The Project Gutenberg EBook of Gleanings from the Harvest-Fields of

Literature, by Charles Carroll Bombaugh

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Gleanings from the Harvest-Fields of Literature

A Melange of Excerpta

Author: Charles Carroll Bombaugh

Release Date: March 21, 2018 [EBook #56805]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GLENINGS ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing, Branden Aldridge and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

“So she gleaned in the field until even, and beat out that she had gleaned: and it was about an ephah of barley.” Ruth 2:17.

“I have here made a nosegay of culled flowers, and have brought nothing of my own but the string that ties them.”—Montaigne.

I am not ignorant, ne unsure, that many there are, before whose sight this Book shall finde small grace, and lesse favour. So hard a thing it is to write or indite and matter, whatsoever it be, that should be able to sustaine and abide the variable judgement, and to obtaine or winne the constant love and allowance of every man, especially if it containe in it any novelty or unwonted strangenesse.—Raynald’s Woman’s Book.

ivBid him welcome. This is the motley-minded gentleman.

—A fountain set round with a rim of old, mossy stones, and paved in its bed with a sort of mosaic work of variously-colored pebbles.

—A gatherer and a disposer of other men’s stuff.

A running banquet that hath much variety, but little of a sort.

They have been at a great feast of languages, and stolen the scraps.

There’s no want of meat, sir; portly and curious viands are prepared to please all kinds of appetites.

A dinner of fragments is said often to be the best dinner. So are there few minds but might furnish some instruction and entertainment out of their scraps, their odds and ends of thought. They who cannot weave a uniform web may at least produce a piece of patchwork; which may be useful and not without a charm of its own.

—It is a regular omnibus; there is something in it to everybody’s taste. Those who like fat can have it; so can they who like lean; as well as those who prefer sugar, and those who choose pepper.

Read, and fear not thine own understanding: this book will create a clear one in thee; and when thou hast considered thy purchase, thou wilt call the price of it a charity to thyself.

In winter you may reade them ad ignem, by the fireside, and in summer ad umbram, under some shadie tree; and therewith passe away the tedious howres.

An earlier edition of Gleanings having attracted the hearty approval of a limited circle of that class of readers who prefer “a running banquet that hath much variety, but little of a sort,” the present publisher requested the preparation of an enlargement of the work. In the augmented form in which it is now offered to the public, the contents will be found so much more comprehensive and omnifarious that, while it has been nearly doubled in size, it has been more than doubled in literary value.

Miscellanea of the omnium-gatherum sort appear to be as acceptable to-day as they undoubtedly were in the youthful period of our literature, though for an opposite reason. When books were scarce, and costly, and inaccessible, anxious readers found in “scripscrapologia” multifarious sources of instruction; now that books are like the stars for multitude, the reader who is appalled by their endless succession and variety is fain to receive with thankfulness the cream that is skimmed and the grain that is sifted by patient hands for his use. Our ancestors were regaled with such olla-podrida as “The Gallimaufry: a Kickshaw [Fr. quelque chose] Treat which comprehends odd bits and scraps, and odds and ends;” or “The Wit’s Miscellany: odd and uncommon epigrams, facetious drolleries, whimsical mottoes, merry tales, and fables, for the entertainment and diversion of good company.” To the present generation is accorded a wider field for excursion, from the Curiosities of Disraeli, and the Commonplaces of Southey, to the less ambitious collections of less learned collaborators.

“Into a hotch-potch,” says Sir Edward Coke, “is commonly put not one thing alone, but one thing with other things together.” The present volume is an expedient for grouping together a variety which will be found in no other compilation. From the nonsense of literary trifling to the highest expression of intellectual force; from the anachronisms of art to the grandest revelations of science; from selections for the child to extracts for the philosopher, it will accommodate the widest diversity of taste, and furnish entertainment for all ages, sexes, and conditions. As a pastime for the leisure half-hour, at vihome or abroad; as a companion by the fireside, or the seaside, amid the hum of the city, or in the solitude of rural life; as a means of relaxation for the mind jaded by business activities, it may be safely commended to acceptance.

The aim of this collation is not to be exhaustive, but simply to be well compacted. The restrictive limits of an octavo require the winnowings of selection in place of the bulk of expansion. Gargantua, we are told by Rabelais, wrote to his son Pantagruel, commanding him to learn Greek, Latin, Chaldaic, and Arabic; all history, geometry, arithmetic, music, astronomy, natural philosophy, etc., “so that there be not a river in the world thou dost not know the name and nature of all its fishes; all the fowls of the air; all the several kinds of shrubs and herbs; all the metals hid in the bowels of the earth, all gems and precious stones. I would furthermore have thee study the Talmudists and Cabalists, and get a perfect knowledge of man. In brief, I would have thee a bottomless pit of all knowledge.” While this book does not aspire to such Gargantuan comprehensiveness, it seeks a higher grade of merit than that which attaches to those who “chronicle small beer,” or to him who is merely “a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles.”

Quaint old Burton, in describing the travels of Paulus Emilius, says, “He took great content, exceeding delight in that his voyage, as who doth not that shall attempt the like? For peregrination charms our senses with such unspeakable and sweet variety, that some count him unhappy that never traveled, a kind of prisoner, and pity his case that from his cradle to his old age beholds the same still; still, still, the same, the same.” It is the purpose of these Gleanings to compass such “sweet variety” by conducting the reader here, through the green lanes of freshened thought, and there, through by-paths neglected and gray with the moss of ages; now, amid cultivated fields, and then, adown untrodden ways; at one time, to rescue from oblivion fugitive thoughts which the world should not “willingly let die,” at another, to restore to sunlight gems which have been too long “underkept and down supprest.” The compiler asks the tourist to accompany him, because with him, as with Montaigne and Hans Andersen, there is no pleasure without communication, and though all men may find in these Collectanea some things which they will recognize as old acquaintances, yet will they find many more with which they are unfamiliar, and to which their attention has never been awakened.

| Alphabetical Whims. | |

|---|---|

| The Freaks and Follies of Literature—Account of certain Singular Books—What are Pangrammata?—The Banished Letters—Eve’s Legend—Alphabetical Advertisement—The Three Initials—A Jacobite Toast—“The Beginning of Eternity”—The Poor Letter II—The Letters of the World—Traps for the Cockneys—Ingenious Verses on the Vowels—Alliterative Verses—“A Bevy of Belles”—Antithetical Sermon—Acrostics—Double, Triple, and Reversed Acrostics—Beautiful and Singular Instances—The Poets in Verse—On Benedict Arnold—Curious Pasquinade—Monastic Verses—The Figure of the Fish—Acrostic on Napoleon—Madame Rachael—Masonic Memento—“Hempe”—“Brevity of Human Life”—Acrostic Valentine—Anagrams—German, Latin, and English Instances—Chronograms. | 25 |

| Palindromes. | |

| Reading in every Style—What is a Palindrome?—What St. Martin said to the Devil—The Lawyer’s Motto—What Adam said to Eve—The Poor Young Man in Love—What Dean Swift wrote to Dr. Sheridan—“The Witch’s Prayer”—The Device of a Lady—Huguenot and Romanist; Double Dealing. | 59 |

| Equivoque. | |

| A Very Deceitful Epistle—A Wicked Love Letter—What a Young Wife wrote to her Friend—The Jesuit’s Creed—Revolutionary Verses—Double Dealings—A Fatal Name—The Triple Platform—A Bishop’s Evasion—The “Toast” given by a Smart Young Man—“The Handwriting on the Wall”—French Actresses—How Mlle. Mars told her Age—A Lenient Judge—What Mlle. Cico whimpered to “the Bench.” | 64 |

| The Cento. | |

| viii“A Cloak of Patches”—How Centos are made—Mosaic Poetry—The Poets in a Mixed State—New Version of Old Lines—Cento on Life—A Cento from thirty-eight Authors—Cento from Pope—Biblical Sentiments—The Return of Israel—Religious Centos. | 73 |

| Macaronic Verse. | |

| “A Treatise on Wine”—Monkish Opinions—Which Tree is Best?—A Lover with Nine Tongues—Horace in a New Dress—What was Written on a Fly-Leaf—“The Cat and the Rats”—An Advertisement in Five Languages—Parting Address to a Friend—“Oh, the Rhine!”—The Death of the Sea Serpent. | 78 |

| Chain Verse. | |

| Lasphrise’s Novelties—Singular Ode to Death—On “The Truth”—“Long I looked into the Sky”—A Ringing Song—A Gem of Three Centuries Old. | 85 |

| Bouts Rimés. | |

| The Skeletons of Poetry—How the Poet Dulot lost all his Ideas—The Flight of three hundred Sonnets—The “Nettle” Rhymes—How a Young Lady teased her Beau—Assisting a Poet—Miss Lydia’s Acrostic—Alfred De Musset’s Lines—What the Duc de Malakoff wrote—Reversed Rhymes—How to make “Rhopalic” verses!—What they are. | 88 |

