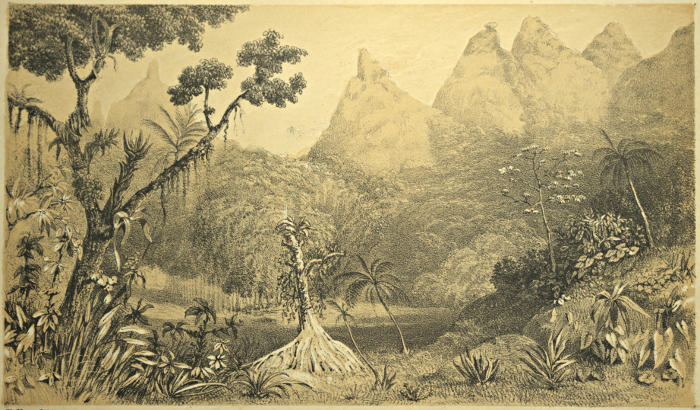

THE ORGAN MOUNTAINS.

E Fry del. Reeve Lith.

Project Gutenberg's Travels in the Interior of Brazil, by George Gardner

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Travels in the Interior of Brazil

Principally through the northern provinces, and the gold

and diamond districts, during the years 1836-1841

Author: George Gardner

Release Date: October 8, 2018 [EBook #58045]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TRAVELS IN THE INTERIOR OF BRAZIL ***

Produced by WebRover, Adrian Mastronardi and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

TRAVELS

IN THE

INTERIOR OF BRAZIL.

THE ORGAN MOUNTAINS.

E Fry del. Reeve Lith.

TRAVELS

IN THE

INTERIOR OF BRAZIL,

PRINCIPALLY

THROUGH THE NORTHERN PROVINCES,

AND

THE GOLD AND DIAMOND DISTRICTS,

DURING THE YEARS 1836-1841.

BY

GEORGE GARDNER, M.D., F.L.S.,

SUPERINTENDENT OF THE ROYAL BOTANIC GARDENS OF CEYLON.

SECOND EDITION.

LONDON:

REEVE, BENHAM, AND REEVE,

KING WILLIAM STREET, STRAND.

1849.

REEVE, BENHAM, AND REEVE,

PRINTERS AND PUBLISHERS OF SCIENTIFIC WORKS,

KING WILLIAM STREET, STRAND.

TO

SIR WILLIAM JACKSON HOOKER,

K.H., D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S.A., AND L.S.,

VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE LINNÆAN SOCIETY, HONORARY MEMBER OF THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY,

MEMBER OF THE IMPERIAL ACADEMY CÆSAR. LEOPOLD. NATURAL. CURIOSORUM, ETC., ETC.,

AND

Director of the Royal Gardens of Kew,

TO WHOM THE SCIENCE OF BOTANY IS SO MUCH INDEBTED, ALIKE FOR HIS

LIBERAL PATRONAGE, AND THE CONTRIBUTIONS MADE TO IT

IN THE NUMEROUS AND VALUABLE WORKS WHICH HAVE ISSUED FROM HIS PEN,

THE FOLLOWING WORK,

CONTAINING THE NARRATIVE OF TRAVELS,

WHICH, BUT FOR HIS KINDNESS AND ENCOURAGEMENT,

COULD NEVER HAVE BEEN UNDERTAKEN,

IS INSCRIBED

WITH FEELINGS OF PROFOUND RESPECT AND ESTEEM,

BY HIS GRATEFUL FRIEND AND PUPIL,

GEORGE GARDNER.

The present volume is not given to the public, because the Author supposes it presents a better account of certain parts of the immense Empire of Brazil, than is to be found in the works of other travellers, but because it contains a description of a large portion of that interesting country, of which no account has yet been presented to the world. It has been his object to give as faithful a picture as possible of the physical aspect and natural productions of the country, together with cursory remarks on the character, habits, and condition of the different races, whether indigenous or otherwise, of which the population of those parts he visited is now composed. It is seldom that he has trusted to information received from others on those points; and he hopes that this fact will be considered a sufficient reason for his not entering into desultory details more frequently than he has done.

Ample opportunities were offered for studying the objects he had in view, of which he never ceased to[viii] avail himself. Besides visiting many places along the coast his journeys in the interior were numerous; and, although he never ventured, like Waterton—whose veracity is not to be doubted—to ride on the bare back of an alligator, or engage in single combat with a boa constrictor, yet he had his full share of adventure, particularly during his last journey, which extended, north to south, from near the equator to the twenty-third degree of south latitude; and east to west, from the coast to the tributaries of the Amazon. The privations which the traveller experiences in these uninhabited, and often desert countries, can scarcely be appreciated by those who have never ventured into them, where he is exposed at times to a burning sun, at others to torrents of rain, such as are only to be witnessed within the tropics, separated for years from all civilized society, sleeping for months together in the open air, in all seasons, surrounded by beasts of prey and hordes of more savage Indians, often obliged to carry a supply of water on horseback over the desert tracks, and not unfrequently passing two or three days without tasting solid food, not even a monkey coming in the way to satisfy the cravings of hunger. Notwithstanding these, however, and one serious attack of illness, his enthusiasm carried him through all difficulties, and they have in some measure[ix] been repaid by the pleasure which such wanderings always afford to the lover of nature, and by the number of new species which he has been enabled to add to the already long list of organized beings.

The Author has only further to add, that the notes from which the Narrative has been drawn up, were, for the most part, written during those hours, which, under other circumstances, should have been devoted to sleep; and that the Narrative itself was principally compiled from them, during a voyage from England to the Island of Ceylon.

Kandy, Ceylon, January 1st, 1846.

The manuscript of Mr. Gardner’s ‘Travels in Brazil’ having been transmitted from Ceylon, and printed during his official residence in that island, the Publishers feel desirous of expressing the great obligation they are under to John Miers, Esq., in the absence of the Author, for his valuable assistance in correcting the technical, botanical, and Brazilian proper names, whilst passing through the press; they also desire to record their sense of the kind services rendered by Robert Heward, Esq., co-operating with Mr. Miers in reading the proofs.

London, October 1st, 1846.

| Page. | |

| CHAPTER I. RIO DE JANEIRO. |

|

| Motives for visiting Brazil—Voyage from England—Arrival at Rio de Janeiro—Description of the City—Its Environs—Geological Character of its Neighbourhood—Its Climate—Its Inhabitants—State of Slavery in Brazil—General good treatment of Slaves—Different Mixed Races—Excursion to the Mountains surrounding the Capital—Its Botanical Garden—Museum of Natural History | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. JOURNEY TO AND RESIDENCE IN THE ORGAN MOUNTAINS. |

|

| Principal Summer Resort of the English Residents—Journey from Piedade to Magé and Frechal—Ascent of the Mountains—Description of Virgin Forests—Mr. March’s Plantation in the Serra—Treatment of his Slaves—Case of One bitten by a venomous Snake—Limb amputated by the Author—Mode of Treatment in such cases among the Natives—Charms—Tapir-Hunting in the Mountains—Beasts, Birds, and Reptiles found there—Visit to a Brazilian Fazendeiro—To Constantia—Ascent of the loftiest Peaks—Vegetable Productions in those elevated regions—Pleasant Sojourn on the Estate | 28 |

| CHAPTER III. BAHIA AND PERNAMBUCO. |

|

| Departure from Rio de Janeiro—Arrival at Bahia—Description of that City—Voyage to Pernambuco—Jangadas—Description of [xii]the City and Environs of Pernambuco—The Jesuits—The Peasantry—Town of Olinda—Its Colleges and Botanic Garden—Visit to the Village of Monteiro—The German Colony of Catucá—The Island of Itamaricá—Pilar—Salt Works of Jaguaripe—Prevalent Diseases in the Island—Its Fisheries—Peculiar Mode of Capture | 55 |

