The Project Gutenberg EBook of Harper's Round Table, June 2, 1896, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Harper's Round Table, June 2, 1896 Author: Various Release Date: September 24, 2018 [EBook #57969] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S ROUND TABLE, JUNE 2, 1896 *** Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, JUNE 2, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 866. | two dollars a year. |

cell in the great Morro Castle of Havana was a strange place for a boy of fourteen; but there sat young Cristobal Nunez on the cold stone floor, his face hidden in his hands, and bitter tears trickling between his fingers. He was a small boy for fourteen, and not dark, like the Cubans, but fair as any sunburnt American boy.

He was not alone in the cell, for it was a great damp vault twenty feet wide by a hundred feet long, with an arched roof of stone, the lower part of a storehouse standing just within the outer wall of the fortress. He was only one of the 108 political prisoners confined in that unhealthy vault, where was not a cot for them to lie upon, nor a chair or bench to sit upon.

"Cheer up, my son," said a well-dressed elderly gentleman, one of his fellow-prisoners, stooping beside him, and laying his hand kindly on Cristobal's shoulder; "these dark days must have an end; and tears, at any rate, will do no good. You are young to be engaged in this business."

"I am not engaged in this business, señor," Cristobal quickly answered, brushing his hand across his eyes and looking up. "I am no insurgent; I am a Spaniard, a Catalan, and know nothing about rebellions. And it is not for myself that I shed tears, but for my young sister, who is alone on this strange island, with no one to take care of her."

As he spoke of his sister the young Catalan again buried his face in his hands, and his little frame shook.

"This is strange," said the gentleman; and he seated himself on the floor beside Cristobal, and kindly drew the young Spaniard's smooth cheek against his shoulder. "If you are a Catalan, and no insurgent, how do you come to be here?"

Though the cell was crowded with prisoners, there was no danger of interruption, for each was amusing himself in his own way. Some played games with strange Spanish cards, on which were pictures of swords and men and horses; some read books, for no newspapers were allowed them; some sang brave songs to keep their spirits up; and others, sickened by the bad air and bad food, lay stretched upon the stones, groaning.

"They have made a mistake," Cristobal answered, as soon as he was able to speak. "I am only a poor boy from Barcelona, trying to take my young sister to our uncle in Cienfuegos. But they have arrested me for an insurgent, and what is to become of my poor sister? We were in a cane-field only twenty-five miles from Cienfuegos, when they tore me away from her; and there I had to leave her, without a friend on the island, unless she finds our uncle. Oh, señor, what is to become of her?"

"They have made many mistakes," the kindly old gentleman replied, ignoring Cristobal's last question. "Here in this miserable cell are old men and young—merchants, professional men, clerks, laborers, and what not—at least half of whom are entirely innocent. It is one of the misfortunes of war that the innocent must suffer with the guilty. But if you are a Catalan from Barcelona, tell me how you come to be in Cuba, and at such a time."

"My mother knew nothing about the troubles in Cuba," Cristobal answered. "She died in Barcelona four months ago, telling us to come to her brother, our uncle, in Cienfuegos. There was barely enough money left to bring us in a sailing vessel to Havana, and from here I wrote and wrote to our uncle, but received no answer, so I am afraid he must be in the field. We started to walk—"

"To walk to Cienfuegos!" the gentleman exclaimed; "a hundred and twenty miles! How old is your sister?"

"She is only twelve," Cristobal answered, sadly; "but she has the sense of a grown woman—a great deal more than I have."

"And then?" the old man said, encouragingly.

"We walked as far as Ysabel," Cristobal went on, "seventy-five miles from here, and there, by accident, I got a situation in a small store. For nearly three months I was able to take care of my sister; but then my employer was arrested for a rebel, and we started on for Cienfuegos."

"Poor little chaps!" exclaimed the old gentleman; "fourteen and twelve; in a strange country; no money or friends! Well?"

"There is not much more," the young Catalan answered. "We were within twenty-five miles of Cienfuegos, and at noon we went into a small patch of cane for our dinner, for sugar-cane was almost our only food. It was part of a great field, but all the cane had been burned but one little corner. We made a spark of fire to boil our coffee, and while it boiled there came along a squad of Spanish troops. They saw the smoke, and accused me of firing the field, and in a minute they had handcuffs on me and tore me away. They took me to Sagua la Grande, and in a few days I was brought here in a steamer. But what they did with me is nothing. What can have become of my poor sister?"

"My son," said the old gentleman, devoutly making the sign of the cross upon his forehead, "your sister is in stronger hands than yours. The Friend of the Fatherless will take care of her. And mark my words, my poor boy, it will be through your sister that you will be released from this unjust imprisonment. For yourself you can do nothing, nor can I aid you in any way. But she is your sister, and at liberty. She will go on foot to the Governor-General, perhaps; perhaps she will besiege every public office in Havana. I cannot say what course she will take; but if she has the wisdom you give her credit for, she will never rest till she sets you free. You Catalans are called 'the Yankees of Spain,' and a Catalonian girl will never desert her brother."

"Every Sunday and Wednesday," he continued, "the friends of prisoners are permitted to visit them here. It may not be next Sunday or next Wednesday, but on some Sunday or some Wednesday you will hear from your sister."

As he arose from his uncomfortable seat the old gentleman laid his hand upon the young prisoner's forehead, and muttered a few words that led Cristobal to believe him a priest in disguise, as in fact he was.

But Wednesdays and Sundays came and went, and Cristobal heard no tidings of his sister. The coming of the visitors, however, made an agreeable break in the terrible monotony. On visiting-days the prisoners' friends were carried across the harbor from Havana in row-boats, and after landing on the pebble-paved road at the base of the fortress, went up through the great portal, where a hundred Spanish soldiers were constantly on guard. There they were formed in line, only one at a time being allowed to approach the barred front of the vault.

Cristobal had spent three weeks of misery in his dismal cell, and one Wednesday afternoon he lay half stretched out on the cold floor watching the visitors and listening to their conversation. They brought all the comforts to their friends that the guards would allow—baskets of food, blankets to lie upon, books, clean linen, medicines—and every package was carefully examined by the guard before it was passed into the cell. He saw a well-dressed young Cuban step up in turn behind the bar with nothing in his hands but three long stalks of sugar-cane tied together. He could hardly believe his ears when the guard called,

"Cristobal Nunez!"

Cristobal sprang to his feet, and made his way up to the front. He was sure that he had never seen his visitor before, and he could not understand why the Cuban, instead of speaking to him at once, stood looking him straight in the eyes, as if he would look through him, and then looked intently at the sugar-canes—at the top cane, Cristobal thought, the one that was gnarled and bent.

"Your sister sends you these," the young Cuban said at length, handing the bundle to the guard for examination. "And be careful of your teeth, Cristobal. Our Cuban cane is tough and hard to bite in March."

The guard twirled the bundle of canes in his hand, and laughed derisively at the meanness of the gift as he passed it through the bars to the prisoner. Even some of the other prisoners laughed to think that one of their number was so poor that his friends could send him nothing but a few canes.

Being one of "the Yankees of Spain," Cristobal knew on the moment that his sister had not sent him sugar-canes merely for the sake of the sweet.

"Be careful of my teeth!" he repeated to himself, with the canes lying across his lap. "That means something, for Maria knows my teeth are all right, and able to chew most anything. And it was this top cane the Cuban looked at so hard—the crooked one."

After a few moments' thought he took out his knife and cut a piece about a foot long from the larger end of the crooked cane, intending, at any rate, to eat it, or to solve the mystery if there was a mystery.

At almost the first bite the cane cracked like a hollow reed, showing that the interior had been cut out—for sugar-cane in its natural state is very hard and solid.

Watching his chance when no one was observing him, he split the hollowed cane open with his hands, and saw in the cavity a small packet wrapped in paper. Quick as a flash he slipped the bit of cane into his pocket, and worked with his fingers to release the packet. It was heavy when he got it loose, and was evidently a roll of coins—gold coins, the weight told him. He was afraid to take them out to look, but he hurriedly removed the wrapping, sure of finding a message upon it. And he was not disappointed, for upon the inner side of the little paper he found this note:

"Dear Kit,—Here are five American gold eagles to help you out of prison.

"I am with kind friends—Americanos—on the Buena Vista plantation, near La Flora, district de Cienfuegos. They have furnished the money. Our uncle has been shot.

"When you get out go to Numero 19, Calle O'Reilly, Havana, and ask for Pedro. He will help get you here.

"Your loving Sister."

