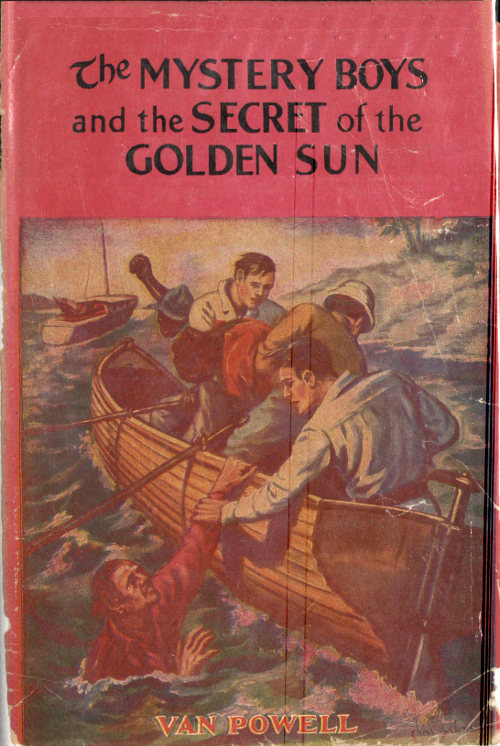

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mystery Boys and the Secret of the Golden Sun, by Van Powell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Mystery Boys and the Secret of the Golden Sun Author: Van Powell Release Date: December 6, 2018 [EBook #58420] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SECRET OF THE GOLDEN SUN *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By VAN POWELL

AUTHOR of

“The Mystery Boys Series,” etc.

THE

WORLD SYNDICATE PUBLISHING CO.

Cleveland, Ohio New York City

Copyright, 1931

by

THE WORLD SYNDICATE PUBLISHING CO.

Printed in the United States of America

“That fellow is watching us again!” whispered Tom Carroll to his companions, Nicky and Cliff, as he adjusted a pack strap on the Mexican burro behind which he sheltered his face as he spoke.

“If he keeps on, I’m going over and ask him what’s next!” Nicky said, “I’ll find out what he means by it or know the reason why.”

Nicky was impulsive and quick: he preferred action to reasoning, and was usually more willing to meet trouble than to avoid it. Tom, who was generally as cool and as level headed as Cliff, the oldest of the trio, seemed inclined to agree with the youngest chum; but Cliff, cinching up his pony’s saddle, shook his head at Nicky.

“We came out here to try to learn something about Tom’s sister, not to court trouble,” he urged. “I guess that chap is simply curious about us and is watching to see that we saddle up properly.”

“Is it any of his business?” demanded Nicky. “He’s just one of the miners having his lunch. What business is it of his what we do or how we do it?”

“He looks pretty mean,” Cliff admitted.

Tom, having taken a moment to consider, as he generally did, came to a conclusion. “I’m not so sure that he is mean,” he told his two friends. “That scar across his face, and his bleary eyes, make him look pretty fierce; but he may be perfectly innocent of any wrong thoughts. As long as he only watches, he isn’t breaking any law or hurting us. Are you fellows ready?”

“All set!” answered Cliff, patting his pony’s flank.

“Then, let’s not bother about a rough looking miner who has hardly taken his eyes off us since we came here this morning. Nicky, run over to the mine office building and tell Mr. Gray we’ve got everything ready to start back.”

Nicky dropped his own pony’s rein over its head, while Tom, with his lithe movements apparent in the ease with which he mounted his own animal, caught the bridle of an extra mount and Cliff took the burro’s leading rope. Nicky ambled across the flat ground toward a zinc sheathed shack at a little distance.

Cliff and Tom sat on their ponies, watching covertly as the man they had been discussing finished the remnants of his chili con carne, wiped his mouth on a ragged coat sleeve, rose and strolled with a seemingly aimless air toward the upper level on which stood the engine house, the mouth of the mine and other timbered and metal covered buildings.

Nicky, on his return, looked around, saw that the man was gone and voiced a proposal.

“Mr. Gray says he won’t be ready to go for more than an hour,” he informed his chums. “The mine superintendent is telling him about some old Aztec curios he owns, and you know how that will chain Cliff’s father in his chair. What do you say if we take a little gallop down the trail—a race, maybe?”

Tom vetoed the race: they had a good ride before them and he did not want to start on winded ponies: however, he agreed to a short ride on a trail that they had not explored and the trio rode off, tying their burro to await their return.

The extra pony, also left standing, may have wondered why his own rider, the older one, had not come; but he waited with the patience of a well trained animal.

As the boys rode along, the trail became rapidly steeper and the small plateau narrowed into a rough, rocky coulee.

“It certainly is too bad,” Nicky said, with a sidewise glance of rueful sympathy toward Tom. “After we came all the way to Mexico City and then rode out here to the old mine, it is too bad that we can’t get even a trace of your missing sister.”

Tom nodded.

“Yes,” he agreed. “You’d think the authorities would know something, after all these years, or that we could pick up some clues.”

“It would have been different in the United States,” said Nicky, with a sense of pride in his native land. “Our detectives don’t let the grass grow under their feet.”

“And yet,” broke in Cliff, “many girls, and men and women, too, disappear in America and never are found.”

“There were no eye-witnesses, except the ones they found dead, after the bandits made their raid—that’s why there were no clues,” Tom added.

“Well,” he finished, sadly, “I guess my own private mystery will never be solved.”

“You can’t tell,” Nicky said, with his usual optimism. “You know, it seemed as though Cliff’s father would never be heard from again, after he went to Peru—but we got a letter, or Cliff did, and we went down there with Mr. Whitley, our history instructor—and not only rescued Mr. Gray from the hidden Inca city, but we saw a lot of adventure and got some of the Inca treasure.”

“And your mystery seemed as though it would never be solved, Nicky,” Cliff reminded his friend. “With only half of a cipher message left to your family by Captain Kidd, it was possible for us to find the hidden treasure in the Florida keys and have a lot of excitement in the bargain.”

“And both adventures started out very tamely,” Nicky was trying hard to brighten up his comrade; but Tom only shook his head.

“This is different,” he said.

Nicky and Cliff referred to two exciting escapades in which all three had participated. Because each of them had had a mystery in his life the three had drawn very close in the bonds of friendship, and had formed themselves into a secret order which they called the Mystery Boys. They had secret gestures by which they could communicate with one another in the presence of others without divulging the fact that they did so: also, they had initiation rites and binding oaths and strict codes which held them together and bound them to help each other in every way to solve their individual mysteries.

Cliff’s mystery, as Nicky said, had been cleared up in the summer past: the following winter the trio, while in Jamaica, had run onto some information which had begun the adventure through which the hidden treasure mystery of Nicky’s family had been brought to a successful end.

While in Cliff’s case the reward had not been financially large, he had found his father. In Nicky’s adventure no life had been involved in danger, but a buried mass of gold bars had been recovered and distributed fairly so that each of the three was, in a modest way, provided for as far as riches went: they were not made millionaires, because the treasure had to be shared with others involved in Captain Kidd’s legacy, but they were “well fixed.”

But in Tom’s case, the mystery was of a different kind, and there was in it not only the element of tragedy, but, as well, the element of uncertainty.

Hardly more than five years ago Tom, confined to his bed by a bad attack of measles, had been thus prevented from going with his father and his sister, a year older than he, to Mexico. That saved his life, which is a curious thing to think about—that sickness saved him from a worse fate.

Mr. Carrol, an engineer and mining expert, sent to inspect some mining property, had left Tom under the care of an older cousin; but so eager had eleven-year-old Margery been to see the strange country that Mr. Carrol had taken her with him.

That farewell, looking out of a darkened room at the bright hair and half-smiling, half-tearful face, had been Tom’s last sight of his beloved sister; and that clasp of hands between father and son had been the last they could ever exchange.

For, shortly after the arrival of the engineer and his daughter at a remote mining property, bandits had descended from the mountains in a raid, seemingly because they knew that gold to a high value had been amassed and stored until time to load it on burros and with armed guards take it to the railway shipping point.

In the news, meagre and disjointed, which Tom had received, it was supposed that the bandits had come to the mine during the night, had been seen and attacked by the engineer and several other Americans who were in charge of the property. A fight must have ensued, but one disastrous to the defenders, because the gold was gone and the mine was deserted when the workmen came from their hovels far down the trail the next day. According to what Tom heard, they had found his father and the other Americans, all past any earthly aid.

But there had been no news of Margery!

With his heart torn by his bereavement and with terror gnawing at his mind day and night, even at the tender age of ten, Tom had begged his father’s cousin to use every effort to learn what had happened to his sister. All that could be done, had been done.