| CHAPTER IV. ALAGOAS AND THE RIO SAN FRANCISCO. |

|

| The Author’s Motive for this Excursion—Voyage to the Southward—Description of the Coast and Observations on the great Restinga—Reaches Barra de S. Antonio Grande—Arrives at Maceio—Description of the Town and surrounding Country—Resolves to visit the Rio San Francisco—Embarks in a Jangada and coasts to the Southward—Batel—Lands at Peba—Journey thence to Piassabassú on the Rio San Francisco—Ascends the River to Penêdo—The Town described—Productions of the District—Its Population—Voyage up the River—Mode of Navigation—Arrives at Propihà—Vegetation of the Country—Description of a Market Fair—Dress of the People—Voyage continued to Traipú—Passes the Ilha dos Prazeres—Barra de Panêma—Abundance of Fish of the Salmon Tribe—Village of Lagoa Funda—Island of S. Pedro—Its Indian Population described—Continues the Voyage—Fearful Storm—Return to S. Pedro, serious Illness and detention there—Scarcity of Food—Renounces in consequence all intention of proceeding further—Returns to Penêdo—Scheme for Navigating the Rio San Francisco—Reason why it will never succeed—Arrives again at Maceio—Visits Alagoas—That City described—Leaves Maceio—Coasting Voyage—Singular Mode of catching Fish—Return to Pernambuco | 76 |

| CHAPTER V. CEARA. PERNAMBUCO TO CRATO. |

|

| The Author leaves Pernambuco in a Coasting Vessel—Description of the Voyage—Touches at Cape San Roque—Arrives at Aracaty—Seaport of Province of Ceará—Town described—Its Trade—Whole Province subject to great droughts—Commencement of Journey into the Interior—Passes Villa de San Bernardo—Arid [xiii]nature of the Country—Catingas—Arrives at Icó—Town described—Journey continued—Villa da Lavra de Mangabeira—Gold Washings abandoned—Country begins to Improve—Reaches the Villa do Crato—Town described—Low state of morals among the Inhabitants—Sugar Plantations—Mode of Manufacture—Coarse kind of Sugar formed into Cakes, called Rapadura, in which state it is used throughout the Province—State of Cultivation in the Neighbourhood—Productions of the Country—Serra de Araripe—Different kinds of Timber—Wild Fruits—Wandering tribes of Gypsies frequent—Great religious Festival—Climate—Diseases | 113 |

| CHAPTER VI. CEARA CONTINUED. |

|

| Reasons for delaying journey into the Interior—Visits, meanwhile, different places in the vicinity of Crato—Crosses the Serra de Araripe—Reaches Cajazeira—Arrives at Barra do Jardim—Description of that Town and Neighbourhood—Meets with an interesting deposit of Fossil fishes—Geological character of the Country—Detects a very extensive range of Chalk formation—First discovery of such beds in South America—The accompanying formation described—This range of Mountains encircles the vast Plain comprising the Provinces of Piauhy and Maranham—Arrives at Maçapé—Great Religious Festival on Christmas Day—Meets with an accident—Visits also Novo Mundo—Discovers other deposits of Fossil Fishes near these places—Vegetable productions along the Taboleira—Different Tribes of uncivilized Indians in that Neighbourhood—Curious account of the fanatical sect of the Sebastianistas—Their extravagant belief—Commit human sacrifices—Their destruction and dispersion—Returns to Crato | 150 |

| CHAPTER VII. CRATO TO PIAUHY. |

|

| Preparations for the Journey—Leaves Crato—Passes Guaribas—Reaches Brejo grande—Discovers more Fossil Fishes—Passes Olho d’Agoa do Inferno—Arrives at Poço de Cavallo—Crauatá—Cachoeira—Marmeleira—Rosario—Os defuntos—Lagoa—Varzea da Vaca—Angicas—Crosses the boundary line of the [xiv]Province of Piauhy—Arrives at San Gonsalvo—Campos—Lagoa Comprida—Difficulties of the road—Reaches Corumatá—Canabrava—Arrives at Boa Esperança, a large Estate owned by an excellent Clergyman—Is now in the midst of the great Cattle Districts—Nature of the Country described—Marked into two kinds, Mimoso and Agreste—Passes Santa Anna das Mercês—San Antonio—Cachimbinho—Vegetation of the surrounding Country—Reaches Retiro—Buquerão—Canavieira—Crosses the River Canindé, arrives at Oeiras, the Capital of the Province of Piauhy | 169 |

| CHAPTER VIII. OEIRAS TO PARNAGUÁ. |

|

| The Author’s reception by the President of Piauhy—City of Oeiras described—Its Population—Its Trade with the Coast—Great want of River Navigation—Its chief exports are hides and cattle—Its Climate—Diseases—Character of the Barão de Parnahiba—His great power in the Province—History of this remarkable Man—And of the Civil War on declaration of the Independence of Brazil—Resources of the Province—National Cattle Farms—Course of the Author’s journey quite changed by an alarming Revolt—This insurrection described—He determines on travelling southwards through Goyaz and Minas Geräes—Leaves Oeiras—Description of the Country—Chapadas—Passes through many Cattle Farms—Curious mode of catching Cattle—Passes Pombas—Algodoes—Golfes—Retiro Alegre—Genipapo—Canavieira—Urusuhy—Prazeres—Description of a Piauhy Family—Reaches Flores—Rapoza—Arrives at Parnaguá—Universal Hospitality of the Natives—Salt found in the Neighbourhood | 193 |

| CHAPTER IX. PARNAGUÁ TO NATIVIDADE. |

|

| Leaves Parnaguá—Arrives at Saco do Tanque—Carrapatos a great pest to Travellers and Cattle—Vegetation of the Country—Crosses the Serras da Batalha and de Mato Grosso, the boundary of the Province of Piauhy—Descends into the District of Rio Preto—Account of the Cherente Indians—Arrives at Santa Rosa—Crosses the River Preto—Reaches the desolate region of Os Geräes—Passes over the elevated table-land Chapada da [xv]Mangabeira—Arrives at the Indian Mission of Duro—Description of these Indians—Reaches Cachoeira—Crosses the Serra do Duro—Fords the River Manoel Alves—Arrives at Almas—Galheiro Morto—Morhinos—Abundance of Wild Honey—Description of several kinds of Bees—Reaches Nossa Senhora d’Amparo—Mato Virgem—Goître not uncommon—Passes Sociedade—Arraial da Chapada—And arrives at Natividade | 223 |

| CHAPTER X. NATIVIDADE TO ARRAYAS. |

|

| The Town of Natividade described—Its Population—Dress and Manners of the People—Its Climate—Diseases—Goître extremely prevalent—Excursion to the neighbouring lofty Mountain Range—Its Geology and Vegetation—Visits the Arraial da Chapada—Leaves Natividade—Passes San Bento, and arrives at the Arraial de Conceição—Its Population—Very subject to Goître—Probable cause of this Complaint—Reaches Barra and crosses the Rio de Palma—Arrives at Santa Brida—Stays at Sapê—Account of the Animal and Vegetable Productions of the Neighbourhood—Reaches the Villa de Arrayas—The Town described—Geological Features of the surrounding Country—Its Climate and Productions—Alarm of the Inhabitants—Muster of the National Guard—Preparations for departure | 256 |

| CHAPTER XI. ARRAYAS TO SAN ROMÃO. |

|

| Departure from Arrayas—Reasons for preferring the route along the Serra Geral—Passes Gamelleira—Bonita—Reaches San Domingo—San João—San Bernardo—Curious Fact respecting the Rio San Bernardo—Passes Boa Vista—Country consists of very elevated table-lands—Its Natural Productions—Arrives at Capella da Posse—San Pedro—San Antonio—Dôres—Riachão—Animals greatly tormented by large Bats—Habits of these Vampires—Reaches San Vidal—Flight of Locusts—Passes Nossa Senhora d’Abbadia—Campinhas—Pasquada—San Francisco—Crosses River Carynhenha and enters the province of Minas Geräes—Country described—Habits of the great Ant-eater—Passes Capão de Casca—Descent of the Serra das Araras—Reaches San Josè—Rio Claro—Boquerão—Santa Maria—Espigão—Taboca—San [xvi]Miguel—Crosses River Urucuya—Passes Riachão—Arrives at San Romão—Town described—Its Population—Habits of the People—Rio de San Francisco—Description of the different varieties of the Salmon tribe found in it | 286 |