Cristobal could hardly help shouting when he finished[Pg 743] reading the note; his sister safe, money to help him, and a friend in Havana to help him through the lines! For many days after the arrival of the sugar-cane it was a mystery to Cristobal how his sister had found friends so quickly in a strange country; but now it is a mystery no longer.

When her brother was dragged away and she was left alone in the cane-field, little Maria Nunez first shed tears, and then stamped her feet with rage. Then she took counsel with herself. She could not stay there alone in the cane-field; she could not travel alone in roads filled with soldiers and lawless men. Surely there must be some good Christian on that island who would give her shelter; and she dropped down upon her knees in the muddy field and fingered the cheap beads that hung about her neck, and made many signs of the cross upon her little chest and forehead.

Far away across the blackened fields she saw a roof of red tiles. There must be a house, she knew, under the roof, and she started in that direction.

On the broad front gallery of the house sat Señor Walter Pickard, of Ohio, the owner of the seven thousand acres of land comprising the Buena Vista plantation, which, in times of peace, produces its fifteen thousand hogsheads of sugar every year. There is one larger sugar plantation in the world, and only one. On one side of him sat the Señora Pickard, also of Ohio, and on the other was the young Señor Pickard, aged seventeen. The three were looking across the lane at the great "works" that should have been alive with men and the hum of machinery, but which stood deserted and silent, its walls riddled with bullets; looking over the seven thousand acres of land that should have been rich with cane, but which lay charred with fire and trampled by troops, ruined for many years to come.

"Who is that pretty little girl I saw you taking out toward the quarters a few minutes ago?" the Señora Pickard asked of the butler through the open window.

"A little Spanish girl, madame," replied the French butler, "who says that her brother has just been arrested for a rebel, and who came to us for shelter."

"Well, I say, we're not such foreigners yet but we can give shelter to a little girl!" exclaimed the Señor Pickard, in remarkably good English for a Cuban planter. He knew the danger of harboring the relative of a suspected rebel.

"Bring her to me," said the Señora, calmly.

The mistress of such a plantation is a queen in her own dominions, and a minute later Maria Nunez stood before her, telling her sad story, much as Cristobal told it to the kind old gentleman in Morro Castle.

Perhaps it was because he was an Ohio boy, and not a real señor at all, that the young Señor Pickard grew excited while the story was a-telling, and walked nervously up and down the gallery. Or it might have been because Maria was a remarkably pretty little Spaniard, with the dark flashing eyes of her countrywoman, and their thick black hair and rich complexion and delicate features. Her little story was soon told, and she stood there looking doubly pretty in her excitement and grief.

"You shall stay with me, you poor child, till the times are settled," said the señora, still calmly, and in good Spanish. "Alphonse, call my maid."

"Is that all?" exclaimed the young señor, in English, looking as if he had determined to drive out the Spanish troops single-handed. "Aren't you going to get the girl's brother out of prison? He will be sent to the Morro, and you know what will get him out of there. Can't Pedro—"

The elder señor stamped his foot impatiently.

"Have you no more sense than to mention that name?" he exclaimed. "Keep quiet, and leave this thing to me. For just about one York shilling I'd hoist the stars and stripes here and fortify the place. I am growing sicker of such doings every day. Go and tell Henry to have his horse ready to start for Havana at eight o'clock to-night."

Ignorant of course of these things, Cristobal had to devise a way of using his money for his liberation. One of those golden eagles, he knew, represented four months' pay of any of the soldiers who were guarding him. There was one young soldier in the guard, a boy of scarcely twenty, barefoot and ragged, whom he had marked long before as a fellow Catalan. For days this young fellow was kept at other work, but at length he appeared on guard again before the bars of the cell.

Cristobal's heart beat fast when he saw who was pacing up and down just outside the bars. Pressing up to the front of the cell, he leaned for some time against the bars without speaking, and then, as the young soldier passed, he asked, softly,

"Cataluna?"

"No," said the guard; "Asturias."

"So much the better!" Cristobal said to himself; "it is only proper that a Catalan should buy an Asturian. He is mine, for I shall buy him with gold."

For some minutes more he stood leaning against the bars, without saying another word, biding his time. When a favorable moment came, he took one of the golden eagles between his thumb and forefinger, and held it in front of his breast, where no one in the cell could see it, and there was no one outside but the young guard.

Up and down paced the soldier, his eyes apparently straight in front of him. But somehow with each walk past he was a little closer to the bars. Seeing this encouraging sign, Cristobal took out another eagle, and held up two. By that time the young guard was so close that Cristobal might have touched him as he passed. After several more turns the soldier raised his eyebrows questioningly as he passed.

There were no other prisoners close up against the bars, but some were near enough to make great caution necessary. Only a single short sentence could be spoken at each passing of the sentinel.

"The first means through the portal," Cristobal whispered, as the soldier went up.

There was not a sign to show that he had been heard or understood.

"The second means a boat on the beach," Cristobal whispered, as the soldier went down.

Still the sentinel's eyes looked dead ahead; but before he was past the bars he shifted his musket from one shoulder to the other, and in doing so the stock struck lightly against one of the bars. Perhaps it was accident; but Cristobal, being one of the Yankees of Spain, did not think so. He instantly knew that it meant, "I cannot get you through these bars." That was an objection that he was ready to meet; and when the guard passed again he hurriedly whispered,

"I can squeeze between the bars; I have tried it."

Still the sentinel looked dead ahead; but for the next few minutes as he passed he was saying something softly to himself every time he put his left foot foremost, just as a drill-master says, "left, left, left!" What he said softly to himself was, "dos," "dos," "dos," meaning, in English, "two," "two," "two."

"Dos!" Cristobal said to himself; "that means the two coins; both propositions accepted;" and he left the bars and went back into the darkness, and sat down satisfied.

When he offered that night to share his little store of gold with the kind old gentleman, his friend patted him upon the head.

"Bless your kind little heart!" said he. "I have no need of gold." Then removing his hat, he added, "Kneel, my son."

When Cristobal arose, after the priestly blessing, he noticed that the top of his friend's head was shaven bare, and the brief benediction made him feel stronger for the night's dangerous work.

For four days and nights he lay hidden in a big closet in the attic of No. 19 in the Calle O'Reilly, and then a Spanish pass was given him that carried him safely through the lines to La Flora. And Pedro? Pedro must remain a mystery till that cruel war is over. Americans are a people of great resources, and can often send their agents even within the walls of Spanish castles. It may safely be told that Cristobal and his sister are together on the Buena Vista plantation, and that Señor Pickard has not yet hoisted the stars and stripes and fortified the place.

FIG. 1.

FIG. 1.

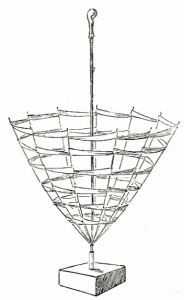

One of the best tricks of De Kolta is called, "The Miraculous Production of Flowers." It may be exhibited on the stage or in the drawing-room, and is equally effective in either place. The performer shows an umbrella from which the covering has been removed and its place supplied by multicolored ribbons, which go from rib to rib, leaving a space between. He then opens this umbrella, and stands it upside down on the stage, resting the ferrule end in a piece of metal tubing, which, in turn, is supported by a stand. He also shows two or three empty shallow wicker baskets, and a sheet of heavy brown paper. His arms being bared to prevent the possibility of anything being concealed in his sleeves, he folds, or rather twists, a sheet of paper into a cone or cornucopia. Every one knows this cone is empty, as they have seen it made, and yet the performer shakes from it enough flowers to fill not only the baskets, but also the inverted umbrella. Every once in a while, when the supply of flowers is apparently exhausted, the paper is opened and shown to be empty, and yet, when again rolled up, the flowers pour from it in as great volume as at first.

The flowers in this case are emphatically spring flowers, though it may be truthfully said that "the flowers that bloom in the spring have nothing to do with the case." They are made in a variety of shapes, but the most simple form is, to my thinking, the best, and any one can make them by following these instructions:

FIG 2.

FIG 2.

