The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Miller in Eighteenth-Century Virginia, by

Thomas K. Ford

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Miller in Eighteenth-Century Virginia

An Account of Mills & the Craft of Milling, as well as a

Description of the Windmill near the Palace in Williamsburg

Author: Thomas K. Ford

Contributor: Horace J. Sheely

Release Date: October 5, 2018 [EBook #58036]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MILLER ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

An Account of Mills & the Craft of Milling, as well as a Description of the Windmill near the Palace in Williamsburg

Williamsburg Craft Series

WILLIAMSBURG

Published by Colonial Williamsburg

MCMLXXVIII

The reader of this account, being of open mind and charitable disposition, as good men and women have ever been, will readily recognize that whatever may appear in these pages to the discredit of millers in times past cannot be taken to reflect in any fashion upon the present master of Mr. Robertson’s windmill. Indeed, the age-old repute of the calling is as distasteful to him and his colleagues of today as it would be inappropriate if applied to them.

Unhappily, it cannot be denied that millers of an earlier day—those of Chaucer’s generation, for example—left something to be desired in the way of scruple. That gifted storyteller and honest reporter of the age in which he lived gave prominent place in his Canterbury Tales to two millers. One of these was the villain and ultimate victim in the Reeve’s Tale: “A thief he was, forsooth, of corn and meal; And sly at that, accustomed well to steal.”

The other miller of the Canterbury Tales was himself one of the pilgrims, as merry and uncouth a rogue as one could find in any band of cathedral-bound penitents: “He could steal corn and full thrice charge his tolls; and yet he had a thumb of gold, begad.” That last remark, an allusion to the proverb that “every honest miller has a thumb of gold,” cut a broad swath indeed. Only Chaucer’s own regard for truth could have moved him thus to dignify the popular 2 belief that among millers integrity was as rare as twenty-four-carat thumbs.

Similar distrust can be discerned in early feudal and manorial laws in England, which prescribed certain methods of operation for grist millers and established corresponding penalties for violation. The miller was directed to charge specified tolls for his services, and no more. The lord of the manor got his grain ground “hopper free,” since he generally owned the mill and held the local milling monopoly. Under the thirteenth-century Statute of Bakers, chartered land-holders paid the miller one-twentieth of the grain he ground for them, and tenants-at-will gave one-sixteenth, while bondsmen and laborers had to part with one-twelfth of what they brought to the mill.

The same law also required that the miller’s “toll-fat” (or dish) and “sceppum” (or scoop) used to measure grain be accurate. The manorial seal on a measure testified that it had been compared with the standard measure and found exact. But millers in all lands and times (the present excepted, of course) have been adept at finding ways to outwit law and customer at the same time.

A method popular among some millers was to build square housings for the millstones, thus providing four innocent corners in which quite a bit of meal could collect. The more artful members of the craft built a concealed spout that carried a small proportion of the meal to a private bin while the visible spout delivered the bulk of it to the customer’s container.

Other stratagems, too varied and too numerous to list here, testify to the craftiness of many millers. The lengths to which the law went in trying to keep up can be seen in an English statute of 1648. This law, closing one loophole through which a miller could levy a hidden toll, allowed him to keep no hogs, ducks, or geese in the neighborhood of the mill, and no more than three hens and a cock.

All of this ingenuity, most of the popular suspicions of the 3 milling craft, and some of the legal restrictions consequent upon both, crossed the Atlantic along with the millers and millwrights who came to the colonies. More details of this in a moment; meantime, what of the mill that belonged to the man that owned the name of rascal?

Some simple grist mills: (A) stone mortar and pestle; (B) saddlestone and metate; (C) sappling-and-stump type of mortar and pestle, often used by early colonists; (D) Roman quern.

For uncounted generations in every pre-mechanical civilization grain has been ground in a variety of one-woman-power devices. Pounding with mortar and pestle was one of the earliest and is still the crudest of these devices. The saddlestone-metate device, still to be seen in some areas of Central and South America, substituted a rolling, sliding motion to the upper stone that rubbed and sheared the grain. Finally, the Roman quern, rotating continually in the same direction and shearing the kernels between grooved faces 4 of matched stones, opened the door to the use of natural instead of muscle power.

History does not record the name of the man, probably a Greek, who first harnessed natural power to grind grain between opposing stones. Possibly it happened when his wife handed him the family quern with the command, “Here, you do it!”—in Greek, of course. What he did, instead of earning his bread by the sweat of his brow, was to apply brain power. He fixed a water wheel to the lower end of a vertical shaft and attached the upper end to the upper stone of his handmill. And then, no doubt, he went fishing in the millstream while the flowing water did his work.

In the anonymous Greek’s footsteps, a Roman named Vitruvius made the arrangement more flexible by introducing wooden gearing to transmit the power. Others made further improvements in the slow progress of time until the watermill was a reasonably efficient and widely used machine. The Domesday Book, or census of the year 1080, recorded 5,624 mills in England alone, all operated either by animal or water power.

The identity of the man or men who invented the windmill is also lost in the mists of antiquity—or at least of the Middle Ages. The earliest authenticated reference to a windmill in western Europe refers to one that stood in France about the year 1180. The next known reference dates from 1191 and concerns a windmill in England. Both were post mills, more or less like the reconstructed windmill of William Robertson in Williamsburg. This is the simplest among several types of wind-operated mills and was the type first adopted in Europe, in England generally, and in the colonies.

