having seized some ships, so far away as

Pontus, having laid waste Greece and Asia, having landed and

done some damage on several parts of the coast of Africa,

actually took Syracuse, which was at one time so renowned

for her naval ascendancy. Thereupon they accomplished a

very long voyage and entered the Ocean at the point where it

breaks through the land (the Straits of Gibraltar), and so by

the result of their daring exploit showed that wherever ships

can sail, nothing is closed to pirates in desperation.”[9]

In the time of Diocletian and Maximian these maritime

tribes so harassed the coasts of Gaul and Britain that Maximian,

in 286, was obliged to make Gesoriacum or Bononia

(the present Boulogne) into a port for the Roman fleet, in

order as far as possible to prevent their incursions.

“About this time (A.D. 287) Carausius, who, though of very

humble origin, had, in the exercise of vigorous warfare,

obtained a distinguished reputation, was appointed at Bononia

to reduce to quiet the coast regions of Belgica and Armorica,

which were overrun by the Franks and Saxons. But though

many of the barbarians were captured, the whole of the booty

was not handed over to the inhabitants of the province, nor

sent to the commander-in-chief, and the barbarians were,

moreover, deliberately allowed by him to come in, that he

might capture them with their spoils as they passed through,

and by this means enrich himself. On being condemned to

death by Maximian, he seized on the sovereign command, and

took possession of Britain.”[10]

Eutropius also records that the Saxons and others dwelt on

the coasts of and among the marshes of the great sea, which

12no one could traverse, but the Emperor Valentinian (320–375)

nevertheless conquered them.

The Emperor Julian calls the

“Franks and Saxons the most warlike of the tribes above

the Rhine and the Western Sea.”[11]

Ammianus Marcellinus (d. circ. 400 A.D.) writes:—

“At this time (middle of the 4th century), just as though

the trumpets were sounding a challenge throughout all the

Roman world, fierce nations were stirred up and began to

burst forth from their territories. The Alamanni began to

devastate Gallia and Rhætia; the Sarmatæ and Quadi Pannonia,

the Picts and Saxons, Scots, and Attacotti constantly

harassed the Britons.”[12]

“The Franks and the Saxons, who are coterminous with

them, were ravaging the districts of Gallia wherever they

could effect an entrance by sea or land, plundering and

burning, and murdering all the prisoners they could take.”[13]

Claudianus asserts that the Saxons appeared even in the

Orkneys:—

“The Orcades were moist from the slain Saxon.”[14]

These are but a few of many allusions to the same effect

which might be quoted.

That the swarms of Sueones and so-called Saxons and

Franks, seen on every sea of Europe, could have poured

forth from a small country is not possible. Such fleets as

they possessed could only have come from a country densely

covered with oak forests. We must come to the conclusion

that Sueones, Franks, and Saxons were seafaring tribes belonging

to one people. The Roman writers did not seem to

know the precise locality inhabited by these people.

13It would appear that these tribes must have come from a

country further eastward than the Roman provinces, and that

as they came with ships, their home must have been on the

shores of the Baltic, the Cattegat, and Norway; in fact,

precisely the country which the numerous antiquities point

to as inhabited by an extremely warlike and maritime race,

which had great intercourse with the Greek and Roman world.

The dates given by the Greek and Roman writers of the

maritime expeditions, invasions, and settlements of the so-called

Saxons and Franks agree perfectly with the date of the

objects found in the North, among which are numerous Roman

coins, and remarkable objects of Roman and Greek art, which

must have been procured either by the peaceful intercourse of

trade or by war. To this very day thousands upon thousands

of graves have been preserved in the North, belonging to the

time of the invasions of these Northmen, and to an earlier

period. From them no other inference can be drawn than

that the country and islands of the Baltic were far more

densely populated than any part of central and western

Europe and Great Britain, since the number of these earlier

graves in those countries is much smaller.