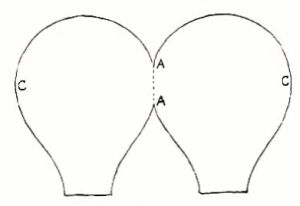

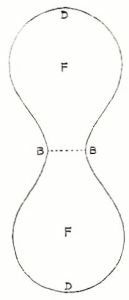

Cut a number of pieces of red, blue, yellow, or pink tissue-paper of the shape shown in Fig. 2, and an equal number of that in Fig. 3. Fold them at the lines A A and B B, shown by the dotted lines, so that C and C and D and D come together. Then cut some flat thin spring steel, not highly tempered, into strips about one-eighth of an inch in width and from an inch and three-quarters to two inches and a quarter in length, according to the size of the "flower." The latter, for the drawing-room, should be about two and a half inches long and two inches at the widest part, while for the stage they are best when three and a quarter long and proportionately wide. The strips of steel must next be cut in two the longer way, until within about a quarter of an inch of one end, and these halves must be bent outward in opposite directions, so that they assume the position shown in Fig. 4.

FIG 3.

FIG 3.

Place the spring between the folds of Fig. 3, so that the arms will lie on F F, and then paste them firmly down by placing over a strip of paper of the same color as the "flower." Next put Fig. 2 between Fig. 3; paste the points C C to E E and G G to B B, and let them dry thoroughly. The flower has now assumed the shape shown in Fig. 5. All that it needs to complete it are two green leaves of paper, silk, or muslin, which are to be pasted one on each side at the smaller end. To make much display, about five hundred of these flowers ought to be used.

FIG. 4.

FIG. 4.

Having made the flowers, the next thing to learn is how to get them into the paper horn without being seen. Some performers load the cone—to load being the technical name for filling—by simply holding a bundle of flowers in the right hand, and deliberately placing the hand inside the cone, under pretence of taking out a flower, but that is anything but artistic.

Do up three bundles of, say, seventy-five flowers each. To do these up place them between two oblong pieces of thin green card-board, putting an elastic over the longer way; and that this may not slip, have nicks in the ends. Pressing these ends will cause the card-boards to bulge out in the centre, and allow the flowers to escape. Two of these bundles must have loops of rather stiff wire run through the elastics, so that when the bundles lie on the table the loops stand up. These bundles are laid at the back of the table, behind a basket, at the performer's left. The third bundle, also on the table, is a little to the right of the others.

PAPER LEAF.

PAPER LEAF.

The performer first bares his arms, then rolls up his cone and throws it on the floor, mouth toward the audience, or lays it on a table. Now picking up the third bundle with his left hand, and putting it, almost in the same movement, under the bottom of a basket which he picks up, he advances to his audience to show that the basket is empty. Returning to the stage, he lays the basket on his table, retaining the bundle of flowers in his left hand. Then picking up the cone by the smaller end, he remarks, "The hands are empty." As he says this he passes the cone to the left hand, which he places inside the mouth, thus dropping the bundle in, shows the right hand empty, and taking the cone in that hand again, shows the left also empty. Putting both hands around the lower part of the cone, he squeezes it and the card-boards, and the flowers being released, he begins to pour them into the basket.

As the flowers fall out, he pretends to guide them with his left hand, and this gives him an opportunity to catch the wire loop of one of the bundles on the table between his fingers.

When the cone is emptied, the performer unrolls it and straightens out the paper, prior to working in the second bundle. This bundle, understand, is back of the left-hand fingers. Taking the sheet of paper at one edge by the tips of the fingers of that hand, and letting the paper fall in front, he smoothes it with the right hand, and presently seizing the lower edge by that hand, he brings the sheet back over his left hand, thus leaving[Pg 745] the second bundle inside the cone thus formed. This is a remarkably neat and clever move, almost impossible to detect, and is well worth the little practice needed to acquire it.

The cone is now emptied, and the third bundle picked up in the same way as the second, and the cone again formed over the back of the hand. The flowers for the umbrella are loaded into the cone in an altogether different way, but one quite as difficult to detect if well done.

FIG 5.

FIG 5.

About three hundred flowers are placed between two sheets of stiff card-board, and these are tied together in a single bow-knot with silk floss, the end which unties the knot being allowed to hang down, and having a tiny shoe-button fastened to it, so that it may be found easily. Hanging from one of the pieces of card-board is a loop of strong black thread. This bundle is placed in the inside right breast pocket of the performer's coat, and the loose end of the loop is passed over a button or small hook sewn on the vest.

To load the bundle into the cone, the performer holds the open flat sheet of paper in his right hand, which hangs at his side. Turning it front and back, he says, "Absolutely empty, as you all can see." And while his audience have their eyes fixed on it, his left thumb finds the loop, and passing through it, lifts it off the button. "I shall hold it away from my body," he continues, and as he says this he raises the sheet in front of him so that it nearly covers his breast. As he does this, almost simultaneously, his left hand grasps the upper edge of the sheet about the centre, and thus pulls the bundle out and holds it dangling behind the sheet. The left hand, still holding bundle and paper, is pushed well out, so that the sheet is not near the body. The right hand now seizes the upper right corner of the paper, and drawing it towards him, the performer twists it into a cone. His hand is thus left inside, and as he withdraws it, what more natural than to catch hold of the shoe-button, give a steady pull, and release the flowers? Walking round and round the umbrella, the performer continues to shake flowers from the cone until the novel receptacle is filled.

The professional conjurer has large deep pockets inside the breast of his coat, the mouth towards the front; but as many of my readers will not care to have specially prepared coats, they may substitute a large oblong black bag, which can be fastened to the coat by small black safety-pins. The mouth should come within about two inches of the front. Similar but smaller pockets can be pinned to the back of the trousers leg, when they will be covered by the coat tails, but will prove handy for small articles.

Some conjurers allow themselves to be firmly tied with ropes, and yet while in this condition perform feats that apparently require the free use of both hands. These, however, are always done behind a curtain or other screen. Just how this is done I may explain later, but for the present here is a very good substitute. The performer locks his hands, and his crossed thumbs are tied tightly together with a long strong cord, the ends of which are held by two of the audience. A soft hat or handkerchief is thrown over the hands, and almost instantly one is waved in the air. It is as quickly thrust back, and on removing the covering the knots are found as firmly tied as at first.

There are two ways of doing this, both of which I shall explain.

FIG. 6.

FIG. 6.

In the one method, when the hands are brought together the forefinger of the left hand is on top; then follow the right forefinger, the left second finger, the right third finger, the left third finger, the right little finger, and last the left little finger, as shown in Fig. 6, the right second finger being inside the hands. When the cord is placed under the crossed thumbs, preparatory to tying them, this right second finger, which will not be missed from the clasped hands, grasps the cord and holds it down, thus gaining slack which is at the bottom of every tie exhibited from the time of the Davenport brothers to the present day. Of course with so much slack it is a very easy matter to release the thumbs, and the next moment to present them apparently tightly tied. At the conclusion of the trick the cord must be gathered up and put out of the way, lest some of the audience should get hold of it, and thus discover the secret.

In the second method the palms of the hands are placed together and the thumbs held up. Then a rope, about the size of an ordinary sash cord, is laid just above the fork of the thumbs. The ends are given to two committee-men chosen from the audience, who are asked to pull, so as to convince themselves that the rope is sound; then the thumbs are crossed and pressed down on the rope, which is tied in a double knot.

As in the first method, a handkerchief is thrown across the hands, and again as in the first method the hands are rapidly freed, and just as rapidly tied again.

In doing the trick this way the slack is gained just after the committee-men are asked to pull on the rope. At that moment the hands are held about two inches apart, and just then the thumbs squeeze hold of the rope, and bringing the hands closely together, the slack is caught between the palms, the crossed thumbs hiding all signs of it.

I once saw a man who claimed to do certain wonders "by the help of unseen powers," but as two of these can be produced by the most ordinary human power, I give them here, so that any of my readers who is so disposed can set up in the "seer" business for himself.

The performer hands out some half-sheets of note-paper, measuring, say, 4½ by 7 inches. These he requests the audience to fold, as nearly as possible, into four equal strips, each of which will then measure 1¾ by 4½ inches. These strips he distributes among the company, who are asked to write a name of man or woman on each strip, which is then to be folded once or twice, and thrown into a hat, when all the strips are to be thoroughly mixed. The performer then places his hand in the hat, and selecting one strip, announces that the name in it is that of a man or of a woman, as the case may be. So he continues until each slip has been taken out.

FIG. 7.

FIG. 7.

Although the performer has nothing to do with cutting the paper, yet the trick depends altogether on the way in which it is cut. Reference to Fig. 7 will explain this at a glance. It will be seen that if the paper is cut into four strips, two of these, No. 1 and No. 4, will each have a sharp edge, A, and a rough edge, B, while Nos. 2 and 3 will have two rough edges. In handing out the papers the performer always gives a sharp-edged strip with the request, "Please write the name of a man on this," while the rough-edged ones are given for the names of women. When he puts his hand into the hat he has merely to run a finger over the[Pg 746] edges of a strip, and he can at once determine whether the name on it is that of a man or of a woman, even without the aid of "unseen powers."