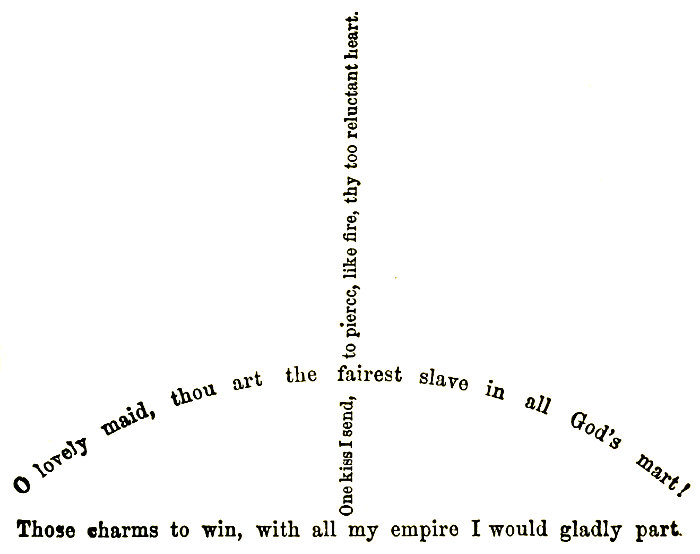

| Emblematic Poetry. | |

| Poetry in Visible Shape—The Bow and Arrow of Love—The Deceitful Glass—Prudent Advice—A Very Singular Dirge—Poetry among the Monks—Sacred Symbols—A Hymn in Cruciform Shape—Ancient Devices—Verses within the Cross—Cypher—“U O a O. but I O U”—Perplexing Printer’s Puzzle—An Oxford Joke—The Puzzle of “The Precepts Ten”—A Mysterious Letter to Miss K. T. J. | 92 |

| Monosyllables. | |

| ixThe Power of Little Words—How Pope Ridiculed them—The “Universal Prayer”—Example of Dr. Watts—Wesley’s Hymns—Writings of Shakespeare and Milton—“Address to the Daffodils”—Geo. Herbert’s Poems—Testimony of Keble, Young, Landor, and Fletcher—Examples from Bailey’s “Festus”—The Short Words of Scripture—Big and Little Words Compared. | 98 |

| The Bible. | |

| Who wrote the Scriptures—Why—And When—Accuracy of the Bible—The Testimony of Modern Discoveries—Scope and Depth of Scripture Teaching—What Learned Men have written of the Bible—Testimony of Rousseau, Wilberforce, Bolingbroke, Sir Wm. Jones, Webster, John Quincy Adams, Addison, Byron, &c.—Who Translated the Bible—Wickliffe’s Version—Tyndale’s Translation—Matthew’s Bible—Cranmer’s Edition—The Geneva Bible—The Breeches Bible—The Bishop’s Bible—Parker’s Bible—The Douay Bible—King James’s Bible—The Number of Books, Chapters, Verses, Words, and Letters in the Old and New Testaments—The Bible Dissected—An Extraordinary Calculation—Distinctions between the Gospels—The Lost Books—What the word “Selah” means—The Poetry of the Bible—Shakespeare’s Knowledge of Scripture—The “True Gentleman” of the Bible—Misquotations from Scripture—A Scriptural “Bull”—Wit and Humor in the Bible—Sortes Sacræ—Casting Lots with the Bible. | 103 |

| The Name of God. | |

| How God is known—His Name in all the tongues of Earth—Ancient Saxon Ideas of Deity—“Elohim” and “Jehovah”—The “Lord” of the Ancient Jews—“God in Shakespeare”—The Fatherhood of God—The Parsee, Jew, and Christian. | 127 |

| I. H. S. | |

| The Name of Jesus—What does I. H. S. Mean?—De Nomine Jesu—What St. Bernardine did—“The Flower of Jesse”—Story of the Infant Jesus—Ancient Legends of Christ—Persian Story; The Dead Dog—Description of Christ’s Person—The Death Warrant of Christ—The Sign of the Cross in Ancient America. | 130 |

| The Lord’s Prayer. | |

| xThy and Us—The “Spirit” of the Lord’s Prayer—Gothic Version of the Fourth Century—Metrical Versions—Set to Music—The Prayer Illustrated—Acrostical Paraphrase—What the Bible Commentators Said—The Prayer Echoed—A Singular Acrostic. | 136 |

| Ecclesiasticæ. | |

| Anecdotes of Clergy—Excessive Civility—A Very Polite Preacher—Dean Swift’s short Sermon—“Down with the Dust”—An Abbreviated Sermon—Dr. Dodd’s Sermon on Malt—Bombastic Style of Bascom—The Preachers of Cromwell’s time—When a man ought to Cough!—Origin of Texts—How the Ancient Prophets Preached—Clerical Blunders—Proving an Alibi—Whitefield and the Sailors—Protestant Excommunication—The Tender Mercies of John Knox. | 143 |

| Puritan Peculiarities. | |

| The Puritan Maiden “Tribby”—A Jury-List of 1658—An Extraordinary List of Names—Singular Similes—Early Punishments in Massachusetts—Virginia Penalties in the Olden Time—Primitive Fines for Curious Crimes—Staying away from Church—The “Blue Laws” of Connecticut—Hard Punishments for Little Faults. | 150 |

| Paronomasia. | |

| The Art of Pun-making—What is Wit?—Puns Among the Hebrews—A Pungent Chapter—Punning Examples—The Short Road to Wealth—A “Man of Greece”—Witty Impromptus of Sydney Smith—Startling toast of Harry Erskine—“Top and Bottom”—The Imp of Darkness and the Imp o’ Light—A Printer’s Epitaph—The “whacks” and the “stick”—“Wo-man” and “Whim-men”—Faithless Sally Brown—Whiskers versus Razors—Pleasure and Payne—Plaint of the old Pauper—To my Nose—Bad “accountants” but excellent “book-keepers”—The Vegetable Girl—On an Old Horse—Grand Scheme of Emigration—“The Perilous Practice of Punning”—“Tu Portu Salus”—On a Youth who was killed by Fruit—The Appeal of Widow-Hood—Swift’s Latin Puns—Puns in Macbeth—Classical Puns and Mottoes—Mottoes of the English Peerage—Jeux-de-Mots—How Schott Willing—A Catalectic Monody—Bees of the Bible—Franklin’s “Re’s”—Funny “Miss-Nomers”—Crooked Coincidences—A Court Fool’s Pun. | 155 |

| English Words and Forms of Expression. | |

| xiDictionary English—Number of words in the English Language—Language of the Bible—Sources of the Language—Helping a Foreigner—Difficulties of the Language—Disraelian English—Why use “Ye”?—Its, His, and Her—How often “That” may be used—How many sounds are given to “ough”—A Literary Squabble—Concerning certain Words—Excise, Pontiff, Rough—Dr. Johnson in Trouble—Americanisms—“No Love Lost”—The Forlorn Hope—Quiz—Tennyson’s English—Eccentric Etymologies—Words which have changed their Meaning—Strange Derivations—Influence of Names—Big Words and Long Names. | 182 |

| Tall Writing. | |

| The Domicile erected by John—New Version of an Old Story—Curiosities of Advertising—Mr. Connors and his big Words—Curiosities of the Post Office—Singular Play Bill—Andrew Borde, his Book—The Mad Poet—Foote’s Funny Farrago—Burlesque of Dr. Johnson—Newspaper Eulogy—“Clear as Mud”—An Indignant Letter—A Chemical Valentine—The Surgeon to his Lady-love—The Lawyers Ode to Spring—Proverbs for Precocious Pupils. | 212 |

| Metric Prose. | |

| Unconscious Poetizing—Cowper’s Rhyming Letter to Newton—Poetic Prose in Irving’s Knickerbocker—Example from Disraeli’s “Alroy”—Unintentional Rhythm in Charles Dickens’ works—Old Curiosity Shop and Nicholas Nickleby—American Notes—Versification in Scripture—Rhymes from Celebrated Prosers—Curious Instance of Abraham Lincoln—Opinion of Dr. Johnson—Examples from Kemble and Siddons. | 223 |

| The Humors of Versification. | |

| The Story of the Lovers—Mingled Moods and Tenses—The Stammering Wife—A Song with Variations—“While She Rocks the Cradle”—A Serio-Comic Elegy—Reminiscence of Troy—Concerning Vegetarianism—W. C. Bryant as a Humorist—Address “To a Mosquito”—The “Poet” of the “Atlantic”—Bryant’s Travesty—A Rare Pipe—The Human Ear—A Lesson in Acoustics—Amusing Burlesque of Tennyson—Sir Tray; an Arthurian Idyl—All About the “Ologies”—The Variation Humbug—Buggins and the Busy Bee—Comical Singing in Church—The Curse of O’Kelly. | 230 |

| Hiberniana. | |

| xiiIrish Bulls and Blunders—Miss Edgeworth on the “Bull”—Comical Letter of an Irish “M. P.”—Bulls in Mississippi—American Bulls—The New Jail—A Frenchman’s Blunder—The “Puir Silly Body” who wrote a Book—The “bulls” of Classical Writers—Bulls from every Quarter and of all kinds. | 252 |

| Blunders. | |

| Slips of the Press—The Bishop Accused of Swearing—The Damp Old Church—From a French Newspaper—The Pig-killing Machine and the Doctor—Slips of the Telegraph—Simmons and the Cranberries—Finishing his Education—The Poets in a Quandary—Blunders of Translators—Rather Gigantic Grasshoppers—“Love’s last Shift”—Amusing Blunder of Voltaire—“A Fortune Cutting Meat”—A New “Translation” of Hamlet—The Frenchman and the Welsh Rabbit. | 259 |

| Misquotations. | |

| Curious Misquotations of Well-known Authors—Example of Collins—Sir Walter Scott in Error—Blunder of Sir Archibald Alison—Cruikshank as the Real “Simon Pure”—Judge Best’s “Great Mind”—Byron’s Little Mistake. | 266 |

| Fabrications. | |

| The Description of Christ’s Person a Fabrication—“Detector’s” Charge against Scott—The “Ministering Angel” not a Fabrication—The Moon Hoax—A Literary “Sell”—Carlyle’s Worshippers Outwitted—Mrs. Hemans’ Forgeries—Sheridan’s “Greek”—Spurious Ballads—The Simple Ballad Trick—A Hoax upon Scott—Psalmanazar’s Celebrated Fabrications—Benjamin Franklin’s Parable—The Forgeries of Ireland—Imitations of Shakespeare. | 269 |

| Interrupted Sentences. | |

| The Judge and the Criminal—“Free from Guile”—Poor Mary “Confined”—Erskine’s “Subscription”—A Satisfactory Note—“Little Hel”—Going to War—The Poet Assisted; the Sun and the Fishes—Giving him the “lie”—De Quincey and the Fiend—Wit in the House of Commons. | 277 |

| Echo Verse. | |

| xiiiAncient Echo Verses—Address to Queen Elizabeth—London before the Restoration—Echo Song by Addison—A Dutch Pasquinade—The Gospel Echo—Echo and the Lover—Dean Swift’s verses on Women—Buonaparte and the Echo—Fatal Verses—Why Palm, the Publisher, was shot—Remarkable Echoes—A Fatal Confession—Extraordinary facts in Acoustics—Hearing Afar Off. | 281 |

