GENERAL GUIDE

TO

THE BRITISH MUSEUM

(NATURAL HISTORY).

HISTORICAL SKETCH.

The British Museum dates its foundation from the year 1753, when an Act of Parliament was passed “for the purchase of the Museum or Collection of Sir Hans Sloane, and of the Harleian Collection of Manuscripts, and for providing One General Repository for the better Reception and more convenient Use of the said Collections and of the Cottonian Library and of the Additions thereto.”

Sir Hans Sloane, an eminent physician in London, was for sixteen years President of the Royal College of Physicians, and in 1727 succeeded Sir Isaac Newton in the Presidential Chair of the Royal Society. He was throughout his long life a diligent and miscellaneous collector, having, as stated in the Preamble of the Act of Incorporation of the Museum, “through the course of many years, with great labour and expense, gathered together whatever could be procured, either in our own or foreign countries, that was rare and curious.” His collection, which at the time of his death in 1753 was contained in his residence, the Manor House, Chelsea, consisted of “Books, Manuscripts, Prints, Medals, and Coins, ancient and modern, Seals, Cameos and Intaglios, Precious Stones, Agates, Jaspers, Vessels of Agate and Jasper, Crystals, Mathematical Instruments, Drawings, and Pictures,” and included numerous zoological and geological specimens, as well as an extensive herbarium of dried plants preserved in 333 large folio volumes.

2 According to the terms of Sir Hans Sloane’s will, this collection was purchased for the sum of £20,000—far below its intrinsic value—in order “that it might be preserved and maintained, not only for the inspection and entertainment of the learned and the curious, but for the general use and benefit of the public to all posterity.”

The valuable collection of manuscripts formed by Sir Robert Cotton at the end of the sixteenth and beginning of the seventeenth centuries was already the property of the nation, having been presented by his grandson, Sir John Cotton, in the year 1700. The Harley Collection was obtained by purchase at the same time as the Sloane, and the three were brought together under the designation of “the British Museum,” placed under the care of a body of Trustees,1 and lodged in Montagu House, Bloomsbury, purchased for their reception in 1754. The Museum was opened to the public on the 15th of January, 1759. Admission to the galleries of antiquities and natural history was at first by ticket only after application in writing, and limited to ten persons, for three hours in the day. Instead of being allowed to inspect the cases at their leisure, visitors were conducted through the galleries by officers of the house. The hours of admission were subsequently extended; but it was not until the year 1810 that the Museum was freely accessible to the general public for three days in the week, from ten to four o’clock. The daily opening, with longer hours in summer, dates from 1879.

At the time of the foundation of the Museum, the site allotted seemed amply sufficient for its purposes; but gradually, as the collections increased, they outgrew the limits, not only of the original Montagu House, but even of its successor, the present classical building, completed in 1845 from the designs of Sir Robert Smirke. The erection of the magnificent reading-room in 1857 disposed for a time of the difficulty3 of finding accommodation for the ever-growing library; but the keepers of other departments continued urgent in their demands for more space, and after much discussion of rival plans for keeping the collections together and obtaining the needful extension of room by acquiring the property immediately around the old Museum, or for severing the collections and removing a portion to another building, the latter course was finally decided upon. At a special general meeting of the Trustees, held on the 21st of January, 1860, attended by many members of the Government in their official capacity, a resolution, moved by the First Lord of the Treasury, was carried “That it is expedient that the Natural History Collection be removed from the British Museum, inasmuch as such an arrangement would be attended with considerably less expense than would be incurred by providing a sufficient additional space in immediate contiguity to the present building of the British Museum.”

The House of Commons, in the Session of 1863, sanctioned the purchase of part of the site of the International Exhibition of 1862 at South Kensington, with a view to appropriating it to the purpose of a Museum of Natural History.

In January, 1864, the Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Works issued an advertisement for designs for a Natural History Museum and a Patent Museum, to be erected on part of the land thus acquired; a plan which had been prepared by Mr. Hunt in September, 1862, from Sir Richard Owen’s suggestions, being proposed as a model in respect to dimensions and internal arrangement.

The plans of the various competitors were submitted to Her Majesty’s Commissioners of Works, who awarded prizes to three of the number, giving precedence to that of Captain Francis Fowke, R.E., and then referred the three selected plans to the Trustees of the British Museum. As the internal arrangements in Captain Fowke’s plan did not meet with the approval of the Museum officers, he was desired to modify them in conformity with the requirements of the Trustees, and was engaged in this labour when his death occurred, in September, 1865.

Early in the year 1866, Mr. Alfred Waterhouse was invited by the Chief Commissioner of Works to take up the unfinished work4 of Captain Fowke, but found himself unable to complete the plan to his own satisfaction. In February, 1868, he was accordingly commissioned to form a fresh design, embodying the requirements of the officers of the Natural History Departments of the Museum.

Mr. Waterhouse was not long in submitting to the Trustees his plan and model of the building, with a disposition of galleries as required, and these were formally accepted by the Trustees in April, 1868. It was not, however, until February 1871 that the working plans had been thoroughly considered, and had received the final approval of the Trustees.

The actual work of erection commenced in the year 1873, and the building was handed over to the Trustees of the British Museum by Her Majesty’s Commissioners of Works in the month of June, 1880. As soon as the exhibition-cases were completed, and the galleries sufficiently dry to receive the collections, the labour of removing the Natural History Collection from Bloomsbury was begun. The departments of Geology, Mineralogy, and Botany were arranged in their respective sections of the Museum in the course of the year 1880, and the portion of the Museum which contained these departments was first opened to the public on April 18th, 1881. It was not until the following year that the cases destined to receive the larger collections of the Zoological Department were sufficiently near completion to allow of these collections following, and three more years were required before all the galleries could be brought into a state fitted for public exhibition.

The following description of the structure was contributed by Mr. Waterhouse:—

“The New Natural History Museum will, from its position, always be more or less identified with the International Exhibition of 1862, which occupied the whole of the site between the Horticultural Gardens and Cromwell Road. It was at one time thought that a portion, at any rate, of the Exhibition buildings could with advantage have been converted into a Museum of Natural History. Parliament, however, decided against the preservation of any part of these buildings, and they were accordingly entirely removed.

“In designing the present building, Captain Fowke’s original5 idea of employing terra-cotta was always kept in view, though the blocks were reduced in size, so as to obviate, as far as possible, the objection to the employment of this material, arising from its liability to twist in burning. For this and other reasons the architect abandoned the idea of a Renaissance building, and fell back on the earlier Romanesque style which prevailed largely in Lombardy and the Rhineland from the tenth to the end of the twelfth century.

“In 1873, a contract was entered into by the Government with Messrs. George Baker and Sons, of Lambeth, for the erection of the building at a cost of £352,000. Other subsequent contracts have been entered into by the Treasury, especially one for the erection of the towers, which in the first instance it was decided to omit.

“On looking at the exterior of the building, one of the first points which strikes a spectator is that the site is lower than the street. This arises from the fact that the whole surface of the ground between the three roads was excavated for the Exhibition building of 1862, and it was not thought desirable, for economical considerations, to refill the space. The building is set back 100 feet from the Cromwell Road, and is approached by two inclined planes, curved on plan and supported by arches, forming carriage-ways. Between the two are broad flights of Craigleith stone steps, for the use of those approaching the building on foot. The extreme length of the front is 675 feet, and the height of the towers is 192 feet. The return fronts, east and west, beyond the end pavilions, have not yet been erected.2

“On entering the main portal, the visitor has before him the great central apartment of the Museum (170 feet long, by 97 feet wide, and 72 feet high), which it is intended to use as an Index or Typical Museum. The double arch in the immediate foreground which spans the nave (57 feet wide), carries the staircase from the first to the second floor. Opposite the spectator, at the end6 of the hall, is the first flight of the staircase, 20 feet wide, which rises from the ground to the first floor. The galleries over the side recesses form the connection between the two staircases, and are also intended for exhibition space, as are also the floor of the main hall and the side recesses under the galleries. The arches under the side-flights of the main staircase at the end of the hall lead into another large apartment, with an extreme length of 97 by 77 feet measured into the arms of the cross.

