The Project Gutenberg EBook of Mary Louise Adopts a Soldier, by

L. Frank Baum and Emma Speed Sampson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Mary Louise Adopts a Soldier

Author: L. Frank Baum

Emma Speed Sampson

Illustrator: Joseph W. Wyckoff

Release Date: December 22, 2018 [EBook #58513]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MARY LOUISE ADOPTS A SOLDIER ***

Produced by Mary Glenn Krause and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The Bluebird Books

Mary Louise

Adopts a Soldier

By

Edith Van Dyne

Author of

“Mary Louise,” “Mary Louise in the Country,” “Mary

Louise Solves a Mystery,” “Mary Louise

and the Liberty Girls.”

Frontispiece by

Joseph W. Wyckoff

The Reilly & Lee Co.

Chicago

Copyright, 1919

by

The Reilly & Lee Co.

Made in U. S. A.

Mary Louise Adopts a Soldier

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Mary Louise Considers the Situation | 7 |

| II | Back Home | 13 |

| III | Danny Dexter | 23 |

| IV | Danny Changes His Uniform | 30 |

| V | Dorfield Girls | 39 |

| VI | A Mysterious Disappearance | 47 |

| VII | A Telegram | 56 |

| VIII | The Arrival of Josie O’Gorman | 62 |

| IX | The Man from Boston | 71 |

| X | Mary Louise Makes a Discovery | 79 |

| XI | The Empty Room | 87 |

| XII | Danny Disappears | 95 |

| XIII | Face to Face | 102 |

| XIV | The Search | 111 |

| XV | A Journey Begun | 117 |

| XVI | Aunt Sally Entertains | 124 |

| XVII | The Birthday Breakfast | 129 |

| XVIII | The Motor Trip | 136 |

| XIX | The Escape | 145 |

| XX | The Desert Bungalow | 150 |

| XXI | A Nest of Conspirators | 155 |

| XXII | The Cave | 167 |

| XXIII | The Ride at Night | 174 |

| XXIV | Mary Louise Loses Her Slipper | 181 |

| XXV | A Successful Ruse | 187 |

| XXVI | A Good Night’s Work | 196 |

| XXVII | On the Balcony | 217 |

“Grandpa Jim,” said Mary Louise one May morning as they sat together at the breakfast table, “I see the Dorfield Regiment is due to arrive home to-day or to-morrow.”

“So I see,” replied the old Colonel, “if we may rightly call it the ‘Dorfield’ Regiment. The newspapers don’t mention the fact, but it takes in the whole surrounding country, because there were not enough Dorfield boys to fill the ranks completely and so we took all who applied. I’m afraid you’ll find many unfamiliar faces among the ranks.”

“Still,” said the girl, “there will be some friends anyhow, and the very fact that this is the Dorfield Regiment should arouse our loyal enthusiasm. Why, I’ve followed them all through the war, and somehow this practice has almost8 made it seem that the whole Dorfield Regiment is a sort of personal possession.”

“I feel much the same way,” said Colonel Hathaway, composedly turning over the Dorfield Gazette. “This is not a delightful country to demobilize in—if we should judge by the Civil War, in which I was somewhat more interested. The regiment may not be free to disorganize for a week, or a month, according to the whim of the War Department.”

“But they’ll enjoy the recreation and the freedom from long marches even if they’re kept here a long time,” returned Mary Louise, “and their pay is the same as when at war. The boys who live here can visit their homes every day, and there may be only a few who come from any great distance. According to the papers, the Dorfield boys saw some real fighting in France.”

“Yes, but new faces in the line are likely to be few,” prophesied the Colonel. “Luckily, not many Dorfield boys lie buried in the French battlefields.”

“What will become of the new men, Grandpa Jim?” asked the girl.

“Well, they will either be furnished money to take them home—second class—or they may9 obtain positions in or near Dorfield. If there are not too many, they will all get positions here. Many of the merchants I have talked with are already grumbling because ‘help’ is scarce.”

“Let’s go down to the depot and see the trains come in,” suggested Mary Louise. “We’ve none of our kith and kin to greet, but some we know and can shake hands with. Besides, some of those substitutes may live far away and don’t know where to go. They may need friends, or a home, or may have been wounded, and have no one here to care for them. I’m sure we can be of use in some way. We are Dorfield’s own people and must show our appreciation of Dorfield’s own soldiers.”

The Colonel reflected for a time. “During the Civil War there wasn’t another Hathaway in the whole army,” he mused; “yet I had my duty to do, and did it. You know my utmost trial during the Great World War has been my inability to take part in it in any way. A soldier is a soldier always, and here I am on the back shelf unable to help my country in its day of need. Beside being outside of the age limit I haven’t a relative to take my place.” This had been the old gentleman’s grievance for many months. He fumbled10 with his cane a few moments and then said, “But get your automobile out, and we’ll go down and give the soldiers the welcome they deserve.”

“It’s too rainy and muddy for the auto to-day,” said Mary Louise, “and I don’t want to punish the dear little car by a mud bath. But we’ll take our umbrellas and try to find one of those substitutes who are stranded here, without friends or regular occupation, wondering what to do with themselves.”

“I hope, my dear, you have no such idea as taking one of those persons—what do you call the fellows?—‘substitutes,’ into our family, even as a servant?”

By servant the precise old gentleman had no reference in any way to a house-servant, as the house was fully cared for by Aunt Sally and Uncle Eben. To introduce a stranger into their domestic affairs was indeed preposterous. But Mary Louise understood him the moment he spoke. “Haven’t the soldier boys all been servants of our glorious country?” asked Mary Louise indignantly. “Yes,” he replied, “but they have come from all classes and sections, some of them gentlemen, or scholars, our equals in every way, while others have scarcely enough wit to bring in an11 armful of wood.” “Even then,” broke in the girl, addressing the aged but stalwart Colonel, “someone must bring in the wood, and it’s an important matter to my mind.” She laughed in her piquant, irresistible way. She continued: “You see, Grandpa Jim, we’ve found at least one good reason for helping the brave soldiers who have so lately fought for the country you fought for many years ago.” “You may be right,” said the old gentleman, “but we are a little premature in this argument, my dear; we only know that the Dorfield Regiment is coming home again, and we only guess that there will be one or more extra men to provide for. Indeed, there may be none at all, for all those big, sturdy fellows had lives to live before they joined the colors. Perhaps half a dozen may be left to find situations and boarding houses for; perhaps two or three are so situated, perhaps one. When all are mustered out and returned to the places from which they enlisted we may have none at all to care for,—and that is a likely probability.”

“True enough, I admit,” said the girl with a little laugh, “so let us patiently wait till the train is in and the boys are mustered out. Then we can tell what duties are required from the loyal citizens12 of dear old Dorfield. It isn’t a big city, nor did it have a very big regiment to send to the front, nor very many soldiers to fight European battles, so I suppose I am borrowing trouble unnecessarily. Anyhow before we start, as the saying is, let us ring the doorbell and see if anyone is at home.”

They put on their raincoats, and with umbrellas started out into the soggy, showery morning, for the drizzle had kept up nearly all the night before. “Even if we still had your old rattle-trap automobile which we exchanged for mine,” observed Mary Louise, “we’d have had hard work to make it go this morning.”

“It’s a shame,” said the old Colonel, as they started along the path, “to bring our soldiers home on such a rainy day. It ought to be a bright and sunny day of welcome.” “Still it’s their home, and they’ll be glad to get here under any circumstances,” asserted Mary Louise. “I think it’s raining harder than ever, Grandpa Jim.”

They were now where they could see the station, which seemed dull and deserted and the few people that were there seemed to be coming toward them. “I don’t believe the boys are coming to-day,” said the Colonel, “don’t you14 remember the paper said to-day or to-morrow?” “True,” added one of a group which had paused before them and knew the Colonel well, as all the earlier settlers did; “we’ll do better to get home where it is warm than hanging around here this miserable day. The weather would discourage any railroad train.” “That suits me,” said Mary Louise, and they started for home, chatting about the Dorfield men and discussing their usefulness.

There were no boys in “Grandpa Jim’s” family. He had had only one daughter who grew to delightful womanhood, married Judge Burrows, a prosperous lawyer, who died a few years later, leaving his baby girl—Mary Louise—to the care of his invalid wife and the staunch old grandfather.

Combining the two estates (the handsome old home belonged to the Hathaways), made a very pretty property for the young girl to inherit, and Mary Louise Burrows was known as the heiress of it all.

Colonel Hathaway naturally idolized this granddaughter, and it was from her baby lips that he first acquired the title of “Grandpa Jim,” which was cordially and affectionately followed by his15 many friends in the pretty but modest little city, where he was regarded as one of the two or three “leading citizens.”

Grandpa Jim’s wealth was sufficient for him to retire from any active business, so he passed his time in cheerful gossip with the other inhabitants and made many “travel trips” with Mary Louise, both in order to educate the young girl and relieve his own ennui.

The Great War had kept him at home during recent years, but he had read daily reports of its progress and talked them over with those of his acquaintances who were most interested in the fray.

He was also tremendously interested in the early education and career of his fascinating granddaughter, the more so after the child’s mother contracted a serious disease which carried her away from them forever.

So here were these two, a big old gentleman and a small young girl, located in one of the most prominent and attractive houses in Dorfield. Here they were, beloved by many but envied by none so far as they knew.

Mary Louise had many girl friends. Indeed, you might say every girl in the town claimed her16 friendship, for she was generous, bright, initiative and had a glad and loving word for every girl she met. Therefore it is no wonder that a lack of boys in the Hathaway family should create an added interest in the one girl of the establishment among the soldiers now returning from their victorious campaign. But the young girl did not know that.

On her side, Mary Louise had no cousins or other relatives, with whom she might intimately hobnob; Grandpa Jim’s male relatives were so remotely connected to him by blood that he could not name you one of them. But there were none in Dorfield—nor out of it—whose hearts were more overflowing with patriotic enthusiasm than this fine old war veteran and his charming granddaughter as they went down the hill the next morning toward the depot. As they passed along, the electric lamps in front of the station were still striving to penetrate the gray gloom of foggy moisture.

Grandpa Jim said in his cheery voice: “It’s another one of those wholly tantalizing mornings, Mary Louise, but that won’t dampen the joy of our soldiers at getting home again.”

“To be sure,” she replied, “so let us hope the17 trains will make up for lost time. Good gracious, Grandpa Jim,” pausing abruptly to peer ahead, “they’re in now!” for her eyes were sharper than those of the Colonel.

She ran on a few steps in excitement, but then, remembering that in the semi-darkness she was her “Grandpa Jim’s cane,” she abated her pace and went back to take his arm.

“It won’t matter, child,” he said, laughing lightly; “we’re not specially interested in those aboard, and they’ve all got to march over to their old cantonment before they are disbanded. But we have the right to shake hands with them.”

“We can say: ‘Hello, Bill!’ anyhow, if we see anyone we used to know,” said Mary Louise, and even the old Colonel was interested enough to hurry forward to join the throng of soldiers who had traveled all the way to France to prove that they were real warriors.

Mary Louise had many humble acquaintances among the throng which moved in well drilled ranks from the depot to the cantonment—a matter of half a mile or so, and she nodded briskly here and there at “the boys,” who flushed and threw out their chests proudly as they formed ranks.

18 A few of the young men were “calling acquaintances,” and these were especially honored by the beautiful girl’s attention.

“Take it easy, my dear,” puffed Grandpa Jim, as he clung to the arm of Mary Louise on the slippery pathway. “They’re marching faster than we can walk, and they’re still covered with the dust and grime of travel. Look down there at the cantonment! The places where they used to pitch their tents are nothing but mud holes. I doubt if our soldiers under present circumstances are as glad to see us as we are to see them. Let’s go home.”

Mary Louise in her heart knew that he was right, but her tone was somewhat peevish when she answered:

“If everyone felt as we do, it would be a nice reception for our soldier boys, wouldn’t it—with just ‘poodle-ground’ to greet them? The earnest shouts of those who are here must carry joy to the hearts of those who have braved many a storm to drive back the Germans, and we must prove we’re as loyal and brave as our men.” Thoroughly in earnest, the beautiful girl continued: “For my part, I’m really enjoying it all, Gran’pa Jim, and—Hello, Ned Clary!” waving her handkerchief19 and nodding smilingly as they reached the beginning of the cantonment, which was now a very busy place.

The girl gazed with interest upon the mud-stained uniforms. But the soldiers themselves received the most of her attention. Their faces were most attractive to her, and she scanned them as closely as if really looking for some relative. Those who worked, worked quietly and doggedly, having performed such duties many times. Others looked on, smoking their cigarettes indifferently. Still others sat upon the stone curbing and waited nonchalantly until something should happen that might prove more interesting.

Mingled with these were all classes of citizens of Dorfield, and suddenly Mary Louise cried out:

“Oh, Laura Hilton! Where on earth did you come from?” as if she had not known that the other girl had followed or preceded her down the hill.

“Me?” answered Laura, as if in amazement; “why, I just came down to see if Cousin Will was in this division. He said in his last letter that he would be home next week; but they may have pushed him on ahead, you know. Cousin Will is a big man—you’ll remember—wherever he happens20 to be. At war he is a Sergeant—or a Corporal—or some such genius, I’ve heard, yet somehow he doesn’t seem to have his own way quite as much as when at home, clerking in the corner grocery store. He says he had one boss in civilian life; in the army, he has a dozen.”

“Well,” said Mary Louise, taking her arm confidentially, “that was only Cousin Will’s banter, you know. No one ever believed in him and I doubt if he ever believed in himself. I am glad he is coming home with a whole skin anyhow, and I wish all our poor boys were as safe to-day as he is.”

“Well,” responded Laura, “neither you nor I can claim any of the Dorfield boys, and yet it’s some satisfaction to see them coming home from that long journey across the seas and know that they have fought for us and died for us—whenever such foolish sacrifice was required.”

“Oh, Laura!” exclaimed Mary Louise, reprovingly. “Do you think it was foolishness to save all our lives—to make the world safe for democracy?”

“Don’t let us argue concerning politics,” said the other girl with a shy shrug. “I am not much posted on such things, as you very well know.”

21 “You belong to the Liberty Girls, though,” said Mary Louise.

“Oh, as for that,” said Laura, “I will do anything I can for my country and its warriors, and the only reason I am not more interested in the return home of the Dorfield Regiment is that none of my flesh and blood is mixed up in it.”

“Then what are you down here for?” inquired Mary Louise.

“Just to watch these men greet their own friends, who must be supremely proud of their work and anxious to see them safely home. They have had some rather severe scrapping over there, I believe, and according to all reports there has not been a shirker or a coward in the whole lot of them. No wonder everybody has turned out to give them an enthusiastic reception! Just look at the number of mothers and fathers and whole families here to welcome their own back! It’s hard to tell who is enjoying it most—the soldier boys who have come back, or their families who have awaited them so long. But why are you here, Mary Louise?”

“Why, for almost the same reason. There has been a hint that some soldiers from other parts of the country have been transferred to the Dorfield22 Regiment, to take the places of those who have fallen in the various battles. Grandpa Jim has an idea that some of these strangers may need work or a home after they are mustered out.”

“How can we tell who are the strangers and who are not?” asked Laura.

“Why—why—by watching them, I suppose,” replied Mary Louise.

They walked through the thronging crowds to the other side of the little city where the main activity was now located.

Here the soldiers were erecting their tents, arranging their personal belongings, preparing for their brief stay—for here they were sworn into the service, and here they hoped to be immediately mustered out. The great war was over, every man had done his duty, and now they were back again, each one determined to do better both in position and ways than when he had left home.

Dorfield was not large enough to import many workers, therefore the merchants were delighted at the return of its men and impatiently waited until they should he mustered out. All the old jobs were awaiting them, with an advance in wages which had followed the increased cost of living.

There were busy scenes at the cantonment during the next few days while the officers were dismissing24 the men who were no longer needed by the government.

In a short time all of the returned soldiers were hard at work at their old jobs, except those who were strangers and had no jobs to return to. The government was supposed to attend to these, but the government was lax in its duty, and though the number of such men gradually grew fewer, there were still plenty for Gran’pa Jim and Mary Louise to choose from. But although the girl begged for this or for that one, the old gentleman was particular and suspicious.

“Why, I’d as soon have Danny Dexter as that fellow!” he would exclaim, for Danny Dexter was quite a well known individual by this time. He would sit upon a taut rope, swinging his feet and smoking his pipe all day long, and if he was called upon to do anything, he was absolutely unresponsive. Both in skin and clothing he was dirty and untidy. But he was a cheery, smiling youth, and the more Mary Louise saw of him the better she liked him.

As the encampment faded away, Danny Dexter alone remained to say good-bye, and Mary Louise remarked that none left without a shake of Danny Dexter’s hand.

25 Finally he alone remained of the big encampment. The tents had gradually been struck and carted away to the government storehouse, but Danny’s tent, with him lazily clinging to the ropes, still remained to show the place that once had sheltered the Dorfield Regiment. One day the inspector noticed this and mustered Danny out, too; but that didn’t seem to make any difference to Danny. He had money, probably left from his pay, so he still occupied the weather-beaten old tent and carted his provisions from the village stores, cooking them himself and gossiping with his old comrades when they were not busy.

“What you goin’ to do, Danny?” he was asked again and again.

“Don’t know yet,” was always the careless reply. “Government seems to have forgot me just now, so I guess I’ll jus’ hang around here this summer and when winter comes, go up to New York and see what’s goin’ on over there. I’m in no great hurry.”

“Why don’t you get a job in Dorfield? It’s a pretty good place and living is cheaper than in New York.”

“Money don’t interest me much,” was the careless answer. “What a fellow needs is to see26 life an’ make the most of it. If you’re happy, money don’t count.”

“Are you happy now?” they asked him.

“Oh, fairly so, but I’m gettin’ tired doing nothing at all; may skip out of Dorfield any day, now.”

More than ever, old Mr. Hathaway had met and studied Danny Dexter and disliked him; and more and more Mary Louise had seen him in the stores and found him worthy her consideration. Often at dinner or breakfast the girl and her grandfather spoke of him and disagreed about him.

“We needn’t adopt him for good, you know,” said Mary Louise. “Just for a few months to see how he works in. And he needn’t be one of the family or eat with us. He can work in the garden and keep the front yard cleared up, and in that way he’ll get his living and fair wages.”

“Well,” said Gran’pa Jim, “I’ll speak to Danny Dexter in the morning.”

He did. Next morning he met the boy leaning over the counter at the grocery store on the corner, where Will White, back at his old job, was waiting on customers. The old gentleman noticed that Will saluted when Danny entered the store soon after Gran’pa Jim did.

27 “Why did you do that?” asked Mary Louise’s grandfather, in a gruff voice.

“Why, he was our top-sergeant, sir, while I was only a private,” replied Will, “and I can’t get over the distinction. In the war I had to salute him, and—don’t you know, sir, that Danny Dexter wears a decoration, or could wear one, if he cared to? But he keeps it buttoned up tight in his pocket-book. Medal of Distinction or something, earned by saving the lives of some of the wounded soldiers. Danny was always modest; they called him ‘The Lamb’ in our regiment—but, gee whiz, how that lad can fight when he gets the thrills into him!”

All this was said while Top-Sergeant Dexter was in the rear of the grocery, examining the labels on a vinegar barrel, so he heard nothing of Will White’s commendation. Shortly after, when Gran’pa Jim had given his own order, the old gentleman walked over to Dexter and said in his point-blank way:

“Dexter, do you want a job?”

Danny sat down on a box, scuttled his feet and regarded his interrogator with a smile that slowly dawned and as slowly faded away.

“I’m getting tired of hanging around here,”28 he announced. “What sort of a job have you to offer?”

“Why, I live in that big corner house facing the park. What I want is a young man to care for my garden—”

“Ah, I love a garden. Flowers are so spicy and bright and fragrant, don’t you think?”

“And also to clear up the front lawn, and to rake up the leaves, and see that the living room grate is supplied with firewood, and keep up the yard generally and to clip the hedges—”

“I see,” said Danny, with another smile; “a sort of Private Secretary as it were.”

“And attend to any errands my granddaughter may require.”

“I thank you, Mr. ——”

“Hathaway is my name, sir.”

“Mr. Hathaway. The job you offer does not impress me.”

“You fool!” roared the old gentleman, exasperated both by the refusal and the dignity with which it was made by this uncleanly, disfigured soldier. “Why do you turn down a position without looking at it? Many a young fellow in Dorfield would be glad of the offer I have made you.” He thought how Mary Louise would laugh29 at him when he told her how, finally, he had offered “the job” to the solitary soldier and had been ridiculed and refused. “Walk over with me to my place and inspect the premises and then you may change your mind.”

“All right!” responded Danny, jumping up with a cheerful face that betrayed he felt no malice at having been labeled a fool by the irascible old gentleman. “Let’s walk over and look at your ranch. I may find it better than I think it is. But I’ve a pretty good estimate now of an old-fashioned country villa ‘facing the park.’ They’re very grand, magnificent, you know, and usually belong to the most prosperous men in town. Come on, Mr. Hathaway.”

“That’s right, Danny,” whispered Will White, as his friend passed out. “It’s a whale of a place; and then, too, there’s Mary Louise!”

Of course, there was Mary Louise.

She was lying lazily on the couch by the front window this bright though chilly May day, reading at times a book, and occasionally hopping up to toss a stick of wood on the fire. Glancing through the window, she noticed Gran’pa Jim and Danny Dexter crossing the park toward the house.

It was early spring in Dorfield and although the numerous trees in the park and surrounding country were leafless, the scene was far from unpleasant to the eye of a stranger. Danny Dexter walked briskly—he had to, to keep pace with Mr. Hathaway—and seemed to enjoy the prospect keenly.

Mary Louise glanced at her gown. It seemed dainty and appropriate for a spring morning, but the girl remembered one with prettier ribbons in a drawer upstairs, so she dashed the book down and flew up the stairway.

Meantime Mr. Hathaway and the soldier had31 reached the house and passed around the brick sidewalk that led to the rear. Danny glanced doubtfully at the brick-paved driveway.

“No horses, I hope?” said he.

“No,” answered his conductor. “I love horses myself, but Mary Louise prefers an automobile; so, as she’s the mistress of the establishment, as you will soon learn, the horses are gone and a shiny little car takes its place in the stable.”

“Employ a chauffeur, then?”

“No; Mary Louise loves to drive the thing herself, and if anything goes wrong—something’s always going wrong with an automobile—there’s a garage just back of us to fix it up again.”

Danny sighed.

“I can run the blamed things,” he remarked, “and I know how to keep them loaded with oil and water and gasoline—”

“Oh, don’t worry about running it,” exclaimed the other. “Why, she won’t let even me run the thing, so I’ve never learned. As for the chauffeurs, Mary Louise despises them.”

“So do I,” agreed Danny. “Your granddaughter, sir, must be a very sensible girl.”

That won Gran’pa Jim’s heart, but just then Mary Louise herself came tripping through the32 archway that led from the kitchen to the back porch and the garden. She was most alluringly attired, as if for a spin on a sunlit winter’s morning, and paused abruptly as if surprised.

“Oh, this is the new man, I suppose,” said she, a touch of haughtiness in her voice. “Your name is Dexter, I believe.”

Danny smiled, slyly.

“What makes you believe that?” he inquired, doffing his little military cap.

“I have heard Will White call you Dexter at the grocery store,” she responded promptly.

“Still, I’m not ‘your new man,’” he said, explaining his presence. “At the invitation of Mr. Hathaway I am merely examining his charming grounds.”

“Yes. What do you think, Mary Louise, this hang-around ne’er-do-well insists on seeing the place before he decides whether he’ll work here!”

Mary Louise gave the soldier a curious look. His wound wasn’t so bad—merely a slash across the forehead, which, had it been properly attended to at the time, would scarcely have left a scar. Otherwise his features were manly enough, and might have been approved by girls more particular than Mary Louise.

33 “I don’t blame him for wishing to see his workshop,” she averred with one of her irresistible smiles. “I wouldn’t take a job myself without doing that. Look around, Dexter, and if things are to your mind—we need a man very badly, I assure you. Otherwise, we hope to serve you in some practical way. I’m going over to Laura Hilton’s now, Gran’pa Jim, so if you need me, I’ll be there until lunch time and you can telephone me.”

The old gentleman nodded. Then with Danny, he followed her to the ample stables—almost as ornate and palatial as the house.

“I preferred a five-passenger to a runabout,” explained Mary Louise to Danny, “for now I can pack my girl friends in until the chariot is positively running over—and I like company.”

She applied the starter, and away sped the gamey little machine, bearing the girl who was admitted to be “the prettiest girl in the county.”

Mr. Hathaway showed Danny the stables. In one tower was fitted up a mighty cozy suite of rooms for the whilom “coachman.” There was another suite in the opposite tower. Then they went down into the garden, and as the boy looked around him his face positively gleamed.

34 “It’s magnificent!” he cried, “and just what I always imagined I’d like to fool with. I shall move that row of roses, though, for the place they’re in is entirely too shady. Probably laid out by a competent gardener, but in all these years the climbing vines on his pergola have got the best of his general scheme.”

“You accept the job, then?” asked Gran’pa, relieved.

“Accept? Of course I accept, sir—ever since I saw Mary Louise and her automobile.”

When Mary Louise returned from her drive she found Danny Dexter raking up the scattered leaves in the garden and merrily whistling as he pursued his work. He came to the stable, though, as soon as she drove in, and looked at the machine admiringly. She stood beside him, well pleased, for she liked her automobile to be praised.

“Do you drive?” asked Mary Louise.

“Fairly well, Miss,” he returned; “but I’m not much of a mechanic.”

“That’s my bother,” she insisted, laughing; “but if you like driving I’ll take you on my next trip and the girls will think I’m all swelled up at having a chauffeur. Only—” she paused, looking at him critically, and Danny saw the look and35 understood it. He blushed slightly, and the girl blushed furiously. She had almost “put her foot in it,” and quite realized the fact.

“The reason I have not kept my face washed,” he said in a quiet voice, “is because our old surgeon at camp told me the wound would heal better if I allowed nature to take her course. It was a bad slash, and while this seemed a curious treatment, the fact has been proved that the wound does better when covered with mud germs than with those from water. The only objection is that it makes me look rather nasty at present, but I made up my mind I could sacrifice anything in the way of looks right now if it would improve my looks in the future.”

“Who was the surgeon?” asked Mary Louise.

“Oh, a crazy old Frenchman who had helped many of our boys and so won their confidence.”

“I don’t believe in his theory,” declared the girl, after another steady look at the cut. “Seems to me that broad gap will always remain.”

“Had you seen it at first,” he said, “you would now realize that it has narrowed more than one-half, and is a healthy wound that is bound to heal naturally. However, this fact assures me I may now wash up and let the thing take care of itself.36 With my mud face there no object in trying to keep the rest of me clean, so I’ve degenerated into a regular tramp.”

“I suppose you’ve no clothes other than your uniform?” she said thoughtfully. “Do you apply treatment of any kind to your wound?”

“Nothing at all—Nature is the only remedy. And as for clothes, I haven’t the faintest idea what became of my old ‘cits.’ I was told to ship them home, but can’t remember whether I did so or not.”

Mary Louise was dusting the car with a big square of cheesecloth. Danny helped her.

“I wish,” said the girl, “you’d go down to Donovans’ and pick out two suits of clothes—one for working in.” Her voice trembled a little. She did not know how this queer fellow would regard such a suggestion. “I’ll telephone Donovan right away to charge the clothes to Gran’pa Jim’s account,” she continued.

Dexter was silent for awhile, plying his cheesecloth thoughtfully. Then he said:

“In the days of the horse and coachman, did you clothe your men in uniform?”

“Y-e-s, a sort of uniform. When mama was with us she loved to see brightness, coupled with37 dignity. The Harrington uniform consists of wistaria broadcloth, with a bit of gold braid. But it’s not so gorgeous as it sounds.”

“Suits me, all right,” returned Danny, carelessly. “Would you mind my getting a Hathaway uniform instead of the other clothes?”

Mary Louise was astonished.

“No, indeed,” was her answer. “The uniform will have to be made for you by Jed Southwick, who keeps the materials. But I’m curious to know, Dexter, why you prefer a badge of servitude to a respectable suit of clothes. Do you mind telling me?”

After a little hesitation the soldier answered:

“That’s just it, Miss Hathaway—”

“My name is Burrows—Mary Louise Burrows. Mr. Hathaway is my grandfather.”

“Thank you. Well, it’s the badge of servitude I’m after and that’s why. My home’s a good way from here, Miss Burrows, and it isn’t likely any of my old friends will wander this way, Dorfield being a half-hidden if attractive old city, more dead than alive. But they might come and—just now—I don’t care to meet them and have to explain why I didn’t do more toward winning the war. Every blamed fellow who set foot in France,38 from private to general, won the war, except me, and that’s rather embarrassing, you’ll admit.”

Mary Louise smiled mischievously, remembering the “medal for distinguished service” even now reposing in Danny Dexter’s pocket-book. But she only said:

“Go to see Jed Southwick at once—the sooner the better—for he’s a good tailor and good tailors are always slow. And order two suits, for something might happen to one of them.”

The boy shook his head.

“I may not stay long enough to wear out two uniforms, Miss Burrows, and a good tailor is expensive, so they’ll cost a lot.”

“We always pay for our men’s uniforms,” protested the girl. “And—how much wages—salary—money—do you get here?”

“Why, I never thought to inquire.”

Mary Louise hung her duster over a rail.

“Gran’pa Jim is always just, and even liberal, so don’t worry,” she said. “Wash your face and then go to town and order your two uniforms. I won’t use you as my chauffeur until you’re all togged out. The girls will admire you more, then, and I’m anxious you should make a hit with them.”

It is to be expected that Mary Louise, by virtue of her own wealth and her grandfather’s political and social position, as well as her own personal beauty and loveliness, was easily admitted “The Queen of Dorfield.” There were many charming girls in the quaint little city, nearly all being members of the “Liberty Girls,” an organization conceived by Mary Louise Burrows which had done a lot of good during the war. Indeed, many of these girls were heiresses, or with money in their own right.

Yet wealth was no latch-key to the affections of Mary Louise. Just next door to Colonel Hathaway’s splendid mansion was a neat story-and-a-half dwelling that had not cost half as much as the Hathaway stables, but it was cozy and home-like, and in it lived Irene Macfarlane, the niece of Mr. Peter Conant, the most important lawyer of Dorfield, but by no means a wealthy man.

With Peter Conant lived Irene, who was treated40 by “Aunt Hannah” (Mrs. Peter Conant) and her husband as a daughter.

Irene had been crippled from birth and was confined to a wheel chair. She was a bright little thing, and Mary Louise, as well as the other girls, was very fond of Irene Macfarlane. Also among the “Liberty Girls” were enrolled Betsy Barnes, the shoemaker’s daughter, and Alora Jones whose father—Jason Jones—was by far the richest man in Dorfield. Alora owned much of the best property in Dorfield but was waiting for her majority to obtain it, for it belonged exclusively to her dead mother. Then there was Laura Hilton, a popular favorite whose father owned some stock in the mill and worked there. The father of Phoebe Phelps was well-to-do, but not wealthy as either Colonel Hathaway or Jason Jones.

Mary Louise never gave a thought to their worldly possessions. If they were “nice girls” she took them to her heart at once.

All girls are prone to gossip (in Dorfield it was a distinctly harmless amusement), and usually Mary Louise and her chums gathered in Irene’s sitting-room, where the surroundings were sweet and “homey.” So, on the day they took their ride with Danny Dexter as chauffeur—Danny41 dressed in his new uniform—the four girls who had been favored by Mary Louise as passengers met at the Conant residence and began to quiz their friend. From them the news would fly throughout the city, where every little thing is of interest, and Mary Louise was quite aware of that fact.

Irene had been with them, of course, but Irene was a general favorite and her “talking machinery,” as all the girls realized, had not been affected by the trouble which made her an invalid. Then there were Alora Jones, Laura Hilton, and last of all Phoebe Phelps.

“It’s really a ‘five-passenger,’” declared Mary Louise, “but it will take six at a pinch, as you saw to-day. Gran’pa Jim’s old gas buggy was called a seven passenger, but only six could ride in it comfortably as the extra seat was always in the way; yet you know, girls, what a time I had to induce him to sell his hayrack and buy me this beauty.”

“Uncle Eben could drive the Colonel’s car though,” remarked Alora, “while you had to get a chauffeur.” Uncle Eben and Aunt Sally, an aged black man and his wife, were the house servants. “That makes it more expensive.”

42 “Well, we’ve the money to pay him, anyhow,” retorted Mary Louise, “and then Eben is too old and stiff now to take care of the garden and do all the outside work. Danny does all that now.”

“Oh, that alters the circumstances,” agreed Phoebe Phelps. “But it seems funny to see an old black man and a young soldier boy wearing the Hathaway uniform.”

“It is funny,” admitted Mary Louise, laughing, “but the soldier wanted it that way. He said it made him proud to wear the Hathaway badge of respectability. He’s a total stranger around here, you know—lives in some Eastern city and has conceived a remarkable admiration for little Dorfield.”

“Is that all you know about him?” asked Laura, suspiciously.

“He’s a soldier,” said Mary Louise proudly, “and entered the service a common private and came out a top-sergeant. That’s something.”

“Shows he’s popular with his mates and a good soldier,” agreed Irene.

“He was appointed to Company C of our regiment, together with some others, after the battle of Argonne,” continued Mary Louise, lauding her hero earnestly, “and was twice wounded before43 being sent home with the Dorfielders. He had been offered an honorable discharge when he got that terrible cut across the forehead, but in a week he was back with the boys, fighting desperately.”

“Did he bring any recommendations?” asked Phoebe.

“Will White told me his story, and so far as recommendation is concerned, every man in the Dorfield Regiment will swear by him and stand for Danny Dexter to the last gasp. Don’t you like my new chauffeur, girls?”

“I do,” responded Laura Hilton. “Father offered him a nice job at the mill, but he turned it down.”

“It was the same with my father,” announced Phoebe.

“The back yard looks neater than it has in years,” commented Irene, “and he surely proved to us this afternoon that he understood driving an auto.”

“Gran’pa Jim declares it was my automobile that won him,” Mary Louise stated. “He wasn’t anxious to be our hired man, either, until he caught sight of the car, when he at once hired out.”

“Well, it is a swell car,” declared Alora Jones,44 “and has every modern appliance. Besides, it shines like a diamond in the sun.”

“My, she’s only had the thing a month,” said Phoebe, “and it’s the most expensive little car in the market. Several have been sold in Dorfield already.” There was envy in this speech, and all the girls sighed in unison. Mary Louise, however, smiled slyly for she knew that with the exception of Irene, any one of the girls present could afford to buy a duplicate of her car.

“Well, the Hathaway establishment is blossoming out,” said Laura lightly, “and one man—a hard-working soldier—seems responsible for the transformation.”

“No, let’s put the auto first,” objected Irene. “First the old Colonel is cajoled into selling his ancient rattle-trap and buying Mary Louise a luxurious car, the latest model offered for sale; then comes along a soldier who falls in love with the car, and to get the fun of handling the machine hires out to the Hathaways. He proves a good man all-around and soon has the old place slicked up as if it were new.”

“That’s all an example of Mary Louise’s luck,” commented Laura. “It couldn’t possibly happen to anybody else.”

45 “I’m inclined to think that’s true,” added Phoebe, laughing at their earnest faces. “Mary Louise seems to get the best of what happens around Dorfield, but that’s not her fault—the dear little heart—and I’m mighty glad things come her way for she deserves it.”

“The dealer, Lou Gottschalk, had six of these cars shipped in one batch, the 1919 model,” explained Mary Louise, “and this was the last to sell—merely because it had a few fixin’s not attached to the others. The fixin’s made it some prettier, but no better running, and there’s no change in the gear.”

Day after day Mary Louise won more praise from her girl friends by taking them to ride in her new automobile, which her new man kept shining as brilliantly as varnish will shine. When perched on the driver’s seat in the Hathaway uniform—modest and inconspicuous—Danny lent an added air of dignity to the outfit, and he certainly found time, after looking after the garden, drives and lawn, to keep the car immaculate also. Night after night Mary Louise could see the light shining in his tower, which proved he did not waste an instant of his time.

One afternoon, when the soldier was at the46 store, Mary Louise visited this tower room and discovered there were several things that might add to his comfort and convenience; so she purchased a cheap but comfortable lounge, several cozy chairs, a new rug and a big “high-boy” full of drawers and shelves. This was done in gratitude for Danny’s faithful work, and he showed his appreciation by means of a smile and nod, without ruining the event by a word of speech.

He kept up well, too, and was never a slacker in his work. If the work got a little ahead of him he got up earlier in the morning and accomplished his tasks in that way. Mary Louise was very proud of her hired man’s ability.

One evening she said to him:

“I’m going to drive to Sherman to-morrow, Danny, so we’ll get an early start. Know where Sherman is?”

He shook his head. “No, Miss Burrows.”

“Well, it’s a straight road after we get to Bridesville, where we went yesterday, so we can’t easily get lost. My dressmaker lives at Sherman, which is fifty miles away. That’s only a short journey in the car, and we’ll have luncheon at Bridesville. Just you and I and Irene Macfarlane, you know.”

“Seven o’clock, Miss Burrows?”

“That’s about right, Danny.”

“I’ll be ready, Miss.”

So Mary Louise dismissed the matter from her thoughts and went to bed without a single misgiving.

At a little before seven next morning Irene Macfarlane was wheeled out upon the front yard48 nearest the driveway, happy and full of good spirits, for a day like this was a rare treat for her. A day with Mary Louise in the splendid new car, with only Mary Louise and her chauffeur for company, luncheon at Bridesville and plenty of room on the back seat was assuredly an event to be regarded with pleasure—and that’s why Mary Louise had chosen her for comrade.

But neither the car nor the uniformed chauffeur were present. The moments rolled on until 7:30 was reached and still no sign of the automobile. Mary Louise ran around to the stables, to find both the car and Danny Dexter absent. Danny had locked the door to his tower and the front door of the stables stood wide open—just as if the young man had prepared for a long day’s trip, but all else seemed in order. There were two checkered robes belonging to the car, but these were gone, as was all else that might be needed on the trip—including the extra gasoline tank, always carried for emergencies. But Danny and car, with its fittings, had absolutely disappeared.

“Perhaps he’s gone for gasoline or oil and been delayed,” pondered Mary Louise on her way back to the side porch. “But it’s quite unlike Danny Dexter to put off such an important thing49 until the last moment, so I’m afraid one of the parts has broken, and Danny is waiting at the garage to have it replaced. We may as well be patient, Irene, for our fate is in Danny’s hands and I am sure he’ll get us started as soon as possible.”

“It isn’t that,” replied Irene dolefully, “but I’ve got two music lessons to give late this afternoon.”

“Oh, send them word you’re sick and have the dates changed,” suggested Mary Louise. “I’m sure that will satisfy them. And after all, Danny may be here any minute and then all our troubles will be over. As a matter of fact, Danny told me yesterday that the carburetor needed adjusting and that may be what is detaining him. So run along and have Aunt Hannah telephone your pupils.”

“Oh, yes, I’ll go and tell Aunt Hannah right away,” responded the crippled girl, “and I’ll tell her why Danny’s late, too.” She immediately wheeled her chair around and started for her home, being gone less than five minutes; but she needn’t have hurried for Danny hadn’t returned by luncheon time. Irene and Mary Louise spread their basket of lunch on the table on the side50 porch and had a merry time of it in spite of the missing soldier and his automobile.

“Of course, if he doesn’t come pretty soon now,” admitted Mary Louise, “we must postpone the trip to another day, but we’ll have all that fun added to this, some day when the car is running properly,” promised the owner, and they ate every bit of Aunt Sally’s delicious luncheon and had a really “good time” in spite of their disappointment. Fortunately most of their girl friends, learning of this intended trip, did not come near them the whole day, so they were left alone to their own devices.

As evening approached, nevertheless, Mary Louise began to be uneasy. Gran’pa Jim came home from town and found the two girls playing “muggins” on the porch.

“What! Back already!” he exclaimed.

“Why, we didn’t go,” answered Mary Louise.

“Dressmaker wasn’t ready for you?”

“No. We—we’ve lost the car—and Danny.”

The old gentleman sat down on a chair and whistled slightly.

“Tell me all about it,” he suggested.

Mary Louise complied. Really, there wasn’t much to tell. Danny Dexter had been ordered to51 be ready with the car at seven o’clock, for a trip to Sherman and had agreed to the proposition. He hadn’t appeared all day; in fact, he and the car were both missing.

“I’ve telephoned the garage and the gasoline station,” concluded the girl, “but he hasn’t been seen at either place to-day. Seems sort of funny, doesn’t it, Gran’pa Jim?”

Grandpa Jim drummed with his fingers rather absently on the rail of the porch.

“I insured the car but not Mr. Dexter,” he remarked slowly. “Odd that a good soldier should turn out a thief, isn’t it?”

“He was absolutely in love with that automobile,” added Irene, eagerly. “He would give anything to own it.”

“Danny is no thief!” asserted Mary Louise, positively. “He may have gotten into trouble with the car, somehow; but steal it—never.”

“Ought—oughtn’t we to do something right away?” asked Irene, diffidently.

“We’ve wasted the whole day already,” Colonel Hathaway replied with a smile; “perhaps a night and a day, if he had already made up his mind to take the car. In that time he could get a long distance away from us. And we’ve no idea52 what direction he took. Some auto thieves go direct to the cities to hide, while others feel they are safer in the country roads. Anyhow, I think we’d best call up Chief Lonsdale and ask his advice.”

“To be sure!” exclaimed Mary Louise, excitedly. “Why didn’t we think of that before? We’ve made mistake after mistake all day long. I’ll go in and telephone him at once.”

The Colonel held her back. “If the Chief’s to understand what we mean and what we want, I’d better talk with him myself. You grow more and more muddled the more you talk with a person over the wire.”

So he rose deliberately and went into the house, and soon they heard the Colonel telling the whole story of Danny Dexter to the Chief of Police. He told it concisely and “without any frills or rigmaroles,” as Irene admitted, and Chief Lonsdale ended by promising to come over at once if they’ll give him some supper. “It won’t be as good as I’d get at home,” he added, “but Aunt Sally isn’t the worst cook in Dorfield by any means.”

The old Colonel chuckled and hung up the receiver, and before long, in drove Chief Lonsdale53 in his Ford and anchored it near the front door.

“Evenin’, Charlie,” was the Colonel’s greeting as they shook hands.

“Evening, Colonel,” responded the Chief, hanging up his overcoat and hat. “Been gettin’ yourself inter trouble, eh?”

“No, ’twas Mary Louise who considered a soldier must be, perforce, an honest man.”

“I know him, and I believe she’s right in this case,” replied Charlie Lonsdale. “If your man-of-all-work isn’t honest, I’m not honest and no judge of an honest man.”

Irene, who had remained to supper, although she lived next door, clapped her hands gleefully. Mary Louise walked around the table and kissed the Chief upon his grizzly chin; the Colonel alone frowned.

“Think I’m going to eat over here and take ‘potluck’ for nothing?” inquired the Chief.

“You’re an old idiot,” declared Colonel Hathaway, who was very fond of the Chief of Police and often had him over for a Sunday dinner.

“If the stranger soldier hadn’t been all right,” responded the other, “do you think I’d let you keep him and allow him to take charge of Mary54 Louise’s precious auto? Or risk my poor stomach on corned beef and cabbage, such as we’re going to have presently?”

“Why, how did you know that?” asked Mary Louise. “I didn’t know that myself until you told me!”

“Eyes—nose—presently, taste,” said the policeman, laughing at them. “Saw Aunt Sally lugging it home in a basket this morning—”

“But—”

“Smelled it when I came into the house just now.” Then he continued, laughingly:

“Have been hankering for corned beef all day, and that’s the reason I invited myself over.”

“You know you’re always welcome, Charlie,” said the Colonel, highly pleased, “and we’ll have a couple of these fine ‘Cannel’ cigars after the meal,” promised the Colonel. “I keep a few of them on hand just for guests like you.”

“This don’t seem much like finding my car—and poor Danny Dexter,” pouted Mary Louise. “That machine can easily go sixty miles an hour, so we may be fifty miles farther away from it since you arrived, Chief Lonsdale.”

“Possible,” admitted the Chief, “and it’ll take an hour more to eat supper and—I may stay55 with you all night. Still we didn’t fix any time limit on capturing the thief, so there’s no hurry that I can see.”

Irene and the Colonel were nervous and—to an extent—so was Mary Louise, but the latter girl was more composed than the others. As for the Chief, he seemed to have forgotten all about the task on which they had embarked—after he had telephoned to some man in his office.

“What do you think of telegraphing to Josie O’Gorman?” asked the Colonel, after taking his granddaughter into a corner after dinner.

“Josie?” cried the Chief, overhearing the question. “That’s a clever idea, and I’m not ashamed to say I’ve been considering Josie for the last hour or more. What that girl can’t stumble against is no work for a detective. She isn’t clever, nor does she consider herself so; but she’s a way of falling into traps set for others that is really remarkable. If you know where Josie is, I advise wiring her the first thing you do.”

“I’ll go down to the telegraph office at once and send the message in your name, Mary Louise,” decided Colonel Hathaway, going into the closet to get his hat and coat. “There’s nothing like promptness in such a case, and my reflections during the past two hours have led me to nothing at all, I must confess. I’ll just step over to the stables a minute and then we’ll start.”

57 The two men and Mary Louise went to the stables, where the Chief unlocked the tower in a wink of an eye, and then carefully examined the contents of Danny’s private room. All was in perfect order, and nothing indicated that the young ex-soldier had intended to be gone more than a day at the most. In the standing room or garage, downstairs, all was as neat as wax and ready for the automobile when it arrived home—if it ever did.

“Nothing to be gained from an inspection here,” remarked the Chief, who had allowed the Colonel to light his cigar but not to smoke it while they were in the building. “You see, Hathaway, it’s a hard thing to trace an automobile, especially if it’s a popular make.”

They stopped at the telegraph office and the girl promised to forward their message at once.

“You see,” said she, “It’s a dull season and a dull hour, and Washington messages supersede all other. This telegram ought to be there in ten minutes, and I’ll send the answer to your house immediately, Colonel Hathaway.”

“Could you send a duplicate to the Police Office at the same time, Miss Girard?” inquired the Chief.

58 She nodded an assent, making her pretty hair flutter in all directions.

“Very well; put everything aside and get our telegram off at once,” said Colonel Hathaway, and they proceeded to the police office.

“That blamed car worries me a good deal; I can’t see how we’re to locate it, with no clue but a tire mark,” remarked the Colonel when they were on the street again.

“Anything can be accomplished if we set our hearts on the task,” returned Chief Lonsdale, somewhat testily.

“There have been six others of this make of machine sold right here,” the Colonel said, “but the one we are looking for had several unusual fittings to mark it. There’s a difference in the wheels of Mary Louise’s car—couldn’t you tell by that; also the driver’s seat is different.”

“I don’t remember having noticed these particular marks myself,” said the Chief, “but a dozen or so of my men have done so, and at this present moment are busy trying to locate Mary Louise’s car.”

“You’re a good fellow, Charlie,” remarked the Colonel gratefully. “I feel sure we’ll get our clutches on the machine sooner or later, even if59 the streets are crowded with automobiles of this and all other makes.”

“You’re skeptical, of course,” replied the Chief, “regarding the power of the police, but I’m not at all, so I’ll plod along and make the best of a poor beginning. So please have faith in our ability and we’ll find your car.”

“Oh, I’m not afraid of your ability,” said Gran’pa Jim.

“Let’s run down to the office,” proposed the Chief. “We’ll get the news as quickly there as here—perhaps a bit quicker, and I can see you’re too nervous—both of you—to get to sleep at your usual hour.” So they got into the Chief’s auto and started for the police office, where the man at the desk listened quietly but without astonishment to the Chief’s story, referring to a sheet of notes at his side, “Guess I got it all, sir,” he said.

“Is Olmstead out?” asked the Chief.

“Not just now, sir, he’s just back from the telegraph office, where he listened to this message to Mary Louise coming over the wire.”

“Let us see it.” Without a word the desk sergeant handed over a paper with some words scrawled upon it, but neither old Mr. Hathaway60 nor the Chief of Police had any difficulty in reading it:

“Dear Mary Louise:

“Will be with you to-morrow morning at eight o’clock. Remind Aunt Sally of my insatiable appetite as that’s usually your breakfast hour. With love,

“Josie.”

“Aha! that’s one thing off my mind,” cried Mary Louise, crushing the paper and then spreading it out the full size of the sheet. “It’s well for us that Josie is at home and willing to pick up a case of such a character. There is too much mystery about the case for us to undertake it without the help and backing of that clever girl, and if she is unable to solve the mystery, her father will give her all the necessary help to find both the automobile and Danny Dexter.”

By the time they had adopted Josie O’Gorman’s leadership and decided to depend upon it, the three had left the police office and started for home. It was very annoying both to the Colonel and to Mary Louise to travel on foot after constant use of an automobile. The Chief,61 having urgent business in another part of the city, was unable to take them in his auto. As they slowly walked toward home, they discussed the mystery and rejoiced that Josie was going to help them solve it.

“She isn’t much of a detective,” remarked the old Colonel, “but she wins as often as she loses, and she’s earnest and hard-working; more-over, she has her father’s brains to appeal to, and there are no more skillful ones in all Washington than those of John O’Gorman.”

“To be sure,” said Mary Louise, as she clung to her grandfather’s arm. “They first sent him to France to take charge of the Secret Service bureau there, but he was recalled because there were more important duties here. Josie wrote me there were a thousand suspects in America to one abroad. Besides, each nation has its corps and band of detectives and some are especially clever.”

“It’s a good thing for us,” declared the old gentleman, “for it gives us Josie, and with her the advice of the shrewdest secret service man in America.”

Josie O’Gorman did not bother to ring the doorbell next morning. She went around to Aunt Sallie’s outside kitchen door, which always stood open at this hour, and after a word of greeting to the black mammy, made her way to the cosy little room which she always occupied when visiting there. Afterward she quietly unpacked the contents of her suitcase. This being accomplished Josie went downstairs to find Colonel Hathaway there alone, sipping his coffee behind his newspaper while awaiting Mary Louise.

“Good mornin’,” she said, and threw her arms around her old friend and heartily kissed him.

“I hope that cackle I hear from the kitchen means an egg, and the egg another kiss,” remarked the old Colonel, smiling at her. “I am very glad you are here. You’ll be a great comfort to Mary Louise, I can assure you, for she63 has already exhausted our resources and I’m quite sure she’s on the ragged edge of nothing.”

“What’s wrong, Colonel?” asked Josie, as Aunt Sallie brought in her coffee.

“Everything—and nothing,” replied Colonel Hathaway, in a way, testily, and yet with an amusing expression. “But here she comes and you can get all the points of the terrible tragedy.”

Mary Louise entered the breakfast room briskly, as if fully expecting to find her old friend there, for she knew that Josie would not lose a minute in answering her summons. Indeed, her telegram of the evening before quite settled the matter as far as she was concerned.

“What’s gone wrong?” she asked again, when they had seated themselves, after the exchange of a hearty kiss, at the table.

Mary Louise, in a despondent voice, replied: “Everything has gone wrong, dear. There was a beautiful automobile at the auto show a while ago, and as Gran’pa Jim’s big old car had no one, from Uncle Sam to a grasshopper, to care for it any longer, I induced him to let me trade it in for the beauty I have referred to. I didn’t care much for Gran’pa’s rattletrap, but its wheels went round nevertheless.”

64 “I know,” nodded Josie, over her ham and eggs.

Then Mary Louise went on about her discovery of Danny Dexter, and his quaint manners, and the methods he employed in abdication.

“We’ve tried every method we could think of,” concluded the girl, “and the result is that yesterday we wired you, at Gran’pa’s suggestion.”

“What!” in amazement. “Do you mean that the dear Colonel has at last acquired sufficient confidence in my ability to entrust me with a job of this sort?”

The Colonel’s eyes could be seen just above the edge of his newspaper, and both Josie and Mary Louise thought they twinkled.

“If it can be done,” he muttered, “Josie is as likely to do it as anyone on earth. And she’s fond of Mary Louise, so I’ve an idea she’s better fitted than anyone else. But it’s a stiff job.”

“Yes, it is,” said Josie, in the same monotonous voice. “To recover lost automobiles is almost impossible in small towns,” added Josie. “Tourists are mighty numerous, and if one of these transients took the machine, such a person would surely drive off as soon as possible.”

65 “But how can that be,” protested Mary Louise, “when Danny Dexter had the car in his keeping, and now he is missing as well as the machine?”

Josie laughed joyously.

“But who told you it was Danny who ran away with your beauty,” demanded Josie. “On the other hand, I’m growing more and more to favor this young man. If he can’t ‘own the dear little thing,’ the next best thing is to be its chauffeur. Tell me some more about him—all you know.”

Mary Louise flushed at this tribute, but she allowed the Colonel to depict Danny’s character before she gave her own glowing opinion of him.

Josie slowly shook her head.

“There’s something wrong about this whole affair,” she reflected; “either he’s suspiciously bad, or he’s undeniably good—one of those perfect examples given us by the good Lord to pattern after. I’m afraid of those goody-goodies till I can make a hole in them and see what they’re stuffed with.”

“At present your chauffeur is as invisible as your machine,” she said at last, “and so we must wait for a more promising clue.”

“Well, what’s to be done first?” inquired66 Mary Louise, impatiently. “While we’re talking and fussing here, that car is getting farther and farther away from us.”

“True,” assented the girl detective, calmly, “but I need a good breakfast to fit me for a hard day’s work—and I’m getting it.”

“You’re stuffing yourself like a cormorant!” said Mary Louise. “Why, I’ve seen you go for twenty-four hours without eating, Josie O’Gorman.”

“Under other circumstances. My! how good this ham and these eggs taste after a foodless night. But I’m thinking while I chatter, Mary Louise, and if you don’t like my methods of detection, discharge me on the spot, Miss Burrows,” she said with mock dignity.

“Oh, hurry up, Josie. What’s first on your program?”

“First, we must visit an old friend, Charlie Olmstead—and—”

“Oh, we’ve been through all that yesterday—and the evening before,” Mary Louise retorted. “What do you imagine we’ve been doing all this time?”

“Can’t imagine,” said Josie, meekly; “but anyone who would let a youth and a bran’ new67 auto get away from them so easily would do ’most anything. I suppose you’ve interviewed the postmaster, also?” She asked in a tone that was meant to be casual.

“One of our first acts, of course.” Josie smiled over Mary Louise’s head, but the old Colonel caught the expression and answered, to assist his dearly beloved grand-daughter:

“We may have acted foolishly, Josie, but you may be sure we acted. The interview has, you must admit, rendered it unnecessary for you to do the same thing and so has saved you the loss of considerable time.”

Josie again smiled.

“You’ve now told me all you know about the automobile, and all you know about the queer fellow who acted as chauffeur and did other jobs around the place. You have practically ended your resources and want to put the case in my hands. I want to take it, for it’s one of those odd cases that appeal to an amateur detective. Why, even daddy has been mixed up in some of these ‘lost automobile’ cases, and has found to his embarrassment that some of them have baffled him to this day. Some of those mysteries of stolen cars proved so tame that dear old daddy68 fairly blushed to discover how cleverly, yet simply, they had fooled him.”

“But you say he recovered some of them?” asked Mary Louise.

“Why, yes; I must credit daddy with the fact that he has recovered most of the machines—and some of the thieves.”

“Is it so hard, then, to arrest the drivers?” inquired the Colonel, curiously.

“Yes, indeed,” was the answer. “For if an auto thief discovers he is being followed by one with a faster engine or more ‘gas’ in his tank, he can just hop out and take to the woods. In some unusual cases the driver is also caught but you can see how easy it is for him to dodge his pursuers.”

“Then if no one is chasing, he can get a long way in a couple of days?” questioned Mary Louise, anxiously.

“So he can,” assented the other girl, “but I’ve had the idea that the periods an auto thief may best be arrested are,—first, just after the theft; and secondly, after time enough has elapsed to create a sense of security in the mind of the thief and cause him to cease to worry.”

“Then you think our pirate has ceased to69 worry?” asked Colonel Hathaway, in a misbelieving tone.

“Yes, and he’s given us a chance to follow one or two clues to our advantage.”

“In what way?” questioned Mary Louise with interest.

“The ‘dear little car’—of course, you must have named it? All automobiles belonging to girls must be named, I believe.”

“Of course. My car is called ‘Queenie.’”

“Certainly; and with a monogram on each side door.”

“Another very good clue,” said Mary Louise, “concerns the driver himself. Danny Dexter is a rather conspicuous returned soldier—not conspicuous because of his garb; he now wears the uniform of the Hathaways’ instead of Uncle Sam’s—but because of a bad scar across his forehead, which he cannot get rid of. So far, I admit we have only circumstantial evidence against the soldier, who won a ‘distinguished service medal’ and through modesty—or for other reasons—keeps this thing in his pocket instead of wearing it on his breast, as others seem proud to do. But that is no warrant for his taking ‘Queenie.’ But now let us visit the police70 headquarters and secure any further information there.”

Josie was following Mary Louise out when she turned and asked: “Coming with us, Colonel Hathaway?”

“Not this morning,” he replied. “You’ll want to get started and have the case well in hand before you need my assistance. If I remember rightly, Josie O’Gorman likes to work alone, so I predict it won’t be long before she’ll fire even Mary Louise and shoulder the whole thing.”

“This isn’t like the other cases in which Josie has come to our rescue,” protested Mary Louise. “It’s more like open warfare—get your eye on the thief, or on the car, and you can raise the hue-and-cry as much as you care to.”

On their way to the police headquarters the two girls gossiped pleasantly concerning the events that had happened since they last saw each other, for there are other things in the world besides lost automobiles and strange young men. There are even winter coats, and how much fur it is good taste to trim them with this year. There were, also, round hats, three-cornered hats and four-cornered hats to discuss, as well as the broad-brimmed hats and matinee, church or street hats. And by the time they reached the police station they had scarcely touched upon shoes and stockings—never mentioned gowns at all!

They found Mr. Charles Lonsdale, Chief of Police, at his desk.

“Oh, here you are,” said Josie. “Good morning, Chief.”

“Good morning, I’ve been waiting for you for over an hour,” was his response.

“Yes,” said Josie, “I knew you’d wait, knowing72 I’d arrived on the morning train. You see, Chief, this is one of those peculiar cases that can begin or stop at any moment, as we may decide. I don’t know what the ‘dear little thing’—eh—eh—‘Queenie,’ I believe, is her proper name—is worth, but—”

“Without a ‘trade,’ and with the accessories we loaded it with, our poor little Queenie is worth thirty-two hundred dollars,” confessed Mary Louise.

The Chief looked astonished; Josie regarded her friend with amazement.

“Whatever its cost,” commented Lonsdale, “the thing has been stolen, and it’s my duty to try and find it. As for you, Josephine, you may tackle it or not, as it pleases you. Thirty-two hundred dollars is a good bit of money for a little automobile.”

“It isn’t entirely the money that bothers me or Gran’pa Jim,” remarked Mary Louise, with another deep sigh. “We’d have paid a thousand more, gladly, if necessary. It’s the thought that Danny would betray the confidence we held in him.”

There was a brief silence, during which Josie took out her memorandum book.

73 “What’s the record, so far?” she asked carelessly. “Well, I’ll answer myself: not much, although the whole town knows that Mary Louise’s new auto has been stolen and Danny Dexter has disappeared at the same time. Meantime certain details have reached my ears that lead me to believe that Danny Dexter is but one of half a dozen assumed names used by this ex-soldier. The fellow accepted his position with the Colonel as half-chauffeur and half-gardener so that, at the slightest warning, he could use the little auto in making a getaway. In other words, he’s playing a bigger game than we’ve given him credit for.”

“Who told you all this?” inquired Mary Louise, in amazement.

Josie O’Gorman laughed, but before she could answer, there burst into the room from a side closet a big man with the marks of smallpox scattered about his face, a broad, sensitive nose, and shrewd eyes. It was evident at once that he was interested in their discussion.

“Anyone could see that with half an eye,” he made answer. “I’ll buy you half a dozen better automobiles than ‘Queenie’ if you’ll find its driver for me.”

74 “What about him?” asked Josie staring at him.

“Well, one name’s as good as another, just now, so we’ll still call him Danny Dexter,” responded the detective, leaning back in the chair so as to rest his feet against the wall. “For instance, I’m from Boston, and my name’s Crocker. Understand?”

Josie shook her head. She’d met a lot of detectives at one time or another, and this one seemed familiar, in a way.

“Then it’s a Boston case, after all,” she said in a disappointed voice.

“No, it’s just a Danny Dexter case, let us say,” responded the big man, also in a disappointed voice. “They gave him up in Boston as a bigger crook than they had time to handle, and the Bank was unwilling to spend more money on so elusive an individual. But I had some information of a floating character that came back to me time after time from the war zone that justified me in resigning from the government deal and taking up the case personally. So I’ve been in Dorfield ever since its famous regiment arrived—for the truth is that the Dorfield boys put up as game a fight as any75 Americans in the Expeditionary Force. Your boys had no press agent, nor any motion picture concern to back them up, so the truth will never be heralded broadcast in newspaper headlines, but take it from me, Dorfield comes under the A-No. 1 class.”

They regarded him a time in silence.

“How did you make your way here?” asked Josie.

“I saw you arrive in town and recognized you as John O’Gorman’s daughter. Was on old John’s force at one time. Josie O’Gorman is a friend of Mary Louise Burrows, whose auto was stolen by the man I’m hunting. That’s simple enough.”

“Have you been searching for him long in this locality?” asked Chief Lonsdale, handing him a business card.

“Oh, you’re not unknown to me, Charles Lonsdale,” he said; “I’ve hung around here for two days or more, and that’s long enough to tag any man.”

“What’s the name of your Boston fugitive?”

“Here they call him Danny Dexter—his war name. In Boston he was best known as Jim O’Hara.”

76 “Oh!” exclaimed Josie O’Gorman, in a low tone of surprise. “Then he’s well worth finding. Forger?”

“Yes—and more,” replied the big man, gravely.

Chief Lonsdale was staring at both of them.

“What is your real name?” he asked the man. “A business card doesn’t amount to much in our profession,” and he spun the proffered card across the table.

“Well, where I live we don’t often resort to aliases. They just call me Bill Crocker.”

“Oh!” again said John O’Gorman’s daughter, both surprised and interested in the turn events had taken. “I’ll go bond for him, Chief,” she continued. “It’ll do us both good to know Bill Crocker.”

The man with the pock-marks, who leaned back against the wall in careless attitude, his clothing wrinkled and unpressed, his whole appearance unkempt and unattractive, returned their looks with a mild smile.

“Reputation is a vague thing,” said he, “and often undeserved or exaggerated. To-day Bill Crocker of Boston might be called the John O’Gorman of his city, but what will he be to-morrow?77 A few failures and he is totally forgotten.”

Josie gave one of her sympathetic nods.

“That’s true,” she affirmed. “If you’re pretty big you’re given a headline; perhaps your picture is printed, but in a few days no one remembers who you were. That’s a good idea, for otherwise the Book of Fate would be packed with nonsense. An author, painter or sculptor stands a chance of living in name, but no one else has a ghost of a chance.”

“Are you prepared to spend some money on this game?” asked Bill Crocker. “The Bank offers a big reward for the man, with all expenses. I’m going to try and get him.”

“Try for it,” repeated the Chief of Police. “We’re prepared to do all the Bank would—and then some,” added Lonsdale calmly. “Eh, Miss Burrows? But we want the auto more than the man.”

“That is true,” agreed Mary Louise, “and yet I will leave the whole matter in your hands. With Charlie Lonsdale, who is regarded as an especially clever Chief, and Josie O’Gorman, whom I have evidence to prove is the brightest girl detective in America, and Bill Crocker of Boston, who is regarded with such awe by his78 confreres, we certainly ought to win against one common soldier who has turned criminal because he likes a pretty automobile and thinks it safe to steal it from a country town.”

“You forget yourself and your own talents, my dear,” said Josie.

“Why, I seem to have a real talent for stirring up criminal cases,” Mary Louise admitted, “but not for unraveling mysteries.”

“The reason we’re not all better detectives,” commented Bill Crocker, “is that we lose too much valuable time. Let us get busy on the case before us. First, I want to see the old stables—lately used as the garage.”

“This seems like doubling on our tracks,” retorted Josie; “we all know this place so well. But as you insist on crowding yourself into this gang of investigators, we’ll make a brief survey of the premises so you may know the exact situation as well as the rest of us.”

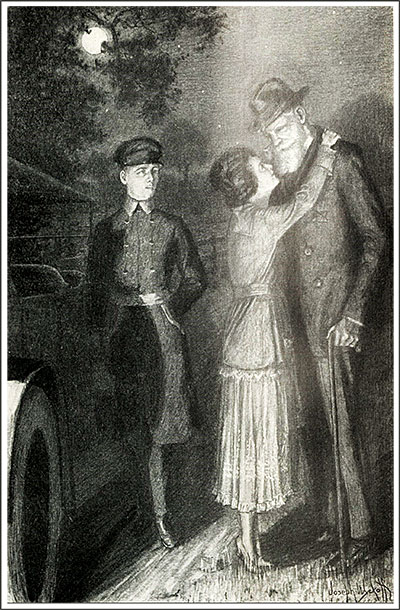

That night the air seemed breathless. A storm was threatening, and by eleven o’clock the wind had risen from a gentle sigh to quite a steady roar and was sending great dark clouds scudding across the full golden face of the moon.

Mary Louise felt breathless too, and was strangely unquiet. A storm was brewing in the very heart of her, and she could not understand just why. All she knew was that there was no use trying to sleep as yet. She simply had to think. So, pulling a silken sweater of a soft rose color over her light dinner frock, she dragged her great wicker chair before the window and curled up therein.

All her being was crying out in rebellion at the thought that Danny, her kind, candid, cheery Danny Dexter, could be a forger. As if she were in his presence, she could see the honest, straight-forward glance of his clear, blue eyes, and as she lay in her big chair in her darkened room80 and watched the wind play havoc in the garden, she suddenly realized that she had at times believed that there was something deeper in his eyes when they rested upon her.

This idea strangely disquieted Mary Louise. She made a remarkably lovely picture as the moon shone full upon her in one of its fleeting moments of freedom. The wind had loosened her soft dark hair and had flung it in little tendrils about her flushed young face, and her lips were parted in the eager recognition of a fact that had suddenly come to her. She knew she believed in and trusted Danny Dexter!

“Oh, what can I do?” she moaned. “Danny, I know you’ve done nothing wrong, but how can I make the others understand? And how can I ask Josie to hunt for someone else; she will hunt down one clue until she knows about it. Oh, dear me!”

And at this point a little sigh escaped from Mary Louise.

The wind evidently being in a mood sympathetic with her own, gave a sudden gusty sigh of despair; it fairly shook the house, and whistling about the chimney, finally expended itself in whirling through the window the tiny bit of81 cambric Mary Louise called a handkerchief.

She rose listlessly to catch it, her thoughts all centered on her problem, but the bit of white fluttered off in gay abandon among the rose bushes. Mary Louise watched the speck of light out there, idly leaning her rose-clad shoulder against the frame of the open window.