But the family had little money and although the Government made inquiries and State departments exchanged notes and the Mexican authorities declared that soldiers had scoured the neighborhood of the mine and the passes in the sierras—and some of the bandits had been caught and punished!—there was no trace of the little girl.

No wonder that Tom suffered anguish every time he thought of her. Was she wandering about in the mountains, alone, starved? Was she a captive among the bandits? Those who had been caught declared by everything they reverenced that they had not seen her at any time nor after the retreat had they seen her in their camp among the cordilleras. Even the gold was gone! A renegade white man—they had not known his nationality—had incited the attack, seeming to guess that there was money to be had. But he had disappeared during the fighting—and so, they averred, had the gold bags and the burros.

Was the little, sunny-haired Margery his prisoner also? Tom never had learned, for no trace of him—or of her—had ever been found.

Naturally, even after five years, the pain was deep and the scar still burned; that is why he had been so anxious to see the summer vacation arrive at Amadale Military Academy, where he and his chums were students. Cliff was glad in one way, also, because the end of the term saw his graduation. That meant that he could devote all of his time, for the summer and as long as might be necessary, to his father, Mr. Gray, a great scholar and student of old civilizations. Mr. Gray wrote books on the subject of ancient history, and went to many strange places to get his facts. Cliff looked forward to the experiences and the knowledge he would gain; but mostly he was glad to be able to help his father whose health was not of the best since his years of captivity among the hidden Inca survivors in the Peruvian cordilleras.

Nicky, in the same class with Tom, and with a year yet to be passed in study and training of an athletic and disciplinary sort, looked forward to the vacation, because he knew that Mr. Gray was going to Mexico to study the Aztec civilization of a time long past, and to collect Indian relics and other material for a Museum in New York—and Cliff would go with him to help him and to write for him when his eyes were tired, and to superintend digging and so on; and Tom had been invited to accompany them, because he could in that way see at first hand the district of Mexico which had bred tragedy in its wild mountains for him. That meant that the inseparables would feel that their ranks were incomplete without the third member of the Mystery Boys, and so, of course, Nicky was with the others.

They had hired ponies and a guide and had ridden out to the mine, with the results which the boys had just discussed during their ride.

“I’ll bet this is the very trail those bandits used,” Nicky was saying as Tom reined in his pony.

“Maybe,” he said listlessly, “but there won’t be any clues or signs on it after five years. We’d better go back.”

“Well—I wish you’d look!” gasped Nicky, turning his head and spying something down the trail. “There comes that fellow who was watching us like a hawk—and he’s—yes, he is!—he’s riding Mr. Gray’s pony.”

“We’ll wait and see what he is after,” suggested Cliff at once. “We’re three to one.”

“Yes,” cried Nicky hotly, “and if he ‘starts’ anything, I’ll start him toward that chasm over yonder!”

The man riding toward them was quite tall, and rangey of build. He did not show his full height for he rode, as he walked, stooped over. He seemed to be in the last stages of physical slovenliness, and—even ignoring the scar across his face from the base of his nose to his left jawbone—his features looked sinister. Actually it was moral laxity, too much drinking and careless living that had pulled down a frame which must at one time have been erect and powerful, and broke a once daring spirit till it looked out of bleary eyes with dull, apathetic boredom.

“Well, are you following us?” Nicky spoke up as soon as the man was close enough to hear.

The man rode up closer still, reined in his pony, dropped the leather onto the animal’s neck and smiled ingratiatingly.

“Yes,” he said, in a husky, whispering sort of way, “I’m follerin’ you. ’Cause why? That’s what you want to know. ’Cause why! Ain’t it so?”

“Certainly we want to know,” chimed in Cliff. “Why are you following us?”

“He-he-he-he!” It was a shrill, cracked sort of laugh. “’Cause Henry Morgan smells money—that’s why!”

“Henry Morgan!——” Nicky started. He read a great deal about pirates and piracy because he had been interested in the cipher which Captain Kidd had given to one of his ancestors, “Henry Morgan! Any relation to the old pirate?” None of them were afraid; they were simply curious, and a little bit annoyed.

“Henry Morgan—the pirate! He-he-he! Maybe. Who knows! Can pirates smell money?”

“They must,” Nicky declared. “They were always crazy about getting it.”

“Well, then, I must be related to ’em. ’Cause why? ’Cause Hen Morgan can smell money. And—’cause Hen Morgan is crazy for it. And——” he fixed them with a bleared eye and rubbed his hands—and the chums drew their ponies closer on the trail as he added:

“Oh, yes! Hen Morgan smells money—an’ he smells it on you, or around you—and he wants some of it!”

“You talk one way and act the opposite!” Tom made his tones sarcastic to cover his inward trepidation. He was not exactly afraid for he did not think that the man had any weapon and they outnumbered him. But Tom wanted to communicate secretly and he did not see just how to do it.

The Mystery Boys had two secret sign manuals: one was for asking and answering questions, and the other was for suggesting a course of action. But neither had been planned for use while seated on ponies, and such signs as the folding of arms, or the tying of a shoelace, were out of the question. So Tom kept on talking while he thought busily.

“You say you can smell money,” he added, “and then you follow us out here to rob us. Why, I don’t think we could get enough money together to buy a bag of chili beans!”

Somewhat to his surprise the man made a violent gesture of denial.

He sidled his pony a little closer, put up a hand as if to drive away any suggestion of robbery, and spoke again in his husky voice.

“No, not that! Hen Morgan aren’t no robber. ’Cause why? ’Cause robbers takes chances. They takes some likely person and risks getting a lot of money—and sometimes they guess wrong. But not Henry Morgan. Oh, no! ’Cause why? ’Cause he don’t guess. He smells money.”

The chums looked at one another dubiously. Was this man off his head? He wasn’t there to rob them! He didn’t guess—he smelled money! What was his purpose? “You smelled wrong, for once!” Tom declared, after a moment.

“Oh, no!” cried the husky voice, “not Hen Morgan. He sees you three come a-ridin’ up to Dead Hope mine, with the old gent. He sees how the super’tendent calls some of us miners in and he asks ’em, later, what it’s all about. ’Cause why? ’Cause Hen Morgan knows something.”

“Knows something? About what?” demanded Tom.

“Light down off your ponies an’ I’ll tell you. ’Cause why? ’Cause it takes too much work keepin’ these critters standing still. Light!”

Tom looked at his companions. Cliff nodded and slid from his saddle. Nicky and Tom followed his example. There was no danger, that they could see, and on the ground they had more freedom of movement than while mounted on strange, and possibly unruly mustangs.

“Now,” said Henry Morgan, seating himself on a boulder and rolling a cigarette expertly with his right hand, while three mystified, rather eager youths stood watching him, “now—Hen Morgan said he smelled money on you or around you, and he was right. ’Cause why? Look at it! You didn’t ride out here to look for mining property; you come a-hunting for some news of a certain thing what happened a good while ago!”

“How do you know we did?” Nicky asked sharply.

“From the miners who was called to the office. But they didn’t know anything. Nobody did. Nobody does—but——”

Tom almost sprang forward, so eager was he as the import of Henry’s words flashed through his mind. “Do you? Do you know about—about my sister——”

With maddening deliberateness the man held up a hand for silence, searched for and found a crumpled card of matches, struck one and carefully ignited the end of his cigarette. Then, at last, he nodded.

“Hen Morgan is the only man who does know anything—but he don’t know much.”

“Well, if you know anything at all, when you found out that we were hunting for facts, why didn’t you come out in the open and tell?” Tom said it angrily, for the suspense was torture to him.

“Hen Morgan uses his head, that’s why!” He blew a cloud of smoke, coughed a little, and resumed his confidential, husky whispering. “You come here lookin’ for news. That means money behind you. ’Cause why? ’Cause no three young lads comes all this way without money. Now, reasons I, they’ll pay for news.”

“Oh!” cried Tom, “I see. You know something and you want to bargain with us and sell your information for all you can get.”

“It’s what I’d expect,” Nicky cut in.

“Come on, then,” Cliff urged. “We’ll pay you all your information turns out to be worth. But we’ll go back and talk it over with my father, out in the open, not up here in the trail.”

“Easy, easy!” begged Henry Morgan. “We won’t go back, right yet. ’Cause why? ’Cause we’ll make our bargain here.”

Nicky impulsively caught his pony’s saddle horn, started to lift a foot for the stirrup.

“Come on, fellows,” he urged. “We’ll go back and get help.”