| CHAPTER XII. SAN ROMÃO TO THE DIAMOND DISTRICT. |

|

| Leaves San Romão—Passes Guaribas—Passagem—Geräes Velhas—Espigão—Caisára—Cabeceira—Arrives at the Villa de Formigas—Town described—Account of the impostor Douville—Country around rich in Botanical products—Passes Viados—Arrives at the Arraial de Bomfim—Reaches San Elo—Sitio—Comes to a Gold Working called Lavrinha—Crosses the River Inhacica—Reaches As Vargems—Registo do Rio Inhahy—Bassoras on the River Jiquitinhonha—Examines a Diamond Mine—Formation in which the Diamond is found—Mode of working it—Arrives at the Arraial de Mendanha—Town described—Ascends the Serra de Mendanha—Reaches Duas Pontes—Arrives at the Cidade Diamantina, formerly the Arraial de Tijuco, the Capital of the Diamond District—Town situated on side of hill—Description of its Population—Their mode of Dress—Its cold Temperature—Productions of its Neighbourhood—Mining for Diamonds, formerly a privileged Monopoly, now open to all—Character of Miners—Extent of Diamond Mines—Privilege of Slaves there employed—Climate very healthy—Women very handsome—Complaints incident to its Climate—Loyalty shown by its Inhabitants—Fatality among Horses | 320 |

| CHAPTER XIII. CIDADE DIAMANTINA TO OURO PRETO. |

|

| Leaves the Cidade Diamantina—Reaches As Borbas—Passes the Arraial do Milho—Tres Barras—Arrives at the Cidade do Serro, formerly Villa do Principe—The Town described—Passes Tapanhuacanga—Retiro de Padre Bento—N.S. de Conceição—Description of an Iron Smelting Work at Girão—Vast abundance of Iron Ores in this District—Reaches Escadinha—Morro de Gaspar Soares and two other Iron Smelting Works and Forges—Ponte Alta—Itambé—Passes Onça—Ponte de Machado, [xvii]where frost was seen—And arrives at Cocaes—Visits the large Establishment of the Cocaes English Mining Company—The Author’s unkind reception by the Director of that Establishment—Reaches S. João do Morro Grande, part of the Mining Establishment of the English Gongo Soco Company—Hospitable reception—And visit to the Gold Mines—Its Workings described—Geological structure of the Mines and the surrounding country—Leaves Gongo Soco and passes Morro Velho—Rapoza—And reaches the Establishment of another English Mining Company at Morro Velho—The Author’s delight on receiving letters after two years’ absence—His kind reception and abode there—Village of Congonhas de Sabará described—Attached to the Gold Mines of Morro Velho—Account of those Mines—Mode of working and extracting Gold from the Ore—Visits the City of Sabará—Mining Establishment of Cuiabá—Serra de Piedade—And Serra del Curral del Rey—Leaves Morro Velho—Reaches the Villa de Caëté—Passes S. José de Morro Grande—Barra—Brumado—Serra de Caraça—Catas altas—Inficionado—Bento Rodriguez—Camargos—And reaches San Caetano—Visits the City of Mariano—Passes the Serra de Itacolumi—Arraial de Passagem—And arrives at the City of Ouro Preto, formerly Villa Rica—City described—Its Population—College and Botanic Garden | 360 |

| CHAPTER XIV. OURO PRETO TO RIO DE JANEIRO, AND SECOND VISIT TO THE ORGAN MOUNTAINS. |

|

| Leaves Ouro Preto—Arrives at San Caetano—Passes Arraial de Pinheiro—Piranga—Filippe Alvez—San Caetano—Pozo Alegre—Sadly incommoded by a thunder-storm—Reaches Arraial das Mercês Chapeo d’Uva—Entre os Morros—Crosses Rio Parahybuna—And enters the Province of Rio de Janeiro—Passes Paiol—Reaches Villa de Parahyba—Crosses the River Parahyba—Mode of Ferrying described—Passes Padre Correa—Corrego Seco—Reaches summit Pass of the Serra d’Estrella—Magnificent view of the Metropolitan City, its Harbour, and surrounding Scenery—Arrives at Porto d’Estrella—Embarks for the City and finally arrives at Rio de Janeiro—All the Collections brought from the Interior are arranged and shipped to England—The [xviii]Author resolves again to visit the Organ Mountains—His departure for the Serra—Adds largely to his Collections—Ascends the loftiest peaks of the Mountains—Their elevation above the sea about 7,500 feet—Departs on an excursion to the Interior—Passes the Serra do Capim—Monte Caffé—Santa Eliza—Sapucaya—Porto d’Anta—Crosses Rio Parahyba—Passes Barro do Louriçal—San José—Porto da Cunha—Recrosses the Rio Parahyba—Reaches Cantagallo—Visits Novo Friburgo—Description of these two Swiss Colonies—Pleasant sojourn in the Organ Mountains | 391 |

| CHAPTER XV. MARANHAM, VOYAGE TO ENGLAND, CONCLUSION. |

|

| Leaves the Organ Mountains and returns to Rio de Janeiro—Embarks for England with large collections of living and dried Plants—Touches at Maranham—City described—Its Population—Public Buildings and Trade—Geology of its Neighbourhood—Visits Alcantarà—Sails for England—Gulf Weed—Its great extent and origin—Flying Fishes—Observations on their mode of flight—Remarkable Phosphorescence at Sea—Description of the singular Animal that causes this Phenomenon—Its curious nests—Scintillations at Sea caused by a very minute kind of Shrimp—Arrives in England—Concluding Remarks | 418 |

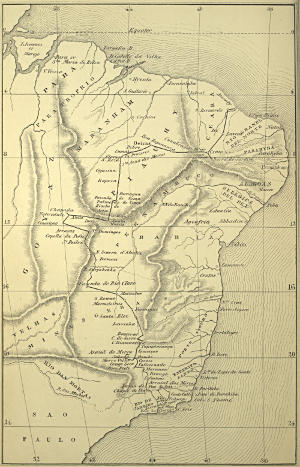

Transcriber’s Note: The map is clickable for a larger version if you’re using a device that supports this.

MAP OF BRAZIL

Reeve, Benham & Reeve, lith.

Motives for visiting Brazil—Voyage from England—Arrival at Rio de Janeiro—Description of the City—Its Environs—Geological Character of its Neighbourhood—Its Climate—Its Inhabitants—State of Slavery in Brazil—General good treatment of Slaves—Different Mixed Races—Excursion to the Mountains surrounding the Capital—Its Botanical Garden—Museum of Natural History.

Having devoted much of my leisure time, during the course of a medical education, to the study of Natural History generally, but more particularly to Botany; and my mind being excited by the glowing descriptions which Humboldt and other travellers have given of the beauty and variety of the natural productions of tropical countries, the magnificence of their mountain scenery, and the splendour of their skies, an ardent desire seized me to travel in such regions.

My early patron and teacher in Botany, Sir William J. Hooker, then professor of that science in the University of Glasgow, aware of my wishes, strongly recommended a voyage to some part of South America; and Brazil was fixed on as the best field for my researches, as the vegetable productions of that immense empire[2] were then less known to the English botanist than those perhaps of any other country of equal size in the world. It was true that it had been visited both by German and French naturalists, but no Englishmen, with the exception of Cunningham and Bowie, and the intrepid Burchell, had penetrated into the interior; whole provinces, particularly in the north, still lay open as virgin fields for the investigations of some future traveller; and these I was desirous to explore.

The preparations necessary for such an undertaking having been completed, I left Glasgow on the 14th of May, 1836, and on the 20th of the same month embarked at Liverpool, on board the barque Memnon, bound for Rio de Janeiro, the capital of Brazil. The voyage across the Atlantic to South America has been too often described for me to say more than that we had a fair share of calms and squalls, of bright skies and brilliant sunsets, of sharks and whales, flying fishes, and phosphorescent waves. A tedious, but not unpleasant voyage, brought us in sight of land on the 22nd of July. When day broke, Cape Frio, as had been predicted by the captain, was seen, bearing N.N.E., about twenty-five miles distant. This Cape is about seventy miles to the eastward of Rio de Janeiro, and a range of high undulating hills stretches between them, covered to their topmost ridge with trees. On their summits, numerous Palms, with their slender shafts surmounted by a ball-like mass of leaves, rising far above the other denizens of the forest, and standing boldly out in relief against a beautiful blue sky, give a marked character to the scene, and silently proclaim to the European his approach to a world the vegetation of which is very different from that of the one he has so recently left. The winds were light all day, and as we sailed close along the coast, my eye, through the medium of the ship’s telescope, was constantly surveying the wild but beautiful scene, and in imagination I was already revelling amid its multiform natural productions.

