The boy had learned much of odd-sounding names and strange sea terms.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Island of Appledore

Author: Cornelia Meigs

Release Date: September 25, 2018 [eBook #57976]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ISLAND OF APPLEDORE***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/islandofappledor00aldo |

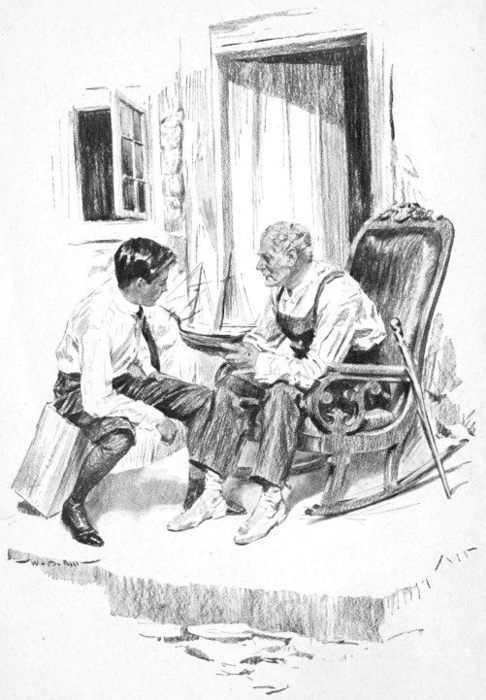

The boy had learned much of odd-sounding names and strange sea terms.

Any one who knows the coast of New England will know also the Island of Appledore and just where it lies. Such a person can tell you that it is not exactly the place described in this book, that it is small and bare and rocky with no woods, no meadows, no church, or mill, or mill-creek road. Perhaps all that the story tells of it that is true is that there the rocks give forth their strange deep song, “the calling of Appledore,” as warning of a storm, that there the poppies bloom as nowhere else in the world, that there the surf comes rolling in, day in and day out, the whole year through, and that there one’s memory turns back with longing, no matter how many years of absence have gone by.

There, also, you can sit for hours to watch the huge, green breakers come foaming and tumbling in endless procession up the stony beach; you can watch the nimble sandpipers and the tireless, wheeling gulls; and if you choose you can spin for yourself just such a story as this one of Billy Wentworth and Captain Saulsby and Sally Shute, a tale of mysteries and perils and midnight adventures on the shores of Appledore.

The boy had learned much of odd-sounding names and strange sea terms.

“Why,” gasped Billy, “it must have been the Flying Dutchman.”

Johann shook his head in mute anguish.

“Would you believe it, there were two boys that put to sea right in the face of it?”

Two big willow-trees guarded the entrance to Captain Saulsby’s place, willow-trees with such huge, rough trunks and such thick, gnarled branches that they might almost have been oaks. For fifty years they had bent and rocked before the furious winter storms, had bowed their heads to the showers of salt spray and had trembled under the shock of the thundering surf that often broke on the rocks below them. They had seen tempests and wrecks and thrilling rescues upon that stretch of sea across which they had looked so long, they had battled with winds that had been too much for more than one of the ships flying for shelter to the harbour of Appledore. It was no wonder that they showed the stress of time.

Billy Wentworth stood hesitating at the gap in the wall, looked up at the swaying, pale-green branches above him and down at the green and white surf rolling in on the shore below, sniffed at the keen salt breeze and tried to tell himself that he did not like it. He was so thoroughly angry and discontented that he could see nothing pleasant in the sunny stretch of open water, the glitter of the tossing whitecaps and the line of breaking waves about the lighthouse a mile away.

“To spend the summer on a little two-by-four island with an old-maid aunt,” was his bitter reflection, “to have nothing on earth to do and no one to do it with—it’s just too hard. I won’t stand it long.”

He stumped the toes of his boots in the dust of the narrow path with as much obstinate sulkiness as though he were six years old instead of sixteen. Perhaps it made him even more angry than he was before, to discover that, in spite of what he had been thinking, he had stood staring for some minutes at the big, curling waves as they rolled in, receded, and came foaming up among the rocks again. Indeed he had been watching with such fascination that he could scarcely tear his eyes away. He had seen the Atlantic Ocean for the first time in his life only a few hours ago, and he was still trying, with some success, to convince himself that he did not like it and never would.

He strolled aimlessly along the path which he had been told led to “Cap’n Saulsby’s little house down on the point.” There was a vague desire in his mind to look upon a live sea-captain since he had never seen one before. The feeling was not strong, only just enough to bring him along the shore road and through the willow-guarded gateway. He had no thought, as he walked slowly between the two big trees, that they marked the door to a new phase in his life, that they were to prove the entrance to adventures and perils of an unknown kind. He merely trudged along, frowning at the sun that shone too brightly on the dazzling blue water and at the wind that blew too sharply in his face.

Somebody was walking up the path before him; so he slackened his pace a little, having no wish to overtake him. As far as he could judge it was a boy of about twenty-one or so, very fair-haired, with broad shoulders and well-shaped hands hanging from sleeves a trifle too short. He carried a bag of tools and was whistling gaily some intricate tune of trills and runs as he walked along. As he turned to look out to sea, Billy saw that he had a pleasant face, cheerful, intelligent and rather sensitive. He stood for a minute, though without seeing Billy, then walked on again, swinging his bag and piping his music in the very best of spirits.

A bobolink was swinging on the branch of a bush that leaned over the wall. The gay black-and-white fellow was a new bird to Billy, so he stopped to look at it more closely. Certainly it was the bird that caught his attention not the unaccountable rustle that he heard immediately after, for that sound he might never have noticed save for the strange thing that followed.

For the rustle was repeated; then a hand rose over the wall, slipped across one of the big lichen-covered rocks and rapped upon it sharply with something metallic. The boy ahead of him stopped dead, hesitated a second, then turned slowly toward the sound. Billy could see now that there was a man there behind the wall, crouching among the bushes, some one rather small, narrow-shouldered and with stiff black hair. He seemed to be peering intently at the boy on the path but did not move or speak. The boy, also, said nothing but presently went upon his way again, swinging his bag and once more trying to whistle. But such a trembling, broken tune as came forth in place of the former cheerful music! The lad looked back once, but was gazing so eagerly at the wall that he did not notice Billy at all. He showed a face turned suddenly gray-white with terror, drawn, haggard and anxious. It was plainly visible that his knees shook under him as he tried to stride onward at his former gait, and that it was because of the trembling of his hands that his bag of tools dropped twice upon the grass.

What could have been in that man’s face that had alarmed him so? The boy looked like a vigorous, spirited sort of person, Billy thought, one that it might be nice to know and be friends with, not a coward. The mild interest that had brought him through the gate now gave place to extreme curiosity as he hurried up the path.

Around the curve of a low knoll Captain Saulsby’s house came into view. It was an oddly-shaped little dwelling, so surrounded with trees and bushes that there was not much to be seen of it except bits here and there: a peering chimney, patches of red-stained roof, a portion of gray wall and the front door painted a bright, cheerful blue. Sloping away to the rocky point lay Captain Saulsby’s garden, with its rows of vegetables and shrubs and flowers. Captain Saulsby himself was sitting in an armchair on the wide, stone doorstep, but alas he did not look in the least as Billy had expected.

He had pictured old sailors as being white-haired, but sturdy and upright, dressed in blue clothes and moving with a rolling walk or sitting to stare out to sea through a brass telescope. Captain Saulsby’s hair was not exactly white, it was indeed no particular color on earth; he wore shabby overalls a world too big even for his vast figure and he had carpet slippers instead of picturesque sea-boots. Yet the flavour of the sea somehow clung to him after all, brought out, perhaps, by the texture of his face which was red and weather-beaten with the skin wrinkled and thickened to the consistency of alligator leather, and by his huge rough hands that resembled nothing so much as the gnarled and stunted willow-trees at his gate.

Instead of grasping a telescope, he was holding a bright blue sock which he was mending as deftly as though well used to the task. The darning needle seemed lost between his big fingers, but it went in and out with great speed, pushed by a sailor’s palm instead of a thimble. That, Billy thought disappointedly, was the only really nautical thing about him.

“Good afternoon, Johann Happs,” the captain called cheerily as the first of his visitors came near. Then peering over his spectacles at Billy, he added, “Who is that behind you?” The boy whom he called Johann wheeled suddenly and turned upon Billy a look that he could never forget. Terror, desperation and defiance all were written on his unhappy face and in his startled eyes. When he saw, however, that it was not the black-haired man who had peered over the wall, but only a boy from the summer colony at the hotel, his evident bewilderment and relief might have been almost ridiculous had they not been pathetic. He laughed shakily and turned to the captain.

“I do not know who it is,” he said, “Perhaps someone to buy strawberries.”

“You’re Miss Mattie Pearson’s nephew, now I’ll be bound,” remarked the old man, surveying Billy carefully from head to foot as he came closer. “She told me all about you, where you had meant to go this summer and how you came here instead and maybe weren’t going to like us here on Appledore Island. Johann, look at that frown on his face; I don’t think he has sized us up very fair so far, do you? Well, he’ll learn, he’ll learn!”

Billy frowned more deeply than ever, partly because he had no taste for being made sport of by a stranger and partly because the memory of his recent disappointments came back to him with a fresh pang. His plan for this summer had been to camp out in the Rockies, to climb mountains, to ride horseback, fish in the roaring, ice-cold little trout streams and to shoot grouse when the season came around. His father and mother had promised him just such a program; they were all three to carry it out together, being the three most congenial camping comrades that ever lived. However, sudden developments of business, due to the war in Europe and the necessity of turning in other directions for trade, had called his father to South America at just the season when Billy could not leave school to go also. It was during the Easter vacation that he had travelled from his school in the Middle West to New York, to see his father and mother off on their long voyage; then he had gone back unwillingly to face continuous days of missing them and of rebelling vainly against the destruction of his hopes for the summer.

When Miss Mattie Pearson, his mother’s sister, had invited her reluctant nephew to stay at Appledore, she must have realized that the resources of the hotel and the little fishing village that the Island boasted, would scarcely be sufficient to satisfy him. She seemed to have been thinking of Captain Saulsby even when she wrote her first letter, for she had said, “I hope you will find one companion, at least, who will interest you.” She had a great affection for the queer, gruff, bent, old sailor, and must have felt that he and the boy were bound to become friends. And now Billy, standing before the captain himself, shifting uneasily from foot to foot and looking into those small, twinkling blue eyes, was beginning, much to his surprise, to feel the same thing.

“There are some strawberries down yonder in the best patch that I have been saving for your Aunt,” the old man went on. “I’m glad you came along, for this isn’t one of my spry days and I couldn’t carry them up to the hotel myself. I have been expecting Jacky Shute to take them, but the young monkey hasn’t turned up. You didn’t see him, did you, Johann, as you came along?”

“No,” replied Johann hastily, much too hastily, Billy thought, “I saw no one, not anyone at all.”

Billy looked at him in amazement. He did not seem at all like the kind of person who could tell such a lie. Nor did he appear to enjoy telling it, for he stammered, turned red, picked up his bag of tools and set them down again.

“I will go in and mend the clock now, if you don’t mind, Captain Saulsby,” he said, perhaps in the desire to escape further questioning.

“Go right in and do anything you like to it,” the old man returned, “and meanwhile this young fellow and I will go down and get the berries. Just reach me that basket of boxes, will you, and give me a hand up out of this chair, and we’ll be off. The clock is ticking away as steadily as old Father Time himself, but I suppose you will find some tinkering to do.”

He took up the heavy wooden stick that leaned against his chair and that looked as rough and knobby and weather-worn as himself. With Johann’s help he rose slowly from his seat, making Billy quite gasp at the full sight of how big he was. Yet he would have been much bigger could he have stood upright, for he was bent and twisted with rheumatism in every possible way; his shoulders bowed, his back crooked, his knees and elbows warped quite out of their natural shape. He wrinkled his forehead under the stress of evident pain and breathed very hard as he stumped down the path, but for a few moments he said nothing.

“Kind of catches me a little when I first get up,” he remarked cheerfully at last. “There have been three days of fog and that’s always bad for a man as full of rheumatics as I am. I hope you won’t mind very much gathering the berries yourself. I—I—” his face twisted with real agony as he stumbled over a stone. “I find it takes me a pretty long time to stoop my old back over the rows and some folks would rather not wait.”

“Indeed I don’t mind,” replied Billy with cordial agreement to the plan. He had no reluctance in owning to himself that, however discontented he was with things in general, here was one person at least whom he was going to like.

“Now,” said Captain Saulsby as they reached the strawberry patch at the foot of the garden, “eat as many as you can and fill the boxes as full as you can carry them away. That is what berries are made for, so go to it.”

This invitation was no difficult one to accept. The berries were big and ripe and sweet, and warm with the warmth of the pleasant June day. It was still and hot there in the sun, with no sound except the booming of the surf along the shore, and the shrill call of a katydid in the hedge at Billy’s elbow.

The glittering sea stretched out on each side of them, for Captain Saulsby’s garden lay along the point that formed the northernmost end of Appledore Island. A coasting schooner, her decks piled high with new, yellow lumber, came beating into the wind on one side of the rocky headland, finally doubled it and, spreading her sails wing-and-wing, went skimming away before the breeze. Billy, whose whole knowledge of boats included only canoes and square, splashing Mississippi River steamers, sat back on his heels watching, open-mouthed, as the graceful craft sped off as easily as a big bird.

“Say, young fellow, your aunt will be waiting a long time for those berries,” was Captain Saulsby’s drawling reminder that brought him back to his senses. He blushed, recollected quickly that he was the boy who hated the Island of Appledore and everything belonging to it, and fell to picking strawberries again with his back to the schooner. The little katydid began to sing again.

“That’s a queer fellow, that Johann Happs,” the old sailor remarked reflectively as he sat watching Billy’s vigorous industry. “He is a German; at least his father was, although Johann was born in this country and is as American as any one of us. He is as honest and straightforward a boy as I have ever known and has been a friend of mine as long as I have lived here. But there is something wrong with him lately that he is keeping from me. I wish I could manage to guess what it is.”

“Did you say he mends clocks for a living?” Billy asked. He decided that he would not betray Johann’s secret, little as he knew of it, and much as he desired to learn more.

“No, clock-mending is his recreation, not his business. He is a mechanic, and a good faithful worker, but when he wants to be really happy he just gets hold of a bunch of old rusty wheels and weights, that hasn’t run for twenty years, and works at them by the hour. To see him tinkering would show you where his real genius is. He gave me a clock that belonged to his father, a queer old thing with gold roses on the face and with wooden wheels, but it runs like a millionaire’s watch. He comes around once in so often to see if it is doing its duty, and has six fits if it has lost a second in a couple of weeks. He’s a queer fellow.”

“Then he isn’t a fisherman,” commented Billy. “I thought that every one who lived on the Island was that.”

“Almost every one is, except that boy and me,” answered the Captain. “No, Johann isn’t a fisherman, but you never saw any one in your life who can sail a boat the way he can. That’s his little craft anchored off the point there; she’s the very apple of his eye. Just see how he keeps her; I do believe he would give her a new coat of paint every week if he could afford it. He’s surely proud of her! He was so happy with her a little while back that I can’t understand what has come over him now.”

He sat staring at the little boat, until Billy finally had filled his boxes and had risen to his feet.

“I have picked all these for Aunt Mattie,” he said, “and have eaten about twice as many besides. Now won’t you let me pick some for you?”

“Why, that’s good of you,” returned the old man gratefully. “I won’t deny that it is easier work sitting here and watching you gather them than to try to get the pesky things myself. I don’t need any myself but I did want to send some to Mrs. Shute, over beyond the creek. They are just right for putting up now and will be almost too ripe in another day. That rascal Jacky should have taken them, but there’s no knowing where he is.”

“I’ll pick them and take them to her, if you will tell me the way,” Billy assured him. “Don’t say no; I would really like to.”

The boxes filled rapidly, to the accompaniment of much earnest talk between Billy and his new friend. He learned how little to be relied upon was Jacky Shute, the Captain’s assistant gardener; what an unusual number of summer visitors on the Island there were, owing to the war in Europe and the impossibility of people’s going abroad; what a cold, windy spring it had been, very bad for vegetables and for the poppies that were the pride of Appledore gardens but—

“Great for sailing,” the old man concluded wistfully.

When the berries were ready, the Captain came with Billy to the edge of the garden to show him the way. Beyond the point, on its western shore-line, was a stretch of curving beach, cut into a deep harbour by the mouth of a little stream.

“You cross that meadow above the rocks,” the Captain directed, “and go straight on down to the creek. You will find a row of stepping stones that makes almost a bridge; the tide is nearly dead low so it will certainly be uncovered and you can cross without trouble. The stream is the mill creek, and that building you see on the other side, among the trees, is the old mill. You go up from the creek right past the mill door and follow the road that leads through the woods. The first lane that turns off from that will take you to the Shutes’, so you see you can’t miss the way. They have a nice girl, Sally Shute; I hope she’ll be at home for I know you’ll like her. She is worth twenty of Jacky, that worthless young brother of hers.” He turned back to the garden. “Well, good-bye; I know you won’t have any trouble getting there but don’t stay too long, the tide is pretty quick to cover the causeway over the creek and then you would have to walk five miles around by the highroad. I will see you when you come back and I surely am obliged to you.”

Billy set off with his load of boxes under his arm, stepping carefully through the tall grass of the meadow where daisies nodded in white profusion and bayberries and brambles grew thickly along the stony edge of the field. He came presently in sight of the stream and the bridge-like stepping stones, finding them, as Captain Saulsby had said, just uncovered by the dropping tide. One huge rock jutted far out into the water at the edge of the little harbour, and here he found himself tempted to stop a minute, staring at the foaming green water, then to climb down from ledge to ledge and finally to seat himself just above where the surf was breaking.

How cool and deep the tumbling waves were, how they came rolling solemnly in, and then seemed to hesitate for one short second before they broke and sent spattering showers up to his very feet. He must go on, of course; it was really a shame to delay longer; he would just watch another breaker come in, and then another—and another, so that he might see again those shining rainbows that came and went in the sunlit spray.

He heard something scurry and scuttle across the rock near by him and, as he looked over the edge, saw a slim, brown mink come out of a hole and stop to look up at him. It must have had a nest near by, for it was fierce in its anger at his intrusion and seemed quite unafraid. Its wicked little eyes fairly snapped with rage, and it made a queer hissing sound as it tried, with tiny fury, to frighten him away. He laughed and turned to go, then started back suddenly as he spied a face peering out at him for a moment from behind the big, grey rock above him. It struck him, startled as he was, that the human face was something like the mink’s; the same narrow cruel jaw, the same retreating forehead, the little beady black eyes and stiff black hair. With a great effort, although his heart hammered at his ribs and his knees shook a little, if the truth must be told, he climbed up to the jutting rock and looked behind it. There was no one there. He drew a sigh of relief at the thought that he must have been mistaken, then checked it sharply when he saw a black shadow, thin, lithe and quickly-moving, slip across the surface of the rocks and vanish.

Billy’s passage over the causeway was a hasty and somewhat perilous one, for the rocks were overgrown with thick, brown seaweed and still wet from the falling tide. Considering what a hurry he was in and how many times he looked back over his shoulder, it was quite remarkable that he made the crossing without mishap. He walked up a strip of sandy beach, climbed a steep bank and came into the cool, dark pine woods. The faint marks of an old road showed before him, covered with a rusty-brown carpet of fallen needles and leading past the big, grey empty mill of which the Captain had spoken. He followed along it, turned down the lane as directed and tramped some distance straight through the forest, the tall black trees towering above him and the partridge berries, trailing ground pine and slender swinging Indian pines growing thick beneath his feet.

It was more than a mile, perhaps nearly two, that he covered before he observed a clearing ahead of him, and then came suddenly to the edge of the woods and to the shore again. A very neat, brown cottage stood in the open space, with a garden around it, a fence of white palings and a green gate at the end of the lane. Beyond the house he could see grey rocks, a little pier stretching out into the water, a fishing boat at anchor and, as a background to everything, the bright, sunlit sea. He opened the gate and came slowly through the garden.

A little girl was stooping over one of the round flowerbeds, picking pansies into her white apron. She was a short and solid little person, with thick yellow braids, very round pink cheeks and, as she looked up at him, a most cordial welcoming smile.

“I’m Sally Shute,” she announced somewhat abruptly and without a particle of shyness; then, as Billy hesitated, “I believe I would like to know who you are.”

“I’m Billy Wentworth, and I brought these strawberries from Captain Saulsby,” the boy answered, a little abashed at this sudden plunge into the business of getting acquainted.

“The Captain said he was sorry not to send them sooner.”

He could not seem to think of anything else to say, that was of especial importance, so turned to go.

“Wait,” Sally commanded, in the tone of one who is used to having her orders obeyed. “I must take the berries to my mother and have her empty them out, because Captain Saulsby will want his boxes back again. And I think,”—here she looked him over solemnly from head to foot—“I think that you look thirsty.”

Billy grinned and admitted that there might be some reason for that appearance.

Getting acquainted with Sally was as rapid a process as had been getting acquainted with Captain Saulsby. The tall glass of cold milk and the plate of fresh gingerbread certainly put an end to any formalities between them, and the expedition down to the hen-house to see the new brood of deliciously round, fat ducklings carried them far on the road toward friendship. Billy thought that the ducks looked rather like Sally herself, they were so small and fat and yellow and so very sure of themselves, but he did not summon courage to say so. Next, they went down to the pier to see, “the biggest big fish you ever saw, that my father brought in last night.”

This, Billy felt, was more worth showing him than were mere ducklings, but he did not admit being impressed by the size of the fish, although in truth it was a monster, nearly as long as the dory that held it. He stood passing his hand over the slippery surface of its silver scales and listening to the thrilling tale of its capture, recounted by Sally with as much spirit as though she herself had been present. She broke off in the middle of her story, however, to exclaim:

“Gracious, I’m keeping you here until maybe the tide will be over the causeway and you can’t get back. That would never do!” They hurried up to the house, gathered the berry boxes together in haste, and went toward the gate.

“I’ll not forgive myself if I have made you miss the tide,” Sally said. “I think I will walk with you as far as the creek to make sure.”

She chattered continuously as they went down the wooded lane, telling him what the different flowers and birds were, what games she and her brother played there among the trees, where her father’s land ended, and where Captain Saulsby’s began.

“The Captain owns almost all of this end of the Island,” she said. “His father or maybe his grandfather built the mill and used to run it. There were grain fields over most of Appledore then, and people farmed more and fished less. Captain Saulsby doesn’t do anything with the land except the little piece his house is on; he has not really lived here a great many years. He ran away when he was a boy and sailed all over the world, and only came back to settle down when he got too old to go to sea.”

Her talk did not remain long on the subject of the Captain, however, but presently, in response to a question of Billy’s, wandered away to Johann Happs.

“Yes, I know him, and I like him too. He comes every so often to fix our clocks, mend the locks and things that won’t work, sharpen up the tools and put us in order generally. He’s so cheerful and honest: there’s not a person on the Island that doesn’t admire Joe and trust him.”

Billy shook his head silently; he could make nothing, so far, of this strange affair of Johann Happs. He had not time to reflect on the puzzle long, for presently they met some one coming down the lane toward them.

“He’s queerer than the Captain or Johann too,” thought Billy, and with some reason. The man who approached was as unusual as were the old sailor and Johann Happs, with one variation. Those two, one liked at once; this person it was impossible not to detest the moment one laid eyes upon him.

He was small and pinched-looking, with greyish sandy hair and a sallow face. His eyes were light-coloured and shifty, seeming to have a rooted objection to looking straight at any one. He wore white shoes that were very shabby and checked clothes of a cut that was meant to be extremely fashionable—and was not. His straw hat was put on at a jaunty, youthful angle, but, when he took it off to greet Sally with a flourish, he betrayed the fact that he was growing bald and a little wrinkled.

“Very pretty woods you have here, very pretty,” he observed, holding out a hand which obstinate Miss Sally pretended not to notice.

“They aren’t our woods; they are Captain Saulsby’s,” she replied ungraciously. “His land begins back there.”

“Ah, very true, Miss Shute,” the man went on. “He’s rather a queer one, our friend the Captain, now isn’t he? He hardly seems to remember the place is his, I think. Doesn’t come here very often and look after his boundary fences and all that, does he?”

Even Billy could see that the man’s eagerness betrayed him and that he asked the last question a shade too anxiously. Sally observed it as plain as day and had no hesitation about saying so.

“If you want to find out all that so much, you had better ask Captain Saulsby himself,” she told him emphatically. “I really think he knows best about his own affairs.”

“You are right,” the other agreed instantly, “and I will ask him. But you see,”—here he dropped his voice to a very confidential tone—“the old Captain is a hard man to do business with, very hard. I am trying to buy this land of him, not for myself, you understand, but for a friend, a man who is a stranger in these parts, and immensely wealthy. He has taken a fancy to Appledore Island and wants to build a summer home here, and an elegant place it is to be; he has actually shown me the plans. It seems he has set his heart on buying the mill-creek property from the Captain, but, dear, dear, what an obstinate creature the old fellow is! We have offered him a good price and of course he is only holding out for more money; but he has tried my patience almost to its end. I am wondering if he has a clear title to all these acres he owns. You never heard your father say anything to that effect, did you, my dear?”

He bent forward and his hard little eyes fairly glittered as he put the question. Sally, however, as a source of information, was quite as disappointing as Captain Saulsby.

“Harvey Jarreth,” she announced firmly, “you are always going round asking questions about other people’s business, but I, for one, won’t answer them. And my father won’t either, and besides, he’s not at home.”

“Very well,” returned Jarreth cheerfully, “very well.”

It was evidently no new thing to him to receive replies as tart as Sally’s. He turned on his heel and marched away down the lane before them, swinging his shoulders and his cane, yet somehow not giving the careless effect that he so plainly wished.

“Everybody hates Harvey Jarreth,” Sally explained when he was out of hearing. “I know it was not polite to talk to him so, but he makes me so angry that I never can help it. He is always getting the best of people and boasting about it, making money on sharp bargains, finding out things that aren’t his concern and then profiting by them. No one can trust him and no one can like him.”

“Does he really want to buy Captain Saulsby’s land, do you think?” Billy asked.

“He says so. My father thinks it would be a good thing for the Captain if he could sell it and if there really is such a person as Harvey Jarreth tells about who wants to buy it for a house. None of us has ever seen any such friend of his. And Captain Saulsby is a queer old man; he is dreadfully poor, yet you can’t possibly tell whether he will agree or not. It would be like Mr. Jarreth to get the land from him some other way, if he can’t buy it. He is so sharp at such things and the Captain is so careless!”

They had come to the mill-creek road by now, and were passing the door of the mill itself.

“That’s a funny old place,” Billy observed. “Does any one live there?”

“People lived in it a good while after it had stopped being used as a mill,” Sally said, “but it is empty now. Would you like to look in?”

The big timbered door was fastened only by an iron latch, so there was no difficulty about pushing it open and peeping in. The whole of the lower floor was one great room, with a crooked flight of rickety stairs at the back, leading up to the second story. The windows were small, making the interior full of shadows and very cool and dark after the hot sunshine outside. There was a big fireplace of rough stones, a bench near it, a table and a broken chair or two, with a three-legged stool in the chimney corner.

“Jacky and I come here to play sometimes,” said Sally, “although he doesn’t like it much. People used to say it was haunted, but of course that’s nonsense. Still it is pretty dark and queer and rather too full of strange creakings when you are alone.”

They closed the door again, went down the steps and along the road and parted on the beach.

“I’m glad you came,” said Sally; “you must come again. Now hurry, or the tide will catch you. I think Harvey Jarreth has gone on to Captain Saulsby’s ahead of you. Good-bye.”

As Billy hastened across the stepping-stones and through the meadow, he looked very sharply and very often down toward the rocks, but could see no signs of any one’s presence. Sally was right; Harvey Jarreth had gone ahead of him and was standing now by the bench near the hedge, in hot dispute with the old Captain.

“I never saw a man so blind to his own interests,” he was saying. “I believe you are out of your senses. Come now, say what figure you will really take.”

“You could cover the land with gold pieces for me and I wouldn’t sell,” returned the old sailor with determination. “I’m not saying that it isn’t a good offer for me in some ways, but I will part with no property to a man who won’t give his name or state his business. If I’m to take his money, I must know where it comes from.”

“It is perfectly natural that my friend should ask me not to give his name,” Jarreth insisted. “And as for the money, what do you care where it comes from, just so you make something? What do you want with all those acres your father left you, when you only can dig up one corner of it to plant a few miserable poppies in?”

“What does your friend want of it?” retorted the Captain; “and by the way, how does it happen you have such a friend? How long have you known him?”

“Why—why, not long,” admitted Jarreth, “but he’s all right, I know that, and able to buy the whole of Appledore Island twice over. Well, I suppose you are standing out for a bigger price and I will just have to tell him so.”

“I’m standing out for nothing of the sort, you everlasting lunkhead,” roared the old man, completely exasperated, “and I’ll waste no more time talking to you.”

“I’ll just step up to the house and rest a little there in the shade,” Jarreth said. “I have a long walk home, so I might as well give you time first to think this well over. You will see reason in the end.”

The Captain made no reply, but deliberately turned his back upon Jarreth as he walked away, and began puffing furiously at his pipe.

“Well, Billy Wentworth,” he said, taking his first notice of the boy, who had stood waiting until the altercation should end, “how did you like Sally Shute?”

“I liked her lots,” Billy replied with enthusiasm, “and I am glad I went. Here are your boxes: I will carry them up to the house.”

“Sit down a bit until I finish my pipe,” the Captain said. “That persistent cuss is waiting up there at the cottage and we may as well let him cool his heels a while. His time isn’t worth anything except to think up mischief.”

Billy took his place on the bench beside the old sailor and sat staring out to sea.

“What is Johann Happs doing out there in his boat?” he inquired at last. “Is he going to sail her?”

“I think not today,” Captain Saulsby answered. “He is always working out there at something or other. He is as fond of her as though she were his own kin. He hasn’t any one belonging to him, maybe that is why he loves her so.”

Just at this moment a small boy came lounging down the path with as little hurry as though all the world were waiting for him. He was short and fat and looked so much like a lesser edition of Sally that there could be no doubt of his being Jacky Shute.

“I’m just a-goin’ to weed those onions, Captain Saulsby,” he said hastily, to prevent the old sailor’s speaking first. “I stayed down by the wharf a little late, fishing, but there’s plenty of time yet. It’s not five o’clock.”

He scurried away across the garden, leaving the Captain sputtering with helpless indignation.

“That’s the kind of helper I have,” he exclaimed. “Comes when he likes, goes when he likes, does what he likes. His mother and Sally can’t do a thing with him. And stupid! Why, there’s nothing you can teach him, no matter how you try. He has fished and paddied along this shore all his life, but he doesn’t know a thing about boats; he can’t tell the difference between a sloop and a knockabout. And what’s more,—” here the old man turned full upon Billy and dropped his voice as though he hated to speak so dreadful a thing aloud—“what’s more, he says he doesn’t want to know.”

Billy opened his mouth to say something in reply, and then shut it again. He realized that the ignorance of which the Captain spoke was as great as would be the inability to distinguish between a dog and a cat, but he was unwilling to betray the fact that he was as much in the dark as Jacky Shute. A few hours ago he would have been quite scornful of any such knowledge; now he felt a strong desire to hide his ignorance, a desire which, in turn, gave way to an even greater wish. He fought against it, reminded himself over and over again how determined he was to despise everything that had to do with the sea, how he hated Appledore and would have no interest in it. But there was something about the rough old sailor’s bent figure, broken by a hundred tempests yet strong and determined still, there was something about the tossing blue water, about the wide, unbroken horizon, about the fresh, sharp, salt air that made him feel—well, different in a most indefinable way.

They sat in silence for a little while until the old man’s pipe was smoked out, and Billy felt that it was time for him to go. He rose, held out his hand to say good-bye, and then suddenly felt his wish so strong within him that it broke forth into words.

“Captain Saulsby,” he said, “I don’t know the difference between a sloop and a knockabout, either. I don’t know anything about the sea or about boats. I wish you would teach me.”

The sailor’s gnarled old brown hand was laid very gently on his shoulder.

“Bless you, how should you know,” he answered; “you that never saw salt water before today? Sure, I’ll teach you anything I know; sit right down again and listen.”

