TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Some minor changes are noted at the end of the book.

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FORMATION OF THE REGIMENT

IN 1685,

AND OF ITS SUBSEQUENT SERVICES

TO 1847.

COMPILED BY

RICHARD CANNON, Esq.

ADJUTANT-GENERAL'S OFFICE, HORSE GUARDS.

ILLUSTRATED WITH PLATES.

LONDON:

PARKER, FURNIVALL, & PARKER,

30 CHARING CROSS.

M DCCC XLVII.

London: Printed by W. Clowes & Sons, Stamford Street,

for Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

HORSE-GUARDS,

1st January, 1836.

His Majesty has been pleased to command that, with a view of doing the fullest justice to Regiments, as well as to Individuals who have distinguished themselves by their Bravery in Action with the Enemy, an Account of the Services of every Regiment in the British Army shall be published under the superintendence and direction of the Adjutant-General; and that this Account shall contain the following particulars, viz.:—

—— The Period and Circumstances of the Original Formation of the Regiment; The Stations at which it has been from time to time employed; The Battles, Sieges, and other Military Operations in which it has been engaged, particularly specifying any Achievement it may have performed, and the Colours, Trophies, &c., it may have captured from the Enemy.

—— The Names of the Officers and the number of Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates Killed or Wounded by the Enemy, specifying the Place and Date of the Action.

—— The Names of those Officers who, in consideration of their Gallant Services and Meritorious Conduct in Engagements with the Enemy, have been distinguished with Titles, Medals, or other Marks of His Majesty's gracious favour.

—— The Names of all such Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers, and Privates, as may have specially signalized themselves in Action.

And,

—— The Badges and Devices which the Regiment may have been permitted to bear, and the Causes on account of which such Badges or Devices, or any other Marks of Distinction, have been granted.

By Command of the Right Honourable

GENERAL LORD HILL,

Commanding-in-Chief.

John Macdonald,

Adjutant-General.

The character and credit of the British Army must chiefly depend upon the zeal and ardour by which all who enter into its service are animated, and consequently it is of the highest importance that any measure calculated to excite the spirit of emulation, by which alone great and gallant actions are achieved, should be adopted.

Nothing can more fully tend to the accomplishment of this desirable object than a full display of the noble deeds with which the Military History of our country abounds. To hold forth these bright examples to the imitation of the youthful soldier, and thus to incite him to emulate the meritorious conduct of those who have preceded him in their honourable career, are among the motives that have given rise to the present publication.

The operations of the British Troops are, indeed, announced in the "London Gazette," from whence they are transferred into the public prints: the achievements of our armies are thus made known at the time of their occurrence, and receive the tribute[iv] of praise and admiration to which they are entitled. On extraordinary occasions, the Houses of Parliament have been in the habit of conferring on the Commanders, and the Officers and Troops acting under their orders, expressions of approbation and of thanks for their skill and bravery; and these testimonials, confirmed by the high honour of their Sovereign's approbation, constitute the reward which the soldier most highly prizes.

It has not, however, until late years been the practice (which appears to have long prevailed in some of the Continental armies) for British Regiments to keep regular records of their services and achievements. Hence some difficulty has been experienced in obtaining, particularly from the old Regiments, an authentic account of their origin and subsequent services.

This defect will now be remedied, in consequence of His Majesty having been pleased to command that every Regiment shall in future keep a full and ample record of its services at home and abroad.

From the materials thus collected, the country will henceforth derive information as to the difficulties and privations which chequer the career of those who embrace the military profession. In Great Britain, where so large a number of persons are devoted to the active concerns of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce, and where these pursuits have, for so[v] long a period, been undisturbed by the presence of war, which few other countries have escaped, comparatively little is known of the vicissitudes of active service, and of the casualties of climate, to which, even during peace, the British Troops are exposed in every part of the globe, with little or no interval of repose.

In their tranquil enjoyment of the blessings which the country derives from the industry and the enterprise of the agriculturist and the trader, its happy inhabitants may be supposed not often to reflect on the perilous duties of the soldier and the sailor,—on their sufferings,—and on the sacrifice of valuable life, by which so many national benefits are obtained and preserved.

The conduct of the British Troops, their valour, and endurance, have shone conspicuously under great and trying difficulties; and their character has been established in Continental warfare by the irresistible spirit with which they have effected debarkations in spite of the most formidable opposition, and by the gallantry and steadiness with which they have maintained their advantages against superior numbers.

In the official Reports made by the respective Commanders, ample justice has generally been done to the gallant exertions of the Corps employed; but the details of their services, and of acts of individual[vi] bravery, can only be fully given in the Annals of the various Regiments.

These Records are now preparing for publication, under His Majesty's special authority, by Mr. Richard Cannon, Principal Clerk of the Adjutant General's Office; and while the perusal of them cannot fail to be useful and interesting to military men of every rank, it is considered that they will also afford entertainment and information to the general reader, particularly to those who may have served in the Army, or who have relatives in the Service.

There exists in the breasts of most of those who have served, or are serving, in the Army, an Esprit de Corps—an attachment to everything belonging to their Regiment; to such persons a narrative of the services of their own Corps cannot fail to prove interesting. Authentic accounts of the actions of the great, the valiant, the loyal, have always been of paramount interest with a brave and civilized people. Great Britain has produced a race of heroes who, in moments of danger and terror, have stood "firm as the rocks of their native shore;" and when half the World has been arrayed against them, they have fought the battles of their Country with unshaken fortitude. It is presumed that a record of achievements in war,—victories so complete and surprising, gained by our countrymen, our brothers,[vii] our fellow-citizens in arms,—a record which revives the memory of the brave, and brings their gallant deeds before us, will certainly prove acceptable to the public.

Biographical memoirs of the Colonels and other distinguished Officers will be introduced in the Records of their respective Regiments, and the Honorary Distinctions which have, from time to time, been conferred upon each Regiment as testifying the value and importance of its services, will be faithfully set forth.

As a convenient mode of Publication, the Record of each Regiment will be printed in a distinct number, so that when the whole shall be completed, the Parts may be bound up in numerical succession.

The natives of Britain have, at all periods, been celebrated for innate courage and unshaken firmness, and the national superiority of the British troops over those of other countries has been evinced in the midst of the most imminent perils. History contains so many proofs of extraordinary acts of bravery, that no doubts can be raised upon the facts which are recorded. It must therefore be admitted, that the distinguishing feature of the British soldier is Intrepidity. This quality was evinced by the inhabitants of England when their country was invaded by Julius Cæsar with a Roman army, on which occasion the undaunted Britons rushed into the sea to attack the Roman soldiers as they descended from their ships; and, although their discipline and arms were inferior to those of their adversaries, yet their fierce and dauntless bearing intimidated the flower of the Roman troops, including Cæsar's favourite tenth legion. Their arms consisted of spears, short swords, and other weapons of rude construction. They had chariots, to the[x] axles of which were fastened sharp pieces of iron resembling scythe-blades, and infantry in long chariots resembling waggons, who alighted and fought on foot, and for change of ground, pursuit, or retreat, sprang into the chariot and drove off with the speed of cavalry. These inventions were, however, unavailing against Cæsar's legions: in the course of time a military system, with discipline and subordination, was introduced, and British courage, being thus regulated, was exerted to the greatest advantage; a full development of the national character followed, and it shone forth in all its native brilliancy.

The military force of the Anglo-Saxons consisted principally of infantry: Thanes, and other men of property, however, fought on horseback. The infantry were of two classes, heavy and light. The former carried large shields armed with spikes, long broad swords and spears; and the latter were armed with swords or spears only. They had also men armed with clubs, others with battle-axes and javelins.

The feudal troops established by William the Conqueror consisted (as already stated in the Introduction to the Cavalry) almost entirely of horse; but when the warlike barons and knights, with their trains of tenants and vassals, took the field, a proportion of men appeared on foot, and, although these were of inferior degree, they proved stout-hearted Britons of stanch fidelity. When stipendiary troops were employed, infantry always constituted a considerable portion of the military force;[xi] and this arme has since acquired, in every quarter of the globe, a celebrity never exceeded by the armies of any nation at any period.

The weapons carried by the infantry, during the several reigns succeeding the Conquest, were bows and arrows, half-pikes, lances, halberds, various kinds of battle-axes, swords, and daggers. Armour was worn on the head and body, and in course of time the practice became general for military men to be so completely cased in steel, that it was almost impossible to slay them.

The introduction of the use of gunpowder in the destructive purposes of war, in the early part of the fourteenth century, produced a change in the arms and equipment of the infantry-soldier. Bows and arrows gave place to various kinds of fire-arms, but British archers continued formidable adversaries; and owing to the inconvenient construction and imperfect bore of the fire-arms when first introduced, a body of men, well trained in the use of the bow from their youth, was considered a valuable acquisition to every army, even as late as the sixteenth century.

During a great part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth each company of infantry usually consisted of men armed five different ways; in every hundred men forty were "men-at-arms," and sixty "shot;" the "men-at-arms" were ten halberdiers, or battle-axe men, and thirty pikemen; and the "shot" were twenty archers, twenty musketeers, and twenty harquebusiers, and each man carried, besides his principal weapon, a sword and dagger.

Companies of infantry varied at this period in numbers from 150 to 300 men; each company had a colour or ensign, and the mode of formation recommended by an English military writer (Sir John Smithe) in 1590 was:—the colour in the centre of the company guarded by the halberdiers; the pikemen in equal proportions, on each flank of the halberdiers; half the musketeers on each flank of the pikes; half the archers on each flank of the musketeers; and the harquebusiers (whose arms were much lighter than the muskets then in use) in equal proportions on each flank of the company for skirmishing.[1] It was customary to unite a number of companies into one body, called a Regiment, which frequently amounted to three thousand men; but each company continued to carry a colour. Numerous improvements were eventually introduced in the construction of fire-arms, and, it having been found impossible to make armour proof against the muskets then in use (which carried a very heavy ball) without its being too weighty for the soldier, armour was gradually laid aside by the infantry in the seventeenth century: bows and arrows also fell into disuse, and the infantry were reduced to two classes, viz.: musketeers, armed with matchlock muskets,[xiii] swords, and daggers; and pikemen, armed with pikes from fourteen to eighteen feet long, and swords.

In the early part of the seventeenth century Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, reduced the strength of regiments to 1000 men; he caused the gunpowder, which had heretofore been carried in flasks, or in small wooden bandoliers, each containing a charge, to be made up into cartridges, and carried in pouches; and he formed each regiment into two wings of musketeers, and a centre division of pikemen. He also adopted the practice of forming four regiments into a brigade; and the number of colours was afterwards reduced to three in each regiment. He formed his columns so compactly that his infantry could resist the charge of the celebrated Polish horsemen and Austrian cuirassiers; and his armies became the admiration of other nations. His mode of formation was copied by the English, French, and other European states; but so great was the prejudice in favour of ancient customs, that all his improvements were not adopted until near a century afterwards.

In 1664 King Charles II. raised a corps for sea-service, styled the Admiral's regiment. In 1678 each company of 100 men usually consisted of 30 pikemen, 60 musketeers, and 10 men armed with light firelocks. In this year the king added a company of men armed with hand-grenades to each of the old British regiments, which was designated the "grenadier company." Daggers were so contrived as to fit in the muzzles of the muskets, and bayonets[xiv] similar to those at present in use were adopted about twenty years afterwards.

An Ordnance regiment was raised in 1685, by order of King James II., to guard the artillery, and was designated the Royal Fusiliers (now 7th Foot). This corps, and the companies of grenadiers, did not carry pikes.

King William III. incorporated the Admiral's regiment in the Second Foot Guards, and raised two Marine regiments for sea-service. During the war in this reign, each company of infantry (excepting the fusiliers and grenadiers) consisted of 14 pikemen and 46 musketeers; the captains carried pikes; lieutenants, partisans; ensigns, half-pikes; and serjeants, halberds. After the peace in 1697 the Marine regiments were disbanded, but were again formed on the breaking out of the war in 1702.[2]

During the reign of Queen Anne the pikes were laid aside, and every infantry soldier was armed with a musket, bayonet, and sword; the grenadiers ceased, about the same period, to carry hand-grenades; and the regiments were directed to lay aside their third colour: the corps of Royal Artillery was first added to the army in this reign.

About the year 1745, the men of the battalion companies of infantry ceased to carry swords;[xv] during the reign of George II. light companies were added to infantry regiments; and in 1764 a Board of General Officers recommended that the grenadiers should lay aside their swords, as that weapon had never been used during the seven years' war. Since that period the arms of the infantry soldier have been limited to the musket and bayonet.

The arms and equipment of the British troops have seldom differed materially, since the Conquest, from those of other European states; and in some respects the arming has, at certain periods, been allowed to be inferior to that of the nations with whom they have had to contend; yet, under this disadvantage, the bravery and superiority of the British infantry have been evinced on very many and most trying occasions, and splendid victories have been gained over very superior numbers.

Great Britain has produced a race of lion-like champions who have dared to confront a host of foes, and have proved themselves valiant with any arms. At Creçy, King Edward III., at the head of about 30,000 men, defeated, on the 26th of August, 1346, Philip King of France, whose army is said to have amounted to 100,000 men; here British valour encountered veterans of renown:—the King of Bohemia, the King of Majorca, and many princes and nobles were slain, and the French army was routed and cut to pieces. Ten years afterwards, Edward Prince of Wales, who was designated the Black Prince, defeated, at Poictiers, with 14,000 men, a French army of 60,000 horse, besides infantry, and took John I., King of France, and his son[xvi] Philip, prisoners. On the 25th of October, 1415, King Henry V., with an army of about 13,000 men, although greatly exhausted by marches, privations, and sickness, defeated, at Agincourt, the Constable of France, at the head of the flower of the French nobility and an army said to amount to 60,000 men, and gained a complete victory.

During the seventy years' war between the United Provinces of the Netherlands and the Spanish monarch, which commenced in 1578 and terminated in 1648, the British infantry in the service of the States-General were celebrated for their unconquerable spirit and firmness;[3] and in the thirty years' war between the Protestant Princes and the Emperor of Germany, the British troops in the service of Sweden and other states were celebrated for deeds of heroism.[4] In the wars of Queen Anne, the fame of the British army under the great Marlborough was spread throughout the world; and if we glance at the achievements performed within the memory of persons now living, there is abundant proof that the Britons of the present age are not inferior to their ancestors in the qualities [xvii]which constitute good soldiers. Witness the deeds of the brave men, of whom there are many now surviving, who fought in Egypt in 1801, under the brave Abercromby, and compelled the French army, which had been vainly styled Invincible, to evacuate that country; also the services of the gallant Troops during the arduous campaigns in the Peninsula, under the immortal Wellington; and the determined stand made by the British Army at Waterloo, where Napoleon Bonaparte, who had long been the inveterate enemy of Great Britain, and had sought and planned her destruction by every means he could devise, was compelled to leave his vanquished legions to their fate, and to place himself at the disposal of the British Government. These achievements, with others of recent dates, in the distant climes of India, prove that the same valour and constancy which glowed in the breasts of the heroes of Crecy, Poictiers, Agincourt, Blenheim, and Ramilies, continue to animate the Britons of the nineteenth century.

The British Soldier is distinguished for a robust and muscular frame,—intrepidity which no danger can appal,—unconquerable spirit and resolution,—patience in fatigue and privation, and cheerful obedience to his superiors. These qualities, united with an excellent system of order and discipline to regulate and give a skilful direction to the energies and adventurous spirit of the hero, and a wise selection of officers of superior talent to command, whose presence inspires confidence,—have been the leading causes of the splendid victories gained by the British[xviii] arms.[5] The fame of the deeds of the past and present generations in the various battle-fields where the robust sons of Albion have fought and conquered, surrounds the British arms with a halo of glory; these achievements will live in the page of history to the end of time.

The records of the several regiments will be found to contain a detail of facts of an interesting character, connected with the hardships, sufferings, and gallant exploits of British soldiers in the various parts of the world where the calls of their Country and the commands of their Sovereign have required them to proceed in the execution of their duty, whether in[xix] active continental operations, or in maintaining colonial territories in distant and unfavourable climes.

The superiority of the British infantry has been pre-eminently set forth in the wars of six centuries, and admitted by the greatest commanders which Europe has produced. The formations and movements of this arme, as at present practised, while they are adapted to every species of warfare, and to all probable situations and circumstances of service, are calculated to show forth the brilliancy of military tactics calculated upon mathematical and scientific principles. Although the movements and evolutions have been copied from the continental armies, yet various improvements have from time to time been introduced, to insure that simplicity and celerity by which the superiority of the national military character is maintained. The rank and influence which Great Britain has attained among the nations of the world, have in a great measure been purchased by the valour of the Army, and to persons who have the welfare of their country at heart, the records of the several regiments cannot fail to prove interesting.

