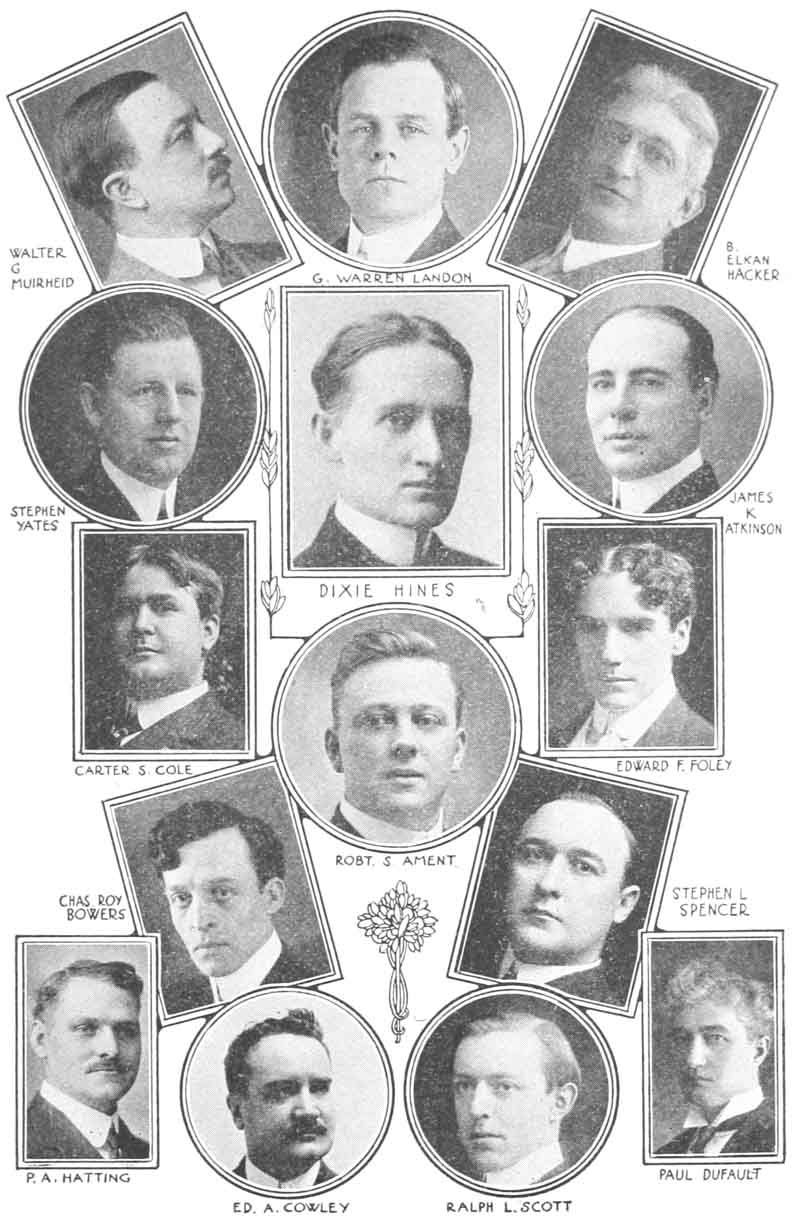

Project Gutenberg's Pleiades Club Year Book 1910, by The N.Y. Pleiades Club This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Pleiades Club Year Book 1910 Author: The N.Y. Pleiades Club Contributor: R. S. Ament Release Date: January 24, 2018 [EBook #56423] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PLEIADES CLUB YEAR BOOK 1910 *** Produced by MFR, RichardW, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

WITHIN

the portals of this

book abound,

Woven with beaten gold, the

thoughts profound,

That stir the soul to ecstasy and

bring

The Poet’s flights of fancy on the

wing

To falter at thy feet. Here may

they reach

The silent chambers of thy heart,

and teach

That this, our only mission, is

to send

To thee a heart-throb, Comrade,

Brother, Friend!

G. Warren Landon.

“A criticism of life,” says Matthew Arnold.

“The rhythmic creation of beauty,” says Edgar Allan Poe—defining the art of lyric poetry.

“The end of art,” says Victor Cousin (combining Plato and Aristotle), “is the expression of moral beauty by the assistance of physical beauty.”

But apply these and other bromidic definitions to the art and literature of to-day—measure them up against the Sunday newspaper, or “Peter Pan” at the theatre, or picture exhibitions of the Independent Artists and the followers of Matisse—and assuredly there is something wrong, either with the definitions or with the art.

Then turn to Emile Zola, and take from him this following dictum, which comes very close to being invulnerable:

“A work of art is a bit of nature seen through a temperament.”

This takes in all the schools, as well as the fiery, untamed spirits who would break away from schools altogether. Art is always the same; temperaments differ and become warped. The academician’s temperamental glass is ruled off into formal geometrical patterns, and he sees nature as a kind of problem in perspective. The rabid “impressionist” looks within himself, and away from nature, and “sees things” which don’t exist for anyone else. The true artist gazes straight out upon nature, and forgets himself, and art comes to him “as easily as lying.”

“Music is a woman,” said Richard Wagner. We may well go further and say: Music is a mother. It is by no mere chance that the Germans speak of Frau Musica. The devotion of Music to humanity, in its varying, growing and innumerable needs, is the eternal and utter devotion of a mother to her child. Music is ever present, ever watchful, ready to sing to man, whatsoever his need, whether of consolation, of courage, or of love. Nor does she forsake him in his evil hour, when none but darker passions can touch his heart. She will go with her children to the deepest depths, and if thus terrible has become their need, she will yield to them her heartbroken sympathy even in their hate and their lust.

Music will make all sacrifice for men. At the cost of fearful pains of growth, she will change her nature with their growing, or even their perverse needs. Let her living sons but call upon her to forsake her earlier nature to sympathize with the broader and deeper consciousness which they have wrung from life in their battle with circumstance, and unhesitatingly she responds. She will indulge a prodigal Strauss or a Debussy, even to his own harm, and she yields her best only to him whose sympathy has made him one with the deep and simple heart of humanity.

In America’s present need of songs breathing the freedom and courage of the New World, Music, the all-mother, is present and watchful, and will stand by her latest son until he is full grown and strong.

If it were proposed to give, in a brief statement on this subject, even a succinct account of the whole field, or the simplest sort of scientific review, there would be little room for anything else to appear in this volume. In fact, one deservedly famous frankly avowed that he would not attempt to say anything on the subject unless he had given the matter at least a month’s careful consideration, and yet it is much more than likely that the clientele for whom this particular book is especially designed would not take the trouble to read an article that had been prepared after such prolonged and ponderous thought.

The one thing that has characterized all literature, even before the art of printing was known, no matter what may be the definition of the word, is this: Whatever has pith, human interest, originality and action, however slowly it may have worried its way through the tired or befuddled brain of those persons whose privilege it is to see the matter before publication, will be quick to catch the eye of an ever alert public.

This is as true of science as of fiction: as universal in poetry as in prose. A single illustration will suffice: Quite recently a book, in many ways abstruse, appealing, apparently, to a limited class of readers, had just that touch of tenderness, that trail of truth, that caused a tremendous sale, and exhausted the edition in a remarkably short time.

It was once asked what part of a newspaper was most interesting; the answer from many readers and from many lands was practically the same: it depends entirely upon who does the reading. This is quite as true of literature in general as of one part. When we reflect for an instant we must acknowledge that in every thinker’s life there are periods that differ materially in the attitude towards reading; that some special line is apt to predominate, even in one who is known to be a general reader: it may vary with time, place, conditions—in fact, under almost all conceivable circumstances—but there is never a time when there are not more readers in any line than there are books worth while to meet their needs, or to satisfy their demands; in short, it is just as true to-day as before or since the thought was expressed in words—Brains are always at a premium.

The profession of the player is one of the oldest recognized and in its growth and achievement stands foremost of all the arts.

In its crudest form little is known, but as a profession it may properly date from the Chinese and Grecian periods, when players were chosen from among the infant slaves and trained to the art by masters, not unlike the painter and the bard.

To the immortal genius of Shakespeare does the world owe its inexpressible appreciation of the artistic development, realizing to the fullest degree the possibilities, and subsequently the mastery, of the art, placing it at once on the highest pinnacle of achievement and according to it the laurel of universal popularity.

To this genius is added that of others, each attaining a greater degree of appreciation, until to-day the art of the player encompasses the highest attributes of the allied arts.

The player is one who loves, and understands, nature. To do so he must feel, in the highest sense, the emotions of the artist, the poet and kindred spirits, because from each he must cull the choicest petals—the inspiration of the poet, that he may portray the character; the genius of the artist, that he may imbue it with life, and the passion of the bard, and to this the sympathy of a Madonna, the tenderness of an angel, the love of a mother and the strength of a giant.

The development of the art of the player records the development of civilization itself. The player and his art obtains wherever there is civilization. In its highest form it is at once Literature, Art and Music in harmonious arrangement. In its possibilities it is Religion, teaching the whole world by its power:

The player, supreme in his art, is master of every emotion.

EAUTY

is only paint-deep at times.

EAUTY

is only paint-deep at times.

Only the brave can handle the fair.

A pretty girl envies but one girl—a prettier one.

Many a poor husband is created from a rich man.

While there is an engagement there’s hope—of liberty.

Men can persuade a woman to do anything she wants to.

Men can be classified; women cannot even be pacified.

A woman’s idea of happiness is to be ideally miserable.

A woman will break a heart as readily as she will crack a smile.

No married man ever was a fool without being told of the fact.

The grass widow is not alone in making hay while the sun shines.

A bachelor is a man who has given serious thought to matrimony.

Bachelors form their opinion of marriage by experience—of others.

There is nothing new under the sun except hat styles for women.

“A woman imagines she can cover up her imperfections by pointing out those of other women.”

Every girl would love to be a thing of beauty and a boy forever.

When a woman proves equal to all a man expects she is a sur-prize.

It isn’t nearly so hard to be a fool over a widow as not to be one.

Every woman secretly admires the wisdom of the man who flatters her.

A woman may conceal her faults, but a decollete gown is less deceptive.

The blush of a bashful girl is a flush that takes any hand—and heart.

“The cup of happiness” with men of experience has a siphon on the side.

Every woman has a horror of old age, but not so much as of young death.

Women are never satisfied. First they want a voter and then they want a vote.

Some men are born to trouble, while others merely achieve it by marriage.

There is but one kind of love, yet every woman has a different idea about it.

Men, manners and morals change, but woman, never—from the changeable.

A man may be “out front” at the opera and yet be able only to “see back”—if he is with her.

Every woman expects a man to think for her, and then she reverses his opinion.

When it comes to singing the praises of another, most women have a sore throat.

Man’s principal safeguard against matrimony is that widows are made, not born.

Many a promising housekeeping career has been ruined in an unpromising stage career.

Men have found many antidotes for a woman, but the surest of all is another woman.

A woman spends one-half of her time telling lies for men and the other half to them.

Women often know a man is in love with them when the man never discovers the fact.

