The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Battle of the Rivers, by Edmund Dane This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Battle of the Rivers Author: Edmund Dane Release Date: December 6, 2018 [EBook #58417] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BATTLE OF THE RIVERS *** Produced by Brian Coe, Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

A Table of Contents has been added.

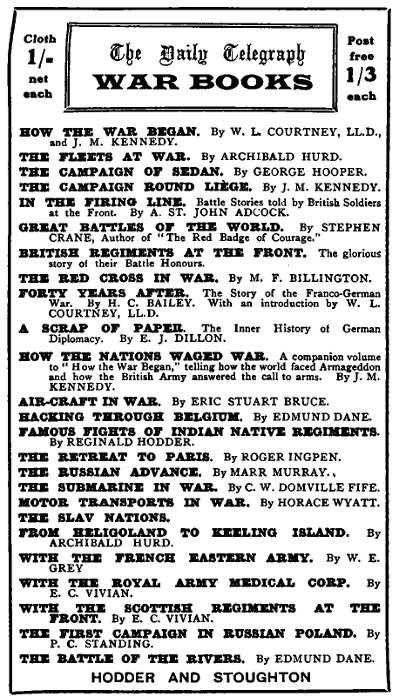

The Daily Telegraph

WAR BOOKS

THE BATTLE OF THE RIVERS

BY

EDMUND DANE

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

MCMXIV

On a scale before unknown in Western Europe, and save for the coincident operations in the Eastern theatre of war, unexampled in history, the succession of events named the "Battle of the Rivers" presents illustrations of strategy and tactics of absorbing interest. Apart even from the spectacular aspects of this lurid and grandiose drama, full as it is of strange and daring episodes, the problems it affords in the science of war must appeal to every intelligent mind.

An endeavour is here made to state these problems in outline. In the light they throw, events and episodes, which might otherwise appear confused, will be found to fit into a clear sequence of causes and consequences. The events and episodes themselves gain in grandeur as their import and relationship are unfolded.

Since the story of the retreat from Mons has been told in another volume of this series, it is only in the following pages dealt with so far as its military bearings elucidate succeeding phases of the campaign.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | THE GERMAN PLANS | 7 |

| II | WHY THE PLANS WERE CHANGED | 25 |

| III | GENERAL JOFFRE AS A STRATEGIST | 42 |

| IV | THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE | 54 |

| V | THE GERMAN OVERTHROW | 69 |

| VI | HOW GENERAL VON KLUCK AVERTED RUIN | 91 |

| VII | THE OPERATIONS ON THE AISNE | 108 |

| VIII | WARFARE BY DAY AND BY NIGHT | 128 |

| IX | THE STRUGGLE ROUND RHEIMS | 146 |

| X | REVIEW OF RESULTS | 172 |

| APPENDIX | 184 |

The Battle of the Rivers

"About September 3," wrote Field Marshal Sir John French in his despatch dated a fortnight later,[1] "the enemy appears to have changed his plans, and to have determined to stop his advance south direct upon Paris, for on September 4 air reconnaissances showed that his main columns were moving in a south-easterly direction generally, east of a line drawn through Nanteuil and Lizy on the Ourcq."

In that passage the British commander summarises an event which changed the whole military aspect of the Great War and changed it not only in the Western, but in the Eastern theatre of hostilities.

What were the German plans and why were they changed?

In part the plans were military, and in part political. These two aspects, however, are so[Pg 8] interwoven that it is necessary, in the first place, briefly to sketch the political aspect in order that the military aspect, which depended on the political, may be the better understood.

The political object was to reduce France to such powerlessness that she must not only agree to any terms imposed, but remain for the future in a state of vassalage to Germany. Further, the object was to extract from France a war fine so colossal[2] that, if paid, it would furnish Germany with the means of carrying on the war against Great Britain and Russia, and, if not paid, or paid only in part, would offer a pretext for an occupation of a large part of France by German troops, indefinite in point of time, and, formalities apart, indistinguishable from annexation. By means of that occupation great resources for carrying on the war might, in any event, be drawn in kind from the French population and from their territory, or drawn in cash in the form of local war levies.

In a passage quoted by M. Edouard Simon,[3] the late Prince von Bismarck once spoke of the difficulty he met with at the end of the war with France in 1871, in restraining the cupidity of the then King of Prussia and in "mixing the water of reflection with the wine of victory."[Pg 9] There was at the time, in Germany, much discussion as to the amount of the War Fine. The staggering total of 15,000 millions of francs (600 million pounds sterling) was freely asserted to be none too high. Fear of possible war with Great Britain mainly kept within bounds this desire of plunder, and led the Emperor William to accept, reluctantly, the 5,000 million francs afterwards paid.

There can be no doubt, however, that it became a settled opinion with the Government, and also, even if to a less extent, a conviction with the public of Germany that, enormous as it was, the levy upon France in 1871 was insufficient. That opinion was sharpened by the promptitude, almost contemptuous, with which the French people discharged the demand, and brought the German military occupation to an end.

The opinion that the War Fine of 1871 had been too small inspired the political crisis of 1875, caused by a threatened renewal of the German attack. The pretext then was that France was forming, with Austria and Italy, a league designed to destroy the new German Empire. The true cause of hostility was that France had begun to reorganise her army. Intervention by the Cabinets of London and St. Petersburg averted the peril. The German Government found itself obliged to put off a further draft upon "opulent France"[4] until a more convenient season.

This discovery that neither Great Britain nor[Pg 10] Russia was willing to see France become the milch cow of Germany dictated the policy which led later to the Triple Alliance. Consistently from this time to the end of his life the Emperor William I. assumed the part of guardian of the peace of Europe. The Triple Alliance was outwardly promoted by Germany with that object.[5]

Meanwhile, every opportunity was taken to strengthen the German military organisation.[Pg 11] Only by possession of an invincible army could the German Empire, it was contended, fulfil its peace-keeping mission.

This growth of military armaments imposed on Germany a heavy burden. Was the burden borne merely for the sake of peace, or for the sake of the original inspiration and policy?

Few acquainted with the character of the Germans will credit them with a tendency to spend money out of sentiment. The answer, besides, has been given by General von Bernhardi.[6] He has not hesitated to declare that the object of these preparations was to ensure victory in the offensive war made necessary by the growth of the German population, a growth calling for a proportionate "political expansion."

Outside Germany the so-called revelations of General von Bernhardi took many by surprise. That, however, was because, outside Germany, not many know much of German history, and fewer still the history of modern Prussia.

It was realised, when General von Bernhardi published his book, that the original inspiration and policy had never been changed. On the contrary, all the efforts and organisation of Prussia had been directed to the realisation of that policy, and the only alteration was that, as confidence in Prussia's offensive organisation grew, the policy had been enlarged by sundry added ambitions until at length it became that grotesque and Gothic political fabric known as Pan-Germanism.

"The military origin of the new German Empire," says M. Simon, "is of vast importance; it gives that Empire its fundamental character; it establishes its basis and its principle of existence. Empires derive their vitality from the principle to which they owe their birth."

The fact is of vast importance because, just as the British Empire had its origin in, and owes its character to, the embodiment of moral force in self-government, so the German Empire had its origin in, and owes its character to, the embodiment of material forces in armies, and existed, as General von Bernhardi says, for the employment of that force as and whenever favourable opportunity should present itself.

The political inspiration and purpose being clear, how was that purpose, as regards France, most readily and with fewest risks to be realised?