Anyone who has read much poetry cannot fail to realize that a watermill is by nature a more romantic machine than a windmill. Poets recognize this as a fact, and perhaps non-poets who have spent some well remembered moments down by the old mill stream will agree. But this is not to say that windmills are lacking in emotional appeal and romantic inspiration. Far from it. As Robert Louis Stevenson wrote:

5“There are few merrier spectacles than that of many windmills bickering together in a breeze over a woody country, their halting alacrity of movement, their pleasant business of making bread all day with uncouth gesticulations, their air gigantically human, as of a creature half alive, put a spirit of romance into the tame landscape.”

One of the earliest medieval illustrations of a windmill in England is this brass plaque (here redrawn) in St. Margaret’s Church, King’s Lynn, Norfolk. It tells the ancient joke on the good farmer riding to the mill: To relieve his tired horse of the burden, he carried the sack of grain on his own back! Note that the mill was a post mill and that it was slightly head sick.

A post mill, as its name suggests, perches somewhat like a flagpole-sitter on the end of a sturdy post held upright by a timber framework. The Laws of Oleron, a breezily worded maritime code adopted in England about 1314, stated that “some windmills are altogether held above ground, and have a high ladder; some have their foot in the ground, being, as people say, well affixed.” In the latter case the substructure of timber bracing was not above ground, but was buried in a mound of earth.

The comparison to a flagpole-sitter is perhaps misleading, for the post does not end where the mill house begins. Rather, it enters the body of the mill through a loose fitting collar beneath the lower floor and extends about half-way up into the mill, where it ends in a pivot bearing. The entire weight of the mill—sails, body, millstones, shafts, gears, grain, meal, and miller (to say nothing of the mill cat, kittens, and resident mice)—rests on this single bearing at the top of the great post.

Keeping so much weight in stable balance was no great problem for the millwright as long as the mill did not move. The collar or ring bearing around the post kept the body from tipping far in any direction—or was supposed to. Moreover, the millwright estimated the weights of the various elements and positioned them appropriately about the pivot. Of course, things sometimes came out wrong. A mill that tipped incurably forward was called “head sick”; one that always tipped backward was “tail sick.”

When the mill was in motion the matter of stability became a good deal more complicated. For various reasons, including aerodynamic and gyroscopic effects that the early millwrights sensed but did not fully understand, the balance of a windmill is different in operation than at rest. The successful millwright, therefore, needed an accumulation of trial-and-error knowledge that might go back for generations.

The result, even though most everything but the millstones was of wood, was a surprisingly stable and exceedingly durable structure. A post mill built in Lincolnshire, England, in 1509 was still in operation in 1909! And although any storm might leave tragedy in its wake, post mills toppled over less often than their precarious position and top-heavy appearance would seem to promise. In this respect the Williamsburg mill is doubly guarded, being equipped with removable metal braces and buried ground anchors for use in the event a hurricane is predicted. This adaptation, to be sure, is a twentieth-century safety measure, not an eighteenth-century custom.

The problem of balance, and the related difficulty of maneuvering a post mill to face the wind because its whole weight is focused on the one bearing, generally limited such mills to one or two pairs of stones. Some English post mills had three pairs and a few even four. But these exceptions demonstrate the limitations of the post mill and the reasons for development of its successor, the tower mill.

The purpose in this development was to transfer weight from the pivoted upper portion of the mill to solid ground beneath it. In the tower mill, almost the whole mill became a firm structure. Only the cap, holding the sails and their axle, needed to be turned to face the wind. Turning this cap was far easier than turning the whole body of a post mill. Small to start with, tower mills became quite large when mechanical means were developed to adjust sail area. The tallest English tower mills were more than one hundred feet high at the hub of the sails, with sweeps that reached out as much as forty feet.

The so-called “smock mill,” common in Holland and brought to England probably in the time of James I, is a tower mill whose structure is framed and covered in wood rather than built up of masonry. Examples of this variety of mill can still be seen on Nantucket Island, Cape Cod, Long Island, in Rhode Island, and perhaps elsewhere. The eastern end of Long Island contains more colonial windmills than any other part of the United States today, and all without exception are smock mills.

Both windmill and watermill have been intimately associated with the development of the English colonies in America from their earliest days. This, of course, is not a matter of wonderment since bread was the staff of life then even more than it is today. No doubt all the early settlements had mortars or small hand mills, and in many cases they also employed larger ones powered by animals.

The first settlers at Jamestown in 1607 brought with them full and detailed instructions drawn up in advance by the Virginia Company of London. The 144 men and boys were to be divided into three working groups: one to build a fort, storehouse, church, and dwellings; the second to clear land and plant the wheat brought from home; and the third 8 to explore the surrounding countryside in search of the Northwest Passage, mineral riches, or other resources that might return dividends to the company’s stockholders.

As it turned out, the planting of grain received less than prime attention. Defense against the Indians was a more pressing demand, and many of the gentlemen settlers were unwilling to soil their hands with menial labor. An exploring party, however, reported that it had observed at the falls of the James River five or six islands “very fitt for the buylding of water milnes thereon.”

From an etching by James D. Smillie entitled “Old Mills, Coast of Virginia.” The original—now in the New York Public Library—was made in 1890, probably on Virginia’s Eastern Shore.

Several years seem to have passed before any mill was built in Virginia. In 1620 the Company sent word that it considered the construction of watermills of first importance. 9 The next year it specifically instructed the colonists to erect corn mills and bake houses in every borough.

Actually by 1621 the first mill had been put up by Governor Yeardley on his own plantation near the falls of the James River. But it was a windmill, not a watermill, and for at least four years seems to have been the sole facility of its kind in the whole coastal wilderness of North America.

The first mill in the Massachusetts Bay colony, where waterfalls were considerably more frequent and closer to the coast than in tidewater Virginia, was also a windmill, built in 1631. In New Amsterdam the first mill, again a windmill, was erected in 1632. In Virginia by 1649 there were nine mills in operation, four windmills and five watermills, and the number had grown as fast or faster in other areas.