Every tumulus described by antiquaries as a Saxon or

Frankish grave is the counterpart of a Northern grave, thus

showing conclusively the common origin of the people.

Wherever graves of the same type are found in other

countries we have the invariable testimony, either of the

Roman or Greek writers of the Frankish and English

Chronicles or of the Sagas, to show that the people of the

North had been in the country at one time or another.

The conclusion is forced upon us that in time the North

became over-populated, and an outlet was necessary for the

spread of its people.

The story of the North is that of all countries whose

inhabitants have spread and conquered, in order to find new

fields for their energy and over-population; in fact, the very

course the progenitors of the English-speaking peoples adopted

in those days is precisely the one which has been followed by

their descendants in England and other countries for the last

three hundred years.

14It is certain that the Franks could not have lived on the

coast of Frisia, as they did later on, for we know that the

country of the Rhine was held by the Romans, and, besides,

as we have already seen, Julian refers to the Franks and

Saxons as dwelling above the Rhine. Moreover, till they

had to give up their conquests, no mention is made by the

Romans of native seafaring tribes inhabiting the shores of

their northern province, except the Veneti, and they would

have certainly tried to subjugate the roving seamen that

caused them so much trouble in their newly-acquired provinces

if they had been within their reach.

From the Roman writers, who have been partially confirmed

by archæology, we know that the tribes which inhabited the

country to which they give the vague name of Germania were

not seafaring people nor possessed of any civilisation. The

invaders of Britain, of the Gallic and of the Mediterranean

coasts could therefore not have been the German tribes referred

to by the Roman writers, who, as we see from Julius Cæsar

and other Roman historians, were very far from possessing the

civilisation which we know, from the antiquities, to have

existed in the North.

“Their whole life is devoted to hunting and warlike

pursuits. From childhood they pay great attention to toil

and hardiness; they bathe all together in the rivers, and wear

skins or small reindeer garments, leaving the greater part of

their bodies naked.”[15]

Tacitus, in recording the speech of Germanicus to his troops

before the battle at Idistavisus, bears witness to the uncivilised

character of the inhabitants of the country.

“The huge targets, the enormous spears of the barbarians

could never be wielded against trunks of trees and thickets

of underwood shooting up from the ground, like Roman swords

and javelins, and armour fitting the body ... the Germans

had neither helmet nor coat of mail; their bucklers were not

even strengthened with leather, but mere contextures of twigs

15and boards of no substance daubed over with paint. Their

first rank was to a certain extent armed with pikes, the rest had

only stakes burnt at the ends or short darts.”[16]

Now compare these descriptions with the magnificent

archæology of the North of that period—as seen in these

volumes—from which we learn that the tribes who inhabited

the shores of the Baltic and the present Scandinavia had at

the time the above was written reached a high degree of civilisation.

We find in their graves and hoards, coins of the early

Roman Empire not in isolated instances, but constantly and

in large numbers, and deposited side by side with such objects

as coats of mail, damascened swords and other examples of

articles of highly artistic workmanship.

