The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Chinese Kitten, by Edna A. Brown This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Chinese Kitten Author: Edna A. Brown Illustrator: Antoinette Inglis Release Date: July 29, 2018 [EBook #57600] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CHINESE KITTEN *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE CHINESE KITTEN

BOOKS BY

EDNA A. BROWN

FICTION

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS

FOR YOUNGER READERS

LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD CO., BOSTON

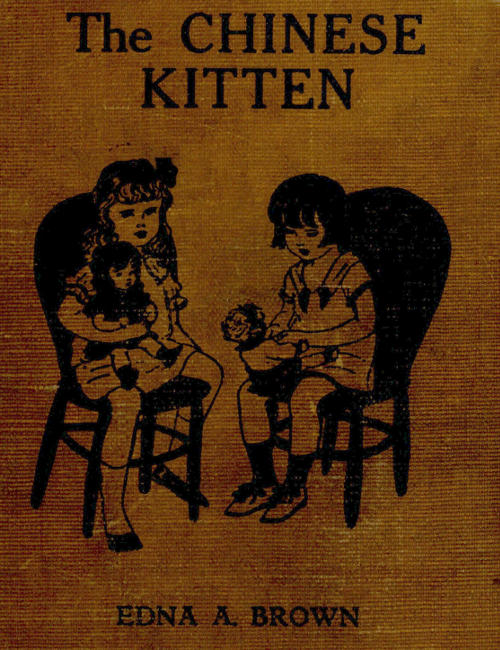

Wrapped in bright red paper so she could not fail to see it, was a small box, tied with a white ribbon—Page 89.

THE

CHINESE KITTEN

BY

EDNA A BROWN

ILLUSTRATED BY

ANTOINETTE INGLIS

BOSTON

LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD CO.

Copyright, 1922,

By Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co.

All Rights Reserved

The Chinese Kitten

Printed in U. S. A.

To Muff, the Dearest Kitten

| I. | The Surprise | 11 |

| II. | At the Beach | 24 |

| III. | About Arcturus | 36 |

| IV. | Friends from Home | 50 |

| V. | When School Begins | 66 |

| VI. | Dora’s Birthday | 83 |

| VII. | About Boston | 94 |

| VIII. | Sunday Afternoon | 111 |

| IX. | The Kitten’s Story | 133 |

| X. | The Victory Park | 148 |

| XI. | Hallowe’en | 166 |

| XII. | A Busy Saturday | 177 |

| XIII. | Thanksgiving | 193 |

| XIV. | Christmas | 209 |

| Wrapped in bright red paper so she could not fail to see it, was a small box, tied with a white ribbon (Page 89) | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Old Father Ocean ran right in through the front door | 34 |

| Dora shivered a little when the squirrel put its paws about her fingers | 102 |

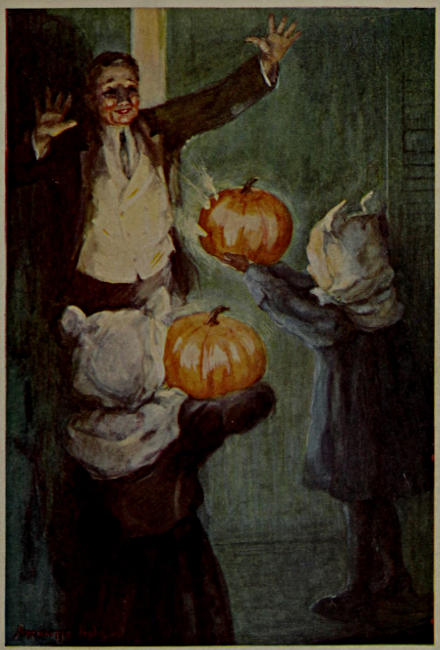

| “Ghosts, Mamma! Come and save me!” | 174 |

| What possessed Timothy just then? | 200 |

| A great star was looking through the open window | 220 |

“I think,” said Lucy Merrill in a whisper to her sister Dora, “that Uncle Dan has a surprise for us.”

Dora was industriously setting the table for supper. Lucy, at the kitchen dresser, was peeling peaches. Lucy had on a big apron belonging to her mother, and it covered both her and the stool on which she sat. Dora wore a pink apron over her checked pink-and-white dress, and Dora’s apron was just like the big one, only the right size.

Lucy owned a proper-sized apron also, but Lucy had been unlucky enough to upset the blueing bottle when she took a dish from the[12] kitchen closet. Her apron wasn’t hurt a bit, but Mrs. Merrill had rinsed it out and now it was flapping on the line in the back yard. The closet floor was bluer than the apron and not so easy to wash.

“What makes you think there is a surprise?” asked Dora, standing back from the table to see whether she had remembered everything that anybody could use during supper. No, she had forgotten the pulverized sugar for the peaches.

“Because,” said Lucy, “he keeps following Mother everywhere she goes, and I know he is teasing her to do something. I heard him say something about the beach.”

Dora stopped in the pantry doorway, her eyes big and blue. “Do you think we can be going to the beach?” she asked eagerly.

“My, I hope so!” said Lucy. “We haven’t been away this summer. And Father[13] said last night that the press was going to shut down for the week after Labor Day.”

Dora looked out of the window across the street at the low brick building where Father Merrill worked in the printing office.

“We had better not ask too many questions,” she said wisely. “Perhaps Uncle Dan is going to take us to White Beach for a day. But we did go to the vacation school, Lucy, and that was a great deal of fun.”

“It was,” agreed Lucy. “And it cost a dollar a week. But just one day at the beach would be lovely. I wish the Sunday-school picnic had gone there.”

Dora didn’t agree with Lucy. That annual picnic had been held at World’s End Pond. Even the salt water could not be nicer than that place.

Just as Lucy finished the last peach, Mrs. Merrill came in. Dora brought the sugar-bowl[14] from the pantry and looked hard at her mother. Sometimes it was possible to tell by Mother’s face how she felt about things.

Mrs. Merrill did not seem disturbed, but neither did she look as though she was thinking of anything especially pleasant. She put the rest of the supper on the table and told Lucy to call her father and Uncle Dan.

It was Uncle Dan who told the secret. Right in the middle of supper he turned to his sister.

“You know, Molly,” he began, “Jack says I may have his tent and we should need only one.”

“Dan!” said Mother Merrill, and everybody was still. The children looked at Uncle Dan. Then Father Merrill laughed.

“A tent!” shrieked Lucy. Dora jumped right out of her chair and ran around the table to her uncle.

“Are we going, too?” she asked quite breathlessly. “Can I sleep in a tent? I never did, you know.”

Mr. Merrill laughed again, and this time Dan laughed with him.

“You’ve done it now, Dan,” said his sister. “You may as well tell them.”

But Uncle Dan didn’t explain. “Oh, Molly, then you will go?” he asked as eagerly as the little girls.

“I suppose I shall have to,” said Mrs. Merrill, but she didn’t look as though she would find it very hard work.

“What is it? What is it?” Dora was asking with her arms around her young uncle’s neck.

“Quit choking me,” said Dan. “Go back and eat your supper.”

Dora gave him one last hard hug before returning to her chair. “I know it is nice,” she[16] said. “But is it the beach, Uncle Dan, and are we to sleep in a tent?”

“Maybe,” said Dan.

“The press is going to shut down for a week,” said Mrs. Merrill, “and Dan can get off, too. He wants to go over to White Beach. There’s a little shack we can have for not much money, but it has only two rooms. Dan thinks he can bunk on the porch. He wants Olive Gates to go with us, and she and you children would have to sleep in the tent.”

“I wouldn’t be scared if Olive was with us,” said Lucy. Dora was too happy to say anything at all. Her eyes shone and looked bluer than ever. When one is only eight, there are a great many important things in life. To go to the beach and to sleep in a tent seemed almost too good to be true.

“Alice Harper is at the beach this summer, but she sleeps in a house,” said Lucy. Nobody[17] was listening. Dan and Mr. Merrill were both talking, and it was plain that they wanted to go just as much as the children did.

“What shall we do with Timmy?” asked Dora, a sudden cloud coming over her face. It would never do to leave the tiger-striped pussy to take care of himself for a week. “Can he go with us?”

“No,” said Mrs. Merrill. “He would be scared to death, if he didn’t run away entirely.”

Dora looked so distressed that Mr. Merrill could not stand it. “We’ll plan for Timmy,” he said kindly. “I never did think much of people who go off for a vacation and leave their cats to take care of themselves. We will leave the key of the house with Jim Baker, and ask his little girl to come over twice a day to feed Timmy and to let him into the kitchen every night if he wants to sleep inside. But these nice nights, Timmy may prefer to stay out.”

