The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hawaii National Park: A Guide for the

Haleakala Section, by George Cornelius Ruhle

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Hawaii National Park: A Guide for the Haleakala Section

Island of Maui, Hawaii

Author: George Cornelius Ruhle

Release Date: June 2, 2018 [EBook #57258]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HAWAII NATIONAL PARK: HALEAKALA ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Copyright 1959 by the

HAWAII NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION

WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

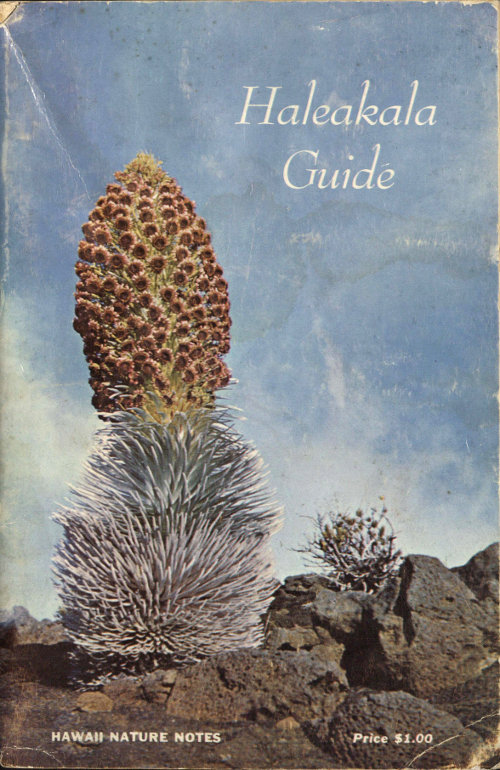

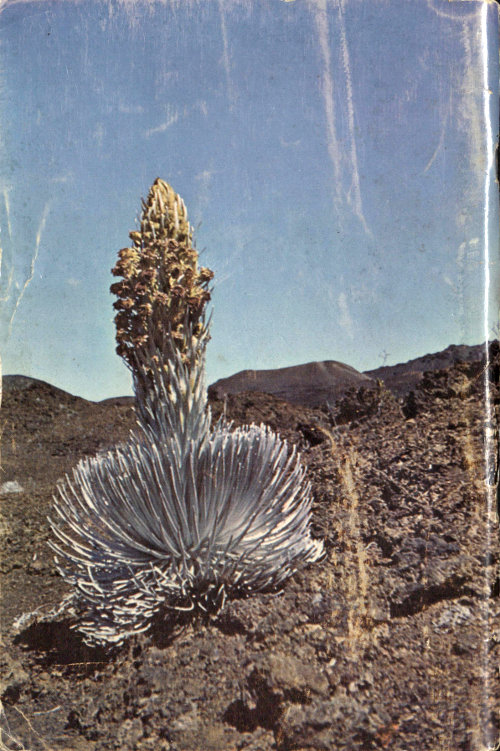

Covers: Silversword in bloom

by

George C. Ruhle

illustrated by Donald M. Black

PUBLICATION OF THE

HAWAII NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION

JUNE, 1959

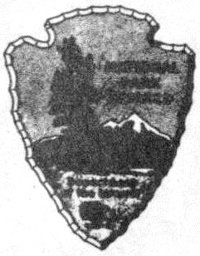

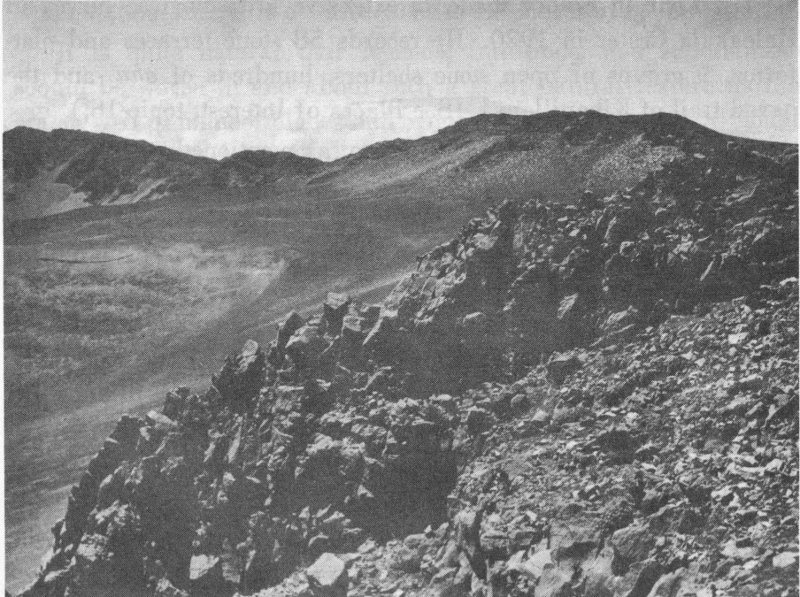

On the Sliding Sands Trail

Most of us yearn to travel, and the preliminary to travel is to choose a place that others, people or books, say is interesting, then find out more about it.

This guide is to help you find out more about Haleakala. It is neither a reference book nor a treatise. It sums up what many have studied and observed. It skims over the myths that the mountain itself created in the imagination of old Hawaiians. It reflects also the labor and thought of the compiler. Its aim is to satisfy your interest while you are here on the brim, or at some other point. For some of you it may be the start of a deeper curiosity, to be satisfied by further reading elsewhere.

Think of this booklet as a chatty companion along the way, and a ready reminder after you have left, of your pleasant experience at Haleakala.

The system of 29 National Parks contains areas of superlative scenic and scientific grandeur essentially in the primitive state. The National Park Service of the Department of the Interior administers these, as well as 152 other areas of outstanding national significance. The law of the land enjoins us to use them in such manner that they may be passed unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.

The story of HAWAII NATIONAL PARK is the story of active volcanism singularly marked by eruptions of very fluent lava. The park is in two sections; that on the island of Maui, discussed in this guide, includes the great eroded crater of Haleakala Volcano; that on the island of Hawaii embraces the summits of Mauna Loa and Kilauea Volcanoes.

The silversword is the pride and distinction of Haleakala.

Haleakala is a great volcano, 33 miles long and 10,025 feet high. During a long period of inactivity, stream erosion cut two deep valleys, Keanae and Kaupo, into its sides. These joined near the summit. When volcanic activity once again resumed, flows of aa and blankets of cinders were spread on the valley floors. A multicolored cover, emphasized by symmetrical cones, formed the new floor of the depression, now loosely called Haleakala Crater.

The well chosen name, Hale-a-ka-la, means House of the Sun. Old Hawaiians associated Maui, a trickster demi-God, with the mountain. He was a legendary figure throughout Polynesia long before a few of its inhabitants discovered and settled in Hawaii, bringing their gods with them.

How Maui brought down or ensnared the sun has several versions. Maui’s mother, Hina, had trouble drying bark cloth, kapa, because the day was too short, its warmth insufficient. The sun just sped too fast across the sky. So Maui fashioned a strong net to snare it in its course. A slight variant, possibly less used, appeals more strongly. In early dawn, one can watch strong streamers of light from the rising sun break through the clouds and stalk across the crater. With these spidery legs the sun progresses through the heavens. As one by one they were placed over Koolau Gap, Maui seized them and bound them with strong thongs to an ohia tree. Thus captured, the sun pleaded for release. This Maui granted on promise of a slower gait, for which Hina as well as the rest of us can be eternally thankful.

Anticipate a restful, invigorating interlude. Islanders consider vacation on the cool mountain an inexpensive, pleasant variant from a mainland trip.

Silversword Inn at an elevation of 6,800 feet is popular with luncheon guests and with those staying overnight to view sunset or sunrise from the summit of the great mountain. Attractive, friendly, comfortable, it is the loftiest hostelry in the islands. There is no formal atmosphere: warm, casual clothing is worn; it is strictly “come in as you are.”

Hiking and riding in the vicinity of the inn are favorite pastimes. Adjacent groves of trees of the Temperate Zone impart an aspect novel to the islands. A visit is highlighted by trips into the crater and to the summit, less than thirty minutes distant by car. The cup runneth over for photographers and nature enthusiasts. You can enjoy cool, restful nights between daytime drives to the many points of interest on Maui. For further details, reservations, and rates, consult the Manager, Silversword Inn, R.R. 53, Waiakoa, Maui, Hawaii, or Mr. William S. Ellis, Jr., 900 Nuuanu Ave., Honolulu 17, Hawaii.

The Haleakala road climbs through plantations and ranchland from Kahului Harbor and Kahului Airport to the park entrance at an elevation of 6,740 feet. The distance by the shortest route is thirty miles. The highway continues eleven miles further to the Park Observatory on the western rim of Haleakala Crater and to the 10,025-foot summit. No bus service exists, but taxis and U-drive cars are hired at the airport and in the towns of Kahului and Wailuku. The sole access into the crater is over good trails for travel on foot or by horse.

The start of a drive to the park is made by one of three paved routes. The shortest is Pukalani Road. The other two turn inland at Paia or Haiku and traverse more interesting country. The three 2 routes converge at Pukalani Junction ten miles up the mountain. PUKALANI means a hole in heaven, which picturesquely describes the fact that the sun breaks through at this place despite a general overcast elsewhere.

As the road rises up and ever up, it unfolds distant views of fields of sugar cane and pineapple, of West Maui Range, 6,000 feet high, and of Molokai, Lanai, Kahoolawe, and Molokini Islands beyond channels of blue sea. 100 miles southward, the tops of the snowy volcanoes on the Island of Hawaii float on billowy clouds. 10,000 feet below, the aquamarine Pacific fringes Maui with white surf.

Three viewpoints along the road overlook the great crater: Leleiwi, at the 9,000-foot switchback; Kalahaku, two miles below the summit: and the Park Observatory, near the top. The roadway extends along the crest one mile southwestward to a scenic point beyond the park boundary and a communication station of the Civil Aeronautics Administration.