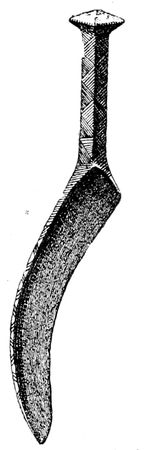

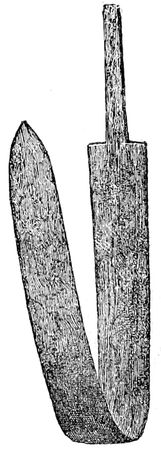

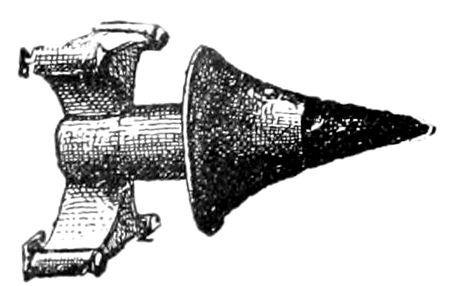

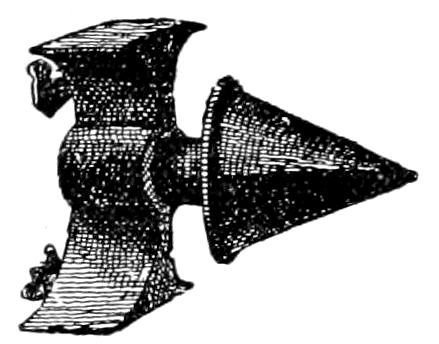

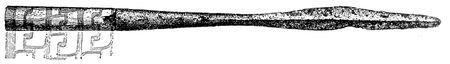

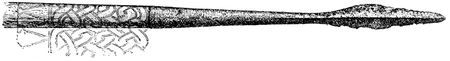

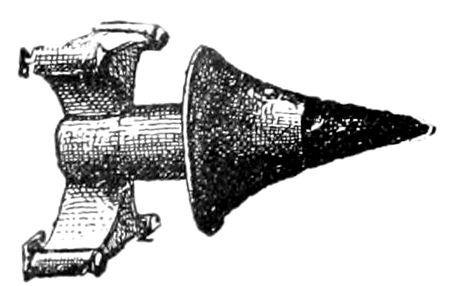

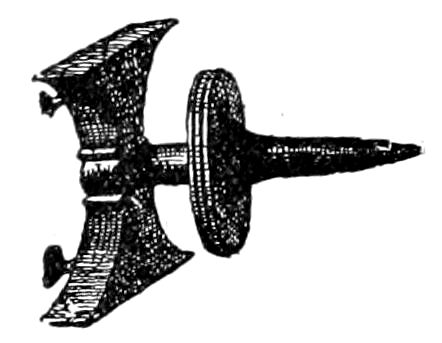

Three kinds of swords are often mentioned by the Northmen—the

mœkir, the sverd, and the sax, while among the spears

there is one called frakki, or frakka.

The double-edged sword was the one that was in use among

the Romans, and they, seeing bodies of men carrying a weapon

unlike theirs—single-edged, and called Sax—may have named

them after it, and the Franks, in like manner, may have been

called after their favourite weapon, the Frakki; but we see

that neither the sax nor the frakki was confined to one tribe

in the North. There is a Saxland in the Sagas—a small

country situated east of the peninsula of Jutland, about the

present Holstein—a land tributary to the Danish or Swedish

Kings from the earliest times, but far from possessing the

warlike archæology of the North, it appears to have held an

insignificant place among the neighbouring tribes.

In the Bayeux tapestry the followers of William the Conqueror

were called Franci, and they always have been recognised

as coming from the North.

The very early finds prove that the Sax was not rare, for it

occurs in different parts of the North and islands of the Baltic.

The different swords and spears used were so common and so

16well known to everybody, that we have no special description

of them in the Sagas, except of their ornamentation; but in

the Saga of Grettir there is a passage which shows that the

Sax was single-edged.

Gretti went to a farm in Iceland to slay the Bondi Thorbjorn

and his son Arnor. We read—

“When Gretti saw that the young man was within reach he

lifted his sax high into the air, and struck Arnor’s head with

its back, so that his head was broken and he died. Thereupon

he killed the father with his sax.”

Whatever may be the origin of local names employed by

the Roman writers we must look to the North for the maritime

tribes described by them; there we shall find the home

of the earlier English people, to whose numerous warlike

and ocean-loving instincts we owe the transformation which

took place in Britain, and the glorious inheritance which they

have left to their descendants, scattered over many parts of

the world, in whom we recognise to this day many of the very

same traits of character which their ancestors possessed.

17

CHAPTER III.

THE SETTLEMENT OF BRITAIN BY NORTHMEN.

The Notitia—Probable origin of the name England—Jutland—The language

of the North and of England—Early Northern kings in England—Danes

and Sueones—Mythical accounts of the settlements of England.