Dora’s face looked bright again. Of course she could not enjoy the beach if Timmy were not cared for. He was used to being petted and fed regularly. Now there was not a cloud in her sky.

Uncle Dan was as pleased as the little girls. He talked much more than usual during supper, and after it was over and the dishes were being washed, he came to where his sister was mixing bread.

“All right for me to ask Olive?” he inquired.

“Yes,” said Mrs. Merrill, smiling a little. “Tell her we all want her to go with us.”

Dan was off in a hurry, but before he went he gave his sister an awkward hug.

Never were dishes done with such speed! Mrs. Merrill looked at them suspiciously but did not say a word. Lucy had washed them properly and Dora had wiped them as dry as[19] could be, even though they worked so fast. And yet neither of them knew why they were hurrying. They were not to go to the beach for three days, not until Saturday.

There was plenty to do between then and the end of the week. First, they had to decide what clothes to take, and were surprised to find that Mother did not think as they did about the dresses. She came and looked at them when Lucy and Dora had laid them out on their bed.

“You won’t need your good clothes,” she said. “Those must be kept for school. You will be playing on the beach all day, and not need to be dressed up. When we go over, you will have on one good dress apiece, and that is enough.”

Lucy and Dora were disappointed. They thought that people who went away on a vacation should take all their best clothes.

“But not people who live in tents,” said Mrs. Merrill. “That makes a great difference. We are only going to camp, you know.”

“But I may take Arcturus?” Dora begged, bringing from her bureau the little silver bear on her neck-chain, the bear which had been named for a star. “Arcturus does really need sea air, Mother.”

“He looks as though he were pining away,” said Mrs. Merrill, but she said that on the way over Dora might wear the necklace.

After Mother had edited that collection of clothes, Lucy and Dora packed them very easily into one suit-case. When they considered that this was to be a camping-trip, it was fun to see how much one could get on without.

Then there was the question of food. Mother made a great many cookies, both of sugar and molasses, and shut them into tin boxes. She also made some cake.

On Friday a pleasant thing happened. The man who owned the printing-press where Mr. Merrill was foreman, said that he would have all their things taken over to the beach in the delivery truck belonging to the press. There would be room on the driver’s seat for Mr. and Mrs. Merrill. The little girls could sit on the soft baggage in the back of the truck.

This made it very easy to take whatever they wished. Mrs. Merrill wrapped up some more blankets and made some more cake. She also filled a basket with apples.

Though they were expecting to find it great fun, Lucy and Dora did not ride on the back of the truck. Jack Simmons, who lent Uncle Dan his tent, had a little Ford car. He offered to take Olive and Uncle Dan and the two children. He would stay and help Uncle Dan pitch the tent.

It was important to have a pleasant day on[22] Saturday. All Friday afternoon, while they were doing the last things, Lucy and Dora kept looking at the sky. Their looking did not seem to make any difference, for it did not become more blue, nor any less so, no matter how hard they gazed.

One of the very last things was to go to the Public Library and choose some books to take with them. For, as Mrs. Merrill said, it might rain at the beach, and then they would be glad of something to read.

The children did not wish to think of rain, but they chose the library books with great care. Lucy decided to take “What Katy Did,” but Dora could not find any book which seemed suited to so important an occasion. Finally she asked the librarian, Miss Perkins, to choose one for her.

When Miss Perkins knew that the story must last a week and was to be read at the[23] beach, she agreed that no ordinary book would do. She went to a shelf in the back of the library and brought Dora the “Story of Doctor Dolittle.”

“You will like this book very much, Dora,” she said. “And I think your Uncle Dan will like it, too. It is a new book, just put into the library, so you will take very good care of it, won’t you?”

“Oh, I will!” said Dora, who had caught sight of the funny pictures in the text. “I will be very careful of it, Miss Perkins.”

“And is Arcturus going to the beach with you?” asked Miss Perkins as she slipped “Doctor Dolittle” into an envelope for safe traveling.

Dora explained that Arcturus would benefit from sea air, and Miss Perkins at once said that it would do him good.

The house where the Merrills lived in Westmore was a brown cottage, but it seemed large and like a palace when the children saw the shack at the beach. Still, they liked the shack very much.

The front room had a couch and chairs, and a square table which could be used for eating. There was one wee bedroom and the smallest kitchen ever seen. That kitchen was hardly so large as a good-sized cupboard. Mrs. Merrill could stand in its centre and reach everything on all four walls. It contained a little sink and an oil stove and some dishes,—not a great many dishes, but that made fewer to wash.

The shack stood on a hard sandy ridge, not near any other house. Behind, the sand sloped[25] to a road where automobiles were always passing. In front there was sand that slid around under foot, and then a broad hard beach and the wonderful ocean. When the children came on that sunny Saturday, for it was sunny in spite of all their watching the sky, the sea was a deep blue, with white fringes on the shore, where the waves ran up and then slid back again. The sand looked grayish-green, but when the water touched it, it turned shiny.

Dora could not take her eyes off the ocean. She forgot that she had wished to see Uncle Dan and Jack Simmons put up the tent. They pitched it near the shack, on the south side, and drove the poles and the pegs in just as hard as they could hammer them, so that the wind would not loosen the ropes.

When the tent was up, Dora and Lucy went inside. They pulled up all the beach peas growing in the enclosed space, so there was[26] only a floor of warm dry sand, soft and fine. Mrs. Merrill had brought on the truck some rag rugs. These were spread on the clean sand and the legs of the cots put on the rugs. If this were not done, a cot might tumble down when somebody was asleep on it.

Between the tent poles Uncle Dan stretched a rope. This was for Olive and the little girls to hang their clothes over. There was not much room left when the three cots had been set up and a chair brought from the house to hold a wash-bowl and pitcher, but Lucy and Dora thought it was beautiful.

“We will keep our suit-cases under the beds,” said Olive. “And we must be careful not to lose little things in this sand.”

It took only a few minutes to get settled in the tent. Lucy and Dora put on some old rompers they had brought for bathing dresses. Olive put on her pretty blue suit and tied a[27] blue handkerchief around her hair. Dora thought she looked extremely nice. She decided that when she was twenty, like Olive, she would have a blue jersey bathing suit. But meantime she liked her rompers very well.

Such a wonderful beach that was! There were not many shells to pick up, but a great many interesting pebbles. Almost immediately the children found a strange creature, shaped like a horse’s hoof, but transparent and with a long, sharp tail. It seemed quite dead and Dora was glad that it was. She really would not like to meet it strolling down the beach. Olive laughed and said that it was a horseshoe crab and would not do her any harm.

Quite soon, Father and Mother Merrill and Uncle Dan came out, dressed to go into the sea. Lucy and Dora waded in to their waists, squealing because the water was so cold. But[28] in just a few minutes it did not seem cold at all, and they wanted to stay in all day.

Mother would not let them. Much sooner than they wished, she told them to go out and dress.

“It won’t do to stay too long the first time,” she said. “Put on your old ginghams and you may go barefooted and wade all you like, but you have been in the water long enough for to-day.”

It seemed hard to come out when Uncle Dan and Olive were still jumping waves and even diving through them, but it would be fun to go without shoes or stockings and to run into the edge of the water whenever they wished. Besides, Mother herself came out when they did.

Lucy and Dora dressed quickly. They hung their wet clothes on a line which Mother stretched from the corner of the shack to the[29] rear tent pole. Something was cooking on the oil stove which smelled very good.

“When will dinner be ready?” asked Lucy. “I am as hungry as can be.”

“It will be ready before the others are dressed,” said her mother. “I wish they would come out.”

Strange to say, Uncle Dan was willing to leave the ocean before Olive. Father Merrill grew cold and waded ashore, but Olive did not look cold at all. It was Uncle Dan who seemed shivery and whose lips turned blue. Olive ran into the tent and presently threw out her suit. Dora hung it on the line, after brushing off what sand she could manage.

What a funny dinner that was! Nobody had more than one spoon, and some of the spoons were not a size any one would choose to eat with. There were just forks enough to[30] go around and Lucy and Dora had to share a knife. But this was only the more sport.

Olive’s hair was wet and tied with a ribbon, so she looked like a little girl with it hanging down her back. There were not chairs for everybody, and Uncle Dan sat on an old crate which kept cracking and acting as though it were going to break and let him down on the floor. But Dan didn’t care if it did.