Exposed coastal areas on Cape Cod, around Newport, Rhode Island, and on the eastern end of Long Island, as well as on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, the Carolinas, and Virginia were found especially well adapted to windmills. Massachusetts in particular saw a rapid rise in milling. It was there, under the aegis of John Pearson, “the father of the milling industry,” that commercial milling got its early start in America.

At somewhat later stages a similar boom in milling activity took place in New Netherland, New Sweden, and their successor English colonies. For several decades New York held the crown as the wheat-growing, grist-milling, and flour-exporting capital of the New World, only to be superseded about 1700 by Pennsylvania.

In Maryland and Virginia, where tobacco was the king-sized money crop, grist-milling developed along a somewhat different path. Throughout the seventeenth and well into the eighteenth century the tobacco colonists grew wheat and corn for home consumption only. And “home 10 consumption” in most instances meant literally that. The typical plantation, an almost self-sufficient community in many ways, raised wheat enough for the owner’s family and sufficient corn to feed the slaves and animals.

In his report of 1724, called The Present State of Virginia, Hugh Jones avowed that:

As for grinding Corn, &c. they have good mills upon the Runs and Creeks; besides Hand-Mills, Wind-Mills, and the Indian invention of pounding Hommony in Mortars burnt in the Stump of a Tree, with a Log, for a Pestle, hanging at the End of a Pole, fixed like the Pole of a Lave.

Often the planter owned and operated a grist mill for his own use and that of the neighboring small farmers. William Fitzhugh, for example, described his fully equipped layout as including, in 1686, “a good water Grist miln, whose tole I find sufficient to find my own family with wheat & Indian corn for our necessitys and occasions.” Fitzhugh thus needed to grow no grain of his own to feed his “family,” an expression that to him included not only the white indentured servants who lived and worked on the plantation, but also his twenty-nine slaves.

Such a mill represented a considerable investment of capital, and it was this initial cost as much as any other factor that determined the pattern of mill ownership in Virginia. So far as records survive to tell the story, all of the colony’s early mills were built on plantations, either by well-to-do colonial officials or by syndicates of neighboring planters. Most of these early mills, if not all of them, were built primarily to grind the owner’s produce. Since few but the very largest plantations could keep a mill busy at grinding home-grown grain, most plantation mills also did custom grinding for nearby farmers. A mill formerly owned by John Robinson, speaker of the House of Burgesses, collected enough toll in this fashion to feed a “family” of nearly sixty persons, plus several horses.

Two tower mills and three post mills can be seen on this map, redrawn from a “Sketch of the East end of the Peninsula Where on is Hampton.” On the same peninsula, thirty miles to the northwest, lies Williamsburg. The original map is at the University of Michigan among the papers of Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of British forces during part of the American Revolution.

It was out of this combination plantation-custom type of mill that the merchant mill finally developed in Virginia. The first William Byrd was well ahead of his fellow planters in developing milling as a business, although he lagged far behind John Pearson of Massachusetts. In 1685 Byrd had 12 erected two water grist mills at the falls of the James River—the very power site of which Captain Newport’s exploring party had remarked. He asked a friend in London to hunt up and send over one or two honest millers to run the mills and sent inquiries to the West Indies about selling the flour he expected to make.

Despite Byrd’s example, commercial or “merchant” milling, as it was known, gained little headway in the colony until the next century was two-thirds over. Then, when wheat became important to the tobacco growers as a second export crop, quite a few planters added a second pair of stones to their mills and began shipping barrels of flour along with hogsheads of tobacco. The additions were usually buhr or “burr” stones from France, preferred for high-quality grinding because their structure included sharp-edged quartz cavities.

In 1769, for instance, George Washington rebuilt his mill on Dogue Run near Mount Vernon, and imported French stones to grind export flour. Robert Carter, probably Virginia’s wealthiest planter-businessman at the time, had been experimenting with other crops on his tobacco-exhausted acres and had fixed on wheat as the best substitute for the “Imperial weed.” By 1772 Carter was buying wheat in 8,000 and 10,000 bushel lots to grind in his mill near Nomini Hall.

The merchant mill was not a business venture in itself, but a facility in the business of exporting flour or supplying ship’s bread. The merchant miller did not make his profit through the provision of a milling service; he actually bought the grain and processed it on his own account, making a profit or loss on the sale of the product. In many instances the merchant miller not only ground wheat into flour, but also baked the flour into bread for export—particularly in the form of ship’s biscuit.

The owner of a custom mill, on the other hand, did not buy and sell grain at all, but found his income as a portion or toll of the grain he milled. The pure custom mill was a 13 rarity in Virginia, however, being limited to a few establishments in and around the towns of Manchester, Petersburg, Norfolk, Alexandria, and Williamsburg.

A mill in Yorktown, too, was presumably of this sort. In 1711 the owners of land on the York River just below Yorktown Creek deeded a parcel to William Buckner for a windmill, on condition that he “grind for the donors 12 bbls. of Indian corn without toll.” A view of Yorktown drawn about 1850 shows an abandoned smock mill—very likely the original one—standing lonely and forlorn on the hill in question.

Very little information about milling in Williamsburg has survived from colonial days—or at any rate has been unearthed by diligent research. We do know that Williamsburg was considered to offer many choice locations, and that several mills were erected in the town or in its immediate vicinity before the Revolution. As far back as 1699, when the burgesses were thinking of moving the capital from Jamestown to Middle Plantation (as Williamsburg was then named), a student of the College of William and Mary extolled the proposed site in a formal speech, one of several made to an audience that included the governor and his council as well as the burgesses.

