Project Gutenberg's One Hundred Years in Yosemite, by Carl Parcher Russell

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: One Hundred Years in Yosemite

The Story of a Great Park and Its Friends

Author: Carl Parcher Russell

Contributor: Newton B. Drury

Release Date: November 17, 2018 [EBook #58295]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ONE HUNDRED YEARS IN YOSEMITE ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

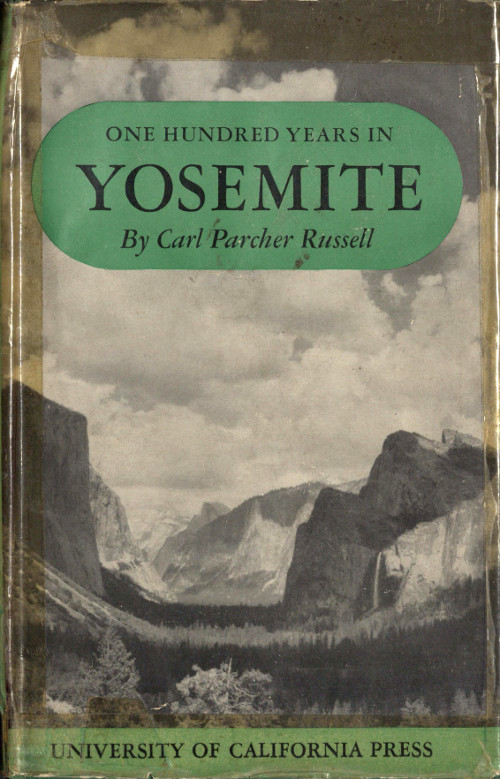

Frontispiece: Yosemite Valley

The Story of a Great Park and Its Friends

BY CARL PARCHER RUSSELL

CHIEF NATURALIST, UNITED STATES NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

With a Foreword by Newton B. Drury

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

Berkeley and Los Angeles · 1947

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES

CALIFORNIA

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON, ENGLAND

COPYRIGHT, 1932

COPYRIGHT, 1947, BY

THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF

WASHINGTON BARTLETT LEWIS

1884-1930

AND

CHARLES GOFF THOMSON

1883-1937

The National Park Service is primarily a custodian of and trustee for lands—lands with unique and special qualities, so distinctive as to make their care a concern of the entire nation; lands, therefore, held under a distinctive pattern and policy, administered according to the national park concept.

Yosemite National Park comprises such lands. It is, so to speak, a type locality for the national park idea. While Yellowstone, established in 1872, was the first real national park, Yosemite Valley, in 1864, under an act signed by President Lincoln, was transferred to the State of California to be protected according to park principles, later to be re-ceded to the Federal Government. Here in Yosemite many of the national park policies and techniques of protection, administration, and interpretation have evolved and are still evolving, within the framework of the basic act of 1916, with its injunction to “conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Dr. Russell’s One Hundred Years in Yosemite, appearing now in its new version, gives not only a chronology of events, and the persons taking part in them, related to this place of very special beauty and meaning. It also portrays, in terms of viii human experience, the growth of a distinct and unique conception of land management and chronicles the thoughts and effort of those who contributed to it. It tells of the obstacles overcome, and of the pressures, present even today, to break down the national park concept, and turn these lands to commercial and other ends that would deface their beauty and impair their significance.

This book, therefore, is more than a history of Yosemite. It traces the evolution of an idea.

In scholarly fashion, sources of information are cited. Many of the documents and other source materials upon which the book is based are preserved in the Yosemite Museum, thus giving special interest to visitors to Yosemite.

Belief in the worth of the national park program cannot but be strengthened by reading One Hundred Years in Yosemite.

Newton B. Drury,

Director, National Park Service

February 13, 1947

It is the purpose of One Hundred Years in Yosemite to preserve and disseminate the true story of the discovery and preservation of America’s first public reservation to be set aside for its natural beauty and scientific interest.

When the original version of this book was written in 1930, I had recently completed the collation of manuscript diaries and correspondence, newspaper files, old journals, hotel registers, state and federal reports, photographs, and a variety of other pertinent historical source materials in the library of the Yosemite Museum. This was the material upon which the book was based. In the preface of the book I made a plea for the contribution of additional Yosemite memorabilia to be added to the Yosemite archives. Perhaps some of the fine response from donors during the past sixteen years is traceable to that plea; more likely, the increased interest in the Yosemite Museum results from the creditable work of the park’s staff members and the message carried by the monthly publication, Yosemite Nature Notes. The notable growth of the Yosemite Museum collections and the improvement of its exhibits and its general program of interpretive work are heartening to all who had a hand in the establishment of the work.

In the original version, and in bringing to the present work the benefit of new material, I have attempted to organize the x published information which has been confirmed by the oral testimony of many Yosemite pioneers and enriched with authentic data from unpublished manuscripts prepared by other “old-timers” to whom I could not speak. In order that a convenient chronology of events might be available to the reader, an outline is appended to the book. This includes the episodes related in the text and in addition mentions many obscure events not treated in the narrative. It also provides ready reference to the sources drawn upon in writing. This method of citing sources has made it unnecessary to encumber the pages of the text with numerous footnotes. Most of the manuscripts referred to are the property of the Yosemite Museum. The whereabouts of other manuscripts is indicated in the bibliography.

To the donors of the expanding collection of source materials and to the Yosemite staff members, also, who have accomplished so much in organizing, interpreting, and publishing upon these materials, I am indebted. Their interest and their labors have facilitated my present writing, and their conscientious handling of file systems, accession records, stored collections, and publication programs will facilitate the work of future investigators of Yosemite history and natural history. At the same time, their good museum practices should inspire further public confidence in the integrity of the Yosemite program, and the collections will continue to grow.

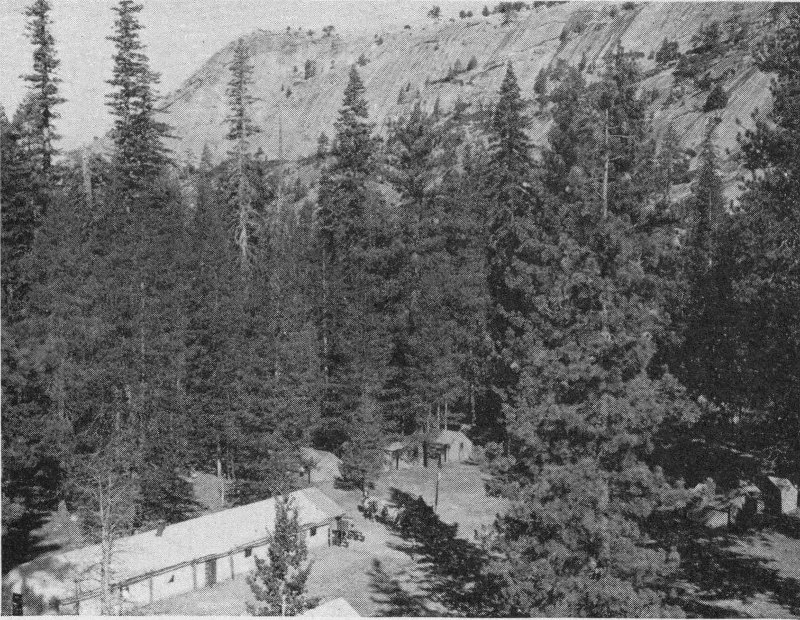

By Ralph Anderson, NPS The Yosemite Museum

A host of friends and associates have contributed to the production of the book. Great thanks are due my wife for her generous help and continuous encouragement. Mrs. H. J. Taylor lent important assistance and advice. Among the Yosemite staff members who gave valuable help, former Park Naturalists C. A. Harwell and C. Frank Brockman and former museum-secretary, Mrs. William Godfrey, made especially important contributions; however, the extraordinary interest of every member of the park naturalist staff has placed me in the debt of the entire organization. The American Association of Museums, in addition to coöperating with the National Park Service in founding the Yosemite Museum, has contributed directly to the production of this book by assisting me in the collecting of rare publications and helping, generally, in assembling Yosemite data. The Yosemite Park and Curry Company has made available many publications and photographs. Mrs. Don Tresidder of that organization, particularly, has given material assistance in establishing dates and historical facts. The Sierra Club has permitted the use of my article, “Mining Excitements East of Yosemite,” which was first published in the Sierra Club Bulletin. To David R. Brower, Editor of the Sierra Club Bulletin and at the University of California Press, I acknowledge particular indebtedness, not only for editorial guidance in producing the book but, also, for his historian’s sense and his basic knowledge of the Yosemite terrain and its story. Some of his contributions to the content of the text are acknowledged elsewhere, but his friendly help has extended to every part of the book. Francis P. Farquhar and Ansel F. Hall, during a quarter of a century of our friendships, have given assistance and encouragement. Mr. Farquhar has read parts of the manuscript and made helpful suggestions. His library has been drawn upon in the course of my work. The more recent photographs reproduced upon the following pages are credited to their makers, to each of whom I am deeply beholden. For xii use of the very old pictures used herein, I am indebted to the Yosemite Museum, and to Superintendent Frank Kittredge I express thanks for this and many other helpful acts performed by him and his staff members in furthering my efforts.