[1] A company of 200 men would appear thus:—

| | |||||||||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Harquebuses. | Muskets. | Halberds. | Muskets. | Harquebuses. | |||||

| Archers. | Pikes. | Pikes. | Archers. | ||||||

The musket carried a ball which weighed 1/10 of a pound; and the harquebus a ball which weighed 1/25 of a pound.

[2] The 30th, 31st, and 32nd Regiments were formed as Marine corps in 1702, and were employed as such during the wars in the reign of Queen Anne. The Marine corps were embarked in the Fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke, and were at the taking of Gibraltar, and in its subsequent defence in 1704; they were afterwards employed at the siege of Barcelona in 1705.

[3] The brave Sir Roger Williams, in his Discourse on War, printed in 1590, observes:—"I persuade myself ten thousand of our nation would beat thirty thousand of theirs (the Spaniards) out of the field, let them be chosen where they list." Yet at this time the Spanish infantry was allowed to be the best disciplined in Europe. For instances of valour displayed by the British Infantry during the Seventy Years' War, see the Historical Record of the Third Foot, or Buffs.

[4] Vide the Historical Record of the First, or Royal Regiment of Foot.

[5] "Under the blessing of Divine Providence, His Majesty ascribes the successes which have attended the exertions of his troops in Egypt to that determined bravery which is inherent in Britons; but His Majesty desires it may be most solemnly and forcibly impressed on the consideration of every part of the army, that it has been a strict observance of order, discipline, and military system, which has given the full energy to the native valour of the troops, and has enabled them proudly to assert the superiority of the national military character, in situations uncommonly arduous, and under circumstances of peculiar difficulty."—General Orders in 1801.

In the General Orders issued by Lieut.-General Sir John Hope (afterwards Lord Hopetoun), congratulating the army upon the successful result of the Battle of Corunna, on the 16th of January, 1809, it is stated:—"On no occasion has the undaunted valour of British troops ever been more manifest. At the termination of a severe and harassing march, rendered necessary by the superiority which the enemy had acquired, and which had materially impaired the efficiency of the troops, many disadvantages were to be encountered. These have all been surmounted by the conduct of the troops themselves: and the enemy has been taught, that whatever advantages of position or of numbers he may possess, there is inherent in the British officers and soldiers a bravery that knows not how to yield,—that no circumstances can appal,—and that will ensure victory, when it is to be obtained by the exertion of any human means."

THE TENTH,

OR

THE NORTH LINCOLNSHIRE,

REGIMENT OF FOOT,

BEARS ON ITS REGIMENTAL COLOUR

THE SPHINX, WITH THE WORD EGYPT;

AND THE WORDS

"PENINSULA" and "SOBRAON;"

IN COMMEMORATION OF ITS DISTINGUISHED SERVICES

IN EGYPT IN THE YEAR 1801;

IN THE PENINSULA FROM 1812 TO 1814;

AND

AT THE BATTLE OF SOBRAON IN 1846.

| Year | Page | |

| 1685 | Formation of the Regiment | 1 |

| —— | Arms and Uniform | 2 |

| —— | Station and Establishment | 3 |

| —— | Earl of Bath, and other Officers appointed to Commissions | 4 |

| 1688 | Declaration of the Regiment, and of the garrison of Plymouth, in favour of King William III. and the Protestant cause | 5 |

| 1689 | Six companies detached to Jersey and Guernsey | 6 |

| 1690 | Embarked for Flanders | - |

| 1691 | Encamped at Anderlecht | - |

| 1692 | Encamped at Halle | 7 |

| —— | Battle of Steenkirk | - |

| —— | Engaged at Furnes and Dixmude | 8 |

| 1693 | The French lines at D'Otignies forced | 9 |

| —— | Battle of Landen | 10 |

| 1694 | Encamped at Ghent | — |

| 1695 | Attack on Fort Kenoque | 11 |

| —— | Siege of Namur | — |

| 1696 | Returned to England and occupied quarters in London; afterwards in Suffolk and Essex | 12 |