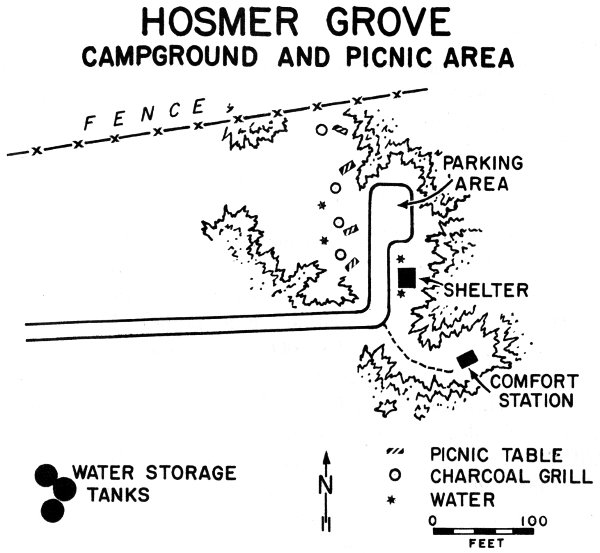

Just above the park entrance, Silversword Inn, a National Park concession, offers meals, rooms, souvenirs, horseback riding and guided horseback trips into the crater. Across from the inn, a paved spur road leads a half mile to Hosmer Grove Campground and Picnic Area.

Haleakala Crater is a favorite with those who like the back-country; its inspiring scenery and restful solitude are great reward for time and effort. The National Park Service maintains three cabins on the crater floor and 30 miles of well-marked trails for hikers and horseback parties.

A quarter mile above the park entrance, opposite the driveway to the inn, a paved lane, one-half mile long, leads to the Hosmer Grove Campground and Picnic Area. It has a shelter for rainy weather that contains two tables and two charcoal burners. Four additional tables with adjacent charcoal burners are in an open site below the road. Running water, parking space for eight cars, and sites for pitching tents are provided. Charcoal may be purchased at the inn. A self-guiding nature trail leads through the grove.

HOSMER GROVE

CAMPGROUND AND PICNIC AREA

The grove was named for the first Territorial forester, Dr. Ralph S. Hosmer, who experimented with planting temperate trees at high altitudes on Haleakala and Mauna Kea. Trees, planted here in 1910, include the deodar, Cedrus deodara from the Himalayas; the tsugi, Cryptomeria japonica from Japan; eucalypti from Australia; and from the mainland a cypress, Cupressus arizonica; a juniper, Juniperus virginiana; Douglas fir, Pseudotsuga taxifolia; incense cedar, Libocedrus decurrens; two spruces, Picea canadensis, P. excelsa; and seven pines: lodgepole, Pinus contorta, Coulter or big-cone, P. coulteri, Jeffrey, P. jeffreyi, longleaf, P. palustris, ponderosa or western yellow, P. ponderosa, white, P. strobus, and Scotch, P. sylvestris. Many of these have survived and have borne fruits. The huge keeled cones of Coulter pines are cherished as ornaments in some homes.

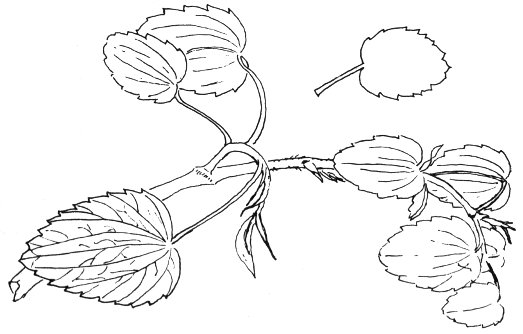

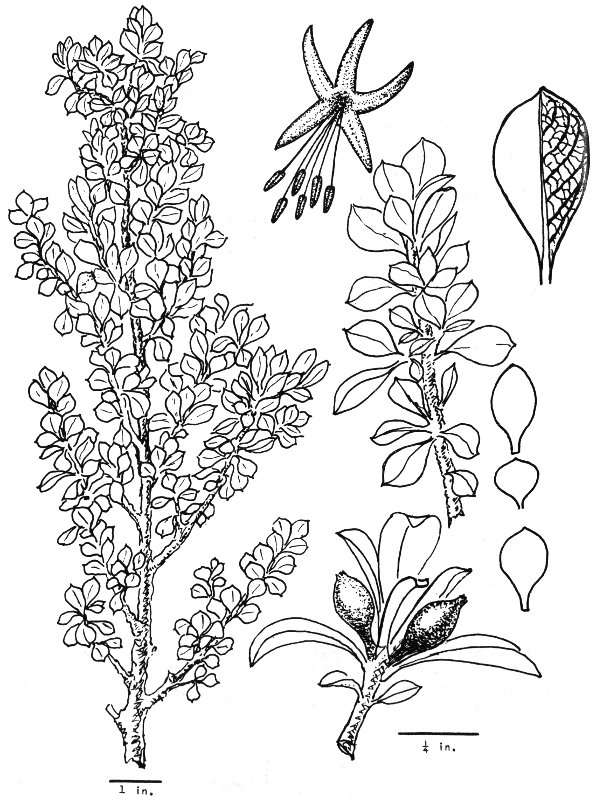

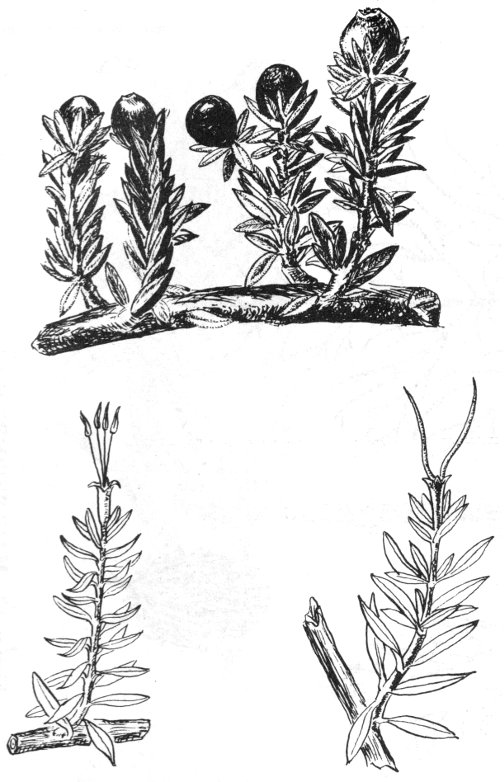

Native plants associated with the area are the shrubs: Haleakala sandalwood, mamane, pukiawe, aalii, mountain pilo, ohelo, silver 4 geranium, kupaoa; two or three ferns; two sedges; and three native grasses.

Two thirds of the distance to the grove, the crater trail from the inn starts up the mountain to the left. This is a connecting link, 1¾ miles long, to the Halemauu Trail which it joins a half mile below its start on the highway. See Numbered Points of Interest, No. 9.

The Sliding Sands Trail, the popular route into the crater, starts from the parking area at the Observatory. It is constructed along the south side of the crater to Kapalaoa Cabin six miles away. Connecting trails go to Paliku Cabin, four miles farther. The Halemauu Trail has two upper ends, at the 8,000-foot elevation on the highway and on the Hosmer Grove Campground Spur near Silversword Inn. Halemauu Trail goes down Leleiwi Pali, the west wall, to Holua Cabin, four miles from the road or six miles from the lodge. The trail continues easterly from Holua for six miles along the north side of the crater floor to Paliku. Branch trails are built to points of interest. The Kaupo Trail through Kaupo Gap leaves Paliku Cabin and the crater to make a rapid descent of the southern, sun-drenched slope.

Each of the three visitor cabins within the crater, Kapalaoa, Paliku, and Holua, is equipped with running water, a wood-burning cookstove, firewood, kerosene lamps, cooking and eating utensils, twelve bunks, mattresses, and blankets. Use of these cabins by hikers on a priority reservation basis is granted free of charge by the Park. In consideration for their use cabins should be left clean and in order by each party. The following arrangements are necessary: write the Park, giving an outline of your proposed trip, number in the party, exact calendar dates, and names of specific cabins which you wish to use each night. The address is: “Hawaii National Park, Haleakala Section, P. O. Box 456, Kahului, Maui, Hawaii.” Cabin reservations can also be made by telephoning the Park. When you arrive in the Park, stop at the Administration Building for your permit, cabin key, and orientation.

For safety reasons, all visitors are required to obtain permits from the rangers for all trips into the crater, other than those with Silversword Inn guides.

Short Walks for the Day Visitor: (1) Along Halemauu Trail from the highway to the Crater Rim, three-quarters of a mile. Views down Keanae Valley, across Koolau Gap to Hanakauhi, and of Halemauu Trail. (2) A short distance down the Sliding Sands Trail. Be careful not to travel too far down. The return climb is exhausting at this high altitude. (3) To the top of White Hill. The trail winds among ancient Hawaiian stonewalled encampment sites.

One-day hikes into crater: (1) Down Halemauu Trail to Holua Cabin and return to the highway, a scenic trip of eight miles that can be taken by any reasonably good hiker. It is not recommended when clouds blanket the pali and Koolau Gap. Allow a half-day for hiking. (2) Down Sliding Sands Trail to the crater floor, across Ka Moa o Pele Trail to Halemauu Trail at Pele’s Paint Pot or Bottomless Pit, and return to the highway via Holua and the Halemauu Trail. This colorful, spectacular twelve-mile trip is recommended only for good hikers. Allow eight hours of hiking time. At your risk, rangers can often arrange to move your car for you to the place at which the Halemauu Trail emerges on the highway.

Overnight crater hikes: Hike down Sliding Sands Trail; spend the night at either Paliku, Kapalaoa, or Holua Cabin; return via Halemauu Trail. The choice overnight hike to Paliku, a 20-mile round-trip, is recommended for good hikers only. The trip with an overnight stop at Kapalaoa is 14 miles long. The shortest route from the foot of Sliding Sands Trail to Holua via Ka Moa o Pele leaves only the four-mile climb via Halemauu Trail for the second day. The Sliding Sands Trail is not recommended for return from a crater trip. The long climb to an elevation of 10,000 feet is too exhausting for most people.

Two and three day crater hikes: Entry via the Sliding Sands and return via Halemauu Trail is recommended. A three-night trip stopping at Kapalaoa, Paliku, and Holua allows leisurely enjoyment of the crater. Good health and fair walking ability are all that are required for these longer trips.