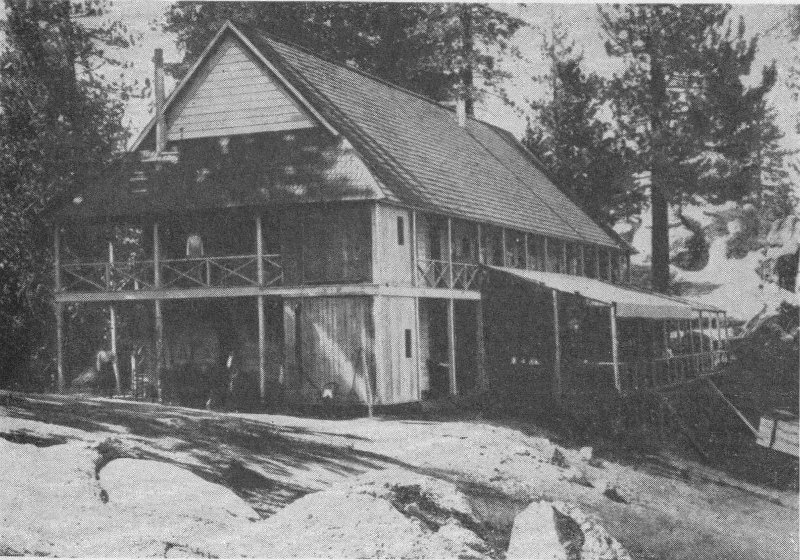

In the sixteen years that have elapsed since One Hundred Years in Yosemite first appeared, notable changes have taken place in the geographical boundaries of the national park, physical developments within the reservation have, so far as possible, kept pace with progressing modes of vacationing, and some eight million visitors have journeyed to its wonders. A number of the historic caravansaries that served so conspicuously during stagecoach days have been removed from the scene, and the one-time dusty, tortuous routes of access have been converted to safe, surfaced roads of beautiful alignment. A world-shaking conflict has been waged, and the superlative values of the park have emerged from that war unaffected by the demands of “production” interests.

Many earnest men have applied themselves in guarding the precious values of the great reservation. Some of these conservationists have virtually died in the harness. A growing appreciation of the work of these men is evident, and there is notable acclaim also of the far-sightedness of unnamed leaders who in 1864 obtained the epoch-making legislation that gave America her first public reservation of national park caliber.

It has been gratifying to me to observe some practical usefulness of my original compilation of Yosemite history, and this new version of the work is offered with the hope that it may continue to guide public attention to the significance of the action of pioneers who led the world along the paths of xiii scenic conservation. Upon the executives who now plan and administer programs of protection and management in Yosemite rests a responsibility that gains in magnitude in proportion to the growing pressure exerted by the hordes of people who seek the offerings of the park. The nation is yet in a pioneering stage in defining Yosemite values and regulating their use. In the light of experience of the past, it should be possible to discern some of the path that lies ahead.

The ability to discern even the more subtle influences affecting the security of Yosemite and other great national parks has become a “must” for National Park Service executives. This sensitivity has not developed overnight, but now it approaches maturity. Director Newton B. Drury has exercised a leadership in this regard which marks his period of service as the apex of clear thinking on national park problems.

Carl P. Russell

United States National Park Service

January 30, 1947

By Thomas A. Ayres, 1855 The First Drawing Made in Yosemite

That picturesque type known as the American trapper ushered in the opening event of Sierra Nevada history. True, the Spaniards of the previous century had viewed the “snowy range of mountains,” had applied the name Sierra Nevada, and even had visited its western base. But penetration of the wild and snowy fastness awaited the coming of Americans.

In the opening decades of the nineteenth century the entire American West was occupied by scattered bands of trappers. From the ranks of the “Fur Brigade” came Jedediah Strong Smith, a youthful fur trader, not yet thirty years old but experienced in his profession and well educated for his time. In the summer of 1826 he took his place at the head of a party of men organized to explore the unknown region lying between Great Salt Lake and the California coast. Smith’s leadership of this party gave him a first place in the history of the Sierra Nevada. His party left the Salt Lake rendezvous on August 22, 1826. A southwest course was followed across the deserts of Utah and Nevada, penetrating the Mojave country and the Cajon Pass. On November 27 they went into camp near Mission San Gabriel. Smith was thus the first American to make the transcontinental journey to California, the harbinger of a great overland human flood.

The Spanish governor of California refused to permit the party to travel north as Smith had planned. Instead, he instructed that they should quit California by the route used in entering. Reinforced with food, clothing, and horses supplied 2 by the friendly Mission San Gabriel, Smith returned to the neighborhood of the Cajon Pass. It was not his intention, however, to be easily deterred in his plan to explore California. He followed the Sierra Madre to the junction of the Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada and entered the San Joaquin Valley.

He found the great interior valley inhabited by large numbers of Indians, who were in no way hostile or dangerous. There were “few beaver and elk, deer and antelope in abundance.” Reaching one of the streams flowing from the mountains, he determined to cross the Sierra Nevada and return to Great Salt Lake. Smith called this stream the Wimmelche after a tribe of Indians by that name who inhabited the region thereabouts. C. Hart Merriam has established the fact that Smith’s “Wimmelche” is the Kings River, and the time of his arrival there as February of 1827. Since the passes of the Sierra in this region are never open before the advent of summer, it is not surprising that his party failed in this attempted crossing of the range. Authorities have differed in their interpretation of Smith’s writing regarding his ultimate success in traversing the Sierra, but there is little doubt that he crossed north of the Yosemite region, perhaps as far north as the American River.

Smith was, then, the first white man known to have crossed the Sierra Nevada. His pathfinding exploits did not take him into the limits of the present Yosemite National Park, but because his manuscript maps were made available to government officials who influenced later expeditions and because he was the first to explore the mountain region of which the Yosemite is an outstanding feature, his expedition provides the opening story in any account of Yosemite affairs.

Smith’s explorations paved the way for a notable influx of American trappers to the valleys west of the Sierra Nevada. Smith, in fact, returned to California that same summer. Pattie, Young, Ogden, Wolfskill, Jackson, and Walker all brought parties to the new fields during the first five years following the 3 Smith venture. Fur traders informed the settlers in the western states of the easy life in California and enticed them with stories of the undeveloped resources of the Pacific slope. Pioneers were then occupying much of the country just west of the Missouri, and a gradual tide of westward emigration brought attention first to Oregon and then to California.

The presence of Americans in California greatly annoyed the Mexican officials of the country. The fears of these officials were justified, for the trappers scarcely concealed their desire to overthrow Mexican authority and assume control themselves. To add to the threatened confusion, revolt brewed among the Mexicans who held the land.

In 1832 Captain B. L. E. Bonneville secured leave of absence from the United States Army and launched a private venture in exploring and trapping. One Joseph Reddeford Walker, who had achieved fame as a frontiersman, was engaged by Bonneville to take charge of a portion of his command. Walker’s party of explorers was ordered to cross the desert west of Great Salt Lake and visit California. Reliable knowledge of the Sierra Nevada and the first inkling of the existence of Yosemite Valley resulted from this expedition, made in 1833.

Joseph Walker, born in 1798 on the Tennessee River near the present Knoxville, Tennessee, had moved westward with the advancing frontier in 1818 to the extreme western boundary of Missouri. There he and his brothers rented government land near the Indian Factory, Fort Osage. They put in a crop and during slack seasons mingled with the Osages and the Kanzas Indians. Here Walker formed his first ideas of trade with the Indians—ideas which bore fruit during his later experiences on the Santa Fe Trail and with the fur brigades in the Rocky Mountains.

Early in 1831, Walker, enroute southward from his home to buy horses, stopped at Fort Gibson in the heart of the Cherokee Nation in the eastern part of the present Oklahoma. Several 4 companies of the 7th U. S. Infantry were stationed here. This circumstance brought about a sequence of events which left permanent marks upon Walker’s personal career and upon the history of the American West. Captain B. L. E. Bonneville was in command of B Company of the 7th Infantry. Bonneville confided in Walker that the government was about to place him on detached service in order that he might conduct a private expedition into the Rocky Mountains for furs and geographical data. He asked Walker to join him as guide and counselor. To this proposal Walker acceded enthusiastically and proceeded forthwith to organize the equipment and personnel needed for the venture.