For his next phenomenon—by which name he attempted to dignify his tricks—he required the assistance of his wife. She was conducted to a room on another floor of the house, and while she was thus out of sight and out of hearing the Professor introduced a pack of cards. One of the company drew a card, and showed it to the rest of those present, the Professor included. Then the gentleman who drew the card wrote on a piece of thick paper the question. "What is the name of the card drawn?" This was placed in an opaque envelope, so that the writing could not possibly be read; the envelope was sealed, and the Professor addressed it to his wife. She placed it for a moment against her forehead, and then seizing a blank card, wrote on it, "The card chosen was the eight of hearts," which was correct.

The secret is in the way the address is written. By previous arrangement it is understood that the suits of the cards are to run as follows: spades, hearts, clubs, and diamonds. Should a spade be drawn, a period is placed after the first word of the address; if a heart, after the second; if a club, after the third; if a diamond, no period appears in the first line of the address. For the number of the suit the cards run in their regular order, ace, deuce, etc., the Jack counting 11, the Queen 12, the King 13. To designate the suit, an initial letter is introduced in the address, the one used being the one in numerical order coming after the number of the suit. Thus, in the first case, the card being the eight of hearts, the address was written

Mrs Sarah. I Smith

—the period after Sarah designated the suit, while I, the ninth letter of the alphabet, showed the number of spots on the card.

Flea's horse threw up his head with a jerk, and wheeled partly around at the jerk upon the bridle; his rider flushed crimson, then grew white.

"Father!" she gasped. "What did you say? Miss Emily! my Miss Emily is going to marry that man?"

"So it is said, lassie. I'm afraid it is true. There has been talk of it all winter, but I don't think the Major had any idea of how things were going until lately. Early in May Mr. Tayloe left Greenfield and went to board at Mr. Thompson's. Of course his moving from Greenfield, where he was so intimate, set tongues wagging; and then it came out that he and Miss Emily were engaged, and that her father opposed the match. I have asked no questions, but I cannot help seeing that the Major is not himself, and how he is ageing."

"I don't see how Miss Emily can disobey such a good father," said Flea, indignantly. "His little finger-nail is worth more than forty thousand Jack Tayloes. If she knows how her father feels, she will surely give up all notion of that little—monster!"

Her father looked amused.

"He isn't a monster, but a well-born, well-educated gentleman, not bad-looking, and with a voice like a church organ. Your mother says he sang his way into Miss Emily's heart. I wonder the Major didn't suspect what might come of all their music and horseback rides and walks together; but he is so open-hearted and aboveboard himself that he probably set it down to young folks' natural enjoyment in each other's society. It hurts me to see him take it so hard. Miss Emily will be of age in a few months, and she can then marry anybody she chooses. Except that he has a hasty temper and an ugly way of showing it, I don't know that there is anything against him. She will have money enough for both. Her grandmother left her a nice little fortune, besides what the Major can give her."

"Nothing against him!" burst forth Flea, passionately. "He is the wickedest man ever created. Mean, spiteful, deceitful, and cruel as a tiger. He looks like a tiger when his eyebrows draw together and his mouth draws up and the roots of his nose draw in. To think of his daring to lift his eyes to my sweet, pretty, darling Miss Emily! If I were her brother, I'd shoot him sooner than he should have her."

"Lassie! lassie! That is strong language."

"Not half as strong as he deserves, father. You don't guess what a creature he is. Aunt Jean never wrote to you about it, for she did not want to distress you; but poor Dee couldn't go to school for a month after he went to Philadelphia. He had terrible pains in his head and was sick at the stomach all the time, and she had him examined by a great doctor there, who said he had been seriously injured by so much beating on the head—that a little more of it would have made him an idiot. That monster of cruelty used to whack the poor boy every day with his heavy ruler, because he was slow at his lessons. Dee cannot study long now without having a sick headache. He can never be a learned scholar. And I did so hope he would be a distinguished man! Instead of getting married, Mr. Tayloe ought to be put into the penitentiary. He deserves hanging—and worse."

The rush of hot words choked her. Her father patted her shoulder soothingly.

"Don't take it so to heart, dear child. It isn't like you to fly into such a passion."

"I never knew that I had a bad temper until he brought it out." Flea could not be quieted. "He would have made me as wicked as himself if I hadn't fallen sick from his treatment of me, and then gone home with Aunt Jean. He will break Miss Emily's heart. He enjoys torturing helpless things, as a cat likes to torture a mouse. Where is he now that the school is closed for vacation?"

"I think he has gone home. I have not seen or heard of him for a week and more."

"I hope he will never come back. I hope he will die while he is away!" uttered Flea, savagely.

"Fie! fie on you!" said her father, trying to look stern. "You'll make me afraid of you if you get so bloodthirsty. Never meddle with people's love-affairs, chick. It's worse than putting your fingers 'twixt bark and tree. Miss Emily knows her own business, and has a fine high spirit of her own."

They were at the outer gate of the avenue leading to Greenfield, and he drew rein.

"Would you mind riding with me as far as the stables? I won't keep you long. Or, perhaps you will go up to the house and see the ladies? They always ask kindly after you."

Mrs. Duncombe was not at home, said a small darky who was pretending to sweep one corner of the piazza. "Miss 'Liza and Miss Em'ly is out-o'-doors somewhar," he added, staring at her until the round black eyes almost slipped out of the lids.

"Don't you know me, Peter?" asked Flea, kindly.

"Yaas, 'm. But you done got mighty pretty sence you been away."

Flea's head was higher, her heart and step lighter, with natural pleasure in the honest praise, as she ran down the steps to look for the young ladies. She had determined to reason with Miss Emily, and could go about it in better style as the well-dressed niece of her Philadelphia aunt than the shabby child of the overseer would have presumed to do. She was glad she had grown prettier. She wanted to look like a lady.

In crossing the lawn she saw, midway in the broad avenue cutting the grounds in two, what brought her courage down on the run and her hopes with it. She turned aside hastily into an arbor thickly draped with vines to take counsel with herself as to her next movement. Miss Emily, dressed in white, a garden hat set jauntily above her curls, sat upon a settee by Mr. Tayloe. Across the avenue Miss Eliza occupied another settee, and seemed absorbed in a[Pg 747] book. Miss Emily was holding a handkerchief to her eyes, while Mr. Tayloe talked earnestly to her. Groups of children were playing on the other side of the lawn. Mr. Tayloe must be pretty confident of his ground to show himself in the sight of so many people.

After five minutes of embarrassed waiting, Flea was on the point of going back to her horse unobserved, when Mr. Tayloe got up, stepped across the avenue, and shook hands in brotherly fashion with Miss Eliza, then, Miss Emily at his side, strolled down the walk in the direction of Flea's hiding-place. They passed so near to it that she could have knocked his hat off with her riding-whip. He was serious, but as bland as the plait between his eyebrows would allow him to look. He was talking low and impressively.

"All you have to do is to be resolute," was all Flea could hear.

"That is more easily said than done," Miss Emily began. The rest was lost to the eavesdropper.

Her blood was at the boiling-point by the time the young lady returned alone. A smile hovered about her red lips, although her eyes were still moist. Flea stepped out of the arbor.

"Miss Emily!"

"Mercy on us!" in a faint scream. "Why, it is Flea Grigsby, as sure as I'm alive! Did you drop from the clouds? How you have grown, and how nice you look! Ain't you going to kiss me, child?"

The caress was almost wasted upon the excited girl.

"Miss Emily"—driving straight at the point—"I have something particular to say to you. Won't you come in here?"

Miss Emily followed her into the summer-house, dropped upon a seat, and drew her dress aside to make room for her guest.

Flea spoke hurriedly, but her voice did not shake. She was too much wrought up to be diffident. "Miss Emily! they tell me you are going to marry Mr. Tayloe. You don't know how I love you. I can't remember the time when I didn't love and almost worship you. You've always been so kind and sweet that I couldn't have helped loving you even if you hadn't been so beautiful."

Miss Emily leaned back on the bench, well pleased and smiling.

"Oh, come now, you've learned how to flatter in Philadelphia," she simpered, hitting Flea with the handkerchief that had wiped the tears from the blue eyes a little while ago. "And who, I should like to know, has been fibbing to you about my getting married?"

Flea seized upon both the pretty hands, her face one flash of ecstasy.

"I might have known it couldn't be true. Oh-h-h!" heaving a long, quivering sigh of relief. "If you only knew what I suffered when I heard you were to marry him! I couldn't bear the thought."

"You jealous little puss!"

Flea had sunk to her knees upon the gravelly floor of the arbor, and was gazing worshipfully into her idol's face. It was like the coming true of another fairy dream when the dainty white hands were laid one on each side of her flashed cheeks, and Miss Emily kissed her between the eyes.

"You unreasonable little monkey! Do you want me to die an old maid? I declare"—inspecting the braided front of the habit-waist—"you look real fashionable. And you used to be such a tomboy that your poor mother threatened to make oznaburg frocks for you. But go on. Then you won't let me marry anybody?"

"I didn't mean that," Flea protested. "But I heard that you were engaged to Mr. Tayloe, and it made me perfectly miserable, and I felt that if I could talk to you for five minutes you would change your mind. I'm so happy that it is nothing but a gossip's story."

"What have you against poor Mr. Tayloe besides his admiration for a foolish little nobody like me?"

Flea raised herself on her knees to bring her eyes on a level with her companion's. Her young face darkened.

"You are not foolish or a nobody. You would be foolish if you were to marry that meanest, cruelest, hardest-hearted of all men. And you would be a nobody—worse than a nobody—when once he had you in his power. Your brothers can tell you how he used to whip the boys and ferule the girls' hands until they were blistered, and he grinning all the time. He tortures people for the love of torturing. He is a bully, and a coward, and a demon."

"Are you calling Mr. Tayloe all those names?" interposed the listener, tartly.

"Yes, Miss Em—"

Before she could utter another syllable her idol drew away to get a better reach, and slapped her with all her might, first upon one cheek, then upon the other, until her astonished ears rang like an alarm-bell, then pushed her off so violently that she fell backward to the ground. Springing up, wild with shock and horror of it all, she faced a red-haired fury with glaring eyes and distorted features.

"You impudent, low-lived minx!" said tones as vulgar as those of a scolding negress. "You ought to be tied up and whipped until you take back every word you have said. Who are you that you come here to insult a gentleman in a lady's hearing? This comes of my taking notice of a low-down overseer's daughter, who is meaner than the dirt under my feet! Begone! and if you ever show your face here again I'll set the dogs on you!"

Flea did not quite know where she was or what she was doing until she found herself in the saddle, gathering up the reins, and telling the negro who had brought the horse up to the inner gate for her to "tell Mr. Grigsby he would find her waiting for him under the big oak-tree on the road."

She managed to get the words out without breaking down, and galloped along the avenue as if the dogs were already on her heels.

Her father rejoined her in less than half an hour. She sat motionless upon the horse under the tree. The reins lay upon the docile animal's neck, and he was grazing in quiet satisfaction, unnoticed by his mistress. Mr. Grigsby must have remarked her white face and swollen eyes had he been less engrossed in his own thoughts.

"Ready, lassie?" was all he said, and "Yes, father," was her only reply.

They jogged, side by side, for a mile before either spoke again. The bitterest cup Experience had ever held to poor Flea's lips was pressed to them now, and the draught was the very wine of astonishment to her soul. Five months with Aunt Jean and in a Philadelphia school had not cured her of ambitious dreams. Miss Emily had still stood with her as the loveliest, daintiest, and gentlest of women. She had described her to her schoolmates as her "patron saint" and her "guardian angel." She had not doubted what would be the outcome of the plain talk she had sought with her angel. Miss Emily would be shocked at first, perhaps incredulous, but in the end she would fall weeping upon her neck, and sob in her ear, "My benefactress! from what an abyss of misery you have saved me!"

Her dream had crashed into dust and ashes about her head. Something was gone forever out of her past, present, and future. There was no Miss Emily in all time for her, and, worst of all, there never had been. The shrill coarseness of the angry woman's speech, her inflamed face and threatening eyes, haunted Flea like a nightmare.

Her father aroused himself at length. "I am a dull companion for you, lassie," he said, threading her horse's mane with his fingers. "But something has gone wrong—'agley,' as we Scotchmen say—at Greenfield that's set me to thinking about other wrong-doings that took place months ago. The dairy was robbed last night of a matter of fifty pounds of butter. The dogs made no noise, so the thieves were not strangers. The Major and Mr. Robert Duncombe searched the plantation this morning, and found nothing. The thieves, most likely, had a boat on the shore, and made off with the butter up to Richmond. You noticed, didn't you, as we rode by to-day that the haunted house had been pulled down?"

"No, sir," answered Flea, in a dull tone. She had not seemed to listen until he asked the question.

"You used to sing a song about it when you had the fever," resumed the father, in a would-be sprightly manner.

"It began,

"'It stands beside the weedy way,'

"and was really tolerable poetry as far as it went. It was queer it should run in your head just then when the Major and I had just found that the cabin was used as a hiding-place for stolen goods. It was a sort of robbers' cave, and we suspected the Fogg family to be the robbers. Mr Tayloe's watch and chain, that he had lost the day before in the school-house, were there in a bag packed to be carried off. You recollect that Mrs. Fogg was at the school-house that day!"

Flea gave no sign of interest or surprise. She only said, in sullen bitterness, "I am sorry he ever found it."

"My child!"

"I am, father! I suppose I am wicked for feeling it, but I wish him all the harm in the world. The Foggs may be thieves and liars and a hundred other dreadful things. The worst of them is a saint compared with him."

"We will let that pass. I promised once never to speak of that day again. I beg your pardon, my dear," said the father, gravely. There was no use in arguing against the girl's prejudice, in which, to tell the truth, he was beginning to share. "I was about to say that some strong measures must be taken to find out if the Foggs are really the ring-leaders of this gang, with the negroes to help them, or if this wretched family do all the stealing themselves. They have been tolerably quiet since the cabin was cleared out and pulled down, but this dairy business looks as if they were beginning business again. If we meet the Major on the road, I will speak to him about it. I wish now I had looked him up in the swamp when we saw Nell."

They relapsed into silence. The country was stilling into the hush of a summer noon. But for the indescribable consciousness of the growth of green and flowering things that fills June days and nights—something which is not motion and surely is not rest, and is, most of all, like the full, slow, contented breathing of the world on which we live and that lives with us—everything except themselves and their horses seemed to be asleep as they passed into the grass-grown swamp road.

"The day is getting hot," observed Mr. Grigsby, presently, "if the breeze should die away entirely we may expect a thunder-storm this afternoon."

At that instant the neigh of a horse, clear and prolonged, pierced the noon-tide; another moment brought them again in sight of the low-hung gig and mare they had seen in the same spot an hour and a half ago. Nell had not stirred from her tracks, except to paw up the earth about her front right foot in anxiety or impatience. She looked around and neighed piteously.

"Nell is getting hungry, poor thing!" said the overseer, stopping to pat her glossy neck. "The flies are troubling her, too. That is the worst of a blooded horse. The skin is as thin as a baby's. So, old lady!" and she threw her head down and up, and again whinnied. He went on brushing off the flies from her head and sides while he talked. "These swamp-flies bite sharply. Any other horse would try to get away. She is the best-broken beast in the State. If a cannon were fired off at her ear she would jump, but she'd never run. The Major broke her himself. It's odd where he is all this time."

A vague uneasiness took hold of him. He looked about him anxiously.

A large spruce-tree lay within ten feet of the gig. The branchy top had bent saplings and bushes down in its fall; the ground for many yards around was strewed with leaves and twigs. Flea glanced idly at the lower end of the trunk. She did not wish to meet Major Duncombe with the memory of the encounter with his daughter fresh in her mind. Still, if her father meant to wait for him, she had no choice. She could never tell how she chanced to notice that the trunk was hollow, and had been partly cut through by the axe. Beyond the cut the wood and bark were splintered roughly.

"Do you suppose he could have been here when that tree fell?" she said. "Could that have been what we heard as we came through the woods this morning? Oh, father!"

He looked in the direction of her pointing finger, threw himself from his saddle, and hurried into the swamp.

HE WAS TEARING AWAY THE BOUGHS IN FRANTIC HASTE.

HE WAS TEARING AWAY THE BOUGHS IN FRANTIC HASTE.

A man's hat lying just beyond the branches of the fallen tree had attracted Flea's eye. When she had slipped from her horse and followed her father into the thicket, he was tearing away the boughs in frantic haste from Major Duncombe's face. The upper part of the prostrate trunk lay right across his chest.

It must have killed him instantly.

The summit of Mount Rainier has only been gained by way of its southern slope, the much steeper and more dangerous northern face having never been scaled. Even over the comparatively easy slope of the south side but one practicable trail has been discovered, and it leads by way of the Cleaver. This gigantic ridge of rock, like the backbone of some colossal monster, forms a divide between the upper Nisqually and Cowlitz glaciers. Its sides are overlaid with confused masses of bowlders and treacherous gravel, through which appear at intervals sheer cliffs and bare ledges of solid rock. The Cleaver leads to a mighty mass of granite, a mountain in itself, that is fittingly called the Gibraltar of Mount Rainier. It bars a further passage to all save the strongest climbers, and to these it affords the only means of access to the lofty realms beyond. Here is the most perilous part of the ascent, and, with Gibraltar once passed, the summit is almost certain of attainment.

It seemed to our weary lads that they had barely fallen asleep when they were wakened by a rude shaking and the voice of their Siwash guide, exclaiming:

"Come, come, lazy boy! Wake up! wake up! 'Mos' sitkum sun [noon]. Breakfus! breakfus!"

"'Most noon!" growled Bonny, crawling reluctantly from his sleeping-bag, rubbing his eyes, and shivering in the bitter cold. "'Most mid-night, more likely."

"Alle same, sitkum sun some place; don't he?" queried the Indian, laughing at his own joke.

By the time they had swallowed a cup of tepid tea, and lightened their packs by making a hearty meal of cold meat and hard bread, dawn was breaking, and there was light enough to pick their way up the treacherous slope of the Cleaver. As they cautiously advanced, many a bowlder slipped from beneath their feet and bounded with mighty leapings into the depths behind them. Dodging these, sliding in the loose gravels, lifting and pulling each other up rocky faces from one narrow ledge to another, and ever looking upward, they finally gained the summit of the mighty ridge.

From here they could gaze down the opposite slope nearly a thousand feet to the gleaming surface of the great Cowlitz glacier, with so much of its ruggedness smoothed away by distance that it looked a river of milk with a line of black drift in its centre, flowing swiftly through a rock-walled cañon and pouring into a sea of cloud. On the far southward horizon could be seen the glistening cone of Mount Hood, kissed by earliest sunbeams, and in the middle distance the volcanic peaks of St. Helens and Adams. Near at hand, pinnacles of the Tatoosh Range were breaking through the clouds like rocky islets in a billowy sea. Before them the rugged backbone of the Cleaver, stripped of every particle of its earthy flesh, stretched away in quick ascent to the frowning mass of Gibraltar.

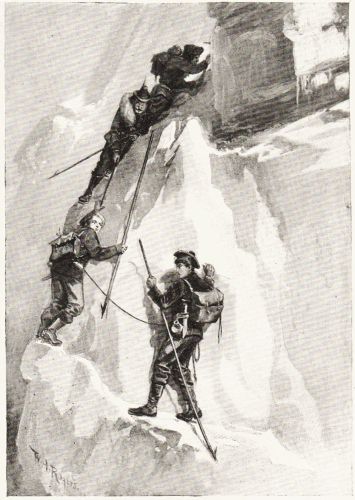

The Cleaver carried them half-way up the sombre face of this mighty rock, and from that point's narrow ledge creeping diagonally up the precipice at a steep angle was the trail they must follow. Not only was this rocky pathway steep and narrow, but it shelved away from the wall, and in many places afforded only a treacherous foothold. At any point along its length a slip, a misstep, or an attack of dizziness would mean almost certain destruction.

Foot by foot and yard by yard M. Filbert's little party ascended this perilous way, here walking and trusting to their alpenstocks for support; there crawling on hands and knees. Sometimes one would go cautiously ahead over a place of peculiar danger, with an end of the rope firmly knotted beneath his arms, while his companions, with firm bracings, retained the other part, ready to haul him up if by chance he should plunge over the verge and dangle above the abyss at the end of his slender tether.

THE ICE ABOVE GIBRALTAR.

THE ICE ABOVE GIBRALTAR.

At the terminus of the ledge they were confronted by a sloping wall of solid ice, in which they must cut steps and grip-holes for feet and hands. As they slowly and painfully worked their way up this precarious ladder they were continually pelted by pebbles and good-sized stones loosened by the sun from an upper cliff of frozen gravel.

At length the toilsome ascent was safely accomplished, and with a panting shout from Alaric and a hurrah from Bonny, the whole party stood on the summit of that mountain Gibraltar. Here they rested and lunched; then, full of eager impatience, pushed on over the narrow causeway connecting the mighty rock with the vastly mightier snow-cap beyond.

This snow, that had looked so faultlessly smooth from below, was found to be drifted and packed into high ridges, over which they slowly toiled, frequently pausing for breath, and inhaling the rarefied air with quick gaspings. At length a bottomless crevasse yawned before them, spanned only by a narrow bridge of snow. With an end of the rope knotted beneath his arms, Bonny, being the lightest, essayed to cross it. Before he reached the farther side the treacherous support broke beneath him, and, with a frightened cry, Alaric saw his comrade plunge out of sight in the yawning chasm. He brought up with a heavy jerk at the end of the rope, and they cautiously drew him back to where they stood.

As he reappeared above the edge of the opening his face was very pale, but he called out, cheerfully. "It's all right, Rick! Don't fret!"

After a long search they discovered another bridge, and it bore them across in safety, one at a time, but all securely roped together. Finally, late in the afternoon, the longed-for summit was attained, and though nearly toppled over by a furious wind, they stood triumphant on the rocky rim of its ancient crater. This was half a mile in diameter, and filled with snow, but its opposite or northern side was the highest. So to it they made their weary way, following the rocky path afforded by the rim, and barely able to hold their footing against the wind.

When they at last attained the point of their ambition, a reading of the barometer showed them to be standing at a height of 14,444 feet above sea-level, and with exulting hearts they realized that, as Bonny expressed it, they had put the highest peak of the Cascade Range beneath their feet.

The view that greeted them from that lofty outlook was so wonderful and far-reaching that for a while they gazed in awed silence. Mount Baker, two hundred miles away, close to the British line, was clearly visible, as were the notable peaks to the southward, even beyond the distant Columbia and over the Oregon border.

"C'est grand! c'est magnifique! c'est terrible!" exclaimed M. Filbert, at length breaking the silence.

As for Alaric! To have achieved that summit was the greatest triumph of his life; but his heart was too full for utterance, and he could only gaze in speechless delight.

The Indian too gazed in silence as, leaning on his ice-axe, he contemplated the outspread empire that but a few years before had belonged solely to the people of his race.

Bonny was as deeply impressed as either of his companions, but found it necessary to express his feelings in words. "This must be the top of the world!" he cried; "and I do believe we can see it all. I tell you what it is, Rick Dale, I've learned something about mountains this day, and now I know that they are the grandest things in all creation."

At their feet the rock wall dropped so sheer and smooth that no man might climb it, and then came the snow, sweeping steeply downward for miles apparently without a break. Far beyond lay the vast sea of forest, seeming to cover the whole earth with its green mantle. The gleaming glaciers, looking like foaming cascades frozen into rigidity, were swallowed by it and hidden. It rolled in billows over the mighty mountain flanks that radiated from where they stood like the spokes of a colossal wheel, and dipped into the intervening valleys. Nowhere was it broken, save by the few bald peaks that struggled above it and by the threadlike waters of Puget Sound. Even on the west there was no ocean, for the volcanic, snow-crowned Olympics, one of which was smoking, as though in eruption, hid it from view.

Our lads could have gazed entranced for hours on the crowding marvels outspread before them had they been warmed and fed and rested and sheltered from the fierce blasts of icy wind that threatened to hurl them from the parapet on which they stood. As it was, night was at hand, they were faint and trembling from weariness, and wellnigh perished with the stinging cold. It was high time to turn from gazing and seek shelter.

Inside the crater's rim numerous steam jets issued from fissures in the rocky wall, and these had carved out caverns from the adjacent ice. Here there were roomy chambers, steam-heated and storm-proof, awaiting occupancy, and to one of these M. Filbert led the way.

In this place of welcome shelter numbed fingers were thawed to further usefulness by the grateful steam, a small fire was lighted, packs were opened, and in less than an hour a bountiful supper of hot tea, venison frizzled over the coals, toasted hard-bread, and prunes was being enjoyed by as hungry and jubilant a party as ever bivouacked at the summit of Mount Rainier.

After supper the Frenchman lighted a cigarette, the Indian puffed with an air of intense satisfaction at an ancient pipe, our lads toasted their stockinged feet before the few remaining embers of the fire, and, in various languages, all four discussed the adventures of the day.

Although they had much to say, their conversation hour was soon ended by their weariness and by the ever-increasing cold which even a jet of volcanic steam could not exclude from that chamber of ice. So they speedily slipped into their sleeping-bags, and, lying close together for greater warmth, prepared to spend a night under the very strangest conditions that Alaric and Bonny, at least, had ever encountered.

Some hours later the occupants of the ice-cave became conscious of the howlings of a storm that shrieked and roared above their heads with the fury of ten thousand demons; but knowing that it could not penetrate their retreat, they gave it but slight heed, and quickly dropped again into the sleep of weariness.

When our lads next awoke they were oppressed with a sense of suffocation and uncomfortable warmth. It was still dark, and M. Filbert was striking a match in order to look at his watch.

"Seven o'clock!" he cried, incredulously. "How can it be?"

"Cole suass!" (snow) exclaimed the Indian, to whom the flare of light had instantly disclosed the cause of both darkness and suffocation. The cave was much smaller than when they entered it, and was also full of steam. Its walls were covered with moisture, and rivulets of water trickled over the floor.

"Cultus snow! Heap plenty! Too much! Mamook ilahie" (must dig), continued the Indian, springing to his feet, and making an attack on the drifted snow that had completely choked the cavern's mouth. When he had excavated a burrow the length of his body, Bonny took his place, while Alaric and M. Filbert removed the loosened snow to the back of the cave, where they packed it as closely as possible.

Although a faint light soon appeared in the tunnel, it was a full hour before it was dug to the surface of the tremendous drift and a rush of cold air was admitted.

A glance outside showed that while no snow was falling at that moment, the day was dark and gloomy, and the mountain was enveloped in clouds that were driven in swirling eddies by fierce gusts of wind.

In spite of the threatening weather, M. Filbert declared that they must begin their retreat at once, as they had but one day's supply of food left, while the storm might burst upon them again at any minute and continue indefinitely. So, after a hasty meal of biscuit and cold meat, the little party sallied forth. The Indian, having no longer a burden of fire-wood, relieved Alaric of his camera, and led the way. M. Filbert followed, then came Alaric, while Bonny brought up the rear.

Oh, how cold it was! and how awful! To be sure, the dangers surrounding them were hidden by impenetrable clouds, but they had already seen them, and knew of their[Pg 751] presence. As they started to traverse the rocky crater rim that still rose slightly above the snow, the entire summit was visible; but a few minutes later a furious gust of wind again shrouded it in clouds so dense as to completely hide objects only a few feet away.

Just then Alaric tripped on one of his boot-lacings that had become unfastened, and very nearly fell. That was no place for tripping, and such a thing must not happen again. So he paused to secure the loosened lacing, and, as he stooped over it, Bonny cried impatiently from behind:

"Hurry up, Rick! the others are already out of sight, and it will never do to lose them in this fog."

The necessity for haste only caused the lad's numbed fingers to fumble the more awkwardly, and several precious minutes were thus wasted.

With his task completed, Alaric, full of nervous dread, started to run after their vanished companions, slipped on a bit of glare ice at a place where the narrow path slanted down and out, and pitched headlong. Bonny saw his danger, sprang to his assistance, slipped on the same treacherous ice, and in another moment both lads had plunged over the outer verge of the sheer wall.

Neither Alaric nor Bonny could ever afterwards tell whether they fell twenty feet or two hundred in that terrible, breathless plunge. Almost with the first knowledge of their situation they found themselves struggling in a drift of soft, fresh-fallen snow, and a moment afterward rolling, bounding, and shooting with frightful velocity down an icy rooflike slope of interminable length.

At length, after what seemed an eternity of this terrible experience, though in reality it lasted but a few minutes, they were flung into a narrow snow-filled valley that cut their course at a sharp angle, and found themselves lying within a few feet of each other, dazed and sorely bruised, but apparently with unbroken bones, and certainly still alive.

As they slowly gained a sitting posture and gazed curiously at each other, Bonny said, impressively:

"Rick Dale, before we go any further I want to take back all I ever said about the life of a sailor being exciting, for it isn't a circumstance to that of an interpreter."

"Oh, Bonny, it is so good to hear your voice again! Wasn't it awful? and how do you suppose we can ever get back?"

"Get back!" cried the other. "Well, if we had wings we might fly back; but there's no other way that I know of. We must be a mile from our starting-point, and even to reach the foot of the place where we dove off we'd have to cut steps in the ice every inch of the way. That would probably take a couple of days, and when we got there we'd have to turn around and come down again, for nothing except a bird could ever scale that wall."

"Then what shall we do?"

"Keep on as we have begun, I suppose, only a little slower, I hope, until we reach the timber-line, and then try and follow it to camp."

"I wonder if we can?"

"Of course we can, for we've got to."

Painfully the lads gained their feet, and with cautious steps began to explore their surroundings. They walked side by side for a few yards, and then each clutched the other as though to draw him back. They were on the brink of a precipice over which another step would have carried them.

While they hesitated, not knowing which way to turn nor what to do, the clouds below them rolled away, though above and back of them they remained as dense as ever, and a view of what lay before them was unfolded.

Rocks, ice, and snow; sheer walls on either side of them, and a precipitous slope forming an almost vertical descent of a thousand feet in front. There were but three things to do: Go back the way they had come, which was so wellnigh impossible that they did not give it a second thought; remain where they were, which meant a certain and speedy death; or make their way down that rocky wall. They crept to its brink and looked over, anxiously scanning its every feature and calculating their chances. The first thirty feet were sheer and smooth. Then came a narrow shelf, below which they could see others at irregular intervals.

"There is only one way to do it," said Bonny, "and that is by the rope. I will go first, and you must follow."

"I'll try," replied Alaric, with a very pale face but a brave voice.

So Bonny, with the knowledge of knots that he had learned on shipboard, made a noose that would not slip in one end of their rope, tied half a dozen knots along its length for hand-holds, and fastened its other end about his body. Then he looped the noose over a jutting point of rock, and, slipping cautiously over the brink, allowed himself to slide slowly down.

It made Alaric so giddy to watch him that he closed his eyes, nor did he open them until a cheery "All right, Rick!" assured him of his comrade's safety. Now came his turn, and as he hung by that slender cord he was devoutly thankful for the strength that the past few weeks had put into his arms. He too reached the ledge in safety, and then, with great difficulty, on account of the narrowness of their foothold, they managed to whip the noose off its resting-place. Now they must go forward, for there was no longer a chance of going back. In vain, though, did they search that smooth ledge for a point that would hold their noose. There was none, and the next shelf was twenty feet below.

"We must climb it, Rick, and this time you must go first. Put the loop under your arms, and I will do my best to hold you if you slip; but don't take any chances, or count too much on me being able to do it."

There were little cracks and slight projections. Bonny held the rope reassuringly taut, and at length the feat was accomplished. Then Alaric took in the slack of the rope as Bonny, tied to its other end, made the same perilous descent.

So, with strained arms and aching legs, and fingers worn to the quick from clutching the rough granite, they made their slow way from ledge to ledge, gaining courage and coolness as they successfully overcame each difficulty, until they estimated that they had descended fully five hundred feet. Now came another smooth face absolutely without a crevice that they could discover, and the next ledge below was further away than the length of their dangling rope. There was, however, a projection where they stood over which they could loop the noose.

"We've got it to do," said Bonny, stoutly, "and I only hope the drop at the end isn't so long as it looks." Thus saying, he slipped cautiously over the edge, let himself down to the end of the rope, dropped ten feet, staggered, and seemed about to fall, but saved himself by a violent effort. Alaric followed, and also made the drop, but whirled half round in so doing, and but for Bonny's quick clutch would have gone over the edge.

There was now no way of recovering their useful rope; and fortunately, though they sorely needed it at times, they found no other place absolutely impossible without it. Now came a rude granite stairway with steps fit for a giant, and then a long slope of loose bowlders, that rocked and rolled from beneath their feet as they sprang from one to another. They crossed the rugged ice of a glacier, whose innumerable crevasses intersected like the wrinkles on an old man's face, and had many hair-breadth escapes from slipping into their deadly depths of frozen blue. Then came a vast snow-field, over which they tramped for miles with weary limbs but light hearts, for the terrors of the mountain were behind them and the timber-line was in sight. Darkness had already overtaken them when they came to a steep rock-strewn slope, down which they ran with reckless speed. They were near its bottom when a bowlder on which Bonny had just leaped rolled from under him, and he fell heavily in a bed of jagged rocks.

As he did not regain his feet, Alaric sprang to his side. The poor lad who had so stoutly braved the countless perils of the day was moaning pitifully, and as his friend bent anxiously over him he said, in a feeble voice,

"I'm afraid, old man, that I'm done for at last, for it feels as though every bone in my body was broken."

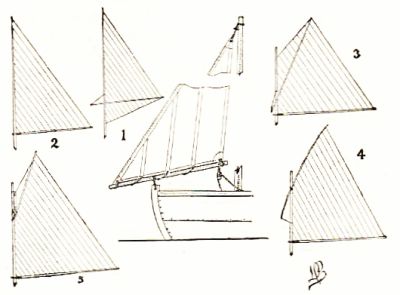

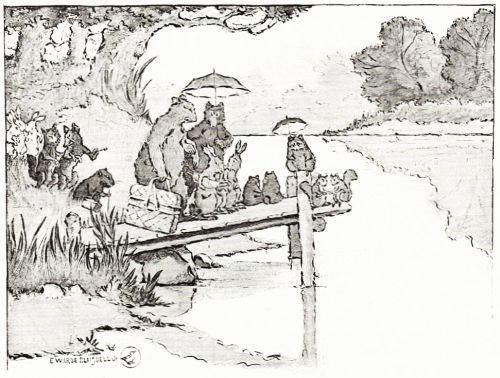

While a boy may not have occasion or the good fortune to handle or own a large boat, he is almost certain, if he lives near water, to have something to do with a bateau, skiff, or small boat of some character. Or perchance he may own a row-boat of the St. Lawrence skiff variety, and may wish to put a sail on it. Now there is nothing more clumsy and dangerous than a badly rigged small boat. By badly rigged is not meant only the boat whose spars are imperfect, or other things connected with her rig radically wrong, but also the boat that carries a rig that may be perfectly suitable for another class, but is entirely out of place in one of this size. A thing to be avoided in all small boats is unnecessary rigging; too many halyards and sheet ropes are in the way, and, where the rigging is on a very small scale, are very apt to get tangled or out of order when most wanted. So it may readily be seen that, for instance, the jib-and-mainsail rig of a twenty-five-foot boat, with its accompanying number of sheets, stays, and halyards would be totally out of place in a fourteen-foot bateau. The whole attention of the natives or "shell-backs" in or near our fishing villages has been devoted to the originating of makeshifts for the avoidance of everything that makes the construction and handling of a boat more difficult. Their idea seems to have been that anything that could be accomplished without the aid of mechanical means, simply by the use of a little extra muscle, had better be done that way.

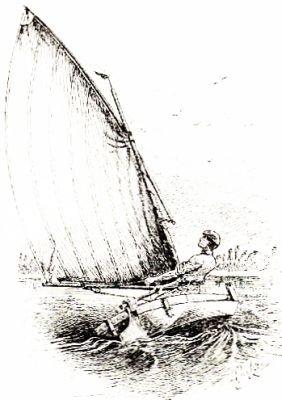

PLATE 1.

PLATE 1.

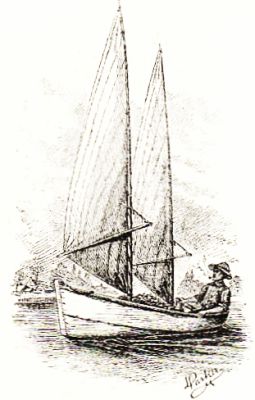

PLATE 2.

PLATE 2.

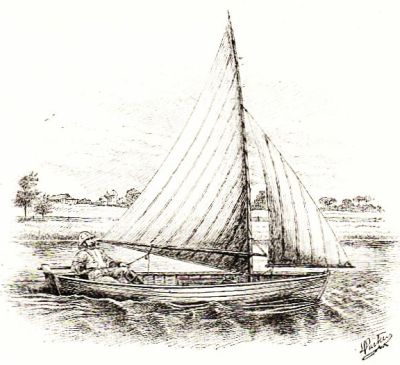

PLATE 3.

PLATE 3.

It might be said that in the small boat are seen the various rigs, in their simplicity, whose principles have been elaborated and altered to meet the different conditions required. Taking them in order of simplicity, we first come to the "leg-o'-mutton" rig. Here only two spars are used, and no halyards. In No. 1 (Plate I) the boom has no jaws, and is held in place at the mast by catching the projecting end in a sling, and by poking the other end through a cringle in the leech. The only lacing required is to fasten the sail to the mast, the sail only being fastened to the boom (more properly sprit) at the points mentioned. If it is found to bag, the remedy is to shorten the sling until the sail sets flatly. This can never be entirely accomplished, as the sail, being supported by the boom only at the extreme outer end and the mast at the other, is very apt to stretch in a stiff breeze.

Advancing a step, we come to the remedy of this trouble (Fig. 2, Plate I). It is the introduction of jaws at the mast, instead of the rope sling. The tendency to bag is removed, as the sail is fastened at frequent intervals by lacing to the boom, along which it may be kept stretched tightly. Also the tendency of the boom to slide forward is effaced as it butts up against the mast. In this method a much lighter spar can be used, as the strain is made to come more or less throughout its whole length, whilst in the first-mentioned it comes wholly at the ends. The principal objection against the "leg-o'-mutton" rig in general is the great length of mast required. This is one of its most serious drawbacks, and the other is the inability to reef the sail. Of course modifications of this rig have been made, introducing halyards and supplying reef points, but a discussion of that is beyond the scope of this paper, such modifications being rarely seen on a small boat.

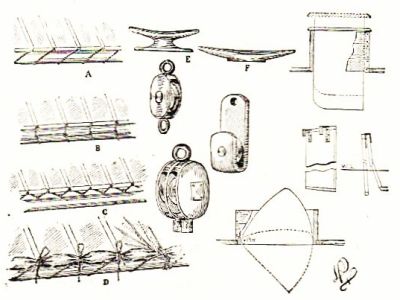

As mention has been made of lacing a sail to spars, perhaps it would be just as well to digress a little here, and speak of three well-known methods of lacing. The first, A, (Plate III), is the simplest and about as effective as any. The sail is fastened to the boom by an "over-and-over" lacing. In B, the sail is held by a series of "half-hitches," and in the third, or C, the lacing runs through eyes screwed into the boom.

The next step in rendering the rig more compact is to shorten the mast. This can only be done at the cost of an increase in the complexity of the rigging. A new spar is introduced, and the sail is cut down from a triangle to an area having four sides. Some means had to be found to support the upper edge, and a study of the last three sail plans will show some of the methods in use. Figs. 3 and 4 are nearly equal, as far as simplicity goes, though Fig. 3 is simpler on account of the absence of lacings on the upper edge. This is commonly known as the "sprit-sail," and, taking all things into consideration, it seems to be the most efficient and handiest of all the rigs. Of course it is not as efficient in some respects as the sail in Fig. 5, the same trouble being experienced on the top edge as in the "leg-o'-mutton"—bagging—but it possesses the advantage of greater simplicity. If we examine this rig we will readily see that it is any large fore-and-aft sail reduced to its simplest form. We find, instead of the gaff and the two halyards to hold the sail up, all this is replaced by the simple device of the pole (sprit), one end of which is stuck in a cringle in the upper corner of the sail, and the other caught in a sling. The sail does not move on the mast, and is laced to it. The boom has jaws at the mast, and the sail is laced on, or sometimes the device shown in No. 1 is resorted to, though the former method will be found to make this sail set better. There are no reef points, and the only way to reef is to drop the peak by removing the sprit. Of course it must be understood that this rig is not at all practicable in a boat of any size, but in any of about the size of a row-boat it will be found to be most convenient.

In the next device (No. 4) we approach nearer to the regular "fore-and-aft" sail. There can be seen the introduction of a yard to which the upper edge of the sail is laced, as to the ordinary gaff. No halyards are used, and the yard is lashed to the mast, and held at the proper angle to keep the sail flat by a rope fastening its lower extremity to the mast. The only objection to this rig is that the yard has a tendency to give and to permit the sail to bag. This rig is frequently seen on duck-boats. There is no method of reefing except dropping the yard, unless reef points are introduced.

A DUCK-BOAT TYPE.

A DUCK-BOAT TYPE.