Project Gutenberg's Harper's Round Table, August 25, 1896, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Harper's Round Table, August 25, 1896 Author: Various Release Date: March 15, 2019 [EBook #59065] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S ROUND TABLE, AUGUST *** Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, AUGUST 25, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 878. | two dollars a year. |

Jack Howard looked with some perplexity at the letter which he had just received from his chum Fred March. The latter had been spending a month of the long vacation at his uncle's, on the northern sea-coast, and that good-natured relative had been kind enough to suggest that the house was quite large enough to entertain Jack also. Hence the letter embodying the invitation, together with an earnest request that Jack should come by the earliest train on Monday morning. That was plain enough, besides being entirely satisfactory; but there was something else, a postscript, and this was the puzzle over which Jack was knitting his brows:

"I'm not to bring my bicycle, since the country roads are too sandy for good riding; but I must send on at once the three bicycle wheels stored in the loft of the machine-shop, together with half a dozen heavy coil springs, as per the enclosed specifications of the foreman of the shop. Well, what on earth—for it can't be a flying-machine—is Fred up to now?"

But the letter vouchsafed no further information upon the mystery, and Jack's duty was clearly to obey and ask no questions. Evidently Fred had some new idea, and that meant fun ahead—possibly an adventure. And so the commission was executed upon the spot, and Jack saw[Pg 1038] that the box was shipped early on Friday morning by the fast freight. It should be delivered to Fred at Agawam Beach by Monday, and Jack would be there himself that evening.

"It's a rattling good place for sailing and blue-fishing, and all that sort of thing," said Fred, on that Monday night, as the two boys left the house for a stroll down to the beach. "Uncle Win has let me knock about the bay in his little sloop—there she is at the pier, the white one, with the red at her water-line—and he says that I've picked it up as though I had been christened with salt-water. Sailing is nailing good fun. But look there!"

The ten-mile stretch of Agawam Beach lay before their eyes, just around the point that jutted out to form Half-Moon Bay. It was dead low tide, and the beach sloped so gradually that the receding water had left a wide floor of hard glistening sand, smooth and firm as a macadam road.

"I should think you could wheel along that easily enough," said Jack.

"So you can, and people often drive up to Cape Fear, ten miles off; they even have trotting matches when the county fair is on. I don't believe there's another beach like it in the world. But my idea will beat bicycling and sulky driving out of sight if it works, and I think it will. We'll go on now and take a look at the 'Jolly Sandboy'."

"The what?" began Jack; but Fred only laughed, and led the way to the boat-house.

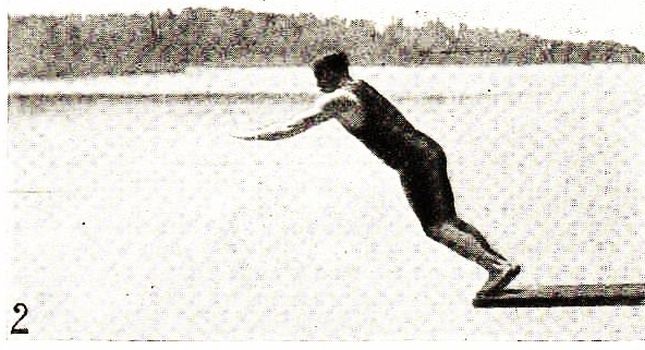

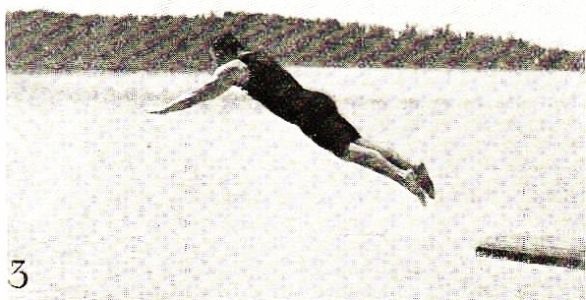

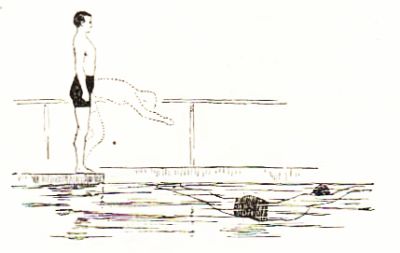

It was a mysterious-looking creation that occupied the centre of the floor. The body of the machine was a skeleton frame-work of hard-wood strongly braced and bolted together, with a shallow-floored box at the acute angle. The centre timber bisected this acute angle and the base, and projected a few feet beyond. The bicycle wheels were attached to and supported the frame-work at the three corners, the one at the apex being pivoted so that it could be turned by a tiller in any direction. Just forward of the base-line, or what corresponds to the runner-plank in an ice-yacht, was a chock that was evidently intended for the reception of a mast, the end of the centre timber serving as a bowsprit, steadied by wire guys that ran to either extremity of the runner-plank. It was certainly original in design and appearance, and Jack Howard examined it with respectful curiosity.

"And what do you call it?" he inquired again.

"A 'beach-comber,'" said Fred. "The principle of an ice-yacht, you know, but with wheels instead of runners, for use on the hard sand at low tide. There was just one thing that bothered me in the way of practical detail, and that was how to provide for the heeling over in a strong breeze or a sudden flaw. You know that when the sails fill, as an ordinary boat, she lies over, and it is her keel or centreboard that keeps her from drifting to leeward. In an ice-yacht the sharp runners keep her up, but there must be some sideways yielding to the force of the wind, and so an ice-boat rears—that is, one runner lifts free of the ice, and thereby takes off the strain. Otherwise you must either luff or be capsized. But with beach-sailing this rearing would probably throw too much weight on the leeward wheel, causing it to sink into the sand, and perhaps stop her way altogether. The sand is fairly hard when wet, but it can't be so unyielding as ice. I was just about to give it up, when I happened to recollect a wrinkle that the Dutchmen use in their ice-yachts on the Zuyder Zee. In their boats the mast is pivoted in the chocks, and consequently the sail and all lie over under the strain. When a squall strikes a fleet of Dutch ice-yachts it looks exactly as though you had winged a whole covey of partridges. It must be safer than our American plan, but of course you lose in speed. The difficulty in my mind was to understand how the mast would come up again to its proper position; but that's always the way with the people who write books—they never tell you clearly the one little thing that is absolutely necessary for a fellow to know to understand what they are describing. So I had to work it out for myself."

"This must be where the coil springs come in," said Jack, with sudden perception.

"Exactly. The mast is to be stayed by wire guys, each one ending in a coil spring attached to the extremities of the runner-plank. Of course we'll have to experiment to see just how many are needed on each side to give her the best results in the way of stiffness. We don't want her lying down at every little puff, or we would never go ahead at all. Neither must she stand up like a church, for something has got to give way when a squall hits her. We'll set up the mast and give the 'Jolly Sandboy' a trial trip the first thing to-morrow morning."

There is little to add to Fred's description, except to say that the wheels were rather different from the ordinary bicycle type. They had been built by Mr. March while he was experimenting on the "Happy Thought," and the two forward ones were twenty-four inches in diameter, while the rear wheel was but twenty inches. Moreover, the spokes were of hickory, and the tires were enormous—four inches in diameter, and of very heavy material. Even in soft sand they would cut in but little, and the spokes, being of hard-wood covered with water-proof varnish, would not be subject to rust and corrosion from the salt air and water. Of course the hubs were fitted with the usual ball-bearing. The sail plan of the "beach-comber" was that of a sloop, as being the easiest to handle, and the pivoted rear wheel acted as the rudder.

The boys, after a little experimenting with the coil springs of the standing rigging, were delighted to find that the "Jolly Sandboy" would really go. Of course there was no such thing as tacking; and, indeed, the "beach-comber's" best point of sailing was with the wind on the beam or on the quarter. As we all know from our physical geographies, the prevailing wind at the sea-shore is off the ocean during the daytime, and consequently favorable to the "Jolly Sandboy." Moreover, the gentle downward slope of the beach, as opposed to the direction of the wind, helped to keep her on an even keel. The speed was not very high, but it was nevertheless great sport to race along the edge of the breakers, and an occasional ducking from an extra big comber only gave the true salt flavor. It was hardly practicable to sail except when the tide was going out or on the half flood, and the best time was when it was dead low, as so much more of the level beach was then available. Fred generally occupied the cockpit and did the steering, while Jack stood on the weather runner-plank and held on to the shrouds, as is the custom in ice-yachting.

The "Jolly Sandboy" had been in commission for a week, and the boys had become fairly expert in her management. On this particular afternoon they had made the ten-mile run up to Cape Fear, and the conditions were so favorable for "beach-combing" that Jack proposed that they should go on past the cape for a mile or two before beginning the homeward journey. Now between Cape Fear and Cape Thunder, a mile further on, was a peculiar formation of the coast-line known as Shut-in Bay. It was surrounded on all sides by precipitous cliffs, unscalable from below, and at high water it was entirely cut off from the rest of the beach by the rocky projections of Capes Fear and Thunder. It was a dangerous trap in which to be caught by the tide, for at ordinary high water there were only two or three small ledges to which one might climb for safety, and even then the thoughtless adventurer would have to remain a prisoner until the ebb. At the time of the spring tides, twice in the month, even these precarious places of refuge were under water, and the only chance of a rescue was in being seen by a passing fishing-smack and taken off by boat. Fred was well acquainted with the dangerous character of the place, and he looked a trifle dubious when Jack proposed going on.

"But it's only a mile across to Cape Thunder, and it's not low water yet for an hour," insisted Jack. "I've got the table here in my pocket; I cut it out of last week's Guardian."

The table, compiled from the government observations, gave low water for four o'clock at Agawam, which would make it half past four at Cape Thunder. Fred looked at his watch and saw that it was just half past three. Certainly there was a plenty of time to run on for two or three miles, and then get back beyond the danger-point[Pg 1039] before the tide was fairly on the flood. Fred hauled in the sheet, and the "Jolly Sandboy" plunged forward.

Well, perhaps they had gone a little further than they intended, and the tide had certainly turned when they started homeward. But the wind was fresh, and Fred kept the "Jolly Sandboy" close to the water's edge, where the sand was the firmest. Every now and then a big wave would break ahead of them, and shoot a wide tongue of white crackling foam athwart the bows of the "beach-comber." But there was no time to make détours, and it was glorious fun, these short, sharp dashes through an acre of shallow water, with the wash filling the cockpit, and the salt spray flying over the head of the mainsail. Finally Cape Thunder loomed up ahead, and ten minutes later the "Jolly Sandboy" had swept around the point, and was ploughing across the treacherous Tom Tiddler's ground of Shut-in Bay.

It must have been a piece of broken bottle, but whatever the cause, the tire of the lee bearing-wheel had suddenly gone flat. It was impossible to proceed; but was there time to repair the damage and yet get around Cape Fear? Fred glanced at his watch. The tide looked as though it were coming in very fast; but the tide-table was authoritative, and the water would not be up to the cape until about half past five o'clock. It was now exactly five by Fred's watch, which would give a margin of at least twenty minutes. If they could repair the puncture in ten they could easily get clear. Otherwise they might be obliged to desert the "Jolly Sandboy," and save themselves by running. Fred shoved his watch back into his pocket, seized the repair kit, and went to work at the injured tire.

It was a good job and quickly done. Certainly not more than five minutes had elapsed when Jack took the pump to blow her up. But surely the water was rising faster than ever. And what was that? A sparkle of foam on the black rocks at the base of Cape Fear! It could not be more than ten minutes past the hour; they still had fifteen minutes to spare, and Fred pulled out his watch again.

The hands still pointed to exactly five o'clock.

With one jump Fred was at Jack's side, and had snatched the pump from his slower hands. How many of the lost minutes had there been since his watch had stopped? Five, ten, fifteen, twenty, or was it but a question of seconds? They were midway between the capes, and it was half a mile to safety. An instant later and the tire was full again. But beyond a doubt there could be but little time to spare. Already the big racers were tossing their white manes against the dark background of the cruel black rocks that formed Cape Fear; and now, too late, Fred recollected that it was a spring tide that was coming to the flood, and one of the highest of the year. Faster and faster the "Jolly Sandboy" drove along, but now it was certainly a question of seconds. A hundred yards away and there was still a narrow strip uncovered at the base of the cape. If they could reach it just after a third wave had gone back they might squeeze through. There came the first breaker, and the "Jolly Sandboy" had gained another twenty yards. The second broke close under the reef, sending a fountain of spray over the rocks and high into the air. The third and largest was slow in coming, and the "Jolly Sandboy" was close to the gap. Fred had made a slight miscalculation in timing his speed, and it was now a question of whether to stop and wait for the backwater or to race the third wave for the one chance of going clear. There was no time to weigh the odds, and on tore the "Jolly Sandboy." For an instant it looked as though they would make it; and then with a sudden roar the long smooth green wall of water seemed to fall forward at double its former speed, and took the ground just this side of the cape. The "Jolly Sandboy," quivering at every rivet, came to a stop as the surge swept over her. The mainsail caught the full force of a ton of salt water, and the mast went over the side, snapping the weather ratlines as though they had been made of tow. It was a matter of hardly two seconds, and the "Jolly Sandboy" was a wreck.

It was a hard pull to get clear, but Fred and Jack finally managed to drag the "beach-comber" back to safer ground. Safer, but for how long? Already the strip of sand had entirely disappeared at the foot of Cape Fear, and a full fathom of salt water was boiling and eddying among the jagged rocks. It would take some ten or twelve minutes for the water to finally cover the beach of Shut-in Bay, and then what? The ledges to which they might climb could only save them at ordinary high water, and at this the highest of the spring tides they would be covered six feet deep. The overhanging cliff offered no way of escape, and not a boat was in sight. Like drowned rats in a trap. But no! the thought was too horrible. There must be some way. There was the mast! Could it not be set up again, and its broken guys spliced with the mainsheet? It was a stout stick, some eleven feet in length, and the rise of the water would be less than ten. The jaws of the gaff would afford a foothold—a precarious one, it is true, but still a chance to keep their heads above water.

With desperate eagerness the "Jolly Sandboy" was run up close to the cliff and the sail unbent. With the water already boiling about their knees the boys worked on. And then Fred did a peculiar thing. With a rapid cut of his knife he severed the stay which had just been spliced, and the mast fell over again. Seizing a hatchet, he knocked out the pin that pivoted the stick in the chocks, and let the mast drift away. Jack looked at him in speechless dismay.

"Too much dead weight," said Fred, coolly. "Don't you see that those big tires filled with air are really life-preservers, and with the wooden frame-work they make a very decent raft?"

And so it turned out. The raft, though deep in the water, still supported them; and a quarter of an hour later the steam-trawler Alice came along and took them on board.

"Well," said Fred, as they walked up to Uncle Win's, wet and weary but safe, "you can't deny that the 'Jolly Sandboy' is a good all-around machine. She carried us on land and saved us in the water; what more do you want?"

"I think," said Jack, softly, as he snuffed up the grateful odors from the kitchen, "that I should like a piece of that fried bluefish."

The rules for keeping cage birds well and happy are few. Cleanliness is the first requisite; then temperance in feeding, fresh air, and exercise, in the order mentioned. But these rules should be followed with care and intelligence if you would keep your birds in good condition.

Some people have an idea that all that you have to do is to get a bird, put it into a cage, and give it food and water as directed. This is very far from being enough. The habits of your bird must be studied; the climate of the room in which it lives, the amount of daylight which it should enjoy, the atmosphere which it breathes, its freedom from sudden alarms, all have to be considered if you wish your bird to be happy, and without happiness there is little chance of its being a pleasant companion.

Canaries are not included in this article, because they are bred in captivity, and have inherited the capacity for living in cages.

In a state of nature small birds flit about and sing only during daylight, and they always retire to rest at sundown. You must look out for this if you keep your birds in cages. They do not understand that they had better keep silent after the lamps are lighted. They instinctively keep on singing, as if it were still daylight. The immediate effect of this is that the birds become over-fatigued; they are apt to moult, grow thin, suffer from exhaustion, and quickly perish. The cage should be removed to a darkened room at nightfall; or, if this is not convenient, cover up the cage with a dark cloth before lighting the lamps. In covering the cage care should be taken so to arrange the cloth that the bird can have plenty of air. In removing birds from one room to another it is important to see that there is no change in temperature. If removed to a different[Pg 1040] temperature there is a strong chance that they will begin to moult, which generally leads to something serious. Remember that Nature supplies a coat to suit heat or cold in which her creatures are placed, and that sudden and frequent changes in temperature are a severe tax upon a bird's vitality.

The object in the construction of a bird's cage should be to furnish plenty of light and air, and the cage should always be kept perfectly clean. It is well to have a night covering of dark cloth, which should cover the top of the cage and extend half-way down the sides, as many birds are likely to take cold.

It is almost impossible to rear woodpeckers and fly-catchers, for they live on a special kind of food, such as grubs and other insects, seldom touching seeds and fruit; and there are some birds that it is exceedingly difficult to keep in a small confined space.

Birds of the thrush variety—and this of course includes robins and blackbirds—are hardy and docile pets, and will live in a cage with varied food from seven to ten years. The principal disease to which they are subject is consumption, and this should be guarded against with care. Of the thrushes, the robin finds it most difficult to accustom himself to cage life, and in the spring, at pairing-time, he usually pines for freedom. I cannot bear to see robins caged, although many people have succeeded in keeping them happy and contented.

All of the finches, birds of the mocking-bird type, which includes the cat-bird, will thrive well in cages.

Birds should not be taken when too young, as they are likely to sicken and die; but if caught about the time the pin-feathers begin to show they will generally live. At this time it is necessary to feed them almost constantly, and they will devour more than their own weight in food every day.

The mocking-bird is by all odds the best American cage bird. The best food for a young mocking-bird is thickened meal and water, or meal and milk, mixed occasionally with tender fresh meat, minced fine. Young and old birds require berries of various kinds, such as cherries, strawberries, etc. Any kind of wild fruit of which they are fond is good for them, but this should not be given too freely. A few grasshoppers, beetles, and other insects, which may easily be obtained, as well as gravel, are also necessary.

The mocking-bird can easily be taught a tune, as can the cat-bird, which, despite his cat-call—generally a cry of warning or distress—is one of the sweetest singers among our common birds.

Finches are very bright and animated, and make very desirable pets. They may be taught many amusing tricks. They will learn to fire small cannons and imitate death. They may be taught to draw up their food and water in a little bucket by means of a fine chain.

Of the finches, the bullfinch is probably the best cage bird. It can be taught to whistle a tune. This is done by keeping it in a dark room, and admitting light only at intervals. Every time the light is let into the room you should whistle one air to it, over and over again. Soon it will pick up a few notes, and often will be able to whistle the whole tune in a very short time. The bullfinch is not indigenous to America, although we have many varieties of finches, and some that closely approach those native to England; but bullfinches can be purchased at any bird-store.

Finches should be fed chiefly on poppy and hemp seed—the first to be given as its usual food. Now and then some unflavored biscuit may be given them, but they should never be fed on sweetened cake.

Game-birds and birds that build their nests on the ground almost never breed in captivity. Birds that are enemies when in their natural state will live together contentedly in a cage.

In regard to the feeding of birds, it may be stated in a general way that birds with short triangular bills, like the finches, live on seeds or some form of vegetable food entirely, and never require any meat. Birds with long slender bills, like the thrushes, mocking-birds, crows, etc., require animal as well as vegetable food, while birds with long hooked bills, like hawks or gulls, live on a diet entirely of meat. The reason that the birds in the bird-stores are always in such good health is because the bird-fancier understands how to feed them, and varies their diet as their condition demands.

The importance of giving a bird plenty of water, both to drink and in which to bathe, cannot be overestimated. Birds suffer frightfully from thirst when neglected, and as they have no power to express their wants, they often go for hours unheeded, when a little thoughtful attention would give them relief. Care should always be taken to see to it that their water-cup is filled, and that it does not become twisted to one side or the other so that the bird cannot reach it.

After Columbus discovered Cuba the island seems to have been forgotten by the Spaniards, who bent all their efforts to explore and colonize the neighboring island of Haiti, to which they gave the name of Hispaniola, meaning pertaining to Spain or "Spanish land." Although the rising promontory of Cape Mayzi could be discerned on a clear day from the coast of Hispaniola, it was not until nearly twenty years after Columbus had made his memorable discovery that Diego, his son, determined to conquer and settle the island of Cuba. Diego Columbus was then Governor of Hispaniola, and under his orders Captain Valazquez disembarked with 300 men on the eastern coast of Cuba and founded the city of Baracoa. Then the Spaniards crawled around to the south and founded Santiago, which they made their capital, and then followed in quick succession the cities of Trinidad, Bayamo, Puerto Principe, Sancti Spiritus, and Remedios.

In 1515 the colonists founded a city near the present site of Batabanó, to which they gave the name of Habana, but the marshy land of the southern coast proved a very undesirable place for such a city as they intended to build. Proceeding to the north about thirty miles, they crossed the island and came to a beautiful little bay, surrounded by hills on one side and a stretch of flat land on the other.[Pg 1041] The bay resembled a huge bowl, with only just one narrow outlet into the sea where the two points of land almost met—the ridge of rock on one side and the flat land on the other. A more delightful nook for a city could not have been hit upon, so the new city of Havana was transplanted from its original site on the south coast to the shore of the bowl-like bay on the north.

A SPANISH TRIAL IN MORRO CASTLE.

A SPANISH TRIAL IN MORRO CASTLE.

Captain Velazquez was enthusiastic over his new city, and cutting loose from the Governor of Hispaniola he set up a government of his own. He made rapid strides in subjugating the peaceful inhabitants, whom he allowed to be treated with great cruelty, and Habana soon rose to be a city of importance. To protect it from any probable invasion from the sea, a fort was built on each of the points of land which nearly met, forming the narrow entrance to the bay. The one constructed on the city side of the bay was called La Punta. Upon the rocks on the opposite side was built the famous El Morro, which, in the Spanish language, is called a castle.

In 1762 the English sailed into the bay in spite of these forts, and took possession of Havana, which they held for nearly a year. After the English went away the Spanish government ordered the forts to be rebuilt, and neither money nor labor was spared to make them impregnable. By the construction of the forts an immense amount of money was put into circulation, which necessarily contributed to the development of many industries.

As the traveller approaches Havana to-day the old castle walls are the most curious thing which greets him, for within those walls has originated many a story of suffering, cruelty, and barbarism. As you gaze upon those walls a ship's officer may stand by your side and tell you, as he points to the towering light-house, a sad story of how the builder of that light—an Englishman, I believe he was—so pleased his Spanish masters that they, jealous that he might impart the secret of his work to his countrymen or build for them another such light, confined him in one of the dungeons and put out his eyes.

When I sailed by that huge fortress for the first time, and a fellow-passenger jokingly pointed out a little square window which he designated as opening into my future cell, I did not think how near his prophecy would be realized. But El Morro is not designed to hold criminals. By criminals I mean men who have sinned against their fellow-beings, men who have robbed and murdered—in fact, have not lived up to the golden rule to do unto others as they would have others do unto them. But men, and even boys, who are suspected of not being in favor of Spain's rule in the island of Cuba, these are called political prisoners, and Morro awaits them. And so I became a political prisoner too. And not till I was finally bound by the arms and marched before soldiers, who held me by a rope as though I was some sort of domesticated animal, did I remember that little window in Morro's walls, and wonder if that really was going to be the prison-barred window from which I could watch the ships bound home. But no; they put me in a cell with sixteen Cubans, who one and all greeted me as though I were a friend come to bring them news and consolation. I did see the other side of that little window, however, and that was when they took me before the judge and gave me a trial.

MORRO CASTLE.

MORRO CASTLE.

The Spanish have a queer way of trying folks, according to our notion. They do not take you into a big court-room full of people, where there is a judge and a jury and a prosecuting attorney, and where your accusers are brought before you and made to tell all they know, and if they tell something they don't know, you have the right to question them and prove that they are not telling the truth. But they send you into a little room, where a prosecuting officer examines you all by himself, and a soldier writes down what you say. And then your trial becomes something like a simple sum in arithmetic. Some one must swear that you have done wrong, and then if you get one witness besides yourself who swears that you did not commit the wrong, then your two statements count against the government's one, and so it goes. If the government produces six witnesses you must produce seven; and then again the officer who takes you into the little room is very powerful, for a great deal depends upon just how he makes out the papers in your case, and he has a hand very susceptible to Spanish gold. So it becomes very easy for a suspect to get off (if he is given a trial), and the government knows this; so instead of giving their political prisoners a trial, unless they are sure of convicting them, they keep them shut up in Morro Castle. They gave me a trial because our government at Washington demanded it, and as by their simple methods they were unable to find out what I had been doing, they were obliged to let me go.

It is not of bows and arrows that I wish to tell in this paper, nor of lacrosse and shinny—games of Indian origin with which most boys are familiar—but of other sports with which our copper-colored friends amuse themselves, and which, I presume, few readers have witnessed.

Spinning Stones.—This is a sport that, as a youth, I often watched the boys of the Winnebago tribe play upon the frozen surface of Wisconsin lakes and rivers. A number of smooth stones, usually three, as round as could be found, and about the size of hens' eggs, were placed in a bunch on the smooth ice. A whip, made of two or three buckskin thongs fastened to a handle three feet long, was swung slowly and brought down upon the ice with a gentle swish, so that the lashes might curl round the stones.

Then a swift, deft jerk, so delicately applied as not to scatter the stones, sent them spinning. When once the stones commenced to rotate, the swing and the jerk were[Pg 1042] gradually quickened, growing faster and faster, until the two motions became merged in one, and the player settled down to a steady stroke that made the stones hum like so many tops. These Indian lads could keep a bunch of stones spinning like this for ten minutes at a time, without allowing one of them to get away. I used to think they must have inherited their skill in this sport, for I could never acquire the art, though I tried a hundred times.

I could start the stones spinning easily enough, but before they fairly began to hum one or two, if not the whole three, would whiz off, each in its own direction, beyond the reach of my whip.

The sport seems to require a peculiar drawing stroke of the whip that I could never acquire.

The Snow-dart.—Another sport, in which I approached a little nearer to the skill of these same Indian boys, was that of throwing the snow-dart. The dart was a perfectly straight piece of hickory about five feet long, made three-cornered, and rounded up at one end. It was about an inch wide and half as thick, and was thrown with the flat side up. It had to be made with the greatest care and polished as smooth as glass. It was always a marvel to me how the Indians, with no other tools than a hatchet and knife, could make these little hickory flyers so perfectly. It was wonderful, too, to see how far these Winnebago youths could send one of them. Selecting a level stretch of snow, as upon a frozen river or lake, and where the surface was somewhat hardened by thawing and freezing, the players would stand at a great distance apart. One of them would take the dart by its middle, lightly balance it between his thumb and the two first fingers, and with a strong underhand throw launch the shaft toward his opponent.

If the snow was just soft enough to allow the sharp under edge of the dart to sink slightly into its surface, and thus hold it straight upon its course, then the sport was at its best.

The Grass Game of the Digger Indians of California.—I first saw it played in the Russian River Valley, a great hop-growing region, where, at the close of the picking season, these Indians, to the number of two or three hundred, gather to feast upon watermelons and other good things, and to indulge in pony-races, foot-races, wrestling-matches, shinny, and other games for several days in succession. I had hard work to make my way through the crowd that pressed around a large circular enclosure made of tall willow bushes stuck in the ground where the game was going on. The players, four in number, were men grown, and squatted on their knees, two on one side of the enclosure, facing the other two on the opposite side. On a third side, and equally distant from both sets of players, sat the umpire. Each player had a little pile of dry grass in front of him; but only the two on one side made use of the grass at the same time, for the game is but an elaborate form of "hide the pencil" that every school-boy is quite familiar with, and while the players on one side did the hiding those on the other did the guessing.

To begin the game the player takes a little round stick about three-quarters of an inch in diameter, sharpened at each end, and about two inches and a half long. This he holds up in plain view of his opponent on the opposite side of the enclosure, whose keen eyes follow every movement as the player takes up handful after handful of the grass in front of him and winds it about the stick until he has formed a ball perhaps as large as his head. During this performance the player works himself into a frenzy of excitement, and makes all manner of frantic endeavors to "rattle" his adversary. Twisting and squirming about, he bends his body in all sorts of contortions. Time and again he pretends to pluck the little stick out of the ball he is forming, and hide it under a knee or a foot. He tosses the ball high in the air, then from hand to hand, then into the air again, and catches it behind his back. Now his chant is low and soft, his movements slow and measured; then higher and higher he pitches his voice, and faster and faster become his motions, until one can scarcely see his hands as they dart about in a cloud of flying grass.

Presently, at a signal from the umpire, he drops the ball of grass in front of him, and holds his closed hands behind his back.

Slowly his adversary extends his left arm as if grasping a bow, and raising his bent right arm to the level of his eye, as if drawing an arrow upon an imaginary enemy, with the forefinger of his left hand he points to the exact spot in which he expects to find the little stick. Every breath is hushed, and a deathlike silence prevails as he points steadily for a moment, then lets his right hand fly back against his chest with a hollow thud, as if he had let fly an arrow.

With a wild yell, in which every spectator joins, the player then produces the little stick—from the ball of grass, from under a knee or a foot, or from one of his closed palms, as the case may be. If he has been cunning enough to deceive the sharp eye of his opponent, the stakes are his; but if the guesser correctly locates the stick, the umpire throws to him the string of wampum, or whatever the stake may be. The sticks are then thrown across to the opposite players, and the game goes on.

Our first night in the Rattletrap passed without further incident—that is, the greater part of it passed, though Ollie declared that it lacked a good deal of being all passed when we got up. The chief reason for our early rise was Old Blacky, a member of our household (or perhaps wagonhold) not yet introduced in this history. Old Blacky was the mate of Old Browny, and the two made up our team of horses. Old Browny was a very well behaved, respectable old nag, extremely fond of quiet and oats. He invariably slept all night, and usually much of the day; he was a fit companion for our dog. It was the firm belief of all on board that Old Browny could sleep anywhere on a fairly level stretch of road without stopping.

But Old Blacky was another sort of beast. He didn't seem to require any sleep at all. What Old Blacky wanted was food. He loved to sit up all night and eat, and keep us awake. He seldom ever lay down at night, but would moon about the camp and blunder against things, fall over the wagon-tongue, and otherwise misbehave. Sometimes when we camped where the grass was not just to his liking, he would put his head into the wagon and help himself to a mouthful of bed-quilt or a bite of pillow. He was little but an appetite mounted on four legs, and next to food he loved a fight. Besides the name of Old Blacky, we also knew him as the Blacksmith's Pet; but this will have to be explained later on.

On this first morning, just as it was becoming light in the east, Old Blacky began to make his toilet by rubbing his shoulder against one corner of the wagon. As he was large and heavy, and rubbed as hard as he could, he soon had the wagon tossing about like a boat; and as the easiest way out of it, we decided to get up. It was cool and dewy, with the larger stars still shining faintly. We found Jack under the wagon. Ollie stirred him up, and said,

"SEE ANY VARMINTS IN THE NIGHT, UNCLE JACK?"

"SEE ANY VARMINTS IN THE NIGHT, UNCLE JACK?"

"See any varmints in the night, Uncle Jack?"

"Yes," answered Jack, as he unrolled himself from his blanket. "Or at least I felt one. That disgraceful Old Blacky nibbled at my ear twice. The first time I thought it was nothing less than a bear."

"Did he disturb Snoozer?"

"I guess nothing ever disturbs Snoozer. He never moved all night. How's the firewood department, Ollie?"

"All right," replied Ollie. "Got up enough last night. Nothing to do this morning but rest."

"Then build the fire while I get breakfast."

This pleased Ollie, and he soon had a good fire going. I caught Old Blacky, who had started off to walk around the lake, woke up Old Browny, who was sleeping peacefully with his nose resting on the ground, quieted the pony, who was still suspicious, with a few pats on the neck, and gave them all their oats. Soon the rest of us[Pg 1043] also had our breakfast, including Snoozer, who seemed to wake up by instinct, and after waiting a little for somebody to come and stretch him, stretched himself, and began waving his tail to attract our attention to his urgent need of food.

"Before we get back home that dog will want us to feed him with a spoon," said Jack.

It was only a little while after sunrise when we were off for another day's voyage. We were headed almost due south, and all that day and the three or four following (including Sunday, when we staid in camp), we did not change our general direction. We were aiming to reach the town of Yankton, where we intended to cross the Missouri River and turn to the west in Nebraska. The country through which we travelled was much of it prairie, but more was under cultivation, and the houses of settlers were numerous. The land on which wheat or other small grains had been grown was bare, but as we got further south we passed great fields of corn, some of it standing almost as high as the top of our wagon-cover.

For much of the way we were far from railroads and towns, and got most of our supplies of food from the settlers whose houses we passed or, indeed, sighted, since the pony proved as convenient for making landings as Jack had predicted she would. Ollie usually went on these excursions after milk and eggs and such like foods. The different languages which he encountered among the settlers somewhat bewildered him, and he often had hard work in making the people he found at the houses understand what he wanted. There were many Norwegians among the settlers, and the third day we passed through a large colony of Russians, saw a few Finns, and heard of some Icelanders who lived around on the other side of a lake.

"It wouldn't surprise me," said Ollie one day, "to find the man in the moon living here in a sod house."

Perhaps a majority—certainly a great many—of all these people lived in houses of this kind. Ollie had never seen anything of the sort before, and he became greatly interested in them. The second day we camped near one for dinner.

"You see," said Jack, "a man gets a farm, takes half his front yard and builds a house with it. He gains space, though, because the place he peels in the yard will do for flower-beds, and the roof and sides of his house are excellent places to grow radishes, beets, and similar vegetables."

"Why not other things besides radishes and beets?" asked Ollie.

"Oh, other things would grow all right, but radishes and beets seem to be the natural things for sod-house growing. You can take hold of the lower end and pull 'em from the inside, you know, Ollie."

"I don't believe it, Uncle Jack," said Ollie, stoutly.

"Ask the rancher," answered Jack. "If you're ever at dinner in a sod house, and want another radish, just reach up and pull one down through the roof, tops and all. Then you're sure they're fresh. I'd like to keep a summer boarding-house in a sod house. I'd advertise 'fresh vegetables pulled at the table.'"

"I'm going to ask the man about sod houses," returned Ollie. He went up to where the owner of the house was sitting outside, and said,

"Will you please tell me how you make a sod house?"

"Yes," said the man, smiling. "Thinking of making one?"

"Well, not just now," replied Ollie. "But I'd like to know about them. I might want to build one—sometime," he added, doubtfully.

"Well," said the man, "it's this way: First we plough up a lot of the tough prairie sod with a large plough called a breaking-plough, intended especially for ploughing the prairie the first time. This turns it over in a long, even, unbroken strip, some fourteen or sixteen inches wide and three or four inches thick. We cut this up into pieces two or three feet long, take them to the place where we are building the house, on a stone-boat or a sled, and use them in laying up the walls in just about the same way that bricks are used in making a brick house. Openings are left for the doors and windows, and either a shingle or a sod roof put on. If it's sod, rough boards are first laid on poles, and then sods put on them like shingles. I've got a sod roof on mine, you see."

Ollie was looking at the grass and weeds growing on the top and sides of the house. They must have made a pretty sight when they were green and thrifty earlier in the season, but they were dry and withered now.

"Do you ever have prairie fires on your roofs?" asked Ollie, with a smile.

"Oh, they do burn off sometimes," answered the man. "Catch from the chimney, you know. Did you ever see a hay fire?"

"No."

"Come inside and I'll show you one."

In the house, which consisted of one large room divided across one end by a curtain, Ollie noticed a few chairs and a table, and opposite the door a stove which looked very much like an ordinary cook-stove, except that the place for the fire was rather larger. Back of it stood a box full of what seemed to be big hay rope. The man's wife was cooking dinner on the stove.

"Here's a young tenderfoot," said the man, "who's never seen a hay fire."

"Wish I never had," answered the woman.

"I'LL SHOW YOU HOW TO TWIST IT."

"I'LL SHOW YOU HOW TO TWIST IT."

The man laughed. "They're hardly as good as a wood fire or a coal fire," he said to Ollie, "but when you're five hundred miles, more or less, from either wood or coal they do very well." The man took off one of the griddles and put in another "stick" of hay. Then he handed one to Ollie, who was surprised to find it almost as heavy as a stick of wood. "It makes a fairly good fire," said the man. "Come outside and I'll show you how to twist it."

They went out to a haystack near by, and the man twisted a rope three or four inches in diameter, and about four feet long. He kept hold of both ends till it was wound up tight, then he brought the ends together, and it twisted itself into a hard two-strand rope in the same way that a bit of string will do when similarly treated. There was quite a pile of such twisted sticks on the ground. "You see," said the man, "in this country, instead of splitting up a pile of fuel we just twist up one." Ollie bade the man good-by, took another look at the queer house, and came down to the wagon.

"So you saw a hay-stove, did you?" said Jack. "I could have told you all about 'em. I once staid all night with a man who depended on a hay-stove for warmth. It was in the winter. Talk about appetites! I never saw such an appetite as that stove had for hay. Why, that stove had a worse appetite than Old Blacky. It devoured hay all the time, just as Old Blacky would if he could; and even then its stomach always seemed empty. The man twisted all of the time, and I fed it constantly, and still it was never satisfied."

"How did you sleep?" asked Ollie.

"Worked right along in our sleep—like Old Browny," answered Jack.

The last day before reaching Yankton was hot and sultry. The best place we could find to camp that night was beside a deserted sod house on the prairie. There was a well and a tumble-down sod stable. There were dark[Pg 1044] bands of clouds low down on the southeastern horizon, and faint flashes of lightning.

"It's going to rain before morning," I said. "Wonder if it wouldn't be better in the sod house?"

We examined it, but found it in poor condition, so decided not to give up the wagon. "The man that lived there pulled too many radishes and parsnips and carrots and such things into it, and then neglected to hoe his roof and fill up the holes," said Jack. "Besides, Old Blacky will have it rubbed down before morning. When I sleep in anything that Old Blacky can get at, I want it to be on wheels so it can roll out of the way."

We went to bed as usual, but at about one o'clock we were awakened by a long rolling peal of thunder. Already big drops of rain were beginning to fall. Ollie and I looked out, and found Jack creeping from under the wagon.

"That's a dry-weather bedroom of mine," he observed, "and I think I'll come upstairs."

The flashes of lightning followed each other rapidly, and by them we could see the horses. Old Browny was sleeping, and Old Blacky eating, but the pony stood with head erect, very much interested in the storm. Jack helped Snoozer into the wagon, and came in himself. We drew both ends of the cover as close as possible, lit the lantern, and made ourselves comfortable, while Jack took down his banjo and tried to play. Jack always tried to play, but never quite succeeded. But he made a considerable noise, and that was better than nothing.

The wind soon began to blow pretty fresh, and shake the cover rather more than was pleasant. But nothing gave way, and after, as it seemed, fifty of the loudest claps of thunder we had ever heard, the rain began to fall in torrents.

"That is what I've been waiting for," said Jack. "Now we'll see if there's a good cover on this wagon, or if we've got to put a sod roof on it, like that man's house."

The rain kept coming down harder and harder, but though there seemed to be a sort of a light spray in the air of the wagon, the water did not beat through. In some places along the bows it ran down on the inside of the cover in little clinging streams, but as a household we remained dry. Jack was still experimenting on the banjo and the dog had gone to sleep. Suddenly a flash of lightning dazzled our eyes as if there were no cover at all over and around us, with a crash of thunder which struck our ears like a blow from a fist. Jack dropped the banjo, and the dog shook his head as if his ears tingled. We all felt dizzy, and the wagon seemed to be swaying around.

"That struck pretty close," I said. "I hope it didn't hit one of the horses."

"THAT'S WHERE OLD BLACKY KICKED AT THE LIGHTNING AND

MISSED IT."

"THAT'S WHERE OLD BLACKY KICKED AT THE LIGHTNING AND

MISSED IT."

"If it hit Old Blacky, I'll bet a cooky it got the worst of it," answered Jack, taking up his banjo again. "Look out, Ollie, and maybe you'll see the lightning going off limping."

It was still raining, though not so hard. Soon we began to hear a peculiar noise, which seemed to come from behind the wagon. It was a breaking, splintering sort of noise, as if a board was being smashed and split up very gradually.

"Sounds as if a slow and lazy kind of lightning was striking our wagon," said Jack.

Ollie's face was still white from the scare at the stroke of lightning, and his eyes now opened very wide as he listened to the mysterious noise. Jack pulled open the back cover an inch and peeped out. Then he said,

"I guess Old Blacky's tussle with the lightning left him hungry; he's eating up one side of the feed-box."

Then we laughed at the strange noise, and in a few minutes, the rain having almost ceased, we put on our rubber boots and went out to look after the other horses. Old Browny we found in the lee of the sod house, not exactly asleep, but evidently about to take a nap. The pony had pulled up her picket-pin and retreated to a little hollow a hundred yards away. We caught her and brought her back. By the light of the lantern we found that the great stroke of lightning had struck the curb of the well, shattering it, and making a hole in the ground beside it. The storm had gone muttering off to the north, and the stars were again shining overhead.

"What a stroke of lightning that must have been to do that!" said Ollie, as he looked at the curb with some awe.

"It wasn't the lightning that did that," returned his truthful Uncle Jack. "That's where Old Blacky kicked at the lightning and missed it."

Then we returned to the wagon and went to bed. The next morning at ten o'clock we drove into Yankton. We found the ferry-boat disabled, and that we would have to go forty miles up the river to Running Water before we could cross. We drove a mile out of town, and went into camp on a high bank overlooking the milky, eddying current of the Missouri.

One night, some days after this, George was awakened in the middle of the night by hearing persons stirring in the house. He rose, and slipping on his clothes, softly opened his door. Laurence Washington, fully dressed, was standing in the hall.

"What is the matter, brother?" asked George.

"The child Mildred is ill," answered Laurence, in much agitation. "It seems to be written that no child of mine shall live. Dr. Craik has been sent for, but he is so long in coming that I am afraid she will die before he reaches here."

"I will fetch him, brother," said George, in a resolute manner. "I will go for Dr. Craik, and if I cannot get him I will go to Alexandria for another doctor."

He ran down stairs and to the stable, and in five minutes he had saddled the best horse in the stable and was off for Dr. Craik's, five miles away. As he galloped on through the darkness, plunging through the snow, and taking all the short-cuts he could find, his heart stood still for fear the little girl might die. He loved her dearly—all her baby ways and childish fondness for himself coming back to him with the sharpest pain—and his brother and sister, whose hopes were bound up in her. George thought, if the child's life could be spared, he would give more than he could tell.

He reached Dr. Craik's after a hard ride. The barking of the dogs, as he rode into the yard, wakened the doctor, and he came to the door with a candle in his hand, and in his dressing-gown. In a few words George told his business, and begged the doctor to start at once for Mount Vernon. No message had been received, and at that very time the negro messenger, who had mistaken the road, was at least five miles off, going in the opposite direction.

"How am I to get to Mount Vernon?" asked the doctor. "As you know, I keep only two horses. One I lent to a neighbor yesterday, and to-night, when I got home from my round, my other horse was dead lame."

"Ride this horse back!" cried George. "I can walk easily enough; but there must be a doctor at Mount Vernon to-night. If you could have seen my brother's face—I did not see my poor sister, but—"

"Very well," answered the doctor, coolly. "I never delay a moment when it is possible to get to a patient; and if you will trudge the five miles home I will be at Mount Vernon as soon as this horse can take me there."

Dr. Craik went into the house to get his saddle-bags, and in a few minutes he appeared, fully prepared, and mounting the horse, started for Mount Vernon at a sharp canter.

George set out on his long and disagreeable tramp. He was a good walker, but the snow troubled him, and it was nearly daylight before he found himself in sight of the house. Lights were moving about, and, with a sinking heart, George felt a presentiment that his little playmate was hovering between life and death. When he entered the hall he found a fire burning, and William Fairfax standing by it. No one had slept at Mount Vernon that night. George was weary, and wet up to his knees, but his first thought was for little Mildred.

"She is still very ill, I believe," said William. "Dr. Craik came, and Cousin Anne met him at the door, and she burst into tears. The doctor said you were walking back, and Cousin Anne said, 'I will always love George the better for this night.'"

George went softly up the stairs and listened at the nursery door. He tapped, and Betty opened the door a little. He could see the child's crib drawn up to the fire, the doctor hanging over it, while the poor father and mother clung together a little way off.

"She is no worse," whispered Betty.

With this sorry comfort George went to his room and changed his clothes. As he came down stairs he saw his brother and sister go down before him for a little respite after their long watch; but on reaching the hall no one was there but William Fairfax, standing in the same place[Pg 1046] before the hearth. George went up and began to warm his chilled limbs. Then William made the most indiscreet speech of his life—one of those things which, uninspired by malice, and the mere outspoken word of a heedless person, are yet capable of doing infinite harm and causing extreme pain.

"George," said he, "you know if Mildred dies you will get Mount Vernon and all your brother's fortune."

George literally glared at William. His temper, naturally violent, blazed within him, and his nerves, through fatigue and anxiety and his long walk, not being under his usual control, he felt capable of throttling William where he stood.

"Do you mean to say—do you think that I want my brother's child to die?—that I—"

George spoke in a voice of concentrated rage that frightened William, who could only stammer, "I thought—perhaps—I—I—"

The next word was lost, for George, hitting out from the shoulder, struck William full in the chest, who fell over as if he had been shot.

The blow brought back George's reason. He stood amazed and ashamed at his own violence and folly. William rose without a word, and looked him squarely in the eye; he was conscious that his words, though foolish, did not deserve a blow. He was no match physically for George, but he was not in the least afraid of him. Some one else, however, besides the two boys had witnessed the scene. Laurence Washington, quietly opening wide a door that had been ajar, walked into the hall, followed by his wife, and said, calmly:

"George, did I not see you strike a most unmanly blow just now—a blow upon a boy smaller than yourself, a guest in this house, and at a time when such things are particularly shocking?"

George, his face as pale as death, and unable to raise his eyes from the floor, replied, in a low voice, "Yes, brother, and I think I was crazy for a moment. I ask William's pardon, and yours, and my sister's—"

Laurence continued to look at him with stern and, as George felt, just displeasure; but Mrs. Washington came forward, and, laying her hand on his shoulder, said, sweetly:

"You were very wrong, George; but I heard it all, and I do not believe that anything could make you wish our child to die. Your giving up your horse to the doctor shows how much you love her, and I, for one, forgive you for what you have done."

"Thank you, sister," answered George; but he could not raise his eyes. He had never in all his life felt so ashamed of himself. In a minute or two he recovered himself, and held out his hand to William.

"I was wrong too, George," said William; "I ought not to have said what I did, and I am willing to be friends again."

The two boys shook hands, and without one word each knew that he had a friend forever in the other one. And presently Dr. Craik came down stairs, saying cheerfully to Mrs. Washington,

"Madam, your little one is asleep, and I think the worst is past."

For some days the child continued ill, and George's anxiety about her, his wish to do something for her in spite of his boyish incapacity to do so, showed how fond he was of her. She began to mend, however, and George was delighted to find that she was never better satisfied than when carried about in his strong young arms. William Fairfax, who was far from being a foolish fellow, in spite of his silly speech, grew to be heartily ashamed of the suspicion that George would be glad to profit by the little girl's death when he saw how patiently George would amuse her hour after hour, and how willingly he would give up his beloved hunting and shooting to stay with her.

In the early part of January the time came when George and Betty must return to Ferry Farm. George went the more cheerfully, as he imagined it would be his last visit to his mother before joining his ship. Laurence was also of this opinion, and George's warrant as midshipman had been duly received. He had written to Madam Washington of Admiral Vernon's offer, but he had received no letter from her in reply. This, however, he supposed was due to Madam Washington's expectation of soon seeing George, and he thought her consent absolutely certain.

On a mild January morning George and Betty left Mount Vernon for home in a two-wheeled chaise, which Laurence Washington sent as a present to his step-mother. In the box under the seat were packed Betty's white sarcenet silk and George's clothes, including three smart uniforms. The possession of these made George feel several years older than William Fairfax, who started for school the same day. The rapier which Lord Fairfax had given him, and his midshipman's dirk, which he considered his most valuable belongings, were rather conspicuously displayed against the side of the chaise; for George was but a boy, after all, and delighted in these evidences of his approaching manhood. His precious commission was in his breast pocket. Billy was to travel on the trunk-rack behind the chaise, and was quite content to dangle his legs from Mount Vernon to Ferry Farm, while Rattler trotted along beside them. Usually it was a good day's journey, but in winter, when the roads were bad, it was necessary to stop over a night on the way. It had been determined to make this stop at the home of Colonel Fielding Lewis, an old friend of both Madam Washington and Laurence Washington.

All of the Mount Vernon family, white and black, were assembled on the porch, directly after breakfast, to say good-by to the young travellers. William Fairfax, on horseback, was to start in another direction. Little Mildred, in her black mammy's arms, was kept in the hall, away from the raw winter air. Betty kissed her a dozen times, and cried a little; but when George took her in his arms, and, after holding her silently to his breast, handed her back to her mammy, the little girl clung to him and cried so piteously, that George had to unlock her baby arms from around his neck and run away.

On the porch his brother and sister waited for him, and Laurence said:

"I desire you, George, to deliver the chaise to your mother, from me, with my respectful compliments, and to hope that she will soon make use of it to visit us at Mount Vernon. For yourself, let me hear from you by the first hand. The Bellona will be in the Chesapeake within a month, and probably up this river, and you are now prepared to join at a moment's notice."

George's heart was too full for many words, but his flushed and beaming face showed how pleased he was at the prospect. Laurence, however, could read George's boyish heart very well, and smiled at the boy's delight. Both Betty and himself kissed and thanked their sister for her kindness, and, after they had said good-by to William, and shook hands with all the house-servants, the chaise rattled off.

Betty had by nature one of the sunniest tempers in the world, and, instead of going back glumly and unwillingly to her modest home after the gayeties and splendors of Mount Vernon, congratulated herself on having had so merry a time, and was full of gratitude to her mother for allowing her to come. And then she was alone with George, and had a chance to ask him dozens of things that she had not thought of in the bustle at Mount Vernon; so the two drove along merrily. Betty chattering a good deal, and George talking much more than he usually did.

They reached Barn Elms before sunset, and met with a cordial welcome from Colonel Lewis and the large family of children and guests that could always be found in the Virginia country-houses of those days. At supper a long table was filled, mostly with merry young people. Among them was young Fielding Lewis, a handsome fellow a little older than George, and there was also Miss Martha Dandridge, the handsome young lady with whom George had danced Sir Roger de Coverley on Christmas night at Mount Vernon. In the evening the drawing-room floor was cleared, and everybody danced, Colonel Lewis himself, a portly gentleman of sixty, leading off the rigadoon with Betty, which George again danced with Martha Dandridge. They had so merry a time that they were sorry to leave[Pg 1047] next morning. Colonel Lewis urged them to stay, but George felt they must return home, more particularly as it was the first time that he and Betty had been trusted to make a journey alone.

All that day they travelled, and about sunset, when within five miles of home, a tire came off one of the wheels of the new chaise, and they had to stop at a blacksmith's shop on the road-side to have it mended. Billy, however, was sent ahead to tell their mother that they were coming, and George was in hopes that Billy's sins would be overlooked, considering the news he brought, and the delightful excitement of the meeting.

The blacksmith was slow, and the wheel was in a bad condition, so it was nearly eight o'clock of a January night before they were in the gate at Ferry Farm. It was wide open, the house was lighted up, and in the doorway stood Madam Washington and the three little boys. Every negro, big and little, on the place was assembled, and shouts of "Howdy, Marse George! Howdy, Miss Betty!" resounded. The dogs barked with pleasure at recognizing George and Betty, and the commotion was great.

As soon as they reached the door Betty jumped out, before the chaise came to a standstill, and rushed into her mother's arms. She was quickly followed by George, who, much taller than his mother, folded her in a close embrace, and then the boys were hugged and kissed. Madam Washington led him into the house, and looked him all over with pride and delight, he was so grown, so manly; his very walk had acquired a new grace, such as comes from association with graceful and polished society. She was brimming with pride, but she only allowed herself to say,

"How much you have grown, my son!"

"And the chaise is yours, mother," struck in Betty. "Brother Laurence sent it to you—all lined inside with green damask, and a stuffed seat, and room for a trunk behind, and a box under the seat."

George rather resented this on Betty's part, as he thought he had the first right to make so important an announcement as the gift of a chaise, and said, with a severe look at Betty:

"My brother sent it you, mother, with his respectful compliments, and hopes that the first use you will make of it will be to visit him and my sister at Mount Vernon."

Betty, however, was in no mood to be set back by a trifling snub like that, so she at once plunged into a description of the gayeties at Mount Vernon. This was interrupted by supper, which had been kept for them, and then it was nine o'clock, and Betty was nearly falling asleep, and George, too, was tired, and it was the hour for family prayers. For the first time in months George read prayers at his mother's request, and she added a special thanksgiving for the return of her two children in health and happiness, and then it was bedtime. Madam Washington had not once mentioned his midshipman's warrant to George. This did not occur to him until he was in bed, and then, with the light heart of youth, he dismissed it as a mere accident. No doubt she was as proud as he, although the parting would be hard on both, but it must come in some form or other, and no matter how long or how far, they could never love each other any less—and George fell asleep to dream that he was carrying the Bellona into action in the most gallant style possible.

Next morning he was up and on horseback early, riding over the place, and thinking with half regret and half joy that he would soon be far away from the simple plantation life. At breakfast Betty talked so incessantly and the little boys were so full of questions that Madam Washington had no opportunity for serious talk, but as soon as it was over she said,

"Will you come to my room, George?"

"In a minute, mother," answered George, rising and darting up stairs.

He would show himself to her in his uniform. He had the natural pride in it that might have been expected, and, as he slipped quickly into it, and put the dashing cap on his fair hair, and stuck his dirk into his belt, he could not help a thrill of boyish vanity. He went straight to his mother's room, where she stood awaiting him.

The first glance at her face struck a chill to his heart. There was a look of pale and quiet determination upon it that was far from encouraging. Nevertheless, George spoke up promptly.

"My warrant, mother, is upstairs, sent me, as my brother wrote you, by Admiral Vernon. And my brother, out of his kindness, had all my outfit made for me in Alexandria. I am to join the Bellona frigate within the month."

"Will you read this letter, my son?" was Madam Washington's answer, handing him a letter.

George took it from her. He recognized the handwriting of his uncle, Joseph Ball, in England. It ran, after the beginning: "'I understand you are advised and have some thoughts of putting your son George to sea.'" George stopped in surprise, and looked at his mother.

"I suppose," she said, quietly, "that he has heard that your brother Laurence mentioned to me months ago that you wished to join the King's land or sea service, but my brother's words are singularly apt now."

George continued to read.

"'I think he had better be put apprentice to a tinker, for a common sailor before the mast has by no means the common liberty of the subject, for they will press him from ship to ship, where he has fifty shillings a month, and make him take twenty-three, and cut and slash and use him like a dog.'"

George read this with amazement.

"My uncle evidently does not understand that I never had any intention of going to sea as a common sailor," he said, his face flushing, "and I am astonished that he should think such a thing."

"Read on," said his mother, quietly.

"'And as to any considerable preferment in the navy, it is not to be expected, as there are so many gaping for it here who have interest, and he has none.'"

George folded the letter, and handed it back to his mother respectfully.

"Forgive me, mother," said he, "but I think my uncle Joseph a very ignorant man, and especially ignorant of my prospects in life!"

"George!" cried his mother, reproachfully.

George remained silent. He saw coming an impending conflict, the first of their lives, between his mother and himself.

"My brother," said Madam Washington, after a pause, "is a man of the world. He knows much more than I, a woman who has seen but little of it, and much more than a youth like you, George."

"He does not know better than my brother, who has been the best and kindest of brothers, who thought he was doing me the greatest service in getting me this warrant, and who, at his own expense, prepared me for it."

Both mother and son spoke calmly, and even quietly, but two red spots burned in Madam Washington's face, while George felt himself growing whiter every moment.

"Your brother, doubtless, meant kindly towards you, and for that I shall be ever grateful; but I never gave my consent—I shall never give it," she said.

"I am sorry to hear you say that, mother," answered George, presently—"more sorry than I know how to say. For, although you are my dear and honored mother, you cannot choose my life for me, provided the life I choose is respectable, and I live honestly and like a gentleman, as I always shall, I hope."

The mother and son faced each other, pale and determined. It struck home to Madam Washington that she could not now clip her eaglet's wings. She asked, in a low voice,

"Do you intend to disobey me, my son?"

"MY SON, MY BEST-LOVED CHILD."

"MY SON, MY BEST-LOVED CHILD."

"Don't force me to do it, mother!" cried George, losing his calmness, and becoming deeply agitated, "I think my honor is engaged to my brother and Admiral Vernon, and I feel in my heart that I have a right to choose my own future course. I promise you that I will never discredit you; but I cannot—I cannot obey you in this."

"You do refuse, then, my son?" said Madam Washington. She spoke in a low voice, and her beautiful eyes looked straight into George's as if challenging him to resist[Pg 1048] her influence; but George, although his own eyes filled with tears, yet answered her gently,

"Mother, I must."

Madam Washington said no more, but turned away from him. The boy's heart and mind were in a whirl. Some involuntary power seemed compelling him to act as he did, without any volition on his part. Suddenly his mother turned, with tears streaming down her face, and, coming swiftly towards him, clasped him in her arms.

"My son, my best-loved child!" she cried, weeping. "Do not break my heart by leaving me. I did not know until this moment how much I loved you. It is hard for a parent to plead with a child, but I beg, I implore you, if you have any regard for your mother's peace of mind, to give up the sea." And with sobs and tears, such as George had never before seen her shed, she clung to him, and covered his face and hair and even his hands with kisses.

The boy stood motionless, stunned by an outbreak of emotion so unlike anything he had ever seen in his mother before. Calm, reticent, and undemonstrative, she had showed a Spartan firmness in her treatment of her children until this moment. In a flash like lightning George saw that it was not that foolish letter which had influenced her, but there was a fierceness of mother-love, all unsuspected in that deep and quiet nature, for him, and for him alone. This trembling, sobbing woman, calling him all fond names, and saying to him, "George, I would go upon my knees if that would move you," his mother! And the appeal overpowered him as much by its novelty as its power. Like her he began to tremble, and when she saw this she held him closer to her, and cried, "Will you abandon me, or will you abandon your own will this once?"

There was a short pause, and then George spoke, in a voice he scarcely knew, it was so strange,

"Mother, I will give up my commission."

The polo pony is becoming such an important and conspicuous feature in modern life that a short article upon his nature, training, and habits may be interesting to those who either hope to make his acquaintance on his native range, or to import him for use in riding or driving, or in playing that most exciting of all games.

The bicycle is said to be driving horseflesh out of the market, that good horses, even thoroughbreds, are being canned by the thousand, and sent to all parts of the world. This may be a necessary and practical use to which to put that noble animal, the friend and companion of man from all ages; but one cannot help being thankful that the pony has so far escaped this fate, and that the demand for these singularly intelligent, plucky little beasts is growing rather than diminishing.

A COW PONY.

A COW PONY.

So long as there are cattle ranges the cow pony will be a necessity. One could not "round up" or "cut out" or "rope" or "corral" on a bicycle or from a self-propelling carriage of any kind, and even if this dreadful day should come and the cow pony lose his prestige, the polo pony will still have his place in the world of sport, from which the most modern and improved wheel could never dispossess him. The cow pony or polo pony, like the poet and the athlete, is born, not made. Out of a drove of a hundred ponies there may be only twenty-five or less that are good for anything, who have the instinct of sport, the quick eye, steady foot, the grit and endurance of the true sportsman.

A good cow pony is good from the start. He learns, of course, much by experience, but he is not only first-class "material," as they say of football candidates, but a star player from the very first. Running wild with the mares, their mothers, on the big ranges of Texas, Mexico, Montana, and Indian Territory, they grow marvellously fleet of foot, and as hardy as mountain-goats.

When about three years old the ponies—all these horses under fifteen hands high—are taken out of the drove, and broken either for cattle or polo. The process of breaking is not a difficult one, though sometimes troublesome and tedious. The pony is first corralled—that is, driven out of the bunch into a pen by himself—then roped, often thrown, and saddled and bridled. As a rule they make a great show of resistance. They buck, they kick, they rear, they lie down and roll, they run into fences or trees—in short, there is nothing that the instinct of self-defence can prompt that a spirited pony will not do, and persist in doing, until he learns the futility of kicking against the pricks. His spurred and booted rider is prepared for any exhibition of temper or ingenuity that he can devise, and wrestles with him gently but firmly, sticking to his seat until the frantic efforts of the rebellious pony have exhausted themselves. Then, subdued, if not overcome, he is unsaddled and staked out, or tied up for the night, only to go through the same performance the next day.

After several days' experience of the bit and bridle, and the singular persistence of the load upon his back in staying there under all provocation, the pony as a rule gives in—all the sensible ones, at least; the bad-tempered broncos—the chronic buckers and kickers and bolters—fight on spasmodically, and sometimes do not become thoroughly broken, if ever, for weeks. When the pony has once recognized and accepted you as his master, his future usefulness depends very largely upon your treatment of him. If he is ridden hard and handled roughly he will grow rough and unmanageable or mean and uncertain in temper; but if treated gently and kindly he becomes docile and dependable, and as faithful as a dog. He learns to know and love his master very soon, and is as susceptible to flattery and petting as a dog or a woman. Some ranchers, especially those with the reputation of being able to "make a pretty good horse talk," will tell you that their favorite ponies, even when in the pasture, come at their whistle like a dog; but it is not very safe to trust to this devotion and obedience, for the majority[Pg 1049] are as wild as hawks, and as difficult to catch, and unless one wishes the exercise of a hard chase, it is better to hobble them when the saddle and bridle are taken off and they are left to graze.

In buying ponies, either for polo or cattle, it is well to know the owner's reputation, and how he breaks and handles them, for a good cow-puncher is sure to have good ponies, fast and bridle-wise—"mighty handy," in the vernacular, and trained to stop quickly and hold hard. In roping, a good pony is as strong as any steer, and ought to be able to hold no matter how hard the steer may jerk or pull when the rope is thrown. There are no particular breeds in this country; any small horse on the range is called "bronco" or "pony" indifferently, and they are taken from all classes indiscriminately, being picked out by their size and build, and the polo pony only differs from others by his superior speed and agility, and his record as a cow pony.

The small fleet Arab horses which are sold so much in England for polo have had no early training in cow-practice, but as a breed are very intelligent, very quick, and yet extremely docile.

The Shetland-pony, which is such a favorite with children, is not agile enough for either polo or cattle, and there are all sorts and conditions of ponies that are useful in other respects, but absolutely useless in rounding up or cutting out, or on the polo-grounds.

POLO PONIES.

POLO PONIES.

In advertising for polo ponies one usually sends out a circular stating the necessary requisites: the size—fourteen hands one inch—and the temper and disposition; and it takes a trained eye to pick out the most promising from all those brought for inspection.