Project Gutenberg's Naval Actions of the War of 1812, by James Barnes This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Naval Actions of the War of 1812 Author: James Barnes Illustrator: Carlton T. Chapman Release Date: September 12, 2018 [EBook #57889] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NAVAL ACTIONS OF THE WAR OF 1812 *** Produced by Greg Bergquist and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY

JAMES BARNES

AUTHOR OF

“FOR KING OR COUNTRY”

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

CARLTON T. CHAPMAN

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

FOR KING OR COUNTRY. A Story of the American Revolution. Illustrated. Post 8vo, Cloth, $1 50.

A story that will be eagerly welcomed by boys of all ages.... It is doubtful whether the reader will be content to lay the story aside until he has finished it. It is a good book for an idle day in the country, and we cordially recommend it both to boys on a holiday and to boys that stay at home.—Saturday Evening Gazette, Boston.

A spirited story of the days that tried men’s souls, full of incident and movement that keep up the reader’s interest to the turning of the last page. It is full of dramatic situations and graphic descriptions which irresistibly lead the reader on, regretful at the close that there is not still more of it.—Christian Work, N. Y.

A fascinating study. It is replete with those Homeric touches which delight the heart of the healthy boy.... It would be difficult to find a more fascinating book for the young.—Philadelphia Bulletin.

A capital story for boys, both young and old; full of adventure and movement, thoroughly patriotic in tone, throwing luminous sidelights upon the main events of the Revolution.—Brooklyn Standard-Union.

Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York.

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers.

TO

MY FATHER

WHOSE ENCOURAGEMENT AND ASSISTANCE ARE HEREBY

ACKNOWLEDGED WITH AFFECTIONATE GRATITUDE

I HAVE THE HONOR TO DEDICATE

THIS BOOK

v

The country that has no national heroes whose deeds should be found emblazoned on her annals, that can boast no men whose lives and conduct can be held up as examples of what loyalty, valor, and courage should be, that country has no patriotism, no heart, no soul.

If it be wrong to tell of a glorious past, for fear of keeping alive an animosity that should have perished with time, there have been many offenders; and the author of the following pages thus writes himself down as one of them. Truly, if pride in the past be a safeguard for the future in forming a national spirit, America should rejoice.

There exists no Englishman today whose heart is not moved at the word “Trafalgar,” or whose feelings are not stirred by the sentence “England expects every man to do his duty.” The slight, one-armed figure of Admiral Nelson has been before the Briton’s eyes as boy and man, surrounded always with the glamour that will never cease to enshroud a nation’s hero. Has it kept alive a feeling of animosity against France to dwell on such a man as this, and to keep his deeds alive? So it may be. But no Englishman would hide the cause in order to lose the supposed effect of it.

In searching the history of our own country, when it stood together as a united nation, waging just war, we find England, our mother country, whose language we speak, arrayed against us. But, on account of this bond of birth and language, should we cease to tell about the deeds of those men who freed us from her grasp and oppressions, and made us what we are? I trust not. May our navy glory in its record, no matter the consequences! May our youth grow up with the lives of these men—our Yankee commanders—before them, and may they profit by their examples!

This should not inculcate a hatred for a former foe. It should only serve to build up that national esprit de corps without which no country ever stood up for its rights and willed to fight for them. May the sons of our new citizens, whose fathers have served kings, perhaps, and come from other countries, grow up with a pride in America’s own national history! How can this be given them unless they read of it in books or gain it from teaching?

But it is not the intention to instruct that has caused the author to compile and collate the material used in the following pages. He has been influenced by his own feelings, that are shared by the many thousands of the descendants of “the men who fought.” It has been his pleasure, and this alone is his excuse.

Mr. Carlton T. Chapman, whose spirited paintings are reproduced to illustrate this volume, has caught the atmosphere of action, and has given us back the old days in a way that makes us feel them.

ix

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| I | |

| The United States frigate Constitution, on July 17th, 1812, falls in with a British squadron, but escapes, owing to the masterly seamanship of Captain Isaac Hull | 23 |

| II | |

| The Constitution, under command of Captain Hull, captures the British frigate Guerrière, under command of Captain Richard Dacres, August 19th, 1812 | 35 |

| III | |

| The United States sloop of war Wasp, Captain Jacob Jones, captures the English sloop of war Frolic, October 18th, 1812; both vessels taken on the same day by the English seventy-four Poictiers | 47 |

| IV | |

| October 25th, 1812, the British frigate Macedonian, commanded by John S. Carden, is captured by the United States frigate, under command of Stephen Decatur; the prize is brought to port | 59 |

| V | |

| Captain Wm. Bainbridge, in the Constitution, captures the British frigate Java off the coast of Brazil, December 29th, 1812; the Java is set fire to and blows up | 73 |

| VI | |

| Gallant action of the privateer schooner Comet, of 14 guns, against three English vessels and one Portuguese, January 14th, 1813 | 91 |

| VII | |

| The United States sloop of war Hornet, Captain James Lawrence, takes the British brig Peacock; the latter sinks after the action, February 24th, 1813 | 103 |

| VIII | |

| The United States frigate Chesapeake is captured by the English frigate Shannon after a gallant defence, June 1st, 1813 | 113 |

| IX | |

| The United States brig Enterprise, commanded by William Burrows, captures H. B. M. sloop of war Boxer, September 5th, 1813; Burrows killed during the action | 129 |

| X | |

| On September 10th, 1813, the American fleet on Lake Erie, under the command of Oliver Hazard Perry, captures the entire English naval force under Commodore Barclay | 139 |

| XI | |

| The American privateer brig General Armstrong, of 9 guns and 90 men, repulses a boat attack in the harbor of Fayal, the British suffering a terrific loss, September 27th, 1813 | 159 |

| XII | |

| March 28th, 1814, the United States frigate Essex, under Captain David Porter, is captured by two English vessels, the Phoebe and the Cherub, in the harbor of Valparaiso | 171 |

| XIII | |

| The United States sloop of war Peacock, commanded by Captain Warrington, takes the British sloop of war L’Epervier on April 29th, 1814 | 191 |

| XIV | |

| The United States sloop of war Wasp, under command of Captain Blakeley, captures the British sloop of war Reindeer, June 28th, 1814. The Wasp engages the British sloop of war Avon on the 1st of September; the English vessel sinks after the Wasp is driven off by a superior fore | 199 |

| XV | |

| September 11th, the American forces on Lake Champlain, under Captain Macdonough, capture the English squadron, under Captain Downey, causing the evacuation of New York State by the British | 209 |

| XVI | |

| The United States frigate President, under command of Captain Decatur, is taken by a British squadron after a long chase, during which the President completely disabled one of her antagonists, January 15th, 1815 | 219 |

| XVII | |

| February 20th, 1815, the Constitution, under Captain Stewart, engages and captures two English vessels that prove to be the Cyane and the Levant; one of her prizes is retaken, and the Constitution again has a narrow escape | 231 |

| XVIII | |

| The British brig of war Penguin surrenders to the United States brig Hornet, commanded by Captain James Biddle; the Penguin sinks immediately after the accident, March 23d, 1815 | 245 |

| XIX | |

| The chase of the Hornet, sloop of war, by the Cornwallis, a British line-of-battle ship | 255 |