Men often find it necessary to choose between the inconstant and the unattractive woman.

A woman keeps a man running all the time—first it is after her and then it is from her.

If women did not know that men could overcome their resistance they would seldom resist.

There are two ways in which a woman may win a man: Her own brilliancy and his inanity.

When a man is at the feet of woman it is pretty sure that another woman threw him there.

Every woman wants a man to be real devilish before marriage and real angelic afterwards.

Anyhow, there was one woman who was never jealous. Adam didn’t have troubles about that.

A woman imagines she can cover up her imperfections by pointing out those of other women.

Some men are born wise, some achieve wisdom by experience, and some just don’t marry.

Two kinds of women make trouble in the world—those that are married and those that are not.

There is but one class of women who are not interested in the fashions and they are the dead ones.

The philosopher said a woman could not argue—he was too wise to say that she could not talk.

The reason so many men find marriage unattractive is because life was so attractive before marriage.

It isn’t a hard matter for a woman to make a man love her. The difficulty is in making him keep it up.

A woman can make up two things at the same time—her face and her mind; but her face lasts longer.

The world has no sympathy to waste on those reckless enough to wed when both have been married before.

If a man does not tell a woman he loves her she thinks him impossible; if he does, he knows himself foolish.

When a woman says that all she wants is what she deserves she really means she deserves all she wants.

When a girl reaches that uncertain age and is yet unmarried, she is often worse than she paints herself.

Sometimes there is more truth than sentiment when a man tells a woman a thing is as plain as the nose on her face.

No one has ever yet discovered why a woman is afraid of a mouse and tackles a six-foot man with confidence.

A woman will start a flirtation in fun and then wonder why a man won’t follow her when she gets serious.

If a man wants to make a fool of himself he can find many opportunities, but the surest way is over a woman.

Men and women both agree that it is inadvisable to live without each other and impossible to live with each other.

Whether a married man pities or envies his bachelor friends depends entirely upon how long he has been married.

If a man really wants to start something with himself, let him try to love a woman just as a woman wants to be loved.

The best way to find out what a girl who is in love with a man thinks of woman suffrage is to find out what he thinks.

A man may escape the measles, or automobiles, or even being indicted, but no man has ever been known to escape a widow.

No woman ever told a man she hated him without meaning it; some women have told men they loved them and meant it.

Rather than a man should be right and belong to another woman, a woman would have him wrong and belong to her.

The reason widows are so attractive to men is because they will allow themselves to be taught things they already know too well.

A girl will gaze for three hours and a half at the moon and then wonder why she hasn’t time to sew a button on her brother’s vest.

The happiest man is he who will take a woman’s protestations like he does a dose of medicine—with celestial faith in the giver.

When a woman fails to see an opportunity to be generous to another woman it is not necessarily a sign of defective eye-sight.

Don’t misunderstand a man when he tells a woman she is sweet enough to eat—maybe he is thinking of the forthcoming restaurant-check.

Between the ages of sixteen and thirty a woman is a general practitioner in the field of love; after that she is satisfied to become a specialist.

A man is willing to worship at the shrine of a woman with whom he is in love until he meets another woman—then he changes his religion.

The question will never be settled between women as to which will win a man quicker, a pair of silk stockings or an ability to bake a good cake.

If ever the fact that there are no marriages in Heaven is generally believed by women, half of the preachers will be obliged to seek other employment.

If a woman were obliged to express a preference, she would choose the man who pleases but does not love, to the man who loves but does not please, her.

Women are said to be more “clean-minded” than men. Men might meet feminine competition if they resorted to the stratagem of changing their minds as often.

The greatest disappointment after marriage comes to a man when he realizes that his wife does not look like the models in the shop windows during a white-goods sale.

A man can protect himself from the things said about him by the women who don’t love him. It’s the things said about him by the woman who does love him that keep him worried.

Women, says a sage, are like books: No man can judge the inside by what is displayed on the outside. It is a poor rule that won’t work both ways. Women are unlike books: When one has finished with a book it can be closed up.

|

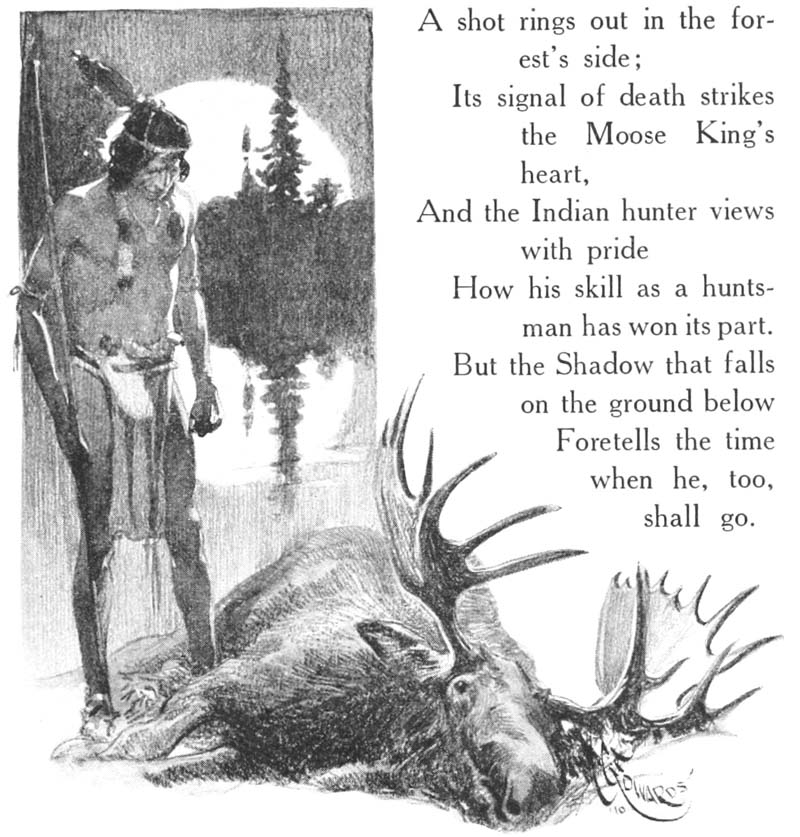

A shot rings out in the forest’s side;

Its signal of death strikes the Moose King’s heart,

And the Indian hunter views with pride

How his skill as a huntsman has won its part.

But the Shadow that falls

on the ground below Foretells the time

when he, too, shall go. |

| |

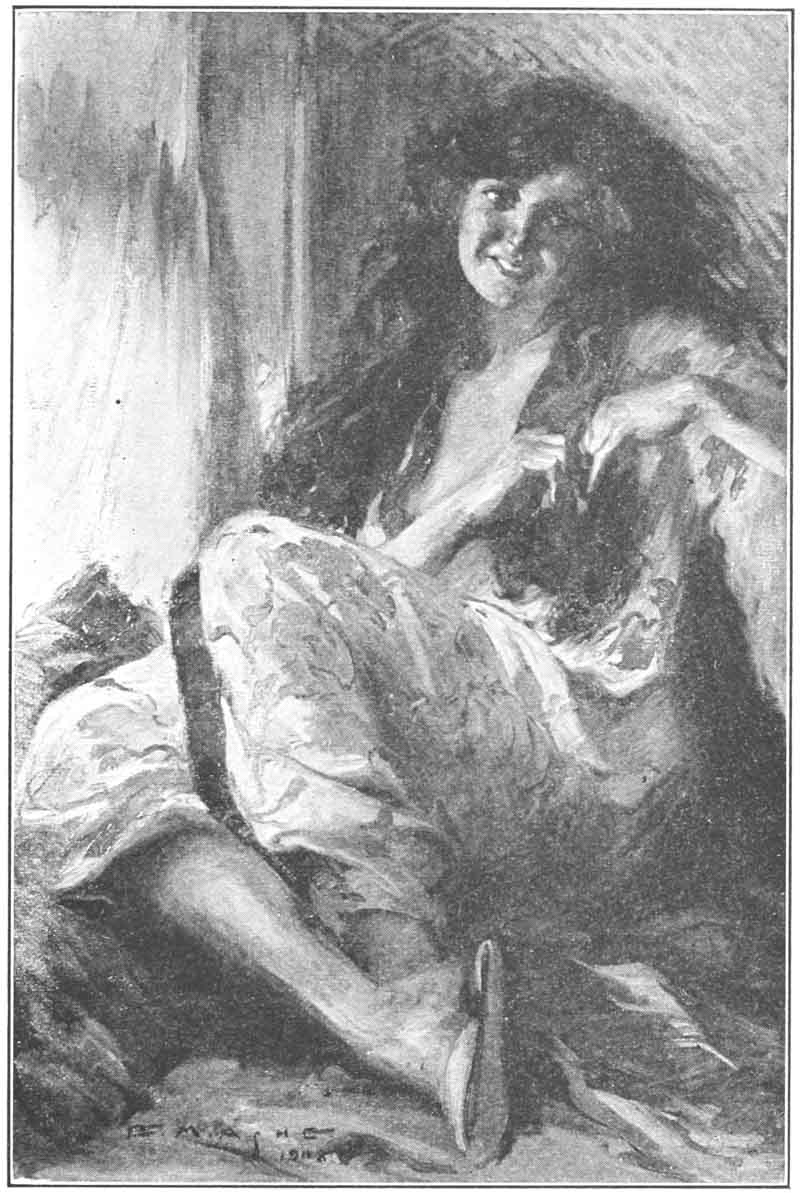

Drawn by R. F. Zogbaum.

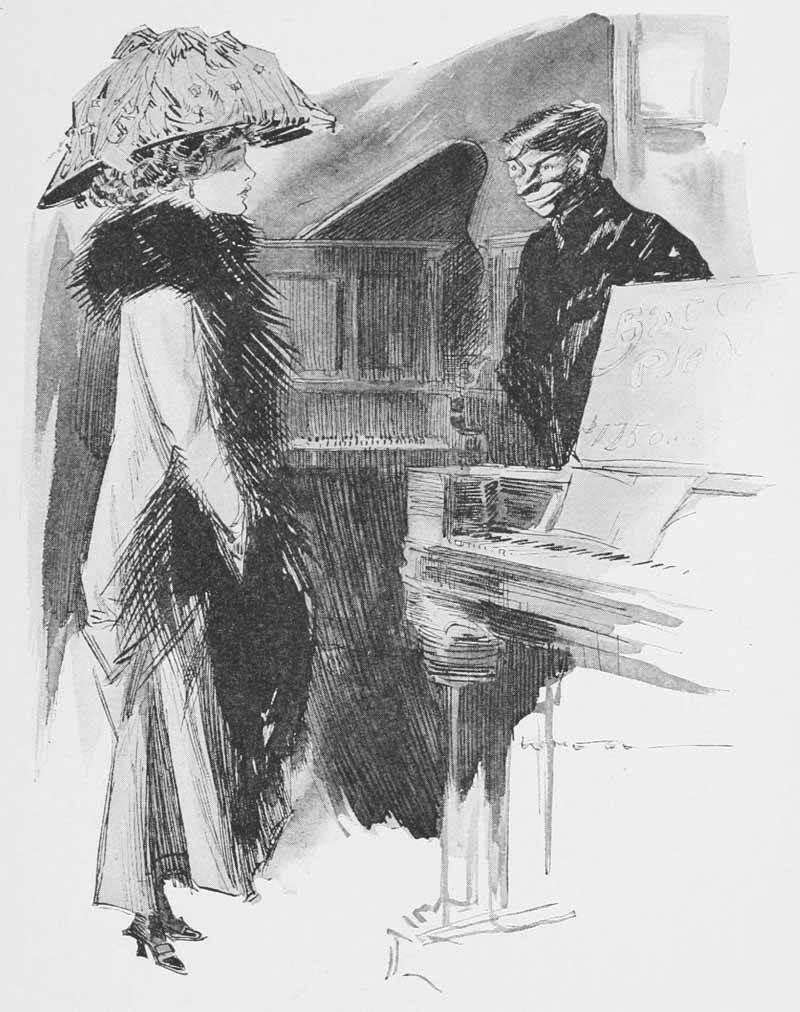

APA

can stand no more! How, then, can I break this to him?” The

speaker, a radiantly beautiful young girl, stood sobbing in the

great musical emporium of Harry M. Daly & Co.