On the first of May, 1832, Bonneville and Walker led westward a caravan of twenty wagons attended by one hundred and ten mounted trappers, hunters, and servants from the Missouri River landing where Fort Osage had once stood. Out upon the Kansas plains they went, up the Platte, to the Sweetwater, and through South Pass. In the valleys of the Green and the Snake they trapped and traded through the winter and spring of 1832-33. After the rendezvous on the Green in July, 1833, Walker was named by Bonneville to be the leader of the now famous Walker expedition to the Pacific.

The reports of Jedediah Smith on his trip of 1826 to California and the much talked about adventures of Smith, as discussed by the mountain men, seem to have been decisive factors which influenced Bonneville to authorize this ambitious undertaking. The fact that a scant 4,000 pounds of beaver was all he had to show for his campaign of the past year also may have contributed to his determination to take another fling at exploration, trapping, and the trade. Walker’s California party consisted of fifty men, with four horses each, a year’s supply of food, ammunition, and trade goods. Zenas Leonard and George Nidever, two free trappers who had joined the Bonneville crowd at the Green River rendezvous, were selected 5 as members of the Walker party. Both were to become conspicuous in California history by virtue of their writings.

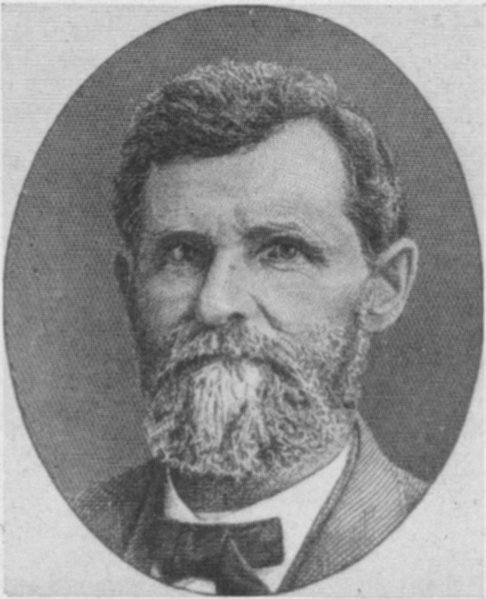

Because Walker was the first white man to lead a party of explorers to the brink of Yosemite’s cliffs, he is given a first place in Yosemite history. It is worthwhile to record here some of the appraisals of Walker, the man, made by his contemporaries and companions.

Zenas Leonard, clerk of the Walker party, wrote, “Mr. Walker was a man well calculated to undertake a business of this kind [the California expedition]. He was well hardened to the hardships of the wilderness—understood the character of the Indians very well ... was kind and affable to his men, but at the same time at liberty to command without giving offence ... and to explore unknown regions was his chief delight.”

Washington Irving said of Walker, “About six feet high, strong built, dark complexioned, brave in spirit, though mild in manners. He had resided for many years in Missouri, on the frontier; had been among the earliest adventurers to Santa Fe, where he went to trap beaver, and was taken by the Spaniards. Being liberated, he engaged with the Spaniards and Sioux Indians in a war against the Pawnees; then returned to Missouri, and had acted by turns as sheriff, trader, trapper, until he was enlisted as a leader by Captain Bonneville.”

Hubert Howe Bancroft, the historian, estimated, “Captain Joe Walker was one of the bravest and most skillful of the mountain men; none was better acquainted than he with the geography or the native tribes of the Great Basin; and he was withal less boastful and pretentious than most of his class.”

Walker’s biographer, Douglas S. Watson, referring to Bonneville’s effort to blame the financial failure of his western enterprises upon a scapegoat, stated, “Whatever may have been Bonneville’s purpose in besmirching Walker in which Irving so willingly lent himself, he has hardly succeeded, for where one person today knows the name Bonneville, thousands 6 regard Captain Joseph Reddeford Walker as one of the foremost of western explorers, worthy to be grouped with Jedediah Strong Smith and Ewing Young as the trilogy responsible for the march of this nation to the shores of the Pacific; the true pathfinders.”

Walker’s perseverance in completing his California journey grew out of a solemn determination to make a personal contribution to the expansion of the United States westward to the Pacific. His cavalcade crossed the Great Basin west of Great Salt Lake via the valley of the Humboldt and, passing south by Carson Lake and the Bridgeport Valley, struck westward into the Sierra Nevada. The exact course they took across the Sierra has been a matter of conjecture; some students have attempted to identify it with the Truckee route, and others have maintained that no ascent was made until the party reached the stream now known as Walker River. It seems probable that they climbed the eastern flank of the Sierra by one of the southern tributaries of the East Walker River. Once over the crest of the range, they traveled west along the divide between the Tuolumne and the Merced rivers directly into the heart of the present Yosemite National Park.

In Leonard’s narrative is found the following very significant comment regarding the crossing:

We travelled a few miles every day, still on top of the mountain, and our course continually obstructed with snow hills and rocks. Here we began to encounter in our path many small streams which would shoot out from under these high snow-banks, and after running a short distance in deep chasms which they have through the ages cut in the rocks, precipitate themselves from one lofty precipice to another, until they are exhausted in rain below. Some of these precipices appeared to us to be more than a mile high. Some of the men thought that if we could succeed in descending one of these precipices to the bottom, we might thus work our way into the valley below—but on making several attempts we found it utterly impossible for a man to descend, to say nothing of our 7 horses. We were then obliged to keep along the top of the dividing ridge between two of these chasms which seemed to lead pretty near in the direction we were going—which was west,—in passing over the mountain, supposing it to run north and south.

Walker’s tombstone, in Martinez, California, bears the inscription, “Camped at Yosemite Nov. 13, 1833.” Leonard’s description of their route belies the idea of his having camped in Yosemite Valley, and the date is obviously an error as there is reliable evidence that Walker had reached the San Joaquin plain before this date. L. H. Bunnell in his Discovery of the Yosemite records the following regarding Walker’s route and his Yosemite camp sites:

The topography of the country over which the Mono Trail ran, and which was followed by Capt. Walker, did not admit of his seeing the valley proper. The depression indicating the valley, and its magnificent surroundings, could alone have been discovered, and in Capt. Walker’s conversations with me at various times while encamped between Coulterville and the Yosemite, he was manly enough to say so. Upon one occasion I told Capt. Walker that Ten-ie-ya had said that, “A small party of white men once crossed the mountains on the north side, but were so guided as not to see the Valley proper.” With a smile the Captain said, “That was my party, but I was not deceived, for the lay of the land showed there was a valley below; but we had become nearly barefooted, our animals poor, and ourselves on the verge of starvation; so we followed down the ridge to Bull Creek, where, killing a deer, we went into camp.”

Francis Farquhar, in his article, “Walker’s Discovery of Yosemite,” analyzes the problem of Walker’s route through the Yosemite region and shows clearly that the Walker party was not guided by Indians. He concludes quite rightly that Bunnell was not justified in depriving Walker of the distinction of discovering Yosemite Valley. Douglas S. Watson, in his volume, West Wind: The Life of Joseph Reddeford Walker, offers further evidence to this end.

It requires no great stretch of the imagination to visualize scouts along the flanks of the Walker party coming out upon the brink of Yosemite Valley and looking down in wonder upon the plunging waters of Yosemite Falls and, perhaps, venturing to the edge of the Hetch Hetchy. In any case we have in the 1839 account by Leonard the first authentic printed reference to the Yosemite region. Another passage from this narrative must be quoted here:

In the last two days travelling we have found some trees of the Redwood species, incredibly large—some of which would measure from 16 to 18 fathom round the trunk at the height of a man’s head from the ground.

This is the first published mention of the Big Trees of the Sierra. If we accept Bunnell’s contention that the Walker party camped at Bull Creek (Hazel Green), we will also agree that the party followed the old Mono Trail of the Indians. This route would have taken them near the Merced Grove of Big Trees. There is probably no way of determining definitely whether the Merced Grove, the Tuolumne Grove, or both, were seen by Walker’s men, but this incident so casually mentioned is clearly the discovery of the famous Big Trees, and here for the first time is a scholarly record of observations made in the present Yosemite National Park. We may accept Leonard’s writings as the earliest document in Yosemite history and the Walker party as the discoverer of both the Yosemite Valley and the Sequoia gigantea.