Henry Morgan stood up. “The minute you rides down the trail, I rides off—up that way.” He waved his arm. “They didn’t ever find the head bandit, that time, did they? Nor the gold? ’Cause why? ’Cause there’s a way they got took to safety, and I know that way! If you don’t want my news, and won’t strike a bargain, well and good. But if you do——” he paused.

Tom was scratching his left ear quietly with his finger, and with one accord Nicky and Cliff folded their arms and the Mystery Boys’ council was in session without an outward evidence that anyone could notice or read.

Tom shifted the visor of his cap a tiny bit one way, then back: it was a silent appeal, “What shall we do?”

Cliff picked up a pebble and shied it aimlessly to one side: that was a code sign which meant that the last word of every sentence in his next speech would have a meaning. Then he spoke up, carelessly.

“Let’s see. You said what? You’ve got news? Likely, that is!”

Mentally, as he spoke, Tom noted the pauses, and then, connecting the words that ended each short sentence, he discerned that Cliff’s advice was: “See—what—news—is!”

Tom moved the little finger of his right hand gently, knowing that Cliff watched for that sign of agreement: to use the left finger would mean denial or rejection of the advice; but Tom took it.

“You’ve got to let us know what you have to sell,” he addressed Henry Morgan. “I’m willing to pass my word and strike hands on it, if you have any knowledge that will help us to find my missing sister, I will pay you anything within reason.”

The three chums half expected Morgan to demur. If he told them what he knew it would be worthless to him; once they knew it they could use it. However, they got a slight surprise, for Morgan merely grinned and nodded.

“I’ll tell you,” he said, “’Cause why? ’Cause I want help. If I tell you, you can see how good it is—what I know. And even when I tell you, I’m still sure of my reward. ’Cause why? ’Cause I’ll tell you everything but one man’s name—and without that, you can’t do a thing—at the same time Hen Morgan can show that he knows what you want to know.”

He told them, quietly. They thrilled, they shuddered; they drew closer. Each and all, the Mystery Boys forgot that they were out on a lonely trail, forgot that the man was bargaining, in a way, for a human life. His story chained them in spellbound attention.

When he completed it, Tom held out his hand.

“It sounds like a real help—your story does,” he said. “I’m not of age to handle my own money, but I know that Mr. Gray, who is acting as the custodian of my money, will agree to give you——” he hesitated, partly to see how much Henry Morgan would name, and partly to plan in his own mind what to do. That they must have the name of a certain important figure in the bandit raid, cost how it might, Tom knew.

“Let’s not make it a set figure,” said Morgan, again surprising the trio. “’Cause why? ’Cause Hen Morgan has got a bigger stake to gain than what you could give. But you could help him to get it. And he could help you to get what you want. And so, everybody would be satisfied.”

“Agree?” asked Tom’s eyes, and the bent first finger that touched his right thumb. Nicky and Cliff signaled a “yes.”

“That’s reasonable,” Tom nodded. “What do you expect us to do?”

“All I ask is that you pay the expense of the search—and take me along!”

“That’s all?”

“Well, only, if I help you find that—certain fellow—and we do find him, and he tells me what I want to know too—you’ve got to sign a paper that you’ll help me to get to locate the Golden Sun——”

“The Golden Sun?” cried Nicky and Cliff together.

Henry nodded. “Yep,” he agreed, “The Golden Sun. It’s a mountain of gold, the way I understand about it. And I got as much right to it as this—other fellow. You’ll see why later on. But I’ve got to have your word—you, the one who wants to find his sister!—that you’ll help me—and maybe share with me in the mine, eh? ’Cause why? ’Cause Hen Morgan is generous, he is—and if you help him he’ll help you.”

“I pass my word,” said Tom, solemnly, and gripped hands with Morgan, just a little hesitantly at the contact with the soiled, rough paw.

“All right, I know you’ll not break your word—you don’t look like that kind. Mount and let’s ride and talk to the old gent.”

“Well!” exclaimed Nicky. “Off again for adventure—and success, I hope!”

They rode back to the mine property quickly. It did not take long to locate Mr. Gray, Cliff’s elderly father: he listened in silence to the eager trio as they broke in upon one another, so excited were they, and so eager to get his opinion in regard to the feasibility of starting at once for the Central American coast.

Henry Morgan had exacted from them all a promise that they would not disclose what he had told them to the mine superintendent, a rather lazy and careless man who seemed to realize that since the mine was hardly paying for its expense, his work was only a means of making a living until the mine finally “petered out” and he went elsewhere. The chums had already discovered that there were many adventurous and roving white men, from Mexico down all the Central American coast and into South America, as well as among the Virgin Islands, who eked out a living wherever and however chance offered. Henry Morgan was of that type, but much drinking and loose living had made him a very poor specimen, indeed, of the adventure-loving, roving American.

“If Mr. Morgan knew so much, why did he not come to us at once?” was Mr. Gray’s natural first question.

“I think he explains it logically,” answered Tom, “and Nicky and Cliff agree with me.” They nodded. “He is afraid that he might get ‘mixed up’ with the Mexican authorities, and that would spoil everything,” Nicky explained. “Let him tell you what he told us, won’t you, Mr. Gray?”

The elderly scholar and writer nodded. Henry Morgan cleared his throat and, in his husky, rusty voice, related the tale again.

“I’ve been a rover all my life,” he began, “from kid days on. ’Cause why? ’Cause I liked to see new places and have excitement. Sometimes I got more nor I bargained for. Sometimes I near starved. But I always come through all right.”

He sketched briefly the years he had spent roving up and down the Caribbean coast of the Central American states, and the adjacent islands, and over to Cuba during an insurrection, and in Haiti, while a revolution was in progress, and gold-prospecting in Spanish Honduras.

“It was while I was in Spanish Honduras, in the Mosquito Indian’s country,” he went on, “I met the fellow I told these lads about. He was lookin’ for gold, and there was supposed to be a gold mountain inland, but the Indians in the interior was too dangerous for us to risk gettin’ in. Well, finally, we decided to give up hunting for any mine there—at least, I did. I was down on the coast, near the sand point at Brower’s Lagoon when a sailing sloop came in over the reef one day, and when I found out they needed a hand, I shipped on her and left—this other fellow—inland, still bound he would some time locate that mine or mountain of gold and claim it.”

He explained to the interested quartet that he went into so much detail because it all had something to do with the later part of his yarn. They nodded and did not interrupt him once.

“This—other fellow—had made great friends with an old Indian, up river—oh, quite a ways up the Rio Patuca. This old Indian must have lived for centuries. ’Cause why? ’Cause he knew legends and history that his own tribe had forgot: and he knew medicines and herbs, the same as the oldest of the other medicine men couldn’t even remember. And Be—this other fellow—had got real close in his confidence and said this old Toosa—that was his name—would show him a way to find the golden mountain, so I left him there.”

He skipped quickly over the following years until the time, about six years before, when he had found himself in Mexico and, hearing of some rich mines in the sierras, had eventually reached and found employment at the mine which, in its prosperity, was called the Great Hope, but which, since, had degenerated in value until it was jokingly styled the Dead Hope.

“But whenever I get in civilized places where there is drink,” Henry continued, “I can’t do nothin’ for myself. ’Cause why? ’Cause it gets me and holds me and drags me down.” He made a gesture of rueful resignation. Then, rolling a fresh cigarette, he began to bring his story into the matters which most intensely gripped the imaginations of the chums.

“I was made assistant to the super’,” he told them, “but it wasn’t long before I got so bad and so low that they kicked me out. Well, I was sore about it and made up my mind to get even. But I didn’t. ’Cause why? Well, I struck up with B—with this other fellow, again.”

Whoever this man with the name he so mysteriously withheld might be, he was evidently of the same general type as Henry. The latter met him, he said, in a “dive” in Mexico City, and in a ribald fit of liquor stupor the friend had gabbled and raved and ranted about finding “the Golden Sun!”

“That was what we had decided we’d name our mountain, when we found it,” Henry explained. “So I was all excited. But he was too far gone to tell me anything I could pin onto. Then I got mad at him and started a fight and——” he pointed to his scarred face, “this is my souvenir! It laid me up in a dinky hospital for weeks.”

When, without money, weak and rather sobered in mind as well as physically, he came out of the hospital, Henry Morgan decided to drift back to the mine, see if he could be reinstated, and live a better life, he told the chums.

“I do not like to interrupt,” began Mr. Gray, “but I fail to see——”

“Just wait, Dad,” begged his son, Cliff, “he’s coming to it, now.”

Mr. Gray leaned back and studied the bleared eyes while Henry Morgan resumed his story and the chums almost held their breath.

“I had to tell all that. ’Cause why? ’Cause it counts in the finish—or will, if you see it the way I do,” declared the rover. “I won’t waste time sayin’ how I got back, what I went through. But get back to Dead Hope I did.