APA

can stand no more! How, then, can I break this to him?” The

speaker, a radiantly beautiful young girl, stood sobbing in the

great musical emporium of Harry M. Daly & Co.

“Consider me a policeman and not a piano-mover.” As he said these words, Paul Postelwaite came forward with his hat in his hand. For all he knew the damsel in distress might be a carriage customer, and, besides, he was afraid if he left his hat in the shipping department a member of the firm might steal it.

“Oh, sir,” replied the beautiful young girl, “I saw a pianola advertisement some time ago which said: ‘With this instrument anyone can play the piano.’ And I, taking all my little savings, bought one for papa!”

“Yes?”

“It arrived to-day. Too late, I perceive that a pianola is an instrument from which music can only be extorted by the feet, and poor papa was run over by an electric car and lost both legs.

“It was all my little savings, as I have said. The firm will not take the pianola back, and my poor papa has no visible means of support.”

“But you can sue the street railway company for damages,” said Paul, soothingly.

“We threatened to do that, but the railroad company only said papa should consider he was sufficiently damaged and they did not see why he should sue for any more. However, they said we might bring the matter into court and they would see what they could do to his character.”

“Go home, little one,” said Paul Postelwaite, kindly, “and I will come around this evening and play the pianola for your papa myself.”

The foregoing will show that although Paul moved in musical circles he was neither a sharp nor a flat. His worst predilection was that he continually talked shop, for his last words to his distressed young confidant were, “Compose yourself!”

Paul Postelwaite had long resolved upon a musical career. He knew the pitfalls of the profession. On every side of him he saw and heard the unfortunates who played the piano to excess. A hater of discord, he resolved to save the victims of piano-playing from themselves. To this end he studied piano-moving.

Most pianos are bought on the instalment plan. Most payers for pianos bought on this plan fall behind in their instalments. It was Paul’s duty to call and take away the pianos of those who had been remiss.

He bore abuse and vituperation, not with stolid indifference but with the conscientious feeling that he was a public benefactor.

He had the reward of public appreciation. People afflicted by proximity to those who played the piano to excess no longer complained to the Board of Health. They ascertained if any payments were overdue on the instrument of torture, and then they sent for Paul.

Paul’s father had been a piano-maker. But he had been overtaken by misfortune. He made pianos for the big department stores.

But while he only made one grade of piano, he was compelled by the exigencies of his trade to stencil them with so many different names that he forgot his own. And one day, while suffering from loss of memory in this regard, he signed a name not his own to a check and was compelled to retire from business to Ossining-on-Hudson.

His father’s parting advice had been, “Never forget who you are, my boy!”

That evening, carrying with him a pair of wooden legs, as a pleasant surprise for the abbreviated parent, Paul called at the cosy Harlem apartment where dwelt the young girl who had so attracted his attention that morning.

As the young girl opened the door for him with a glad cry, Paul proffered the wooden legs. “These are for your father,” he said; “he has a heart of oak, I know, and now he will have legs to match.”

“Bless you, young sir,” cried the father of the girl. “This will place me on a better footing with the world! And should I die they will be a legacy for both of you. And now, thank gracious! I can play the pianola!”

“The grateful father adjusted the artificial limbs and was soon playing Handel with his feet.”

So saying the grateful father adjusted the artificial limbs and was soon playing Handel with his feet, extracting from the music chords of wood, as it were, of a timbre most surprising.

This was not all. Paul secured the old man a political position as a stump speaker, at which he was doubly successful, and how he stood on public questions is well known; his physical disability, of course, stood in the way of his ever running for office.

As for the daughter, Paul married her. There is no need to tell you her name. She is Mrs. Postelwaite now and that is enough.

They are still a musical family, and the pride of their home is a Baby Grand.

For Success—initiative, concentration and perseverance;

For Happiness—love, cheerfulness and a sense of humor;

For Good-fellowship—the Pleiades.

HERE

was once a Sagacious Youth, with a High Brow, who Opined that the

World owed him a Living.

HERE

was once a Sagacious Youth, with a High Brow, who Opined that the

World owed him a Living.

“It is all very well,” he reflected, “for Ordinary Dubs who have not been blessed with a Superabundance of Gray Matter as I have, to Strain on the Collar in the Tread Mill of Business, but the very thought of Work makes me Tired, and I apprehend that there are Easier ways of getting the Pelf than by Earning it.

“It is, of course, a Good Thing that not every one is as Brilliant as I am, for if they were the world would blow up with Spontaneous Combustion. It really pains me to see others toiling along day after day for Measly Salaries, when they might have money coming to them on Wings if they only used their Wits instead of their Paws.”

With that the Sagacious Youth worked out a system that was a Sure Thing on paper for Divorcing the Public from its Long Green.

“I learned from the Census Report,” he said to himself, “that every Minute a Sucker is Born, and I apprehend that they are Providentially provided to furnish Automobiles and Wealth Water for Wise Guys like Me, and that all that I shall have to do is to take advantage of their Gullibility in order to Hook Them and have a Fish Chowder that will be a Perpetual Picnic.

“I have perceived that most of my Fellow Creatures are so Greedy that they will swallow any sort of Bait if it looks Fat, and that if you only Promise them enough, it Razzle-dazzles them so they do not investigate your means of Making Good.”

Thereupon the Youth began burning the midnight Carbon concocting a Prospectus of Speculation made Easy, by which Widows and Orphans and Clergymen could be separated from their Pile and enjoy all the Excitement and Losses of Wall Street at Home.

As an idea it was a Jim Dandy that commanded the respect of the Financial World, but before the Youth could realize it the Post-Office Department got Wise, and he felt it best to Travel in Europe for his Health.

“Alas!” cried the Youth, “I fear that the Confidence Game is getting Over-Crowded, and it is evidently up to me to either Marry and give some Female the Pleasure of Supporting me, or else go to Work.

“Personally, my tastes are not Domestic, and I prefer Single Blessedness to Double Wretchedness, but it is clear that it will be less Fatiguing to hold a Lady’s Hand than to call Stations in the Subway; it’s me for the Altar. Besides, as soon as I have annexed little Tootsey-Wootsey for my own, I will take possession of her Bank Account and then all will be well.”

So the Youth espoused an Elderly Widow whose No. 1 husband had left her a Large and Juicy slice of Insurance, but contrary to his expectations she was a Foxy Lady with a Time Lock on her Pocketbook, and he could not work the Combination that opened it.

At this the Youth shed bitter Tears, but when he began knocking Fate his Friend called him down.

“It may be True,” said the Friend, “that the World owes you a living, but there are many Small Debts that we have to Personally Collect.

“If you had displayed as much Imagination in writing Fiction as you have in Telling Lies that deceive no one, you would have received an Honorary Degree from Yale instead of the Double Cross from your Fellow Creatures, and if you had worked as hard at some Honest Calling as you have in trying to Rob Others you would be a Millionaire instead of a Tramp. It is my observation that the Beater always gets Beaten in the end. Farewell!”

Moral: This Fable teaches that Most of the Short Cuts to Success end on the Dump.

Somewhere I have heard that the “Pleiades all sang together,” and I therefore submit these all-star verses as a song.

P. S.—There are said to be seven seas. It ought to be seventy.

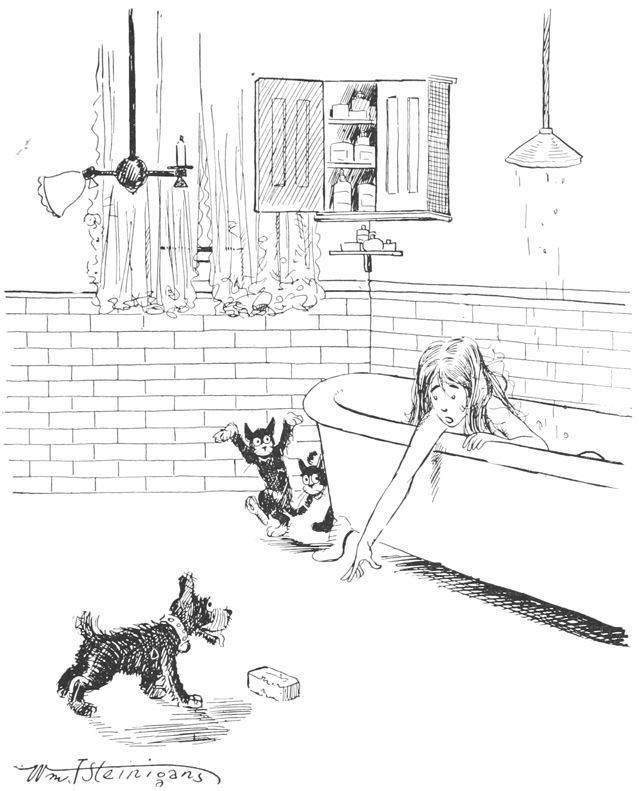

Drawn by Wm. J. Steinigans.

See the lady? Does the lady want the soap? The lady certainly does. Will the pup bring the soap to the lady? It will not—the pup is a gentleman pup and the lady is a suffragette. The pup wants her to get it herself.

OU—you

will come over Wednesday evening?”

She asked it hesitatingly, timidly

almost.

OU—you

will come over Wednesday evening?”

She asked it hesitatingly, timidly

almost.

“I’m afraid I can’t Wednesday,” as he picked up his hat and cane.

“Then Thursday—have you an engagement for Thursday?”

“Thursday is the dinner of the Civic Club.”

“Oh, yes; of course you must go to that.” There was a slight quiver in her voice now. “Could—could you come—Friday?”

“That’s so far ahead. I don’t like to make an engagement so far in advance. But I’ll phone you some time during the week.”

She smiled a wan little assent. With a brief good-by he was gone. His step down the hall—the click of the elevator—then she ran to the window and followed him with strained eyes as he swung down the street.