| Puzzles. | |

| Puzzles defended: their use and value—Exercise for the Mind—Ancient Perplexities—“The Liar”—“Puzzled to Death”—A French rebus—Napoleon Buonaparte’s Cypher—A Queer-looking Proclamation—A curious Puzzle for the Lawyers—Sir Isaac Newton’s Riddle—Cowper’s Riddle—Canning’s Riddle—A Prize Enigma—Quincy’s Comparison—Perplexing Intermarriages—Prophetic Distich—The “Number of the Beast”—Galileo’s Logograph—Persian Riddles—The Chinese Tea Song—Death and Life—The Rebus—What is it?—The Book of Riddles—Bishop Wilberforce’s Riddle—Curiosities of Cipher—Secret Writing—Remarkable Cryptographs. | 290 |

| The Reason Why. | |

| Why Germans Eat Sauer-Kraut—Why Pennsylvania was Settled—Whence the Huguenots derived their name—How Monarchs Die—Origin of the name of Boston—Concerning Weathercocks—Cutting off with a Shilling—Why Cardinals hats are red—The Roast Beef of England—A Sensible Quack—Who was the first Gentleman—Solution of a Juggler’s Mystery. | 310 |

| Weather-Wisdom. | |

| Sheridan’s Rhyming Calendar—Sir Humphrey Davy’s Weather Omens—Jenner’s “Signs of the Weather”—“The Shepherd’s Calendar”—Predictions from Birds, Beasts, and Insects—Circles round the Sun and Moon—Quaint Old-time Prophecies—The Evil Days of every Month. | 317 |

| O. S. and N. S. | |

| The Julian and the Gregorian Calendars—How Cæsar arranged the Calendar—The Julian Year—Going faster than the Sun—Pope Gregory’s Efforts—Origin of the New Style—“Poor Job’s Almanac”—The Loss of Eleven Days—How the matter was Explained. | 325 |

| Memoria Technica. | |

| xivThe Books of the Old Testament—The Books of the New—Versified helps to Memory—Names of Shakespeare’s Plays—List of English Sovereigns—Names of the Presidents—The Decalogue in verse—Short Metrical Grammar—Number of days in each Month—How Quakers Remember. | 327 |

| Origin of Things Familiar. | |

| Mind your P’s and Q’s—All Fool’s Day—The First Playing Cards—“Sub Rosa”—“Over the Left”—“Kicking the Bucket”—The Bumper—A Royal Saying—Story of Joe Dun, the Bailiff—The First Humbug—Pasquinade—The First Bottled Ale—The Gardener and the Potatoes—Tarring and Feathering—The Stockings of Former Time—The Order of the Garter—Drinking Healths—A Feather in his Cap—The Word “Book”—Nine Tailors and One Man—“Viz”—Signature of the Cross—The Turkish Crescent—The Postpaid Envelopes of the 17th Century—Who first sang the “Old Hundredth?”—Who wrote the “Marseillaise Hymn?”—Thrilling Story of the French Revolution—The Origin of “Yankee Doodle”—Story of Lucy Locket and Kitty Fisher—How Dutchmen sing “Yankee Doodle”—How the American Flag was chosen—Who was Brother Jonathan? What is known of “Uncle Sam!”—The Dollar Mark [$]: what does it mean?—Bows and Arrows in the Olden Time—All about Guns—The first Insurance Company—The Banks of three Centuries ago—The Invention of Bells—Who first said “Boo!”—Who made the first Clock—The Watches of the Olden Time—All about the Invention of Printing—The first Cock-fights—Meaning of the word “Turncoat”—Who invented Lucifer Matches?—When was the Flag of England first unfurled—Why are Literary ladies called “Blue Stockings?”—Origin of the word “Skedaddle”—How Foolscap Paper got its name—The First Forged Bank-Note—Who made the first “Piano Forte?”—The first Doctors—The first Thanksgiving Proclamation—First Prayer in Congress—The first Reporters—Origin of the word “News”—The Earliest Newspapers—Who sent the first Telegraphic Message. | 331 |

| Nothing New Under the Sun. | |

| xvFirst idea of the Magnetic Telegraph—Telegraph before Morse—Telegraph a Century Ago—Who made the first Steam Engine?—What Marian de l’Orme saw in the Mad-house—What the Marquis of Worcester Did—Richelieu’s Mistake—Wonderful Invention of James Watt—The first Ocean Steamer—Fulton and the Steam Engine—The first Balloon Ascension—What Franklin said about the Baby—An Inventor’s Mistake—Discovery of the Circulation of the Blood—What is “Anæsthesia?”—How the First Anodynes were made—How Adam’s “Rib” was taken from him—All about the Boomerang—Who Discovered the Centre of Gravity?—The first Rifle—Table-moving and Spirit-rapping in Ancient Times—What is “Auscultation?”—The Stereoscope—Ancient Prediction of the Discovery of America. | 375 |

| Triumphs of Ingenuity. | |

| How the Planet Neptune was Discovered—Le Verrier’s Wonderful Calculation—The Story of a poor Physician—An Astronomer at Home—How Lescarbault became Famous—The Discovery of the Planet Vulcan—Ingenious Stratagem of Columbus—How an Eclipse was made Useful—Story of King John and the Abbot—A Picture of the Olden Time—Clever Reply to Three Puzzling Questions—The Father Abbot in a Fix. | 395 |

| The Fancies of Fact. | |

| xviThe Wounds of Julius Cæsar—Some Curious Old Bills—“Mending the Ten Commandments”—Screwing a Horn on the Devil—Gluing a bit on his Tail—Repairing the Virgin Mary before and behind—Making a New Child—Why Bishops and Parsons have no Souls—The Story of a Curious Conversion—Singular Prayer of Lord Ashley—A Moonshine Story of Sir Walter Scott—Do Lawyers tell the Truth?—Patrick Henry’s Little Chapel—The True Form of the Cross—How Poets and Painters have led us astray—Curious Coincidences—How a Bird was Shot with a Stick—How a Musket-shot in the Lungs saved a Man’s life—Mysterious Tin Box found in a Shark’s Stomach—A Curious Card Trick—Which was the right Elizabeth Smith?—How Mrs. Stephens’s Patients were Cured—How a Girl’s Good Memory Caught a Thief—Choosing a Motto for a Sun-dial—Strange Story of a Murdered Man—The Chick in the Egg—Innate Appetite—The Indian and the Tame Snake—Why do Alligators Swallow Stones?—Curious Anecdote about Sheep—Celebrated Journeys on Horseback—A Horse that went to top of St. Peters’ at Rome—A Wonderful Lock—Wonders of Manufacturing—How Iron can be made More Precious than Gold—The Spaniard and his Emeralds—How a Cat was sold for Six Hundred Dollars—Another Cat sold for a Pound of Gold—The amount of Gold in the World—Amount of Treasure collected by David—How much Gold was found in California—What was brought from Australia—The Wealth of Ancient Romans—Wine at Two Million dollars a Bottle or $272 per drop—Who is permitted to drink it—Monster Beer Casks, and who made them—Gigantic Wine-tuns at Heidelberg and Königstein—A Beer-vat in which Two Hundred People Dined—Difference between the English Poets—Perils of Precocity—Children who were too Knowing—What became of 146 Englishmen who were confined in the Black Hole—How the Finns make Barometers of Stone—Singular Bitterness of Strychnia—Something about Salt—Curious Change of Taste—The Children of Israel armed with Guns—Simeon with a pair of “Specs”—Eve in a handsome Flounced Dress—St. Peter and the Tobacco Pipe—Abraham shooting Isaac with a Blunderbuss—The Marriage of Christ with St. Catherine—Cigar-lighters at the Last Supper—Shooting Ducks with a Gun in the Garden of Eden—Wonderful Specimens of Minute Mechanism—Homer in a Nutshell—The Bible in a Walnut—Squaring the Circle—Mathematical Prodigies—Story of a Wonderful Boy—Babbage’s Calculating Machine—Extraordinary Feats of Memory—A Bishop’s Heroism—Silent Compliment. | 406 |

| The Fancies of Fact.—Continued. | |

| The Exact Dimensions of Heaven—The cost of Solomon’s Temple—The Mystic Numbers “Seven” and “Three”—Curious power of Number Nine—Size of Noah’s Ark and the Great Eastern—About Colors: their Immense Variety—Vast Aerolites, and what they are—Fate of America’s Discoverers—Facts about the Presidents—Value of Queen Victoria’s Jewels—An Army of Women—The Star in the East—Benjamin Franklin’s Court Dress—Extraordinary instances of Longevity—Do Americans live long?—A man who lived more than 200 years—“Quack-quack” and “Bow-wow”—A Marriage Vow of the Olden Time—“Buxum in Bedde and at the Borde”—What came in a dream to Herschel—Singular Facts about Sleep—Curious Chinese Torture—Do Fishes ever Sleep?—How a Bird Grasps his Perch when Asleep—How to gain Seven Years and a half of Life—Effects of Opium and Indian Hemp—Confession of an English Opium-Eater—Strange Effects of Fear—The Thief and the Feathers—The Poisoned Coachman—How a Man Died of Nothing—What Chas. Bell did to the Monkey—A Man with Two Faces—Thrilling Story of a “Broken heart”—No Comfort in being Beheaded—A Man who Spoke after his Head was cut off—A Man who Lived after Sensation was Destroyed—Comical Antipathies—Afraid of Boiled Lobsters—A Fish and a Fever—Why Joseph Scaliger couldn’t Drink Milk—The Man who Ran away from a Cat—About the Cock that Frightened Cæsar—The Two Brothers with One Set of feelings—How Dennis Hendrick won his Strange Bet—Walking Blindfolded—How to Tell the Time by Cats’ Eyes—How a Young Woman was Cured by a Ring—The Story told by a Skull—A Romantic Highway Robber. | 435 |

