The Project Gutenberg EBook of Stage-coach and Mail in Days of Yore,

Volume 1 (of 2), by Charles G. Harper

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Stage-coach and Mail in Days of Yore, Volume 1 (of 2)

A picturesque history of the coaching age

Author: Charles G. Harper

Release Date: January 11, 2019 [EBook #58667]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STAGE=COACH, MAIL IN DAYS OF YORE, VOL 1 ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Brighton Road: Old Times and New on a Classic Highway.

The Portsmouth Road, and its Tributaries: To-day and in Days of Old.

The Dover Road: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike.

The Bath Road: History, Fashion, and Frivolity on an Old Highway.

The Exeter Road: The Story of the West of England Highway.

The Great North Road: The Old Mail Road to Scotland. Two Vols.

The Norwich Road: An East Anglian Highway.

The Holyhead Road: The Mail-Coach Road to Dublin. Two Vols.

The Cambridge, Ely, and King’s Lynn Road: The Great Fenland Highway.

Cycle Rides Round London.

The Oxford, Gloucester, and Milford Haven Road: Two Vols.[In the Press.

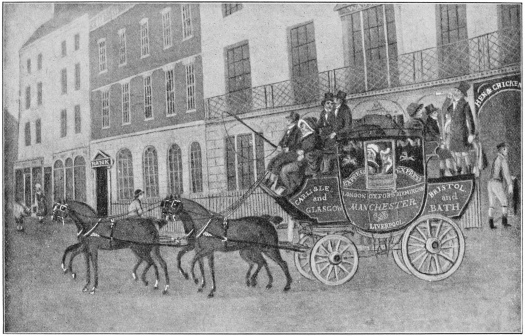

THE MAIDENHEAD AND MARLOW POST-COACH, 1782.

From a contemporary painting.

STAGE-COACH

AND MAIL IN

DAYS OF YORE

A PICTURESQUE HISTORY

OF THE COACHING AGE

VOL. I

By CHARLES G. HARPER

Illustrated from Old-Time Prints

and Pictures

London:

CHAPMAN & HALL, Limited

1903

All rights reserved

PRINTED BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

vii

“HANG up my old whip over the fireplace,” said Harry Littler, of the Southampton “Telegraph,” when the London and Southampton Railway was opened, in 1833,—“I shan’t want it never no more”: and he fell ill, turned his face to the wall, and died.

The end of the coaching age was a tragedy for the coachmen; and even to many others, whose careers and livelihood were not bound up with the old order of things, it was a bitter uprooting of established customs. Many travellers were never reconciled to railways, and in imagination dwelt fondly in the old days of the road for the rest of their lives; while many more never ceased to recount stories of the peculiar glory and exhilaration of old-time travel, forgetting the miseries and inconveniences that formed part of it. But although reminiscent oldsters have talked much about those vanished times, they have rarely attempted a consecutive story of them. Such an attempt is that essayed in these pages, confined within the compass of two volumes, not because material for a third was lacking, but simply for sake of expediency. Itviii is shown in the body of this book, and may be noted again in this place, that the task of writing anything in the nature of a History of Coaching is rendered exceeding difficult by reason of the disappearance of most of the documentary evidence on which it should be based; but I have been fortunate enough to secure the aid of Mr. Joseph Baxendale in respect of the history of Pickford & Co., of Mr. William Chaplin, grandson of the great coach-proprietor, and of Mr. Benjamin Worthy Horne, grandson of Chaplin’s partner, for information concerning their respective families. Colonel Edmund Palmer, also, communicated interesting notes on his grandfather, John Palmer, the founder of the mail-coach system. To my courteous friend, Mr. W. H. Duignan, of Walsall, whose own recollections of coaching, and whose collections of coaching prints and notes I have largely used, this acknowledgment is due. Mr. J. B. Muir, of 35, Wardour Street, my obliging friend of years past, has granted extensive use of his collection of sporting pictures, and Messrs. Arthur Ackermann & Son, of 191, Regent Street, have lent prints and pictures from their establishment.

CHARLES G. HARPER.

Petersham, Surrey,

April 1903.

ix

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Introduction of Carriages | 1 |

| II. | The Horsemen | 14 |

| III. | Dawn of the Coaching Age | 57 |

| IV. | Growth of Coaching in the Eighteenth Century | 87 |

| V. | The Stage-Waggons and what they Carried: How the Poor Travelled | 103 |

| VI. | The Early Mail-Coaches | 146 |

| VII. | The Nineteenth Century: 1800–1824 | 181 |

| VIII. | Coach Legislation | 194 |

| IX. | The Early Coachmen | 221 |

| X. | The Later Coachmen | 231 |

| XI. | Mail-guards | 249 |

| XII. | Stage-coach Guards | 272 |

| XIII. | How the Coaches were Named | 282 |

| XIV. | Going by Coach: Booking Offices | 320 |

| XV. | How the Coach Passengers Fared: Manners and Customs down the Road | 333 |

xi

SEPARATE PLATES

| PAGE | ||

| 1. | The Maidenhead and Marlow Post-coach, 1782. (From a contemporary Painting) | Frontispiece |

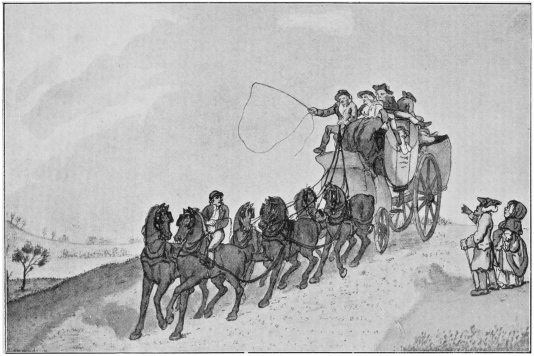

| 2. | The Stage-coach, 1783. (After Rowlandson) | 83 |

| 3. | The Waggon, 1816. (After Rowlandson) | 115 |

| 4. | The Stage-waggon, 1820. (After J. L. Agasse) | 121 |

| 5. | The Road-waggon: a Trying Climb. (After J. Pollard) | 131 |

| 6. | The Stage-waggon, 1816. (By Rowlandson) | 137 |

| 7. | Pickford’s London and Manchester Fly Van, 1826. (After George Best) | 141 |

| 8. | John Palmer at the Age of 17. (Attributed to Gainsborough, R.A.) | 149 |

| 9. | John Palmer. (From the Painting by Gainsborough, R.A.) | 153 |

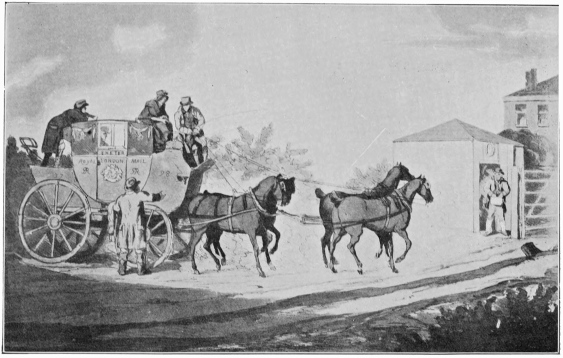

| 10. | The Mail-coach, 1803. (From the Engraving after George Robertson) | 169 |

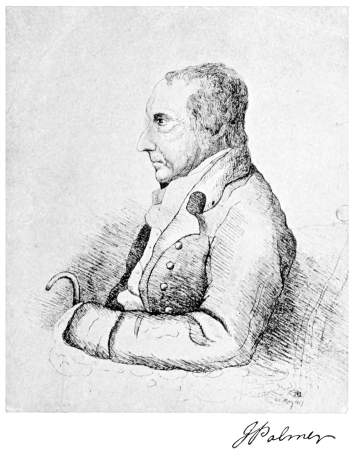

| 11. | John Palmer in his 75th Year. (From an Etching by the Hon. Martha Jervis) | 175 |

| 12. | Mrs. Bundle in a Rage; or, Too Late for the Stage. (After Rowlandson, 1809) | 183 |