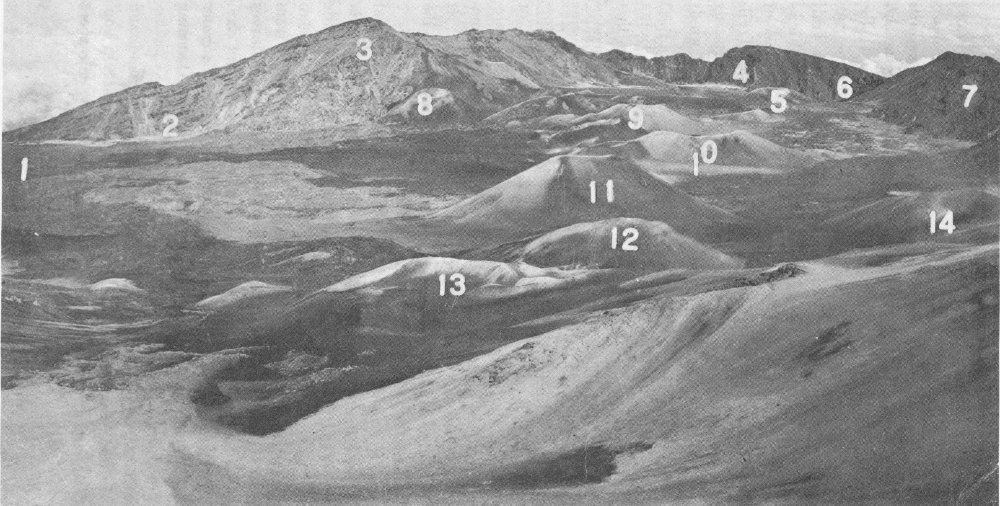

1. Koolau Gap; 2. Waikau; 3. Hanakauhi Peak; 4. Paliku; 5. Puu Maile; 6. Kaupo Gap; 7. Haleakala Peak; 8. Puu Kumu; 9. Puu Naue; 10. Ka Moa o Pele; 11. Puu o Maui; 12. Kamohoalii; 13. Ka Lua o ka Oo; 14. Puu o Pele.

No guide service is available or necessary for parties hiking or riding their own stock into the crater. However, a permit is required before you start your trip within the crater. For details, consult the section labelled “Park Cabins.”

Clothing should consist of hiking shoes, slacks, shirt, jacket, hat, and preferably a light raincoat. Basketball shoes or keds are preferred by some. Because of the chill climate at elevations of seven to ten thousand feet, warm clothing is advisable. In climbing, temperature goes down as you go up. The top of Haleakala averages thirty degrees cooler than sea level. You should bring your food for the trip, a knapsack, sunburn lotion, soap, hand towel, dish towel, matches, and simple first aid. As cooking facilities in the cabins are adequate, food need not be precooked.

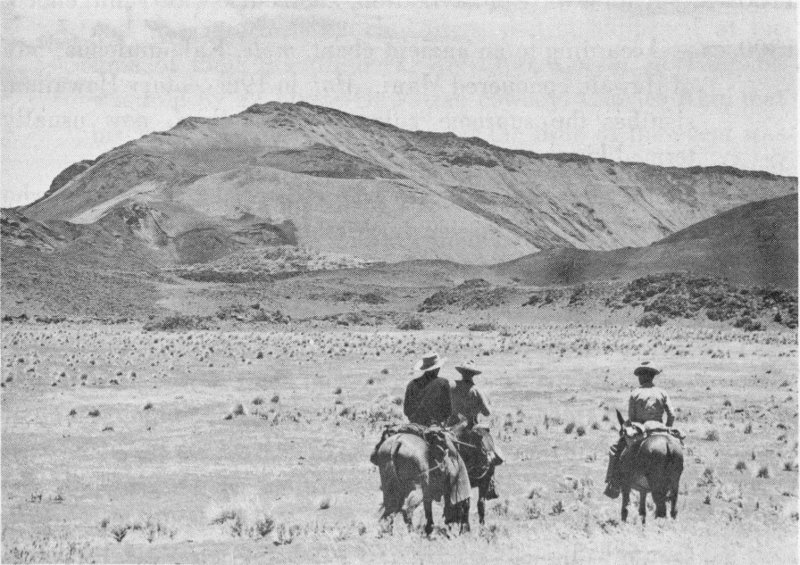

Silversword Inn provides horseback trips on good stock with a competent guide. Food is provided, cooking is done by the guide, and sleeping accommodations are arranged by the management. A guest need only concern himself about personal effects and clothing suitable for riding in a cool climate. For rates and trip reservations, telephone or write to the Manager, Silversword Inn, R.R. 53, Waiakoa, Maui, Hawaii, or to Mr. William S. Ellis, Jr., 900 Nuuanu Ave., Honolulu 17, Hawaii.

If you have your own horses make the same arrangements as hikers for entry into the crater and for cabin use. You may travel on any of the crater trails. Fenced horse pastures are adjacent to each of the cabins.

Basic data for this section was compiled by the park staff and submitted by Eugene J. Barton, Assistant Superintendent in charge of Haleakala from 1949-1955. The map is in the center of the booklet.

1. Park entrance (elev. 6,740′) and inn: The park entrance, marked by a rustic sign, is on the slope of Puu Nianiau, an ancient cinder cone. Nianiau is Hawaiian for swordfern. One quarter mile above the entrance turn right to the Silversword Inn for meals, lunches, overnight accommodations, color pictures, slides, and souvenirs of the park. The inn arranges guided trips through Haleakala Crater.

2. Ralph S. Hosmer Grove: Across from the lodge, a paved spur road leads to the Hosmer Grove Campground and Picnic Area.

3. Headquarters of the Haleakala Section of Hawaii National Park: Stop at the Administration Building beside the road for information, permits, cabin keys needed on crater trips, and for assistance in case of trouble or accident. The park maintenance area is located behind the station. As you drive toward the summit, note the small native trees and shrubs growing along the road. This elfin forest was all but destroyed by goats and cattle; it has recovered under National Park protection. The book, “Plants of Hawaii National Park,” and the section on plants in this guide may help you identify the different species. These and other publications of the Hawaii Natural History Association may be purchased at the inn or at Park Headquarters.

4. Leleiwi Overlook; Kalahaku Overlook: At the switchback near the 9,000-foot contour, a parking space has been constructed that is labelled LELEIWI OVERLOOK. This is above Holua and the Halemauu Trail, so that parties can be watched as they go down Leleiwi Pali. On clear days, the whole length of Keanae Valley can be seen through Koolau Gap. The lateral view extends from Hana Airport across the big isthmus to Kihei on Maalaea Bay. On afternoons, clouds roll into the gap, making this a good place to see the Brocken Specter. One’s shadowy image appears within a circular 9 rainbow, projected against the bank of cloud. KALAHAKU OVERLOOK (elev. 9,325′) is a remarkable view point on the crater rim that is reached by a short spur off the main park road. It is the site of the Old Rest House, in which travellers on foot or horseback stayed overnight before the road was built. Silversword plants may be seen just below the main parking area. KALAHAKU is the name of the rugged pali forming the crater wall at this point. The name means “meeting place of the headmen or chiefs.”

5. The Observatory commands a spectacular view of the crater near the summit of Haleakala. It was erected in 1937 by the National Park Service for your comfort and convenience. The observatory is the main objective of most visitors to Haleakala. Besides being a welcome shelter during inclement weather, it has a large relief map and interpretive orientation devices. Modern rest rooms are located to the rear of the building.

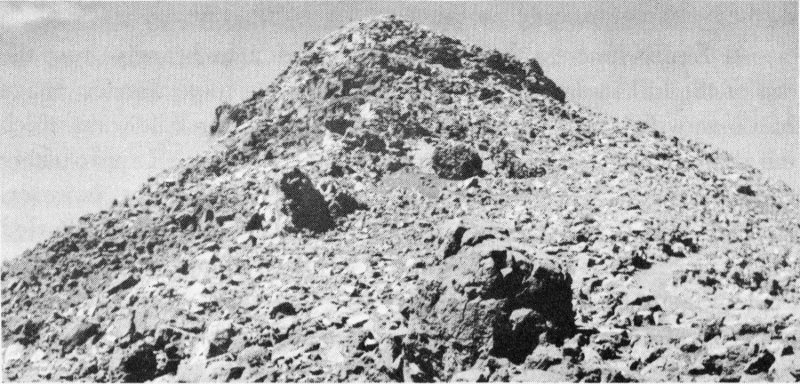

6. White Hill, Pakaoao (elev. 9,865′); start of Sliding Sands Trail: The rocky hill, just above the observatory, is capped with andesite, a volcanic rock lighter in color and different in composition from the common basaltic lava of Hawaii. The southwest slope, up which the trail leads, is covered with Hawaiian sleeping shelters consisting of oval stone-walled enclosures. These gave protection against the wind, fog, and cold that is common here. They may have been used long ago by wayfarers or by sentries and groups of warriors stationed at this commanding site. They may also have served as ambush for professional robbers, aihue, who waylaid travellers in lonely places. Refer to the topic, “The Tradition of Kaoao” in “Haleakala Hawaiiana” for more of the story.

7. Red Hill, Pakaoao, Summit of Haleakala (original English name, Pendulum Peak; elev. 10,025′): To drive to the summit take the paved road, turning sharply left below the observatory parking area. Red Hill is the highest of the three prominent recent cinder cones. Early morning is a good time to view extended panoramas and distant seascapes, before streaks of clouds form shelves along the sides of the mountain. But afternoon is better for viewing the crater, as its features appear in excellent light and color at that time. A pointer table by the road indicates the names of islands and peaks seen. An Army radar and radio communication station was located on Red Hill during World War II.

Halemauu Trail on Leleiwi Pali.

8. Skyline Drive: An improved driveway to the Civil Aeronautics Repeater Station leaves the park at the pass between Red Hill and Kolekole. Views stretch down the vast, precipitous southwest outer slope of Haleakala to the Lualailua Hills and a desert seashore, ten thousand feet below. Morning will most likely yield the cloud-free views. The Aeronautics Station is open to visitors. A parking area is just outside the gate to the station. Kolekole is the site of television relays and a satellite tracking station. It is a mile from the Observatory to the summit of Kolekole. It is 1.7 miles from the Observatory at the FAA Station. Magnetic Peak is across the road from Red Hill. A huge curiously shaped bomb on its skyline has a silhouette that looks much like a sitting duck.

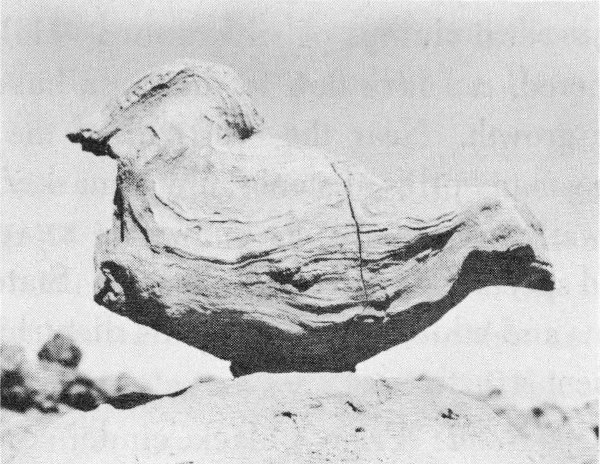

Volcanic bomb on Magnetic Peak.