“And it was on the night of the bandits’ raid!”

Then Mr. Gray saw why the boys were so absorbed. They knew what was coming.

“That dark night I come a-stumblin’ up the path, yonder, weak and hungry and staggerin’—I hadn’t eat no food for a day. All of a sudden there was a yelling and a shouting and guns a-popping!”

“What did you do?” gasped Nicky, thrilled anew by the recital.

“I stopped,” said Henry, matter-of-factly, “I stopped. There was flashes of guns and people running around and the men on horses shooting and riding after people in their night-clothes—the ones that was on the ground, I mean, not the bandits. They was dressed, of course! One o’ the men a-horseback rode right close to where I had dropped back behind the rock, and he saw me. ‘Here, grab this rein,’ he snapped at me—and you can believe it or not—it was B—it was my old pal I had last seen in Mexico City, drunk, and he had give me this slash with a broken bottle!”

“B—who’s Be—?” asked Tom quickly, trying a clever way to surprise the man into revealing the name they sought, without having to wait.

“Be—oh, he’s the man I’ve been talkin’ of,” said Henry, favoring Tom with a steady stare and then, suddenly, breaking into his high chuckle. Then he sobered down and went on.

“Little boys what asks questions finds out just what they wants to know—he-he-he!” he reproved Tom who apologized for interrupting.

“All right,” Henry said. “Well, I yelled after him, but he was runnin’ towards the excitement, hollering and shouting, and I was too busy with that horse of his to run after him. I was scared to let the critter loose for fear o’ what he’d do to me. I guessed he’d fell in with a rough gang and had decided to lead them or be with them on this raid. I judged there must be a lot of gold laid up in the mine house, waiting for burros and guards to carry it to the railroad. If I let the horse go, this fellow would maybe give me a dose of lead. So I hung on.”

“The horse was excited and scared, wasn’t he?” asked Tom.

“He was, and no mistake! He began to drag me and I hung on, yellin’ at him to quit, and him draggin’ and rearing up. First thing I knew, I was bein’ dragged over to that pass we rode in this afternoon. The bandits must o’ come out of it earlier and the horse wanted to get home, maybe. Anyhow, towards that he was draggin’ me. And then—I saw a couple of Mex. desperadoes, so they looked with their tall straw hats and dirty, raggedy clo’es, and they was drivin’ about six burros with heavy sacks tied over their backs, all they could carry!”

“Gold!” gasped Nicky.

“Gold it most likely was. Anyhow, here come that friend of mine—he was my friend once, I mean, before—” he touched his scar. “He had a rifle and was runnin’. There was still shootin’ going on, and a horse was down one place and a bandit another, and men stretched out yonder and hither. This fellow he run to me and pushed me to one side and pushed a rifle in my hand, and he said, ‘Hold this pass for ten minutes with this rifle, and then retreat up it about fifty feet, and I’ll be in ambush and I’ll surprise the guys, and what you can’t stop—I will! Then we’ll divvy the gold!’ So I grabbed the rifle and took a place. At the same minute I hear a screech and yonder, out of the sleepin’ quarters, comes a little girl, a-runnin’ as tight as she could run, with a big ruffian a-chasin’ her!”

“Oh!” cried Tom, aghast and almost shaking in his excitement, “Oh—my sis—little Margery!”

“Little girl with bright hair!” agreed Henry. “Well, before I scarcely knowed what was what that—er, friend—had shot down the ‘greasers’ with the burros, stopped the fellow chasin’ the little girl, scooped her in his arms and set her onto the saddle of his horse and was up behind her.”

“Didn’t the bandits see it?” asked Cliff.

“They had been so busy finishin’ off the engineer and the other white men—and they made a good stand, let me say it!—they was occupied too much to notice the actions goin’ on up by the pass. But they saw what was what about then, and come a-yellin’. I took cover, and begun to use that rifle. There was a full clip in it and I had another one shoved into my hands, and while that wild pal of mine rode up the pass, drivin’ the burros, I stood off about four of the bandits that wasn’t wounded.”

Henry Morgan wiped his dry lips and cleared his roughened throat. Tom hurried him along.

“When you backed down the trail—what?”

“Nothing!” said Henry.

“Nothing?” Mr. Gray exclaimed, adding to the chorus of the younger voices, for they had not heard the details before.

“Nothing!” Henry repeated. “Not a sign of help. That fellow was gone, slicker’n grease, with the little girl and the burros and the gold. I was caught, of course. The bandits tried to get out of me what I knew and I told them exact facts like you’ve just heard. I was mad at being made to help him ‘double-cross’ his gang and they saw I was telling the truth. Well——” he broke off.

“But he got a letter, a couple of months ago, he says,” Tom took up the recital. “Another adventurer Mr. Morgan knows, wrote him, and—what did you say he wrote?”

“He wrote me that he had run onto—this fellow we been talking about, down in Colon—Panama, you know! Said he was livin’ like a millionaire, and was talkin’ that he was gettin’ gold off of——” ‘from’ he meant, of course—“off of some Indians. I guess it’s out of the Golden Sun. So, now, gent, my proposal is this:

“I know how to get where that Toosa, the old Indian, is. He will know about—this fellow—if he’s located that Golden Sun. But I couldn’t pay the fare from here to the coast, let alone get to Spanish Honduras. That’s where you come in. You finance me, while I try to find—that man. Then we’ll all learn what we want—you, where he took the little girl, what happened to her. Me, where that mine is. I staked him plenty of times, I have right to a share in it.”

“How would we get there?” asked Tom.

“Have to hire a boat to coast along to the outer reefs and the mouth o’ the Rio Patuca, then we’d have to get them Mosquito Indians to take us up the river in canoes. It’s rough country. What say if I go alone?”

The three young fellows shook their heads violently, thus indicating how much they trusted him.

Mr. Gray, also, shook his head.

“I will have to take time to think this over very seriously,” he said. “I am too old and weak to brave the dangers of such a trip. I can’t let you lads go alone, or with Mr. Morgan——”

“Just call me ‘Hen’—the ‘Hen that lays the golden eggs!’”

“Or with ‘Hen,’” smiled Mr. Gray, “but——” And there he stopped.

Their mounts were unsaddled and they stayed on overnight because of the new development. But after an evening of eager discussion, with urgent pleas for action by the youths and hesitancy on the part of Mr. Gray, their course of action was still undecided. Leaving Morgan with a promise to “get in touch” the minute they made a plan, they rode slowly away down the trail the next day.

“I wish Mr. Gray would let us go ‘on our own,’” Nicky said wistfully.

“He feels that there are a lot of holes in Henry’s story,” said Cliff. “We looked at the trail, and how any half dozen burros and their load of gold could get away in ten minutes is more than he can understand. And, if he was ‘fired’ from the mine, why is he there?”

“Those things are easy to explain, I think,” Tom stated. “About the burros—I asked him and he said he guessed his former friend must have unloaded them and dropped the gold sacks over the cliffs or into some hole and covered it up and turned the burros loose, or drove them into the chasm up the trail. He came to work at the mine again when the new superintendent was employed there, and that was natural because the new man did not know him or his record.”

“That makes it sound better, but there are still funny points,” Cliff replied.

“Well,” said Tom, suddenly squaring his shoulders, “Cliff, you know how anxious you were to leave no stone unturned when you were trying to learn about your father!”

“I don’t want to leave any stone unturned in this case, either,” agreed his chum, and Nicky nodded emphatically.

“Nor I,” said Tom. “And there is one stone I know about that I am going to turn as soon as we reach Mexico City again!”

What it was he kept to himself.

The next ten days were dull ones for the Mystery Boys. Mexico was in a state of excitement, due to the approach of the Presidential election; and, while the revolutionary times were gone and a more orderly election would take place, there were some excitable spirits in the city whose outbreaks made it unwise for the youths to go out on the streets too often.

Cliff was busy enough for he worked with his father: Mr. Gray was working on a theory that all of the Indian tribes from North America, through Mexico, Central America, Venezuela and down to Peru, were offshoots of the same original migration from some other continent, many centuries before the white people discovered the new continents. He was writing a book about that migration, and his work in Mexico dealt with studies of the old Toltecs, who preceded the establishing of the Aztec empire.

It surprised the youths to learn how closely the Toltecs, and the Aztecs later, were allied with the Incas of Peru in certain ways: both were agriculturists of a high order, as were the Texcucans, kindred with the Azteca. But there was a great contrast in the nature of the people; while the Incas had been a mild people, ruling kindly, punishing justly, fighting only for a necessary cause, the Aztecs had been a fierce, cruel, actually brutal people, even giving the name of their war god, Mexitli, to their land in the corrupted form, Mexico.