Britain being an island could only be settled or conquered

by seafaring tribes, just in the same way as to-day distant

lands can only be conquered by nations possessing ships.

From the Roman writers we have the only knowledge we

possess in regard to the tribes inhabiting the country to

which they gave the vague name of Germania. From the

Roman records we find that these tribes were not civilised

and that they were not a seafaring people.

Unfortunately the Roman accounts we have of their conquest

and occupation of Britain, of its population and inhabitants,

are very meagre and unsatisfactory, and do not help us much

to ascertain how the settlement in Britain by the people of the

North began. Our lack of information is most probably due

to the simple reason that the settlement, like all settlements

of a new country, was a very gradual one, a few men coming

over in the first instance for the purpose of trade either

with Britons or Romans, or coming from the over-populated

North to settle in a country which the paucity of archæological

remains shows to have been thinly occupied. The Romans

made no objection to these new settlers, who did not prove

dangerous to their power on the island, but brought them

commodities, such as furs, &c., from the North.

We find from the Roman records that the so-called Saxons

had founded colonies or had settlements in Belgium and

Gaul.

Another important fact we know from the records relating

18to Britain is that during the Roman occupation of the island

the Saxons had settlements in the country; but how they came

hither we are not told.

In the Notitia Dignitatum utriusque imperii, a sort of catalogue

or “Army List,” compiled towards the latter end of the

fourth century, occurs the expression, “Comes litoris Saxonici

per Britannias”—Count of the Saxon Shore in Britain. Within

this litus Saxonicum the following places are mentioned:—Othona,

said to be “close by Hastings”; Dubris, said to be

Dover; Rutupiæ, Richborough; Branodunum, Brancaster;

Regulbium, Reculvers; Lemannis, West Hythe; Garianno,

Yarmouth; Anderida, Pevensey; Portus Adurni, Shoreham or

Brighton.

This shows that the so-called Saxons were settled in Britain

before the Notitia was drawn up, and at a date very much

earlier than has been assigned by some modern historians.

The hypothesis that the expression “litus Saxonicum” is

derived from the enemy to whose ravages it was exposed

seems improbable. Is it not much more probable that the

“litus Saxonicum per Britannias” must mean the shore

of the country settled, not attacked, by Saxons? The mere

fact of their attacking the shore would not have given rise to

the name applied to it had they not settled there, for I

maintain that there is no instance in the whole of Roman

literature of a country being named after the people who

attacked it. If, on the other hand, the Saxons had landed and

formed settlements on the British coasts, the origin of the

name “Litus Saxonicum” is easily understood.

Some time after the Romans relinquished Britain we find

that part of the island becomes known as England; and, to

make the subject still more confusing, the people composing

its chief population are called Saxons by the chroniclers and

later historians, the name given to them by the Romans.

That the history of the people called Saxons was by no means

certain is seen in the fact that Witikind, a monk of the tenth

century, gives the following account of what was then considered

to be their origin[17]:—

19“On this there are various opinions, some thinking that

the Saxons had their origin from the Danes and Northmen;

others, as I heard some one maintain when a young man,

that they are derived from the Greeks, because they themselves

used to say the Saxons were the remnant of the Macedonian

army, which, having followed Alexander the Great, were by

his premature death dispersed all over the world.”

As to how Britain came to be called England the different

legends given by the monkish writers are contradictory.

The Skjöldunga Saga, which is often mentioned in other

Sagas, and which contains a record down to the early kings

of Denmark, is unfortunately lost: it would, no doubt, have

thrown great light on the lives of early chiefs who settled in

Britain; but from some fragments which are given in this

work, and which are supposed to belong to it, we see that

several Danish and Swedish kings claimed to have possessions

in England long before the supposed coming of the Danes.