| 1697 | Re-embarked for the Netherlands, and joined the army at Brussels | — |

| —— | Treaty of Ryswick | — |

| —— | Returned to England | — |

| 1698 | Proceeded to Ireland | 13 |

| 1701 | [xxvi] War renewed | 13 |

| —— | Embarked for Holland, and reviewed at Breda by King William III. | — |

| —— | Encamped at Rosendael | — |

| 1702 | Decease of King William III., and accession of Queen Anne | — |

| —— | March to Duchy of Cleves | — |

| —— | Arrival at Nimeguen | 14 |

| —— | War declared against France | — |

| —— | Siege of Venloo | — |

| —— | ———– Ruremonde | — |

| —— | ———– Stevenswart | — |

| —— | ———– the Citadel of Liege | — |

| 1703 | Proceeded to Maestricht | 15 |

| —— | —————– Tongres | — |

| —— | Siege of Huy | — |

| —— | ———– Limburg | 16 |

| —— | Spanish Guelderland wrested from France | — |

| —— | Marched back to Holland | — |

| 1704 | Proceeded from Holland to the Danube | — |

| —— | Joined the Imperial Army | — |

| —— | Battle of Schellenberg | — |

| —— | Crossed the Danube | 17 |

| —— | Joined the Imperial Army under Prince Eugene of Savoy | 18 |

| —— | Battle of Blenheim | — |

| —— | Marshal Tallard and many officers and soldiers made prisoners | 19 |

| —— | Marched to Holland with prisoners | — |

| 1705 | Attacks on Helixem, Neer-Winden, and Neer-Hespen | 20 |

| 1706 | Encamped at Tongres | 22 |

| —— | Battle of Ramilies | — |

| —— | Surrender of Brussels, Ghent, and principal towns of Brabant | — |

| 1706 | [xxvii] Surrender of Ostend | 23 |

| —— | Siege of Menin, on the River Lys | — |

| —— | Capture of Dendermond and Aeth | — |

| 1707 | Encampment near the village of Waterloo | 24 |

| 1708 | Re-embarked for England to repel invasion by the Pretender | — |

| —— | Returned to Flanders, landed at Ostend, and proceeded to Ghent | — |

| —— | Re-taking of Ghent and Bruges by the French | — |

| —— | Battle of Oudenarde | 25 |

| —— | Siege of Lisle | — |

| —— | Town of Ghent re-captured | 26 |

| 1709 | Siege and capture of Tournay | 27 |

| —— | Battle of Malplaquet | 28 |

| —— | Siege and surrender of Mons | 29 |

| —— | Marched into winter-quarters at Ghent | — |

| 1710 | Forcing the French lines at Pont-à-Vendin | — |

| —— | Siege and surrender of Douay | 30 |

| —— | Attack and surrender of Bethune | — |

| —— | ————————– of Aire and St. Venant | 31 |

| —— | Proceeded to Courtray | — |

| —— | Winter-quarters at Courtray | — |

| 1711 | Encamped at Warde and on the plains of Lens | — |

| —— | Forcing the lines at Arleux | — |

| —— | Siege of Bouchain | 32 |

| 1712 | Negociations for peace | — |

| —— | Duke of Ormond assumed the command of the army | — |

| —— | Surrender of Quesnoy | — |

| —— | British troops withdrawn to Ghent, and thence to Dunkirk | — |

| 1713 | Removed to Ghent | 33 |

| 1714 | ————— Nieuport | — |

| 1715 | Returned to England | — |

| 1722 | [xxviii] Encamped on Salisbury Plain | 34 |

| —— | Reviewed by King George I. and the Prince of Wales | — |

| 1723 | Proceeded to Scotland | — |

| 1724 | Returned to England | — |

| 1730 | Embarked for Gibraltar | — |

| 1749 | Returned to Ireland | 35 |

| 1751 | Colours and costume regulated by Royal Warrant | — |

| 1767 | Embarked for North America | 36 |

| 1768 | Proceeded to Boston | — |

| 1775 | Advanced to Concord and Lexington;—commencement of American War | 36 |

| —— | Returned to Boston | — |

| —— | Victory at Bunkers-Hill | 38 |

| 1776 | Evacuation of Boston | 39 |

| —— | Returned to Nova Scotia | 40 |

| —— | Attack and capture of Long Island | — |

| —— | Capture of New York | — |

| —— | ————– White Plains | — |

| —— | ————– Forts Washington and Lee | 41 |

| —— | ————– Rhode Island | — |

| 1777 | Embarked for Philadelphia | — |

| —— | Attack at Brandywine Creek | 42 |

| —— | March to Germantown | — |

| —— | Capture of Philadelphia | — |

| —— | ————– Billing's-Point | 43 |

| —— | Fight at Germantown | — |

| —— | Returned to Philadelphia | — |

| —— | Attack at Whitemarsh | — |

| 1778 | Concentrated at New York | — |

| —— | Evacuation of Philadelphia | — |

| —— | Attack at Freehold in New Jersey | 44 |

| —— | Returned to England | 45 |

| 1783 | [xxix] Establishment reduced on termination of the American War | 45 |

| —— | Embarked for Ireland | — |

| 1786 | —————– Jamaica | — |

| 1795 | Returned to England | — |

| —— | Embarked for West Indies | 46 |

| —— | Disembarked on account of a storm, and casualties at Sea | — |

| 1797 | Proceeded to Portsmouth | — |

| 1798 | Embarked for Madras | — |

| 1799 | Removal to Bengal | — |

| 1800 | Embarked for Egypt | 47 |

| 1801 | Landed at Cosseir | — |

| —— | Crossed the Desert of Arabia | 48 |

| —— | Arrived at Kenna and Girgee in Upper Egypt | — |

| —— | Proceeded down the Nile to Rosetta, and El-Hamed | 49 |

| —— | Surrender of Alexandria | — |

| —— | French Army evacuate Egypt | — |

| —— | Authorized to bear the Sphinx with the word "Egypt" | 50 |

| 1802 | Encamped at Alexandria | — |

| 1803 | Arrived at Malta | — |

| 1804 | Removed to Gibraltar | 51 |

| —— | Second Battalion added to the establishment, and formed in Essex | — |

| 1806 | Battle of Maida | 53 |

| 1807 | Embarked for Sicily | — |

| 1809 | Proceeded on an expedition to Naples | 54 |

| —— | Returned to Sicily | 55 |

| —— | Second Battalion embarked for Walcheren | — |

| —— | Returned to England | — |

| 1810 | Embarked for Gibraltar | — |

| —— | Proceeded to Malta | 56 |

| 1811 | Embarked for Sicily | — |

| 1812 | [xxx] First Battalion embarked for Spain | 56 |

| 1813 | Second Battalion proceeded against the Island of Ponzo | 57 |

| —— | Returned to Sicily | — |

| —— | First Battalion—Battle of Castalla | 58 |

| —— | Siege of Tarragona | — |

| —— | Proceeded to Balaguer | 60 |

| —— | Accidental and destructive Fire | — |

| —— | Marched to Valls and thence to Vendrills | 61 |

| —— | Blockade of Barcelona | — |

| 1814 | Cessation of hostilities | — |

| —— | Arrived at Palermo | 62 |

| —— | Second Battalion embarked from Sicily for Malta | — |

| 1815 | Return of Napoleon Buonaparte to France | — |

| —— | First Battalion embarked for Naples | — |

| —— | Proceeded to Malta | — |

| 1816 | Peace restored; the First and Second Battalions incorporated | 63 |

| —— | Authorised to bear the word "Peninsula," on the Colours and Appointments | — |

| 1817 | Embarked for the Ionian Islands | — |

| 1819 | Re-embarked for Malta | — |

| 1821 | Embarked for England | — |

| 1823 | Embarked for Ireland | 64 |

| 1826 | Embarked for Portugal | 65 |

| 1828 | Embarked for Corfu | — |

| 1837 | Returned to Ireland | 66 |

| 1839 | Embarked for England | — |

| 1841 | Proceeded to Scotland | — |

| 1842 | Removed from Scotland | — |

| —— | Embarked for India | 67 |

| 1845 | Proceeded to Meerut | — |

| 1846 | Joined the army on the Sutlej | — |

| —— | Battle of Sobraon | 68 |

| 1846 | [xxxi] Authorised to bear the word "Sobraon," on the Colours and Appointments | 71 |

| —— | Occupation of Lahore | 72 |

| 1685 | John Earl of Bath | 73 |

| 1688 | Sir Charles Carney | 74 |

| —— | Earl of Bath (re-appointed) | — |

| 1693 | Sir Beville Granville | 75 |

| 1703 | Lord North and Grey | — |

| 1715 | Henry Grove | 76 |

| 1737 | Francis Columbine | 77 |

| 1746 | James Lord Tyrawley | — |

| 1749 | Edward Pole | 78 |

| 1763 | Edward Sandford | 79 |

| 1781 | Sir Robert Murray Keith, K.B. | — |

| 1795 | Hon. Henry Edward Fox | — |

| 1811 | Hon. Thomas Maitland | 80 |

| 1824 | Sir John Lambert, G.C.B. | 81 |

| 1847 | Sir Thomas McMahon, Bt. and K.C.B. | 82 |

| Original Costume of the Regiment | to face | 1 |

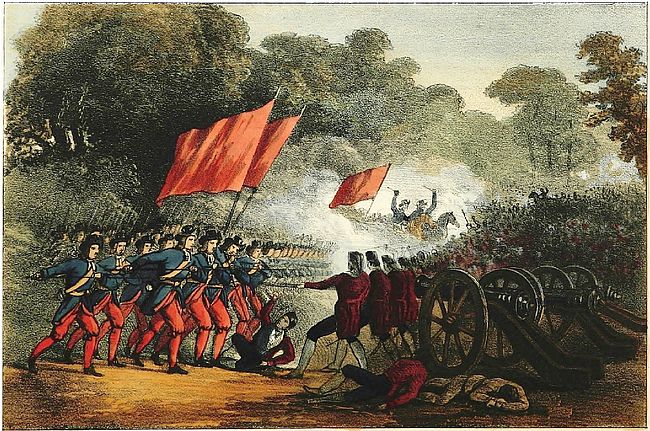

| At the Battle of Steenkirk | " | 7 |

| Colours of the Regiment | " | 36 |

| Costume of the Regiment 1848 | " | 72 |

OF

THE TENTH,

OR

THE NORTH LINCOLNSHIRE

REGIMENT OF FOOT.

After the Restoration, when King Charles II. had disbanded the army of the commonwealth, a small military force was embodied under the title of "guards and garrisons;" one of the independent companies of infantry incorporated for garrison duty was commanded by that distinguished nobleman, John, Earl of Bath, who had evinced fidelity and attachment to the royal cause in the rebellion in the reign of King Charles I., and during the usurpations of Cromwell; this company was stationed in the fortress of Plymouth, of which the Earl of Bath was governor, and it was the nucleus of the regiment which forms the subject of this memoir.

In June, 1685, when James, Duke of Monmouth, had landed in the West of England, with a band of armed followers from the Netherlands, and erected the standard of rebellion, commissions were issued, by King James II., for raising eleven companies of foot, of one[2] hundred private soldiers each, which companies were united to the Plymouth independent garrison company, and constituted a regiment, of which the Earl of Bath was appointed colonel, by commission dated the 20th of June, 1685, and the corps thus formed now bears the title of "The Tenth Regiment of Foot."

These eleven companies were raised in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire; the town of Derby being the general rendezvous of the corps; and they were raised under the authority of royal warrants, bearing date the 20th of June, by the following gentlemen, who evinced their loyalty by coming forward to the support of the crown at that important crisis:—viz., Colonel, John, Earl of Bath; Lieut.-Colonel, Sir Nicholas Stannings; Major, Sir Charles Carney; Captains, Michael Bourk, Charles Powell, Sir Thomas Windham, Edward Scott, Bernard Strode, John Sydenham, Francis Vivian, and Sydney Godolphin.

After the suppression of this rebellion, many newly raised corps were disbanded, and the Earl of Bath's regiment was reduced to ten companies of fifty private soldiers each.

The regiment was armed with muskets and pikes; the uniform was blue, coats lined with red, red waistcoats, breeches, and stockings; round hats with broad brims, the brim turned up on one side and ornamented with red ribands; the pikemen wore red worsted sashes. This was the only infantry regiment clothed in blue coats; the other corps wore red coats; red had been generally worn by the English soldiers from the time of Queen Elizabeth; but several of Cromwell's regiments were clothed in blue, and King Charles II. clothed the royal regiment of horse guards in blue, and a regiment[3] of marines, raised in his reign, in yellow. A few years after the revolution in 1688, the Tenth were clothed in red.

In August, 1685, the Earl of Bath's regiment marched from Derby to Hounslow, and encamped upon the heath, where it was reviewed by the King, and afterwards marched to Plymouth, to relieve the Queen Dowager's regiment, now second foot.