9. The Halemauu Trail starts from a curve on the park road at the 8,000 foot elevation. It leads down a gentle slope for eight-tenths of a mile to the crater rim. An alternate start is on the driveway into Hosmer Grove Campground, near Silversword Inn. Built by the National Park Service in 1937, the trail drops with a gentle grade down the 1500-foot Leleiwi Pali to the crater floor. It suggests thrilling trails in Glacier National Park and other rugged mainland areas as it swings and clings to the vertical cliffs. Hike to the crater rim for spectacular views of Windward Maui and Keanae Valley in fair weather; if clouds are rolling up Koolau Gap in the evening, you 12 may possibly be greeted by the Specter of the Brocken. Silver geraniums, Hinahina, small spherical shrubs peculiar to Haleakala, grow along the upper trail and road. HALEMAUU, grass house, is said to be derived from one formerly located near the head of the trail.

10. Holua Cabin rests in a grassy plot at the foot of the towering, 3,000-foot Leleiwi Pali. Introduced grasses grow in the meadow near it. The pale “moss” on the rough lava flow is Stereocaulon, actually a lichen, that strange combination of an alga and a fungus growing together to appear as one plant. This pioneer on barren new lavas is sometimes called Hawaiian Snow. The comparatively recent flow in front of the cabin contains lava tubes or caves. These are rough and dangerous, and should not be entered except by especially equipped parties. Holua Cave, above the cabin, was used as a night shelter before the cabin was built.

11. Silversword Loop, a quarter-mile long, deviates from Halemauu Trail past several clumps of silversword. Hollows and slopes of the old, weathered, red lava flow in this area have favorable conditions for their growth. Near the east end of the loop, the main trail passes among many piles of stones, ahus, markers, and platforms built by the Hawaiians. This place, known as KEAHUOKAHOLO, appears to have had special or sacred significance. State law, as well as Hawaiian customs and ethics, strictly forbids disturbing or damaging any of these ancient structures.

12. Kihapiilani Road: From a black, cinder-covered flat, an old Hawaiian pathway crosses the rough shoulder of the small cone on Halalii to smoother surface between Mamane Hill and Puu Kumu. It is six to eight feet wide and is paved with flat stones. The start, difficult to locate, is to the right of a small, horned spattercone seen from the trail as you look toward Hanakauhi Peak. A chief, Kihapiilani, built the trail over Mauna Hina along the North Rim to a pond, Wai Ale, probably the present Wai Anapanapa on the exterior slope. Refer to “The Legend of Kihapiilani” in “Haleakala Hawaiiana” for the story.

13. Bottomless Pit is a yawning black well, ten feet in diameter, rimmed with colored lava spatter a few feet high. Use caution approaching its edge. Baseless legend claims that it sinks to sea level. 13 Although no bottom can be seen, debris chokes the opening sixty or seventy feet below. It is a vent, through which superheated gases were emitted in an eruption of long ago. The rim around the throat indicates that a little lava sputtered out with the gas. During the flank eruptions of Mauna Loa and Kilauea similar vents exhale columns of blue, incandescent gases at intervals. Old Hawaiians at Kaupo say that the pit was used for disposition of umbilical cords of babies. Various reasons are assigned to the custom, such as to make the child strong, or to prevent its becoming a thief.

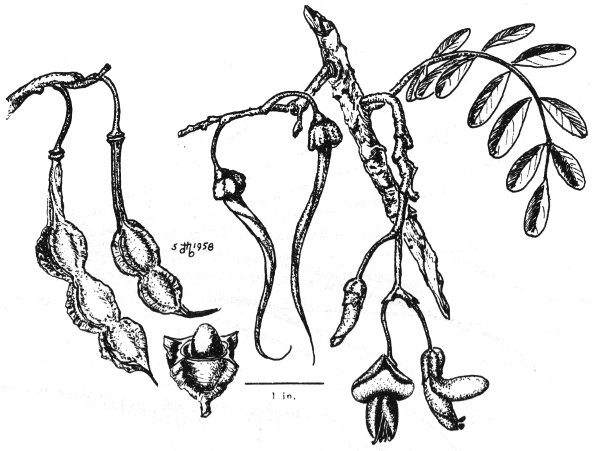

14. Ka Moa o Pele Trail branches from the foot of the Sliding Sands Trail to join the Halemauu Trail across the crater. It is a scenic route between silverswords on Ka Moa o Pele, a red cinder cone. Flowering plants can usually be seen from June to September. Pa Puaa o Pele, Pele’s Pig Pen, is the rim of a spatter cone, now buried, in the low pass between Halalii and Ka Moa o Pele. Hikers from Sliding Sands to Holua should go around the right or east side of Halalii to see the Bottomless Pit and Pele’s Paint Pot, a colorful pass just a short distance beyond.

15. Bubble Cave is a large, collapsed bubble with heavy walls. It was blown by gases in ancient molten lava. Only a small segment collapsed in the center of the roof, which serves as entrance and smoke-hole; old-timers were wont to camp in this natural shelter. It was the rest stop now supplanted by Kapalaoa Cabin.

16. Wailuku Cabin, outside the park, was built by the State Board of Agriculture and Forestry for the use of hunters. Arrangements for its use must be made at the Maui Office of the Board in Kahului. Trails to it are not of park standards and are not recommended to sightseers.

17. Old and New Volcanics: Dikes that protrude as slabs of light-colored rock from slopes of the ridge toward Hanakauhi mark part of the ancient divide between Koolau and Kaupo Valleys, the great erosional canyons worn into the mountain during an age of quiescence. This divide is deeply buried inside the crater under the cinders and flows of renewed eruptions that form the present floor. Adjacent Mauna Hina and Namana o ke Akua, green with shrubs, grass, and scrub mamane, are cinder cones from ancient eruptions. 14 Puu Nole, a garish, black youngster in the community, has only silverswords on its barren slopes. Towards Paliku the trail is flanked by some of the most recent lava flows, only a few hundred years old. Their source vents are visible on the slopes of Hanakauhi and the north wall of the crater.

18. Lauulu Trail is plainly visible as it zigzags up the north wall. Although not maintained at present, it is passable and allows rugged enthusiasts to climb the rim for views of the crater. On the outer slopes, moist grassy plots, often fog-bound, blend into jungle that drops to the Hana Coast, 8,000 feet below. Kalapawili Ridge extends from the summit of Hanakauhi Mountain eastward around the head of Kipahulu Valley to the tiny lake, Wai Anapanapa. It is readily traversable for the good hiker.

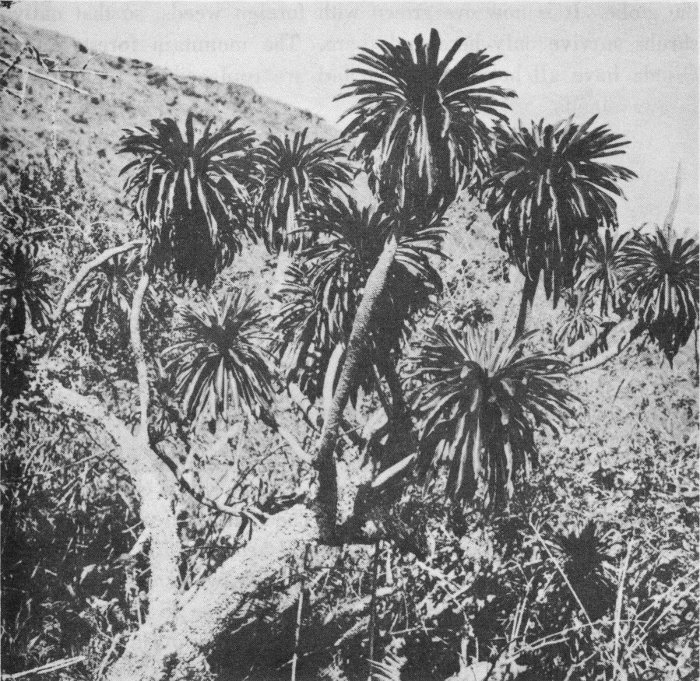

19. Paliku is very different from the desert wastes in the other parts of the crater. Lush grass and ferns, overhanging forest trees, and a verdant cover on a towering pali result from abundant clouds pushed by the trade winds over the east wall. AKALA, the giant Hawaiian raspberry, ripens abundantly back of the cabins in July. It is excellent for pie, conserves, or dessert. Native Hawaiian trees include: MAMANE, far larger than the scrubby growth in the crater; OHIA, with gray-green leaves and red lehua flowers; KOLEA, with thick magnolia-like leaves four inches long; OLAPA, with leaves that tremble in the slightest breeze, like those of quaking aspen. The conifer above the Ranger Cabin is a cryptomeria, a Japanese evergreen planted early in this century.

20. Kipahulu Valley, beyond the eastern rim, is a remote, jungle wilderness walled in by loftiest cliffs; a no man’s land, it has barely been explored, let alone touched or altered by civilization. Look from the cabin at Paliku across the pasture to the lowest notch in the sheer eastern pali. For a view into Kipahulu, a good climber can follow an old goat trail, steep and tortuous, that leads up the left side of the draw to this notch. A chorus of bird songs rises from the primeval forest in Kipahulu. With them you may hear complacent squeals of wild pigs that have been undisturbed for generations.

21. Kaupo Trail is a good trail that winds down Kaupo Gap, across little meadows, through groves of small AALII trees, and under 15 spreading KOA trees to the park boundary which is below the 4,000-foot contour. Wild goats may be heard on the pali or on the lavas in the gap. Kaupo Ranch extends below the park. From the redwood water tanks, a jeep trail descends through pastures to ranch headquarters. It is 8 miles from Paliku to ranch headquarters, which can be hiked in a half day. Kaupo Village on the belt road around Haleakala is 1½ miles further. The route is interesting, but arrangements must be made in advance to be met by car either at the ranch or the village. It is fifty miles from Central Maui by the shortest road. Although Kaupo Trail crosses private property, advance permission is not required to use it; but, in due consideration, please use care to close gates and do not molest or damage any property. The reverse trip from Kaupo Village into the crater is not recommended because of the long, arduous climb up the unsheltered, south-facing mountain slope.

Paliku Cabin.

Thus starts the story of Maui, beloved demi-god of all Polynesia in the never-never land of long ago. Not wanted as a babe, for he was scrawny and deformed, his mother, Hina, wrapped him in a lock of her hair and cast him into the sea. But jellyfish rescued and mothered him, and the god, Kanaloa, gave him protection. For all that, the growing youngster yearned for his own, so that one day he crept back and stealthily mingled with his four brothers. He was accepted in the family circle only after much pleading by the eldest boy.