“Alice Palmer lives in a house somewhere at this beach,” said Lucy contentedly. “It is much more fun to camp.”

After dinner Mrs. Merrill told them all to go down on the beach and she would wash the dishes.

“We will do nothing of the kind,” said Olive. “You got dinner alone and I shall wash the dishes myself and the children will wipe them. You will not be allowed in the kitchen, Molly Merrill, and indeed, there is not[31] room for anybody but Lucy and Dora and me.”

“Well!” said Mrs. Merrill, and she put on her hat and went down to the edge of the water with Father Merrill.

There was no can for the garbage, so Olive gave the dish to Uncle Dan and told him to take it down the beach away from all the houses and dig a hole and bury it.

“What for?” asked Dan. “Why not throw it out for the gulls to eat?”

Olive said he was not to do this. The gulls might not eat it immediately and the flies would collect and it would be unpleasant for people who were passing. It must be buried, and quite deep at that.

Lucy and Dora were amused to see Uncle Dan go off to bury the garbage just as Olive said. But she looked so pretty with her wavy hair tied back with the blue ribbon that it[32] was no wonder Uncle Dan did what he was told.

For dinner, they had used every dish in the shack, except one big and very black kettle, but even then it did not take long to wash them. Just for fun, Lucy and Dora counted as they wiped. There were precisely forty-three dishes, and that included all the spoons and knives and forks.

“Now,” said Olive as they finished, “don’t you think it would be nice to have sandwiches for supper and eat them on the beach?”

Lucy and Dora both thought it would be an excellent plan.

“Then let’s go and ask your mother,” said Olive. “Because if she is willing, we will make the sandwiches right now, and then we shall not have anything to do for supper except eat it.”

Olive and the little girls ran a race to see[33] which would first reach Mrs. Merrill. Lucy won, because her legs were longer than Dora’s and, anyway, Dora wasn’t trying very hard to beat Olive.

Mrs. Merrill approved of the sandwiches. She said that Olive might plan supper exactly as she liked. So they ran back to the shack.

By this time Uncle Dan had buried the garbage and he helped make the sandwiches. Some were filled with peanut butter and some with orange marmalade. Olive also boiled six eggs, one for each. She wrapped the sandwiches in waxed paper, and put them in a basket covered with a damp cloth. She put in the eggs and the salt and the pepper, and a loaf of cake and a knife to cut it with. She put in some peaches and some paper napkins.

“Our supper is ready,” she announced. “All we have to do is to come for the basket when we want to eat.”

Uncle Dan wanted to walk up the beach to see the life-saving station. Olive’s hair was dry now, so she twisted it up and pinned on a pretty hat made of blue silk ribbon. They invited the little girls to go, but both preferred to play in the sand.

Lucy took a big spoon from the kitchen to dig a well, but Dora planned to collect shiny white and gray-green pebbles and make a house for herself. This she did by outlining the walls with pebbles and leaving spaces for doors and windows. The beach was so wide that there was room for a large house. Quite soon Lucy came and began to make herself a house next door to Dora’s.

To build the house took a long time, but just as it was finished, Dora had a visitor. The tide was coming, and the first she knew, old Father Ocean ran right in through her front door without even so much as knocking! He did not stay, but ran promptly out again, leaving wet marks all over the front hall of Dora’s new house.

Old father ocean ran right in through the front door—Page 34.

Dora did not say anything then, but the next time a big wave rushed up, the water came into her parlor and curled about her bare toes.

“I shall have to move,” she said to Lucy.

“Or go away until to-morrow,” suggested Lucy. “Look! How low the sun is.”

Where had that afternoon gone? It did not seem as though they had been playing more than a few minutes. But the sea was growing gray instead of blue, and the sun struck long level lines through the air. Up by the shack Father and Mother were enjoying themselves; Mother sitting quite idle, just looking at the water; Father lying on his back in the sand. Away down the beach Olive and Uncle Dan were coming. It must be time for that picnic supper.

Lucy and Dora thought it was great fun to go to bed in the tent. They were even willing to undress at their usual hour and not tease to be out on the moonlit beach.

The only place to put their clothes was over the rope Uncle Dan had stretched between the poles. They hung them there, and the clothes immediately slid into a heap in the middle of the rope. Dora could not make hers stay neatly at one end.

Olive did not go to bed with the children. She and Uncle Dan took the trolley car which ran along the road behind the shack and went to another beach where there was a Saturday night dance. Lucy and Dora did not mind.[37] The window of the room where Father and Mother were to sleep was close at the end of the tent.

After Mother had tucked them into their cots, Lucy went quickly to sleep but Dora lay with eyes wide open. Because of the moon the tent was bright, and through its open flaps she could see the waves breaking lazily on the shore, and hear the surge of the water. Across from the moon came a path of light.

For quite a long time Dora watched the sparkles and then suddenly she began to think about bears, not tiny silver bears like Arcturus, but real ones, full-sized and covered with hair. This was not a pleasant thought.

Dora knew there were no bears anywhere near White Beach. Still, it seemed possible that one might walk into that open tent. And then she heard a rustle outside.

Dora gave a little gasp. At first, she[38] thought she would call Mother, but she remembered that she had wanted to sleep in the tent and that doing so was a part of camping. To be sure, she had not expected that Lucy would be asleep when she wasn’t.

After that first gasp, Dora decided not to scream. She lay still, and listened hard. In a minute, a cricket began to chirp.

When she heard the cricket, Dora felt much better. It surely would not be chirping if a bear were walking round the tent. It would not dare to make any noise. But she thought it would be comforting to have Arcturus for a bed-fellow.

The suit-case was under Lucy’s cot, so Dora got up and pulled it into the moonlight. Without any trouble she found the silver bear on his slender chain and snapped it about her neck. Then she went back to bed and did not think any longer about real bears.

Instead, she thought of fairies and of a poem she had once read in a library book. She tried hard to remember how it went.

While Dora was thinking about the poetry, she watched the edge of the sea and thought she saw one fairy creep out and shake the spray from its wings. She wasn’t quite sure, for it might have been a sandpiper. When Olive came in softly, about midnight, Dora was as sound asleep as Lucy.

Next morning, the sun touched Dora’s cot rather than either of the others, just as the[40] moon had done. When she opened her eyes, the sun was just above the horizon, its lower rim not clear from the water. Never before had she seen it so tremendous! It looked a perfect elephant of a sun.

A soft little breeze came into the tent, blowing straight from sea. Sandpipers really were running along the edge of the foam and the beach was washed hard and smooth. Not a trace was left of Dora’s house except a huddle of the larger pebbles. Every footmark was gone. A perfectly new and fresh playground lay before them.

Just then Lucy woke and she and Dora looked at the sunrise sky and talked in whispers because Olive was still asleep. Her hand was tucked under one cheek, and a long braid of hair lay across her pillow.

They decided to get up and dress very quietly. It was easy to be quiet because the[41] sand under foot muffled every step, and easy to be quick because they had very few clothes to put on.

Just as they were dressed, Lucy stopped short. “O my!” she said in a whisper, and stood on one foot.

Twisted about her bare toes was a little silver chain.

Dora looked at it. Then she put her hand to her neck. Arcturus and his leash were gone. That was her silver chain tangled in Lucy’s toes, but where was the bear? She gave a frightened sob, which woke Olive.

Olive sat up in her cot and looked from one to the other. “What’s the matter?” she asked.

Between sobs, Dora explained that she had felt lonely after Lucy went to sleep and had taken Arcturus into bed with her. When she awoke, she never thought of him. There was the chain, but where was Arcturus?

Olive got up at once. She put on her kimono and her slippers. Then she took the top blanket from her bed and spread it carefully on the sand. Next, she took Dora’s blankets and shook them carefully over hers. If Arcturus were hiding in the bed, he must come out. But he did not.

Olive shook Dora’s pillow and her mattress and her nightdress, and felt the pockets of her dress and looked in the suit-case. She emptied the suit-case and shook every garment. Trying not to cry, Dora watched Olive and Lucy helped her. But Arcturus was not anywhere.

“I am afraid he is in the sand,” said Olive. “Show me just where you have walked since you got up.”

“I have been right by my cot except when I washed myself,” choked Dora.

Olive felt all about in the sand by Dora’s bed and sifted it through her fingers. Then[43] she sat back against the cot, for she really did not know what else to do. She was very sorry for Dora, and Dora knew it. She crept into Olive’s arms and cried softly, so as not to wake the people in the shack.

Arcturus had certainly run away, but after her cry Dora felt better. Lucy and Olive both were hugging her tightly and though it was hard to lose her dear bear, she still had those who loved her.

