The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of the British Army Vol. 2 (of 2), by J. W. Fortescue This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: A History of the British Army Vol. 2 (of 2) Author: J. W. Fortescue Release Date: February 20, 2018 [EBook #56609] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF BRITISH ARMY, VOL 2 *** Produced by Brian Coe, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

This book is Vol. ii. The first volume can be found in Project Gutenberg at

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/55968

This volume covers the period from 1713 to 1763. The Julian calendar was still in use in England for much of this time. The change to the Gregorian calendar took place in Europe beginning in 1582, but in Britain not until 1752, producing a difference of eleven days between the Julian Old Style (OS) and the modern Gregorian New Style (NS) dates. Many Sidenotes and some Footnotes for the years before 1753 give both dates since contemporary English reference documents of that period used the OS date.

The OS/NS dates are shown for example as Sept. 20 Oct. 1. or Mar. 2 13 .

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes themselves have been placed near the end of the book in front of the Index.

The Index in this book covers both volumes. References in the Index to Vol. i or Vol. ii pages are indicated for example by "i. 123, 456" or "ii. 234". The link will go to the correct page in that volume.The links to vol i are not active on handheld devices.

Some minor changes to this volume are noted at the end of the book.

A History of

The British Army

BY

The Hon. J. W. FORTESCUE

FIRST PART—TO THE CLOSE OF THE SEVEN YEARS' WAR

VOL. II

Quæ caret ora cruore nostro

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1899

All rights reserved

CONTENTS | |

| BOOK VII | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| The Reduction of the Army | 3 |

| Mischievous influence of Bolingbroke and Ormonde | 3 |

| Death of Queen Anne; Return of Marlborough | 4 |

| King George I.; the New Ministry | 4 |

| The Jacobite Rebellion of 1715 | 5 |

| Increase of the Army; Ninth to Fourteenth Dragoons raised | 6 |

| Chelsea Pensioners recalled; Forty-first Foot raised | 6 |

| Sheriffmuir and Preston | 7 |

| Reduction of the Army, 1717-1718 | 8 |

| War with Spain | 8 |

| Invasion of Scotland; Action of Glenshiel | 9 |

| Attack on Vigo | 10 |

| Death of Marlborough | 10 |

| His Funeral | 11 |

| The Condition of England under George I. | 14 |

| The Army the only force for Maintenance of Order | 15 |

| The cry of No Standing Army | 15 |

| The British Establishment Fixed by Walpole | 17 |

| Attacks on the Army in Parliament | 17 |

| Opposition to the Mutiny Act | 18 |

| Parliament asks for the Articles of War | 19 |

| Officers cashiered for Political Disobligations | 20 |

| [vi] Omnipotence of the irresponsible Secretary-at-War | 21 |

| Hostility of Civilians against Soldiers | 24 |

| Discipline ruined by the Secretary-at-War's Supremacy | 26 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| King George's efforts to arrest Indiscipline and Peculation | 29 |

| His dislike of Purchase | 30 |

| General Apathy of Officers | 31 |

| Bad Standard of Character among Recruits | 32 |

| Desertion and Fraudulent Enlistment | 32 |

| Other Scandals | 34 |

| System of Imperial Defence | 36 |

| The Colonies; "White Servants" | 37 |

| Gradual necessity for Increasing the Regular Garrisons in the | |

| Colonies | 42 |

| Helplessness of the War Office in face of the problem | 42 |

| Unpopularity of Garrison Service Abroad | 45 |

| Technical Improvements in the Army | 48 |

| Royal Regiment of Artillery formed | 49 |

| Rise of the Forty-second Highlanders | 49 |

| Contemporary Reforms in Prussia | 51 |

| Their Evil Influence in England | 51 |

| The Officers of the Past and of the Future | 53 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Waning of Walpole's Popularity | 55 |

| The Quarrel with Spain | 55 |

| Popularity of a Spanish War | 57 |

| An Expedition to the Spanish Main resolved on | 58 |

| The Preparations; Cathcart and Wentworth | 59 |

| Incredible Mismanagement of the War Office | 60 |

| Death of Cathcart | 62 |

| The British and American Contingents meet at Jamaica | 62 |

| Decision to Attack Carthagena | 63 |

| [vii] The Operations begun; Vernon and Wentworth | 64 |

| The Attack on Fort St. Lazar | 68 |

| Frightful Condition of the Troops | 72 |

| The Enterprise against Carthagena abandoned | 73 |

| Descent upon Cuba | 74 |

| The Descent abandoned; continued Mortality among the Troops | 75 |

| The Spanish War ended by Yellow Fever | 76 |

| Anson's Voyage | 77 |

| Wentworth's responsibility for the disasters of Carthagena | 77 |

| The blame due also to the War Office and Ordnance Office | 78 |

| Faction in Parliament the true secret of the catastrophe | 79 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Dispute over the Austrian Succession | 80 |

| Aggression of Frederick the Great | 81 |

| Ambitious Projects of France | 81 |

| England sends aid to Queen Maria Theresa | 81 |

| Army increased; Forty-third to Forty-eighth Regiments raised | 82 |

| John, Earl of Stair | 83 |

| His Advice and his Plans | 84 |

| The Campaign of 1742 | 86 |

| Stair's Plans for the winter rejected | 87 |

| The British Army marches to the Main | 88 |

| Fresh Projects of Stair rejected | 89 |

| He forms new Plans | 90 |

| He disobeys Orders to prove their soundness | 91 |

| Desperate Peril of the Allies owing to disregard of his counsel | 92 |

| Battle of Dettingen | 92 |

| Stair resigns the Command | 102 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Insufficiency of the British Preparations for 1744 | 103 |

| Saxe's Operations | 104 |

| [viii] Wade paralysed by the Dutch and Austrians | 105 |

| Stair's Plan of Campaign | 106 |

| Inactivity of Dutch and Austrians; Wade Resigns | 107 |

| Ligonier's proposals for a great effort in 1745 | 108 |

| Cumberland appointed to the Command | 109 |

| The French Position at Fontenoy | 110 |

| Battle of Fontenoy | 111 |

| Cumberland's False Movements after Fontenoy | 121 |

| Extreme Peril of his situation | 122 |

| Recall of the Army to England | 123 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Designs of Charles Stuart | 124 |

| His Landing in Scotland | 125 |

| General Cope marches northward | 126 |

| He Retires by Sea; Advance of the Rebels | 127 |

| The "Canter of Coltbrigg" | 128 |

| Cope Lands at Dunbar; Action of Prestonpans | 129 |

| Charles enters Edinburgh; the Castle holds out | 131 |

| Preparations in England | 132 |

| Charles invades England | 133 |

| He out-manœuvres Cumberland and enters Derby | 136 |

| He retreats northward and besieges Stirling | 137 |

| Hawley appointed to Command in Scotland | 138 |

| Action of Falkirk | 139 |

| Cumberland assumes Command in Scotland | 141 |

| He advances northward; Charles retreats | 142 |

| Battle of Culloden | 144 |

| Good service rendered by Cumberland | 146 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| French Capture Antwerp; British base shifted | 149 |

| Saxe's Plan of Campaign and Operations | 150 |

| [ix] Battle of Roucoux | 153 |

| Futile Expedition to L'Orient | 156 |

| The Campaign of 1747 | 156 |

| Battle of Lauffeld | 159 |

| Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle | 164 |

| BOOK VIII | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Mohammedan Conquest of India | 167 |

| The Mahrattas | 168 |

| European Voyages to India | 168 |

| The English East India Company | 169 |

| First British Troops sent to India | 171 |

| The first Military Establishment in Bombay | 171 |

| The French East India Company | 172 |

| Settlements of the Rival Companies in 1701 | 173 |

| Skill of the French in handling natives | 174 |

| Death of Aurungzebe; virtual Independence of the Deccan | 175 |

| Joseph François Dupleix | 175 |

| La Bourdonnais; Dumas | 176 |

| Native Disputes in the Carnatic | 176 |

| Dumas raised to rank of Nabob | 178 |

| War between France and England declared | 179 |

| Siege and Capture of Madras | 180 |

| Quarrel of Dupleix and La Bourdonnais | 181 |

| Paradis at St. Thomé | 183 |

| French invest Fort St. David | 185 |

| Stringer Lawrence at Cuddalore | 187 |

| Boscawen arrives and besieges Pondicherry | 188 |

| Misconduct of the Siege | 189 |

| The Siege raised; Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle | 190 |

| [x] | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| British Interference at Tanjore | 192 |

| Dupleix's Schemes for French Predominance in the Deccan | 193 |

| Bussy installed at Aurungabad | 197 |

| Zenith of French Rule in India | 197 |

| The British resolve to Oppose the French | 198 |

| The Contest centres about Trichinopoly | 198 |

| The British shut up in Trichinopoly | 199 |

| Clive proposes a diversion against Arcot | 200 |

| His Operations | 200 |

| Action of Covrepauk | 204 |

| Lawrence Marches to relieve Trichinopoly | 209 |

| The French retire to Seringham | 210 |

| Surprise of Clive's Force at Samiaveram | 211 |

| Surrender of the French Force | 214 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Intrigues of Dupleix; British Successes Neutralised | 215 |