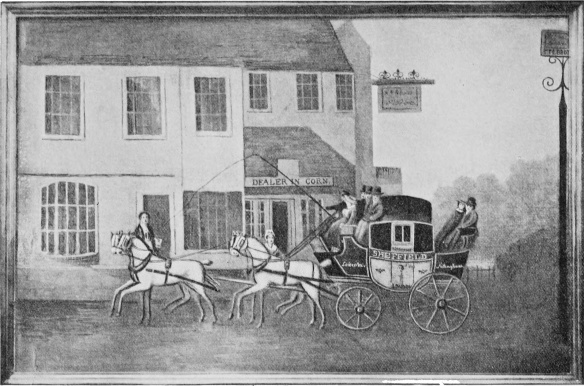

| 13. | The Sheffield Coach, about 1827. (From a contemporary Painting) | 187xii |

| 14. | The “Birmingham Express” Leaving the “Hen and Chickens.” (From a contemporary Painting) | 191 |

| 15. | “My Dear, You’re a Plumper”: Coachman and Barmaid. (After Rowlandson) | 223 |

| 16. | The Old “Prince of Wales” Birmingham Coach. (After H. Alken) | 233 |

| 17. | In Time for the Coach. (After C. Cooper Henderson, 1848) | 243 |

| 18. | Stuck Fast. (After C. Cooper Henderson, 1834) | 267 |

| 19. | The “Reading Telegraph” passing Windsor Castle. (After J. Pollard) | 297 |

| 20. | The Exeter Mail, 1809. (After J. A. Atkinson) | 301 |

| 21. | The Brighton “Comet,” 1836. (After J. Pollard) | 307 |

| 22. | Matthews’ Patent Safety Coaches on the Brighton Road | 313 |

| 23. | A Coach-Breakfast. (After J. Pollard) | 349 |

ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

| PAGE | |

| Vignette | (Title-page) |

| Preface | vii |

| List of Illustrations | xi |

| Stage-coach and Mail in Days of Yore | 1 |

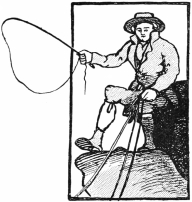

| Arms of the Worshipful Company of Coach and Harness Makers | 12 |

| Epigram Scratched with a Diamond-ring on a Window-pane by Dean Swift | 46 |

| Old Coaching Bill, Preserved at the “Black Swan,” York | 75 |

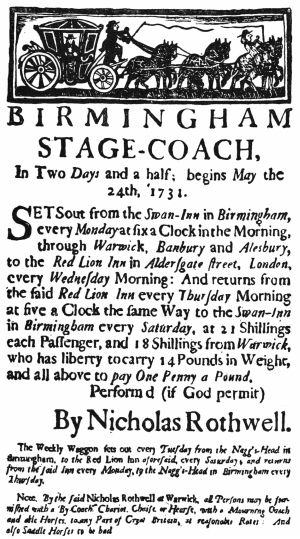

| Old Birmingham Coaching Bill | 81 |

| Coaching Advertisement from the Edinburgh Courant, 1754 | 89 |

| One of Three Mail-coach Halfpennies struck at Bath, 1797 | 173 |

| Moses James Nobbs, the Last of the Mail-guards | 265 |

1

The lines quoted above are not remarkably good as poetry. Nay, it is possible to go farther, and to say that they are exceptionally bad—the product of one of those corn-box poets who were accustomed to speak of steam as a “demon foul”; but if his lines are bad verse, the central idea is good. That man who first essayed to drive four-in-hand must indeed have been more than usually courageous.

To form anything at all like an adequate idea of the Coaching Age, it is first necessary to discover how people travelled before that age dawned. As a picture is made by contrasted light and shade, so is the story of the coaching2 period only to be properly set forth by first narrating how journeys were made from place to place before the continuous history of wheeled traffic begins. That history, measured by mere count of years, is not a long one. It cannot, in its remotest origin, go back beyond the first appearance of the stage-waggon, about 1590, when the peasantry of this kingdom began to obtain an occasional lift on the roads, and sat among the goods which it was the first business of those waggons to carry. The peasant, then, was the first coach-passenger, for while he was carried thus, everyone else, in all the estates of the realm, from King and Queen down to the middle classes, rode horseback, and it was not until 1657 and the establishment of the Chester Stage that the Coaching Age opened for the public in general.

If, then, we please to pronounce for that event as the true beginning, and allow 1848, the year when one of the last coaches, the Bedford “Times,” was withdrawn from the London and Bedford road in consequence of the opening of the Bletchley and Bedford branch railway, to be the end, we have the beginning, the growth and perfection of the old coaching era, and its final extinction, all comprised within a period of a hundred and ninety-one years.

Wheeled conveyances are generally said by the usual books of reference to take their origin in this country with the introduction of Queen Mary’s Coronation carriage in 1553; but, so far3 from that being correct, mention of carriages is often found in authorities of a period earlier by almost two centuries. Thus, in her will of September 25th, 1355, Elizabeth de Burgh, Lady Clare, bequeathed her “great carriage, with the covertures, carpets, and cushions,” to her eldest daughter; and carriage-builders at the close of Edward III.’s reign charged £100 and £1000 for their wares. Carts were not unknown to the peasantry; Froissart tells us that the English returned from Scotland in 1360 in “charettes,” a kind of carriage whose make he does not specify; and ladies are discovered in 1380 travelling with the baggage in “whirlicotes,” which were cots or beds on wheels, or a species of wheeled litter. We have, by favour of one of the old chroniclers, a fugitive picture of Richard II., at the age of seventeen, travelling in one of these whirlicotes, accompanying his mother, who was ill.

But such instances do not prove more than occasional use, and it certainly appears that when Queen Mary rode from the Tower of London to Westminster on her Coronation Day, September 20th, 1553, in her State coach, she thereby revived the use of carriages, which, for some reason or another, had fallen into disuse since those early days. Her coachmaker, by a grant made on May 29th in the first year of her reign, was one Anthony Silver.

We may seek the cause of wheeled conveyances going out of use in the two centuries before this date in the steady and continuous decay of the4 roads consequent upon the troubled state of the kingdom in that intervening space. Rebellions, pestilences, foreign wars, and domestic strife had marked that epoch. The Wars of the Roses themselves lasted thirty years, and in all that while the social condition of the people had not merely stood still, but degenerated. Towns and districts were half depopulated, and the ancient highways fell into disuse. It is significant that the first General Highway Act, a measure passed in 1555, was practically coincident with the reintroduction of carriages.

Queen Mary’s Coronation carriage—or, as it was called in the language of that time, “coach”—was drawn by six horses, less for reasons of display than of sheer necessity, for, with a less numerous and powerful team, it would probably have been stuck fast in the infamously bad roads that then set a gulf of mud between the twin cities of London in the east and Westminster in the west. Only three other carriages followed her Majesty on that historic occasion, and the ladies who attended rode horseback.

Two years after this new departure mention is found of a “coach”—still, of course, a carriage—made for the Earl of Rutland by one Walter Rippon, who in the same year appears to have built a new one for the Queen.

The next patron of carriages seems to have been Sir Thomas Hoby, sometime Her Britannic Majesty’s Ambassador to the French Court: that Sir Thomas who lies beside his brother, Sir Philip,5 in their magnificent tomb in the little Berkshire village church of Bisham, beside the Thames. He owned a carriage in 1566.

The progressive age of Elizabeth now opens. In 1564, six years after her accession, she was using a carriage brought over from Holland by a certain William Boonen, himself a Hollander. Boonen, indeed, became her Majesty’s coachman, but his services cannot often have been required, for, if we are to believe Elizabeth’s own words to the French Ambassador in 1568, driving in these early carriages, innocent of springs, must have been as uncomfortable as a journey in a modern builder’s cart or an ammunition-waggon would be. When his Excellency waited upon her, she was still suffering “aching pains, from being knocked about in a coach driven too fast a few days before.”

Little wonder, then, that the great Queen used her coach only when occasions of State demanded. She journeyed to her palace at Greenwich by water, between Greenwich and her other palace of Eltham on horseback, and to Nonsuch and Hampton Court and on her many country progresses in like manner, resorting only to wheels with advancing years. How bad were even the roads especially repaired for her coming may be judged from a contemporary description of her journey along that “new highway” whose “perfect evenness” is the theme of the writer. “Her Majesty left the coach only once, while the hinds and the folk of a base sort lifted it on6 with their poles.” Majesty must have been sore put to it to look majestic on such occasions, and in the bad condition of all roads at that time we find a new significance in the courtliness of Sir Walter Raleigh, who at Greenwich threw his velvet cloak upon the ground for Elizabeth to walk over.

Elizabeth was an accomplished horsewoman, and it is not surprising, under these circumstances, that she made full use of the accomplishment, continuing on all possible public occasions to appear in this manner. On longer journeys she rode on a pillion behind a mounted chamberlain, holding on to him by his waistbelt just as ladies continued to do for centuries yet to come. The curious in these things may find interest in the fact that the modern groom’s leathern waistbelt, which now serves no practical function, is merely a strange survival of that old necessity of feminine travel. The commonly-received opinion that Elizabeth objected to carriages from the supposed “effeminacy” of using them receives a severe shock from her carriage experiences, which make it quite obvious that travelling in the earliest of them was only to be indulged in by persons of the strongest frame and in the rudest health. She who mounted on her palfrey before her troops at Tilbury, when the Armada threatened, could justly claim that though but a woman she had the spirit of a King—aye, and a King of England—quailed before the rigours of a carriage-drive.

In 1579 the Earl of Arundel imported one of7 these new and strange machines from Germany. How novel and strange they were may be gathered from the particular mention thus accorded them in the annals of the time. When we consider how bad was the condition even of the streets of London, it will be abundantly evident that a desire for display rather than comfort brought about the increasing use of carriages that marked the closing years of Elizabeth’s reign. By 1601 they had become so comparatively numerous that it was sought to obtain an Act restraining their excessive use and forbidding men riding in them. This projected ordinance especially set forth the enervating nature of riding in carriages; but it would seem that the real objection was the growing magnificence displayed in this way by the wealthy, tending to overshadow the public appearances of Royalty itself. Whatever the real reason of this disabling measure, it was rejected on the second reading and never became law, and four years later both hackney and private carriages were in common use in London. Carters and waggoners hated them with a bitter hatred, called them “hell-carts,” and heaped abuse upon all who used them. Both their primitive construction and the fearful condition of the roads rendered their use impossible in the country. Teams of fewer than six horses were rarely seen drawing coaches in what were then regarded as London suburbs, districts long since included in Central London; and perhaps even the haughty and arrogant Duke of Buckingham, favourite of8 James I. and Charles, was misjudged when, in 1619, the people, seeing his carriage drawn by that number, “wondered at it as a novelty, and imputed it to him as a mastering pride.” Had he employed fewer horses he certainly would have been obliged to get out and walk, or to have again resorted to the use of the sedan-chair, in which, before he had set up a carriage, he was used to be carried, greatly to the indignation of the populace, to whom sedan-chairs were at that time novelties. “The clamour and the noise of it was so extravagant,” we are told, “that the people would rail upon him in the streets, loathing that men should be brought to as servile a condition as horses.” Yet no one ever thought of denouncing Buckingham or any other of the magnificos when they lolled in easy seats under the silken hangings of their state barges and were rowed by the labour of a dozen lusty oarsmen on the Thames. The work was as servile as the actual carrying of a passenger, but the innate conservatism of mankind could not at first perceive this. On the whole, Buckingham therefore has our sympathy. The most innocent doings of a favourite with Royalty are capable of being twisted into haughty and malignant acts, and had it not been for Buckingham’s position at Court his displays would not have brought him the hatred of the people and the rivalry of his own order which they certainly did arouse. The Earl of Northumberland was one of those who were thus goaded into the rivalry of display. Hearing that the favourite had six9 horses to his carriage, he thought that he might very well have eight, “and so rode,” we are told, “from London to Bath, to the vulgar talk and admiration.”

The first public carriages, according to a statement made to Taylor, the “water poet,” by Old Parr, the centenarian, were the “hackney-coaches,” established in London in 1605. “Since then,” says Taylor, writing on the subject at different times between 1623 and 1635, “coaches have increased with a mischief, and have ruined the trade of the watermen by hackney-coaches, and now multiply more than ever.” The “watermen” were, of course, those who plied with their boats and barges for hire upon the Thames, chiefly between London and Westminster, the river being then, and for long after, the principal highway for traffic in the metropolis. So greatly, indeed, was the river traffic for the time affected, that the sprack-witted Taylor relinquished his trade of waterman and embarked upon the more promising career of pamphleteering.

“Thirty years ago,” he says, in one of these outbursts, “The World runnes on Wheeles,” “coaches were few”:—

10 “This,” we find him saying, on another occasion, “is the rattling, rowling, rumbling age, and the world runnes on wheeles. The hackney-men, who were wont to have furnished travellers in all places with fitting and serviceable horses for any journey, are (by the multitude of coaches) undone by the dozens.”

The bitter cry of Taylor and the Thames watermen may or may not have been hearkened to, but certainly hackney-coaches were prohibited in 1635. This, however, was probably due rather to Royal whim or prejudice than to any consideration for a decaying trade.

It was an arbitrary age, and it only needed a Star Chamber order for public carriages, considered by the Court to be a nuisance, to be suppressed. The reasons advanced read curiously at this time: “His Majesty, perceiving that of late the great numbers of hackney-coaches were grown a great disturbance to the King, Queen, and nobility through the streets of the said city, so as the common passage was made dangerous and the rates and prices of hay and provender and other provisions of the stable thereby made exceeding dear, hath thought fit, with the advice of his Privy Council, to publish his Royal pleasure, for reformation therein.” His Majesty therefore commanded that no hackney-coaches should be used in London unless they were engaged to travel at least three miles out of town, and owners of such coaches were to keep sufficient able horses and geldings, fit for his Majesty’s11 service, “whensoever his occasion shall require them.”

This despotic measure was amended in 1637, when fifty hackney-coachmen for London were licensed, to keep not more than twelve horses each. This meant either that three hundred or a hundred and fifty public carriages then came into use, according to whether two or four horses were harnessed. “And so,” says Taylor, “there grew up the trade of coach-building in England.”

These early carriages, whether hackney or private, were not only without springs, but were innocent of windows. In their place were shutters or leather curtains. The first “glass coach” mentioned is that made for the Duke of York in 1661. Pepys at this period becomes our principal authority on this subject. On May 1st, 1665, he is found witnessing experiments with newly-designed carriages with springs, and again on September 5th, finding them go not quite so easy as their inventor claimed for them. Yet, since private carriages were clearly becoming the fashion, Mr. Secretary-to-the-Admiralty Pepys must needs have one; and accordingly, on December 2nd, 1668, he takes his first ride: “Abroad with my wife, the first time that I ever rode in my own coach.”

Pepys always delighted in being in the fashion. He would not be in advance of it, and not, if he could help it, behind. The fact, then, of his setting up a carriage of his own is sufficient to show how largely the moneyed classes had begun12 to go about on wheels. But better evidence still is found in the establishment, May 1677, of the Worshipful Company of Coach and Harness Makers, whose arms still bear representations of the carriages in use at that period. The armorial bearings of the Coach-makers are, when duly tricked out in their proper colours, somewhat striking. Stated in plain terms, done into English out of heraldic jargon, they consist of a blue shield of arms with three coaches and a chevron in gold, supported on either side by a golden horse, harnessed and saddled in black studded with gold; with blue housings garnished with red, and fringed and purfled in gold. The horses are further adorned with plumes of four feathers in gold, silver, red, and blue. A crest above displays13 Phœbus driving his chariot, and the motto beneath declares that “After clouds rises the sun.”

The hackney-carriages of London in 1669, the year following Pepys’ establishment of his own private turn-out, numbered, according to the memoirs of Cosmo, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who travelled England at that time, eight hundred. The age of public vehicles was come.

14

“The single gentlemen, then a hardy race, equipped in jack-boots and trousers up to their middle, rode post through thick and thin, and, guarded against the mire, defying the frequent stumble and fall, arose and pursued their journey with alacrity.”—Pennant, 1739.

Long before wheeled conveyances of any kind were to be hired in this country, travellers were accustomed to ride post. To do so argued no connection with that great department we now call the Post Office, although that letter-carrying agency and the custom of riding post obtain their name from a common origin. The earliest provision for travelling post seems to have been in the reign of Henry VIII., when the office of “Master of the Postes” was established. Sir Brian Tuke then held that appointment, and to him were entrusted the arrangements for securing relays of horses on the four great post roads then recognised: the road from London to Dover, on which the carriers came from and went to foreign parts; the road to Plymouth, where the King’s dockyard was situated; and the great roads to Scotland and Chester, and on to Conway and Holyhead. These relays of horses were established exclusively for use of the despatch-riders who went on affairs of State; but by the time of Elizabeth15 these messengers were, as a favour, already accustomed to carry any letters that might be given into their charge and could be delivered without going out of their way; while travellers constantly called at the country post-houses, and on pretence of going on the Queen’s business, obtained the use of horses, which they rode to exhaustion, or overloaded, or even rode away with altogether.

These abuses were promptly suppressed when James I. came to the English throne. In 1603, the year of his accession, a proclamation was issued under which no person claiming to be on Government business was to be supplied with horses by the postmasters unless his application was supported by a document signed by one of the officers of State. The hire of horses for public business was fixed at twopence-halfpenny a mile, and in addition there was a small charge for the guide. A very arbitrary order was made that if the post-houses had not sufficient horses, the constables and the magistrates were to seize those of private owners and impress them into the service. Post-masters, who were salaried officials, were paid at the very meagre rate of from sixpence to three shillings a day. They were generally innkeepers on the main roads; otherwise it is difficult to see how they could have existed on these rates of pay. Evidently these were considered merely as retaining fees, and so, in order to give them a chance of earning a more living wage, they were permitted to let out horses16 to “others riding poste with horse and guide about their private business.” Those private and unofficial travellers could not demand to be supplied with horses at the official rate: what they were to pay was to be a matter between the post-masters and themselves. In practice, however, the tariff for Government riders ruled that for all horsemen, as made clear in Fynes Morison’s Itinerary, 1617, where he says that in the south and west of England and on the Great North Road as far as Berwick, post-horses were established at every ten miles or so at a charge of twopence-halfpenny a mile. It was necessary to have a guide to each stage, and it was customary to charge for baiting both the guide’s and the traveller’s horses, and to give the guide himself a few pence—usually a four-penny-piece, called “the guide’s groat”—on parting. It was cheaper and safer for several travellers to go together, for one guide would serve the whole company on each stage, and it was not prudent to travel alone. Morison says that, although hiring came expensive in one way, yet the speed it was possible to maintain saved time and consequent charges at the inns. The chief requisite, however, was strength of body and ability to endure the fatigue.

As to that, the horsemen of the period were, equally with those of over a hundred years later, mentioned by Pennant, “a hardy race.” In March, 1603, for example, Robert Cary, afterwards Earl of Monmouth, eager to be first in acclaiming James VI. of Scotland as James I. of England,17 left London so soon as the last breath had left the body of Queen Elizabeth, and rode the 401 miles to Edinburgh in three days. He reached Doncaster, 158 miles, the first night, Widdrington, 137 miles, the second, and gained Edinburgh, 106 miles, the third day, in spite of a severe fall by the way. About the same time a person named Coles rode from London to Shrewsbury in fourteen hours.

When Thomas Witherings was appointed Master of the Post, in 1635, the Post Office, as an institution for carrying the correspondence of the public, may be said to have started business, although as early as 1603 private persons were forbidden to make the carrying of letters a business. Like all such ordinances, this seemed made only to be broken every day. It was particularly unreasonable because, before Witherings came upon the scene in 1635 and reorganised the posts, there existed no means by which letters could be sent generally into the country. Only the post-riders on business of State on the four great roads were in the habit of taking letters, and their doing so was a matter of private arrangement.

The postmasters now, on the appointment of Witherings, first officially made acquaintance with letters, and their name began to take on something of its modern meaning. They still supplied horses to the King’s messengers and the King’s liege subjects, and held a monopoly in these businesses.

In 1657 the so-called “Post Office of England”18 was established by Act of Parliament, and the office of Postmaster-General created, in succession to that of Master of the Posts. His business was defined as “the exclusive right of carrying letters and the furnishing of post-horses,” and these two functions—the overlordship of what were officially known for generations afterwards as the “letter post” and the “travelling post”—the long line of Postmasters-General continued to exercise for a hundred and twenty-three years.

In 1658 the mileage the country postmasters were entitled to charge was, according to an advertisement of July 1st in that year, increased from twopence-halfpenny to threepence, and on the Chester Road, at least, there was no longer any obligation to take a guide:—

“The postmasters on the Chester Road, petitioning, have received order, and do accordingly publish the following advertisement: All gentlemen, merchants, and others who have occasion to travel between London and West Chester, Manchester, and Warrington, or any other town upon that road, for the accommodation of trade, dispatch of business, and ease of purse, upon every Monday, Wednesday and Friday morning, between six and ten of the clock, at the house of Mr. Christopher Charteris, at the sign of the Hart’s Horns, in West Smithfield, and postmaster there, and at the postmaster of Chester, and at the postmaster of Warrington, may have a good and able horse or mare, furnished at threepence the mile, without the charge of a guide; and so likewise at the19 house of Mr. Thomas Challoner, postmaster at Stone in Staffordshire, upon every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday mornings, to go to London; and so likewise at all the several postmasters upon the road, who will have such set days, so many horses, with furniture, in readiness to furnish the riders, without any stay, to carry them to and from any of the places aforesaid in four days, as well to London as from thence, and to places nearer in less time, according as their occasions shall require, they engaging, at the first stage where they take horse, for the safe delivery of the same to the next immediate stage, and not to ride that horse any farther without consent of the postmaster, by whom he rides, and so from stage to stage to their journey’s end. All those who intend to ride this way are desired to give a little notice beforehand, if conveniently they can, to the several postmasters where they first take horse, whereby they may be furnished with as many horses as the riders shall require, with expedition. This undertaking began the 28th of June 1658, at all the places aforesaid, and so continues by the several postmasters.”

The Chester Road—the road to Ireland—was of great moment at that age. Indeed, it had been of importance for centuries past. It was in a lonely hollow near Flint, on his landing from Ireland, that Richard II. was waylaid in 1399 by Henry Bolingbroke, and his progress to London barred; and from Chester as well as from Milford Haven English expeditions were wont to20 sail—some carrying fire and sword across St. George’s Channel, and later ones taking English colonists to occupy and cultivate the lands from which the shiftless Irish had been driven. But it was not until the close of Elizabeth’s reign, when Ireland was subjugated, that this road began to be constantly travelled.

Under James I. the Irish chieftains came to these shores to swear fealty, and in the wild and whirling series of events that filled the years from 1641 to 1692 with horror, a continual flux and reflux of military travellers and trembling refugees came and went along these storied miles.

Already, in the year before the announcement of post-horses on the Chester Road, the first stage-coach of which we have any particulars had been established on this very route. It did not continue to Holyhead, for the individually sufficient reasons that no practicable road to that port existed for anything going on wheels, and that Chester itself, and Parkgate, a few miles down the estuary of the Dee, were the most convenient ports of embarkation for Ireland. No direct road to Holyhead existed until 1783, when coaches began to run to that port. Before that time, those who wished to cross from Holyhead generally rode horseback. Few ventured across country by Llangollen and Bettws-y-Coed; most, like Swift, leaving civilisation behind at Chester, took horse and guide, and going by Rhuddlan and Conway, dared the precipitous heights of that great headland called Penmaenmawr, or, even21 more greatly daring, crept round by the rocks underneath at ebb tide. Swift wrote two couplets for the inn that then stood beside the track on Penmaenmawr. As the traveller approached he read, on the swinging sign:—

while the returning wayfarer was cheered by:—

One personage, greatly daring, did in 1685 succeed in passing his carriage over this height. This was the Viceroy, Henry, Earl of Clarendon, who, ill enough advised to try for Holyhead, embarked his baggage at Chester, and essayed this perilous undertaking. “If the weather be good,” he wrote, before setting out, “we go under the rocks in our coaches.” But it was December, the weather was not good, and so they had to take to the hill-top. His Excellency had ample cause to regret the venture, for he was five hours travelling the fourteen miles between St. Asaph and Conway, and on the crossing of Penmaenmawr the “great heavy coach” had to be drawn by the horses in single trace, while three or four sturdy Welsh peasants, hired for the job, pushed behind, so that it should not slip back. His Excellency walked all the way across, from Conway to Bangor, and Lady Clarendon was carried in a litter. How the Menai Straits were crossed does not appear, but22 there is evidence in the tone of his letters that he was astonished at last to find himself safely come to Holyhead.

In 1660, on the Restoration, the law of 1657, constituting the Post Office and regulating the letting of post-horses, was re-enacted. By some new provisions and amendments of old ones, travellers might now hire horses wherever they could if the postmasters could not supply them within half an hour. This concession, together with that which repealed the power given by the earlier Act for horses to be seized, was evidently made in deference to the indignation of travellers delayed by lack of horses in the hands of the only persons who could legally hire them out, and by the fury of private individuals who had seen their own choice animals not infrequently requisitioned in the King’s name and hack-ridden unconscionable distances by travellers or King’s messengers whose first and last thoughts were for speed, and who had not the consideration of an owner for the steeds that carried them. The term “postage,” occurring in the Act of 1660, shows that a widely different meaning was then attached to the word: “Each horse’s hire or postage” is a phrase that sufficiently explains itself.

Such were the methods and costs of riding horseback when stage-coaching began. The Government monopoly, however, was infringed with increasing impunity as time went on, and as the letter-carrying business of the Post Office developed, so23 was the “travelling post” allowed to decay. The growing number and increasing convenience of the coaches, too, helped to make the monopoly less valuable, for when travellers could be conveyed without exertion by coach at from twopence to threepence a mile, they were not likely to pay threepence a mile and a guide’s groat at every ten miles for the privilege of bumping in the saddle all day long. Those who mostly continued in the saddle were the gentlemen who owned horses of their own, or those others to whom the chance company of a coach was objectionable.

The Post Office monopoly in post-horses was, accordingly, not worth preserving when it was abolished by the Act of 1780. From that time the Postmasters-General ceased to have anything to do with horse-hire, and anything lost by their relinquishing it was amply returned to the State by the new license duties levied upon horse-keepers or postmasters, and coaches. A penny a mile was fixed as the Government duty upon horses let out for hire, whether saddle-horses or to be used in post-chaises. All persons who made that a business—generally, of course, innkeepers—were to take out an annual five-shilling license, and were under obligation to paint in some conspicuous place on their houses “Licensed to let Post-Horses.” In default of so doing the penalty was £5. As a check upon the business done, travellers hiring post-horses were to be given a ticket, on which the number of horses so hired, and the distance, were to be specified. These tickets were to be delivered24 to the turnpike-keeper at the first gate, and the vigilance of these officials was made a matter of self-interest by the allowance to them of threepence in the pound on all tickets thus collected. At certain periods the tickets were delivered to the Stamp Office, and the innkeepers and postmasters themselves were visited by revenue officers, who required to see the books and the counterfoils from which these tickets had come.

But the Government did not for any length of time directly collect these duties. They were farmed out by the Inland Revenue Department, just as the turnpike tolls were farmed by the Turnpike Trustees, and men grew rich by buying these tolls and duties at annual auctions, relying for their profit on the increased vigilance they would cause to be exercised. The Jews were early in this field. In the golden era of coaching a man named Levy farmed tolls and duties to the annual value of half a million sterling.

But to return to our horsemen. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the country gentlemen, the members of Parliament, the judges on circuit, every hale and able-bodied man of means sufficient, rode his horse, or hired one on his journeys, for the reason that carriages could only slowly and with great difficulty and expense be made to move along the distant roads. The passage from Pennant’s recollections, quoted at the head of this chapter, shows the miseries made light of by the single gentlemen, and endured by those married ones whose wives rode behind them25 on a pillion and clutched them convulsively round the waist as the horse stumbled along.

Nor did stage-coaches immediately change this time-honoured way of getting about the country, for there existed an aristocratic prejudice against using public vehicles. Offensive persons who never owned carriages of their own were used to give themselves insufferable airs when journeying by coach, and hint, for the admiration or envy of their fellow-passengers, that an accident had happened to their own private equipage. Satirists of the time soon seized upon this contemptible resort of the snob, and used it to advantage in contemporary literature. Thus we find the committeeman’s wife in Sir Robert Howard’s comedy explaining her presence in the Reading coach to be owing to her own carriage being disordered, adding that if her husband knew she had been obliged to ride in the stage he would “make the house too hot to hold some.”

Here and there we find exceptions to this general rule. In the coach passing through Preston in 1662, one Parker was fellow-traveller with “persons of great qualitie, such as knightes and ladyes”; and on one occasion in 1682 the winter coach on its four days’ journey between Nottingham and London had for passenger Sir Ralph Knight, of Langold, Yorks; but the single gentlemen in good health continued for years after the introduction of stage-coaches to go on horseback, and when their families came to town they usually took the family chariot, and either contracted with26 stable-keepers for horses on the way, or else, taking their most powerful horses from the plough, harnessed four or six of them to their private vehicle, and so, with the driving of their best ploughman, came to the capital in state, much to the amusement of the fashionables of Piccadilly and St. James’s.

We must, however, suppose, from the fury of Cresset’s Reasons for Suppressing Stage Coaches, of 1662, that some of the less energetic among the country gentlemen had already succumbed to the discreditable practice of travelling in them. In his pages we learn something of what a horseman’s life on the road was like, and what he escaped by taking to the coach. The hardy race became soft and grievously enervated by the unwonted luxury; their muscles slackened, and they developed an infirmity of purpose that rendered them no longer able to “endure frost, snow, or rain, or to lodge in the fields”—trifling inconveniences and incidents of travel which, it appears, they had previously been accustomed to support with that cheerfulness or resignation with which one faces the inevitable and incurable.

But Cresset had other indictments, throwing a flood of light upon what the horseman endured in wear and tear of body, mind, and wearing apparel: “Most gentlemen, before they travelled in coaches, used to ride with swords, belts, pistols, holsters, portmanteaus and hat-cases, which in these coaches they have little or no use for; for, when they rode on horseback, they rode in one27 suit and carried another to wear when they came to their journey’s end, or lay by the way; but in coaches a silk hat and an Indian gown, with a sash, silk stockings, and beaver hats, men ride in, and carry no other with them, because they escape the wet and dirt, which on horseback they cannot avoid; whereas, in two or three journeys on horseback these clothes and hats were wont to be spoiled; which done, they were forced to have new ones very often, and that increased the consumption of the manufactures and the employment of the manufacturers; which travelling in coaches doth in no way do.”

Fortunately, the biographical literature of our country is rich in records of the horsemen who, still relying upon their own exertions and those of their willing steeds, rode long distances and left the toiling stage leagues behind them at the close of each day’s journey. Ralph Thoresby, of Leeds, a pious and God-fearing antiquary who flourished at this time, gives us, on the other hand, the spectacle of one who generally rode horseback trying the coach by way of a change. He had occasion to visit London in February 1683, and as there was at that time no coach service between Leeds and London, he rode from Leeds to York to catch the stage, which seems to have kept the road in this particular winter. He rose at five one Saturday morning, and was at York by night, ready for the coach leaving for London on the Monday. Four years earlier he had scorned the coach, and did not now take it for sake of speed,28 for he commonly rode from Leeds to London in four days, and the York stage at this period of its career took six; so, including the two days expended in coming to York, he was clearly twice as long over the business. He looked forward to the coach journey with misgivings, “fearful of being confined to a coach for so many days with unsuitable persons and not one I know of.”

On other occasions, when he rode horseback, his diary is rich with picturesque incident. He finds the waters out on the road between Ware and Cheshunt, and waits until he and a party of other horsemen can be guided across by a safe way, and so avoid the pitiful fate of a poor higgler, who blundered into the raging torrent where the road should have been, and was swept away and drowned. He loses his way frequently on the high-road; shudders with apprehension when crossing Witham Common, near Stamford, “the place where Sir Ralph Wharton slew the highwayman”; and, with a companion, has a terrible fright at an inn at Topcliffe, where they miss their pistols for a while and suspect the innkeeper of sinister designs against them. Hence, at the safe conclusion of every journey, with humble and heartfelt thanks he inscribes: “God be thanked for his mercies to me and my poor family!”

In 1715, when John Gay wrote his entertaining poem, A Journey to Exeter, describing the adventures of a party of horsemen who rode down from London, things were, we may suppose, much29 better, for the travellers found amusement as well as toil on their way.

They took five days to ride to Exeter. The first night they slept at Hartley Row, 36 miles. The second day they left the modern route of the Exeter Road at Basingstoke, and, like some of the coaches about that time, struck out along the Winchester road as far as Popham Lane, where they branched off across the downs to Sutton and Stockbridge, at which town they halted the night, after a day’s journey of 30 miles. The third morning saw them making for Salisbury. Midway between Stockbridge and that city their road falls into the main road to Exeter. That night they were at Blandford. The fourth day took them to Axminster, and the fifth to Exeter:—

30

Dean Swift, too, was a frequent traveller on horseback, particularly on the Chester and Holyhead road. He seems once to have tried the Chester stage, and ever after to have taken to the saddle. Riding thus in 1710 from Chester to London in five days, he describes himself as “weary the first, almost dead the second, tolerable the third, and well enough the rest,” but “glad enough of the fatigue, which has served for exercise.” After making the journey from London to Holyhead and Dublin in 1726, he wrote to Pope, describing “the quick change” he had made in seven days from London to Dublin, “through many nations and languages unknown to the civilised world.” He had expected the enterprise, “with moderate fortune,” to take ten or eleven days. “I have often reflected,” he adds, “in how few hours, with a swift horse or a strong gale, a man may come among a people as unknown to him as the Antipodes.” Swift was by no means indulging in playful banter when he wrote this.34 He felt a genuine cause for wonder in such expedition; and certainly if the rustic speech of rural England was like a strange and uncivilised tongue, how much more strange and uncivilised the languages of Wales and Ireland must have sounded!

The Dean’s last recorded journey was made in September 1727. The little memorandum-book, tattered and discoloured, in which he noted down many of its incidents is still in existence, and is not only a valuable document in the story of Swift’s life, but is equally precious and interesting as an intimate record of the daily trials and troubles of a traveller in those times, set down while he was still on his journey and thus echoing every passing feeling. Swift was in bad health and worse spirits when he wrote this diary at Holyhead, where he was detained for seven days by contrary winds. It was written for lack of employment afforded to a cultivated mind in the dreary little seaport, and under the influence of a great sorrow. “Stella” lay dying over in Ireland, and he, raging with impatience at Holyhead, filled his notebook with aimless scribbling. “All this to divert thinking,” he writes, sadly, in the midst of it.

The original notebook is still in existence, and is carefully preserved at the South Kensington Museum, to which it was bequeathed by John Forster. Inside its cover the handwriting of successive owners gives the relic an authentic pedigree, and Swift himself humorously declares35 how he came into possession of the blank book: “This book I stole from the Right Honourable George Dodington, Esq., one of the Lords of the Treasury, but the scribblings are all my own.” This George Dodington was George Bubb Dodington, afterwards Lord Melcombe.

On the first page are hastily-scribbled memoranda for appointments: “In Fleet Street, about a clerk of St. Patrick’s Cathedral”; “Spectacles for seventy years old”; “Godfrey in Southampton Street”; “Hungary waters and palsy drops.”

Then the Dean left London, riding horseback, with his servant, Watt, for company on another nag, and carrying his master’s travelling valise. The heavy luggage had been sent on by waggon to Chester. Watt, as we shall presently see, was a veritable Handy Andy, always doing the wrong thing, or the right thing in a wrong way. Swift carried the notebook in his pocket, without writing anything of his journey in it until Holyhead was reached.

A few unfinished lines on an old cassock, out at elbows, preface the diary, which begins abruptly: “Friday at 11 in the morning I left Chester. It was Sept. 22, 1727. I baited at a blind ale house 7 miles from Chester. I thence rode to Ridland (Rhuddlan), in all 22 miles. I lay there: bred, bed, meat and tolerable wine. I left Ridland a quarter after 4 morn on Saturday, slept, on Penmanmaur (Penmaenmawr), examined about my sign verses the Inn is to36 be on t’other side, therefore the verses to be changed.”A

Here, on the verge of the wild Welsh coast, the way was so uncertain and dangerous that travellers had of necessity to employ guides, who conducted them thence to Bangor, and across Anglesey to Holyhead. The roads in Anglesey were unworthy of the name, and only a little better than horse-tracks; while the inhabitants of the isle spoke only Welsh, and understood not a word of English. Nearly two hundred years have passed, but although the roads have been made good, the folks of Anglesey speak English no more than they did then, when the guides acted the part of interpreters as well.

Swift, therefore, is found at Conway, mentioning the guide who had already brought him safely over Penmaenmawr: “I baited at Conway, the guide going to another Inn; the maid of the old Inn saw me in the street and said that was my horse, she knew me. There I dined, and sent for Ned Holland, a Squire famous for being mentioned in Mr. Lyndsay’s verses to Day Morice. I there again saw Hook’s tomb, who was the 41st child of his mother, and had himself 27 children, he dyed about 1638. There is a note here that one of his posterity new furbished up the inscription. I had read in Abp. Williams’ Life that he was buryed in an obscure Church in North Wales. I enquired, and heard37 that it was atB ... Church, within a mile of Bangor, whither I was going. I went to the Church, the guide grumbling. I saw the Tomb with his Statue kneeling (in marble). It began thus (Hospes lege et relege quod in hoc obscuro sacello non expectares. Hic jacet omnium Praesulum celeberrimus). I came to Bangor and crossed the Ferry, a mile from it, where there is an Inn, which, if it be well kept, will break Bangor. There I lay; it was 22 miles from Holyhead.”

B It was Llandegai.

This was the “George” at Menai Straits, a house that until the building of Telford’s suspension bridge in 1825, flourished greatly on the traffic of the ferry that then plied between it and the opposite shore. Large additions have been made to the hotel, but the original wing that Swift knew is still in existence, and is a characteristic specimen of the architecture in vogue about the time of Queen Anne.

Swift unfortunately tells us nothing of the actual crossing of the Straits. He must have been up at an unconscionable hour, for he was already on the Anglesey side by four o’clock the next morning, Sunday: “I was on horseback at 4 in the morning resolving to be at Church at Holyhead, but we then lost Owain Tudor’s tomb at Penmarry.” This was Penmynydd, a very steep and craggy place, whence came those Tudors who through the fortunate marriage of Owain Tudor came at last to the throne of England.

38 “We passed the place,” says Swift, “being a little out of the way, by the Guide’s knavery, who had no mind to stay. I was now so weary with riding that I was forced to stop at Langueveny (Llangefni), 7 miles from the Ferry, and rest two hours. Then I went on very weary, but in a few miles more Watt’s horse lost his two fore-shoes. So the Horse was forced to limp after us. The Guide was less concerned than I. In a few miles more my Horse lost a fore-shoe and could not go on the rocky ways. I walked above two miles, to spare him. It was Sunday, and no Smith to be got. At last there was a Smith in the way: we left the Guide to shoe the horses and walked to a hedge Inn 3 miles from Holyhead. There I stayed an hour with no ale to be drunk. A boat offered, and I went by sea and sayled in it to Holyhead. The Guide came about the same time. I dined with an old Innkeeper, Mrs. Welch, about 3, on a Loyne of mutton very good, but the worst ale in the world, and no wine, for the day before I came here a vast number went to Ireland after having drunk out all the wine. There was stale beer, and I tryed a receit of Oyster shells which I got powdered on purpose; but it was good for nothing. I walked on the rocks in the evening, and then went to bed and dreamt I had got 20 falls from my Horse.

“Monday, Sept. 25.—The Captain talks of sailing at 12. The talk goes off, the wind is fair, but he says it is too fierce. I believe he wants more Company. I had a raw Chicken for39 dinner and Brandy with water for my drink. I walked morning and afternoon among the rocks. This evening Watt tells me that my landady whispered him that the Grafton packet-boat just come in had brought her 18 bottles of Irish Claret. I secured one, and supped on part of a neat’s tongue which a friend at London had given Watt to put up for me, and drank a pint of the wine, which was bad enough. Not a soul is yet come to Holyhead, except a young fellow who smiles when he meets me and would fain be my companion, but it has not come to that yet. I writ abundance of verses this day; and several useful hints, tho’ I say it. I went to bed at ten and dreamt abundance of nonsense.

“Tuesday 26th.—I am forced to wear a shirt 3 days for fear of being lowsy. I was sparing of them all the way. It was a mercy there were 6 clean when I left London;—otherwise Watt (whose blunders would bear an history) would have got them all in the great Box of goods which went by the Carrier to Chester. He brought but one crevat, and the reason he gave was because the rest were foul and he thought he should not get foul linen into the Portmanteau. For he never dreamt it might be washed on the way. My shirts are all foul now, and by his reasoning I fear he will leave them at Holyhead when we go. I got a small Loyn of mutton but so tough I could not chew it, and drank my second pint of wine. I walked this morning a good way among the rocks, and to a hole in one of them from whence40 at certain periods the water spurted up several feet high. It rained all night and hath rained since dinner. But now the sun shines and I will take my afternoon walk. It was fiercer and wilder weather than yesterday, yet the Captain now dreams of sailing. To say the truth Michaelmas is the worst season in the year. Is this strange stuff? Why, what would you have me do? I have writ verses and put down hints till I am weary. I see no creature. I cannot read by candle-light. Sleeping will make me sick. I reckon myself fixed here, and have a mind like Marshall Tallard to take a house and garden. I wish you a Merry Christmas and expect to see you by Candlemas. I have walked this morning about 3 miles on the rocks; my giddiness, God be thanked, is almost gone and my hearing continues. I am now retired to my chamber to scribble or sit humdrum. The night is fair and they pretend to have some hopes of going to-morrow.

“September 26th.—Thoughts upon being confined at Holyhead. If this were to be my settlement during life I could content myself a while by forming new conveniences to be easy, and should not be frightened either by the solitude or the meanness of lodging, eating or drinking. I shall say nothing about the suspense I am in about my dearest friend because that is a case extraordinary, and therefore by way of comfort. I will speak as if it were not in my thoughts, and only as a passenger who is in a scurvy, unprovided comfortless place without one companion, and who41 therefore wants to be at home where he hath all conveniences proper for a gentleman of quality. I cannot read at night, and I have no books to read in the day. I have no subject at present in my head to write upon. I dare not send my linen to be washed for fear of being called away at half an hour’s warning, and then I must leave them behind, which is a serious Point. I live at great expense without one comfortable bit or sup. I am afraid of joyning with passengers for fear of getting acquaintance with Irish. The days are short and I have five hours a night to spend by myself before I go to Bed. I should be glad to converse with Farmers or shopkeepers, but none of them speak English. A Dog is better company than the Vicar, for I remember him of old. What can I do but write everything that comes into my head? Watt is a booby of that species which I dare not suffer to be familiar with me, for he would ramp on my shoulders in half an hour. But the worst part is in my half-hourly longing, and hopes and vain expectations of a wind, so that I live in suspense which is the worst circumstance of human nature. I am a little wrung from two scurvy disorders, and if I should relapse there is not a Welsh house-cur that would not have more care taken of him than I, and whose loss would not be more lamented. I confine myself to my narrow chamber in all unwalkable hours. The Master of the pacquet-boat, one Jones, hath not treated me with the least civility, although Watt gave him my name. In short I come from being42 used like an Emperor to be used worse than a Dog at Holyhead. Yet my hat is worn to pieces by answering the civilities of the poor inhabitants as they pass by. The women might be safe enough who all wear hats yet never pull them off, and if the dirty streets did not foul their petticoats by courtesying so low. Look you; be not impatient, for I only wait till my watch makes 10 and then I will give you ease and myself sleep, if I can. O’ my conscience you may know a Welsh dog as well as a Welsh man or woman, by its peevish passionate way of barking. This paper shall serve to answer all your questions about my journey, and I will have it printed to satisfy the kingdom. Forsan et haec olim is a damned lye, for I shall always fret at the remembrance of this imprisonment. Pray pity your Watt for he is called dunce, puppy and lyar 500 times an hour, and yet he means not ill for he means nothing. Oh for a dozen bottles of Deanery wine and a slice of bread and butter! The wine you sent us yesterday is a little upon the sour. I wish you had chosen a better. I am going to bed at ten o’clock because I am weary of being up.

“Wednesday.—To-day we were certainly to sayl: the morning was calm. Watt and I walked up the mountain Marucia, properly called Holyhead or Sacrum Promontorium by Ptolemy, 2 miles from this town. I took breath 59 times. I looked from the top to see the Wicklow hills, but the day was too hazy, which I felt to my sorrow; for returning we were overtaken by a furious43 shower. I got into a Welsh cabin almost as bad as an Irish one. There were only an old Welsh woman sifting flour who understood no English, and a boy who fell a roaring for fear of me. Watt (otherwise called unfortunate Jack) ran home for my coat, but stayed so long that I came home in worse rain without him, and he was so lucky to miss me, but took good care to convey the key of my room where a fire was ready for me. So I cooled my heels in the Parlour till he came, but called for a glass of Brandy. I have been cooking myself dry, and am now in my night gown.... And so I wait for dinner. I shall dine like a King all alone, as I have done these six days. As it happened, if I had gone straight from Chester to Park-gate 8 miles I should have been in Dublin on Sunday last. Now Michaelmas approaches, the worst time in the year for the sea, and this rain has made these parts unwalkable, so I must either write or doze. Bite, when we were in the wild cabin I order Watt to take a cloth and wipe my wet gown and cassock: it happened to be a meal-bag, and as my gown dryed it was all daubed with flour well cemented with the rain. What do I but see the gown and cassock well dryed in my room, and while Watt was at dinner I was an hour rubbing the meal out of them, and did it exactly. He is just come up, and I have gravely bid him take them down to rub them, and I wait whether he will find out what I have been doing. The Rogue is come up in six minutes, and says there were but few specks44 (tho’ he saw a thousand at first), but neither wondered at it, nor seemed to suspect me who laboured like a horse to rub them out. The 3 packet boats are now all on their side, and the weather grown worse, and so much rain that there is an end of my walking. I wish you would send me word how I shall dispose of my time. I am as insignificant a person here as parson Brooke is in Dublin; by my conscience I believe Cæsar would be the same without his army at his back. Well, the longer I stay here the more you will murmur for want of packets. Whoever would wish to live long should live here, for a day is longer than a week, and if the weather be foul, as long as a fortnight. Yet here I could live with two or three friends in a warm house and good wine; much better than being a slave in Ireland. But my misery is that I am in the very worst part of Wales under the very worst circumstances, afraid of a relapse, in utmost solitude, impatient for the condition of our friend, not a soul to converse with, hindered from exercise by rain, caged up in a room not half so large as one of the Deanery closets; my Room smokes into the bargain, but the weather is too cold and moist to be without a fire. There is or should be a proverb here: When Mrs. Welch’s chimney smokes, ’Tis a sign she’ll keep her folks, But when of smoke the room is clear, It is a sign we shan’t stay here. All this to divert thinking. Tell me, am not I a comfortable wag? The Yatcht is to leave for Lord Carteret on the 14th45 of October. I fancy he and I shall come over together. I have opened my door to let in the wind that it may drive out the smoke. I asked the wind why he is so cross; he assures me ’tis not his fault, but his cursed Master, Eolus’s. Here is a young Jackanapes in the Inn waiting for a wind who would fain be my companion, and if I stay here much longer I am afraid all my pride and grandeur will truckle to comply with him, especially if I finish these leaves that remain; but I will write close and do as the Devil did at mass, pull the paper with my teeth to make it hold out.

“Thursday.—’Tis allowed that we learn patience by suffering. I have not spirit enough now left me to fret. I was so cunning these three last days that whenever I began to rage and storm at the weather I took special care to turn my face towards Ireland, in hope by my breath to push the wind forward. But now I give up.... Well, it is now three in the afternoon. I have dined and revisited the master; the wind and tide serve, and I am just taking boat to go to the ship. So adieu till I see you at the Deanery.

“Friday, Michaelmas Day.—You will now know something of what it is to be at sea. We had not been half an hour in the ship till a fierce wind rose directly against us; we tryed a good while, but the storm still continued; so we turned back, and it was 8 at night dark and rainy before the ship got back, and at anchor. The other passengers went back in a boat to Holyhead; but to prevent46 accidents and broken shins I lay all night on board, and came back this morning at 8. Am now in my chamber, where I must stay and get a fresh stock of patience.”

So ends this curious diary. This is the last time that Swift is known to have visited England, and it has always been assumed, from the lack of evidence of his again touching these shores, that he never did return. But he was mentally active until 1736, and it was not until 1745 that he died, in madness and old age. Meanwhile, there still exists indisputable evidence of his travelling along the Holyhead Road in 1730; for an old diamond-shaped pane of glass, formerly in a window of the “Four Crosses” Inn at Willoughby, and deeply tinged with a greenish hue, as much old glass commonly is, may be found in private possession at Rugby, inscribed by him with a diamond ring. The handwriting compares exactly with that of his diary and other manuscripts still extant, and the ferocity of the humour in the lines is characteristic of him. Other windows, at Chester and elsewhere, are known to have been inscribed by him with epigrams and satirical verses, but they do not appear to have survived. The occasion of47 his offering this advice to the landlord of what was then the “Three Crosses” has always been said to have been the landlady’s disregard of his importance. Anxious to set off early in the morning, he could by no means hurry the good woman over the preparation of his breakfast. She told him; “he must wait, like other people.” He waited, of necessity, but employed the time in this manner.

John Wesley was of this varied company of horsemen, and in a long series of years rode into every nook and corner of England. His “Journal,” abounding with details of his adventures on these occasions, proves him to have been a hard rider and among the most robust and enduring of travellers in that age. He rode incredible distances in the day, very frequently from sixty to seventy miles. Once, in 1738, he travelled in this way from London to Shipston-on-Stour, a distance of 82¾ miles, and ended the long day, as usual with him, in religious counsel. “About eight,” he says, “it being rainy and very dark, we lost our way, but before nine came into Shipston, having rode over, I know not how, a narrow footbridge which lay across a deep ditch near the town. After supper I read prayers to the people of the inn, and explained the Second Lesson; I hope not in vain.” The next day this indefatigable traveller and missioner rode 59 miles, to Birmingham, Hednesford, and Stafford; and the next a further 53 miles, to Manchester, feeling faint (and no wonder!) on the way, at Altrincham. In November 1745, riding from Newcastle-on-Tyne48 to Wednesbury, he did not experience many difficulties until he came, in the dark, to Wednesbury Town-end, where he and his companion stuck fast. That is indeed a bad road in which a horse sticks. However, people coming with candles, Wesley himself got out of the quagmire and went off to preach, while the horses were disengaged from their awkward position by local experts. The spot where Wesley was bogged is now a broad and firm macadamised road through Wednesbury, part of the great Holyhead Road. Eighteen years before this happening, an Act of Parliament had been passed for repairing and turnpiking the road between Wednesbury and Birmingham; but, although the turnpike gates may have been in existence, the road itself certainly does not seem to have been repaired, and must have remained in the condition described in the preamble to that Act, when it was “so ruinous and bad that in the winter season many parts thereof are impassable for waggons and carriages, and very dangerous for travellers.” At the same time, the road on the other side of Wednesbury was “in a ruinous condition, and in some places very narrow and incommodious”; so it is evident that Wednesbury was in the unenviable but by no means unique position of being islanded amid execrable and scarcely practicable roads.

In his old age Wesley occasionally made use of coaches and chaises, which were then a great deal better and more numerous than they had49 been forty years earlier, when he commenced his labours; but he did not give up the saddle until very near the last. In 1779, being then in his seventy-seventh year, he was still so active that on one day he rode from Worcester to Brecon, sixty miles, and preached on his arrival there. In 1782, when eighty, he still travelled, according to his own computation, four or five thousand miles a year, rose early, preached, and possessed the faculty of sleeping, night or day, whenever he desired to do so. When he began to travel he rose at the most astonishing hours—hours unknown even to the early-rising, hard-riding, hard-living travellers of that time. Let us look at his record for February 1746, along the Great North Road:—

“16th February.—I rose soon after three. I was wondering the day before at the mildness of the weather, such as seldom attends me in my journeys; but my wonder now ceased. The wind was turned full north, and blew so exceeding hard and keen that when we came (from London) to Hatfield neither my companions nor I had much use of our hands or feet. After resting an hour, we bore up again through the wind and snow, which drove full in our faces; but this was only a squall. In Baldock field the storm began in earnest; the large hail drove so vehemently in our faces that we could not see, nor hardly breathe; however, before two o’clock we reached Baldock, where one met and conducted us safe to Potton. About six I preached to a serious congregation.

50 “17th.—We set out as soon as it was well light; but it was hard work to get forward, for the frost would not well break or bear; and, the untracked snow covering all the roads, we had much ado to keep our horses on their feet. Meantime the wind rose higher and higher, till it was ready to overturn both man and beast. However, after a short bait at Bugden, we pushed on, and were met in the middle of an open field with so violent a storm of rain and hail as we had not had before; it drove through our coats, great and small, boots, and everything, and yet froze as it fell, even upon our eyebrows, so that we had scarce either strength or motion left when we came into our inn at Stilton.

“We now gave up our hopes of reaching Grantham, the snow falling faster and faster. However, we took the advantage of a fair blast to set out, and made the best of our way to Stamford Heath; but here a new difficulty arose from the snow lying in large drifts. Sometimes horse and man were a well nigh swallowed up, yet in less than an hour we were brought safe to Stamford. Being willing to get as far as we could, we made but a short stop here; and about sunset came, cold and weary, but well, to a little town called Brig Casterton.

“18th.—Our servant came up and said, ‘Sir, there is no travelling to-day; such a quantity of snow has fallen in the night that the roads are quite filled up.’ I told him, ‘At least we can walk twenty miles a day, with our horses in our51 hands.’ So in the name of God we set out. The north-east wind was piercing as a sword, and had driven the snow into such uneven heaps that the main road was not passable. However, we kept on on foot or on horseback, till we came to the White Lion at Grantham”—from whence Mr. Wesley continued his journey to Epworth, his birthplace, in Lincolnshire.

Wesley’s economy of time and his methods when riding are indicated in an interesting way in his observations on horsemanship:—

“I went on slowly, through Staffordshire and Cheshire, to Manchester. In this journey, as well as in many others, I observed a mistake that almost universally prevails; and I desire all travellers to take good notice of it, which may save them both from trouble and danger. Near thirty years ago I was thinking, ‘How is it that no horse ever stumbles while I am reading?’ (History, poetry, and philosophy, I commonly read on horseback, having other employment at other times.) No account can possibly be given but this—because when I throw the reins on his neck, I set myself to observe: and I aver that in riding above a hundred thousand miles, I scarce ever remember any horse, except two, (that would fall head over heels any way,) to fall, or make a considerable stumble, while I rode with a slack rein. To fancy, therefore, that a tight rein prevents stumbling is a capital blunder. I have repeated the trial more frequently than most men in the kingdom can do. A slack rein will52 prevent stumbling, if anything will, but in some horses nothing can.”

Dr. Johnson’s is a figure more often associated with coach and chaise travelling than with horsemanship, but in his younger days he could ride horseback with the best. He only lacked the money to afford it. His wedding-day—when he took the first opportunity of teaching his Tetty marital discipline—was passed in a journey from Derby. His wife rode one horse and he another. “Sir,” he said, a few years later, “she had read the old romances, and had got into her head the fantastical notion that a woman of spirit should use her husband like a dog. So, sir, at first she told me that I rode too fast, and she could not keep up with me; and when I rode a little slower she passed me and complained that I lagged behind. I was not to be made the slave of caprice, and I resolved to begin as I meant to end. I therefore pushed on briskly, till I was fairly out of her sight. The road lay between two hedges, so I was sure she could not miss it; and I contrived that she should soon come up with me. When she did, I observed her to be in tears.”

It has already been noted that judges and barristers formerly rode circuit on horseback. As Fielding says, “a grave serjeant-at-law condescended to amble to Westminster on an easy pad, with his clerk kicking his heels behind him.” In such cases, and when a lady rode pillion behind her squire, clutching him by the53 waistbelt, the “double horse” was used. This, which was by no means a zoological freak, was the type of horse asked for and supplied by postmasters to two riders going in this fashion on one animal. Like the brewers’ double stout, the “double horse” was specially strong, and possessed more the physique of the cart-horse than the park hack. It was chiefly for the use of the ladies thus riding that the “upping blocks,” or stone steps, still occasionally seen outside old rustic inns, were placed beside the road. They enabled them to get comfortably seated.

Travellers from Scotland to London about the middle of the eighteenth century were accustomed to advertise for a companion. Thus, in the Edinburgh Courant for January 1st, 1753, we find:—

“A Gentleman sets off for London Tomorrow Morning, and will either post it on horses or a Post-Chaise, so wants a Companion. He is to be found at the Shop of Mr. Sands, Bookseller.”

It was then generally found cheap, and sometimes profitable as well, to buy a horse when starting from Edinburgh, and to sell him on arrival in London. Prices being higher in the Metropolis, the canny travellers who adopted this plan often got more for the horse than they had given. This method had, however, the defect of not working in reverse, and so those Scots who returned would have had to hire at some considerable expense, or buy dear to sell cheap, a thing peculiarly abhorrent to the Scottish mind. Dr. Johnson would have characteristically brushed54 this argument away by declaring that the Scot never did return.

During many long years Scots travelling in their own country followed an equally economical plan. “The Scotch gentry,” said Thomas Kirke in 1679, “generally travel from one friend’s house to another; so seldom require a change-house. Their way is to hire a horse and a man for twopence a mile; they ride on the horse thirty or forty miles a day, and the man who is his guide foots it beside him, and carries his luggage to boot.” The “change-house” was, of course, an inn; and from this custom, when every man’s house was an hotel, the Scottish inns long remained very inferior places.

Fielding throws a very instructive light upon the device hit upon by any two travellers who wished to go together and yet had only one horse between them. This was called “Ride and Tie.” He says: “The two travellers set out together, one on horseback, the other on foot. Now, as it generally happens that he on horseback outgoes him on foot, the custom is, that when he arrives at the distance agreed on, he is to dismount, tie the horse to some gate, tree, post, or other thing, and then proceed on foot; when the other comes up to the horse, he unties him, mounts, and gallops on, till, having passed by his fellow-traveller, he likewise arrives at the place of tying. And this is that method of travelling so much in use among our prudent ancestors, who knew that horses had mouths as well as legs, and that they55 could not use the latter without being at the expense of suffering the beasts themselves to use the former.”

Not until the first decade of the nineteenth century had gone by did the horseman wholly disappear from the road into or on to the coaches. Let us attempt to fix the date, and put it at 1820, when the fast coaches began to go at a pace equal or superior to that of the saddle-horse. The curious may even yet see the combined upping-blocks and milestones placed for the use of horsemen on the road across Dunsmore Heath.