| Singular Customs. | |

| xviiThe Coffin on the Table—Queer Mode of Enjoying Oneself—A Beautiful Indian Custom—Why the People of Carazan Murder their Guests—Danger of Being Handsome—How an Evil Spirit was Frightened Away—Beefsteaks from a Live Cow—Compliments Paid to a Bear—How Noses are Made—How Lions are Caught by the Tail—A Picture of High Life Four Centuries Ago—Why Hairs were put in Ancient Seals—Fining People for not Getting Married—A Curious Matrimonial Advertisement. | 477 |

| Facetiæ. | |

| Odd Titles for a Sham Library—Puns of Tom Hood—The Jests of Hierocles—Curious Letter of Rothschild’s—Some Singularly Short Letters—A Disappointed Lover—“The Happiest Dog Alive”—What Happened Between Abernethy and the Lady—Witty Sayings of Talleyrand—Why Rochester’s Poem was Best—How the Emperor Nicholas was “Sold”—Difference Between “Old Harry” and “Old Nick”—Comical Story of a very Mean Man—Instances of Audacious Boasting—Chas. Mathews and the Silver Spoon—How a King Upset his Inside—Curious Story of Some Relics—What “Topsy’s” Other Name Was—Minding their P’s and Q’s—Practical Jokes of a Russian Jester. | 482 |

| Flashes of Repartee. | |

| Curran and Sir Boyle Roche—Witty Reply of a Fishwoman—Cobden and the American Lady—Witty Suggestion of Napoleon—Making “Game” of a Lady—The Road that no Peddler ever Traveled—“A Puppy in his Boots!”—A Quaker’s Queer Suggestion—What the Girl said to Curran—A Man who had “never been Weaned”—Ready Wit of Theodore Hook—“Chaff” between Barrow and Rochester—A Windy M. P.—A Clergyman known by his “Walk”—A Man who “had a Right to Speak”—The “Weak Brother” and Tobacco Pipes—Beecher Lecturing for F-A-M-E—Admiral Keppel and the He-Goat—Thackeray and the Beggar-Woman—What Paddy said about “Ayther and Nayther”—Scribe and the French Millionaire—Voltaire and Haller—Why Paddy “Loved her Still”—Bacon and Hogg—“A Most Excellent Judge”—Thackeray Snubbed—Christian Cannibalism—How a Barrister’s Eloquence was Silenced. | 495 |

| The Sexes. | |

| xviiiMasculine and Feminine Virtues and Vices—Character of the Happy Woman—What Mrs. Jameson said about Women—Old Ballad in Praise of Women—The Two Sexes Compared—What John Randolph said in Praise of Matrimony—Wife; Mistress; or Lady?—St. Leon’s Toast to his Mother. | 501 |

| Moslem Wisdom. | |

| The Caliph of Bagdad—Shrewd Decision of a Moslem Judge—A Question of Dinner—How the Money was Divided—The Wisdom of Ali—The Prophet’s Judgment: Wisdom and Wealth—Mohammedan Logic—The Foolish Young Man who Fell in Love—Queer Case of Consequential Damages—Sad Blunder of Omar—A Perplexing Turkish Will—The Dervise’s Device. | 508 |

| Excerpta from Persian Poetry. | |

| Earth an Illusion—Heaven an Echo of Earth—A Moral Atmosphere—Fortune and Worth—Broken Hearts—To a Generous Man—Beauty’s Prerogative—Proud Humility—Folly for Oneself—An Impossibility—Sober Drunkenness—A Wine Drinker’s Metaphors—The Verses of Mirtsa Schaffy—The Unappreciative World—The Caliph and Satan—Curious Dodge of the Devil. | 511 |

| Epigrams. | |

| xixAn Epigram on Epigrams—Midas and Modern Statesmen—“Come Gentle Sleep”—A Man who Wrote Long Epitaphs—The Fool and the Poet—“Dum Vivimus Vivamus”—Dr. Johnson and Molly Ashton—A Know-Nothing—Epigram on “Our Bed”—On a Late Repentance—A Pale Lady with a Red-Nosed Husband—Snowflakes on a Lady’s Breast—To John Milton—Wesley on Butler—Ridiculous Compliment to Pope—Athol Brose—What is Eternity—Stolen Sermons—Comical Advice to an Author—A Frugal Queen—Man With a Thick Skull—Miss Prue and the Kiss—A Ready-Made Angel—The Lover and the Looking-Glass—A Capricious Friend—A Man who Told “Fibs”—Unlucky End of a Scorpion—The Lawyer and the Novel—A Woman’s Will—Wellington’s Big Nose—The Miser and his Money—On Bad Singing—Old Nick and the Fiddle—Foot-man versus Toe-man—“Hot Corn”—Bonnets of Straw—An “Original Sin” Man—On Writing Verses—Prudent Simplicity—A Friend in Distress—Hog v. Bacon—A Warm Reception—Taking Medical Advice—Definition of a Dentist—Dr. Goodenough’s Sermon—What Might Have Been—A Reflection—The Woman in the Case—How Lawyers are “Keen”—Dux and Drakes—The Parson’s Eyes—“He Didn’t Mean Her”—Affinity Between Gold and Love—The Crier who Could not Cry—The Parson and the Butcher—A Hard Case of Strikes—Coats of Male—The Beaux upon the Quiver—On Burning Widows—Learning Speeches by Heart—A Golden Webb—The Jawbone of an Ass—Walking on her Head—Marriage à la mode—Quid Pro Quo—Woman pro and con—Abundance of Fools—The World—“Terminer Sans Oyer”—Seeing Double. | 515 |

| Impromptus. | |

| Dr. Young and his Eve—How Ben Jonson Paid his Bill—What Melville said to Queen Elizabeth—The “Angel” in the Pew—How Andrew Horner was Cut up—What Hastings Wrote of Burke—Impromptu of Dr. Johnson—Burlesque of Old Ballads—What was “Running in a Lady’s Head”—Improvised Rhymes—Like unto Judas—How the Devil got his Due—The Writing on the Window—“I Thought so Yesterday”—What is Written on the Gates of Hell—Burns’ “Grace before Meat”. | 528 |

| Refractory Rhyming. | |

| Julianna and the Lozenges—Brougham’s Rhyme for Morris—The French Speculator’s Epitaph—What is a Monogomphe—Rhymes for Month, Chimney, Liquid, Carpet, Window, Garden, Porringer, Orange, Lemon, Pilgrim, Widow, Timbuctoo, Niagara, Mackonochie—Rhyme to Gottingen—The Ingoldsby Legends—Punch’s Funny Rhymes—Chapin’s Rhyme to Brimblecomb—Butler’s Rhyme to Philosopher—A Rhyme to Germany—Hood’s Nocturnal Sketch. | 534 |

| Valentines. | |

| A Strategic Love-Letter—Love-Letter in Invisible Ink—Secret Invitation Concealed in a Love-Letter—Macaulay’s Essay to Mary C. Stanhope—Love-Verses of Robert Burns—Teutonic Alliteration—Singular Letter in Three Columns—Love-Letter Written in Blood—A Valentine in Many Languages—Practical Joke on a Colored Man—Unpublished Verses of Thomas Moore—An Egyptian Serenade—Petition of Sixteen Maids against the Widows of South Carolina—Unlucky Petition to Madame de Maintenon. | 544 |

| Sonnets. | |

| How the Fourteen Lines were Written—Sonnet on a Fashionable Church—On the Proxy Saint—About a Nose—On Dyspepsia—Humility—Ave Maria! | 551 |

| Conformity of Sense to Sound. | |

| xxArticulate Imitation of Inarticulate Sounds—Example from Pope—Milton’s “Lycidas”—From Dyer’s “Ruins of Rome”—Imitations of Time and Motion—“L’Allegro”—Pope’s “Homer”—Dryden’s “Lucretius”—Milton’s “Il Penseroso”—Fine Examples from Virgil—Imitations of Difficulty and Ease. | 554 |

| Familiar Quotations from Unfamiliar Sources. | |

| “No Cross, no Crown”—“Corporations have no Souls”—“Children of a Larger Growth”—“Consistency a Jewel”—“Cleanliness next to Godliness”—“He’s a Brick”—“When at Rome, do as the Romans”—“Taking Time by the Forelock”—“What will Mrs. Grundy Say?”—“Though Lost to Sight, to Memory Dear”—“Conspicuous by its Absence”—“Do as I Say, not as I Do”—“Honesty the Best Policy”—“Facts are Stubborn Things”—“Comparisons are Odious”—“Dark as Pitch”—“Every Tub on its own Bottom”—Two Pages of Examples, Interesting, Amusing, and Instructive. | 556 |

| Churchyard Literature. | |

| Epitaphs of Eminent Men—Appropriate and Rare Inscriptions—Franklin’s Epitaph on Himself—Touching Memorials of Children—Historical and Biographical Epitaphs—Self-Written Inscriptions—Advertising Notices—Unique and Ludicrous Epitaphs—Puns in the Churchyard—Puzzling Inscriptions—Parallels Without a Parallel—Bathos—Transcendental Epitaph—Acrostical Inscriptions—Indian, African, Hibernian, Greek Epitaphs—Patchwork Character on a Tombstone—The Printer’s Epitaph—Specimens of Exceedingly Brief Epitaphs—Highly Laudatory Inscriptions—A Chemical Epitaph—On an Architect—On an Orator—On a Watchmaker—On a Miserly Money-Lender—On a Tailor—On a Dancing Master—On an Infidel—On Voltaire—On Hume—On Tom Paine—“Earth to Earth”—Byron’s Inscription on his Dog. | 564 |