| Defeat of Major Kinnear | 216 |

| Lawrence's Victory at Bahoor | 217 |

| Clive at Chingleput and Covelong | 218 |

| Contest for Trichinopoly renewed | 221 |

| Perilous Situation of the British | 223 |

| Lawrence's First Victory before Trichinopoly | 224 |

| His Second Victory | 226 |

| His Third Victory | 230 |

| Dupleix's attempt to surprise Trichinopoly fails | 233 |

| His Proposals for Peace rejected | 233 |

| Lawrence's situation at Trichinopoly still critical | 234 |

| Suspension of Arms; Recall of Dupleix | 236 |

| [xi] BOOK IX | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| French Explorers in North America | 241 |

| The English Settlements | 243 |

| Predominance of Massachusetts in the North | 244 |

| New York Captured by the British | 245 |

| French Explorations in the West | 246 |

| Their Design to confine the British to a strip of the Sea-board | 246 |

| Governor Dongan; the Iroquois | 248 |

| French and English Settlers and Military Systems | 249 |

| English Regular Troops in America | 251 |

| The War of 1689; Peril of New York | 251 |

| Failure of the Colonial Counterstroke on Canada | 252 |

| Massachusetts appeals to England for help | 252 |

| War of the Spanish Succession; Colonial Operations | 254 |

| Capture of Nova Scotia; British failure before Quebec | 255 |

| The Building of Louisburg | 256 |

| French Forts at Crown Point and Niagara | 257 |

| Colonial Apathy | 257 |

| War of the Austrian Succession; Colonists Capture Louisburg | 257 |

| Projected Operations for 1746 | 259 |

| Neglect of America by Newcastle's Government | 260 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Reduction of the Army at Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle | 261 |

| Foundation of Halifax | 262 |

| British and French on the Ohio | 263 |

| Obstinacy of the Virginian Assembly | 264 |

| Washington's Mission; Apathy of the Colonies | 265 |

| Washington's First Skirmish with the French | 266 |

| Continued Apathy of the Colonies | 267 |

| General Braddock sent from England | 268 |

| His difficulties and their Causes | 270 |

| [xii] Boscawen's Action with French Ships; War inevitable | 272 |

| Braddock's March to the Monongahela | 273 |

| Dispositions of the French | 274 |

| Action of the Monongahela | 275 |

| Braddock and the School of Cumberland | 278 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Monckton's Capture of Fort Beauséjour | 282 |

| Johnson's Advance against Crown Point | 283 |

| Shirley's failure against Niagara | 284 |

| Close of the Campaign | 285 |

| Feebleness of the English Administration | 286 |

| New Treaties and New Ministers | 287 |

| Fiftieth to Fifty-ninth Regiments raised | 288 |

| The Sixtieth Regiment | 289 |

| Ill faith of the Government towards Soldiers | 290 |

| Germans imported to defend Britain | 290 |

| The French besiege Minorca | 291 |

| Fall of Minorca | 294 |

| Rage of the Nation; Byng; Newcastle | 295 |

| Lord Loudoun sent to Command in America | 296 |

| Inadequacy of his Force | 296 |

| Montcalm Captures Oswego | 297 |

| Close of American Campaign of 1756 | 298 |

| Outbreak of the Seven Years' War | 298 |

| Pitt made Secretary-of-State | 299 |

| His Measures; Highland Regiments | 300 |

| The Militia Bill | 301 |

| Cumberland sent to Command in Hanover | 303 |

| Dismissal of Pitt | 303 |

| Restoration of Pitt | 304 |

| Loudoun's Campaign of 1757 | 304 |

| Montcalm Captures Fort William Henry | 305 |

| Defeat of Cumberland at Hastenbeck | 307 |

| The Expedition against Rochefort | 307 |

| [xiii] BOOK X | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Ligonier made Commander-in-Chief | 313 |

| Preparations for 1758; Amherst | 314 |

| The Plan of Campaign for America | 315 |

| The Expedition against Louisburg | 316 |

| The Siege opened | 319 |

| Fall of Louisburg | 321 |

| The Operations of General Abercromby | 322 |

| Lord Howe; New Views as to Equipment of Troops | 323 |

| Embarkation of Abercromby's Army | 324 |

| The Skirmish by Lake Champlain; Death of Howe | 326 |

| Montcalm's Plan of Defence | 327 |

| Action of Ticonderoga | 328 |

| Retreat of Abercromby | 331 |

| Bradstreet's Capture of Fort Frontenac | 332 |

| Forbes's Operations on the Ohio | 333 |

| Defeat of Major Grant | 335 |

| French evacuate Fort Duquêsne | 336 |

| Burial of Braddock's dead | 337 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Allied Army in Germany | 339 |

| Ferdinand of Brunswick | 339 |

| Expedition to Cancalle Bay | 340 |

| British Troops sent to Germany | 341 |

| Expedition against Cherbourg | 342 |

| The Reverse of St. Cast | 344 |

| Observations on Raids on the French Coasts | 345 |

| The Expedition to Senegal | 346 |

| The Expedition to Martinique | 347 |

| [xiv] The Army leaves Martinique for Guadeloupe | 349 |

| Sickness among the Troops | 350 |

| Death of General Hopson | 351 |

| Barrington resolves on Active Operations | 351 |

| His Plan of Campaign | 352 |

| Successes of Crump and Clavering | 353 |

| Surrender of Guadeloupe | 356 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Establishment of the Army for 1759 | 358 |

| Pitt's Designs against America; Wolfe | 359 |

| Strength of Wolfe's Army | 361 |

| The Defences of Quebec | 362 |

| The British arrive before the City | 363 |

| Wolfe's Difficulties | 364 |

| His Abortive Attack | 366 |

| He shifts Operations to west of the City | 368 |

| Amherst's Designs against Canada | 368 |

| Prideaux and Johnson at Niagara | 369 |

| Fall of Niagara | 370 |

| Amherst's Advance to Ticonderoga and Crown Point | 371 |

| His Operations closed | 371 |

| Discouragement of the British before Quebec | 372 |

| Wolfe's Brigadiers suggest New Plans | 373 |

| The Operations undertaken in consequence | 373 |

| The British climb to the Heights of Abraham | 375 |

| Wolfe's Order of Battle | 377 |

| Distraction of Montcalm | 378 |

| His Order of Battle | 379 |

| Battle of Quebec | 380 |

| Death of Wolfe | 383 |

| Energetic Operations of Townsend | 383 |

| Capitulation of Quebec | 384 |

| General Survey of the Operations in Canada | 385 |

| [xv] | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Sufferings of the British in Quebec | 389 |

| French Preparations for Recapture of Quebec | 390 |

| Advance of Lévis | 391 |

| Action of Sainte Foy | 392 |

| The Siege of Quebec | 394 |

| Relief of Quebec | 395 |

| Amherst's Designs on Canada | 395 |

| Advance of Murray and Haviland | 397 |

| Advance of Amherst | 398 |

| Surrender of Montreal | 400 |

| Expedition against the Cherokee Indians | 400 |

| Occupation of Canada | 401 |

| Amherst | 402 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| India: Hollowness of the Truce of 1755 | 406 |

| It is infringed by both sides | 407 |

| Bussy | 408 |

| Surajah Dowlah | 409 |

| His Advance against Calcutta; the Black Hole | 410 |

| Madras sends aid to Bengal | 411 |

| Clive surprised at Budge Budge | 412 |

| Surajah Dowlah again Advances on Calcutta | 413 |

| Clive surprises his Camp | 414 |

| Alliance of Surajah Dowlah and the British | 415 |

| Capture of Chandernagore | 415 |

| Conspiracy against Surajah Dowlah | 415 |

| Clive Advances on Moorshedabad | 416 |

| Anxiety of his position; he Advances to Plassey | 417 |

| Battle of Plassey | 418 |

| Death of Surajah Dowlah; Meer Jaffier installed in his place | 424 |

| [xvi] | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Southern India | 426 |

| Arrival of French Reinforcements under Lally | 428 |

| Admiral Pocock's First Action with d'Aché | 429 |

| Lally besieges Fort St. David | 430 |

| Fall of Fort St. David; Capture of Devicotah | 431 |

| Lally's disastrous March to Tanjore | 432 |

| Pocock's Second Action against d'Aché | 434 |

| Lally's Preparations against Madras | 435 |

| Counter-preparations of the British | 435 |

| Bussy recalled from Hyderabad | 436 |

| Lally Advances upon Madras | 437 |

| Abortive Sortie of the British | 438 |

| Lally's difficulties during the Siege | 439 |

| The Siege raised | 440 |

| Clive's counter-stroke against the Northern Sirkars | 441 |

| Forde's Advance against Conflans | 442 |

| Battle of Condore | 442 |

| Forde delayed in his Advance on Masulipatam | 445 |

| He lays Siege to the Fort | 447 |

| His desperate Position | 447 |

| Storm of Masulipatam | 449 |

| The Fruits of the Victory | 453 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| British Operations in the Carnatic | 454 |