If only he would look up and wave her a good-by as he used to—but he did not.

She threw herself on the couch, her face in the pillows—the ache in her heart keener than any physical pain. Was it hopeless—the fight she was making? Could she never win back the love she had lost?

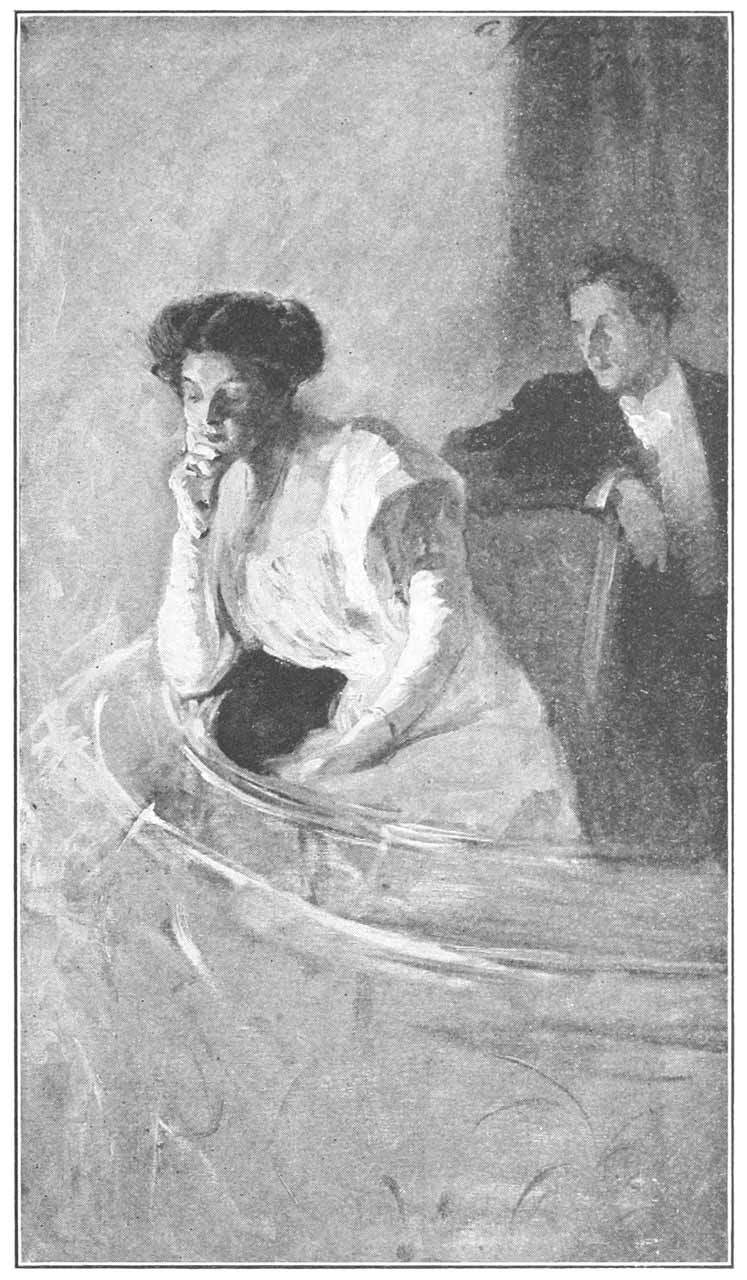

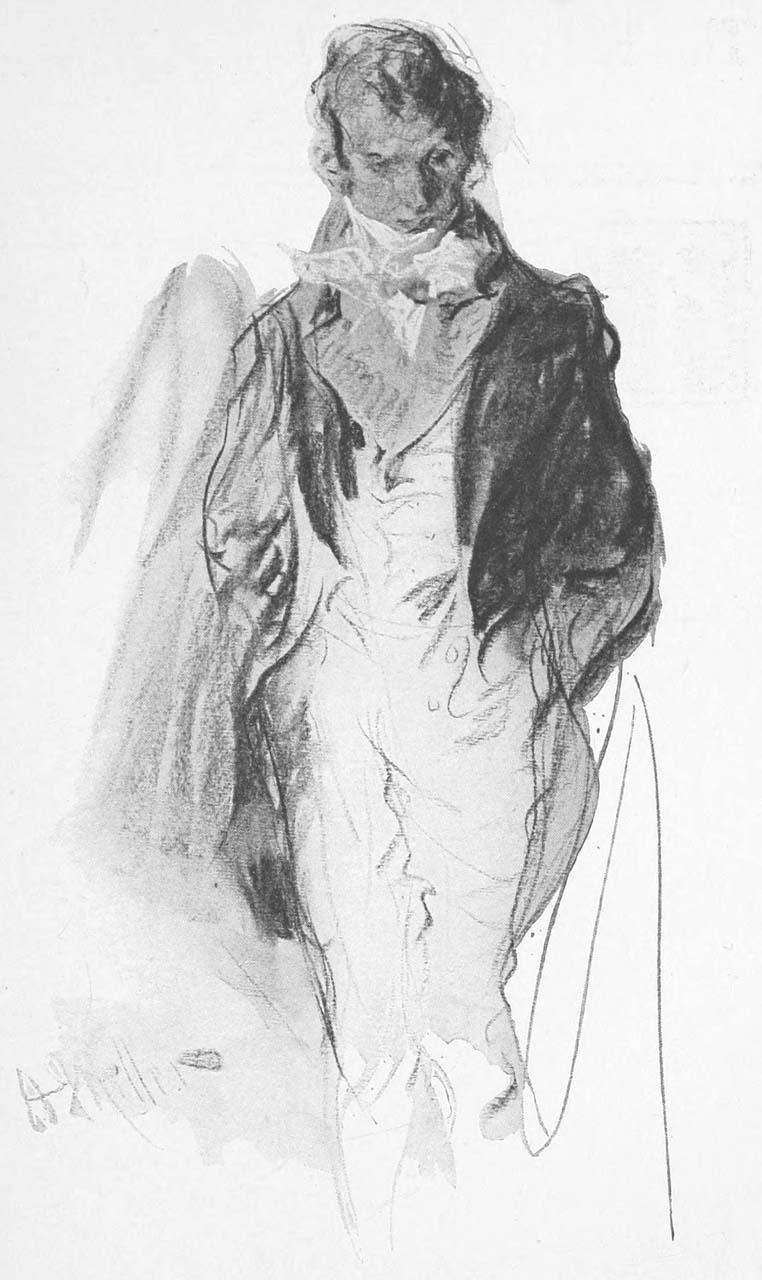

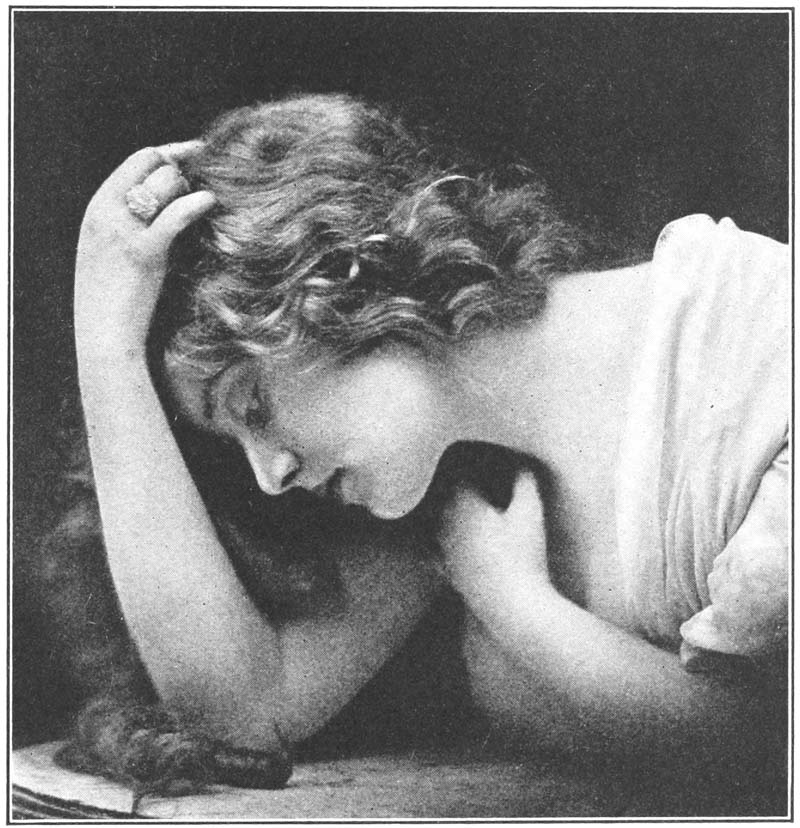

“There she sat, with her head bending low, thinking, thinking, thinking.”

And she had never known how she had lost it—unless it was because she had grown to care too much and to show it too plainly. Could it be that? Had he cared only for the uncertainty—the love of pursuit? And without that—being sure of his conquest—his interest had died?

Ah, no—no! passionately she denied that. The man she loved was bigger, finer than that! He could not have stooped to a merely cheap desire for conquest. If he had ceased to love her, it was some fault of hers, some failing, some lack within herself of which she was unconscious.

She had spent long hours of torturing self-analysis trying to find where she had failed—what it was that in the beginning he might have thought she possessed—and then found she did not. So great was her love for him that she felt she could almost make of herself what he wanted—just by the sheer strength of willing it!

If only she could be with him enough! If she could but have the chance to make him care for her again! He used to come almost every day—and now—now, sometimes many days would pass.

She knew it was a mistake to ask him when he was coming—to try to name any particular time. He seemed to resent that now. If only she could let him go without a word! But the thought of the long, silent absence that might follow always terrified her. Once, for two weeks, she had not heard from him; and the memory of those two weeks’ suffering always weakened her to the point of trying to make some definite engagement to escape the sickening uncertainty of the days to come.

Oh, she was so helpless—so pitiably helpless! Wholly dependent on him for her happiness, yet powerless to break down this wall he was placing between them!

She slowly arose and threw herself into a chair. There she sat, with her head bending low, thinking, thinking, thinking.

Then gradually there stole over her a sense of quiet—almost of peace. It was partly the relaxation that comes after any emotional strain, and partly because of a faint hope, a belief that sometimes came to her and that comforted her above everything else—the thought that because she gave of her best—because the love she gave was a great and good love—some time he could come to know, to understand, and to love her again, if only for her unfaltering love of him!

If she could but wait long enough—patiently enough—in the end the love she so wanted might be hers!