Maui-of-a-thousand-tricks is the favorite nickname given this delightful, oft thoroughly human scamp. Throughout his escapades he was ever faithful to man, so frequently fickle and unworthy. Maui made the birds visible, for at first they could only be heard as they sang and fluttered through the air. Maui invented spears and barbed fishhooks. His greatest catch, so runs his fish story, was with a huge hook of powerful magic made from the lifeless jawbone of his grandmother, who was remarkable, for only one side of her body was alive. He tricked his brothers into the task of manning the paddles while he, equipped with his potent tackle, fished up the Hawaiian Islands from the depths of the ocean. Maui first had strictly admonished the brothers not to watch him, but only to look straight ahead. When curiosity overcame the belabored paddlers, they disobeyed. The line parted as they looked back, leaving the land only partly emerged, a chain of islands instead of a continuous whole.

The story of the island of Maui thus begins and—so runs one version—Maui lived in plain fashion on simple fare in a humble grass hut at Kauiki, the famous foothill of Haleakala in the district of Hana. Hawaii at the time was covered by darkness and fog, so Maui pushed the heavens to their present position far above the highest mountains, Haleakala, Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa, and Hualalai. Before this feat, man had to stoop and crawl, pressed closely to the ground, for the skies were low, and were held up by the plants whose 17 leaves became flattened by their burden, even as they remain today. Yet even now, when Maui is asleep, the heavens rush back as somber clouds and darken the country with storms. From Kauiki, Maui made his important journey to the crater to capture the sun and force it to move slowly through the heavens that tapa may be dried and fruits can mature. Also there are more daylight hours for fishing and ceremonial preparations in the heiau. This legend, the most pertinent to this guide, is sketched in the Introduction to Part I.

Most Hawaiian legends place Maui’s home in the black lava bank of the Wailuku River above Hilo, while his mother chose the dark cave behind Rainbow Falls. His exploits, so often capricious, more frequently reflect a benefactor’s concern for mankind. Maui disclosed the art of making fire by rubbing sticks together. Previously, man was dependent on Pele’s volcanic furnace or on embers carefully nurtured to kindle his fires. Maui wrung the secret from Alae, the reluctant mud-hen, who alone knew it and guarded it with greatest care. Exasperated by repeated frustration and deception, Maui, once he had gained her secret, punished the stubborn bird by rubbing her head with a stick so roughly that all the feathers came off and raw flesh appeared, which is how it remains today.

Maui in his noblest moment gave his all for man, whose frailty brought about the downfall of both. For Maui, too, was doomed to die some day, since his father, like Achilles’ nurse Cynosura, had neglected a part of the proper ceremony to make him immortal. Maui abhorred the fact that man must die, for he regarded death as degrading and an insult to the dignity of man. The secret of life was hidden within the heart of Hina-nui-kepo, the dread ogress of death. To win immortality one had to steal through her jaws, which had sharp basalt teeth, enter into the inky blackness of the stomach, and tear out the heart. This could only be done while Hina slept. First, Maui turned man into a little bird, and advised him to keep very quiet, lest he awaken the fearful goddess from her slumber. Then he went stealthily about his fearsome task, speedily and alone. All went well until the return journey; alas! poor, weak man could not restrain himself, but burst into uncontrollable laughter as he watched the plight of 18 the demigod within the ugly, gaping fish-mouth of Hina. The great jaws closed with a snap that crushed Maui and left Death ever after the victor. Greater love hath no man!

It would seem that the crater so high in the sky, so remote in location, so difficult in access, so desolate in appearance, so dread in origin, should have been shunned by the early native. Quite the contrary, many marks of frequent and varied use may be discovered in the crater. A trail through it connected the busy sites on West Maui and the isthmus with Kaupo and Hana near the eastern shore. This direct route avoided the wet heavily forested northern slopes of the mountain as well as the precipitous, arid, rough terrain on the southwest. It was easily traversed, in spite of the climb involved.

“Kihapiilani was one time King of Maui. It was he who caused the road from Kawaipapa to Kahalaoaka to be paved with smooth rocks, even to the forests of Oopuloa in Koolau, Maui. He also was the one who built the road of shells on Molokai.” “And,” the great Hawaiian antiquarian, Abraham Fornander, might have continued, “he caused the trail across the crater of Haleakala to be paved with water-worn stones, to the foot of Hanakauhi of the mists.” Kihapiilani was the great public works king of the islands.

Because of Kihapiilani a most remarkable event of ancient Hawaiian history came to pass, the expedition of numberless canoes.

Three and a half centuries ago, Piilani, a king of Maui, had four children: two sons, Lonoapii who was the eldest child, and Kihapiilani, the youngest; and two daughters, Piikea, who became the wife of King Umi of Hawaii, and Kihawahine, now regarded as the lizard god. When the old king was dying, he adjured his successor, Lonoapii, to take his place as father and to be kind to the younger brother. But alas, the young prince was neglected and treated with contempt. One day at Waihee, two calabashes of small fish, nehu, still wet with sea water, were brought to Lonoapii. These he gave 19 to everybody except the younger brother, who, therefore, reached out and helped himself. This angered the king so that he hurled the calabash and its contents into Kihapiilani’s face. Without a word, Kihapiilani arose and travelled to Kula. After some time, he told his story to the kahuna Apuna and asked what he should do. Apuna replied that he should seek advice at Keanae from a kahuna named Kahoko. Kahoko sent him to Hana, and from there to Hawaii, following a certain dark object as guide. Kihapiilani and his retinue travelled the windward side of Kohala on foot, swimming through shark-infested waters around the bold headlands. Everywhere people gathered to him, for he was handsome and brave. When he reached Laupahoehoe, in Hamakua, he found his sister, Piikea, living with her husband, Umi. Umi had already become a great chief for he had overthrown his tyrant brother, Hakau, but his greatest deeds were yet to follow. These include the union of all of the island of Hawaii under his rule.

When Kihapiilani explained that he was seeking someone to avenge him, for Lonoapii had thrown salt water into his face, Piikea goaded Umi to help him, for he had crossed the seas. So Umi sent messengers with orders that koa be felled and many canoes made ready for the crossing to Maui. These were so numerous that when the first canoe reached Kauiki, the last were still in Waipio. The sea was covered with canoes. Umi ordered the canoes to be fastened bow to stern by twos, and in this way the men walked across instead of sailing, the canoes being a dependable road. This is known in legend as the sailing of numberless canoes.

At Kauiki fortress the leader, Hoolae, fought bravely from the top of the hill in daytime, but at night he set a huge wooden image of a man with a bristling war club at the head of the ladder up which the attackers had to climb. The trick frightened away all approaching enemies, while the defenders slept in peace. One night, however, Piimaiwaa took his war club and approached the giant. He hurled insults at him from a safe distance. As his taunts drew no response or movement, Piimaiwaa twirled his war club, threatened with gestures, and gradually crept closer to discover the clever ruse that had fooled the forces of Umi. With that obstacle gone, Umi’s men 20 surprised and slew the enemy. Hoolae was captured and killed on the eastern side of Haleakala. War spread over all of Maui, until Lonapii was slain at Waihee and Kihapiilani became king of the island. It could well be that during this campaign Kihapiilani became acquainted with our crater, across which he later constructed the paved trail, another monument to his reign.

Some believe that the trails paved with waterworn rocks were built by menehune, the dwarf race supposed to work secretively at night. Actually, the commoners performed the labor, being pressed into service for the task. They formed an endless chain from the coast, so that rocks could be passed from hand to hand until carefully fitted into place on the walkway. The spaces between the larger stones were often filled with sand or gravel.

The early Mauians had many names for different parts of the crater. Some places had two names; sometimes one name served more than one place. Thus there is duplication of use of the name Haleakala, for besides being the name of the whole volcano, it is also applied to the peak on the rim west of Kaupo Gap. Or could haole confusion have given rise to use for the whole mountain a name that once applied only to a prominence on the rim?

White Hill, Pokaoao.

White Hill, Pakaoao, (see Numbered Points of Interest, topic 6) is of pale gray andesitic basalt that splits into slabs. On the leeward side are many enclosures built of stone, 3 or 4 feet high, which are believed to have been erected as shelters or bivouacs by the men of Kaoao, a quarrelsome chieftain who sought refuge on the mountain after he was driven out of Kaupo, early in the 18th century. Dr. Kenneth Emory of Bishop Museum has an unpublished manuscript, in Hawaiian, of a legend given to him on June 22, 1922 by Joseph V. Marciel, an old native of Maui. Copy of the translation by Maunupau of Honolulu was graciously given to me so that the story could be told here.

The South Wall: Haleakala Peak on left, Puu Kumu on right.

The heiau of Keahuamanono on Haleakala Peak was built by Kaoao, younger brother of Kekaulike, great king of Maui. The brothers were not friends. Kaoao lived on the mountain, but Kekaulike 22 and his men lived by fishing and raising crops in Nuu, the district west of Kaupo Valley. One day Kaoao sent his men north to find food from Keanae to Hana. After they had departed, Kaoao journeyed to his brother’s house, which he found deserted since Kekaulike had gone fishing. Kaoao proceeded to pull and destroy all of his brother’s crops, and then returned up the mountain.

Kekaulike was very angry when he discovered all his crops had been destroyed. As he knew whom to blame, he ordered his men to wrap ’ala, sling stones, in ti leaves as if they were potatoes. Armed with these they marched up the mountain, and found Kaoao with his bodyguard only, for his men had not returned from the foray for food. The defenders were soon overpowered, but Kaoao jumped over a cliff in an attempt to escape. Kekaulike found him dying, and quickly put an end to him. When Kaoao’s men returned from Koolau they found that their leader had been dead many days.

Dr. Kenneth Emory made an extensive archeological survey of Haleakala Crater in 1920. He records 58 stone terraces and platforms, 9 groups of open stone shelters, hundreds of ahu, and the paved trail of Kihapiilani.[1] (See Numbered Points of Interest, topic 18.)