The college itself was already located at Middle Plantation, on the ridge between the James and York rivers and with creeks flowing to each. In the words of the student orator, “The neighbourhood of these two brave creeks gives an Opportunity of making as many water mills as a good Town can have occasion for, and the highness of the land affords great conveniency for as many Wind mills as can ever be wanting.”

All the known watermills lay outside the corporate limits of the city. The nearest, apparently, was a paper mill built by William Parks, founder of the Virginia Gazette, and described by him as “The first Mill of the Kind, that 14 ever was erected in this Colony.” It stood about a half-mile south of town on a stream that is known to this day as “Paper Mill Creek.”

When he married the rich Widow Custis, George Washington became the owner of two plantations close to Williamsburg and a water grist mill not three miles from the town. Samuel Coke, the Williamsburg silversmith, owned a grist mill, also water powered, less than one mile away.

What information we have concerning Williamsburg windmills is limited to three fragmentary items. First, in 1723 William Robertson, clerk of the General Assembly, holder of a number of other government offices, lawyer, and land speculator, deeded to John Holloway four lots in Williamsburg, “being the lots whereon the said William Robertson’s wind mill stands.”

Post mill symbol, redrawn and enlarged, from the “Frenchman’s Map” of Williamsburg, 1782.

Second, during the Revolution an American soldier who kept a diary of his experiences mentioned being “near the windmill, in Williamsburgh” one night before the siege of Yorktown.

Finally, an unknown French mapmaker, presumed to be in the service of Rochambeau, drew a very careful and complete billeting map of Williamsburg and the buildings in it. On this map appears a representation of a post mill just on the southern edge of the town.

Beyond these three items the story of milling in Williamsburg has to rest on careful deduction, the cross checking of every pertinent fact, the following of every lead, the consultation of every source—in sum, on a mass of research.

For example, evidence as to how the Williamsburg windmills functioned has long since disappeared. Because Robertson’s mill was within the city, however, it can be said with reasonable certainty that it operated as a custom mill, not a plantation mill.

If not much is now known about milling within the confines of Williamsburg itself, a great deal can be related of milling in the larger expanse of the Virginia colony. For despite the late start of merchant milling in the tobacco colonies, the grinding of grain for export had become big business by the time of the Revolution. In 1766 Governor Fauquier noted in a report to the Board of Trade (albeit almost as an afterthought) that the Virginians “daily set up mills to grind their wheat into flour for exportation.”

Such merchant mills, as advertisements in the Virginia Gazette attest, were usually connected with a plantation. Advertisements for the lease or sale of other farm property repeatedly contained the phrase “convenient to church and mills.” A mill scheduled to be built near Robert Carter’s on Nomini Creek—too near, he thought—would be the twenty-fourth within twelve miles on the Virginia side of the Potomac, an area that included no towns.

Carter’s “new mill,” completed in 1773, had a capacity of 25,000 bushels a year and cost him £1,450 in materials and wages. Carter also built in connection with the mill a bake house, the two ovens of which would bake one hundred pounds of flour at each heating. And he hired a cooper to “get up 10 good flower caskes per day” at an annual salary of £30.

Carter estimated his total outlay to keep the mill running at £5,000 per year, but the return was correspondingly great. The mill was a success from the start, and the Revolution soon added to its importance and its business. For several months in 1780 the mill worked eighteen hours a day grinding for the state, and Carter received six bushels of corn a day in toll. After 1785, however, Carter found it unprofitable to work the mill himself, and leased it to other operators.

Although on a smaller scale, George Washington also engaged in merchant milling. His Dogue Run mill, formerly a plantation mill only, was rebuilt in 1769 as a merchant 16 mill. He installed a pair of French burr stones to grind the export flour, while a pair of Cologne stones did the country work and ground Washington’s own crops. Washington also provided a nearby dwelling house and garden for the miller and his family, who could raise chickens for their own table but never for sale.

“The whole of my Force,” Washington wrote in 1774, “is in a manner confind to the growth of Wheat and Manufacturing of it into Flour.” Some of the wheat he proposed to sell in London if the price were right, if the freight and commission charges were not too high, and “if our Commerce with Great Britain is kept open (which seems to be a matter of great doubt at present).” He did ship some flour directly to the West Indies but disposed of most of his “superfine flour of the first quality” through merchants in Norfolk and Alexandria.

Washington, like Carter and other Virginia merchant millers, felt the loss of West Indian markets after the Revolution. But he continued his interest in milling into the better times that followed the establishment of a stable national government. Washington, in fact, received one of the first licenses to use the milling improvements invented by the Delaware millwright, Oliver Evans. As late as 1799, the year of his death, he wrote that “as a farmer, Wheat and Flour constitute my principal Concerns.”

As a millowner, one of Washington’s chief worries seems to have been very much the same as that of William Byrd a century earlier, namely, to obtain the services of an honest and diligent miller to operate his mill. The problem had faced Robert Carter, too, who sent inquiries as far as New Jersey. That other Virginia planter-entrepreneurs faced the same challenge is apparent in many advertisements in the Virginia Gazette of the time.

When Washington rebuilt the Dogue Run mill, he was fortunate in hiring William Roberts as miller. Not only was Roberts an honest man in his employer’s opinion, but also a highly capable miller. Washington gave him full 17 credit for the fact that flour from Dogue Run commanded top prices in Alexandria and the West Indies markets.

For several years the arrangement was ideal. Then Roberts grew more and more interested in a wheat product other than flour. By 1783 he had become such a drunken sot that the squire of Mount Vernon began seeking a replacement, only to relent when the miller promised to reform his ways. However, this pledge, like its predecessors, soon dissolved in alcohol, and Washington finally fired Roberts.

A substitute, Joseph Davenport by name, was lured from Pennsylvania but turned out to be an inferior miller and as slothful as Roberts had been unreliable. Even so, Washington tolerated him until Davenport’s death in 1796. His successor, Callahan, was a competent miller but again far from industrious, and demanded higher wages than the mill could support. In desperation, Washington hunted up Roberts and offered to rehire him on condition of “a solemn and fixed determination to refrain from liquor.” This arrangement fell through—perhaps Roberts celebrated too heartily—and the President finally leased the mill to his overseer, James Anderson.

It was said earlier that legal restrictions on milling crossed the Atlantic along with the jolly practitioners of that craft. Indeed, the history of milling in the colonies is fully punctuated by the regular passage or amendment of laws to “rectifie the great abuse of millers,” as the first such law in Virginia put it. This first Virginia law appeared as early as 1645 and fixed the allowable toll at a generous one-sixth. Such a law had been passed ten years earlier in the Massachusetts Bay colony.

In neither colony, however, did the law seem to be effective without frequent amendment. The Massachusetts General Court repassed and strengthened its regulation five separate times in thirty years; the Virginia burgesses acted 18 the same number of times in an even shorter period. A prohibition against taking excessive toll and the setting of penalties and fines for violation figured in every revision of the Virginia law throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The basic regulation, passed in 1705, provided:

That all millers shall grind according to turn; and shall well and sufficiently grind the grain brought to their mills; and shall take no more for toll or grinding, than one eighth part of wheat, and one sixth part of Indian corn.

Other phases of governmental interest in grist milling involved the exercise of the right of eminent domain to provide watermill sites; the requirement that roads be established and maintained leading to mills; that mill dams be wide enough at the top for a carriage way, include locks for navigation and fish slopes if necessary, and not be built above or too close below an existing dam; the inspection of flour to assure uniformly high quality, free from impurities; the requirement that millers have and use measures tested for accuracy; and so on. From such legislation it will be seen that milling, ostensibly a purely private venture, partook strongly of the nature of a public utility.

In view of the mill’s vital importance to the community, as revealed in this legislative history, it is no surprise to learn that the miller was considered essential too. Along with certain officials of the colony, clergymen, plantation overseers, the gaoler, schoolmasters, and some other groups deemed necessary to orderly civil life, millers were exempt from service in the militia. Furthermore, since militia musters were often occasions of prolonged revelry, any miller who “shall presume to appear at any muster” was to be fined one hundred pounds of tobacco or be “tied Neck and Heels” for up to twenty minutes. Only when the need for foot soldiers became all-consuming in 1780 was the militia exemption lifted. Until then the miller was expected, and obliged, to keep his nose to the millstone.

“Militia musters were often occasions of prolonged revelry.” Adapted from an engraving by the English painter and caricaturist of the eighteenth century, William Hogarth.

The miller, thus, seems to have had a split personality—at least in the public mind. On the one hand he possessed an ancient reputation for dishonesty that called for repeated legislative curbs and punishments. On the other hand, he was so indispensable to community welfare that the law got after him if he took a day off for public carousing as other men did.

At least since Greek and Roman times the miller, who performed a task once relegated to women and slaves, was traditionally held in low esteem by reason of his calling. Yet some colonial millers were respected and influential men, and sometimes men of substance. John Jenny built the windmill in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1636 and was chosen by his fellow townsmen to represent them in the General Court. Two years later he was indicted for failing to grind his neighbor’s grain well and seasonably. The 20 nearby town of Rehoboth similarly elected its miller to the General Court. But he refused to leave his mill in order to serve as deputy and was fined!

In colonial Virginia the social position of the miller was less subject to violent fluctuation than would seem to have been the case in New England. In fact, the Virginia miller was uniformly a man of low estate, far inferior to the owner-operator of a mill in a New England town, and outranked also by the sturdy bourgeois millers of the middle colonies. Those who worked for wages enjoyed few privileges, while the many Virginia millers who were either Negro slaves or white indentured servants had little social standing. The records contain a goodly number of references to runaway millers who were indentured servants, convict servants, or slaves; if any Virginia miller in colonial times rose to a position of importance, no record has yet been found.

Most windmills belonged to one or other of the two basic categories: post mill or tower mill. The truth of this general rule is easily proved by the exception—the composite mill that belonged to neither group, but was in effect a post mill set on top of a tower. Another truism—perhaps without any exception—states that since every mill was custom designed and made by hand, no two were exactly alike.

Every English and colonial millwright had his favorite tricks of design and construction, and often the mills of a region showed a family resemblance that distinguished them from the mills of the neighboring shire or colony. In addition, improvements and refinements were developed from time to time and gradually put into use. Many of them, like the grain elevating machinery invented by Oliver Evans of Delaware and the adjustable lattice sails of the English inventor Sir William Cubbitt, came long after 1716-1723, the years during which Robertson’s original mill was built.

Clearly, this is not the place in which to describe the almost infinite variety in structure and operation of windmills in different places and at succeeding stages in the perfection of the mill as a machine. A list of a few easily procured books appears on page 32 for those who wish to pursue the subject further. This little pamphlet must be limited to a description of the reconstructed mill in Williamsburg and how it operates.

First, a word needs to be said about the men behind the mill, Edward P. Hamilton, former director of historic Fort Ticonderoga, New York, and Rex Wailes, then of London, who were Colonial Williamsburg’s consultants in the careful process of design and construction. Mr. Wailes, a world authority on mills and milling machinery, furnished information on all phases of the use of windmills in England, and in particular provided measured drawings of a seventeenth-century mill still standing at Bourn in Cambridgeshire. Mr. Hamilton carried on from there. By vocation an investment counselor (retired) and by avocation a collector of watch and clock mechanisms, an authority on windmills in America, and a skilled model builder, he transformed the drawings into miniature reality, creating a perfect working model in which every part performs the function assigned to its larger counterpart in the mill itself.

