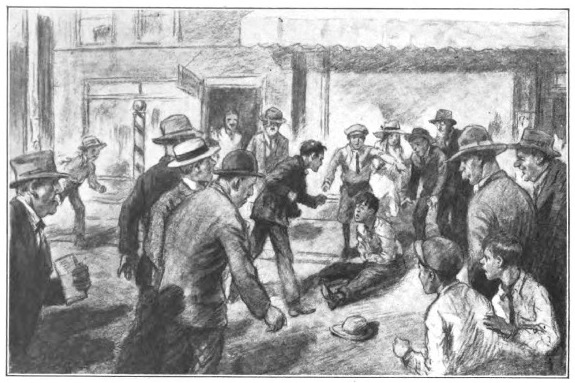

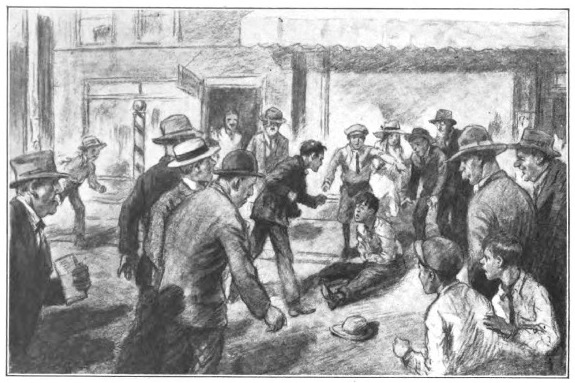

All of a sudden he jumped at Skoodles and quicker than a cat he hit him twice, once on the nose and once on the stummick, and Skoodles sat down to think it over

All of a sudden he jumped at Skoodles and quicker than a cat he hit him twice, once on the nose and once on the stummick, and Skoodles sat down to think it over

I put a bottle on a box against the side of the barn and aimed as careful as all-git-out. My idea was to bust it right at the neck. Well, I jerked on the trigger and the gun went off and I looked at the bottle. It was still there, neck and all.

After the aim I took it didn’t seem possible, so I walked up close to find out if maybe I hadn’t slammed a hole right through it that couldn’t be seen—but there wasn’t any hole. I knew right off there must be something wrong with that gun. It was the very first time I’d ever shot it, and if a gun don’t shoot straight the first time, when it’s spang-whang new, what kind of shooting will it do when it gets to be old and worn? I was dog-gone disappointed.

Dad gave me that rifle for my birthday and I’d come hustling out right after breakfast to give it a try—and it wasn’t any good! I put in another cartridge and got some closer to the bottle and tried again. The bottle never wiggled. I came some closer and shot again, and then I came still closer and shot again. Six times I shot before I hit the danged thing and then I was so close I could have knocked it over with the rifle-barrel.

“Pretty middlin’ shootin’,” says somebody behind me, and I turned around quick. There was a kid I’d never seen. He was kind of small, with bare feet and clothes that looked as if he’d found them in an ash-barrel and then slept in them. His hair was kind of bristly, and he didn’t have on any hat. He wasn’t smiling or making fun of me as far as I could see, for his face was as sober as a houseful of deacons. It was a kind of a thin face with a sharp chin and a straight nose and funny crinkles around the eyes. But the eyes were gray and kind of sparkly. I looked at him a minute, wondering who he was, before I said anything. Then I says:

“Calc’late this gun ain’t much good.”

“Is it a reg’lar gun,” says he, “or jest a kind of a cap pistol?”

That made me mad, so I says, sarcastic: “Naw, this ain’t a gun. This is a pan of mush and milk.”

“Maybe,” says he, kind of slow and solemn, like he was thinking it over mighty careful—“maybe you could hit things better with it if it was mush and milk. It would spatter more.”

“Say,” says I, “who are you, anyhow?”

“I wa’n’t brung up to give anythin’ away free,” says he, “but I’ll trade you—my name for yourn.”

“It’s a trade,” says I. “Mine’s Moore. Mostly the kids call me Wee-wee.”

“Mine’s Atkins,” says he, “and folks call me Catty because I can climb like one.”

“One what?” says I.

“Mud turtle,” says he; “that’s plain. C-a-t-t-y—mud turtle. Spells it every time where I come from.”

“Where’d you come from?”

“Different places.”

“Goin’ to live here?”

“Maybe.”

“Don’t you know?”

“Hain’t thought about it much.”

“If you’re not goin’ to live here, what made you come here?”

“A body’s got to go some place,” says he, very solemn. “Dad and me wasn’t p’tic’lar. We didn’t start out to come here, we just got here, and here we be!”

“What’s your Dad do?”

“Dad don’t do much. He calc’lates to be shiftless.”

“Don’t he work?”

“I’ve seen him,” says Catty, “but it hain’t usual.”

“Are you rich?”

“Well—we got our health and these here clothes is mine, free and clear. No mortgages on ’em nor nothin’. Dad’s clothes is his’n, too, but they hain’t so gaudy as mine.”

“Kind of tramps?” says I, getting interested.

“Not tramps—j’st shiftless. Didn’t I tell you?”

“Where you sleepin’?”

“If you ain’t careful,” he says, as solemn as an owl, “you’ll ketch yourself askin’ a question. We been livin’,” says he, “in a little house down by the bayou.”

“That tumble-down shanty not far from the waterworks?”

“That’s the one.”

“There isn’t any furniture in it,” says I. “Movin’ about like Dad and me, furniture would be a nuisance.”

“There’s no glass in the windows.”

“We’re partial to fresh air.”

“Huh!” says I. “You’re dog-gone easy suited. If your Dad doesn’t work, how do you get to eat?”

“Well, there’s times when we have more mealtimes than we do meals, but Dad he gits an odd job, and I git an odd job and mostly we do pretty well, thank you kindly.” Just then Dad came out through the back gate, and right here I want to say something about my Dad. I heard a couple of women say one day that they guessed he was a little crazy, but I want to let you know that he ain’t crazy a bit, and I can lick any feller that says he is. Dad ain’t old, either. He ain’t forty yet. Only thing I got to complain about is the way he cusses over my grammar. He always talks as correct as Mother does, only more so, and he’s got manners. Not the kind of manners folks put on at a party or in church, but the kind you have always and use always and that look to people as if you didn’t really try to have ’em, but as if they came natural.

The reason those women said he was kind of crazy is because he don’t act just like everybody else in town. He’s polite even to the man that comes to get our garbage, and he treats boys as if they were just as old as he is, and don’t call them “My boy” and “Bub” and such like names. And he fusses around with me just like he was a kid. Why, he can do more things than any kid I ever saw!

“How’s the gun?” says he.

“Somethin’ seems to be wrong with it,” I says. “It don’t hit things.”

“Let me see,” he says, and just then a big rat went running along the alley. Well, sir, quick as a wink Dad snapped the gun to his shoulder, and off it went, and the rat went end over end. I ran over and picked it up by the tail. It was shot right plumb through the head.

“Huh!” says I.

“Maybe,” says Dad, “something was wrong with the way you aimed it.”

“Maybe,” says I.

Dad looked over at Catty and smiled. “Good morning,” says he.

“Good morning,” says Catty.

“Don’t believe I know you,” says Dad.

“He’s Catty Atkins,” says I. “He and his Dad just came to town. They’re shiftless.” Dad looked quick at Catty to see if I’d said something that hurt his feelings, but Catty only nodded that I was right.

“Do you find it hard work, being shiftless?” says Dad.

“We make out to enjoy it,” says Catty. “It must be pleasant,” says Dad. “I’ve often wished I was fixed so I could be shiftless. But when you’ve a family—”

Catty nodded. “There’s just Dad and me. He didn’t used to be shiftless till Ma died, so he says.”

“Are you going to make a profession of it,” Dad says, “or do you plan to do something else when you grow up?”

“Hain’t thought about it,” says Catty. “It must be fine,” says Dad, “to start off in the morning and not know where you are going, and not to care, and not to feel that you’ve ever got to come back. It must be splendid to go fishing when you want to, or to lie on your back in the sun when you want to, and to know that there’s no reason why you shouldn’t. Somehow it seems to me that if I could be shiftless I’d rather work at it in the country, in the woods or mountains, than around towns.” He nodded his head and so did Catty. “I’d rather be shiftless like a squirrel than like an alley cat,” Dad says.

“The bear’s the feller,” says Catty. “He pokes around and does what he wants to all summer when it’s fine, and then he goes to sleep warm and comfortable all winter, with no bother about grub or fuel. I wisht I was a bear.”

“Do you like corners?” says Dad, and I didn’t know what he meant, but Catty did.

“Dad and me talk a lot about corners,” says he. “Seems like corners is the most int’restin’ things in the world. Country roads is full of ’em. Heaps of times Dad and me will set down when we’re comin’ to a corner and argue about it for half an hour—about what we’ll see when we come to turn it. It’s a funny thing, but there’s a different thing around every corner you turn. No two of ’em’s alike.”

“And brooks,” said Dad, “especially mountain brooks.”

“They’re jest like stories,” says Catty. “Like them intrestin’ stories that you can’t git to sleep till you finish. I’d rather foller down a brook than anything.”

“Shoot?” says Dad.

“Never shot a gun.”

“Try it.”