The huge structure built by Kaoao, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, stands in the saddle above Kapalaoa, due south of Puu Maile. This is west of the highest point on Haleakala Peak. It measures 57 × 36 feet and has an eastern supporting wall 18 feet high. This has the appearance of a heiau, possibly used for the worship of Pele. As such, it resembles Oalalauo which was located on the rim of Kilauea Iki in the Kilauea Section of Hawaii National Park. Oalalauo, seen in ruins in 1823, was described by the missionary William Ellis, who, probably the first European to go to Kilauea Crater, has given us the first record of a visit.[2]

Since the crater is a place of restricted access, it was used for burial sites, which is quite in keeping with practice elsewhere in the 23 Hawaiian Islands. A curious local custom was the deposit of umbilical cords of Kaupo babies in certain localities, principally in the Bottomless Pit (Numbered Points of Interest, topic 13), and in Na Piko Haua, a pit 15 feet in diameter and 10 feet deep that is located northeast of Halemauu Trail, less than a half mile east of Holua Cabin. The cord was wrapped in a small piece of tapa, or, in recent days, in a scrap of gay calico and tied with string. Sometimes it was placed in a bottle or other container. This was then carefully stowed in crevices or cast into Bottomless Pit. Reasons given for the practice vary. It was believed that if the cord were destroyed or eaten by rats the child would become a thief. Some claimed that proper disposition made a child strong. Some aver that the custom persists to this day, showing, like belief in the existence of Pele, the durability of ancient superstitions.

On the north wall above Paliku is a rock, Pohaku Palaha or Broad Rock, which is called the “hub of East Maui.” Boundary lines radiating from it mark off the pie-shaped land divisions, ahupuaa, that extend in all directions to the shores of the ocean.

It is quite natural that legends, traditions, and superstitions should be woven in and about such a great natural feature as this crater. All prominent places had original Hawaiian names, although some were changed with time and some are now lost. Ka Lua o ka Oo was the residence of Kamohoalii, the brother of Pele and the king of vapor. Between Halalii and Ka Moa o Pele is the rim of a spatter cone, Pa Puaa o Pele, which is 30 feet square with an opening on the northwest side. It protrudes only 10 feet above later volcanic deposits. This was a place of highest kapu (taboo). Merely to disturb a single grain of sand within it will bring fog and rain, possibly death. Emory discloses the local belief that a stone structure, 9 × 5 feet, located 45 feet east of the rim, holds the bones of two men and a woman who had violated this kapu and who had perished in the ensuing fog. His investigation failed to reveal any burial within the structure. In vaguer vein, it was held that a similar fate would be meted to those disturbing a silversword. Were the National Park committed to a policy of nature protection through fear, this belief would be helpful indeed.

Captain James Cook discovered Maui on November 26, 1778, as he sailed southwestward from Alaska on his last voyage. His record for the day gives us the first description of Haleakala: “An elevated hill appeared in the country, whose summit rose above the clouds. The land, from this hill, fell in a gradual slope, terminating in a steep, rocky coast; the sea breaking against it in a most dreadful surf.... On the 30th ... another island was seen to the windward, called, by the natives, Owhyhee. That along which we had been for some days, was called Mowee.”[3]

After sailing along the eastern and southern coasts of the island of Hawaii in its two armed ships, Resolution and Discovery, the expedition landed at Kealakekua Bay on January 17, 1779. Captain Cook was worshipped as the incarnation of the god Lono, but he overstayed his welcome, ill-will and violence taking its place. A climax was reached over the theft of a ship’s cutter, which was broken up merely for its nails and ironware. On February 14, Cook tried to seize the aged king Kalaniopuu to hold as a hostage until reparation was made. In the scuffle that ensued, the Great Mariner was killed by an alii, who thrust quite through his back an iron dagger, a chief article of trade of the Expedition. Upon departure toward the northwest, the survivors reached Maalaea Bay on February 24, on which date the journal remarks about Maui: “This side of the island forms the same distant view as the north-east; ... the hilly parts, connected by a low flat isthmus, having, at the first view, the appearance of two separate islands.”

The ill-fated French explorer, Count Jean Francois de Galaup de la Perouse, arrived with his two frigates on May 28, 1786, in the bay southwest of Haleakala that today bears his name. He recorded: “At every instant we had just cause to regret the country we had left behind us; and to add to our mortification, we did not find an anchoring place well sheltered till we came to a dismal coast where 25 torrents of lava had formerly flowed like the cascades which pour forth their water in other parts of the island.”[4] This reference is to the latest flows of Haleakala. See page 37.

On Vancouver’s first exploring expedition to the islands, Edward Bell made the following entry for March 6, 1792 in the log of the Chatham: “... the south shore ... had by no means a very inviting appearance,—it was remarkably high and seemed extremely barren;—from the top of the Mountains to the waters edge are deep Gullies or ruts form’d I suppose by the water running down,—and there appeared but little wood on this side (except towards the Top) and as little Cultivation, here and there we saw a few Huts and a small Village, several of which appeared half way up.”

On Vancouver’s next visit, Thomas Manby recorded in the journal for March 10, 1793: “... south side of the island which presented a prospect not very grateful to the eye as the land was high and rugged with frequent mounds of Cinders caused by volcanic eruptions.” On March 14, 1793, the botanist A. Menzies, with some of Vancouver’s crew, climbed a valley back of Lahaina and made botanical observations.

When the first missionaries from New England came to Hawaii, Elisha Loomis, a printer, remarked in his journal for March 30, 1820: “As we double the northern extremity of Owhyhee the lofty heights of Maui are on our right.” The spelling, Maui, is evidently a correction made later, as the original spelling appears elsewhere in early missionary usage. Already by 1822, the members of this expedition had adopted the five vowels and seven consonants of the Romance languages used today in reducing the Hawaiian language to writing and printing. Thus, the confusion of earlier English writers was dispelled.

Lorrin Andrews and Jonathan F. Green, ordained missionaries, and Dr. Gerrit P. Judd, physician, were with the third mission from New England. They arrived in Honolulu on March 30, 1828. They visited Rev. William Richards in Lahaina and toured Maui the following summer. Extracts concerning the trip of Dr. and Mrs. Judd 26 were published in 1880 with an introductory note by Albert Francis Judd, a son. In the preface, dated May 1861, Mrs. Judd states that the sketches were “culled and abridged from a mass of papers” without pretense of writing a history. Under the date of July 1828, the narrative relates a Fourth of July excursion and includes: “The mountain on the east division is Haleakala (house of the sun), and is the largest crater in the world, but is not in action.”[5] Unfortunately, the original notes have been lost, and the reference to the mountain by name must have been inserted at a much later date in preparing the manuscript for publication. It would be hard to believe that Mrs. Judd could possibly have started the fiction, “largest crater on earth,” at the early date of 1828. The Judds did not climb the mountain during their visit, and Hawaiians were not in a position to make comparisons among craters of the world.

On August 21, 1828, Richards, Andrews, and Green made the first recorded ascent of Haleakala. They could not have known a name for the mountain, for they refer to it only as “the highest land on Maui” and as “an extinct volcano.” Not until six years later was their account published. The following quotations relate to their trip:[6] “Mr. Richards had for years been particularly desirous of making the tour of this island for the purpose of examining and improving the schools, etc., but having been alone, it has hitherto been impracticable for him to leave his family for a sufficient length of time. During the present season this object has been accomplished.” Mr. Richards had arrived in Hawaii in 1823, and had taken over the mission in Lahaina shortly afterwards at the request of Queen Keopuolani. He had not mentioned the big mountain in previous correspondence and reports.

“Here (at ’Kaalimaile,’ perhaps the Haliimaile of today) we tarried overnight, intending, in the morning, to ascend the mountain, near which we were, and sleep on the highest land on Maui. We were told by the natives, that the way was long, but the ascent very easy. We suppose no English travellers had ever ascended this mountain.

“21. We rose early, and prepared for our ascent. Having procured a guide, we set out; taking only a scanty supply of provisions. Half way up the mountain, we found plenty of good water, and, at a convenient fountain, we filled our calabash for tea. By the sides of our path, we found plenty of ohelos, (a juicy berry, very palatable,) and, occasionally, a cluster of strawberries. On the lower part of the mountain, there is considerable timber; but as we proceeded, it became scarce; and, as we approached the summit, almost the only thing, of the vegetable kind, which we saw, was a plant which grew to the height of six or eight feet, and produced a most beautiful flower. It seems to be peculiar to this mountain, as our guide and servants made ornaments of it for their hats, to demonstrate to those below, that they had been to the top of the mountain.

“It was nearly 5 o’clock, when we reached the summit; but we felt ourselves richly repaid for the toil of the day, by the grandeur and beauty of the scene, which at once opened up to our view. The day was very fine. The clouds, which hung over the mountains on West Maui, and which were scattered promiscuously, between us and the sea, were far below us; so that we saw the upper side of them, while the reflection of the sun painting their verge with varied tints, made them appear like enchantment. We gazed on them with admiration, and longed for the pencil of Raphael, to give perpetuity to a prospect, which awakened in our bosoms unutterable emotions. On the other side, we beheld the seat of Pele’s dreadful reign. We stood on the edge of a tremendous crater, down which, a single misstep would have precipitated us, 1,000 or 1,500 feet. This was once filled with liquid fire, and in it, we counted sixteen extinguished craters. To complete the grandeur of the scene, Mouna Kea, and Mouna Roa lifted their lofty summits, and convinced us, that, though far above the clouds, we were far below the feet of the traveller who ascends the mountains of Hawaii. By this time, the sun was nearly sunk in the Pacific; and we looked around for a shelter during the night. Our guide and other attendants we had left far behind; and we reluctantly began our descent, keeping along on the edge of the crater.

“After descending about a mile, we met the poor fellows, who were hobbling along on the sharp lava, as fast as their feet would suffer them. They were glad to stop for the night, though they complained of the cold. We kindled a fire, and preparations were made for tea and lodgings. The former we obtained with little trouble. We boiled part of a chicken, roasted a few potatoes, and, gathering round the fire, we made a comfortable meal; but the place of lodging, we obtained with some difficulty. At length, we spread our mats and blankets in a small yard, enclosed, probably, by natives, when passing from one side of the island to the other. We were within twenty-feet of the precipice, and the wind whistled across the valley, forcibly reminding us of a November evening in New England. The thermometer had fallen from 77 to 43* (*The next morning, the thermometer stood at 40.), and we shivered with the cold. The night was long and comfortless.

“22. Early in the morning, we arose, and reascended the mountain, to its summit, and contemplated the beauties of the rising sun, and gazed a while longer, on the scenery before us. There seemed to be but two places, where the lava had found a passage to the sea, and through these channels, it must have rushed with tremendous velocity. Not having an instrument, we were unable to ascertain the height of the mountain. We presume it would not fall short of 10,000 feet.* (*This, I believe, is the height at which it has generally been estimated.) The circumference of the great crater, we judged to be no less than fifteen miles. We were anxious to remain longer, that we might descend into the crater, examine the appearance of things below, and ascend other eminences; but as we were nearly out of provisions, and our work but just commenced, we finished our chicken and tea, and began our descent.