“Branching out of the Central Hall, near its southern extremity, are two long galleries, each 278 feet 6 inches long by 50 feet wide. These galleries are repeated on the first floor, and in a modified form on the second floor. They are divided into bays by coupled piers arranged in two rows down the length of the galleries, and planned in such a manner as to allow of upright cases being placed back to back between the piers and the outer walls, so as to get the best possible light upon the objects displayed in the cases with the least amount of reflection from the glass, and leaving the central space free as a passage. Owing to the nature of the specimens exhibited in one or two of these galleries requiring for their exhibition rather table-cases than wall-cases, advantage has only been taken to a limited extent of this disposition of the plan. These terra-cotta piers, however, are constructively necessary, not only to conceal the iron supports for the floor above, but to prevent these supports being affected in case of fire. Behind these galleries on the ground floor are a series of toplighted galleries, devoted, on the east side to Geology and Palæontology, and on the west to Zoology.

“The towers on the north of the building have each a central smoke-shaft from the heating apparatus, the boilers of which are placed in the basement, immediately between the towers, while the space surrounding the smoke-shafts is used for drawing off the vitiated air from the various galleries contiguous thereto. The front galleries are ventilated into the front towers, which form the crowning feature of the main front. These towers also contain, above the second floor, various rooms for the work of the different departments, and on the topmost storey large cisterns for the purpose of always having at hand a considerable storage of water in case of fire. On the western side of the building, where it is intended that the Zoological collection7 shall be placed, the ornamentation of the terra-cotta (which will be found very varied both within and without the building) has been based exclusively on living organisms. On the east side, where Geology and Palæontology find a home, the terra-cotta ornamentation has been derived from extinct specimens.

“The Museum is the largest, if not, indeed, the only, modern building in which terra-cotta has been exclusively used for external façades and interior wall-surfaces, including all the varied decoration which this involves.”

The gardens on the south, east, and west sides of the Museum are open to the public whenever the Museum itself is open, under certain regulations, posted at the entrance gates.

9

GENERAL ARRANGEMENT.

Natural History is an old term, used to describe the study of all the processes or laws of the Universe, and the results of the action of those processes or laws upon such of its constituent materials as are independent of the agency of man.

It is thus contrasted with the history of Man and his works, and the changes which have been wrought in the World by Man’s intervention.

This distinction afforded a convenient and rational basis for the division of the numerous and multifarious objects which had been collected together in the British Museum at Bloomsbury. When it was decided to effect a separation of the collections, those that were purely the products of what are commonly called “natural” forces were removed to South Kensington, while those showing the effects of Man’s handiwork remained at Bloomsbury. Like most others of the kind, this distinction cannot be applied very rigidly. Such lines of demarcation almost always overlap. For instance, examples of modification of animal or plant structure under Man’s influence legitimately find a place in a Museum of Natural History, especially as they may afford illustrations of the mode of working of natural laws. Prehistoric stone-implements, again, are shown in the Geological Department, in order to illustrate the co-existence of Man with extinct Mammals.

Processes or laws cannot, however, be satisfactorily demonstrated in a museum; therefore such branches of knowledge as deal chiefly with these, as Astronomy, Geology (in the stricter sense of the word), and the experimental sciences, as Physics, Chemistry and Physiology, though essentially belonging to the domain of Natural History, have not found a place in the10 Natural History Museum. It is only the results of the working of these processes or laws, as shown in the modifications of the arrangement of the elementary substances of which the material of the Universe is composed, which can be fully illustrated by specimens admitting of being readily preserved and permanently exhibited in a museum. A Natural History Museum, therefore, in the sense in which the term is now usually understood, is a collection of the various objects, animate and inanimate, found in a state of nature. It will be readily understood that as the study of such objects is one of the principal means by which the laws leading to their formation or arrangement may be traced out, it is of the utmost importance for the progress of those departments of knowledge which the Museum is designed to cultivate, to bring together as full an illustrative series of these objects as possible.

Although the validity of the division of natural objects into inorganic and organic or living has been the subject of some discussion, and although the separation of the latter into vegetable and animal is less absolute than was once supposed, yet for practical purposes, Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal remain the three great divisions or “kingdoms” into which natural bodies are grouped, and this classification has formed the basis of the arrangement of the collections in the Museum.

I. Inorganic substances occur in nature in a gaseous, liquid, or solid form. With few exceptions, it is only in the latter state that they can be conveniently preserved and exhibited in a museum, and it is to such that the term “mineral” is commonly limited. The collection, classification, and exhibition of specimens of this kind is the office of the Mineral Department of the Museum, to which is devoted the large gallery on the first floor of the east wing of the building.

II. The study of the vegetable kingdom, so far as it can be illustrated by preserved specimens, is the province of the Department of Botany, which occupies the upper floor of the east wing.

III. In the same way the animal kingdom belongs to the11 Department of Zoology, from which it has been found necessary to separate an Entomological Department. To these two is assigned the whole of the western wing of the building.

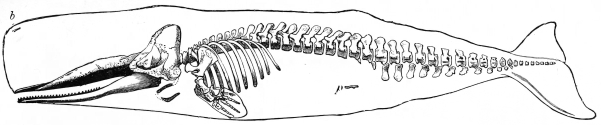

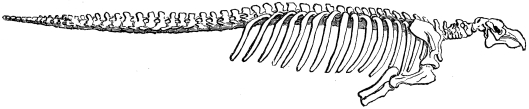

There is, however, a fifth department, which owes its separate existence to a time when the terms Zoology and Botany were limited to the study of the existing forms of animal and plant life, and the extinct or fossil forms were associated with minerals, rather than with their living representatives. This arrangement prevailed in the British Museum until the year 1857. The fossils were then severed from this incongruous connection, and placed in a separate department to which the name of “Geology” was given.3 The result is that there are two distinct zoological and botanical collections in the building, one containing the remains of the animals and plants which lived through successive ages of the world’s history from the earliest dawn of life down to close upon the present time, and the other including those living at the particular period in which we dwell. Notwithstanding the objections which may be urged against this separation, it prevails largely in museums, and (owing to certain conveniences, as well as to the difficulty and expense of rearranging extensive collections and reorganising the staff in charge of them) will probably be retained for some time to come. It should, however, be mentioned that a few specimens illustrating some of the more important extinct forms have been intercalated among the recent Mammals and Reptiles; while, conversely, skeletons and other specimens of recent animals have been introduced among the fossil Vertebrates in the Geological Department. Again, the more important remains of extinct Cetaceans are now shown in the Whale-Room, and some of the specimens of recent Elephants, as well as all the Sea-Cows, in the Geological Department.

Besides the five Departments, into which the collection is divided for the purposes of custody and administration, each of which is under the charge of an officer styled “Keeper”12 and a staff of Assistants, there is a sixth, under the supervision of the Director, and arranged in the Central Hall, some of the specimens in which are intended to serve as an introduction to those exhibited in the others.

Inclusive of the last-named collection, the whole of the specimens contained in the Museum, whether Animal, Vegetable, or Mineral, are arranged in the three following distinct series, as follows:—

I. An Elementary or Introductory Series, by which the study of every group should commence. In this series, limited, so far as the cases in the Central Hall are concerned, to Vertebrated Animals and Botany, the leading features of the structure, and, so far as may be, the development of the various parts of some of the more typical members of each group, are demonstrated in a simple manner, and the terms used in describing and defining them explained by means of illustrative examples. This idea is carried out in the Department of Minerals in a series of cases placed on the north or left-hand side of the gallery containing the rest of the collection.

II. The Exhibited Systematic Series, in which the more important types of animals, plants, or minerals are shown, by means of specimens, arranged in a systematic manner; or one which exhibits, so far as may be, their natural relations to each other. Classification is an important feature in this series, which properly should be so extensive and so arranged as to enable visitors to the Museum, without recourse to assistance from the officials, to find every well-known and markedly distinct type of animal, plant, or mineral, and satisfy themselves about, at least, its external characters. In practice, with the amount of space available, and the resources at the disposal of the authorities, it has, however, been found impracticable to carry out this ideal in anything like its entirety, and in most instances only a selection of specimens is in consequence exhibited.