“Perhaps we shall find him yet,” said Olive. “Let’s think so, Dora, and don’t let it spoil your nice time at the beach. Perhaps Dan will know something more to do. Perhaps Arcturus has just gone to be a sand-bear for a little while.”

At this Dora smiled through her tears. She kissed Olive. Of course it would not be right to spoil things by being sad, and she would hope for the best. There might be a worse[44] fate for Arcturus than being a jolly little sand-bear.

So they all got up from the rag rugs and Lucy picked up Olive’s pretty rose-trimmed hat which had slipped from the nail where she tried to hang it.

“You might put that under my cot, Lucy,” said Olive. “It won’t stick on that nail, and I don’t believe I shall wear it here. I like my ribbon one better for the beach.”

Lucy tucked the hat under Olive’s bed and then she and Dora went down on the shore. Olive said that she knew it would be hard for Dora to speak about Arcturus, so she would do it for her. She would ask the others not to say very much about him, only to look for him everywhere they went.

This made it easier for Dora to come to breakfast. She could even smile when they all called her Theodora. Usually, only[45] Mother remembered that on Sundays she wished to have her whole name used. This morning even Uncle Dan thought about it.

The tide was going out, and away to the right were some shining mud-flats. Uncle Dan and Olive said they were going to dig clams and Lucy and Dora went with them to pick up the clams after they were dug. There was only one clam-fork, but Mr. Merrill found an old spade which he thought he could use. They all put on their bathing suits.

When Dora reached the clam-flat, she did not like it very well. She had not known that clams chose to live in such queer mud. It seemed much dirtier than ordinary wet earth, and after Dora and Lucy had sunk into it far above their ankles, they told Olive that they would let her pick up the clams. If she needed help, she might call, and they would come, but[46] it did not look as though three people would be needed to collect clams for Father and Uncle Dan.

Olive thought she could manage all the clams, so Lucy and Dora went back to the hard beach and made some more houses. Lucy’s had a great many large rooms and long halls with plenty of windows. Dora made a small one which was just like the brown cottage she lived in on Main Street.

Father and Uncle Dan heard what Olive and the children were saying about the clams, and so they dug very hard and very fast. The clams were not so many that Olive needed help to pick them up, but there were plenty for a chowder and for steaming, which was much more than either she or Mrs. Merrill had expected. They decided to have the steamed clams for dinner and to make the chowder for supper.

When the clams were dug, Mr. Merrill carried the basket home and Lucy and Dora saw Uncle Dan and Olive coming up the beach. Olive was carrying a heavy shovel and Uncle Dan had a queer-looking thing over his shoulder. Even when he came up to the shack the children did not know what the thing could be. It was a large oblong frame of wood, with a wire screen bottom, and was tilted up on one end.

“We are going to look for Arcturus,” said Olive, as Uncle Dan dumped the frame beside the tent. “Some men have been getting gravel from the ridge and using this. We have borrowed it for a little while.”

Neither Lucy nor Dora could guess how this frame was to help find the silver bear. Uncle Dan and Olive took out of the tent the three cots and the single chair. Olive shook each rag rug carefully.

Then Uncle Dan carried the frame into the tent. He set it up and lifted a shovelful of sand and threw it against the screen bottom. All the sand went straight through, but the pebbles, even some smaller than Arcturus, fell back in a pile. It would not be possible for Arcturus to go through that wire screening.

Uncle Dan took every single bit of loose sand from the space covered by the tent, and threw it against the screen. Olive and Lucy and Dora watched the pebbles which fell back. Arcturus could not escape three pairs of eyes. But finally there was no more loose sand, only a kind of stiff dry clay, and no Arcturus.

Dora tried hard not to cry but she felt much grieved. It did not seem possible that the bear could evade a search like that. She managed to thank Uncle Dan, who was as sorry as Olive that it had been of no use. They smoothed the sand floor and Uncle Dan returned the screen[49] and the shovel. No, there was nothing left but to think of Arcturus as being a sand-bear now, enjoying himself by the sea.

Then they went swimming, and how Uncle Dan and Father Merrill did laugh at Olive. Olive said that it was Sunday morning and that she usually went to church instead of into the ocean. She should take with her a cake of salt-water soap and call it a bath. She wasn’t sure it was quite right to go swimming just for fun. She should feel more comfortable about it if she took the soap.

Mrs. Merrill did not laugh at Olive. She said she was glad that Olive liked to keep Sunday different from other days.

During all that week at White Beach it rained only a part of one afternoon. Both “Doctor Dolittle” and “Katy” stayed shut into Mother’s suit-case. After the mishap to Arcturus, nothing precious was trusted in the tent. Even on the day the rain fell, the air was so warm and soft that Lucy and Dora played on the shore just the same and thought the sprinkles only the more fun.

Every day people passed up and down the beach. Sometimes they were children who would stop and help Lucy and Dora build a sand fort or run races with them in the edge of the water. Sometimes they had a collection of pebbles to be admired, or a sea-urchin picked up in the sand. These were considered great[51] treasures. Some were worn smooth by the waves, and some—but these were fewer—still had long green spines sticking to their shells.

Except for the friendly children, Lucy and Dora paid very little attention to the passers-by. They could see as many people as they wished in Westmore, but in Westmore there were no gulls and no beach and no sea.

One afternoon Dora did look up when a gentleman on horseback came down the shore. The horse was the color of a bright chestnut and his hair reflected the sun. Somebody must have brushed that horse extremely hard to make him so shiny.

Dora looked at the horse and Lucy looked at the rider and presently Lucy smiled a little.

The gentleman glanced at the children and smiled also. “Aren’t you Mr. Merrill’s little girls?” he asked.

At this Dora looked up. It was Alice[52] Harper’s father. They often saw him in church.

Mr. Harper made the pretty horse stop. He asked Lucy where they were staying. He looked at the shack and at the tent beside it.

“And do you sleep in the tent?” he asked. Lucy explained that they did.

“Alice has wanted to sleep in one this summer, but her mother wasn’t willing. I know it is great fun. I will tell Alice that you are here and I think she will be down to see you. Our house is the other side of the life-saving station.”

Mr. Harper and the shiny horse went on along the beach. Dora watched for some time. The horse walked down by the water where the sand was hard, but whenever a wave came curling in, he danced up the beach. Evidently he did not like to get his feet wet.

When the children went up to supper they told Mrs. Merrill about their visitor.

“He had a very pretty horse. It shone like a bottle,” said Dora.

“Do you think Alice will come to see us?” asked Lucy.

“I wouldn’t set my heart on it,” said Mrs. Merrill.

“Mrs. Harper is always very nice to everybody in the church,” said Olive, who was trying to make toast over the oil stove and was not succeeding very well.

“I know she is,” agreed Mrs. Merrill. “But church isn’t the beach, and people who live in big houses don’t always want to know people who live in small ones.”

Olive burned a slice of bread and gave a little moan over it, so Dora forgot to ask just what Mother meant. She felt quite sure that Alice would come. Of course, her father[54] might forget to tell her. Fathers did sometimes forget very important things, like posting letters and giving messages and bringing home yeast-cakes.

Lucy also thought that Alice would come, and they were not disappointed. The very next afternoon, which was Friday, while they were playing on the beach, Alice came, and Mrs. Harper with her. Alice stopped with the children and Mrs. Harper went straight to the shack to speak with Mrs. Merrill and Olive. Father and Uncle Dan had gone fishing.

Alice asked a great many questions. She wished to know how long they had been there, how long they were going to stay, and why they had not been to see her.

It was easy to answer the first question and the second answered itself, because school began the next Monday and the printing-press[55] started work again, but the third question was not so easy.

“We did not know where your house was,” said Lucy at last.

“You could have asked,” said Alice. “There are no girls my age anywhere near me. I have had nobody to play with all summer but babies and boys. The babies are very well for a time, but they can’t do much but dig holes in the sand, and I don’t like the boys at all. They do horrible things, like putting crabs in shoes and dead fish in playhouses.”

“Girls are nicer to play with,” said Lucy. “Would you like to make a pebble house, Alice, or would you like to wade?”

“I would like to go into your tent,” said Alice eagerly.

The children took Alice up to the tent, which she admired very much. “What fun[56] it must be!” she said. “I wish I could sleep here with you just one night.”