“Nothing remarkable occurred, on our way down....”

The United States Exploring Expedition under the command of Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, USN, visited Hawaii in 1840 and 1841. On February 15, 1841, Wilkes dispatched Messrs. Pickering, Drayton, and Breckenridge from Hilo to explore Maui. They were joined at Lahaina by Rev. Andrews, his son, four students of the seminary, and six kanakas to carry their food. At Wailuku they were joined 29 by Mr. Bailey (see page 40). They spent the night at an elevation of 1,692 feet on the sugar plantation of Lane and Minor, two Bostonians. The story of their ascent, which is the second recorded, is told by quoting from their report:[7]

“The next day, the party set out at an early hour, in hopes of reaching the summit, but it began to rain violently, in consequence of which they took shelter in a large cave, at an altitude of eight thousand and ninety feet. Here many interesting plants were found, among which were two species of Pelargonium, one with dark crimson, the other with lilac flowers; the Argyroziphium began to disappear as they ascended, and its place was taken up by the silky species, which is only found at high altitudes. From the cave to the summit they found shrubby plants, consisting of Epacris, Vaccinium, Edwardsia, Compositae, and various rubiaceous plants.

“On their arrival at the edge of the crater, on the summit, the clouds were driving with great velocity through it, and completely concealed its extent. The height, as ascertained by the barometer, was ten thousand two hundred feet. The driving of the sleet before the strong gale soon affected the missionaries and native students, the latter of whom for the first time, felt the effects of cold. The limit-line of woods was ascertained to be at six thousand five hundred feet.

“Some sandalwood bushes were noticed about five hundred feet above the cave. Above the cave the ground assumed a more stony appearance, and the rock became now and then more visible, which had not before been the case. Where the rock was exposed it was found to be lava more or less vesicular, but no regular stream was observed. The surface of the lava appeared to be more thickly covered with earth than that of Mauna Kea, and consequently a greater proportion of soil existed, as well as a thick coating of gravel. Near the summit, bullock-tracks were observed, and likewise those of wild dogs, but no other animals were seen except a few goats.

“The crater of Haleakala, if so it may be called, is a deep gorge, open at the north and east, forming a kind of elbow: the bottom of 30 it, as ascertained by the barometer, was two thousand seven hundred and eighty-three feet below the summit peak, and two thousand and ninety-three feet below the wall. Although its sides are steep, yet a descent is practicable at almost any part of it. The inside of the crater was entirely bare of vegetation, and from its bottom arose some large hills of scoria and sand: some of the latter are of an ochre-red colour at the summit, with small craters in the centre. All bore the appearance of volcanic action, but the natives have no tradition of an eruption. It was said, however, that in former times the dread goddess Pele had her habitation here, but was driven out by the sea, and then took up her abode on Hawaii, where she has ever since remained. Can this legend refer to a time when the volcanoes of Maui were in activity?

“The gravel that occurred on the top was composed of small angular pieces of cellular lava, resembling comminuted mineral coal. The rock was of the same character as that seen below, containing irregular cavities rather than vesicles. Sometimes grains of chrysolite and horn-blende were disseminated. In some spots the rock was observed to be compact, and had the appearance of argillite or slate: this variety occurred here chiefly in blocks, but was also seen in situ. It affords the whetstones of the natives, and marks were seen which they had left in procuring them.

“Of the origin of the name Mauna Haleakala, or the House of the Sun, I could not obtain any information. Some of the residents thought it might be derived from the sun rising from over it to the people of West Maui, which it does at some seasons of the year.

“Having passed the night at the cave, Mr. Baily (sic) and young Andrews preferred returning to the coast, rather than longer to endure the cold and stormy weather on the mountain.

“Our gentlemen made excursions to the crater, and descended into it. The break to the north appears to have been occasioned by the violence of volcanic action within. There does not appear any true lava stream on the north, but there is a cleft or valley which has a steep descent: here the soil was found to be of a spongy nature, and many interesting plants were found, among the most remarkable of which was the arborescent Geranium.

“The floor of the crater, in the north branch, is extremely rough and about two miles wide at the apex, which extends to the sea. In the ravines there is much compact argillaceous rock, similar to what had been observed on Mauna Kea, retaining, like it, pools of water. The rock, in general, was much less absorbent than on the mountains of Hawaii.

“Mr. Drayton made an accurate drawing or plan of the crater, the distances on which are estimated, but the many cross bearings serve to make its relative proportions correct. Perhaps the best idea that can be given of the size of this cavity, is by the time requisite to make a descent into it being one hour, although the depth is only two thousand feet. The distance from the middle to either opening was upwards of five miles; that to the eastward was filled with a line of hills of scoria, some of them five or six hundred feet high; under them was lying a lava stream, that, to appearance, was nearly horizontal, so gradual was its fall. The eastern opening takes a short turn to the southeast, and then descends rapidly to the coast.

“At the bottom were found beds of hard gravel, and among it what appeared to be carbonate of lime, and detached black crystals like augite, but chrysolite was absent.

“From the summit of the mountain the direction of the lava stream could be perceived, appearing, as it approached the sea, to assume more the shape of a delta.

“From the summit the whole cleft or crater is seen, and could be traced from the highest point between the two coasts, flowing both to the northward and eastward. Volcanic action seems also to have occurred on the southwest side, for a line of scoria hills extends all the way down the mountain, and a lava stream is said to have burst forth about a century ago, which still retains its freshness. The scoria hills on the top very much resemble those of Mauna Kea, but the mountain itself appears wholly unlike either of the two in Hawaii, and sinks into insignificance when compared with them.

“Although I have mentioned lava streams on this mountain, yet they are not to be understood as composed of true lava, as on Mauna Loa; none of the latter were seen except that spoken of on the southwest side, and none other is believed to exist. No pumice or capillary 32 glass was at any time seen, nor are they known to exist on this island. On the wall of the crater, in places, the compass was so much affected by local attraction as to become useless.

“Near the summit is a small cave, where they observed the silkworm eggs of Mr. Richards, which were kept here in order to prevent them from hatching at an improper season. The thermometer in the cave stood at 44°; the temperature at the highest point was 36°, and in the crater 71°. After three days’ stay, the party returned to the establishment of Messrs. Lane and Minor, and thence to Wailuku. They were much gratified with their tour.”

The name Haleakala can thus be regarded as having been formally introduced by members of the Wilkes Expedition. As the fame of the beauties and wonders of the mountain spread, visitors from all parts of the globe came to make the arduous climb to the summit. Most found shelter from the elements in natural caves. Big Flea and Little Flea caves, a quarter of a mile from the summit, are often mentioned in early accounts. That their accommodation was not highly relished can be seen from a description by Damon in 1847: “... which did not hold out many attractions, and I have good reasons for believing it already possessed tenants that would sharply contend for occupancy with any way-faring and luckless wight.”[8] In tales of early visits, literature—especially the Bible—was gleaned for phraseology that might help portray emotions felt; fantastic similes and metaphors were drawn to transmit comprehension of the scene. On a visit in 1853, G. W. Bates mentioned: “From the point where I stood a huge pit, capable of burying three cities as large as New York—opened before me.”[9] True, New York then lacked its present colossal stature, but a milder expression, “could hold the whole of New York City” still is in use today. For information, the following areas are given from Thrum’s Annual and the World Almanac: area of Haleakala “crater,” 19.0 sq. mi.; area of Maui, 728 sq. mi.; area of Manhattan borough, 31.2 sq. mi.; area of New York City, 381 sq. mi. Discomforts, silversword, sandalwood, wild dogs, cattle, goats, the weather, and personal impressions form much of the subject matter of early essays.

The early residents of Maui recognized the value of the mountain as a scenic feature and tourist attraction. Their first move was for better overnight shelter on the mountain. C. W. Dickey in 1894 raised $850 by popular subscription for material with which to build a simple shelter at Kalahaku Lookout. H. P. Baldwin and the sugar plantations furnished labor and pack animals. The long trip of 25 miles to the location had to be made on foot or by saddle, and required a full, tiring day; all building material except rock had to be transported by pack stock. In painfully characteristic manner, many of those for whose benefit the sweat and toil were expended proved unworthy since they roughly abused the structure. Windows were broken, timber in the floor and walls was ripped out and used for firewood, and garbage and filth accumulated. A tropical storm added to the damage by unroofing the house; Worth Aiken raised $1,500 for its renovation and repair. In 1914-15, the cabin was improved with a concrete floor, metal doors, and metal shutters. Two additional dormitories were added in 1924-25 at a cost of $11,000 and operation of the building was turned over to E. J. Walsh, manager of the Grand Hotel, Wailuku. Usefulness dropped with the opening of the Haleakala Road, so that on September 24, 1934 its custodian, the Maui Chamber of Commerce, transferred ownership to the National Park Service. The structures were razed in 1957, but plans are underway to replace them with a modern observatory in which people may look at the scene in glass-enclosed comfort.

In the movement to create a National Park in Hawaii in the early part of the 20th century, the idea developed that it should consist of the craters of Kilauea, Mauna Loa, and Haleakala. The citizens of Maui gave full approval for including their beloved mountain. Hawaii National Park, composed of these three sections, was established by Act of Congress on August 1, 1916, but formal dedication was delayed until 1921. Following improvement of Halemauu Trail in 1929, a permanent ranger position was set up for continuous attention to the area. Today it is administered by an assistant superintendent who has a staff of two rangers and a naturalist.

The building of a road to the summit was fulfillment of a promise to the people of Maui when the park was created. The first step had 34 to be construction by the Territory of a highway from Pukalani Junction to the park boundary near Puu Nianiau. This was completed at a cost of $504,000 in April 1933 after 39 months of work. As with similar projects elsewhere in Hawaii, superstitions of long-ago reappeared. Although not antagonistic to progress, Hawaiians raised a cry that all effort was futile; the chicken god, Kalau-heli-moa, would conspire and never permit the project to be completed. Every mishap was attributed to this nemesis.

The Park Service completed its commitment soon afterwards at the cost of $376,000. The road was armor-surfaced in the fall of 1935. Extensive, appropriate dedication ceremonies were held for the opening.