William Robertson, who sold to John Holloway in 1723 four lots near the Palace “whereon the said William Robertson’s wind mill stands,” was not a miller. Neither was Holloway. The records left by both men provide no clue as to the exact appearance of the mill in question. In fact, the deed to the land itself did not give any more precise location for the mill.

Reconstruction of the mill, therefore, had to depend on answers to two questions: Just where did Robertson’s windmill originally stand? and What kind of a mill was it?

Robertson’s Windmill, a faithfully authenticated post mill, stands in Williamsburg today on a spot near the Governor’s Palace where its predecessor is believed to have stood about 1720.

By eliminating every other possibility, the site of the lots was established with certainty at the corner of North England and Scotland streets. By elimination again, the spot where the mill must have stood was placed at or near the present site—simply because other buildings were known to occupy various other locations in the tract. Thorough archeological excavation of the whole area, however, disclosed no corroborative evidence to show the precise location of the mill.

At the same time, the absence of such evidence was itself almost conclusive evidence that the mill was a post mill such as were common in tidewater Virginia at that time. A tower mill, which was the second variety often built hereabouts in colonial days, would have had foundations in the ground. Traces of these would have been revealed by digging at the site. Since none of the foundations excavated in the four lots was suitable to the underpinning of a tower mill—ergo the mill must have been supported above ground on a wooden post.

And so it was rebuilt: a small post mill, simple in design and operation, with but a single pair of millstones. The tail pole, extending to the rear, ends in a wagon-wheel support that eases the miller’s task of turning the mill by hand to face the wind. Other millers sometimes had shoulder yokes attached to the tail pole, or pulled it around with the help of a small winch anchored to one of a circle of posts.

The stairway from the ground up to the body of the mill, called the “ladder,” is hinged at the upper end so that when the mill is to be turned, a lever raises the foot of the ladder off the ground. When the mill has been positioned to face the wind, the end of the ladder is lowered to the ground again where it helps hold the mill against further turning.

Beneath the body of the mill are the heavy timbers on which it rests: the horizontal “crosstrees,” the sloping “quarterbars,” and the great post, all hand hewn of well-seasoned oak. The tree from which the post is hewn was itself young when Williamsburg first became the colonial capital. A count of its annual rings shows it to have been a sapling in 1675, which makes it one of the town’s oldest “antiques.”

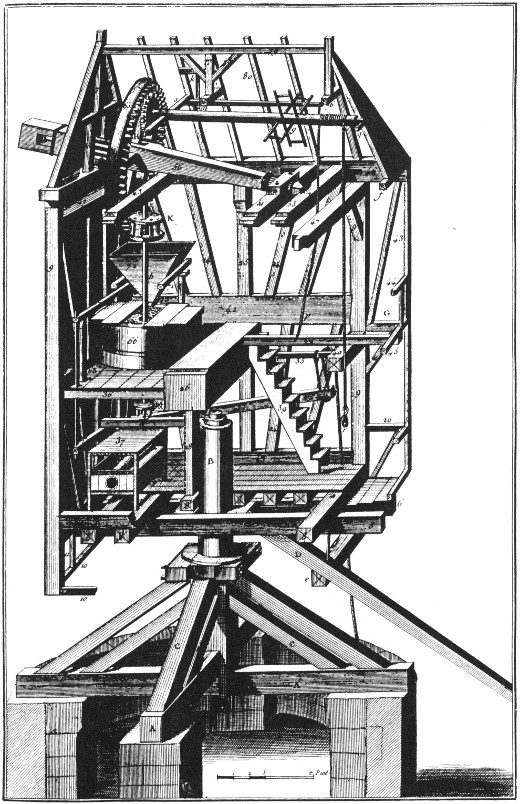

An eighteenth-century cutaway drawing, from Diderot’s great French encyclopedia, showing the structure and mechanism of a post mill. The artist has “lifted” the body of the mill a few feet off the post to reveal the pivot bearing on which the massive crowntree would in fact rest. Note also the power takeoff from the brake wheel for the sack hoist.

Mounting the ladder and looking into the mill’s lower or “meal floor,” we see that the post ends in a wrought-iron bearing set into another beam of impressive size that “crosses” the post like the top of a giant “T.” This beam is the “crowntree,” on which the framework of the mill body is built. Below the lower floor is another bearing or loose collar around the post to keep the body steady on its perch.

The primary machinery of the mill consists of sails, stones, and the necessary shafts and gearwheels to transmit power from the sails to the stones. In addition, there are devices for braking the sails, for hoisting bags of grain from the ground to the upper or “stone floor,” for feeding grain at the proper speed to the stones, for warning the miller when the supply of grain in the hopper is getting low, for adjusting the distance between stones, and for separating the meal from the bran.

The sails of the Williamsburg mill are of the early pattern in which the backbone of each sail frame extends along the centerline of the sail. That is, the area of sail ahead of the backbone—in the direction of turning—is the same as the area following it. Incidentally, windmill sails usually turn counterclockwise (viewed from in front of the mill).

The sailcloths themselves are handmade, of imported Scottish linen. To meet changes of weather they are furled by hand, each arm in turn being stopped at the lowest position while the miller unties the outward corners and twists the long strip into a more or less tight roll. For this purpose he can set and release the brake from the ground, using the rope that hangs out the side of the mill.