Lucy and Dora began to wonder if this could be planned. It did not seem easy, for there was not room for another cot, even if there were one to bring from the house. It would be hard to find space for even a doll’s bed. As it was, Lucy’s doll had to sleep with her. Dora’s Teddy wore a fur coat and he sat up all night. It would not be polite to ask Olive to give Lucy her cot, and there was no place for her to sleep if she did. There seemed no way to make Alice’s wish come true.

When the children came out of the tent, they saw Mrs. Merrill on the porch with her hat on and a coat over her arm.

“Goody!” said Alice. “Mother was going to ask your mother if she didn’t want to go over to the Port in the motor-boat. We are going, too.”

What a pleasant surprise this was! Lucy and Dora thought it very kind of Mrs. Harper. They had half envied Father and Uncle Dan their trip.

Everybody walked up the beach beyond the life-saving station where the boats lay ready to be launched the moment they were needed. Ships need help sometimes as well as people, and these boats were always waiting for a call from sea.

Beyond the station lay a row of pretty houses on a curving strip of land which ran around a big bay. Across, was the town which Alice called the Port.

Mrs. Harper took them up on the porch of her cottage and gave them some lemonade and cookies. She brought out the pitcher herself and Alice brought the glasses. It tasted very good because there was no ice at the shack to keep things cool.

After drinking the lemonade they went down to the boat-house where a man helped them into the motor-boat. Lucy and Dora had been around World’s End Pond in a launch, but this one was much more trim and tidy and went through the water much faster. Its boards were very white and all the brass shone and it plunged right at each wave as though it were going to dive through rather than sit on top.

Dora became very quiet. The foam flew on either side, and the waves were as blue as Mother’s blueing water, but on the whole she liked the pond better than the sea. For one thing, there was not so much of it.

Lucy and Alice went forward in the launch. Alice wanted to sit on the roof of the little cabin. Mrs. Harper said she might if the man at the wheel thought it was safe.

“Safe as lying in a cradle,” said the man,[59] so Lucy and Alice climbed up where they could get all the wind that blew.

“Don’t you want to go with them?” Mrs. Harper asked Dora.

“No, thank you,” said Dora shyly. She was sitting next Olive and presently she cuddled so close that Olive understood and put an arm around her.

Before long the waves grew even larger and some of them broke over the bow of the launch. Alice and Lucy were spattered with spray and both gave little shrieks.

“Don’t you feel well, Dora?” asked Olive in a whisper. “Don’t you want to go to the Port?”

“I’d rather go on land,” said Dora. “Any land.”

Dora spoke softly but Mrs. Harper heard. “Poor child!” she said. “And I thought she would enjoy a ride.”

Mrs. Harper opened a locker, which was a cupboard under the seat, and took out a big soft shawl. She spread it on the seat and told Dora to lie down.

Dora was extremely glad to feel herself on something flat. She shut her eyes and kept still while Mother and Mrs. Harper wrapped her in the rug. Then Mrs. Harper spoke to the man at the wheel. He turned the launch in a different direction so that the bow did not hit the waves quite so hard.

It seemed a long time to Dora before they were back at the boat-house. The launch had been out only about an hour, but she thought it was the whole afternoon. Alice and Lucy thought it was about ten minutes.

Just as soon as she stepped ashore, Dora began to feel better, and she did not really need the hot soup which Mrs. Harper insisted she should drink. By the time they were home[61] at the little shack, Dora could hardly believe that she had not enjoyed the trip.

“But would you like to go again in the launch?” asked Olive.

No, Dora would not go so far as to say that. She felt surprised and hurt, that the sea which looked so lovely, could make her feel so disagreeable.

When the fishermen came they brought with them five fish. Four were ordinary plain fish such as the children often saw at the market, but the fifth one, which Uncle Dan had caught, was much longer and broader and looked strange. Dora at once asked Uncle Dan its name.

“I think it is a walrus,” said Dan gravely.

Lucy looked respectfully at the fish but Dora looked at Uncle Dan. Though his face was quite unsmiling, there was a twinkle in his eyes.

“It must be a walrus,” he went on, “because I am a carpenter, you see.”

Lucy didn’t “see” at all, but Dora laughed in delight. Of course it must be a walrus. She remembered the poem perfectly.

Dora laughed hard at Uncle Dan waving the fish and pretending to wipe his eyes. Olive understood and laughed also, but Lucy and Mrs. Merrill didn’t understand the joke at all.

Then the fishermen were told about the[63] launch trip and Dora was rather sorry they had to know that she did not enjoy it. But she felt comforted when Father confided to her that he did not like the motion of the boat himself.

“It was all right as long as we kept moving,” he said, “but when we anchored to fish, I felt as though my dinner wasn’t to be depended upon.”

“I know just how you felt,” said Dora earnestly. “I grew so jiggly that my stomach came up on top of me.”

And the very next day they had to go home. The truck was to come over early in the afternoon and everything must be ready. Uncle Dan and Olive were going back by trolley and they said they would take the children, but Lucy and Dora decided to ride on the truck.

For that last dinner they had another chowder, because it was easy to make and to heat when there was not a great deal of time for[64] cooking. And it was odd how easy the packing seemed. Scarcely five minutes were needed to tuck into the suit-case the clothes it had taken so long to choose. The cookies and cake and apples were all eaten.

Only, as Dora folded the last rug and looked around the empty tent, ready now to be taken down, she thought of Arcturus and the tears came to her eyes. She did not mean anybody to see them, because they had all been so kind. Mother had not said one word about her being careless and Lucy offered to give back the pink coral heart Dora had lent to her. But when the tent was all pulled to pieces, the thought of her dear bear was more than she could stand. Olive saw her wipe away a tear and put an arm around her.

“I am so sorry, Dora,” she said. “Indeed, if I could, I would get you another bear.”

“It wouldn’t be Arcturus,” choked Dora.

“No,” agreed Olive, “but it might be his twin brother. I don’t suppose it would be possible to buy one in this country, and I shall never be lucky enough to go to Switzerland. But I am thinking you a little bear, Dora. Can’t you feel him growing?”

Dora pretended she could, and when she came out of the tent, nobody could have suspected any tears. But as they left White Beach, her last look was not for the sea nor the sky nor the gulls, nor the goldenrod and asters along the sandhills, but for the place where the tent had stood, and in her heart she was hoping that Arcturus would be very happy in his new life by the shore.

Timothy was glad to see Lucy and Dora come home. He looked fat, and Marion Baker said he had slept in the kitchen every night but one. On Wednesday evening he chose to visit his friends. But Timmy had evidently been lonesome, for he purred loudly and followed the children up to their room. As soon as the suit-case was opened, he got into it to see whether they had brought anything for him. Dora had done so. There was in the suit-case a stalk of catnip for Timothy.

Some mail and papers were at the house and when Mother looked over the letters there was one for Dora from Miss Chandler, whom she called Aunt Margaret.

Dora planned to answer the letter on Sunday. There was much to tell about the beach. Only, when she began to write, she thought of Arcturus and felt quite sad. When she spoke of him, Mother suggested that Dora should tell Miss Chandler how Arcturus had run away. It was right that she should know, because she gave Dora the little bear.

To write about it in a letter was easier than speaking of it when she saw Miss Chandler, so Dora wrote what had happened and how sorry she was. Then she told her about the nice time at the beach, and what fun it was to sleep in a tent, and how she and Lucy rode home sitting on a roll of blankets in the back of the truck.

When the letter was finished, Mother looked at it. She told Dora about one word which was spelled wrong and said that the writing looked neat. Then she told Dora how to direct[68] the envelope and gave her a postage stamp from Father’s desk.

Dora stuck the stamp on the proper corner and put the letter in the box on the post by Mr. Giddings’ drug-store. Then she came back to the house and read the “Story of Doctor Dolittle.” She thought it was one of the most interesting and funniest stories she had ever read. She tried to have Lucy enjoy it, but Lucy liked “What Katy Did” better.

After supper that Sunday night, Dora followed Mother into her bedroom.

“I have a plan,” she said. “Mother, you know Aunt Margaret told me that her birthday is the same as mine. Both are next Friday. I would very much like to make her a birthday present, Mother. You see she gave me Arcturus and the other little charms. And anyway, it would be nice, because she was so kind to us in the vacation school.”

Mrs. Merrill thought this was a nice plan. She asked Dora what she wanted to give Miss Chandler.

“I have twenty-five cents,” said Dora, “which I earned picking blackberries. I thought I could buy her some paper to write letters on.”

“I think,” said Mrs. Merrill, “that Miss Chandler would like better a gift which you made for her. You know you did some cross-stitching for the bedspread this summer. Haven’t you still the paper with the pattern showing the colored squares?”

Yes, Dora still had the paper pattern of the roses.

“I am going to the city to-morrow,” said Mrs. Merrill. “Would you like me to buy a bit of the canvas they use for cross-stitching, and four skeins of colored cotton? Then you could make a pincushion for Miss Chandler[70] with the cross-stitched roses on it. I have a piece of pretty white linen you may use for the top, and I will help you put the cushion together. Don’t you think that would be a nice present?”

Dora was perfectly delighted with Mother’s plan. She begged her to find the piece of white linen at once, and when she saw it, she was sure that it would make an unusual cushion. She was so afraid that Mother would forget what an important errand that canvas was, that she took a pencil and wrote it down on a piece of paper and stuck the paper into Mother’s purse, where she could not fail to see it.

Next morning school began. Lucy and Dora were glad, for both liked to go to school. Lucy was one grade ahead of Dora and so each year, Dora had the teacher Lucy was leaving. Because she heard Lucy talk about them at home, she felt acquainted immediately,[71] and it was not hard to change into a higher grade.

This year Lucy was sorry to leave Miss Leger, and she was not sure she should like Miss Scott, into whose room she was going. Some of the older girls did not like her.

While Mother was tying their hair-ribbons, Lucy spoke to her about it. Mother did not think Miss Scott would be cross.

“If you learn your lessons, Lucy, and behave yourself as well as you should do, your teacher will not be cross. It is only sick or naughty children who can’t get on at school.”

Lucy admitted that Mother’s advice sounded sensible, and she and Dora started for school. Lucy had on a white waist, which had buttoned to it a pink plaid kilted skirt. On the waist was a collar of the pink plaid gingham. When Mother planned that dress, Lucy[72] did not think she should like it, but now the dress was made, she liked it very much.

Dora wore a new dress, too. Hers was a loose blue gingham which was smocked at the shoulders and had a round white collar. They both wore socks and sneakers, because Mother thought best to save their leather shoes for colder weather.

All the children seemed glad to come back to school. All the little girls wore clean crisp dresses, slipped on five minutes before they started for the schoolhouse. All the little boys had clean shirt-waists and their hair brushed back very hard and very wet.

The children went into the rooms belonging to their new grades. Lucy hoped to get a back seat in a row of desks, for all the girls considered the back seats the most desirable. Lucy didn’t get the seat she wanted, but the one she did get was the third from the back,[73] and beside a window, so that was not so bad.

Dora didn’t care where she sat, and this was lucky, because Miss Leger told the children to stand, and then arranged them according to how tall they were, with the smallest ones in front. This put Dora in the first seat of all, but she liked it as well as any other.

Everything went well until recess and then an accident happened to Dora. The little girls were playing tag on the grassy grounds about the schoolhouse. The older girls were walking up and down with arms around each other’s waists, talking of the many things which had happened during the long vacation.

Dora was playing with five other little girls and running as fast as she could when suddenly something hit her hard and everything turned black.

The next Dora knew she was lying flat on[74] the soft grass and Lucy was holding her hand and one of the big girls was putting water on her face. And ever so many girls were standing around and looking at her.

“What is the matter?” asked Dora. “What hit me?”

“You and Marion Baker ran into each other,” said the big girl who was mopping her face.

Dora thought this odd. She had not even seen Marion. How queer that she could run into a person whom she didn’t see!

The next second Dora discovered that her lip was cut and bleeding. It hurt worse than her head and the blood was dropping on the pretty blue dress which had been so fresh and clean that morning.

When the littler girls saw the blood-stains, they were frightened. Some of them ran to tell Miss Leger that Dora was hurt.

Miss Leger came out at once. She bathed Dora’s lip and found that there was only a small cut. It was very small to produce so many drops of blood. She told Dora to hold the wet cloth against it. Then she looked at Marion, who had a big bump on her forehead.

For a time both Dora and Marion felt very sorry for themselves, but in a few minutes Marion’s head stopped aching and Dora’s lip no longer shed bright drops of blood. They could even think it funny that with all that big school-yard, both should have tried to stand in the same place at the same second.

Lucy was disturbed about Dora’s dress. It looked worse than Dora could see. Mother was shopping and would not be at home until afternoon school was over. Lucy did not know what was best to do about the dress.

Luckily Father knew. He was sorry that Dora’s lip was cut, but glad she was not badly[76] hurt. He said that Dora had better take off the dress and put it to soak in cold water. He was sure that cold water would not hurt it and that it would be safe to leave it soaking until Mother came and decided what should be done to it next. He asked Dora if she did not have another clean dress.

Yes, there was a clean dress, but not perfectly new, like the blue gingham. Dora was sorry to change, but she saw that even a dress which wasn’t brand-new looked more tidy than one dribbled with red spots. She took off the spotted one and Lucy buttoned the other and they went back to school.

When they were through at four, Mrs. Merrill was at home. She had attended to the blue gingham and it was hanging on the line, just as clean as ever. Of course she wanted to know about the spots.

Lucy and Dora told her about them and then[77] Dora asked anxiously if Mother found the note in her purse and if she remembered to buy the canvas and the colored cottons.

Mrs. Merrill had remembered. There was a piece of canvas and two shades of green cotton and two of pink. They had cost seventeen cents.

Dora ran to bring Mother her quarter, for she wanted to pay for them so that her gift to Aunt Margaret should be entirely hers. Mrs. Merrill gave her eight cents in change.

“And will you fix the top of the cushion so I can begin on it right away?” she asked.

“I can’t do it just this minute,” said Mrs. Merrill, “because I have to cook something for supper. I will try to do it early this evening.”

“Dora and I will wash the dishes and do all the clearing away, so you can have plenty of time,” offered Lucy.

After supper, Mrs. Merrill sat down with[78] the pattern and the cross-stitch canvas and the linen for the cushion top. She measured and planned carefully. She basted the canvas in the proper place so it could not slip while Dora was working. She made one cross-stitch so Dora could start easily.

When the last dish was put away, Dora came eagerly to see the cushion. From the one stitch Mother had set, it was easy to follow the pattern and she sat down at once to sew. Before bedtime, the roses and their leaves were made and she was ready to pull out the canvas.

Mother showed her how to do this, just one thread at a time. They were stiff and hurt her fingers, but she kept on and soon the linen top with its design of roses lay before her.

“You have done the pretty part now,” said Mrs. Merrill. “The rest will be plain sewing, but you must set every stitch as well as you possibly can. I want Miss Chandler to think[79] that you work neatly. I will baste it for you.”

“I will try very hard,” said Dora. “I suppose I couldn’t begin that part this evening?”

“No,” said Mrs. Merrill. “Tell Father good-night, and then you and Lucy run up to bed. When you are ready, knock on the floor and I will come and put out the light.”

Both Lucy and Dora laughed at forgetful Mother. Almost always she said that when they were going to bed. It sounded all right any time, and it was all right in winter, when there really was a light to put out. But in September, with daylight-saving time, there was twilight when they went to bed. What Mother meant was that she would come and kiss them and see that the window was open and their clothes properly picked up.

Next day Dora back-stitched the case for the cushion and filled it with some old knitting[80] wool which she snipped into tiny pieces. Dora was surprised to learn from Mother that pins stick much better into a cushion stuffed with wool. It is no use to stuff one with cotton.

Next, the embroidered top was pressed, and this Dora did herself after Mother had finished ironing. Mother basted the top and bottom together and Dora sewed the edges over and over. She tried so hard to make the stitches even and small that her cheeks grew pink and she felt hot all over. Into each stitch she sewed a loving thought for Miss Chandler.

When the cushion was done, Mother said that it looked very neat and Lucy thought it was beautiful. She liked it so much that Dora had another idea. If Mother would help her, she would make a second cushion for Lucy’s Christmas present. There was plenty of cotton for more roses and there were canvas and linen, too. Perhaps it might be possible to[81] make one for Olive. To make three pretty gifts and have them cost but seventeen cents would be a good deal for a little girl to accomplish.

Dora could hardly wait until Lucy left the room before asking Mother about the other cushions. Mrs. Merrill said at once that she would help. They would be desirable Christmas presents for both Lucy and Olive.

Dora found a clean empty candy-box into which the cushion fitted exactly. She wrapped it neatly in tissue paper and put in a card so Miss Chandler would know from whom it came.

“You might tell her that you made it yourself,” suggested Mother, who was now darning Uncle Dan’s socks.

So Dora put on the card: “I made it myself.” Then she thought a moment and wrote some more: “All but one stitch which Mother[82] made so I could get the roses in the middle. And the bastings. She sewed those, but they are all pulled out.”

Mother smiled a little over Dora’s card, but she said that it would do, and that she thought Dora was improving in her writing. Then Dora wrapped the box in brown paper and directed it to Miss Chandler in Boston. She decided to pay the postage with her eight cents. Then there would be nothing about the gift not wholly hers.

The seventeenth of September was Dora’s birthday. On Thursday night she went to bed expecting to feel quite different when she waked in the morning and was nine instead of eight. But she didn’t. She felt just the same.

The day was bright and sunny but cold. Lucy looked out to see whether there had been a frost. So far as she could see, nothing was touched in the garden. Even the nasturtiums, which get discouraged and turn black if the thermometer casts a glance toward the freezing-point, were looking as alert and cheerful as usual.

When the children were dressed, they ran[84] down-stairs. Lucy went into the kitchen to help Mother. Dora sat down in the parlor and tried to read. The birthday girl never helped about breakfast. She didn’t even come near the table till she was called.

Dora simply couldn’t read. She knew there was to be a surprise and she wanted to think how pleasant it would be. Out in the kitchen she could hear Lucy whispering to Mother and then came a rustle of paper as though somebody was arranging soft packages.

“Breakfast is ready,” called Lucy at last. “All right for you to come, Dora.”

Dora didn’t need to be called but once. Nobody does on a birthday morning.

She saw that her plate was covered with bundles, and then she had to hide because Uncle Dan said that her nose must be buttered and that she should have nine spanks, and one to grow on.

Dora had to dodge around the table till Mother told Uncle Dan to sit down and behave properly. Uncle Dan put down the butter-knife and Dora let him catch her and give her ten love pats and a big hug.

Then Father kissed her, and Mother said if they wasted any more time the children would be late for school and Father and Uncle Dan would be late for work.

Dora sat down at her place and picked up the first package. It was fat and not a bit heavy. She opened it to find some yarn, soft, and of the prettiest blue you can imagine. Dora didn’t know it, but it was the color of her eyes.

“That is to make you a sweater,” said Mother. “I am going to knit one like Mary Burton’s. You said you liked hers so much.”

Dora was delighted. She kissed Mother and looked very happy.

“My old sweater is growing so small,” she said. “Will you knit it soon, Mother?”

“I will begin it this evening,” said Mrs. Merrill. “I want some work to pick up after supper.”

“It is the color I like best,” said Dora, and she opened another package.

This was from Olive and it contained two new hair-ribbons. One was blue and exactly matched the sweater yarn. The other was pink. Dora liked them both.

The next package was small and heavy and Dora wondered what it could be. It was a paint-box with paints of all the different colors that any picture could possibly need. This was from Uncle Dan, and Dora went straight and hugged him.

“How did you know I wanted a paint-box?” she asked. “I wanted it very much and I didn’t expect to have one.”

“A little bird told me,” said Dan promptly.

“I guess it was an Olive-bird,” laughed Dora. “I don’t remember telling anybody but Olive how much I wanted one.”

Lucy was eager for Dora to open her gift. Dora thought it was lovely. It was a roll of colored papers and paper lace, for making hats and dresses for paper dolls. Such a gift was most desirable for work on winter evenings.

Now two packages were left, one of which had come through the mail. Dora opened the other first. This was from Father and was a copy of “Alice in Wonderland.”

Dora loved that story. She had borrowed it many times from the Public Library and never expected to have a copy of her own. Father explained that he had a chance to buy it through the printing-press and knew she would like it.

“There is another part to my present,” he[88] said. “Next week there is to be a good film at the movies, ‘Anne of Green Gables.’ You and Lucy and Mother are to see the afternoon performance.”

Lucy and Dora both had to hug Father now. It was not often that Mother let them go to the movie theatre. She thought the pictures were not as nice as books. It would be great fun to see “Anne,” and all the more fun to know about it so long before.

Now there was one package left to open, but under it were two post-cards and a letter. One card was from Mr. Thorne, the rector of the church where the Merrills went and where Uncle Dan sang in the choir. The other was from Miss Page, Dora’s Sunday school teacher. Both had remembered to send a birthday greeting.

The letter and the package were from Miss Chandler. Dora took off the outer wrapper of[89] the package and found a candy-box, much like the one her pincushion had gone traveling in. But no candy, unless made of sea-foam, could be so light as that box. When she opened it, nothing showed but tissue paper.

Very carefully, Dora pulled this out and in the middle, wrapped in bright red paper so she could not fail to see it, was a small box, tied with white ribbon. When she opened it Dora gave a gasp. She was so surprised that she could not speak.

Inside the box was a little thing rolled in cotton, and when Dora’s trembling fingers took it out, it was another charm for her to wear on her silver chain.

This charm was a tiny kitten, about three-quarters of an inch high. Unless it had upset a blueing bottle, no earthly kitten was ever that color. This one was deep blue, and it didn’t seem to be made either of glass or metal. Its[90] pointed ears gave it a surprised look and its kitten face wore a pleasant expression. About its neck was a silver collar with a ring at the back to slip on a chain. About its feet its tail coiled tight as though to keep its paws from scattering. Anybody could see that it was an unusual kitten. Dora felt sure it must have a story.

“The letter is from Miss Chandler,” said Mother. “If you open it, Dora, it may tell you where the little cat came from. I suppose it is something she brought from Europe.”

The kitten had come from even farther than Europe! Dora read the letter aloud.

“Dear Little Dora:

“Many happy returns of your birthday! I hope you may have the nicest possible time. I am sorry Arcturus was so ungrateful as to run away from his kind mistress, but you know bears are wild at heart. I am sending you another pet in his place, one which I hope will be willing to stay at home. This is a[91] Chinese kitten which came from the city of Hong Kong. If you drop it, it will not break because it is made of stained ivory.

“Since you named your bear for a star, perhaps you may like a star name for this kitten. Would you like to call it Vega? That is the name of a brilliant star which in summer is almost directly overhead. I am sure your uncle will help you find it. It is a star which shines with a blue light, so its name is suited to a blue kitten.”

Dora was delighted that the blue kitten should be named for a blue star. She stopped to say so before finishing the letter.

“I wanted to spend our birthday together, but I have to teach all day. So I made another plan which Mother will tell you.”

Dora at once turned to Mother. “I will tell you when you have eaten your porridge,” said Mrs. Merrill. “Your breakfast is getting cold, Dora. Eat your oatmeal and drink your milk.”

“No eat—no go,” said Uncle Dan.

“Dan, keep still,” said Mrs. Merrill. “Begin to eat, Dora.”

Dora was too happy to feel hungry, but she knew the oatmeal must go down and that she must eat an egg and a slice of toast. When she had almost finished, Mrs. Merrill told the plan.

“I had a letter, too, from Miss Chandler,” she said. “She has invited you and Lucy to come into Boston to-morrow morning and stay with her until Sunday afternoon.”

“Mother! May we?” exclaimed Lucy and Dora in one breath.

“I never went to Boston but twice in my life,” said Lucy.

“I never visited anybody over night,” said Dora and then they both said, “Mother, do let us!”

“Father and I are willing you should go,” replied Mrs. Merrill. “Miss Chandler sent a[93] dollar to pay for your tickets, and Father will put you on the eight o’clock train and Miss Chandler will meet you in the North Station.”

“I didn’t know Aunt Margaret kept house,” said Lucy.

“It isn’t a real house,” said Mrs. Merrill, “that is, not like this one. She has some rooms in a big building.”

“Mother!” said Dora, “oh, Mother, may I take Aunt Margaret a piece of my birthday cake?”

“How do you know there will be a birthday cake?” asked Mrs. Merrill.

“Because there always is,” said Dora.

You may be sure that Lucy and Dora did not oversleep next morning. For supper there had been pink ice-cream and a proper birthday cake with nine pink candles, and the holiday feeling lasted all night.

Father took them to the station and put them on the train. He spoke to the conductor and then to Lucy.

“Now, Lucy,” he said, “if Miss Chandler is not on the platform where the train comes in, you and Dora are to walk right back to the car where you got off, and this gentleman will bring you home on his next train.”

“But, Father,” said Dora, “Aunt Margaret will be there. She said she would meet us.”

“Yes, I know,” said Father, “and I think she will be waiting. This is so you will know what to do if anything happens to prevent her being there.”

Father kissed them and the conductor said, “All aboard!” Father stepped off quickly.

Neither Lucy nor Dora often went on a train. They traveled so seldom that it was great fun to see the farmhouses and cows and hens as the train scurried past, and to watch the telegraph poles swooping down to gather up their wires.