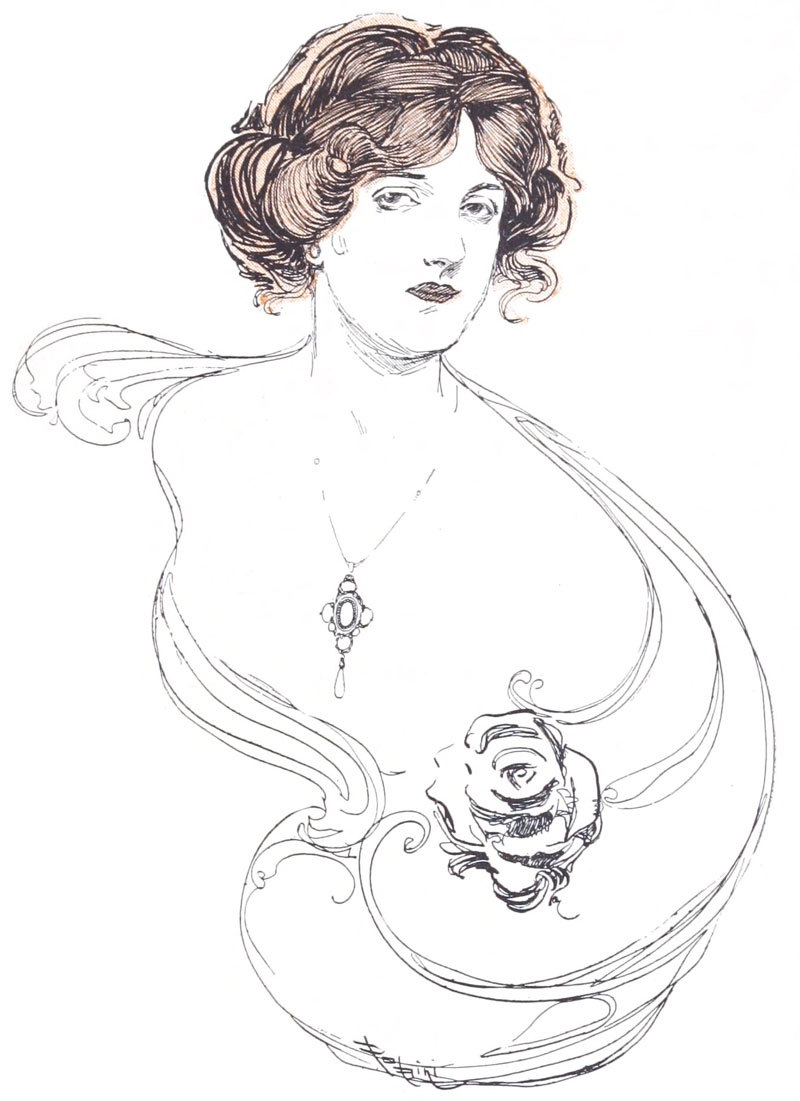

Drawn by Albert Sterner.

VERY long time ago, when the Heavens

were quite new and the Earth was still in

the Golden Age, a strange event occurred—quite

unheard of even in those early

times.

VERY long time ago, when the Heavens

were quite new and the Earth was still in

the Golden Age, a strange event occurred—quite

unheard of even in those early

times.

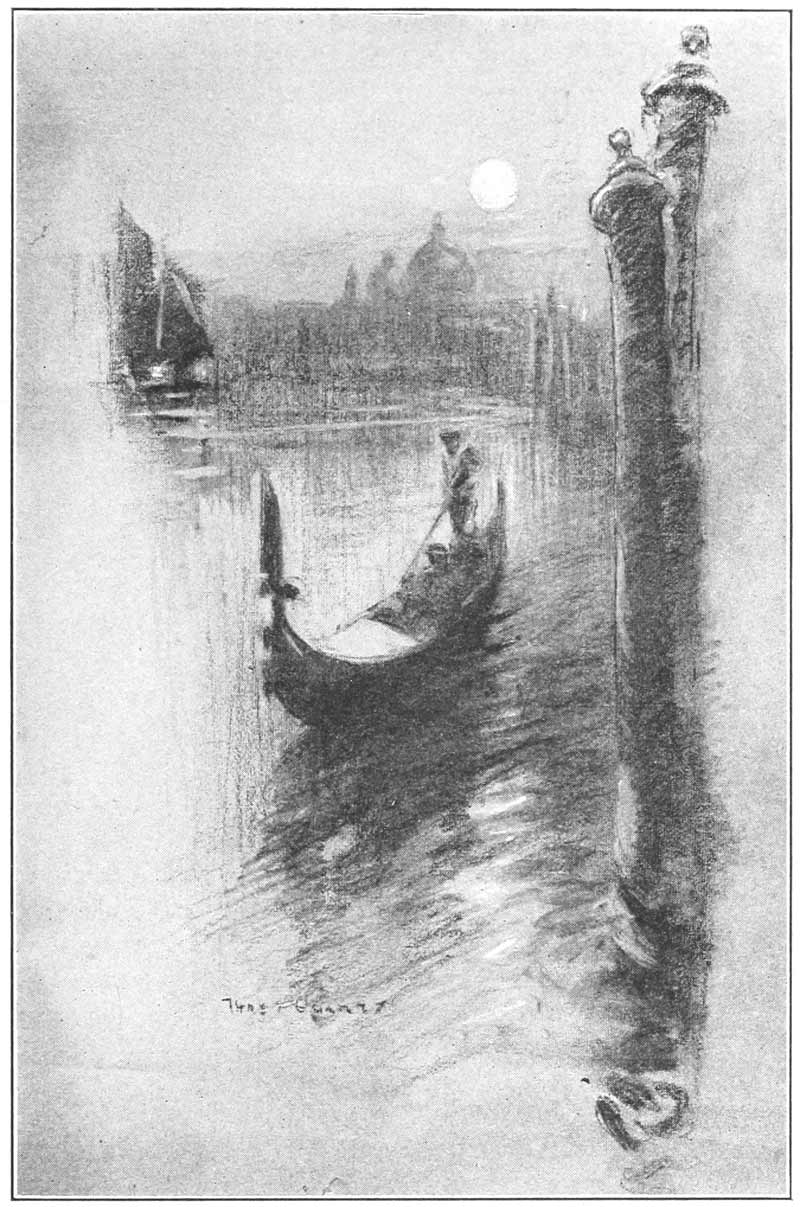

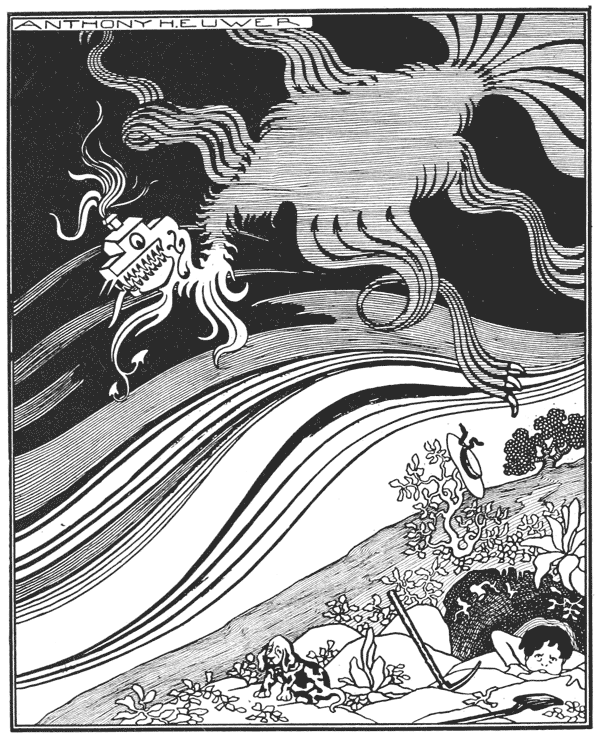

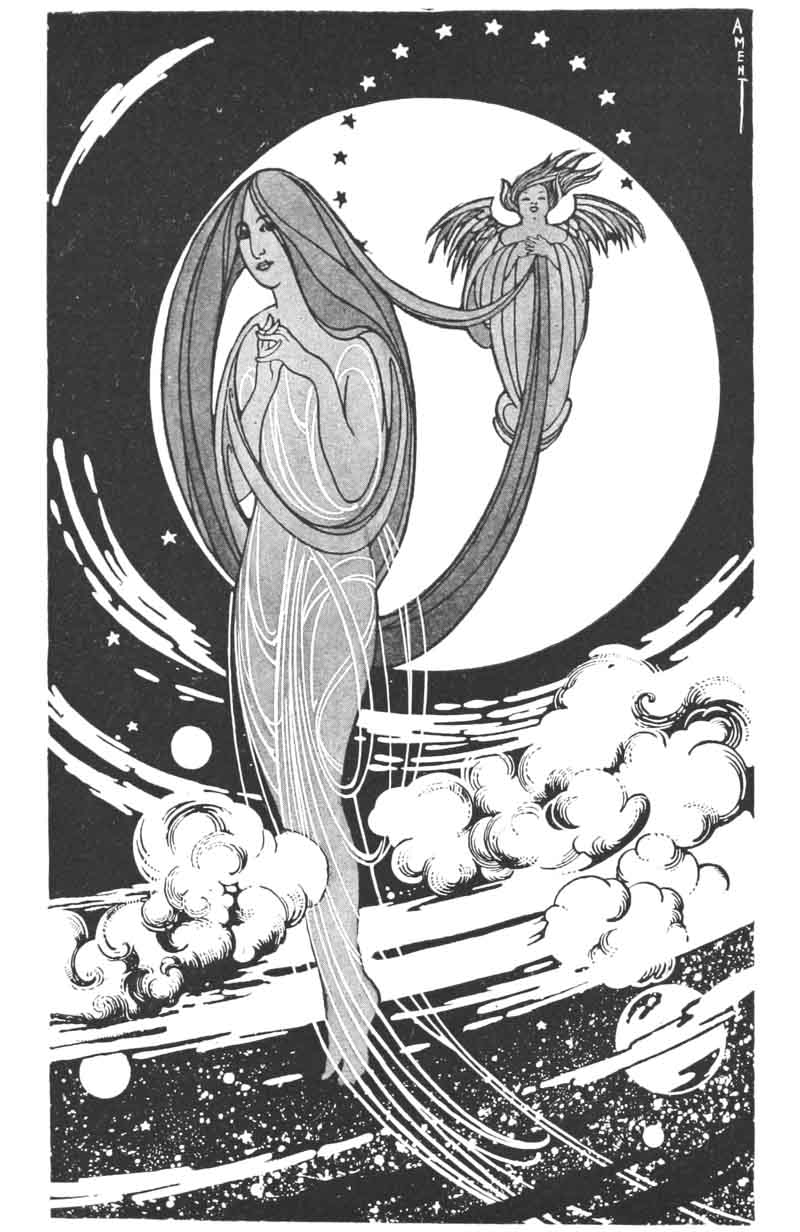

The Sun, vigorous and lusty, had rubbed his blinking eyes and hurried away to the west. The boy-child, Twilight, his chubby hands still clutching after the last red rays left behind by the Sun, winked his sleepy eyes, as, protestingly, he was pushed along in his crimson cart by Old Sandman. Close behind came his three sisters, the Evening Shadows, in their long, trailing, gray robes. A hush fell upon the Heavens. From far below came the hum of the Crickets and the low murmur of the Katydids, having their final good-night gossip, but in the Sky all was still until the Moonlady came softly creeping along, her silver mantle enfolding her slight form, her long silken hair caught by the Evening Breeze, who followed close in her wake. At her appearance there arose from the Earth songs of gladness and hymns of praise. Lovers looked up at her enraptured, poets sang of her, and even the brute creation sent Heavenward their low murmur of joy at her being. Silently she smiled down upon them all as she passed on her way.