Whereas each sailcloth of Robertson’s windmill must be wholly furled or not trimmed at all, the sails of many early mills could be partially reefed. The four degrees of reefing were known as full sail, first reef, dagger point, 26 and sword point. Trimming the sails was a difficult and sometimes dangerous task, for a sudden storm with sleet and shifting gusts of wind could make the job almost impossible at the very moment that it had to be accomplished quickly. A miller caught with his sails up in such a storm might suffer what was known as “tail winding” if the wind veered faster than he could work. In this event he might be lucky to get off with nothing worse than having the sailcloth stripped from the frame.

A hurricane could do more serious damage—and might overturn the whole mill—no matter which way it faced. For the wind was the miller’s master as well as his servant, an evil genius that he feared as well as a heavenly blessing for which he prayed. Without wind the mill stood idle and the miller earned nothing. When the wind arose the miller must heed its call to work, whether in the middle of a meal or in the middle of the night. And always, he must keep a weather eye on the horizon for signs of too much wind.

Fire and lightning were other great perils to every windmill. If the hopper ran empty of grain, the friction of the stones rubbing against one another could generate enough heat for combustion. So could the friction of the brake if it were used continuously in a strong wind. In either event, a building made entirely of wood and open to every breeze burned readily, and more windmills probably fell victim to fire and storm than to old age. Similarly, its height and exposed position made the windmill an attractive target for lightning.

The sail wheel of the Williamsburg mill has a diameter of fifty-two feet—about average for a small post mill of this type. In a wind of about twenty miles an hour, which seems to be generally best for windmill operations, it will turn at about twenty revolutions per minute. This apparently slow and majestic rate is deceptive; for at twenty rpm the tips of the sails travel at a linear speed of 3,266 feet a minute or about thirty-seven miles an hour! An operating windmill is something to stay well clear of, as Don Quixote 27 and uncounted innocently grazing cows and sheep have discovered to their sorrow.

The four arms are fixed into the hub of the massive “windshaft.” This is the main horizontal axle that brings the power of the turning sails into the mill. Actually, it is not exactly horizontal but slants at a ten-degree angle. Since the wind has always been thought to descend from heaven, this ancient arrangement may at one time have been intended to let the sail wheel “look up” a bit into the wind. It has, in any case, both structural and aerodynamic advantages.

Just inside the front wall of the mill the windshaft rests in a metal bearing, and next to it is the large gear wheel, known as the “brake wheel,” that can be seen when one looks up through the trap door from the mill’s little back platform. The platform, incidentally, was not unusual in post mills, although it was often a convenience added after the mill was built and on which the miller could enjoy a pipe and a moment of repose while the mill ground merrily away.

The brake wheel, a little more than seven feet in diameter, is firmly fixed to the windshaft and turns at the same speed as the sails. Its fifty-one hickory gear teeth and eighteen other major pieces, plus at least as many wooden pegs to hold the pieces together, were all carefully shaped and fitted together by hand. Around its outer edge is the brake band—of bent hickory—that can stop the sails and hold them at any position when the long, heavy brake lever is lowered. As an emergency aid in slowing down the sails in a strong wind, the stones can be choked with grain, thus making them harder to turn. The mill can also be operated with partially furled sails.

The stones themselves consist of the lower or “bed stone,” which does not move, and the upper or “runner stone,” which turns at a little more than five times the rate of the sails. Its normal speed for best results is 108 revolutions per minute, at which speed it produces five to ten pounds of meal per minute.

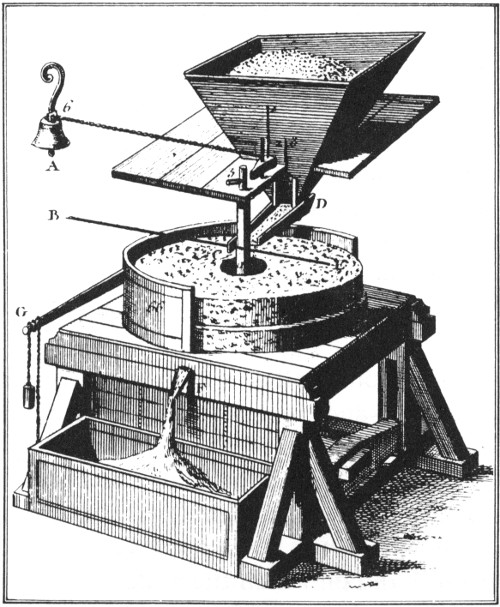

Another engraving from Diderot’s encyclopedia showing the passage of grain from hopper to millstones, and its reappearance as meal. Notice the arrangement to set the bell ringing when the hopper is about empty and the weighted lever at the left by which the miller can control the distance between the millstones.

The cogs of the brake wheel stay in constant mesh with the staves of a sort of wooden-bird-cage gear called a “wallower.” This is fixed to the upper end of the wrought-iron vertical drive shaft, whose lower end stands in the center or “eye” of the runner stone and turns it.

This simple drive mechanism is complicated by the fact that the runner stone must be held suspended above the bed stone. Ideally, the faces of the two stones—however close together—should never touch. To accomplish this, the runner stone is balanced to turn freely on the point of a spindle that comes up from below through the eye of the bed stone. The spindle, in turn, rests at its lower end in a pivot bearing that can be raised or lowered very slightly by a series of levers.

By this means the miller can adjust the distance between stones according to the kind of grain he is grinding and also according to the speed at which his mill is operating. In a variable wind, for instance, he may have to make the adjustment continuously as the feel of the meal coming from the stone indicates.