With the establishment of a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp in Kilauea, a strip camp of 25 men was set up near Puu Nianiau cinder cone. Part of the time, a tent camp was also established within the crater. Many improvements became possible through this undertaking. The observatory building on the summit was constructed in 1936; the three shelters within the crater, Kapalaoa, Paliku, and Holua, were built a year later. Prior to their completion, overnight shelter was sought in caves, the best known being Bubble Cave (see Numbered Points of Interest, topic 15) and Holua Cave which is in the pali wall behind the cabin.

The CCC camp was abandoned in April 1941, and its structures were turned over to the Army that greatly improved them. During the period of its occupancy, the Army constructed for radar installation the ugly concrete block house that still protrudes on the summit of Red Hill. With evacuation of the military, the CCC quarters were adapted for the service of a concessioner to supply meals and lodging within the park.

Normal travel to Haleakala was interrupted for a year when the section was closed following the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. Annual travel had passed the 25,000 mark in 1939. Travel for the year 1958 reached a high of 56,940 visitors.

The summit of Haleakala attracted early consideration as a site for various scientific studies. It is a prime target for many scientific planners, because the high mountain is situated in the middle of a 35 broad ocean, yet the summit is readily accessible by road. Often this eagerness has obscured possible use of other suitable sites and has clashed with the basic purpose of the area as a National Park. The National Park Service strives to keep the scene as primitive as possible, assiduously blending buildings and structures into the landscape, whereas the non-conformist gives no thought to this but follows the easiest way. Too often economy of construction and operation, together with careless housekeeping, invert an attraction to a repulsion which even the splendor of the scene cannot offset. Skyline buildings, obtrusively strung wires, thoughtlessly gouged land, and abandoned debris are not conducive to aesthetic experience, whatever their purpose or whoever the offender.

Haleakala holiday.

The earliest scientific study associated with the mountain concerned weather. It is said that the Hawaiian Islands are situated near a critical area in the Pacific which is a birthplace of weather. The summit offers an ideal place for detection and observance of the formation of high clouds. Much additional research is needed to provide a steady flow of data for successful and safe operation of 36 air transportation. Many crashes have been blamed on lack of weather data. The task is not always simple, as statistical readings may be confusing. Those made on Red Hill, for example, are influenced by local circulation set up by the heating of several square miles of black, barren lava and cinders.

The Federal Aeronautics Administration maintains a station a mile beyond Red Hill. In the earlier fifties cosmic radiation was studied with a huge revolving truss located back of Red Hill. The military has set up apparatus and teams from time to time for experiments with radio, radar, and radiation. Finally, for the International Geophysical Year, Haleakala summit was chosen for one of the important satellite tracking stations supervised by the Smithsonian Institution of Washington.

500 A. D., ca.—Hawaii discovered by Hawaii-loa, Polynesian fisherman-navigator who, tradition says, came from Kahiki (Tahiti?), an island to the south. He made several round trips, bringing with him a large company of retainers.

1100 ca.—After a wave of navigation, intercourse with Tahiti ended.

1300 ca.—According to an ancient chant, mele, Kalaunuiohua, moi of Hawaii, conquered Maui. Moi, in 19th century Hawaiian, signifies the supreme ruler or head chief, now usually termed king.

1500—Piilani, king of Maui. He was succeeded by Lonoapii who in turn was overthrown by his brother Kihapiilani and his brother-in-law, King Umi of the Big Island. Bloody battles stretched from Kauiki to the sands of Waihee.

1555—Possible discovery of Hawaii by Juan Gaetano, Spanish navigator. He prepared a manuscript chart now in the Spanish archives which contains a group of islands in the latitude of Hawaii but whose longitude is 10 degrees too far to the east. What corresponds to Maui is called La Desgradiada, the unfortunate. The largest, most southerly island, which should be the present Hawaii is labelled La Mesa, the table. 37 Three other islands, appearing to be Kahoolawe, Lanai, and Molokai, are called Los Monjes, the monks.

1736—King Kekaulike died and was succeeded by Kamehamehanui.

1737—Alapainui, moi of Hawaii, invaded Maui via Kaupo. He took with him two young princely half-brothers, Kalaniopuu and Keoua. Keoua was father of Kamehameha I. Since Alapainui found his adversary, Kekaulike, dead, he made peace with the nephew, Kamehamehanui. The two joined forces to repel the invader, Kapiiohokalani of Oahu, in bloody, obstinate battles that ended in the rout of the Oahu army at Kawela, Molokai.

1738—At Keawawa, West Maui, Alapanainui and Kamehamehanui decisively defeated Kauhi, the latter’s brother and usurper of power.

1750 ca.—The calculated date of the most recent activity of Haleakala, the Keoneoio flow above La Perouse Bay. The flow originated at Kaluaolapa at an elevation of 575 feet, and from vents one mile further northeast at an elevation of 1,550 feet. The method of dating is interesting. In 1841, Rev. Edward Bailey of Wailuku inquired about the eruption and was informed by Hawaiians that it happened at the time of their grandfathers. In 1906, Lorrin A. Thurston was told by a Chinese-Hawaiian cowboy, Charles Ako, that his father-in-law’s grandfather at the time of the event was just old enough to carry “two” coconuts 4 or 5 miles from the sea to the upper road at an elevation of 2,000 feet. Since Hawaiians counted coconuts by fours, “two” probably refers to a total of eight nuts. Mr. Bailey was told that a woman and child were trapped by the flow but escaped after it cooled. By 1922, 80 years later, this tale had grown into a neo-myth about a husband and wife with their two children. The mother and her young daughter fled mauka, but were seized by Pele, and turned into the two lava columns that stand beside the vent at Kaluaolapa. The father and son, plunged into the sea and started swimming toward Kahoolawe. Pele cast rocks after them and turned the two 38 to stone. The two rocks, a big and a little one, can be seen today rising out of the sea several hundred feet out from shore as proof of the tale. Mr. Thurston’s estimate of the date of the eruption is 1750 while J. F. G. Stokes, Hawaiian ethnologist, favors a later date, possibly 1770.

1754—Kalaniopuu, warlike king of Hawaii, captured the fortress Kauiki and held it successfully for more than 20 years.

1765—Kamehamehanui died and was succeeded by his brother, Kahekili.

1768—Queen Kaahumanu was born at Kauiki. She became the favorite wife of Kamehameha I.

1775—Kalaniopuu was defeated by Kahekili at Kaupo.

1776—Kalaniopuu invaded Maui at Maalaea; his army was annihilated on the sand hills near Wailuku.

1777—Kalaniopuu took Lanai but again was repelled when he tried to invade Maui.

1778, November 26—Captain James Cook, Royal British Navy, discovered Maui.

1781—Kahekili reconquered East Maui. He recaptured the fort at Kauiki by cutting off the water supply. To show contempt, he baked the bodies of the defenders in earth ovens.

1786—Kamehameha I sent an expedition to recapture East Maui. It was defeated at Kipahulu by Kalanikapule, the son of King Kahekili.

1786, May 28—La Perouse visited Maui and camped on Keoneoio lava flow.

1790—Olowalu massacre. The snow, Eleanor, under Captain Simon Metcalf, treacherously opened fire on native boats following a truce made after one white sailor had been murdered. More than a hundred natives were slaughtered.

1790—Conquest of Maui by Kamehameha I after landing at Hana. He decisively defeated Kalanikapule, in the Battle of Iao Valley or Kepaniwai.

1793—Vancouver visited Maui on his second expedition. He tried to bring about an end to the wars and to establish a lasting peace between Maui and Hawaii.

1795—Maui was subdued by Kamehameha I without a battle.

1819—Kamehameha I, king of all Hawaii, died. Abolition of the kapu system by Kamehameha II, incited by his guardian, Queen Kaahumanu.

1823—The Christian mission at Lahaina was founded by Rev. William Richards and A. S. Stewart. On September 16, Queen Keopuolani, a wife of Kamehameha I and a devout Christian, died at Lahaina. She was buried with services by Rev. William Ellis.

1824—At Lahaina, Queen Regent Kaahumanu orally proclaimed a law forbidding desecration of the Sabbath, fighting, murder, and theft.

1825—The English frigate The Blonde anchored off Lahaina with the bodies of King Liholiho (Kamehameha II) and his queen, Kamamalu. They had died from measles while on a visit to London.

1825—The crew from the Whaler Daniel attempted to demolish the home of Rev. Richards, Lahaina.

Sliding Sands Trail.

1826—Mosquitoes from Mexico were introduced at Lahaina by the SS Wellington.

1827—The Whaler John Palmer fired on the home of Rev. Richards.

1829—Ascent of Haleakala by a missionary party.

1834—First Hawaiian newspaper Lama Hawaii was published at Lahainaluna Mission School.

1839—An Hawaiian “Bill of Rights” was signed at Lahaina by Kamehameha III. It afforded protection to all people and their property while they conformed to the laws of the kingdom.

1841—Haleakala Crater was visited by Pickering and Breckenridge of the United States Exploring Expedition under Captain John Wilkes, U. S. Navy.

1841-1849—Peak of whaling industry in Hawaii. Lahaina was visited by 596 Whalers in 1846.

1850—David Malo, Hawaiian antiquarian and teacher at Lahainaluna School, Lahaina, conducted Rev. William P. Alexander and Curtis Lyons from Kaupo through Haleakala Crater, to Makawao, “a trip never before undertaken by white men.”

1876—S. F. Alexander and H. P. Baldwin started construction of the Hamakua Ditch, first big irrigation project in Hawaii.

1890—First pineapples were planted at Haiku.

1893—Overthrow of the monarchy and establishment of the Republic of Hawaii. Queen Liliuokalani was the last reigning sovereign.

1898, August 12—Hawaii was annexed to United States by joint legislation of Congress. President Dole was appointed first governor.

1916—Hawaii National Park was established by Act of Congress on August 1 with Haleakala Crater forming the Section on Maui.

1921—Hawaii National Park was formally opened.

1929, November 11—Establishment of commercial air service between the islands.

1930—First permanent park position (ranger) was established to give continuous service at Haleakala.

1931—First permanent park naturalist was appointed for Hawaii National Park, although temporary, summer interpretive services were started in the late twenties by the employment of Otto Degener, formerly botanist at the University of Hawaii. Dr. Degener, presently writing Book 6 of his “Flora Hawaiiensis,” kindly supplied many of the scientific plant names for this guide.

1935 February 23—Dedication ceremonies of Haleakala Road in Hawaii National Park.

1937—Kapalaoa, Paliku, and Holua cabins were constructed.

1941—Haleakala closed to travel for military reasons.

1952-3—Present exhibits were installed in Summit Observation Station.

1958—Permanent naturalist position established for Haleakala.

1959—Hawaii becomes the 50th state in the Union.