xiii

| THE SURRENDER OF THE “GUERRIÈRE” | Frontispiece |

| Facing p. | |

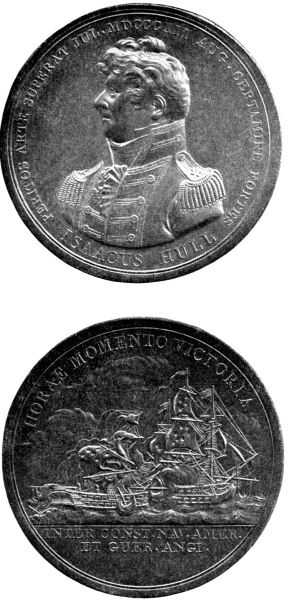

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL | 22 |

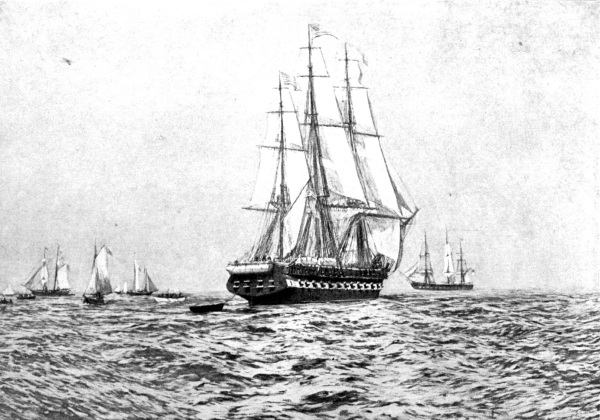

| THE “CONSTITUTION” TOWING AND KEDGING | 26 |

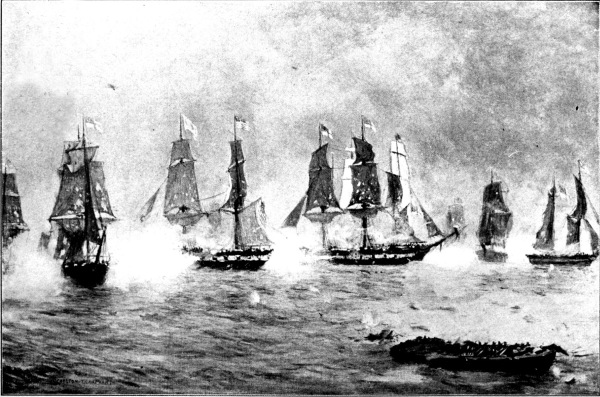

| THE “WASP” RAKING THE “FROLIC” | 50 |

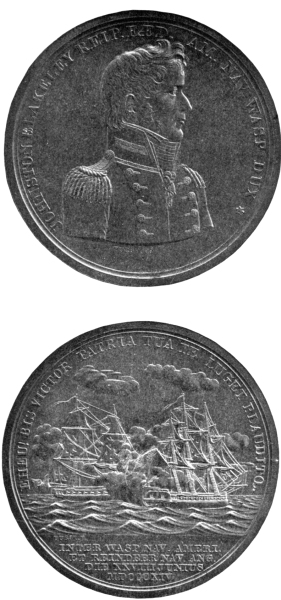

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN STEPHEN DECATUR | 58 |

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN WILLIAM BAINBRIDGE | 72 |

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN JAMES LAWRENCE | 102 |

| THE “PEACOCK” AND “HORNET” AT CLOSE QUARTERS | 106 |

| THE “CHESAPEAKE” LEAVING THE HARBOR | 116 |

| MEMORIAL MEDAL IN HONOR OF CAPTAIN WILLIAM BURROWS | 128 |

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO LIEUTENANT EDWARD R. McCALL | 128 |

| THE “ENTERPRISE” HULLING THE “BOXER” | 132 |

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN OLIVER HAZARD PERRY | 138 |

| THE “NIAGARA” BREAKS THE ENGLISH LINE | 148 |

| THE “ESSEX” BEING CUT TO PIECES | 184 |

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN LEWIS WARRINGTON | 190 |

| THE “PEACOCK” CAPTURES THE “EPERVIER” | 192 |

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN JOHNSTON BLAKELEY | 198 |

| THE “WASP’S” FIGHT WITH THE “AVON” | 204 |

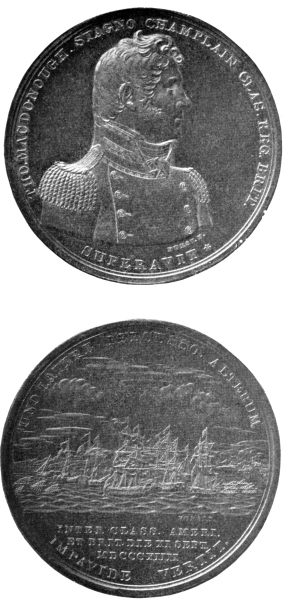

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN THOMAS MACDONOUGH | 208 |

| THE “PRESIDENT” ENDEAVORING TO ESCAPE | 222 |

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN CHARLES STEWART | 230 |

| THE “CONSTITUTION” TAKING THE “CYANE” | 236 |

| MEDAL PRESENTED BY CONGRESS TO CAPTAIN JAMES BIDDLE | 244 |

| THE “PENGUIN” STRIKES TO THE “HORNET” | 252 |

To study the condition of affairs that led up to the declaration of the second war against Great Britain we have but to turn to the sea. Although England, it must be confessed, had plenty of fighting on her hands and troubles enough at home, she had not forgotten the chagrin and disappointments caused by the loss of the American colonies through a mistaken enforcement of high-handedness. And it was this same tendency that brought to her vaunted and successful navy as great an overthrow as their arms had received on land some thirty-seven years previously.

The impressment of American seamen into the English service had been continued despite remonstrances from our government, until the hatred for the sight of the cross of St. George that stirred the hearts of Yankee sailor men had passed all bounds. America under these conditions developed a type of patriot seafarer, and this fact may account for his manners under fire and his courage in all circumstances.

The United States was an outboard country, so to speak. We had no2 great interstate traffic, no huge, developed West to draw upon, to exchange and barter with. Our people thronged the sea-coast, and vessels made of American pine and live-oak were manned by American men. They had sought their calling by choice, and not by compulsion. They had not been driven from crowded cities because they could not live there. They had not been taken from peaceful homes and wives and children by press-gangs, as was the English custom, to slave on board the great vessels that Great Britain kept afloat by such means, and such alone. But of his own free-will the Yankee sailor sought the sea, and of his own free-will he served his country. It would be useless to deny that the greater liberty, the higher pay, the large chance for reward, tempted many foreigners and many ex-servants of the king to cast their lot with us. But when we think that there were kept unwillingly on English vessels of war almost as many American seamen as were giving voluntary service to their country in our little navy, we can see on which side the great proportion lies.

It is easy to see that the American mind was a pent furnace. It only needed a few more evidences of England’s injustice and contempt to make the press and public speech roar with hatred and cry out for revenge. So when in June, 1812, war was declared against Great Britain, it was hailed with approbation and delight. But shots had been exchanged before this, and there were men who knew the value of seamanship,3 recognized the fact that every shot must tell, that every man must be ready, and that to the navy the country looked; for the idea of a great invasion by England was scouted. It was a war for the rights of sailors, the freedom of the high-seas, and the grand and never thread-worn principles of liberty.

So wide-spread had been the patriotism of our citizens during the revolutionary war that our only frigates, except those made up of aged merchant-vessels, had been built by private subscription; but now the government was awake, alert, and able.

To take just a glance at the condition of affairs that led up to this is of great interest.

So far back as the year 1798 the impositions of Great Britain upon our merchantmen are on record, and on November 16th of that year they culminated in a deliberate outrage and insult to our flag.

The U. S. ship of war Baltimore, of 20 guns, was overhauled by a British squadron, and five American seamen were impressed from the crew. At this time we were engaged in the quasi-war with France, during which the Constellation, under Captain Truxton, captured the French frigate L’Insurgent, of 54 guns. On February 1st, 1800, a year after the first action, the same vessel, under the same commander, captured La Vengeance, of 54 guns. On October 12th of the same year the U. S. frigate Boston captured the French corvette Le Berceau. Minor actions between the French privateers and our merchantmen occurred4 constantly. We lost but one of our national vessels, however—the schooner Retaliation, captured by two French frigates.

England was protecting the Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean at this time, in order to keep out competitive commerce—a fine bit of business! Europe and America bought immunity.

On June 10th, 1801, war was declared, however, by the Bashaw of Tripoli against the United States, because we failed to accede to his demands for larger tribute, and a brief summary of the conduct of this war will show plainly that here our officers had chances to distinguish themselves, and the American seamen won distinction in foreign waters.

Captain Bainbridge, in command of the frigate Philadelphia, late in August, 1803, captured off the Cape de Gatt a Moorish cruiser, and retook her prize, an American brig. About two months later the Philadelphia, in chase of one of the corsairs, ran on a reef of rocks under the guns of a battery, and after four hours’ action Bainbridge was compelled to strike his flag to the Tripolitans. For months, now, it was the single aim of the American squadron under Preble to destroy the Philadelphia, in order to prevent her being used against the United States, and on February 15th, 1804, this was successfully accomplished by Lieutenant Stephen Decatur and seventy volunteers, who entered the harbor on the ketch Intrepid, set fire to the Philadelphia, and escaped.

5 All through August Preble’s squadron hovered about the harbor of Tripoli, and bombarded the town on four separate occasions. On June 3d, 1805, he arranged a peace with the Tripolitans, and two days later Bainbridge and the American prisoners were liberated. But the bashaw could not control the piratical cruisers who made his harbor a rendezvous, and in September hostilities were again commenced, during which occurred the sad accident, the premature blowing up of the fire ship Intrepid, by which the navy lost Captain Richard Somers, one of its bravest officers, two lieutenants, and ten seamen.