The following statement of the numbers and rates of pay is copied from the establishment of the army, under the sign manual, dated the 1st of January, 1686.

| The Earl of Bath's Regiment. | Pay per day. | |||

| Staff. | £. | s. | d. | |

| 1 | Colonel, as Colonel | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| 1 | Lieut.-Colonel, as Lieut.-Colonel | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 1 | Major, as Major | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 1 | Chaplain | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| 1 | Chirurgeon, ivs. 1 Mate, iis. vid. | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| 1 | Adjutant | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 1 | Quarter-Master and Marshal | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Total for Staff | 2 | 5 | 2 | |

| The Colonel's Company. | ||||

| The Colonel, as Captain | 0 | 8 | 0 | |

| 1 | Lieutenant | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 1 | Ensign | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | Serjeants, xviiid. each | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 3 | Corporals, is. each | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 1 | Drummer | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 50 | Private Soldiers, at viiid. each | 1 | 13 | 4 |

| Total for one Company | 2 | 15 | 4 | |

| Nine Companies more | 24 | 18 | 0 | |

| Total | 29 | 18 | 6 | |

| Per Annum, £10,922 12s. 6d. | ||||

Leaving Plymouth in March, 1686, the regiment occupied quarters at Guildford and Godalming until the[4] 24th of May, when it pitched its tents on Hounslow-heath, where a numerous body of troops was assembled for exercise and review. At this camp the regiment had an independent company of grenadiers attached to it, and after the reviews it marched into garrison at Portsmouth.

In 1687, the following officers were holding commissions in the regiment:—

| Captains. | Lieutenants. | Ensigns. |

| Earl of Bath, (col.) | Maurice Roch. | James Mohun. |

| Sir Cha. Carney, (lt.-col.) | John Prideaux. | Richd. Nagle. |

| Sir Bev. Granville, (major) | D. Bradshaw. | Jas. Granville. |

| Sir Thomas Windham. | Cha. Harbine. | Jacob Breams. |

| Edward Scott. | Richard Scott. | James Steukly. |

| Sydney Godolphin. | Wm. Morgan. | Jno. Granville. |

| John, Lord Arundel. | Thos. Trevanion. | Edw. Chard. |

| Bernard Strode. | Thos. Lamb. | Thos. Cary. |

| Ranald Graham. | John Long. | Hercules Low. |

| John Sydenham. | Hy. Hook. | John Jacob. |

| John Granville. | { | Roger Elliott | } | Grenadier Co. |

| { | Roger Evans | } | ||

| Chaplain, Thos. Nixon. | Adjutant, R. Elliott. | |||

| Chirurgeon, James Yong. | Quarter-Master, Jno. Freeman. | |||

The regiment left Portsmouth, in April, 1687, for Winchester and Taunton; in June, it once more pitched its tents on Hounslow-heath, and in August marched into quarters in London. It did not remain long in the metropolis: and after several changes of quarters it was placed in garrison at Plymouth.

When King James II., who was a zealous Roman Catholic, pursued the interests of papacy so far as to occasion much alarm among his Protestant subjects, the Earl of Bath stood aloof from the measures of the Court, and he was one of the noblemen who communicated[5] privately with the Prince of Orange, to whom the nation looked for aid to oppose the arbitrary proceedings of the King. In November, 1688, when the Prince of Orange arrived with a Dutch armament, the Tenth and Thirteenth regiments were in garrison at Plymouth,—the Tenth occupying the citadel, and the two colonels were with their regiments. The Earl of Bath was in the interest of the Prince of Orange; but the Earl of Huntingdon adhered to King James: the lieut.-colonel of the Tenth, Sir Charles Carney, was a steadfast supporter of the Court, and the lieut.-colonel of the Thirteenth, Ferdinando Hastings, was a warm advocate for the Prince of Orange; thus the interest of the superior officers of the two regiments was equally divided. It appeared doubtful, for some time, to which party the garrison of Plymouth would devote itself; but eventually, the Earl of Bath, being the senior officer and governor of the fortress, ordered the Earl of Huntingdon to be arrested: he also ordered four Roman Catholic officers of the Thirteenth,—viz., Captain Owen Macarty, Lieutenants William Rhodesby, Talbot Lascelles, and Ensign Ambrose Jones, to be arrested; he then declared for the Prince of Orange, and induced the two regiments to engage in the same interest. The garrison having been settled in the name of the Prince of Orange, the Earl of Huntingdon and the Roman Catholic officers of his regiment were released.

The news of the loss of Plymouth, and of the two regiments having declared for the Prince of Orange, together with similar events taking place in other parts of the kingdom, proved to King James that his soldiers would not fight against the Protestant religion and the laws of the realm. His Majesty deprived the Earl of[6] Bath of his commissions, and appointed Lieut.-Colonel Sir Charles Carney to the colonelcy of the Tenth foot by commission dated the 8th of December. The regiment had, however, engaged in the interest of the Prince of Orange, and this change in the colonel produced no alteration in the sentiments of the regiment. King James fled to France, and on the 31st of December the Prince restored the Earl of Bath to the colonelcy.

The accession of the Prince and Princess of Orange to the throne was followed by a civil war in Scotland and Ireland; but the Tenth were intrusted with the charge of the citadel of Plymouth, and they were not employed in the field in 1689 or 1690; they, however, detached six companies to the islands of Jersey and Guernsey.

In 1690, the powerful efforts of the French monarch to reduce the Spanish provinces in the Netherlands under his dominion, occasioned the regiment to be called into active service. Embarking from Jersey, Guernsey, and Plymouth, the Tenth foot, commanded by Lieut.-Colonel Sir Beville Granville, nephew of the Earl of Bath, sailed to Ostend, and landing at that port marched up the country, and joined the army commanded by King William III. The regiment enjoyed the confidence of the King to a great extent, and on joining the army, it was ordered to pitch its tents near His Majesty's quarters at Anderlecht. It was formed in brigade with the seventh, sixteenth, and Fitzpatrick's (afterwards disbanded), under Brigadier-General Churchill, and after taking part in several movements, went into winter-quarters.

J. M. Jopling delt.

Madeley lith. 3 Wellington St. Strand.

TENTH REGIMENT OF FOOT.Quitting its cantonments among the Flemish peasantry, in May, 1692, the regiment again took the field, [7]and was employed in several operations. In the beginning of August it was encamped at Halle, and, early on the morning of the 3rd of that month, it advanced at the head of the main body of the confederate army to attack the French in position at Steenkirk. After passing through some narrow defiles among trees, the Third and Tenth foot halted at the extremity of a wood, at the moment when the brigades forming the van of the army were severely engaged with very superior numbers. A short distance in front of the Tenth, and near the skirt of the wood a little to the left, a regiment of Lunenburgers, commanded by the Baron of Pibrack, was contending with two French battalions, and was nearly overpowered; it was falling back, fighting, and in some disorder; the French were gaining ground; and its colonel, the Baron of Pibrack, lay dangerously wounded a few yards in front of the muzzles of the enemy's muskets. Prince Casimir of Nassau galloped up to the Tenth, and requested them to advance to the aid of the Lunenburgers; when the regiment formed line, the pikemen in the centre, and the musketeers and grenadiers on each flank, and Lieut.-Colonel Sir Beville Granville led it forward with great gallantry. At that moment the Lunenburgers were overpowered, and the French were hurrying forward with shouts, and a heavy fire of musketry, when suddenly the Tenth, conspicuous by their blue coats, scarlet breeches and stockings, and three stand of scarlet colours floating in the breeze, were seen issuing from among the trees in firm array. So noble a line of combatants, separating itself from the broken sections of the retreating Lunenburgers, startled the enemy; the French artillery thundered against its flanks,—their musketry smote it in front,—yet the regiment bore sternly forward[8] to close on its numerous enemies, when the French fell back. Two serjeants of the Tenth sprang forward and rescued the Baron of Pibrack, bearing him from among his enemies to the rear, and the regiment pressed forward, without firing a shot, until it gained a hollow way beyond the skirts of the wood, where it halted, and the musketeers, taking sure aim over the bank, soon cleared the ground in their front of opponents. Numerous narrow defiles and other obstructions prevented the main body of the British infantry from arriving in time to support the brigades in advance; King William ordered a retreat, and Prince Casimir of Nassau arrived with orders for the Tenth to withdraw from their post. The Prince highly commended the conduct of the regiment on that, the first occasion of its being engaged, and its bearing proved a presage of future renown.

The regiment had a number of private soldiers killed and wounded; also Captain Elliott, Lieutenants Thomas Granville and John Granville, wounded.

Towards the end of August, the Tenth were detached from the main army, and having joined a number of troops which had arrived from England under Lieut.-General the Duke of Leinster, they were employed in seizing and fortifying the towns of Furnes and Dixmude. On the 22nd of September, as working parties of the seventh and Tenth foot were enlarging the ditch of a bastion, they found a quantity of hidden treasure, consisting of old French coins, amounting to nearly five hundred pounds sterling, supposed (according to D'Auvergne's history of the campaign of 1692) to have been concealed there during the civil war in Flanders towards the close of the preceding century.

In the middle of October, the regiment marched to[9] Damme, a little strong town, situated between Bruges and Sluys, where it passed the winter.

The Tenth regiment of foot appears in the list of troops under King William III., at Parck camp near Louvain, in June, 1693, and they were ordered to pitch their tents in the fields adjoining the defiles of Berbeck, to guard that avenue to the camp. While the army was at this place, several skirmishes occurred; but the only loss sustained by the Tenth was on the 25th of June, when an outpost of a serjeant's party, covering a number of horses at grass, was attacked, and three men were severely wounded.

On the 1st of July, the regiment was detached from the main army, with other forces under the Duke of Wirtemberg, to attack the enemy's fortified lines between the rivers Scheldt and Lys. After a march of eight days, the troops arrived in front of the lines near D'Otignies, and on the following day the works were attacked at three points. The grenadiers formed the van of each attack; the right column was composed of Danes; the Argyle highlanders headed the centre column, and the Tenth foot took the lead of the column on the left. When the signal for the assault was given, the Tenth raised a loud shout and ran forward. The pikemen arrived at the little river Espiers, which ran in front of the lines, and cast a number of fascines into the water, but the stream carried them away. The grenadiers of the Tenth and other regiments, being anxious to signalize themselves, dashed into the current, at the same time the musketeers advanced to the bank and fired upon their opponents on the works. The river was so deep that many of the soldiers were up to the chin in water; but they gained the shore without serious loss,—sprang[10] forward with astonishing rapidity,—forded the ditch,—pulled down the palisadoes,—and ascended the lines, sword in hand; the officers and grenadiers of the Tenth being the first that entered the works. As the soldiers climbed the entrenchments, shouting and flourishing their swords, the French fled, and the lines were carried with little loss. D'Auvergne states that the grenadiers of the Earl of Bath's regiment (Tenth) found a cask of brandy in one of the abandoned redoubts, which proved very welcome, as the soldiers had been exposed to a heavy rain for several days.

After forcing the lines, contributions were levied on the territory subject to France, as far as Lisle: and the Duke of Wirtemberg was so well pleased with the conduct of the Tenth, that he made a donation of a ducat to each man, and the same to the men of the other regiments engaged in forcing the lines.

While the Tenth were levying contributions, the main army under King William was defeated at Landen; after this disaster the regiment was ordered to join the army, but it was not engaged in any service of importance, and in October it marched into winter-quarters at Bruges.

On the 29th of October, the Earl of Bath was succeeded in the colonelcy by his nephew, Lieut.-Colonel Sir Beville Granville.

Leaving Bruges in May, 1694, the regiment pitched its tents near Ghent. It served the campaign of that year in Brigadier-General Stewart's brigade, in the division commanded by Major-General Sir Henry Bellasis; and after taking part in several operations, and performing many long and toilsome marches, it proceeded into quarters at the pleasant town of Malines.

Early in the spring of 1695, the French commenced some new works between the Lys and the Scheldt, when five hundred men of the Tenth were withdrawn from Malines in the expectation of taking part in an attempt to interrupt the enemy's proceedings; but this enterprise was laid aside, and the regiment encamped at Marykirk until the army took the field, when it was joined by the men left in quarters.

The Tenth were subsequently detached to Dixmude, in West Flanders; and they were one of the corps which pitched their tents before the Kenoque, a fortress at the junction of the Loo and Dixmude canals, where the French had a garrison.

On the 9th of June, the grenadiers of the Tenth were engaged in driving the French from the entrenchments and houses near the Loo canal. A redoubt was afterwards taken, and a lodgment effected on the works at the bridge; in which service the regiment had several men killed and wounded.

This enterprise was only designed as a diversion to favour the operations of the main army, and when King William had besieged the strong fortress of Namur, the regiment traversed the country to the banks of the Lys, and joined the covering army under the Prince of Vaudemont.

When Marshal Villeroy advanced, with a force of very superior numbers, to attack the covering army, the Prince of Vaudemont retreated to Ghent, and during this retrograde movement, the commanding officer of the Tenth, Lieut.-Colonel Sydney Godolphin, and a serjeant and twelve men, resting at a house on the road too long, were made prisoners.

The regiment was subsequently employed in several[12] movements to protect the maritime and other towns of Flanders, and to cover the army carrying on the siege of Namur. In August it was encamped between Genappe and Waterloo, and after the surrender of the castle of Namur, it marched into quarters in the villages between Nieuport and Ostend.

In the spring of 1696, Louis XIV. endeavoured to weaken the power of the confederate army in Flanders, by causing England to become the seat of civil war. The partisans of King James were excited to rise in arms; a plot was formed for the assassination of King William, and a French army approached the coast to embark with King James for England. The Tenth foot was one of the corps selected to return to England on this occasion, and the regiment, having embarked at Ostend, arrived at Gravesend in March. In the meantime the conspirators had been discovered; a British fleet was sent to blockade the French ports, and the designs of Louis XIV. were frustrated.

Several corps returned to Flanders; but the Tenth were selected to remain on home service.

The regiment landed at Gravesend, occupied quarters a short period in London, and afterwards marched into extensive cantonments in the counties of Suffolk and Essex.

In May, 1697, the regiment was ordered to embark for the Netherlands, and it joined the army at the camp in front of Brussels in July; but in a few weeks afterwards the treaty of Ryswick gave peace to Europe.

During the winter, the regiment returned to England; it landed at Gravesend and Tilbury in December, and marched into quarters in Essex.

Considerable reductions were made in the strength[13] of the army, after the peace of Ryswick, and the Tenth regiment was one of the corps selected to proceed to Ireland; it embarked at Highlake in July, 1698, and was stationed in Ireland during the following two years.

Pursuing his schemes for the aggrandizement of his family with unceasing assiduity, the King of France procured the accession of his grandson, Philip, Duke of Anjou, to the throne of Spain, and this open violation of existing treaties involved Europe in another war. Among the corps first ordered to proceed on foreign service to aid the continental powers in arresting the progress of French usurpations, was the Tenth regiment of foot. It embarked at Cork on the 15th of June, 1701, sailed to Holland, and was placed in one of the frontier garrisons of that country. In September it was encamped on Breda-heath, where it was reviewed, with the remainder of the British troops in Holland, by King William III., and afterwards returned to its former station in garrison.

In the spring of 1702, the regiment took the field to serve as auxiliaries to the army of the Emperor of Germany, England not having declared war against France; and at the camp at Rosendael, news was received of the death of King William III. and of the accession of Queen Anne on the 8th of March. From Rosendael the Tenth marched to the Duchy of Cleves, and encamped at Cranenburg on the Lower Rhine, forming part of the covering army during the siege of Kayserswerth. In June a French force of superior numbers marched through the forest of Cleves and plains of Goch to cut off the allied army from Grave and Nimeguen; in consequence of this movement the British,[14] Dutch, and Germans at Cranenburg, struck their tents a little before sunset on the 10th of June, and, by a forced march, arrived within a few miles of Nimeguen, about eight o'clock on the following morning, at which time the French columns appeared on both flanks and in the rear. Some sharp fighting occurred; the British corps forming the rear-guard evinced signal gallantry, and the Tenth regiment distinguished itself: the enemy was held in check until the army effected its retreat under the works of Nimeguen.

England declared war against France: additional troops arrived in Holland, and the Earl of Marlborough assumed the command. The Tenth were engaged in the movements by which the French were driven from their menacing position near the confines of Holland. The regiment also formed part of the covering army during the siege of Venloo,—a fortress on the east side of the river Maese, which surrendered on the 25th of September. The regiment was next engaged in covering the sieges of Ruremonde and Stevenswart, both of which places were captured in the early part of October. The army afterwards advanced to the city of Liege, which immediately opened its gates, but the citadel, and a detached fortress called the Chartreuse, held out. The Tenth regiment was employed in the siege of the citadel, and the grenadier company behaved with great gallantry at the capture of that fortress by storm on the 23rd of October. The citadel being carried by assault, the garrison was nearly annihilated; the garrison of the Chartreuse were eye-witnesses of this event, and surrendered immediately afterwards, from apprehension of a similar fate.

The city of Liege being rescued from the power of[15] the enemy, the regiment marched back to Holland, and passed the winter in garrison at Breda.

Sir Beville Granville having been appointed governor of Barbadoes, the colonelcy of the Tenth foot was conferred on William, Lord North and Grey, by commission dated the 15th of January, 1703.

Colonel Lord North and Grey proved a very gallant aspirant for military fame; serving at the head of his regiment, and distinguishing himself on numerous occasions. The Tenth left their winter-quarters towards the end of April, 1703; on the 6th of May, they arrived at Maeswyck, where they halted on the following day; but, information having been received of the approach of a powerful French army to cut off the detachments of the confederate forces, the regiment struck its tents at sunset, with several other corps, and, by a forced march, arrived at the city of Maestricht about noon on the following day. When the French army approached that city, the regiment was in position, being one of the corps stationed at Lonakin; some skirmishing and cannonading occurred, and the French withdrew without venturing a general engagement.

When the Duke of Marlborough advanced against the French at Tongres, the Tenth were formed in brigade with the second battalion of the royals, and the sixteenth, twenty-first, and twenty-sixth regiments, under Brigadier-General the Earl of Derby. The enemy took refuge behind an extensive line of works, and the English General besieged the strong fortress of Huy, situate on the Maese above Liege. The Tenth foot were employed at the siege; and, on the 18th of August, when the enemy had vacated that portion of the town which lay beyond the river, Colonel Lord[16] North and Grey took possession of it with the Tenth: another corps was afterwards placed under his lordship's command, and the regiment held this post during the remainder of the siege.

Huy having been captured, the siege of the city of Limburg was next undertaken, and this fortress was surrendered before the end of September. Thus Spanish Guelderland was wrested from the power of France, and in October the regiment marched back to Holland, where it passed the winter.

While the Duke of Marlborough was capturing fortress after fortress in the Netherlands, the French and Bavarians had great success in Germany; their united efforts threatened to overturn the imperial throne, and, in 1704, the British commander led his army from Holland to the Danube, to the succour of the Emperor Leopold. The Tenth foot, commanded by Colonel Lord North and Grey, had the honour of being employed in this splendid enterprise, which elevated the reputation of the British arms, and immortalized the name of Marlborough for the conception of the movement, and the secrecy and rapidity with which it was executed.

To engage in this undertaking, the regiment left its winter-quarters early in May, 1704, and directing its march to the Rhine, proceeded along the banks of that river to Coblentz, where it passed the Rhine and the Moselle on the 25th and 26th of that month. From Coblentz the army marched towards the Maine, and traversing the several states of Germany, arrived at the seat of war to co-operate with the forces of the empire.

On the 2nd of July, after a long march through a difficult country, the British approached the fortified post of Schellenberg, a commanding height on the left[17] bank of the Danube, where a body of French and Bavarians were stationed under the Count d'Arco, and about six in the evening, a detachment from each British regiment, with the foot guards, royals, and twenty-third, under Brigadier-General Fergusson, and a Dutch force under General Goor, advanced to attack the entrenchments. A very spirited resistance was made by the enemy, and, eventually, the Tenth were led up the contested height to join in the attack. Firmly and steadily the soldiers of the Tenth moved up the steep ascent, which was strewed with killed and wounded; arriving within range of the enemy's fire, an iron tempest smote the ranks, and the firm order of the regiment was shaken: a short pause ensued. At that moment the British cavalry approached to support the infantry, and the Germans under the Margrave of Baden arrived to prolong the attack and assail the enemy in the rear. Encouraged by these circumstances, the British and Dutch infantry raised a loud shout, and, breaking with terrific violence into the entrenchments, overpowered all resistance. The Duke of Marlborough led the British cavalry forward, and completed the overthrow of the enemy.

The Tenth had Captain Crow and fifteen rank and file killed; three serjeants, and thirty-six rank and file wounded.

Crossing the Danube, and advancing into Bavaria, the regiment was engaged in various operations; it proceeded to the vicinity of the enemy's fortified camp at Augsburg, and afterwards returned to the Danube at Donawerth: in the meantime a numerous body of French troops had traversed the Black Forest and joined the enemy.

About ten o'clock on the night of the 11th of August, the army under the Duke of Marlborough joined the imperialists commanded by Prince Eugene of Savoy, at the village of Munster, near the bank of the Danube. On the following day the regiment was ordered forward to support the piquets, which were attacked by the enemy's hussars.

At daybreak, on the morning of the memorable 13th of August, the regiment was under arms, to engage in a battle which appeared to involve the fate of the Christian world: it formed, on this occasion, part of the brigade under Brigadier-General Row.

Advancing from the camp-ground, the soldiers arrived in front of the enemy's position, and the Tenth, commanded by their gallant young colonel, Lord North and Grey, were destined to attack the village of Blenheim, where the enemy had posted a numerous body of troops, thrown up entrenchments, and constructed palisades. Against this village, Brigadier-General Row's brigade advanced with great gallantry: the Tenth and Royal Scots Fusiliers led the attack, and were distinguished for their intrepid bearing; but all efforts to force the village against an enemy of so very superior numbers, and advantageously posted, proved ineffectual. As the brigade withdrew, it was charged by some French cavalry, who were repulsed by the fire of a Hessian brigade. Brigadier-General Fergusson led a brigade against the other side of the village; but without success. A sharp fire was afterwards kept up at this point, and the army deployed to engage the main body of the French and Bavarians. In the conflict which followed, British valour was conspicuous, and after a contest of several hours' duration, the French[19] and Bavarian armies were overthrown and nearly annihilated; Marshal Tallard, and many officers and soldiers being made prisoners.

When the main body of their army was overthrown, the French troops in Blenheim were insulated; thrice they attempted to escape, but they were forced back. They took shelter behind the houses and enclosures; but they were soon surrounded, and twelve squadrons of cavalry, with twenty-four battalions of infantry, surrendered prisoners of war. Thus ended the mighty struggle of this eventful day, so glorious to the British arms!

The honours acquired by the regiment had been attended with the loss of many valuable lives. Captains Dawes, Sir John Sands, Cavendish, and Burton; Lieutenants Frazer and Wycks; Ensigns Breams and Dawson, were killed: Colonel Lord North and Grey lost his right hand; Major Granville; Captains Cunningham and Spotswood; Lieutenants Bulwer, Boylblanc, and Hornby; Ensigns Crow and Rossington, were wounded. The number of non-commissioned officers and private soldiers of the regiment, killed and wounded, has not been ascertained.

After passing the night on the field of battle, surrounded with the ensanguined trophies of victory, the Tenth were selected to guard the prisoners from Germany to Holland, in which service five British battalions were employed. The prisoners were marched to Mentz, where they were put on board of small vessels, and sailed to Holland. The regiment arrived at the Hague in October, and, having delivered up the prisoners, it was placed in garrison for the winter: its services are not, therefore, connected with the operations of the army in Germany after the victory at Blenheim.

A numerous body of fine recruits arrived from England, in the spring of 1705, to replace the losses of the preceding campaign, and in May, 1705, when the regiment took the field, its appearance was admired. It was reviewed by the Duke of Marlborough, at the camp on the left bank of the Maese, and afterwards marched to Juliers. From Juliers the regiment marched through a mountainous country to the valley of the Moselle, and pitched its tents near the ancient city of Treves. The army being united, it passed the rivers Moselle and Saar on the 3rd of June, traversed the difficult defile of Tavernen, and encamped within seven miles of Syrk. At this place the army halted, waiting for the imperialists, whose tardy movements and inefficient state disappointed the expectations of the English commander, and rendered it necessary for him to hurry back to the Netherlands to arrest the progress of the French on the Maese.

In the forced march from Syrk to the Maese, the regiment lost many men from fatigue; and soon after its arrival, it was selected to take part in storming the enemy's fortified lines, which were protected by a numerous army. To render this great undertaking as certain as possible, these formidable barriers were menaced on the south of the Mehaigne, and the French troops being drawn in that direction, the point selected for the attack was thus weakened. On the evening of the 17th of July, the corps selected to commence the attack marched in the direction of Helixem and Neer-Hespen, the Tenth forming part of the leading brigade of infantry; and they were followed by the remainder of the army. About four o'clock on the following morning, they approached the lines and surprised[21] the enemy's guards. Inspired with emulation, the soldiers soon cleared the villages of Neer-Winden and Neer-Hespen, seized the village and bridge of Helixem, and carried the castle of Wange with little loss; the enemy being surprised and confounded by the suddenness of the attack. Encouraged by this success, and stimulated by the noble example of several officers, the troops rushed through the enclosures and marshy grounds, forded the river Gheet, and crowded across the fortifications; the French retreating in a panic. Thus the lines were forced, and the soldiers of the Tenth stood triumphant on the captured works, where the cross of St. George, floating in the air, served as a beacon to impart a knowledge of this splendid success to the main body of the army, still at some distance. A numerous body of the enemy's cavalry and infantry hurried to the spot to drive back the troops which had passed the lines, when some sharp fighting occurred, which ended in the overthrow of the enemy, who made a precipitate retreat behind the river Dyle. This daring enterprise was thus achieved; and the talents of the Duke of Marlborough, with the intrepidity and valour of the British soldiers, were admired by all nations. The English commander stated in his despatch, that the troops acquitted themselves with a bravery surpassing all that could have been hoped of them.

The Tenth shared in the operations of the main army during the remainder of the campaign, but had no opportunity of distinguishing themselves in action: they passed the winter in garrison in Holland.

Each successive victory had inspired the troops with additional confidence in their commander, and in their own prowess: to besiege a town, or fight a battle, and[22] not conquer, when the Duke of Marlborough commanded, appeared impossible. With a bold assurance that fresh triumphs awaited them, the soldiers took the field in May, 1706, and the Tenth foot joined the camp near Tongres on the 19th of that month. On the 23rd of May, as the army was advancing in eight columns, information was received that the French, Spaniards, and Bavarians, commanded by Marshal Villeroy and the Elector of Bavaria, were taking up a position at Mont St. André, with their centre at the village of Ramilies, and the allies prepared for battle.

Diverging into the open plain, the allied army formed line and advanced against the enemy. The Tenth foot, being on the right of the line, proceeded, with a number of other corps, in the direction of the village of Autreglise, and made a demonstration of attacking the enemy's left. The French weakened their centre to support their left, and the British commander instantly seized the opportunity and attacked the weakened point. The Tenth foot were among the corps which, occupying some high ground on the right, were not engaged during the early part of the battle; but they had a full view of the conflict on the plain. At length a crisis arrived: the brigades on the right were ordered into action, when the Tenth evinced that intrepidity and firmness for which the regiment had been distinguished on former occasions, and another decisive victory exalted the fame of the British arms. The broken remains of the French, Spanish, and Bavarian legions were pursued for many miles, and an immense number of prisoners, cannon, standards, and colours was captured.

The effect of this surprising victory was the immediate surrender of Brussels, Ghent, and the principal towns[23] of Brabant, and the intelligence of these events produced such an electric sensation throughout England, that the gallant exploits of the heroes of Ramilies became a general theme of conversation, and the subject of numerous addresses to the throne. Rewards were conferred on officers who had distinguished themselves, and the commanding officer of the Tenth, the gallant Lord North and Grey, was promoted to the rank of brigadier-general, and placed at the head of three battalions of infantry.

Several towns in Flanders held out; and in June the Tenth marched to Arseele, and afterwards to Rouselaer, and formed part of the covering army during the siege of Ostend, which fortress was delivered up on the 8th of July.

After the surrender of Ostend, the regiment was selected to take part in the siege of Menin, a strong town pleasantly situated on the little river Lys. This fortress was accounted the key to the French conquests in the Netherlands, and one of the masterpieces of the celebrated Vauban: the siege therefore excited an unusual degree of interest. The town was invested on the 23rd of July; and the conduct of the Tenth during the progress of the siege, corresponded with the high character of the regiment. Considerable loss was sustained in carrying on the attacks, but the soldiers had the gratification of witnessing this place added to the numerous conquests made during this memorable campaign.

Dendermond and Aeth were afterwards captured; and in November the regiment took up its winter-quarters at Ghent.

During the campaign of 1707, the regiment formed part of the brigade commanded by its colonel, Brigadier-General[24] Lord North and Grey, and it was some time encamped near the village of Waterloo. The English commander was unable, this year, to bring his cautious opponents to a general engagement. In October, the regiment returned to Ghent.

While the regiment was reposing in quarters at this city, the king of France fitted out a fleet, and embarked troops at Dunkirk, for the invasion of Great Britain, with a view of placing the Pretender on the throne. To repel the invaders, the Tenth regiment embarked for England in the middle of March, 1708, and arrived at Tynemouth on the 21st; but the French squadron, with the Pretender on board, was chased from the British coast by the English fleet, and the Tenth were ordered to Flanders: they landed at Ostend, and proceeded in boats to Ghent, where they arrived towards the end of April.

In May the regiment quitted Ghent, and was engaged in the operations of the main army; and soon afterwards the French, by treachery and stratagem, obtained possession of the two towns of Ghent and Bruges. They also invested Oudenarde, and this circumstance led to a general engagement, in which the Tenth gained new honours.

Passing the Scheldt on pontoon bridges near Oudenarde, on the 11th of July, the allied army encountered the legions of the enemy, commanded by his Royal Highness the Duke of Burgundy and the Duke of Vendome, in the fields beyond the river, and the battle immediately commenced. The Tenth, commanded by Lieut.-Colonel Grove, passed the Scheldt by the bridge between Oudenarde and the abbey of Eename, and ascended the heights of Bevere. At this place they halted[25] a short time, then descended into the plain, and engaged the French battalions in the grounds beyond the rivulet, near the village of Eyne. About five o'clock in the afternoon the regiment opened its fire, and it continued to gain ground upon its opponents, until the shades of evening gathered over the field of battle. The wings of the allied army gained upon the enemy, and the circling blaze of musketry enveloped the French troops, whose destruction appeared inevitable, but the darkness of the night soon rendered it impossible to distinguish friends from foes, and the Duke of Marlborough ordered his soldiers to cease firing, and to halt. The darkness favoured the escape of the enemy, and the wreck of the French army retreated in disorder towards Ghent.

This victory prepared the way for an undertaking of great magnitude,—viz., the siege of Lisle, the capital of French Flanders,—a fortress deemed almost impregnable, and garrisoned by fifteen thousand men, commanded by the veteran Marshal Boufflers. This enterprise put the abilities of the generals, and the courage and endurance of the troops, to a severe trial. The Tenth formed part of the covering army under the Duke of Marlborough, while the siege was carried on by the brigades under Prince Eugene of Savoy. The services of the Tenth were of a varied character,—escorting supplies,—furnishing out-posts,—confronting the French army which advanced to raise the siege; and eventually the grenadier company joined the besieging army, and took part in the attacks on the town.

When the Elector of Bavaria besieged Brussels, the Tenth formed part of the force which advanced to raise the siege. The enemy's strong positions on the Scheldt were forced on the 27th of November; and[26] the Elector made a precipitate retreat from before Brussels.

The citadel of Lisle surrendered on the 9th of December, and, notwithstanding the lateness of the season, the soldiers of the Tenth were called upon to engage in another enterprise. They appeared before Ghent,—drove back the enemy's out-guards, and took part in opening the trenches between the Scheldt and the Lys, on the night of the 24th of December, on which occasion their colonel, Lord North and Grey, evinced signal gallantry, and he was rewarded, a few days afterwards, with the rank of major-general. On the 26th of December, ten companies of French grenadiers issued from the town to attack the besieging troops, and they put the first regiment they came in contact with in some confusion.

The Tenth were immediately led to the spot, and they engaged the French grenadiers with spirit. The commanding officer of the regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel Grove, was made prisoner, and Brigadier-General Evans, who commanded the troops at that point, was also captured; but the enemy was soon driven back into the town. On the 2nd of January, 1709, the governor surrendered; and the Tenth took up their quarters for the winter in the captured town.

From Ghent, the regiment marched, in the spring of 1709, to the plain of Lisle; and was afterwards encamped on the Upper Dyle. After menacing the enemy's lines, and causing Marshal Villars to draw all the troops out of the fortified towns, which could possibly be spared, to strengthen his army in the field, the allies suddenly invested Tournay. During the siege of the town the Tenth regiment formed part of the covering army, but when the citadel was attacked, this, with[27] several other regiments, left the covering army, and marched to Tournay to take part in the siege.