Mr. Gray was anxious to fill in many gaps in his history by studying the life and customs and legends of the host of Central American tribes, the Mayas, the Chocos, the Mosquito and Talamanca tribes, as well as the Goajiras, the San Blas, and others.

But he hesitated, although the adventure offered in Henry Morgan’s proposal would give him close contact with some of the natives of at least one section—Spanish Honduras. The tribes were all rough, rather fierce, very primitive; and he was aged, as well as having been weakened, during his stay among the Incas. Nevertheless, had he seen a way, he would have gone into the adventure.

Nicky, staying rather idly in their hotel with Tom, was glum. He craved excitement; not only was he active and impulsive, but he was adventure-loving, athletic and quick, and he liked to go into strange places and meet new situations. Also Nicky sympathized keenly with Tom over the loss of the latter’s sister, and the uncertainty of her fate.

Tom, for his part, most eager of all to go to the Mosquito country and learn what could be learned about Margery, did not seem nearly as despondent as Nicky, nor was he as busy as Cliff; yet he seemed able to wear a confident air which puzzled both of his comrades.

Nicky sat with Tom in their hotel room, chafing at his long inactivity. Tom was busy going over some books which Cliff’s father had found for him in the public library.

“Here’s a funny one,” he exclaimed, indicating a passage in the book he held. “One explorer was down in the Central Americas, and because it is so rainy at times he had a mackintosh. Do you know, Nicky, that mackintosh gave him more trouble than anything else, because when the Indians saw him wearing it, as he came toward their villages on the river in his canoe, they thought he was a priest, and because some priests had sometimes been harsh in trying to compel the Indians to adopt their creeds, the Indians all ran and hid and this explorer couldn’t get any pictures of them or any stories.”

Nicky smiled forlornly. Cliff, coming in, with his father, saw Tom with a grin on his face and his companion looking glum.

“I wish I knew what makes Tom so joyful,” Cliff said. “Tom, why don’t you be a good fellow and tell your chums what you know that makes you feel so good. Is it that telegram you got last Saturday?”

Tom grinned with a touch of malice.

“Maybe,” he admitted.

“Say, look here!” burst out Nicky, “you’re not acting fairly to the Mystery Boys’ order. You are keeping a secret.”

“No,” Tom answered, grinning still more, “I’m simply living up to our oath—with a vengeance. ‘Telling all, I tell nothing; Seeing All, I see nothing, Knowing All, I know nothing!’” he quoted their oath of allegiance.

“Father, do you know what it is that he knows?” Cliff appealed to Mr. Gray who smilingly shook his head.

“Well, I’m going to shake it out of him,” cried Cliff. “Come on, Nicky.” The two attacked Tom with gusto, letting off some of their pent-up “steam” in an old-fashioned tussle that boded ill for the hotel furniture. Mr. Gray, only watchful lest they harm any of his old records, let them have their fun. Panting and laughing, at last they gave up, still none the wiser. A knock on the door panels halted their fun.

“Tom,” said Mr. Gray, turning from a brief conversation at the door, “There is a gentleman in the office asking for you.”

“A gentleman?” cried Nicky. “Who is it?”

“Have him come on up, please, sir,” begged Tom, and then turned his back deliberately on his companions while he stared out of the window; but Cliff, watching, saw his shoulders shaking.

Tom expected this arrival! Who could it be? The door opened. With a simultaneous shout three youths launched themselves toward the tall, thin, lank figure that appeared.

“Bill—‘quipu’ Bill!”

They grabbed him: they pawed him; they pounded him.

Bill Saunders had been prospecting in the Peruvian Andes at the time that Cliff had gone to try to discover if his father was still alive among a hidden Inca tribe in the cordilleras. Bill had taken active part in their adventures. After the successful end of the trip he had, with his share of money paid him by Mr. Gray, bought a Texas ranch. The youths heard from him often. Now, here he was.

“What are you doing here—how did you know——” Nicky began. Then he turned suddenly on Tom.

“So that’s why you ran off by yourself to telegraph when we got back to the city, and that’s why you wouldn’t tell us what was in the telegram you got!” he accused. “You sent for Bill.”

“I told you at the mine, I would leave no stone unturned to get news of Margery,” Tom admitted. “I said I knew one stone I’d turn.”

“And I guess I was it,” grinned Bill Saunders, depositing his long length in a chair. “Your telegram hit me just in time. I don’t know your mind and you don’t know mine, but if there’s any chance for a rolling stone to gather a little more moss, here’s the stone, all ready to roll. Cow-raisin’ is not very profitable, just now, and my bank book could stand a little more fattening. I never did—and I never will—forgive you fellows for leaving me out when you found the Captain Kidd treasure—and me a full-fledged member, paying dues and all, in the Mystery Boys.”

“We got ourselves into that adventure so fast that we didn’t have time to send word or even to think about you,” Tom admitted, with some regret, for Bill was a good companion on adventure trails, and he was, as he said, a regular member of their order since they had initiated him during their Inca experience.

“Well, give me the adventure, this time, anyhow,” urged Bill.

“And maybe some gold, too,” supplemented Cliff.

Then Tom related the story of their mine adventure and Henry Morgan’s tale.

To say that Bill was intrigued and eager would put it mildly. The ranch life had begun to grow tame to him: he loved adventure for its own sake, and for its thrills, as did Nicky. He began planning a trip without a delay.

Of course Mr. Gray’s last objection was removed. He had good reason to know and to trust Bill Sanders, and he did both to the full.

“I wasted no time,” Bill said. “I hopped my cayuse and galloped for the railroad, leaving my top hand in charge: but while I was laying over in a Texas town I got a long-distance telephone call in to a chum of mine in Galveston, asking if he had that cruising boat of his that he used to take me on hunting trips in. He did. We can charter it. It’s got an engine. Lots of cabin and storage room. It can go up pretty shallow rivers. It’s just what we need to go on an exploring trip.”

“You wasted no time,” said Mr. Gray. “You took it for granted that you and the boys would go.”

“That’s Bill!” praised Tom. “My telegram told him enough to get him started. I thought I’d better break a trail—we seemed to be stuck down here in this old hotel.”

His comrades praised his idea of summoning their former comrade. The very next day Bill and Tom returned to the mine, found Henry Morgan and had a talk. Bill asked some pretty sharp questions, but “Hen” gave satisfying replies and Bill arranged with him to return to Mexico City with them at once. This he did.

It seemed no time at all until the trim, staunch cruiser Porto Bello was in harbor, with the chums, Bill and Henry aboard, well supplied. with gasoline, both in her tanks and in five gallon reserve cans, and with plenty of tinned food, as well as some arms and ammunition aboard. They waited only for Mr. Gray who had determined to become a passenger. He could explore the coast, he said, and if any real information could be gleaned he was determined to secure it. He had as much enthusiasm for his historical records as the chums had for Tom’s quest, or Henry Morgan and Bill for news of the mine—the one Henry’s unnamed friend called “The Golden Sun.”

“Anchor a-weigh!” cried Nicky, when Mr. Gray came aboard with clearance papers from the port authorities. “Man the capstan, me bully boys!”

“Man it yourself,” laughed Cliff, working with his chum at the small winch forward which drew the cable: they had been off on a trial spin to see that the engine worked perfectly, and had dropped anchor a little away from the wharves. “To be nearer being somewhere else,” as Nicky put it.

“Full speed ahead, Andy,” called Bill, already elected Captain by unanimous consent. The engineer, who accompanied the cruiser to help and to represent his employer, the boat’s owner, eased his throttle forward, and engaged the clutch sending the propeller around in the proper direction. The bow parted the waters of the bay, and with caps waving, and hurrah after hurrah, Tom, Nicky and Cliff stood on the after deck and watched Mexico’s humid, sweltering coastline drop away aft.

“Lay your course for the Golden Sun!” begged Nicky.

“And the mystery man of Hen-ry Mo-r-r-r-gan!” chanted Cliff.

“And news of Margery!” added Tom, soberly, but hopefully.

Out into the sparkling waters of the Gulf of Mexico the sturdy cruiser, Porto Bello, ploughed her way. Laying her course in a quartering slant, partly South and partly East, Bill Sanders, who was agreed by all to be in command, shaped up a plan to round the nose of Yucatan, passing between it and the more Eastward island of Cuba.

There they turned South, and giving the reefy, island studded coast of Yucatan a wide berth because of the jagged rocky formation and the heavy surf close to shore, they forged steadily ahead. Their boat was not fast, but she was steady in heavy seas and had a good reserve of power in her heavy motor.

Henry Morgan knew the coast line very well, and Bill often consulted his judgment. They did not try to make landings or lie-to during the nights, preferring to hold on their course, well out in deep water, for every one on board was anxious to get to the coast of Honduras as quickly as possible. Tom and Nicky supplemented the work of Bill and of Henry as deckhands and sailors, watching and keeping everything clean and ship-shape. Cliff, who had a good deal of mechanical ability, soon made himself indispensable to Joe Anderson, the engineer, who was a quiet, rather moody Scotchman. The boys, without any intention of disrespect, promptly named him “Andy.” He accepted the new name without comment and, commandeering Cliff’s services in the engine room, soon had as clever an assistant as he could desire, although he gave few signs of his inward appreciation. Mr. Gray spent most of his time arranging the numerous glass beads and other tawdry, cheap ornaments and fancy trifles which would be very dear to the untutored Indians and would serve as trade items and presents to the chiefs of various tribes. The youths made a gay jaunt of their trip.

There was only one thing that clouded their delight: that was the misconduct of Henry Morgan.

“I don’t like the way Henry does, very much,” Tom confided to his two chums, as they rubbed up the brass work in the small wheelhouse, while Tom held the wheel, giving and taking a spoke or two as the little vessel felt the heavy surge of the Caribbean swells, rolling in great, lifting pulsations from the East, and heeled under the strong thrust of the trade wind. “Almost as soon as we left port I caught him with a bottle——”

“I know,” broke in Nicky. “He told me it was a ‘Mexican Tonic’ to keep him from being seasick.”

“But we know better,” Cliff spoke the thought in all three minds.

“Listen to him, now,” Tom said, disgustedly.

From the after deck came a strident, but husky roar:

“For, I’m a buccaneer, oh,

A rowdy-dowdy Buccaneer.

I cuts ’em down and I shoots ’em down

’Cause why?—I’m a buc—ca—nee-e-e-e-e-r!”

“Buccaneer, my hat!” said Tom, “Bill,” to their clean-living, high-principled friend as he sauntered to the doorway of the steering room, “Why don’t you throw Hen’s ‘Mexican Tonic’ overboard?”

“I can’t find it,” Bill said, “or I would, in a minute. We’re getting into Caribbean waters and it won’t be long before we are in among the tricky rocks. We have to steer down through the Gulf of Honduras and pick up the reefs outside the Rio Patuca, and that is no place to be ‘half-seas-over,’ let me tell you. Henry knows the course and he can navigate pretty well when he’s ‘straight’ but I don’t like him in his present condition——”

“——A rowdy-dowdy Buccane-e-e-e-er!” sang Henry.

“He’s a rowdy in his actions, and, goodness knows! he’s dowdy enough in his clothes and habits,” said Tom. “Nicky, why did you ever let him look at that book about pirates? He thinks he’s one.”

“I thought he would be interested, having a name the same as one of the most notorious pirates,” Nicky replied. “It isn’t the book that’s to blame, it’s the ‘Tonic.’”

“I’m going down in the cabin and have another good look,” Tom said, letting Bill take over the wheel, and indicating the course as Henry had last given it to him. “Cliff’s father is very nervous about Henry but he says not to argue with him, but to make the best of it.”

He did not find anything: Henry, whatever his failings, was of a cunning nature when it came to his own desires and he seemed to know of places on the boat that the chums could never think of. As Tom searched, he felt the boat rising and falling more violently, and lurching in a half-roll, half-plunge that was not very pleasant. The cabin was stuffy and close, and he opened the portholes, wrinkling his nose at the unpleasant odor in the small space; but a dash of salt spray flung itself in his face and hastily he closed the small brass-bound port glasses and fastened them securely, then went on deck, clinging to the companion rail to avoid being thrown down.

“She’s blowing up for a storm,” said Henry, clinging to the port rail as Tom came into view, and lurching wildly. “We’re due for a storm, my hearty! Oh—I’m a buc—buc——”

“You’d better stop being a ‘buc’ and get up to the wheel house,” Tom said snappishly. “Maybe the course ought to be changed.”

“What do I care?” Henry cried with a hoarse, choking guffaw. “Many’s the pirate has piled up on the rocks. ’Cause—— ’Cause Why? I’m a rowdy-dowdy buc—ca——”

Just then a comber, its green crest froth-flecked, reared its great top on their starboard quarter. “Look out!” yelled Tom. “Grab something!” for Henry was starting in a lurching gait toward the enclosed cabin companionway.

Tom, himself, caught a stanchion and clung, holding his breath. The Porto Bello lurched and staggered under the impact of a huge wave, and there came a gurgling yell, cut short, the surge of powerfully dragging water rushing at Tom.

Before it struck, almost burying him, tugging at his arms, he saw Henry meet the wave, spinning around in a mad, fruitless effort to clutch at the cabin coaming.

Down went Henry, and along the deck he was washed by the wave. Tom, at the risk of being himself torn loose and washed away, released one hand. He made a swift, reaching grab. His fingers caught Henry’s coat, in the surging inferno of water that swung along the deck. It seemed as though his arm would be torn from its socket: his face was stung and flailed by spume and great gouts of hard-flung water.

He braced and clung as the washing water swung Henry along: the check of his clutch slowed Henry’s body and Tom’s arms ached with the pull. He dared not let go until the wave should pass. Henry, caught off his guard, and with his brain befuddled, was helpless.

Came the thud of the companion door as Mr. Gray slammed it shut in bare time to prevent the cabin from being inundated.

From the wheelhouse door, now beyond the higher wash of the receding water, Bill leaped, with Cliff at his heels, Nicky clinging madly to the spokes of the wheel and fighting to hold the cruiser on her way, nose to wind and wave.

Gripping every foot and hand hold, Bill and Cliff fought through the swirl of water, while Tom clung grimly. The water receded and Henry was dumped, inert and gasping, onto the deck just as the hold Tom had was broken by the strain. Swiftly Bill grasped Henry’s shoulder and began to drag him toward the cabin companionway, while Cliff caught Tom and steadied him.

Another huge wave was rearing its white curl to the quarter. In the wheelhouse Nicky, a little frightened at his responsibility, and yet manfully rising to the occasion, knew that the boat must not be allowed to pay off so that she would catch the waves on her side—she would be rolled over, and over. He bore with his whole weight on the spokes, holding the rudder hard over as the valiant craft struggled against the rush of waters and the roar of the swiftly rising wind.

With Cliff aiding him, while Bill dragged at the gasping Henry, Tom got to the cabin. His father opened the door, and all three grasped Henry and fairly flung him in through the door and down the several steps. Then in they plunged, and just in time to close the door before the tumult of water was over the decks again.

The brave little vessel shuddered and groaned under the water, and Nicky said a little prayer for strength to hold the wheel against his enemies of wave and rushing air. Tom sputtered and got rid of some water he had taken in, while Henry, sitting up, gulping and choking, began to thank him.

“You saved my—” he began.

Totally unconscious that he was taking the command, or that his words rang with the authority of anger and just censure, Tom cried, “Never mind. Get yourself together and get to that wheel. Nicky’s alone there. Joe’s calling. Cliff, go help Joe. Bill, you drag this Henry up to that wheel and stand over him. Cliff’s father is battening down the ports. We’re all safe inside, but we don’t know what’s going to happen. Get going, you Henry!”

As if every one of them recognized the voice of command, Bill caught Henry’s collar and almost yanked him to his feet. Henry, sobered and now beginning to recover himself, and with the just rebuke and the evident menace of their position clearing his mind, obediently staggered along with Bill, while Cliff raced past them on the other side of the churning, coughing engine, to help Joe.

“What will you do, Tom?” asked Mr. Gray, thrusting home a heavy steel bar across the companion door, although, being aft, it was not subjected to the crushing force of the waves.

“I’ll find that Henry Morgan’s ‘tonic,’ if it’s my last act!” cried Tom and began flinging things out of the lazarette, or storage cubby in the floor, where their food was kept.

He had no success there, but he began on the bunks lining the sides of the long, low, narrow cabin, at whose forward end was the wheel, with the engines just a little aft of amidships.

Still the storm, sudden and furious, mounted in ferocity. The vessel plunged and reared, rolled and twisted; her timbers creaked and her decks echoed to the roar and thunder of waves. Cliff and “Andy” stuck, one on either side of the motor, oiling, wiping, Andy watching the gasoline pressure glass, and the oil flow, Cliff jumping, clinging to the bunks, to bring a rag, or to steady Andy while he made an adjustment of the carbureter to compensate for the slight and occasional “miss” in one cylinder.

Forward, Bill, Nicky and Henry clung to the wheel, all swinging together at Henry’s order, or releasing a spoke or two to pay off for more way between the great, onrushing combers.

“Are we close in, yet?” gasped Nicky, half out of breath.

“No,” said Henry, between his teeth. “I’m going to swing her around if I can get steerage way in some minute when it’s quieter—we’d better run before it—but I das’sent try now—’cause why? She’d roll like a barrel and maybe dive under!”

“A drop of oil on that propeller shaft bearing,” shouted Andy to Cliff.

“Right!” cried Cliff, above the thud of water and the groan of the timbers and the thrashing pulsation of the propeller, racing as it was lifted from the surging water. “Ease her when she races, Andy,” but he knew that Andy did so before his young aide spoke.

“If we could get a chance to swing her around,” choked out Henry, a thoroughly sober and frightened man.

“Hold her as she is,” Nicky urged. “It’s too wild to turn here!”

“I’ve found it!” exulted Tom, rising from an old airtight waste can, bolted down aft of the engine; it had been filled with oily waste and old wiping rags, and he had found, at the bottom, the bottles Henry had concealed there. “Mr. Gray—don’t say a word. I’ll put them back until this storm blows by and then I’ll break them on the rocks when we get in to shore.”

With the suddenness which characterizes tropical storms of certain sorts, less than hurricanes, the wind began to drop, and soon to fall to the steady trade wind velocity, while the clouds broke, the rain squalls ceased, blue sky appeared, and only the lifting heave of the turbulent Caribbean remained of the time of stress. They all breathed a sigh of relief; but the respite was brief.

“We’re closer in than I thought!” shouted Henry, at the wheel. “Quick, somebody, get forward with the lead. Half-speed, Andy! We may be close on a reef!”

Tom flung aside the brace of the after door, and with Nicky at his side, leaped on deck while Mr. Gray closed the door. Bill was already out of the side door to port, while Andy and Cliff stood by their engine.

“Reverse—back water!” cried Henry. “We’ve got to fight her off the shore and stand off and on until we can see what we’re doing.”

At the same minute came an agonized cry from Tom.

“Port—port—hard a-port! Rocks dead ahead!”

Henry flung his weight on the small wheel. Over it swung.

Before their bow, disclosed by an onrushing comber which had obscured them, great black fangs of rock held their bared teeth in readiness to crunch joyously, grimly, as the Porto Bello staggered and strove to claw around!

Gleaming and flashing like the huge tusks of a water wolf, waiting, submerged, to gnash upon the defenseless cruiser, Tom saw the rocks, great needles of terror, for only an instant. Then a great, great, green-blue wave lifted between his straining eyes and the danger.

The wave swept on, while under their keel, another equally huge mass of water bellied up and flung the boat aloft on its surface.

Slowly the bow swung. The next glimpse Tom caught of the menace, it was off to port—but did a range of submerged reefs extend far across their path? Tom pointed out the threat to Bill and Nicky. They gasped, so close was the nearer of the needles.

All along the coast of Central America these reefs and islands, huge barrier reefs, wide, low-lying circle reefs, atolls enclosing tiny islets—all are a menace to navigation, and it is a skillful pilot who will try to take a boat in among them.

Henry Morgan was not a skillful pilot, but he had been through the barriers about the Rio Patuca mouth many times and he felt sure of his ability, coupled with an abiding faith in his “luck.”

But just after a storm, and with the seas even more wild than was their usual turbulent state, the task of getting through the reefs was one to whiten his face and shake his very marrow. Bill, looking back, saw his face of terror and, with a word to the boys, scrambled to the cabin and snatched the wheel from fingers already nerveless with fear. But the boat had paid off, the signal for full speed ahead had been obeyed, the steerageway, aided by the surge and force of the waves, had enabled them to turn aside. They swept over the first barrier on a huge swinging crest, seeing, through the clear water, that the jaws of rock seemed to gnash in fury at the loss of their prey. Tom and Nicky, gripping the capstan with one hand each, clutched one another with the other, clinging in tense, breathless waiting.

But the boat did not strike. She missed the rocks by almost a miracle. Had Henry kept his senses earlier in the voyage he would hardly have exposed them to such peril. For it was not over; it had scarcely begun!

“It isn’t only the rocks,” Nicky shrilled. “It’s—sharks!”

“Keep still,” Tom called back, squeezing Nicky’s arm reassuringly. “Watch to the fore and on your side.”

Nicky’s eyes were fixed on the swirl in the water just ahead, and on the triangular black fin to port than on his duty, and it was fortunate that no rock loomed near his post; the sharks were gathering with seemingly uncanny instinct, waiting—waiting—waiting!

Bill, once the menace of the outer reef was passed, swung the bow down the coast, and because the most powerful thrust of the waves had been subdued, although they still were big enough to roll the cruiser sickeningly, they were able to make headway, always fighting outward a few points to overcome the inswing of the water.

Along the coast Tom and Nicky could see low, sandy stretches of beach, under the broil of the sun, now full out and very hot; beyond the wide strips of sand there were dense, tangled masses of jungle, and even in the cleared air after the storm they could scent that queer, fetid odor of decaying vegetation and mold which is characteristic of the tropics. Far in the distance, landward, back of sand and jungle, bluish mountains loomed.

“Where are we heading for?” Nicky wondered, and Tom shook his head. “I hope Henry knows,” he replied. “I don’t see any opening.”

Nor, at the moment, did Henry, who, thoroughly subdued, but with a remnant of his former manhood forcing him to steel his nerves to save his own precious life, and theirs, came forward and stood, eyes roving the shore and the waters.

“What are those big waves?” Nicky asked, pointing shoreward.

“Shifting sand banks,” Henry replied huskily. “They always change. If we once get aground there, the waves would pound the boat to a pulp! And—the—” He felt a kick from Tom, and, with a glance of surprise, saw Tom’s eyes warning him not to frighten Nicky.

Tom, himself no coward, had sometimes yielded to a nameless dread of things unseen, but any visible danger tightened his muscles to their athletic perfection, settled his nerves and steadied his whole body to its dominating mind’s demands. He knew Nicky was not a coward, but he also knew that for anybody’s mind to settle on fear and think about it and worry about it, made them helpless when the need for action came.

For once Henry took a hint.

Cliff, with the tense moment at the engines over, came on deck and joined his chums for a breath of the heated, but fresher air.

“Those are shifting sandbanks,” Tom explained, pointing. “We are hunting for the channel.”

“There’s Brower’s Inlet, that place inshore,” Henry said. “Now, form a line to pass word quick to Bill how to steer, and you, Cliff, be by the engine room port to call directions—we’ll try for the shore—but I don’t guarantee—” Tom kicked his shins again and Henry, scowling, became still and intent.

Suddenly, peering hard, Henry called his orders and the chums relayed them.

“Swing her head to that swirl of water.”

Around came the bow till the wind was from directly aft.

“Full speed ahead!” And the engine picked up its heavy thud.

“Ease her off a point to port. Slow down to quarter speed.”

Toward land the great rollers, muddy and moiled, rose into swirling lines of dirty foam, then drew off to the shore.

Seaward, greater combers reared their heads and growled their fury that they had not succeeded in flinging these daring people onto their fang-like reefs.

There was a moment of silence—of quiet.

Then came a sort of sighing, from the waves, as the Porto Bello swung her nose among them. She rose up over a wave, then settled; there came a trembling and a dragging as the bottom grated on the sand. She wrenched and tore herself free, like a living thing striving to help her friends at wheel and engine.

A great wave came rolling, its speed seeming to threaten that it would roar down upon the boat, her own speed diminished by the friction of her keel.

“We’re—we’re—” Henry began.

“No we’re not! We’re off!” shrilled Tom as the wave caught up to them and the Porto Bello, with a staggering effort, let herself be swung up into the cradling arms of the mighty water.

She staggered on; she lost the supporting force of the water and sunk down on one side; once again—and ever again for what seemed an eternity, she was lifted, borne forward, slumped down to roar and grind along the sand, or to lie, like a stricken thing, on her bulging side, the sole thing that kept her from turning over.

Bill did noble work, with Cliff again at his side, at the wheel, while Nicky and Tom stood by at the bows, one with the lead held ready if they ever got through this moiling mud and spume.

Came a wave, the greatest yet, as the Porto Bello was dumped on the sand. Crash! while they all grabbed and clung to stanchions with all their strength a huge swirl of muddied water swept over them. They emerged, gasping and coughing—came another grinding, forward movement—and then, like a tired bird, safe at last in her nest, the cruiser slid over the last sand of the bar and into quiet water where, as her engine slowed, she rocked in a soft, gentle swell.

“Phew!” coughed Bill, poking out a porthole glass, and sticking his head out through the opening. “That was——”

“Stand by!” shouted Henry, wildly. “We’re in a current running back out to sea like a torrent—get her around—get her around—hard a-starboar—no, hard a——”

Simultaneously he broke off his calls and stared ahead as if chained to the spot, speechless. Tom and Nicky, staring too, stiffened.

Out from the sand protruded needles of rock, with swirling water and roiling sand partly concealing the black doom!

“Back water!” yelled Cliff. “Swing her off!”

“No—forward—full speed ahead!” cried Nicky.

Henry had sunk down and covered his eyes from the vision of the black-finned monsters congregating in the muddy waters—sharks!

Bill had the tiller ropes roaring in their channel, for he had paid no heed to the conflicting orders but, with a little prayer of devout trust that he did not mention later, he stood, gripping the spokes.

The boat had lost way, and swung sideways across the rushing water. Tom saw what was coming. Instantly he snatched loose a life preserver! Not to leap and save his life. To save all of them!

He bent low, hanging over the bow, dropping the preserver so that it met the rock, was between it and the boat as she touched.

She shuddered, and there was a crunch, but no smash. Madly yelling for full speed astern, Bill pawed his wheel over; the boat hesitated, her back-lashed propeller striving against the stream; slowly she receded from the rocks. Tom released his clutch on the preserver rope; from aft came the grind and shiver of sickening contact; the engine grated to a stop with a jar and a cough. The boat shuddered, ran forward again in the current.

“The propeller hit!” shouted Cliff, from the after deck, staring overside at a wicked fang, seeming to lick its glistening lips at him.

“It’s probably bent beyond help!” called Andy, from the engine. “The gears in the shift box are stripped. When the propeller caught it tore the gear teeth off—lucky it didn’t crack the crankshaft!”

“But we have no power,” ruefully Bill called.

There was no use for it, had they possessed it. With the strong outsweep of the water, and with a low, sandy spit jutting before them, there was nothing to be done but wait.

Gently, almost at the inlet, the Porto Bello lifted her nose on a swell, and poked it experimentally into the sand.

She liked the soft bed, burrowed forward on the next low swell, and then settled down, like a baby in its cradle.

“We may thank goodness for being here,” cried Tom. “It’s not so bad!”

“Not so bad—to be stranded?” demurred Cliff.

“Better here than—out there!” Tom waved his arm toward the roaring surf of the outer reef.

“Yes,” Nicky agreed, then, ruefully, he added, “but we’re stranded!”

“Unless it’s quicksand, we’re all right,” Tom declared. “When it’s low tide we can examine the propeller.”

“But how can we get off?” urged Nicky.

“Let’s take one thing at a time—and take it as it comes!” said Tom. And Mr. Gray, somewhat shaken, but very calm, as well as Bill, agreed with Tom.

Notwithstanding the youthful efforts to be optimistic, the Porto Bello’s position was bad. She lay with her stern in deeper, swift water. Sharks and the rapid flow of the tide made it impossible to get under her stern to examine the propeller. They had spare parts, and would be able to repair the stripped gearing, or, at least, to render the clutch and shifts possible to use by substituting new gears. But the damage to the propeller must be estimated.

“My idea,” said Tom, with proper diffidence, when the entire party discussed the situation while they ate the dinner Bill prepared, “my idea would be to get a rope over to those snags of rock, put pulleys fore and aft on the top of the cabin, reave a rope through them, run it to the capstan, forward, then carry it out to the snags, fasten it, and then, steadily take up on it with the winch. The pull would work on the whole boat that way, and if we moved most of our stuff aft and lightened the bow, she might drag off.”

“How would we get a line to those snags—across that deep water?” objected Henry. “I, for one, won’t risk those sharks! They say they don’t trouble the Indians, or Negroes, but white men are different.”

“Probably Indians will come out in canoes,” Tom said hopefully.

This prediction proved true, but not until the next morning; then a canoe containing two stolid Mosquito Indians came out. They wore ragged trousers and shirts worn outside the trousers, hanging down, and their dark faces were almost as expressionless as those of the North American Indians.

They paddled down the water near the stern, and coming into a small bight of water where the current was less violent, they sat still for almost an hour, staring fixedly and without answering a number of hails sent them by various ones.

Finally, however, they did respond. They spoke little, but seemed to comprehend a little English and a trifle more of Spanish. Henry Morgan, who was morose and angry about something, bellowed orders at them. Tom, who knew what made Henry sour, since Tom had already dropped several fat bottles into a swift eddy astern, remonstrated at his angry commands.

“They don’t like to be yelled at,” Tom said.

“You be still!” snapped Henry. “I guess I know how to handle these Indians. You’ve got to bellow and roar at them to get them started. They’re lazy and they’re rough and they’d never move if you don’t get them waked up.”

“They may be all that,” agreed Tom, “but they’re human, too!”

Henry walked away.

Nevertheless, Tom’s way proved the better one, for when Bill held up a flashing bit of ornamental glass, like the crystal pendant from a glass chandelier, they spoke. In time they were induced to catch a rope and carry it out and, in the canoe, fix it fast to a projecting tooth of rock located in the proper direction to help pull the boat out of her sand bed, into which she was burrowing her nose more deeply with every roll.

“We’ll use the rocks that tried to injure us, and make them help us!” Cliff cried, and with a good will they took up slack on the rope until it was taut and throbbing with its tension.

After a long day of effort and patience they saw their craft float free, and, for another bribe, several more Indians were procured, in canoes, to tow them to a convenient beach where their rope was taken well inland to a coco-palm, secured there, and the boat was unloaded the next day, the stuff piled on the hot sand under an improvised shelter of canvas stretched over four upright pieces of timber found by the chums in a search of the beach.

Under another shelter, to which they brought heavy mosquito netting and with it made a tight enclosure, they spent the night. It was no pleasant slumber that came to them, for the Central American mosquitos are not only vicious and persistent, but they are large and their bite, on any but the toughest skin, produces red welts and a sort of itching that is as maddening as it is persistent and painful.

The next day, while Bill and Henry bargained with the Indians for canoes and guides to take them up the Rio Patuca to a tribe further inland where the old Indian, Toosa, lived, and while Cliff and Mr. Gray aided Andy in work of examining the gear and shafting, Nicky joined Tom on the beach.

“Some of the Indians are going turtle hunting,” he said. “Let’s us go along. They’ll take us. I let one young Indian play with my watch, and he promised to take us if I let him wear the watch during the trip.”

They accordingly joined the Indians. The method of hunting was interesting: they went along the beach and, watching until they saw a turtle sunning itself, or, possibly, laying its eggs, they managed to get between it and the water.

Sometimes they were not adroit enough. A turtle will instinctively try for its native element, and once in it, no expert can capture it. On land, however, once headed off, it may be turned on its back, and thus secured. After several wasted tries they managed to get a big fellow, weighing several hundred pounds, headed off and surrounded.

It was both a job and a tussle to get the huge and clumsy shell reversed; and then the boys were amazed at the cleverness of the Indians’ method of getting the creature back to their village, or near to it. To drag such a weight would be very hard. To make it “do its own driving” as Tom said, was the easier way. The Indians fastened ropes to each of its flippers, and then turned it over.

With slackened ropes, the creature instantly drove for the water. But once it plunged into its favorite retreat, the ropes were manipulated in such a way that the animal was actually made to swim and, in addition, was pulled, along the shore line, with comparatively little effort. Once opposite the camp, the turtle was dragged onto the beach and despatched, to be cut into choice portions. For their efforts during the hunt, Tom and Nicky were given some large chunks of the meat which made a wonderful addition to eggs they had discovered, and their regular fare.

Days passed with little happening. Outside of the tedious work of dismantling the gear assembly, and taking out the propeller shaft and bearings to be certain that all was sound, and hammering at the propeller to get its bent flanges back to proper pitch, there was only eating, fighting mosquitos and other annoying insects, and trying to be patient.

In spite of, or, maybe, because of Henry’s shouts and orders, the Indians made no move to take the party upstream.

It was only when the combined arguments of Mr. Gray, Bill, Tom and his chums made Henry desist, that finally, after about ten days, the Indians signified that on the morrow two canoes would start.

“Bill, and Henry will go, of course,” said Mr. Gray. “Tom, I feel, has a right to be with them because of his intense interest in any news concerning his sister.”

“But Nicky is all bitten up with—or by—mosquitos,” said Cliff, “and he can’t risk getting away from the ointment jars—and I must help with the readjustment of the engine and stay with Andy and Dad.”