Miss Mattie Pearson, up at the hotel, must have rocked and knitted and knitted and rocked a long, long time that day as she watched for her nephew’s return. The bright red sock that she was making for the Belgians grew several inches, the other guests went in to dinner, but still she waited, nor did she seem impatient. She was spare and elderly and beginning to be white-haired; she might have answered well enough to Billy’s description of her as an “old maid aunt” but she had keen grey eyes that had been able to look pretty deeply into her nephew’s rebellious young soul. He had been sullen and discontented ever since his arrival that morning and, if he had made any efforts to conceal his state of mind, they had not been successful ones. So she had sent him off in the direction of Captain Saulsby’s house and seemed not in the least surprised or displeased that he was so long in coming back. Old maid aunts sometimes have a way of knowing things, just from the fact that they have lived so long.

Meanwhile Billy was still sitting on the bench listening, entranced, to details of full-rigged ships, schooners, yawls, raceabouts and dories. His head began to reel under the weight of all the knowledge poured out upon him, so that, finally, it was only with mighty effort that he followed what the Captain was saying. Even the old sailor realized this at length and decided to have mercy.

“I will tell you what we can do,” he said. “We will make you a model; schooner-rigged, we will have her, with everything complete and shipshape, so that you can learn the ropes too well ever to forget them. No,” as Billy tried to remonstrate, “of course I will have time. What is an old man good for, when he can’t follow the sea any longer, but to hand on what he knows to some one who will do him credit some day? Yes, we will build you a model and she shall be called the Josephine, after the first ship I ever sailed in; the finest one that ever crossed the seas.”

As Billy finally took his way homeward, his mind was a seething mass of nautical terms which he vainly tried to set in order.

“The gaff holds the top of the mainsail,” he was saying to himself, “and the jib-boom—”

Here he was obliged to interrupt the repetition of his lesson by laughing aloud at the memory of his last view of Captain Saulsby. Harvey Jarreth had been waiting at the cottage, true to his word, so that Billy’s final sight of the two had shown him the little eager man still pouring out a flood of argument, while the Captain sat unconcernedly darning his blue sock once more, and whistling as gaily as though Jarreth and his real-estate project were a thousand miles away.

However, just before Billy passed out through the gap in the wall, he saw something that drove both lesson and laughter completely from his mind. He had stopped to take one more look at the little house, the sloping garden, the steep rocks running out into the foaming surf and at Johann Happs’ trim little boat riding at anchor just inside the harbour. One glance showed him clearly that the vessel was in distress, but how or why he could not tell. She seemed to be settling slowly in the water, indeed had already sunk so deep that the waves were breaking over her. And, strangest of all, Johann Happs was standing, with folded arms, upon the beach, staring at her but quite unmoving, never lifting a hand to rescue his beloved boat.

The North Atlantic fleet of the United States Navy was playing its war game off the coast of New England, with a large part of the manœuvres apparently arranged for the especial benefit of the visitors on Appledore Island. For three days ships had been plying steadily back and forth in the offing; huge dreadnaughts whose like Billy had never seen before, smaller cruisers and swift slender destroyers that ran in and out amongst the rest of the fleet like greyhounds. Even the knitting brigade on the hotel verandah deserted its usual task of rocking and gossiping and plying swift needles for the relief of the Belgians, and instead came down to the wharf to stare out to sea, to wonder what this boat was, or what that ship could be doing, and what it was all about anyway. The one or two men in the company were able to tell much of just what the whole plan was, and just what each division of the fleet was trying to do to the other. Unfortunately none of these learned dissertations on naval strategy ever seemed to agree, and the eager questioners went back to their watching rather more puzzled than before.

Two young naval officers were actually quartered at the Appledore Hotel, but they spent all their time observing the ships’ movements from the highest point of the island, or signalling from one of the headlands. When they could be stopped and questioned they seemed to display such pitiful ignorance alongside of the fluent knowledge of the lecturers on the wharf that it hardly seemed worth while to ask them anything.

The first three days had been dull and foggy, making the manœuvres even more confusing than usual to the uninstructed mind; so Billy, who had done his best to have no interest in the matter, finally proclaimed loudly that the whole business was a great bore and that he would waste no more time in watching it. But on the fourth day, a clear cloudless one, with brisk winds and a sea so bright that it fairly hurt your eyes to look at it, he went down to see his friend Captain Saulsby and found that he, too, was caught by the fascination of this same war game.

“I wish I could see the way I used to,” the old man sighed as he put down his battered telescope—Billy felt better about him when he found that he actually had one—and leaned back in his chair by the door. “That ship that’s going by now is either the Kentucky or the Alabama and for the life of me I can’t tell which. I’ve watched them off this point for a lot of years now, and never could see so little before. I do believe,”—he spoke as though the suspicion had only just occurred to him—“that I’m getting old!”

A week ago Billy might have felt inclined to laugh at any one who was so bowed down with years but who seemed so surprised on discovering the fact. Now, however, he had become too fast a friend of the Captain’s for that. A man who could endure pain as unfalteringly as Captain Saulsby did, who, although nearly a cripple, could still work for his scanty living and never complain of the toil and hardship, such a person was not to be laughed at.

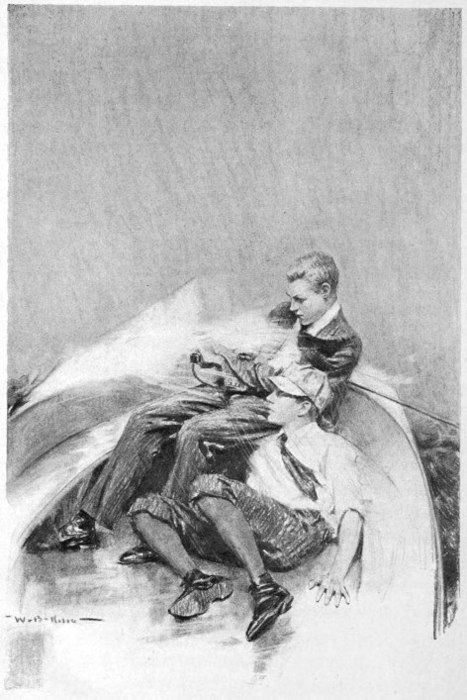

Moreover, on the Captain’s knee was the model of the boat that was to teach Billy something of seamanship, the Josephine, a very marvel of graceful lines and intricate rigging. Such loving, patient care as had gone into the building of the little craft only those two would ever know. The Captain’s rough thick fingers had worked wonders; Billy’s impatient, unskilled ones had done their full share. The two had had long talks together over their labours, in which the boy had learned much of odd sounding names and strange sea terms, but more of the adventures and hardships and restlessness of the life of those who follow the sea.

He did not admit to himself yet that he liked the sea, or that he was anything but disappointed and angry that he must spend his summer on the Island of Appledore, but he could not deny that there was a charm in the company of the old captain and that his stories of all that happened off this bit of rugged, rocky coast; of the smugglers that had hidden in the little harbour below the mill, of the privateers that had lain behind the island waiting until the enemy should pass, of the wrecks and daring rescues by the fishermen of the Island, all these were tales of which he never tired. He was full of questions to ask today, and wanted first of all to know what the war game really meant.

“It’s just practice,” Captain Saulsby explained, “just to learn what to do if there was real war. Over across the sea they’re playing the game in earnest; a mistake there means a lost ship and the crew drowned, and a greater danger to the country they’re guarding like grim death. Please Heaven we won’t have that over here, but there’s many that are saying it is coming with another year.”

“War—us!” exclaimed Billy incredulously. “Why, surely we couldn’t have war!”

“It could come mighty easy,” the Captain insisted, “but well, it’s not here yet and that’s something to be thankful for. But in this war game, they bring the fleet out for manœuvres and they play out their problems in naval tactics like a great big match of chess, with dreadnaughts and destroyers and submarines for the pieces and the whole wide ocean for their board. They divide up into two fleets and each one tries to destroy the other. There’s no real sinking, you understand, but, for instance, a torpedo-boat tries to creep up to a battleship in the dark, and send up a rocket to show that she’s supposed to have fired a torpedo, then if she’s near enough for an undoubted hit, why that vessel is counted as sunk. Or if the battleship finds her with the searchlights and she is so close that she could be smashed with a volley from the guns, why, it’s the torpedo-boat that’s sunk. So it goes.”

“It sounds to me pretty silly,” remarked Billy with some disdain.

“Wait until you’ve played it once, son,” returned the sailor. “When you creep along in the dark to make an attack, or put on every ounce of steam you can to get away, when you know that each man must do his own part the best way he knows how, and that the honour of his ship may hang on every move he makes, why you forget a little that it’s just a game. When it’s over you surely come down with a bump, you have been so sure all along that it was the real thing.”

Billy considered the matter idly for a little, scorning to show too much interest, even in spite of Captain Saulsby’s enthusiasm. The old sailor himself seemed to be full of other thoughts, for when he spoke again it was as much to himself as to Billy.

“I wish I knew whatever could have sunk Johann’s boat,” he said. “There was no storm nor any accident, and he certainly kept her in such good order that there was no chance of her having sprung a leak without his knowing it. The poor fellow surely loved her; he seems broken-hearted whenever you talk to him about her sinking, but he doesn’t do a thing to try to raise her. I don’t understand it.”

It had seemed very strange to Billy also, especially in the light of what he had seen that day upon the shore. He made no comment now, however; indeed he had scarcely been listening, but had let his wandering wits take a sudden jump in the direction of quite different matters. When the old man had finished speaking he put a question that, had he known more of the ways of the sea and of sailor men, he would never have dared to ask.

“Captain Saulsby,” he said, “what were you captain of? Was it in the Navy or just of the Josephine?”

“Bless you, no; not in the Navy or of the Josephine, either,” replied his friend. “The Josephine was the first ship I ever sailed on when I was an apprentice boy, and the captain of her was such a great man that he hardly knew I was on board. No, I wasn’t captain of the Josephine.”

“Well,” insisted Billy, not to be put off, “what ship were you captain of?”

Captain Saulsby heaved a great sigh and was silent for a long time. He took up the little model from his knee and turned it over and over before he spoke.

“No, not of the Josephine,” he said again, “although I fully intended to be. Do you see that little catboat riding at anchor down by the wharf; the old, old grey one that’s needed a coat of paint these two years past and a new sail for at least five? Well, that’s the only craft that Ned Saulsby ever was skipper of, or ever will be.”

He made this statement very abruptly and fell immediately to work on stepping a mast of the little vessel.

“There’s a lot of kind-hearted folks in the world,” he went on after a pause, “and some of them started calling me ‘Captain’ about the time my rheumatism got so bad that I could never go to sea again. They thought giving me the name would make me feel better, and I guess it did, perhaps. When you’ve followed the sea since you were hardly more than so high, and suffered by it, won and lost by it, hated it and loved it, why it’s not easy to find out, all of a sudden, that you’ve got to stop on shore for all the rest of your days.”

Billy would have pursued the subject further, but the old man changed the course of the talk. He took up the model of the Josephine and set it down upon the doorstep beside the boy.

“Now, young fellow,” he said cheerily, “suppose you name over these ropes as far as we have gone, and we’ll see if you are as much of a landlubber as you were when you came here a week ago.”

Billy, nothing loth, took up the challenge and went through his lesson with great credit, making nothing of naming the parts of the rigging of the little schooner and of running off lightly many terms that had so lately been pure Greek to him.

“Good,” said the old man when he had finished. “I do believe that you can hope to be a sailor yet.”

He said it with such confidence that this must surely be Billy’s one ambition, that the boy made haste to correct him.

“I’m not going to be a sailor ever,” he said. “I’m going into business and—and make a pile of money.”

Captain Saulsby did not answer at once, for he was staring out beyond the point where one of the big battleships had chanced to come close in and was steaming by at full speed. Billy could see the tremendous wave that surged up before her bow; he watched the cloud of drifting smoke that poured from her funnels and he had suddenly a vision of what gigantic power must drive her so swiftly through the sea. It gave him a queer thrill, unlike anything that he had ever felt before, and, oddly enough, seemed to fill him with a sudden doubt as to the wisdom of his choice of a career. Buying and selling and making money might after all prove a dull occupation. Were there after all bigger things than Big Business? Such a question had never occurred to him before.

“Now,” said the Captain, interrupting his reverie, “you just tell your aunt to come down on the beach this afternoon and see the best boat this side of Cape Hatteras put to sea. These good warm days have baked some of the rheumatism out of me and I’m almost as good a man as you this morning. We’ll go down to the rocks below the willows there and put the Josephine into the water. I hope she’ll sail as pretty as she looks.”

It was a great occasion, the launching of the Josephine. Aunt Mattie attended it, and broke a bottle of cologne over the little vessel’s newly painted bow, to make a formal christening. There was a fresh wind that flecked the water with dancing white caps on one side of the point, but on the other, inside the harbour, afforded the best sort of breeze for a maiden trip. The sails were hoisted, the rudder adjusted and the little boat breathlessly lowered off the edge of a rock. She rocked and dipped upon the ripples in a bit of quiet water, then was pushed out until the wind caught her new white sails. How they curved to the breeze, how she heeled over just as a real vessel should and skimmed away as though she had a sailor at her helm and had set her course for far and foreign lands! The cord by which she was held trailed out behind her, grew taut, and at last brought her successful journey sharply to an end.

“Pull her in and we’ll try her on a different tack,” directed Captain Saulsby much excited; “she surely can sail! We didn’t hit it wrong when we named her the Josephine.”

Billy, who had no leanings of sentiment toward the name of Captain Saulsby’s well-beloved first ship, had felt that Josephine was not the most perfect title in the world for his new and cherished vessel. Captain Saulsby, however, had seemed so hurt and disappointed when he even hinted at the possibility of another choice, that the idea had been dropped at once. Certainly the little boat was doing her best to be worthy of her so-famous namesake.

“I wish I had a longer string,” said Billy; “it seems as though she only got a good start every time before I have to pull her in again.”

“She doesn’t have any chance to show what she can do,” answered the Captain, regarding his handiwork with as proud and pleased an eye as did Billy himself. “Here, now, the wind is right and the tide is running in; why shouldn’t we just launch her and let her sail across the harbour. She will come ashore, surely, on that bit of sandy beach and we can walk round and pick her up. That will give her a chance to do a bit of real sailing.”

The plan was readily agreed to by all concerned, apparently with the most heartiness by the Josephine herself. She dipped and danced irresolutely for a moment when first she was launched upon her new voyage, then spread her sails to the wind and scudded off like a racing yacht. Even Aunt Mattie joined in the chorus of cheers that celebrated the triumphant setting sail. Captain Saulsby’s rheumatism seemed completely forgotten as he set off along the shore path to meet the boat when she came to port, with Aunt Mattie walking beside him.

Billy, lagging a little behind, looked up suddenly toward the rocks above him and caught a movement of something behind the biggest of the stones. The brown mink perhaps it was, but—possibly—something else. He climbed up to investigate, but found the rocks were slippery and not easy to scale, and that the smooth surface was hot under his hands. He reached the top of the biggest one at last and, not much to his surprise, found no one there. Not a sign could he see of any presence but his own. He had been foolish to climb up—but wait—what was that?

Wet footprints showed on the grey stone surface, as though somebody had but now walked across the weed-fringed rocks, uncovered by the half tide, and had then crossed the drier space above. Such marks would only last for a moment under this hot sun; indeed, they faded and disappeared even as he stood staring at them. What was that gleam of sunlight on metal just beyond that stone? He went quickly to see and discovered a pair of field glasses, binoculars of the highest power, lying half tumbled out of their case, as though dropped in hasty flight. He picked them up, adjusted them to his eyes with some slight difficulty and turned them out to sea. At first he saw only a dazzling expanse of blue sky, then, as he shifted, an equally dazzling glare of blue water. Then quite by chance, the glass fell upon the warship, and he could see the sparkle of her shining brass work, the blue uniforms of tiny figures moving on her deck, the black gaping mouths of her big guns. He laid the glasses upon a ledge of rock, so that he should not break them as he clambered down to a lower level. It was not easy climbing and he had to watch his footing carefully. Once below he reached up to get the binoculars down, failed to touch them and reached again. Still the rock was bare to his hand so he scrambled up to see what was the matter. The ledge was empty, they were gone!

Billy had a sudden feeling that it would be pleasant to rejoin Captain Saulsby and his Aunt as soon as it was possible. He was not afraid but—well such things were queer. There was something warmly comforting about the old sailor’s hearty laugh as it came drifting back to him. He hurried quickly after the two with the unpleasant feeling that a pair of peering black eyes were watching him from somewhere as he passed along.

