The Project Gutenberg EBook of Guy Harris, the Runaway, by Harry Castlemon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Guy Harris, the Runaway Author: Harry Castlemon Release Date: January 16, 2018 [EBook #56381] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GUY HARRIS, THE RUNAWAY *** Produced by David Edwards, Barry Abrahamsen and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

“For once that day, Guy was supremely happy.”

“WELL, Guy Harris, I have only one word to say to you. If you think you can play off on me in this way, you are very much mistaken. I will post you among the fellows as a boy who is too mean to pay his honest debts.”

“I don’t care if you do, George Wolcom. I’ll tell the fellows in return that I have no debts hanging over me, and that you are a boy who doesn’t do as he agrees. I wanted a cross-gun; I tried to make one and failed. You said you knew how to handle carpenters’ tools and would make me one. I described to you just what I wanted, and you told me that you could fill the bill, and that the gun, when completed, would be worth half a dollar. What sort of a thing have you given me? Look at this,” continued the speaker, holding out at arm’s length a piece of wood which might have been taken for a cross-gun, although it looked about as much like a ball-club; “I can make a better one myself.”

“Then you don’t intend to pay me?”

“Of course I do, when you bring me such a gun as I told you I wanted.”

“But you won’t pay me for the one I have already made for you?”

“No, sir, I won’t.”

“Very well; but bear in mind that I am a boy who never let’s one do him a mean trick without paying him back in his own coin. I’ll be even with you for swindling me.”

“Oh, Guy! I say. Guy Harris, hold on a minute.”

The two boys, between whom the conversation above recorded took place, stopped when they heard these words, and looking across the street saw Tom Proctor running toward them. One arm was buried to the elbow in his pocket, and under the other he carried a beautiful snow-white dove, which was fluttering its wings and trying to escape from his grasp.

“See here, Guy!” exclaimed Tom as he came up, “I have just been over to your house, where I found my pigeon, which I lost about a week ago. Your mother said it came to your barn, and that you shut it up to keep it for me. Now that was a neighborly act, and I want to repay it. Here’s that box you have so often tried to buy from me.”

As Tom said this he pulled his hand out of his pocket and gave Guy the article in question, which proved to be a brass match-box. It was not a very valuable thing, but it had a revolving top secured by a curiously contrived spring, was stamped all over with figures of wild ducks, deer and rabbits, and was altogether different from anything of the kind that Guy had ever seen before.

For some reason or other he had long shown a desire to obtain possession of this box, but the owner could not be induced to part with it.

Before he could express his thanks for the gift Tom was half-way across the street on his way home.

“This is just the thing I wanted,” said Guy joyfully, as he and George Wolcom resumed their walk. “I shall think of Tom every time I look at this box when I am out on the prairie.”

“When you are out on the prairie?” echoed George. “What do you mean by that?”

“Oh, it is my secret. You may know it some day, but not now. What do you suppose is the reason why I want a cross-gun?”

“Why, to kill birds with.”

“No, sir; I want to practice shooting at a mark. I shall have use for a rifle every hour in the day before I am many months older.”

“You will? Where are you going?”

“You needn’t ask questions, for I sha’n’t answer them,” said Guy, shutting the box with a click, and making a motion to put it into his pocket.

“Wait a second,” exclaimed George suddenly. “I know why Tom Proctor was generous enough to give you that box. It will be of no use to you for the spring is broken.”

“It isn’t either,” replied Guy.

“Yes it is; I saw it. Hand it out here and I will show you.”

Without hesitation Guy passed the box over to his companion, who, after opening and shutting it a few times, and making a pretense of examining the spring, coolly put it into his own pocket. Guy looked at him in great surprise, but George walked on without noticing him.

“Now that’s the biggest piece of impudence I ever witnessed,” said Guy at length. “I’d like to know what you mean by it.”

“Didn’t I tell you that I always get even with a fellow who does me a mean trick?” asked George, in reply. “I’ll keep this box as part payment for the cross-gun I made you.”

“Do you call this thing a cross-gun?” demanded Guy, once more holding up the stick he carried in his hand; “I don’t, and I sha’n’t pay you a cent for it either. Give me that box.”

“Give me that half-dollar you owe me.”

“I don’t owe you any half-dollar. Here, take your old cross-gun and give me my box.”

“It isn’t my gun—it is yours; and you can’t have your box till I get my just dues. You may depend upon that.”

A long and spirited debate followed this reply, and would most likely have ended in blows had the two boys been of equal age and size, for Guy was a spirited fellow, and always ready to stand up for his rights.

George was an overgrown lout of a boy, and plumed himself on being the bully of his school. Guy knew better than to attempt to take the box from him by force, so he followed along after him, talking all the while, and trying to convince him that he was in the wrong, and that he showed anything but a manly spirit in taking so unfair an advantage of a boy so much smaller than himself.

But George, being pig-headed and vindictive, could not be made to look at the matter in that light. He kept tantalizing his companion by turning the box in his hand, praising the beauty of the figures stamped upon it, and asking Guy now and then if he had anything else he could keep his matches in when he reached the prairie.

Presently the two boys arrived in front of the house in which Guy lived—a neat little edifice, with a graveled carriage-way leading upon one side, and trees and shrubbery growing all around it. Guy halted at the gate, and George, believing that if his companion would not pay him for his cross-gun he might be willing to give half a dollar to get possession of the match-box again, stopped also to argue the matter.

While the discussion of the points Guy had raised was going on, the gate leading into the next yard was opened, and a bright, lively-looking fellow, Henry Stewart by name, and one of Guy’s particular friends, came out. He greeted Guy pleasantly, and was about to pass on, when he noticed the look of trouble on his face, and stopped to inquire the reason for it. The matter was explained in few words, and Henry turned and gave the bully a good looking over. Being a great lover of justice, he was indignant at the treatment his crony had received.

“Well,” said George, returning Henry’s gaze with interest; “you have nothing to do with this business, and if you are wise you will keep out of it.”

“I want that box!” said Henry firmly.

“If you get it before I am ready to give it to you,” returned George, “just send me word, will you?”

Before this defiance had fairly left his lips the bully was rolling over and over in the gutter, which was in a very moist condition, owing to the heavy rain that had fallen during the previous night, while his antagonist stood erect on the sidewalk, flushed and excited, but without even a wrinkle in his clean, white wristbands, or a spot of mud on his well-blacked boots. In falling, George dropped the match-box, which Henry caught up and put into his pocket.

This proceeding was witnessed by two women—Henry’s mother and Guy’s step-mother. The latter made no move, but treasured up the scene in her memory to be repeated in a greatly exaggerated form to Mr. Harris when he came home to dinner, while Henry’s mother hurried down the stairs and out to the gate. She called to her son, who promptly answered the summons, and in reply to her anxious inquiries repeated the story of Guy’s troubles.

I do not know what his mother said to him, but I am sure it could not have been anything very harsh, for a moment afterward Henry came gayly down the walk, winked at Guy as he passed, and looked pleasantly toward the discomfited bully, who, having picked himself up from the gutter, was making the best of his way to the other side of the street, holding one hand to his head and the other to his back, both of which had been pretty badly bruised by the hard fall he had received.

“Now, that Hank Stewart is the right sort!” thought Guy, gazing admiringly after the erect, slender figure of his friend as it moved rapidly down the street. “If it hadn’t been for him I should never have seen this box again. I shouldn’t like to lose it, for I shall have use for matches after I become a hunter and trapper, and I shall need something to carry them in. This box is just the thing. If I wasn’t afraid Hank would refuse, I would ask him to go with me, I must have a companion, for of course I don’t want to go riding about over those prairies on my wild mustang all by myself while there are so many hostile Indians about, and Hank is the fellow I’d like to have with me. He knows everything about animals and the woods; he’s the best fisherman in Norwall; he never misses a double shot at ducks or quails; and I never saw a boy that could row or sail a boat with him. Why, it wouldn’t be long before he would be the best hunter and trapper that ever tracked the prairie. I’ll think about it, and perhaps I shall make up my mind to ask him to go with me instead of Bob Walker.”