| Inscriptions. | |

| xxiOld English Tavern Sign-Boards—Curious Origin of Absurd Signs—“The Magpie and Crown”—“The Hen and the Razor”—“The Swan-with-two-Necks”—Singular Statement of Sir Joseph Banks—“The Goat and Compasses”—The “Signs” of Puritan Times—A Curious “Reformation”—“The Cat and the Fiddle”—“Satan and the Bag of Nails”—Ancient Signs in Pompeii—The Four Awls and the Grave Morris—The “Queer Door,” and the “Pig and Whistle”—Heraldic Signs of the Middle Ages—“I have a Cunen Fox, &c.”—Versified Inscriptions—Cooper and his “Zwei Glasses”—How a Sign Cost a Man his Life—An Inscription in Four Columns—Beer-Jug Inscriptions—Inscriptions on Window-Panes—Quaint Description of an Inn in the Olden Time—Curious Inscriptions on Bells—Baptising and Anointing Bells—The Great Tom of Oxford—Amusing Old Fly-Leaf Inscriptions—Sun-Dial Inscriptions—Memorial Verses—Francke’s Singular Discovery—Golden Mottoes—“Posies” from Wedding Rings. | 615 |

| Parallel Passages. | |

| Imitations and Plagiarisms of Authors—Curious Coincidences—Examples from Young, Congreve, Blair, and Shakespeare—Imitations of Otway, Gray, Milton, and Rogers—The Blindness of Homer and Milton—What Hume said of the Clergy—How Praise Becomes Satire—Parallel Passages from the English Poets—Singular Examples from Shakespeare—Shakespeare’s Acquaintance with the Latin Poets—Thoughts Repeated from Age to Age—Which was the True Original?—Historical Similitudes—What Radbod said with his Legs in the Water—Why Wulf, the Goth, wouldn’t be Baptised—Why an Indian Refused to go to Heaven—Curious Choice of a Woman—Last Words of Cardinal Wolsey—Death of Sir James Hamilton—Solomon’s Judgment Repeated—Why two Women Pulled a Child’s Legs—How Napoleon Decided Between two Ladies—The Hindoo Legend of the Weasel and the Babe—The Faithful Dog: a Welsh Ballad—Singular Murder of a Clever Apprentice—Ballads and Legends—Terrible Story of an old Midwife—What a Clergyman did at Midnight—How Genevra was Buried Alive—The Ghost which Appeared to Antonio—Strange Story of a Ring—Death Prophecies—What was done before three Battles—How an Army of Mice Devoured Bishop Hatto. | 640 |

| Prototypes. | |

| The Oldest Proverb on Record—Curious Wish of an Old Lady—Cinderella’s Slipper—How an Eagle Stole a Shoe, and a King Chose a Wife—Mrs. Caudle’s Curtain Lectures—“The Charge of the Light Brigade”—Dr. Faustus and the Devil—“Blown up” Cushions—What the “Poor Cat i’ the Adage” Did—The Lady with Two Cork Legs—The Pope’s Bull against the Comet—Lincoln “Swapping Horses”—Wooden Nutmegs—Trade Unions Two Centuries Ago—Consequential Damages—The Babies that Never were Born—The Original Shylock—Druidical Excommunication—Fall of Napoleon I.—Lanark and Lodore—The Song of the Bell—Turgot’s Eulogistic Epigraph on Franklin—Origin of the Declaration of Independence—The Know-Nothings—The first Conception of the Pilgrim’s Progress—Did Defoe Write Robinson Crusoe?—Talleyrand’s Famous Saying: Whence?—Mistake about Drinking out of Skulls—Great Literary Plagiarism—Origin of Old Ballads—The Story of the Wandering Jew. | 699 |

| Curious Books. | |

| xxiiOld Books with Odd Titles—“Shot Aimed at the Devils Headquarters”—“Crumbs of Comfort for the Chickens of the Covenant”—“Eggs of Charity Layed by the Chickens of the Covenant, and Boiled with the Water of Divine Love”—“High-heeled Shoes for Dwarfs in Holiness”—“Hooks and Eyes for Believers’ Breeches”—“Sixpennyworth of Divine Spirit”—“Spiritual Mustard Pot”—“Tobacco Battered and Pipes Shattered”—“News from Heaven”—The Most Curious Book in the World—A Book that was never Written or Printed, but which can be Read—The Silver Book at Upsal—What is a Bibliognoste?—What a Bibliographe?—What a Bibliomane?—What a Bibliophile and a Bibliotaphe? | 720 |

| Literariana. | |

| The Mystery of the “Letters of Junius”—Who Wrote Them?—What Canning and Macaulay Thought—A Well-kept Secret—Original MS. of Gray’s Elegy—The Omitted Stanzas—Imitations—How Pope Corrected his Manuscript—Importance of Punctuation: Comical Errors—“A Pigeon Making Bread”—How many Nails on a Lady’s Hand—A Comical Petition in Church—The Soldier who Died for want of a Stop—Indian Heraldry—Anachronisms of Shakespeare—King Lear’s Spectacles—The Heroines of Shakespeare—Shakespeare’s Life and Sonnets Compared—Was He Lame?—The Age of Hamlet—Was He Really Mad?—Additional Verses to “Home, Sweet Home”—The Falsities of History—Two Views of Napoleon—Clarence and the Butt of Malmsey—True Character of Richard III—The Name “America” a Fraud—Lexington and the “First Blood Shed”—Eye-Witnesses in Error—Curious Story of Sir Walter Raleigh—The Difference between Wit and Humor—A Rhyming Newspaper—Buskin’s Defence of Book-Lovers—Letters and their Endings—Shrewd Words of Lord Bacon. | 723 |

| Literati. | |

| xxiiiAccount of some Famous Linguists—A Man who Knew One Hundred and Eleven Languages—A Cardinal of Many Tongues—Elihu Burrito, the Learned Blacksmith—Literary Oddities—Curious Habits of Celebrated Authors—How they have Written their Books—Racine’s Adventure with the Workmen—Luther in his Study—Calvin Scribbling in Bed—Rousseau, Le Sage, and Byron at Work—Fontaine, Pascal, Fénélon, and De Quincey—Whence Bacon Sought Inspiration—Culture and Sacrifice—The Sorrows and Trials of Great Men—Sharon Turner and the Printers—A Stingy Old Scribbler—Dryden and His Publisher—Jacob Tonson’s Rascality; how He Tried to Cheat the Poet. | 756 |

| Personal Sketches and Anecdotes. | |

| Anecdote of George Washington—What Lafayette said to the King of France—Peculiarities of the Name Napoleon—How Napoleon Remembered Milton at the Dreadful Battle of Austerlitz—The Emperor’s Personal Appearance—His Opinion of Suicide—Benjamin Franklin’s Frugal Wife—Major André and the “Cow-Chase”—An English View of André and Arnold—How the Astronomer Royal Found an Old Woman’s Clothes—The Boy who set Fire to an Empty Bottle—Curious Views of Martin Luther—The Hero of the Reformation—Carlyle’s Translation of Luther’s Hymn—Curious Account of Queen Elizabeth—What She Said to the Troublesome Priest—What was the Real Color of Her Hair?—Was Shakespeare a Christian?—Personal Description of Oliver Cromwell—How Pope’s Skull was Stolen—What Became of Wickliffe’s Ashes—The Folly of Two Astrologers—Anecdotes of Talleyrand—Parson’s Puzzles. | 763 |

| Historical Memoranda. | |

| The First Blood of the Revolution—The “Tea-Party” at Boston—Tea-Burning at Annapolis—The First American Ships of War—How Quinn Borrowed Twenty Pounds of Shakespeare—Diabolical Proposition of Cotton Mather—A Rod in Pickle for William Penn—How he Escaped—An American Monarchy—Origin of the “Star-Spangled Banner”—Origin of the French Tri-Color—How the Newspapers Changed their Tune—Story of Eugenie’s Flight from France—Rise and Fall of Napoleon III—“L’Empire c’est la Paix”—Jefferson’s Idea of Marie Antoinette—Blücher’s Insanity—The Secret of Queen Isabella’s Daughter—Was Mary Magdalene a Sinner?—The Husband of Mother Goose, and what He Did—History and Fiction: which true?—Verdicts which Posterity have Reversed—Great Events from Little Causes—Why Queen Eleanor Quarreled with her Husband—Story of Queen Anne’s Gloves—How the Flies Helped Forward the Declaration of Independence—The Discovery of America—Story of Annie Laurie—Who was Robin Adair?—Was Joan of Arc Really Burnt?—The Mystery of Amy Robsart’s Death—Anecdotes of William Tell—Who Was He?—“Society” in the Time of Louis XIV—How Cromwell Tricked his Chaplain—The Last Night of the Girondists—Elizabeth, Essex, and the Ring. | 782 |

| Multum in Parvo. | |

| xxivMuch Meaning in Little Space—Coleridge and the Beasts—“Boxes” that Govern the World—“I Cannot Fiddle”—“Like a Potato”—The Vowels in Order—Balzac’s Instance of Self-Respect—Whom do Mankind Pay Best?—Comical Instance of Wrong Emphasis—“Vive la Mort!”—Motto for all Seasons—Curious Grace before Meat. | 823 |

| Life and Death. | |

| What is Death?—Bishop Heber’s “Voyage of Life”—Curious Poem of Dr. Horne—“The Round of Life”—Hugh Peters’ Legacy to his Daughter—Franklin’s Moral Code—How to Divide Time—Living Life over Again—Rhyming Definitions—What is Earth?—Curious Replies—Rhyming Charter of William the Conquerer—Puzzling Question for the Lawyers—What Rabbi Joshua Told the Emperor—Dying Words of Distinguished Persons—Last Prayer of Mary, Queen of Scots—Extraordinary Case of Trance—Curious Question about Lazarus—Preservation of Dead Bodies—Corpse of a Lady Preserved for Eighty Years—Bodies of English Kings Undecayed for many Centuries—Three Roman Soldiers Preserved “Plump and Fresh” for Fifteen Hundred Years—Bodies Converted into Fat—About Mummies—Wonderful Discovery in an Etruscan Tomb—The Reign of Terror—What Became of the Bodies of the French Kings—Jewish Tombs in the Valley of Hinnom—A Whimsical Will—The Tripod of Life—How Many Kinds of Death there Are—Curious Irish Epitaph—Significance of the Fleur de lis—Death of the First Born—Jean Ingelow’s “Story of Long Ago”—“This is not Your Rest”—Causes of Ill Success in Life—Futurity—Longfellow on “The Heart”—An Evening Prayer—Beautiful Thought—Life’s Parting—Destiny—Sympathy—“After;” Death’s Final Conquest—“There is no Death”—Euthanasia. | 826 |

In No. 59 of the Spectator, Addison, descanting on the different species of wit, observes, “The first I shall produce are the Lipogrammatists, or letter droppers of antiquity, that would take an exception, without any reason, against some particular letter in the alphabet, so as not to admit it once in a whole poem. One Tryphiodorus was a great master in this kind of writing. He composed an Odyssey, or Epic Poem, on the adventures of Ulysses, consisting of four-and-twenty-books, having entirely banished the letter A from his first book, which was called Alpha, (as lucus a non lucendo,) because there was not an alpha in it. His second book was inscribed Beta, for the same reason. In short, the poet excluded the whole four-and-twenty letters in their turns, and showed them that he could do his business without them. It must have been very pleasant to have seen this Poet avoiding the reprobate letter as much as another would a false quantity, and making his escape from it, through the different Greek dialects, when he was presented with it in any particular syllable; for the most apt and elegant word in 26the whole language was rejected, like a diamond with a flaw in it, if it appeared blemished with the wrong letter.”