Before long, the farms grew fewer, and the houses came closer together and instead of having only two tracks, one for the trains going to Boston and the other for trains going in the[96] opposite direction, there were many tracks on both sides, with engines puffing past or cars standing in long lines.

Quite soon the trainman came and took their suit-case. Lucy looked at it anxiously for it contained a clean white dress for her and one for Dora. These were to be worn on Sunday if Aunt Margaret wished to take them to church. Lucy was not sure what the man meant to do with the suit-case.

Dora did not notice his taking it. The train was moving across a bridge with water coming quite close on either side. In the air, gulls were flying, and in the distance she could see some big ships.

The trainman saw that Lucy looked troubled. “The conductor told me to take this,” he said. “I’ll go with you to meet the party you are looking for.”

Lucy didn’t know what he meant. “But we[97] aren’t going to a party,” she said shyly. “We are going to meet Aunt Margaret.”

The trainman smiled. “I’ll help you meet her,” he said, and he looked so pleasant that Lucy was willing he should take the suit-case.

When the train stopped, the children followed the other people to the door and there the trainman stood with the suit-case. He lifted Dora down and took Lucy by the elbow to help her just as he did the grown-up ladies. Then he walked with them down a long platform.

Lucy and Dora were glad that he came with them. The train was standing under a big shed with a very high roof and many people were hurrying about. Huge engines snorted and made so much noise that it seemed most confusing.

Miss Chandler stood by the gate which let the people through from the train-shed into the[98] other part of the station. She kissed the little girls and thanked the kind trainman for helping them find her.

The first thing was to dispose of the suit-case. Miss Chandler called a messenger-boy and sent him to take it to her rooms.

“Now,” she said to the children, “we will go by the elevated train.”

Lucy and Dora had read about the elevated railways in big cities, but neither had been on one. They went through the big station and up some steps and through a turnstile and along a corridor above a street where the trucks and electric cars were, and up some more steps to a platform. Soon a train of cars came, but it did not have a smoky engine. This train ran by electricity.

“Is this the evelated train?” asked Dora.

“Yes, this is the elevated,” said Miss Chandler, laughing. “We will step into this car.”

In half a minute the train was again moving, but the children were surprised because it did not stay on the tracks above the street. Instead, it promptly plunged underground, into a lighted tunnel which ran under the street instead of above it.

“It is a funny kind of elevated train which runs underground, isn’t it?” said Miss Chandler. “But it does in Boston.”

Lucy and Dora thought it was odd, but they liked the brightly lighted stations where the train stopped. Quite soon, Miss Chandler said they would get out.

When they left the car they were still underground and climbed many stairs before seeing daylight. When they came out, it was on a sidewalk in the midst of tall buildings, much higher than any in the city where Mother went shopping. The streets were very narrow and at almost every crossing stood a policeman. He[100] told the automobiles to stop and let people cross the street, or he told the people to wait on the sidewalk until it was safe for them to come. Everybody did exactly what he told them to do.

“I think it is very kind of that policeman to stand there and help the people,” said Dora.

Miss Chandler smiled. “Do you, Dora?” she asked. “He says we may cross now.”

Such wonderful shop-windows! Lucy and Dora were really obliged to stop and look, for they had never imagined anything so beautiful. One big window was draped with silks of different shades of orange and flame.

“Is it a fairy palace?” asked Dora. “It is like a story I read once.”

No, it was not a palace, only a big shop and people could go in and buy those very silks if they liked. Miss Chandler let the children look in a number of windows and then she called[101] their attention to an open space across the street.

“Let us go over on the Common,” she said. “Perhaps the squirrels will come to be fed.”

Directly across from the beautiful shops was a big park with great elms and green grass and seats where men and women were sitting. When the children entered, they saw three fat gray squirrels with bushy tails climbing over a man who sat on one of the seats.

“They know he has nuts for them,” said Miss Chandler.

The man saw the children looking at him. He drew his hand from his pocket and it contained some peanuts.

“Would you like to feed the squirrels?” he asked.

“Will they bite?” asked Lucy.

“Not if you don’t scare them. Don’t touch[102] them nor try to grab them, but just hold the nut in your fingers.”

“Thank you,” said Lucy and took one nut.

“May we?” Dora asked Miss Chandler, and when she smiled, Dora took a nut and thanked the man.

The squirrels came at once. Dora shivered a little when her squirrel put its paws about her fingers to steady the nut. Its wee hands felt so queer!

The third squirrel sat on the man’s knee and nibbled a peanut. When it was eaten, it put its paws over its heart in a beseeching way. As well as it knew how, it was begging for another.

Perhaps it was lucky that the man did not have many peanuts, for Lucy and Dora would have stayed until they were all gone. When there were no more, they thanked the man again and followed Miss Chandler across the Common.

Dora shivered a little when the squirrel put its paws about her fingers—Page 102.

“Who takes care of the squirrels in the winter?” asked Lucy. “Who would feed them if the people didn’t?”

“The park commissioners feed them,” said Miss Chandler. “Did you know that the State legislature of Massachusetts once stopped some important work to provide for a family of orphan gray squirrels on Boston Common?”

“Did they really?” asked Lucy.

“They really did. So you see that the squirrels would be looked after even if people didn’t like to feed them with peanuts. Did you ever hear of the Frog Pond?”

“I have,” said Lucy eagerly. “I have just studied about it in my history class. Dora hasn’t had history yet, but we can tell her.”

Dora looked at the small pond before them. She didn’t see any frogs.

“Just think, Dora,” said Miss Chandler,[104] “that pond has been here since the first people came to Boston. The boys always slide on it in winter. Once during the Revolutionary War, British soldiers camped on the Common. They spoiled the ice where the children wanted to slide.”

“I know what happened,” said Lucy proudly. “The general in command of the British army was a very cross man, but the boys didn’t care if he was. They went straight and told him what the soldiers had done. And the General said they were to let the slide alone. Didn’t he, Aunt Margaret?”

“He did,” said Miss Chandler.

Dora looked respectfully at the Frog Pond. There were better places in Westmore for sliding when winter came, but it was interesting to know that children had played with the Frog Pond ever since there were any children in Boston to play there.

Beyond the Common lay a pretty park, called the Public Garden, and here they came to a larger body of water with white birds swimming on it. Some were ducks and some were swans, and the children stopped to watch them. Miss Chandler kept looking at a wooden platform not far away. Part of it was on the bank and part floated on the water.

Presently a boat came in sight, but it was like no boat Lucy and Dora had ever seen. It was not like the launch on World’s End Pond nor like the one at the beach. It looked like a tremendous great bird, floating lightly on the water.

“Would you like to go in the swan boat?” asked Miss Chandler.

Would they like to! Dora and Lucy could hardly speak for joy. But Dora asked one question.

“There won’t be any waves, will there?” she inquired anxiously. “Not to tip the swan about?”

“It will be perfectly smooth,” said Miss Chandler, and it was. Dora enjoyed every second she spent in the swan boat.

Next, Miss Chandler took them to the Boston Public Library. The children were very fond of the library in Westmore, but they had never imagined a library as big as this great building. Miss Chandler told them that Boston was a large city and the people needed many books to read.

They stayed a long time in the Public Library. In it were many rooms and in some were beautiful paintings. To see them, they climbed a marble stair where great lions kept guard. Dora at once revised her ideas of fairy palaces. If only that windowful of silks could be hung on the walls of the marble stair, it[107] would be better than any palace of which she had read.

On the walls of one room were paintings about Sir Galahad. Lucy and Dora knew his story and how he went to seek the Holy Grail. Miss Chandler explained each painting.

Then she took them into a pleasant room with low bookcases and small tables and chairs and told them that it belonged to the children of Boston. All the books on the shelves were books which children liked to read.

Dora looked at the shelves carefully. It would be nice to have a library just for children, with no grown-ups at all. Still, the Westmore library was nice, and a little town didn’t need a big library like Boston. Some of the books she saw on the shelves were in the children’s corner of the Westmore library.

“Now I think it is time for luncheon,” said Miss Chandler. “We will have it rather early[108] because I have a plan for this afternoon and I don’t want you to get too tired.”

Lucy and Dora had not thought about eating, but now it was mentioned, they both felt hungry.

Miss Chandler stopped an electric car near the library. To the amusement of the children, after running a few blocks down a wide street, the car dived underground. Cars in Boston seemed to have this habit.

When they came out of the subway they were in a different part of town, one which was crowded with people and had many large stores.