Miss Pearson had elected not to meet the Josephine when she came to port, but had turned aside to go down to the steamboat landing. She was going to Boston by the afternoon boat and had just heard the whistle calling her on board. She waved good-bye to Billy but motioned him to follow the Captain, who was trudging on alone. Billy would have come down to see her off, none the less, had he not suddenly noticed something that knocked both the departure of Aunt Mattie and the affair of the field-glasses completely out of his head.

“Oh, look, Captain Saulsby,” he cried; “look what’s happened to the Josephine!”

Not one of them had noticed that the wind had changed. But the little Josephine had, for she had altered her course and instead of heading for the sandy beach opposite, was speeding away for the harbour’s mouth and the open sea. The breeze was steadily freshening, the little boat as steadily gathering headway, so that it would not be long before she would pass the headland and be out of sight.

“Oh, stop her,” cried Billy, in frantic excitement. “Oh, isn’t there any way to stop her.”

The old man was quite as distressed as he.

“We can’t lose her,” he exclaimed; “we never could lose the Josephine!” He stood gazing helplessly after the fast-vanishing little vessel. “What on earth can we do?”

He thought a minute and then turned to hurry awkwardly down the path toward the wharf.

“We’ll take my catboat,” he said; “she’s not been sailed for a month of Sundays but she’s seaworthy all right. The Josephine may have the start of us while we’re getting up sail, but we’ll catch her in the end.”

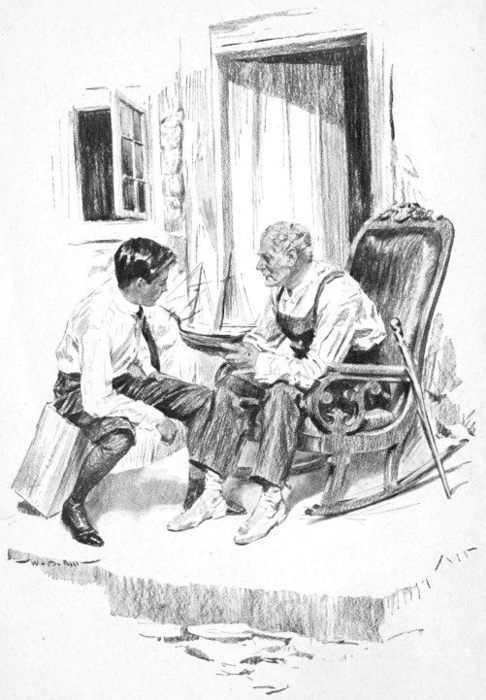

It was wonderful what short work the old captain made of seizing upon a dory, rowing out to the little catboat that bobbed in the tide, boarding her and getting up sail. Billy’s assistance was willing but extremely awkward, so that he hindered far more than he helped. At length, however, they were under weigh, riding gaily the gradually rising waves, and skimming along in the wake of the fleeing Josephine.

Captain Saulsby’s burst of energy seemed to wear itself out with surprising quickness. Once they were well started he put the tiller into Billy’s hand and went and sat down in the cockpit.

“I’m an old man,” he said gloomily. “I’m not a sailor any longer, just an old man, and good for nothing.”

Billy hardly heard him, so intent was he upon the responsibility of steering the boat. She was a clumsy little craft with a rather daring expanse of sail, she cut through the water swiftly but was not easy to keep upon her course. The tiller jerked and kicked under his hand; there were times when he could scarcely hold it, and when the bow veered threateningly to one side or another. The Captain paid little attention to his difficulties but sat hunched up in his corner staring idly before him.

“There’s a shoal place here off the headland,” he remarked at last; “you’ll have to make two or three tacks to get around it. That pesky Josephine can sail right over and will get more of a start than ever. If the tide were half an hour higher I would risk following. Now we’ve come so far we’ve got to get her.”

“But—but—what do I do?” inquired Billy, quite bewildered at the task set him. A boy who has never sailed a boat before finds suddenly a whole world of things that he would like to know.

“Why, nothing but just come up into the wind, loose the sheet, lay your new course over toward the lighthouse there. Now’s the minute—Ready about!”

Somehow, Billy never quite knew how, the thing was done. The bow swung round, the big sail fluttered and trembled a moment, then came over with a rush, and the catboat was off on her new tack. To Billy it seemed as though the wind had totally changed in direction, as though the small vessel were tipping dangerously, and as though anything might happen at any moment, but he kept manfully silent about it all. If this was the way one learned to sail a boat, he supposed that he could master it as well as another.

Captain Saulsby seemed to be totally unaware of his torment of mind. He still sat, gazing moodily out to sea and saying not a word.

“You’d better come about now,” he remarked suddenly when they had sailed some distance toward the lighthouse. After an instant of indecision and fumbling awkwardness, come about Billy did, with more ease this time, but no great knowledge of just what was happening. Once more they stood off on the new course, the tubby little craft rising and dipping bravely, Billy clinging to the tiller and beginning to feel suddenly that the boat was a live thing under his hand, ready to do his slightest bidding.

“Once more,” ordered Captain Saulsby when it was time to tack, and this time Billy accomplished it without a hitch.

“Captain Saulsby,” he cried in beaming delight, “I can sail her, I know how to sail her!” A slow broad grin illuminated Captain Saulsby’s mahogany-colored countenance.

“I thought you could,” he said slowly, “but it was a little ticklish at first, wasn’t it? And, good Heavens, the wake you leave!”

Billy glanced backward at the line upon the water that marked the pathway of his course.

“It’s not very straight,” he admitted, “but the waves have mussed it up some. Oh, but it’s great to sail a boat!”

The wind hummed in the rounding curve of the sail, the waves slapped and splashed along the boat’s side, the Island of Appledore fell away behind them, and they came out into the full sweep of the open sea. Aunt Mattie’s steamer was a black speck off toward the south, trailing a long, thin line of smoke. The sun that had shone so hot vanished presently behind a cloud, the water seemed to be a shade less blue, the little white sail of the fugitive Josephine seemed now and then to show mockingly ahead of them and now to disappear entirely. On they sped and on and on, while Billy with the wind blowing through his hair and with his hand upon the quivering tiller, felt that he was quite the happiest boy in the world.

“Tell me, Captain Saulsby,” he asked idly at last, “what makes the water look so queer over there to the north?”

The Captain, who had been puffing comfortably upon his pipe and had almost, it seemed, fallen into a doze, turned slowly and awkwardly to look where Billy pointed. In the twinkling of an eye he became transformed into a different man.

“Old fool that I am,” he cried, “sitting here and not keeping a look-out! Half asleep I must have been and in such tricky weather, too.”

He sprang up and was at Billy’s side in one movement. What pain such activity must have cost him it would be hard to tell; his weather-beaten face turned almost pale, and drops of moisture stood on his forehead. He seized the tiller and gave Billy a sharp succession of orders, which the poor boy was too bewildered to more than half understand.

“Cast off that rope, not that one, no, no, the other, quick, oh, if only I could reach it!”

He groaned aloud, not so much with the pain he must have felt, but with the helpless impatience of knowing himself to be unequal to the crisis. The deeper blue streak of water that Billy had pointed out, became rapidly darker and darker until it was grey, then black, and came rushing toward them at furious speed. The little catboat swung round to meet it. Billy tugged manfully at the sheet and noticed, with sudden consternation, that the strands of the rope had been frayed against the cleat and showed a dangerously weak place.

“What shall I do?” he cried. “Look, quick—” but he spoke too late.

The squall struck them, the sheet parted with a crack like a pistol shot and in an instant the great sail was flapping backward and forward over their heads like a mad thing. The heavy boom swung over and then back with sickening jerks, the old rotten mast groaned, creaked, then suddenly, with a splintering crash, went overboard dragging with it a mass of cordage and canvas.

In wild haste Captain Saulsby and Billy strove to cut away the wreckage, but they were not quick enough. The boat heeled over farther and farther, the water came pouring in over the gunwale. There was a harrowing moment of suspense, then their little craft turned completely over, throwing them both into the water, amid the tangle of sail and rigging.

For full half a minute Billy was quite certain that he was drowned and did not like it at all. The wet ropes and the heavy canvas clung to him, apparently determined that once he went down he should never come up again. For a gasping moment he managed to get his head above water, had a sharp, clear vision of the wide sea, the cloudy sky and Appledore Island with its green slopes and wooded hills: then he went down again. His next attempt was more fortunate, however, for he came up clear of the wreckage and not far from the boat, which was still afloat, bottom upwards. He swam to her in a few strokes and, after one or two efforts, managed to clamber up her slippery hull. What was his joy and relief, on scrambling high enough to peer over the centreboard, to see Captain Saulsby slowly and laboriously crawling up the other side.

“Give us a hand up, boy,” he said a little breathless, but speaking in the calmest and cheeriest of tones. “I’m not so spry as I used to be, but I’ll make it all right—er—ouch, but those barnacles are sharp. I should never have let the boat get such a foul bottom. Now,” as he came up beside Billy, “there we are as fine as you please. We’ll just have to wait a couple of hours, and some one will be sure to pick us up. There’s nothing to worry about in a little spill like this. See, the squall’s gone by and the clouds are clearing away already.”

Billy looked about him and was not so sure. To be perched upon the keel of a capsized boat, rocking precariously with every wave, to have miles of empty ocean on every side is a little disturbing the first time you try it. So at least he concluded as he watched the sun drop slowly toward the horizon.

The war game had drifted away to the north, so that, for the first time in days, there was not a vessel of any kind in sight. Above them the clouds were assuredly blowing away, but over in the west another bank of them, thick and grey and threatening, was rising very slowly to meet the sun. There could also be little doubt that the wind was steadily freshening and the waves splashing higher and higher along the sides of their little boat. All these things Captain Saulsby seemed cheerfully determined to ignore, so Billy decided that it was best for him to say nothing.

“I’ve had a lot of little adventures like this in my day,” the old sailor went on. “It makes me feel quite young again to be in just one more. Why, the first time was when a sampan capsized when we were landing from the Josephine in the harbor of Hongkong. I’ll never forget how I laughed out loud with the queer, warm tickle of the water, when I’d thought for sure it was going to be icy cold. I couldn’t have been much bigger than that.”

He tried to hold up a hand to show Billy the exact height he had been, but so nearly lost his balance in the process that he was obliged to clutch hastily at the slippery support again.

“Did you really go to sea when you were so little?” Billy asked. “I wonder your people let you.”

“They weren’t any too willing,” returned the Captain; “in fact, they weren’t willing at all. My folks were like yours, though you wouldn’t think it; they were people with book-learning, doctors and lawyers and the like. They wanted me to be the same, and when I wouldn’t, but was all for going to sea, they said very well, a sailor I could be, but first I must go to school, for sailors must have learning too. But I couldn’t wait; the wish for the blue water was in my very blood, so I slipped away and shipped for China before they knew it. That was a hard voyage in some ways, but a wonder of a one in others, and when I came home I would listen to nothing they said, but was off and away again before I had been in port much more than a week.”

“And you’ve sailed and sailed and sailed ever since?” Billy asked. A sharp dip of the boat nearly upset him but he managed to speak calmly. He thought it a good plan to keep the old man talking that he might not notice the rising clouds behind him.

“Yes, sometimes on sailing ships and sometimes on steamers, in every trade and bound for every port on earth. I drifted into the Navy at last, and was a bluejacket on just such a battleship as we saw go by today, and it was in that service that I first began to see what a mistake I had made. There were, among the young officers, boys not half my age, but knowing four times more than I ever would. I had to salute when they spoke to me, and I was glad to do it, for it is the like of them and not the like of me that makes the big ships go. I vowed then that I would turn to and learn something, that I would study navigation yet and have a ship of my own some day. But I didn’t stick to it. I drifted here and drifted there, lost or spent my money the day after I got to port, and had to ship again in any berth I could.

“When I was here in New England I was always longing for a sight of palm trees, and the hot sandy beaches, and the brown people and their queer-built houses round the harbours at Singapore or Bangkok or Bombay. But when I was there I was somehow always thinking of how our great, cool, grey rocks looked along this coast with the surf tumbling below and the pine covered hills behind them. I would remember the smell of bayberry and sweetbriar and mayflowers and think it would be the breath of life to me. So it was always, drifting first in one direction and then in another, until I came to port at last with less than I had when I put to sea. When I started out in life I was bound I would be a sea-captain before I was twenty: now that I am nearly four times that it hurts me still to think that the chance is gone forever. It’s a nice end for a man who once thought the sea was all his very own!”

“Was it hard to make up your mind to stay ashore?” asked Billy. He was watching the bank of clouds that had spread across the western sky and praying the Captain would keep on talking. The sun had begun to dip into the mass of heavy grey, and was sending up long shafts of red-gold light.

“It wasn’t so bad the day the doctor told me that I could never go out of port again,” Captain Saulsby said; “the hard life had done for me and the sharp sea winds had bitten so deep into my bones that I knew, long before he said so, that my usefulness was done. No, the end really came a year before when I found, all of a sudden, that the sailor I thought I was, the Ned Saulsby who could face any hardship, do any duty without faltering and without tiring, that he was gone as completely as though he had died.

“It was on the schooner Mary Jameson, bound out of Portland with lumber and coal. We had had fearful weather for three days out, blowing so hard that there was no peace or rest for any one. We were all dog-tired and could have slept where we stood, but the wind was still up and it wasn’t easy going yet. It was my watch and I was dropping with sleepiness and weariness, but so I had been many times before and it was part of being a good sailor to be able to keep awake. I stood peering and peering into the dark, my eyes trying to go shut, but my whole will set to keep them open. All of a sudden, as I stood there looking, I saw a full-rigged ship dead ahead of us, every sail spread out to the wind, her bow-wave slanting sharp out on each side from her cut-water, her wake showing clear in a white line of foam. She was so near I could see the men moving on her decks, could see her open hatchways and the flag flying from her main truck. We were right in line to ram her amidships; it seemed we couldn’t miss her except by a miracle. I roared to the man at the wheel, ‘Port your helm, port your helm, put her hard over,’ and the schooner came about with a rush that almost capsized her. The captain ran up on deck, the men turned out of their bunks and came swarming up from below, all wanting to know what the matter was. I told them about the ship and turned to point her out—but she wasn’t there! The clouds parted just then and the moon came out, just to show that the sea was empty for miles on every side, and that old Ned Saulsby had been sleeping on watch. Of course if I had thought two seconds I would have known that never a ship on earth would have all sail set in such a wind as that, but I had not stopped to think.”

“Why,” gasped Billy, “it must have been the Flying Dutchman.”

“Why,” gasped Billy, “it must have been the Flying Dutchman.”

“Some of the men whispered around that it might have been just that ship, but the captain knew better and so did I. It was only a dream and I had been asleep when I had no business to be, and if I had done it once I would do it again. If I had been young it would have been different, when lads aren’t used to standing watch such a thing may happen and we know they’ll learn better, but when an old sailor does it he can be sure of just one thing: his days at sea are near their end. I left the Mary Jameson at the next port, before the captain could turn me off. I knocked about for nearly a year, trying one berth and then another, falling lower and lower, and knowing I was failing in my duty whatever I tried to do. So at last I came limping into the harbour of Appledore Island and I knew, when I stepped ashore, that I would never set sail again.”

Captain Saulsby finished his story and shifted warily in his place. He glanced over his shoulder at the rising bank of clouds, but betrayed no surprise.

“I knew by the feel of the wind that some such thing was coming,” he said calmly. “If somebody’s going to pick us up in time they’ll have to hurry a bit.”

He made one or two efforts to talk further, but the pauses between his sentences became longer and longer. Billy suddenly realized that each had been trying to keep the other interested so that the ominous bank of clouds might go as long as possible unnoticed. He observed that the old sailor seemed very weary, that more than once his hands slipped from their hold and had to take a fresh grip. He tried to whistle to keep up the spirits of both of them, but the tune sounded high and queer and cracked, and he gave it up. At last Captain Saulsby broke silence suddenly.

“No one seems to be finding us,” he said, “and we can’t hold on forever. There’s something I must tell you, in case you should be able to last longer than I. That land of mine, you know, that Jarreth and the other fellow are trying to buy, well, they are not to have it. You will see to that, won’t you?”

“You don’t want to part with it?” asked Billy, not quite understanding.