In No. 63, Addison has again introduced Tryphiodorus, in his Vision of the Region of False Wit, where he sees the phantom of this poet pursued through the intricacies of a dance by four-and-twenty persons, (representatives of the alphabet,) who are unable to overtake him.

Addison should, however, have mentioned that Tryphiodorus is kept in countenance by no less an authority than Pindar, who, according to Athenæus, wrote an ode from which the letter sigma was carefully excluded.

This caprice of Tryphiodorus has not been without its imitators. Peter de Riga, a canon of Rheims, wrote a summary of the Bible in twenty-three sections, and throughout each section omitted, successively, some particular letter.

Gordianus Fulgentius, who wrote “De Ætatibus Mundi et Hominis,” has styled his book a wonderful work, chiefly, it may be presumed, from a similar reason; as from the chapter on Adam he has excluded the letter A; from that on Abel, the B; from that on Cain, the C; and so on through twenty-three chapters.

Gregorio Letti presented a discourse to the Academy of Humorists at Rome, throughout which he had purposely omitted the letter R, and he entitled it the exiled R. A friend having requested a copy as a literary curiosity, (for so he considered this idle performance,) Letti, to show it was not so difficult a matter, replied by a copious answer of seven pages, in which he observed the same severe ostracism against the letter R.

Du Chat, in the “Ducatiana,” says “there are five novels in prose, of Lope de Vega, similarly avoiding the vowels; the first without A, the second without E, the third without I, the fourth without O, and the fifth without U.”

The Orientalists are not without this literary folly. A Persian poet read to the celebrated Jami a ghazel of his own composition, which Jami did not like; but the writer replied it was, notwithstanding, a very curious sonnet, for the letter Aliff was 27not to be found in any of the words! Jami sarcastically answered, “You can do a better thing yet; take away all the letters from every word you have written.”

This alphabetical whim has assumed other shapes, sometimes taking the form of a fondness for a particular letter. In the Ecloga de Calvis of Hugbald the Monk, all the words begin with a C. In the Nugæ Venales there is a Poem by Petrus Placentius, entitled Pugna Porcorum, in which every word begins with a P. In another performance in the same work, entitled Canum cum cattis certamen, in which “apt alliteration’s artful aid” is similarly summoned, every word begins with a C.

Lord North, one of the finest gentlemen in the Court of James I., has written a set of sonnets, each of which begins with a successive letter of the alphabet. The Earl of Rivers, in the reign of Edward IV., translated the Moral Proverbs of Christiana of Pisa, a poem of about two hundred lines, almost all the words of which he contrived to conclude with the letter E.

The Pangrammatists contrive to crowd all the letters of the alphabet into every single verse. The prophet Ezra may be regarded as the father of them, as may be seen by reference to ch. vii., v. 21, of his Book of Prophecies. Ausonius, a Roman poet of the fourth century, whose verses are characterized by great mechanical ingenuity, is fullest of these fancies.

The following sentence of only 48 letters, contains every letter of the alphabet:—John P. Brady, give me a black walnut box of quite a small size.

The stanza subjoined is a specimen of both lipogrammatic and pangrammatic ingenuity, containing every letter of the alphabet except e. Those who remember that e is the most indispensable letter, being much more frequently used than any other,[1] will perceive the difficulty of such composition.

The Fate of Nassan affords another example, each stanza containing the entire alphabet except e, and composed, as the writer says, with ease without e’s.

Lord Holland, after reading the five Spanish novels already alluded to, in 1824, composed the following curious example, in which all the vowels except E are omitted:—

Men were never perfect; yet the three brethren Veres were ever esteemed, respected, revered, even when the rest, whether the select few, whether the mere herd, were left neglected.

The eldest’s vessels seek the deep, stem the element, get pence; the keen Peter, when free, wedded Hester Green,—the slender, stern, severe, erect Hester Green. The next, clever Ned, less dependent, wedded sweet Ellen Heber. Stephen, ere he met the gentle Eve, never felt tenderness: he kept kennels, bred steeds, rested where the deer fed, went where green trees, where fresh breezes, greeted sleep. There he met the meek, the gentle Eve: she tended her sheep, she ever neglected self: she never heeded pelf, yet she heeded the shepherds even less. Nevertheless, her cheek reddened when she met Stephen; yet decent reserve, meek respect, tempered her speech, even when she shewed tenderness. Stephen felt the sweet effect: he felt he erred when he fled the sex, yet felt he defenceless when Eve seemed tender. She, he reflects, never deserved neglect; she never vented spleen; he esteems her gentleness, her endless deserts; he reverences her steps; he greets her:—

29“Tell me whence these meek, these gentle sheep,—whence the yet meeker, the gentler shepherdess?”

“Well bred, we were eke better fed, ere we went where reckless men seek fleeces. There we were fleeced. Need then rendered me shepherdess, need renders me sempstress. See me tend the sheep; see me sew the wretched shreds. Eve’s need preserves the steers, preserves the sheep; Eve’s needle mends her dresses, hems her sheets; Eve feeds the geese; Eve preserves the cheese.”

Her speech melted Stephen, yet he nevertheless esteems, reveres her. He bent the knee where her feet pressed the green; he blessed, he begged, he pressed her.

“Sweet, sweet Eve, let me wed thee; be led where Hester Green, where Ellen Heber, where the brethren Vere dwell. Free cheer greets thee there; Ellen’s glees sweeten the refreshment; there severer Hester’s decent reserve checks heedless jests. Be led there, sweet Eve!”

“Never! we well remember the Seer. We went where he dwells—we entered the cell—we begged the decree,—

“He rendered the decree; see here the sentence decreed!” Then she presented Stephen the Seer’s decree. The verses were these:—

The terms perplexed Stephen, yet he jeered the terms; he resented the senseless credence, “Seers never err.” Then he repented, knelt, wheedled, wept. Eve sees Stephen kneel; she relents, yet frets when she remembers the Seer’s decree. Her dress redeems her. These were the events:—

Her well-kempt tresses fell; sedges, reeds, bedecked them. The reeds fell, the edges met her cheeks; her cheeks bled. She presses the green sedge where her check bleeds. Red then bedewed the green reed, the green reed then speckled her red cheek. The red cheek seems green, the green reed seems red. These were e’en the terms the Eld Seer decreed Stephen Vere.

TO WIDOWERS AND SINGLE GENTLEMEN.—WANTED by a lady, a SITUATION to superintend the household and preside at table. She is Agreeable, Becoming, Careful, Desirable, English, Facetious, Generous, Honest, Industrious, 30Judicious, Keen, Lively, Merry, Natty, Obedient, Philosophic, Quiet, Regular, Sociable, Tasteful, Useful, Vivacious, Womanish, Xantippish, Youthful, Zealous, &c. Address X. Y. Z., Simmond’s Library, Edgeware-road.—London Times, 1842.

The following remarkable toast is ascribed to Lord Duff, and was presented on some public occasion in the year 1745.

| A. B. C. | A Blessed Change. |

| D. E. F. | Down Every Foreigner. |

| G. H. J. | God Help James. |

| K. L. M. | Keep Lord Marr. |

| N. O. P. | Noble Ormond Preserve. |

| Q. R. S. | Quickly Resolve Stewart. |

| T. U. V. W. | Truss Up Vile Whigs. |

| X. Y. Z. | ’Xert Your Zeal. |

The following couplet, in which initials are so aptly used, was written on the alleged intended marriage of the Duke of Wellington, at a very advanced age, with Miss Angelina Burdett Coutts, the rich heiress:—

The letter E is thus enigmatically described:—

The letter M is concealed in the following Latin enigma by an unknown author of very ancient date:

The celebrated enigma on the letter H, commonly attributed to Lord Byron,[2] is well known. The following amusing petition is addressed by this letter to the inhabitants of Kidderminster, England—Protesting:

Rowland Hill, when at college, was remarkable for the frequent wittiness of his observations. In a conversation on the powers of the letter H, in which it was contended that it was no letter, but a simple aspiration or breathing, Rowland took the opposite side of the question, and insisted on its being, to all intents and purposes, a letter; and concluded by observing that, if it were not, it was a very serious affair to him, as it would occasion his being ILL all the days of his life.

When Kohl, the traveller, visited the Church of St. Alexander Nevskoi, at St. Petersburg, his guide, pointing to a corner of the building, said, “There lies a Cannibal.” Attracted to the tomb by this strange announcement, Kohl found from the inscription that it was the Russian general Hannibal; but as the Russians have no H,[3] they change the letter into K; and hence the strange misnomer given to the deceased warrior.

32A city knight, who was unable to aspirate the H, on being deputed to give King William III. an address of welcome, uttered the following equivocal compliment:—

“Future ages, recording your Majesty’s exploits, will pronounce you to have been a Nero!”