| Lally's difficulties with his Troops | 455 |

| Alarm of Dutch Aggression in Bengal | 456 |

| Third Engagement of Pocock and d'Aché | 457 |

| Defeat of Brereton at Wandewash | 457 |

| Lally turns to the Court of the Deccan | 457 |

| His diversion in the South; British Operations in the Carnatic | 458 |

| The Dutch in Bengal | 459 |

| Forde defeats them at Chandernagore | 460 |

| Battle of Badara | 461 |

| [xvii] Lally Advances upon Wandewash | 462 |

| Coote follows him; the French position | 463 |

| Coote's Manœuvres | 463 |

| Battle of Wandewash | 464 |

| Coote's Movements after the Victory | 470 |

| Siege of Pondicherry | 472 |

| Fall of Pondicherry | 473 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Establishment of the Army for 1759 | 475 |

| Fifteenth Hussars raised | 476 |

| Purport of Ferdinand's Operations in Germany | 477 |

| He opens the Campaign of 1759 | 480 |

| Movements of Contades and Broglie | 481 |

| Critical position of Ferdinand | 482 |

| Continued success of the French | 483 |

| Ferdinand Occupies Bremen; Contades's position at Minden | 484 |

| Ferdinand's Manœuvres before Minden | 485 |

| Their success; Battle of Minden | 487 |

| Sackville | 496 |

| Recovery of Cassel and Minden | 497 |

| Subsequent Operations | 497 |

| Close of the Campaign | 498 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Increase of the Army for 1760 | 499 |

| Sixteenth and Seventeenth Lancers raised | 500 |

| Thurot's Descent on Carrickfergus | 501 |

| Reinforcements for Ferdinand | 501 |

| Opening of the Campaign | 502 |

| Imhoff's Disobedience mars Ferdinand's Plans | 502 |

| Defeat of the Hereditary Prince at Sachsenhausen | 503 |

| The Prince's Counter-stroke; Action of Emsdorff | 504 |

| Broglie sends De Muy to cut off Ferdinand from Westphalia | 507 |

| [xviii] Action of Warburg; Defeat of De Muy | 508 |

| Evacuation of Cassel by the Allies | 512 |

| Embarrassing position of Ferdinand | 513 |

| Ferdinand makes a Diversion against Wesel | 514 |

| Action of Kloster Kampen; Defeat of the Allies | 515 |

| The Hereditary Prince and British Troops | 518 |

| Close of the Campaign | 519 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Accession of King George III | 520 |

| Increase of the Army | 521 |

| The Expedition to Belleisle | 521 |

| The War in Germany | 522 |

| Ferdinand's Fruitless Winter March through Hesse | 523 |

| Great Preparations and Designs of the French | 524 |

| Supineness of Soubise | 525 |

| The Campaign opens; Ferdinand's March round Soubise's rear | 526 |

| Ferdinand's Position at Vellinghausen | 527 |

| Action of Vellinghausen | 528 |

| Ferdinand's skilful Manœuvres from July to November | 531 |

| Close of the Campaign | 533 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Rise of Lord Bute to power | 535 |

| Trouble with Spain; Pitt advocates War | 536 |

| Resignation of Pitt; Bute compelled to Declare War | 536 |

| The Expedition against Martinique | 537 |

| Fall of Martinique, Grenada, St. Vincent and St. Lucia | 541 |

| Expedition to Havanna | 541 |

| Mortality among the Troops | 543 |

| Expedition to Manilla | 544 |

| The War in Portugal | 545 |

| Burgoyne and the Sixteenth Light Dragoons | 546 |

| Ferdinand's Last Campaign | 547 |

| [xix] The Position of Wilhelmsthal | 548 |

| Action of Wilhelmsthal | 549 |

| The Race for Cassel | 553 |

| Position of the opposing Armies in the Ohm | 554 |

| Action of the Brückemühle | 555 |

| Fall of Cassel; Conclusion of the War | 557 |

| Ferdinand of Brunswick | 557 |

| His Difficulties with the British Troops | 558 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Decay of the Army's Unpopularity | 562 |

| Inefficiency of the War Office and Ordnance Office | 563 |

| Defects in the Colonial Stations | 564 |

| Reformers in the Army; Cumberland | 566 |

| Pitt; the New School of Officer | 568 |

| The Recruiting of the Army | 572 |

| Depots and Drafts | 576 |

| Recruiting in America | 578 |

| Condition of the Private Soldier | 579 |

| Nicknames; Bands; Medals | 583 |

| Reforms in the Cavalry; Increase of Dragoons | 584 |

| Light Dragoons | 585 |

| Reforms in the Artillery | 587 |

| Reforms in the Infantry | 589 |

| German Models and British Experience | 592 |

| APPENDIX A. | 595 |

| APPENDIX B. | 598 |

| INDEX | 607 |

| Carthagena, 1741 | To face page | 78 |

| Main Country: Campaign of 1743 | " | 122 |

| Dettingen, 1743 | " | 122 |

| Fontenoy, 1745 | " | 122 |

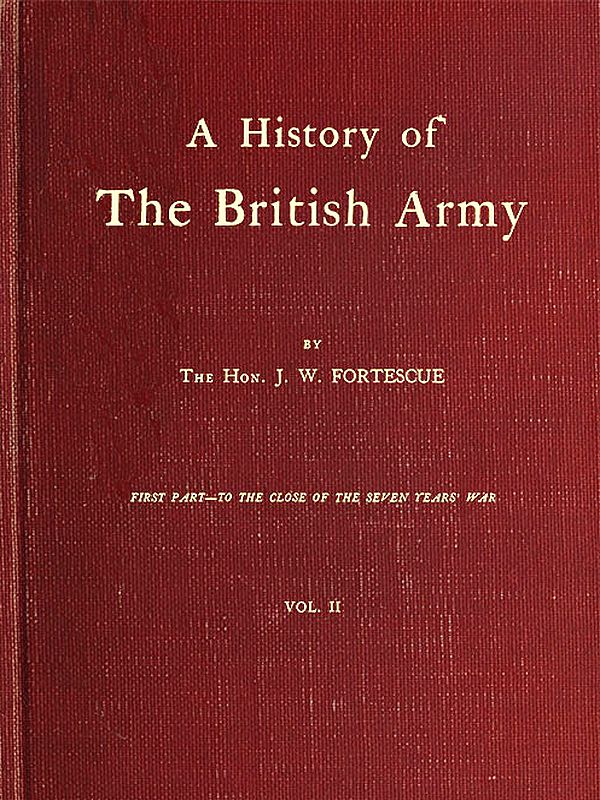

| Roucoux, 1746 | " | 164 |

| Lauffeld, 1747 | " | 164 |

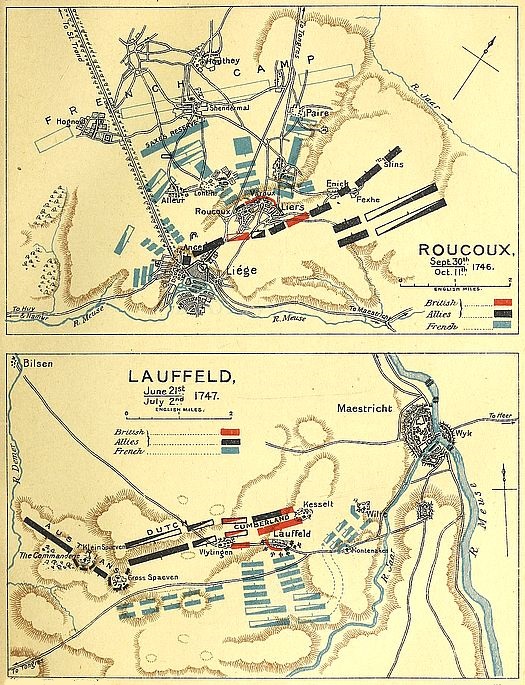

| Monongahela, 1755 | " | 338 |

| Region of Lake George, 1755 | " | 338 |

| Ticonderoga | " | 338 |

| Amherst's Flotilla, 1759 | " | 338 |

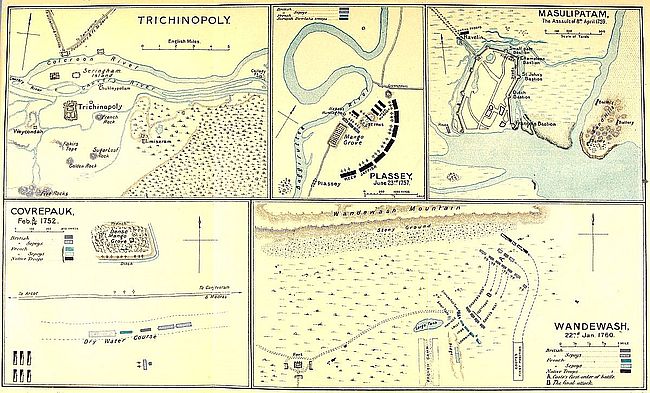

| Covrepauk, 1752 | " | 474 |

| Trichinopoly | " | 474 |

| Plassey, 1757 | " | 474 |

| Masulipatam, 1759 | " | 474 |

| Wandewash, 1760 | " | 474 |

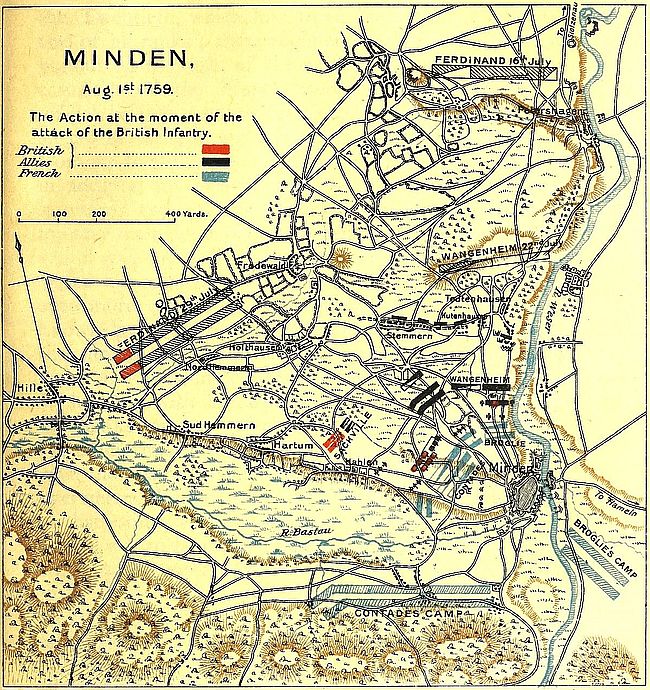

| Minden, 1759 | " | 494 |

| Martinique, 1762 | " | 544 |

| Guadeloupe, 1759 | " | 544 |

| Belleisle, 1761 | " | 544 |

| Havanna, 1762 | " | 544 |

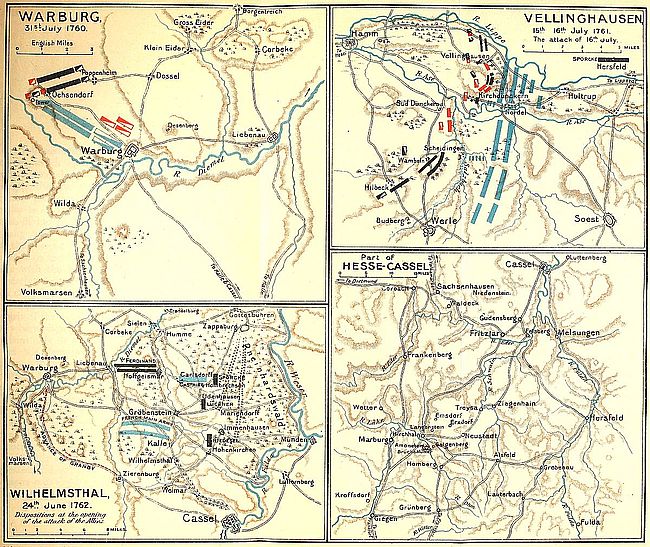

| Part of Hesse-Cassel | " | 560 |

| Warburg, 1760 | " | 560 |

| Vellinghausen, 1761 | " | 560 |

| Wilhelmsthal, 1762 | " | 560 |

| [xxii] Canada and the North American Colonies, 1680-1760 | ||

| (with Plans of Louisburg and Quebec): Map 1 | End of volume | |

| Louisburg: see Map 1 | ||

| Quebec: see Map 1 | ||

| Siege of Quebec, 1759: see Map 1 | ||

| Hindostan, the Deccan, and the Carnatic | ||

| (with Plans of Calcutta and Madras): Map 2 | End of volume | |

| Calcutta, 1757: see Map 2 | ||

| Madras, 1758: see Map 2 | ||

Note.—Maps of the British Isles and Northern France for 1745-1746; of the Low Countries for the Campaigns of 1743-1748; of Spain and Portugal; and of Germany for the Campaigns of 1759-1762, will be found at the end of the First Volume.

Page 160, line 4 for "left" read "right."

Page 192, line 13, delete the words "the capital of Tanjore."

Page 195, line 10, for "Deccan" read "Southern India."

Page 203, line 13, for "southward" read "westward."

Page 247, line 29, for "Erie" read "Michigan."

Page 463, line 34, for "In advance of their left front was another smaller tank which had been turned into an entrenchment," etc., read "In advance of their left front were two smaller tanks, of which the foremost had been turned into an entrenchment," etc.

The work of disbanding the Army began some months before the final conclusion of the Peace of Utrecht. By Christmas 1712 thirteen regiments of dragoons, twenty-two of foot, and several companies of invalids who had been called up to do duty owing to the depletion of the regular garrisons, had been actually broken. The Treaty was no sooner signed than several more were disbanded, making thirty-three thousand men discharged in all. More could not be reduced until the eight thousand men who were left in garrison in Flanders could be withdrawn, but even so the total force on the British Establishment, including all colonial garrisons, had sunk in 1714 to less than thirty thousand men. The soldiers received as usual a small bounty on discharge; and great inducements were offered to persuade them to take service in the colonies, or, in other words, to go into perpetual exile.

But this disbandment was by no means so commonplace and artless an affair as might at first sight appear. One of the first measures taken in hand by Bolingbroke and by his creature Ormonde was the remodelling of the Army, by which term was signified the elimination of officers and of whole corps that favoured the Protestant succession, to make way for those attached to the Jacobite interest. Prompted by such motives, and wholly careless of the feelings of the troops, they violated the old rule that the youngest regiments should always be the first to be disbanded, and laid violent hands on several veteran corps. The Seventh and[4] Eighth Dragoons, the Thirty-fourth, Thirty-third, Thirty-second, Thirtieth, Twenty-ninth, Twenty-eighth, Twenty-second, and Fourteenth Foot were ruthlessly sacrificed; nay, even the Sixth, one of the sacred six old regiments, and distinguished above all others in the Spanish War, was handed over for dissolution like a regiment of yesterday.[1] There were bitter words and stormy scenes among regimental officers over such shameless, unjust, and insulting procedure.

All these designs, however, were suddenly shattered by the death of Queen Anne. The accession of the Elector of Hanover to the throne was accomplished with a tranquillity which must have amazed even those who desired it most. Before the new King could arrive the country was gladdened by the return of the greatest of living Englishmen. Landing at Dover on the very day of the Queen's death, Marlborough was received with salutes of artillery and shouts of delight from a joyful crowd. Proceeding towards London next day he was met by the news that his name was excluded from the list of Lords-Justices to whom the government of the country was committed pending the King's arrival. Deeply chagrined, but preserving always his invincible serenity, he pushed on to the capital, intending to enter it with the same privacy that he had courted during his banishment in the Low Countries. But the people had decided that his entry must be one of triumph; and a tumultuous welcome from all classes showed that the country could and would make amends for the shameful treatment meted out to him two years before.

On the 18th of September King George landed at Greenwich, and shortly afterwards the new ministry was nominated. Stanhope, the brilliant soldier of the Peninsular War, became second Secretary-of-State; William[5] Pulteney, afterwards Earl of Bath, Secretary-at-War; Robert Walpole, Paymaster of the Forces; while Marlborough with some reluctance resumed his old appointments of Captain-General, Master-General of the Ordnance, and Colonel of the First Guards. He soon found, however, that though he held the titles, he did not hold the authority of the offices, and that the true control of the Army was transferred to the Secretary-at-War.

How weak that Army had become was presently realised at the outbreak of the Jacobite rebellion in the autumn of 1715. The estimates of 1714 had provided for a British establishment of twenty-two thousand men, of which two-thirds were stationed in Flanders and in colonial garrisons, leaving a dangerously small force for the defence of the kingdom. Even this poor remnant the Jacobite Lords had tried to weaken, by introducing a clause in the Mutiny Act to confine all regiments to the particular districts allotted to them in the British Isles. This insidious move, which was designed to prevent the transfer of troops between Ireland and England, was checked by the authority of Marlborough himself. The King, it seems, had early perceived the perils of such a situation; and accordingly, in January, the Seventh Dragoons were recreated and restored under their old officers, together with four more of the old regiments.[2] In July the prospect of a rising in Scotland made further increase imperative, and orders were issued for the raising of thirteen regiments of dragoons and eight of foot, some few of which must for a brief moment detain us.

The first of the new regiments of dragoons was Pepper's, the present Eighth Hussars, which for a time had shared the hard fate of the Seventh, and was now, like the Seventh, restored to life. The next six, Wynn's, Gore's, Honeywood's, Bowles's, Munden's, and[6] Dormer's, are now known respectively as the Ninth Lancers, the Tenth and Eleventh Hussars, the Twelfth Lancers, and the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Hussars, regiments which have made their mark on many a field in the Peninsula and in India, while two of them bear on their appointments the name of Balaclava. The remaining six were disbanded in 1718.[3] Of the foot six regiments also perished after a short life in 1718;[4] the remaining two were old regiments, the Twenty-second and the Thirty-fourth, each of which was destined in due time to add to its colours the name of a victory peculiar to itself.

It may be asked whether no use was made of the hundreds of veterans who had returned from the wars of Flanders. The answer gives us a curious insight into the old conception of a reserve. On the first alarm of a rising, the whole of the officers on half-pay were called upon to hold themselves ready for service;[5] and concurrently twenty-five companies of Chelsea pensioners were formed to take over the duties of the garrisons and to release the regular troops for work in the field. For many years after as well as before this date the same system is found in force; and of this, as of so many obsolete institutions, there is fortunately a living relic still with us. In March 1719 ten of these veteran companies were incorporated into a regiment under Colonel Fielding, and having begun life with the name of Fielding's Invalids, survive to this day as the Forty-first Foot.[6]

I shall not detain the reader with any detailed [7]account of the abortive insurrection of 1715. The operations entailed by an invasion of England from the north are always the same. The occupation of Stirling cuts off the Highlands from the Lowlands, and bars any advance from the extreme north. An invasion from the Lowlands may be checked on either flank of the Cheviots, on the east coast at the lines of the Tweed or the Tyne, or, if headed back from thence, on the west coast at the line of the Ribble. If both Highlands and Lowlands are in revolt, there is the third resource of a simultaneous attack from north and south upon Stirling. This last course lay open to the insurgents on this occasion but was not accepted. The two decisive engagements were accordingly fought, one at Sheriffmuir, a little to the north of Stirling, the other at Preston, whither the insurgents of the Lowlands, checked by an insignificant force on the east coast, made a hopeless and futile march to the west, and were enveloped by English forces marching simultaneously from east, west, and south. None the less the peril to England was great. The force at Stirling was far too weak for the duty assigned to it; and Sheriffmuir was one of those doubtful actions from which each army emerges with one wing defeated and the other victorious. The English force on the Tweed was made up of raw recruits, and was so weak in numbers that General Carpenter, a veteran of Flanders and Spain, who commanded it, accomplished his work chiefly by the bold face with which he met a dangerous position. Such was the military impotence of England after a bare two years of peace.[7]

The panic caused by the insurrection swelled the military estimates of 1716 very considerably. Apart from the new regiments raised for the occasion, the strength of every existing troop and company had been augmented, while the addition of a battalion to each regiment of Guards increased the brigade to the total of seven battalions, which constituted its strength unaltered almost for the next two centuries. The full establishment voted by Parliament for Great Britain was thirty-six thousand men, exclusive of course of troops in Ireland, and of six thousand Dutchmen, who had been sent over by the States-General in fulfilment of obligations by treaty. The very next year, however, saw the establishment diminished by one-fourth, and in May the King announced that he had given orders to reduce the army by ten thousand men more. The estimates for 1718 accordingly provided for but sixteen thousand men in Great Britain, while those for 1719 diminished even that handful by one-fourth, and brought the total down to the figure of twelve thousand men.

Then as usual the numbers were found to be dangerously weak. A quarrel between Spain and the Empire, and the ambitious designs of Cardinal Alberoni brought about a breach between England and Spain, which finally culminated in the attack and defeat of the Spanish fleet by Admiral Byng off Cape Passaro. The action was fought before war had actually been declared, and Byng affected to treat it as an unfortunate accident; but Alberoni was too much incensed at the subversion of his designs to heed such empty blandishment as this. He prepared to avenge himself by making terms with the Jacobites and by fitting out an expedition from Cadiz for the support of the Pretender. The force was to be commanded by Ormonde, the same poor, misguided man who had supplanted Marlborough in Flanders; but the menace was formidable none the less. At the meeting of Parliament the King gave warning that an invasion[9] must be looked for, and received powers to augment the Army to meet it. Nevertheless, it was thought best once more to borrow six thousand foreigners from the Dutch and Austrian Netherlands; and England's contribution to her own defence consisted in no more than the transfer of four weak battalions from the Irish to the British establishment. The King's ministers took credit, when the danger was over, for the moderation with which they had exercised the powers entrusted to them, failing to see that resort to mercenary troops at such a time was a policy wanting as much in true statesmanship as in honour.

For the rest the peril vanished, as four generations earlier had the peril of a still greater Spanish invasion, before wind and tempest. The Spanish transports were dispersed by a gale in the Bay of Biscay, and the great armament crept back by single ships to Cadiz, crippled, shattered, barely saved by the sacrifice of guns, horses and stores from the fury of the storm. Two frigates only reached the British coast and landed three Scottish peers—Lords Tullibardine, Marischal and Seaforth—with three hundred Spanish soldiers, at Kintail in Ross-shire. Here the little party remained unmolested for several weeks, being joined by some few hundred restless Highland spirits, but supported by no general rising of the clans. At length, however, General Carpenter detached General Wightman with a thousand men from Inverness, who fell upon the insurgents in the valley of Glenshiel and, though their force was double that of his own, dispersed them utterly.[8] The campaign ended, like all mountain-campaigns, in the burning of the houses and villages of the offending clans; and thus ignominiously ended this hopeless and futile insurrection. Its most remarkable result was that it drove Lord Marischal and his brother into the[10] Prussian service, and gave to Frederick the Great one of his best officers and most faithful friends—that James Keith who fell forty years later on the field of Hochkirch.

Such aggression, failure though it was, naturally led the English to make reprisals; and in September a British squadron sailed from Spithead with four thousand troops on board for a descent on the Spanish coast. The original object of the expedition had been an attack on Corunna, but Lord Cobham,[9] who was in command, thought the enterprise too hazardous, and turned his arms against Vigo. The town being weakly held was at once surrendered, and the citadel capitulated after a few days of siege. A considerable quantity of arms and stores, which had been prepared for Ormonde's expedition, was captured, and with this small advantage to his credit, Cobham re-embarked his troops for England.[10] Shortly afterwards Alberoni opened negotiations for peace, which he purchased at the cost of his own dismissal. The treaty was signed on the 19th of January 1720, and England entered upon twenty years of unbroken peace.

But before I touch upon the history of that peace I may be allowed to advance two years to record an event which may fittingly close the first thirty years of conflict with Jacobitism and its allies. On the 16th of June 1722 died John, Duke of Marlborough. Constantly during his later campaigns he had suffered from giddiness and headache, and in May 1716 the shock caused by the death of his daughter, Lady Sunderland, brought on him a paralytic stroke. He rallied, but was struck down a second time in November of the same year; and although, contrary to the received opinion, he again rallied, preserving his speech, his memory, and his understanding little impaired, yet it was evident that his life's work was done. In the few [11]years that remained to him he still attended the House of Lords, spending the session of 1721 as usual in London, and retiring at its close to Windsor Lodge. There at the beginning of June in the following year he was smitten for the third time, and after lingering several days, helpless but conscious, he at dawn of the 16th passed peacefully away.

On the 14th of July the body was brought to Marlborough House. In those days London was empty at that season, and only in Hyde Park, where the whole of the household troops were encamped, was there sign of unusual activity. Day after day the Foot Guards were drilled in a new exercise to be used at the funeral; the weeks wore on, the day of Blenheim came and went, and at length on the 9th of August all was ready. From Marlborough House along the Mall and Constitution Hill to Hyde Park Corner, from thence along Piccadilly and St. James's Street to Charing Cross and the Abbey, the way was lined with the scarlet coats of the Guards. The drums were draped in black, the colours wreathed with cypress; every officer wore a black scarf, and every soldier a bunch of cypress in his bosom. Far away from down the river sounded minute after minute the dull boom of the guns at the Tower.

The procession opened with the advance of military bands, followed by a detachment of artillery. Then came Lord Cadogan, the devoted Quartermaster-General who had prepared for the Duke so many of his fields, and with him eight General Officers, veterans who had fought under their great Chief on the Danube and in Flanders. Among these was Munden, the hero who had led the forlorn hope at Marlborough's first great action of the Schellenberg, and had brought back with him but twenty out of eighty men. Then followed a vast cavalcade of heralds, officers-at-arms and mourners, with all the circumstance and ceremony of an age when pomp was lavished on the least illustrious of the dead; and in the midst, encircled by a forest[12] of banners, rolled an open car, bearing the coffin.[11] Upon the coffin lay a complete suit of gilt armour, above it was a gorgeous canopy, around it military trophies, heraldic devices, symbolic presentations of the victories that the dead man had won and of the towns which he had captured, strange contrast to the still white face, serene beyond even the invincible serenity of life, that slept within.

As the car passed by there rang out to company after company of the silent Guards a new word of command. "Reverse your arms." "Rest on your arms reversed." The officers lowered their pikes, the ensigns struck their colours, and every soldier turned the muzzle of his musket to the ground and bent his head over the butt "in a melancholy posture." The procession moved slowly on, and the troops, still with arms reversed, formed up in its rear and marched with it. Fifty-two years before, John Churchill, the unknown ensign of the First Guards, had marched in procession behind the coffin of George Monk, Duke of Albemarle; now he too was faring on to share Monk's resting-place.

At the Horse Guards the Guards wheeled into St. James's Park and formed up on the parade-ground, where the artillery with twenty guns was already formed up before them. The car crept on to the western door of the Abbey, and then rose up for the first time that music which will ever be heard so long as England shall bury her heroes with the rites of her national Church. Within the Abbey the gray old walls were draped with black, and nave and choir and transept were ablaze with tapers and flambeaux. Of England's greatest all were there, the living and the dead. The helmet of Harry the Fifth, still dinted with the blows of Agincourt, hung dim above his tomb, looking down on the stolid German who now sat upon King Harry's throne, and on his heir the Prince of Wales, who had[13] won his spurs at Oudenarde. And at the organ, humble and unnoticed, sat William Croft, little dreaming that he too had done immortal work, but content to listen to the beautiful music which he had made, and to wait till the last sound of the voices should have died away.[12]

Then the organ spoke under his hand in such sweet tones as are heard only from the organs of that old time, and the procession moved through nave and choir to King Henry the Seventh's chapel. By a strange irony the resting-place chosen for the great Duke was the vault of the family of Ormonde, but it was not unworthy, for it had held the bones of Oliver Cromwell.[13] Then the voice of Bishop Atterbury, Dean of Westminster, rose calm and clear with the words of the service; and the anthem sang sadly, "Cry ye fir-trees, for the cedar is fallen." The gorgeous coffin sank glittering into the shadow of the grave, and Garter King-at-Arms, advancing, proclaimed aloud, "Thus has it pleased Almighty God to take out of this transitory world unto his mercy the most high, mighty and noble prince, John, Duke of Marlborough." Then snapping his wand he flung the fragments into the vault.

As he spoke three rockets soared aloft from the eastern roof of the Abbey. A faint sound of distant drums broke the still hush within the walls, and then came a roar which shook the sable hangings and made the flame of the torches tremble again, as the guns on the parade-ground thundered out their salvo of salute. Thrice the salvo was repeated; the drums sounded faintly and ceased, and all again was still. And then burst out a ringing crash of musketry as the Guards, two thousand strong, discharged their answering volley. Again the volley rang out, and yet again; and then the drums sounded for the last time, and the great Duke was left to his rest.[14]

From such a scene I must turn to the further work that lies before me in the events of the next twenty years; and it will be convenient to deal first with the political aspect of the Army's history. England, it must be observed, had not yet recovered from the indiscipline and unrest of the Great Rebellion. Since the death of Elizabeth the country, except during the short years of the Protectorate, had not known a master. William of Orange, who had at any rate the capacity to rule it, was unwilling to give himself the trouble; Marlborough, while his power lasted, had been occupied chiefly with the business of war; and during the reign of both war had been a sufficient danger in the one case and a sufficient cause of exultation in the other to distract undisciplined minds. Now, however, there was peace. A foreign prince had ascended the throne, a worthy person and very far from an incapable man, but uninteresting, ignorant of England, and unable to speak a word of her language. The tie of nationality and the reaction of sentiment which had favoured the restoration of Charles the Second were wanting. The country too, after prolonged occupation with the business of pulling down one king and setting up another, had imbibed a dangerous contempt of all authority whatsoever.

Other influences contributed not less forcibly to increase the prevalent indiscipline. Many old institutions were rapidly falling obsolete. The system of police was hopelessly inefficient, and the press had not yet concentrated the force of public opinion into an ally of law and order. In all classes the same lawlessness was to be found; showing itself among the higher by a fashionable indifference to all that had once been honoured as virtue, an equally fashionable indulgence towards debauchery, and an irresistible tendency to decide every dispute by immediate and indiscriminate force. Among the lower classes, despite the most sanguinary penal code in Europe, brutal crime, not of violence only, was dangerously rife. No man who was worth robbing could consider himself safe in London,[15] whether in the streets or in his own house. Patrols of Horse and Foot Guards failed to ensure the security of the road between Piccadilly and Kensington;[15] and further afield the footpad and the highwayman reigned almost undisturbed. Nor did great criminals fail to awake lively sympathy among the populace. The names of Dick Turpin and Jack Sheppard enjoy some halo of heroism to this day; and frequently, when some desperate malefactor was at last brought to Tyburn, it was necessary to escort him to execution and, supposing that the gallows had not been cut down by sympathisers during the night, to surround him with soldiers lest he should be rescued by the mob. All over England the case was the same. Strikes, riots, smuggling, incendiarism and general lawlessness flourished with alarming vigour, rising finally to such a height that, by the confession of a Secretary-of-State in the House of Commons, it was unsafe for magistrates to do their duty without the help of a military force.[16]

Against this mass of disorder the only orderly force that could be opposed was the Army. It will presently be seen that the Army had grave enough faults of its own, but the outcry against it was levelled not at its faults but at its power as a disciplined body to execute the law. So far, therefore, the unpopularity of the Army was fairly universal. But its most formidable opponents were bred by faction, the Jacobites who wished to re-establish the Stuarts naturally objecting to so dangerous an obstacle to their designs. The howl against the Army was raised in the House of Commons as early as in 1714, and in 1717 a Jacobite member who, being more conspicuous for honesty than for wisdom, was known as "Downright Shippen," opened a series of annual motions for the reduction of the forces. This self-imposed duty, as he once boasted to the House, he fulfilled on twenty-one successive occasions, though on thirteen of them he had found no seconder [16]to support him.[17] If this had been all, no great harm could have resulted; but the watchword of a baffled opposition, artfully stolen from old times of discontent, was too useful not to be generally employed, and "No Standing Army" became the parrot's cry of every political adventurer, every discontented spirit, every puny aspirant to importance. Walpole himself did not disdain to avail himself of it during the four years which he spent out of office between 1717 and 1721, and the stock arguments of the malcontents were never urged more ably nor more mischievously than by Marlborough's Secretary-at-War.[18] The Lords again were little behind the Commons, and Jacobite peers who had commanded noble regiments in action were not ashamed to drag the name of their profession through the dirt.

In such circumstances, where the slightest false step might have imperilled the very existence of the Army, the administration of the forces and the recommendation of their cost to the House of Commons became matters of extreme delicacy. It has already been told how the King, as the alarm of the first Jacobite rebellion subsided, voluntarily reduced the Army by ten thousand men at a stroke. Such policy, dangerous though it was from a military standpoint, was undoubtedly wise; it was the sacrifice of half the cargo to save the ship, an ingenious transformation of a necessity into a virtue. Even before the Spanish War was ended but fourteen thousand men were asked for as the British establishment, the remainder of the Army being hidden away in Ireland; and the same number was presented on the estimates up to the year 1722. In the autumn of that year, however, the administration insisted that the number should be raised to eighteen thousand. The spirits of the Jacobites had been raised by the birth of Prince Charles Edward; there had been general uneasiness in the country; troops had been [17]encamped ready for service all the summer, and six regiments had been brought over from Ireland. The augmentation was bitterly opposed in Parliament, but was carried in the Commons by a large majority, and was judiciously executed, not by the formation of new regiments but by raising the strength of existing corps to a respectable figure.[19] Until this increase was made, said Lord Townsend in the House of Lords in the following year, it was impossible to collect four thousand men without leaving the King, the capital, and the fortified places defenceless.[20]

Having secured his eighteen thousand men, Walpole resolved that in future this number should form the regular strength for the British Establishment. In 1727 the menace of a war with Spain brought about the addition of eight thousand men, but in 1730 the former establishment was resumed and regularly voted year after year until the outbreak of the Spanish War in 1739. Year after year, of course, the same factious motives for reduction were put forward and the same futile arguments repeated for the hundredth time. "Slavery under the guise of an army for protection of our liberties" was one favourite phrase, while the valour of the untrained Briton was the theme of many an orator. Men who, like Sir William Yonge and William Pulteney, had held the office of Secretary-at-War, were, when in opposition, as loud as the loudest and as foolish as the most foolish in such displays. "I hope, sir," said the former in 1732, "that we have men enough in Great Britain who have resolution enough to defend themselves against any invasion whatever, though there were not so much as one red-coat in the whole kingdom." On the side of the Government the counter arguments were drawn from an excellent source, namely, from the disastrous results of wholesale disbandment [18]after the Peace of Ryswick. The establishment was, in fact, far too small. It would have been impossible (to use Walpole's own words) even after several weeks' time to mass five thousand men at any one point to meet invasion, without stripping the capital of its defences and leaving it at the mercy of open and secret enemies.

Foiled in its attempts to reduce the numbers of the Army, the Opposition sought to weaken it by interference with its administration and discipline, for which mischief the discussion of the Mutiny Act gave annual opportunity. Here again it was Walpole who set the evil example. He it was who maintained that the Irish Establishment must be counted as part of the standing Army, who insinuated that the British regiments, with their enormous preponderance of officers as compared with men, were potentially far stronger than they seemed to be, who encouraged the Commons to dictate to the military authorities the proportion that should be observed between horse, foot, and dragoons.[21] He too it was who imperilled the passing of the Mutiny Act by advancing the old commonplace that a court-martial in time of peace was unknown to English law, and that mutiny and desertion should be punished by the civil magistrate. He it was once more who blamed the ministry for sending the fleet to the Mediterranean instead of keeping it at home to guard the coast, and gave his authority to the false idea that the function of a British fleet in war is to lie at anchor in British ports. Such were the aberrations of a conscience which fell blind directly it moved outside the circle of office.

The Opposition was not slow to take advantage of such powerful advocacy, but fortunately with no very evil results. An address to the King was carried, praying that all vacancies, except in the regiments of Guards, should be filled up by appointment of officers on the list of half-pay. The King willingly acceded,[19] for indeed he had already anticipated the request; and this rule was conscientiously adhered to, both by him and by his successor. It made for economy, no doubt, but it also weakened what then counted as the most efficient form of military reserve; and the result was that officers were forbidden to resign their commissions, being allowed to retire on half-pay only, so that their services might still be at command.[22] The Articles of War were also sent down to the Commons, and may still be read in their journals.[23] It must suffice here to say that they made careful provision for the trial of all but strictly military crimes by the civil power. Here, however, was a new precedent for allowing Parliament a voice not only in the broad principles, but in the details of discipline.

The Opposition in both Houses did not at once take advantage of this innovation, but confined itself to discourses on the inutility and danger of a Mutiny Act at large. It was not surprising that the ignominious Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford, should have declaimed against the Act, but it was a sad revelation of factious feeling to find an old colonel, Lord Strafford, declaring that the country got on very well without it in King William's time. Nor must it be thought that, because the Act was ultimately passed every year, no inconvenience resulted from the obstruction in Parliament. On at least one occasion it was not renewed in sufficient time. The courts-martial held after its expiration were therefore invalid, and as prisoners could not be tried twice for the same offence, a number of them escaped scot-free.[24] It was not until 1726 that the attacks upon the measure began to subside, and even then the Government was afraid to introduce necessary [20]amendments, lest by calling attention to the Act it should blow the dull embers of hostility anew into flame.[25]

The next attempted encroachment of Parliament was of a more dangerous nature, though it was more than a little excused by extreme provocation. In the heat of resentment against the opposition to his favourite scheme of an Excise Bill, Walpole in 1733 persuaded the King not only to dismiss his opponents from their places about the court, but to deprive the Duke of Bolton and Lord Cobham, Colonels of the King's Dragoon Guards and of the Blues, and Cornet William Pitt of the King's Dragoon Guards[26] of their commissions. This was to inflict the severest of military punishments short of death for a political disobligation, and was justly seized upon by the Opposition as a monstrous abuse. Lord Morpeth accordingly brought forward a motion in the Commons to make officers of the rank of lieutenant-colonel or above it irremovable except by sentence of court-martial or upon address of either House. The issue thus raised was direct, since by the Articles of War no officer could be dismissed except by Royal Order or sentence of a general court-martial. The debate was very ingenious on both sides, but the motion was lost without a division. The most remarkable speech was that of General Wade, who opposed Lord Morpeth on the ground that he had the greatest difficulty in collecting officers for a court-martial, and that they would be still more negligent if they could be dismissed only by sentence of their fellows. "In short, sir," he said, in words of significant warning, "the discipline of our army is already in a very bad way, and, in effect, this alteration will only make it worse."

The study of the mingling of political and military influence on the Army will enlighten us as to the cause of this indiscipline. In the first place, it will be noticed that there was no Commander-in-Chief. Lord Cadogan had succeeded Marlborough as captain-general, but even Marlborough had been powerless since his restoration, and he was not in the modern sense of the word a commander-in-chief. The result was that the whole of the authority attached to the office fell into the hands of the Secretary-at-War. That functionary still received as heretofore a military commission, and was nominally a mere secretary, not a minister nor secretary-of-state; and early in the reign he took the opportunity in the person of William Pulteney to repudiate anything approaching to a minister's responsibility.[27] So far as any one was answerable for the Army, it was that secretary-of-state whose duties were later apportioned to the Home Office; and hence we find the Secretary-at-War, though really in control of the whole Army, sending daily requests to the Secretary-of-State for the preparation of commissions,[28] since he himself in theory could sign documents not as the King's adviser, but only as his clerk. As a mere matter of routine this arrangement was most inconvenient, but this would have signified little had it not also been dangerous.[29]

Peculiar circumstances, now long obsolete, gave this irresponsible secretary peculiar powers. In the first place, it must be remembered that as yet barracks were [22]almost unknown. There were, it is true, barracks at the Tower, at the Savoy, at Hull, and at Edinburgh, wherein there was accommodation for the half or even the whole of a battalion; and there was also a barrack at every garrisoned town capable of holding at least the handful of men who were supposed to keep the guns in order. But for the most part the Army was scattered all over the country in minute detachments,[30] for inns were the only quarters permitted by the Mutiny Act, and the number of those inns was necessarily limited. In Ireland the paucity of ale-houses had led comparatively early to the construction of barracks, with great comfort alike to the soldiers and to the population, but in England the very name of barrack was anathema.[31] It was in vain that military men pointed to the sister island and urged that Great Britain too might have barracks. The Government was afraid to ask for them, and the opposition combated any hint of such an innovation, "that the people might be sensible of the fetters forged for them."[32]

The apportionment of quarters fell within the province of the Secretary-at-War; and it is obvious that whether the presence of soldiery were an advantage to a town or the reverse, the power to inflict it could usefully be turned to political ends. A frequent accusation was that troops were employed to intimidate the voters at elections; and indeed the newspapers, not very trustworthy on such points, assert that at the election at Coventry in 1722 the foot-soldiers named two persons and the sheriff returned them.[33] Whether this be true [23]or false it was not until 1735 that the Mutiny Act provided for the withdrawal of the troops to a distance of at least two miles from the polling-place during an election. But it was not so much for their interference with the free and independent voter as for the burden which they laid on the innkeeper that the soldiers were disliked. Whether this burden was really so grievous or not is beside the question; it was, at any rate, believed to be intolerable.[34] As early as in 1726 the King had asked for additional powers in the Mutiny Act to check the evasion by the civil authorities of their duty of quartering the men, and it was just after this date that municipalities began to abound in complaints.[35] The question was one of extreme difficulty for the Secretary-at-War, since the outcry of the civilians was balanced by a no less forcible counter-cry of officers. Municipalities seemed to think that no military exigency could excuse the violation of their comfort. Riots, for instance, were expected at Bath which, as a watering-place, was exempt from the duty of finding quarters for soldiers. The Secretary-at-War, though he did not shrink from sending troops thither to put down the rioters, looked forward to a disturbance between the civil and military elements as inevitable.[36] Southampton, again, cried out bitterly against the arrival within her boundaries of a whole regiment of dragoons. [24]The colonel retorted that the regiment in question had been dispersed in single troops ever since its formation, and that this was actually his first opportunity of reducing it to order and discipline.[37] On some occasions the officers were certainly to blame, though they appear rarely to have misbehaved except under extreme provocation. Thus we find an officer, who had been denied a guard-room at Cirencester, solving the difficulty by the annexation of the town hall,[38] another still more arbitrary putting the Recorder of Chester under durance,[39] and a cornet of dragoons revenging himself upon an innkeeper by ordering eight men to march up and down before the inn for an hour every morning and evening, in order to disturb the guests and spoil the pavement.[40] On one occasion, indeed, we see two officers making the wealthiest clothier of Trowbridge drunk and enlisting him as a private.[41] These are specimens of the petty warfare which was waged between soldiers and civilians all over the kingdom, actions which called forth pathetic appeals from the Secretary-at-War to the offenders not to make the Army more unpopular than it already was. The warning was the more necessary, since, to use Pulteney's words, giddy insolent officers fancied they showed zeal for the Government by abusing those whom they considered to be of the contrary party. This, however, was but the natural result of making the Army a counter in the game of party politics. The only moderating influence was that of the King, who, if once convinced of any abuses committed by the soldiery was inexorably severe.[42]

Yet, on the whole, it should seem that soldiers were far less aggressive towards civilians than civilians towards soldiers. It is abundantly evident that in many places the civil population deliberately picked quarrels with [25]troops in order to swell the clamour against the Army;[43] and officials in high local and municipal station, in their rancour against the red-coats, would stoop to lawlessness as flagrant as that of the mob. Lord Denbigh falsely accused the soldiers employed against the famous Black Gang of poachers, a sufficiently dangerous duty, of leaguing themselves with them for a share in the profits.[44] The Mayor of Penzance deliberately obstructed dragoons, who had been sent down to suppress smuggling, in the execution of their duty; the inference being that his worship was the most notorious smuggler on the coast.[45] The Mayor of Bristol threw every obstacle, technical or captious, that he could devise, in the way of recruiting officers.[46] The Mayor of St. Albans, most disgraceful of all, took the Secretary-at-War's passes from certain discharged soldiers, whipped them through the streets, and gave them vagrant's passes instead, with the result that the unhappy men were stopped and shut up in gaol for deserters.[47] Redress for such injuries as these was not easily to be obtained; for of what profit could it be to these poor fellows to speak to them of their legal remedy? The soldiers were subject to a sterner and harder law than the civilians, and the civilians never hesitated to take advantage of it. They thought nothing of demanding that an officer should be cashiered unheard, solely on their accusation, and that too when redress lay open to them in the courts of law.[48] The difficulties of the Secretary-at-War in respect of these complaints are pathetically summarised by Craggs: "If I take no notice of such things I shall be petitioned against by twenty and thirty towns; if I inquire into them the officers think themselves discouraged; if I neglect them I shall be speeched every day in the House of Commons; if I give any countenance to them I shall disoblige the officers. My own opinion is that I can do no greater [26]service to the Army than when, by taking notice of such few disorders as will only affect a few, I shall make the whole body more agreeable to the country and the clamour against them less popular in the House of Commons.[49]"

With traps deliberately laid to draw the troops into quarrels, with occasional experience of such brutality as has been above described, and with members of the House of Commons incessantly branding soldiers as lewd, profligate wretches, it is hardly surprising that there should have been bitter feeling between the Army and the civil population. But even more mischievous than this was the tendency of civilians, as of the House of Commons, to interfere with military discipline. It is tolerably clear, from the immense prevalence of desertion, and from the effusive letters of thanks written to magistrates who did their duty in arresting deserters, that the great body of these functionaries were in this respect thoroughly disloyal. Men could hardly respect their officers when they saw the civil authorities deliberately conniving at the most serious of military crimes. But this was by no means all. We find Members of Parliament interceding for the ringleaders of a mutiny,[50] for deserters,[51] for the discharge of soldiers, sometimes, but not always, with the offer to pay for a substitute;[52] and finally, as a climax, we see one honourable gentleman calmly removing his son from his regiment on private business without permission either asked or received.[53] And the Secretary-at-War liberates the mutineers, warns the court-martial to sentence the deserter to flogging instead of death, since otherwise interest will procure him a pardon, and begs General Wade, one of the few officers who had the discipline of the Army at heart, to overlook the absence of the member's son without leave.

A parallel could be found to all these examples at this day, it may be said. It is quite possible, for such ill weeds once sown are not easily eradicated, but the roots of the evil lay far deeper then than now in the overpowering supremacy of the Secretary-at-War. That official throughout this period continued to correspond directly with every grade of officer from the colonel to the corporal, whether to give orders, commendation, or rebuke, wholly ignoring the existence of superior officers as channels of communication and discipline.[54] His powers in other directions are indicated by the phrase, "Secretary-at-War's leave of absence,"[55] which was granted to subalterns, without the slightest reference to their colonels, to enable them to vote for the Government's candidate at by-elections.[56] We find him filling up a vacancy in a regiment without a word to the colonel,[57] instructing individual colonels of dragoons when they shall turn their horses out to grass,[58] and actually giving the parole to the guard during the King's absence from St. James's.[59] All these orders, relating to purely military matters, were issued, of course, by the King's authority, though not always in the King's name; and, indeed, as the volume of work increased, directions, criticisms, and reproofs tended more and more to be communicated by a clerk by order of the Secretary-at-War. In fact, the absolute control of the Army was usurped by a civilian official who, while arrogating the exercise of the royal authority, abjured every tittle of constitutional responsibility.

The result of such a system in such an age as that of Walpole may be easily imagined. All sense of military subordination among officers was lost. Their road to advancement lay, not by faithful performance of their duty for the improvement of their men and the satisfaction of their superiors, but by gaining, in what fashion [28]soever, the goodwill of the Secretary-at-War,[60]—by granting this man his discharge, advancing that to the rank of corporal, pardoning a third the crime of desertion. "Our generals," said the Duke of Argyll in the House of Lords at the opening of the Spanish War, "are only colonels with a higher title, without power and without command ... restrained by an arbitrary minister.... Our armies here know no other power but that of the Secretary-at-War, who directs all their motions and fills up all vacancies without opposition and without appeal."[61] Well might General Wade be believed when he asserted that the discipline of the Army was as bad as it could be.

From the political I turn to the purely military side of the Army's history. Treating first of the officers, it has, I think, been sufficiently shown that there were influences enough at work to demoralise them quite apart from any legacies of corruption that they might have inherited from the past. Against their indiscipline and dishonesty George the First seems to have set his face from the very beginning. He had a particular dislike to the system of purchasing and selling commissions. If (so ran his argument) an officer is unfit to serve from his own fault, he ought to be tried and cashiered, if he is rendered incapable by military service, he ought to retire on half-pay; and so firm was the King on this latter point that the Secretary-at-War dared not disobey him.[62] As early, therefore, as in June 1715 the King announced his intention of putting a stop to the practice, and as a first step forbade all sale of commissions except by officers who had purchased, and then only for the price that had originally been paid. One principal cause that prompted him to this decision appears to have been the exorbitant price demanded by colonels, on the plea that they had discharged regimental debts due for the clothing of the men, and suffered loss through the carelessness of agents.[63] It should seem, however, that as the rule [30]applied only to regiments on the British and not to those on the Irish Establishment, the desired reforms were little promoted by this expedient. In 1717, therefore, the King referred the question to the Board of General Officers, with, however, a reservation in favour of sale for the benefit of wounded or superannuated officers, which could not but vitiate the entire scheme. He thought it better, therefore, to regulate that which he could not abolish, and in 1720 issued the first of those tariffs for the prices of commissions which continued to appear in the Queen's Regulations until 1870. At the same time he subjected purchase to certain conditions as to rank and length of service, adding somewhat later that the fact of purchase should carry with it no right to future sale.[64] Evidently ministers kept before his eyes not only the usefulness of the system from a political standpoint, since every officer was bound over in the price of his commission to good behaviour, but still more the impossibility of obtaining from Parliament a vote for ineffective men. They followed, in fact, the precept of Marlborough, and it is hard to say that they were not right.

Concurrently the King took steps, not always with great effect, to check the still existing abuse of false masters.[65] A more real service was the prevention of illegal deductions from the pay of the men, a vice from which hardly a regiment was wholly free, by the regulation of all stoppages by warrant.[66] As part of the same principle, he endeavoured also to ensure honesty towards the country and towards the soldiery in the matter of clothing. In fact, wherever the hand of King George the First can be traced in the administration of the Army, it is found working for integrity, economy, and discipline; and it is sufficiently evident that when he [31]gave decided orders the very officials at the War Office knew better than to disregard them.

It is melancholy to record the fact that he was ill supported by the General Officers of the Army. The Board of Generals, to which the settlement of all purely military questions was supposed to be referred, seems to have been lazy and inert, requiring occasionally to be reminded of its duty in severe terms.[67] It may well be that this supineness was due to the general arrogation of military authority by civilians, but even so it remains unexcused. Colonels again appear to have been scandalously negligent and remiss in every respect; and it may have been as a warning to them that the King on one occasion dismissed seven of their number in one batch from his service.[68] But issue orders as he might, the King could never succeed, owing to the prevailing indiscipline, in making a certain number of officers ever go near their regiments at all. This habit of long and continued absence from duty, especially on colonial stations, is said to have troubled him much, and to have caused him greater uneasiness than any other abuse in the Army. It will be seen when we read of the opening of the Seven Years' War that he had all too good ground for misgiving. Yet the regimental officers must not be too hardly judged. In foreign garrisons, as shall presently be shown, they were exiles, neglected and uncared for; at home they were subject to incessant provocation, to malicious complaints, and in every quarter and at all times to the control of civilians. Lastly, though frequently called out in aid of the civil power, they had the fate of Captain Porteous before their eyes, and indeed took that lesson so speedily to heart that for want of their interposition the life of that unlucky man was sacrificed.[69]

When officers flagrantly neglected their duty and civilians deliberately fostered indiscipline, it is hardly astonishing that there should have been much misconduct among the men. It was natural, in the circumstances, that after the Peace of Utrecht the profession of the soldier should have fallen in England into disrepute. The greatest captain of his time, and one of the greatest of all time, had been rewarded for his transcendent services with exile and disgrace. Many officers had quitted the service in disgust, some of them abandoning even regiments which they loved as their own household. Wholesale and unscrupulous disbandment did not mend matters; and the survivors of that disbandment were confronted with the railings of the House of Commons, the malice of municipalities, the surliness of innkeepers and the insults of the populace. The most honest man in England had but to don the red coat to be dubbed a lewd profligate wretch. Small wonder that, clothed with such a character, ready made and unalterable, soldiers should have made no scruple of living their life in accordance with it.