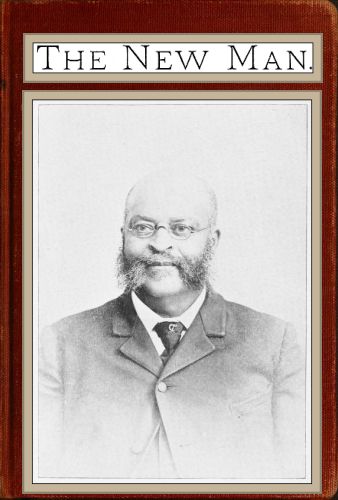

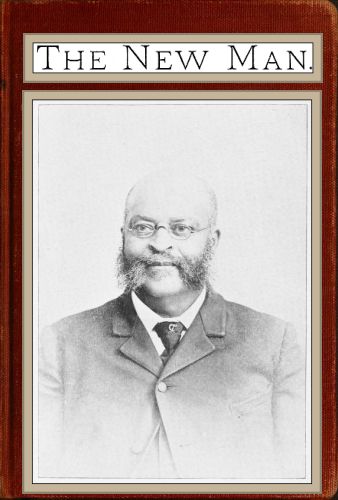

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The New Man, by Henry Clay Bruce

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The New Man

Twenty-nine years a slave, twenty-nine years a free man

Author: Henry Clay Bruce

Release Date: August 2, 2018 [EBook #57625]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NEW MAN ***

Produced by Chuck Greif, MFR and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Twenty-nine Years a Slave.

Twenty-nine Years a Free Man.

RECOLLECTIONS OF

H. C. BRUCE.

YORK, PA.

P. ANSTADT & SONS,

1895.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1895, by

H. C. BRUCE,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

The author offers to the public this little book, containing his personal recollections of slavery, with the modest hope that it will be found to present an impartial and unprejudiced view of that system. His experience taught him that all masters were not cruel, and that all slaves were not maltreated. There were brutal masters and there were mean, trifling lazy slaves. While some masters cruelly whipped, half fed and overworked their slaves, there were many others who provided for their slaves with fatherly care, saw that they were well fed and clothed, and would neither whip them themselves, nor permit others to do so.

Having reached the age of twenty-nine before he could call himself a free man, and having been peculiarly fortunate in all his surroundings during the period of his slavery, the author considers himself competent to deal with all concerned, fairly and without prejudice, and he will feel more than repaid for his labor, if he can throw even some little new light upon this much mooted question. He believes that we are too far removed now from the heart burnings and cruelties of that system of slavery, horrible as it was, and too far removed from that bloody strife that destroyed the system, root and branch, to let our accounts of it now be colored by its memories. Freedom has been sweet indeed to the ex-bondman. It has been one glorious harvest of good things, and he fervently prays for grace to forget the past and for strength to go forward to resolutely meet the future.

The author early became impressed with the belief, which has since settled into deep conviction, that just as the whites were divided into two great classes, so the slaves were divided. There are certain characteristics of good blood, that manifest themselves in the honor and ability and other virtues of their possessors, and these virtues could be seen as often exemplified beneath black skins as beneath white ones. There were those slaves who would have suffered death rather than submit {iv}to dishonor; who, though they knew they suffered a great wrong in their enslavement, gave their best services to their masters, realizing, philosophically, that the wisest course was to make the best of their unfortunate situation. They would not submit to punishment, but would fight or run away rather than be whipped.

On the other hand there was a class of Negroes among the slaves who were lazy and mean. They were as untrue to their fellows as to themselves. Like the poor whites to whom they were analogous in point of blood, they had little or no honor, no high sense of duty, little or no appreciation of the domestic virtues, and since their emancipation, both of these inferior blooded classes have been content to grovel in the mire of degradation.

The “poor white” class was held in slavery, just as real as the blacks, and their degradation was all the more condemnable, because being white, all the world was open to them, yet they from choice, remained in the South, in this position of quasi slavery.

During the slave days these poor whites seemed to live for no higher purpose than to spy on the slaves, and to lie on them. Their ambitions were gratified if they could be overseers, or slave drivers, or “padrollers” as the slaves called them. This class was conceived and born of a poor blood, whose inferiority linked its members for all time to things mean and low. They were the natural enemies of the slaves, and to this day they have sought to belittle and humiliate the ambitious freeman, by the long catalogue of laws framed with the avowed intention of robbing him of his manhood rights. It is they who cry out about “social equality,” knowing full well, that the high-toned Negro would not associate with him if he could.

If there had been no superior blooded class of blacks in the South, during the dark and uncertain days of the war, there would not have been the history of that band of noble selfsacrificing heroes, who guarded with untiring and unquestioned faith, the homes and honor of the families of the very men who were fighting to tighten their chains. No brighter pages of history will ever be written, than those which record the services of the{v} slaves, who were left in charge of their masters’ homes. These men will be found in every case to have been those, who as slaves would not be whipped, nor suffer punishment; who would protect the honor of their own women at any cost; but who would work with honesty and fidelity at any task imposed upon them.

The author’s recollections begin with the year 1842, and he will endeavor to show how slaves were reared and treated as he saw it. His recollections will include something of the industrial conditions amidst which he was reared. He will discuss from the standpoint of the slave, the conditions which led to the war, his status during the war, and will record his experiences and observations regarding the progress of the Negro since emancipation.

It is his belief, that one of the most stupendous of the wrongs which the Negro has suffered, was in turning the whole army of slaves loose in a hostile country, without money, without friends, without experience in home getting or even self-support. Their two hundred and fifty years of unrequited labor counted for naught. They were free but penniless in the land which they had made rich.

But though they were robbed of the reward of their labor, though they have been denied their common rights, though they have been discriminated against in every walk of life and in favor of every breed of foreign anarchist and socialist, though they have been made to feel the measured hate of the poor white man’s venom, yet through it all they have been true; true to the country they owe (?) so little, true to the flag that denies them protection, true to the government that practically disowns them, true to their honor, fidelity and loyalty, the birthrights of superior blood.

H. C. BRUCE,

Washington, D. C.

{vi}

| PAGE. | |

| CHAPTER I | |

|---|---|

| Correct Date of Birth.—Reasons Ex-Slaves Cannot give their Ages.—Childhood Days in Slavery.—Emigration to Missouri in 1844.—Return to Virginia in 1847.—Life in the New Country.—Hunting, Fishing and Playing.—Treed by Wild Hogs.—Narrow Escape from Abolitionists at Cincinnati, Ohio, and Service as a Slave for Seventeen Years Thereafter as a Result | 11 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Happy Days Spent Till Thirteen Years Old.—The Old Millpond and the Trusted Old Slave Miller.—Slave Children Treated Tenderly and Kindly.—Overseer’s Brutality Checked by Old Mistress.—Whipped on Account of a Lie Told by a Poor White Man.—Status of Poor White Trash.—Fewer Liberties Than Slaves.—No Association or Intermarriage with the Ruling Class.—Hauled to the Polls and Forced to Vote as the Master Class Directed.—Poor Whites as Well as the Slaves Freed by the War.—Both Classes Equally Illiterate.—The Old Master Class and the Colored People Can Live in Peace, were it not for the Poor White Trash | 24 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Runaway Negroes.—Cause and Effect.—Some Dangerous to Capture.—Mean Masters and Good Ones.—The Good and the Mean Slave.—The Unruly and Fighting Class, Who Would not Submit.—Inferior and Superior Blood and How Divided.—The Typical Poor Whites Have Inferior Blood in Their Veins.—Superior Blood in Slave Veins.—How Superior Blooded Slaves Took in Their Situation and Spent Life in Their Master’s Service and are the Better Class of Colored Citizens To-day.—Blood Will Tell, Regardless of the Color of the Individual in Whose Veins it Flows | 32 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Visit to the Old Home, July, 1893.—Great Changes Since 1849.—Plantations Deserted.—Masters and Slaves Gone.—Land Returned Almost to Primeval Condition.—Few Old Inhabitants Found.—Old Major Still Active at Ninety-five Years.—That old Public Highway, that was the Pride of the Community.—Its {vii}Old Bed Cut in Gullies or Grown up in Forest.—What Railroads Have Done for that Country and the South | 43 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Extent to Which Education Has Stamped Out Belief in Superstition, Voodooism, Tricking and Conjuring Among Colored People.—More Dense the Ignorance the More Prosperous the Business of the Conjurer.—All Pains and Aches Due to Tricking.—Conjurers Boast of Their Ability to do the Impossible, and How They Were Feared.—A Live Scorpion Taken Out of a Man’s Leg.—A Noted Old Conjurer Places His “Jack” Under the Master’s Door Step, Which Prevents Him from Carrying His Slaves out of the Country.—Slaves in Missouri not Believers in Voodooism Much.—Indians Believe in Spirit Dance, Colored in Voodooism and the White People in Witchcraft | 52 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Carried to the Cotton Fields of Mississippi in 1849.—Cotton Picking Under a Mean Overseer and Method of Treatment.—Good Masters Even in That State.—Master Decides to Carry His Slaves Back to Missouri, Which Causes Great Rejoicing.—Handshaking When they Reached Brunswick, Mo.—Work in a Tobacco Factory.—Positive Refusal to go with Master to Texas in 1855.—His Anger, but Final Acquiescence.—Pleasant Life in Tobacco Factories Because Master did not whip his Slaves nor Allow it to be Done by Others.—White and Colored preachers.—Rev. Uncle Tom Ewing and his Objectionable Prayer.—Virtue and Marital Relations Encouraged by Masters Among Slaves.—High Toned Slaves.—Death by Suicide rather than Disgrace | 60 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Status of Free Negroes in Missouri Prior to the War.—Had but Little More Liberties than Slaves.—Guardians to Attend to their Business.—Could not Leave Home without a Pass.—Free Davy an Exception.—Respected and Treated like a Man by all who Knew Him.—Blood will Tell and he had Superior Blood.—Free Born People Considered Themselves Better than Those Freed by the War.—Bitter Feeling Between the two Classes ended Several Years after the War.—The War Freed Both Classes.—Rev. Jesse {viii}Mills and Rev. Moses White, Ex-Slaves and Failure to get Assignments.—Rev. W. A. Moore and J. W. Wilson, Ex-Slaves Occupying good Charges | 76 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Life on a Farm and Master hard to Please.—Slaves Raised their Own Crop which Master sold for Them.—Good Old Father Ashby Treated his Slaves Kindly while Rev. S. J. M. Beebe was the Meanest Master in the Neighborhood.—Chas. Cabell, Called Hard Master.—Personal Experience Shows he had a Lazy lot of Slaves.—Ill-treated beast of Burden and Ill-treated Slaves are much Alike.—Dan Kellogg as a Free Sailer Before the War and as a Rebel Bushwhacker During it | 82 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Campaign of 1860, more Exciting than the Hard Cider One of 1840.—Bob Toombs’ Declaration.—Split in the National Democratic Party at Charleston, S. C., April 23, 1860.—Cause and Results.—Lincoln Elected.—Missouri’s Vote for S. A. Douglass.—Higher Power than Man in Control.—All Classes Suffered by the War, but Neutrals Most.—Poor Illiterate Whites out as Patrols to Keep Slaves Quiet.—Fun with those Patrols who Could not Read Passes.—Lindsey Watts, and How He Fooled Them.—Who Set the Town on Fire?—No Judas Among Slaves.—They Believed the War was for their Freedom.—Best Blood Went South to Shoot and be Shot at While Cowards Remained as Bushwhackers.—James Long, the Original Lincoln Man.—His Misfortune a Blessing.—Slave Property a Dead Weight to Owners After 1862.—Business of Negro Traders at an End for Ever.—Master’s Slave his best Friend After All.—Master’s Property Stolen by White Thieves in Uncle Sam’s Uniform.—Young Master Returns after the War, Broken in Health, Cash and Disfranchised | 93 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Enlistment of Colored Troops at Brunswick, Mo., from 1863 to the Close of the War and how Assigned.—Master gave his Slaves free Passes to Induce them to Remain with Him and out of the Army.—Contract to Remain with Him One Year Broken, and the Cause.—Elopement with the Girl I Loved.—Exciting Chase Thirty Miles on Horseback, Armed with {ix}a Pair of Colt’s Navies.—Pursued by the Girl’s Master and His Friends.—Laclede Reached in Safety and Pursuers Fooled.—Full History of Flight, Escape, Marriage by Rev. John Turner of Leavenworth, Kansas.—Visit to Old Master in January, 1865.—Found him Dejected.—Farm Rifled by Thieves Dressed as Soldiers, but They Left Him the Land | 107 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| New Problem to Solve.—Self Sustenance and Economy.—All Bills to Pay and Furnish Necessaries.—Difference Between White Men in a Free State and Old Master Class in Dealing with Ex-Slaves.—Great Confidence in the Word of Old Master Class, Who Would Not Lie to Slaves.—Cheated by White Men in Kansas.—Has Old Master Class Degenerated?—Colored People set Free Without a Dollar or Next Meal and Told to “Root Hog or Die” by a Great Christian Nation.—Who Made this Country Tenable for the White Man and Whose Service Brought Millions of Dollars to it, which Benefited the North as well as the South?—Jealousy of Unskilled White Laborers caused Prejudice Against Colored People.—Poor White Trash and Foreign Laborers are the Colored People’s Enemies.—Irish Enmity and the Cause.—Similar past History Should have Made them Friends, Rather than Enemies.—Lynching not Done by Old Master Class.—Opening of the Eyes of the Old Master Class.—Is it Too Late? | 112 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| The Progress Made by the Colored People, Morally, from 1865 to 1894.—They are the Equals in Scholarship of any Other Class of Students.—There is no Such Thing as a Negro Race in This Country.—They are Colored Americans, Nothing More.—This is Their Home and They Are Here to Stay by the Will of God.—Old Flag is His.—He has Defended it in the Past and Will Defend it Again.—He Will Stand or Fall With the Loyalist.—How Colored Families Were Established.—Their Names.—They are the Equals of any Other Class With no More Cash.—Contented and Faithful Laborers.—They are Not Anarchists, But can be Relied Upon in Case of War.—Can Same be Said of Other Adopted Citizens?—The Negro Will Stand by the True Americans in all Cases.—Why Should Colored Loyalists Suffer {10}Injustice at the Hands of the American People?—Not Treated Fairly by the Press.—Injustice of Mine Owners and Manufacturers.—All the Colored People Ask of the Americans is Fair Play in the Race of Life, With its Other Adopted Citizens | 128 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| The Colored People are Charged with Being Imitators and it is Admitted.—Mistakes made by Following White People.—Advice Given in Good Faith.—The Hand Should be Trained With the Head.—Have we as Many Colored Artisans Now as we had at the Close of the War?—History of Tuskeegee Industrial Institute and its Founder.—How Managed.—Not a White Man in It.—$15,000, Donated to it by a Southern White Woman, Descendent of the Old Master Class.—Similar Institutions Springing up in the Southland | 137 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Need of Money and How to Get It.—Business Houses and How to Sustain Them.—Take the Jew for a Pattern.—We are Producers.—He Is Not, yet Accumulates Capital.—Our Preachers, Teachers and Leaders Should Lead us to be a United People.—Prejudice due to Condition, not Color.—We are Responsible for our Children’s Idle Condition.—Failure to Educate the Hand as Well as the Head.—White Men Have Used the Advantage we Gave them.—Duty of Our Ministers not Fulfilled.—We Cannot Always Rely Upon White Philanthropists, But Must Help Ourselves | 143 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Went Into Business in 1866, Which was Destroyed by Fire With Great Loss.—Reopened and Burnt Out Again, Losing Six Hundred Dollars.—Reopened and After Three Years Failed.—Went Into Politics and Beaten by Twenty-Five Votes by Ex Governor Glick, For the Kansas Legislature.—Pressed for Cash to Buy Bread.—Elected Doorkeeper State Senate in 1881.—Foreman on Construction Train, A. N. R. R.—Appointed to Position at Washington.—Promoted Three Times.—Personal Experience in Pension Office.—Different Commissioners Compared.—Gen. J. C. Black, the Ideal One.—Advice to New Appointees and What They May Expect.—Life in Washington as a Clerk.—Old Clerks are the Reliables and Cannot be Displaced | 155 |

My mother often told me that I was born, March 3rd, of the year that Martin Van Buren was elected President of the United States, and I have therefore always regarded March 3rd, 1836, as the date of my birth. Those who are familiar with the customs that obtained at the South in the days of slavery, will readily understand why so few of the ex-slaves can give the correct date of their birth, for, being uneducated, they were unable to keep records themselves, and their masters, having no special interest in the matter, saw no necessity for such records. So that the slave parents, in order to approximate the birth of a child, usually associated it with the occurrence of some important event, such, for instance, as “the year the stars fell,” (1833), the death of some prominent man, the marriage of one of the master’s children, or some notable historical event. Thus by recalling any one of these occurrences, the age of their own children was determined. Not being able to read and write, they were compelled to resort to the next best thing within reach, memory, the only diary in which the records of their marriages, births and deaths were registered, and which was also the means by which their mathematical problems were solved, their accounts kept, when they had any to keep.{12}

Of course there were thousands of such cases as E. M. Dillard’s, the one which I shall mention, but as his case will represent theirs, I will speak of his only. He was an intimate acquaintance of mine, a man born a slave, freed by the emancipation proclamation when over thirty years old, without even a knowledge of the alphabet, but he had a practical knowledge of men and business matters, which enabled him to acquire a comfortable living, a nice home, to educate his children and conduct a small business of his own. But the greatest wonder about this man was the exactness and correct business way in which he conducted it in buying and selling, and especially in casting up accounts, seemingly with care, accuracy, and rapidity as any educated man could have done. But it was the result of a good memory and a full share of brain.

The memories of slaves were simply wonderful. They were not unmindful, nor indifferent as to occurrences of interest transpiring around them, but as the principal medium through which we obtain information was entirely closed to them, of course their knowledge of matters and things must necessarily have been confined within a very narrow limit; but when anything of importance transpired within their knowledge, they knowing the date thereof, could, by reference to it as a basis, approximate the date of some other event in question. Then there were a great many old men among them that might be called sages, men who knew the number of days in each month, in each year, could{13} tell the exact date when Easter and Whit Sunday would come, because most masters gave Monday following each of these Sundays as a holiday to slaves.

These old sages determined dates by means of straight marks and notches, made on a long stick with a knife, and were quite accurate in arriving at correct dates. I have often seen the sticks upon which they kept their records, but failed to understand the system upon which they based their calculations, yet I found them eminently correct. It was too intricate for me.

My parents belonged to Lemuel Bruce, who died about the year 1836, leaving two children, William Bruce and Rebecca Bruce, who went to live with their aunt, Mrs. Prudence Perkinson; he also left two families of slaves, and they were divided between his two children; my mother’s family fell to Miss Rebecca, and the other family, the head of which was known as Bristo, was left to William B. Bruce. Then it was that family ties were broken, the slaves were all hired out, my mother to one man and my father to another. I was too young then to know anything about it, and have to rely entirely on what I have heard my mother and others older than myself say.

My personal recollections go back to the year 1841, when my mother was hired to a lady, Mrs. Ludy Waddel by name. Miss Rebecca Bruce married Mr. Pettis Perkinson, and soon after her slaves were taken to their new home, then known as the Rowlett Place, at which point we began a new life. It is but simple{14} justice to Mr. Perkinson to say, that though springing from a family known in that part of the country as hard task-masters, he was himself a kind and considerate man. His father had given him some ten or twelve slaves, among whom were two boys about my own age. As we were quite young, we were tenderly treated.

To state that slave children under thirteen years of age were tenderly treated probably requires further explanation. During the crop season in Virginia, slave men and women worked in the fields daily, and such females as had sucklings were allowed to come to them three times a day between sun rise and sun set, for the purpose of nursing their babes, who were left in the care of an old woman, who was assigned to the care of these children because she was too old or too feeble for field work. Such old women usually had to care for, and prepare the meals of all children under working age. They were furnished with plenty of good, wholesome food by the master, who took special care to see that it was properly cooked and served to them as often as they desired it.

On very large plantations there were many such old women, who spent the remainder of their lives caring for children of younger women. Masters took great pride in their gangs of young slaves, especially when they looked “fat and sassy,” and would often have them come to the great house yard to play, particularly when they had visitors. Freed from books and mental worry of all kinds, and having all the out{15}door exercise they wanted, the slave children had nothing to do but eat, play and grow, and physically speaking, attain to good size and height, which was the special wish and aim of their masters, because a tall, well-proportioned slave man or woman, in case of a sale, would always command the highest price paid. So then it is quite plain, that it was not only the master’s pride, but his financial interest as well, to have these children enjoy every comfort possible, which would aid in their physical make up, and to see to it that they were tenderly treated.

But Mr. Perkinson’s wife lived but a short time, dying in 1842. She left one child, William E. Perkinson, known in his later life as Judge W. E. Perkinson, of Brunswick, Missouri. Mr. Perkinson built a new house for himself, “The great house,” and quarters for his slaves on his own land, near what is now known as Green Bay, Prince Edward County, Virginia. But I don’t think that Mrs. Perkinson lived to occupy the new house. My mother was assigned to a cabin at the new place during the spring of 1842. But after the death of his young wife, Mr. Perkinson became greatly dissatisfied with his home and its surroundings, showing that all that was dear to him was gone, and that he longed for a change, and being persuaded by his brother-in-law, W. B. Bruce, who was preparing to go to the western country, as Missouri and Kentucky were then called, he decided to break up his Virginia home, and take his slaves to Missouri, in company with Mr. W. B. Bruce.{16}

The time to start was agreed upon, and those old enough to work were given a long holiday from January to April, 1844, when we left our old Virginia home, bound for Chariton County, Missouri. In this event there were no separations of husbands and wives, because of the fact that my father and Bristo were both dead, and they were the only married men in the Bruce family.

Among the slaves that were given to Mr. Perkinson by his father was only one married man, uncle Watt, as we called him, and he and his wife and children were carried along with the rest of us.

I shall never forget the great preparations made for our start to the West. There were three large wagons in the outfit, one for the whites and two for the slaves. The whites in the party were Messrs. Perkinson, Bruce, Samuel Wooten, and James Dorsell. The line of march was struck early in April, 1844. I remember that I was delighted with the beautiful sceneries, towns, rivers, people in their different styles of costumes, and so many strange things that I saw on that trip from our old home to Louisville. But the most wonderful experience to me was, when we took a steamer at Louisville for St. Louis. The idea of a house floating on the water was a new one to me, at least, and I doubt very much whether any of the white men of the party had ever seen a steamboat before.{17}

I am unable to recall the route, and the many sights, and incidents of that long trip of nearly fifteen hundred miles, and shall not attempt to describe it. But finally we reached our destination, which was the home of Jack Perkinson, brother of Mr. Pettis Perkinson, about June or July, 1844. His place was located about seven or eight miles from Keytesville, Missouri. At that time this country was sparsely settled; a farm house could be only seen in every eight or ten miles. I was greatly pleased with the country; for there was plenty of everything to live on, game, fish, wild fruits, and berries. The only drawback to our pleasure was Jack Perkinson, who was the meanest man I had ever seen. He had about thirty-five slaves on his large farm and could and did raise more noise, do more thrashing of men, women and children, than any other man in that county.

Our folks were soon hired out to work in the tobacco factories at Keytesville, except the old women, and such children as were too small to be put to work. I was left at this place with my mother and her younger children and was happy. I was too young to be put to work, and there being on the farm four or five boys about my age, spent my time with them hunting and fishing. There was a creek near by in which we caught plenty of fish. We made lines of hemp grown on the farm and hooks of bent pins. When we got a bite, up went the pole and quite often the fish, eight or ten feet in the air. We never waited for what is called a good bite, for if we did the fish would get the bait and escape capture, or get off when hooked if not thrown quickly upon the land. But fish then were very plentiful and not as scary as now. The hardest{18} job with us was digging bait. We often brought home as much as five pounds of fish in a day.

There was game in abundance, but our hunting was always for young rabbits and squirrels, and we hunted them with hounds brought with us from Virginia. I had never before seen so many squirrels. The trees there were usually small and too far apart for them to jump from tree to tree, and when we saw one “treed” by the dogs, one of us climbed up and forced it to jump, and when it did, in nine cases out of ten the dogs would catch it. We often got six or eight in a day’s hunting.

Another sport which we enjoyed was gathering the eggs of prairie chickens. On account of the danger of snake bites, we were somewhat restricted in the pursuit of this pleasure, being forbidden to go far away from the cabins. Their eggs were not quite as large as the domestic hen’s, but are of a very fine flavor.

North of Jack Perkinson’s farm was a great expanse of prairie four or five miles wide and probably twenty or thirty long—indeed it might have been fifty miles long. There were a great many snakes of various sizes and kinds, but the most dangerous and the one most dreaded was the rattlesnake, whose bite was almost certain death in those days, but for which now the doctors have found so many cures that we seldom hear of a death from that cause. When allowed to go or when we could steal away, which we very often did, we usually took a good sized basket and found eggs enough to fill it before returning. We saw a great many snakes, killing some and passing others by, especially the large ones. There were thousands of prairie chickens scattered over this plain, and eggs{19} were easily found. One thing was in our favor; these wild chickens never selected very tall grass for nests. But it almost makes me shudder now, when I think of it, and remember that we were barefooted at the time, with reptiles on every side, some of which would crawl away or into their holes while others would show fight. But none of us were bitten by them. On these prairies large herds of deer could be seen in almost any direction. I have seen as many as one hundred together. Jack Perkinson was not a hunter, kept no gun, and of course we had none, so we could not get any deer. There were a great many wolves around that place and I stood in mortal fear of them, but never had any encounter with one. They usually prowled about at night and kept the young slave men from going to balls or parties.

The most vicious wild animal I met or encountered was the hog. There were a great many of them around the farm, especially in the timber south of it. In that timber were some very large hickory nuts—the finest I ever saw. I remember one occasion when we were out gathering nuts, having our dogs with us. They went a short distance from us, but very soon we heard them barking and saw them running toward us followed by a drove of wild hogs in close proximity. We hardly had time to climb trees for safety. I was so closely pressed that an old boar caught my foot, pulling off the shoe, but I held on to the limb of the tree and climbed out of danger, although minus my shoe. One minute later and I would not have been here to pen these lines, for those hogs would have torn and eaten me in short order. From my safe position in the tree I looked down on those vicious wild animals{20} tearing up my shoe. We had escaped immediate death, but were greatly frightened because the hogs lay down under the trees and night was coming on. We had shouted for help but could not make ourselves heard. Every time our dogs came near, some big boar would chase them away and come back to the drove. We reasoned together, and came to the conclusion that if we would drive the dogs farther away the hogs would leave. Being up trees we could see our dogs for some distance away and we drove them back. After a while the hogs seemed to have forgotten us. A few large ones got up, commenced rooting and grunting, and soon the drove moved on. When they had gotten a hundred yards away we slid down, and then such a race for the fence and home. It was a close call. But we kept that little fun mum, for if Jack Perkinson had learned of his narrow escape from the loss of two or three Negro boys worth five or six hundred dollars each, he would have given us a severe whipping.

About January 1, 1845, my mother and her children, including myself and those younger, were hired to one James Means, a brickmaker, living near Huntsville, Randolph County, Missouri. I remember the day when he came after us with a two-horse team. He had several children, the eldest being a boy. Although Cyrus was a year older than I, he could not lick me. He and I had to feed the stock and haul trees to be cut into wood for fire, which his father had felled in the timber. Mr. Means also owned a girl about fourteen years old called Cat, and as soon as spring came he commenced work on the brick yard with Cat and me as offbearers. This, being my first real work, was fun{21} for a while, but soon became very hard and I got whipped nearly every day, not because I did not work, but because I could not stand it. Having to carry a double mold all day long in the hot sun I broke down. Finally Mr. Means made for my special benefit two single molds, and after that I received no more punishment from him.

Mr. Perkinson soon became disgusted with Missouri, and leaving his slaves in the care of W. B. Bruce to be hired out yearly, went back to Virginia. Some said it was a widow, Mrs. Wooten, who took him back, while others believed that it was because he could not stand the cursing and whipping of slaves carried on by his brother Jack whom he could not control. This man, Jack Perkinson, died about the year 1846, and left a wife and three children. Although he had borne the reputation of being the hardest master in that county, his wife was quite different. When she took charge of the estate, she hired out the slaves, most of them to the tobacco factory owners, and really received more money yearly for them than when they worked upon the farm. After her death the estate passed to her children and was managed by the eldest son, Pettis, who was very kind to his slaves until they became free by the Emancipation Proclamation. I am informed that the very best of friendship still exists between the whites and blacks of that family.

In January, 1846, with my older brothers I was hired to Judge Applegate, who conducted a tobacco factory at Keytesville, Missouri. I was then about ten years old, and although I had worked at Mr. Mean’s place, I had done no steady work, because I was allowed many liberties, but at Judge Applegate’s I was{22} kept busy every minute from sunrise to sunset, without being allowed to speak a word to anyone. I was too young then to be kept in such close confinement. It was so prison-like to be compelled to sit during the entire year under a large bench or table filled with tobacco, and tie lugs all day long except during the thirty minutes allowed for breakfast and the same time allowed for dinner. I often fell asleep. I could not keep awake even by putting tobacco into my eyes. I was punished by the overseer, a Mr. Blankenship, every time he caught me napping, which was quite often during the first few months. But I soon became used to that kind of work and got along very well the balance of that year.

Orders had been sent to W. B. Bruce by Mr. Perkinson to bring his slaves back to Virginia, and about March, 1847, he started with us contrary to our will. But what could we do? Nothing at all. We finally got started by steamboat from Brunswick to St. Louis, Missouri, and thence to Cincinnati, Ohio. Right here I must tell a little incident that happened, which explains why we were not landed at Cincinnati, but taken to the Kentucky side of the river, where we remained until the steamboat finished her business there and crossed over and took us on board again. Deck passage on the steamer had been secured for us by W. B. Bruce, and there were on the same deck some poor white people. Just before reaching Cincinnati, Ohio, some of these whites told my mother and other older ones, that when the boat landed at Cincinnati the abolitionists would come aboard and even against their will take them away. Of course our people did not know what the word abolitionist meant; they evidently{23} thought it meant some wild beast or Negro-trader, for they feared both and were greatly frightened—so much so that they went to W. B. Bruce and informed him of what they had been told. He was greatly excited and went to the captain of the boat. I am unable to state what passed between them, but my mother says he paid the captain a sum of money to have us landed on the Kentucky side of the river. At any rate I know we were put ashore opposite Cincinnati, and remained there until the streamer transacted its business at Cincinnati and then crossed over and picked us up. The story told us by the white deck passengers had a great deal of truth in it. I have since learned that a slave could not remain a slave one minute after touching the free soil of that state, and that its jurisdiction extended to low water mark of the Ohio River. Slaves in transit had been taken from steamers and given their freedom in just such cases as the one named above. A case of this kind had been taken upon appeal to the Supreme Court of the state of Ohio, and a decision handed down in favor of the freedom of the slave. The ignorance of these women caused me to work as a slave for seventeen years afterwards.{24}

Early in the spring of 1847, we reached the Perkinson farm in Virginia, where we found our master, whom we had not seen for nearly three years, and his son Willie, as he was then called, with hired slaves cultivating the old farm. My older brothers, James and Calvin, were at once hired to Mr. Hawkins, a brickmaker, at Farmville, Prince Edward County, Virginia.

In as much as it was not the custom in that state to put slaves at work in the field before they had reached thirteen years of age, I, being less, was allowed to eat, play and grow, and I think the happiest days of my boyhood were spent here. There were seven or eight boys about my age belonging to Mrs. Perkinson, living less than a mile distant on adjoining farms, who also enjoyed the same privileges, and there were four or five hounds which we could take out rabbit hunting when we wished to do so. It was grand sport to see five or six hounds in line on a trail and to hear the sweet music of these trained fox hounds. To us, at least, it was sweet music. We roamed over the neighboring lands hunting and often catching rabbits, which we brought home. During the fishing season we often went angling in the creeks that meandered through these lands to the millpond which furnished the water for the mill near by, which was run by Uncle Radford, an old trustworthy slave belonging to Mrs. Prudence Perkinson. He was the lone{25} miller, and ground wheat and corn for the entire neighborhood.

There were several orchards of very fine fruit on these farms. We were allowed to enjoy the apples, peaches, cherries and plums, to our heart’s content. Besides, there were large quantities of wild berries and nuts, especially chinquapins. When we had nothing else to do in the way of enjoyment we played the game of “shinney”—a game that gave great pleasure to us all. I was playmate and guardian for Willie Perkinson, and in addition to this I had a standing duty to perform, which was to drive up three cows every afternoon. At this time Willie was old enough to attend the school which was about two miles away, and I had to go with him in the forenoon and return for him in the afternoon. He usually went with me after the cows.

I had been taught the alphabet while in Missouri and could spell “baker,” “lady,” “shady,” and such words of two syllables, and Willie took great pride in teaching me his lessons of each day from his books, as I had none and my mother had no money to buy any for me. This continued for about a year before the boy’s aunt, Mrs. Prudence Perkinson, who had cared for Willie while we were in Missouri, found it out, and I assure you, dear reader, she raised a great row with our master about it. She insisted that it was a crime to teach a Negro to read, and that it would spoil him, but our owner seemed not to care anything about it and did nothing to stop it, for afterward I frequently had him correct my spelling. In after years I learned that he was glad that his Negroes{26} could read, especially the Bible, but he was opposed to their being taught writing.

But my good time ended when I was put to the plow in the Spring of 1848. The land was hilly and rocky. I, being of light weight, could not hold the plow steadily in the ground, however hard I tried. My master was my trainer and slapped my jaws several times for that which I could not prevent. I knew then as well as I know now, that this was unjust punishment. But after the breaking season and planting the crop of corn and tobacco was over, I was given a lighter single horse plow and enjoyed the change and the work. Compared with some of his neighbors, our master was not a hard man on his slaves, because we enjoyed many privileges that other slaves did not have. Some slave owners did not feed well, causing their slaves to steal chickens, hogs and sheep from them or from other owners. Bacon and bread with an occasional meal of beef was the feed through the entire year; but our master gave us all we could eat, together with such vegetables as were raised on the farm. My mother was the cook for the families, white and black, and of course I fared well as to food.

Willie Perkinson had become as one of us and regarded my mother as his mother. He played with the colored boys from the time he got home from school till bedtime, and again in the morning till time to go to school, and every Saturday and Sunday. Having learned to spell I kept it up, and took lessons from Willie as often as I could. My younger brother, B. K. Bruce (now Ex-Senator) had succeeded me as playmate and guardian of Willie, and being also anxious to learn, soon caught up with me, and by Willi{27}e’s aid went ahead of me and has held his place during all the years since.

Mrs. Prudence Perkinson and her son Lemuel, lived about one mile from our place, and they owned about fifty field hands, as they were called. They also had an overseer or negro-driver whose pay consisted of a certain percentage of the crop.

The larger the crop the larger his share would be, and having no money interest in the slaves he drove them night and day without mercy. This overseer was a mean and cruel man and would, if not checked by her, whip some one every day. Lemuel Perkinson, was a man who spent his time in pleasure seeking, such as fox-hunting, fishing, horse racing and other sports, and was away from home a great deal, so much so that he paid little attention to the management of the farm. It was left to the care of his mother and the overseer. Mrs. Sarah Perkinson, wife of Lemuel Perkinson, was a dear good woman and was beloved by all her slaves as long as I knew her, and I am informed that she is living now and is still beloved by her ex-slaves. Mrs. Prudence Perkinson would not allow her overseer to whip a grown slave without her consent, because I have known of cases where the overseer was about to whip a slave when he would break loose and run to his old mistress. If it was a bad case she would punish the slave by taking off her slipper and slapping his jaws with it. They were quite willing to take that rather than be punished by the overseer who would often have them take off the shirt to be whipped on their bare backs.

Mrs. Prudence Perkinson was a kind hearted woman, but when angry and under the excitement of{28} the moment would order a servant whipped, but before the overseer could carry it out would change her mind. I recall a case where her cook, Annica, had sauced her and refused to stop talking when told to do so. She sent for the overseer to come to the Great House to whip her (Annica). He came and called her out; she refused to obey. He then pulled her outside and struck her two licks with his whip, when her “old mistress” promptly stopped him and abused him, and drove him out of the Great House yard for his brutality. She went to Annica, spoke kindly to her and asked her if she was hurt.

I write of this as I saw it. I can recall only one or two instances where our master whipped a grown person, but when he had it to do or felt that it should be done, he did it well.

Our owner had one serious weakness which was very objectionable to us, and one in which he was the exception and not the rule of the master class. It was this: He would associate with “poor white trash,” would often invite them to dine with him, and the habit remained with him during his entire life.

There lived near our farm two poor white men, better known at the South as “poor white trash,” named John Flippen and Sam Hawkins. These men were too lazy to do steady work and made their living by doing chores for the rich and killing hawks and crows at so much a piece, for the owner of the land on which they were destroyed. These men would watch us and report to our master everything they saw us do that was a violation of rules. I recall one instance in which I was whipped on account of a lie told by Sam Hawkins. The facts in the case are as follows: I was{29} sent one Saturday afternoon to Major Price’s place after some garden seed and was cautioned not to ride the mare hard, and I did not therefore take her out of a walk or a very slow trot as it was not to my interest to do otherwise, for the distance was but two miles and if I came back before sundown I would have to go into the field to work again. I got back about sundown, but had met Sam Hawkins on the road as I went, and he was at our house when I returned. He was invited to supper, and while at the table told my master that I had the mare in a gallop when he met me. Coffee was very costly at that time, too high for the “poor white trash;” none but the rich could afford it, and the only chance these poor whites had to get a cup of coffee was when so invited. It was always a Godsend to them, not only the good meal, but the honor of dining with the “BIG BUGS.” Being illiterate their conversation could not exceed what they had seen and heard, and to please their masters, for such they were to these poor whites almost as much as to their slaves, they told everything they had seen the slaves do, and oftener more.

After supper that evening my master sent for me. When I came, he had a switch in his hand and proceeded to explain why he was going to whip me. I pleaded innocence and positively disputed the charge. At this he then became angry and whipped me. When he stopped he said it was not so much for the fast riding that he had punished me as it was for disputing a white man’s word. Fool that I was then, for I would not have received any more whipping at that time, but knowing that I was not guilty I said so again and he immediately flogged me again. When he stopped he{30} asked me in a loud tone of voice, “Will you have the impudence to dispute a white man’s word again?” My answer was “No sir.” That was the last whipping he ever gave me, and that on account of the lie told by a poor white man. But I lived not only to dispute the word of these poor whites in their presence, but in after years abused and threatened to punish them for trespassing upon his lands.

Other ex-slaves can relate many such cases as the Hawkins’ case and such instances, in my opinion, have been the cause of the intense hatred of slaves against the poor whites of the South, and I believe that from such troubles originates the term “poor white trash.” In many ways this unfortunate class of Southern people had but a few more privileges than the slaves. True, they were free, could go where they pleased without a “pass,” but they could not, with impunity, dispute the word of the rich in anything, and obeyed their masters as did the slaves. It has been stated by many writers, and I accept it as true, that the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Lincoln, not only freed the slaves, but the poor whites of the South as well, for they occupied a condition nearly approaching that of slavery.

They were nominally free, but that freedom was greatly restricted on account of the prejudice against them as a class. They were often employed by the ruling class to do small jobs of work and while so engaged were not allowed, even to eat with them at the same table, neither could they in any way associate or intermarry with the upper classes. Of course this unfortunate class of people had a vote, but it was always cast just as the master class directed, and not{31} as the voter desired, if he had a desire. I recall very clearly the fact, that at each County, State or National election the poor white people were hauled to the voting places in wagons belonging to the aristocratic class. They also furnished a prepared ballot for each man and woe unto that poor white man who failed to vote that ticket or come when sent for. Each one of the master class kept a strict lookout for every poor white man in his neighborhood and on election days sent his wagons and brought each one of these voters to the polls.

When the war of the Rebellion broke out this class of men constituted the rank and file of the Confederate army and rendered good service for their masters, who had only to speak a kind word to them when they would take the oath and obediently march to the front, officered by the aristocratic class. These poor people contributed their full share to the death roll of the Southern Army.

True to his low instinct, the poor white man is represented at the South as the enemy of the Colored people to-day, just as he was before the war, and is still as illiterate as he was then. He is not far enough up the scale to see the advantage of education, and will not send his children to school, nor allow the Colored child to go, if it is in his power to prevent it. It is this class who burn the school houses in the Southland to-day. The aristocracy and the Colored people of the South would get along splendidly, were it not for these poor whites, who are the leaders in all the disorders, lynchings and the like. The South will be the garden spot, the cradle of liberty, the haven of America, when the typical poor whites of that section shall have died off, removed, or become educated, and not till then.{32}

During the summer, in Virginia and other southern states, slaves when threatened or after punishment would escape to the woods or some other hiding place. They were then called runaways, or runaway Negroes, and when not caught would stay away from home until driven back by cold weather. Usually they would go to some other part of the state, where they were not so well known, and a few who had the moral courage would make their way to the North, and thus gain their freedom. But such cases were rare. Some, if captured and not wishing to go back to their masters, would neither give their correct name nor that of their owner; and in such cases, if the master had not seen the notice of sale posted by the officers of the county wherein they were captured, and which usually gave the runaway’s personal description, they were sold to the highest bidders, and their masters lost them and the county in which the capture was effected got the proceeds, less the expense of capture. A runaway often chose that course in order to get out of the hands of a hard master, thinking that he could not do worse in any event, while he might fall into the hands of a better master. Often they were bought by Negro traders for the cotton fields of the South.

The white children had great fear of runaway Negroes, so much so that their mothers would use the term “runaway nigger” to scare their babies or to quiet them. I was greatly afraid of them, too, because{33} I had heard so many horrible stories told of their brutality, but I have no personal recollections of any such case. I recall two instances where I had dealings with them. The first was as follows:—One of our cows had a calf two or three days old hid in the timber land, and I was sent to find it, and in doing so went into the woods where the underbrush was quite thick, and suddenly came upon a rough-looking, half-clad black man. I was too close or too much frightened to run from him and stood speechless. He spoke pleasantly, telling me where I could find the calf, and stated that if I told the white people about him he would come back and kill me. He had a piece of roasted pork and “ashcake,” and offered me some which I was afraid to refuse. Of course I did not inform on him.

The other occasion was when I was sent to the mill about three miles distant with an ox-team and two or three bags of corn and wheat. I did not get away from the mill until near sundown, and when near home, while passing through a body of timber land, a black man stepped out in front of my oxen and stopped them. He looked vicious but said nothing. He got into the cart and cut one bag in half, taking about one bushel of meal, jumped out and let me go without further trouble. I told my master about this but nothing was done, it being Saturday night, and the only man near by who kept Negro hounds was Thomas Rudd, who would not go Negro hunting on Sunday.

These runaways lived upon stolen pigs and sheep, and the hardest thing for them to get was salt and bread. It was really dangerous for any person to betray one of these fellows, for when caught and carried home to their masters, they were usually whipped.{34} But they would run away again, come back, lie in wait for their betrayer, and punish him severely. Those who hired slaves belonging to estates, which under the law had to be hired out every year, often suffered in this respect, for it sometimes happened that the slaves would run away in the spring and remain away until Christmas, when they would report to the guardian of the estate, ready to be hired out for another year, while the employer was compelled to pay for the last year’s service. I have known of several such cases.

I hope from what I have said about “runaways,” that my readers will not form the opinion that all slave men who imagined themselves treated harshly ran away, or that they were all too lazy to work in the hot weather and took to the woods, or that all masters were so brutal that their slaves were compelled to run away to save life. There were masters of different dispositions and temperaments. Many owners treated their slaves so humanely that they never ran away, although they were sometimes punished; others really felt grieved for it to be known, that one of their slaves had been compelled to run away; others allowed the overseer to treat their slaves with such brutality that they were forced to run away, and when they did, the condition of those remaining was bettered, because the master’s attention would be called to the fact, and he would limit the power of the overseer to punish at will; others never whipped grown slaves and would not allow any one else to do so. I recall an instance showing the viciousness of these runaway Negroes, which I think illustrates the point as to their hard character.

There was a slave named Bluford, belonging to a hemp raiser in Saline County, Missouri, who owned a{35} large plantation, and owned a large number of slaves, and who had a poor white man employed as overseer. This overseer got angry at Bluford for some offence or neglect, and attempted to flog him, but instead got flogged himself and reported to the master the treatment he had received. The master sent for Bluford, and without making inquiry to ascertain the facts, proceeded to punish the slave, who in turn flogged his master and then ran away. The Missouri River is a very wide, rapid and dangerous stream, and runs between Howard and Salem counties, only a few miles from his master’s plantation. By some means Bluford crossed it and hid himself in a wheat field on the other side of the river to wait till dark. He told me that he was hid in a corner of a fence, and the wheat being ripe was ready to be cut. Now what spirit lead the owner of the field to get over the fence right in that corner can never be known, but he did, and found Bluford, whom he grabbed in the collar, and refused to let go after being warned. Bluford was armed with a butcher’s knife, and with it he cut the man across the abdomen, severing it to the backbone, causing death in a very short time. Hunting parties were immediately organized, who searched the surrounding country in vain for the murderer. I think this occurred in July, 1855. I had been acquainted with Bluford previous to that time.

Some time during the spring of 1865, I met Bluford on the street in Leavenworth, Kansas, after he had been to Kansas City, Missouri, to meet some relative. He gave me the facts in the case, and told me that he followed Grand River to its head water, which was in Iowa, then made his way to Des Moines, where he re{36}mained until the war, when he enlisted and served to the close of the war.

Bluford could read quite well when I knew him in 1855, and had paid attention to the maps and rivers of the state of Missouri.

Then there were different kinds of slaves, the lazy fellow, who would not work at all, unless forced to do so, and required to be watched, the good man, who patiently submitted to everything, and trusted in the Lord to save his soul; and then there was the one who would not yield to punishment of any kind, but would fight until overcome by numbers, and in most cases be severely whipped; he would then go to the woods or swamps, and was hard to capture, being usually armed with an axe, corn knife, or some dangerous weapon, as fire arms at that time were not obtainable. Then there was the unruly slave, whom no master particularly wanted for several reasons; first, he would not submit to any kind of corporal punishment; second, it was hard to determine which was the master or which the slave; third, he worked when he pleased to do so; fourth, no one would buy him, not even the Negro trader, because he could not take possession of him without his consent, and of course he could not get that. He could only be taken dead, and was worth too much money alive to be killed in order to conquer him. Often masters gathered a gang of friends, surrounded such fellows, and punished them severely, and at other times the slave would arm himself with an axe, or something dangerous, and threaten death to any one coming within his reach. They could not afford to shoot him on account of the money in him, and of course they left him. This class of slaves were usually industrious, but{37} very impudent. There were thousands of that class, who spent their lives in their master’s service, doing his work undisturbed, because the master understood the slave.

I am reminded of a fight I once witnessed between a slave and his master. They were both recognized bullies. The master was a farmer, whose name I shall call Mr. W., who lived about three miles from Brunswick, Missouri. He had, by marriage I think, gained possession of a slave named Armstead. Soon after arriving at his new home his master and he had some words; his master ordered him to “shut up,” which he refused to do. The master struck him and he returned the blow. Then Mr. W. said, “Well, sir, if that is your game I am your man, and I tell you right now, if you lick me I’ll take it as my share, and that will end it, but if I lick you, then you are to stand and receive twenty lashes.”

They were out in an open field near the public road, where there was nothing to interfere. I was on a wagon in the road, about forty yards distant. Then commenced the prettiest fist and skull fight I ever witnessed, lasting, it seemed, a full half hour; both went down several times; they clinched once or twice, and had the field for a ring, and might have occupied more of it than they did, but they confined themselves to about one fourth of an acre. Of course Armstead had my sympathy throughout, because I wanted to see whether Mr. W. would keep his word. They were both bloody and also muddy, but grit to the backbone. Finally my man went down and could not come to time, and cried out, “Enough.” There was a creek near by, and they both went to it to wash. I left, but was informed that{38} the agreement was carried out, except that Mr. W. gave his whipped man but six light strokes over his vest. Could he have done less? But I have been informed that these men got along well afterwards without fighting, and lived together as master and slave until the war.

I believe in that old saying, that blood will tell. It is found to be true in animals by actual tests, and if we will push our investigations a little further, we will find it true as to human beings.

Of course I do not wish to be understood as teaching the doctrine, that blood is to be divided into white blood and black blood, but on the contrary, I wish to be understood as meaning that it should be divided into inferior and superior, regardless of the color of the individual in whose veins it flows.

The fact of the presence in the South, especially, of the large number of the typical poor whites, held, as it were, in a degree of slavery, is a contradiction of the assertion, that white blood alone is superior.

If this class had superior blood in their veins, (which I deny) is there a sane man who will believe that they would have remained in the South, generations after generations, filling menial positions, with no perceptible degree of advancement? I venture to say not. The truth is, that they had inferior blood; nothing more. To further explain what I mean relative to inferior and superior blood among slaves, I will state, that there were thousands of high-toned and high-spirited slaves, who had as much self-respect as their masters, and who were industrious, reliable and truthful, and could be depended upon by their masters in all cases.{39}

These slaves knew their own helpless condition. They also knew that they had no rights under the laws of the land, and that they were, by those same laws, the chattels of their masters, and that they owed them their services during their natural lives, and that the masters alone could make their lives pleasant or miserable. But having superior blood in their veins, they did not give up in abject servility, but held up their heads and proceeded to do the next best thing under the circumstances, which was, to so live and act as to win the confidence of their masters, which could only be done by faithful service and an upright life.

Such slaves as these were always the reliables, and the ones whom the master trusted and seldom had occasion to even scold for neglect of duty. They spent their lives in their master’s service, and reared up their children in the same service.

Such slaves were to be found wherever the institution of slavery existed, and when they were freed by the war, these traits which they had exhibited for generations to such good effect, were brought into greater activity, and have been largely instrumental in making the record of which we feel so proud to-day. This class of slaves not only looked after their own interests, but their master’s as well, even in his absence.

I recall a case in point. Some time during the fall of 1857, in company with a man belonging to Dr. Watts, who lived near Brunswick, Missouri, as we were passing his master’s farm, one Sunday night, we heard cattle in the corn field destroying green corn. These cattle had pushed down the fence. I said to the man: “Let us drive them out and put up the fence.{40}” His reply was, “It’s Massa’s corn and Massa’s cattle, and I don’t care how much they destroy; he won’t thank me for driving them out, and I will not do it.”

To the class of superior blooded slaves may be added the fighting fellows, or those who knew when they had discharged their duty, and by virtue of knowing this fact, would not submit to any kind of corporal punishment at the hand of their master, and especially his overseer.

Just as among the whites in the South there was an inferior blooded class, so among the slaves there was an inferior blooded class, one whose members were almost entirely devoid of all the manly traits of character, who were totally unreliable and were without self-respect enough to keep themselves clean.

They spent their lives much like beasts of burden. They took no interest in their master’s work or his property, and went no further than forced by the lash, and would not go without it.

They reared their children in the same way they had come up, with no perceptible change for the better. They had not the spirit nor the courage to resist punishment, and bore it submissively. From that class, I believe, springs the worthless, the shiftless, the dishonest and the immoral among us to-day, casting unmerited blame upon the honest, thrifty and intelligent colored people, who strive to live right in the sight of God and man.

Another view held by people who have given the matter some thought, is this: there were masters of quite different temperament and disposition. Some had no humane feelings, and regarded their slaves as brutes, and treated them as such, while there were{41} others, (a very large class) who were good men, and I might say, religious men, and who regarded slavery as wrong in principle, but as it was handed down to them, they took it, believing that they, by fair treatment, could improve the slave, morally at least, for it was generally believed, that if he was freed and returned to Africa, he would relapse into barbarism. This latter class of slave owners treated their slaves better by far, than the other class, and my belief and experience tend to show that they got better service from their slaves, and enjoyed more pleasure, being almost entirely freed from the disagreeable duty of inflicting corporal punishment. I have personal knowledge of cases where young slaves had violated important rules, and the master, instead of punishing them himself, would go to their parents, lay the case before them, and demand that they take action.

In cases where the master had confidence in his slaves, and they in turn had confidence in him, both got along agreeably.

So that the point I wish to make is, that with few exceptions, a good master made good slaves, intelligent, industrious and trustworthy, while on the other hand, a mean and cruel master made shiftless, careless, and indolent slaves, who, being used to the lash as a remedy for every offence, had no fears of it, and would not go without it. Some people assert that long-continued ill-treatment had taken all the spirit of manhood out of this class of slaves, and that it will take generations of schooling and contact with intelligent people to instill into them the spirit of manhood, self-respect, and correct ideas of morality.

Admitting this to be true, I believe it is as much{42} the duty of the American white people to extend the necessary aid to these unfortunate people, as it is the duty of the better class among us, (the colored people), to do this work of uplifting them.

![[Image of text decoration unavailable.]](images/bow.png)

I recently visited my old home in Prince Edward County, Virginia, after an absence of forty-four years, and was greatly surprised at the changes which had taken place during that period. I had much trouble to find farms which I had knowledge of, because I remembered them only by the names they were called by in 1849. The owners of them had died or moved away and others had acquired the lands, changing the names of them, while other farms had been deserted and allowed to grow up in forests, so that with a few exceptions the country for miles in every direction was an unbroken forest of young trees.

Among the many notable changes which have taken place in this part of the State since 1849, are two or three to which my attention was particularly directed. The first is the entire change in the method of travel and transportation of freight and produce between Richmond, the western portion of the State and the Southern States.

The entire absence of the large number of six-horse teams, in charge of a colored driver and a water boy, that used to pass up and down the public road, which ran in front of our old home, and which extended from Richmond to the Blue Ridge Mountains, was quite noticeable, because that was the principal method by which freight and produce were carried.

That system of travel and transportation has been superseded by railroads, and goods are now delivered{44} by the Richmond & Danville inside of three days after purchase, to any place on that railroad within two or three hundred miles. This railroad now runs parallel with the old public road from Richmond to the Blue Ridge Mountains and the South, and has entirely usurped the trade formerly monopolized by the old six-horse team system.

Very vividly do I recall the many six-horse teams which used to pass daily up and down that old road with their great loads of corn, wheat and tobacco, and return loaded with drygoods and groceries for the country merchants. I have seen as many as twenty of these teams pass our old home in one day. The teamsters, though slaves, were absolutely reliable and therefore, were intrusted with taking orders and produce from country storekeepers to the wholesale merchants in Richmond and on their return they would bring back the drygoods and groceries that had been ordered by the country dealers living along the road. Usually these wagoners went in squads of four or five and camped at the same camping grounds. The owners of these teams would come along about once a month paying and collecting bills.

These great wagons, covered with white canvas to protect the freight they bore, sometimes carrying from seven to ten thousand pounds and each drawn by six fine blooded horses, made to me at least, a grand and impressive picture, as the procession moved along the old road in front of our place. This picture was heightened by the picturesqueness of the colored driver in charge and his peculiar and characteristic dress. As he rode along on the saddle horse of the team he seemed conscious of the great responsibility resting upon his{45} shoulders, and to the simple-minded colored people along the road he was simply an uncrowned king. When the wagons stopped at the camping grounds, located at regular intervals along the road, the colored people of the neighborhood flocked around to get a glimpse of this great man.

Although the freight was very valuable sometimes and often carried great distances, robbing or molesting these trains was something unheard of. They were perfectly secure while on the move or in camp, even in the most sparsely settled districts, because there were no robbers or gangs of thieves organized in those days to plunder passing teams. It is quite doubtful whether the same would be true nowadays if a return to the old method of transportation was resorted to.

The country merchants in those days were contented and happy, I suppose, to be able to get their orders filled and goods delivered inside of from thirty to ninety days.

This great public highway, which was kept in such splendid condition in 1849 and prior thereto, and which had so many beautiful camping grounds where wood and water were convenient and not far apart, with little villages every ten or fifteen miles, where there were inns for travellers to rest and feed their horses has become a thing of the past along with that old system of travel and transportation. I have seen many men, called travelers in those days, pass over that old road going to, or from the South or West on horseback, with large saddlebags strapped behind them armed with a horse pistol, which was about twenty inches long and as large as an old flint musket. Usually they carried a pair of these pistols hanging down in{46} front of them, one on each side of the horse’s neck.

That was the usual way of travel in those days when persons wished to go a long distance, particularly to the West or South. Signs of this old road can yet be seen in places, but the road has been almost deserted, and has grown up in forest.

In front of our old place, and in fact from Miller’s Store, a little village with a post-office, to Scofields, a similar place, a distance of ten miles, that old road was nearly on a straight line, was broad and almost level, and was the pride of that community; but when I saw it in July, 1893, and attempted with a horse and buggy to pass over it for a distance of a few miles I found it impassable. From John Queensbury’s Public Inn and Camping ground to our old home, a distance of three miles the old road has been entirely obliterated.

This road was kept in such a fine condition up to 1849 that many tobacco raisers used to put rollers around one or two hogs heads of tobacco, weighing about a thousand pounds each, then attach a pair of shafts and with a single horse draw them to Richmond, a distance of sixty miles.

I readily recall many different kinds of travel and trade which once thrived on this public highway. Richmond at that date being a great pork market and the most convenient one for the pork raisers of West Virginia and the Eastern portion of Kentucky, and this old public highway being the most direct route for travel from the West to Richmond, these hog raisers, in order to reach a market for their hogs, were compelled to drive them on foot over the road a distance of over two hundred miles. I have seen as many as three hundred hogs in one drove pass our old home in one{47} day going towards Richmond. Usually these hog drivers brought along several wagon loads of corn to feed their hogs while en route. They could and did travel from ten to twelve miles a day, and from early fall to spring each year many thousand hogs were driven into Richmond over this public highway.

Besides supplying Richmond with pork, which in turn, furnished other places, especially in the South, these hog raisers sold hogs to planters on the road, who had failed to raise enough pork for home consumption. Pork was the principal meat diet at that time for both white and black, there being few sheep or beef cattle killed for table use, and then always for the table of the master classes.

To advise a farmer now living in West Virginia or Eastern Kentucky, who owns a hundred head of marketable hogs, to drive them two hundred miles to market, as his father had done, would be considered by him very foolish advice. But such was the only way of transportation of that kind of product prior to the year 1849, of which the writer has personal recollections.

These cases mentioned show clearly what railroads have done, not only for Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, but the whole country and especially the Southern portion of it.

Richmond was also the principal slave market and this public highway the most direct route to the Southern cotton fields, especially those of Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee, and Negro traders passed over it many times each year with gangs of slaves bought at the public auction block in Richmond. I have seen many gangs of slaves driven{48} over this old road. Usually, the slave men were handcuffed together with long chains between them extending the whole length of the gang, which contained as many as forty, sometimes, or twenty on each side of the chain marching in line. The women and small boys were allowed to walk unchained in the line while the children and the lame and those who were sick rode in wagons. The entire caravan would be under the charge of the owner and a guard of four or five poor white men armed each with a rawhide whip, with which to urge the gang along and to keep them in line or at least in the road.

It was not the custom, neither was it to the owner’s interest, to treat these slaves brutally, for, like mules brought up to be carried to a better market, or where larger prices prevailed, it was absolutely necessary that they should not show any signs of ill-treatment; and I cannot recall ever having seen the punishment of one of them. Of course these Negro traders could not allow grown men to march in line unchained, particularly those who did not want to go, because they might become unmanageable, run away, and escape capture, thus causing the loss of the price paid for them, or at least give considerable trouble. As a general rule, many of these slave men were sold in the first place on account of insubordination—had resisted their masters, or had beaten their overseers, and such slaves were considered by their owners dangerous fellows on the farm with others, especially young men who might follow such examples. Then again many slaves were sold because they had committed murder or some other crime not deserving the death penalty, and there were no penitentiaries for slaves.{49}

These and many other recollections of my early life crowded upon me as I looked upon the old familiar scenes. The absence of familiar faces was no less remarkable than the changes in lands and improvements, for I found only one man I had seen before. There were two others whom I knew in that vicinity and who had never left it, but I failed to find them at their homes. I visited the home of Mrs. Sarah Perkinson, widow of Lemuel Perkinson, mentioned in a previous chapter, but did not see her, as she had left a few days prior on a visit to relatives in North Carolina. I was really sorry I did not see her, for I could have obtained much valuable information from her, as she had remained in that community ever since the year 1849, and could have given me an interesting history of past events. She still owns the old Perkinson farm consisting of about two thousand acres. The old frame mansion which was built before 1841 was still there and in a fair state of preservation, and without any apparent change since I last saw it forty-four years ago. I found old man, Major Perkinson, one of Mrs. Perkinson’s former slaves, occupying the Great House and tilling the land. There were about fifty acres under cultivation; the balance had grown wild. The old Major who is now ninety years of age and quite active, remembered me very well and proceeded to treat me like a southern gentleman of the old school would have done. I next visited our old home which was one mile away. Here I found the great house, also a frame building, built in the summer of 1842, in a good state of preservation, and as I went through every room I am sure that there had been but little change in its structure. I also visited the spot where my{50} mother’s cabin stood, and then how forcibly those lines of the poet touched my mind, “Childhood days now pass before me, forms and scenes of long ago,” etc. The quarters for the colored people had disappeared here as well as those at Mrs. Perkinson’s place. This place is now owned by a Yankee lady in New York, and of the six hundred acres under fence when we left it in 1849, only four acres are now in use, the balance having grown up in forest.