Mrs. Crawford says she wrote one line in her song, Kathleen Mavourneen, for the express purpose of confounding the cockney warblers, who sing it thus:—

Moore has laid the same trap in the Woodpecker:—

And the elephant confounds them the other way:—

A young English lady, on observing a gentleman’s lane newly planted with lilacs, made this neat impromptu:—

Pulci, in his Morgante Maggiore, xxiii. 47, gives the following remarkable double alliterations, two of them in every line:—

In the imitation of Laura Matilda, in the Rejected Addresses occurs this stanza:—

Cherished chess! The charms of thy checkered chambers chain me changelessly. Chaplains have chanted thy charming choiceness; chieftains have changed the chariot and the chase for the chaster chivalry of the chess-board, and the cheerier charge of the chess-knights. Chaste-eyed Caissa! For thee are the chaplets of chainless charity and the chalice of childlike cheerfulness. No chilling churl, no cheating chafferer, no chattering changeling, no chanting charlatan can be thy champion; the chivalrous, the charitable, and the cheerful are the chosen ones thou cherishest. Chance cannot change thee: from the cradle of childhood to the charnel-house, from our first childish chirpings to the chills of the churchyard, thou art our cheery, changeless chieftainess. Chastener of the churlish, chider of the changeable, cherisher of the chagrined, the chapter of thy chiliad of charms should be chanted in cherubic chimes by choicest choristers, and chiselled on chalcedon in cherubic chirography.

38Hood, in describing the sensations of a dramatist awaiting his debut, thus uses the letter F in his Ode to Perry:—

The repetition of the same letter in the following is very ingenious:—

“A famous fish-factor found himself father of five flirting females—Fanny, Florence, Fernanda, Francesca, and Fenella. The first four were flat-featured, ill-favored, forbidding-faced, freckled frumps, fretful, flippant, foolish, and flaunting. Fenella was a fine-featured, fresh, fleet-footed fairy, frank, free, and full of fun. The fisher failed, and was forced by fickle fortune to forego his footman, forfeit his forefathers’ fine fields, and find a forlorn farm-house in a forsaken forest. The four fretful females, fond of figuring at feasts in feathers and fashionable finery, fumed at their fugitive father. Forsaken by fulsome, flattering fortune-hunters, who followed them when first they flourished, Fenella fondled her father, flavored their food, forgot her flattering followers, and frolicked in a frieze without flounces. The father, finding himself forced to forage in foreign parts for a fortune, found he could afford a faring to his five fondlings. The first four were fain to foster their frivolity with fine frills and fans, fit to finish their father’s finances; Fenella, fearful of flooring him, formed a fancy for a full fresh flower. Fate favored the fish-factor for a few days, when he fell in with a fog; his faithful Filley’s footsteps faltered, and food failed. He found himself in front of a fortified fortress. Finding it forsaken, and feeling himself feeble, and forlorn with fasting, he fed on the fish, flesh, and fowl he found, fricasseed, and when full fell flat on the floor. Fresh in the forenoon, he forthwith flew to the fruitful fields, and not forgetting Fenella, he filched a fair flower; when a foul, frightful, fiendish figure flashed forth: ‘Felonious fellow, fingering my flowers, I’ll finish you! Fly; say farewell to your fine felicitous family, and face me in a fortnight!’ The faint-hearted fisher fumed and faltered, and fast and far was his flight. His five daughters flew to fall at his feet and fervently felicitate him. Frantically and fluently he unfolded his fate. Fenella, forthwith fortified by filial fondness, followed her father’s footsteps, and flung her faultless form at the foot of the frightful figure, who forgave the father, and fell flat on his face, for he had fervently fallen in a fiery fit of love for the fair Fenella. He feasted her till, fascinated by his faithfulness, she forgot the ferocity of his face, form, 39and features, and frankly and fondly fixed Friday, fifth of February, for the affair to come off. There was festivity, fragrance, finery, fireworks, fricasseed frogs, fritters, fish, flesh, fowl, and frumentry, frontignac, flip, and fare fit for the fastidious; fruit, fuss, flambeaux, four fat fiddlers and fifers; and the frightful form of the fortunate and frumpish fiend fell from him, and he fell at Fenella’s feet a fair-favored, fine, frank, freeman of the forest. Behold the fruits of filial affection.”

The following lines are said to have been admirably descriptive of the five daughters of an English gentleman, formerly of Liverpool;—

A remarkable example of the old fondness for antithesis and alliteration in composition, is presented in the following extract from one of Watts’ sermons:—

The last great help to thankfulness is to compare various circumstances and things together. Compare, then, your sorrows with your sins; compare your mercies with your merits; compare your comforts with your calamities; compare your own troubles with the troubles of others; compare your sufferings with the sufferings of Christ Jesus, your Lord; compare the pain of your afflictions with the profit of them; compare your chastisements on earth with condemnation in hell; compare the present hardships you bear with the happiness you expect hereafter, and try whether all these will not awaken thankfulness.

The acrostic, though an old and favorite form of verse, in our own language has been almost wholly an exercise of ingenuity, and has been considered fit only for trivial subjects, to be classed among nugæ literariæ. The word in its derivation includes various artificial arrangements of lines, and many fantastic conceits have been indulged in. Generally the acrostic has been formed of the first letters of each line; sometimes of the last; sometimes of both; sometimes it is to be read downward, 40sometimes upward. An ingenious variety called the Telestich, is that in which the letters beginning the lines spell a word, while the letters ending the lines, when taken together, form a word of an opposite meaning, as in this instance:—

| U | nite and untie are the same—so say yo | U. |

| N | ot in wedlock, I ween, has this unity bee | N. |

| I | n the drama of marriage each wandering gou | T |

| T | o a new face would fly—all except you and | I— |

| E | ach seeking to alter the spell in their scen | E. |

In these lines, on the death of Lord Hatherton, (1863), the initial and final letters are doubled:—

| H | ard was his final fight with ghastly Deat | h, |

| H | e bravely yielded his expiring breat | h. |

| A | s in the Senate fighting freedom’s ple | a, |

| A | nd boundless in his wisdom as the se | a. |

| T | he public welfare seeking to direc | t, |

| T | he weak and undefended to protec | t. |

| H | is steady course in noble life from birt | h, |

| H | as shown his public and his private wort | h. |

| E | vincing mind both lofty and sedat | e, |

| E | ndowments great and fitted for the Stat | e, |

| R | eceiving high and low with open doo | r, |

| R | ich in his bounty to the rude and poo | r. |

| T | he crown reposed in him the highest trus | t, |

| T | o show the world that he was wise and jus | t. |

| O | n his ancestral banners long ag | o, |

| O | urs willingly relied, and will do s | o. |

| N | or yet extinct is noble Hatherto | n, |

| N | ow still he lives in gracious Littleto | n. |

Although the fanciful and trifling tricks of poetasters have been carried to excess, and acrostics have come in for their share of satire, the origin of such artificial poetry was of a higher dignity. When written documents, were yet rare, every artifice was employed to enforce on the attention or fix on the memory the verses sung by bards or teachers. Alphabetic associations formed obvious and convenient aids for this purpose. In the Hebrew Psalms of David, and in other parts of Scripture, striking specimens occur. The peculiarity is not retained in the translations, but is indicated in the common 41version of the 119th Psalm by the initial letters prefixed to its divisions. The Greek Anthology also presents examples of acrostics, and they were often used in the old Latin language. Cicero, in his treatise “De Divinatione,” has this remarkable passage:—“The verses of the Sybils (said he) are distinguished by that arrangement which the Greeks call Acrostic; where, from the first letters of each verse in order, words are formed which express some particular meaning; as is the case with some of Ennius’s verses, the initial letters of which make ‘which Ennius wrote!’”

Among the modern examples of acrostic writing, the most remarkable may be found in the works of Boccaccio. It is a poem of fifty cantos, of which Guinguenè has preserved a specimen in his Literary History of Italy.

A successful attempt has recently been made to use this form of verse for conveying useful information and expressing agreeable reflections, in a volume containing a series of acrostics on eminent names, commencing with Homer, and descending chronologically to our own time. The alphabetic necessity of the choice of words and epithets has not hindered the writer from giving distinct and generally correct character to the biographical subjects, as may be seen in the following selections, which are as remarkable for the truth and discrimination of the descriptions as for the ingenuity of the diction:

Oliver, a sailor and patriot, with a merited reputation for extempore rhyming, while on a visit to his cousin Benedict Arnold, after the war, was asked by the latter to amuse a party of English officers with some extemporaneous effusion, whereupon he stood up and repeated the following Ernulphus curse, which would have satisfied Dr. Slop[4] himself:—

The following alliterative acrostic is a gem in its way. Miss Kitty Stephens was the celebrated London vocalist, and is now the Dowager Countess of Essex:—

On the election of Pope Leo X., in 1440, the following satirical acrostic appeared, to mark the date

The merit of this fine specimen will be found in its being at the same time acrostic, mesostic, and telestic.

| Inter cuncta micans | Igniti sidera cœlI |

| Expellit tenebras | E toto Phœbus ut orbE; |

| Sic cæcas removet | JESUS caliginis umbraS, |

| Vivificansque simul | Vero præcordia motV, |

| Solem justitiæ | Sese probat esse beatiS. |

The following translation preserves the acrostic and mesostic, though not the telestic form of the original:—

| In glory see the rising sun, | Illustrious orb of day, |

| Enlightening heaven’s wide expanse, | Expel night’s gloom away. |

| So light into the darkest soul, | JESUS, Thou dost impart, |

| Uplifting Thy life-giving smiles | Upon the deadened heart: |

| Sun Thou of Righteousness Divine, | Sole King of Saints Thou art. |

The figure of a FISH carved on many of the monuments in the Roman Catacombs, is an emblematic acrostic, intended formerly to point out the burial-place of a Christian, without revealing the fact to the pagan persecutors. The Greek word for fish is Ιχθῦς, which the Christians understood to mean Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Saviour,—the letters forming the initials of the following Greek words:—

| Ιησους |

Jesus |

| Χριστος |

Christ, |

| Θεου |

of God, |

| Υιος |

Son, |

| Σωτηρ |

Saviour. |

The names of the male crowned heads of the extinct Napoleon dynasty form a remarkable acrostic:—

Rachel, on one occasion, received a most remarkable present. It was a diadem, in antique style, adorned with six jewels. The stones were so set as to spell, in acrostic style, the name of the great artiste, and also to signify six of her principal rôles, thus:

| R uby, | R oxana, |

| A methyst, | A menaide, |

| C ornelian, | C amille, |

| H ematite, | H ermione, |

| E merald, | E milie, |

| L apis Lazuli, | L aodice. |

This mode of constructing a name or motto by the initial letters of gems was formerly fashionable on wedding rings.

The following curious memento was written in the early part of last century:—

Which is explained thus:—

| Masonry, of things, teaches how to attain their just | Magnitude. |

| To inordinate affections the art of | Moderation. |

| It inspires the soul with true | Magnanimity. |

| It also teaches us | Affability. |

| To love each other with true | Affection. |

| And to pay to things sacred a just | Attention. |

| It instructs us how to keep | Silence, |

| To maintain | Secrecy, |

| And preserve | Security; |

| Also, to whom it is due, | Obedience, |

| To observe good | Order, |

| And a commendable | Œconomy. |

| It likewise teaches us how to be worthily | Noble, |

| Truly | Natural, |

| And without reserve | Neighborly. |

| It instils principles indisputably | Rational, |

| And forms in us a disposition | Reciprocative, |

| And | Receptive. |

| It makes us, to things indifferent, | Yielding, |

| To what is absolutely necessary, perfectly | Ypight, |

| And to do all that is truly good, most willingly | Yare. |

Bacon says, “The trivial prophecy which I heard when I was a child and Queen Elizabeth was in the flower of her years was—

whereby it was generally conceived that after the sovereigns had reigned which had the letters of that word HEMPE, (which were Henry, Edward, Mary, Philip, Elizabeth,) England should come to utter confusion; which, thanks be to God, is verified in the change of the name, for that the King’s style is now no more of England, but of Britain.”

The reader, by taking the first letter of the first of the following lines, the second letter of the second line, the third of the third, and so on to the end, can spell the name of the lady to whom they were addressed by Edgar A. Poe.

Camden, in a chapter in his Remains, on this frivolous and now almost obsolete intellectual exercise, defines Anagrams to 50be a dissolution of a name into its letters, as its elements; and a new connection into words is formed by their transposition, if possible, without addition, subtraction, or change of the letters: and the words should make a sentence applicable to the person or thing named. The anagram is complimentary or satirical; it may contain some allusion to an event, or describe some personal characteristic. Thus, Sir Thomas Wiat bore his own designation in his name:—

Astronomer may be made Moon-starer, and Telegraph, Great Help. Funeral may be converted into Real Fun, and Presbyterian may be made Best in prayer. In stone may be found tones, notes, or seton; and (taking j and v as duplicates of i and u) the letters of the alphabet may be arranged so as to form the words back, frown’d, phlegm, quiz, and Styx. Roma may be transposed into amor, armo, Maro, mora, oram, or ramo. The following epigram occurs in a book printed in 1660:

It is said that the cabalists among the Jews were professed anagrammatists, the third part of their art called themuru (changing) being nothing more than finding the hidden and mystical meaning in names, by transposing and differently combining the letters of those names. Thus, of the letters of Noah’s name in Hebrew, they made grace; and of the Messiah they made he shall rejoice.

Lycophron, a Greek writer who lived three centuries before the Christian era, records two anagrams in his poem on the siege of Troy entitled Cassandra. One is on the name of Ptolemy Philadelphus, in whose reign Lycophron lived:—

The other is on Ptolemy’s queen, Arsinoë:—

51Eustachius informs us that this practice was common among the Greeks, and gives numerous examples; such, for instance, as the transposition of the word Αρετη, virtue, into Ερατη, lovely.

Owen, the Welsh epigrammatist, sometimes called the British Martial, lived in the golden age of anagrammatism. The following are fair specimens of his ingenuity:—

In a New Help to Discourse, 12mo, London, 1684, occurs an anagram with a very quaint epigrammatic “exposition:”—

Cotton Mather was once described as distinguished for—

Sylvester, in dedicating to his sovereign his translation of Du Bartas, rings the following loyal change on the name of his liege:—

Of the poet Waller, the old anagrammatist said:—

The author of an extraordinary work on heraldry was thus expressively complimented:—

52The following on the name of the mistress of Charles IX. of France is historically true:—

In the assassin of Henry III.,

they discovered

The French appear to have practised this art with peculiar facility. A French poet, deeply in love, in one day sent his mistress, whose name was Magdelaine, three dozen of anagrams on her single name.

The father Pierre de St. Louis became a Carmelite monk on discovering that his lay name—

yielded the anagram—

Of all the extravagances occasioned by the anagrammatic fever when at its height, none equals what is recorded of an infatuated Frenchman in the seventeenth century, named André Pujom, who, finding in his name the anagram Pendu à Riom, (the seat of criminal justice in the province of Auvergne,) felt impelled to fulfill his destiny, committed a capital offence in Auvergne, and was actually hung in the place to which the omen pointed.

The anagram on General Monk, afterwards Duke of Albemarle, on the restoration of Charles II., is also a chronogram, including the date of that important event:—

The mildness of the government of Elizabeth, contrasted with her intrepidity against the Iberians, is thus picked out of her title: she is made the English lamb and the Spanish lioness.

53The unhappy history of Mary Queen of Scots, the deprivation of her kingdom, and her violent death, are expressed in the following Latin anagram:—

In Taylor’s Suddaine Turne of Fortune’s Wheele, occurs the following very singular example:—

The anagram on the well-known bibliographer, William Oldys, may claim a place among the first productions of this class. It was by Oldys himself, and was found by his executors among his MSS.

The following anagram, preserved in the files of the First Church in Roxbury, was sent to Thomas Dudley, a governor and major-general of the colony of Massachusetts, in 1645. He died in 1653, aged 77.

54In an Elegy written by Rev. John Cotton on the death of John Alden, a magistrate of the old Plymouth Colony, who died in 1687, the following phonetic anagram occurs:—

The Calvinistic opponents of Arminius made of his name a not very creditable Latin anagram:—

while his friends, taking advantage of the Dutch mode of writing it, Harminius, hurled back the conclusive argument,

Perhaps the most extraordinary anagram to be met with, is that on the Latin of Pilate’s question to the Saviour, “What is truth?”—St. John, xviii. 38.

A lady, being asked by a gentleman to join in the bonds of matrimony with him, wrote the word “Stripes,” stating at the time that the letters making up the word stripes could be changed so as to make an answer to his question. The result proved satisfactory.

The two which follow are peculiarly appropriate:—

This word, Time, is the only word in the English language which can be thus arranged, and the different transpositions thereof are all at the same time Latin words. These words, in English as well as in Latin, may be read either upward or downward. Their signification as Latin words is as follows:—Time—fear thou; Item—likewise; Meti—to be measured; Emit—he buys.

Some striking German and Latin anagrams have been made of Luther’s name, of which the following are specimens. Doctor Martinus Lutherus transposed, gives O Rom, Luther ist der schwan. In D. Martinus Lutherus may be found ut turris das lumen (like a tower you give light). In Martinus Lutherus we have vir multa struens (the man who builds up much), and ter matris vulnus (he gave three wounds to the mother church). Martin Luther will make lehrt in Armuth (he teaches in poverty).

Jablonski welcomed the visit of Stanislaus, King of Poland, with his noble relatives of the house of Lescinski, to the annual examination of the students under his care, at the gymnasium of Lissa, with a number of anagrams, all composed of the letters in the words Domus Lescinia. The recitations closed with a heroic dance, in which each youth carried a shield inscribed with a legend of the letters. After a new evolution, the boys exhibited the words Ades incolumis; next, Omnis es lucida; next, Omne sis lucida; fifthly, Mane sidus loci; sixthly, Sis columna Dei; and at the conclusion, I scande solium.

Anagrams are sometimes found in old epitaphial inscriptions. For example, at St. Andrews:—

At Newenham church, Northampton:—

At Keynsham:—

At Mannington, 1631:—

57Maitland has the following curious specimen:—

How much there is in a word—monastery, says I: why, that makes nasty Rome; and when I looked at it again, it was evidently more nasty—a very vile place or mean sty. Ay, monster, says I, you are found out. What monster? said the Pope. What monster? said I. Why, your own image there, stone Mary. That, he replied, is my one star, my Stella Maris, my treasure, my guide! No, said I, you should rather say, my treason. Yet no arms, said he. No, quoth I, quiet may suit best, as long as you have no mastery, I mean money arts. No, said he again, those are Tory means; and Dan, my senator, will baffle them. I don’t know that, said I, but I think one might make no mean story out of this one word—monastery.

Addison, in his remarks on the different species of false wit, (Spect. No. 60,) thus notices the chronogram. “This kind of wit appears very often on modern medals, especially those of Germany, when they represent in the inscription the year in which they were coined. Thus we see on a medal of Gustavus Adolphus the following words:—

If you take the pains to pick the figures out of the several words, and range them in their proper order, you will find they amount to MDCXVVVII, or 1627, the year in which the medal was stamped; for as some of the letters distinguish themselves from the rest and overtop their fellows, they are to be considered in a double capacity, both as letters and as figures. Your laborious German wits will turn over a whole dictionary for one of these ingenious devices. A man would think they were searching after an apt classical term; but instead of that they are looking out a word that has an L, an M, or a D, in it. When therefore we meet with any of these inscriptions, 58we are not so much to look in them for the thought as for the year of the Lord.”

Apropos of this humorous allusion to the Germanesque character of the chronogram, it is worthy of notice that European tourists find far more numerous examples of it in the inscriptions on the churches on the banks of the Rhine than in any other part of the continent.

On the title-page of “Hugo Grotius his Sophompaneas” the date, 1652, is not given in the usual form, but is included in the name of the author, thus:—

Howell, in his German Diet, after narrating the death of Charles, son of Philip II. of Spain, says:—

If you desire to know the year, this chronogram will tell you: