THE JOURNAL

OF

PRISON DISCIPLINE

AND

PHILANTHROPY

PUBLISHED ANNUALLY

BY THE

Pennsylvania Prison Society

INSTITUTED MAY 8, 1787

NOVEMBER, 1911

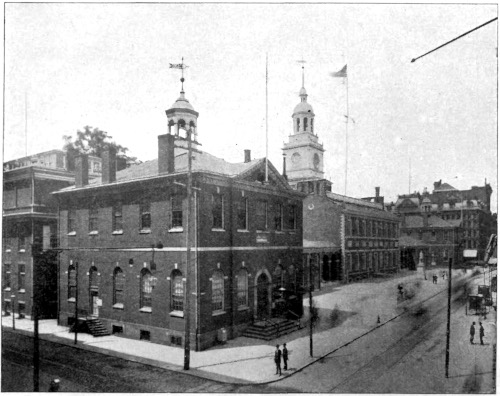

OFFICE: STATE HOUSE ROW

S. W. CORNER FIFTH AND CHESTNUT STREETS

PHILADELPHIA, PA.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Journal of Prison Discipline and Philanthropy (New Series, No. 50) No, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Journal of Prison Discipline and Philanthropy (New Series, No. 50) November 1911 Author: Various Release Date: February 25, 2019 [EBook #58963] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JOURNAL OF PRISON DISCIPLINE, NOV 1911 *** Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Wayne Hammond and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

i

ii

No person who is not an official visitor of the prison, or who has not a written permission, according to such rules as the Inspectors may adopt as aforesaid, shall be allowed to visit the same; the official visitors are: the Governor, the Speaker and members of the Senate; the Speaker and members of the House of Representatives; the Secretary of the Commonwealth; the Judges of the Supreme Court; the Attorney-General and his Deputies; the President and Associate Judges of all the courts in the State; the Mayor and Recorders of the cities of Philadelphia, Lancaster, and Pittsburg; Commissioners and Sheriffs of the several Counties; and the “Acting Committee of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons.” (Note: Now named “The Pennsylvania Prison Society.”)—Section 7, Act of April 23, 1829.

The above was supplemented by the following Act, approved March 20, 1903:

To make active or visiting committees of societies incorporated for the purpose of visiting and instructing prisoners official visitors of penal and reformatory institutions.

Section i. Be it enacted, etc., That the active or visiting committee of any society heretofore incorporated and now existing in the Commonwealth for the purpose of visiting and instructing prisoners, or persons confined in any penal or reformatory institution, and alleviating their miseries, shall be and are hereby made official visitors of any jail, penitentiary, or other penal or reformatory institution in this Commonwealth, maintained at the public expense, with the same powers, privileges, and functions as are vested in the official visitors of prisons and penitentiaries, as now prescribed by law: Provided, That no active or visiting committee of any such society shall be entitled to visit such jails or penal institutions, under this act, unless notice of the names of the members of such committee, and the terms of their appointment, is given by such society, in writing, under its corporate seal, to the warden, superintendent or other officer in charge of such jail, or other officer in charge of any such jail or other penal institution.

Approved—The 20th day of March, A. D. 1903.

The foregoing is a true and correct copy of the Act of the General Assembly No. 48.

iii

iv

The Pennsylvania Prison Society Office, S. W. Cor. 5th and Chestnut Sts. 1

2

All correspondence with reference to the work of the Society, or to the Journal of Prison Discipline and Philanthropy, should be addressed to The Pennsylvania Prison Society, 500 Chestnut St., Philadelphia, Pa.

The National Prison Congress of the United States for the past ten years has designated the fourth Sunday in October, annually, as Prison Sunday. To aid the movement for reformation, some speakers may be supplied from this Society. Apply to chairman of the Committee on Prison Sunday.

Frederick J. Pooley is the General Agent of the Society. His address is 500 Chestnut St., Philadelphia.

Contributions for the work of the Society may be sent to John Way, Treasurer, 409 Chestnut St., Philadelphia.

I give and bequeath to “The Pennsylvania Prison Society” the sum of .... Dollars.

I give and devise to “The Pennsylvania Prison Society” all that certain piece or parcel of land. (Here describe the property.) 3

JOSHUA L. BAILY, 30 S. Fifteenth Street, Philadelphia.

Rev. HERMAN L. DUHRING, D. D., 225 S. Third Street, Philadelphia.

Rev. F. H SENFT, 560 N. Twentieth Street, Philadelphia.

JOHN WAY, 409 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia.

1JOHN J. LYTLE, Moorestown, N. J.

ALBERT H. VOTAW, 500 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia.

Hon. WILLIAM N. ASHMAN, 44th and Spruce Streets, Philadelphia.

HENRY S. CATTELL, ESQ., 1218 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia.

OWEN J. ROBERTS, ESQ., West End Trust Building, Philadelphia.

FREDERICK J. POOLEY, 500 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia.

FOR ONE YEAR

Rev. Floyd W. Tomkins, D.D.,

Rev. J. F. Ohl,

Harry Kennedy,

Layyah Barakat,

William E. Tatum,

Mary S. Wetherell,

George S. Wetherell,

Henry C. Cassel,

Albert Oetinger,

Rev. Philip Lamerdin,

Mrs. E. W. Gormly,

A. Jackson Wright,

Frank H. Longshore,

Charles H. LeFevre,

Rev. M. Reed Minnich.

FOR TWO YEARS

1John J. Lytle,

P. H. Spellissy,

Fred J. Pooley,

William Scattergood,

Mrs. P. W. Lawrence,

William Koelle,

Rev. R. Heber Barnes,

Dr. William C. Stokes,

Deborah C. Leeds,

Mrs. Horace Fassitt,

Joseph C. Noblit.

Miss C. V. Hodges,

Rebecca P. Latimer,

Joseph Rhoads.

FOR THREE YEARS

Charles P. Hastings,

Isaac P. Miller,

Elias H. White,

John Smallzell,

John A. Duncan,

Samuel B. Garrigues,

Charles McDole,

Harrison Walton,

Mrs. Mary S. Grigg,

Robert B. Adams,

William Morris,

Emma L. Thompson.

Annie McFedries,

1Robert P. Nicholson,

Rev. Thomas Latimer.

1 Deceased 1911.

4

| Visiting Committee for the Eastern State Penitentiary: | ||

| 2John J. Lytle, | Frank H. Longshore, | William Morris, |

| P. H. Spellissy, | A. Jackson Wright, | Robert B. Adams, |

| Dr. William C. Stokes, | Charles H. LeFevre, | Rev. M. Reed Minnich, |

| Rev. F. H. Senft, | Charles P. Hastings, | 2 Robert P. Nicholson, |

| William Koelle, | John Smallzell, | Deborah C. Leeds, |

| Joseph C. Noblit, | Charles McDole, | Mrs. Horace Fassitt, |

| Rev. Philip Lamerdin, | Samuel B. Garrigues, | Miss Rebecca P. Latimer, |

| Harry Kennedy, | Harrison Walton, | Layyah Barakat, |

| Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Albert H. Votaw, | Mary S. Wetherell, |

| William E. Tatum, | Rev. Thomas Latimer, | Mrs. Mary S. Grigg, |

| George S. Wetherell, | J. A. Duncan, | Emma L. Thompson. |

| Henry C. Cassel, | Isaac P. Miller, | |

| Visiting Committee for the Philadelphia County Prison: | ||

| Joseph C. Noblit, | Albert H. Votaw, | Miss C. V. Hodges, |

| John A. Duncan, | Mrs. P. W. Lawrence, | Miss Rebecca P. Latimer. |

| Isaac P. Miller, | Deborah C. Leeds, | |

| William Morris, | Mrs. Horace Fassitt, | |

| For the Holmesburg Prison: | ||

| Frederick J. Pooley, | Rev. Philip Lamerdin, | William Morris. |

| For the Philadelphia House of Correction: | ||

| William Koelle, | William Morris, | Deborah C. Leeds. |

| Layyah Barakat, | ||

| For the Chester and Delaware County Prison: | ||

| William Scattergood, | John Way, | Mrs. Deborah C. Leeds. |

| Joseph Rhoads, | ||

| For the Bucks County Prison: | ||

| (One vacancy.) | ||

| Albert Oetinger. | ||

| Committee on Western Penitentiary and Allegheny County Prison: | ||

| Miss Annie McFedries, | Mrs. E. W. Gormly. | |

| Committee on Discharged Prisoners: | ||

| Joseph C. Noblit, | George S. Wetherell, | Miss C. V. Hodges. |

| Dr. William C. Stokes, | Mrs. Horace Fassitt, | |

| Committee on Police Matrons: | ||

| Mrs. Mary S. Grigg, | Miss C. V. Hodges, | Miss Rebecca P. Latimer. |

| Committee on Prison Sunday: | ||

| Rev. H. L. Duhring, D.D., | Rev. R. Heber Barnes, | Rev. Philip Lamerdin. |

| Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Rev. F. H. Senft, | |

| Editorial Committee: | ||

| Rev. R. Heber Barnes, | Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Dr. William C. Stokes. |

| Albert H. Votaw, | The President (ex officio) | |

| Committee on Legislation: | ||

| Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Elias H. White, | 2Robert P. Nicholson. |

| Rev. R. Heber Barnes, | Joseph C. Noblit, | |

| Membership Committee: | ||

| Dr. William C. Stokes, | Elias H. White, | Henry C. Cassel. |

| George S. Wetherell, | Isaac P. Miller, | |

| Finance Committee: | ||

| George S. Wetherell, | Isaac P. Miller, | Joseph Rhoads. |

| Joseph C. Noblit, | A. Jackson Wright, | |

| Auditors: | ||

| Charles P. Hastings, | John A. Duncan, | 2Robert P. Nicholson. |

2 Deceased 1911.

5

The 124th Annual Meeting of “The Pennsylvania Prison Society” was held January 27, 1911, at the office of the Society at the S. W. Corner of Fifth and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia.

The meeting was called to order by the President, Joshua L. Baily.

The Minutes of the 123d Annual Meeting were read and approved.

Twenty-six members of the Society were present.

Reports were read from the Acting Committee and from the General Agent, Fred. J. Pooley, which were approved and directed to be printed in the forthcoming Journal.

The Treasurer, John Way, produced a detailed statement of the receipts and disbursements for the fiscal year ending December 31, 1910. (See page 15.)

The following Amendment to the Constitution was proposed, and directed to be laid before the next meeting of the Society, viz.:

“The number of Members of the Acting Committee may be increased to not exceeding sixty, provided the additional members shall be residents of Pennsylvania outside of Philadelphia.

“These Members may be elected from time to time at any meeting of the Acting Committee, according to the provisions of the By-Laws for filling vacancies, but the terms for which they are elected shall be for the unexpired portion of the current fiscal year only. These additional Members will be eligible for reëlection at the next Annual Meeting, and their respective terms of service shall then be assigned so as to be 6 coördinate with the terms of service of the other Members of the Committee.”

John J. Lytle, on behalf of the Nominating Committee, appointed at the last Annual Meeting, presented in writing the nominations for the officers of the Society and for the members of the Acting Committee whose terms expire at this time. The President appointed as Tellers, Joseph C. Noblit, A. Jackson Wright and William E. Tatum. The election having been duly conducted, the Tellers announced that a unanimous vote of the Society was cast for the ballot as presented by the Nominating Committee. (See page 3.)

The Nominating Committee proposed that Hon. William N. Ashman be elected Honorary Counselor. On motion the recommendation of the Committee was adopted with expression of appreciation of the long and faithful services of Judge Ashman for the Society.

The President appointed the following committee to nominate to the next Annual Meeting the names of officers, and members of the Acting Committee to fill the place of those whose terms then expire, viz.: George S. Wetherell, Joseph C. Noblit, Mrs. Horace Fassitt, Mrs. Mary S. Grigg and Paul D. I. Maier.

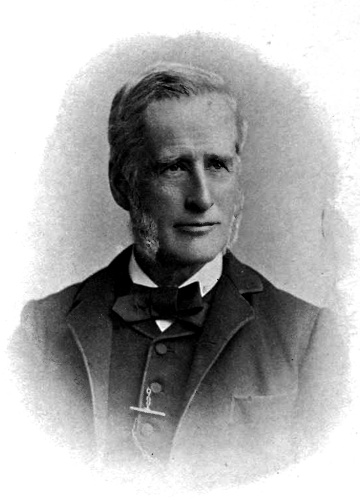

The President (Joshua L. Baily) expressed his appreciation of the honor done him by his reëlection for a fifth term. He said it was sixty years ago this month that he was elected a member of the Prison Society. Soon thereafter he was placed on the Acting Committee and for ten or twelve years he was a regular visitor at the Eastern Penitentiary. He also visited a number of our county jails and most of the penitentiaries of the Atlantic States and some of those in the West. But not being satisfied with the results, he gave up prison visiting and took up what he then believed to be more hopeful service.

“Now, after the lapse of many years,” he said, “I find myself again among you with a new vision as to the obligations and possibilities of the work in which we are engaged.” In the few recent years, he said, that he had had opportunity for observation, he had not found the evidence that the prisons of this state (perhaps with a few exceptions) are in any better condition as to equipment and administration and facilities for the improvement of the inmates than they were fifty years ago.

“In all other lines of humanitarian and benevolent endeavor there has been a wonderful augmentation of the efforts 7 put forth, and the means provided, and with corresponding beneficent results, but the work of prison reform has not kept pace with what is so observable in other fields of service.

“People generally are not much interested in the inmates of our prisons. They think that those who have committed crimes should be punished, and so they should; but it is not Christian to think that their criminality places them outside the pale of human sympathy and help. Even some of the greatest offenders may by kindness and good influences be restored to society, as some have, and become exemplary and useful citizens.

“I may not enlarge upon this subject at this time, but I want to say to you that I know of no line of benevolent activity that has a greater claim upon our intelligent and hearty service.”

A. Jackson Wright expressed his concurrence in the views of the President, especially as to this great opportunity which our work offers for service in the cause of humanity.

No letters, notes, monies, or contraband goods of any kind shall be brought into or taken out of any Prison, except after inspection and with the permission of the Warden.

The Warden or Superintendent of the Prison is hereby authorized to search or to have searched any person coming to the Prison as a visitor, or in any other capacity, who is suspected of having any weapon or other implement which may be used to injure any convict or person, or in assisting any convict to escape from imprisonment, or any spirituous liquor, drug, medicine, poison, opium, morphine, or any other kind or character of narcotics, upon his person.

Any person violating any of the provisions of this Act shall be deemed guilty of a felony, and upon conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars, or imprisonment in the State Prison not exceeding five years, or by both such fine and imprisonment, in the discretion of the Court.

Approved the eleventh day of May, A. D. 1911.

During the year 1910 the monthly meetings of the Acting Committee have been regularly held with the usual exception of two meetings of the summer months.

It has been a year of much interest and importance to students of penology and especially to the active workers who have charge of our prisons and reformatories.

In the State of Pennsylvania the law providing for probation or suspended sentences for adult offenders under the care of probation officers, to whom reports must be made, has been in effect for almost eighteen months. Very general approval is expressed regarding the operation of this law. It is believed to be a very efficient means of restoring those who have lapsed from the right path to better methods of life and to a deeper realization of their duties to society. They have not become inoculated with the prison virus. The law applies to certain classes of crimes and to first offenders. It is understood that much of the efficiency of such a law depends on the character and vigor of the probation officer, who should be most earnest in presenting before such offenders higher ideals of civic virtue.

Since the last annual report of this Committee, in the State of Pennsylvania a system of parole for criminals sentenced to the Eastern and to the Western Penitentiaries in accordance with legislative enactment, went into effect. The act provides that the court in pronouncing sentence shall state the minimum and maximum limits thereof, with the understanding that the minimum time of such imprisonment shall be the minimum now or hereafter prescribed by statute for the punishment of such offense, and that the maximum shall be the maximum now or hereafter prescribed as the penalty. Hence it does not follow, as has been supposed by many, that 9 the minimum sentence is in every case one fourth of the maximum sentence, though there is a provision that when there is no minimum time prescribed by law, then the court shall impose a minimum sentence, which is not to exceed one fourth of the maximum time for the crime in question. Neither is a prisoner entitled to release at the expiration of his minimum sentence, unless it shall have appeared to the officers of the prison and to the inspectors that the applicant for parole has given evidence of being ready to become useful to the community. The new law has not been in force for a period sufficiently long to enable us to decide absolutely as to its merits, yet, if we are to have confidence in reports from other States which have tested such a law, we hope that a fair trying out of its provisions will demonstrate its benefit both to the convict and to society. The man or woman on parole by the necessity of the conditions involved therewith must give satisfaction until the maximum time for which he was sentenced has expired, by which time we believe many of them will have formed a habit of living decently and orderly. Ex-Governor Hanly, of Indiana, acknowledges that when he took office he felt great antagonism toward a law providing for parole before the expiration of the conventional sentence, but after closely observing the practical working of such system of parole during his term of four years, he became an enthusiastic advocate of the principle of the indeterminate sentence. State after State, nation after nation, have been for some years applying this principle in some form or other, and now many intelligent jurists and administrators of prison discipline have recognized that this element of the new penology has come to stay. This method of reforming criminals, moreover, was approved, after spirited discussion, by the late International Prison Congress, held at Washington, D. C., October 2-8, 1910. This Congress was not composed of mere theorists. Men of national and international renown as wardens and superintendents of great prisons and reformatories took part in the discussions and acquiesced in the conclusions. Warden Benham, of the New York State Penitentiary at Auburn, regards the indeterminate sentence as a leading influence in the process of reforming the lives of those who have fallen. By some jurists in this and other States, fears have been expressed with regard to the practical service and to the execution of such a system of curtailed punishment. It is quite possible that experience may show that in this State some modification 10 of the existing law may at some time be adopted, but great care should be exercised lest the reforming possibilities of the act should be weakened. It is to be hoped that a full opportunity may be given to observe the effects of this law, the essential principles of which are the same as have been found successful in other States.

The reports from those who have been paroled within the last year in this State are so far very encouraging.

Parole Officer John Egan of the Western Penitentiary reports on the first day of the current year that there were twenty-three under his charge on parole, and that the reports from them were with one exception satisfactory. There were ten then confined in the Western Penitentiary who were proper subjects for parole provided sponsors and employment could be obtained for them.

Full statistics from the Eastern Penitentiary have not been obtained. About thirty had been paroled by the end of last year from whom satisfactory reports had been received. About the same number were awaiting decisions from the Board of Pardons.

We desire to commend to the special attention of the Society and to the public, the efficient work of our General Agent, Fred. J. Pooley.

He has been constantly engaged in giving counsel to the prisoners, and particular attention to them at the time of their release. A large number of cases have been investigated, and where there have appeared to be mitigating circumstances, or where some relative or judicious friend has agreed to stand as sponsor, a remission or suspension of the sentence has been obtained from the court. We have heard of no instance in which such favor has been abused. In one month of the last year over one hundred arrested and accused persons were discharged without receiving the stigma of a convicted felon. In the latter part of the autumn the privilege of an interview at the Central Station with the prisoners who have been committed to the County Prison after a hearing before the magistrates, was accorded to our General Agent by the Director of Public Safety. In order that he may thus occupy this very promising field for service, the Secretary has assumed a portion of the duties at the Eastern Penitentiary which had formerly been under the care of the agent. A full 11 report of the work of the agent will be presented at the Annual Meeting, and will be printed in the Journal.

Reports of the various members of this Committee show that besides a considerable number of visits that have not been reported, 6,130 visits to prisoners have been made during the past year. Some of our members have participated in the gospel services at the Penitentiary. We are firmly of the opinion that this work of visitation, which has been carried on by this Society for nearly a century and a quarter has been very helpful, although from the nature of the circumstances accurate statistics cannot be presented. The officials of the Penitentiary manifestly sympathize with the objects of these visits. Cleanliness and good order characterize the various departments of this large prison, to which ends a general overhauling of the plumbing with other improvements have been made conducive. A new three-story block, containing one hundred and twenty cells is in process of construction, and it is quite gratifying to report that nearly all the work of construction is being done by the prisoners. This affords employment for from one hundred and fifty to two hundred and fifty prisoners. While some other prisoners have employment in weaving, knitting stockings, chair seating and in helping in the kitchen and laundry, still many of them spend a large portion of their time in enforced idleness. This is a condition which is conducive to most serious evils, since it is liable to affect their entire career after they have left the prison walls. Is the State justified in forcing these unfortunate human beings to remain idle year after year? Should we not rather use every means in our power to prepare them for useful citizenship?

Reports of the agent show that 333 prisoners have been supplied at the time of their discharge with suits either entirely or in part. We are increasing our efforts to find positions for such as need employment.

The warden, Robert J. McKenty, is untiring in efforts to promote the welfare of those under his charge. To him and to the other officials the members of the Committee are under obligation for the facilities afforded in making their visits.

Our General Agent is unremitting in his endeavors to assist those confined in the prisons of the City of Philadelphia. 12 The ladies of the Committee to visit the women prisoners at Moyamensing have been faithful in looking after their interests. Situations have been found for many, and not a few have been restored to their families. In all, 6,707 visits have been made to the inmates of the County Prisons.

We take pleasure in reporting that striped clothing as a distinctive prison garb was relinquished, except as a punishment for misbehavior, at the Holmesburg Prison on the first day of July, 1910. Gradually both in this country and England this ancient custom is being dropped. This is a further indication of the growing belief that the convict, after all, is a human being, and does not need the degradation of stripes in order to be distinguished from the rest of humanity.

The Western Penitentiary and the Allegheny County Prison have been regularly visited by one of our committees, and there has also been regular visitation of some of the county jails. The evidence afforded that this service has been acceptable and useful has been encouraging to us, and arrangements are being made for its extension to other parts of the state.

There is need of continual agitation to educate the public with regard to the necessity of some change in the administration of many of the smaller county jails of the State. They furnish little or no employment, herd a miscellaneous lot of lawbreakers in entire idleness, often keep the young and the old, the suspected, who may be innocent, and the hardened criminals in the same apartments, and thus become hotbeds for the dissemination of vice and lawlessness. We have already in these reports spoken of the usefulness of establishing district workhouses where employment can be furnished and where habits of industry may be engendered. The labor of the prisoners should so far contribute to the maintenance of the jails as to relieve the counties from the chief part of this burden. Sooner or later, we believe, all our States will adopt some such plan, and why should not the legislators of this great commonwealth give some earnest attention to the improvement of the county jails? Already we have in this State an institution which in many respects could be taken as a model for an industrial penal establishment. We refer to the Allegheny County Workhouse at Hoboken, Pennsylvania. Without infringing on the present laws of the State respecting 13 prison labor, they give employment to all the prisoners. Located on a large farm, they supply their tables with vegetables from their own gardens and often have a surplus for the market. When new buildings are constructed, most of the work is done by the convicts. They have those who have been sentenced to terms of from twenty days to some years, and without difficulty they find work for all of them.

The legislature of Massachusetts has been considering a measure contemplating the establishment of such a system of district workhouses. It is quite possible that the State of Indiana may enact a measure of this kind within the next two years. Let Pennsylvania move forward in this work.

The President of the Society has made visits to the Eastern Penitentiary, and to some of the County Jails of Pennsylvania. He has also visited the Maryland Penitentiary and the city jail of Baltimore; and has made two visits to the United States jail at Washington, D. C.

In the Washington jail and at the Maryland Penitentiary, he addressed the assembled convicts at their respective Sabbath afternoon chapel services.

An event of great interest to all students of penology and of far-reaching influence in prison administration all over the world, was the quinquennial meeting of the International Prison Congress, which this year held its sessions in Washington, D. C. This occasion brought together jurists, superintendents of prisons and reformatories, eminent lawyers and philanthropic workers from thirty-four different countries of the world. Ninety delegates were enrolled from foreign countries. Not only were the conclusions of this Congress of importance, but the social intermingling of so many earnest men and women in a common cause had an equal value. The American Prison Congress also held its sessions in Washington, D. C., for two days prior to the opening of the International meeting. It was a notable gathering, and while its proceedings were weighty and not to be overlooked, yet it was somewhat overshadowed by the great interest felt in the International assemblage, as the latter was attended by so many who had already beyond the seas distinguished themselves 14 as students of penological problems, and as practical administrators of prisons.

The Acting Committee deemed the conclusions of the International Prison Congress and the proceedings of the American Prison Congress of such immediate interest and importance as to justify the issue of a supplement to our Journal, which should contain these conclusions and proceedings. In this supplement were included an article by President Baily on the Eastern Penitentiary and the account of the Pennsylvania Prison Society which was prepared by the Secretary for publication in one of the bulletins issued by the International Congress during its sessions. Three thousand copies were printed and distributed.

The deaths of John H. Dillingham and David Sulzberger, both occurring near the same time in early spring, removed two valuable members from your Committee. Appropriate notices of the life and faithful labors of each of these have been prepared and read in our meetings, and it is proposed to publish them in the forthcoming number of our Journal.

Our prayers and sympathy go out to all who have the oversight of those offenders, whom society, for its own protection and for the reformation of the sinner, declares must be debarred from freedom. Upon these officials devolves the duty not only of restraining the criminals within physical bounds, but—what is their chief mission—of implanting in their charges incentives for a change in their attitude in society. They should endeavor to inspire them with some sense of self-confidence and self-respect, so that they may be prepared to face the world with new aims and a spirit of hopefulness. The Pennsylvania Prison Society has from its inception desired to work in harmony with the administrators, and we trust has been comparatively free from the errors of a misdirected zeal. In another year this Society shall have rounded out a century and a quarter of existence. While we may contemplate with a good degree of satisfaction the achievements of past years, we are aware that in some lines progress has been slow, but we trust under Divine guidance to go on with the work with greater zeal and consecration.

On behalf of the Acting Committee,

January 27, 1911. 15

| General Fund Receipts for the Year 1910 |

||

| To | Balance on hand, December 31, 1909 | $697 50 |

| “ | Members’ Dues | 278 75 |

| “ | Collections by Secretary | 3,253 00 |

| “ | Income from Invested Funds | 1,911 52 |

| “ | Income from I. V. Williamson “Charities” | 561 00 |

| “ | Interest on Deposits | 20 31 |

| “ | Life Membership | 50 00 |

| “ | Proceeds Sale of Bond | 1,032 50 |

| “ | Legacy, Estate of Marianna Gillingham | 805 54 |

| Total Receipts | $8,610 12 | |

| Payments, 1910 | ||

| For | Clothing Discharged Prisoners, Eastern Penitentiary | $2,324 45 |

| “ | Appropriations for Prisoners Discharged from Philadelphia County Prison | 835 00 |

| “ | Salaries | 2,650 00 |

| “ | Expenses on Account of “Journal,” 1910 | 437 20 |

| “ | Expenses Delegates to Prison Congress | 56 72 |

| “ | Sundry Printing and Postage | 249 29 |

| “ | Office Expenses, Incidentals | 148 52 |

| “ | Rent, Janitor Service | 184 00 |

| “ | Capital Moneys Paid to Fiscal Agent for Investment | 855 54 |

| “ | Balance, December 31, 1910 | 869 40 |

| Total | $8,610 12 | |

| Barton Fund | ||

| Balance on hand December 31, 1909 | $193 48 | |

| Income from Investments (net) | 94 66 | |

| Loan to Discharged Prisoner, Returned | 10 25 | |

| Total | $298 39 | |

| Payments | ||

| Tools to Discharged Prisoners | $36 74 | |

| Amount Transferred to Principal Account | 375 10 | |

| $411 84 | ||

| Less Overdraft December 31, 1910 | 113 45 | |

| Balance | $298 3916 | |

| Home of Industry Fund | ||

| Balance, December 31, 1909 | $107 80 | |

| Income from Investments (net) | 24 50 | |

| Income from Caroline S. Williams Legacy | 150 85 | |

| Income from H. S. Benson Legacy | 196 00 | |

| Total | $479 15 | |

| Summary of Balances | ||

| General Fund | $869 40 | |

| Home of Industry Fund | 479 15 | |

| $1,348 55 | ||

| Less Overdraft (Barton Fund) | 113 45 | |

| Total Cash on hand December 31, 1910 | $1,235 10 | |

We, the undersigned, members of the Auditing Committee, have examined the accounts of John Way, Treasurer, have compared the payments with the vouchers, and believe the same to be correct, there being a balance to the credit of our deposit account under date of December 31, 1910, of $1,235.10.

We have also examined the securities in the possession of our agents, The Provident Life and Trust Company of Philadelphia, and have found them to agree with an accompanying schedule.

Another year has passed and it becomes my duty to present to you a report of the work of the General Agent. During the past year I have visited over 6,000 men and women in the prisons in Philadelphia, and talked to them of the past and the future. I feel that much good has been accomplished and that while it is impossible to measure the amount of good accomplished by any fixed rule, yet there is evidence in all directions that the seed sown in the Master’s name is bearing fruit abundantly. All over this broad land of ours, in every prison may be found the lost son or daughter; it gives the world but little concern so long as it is some one else’s son or daughter who occupies a prison cell. Go through the prisons of our State and nine times out of every ten the prisoners will tell you they never would have thought of getting into prison; in a moment of temptation they fell and the world turns from them when the walls of the prison separates them from the outer world. My experience has taught me that if we were more sympathetic, more interested in fallen humanity, there 17 would be less of crime. One Sabbath afternoon I visited a prison in western Pennsylvania. I arrived at the prison just about the time for service. As I was a member of the Pennsylvania Prison Society I was requested to say a few words to the men and women. My remarks were brief, and I closed with, “Your mother or wife, or sister is praying for you to-day, and when you leave your prison cell, go home to your mother, your wife, or to your sister; go back to your church, and God will bless and help you to be a better man or woman.” One prisoner went to his cell weeping. I followed him to his cell and said to him, “Brother, why do you weep?” and he answered, “When you said ‘mother’ it touched a tender spot, and when I leave here I will go right home to her and will be a better man.”

Scattered over the ocean there are many pieces of wreckage floating in different directions, first carried by one current and then by another; they are simply drifting. They have no purpose; they are afraid to trust themselves. I believe it to be our duty to bring to these men and women in prison the strongest force we know, the power of love. Faith is a great power; so is hope; but charity, or love, is the greatest. Geologists tell us that the silent influences of the atmosphere are far more powerful than the noisy forces of nature. Quiet sunshine is mightier than the thunder, and gentle rain influences the earth more than an earthquake. Guided by this gentleness and faith, I have tried to be the instrument in God’s hands of leading some poor souls to the path which leads to happiness and peace. It will probably be of interest to know something of the work of the General Agent at the Eastern State Penitentiary.

From January 1 to December 1, 1910: 493 prisoners were discharged: to these were given 298 suits of clothing, 382 hats, 301 shirts, 425 suspenders and neckties and 321 suits of underclothes.

In addition tools, etc., have been provided for several of these prisoners.

On December 1, 1910, Secretary Albert H. Votaw took charge of the work of the Pennsylvania Prison Society at the Eastern State Penitentiary in consequence of your General Agent having other duties at the Central Police Station, City Hall. I desire to thank the Inspectors, Warden, Chaplain and all the officials connected with the Eastern Penitentiary for assistance rendered me in the performance of my official duties. 18

Since October 1, 1898, I have made regular visits to Moyamensing Prison and the Philadelphia County Prison at Holmesburg. During 1910 more than 600 discharged prisoners were assisted with railroad tickets, board, lodging, room rent, tools, etc., and more than 700 letters written to relatives and friends at a distance, thus getting them quickly in touch with folks at home, and in many cases resulting in acquittal at court when a prisoner’s good record was shown. The Inspectors, Superintendent, Assistant Superintendent, Prison Agent and Matron, and all connected with the prison have rendered me every possible assistance, which I more than appreciate. The commitments to Moyamensing Prison during 1910 were as follows:

| White Males | White Females | Black Males | Black Females | Total |

| 13,518 | 1,138 | 2,547 | 706 | 17,909 |

| Total Committed 1909, | 17,685 | |||

From October 1, 1909, to September 30, 1910, 914 prisoners were sent to the County Prison at Holmesburg and 867 prisoners were discharged.

A glance at the above figures will show what a wonderful field of work there is for the Prison Agent and General Agent of the Pennsylvania Prison Society.

For the past two years I have felt very strongly the importance of visiting the prisoners at the Central Station, City Hall. The reason for this desire was brought about through a young man who was held in Moyamensing Prison on suspicion of larceny for a further hearing. I had a talk with him and he told me he left Louisville, Ky., seventeen years since, and had not written home in that time, and now he felt ashamed to write. After a long talk with him, he consented to let me write. When the letter came from the mother telling of her joy at the news of her long-lost son, whom she had long thought dead, I at once went to the prison and found the man had that morning been discharged—the letter came too late. Had I met the man when he was first arrested, that letter would have arrived before the second hearing, and upon his discharge he would have gone home.

It is with much pleasure I am able to state that on November 16, 1910, Director Clay granted me permission to visit the cell room at City Hall and directed the Superintendent of Police to issue me a permit, which reads as follows: 19

Department of Public Safety,

Bureau of Police.

Philadelphia, November 16, 1910.

Permission is hereby granted Frederick J. Pooley, General Agent Pennsylvania Prison Society, the courtesy and privilege of visiting prisoners in Central Station committed to County Prison.

Since receiving permission I have made daily visits to the Central Station and have written 126 letters to different parts of the country. One letter brought a young man’s father from Johnstown, Pa., and another from Richmond, Va., and when the cases came to court they were discharged. At the request of the Detective Department three women who were found on the street without a home were placed in care of Mrs. H. Fassitt, and Mrs. Fassitt had them sent to the Door of Blessing, and afterwards had one woman sent to her home in West Virginia and another to her home in Maryland, and the other to a hospital for treatment. In some cases the magistrates have requested me to look into the case, and upon my report they were discharged and sent home. I look for wonderful results from this field of work. Only the other day a man came to me and said, “We had not heard from sister for five months and had it not been for your talk with her at the City Hall we do not know when she would have decided to come home.” I think the words of our President, Joshua L. Baily, to the Magistrate when he visited the City Hall recently explains the new work of the Pennsylvania Prison Society when he said. “Our new work here is to try to keep men and women from going to prison.” The Magistrates and officials of the City Hall are doing all they can to help to make the work of your General Agent a success.

In the spirit of these words I enter upon my new work. The Motto Calendars, so kindly given us each year for 20 distribution at the Eastern State Penitentiary, Holmesburg and Moyamensing, with message of inspiration, are much appreciated.

The thanks of the members of the Pennsylvania Prison Society are due to the following for sending magazines and religious papers for the prisoners: Rev. R. H. Barnes, Louis C. Galenbeck, the late Miss Mary S. Whelen, Attorney-at-Law William A. Davis, Mrs. Charles Chauncey, Miss A. M. Johnson, Robert P. Nicholson, Estelle A. King, C. Langenstein, Anna M. Tarr, Miss M. Louisa Baker, C. deB. L. Bright, Mrs. R. T. Taylor and Friends’ Institute. Thanks are also due John J. Lytle for several hundred copies of Sabbath Reading which have been sent weekly to Eastern Penitentiary, Moyamensing and County Prison, Holmesburg. In addition I have recently received, through the kindness of Dr. Beverley Robinson, of New York City, $25.00 from Mrs. Charles Chauncey, and from Mrs. A. Sydney Biddle the same amount to help along the work, and from Mr. Emlen Hutchinson, Chairman of the Board of Inspectors Philadelphia County Prison, $60.00 with which to send home runaway boys. These amounts have been handed to our Treasurer for use when necessary.

I feel the work that the Pennsylvania Prison Society is doing is becoming more appreciated as the years roll on. With much faith in the future of our Society,

Joshua L. Baily, Esq., President of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, 500 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia.

Dear Sir:—Your General Agent, Mr. Frederick J. Pooley, commenced work (as you know) at the Central Police Station last November, and we have found his work very helpful to this department and hope the good work your Society is doing through Mr. Pooley may be continued for many years to come.

Wm. H. Griffing, Clerk.

I most cheerfully endorse the above letter and can vouch for the good work Mr. Pooley does in connection with this Court.

After the hopeful beginning in improved penal legislation made by the Legislature of Pennsylvania two years ago in the enactment of a probation, indeterminate sentence and parole law, the work done and left undone by the recent session is, to say the least, most discouraging. Not only did a number of admirable bills receive no consideration whatever, but the law referred to above, which the Committee on Criminal Law Reform in its report at the last Prison Congress (Washington, 1910) pronounced “admirable,” was so amended as virtually to eliminate from it the vital principle underlying the indeterminate sentence and parole.

The act of 1909 was based on a very careful study of the writings of the most advanced penologists, and of the statutes of those progressive states that have introduced the indeterminate sentence and parole with the largest measure of success. Its viewpoint was that of those who seek the reformation of the wrongdoer, and not of those who still have in their minds the old idea of retributive justice only; it made a break with the old codes, aimed to deal with the man and not with his crime, and had regard to his future rather than to his past; and possibly this radical departure from the traditional mode of thought and procedure, and the introduction of something evidently so new to many legal minds in Pennsylvania, though no longer so in some other States, was responsible for the hostility which the law encountered here and there.

Section 6 of said law reads as follows:

“Whenever any person, convicted in any court of this Commonwealth of any crime, shall be sentenced to imprisonment in either the Eastern or Western Penitentiary, the court, instead of pronouncing upon such convict a definite or fixed term of imprisonment, shall pronounce upon such convict a sentence of imprisonment for an indefinite term; stating in such sentence the minimum and maximum limits thereof; fixing as the minimum time of such imprisonment, the term now or hereafter prescribed as the minimum imprisonment for the punishment of such offense; but if there be no minimum time so prescribed, the court shall determine the same, but it shall not exceed one fourth of the maximum time, and the maximum limit shall be the maximum time now or hereafter prescribed as a penalty for such offense: Provided, however, That when a person shall have twice before been convicted, sentenced and imprisoned in a penitentiary for a term of not less than one year, for any crime committed in this State, or elsewhere within the limits of the United States, the court shall 22 sentence said person to a maximum of thirty years: And provided further, That no person sentenced for an indeterminate term shall be entitled to any benefits under the act, entitled ‘An act providing for the commutation of sentences for good behavior of convicts in prisons, penitentiaries, workhouses, and county jails in this State, and regulations governing the same,’ approved the eleventh day of May, Anno Domini one thousand nine hundred and one.”

This section has been amended to read:

“Whenever any person, convicted in any court of this Commonwealth of any crime, shall be sentenced to imprisonment in any penitentiary of the State, the court, instead of pronouncing upon such convict a definite or fixed term of imprisonment, shall pronounce upon such convict a sentence of imprisonment for an indefinite term; stating in such sentence the minimum and maximum limits thereof; and the maximum limit shall never exceed the maximum time now or hereafter prescribed as a penalty for such offense: Provided, That no person sentenced for an indeterminate term shall be entitled to any benefits under the act, entitled ‘An act providing for the commutation of sentences for good behavior of convicts in prisons, penitentiaries, workhouses and county jails in this State, and regulations governing the same,’ approved the eleventh day of May, Anno Domini one thousand nine hundred and one.”

It will be seen that this amendment puts it into the power of the court to fix any minimum below the maximum, instead of a minimum not exceeding one fourth of the maximum; that it permits the court to name a lower maximum than the one now prescribed by law for any given offense; and that it strikes out the thirty-year clause altogether.

The practical effect of the former change is to destroy in great measure the value and efficacy of the indeterminate sentence as a remedial and reformatory measure. In other words, the amendment restores the vicious inequality of sentences, which is always so apt to breed a feeling of injustice and resentment in the one convicted, and which therefore greatly unfits him as a subject for reformatory treatment. It proceeds upon the long-accepted but false assumption that the court can in every case determine the exact degree of culpability and then adjust the punishment accurately to the crime. This is not only absurd, but it is impossible. A Solomon with all his wisdom could not have done this! As the law now stands, we shall again find, as is indeed already the case, that the same court or adjoining courts may, even under practically identical conditions, impose greatly varying sentences, instead of putting all upon whom sentence is passed on an equality and giving all, under identical conditions, an equal chance, as the law originally contemplated. Thus since the amended law went into effect sentences like these have been pronounced: 23 Minimum 5 years, maximum 7; minimum 8 years, maximum 10; minimum 6 months, maximum 1 year; minimum 6 years, maximum 7; minimum 7 years, maximum 15. In two cases of burglary the one man received a minimum of 5 years, and a maximum of 10, but the other a minimum of only 2 years and a maximum of 5; while in another case an old crook, who had been convicted for the sixth time, and whose new crimes should have brought him a maximum sentence of 16 years, received a minimum of 3 months and a maximum of 1 year. Since the law first went into effect several courts have also imposed flat sentences, without a minimum. This is clearly in conflict with the law, which is mandatory. It does seem as if courts that try and sentence lawbreakers should be the first to have a reverent regard for law!

Again, under the amended law the court virtually determines when a prisoner shall be eligible to parole. This is, however, utterly subversive of the theory upon which the indeterminate sentence is based, namely, that parole is to be granted when a prisoner is believed to be fit to be restored to society as a law-abiding citizen. The time when this may be done no court under the sun can fix, but only those who have the prisoner in charge and under observation, and even they may make mistakes. In the argument on the amended bill before the Senate Committee, it was said by those who opposed the original law, that it conferred judicial functions on the Penitentiary Boards, and that there was not a State in the Union whose statutes prescribed both the maximum and the minimum. But it was shown that under the laws relating to the Huntingdon Reformatory the courts in imposing sentence do not fix the duration thereof, but that the Board of Managers is authorized to terminate the sentence at its discretion, provided the detention shall not exceed the maximum of the term assigned by law for the offense of which the prisoner was convicted; also, that in many States, such as Massachusetts, Connecticut, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota and others, the minimum as well as the maximum sentence to the state prison is fixed by law. It seems strange, indeed, that those who opposed the law of 1909 should have forgotten the law as regards Huntingdon; and that they should have been totally ignorant of the laws of other States on a subject that is to-day receiving the serious attention of many of the most thoughtful minds the world over!

On the benefits of a just and equal indeterminate sentence, 24 Dr. Frederick Howard Wines, one of the best informed and most eminent penologists in the United States, expresses himself as follows:

“There is not, and in the nature of things there cannot be, any aid to a truly reformatory discipline like that afforded by the indeterminate sentence. Every prison official can testify to the dissatisfaction and unrest caused by the palpable inequality of sentences; an inequality which neither the legislature nor the courts can avoid or correct. The only equal sentence is the indeterminate sentence, with an identical maximum for all who violate a given section of the code, coupled with identical conditions by which to reduce it to the minimum prescribed by law. Its imposition removes all ground for complaint on this score. It also puts an end to the fallacious hope of an unconditional pardon. The prisoner is given to understand that the date of his release on parole depends entirely upon himself. The authorities desire his release and will help him to earn it; they are not his enemies, but his friends. This disarms him of his hostility to them. He is in a favorable state of mind to receive treatment, and is disposed to yield obedience to them, if they keep their promise to him. This leads to coöperation in the effort made for his restoration, without which a cure cannot be effected. The hope of an early release sustains him under the depressing influence of prison life and stimulates him to exert himself to avoid losing whatever he has gained by diligence and good conduct. He is aided to form habits of industry and obedience, which tend to become fixed. He is trained and transformed.

“Under the indeterminate sentence the prison itself undergoes a gradual process of transformation. The moment that reformation rather than punishment becomes the watchword of the administration, a new spirit takes possession of it. The governor chooses better and abler men to govern it—men imbued with reformatory ideas and qualified to exert a reformatory influence; men of higher education, purer moral character, broader culture, loftier aims in life, greater devotion to their work. These wardens of the new school grow stronger with the passing years; their habit of opposition to everything that is low or crooked or mean or vile lifts them to higher and still higher levels. Failure to show reformatory results means failure in their chosen profession. They have a new responsibility, and they rise to meet it. They are open to every suggestion that can be of service to them in the accomplishment of their difficult task, a task from which an angel might shrink, and in which an angel might rejoice.”

The thirty-year clause of the act of 1909 was designed to protect society against the professional criminal. It is another absurdity of our criminal procedure that we release such periodically to renew their depredations on society. A dangerously insane person we put away until he is cured; and if he is never cured he is never released. We guard society against the contagion of certain virulent diseases. But when the habitual criminal has every now and then squared himself with the State by serving a term in the penitentiary, we again give him his freedom, though he may have hatched out another plot even before he leaves his place of confinement. Some 25 other States have grown wiser. New York and Indiana sentence the habitual criminal for life on a third or fourth conviction; Connecticut to thirty years on a third conviction; but in Pennsylvania a thirty-year sentence, with a minimum not exceeding seven years and a half, seems to have been considered too drastic. Better let society suffer than the criminal!

In amending the law of 1909, which, under its intelligent administration for two years was yielding most happy results, Pennsylvania has clearly been compelled to take a backward step. There was no public demand for a change; those charged with the administration of the law did not desire a change, but opposed it; and there is ample ground for the belief that the change was inspired by reasons of a purely private and personal character.

Nor is the last Legislature to be commended for what it failed to do.

In his report of November 10, 1909, Mr. Bromley Wharton, General Agent and Secretary of the Board of Public Charities, called attention to the needs of the county jails in these words: “This is a matter which has received serious attention at the hands of your Board. The prevailing system of government of the county jails is, in many respects, unsatisfactory. In most of the counties the jails are in charge of the sheriff, who, as a rule, knows little or nothing of hygiene or sanitation. Few jails have yards for exercise, or workshops, which results in the prisoners loafing in the corridors, smoking and playing cards. The filthy and unsanitary condition of some of the jails causes the long-term prisoners to welcome their transfer to the penitentiary.”

At the subsequent session of the Legislature a bill, approved by the Board, was introduced designed to remedy the unsatisfactory and often disgraceful conditions existing in the prisons of various counties, and placing the control and management of all the county prisons and jails and the inmates thereof in Boards of Prison Inspectors to be named by the courts, one inspector to be a physician, and another, if desired, a woman. This carefully drawn bill, which, if it had become a law, would have inaugurated a most salutary reform where it is most needed in our penal system, passed the House, but was killed in the Senate. It was re-introduced in the last Legislature, but never even came out of committee.

A joint resolution, likewise approved by the Board of 26 Charities, providing for the appointment of a commission to consider and report upon the advisability of establishing a state system of workhouses for misdemeanants, so that county jails and prisons could be used solely for the imprisonment of persons awaiting trial or otherwise detained, and for convicts sentenced to brief terms, met a similar fate. So also an act authorizing the pensioning of deserving superannuated employés of penal, reformatory and charitable institutions of the State.

Another bill, strongly approved by the Board, but which after its introduction never again saw the light of day, provided for the establishing of a State Reformatory for Women between the ages of fourteen and twenty-one. That such an institution is most urgently needed is only too well known to charity workers throughout the State. It is almost incredible that such a wealthy and otherwise progressive State like Pennsylvania should be considered too poor to make at least a beginning of an institution of this kind. Were the people of this Commonwealth familiar with the work done and the results achieved by such an institution as the Massachusetts Reformatory Prison for Women, they would compel their legislators to take action. Great movements in behalf of the social welfare can after all be carried through only when there is an intelligent, widespread and persistent public sentiment behind them.

The one progressive penal act for which the last Legislature deserves credit is the bill “providing for the selection and purchase, or the appropriation from State forest reserves, of a tract of land and the erection thereon of buildings for the Western Penitentiary; making an appropriation therefor; authorizing the removal thereto of the inmates of the said penitentiary, and directing the sale of the site now occupied by the said penitentiary, and the buildings and materials thereon.” This is in line with the recommendation of the Board of Charities, which, in its preliminary report for the years 1911-12, called renewed attention to the very unsatisfactory conditions surrounding the Western Penitentiary, and strongly urged its removal to some large tract of land in a rural section, so that labor, not in conflict with existing laws, might be provided for the inmates. In pursuing this course Pennsylvania will only be doing what some other States have already done or are about doing; and it is to be hoped that in due time similar provision will be made for the eastern part 27 of the State. Might it not be well to keep in mind, however, the need of a central state prison for the confinement of habitual criminals, so that the two penitentiaries now in existence could be used only for first-termers? This would make the reformatory process contemplated by the indeterminate sentence infinitely easier.

Another bill of extremely doubtful utility passed by the last Legislature, authorizes the judges of the courts of quarter sessions and the courts of oyer and terminer, after due inquiry, to release on parole any convict confined in the county jail or workhouse of their respective districts, and place him or her in charge of and under the supervision of a designated probation officer. County jails as now conducted are not reformatory institutions.

It will be seen from this survey that Pennsylvania is not making rapid progress in improved penal legislation; nor is it likely that we can hope for better things until some future Legislature will see fit to empower the Board of Charities or a specially appointed commission of expert penologists to devise a carefully articulated and homogeneous system of penal and reformatory institutions for the State. Such a system should provide for a radical change in the construction, management and internal administration of the county prisons; it should include a state system of workhouses, a woman’s reformatory, a central penitentiary for recidivists, and a favorably located institution for criminals suffering from tuberculosis or dementia, where they could receive skillful treatment; it should make a strict separation between habitual criminals and first offenders, between young delinquents and those of mature years; and it should everywhere introduce approved reformatory methods, and make it possible to give those in confinement ample indoor and outdoor employment. It might, of course, be objected that a system so carefully planned and wrought out would be too expensive; but let it never be forgotten that in the end it is far better for the State, and indeed cheaper, to make men than to arrest, try and support criminals, and suffer the results of their depredations.

Philadelphia.

It is a pamphlet of eighty pages, bearing on the reverse of the title-page this inscription: “Printed and Bound at the Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia, 1911.”

There were in the Penitentiary on the first of January, 1910, as follows, viz.:

| White Males, 1,157; White Females, 21; Total White | 1,178 |

| Colored Males, 332; Colored Females, 17; Total Colored | 349 |

| 1,527 | |

| Received during the year: | |

| White Males, 310; White Females, 4; Total White | 314 |

| Colored Males, 89; Colored Females, 6; Total Colored | 95 |

| 409 | |

| Remaining at the close of the year as follows: | |

| White Males, 1,073; White Females, 18; Total White | 1,091 |

| Colored Males, 301; Colored Females, 15; Total Colored | 316 |

| 1,407 | |

| The number at same date last year | 1,527 |

| Showing a decrease of | 120 |

| The discharges were: | |

| By Commutation Law | 471 |

| By Parole | 23 |

| By Order of Court | 14 |

| By Order of Huntingdon Reformatory | 3 |

| By Pardon | 6 |

| Died (1 Suicide) | 11 |

| Expiration of term (only) | 1 |

| 529 |

The number who served out their terms in 1909 was 7.3

3

It would seem that by the actions of the commutation and parole

laws it will become very unusual for a prisoner to serve out his term.

The inspectors state that “the influence of commutation and parole which are now in action is having a restraining effect on both the thoughtless and vicious,” but they further say, “the administration of the Parole Law has been too limited in its time and extent for us to do more than make mention of our efforts to intelligently apply it.” 29

Some other interesting statistics are as follows, viz.:

| Number claiming this as their first imprisonment | 223 |

| Known to have been previously imprisoned | 186 |

| 409 | |

| Number under 30 years of age | 257 |

| Number over 30 years of age | 152 |

| 409 | |

| Number having trades | 67 |

| Number without trades | 342 |

| 409 | |

| Number idle at time of arrest | 149 |

| Natives of United States | 324 |

| Natives of foreign countries | 85 |

| 409 | |

| Conjugal relations: | |

| Single | 230 |

| Married | 152 |

| Widowed | 27 |

| 409 | |

| Number having children | 111 |

| Number of children | 296 |

| Crimes against person | 124 |

| Crimes against property | 251 |

| Crimes against person and property | 34 |

| 409 | |

Twenty-four pages of the Report are devoted to “Criminal Histories” of sixty-four prisoners received during 1910 who had previously served one or more terms in this penitentiary (a considerable number of them in other penitentiaries or prisons), and who are reported as “illustrations of persistency in courses of crime, indicating the growth of a permanent class, calling for the most serious consideration.”

There is also a record of forty-three prisoners received in 1910 who have relatives in this penitentiary or in other prisons.

The inspectors refer with satisfaction to the new building of concrete construction containing one hundred and twenty cells “now rapidly nearing completion,” and say “the plumbing, 30 steam fitting and electrical work needed is under the care of experts, and furnishing the opportunity of training many of our inmates for future positions of usefulness and trust.”

Report is made that the library now contains 12,057 bound volumes, 852 of them in foreign languages, and that 66,887 books were taken out by the prisoners in the course of the year. A bookbinding and printing room affords employment to several prisoners; 1,419 books were bound and 743,248 pages of matter were printed for the various purposes of the penitentiary.

A school has been maintained for those classed as “illiterates,” and instruction in reading, writing and arithmetic given to 346 prisoners. The inspectors acknowledge the honor done them “by the visits of distinguished representatives of the prison systems and state departments of the nations of Europe, Asia and South America, with others of Canada and our own country, who were in attendance at the recent International Prison Congress in Washington.”

Grateful recognition is also made of “the valuable services of the visitors of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, the American Society for Visiting Catholic Prisoners, the Protestant Episcopal City Mission and the Prisoners’ Guild of the King’s Daughters, contributing to the comfort, encouragement and upbuilding of the prisoners,” and especial mention is made of the services of the Pennsylvania Prison Society in providing clothing for those prisoners in need at the time of their discharge.

The cost of maintenance for the year 1910 is reported as $99,296.70, and the following is presented as “Account With Convicts for 1910”:

| Dr. | Cr. | |

| Balance to credit of convicts January 1, 1910 | $11,644 96 | |

| Sent in by relatives and friends | 20,798 33 | |

| Brought in by convicts on reception | 1,013 81 | |

| Earned by over work | 13,084 88 | |

| Allowance | 426 00 | |

| Profit and loss | 1 39 | |

| Paid to convicts on discharge | $5,939 61 | |

| Sundry goods, shoes, etc. | 3,564 09 | |

| Paid relatives and friends | 19,249 22 | |

| Paid for tobacco, tooth brushes, soap, etc. | 6,554 32 | |

| Balance due convicts January 1, 1911 | 11,662 13 | |

| $46,969 37 | $46,969 37 |

31

This report is contained in a pamphlet of one hundred and sixteen pages, of which about twenty pages are devoted to a historical account of the institution.

It appears that the first buildings were completed November 22, 1827, and on the supposition that very soon after prisoners were received at the institution, its penal history covers more than eighty-three years.

The statistics show that on January 1, 1910, the number of convicts was 1,261.

| Received during the year 1910 | 297 |

| Discharged during the year 1910 | 502 |

| Population December 31, 1910 | 1,056 |

| Showing a decrease of | 205 |

Of the 1,056 prisoners there at the beginning of 1911, there were:

| White Males | 845 |

| White Females | 20 |

| Colored Males | 185 |

| Colored Females | 6 |

Those who were discharged may be classified:

| Pardoned by the Governor | 5 |

| Expiration of Sentence | 10 |

| Commutation of Sentence | 448 |

| Transferred to Insane Asylum | 8 |

| Order of President (United States Prisoner) | 1 |

| Paroled | 26 |

| Died | 4 |

| 502 |

The parole officer, John M. Egan, states that “the parole system ... has already been productive of good results, and promises development that will compare favorably with the most successful reformative work of other States.... The good deportment of our indeterminately sentenced inmates, their sincere efforts to map out for themselves a future foreign 32 to their previous lives of crime and the faithful manner in which all, save two, of the convicts who have been granted conditional freedom are complying with the provisions of their parole, is gratifying.”

Of the 297 received during the year:

| Those who are serving sentence for the first time | 221 |

| Those known to have been previously imprisoned | 76 |

| Under thirty years of age | 152 |

| Over thirty years of age | 145 |

| 297 | |

| Number apprenticed to some trade, including the unapprenticed who had worked at least four years at a trade | 74 |

| Number unapprenticed | 223 |

| 297 | |

| Natives of United States | 202 |

| Foreign Born | 95 |

| 297 | |

| Social Relations: | |

| Single | 159 |

| Married | 114 |

| Widowed | 23 |

| Divorced | 1 |

| 297 | |

| Nature of Crimes: | |

| Against Person | 172 |

| Against Property | 125 |

| 297 |

The gratuities to prisoners discharged in 1910 amounted to $3,195.00. This sum presumably was given in cash and clothing.

The bill for provisions amounted to $63,361.00.

Tobacco for the prisoners cost the State $2,471.00.

The various industries in operation at the penitentiary show substantial gains:

During the year the sales of mats and matting amounted to $114,475.00.

The profit from this industry was $29,696.00.

The profit in the hosiery department was $5,191.00.

The profit in the shoe department was $1,665.00.

The earnings by labor, piece price, in the broom department, $4,069.00.

It appears that the officials make effort to find work for the large majority of the convicts. 33

The number of days of labor reported by those in fair health is 275,051.

The number of days of idleness seems large, 85,074, but indicates that the convicts are at work a little over three fourths of the time.

They now have a regular optical department equipped with modern appliances, and in 1910 386 prisoners were fitted with glasses. The physician reports that in many instances those who were thus supplied showed both physical and mental improvement, to say nothing of the satisfaction of having deficiencies of eyesight remedied.

The chaplain reports that the number of bound volumes in the library is 11,882. During the year the number of books issued to the prisoners was 73,070.

The report contains resolutions of the Board of Inspectors in memoriam of John Linn Milligan, whose mission since 1863 had been in looking after the spiritual interests of the inmates of the Western Penitentiary. The following paragraph from one of his recent reports illustrates the spirit of the man and of his work: “Since my official relation with this prison began, 11,624 convicted men have passed within these gates. Many of these have gone out to struggle into the cold and suspicious world, friendless and alone, to struggle against the handicap that conviction and punishment of crime bring. Doubtless many have died, bruised under the burdens they have had to bear. Doubtless many more than the public believes have been absorbed into the ranks of industrial honesty of life and purpose. A small per cent. were instinctive and professional criminals, and nothing but the sovereign grace and mercy of the good Lord, who said to the poor sinner in the face of the murderous crowd, ‘Neither do I condemn thee; go, sin no more,’ could cure the crime habit for them.

“When I look back along the line of the regiment of convicted criminals, whom I have tried to strengthen with a new and manly purpose, the busy efforts do not seem long, nor has my knowledge and familiarity with their character hardened my heart nor diminished my desire to uplift them. Nor has the backward glance lessened my hope in true reformative efforts, patient, firm and kind, and I believe more sincerely in the deep necessity of Divine love and power for their spiritual reclamation.”

Warden Francies earnestly recommends that immediate steps be taken to remove the prison to a more healthful location 34 on some large tract of land on which buildings may be erected largely by convict labor, and where the inmates may in the future be employed in producing their own sustenance thus saving a large part of the expense of the maintenance of the prison.

This is one of the two or three penal institutions of the State of Pennsylvania to which a farm is attached. The Allegheny County Workhouse has, during the last year, added 175 acres to its holdings of real estate, at a cost of over $288.00 per acre, and the total acreage now belonging to the institution is about 280 acres. The total number of prisoners at the close of last year was 863, an increase of 70 over the number at the close of the year 1909. The daily average of inmates was 824. During the year 1910 there were received at the workhouse 3,836 male prisoners and 606 female prisoners. The entire number was 4,442, of whom 3,606 were from Allegheny County, and 836 were sent from other counties. For the maintenance of prisoners outside of Allegheny County, the institution received $23,396.

Of the 4,442 committed, there were committed for the first time 2,301. One hundred and five had been committed seven times. One hundred and fifteen had been committed twenty times or oftener. Twelve prisoners were serving sentences for the fiftieth time or more. It is not a place for juvenile offenders. Of the whole number, 227 only were under twenty years of age. The greater part of them are between twenty and forty years of age. Only 630 could neither read nor write, of which number 438 were foreign born. Austria furnished the largest proportion of illiterates.

Four hundred and eighteen of these prisoners professed to be total abstainers from intoxicants, and 540 are classified as intemperate; 3,484 are occasionally intemperate or are moderate drinkers. 35

Thirty-seven hundred and forty-seven prisoners weighed at the time they were discharged 14,796 pounds more than when they commenced to serve sentence, or an average of three and ninth-tenth pounds increase for each individual. Six hundred and twenty-five women prisoners showed an increase of one and four-fifth pounds per individual.

Superintendent Leslie reports that the new wing is almost completed. It will contain 478 reinforced concrete cells, in four floors of about 120 cells each. At the back of the cells is a five-foot utility corridor, in which all plumbing, waste pipes and foul-air ducts are placed. Five feet in front of the rows of the cells is a steel proof cage, extending the full length of the rows. Between these cages and the outside wall is a corridor which is lighted by large tool proof, obscure wire-glass windows. The building is equipped with the best sanitary appliances. The entire cost will be about $210,000.00, which includes dynamos, engines and power plant of sufficient capacity for another building of similar size. The larger part of the work was done by the prisoners. During this last year the total days’ work performed by the inmates on the new building was 18,821.

But work on the new building is not by any means the sole industrial employment. The total number of days’ work of inmates is reported as 171,952. The industries comprise broom and brush making, carpet weaving, farming operations, wall building and domestic employments.

The revenue from brooms is estimated at $16,935.00; brushes, $2,062.00, carpets, $4,610.00; boarding prisoners, $31,620.00; farm products, $2,677.00.

The farm products of which the greater part was consumed on the premises include 5,865 bushels potatoes, 1,550 bushels wheat, 424 bushels sweet corn, 1,058 bushels green beans, 1,313 bushels tomatoes, 30,025 heads cabbage, 8,000 heads celery, 1,252 pounds butter, 3,039 gallons milk, 200 chickens, 496 dozen eggs. The total number of days’ employment outside the walls was 28,857, and yet but one prisoner made his escape.

Chaplain Imbrie reports that there is a Sabbath service in the prison chapel, at which attendance is voluntary. “But few absent themselves from this service.” They have a choir of their own, with an efficient musical director. During the winter there are frequent entertainments held in the chapel, consisting of lectures, elocution and music. They have a 36 judiciously selected library of 6,000 volumes, and the number of books taken out during the year was 18,167.

They have a total enrollment in the night school of 185, with an average attendance of about 176. This school is maintained largely for the benefit of the illiterates and of those whose education has been extremely limited. The difficulties of presenting statistics of those who are permanently reformed is well illustrated by the following extract from the chaplain’s report: “As the year closes I find myself looking back and counting the meetings and partings with more than four thousand souls, who have come and gone during the past twelve months.... I have known each one for a few weeks or months, then they have gone like the ships that pass in the night.... A few have written kind letters to me after having reached their homes, a few have sent messages, ... some I have met on the streets of the city, and a few have been returned as prisoners to this institution, but the greater number have been absorbed in the great mass of humanity, and I have no further trace of them. The promises made at parting may be broken, the influence of the few weeks spent here may soon be effaced by the environments of the world, the seed sown in the gospel messages may never mature, but yet the effort has been made, and the increase is with the Father.”

Mt. Lebanon Prison, Syria.

... This prison is located in Bate-id-deen, where the governor-general and all the government officials reside. There I had an interesting call on the governor of Mt. Lebanon, Yusuf Pasha Kusa.