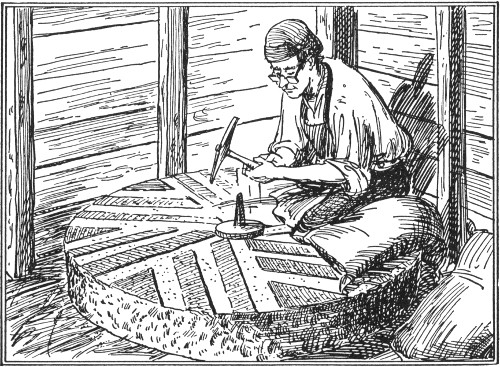

The faces of both stones must be “dressed” periodically—perhaps once every ten days when the mill is in constant operation. For this the runner stone must be removed and turned over so that the stone dresser, with his pickaxe-like “millbill,” can operate on both faces. The dresser deepens the furrows, if necessary, and roughens the “lands” between the furrows toward the outer edges of the stones.

When the stones are in good condition, the grain kernels are opened out near the eye of the stones, gradually reduced in the middle area, and the bran scraped and cleaned in the outer one-third of the face. The condition of the bran is the best index of the stone dressing, while the feel of the meal tells the miller whether his mill is running at the best speed and if the stones are set at the proper distance apart.

French burr stones produced the best quality flour in colonial mills, and most Virginia mills that ground for export seem to have had a pair of them. Cologne, or “cullin,” stones from the Rhine were somewhat less choice, and the same mills often had a pair of these for country work, especially for grinding corn. Stones quarried in Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, and elsewhere were also used. The pair in the Williamsburg mill are of quartz-bearing granite quarried in Rowan County, North Carolina. They are four and one-half feet in diameter. The bed stone is seven inches thick and the runner stone ten inches. Together they weigh more than two tons.

Although colonial millers ground all varieties of grain between the same set of stones—making only the necessary adjustment in distance between the stones—Robertson’s windmill today processes only corn. But whatever the grain, the difference of a newspaper’s thickness makes the 30 difference between a good grind and a poor one. So for all its clumsiness in appearance and lumbering clatter in operation, the windmill is an extremely precise mechanism at the point where precision counts.

The stone dresser often steadied his forearm on a sack of meal as he worked. His hands were constantly bombarded with bits of stone and slivers of metal from the point of his pick or “millbill.” Some of these slivers became imbedded under the skin, and an itinerant stone dresser looking for work could prove his experience by “showing his metal,” i.e., the backs of his hands.

The grain, raised bag by bag through trapdoors on a rope sack hoist, is poured into a hopper above the stones, which are themselves entirely enclosed in an octagonal wooden box called the “stone casing” or “vat.” Suspended from the bottom of the hopper, an inclined trough or “shoe” carries the grain to the central opening of the runner stone. The turning of the drive shaft constantly joggles the shoe, and by raising or lowering one end of it the miller can regulate the flow of grain to the stones.

The grain is ground as it works its way outward between the stones. At the outer edge of the bed stone the meal falls into the narrow space between the stone and the casing. 31 There, air currents moving with the turning stone continually sweep the meal around to an opening in the floor of the casing.

From this opening a chute leads downward to the sifting device on the lower floor. The sifter, on the left side of the mill as you look in from the platform, separates the bran from the meal. The miller can bag each product almost automatically, since the sifter, too, is constantly shaken by an ingenious connection to the mill’s driving mechanism.

The entire mill, thus, is about as simple a machine as one could devise. The moving parts are few and could be called primitively clumsy in comparison to some of the sleek masterpieces of modern industrial design. The miller can make only three operating adjustments: in the sail area presented to the wind, in the rate of grain fed to the stones, and in the distance between the stones. He has no control over wind speed, cannot shift the gear ratio of the mill—or even shift the stones out of gear—and, finally, cannot determine his own hours of work and rest.

Perhaps the reader will be inclined to marvel a bit that the product of such a mill is so good. And perhaps he will look with some compassion on a man who is so completely a slave to the elements. If some of the miller’s fellows have been disposed—on occasion—to take just a trifle more toll than law and custom allow, well, let him who is without fault cast the first stone. Millstone, that is.

Greville Bathe and Dorothy Bathe, Oliver Evans: A Chronicle of Early American Engineering. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1935.

Richard Bennett and John Elton, History of Corn Milling. 4 vols. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co., 1897-1904.

Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in the Wilderness: The First Century of Urban Life in America, 1625-1742. New York: Ronald Press Co., 1938.

——. The Colonial Craftsman. New York: New York University Press, 1950.

Philip Alexander Bruce, Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century. 2 vols. reprint ed. New York: Peter Smith, 1935.

William Coles Finch, Watermills & Windmills: A Historical Survey of Their Rise, Decline and Fall as Portrayed by Those of Kent. London: C. W. Daniel Co., 1933.

Douglas Southall Freeman, George Washington: A Biography. 6 vols. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948-1954.

Stanley Freese, Windmills and Millwrighting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957.

Louis Morton, Robert Carter of Nomini Hall: A Virginia Tobacco Planter of the Eighteenth Century. Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg, 1945.

John Storck and Walter Dorwin Teague, Flour for Man’s Bread: A History of Milling. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1952.

Rex Wailes, The English Windmill. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1954.

——. Windmills in England: A Study of Their Origin, Development and Future. London: Architectural Press, 1948.

The Miller in Eighteenth-Century Virginia was first published in 1958 and was reprinted in 1966 and 1973. Written by Thomas K. Ford, editor of Colonial Williamsburg publications until 1976, it is based largely on an unpublished monograph by Horace J. Sheely, formerly of the Department of Research.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Miller in Eighteenth-Century

Virginia, by Thomas K. Ford

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MILLER ***

***** This file should be named 58036-h.htm or 58036-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/8/0/3/58036/

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.