While the two series above mentioned have for their object the diffusion of scientific knowledge, the next ministers mainly to its advancement, so that between them the twofold object of a National Museum of Natural History is carried out.

13

III. The Reserve or Study Systematic Series contains the exceedingly numerous specimens (in many groups the great bulk of the collection) showing the minute distinctions required for working out the problems of variation according to age, sex, season and locality, for fixing the limits of geographical distribution, or determining the range in geological time: distinctions which, in most cases, can only be appreciated when the specimens are kept under such conditions as to admit of ready and close examination and comparison. It is to this part of the collection that naturalists resort to compare and name the animals and plants collected in exploring expeditions, to work out natural-history problems, and generally to advance the knowledge of science. In fact, these reserve collections, occupying comparatively little space, kept up at relatively small cost, and visited by comparatively few persons, constitute, from a scientific point of view, the most important part of the Museum; for by their means new knowledge is obtained, which, given forth to the world in the form of memoirs and books, is ultimately diffused over a far wider area than that influenced even by the exhibited portions of the Museum. Indeed, without the means of study afforded by the reserve series, the order displayed in the arrangement of the exhibition galleries, and the instruction which may be gleaned from the same, would not be possible.

It is important to bear in mind that if all the specimens required for enlarging the boundaries of knowledge were displayed in the public galleries, so that each could be distinctly seen, a museum many times larger than the present one would not suffice to contain them; the specimens themselves would be inaccessible to those capable of deriving instruction from their examination, while, owing to the effects of exposure to light upon preserved natural objects, many would lose their chief characteristics. This portion of the collection must, in fact, be treated as are the books in a library and used for consultation and reference by accredited students.4

In some parts of the Museum the reserve collections are contained in drawers beneath the cases in which the corresponding exhibited portion is placed. This applies principally to the fossil specimens, the shells, and the minerals.14 The reserve birds and insects have special rooms devoted to them, and the extensive series of reptiles, fishes, and other animals preserved in spirit is kept, for the purpose of safety, in a separate building behind the Museum. In the Botanical Department the reserve collections are kept in the well-known form of an Herbarium, or Hortus siccus.

The great bulk of the specimens being arranged in these three series, supplementary collections for facilitating the study of the distribution of animals and plants in space and in time would be advantageous. The first, constituting a geographical series, might show by illustrative examples the leading characteristics of the fauna and flora of each great region of the earth’s surface; the second, or palæontological series, would give examples of the fossil remains found most abundantly in each formation, arranged so far as may be in chronological order.

The only attempt hitherto made at exhibiting a geographical series in the Museum is the collection of terrestrial and fresh-water vertebrated animals of the British Isles, arranged in the pavilion at the west end of the bird gallery. It would be difficult in the present building to find room for other geographical collections, however interesting and instructive. With regard to palæontological collections, although the specimens in the Department of Geology, so called, are mainly arranged not geologically, or according to stratigraphical position, but according to their natural affinities, yet, in many cases, it has been found convenient to adopt a mixed arrangement, the specimens within each large natural group being classified according to the sequence in age of the strata in which they were buried. Such an arrangement, however, is only applicable to the fossils of a particular region, owing to the difficulties in accurately determining the correspondence in age of formations occurring in distant parts of the earth’s surface; hence a large and varied palæontological collection, such as that of the British Museum, is best arranged in the main upon a systematic or zoological and botanical basis. A limited series showing the more characteristic British rock-formations with their included fossil remains, placed in chronological sequence, is arranged in one of the galleries of the Geological Department.

15

DESCRIPTION OF THE MUSEUM AND ITS CONTENTS.

On entering the Museum, the visitor should bear in mind that the principal front faces the south, so that he will be looking due north, with the east on his right, and the west on his left hand.

It must also not be forgotten that a museum in a state of active growth is continually receiving additions as well as undergoing changes in the arrangement of its contents, and since these often occur faster than new editions of the Guide can be produced, there may be variations in the positions of some of the specimens from those here given.

The Central Hall.

On entering the hall the visitor will notice the bronze statue of the late Sir Richard Owen, K.C.B., Superintendent of the Natural History Departments of the British Museum (1856–1884). It is the work of Mr. T. Brock, R.A., and was placed in the Museum on March 17th, 1897. To the right of this is a marble statue of the late Professor T. H. Huxley, sculptured by Mr. E. Onslow Ford, R.A., which was unveiled on April 28th, 1900. In the first bay on the left is a bust, by Mr. Brock, of the late Sir W. H. Flower, Director of the Natural History Departments of the British Museum from 1884 to 1898. Most of the cases placed on the floor of the hall illustrate general laws or points of interest in natural history which do not come appropriately for illustration within the systematic collections of the departmental series.

One group, in a case near the entrance to the hall, on the right, shows the great variation to which a species may become subject under the influence of domestication, as illustrated by examples of the best-marked breeds of Pigeons, all derived by selection from the wild Rock-Dove (Columba livia), specimens of which are shown at the top of the case.

16

In the corresponding case on the left are further illustrations of the same subject. A pair of red Jungle Fowl (Gallus bankiva, or G. ferrugineus) of India represents the species from which the breeds of Domesticated Fowls are generally considered to have been derived. As examples of extreme modifications in opposite directions produced by selection, are exhibited the Japanese Long-tailed Fowls, in which some of the feathers (tail-coverts) attain a length of nine feet, and specimens of a breed in which the tail is absent. There is also shown a group of Fowls living wild in the woods of the Fiji Islands, which are descendants from domesticated birds introduced in the eighteenth century. A pair of Cochin Fowls is exhibited in the same case to display development in point of size and in the abundance of feathers on the limbs; while a pair of white “Silkies” illustrates a modification of the plumage, accompanied by a rudimentary condition of the tail-feathers. The pair of Coloured Dorkings exemplifies a breed cultivated in England.

A series of Canaries is shown in a case in the archway leading from the east side of the central hall to the north hall, as an example of a late addition to domesticated animals, these birds having been first imported into Europe from the Canary Islands in the early part of the sixteenth century. Specimens are exhibited of the wild birds, and of some of the modifications produced by selection.

A case placed to the north of the one containing Fowls illustrates a remarkable instance of external differences in the two sexes and changes in plumage at different seasons, not under the influence of domestication. The birds in it belong to one species, the Ruff (Pavoncella, or Machetes, pugnax), of which the female is called Reeve; a member of the Plover family (Charadriidæ). In the upper division of the case are shown the eggs, newly-hatched young, and young males and females in the first autumn plumage; as well as adult males and females in winter, when both sexes are exactly alike in colour and distinguishable externally by size alone. The large group occupying the lower part of this case consists of adult birds in the plumage assumed in the breeding time (May and June). In the female the only alteration from the winter state is a darker and richer colouring, but in the17 males there is a special growth of elongated feathers about the head and neck, constituting the “ruff” from which the bird derives its name. In addition to this peculiarity, another, rare among wild animals, may be observed, namely, striking diversity of colour in different individuals. Of the twenty-three specimens shown no two are entirely alike.

Next in order stands a case displaying the variations, according to season and age, in the plumage of the Wild Duck, or Mallard (Anas boscas). The most noticeable feature in the plumage-changes is the assumption in summer by males of an “eclipse-plumage,” resembling the one worn by females at all seasons. At other times the males are more brilliantly coloured than their partners. The eclipse-plumage corresponds to the winter, or non-breeding, dress of other birds which have a seasonal change.

On the same side of the hall follow two cases illustrating the adaptation of the colour of animals to their natural surroundings, by means of which they are rendered less conspicuous to their enemies or their prey. The first contains a specimen of a Mountain or Variable Hare (the common species of the north of Europe), a Stoat, and a Weasel, together with some Willow-Grouse and Ptarmigan, as well as an Arctic Fox, in their summer dresses. All were obtained in Norway, and show the general harmony of their colouring at this season with that of the rocks and plants among which they live. The second case displays examples of the same animals obtained from the same country in winter, when the ground was covered with snow. Such striking changes as these only occur in latitudes and localities where the differences between the general external conditions in the different seasons are extreme, where the snow disappears in summer and remains on the ground during most of the winter. Even some of the species here shown do not habitually turn white in the less severe winters of their southern range, as the Stoat in England and the Variable Hare in Ireland. A few permanent inhabitants of still more northern regions, where the snow remains throughout the year, such as the Polar Bear, Alaskan Bighorn Sheep, Greenland Falcon, and Snowy Owl, retain the white dress throughout the year. The whiteness of these animals must not be confounded with18 albinism, or whiteness occurring in individuals of species normally of a different colour, which is illustrated in a case on the other side of the hall.