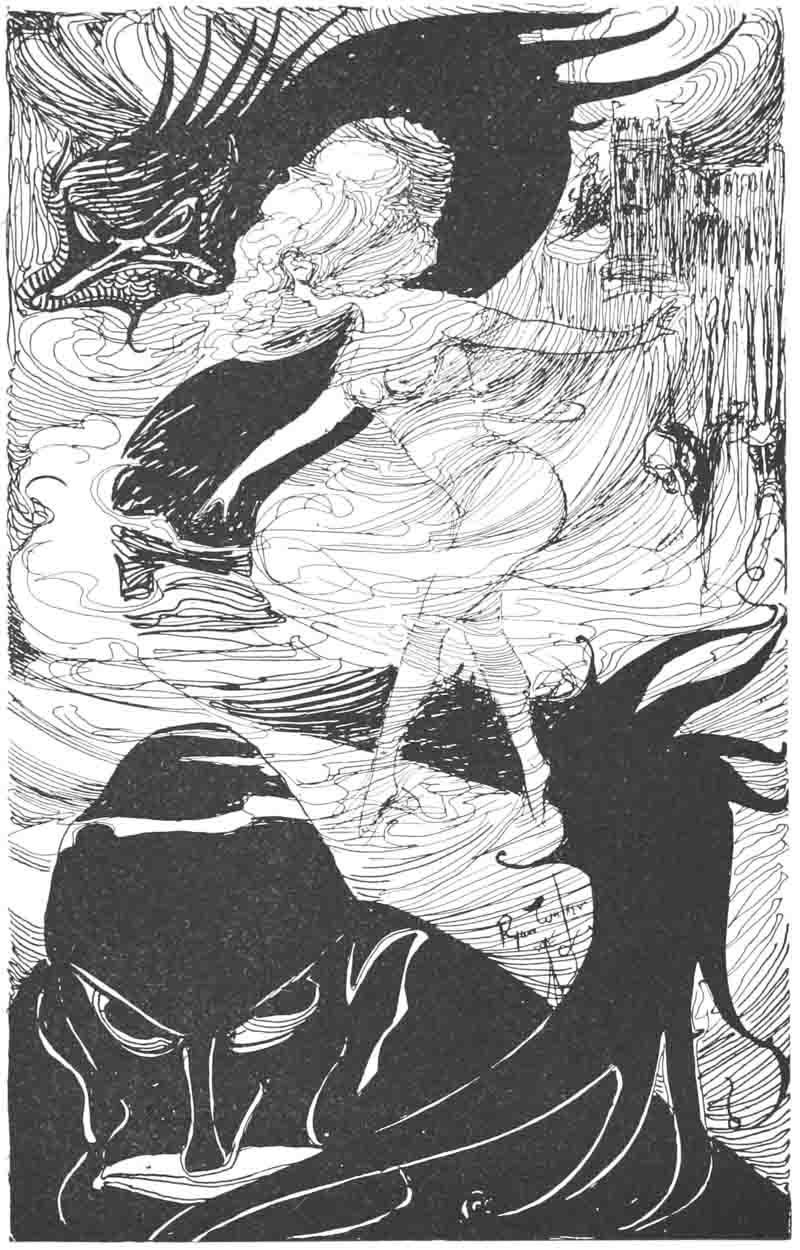

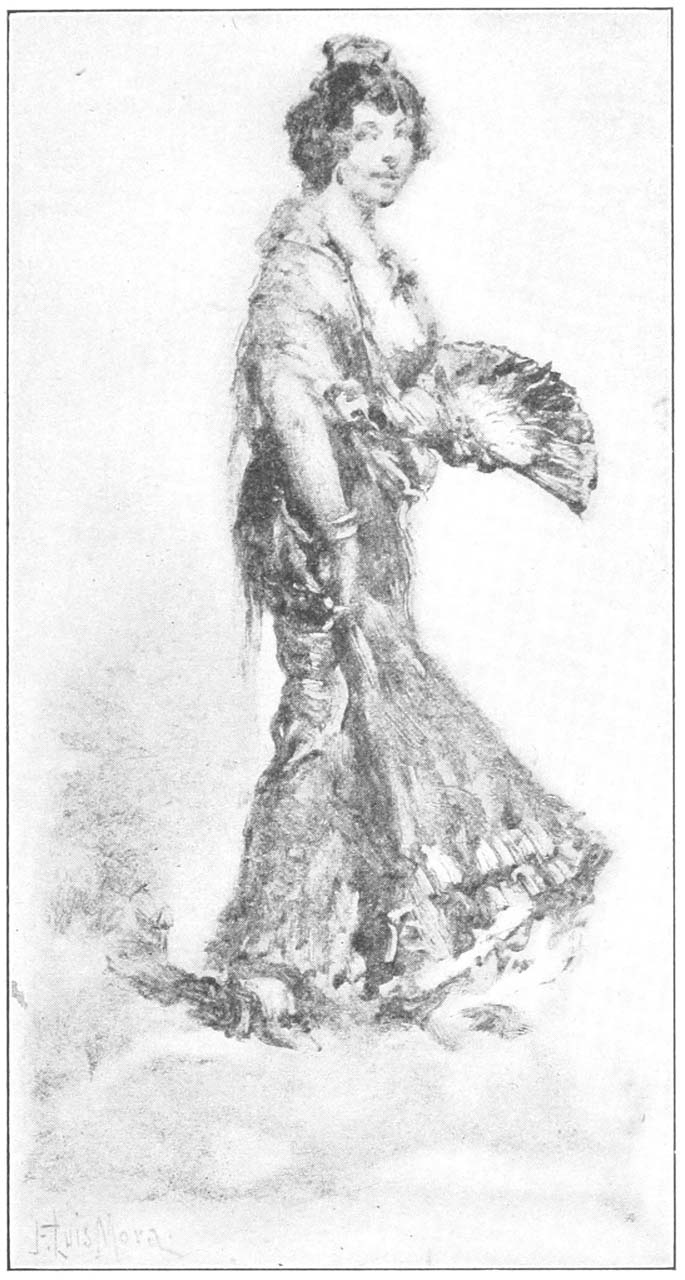

“The Moonlady stole softly across the sky.”

Then a strange thing happened. Black clouds skurried here and there across the Heavens, and low mutterings were heard. The Stars had revolted!

Venus, her cold beauty marred by a frown of discontent, was the center of a murmuring group, to whom she spoke in words of passion:

“Let us take a firm stand. Why should we go on shining, shining through countless ages? We are not appreciated. We never receive any praise. There are so many of us and our light is so feeble, who cares whether we shine or not? The Moon comes along and takes away our glory; let her do all the work then. Why should we waste our light trying to outshine the Moon and the Sun? Unless we can be as brilliant as they and receive as much praise, let us not shine at all.”

Each Star blinked a sullen assent, and gradually each little light flickered and went out. The Dog Star barked and the Great Bears growled—the low mutterings became a loud rumble, and the Heavens for once were dark, save for a faint light that still gleamed away off in the north. Seeing the feeble light still shining, all the Stars rushed to it, surrounding the feeble Star that persisted in shining, and jeered at her folly.

“Put out your light, you foolish one. Do you hope to vie with the Sun or the Moon with that feeble flame of yours? What use can you be in this great space of darkness?”

“I do not know,” replied the Star, faintly, “but I can

go on shining and do my best, though my light is small

and goes but a little way. I do not envy the Moonlady

her glory. Is it not a great thing that she can shine so

radiantly upon the Earth and make so many happy? And

if there were no Sun, what would the poor little Flowers

do, and the Birds and the Beasts? My little light cannot

do much good, but I can do my best to keep it bright, and

if it reaches to Earth but faintly I shall be grateful. I

had rather light one soul onward and upward than to have

a choir of Angels sing my praises; I had rather one

person should be glad he had seen my rays, than to be

crowned with a crown of brilliant jewels and never have

made anyone glad; I had rather one tearful soul should

look to me and find comfort in my steady light than to

have a million people bow down to me in worship of my

beauty; I had rather one soul should be truly sorry when

my light goes out than that a thousand should praise me for

my brilliancy and not know when I ceased to shine; I

had rather a baby’s face looked up at me and smiled and

called my name than to be praised in a poet’s song and

know he was paid so much a line for it; I had rather

send one faint ray of hope into some troubled heart than

to light the World’s Great White Way; I had rather

shine on for ages unnoticed than to shine with borrowed

light and be afraid of being blown out; I had

rather ”

But the little Star found herself all alone, and as she looked

about her she saw that each Star was in its accustomed

place, and that each light was more brilliant than it had

ever been before. Even the dark clouds had vanished, and

a little child looked up at the Sky from her bedroom window

and said, “O, mother dear, see how beautiful are the

stars to-night! They are God’s jewels, set in His Crown

of Glory, aren’t they? If we are very good shall we be

beautiful stars some day and shine for Him?”

”

But the little Star found herself all alone, and as she looked

about her she saw that each Star was in its accustomed

place, and that each light was more brilliant than it had

ever been before. Even the dark clouds had vanished, and

a little child looked up at the Sky from her bedroom window

and said, “O, mother dear, see how beautiful are the

stars to-night! They are God’s jewels, set in His Crown

of Glory, aren’t they? If we are very good shall we be

beautiful stars some day and shine for Him?”

And the Stars looked down and smiled Good-night. And the brightest of all the Stars were the Pleiades.

HE Boarderland is a drear domain bounded

on the north by top-floor bedrooms, lying

above the frost-line, because the steam register

always gets discouraged and quits one

story below. It is bounded on the south

by basement dining-rooms, where it is night

six months a year and just before daylight the rest of the

time; on the east by an entrance hall agreeably perfumed

with the combined aroma of kerosene, mother-of-onion,

veteran linoleum and the stuffing in the red-plush sofa, and

on the west by a parlor nine feet wide and thirty-two feet

long, with one window in it and a doctor’s sign in the window.

The doctor’s private office lies just back of the parlor,

so the parlor smells mildewed when the connecting door is

closed and iodoformed when it’s open.

HE Boarderland is a drear domain bounded

on the north by top-floor bedrooms, lying

above the frost-line, because the steam register

always gets discouraged and quits one

story below. It is bounded on the south

by basement dining-rooms, where it is night

six months a year and just before daylight the rest of the

time; on the east by an entrance hall agreeably perfumed

with the combined aroma of kerosene, mother-of-onion,

veteran linoleum and the stuffing in the red-plush sofa, and

on the west by a parlor nine feet wide and thirty-two feet

long, with one window in it and a doctor’s sign in the window.

The doctor’s private office lies just back of the parlor,

so the parlor smells mildewed when the connecting door is

closed and iodoformed when it’s open.

Boarders, as the natives of this land are commonly called, are never allowed in the parlor except once, that occasion being when they first apply for board. Thereafter they entertain their company on the front stoop in the summer and on the telephone in the winter. Winter company is the more expensive.

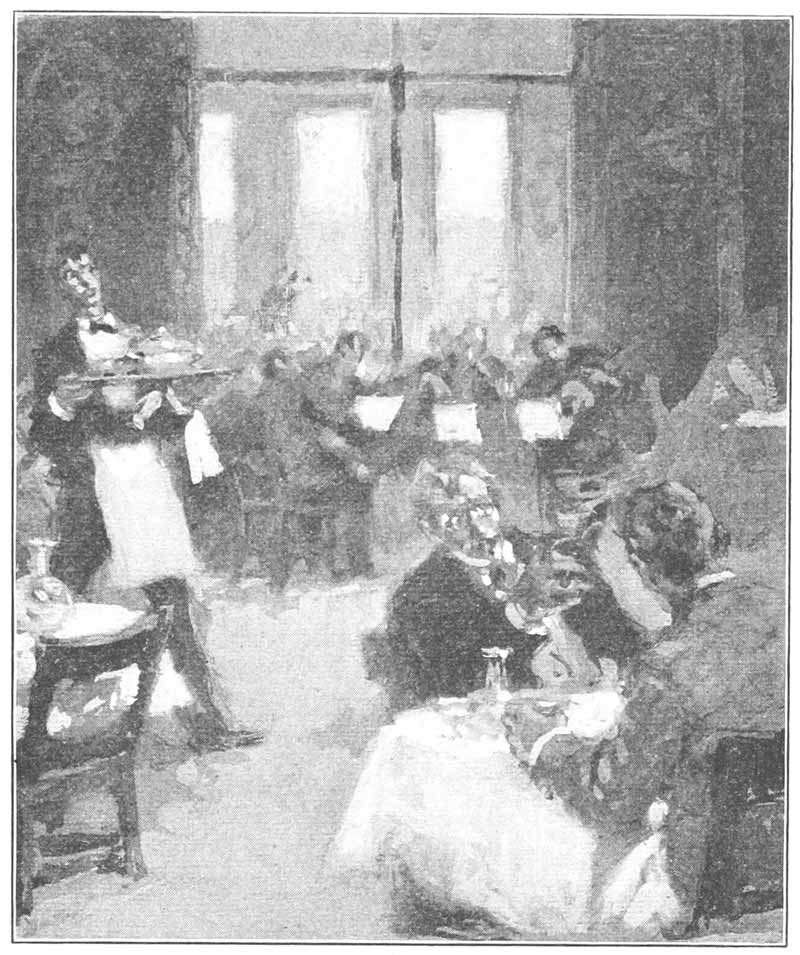

“Thereafter they entertain their company on the front stoop.”

The ruling classes of Hallroumania are known as Landladies and may be classed generally into the following subdivisions: Landladies who belong to Old Southern Families and formerly rode in Their Own Carriages, but suffered Heavy Financial Reverses through the Cruel War brought on By Your Mister Lincoln; Landladies who never married and don’t regret it; Landladies who did marry and frequently regret it; Landladies who have no use for husbands, and Landladies who have husbands and use them to take the dog out.

The inhabitants are indeed a weird race, including unrecognized geniuses, earnest hopers, chronic grouches, back files and innocent bystanders; also single gentlemen who are believed to have had what is known as A PAST, and who are suspected of leading the dissipated life because they come in of an evening with the odor of rum and Business Men’s Lunch on their breath; also young women of undoubted dramatic power, who won the first prize for elocution at the Rome Centre School of Expression and came on two winters ago to put Julia Marlowe out of the business, but are being kept back temporarily owing to a jealous compact on the part of the theatrical syndicate; also other young women who think they are entitled to bird-like notes because they had the thrush once, and were sent here at heavy expense by fond parents who imagine New York as a place full of talented voice-plumbers who know how to weld Nellie Melba pipes on a Ruth Ann larynx; also single ladies who spend part of the time drying handkerchiefs on the window-panes and doing light laundry work in a toothbrush-mug, and the rest of the time making life brighter and sweeter for a pug dog with the asthma.

Also dashing gents connected with leading brokerage offices downtown, who wear priceless marquise rings on the little finger of the right hand, and go secretly away at night owing for two weeks; also persons of both sexes who have been misunderstood by the world and crave A Little Sympathy—that is all; also ladies who are constantly on the verge of moving to a perfectly delightful place up in Ninety-third Street because a fur-bearing foreigner has opened a Pants-Pressery next door and the neighborhood is rapidly losing its tone; also, just plain boarders.

A boarder is often likened to a worm. And this is a proper comparison if it is a tapeworm that is meant, because a tapeworm always knows in advance what it is going to have for dinner, and so does a boarder. For instance, he knows that on Monday night he will have a New England boiled dinner that tastes like the family wash on Friday night, one gill and part of the dorsal fin of a boiled fish, and on Sunday evening that nourishing repast known as cold Sunday-night tea.

This cold tea is probably the most noted of the established institutions of Hallroumania, being constituted as follows: A dank cold platter, veneered at rare intervals with specimens of the Old Red Corned-Beef Period of Geology, cut to the generous thickness of gold leaf; a peculiar variety of potato-salad, in a free state of perspiration and garnished at intervals with slices of pickled beets, like a few red chips strewn on the kitty; four small squares of petrified pastry (not suitable for food, but could be given to hardy children to cut their teeth on); a prune-floater, bloated up and nine days drowned in its own juice; a cup of ostensible tea.

The common recreations of The Boarderland are rushing the washstand-duck in a dress-suit case; wondering how the other boarders can afford the clothes they wear; progressive knocking and raising scandals from the slip. The prevalent disease is Furnished Rheumatism, brought on by living in a single-breasted apartment, and is marked by a cramped, choking sensation, the symptoms being almost identical with those of Harlem Flatulency.

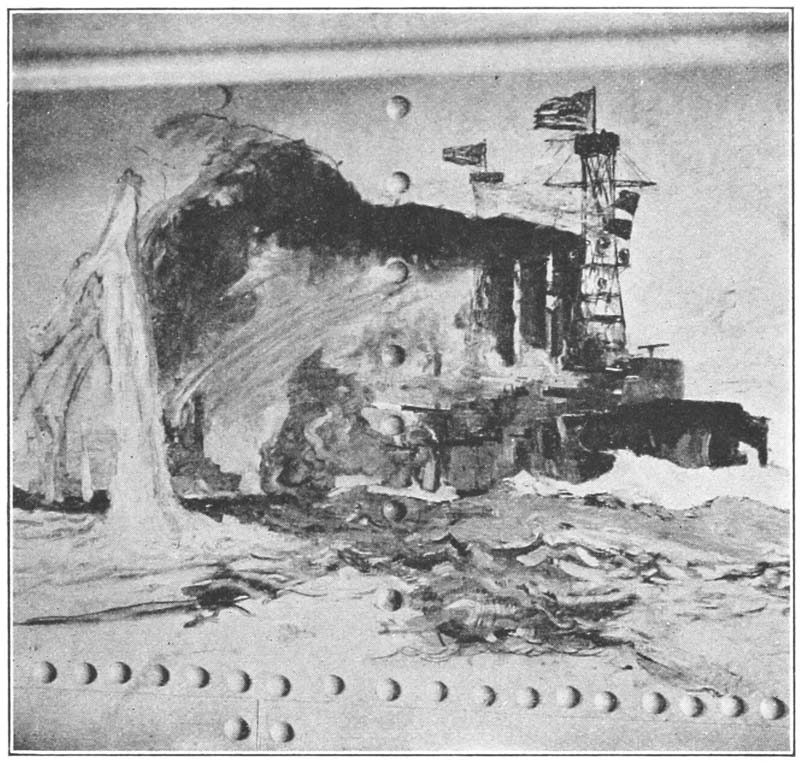

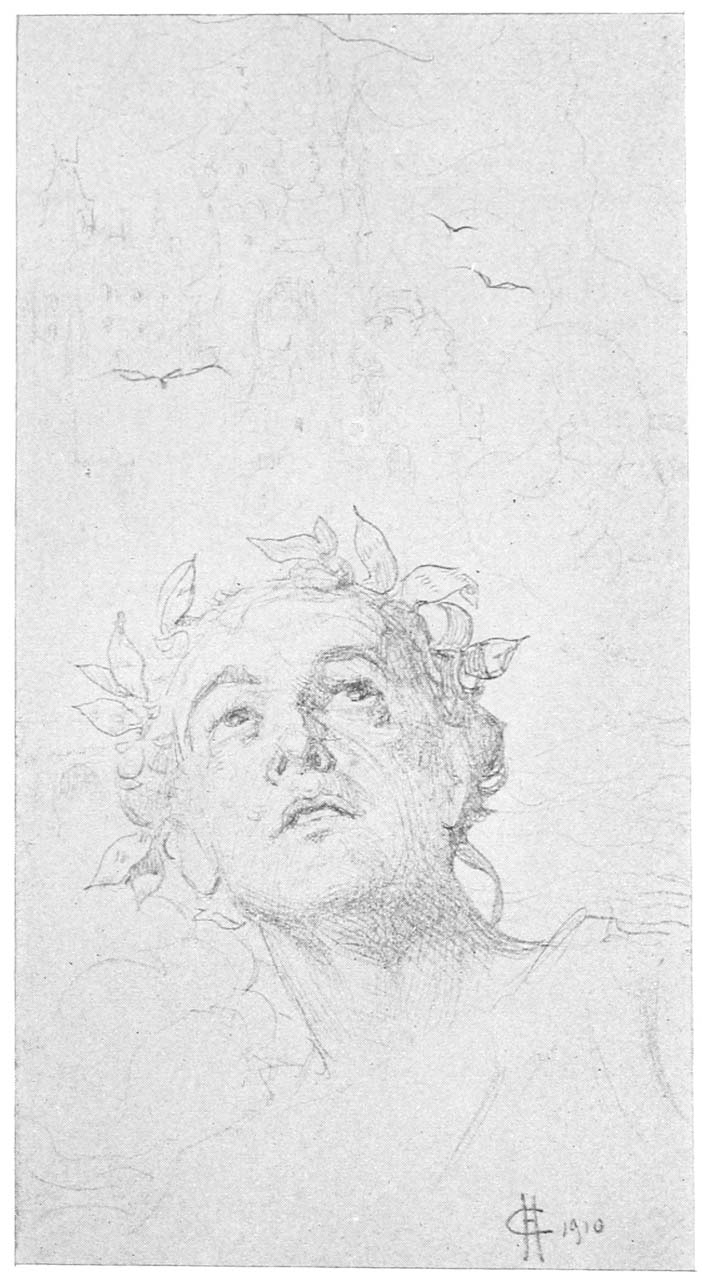

Drawn by Henry Reuterdahl.

Drawn by Alexander Popini.