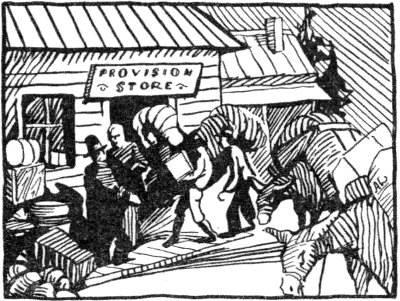

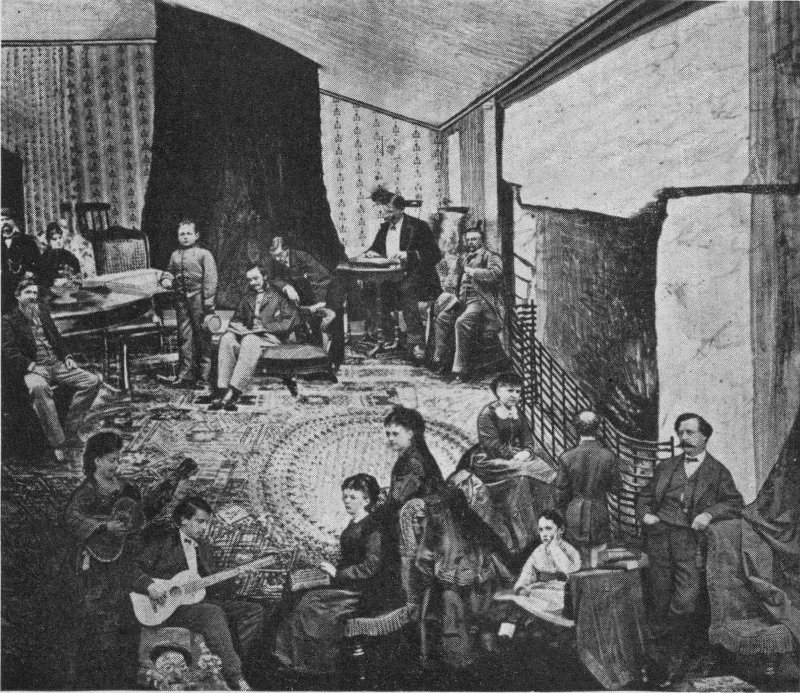

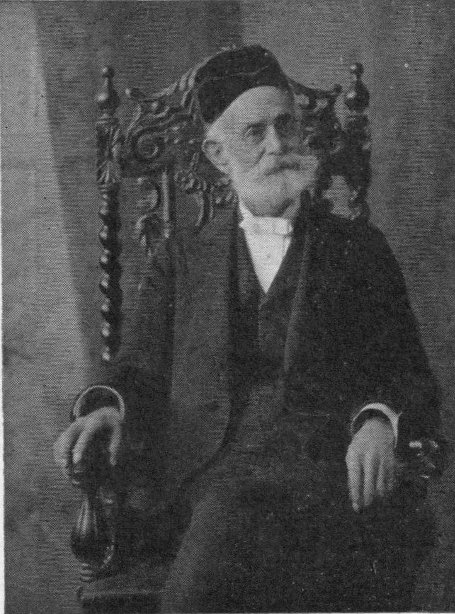

By Schwartz Mariposa in the ’Fifties

Following the significant work of the early overland fur traders there came a decade of immigration of bona fide California settlers. The same forces that led the pioneer across the Alleghenies, thence to the Mississippi, and from the Mississippi into Texas, explain the coming of American settlers into California. Hard times in the East stimulated land hunger, and California publicity agents spread their propaganda at an opportune time. Long before railroads, commercial clubs, and real estate interests began to advertise the charms of California, its advantages were widely heralded by the venturesome Americans who had visited and sensed the possibilities of the province. The press of the nation took up the story, and the people of the United States were taught to look upon California as a land of infinite promise, abounding in agricultural and commercial possibilities, full of game, rich in timber, possessed of perfect climate, and feebly held by an effeminate people quite lacking in enterprise and disorganized among themselves.

The tide of emigration resulting from this painting of word pictures began its surge in 1841 with the organization of the Bidwell-Bartleson party. Other parties followed in quick succession, and many of the pioneer fur hunters of the preceding decade found themselves in demand as guides. The settlers came on horseback, in ox wagon, or on foot, and with the men came wives and children. They entered the state by way of the Gila and the Colorado, the Sacramento, the Walker, the Malheur and the Pit, and the Truckee. Some journeyed to the 10 Mono region east of Yosemite and either struggled over difficult Sonora Pass just north of the present park or tediously made their way south to Owens River and then over Walker Pass. The Sierra Nevada experienced a new period of exploration, and California took a marked step toward the climax of interest in her offerings.

This pre-Mexican War, pre-gold-rush immigration takes a prominent place in the history of the state, and the tragedy and success of its participants provide a story of engrossing interest. They had forced their slow way across the continent to find a permanent home beside the western sea, and their arrival presaged the overthrow of Mexican rule in California. The Mexican, Castro, stated before an assembly in Monterey: “These Americans are so contriving that some day they will build ladders to touch the sky, and once in the heavens they will change the whole face of the universe and even the color of the stars.”

In one of the parties of settlers was a man of no signal traits, who, by a chance discovery, was to set the whole world agog. This was James W. Marshall, an employee of John A. Sutter of the Sacramento. On January 24, 1848, he found gold in a millrace belonging to Sutter. About a week later the inevitable took place. California became a part of the United States.

The news of the gold discovery spread like wildfire, and by the close of 1848 every settlement and city in America and many cities of foreign lands were affected by the California fever. Gold seekers swarmed into the newly acquired territory by land and by sea. The overland routes of the fur trader and the pioneer settler found such a use as the world had never seen. From the Missouri frontier to Fort Laramie the procession of Argonauts passed in an unbroken stream for months. Some 35,000 people traversed the Western wilderness and 230 American vessels reached California ports in 1849. The western slope of the Sierra from the San Joaquin on the south to 11 the Trinity on the north was suddenly populous with the gold-mad horde. On May 29, the Californian of Yerba Buena issued a notice to the effect that its further publication, for the present, would cease because its employees and patrons were going to the mines. On July 15 its editor returned and published an account of his personal experiences as a gold seeker. He wrote: “The country from the Ajuba [Yuba] to the San Joaquin, a distance of about 120 miles, and from the base toward the summit of the mountains ... about seventy miles, has been explored and gold found on every part.”

By 1849 the Mariposa hills were occupied by the miners, and the claims to become famous as the “Southern Mines” were being located. Jamestown, Sonora, Columbia, Murphys, Chinese Camp, Big Oak Flat, Snelling, and Mariposa, all adjacent to the Yosemite region, came to life in a day. Stockton was the immediate base of supply for these camps.

The history of Mariposa is replete with fascinating episodes. May Stanislas Corcoran, a daughter of Mariposa, has supplied the Yosemite Museum with a manuscript entitled “Mariposa, the Land of Hidden Gold,” which comes from her own accomplished pen. From it the following brief account is abstracted as an introduction to the beginnings of human affairs in the Mariposa hills.

In 1850, Mariposa County occupied much of the state from Tuolumne County southward. A State Senate Committee on County Subdivision, headed by P. H. de la Guerra, determined its bounds, and a Select Committee on Names, M. G. Vallejo, Chairman, gave it its name—a name which was first applied by Moraga’s party in 1806 to Mariposa Creek.[1] Gradually through the years, the original expansive unit was reduced by the creation of other counties—Madera, Fresno, Tulare, Kings, and Kern, and parts of Inyo and Mono counties.

Agua Fria was at first the county seat, but even in the beginning the town of Mariposa was the center of the scene of activity. Four mail routes of the Pony Express converged upon it. Prior to the arrival of Americans, the Spanish Californians had scarcely penetrated the Sierra in the county, but these uplands were well populated with Indians. One of the strongest tribes, the Ah-wah-nee-chees, lived in the Deep Grassy Valley (Yosemite) during the summer months and occupied villages along the Mariposa and Chowchilla rivers in the winter.

Mariposa proved to be the southernmost of the important southern mines. Of the people who were drawn to it during the days of the gold rush, many were from the Southern States. They brought “libraries ... horses from Kentucky ... silk hats, chivalry, colonels, and culture from Virginia; and from most of the states that later became Confederate, lawyers, doctors, writers, even painters—miners all.... Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New York, and Europe also sent representatives, and there were Mexican War veterans, such as Jarvis Streeter, Commodore Stockton, Colonel Fremont, and Capt. Wm. Howard.” By Christmas, 1849, more than three thousand inhabitants occupied the town of Mariposa, which extended from Chicken Gulch to Mormon Bar.

In February, 1851, a remarkable vein of gold was discovered in the Mariposa diggings, first designated as the “Johnson vein of Mariposa,” and extensive works were developed from Ridley’s Ferry (Bagby) to Mount Ophir. These properties were acquired by a company having headquarters in Paris, France, which became known as “The French Company.”

The Frémont Grant, also known as the Rancho Las Mariposas, was a vast estate of 44,386 acres of grazing land in the Mariposa hills, which Colonel J. C. Frémont acquired by virtue of a purchase made in 1847 from J. B. Alvarado. It was one of several so-called “floating grants.” After gold was discovered in the Mariposa region in 1848, Frémont “floated” his rancho far from the original claim to cover mineral lands including properties already in the possession of miners. The center of Frémont’s activities was Bear Valley, thirteen miles northwest of Mariposa. Lengthy litigations in the face of hostile public sentiment piled up court costs and lawyer fees. However, the United States courts confirmed Frémont’s claims, and other claimants, including the French Company, lost many valuable holdings. Tremendous investments were made in stamp mills, tunnels, shafts, and the other appurtenances related to the mining towns as well as to the mines which Frémont attempted to develop.

In spite of its phenomenal but spotty productiveness, the Frémont Grant brought bankruptcy to its owner and was finally sold at sheriff sale. The town of Mariposa, which was on Frémont’s Rancho, became the county seat in 1854, and the present court house was built that year. The seats and the bar in the courtroom continue in use today, and the documents and files of the mining days still claim their places in the ancient vault. They constitute some of the priceless reminders of a dramatic period in the early history of the Yosemite region. In these records may be traced the transfer of the ownership of the Mariposa Grant from Frémont to a group of Wall Street capitalists. These new owners employed Frederick Law Olmsted as superintendent of the estate. He arrived in the Sierra in the fall of 1863 to assume his duties at Bear Valley. The next year he was made chairman of the first board of Yosemite Valley commissioners, so actively linking the history of the Mariposa estate with the history of the Yosemite Grant. Olmsted 14 continued his connection with the Mariposa Grant until Aug. 31, 1865, at which time he returned to New York and proceeded to distinguish himself as the “father” of the profession of landscape architecture.

His son, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., born July 24, 1870, has continued in the Olmsted tradition. As an authority on parks, municipal improvements, city planning and landscape architecture, and the preservation of the American scene he has exerted a leadership comparable to his father’s pioneering. He has entered the Yosemite picture as National Park Service collaborator in planning and as a member of the Yosemite Advisory Board, to which organization he was appointed in 1928.

One of the few members of the small army of early miners in the Mariposa region who left a personal record of his experiences was L. H. Bunnell. His writings provide most valuable references on the history of the beginning of things in the Yosemite region. He was present in the Mariposa hills in 1849, and from his book, Discovery of the Yosemite, we learn that Americans were scattered throughout the lower mountains in that year. Adventurous traders had established trading posts in the wilderness in order that they might reap a harvest from the miners and Indians.

James D. Savage, the most conspicuous figure in early Yosemite history, whose life story, if told in full, would constitute a valuable contribution to Californiana, was one of these traders. In 1849 he maintained a store at the mouth of the South Fork of the Merced, only a few miles from the gates of Yosemite Valley. Now half a million people each year hurry by this spot in automobiles; yet no monument, no marker, no sign, indicates that the site is one of the most significant, historically, of all localities in the region. It was here that the first episode in the drama of Yosemite Indian troubles took place. The story of the white man’s occupancy of the valley actually begins at the mouth of this canyon in the Mariposa hills.

The entire story of very early events in the Yosemite region is pervaded by the spirit of one individual. In spite of the fact that no historian has chronicled the events of his brief but exciting career, the name of James D. Savage is legendary throughout the region of the Southern Mines. It has been the ambition of more than one writer of California history to pin down the fables of this pioneer and to establish his true life story on stable supports of authentic source. Scattered through the literature of the gold days are sketchy accounts of his exploits, and rarely narratives of firsthand experiences with his affairs may be found. Before relating Savage definitely to Yosemite itself we shall do well to consider his personal history.

During the beginning years of the gold excitement, his fame spread throughout the camps and to the ports upon which the mines depended for supplies. Savage was the subject of continual gossip, conjecture, and acclaim. His career was short, but it was crowded with thrilling happenings and terminated with violence in a just cause. Throughout it, Savage was brave—a man born to lead.

Because he played a leading role in the discovery of Yosemite Valley, national park officials have been energetic in their attempt to complete his life story and give it adequate representation in the Yosemite Museum. For several years, as historical material had been accumulating there, and details of most events in the Yosemite drama unfolded and took their proper place in the exhibits, Savage still remained a mystery.

At last there came a Yosemite visitor who was descended from the grandfather of James D. Savage. This lady, Ida Savage Bolles, after learning of the local interest in her relative, communicated with yet another relative, who today resides in the same Middle Western state from which “Jim” Savage came. The result was that Mrs. Louise Savage Ireland took up the challenge and devoted many months to the determining of the California pioneer’s ancestry. To her we acknowledge indebtedness for her persevering search, which involved considerable travel and correspondence. Not only did she reveal the ancestry of Jim Savage, but she located a “delightful old lady” who, as a girl, knew Jim of California fame. This unexpected biographical material provides firsthand information about the youth of James D. Savage such as has not been obtained from any living Californian who knew him in his halcyon days.

The following story of the life of the first white man to enter Yosemite Valley, though incomplete, is much more comprehensive than anything that has previously appeared in print, and is, we believe, gathered from sources[2] wholly dependable.

James D. Savage was one of six children born to Peter Savage and Doritha Shaunce. Henry C. Pratt of Virginia, Illinois, a second cousin, writes, “My mother, Emily Savage, born in 17 1817, and her cousin, James Savage, were near the same age.” This is the best approximation of his age contained in the biographical material accumulated by Mrs. Ireland. The parent, Peter Savage, went by ox cart and raft from Cayuga County, New York, to Jacksonville, Morgan County, Illinois, in 1822. Sixteen years later Peter’s family removed to Princeton, Bureau County, Illinois.

Mrs. Ireland in her quest met Mrs. Sarah Seton Porter of Princeton, who at the time of the interview in 1928 was ninety-eight years old. Mrs. Porter knew James D. Savage as a youth. She recalls that

Jim Savage was grown when his father, Peter, brought the family to Princeton from Morgan County. Jim was smart as a whip, shrewd, apt in picking up languages, such as German and French—for both tongues were spoken here, the two races having settlements in and about Princeton. He was vigorous and strong, had blue eyes and a magnificent physique, loved all kinds of sports engaged in in his day, was tactful, likable, and interesting....

Sometimes Jim would come to church, but, oh, he was such a wag of a youth. More often than not, he would remain outside, and when he knew time had come for prayer, he’d flick the knees of his horse and make him kneel, too, and then wink at us inside. We couldn’t laugh of course, but we always watched for this trick of Jim’s. He got such a lot of fun out of doing it.

Savage took a wife, Eliza, and settled in Peru, Illinois. A daughter was born to this union. He and his brother, Morgan, were caught in the wave of California fever that affected many of the border settlements in the ’forties and they joined one of the overland parties in 1846. Lydia Savage Healy, another second cousin, expresses the opinion that the brothers joined Frémont’s third expedition. However, since it is known that Savage’s wife and child made the start, it is evident that they were with one of the parties of emigrants who, that year, made the journey. Mrs. Porter, then Sarah Seton, with two brothers and a sister drove from Princeton to Peru to bid them farewell.

On this journey, “suffering and discouragement went hand in hand.” The wife and child did not survive the trip. Only the physically fit endured the hardships, and among these were Savage and his brother. By what route they entered California is not known, but S. P. Elias reports that Savage

volunteered beneath the Bear flag and fought through the war against the Mexicans. A member of Frémont’s battalion, he was with Frémont both in Oregon and in California. After peace and before the discovery of gold, and shortly after the disbanding of Frémont’s battalion, he went to the south, settled among the Indians, and through José and Jésus, two of the most powerful chiefs in the valley of the San Joaquin, he established an intimacy with the principal tribes. By his indomitable energy, capability of endurance, and personal prowess he acquired a complete mastery over them to such an extent that he was elected chief of several of the tribes. He obtained great influence over the Indians of the lowlands and led them successfully against their mountain enemies, conquering a peace wherever he forayed.

In any event, when Frémont and Pico put their signatures to the Cahuenga peace treaty on January 13, 1847, the Mexican War, so far as California was concerned, was at an end. Frémont’s battalion was disbanded, and we may believe, with Elias, that James D. Savage then established his intimacy with the principal Indian tribes of the San Joaquin.

His aptitude for “picking up languages” apparently came to the fore, for he mastered the Indian dialect and extended his influence until it amounted to something of a barbaric despotism. The Indians acknowledged his authority, and he, no doubt, improved their condition. In the wars with the mountain tribes Savage’s tactics won them victories, and he brought about progress, generally.

Prior to the gold rush, his territory was seldom visited by whites, but early in 1848, hardly a year subsequent to his conquest of the Indians, there poured in that flood of miners which transformed the entire picture. Savage adapted himself 19 to it forthwith, and soon his name was on the lips of everyone. When he let it be known among his Indian followers that he would like to acquire a lot of the yellow metal, the squaws set to work and turned the product of their labors into the lap of the white chief. W E. Wilde writes that Savage was associated with the Rev. James Woods in 1848 and that he and his Indians were working the gravel deposits at what became known as Big Oak Flat. It was here that a white Texan stabbed Luturio, one of the Indian leaders, and the Texan in turn was killed by the Indians. Savage, knowing the potentialities of enraged Indians, pacified them and withdrew with them to other localities.

George H. Tinkham next throws a spotlight on Savage at Jamestown in May (?) 1849. Cornelius Sullivan related to Tinkham that

under a brushwood tent, supported by upright poles, sat James D. Savage, measuring and pouring gold dust into the candle boxes by his side. Five hundred or more naked Indians, with belts of cloth bound around their waists or suspended from their heads brought the dust to Savage, and in return for it received a bright piece of cloth or some beads.

Just how much gold dust Savage acquired was never reported, but that it was an enormous amount is not to be questioned. For some two years his army of Indian followers busied themselves in gleaning the creeks and ravines of the foothills, and considering the facility with which gold could be gathered it is small wonder that he was reputed to have barrels full of it.

We learn from L. H. Bunnell, one of Savage’s intimate acquaintances of long standing, that in 1849-1850 Savage had established his trading post at the mouth of the South Fork of the Merced, not more than fifteen miles below Yosemite Valley, and on the line of the present Merced-Yosemite highway.

At this point, engaged in gold mining, he had employed a party of native Indians. Early in the season of 1850 his trading-post and mining camp were attacked by a band of the Yosemite Indians. This 20 tribe, or band, claimed the territory in that vicinity, and attempted to drive Savage off. Their real object, however, was plunder. They were considered treacherous and dangerous, and were very troublesome to the miners generally.

Savage and his Indian miners repulsed the attack and drove off the marauders, but from this occurrence he no longer deemed this location desirable. Being fully aware of the murderous propensities of his assailants, he removed to Mariposa Creek, not far from the junction of the Agua Fria, and near to the site of the old stone fort. Soon after, he established a branch post on the Fresno, where the mining prospects became most encouraging, as the high water subsided in that stream. This branch station was placed in charge of a man by the name of Greeley.

This event on the South Fork constitutes the initial step in the hostilities that were to result in Savage’s renown as the discoverer of Yosemite Valley. Since he had remained so close to the remarkable canyon for some months prior to the Indian attack, and because the threatening Indians frequently boasted of a “deep valley in which one Indian is more than ten white men,” Bunnell once asked Savage whether he had ever entered the mysterious place. Savage’s words were: “Last year while I was located at the mouth of the South Fork of the Merced, I was attacked by the Yosemites, but with the Indian miners I had in my employ, drove them off, and followed some of them up the Merced River into a canyon, which I supposed led to their stronghold, as the Indians then with me said it was not a safe place to go into. From the appearance of this rocky gorge I had no difficulty in believing them. Fearing an ambush, I did not follow them. It was on this account that I changed my location to Mariposa Creek. I would like to get into the den of the thieving murderers. If ever I have a chance I will smoke out the Grizzly Bears [the Yosemites] from their holes, where they are thought to be so secure.”

Savage built up an exceedingly prosperous business at his trading posts on the Fresno and on Mariposa Creek. He stocked 21 his stores with merchandise from San Francisco Bay and exchanged the goods at enormous profits for the gold brought in by the Indians. An ounce of gold bought a can of oysters, five pounds of flour, or a pound of bacon; a shirt required five ounces, and a pair of boots or a hat brought a full pound of the precious metal. His customers included white prospectors as well as his subservient Indians, for the white men would agree to his exacting terms in preference to leaving their diggings to make a trip for supplies to the growing village of Mariposa.

The Indians never questioned the rate of exchange, for to them it seemed that their white chief was working miracles in providing quantities of desirable food and prized raiment in return for something that was to be had for the taking. To guarantee a continuance of cordial relations with his Indian friends, and to cement the alliance of several tribes, Savage had taken wives from among the young squaws of different tribes. Two of these were called Eekino and Homut. It is not known which tribes were represented in his household, but the wives are reported to have totaled five. If their bridal contract was recognized by all their tribesmen, it is not difficult to understand how Savage’s supporters numbered five hundred.

The Mariposa Creek store retinue of whites was thrown into a state of some agitation one fall day in 1850 when one of Savage’s wives confided the information that the mountain Indians were combining to wipe the whites from the hills. Confirmation of her rumor was obtained from some of the friendly bucks who had long followed Savage. These Indians declared that they had learned that the mountain tribe, the Yosemites, were ready to descend upon Savage again for the purpose of plunder and that they were maneuvering to secure the combined forces of other tribes.

Savage did not misunderstand the threat, as did some others of the white men. Hoping to impress the Indians with the wonders, 22 numbers, and power of the whites, he conceived the idea of taking some of them to that milling base of supply, San Francisco. It is probable, too, that he planned to put some of his great store of accumulated gold in safekeeping on the same trip. Accordingly, he announced that he was going to “the Bay” for a new stock of goods and invited José Juarez, a chief of influence with the Chowchillas and Chukchansies, to accompany him. José accepted the invitation. With them went some of Savage’s dependable Indian friends, including a wife or two.

It was the occasion of this trip that provided the crowning touch for Savage’s reputation among the whites of all the gold camps. The story of the affair spread to as many localities as were represented in San Francisco’s picturesque population at the time of the visit, and legends of Jim Savage’s barrel of gold are handed down to this day. How large the barrel may have been it is now impossible to ascertain, but certainly a fabulous fortune traveled with the strange party.

They made their headquarters at the Revere House and became the sensation of the hour.[3] The Indians arrayed themselves in gaudy finery and gorged themselves with costly viands and considerable liquor. To the great distress of Savage, José maintained himself in a state of drunkenness throughout most of their stay. In order to prevent disturbances Savage locked him up on one occasion and when he was somewhat sobered remonstrated with him. José flew into an excited rage, became abusive with his tongue, and finally disclosed his secret of the war against the whites. Savage knocked him down.

The party remained to witness the celebration of the admission of California into the Union on October 29, 1850. Savage deposited his gold in exchange for goods to be delivered as needed, gilded his already colorful visit with enough gambling 23 and reckless spending to stagger the residents, and gathered his retinue for the return journey.

José had maintained a silence and dignity ever after the violent quarrel with his chief.

No sooner had they reached the foothill territory from which they had traveled a fortnight before than they were greeted with news of Indian threats. As the Fresno station maintained by Savage seemed to be in immediate danger, the party went there at once. Numerous Indians were about, but all seemed quiet. However, the white agents employed by Savage revealed that the Indians were no longer trading.

Savage thereupon invited all Indians present to meet with him and proceeded at once to conduct a peaceful confab before his store. Addressing them he said:

“I know that some of the Indians do not wish to be friends with the white men and that they are trying to unite the different tribes for the purpose of a war. It is better for the Indians and white men to be friends. If the Indians make war on the white men, every tribe will be exterminated; not one will be left. I have just been where the white men are more numerous than the wasps and ants; and if war is made and the Americans are aroused to anger, every Indian engaged in the war will be killed before the whites will be satisfied.”

Having made himself clearly understood in the Indian language he turned to his fellow traveler, José, for confirmation of his statements regarding the power of the whites. José stepped forward and delivered himself of the following brief but energetic oration:

“Our brother has told his Indian relatives much that is truth; we have seen many people; the white men are very numerous; but the white men we saw on our visit are of many tribes; they are not like the tribe that dig gold in the mountains.” He then gave an absurd description of what he had seen while below, and continued: “Those white tribes will not come to the mountains. 24 They will not help the gold diggers if the Indians make war against them. If the gold diggers go to the white tribes in the big village, they give their gold for strong water and games; when they have no more gold, the white tribes drive the gold diggers back to the mountains with clubs. They strike them down [referring to the police], as your white relative struck me while I was with him. The white tribes will not go to war with the Indians in the mountains. They cannot bring their big ships and big guns to us; we have no cause to fear them. They will not injure us.”

His climax came as a bold argument for the immediate declaration of war upon the whites.

Chief José Rey of the Chowchillas then contributed his plea for immediate hostilities, and Savage withdrew before the two hostile chiefs. Upon his return to the Mariposa Station, his appeals for immediate preparation for war were given small hearing by the whites. A few were inclined to scoff.

Close on the heels of the warnings, however, came news of an attack on the Fresno store. All the whites except the messenger who had brought the news were killed. The Mariposa Indian War was on.

Savage had gone to Horse Shoe Bend in the Merced Canyon to solicit aid. He had hoped to find a more attentive audience there than among the county officials at Agua Fria. In his absence his Mariposa store was burned, its three white attendants were killed, and his wives were carried off by the assailants.

Cassady, one of the rival traders who had scoffed at Savage’s first news of impending disaster, was surprised in his establishment and met quick death. Three other murderous attacks took place in the immediate vicinity, and the whites finally leaped to the defense of their holdings.

James Burney, the county sheriff, took a place at the head of a body of volunteers who had banded for mutual protection. On January 6, 1851, James D. Savage accompanied this party 25 in an attack made upon an Indian encampment of several hundred squaws and bucks under the leadership of José Rey. This was the first organized movement of the whites against the Indians of the Mariposa Hills.

