Maria Stella, Lady Newborough, as a Gypsy.

From a picture at Glynllifon

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Memoirs of Maria Stella (Lady Newborough), by Maria Stella Ungern-Sternberg This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Memoirs of Maria Stella (Lady Newborough) Author: Maria Stella Ungern-Sternberg Contributor: Boyer d'Agen Translator: M. Harriet M. Capes Release Date: February 25, 2018 [EBook #56643] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MEMOIRS OF MARIA STELLA *** Produced by Clarity and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

THE MEMOIRS OF MARIA STELLA

(LADY NEWBOROUGH)

Maria Stella, Lady Newborough, as a Gypsy.

From a picture at Glynllifon

THE MEMOIRS OF

MARIA STELLA

(LADY NEWBOROUGH)

BY

HERSELF

Translated from the original French by M. Harriet M. Capes

and with an introduction by B. D’Agen

LONDON

EVELEIGH NASH

1914

| To face page | |

| * Maria Stella, Lady Newborough, as a Gypsy | |

| (From a picture at Glynllifon) | Frontispiece |

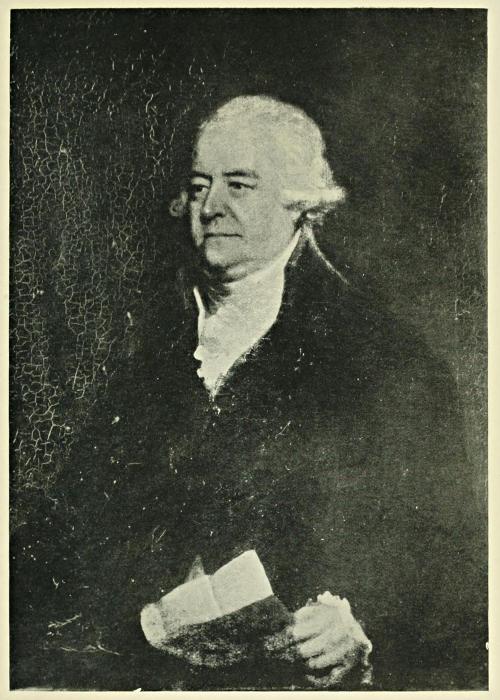

| * Lord Newborough | 76 |

| (From a picture at Glynllifon) | |

| * Glynllifon | 88 |

| (From a drawing by the late Sir John Ardagh) | |

| * Maria Stella, Lady Newborough | 104 |

| (From a bust at Glynllifon) | |

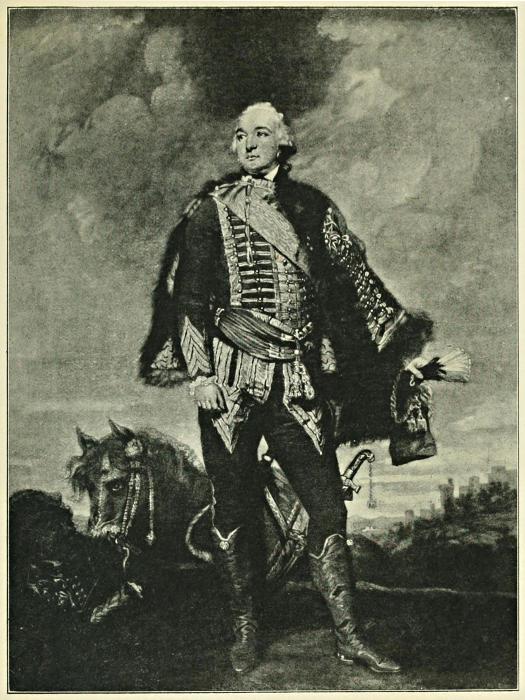

| The Duke of Orleans (Philippe-Égalité) | 152 |

| Mme. de Genlis | 198 |

| (Photo, Braun Clement et Cie) | |

| Maria Stella, Lady Newborough, Baronne de Sternberg | 228 |

| The Duchess of Orleans (Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon-Penthièvre) Wife of Philippe-Égalité | 244 |

| Louis-Philippe, King of France | 280 |

* The thanks of the publisher are due to the Hon. F. G. Wynn for permission to reproduce these pictures, and to Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey, Bart. (author of The Mystery of Maria Stella, Lady Newborough: Edward Arnold), for the use of his copyright photographs of the same.

Whereas the plaintiff has claimed that the rectification of her certificate of baptism should be properly carried out, etc. That Lorenzo Chiappini, being near his death, wrote a letter to the plaintiff, in which, to ease his conscience, he declared that she was not his daughter.

That the words of a dying man must bear the impress of truth.

That, according to the evidence of the witnesses Bandini, it is absolutely proved that Count Louis Joinville exchanged his daughter for a boy of Lorenzo Chiappini’s, and that the Demoiselle de Joinville was baptized under the name of Maria Stella, falsely described as the daughter of Chiappini and his wife.

That the Lady Maria Stella therefore justly claims the rectification of her birth-certificate.

Moreover, that the evidence of the aforesaid witnesses is supported by public notoriety and the difficulties the Comte de Joinville experienced.

Finally, that the legitimacy of the claim is proved by the careful education given to the plaintiff—an education unsuitable to the daughter of a jailer, as well as by the improvement in the fortunes of Chiappini which ensued.

For these reasons, which will be established both in fact and law by the proofs put in, and for all others resulting from the proceedings, it is held that the plaintiff’s request should be granted, etc.

Whereas the plaintiff, in both her birth and baptismal certificates, is described as the daughter of Lorenzo Chiappini, who brought her up as such, and that so she acknowledged herself for nearly fifty years, etc.

That this plainly establishes the fact of her birth and consequent rights, etc.

That the proofs brought forward by the plaintiff amount to no more than the depositions of a few witnesses, whereas the proof should be in writing, etc.

That failing the necessary proofs of affiliation and paternity, the law holds good that given in the birth-certificate, etc.

That, even if the proofs given in evidence were alone sufficient, the witnesses produced by the plaintiff do not plainly report the fact of the substitution, etc.

Moreover, doubt is not dispelled by Chiappini’s declaration, because it is not expressed in authentic or documentary terms, etc.

Finally, that to claim to be the daughter of a certain person not that named in the certificate of birth or shown as in possession, it is necessary to prove that such person has really existed, etc.

For these reasons, it must be held that the claims of the plaintiff be refused, and that she be condemned in all the costs of the trial, etc.

In Le Matin of March 17, 1913, appeared the following article, with which we will begin the account of some abridged documents.

“While examining the Archives of the Office of Foreign Affairs, a young historian, M. Maugras, has unearthed a very curious love-story, deposited by the ‘guilty couple’s’ own hands, relating to the Duke of Orleans, later Philippe-Egalité, and the governess of his children, the virtuous and pedagogic Mme. de Genlis.[1]

“In consequence of this liaison, Mme. de Genlis was made Captain of the Guards; and the[10] ‘governess’ of the future Louis-Philippe and Mme. Adélaïde gave birth to two charming little daughters, who were brought up in England and known as Pamela and Miss Campton.

“Mme. de Genlis was also the mother of a legitimate daughter, who later on married M. de Valence. Mme. de Valence was to have for her son-in-law the Maréchal Gérard, lineal ancestor of the brilliant poetess, Rosemonde Gérard.

“On the other hand, Miss Campton married a Gascon, M. Collard, and was grandmother to Marie Cappelle (Mme. Lafarge).

“Thus, by legitimate descent, Mme. de Genlis is the ancestress of Rosemonde Rostand, and, illegitimate, of Mme. Lafarge.

“The latter wrote six thousand letters, not to speak of her Mémoires and her Heures de Prison.

“As for the author of the play, Un Bon Petit Diable, ‘he’ proposed nothing less than to tune his pipe to all history and legend, in spite of what his own descent might imply.…

“The heritage of the Governess of the Children of France has not fallen to the distaff side.”

The next day, March 18, the same journal published[11] this other article, which impartiality obliges us to reproduce here—

“Through the assiduous researches of a pious inquirer into the things of the past, the Mercure de France has just published a touching series of letters, written by Mme. Lafarge from her prison at Montpellier, to her Director, l’Abbé Brunet, residing in the Bishop’s Palace at Limoges. This is a twofold revelation, in that it testifies both to the delicate skill of the writer and the innocence of the accused, but the correspondence is unfortunately incomplete.

“Some of these letters were given to M. Boyer d’Agen by M. Albris Body, Keeper of the Records at Spa in Belgium; others were discovered amongst the posthumous papers of Zaleski, the classic poet of the Ukraine; those that remain are doubtless buried in the dusty catacombs of some library.… It could be wished that one of those lucky chances which are the providence of the erudite might allow of their disinterment.”

To complete this and prove something definite, these two quotations ought to be accompanied by[12] a third which I take from one of the letters given by Le Matin, in which the celebrated Mme. Lafarge ventures to disclose the secret reason for her notorious misfortunes by at last revealing the mystery of her illegitimate origin, which, through the house of Orleans, of which her grandmother was issue, made her a near relation of Louis-Philippe, who during his reign, moved by fear, permitted the trial of this cousin by blood, whom he dared not have acquitted after ten years of imprisonment.

“The Queen charged the Maréchale Gérard,” writes Marie Cappelle in this painful confession, “to tell me that she would make it her business to interest herself in me. She went herself to speak to the Ministers. It was last spring (1848), and the men condemned for the riots at Basanceney had just been executed. The Ministers said that there would be an outcry, that it would get mixed up with politics; that the left-handed relationship that was suspected would be exploited by parties and newspapers. In the month of August there was some hope; but the Praslin affair put a stop to everything. Now, I don’t know what has become of the goodwill of our[13] saintly Queen; I don’t know if the Maréchale (Gérard) seriously means to carry out all the provisions of her poor mother’s (Mme. de Valence) bequest. I have not written to her. It is painful to me to address prayers to men; I scorn to ask for pardon when I have the right to ask for justice.”

The rest is known. Four years later, on June 1, 1852, Napoleon III opened a door Louis-Philippe had kept closed during the whole of his reign, and Marie Cappelle left her prison at Montpellier to go and die of exhaustion, four months later, at the little hot-spring town of Ussat, which could not give her back her lost life.

For my part, I was counting, letter by letter, the steps to Calvary climbed by this poor woman, and which, letter by letter, may be followed in a forthcoming book which is to contain all that I have been able to collect to the honour of this possessor of so fine an intelligence and so polished a style; when, all of a sudden, the episode of Marie Cappelle reminded me of that of Lorenzo Chiappini—with the house of Orleans as the origin of those doubtful births and as the clue to these yet unsolved historical enigmas.

What was the Orleans Chiappini affair?

In the spring of 1902 I was rummaging amongst the Archives of the Vatican, of whose secular secrets Pope Leo XIII, of august memory, had made an end by opening them to the world of inquirers, with no fear that the dangerous resurrection of this Lazarus of history would be for that liberal Pontiff—as it was for the Divine Miracle-worker of Bethany—the prelude to the maledictions of a scandalized Sanhedrin, and to another painful Passion—a renewal of that of old.

While waiting for the crucifigation of the Pharisees—those lovers of darkness and the unfathomable crimes of secret history—I took pleasure, as a simple Publican and lover of the light, in admiring the daylight making its cheerful way under the corniced vaults of the Archivio Segreto, and disclosing those files of dusty manuscripts, which, each stripping off his registered shirt, emerge naked from the tomb at the call of the first passer-by who, recognizing his dead, simply says, “Come forth!” and they come.

Standing before those desks over those deep tomblike cases of archives wherein slumber the[15] secrets of the dead, my ears open to the miraculous, “Lazarus, come forth!” which the patient seekers for silent memories are prepared to utter at the turning of each yellow leaf, I let my dreaming eye, that afternoon, rest upon a ray of that Roman sunshine, as, with its soft radiance, it gave life to the solitude of a vault, scattering its riches broadcast through the windows, prodigal as the gambler staking with both hands just for the pleasure of playing, and losing.

“I’ve been using in your service the time you waste here!” said a searcher in this Vatican vault, as he came and sat down at my work-table. He is one who knows all the treasures of the place, since he has frequented it for over thirty years, working for the most learned of the best Reviews—the Civilta Cattolica, to which my honourable colleague is one of the most authoritative contributors.… “Well, what do they say in Paris about Louis-Philippe?”

“That he has been dead for some time!” I could not help answering, with a laugh at this not over-retrospective interruption.

“But is it known how he was born?” continued my interlocutor, more mysteriously than if he were[16] simply talking nonsense; and without another word, “Here!” he added; “read this letter. I found it amongst the papers of Cardinal Joseph Albani, whom the celebrated Secretary of State Chateaubriand used to visit during his Embassy to Rome, and of whom he has left, in his Mémoires d’outre-Tombe, a witty enough portrait. Read this document; it is well worth while.” In the Secret Archives of the Vatican it is inscribed (B. 43242, anno 1830)—

Cardinal Macchi to Cardinal Albani, Secretary of State.

“Ravenna, Nov. 19, 1830.

“Emˢˢⁱᵐᵉ Maître,

“Enclosed in this letter you will find a copy of the decision, given on May 29, 1824, by the Episcopal Tribunal of Faenza, in favour of the Lady Maria Newborough, Baronne de Sternberg, by the terms of which it is declared that this person is the daughter of the Comte and the Comtesse de Joinville, and not the daughter of the two Chiappinis. The documents concerning this affair are pretty numerous, but there is no[17] mention made of the Orleans family. It is true that the aforesaid title of Joinville belongs to that Royal Family, and is borne at the present time, if I am not mistaken, by the daughter, born fourth of the family. It is true, likewise, that it is generally believed here that the Comte de Joinville was no other than the famous Duc d’Orléans-Egalité.

“Moreover, not only is there no proof that the Duc d’Orléans was travelling in Italy in 1773, but, on the contrary, we read in his biography that in 1778 he travelled in Italy in the company of the Duchess.

“I notice, besides, that Lady Newborough was born at Modigliana on April 17, 1773, and that the present King of France was born six months later. How, then, could the supposed exchange have been managed? It seems to me that this is a mere fable which might, and not a little, compromise us. I should advise your Eminence to claim those documents from the Tribunal of Faenza, so as to keep them from the public eye and in Rome.

“Having thus carried out your esteemed orders, I pray your Eminence to accept the humble[18] expression of the profound respect with which, etc.

“Signed: V. Cardinal Macchi.”

“But,” said I, as I returned the folio to its obliging discoverer, “it seems to me that this letter is conclusive, and that the Louis-Philippe Chiappini case is settled as soon as heard.”

“Precisely, because it has not yet been heard. You are stopping your ears, like the Eminentissimo Macchi, Cardinal-Legate of Ravenna, who did not want to hear any more of the affair. But no, no!—and besides, you haven’t the same excuse. Would you like, in connection with this letter, to read the document that goes with it? It is the Italian text of the sentence solemnly pronounced by the Episcopal Tribunal of Faenza, on the 29th of May, 1824; fifty years after this criminal business; all surviving witnesses heard; all inquiries scrupulously made; the Holy Trinity invoked in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.…”

“The devil!” I ventured to exclaim, at a matter beginning with so sacramental a formula.

And I read in Italian what I am going to give[19] here in a translation, and the number of which, 43-242, is that of its place in the Secret Archives of the Vatican.

“Having invoked the most holy Name of God:

“We, seated in our Tribunal, and having before our eyes nothing but God and justice, by our final decision from the pleadings of the lawyers and the documents, we deliver judgment on the action or actions debated before us in the inferior or any other higher Court, between her Excellency Marie Newborough-Sternberg, the Plaintiff, on the one part, and M. le Comte Charles Bandini on the other, acting as legally delegated trustee to represent M.M. le Comte Louis and la Comtesse de Joinville, and any other absent person who has, or claims to have, any interest in the case; these two parties to it having submitted to jurisdiction, in default of the Excellentissime M. le Docteur Thomas Chiappini, domiciled at Florence, who has not so submitted himself.

“Whereas, before our Episcopal Curia acting as a Tribunal competent to judge the ecclesiastic cases named below submitted to their jurisdiction, the Plaintiff has asked that orders may be given,[20] by means of suitable alteration, to correct her baptismal certificate, etc.

“That, on the part of the delegated Trustee Defendant, it is asked that the Plaintiff’s claim should be rejected and the costs repaid. That the other proper Defendant, Doctor Chiappini, has not submitted to jurisdiction, though, according to the custom of this Curia, he has been twice summoned by a Sheriff of the Episcopal Tribunal of Florence, and that the report of contumacy has been added to the decision on the suit.

“Considering the documents, etc.

“Having heard the respective counsel, etc.

“Whereas Lorenzo Chiappini, being near his end, did, in a letter which was given to the Plaintiff after the decease of the aforesaid Chiappini, reveal to the same Plaintiff the secret of her birth, by clearly making known to her that she was not his daughter, but the daughter of a person he declared he could not name.

“That it has been legally acknowledged by the experts that this letter is written in the hand of Lorenzo Chiappini.

“That the word of a dying man is proof in full, since he has no longer any interest in lying, and[21] it is to be presumed that he is thinking only of his eternal salvation.

“That such a confession ought to be looked upon as a solemn oath, and as a bequest made for the good of his soul and his own salvation.

“That the Trustee would vainly endeavour to deprive the said letter of its force, on account of its containing no indication as to who were the real father and mother of the Plaintiff; since although, in fact, such indication is really wanting, recourse has been had, on the part of this same Plaintiff, to the testimony of witnesses, to presumptions and conjectures.

“That, where there exists in writing a beginning of proof, as in the present case, it is allowable, even in State questions, to introduce testimonial proof and all other evidence.

“That if, in questions of State, after the original written proof, that by means of witnesses is admissible; there is still stronger reason to accept the same proof in this case when a document is produced to be used in the question of State.

“Whereas, from the sworn legal depositions of the sisters, Maria and Dominica Bandini, it is[22] clearly shown that there was an agreement between M. le Comte and le Sieur Chiappini to exchange their respective children, should Mme. la Comtesse give birth to a girl and Chiappini’s wife to a boy; that the agreed exchange did really take place, the case having been provided for; that the girl was baptized in the church of the Priory at Modigliana, by the name of Maria Stella, and falsely registered as the daughter of the Chiappini couple.

“Whereas the said witnesses swear as to the time of the exchange as coinciding with that of the Plaintiff’s birth.

“Whereas, the Trustee, likewise in vain, urges the improbability of this evidence; since, not only no improbability is to be met with in the witnesses’ statement, but, on the contrary, it is upheld and verified by a great number of other presumptions and conjectures.

“That one very forcible conjecture is deduced by the public voice and the rumours which were then spread as to the fact of the exchange.

“Whereas, this rumour is proved, not only by the testimony of the aforesaid sisters Bandini, but also by the attestation of M. Dominique Della[23] Valle, and that of other witnesses in Brisighella and Ravenna, all equally judicially examined in their own towns and before their respective tribunals.

“That the vicissitudes to which M. le Comte was exposed are a convincing proof of the reality of the exchange.

“That there is documentary proof that in consequence of the rumours spread abroad in Modigliana concerning the exchange in question, the Comte de Joinville was forced to leave that place and take refuge in the Convent of St. Bernard at Brisighella; that having gone out for a walk, he was arrested, taken to, and kept some time in, the Public Palace of Justice of Brisighella, and that afterwards he was conducted by the Swiss Guards of Ravenna before his Eminence the Cardinal-Legate, who set him at liberty, etc., etc.

“Whereas, Querzani, of Brisighella, swears to having shaved a great French nobleman who was for some time living in seclusion in the Convent of St. Bernard at Brisighella.

“Whereas, in the evidence of the aforesaid Della Valle, he declares that, while he was assisting in making out the inventory of the aforesaid[24] Convent of St. Bernard, he saw two letters signed ‘le Comte de Joinville’; that one of these was dated from Modigliana, and that in it the writer thanked the Abbot of St. Bernard’s for having allowed him to retire into his convent; that, in the other letter, dated from Ravenna, the same correspondent tells of his liberation to the same Abbot; that both these letters bore the date of 1773.

“Whereas, one of the soldiers charged with the surveillance of the Count at Brisighella during his stay at the Palace of Justice of that town, is still living, which soldier has given evidence on the subject judicially and of his own free will.

“That M. le Comte Nicolas Biancoli-Borghi testifies in his judicial examination that, while he was looking through old papers of the Borghi house, he came upon a letter written from Turin to M. le Comte Pompeo-Borghi, the date of which he could not remember, signed Louis C. Joinville, which said that the exchanged child was dead and that there was now nothing more to fear on its account.

“Whereas, the same Count Biancoli-Borghi alleges his own knowledge to be the motive of his evidence, etc.

“That the exchange is proved also by the change in the fortunes of Chiappini, etc.

“That in fact, after this event, Chiappini paid ready money for the cereals needed for the support of his family, and that he bought them at the Borghi place of business, while before that time he had discharged his debts by the giving up of his monthly pay; which Biancoli-Borghi testifies to having found as a fact in the books of the Borghi firm.

“Whereas, it is proved beyond doubt by many documents that Chiappini, after he retired to Florence, acquired means that enabled him to live at ease, as the sisters Bandini and other witnesses testify.

“Whereas, the Sieur Della Valle asserts that he saw Chiappini at Florence in flourishing circumstances, and that, moreover, the same Chiappini spoke of the exchange to a certain Sieur D. Bandini of Verifolo who was often in his company, as the same Bandini declared to Della Valle.

“Whereas, the Plaintiff received an education suited to her distinguished rank, and not such as would have been given to the daughter of a jailer, etc., etc.

“That, it clearly follows in view of all the matters up to now alleged and of many others existing in the documents, that Maria Stella was falsely described in her certificate of birth as being the daughter of the Chiappini husband and wife, and that she owes her birth to M. le Comte and Mme. la Comtesse de Joinville.

“That, in consequence, it is a matter of justice to grant the correction of the certificate of birth now claimed by this same Maria Stella.

“Finally, that M. le Docteur Chiappini, instead of opposing the claim, is guilty of contumacy.

“Having repeated the most holy Name of God, we declare, decree, and give final judgment, that the pleas of the aforesaid delegated Trustee must be rejected, as we reject them; we desire and order that they be held as annulled; and, in consequence, we have declared, decreed and given final judgment, that the certificate of birth of April 17, 1773, inscribed in the Baptismal Registers of the Prioral Church of St. Stephen, Pope and Martyr, at Modigliana, in the Diocese of Faenza, wherein Maria Stella is described as the daughter of Lorenzo Chiappini and Vincenzia Viligenti, be corrected; and that, on the contrary, she is to be[27] described as the daughter of M. le Comte Louis and Mme. la Comtesse N. de Joinville, French; to which end we have likewise decreed that the rectification in question shall be executed officially by our Registrar, also empowering M. le Prieur, of the Church of St. Stephen, Pope and Martyr, at Modigliana, in the Diocese of Faenza, to give copies of the rectified and corrected paper to all such as may ask for it, etc.

“Le Chanoine Prévot,

“Valerio Boschi, Pro-vicaire Général.”

“The devil! the devil!” I repeated, astonishment increasing by leaps and bounds in the face of two such grave and contradictory statements. Was the Cardinal of Ravenna wrong? Was the Bishop of Faenza right? And did one ever see a scarlet-clad Eminence break a more vigorous rod over the violet-clad shoulders of a Counsel of Prelates than this reversion of a decree so solemnly pronounced, a few years earlier, before a plenary court of all the officers of a diocese?

“You forget,” answered my colleague, “that the then Legate of Ravenna had been Nuncio at Paris under Charles X, and a special friend of[28] the King’s. So great a friend that the pasquinades on the Conclaves of 1829 and 1830, at which this Cardinal was present, always called him the ‘Joueur de Gherardo della Notte,’ in memory of the royal card-parties at the château, where this ex-Nuncio was always the favoured partner. He was so loaded with presents, that the distended skirts of the prelate’s gown became legendary in Paris as in Rome. And the least he could do amidst the amplitude of the cloth out of which he had shaped such a gown, was for the Cardinal Macchi to attempt later to shield the honour of the new King that, in this same 1830, Charles X, on abdicating, had left to France. But however deep they be, the well-furnished pockets of a modern Cardinal can’t take the place of the ancient oubliettes of history.”

“True! true!”

“To throw light upon this strange business, there is more than the affirmations of the Ecclesiastical Tribunal of Faenza and the denials of the Cardinal-Legate of Ravenna. There is a heap of proofs got together by the plaintiff in a voluminous memoir. Lady Newborough, Baronne de Sternberg, wanted it to be published in Italian[29] and French at the same time. But the date of 1830, chosen for these startling revelations, was also that when the person principally interested mounted the throne of France. Is it to be wondered at that these compromising documents were at once destroyed wherever the representatives of the King Louis-Philippe could find them?”

“And then?”

“Then, there existed, and exists, a copy, thank God! Written in an elegant and easy hand, it once more proves the distinction of its author, as well as the sincerity of her words. You will easily discover the Italian text at Recanati, in the celebrated house of the Leopardis; for the Count Monaldo, father of the great poet Giacomo Leopardi, was not afraid of preparing an edition of this document for the edification of his contemporaries speaking the same tongue. The French text, which the supposed daughter of Philippe-Egalité undertook to publish in your language, and which she signed with the actual name of Joinville, which had at the first concealed the criminal incognito, would perhaps be more difficult to recover in France after the hunt for it[30] But here is a copy which will console you for the loss of the rest. Shall we look through it together?”

“Certainly; it is enough that the Vatican should shelter such noble victims within the silence of its protecting walls, without Herod having to impeach the Pope for his guilty connivance in a repetition of the Massacre of the Innocents.”

So here we are in the presence of Lady Newborough’s Memoirs, which relate that she was born on April 17, 1773, at Modigliana; her supposed father being Lorenzo Chiappini, sbirro, or factotum, to the Count Borghi. Her supposed mother was one Vincenzia Viligenti, attached, as concierge, to the kind of prison of which her husband was warder.

This birth took place at the precise time that a certain Comte de Joinville and the Comtesse, his wife, who were staying at the Palazzo Borghi, opposite the prison of which Chiappini was warder, had also a child born to them. The child of Chiappini was baptized on the very day of its birth under the names of Maria Petronilla; that of the Comte de Joinville does not appear in the[31] Baptismal Registers of the Parish of San Stefano, common to both families.

Maria Petronilla, always ignorant of her true origin and problematic destiny, lived until she was four years old between the indifference of her mother, who gave all her love to her other children, and the marked affection of the Countess Borghi, who greatly appreciated the natural distinction of the little girl, quite incompatible with so low an origin.

But the lowly estate of the Chiappinis improving day by day, Maria was only four years old when she had to leave for Florence, the Grand Duke having summoned the humble warder of the Modigliana prison to unhoped-for good fortune there.

Maria Stella’s education kept pace with the growing prosperity of her father Lorenzo.

When the little girl had learnt enough of dancing and accomplishments, her father got her an engagement as ballet-dancer in a large theatre in the town.

Scarcely of marriageable age, she had first to spurn and then to accept the passionate addresses of an elderly English nobleman, who asked her[32] hand. The parents granted what the daughter refused, and one day, against her will, Maria Petronilla became the wife of Lord Newborough.

Lady Newborough’s Memoirs continue as tales of travel up to the page wherein she records the death of Lorenzo Chiappini, with this autograph letter from the dying man.

“Milady,

“I have come to the end of my days without having ever revealed to any one a secret which directly concerns you and me.

“This is the secret.

“The day you were born of a person I must not name, and who has already passed into the next world, a boy was also born to me. I was requested to make an exchange, and, in view of my circumstances at that time, I consented after reiterated and advantageous proposals; and it was then that I adopted you as my daughter, as in the same way my son was adopted by the other party.

“I see that Heaven has made up for my fault, since you have been placed in a better position than your father’s, although he was of almost similar rank; and it is this that enables me to end my life in something of peace.

“Keep this in your possession, so that I may not be held totally guilty. Yes, while begging your forgiveness for my sin, I ask you, if you please, to keep it hidden, so that the world may not be set talking over a matter that cannot be remedied.

“Even this letter will not be sent to you till after my death.

“Lorenzo Chiappini.”

“Stranger and still stranger!”

“This letter, sent through the post from Florence to Lady Newborough, then at Siena, about the middle of December 1821, was the beginning of the lengthy investigations to which this daughter of noble but unknown parents henceforth entirely devoted herself. You must read the rest of the Memoirs, of which I venture to recommend whole pages to your consideration. Here is an extract—

“‘After leaving my two eldest sons,’ writes Lady Newborough, ‘I took the road to Rome, where I had already made the acquaintance of Cardinal Consalvi, who showed me the greatest kindness. By his order, all the archives were[34] thrown open to me; everything was examined into, not only in the capital, but in the country round about the Apennines; but everywhere the answer was the same: “Nothing whatever has been discovered; everything must have been destroyed during the Revolution.”

“‘Seeing that there was nothing to be done there, I set out for Faenza, where I was informed that the Count Borghi was absent, and that, moreover, it would be useless for me to see him, as he had declared that he would never tell me anything at all. I heard even that he had threatened the old servant-women with the withholding of their modest pensions if they had the ill-luck of speaking to me. But they could not restrain their longing to see me or the cry of their consciences. Their first words when they met me were a simultaneous exclamation of “O Dio! how like you are to the Comtesse de Joinville!”

“‘I joyfully welcomed them and treated them kindly; and having implored them to acquaint me with the details concerning my birth, they at last consented to speak perfectly openly.

“‘“Our father, Nicholas Bandini,” they told me, “at the age of seventeen entered the Borghi[35] mansion as chief steward, and never left it till his death. We also were taken on there in our youth as maids to the Countess Camilla. That lady, with her son, the Count Pompeo, was in the habit of spending a good part of the year at the castle at Modigliana, and in the beginning of the spring of 1773 we accompanied them there.

“‘“On our arrival we found, already established in the Pretorial Palace, a French couple, called the Comte Louis and the Comtesse Joinville. The Comte had a fine figure, a rather brown complexion, and a red and pimpled nose. As to the Comtesse, you can see almost her perfect image in your own person, milady.

“‘“Being such near neighbours, the greatest intimacy soon came to pass between them and our masters. Every day the two families met, sometimes at one house, sometimes at the other.

“‘“The foreign stranger was extremely familiar with people of the lowest rank, especially with Chiappini, the jailer, who lived under the same roof. As it happened, both their wives were then enceinte, and the two confinements appeared to be imminent.

“‘“But the Comte was seriously anxious; his[36] wife had not yet given him a male child; and he was intensely uneasy lest he should never have one, when of this very fear was born an idea, both barbarous and advantageous. First he broached the subject to the Count Pompeo and his mother, from a very charming point of view; then he endeavoured to worm himself more and more into the warder’s confidence, and ended by telling him that seeing himself about to lose a great inheritance absolutely dependent on the birth of a son, he was quite willing, in case he should have a daughter, to exchange her for a boy, whose father he would largely recompense.

“‘“The man who listened to his words, delighted to find unlooked-for luck at so appropriate a moment, did not hesitate for an instant; he accepted the offer, and the matter was settled on the spot.

“‘“We know it,” the sisters Bandini went on, “because we heard it with our own ears; and we know, too, that the event justified the precautions taken; the Comtesse gave birth to a daughter, and the other woman to a son. The news was brought to our master, and one of us going into the Pretorial Palace to see the newly-born[37] children, was assured by some women of the house that the exchange had really taken place. Chiappini, who was present, confirmed it in his own words. Later on, the Countess Camilla often repeated it to us; she used to say that the Comtesse Joinville had been told all about it, and had seemed quite content.

“‘“Soon after this abominable crime we ourselves saw the Comte and the jailer on the best of terms; the first because he had secured immense profit; the other because he had received much money. Although silence had been promised, there were indiscreet people, and public rumour soon accused the authors of this horrible transaction. The Comte Louis, dreading the general indignation of his accusers, fled and hid himself at Brisighella, in the convent of St. Bernard. We knew he had been arrested and then set at liberty, but we never saw him again.

“‘“The lady left with her servants and her reputed son, while her own daughter, baptized by the name of Maria Stella Petronilla, and described as belonging to Lorenzo Chiappini and Vincenzia Viligenti, always remained with these[38] last. Our mistress was constantly distressed about this misfortune. To repair it as much as possible she kept the unfortunate child near her, caressing her and giving her all kinds of presents, treating her not with ordinary friendliness, but with every mark of ardent love. So she behaved to this child for the first four years, that is to say till Chiappini took her with him to Florence, where he had her educated, and where he bought property with the price of his frightful bargain.”

“‘Thus spoke my venerable septuagenarians.

“‘Fully satisfied with their story, there seemed no need of more, and that now it would be enough to appear before my iniquitous parents and obtain from them just reparation.

“‘With this plan I set out for France with my third son, his drawing-master, my maid, and my courier, a faithful and intelligent servant.

“‘By the Sieur Fabroni’s advice, we went straight to Champagne, and the mere name of the place led us to Joinville. I asked the magistrates for information, and was told by them all that no nobleman of the neighbourhood bore the name of their city, and that it belonged solely to the Orleans family.

“‘After several attempts, which all had the same result, I went to Paris, arriving on July 5, 1823. As a cleverly used ruse may bring about an act of justice, and as the bait of riches is nowadays the most powerful of motives, I had the following advertisement inserted in several newspapers—

“‘“The widow of the late Count Pompeo Borghi has asked Lady N. S. to find for her in France a certain Louis, Comte Joinville, who, with the Comtesse, his wife, was at Modigliana, a little town in the Apennines, where the Comtesse gave birth to a son on the 16th of April, 1773. If these two persons are still living, or the child born at Modigliana, Lady N. S. has the honour to announce to them that she has been empowered to make them a communication of the highest interest. Supposing that these persons can prove their identity, they have only to apply to the Baronne de Sternberg, Hôtel de Belle-Vue, Rue de Rivoli.”

“‘Two days later appeared a colonel bearing the much-desired name; I received him with the[40] warmest welcome. He spoke, recounting his various titles. Alas! the one that had at first interested me so immensely was quite recent, and came to him from Louis XVIII.

“‘At that moment I was told that M. l’Abbé de Saint-Fare solicited the honour of an interview; the colonel looked much astonished, and withdrew. In his place entered an enormous man, wearing spectacles and supported by two footmen. As soon as he was seated, the following conversation took place.

“‘“The Duke of Orleans, having seen your advertisement, has this morning begged me to come and make inquiries about this inheritance; for we presume that that is the matter in question, and at the date you mention there was no one in existence outside the family to whom the title of Comte Joinville could belong.”

“‘“Was Monseigneur the Duke of Orleans born at Modigliana on the 16th of April, 1773?”

“‘“He was born that year, but in Paris, on the 6th of October.”

“‘“Then I am very sorry that you should have taken the trouble to come; for in that case[41] he has no connection with the person I am looking for.”

“‘“No doubt you have heard it said that the late Duke was very gay with the fair sex, and the child in question might well be that of one of his favourites.”

“‘“No, no, its legitimacy is incontestable.”

“‘“Could anything be more surprising! It is true, the late Duke lived in the midst of mysteries.”

“‘“Could you not describe him to me, Monsieur?”

“‘“Willingly, madame. He was a fine man with a good leg; his complexion was of a rather dark red, and, if it had not been for the numerous pimples on his face, he would have been very good-looking.”

“‘“And his character?”

“‘“What people principally admired in him was his extreme affability to every one.”

“‘“Your description agrees exactly with that that was given me of the Comte de Joinville.”

“‘“Then it must be supposed that it was the Duke himself.”

“‘“That can’t be if it is true that his son was born in Paris.”

“‘“May I ask you if there is a large sum to be had, and when?”

“‘“I am truly sorry not to be able to inform you; I am not at liberty to say more.”

“‘During the whole of this conversation, the big abbé had never left off looking at me in an almost offensive way; and, trying to find out what was my native tongue, he had spoken now in English, now in Italian, without being able to make up his mind, in consequence of my speaking both languages equally well.

“‘After an hour’s talk, he took leave, asking my permission to come again. I replied that I should be delighted to see him again, and, in my turn, begged him to be so good as to make inquiries amongst his many acquaintances.

“‘He kindly promised to do so, and added that he knew a very aged lady from Champagne very well, and that she might be able to give him much information, which he would transmit to me at once.

“‘As nothing came of it, I sent M. Coiron, a teacher of French, who was giving lessons in it to my son, to him.

“‘M. de Saint-Fare treated him politely, pleaded indisposition, and made great protestations.

“‘On Coiron presenting himself a second time, he was received very coldly, and simply told that nothing had been yet done.

“‘Moved by his own zeal and without my authority, he made a third attempt. Then the abbé told him plainly that he might discontinue his visits; that the lady knew nothing at all, and that he himself did not want to have anything to do with this fuss.

“‘Still, the first impression his visit made on me could not be effaced. I procured a ticket, and went with my friends to the Palais Royal. What was my surprise on seeing in some of the portraits their extreme resemblance either to me or to my children. My astonishment increased when my young Edward, catching sight of a picture I had not yet noticed, exclaimed: “Dieu! Maman, how much that face is like old Chiappini’s and his son’s!”

“‘We discovered that it was actually the portrait of the present Duke.…

“‘Thinking seriously over this, I realized that I owed to him in fact the important service of[44] being the first to tear the impenetrable veil by deputing that Abbé de Saint-Fare, who, I was told, was not only his great friend, but his natural uncle, to see me.

“‘It will be believed that, from that moment, all my researches went in the direction so clearly pointed out.…’

“The proofs Lady Newborough goes on heaping up in her startling Memoirs ought to be quoted as a whole,” ended my guide, as he tied up the heap of papers. “But that will need another sitting, longer than the first. Here is the sun beginning to set, and the custodian of the Archives of the Vatican inviting us to go. Will this historical puzzle awake your curiosity? In that case you will have to endeavour to reconcile these undeniable yet contradictory documents, since they repose in the shadow of these protecting walls, where you may read on the face of the Archivio which Leo XIII set open for the truth of History, the proud device that bold and beneficent Pontiff had cut upon it when he invited the whole civilized world to enter its doors.

“‘The first law of History is not to dare to lie; the second, not to fear to tell the truth; further, the historian must not lay himself open to a suspicion of either flattery or animosity.’

“The survivors of this domestic drama still draw breath at Modigliana and Brisighella, where Lorenzo Chiappini and Philippe-Egalité have left traces of their sojourn and their crime. At Glynllifon, in the Principality of Wales, the lineage of Lady Newborough, in the shape of her grandsons, still flourishes, if not the claims that died with her. Shall you go there, too, to examine into them?”

“Most assuredly,” I answered; “for the honour of the blood of France, which cannot lie, and of the truth which could not well serve a nobler cause than this.”

But, while waiting for the information which cannot fail to bring order and light into this still confused and perplexing affair, it was important that the actual text of these Memoirs, hunted for by those interested in them for nearly two-thirds of a century, so that there is scarcely a copy left that is not worth its weight in gold, should be put in reach of honest minds which have likewise[46] a full right to form an opinion on a case of such barbarity and of such national interest.

But what was to be expected of a Philippe-Egalité, who, to secure the great inheritance of Penthièvre, and needing a male firstborn, did not hesitate to sacrifice his own legitimate daughter for it? Would he be likely, a few years later, to hesitate before voting for the death of Louis XVI, who could no longer do anything for him? Had he not shown the extent of his complaisance in his preference for Madame de Genlis over his wife, whose confidante the mistress became under the very roof of the infamous husband of one and lover of the other?

The Memoirs of de Genlis have been widely read; let the Memoirs of Maria Stella be read likewise. After that we can talk with better knowledge of the facts.

Boyer d’Agen.

My Birth—Kindness of the Comtesse Borghi—We leave for Florence—My Circumstances in that Town—Domestic Troubles—My Parents’ good Fortune—My Tastes—My Education—Journey to Pisa—My Illness.

I was born in 1773, in the little town of Modigliana, situated on the heights of the Apennines, which could be reached only by very bad roads. It belongs to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, though dependent on the Diocese of Faenza in the Papal States.

On April 17 of the same year I was baptized in the parish church, receiving the names of Maria Stella Petronilla. My father’s name was Lorenzo Chiappini; my mother’s, Vincenzia Viligenti.

The family of Borghi Biancoli of Faenza owned, in my birthplace, a magnificent palace almost opposite the Pretorial Palace, where my father lived in the position of jailer.

The Count Pompeo Borghi, with his mother, the Countess Camilla, came there every year to[50] spend the summer. The Countess happened to see me, and despite my father’s ignoble profession, she was very fond of me and showed me immense kindness. I was admitted to her table, and often even shared her bed; she heaped presents upon me, and I lived almost entirely with her; I may even say that she inspired all the people of her house with the same sentiments, and that I was generally loved.

It was a precious compensation for the ills I suffered at home, where I had to endure the cruel brutality of a barbarous mother, to whom I was an object of detestation!

I well remember that as the first germ of gratitude developed in my little heart, I loved my benefactress as myself. When she was absent, I longed for her return, and when I had got her back, I couldn’t tear myself away from her; in a word, she was all the happiness of my life; but, alas! it was soon to be torn from me.

I had not yet reached my fourth year, when my father was summoned to Florence by the Grand Duke Leopold, who put him in command of a company of archers (capo squadra sbirri). A[51] few months later my father, in his turn, sent for us. I was his eldest child; two brothers were born after me, and the first had been dead some time.

The day we left, I was awakened very early, and in a few minutes my brother and I were each put into a pannier on a mule, and my mother got upon another animal of the same kind, our sole guide, protector and companion being the muleteer.

What tears I shed at leaving my dear Countess! It almost seemed as if I had foreseen that in losing this loving friend I should lose everything, absolutely everything!…

During the journey, which lasted two days, my mother seemed to care for nothing but my little brother, to whom she gave all her attention. Her neglect of me filled me with such bitterness that I felt like complaining to my father the instant we reached Florence.

In this new abode small-pox attacked our family; I got off with some small suffering; but my brother fell a victim to it, and my mother was not consoled for his loss till she gave birth to a third son six months later.

Scarcely convalescent, I was sent to a school, taken every morning by an ancient maidservant.

My appearance and manners, my native tongue, which nobody spoke at Florence; my rich attire, my splendid bracelets, my coral necklace, and all the gifts of the Countess Borghi, soon attracted much attention. I was sent for; people were pleased to see me, and liked to listen to me.

But what struck other people so pleasingly made only an unfavourable impression on my mother; for the slightest fault I was punished with the greatest severity.

On one occasion she gave me such a violent blow with her heavy hand that I fainted, and, falling backwards, hurt myself terribly. When I recovered from my fainting fit, I could not restrain my grief. Going into a corner, I gave myself up to the most frightful despair, invoking my protectress with loud cries and calling to her for help.

Vain lamentations! Henceforth given over to my ill fortune, I was never again to find maternal consolation.

My father had a sister who was very unfortunate in her marriage; she left her husband and[53] came to live with us. She and my mother could never get on; they detested each other, and were perpetually quarrelling.

Witnessing their disputes, my father sometimes took the part of one, sometimes of the other; still more often he reproved both of them, and drew their anger upon himself. The arrival of my paternal grandmother, who, growing old, came to be with her son, led to fresh subjects for wrangling; and as they were all violent and passionate, our house was like a veritable hell upon earth.

These interminable quarrels were not caused, as might be supposed, by the cares attending poverty. Though my father’s post brought him in no more than a hundred francs a month, he had always plenty of money. He was well dressed, and often gave large dinners. He had abundance of provisions, and his cellar contained wines of the best kinds. He had a very pretty house and a splendid garden.

But these advantages were far from making up to me for my annoyances, or from doing away with the mortal weariness I felt in the bosom of my family.

I bewailed my fate unceasingly; I felt humiliated by my circumstances; I envied the ladies who possessed many servants, beautiful mansions, fine equipages, and most of all those who were received at Court.

These lofty aspirations were always with me; they were so deeply graven on my mind, so natural to me after a fashion, that I should have liked always to live with the great, and felt myself grievously hurt when I was obliged to keep company with common people.

I had, too, a decided taste for the fine arts; I had a passion for antiquities, and I do not doubt that I should have made great progress if my talents had been cultivated.

However, from the age of seven I was given lessons in writing, dancing, music, etc.

As my voice and my skill were remarkable, my parents made me early an object of speculation, and I was forced into practising cruelly. They made me sing, or play the piano eight hours a day, which inspired me with an insurmountable detestation of that instrument.

If my master complained of my inattention, I was shut up in the music-room from six in the[55] morning till eight in the evening and given hardly anything to eat. If by chance I got a good report, I was pretty well treated, my father made me a present of twopence, and my mother told me ghost stories, which terrified me to such an extent that I scarcely dared to be alone during the night.

One day when they had forgotten to open my prison at the usual hour, I was suddenly seized with a panic of terror, and, quite beside myself, I opened the window and threw myself out into the garden, without doing myself any harm, however.

About this time great rejoicings were taking place in Pisa in honour of their Neapolitan Majesties, who were on a visit to the Grand Duke Leopold.

My mother, wishing to take the opportunity of going to see her sister, who lived in that town, my father gave his consent, on condition that my aunt and I should be of the party.

With what transports of joy did I receive this agreeable news! What a delightful and lively satisfaction it would be to let my dear piano rest!

Great preparations were made for my toilette; several frocks were bought for me; my father gave me two gold watches and a very valuable[56] ring. He did not forget to make me take my shoes with their very high red heels, whose sound much delighted me.

We embarked on a public boat, and, although it was my first journey by water, my young imagination, far from dreading the perils of the furious element, was at once wonderfully diverted.

In twenty-four hours we landed at Pisa, where my uncle and aunt Fillipini, as well as their son and daughters, received us with open arms. They were greatly surprised to see me so richly clad, and said to my mother that no doubt her husband was very well off.

She answered only that I was a bastard, a name she gave me pretty often, and the meaning of which I did not understand.

Profiting by my father’s absence to treat me with greater harshness, she was eternally scolding and tormenting me; she went so far as to take away my watches and my ring, to give them, as she said, to the great Madonna. Unluckily for me, she managed to procure a piano, at which I was pitilessly forced to work.

One day, having suddenly sent for me, she[57] ordered me to sing for the amusement of two ragged and unpleasant-looking women she told me were intimate friends of hers.

Indignant at such a proposal, I said that a bit of bread was all they needed just at present.

She rose; I rushed to my room; but nothing could save me from her fury.

In vain did I beg her pardon, in vain entreated for mercy; a hail of blows fell upon me; my body was a mass of bruises; the blood streamed from my nose. I could not stand the overcoming pain; I went to bed, and did not rise from it again till we set out for Florence.

In this fashion my visit to Pisa became a real martyrdom for me instead of an amusement.

During my infancy I had been very subject to eruptions which from time to time appeared all over my body; but none had ever equalled that which was caused after my return by weariness and wretchedness. After the doctors had prescribed a lengthy course of cooling remedies, my parents, to rid themselves of such a nuisance, determined to send me to a hospital maintained at the expense of the Grand Duchess, and the admission to which needed great interest. Nevertheless,[58] my father got an order without any difficulty.

I stayed there several weeks, and I must proclaim aloud that I felt as if I had refound my dear Countess in the person of each of the sisters who managed the hospital. Their constant care soon cured me; they were always near me, caressing me, and giving me fruit and sweetmeats.

No, no one could have been kinder, more courteous than those charitable women, to whom I vowed eternal gratitude, and whom I could not leave without anguish.

Fresh Tortures—My Parents’ Talks—Theatres—Mysterious Letter—Troublesome Visits—Useless Prayers—My Protests.

Nature had given me a good figure; nevertheless, my father maintained that I stooped, that one of my shoulders was higher than the other, and that my feet grew large too quickly.

To remedy these imaginary defects he made me wear an iron collar, which was taken off only at meal-time, a steel corset that increased the torture and really made me deformed, and shoes so narrow and short that I could hardly walk.

When I begged him to take off this painful apparatus, a box on the ear was his usual answer.

He often took me to the opera, to teach me, he said, to hold myself properly; to move my arms easily; to behave with grace.

All this rigmarole was an enigma to me, until at last he explained it to me in these terms—

“Isn’t it about time, my dear Maria, that you repaid what I have spent on your education?”

“How can I do that?” I answered quickly, and with a smile, “since all I have comes from you.”

Instantly he replied—

“This is the way you are going to do it. I have got you an engagement at the Piazza-Vecchia, where you will certainly make a great success.”

Dismayed by these words, I blushed, I trembled, and, concealing some of my trouble, I exclaimed—

“But the thing would be impossible. Don’t you know, father, that the presence of two or three lookers-on is enough to confuse me when I am taking my lessons?”

Vain subterfuge.

“Make a beginning,” he said harshly; “after you’ve done it a few times you’ll find all the courage you need.”

There was one last expedient left me. I flew to my mother and, with tears, begged her to remember how often she had told me that actresses deserved the most profound contempt. You may judge of my astonishment when I heard her answer thus—

“It was so formerly, my daughter; nowadays all that is changed; on the contrary, those ladies are admired and loved by everybody, and if they sing well they gain great wealth, and even sometimes marry great noblemen.”

After that I saw there was nothing more to hope for; my doom was fixed and my misfortune inevitable.

I was made to study my part, which my unwillingness made a very slow business, and when the day for acting it arrived, my parents themselves came to introduce me.

When my turn came I found it impossible to open my mouth. My youth and my simplicity stirred the pity of the whole audience, while my father endeavoured to express his displeasure and anger to me by frightful grimaces, which at last forced me to stammer out a few notes.

The spectators made the building echo with their loud cries of brava! brava! coraggio! and at the end of the play several ladies of quality asked to see me, praising me repeatedly and lavishing all sorts of endearments upon me.

All the time the carnival lasted I was compelled to carry out the painful task imposed on[62] me. One day, having tried to play the invalid, my father discovered the trick, and made me pay for it so dear that I did not again think of making that sort of excuse.

God alone knows how delighted I was when my engagement came to an end; but, alas! the relief was a short one. After a few months’ rest, my father announced to me that I was about to have the honour of appearing on a larger stage, adding that everything was arranged and settled and there was nothing left for me but to obey his orders.

The news came upon me like a clap of thunder. Putting aside my nervousness, I felt myself degraded and debased.

More especially did I feel ashamed when I heard the actresses saying to one another: “It is disparaging to us to have the daughter of a constable put amongst us.”

At this period I had two brothers and one sister, three little tyrants all of whose whims I had to humour; for if I made the smallest objection my mother encouraged them to abuse me and beat me, and throw stones at me. Fed and brought up delicately, nothing was good enough for them;[63] but I had no difficulty, nevertheless, in realizing that they were being prepared for no better fate than mine, and they, too, were destined for my degrading profession.

Too unfortunate already in that I belonged to such a family, I was far from expecting fresh troubles, when my father read aloud to us the following letter, which he had just received, addressed to me—

“I have seen you, you beautiful star, and listened to the melodious tones of your angelic voice; they have intoxicated my heart. I implore you, my angel, to come at ten o’clock to the least frequented walls of the town; there you will receive the faithful promises of your unknown adorer.”

This letter sent us into fits of laughter; my father alone was angry, and declared that if he could discover the impertinent author of such an anonymous letter he would severely punish him for his temerity.

The next day a messenger asked for me at the door. My father went in my stead, had a long talk with him, and I heard nothing further about it, till one day, having dressed me up like a goddess[64] and given me all my mother’s rings—carefully reduced in size with wax—to wear, I was told of the coming visit of an illustrious personage whom I was ordered to welcome.

At his arrival my parents bent themselves nearly double to show their respect, and motioned me to do the same.

I was inclined to mockery and could hardly contain myself, when I saw enter an old greybeard, from behind whose few and discoloured teeth came forth an offensive breath.

He was dressed in a blue coat braided with red, and wore a little white cloak with gold fringe, over which hung a thin queue, an ell long.

This gentleman, who, moreover, was stout, and might have been a fine-enough-looking man in his earlier years, introduced himself as Lord Newborough, an English nobleman, and, as he entered, told me he had come solely for the pleasure of hearing me sing.

How great was my reluctance to do as he asked! With what bad grace I sang!

My bravura ended, I made some excuse and retired.

A few days later milord appeared again; his visits became more and more frequent; soon they were daily.

Each time he talked to me of his wealth; boasted of his immense possessions; gave me the most magnificent descriptions of England; and was constantly repeating that he was a widower with only one son.

His Italian was so bad that I should never have understood his jargon without my father’s help.

I understood no better why I was always so well got-up, so adorned with jewels and diamonds. When I asked the reason, I was told that all this finery would induce the great lord to increase the value of the presents he could not fail to make me.

In vain I did my utmost to convince my parents that I hated the very idea of receiving the least thing from him. They overwhelmed me with reproaches, asking me if this was the way I meant to repay them; representing to me that they had to provide for the education of three other children; and at last saying plainly—

“How would it be if you had to marry this[66] man whom you had no right to look for, and who is so much above you?”

Unhesitatingly I cried, “O Dio! Dio! I would rather die!”

Then my father bade me remember that his power over me was absolute and that I was bound to obey his commands; my mother joined in and declared, with an oath, that, willing or not, I should be the wife del signore inglese.

Realizing that it was not a joke, I implored them to let me become a nun, or to do with me what they pleased so long as I was not forced to make such a detestable match; but my words, my tears, my sighs, resulted only in making them more angry and eliciting more hateful oaths.

Then I ran to my grandmother and my aunt, begging them to take my part. They did as I asked, but without success; they were only forbidden to mention the subject again.

Wounded to the very depths of my heart, I gave myself up wholly to my grief, scarcely alive or able to breathe.

Milord himself came to rouse me from my stupor.

At the sight of him I gave a wild cry, and, falling[67] at his knees, with sobs implored him not to exact such a sacrifice from me; to think of my youth; to see that I could not reasonably give my hand to a man old enough to be my grandfather and for whom I felt an insurmountable aversion.

He did nothing but laugh at my pitiful simplicity; and, raising me from my lowly attitude, he said to me that if I did not love him yet, I would later on; that his rank, his estates, his wealth, and all the fine things I should enjoy, would oblige me to love him dearly.

At these words my whole being was possessed by fury; I violently thrust back my insupportable persecutor, looking at him with blazing eyes; I abused him, passionately declaring that I would rather endure any plague than the union he offered me; that I would rather face all the miseries in the world; that death itself would be nothing to dread; that, besides, my hatred of him had come to its height; that it was so deeply rooted in my heart that nothing could tear it up, and that my greatest happiness would be to be rid of his presence for ever.

Arrangements with Milord—His Son—Brain-fever—Fruitless Attempts—My Marriage—My Husband’s Conduct—The Avarice of my Parents—An Envoy from England.

Though my engagement at the theatre was to end in a fortnight, my father got a substitute for me, and himself gave up his post; maintaining that all that was henceforth incompatible with the high rank I was to attain.

Nevertheless, he did not forget to take his precautions, but effected an agreement greatly to his own advantage, and, with no thought for my future, simply put me at the mercy of my elderly adorer in consideration for a sum of fifteen thousand francesconi, a pension of thirty ducats a month, and the proprietorship of a magnificent country house at Fiesole, very well furnished, with a courtyard, gardens, and two immense vineyards.

Moreover, milord promised to pay the expenses of the whole family during his whole stay in Italy on condition that he and his son were allowed to live with us.

That young man was then sixteen years old, tall and well made; Nature had endowed him with ability and a good heart, but he was so ignorant and uncouth that it was pitiful to see him. He could neither read nor write, and used the coarsest expressions; his greatest pleasure was the company of low people or servants.

He talked a great deal about a Signora Bussoti, wife of milord’s cook, telling any one who choose to listen that this very respectable person had caused his mother’s death, and was daily eating up his father’s fortune; that she had children whose legitimacy was anything but certain, and for whose sake he himself had often been beaten.

These speeches, and many other blemishes I caught sight of through the trouble my future husband took to prevent my being entirely disgusted with him, finished by making me realize completely the depth of the abyss into which I was to be thrown. My youthful imagination took fright, and I could no longer bear the weight of my misery.

All at once I was seized with violent pain, my senses were benumbed, my head turned, and for[70] twenty-six days my life was despaired of. Even in my delirium the thought of my unhappiness did not leave me; I cried aloud; I breathed complaints; I made incoherent murmurs. My grandmother and my aunt were inconsolable; they were always with me, and their constant and affectionate care greatly contributed to my recovery.

Alas! as soon as I recovered consciousness, I regretted that I was alive; I rose and rushed to the balcony; but my father came in, took hold of me and stopped me.

Vainly I took the opportunity to repeat my humble remonstrances and to swear perfect obedience to him in every other respect; he only put before me, in his turn, all the supposed advantages I should gain, and averred that the Grand Duke, knowing all about me, absolutely required me to be ennobled.

As soon as I was well enough to go out, the doctors advised country air, and we went to Fiesole, a little town three miles from Florence.

There a new idea came to me, which at first I believed might be very useful. I urged the difference of religion and the impossibility of my marrying a Protestant.

But the old heretic did away with that difficulty at once.

“I’ll turn Jew!” he exclaimed; “I’ll turn Mussulman; I’ll turn idolater; I’ll turn anything you like so long as you’ll consent to be my wife.”

And he called in priests and monks to instruct him, and neglected nothing necessary for becoming a member of the Roman Church.

After that there was nothing to be done but fix the day for my immolation.

The fatal day arrived, and by the first light of dawn we made ready to start for Florence.

Before getting into the carriage, for the last time I threw myself at the feet of my inexorable parents, watering them with my tears, while sobs choked my voice.

My mother grew angry and heaped abuse on me; my father raised me roughly, saying crossly, “The Grand Duke wishes it; there’s no way of going back now.”

We set off at once, and fearing that the populace might rise against the unjust violence done to a girl of thirteen, we went not to a public church but to a private chapel.

I was led to the foot of the altar and placed by the side of the man I abhorred.

Questioned by the minister, I had nearly answered in the negative, when my father pinched me, and, with a muttered threat that he would kill me, somehow extorted from me the fatal vow which put the seal on my wretched fate.

The ceremony over, we returned to Fiesole, where a number of friends came to offer their congratulations.

Instead of receiving them, I shut myself up in my room, and it was in vain that they sent for me. I took no food but what my grandmother and aunt brought to me in secret.

At the end of four days my father burst open the door, forced me to go out, and put me into the arms of my husband, or rather my insufferable keeper; for he was so full of jealousy that he could not endure the presence of a man. If I went out, he wanted to accompany me, or sent some one after me.

Scores of times he was guilty of rudeness to people who honoured me with their salutations, and on every hand he thought he saw favoured rivals or dangerous emissaries.

Every day the fumes of wine upset his weak mind; he gave way to frightful fits of anger, and after having infinitely increased the usual discomforts of our dreary household, he would fall into a deep sleep in which he snored loudly.

He speedily conceived such an antipathy for the various members of my family that he never spoke of them but by the most filthy names.

When I reminded him of the affectionate and loving names he constantly called me by, he always answered, “As for you, my dear better-half, you may feel quite sure there is nothing in common between your charming self and that odious stock.”

And truly I was often astonished myself that there was so obvious a difference, whether in the colour and shape of the face, whether in the disposition and temperament, the bearing and speech, or the mental faculties and the inclinations of the heart.

The contrast was especially striking between my generosity and the well-known avarice of the Chiappinis.

They were in constant torment from this passion; they were for ever exhorting me, urging me[74] to ask for money, to demand ornaments, to go to shops to buy them whatever they wanted.

My humouring them, their own extravagances, and, even more, the insatiable claims of the charming Bussoti, soon exhausted the exchequer of milord, whose credulity let him be robbed of nearly his last farthing.

I don’t know what would have become of him if Mr. Price, his man of business, had not opportunely arrived.

This gentleman handed over some ready money to him, and prepared to return and send him back some larger sums.

There was waiting, and impatience, and counting of days and hours! At last the post brings a letter. My father goes to fetch it, breaks the seal, has it translated, and its contents are known before it reaches the person to whom it is addressed.

It announces the sending off of several trunks. Joyful news! Clapping of all hands!

But what a surprise! When the trunks, so longed for, were opened, nothing was to be seen but a heap of old rubbish that Mr. Price had doubtless got together from the wardrobes of[75] milord’s grandmamas, and by which he had thought he might temporarily assuage the raging thirst of my greedy relatives.

I could not help laughing, while my mother, bawling at the top of her voice, accused me of carelessness, declaring that if there was nothing better, it was because I had not been willing to ask for anything.

Return to Florence—Rupture and Reconciliation—The British Minister—English Lady’s-maid—Milord’s Imprisonment—My Flight—Presents and Promises—My Father’s Avowal—My Behaviour Towards Him—His Obliquity.

My husband soon wearied of the country and wanted to return to Florence. There he hired a fine house, big enough to hold us all; the first storey was to belong to him, his son and me; my parents occupied the second. We were to be independent of each other, but Lord Newborough was still responsible for the expenses of the double household.

Although forty-five years old, my mother was then enceinte, and gave birth to a fifth boy, who was named Thomas, after milord, his godfather.

LORD NEWBOROUGH

FROM A PICTURE AT GLYNLLIFON

The education of my brothers took a quite different direction from what had seemed probable at first. My husband placed them in a large school, with his own son, who could not stay there more than a few months. Afterwards an attempt was made to give him a tutor; but the[77] young man was irrevocably ruined. When the tutor saw him he said, “I have come too late.”

In changing my abode I had in no way changed my situation; milord kept up his usual style of living, giving me endless trouble; and those who ought to have been a comfort to me, treated me with contempt, only saying, “Really, you are not worthy of your lot; don’t you understand that you are on the eve of becoming a very wealthy widow, and that soon you will be able to do just what you please?”

But in spite of these fine words, they did not show themselves very willing at times to put up with the fits of rage of the irascible old man.

One day, when the intoxicating fumes had got greatly into his head, he provoked my father by his abuse and rushed at him to strike him. Armed with a big stick and wild with rage, my father vigorously returned the assault, till the noise they made and their outcries attracted a crowd which separated them.

The assailant left his house and ordered me to follow him. As I clearly and positively refused to do so, I received a note in which he informed me that if I did not do as he asked, he should put[78] an end to his life. I seized a pen and wrote him these few words—

“My old fool, if you wish to give me a proof of your affection, make haste and carry out what you announce to your unhappy victim,

“Maria.”

Several days went by without my hearing anything about him, and I was almost happy; but this calm was but the prelude to the storm.

One of his servants came to tell me that he was dangerously ill, and that, feeling his last hour to be at hand, he begged to see me that he might make important communications to me.

It was in vain I answered that I had no wish to receive any; my father pointed out to me that such conduct on my part could not fail to be very prejudicial to us.

He added that he would go with me, and swore that he would bring me back with him.

Reassured by this promise, I agreed, on condition that our visit should be a short one.

As I entered, I was greatly astonished at seeing the British Minister beside milord’s bed.

The supposed sick man held out his hand to me and assured me that it needed only my presence for his complete recovery; that he was very sorry for having given me so much trouble, and that it should not happen again.

“I wish you good health,” I replied quickly; “but to return to you is quite impossible; and I declare to you that if it had not been to please my father, you would never have seen me here.”

I got up at once, and signed to my father to leave.

He did not stir; his look revealed the plot to me, and I realized his deceitfulness.

The Minister did all he could to lessen my vexation, and averred that he took upon himself the responsibility for the conduct of my husband in the future.

From that moment that gentleman showed me much attention; he introduced me to his wife, and procured me the acquaintance of several English ladies, among others the Misses C., with whom I became very intimate, especially the second, afterwards the Marchioness of B., my greatest friend.

Still I had to endure numberless mortifications; the Italian nobility looked down on me, and milord was invited by himself to the great receptions. Moreover, my domestic circumstances had become more unbearable than ever.

My husband had insisted on giving me a lady’s-maid of his own country and choice, the most worthless of women. In a short time she had succeeded in wholly captivating her old master, and even more, his son, so that she ruled despotically in the house; nothing was done without her, her advice was received like an oracle, and her words were commands no one dared disobey. If I allowed myself a comment, she treated me like a child, and took pleasure in secretly taunting me with my lowly origin and the contemptible part I had played in my own despite. I could not take a step without having her at my heels, finding fault with everything I did; and as my most innocent doings were always malignantly misconstrued, I made up my mind to give up all outside amusements.

Keeping to my own room, I had no recreation but music and the care of my birds.

One day when I was petting my favourite[81] sparrow, they came to tell me that milord was asking for me to go out driving with him. I went down, quite resolved to make my rightful complaints to him.…

Our carriage, having crossed the town, was stopped at the barrier. We went to another of the gates and were treated in the same fashion.

My husband, in a fury, accused Chiappini of this, and swore to have his revenge. He forbade me to hold any communication with him, and ordered his abominable confidante never to let me out of her sight. Paying no attention to his reproofs, I went back quietly to my room.

Suddenly there arose a great uproar in the next room; I opened the door and saw milord, followed by three constables, who seized him and dragged him away to the fortress.

The lady’s-maid screamed aloud and hurled a torrent of abuse at me.