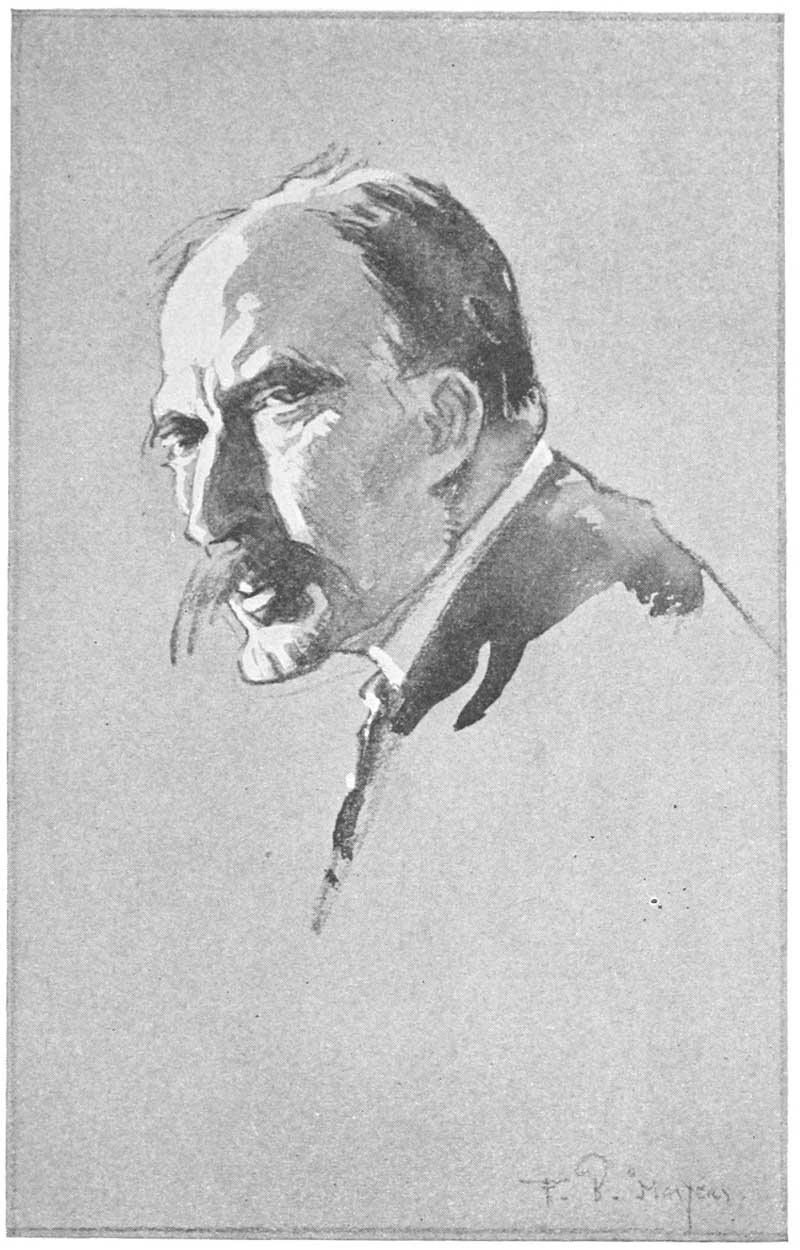

Drawn by F. B. Masters.

Original spelling and grammar have been generally retained, with some exceptions noted below. The transcriber produced the cover image by slightly altering the original, and hereby assigns it to the public domain. Illustrations, other than drop-caps, have been moved from within paragraphs of text to nearby locations between paragraphs. For this purpose, I have treated stanzas of poetry like paragraphs of text. Original page images are available from archive.org—search for “pleiadesclubyear00plei”.

The List of Contributors mentions a W. Krieghof, but the poem A TOAST was said to be illustrated by Krieghoff, and that is also the signature on the illustration. The Tale of the Store Girl was illustrated by “Adrian Machefert”, but the List of Contributors mentions an “Adrien Machefert”. A Song was written by “Philip Verrill Mighels”, but the List of Contributors has it “Phillip Verrill Mighels”. The Old, Old Prayer was supposedly written by “John W. Postgate”, but the List of Contributors mentions only “J. W. Postgare”.

In the sixth paragraph of Waiting!, a new right double quotation mark was inserted after ‘But I’ll phone you some time during the week.’.

At the bottom of the poem At the Pleiades, by Maurice V. Samuels, there was in our copy of the book what appears to be a hand-written signature of Maurice Samuels. This is retained as an image in this transcription, although we don’t know whether it was present in only one or all printed copies of this book. The image was edited slightly, to remove traces of text from the last line of the poem where the signature and poem overlapped. What appears to be the signature of Francesca di Maria Spaulding, following her poem, The Wanderer, is also retained.

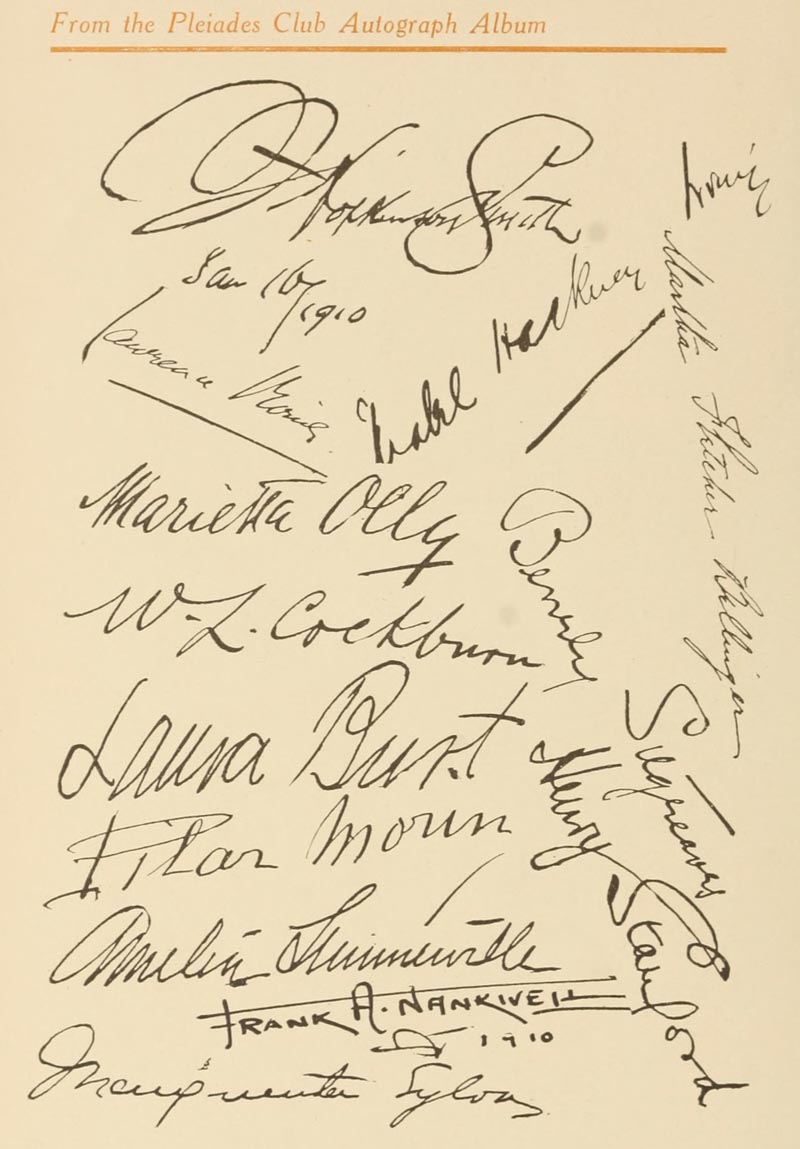

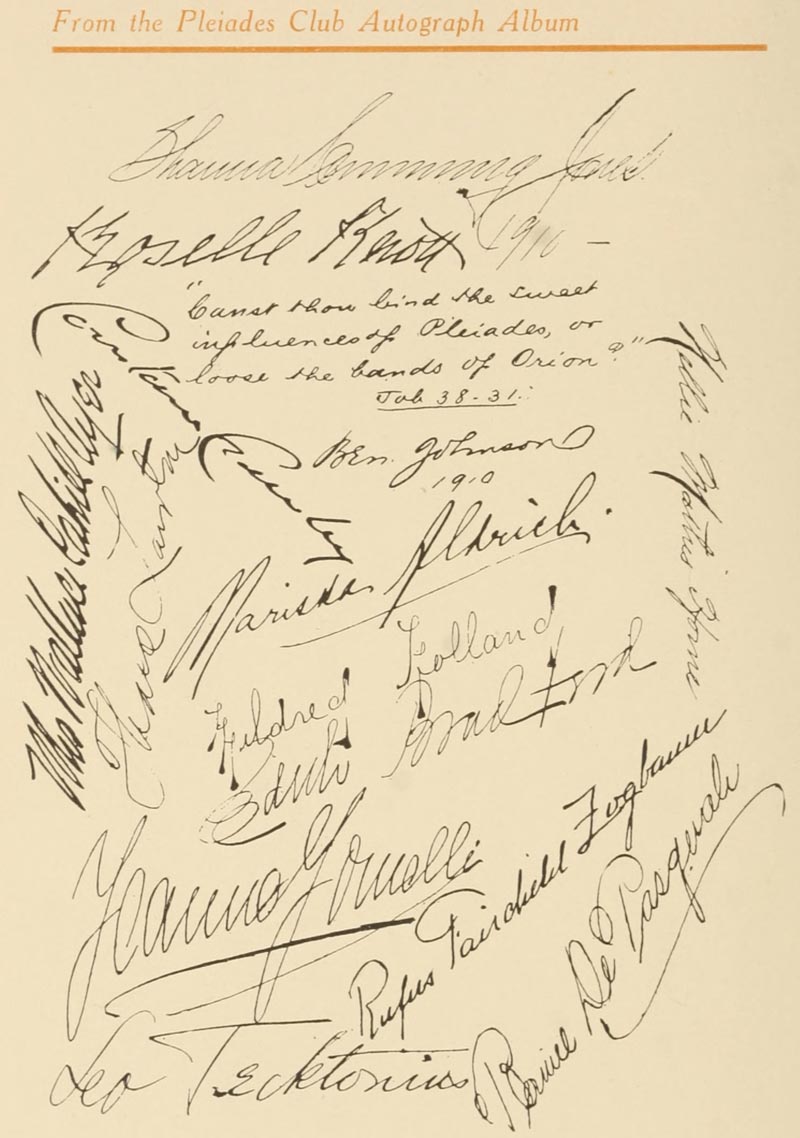

Near the end of the book there were five pages dedicated to Autographs of club members, two of which were blank, followed by a blank page, followed by a sort of collophon with an emblem and the name of the publishing company, followed by more blank pages. The autographs are retained, although we don’t know whether they were present in one or all printed copies of the book. The blank pages have been ignored in this transcription.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Pleiades Club Year Book 1910, by

The N.Y. Pleiades Club

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PLEIADES CLUB YEAR BOOK 1910 ***

***** This file should be named 56423-h.htm or 56423-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/6/4/2/56423/

Produced by MFR, RichardW, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.