The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Civil War, by James I. Robertson, Jr. This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Civil War Author: James I. Robertson, Jr. Release Date: December 26, 2018 [EBook #58549] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CIVIL WAR *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

by

JAMES I. ROBERTSON, JR.

Washington 25, D. C.

U. S. Civil War Centennial Commission

1963

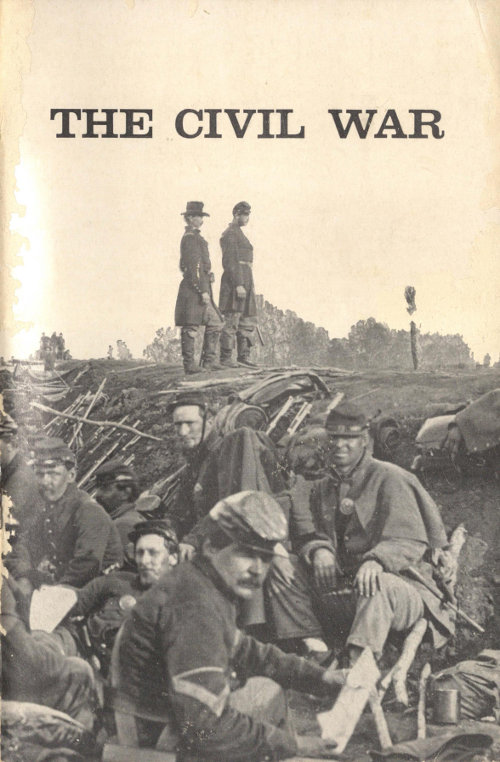

Thousands of student requests for information on the Civil War prompted the publication of this booklet. Its purpose is to present in simple language a survey of the eleven most popular aspects of the 1861-1865 conflict. This guide is intended as a supplement, not a substitute, for American history textbooks.

Space limitations prevented mention of each of the 6,000 engagements of the Civil War. Thus, while such actions as the battle of Picacho Pass, Ariz., and Quantrill’s sacking of Lawrence, Kan., had import for their particular locales, they of necessity had to be omitted. In those battles herein discussed, statistics for armies and losses are those generally accepted. The map midway in the booklet may help familiarize the student with the various theaters of military operations. After each section is a list of works recommended for those who desire more detailed information on the subject.

Relatively little consideration of the political, economic, and social history of the period was possible within the limits of this small work. However, the Commission can supply upon request and without charge the following pamphlets treating in part of those subjects: Emancipation Centennial, 1962: A Brief Anthology of the Preliminary Proclamation; Free Homesteads for All Americans: The Homestead Act of 1862, by Paul W. Gates; The Origins of the Land-Grant Colleges and State Universities, by Allan Nevins; and Our Women of the Sixties, by Sylvia G. L. Dannett and Katharine M. Jones.

The Commission is deeply indebted to the Editorial Advisory Board members, each of whom rendered valuable assistance toward the final draft of the narrative.

James I. Robertson, Jr., Executive Director U. S. Civil War Centennial Commission

Construction of the U. S. Capitol was still in progress when civil war began.

Historians past and present disagree sharply over the major cause of the Civil War.

Some writers have viewed the struggle of the 1860’s as a “war of rebellion” brought on by a “slavepower conspiracy.” To them it was a conflict between Northern “humanity” and Southern “barbarism.” James Ford Rhodes, who dealt more generously with the South than did many other Northern writers of his time, stated in 1913: “Of the American Civil War it may safely be asserted that there was a single cause, slavery.”

Other historians, such as Charles A. Beard and Harold U. Faulkner, have argued that slavery was only the surface issue. The real cause, these men state, was “the economic forces let loose by the Industrial Revolution” then taking place in the North. These economic forces were strong, powerful, and “beating irresistibly upon a one-sided and rather static” Southern way of life. Therefore, the 1860’s produced a “second American Revolution,” fought between the “capitalists, laborers, and farmers of the North and West” on the one hand, and the “planting aristocracy of the South” on the other.

A third theory advanced by historians is that the threat to states’ rights led to war. The conflict of the 1860’s was thus a “War between the States.” Many in this group believe that the U. S. Constitution of 1787 was but a compact, or agreement, between the independent states. Therefore, when a state did not like the policies of the central government, it had the right to withdraw—or secede—from this compact.

Still other writers believe “Southern nationalism” to have been the basic cause of the war. Southerners, they assert, had so strong a desire to preserve their particular way of life that they were willing to fight. This then became a struggle between rival sections whose differences 6 could not be settled peacefully. The result was a “War for Southern Independence.”

Slaves working in a field across the river from Montgomery, Ala., first capital of the Confederacy.

A recent group of historians, known as “revisionists,” rejects these earlier theories. Leader of the revisionist school was the late James G. Randall, who once stated: “If one word or phrase were selected to account for the war, that word would not be slavery, or economic grievances, or states rights, or diverse civilizations. It would have to be such a word as fanaticism.” Another revisionist, Avery O. Craven, agrees. The Civil War, he wrote, resulted because the great mass of American people “permitted their short-sighted politicians, their overzealous editors, and their pious reformers” to control public opinion and action. Primarily through the slavery issue, these radicals created more and more hatred between North and South. In the end, and as a result of these radicals, the differences between the sections, swelled by “a blundering generation,” burst into a war.

Fort Sumter in 1865, as viewed from a sandbar. The fort’s battered walls are clearly visible.

Few nations have been as unprepared for a full-scale war as was the United States in 1861. The U. S. Army consisted of barely 17,000 men. Most of the soldiers were stationed at remote outposts on the western frontier. To make matters worse for the Union, a large number of army officers who had been born in the South and educated at West Point resigned from the army and offered their services to the Confederacy.

The U. S. Navy was in an equally bad state. It had performed little duty since the War of 1812. The Navy had a total of 90 ships, but only 42 of them were in active service at the outbreak of civil war. Of this number, 11 fell into Confederate hands with the capture of the naval base at Norfolk, Va., in April, 1861. The remaining vessels were scattered around the world. Moreover, 230 of 1,400 naval officers joined the forces of the Confederacy.

At the beginning of the Civil War, the North seemed to possess every advantage:

(1) 23 Northern states aligned against only 11 Southern states. (Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri were slave states, but they remained in the Union. Also, the western counties of Virginia revolted and formed their own state when the Old Dominion cast her lot with the Confederacy.)

(2) The population of the Northern states was approximately 22,000,000 people. The Southern states had only 9,105,000 people, and one-third of them (3,654,000) were slaves. The great difference in population, plus a steady flow of European immigrants into the Northern states, gave the Union tremendous manpower. Over 2,000,000 men served in the Federal armies, while no more than half that number fought for the South.

The “General Haupt” was one of several locomotives seized by Federals on the Orange & Alexandria (now Southern) Railroad.

(3) The North had 110,000 manufacturing plants, as compared with 18,000 in the Confederate States. The North produced 97% of all firearms in America, and it manufactured 96% of the nation’s railroad equipment.

Although the South possessed few manufacturing plants in 1861, Richmond’s Tredegar Iron Works produced such items as machinery, cannon, submarines, torpedoes, and plates for ironclad ships.

(4) Most of the country’s financial resources were in the North.

In view of the North’s statistical superiority in so many areas, people often do not understand how the Civil War lasted four long years. Many reasons account for this:

(1) Both North and South needed many months of preparation before they were ready for full-scale war.

(2) For at least the first eighteen months of the war, the Confederacy was able to obtain many supplies from sympathetic nations in Europe. Not until late in 1862 did the Federals have enough ships to blockade effectively the major Southern ports.

(3) Southern armies generally fought on the defensive. It does not require as many men to hold a position as it does to attack and seize that position.

(4) Moreover, every time the Federals captured a city, bridge, road junction, or other important point, men had to be left behind to guard these places. To the Northern armies also went the task of sheltering, feeding, and to some extent training thousands of freed or runaway slaves. Therefore, even though the Federal armies greatly outnumbered the Confederate forces, the North needed more men to fight the war.

(5) In that age armies rarely fought in wintertime, a season of cold weather and deep mud. Most of the military campaigns took place 9 between April and October. Hence, little activity occurred for about half of each year.

Before surveying the military campaigns, the student should bear in mind two more important, but somewhat confusing, points: each side named its armies by different systems, and each side used different methods for identifying battles.

The North named its armies for large rivers, while the South designated its forces by large areas of land. For example, the Federal Army of the Potomac fought against the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. This difference of names could and did sometimes become perplexing. An illustration of this occurred in the Western theater, where the Federal Army of the Tennessee (river) campaigned against the Confederate Army of Tennessee (state).

Likewise, both sides used different methods in naming battles. The North referred to a battle by the closest stream, river, run, or creek in the area. The South designated a battle by the name of the nearest town. Thus, the bloodiest one-day engagement of the Civil War is known in the North as the battle of Antietam Creek, and in the South as the battle of Sharpsburg, Maryland. In some cases, such as the battles of Gettysburg and Wilson’s Creek, both sides adopted the same name.

Now let us turn to the war itself and “follow the armies.”

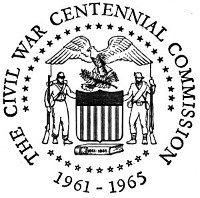

CHART OF CIVIL WAR ARMY ORGANIZATION

ARMY

General (CSA)

Major General (USA)

CORPS

Lieutenant General (CSA)

Major General (USA)

DIVISION

Major General

BRIGADE

Brigadier General

BATTALION (less than 10 companies)

Lieutenant Colonel or Major

COMPANY

Captain

REGIMENT (10 companies)

Colonel or Lieutenant Colonel

COMPANY

75-100 men

Late in April, 1861, the Confederate government moved its capital from Montgomery, Ala., to Richmond, Va. This transfer was intended to bind Virginia closer to the other Southern states and to put the Confederate government nearer Washington when the time came to discuss the peace treaty. In reality the move backfired. It made Richmond the primary Federal target and Virginia the major battleground of the Civil War.

Few engagements occurred in 1861, when neither North nor South had a highly organized, efficient army. What both sides in 1861 called armies were more like armed and unruly mobs. Yet President Lincoln and the Congress, hoping to end the war quickly, were anxious to capture Richmond.

As a result, Federal forces made three thrusts into Virginia. They first moved from Ohio into the pro-Northern counties of western Virginia, where Confederate regiments as “green” as the Federal units were stationed. In a series of small battles, including Philippi (June 3), Rich Mountain (July 11), and Corrick’s Ford (July 13), the Federals were victorious. In 1863 this region entered the Union as the loyal state of West Virginia.

The other two Federal invasions were less successful. The main Virginia defenses stretched from Norfolk northward to the Potomac River, thence westward to Harpers Ferry. Early in June, Gen. Benjamin F. Butler left Fort Monroe with a Federal force and struck at Richmond by way of the peninsula between the James and York rivers. At Big Bethel Church, just west of Yorktown, Confederates attacked and sent Butler’s men stampeding back to their base at Fort Monroe.

Benjamin F. Butler, a politician with little military experience, led two ill-fated campaigns against Richmond.

The third and main Federal push into Virginia resulted in the largest battle fought in 1861. In mid-July, Gen. Irvin McDowell moved from Washington with some 35,000 recruits. McDowell’s ultimate target was Richmond, but first he had to capture the important railroad junction of Manassas. Through espionage agents the Confederates 12 learned of McDowell’s advance. Quickly Gens. P. G. T. Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston concentrated 30,000 Southern troops near Manassas to block the Federal move. On a very hot Sunday, July 21, McDowell attacked Beauregard and Johnston near a stream known as Bull Run. As in the case of many Civil War battles, the main attack was against the flank (or end) of the line, while for deception a lesser assault force struck at the center of the defending force’s position.

A great-nephew of Patrick Henry, “Uncle Joe” Johnston proved a superb army commander. Yet he and President Davis had too many personal and official differences during the war.

The Federals might have won a smashing victory that day but for a stubborn brigade of Virginians under Gen. Thomas J. Jackson. The refusal of Jackson and his men to give ground not only helped save the day for the South but also earned for that general and his brigade the name “Stonewall.”

Losses in the battle of First Manassas, or First Bull Run, were much less than those in the larger battles to come. The Federals lost 2,896 men killed, wounded, and missing. The Confederates suffered 1,982 casualties.

This battle at Manassas had several important effects. Southerners were convinced that Yankees were poor fighters, and that the war would be brief. On the other hand, Northerners realized that defeating the Confederacy would take longer than anticipated. Thus, while Southerners celebrated a great victory, the North began raising and equipping large armies for full-scale war.

A month later occurred an engagement in the West. On August 10, a Federal army sought out and attacked a Confederate force at Wilson’s Creek, near Springfield, Mo. In this battle, often called “Bull Run of the West,” the Federals met defeat. The Union commander, Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, was killed in the midst of the fighting.

On October 21, the North suffered another costly setback. Near Ball’s Bluff, Va., Confederate defenders all but annihilated a Federal scouting force. The “Ball’s Bluff disaster” spurred into action the “Committee on the Conduct of the War.” Seven U. S. congressmen made up this investigating body. Although not one had had army training, they continually inquired into the military affairs of every Federal army and often embarrassed generals in the field.

While Confederates in 1861 won most of the battles, Lincoln and his government by no means felt defeated. Gen. George B. McClellan 13 was building an army at Washington that would soon number 100,000 volunteer troops. This force would be the largest ever amassed in the Western Hemisphere up to that time. Moreover, the North had won a few victories. On November 7, a Federal amphibious force had captured Port Royal, S. C., thus gaining a beachhead on the South Atlantic coast. Yet on that same day, another Federal army suffered defeat at Belmont, Mo. The losing general was an unknown officer from Illinois, and this was his first Civil War battle. His name was Ulysses S. Grant.

War’s full fury struck in 1862. To understand the complicated movements of many armies, bear in mind two points:

(1) Not one, but two, separate areas of military operations existed. The Appalachian Mountains, extending in an almost unbroken line from Pennsylvania to Alabama, prevented armies from moving freely from eastern states (Virginia, the Carolinas, etc.) to western or trans-Appalachian states (Tennessee, Kentucky, etc.), and vice versa. As a result, different armies in the East (east of the mountains) and in the West fought practically two almost independent wars. Only in 1864 were the campaigns of the two areas effectively coordinated.

(2) In the 1800’s, in contrast to modern military tactics, an invading army did not always move directly against an enemy force. Rather, its primary target was usually an important city. Once the invading army was in motion, the defending force then tried to place itself between the invader and his target. This set the stage for battle. Five such Confederate cities became principal Federal targets. In the East was Richmond; in the West were New Orleans and Vicksburg, both strongholds on the all-important Mississippi River, and Chattanooga and Atlanta, vital railroad centers.

Bearing these two points in mind, let us turn to the Western campaigns of 1862.

At the beginning of 1862 some 48,000 Confederate soldiers guarded a 600-mile line extending from the Appalachian Mountains westward to the Mississippi River. Obviously the Southern defenses were thinly manned. Early in February, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant left Cairo, Ill., with 15,000 men to attack the center of this line. His goal was to gain control of two important rivers, the Tennessee and the Cumberland.

To protect these streams, the Confederates had constructed twin forts in Tennessee just south of the Kentucky border. Fort Henry guarded the Tennessee; Fort Donelson stood menacingly on the banks 14 of the Cumberland. On February 6 a Federal river fleet cooperating with Grant battered Fort Henry into submission. Ten days later Grant had surrounded Fort Donelson and its 12,000 defenders. Answering the Confederate commander’s request for surrender terms, Grant replied: “No terms but unconditional surrender.” Thereafter, U. S. Grant was “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

Grant’s victories brought great rejoicing in the North. Some writers consider the Henry-Donelson campaign as “the critical operation” of the Civil War. Capture of these forts assured Union control of Kentucky and Tennessee and opened Mississippi and Alabama to Federal invasion. The loss of the forts was a severe blow to Southern morale. With these successes the North had also demonstrated its ability and willingness to fight.

Meanwhile, an important battle occurred farther to the west for control of Arkansas and Missouri. On March 7-8, at Pea Ridge (or Elkhorn Tavern), Ark., a Confederate army of 16,000 men attacked 12,000 Federals under Gen. Samuel R. Curtis. Most of the Confederates lacked uniforms and were armed with shotguns and squirrel rifles. This force also included 3,500 Indians of the Creek, Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw and Seminole tribes. After two days of fighting, a Federal counterattack broke the Confederate “army.” With the defeat at Pea Ridge the Confederates permanently lost Missouri and northern Arkansas.

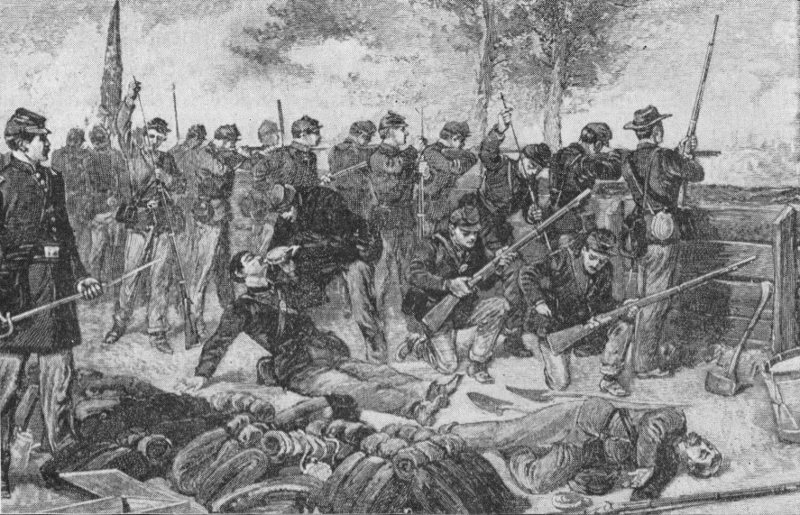

Gunfire and fighting at Shiloh was so intense that one area of the battlefield became known as the “Hornet’s Nest.” This drawing depicts the stubborn resistance of two Federal divisions in that area.

By the end of March Grant’s army was near the Mississippi border. Just across the line Gens. Albert Sidney Johnston and Beauregard had collected a force of 40,000 Confederates. Even though most of his 15 troops were ill-equipped, Johnston attacked Grant’s encamped forces in an effort to destroy the Federal invaders. The battle of Shiloh (April 6-7), one of the war’s most costly engagements, followed.

The initial Confederate attack caught Grant by surprise, bent his line, but never broke it. Several events then swung the battle to the North’s favor. Gen. Johnston bled to death from a leg wound. Exhaustion and disorganization blunted the drive of the Southerners, and Federal artillery posted in great strength near the Tennessee River proved an effective barrier to the Confederate advance. Heavy Federal reinforcements under Gen. Don C. Buell arrived during the night. The next morning Grant counterattacked. The Confederates retreated grudgingly to Corinth, thus ending the battle. Grant’s hard-won victory cost him 13,047 casualties. The Confederates lost 10,694 soldiers, roughly one-fourth of Johnston’s forces.

For the next four months the armies of Grant and Bragg (who eventually succeeded to command) did not meet in battle. However, three significant events took place elsewhere in the Western theater.

One was the Federal capture of the mouth of the Mississippi River. In April a fleet under Flag Officer David G. Farragut blasted its way upriver past Forts Jackson and St. Philip. By the end of May the strategic river cities of New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Natchez were under Federal control. Yet a river attack on Vicksburg failed.

The second event was one of the boldest raids in American history. In April James J. Andrews, a Federal espionage agent, and twenty-one Northern soldiers sneaked through Confederate territory to Big Shanty Station, Ga., only thirty miles from Atlanta. There they stole the engine “General” and two cars of a Western & Atlantic passenger train. The Federals’ plan was to race up the tracks to Chattanooga, removing rails, burning bridges, and thus ruining this important line.

The coup might have succeeded but for the perseverance of a handful of citizens and soldiers, who gave immediate pursuit on foot, by handcar, and eventually on an engine (“The Texas”) running in reverse. All of the raiders were soon captured. Andrews and seven of his men were subsequently hanged in Atlanta.

Southern raiders soon gained a measure of revenge. In July, 1862, Col. John Hunt Morgan led his Confederate cavalrymen on a two-week slash through Kentucky. Morgan won four small battles, captured 1,200 Federals, and returned safely to Tennessee with less than 100 casualties. In December Morgan again struck into Kentucky. This “Christmas Raid” netted 1,900 prisoners and large quantities of horses and military stores.

Shortly after Morgan’s First Kentucky Raid, Gen. Bragg invaded the same state. Bragg hoped to occupy the chief cities and, by “military 16 persuasion,” to bring Kentucky into the Confederacy. Yet caution eventually got the better of Bragg. He retreated, even after winning a tactical victory over Gen. Don C. Buell at Perryville on October 8. This invasion marked the end of Confederate efforts to wrest Kentucky from the Union.

Braxton Bragg is one of the most controversial generals of the Civil War. Although a devoted soldier and skillful organizer, he lacked that necessary spark of leadership.

William S. Rosecrans was a tireless, conscientious officer whom the men affectionately called “Old Rosy.”

Bragg returned to Tennessee. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, who had gained fame in two Mississippi campaigns, assumed command of the Federal army opposing Bragg. Then in November Grant started southward from Tennessee through Mississippi toward Vicksburg, the chief Confederate stronghold on the “Father of Waters.” Grant’s strategy called for a two-pronged attack: he and Gen. William T. Sherman would deliver simultaneous assaults on Vicksburg from different directions. The plan was a costly failure. Confederate cavalry under Gen. Earl Van Dorn destroyed Grant’s main supply base at Holly Springs. Grant was forced to fall back to Memphis. Sherman’s assaults on December 28-29 at Chickasaw Bayou were repulsed with heavy losses. Grant then moved his entire army down the Mississippi and prepared to take Vicksburg by attack or siege.

The final Western engagement of 1862 began on the last day of the year near Murfreesboro, Tenn. For the better part of four days Bragg’s Confederate army waged a desperate fight along the banks of Stone’s River with Rosecrans’s Federal forces. Tactically the battle was a draw. Yet the Federals lost 31% in killed, wounded, and missing, while the Confederates suffered 25% casualties.

For seven months McClellan’s large army lay inactive around Washington. Finally Lincoln, his patience exhausted, ordered McClellan to advance into Virginia. McClellan dismissed the dangerous overland route to Richmond. Rather, he proposed to transport his forces by water to Fort Monroe. Thence he would advance westward on Richmond by way of the same peninsula where Butler had met defeat the preceding year. This was the framework of the Peninsular Campaign.

The creation of the Army of the Potomac was the work largely of George B. McClellan. In 1864 he ran unsuccessfully as Democratic candidate for President.

Lincoln finally agreed to the plan. To protect Washington, however, he ordered McDowell’s corps of 37,000 soldiers to remain in the Fredericksburg-Manassas area.

By April McClellan was on the Virginia peninsula with 105,000 men. In the meantime, Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, commanding the Confederate forces in Virginia, had concentrated his small army on the peninsula between McClellan and Richmond. McClellan slowly advanced westward; Johnston, with only 60,000 men, had no choice but to fall back and fight delaying actions. Driving rains turned the country into a vast sea of mud. By the end of May McClellan’s army had reached Seven Pines. The spires of Richmond were visible, nine miles away.

But Seven Pines was as close as McClellan ever got to the Confederate capital. Johnston noticed that the Federal army had been divided into two parts by the flooded Chickahominy River. He then launched attacks against McClellan’s left (southern) flank. The muddy battles of Seven Pines and Fair Oaks (May 31-June 1) permanently halted McClellan’s advance. Johnston was seriously wounded in the fighting, and Gen. Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Confederate forces on the Peninsula.

Elsewhere in Virginia, in the Shenandoah Valley, Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson was performing brilliantly in what became known as the Valley Campaign. Control of the Valley was vital to both sides. This narrow slit of land between two ranges of mountains is a direct avenue into both North and South. Neither side could move safely between the 18 mountains and the seacoast unless the Valley’s northern door—the region around Winchester—was shut.

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson was a man of both military genius and peculiar habits. Known as “Old Jack” to his men, he was probably one of the most devout soldiers of the war.

When McClellan moved up the Peninsula, Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks and another Federal army advanced southward into the Valley. Jackson had only 8,500 men at his command. Yet he was determined to hold Banks at Winchester and McDowell at Fredericksburg so as to prevent them from reinforcing McClellan. On March 23 Jackson attacked part of Banks’s army at Kernstown. The wily Confederate was repulsed, but his daring prevented Banks and McDowell from marching to the aid of McClellan.

Soon three separate Federal armies entered the Valley for the sole purpose of destroying Jackson. Reinforced by Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s division, Jackson and his “foot cavalry” then swung into high gear. The full impact of “Stonewall’s” successes in the Valley Campaign can be seen from statistics. Between March 22 and June 9 the Confederates marched 630 miles, fought 4 major battles and numerous skirmishes, defeated 3 Federal armies totaling over 60,000 troops, inflicted 7,000 casualties, and captured 10,000 muskets and 9 cannon. Jackson’s army, never exceeding 17,000 men, accomplished all this at a cost of 3 cannon and 3,100 casualties. And all the while, Jackson kept Washington under threat of attack.

After a week of rest, Jackson moved rapidly to Richmond to assist Lee in a new campaign against McClellan. By then Lee had verified that McClellan’s army was still dangerously astride the swollen Chickahominy. The Confederate commander obtained this information from his colorful cavalry chief, Gen. J. E. B. “Jeb” Stuart, who in mid-June boldly rode all the way around McClellan’s huge army. On the basis of Stuart’s report, Lee attacked McClellan’s exposed right flank north of the river in the first of a series of battles known as the Seven Days Campaign.

A full beard concealed the fact that “Jeb” Stuart at the time of the Peninsular Campaign was only twenty-nine years old.

On June 26 the Confederates launched their offensive at Mechanicsville, northeast of Richmond. They suffered defeat from Federal troops under Gen. FitzJohn Porter. Lee struck again on June 27 and finally broke the Federal lines at Gaines’s Mill after an all-day fight. McClellan then ordered his army to retire to Harrison’s Landing, the Federal supply base on the James River. Lee’s troops tried again and again to destroy the Federal army. But after hard fighting at Savage Station (June 29), Frayser’s Farm (June 30), White Oak Swamp (June 30), and Malvern Hill (July 1), McClellan safely reached Harrison’s Landing and the protection of a Federal river fleet. His dream of capturing Richmond had ended.

In a few weeks another Federal threat confronted Lee. Gen. John Pope moved overland from Washington with a newly formed army. His target was also Richmond. Lee shifted his army northward to block the advance. On August 9 Jackson checked Pope’s lead elements at Cedar Run, a few miles south of Culpeper. Then, while Pope warily eyed Lee’s main force, Jackson’s men swept around the Federal right flank and captured Pope’s all-important supply base at Manassas. An angry Pope turned around and started in pursuit of Jackson.

Pope soon found Jackson. But Gen. James Longstreet, commanding the other half of Lee’s army, found Pope. The August 28-30 campaign of Second Manassas—or Second Bull Run—resulted. As in the first battle in that area, the Federals met defeat. Pope managed to check a thrust by Lee at Chantilly (September 1), then retired to Washington.

Virginia was now clear of Federal forces. The time was ripe, Lee thought, to invade the North. Success might secure Maryland for the Confederacy and bring official recognition to the Southern nation from England and France. Then both foreign powers would send supplies, and possibly troops, to aid the Southern cause.

Lee’s grayclad regiments waded across the Potomac River on September 5, 1862. At Frederick, Md., Lee divided his army. Jackson marched southward to capture Harpers Ferry and keep the Valley avenue open, while Lee proceeded westward to Sharpsburg.

Harpers Ferry first gained prominence in history with John Brown’s 1859 raid. During the Civil War it was a key point in Eastern military operations.

Meanwhile, Lincoln assigned what was left of Pope’s force to McClellan and sent “Little Mac” in pursuit of the Confederate invaders. On September 14 McClellan fought his way through the passes of South Mountain, Maryland. The next day, as McClellan’s troops converged on Lee, Jackson seized Harpers Ferry. Jackson then hastened northward and rejoined Lee at Sharpsburg late on September 16.

Wednesday, September 17, produced the largest one-day bloodbath on American soil. From sunrise until dusk Federal units made repeated assaults on Lee’s lines. Had McClellan thrown his entire army against Lee’s position, the weight of numbers probably would have destroyed the Army of Northern Virginia. Instead, the Federal commander shifted his attacks from one sector to another. Casualties mounted frightfully in such areas as the East Wood, West Wood, Dunker Church, Sunken Road, and around Burnside’s Bridge. By nightfall Lee’s battered army still held its position. McClellan had lost 12,000 men, the Confederates 9,000.

The battle of Antietam Creek ended Lee’s invasion, and he retired to Virginia. Five days after the engagement, Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. This document promised freedom to all slaves in Confederate-held territory after January 1, 1863. As such, it converted the war into a struggle for human freedom and deterred European nations from granting aid or recognition to the Confederacy. Many historians therefore maintain that Antietam Creek and its aftermath were the turning points of the Civil War.

For six weeks after Antietam, McClellan seemed to make little effort to resume the campaign against Lee. Lincoln tired of waiting; on November 5 he replaced McClellan with Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside.

Fredericksburg, viewed from Federal gun emplacements north of the city. The battle occurred on the heights in the left background.

“I am not competent to command such a large army,” Burnside stated. He demonstrated this truth in his one battle at the head of the Army of the Potomac. On December 13, a freezing Saturday, Burnside 21 ordered six grand assaults against Lee’s entrenched army on the heights overlooking Fredericksburg, Va. The result was a useless slaughter, and a defeated Burnside wept over the killing and wounding of 10,000 of his men. Confederate losses were less than half that number.

A few weeks later Burnside attempted a secret march around Lee’s left (western) flank. The Federal army bogged down in winter mud and made barely a mile a day. This “Mud March” finished Burnside. He soon relinquished command to Gen. Joseph Hooker, a strong-willed officer known to the soldiers as “Fighting Joe.”

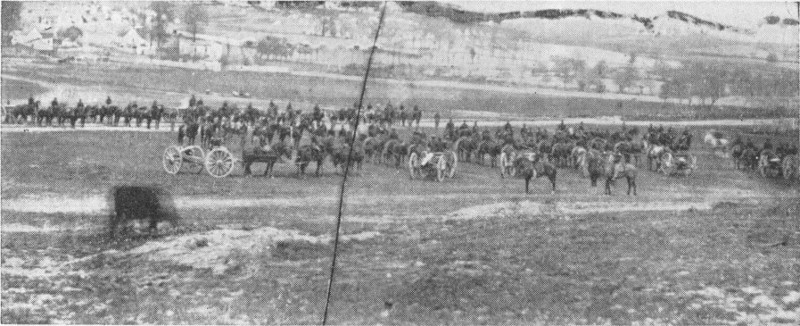

Cavalry raids by both sides occupied the early months of this third year of conflict. One of the longest was that of Col. Benjamin H. Grierson and 17,000 Federal horsemen. Leaving La Grange, Tenn., in April, Grierson’s troopers wrecked railroads and supply depots all the way to Baton Rouge, La. The raid lasted two weeks and helped clear the way for Grant’s campaign against Vicksburg.

Two of the Confederacy’s celebrated cavalry leaders were Nathan Bedford Forrest and John Hunt Morgan. Forrest was a semi-illiterate with no prior military training. But he became a fearless fighter and an unequalled cavalry commander.

Morgan led an independent group of horsemen known popularly as “Kentucky Cavaliers.” He was ambushed and killed at Greenville, Tenn., in 1864.

On the other hand, Gen. Bedford Forrest and his Confederate cavalry made a series of quick attacks in Tennessee throughout March and April. Gen. John Hunt Morgan followed this with a summer foray through Kentucky, southern Indiana, and across Ohio.

Throughout the first half of 1863 Grant slowly tightened the noose around Vicksburg. Moving down the west bank of the Mississippi and crossing below Vicksburg, Grant won clear victories at Port Gibson (May 1), Raymond (May 12), Jackson (May 14), Champion’s Hill (May 16), and Big Black River (May 17). On May 18 Grant began his siege of Vicksburg itself, and for six weeks the Federals isolated Gen. John C. Pemberton and his Vicksburg defenders. Confederate soldiers inside the besieged city eventually found it necessary to eat rats, mules and grass in an effort to stay alive.

With escape hopeless, Pemberton on July 4 surrendered Vicksburg. Not only did Grant capture an entire Southern army of 30,000 men, but the mighty Mississippi, from Minnesota to the Gulf, lay in Federal hands. The North had severed Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, and most of Louisiana from the Confederacy.

As Grant was accepting the surrender of Vicksburg, Gen. Rosecrans and his Federal army of 60,000 men were pushing forward in middle Tennessee. Rosecrans forced Bragg’s army of 47,000 Confederates out of Tullahoma and across the Tennessee River. The Federals slowly began to envelop the key city of Chattanooga. Bragg, in fear of being flanked, retreated into Georgia. Rosecrans seized the strategic rail center, then started in quest of Bragg’s army.

This brought on the desperate battle of Chickamauga (September 19-20). On the first day Bragg attacked but failed to break Rosecrans’s line. That night Gen. James Longstreet arrived from Lee’s army with fresh Confederate troops. Bragg renewed the attack the following morning. After several hours of intense fighting, the Confederates pierced the Federal lines. Rosecrans’s right flank, and the general himself, retreated in disorder to Chattanooga. But the Federal left held fast until darkness ended the conflict.

Confederate troops at Chickamauga tried desperately to rout the Federal army, but a determined stand by blueclad soldiers under Virginia-born George H. Thomas, the “Rock of Chickamauga,” prevented a complete collapse.

George H. Thomas.

In the two-day battle of Chickamauga, 35,000 men were killed, wounded, or captured. Bragg’s victory, while complete, became hollow 23 when he failed to pursue the broken and beaten Federal army. The Federals were able to reorganize and prepare for a new campaign. Grant soon arrived at Chattanooga and took command of all Federal operations in the West. Bragg’s Confederates took positions on the major hills overlooking the city.

From November 23 to 25, the Federals made a series of attacks on Lookout Mountain, Orchard Knob, and Missionary Ridge. In the end, and for the first time, Southern soldiers ran in mass panic from a field. Half-starved Confederate soldiers continued their retreat all the way to Dalton, Ga. Bragg was finished as a field commander.

On the night of March 8, dapper John S. Mosby and his Confederate partisan rangers attacked Fairfax Court House, Va., only a few miles from Washington. The most important item bagged at Fairfax by the Confederates was the garrison commander, Gen. Edwin Stoughton, who was captured while asleep in bed.

John S. Mosby (the hatless figure fourth from left), pictured with some of his partisan rangers. The “Gray Ghost” weighed only 125 pounds.

From April 29 until May 8, Federal cavalry under Gen. George Stoneman cut a swath of destruction through Virginia almost to Richmond itself. Yet Stoneman’s absence from the Army of the Potomac helped Lee win perhaps his greatest victory. Late in April, Gen. Joseph Hooker started southward toward Richmond with an army of 133,000 soldiers. His line of march was through a mass of thick woods and dense undergrowth known as the Wilderness. There “Stonewall” Jackson delivered a surprise flank attack at a road junction called Chancellorsville.

Intense fighting lasted three days and extended from Chancellorsville ten miles eastward to Fredericksburg. Hooker suffered 17,000 losses. Soon the defeated Federal army was limping up familiar roads toward Washington.

Over 12,800 Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded at Chancellorsville. Yet the hardest blow of all was the death of Jackson. Accidentally shot by his own men, Jackson died of complications on May 10.

Lee’s army soon started on a second invasion of the North. Four reasons prompted this thrust: (1) Southern hopes that Lee might capture 24 an important city such as Harrisburg, Baltimore or Washington, relieve the pressure on Vicksburg in the West, and possibly effect a victorious peace; (2) the hope too that a great victory on Northern soil might cause England to offer mediation in the war; (3) the desire to transfer the war from ravaged Virginia; and (4) the need to acquire supplies for Confederate soldiers.

With his army at a peak strength of 75,000 men, Lee crossed the Potomac in mid-June. Lincoln soon replaced Hooker with a Pennsylvanian, Gen. George G. Meade. By the end of June the 90,000-man Federal army was moving northward from Maryland into Pennsylvania in search of the Confederates, who had turned southward in search of supplies. Advancing from opposite directions, these two mighty forces collided at Gettysburg, Pa.

For three days (July 1-3) Lee delivered one attack after another. The climax of the battle came on the afternoon of July 3. Gen. George Pickett’s 15,000 men charged across an open field against the center of the Federal line. Pickett’s assault failed, with 50% casualties, and the battle ended with this attack. Over 43,000 men were killed, wounded, or listed as missing at Gettysburg. The Army of the Potomac had won its first clear-cut victory. Coupled with the fall of Vicksburg on July 4, this defeat brought Southern morale to a new low.

Lee retreated to Virginia. Both armies took strong positions on opposite banks of the Rapidan River and awaited possible movements by one another. Cavalry engagements and infantry skirmishes occupied most of the remainder of that year.

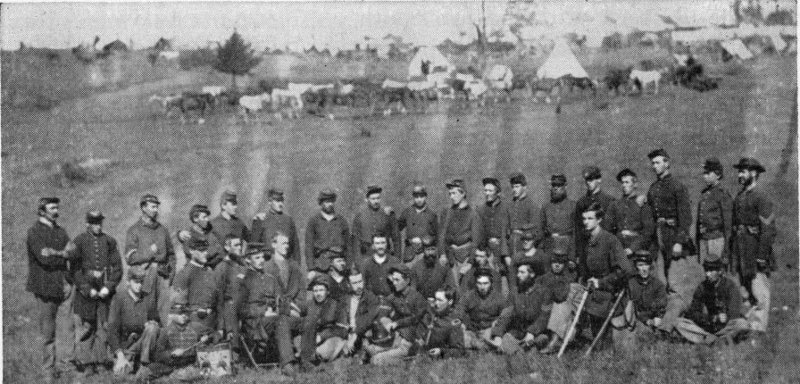

George G. Meade (4th from right) and some of his officers at their winter headquarters in Virginia. Note the barrel used as a chimney for one of the winter huts.

In 1864 the Federal war machine moved into high gear. The two men most responsible were Abraham Lincoln, who on March 9 named U. S. Grant as supreme army commander, and Grant himself, who made immediate preparations to strangle the Confederacy.

Grant’s master plan was simple: Attack. Federal forces would attack simultaneously at all points and apply constant pressure on the ever-weakening Southern states. The Confederacy, Grant reasoned, could not withstand such a continual onslaught.

Grant went east to campaign with the Army of the Potomac. Gen. Sherman took over command of the western forces. Federal drives in both East and West would henceforth proceed from one consistent strategy. While these two generals mapped out details for their joint offensive, a third Federal force met defeat in one of the fiascos of the war. On March 14 Gen. Nathaniel Banks, 40,000 troops, and 50 ships started up the Red River. Their objectives were to gain control of Louisiana and East Texas, to counteract threats from the Emperor Maximilian in Mexico, and to seize large stores of cotton. The expedition was a failure in every respect.

To make matters worse for the North, Nathan Bedford Forrest and his Confederate horsemen stormed Fort Pillow, Tenn., on April 12 and killed most of the Negro troops garrisoned there. Sherman dispatched all available cavalry to rid the West once and for all of the elusive Forrest. The result was the June 10 battle of Brice’s Cross Roads, Miss., in which Forrest won his greatest victory.

In spite of the activities of such Confederate horsemen as Forrest, Morgan, Mosby, and Stuart, Grant and Sherman went ahead with their grand offensives. The main Confederate defenses extended from northwestern Georgia along the eastern edge of the mountains to Winchester, Va., thence southeastward across Virginia through Fredericksburg and Richmond. Early in May both Grant and Sherman struck southward. Sherman, leading over 100,000 veterans, marched toward the key city of Atlanta. Grant, with an Army of the Potomac that numbered 118,000 men, retraced Hooker’s steps through the Wilderness in a new “On to Richmond” drive.

The going proved rough and costly for both generals. Opposing Sherman were Gen. Joseph Johnston and a reorganized Army of Tennessee. Johnston realized that his 53,000 ill-equipped soldiers were no match for a stand-up fight with Sherman’s massed divisions. The Confederate commander therefore resorted to delaying actions and defensive battles while Sherman tried flanking movements and sharp probes in an effort to trap Johnston.

In the Federal siege lines around Atlanta, “Cump” Sherman (legs crossed, leaning against a Parrott gun) and his aides posed for this photograph.

By mid-July Sherman had forced Johnston into the trenches of Atlanta. On July 18 President Davis replaced Johnston with Gen. John B. Hood, who, although minus a leg and the use of an arm, had a reputation as a hard fighter. Hood quickly lived up to that reputation. On July 20, two days after assuming command, Hood attacked Sherman along Peachtree Creek. The Southerners were repulsed. Two days later Hood attacked again in East Atlanta. Again the Confederates were hurled back with heavy losses. Hood then strengthened his defenses around Atlanta, and Sherman tightened his siege.

Meanwhile, Grant in Virginia had met with a similar stalemate—and at a more terrible cost. Grant encountered no opposition as he started through the Wilderness toward Lee and Richmond. But as the Federal army crept through the tangled undergrowth, Lee’s 60,000 Confederates struck suddenly and viciously. Two days (May 5-6) of savage fighting occurred in which Grant met a bloody checkmate.

Yet Grant did not retreat as other generals before him had done. Instead he unfolded his new and radical policy of hammering at Lee while edging closer to Richmond. Grant knew that Lee could not replace his losses, for Southern manpower was all but exhausted. On the other hand, Grant could draw on the vast manpower of the north. With Grant the Civil War was to be a fight to the finish.

Bitter fighting in the “Bloody Angle” at Spotsylvania was typical of the action in the six-week Wilderness Campaign of 1864.

The Army of the Potomac pushed stubbornly toward Richmond. Lee tried desperately to block it, winning victories at Spotsylvania (May 12), North Anna (May 23), and Cold Harbor (June 3). In the last-named engagement, over 7,200 Federals fell in less than twenty minutes of fighting. While Lee contested Grant’s moves, another and makeshift Confederate force under Gen. Beauregard repelled a Federal stab (May 15-19) at Richmond and Petersburg by Gen. Benjamin Butler.

Grant recognized that he could not take Richmond by direct approach. He shifted his army around the city and moved on Petersburg, a rail junction and important link in the Confederate chain of defenses. Lee at first was unaware of Grant’s plans to attack Petersburg. But Beauregard successfully beat back the initial Federal thrusts, thus forcing Grant to begin what became a nine-month siege of Petersburg. Many probes were made of Lee’s defenses. The most spectacular of these occurred on July 30 and is known as the Battle of the Crater.

Coal miners in the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry dug a long tunnel under the Confederate earthworks. Their plan was to explode 8,000 pounds of black powder, blast a mighty gap in the Confederate defenses, and then to use the resulting confusion for a large-scale Federal attack.

The explosion and confusion came off as planned. But the Federal assault failed. Grant resumed his tight siege. In the fighting from the Wilderness to Petersburg, the Federal army had suffered 60,000 casualties—more men than were in Lee’s whole army. Yet Grant knew, as did many Confederates, that Lee was now pinned down. The well-equipped and well-fed Federal army could afford to wait.

The July 30, 1864, mine explosion, as seen from the Federal lines. Newspaper correspondent Alfred A. Waud made this sketch.

Other related actions took place in Virginia. On May 11, Gen. Philip Sheridan’s cavalry clashed with “Jeb” Stuart’s horsemen a few miles north of Richmond at Yellow Tavern. Sheridan’s men were driven back. Yet this battle cost the Confederacy the colorful Stuart, mortally wounded while leading his troops.

On May 15 the Confederates scored another victory in the Shenandoah Valley. Gen. Franz Siegel and 8,000 Federal horsemen advanced up the Valley as far as New Market. There they encountered a hastily assembled Confederate force less than half the size of Siegel’s division. The highlight of the battle was the successful charge of 225 youthful cadets from the Virginia Military Institute. Siegel’s force suffered an embarrassing defeat and fled down the Valley.

Both Lee and Grant recognized the importance of control of the Valley. Yet neither could afford to dislodge his army from Petersburg. Grant therefore organized a separate force under Gen. David Hunter 28 with orders to move into the Valley and “to eat up Virginia clear and clean as far as [you] can go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of this season will have to carry their provender with them.”

To oppose Hunter, Lee rushed westward a small Confederate army under Gen. Jubal Early. Hunter burned and looted his way as far as Lynchburg before Early sent them scurrying over the mountains. Early then decided to make an invasion of his own. Sweeping down the Valley, he crossed the Potomac and moved to the outskirts of Washington. Yet “Jubal’s Raid” (July 4-20) failed when Early decided not to attack the Northern capital.

Grant resolved that no such threat to Washington would again occur. He dispatched a large Federal army under Sheridan into the Valley. Early, woefully outnumbered, nevertheless put up stiff resistance. Only after victories at Winchester (September 19), Fisher’s Hill (September 22), and Cedar Creek (October 19) could Sheridan declare the Valley once and for all cleared of Confederate forces.

In Georgia at this time, Sherman was also meeting with success. Federal victories at Ezra Church (July 28) and Jonesboro (August 31-September 1) compelled Hood to evacuate Atlanta. Sherman occupied the city on September 2. The fall of Atlanta was a valuable assist to Lincoln in his reelection to the presidency that autumn.

The railroad yards and ruins of Atlanta, photographed shortly after the fall of the city.

Sherman felt strongly that the war had to be carried to the Southern people themselves before the Confederacy would collapse. He therefore laid plans to slash through the very heart of the South. The campaign that followed is known as the “March to the Sea.”

Sherman first sent part of his army under Gen. Thomas back to Tennessee to watch Hood, whose Confederates had moved northward in an effort to force Sherman from Georgia. With Thomas blocking Hood, Sherman on November 16 left Atlanta in flames and started toward the Georgia coast with 68,000 veteran fighters. Sherman met little opposition during his advance, and on December 22 he telegraphed Lincoln: “I beg to present you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.”

Kentucky-born John B. Hood first gained fame as commander of a Texas infantry brigade. He was an excellent division or corps commander, but unsuited for the leadership of an army.

Meanwhile, Hood’s strategy in Tennessee backfired tragically. At Franklin, Tenn., on November 30, Hood hurled his army against a part of Thomas’s force under Gen. John M. Schofield. Hood’s assaults cost 6,000 Confederates, including 5 generals and 53 regimental colonels. Two weeks later, Thomas’s troops all but destroyed Hood’s army when the Confederates made repeated assaults at Nashville.

Sherman’s strategy had cut the Confederacy in two. Although Grant was then no closer to Richmond than McClellan had been two years earlier, all that remained of the Confederacy were Virginia, the Carolinas, and isolated areas of the Trans-Mississippi.

Fort Darling, a Confederate defense overlooking the James River at Drewry’s Bluff. In the left foreground can be seen one of the bombproof shelters used by defenders.

After a month’s rest at Savannah, Sherman on February 1 started northward to strike through the Carolinas and join Grant in Virginia for the final blow against Lee. Sherman’s major opposition was the remnant of the Army of Tennessee, which had been placed again under the command of Gen. Joseph Johnston.

Johnston could offer but feeble resistance to Sherman. Federal troops occupied Charleston and were in Columbia when the latter was gutted by fire. On March 10 Sherman’s forces seized Fayetteville in central North Carolina, brushed back part of Johnston’s army six days later at Averysboro, and successfully withstood a Confederate attack at Bentonville (March 19-21).

Meanwhile, Grant had been mustering his forces for a grand drive against Lee’s weak defenses. Throughout the long siege of Petersburg Grant had slowly extended his lines farther to the south and west. Lee had no choice but to stretch his own meager defenses accordingly. Soon the Southern defenses were dangerously overextended.

This was the situation which Grant had sought. On April 1 he attacked Lee at Five Forks, sixteen miles southwest of Petersburg. The Confederate line bent and then broke. That night the Army of Northern Virginia abandoned the Richmond-Petersburg trenches and slowly moved westward in retreat. At the same time President Davis transferred the Confederate capital to Danville near the North Carolina border, Lee’s major hope was to rendezvous at Danville with Johnston’s army, then falling back in the face of Sherman’s advance. Together, Lee speculated, he and Johnston might be able to defeat first Sherman and then Grant.

This April, 1865, photograph shows the gutted business district of Richmond. The prominent building in the center was the Confederate capitol.

The dream quickly faded. As Lee’s army plodded westward, Grant’s divisions snipped at its heels at Amelia Court House (April 31 4-5), Sailor’s Creek (April 6), High Bridge (April 7), and Farmville (April 7). On April 8, near Appomattox Court House, Lee found the way blocked by massed infantry and cavalry under Sheridan. The Confederates were surrounded. On Palm Sunday, April 9, Lee surrendered to Grant. Three days later, 28,000 Confederates in the Army of Northern Virginia stacked their muskets before silent lines of Federal soldiers.

Lee’s surrender left Johnston with no place to go. On April 26, near Durham, N. C., the Army of Tennessee laid down its arms before Sherman’s forces. With the surrender of isolated forces in the Trans-Mississippi West on May 4, 11, and 26, the most costly war in American history came to an end.

The imposing farmhouse of Wilmer McLean was the site of Lee’s surrender to Grant.

In contrast, Johnston surrendered to Sherman in the small frame cottage of James Bennett.

(Students should also consult bibliographies in the above works for additional readings.)

Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery is one of the larger depositories for Confederate dead. This 1865 photograph shows the wooden slabs then used for headstones.

More Americans died in the Civil War than in all of America’s other wars combined. From the French and Indian wars of the 1750’s through the hostilities in Korea in the 1950’s (with the exception of the Civil War), 606,000 American soldiers died in the line of duty. In the Civil War alone, over 618,000 men perished in four years of fighting.

The North lost 360,022 soldiers. Of that number, 67,058 were killed in action, while 43,012 later died of battle wounds. A total of 275,175 Federals received wounds while fighting.

Accurate records do not exist for the Confederate side. The total number of Southern soldiers killed was approximately 258,000. About 94,000 were killed or fatally wounded in battle. No figures exist for the number of Confederates who were wounded in action.

Lord Alfred Tennyson’s famous poem, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” tells of the assault of a British cavalry unit in the Crimean War. In its charge the Light Brigade sustained 37% losses. Yet at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, the 1st Minnesota Infantry lost 82% of its strength in that day’s fighting. At Antietam the 1st Texas suffered 82% casualties in a few hours of combat. The 27th Tennessee had 54% losses at Shiloh; six months later, the same regiment lost 53% of its remaining strength at the battle of Perryville. In all during the Civil War, no less than 63 Federal and 52 Confederate regiments lost over 50% of their strength in a single engagement.

After a battle it was not always possible to bury the dead. Here bleached bones mark the spots where soldiers died in the fighting at Gaines’s Mill.

Other statistics of the Civil War give an equally horrible picture. Over 400,000 soldiers died of sickness and disease. For every man killed in battle, two men died behind the lines from such maladies as smallpox, measles, pneumonia, and intestinal disorders. It is a sad fact that almost as many Federal soldiers (57,265) died of dysentery and diarrhea as were killed outright on the battlefield (67,058). Since conditions in Confederate armies were worse, the number of Southern deaths from sickness was probably higher.

Field hospitals, such as this one established near Mechanicsville in June, 1862, could usually be found near the battlefield. The man in the center foreground is a doctor examining the leg wound of a soldier.

Naval affairs were among the most critical problems facing each side in 1861. The Federal navy was woefully small and widely scattered. Moreover, the Confederate seacoast extended 3,500 miles from the Chesapeake Bay to the Mexican border. It contained hundreds of inlets, bays, and river openings. Not even a drastically enlarged Federal navy could patrol so vast a region.

Lincoln and his Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, soon devised an effective plan. The North would weaken the Confederacy by blockading its chief ports—Norfolk, New Bern, Wilmington, Beaufort, Charleston, Savannah, Pensacola, Mobile, New Orleans, and Galveston.

A former Hartford, Conn., newspaper editor, Sec. of the Navy Gideon Welles was one of the more industrious and loyal members of Lincoln’s cabinet.

His Confederate counterpart, Stephen R. Mallory of Florida, was one of only two men who remained in Davis’s cabinet throughout the war.

Lincoln accordingly proclaimed a blockade shortly after war began. Several months passed before Federal Squadrons could begin to enforce this blockade. Yet the Federal ring of ships became increasingly stronger as the war progressed. As a result, Federal forces were able to peck away at Southern coastal defenses.

In 1861 Union amphibious forces captured Fort Hatteras, N. C., and Port Royal, S. C. During the next year Roanoke Island, N. C., New Bern, N. C., Fort Pulaski, Ga., Fort Macon, N. C., New Orleans, La., and Pensacola, Fla., fell into Federal hands in that order. The Confederates rallied in 1863 and managed to hold their remaining coastal works, particularly Charleston, S. C.

Northern fleets continued to apply pressure all along the Southern coast. Two engagements marked the effectiveness of coastal attacks. On August 5, 1864, Admiral David Farragut—the greatest naval figure produced by the war—led his Federal squadron into mine-infested Mobile Bay with the battle cry: “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!” Farragut so neutralized this last Confederate port on the Gulf of Mexico that its surrender was an anticlimax. Then, five months later, on January 15, 1865, Federal forces stormed and captured Fort Fisher, N. C., the last great Southern defense on the Atlantic coast.

David G. Farragut’s exploits in the Civil War made him the first man in American naval history elevated to the rank of full admiral.

Federal navies also saw much service on the Mississippi River. A wide assortment of Federal vessels campaigned against such Confederate strongholds as Memphis, Tenn., and Vicksburg, Miss. Some were little more than steamboats converted into warships by means of steel plating and deck guns. Others were sailing craft, with high decks and tall masts. One new type of gunboat made its appearance on the Mississippi: the steel ram. Designed by a civilian engineer, Charles Ellet, Jr., this little ship had great speed and maneuverability. Its principal weapon was a heavy prow, which was used to sink a ship by striking it broadside.

Ellet’s steam rams had no guns and little beauty, but by their speed they opened the Mississippi past Memphis for Federal movements.

The Confederacy was born without a navy. Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory was never able to develop a fleet that could contest the ever-increasing Federal navy. Lack of funds, lack of shipbuilding facilities, and effective Northern diplomacy overseas restricted Confederate efforts to privateers, to blockade-running, and for the most part, to undertakings by individual ships.

Most of the twenty Confederate raiders achieved a measure of fame and success before they were destroyed. For example, the C.S.S. Florida, under Capt. John Newland Maffitt, captured thirty-four ships before 39 she herself was seized in Brazil in 1864. The English-built Alabama, commanded by Capt. Raphael Semmes, compiled a more remarkable record. In two years on the high seas, the Alabama took sixty-two prizes. On June 19, 1864, however, this Confederate vessel went to the bottom off the coast of France after an historic duel with the U.S.S. Kearsage. Captain James I. Waddell’s steam raider, the Shenandoah, roamed the Pacific Ocean in quest of Federal game. Her crew bagged forty ships, including eight seized two months after the war on land had ended. On November 6, 1865, the Shenandoah furled its Confederate colors in Liverpool, England.

In their famous battle, the Alabama (right) and Kearsage circled and fired for an hour at a range of 900 yards. The Alabama sank after many direct hits.

The most famous Civil War contest between ships occurred March 9, 1862, in Hampton Roads, Va. The Confederates had raised from the bottom of Norfolk harbor the Federal warship, Merrimac. John Mercer Brooke and John L. Porter had then converted the craft into an ironclad vessel which the Confederates rechristened the Virginia. Sloping iron plates four inches thick protected her decks. The ironclad carried a battering ram weighing 1,500 pounds, plus ten guns. On March 8 the Virginia steamed into Hampton Roads. She easily destroyed two wooden Federal warships and ran a third aground.

The Monitor (left) was the creation of Swedish-born John Ericsson, who had difficulty in selling his strange vessel to the Federal navy. The re-christened Merrimac (right) carried more guns, but so difficult was the ship to maneuver that it required 30 minutes to turn it around.

On the following day, however, the North came forward with a revolutionary weapon of its own. This was the Monitor, so weird-looking 40 a craft that sailors referred to it as a “tin can on a shingle.” The three-hour battle between the Monitor and the Virginia was a draw. Neither ship could pierce the plating of the other. Yet this indecisive battle caused a revolution in naval craft, for it foreshadowed the day when wooden ships would be obsolete.

Two months later, trapped in Hampton Roads, the Virginia was run aground and destroyed. In December, 1862, the Monitor went down in an Atlantic storm near the North Carolina coast.

The Confederates made several notable innovations in the field of naval warfare.

One was an ironclad ram that had the appearance and characteristics of a monster. This was the Arkansas, which the Confederates somehow put together in the summer of 1862 to combat Federal ships on the Mississippi. Constructed of wood, railroad rails, wire, and bits and pieces of iron collected from all over the South, the Arkansas scattered several Federal gunboats, created panic on the Mississippi, and managed to survive a heavy Federal bombardment near Vicksburg.

At Baton Rouge, however, the ironclad’s engines failed. The ram’s commander, Lieutenant H. K. Stevens, ordered the helpless ship destroyed. The Arkansas enjoyed only one month of action; yet Federal Admiral David Farragut called the end of the Arkansas “one of the happiest moments of my life.”

The Confederacy also had the first submarine of modern design. Built in 1863 at Mobile, the H. L. Hunley was named for its inventor. In the process of its trial runs, the thirty-five-foot vessel sank four times and drowned as many crews. Nevertheless, the Hunley was borne overland to Charleston, S. C., to campaign against a fleet of Federal blockaders. On the night of February 17, 1864, the little submarine torpedoed and sank the Federal warship, Housatonic. But the Hunley and its fifth crew of seven men perished in the explosion.

This Official U. S. Navy photograph shows the Confederate torpedo boat David aground in Charleston harbor. Semi-submersible, the David is often called a submarine.

In addition to the submarine, Confederates also developed the water mine and the torpedo boat. The latter was a small vessel, propelled by a steam engine. It drifted along the surface of the water and attacked enemy ships with a torpedo suspended from a long spar. The first of these torpedo boats, the David, appeared in 41 Charleston harbor early in October, 1863, and seriously damaged the blockading warship, New Ironsides.

But such innovations could not overcome the constant and painful pressure of large Federal fleets all along the Southern coast. So vital were the navies to the Northern war effort, James G. Randall wrote, “that Union victory without the naval contribution seems inconceivable.”

Young boys known as “Powder Monkeys” served on almost every warship in the Civil War. This little sailor stands on the deck of the U.S.S. New Hampshire.

What the nations of Europe did—or did not do—were matters of constant and vital concern to both North and South during the Civil War. President Davis and other Confederate officials hoped earnestly that England, and possibly France as well, would recognize the independence of the Southern nation and grant it much-needed aid. President Lincoln and the Federal authorities were just as desirous that European powers should not intervene in the American struggle. Thus, starting in 1861, both sides began a determined tug-of-war to woo the statesmen of Europe to their respective cause.

James Mason and John Slidell were both former U. S. senators. Mason chewed tobacco arduously and could be crude in manner.

Slidell spoke French fluently and had married into Louisiana Creole aristocracy.

The first major international incident occurred in the autumn of 1861 and is known as the “Trent Affair”. Two Confederate commissioners, James M. Mason and John Slidell, were sent to plead the South’s cause at London and Paris, respectively. The agents were en route on the British mail steamer, Trent, when, on November 8, a Federal warship, the San Jacinto, stopped the British vessel on the high seas. Mason and Slidell were removed from the Trent and imprisoned at Fort Warren in Boston.

Northern officials were unprepared for the storm of indignation that came from England. The San Jacinto, it was pointed out, had violated English neutrality by intercepting the Trent. Equally outrageous to the British was the fact that the San Jacinto had fired two warning shots across the Trent’s bow. This was equivalent to firing at the British flag; as such, it constituted an act of war against England.

Fortunately for the North, Lincoln and his Secretary of State, William H. Seward, were able to resolve the incident with a minimum of ill feelings. Apologies were dispatched to London. Mason and Slidell were released from prison and allowed to continue their overseas journey without further Federal interference.

Only five feet, four inches tall, William H. Seward nevertheless became the most powerful and respected member of Lincoln’s cabinet.

In addition to Mason and Slidell, the Confederacy utilized a number of foreign agents. Most of these commissioners pursued a policy of “King Cotton diplomacy”—that is, promising England and France large quantities of the popular staple in return for official recognition of, and active aid to, the Southern Confederacy. When the demand for American cotton dropped sharply in Europe, this approach failed.

Southern agents Henry Hotze, Edwin DeLeon, and James D. Bulloch then tried new strategy. They wrote extensively about the close ties in business and society between the English aristocracy and the great Southern planters, a lower tariff on foreign-made goods if the Confederacy triumphed in the war, and a more active European participation in American commerce.

The nations in Europe had other reasons for wishing to assist the Southern cause. The Federal blockade prevented English goods from reaching eager Southern markets. Many persons abroad looked on the Civil War as a struggle of the South for the right of self-determination. On the other hand, the British middle and working classes detested slavery. After Lincoln’s Emancipation, most Europeans believed that the North was waging a great struggle for freedom.

Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana served successively as Confederate Attorney General, Secretary of War, and Secretary of State.

Although the South tried desperately to gain much-needed European support, it was largely unsuccessful. British and French shipbuilders did sell several vessels to the Confederate government. Yet this 44 aid dropped to a thin trickle following Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Spectacular Federal victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg forever doomed the South’s hopes for foreign aid.

Charles Francis Adams was the son of the 6th President of the U. S. In 1860 his affiliation with the Whig Party prevented him from receiving a post in Lincoln’s cabinet.

The one man who unquestionably did most to keep Europe neutral during the Civil War was the American minister to England, Charles Francis Adams. He skillfully thwarted the efforts of Confederate emissaries, expounded the North’s cause with vigor and tact, and let it be known at opportune times that assistance to the Confederacy could occasion war with the United States. Adams fought a host of Southern agents around the diplomatic tables of Europe. “When all the facts are considered,” one author has stated, “it must be admitted that the character and ability of Charles Francis Adams were as valuable as Union military victories in contributing to ultimate success in the war.”

Confederate prisoners at Camp Douglas, near Chicago, Ill. This photograph was taken soon after the camp became a compound for prisoners.

The Civil War was the first time that the nation had to contend with large numbers of war prisoners. As might be expected, therefore, policies and treatment varied greatly—and oftentimes sadly.

During the war the Confederates captured about 211,000 Federal soldiers. Of this number, 16,000 agreed to battlefield paroles—signed promises that they would not bear arms again. Conversely, Federal forces took some 215,000 Confederates as prisoners. At various times throughout the war, both sides made efforts to establish a workable program of prisoner exchange. (A ratio of exchange once existed whereby forty privates equalled one major-general.) However, owing to misunderstandings, violations of terms, and Grant’s determination late in the war to bring the South to its knees at all costs, prisoner exchange was slight and sporadic.

The most notorious Southern prisons were: Libby and Castle Thunder, which were converted warehouses in Richmond; Belle Isle in the James River; “Camp Sorghum” at Columbia, S. C.; and Camp Sumter at Andersonville, Ga. Among the worst of the Northern compounds were: Elmira Prison Camp in southwestern New York State; Point Lookout, on the Chesapeake Bay; Johnson’s Island, in Lake Erie a few miles offshore from Ohio; Camp Douglas, near Chicago; and Rock Island Prison Camp, Illinois.

Writing of these compounds in general, one historian has observed: “The prisons of the Civil War were of a considerable variety in structure and general make-up and for the most part consisted of 46 temporary structures or old unused buildings not originally intended to confine prisoners. Most of them, judged by present-day standards of sanitation and safety, would have been condemned as uninhabitable.”

This is an artist’s conception of the horrors of life in Andersonville. The hastily built camp spread over 26 acres.

A Harper’s Weekly artist sketched an orderly and clean Elmira Prison that was a far cry from actual conditions. For a modest sum, curious townspeople were permitted to mount observation towers and view the prisoners.

Small wonder that great suffering existed in most prison camps, both North and South. In the nine-month history of the huge prison at Andersonville, Ga., a total of 45,613 Federals were jammed into a Stockade containing one polluted stream of water, few shelters, less food, and no sanitation. Over 12,900 prisoners died of disease, exposure, and starvation at Andersonville. Confederate authorities maintained that Federal prisoners in Andersonville received the same slim food ration as did their guards, and that the whole South suffered badly for want of medicines.

Only captured Federal officers were confined in Libby Prison. Several escapes, and innumerable charges of inhuman treatment, marked this compound’s four-year history.

The North’s prison camp at Elmira, N. Y., had many similarities to Andersonville. This Federal compound existed for a year. During that time, 2,963 of 12,123 Confederate prisoners died from various causes. In the twenty-month life of Rock Island Prison Camp, 1,960 of 12,400 Southern inmates succumbed to exposure and disease. At six remote tobacco warehouses in Danville, Virginia, 1,400 of 7,000 Federal prisoners died of smallpox, malnutrition, and intestinal disorders in the space of a year.

In all, the Chief of the U. S. Record and Pension Office reported in 1903, 25,976 Confederates and 30,218 Federals died in Civil War prisons.

It is difficult still to give an accurate and impartial summary of Civil War prisons. Conflicting facts, lost records, and bitter feelings hamper attempts to arrive at a just verdict. But perhaps Prof. James Ford Rhodes was not far from the truth when he stated: “All things considered the statistics show no reason why the North should reproach the South [about atrocious prison conditions]. If we add to one side of the account the refusal to exchange the prisoners and the greater resources, and to the other the distress of the Confederacy, the balance struck will not be far from even. Certain it is that no deliberate intention existed either in Richmond or Washington to inflict suffering on captives more than inevitably accompanied their confinement.”

The Confederate Commissary General Of Prisons was Gen. John H. Winder of Maryland.

Winder’s Federal counterpart, Gen. William H. Hoffman of New York, likewise was accused of many atrocities.

About forty-eight different types and sizes of cannons were used in the Civil War. Identifying a particular weapon thus requires knowing such facts as the name of the gun, howitzer, rifle or mortar; whether it was a smoothbore (without rifling in the barrel) or a rifled gun (with barrel groovings), etc.

The two most popular cannons in the Civil War were the 12-pounder Napoleon smoothbore howitzer and the 10-pounder Parrott rifled field gun.

The Napoleon weighed about 1,200 pounds, fired a 12-pound spherical shell with a time fuse, and was very effective up to a range of 1,500 yards. The Parrott rifle—identifiable by a reinforced barrel seat—weighed 900 pounds. At a maximum range elevation of 12°, this piece was accurate to 3,000-3,500 yards (1¾-2 miles).

A Negro soldier stands guard over a Napoleon gun at Grant’s City Point, Va., supply-base. The Napoleon is attached to its caisson, which carried ammunition.

The Federals also made extensive use of mortars. Because of the ability of these squat, heavy weapons to lob large shells a great distance by high-angle fire, mortars were ideal for siege operations.

Artillerists used various types of shells, depending upon the action in which they were engaged. Solid shot was good for battering a fortification or for striking an enemy column in flank. Explosive shells and “spherical case” blanketed an area with what is known today as shrapnel. Canister, a shell filled with lead balls about the size of plums, was deadly for close action up to 300 yards. Somewhat similar to canister was grape shot. This type of shell, filled with balls the size of oranges, was effective to 700 yards. Yet grape shot was rarely used in land warfare.

The basic artillery unit was known as a battery. It normally consisted of 4-6 guns commanded by a captain. In battle, batteries normally supported infantry divisions.

A popular field piece among Confederates was the 12-pounder, breech-loading Whitworth gun. Made in England, these weapons fired a solid shot accurately to a range of 5 miles.

During the conflict of the 1860’s the North experimented with and used many new types of field weapons, including the machine gun and such cannons as Rodmans, Columbiads, and Dahlgrens. Despite the large variety, however, the Napoleons and Parrotts remained the “old reliables” to gunners on both sides.

Mortars were very effective during bombardments or siege operations. The most famous of these squat, heavy weapons was the “Dictator” (shown above). Used during Grant’s 1864 siege of Petersburg, this mortar fired a 200-pound ball at distances over 2 miles.

The weapon most used by Civil War infantrymen was known officially as the United States Rifle Musket, Model 1861. Soldiers popularly called it the “Springfield”, since the Springfield, Mass., arsenal manufactured a majority of these guns.

The Springfield was a percussion-cap, muzzle-loading weapon, caliber .58, and weighed 9¾ pounds. The Springfield’s effective range was 500 yards, although it could deliver a ball twice that distance. It fired a soft lead Minie bullet—known then as now as the “minnie ball.” In all, over 670,000 Springfields were manufactured during the Civil War. They cost the government about $19 each.

The Springfield musket, not including its 18-inch bayonet, was 58½ inches in length. Contrary to popular belief, Civil War soldiers rarely used bayonets in battle.

Very popular among soldiers on both sides was the English Enfield Rifle Musket, Model 1853. About 820,000 of these rifles were purchased by North and South. The Enfield weighed 9 pounds, 3 ounces, had a caliber of .577, and was deadly up to 800 yards. It fired a bullet similar to the Minie projectile.

Great strides were made at this time in breechloaders. These weapons fired ready-made bullets, a series of which were inserted at one time in the rear of the barrel. Breechloaders could fire faster and more accurately than the single-shot, muzzle-loading Springfield or Enfield. The Spencer Repeating Carbine, first patented in 1860, was a seven-shot repeater that weighed 8¼ pounds and had an effective range of 2,000 yards. The Spencer was capable of 15 shots per minute—three times the firepower of the Springfield. Another popular carbine among Federal soldiers was the 15-shot Henry repeater, which was a .42-caliber, rimfire carbine of extraordinary accuracy. About 10,000 of these weapons saw service in the Civil War. This gun was the forerunner of the modern Winchester carbine. Unfortunately for the North, red tape and political conservatism by its leaders prohibited the wide and prompt adoption of the repeating rifle.