But to return to the relations existing between America and England. A crisis was fast approaching. Off the shore of Maryland on June 22d, 1807, the crowning outrage attending England’s self-assumed “right of search” took place, when the British sloop of war Leopard, 50 guns, fired upon the Chesapeake, 36 guns, which vessel, under command of Captain Barron, had just shipped a green crew, and could return, owing to her unprepared condition, but one shot to the Englishman’s broadside. Barron hauled down his flag, and had to allow himself to be searched by the orders of Captain Humphries, commander of the Leopard, and four American-born seamen were taken out of his crew and sent on board the Englishman. It was claimed by Captain Humphries that three of these men were deserters from the British frigate Melampus. Although the Chesapeake had hauled down her flag and surrendered,6 the Leopard paid no attention to this, and sailed away, leaving Barron with three men killed and eighteen wounded, and his ship badly damaged in hull, spars, and rigging. Barron was censured by a court of inquiry and suspended from his command. Looking at this sentence dispassionately, it was most unjust.

But the indignation that was felt throughout the country over this affair wrought the temper of the people to a fever-heat. Congress passed resolutions, and the President of the United States issued a proclamation, forbidding all British armed vessels from entering the ports of the United States, and prohibiting all inhabitants of the United States from furnishing them with supplies of any description.

Great Britain’s disavowal of the act of Admiral Berkeley (under whose command Captain Humphries had acted) was lukewarm, and the Admiral’s trial was something of a farce, and gave little satisfaction to America.

Napoleon at about this time had begun his senseless closing of French ports to American vessels, and once more the French cruisers apparently considered all Yankee craft their proper prey. They would interrupt and take from them stores, water, or whatever they considered necessary, without remuneration or apology. As the English were taking our seamen and showing absolute contempt for our flag wherever found, the7 condition of our merchant marine was most precarious. No vessel felt secure upon the high seas, and yet the English merchant ships continued to ply their trade with us.

On May 1st, 1810, all French and English vessels of any description were prohibited from entering the ports of the United States. On June 24th of this year the British sloop of war Moselle fired at the U. S. brig Vixen, off the Bahamas, but fortunately did no damage. Another blow to American commerce just at this period was the closing of the ports of Prussia to American products and ships. But an event which took place on May 16th, 1811, had an unexpected termination that turned all eyes to England. The British frigate Guerrière was one of a fleet of English vessels hanging about our coasts, and cruising mainly along the New Jersey and Long Island shores. Commodore Rodgers was proceeding from Annapolis to New York in the President, 44 guns, when the news was brought to him by a coasting vessel that a young man, a native of New Jersey, had been taken from an American brig in the vicinity of Sandy Hook, and had been carried off by a frigate supposed to be the Guerrière. On the 16th, about noon, Rodgers discovered a sail standing towards him. She was made out to be a man-of-war, and concluding that she was the Guerrière, the commodore resolved to speak to her, and, to quote from a contemporary, “he hoped he might prevail upon her commander to release the impressed young man” (what8 arguments he intended to use are not stated). But no sooner had the stranger perceived the President, whose colors were flying, than she wore and stood to the southward. Rodgers took after her, and by evening was close enough to make out that she was beyond all doubt an English ship. But owing to the dusk and thick weather it was impossible to count her broadside, or to make out distinctly what was the character of the flag that at this late hour she had hoisted at her peak. So he determined to lay his vessel alongside of her within speaking distance, and find out something definite. The strange sail apparently wished to avoid this if possible, and tacked and manoeuvred incessantly in efforts to escape. At twenty minutes past eight the President, being a little forward of the weather beam of the chase, and within a hundred yards of her, Rodgers called through his trumpet with the usual hail, “What ship is that?” No answer was given, but the question was repeated from the other vessel in turn. Rodgers did not answer, and hailed again. To his intense surprise a shot was fired into the President, and this was the only response. A great deal of controversy resulted from the subsequent happenings. The English deny having fired the first gun, and assert that Rodgers was the offender, as a gun was discharged (without orders) from the American vessel almost at the same moment. Now a brisk action commenced with broadsides and musketry. But the commodore, noticing that he was having to deal with a very inferior9 force, ceased firing, after about ten minutes of exchanging shots. He was premature in this, however, as the other vessel immediately renewed her fire, and the foremast of the President was badly injured by two thirty-two-pound shot. By this time the wind had blown up fresh, and there was a heavy sea; but notwithstanding this fact and the growing darkness, a well-directed broadside from the President silenced the other’s fire completely. Rodgers approached again, and to his hail this time there was given some reply. Owing to his being to windward, he did not catch the words, although he understood from them that his antagonist was a British ship. All night long Rodgers lay hove to under the lee of the stranger, displaying lights, and ready at any moment to respond to any call for assistance, as it had been perceived that the smaller vessel was badly crippled.

At daylight the President bore down to within speaking distance and an easy sail, and Rodgers sent out his first cutter, under command of Lieutenant Creighton, to learn the name of the ship and her commander, and with instructions to ascertain what damage she had received, and to “regret the necessity which had led to such an unhappy result.” Lieutenant Creighton returned with the information that the British captain declined accepting any assistance, and that the vessel was His Britannic Majesty’s sloop of war Little Belt, 18 guns. She had10 nine men killed and twenty-two wounded. No one was killed on board the President, and only a cabin-boy had been wounded in the arm by a splinter.

The account given to his government by Captain Bingham, of the Little Belt, gives the lie direct to the sworn statement of the affair, confirmed by all the officers and crew of the President, an account, by-the-way, that after a long and minute investigation was sustained by the American courts. It was now past doubting that open war would shortly follow between this country and England. Preparations immediately began in every large city to outfit privateers, and the navy-yards rang with hammers, and the recruiting officers were besieged by hordes of sailor men anxious to serve a gun and seek revenge.

Owing to circumstances, the year of 1812, that gave the name to the war of the next three years, found the country in a peculiar condition. Under the “gunboat system” of Mr. Jefferson, who believed in harbor protection, and trusted to escape war, an act had been passed in 1805 which almost threatened annihilation of a practical navy. The construction of twenty-five gunboats authorized by this bill had been followed, from time to time, by the building of more of them under the mistaken idea that this policy was a national safeguard. They would have been of great use as a branch of coast fortification at that time, it may be true, but they were absolutely of no account in the prosecution of a war at sea. Up to the year 1811 in the neighborhood of two hundred of these miserable vessels had been constructed, and11 they lay about the harbors in various conditions of uselessness.

From an official statement it appears that there were but three first-class frigates in our navy, and that but five vessels of any description were in condition to go to sea. They were the President, 44 guns; the United States, 44 guns; the Constitution, 44 guns; the Essex, 32 guns; and the Congress, 36 guns. All of our sea-going craft taken together were but ten in number, and seven of these were of the second class and of inferior armament. There was not a single ship that did not need extensive repairs, and two of the smaller frigates, the New York and the Boston, were condemned upon examination. The navy was in a deplorable state, and no money forthcoming.

But the session of Congress known as the “war session” altered this state of affairs, and in the act of March 13th, 1812, we find the repudiation of the gunboat policy, and the ridiculous error advanced, to our shame be it said, by some members of Congress, that “in creating a navy we are only building ships for Great Britain,” was cast aside. Not only did the act provide for putting the frigates into commission and preparing them for actual service, but two hundred thousand dollars per annum was appropriated for three years for ship timber. The gunboats were laid up “for the good of the public service,” and disappeared. Up to this period all the acts of Congress in favor of12 the navy had been but to make hasty preparations of a few vessels of war to meet the pressure of some emergency, but no permanent footing had been established. The conduct and the result of the war with Tripoli had not been such as to make the American Navy popular, despite the individual brave deeds that had taken place and the respect for the flag that had been enforced abroad. But the formation of a “naval committee” was a step in the right direction. There was a crisis to be met, the country was awake to the necessity, and the feelings of patriotism had aroused the authorities to a pitch of action. Many men, the ablest in the country, were forced into public life from their retirement, and a combination was presented in the House of Representatives and in the Senate that promised well for the conduct of affairs. The Republican party saw that there was no more sense in the system of restriction, and that the only way to redress the wrongs of our sailors was by war.

Langdon Cheves was appointed chairman of this Committee of Naval Affairs of the Twelfth Congress, and took hold of the work assigned to him with energy and judgment. There was some slight opposition given by people who doubted our power and resources to wage war successfully against Great Britain, but this opposition was overwhelmed completely at the outset. The report of the naval committee shows that the naval establishments of other countries had been carefully looked into,13 and experienced and intelligent officers had been called upon for assistance; that the needs and resources of the country had been accurately determined, and the result was that the committee expressed the opinion “that it was the true policy of the United States to build up a navy establishment as the cheapest, the safest, and the best protection to their sea-coast and to their commerce, and that such an establishment was inseparably connected with the future prosperity, safety, and glory of the country.”

The bill which was introduced and drafted by the committee recommended that the force to be created should consist of frigates and sloops of war to be built at once, and that those already in commission be overhauled and refitted. To quote from the first bill for the increase of the navy, communicated to the House of Representatives September 17th, 1811 (which antedated the final act of March 13th, 1812), Mr. Cheves says for the committee: “We beg leave to recommend that all the vessels of war of the United States not now in service, which are worthy of repair, be immediately repaired, fitted out, and put into actual service; that ten additional frigates, averaging 38 guns, be built; that a competent sum of money be appropriated for the purchase of a stock of timber, and that a dock for repairing the vessels of war of the United States be established in some central and convenient place.” There was no dock in the country at this date, and vessels had to be “hove down” to repair their hulls—an expensive and lengthy14 process.

A large number of experiments had also been made during this year in reference to the practical use of the torpedo. They were conducted in the city and harbor of New York, under the supervision of Oliver Walcott, John Kent, Cadwallader B. Colden, John Garnet, and Jonathan Williams. Suggestions were also made for the defence of vessels threatened by torpedo attack in much the same method that is employed to this date—by nets and booms. Mr. Colden says in a letter addressed to Paul Hamilton, Secretary of the Navy, in reference to the experiments with Mr. Fulton’s torpedoes, “I cannot but think that if the dread of torpedoes were to produce no other effect than to induce every hostile vessel of war which enters our ports to protect herself in a way in which the Argus (the vessel experimented with) was protected, torpedoes will be no inconsiderable auxiliaries in the defence of our harbors.” Strange to say, a boom torpedo rigged to the end of a boom attached to the prow of a cutter propelled by oars was tried, and is to this day adopted in our service, in connection with fast steam-launches. All this tends to show the advancing interest in naval warfare. Paul Hamilton suggested, in a letter dated December 3d, 1811, that “a naval force of twelve sails of the line (74’s) and twenty well-constructed frigates, including those already in commission, would be ample to protect the coasting trade”; but there was no provision15 in the bill as finally accepted, and no authority given for the construction of any line of battle ships, although Mr. Cheves referred in his speech to the letter from Secretary Hamilton. Plans were also made this year to form a naval hospital, a much-needed institution.

When war was declared by Congress against Great Britain, on June 18th, 1812, and proclaimed by the President of the United States the following day, the number of vessels, exclusive of those projected and building, was as follows:

16

| FRIGATES | |||

| Rated | Mounting | Commanders | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitution | 44 | 56 | Capt. Hull |

| United States | 44 | 56 | Capt. Decatur |

| President | 44 | 56 | Com. Rodgers |

| Chesapeake | 36 | 44 | Capt. Evans |

| New York | 36 | 44 | |

| Constellation | 36 | 44 | Capt. Stewart |

| Congress | 36 | 44 | Capt. Smith |

| Boston | 32 | ||

| Essex | 32 | Capt. Porter | |

| Adams | 32 | ||

| CORVETTES | |||

| John Adams | 26 | Capt. Ludlow | |

| SLOOPS OF WAR | |||

| Wasp | 18 | 18 | Capt. Jones |

| Hornet | 18 | 18 | Capt. Lawrence |

| BRIGS | |||

| Siren | 16 | Capt. Carroll | |

| Argus | 16 | Capt. Crane | |

| Oneida | 16 | Capt. Woolsey | |

| SCHOONERS | |||

| Vixen | 14 | Lieut. Gadsden | |

| Nautilus | 14 | Lieut. Sinclair | |

| Enterprise | 14 | Capt. Blakely | |

| Viper | 10 | Capt. Bainbridge | |

| BOMB-KETCHES | |||

| Vengeance | Ætna | ||

| Spitfire | Vesuvius | ||

As we have stated before, the Boston, that was burned afterwards at Washington, never put to sea, and the New York was a worthless hulk.

The Constitution, the United States, and the Constellation were built in the year 1797, the Constitution at Boston, the United States at Philadelphia, and the Constellation at Baltimore. They had been built in the most complete manner, and it might be of interest to give some figures in connection with the construction of these vessels, thus forming an idea of how they compare with the tremendous and expensive fighting-machines of today. The first cost of the Constitution was $302,718. Her annual expenses when in commission were $100,000. Her pay-roll per month was in the neighborhood of $5000. There had been spent in repairs upon the Constitution from October 1st, 1802, to October 1st, 1811, the sum of $302,582—almost as much as her original cost, it is thus seen; but upon the outbreak of the war only $5658 had to be spent upon her to fit her for sea. The first cost of a small vessel like the Wasp, carrying 18 guns, was $60,000; the17 annual expense in commission, $38,000.

Although the Constitution was in such good shape, the Chesapeake and the Constellation were not seaworthy, and required $120,000 apiece to be expended on them before they would be considered ready for service.

An American 44-gun frigate carried about 400 men. The pay appears ridiculously small, captains receiving but $100; masters-commandant, $75 a month; lieutenants’ pay was raised from $40 to $60. Midshipmen drew $19, an ordinary seaman $10, and a private of marines but $6 a month.

A 44-gun frigate was about 142 feet long, 38 feet 8 inches in breadth, and drew from 17 to 23 feet of water, according to her loading. An 18-gun sloop of war was between 110 and 122 feet in length, and drew 15 feet of water.

At the time of the declaration of war the officers holding captains’ commissions were: Alexander Murray, John Rodgers, James Barron (suspended), William Bainbridge, Hugh G. Campbell, Stephen Decatur, Thomas Tingey, Charles Stewart, Isaac Hull, Isaac Chauncey, John Shaw, John Smith—there was one vacancy. On the pay-rolls as masters-commandant we find David Porter, Samuel Evans, Jacob Jones, and James Lawrence.

It is hard to imagine nowadays the amount of bitterness, the extreme degree of hatred, that had grown up between America and Great Britain. Before the outbreak of hostilities, smarting under the defeats of18 ’76 and the struggle of the following years, with few exceptions English officers burned to show their contempt for the service of the new country whose flag was being sent about the world. During the presence of the American fleets under Preble and Bainbridge in the Mediterranean, insults were frequently forced upon them by the English. An anecdote which brings in one of our nation’s heroes will show plainly to what extent this feeling existed. From an American vessel of war anchored at Malta a number of the junior officers had obtained shore leave; among them was a tall, handsome lad, the brother of the commander of the Philadelphia. Orders had been given for the young gentlemen to mind their own affairs, to keep close together, and to pay no attention to the treatment they might receive from the officers of the English regiments or navy. Owing to the custom then holding, the man who had not fought a duel or killed a man in “honorable” meeting was an exception, even in our service. There was no punishment for duelling in either the army or navy, even if one should kill a member of his own mess, so there may be some excuse for the disobedience, or, better, disregard, of the order given to the midshipmen before they landed. There was an English officer at Malta, a celebrated duellist, who stated to a number of his friends, when he was informed that the American young gentlemen had landed, that he would “bag one of the Yankees before ten the next morning.” He ran across them in the lobby19 of a playhouse, and, rudely jostling the tallest and apparently the oldest, he was surprised at having his pardon begged, as if the fault had been the other’s. So he repeated his offence, and emphasized it by thrusting his elbow in “the Yankee’s” face.

This was too much. The tall midshipman whipped out his card, the Englishman did likewise. A few words and it was all arranged. “At nine the next morning, on the beach below the fortress.” As he turned, the middy saw one of his senior lieutenants standing near him. He knew that it would be difficult to get ashore in the morning, and he made up his mind that, as the chances were he would never return to his ship at all, he would not go back to her that night. But what was his dismay when the officer approached and ordered him and all of his party to repair on board their vessel. Of course the rest of the youngsters knew what had occurred, and they longed to see how their comrade would get out of the predicament. He had to be on shore! But as he sat in the stern-sheets the lieutenant, not so many years his senior, bent forward. “I shall go ashore with you at nine o’clock to-morrow, if you will allow me that honor,” he said, quietly. Now this young officer was a hero with the lads in the steerage, and the middy’s courage rose.

At nine o’clock the next morning he stood in a sheltered little stretch of beach with a pistol in his hand, and at the word “Fire!” he shot20 the English bully through the heart. The midshipman’s name was Joseph Bainbridge, a brother of the Bainbridge of Constitution fame, and his second upon this occasion was Stephen Decatur.

This encounter was but one of many such that took place on foreign stations between American and English officers. The latter at last became more respectful of the Yankees’ feelings, be it recorded.

The following series of articles is not intended as a history of the navy, but as a mere account of the most prominent actions in which the vessels of the regular service participated. Two affairs in which American privateers took part are introduced, but of a truth the doings of Yankee privateersmen would make a history in themselves.

It will be noticed that the names of several vessels occur frequently, and we can see how the Constitution won for herself the proudest title ever given to a ship—“Old Ironsides”—and how the victories at sea united the American nation as one great family in rejoicing or in grief. To this day there will be found songs and watchwords in the forecastles of our steel cruisers that were started at this glorious period. “Remember the Essex!” “Don’t give up the ship!” “May we die on deck!” are sayings that have been handed down, and let us hope that they will live forever.

21

22

23

If during the naval war of 1812 any one man won laurels because he understood his ship, and thus triumphed over odds, that man was Captain Hull, and the ship was the old Constitution.

Returning from a mission to Europe during the uncertain, feverish days that preceded the declaration of war between England and America, Hull had drawn into the Chesapeake to outfit for a cruise. He had experienced a number of exciting moments in European waters, for everything was in a turmoil and every sail suspicious—armed vessels approached one another like dogs who show their fangs.

Although we were at peace, on more than one occasion Hull had called his men to quarters, fearing mischief. Once he did so in an English port, for he well remembered the affair of the Leopard and the Chesapeake.

At Annapolis he shipped a new crew, and on July 12th he sailed around the capes and made out to sea. Five days later, when out of sight of land, sailing with a light breeze from the northeast, four sail were discovered to the north, heading to the westward. An hour later a fifth sail was seen to the northward and eastward. Before sunset it could be declared positively that the strangers were vessels of war, and24 without doubt English. The wind was fair for the nearest one to close, but before she came within three miles the breeze that had brought her up died out, and after a calm that lasted but a few minutes the light wind came from the southward, giving the Constitution the weather-gage.

And now began a test of seamanship and sailing powers, the like of which has no equal in history for prolonged excitement. Captain Hull was almost alone in his opinion that the Constitution was a fast sailer. But it must be remembered, however, that a vessel’s speed depends upon her handling, and with Isaac Hull on deck she had the best of it.

All through the night, which was not dark, signals and lights flashed from the vessels to leeward. The Constitution, it is claimed by the English, was taken for one of their own ships. She herself had shown the private signal of the day, thinking perhaps that the vessel near to hand might be an American.

Before daybreak three rockets arose from the ship astern of the Constitution, and at the same time she fired two guns. She was H. M. S. Guerrière, and, odd to relate, before long she was to strike her flag to the very frigate that was now so anxious to escape from her. Now, to the consternation of all, as daylight broadened, three sail were discovered on the starboard quarter and three more astern. Soon another one was spied to the westward. By nine o’clock, when the mists had lifted, the Constitution had to leeward and astern of her seven25 sail in sight—two frigates, a ship of the line, two smaller frigates, a brig, and a schooner. There was no doubt as to who they were, for in the light breeze the British colors tossed at their peaks. It was a squadron of Captain Sir Philip Vere Broke, and he would have given his right hand to have been able to lessen the distance between him and the chase. But, luckily for “Old Ironsides,” all of the Englishmen were beyond gunshot. Hull hoisted out his boats ahead, and they began the weary work of towing; at the same time, stern-chasers were run out over the after-bulwarks and through the cabin windows. It fell dead calm, and before long all of the English vessels had begun to tow also. But the Constitution had the best position for this kind of work, as she could have smashed the boats of an approaching vessel, while her own were protected by her hull. One of the nearest frigates, the Shannon, soon opened fire, but her shot fell short, and she gave it up as useless. At this moment a brilliant idea occurred to Lieutenant Morris of the Constitution. It had often been the custom in our service to warp ships to their anchorage by means of kedge-anchors when in a narrow channel; by skillful handling they had sometimes maintained a speed of three knots an hour. Hull himself gives the credit for this idea to Lieutenant Charles Morris.

All the spare hawsers and rope that would stand the strain were spliced together, and a line almost a mile in length was towed ahead of the26 ship and a kedge-anchor dropped. At once the Constitution began to walk away from her pursuers—as she tripped one kedge she commenced to haul upon another. Now for the first time Hull displayed his colors and fired a gun; but it was not long before the British discovered the Yankee trick and were trying it themselves.

A slight breeze happily sprang up, which the Constitution caught first and forged ahead of the leading vessel, that had fifteen or sixteen boats towing away at her. Soon it fell calm again, and the towing and kedging were resumed. But the Belvidera, headed by a flotilla of rowboats, gained once more, and Hull sent overboard some twenty-four hundred gallons of water to lighten his vessel. A few shots were exchanged without result. But without ceasing the wearisome work went on, and never a grumble was heard, although the men had been on duty and hard at work twelve hours and more.

This was to be only the beginning of it. Now and then breezes would spring from the southward, and the tired sailors would seize the occasion to throw themselves on the deck and rest, often falling asleep leaning across the guns—the crews had never left their quarters.

From eleven o’clock in the evening until past midnight the breeze held strong enough to keep the Constitution in advance. Then it fell dead calm once more. Captain Hull decided to give his men the27 much-needed respite; and, except for those aloft and the man at the wheel, they slept at their posts; but at 2 A.M. the boats were out again.

During this respite the Guerrière had gained, and was off the lee beam. It seemed as if it were impossible to avoid an action, and Hull had found that two of his heavy stern-chasers were almost worse than useless, as the blast of their discharge threatened to blow out the stern-quarters, owing to the overhanging of the wood-work and the shortness of the guns. The soundings had run from twenty-six to twenty-four fathoms, and now Hull was afraid of getting into deeper water, where kedging would be of no use.

At daybreak three of the enemy’s frigates had crept up to within long gunshot on the lee quarter, and the Guerrière maintained her position on the beam. The Africa, the ship of the line, and the two smaller vessels had fallen far behind. Slowly but surely the Belvidera drew ahead of the Guerrière, and at last she was almost off the Constitution’s bow when she tacked. Hull, to preserve his position and the advantage of being to windward, was obliged to follow suit. It must have been a wondrous sight at this moment to the unskilled eye; escape would have seemed impossible, for the American was apparently in the midst of the foe. Rapidly approaching her on another tack was the frigate Æolus within long range, but she and the Constitution passed one another without firing. The breeze freshening, Hull28 hoisted in his boats, and the weary rowers rested their strained arms.

All the English vessels rounded upon the same tack as the Constitution, and now the five frigates had out all their kites, and were masses of shining canvas from their trucks to the water’s edge. Counting the Constitution, eleven sail were in sight, and soon a twelfth appeared to the windward. It was evident that she was an American merchantman, as she threw out her colors upon sighting the squadron. The Englishmen did not despatch a vessel to pursue her, but to encourage her to come down to them they all flew the stars and stripes. Hull straightway, as a warning, drew down his own flag and set the English ensign. This had the desired effect, and the merchantman hauled on the wind and made his best efforts to escape.

Hull had kept his sails wet with hose and bucket, in order to hold the wind, and by ten o’clock his crew had started cheering and laughing, for they were slowly drawing ahead; the Belvidera was directly in their wake, distant almost three miles. The other vessels were scattered to leeward, two frigates were on the lee quarter five miles away, and the Africa, holding the opposite tack, was hull down on the horizon. The latitude was made out at midday to be 38° 47´ north, and the longitude, by dead reckoning, 73° 57´ west.

The wind freshened in the early afternoon, and, the sails being trimmed and watched closely, Hull’s claim that his old ship was a stepper,29 if put to it, was verified, for she gained two miles and more upon the pursuers. And now strategy was to come into play. Dark, angry-looking clouds and deeper shadows on the water to windward showed that a sudden squall was approaching. It was plain that rain was falling and would reach the American frigate first. The topmen were hurried aloft, the sheets and tacks and clew-lines manned, and the Constitution held on with all sails set, but with everything ready at the command to be let go. As the rush of wind and rain approached all the light canvas was furled, a reef taken in the mizzen-topsail, and the ship was brought under short sail, as if she expected to be laid on her beam ends. The English vessels astern observed this, and probably expected that a hard blow was going to follow, for they let go and hauled down as they were, without waiting for the wind to reach them. Some of them hove to and began to reef, and they scattered in different directions, as if for safety. But no sooner had the rain shrouded the Constitution than Hull sheeted home, hoisted his fore and main topgallant-sails, and, with the wind boiling the water all about him, he roared away over the sea at a gait of eleven knots.

For an hour the breeze held strong—blowing almost half a gale, in fact—and then it disappeared to leeward. A Yankee cheer broke out in which the officers joined, for the English fleet was far down the wind, and the Africa was barely visible. A few minutes’ more sailing, and30 the leading frigates were hull below the horizon.

Still they held in chase throughout all the night, signalling each other now and then. At daybreak all fear was over; but the Constitution kept all sail, even after Broke’s squadron gave up and hauled to the northward and eastward.

The small brig that had been counted in the fleet of the pursuers was the Nautilus, which had been captured by the English three or four days previously. She was the first vessel lost on either side during the war. She was renowned as having been the vessel commanded by the gallant Somers, who lost his life in the harbor of Tripoli.

Lieutenant Crane, who had command of her when taken by the English, and who saw the whole chase, speaks of the wonder and astonishment of the British officers at the handling of the Constitution. They expected to see Hull throw overboard his guns and anchors and stave his boats. This they did themselves in a measure, as they cut adrift many of their cutters—and spent some time afterwards in picking them up—by the same token. Nothing had been done to lighten the Constitution but to start the water-casks, as before mentioned.

So sure were the English of making a capture that Captain Broke had appointed a prize crew from his vessel, the Shannon, and had claimed the honor of sailing the Constitution into Halifax; but, as a contemporary states, “The gallant gentleman counted his chickens31 before they were hatched”—a saying trite but true.

To quote from the Shannon’s log, under the entry of July 18th, will be of interest: “At dawn” (so it runs) “an American frigate within four miles of the squadron. Had a most fatiguing and anxious chase; both towing and kedging, as opportunity offered. American exchanged a few shots with Belvidera—carried near enemy by partial breeze. Cut our boats adrift, but all in vain; the Constitution sailed well and escaped.”

It is recorded in English annals that there were some very sharp recriminations and explanations held in the Shannon’s cabin. Perhaps Captain Hull would have enjoyed being present; but by this time he was headed northward. He ran into Boston harbor for water on the following Sunday.

Broke’s squadron separated, hoping to find the Constitution on some future day and force her to action. In this desire Captain Dacres of the Guerrière was successful—so far as the finding was concerned; but the well-known result started American hearts to beating high and cast a gloom over the Parliament of England.

The ovations and praises bestowed upon the American commander upon his arrival at Boston induced him to insert the following card on the books of the Exchange Coffee-House:

“Captain Hull, finding that his friends in Boston are correctly informed of his situation when chased by the British squadron off New32 York, and that they are good enough to give him more credit for having escaped it than he ought to claim, takes this opportunity of requesting them to transfer their good wishes to Lieutenant Morris and the other brave officers, and the crew under his command, for their very great exertions and prompt attention to his orders while the enemy were in chase. Captain Hull has great pleasure in saying that, notwithstanding the length of the chase, and the officers and crew being deprived of sleep, and allowed but little refreshment during the time, not a murmur was heard to escape them.”

It is rather a remarkable circumstance that the Belvidera, which was one of the vessels that in this long chase did her best to come up with the Constitution, had some months before declined the honor of engaging the President. For, on the 24th of June, Captain Rodgers had fired with his own hand one of the President’s bow-chasers at the Belvidera, and thus opened the war. After exchanging some shots, Captain Byron, of the Belvidera, decided that discretion was the better part, and, lightening his ship, managed to escape.

33

35

The history of the naval combats of our second war with Great Britain, the career of the frigate Constitution, and the deeds of our Yankee commodores will never be forgotten as long as we have a navy or continue to be a nation. England, it must be remembered, had held the seas for centuries. In no combat between single ships (where the forces engaged were anything like equal) had she lost a vessel. The French fleets, under orders of their own government, ran away from hers, and the Spanish captains had allowed their ships’ timbers to rot for years in blockaded harbors. Nevertheless, this was the age of honor, of gallantry, of the stiff duelling code, when men bowed, passed compliments, and fought one another to the death with a parade of courtesy that has left trace today in the conduct of the intercourse between all naval powers. In the duels of the ships in the past that have stirred the naval world, America has records that are monuments to her seamen, and that must arouse the pride of every officer who sails in her great steel cruisers today.

Up to the affair of the Constitution and the Guerrière, in 1812, the British had not fairly tested in battle the seamanship or naval metal of the Americans. With the exceptions of the actions between the36 Bonhomme Richard and the Serapis, the Ranger and Drake, and the Yarmouth and Randolph, the war of ’76 was a repelled invasion.

The twenty-four hours of the 19th of August, 1812, began with light breezes that freshened as the morning wore on. The Constitution was slipping southward through the long rolling seas.

A month before this date, under the command of Commodore Hull, she had made her wonderful escape from Broke’s squadron after a chase of over sixty hours.

Her cruise since she had left Boston, two weeks before, had been uneventful. Vainly had she sought from Cape Sable to the region of Halifax, from Nova Scotia to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, for any sign of a foe worthy her metal. It was getting on towards two o’clock; her men had finished their midday meal, the afternoon drills had not begun, and an observation showed the ship to be in latitude 41° 40´ and longitude 55° 48´. Suddenly “Sail ho!” from the mast-head stirred the groups on the forecastle, and caused the officer pacing the weather side of the quarter-deck to stop suddenly and raise his head.

“Where away?” he shouted to the voice far up above the booming sails.

Almost before he could get the answer the stranger’s top-sails were visible from the lower rigging, into which the midshipmen and idlers had scrambled, and a few moments later they could be seen from the37 upper deck. The vessel was too far off to show her character, but bore E.S.E., a faint dot against the horizon.

Hull came immediately from his cabin. He was a large, fat man, whose excitable temperament was held in strong control. His eye gleamed when he saw the distant speck of white. Immediately the Constitution’s course was altered, and with her light sails set she was running free, with kites all drawing, and the chase looming clearer and clearer each anxious minute of the time. At three o’clock it was plainly seen that she was a large ship, on the starboard tack, close-hauled on the wind, and under easy sail. In half an hour her ports could be descried through the glass, and loud murmurs of satisfaction ran through the ship’s company. The officers smiled congratulations at one another, and Hull’s broad face shone with his suppressed emotion. In the official account Hull speaks of the conduct of his crew before the fight in the following words: “It gives me great pleasure to say that from the smallest boy in the ship to the oldest seaman not a look of fear was seen. They went into action giving three cheers, and requesting to be laid close to the enemy.” The Constitution gained on the stranger, who held her course, as if entirely oblivious of her pursuer’s presence.

When within three miles, and to leeward, Hull shortened sail and cleared the decks; the drum beat to quarters, and the men sprang to38 their stations. No crew was ever better prepared to do battle for any cause or country. Although few of the men had been in action before, they had been drilled until they had the handling of the clumsy iron guns down to the point of excellence. They had been taught to fire on the falling of a sea, and to hull their opponent, if possible, at every shot. They loved and trusted their commander, were proud of their ship, and burned to avenge the wrongs to which many had been subjected, for the merchant service had furnished almost half their number.

As soon as Hull took in his sail the stranger backed her main-topsail yard, and slowly came up into the wind. Then it could be seen that her men were all at quarters also. Hull raised his flag. Immediately in response up went to every mast-head of the waiting ship the red cross of old England. It was growing late in the afternoon, the breeze had freshened, and the white-caps had begun to jump on every side. The crew of the Constitution broke into three ringing cheers as their grand old craft bore down upon the enemy. When almost within range the English let go her broadside, filled away, wore ship, and fired her other broadside on the other tack. The shot fell short, and the Constitution reserved her fire. For three-quarters of an hour the two yawed about and manoeuvred, trying to rake and to avoid being raked in39 turn. Occasionally the Constitution fired a gun; her men were in a fever of impatience.

At six in the evening the enemy, seeing all attempts to outsail her antagonist were in vain, showed a brave indication of wishing to close and fight. Nearer the two approached, the American in silence.

“Shall I fire?” inquired Lieutenant Morris, Hull’s second in command.

“Not yet,” replied Hull, quietly.

The bows of the Constitution began to double the quarter of the enemy. The latter’s shot began to start the sharp white splinters flying about the Constitution’s decks.

“Shall I fire?” again asked Lieutenant Morris.

“Not yet, sir,” was Hull’s answer, spoken almost beneath his breath. Suddenly he bent forward. “Now, boys,” he shouted, loudly, so that his voice rang above the enemy’s shots and the roaring of the seas under the quarter, “pour it into them!” It was at this point, so the story goes, that Hull, crouching in his excitement, split his tight knee-breeches from waistband to buckle.

The Constitution’s guns were double-shotted with round and grape. The broadside was as one single explosion, and the destruction was terrific. The enemy’s decks were flooded, and the blood ran out of the scuppers—her cockpit filled with the wounded. For a few minutes, shrouded in smoke, they fought at the distance of a half pistol-shot, but in that short space of time the Englishman was literally torn to40 pieces in hull, spars, sails, and rigging.

As her mizzen-mast gave way the Englishman brought up into the wind, and the Constitution forged slowly ahead, fired again, luffed short around the other’s bows, and, owing to the heavy sea, fell foul of her antagonist, with her bowsprit across her larboard quarter. While in this position Hull’s cabin was set on fire by the enemy’s forward battery, and part of the crew were called away from the guns to extinguish the threatening blaze.

Now both sides tried to board. It was the old style of fighting for the British tars, and they bravely swarmed on deck at the call, “Boarders away!” and the shrill piping along the ’tween-decks. The Americans were preparing for the same attempt, and three of their officers who mounted the taffrail were shot by the muskets of the English. Brave Lieutenant Bush, of the marines, fell dead with a bullet in his brain.

The swaying and grinding of the huge ships against each other made boarding impossible, and it was at this anxious moment that the sails of the Constitution filled; she fell off and shot ahead. Hardly was she clear when the foremast of the enemy fell, carrying with it the wounded main-mast, and leaving the proud vessel of a few hours before a helpless wreck, “rolling like a log in the trough of the sea, entirely at the mercy of the billows.”

41 It was now nearly seven o’clock. The sky had clouded over, the wind was freshening, and the sea was growing heavy. Hull drew off for repairs, rove new rigging, secured his masts, and, wearing ship, again approached, ready to pour in a final broadside. It was not needed. Before the Constitution could fire, the flag which had been flying at the stump of the enemy’s mizzen-mast was struck. The fight was over.

A boat was lowered from the Constitution, and Lieutenant Read, the third officer, rowing to the prize, inquired, with “Captain Hull’s compliments,” if she had struck her flag. He was answered by Captain Dacres—who must have possessed a sense of humor—that, for very obvious reasons, she certainly had done so.

To quote a few words from Hull’s account of the affair—he says: “After informing that so fine a ship as the Guerrière, commanded by an able and experienced officer, had been totally dismasted and otherwise cut to pieces, so as to make her not worth towing into port, in the short space of thirty minutes (actual fighting time), you can have no doubt of the gallantry and good conduct of the officers and ship’s company I have the honor to command.”

In the Constitution seven were killed and seven wounded. In the Guerrière, fifteen killed, sixty-two wounded—including several officers and the captain, who was wounded slightly; twenty-four were missing.

42 The next day, owing to the reasons shown in Hull’s report, the Guerrière was set on fire. At 3.15 in the afternoon she blew up; and this was the end of the ship whose commander had sent a personal message to Captain Hull some weeks before, requesting the “honor of a tête-à-tête at sea.”

Isaac Hull, who had thus early endeared himself in the hearts of his countrymen, and set a high mark for American sailors to aim at, was born near the little town of Derby, not far from New Haven, Connecticut, in the year 1775. He was early taken with a desire for the sea, and at the age of twelve years he went on board a vessel that had been captured by his father from the British during the Revolution.

Although he entered the navy at the age of twenty-three, he had already made eighteen voyages to different parts of Europe and the West Indies, and had seen many adventures and thrilling moments.

During the administration of John Adams there occurred “that exceedingly toilsome but inglorious service” of getting rid of the French privateers who infested the West Indian seas. During this quasi-war Hull was first lieutenant of the frigate Constitution under Commodore Talbot. In May, 1798, he had a chance to distinguish himself, and did not neglect the opportunity, although the upshot of it was tragic but bloodless.

It might not be out of place to relate the incident here. In the harbor Porto Plata, in the island of St. Domingo, lay the Sandwich, a43 French letter-of-marque. Hull was sent by his superior, in one of the cutters, to reconnoitre the Frenchman. On the way he found a little American sloop that rejoiced in the name of Sally. Hull threw his party of seamen and marines on board of her, and hid them below the deck. Then the Sally was put into the harbor, and, as if by some awkwardness, ran afoul of the Sandwich, which, as a jocose writer remarks, “they devoured without the loss of a man.” At the same time this rash proceeding was being carried on under the eyes (or, better, guns) of a Spanish battery, Lieutenant Carmick took some marines and, rowing ashore, spiked the guns. The Sandwich was captured at midday, and before the afternoon was over she weighed her anchor, beat out of the harbor, and joined the Constitution.

In the opinion of nautical judges this was the best bit of cutting-out work on record, for Hull’s men were outnumbered three to one; and if he had not taken precautions, the battery could have blown him out of the water. But, alas and alack! all this daring and bravery went for worse than naught. Spain complained of the treatment she had received, and the United States government acknowledged that the capture was illegal, having taken place in a neutral port. The Sandwich was restored to her French owners, and, worst of all, every penny of the prize money due the Constitution’s officers and men for this cruise went to pay the damages.

44 Before the war of 1812, Hull distinguished himself by his fearlessness and self-reliance during the Tripolitan war. The two occasions that gave him renown during our struggle with Great Britain have been recorded at length, and there is but to set down that, after the conclusion of the war with Great Britain, Commodore Hull was in command at the various stations in the Pacific and the Mediterranean, and departed this life on the 13th of February, 1843. Of him John Frost writes, in 1844, “He was a glorious old commodore, with a soul full of all noble aspirations for his country’s honor—a splendid relic of a departed epoch of naval renown.”

45

47

Jacob Jones, of the United States Navy, was a native of Kent County, in the State of Delaware. He rose rapidly through the various grades of the service, attracting notice by his steadfastness and attention to duty, and in 1811 he was transferred to the command of the Wasp, a tidy sloop of war then mounting eighteen 24-pound carronades. She was a fast sailer, given any wind or weather.

In the spring of 1812, Captain Jones was despatched to England with communications to our minister at the Court of St. James. After fulfilling his mission he immediately set sail for America. The declaration of war between England and this country took place while the Wasp was on the high seas on her returning voyage; but as soon as he had landed, the news greeted her commander, and he was eager to put to sea again.

Captain Jacob Jones knew his ship, he knew his crew, and he rejoiced in having about him a set of young officers devoted to the service. Their names were James Biddle, George W. Rogers, Benjamin W. Broth, Henry B. Rapp, and Lieutenants Knight and Claxton, and they were soon destined to win laurels and glory for their country.

48 The first short cruise yielded no adventure of importance, but on the 13th of October the Wasp left the Delaware and two days later encountered a heavy gale, during which her jib-boom was unfortunately carried away and two of her people lost overboard. For some hours she was thrown about like a shuttlecock, and all hands were called time and again to shorten sail. The night of the 17th the sky cleared and the stars shone brightly. To Captain Jones’s surprise several sail were reported as being close at hand to the eastward. They were clearly seen through the night-glass to be large, and apparently armed. Jones stood straight for them, and gave orders to lay the same course that the strangers were then holding, and so they kept until dawn of the next day, which was a Sunday.

A heavy sea was running, and the Wasp, close-hauled, crept up to windward of the fleet that she had followed through the night. At the beginning of the early morning watch they were made out to be four large ships and two smaller vessels under a spread of canvas, all keeping close together.

But what was more interesting to the eager American crew was a sturdy sloop of war, a brig, that was edging up slowly into the wind, evidently guarding the six fleeing vessels to leeward—the sheep-dog of the flock.

The Wasp, having the weather-gage, swung off a point or so to lessen the distance.

As the stranger brig came nearer she heeled over until her broadside49 could be counted with the eye, and her lower sails were seen to be wet with the spray that dashed up over her bows.

For some time the Americans had been aloft getting down the topgallant yards, and at eleven o’clock the stranger brig shortened sail and shook out the Spanish flag. But this did not deceive the wary Yankee captain for half an instant. No one but an American or an Englishman would carry sail in that fashion or bring his ship up to an enemy like that, and the Wasp’s drummer beat to quarters.

Now for over thirty minutes the two vessels sailed on side by side, but constantly nearing. At last they were so close that the buttons of the officers’ coats could be seen, the red coat of a marine showed, and all doubt on board the Wasp of the other being anything but English was dispelled in a flash. The matches had been smoking for a full quarter of an hour.

When within near pistol-shot Captain Jones hailed through his trumpet. Down came the colors of Spain and up went the cross of St. George. The distance was scarcely sixty yards, and as the flags exchanged the brig let go her broadside. A lucky incident occurred just then that probably saved many lives on board the Wasp. A sudden puff of wind heeled the enemy over as she fired, and her shot swept through the upper rigging and riddled the sails. Jones immediately replied with all his guns,50 that tore and hulled his antagonist with almost every shot; then, as fast as his crew could load and fire, he kept at it. Now and then the muzzles of his little broadside would sweep into the water; but those of the enemy, aimed high, were mangling his rigging and sweeping away braces, blocks, and running gear.

At the end of a hot five minutes there was a sharp crack aloft, and the main-topmast of the Wasp swayed and fell, bringing down the main-topsail yard across the fore-topsail braces and rendering the head-sails unmanageable. Three minutes more and away went the gaff at the jaws, and the mizzen-topgallant-sail fluttered to the deck like a huge wounded bird.

The American, slightly in advance, fell off her course and crossed her enemy’s bows, firing and raking her at close range most fearfully. At once the fire of the Englishman slackened, and the Wasp drifted slowly back to her former position.

Both vessels were jumping so in the seaway that boarding would be attended by mutual danger. The enemy revived from the destructive broadside, fired a few more shots, and the last brace of the Wasp fell over her side, leaving the masts unsupported, and, badly wounded as they were, in a most critical condition.

“We must decide this matter at once,” said Captain Jones, as he looked at the creaking spars, and he gave orders to wear ship. Slowly his vessel answered, and, paying off, the collision followed. With a51 grinding jar the Wasp rubbed along the Englishman’s bow, and the jib-boom of the latter, extending clear across the deck immediately over the American commander’s head, fouled in the mizzen-shrouds. It was not necessary to make her fast, and she lay so fair for raking that Jones gave orders for another broadside.

As the gunners of the Wasp threw out their rammers the ends touched the enemy’s sides, and the muzzles of two 12-pounders went through the latter’s bow-ports and swept the deck’s length.

Jack Lange was an able American seaman who had once been impressed into the British service, and the excitement of the moment was too much for his feverish blood. Taking his cutlass in his teeth, he leaped atop a gun and laid hold of the enemy’s nettings.

“Come out of that, sir! Wait for orders!” roared Captain Jones, who wished to fire again.

But if Jack Lange heard he did not hesitate, and, despite the command, hauled himself alone over the bows. Some of the men left their guns at this and picked up pikes and boarding-axes.

Lieutenant Biddle glanced at his commander, the latter nodded grimly, and with a spring the lieutenant gained the hammock cloth and reached up for the ropes overhead. The vessels lurched and one of his feet caught in a tangle, from which he vainly tried to free himself.

52 Little Midshipman Baker, who was too short to make a reach of it, thought he saw his chance, and, laying hold of Lieutenant Biddle’s coat-tails in his eagerness, tried to swarm up his superior’s legs. The result was, however, that both fell back on the rail, and came within an ace of pitching overboard into the sea. Jumping up quickly, Lieutenant Biddle took advantage of a heave of the Wasp and scrambled over the enemy’s bowsprit on to the forecastle.

There stood Jack Lange, with his cutlass in his folded arms, gazing at a wondrous sight. Not a living soul was on the deck but a wounded man at the wheel and three officers huddled near the taffrail! But the colors were still whipping and snapping overhead, and, two or three more of the Wasp’s boarders tumbling on board, the little party, headed by Biddle, made their way aft. Immediately the officers, two of whom were wounded, threw down their swords, and one of them leaned forward and hid his face in his hands.

The young lieutenant jumped into the rigging and hauled down the flag. It was almost beyond belief that such carnage and complete destruction could have taken place in a time so short. But a small proportion of the crew had escaped. The wounded and dying lay everywhere, the berth-deck was crowded, and there were not enough of the living to minister to their comrades. H. M. S. Frolic was a charnel-ship.

53 The Wasp’s crew brought on board all their blankets, and the American surgeon’s mate was soon busy attending to the wounded.

With great difficulty the two vessels were separated, for the Frolic had locked her antagonist, as it were, in a dying embrace; and no sooner were they clear than both of the prize’s masts fell (one bringing down the other), covering the dead and wounded, and hampering all the efforts of Lieutenant Biddle and his crew to clear the decks.

All this time three great white topsails had been pushing up above the horizon, and soon it was made out that a large ship of some kind was bearing down, carrying all the canvas she safely could in the sharp blow.

Jones, thinking that it might be one of the convoy returning to seek the Frolic, called his tired crew to quarters, instructing Lieutenant Biddle to fit a jury rig and to make with his charge for some Southern port. It was not to be, however, and the gallant victory was to have a different termination.

The lookout on the foremast called down something that changed the complexion of matters entirely.

“A seventy-four carrying the English flag!” he shouted. That was all. The men at the Wasp’s guns put out their matches. There was nothing to do but wait and be taken. Any resistance would be worse than foolish.

As the great battle-ship came bowling along she passed so close that54 the faces could be seen looking through her three tiers of great open ports. She disdained to hail, fired one gun over the little Wasp, and swept on. Captain Jones hauled down his flag, and read the word Poictiers under the Britisher’s galleries. In a minute or two the latter retook the Frolic, and, lowering her boats, placed prize crews on board both her and the Yankee sloop. After some repairing, she set sail and carried her captives to Bermuda.

As in all the separate engagements of the time, comparisons were made between the armaments and crews of the fighters, and the press of Great Britain and America began the customary argument. Probably the Wasp had a few more men, but to quote:

“The Frolic mounted sixteen 32-pound carronades, four 12-pounders on the main-deck and two 12-pound carronades. She was, therefore, superior to the Wasp by exactly four 12-pounders. The number of men on board, as stated by the officers of the Frolic, was 110. The number of seamen on the Wasp was 102. But it could not be ascertained whether in this 110 were included marines and officers, for the Wasp had, besides her 102 seamen, officers and marines, making the whole crew about 135. What, however, is decisive as to their comparative force is that the officers of the Frolic acknowledged that they had as many men as they knew what to do with, and, in fact, the Wasp could have spared fifteen men.... The exact number of killed and wounded on board55 the Frolic could not be determined, but from the observations of our officers and the declarations of those of the Frolic the number could not be less than about thirty killed, including two officers, and of the wounded between forty and fifty, the captain and lieutenant being of the number. The Wasp had five killed and five slightly wounded.”

Captain Jones in his report speaks of the bravery of his officers, the gallantry of his adversary, Captain Whinyates, and makes little mention of himself. Upon his exchange and return to the United States he was received with every honor belonging to a victor, and the sum of $25,000 was voted by Congress to be divided as prize money among his crew. The Wasp soon flew the British flag, but was lost at sea. Strange to relate, this was also the fate of the second Wasp that was soon afloat in the American service, and that had a career which was surpassed by none of the smaller vessels of the day.

56

59

Eighty-four years ago, throughout the country, the name Decatur was toasted at every table, was sung from the forecastle to the drawing-room, from the way-side tavern to the stage of the city playhouse. Today, written or spoken, it stands out like a watchword, reminiscent of the days of brave gallantry and daring enterprise at sea.

Those writers who have been tempted by their Americanism and pride to take up the navy as a field have repeated over and over again, more than likely, everything that could be said about Stephen Decatur.

On his father’s side he was of French descent, as his name shows, his grandfather being a native of La Rochelle in France, and his grandmother an American lady from Rhode Island. He was named after his father, Stephen Decatur, who was born at Newport, but who had at an early age removed to Philadelphia, where he had married the beautiful Miss Pine.