The Project Gutenberg EBook of Red Ben, by Joseph Wharton Lippincott

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Red Ben

the fox of Oak Ridge

Author: Joseph Wharton Lippincott

Release Date: August 14, 2018 [EBook #57688]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RED BEN ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

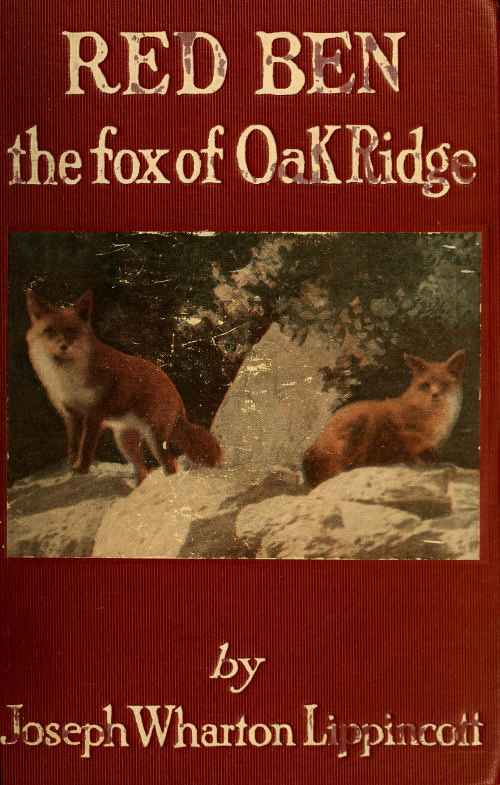

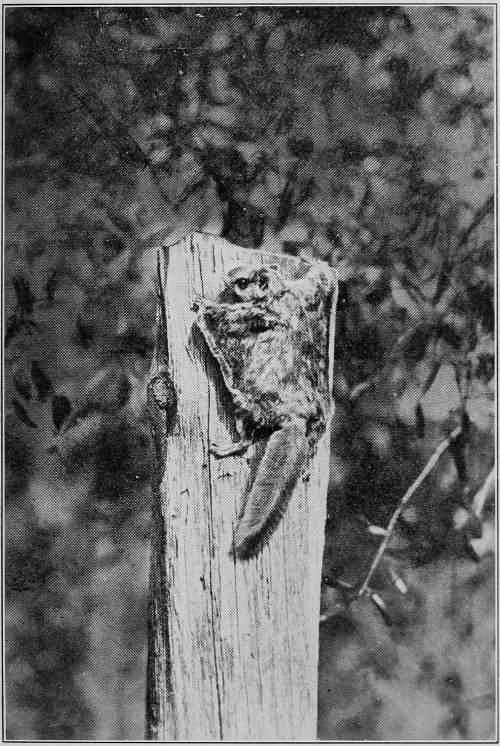

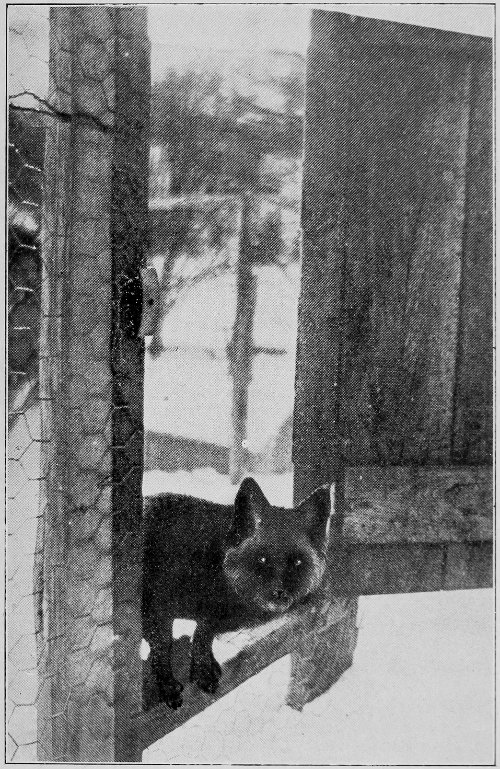

Courtesy Black Fox Magazine “Blackie instantly stopped”

by

Joseph Wharton Lippincott

Author of BUN—a wild rabbit

Illustrations by the author

THE PENN PUBLISHING

COMPANY PHILADELPHIA

1919

COPYRIGHT

1919 BY

THE PENN

PUBLISHING

COMPANY

RED BEN—THE FOX OF OAK RIDGE

To

a true lover of nature

—my father

There is reason for the fox being termed the shrewdest of wild creatures. Unlike the deer and other vegetarians whose dinners often grow under their noses, he rarely gets a meal without outwitting other animals. He lacks the climbing ability of the opossum, the sharp claws of the lynx, the protective odor of the skunk, the diving powers of the otter—he is indeed just a little wild dog, a wonderfully bright, hardworking little animal whose cunning alone can lead him from his enemies and keep away the pangs of hunger.

He has been so persistently hunted by man that he is almost untameable; but as far as he dares to be, he is friendly under ordinary circumstances and fond of wandering around man’s dwellings. Chicken stealing is charged against him; but after all he holds the same position in the animal world that the wise old crow does among the birds—his good deeds and his crimes nearly balance. In “Bun, a Wild Rabbit,” the fox appeared as one of many woods creatures encountered by that doughty cottontail; but, to do him justice, a separate volume was required.

Foxes are much more plentiful than generally supposed. It is almost safe to say that wherever there are woods there are foxes, yet so wonderfully clever are they that few are seen. Whoever can distinguish their tracks from those of other animals is usually not disposed to tell of the discovery of fox “sign.” The friend of the fox fears the fox’s enemy; the trapper fears a competitor; and so the wily creature weaves his trail endlessly about the country side, unwatched except by the very few “who know.”

Imagination must play a part in making the story of a wild animal complete, especially that of such an intensely shy and crafty creature as a fox; but nothing is included here which does not fall within the actual powers of the swift and wily red fox of today. Indeed there are numbers of them very much like Red Ben. Parts of his story are written in the snows of many woodlands besides Oak Ridge, and adventures such as his are still happening in the quiet of moonlit nights.

As fast as man thinks out new methods of destruction, the fox finds fresh tricks through which to escape. And may he ever escape! For when the edges of our old fields no longer bear the imprint of his tireless feet, when the woodlands that delighted his wild little heart have been usurped by the tame dog and the tame cat, then indeed will have departed half their charm, half the thrill of winter walks.

J. W. G.

Bethayres, Pa.

In the state of New Jersey there are still thousands of acres of low-lying woodlands, called pine barrens, where man has done little except chop down a few trees. Slowly but surely, however, the farmers are each year pushing their clearings deeper into this section, gradually overcoming the last barriers which Nature sets up to protect her own.

Ben Slown was one of these farmers. When the forest had been cut, he built a square house and a square barn. He planted straight-rowed orchards, he fenced in square, flat fields. He succeeded so well in stamping out all the natural loveliness that other practical farmers came there to start practical farms like his.

Soon there was a village; but Ben Slown’s square fields and the edge of the wild, interesting Pine Barrens were never separated, because no plow could conquer Oak Ridge and Cranberry Swamp.

The Ridge was a long mound covered with laurel, pines and white oaks. Cranberry Swamp, on the other hand, was low, wet ground which bore a nearly impenetrable mass of greenery, largely made up of tall cedars, holly bushes and cat briars. Through the swamp flowed a little creek in whose deep eddies green waterweeds swung with the current, giving glimpses now and then of turtles and slender, watchful pike.

When Ben Slown first planned to come to the Pine Barrens, his friends gloomily shook their heads.

“The foxes and other varmints will drive you out,” they warned. “You won’t be able to raise a chicken. The coons and crows will eat your corn. The woodchucks will destroy your vegetables. There are critters enough in the Barrens to keep you from being lonely, but they won’t be the kind of neighbors you want.”

“You just watch me,” boasted the farmer, “I’ll fix the varmints.”

He was no sooner settled in his new place than he began to put traps and poison around the cleared ground. All the little creatures that still lived there, and the others which came out of the woods at night to marvel at the strange new things to be seen—mice, snakes, birds, rabbits, mink, muskrats, woodchucks, coons, possums, skunks, foxes, deer and a lot of others—all suffered the same ill-treatment. But most of all he feared and hated the foxes, for they were clever enough to give him a little trouble. One after another was destroyed, however, and the farmer was having everything his own way when all at once there was a newcomer on the Ridge.

This was a red fox, a beautiful creature several inches taller than any of the gray foxes that lived in the Barrens. She found the farmer’s poisoned baits, but instead of taking them she took a chicken, and that right before his face.

This was the first fowl a fox had taken from Ben Slown, and therefore he complained all the more loudly; so loudly indeed that the neighbors began to think the destruction of the red fox the only thing that interested him. Instead of asking about his health, whoever met him would say, “Well, Ben, have you caught that pesky fox yet?” or perhaps, “Say, Ben, that old red fox of yours is bothering me now. Why don’t you keep her at home?”

Ben would mutter something, then pass on, his brows puckered from worrying over how to get rid of her. He might have worried far more had he known that in a burrow near the south end of Oak Ridge the red fox had four fine little fox pups.

Weeks went by, and still the fox and her tracks were seen occasionally, and still the farmer worried over that chicken he had lost. Then, one fine day, when the mice seemed scarce and the pups were very hungry, the fox dashed among the hens and took away another, this time a big white one.

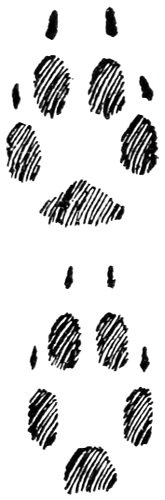

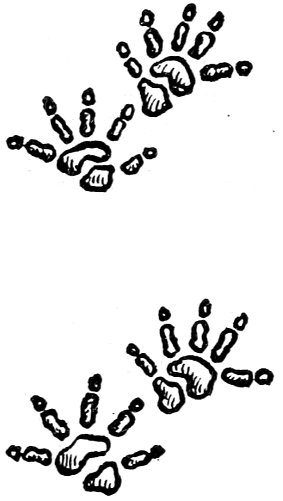

Fox Track.

The farm yard was in an uproar. Chickens cackled and rushed about, cows mooed, sheepdogs barked, and Ben Slown, snatching his rifle from the rack, shot twice at the fox before she reached the woods, two fields away.

He was too much excited to aim well; the bullets went wild and the fox went on. The farmer, however, would not believe he had made a clean miss. Out to the fields he ran to see if a tuft of fur could be found on the ground.

He was walking around and around, growing more and more angry because where the fox had been he found only the white feathers of his pet hen, when out from the woods burst a neighboring farmer.

“Ben,” this man called, “Ben, get your shovel, quick! I’ve just found the red fox’s den!”

When the fox was making her wild rush to the woods, with the white hen held high in her strong jaws, she was thinking more about the four hungry pups in the home burrow than about the fuss she had left behind in the farmyard. In the friendly shelter of the woods, however, she began to feel very uneasy about it all. Everything had certainly gone wrong.

She laid down the limp body of the hen and looked back. Through the laurel and the straight trunks of the pines she could see the flat stretch of the fields she had just left. Ben Slown’s hurrying figure was there, but too far back to worry her now. There were no dogs loose, nothing else moving except three crows that were circling to find out what had happened to arouse the farmer.

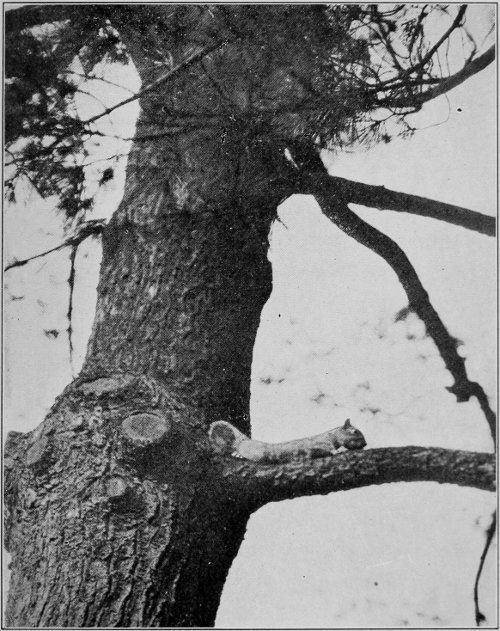

“A gray squirrel was watching her”

Ahead of her lay Oak Ridge and the Swamp. What breeze there was came from that direction, laden with the smell of sweet fern. Still she felt uneasy. Her quick ear caught the scratching of claws on bark—a red headed woodpecker was examining a dead oak; that was all right. So also was the barking of a gray squirrel which was watching her from the limb of a pine. But why were the blue jays calling so loudly on the Ridge? Perhaps some enemy was near the pups.

Quickly picking up the hen she galloped towards the Ridge in that wonderfully silent way known only to the wild things.

She did not know that, though her own graceful body fitted into the woods like an illusive shadow, the white hen stood out like a beacon light. She did not know that on the Ridge it caught the eye of a friend of Ben Slown and held it while she circled the den and then called out the puppies to the feast. Her mother love had indeed overcome natural caution.

The den was nothing more than the enlarged burrow of an old woodchuck, who, years before, had been driven from the fields below. To the four puppies, however, it was all that a home ought to be. Wonderful to these was its narrow passage with the half turn at the end and the snug bed so far from the dangers of the world outside; wonderful too its collection of feathers and pieces of fur which told of happy feasts; but best of all was the sandy, sun bathed entrance in which they had basked and played on never to be forgotten May mornings in their early puppyhood.

Their father had never come to Oak Ridge to help the mother in feeding and protecting them. To her tireless energy they owed everything. Therefore to her they looked for everything, and she had never disappointed them. Nor would she ever disappoint them as long as they needed her and there was breath in her faithful body, for such is mother love in the fox world!

Here Ben Slown’s pet white hen found her last resting place. Into the mouth of the den, among the waiting pups, she was dropped, feathers and all, and down their little throats she passed, piece-by-piece, amid growling and crunching and pulling and fighting, for in no other way did they know how to show their thorough enjoyment.

A glorious feast it was! And when they were through, the mother, who had all this time been on guard, picked up for her share the bones that were left. She was still nosing about among the feathers when a man’s cough, from somewhere below in the woods, gave sudden warning of danger. Down she crouched, motionless in a moment; and without need of further signal, into the den tumbled the frightened pups.

The mother waited, with ears pointed to catch the slightest new sound. In the burrow behind her appeared a small head with ears cocked in the same way. Both heard the crack of a breaking twig.

Now the old fox slipped into the bushes and cautiously circled until she caught the scent of Farmer Slown and his friend, and heard their clothes scraping through the bushes. Amid the laurel she caught a glimpse of them sneaking along as noiselessly as they knew how to, the farmer in the lead, holding his long gun. They certainly looked as if they meant mischief.

Between them and the den the anxious fox ran to lead them away. A dog would have followed her in a rush, but the men were so busy in “pussy-footing” that they did not see her pass.

“Now,” whispered Ben’s friend, “look for the den right above that bunch of bushes ahead. Careful!”

Ben looked. First he saw a lot of white feathers which made him growl to himself; then he made out the mouth of the burrow, and last of all the sharp nose and bright eyes of the inquisitive pup. Ben looked at the pup and the pup looked back at him; neither had ever seen the other before, but fate had already decreed that they should meet often in the days to come. And so they watched each other now, until a fluffy feather, a beautiful white one, was picked up by an eddy of wind and whirled around and around the little fox’s head.

That reminded Ben of his troubles. He threw his rifle to his shoulder, only to find that at his first movement the pup had vanished in the burrow.

“Shucks! You little varmint!” he muttered. “We’ll get you all right. Up with the shovel, John, and let’s see dirt fly. Remember though, when we get the pups, that sharp faced one must be mine. He thinks he’s smart.”

Friend John took off his coat and dug with a will, while Ben sat on the wheat sack they had brought along to put the pups in. Both became greatly excited at actually having the young red foxes in their power. After the friend had dug a long while he looked inquiringly at Ben.

“When are you going to do a little digging yourself, Ben?” he asked suspiciously. Ben saw that the end was nearly reached, so took up the shovel with a laugh. The bag he stuffed well into the burrow to stop it up and to keep any fox from dashing out.

Meanwhile the four pups were cowering against the wall of earth at the very end of their home. Three were in one corner and the inquisitive one in another, all listening to the shovel coming nearer and nearer. Every time it jarred on a stone, the shivers ran up and down their spines; but they could do nothing, the burrow had no outlet besides the one the men were in.

Ben had a very healthy fear of being bitten; therefore the sight of the first little fox unnerved him completely. He knew that all of them were lightning quick, like bombshells on four legs. But Ben was cunning. He quickly thought out an elaborate plan of capture.

First of all he threw several shovels of earth over them, and pushed it in solidly so that they were buried tight. After that they could not move until Ben’s big hand picked them out by the scruff of the neck, one at a time.

The first poor, scared little fellow glared and kicked, but was somehow stuffed into the empty wheat sack. Two more followed him in the same way. Then the exultant farmer felt all around in the earth for more, and found none. He dug a little and felt around again. His hand slipped along the flank of the last pup, the inquisitive one that had crawled into a far corner of the den.

Suspicious at once, Ben poked a little farther. Had the little fox growled or moved an inch, or even trembled, he would have been discovered. But the loose, cold earth was mixed with his fur and his body was as rigid as the side of the burrow. Ben’s fingers at last moved on and the danger was past.

“Have you really got them all?” the other man asked.

“Every one!” growled Ben, getting up and giving the bag a shake. “Fill up the hole a bit, John, so no old cow can break her leg in it.”

Some minutes later the men reached the fields with their precious bag. Here Ben passed it over for his friend to carry awhile, and the latter took his first peep inside.

“Why, there are only three here!” he exclaimed. “I saw at least four when the old vixen carried that hen of yours to the den. You’ve certainly left one. Good thing we buried him. Back we’ll have to go.”

Meanwhile, however, there was frantic work going on at the den. The mother, who during the digging had been anxiously running to and fro in cover of the bushes, crept cautiously to the ruined home as soon as the men had left. She found a great ugly hole, with fresh dirt on all sides, but no sign of the happy pups who used to welcome her.

Around and around the lonely creature wandered, hunting with all her mother’s love. At last she jumped into the partly filled hole and sniffed and dug a little and then sniffed some more and listened. Something there suggested to her to dig deeper. So she set to work in earnest, tearing up the loose dirt with her forepaws and pulling it back in a heap behind her.

Every little while she jumped out to look around, then whisked back to her work, until at last she heard the buried pup sniffing and burrowing in his prison. Now she dug as she had never dug before, spurred by noisy activity of the little fox, who knew perfectly well that his mother was trying to reach him.

Rip, rip, rip, went her claws through the last strip of earth, and out popped the head of the pup, only to be seized and pulled almost off his body in his mother’s haste to get him out. She had heard the men coming.

The heavy pup was almost more than the old fox could carry; but somehow she dragged him out of the hole and leaped for the bushes, pulling him along by the loose skin at the back of his neck. The sudden shouts from the surprised men only served to spur her on, not, as they hoped, to make her drop her burden.

She knew the farmer had a gun. Bang! She was not hurt! The bullet only tore up the ground behind her. Bang! Another shot whizzed past. And then her jaws slipped on the pup’s neck and she dropped him.

The little fox rolled over, caught his balance and began to run entirely on his own hook. His legs were a bit wabbly, he did not know just where to go, but how he did work to get away! Into the bushes he went and on to more bushes; and then, right before him, he found his mother loping along, a safe, loving guide. His little heart beat easier then, but on he went, ever following that beautiful furry tail with the pure white tip. On and on and on, the two ran into the heart of Cranberry Swamp and to safety.

The pup went to sleep beside his mother in a bed of leaves under a fallen tree. With her there, he did not feel cold nor miss the other pups so much. He wondered where they were and would not have been surprised had they joined him at any moment; but his mother knew they were gone forever. Her joy at having this one little fellow left to her was almost pitiful. All through the long night she cuddled and tenderly licked him.

Just as the sky began to brighten for the day, she slipped out to get a drink and something to eat. A little distance from the fallen tree was a path. Here she made her first stop, to examine the ground and find out what creatures had passed that way during the night. Moving slowly, with her keen nose to the earth, she suddenly became aware of something following her. Around she whirled with teeth bared for defense, only to find herself looking into the mild, half ashamed eyes of the pup who, too lonely to stay in the bed, had noiselessly crept after her.

He hung his head now and looked wistfully at his mother until she licked his nose to show she forgave him and would let him come with her. In this way he started on his first big hunt.

A rabbit had travelled the path shortly before them, so the mother moved with caution. Whenever she sniffed at the fresh tracks, the pup, who followed close at her heels, sniffed too and understood perfectly well that a rabbit was near. When she at last sighted Bunny and crouched, the pup copied her movement exactly, and when she leaped he sprang too, all atremble with excitement. The old rabbit jumped quickly enough to get away, but the pup saw him and enjoyed all the thrills of his first chase.

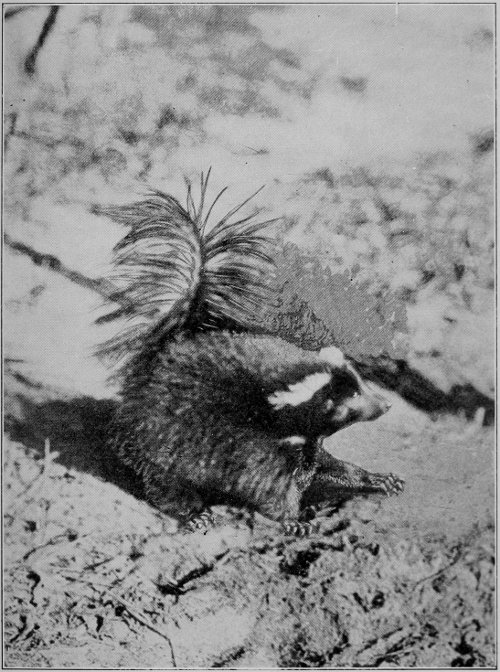

Farther on they met a black and white skunk ambling home to his den. The pup, seeing him far ahead, crouched in readiness for attack. Here was a beautiful creature, no larger than the rabbit, actually coming towards him as though it wanted to be caught for breakfast. It never occurred to him that the skunk was a privileged character in the woods, whom foxes as well as smaller and larger animals had learned to let pass with plenty of room between. The mother, however, knew all about skunks and saw that trouble was coming. She rushed at the pup, nipped his ear and fairly shouldered him out of the way of the other animal.

The skunk saw at once that all the disturbance was only over a young fox who had not sense enough to know that every path belonged to him. Therefore, he passed grandly, without even slackening his pace or changing his direction one inch.

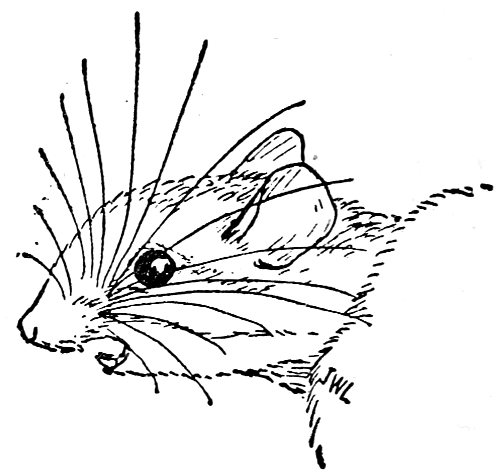

“He became indignant”

The pup, sniffing along the trail behind him, caught a disagreeable, musky smell which told, far better than his eyes could, that this animal was to be left alone. He followed him very carefully at what seemed a safe distance, until he became indignant and whirled half around with feathery tail straight in the air. That was warning enough to satisfy even the pup’s inquisitive mind, so he turned back with a bound and found his mother sitting in the path amusedly watching him. She saw that the little fox had already learned caution—the most important lesson of the woods.

A few yards farther they circled a marshy place where spring frogs were singing merrily; “peep, peep—peep,” they sang, over and over again. There seemed to be one piping from the bank, almost under the pup’s nose, but he could not find it, nor could he find any of the others, for they were in the water with only their small noses and eyes stuck out behind the blades of grass and twigs.

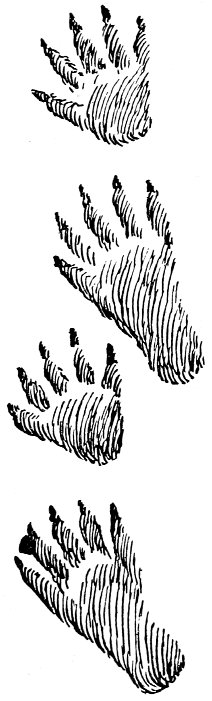

Coon Tracks

The old fox examined the mud for tracks, satisfied herself that those she found were made by a coon and not by man or dog, then turned to look for the pup. He was in the act of springing on something he had found in the grass. Up went his front paws, and then down he came right on top of a mouse which had been feeding on winter dried cranberries clinging to vines near the water. The pup had smelled it and found its hiding place all by himself. Now he tussled with the furry little creature until it had squeaked its last squeak.

The mother let him eat it all, then led away to Goose Creek. Here the incautious pup surprised a great blue heron in the act of catching a minnow. With a mighty flapping of big wings the scared bird started over the water, his long legs tucked up under his tail, his neck doubled back, so that it seemed only half its real length. When he got well away, his angry challenge—“u-r-g-h-h-, u-r-g-h, urgh, urgh”—could be heard all over Cranberry Swamp, warning his mate and all the other birds and animals, too, that there was danger lurking near.

A red squirrel ran out on a limb nearby to see what had disturbed the old fisherman. Two crows circled cautiously in that direction, a pair of wood ducks sprang from a pool below and winged their way up the creek towards a safer feeding ground; the frogs stopped peeping, and the lone kingfisher, sitting on a stub in the stream, enjoying the first rays of the morning sun, darted away with a rattling scream.

It was a wonderful lesson to the pup. It taught him that he must be careful not to disturb any creature that can spread alarm and excite the whole wood. It awoke in him the true fox nature which prompts the wisest of them to travel with all the noiseless stealth of a crafty Indian. He found out then what he saw more and more clearly the longer he lived, that there is a bond joining together the woods folk into one great family, for mutual protection.

He was the one feared, the outcast, this time; but at another time it might be a man with a gun, or a big hound, whom he would flee from, when warned, with the same dread as Blue Heron.

Now, he slunk back of some bushes and waited there while the noise and excitement died down.

Red Squirrel, however, kept his bright eyes on him, and fussed and scolded, without a stop. To him the branches were just like so many paths, over which he could run like the wind from one tree to another, until he reached the little hole in the hollow cedar he lived in, or dashed to another safe little hole under the roots of a magnolia, not far away. Therefore, when he was off the ground, why should he fear a fox, especially a young one like this? “Bur-r-r-r-r-r-r,” he fairly shouted as he danced and fumed first on one limb, then on one nearer, until so close overhead that the fox could see the four sharp teeth with which he gnawed nuts so easily.

There was something, however, which Red Squirrel had not thought about. With a young fox, or with any young animal, there is usually a mother. The annoying little nut eater had one glimpse of a red streak flinging itself at him from behind, then in a fright he lost his footing on the low limb, fell into the bushes, and had to run with all his might to get up the next tree without being punished. Very quiet after that, he let the foxes trot off unmolested.

The mother led the way towards the nest under the fallen tree, but was stopped in the old path by the sound of a man’s footsteps. Quickly she slipped into the bushes. The pup was not sure what to do. However, when he saw Farmer Ben’s friend, John, stalking down the path, he scrambled out of the way in a hurry.

“Well, if there isn’t Ben’s little sharp-nosed fox!” muttered the man in surprise. “Ben’s fox! Ha, ha. I should like to see Ben catch him now!” He saw how wonderfully the wild little animal melted away among the shadows, then he stalked off with many a shake of the head as he thought of his chickens at home.

Everyone he met after that had to be told the good joke about the den and Ben’s sharp-nosed fox, so the story spread, and “Ben’s fox” became for a time the special joy of all the village gossips, who liked Ben none too well. Those whom he had angered with sly bargains in the past, said that he himself was like a cunning fox—a black one; so it was a fox against a fox. “Black Ben against Red Ben,” someone of doubtful wit expressed it. This amused a number of the boys, and at once gave the little red fox a nickname. Through all his later career he was known as Red Ben.

When people good naturedly teased Ben Slown, who never could enjoy a joke on himself, he grew more and more surly. He soon saw that, until he caught the foxes, he would always be plagued, especially when someone lost a chicken. So he began to scheme and set more traps. He had always hated foxes, but never more bitterly than now.

With little suspicion of this, the mother was teaching Red Ben the tricks that every wise fox must know. Night after night they hunted mice together, or lay in wait for fat muskrats in the swamp, or chased big Bun or the other cottontail rabbits.

Often they played in the moonlight and wrestled and rolled by the hour in a sandy hillock near the Ridge. Both thoroughly enjoyed this. The usual game was a mock fight. The mother would rush at the pup and roll him head over heels, then hold him to the ground while he tried with all his might to break away. Sometimes she would pretend to bite a foot or a leg, or to tear an ear, he meanwhile striving to protect himself.

At first she was very careful not to hurt him, but as he grew stronger he also gained a wonderful quickness which often surprised the mother, whose own motions, although almost like lightning, were soon no match for his. Then the games became wildly exciting. The pup could escape the old fox’s rushes, and himself nip and worry and trip and get away, and then roll over and over with her, in a lightning battle to get the throat-hold which ended every game.

All this was splendid training for Red Ben. He could practice all kinds of fighting tricks and learn how to deal with an animal larger and stronger than himself. Had his little brothers lived to be his playmates, he might never have had this experience, which meant so much to him later on.

His cleverness and growing strength made him a wonderful companion for the old fox. She would go nowhere without him, and began to rely more and more on his help in their hunts.

It happened that wild strawberries were especially good that year, and so were eaten occasionally by the foxes, who picked up those the village children did not find. After them the cherries ripened, and the big mulberry tree at the corner of Ben Slown’s fence began to drop delicious fruit. Fat robins, starlings and black birds picked their share, but at night, especially after a rain heavy enough to knock down a good supply, the Oak Ridge animals fairly swarmed around the mulberry tree.

The shy red foxes usually reached it after the last sign of the sun had left the sky, so it was not strange that on one evening they found there ahead of them one of the deer from Cranberry Swamp with her two spotted fawns. The watchful doe scented them, gave one quick snort and led the fawns away in great bounds, for fear they were in danger. All three leaped over the field fence as if it had been a bush in the path.

The rush of the deer to cover frightened two rabbits just as the foxes came cautiously out of the wood. Away dashed Red Ben to head them off, but too late. When he returned, a huge coon hurried to the tree and began to swallow mulberries as fast as he could pick them up. The mother fox, however, took no notice of old Ring Tail, and he was too busy to worry over the foxes just then.

Up in the tree, Red Ben heard an occasional squeak, and soon spied a little brown squirrel which was quite the prettiest creature he had ever seen. While he watched, it suddenly sprang into the air with feet outstretched and sailed to a fence post near the wood; there it alighted almost as softly as a leaf, looking so much like a clinging piece of bark that the pup could hardly believe it was anything alive. This was Flying Squirrel, one of the very nicest of the woodsfolk.

While he was busy with the juicy mulberries the pup did not keep a very good watch behind him, and so was surprised suddenly to find White Stripe, the skunk, nosing around close by. He, too, liked the mulberries, it seemed. The fox kept one eye on him, but found he attended strictly to his own business.

A moment later a furry gray creature, nearly his own size, came stealthily along the fence. The pup was worried and ready to run at the slightest sign from his mother, but she kept right on nosing about, and old Possum joined the feeding. He, however, crawled up the big tree, where he wandered from limb to limb, picking off the ripest fruit and often by mistake knocking down some to the creatures below.

“Flying Squirrel, one of the very nicest of the woodsfolk”

It was a weird assemblage that the moon looked down upon that night. Two small coons came from the swamp with their mother for a hurried look around; White Stripe’s mate, a wonderful white skunk, also appeared, and a brown screech owl sat on a nearby pine limb to watch and whinny softly, so that his mate, who was looking for mice farther along the fence, might always know where to find him.

By this time Red Ben knew most of the wood creatures, and they knew him. Ringtail, Possum, White Stripe and Screech Owl were hunters; like himself they preferred meat to grass, fruit, roots and nuts. Although each had a scent entirely his own, each also had the “hunter” smell, quite different from the meadow mice, who lived on seeds and grass, or from Red Squirrel, who ate nuts, mushrooms and buds. Quite different too from the deer and from Bun, the big rabbit who lived near one of the farm gardens and enjoyed parsnips, string beans and other vegetables, whenever the clover was scarce.

The woodsfolk could be divided into two big families—the first one made up of those who hunt and the other of those who are hunted. The hunters get used to seeing each other and to running across each other’s trails at night. As long as there is food enough for all, they rarely quarrel; but jealousy and suspicion keep them from being real friends. Red Ben did not think of playing with the young coons; nor would young skunks have interested him at all as playmates.

The four-footed hunters all had teeth very much like those of a dog or a cat, while the little animals that they hunted had gnawing teeth, like those of the mouse. Even the woodchuck and the muskrat had gnawing teeth; they liked to eat grass and tender roots. Screech Owl and other hunters among the birds, from big Bald Eagle all the way down to little Sparrow Hawk, had hooked beaks and long sharp claws or talons, with which to catch their prey.

At first Red Ben saw no other foxes, and rarely came across the tracks of any, for Ben Slown’s traps did their work well. There was, however, one cunning old fellow who paid a visit to the Ridge whenever there was especially good hunting weather. With him, on one never to be forgotten night in late August, Red Ben had an adventure.

He and his mother had gone to Ben Slown’s fields to hunt the little short tailed meadow mice which were so plentiful there that their paths had been gnawed through the grass in every direction. They had caught two, and were once more entering Oak Ridge wood, when Red Ben noticed that his mother hesitated to go farther and kept anxiously looking into the shadows. He heard a deer snort; then, in the half darkness of the wood, he caught the glint of two eyes.

This new creature was certainly no coon or possum; the eyes were higher above the ground than either of these would hold its head. Quickly it moved into the moonlight and showed itself to be a fox, not unlike the mother in form, but gray in color, with reddish legs and a tail entirely lacking the beautiful roundness of the red fox’s.

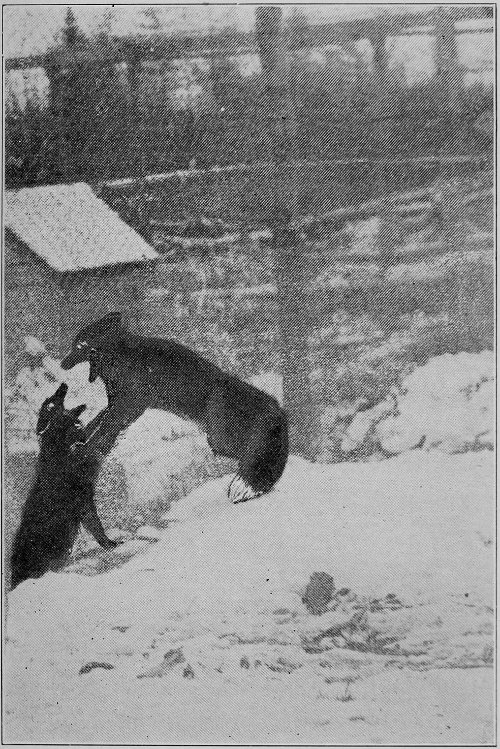

Instinctively the pup stood as straight and tall as he could, while along his back the hair fairly tingled with dislike. He saw his mother try to slip away, and then crouch suddenly with ears back and warning whine. He saw Gray Fox trot up, walk around her, and then bare his teeth in a snarl that sent off the soft-eyed mother in a hurry. How his heart pounded then, and how the fury welled up in his breast!

Gray Fox next turned in the direction of Red Ben, but stopped short when he found the young fox facing him without flinching. Stiff legged and disdainful he slowly walked forward, and got the surprise of his life as Red Ben flew at him like a fury, bit him on the side of the head, again on the foot when he reared up, and then on the tip of his precious nose. Back he staggered, snarling angrily, but scarcely knowing what to do.

Then Red Ben, remembering well the holds his mother had taught in their games, flew at his thick neck, caught the heavy, loose skin behind the ear and closed his sharp teeth until they nearly met.

Gray Fox’s red eyes glared back at him furiously, as he struggled this way and that, but he could not turn to bite while those jaws kept their hold. Fear grew until he was in a panic. What if the mother fox were to return now and fall on him from behind? He threw himself on the ground, then rolled over, clawing like a cat, and dragging Red Ben down with him so suddenly that all the breath was knocked out of him and his fine hold loosened.

This gave Gray Fox a wonderful chance. He was the first on his feet. He leaped for the throat hold.

Red Ben, still gasping, was pinned to the ground, almost throttled. The big, heavy enemy had all the advantage—it never had been an equal fight, and now Red Ben was down.

Oh, if his mother would only come! That wonderful, faithful, swift little mother who could be so very fierce when he was in danger. Somehow the very thought of her gave him courage. He made one mighty kick and at the same instant snapped at the fat ear of the beast above.

Luck was with him; he nipped its tender edge, and Gray Fox gave a scream. The jaws were loosened, and in that instant Red Ben’s lightning speed saved him. He rolled over, leaped to his feet and shot away. Dizzily he circled some bushes, with the other close behind; then something warned him to stop. Gray Fox had vanished.

“Gray Fox was waiting to trap him”

Had he not been a red fox, raised by one of the wisest of mothers, Red Ben would probably have made a fatal mistake, for, well hidden behind the bushes, Gray Fox was waiting to trap him when he came around. The thing was planned so well that had Red Ben kept on, he would almost have walked into the other’s mouth.

Just in time he guessed the trick and crouched to look all around. He was out of breath; he could hardly stop his panting to listen. His neck ached and strained muscles quivered, but what mattered that, when he was free and able to match wits against wits?

Often his mother had hidden this way to catch him in their games. He remembered now that she had always lain in wait somewhere ahead, therefore Gray Fox would do the same—the safest road was that by which he had come.

Dodging bushes and shadowy places he started back. There was no sound, no movement anywhere ahead; the noise and fury of the fight had scared away the other wild things and even quieted the night singing insects. Red Ben himself felt the awe of it all. He moved without stirring a leaf, at first in a cautious trot, then a gallop and at last a full run. Faster, faster—until on the hard woods path he let out every ounce of speed he had. It was the wonderful speed of the red fox, no longer just a cub.

Red Ben

Gray Fox was left far behind: and to prevent his following the trail, Red Ben made circles in the dense swamp, circles that went around and around with apparently no end, for he leaped far to one side before shooting away to his old haunt by the fallen tree.

Here he crouched, waiting for whatever might happen next. Had Gray Fox been able to follow him, Red Ben would have fought to the death. He was on home ground here; he would run no more. His spirit had not been broken; far from it! From the bottom of his heart he despised the big gray bully. He hated the strong smell of him still lingering in his nostrils. But he knew Gray Fox was the stronger.

When, after hours of searching, his mother at last found him, the fierce glitter was still in his eyes. He was crouching in the same spot, watching with all the intense excitement of the young creature which, for the first time, is forced to take care of itself in a big world.

Anxiously sniffing his head and neck, the old fox quickly learned through the scent much of the story of the fight. She found the cuts about the throat and licked them free from poison. She also licked off the dirt that still clung to his soft fur, looked him all over for other scars, and then mothered him until his high strung nerves were soothed and he limped stiffly after her for a sleep under the fallen tree.

While he curled up in a round ball, with head buried between his fluffy tail and the even softer fur of his flank, the mother kept watch. She too was curled up in a tight, comfortable little ball, but she kept her chin resting on her fluffy tail so that her nose and eyes as well as both ears could be on guard.

The moon had gone down, and around them now were the blackness and the stillness of that weird part of the night which comes just before the light of day. Night prowlers, large and small, were resting, waiting for the Sun’s signal which would drive them to their beds. Day loving creatures felt the coming of the dawn, but dared not stir yet. The red fox’s eyes drowsily closed, then opened with a snap: from far away floated the clear baying of a hound.

Well the mother knew what that baying meant. Months before she had left her own hills beyond the big river, to escape the keen scented hounds and to raise her family here in the Pine Barrens, unmolested by them. Had one at last traced her? Was he on her trail now, following her footprints unerringly to the fallen tree?

She looked at the sleeping pup. He certainly could not take care of himself in a long chase. If the hound found where they were, she would have to run for both of them. But she must wait until there was no doubt that he was on her trail and not following Gray Fox or some other woods creature.

For an hour she lay there, while the musical notes of the hound rang out in the breezeless morning air. He was working out a difficult trail, the one left by Red Ben in his night escape. How well those circles had been made! But circles could only delay, not stop a trailer like this hound. The oftener he found himself going around in aimless rings, the more determined he grew, until at last he was working along the swamp dangerously near the foxes.

Red Ben was wide awake, but understood that he was to hide there while his mother took care of the dog. He had never seen a hound, so was full of curiosity. Just as he had once watched Ben Slown from the mouth of the burrow, he now peeped between the limbs of the old tree to see the lanky black and white creature with the flapping ears come roaring up the trail.

Behind the hound came Farmer Slown’s woolly dog Shep and a white fox terrier. Their noses were not keen enough for trailing, so they encouraged the hound to do the work while they enjoyed the fun of it. Red Ben had seen them before; they usually accompanied the farmer in his walks.

Instinctively he knew then that Farmer Slown was somehow connected with the hound and this hunt. He was instantly more than ever on the alert; undoubtedly the farmer was somewhere near.

Through the bushes came the clumsy dogs, with a great crashing of dry twigs, quite different from Red Ben’s silent way of moving. He could see the excited glare of their eyes, the red tongues and white teeth. The hound, a huge creature, seemed to guess the fallen tree was a “foxy” place: nose in air, he turned to it, full of suspicion. The other dogs followed expectantly.

Red Ben’s heart beat against his ribs. Should he run? Did they see him? Something inside him seemed to warn, “wait, wait, don’t move!”

And then a wild cry of joy came from the little fox terrier. He had seen the mother. She had deliberately run past him to draw attention from the pup, but he did not have sense enough to guess that. With another yell he bounded after her, and after him came Shep. The hound alone stood there doubtfully, but he could not bear to be left alone. With a mighty bellow from his deep lungs he too rushed after the old fox, and went crashing towards Oak Ridge on the fresh trail.

Again Red Ben had escaped. He heard the hound go farther and farther into the Barrens; fainter came the baying, always fainter until it died away entirely.

The swamp once more breathed freely and naturally. Blue jays called, flickers whinnied, two of Red Squirrel’s cousins came out of their hole under a cedar root, Gray Squirrel was calling out, “Fee-we-e-e-e-k, kek, kek, kek, fee-wee-e-e-e-k”—everywhere within sight things seemed peaceful and happy.

Yet, somewhere in the Pine Barrens, Red Ben knew his mother was running on and on, with death on her trail. One slim red fox against three dogs. Would she ever come back?

Red Ben’s Mother

Red Ben crept from under the tree and looked all around. The red squirrels scolded at him, but he did not notice them; he had made up his mind to follow his mother. Full of trouble and scarcely knowing where to go, he at last wandered to Oak Ridge. Through its leafy tangles he trotted, in the direction he had last heard the hound. A branch of the old woods path ran here, and with the instinct of the fox to take always the best road, he followed it.

Suddenly, however, something unfamiliar appeared ahead and caused him to stop as if frozen. It did not move, he could not make out what it was, but he knew that never before had it been there when he followed this path.

Cautiously he slipped into the woods and circled until he caught the scent on the faint breeze. One sniff was enough. It was Farmer Slown!

Away ran Red Ben, not knowing, however, how narrow had been his escape. Ben Slown, gun in hand, was sitting there watching the trail. At that moment he was looking in the other direction, whence he expected the mother to run ahead of the hound.

Red Ben knew now the danger of moving about in daytime. At night man is asleep or else blundering about blinded by the dark. His traps and his poisoned baits may do harm then, but he himself is made harmless. There is not a creature of the wild that does not learn this.

To Red Ben the world seemed full of enemies. He dared not go farther, nor wander back; so he crouched in the laurel bushes and waited. And then he heard, far away, the baying of the hound. Nearer it came. It thrilled the young fox: he knew his mother was not far off.

Nervously Red Ben wandered out of the laurel and up the Ridge. Something seemed to lead him in that direction. Ahead rang the clear notes of the eager hound and another sound, the sharp yelp of Shep; the fox terrier had dropped far behind. Then Red Ben caught a glimpse of a brilliantly red body weaving its way among the laurel clumps, his mother, at last!

Down the Ridge he loped to meet her, into her path, directly before her. Joyfully he sprang to lick her lips in greeting.

She stopped, but only for an instant. Her mouth was open, the hot breath came in quick pants, and her beautiful tail dragged the ground.

Had something gone wrong? Red Ben had only to listen to the coming hound to know. In her own hilly country beyond the river, the mother could have dodged the dogs and lost them among the rocks, but on this luckless morning in the flat Barrens, when there was no wind, and when the damp ground held the scent no matter how she broke and twisted the trail, they could not be shaken off.

She loped bravely on, with Red Ben close behind. On the Ridge, every part of which she knew so well, it might be possible to fool the hound before her strength gave way. She went to the top, then tried the trick of making two circles and running back on her trail until there was a good chance to leap far to one side. If the dogs did not see her, nor find where the trail began again after her great leap, she would be safe. Up to this time Red Ben had stayed with her, listening, watching, scheming as he ran. Now he deliberately went in the other direction, leaving the double track just in time to miss being seen. Up the Ridge behind him rushed the dogs in full cry. But suddenly there was quiet; they were trying to unravel the trail at the place where the foxes doubled back.

When next Red Ben heard them they were strangely near. He ran to the other side of the Ridge, but heard them still—they were following him! No longer was the mother between. It was Red Ben now who had to show his cunning.

Down to Cranberry Swamp he ran and through it to a log he knew about, which lay across Goose Creek. Beyond this was more swamp and then another long stretch of the Pine Barrens.

Red Ben, hot, mud splashed and winded, was loping through the Barrens, clambering under fallen trees, running along the tops of logs and doing everything else he could think of to make the trail hard to follow, when all at once an animal sprang up from its bed almost under his nose.

Red Ben whirled back as he recognized the furious snarl of Gray Fox! The hound and Shep could be no worse than this enemy. What ill luck had brought him here? He ran the way he had come, dodging under the fallen trees as before, until close ahead he heard the dogs, coming surely and fast. Then with a mighty leap to one side, such as his mother had made, he left a gap in the trail and ran in a new direction. The hound lost his trail, found the fresh one of Gray Fox, and after a moment’s hesitation followed it straight away into the Pine Barrens. Red Ben was saved!

Now he could rest and enjoy the music of the chase and wonder how Gray Fox liked it all; but soon he started back to find his mother. Fear was gone. He had done big things.

Night found Red Ben still alone. The old fox had not come to the bed under the fallen tree in Cranberry Swamp, so all alone he curled up and slept. Towards morning he crawled stiffly out and wandered over to the Ridge. It was strangely quiet and deserted there too. Red Ben stood beside a great oak and called. It was just a short, lonely cry, but had the mother heard it she would have answered and come bounding to find him.

For a long time he waited there, hopefully. Then he called again and waited, and still again; but that time there was such a lonely wail in the cry that Jim Crow and his mate came flying over, to find out what was going on. They saw Red Ben crouching miserably against the butt of the old oak, and at once set up a great cawing.

If there is anything unusual happening in the woods, a crow will call together all the other crows within hearing, to look into the matter. That is why every crow knows so much; what one finds, all are given a chance to see.

Red Ben, sick at heart and more lonely than ever, slipped into the bushes and hid. This was the best thing he could have done, for when the flock of crows could no longer see him, they feared he might be playing some trick on them. Up they flew with more cawing and scolding; but there was no fun in scolding an animal that could not be seen, so one after another drifted away and left him.

He called no more, but wandered about the Ridge where he had last seen his mother. In this way he came to the place in which Ben Slown had crouched with his gun the day before. He examined the spilled tobacco and tracks in the path, then sniffed them all over again. Impossible as it seemed for his mother’s and Ben Slown’s tracks to be found together, he had nevertheless caught a trace of her scent here.

He did not know that while he led the hound into the Barrens beyond the Swamp, the tired mother had started after him along the path where crouched the waiting, sinister figure of the farmer. He only knew that she had gone, leaving him—the fatherless, brotherless, playmateless little fox pup of Oak Ridge—alone.

The moon was shedding its silvery light in checkerboard patches under the high oaks on the Ridge. In the fields below hung a heavy mist, and everywhere was the glitter of wet leaves, for a thunder storm had only recently passed.

All the woodsfolk were out playing or feeding, while the insects drummed and sang their loudest, since the moisture had refreshed the whole woods world.

Under one of the oaks sat Red Ben. This new feel of the air and ground, after many hot, dry days and nights, had awakened in him too a longing to play or rather, perhaps, a longing to have someone to play with. Three miserable, lonely days had passed since he lost his mother, three nights of watching and waiting and hoping for her return.

Now he could find nothing better to do than watch the other creatures enjoying themselves in the moonlight. Already a few acorns were sweet enough to be eaten by the little animals that gnaw, and already the hunters, knowing this, were wandering from tree to tree searching for any little nut eater that was unwary enough to be caught.

So still was Red Ben that the others scarcely noticed him. One tiny shrew mouse after another went skipping by, in their search for insects; sometimes one would burrow swiftly under the leaves and come out at quite another spot. Restless little creatures they were, with long noses and eyes so small they could scarcely be seen.

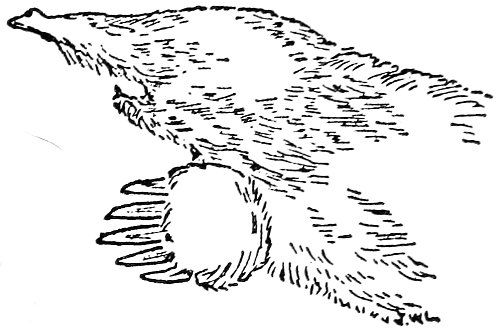

The Mole

If they had flat front feet like those of the mole, and were not the tiniest little furry creatures in the woods, they would often be taken for moles. Their fur is almost the same.

The mole, living entirely in his narrow burrows under the ground, has no need for eyes and so has lost the use of those nature first gave him; the shrew, living partly above the ground but mostly in burrows, needs to see a little, and so has very small eyes; the active deer mouse which scorns burrowing and usually lives in hollow trees like the squirrels, needs sharp eyes and so has immense ones.

To protect his big eyes from twigs and briars in the dark, Deer Mouse has a regular fence of whiskers, while Shrew’s little eyes only need a few small whiskers and old Mole needs no whiskers at all.

Deer Mouse

Shrew

In his habit of running around in the woods at night, Red Ben was very much like Deer Mouse, and so had many long whiskers. Some stuck up from each side of his nose and curved over the eyes; some, and these were really eyebrows, started above his eyes and curved down.

Therefore, on the darkest night, Red Ben could safely wander through the woods. Before a hidden briar could touch either eye, it would hit one of the hairs and give warning in time for the fox to shut his eyes quickly and also duck his head. The long whiskers were often very useful to him.

The shrews interested Red Ben, but because they had the hunter smell, he did not try to catch them. They were so small that worms and beetles were their chief prey.

On the damp ground the woods creatures could jump about without a rustle. That is what they like to do. The mice wait at the entrance of their homes until the way seems safe, then dash to the nearest bush and hide. If they see no owl or other hunter they make a dash to the next bush and so on until they safely reach the feeding ground. A rustle would catch the attention of any waiting owl and bring him swooping down.

Red Ben saw deer mice watching inquisitively from the edges of laurel clumps, also little burrowing pine mice whose sharp eyes fairly twinkled in the moonlight. He saw Brown Weasel chase a nimble deer mouse up an oak, and then he saw Flying Squirrel and his family having a rollicking game of tag around the largest limbs. Fat toads sat about, lazily watching for beetles. The pleasant rain had been taken in through the pores of their skin instead of through their mouths, but they had had enough to satisfy them.

On all sides there were little things moving, even from up in the air and down in the ground came squeaks of various kinds. Everyone seemed to have a play fellow—except Red Ben.

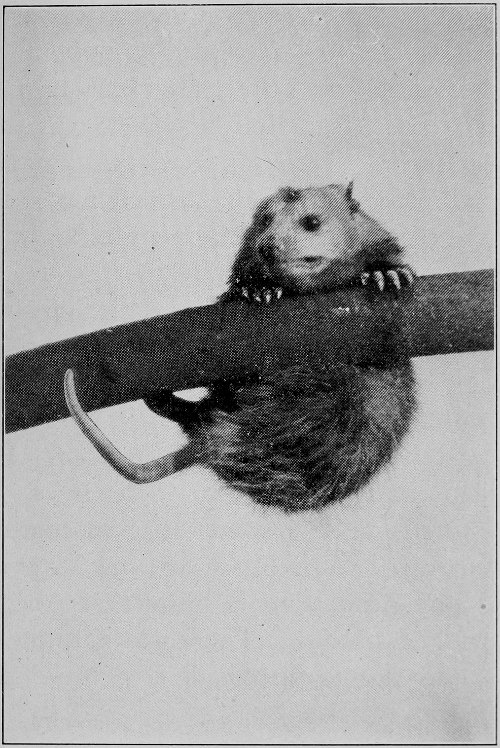

At last, however, a little possum came ambling through the wood all alone. Red Ben watched him sniff about and climb among some fallen branches. When the gray creature, with little bright eyes, caught sight of the interested fox, he crouched on one of the limbs and gazed back just as interestedly.

Red Ben’s playfulness surged over him; he pranced forward, reared on his hind legs and waved his front paws enticingly in front of the little possum’s nose. But Possum fell over backwards, terror in his eyes. Once on the ground he scurried for a tree, and climbed up in a panic. Red Ben, however, was just as quick. Thinking it was all a game, he chased after him, leaped high into the air and caught the scaly tail just as it was getting out of reach.

Down plumped the little possum, with wide open, hissing mouth. But instead of running, he lay where he had fallen.

Red Ben was greatly surprised. He had meant no harm. Carefully he sniffed and pawed the motionless creature. Yes, his playfellow was certainly dead. For a minute or two he walked around. There was nothing he could do, so he decided to leave the place.

“Possum fell over backwards”

Just as he reached the next tree, however, he heard a scraping noise and whirled around in time to see the apparently dead possum go up the oak’s trunk even faster than the first time. Sticking his sharp little toe nails into the crevices of the rough bark, he could get a good hold where Red Ben’s toes, which were formed for running, could not have gripped at all. When nearly at the top of the tree, he stopped to look down at Red Ben, grinning. The fox had at first fooled the little possum, but now the little fellow had done some fooling himself.

Red Ben looked around for the mice and other little creatures, but found that they had vanished. Being the color of the dead leaves and limbs near which they played and fed, and knowing all the holes and how best to reach the nearest one, all of them could hide quickly. They had been frightened. Many minutes would pass before they dared to crawl out again.

When Red Ben was trotting back to the Swamp, he heard Farmer Slown’s hound baying. He stopped at once to listen. It was not the joy cry that comes with the scent of a fresh trail; there was, indeed, a wail at the end that puzzled him. He listened a while in silence, then, pointing his sharp nose in that direction, barked back his defiance. “Yap, yap, ya-rrrrr.” After a pause he barked again.

The hound, who was tied in the barnyard and howling simply because he felt lonely, heard the fox and at once grew quiet. Farmer Slown heard him too, through his open window. He, however, did not remain quiet. He fussed and fumed the rest of the night, and made more plans to catch the fox which was so bold as to bark at him.

Red Ben, meanwhile, stole along the fence towards the farm buildings. He was drawn by an irresistible curiosity. It was here his greatest enemy lived, the one who was somehow connected with the disappearance of his mother and of his brothers.

The farm was very quiet in the darkness. The chickens were still asleep on their roosts, and no animal stirred. Even the windmill over the well had stopped turning, and so gave forth none of its usual creaks and groans.

The damp air, however, was laden with scents. The fox’s keen nose picked out the odor of perspiring horses, of sheep and of pigs. It caught, too, the peculiar smell of man and the smell of smoke and cooked food and slops, which always is found where man lives. There was also a dull, nameless scent made up of a hundred different things, like the grease on wagon axles, old harness, rusting iron, clothes out to dry and other things about which Red Ben knew nothing.

This was indeed a new world to the young fox, who had often wandered near the place with his mother, but never before ventured so close. Weird shapes of wagons made him keep away from the barn shed. He feared, too, the windmill, which he had once seen move in a suspicious way. Nor did he care about coming closer to the pigs, lying in filthy sties and grunting in their sleep. Altogether he much preferred the clean woods, where sweeter scents filled his nostrils and no weird creations of man lay strewn about in all their ugliness.

It was the chicken house that interested Red Ben most. From its open windows came occasional sleepy clucks and murmurs as the closely packed fowls jostled each other in their dreams. Suddenly, too, a rooster crowed, so sharply that the fox leaped to one side. Other roosters in the little house took up the challenge and crowed. They were heard by roosters at the next farm, who thereupon crowed too and woke up the roosters in the village, who also felt like crowing. Day had not yet come, however; it was only the moonlight they saw, so all promptly went to sleep again.

Red Ben knew very well that each crow came from a toothsome fowl, so he took a most natural interest in this chorus. When once it was over, however, he felt uneasy. Instinct warned him he was being watched. He looked all around and then, happening to glance up, caught the hostile eye of a big gray cat, watching him from the hen house roof.

He had never before seen a cat, and so was suspicious at once, especially as this one now opened its mouth to give vent to a yowl of indignation. He sidled off towards the wood, keeping a watchful eye on grim pussy.

There was straw scattered around on the ground, and from a bunch of this he startled a feathered whirlwind, in the shape of a guinea hen who had been sitting there on a nest of her eggs. Red Ben jumped backwards, ready for a dash in any direction.

“Chah! Che, che, chahhh!” screamed the guinea as she ran about. “Chah! Chah!” came shrilly from the trees nearby where all the other guineas were roosting. The chickens awoke and cackled, the hound bayed, Shep barked from the locked stable, and in the midst of it the little fox, the innocent cause of all this hubbub, slipped away towards the quiet, friendly wood.

His anxiety lest something follow made him careless and brought him face to face with a cow, lying down in the meadow. Dodging her surprised snort, he ran full tilt into another who, in turn, drove him to a third, and so on until he had somehow escaped the herd and was fairly flying towards the wood. Not till he was in its cool shadows, among the silent woodsfolk, could he once more feel safe.

From the farm still came the “chahhh” of the excited guineas, and when, with the first rays of the sun, Ben Slown stepped out of his house, a mass of guinea feathers met his gaze. They were strewn all about the half eaten body of the guinea hen who once had faithfully sat on her nest back of the hen house.

Farmer Slown did not look for feathers on the nose of the big cat. He never found out that the sight of the guinea running about in the dark was too much for the hunter instinct of his pet. Instead, he remembered only the barking of the fox in the night, and shook his fist in the direction of the Ridge.

Instead of sleeping under the fallen tree in Cranberry Swamp, where the fleas had become too lively for comfort, Red Ben had made it a practice to pick out a new place nearly every day. This time he chose a laurel clump on the top of Oak Ridge. There was an advantage in this high bed; he could keep an eye on Ben Slown’s farm, whence he now expected trouble of some kind to come.

He had lately paid special attention to the danger signals of all the wild creatures, and on them relied for first warning, so he curled up in his usual tight ball, with eyes closed, but ears uncovered to take in every sound.

The “check, check” of red wing blackbirds, the rasp of brown thrashers, the screech of sparrow hawks and the rustlings of a great wood full of happy life went through his ears unheeded. The bark of Red Squirrel made him look up for a moment, to make sure that the little fellow was only talking to his mate; so also did the whirring of a grouse that some prowling hunter had scared up nearby; but during most of the time he could doze.

From a pine, near the fields below, came an occasional reassuring “caw” from Jim Crow, who was keeping guard while the crow flock fed in the sheep pasture. Everything seemed all right to him. To be sure there were two red-tail hawks soaring high in the sky, but they were not worth bothering over at that distance. All at once, however, a man, followed by dogs, came from behind the farm buildings.

“Caw, caw!” called the old crow sharply, to tell the others that something suspicious was in sight. A moment later he recognized Ben Slown and instantly flew out of his tree with the real danger call. “Cawr, cawr, cawr!” repeated again and again, as the other crows flew up too and scattered in the direction of the Barrens.

The first call awoke Red Ben, and the second brought him to his feet in a bound. All he needed was the sight of the crows, flying towards the Barrens, to convince him that it was Ben Slown who was coming. Only the approach of a well known gun carrier could make those wise birds leave the neighborhood of the Ridge like that.

He watched the farmer and his three dogs, then trotted down the far side of the Ridge, crossed Cranberry Swamp and entered the Barrens. There was a definite plan in all this. Gray Fox had freed him from Ben Slown’s dogs once before, now he could do it again.

Red Ben knew the old bully’s range rather well, and wasted no time in reaching the most likely thicket. Sure enough, the smell of Gray Fox was there in plenty, the smell Red Ben had such reason to fear and dislike. He sneaked cautiously up wind and spied the sleeping fox curled up under a pepper bush.

He stood there undecided what to do. It was dangerous to trifle with Gray Fox. But matters were decided for him by an eddy of wind which carried his own scent into the thicket.

Gray Fox’s nose twitched; he looked up, recognized Red Ben and sprang to his feet with a snarl. Back dashed the young fox, and after him came the angry gray. Through the woods they sped towards Cranberry Swamp where, Red Ben felt sure, the farmer was already hunting for him.

The gray bully was bent on revenge this time; he would teach the red upstart a thing or two! But just as they neared the log that crossed Goose Creek, the bay of a hound floated through the woods from straight ahead. Red Ben dashed across the log, but Gray Fox hung back and finally sneaked away to hide. And so it happened that when the black and white hound, Shep and the fox terrier crossed the log on Red Ben’s trail from the Ridge, they found the fresh, straight-away track of Gray Fox, and followed it.

While Ben Slown sat on the Ridge waiting for a shot and while Red Ben lay comfortably in the Swamp, Gray Fox, rage in his heart, was leading the dog chorus on a wild chase far into the Barrens, to a deep hole he knew about. The entrance was too narrow to admit the large dogs, and the little fox terrier could be held at bay. It was well for Gray Fox that this hole was so far from the Ridge that Ben Slown could not hear the hound baying there.

All this time Jim Crow was keeping his eye on the whereabouts of the farmer. Silently he would circle the Ridge, high over the trees, until he saw the crouching figure, then he would alight in a tall tree at some distance in the Swamp and by his “cawr, cawr, cawr,” keep back all the crows that started to return in the direction of the Ridge. By watching him Red Ben, too, knew where the enemy was lying in wait.

When later Jim Crow saw the disgusted farmer start for his home, he flew joyously over the woods spreading the news with a “caw—caw—caw.” Soon afterwards he drew all the crows to the meadow by calling as rapidly as he could get out the sounds, “Cehr, cehr, cehr, cehr, cehr.”

Jim Crow’s language was becoming well known to Red Ben. Before the sun rose each morning, Jim would talk to the other crows. “Caw-caw,” he would begin. Another would answer, “Caw-cehr, cehr, cehr,” and then from all over the Ridge would come other caws of various kinds. No two crows spoke at once. If Jim had something important to tell, all the rest listened. By the time the sun was nearly showing above the horizon the band had started towards the feeding ground. Usually this was in one of the fields, but visits to the river flats and to cranberry bogs were not uncommon.

If a large hawk, or owl, was discovered by a crow, he called, “Caw, caw, caw, caw, caw,” and brought to the spot every full grown crow within hearing. One after another would then dive at the big bird and harass him until he escaped from the neighborhood.

Once when Red Ben had discovered a dead crow and had pulled it out for inspection, another crow, flying over, caught sight of the apparently murdered bird and shot down with a furious “Cahrrrr,” which others, appearing from all sides at this harsh call, repeated until the woods resounded.

Sometimes a crow would vary his caws with a melodious “Kruck—kruck,” which resembled one of Blue Jay’s favorite notes, but was much louder.

As Red Ben now rolled himself into the usual tight little ball, for sleep, he heard once more the joyous “Caw—caw—caw” of the old black sentinel and, with that ringing in his ears, contentedly closed his eyes.

With the first signs of darkness, Red Ben uncurled himself and took a long stretch. Then he gaped until nearly every tooth in his head was bared. After that he realized how ravenously hungry he felt, also how bad this dry, hot night would be for hunting.

Far away he heard a great horned owl hooting. “Who—who, who—whoo,” it said, over and over again. Nearby, Screech Owl was crooning to his little mate, very softly. They, too, were hunters and knew that there was little use in settling down to work until the dew had gathered in the fields and made the withered grass luscious enough to entice the rabbits and mice into the open. All had to have water, and for most of the little creatures that gnaw, it was safer to sip the dew than to take the long trip to Goose Creek.

Suddenly a weird scream filled the woods. It had scarcely ceased when another pierced the air, this time much closer to Red Ben. The fox cowered back and waited. Again the scream, and then a ghostlike, whitish shadow flitting between the trees.

Barn Owl, strangest of all the creatures of the night, was flying to his hunting ground. Many a silly ghost story has been started by a glimpse of him—innocent old mouse eater—in his moonlight travels through the woods. By day he rested in a hollow tree, or hid in dense tangles high above the ground. Now and then he found a roosting place on the rafters of some tumble down barn. By night he searched the meadows for mice and moles, doing great good to the lands of the farmers.

Red Ben had often seen Barn Owl’s white form, but never before heard his call so near at hand. In the summer he had come across two of the old bird’s youngsters squatting forlornly beside the stump of an old hollow tree, which had been their home until a woodcutter had felled it the day before.

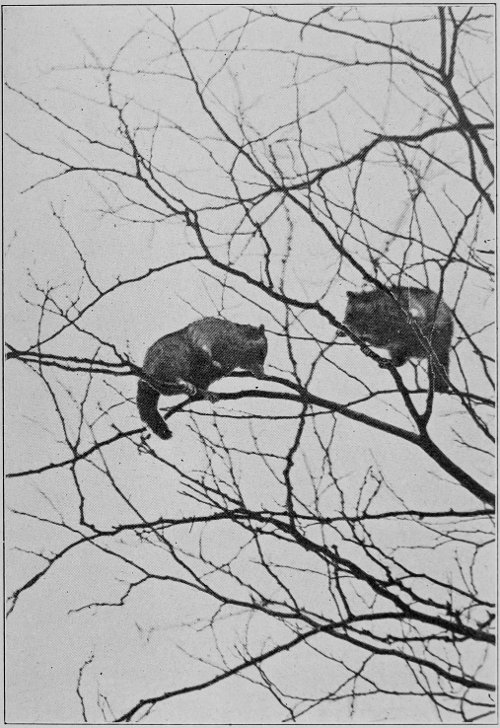

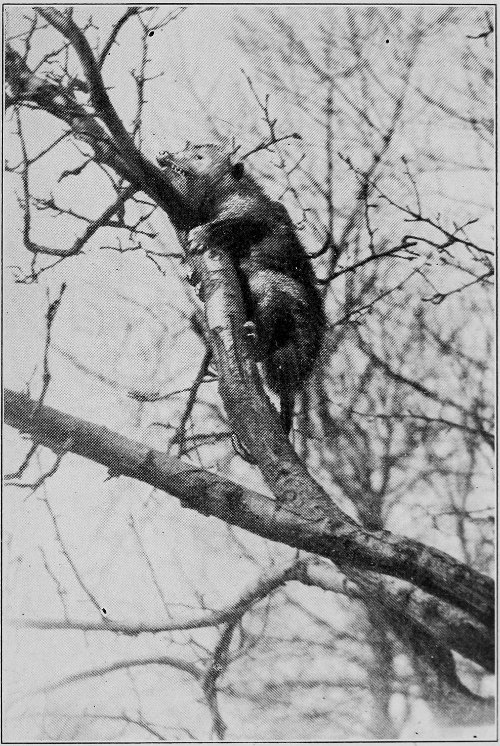

“They sat on their tails and held hands”

The fox had come too close to the suspicious birds and had nearly been caught by the quick blow both aimed at him with their long talons. One reached out so far that he lost his balance and toppled over. Struggling violently to get on his feet, he clawed his brother, by mistake, and received a sound whack in punishment.

Forgetting brotherly love and fear of the fox pup, they then flew at each other in a fury and had a good fight. At last, exhausted, they sat on their tails and held hands while hissing defiance at each other in a comical way.

Red Ben was very much interested in the strange pair, and made a practice of taking a look at them every night. The devoted old mother fed them regularly, often leaving beside them several more mice than their stomachs had room for. These, however, they ate during the day, swallowing fur, tails, feet and everything, but later spitting up in neat balls all the bones and undigestible parts.

At last a day came when they were not to be found near the tree. Overhead, however, sounded a rasping call. Red Ben looked up and saw two monkey faces, rimmed in white, looking down at him from a high limb. Their wings had grown long and they had learned to fly. Soon four big barn owls, instead of two, would be quartering the meadows in moonlit nights.

The pangs of hunger soon drove Red Ben to begin to hunt along Goose Creek. In daytime, rows of mud turtles, coiled water snakes and greenish black bull frogs were usually to be found there on floating logs, warming themselves in the sunshine. At night, some of these ventured to come ashore after insects.

“Muskrat was busy pulling up grass”

Picking his way cautiously along the water’s edge, Red Ben noticed a muskrat swimming in the middle of the sluggish stream. Hoping it would land near him, he hid, but the wily rat went ashore on the far bank where he was safe from the fox, but not from a brown mink whose fierce eyes were also watching.

Mink was a swift swimmer whose thick fur shed water quite as well as that of Muskrat. He dove into the stream as noiselessly as a snake, swam under the surface until at a point below Muskrat, who just then was busy pulling up grass which he expected to carry to the stream and wash before eating.

Red Ben, in his excitement, leaped out on a bar of sand where he could see the chase more easily. Screech Owl, too, having caught a glimpse from a distant cedar, flew to a limb over the stream. All the creatures within that angle of the creek except poor old Muskrat seemed to know that something was going to happen. Even the bats flitted about without their usual dips and rushes after low flying bugs.

Muskrat, with mouth full of grass and roots, turned back just as Mink’s head came above the steep bank. For one breathless second the two furry creatures looked at each other, then the rat plunged headlong for the stream. Like a football player he charged down the bank, throwing the small but fierce Mink head over heels into the water. Muskrat dove and vanished so quickly among the stems of the spatterdocks and golden clubs that Mink was confused, and actually lost him.

A swirl near Red Ben showed him where Muskrat entered the under-water burrow in the bank, leading to his home. In the clear stream the fox had a glimpse of the brown body with forepaws held against its sides, driving itself through the water by great strokes of its webbed hind feet. Its long, flat, almost hairless tail acted as a rudder to guide its course.

Seeing nothing more of either animal, Red Ben trotted on. Ahead was a dead tree on which were large, black objects. These he knew were turkey buzzards which by day soared far and wide over the Barrens, searching for any dead animals that would afford them a feast. Here they gathered in the evening, a gruesome, ill smelling assemblage.

The fox avoided the tree and swung into the old wood path. It was the best thing he could have done that night, for it brought him face to face with a meal. Trotting along quite unconcernedly, his attention held by the buzzard tree, he was met by an explosion of rage, almost under his nose. He leaped wildly, to avoid he knew not what. Almost at the same moment he recognized the big gray tom-cat which had treated him so uncivilly when he visited Ben Slown’s farm.

His dignity had been badly jarred, and he felt angry all over. This stealthy, hostile creature, which belonged at the farm, had no right to dispute his way in the wild Barrens. Besides which it had a freshly killed wild rabbit under its paws.

As the two eyed each other, Red Ben felt the fur tingling along his spine. The alluring scent of the rabbit filled his hungry nostrils. He stepped closer—yes, the rabbit certainly was a fat one! Still nearer he went, always watching the furious eyes that glared at him. How the cat could growl! Now his nose was within a few inches of the rabbit. His eyes dropped for the fraction of a second, just to have one good look at it, and in that instant the raging cat struck with both front paws.

But Red Ben was not there. He had been quick enough to leap away from those claws. Back he circled and again dodged a furious blow. The hateful growl of the cat rose into a high pitched shriek of rage. Losing all caution, he made a spring after the fox, who neatly side stepped it and picked up the rabbit on the run. A yowl followed him, but as he looked over his shoulder, he saw the cowardly cat actually turn tail and dash for home.

This was the beginning of Red Ben’s rule over Oak Ridge and Cranberry Swamp. Before October ended, every animal who lived there had learned not to trifle with him. He knew them all by that time and respected their rights, but woe to the one that tried any mean tricks on him. He was growing big and strong, and very wonderful looking, in his orange-red fur, which, responding to the first frosts, was becoming long and rich. The most conspicuous thing to be seen on the Ridge was Red Ben, but he took care that he seldom was seen. Nevertheless his fame was growing.

Ben Slown had a good many days of corn husking ahead of him that Autumn. Every morning he carried his gun out to the field, turned loose the eager black and white hound with instructions to “sick ’em,” then busied himself in the profitable task of stripping the long yellow ears.

The hound would hunt through the woods, and, by the manner of his yelping, tell Ben Slown what he was finding there. A quick short yelp or two meant he had scared up a rabbit. An angry, loud baying in one spot meant that Gray Squirrel, or Red Squirrel, had been treed and was making fun of him from a safe height.

When the hound ran Woodchuck, or Muskrat, into a burrow, his baying was muffled, on account of his nose being in the mouth of the hole. But when he rushed full tilt through the woods with a musical “wu—uh, wu-uh, wu—uh” at regular intervals, that meant fox; and, near the Ridge, fox meant Red Ben.

Ben Slown no sooner would hear that, than down he would throw the corn bundle and off he would run for his gun, which was never left very far from his hands. Off, too, would dash Shep and the fox terrier, who ordinarily busied themselves with digging for mice around the corn shocks.

In the excitement, Red Ben always managed to get away, usually by hunting up Gray Fox, or some other member of the gray family, whom he had learned to find in the Pine Barrens a mile down Goose Creek. The hound had discovered that any other fox was easier to follow than Red Ben, so he gladly changed trails.

On one occasion, after a long, hard run, Red Ben, circling back by a new route, came across the scent of a fox entirely a stranger to him. With his usual caution he looked about and presently caught sight of a red creature like himself, watching him intently.

For a full minute he and the other fox studied each other without moving. Not since his mother vanished had Red Ben seen a red fox, and never before had he seen an animal quite so unkempt looking as this one. The red fur was all mangy and torn, the tail almost a stick.

Red Ben, in all the magnificence of his perfect coat, seemed like a different kind of animal from this wretched little she-fox. And yet there was a brightness of eye, as well as an alertness about her which commanded attention.

The baying of the hound close by changed the scene all too quickly. Red Ben went on his way in graceful bounds, the little she-fox watching him till out of sight, then herself vanishing in the wood.

This kind of daily persecution by Ben Slown and his hound wore heavily on Red Ben. The sleepless days, hard runs and constant worry made him unfit for hunting during the night. Often he went hungry. He quickly became embittered and reckless. Instead of running after swift rabbits and spending hours in digging out mice, he fell into the easy habit of catching the fat, stupid chickens and ducks that could be picked up at any farm yard without his expending much energy.

His cunning in work of this kind seemed endless. He learned how to catch the guinea hens in the gray light of early morning, how to climb over and under chicken yard fences and how to enter hen houses through windows. He became the vexation and terror of every poultry man within three or four miles of the Ridge. Bounties were offered in three villages for his capture. One hundred dollars in all hung over his head; and still he somehow managed to live on his much loved Ridge—the only place he knew as home.