Some writers assert that the new settlers gave to their new

home in Britain the name of the country which they had left,

called Angeln, and which they claim to be situated in the

southern part of Jutland; but besides the Angeln in Jutland

there is in the Cattegat an Engelholm, which is geographically

far more important, situated in the land known as the

Vikin of the Sagas, a great Viking and warlike land, from

which the name Viking may have been derived, filled with

graves and antiquities of the iron age. There are also other

Engeln in the present Sweden.

In the whole literature of the North such a name as Engeln

is unknown; it may have been, perhaps, a local name.

In the Sagas the term England was applied to a portion

only of Britain, the inhabitants of which were called Englar,

Enskirmenn. Britain itself is called Bretland, and the people

Bretar.

“Öngulsey (Angelsey) is one third of Bretland (Wales)”

(Magnus Barefoot’s Saga, c. 11).

20Another part of the country was called Nordimbraland.

It is an important fact that throughout the Saga literature

describing the expeditions of the Northmen to England not a

single instance is mentioned of their coming in contact with a

people called Saxons, which shows that such a name in Britain

was unknown to the people of the North. Nor is any part of

England called Saxland.

To make the confusion greater than it is, some modern

historians make the so-called Saxons, who were supposed to

have come over with the mythical Hengist and others, a

distinct race from the Northmen, who afterwards continued to

land in the country.

In the Sagas we constantly find that the people of England

are not only included among the Northern lands, but that the

warriors of one country are helping the other. In several

places we find, and from others we infer, that the language in

both countries was very similar.

“All sayings in the Northern (norræn) tongue in which there

is truth begin when the Tyrkir and the Asia-men settled in

the North. For it is truly told that the tongue which we call

Norræn came with them to the North, and it went through

Saxland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and part of England”

(Rimbegla, iii. c. i.).

“We are of one tongue, though one of the two, or in some

respects both, are now much changed” (Prose Edda, ii.)

“Then ruled over England King Ethelred, son of Edgar

(979). He was a good chief; he sat this winter in London.

The tongue in England, as well as in Norway and Denmark,

was then one, but it changed in England when William the

Bastard won England. Thenceforth the tongue of Valland

(France) was used in England, for he (William) was born

there” (Gunnlaug Ormstunga’s Saga, c. 7).

That the language of the North should have taken a footing

in a great part of England is due, no doubt, to the continuous

flow of immigration, from the northern mother country, which

entirely swamped the former native or British element.

The story given in the English or Irish chronicles of the

appearance of the Danes, in A.D. 785, when their name is first

mentioned, is as little trustworthy as that of the settlement of

21England, and bears the appearance of contradiction and

confusion in regard to names of people and facts.

We must remember that the Sueones are not mentioned from

the time of Tacitus to that of Charlemagne (772–814), and

certainly they had not disappeared in the meantime.

What were the Danes doing with their mighty fleets before

this? Had their ships been lying in port for centuries?

Had they been built for simple recreation and the pleasure of

looking at them, or did their maritime power arise at once as

if by magic? Such an hypothesis cannot stand the test of

reasoning. The turning of a population into a seafaring

nation is the work of time. Where in the history of the world

can we find a parallel to this story of a people suddenly

appearing with immense navies? Let us compare by analogy

the statement of the chronicles with what might happen to

the history of England in the course of time.

Suppose that for some reason the previous history of England

were lost, with the exception of a fragment which spoke of her

enormous fleet of to-day. Could it be reasonably supposed

that this great maritime power was the creation of a few years?

A few years after the time fixed as that of their first supposed

appearance we find these very Danes swarming everywhere with

their fleets and warriors, not only in England, but in Gaul, in

Brittany, up the Seine, the Garonne, the Rhine, the Elbe, on

the coasts of Spain, and further eastward in the Mediterranean.

The Sueones, or Swedes, reappear at the close of the eighth

and commencement of the ninth centuries by the side of the

Danes, and both called themselves Northmen. Surely the

maritime power of the Sueones, described by Tacitus, could

not have been destroyed immediately after his death, only to

reappear in the time of Charlemagne, when it again becomes

prominent in the Frankish annals.

A remarkable fact not to be overlooked is that, in the time

of Charlemagne, the Franks and Saxons were not a seafaring

people, though their countries had an extensive coast with

deep rivers. The Frankish annals never mention a Frank or

Saxon fleet attacking the fleets of the Northmen, or preventing

them from ascending their streams, though Charlemagne

ordered ships to be built in order to resist their incursions.

22While the country of the Saxons was being conquered by

this Emperor, we find that the Saxons themselves had no

vessels on the Elbe or Weser in which, if defeated, they could

retire in safety, or by help of which they could prevent the

army of their enemies from crossing their streams. Such

tactics were constantly used by the Northmen in their invasions

of ancient Gaul, Britain, Germania, Spain, &c.

Thus we see that, though hardly more than three hundred

years had elapsed since the time when, according to the

Roman writers, the fleets of the Franks and Saxons swarmed

over every sea of Europe, not a vestige of their former

maritime power remained in the time of Charlemagne, and

the Saxons were still occupying the same country as in the

days of Ptolemy.

Pondering over the above important facts, the question

arises: Were not the Romans mistaken in giving the names of

Saxons and Franks to the maritime tribes of whose origin,

country, and homes they knew nothing, but who came to

attack their shores? Were not these so-called Saxons and

Franks in reality tribes of Sueones, Swedes, Danes, Norwegians?

The Romans knew none of the countries of these

people. It seems strange, if not incredible, to find two

peoples, whose country had a vast sea-coast and deep rivers,

totally abandoning the seafaring habits possessed by their

forefathers.

It cannot be doubted that Ivar Vidfadmi, after him Harald

Hilditönn, then Sigurd Hring and Ragnar Lodbrok and his

sons, and probably some of the Danish and Swedish kings

before them, made expeditions to England, and gained and

held possessions there. Several distinct records, having no

connection with each other, being parts of different Sagas and

histories, with the archæology, form the evidence.

“Ivar Vidfadmi (wide-fathomer) subdued the whole of

Sviaveldi (the Swedish realm); he also got Danaveldi (Danish

realm) and a large part of Saxland, and the whole of Austrriki

(Eastern realm, including Russia, &c.) and the fifth part of

England. From his kin have come the kings of Denmark and

the kings of Sweden who have had sole power in these lands”

(Ynglinga Saga, c. 45).

23The above is corroborated by another quite independent

source.

“Ivar Vidfadmi ruled England till his death-day. As

he lay on his death-bed he said he wanted to be carried to

where the land was exposed to attacks, and that he hoped

those who landed there would not be victorious. When he

died it happened as he said, and he was mound-laid. It is

said by many men that when King Harald Sigurdsson came

to England he landed where Ivar’s mound was, and he was

slain there. When Vilhjálm Bastard came to the land he

broke open the mound of Ivar and saw that the corpse was not

rotten; he made a large pyre, and had Ivar burned on it;

then he went up on land and got the victory” (Ragnar

Lodbrók’s Saga, c. 19).

We find that not only did the Norwegians call themselves

Northmen, but that both Danes and Sueones were called

Northmen in the Frankish Chronicles.[18]

“The Danes and Sueones, whom we call Northmen, occupy

both the northern shore and all its islands.”

So also Nigellus (in the reign of Louis Le Debonnaire).[19]

“The Danes also after the manner of the Franks are called

by the name of Manni.”

The time came when the people of the North, continuing

their expeditions to Britain, attacked their own kinsmen.

After the departure of the Romans the power of the new

comers increased, and as they became more numerous, they

became more and more domineering: the subsequent struggles

were between a sturdy race that had settled in the country

and people of their own kin, and not with Britons, who had

been so easily conquered by the Romans, had appealed to

them afterwards for protection, and had for a long period

been a subject race. It is not easy to believe that the

inhabitants of a servile Roman province could suddenly

become stubborn and fierce warriors, nor are there any

antiquities belonging to the Britain of yore which bear

24witness to a fierce and warlike character displayed by the

aboriginal inhabitants.

From the preceding pages we see that Franks and Saxons

are continually mentioned together, and it is only in the

North we can find antiquities of a most warlike and seafaring

people, who must have formed the great and preponderating

bulk of the invading host who conquered Britain.

Britain after a continuous immigration from the North,

which lasted several hundred years, became the most powerful

colony of the Northern tribes, several of whose chiefs claimed

a great part of England even in the seventh century. Afterwards

she asserted her independence, though she did not

get it until after a long and tedious struggle with the North,

the inhabitants and kings of which continued to try to assert

the ancient rights their forefathers once possessed. Then the

time came when the land upon which the people of these

numerous tribes had settled became more powerful and more

populous than the mother country; a case which has found

several parallels in the history of the world. To-day the

people of England as they look over the broad Atlantic may

perhaps discern the same process gradually taking place.

In the people of the United States of North America, the

grandest and most colossal state founded by England or

any other country of which we have any historical record, we

may recognise the indomitable courage, the energy and spirit

which was one of the characteristics of the Northern race to

whom a great part of the people belong. The first settlement

of the country, territory by territory, State by State—the

frontier life with its bold adventures, innumerable dangers,

fights, struggles, privations and heroism—is the grandest

drama that has ever been enacted in the history of the world.

The time is not far distant, if the population of the United

States and Canada increases in the same ratio as it has done for

more than a hundred years, when over three or four hundred

millions of its people will speak the English tongue; and I

think it is no exaggeration to say that in the course of time

one hundred millions more will be added, from Australia, New

Zealand and other colonies which to-day form part of the British

Empire, but which are destined to become independent nations.

25In fact we hesitate to look still further into the future of the

English race, for fear of being accused of exaggeration.

There is a mythical version of the settlement of Britain

contradictory of the Roman records. This version is that of

Gildas whose ‘De Excidio Britanniæ’ is supposed to have

been composed in the sixth century (560 A.D.), and whose

statements have unfortunately been taken by one historian

after the other as a true history of Britain. His narrative,

which gives an account of the first arrival of the Saxons in

Britain and the numerous wars which followed their invasion,

has been more or less copied by Nennius, Bede and subsequent

chroniclers, whose writings are a mass of glaring

contradictions, diffuse and intricate, for they contain names

which appear to have been invented by the writers and which

cannot be traced in the language of those times, while the

dates assigned for the landing of the so-called Saxons do not

agree with one another.

The historians who use Gildas as an authority and try to

believe his account of the settlement of Britain by Hengist

and Horsa (the stallion and the mare) are obliged, in order to

explain away the Roman records, to give a most extraordinary

interpretation to the Notitia.

We are all aware that the people of every country like to

trace their origin or history as far back as possible, and that

legends often form part of the fabric of those histories. The

early chroniclers, who were credulous and profoundly ignorant

of the world, took these fables for facts, or they may have

possibly been incorporated in the text of their supposed works

after their time. The description of the settlement of a

country must be founded on facts which can bear the test of

searching criticism if they are to be believed and adopted;

Gildas and his copyists cannot stand that test, and the Roman

records, as corroborated by the archæology and literature of

the North and the archæology of England, must be taken as

the correct ones.

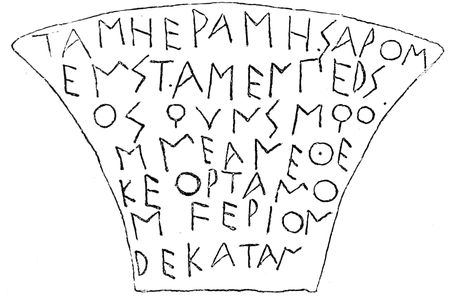

The mythological literature of the North bears evidence