It was long past noon before we reached the entrance to the Bay of Rio, which is very remarkable for the number of conical hills and islands which are to be seen on both sides of it. One[3] of these hills is the well-known Pão d’Açucar, so called from its resemblance to a sugar-loaf. It is a solid mass of granite, rising to the height of about one thousand feet, and destitute of vegetation, with the exception of a few stunted shrubs on its eastern declivity. Seen from a great distance at sea, it is an admirable land-mark for ships making the port. Passing through the magnificent portal, we came to an anchor a few miles below the city, not being allowed to proceed further till we were visited by the authorities. It is quite impossible to express the feelings which arise in the mind while the eye surveys the beautifully varied scenery which is disclosed on entering the harbour—scenery which is perhaps unequalled on the face of the earth, and on the production of which nature seems to have exerted all her energies. Since then I have visited many places celebrated for their beauty and their grandeur, but none of them have left a like impression upon my mind. As far up the Bay as the eye could reach, lovely little verdant and palm-clad islands were to be seen rising out of its dark bosom, while the hills and lofty mountains which surround it on all sides, gilded by the rays of the setting sun, formed a befitting frame for such a picture. At night the lights of the city had a fine effect; and when the land-breeze began to blow, the rich odour of the orange and other perfumed flowers was borne seaward along with it, and, by me, at least, enjoyed the more from having been so long shut out from the companionship of flowers. Ceylon has been celebrated by voyagers for its spicy odours, but I have twice made its shores with a land breeze blowing, without experiencing anything half so sweet as those which greeted my arrival at Rio.

On the following morning, the 23rd of July, I first put foot on the shores of the great continent of the new world. If the aspect of the country, and the nature of the vegetation were so different from those of the old country, how much more strange were the human beings which first met my sight on landing. The numerous small boats and canoes which ply about in the harbour, are all manned with African blacks; the long narrow streets through which we passed were crowded with the same race, nearly naked,[4] many of them sweating under their loads, and smelling so strongly as to be almost intolerable. Scarcely a white face was to be seen. The shops, in the most of which both the doors and windows are thrown open during the day, seemed to be attended to by mulattos, or by Portuguese of nearly as dark a hue. Seen from the ship in the morning, the city had a most imposing appearance, from its position, and the number of its white-washed churches and houses; but nearer contact with it dispelled the illusion. The streets are narrow and dirty, and what with the stench from the thousands of negroes which throng them, and the effluvia from the numerous provision shops, the first impressions are anything but agreeable. I could not help recalling to mind the lines in ‘Childe Harold,’ which Byron has applied to the capital of the mother country:—

The city of Rio occupies part of an irregular triangular tongue of land, which is situated on the west side of the Bay, about three miles northward from the entrance. The ground on which it stands is, for the most part, level, but towards the north, the west, and the south-east, it is bounded by a series of hills. The long narrow streets run at right angles to each other, by which the houses are thrown into great square masses. The new town stretches out in a north-west direction, and is separated from the old one by a large square called the Campo de Santa Anna. Beyond it a narrow branch of the Bay runs inland, to the left of which is the extensive suburb of Catumbi, and farther on those of Mataporco and Engenho Velho. Besides the Campo de Santa Anna there are two other large squares, one before the theatre, and another at the landing-place, in which is situated the palace formerly occupied by the Viceroys. The Royal Palace of S. Cristovão, the residence of the Emperor, is a great and irregular mass of building, situated a little way beyond the new town.

Not only are the streets narrow and dirty, but they are also badly lighted and worse paved, notwithstanding the city is immediately surrounded by mountains of the most beautiful granite. The houses are very substantially built, for the most part of granite, consisting principally of only two or three stories. It contains several fine churches, but few of them are so situated as to be seen to advantage. That of Nossa Senhora da Gloria is one of the most conspicuous, being placed on a rounded hill of the same name, that juts into the sea between the city and the Praia de Flamengo. Besides the churches there are many other public buildings, among which may be mentioned the Monastery of San Bento, near the harbour, the Convent of Santa Thereza on the brow of a hill, beside the noble aqueduct by which the water for the supply of the city is conveyed from the mountains, a Mint, an Opera House, a Theatre, a public Library, which is said to contain about one hundred thousand volumes, a Museum of Natural History, a Medical School, two Hospitals, and, what the inhabitants boast very much of, the Camara dos Senadores, which is equivalent to our House of Lords. It is a very handsome building, which was erected a few years ago on the north side of the Campo de Santa Anna. Scattered through the city there are some fine fountains, to which water is conveyed by an aqueduct. One of them is in the palace square, for the supply of the ships in the harbour. The aqueduct itself is upwards of six miles in length, and is terminated city-wards by a magnificent row of double arches.

From an eminence within the city, called the Castle Hill, a fine view both of the city and bay is obtained. It also commands a delightful prospect of the country on the opposite side of the bay, with the city of Nitherohy, or Praia Grande, in the foreground, and the lofty Organ mountains towering in the distance to the left. There are many parts of the country in the immediate neighbourhood of Rio, which remind a Scotchman of some of the highland scenery of his native country, but with this difference, that, whilst there the mountains are bleak and barren, here they are covered to their summits with a luxuriant tropical vegetation.

The great desire of the inhabitants seems to be to give a European air to the city. This has already been accomplished to a great extent, partly from the influx of Europeans themselves, and partly by those Brazilians who have visited Europe, either for their education or otherwise. It is but seldom now that those extraordinary dresses, both of ladies and gentlemen, which we see represented in the publications of those travellers who visited Rio, even in the early part of the present century, are to be seen in the streets. A few old women only, and those mostly coloured, are observed wearing the comb and mantilla; and the cocked hat and gold buckles are also all but extinct. Now, both ladies and gentlemen dress in the height of Parisian fashion, and both are exceedingly fond of wearing jewellery. One of the finest streets in the city is the Rua d’Ouvidor, not because it is broader, cleaner, or better paved than the others, but because the shops in it are principally occupied by French milliners, jewellers, tailors, booksellers, confectioners, shoe-makers, and barbers. These shops are fitted up with an elegance which the stranger is quite unprepared to meet. Many of them are furnished with windows formed of large panes of plate glass, similar to those which are now so common in every large town in Great Britain. Indeed, it is the Regent Street of Rio, and in it almost any European luxury can be obtained.

A few years ago omnibusses were started to run from the city to the different suburbs. Small steamers ply regularly between Rio and the city of Nitherohy on the opposite side of the bay, and one runs daily to Piedade at the head of it. There is a yearly exhibition of the fine arts, in which are exposed many tolerable pictures, both by native and foreign artists. Music is very much cultivated, and the piano, which at the time when Spix and Martius visited Rio, in 1817, was only to be met with in the richest houses, has now become almost universal. The guitar was formerly the favourite instrument, as it still is all over the interior. There are excellent schools for the education of boys; and boarding schools have been established for young ladies, which are conducted on the same principles as those of a similar nature[7] in England. Being the capital of the empire, and there being residents at the court from most of the European nations, Rio is the scene of much greater gaiety than is generally supposed by those who have never visited it. But as all these matters have been more learnedly “discoursed of” than I profess to be able to do, I shall pass over in silence the levees, the opera, the theatres, whether French or Portuguese, and the balls, public as well as private, which engross quite as much of the attention of the fashionable world here as elsewhere.

Of the many European merchants established here, who for the most part are English, few reside in the city, most of them having country houses in the suburbs. One of the most fashionable resorts is a lovely spot about two miles out, called Botafogo. There the houses are built along the semicircular shore of a quiet bay, which is nearly surrounded by high hills. Immediately behind the houses, and almost overhanging them, stands a very remarkable mountain called the Corcovado, which rises to upwards of two thousand feet above the level of the sea, about two-thirds of its eastern face being a perpendicular precipice. Many other European residences are situated in Catete and on the Praia de Flamengo, between Botafogo and the city; and in the Larenjeiras valley, which stretches up from Catete towards the mountains; others exist at the opposite extremity of the city, in the district of Engenho Velho.

There is one thing wanting in the neighbourhood of Rio which no large city should be without—a public drive. This, I find in India, is a point particularly attended to, whenever, even a few, Europeans are located together. At Rio, those who wish to take a morning or an evening drive, can only do so on the public roads, which are only fit for carriages to run on for a few miles out of the city. There is, indeed, quite close to it what is called the Passeio Publico, a large garden with shady walks, but it is only intended for those who walk. Of an evening, when the weather is fine, it is much frequented by the citizens. The Botanic Garden, which is about eight miles distant from the city, is a place of great resort.

On landing, I took up my residence at an Italian hotel, in one of the principal streets, but as this was not a place fitted to my pursuits, as soon as all my luggage was landed, I removed to the boarding-house of an old English lady, who had then been about thirty years in the country. It was about three or four miles from the city, situated in a beautiful valley which stretches from the suburb of Engenho Velho towards the Corcovado mountain, and called Rio Comprido, from a small stream so named which runs through it. Here I had my head-quarters for about five months, and during that period my excursions extended in all directions round the city. Frequent visits were made to the mountains, which are all covered with dense virgin forests—to the humid valleys—to the swampy tracts which lie to the north of the city—to the sea-shores—and to the islands in the bay. From these rambles there resulted a rich botanical harvest, besides numerous specimens belonging to other branches of natural history. But as an eternal spring and summer reign in this happy climate, and as almost every plant has its own season for the production of its flowers, every month is characterized by a different flora. It is, then, scarcely to be expected that a residence of but a few months can afford more than a very partial knowledge of its vegetable riches.

The whole of the country around Rio is essentially granitic, all the rocks being of that nature to which the name of Gneiss-granite has been applied, from their possessing decided marks of stratification. The mountains generally run in chains having no particular direction, and are of all sizes, from slight eminences to mountains which rise from 2,000 to 3,000 feet above the level of the sea. The loftier of these mountains, such as the Peak of Tejuca, the Corcovado, and the Gavea, have their south-east sides bare and precipitous, while those to the northward have a gradual ascent, and are wooded to their summit. Notwithstanding the enormous length of time which the sides of these mountains have been covered with their mighty forests, the alluvial layer of soil which rests on them is very thin. This, however, may be accounted for by the heavy rains washing it, as well as the materials from which it is formed, down into the valleys, where the alluvium is often[9] found to be many feet deep. Hence it is that the deep valleys which intersect the mountain ranges are the principal seats of agricultural industry; and some of them, particularly in the vicinity of the city, are thickly studded with habitations, surrounded with plantations of Coffee, Oranges, Bananas, and Mandioca. Many of the lower hills near the city are now also cleared and planted with Coffee, but the plantations were too young when I left to form any idea of their success at so low a level. Beneath the alluvium there is a bed of reddish-coloured clay, which is very tenacious when wet. It is often from thirty to forty feet in thickness, and is not peculiar to the province, as I have met with it in every part of Brazil where I have travelled. It frequently contains numerous boulders, consisting of rounded, as well as angular, fragments of Gneiss, Granite, and Quartz, and is often inter-stratified with various beds of sand and gravel. It is obvious then from these observations, that the soil around Rio itself is not generally rich. Indeed, the first thing which strikes a stranger on his arrival, is the apparent poverty of the soil contrasted with the richness of the vegetation. But for the humidity of the atmosphere, the heavy dews of the dry season, and the rains of the wet, combined with the heat of a tropical sun, the greater part of the country immediately surrounding Rio would not be worthy of cultivation. The very small quantity of soil which suffices for some plants is quite astonishing to a European. Rocks, on which scarcely a trace of earth is to be observed, are covered with Vellozias, Tillandsias, Melastomaceæ, Cacti, Orchideæ, and Ferns, and all in the vigour of life.

The climate of Rio has been very much modified by the clearing away of the forests in the neighbourhood. Previous to this, the seasons could scarcely be divided into wet and dry as they are at present. Then rains fell nearly all the year round, and thunder-storms were not only more frequent, but more violent. So much has the moisture been reduced, that the supply of water for the city has been considerably diminished, and the government has, in consequence, forbidden the further destruction of the forests on the Corcovado range, towards the sources of the aqueduct. During[10] the months of May, June, July, August, and September, the climate is usually delightful, being the dry as well as the cool season. The mean temperature of the year is 72°. Although frequent showers fall during the dry season, yet they are not to be compared with the continued rains of the other, which generally commence in October. The rainy season sets in with heavy thunder-storms, which are of most frequent occurrence in the afternoon.

The population of Rio consists principally of Portuguese and their descendants, both white and coloured; those only born in the country are styled Brazilians; and ever since its independence as an empire in 1820, a very bad feeling has existed between them and those who are natives of Portugal. But this feeling is less common among the higher than the lower orders, and is, perhaps, more strongly marked in the inner provinces than on the coast. Wherever any riot, or any attempt to revolt takes place in the interior—and such occurrences are now, unfortunately, but too common—the poor Portuguese are the first to fall victims, being butchered without mercy, and robbed of all they possess. Notwithstanding the ill usage they receive, hundreds of them arrive yearly to push their fortune in the country, which, at one time, formed the richest gem in the crown of Portugal. Many of those who call themselves white in Brazil, scarcely deserve the title, as few of those families who have been long in the country, have preserved the purity of the original stock. The inhabitants of Rio are in general short and slightly made, and form a great contrast to the tall and handsome inhabitants of the Provinces of San Paulo and Minas Geräes, and even those of several of the northern provinces. The Brazilian wherever he is met with is always polite, and but very seldom inhospitable, especially in the less frequented parts of the country. He is much more temperate in his drinking than in his eating, and much more addicted to snuff-taking as well as to smoking: hence the prevalence of dyspeptic and nervous complaints among them. Marriage is less common in Brazil than in Europe, a fact which accounts for the greater laxity of morals which exists here among both sexes. The women are generally short, and when young are pretty agreeable,[11] but as they increase in years they mostly get very corpulent, from their living well and taking but little exercise. In Rio and the other large towns, they always make their appearance when strangers call, but such is not the case in most parts of the interior; there they still remain shy, but with an abundance of curiosity. I have lived for a week at a time in houses where I was well aware there were ladies, without ever seeing more of them than their dark eyes peering through the chinks about the doors of the inner apartments. In the distant province of Goyaz, Matto-Grosso, and Piauhy, nearly all classes of them are as much addicted to the use of the pipe as the men. It is but very seldom that native Indians are to be seen in Rio; I was several months in the country before I saw one. The brown boatmen, in the harbour, who have been taken for Indians, are, as Spix and Martius have already observed, mulattoes of various shades of colour.

Much has been written on slavery as it exists in Brazil. It is a subject of great importance, and demands a much greater amount of observation than has generally occurred to those who have written on it at greatest length. Those have mostly been voyagers, en passant, who have derived their knowledge from others, and not from personal observation. The most ridiculous stories are told by the European residents to strangers on their arrival, as I well know from personal experience. One of the more recent works on Brazil, which on its appearance was the most accredited in Europe, is, perhaps, the least to be depended on. I have good authority for stating that the author noted down every statement that was made to him, however extraordinary, without the slightest examination as to its truth. More than one individual has informed me, that at dinner parties, they have heard persons present, who were more famed for their wit than their veracity, cramming him with information about Brazil, which, in truth, was worse than no information at all; but everything seemed to be acceptable, and was immediately entered in his note-book.

In the year 1825, Humboldt estimated the entire population of Brazil at about 4,000,000; of this number he calculated that[12] 920,000 were whites, 1,960,000 negroes, and 1,120,000 mixed races and native Indians. Here the proportion of the coloured races to the white is about three to one. Later estimates give an entire population of 5,000,000; and the proportion of the coloured race to the whites stands as four to one. It was supposed at the time when the law was passed to render illegal the introduction of new slaves, that the proportional number would speedily decline. Had this law been strictly observed, such would, no doubt, have been the case, as it is well known that the number of births falls far short of the deaths among the slave population in Brazil. This does not arise from their ill usage, as some writers have supposed, but from the well-known fact that a greater proportion of males than of females has at all times been introduced to the country. On some estates in the interior the proportion of females to males is often as low as one to ten. In the Diamond District, in particular, females are very scarce. The law, however, has not been attended to, and the consequence of incessant introduction is, that the number of slaves in the country has not declined. During the five years which I spent in Brazil, I have good reason for believing that the supply was always nearly equal to the demand, even in the most distant parts of the empire.

Notwithstanding the vigilance of the cruisers both on the coast of Brazil and that of Africa, it was well known to every one in Rio, that cargoes of slaves were regularly landed even within a few miles of the city; and during several voyages which I have made in canoes and other small craft along the shores of the northern provinces, I have repeatedly seen cargoes of from one to three hundred slaves landed, and have heard of others. There are many favourite landing-places between Bahia and Pernambuco, particularly near the mouth of the Rio San Francisco. Again and again, while travelling in the interior, I have seen troops of new slaves of both sexes, who could not speak a single word of Portuguese, varying from twenty to one hundred individuals, marched inland for sale, or already belonging to proprietors of plantations. These bands are always under the escort of armed men, and those who have already been bought, are not unfrequently[13] made to carry a small load, usually of agricultural implements. There is no secrecy made of their movements, nay, magistrates themselves are very often the purchasers of them. It is likewise well known that the magistrates of those districts where slaves are landed, receive a certain per-centage on them as a bribe to secrecy. The high price which they bring in the market, is a very great temptation to incur the risk of importing them. It is said that if only one cargo be saved out of three, that one will cover the whole expenses, and leave a handsome profit besides.

Previous to my arrival in Brazil, I had been led to believe, from the reports that have been published in England, that the condition of the slave in that country was the most wretched that could be conceived; and the accounts which I heard when I landed—from individuals whom I now find to have been little informed on the point—tended to confirm that belief. A few years’ residence in the country, during which I saw more than has fallen to the lot of most Europeans, has led me to alter very materially those early impressions. I am no advocate for the continuance of slavery; on the contrary, I should rejoice to see it swept from off the face of the earth—but I will never listen to those who represent the Brazilian slave-holder to be a cruel monster. My experience among them has been very great, and but very few wanton acts of cruelty have come under my own observation. The very temperament of the Brazilian is adverse to its general occurrence. They are of a slow and indolent habit, which causes much to be overlooked in a slave, that by people of a more active and ardent disposition, would be severely punished. Europeans, who have this latter peculiarity more strongly inherent in them, are known to be not only the hardest of task-masters, but the most severe punishers of the faults of their slaves.

In Brazil, as in all other countries, there is more crime in large towns than in the agricultural districts. This arises from the greater facilities which exist in the former for obtaining ardent spirits; yet, among the black population, intoxication is not often observed, even dense as it is in Rio de Janeiro. It was on a Sunday morning that I arrived in Liverpool from Brazil, and during the course of[14] that day I saw in the streets a greater number of cases of intoxication, than, I believe, I observed altogether among Brazilians, whether black or white, during the whole period of my residence in the country. In the large towns the necessity for punishment is of frequent occurrence. The master has it in his own power to chastise his slaves at his own discretion. Some, however, prefer sending the culprit to the Calabouça, where, on the payment of a small sum, punishment is given by the police. Many of the crimes for which only a few lashes are awarded, are of such a nature that in England would bring upon the perpetrator either death or transportation. It is only for very serious crimes that a slave is given up entirely to the public tribunals, as then his services are lost to the owner, either altogether, or at least for a long period.

On most of the plantations the slaves are well attended to, and appear to be very happy. Indeed, it is a characteristic of the negro, resulting no doubt from his careless disposition, that he very soon gets reconciled to his condition. I have conversed with slaves in all parts of the country, and have met with but very few who expressed any regret at having been taken from their own country, or a desire to return to it. On some of the large estates at which I have resided for short periods, the number of slaves often amounted to three or four hundred, and but for my previous knowledge of their being such, I could never have found out from my own observations that they were slaves. I saw a set of contented and well-conditioned labourers turning out from their little huts, often surrounded by a small garden, and proceeding to their respective daily occupations, from which they returned in the evening, but not broken and bent down with the severity of their tasks. The condition of the domestic slave is, perhaps, even better than that of the others; his labour is but light, and he is certainly better fed and clothed. I have almost universally found the Brazilian ladies kind both to their male and female domestic slaves; this is particularly the case when the latter have acted as nurses. On estates, where there has been no medical attendant, I have often found the lady of the proprietor attending to the sick in the hospital herself.

Slaves, however, are variously inclined; from the very nature of a negro—his well-ascertained deficient intellectual capacity—the want of all education—the knowledge of his position in society, and the almost certainty of his never being able to raise himself above it—we need not wonder that there should be among them some who are restless, impatient of all control, and addicted to every vice. It is the frequent necessity which arises for the punishment of the evil-disposed, that has led to the supposition of the indiscriminate and universal use of the lash. If the intellectual capacity of the negro be contrasted with the native Indian, it will not be difficult, on most points, to decide in favour of the latter. It is no small proof of the deficient mental endowment of the negro, that even in remote parts of the empire, three or four white men can keep as many as two or three hundred of them in the most perfect state of submission. With the Indian this could never be accomplished, for they too once were allowed to be held as slaves, and even still are, on the northern and western frontier, although contrary to law. The Indian has the animal propensities less fully developed than the negro; hence he is more gentle in his disposition, but at the same time, is much more impatient of restraint.

The character and capacity of the negro vary very much in the different nations. Those from the northern parts of Africa are by far the finest races. The slaves of Bahia are more difficult to manage than those of any other part of Brazil, and more frequent attempts at revolt have taken place there than elsewhere. The cause of this is obvious. Nearly the whole of the slave population of that place is from the Gold Coast. Both the men and the women are not only taller and more handsomely formed than those from Mozambique, Benguela, and the other parts of Africa, but have a much greater share of mental energy, arising, perhaps, from their near relationship to the Moor and the Arab. Among them there are many who both read and write Arabic. They are more united among themselves than the other nations, and hence are less liable to have their secrets divulged when they aim at a revolt.

To sum up these observations, I have had ample opportunity, since I left South America, for contrasting the condition of the slave of that country with that of the coolie in the Mauritius and in India, but more particularly in Ceylon; and were I asked to which I would give the preference, I should certainly decide in favour of the former, although, at the same time I could not but exclaim with Sterne, “still, Slavery! still thou art a bitter draught!”

A general rise of the black population is much dreaded in Brazil, which is not unreasonable, when the great proportion it bears to the white is taken into consideration. Were they all united by one common sympathy, this would have happened long ago, but the hostile prejudices existing among the different races of Africans, have hitherto prevented it. In the northern and interior provinces, considerable encouragement to their insubordination has been offered, by the general feeling that animates a large proportion of the free class, who are mostly of mixed blood, and who desire to throw off the yoke of monarchy and replace it by a republican form of government, a feeling which I know to be general, not only among the lower orders, but among the magistrates, priests, officers in the army, and owners of landed property, and hence I believe the time is not far distant, when Brazil will share the fate of the other South American states. In such an event the white population will be sure to suffer from the savage rapacity of the mixed races, especially those who have African blood in them: for it is to be remarked, that the worst of criminals spring from this class, who inherit in some degree the superior intellect of the white, while they retain much of the cunning and ferocity of the black; they are mostly free, and bear no good will towards the whites, who form the smaller part of the entire population. It should be observed, however, that in the class of wealthier landed proprietors and commercial men, who have received the benefits of a more liberal education, especially those nearer the capital, and those belonging to the provinces along the coast, this tide of public opinion, that at one time nearly threatened the ruin of the empire, has been in a great measure[17] arrested, and many of those who formerly advocated republican principles, are now the staunchest supporters of the constitutional monarchy, convinced of its being the strongest guarantee they can have for the security of their lives and property, and the developement of the industry and resources of the empire.

In Brazil the mixed races receive different names from those in the Spanish territories. The offspring of Europeans and negroes are called Mulattos; those of Europeans and native Indians, Mamelucos; those of the negro and Indian, Caboclos; while those which spring from the mulatto and negro are called Cabras; the term Creole is applied to the offspring of the negroes.

I considered myself fortunate, shortly after my arrival at Rio, to make the acquaintance, and gain the friendship, of a family that had already travelled in distant parts of South America. It is only he who, day after day, is pursuing his solitary rambles through the dark forests, in the shady glens, on the mountain summits, or by the surf-beaten shores of such a country as Brazil, where all is new, and all is strange, who can fully estimate the privilege of being received with welcome into a family whose leisure hours are devoted to pursuits similar to his own. Many of my excursions in the vicinity of Rio, were undertaken in company with these friends, and to their local knowledge of the country I owe some of my finest botanical acquisitions. To them, as well as to most of the English residents at Rio, I am indebted for many attentions during the different periods of my residence in that neighbourhood.

In order to present some general idea of the splendid scenery of the country, and the leading features of this part of Brazil, I will give an account of some of these excursions. There is a path by the side of the great aqueduct which has always been the favourite resort of naturalists who have visited Rio; and there is certainly no walk near the city so fruitful either in insects or plants. The following notes were made on the return from my first visit along the whole length of the aqueduct. After reaching the head of the Laranjeiras valley, which is about two miles in extent, the ascent becomes rather steep. At this time it was[18] about nine A.M., and the rays of the sun, proceeding from a cloudless sky, were very powerful; but a short distance brought us within the cool shade of the dense forest which skirts the sides of the Corcovado, and through which our path lay. In the valley we saw some very large trees of a thorny-stemmed Bombax, but they were then destitute both of leaves and flowers, nearly all the trees of this tribe being deciduous. There we also passed under the shade of a very large solitary tree which overhangs the road, and is well known by the name of the Pao Grande. It is the Jequetibá of the Brazilians, and the Couratari legalis of Martius. Considerably further up, and on the banks of a small stream that descends from the mountain, we found several curious Dorstenias, and many delicate species of Ferns. We also added here to our collections fine specimens of the Tree-fern (Trichopteris excelsa), which was the first of the kind I had yet seen. The forests here exhibited all the characteristics of tropical vegetation. The rich black soil, which has been forming for centuries in the broad ravines from the decay of leaves, &c., is covered with herbaceous ferns, Dorstenias, Heliconias, Begonias, and other plants which love shade and humidity; while above these rise the tall and graceful Tree-ferns, and the noble Palms, the large leaves of which tremble in the slightest breeze. But it is the gigantic forest trees themselves which produce the strongest impression on the mind of a stranger. How I felt the truth of the observation of Humboldt, that, when a traveller newly arrived from Europe penetrates for the first time into the forests of South America, nature presents itself to him under such an unexpected aspect, that he can scarcely distinguish what most excites his admiration, the deep silence of those solitudes, the individual beauty and contrast of forms, or that vigour and freshness of vegetable life which characterize the climate of the tropics.[1] What first claims attention is the great size of the trees, their thickness, and the height to which they rear their unbranched stems. Then, in place of the few mosses and lichens which cover the trunks and boughs of the forest trees of temperate climes, here they are bearded from the roots to the very[19] extremities of the smallest branches, with Ferns, Aroideæ, Tillandsias, Cacti, Orchideæ, Gesnereæ, and other epiphytous plants. Besides these, many of the larger trunks are encircled with the twining stems of Bignonias, and shrubs of similar habit, the branches of which frequently become thick, and compress the tree so much, that it perishes in the too close embrace. Those climbers, again, which merely ascend the trunk, supporting themselves by their numerous small roots, often become detached after reaching the boughs, and, where many of them exist, the stem presents the aspect of a large mast supported by its stays. These rope-like twiners and creeping plants, passing from tree to tree, descending from the branches to the ground, and ascending again to other boughs, intermingle themselves in a thousand ways, and render a passage through such parts of the forest both difficult and annoying.

Having reached, by mid-day, the level on which the water of the aqueduct is brought from its source, we continued our walk along it for upwards of two miles. Our progress, however, was slow, from the number of new objects continually claiming our attention. In damp shady spots by the side of the aqueduct we found the common water-cress (Nasturtium officinale) of Europe, which is one of the few plants that are truly cosmopolite; and on the rocks grew some little European mosses, which, being old acquaintances, recalled pleasing thoughts of home. Numerous ferns, and many strange-leaved Begonias grew along the side of the little stream. While collecting specimens of a moss, I had a providential escape from a poisonous snake: I caught it in my hand along with a handful of the moss, which was soon dropped when I perceived what accompanied it. Venomous snakes are not uncommon in the province of Rio de Janeiro; but accidents do not so often result from them as might be supposed.

About seven o’clock P.M., we regained the spot where we had left the servants, the horses, and the materials for our dinner; and by the time we had partaken of this repast, darkness had already set in. As the road is by no means of easy descent, even by day, we should not have thought of remaining so long, had we[20] not been certain of moonlight. During the half hour we delayed for the rising of the moon, we listened to the sounds produced by the various animals which are in a state of activity at this hour of the evening. Pre-eminent above all the others, is that emitted by the blacksmith frog; every sound which he produces ringing in the ear like the clang of a hammer upon an anvil, while the tones uttered by his congeners strikingly resemble the lowing of cattle at a distance. Besides these, the hooting of an owl, the shrill song of the cicada, and the chirping of grasshoppers, formed a continued concert of inharmonious tones; while the air was lighted up by the fitful flashes of numerous fire-flies.

When the moon rose we continued our journey, but the lowering clouds, together with the dark shade of the overhanging trees, prevented our deriving much advantage from its light. When we emerged from the forest and gained a glimpse of the horizon, everything betokened an approaching storm. Towards the north lay a mass of the darkest clouds, whence streamed, from time to time, sheets of the most brilliant lightning. This continued till we reached home, shortly after ten o’clock, and we were scarcely seated when the storm broke forth in all its fury, accompanied with a deluge of rain.

From various parts of the watercourse fine views of the low country are obtained. The finest, perhaps, is that which discloses the Lake of Rodrigo Freitas. We looked, as it were, through a large portal; on the left is the Corcovado, covered with a dense forest of various tinted foliage, and on the right, the nearly perpendicular face of another mountain, covered with a few Cacti and other succulent plants, but richly wooded towards the summit. From this point there runs a large wide valley, at the bottom of which lies the Botanic Garden, and still further on, the lake. On the flat grounds by the shores of the lake are a number of cottages, surrounded by cultivated fields. Immediately beyond these is the sea-shore, with its broad belt of white sand on which a heavy surf is always breaking. All beyond, with the exception of a small island or two to the left is the great Southern Atlantic Ocean, bounded by the blue sky. In the course of our walk we[21] often sat down to rest ourselves, and to enjoy, in the silence and repose which surrounded us, the romantic prospects which were constantly presenting themselves.

The Corcovado mountain offers a rich field to the botanist. I frequently visited the lower portions, but only once ascended to the summit. The ascent is from the N.W. side, and although rather steep in some places, may be ridden on horseback all the way up. Some of the trees on the lower parts of it are very large. The thick underwood consists of Palms, Melastomaceæ, Myrtaceæ, Tree-ferns, Crotons, &c.; and beneath these are many delicate herbaceous ferns, Dorstenias, Heliconias, and, in the more open places, a few large grasses. Towards the summit the trees are of much smaller growth, and shrubs belonging to the genus Croton are abundant, as well as a small kind of bamboo. The summit itself is a large mass of very coarse-grained granite. In the clefts of the rocks grow a few small kinds of Orchideous plants, and a beautiful tuberous-rooted scarlet-flowered Gesneria. From this point a magnificent panoramic view of the bay, the city, and the surrounding country is obtained. The temperature at this elevation is so much reduced, that it is not difficult to fancy one’s self suddenly transported to a higher latitude. A strong breeze was blowing, and just before leaving, the top of the mountain became enveloped in one of those dark clouds which so frequently hang over it towards the beginning of the rainy season.

Another interesting journey made during my stay at Rio, was to the Tijuca mountains, whither I was accompanied by a friend, and where we remained ten days. Instead of the direct road from Rio, we preferred the worst and more circuitous one which leads along the shore. Near the sea, and about fifteen miles distant from the city, rises the Gavea, or Topsail Mountain, so called from its square shape, and well known to English sailors by the name, of Lord Hood’s Nose. It has a flat top, and rises about two thousand feet above the level of the sea, to which it presents a nearly perpendicular precipitous face. We remained a night at the house of a Frenchman, who possessed a small coffee estate. The coffee is planted on the rocky sloping ground which[22] lies between the base of the mountain and the sea. The situation is cool, and possesses a moist climate. Among the loose rocks at the foot of the mountain we made a fine collection of beautiful land-shells, and on the rocks by the sea-shore, we found the beautiful Gloxinia speciosa, which is now so common in the hot-houses of England, growing in the greatest profusion, and covered with flowers. Along with it grows a kind of wild Parsley, and twining among the bushes, a new kind of Indian cress (Tropæolum orthoceras, Gardn.). On the face of the mountain, at an elevation of several hundred feet, we observed some large patches of one of those beautiful large-flowered Orchideous plants which are so common in Brazil. Its large rose-coloured flowers were very conspicuous, but we could not reach them. A few days afterwards we found it on a neighbouring mountain, and ascertained it to be Cattleya labiata. Those on the Gavea will long continue to vegetate, far from the reach of the greedy collector.

The road, after winding round the Gavea, terminates at a small salt water lake, which passengers, who follow this route, are obliged to cross, or rather to pass from one end to the other, in consequence of the flank of a high hill which runs into it, and prevents a passage along its margin. We passed the lake in a rotten leaky canoe, and saw on the face of the steep rocks many curious plants which we could not reach. The path which led to the house where we were to take up our quarters, lay for about two miles through a flat meadow-land, partly in its original state, and partly planted with Indian corn, Mandiocca, and Bananas. We passed many small habitations belonging to poor people of colour, mostly fishermen. Before reaching the foot of the mountain over which the road leads to Tijuca, we passed a migrating body of small black ants. The immense number of individuals comprising it may be imagined from the fact, that the column was more than six feet broad, and extended in length to upwards of thirty yards. The ground was completely covered with the little creatures, so closely were they packed together. The natural history of ants has as yet been but little studied, particularly with regard to the enumeration of species. They are more numerous than naturalists[23] are aware of. In those parts within the tropics where humidity prevails, they are neither so varied in species, nor so abundant in individuals, as in drier districts. While residing at Pernambuco, I remember taking notice of all the species I met with in the course of a single day, and they amounted to about twenty-five.

Before ascending the hill we visited the falls of Tijuca, which are only at a short distance from the road. The crystal water of a large rivulet falls over two successive gently inclined masses of rock, upwards of one hundred feet high. It rather glides in a broad broken sheet than falls, and is received in a large pool below. This cascade reminded me of those which are so often to be met with in the wooded glens of Scotland. By dusk, after gradually ascending the mountains, we reached the house; it is situated in an old coffee plantation, belonging to a Brazilian nobleman, but it was then rented by a party of young English merchants in Rio, who used it as a holiday resort, and, by the kindness of one of them, we were allowed to remain at it for a few days.

Early on the following morning we made an excursion to a mountain called the Pedra Bonita, immediately opposite the Gavea. In our way thither we visited the coffee plantations of Mrs. Moke, and Mr. Lescene. They adjoin each other, and were then considered the best managed near Rio. The great coffee country is much farther inland, on the banks of the Rio Parahiba. The trees are planted from six to eight feet apart. Those plants which have been taken from the nursery with balls of mould round their root are found to bear fruit in about two years, whereas those which have been detached from the earth do not produce till the third year, and a greater proportion of the plants die. They are planted when about a foot high, on the slopes of the hills, in the alluvial soil from whence the virgin forest has been cleared. They are only allowed to grow to the height of from ten to twelve feet, so that the crop may lie within reach. Till the trees are in full bearing, one negro can take charge of, and keep clean, two thousand plants: but afterwards only half that number is allotted him. Large healthy coffee trees have been found to produce as much as from eight to twelve pounds of coffee; the average produce,[24] however, varies from a pound and a half to three pounds. When the berry is ripe, it is about the size and colour of a cherry; and of these berries a negro can collect about thirty-two pounds daily. In the course of the year there are three gatherings, but the greater part of the crop ripens during the dry season. The berries are spread out to dry in the sun, on large slightly convex floors; the dry shell is afterwards removed, either by mills, or by a series of large wooden mortars. It is only in some few estates in Brazil that the pulper is seen, which is so commonly used in the West Indies and Ceylon, for taking off the pulp from the fresh berries. Nothing is more beautiful than a coffee plantation in full bloom; the trees come into flower at the same time, but the blossoms do not last more than twenty-four hours. Seen from a distance the plantation seems covered with snow; and the flowers have a most delightful fragrance.

By the side of a stream which flows through the valley where these plantations are, we noticed a nettle-like tree, with a stem eight inches in diameter, and nearly twenty feet high, which proved to be a new species of Bæhmeria (B. arborescens, Gardn.). For a considerable way our ascending path was bordered with bitter orange trees, the shade afforded by which was no less acceptable than their fruit was grateful; for the juice though a little bitter is not disagreeably so. Both here, and in many other parts about Rio, this bitter kind of orange grows apparently wild; it is called the wild orange by the Brazilians (Laranja da Terra), but it is certainly not indigenous. Thence, we came to a tract where the original forest having been felled, was replaced by a thick wood of young trees, consisting chiefly of arborescent Solanums, Crotons, Vernonias, &c., while great numbers of Cecropia peltata and palmata reared their heads above the rest, conspicuous at a great distance from their white bark, their large lobed leaves, the snowy under-surface of which, when agitated by the wind, gives the tree the appearance of being covered with large white blossoms.

Near the summit of the Pedra Bonita, there is a small Fazenda, or farm, the proprietor of which was then clearing away the forest which covers it, converting the larger trees into charcoal. From[25] the massive trunks of some of them which had just been felled, we obtained some very pretty Orchideous plants, and several of the larger denizens of the forest, found to belong to the natural orders Melastomaceæ, Myrtaceæ, Compositæ, and Leguminosæ. The ascent of the Pedra Bonita is made from the north side. Immediately on emerging from the forest, and attaining the summit, a most magnificent view of the surrounding country presented itself. It was then nearly sunset, so we had but little time for botanizing. We only saw enough to convince us that the vegetation of the top of this mountain had a very different character from those of any others we had visited near Rio: resembling more, as I have since ascertained, that of the mountains of the interior. A few days afterwards we made another journey to it, but on this occasion the whole mountain was enveloped in clouds, the minute globules of which they were composed being distinctly visible, as they swept past under the influence of a strong breeze which was blowing from the north. A great part of the top we found to be covered with the beautiful lily-like Vellozia candida, on the branches of which grew a pretty Epidendrum, with rose-coloured flowers. Along with the Vellozia grew two beautiful subscandent species of Echites,[2] one with large dark violet-coloured flowers, the other with white ones of a similar size. They both exhale an odour not unlike that of the common primrose, but more powerful. On the edge of a precipice on the eastern side, we found, covered with its large rose-coloured flowers, the splendid Cattleya labiata, which a few days before we had seen on the Gavea.

The following year, on my return from the Organ Mountains, I again visited this spot, and found that a great change had taken place. The forest, which formerly covered a considerable portion of the summit, was now cut down and converted into charcoal; and the small shrubs and Vellozias which grew in the exposed portion, had been destroyed by fire. The progress of cultivation is proceeding so rapidly for twenty miles around Rio, that many of the species which still exist, will in the course of a few years, be[26] completely annihilated, and the botanists of future times who visit the country, will look in vain for the plants collected by their predecessors.

Other excursions to the islands in the bay, and to Jurujuba, on the opposite side of it, were also productive of many interesting species of plants. It was at the latter place, on dry bushy hills, that I first saw the really beautiful Buginvillea spectabilis growing wild. It climbs up into the tops of the bushes and trees near which it grows, and the brilliant colour of the flowers, which it produces in the greatest profusion, renders it conspicuous in the woods at a great distance. This, as well as the equally beautiful Bignonia venusta, are much cultivated as ornamental climbers in the suburbs.

Before leaving Rio, I visited the Botanic Garden, and the Museum of Natural History. The former, as has already been observed, is situated at the foot of a valley near the sea, about eight miles to the south-west of the city. It is more a public promenade than a Botanic Garden, for, with the exception of a few East Indian trees and shrubs, and a few herbaceous European plants, there is but little to entitle it to that name. Of the immense number of beautiful plants indigenous to the country, I saw but few. The European botanist is, however, well recompensed for his visit, by the sight of some large Bread-fruit trees and the Jack, with its much smaller entire leaves, and monstrous fruit pendent from the stem and large branches. There are also some fine Cinnamon and Clove trees. Near the centre of the garden several clusters of Bamboos, with stems upwards of fifty feet in height, give it a marked tropical character. The avenue which leads up from the entrance, is planted on each side with the pine-like Casuarina. It is on a piece of ground, about an acre in extent, on the left hand side of this avenue, that the Tea plants grow which were imported from China by the grandfather of the present Emperor. It was thought that the climate and soil of Brazil would be suitable for its cultivation, but the success of the experiment has not equalled the expectations which were formed of it, notwithstanding that the growth of the plants, and the preparation of the leaves, were managed by natives of China accustomed[27] to such occupations. In the province of San Paulo a few large plantations of Tea have been established; that belonging to the ex-regent Feijó, containing upwards of 20,000 trees. The produce is sold in the shops at Rio, and in appearance is scarcely to be distinguished from that of Chinese manufacture, but the flavour is inferior, having more of an herby taste. It is sold at about the same price, but it is now ascertained that it cannot be produced, so as to give a sufficient recompense to the grower, the price of labour being greater in Brazil than in China. To remunerate, it is said that Brazil Tea ought to bring five shillings per pound.