It was most readily to be realised by seizing Paris. As everybody is aware, the Government of France is more centralised than that of any other great State. Paris is the hub of the French roads and railways; Paris is also the hub of French finance; Paris is at once the brain and the heart of the country; the place to which all national taxes flow; the seat from which all national direction and control proceed. It was believed, therefore, that, Paris occupied, France would be stricken with political paralysis. Resistance might be offered by the provinces, for the area of France is roughly equal to the area of Germany, but the resistance could never be more than ineffectual.

Such was the plan on its political side. What were its military features?

A political plan of that character plainly called for a swift and, if possible, crushing military offensive. Rapidity was one of the first essentials. That affected materially the whole military side of the scheme. It meant that to facilitate mobility and transport, the equipment of the troops must be made as light as possible. Hence all the usual apparatus of field hospitals and impedimenta for encampment must be dispensed with. It meant that the force to be dispatched must be powerful enough to bear down the maximum of estimated opposition, and ensure the seizure of Paris, without delay. It meant again that the force must move by the shortest and most direct route.

If we bear in mind these three features—equipment cut down to give mobility, strength to ensure an uninterrupted sweep, shortest route—we shall find it the easier to grasp the nature of the operations which have since taken place. The point to be kept in mind is that what the military expedition contemplated was not only on an unusual scale, but was of an altogether unusual, and in many respects novel, character.

The most serious military problem in front of the German Government was the problem of route. The forces supposed to be strong enough Germany had at her disposal. Within her power, too, was it to make them, so far as meticulous preparation could do it, mobile. But[Pg 14] command of the shortest and most direct route she did not possess.

That route we know passes in part through the plain of northern Belgium, and in part through the parallel valley of the Meuse to the points where, on the Belgium frontier, there begin the great international roads converging on Paris. All the way from Liége to Paris there are not only these great paved highways, but lines of main trans-continental railroads. The route, in short, presented every natural and artificial facility needed to keep a vast army fully supplied.

Here it should be recalled that two things govern the movements of armies. Hostile opposition is one; supplies are the other. In this instance, the possible hostile opposition was estimated for. It remained to ensure that neither the march of the great host, as a whole, nor the advance of any part of it should at any time be held up by waiting for the arrival of either foodstuffs, munitions, or reinforcements, but that the thousand and one necessaries for such an army, still a complex list even when everything omissible had been weeded out, should arrive, as, when, and where wanted.

Little imagination need be exercised to perceive that to work out a scheme like that on such a scale involves enormous labour. On the one side were the arrangements for gathering these necessaries and placing them in depots; on the other were the arrangements for issuing them, sending them forward, and distributing them.[Pg 15] Nothing short of years of effort could connect such a mass of detail. If hopeless confusion was not almost from the outset to ensue, the greatest care was called for to make it certain that the mighty machination would move successfully.

A scheme of that kind suited the methodical genius of Germany, and there can be no doubt that the years spent upon it had brought it to perfection. It had been worked out to time table. Concurrently, arrangements for the mobilisation of reserve troops had become almost automatic. Every reservist in the German Army held instructions setting out minutely what to do and where and when to report himself as soon as the call came.

Now this elaborate plan had been drawn up on the assumption of an invasion of France by the route through Belgium. That assumption formed its basis. Not only so, but the extent to which the resources of Belgium and North-east France might, by requisitioning, be drawn upon to relieve transport and so promote rapidity, had been exactly estimated.

It is evident, therefore, that the adoption of any other route must have upset the whole proposal. In any other country the fact of the Government devoting its energies over a long period of time to such a scheme on such a footing would appear extraordinary, and the more extraordinary since this, after all, was only part of a still larger plan, worked out with the same minuteness, for waging a war on both frontiers.

The fact, however, ceases to be extraordinary if we bear in mind that the modern German Empire is essentially military and aggressive.

Obviously, the weak point of plans so elaborate is that they cannot readily be changed. Neither even can they, save with difficulty, be modified. Even in face, therefore, of a declaration of war by Great Britain, the plan had to be adhered to. Unless it could be adhered to, the invasion of France must be given up.

Bearing in mind the labour and cost of preparation, the hopes built upon the success of the invasion, and the firm belief that the opposition to be expected by Belgium could at most be but trifling, it ceases to be surprising that, though there was every desire to put off that complication, a war with Great Britain proved no deterrent.

Further, the construction by the French just within their Eastern frontier of a chain of fortifications extremely difficult to force by means of a frontal attack, and quite impossible to break if defended by efficient field forces, manifestly suggested the plea of adopting the shorter and more advantageous route on the ground of necessity. In dealing with that plea it should not be forgotten that the State which elects to take the offensive in war needs resources superior to those of the State which elects to stand, to begin with, upon a policy of defence. Those superior resources, save in total population, Germany, as compared with France, did not possess.[Pg 17] In adopting the offensive, therefore, on account of its initial military advantages, Germany was risking in this attack means needed for a prolonged struggle. It was necessary in consequence for the attack to be so designed that it could not only not fail, but should succeed rapidly enough to enable the attacking State to recoup itself—and, possibly, with a profit.

The conditions of first rapidity, and second certainty, formed the political aspects of the plan, and they affected its military aspects in regard to first numbers, secondly equipment, thirdly route.

But there were, if success was to be assured, still other conditions to be fulfilled, and these conditions were purely military. They were:—

(1) That in advancing the line of the invading armies must not expose a flank, and by so doing risk delay through local or partial defeat.

(2) That the invading armies must not lay bare their communications. Risk to their communications would also involve delay.

(3) That they must at no point incur the hazard of attacking a defended position save in superior force. To do so would again risk repulse and delay.

Did the plan drawn up by the German General Staff fulfil apparently all the conditions, both political and military, and did it promise swift success? It did.

The plan, in the first instance, covered the operations of eight armies, acting in combination. These were the armies of General von Emmich; General von Kluck; General von Bülow; General von Hausen; Albert, Duke of Wurtemberg; the Crown Prince of Germany; the Crown Prince of Bavaria; and General von Heeringen. Embodying first reserves, they comprised twenty-eight army corps out of the forty-six which Germany, on a war footing, could put immediately into the field.[7]

Having reached the French frontier from near the Belgian coast to Belfort, the eight armies were to have advanced across France in echelon. If you take a row of squares running across a chessboard from corner to corner you have such squares for what is known in military phraseology as echelon formation.

Almost invariably in a military scheme of that character the first body, or "formation" as it[Pg 19] is called, of the echelon is reinforced and made stronger than the others, because, while such a line of formations is both supple and strong, it becomes liable to be badly disorganised if the leading body be broken. On the leading body is thrown the main work of initiating the thrust. That leading body, too, must be powerful enough to resist an attack in flank as well as in front.[8]

Advancing on this plan, these armies would present a line exposing, save as regarded the first of them, no flank open to attack. Indeed, the first object of the echelon is to render both a frontal and a flank attack upon it difficult.

Had the plan succeeded as designed, we should have had this position of affairs: the eight armies would have extended across France from Paris to Verdun by the valley of the Marne, the great natural highway running across France due east to the German frontier, and one having both first-rate road and railway facilities. It was hoped that by the time the first and strongest formation of this chain of armies had reached Paris and had fastened round it, the sixth,[Pg 20] seventh, and eighth armies would, partly by attacking the fortified French frontier on the east, but chiefly by enveloping it on the west, have gained possession of the frontier defence works.

The main French army must then have been driven westward from the valley of the Marne, across the Aube, brought to a decisive battle in the valley of the Seine, defeated, and, enclosed in a great arc by the German armies extending round from the north and by the east to the south of Paris, have been forced into surrender.

There is a common assumption that the German plan was designed to repeat the manœuvres which in the preceding war led to Sedan, and almost with the same detail. That is rating the intelligence of the German General Staff far too low. They could not but know that the details of one campaign cannot be repeated in another against an opponent, who, aware of the repetition, would be ready in advance against every move.

Naturally, they fostered the notion of an intended repetition. That promoted their real design. The design itself, however, was based not merely on the war of 1870-1, but on the invasion of 1814, which led to the abdication of Napoleon, and the primary idea of it was to have only one main line of advance.

The reason was that if an assailant takes two main lines of advance simultaneously and has to advance along the valleys of rivers[Pg 21] converging to a point, as the Oise, the Marne, and the Seine converge towards Paris, his advance may be effectively disputed by a much smaller defending force than if he adopts only one line of advance, provided always, of course, that he can safeguard his flanks and his communications.

Bear in mind the calculation that the main French army would never in any event be strong enough successfully to resist an invasion so planned. Bear in mind, too, that an echelon formation is not only supple and difficult to attack along its length on either side, but that it can be stretched out or closed up like a concertina. To maintain a formation of that kind with smaller bodies of troops is fairly easy. To maintain it with the enormous masses forming the German armies would be difficult. But the Germans were so confident of being able to compel the French to conform to all the German movements, to stand, that is to say, as the weaker side, always on the defensive, leaving the invaders a practically unchallenged initiative, that they believed they could co-ordinate all their movements with exactitude. This was taking a risk, but they took it.

It is a mistake to suppose that they entered on the campaign with every movement mapped out from start to finish. No plan of any campaign was ever laid down on such lines, and none ever will be. The plan of a campaign has to be built on broad ideas. Those ideas, by taking all the essentials into consideration, the[Pg 22] strategist seeks to convert into realised events. In this instance, there can be very little doubt that certain assumptions were treated as so probable as almost to be certainties. The first was that such forces as France could mobilise in the time would be mainly drafted to defend the fortified frontier. The next was that such forces as could be massed in time along the boundary of Belgium would be too weak seriously to impede the invasion. The third was that in any subsequent attempt to transfer forces from the fortified frontier to the Belgian boundary the French would be met and defeated by the advancing echelon of German masses. The fourth was that such an attempted transfer, followed by its defeat, would leave the fortified frontier so readily seizable, that German armies advancing swiftly into the valley of the Marne would fall upon these defeated French forces on the flank and rear. Besides, that attempted transfer would be the very thing that would promote the German design of envelopment.

If Paris could be reached by the strongest of the chain of armies in eight days, then the mobilisation of the French reserves would still be incomplete. Under the most favourable conditions, and even without the disturbance of invasion, that mobilisation takes a fortnight. Given a sudden and successful invasion with the resultant upset of communications and the mobilisation could never be completed. All, therefore, that the 1,680,000 men forming the[Pg 23] invading hosts[9] would have to encounter would be the effectives of the French regular forces, less than half the number of the invaders.

When we speak of twenty-eight army corps moving in echelon, approximately like so many squares placed diagonally corner to corner, it is as well not to forget that such a chain of masses may assume quite sinuous and snake-like variations and yet remain perfectly intact and strong. For example, the head of the chain might be wound round and pivot upon Paris, and the rest of the chain extended across France in curves. This gigantic military boa-constrictor might therefore crush the heart out of France, while the defenders of the country remained helpless in its toils.

Such in brief was the daring and ambitious scheme conceived and worked out by the German General Headquarters Staff, and worked out in the most minute detail.

It will be seen from this summary that so far as its broad military features are concerned, the plan promised an almost certainly successful enterprise. There were concealed in its calculations, nevertheless, fatal flaws. What they were will appear in the course of the present narrative. Meanwhile it is necessary to add that possible opposition from Belgium had not been overlooked; nor the possibility, consequent upon that opposition, of intervention by Great Britain.[Pg 24] From the military standpoint, however, it was never calculated that any British military force would be able to land either in France or in Belgium promptly enough to save the French army from disaster. In any event, such a force would be, from its limited numbers, comparatively unimportant.

[1] Despatch from Sir John French to Earl Kitchener of September 17th, 1914. For the text of this see Appendix.

[2] The contemplated fine has been alleged to be 4,000 millions sterling, coupled with the formal cession of all North Eastern France. This statement was circulated by Reuter's correspondent at Paris on what was asserted to be high diplomatic authority. Such a sum sounds incredible, though as a pretext it might possibly have been put forward.

[3] Simon: The Emperor William and his Reign.

[4] This phrase is that of General F. von Bernhardi.

[5] After the Berlin Congress in 1878, Prince Gortschakov mooted the idea of an alliance between Russia and France. In 1879 Bismarck, in view of such a development, concluded the alliance between Germany and Austria. Italy joined this alliance in 1883, but on a purely defensive footing. The account given of the Triple Alliance by Prince Bernhard von Bülow, ex-Imperial Chancellor, is that it was designed to safeguard the Continental interests of the three Powers, leaving each free to pursue its extra-Continental interests. From 1815 to 1878 the three absolutist Powers, Russia, Prussia, and Austria, had aimed at dominating the politics of the Continent by their entente. For many years, however, German influence in Russia has been giving way before French influence. This is one of the most important facts of modern European history. The Triple Alliance was undoubtedly designed to counteract its effect. Germany, with ambitions in Asia Minor, backed up Austria, with ambitions in the Balkans. Both sets of ambitions were opposed to the interests of Russia. Russia's desertion of the absolutist entente for the existing entente with the liberal Powers of the West has been due nevertheless as much to the growth of constitutionalism as to diplomacy. The entente with Great Britain and France is popular. On the other hand, the entente with Germany and Austria was unpopular. The view here taken that one of the real aims of the Triple Alliance was the furtherance of Prussia's designs against France is the view consistent with the course of Prussian policy. For Prince von Bülow's explanations, see his Imperial Germany.

[6] F. von Bernhardi: The Next War: see Introduction.

[7] Of the remaining corps, five were posted along the frontier of East Prussia to watch the Russians. The rest were held chiefly at Mainz, Coblentz, and Breslau as an initial reserve.

The now definitely ascertained facts regarding the military strength of Germany appear to be these:—

| 25 corps and one division of the active army mustering | 1,530,000 men |

| 21 corps of Landwehr mustering | 1,260,000 men |

| ———— | |

| Total | 2,790,000 men |

In addition, there were raised 12 corps of Ersatz Reserve, and there were also the Landsturm and the Volunteers, whose numerical strength is uncertain. These troops, however, were not embodied until later in the campaign.

[8] The leading army, that of General von Kluck, consisted of 6 corps; and the second army, that of General von Bülow, of 4 corps. The others were formed each of 3 corps, making an original total of 28 corps.

Following the disaster at Liége, however, the army of General von Emmich was divided up, and the view here taken, which appears to be most consistent with the known facts, is that it was, after being re-formed, employed to reinforce the armies of Generals von Kluck and von Bülow. That would make the strength of the German force, which marched through northern Belgium, 780,000 men.

[9] A German army corps is made up, with first reserves, embodied on mobilisation, to 60,000 men. Twenty-eight army corps, therefore, represent a total of 1,680,000 of all arms.

Let us now pass from designs to events, and, reviewing in their military bearing the operations between August 3, when the German troops crossed the Belgian frontier, to the day, exactly one month later, when the German plans were apparently changed, deal with the question: Why were the plans changed?

The Germans entered Liége on August 10. They had hoped by that time to be, if not at, at any rate close to, Paris. In part they were unable to begin their advance through Belgium until August 17 or August 18, because they had not, until that date, destroyed all the forts at Liége, but in part, also, these delays had played havoc with the details of their scheme.

Consider how the shock of such a delay would make itself felt. The mighty movement by this time going on throughout the length and breadth of Germany found itself suddenly jerked into stoppage. All its couplings clashed. Excellently designed as are the strategic railways[Pg 26] of Germany they are no more than sufficient for the transport of troops, guns, munitions, foodstuffs, and other things necessary in such a case. If, owing to delays, troop trains got into the way of food trains, and vice versa, the resultant difficulties are readily conceivable. All this war transport is run on a military time table. The time table was there, and it was complete in every particular. But it had become unworkable. Gradually the tangle was straightened out, but the muddle, while it lasted, was gigantic, and we can well believe that masses of men, arriving from all parts of Germany at Aix-la-Chapelle, found no sufficient supplies awaiting them, and that sheer desperation drove the German Government to collect supplies by plundering all the districts of Belgium within reach. As the Belgians were held to be wilfully responsible for the mess, the cruelty and ferocity shown in these raids ceases to be in any sense unbelievable.

Dislocation of the plan, however, was not all. In the attempts to carry the fortress of Liége by storm the Germans lost, out of the three corps forming the army of General von Emmich, 48,700 men killed and wounded.[10] These corps, troops from Hanover, Pomerania, and Brandenburg, formed the flower of the army. The work had to be carried out of burying the dead and [Pg 27]evacuating the wounded. The shattered corps had to be reformed from reserves. All this of necessity meant additional complications.

Then there was the further fighting with the Belgians. What were the losses sustained by the Germans between the assaults on Liége and the occupation of Brussels is, outside of Germany, not known, nor is it known in Germany save to the Government. To put that loss as at least equal to the losses at Liége is, however, a very conservative estimate.

Meanwhile, the French had advanced into Belgium along both banks of the Meuse and that further contributed to upset the great preparation.

We have, therefore, down to August 21, losses, including those in the fighting on the Meuse and in Belgian Luxemburg, probably equal to the destruction of two reinforced army corps.

Now we come to the Battle of Mons and Charleroi, when to the surprise of all non-German tacticians, the attacks in mass formation witnessed at Liége were repeated.

To describe that battle is beyond the scope of this narrative. But it is certain that the estimates so far formed of German losses are below, if not a long way below, the truth.

There is, however, a reliable comparative basis on which to arrive at a computation, and this has a most essential bearing on later events.

At Liége there were three heavy mass attacks against trenches defended by a total force of[Pg 28] 20,000 Belgian riflemen with machine guns.[11] We have seen what the losses were. At Mons, against the British forces, there were mass attacks against lines held by five divisions of British infantry, a total roughly of 65,000 riflemen, with machine guns, and backed by over sixty batteries of artillery.

Now, taking them altogether, the British infantry reach, as marksmen, a level quite unknown in the armies of the Continent. Further, these mass attacks were made by the Germans with far greater numbers than at Liége, and there were far more of them. Indeed, they were pressed at frequent intervals during two days and part of the intervening night. The evidence as to the dense formations adopted in these attacks is conclusive.

What, from facts such as these, is the inference to be drawn as to losses incurred? The inference, and it is supported by the failure of any of these attacks to get home, is, and can only be, that the losses must have been proportionally on the same scale as those at Liége, for the attacks were, for the most part, as at Liége, launched frontally against entrenched positions. Though at first sight such figures may appear fantastic, to put the losses at three times the total of the losses at Liége is probably but a very slight exaggeration, even if it be any exaggeration at all.

There is, however, still another ground for[Pg 29] such a conclusion. While the British front from Condé past and behind Mons to Binche allowed of the full and effective employment of the whole British force, even when holding in hand necessary reserves, it was obviously not a front wide enough to allow of the full and effective employment on the German side of a force four times as numerous. It must not be forgotten that troops cannot fight at their best without sufficient space to fight in.

But to employ in the same space a force no greater than the British, considering the advantage of position given with modern arms to an army acting on the defensive on well-chosen ground, would have meant the annihilation of the German army section by section.

That in effect, apart from the turning movement undertaken through Tournai, and the attempt at Binche to enfilade the British position by an oblique line of attack, was the problem which General von Kluck had to face. His solution of it, in the belief that his artillery must have completely shaken the British resistance, was to follow up the bombardment by a succession of infantry attacks in close formation, one following immediately the other, so that each attack would, it was thought, start from a point nearer to the British trenches than that preceding it, until finally the rush could not possibly be stopped. In that way the whole weight of the German infantry might, despite the narrow front, be thrown against the British positions, and though the losses incurred must of necessity be[Pg 30] severe, nevertheless, the British line would be entirely swept away, and the losses more than amply revenged in the rout that must ensue. Not only so, but the outcome should be the destruction of the British force.

That this is as near the truth as any explanation which can be offered is hardly doubtful. The conclusion is consonant, besides, with what have been considered the newest German views on offensive tactics. To suppose that General von Kluck, or any other commander, would throw away the lives of his officers and men without some seemingly sufficient object is not reasonable.

Here we touch one of the hidden but fatal flaws in the German plan—the assumption that German troops, if not superior, must at any rate be equal in skill to any others. The German troops at Mons, admittedly, fought with great daring, but that they fought or were led with skill is disproved by all the testimony available. It is as clear as anything can be that not merely the coolness and the marksmanship of the British force was a surprise to the enemy, but the uniformity of its quality. Of the elements that go to make up military strength, uniformity of quality is among the most important. The cohesion of an army with no weak links is unbreakable. It is not only more supple than an army made up of troops of varying quality and skill, but it is more tenacious. Like a well-tempered sword, it is at once more flexible yet more unbreakable than an inferior weapon.

Against an inferior army the tactics of General von Kluck must infallibly have succeeded. Against such a military weapon as the British force at Mons they were foredoomed to failure. Assuming the British army to be inferior, General von Kluck threw the full weight of his troops upon it before he had tried its temper.

Studying their bearing, the importance of these considerations becomes plain. Powerful as it was, the driving head of the great German chain had yet not proved powerful enough inevitably to sweep away resistance. That again disclosed a miscalculation. It is true that the British force had to retire, and it is equally true that that retirement exposed them to great danger, for the enemy, inflamed by his losses, was still in numbers far superior, and what, for troops obliged to adopt marching formations, was even more serious, he was times over superior in guns. Few armies in face of such superiority could have escaped annihilation; fewer still would not have fallen into complete demoralisation.

The British force, however, not only escaped annihilation, but came out both with losses relatively light, and wholly undemoralised. This was no mere accident. Why, can be briefly told. Remember that quality of uniformity, remember the value of it in giving cohesion to the organic masses of the army. Remember further the hitting power of an army in which both gunners and riflemen are on the whole first-rate shots, and with a cavalry which the hostile horse had shown itself unable to contend[Pg 32] against. On the other hand, bear in mind that the greater masses of the enemy were of necessity slower in movement, and that the larger an army is, the slower it must move.

Naturally the enemy used every effort to throw as large forces as he could upon the flanks of the retiring British divisions. He especially employed his weight of guns for that purpose. On the other hand, the British obviously and purposely occupied all the roads over as broad an extent of country as was advisable. They did so in order to impose wide detours on outflanking movements. While those forces were going round, the British were moving forward and so escaping them.

The difficulties the Germans had to contend against were first the difficulty of getting close in enough with bodies of troops large enough, and secondly that, in flowing up, their mass, while greater in depth from van to rear than the British, could not be much, if anything, greater in breadth. The numerical superiority, therefore, could not be made fully available.

Broadly, those were the conditions of this retirement; and when we come to examine them, comparing the effective force of the opponents, the relatively light losses of the British cease to be surprising. The retirement, of course, was full of exciting episodes. Sir John French began his movement with a vigorous counter-attack.[12] This wise tactic both misled the enemy and taught him caution.

It was by such tactics that the British General so far outpaced the enemy as to be able to form front for battle at Cambrai. Here again some brief notes are necessary in order to estimate the effect on later events.

On the right of the British position from Cambrai to Le Cateau, and somewhat in advance of it, the village of Landrecies was held by the 4th Brigade of Guards. Just to the north of Landrecies is the forest of Mormal. The forest is shaped like a triangle. Landrecies stands at the apex pointing south. Round the skirts of the forest both to the east and to the west are roads meeting at Landrecies. Along these roads the Germans were obliged to advance, although to obtain cover from the British guns enfilading these roads large bodies of them came through the forest.

The British right, the corps of General Sir Douglas Haig, held Marailles, and commanded the road to the west of the forest.

Towards the British centre a second slightly advanced position like that of Landrecies was held to the south of Solesmes by the 4th Division, commanded by General Snow.

The British left, formed of the corps of General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, was [Pg 34]"refused" or drawn back, because in this quarter an attempted turning movement on the part of the enemy was looked for. In the position taken up, the front here was covered by a small river continued by a canal.

On the British left also, to the south of Cambrai, were posted the cavalry under General Allenby.

These dispositions commanded the roads and approaches along which the enemy must advance in order to obtain touch with the main body, and they were calculated both to break up the unity of his onset and to lay him open to effective attack while deploying for battle. They were, in fact, the same tactics which, in resisting the onset of a superior force, Wellington employed at Waterloo by holding in advance of his main line Hugomont and La Haye Sainte for a like purpose.

Sir John French had foreseen that, taught at Mons the cost of a frontal assault against British troops, General von Kluck would now seek to employ his greater numerical strength and weight of guns by throwing that strength as far as he could against the flanks of the British, hoping to crush the British line together and so destroy it.

That, in fact, was what General von Kluck did try to do. In this attack five German army corps were engaged. The German General concentrated the main weight of his artillery, comprising some 112 batteries of field guns and howitzers, against the British left. The terrific[Pg 35] bombardment was followed up by infantry attacks, in which mass formations were once more resorted to. Evidently it was thought that against such a strength in guns the British could not possibly hold their lines, and that the infantry, completely demoralised, must be so shaken as to fire wildly, rendering an onslaught by superior forces of the German infantry an assured and sweeping victory.

For a second time these calculations miscarried. As they rushed forward, expecting but feeble opposition, the hostile infantry masses were shot down by thousands. The spectacle of such masses was certainly designed to terrify. It failed to terrify. In this connection it is apposite to recall that the destruction of Baker Pasha's army at Suakim by a massed rush of Arab spearmen long formed with the newer school of German tacticians a classic example of the effect of such charges on British troops. No distinction seems to have been made between the half-trained Egyptian levies led by Baker Pasha and fully trained British infantry. The two are, in a military sense, worlds apart. Yet German theorists, their judgment influenced by natural bias, ignored the difference.

Nor was the fortune of the attacks upon the British right any better. The defence of Landrecies by the Guards Brigade forms one of the most heroic episodes of the war. Before it was evacuated the village had become a German charnel-house. Hard pressed as they were at both extremities of their line, the British[Pg 36] during these two days fought to a standstill an army still nearly three times as large as their own.

That simply upset all accepted computations. As Sir John French stated in his despatch of September 7, the fighting from the beginning of the action at Mons to the further British retirement from Cambrai formed in effect one continuous battle. The British withdrawal was materially helped by a timely attack upon the right flank of the German forces delivered by two French divisions which had advanced from Arras under the command of General d'Amade, and by the French cavalry under General Sordêt.

Now consider the effect upon the German plans. There is, to begin with, the losses. That those at Cambrai must have been extremely heavy is certain. The failure of such an attack pushed with such determination proves it.[13] We are fully justified in concluding that the attack did not cease until the power to continue it had come to an end. Losses on that scale meant, first, the collection of the wounded and the burial of the dead; and, secondly, the reforming of broken battalions from reserves. The latter had to be brought from the rear, and that, as well as their incorporation in the various corps, involved delay. Again, the vast expenditure of artillery munitions meant waiting for[Pg 37] replenishment; and though we may assume that arrangements for replenishment were as complete as possible, yet it would take time. For all these reasons the inability of General von Kluck to follow up becomes readily explicable.

Bear in mind that the whole German scheme of invasion hung for its success on his ability to follow up and on the continued power and solidity of his forces. It must not be supposed that that had not been fully foreseen and, as far as was thought necessary, provided for. There is ample evidence that, in view alike of the fighting in Belgium and of the landing of the British Expeditionary Force on August 17, this leading and largest formation of the German chain of armies had been made still larger than the original scheme had designed. Apparently at Mons it comprised eight instead of the originally proposed six army corps. After Cambrai, as later events will show, the force of General von Kluck included only five army corps of first line troops.

To account for that decrease, the suggestion has been made that at this time, consequent upon the defeat met with by the Germans at Gunbinnen in East Prussia and the advance of the Russians towards Königsberg, there was a heavy transfer of troops from the west front to the east. Not only would such a transfer have been in the circumstances the most manifest of military blunders, but no one acquainted with the methods of the German Government and of[Pg 38] the German General Staff can accept the explanation. Whatever may be the shortcomings of the German Government, vacillation is not one of them. What evidently did take place was the transfer of the débris of army corps preparatory to their re-formation for service on the east front and their replacement by fresh reserves.

But though the mass was thus made up again, there is a wide difference between a great army consisting wholly of first line troops and an army, even of equal numbers, formed of troops of varying values. The driving head was no longer solid.

In the battle on the Somme when the British occupied positions from Ham to Peronne, and the French army delivered a flank attack on the Germans along the line from St. Quentin to Guise, the invaders were again checked.

From St. Quentin to Peronne the course of the Somme, a deep and dangerous river, describes an irregular half-circle, sweeping first to the west, and then round to the north. General von Kluck had here to face the far from easy tactical problem of fighting on the inner line of that half-circle. He addressed himself to it with vigour. One part of his plan was a wide outflanking movement through Amiens; another was to throw a heavy force against St. Quentin; a third was to force the passage of the Somme both east and west of Ham.

These operations were undertaken, of course, in conjunction with the army of General von Bülow. Part of the troops of von Bülow, the[Pg 39] 10th, and the Reserve Corps of the Prussian Guard were heavily defeated by the French at Guise. But while it was the object of the French and British to make the German operations as costly as possible, it formed, for reasons which will presently appear, no part of their strategy to follow up local advantages.

Why it formed no part of their strategy will become evident if at this point a glance is cast over the fortunes of the other German armies.

The army of General von Bülow had been engaged against the French in the battle at Charleroi and along the Sambre, and again in the battle at St. Quentin and Guise, and admittedly had in both encounters lost heavily.

The army of General von Hausen had been compelled to fight its way across the Meuse in the face of fierce opposition. At Charleville, the centre of this great combat, its losses, too, were severe. Again, at Rethel, on the line of the Aisne, there was a furious six days' battle.

The army of Duke Albert of Wurtemberg had twice been driven back over the Meuse into Belgian Luxemburg.

The army of the Crown Prince of Germany, notwithstanding its initial success at Château Malins, had been defeated at Spincourt.

The army of the Crown Prince of Bavaria had been defeated with heavy loss at Luneville.

Divisions of the German army operating in Alsace had been worsted, first at Altkirch, and again at Mulhausen.

Taking these events together, the fact stands[Pg 40] out that the first aim in the strategy of General Joffre was, as far as possible, to defeat the German armies in detail, and thus to hinder and delay their co-operation. He was enabled to carry out that object because the French mobilisation had been completed without disturbance.

These two facts—completion of the French mobilisation and the throwing back of the German plan by the defeat of the several armies in detail—are facts of the first importance.

The aggregate losses sustained by the Germans were already huge. If, up to September 3, we put the total wastage of war from the outset at 500,000, remembering that the fatigues of a campaign conducted in a hurry mean a wastage from exhaustion equal at least to the losses in action, we shall, great as such a total may appear, still be within the truth.

But more serious even than the losses was the dislocation of the plan. The army of the Crown Prince of Germany, which was to have advanced by rapid marches through the defiles of the Argonne, to have invested Verdun, and to have taken the fortified frontier in the rear, found itself unable to effect that object. It was held up in the hills. That meant that the armies of the Crown Prince of Bavaria and the army of General von Heeringen were kept out of the main scheme of operations.

Consider what this meant. It meant that the freedom of movement of the whole chain of armies was for the time being gone. It meant further that, so long as that state of things [Pg 41]continued, the primary condition on which the whole German scheme depended—a superiority of military strength—could not be realised. Not only were the German armies no longer, in a military sense, homogeneous, but a considerable part of the force, being on the wrong side of the fortified frontier, could not be brought to bear, and another considerable part of the force, the army of the Crown Prince of Germany, had fallen into an entanglement. Were the armies of von Kluck, von Bülow, von Hausen, and Duke Albert, the latter already badly mauled, sufficient to carry out the scheme laid down? Quite obviously not.

Obviously not, because on the one hand there was the completion of the French mobilisation, and the presence of a British army; and on the other hand there were the losses met with, and the reductions in the applicable force.

Something must be done to pull affairs round. The something was to begin with the extraction of the Crown Prince of Germany from his predicament. If that could be effected and the fortified frontier turned, then the armies of the Crown Prince of Bavaria and of General von Heeringen could make their entry into the main arena; and the primary condition of superiority in strength restored.

Thus it is evident that the events preceding September 3, dictated the movement which, on September 3, changed for good the aspect of the campaign.

[10] These figures are given on the authority of M. de Broqueville, Belgian Prime Minister and Minister of War, who has stated that the total here quoted was officially admitted by the German Government.

[11] There are usually two machine guns to each section of infantry.

[12] "At daybreak on the 24th (Aug.) the Second Division from the neighbourhood of Harmignies made a powerful demonstration as if to retake Binche. This was supported by the artillery of the first and second divisions, while the First Division took up a supporting position in the neighbourhood of Peissant. Under cover of this demonstration the Second (Army) Corps retired on the line Dour—Quarouble—Frameries."—Despatch of Sir John French of September 7.

[13] The reported extraordinary Army Order issued by the German Emperor commanding "extermination" of the British force has since been officially disavowed as a fiction.

From the strategy on the German side let us now turn to that on the side of the French. Between them a fundamental distinction at once appears.

Of both the aim was similar—to compel the other side to fight under a disadvantage. In that way strategy helps to ensure victory, or to lessen the consequences of defeat.

The strategy of the German General Staff, however, was from the outset obvious. The strategy of General Joffre was at the outset a mystery. Only as the campaign went on did the French scheme of operations become apparent. Even then the part of the scheme still to come remained unfathomable.

It has been assumed that with the employment of armies formed of millions of men the element of surprise must be banished. That was a German theory. The theory is unsound. Now, as ever, intellect is the ultimate commanding quality in war.

In truth, the factor of intellect was never more[Pg 43] commanding than under conditions of war carried on with mass armies.

Reflect upon the difference between an opponent who, under such conditions, is able to fathom and to provide against hostile moves, and the opponent who has to take his measures in the dark as to hostile intentions.

The former can issue his orders with the reasonable certainty that they are what the situation will call for. Never were orders and instructions more complex than with modern armies numbering millions; never were there more contingencies to provide against and to foresee. To move and to manipulate these vast masses with effect, accurate anticipation is essential. Such complicated machines cannot be pushed about on the spur of the moment when a general suddenly wakes up to a discovery.

It follows that to conduct a campaign with mass armies there must either be a plan which you judge yourself strong enough in any event to realise or a plan which, because your opponent cannot fathom it, must throw him into complete confusion. The former was the German way; the latter the French.

That General Joffre would try in the first place to defeat the German armies in detail was not, of course, one of the surprises, because it is elementary, but that he should have so largely succeeded in defeating them was a surprise.

In these encounters, as during later battles of the campaign, the French troops discovered a cohesion and steadiness and a military habit of[Pg 44] discipline assumed to be foreign to their temperament. But their units had been trained to act together in masses on practical lines. Of the value of that training General Joffre was well aware.

He knew also that success in the earlier encounters, which that training would go far to ensure, must give his troops an invaluable confidence in their own quality.

There were, however, two surprises even more marked. One of these was the quite unexpected use made of the fortified frontier; the other, associated with it, was that of allowing the Germans to advance upon Paris with an insufficient force, in the belief that French movements were being conformed to their own.

Undoubtedly as regards the fortified frontier the belief prevailed that the chief difficulty would be that of destroying its works with heavy guns. It had never been anticipated that the Germans might be prevented from getting near enough for the purpose. But in the French strategy Verdun, Toul, and Belfort were not employed as obstacles. They were employed as the fortified bases of armies. Being fortified, these bases were safe even if close to the scene of operations. Consequently the lines of communication could be correspondingly shortened, and the power and activity of the armies dependent on them correspondingly increased. So long as these armies remained afoot, the fortresses were unattackable. Used in that way, a fortress reaches its highest military value.

The strategy adopted by General Joffre in association with the German advance upon Paris is one of the most interesting phases of the war. His tactics were to delay and weaken the first and driving formation of the German chain of armies; his strategy was, while holding the tail of that chain of armies fast upon the fortified frontier, to attract the head of it south-west. In that way he at once weakened the chain and lengthened out the German communications. Not merely was the position of the first German army the worse, and its effective strength the less, the further it advanced, thus ensuring its eventual defeat, but in the event of defeat retirement became proportionally more difficult. The means employed were the illusion that this army was driving before it, not a wing of the Allied forces engaged merely in operations of delay, but forces which, through defeat, were unable to withstand its march onward.

It cannot now be doubted that the Germans had believed themselves strong enough to undertake the investment of Paris concurrently with successful hostilities against the French forces in the field. But by the time General von Kluck's army arrived at Creil, the fact had become manifest that those two objectives could not be attempted concurrently. The necessity had therefore arisen of attempting them successively.

In face of that necessity the choice as to which of the two should be attempted first was not a choice which admitted of debate. Defeat of the[Pg 46] French forces in the field must be first. Without it, the investment of Paris had clearly become an impossibility. How far it had become an impossibility will be realised by looking at the position of the German armies.

Five of them were echeloned across France from Creil, north-east of Paris, to near the southern point of the Argonne.

The army of von Kluck was between Creil and Soissons, with advanced posts extended to Meaux on the Marne.

The army of von Bülow was between Soissons and Rheims, with advanced posts pushed to Château-Thierry, also on the Marne.

The army of von Hausen held Rheims and the country between Rheims and Chalons, with advanced posts at Epernay.

The army of Duke Albert, with headquarters at Chalons, occupied the valley of the Marne as far as the Argonne.

The army of the Crown Prince of Prussia, with headquarters at St. Menehould, held the Argonne north of that place, with communications passing round Verdun to Metz.

If the line formed by these armies be traced on the map, it will be found to present from Creil to the southern part of the Argonne a great but somewhat flattened arc, its curvature northwards. Then from the southern part of the Argonne the line will present a sharp bend to the north-east.

Now these five armies, refortified by reserves, comprised nineteen army corps, plus divisions[Pg 47] of cavalry—a vast force aggregating well over one million men, with more than 3,000 guns. Powerful as it appeared, however, this chain of armies was hampered by that capital disadvantage of being held fast by the tail. Held as it was, the chain could not be stretched to attempt an investment of Paris without peril of being broken, and the great project of defeating and enveloping the Allied forces was impossible.

No question was during the first weeks of the war more repeatedly asked than why, instead of drafting larger forces to the frontier of Belgium, General Joffre should have made what seemed to be a purposeless diversion into Upper Alsace, the Vosges, and Lorraine.

The operations of the French in those parts of the theatre of war were neither purposeless nor a diversion.

On the contrary, those operations formed the crux of the French General's counter-scheme.

Their object was, as shown, to prevent the Germans from making an effective attack on the fortified frontier. General Joffre well knew that in the absence of that effective attack, and so long as the German echelon of armies was pinned upon the frontier, Paris could not be invested. In short, the effect of General Joffre's strategy was to rob the Germans of the advantages arising from their main body having taken the Belgian route.

On September 3, then, the scale of advantage had begun to dip on the side of the defence. It remained to make that advantage decisive. The[Pg 48] opportunity speedily offered. Since the opportunity had been looked for, General Joffre had made his dispositions accordingly, and was ready to seize it.

Let it be recalled that the most vulnerable and at the same time the most vital point of the German echelon was the outside or right flank of the leading formation, the force led by General von Kluck. Obviously that was the point against which the weight of the French and British attack was primarily directed.

To grasp clearly the operations which followed, it is necessary here to outline the natural features of the terrain and its roads and railways. For that purpose it will probably be best to start from the Vosges and take the country westward as far as Paris.

On their western side the Vosges are buttressed by a succession of wooded spurs divided by upland valleys, often narrowing into mere clefts called "rupts." These valleys, as we move away from the Vosges, widen out and fall in level until they merge with the upper valley of the Moselle. If we think of this part of the valley of the Moselle as a main street, and these side valleys and "rupts" as culs-de-sac opening off it, we form a fairly accurate notion of the region.

From the valley of the upper Moselle the valley of the upper Meuse, roughly parallel to it farther west, is divided by a ridge of wooded country. Though not high, this ridge is continuous.

On the points of greatest natural strength commanding the roads and railways running across the ridge, and mostly on the east side of the valley of the Meuse, had been built the defence works of the fortified frontier.

Crossing the valley of the Meuse we come into a similar region of hills and woods, but this region is, on the whole, much wilder, the hills higher, and the forests more extensive and dense. The hills here, too, form a nearly continuous ridge, running north-north-west. The highlands east of the Meuse sink, as we go north, into the undulating country of Lorraine, but the ridge on the west side of the Meuse extends a good many miles farther. This ridge, with the Meuse flowing along the east side of it and the river Aire flowing along its west side, is the Argonne. It is divided by two main clefts. Through the more northerly runs the main road from Verdun to Chalons; through the more southerly the main road from St. Mihiel on the Meuse to Bar-le-Duc, on the Marne.

Thus from the Vosges to the Aire we have three nearly parallel rivers divided by two hilly ridges.

North of Verdun the undulating Lorraine country east of the Meuse again rises into a stretch of upland forest. This is the Woevre.

Now, westward of the Argonne and across the Aire there is a region in character very like the South Downs in England. It extends all the way from the upper reaches of the Marne north-west beyond the Aisne and the Oise to[Pg 50] St. Quentin. In this open country, where the principal occupation is sheep grazing, the lonely main roads run across the downs for mile after mile straight as an arrow. Villages are far between. The few towns lie along the intersecting valleys.

But descending from the downs into the wide valley of the Marne we come into the region which has been not unaptly called the orchard of France, the land of vineyards and plantations, and flourishing, picturesque towns; in short, one of the most beautiful spots in Europe. The change from the wide horizons of the solitary downs to the populous and highly-cultivated lowlands is like coming into another world.

From the military point of view, however, the important features of all this part of France are its roads and rivers, and most of all its rivers.

The three main waterways, the Oise, the Marne, and the Seine, converge as they approach Paris. Between the Oise and the Marne flows the main tributary of the Oise, the Aisne. Also north of the Marne is its tributary, the Ourcq; south of the Marne flows its tributaries, the Petit Morin and the Grand Morin. All join the Marne in the lower part of the valley not far from Paris. Between the Marne and the Seine flows the Aube, a tributary of the Seine. The country between the Marne and the Seine forms a wide swell of land. It was along the plateaux forming the backbone of this broad ridge that the Battle of the Marne was, for the most part, fought.

That brings us to the question of the roads.

Eastward from Paris, along the valley of the Marne, run three great highways. The most northerly, passing through Meaux, La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, Château Thierry, and Epernay to Chalons, follows nearly the same course as the river, crossing it at several points to avoid bends. The next branches off at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, and also runs to Chalons by way of Montmirail. The third, passing through La Ferté-Gaucher, Sezanne, Fère Champenoise, and Sommesons to Vitry-le-François, follows the backbone of country already alluded to. All these great roads lead farther east into Germany, the northerly and the middle roads to Metz and the valley of the Moselle, the third road to Nancy and Strasburg.

Now, it must be manifest to anybody that command of these routes, with command of the railways corresponding with them, meant mastery of the communications between Paris and the French forces holding the fortified frontier all the way from Toul to Verdun.

If, consequently, the invading forces could seize and hold these routes and railways, and, as a result, which would to all intents follow, could seize and hold the great main routes and the railways running eastward through the valley of the Seine from Paris to Belfort, the fortified frontier—the key to the whole situation—would in military phrase, be completely "turned." Its defence consequently would have to be abandoned.

Not only must its defence have been abandoned, with the effect of giving freedom of movement to the German echelon, but, that barrier removed, the German armies would no longer be dependent for munitions and supplies on the route through Belgium. They could receive them just as conveniently by the route through Metz. Their facilities of supply would be doubled.

It will be seen, therefore, to what an extent the whole course of the war hung upon this great clash of arms on the Marne. German success must have affected the future of operations alike in the western theatre and in the eastern.

But there is another feature of the roads in the valley of the Marne which is of consequence. Great roads converge into it from the north. Sezanne has already been mentioned. It is half-way along the broad backbone dividing the valley of the Marne from the valley of the Seine. Five great roads meet there from La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, Soissons, Rheims, Chalons, Verdun, and Nancy. Hence the facility for massing at that place a huge body of troops.

It will be seen, therefore, that in making Sezanne the point at which they aimed their main blow at the whole French scheme of defence, the Germans had selected the spot where the blow would, in all probability, be at once decisive and possibly fatal. Clearly they had now grasped, at all events in its main intention, the strategy of the French general. They saw that he was[Pg 53] using the fortified frontier to checkmate their Belgian plan.

Summing up the consequences, had success attended the stroke we find that it would have:

Opened to the invaders the valley of the Seine.

Turned the defence of the fortified frontier.

Released the whole of the German armies.

Given them additional, as well as safer, lines of supply from Germany.

Enabled the German armies to sweep westward along the valley of the Seine, enveloping or threatening to envelop the greater part of the French forces in the field.

Why, then, if it was so necessary and the object of it so important, was the move begun by General von Kluck on September 3 a false move?

It was a false move because he ought to have stood against the forces opposed to him. The defeat of those forces was necessary before the attack against Sezanne could be successful. Conversely, his own defeat involved failure of the great enterprise.

Instead, however, of facing and continuing his offensive against the forces opposed to him, he turned towards Sezanne. By doing that he exposed his flank to the Allied counter-stroke.

This blunder can only be attributed to the combined influences of, firstly, hurry; secondly, bad information as to the strength and positions of the Allied forces; thirdly, the false impression formed from reports of victories unaccompanied by exact statements as to losses; and fourthly, and perhaps of most consequence, the failure of the Crown Prince of Germany in the Argonne.

General von Kluck doubtless acted upon imperative orders. His incomplete information and the false impression his advance had created probably also led him to accept those orders without protest. But it should not be forgotten that the Commander primarily responsible for the blunder, and for the disasters it involved, was the Crown Prince of Germany.

Primarily the Crown Prince of Germany was responsible, but not wholly. In the responsibility General von Kluck had no small share. He was misled. When the British force arrived at Creil General Joffre resolved upon and carried out a masterly and remarkable piece of strategy. The British army was withdrawn from the extreme left of the Allied line on the north-east of Paris, and transferred to the south-east, and its former place taken by the 6th French army. This move, carried out with both secrecy and rapidity, was designed to give General von Kluck the impression that the British troops had been withdrawn from the front. That the ruse succeeded is now clear. So far from being withdrawn, the British army was brought up by reinforcements to the strength of three army corps. Leaving out of account a force of that strength, the calculations of the German Commander were fatally wrong.

Let us now see what generally were the movements of the German and of the Allied forces between September 3 and September 6 when the Battle of the Marne began.

Leaving two army corps, the 2nd and the[Pg 56] 4th Reserve corps, on the Ourcq to cover his flank and rear, General von Kluck struck south-east across the Marne with the 3rd, 4th, and 7th corps. The main body crossed the river at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, and took the main route to Sezanne. Others crossed higher up between La Ferté-sous-Jouarre and Château-Thierry. For this purpose they threw bridges across the river. The Marne is deep and for 120 miles of its course navigable.

These movements were covered and screened by the 2nd division of cavalry, which advanced towards Coulommiers, and the 9th division, which pushed on to the west of Crecy. Both places are south of the Marne and east of Paris.

Writing of these events at the time, Mr. W. T. Massey, special correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, observed that:—

The beginning of the alteration of German plans was noticeable at Creil. Hidden by a thick screen of troops from the army in the field, but observed by aerial squadrons, the enemy were seen to be on the move. Ground won at Senlis was given up, and the German troops, which at that point were nearer Paris than any other men of the Kaiser's army, were marched to the rear. Only the commandants in the field can say whether the movement was expected, but it is the fact that immediately the enemy began their strategic movement British and French dispositions were changed.

The movement was expected. Indeed, as we have seen, the whole strategy of the campaign[Pg 57] on the French side had been designed to bring it about.

The Germans must have observed that their new intentions had been noticed, but they steadily pursued their policy. Their right was withdrawn from before Beauvais, and that pretty cathedral town has now been relieved of the danger of Teuton invasion. The shuttered houses are safe, temporarily at any rate.

The ponderous machine did not turn at right angles with any rapidity. Its movements were slow, but they were not uncertain, and the change was made just where it was anticipated the driving wedge would meet with least resistance.

In the main the German right is a tired army. It is a great fighting force still. The advance has been rapid, and some big tasks have been accomplished. But the men have learnt many things which have surprised them. They thought they were invincible, that they could sweep away opposition like a tidal wave. Instead of a progress as easy as modern warfare would allow, their way has had to be fought step by step at a staggering sacrifice, and in place of an army which took the field full of confidence in the speedy ending of the war and taught that nothing could prevent a triumph for German arms, you have an army thoroughly disillusioned.

In this connection the service of the British Flying Corps proved invaluable. Covering though they did a vast area, and carefully as they were screened by ordinary military precautions, the movements of the Germans were watched and notified in detail. Upon this, as far as the dispositions of the Allied forces were[Pg 58] concerned, everything depended, and no one knew that better than General Joffre. On September 9 he acknowledged it in a message to the British headquarters:—

Please express most particularly to Marshal French my thanks for services rendered on every day by the English Flying Corps. The precision, exactitude, and regularity of the news brought in by its members are evidence of their perfect organisation, and also of the perfect training of pilots and observers.

Farther east the army of General von Bülow (the 9th, 10th, 10th Reserve corps, and the Army corps of the Prussian Guard), advancing from Soissons through Château-Thierry, and crossing the Marne at that place as well as at points higher up towards Epernay, was following the main road to Montmirail on the Petit Morin.

The army of General von Hausen (the 11th, 12th, and 19th corps), advancing from Rheims, had crossed the Marne at Epernay and at other points towards Chalons, and was following the road towards Sezanne by way of Champaubert.

The army of Duke Albert, having passed the Marne above Chalons, was moving along the roads to Sommesous.

The army of the Crown Prince of Germany was endeavouring to move from St. Menehould to Vitry-le-François, also on the Marne.

On the side of the Allies,

General Maunoury, with the 6th French army, advanced from Paris upon the Ourcq. The right of this army rested on Meaux on the Marne.

General French with the British army, pivoting on its left, formed a new front extending south-east to north-west from Jouey, through Le Chatel and Faremoutiers, to Villeneuve-le-Comte.

General Conneau with the French cavalry was on the British right, between Coulommiers and La Ferté Gaucher.

General Desperey with the 5th French army held the line from Courtagon to Esternay, barring the roads from La Ferté-sous-Jouarre and Montmirail to Sezanne.

General Foch, with headquarters at La Fère Champenoise, barred with his army the roads from Epernay and Chalons.

General de Langle, holding Vitry-le-François, barred the approaches to that place and to Sommesous.

General Serrail, with the French army operating in the Argonne, held Revigny. His line extended north-east across the Argonne to Verdun, and was linked up with the positions held by the French army base on that fortress.

General Pau held the line on the east of the fortified frontier.

Some observations on these dispositions of the Allies will elucidate their tactical intention.

The position of the Allied armies formed a great bow, with the western end of it bent sharply inwards.

The weight of the Allied forces was massed round that western bend against the now exposed[Pg 60] flank of von Kluck's army. Here lay the most vulnerable point of the German line.

The tactical scheme of the Allied Commander-in-Chief was simple—a great military merit. He aimed first at defeating the German right led by Generals von Kluck and von Bülow. Having by that uncovered the flank of General von Hausen's army, his intention was to attack it also in both front and flank and defeat it. The same tactic was to be repeated with each of the other German armies in succession.

For that purpose the allied armies were not posted directly on the front of the German armies, but between them. Consequently the left of one German army and the right of another was attacked by the same French army. In that way two German Generals would have to resist an attack directed by one French General, and every German General would have to resist two independent French attacks. Hence, too, if a German army was forced back the French could at once double round the flank of the German army next in the line if that army was still standing its ground.

Choice of the battle ground and command of the roads leading to it ensured that this would happen. As a fact, it did.

Finally, all the way behind the French line ran the great road leading across the plateaux from Paris to the fortified frontier. This, with railway communication, gave the needed facilities for the movement of reserves and the transport of munitions and food supplies.

Now let us glance at the tactical scheme on the German side.

The fact that General von Kluck had left two out of the five corps forming his army on the Ourcq, and was covering his movement to the south of the Marne with his cavalry, proves that he did not, as was supposed, intend to lose contact with Paris. His scheme was to establish an echelon of troops from the Ourcq to La Ferté Gaucher on the great eastern road, believing that to be meanwhile a quite sufficient defence.

With the rest of his force he was to join with von Bülow and von Hausen in smashing through the French position at Sezanne. Against that position there was to be the overwhelming concentration of ten army corps.

To assist the stroke against Sezanne there was a concurrent intention to break the French line at Vitry-le-François. The French line between Sezanne and Vitry-le-François would then be swept away.