Thus soliloquizing Guy made his way through the yard to the carriage-house and mounted the stairs leading to the rooms above. There were three of them. The first and largest served in summer as a place of storage for Mr. Harris’ sleighs and buffalo-robes, and in winter for his buggy and family carriage. The second was the room in which the coachman slept, and the third Guy had appropriated to his own use.

Here he had collected a lot of trumpery of all sorts, which he called his “curiosities,” and of which he took the greatest possible care. The members of the family, and those of his young friends who had seen the inside of this room, thought that Guy had shown strange taste in making his selections, for there was not an article in it that was worth saving as a curiosity, and but few that could under any circumstances be of the least use to him.

On a nail opposite the door hung a rubber blanket with a hole in the center, so that it could be worn over one’s shoulders like a cloak; from another was suspended a huge powder-horn; and on a third hung a rusty carving-knife, which one of Guy’s companions had sold to him with the assurance that it was a hunting-knife. Then there was a portion of an old harpoon which Guy said was a spear-head, a pair of well-worn top-boots, an old horse-blanket and a clothes-line with an iron ring fastened to one end of it. This last Guy called a lasso. He spent many an hour in practicing with it, whirling it around his head and trying to throw the running noose over a stake he had planted in the yard.

One corner of the room was occupied by a pile of old iron, to which horseshoes, broken frying-pans and articles of like description were added from time to time. Whenever this pile attained a certain size it would always disappear, no one seemed to know how or when, and Guy would go about for a day or two jingling some coppers in his pocket. When he had handled them and feasted his eyes on them to his satisfaction, he would stow them in an old buckskin purse which he kept in his trunk.

In another corner of the room was a large bag, into which Guy put everything in the shape of rags that he could pick up about the house. When filled it was emptied somehow, and Guy had a few more coppers to be put away in his purse. It was well for our hero that his father and mother did not know what he intended to do with the money he earned in this way.

“Nobody except me sees any sense in all this,” said Guy, as he closed the door behind him, and gazed about the room with a smile of satisfaction. “There isn’t a thing here that will not be of use to me by and by. That rubber blanket will keep me dry when it rains. That powder-horn I shall have filled at St. Joseph or Independence, and, as a rifle requires but little ammunition, it will hold enough to last me during a year’s hunting. That knife will answer my purpose as well as one worth two dollars and a half, for I can sharpen it, and make a sheath for it out of the skin of the first buffalo or antelope I kill. I must sell my iron again before long. How the fellows laugh at me because I am all the while looking out for old horseshoes and such things! But I don’t care. I’ve made many a dime by it, and dimes make dollars. I never neglect a chance to turn a penny, but I haven’t yet saved a quarter of what I need. I found half a dollar the other day by keeping my eyes turned down as I walked along the street, and that was a big lift, I tell you.”

As Guy said this he opened a small tool-chest that stood beside the pile of old iron. In this were stowed away a variety of articles he had picked up at odd times and in different places, and which he thought he might find useful when he reached the prairie.

There was a small bundle of wax-ends, such as shoemakers use. These would come handy when he needed a pair of good leggings, or when his moccasins, saddle, or bridle, got out of repair. There were several iron and bone rings he could use in making lassos or martingales for his horse; three or four pounds of lead for his bullets, and a ladle to melt it in; half a dozen jackknives, some whole and sound, others broken beyond all hope of repair; a multitude of lines, fish-hooks, sinkers and bobbers, which he intended to use on the mountain streams and lakes of which he had read so much; a few steel-traps, all bent and worthless, and also several “figure fours” which he had made so as to have them ready for use when he reached his hunting-grounds. In this receptacle Guy placed his match-box, congratulating himself on having secured another valuable addition to his outfit. This done, he bent his steps toward his house.

When he entered the dining-room he found his father and mother seated at the table, and he knew by the expression on their faces, as well as by the words that fell upon his ear, that there was a storm brewing. His mother had been relating the particulars of the encounter between Henry Stewart and George Wolcom, and repeating the discussion between Guy and the bully that led to it, all of which she had seen and overheard from her chamber window, and our hero came in just in time to hear her declare:

“I never in my life saw boys behave so disgracefully. Mrs. Stewart ran out of the house and tried to put a stop to the disturbance, but they paid not the least attention to her.”

“Guy,” said Mrs. Harris, “where is that article, whatever it is, that has been the cause of all this trouble?”

“I have put it away,” was the reply.

“Go and get it immediately.”

Guy retraced his steps to the carriage-house, and taking out the match-box, carried it to his father, who looked at it contemptuously.

“This is a pretty thing to raise a fight about, isn’t it?” he exclaimed. “Take it and throw it away.”

“But, father,” began Guy.

“Do you hear me?” demanded Mr. Harris fiercely. “Throw it away.”

Guy knew better than to hesitate longer. Mr. Harris was a stern man, and in his efforts to “bring his boy up properly,” sometimes acted more like a tyrant than a father.

Taking the box, Guy walked out of the door and disappeared behind the carriage-house.

“I will throw it away,” said he to himself, “but I’ll be careful to throw it where I can find it again. I never heard of such injustice. I wasn’t in any way to blame for the trouble, for I didn’t ask Hank to pitch into George Wolcom and get my box for me; and neither did Mrs. Stewart run out and try to put a stop to the fight. It was all over before she showed herself. But that’s just the way with all step-mothers, I have heard, and I know it is so with mine. She runs to father with every little thing I do, and seems to delight in having me hauled over the coals. It isn’t so with Ned. He can do as he pleases, but I must walk straight, or suffer for it. I sha’n’t stand it much longer, and that’s all about it. Stay there till I want you again.”

Guy threw the box into a cluster of currant bushes at the back of the garden, and after noting the spot where it fell, went slowly back to the dining-room and sat down to his dinner.

I MUST say before I go further, that Guy Harris is not an imaginary character. He has an existence as surely as you have, boy reader. He is to-day an active professional man, and he has consented to have the story of his boyhood written in the hope that it may serve as a warning, should it chance to fall into the hands of any discontented young fellow who is tempted to do as he did.

Guy lived in the city of Norwall—that name will do as well as any other—on the shore of one of the great lakes. When he was a few months old his mother died, and a year afterward his father married again. Of course Guy was too young to remember his lost parent, and until he was fourteen years old he knew nothing of this little episode in the family history. Mr. and Mrs. Harris never enlightened him, because they feared that something unpleasant might result from it. Having often heard the boy express his opinion of step-mothers in the most emphatic language, and declare that he would not live a day under his father’s roof with a stranger to rule over him, they thought it best to allow him to remain in ignorance of the real facts of the case. And Guy never suspected anything. It is true that he was sometimes sadly puzzled to know how it happened that he had three grandfathers, while all the boys of his acquaintance had only two; but when he spoke of it to his mother, she always had the headache too badly to talk about that or anything else.

Guy often told himself that his mother was not like other boys’ mothers. He cherished an unbounded affection for her, and stood ready to show it by every means in his power; but there was something about her that kept him at a distance. There was not that familiarity between him and his mother that he saw between other boys and their mothers. There was a coolness in her demeanor toward him that she did not even exhibit toward strangers. There was a wonderful difference, too, in her treatment of him and his half-brother, Ned, who was at this time about nine years of age. Ned came and went as he pleased. The front gate was no barrier to him, and he always had a dime or two in his pocket to spend for peanuts and chocolate creams. If he wanted to go over to a neighbor’s for an hour’s visit, or wished to spend an afternoon skating on the pond, he applied to his mother, who seldom refused him permission. If Guy desired the same privilege, he was told to consult with his father, who generally said: “No, sir; you’ll meet with bad company there;” or, “You’ll break through and be drowned;” or, if he granted the request, he would do it after so much hesitation, and with so great reluctance that it made an unpleasant impression on Guy’s mind, and marred his day’s sport.

At last a few scraps of the family history, which his parents had been so careful to keep from him, came to Guy’s knowledge. Through one of the neighborhood gossips he learned, to his intense amazement, that Mr. Harris had been twice married; that his first wife had lain for almost fourteen years in her grave in a distant State; and that the woman who sat at the head of the table, who so closely watched all his movements during his father’s absence, and whom he called mother, was not his mother after all. Then a good many things which hitherto he had not been able to understand became perfectly clear to him. He knew now where his three grandfathers came from, and could easily account for the partiality shown his half-brother, Ned. But he wanted proof, and to obtain it laid the matter before his Aunt Lucy, who, after telling him how sorry she was that he had found it out, reluctantly confirmed the story.

Guy felt as if he were utterly alone in the world after this; but when he had thought about it a while, he took a sensible view of the case. He loved his father’s wife, and he did not allow the facts with which he had just been made acquainted to make any change in his feelings or demeanor toward her. Indeed, he was more attentive to her than before; he tried to anticipate and gratify her desires as far as lay in his power, and in every way did his best to please her; but the result was most discouraging. With all his efforts he could not win one approving word or smile. His mother was colder and more distant than ever, and from that time Guy’s home was somehow made very uncomfortable for him.

Mr. and Mrs. Harris were good people, as the world goes. They were prominent members of the church, and held high positions in society. Abroad they were as agreeable and pleasant as people could be, but the atmosphere of home grew dark the moment they crossed the threshold. Mr. Harris, especially, was a perfect thunder-cloud; his very presence had a depressing effect upon the family circle. When he came home from his place of business at night, he generally had something to say in the way of greeting to his wife and Ned, but Guy was seldom noticed, unless he had been doing something wrong, and then more words were devoted to him than he cared to listen to.

When supper was over, Mr. Harris sat down to his paper, and until ten o’clock never looked up or spoke. His wife sewed, read novels, or played backgammon with Ned, and Guy was left to himself. His father never talked to him about his sports and pastimes, his boyish trials, disappointments, hopes and aspirations, as other fathers talk to their sons. He never allowed him to go outside the gate—except upon very rare occasions—unless he was going to school or was sent on an errand. He never gave him a cent to spend for himself, except on Christmas, when, in addition to making him numerous presents (which Guy was so repeatedly and emphatically enjoined to take care of that he almost hated them as well as the giver), he opened his heart and presented him with a quarter of a dollar. He wasn’t going to ruin his boy by giving him money, he said.

Up to the time that he was fourteen years old Guy had the making of a man in him. He was smart, honest, truthful, generous to a fault, and attentive to his books, it being his father’s desire, as well as his own, that he should enter college. I wish I could take him through my story with all these good traits about him; but candor compels me to say that at the time he was presented to the reader he was a different sort of boy altogether. In the neighborhood in which he lived he bore an excellent reputation. People called him a good boy, referred to the fact that he was never seen prowling about the streets after dark, and spoke of the promptness with which he obeyed the commands of his parents. But the truth was that at heart Guy was no better than any other boy. He stayed at home of evenings, not because it was a pleasant place and he loved to be there, but for the reason that he was not allowed to go out; and he obeyed his parents’ orders the moment they were issued, because he knew that he would be whipped if he did not. All his generous impulses had been crushed out of him by the stern policy pursued by his father, who believed in ruling by the rod, instead of by love. From being a frank, honorable boy, above doing a mean action and abhorring a lie, Guy became sneaking and sly—so sly that it was almost an impossibility to fasten the guilt of any wrong-doing upon him. He learned to despise his home, with its thunder-clouds and incessant reprimands and fault-findings, and longed to get off by himself somewhere—anywhere, so that he could enjoy a few minutes’ peace. He had hit upon a plan to rid himself of his troubles, and now we will tell what it was, and how it resulted.

AS CAN well be imagined, Guy felt very sore after the affair of the match-box. His whole soul rebelled against the petty tyranny and injustice of his father, and while he was at school that afternoon his mind dwelt so much upon it that he stood “zero” in every one of his lessons, and failed so miserably in his philosophy that he narrowly escaped the disgrace—and it was considered a lasting disgrace by the boys belonging to the Brown Grammar School—of being kept after hours to commit his task.

When four o’clock came Guy drew a long breath of relief, and chucked his books under his desk so spitefully that he made a great deal of racket, which caused the teacher to look sharply in his direction. Guy, knowing that he was suspected, turned and stared at Tom Proctor, who sat next behind him, as if to say, “There is the guilty one,” and Tom gave the accusation a flat denial by turning about and looking at the youth who sat next behind him. This is a way that some school-boys have of doing business, as you know. In a case like this a scholar can “carry tales” and accuse a school-mate of breaking the rules without saying a word.

When school was dismissed Guy was the first one out of the gate. Some of the Delta Club were going over to their grounds to engage in a practice game of ball, and as Guy belonged to the first nine, of course he was expected to accompany them; but he, knowing that he must first go home and ask permission of his mother, which would most likely be refused, replied that he had something else to do, and hurried off as fast as his legs could carry him. Arriving at his father’s gate, he slackened his pace and walked leisurely through the yard into the garden. He went straight to the currant bush, behind which he had thrown his match-box, and finding his treasure safe, put it into his pocket and returned to the carriage-house. When he thought he could do so without being seen by any one, he bounded up the stairs, entered his curiosity shop, and noiselessly closing the door, locked himself in.

“Now then,” he exclaimed with a triumphant air, “if mother and Ned will only let me alone for about an hour, I can enjoy myself. I haven’t seen a minute’s peace since twelve o’clock. Father thought he was very sharp when he ordered me to throw this box away,” he added, as he opened the small tool-chest and deposited his recovered property therein, “but I am a little sharper than he is. Whew! wouldn’t I get my jacket dusted though, if he knew what I have done?”

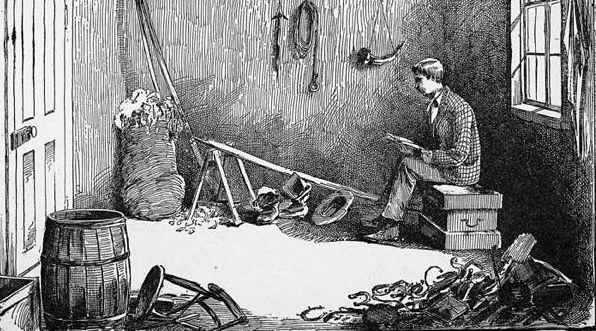

As Guy said this, he unlocked a small compartment in the tool-chest and took out a book bound in brown and gold, and bearing the title, “The Boy Trappers of the Platte.” Closing the chest, and seating himself upon it, he opened the book, and for two hours reveled in bear fights, adventures with the Indians, and hunting and trapping scenes without number. For once that day he was supremely happy. He forgot all his troubles, and lived only among the imaginary characters and amid the imaginary scenes presented to him on the printed page. Two or three times while he was thus engaged, Ned came up, tried the door, and called to him; but Guy only stopped long enough to flourish his fist in the air with a significant gesture, as if he would have been glad of a chance to use it on Ned’s head, and then went on with his reading, until the creaking of the gate, and the sound of wheels on the carriage-way, told him that his father had arrived.

“Dear me, how provoking!” exclaimed Guy, jumping quickly to his feet and putting the book away in the tool-chest, “Just as I get to the most interesting part of a chapter, I must be interrupted. I wish father had stayed away ten minutes longer; or, better than that, I wish he was like other fathers, and would let me take this book into the house and read it openly and aboveboard, as I should like to do. He is so opposed to works of fiction that I wonder he lets Ned read Robinson Crusoe. He talks of going to the White Mountains this summer, and taking mother and Ned with him, and leaving me at home to punish me for going in swimming the other day. Don’t I hope he will do it, though? It wouldn’t be punishment at all, if he only knew it. I’d have more fun than I have seen for ten years. I’d read every book in Henry Stewart’s library.”

Having closed and locked the tool-chest, Guy went cautiously to the window, and when he saw his father get out of his buggy and enter the house, he slipped quietly out of the room and down the stairs. He passed an uncomfortable quarter of an hour before the supper-bell rang, strolling about the yard with his hands in his pockets, and scarcely knowing what to do with himself. It seemed so hard to come back to earth again after living for two hours among the exciting scenes which his favorite author had created for his amusement.

Supper over, there was another hour to be passed in some way before the gas was lighted. His father talked politics with the next-door neighbor; Ned played graces with his mother; and wide-awake, restless Guy was as usual left to himself. No one took the least notice of him. He must have something to do—it wasn’t in him to remain long inactive—and as there was a strong breeze blowing, he thought he would raise his kite. He could not go into the street for that purpose, so he climbed to the top of the barn; but his father quickly discovered him, and ordered him down.

Then he tried it in the garden, but the trees were thick, and the kite’s tail was always in the way. It caught in a cherry tree, and as Guy was about to mount among the branches to disengage it, his father again interfered. He wasn’t going to have his fine ox-hearts broken down for the sake of all the kites in the world.

“For once that day, Guy was supremely happy.”

By the aid of the step-ladder Guy finally released the kite, and made one more attempt to raise it, this time by running along the carriage-way; but by an unlucky step he left the point of his boot on one of the flower-beds, and that set his mother’s tongue in motion. His father heard it, and turned sharply upon him.

“Guy,” said he, “what in the world is the matter with you to-night? Put that kite away, and go into the house.”

Guy’s under lip dropped down, and with mutterings not loud, but deep, he prepared to obey.

His father’s quick eye noticed the drooping lip, and his quick ear caught the muttering.

“Come here, sir,” said he angrily.

Guy approached, and his father, seizing his arm with a grip that brought tears to his eyes, shook him until every tooth in his head rattled.

“What do you mean by going into the sulks when I tell you to do anything?” he demanded. “Straighten out that face! Now, then,” he added after a moment’s pause, during which Guy choked back his tears and assumed as pleasant an expression as could be expected of a boy whose arm was being squeezed by a strong man until it was black and blue, “go into the house and stay there.”

The father could compel obedience, but his son was too much like himself to be easily conquered. He could control his actions as long as he was in sight, but he could not control his thoughts. Guy’s heart was filled with hate.

“This is a fair sample of the manner in which I am treated every day of my life,” he muttered under his breath as he stowed his kite away in its accustomed place. “They’ll think of it and be sorry some day, for if I once get away from here I’ll never come back. I never want to see any of them again. I can’t please them, and there is no use trying. Nobody cares for me, and the sooner I am out of the way the better.”

When Guy entered the sitting-room he found his mother there reading a highly-seasoned novel by a popular sensational writer, and Ned deeply interested in “Robinson Crusoe.” The piano was open and Guy walked to it and sat down. There was a piece of music upon it, entitled “’Tis Home Where’er the Heart Is.” As Guy ran his fingers over the keys he thought of all that had happened that day, and told himself that if those words were true his home was a long way from Norwall.

“That will do, Guy,” said his mother suddenly. “My head aches, and it is not necessary that you should practice now.”

Guy began to get desperate. He couldn’t sit around all the evening and do nothing—no healthy boy could. He went to the library, and knowing that he was doing something that would certainly prove the occasion of more fault-finding, took a book from some snug corner in which he had hidden it, and sat down to read.

In a few minutes his father came in. He picked up his paper and was about to seat himself in his easy chair when he caught sight of Guy and stopped. The latter did not look up, but watched his father out of the corner of his eye.

“Guy,” said Mr. Harris sharply.

“Sir!” said the boy.

“What have you there?”

“‘Cecil,’” was the reply.

“Cecil who? Cecil what?”

“That’s the name of the book.”

“Let me see it.”

Mr. Harris took the volume and ran his eye over the pages, while a look of contempt settled on his face. Had he taken the trouble to read the book he would have found that it was the history of a youth who was turned out into the world at an early age by the death of his parents; that it described the trials and temptations that fell to his lot, and told how he made a man of himself at last. But Mr. Harris, like many others, condemned without knowing what he was condemning.

Three words on the title-page told him all he cared to know about the work. It was a “Book for Boys.” All books for boys were works of fiction, and he never intended that Guy should read a work of fiction if he could prevent it.

“Where did you get this?” demanded Mr. Harris.

“I borrowed it of Henry Stewart. His father bought it for him last week, and he is a member of your church, too,” answered Guy, seizing the opportunity to put in a home-thrust.

“I don’t care if he is. I have no objection to your associating with Henry, for he is a good boy in some respects, although it is the greatest wonder in the world to me that he hasn’t been ruined by his father’s ignorance beyond all hope of redemption. I am surprised at Brother Stewart—I am really. What’s that sticking out of your pocket?”

“It is a copy of the New York Magazine.”

“Let me see it.”

Guy handed out the paper, and as Mr. Harris slowly unfolded it the sneer once more settled on his face. He handled the sheet with the tips of his fingers, as if he feared that the touch might contaminate him.

“‘Nick Whiffles!’” said he, reading the title of one of the stories. “Who is he? Who owns him?”

“I borrowed the paper of Henry Stewart. His father has taken it for years, and says he couldn’t do without it.”

“I don’t care what his father says. His opinions have no weight with me. Who’s Nick Whiffles?”

“He was a famous Indian-fighter and guide.”

“Oh, he was, was he? Well, you just guide him out of this house, and never bring him or anybody like him here again. I won’t have such trash under my roof. Guy, it does seem as if you were determined to ruin yourself. Don’t you know that the reading of such tales as this unfits you for anything like work? Don’t you know that after a while nothing but this light reading will satisfy you?”

“No, sir, I don’t,” replied Guy boldly. “Henry Stewart told me that he didn’t care a snap for history until he had read the ‘Black Knight.’ Through that story he became interested in the manners and customs of the people who lived during the Middle Ages, and he wanted to know more about them. He read everything on the subject that he could get his hands on, and Professor Johnson says he is better posted in history than half the teachers in the public schools.”

“And all through the reading of a novel?” exclaimed Mr. Harris. “I know better. There’s not a word of truth in it. This bosh has a very different effect upon you at any rate. You waste all your spare time upon it, and the consequence is, you are getting to be a worthless, disobedient boy.”

“But, father, I must have something to read.”

“Don’t I know that; and don’t I get you a new book every Christmas? Where’s that volume entitled ‘Thoughts on Death; or, Lectures for Young Men,’ that I bought for you three weeks ago? You haven’t looked into it, I’ll warrant.”

Mr. Harris was wrong there. Guy had looked into it, and he had tried to read it, but it was written in such language that he could not understand it. At the time his father gave him this book he had presented Ned with a box of fine water-colors—the very thing Guy had long wished for. Why had not Mr. Harris consulted the tastes and wishes of the elder, as well as those of the younger son?

“Return that book and paper to their owner at once, and don’t bring anything like them into this house again,” repeated Mr. Harris.

“May I visit with Henry a little while?” asked the boy.

“Well—I—y-es. You may stay there a quarter of an hour.”

“It’s a wonder,” thought Guy, as he picked up his cap and started for Mr. Stewart’s house. “Why didn’t he tell me that home is the place for me after dark? That’s the reply he generally makes.”

As Guy climbed over the fence that ran between his father’s yard and Mr. Stewart’s he heard a great noise and hubbub. He listened and found that the sounds came from the house he was about to visit.

As he drew nearer he saw that one of the window curtains was raised, and that he could obtain a view of all that was going on in Mr. Stewart’s back parlor. The occupants were engaged in a game of blind-man’s buff. Mr. Stewart, his eyes covered with a handkerchief, and his hands spread out before him, was advancing cautiously toward one side of the room, evidently searching for Henry, who had squeezed himself into one corner, with a chair in front of him. The other children were probably trying to divert their father’s attention, for two of them were clinging to his coat-tails, while the eldest daughter would now and then go up and pull his whiskers or pat him on the back. Mrs. Stewart sat in a remote corner sewing and smiling pleasantly, seemingly unmindful of the deafening racket raised by the players.

“Humph!” said Guy, “it will be of no use for me to ask Henry to go with me. I wouldn’t go myself if I had a home like this. How would my father look with a handkerchief over his eyes, and Ned and me hanging to his coat-tails? And wouldn’t mother have an awful headache though, if this was going on in her house?”

It certainly was a pleasant scene that Guy looked in upon, and he stood at the window watching the players until he began to be ashamed of himself. Then he mounted the steps and knocked at the door.

Mrs. Stewart admitted him, and he entered the parlor just in time to see Henry’s father pounce upon him and hold him fast.

“Aha! I’ve caught you, sir,” said Mr. Stewart, with a laugh that did one’s heart good, “and now we had better stop, for we are arousing the neighbors. Here’s Guy come in to see what’s the matter.”

“No, sir,” replied the visitor, “I just came over to return a book and paper I borrowed of Henry.”

“Why, you haven’t read them, have you?” asked his friend. “I gave them to you only yesterday.”

“I know it; but father told me to bring them back. He won’t permit me to read them. He says they are nothing but trash.”

Henry elevated his eyebrows and looked at his father, who in turn looked inquiringly at Guy.

“Does your father ever read the New York Magazine?” asked Mr. Stewart.

“No, sir!” replied Guy emphatically.

“Ah! that accounts for it. If he would take the trouble to look at it, he might change his opinion of it. A paper that numbers ministers among its contributors, that advocates temperance and reform, and shows up the follies of the day in its stories, can’t be a very dangerous thing to put into the hands of the youth of the land. Here is an article by a minister in the paper we have been reading to-night. Take it over and show it to your father.”

“I wouldn’t dare do it, sir,” returned Guy blushing. “He told me to guide Nick Whiffles out of the house, and never guide him in again.”

“Oh, that’s where the shoe pinches, is it? Well, I think Nick very good in his place. Indeed, I confess to a great liking for the old fellow.”

“He’s just splendid,” said Henry.

“All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy, you know,” continued Mr. Stewart. “After you and Henry have sat for six long hours on your hard desk at school, a game of ball or a sail on the lake does you a world of good. If you should live a week or two on corn bread and bacon, or pork and beans, you would be glad to have a piece of pie or cake, wouldn’t you? The mind requires recreation and change as much as the body, and where can you find it if it be not in a good story by some sprightly author? Of course the thing can be carried to excess, and so can eating. One can read himself into an unhealthy frame of mind as easily as he can gorge himself into dyspepsia.”

When Mr. Stewart had said this much he stopped and took up his paper. It wasn’t for him to criticise or find fault with the rules his neighbor had made regarding his son’s reading.

Guy, having an object to accomplish before he returned home, and knowing that time was precious, declined the chair offered him, and after taking leave of the family, intimated to Henry that he had something particular to say to him. The latter accompanied him to the fence, and Guy leaned upon it, utterly at a loss how to broach the subject uppermost in his mind.

GUY DID not know how to begin the conversation. He wanted to approach the subject gradually, for he believed that some little strategy would be necessary in order to bring Henry to his way of thinking, but somehow the words he wanted would not come, and seeing that his friend was getting impatient, he plunged into it blindly:

“How would you like to be a hunter and trapper?” he asked.

“I don’t know anything about trapping, but I like hunting as well as any boy in the world,” said Henry.

“I mean how would you like to make a business of it, and spend your life in the woods or on the prairie?”

“I don’t know, but I am going to try it a little while this fall. Father owns some land in Michigan that he has never seen, and about the first of September he and I are going up to take a look at it. His agent writes that game is abundant, and I am going to buy a rifle before we start.”

“Well, if I had a chance like that I’d never come back again. I’d stay in the woods.”

“Oh, my father wouldn’t let me.”

“I don’t suppose he would, but you could do as I intend to do—run away.”

Henry straightened up and looked at his companion without speaking.

“Oh, I mean it,” said Guy with a decided nod of his head. “I am tired of staying here. I am weary of this continual scolding and fault-finding, and am going to get away where I can take a little comfort. I have always wanted to be a hunter. I have got my plans all laid, and I want some good fellow for a companion, for I should be lonely if I were to go by myself. I’d rather have you than anybody else, and if you will go we’ll take the ‘Boy Trappers’ with us. That book will tell us just what we will have to do. It tells how to build wigwams, how to trap beaver and otter, and catch fish through the ice; how to make moccasins, leggings and hunting-shirts; how to catch wild horses; how to preserve the skins of wild animals—in fact, everything we want to know we will find there.”

“Where do you want to go?” asked Henry.

“Out to the Rocky Mountains.”

“What will you do when you get there?”

“We’ll hunt and trap during the spring and fall, and when summer comes we’ll jump on our horses, take our furs to the trading-posts and sell them.”

“And what will we do during the winter?”

“We’ll have a nice little cabin in some pleasant valley among the mountains, such as the boy trapper had, and we’ll pass the time in curing our furs and fighting the Indians. That is what they did, you know. I tell you, Hank,” said Guy with great enthusiasm, “it wouldn’t be long before we would become as famous as either Kit Carson or Captain Bridges! What’s the matter with you?” he added, looking suspiciously at his friend, who seemed on the point of strangling.

Henry, who had listened in utter amazement to what Guy had to say, could control himself no longer. Clinging to the fence with both hands he threw back his head and broke out into a shout of laughter that was heard full a block away.

“I don’t see anything so funny about it,” said Guy indignantly. “I am in earnest.”

“Oh, dear!” said Henry, after he had laughed until his jaws and sides ached. “I know this will be the death of me. Why, Guy, what in the world put such a ridiculous notion into your head?”

“I don’t call it a ridiculous notion. If the boy trappers could live that way I don’t see why we couldn’t. I guess we are as smart and as brave as they were.”

This set Henry to going again. It was some minutes before he could speak.

“Do you believe that book is true?” he asked.

“Of course I do.”

“Why, Guy, I didn’t think you were such a dunce. The idea that three boys, the oldest of them only seventeen years of age, could live as they did, surrounded by savage beasts and hostile Indians, and get into such scrapes as they did, and come out without a scratch. Common sense ought to teach you better than that. Those boy trappers never had an existence except in the brain of the man who wrote the book.”

“Then why did he write it?” demanded Guy.

“What makes you play base-ball and cricket, and why do you go fishing and boat-riding every chance you get? Such sports are not necessary to your existence—you could live without them—but they serve to fill up the time when you don’t feel like doing anything else. That’s one reason why books like ‘Boy Trappers’ are written—to keep you in the house and help you while away a leisure hour that you might otherwise spend in the streets with bad boys. Oh, Guy! Guy!”

“Now, don’t you begin your laughing again,” said his companion.

At this moment a door opened and the boys heard Mr. Harris calling.

“Guy!” he shouted.

“Sir!” was the response.

“Come in now.”

“What’s the matter?” asked Henry.

“Oh, we have a reading lesson every night, and I have to help,” replied Guy with great disgust. “We’re reading Bancroft’s History of the United States, and I despise it. I can’t understand half of it, but father makes me read aloud twenty minutes every night, and scolds because I can’t tell him the meaning of all the hard words. Now, Hank, are you going with me or not?”

“Of course I am not. I’ll not give up such a home, and such a father and mother as I’ve got for the sake of living in a wilderness all my life.”

“Well, you won’t repeat what I have said to you, will you?”

“No, indeed; but you must promise me that you will give up that idea.”

“All right, I will.”

“You’ll never speak of running away from home again, or even think of it?”

“No, I never will—honor bright.”

“Then you may rely upon me to keep your secret. Now I have a plan to propose: Let’s go fishing on the pier to-morrow—it’s Saturday, you know—and talk the matter over. I can convince you in five minutes that you had better stay at home. Come over early—say five o’clock.”

“I’ll see what father says about it; good-night. I might have known better than to ask him to go with me,” added Guy mentally, as he walked slowly toward the house. “If I had as pleasant a home as he has I wouldn’t go either. Why don’t my father and mother take some interest in me, and talk to me as Mr. and Mrs. Stewart talk to Hank? I haven’t changed my mind, and I never shall. I promised that I would never again think of running away from home, but I did it just to keep Hank’s mouth shut. As long as he thinks I have given up the idea, he won’t say a word to anybody. He’ll be astonished some fine morning, for I shall leave here as soon as I can scrape the money together. I wish I could find a pocket-book with a hundred dollars in it. I’d never return it to the owner, even if I found him. I must try Bob Walker now.”

When Guy entered the sitting-room he found his father and mother waiting for him. The former handed him an open volume of Bancroft’s History and Guy, seating himself, began reading the author’s elaborate description of the passage of the Stamp Act and the manner in which it was received by the colonists—a subject in which he was not in the least interested. His father often took him to task for his bad reading and pronunciation, but he managed to get through with the required twenty minutes at last, and with a great feeling of relief handed the book to his mother and moved his chair into one corner of the room. In forty minutes more the lesson was ended and Mr. Harris turned to question Guy on what had just been read. To his surprise and indignation he saw him sitting with his feet stretched out before him, his chin resting on his breast and his eyes closed. The boy was fast asleep.

“Guy!” Mr. Harris almost shouted.

“Sir!” replied his son, starting up quickly and rubbing his eyes.

“This is the way you give attention to what is going on, and repay the pains I am taking to teach you something, is it?” demanded his father. “Do you think ignorance is bliss? You don’t know anything a boy of your age ought to know. Tell me how many distinct forms of government this country has passed through.”

“I can’t,” replied Guy.

“Who was the third President of the United States?”

“I don’t know.”

“What were the names of the two men who were hanged in effigy by the Massachusetts colonists when the news of the passage of the Stamp Act was received?”

“I don’t know,” said Guy again.

“And yet that is just what we have been reading about to-night. I saw a picture in that paper you had in your possession a little while ago,” continued Mr. Harris with suppressed fury. “It was a man dressed in furs, who stood leaning against a horse, holding a gun in one hand and stretching the other out toward a dog in front of him. Who was that man intended to represent?”

“Nick Whiffles,” said Guy promptly.

“What was the name of his dog?”

“Calamity.”

“Did his horse have a name?”

“Yes, sir—Firebug; and he called his rifle Humbug.”

“There you have it!” exclaimed Mr. Harris with a sneer. “You know all about that, and you’ve no business to know it either, for it will do you more harm than good. If we had been reading that trash to-night you would have been wide-awake and listening with all your ears; but because we were reading something worth knowing—something that would be of benefit to you in after life, if you would take the trouble to remember it—you must needs settle yourself and go to sleep. Now, then, draw up beside this table and read five pages in that history; and read them so carefully, too, that you can answer any question I may ask you about them to-morrow.”

Guy, so sleepy that he could scarcely keep his eyes open, staggered to the chair pointed out to him and sat down, while his father once more picked up the evening paper and his mother resumed her needle.

When he had read the required number of pages and looked them over two or three times to fix the names and dates in his memory, he arose and put the book away in the library.

“Father,” said he.

“Don’t you know that it is very rude to interrupt a person who is reading?” replied Mr. Harris, looking up from his paper. “What do you want?”

“May I go fishing with Henry Stewart on the pier to-morrow?”

“No, sir, you may stay at home. A boy who behaves as you do deserves no privileges. I have learned that I cannot trust you out of my sight.”

Knowing that it would not be safe to show any signs of anger or disappointment, Guy kept his face as straight as possible and turned to leave the room. But when he put his hand on the door-knob his father called to him.

“Guy,” said he, “where are you going?”

“I am going to bed.”

“And do you intend to leave us with that frown on your face and without bidding us good-night? One or the other of us might die before morning and then you would be sorry you parted from us in anger. I’ve a good mind to whip you soundly, for if ever a boy deserved it you do. Come back here and kiss your mother.”

Almost ready to yell with rage, Guy returned and kissed his mother, who presented her cheek without raising her eyes from her novel, bid his father good-night, and this time succeeded in leaving the room without being called back.

When he was safe out of his father’s sight he turned and shook his fist at him, at the same time muttering something between his clenched teeth that would have struck Mr. Harris motionless with horror could he have heard it. He went to bed with his heart full of hate, and not until his mind wandered off to other matters, and he begun to dream of the wild, free and glorious life he expected to lead in the mountains and on the prairies of the Far West, did he recover his usual spirits. He fell asleep while he was building his air-castles, and awoke to hear the breakfast bell ringing and to see the morning sun shining in at his window.

When he descended to the dining-room he was met by Ned, who was dressed in his best, and who informed him, with evident satisfaction, that Henry Stewart had been over to see if he was going fishing, and that his father had said that he couldn’t go to the pier or do anything else he wanted to do until he had learned to behave himself. Ned added that he and his father and mother were going to ride out to visit Uncle David, who lived nine miles in the country, and that he, Guy, was to be left at home because there was no room in the buggy for him, and that he was not to stir one step outside the gate until their return.

“I’ll show you whether I will or not,” said Guy to himself. “It’s a pretty piece of business, indeed, that I am to be shut up here at home while the rest of you go off on a visit. I won’t stand it. I’ll see as much fun to-day as any of you, and if I only had all the money I need, you wouldn’t find me here when you return.”

Breakfast over, the buggy was brought to the door, and Mr. Harris, after assisting his wife and son to get in, turned to say a parting word to Guy.

He was to remain in the yard all day, bring no boys in there to play with him, and be very careful not to get into any mischief. If these commands were not obeyed to the very letter there would be a settlement between them when Mr. Harris came back.

Guy drew on a very long face as he listened to his father’s words, meekly promised obedience and opened the gate for his father to drive out. He watched the buggy as long as it remained in sight and then, closing the gate, jumped up and knocked his heels together, danced a few steps of a hornpipe, and in various other ways testified to the satisfaction he felt at being left alone.

“I shouldn’t feel sorry if I should never see them again,” said he. “I am my own master to-day, and I am going to enjoy my liberty, too. But before I begin operations I must put Bertha and Jack on the wrong scent. They would blow on me in a minute.”

Guy once more assumed a very sober expression of countenance, and walked into the kitchen where the servant-girl was at work.

“Bertha,” said he, “I am going up to my curiosity shop, and I don’t want to be disturbed. You needn’t get dinner for me, for I sha’n’t want any.”

“I am glad of it,” replied the girl, “I am going visiting myself to-day.”

Guy strolled out to the carriage-house, and here he found Jack, the hostler and man-of-all-work, to whom he gave nearly the same instructions, adding the request that if any of his young friends called to see him, Jack would say to them that Guy had gone off somewhere, which, by the way, had Jack had occasion to tell it, would have been nothing but the truth.

The hostler promised compliance, and Guy, having thus opened the way for the carrying out of the plans he had determined upon, went up to his curiosity shop, locking the door behind him, and putting the key into his pocket. He lumbered about the room for a while, making as much noise as he conveniently could, to let Bertha and Jack know that he was there, and then stepped to the window that overlooked the garden and peeped cautiously out. Having made sure that there was no one in sight, he crawled out of the window, feet first, and hanging by his hands, dropped to the ground. As soon as he touched it he broke into a run, and making his way across the garden, scaled a high board-fence, dropped into an alley on the opposite side, and in a few minutes more was two blocks away.

“There!” he exclaimed, as he slackened his pace and wiped his dripping forehead with his handkerchief; “that much is done, and no one is the wiser for it. Now, the first thing is to go down to Stillman’s and buy a copy of the Journal. I wrote to the editors of that paper three weeks ago, telling them that I am going to be a hunter, and asking what sort of an outfit I shall need, and how much it will cost, and I ought to get an answer to-day.

“The second thing is to hunt up Bob Walker and feel his pulse. He once told me that he would run away and go to sea if his father ever laid a hand on him again, so I know I shall have easy work with him. He won’t be as pleasant a companion, though, as Henry Stewart, for he swears, and is an awful overbearing, quarrelsome fellow. But I can’t help it; I must have somebody with me.”

A walk of a quarter of an hour brought Guy to Stillman’s news-depot, where he stopped and purchased a copy of the paper of which he had spoken. Seeing a vacant chair in one corner of the store, he seated himself upon it, and with trembling hands unfolded the sheet, looking for the column containing the answers to correspondents. When he found it he ran his eye over it until it rested on the following paragraph:

“An Abused Dog.—If you are going to become a hunter you will need an expensive outfit. A good rifle will cost from $25 to $75; a brace of revolvers, from $16 to $50; a hunting-knife, $1.25 to $3.50. Then you will need a hatchet or two, an abundance of ammunition, blankets, durable clothing, horse, etc., which, together with your fare by rail and steamer to St. Joseph, will cost you at least $200 more. We know of no hunter or trapper to whom we could recommend you, and neither can we say whether or not you will be able to find a wagon train that you could join. Now that we have answered your questions, we want to offer you a word of advice. Give up your wild idea, and never think of it again. As sure as you are a live boy, it will end in nothing but disappointment and misery. We are inclined to believe that the story of your grievances is greatly exaggerated; but even if it is not, you cannot better your condition by running away from home. Your parents have your welfare at heart, and if you are wise you will remain with them, even though their requirements do sometimes seem harsh and unnecessary. It may be that you will some day be left to fight your way through the world with no father or mother to advise or befriend you, and then you will find how hard it is. Take our word for it, if you live to be five years older, you will laugh at yourself whenever you reflect that you ever thought seriously of becoming a professional hunter.”

Guy read this paragraph over twice, and then folded the paper and walked slowly out of the store.

IT IS beyond my power to describe Guy’s feelings at that moment. He had never in his life been more grievously disappointed. It had never occurred to him that anybody who knew anything would discourage his project, much less the editors of his favorite journal, to whom he had made a full revelation of his circumstances and troubles. And then there was the expense, which greatly exceeded his calculations. That was the great drawback.

“Humph!” soliloquized Guy, after he had thought the matter over, “the man who wrote that article didn’t know my father and mother. If he did, he wouldn’t be so positive that everything they do is for the best. I know better, and won’t give up my idea. I am determined to succeed. There are plenty of men who make a living and see any amount of sport by hunting and trapping, and why shouldn’t I? Kit Carson is a real man and so is Captain Bridges. So is Adams, the great grizzly bear tamer. One of these days, when I am as famous as they are, I shall laugh to think I did become a professional hunter. But the money is what bothers me now. I shall need at least three hundred dollars. Great Cæsar! Where am I to get it? I’ve worked and scraped and saved for the last six months, and I’ve got just fifteen dollars. That isn’t enough to buy a rifle. Where is the rest to come from? That’s the question.”

Guy walked along with his hands behind his back and his eyes fastened thoughtfully on the ground, revolving this problem in his mind. His prospects did not look nearly so bright now as they did an hour ago. He was learning a lesson we all have to learn sooner or later, and that is that we cannot always have things as we want them in this world, and that the best laid schemes are often defeated by some unlooked-for event. Three hundred dollars! He never could earn that amount. His rags brought him but two cents a pound, and although he kept a sharp lookout and pounced upon every piece of cloth he found lying about the house, it sometimes took him a whole month to fill his bag, which held just five pounds. Old iron was worth only a cent a pound, and business in this line was beginning to get very dull, for he had not found a single horseshoe during the last two weeks, and he had purchased the last thing in the shape of broken frying-pans and battered kettles that any of his companions had to dispose of. He must find some other way to earn money. He had thought of carrying papers, which would add a dollar and a quarter a week to his income, besides what he would make out of his Carriers’ Addresses on New Years. But Mr. Harris had vetoed that plan the moment it was proposed.

Guy did not know what to do next.

“Dear me, am I not in a fix?” he asked himself. “I read in the paper the other day of a boy picking up five thousand dollars that some banker dropped in the street. Why wasn’t I lucky enough to find it? That banker might have whistled for his money when once I got my hands upon it. I must have three hundred dollars and I don’t care how I get it.”

Guy was gradually working himself into a very dangerous frame of mind. When one begins to talk to himself in this way it needs only the opportunity to make a thief of him. If Guy thought of this, he did not care, for he continued to reason thus, and was not at all alarmed when a daring project suddenly suggested itself to him. Twenty-four hours ago he would not have dared to ponder upon it; but now he allowed his thoughts to dwell upon it, and the longer he turned it over in his mind the more firmly he became convinced that it was a splendid idea and that it could be successfully carried out. He wanted to get away by himself and look at the matter in all its bearings. With this object in view he turned down Erie Street and bent his steps toward Buck’s boat-house, intending to spend an hour or two on the lake. In that time he believed he could make up his mind what was best to be done.

Arriving at the boat-house, Guy entered and accosted the proprietor, who stood behind his bar dispensing liquor and cigars to a party of excursionists who had just returned from a sail on the lake.

“Mr. Buck, is the Quail in?” asked Guy, giving the name of his favorite sail-boat.

“Yes, she is,” replied a voice at his elbow; “but what do you want with her?”

Guy recognized the voice and turned to greet the speaker. He was a boy about his own age, who sat cross-legged in an arm-chair beside the door, his hat pushed on the side of his head rowdy fashion, one hand holding a copy of a sporting paper, and the other a lighted cigar, at which he was puffing industriously. His name was Robert Walker. He was a low-browed, black-haired fellow, and although by no means ill-looking, there was something in his face that would have told a stranger at the first glance that he was what is called a “hard customer.” And his looks were a good index of his character and reputation. He was known as one of the worst boys in the neighborhood in which Guy lived. Parents cautioned their sons against associating with him, for he would fight, smoke, swear like any old sailor, and it was even whispered about among the boys belonging to the Brown Grammar School that he had been seen rather the worse for the beer he had drank. But Guy had always admired Bob; he was such a free and easy fellow! Besides, he knew so much that boys of his age have no business to know, that he was looked upon even by such youths as Henry Stewart as a sort of oracle. He and Guy represented two different classes of boys—one having been spoiled by excessive indulgence, and the other by unreasonable severity.

Robert’s father was Mr. Harris’ cashier and book-keeper, and the two families would have been intimate had not Bob been in the way. The fathers and mothers visited frequently, but the boys never did; their parents always tried to keep them apart. But in spite of this they were often seen together on the streets, and a sort of friendship had sprung up between them. This was the boy Guy wanted for a companion on his runaway expedition, now that Henry Stewart had declined his invitation.

“The Quail is in,” continued Bob, extending his hand to Guy, who shook it cordially, “but you are just a minute too late. Mr. Buck is going to get her out for me as soon as he is done serving these gentlemen. However, seeing it is you, I’ll take you along, and we can divide the expenses between us.”

“All right,” replied Guy. “Do you know that you are just the fellow I want to see?”

“Anything particular?” asked Bob, knocking the ashes from his cigar.

“Yes, very particular.”

“Well, that’s curious. During the last week I have had something on my mind that I wanted to speak to you about—it’s a secret, too, and one that I wouldn’t mention to any fellow but you—but somehow I couldn’t raise courage enough to broach the subject. We’ll go out on the lake where we can say what we please without danger of being overheard. Let’s take a drink before we go. Come on.”

“I am obliged to you,” answered Guy, “but I never drink.”

“Take a cigar, then.”

“No, I don’t smoke.”

“Nonsense. Be a man among men. Give me some beer, Mr. Buck. Take a glass of soda, Guy. That won’t hurt you, and it is a temperance drink, too.”

Guy leaned his elbows on the counter and thought about it. This was a temptation that he had never been subjected to before. What would his father say if he yielded to it? But, on the whole, what difference did it make to him whether his father liked it or not? He was going away from home to be a hunter, and from what he had read he inferred that hunters did not refuse a glass when it was offered to them. If he was going among Romans, and expected to hold a high place among them, he must follow their customs. So he said he would take a bottle of soda, and when it was poured out for him he, not understanding the etiquette of the bar-room, watched Bob and followed his motions—bumped his glass on the counter, said “Here are my kindest regards,” and drank it off.

“Now,” said Bob, smacking his lips over his beer, “we’re all ready. I’ve got half a dollar’s worth of cigars in my pocket, and they will last us until we get back.”

The boys followed Mr. Buck out of the house, and along a narrow wooden pier, on each side of which were moored a score or more of row and sail-boats of all sizes and models. When they reached the place where the Quail was lying they clambered down into her, Mr. Buck cast off the painter, and the little vessel moved away. Guy never forgot the hour he spent on the lake that day. A week afterward he would have given the world, had he possessed it, to be able to wipe it out or live it over again.

As the harbor was long and narrow and the wind unfavorable, considerable maneuvering was necessary, and for the first few minutes the attention of Guy and his companion was so fully occupied with the management of their craft that they could find no opportunity to begin the discussion of the subject uppermost in their minds. But when they rounded the light-house pier and found themselves fairly on the lake, Bob resigned the helm to Guy, and relighting his cigar, which he had allowed to go out, stretched himself on one of the thwarts, and intimated that he was ready to listen to what his friend had to say, adding:

“You may think it strange, but I believe I can tell you, before you begin, what you want to talk about.”

“You can!” exclaimed Guy. “What makes you think so?”

“The way you act, and the pains you are taking to make money. Does your father know that you are a dealer in rags and old iron?”

“Of course not.”

“I thought so. What do you want with the little money you are able to make in that way? You don’t see any pleasure with it, for you never spend a cent. What are you going to do with that powder-horn you’ve got hung up in your curiosity shop? It is of no use to you, for your father won’t allow you to own a gun. And then there’s that lead bullet-ladle, rubber blanket, and cheese-knife. They are not worth the room they occupy as long as you stay here. But you are laying your plans to run away from home, young man—that’s what you are up to. Indeed, you have almost as good as said so in my hearing two or three different times.”

“Well, it’s a fact, and there’s no use in denying it,” said Guy. “You won’t blow on me?”

“Certainly not. That’s just what I wanted to see about, for I am going to do the same thing myself.”

“Are you? Give us your hand. We’ll go together. I’m going to be a hunter.”

“I know you are; I’ve heard you say so. I had some idea of becoming a sailor, but since I have thought the matter over I have made up my mind that your plan is the best. If one goes to sea he has to work whenever he is ordered, whether he feels likes it or not; but if he lives in the woods he is his own master, and can do as he pleases. Have you any definite plan in your head?”

“Yes. As soon as I get money enough. I am going to step aboard a propeller some dark night and go to Chicago. I can travel cheaper by water than I can by land, you know, and money is an object, I tell you. From Chicago I shall go to St. Joseph, purchase a horse and whatever else I may need, join some wagon train that is going to California, and when I reach the mountains and find a place that suits me, I’ll stop there and go to hunting.”

“That’s a splendid plan,” said Bob with enthusiasm. “It is much better than going to sea. When do you intend to start?”

“Ah! that’s just what I don’t know. I find by a paper I bought this morning that I shall need at least three hundred dollars; and that’s more than I can ever raise.”

“By a paper you bought!” repeated Bob.

“Yes; there it is,” said Guy, taking it from his pocket and tossing it toward his companion. “You see I wrote to the editors, telling them just how I am situated and what I intend to do, and they answered my letter this week. Look for ‘An Abused Boy’ in the correspondents’ column, and you will see what they said.”

After a little search Bob found the paragraph in question, and settled back on his elbow to read it.

When he finished, the opinion he expressed concerning it was the same Guy had formed when he first read it.

“It is rather discouraging, isn’t it?” asked the latter.

“Not to me,” answered Bob. “These editors don’t know any more than anybody else. Why should they? In the first place the man who wrote this is not acquainted with our circumstances; and in the next, he is not so well posted on the price of some things as I am. He says a rifle will cost twenty-five dollars. Pat Smith has a cart-load of them, good ones, too, that you can buy for twelve dollars apiece.”

“Is that so?” asked Guy.

“Yes; and after we get through with our sail we’ll go around and look at them. He has hunting-knives, which he holds at a dollar and a quarter. I know, because I asked the price of them. Blankets are not worth more than five dollars per pair; and if you take steerage passage on the steamer and a second-class ticket from Chicago you can go through to St. Joseph for twenty-five dollars. Then how are you going to spend the rest of your three hundred? Not for a horse, certainly; for I have heard father say that when he went to California in ’49 he bought a very good mustang for thirty dollars. However,” added Bob, “it will be well enough to have plenty of money, for we don’t want to get strapped, you know.”

“But where is it to come from?” asked Guy.

“I know. I have been thinking it over during the last week, and I know just how to go to work. Perhaps you won’t like it, and if you don’t you can go your way and I’ll go mine. Here, smoke a cigar while I tell you about it.”

“No, no! I can’t smoke.”

“What will you do when we are in the mountains? There’ll be plenty of stormy days when we can’t hunt or trap, and you’ll need a pipe or cigar for company.”

“It will be time enough for me to learn after I get to be a hunter.”

“Perhaps it is just as well,” returned Bob, after a moment’s reflection. “If I carry out my plans you will have to help me, and you will need a clear head to do it. Listen now and I will tell you what they are.”

Bob once more settled back on his elbow, and to Guy’s intense amazement proceeded to unfold the details of the very scheme for raising funds which he himself had had in contemplation when he came to Mr. Buck’s boat-house, and which Bob proposed should be put into execution at once, that very day.

Guy trembled with excitement and apprehension while he listened, and nothing but the coolness and confidence with which his companion spoke kept him from backing out. He had always imagined that the day for the carrying out of his wild idea was in the far future, and from a distance he could think of it calmly; but if Bob’s plans were successful they would be miles and miles away ere the next morning’s sun arose, and with the brand of thief upon their brows.

He begun to realize now what running away meant. He did not once think of his home—there was scarcely a pleasant reminiscence connected with it that he could recall—but now that the great world into which he had longed to throw himself seemed so near, he shrunk back afraid. This feeling quickly passed away.

The wild, free life of which he had so often dreamed seemed so bright and glorious, and his present manner of living seemed so dismal by contrast that, feeling as he did, he could not be long in choosing between them. He fell in with Bob’s plans and caught not a little of his enthusiasm. He even marked out the part he was to play in the scene about to be enacted, making some suggestions and amendments that Bob was prompt to adopt.

The matter was all settled in half an hour later, and the Quail came about and stood toward the pier. When she landed and the boys entered the boat-house, Bob reminded Guy that it was his turn to stand treat. The latter was prompt to respond, and won a nod of approval from his companion by calling for a glass of beer.

Having settled their bill at the boat-house the boys started for the gunsmith’s. There they spent twenty minutes in looking at the various weapons and accouterments they thought they might need during their career in the mountains, and Bob excited the astonishment of his friend by selecting a couple of rifles, as many hunting-knives, powder-horns, bullet-pouches and revolvers, and requesting the gunsmith, with whom he seemed to be well acquainted, to put them aside for him, promising to call in an hour and pay for them.

“Isn’t that carrying things a little too far?” asked Guy when they were once more on the street. “What if we should slip up in our arrangements?”

“But I don’t intend to slip up,” returned Bob confidently. “There’s no need of it. Why, Guy, what makes your face so pale?”

“I feel nervous,” replied the latter honestly.

“Now don’t go to giving away to such feelings, for if you do you will spoil everything. Remember that our success depends entirely upon you. If I fail in doing my part the fault will be yours. But I must leave you here, for it won’t be safe for us to be seen together. If you are going to back out do it now before it is too late.”

“I’m not going to do anything of the kind. I’ll stick to you through thick and thin.”

“All right. Remember now that when the South Church clock strikes one I will be on the corner above your father’s store, and shall expect to find you there all ready to start.”

“You may depend upon me,” replied Guy. “I’ll be there if I live.”

The two boys separated and moved away in nearly opposite directions, their feelings being as widely different as the courses they were pursuing. Bob, cool and careless, walked off whistling, stopping now and then to exchange a pleasant nod with an acquaintance, while Guy was as pale as a sheet and trembled in every limb. It seemed to him that every one he met looked sharply at him, and with an expression which seemed to say his secret was known. He felt like a criminal; and actuated by a desire to get out of sight of everybody, and that as speedily as possible, he broke into a run, and in a few minutes reached his home.