The case on the east side of the hall nearest the great staircase contains examples of conformity of general style of colouring to surrounding conditions, as exemplified by some of the commoner Birds, Mammals, and Reptiles of the Egyptian desert, placed on the stones and sand amid which they habitually dwell. The advantage of this colouring in concealing the herbivorous species from their enemies, and in enabling the carnivorous to approach their prey unperceived, is obvious. Many excellent cases of concealment by adaptation to surroundings, especially in eggs and young Birds, may be seen among the groups in the Bird-gallery.

More special modifications for the same purpose are shown in the adjacent bay on the east side of the hall by Insects which closely resemble the objects, such as leaves, twigs, etc., among which they dwell. The close imitation of a dead leaf, presented by the Leaf-Butterfly (Callima inachis), when its wings are closed, could not be surpassed. In a further stage of the same condition, called “Mimicry,” the object resembled, or mimicked, is another living animal, belonging to a different species, family, or even order. The resemblance in these instances is also believed to be for protection, or to be in some way advantageous to the animal in which it occurs. We know, however, so little of the habits and life-history of animals in a state of nature that many of the purposes supposed to be served by particular colours or appearances can only be regarded at present as conjectural. Whatever be the real explanation, the facts shown by the specimens in this bay are very curious, and worthy of careful consideration.

The next case on the east side of the middle of the hall contains a series of specimens illustrating albinism, a condition in which the pigment, or colouring matter, usually present in the skin, hair, or feathers, and giving the characteristic hue, is absent. Individuals in this condition occur among many animals of various kinds, and are called “albinos.” In some of the specimens shown in the case the albinism is complete, but in many it is partial, the absence of colouring matter being19 limited to certain portions of the surface. Other examples of complete or partial albinism are shown in the North Hall.

The adjacent case shows examples of the opposite condition called melanism, depending upon an excess of dark colouring matter or pigment in the skin and its appendages, such as hair, feathers, etc., beyond what is commonly met with in the species. This is by no means so frequent as albinism. A black Leopard in the middle of the case is a good illustration. This is not a distinct species, but merely an individual variety of the common Leopard, born from parents of the normal colour. A black Bullfinch is introduced as an example of acquired melanism, this bird having turned black in captivity.

20

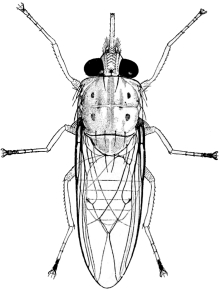

Fig. 2.—The Somali Tsetse-Fly (Glossina longipennis). Enlarged 4 diameters.

Shows the complete closure of the wings in the resting position, and the prominent proboscis, characteristic of the genus.

Another group shows that two forms of Crows which appear quite distinct, and, judged by their external characters, might be regarded as different species, may in a state of nature unite, and produce hybrid offspring. In the same case is exhibited a series of Goldfinches to show a complete gradation between birds of different colouring, which have been regarded as different species. Both these examples may by some naturalists be considered instances, not of the crossing of distinct species, but of “dimorphism,” or the occurrence of a single species in nature in two different phases. From whatever point of view they may be regarded, they illustrate the difficulty of defining and limiting the meaning of the term “species,” of such constant use in natural history.

21

In the middle line of the hall are placed cases containing greatly enlarged models of certain Insects concerned in the spread of disease, such as Mosquitoes or Gnats (figs. 3 and 4), a House-Fly, Tsetse-Fly (fig. 2), and Plague-Flea; also still more enlarged gelatine models of mammalian blood-corpuscles, showing the parasites by which they are infested in the diseases respectively communicated by means of Mosquitoes and Tsetses. Models of the parasites themselves are also shown (figs. 5 and 6).

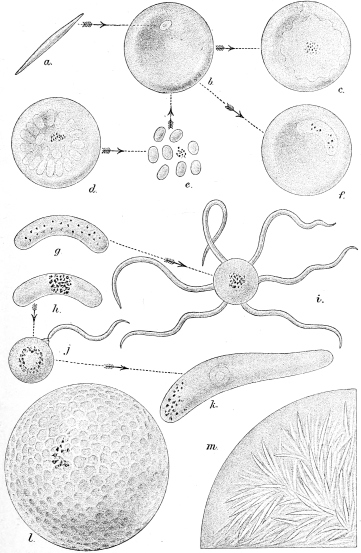

Malaria, or ague, is a disease caused by extremely minute parasites which live in the red corpuscles of the blood. Formerly malaria was believed to be contracted by merely breathing the air of marshy districts, but it is now proved that the parasites are transmitted from man to man by the “bite,” or rather “stab,” of a Mosquito or Gnat. The Common Mosquito or Stabbing Gnat (Culex pipiens), fig. 3, does not transmit the malaria-parasite; the Spot-winged Mosquitoes (fig. 4) of the genus Anopheles, abundant in England and nearly all parts of the world, being the carriers. The parasite multiplies not only in the human blood, but in the stomach and tissues of the Gnat—as shown in the models (fig. 5).

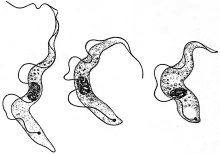

Tsetse-Flies are African blood-sucking Flies, with the mouth-parts adapted for piercing the skins of wild and domesticated mammals, human beings, and even crocodiles. The blood of some of the larger African animals is sometimes infected with a microscopic parasite (fig. 6), which, if sucked up by Tsetse-Flies when feeding, and subsequently introduced by them into the veins of domesticated animals such as horses and cattle, produces the fatal nagana, or Tsetse-Fly disease. Sleeping-sickness in man is caused in a similar manner, and is conveyed from infected to healthy individuals by two kinds of Tsetse-Fly, including that of which an enlarged model, 28 times (linear) natural size, is exhibited. The parasites and the red blood-corpuscles are enlarged 6,000 diameters.

22

Fig. 3.—(a) The Common Gnat (Culex pipiens). Enlarged.

Fig. 4.—(b) The Spot-winged Mosquito (Anopheles maculipennis). Enlarged.

23

Fig. 5.—Life-History of the Malaria Parasite.

a, malarial germ, or sporozoite, as introduced into the blood by the mosquito; b, sporozoite after entry into blood-corpuscle; c, growth of sporozoite into an amœbula; d, division of amœbula to form merozoites; e, liberated merozoites; f, growth of merozoites into a crescent at expense of corpuscle; g, male, and h, female crescent; i, male cell with projections, which lengthen and are set free as spermatozoa; j, fertilisation of ovum by spermatozoon; k, fertilised egg as the active motile vermicule; sphere formed from the l, enlarged vermicule, after this has bored through the stomach-wall of the mosquito; m, segment of sphere at final stage of development, containing countless needle-shaped spores, which, when it bursts, escape as sporozoites into the organs of the mosquito’s body and pass through the salivary glands into the proboscis, and so infect a man bitten or pricked by the mosquito.

24 The House-Fly—see enlarged models of the perfect insect and its preliminary stages,—although not provided with a piercing proboscis, and consequently incapable of biting, sometimes plays an important part in spreading deadly diseases, such as cholera and enteric (typhoid) fever. In this case the disease-causing organisms are carried by the insect either in its intestine or adherent to the outer surface of its body, and thus House-Flies may spread disease by contaminating food.

Plague, which is a disease of rats and a few other rodents, especially the bobac Marmot, is communicated to man by the bite of the flea known as Xenopsylla cheopis, one of several species of fleas with which rats are infested. When a rat dies, the fleas that it has been harbouring seek another host, and may bite human beings, in which case, if the rat itself was suffering from the disease, an epidemic of plague may be the result. The model of the Plague-Flea exhibited is enlarged 200 times (linear).

The Arachnida, a group which includes the Spiders and can generally be distinguished from Insects by the number of their legs (four pairs instead of three pairs), include also the Ticks, which are responsible for the transmission of many deadly diseases which attack Man and Domestic animals. Enlarged models of a disease-carrying Tick are in course of preparation.

Fig. 6.

Trypanosoma gambiense, the parasite of Sleeping-sickness, very highly magnified. The occurrence of three kinds of individual, as shown in the figure, appears to be characteristic of this and certain other species of Trypanosoma.

(After Col. Sir D. Bruce.)

In the middle line of the hall is placed a magnificent mounted skin of an African Elephant (Elephas africanus), fig. 7, from Rhodesia, standing about 11 feet 4 inches in height. The skull of the same individual is mounted on a stand below. Near by are exhibited three tusks, the largest of which measures 10 feet 2½ inches in length. On the north wall, on either side of the Darwin statue, are mounted two African Elephant heads.

Most of the bays or alcoves round the hall, five on each side, are (with the exception of the one at the north end of25 the right side) devoted to the Introductory or Elementary Collection, designed to illustrate the more important points in the structure of certain types of animal and plant life, and the terms used in describing them. This has been called the “Index Museum,” as it was thought at one time that it would form a sort of epitome or index of the general collections in the galleries. It is now mainly restricted to a display of the leading structural features in Vertebrated Animals and in Plants. The space being limited, the number of specimens is necessarily restricted. In examining this collection the visitor should follow each case in the usual order of reading a book, from left to right, and carefully study the printed explanatory labels, to which the specimens are intended to serve as illustrations.

Fig. 7.—African Elephant (Elephas africanus).

The skull and tusks seen in the foreground are those of the stuffed specimen, the tusks in which have been modelled from another individual.

The bays on the west side (left-hand on entering the hall) are26 devoted to the Vertebrata, or Animals possessing a “backbone.” In Nos. I and II are shown the characters of the Mammals, which form the highest modification of this type; the wall-cases of No. I containing specimens of the bony framework (internal skeleton).

In the first case (south side of the recess) may be seen a complete skeleton of a good example of the class—a Baboon Monkey, with the bones laid out on a tablet, and their names affixed. Below is a skeleton of the same animal articulated, or with the bones in their natural relation to each other, and also named. By examining these two specimens an idea may be obtained of the general framework of the bodies of animals of this class. In other parts of the case are exhibited various modifications of the skeleton to suit different conditions of life.

1. Man, showing a skeleton adapted for the upright posture.

2. A Bat, or flying Mammal, in which, by the great elongation of the fingers, the fore-limbs are converted into wings (fig. 8), supporting a web of skin stretched between them.

3. A Sloth, in which the tips of both limbs are reduced to mere hooks, by the aid of which the creature hangs back-downwards from the boughs of the trees among which it passes its entire existence.

4. The Baboon serves as an example of an animal walking on all four limbs in the “plantigrade” position, i.e., with the whole of the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet applied to the ground.

5. A small species of Antelope shows the characteristic form of a running animal, in which the limbs perform no office but that of supporting the body on the ground. This animal stands on the tips of the toes of its elongated, slender feet in the “digitigrade” fashion.

6. A Porpoise, adapted solely for swimming in the water. The fore-limbs are converted into flattened paddles, and the hind-limbs are entirely absent, their function being performed by the tail. The rudimentary pelvic bones are preserved.

The rest of the case is occupied by details of the skull in some of its principal modifications. At the top are diagrams of the structure of bone and cartilage as shown by the microscope.

27

Fig. 8.—The Skeleton of a Flying-Fox, or Fox-Bat (Pteropus medius).

cl, clavicle; cv, cervical vertebræ; d, dorsal vertebræ; fb, fibula; fm, femur; h, humerus; hx, great toe, or hallux; l, lumbar vertebræ; mc, metacarpals; mt, metatarsals; ph, phalanges, or finger- and toe-bones; pv, pelvis; px, thumb, or pollex; r, radius; s, sacral vertebræ; sc, scapula; sk, skull; tb, tibia; ts, tarsus; u, ulna.

In the wall-case on the opposite (north) side of the bay the study of the skeleton of Mammals is continued by illustrations of the structure of the limbs. At the top of the case is a diagram showing the correspondence of the hand and the foot in their complete typical form, with the names applied to the different bones. The series of specimens below shows the principal deviations actually occurring from this typical condition, which, as may be seen, is very nearly preserved in the human hand. One series shows some of the stages of modification for special purpose (specialisation) by which a typical five-fingered hand becomes converted into the single-toed fore-foot of the Horse; while another series ends with the fore-foot of the Ruminants, sometimes, but erroneously, called a “cloven hoof,” in which only two toes remain. Similar changes are shown in the toes of the hind-foot, illustrating the same common plan running through infinite modifications in detail, enabling the28 organ to perform such a variety of purposes, and to exhibit such diversity of outward appearance. The existence of this common plan is now generally regarded as due to inheritance from a common ancestor.

The central case of the bay contains a collection illustrating the principal characters of the teeth of Mammals. Its inspection should commence at the north-east corner, where the visitor will find himself after completing the survey of the specimens of skeletons in the wall-cases. In the first division are placed specimens showing the general characters of teeth, their form, the different tissues of which they are composed, the two great types of dentition in Mammals, homœodont and heterodont,5 the names and serial correspondence of the different teeth, and their development and succession. The principal modifications of teeth according to function are next shown by examples of forms adapted for fish-eating, flesh-eating, insect-eating, grass-eating, etc. The remainder of the case is taken up by examples of the dentition of the families of Mammals arranged in order, and prepared so as to display not only the shape of the crowns, but also the number and character of the roots by which they are implanted.

In bay No. II the two wall-cases contain a collection arranged to show in a serial manner the orders and sub-orders of existing Mammals, by examples selected to illustrate the predominating characters by which these are distinguished. A brief popular account of the characteristics of the group, and a map showing its geographical distribution, are placed with each. This is intended to serve not only for an introduction to the study of the class by visitors to the museum, but also as a guide to a method of arrangement which may be adopted in smaller institutions.

Among the illustrations of the order Primates is placed the skeleton of a young Chimpanzee dissected by Dr. Tyson, which formed the subject of his work on the “Anatomy of a Pigmie,” published in 1699, the earliest scientific description of any Man-like Ape.

29

The central case of this bay contains illustrations of the outer covering or skin and its modifications in the class of Mammals, divided into the following sections:

1. Expansion of skin to aid in locomotion, as the webs between the fingers of swimming and flying animals, the parachutes of flying animals.

2. The development of bony plates in the skin, found among Mammals only in the Armadillos and their allies. The cast of a section of the tail of a gigantic extinct species (Glyptodon) shows a bony external as well as an internal skeleton.

3. The outer covering modified into true scales, much resembling in structure the nails of the human hand. This occurs in only one family of Mammals, the Pangolins, or Manidæ.

4. Hair in various forms, including bristles and spines. The two kinds of hair composing the external clothing of most Mammals, the long, stiffer outer hair, and the short, soft under-fur, are shown by various examples.

5. The special epidermal appendages found in nearly all Mammals on the ends of the fingers and toes, called according to the various forms they assume, nails, claws, or hoofs.

6. The one or two unpaired horns of the Rhinoceroses, shown by sections to consist of a solid mass of hair-like epidermic fibres.

7. The horns of Oxen, Goats, and Antelopes, each consisting of a hollow conical sheath of horn, covering a permanent projection of the frontal bone (the horn-core).

8. The antlers of Deer, forming solid, bony, and generally branched projections, covered during growth with soft hairy skin, and in most cases shed and renewed annually.

On the wall is arranged a series of antlers of an individual Stag or Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), grown and shed (except the last) in thirteen successive years, showing the changes which took place in their size and form, and the development of the branches, or tines, in each year. In old age the number of these tines tends to diminish.

On the north side of the table-case are shown dissections of the principal internal organs of Mammals.

Bay No. III is devoted to the class of Birds. An Albatross (Diomedea exulans) mounted with the wings expanded shows30 the most important characters by which a Bird is externally distinguished from other animals. The body is clothed with feathers, which (in the majority of Birds), by their great size and special arrangement upon the fore-limbs, enable these to act as organs of flight. The mouth is in the form of a horny beak. A nestling Albatross shows that at this stage of its existence the bird is not clothed with ordinary feathers, but with soft down, which serves to keep the body warm, although it confers no power of flight. An Emu and an Apteryx in the lower compartment of the case display the exceptional condition (found only in a comparatively few members of the class) of Birds with wings so small as to be concealed beneath the general feathery covering of the body, and quite useless. In the Penguins, of which two species are shown in the case, the wings are reduced to the condition of fins, and are serviceable only for progress through water.

In the first wall-case the principal features of the skeleton of the class are shown. Sections of bones exhibit the large air-cavities within; a complete skeleton of an Eagle, with the bones separated and named, and mounted skeletons of the Ostrich, Penguin, Pelican, Vulture, Night-Parrot, Fowl, etc., show the chief modifications of the skeleton. The Apteryx possesses the smallest, and the Frigate-bird the longest bones of the wing, the correspondence of which can be readily traced by means of the labels attached to them. The under surfaces of the skulls of various birds are shown with the different bones coloured to indicate their limits and relations; these are followed by a series of the different types of sternum or breast-bone.

The second wall-case contains further illustrations of the anatomy of Birds. In the left-hand part a series of wings of Birds displays the form characteristic of different groups; while above them are a few of the different types of tails, supplementing the series of tails in the table-case. Very instructive is a series of skins of white chickens of the same brood at different ages, displaying the gradual replacement of the down by the adult plumage.

The table-case in the middle of the bay contains illustrations of the external characters, the beak, the feathers, and the tail, as well as of the fore and hind limbs, or wings and feet. By the31 aid of the explanatory labels, the essential characters and the principal modifications of all these parts may easily be followed.

Two cases on the wall in the vestibule leading to the Fish Gallery illustrate the chief modifications of the eggs of Birds, and their differences in structure, number, form, size, texture of surface, and colour. On the side of the main staircase opposite are specimens illustrating the parasitic nesting habits of certain Cuckoos and various other Birds; while near by is a remarkably fine series of the eggs of Cuckoos with those of the Birds among which they were respectively deposited. On the opposite (east) side of the staircase the visitor will find a case showing the remarkable variation in colouring and markings displayed by the eggs of the Guillemot.

The fourth bay on the west side of the hall exhibits the leading peculiarities in the structure of Reptiles and Amphibians. Owing to the large number of groups in the former class now extinct, many fossil specimens, or plaster reproductions of the same, are shown. The wall-case on the south side of this bay illustrates the different ordinal groups of Reptiles—living and extinct. Very instructive are the skeletons of Tortoises and Turtles, showing the relations of the vertebræ and limb-bones to the bony part of the shell. Lizards and Snakes are mostly represented by coloured casts. The extinct Dinosaurs are represented by a small-sized model of Iguanodon, together with a photograph of the skeleton and a plaster-cast of the bones of the hind-foot showing the three toes.

The adjacent side of the table-case shows the modifications of the backbone, or vertebral column, of the ribs, and of the limbs, in the different groups of the class. Specially noticeable are examples of five types of Skink-like Lizards, exhibiting the gradual diminution in the size of the limbs and their final disappearance.

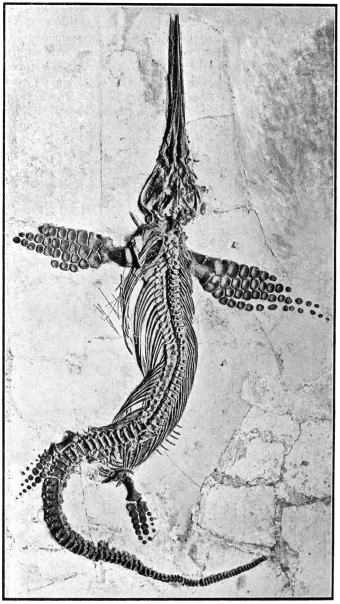

The opposite, or north, side of the table-case displays the different modifications of the skull and teeth of living and extinct Reptiles. In some, like Crocodiles and Ichthyosaurs, the jaws are armed with a full series of sharply pointed teeth, while in others, like the Tortoises and Turtles, they are devoid of teeth and encased in horn. Very remarkable is the32 approximation to a carnivorous mammalian type presented by the dentition of some of the extinct mammal-like Reptiles, or Theromorphs, and equally noticeable are the palatal crushing teeth of certain other extinct Reptiles known as Placodus and Cyamodus. The peculiar dentition of the New Zealand Tuatera, and likewise that of its extinct European and Indian ally Hyperodapedon (fig. 9), are also shown.

Fig. 9.—Skull of the Giant Tuatera (Hyperodapedon gordoni), from the Triassic Sandstone of Lossiemouth, Elgin, (¼ nat. size). A, upper surface of skull; B, palatal aspect of skull; C, under side of front of lower jaw; Pmx, premaxillary bone; Mx, maxillary; Pl, palatal teeth; Md, lower jaw; O, orbit, or eye-socket; N, nostrils; S, temporal pit; S’, lateral temporal fossa.

The brain and other internal organs of Reptiles are displayed in the left half of the wall-case on the north side of this bay, in which are also shown the eggs of many species, in some cases with the embryo.

33

Fig. 10.—Skeleton of the Great Blue Shark (Carcharodon rondeletii), with portion of backbone on a large scale. pl, functional upper jaw, and su, its reflected portion; md, lower jaw; hy, ceratohyal; br, branchial arches; co, pectoral girdle; ph, cartilaginous portion of pectoral, or front paired fin; r, dermal portion of pectoral fin; pu, pelvic, or hind paired, fin; c, centra, or bodies, of the vertebræ; na, neural, or upper, and ha, hæmal, or lower, arch. The median fins are not lettered.

In the right half of the same case are exhibited a number of preparations showing the external form and internal structure of Frogs and Salamanders, or Amphibians, living and extinct. The Giant Salamander of Japan (Megalobatrachus or Cryptobranchus) is represented by a stuffed specimen; but the Newts, Salamanders, and Frogs are shown in spirit. Very curious is the almost colourless and blind Olm (Proteus) from the caves of Carniola; as also are the so-called Cœcilians, or Apoda, which have the habits and, in some degree, the appearance of large worms. Special specimens exhibit the structure of the extinct Labyrinthodonts, in which the hinder half of the skull is completely roofed over by bone; while34 the teeth in many instances exhibit a curious in-folded arrangement from which the group derives its name.

The last bay (No. V) on the west side of the Central Hall is devoted to the display of the form and structure of Fishes.

The wall-case on the left side of this bay exhibits the external form of several characteristic types of Fishes, such as the Pike, Cod, Turbot, Dog-fish, and Skate, with the names of the various fins affixed. A striking specimen is the skeleton—mainly cartilaginous—of the Great Blue Shark (Carcharodon rondeletii), fig. 10, which occupies the greater portion of this case. It should be noted that, as in all Sharks and Rays, the upper jaw does not correspond with that of the higher Vertebrates; and particular attention should be devoted to the structure and arrangement of the arches supporting the gills.

In the south side of the table-case in this bay are shown a number of dissections, mounted in spirit, displaying the different types of skeletal structure presented by the fins in various groups of Fishes. One of the most remarkable of these types occurs in Ceratodus forsteri, the Queensland Lung-fish, in which the skeleton of the fin consists of a central jointed rod, from each side of which diverge narrower jointed rods. Alongside are specimens showing special modifications of certain fins, as in the Flying Fish (fig. 11) and Flying Gurnard (fig. 12), for the purpose of sustaining the body in the air, or, as in Pentanemus, to serve as organs of touch. Specimens of the West Indian Goby and the Lump-Sucker show modifications of the pelvic fins in connection with a sucker on the lower surface of the body; while other preparations display the pectoral (Doras) and pelvic fins (Monocentris) reduced to the condition of saw-like spines.

The structure of the skull of Fishes is illustrated in another part of the same side of this case. From this the visitor may learn how the primitive cartilaginous skull of the Sharks (fig. 10), Rays, Chimæras, and Lung-fishes has been gradually modified, by the addition of superficial sheathing-bones, into the bony skull of modern Fishes, such as the Cod and Perch.

Fig. 11.—The Flying Fish (Exocœtus).

Fig. 12.—The Flying Gurnard (Dactylopterus).

The north side of the table-case in bay V is mainly devoted to the display of the different types of scales, spines, and teeth found among Fishes. In one corner are the enamelled “ganoid”35 scales of the modern American Bony Pike (Lepidosteus) and the African Bichir (Polypterus) alongside those of certain extinct forms. A scale of the Tarpon, or King-of-the-Herrings, illustrates the largest development in point of size of the modern “cycloid” type. Spines of the Porcupine-fish show an extreme development of this kind of structure. Diagrams and spirit-preparations illustrate the mode of attachment and succession of fish-teeth. A large series of the teeth of Sharks and Rays displays the gradual passage from those of the ordinary pointed form to others arranged in a pavement-like manner and adapted solely for crushing. Both types occur in the Port Jackson Shark (fig. 13), but those of some Rays are solely of the pavement modification. Very remarkable is the dental structure in the Parrot-fish. The west end of this side of the case shows the various modifications assumed by the36 teeth of the modern Bony Fishes; among which, as exemplified by the Wrasse, teeth are developed on the bones of the throat, as well as on those of the jaws. Throughout this case specimens, or models, of the teeth of extinct Fishes are placed side by side with those of their nearest living relatives.

The wall-case on the north side of this bay shows the history of the development of various Fishes, together with the form and structure of the gills, brain, heart, digestive system, and other organs.

A small case affixed to the pillar at the entrance of the fifth bay illustrates the structure of the Lancelet (Branchiostoma, or Amphioxus), by the aid of spirit-specimens, enlarged models, and coloured diagrams. One of the most remarkable features in the structure of this strange and primitive little creature is the outer cavity enclosing the part of the body which contains the large and complex pharynx. The Lancelet was formerly37 included among the Fishes, but is now accorded the rank of a class (Cephalochorda) to itself.

Leaving bay VI, next the principal staircase on the east side of the central hall, which is devoted to illustrations of heredity, especially in relation to the Mendelian theory, and to modes of Flight in Vertebrates and Insects, we pass on to a table-case assigned to the illustration of “Mimicry” and kindred phenomena. Most of the examples shown occur among Insects; but one example among Mammals and a second in Birds are illustrated. Very striking is a coloured sketch showing a group of red and black caterpillars from Singapore grouped side by side on the stem of a plant so as to present a remarkable similarity to a succulent fruit.

In bay VIII, on the eastern side of the central hall, is displayed an exhibition illustrating trees, native to or grown in Britain. The winter and summer states are indicated by photographs, and the foliage, flowers, fruits, seedlings, and texture of wood and bark by specimens, models, and drawings. Bays IX and X are intended to illustrate the general characters of the great groups of the Vegetable Kingdom. Bay IX, in course of arrangement, is devoted to the Cryptogams (Ferns, Mosses, Fungi, Seaweeds, and Lichens).

At the back of the bay is a fine polished section of a buttress from the base of the Tapang (Abauria excelsa), the largest tree in Borneo, which attains a height of 250 feet.

The last bay (No. X) is devoted to the Seed-bearing Plants, which are characterised by the formation of a seed—the result of the fertilisation of an ovule by the male cell which is developed in the pollen. The series begins on the left hand side with the Pteridosperms, an extinct group combining the characters of Ferns and Seed-plants and forming a link between them. Then follow the Gymnosperms (Cycads, Pines, Firs, etc.), in which the seed is borne naked on an open scale which generally forms, with others like it, the characteristic cone. Certain points in the development of pollen and ovule recall similar stages in the Fern group, and indicate that the Gymnosperms stand nearer to the Cryptogams than do the Angiosperms, the other and larger group of Seed-plants. The Gymnosperms are also the older group, and contain many extinct forms. In38 the Angiosperms the seed is enclosed in the fruit, and in the development of pollen and ovule almost all traces of a cryptogamic ancestry have been lost; the great development of the flower is a characteristic feature of the Angiosperms. The arrangement of the vegetative parts of the plant is based on its separation into root, stem, and leaf. In the right-hand wall-case the upper series of specimens illustrates the leaf, its form, veining, direction, the characters of its stalk and stipules, its modification for special purposes, and its arrangement on the stem and in the bud. Below, the stem and root are similarly treated, and above are some anatomical drawings. The display of the root is continued in the lower part of the opposite wall-case. In the central case the chief types of the flower with its parts, the fruit, and the seed are exhibited.

At the back of the bay is a large transverse section of the Karri tree (Eucalyptus diversicolor) of Western Australia, a species which grows to a height of 400 feet. The tree from which the section was cut was about 200 years old when felled.

The Introductory Collection of Minerals will be found in the gallery devoted to the Mineral Department (see p. 90).

The North Hall.

The North Hall, or that portion of the building situated to the northward of the principal staircase, is used for the exhibition of the more important breeds of Domesticated Animals, as well as of examples of Hybrids and other Abnormalities. A series of specimens illustrative of Economic Zoology is likewise temporarily placed here.

The examples of Domesticated Mammals include Horses, Cattle, Sheep, Goats, Llamas, Dogs, Cats, and Rabbits. One of the main objects of this series is to show the leading characteristics of the well-established breeds, both British and foreign. In addition to Domesticated Animals properly so called, there are also exhibited examples of what may be termed Semi-domesticated Animals, such as white or parti-coloured Rats and Mice.

39 The skulls and skeletons of celebrated Horses7 of all breeds, including those of the Thoroughbreds “Persimmon” (presented by His Majesty King Edward VII.), “Stockwell,” “Bend Or,” and “Ormonde,” and of the Shire “Blaisdon Conqueror,” form a notable feature of the series. In another case is exhibited the dentition of the Horse at different periods of existence; while on the opposite side of the same is illustrated the evolution of the Horse from three-toed and four-toed ancestors, and also certain peculiarities distinguishing the skulls of Thoroughbreds and Arabs from those of most other breeds.

Among the more notable exhibits are a mounted specimen of a Spanish Fighting Bull, which belongs to an altogether peculiar breed, and heads of Spanish Draught Cattle, presented by H.M. King Edward VII. Among the Sheep, attention may be directed to the four-horned, fat-tailed, and fat-rumped breeds, and also to the small breed from the island of Soa, as well as the curious spiral horned Wallachian Sheep. The so-called wild cattle of Chillingham Park are included in this series, since they are not truly wild animals, but are descended from a domesticated breed. The celebrated Greyhound “Fullerton” is shown among the series of Dogs, which also comprises examples of the Afghan Greyhound, and of the Slughi or Arab Greyhound. Small-sized models of Cattle, Horses, Sheep, and Pigs also form a feature of the series.

A hybrid between the Zebra and the Ass is shown in one of the cases; while photographs illustrate the results of experiments undertaken by Professor Ewart in cross-breeding between Burchell’s Zebra and the Horse. An example of the Lion-Tiger hybrids born many years ago in Atkins’ menagerie is likewise shown.

A fine series of hybrid Ducks and hybrid Pheasants is exhibited in the north hall.

Facing the visitor as he approaches the middle of the north hall are the skeletons of a Man and of a Horse, arranged for comparison with each other, and also to show the position of the bones of both in relation to the external surface. In the case of the Horse, the skin of the same animal from which the skeleton was prepared was carefully mounted, and, when dry,40 divided in the middle line; one half, lined with velvet, has been placed behind the skeleton. In the case of the Man, the external surface is shown by a papier-maché model, similarly lined and placed in a corresponding position. As all the principal bones of both skeletons have their names attached, a study of this group will not only afford a lesson in comparative anatomy, but be of practical utility to the artist.

Against the wall dividing the north hall from the central hall is placed a section of a very large Wellingtonia or “Big Tree” (Sequoia gigantea), which was cut down in 1892 near Fresno, in California. It is about fifteen feet in diameter, and perfectly sound to the centre, showing distinctly 1,335 rings of annual growth, which afford exact evidence of the age of the tree. An instantaneous photograph, taken while the tree was being felled, is placed near by, and shows its general appearance when living. The height of the tree was 276 feet.

The exhibits of Economic Zoology at present occupy the northern division of this hall. In the western wall-case are specimens showing the injuries caused to trees by various insects. The table-cases contain examples of the damage done in Britain to fruit, roots, corn, and garden and vegetable produce, with specimens of the insects, and hints as to methods of destruction. There are also examples of injury done by insects abroad to cotton, tea, coffee, etc. In the cases under the windows are various parasites affecting man and domesticated animals.

Staircase and Corridors.

On the first landing of the great staircase, facing the centre of the hall, is placed the seated marble statue of Charles Darwin (b. 1809, d. 1882), to whose labours the study of natural history owes so vast an impulse. The statue was executed by Sir J. E. Boehm, R.A., as part of the “Darwin Memorial” raised by public subscription. It was unveiled and placed under the care of the Trustees of the Museum on the 9th of June, 1885, when an address was delivered on behalf of the Memorial Committee by the late Professor Huxley, P.R.S., to which His late Majesty King Edward VII. (then Prince of Wales), as representing the Trustees, replied.

41

Above the first landing the staircase divides into two flights, each leading to one of the corridors which flank the west and east sides of the hall and give access to the galleries of the first floor of the building. Near the southern ends of these corridors two staircases join to form a central flight leading to the second floor. On the landing at the top is a marble statue by Chantrey of Sir Joseph Banks (b. 1743, d. 1820), who for 41 years presided over the Royal Society and was Trustee of the Museum. His botanical collections are preserved in the adjoining gallery, but his library of works on natural history, also bequeathed to the Museum, remains at Bloomsbury, where the statue, erected by public subscription in 1826, stood until it was removed to its present situation in 1886. On the wall above is displayed a series of unusually fine heads of Indian Big Game Animals, bequeathed by Mr. A. O. Hume, C.B., in 1912.

The west, south, and east corridors contain a portion of the collection of mounted Mammals for which there is not room in42 the gallery immediately adjoining. The specimens placed here include a large number of species of the finest African Antelopes, animals remarkable for their beauty, for their former countless numbers, and for their threatened extermination in consequence of the inroads of civilized man into their domain.

In a case at the head of the staircase leading to the east corridor are several mounted specimens of Giraffes, and near by a skeleton of the same. Alongside the former is placed a case containing the heads and necks, together with skulls, of the various local races of Giraffes; while in a third are displayed three specimens of their near ally the Okapi (fig. 14) of the Congo Forest, as well as a skeleton of the same.

The collection of Humming-Birds (Trochilidæ) arranged and mounted by the late Mr. John Gould, and purchased for the Museum in 1881, is principally shown in the vestibule leading from the hall to the Fish-gallery, but a few cases are placed on the pillars of the staircase. Another large collection of these birds, presented in 1913 by Mr. E. J. Balston, of Maidstone, is exhibited in the corridor leading to the Whale-room.

WEST WING.

The whole of the west wing of the building is devoted to the collections of recent Zoology.

(A) Ground Floor.

The ground floor is entered from the west side (left hand) of the central hall, near the main entrance of the building. The long gallery, extending the entire length of the front of the wing as far as the west pavilion, is assigned to the exhibited collection of Birds, the study-series of the same group being kept in cabinets in a room behind.

The wall-cases contain mounted specimens of all the principal genera, placed in systematic order, beginning with the Crows and Birds of Paradise on the left hand on entering, and ending with the Ostriches, Emus, etc., on the right.

British Museum (Natural History)

Ground Floor.

43

Among the multitude of species exhibited in this gallery, which form, however, but a small proportion of the different kinds of Birds known to inhabit the globe, only a few of the more striking can be mentioned. The various types of the Birds-of-Prey are very fully represented: from the Condor of the Andes, the large Sea-Eagle of Bering Strait, and the Great Eagle-Owl of Europe (all of which are placed in separate cases), to the Dwarf Falcon in case 53, which is not much larger than a sparrow, and preys upon insects. Among the large group of Perching-Birds, attention may be directed to the cases of Birds of Paradise and Bower-Birds in the first bay on the left. In separate cases in the sixth bay on the opposite side of the gallery are placed skeletons of the Dodo and Solitaire, large Pigeon-like birds with wings too small for flight, once inhabiting the islands of Mauritius and Rodriguez, respectively, but now extinct. Other cases on the right-hand side of the gallery are occupied by the Game-Birds, and the Wading and Swimming Birds. Here may be noticed a nearly complete series of the genera of44 Pheasants and Pigeons, showing the various forms. Special attention may be directed to the Great Auk (fig. 15), from the Northern Atlantic, which became extinct only in the last century. Casts of the eggs (fig. 16) of this curious bird are also exhibited. A case in the 7th bay contains a series of Penguins, flightless birds which may be regarded as representing the northern Auks and Guillemots in the southern oceans. Particularly interesting is the great Emperor Penguin, which lays its eggs and rears its young in winter amidst the ice of the Antarctic. Most of the specimens exhibited were obtained during the British Antarctic Expedition of 1839–43, under the command of Captain Sir James Clark Ross.

Other noteworthy types are the Great Bustard, once an inhabitant of England, and the Flamingos; a pair of the latter being exhibited with their nest.

In the first two bays on the right side of the gallery are placed specimens of the Ostrich group, characterised by the flat or raft-like form of the breast-bone. Owing to the rudimentary character of their wings, these Birds lack the power of flight. They include the largest existing Birds, the Ostriches, Emus, and Cassowaries, as well as the small Kiwis (Apteryx) of New Zealand, together with the extinct Moas (Dinornis, etc.), of the same country, and the Roc (Æpyornis) of Madagascar. A fossil egg of the latter is placed alongside eggs of the existing species of the group.

Down the middle line of the gallery, as well as in many of the bays, are placed groups showing the nesting-habits of various species of British birds. The great value of these groups consists in their absolute truthfulness to nature. The surroundings are not selected by chance or from imagination, but in every case are carefully executed reproductions of those that were present round the individual nest. When it has been possible, the actual rocks, trees, or grass, have been preserved, but in cases where these could not be used, they have been accurately modelled from nature. Great care has also been taken in preserving the natural form and characteristic attitudes of the Birds themselves. Among the more attractive cases are, near the centre of the gallery, a pair of Puffins feeding their single young one, and Black-throated Divers with their eggs46 in a hollow in the grass on the edge of a mountain-loch in Sutherland. Hen-harriers—the male grey and the female brown—are shown with their nest among the heather from the moorland of the same county. On the left of these is a Peregrine Falcon’s eyrie, on the ledge of a rocky cliff, containing three white downy nestlings. Near by are various species of Ducks, notably the Red-headed Pochard on the sedgy border of a Norfolk mere. In the last bay but one on the right side is a nest of the Heron, in a fir-tree, with the two old birds and three nearly fledged young. Various species of Gulls and a particularly beautiful group of Arctic Terns from the Shetland Islands are exhibited in the middle line towards the west end of the gallery and in the eighth and ninth bays. In the eighth bay on the right side and in the adjoining passage are Plovers, Sandpipers, Snipes, etc., some of which (especially the Ringed and Kentish Plovers) show the wonderful adaptation of the colouring of the eggs and young birds to their natural surroundings for the purpose of concealment. In the second passage leading to the Coral-gallery are Ptarmigan and Capercaillie from Scotland, and in the adjacent part of the middle line Wood-Pigeons and Turtle-Doves building their simple, flat nests of sticks in ivy-clad trees. In the fourth, sixth and seventh bays on the left are Sand-Martins and Kingfishers, showing, by means of sections of the banks of sand or earth, the form and depth of the hole in which the eggs are placed; and also nests of the Swift, Swallow, and House-Martin, all in portions of human habitations.