Catty aimed at my bottle and missed it as far as I did. He sort of wrinkled his nose and says something to himself and waggled his head. You could see he didn’t like missing. When I got to know him better I found out that he was always like that. He didn’t like not being able to do things, and if he found out he couldn’t do something, he wouldn’t rest till he could do it. He went over and snooped around the ground till he had picked up six cartridges that had been shot, and sat them in a row on top of the fence. Then he walked off a ways and took a piece of rubber band out of his pocket. There was a leather pocket on it.

“What’s that?” says I.

“A beanie,” says he.

I’d never seen one. In our part of the country we used a sling-shot made of two rubber bands and a crotch.

Catty fingered in his pocket and piffled out a round pebble and fixed it in the leather. Then he drew back the rubber over the first finger of his left hand and shot quick. The pebble knocked off the first cartridge. And then, almost quicker than I can say it, he shot five more times, and every pebble knocked off a cartridge. I never saw such shooting.

“There!” says he.

“Fine shooting,” says Dad, and Dad’s eyes were shining like they always do when he’s pleased. “I’m glad I saw that.”

Then Dad put in about half an hour showing Catty and me how to shoot a gun, and we got so we could do a little better.

“The only way to get to be a marksman,” he says, “is to stick to it and shoot and shoot. Isn’t that so, Catty?”

“Yes,” says Catty.

Then Dad went away after telling Catty to come around often. “Tell your father I’ll drop in to see him—and talk about roads and brooks and the pleasures of shiftlessness,” he said, as he went through the gate.

I heard somebody whistle, and knew it was either Banty Gage or Skoodles Gordon. I whistled back.

“Here come the fellers,” says I. “Now we kin have a reg’lar shootin’-match.”

“Guess I’ll be moggin’ along,” says Catty.

“Why?”

“Oh, I dunno. Just guess I’ll be goin’.”

“I wisht you’d show those kids how you can shoot that beanie.”

“I ain’t much for kids. Don’t have much to do with ’em.”

“Why not? You stopped and talked with me.”

“I was sort of int’rested in the way you was missin’ that bottle. Glad I stopped, too. I got to see your Dad. He’s mighty near as good a Dad as mine.”

“Aw, rats!” says I. “Banty and Skoodles is heaps of fun.”

“I don’t git along with kids,” he says, stubborn. “Got so’s I never have anythin’ to do with ’em. Mostly I never have anythin’ to do with anybody but Dad.”

“Why?”

“We jest don’t git along. It’s on account of our bein’ shiftless. I’ve had to lick a sight of kids on account of callin’ me or Dad names. And then their Mas see ’em playin’ with me and makes ’em stop—and I have to lick ’em on that account.”

“Why don’t their Mas want them to play with you?”

“’Cause we’re shiftless.”

“My mother wouldn’t care.”

“Bet she would.”

“Anyhow, Dad wouldn’t. You seen him. He told you to come around, didn’t he?”

“I hain’t never seen anybody jest like your Dad before,” says Catty. “Mostly I get told to clear out.”

“Aw, shucks!” says I.

“Good-by,” says he. “Hope you git to shoot that gun like a champeen. Maybe I’ll see you ag’in some day.”

“Come around any time,” says I; “and, if you hain’t got any objection, I’ll drop around your place.”

“Come ahead,” says he. “Maybe we’ll still be there, and I guess I kin stand it if you kin.” He started off, but he stopped and says: “Your Dad—die’s all right. I like your Dad.”

It was a day or two afterward that I run across Catty Atkins poking along the road on the edge of town, all alone. I hollered to him and he stopped.

“How’s things?” says I.

“Sich as there is, they’re perty fair,” says he. “Hain’t moved on yet?”

He sort of grinned. “Oh yes. We left for Philadelphy two days ago. Arrived there about ten this mornin’.”

“Huh!” says I. “Come on back to my house and let’s shoot with my rifle.”

“Don’t guess I better,” he said, kind of hesitating, but I could see he wanted to come.

“Come on,” says I. “Dad was askin’ after you this mornin’.”

“Was he?” says Catty, and his eyes got bright as anything. “Was he really?... I’ll come.”

When we got there Banty Gage, who lives next door, and Skoodles Gordon were sitting on top of the shed, waiting for me to turn up. I had told them about Catty Atkins, and they were interested to see him and to watch him shoot with that beanie of his. When Catty saw them he came close to turning around and going off, but I hung onto him, and Skoodles and Banty came down off of the shed.

“This is Catty Atkins that I told you about,” says I, and then I told him what their names were. He didn’t say much and acted sort of offish and quiet, but that didn’t last. In a while we were shooting away and having a bully time. Dad came out on the porch a minute and asked how we were getting along, and spoke special to Catty, and then sat down to read his paper.

About ten minutes after that Banty Gage’s mother came out and stood looking at us. Then she called to Banty and he went over to the fence. We could hear what she said.

“Who is that boy?” she asked, sort of cold and severe.

“Catty Atkins,” says Banty.

“Who is he? Where did you get acquainted with him?”

“Wee-wee brought him home with him.”

“Is he that boy you were talking about the other evening? The one whose father is a tramp and who is hanging around that old shanty down by the waterworks?”

“Yes, ’m.”

“Then you come right straight home. If Mrs. Moore wants her boy to play with that sort of people, all right, but my boy can’t. No telling what he’ll lead you into.” She stopped and looked hard at Catty, who was standing very still, with his lips set and his eyes kind of like they was made out of pieces of polished steel. “He’s a tramp, and there’s no telling what else. Such people aren’t fit to be let at large. I don’t see what the town is thinking of not to shut them up or make them go away. You come right home, and never let me see you with that boy again. Now march.”

Catty looked at Mrs. Gage and looked at me and looked at Dad, and then he says to himself, “I sort of knew folks thought that about us, but I didn’t ever hear one of ’em say it before.” And he turned around and started for the back gate.

“Where you goin’?” says I, and I was good and mad.

He didn’t answer, but kept right on. Then Dad spoke from the porch.

“Catty,” says he, and his voice had something in it that sounded good.

Catty stopped and looked at him, very sober, with his lips shut tight.

“Wait just a moment, Catty,” says Dad, and then he turned to Mrs. Gage.

“Mrs. Gage,” says Dad, “Catty is my guest, and as my guest he is entitled to the courtesy of those who are my friends and neighbors. I know Catty, and I am very glad to have him come to my home and play with my son. I am going to give myself the pleasure of calling on Catty’s father. I am sure you spoke hastily and had no wish to hurt this boy as you have hurt him.”

“Mr. Moore,” said Mrs. Gage, as sharp as a needle, “you can have any tramp or criminal or anybody you want to play with your family, but you can’t force them on mine.... You heard me tell you to come home, Thomas.” Banty’s right name was Thomas.

“I know, Mrs. Gage,” said father, in a gentle sort of way he has, “that you will be sorry you have hurt this boy. If you knew him, when you know him, I am sure you will want to apologize.”

“Know him!... Apologize to a young tramp!...” Mrs. Gage turned and went into the house, slamming the screen after her, and Banty followed. Then she gave Banty what for, and didn’t take a bit of trouble to lower her voice. “You heard what I said,” she says. “You keep away from that ragamuffin.”

“But Mr. Moore says—”

“I don’t care what Mr. Moore says. I sha’n’t put up with his crazy ideas. The idea! Mr. Moore ought to know better, but he doesn’t seem to. After this you keep away from the Moores.”

Dad looked down at me and smiled sort of humorous and at the same time sort of sad, and then he came down off the porch and walked right up to Catty.

“I can’t tell you how sorry I am that this thing happened,” he said, and looked straight into Catty’s eyes. “I know Mrs. Gage didn’t intend to be cruel. She doesn’t understand, that’s all. You mustn’t be hard on the rest of us because some people don’t understand things. You won’t, will you?... And remember that you are always welcome here and that I am glad to have Wee-wee play with you. We’re going to have dinner in a few minutes and I shall be very glad indeed if you will stay and eat with us.”

“Eat with you!” says Catty, and looked down at his clothes.

“Of course.”

“I hain’t never been invited to dinner no-wheres. I wouldn’t know how to act.”

“Catty, there’s folks in this world who always know how to act. The finest manners I ever saw were shown by a French lumberjack who couldn’t write his name. Being a gentleman doesn’t consist in knowing which fork to use first, Catty. Those things are just trimmings, but a gentleman is a gentleman because he’s got something inside—something that I know you’ve got. Do you know what a gentleman is, Catty, and what it is that makes any man good enough to dine with any other man, or to do anything else in the world with any other man?”

“No, sir,” says Catty.

“It’s a feeling inside him that he wants to act toward everybody just as he wants everybody to act toward him.”

“I thought,” said Catty, “that a gentleman was somebody with a white shirt who thought most folks was beneath him.”

Dad laughed. “Come on in and wash for dinner—and meet Wee-wee’s mother.”

“Will she—will she want me, sir?”

Dad laughed again, and I laughed this time, because that was really funny. If Dad was to bring home a hippopotamus to dinner Mother would be glad of it—just because Dad brought him. I’ve took notice that Mother always thought that whatever Dad did was just right, and, now that I come to think it over, she thought so because everything that Dad did was just right.

Mother shook hands with Catty just as if nothing out of the ordinary run was happening at all, and acted just as she would act if Catty had been the Presbyterian minister or president of the bank, or anybody else. Then Catty and me washed up and came down to dinner, and Dad talked a lot until pretty soon he got Catty to talking some, and what he said was mighty interesting to me—all about walking around the country, and what they saw, and how they lived. I kept my eye on him jest to find out what kind of table manners he had, but I couldn’t find out, because he kept his eyes on my mother all the time, and never did a thing until he saw her do it first, and then did it just like she did. I saw Dad grin to himself a couple of times.

“Mr. Moore,” said Catty, serious as all-git-out, “I wonder kin I ask you a piece of advice?”

“Fire ahead, Catty.”

“Well, I’m wonderin’ if I ought to lick that kid before Dad and me goes away.”

“What kid?”

“Banty Gage.”

Dad kept his face very straight, but I knew by the looks of him that he wanted to laugh. “What has Banty done to you?”

“He didn’t do anythin’—but his Ma did. I can’t lick his Ma, because fellers don’t pick fights with wimmin, but it seems as if I ought to lick somebody, and, her bein’ his Ma, he comes closest to bein’ the right person.”

“You feel like fighting, eh? Well, I don’t blame you.... You said before you and your father went away. Are you going away?”

“When I git home I’m goin’ to tell Dad it’s time to move on.”

“And he’ll go?”

“’Course. Dad’s always willin’ to go.”

“And you’re going because of what Mrs. Gage said?”

Catty nodded.

“Um!...” said Dad. “Looks kind of like running away, doesn’t it? As if you had been scared out?”

“Eh? Scared out?” Catty’s lips came together thin again and his eyes got glittery. “I don’t allow nobody to say I’m scared, Mr. Moore.”

Dad nodded and says: “That’s right. But you can’t stop them from thinking it. Not by fighting with your fists, anyhow. There’s only one way to keep folks from thinking you’re afraid of a thing, and that is to show them you aren’t.”

Catty looked at Dad a long time and didn’t say a word, but you could see he was trying to study out what Dad meant.

“Aren’t you ever kind of lonesome when you’re walking about the country—and never settling down any place to get acquainted with folks?” asked Dad.

“Not when I’m with my Dad,” said Catty, and the way he said it you almost got the idea he was proud of his father.

“Good boy!... But don’t you ever want to have other boys to play with, and go to school, maybe, and know folks, and have a chum like most boys have?”

Catty didn’t answer, but sat looking out of the window.

“Do you know what would hurt Mrs. Gage’s feelings more than anything else in the world?”

“No, sir.”

“To be shown that she was wrong about you, and to know that she ought to beg your pardon for what she said. I don’t know that she ever would beg your pardon, because lots of people are queer, but it would be about as bad a thing for her as I can think of if she came to know that she ought to do it. Wouldn’t it?”

“I don’t know much about folks,” said Catty. “Maybe so.”

“If you were to run away now you never could make her feel that way, could you?”

“No.”

“Catty, there is something you would like to have very much.”

Catty looked at Dad quicklike and then looked away.

“It’s the respect of people,” said Dad, quietlike and kind of gentle.

“Jest because we’re shiftless they think we’re bad,” said Catty. “We ain’t. We mind our own business and never do no damage to anybody.”

“But things like this that happened to-day have happened before, haven’t they? And you’re afraid they’ll happen again?”

“I’m not afraid they’ll happen, but I know they’ll happen.”

“If I were a boy,” says Dad, “and wanted something very much, I’ll bet I’d get it.”

“You can’t steal the respect of people that don’t know you off’n the clothes-line,” says Catty, stubborn-like.

“Isn’t part of your trouble that you never let folks know you? You never stay any place long enough to let them get acquainted.”

“Nobody wants to get acquainted.”

“How do you know? Didn’t we want to get acquainted? And there are thousands of other folks just like us.”

“I hain’t never seen anybody like you, Mr. Moore.”

“Well,” says Dad, “I won’t pester you about it, but think it over. If you should decide to change your mind and not let Mrs. Gage have her way and drive you out of town, why, you’ve got some friends here to start with. Hasn’t he, Mother?”

“Yes,” said Mother. She didn’t say any more, but just that one word. You knew she meant it, and that was enough.

We all got up from the table and I was dragging Catty away, when he stopped and turned to Mother.

“I—I enjoyed the dinner a heap, Mrs. Moore,” said he, “but what done me most good was jest a-lookin’ at you. I calc’late it must be awful nice to have a mother—and her as dog-gone perty as you be.”

“Catty,” said Mother, “I think that’s the nicest thing I ever had said to me,” and she leaned right over and give him a kiss. Then we went out, but all the rest of the afternoon I noticed that every little while he reached up and touched his cheek where the kiss had landed, kind of stroked the spot and patted it like it had got to be the most valuable part of his face.

Catty was pretty quiet all the afternoon. He seemed to be figuring something out, and every little while he acted as if he had forgotten I was around at all, and would sit down some place and look off at the distance and squint, and bend his thumb back and forth like he expected to pump water with it. When I got to know him better I found out he always worked his thumb when he was het up over something or didn’t know what to do. Once I told him I guessed his brains was in his wrist instead of in his head, and that he had to pump them like they do the pipe-organ in church, or they wouldn’t work.

Pretty soon he jumped up all of a sudden, and says to me, in a warlike kind of a voice: “It would be runnin’ away. We’ve been runnin’ away right along.”

“Do tell,” says I. “From what?”

“Folks,” says he, and then shut his mouth up like a steel trap and began to walk away fast.

“Hey!” says I. “Where you goin’?”

“To see Dad,” says he.

I kept right up with him, but he didn’t speak again till we were right by that little shanty near the waterworks where he and his father were sleeping. It was no kind of a place to sleep at all. There wasn’t a whole window in it; the front door was off the hinges and there was more roof where the shingles was off than where they was on. Honest Injun, it looked as if a good stiff shove would topple the whole shooting-match over. Inside there wasn’t a stick of furniture and the floor was full of holes. It smelled kind of musty and damp. The minute I saw it I knew I wouldn’t enjoy tramping. No, sir. I wouldn’t mind sleeping in the woods or in the hay, but to use a place like this was something I jest naturally would be dead set against.

Catty called, but nobody answered.

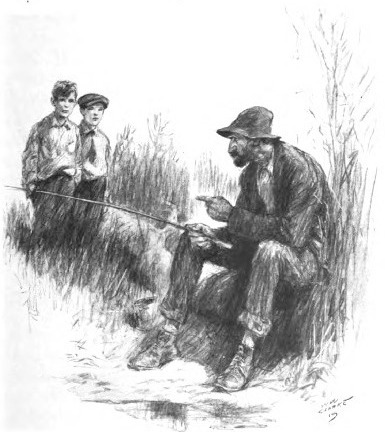

“Dad’s fishin’,” says he, and off we went to the bayou, where, after a few minutes, we came across a man a-sitting on a log with a long cane pole in his hands. I couldn’t see him move so much as his eye-winkers. He was kind of long and narrow, and whiskers that was a sort of red and yellow, mixed, stuck out around his face like the spokes of a wheel.

“Who’s he?” said Mr. Atkins, pointing very sudden at me

What he had on his head might have been a hat and it might have been part of a horse-blanket, and it might have been a busted waste-basket. It might have been almost anything, but the thing it looked like least was a hat. He had a nose with a hook in it and a drooping end. Most of his face was nose. That was about all I saw of him first off. Then Catty spoke to him and he turned around slow.

“Howdy, Sonny!” says he, and smiled. I saw then that his eyes were brown, with wrinkles all around them. Not laughing wrinkles, but the kind you get from the sun shining in your eyes. I never saw a smile just like his smile. It was kind of patient, and kind of glad, and kind of thoughtful, and kind of sorry—all mixed in—and right off I liked him.

“Who’s he?” said Mr. Atkins, pointing very sudden at me.

“Wee-wee Moore,” says Catty. “Been to his house to dinner.”

“Eh?” says Mr. Atkins, opening his eyes wide.

“Right in the house, at the table, with him and his Pa and Ma.”

“No! I swan to man! Wa’n’t you nigh scairt to death?”

“Nobody’d be scairt with Mr. Moore and Wee-wee’s mother.”

“How’d it come about, Sonny?”

“It was after a woman called me a tramp and other names and ordered her boy not to come near me. Mr. Moore he told her what he thought about her, and that I was his guest, and then he made me come to dinner, and we talked.”

“I’d like to git a squint at that Mr. Moore,” says Mr. Atkins, reflective-like.

“He’s comin’ to call on you,” says Catty.

“I want to know! Um!... Calc’late I better wait for him right here in my office. Men likes to talk in their places of business. He kin set on one end of this log and I’ll set on the other. Mighty cozy. When you calc’late he’s comin’?”

“Maybe to-day.”

“Um!... Don’t call to mind havin’ a caller these fifteen year. Guess maybe I better comb out my whiskers.”

“Dad,” says Catty.

His father turned to look at him, and saw that Catty’s face was kind of sober and set. “What is it, Sonny?”

“Did you ever figger any on settlin’ in one place, Dad?”

“Can’t say’s I have. There’s things ag’in’ it. When you’re settled you hain’t on the move, be you? Nobody could claim you was, I guess. And, take the opposite, when you’re always on the move you hain’t settled in one place.” He sat back and eyed us like he was mighty proud of figuring a thing out that way.

“Do you like movin’ so much, Dad, that you couldn’t be contented to settle?”

“Movin’ about’s an occupation, Sonny—a reg’lar profession like law or storekeepin’. There’s got to be folks in all trades, or business would go smash! Every feller ought to do what he kin do best, and the best thing I ever done was bein’ shiftless and moggin’ from place to place. Seems like I’m fitted for it by nature. Yes, sir, I was cut out for it. I hain’t never seen anybody that does it as thorough and conscientious as me. Now, as to settlin’ down, I hain’t had the experience, and how’s a man goin’ to succeed at a trade he hain’t had experience in?”

“If I was to ask you to settle here, and say that I wanted to do it mighty bad, and that I didn’t want to move around any more, what would you say?”

“I calc’late I’d ask you what the reason was.”

“I hain’t sure I want to, but if I did want to there would be reasons.”

“There gen’ally is reason for ’most everything a feller wants. I’ve noticed it. I’ve noticed it most special and p’tic’lar. Take a dog, for instance. He wants to chase his tail. Why does he want to chase his tail? Because he’s got reasons for it, and them reasons is that he wants to satisfy a curiosity in his mind whether he kin catch it. If you had reasons for wantin’ to stop here permanent, what would them reasons be?”

“They’d be,” says Catty, slow and deliberate, “that Mrs. Gage up and called me names, and that I wouldn’t want to run away without showin’ her that she didn’t have no business callin’ me names. And they’d be that I’d want to learn myself table manners so’s I wouldn’t be scairt if I ever et with Wee-wee’s mother ag’in. But mostly they’d be that folks seems to think that shiftlessness hain’t respectable, and that it gits under my skin to have folks sneerin’ at you and me.”

“Folks sneers, do they?”

“Stiddy and constant,” says Catty.

“Hain’t got no business to. It takes brains to be shiftless, Sonny, and folks hain’t able to appreciate it. Anybody kin work and earn a livin’ and stay in one place and never have no fun. But you take one of them stiddy men and turn him to live like we do, and what ’ll happen? He’ll starve, and before he starves he’ll die from sleepin’ on the ground, and before that he’ll have blisters onto his feet. We don’t do none of them things, and why? I ask you why. It’s because we’re smart and we’ve learned our trade.”

“Is it awful hard to work all the time?”

“Easy as fallin’ off a log. Everybody can do it.”

“Could you run a store, Dad?”

“I could run a train if I owned one. Trouble is I don’t own no store.”

“How do folks git to own stores?”

“Mostly their folks leave stores to ’em when they die, or money to buy ’em with. Some saves up money and buys ’em.”

“We never have any money to save.”

“Never had much need for money.”

“Would you like to own a store, or have a stiddy job, and never have anybody sneer at you any more and call you a tramp?”

“Sonny,” says Mr. Atkins, “you don’t never need to worry about what folks thinks of you. What you want to worry about is what you think of yourself.”

“I’ve been doin’ that, Dad.”

“And what do you think of yourself?”

“I hain’t sure, but it looks kind of like I was goin’ to think that the way we live hain’t what you’d call valuable. Seems like everybody ought to be makin’ somethin’ or doin’ somethin’. Seems like I’d like to have folks respect me—and it seems like I’d like sort of to live the same way other boys does and play with ’em without their folks tellin’ them to git away from me.”

“Sonny, you hain’t gone and got ambitious, have you?”

“What’s ambitious, Dad?”

“Ambitious means wantin’ to git to a place where you can look down on other folks.”

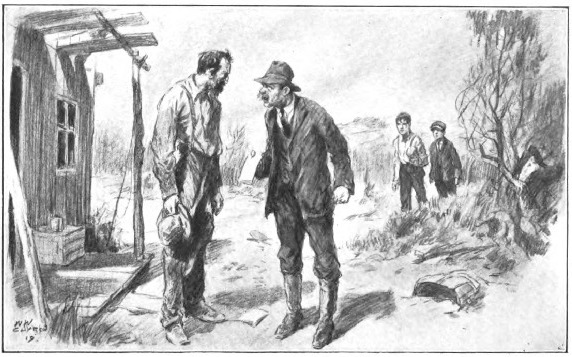

“I don’t quite agree with you, Mr. Atkins,” says a voice, and we looked around to see my Dad standing there. “I believe ambition means a desire to improve yourself and to become something more valuable than you are. It means that you’re not satisfied with yourself.”

Mr. Atkins got up and looked at Dad, and Dad looked back at Mr. Atkins.

“Be you Mr. Moore?” says Catty’s Dad.

“Yes, Mr. Atkins.”

“I’m much obleeged to meet you,” says he, and he shook hands with Dad very polite.

“Glad you’ve moved to Athens, Mr. Atkins.” Athens was the name of our town. “We’ve seen quite a little of Catty, and we hope you’re both going to stay here.”

“Um!...” says Mr. Atkins. “Catty’s been mentionin’ it.”

“Haven’t reached a decision?”

“Catty hain’t sure he wants to stay.”

“If he were sure, and wanted to stay very much, what would you do?”

“Stay,” says Mr. Atkins, very short and prompt.

“Why?”

“Because I hain’t got nothin’ to do in this world but look after Catty and kind of make him glad he’s alive. Folks ought to be glad they’re alive. I be. I don’t want Catty to grow up and think that I ever denied him anythin’ that I could give to him that wasn’t harmful. Yes, if Catty says stay, why, we stay.”

“And what do you say, Catty?”

“I don’t say nothin’ yet. I hain’t ready to say. I got to think about a lot of things, and make up my mind what we’d do if we was to stay, and if Dad could be happy stayin’ instead of movin’ around. If Dad wouldn’t be happy I wouldn’t ever stay, even if I wanted to so bad I couldn’t stand it.”

“I like to hear you say that,” says Dad.

“If you won’t figger it’s bad manners,” says Catty, “I want to go off alone and kind of wander around and figger things out. I don’t want nobody with me—not even Dad. As soon’s I know what’s best I’ll come and let you know about it.”

“Go ahead,” says Dad. “That’s the way to go after things. Reason them out. Don’t take anybody’s word for it, but make sure yourself.”

“I’m a-goin’ to,” says Catty, and off he went. Dad and I stayed there and talked to Mr. Atkins. It was mighty interesting, for he had been so many places and he had a funny kind of a way to tell about them, and then he had some notions that was funny, too. We had a good time, and when we started home Dad and Mr. Atkins shook hands again, and Dad said that he hoped Mr. Atkins would live there, because he liked to talk to him, and Mr. Atkins said that if he did come to live there Dad would make it a heap easier.

It was about nine o’clock that night when somebody rang our bell and Dad went to the door. It was Catty, because I heard his voice. He didn’t say good evening, or anything else but jest one sentence:

“We’re a-goin’ to stay.”

“Good for you,” says Dad, and held out his hand.

Catty shook it a minute, and then, without a word, he turned and ran down the steps and disappeared into the dark.

I was glad he was going to stay, because I liked him and I liked his Dad. My Dad was glad, too. Mother says:

“I hope it’s best. They’ll have some hard things to put up with—especially the boy.”

“I’m not worrying about the boy,” says Dad, “now that his mind is made up.”

Somehow I didn’t worry about Catty, either.

Next morning bright and early I hustled down to the shanty where Catty and his father were staying. Mr. Atkins was sitting on his log, fishing for pickerel and looking pretty sober and dubious. Catty was sitting alongside of him, looking into the bayou and never saying a word.

“Mornin’,” says I.

“Mornin’,” says Catty.

Mr. Atkins turned his head and waggled it at me. “He’s went and gone and done it,” says he.

“What?”

“Made up his mind to hitch up to this town.”

“Good!” says I. “He told us last night.”

“Dad don’t like it much,” said Catty, “but it ’ll be good for him. I’ve thought it out.”

Now wasn’t that a funny way for a boy to talk—about something being good for his Dad? You would have thought Catty was the Dad and his father was the boy.

“Yes,” says Catty, “it won’t be so much fun, maybe, and maybe it ’ll be more. I think Dad ’ll grow to like it, and he might even grow to like workin’ reg’lar. I hain’t expectin’ that, ’cause he’s been shiftless so many years, but maybe.”

“Work,” says Mr. Atkins, sadlike.

“Lots of folks does it constant,” says Catty.

“They have to,” says his father.

“You’ll have to now—some. Mind, I don’t expect you to work every day and all day long. You kin sort of git the habit by degrees. But if you don’t work some we’ll never git the respect of these here folks. I’ve been studyin’ it over, and seems like a body’s got to work to git folks’s respect. Don’t matter how good you be nor how happy you be, nor that you hain’t never done nobody any harm. You got to work. Seems kind of funny to me. If you jest work you git some respect. If you work a lot and make a little money you git more respect. But the feller that gits most respect is the one that works at makin’ other folks work for him. I’m goin’ to be that kind.”

“Meanin’ me?” says his father, as doleful as a tombstone.

“Have to start with you, I calc’late. Hain’t figgered out what to do first, exceptin’ that it ’ll have to be somethin’ to git me some money. ’Course I could start out runnin’ errants or cuttin’ grass, or even workin’ in a store, but there hain’t nothin’ in that. What I got to do is to figger out a business that’s mine and that I kin run, and where I can hire some other kid instead of somebody hirin’ me. That’s the way to git ahead.”

“But you’ll have to work for somebody to make some money to start,” says I.

“I dunno,” says he. “I’m huntin’ for a scheme—and then I’m studyin’ out what kind of a business I want to git into.”

“Hain’t it miserable?” says Mr. Atkins. “Here we been goin’ along for years with nothin’ to bother us. Didn’t have to work and didn’t have to study about schemes. Now all of a sudden this here thing comes down on top of us. Don’t know where Catty gits sich notions from. Not from me. Must come off’n his mother’s side.”

“How much money you got to have?” I asked Catty.

“Dunno, ’cause I dunno what I want it for.”

“Maybe my Dad ’u’d lend it to you,” says I.

“He won’t,” says Catty, emphatic.

“Why?”

“’Cause I won’t let him,” says he. “I’m goin’ to make it. Got to. Be more fun.”

“Fun!” says Mr. Atkins. “D’you call workin’ and makin’ money fun? Strange idee of fun. Fun’s somethin’ you laugh at and enjoy. Who ever heard of anybody laughin’ at work?”

“And we can’t live here,” says Catty.

“Why?” says Mr. Atkins.

“’Tain’t respectable. Houses without no winders into ’em hain’t respectable, and folks looks up to furniture and carpets.”

“Ho!” says Mr. Atkins. “Hain’t slept in a bed in ten year. Don’t believe I could do it.”

“It’s easy,” says I. “I do it every night.”

“All in bein’ used to it,” says he.

In spite of Mr. Atkins’s bein’ so lazy and shiftless, I took a liking to him. Somehow it didn’t seem like laziness, but like something different altogether. He was so simple and kind of gentle and his eyes was kind. You almost got the idea that he didn’t know about things, especial’ about how to work, and that it wasn’t his fault at all.

“Didn’t you ever work?” says I, because I was curious about it.

“Once,” says he.

“What at?” says I.

“Painter,” says he.

“House or picture?” says I.

“Houses mostly.”

“Must be fun—paintin’ houses,” says I.

“Would be if it wasn’t work. I calc’late I could enjoy to paint a house if I wasn’t paid for it—if I was jest doin’ it to show folks I could. But when you’re doin’ it as a job it hain’t the same.”

Catty was thinking hard. “What d’you need to go into the paintin’ business, Dad?”

“Paints,” says Mr. Atkins.

“What else?”

“Ladders and planks and brushes and oils.”

“Um!... Cost much?”

“Heaps.”

For a minute Catty didn’t say a word, but just stared at the water. Then he says to himself, “Where in tunket be I goin’ to git ladders and brushes and them things?”

“Hain’t thinkin’ of makin’ me go to paintin’, be you?”

“Thinkin’ of it some,” says Catty, “but thinkin’ ’s as far’s I kin git jest now.”

“Then I’ll keep on fishin’,” says Mr. Atkins. “No use gittin’ het up and worried before it’s time.”

“We got to have respectable clothes, too.” says Catty.

“Next thing I’ll be wearin’ a plug-hat,” says Mr. Atkins.

“Maybe on Sundays,” says Catty, serious as anything. I guess he was thinking quite a ways ahead.

“Ho!” says Mr. Atkins.

“Come on,” says Catty to me.

“Where?”

“Look around and think. I wonder if there are any ladders in this town.”

“Fire company’s got some,” says I, and grinned.

We walked up past the waterworks and down to Main Street. Catty didn’t say a word, but kept looking and looking, and sort of tucking away information about our town in his head. We walked from one end of Main Street to the other, and when we got to the town pump that stands at the end of the bridge he stopped and says:

“There hain’t a painter and paperhanger shop in town.”

“No,” says I. “We got two painters that puts up wall-paper sometimes, but they don’t keep any shop. Jest have their stuff in their barns.”

“Who sells paper?”

“Drug-stores.”

“And paint?”

“Hardware-stores.”

“What’s that?” he asked, pointing across the river.

“Kind of a furniture-factory. Make all sorts of things. That new buildin’ that’s jest bein’ finished up is a warehouse. Never saw a bigger buildin’. Two hunderd foot long and sixty wide.”

“’Tis kind of big,” says he, and began to squint at it. “Looks ’most done. Shinglin’ ’most finished.”

“Uh-huh,” says I.

“Come on,” says he, and his eyes began to kind of shine and his lips pressed together.

“Where?”

“Over there to the mill.”

“What for?”

“See the boss.”

“Mr. Manning?”

“If that’s his name.”

“He’ll kick us out. That’s the kind he is. Talks loud and bosses things, and hain’t got a mite of patience with anybody.”

“We kin outrun him,” says Catty, and he grinned kind of mischievous. “Any man kin kick me that kin catch me. Come on if you hain’t scairt.”

“Guess I dast go where you dast,” says I, and I mogged right along with him.

The office was in a little square building off to the side, and while we were going up to it I was looking around me careful to see what would be the best way to run when Mr. Manning started after us. I’d picked out just how I was going to dodge in among the lumber-piles by the time we got to the door. We went right in.

First there was a kind of an outside office where there was a bookkeeper and a typewriter working, and back of that was Mr. Manning’s office with the door shut.

Catty walked right up to the railing and says to the bookkeeper, who was Johnnie Hooper, and not very old and a lot dressy, with his hair plastered onto his head, “Is Mr. Manning in?”

“Who wants to know?” says Johnnie, with the kind of a grin that makes you mad.

“Somebody to see him on business,” says Catty.

“What kind of business?”

“Is he in?” says Catty.

“He is, but you don’t think a couple o’ kids like you can bother him, do you? He’d throw you out by the seat of the pants.”

“Hired to tell folks what he’d do?” says Catty.

Johnnie kind of scowled and didn’t think of anything to say back.

“We’re here on business,” says Catty, “and if you know what’s good for you you’ll tell Mr. Manning so. It’s for him to say whether he’ll see us, and not you.”

“You skedaddle out of here,” says Johnnie, getting off his stool.

Catty grinned at him, but it wasn’t a friendly grin. I got to know it after a while, and whenever he grinned like that I knew he was ready and willing to fight, and that he would fight until he couldn’t see or hear or stand.

“Maybe you kin kick me out,” says he, “and maybe you can’t. You don’t look like much of a kicker. But I kin tell you that you’ll git mussed tryin’ and there’ll be a rumpus in this office that Mr. Manning will hear—and he’ll come bustin’ out to find out what’s the trouble. Then where’ll you be? Kicked out yourself. Jest come right on and try it.”

“Git out!” says Johnnie, but he didn’t come any nearer.

“Are you going to tell Mr. Manning I want to see him?

“No. Git!”

Catty walked up to the rail and looked at Johnnie a second. Then what did he do but open his mouth and holler, “Mr. Manning!” as loud as he could. Johnnie looked half scared to death, and I made sure the door was where I could use it prompt. “Mr. Manning!” yelled Catty again.

The door of the private office smashed open and there stood Mr. Manning, scowling like all-git-out.

“What’s this racket? What’s this racket?” he says, sharp and angry.

“This boy—” Johnnie started to say, but Catty broke right in:

“Does this feller know everybody you want to see or don’t want to see?” he asked, and he wasn’t frightened a bit. He spoke right up, like he was a grown man—not impudent, but kind of severe.

Mr. Manning almost jumped. For a second he didn’t know what to say, and then, because he was so surprised, I guess, he didn’t roar or chase us out, but just answered. “No,” he says.

“I thought so,” says Catty, “so when he wouldn’t tell you I wanted to see you I thought I’d tell you myself.”

“What’s this, Hooper?” says Mr. Manning.

“These boys came in here—and I didn’t want you disturbed. I tried to chase them away.”

“Did this boy say he wanted to see me?”

“Yes.”

“Did you ask him why?”

“He said business.”

“Then what do you mean by not telling me? How do you know he isn’t bringing an important message from somebody? After this when people come here and ask for me you consult me before you send them away. Understand?”

“Yes, sir,” says Johnnie.

“It isn’t a message,” says Catty. “It’s business, my own business, and I want to talk to you a few minutes about it.”

“Come in here,” says Mr. Manning, “but if you’re wasting my time you’ll wish you’d stayed out.”

We went in, and I was so surprised I couldn’t have spoken if I was paid for it.

“Now what?” says Mr. Manning, sharplike.

“Have you let the job of painting your new warehouse?” says Catty.

I almost dropped in my tracks.

“No,” says Mr. Manning.

“I’ve come to apply for it,” says Catty. “I can guarantee a first-class job with the right kind of bossing. It will be hustled through as fast as anybody can hustle it, and we’ll use only the best materials.”

“I’ll say this for you, young man, you can speak up and not waste any words. Are you going to do the painting yourself?”

“Of course not. The best painters that can be had.”

“Who are you speaking for?”

“Myself.”

“What?”

“Myself,” says Catty again, kind of stiff and formal. “I calc’late to boss the job and see it is done right. I calc’late to hire both the local painters, and you know they are good men. My father is a first-class painter. I’m willing to take this job cheap to get established here, because we are going into business here and expect to live here. I guarantee satisfaction.”

“Well, I swanny!” says Mr. Manning. He sat down and didn’t act mad nor offer to throw us out. “Sit down,” says he. “I want to know more about this.... You’re young Moore, aren’t you?” says he. “What have you got to do with it?”

“Nothing,” says I, “except that Catty is a friend of mine and Dad’s, and I come along.”

“Do you recommend this young man?” says he.

“Yes,” says I, “and so will Dad.” I knew Dad would.

“What’s your proposition?” says Mr. Manning to Catty.

“I’ll do this job for cost—exactly what it costs, and ten cents on each dollar besides for my profit. If you want to you can buy the paints and supplies and pay me the profit when it’s all done. Then you’ll know you’re getting a fair deal.”

“Who are you, anyhow?”

“Catty Atkins,” says he.

“Where’s your shop?”

“Haven’t one yet.”

“Where do you live?”

“Nowheres—yet.”

“I can’t give you such a job as this until I know something about you,” says Mr. Manning.

“Dad and me, we jest come to town,” says Catty. “We always been shiftless, but I got to be respectable now and make folks respect me. I’ve made Dad agree to live here, and he’s got to work. We hain’t never done nothin’ but be shiftless and traipse around since Mother died.”

“Tramps, eh?”

“I calc’late you’d call us that.”

“Expect me to trust a couple of tramps with this job?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Because,” says Catty, “you know I mean business. You do know it, and you know I’ll give you a good job or bust.”

“Huh!...” says Mr. Manning. “Where’s your equipment? Your ladders and staging and brushes and paints?”

“Give me this job and I’ll have ’em. I’ll start work here Monday. This is Thursday.”

“I’ll be jiggered!” says Mr. Manning. “How old are you?”

“Fifteen.”

Mr. Manning scowled at Catty, and I thought it was coming then, but in a minute he spoke. “Young man,” says he, “if you can be here with proper equipment and workmen at seven o’clock Monday morning, you can have the job. If a kid like you has the crust to tackle a thing like this, and, without a cent, can scrape together equipment and workmen, I’ll make a bet you can do the job. Satisfy you?”

“Yes.”

“Git!” says Mr. Manning.

“Monday at seven,” says Catty, and we walked out.

“There,” says he, “that’s done. Now I hain’t got anything to do but git together the ladders and brushes and paints and workmen to do the job.”

It looked to me like that was quite a chore, but Catty didn’t seem discouraged any. “We got to git busy,” says he.

Catty had the rest of Thursday and Friday, Saturday, and Sunday to get together the things he had to have to paint Mr. Manning’s warehouse—and to convince his father he had to go to work. That last looked to me to be about as difficult as the other was. Mr. Atkins didn’t look like work. I never saw a man who looked less like it in my life. But then I looked at Catty, and his jaw was all squared up and there was a kind of a spark in his eye. Right then I made up my mind that Mr. Atkins was in for a time of it.

All of a sudden Catty started to talk.

“There’s lots of things folks thinks is necessary that I don’t see any use in. There’s being well off, for instance. What’s the use? Nobody ever had a better time ’n Dad and me has had. There’s them tall silk hats. Some day Dad’s got to wear one, though I’ll bet it ’ll be a job to git it on his head. He’d shy off a hat like that jest the same way a horse shies away from an elephant. Then there’s this thing of being respectable.”

“But you got to be respectable,” says I.

“Why? All I can see to bein’ respectable is workin’ and gittin’ tired out and bein’ tied down to one place instead of bein’ shiftless and moseyin’ along wherever you want to, and enjoyin’ yourself. I can’t see why folks set so much store by makin’ themselves miserable.”

“There’s more ’n that to bein’ respectable,” says I. “There’s bein’ honest and havin’ manners and—oh, a heap of things.”

“We always calc’lated to be honest,” says Catty. “As for manners, them we had was plenty for us. Dad he never complained of mine and I never complained of his’n. ’Twasn’t nobody else’s business that I kin see.”

“But you eat with your knife,” says I.

“’Twouldn’t cut nobody’s mouth but mine,” says he.

“Respectable folks don’t do it. Eatin’ with your knife is the worst thing a feller kin do.”

“Worse’n stealin’?”

“I wouldn’t go so far’s to say that.”

“Bet Mrs. Gage would think it was,” says Catty. “She’s one of them kind of folks that don’t see nothin’ but the trimmin’s. If Dad and me had drove into town behind a team of milk-white horses, and each of us wearin’ stovepipe hats, and a bushel of dollar bills scattered on the floor of the buggy, she’d ’a’ invited us to dinner, and wouldn’t have cared how much her boy played with me. Not even if we stole them dollar bills.”

“I dunno,” says I.

“I do,” says he. “The way I see it there’s jest good folks and bad folks. If you’re good you’re good, no matter if you’re respectable or not, nor if you eat with a shingle instead of a fork; and you’re bad if you’re bad, and no amount of eatin’ with the right kind of tools nor wearin’ silk hats kin make you good.”

“That’s right,” says I.

“Well, then?”

“Why, clothes and manners is—well, maybe I can’t tell you, but my Dad kin. He’d know, and he’d tell you so’s you wouldn’t have no arguin’ and wranglin’ to do about it.”

“Let’s find him, then,” says he. “I got my mind made up to be respectable and all, but I’d kinder like to know what I’m bein’ it for and what good it’s doin’ me.”

“Come on,” says I.

We went up to my house, and Dad was fussing around in the garden.

“Hello!” says he, and straightened up, with a smile.

“Hello!” says I. “Here’s Catty and he wants you should explain to him what good it is to be respectable.”

“Um!... What’s your idea of being respectable, Catty?”

“Why, to work and git all tired out, and to eat with somethin’ besides a knife, and to wear good clothes. Then folks respects you. I dunno why.”

“I thought you could think, Catty,” says Dad.

“I calc’late to.”

“But you’re not thinking. When you think you have to dig down into things and not just look at the skin. You’re looking at the skin.”

“If I be,” says Catty, “I hain’t enjoyin’ the looks of it.”

“You’re all wrong. Work and clothes and manners aren’t respectability. They’re just signs of it. How do you know, in the wintertime, when a rabbit has run across a field?”

“You see his tracks in the snow.”

“That’s the way it is with manners and work and clothes. They’re nothing but the tracks of the rabbit of respectability. There might be respectability without any tracks at all, but then folks wouldn’t know it had been past.”

“But rabbit tracks is always rabbit tracks, and clothes and manners and sich might be had by a feller that wasn’t respectable at all, but by some feller that wanted to fool folks.”

“Now you’re thinking,” says Dad. “Manners and clothes aren’t respectability, as I told you. They’re just an advertisement of it. Some advertisements aren’t true, but most are. Now take a case like this. You see a stranger. He’s dirty and slouchy and he doesn’t do any work. Right off you’re prejudiced against him. He may be perfectly good and respectable, but he doesn’t look it. Take another stranger. He is well dressed. You see him working. He is polite and pleasant. Right away you get the idea that he is respectable. Now, he might be a very bad man, but he doesn’t look it. One man advertises that he isn’t respectable; the other advertises that he is. Do you see?”

“Yes,” says Catty.

“Now about work. Work is always respectable. A man that doesn’t work may get along and enjoy himself and be honest, but he isn’t doing anybody any good. You can’t work without doing some good for somebody else. You’re helping the world along every time you do a bit of work, no matter how small it is. You’re contributing your share to the world. Here’s your common laborer who is digging a cellar. He’s an Italian, maybe, and doesn’t get much pay, but the world can’t get along without him. Until he has dug his cellar the skilled mason or bricklayer can’t lay a brick. They’ve got to have the hole dug for their foundation, and so they’re dependent on him. The carpenter can’t drive a nail until the bricklayer has the foundation dug. The plasterer can’t plaster till the house is up; the plumber and the paperhanger and the painter are dependent on the others. See all that? Every man that works is helping some other man that works, and all of them are providing a house for somebody to live in and be comfortable.”

“I see,” says Catty.

“And the man that hires the others to build him a house is helping his town by increasing the amount of property in it. He helps the bank by borrowing money, maybe. He pays taxes to help run the country. He has provided labor for a lot of men—and he, in his turn has had to work somewhere to get the money to build the house. So all of it comes back to work. You can’t work a second without helping the whole world a little.”

“I’ll be dog-goned!” says Catty.

“And that’s why work is respectable—because you can’t do a stroke of work without benefiting everybody in the country and maybe in the whole world. Just so, the fellow who never works is looked down on because he isn’t helping anybody, but is really a detriment, because he is getting food that somebody else has to work to produce, and doesn’t do his share to pay for it. See?”

“Yes. But manners, how about manners?”

“Manners,” says Dad, “are just to make life more pleasant for everybody—like music or pictures or scenery. When the world was made it could have been fixed so it would have been just as useful without ever being beautiful at all. The coal and iron could have been piled on top and not hidden under the ground. There needn’t have been valleys and hills, but just an ugly flat. The Lord could have made it that way if He wanted to, most likely, but He didn’t want to. He wanted folks to love the earth and He made it beautiful so they would enjoy living on it. Now, manners are like that. You can get along without them. But the more of the right kind of manners you have the more people enjoy being with you. Manners, when you get right down to brass tacks, are nothing but actions agreed upon by people with good sense to make it easier and more pleasant to get along with one another.”

“Um!” says Catty, kind of thoughtful. “I git the idee. Never thought of that. Guess I’ll git me a set of manners.”

“But you can work and have manners and clothes—good clothes are merely the best way to be clean—and still not be respectable. Respectable means worthy of being respected, and to be that you have to act in just one way. It only takes a few words to tell you what that is; it is always to give the other fellow a fair deal. Just be fair, that’s all. If you’re always fair you can’t help being respected.”

“Uh-huh!” says Catty. “Much ’bleeged to you, Mr. Moore. Guess I’ll be moseyin’ along. Got a lot of things to do.”

“Catty’s took a contract to paint Mr. Manning’s new warehouse,” says I, “and all he’s got to do is convince his Dad to go to work and then get the ladders and brushes and paints to do the job.”

Dad looked at Catty a second or so before he said anything, and then he says, “Want any help?”

“No, thankee,” says Catty. “I got to do this myself—jest to show wimmin like her”—and he pointed over at Gage’s house—“that they hain’t got no business talkin’ about me like she did. I got to show ’em all, and I’m a-goin’ to.”

“Good for you, Catty. Go at it.... Good-by.”

“G’-by,” says Catty, and we moved off toward the bayou where his Dad was fishing.

We found Mr. Atkins sitting on an old log about nine-tenths asleep and the other tenth drowsy. Catty tickled his ear with a straw, and after he had batted at it a couple of times with his hand he woke up and turned around.

“Pesterin’ your ol’ Dad, eh? Crept up jest to pester me when I was a-sittin’ and thinkin’ and reasonin’ out how to ketch a big fish. One of these here times, young feller, I’m a-goin’ to ketch you jest when you start to pester me, and pieces of you ’ll come rainin’ down more ’n six mile away.”

What he said was awful ferocious, but the way he said it wasn’t ferocious a mite. “Go ’way,” says he, “and pester somebody else.”

“Dad,” says Catty, “you used to be a painter, didn’t you?”

“Who? Me?... Say, young feller, since I quit there hain’t been no real painters ’cause there hain’t nobody to teach ’em. Paint! Now I come to think back there never was sich a painter as me, not for speed nor for skill nor for nothin’. One time I call to mind a man and his wife that wanted their house painted. He wanted it red and she was sot on blue. They called me in and give me the job of satisfyin’ both of ’em, and I done it. Nobody else could ’a’ managed it.”

“How’d you do it?” I asked, because it looked like a puzzler to me.

“Painted it blue,” says he.

“But that only satisfied the woman. Didn’t her husband complain?”

“Nary. Come to find out he was colorblind. Jest let on to him that I was paintin’ it bright red, and he never knowed the difference. Don’t to this day. Figgers he’s got a red house when ’tain’t no more red than a blue jay. That’s the kind of a painter I was.”

“Do you remember how, Dad? Could you paint now if you was of a mind to?”

“Could I paint now? Ho! Why, if folks was to see me paint once all the other painters ’u’d be out of a job. I kin shut both my eyes and tie my right hand and outpaint any other man in the U-nited States of America, with Canady throwed in. I kin paint more in a day than any other feller kin in four, and do it better and more artistic.”

“That’s fine,” says Catty, with a kind of a funny look around his eyes, “because you’re goin’ to start in Monday.”

“Start in what?”

“Paintin’.”

“Paintin’ what?”

“Big warehouse.”

“You mean me—your own Dad that raised you?”

“Yes.”

“Now you look here. You hadn’t ought to of done that. Why, I hain’t used to paintin’. It’s been nigh ten year since I touched a paint-brush! Why, I plumb lost the habit! Dunno’s I could dip a brush in a paint-pail. Never was much of a painter, nohow.”

“You said you was the best.”

“So I was,” said Mr. Atkins, stubbornly.

“Said you could do it better now than anybody.”

“Kin.”

“Then what you mean by sayin’ you lost the habit and never was any good?”

“Jest a way of speakin’. Didn’t want to scare you. I kin paint and I could paint, but I been so long away from paint that it would be mighty dangerous for me to git near it agin.

“Why?”

“Painters’ colic. I’d git doubled up with it in a minnit. Frightful ailment. Nothin’ worse. If I was to be took with it when I was on top of a ladder nothin’ ’u’d save me. Down I’d come, ker-plop, and most likely bust my neck. Then what ’u’d you do?”

“That’s bad, Dad, but we got to risk it.”

“Besides, I hain’t got no paint-brush. Can’t paint without a brush.”

“I’ll git you a brush.”

Mr. Atkins stared at the water and waggled his head. “Looks to me like you was goin’ to crowd me right into this paintin’ job. What’s the idee?”

“You and me is goin’ to be respectable. You’re a-goin’ to have a store and hire men, and maybe wear a silk hat, and we’re goin’ to have money and a house, and go to church, and have folks invite us to dinner, and all sich.”

“I snummy!... What’s that about hirin’ men? Like the sound of it. Why can’t we start out like that? No need of my paintin’ if we kin hire men to do it for me.”

“We’ve got to begin small. What we make on this job we’ll put into stock and git a start. In a little while you won’t have to do anythin’ but boss and look after the work, and maybe paint a little on jobs that’s too good to trust to anybody else.”

“Hope we don’t git many of them kind of jobs,” said Mr. Atkins, mighty sadlike.... “Wa-al, Sonny, if you’re sot on your ol’ Dad a-fallin’ off a ladder with the colic, why, you go ahead, and I’ll tumble for you as often as I kin till I wear out. Maybe we won’t git no job, though,” he said, with what looked to me like a hopeful look.

“We got one—and a big one. Start in Monday. All I got to do is git brushes and ladders and paints and sich.”

“That all you need to git?”

“Yes.”

“Um!... Guess I’ll go on fishin’, then. We kin eat fish, but a feller that starts in to eat a paintin’ job when he hain’t got paint to spread nor brushes to spread it, nor yet ladders to climb up onto, is goin’ hungry for a spell. When you git all them things you come back and tell me, and I’ll go to work.”

“Promise that?”

“Yes indeedy.”

“G’-by, Dad. I got to hustle around spry.”

“Looks that way. I’ll have fish for supper, Sonny.”

We walked off, but Catty acted like he was perfectly satisfied.

“Dad he never made no promise he didn’t keep,” says he. “When once he’s give out his word, that’s the end. Now let’s see about them ladders.”

“Know of any ladders in town?” Catty asked, after a while.

“Fire company’s got some,” says I. “New hook-and-ladder was bought this spring.” Catty thought it over awhile. “Don’t b’lieve we could borrow them,” says he. “Them fire companies is p’tic’lar about lendin’ things. Still, if we can’t git ’em anywheres else, we’ll try.”

When I got to know him better I saw that he was perfectly serious about it, too. If he knew there was a thing he wanted, he figured there must be some way to get it. He told me once that a fellow could get anything if he just sat down and thought long enough. “I’ll bet,” says he, “that you could get anything just by asking for it, if you could think of exactly the right way to ask.”

Maybe that was so. I wish I could believe it and learn how to do it. There’s a heap of things that I want bad and haven’t any chance ever to get unless I do get ’em by asking right.

“Who are the painters here?” says he. “Sands Jones is one and Darkie Patt is the other. Patt’s a darky,” says I, “and they don’t even speak. Mad at each other. Always was and always will be, I guess.”

As we were going along we met Banty Gage and Skoodles Gordon. Skoodles hollered to me to come on, that they were going up to the dam fishing. He said there was a hole washed out behind the spiles where a fellow could catch rookies as fast as he dropped in his line.

“How about it?” says I to Catty, and he looked like he was pretty interested.

“Wait a minute,” I yelled to Banty, “till I see if Catty wants to come.”

“Needn’t wait on our account,” says Banty. “If he comes I can’t. Ma says so, and I don’t want to, neither. I hain’t goin’ to have folks say I’m always runnin’ around with tramps and sich.”

Catty didn’t say a word, but there was a line all the way around his mouth that was white as white, and he looked kind of stiff like he was frozen.

“Me, too,” says Skoodles. “Come on, Wee—wee. You hain’t goin’ to give us the go-by for no tramp, be you?”

It made me mad.

“Come on,” says I to Catty. “Let’s knock some manners into ’em. A good lickin’s goin’ to open up their eyes to who’s a tramp and who hain’t.”

“No,” says he, after a minute. “I’d like to. Gosh! how I’d like to, but it wouldn’t do. I’m tryin’ to be respectable. If you was to fight, nobody’d think anything about it; but if I was to fight, everybody ’d say I was a rowdy and maybe I’d git arrested or somethin’. Wee-wee, I jest got to be respectable.”

“You hain’t afraid, be you?” says I, kind of looking at him edgeways.

“If you think I be,” says he, “come on off alone somewheres where nobody ’ll see us. I figger to show you mighty sudden.”

So that was all right. If he was the kind of a fellow that was afraid of a bang in the nose I didn’t want to take any trouble for him, but he wasn’t. So Banty and Skoodles got off without a licking that day. I just yelled to them to mosey along because I was able to pick my company and ’most generally stuck to what I picked. So they hollered back something disagreeable and went along.

I made up my mind right there that the first time I ketched either of them alone I’d knock him into a peaked hat. Nobody could blame Catty for what I did.

“We will go to see that painter—Mr. Jones,” said Catty.

So we went up to Sands Jones’s house, and there he was, standing just outside the kitchen door with an ax in his hand, like he was going to chop wood. He looked at the ax and then he looked at the wood and then he breathed hard and rested the ax-head on the ground and looked over the garden fence. Mrs. Jones poked her head out of the door.

“Sands Jones,” she said, “don’t you think I can’t see where you’re lookin’—over the back fence toward the river. I’m watchin’ you, too. You git to splittin’ if you expect to eat. Now chop, Sands, chop. I hain’t goin’ to move off’n this spot till that ax-head hits a block of wood.”

“Now, Maw,” says Sands, “can’t a feller look around a bit?”

“He kin look after he splits,” she says. “Lift that there ax.”

He lifted it.

“Now chop.”

He chopped.

“Howdy, Mr. Jones?” says I.

He dropped his ax and looked at me kind of pleased.

“I come to talk business to you—paintin’ business,” says I.

“You chop,” says Mrs. Jones.

“How kin I chop and talk business, Maw? My perfession hain’t choppin’, it’s paintin’. Now hain’t it, Maw? You can say no other ways if you was to try.”

“This feller,” says I, pointing to Catty, “is named Atkins, and he’s got paintin’ work.” Mr. Jones looked Catty over kind of hopeless, and then says: “Paintin’ work? How much? Dog-kennel maybe. I hain’t no time to be paintin’ dog-kennels.”

“It’s a big job, Mr. Jones,” says Catty, “and my father has to hire several good men to help him.”

“Your father! Who’s your Paw, Sonny?”

“Mr. Atkins, the master painter,” says Catty, without wiggling an eyebrow. “He calc’lates to hire several men, and sent me to see if you wanted a job beginning Monday.”

“What’s the job?”

“Paintin’ Mr. Manning’s new warehouse.”

“All of it?”

“All of it.”

“Can’t do it. Too big. Before I got t’ other end of it painted the paint on the first end ’u’d be wore out and I’d have to start in repaintin’ ag’in. Hain’t lookin’ for no permanent paintin’ job. I like variety. Different jobs every day or so; that’s me.”

“You don’t have to do it alone,” says Catty. “There’ll be other men. There’ll be my father to boss and to work, and this Mr. Patt—”

“Darkie Patt?”

“Yes.”

“Won’t work with him. Have nothin’ to do with him. Wouldn’t lean a ladder ag’in’ the same buildin’ he was leanin’ a ladder agin.

“That’s what he says about you,” Catty says.

“Eh?”

“He says you can’t paint, nohow,” says Catty. “He says he was willin’ to work, but that if you was on the same job he’d want twice the wages you was gittin’ because he could paint twice as much and twice as well with one hand.”

“Did, did he?”

“Yes, but I says I didn’t think so, and I says I’d like to have a chance to prove it. It was a kind of a challenge to a paintin’-race. Yes, sir. I says to Mr. Patt that I’d start him out paintin’ on one side and you on the other. Even start. Then there’d be a race betwixt you two to see who could do the most and the best. Yes, sir, and there was to be a prize. Five dollars it was to the feller that got his side done first.”

“You mean Patt was willin’ to race me?”

“He’ll race you, all right.”

“Huh! Hear that, Maw?”

“I heard it,” says Mrs. Jones, “and if you paint like you split wood, Patt kin sleep half a day and beat you with one hand tied.”

“Think so, do you? Think so? That’s your idee? Wa-al, I’ll show you. That’s what I’ll do.... Maw, you jest walk down to that job and cock your eyes up at me a-workin’ if you want to see paint fly. Paint hain’t never flew as I’ll make it fly. You watch.”

“Then you agree?” says Catty.

“You kin bet your bottom dollar. When do we start?”

“Monday morning at seven. By the way, have you any ladders we can rent?”

“Jest rented my ladders to a feller in the next town. Wasn’t no paintin’ jobs in sight, so I figgered to realize on my investment.”

“All right.” says Catty, not showing a mite that he was disappointed. “At seven sharp, on Monday.”

“I’ll be there,” says Mr. Jones.

After that we went over to Darkie Patt’s, and made about the same kind of talk, and got the same results. Patt had two ladders, but both of them was busted or something and couldn’t be used. Said he hadn’t figured on painting much this summer, because, what with night lines and one thing and another, he calc’lated to make a living a heap pleasanter than by buttering the side of a house with yellow paint.

“Well,” says I, when we had gone off, leaving Mr. Patt hired for Monday morning at seven, “you got your men hired to paint, but you hain’t either ladders or brushes. How be you goin’ to make out?”

“Main thing is to find ladders, or scaffoldin’ or somethin’. When I git them I calc’late to git the brushes and paints.”

I was trying hard to think of any ladders I’d ever seen, but I couldn’t think of any. So we just walked along, down alleys and every place we could think, looking to see if we couldn’t see some. After a while we walked down Main Street, and just in front of the drug-store I saw Mrs. Gage and Mrs. Gordon, Skoodles’s mother. Catty didn’t notice them, and I thought maybe we would get past without being seen, but we didn’t. Just as we were alongside Mrs. Gage looked up and saw us.

“There,” she says to Mrs. Gordon. “That’s the boy I mean—there, with the Moore boy. Nice thing to have coming to town, isn’t it? I thought there was a law or something about vagrants.... That Mr. Moore must be out of his head to allow his son to play around with a young tramp like that.”

Mrs. Gordon looked and sniffed. “He’s got a hard face,” says she. “I told my boy never to let me catch them together, and he promised.”

“When my husband comes home to-night I’m going to see if something can’t be done about it,” says Mrs. Gage. “I wonder if that boy ’ll have the cheek to go to school.”

“Oh, that isn’t likely,” says Mrs. Gordon. “That sort don’t take to school much, I imagine.”

Catty let on like he didn’t hear, but I knew he heard, because in about five minutes he spoke up and says: “When school starts this fall I be a-goin’ and nobody hain’t goin’ to keep me away from it. I got a right to go. When my Dad’s a business man in this town I’ll have as good a right to go to school as anybody.”

“Sure,” says I.

“We got to have a place of business right on Main Street,” says he, kind of to himself. “It won’t do jest to work, but we got to make a show of it and look as big as we kin. I wonder if there’s a store we kin git?”

“One down to the end of the block,” says I. “Let’s look at it,” says he.

We walked along until we came to the building I meant. It was wood with a false front—jest one story, but made to look like it had two, and there was an iron hitching-rail in front of it. There was a good-sized store and a small shop right next to it and opening into it. It was kind of run down and needed painting and a window or so, but it was on Main Street, and a good corner, too. Used to be a bakery there, but it went out of business and nobody had rented it since.

“That ’ll do fine,” says Catty. “Dad kin use the big store for paints and wall-papers and sich like, and I kin use the little shop.”

“What for?” says I.

“Oh,” says he, “so’s I kin sort of have a little business of my own and maybe make a dollar or two. I kin tend it and Dad’s store, too, when he’s out on a job.”

“Seems to me like you was cuttin’ out quite a spell of work for yourself,” says I.

“I wonder if there’s rooms behind where we kin live?” says he.

So we took a look, and there were rooms there—four of them—a kitchen and a dining-room and two bedrooms.

“Jest suits,” says Catty. “Who owns her?”

“Mr. Gage,” says I, with a chuckle.

Catty looked at me and then he grinned. “Guess maybe I better see him ’fore his wife gits a chance to talk to him to-night like she said she was going to. Where’s he at?”

“Runs the grocery up the street.”

We walked right up there and found Mr. Gage shooing flies off the fruit up in front.

“Howdy-do, Mr. Gage?” says I. “This is my friend, Catty Atkins.”

“Howdy?” says Mr. Gage. “What kin I do for you?”

“I’m sorter running errands for my Dad,” says Catty. “He’s goin’ into business here, and wants to find out about that store buildin’ of you down the street.”

“What business?” says Mr. Gage.

“Paintin’ and decoratin’,” says Catty.

“Jest come to town?”

“Yes. What rent do you ask?”

“Figger I ought to git twenty dollars a month for that buildin’.”

“Give you seventeen and a half,” says Catty, “and take it for not less ’n a year.”

“Rent payable in advance,” says Mr. Gage, cautious-like.

“We take it from the first of the month. Pay a month’s rent the mornin’ we move in. That all right?”

“Calc’late so.”

“Write it,” says Catty.

“Eh?”

“Set it down in pen and ink, so’s I kin show it to Dad and he’ll know I’ve done what’s right,” says Catty.

So Mr. Gage went in and wrote it down like Catty said, and signed his name to it. After that we went on hunting up ladders, but we didn’t find any. It got supper-time and I left Catty and went home.

About nine o’clock that night our door-bell rang, and I went, and it was Catty. He looked mad and he looked queer and he looked worried.

“Jest come over to tell you the town marshal just come to our house and ordered us to git out of town within forty-eight hours. Says as how he’ll put us in the calaboose for vagrants if we don’t move on.”

“What you goin’ to do?” says I, too surprised and hit all of a heap to even say I was sorry.

“I dunno what I’m goin’ to do,” says Catty, with his jaw shoved out and his eyes kind of hard and mad, “but I kin tell you what I hain’t goin’ to do. I hain’t goin’ to move an inch.”

“Bully for you,” says I, and in another second he had turned around and run off into the dark. I dunno to this day what made him come and tell me about it, because he didn’t ask for any help or anything. But I got a sneaking suspicion it was jest because he was sort of lonesome and kind of wanted to make sure he really did have a friend in the world.

I could hardly wait for breakfast to be over in the morning so that I could hunt up Catty Atkins and find out just exactly what had happened. I told Dad about it, but he didn’t say much.

“Catty said he wasn’t going to leave town, did he?” Dad asked.

“Yes,” I says.

“Well,” says Dad, with a kind of a hint of a grin, “I shouldn’t be surprised if folks had to get used to Catty being here, then.”

“Can’t they make him go?” I asked.

“They could make some folks go. I guess it depends a lot on the folks.”