By this time Governor McDougal had issued a proclamation calling for volunteers, and the Mariposa Battalion came into existence. Savage was made major in full command. Three companies, under John J. Kuykendall, John Boling, and William Dill, were organized and drilled near Savage’s ruined Mariposa store.[4] The affairs of this punitive body of men are dealt with in another chapter. Let it here suffice to say that its activities were especially directed against the mountain tribe of “Grizzlies,” and that on March 25, 1851, Savage and his men entered the mysterious stronghold, Yosemite Valley.

In 1928 it was my privilege to interview Maria Lebrado, one of the last members of the Yosemite tribe who experienced subjection by the whites. I eagerly sought ethnological and historical data, which was forthcoming in gratifying abundance. Purposely I had avoided questioning the aged squaw about Major Savage; but presently she asked, in jumbled English and Spanish, if I knew about the “Captain” of the white soldiers. She called him “Chowwis,” and described him as a blond chief whose light hair fell upon his shoulders and whose beard hung halfway to his waist. She had been much impressed by his commanding blue eyes and declared that his shirts were always red. To this member of the mountain tribe of Yosemite the Major was recalled as something of a thorn in her flesh. That he was a beloved leader of the foothill tribes she agreed, but hastened to explain that those Indians, too, were enemies of her people. Maria is the only person I have met who had seen Savage.

For five months Savage commanded the movements of the 26 Mariposa Battalion. Its various units were active in the Sierra Summit region above Yosemite, at the headwaters of the Chowchilla, and on the upper reaches of the San Joaquin. In every encounter the Indians were defeated and they finally sued for peace. The prowess of Savage as a mountaineer and military leader is borne out in a letter, published in Alta California on June 12, 1851, in which the battalion’s sergeant major describes at length for the adjutant a foray at the headwaters of the San Joaquin:

... I am aware that you have been high up and deep in the mountains and snow yourself, but I believe this trip ranks all others. The Major himself has seen cañons and snow peaks this trip which he never saw before. It is astonishing what this man can endure. Traveling on day and night, through snow and over the mountains, without food, is not considered fatigue to him, and as you are well aware the boys will follow him as long as he leaves a sign.

The same Alta carries a resolution, signed by men in Dill’s and Boling’s companies, affirming in great detail their high confidence in Savage.

In addition to his activities with the battalion in the field, Major Savage functioned conspicuously in aiding the United States Indian Commissioners in preparing a peace treaty. He maintained a friendly attitude toward the oppressed Indians and, had the government made good its promises, or had the appropriations not been absorbed elsewhere, the tribes of the Sierra would have been more adequately provided for. The treaty, signed April 29, 1851, does not carry the “signatures” of Tenaya of the Yosemites or of the leader of the Chowchillas.

On July 1, 1851, the Mariposa Battalion was mustered out. Major Savage resumed his trading operations in a store on the Fresno River near Coarse Gold. In compliance with the treaty, a reservation for the Indians was set aside on the Fresno, and another on the Kings River. In the fall of 1851 the Fresno store was the polling place for a large number of voters for county 27 officers. That winter Savage built Fort Bishop, near the Fresno reservation, and prepared to carry on a prosperous trade. He spoke as follows on this subject to L. H. Bunnell:

If I can make good my losses by the Indians out of the Indians, I am going to do it. I was the best friend the Indians had, and they would have destroyed me. Now that they once more call me “Chief,” they shall build me up. I will be just to them, as I have been merciful, for, after all, they are but poor ignorant beings, but my losses must be made good.

During the first months of 1852, Major Savage conducted a substantial, if not a phenomenal, business with the miners of the Fresno and surrounding territory, and with the Indians at the agency. No Indian hostilities were in evidence, but a policy of excluding them from the store proper was adhered to. The goods which they bought with their gold dust were handed out to them through small openings left in the walls. These openings were securely fastened at night.

Not infrequently the Indians were subjected to abusive treatment at the hands of certain whites. The mistreatment was enough to provoke an uprising, but with a few exceptions they remained on the reservations. An important light on subsequent events in Savage’s life is brought out in this statement by L. H. Bunnell:

As far as I was able to learn at the time, a few persons envied them the possession of their Kings River reservation and determined to “squat” upon it, after they should have been driven off. This “border element” was made use of by an unprincipled schemer, who it was understood was willing to accept office, when a division of Mariposa County should have been made, or when a vacancy of any kind should occur. But population was required, and the best lands had been reserved for the savages. A few hangers-on, at the agencies, that had been discharged for want of employment and other reasons, made claims upon the Kings River reservation; the Indians came to warn them off, when they were at once fired upon, and it was reported that several were killed.

Further details of the deplorable act committed by the would-be “squatters” are provided by the following news item which appeared in the Alta California of July 7, 1852:

Anticipated Indian Difficulties on King’s River

By Mr. Stelle, who came express to Stockton on the 5th inst., we have received the annexed correspondence from

San Joaquin, (Evening,) July 2, 1852.

Editors Alta California:—A few days ago, the Indians on King’s River warned Campbell, Poole & Co., ferrymen, twenty miles from here, to leave, showing at the same time their papers from the Indian Commissioners. The Indians then left, and threatened to kill the ferrymen if on their reservation when they returned. Mr. Campbell has been collecting volunteers, many have joined him. Major Harvey left this evening with some eighteen or twenty men. A fine chance for the boys to have a frolic, locate some land, and be well paid by Uncle Sam.

These agitations and murders were denounced by Major Savage in unsparing terms. Although the citizens of Mariposa were at the time unable to learn the details of the affair at Kings River, which was a distant settlement, the great mass of the people were satisfied that wrong had been done to the Indians; however, there had been a decided opposition by citizens generally to the establishment of two agencies in the county, and the selection of the best agricultural lands for reservations. Mariposa then included nearly the whole San Joaquin Valley south of the Tuolumne.

The opponents to the recommendations of the commissioners claimed that “The government of the United States has no right to select the territory of a sovereign State to establish reservations for the Indians, nor for any other purpose, without the consent of the State!” The state legislature of 1851-1852 instructed the senators and representatives in congress to use their influence to have the Indians removed beyond the limits of the state.

W. W. Elliott, in his History of Fresno County (1881), reveals further details: “Sometime previous to August 16, 1852, one Major Harvey, the first county Judge of Tulare County, and Wm. J. Campbell, either hired or incited a lot of men, who rushed into one of the rancherias on Kings River and succeeded in killing a number of old squaws.”

Elliott’s assertions are supported by the following news item from the San Francisco Daily Herald, August 21, 1852:

Among other acts by white men calculated to excite the Indians, a ferry was established over the San Joaquin, within an Indian reservation, above Fort Miller, some miles above Savage’s. The Indians, no doubt, considered this an encroachment; and from an idea that the ferry stopped fish from ascending the river, some straggling Indian, acting without authority from chiefs or council, spoke of this notion about the fish at the ferry, and saying that the ferry was within their lands, added that it would have to be broken up. The proprietor of the ferry, assuming this as a threatened hostility, or making a pretence of it, assembled a few willing friends, who, armed with rifles, appeared suddenly among some Indian families while most of the men were many miles off, peaceably at work at Savage’s, without dreaming of danger, and without justifiable provocation the white men fired upon the families, killing two women, as it is stated, and some children, and wounding several others.

With such conditions prevailing on the Kings, it is small wonder that numerous Kings Agency Indians traveled to the Fresno in order to trade with Savage. Needless to say, this aroused the further ire of the traders on the Kings. The white malcontents continued their agitation, and the wronged Indians of the Kings wailed to Savage of their troubles. Consistently with his earlier acts, wherein the public good was involved, Major Savage attempted to pacify the Indians. He also denounced the “squatters” with all the emphasis of his personality and high standing. He asserted that they should be punished under the laws which they had violated and presented the case to the Indian Commissioners.

Harvey and the trader Campbell made common cause of denouncing Major Savage in return. Word was sent to the Major that they dared him to set foot in Kings River region. Upon its receipt, Savage mounted his horse and traveled to the Kings River Agency.

The events that occurred upon his arrival have been variously described by half a dozen writers. Elliott’s description, which agrees essentially with Bunnell’s, is as follows:

On the 16th day of August, 1852, Savage paid a visit to the Kings River Reservation, but previously to this Harvey declared that if Savage ever came there he would not return alive. Arriving at the reservation early in the forenoon, Savage found there Harvey and Judge Marvin, and a quarrel at once ensued between Savage and Harvey, the latter demanding of Savage a retraction of the language he had used regarding Harvey, whereupon Savage slapped Harvey across the face with his open hand, and while doing so, his pistol fell out of his shirt bosom and was picked up by Marvin. Harvey then stepped up to Marvin and said: “Marvin you have disarmed me; you have my pistol.” “No” said Marvin, “this is Major Savage’s pistol,” whereupon Harvey, finding Savage unarmed, commenced firing his own pistol, shooting five balls into Savage, who fell, and died almost instantly. Marvin was standing by all this time, with Savage’s pistol in his hands, too cowardly or scared to interfere and prevent the murder. At this time Harvey was County Judge of Tulare County, and one Joel H. Brooks, who had been in the employment of Savage for several years, and who had received at his hands nothing but kindness and favors, was appointed by Harvey, Justice of the Peace, for the sole purpose of investigating Harvey’s case for the killing of Savage. Of course Harvey was acquitted by Brooks—was not even held to answer before the Grand Jury. Harvey finally left, in mortal fear of the Indians, for he imagined that every Indian was seeking his life to avenge the murder of Savage. Afterwards, Harvey died of paralysis.

In 1926 the late Boutwell Dunlap unearthed 169 pages of depositions in manuscript form, taken in a law case of 1858 in which the death of Savage was made an issue. The incidents related by the witness under oath are redolent of the old wild 31 days. This testimony comes from the same Brooks who as magistrate had acquitted Harvey. It is quoted as follows:

Twenty-four hours after the Indians had ordered Campbell to leave, Harvey and his company had a fight with the Indians, killing some and whipping the balance. Savage was then an Indian agent appointed by Wozencroft. Savage and Wozencroft made a great fuss about the American people abusing the Indians and succeeded in getting the Commanding General of the U.S. forces on the Pacific to send up a couple of companies of troops to Tulare County, to take up Major Harvey and the men that were under his command and that had assisted him in this horrible murder of “the poor innocent savages.”

The circumstances which led to Savage’s death grew out of this difficulty. The troops had crossed Kings River. This was some time in August 1852 in the morning. Major Savage and Judge John G. Marvin rode up to the door of Campbell’s trading-house. Savage called for Harvey. Harvey stepped to the door. Savage remarked, “I understand, Major Harvey, that you say I am no gentleman.” Harvey replies, “I have frequently made that statement.” Savage remarked, to Harvey, “There is a good horse, saddle, bridle, spurs and leggings which belong to me. I fetched them, for the purpose of letting you have them to leave this country with.” Harvey replied, “I have got a fine mule and I will leave the country on my own animal, when I want to leave it.” Savage called for breakfast. Savage and Marvin ate breakfast by themselves in a brush house outside the store. After they had got through their breakfast, Savage tied up his hair, rolled up his sleeves, took his six-shooter out of its scabbard and placed it in front of him under the waistband of his pantaloons. He then walked into Campbell’s store and asked Major Harvey if he could not induce him to call him a gentleman. Harvey told him that he had made up his mind and had expressed his opinion in regard to that, and did not think he would alter it. He knocked Harvey down and stamped upon him a little. They were separated by some gentlemen in the house, and Harvey got up. Savage says, “To what conclusion have you come in regard to my gentlemancy?” Harvey replies, “I think you are a damned scoundrel.” Savage knocked Harvey down again. They were again separated by gentlemen present. As Harvey straightened himself onto his feet, he presented a six-shooter and shot Major Savage through 32 the heart. Savage fell without saying anything. It was supposed that Harvey shot him twice after he was dead, every ball taking effect in his heart. That is all I know about the fight. I gained this information by taking the testimony as magistrate of those who saw it.

What may have become of the court records of the so-called trial is unknown, but a scrap of testimony by the proprietor of the house in which the killing took place was preserved by the San Francisco Daily Herald, September 3, 1852, as follows:

The People of the State of California vs. Walter H. Harvey, for the killing of James D. Savage, on the 16th day of August, 1852, contrary to the laws of the State of California, &c.

Mr. Edmunds sworn, says—“Yesterday morning Major Savage came into my house and asked Major Harvey if he had said he was no gentleman. Major Harvey replied he had said it. Major Savage struck Major Harvey on the side of the head and knocked him down on some sacks of flour, and then proceeded to kick and beat him. Judge Marvin and some one else interfered, and Major Savage was taken off of Major Harvey. Major Savage still had hold of Major Harvey when Major Harvey kicked him. Major Savage then struck Major Harvey on the cheek, and knocked him down the second time, and used him, the same as before. By some means I cannot say, Major Savage was again taken off, and they separated. Major Savage was in the act of attacking him again, when Major Harvey draw his pistol and shot him.”

Question by the Court—Did Major Harvey shoot more than once?

Answer—I think he did; I found four holes in him.

Question—Did Major Savage knock Major Harvey down before he drew his pistol?

Answer—The prisoner had been knocked down by Major Savage twice before he drew his pistol, or made any attempt to shoot him.

Mr. Gonele sworn—corroborates the evidence of Mr. Edmunds. Mr. Knider sworn, also does the same.

This is all the testimony given in as to the fight, Major Fitzgerald, U.S.A., sworn, testified to some facts which induced him to think Major Savage not a gentleman.

The Court, upon this testimony, discharged Major Harvey without requiring bail.

So passed the leading figure in early Yosemite history. In this day of greater appreciation of individual heroism, sacrifice, and pioneer accomplishment in public service, how one covets unprejudiced narratives of such lives as was that of James D. Savage! Bunnell comments feelingly on “his many noble qualities, his manly courage, his generous hospitality, his unyielding devotion to friends, and his kindness to immigrant strangers.” A writer in the Daily Herald of September 4, 1852, contributes more details of events that followed the murder.

Effect of Major Savage’s Death upon the Indians

We have received a letter dated August 31st. on the Indian Reservation, Upper San Joaquin, giving some further particulars of the murder of Major James Savage and the effect produced thereby upon the Indians. The writer has resided among them upwards of two years, understood their language and their habits, and for a long time assisted Major Savage in managing them. His opinions therefore are entitled to weight. The following extracts will show the probable effect this murder will have on the prospects of the southern section of the State:

“You have doubtless ere this heard of the death, or rather murder, of Major Savage upon King’s River. It has produced considerable sensation throughout the country and is deeply regretted, for the country and the government have lost the services of a man whom it will not be easy to replace. He could do more to keep the Indians in subjection than all the forces that Uncle Sam could send here. The Indians were terribly excited at his death. Some of them reached the scene of the tragedy soon after it occurred. They threw themselves upon his body, uttering the most terrific cries, bathing their hands and faces in his blood, and even stooping and drinking it, as it gushed from his wounds. It was with difficulty his remains could be interred. The Chiefs clung to his body, and swore they would die with their father.

“The night he was buried the Indians built large fires, around which they danced, singing the while the mournful death chaunt, until the hills around rang with the sound. I have never seen such profound manifestations of grief. The young men, as they whirled wildly and distractedly around in the dance, shouted the name of 34 their ‘father’ that was gone; while the squaws sat rocking their bodies to and fro, chaunting their mournful dirges, until the very blood within one curdled with horror at the scene.

“I have not the slightest doubt that there will be a general outbreak this winter. Just as soon as the rainy season sets in we shall have the beginning of one of the most protracted and expensive wars the people of California have ever been engaged in. The Indians are quiet now, but are evidently contemplating some hostile movement. They told me, a few days since, that their ‘father’ was gone and they would not live with the whites any longer.

“I have studied the character of these Indians, as you know, for more than two years, and have acquired my experience in managing them under Savage himself. I do not speak lightly nor unadvisedly, therefore, when I assert that no more disastrous event could have occurred to the interests of this State, than the murder of the gallant Major Savage.”

It is possible that more details of Savage’s biography may be brought to light, and it is with that hope, coupled with the desire to give his memory just due, that this material is presented for public perusal.

On the Fresno River, near the site of his old trading post, rest the bones of the “white chief.” In 1855, Dr. Leach, who had been associated with Savage in trading with the Indians, journeyed to the Kings River, disinterred the remains, and transferred them to their present resting place. A ten-foot shaft of Connecticut granite, bearing the simple inscription, “Maj. Jas. D. Savage,” marks the spot. On July 4, 1929, the little city of Madera, California, honored the memory of Savage by placing an inscribed plaque on a city gate. These memorials, presumably, are the only public reminders of the importance of James D. Savage in the history of the state.

The story of Major Savage may be concluded with a reference to his family ties. As has been related, Californians were, until 1928, wholly mystified about his origin. Through the researches of Louise Savage Ireland we are made to sense the human side of his saga and are brought to an understanding 35 of his intimate family connections and his faithfulness to blood ties. L. H. Savage of El Paso, Texas, writes that his father, John W. Savage, first cousin of James D. Savage, made a vain attempt to join the Major in California. Returning miners in 1850 told the Illinois Savages that “Jim” invited them to come to California, where he would make them rich. John, then a boy of nineteen years, financed by older members of the family, shipped for the Golden State and sailed around the Horn. Almost a year elapsed before he reached San Francisco. There he learned that his noted relative had met death six months before.

What became of any wealth that the Major may have amassed remains a mystery. The Indians he struggled to protect and the lands he tried to save for them long ago passed out of the reckoning. By way of explanation we quote from Hutchings’ In the Heart of the Sierras: