Project Gutenberg's R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots), by Karel Capek

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots)

A Fantastic Melodrama in Three Acts and an Epilogue

Author: Karel Capek

Contributor: Nigel Playfair

Translator: Paul Selver

Release Date: March 22, 2019 [EBook #59112]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK R.U.R. (ROSSUM'S UNIVERSAL ROBOTS) ***

Produced by Tim Lindell, David E. Brown, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

A Fantastic Melodrama in Three Acts and

an Epilogue

By Karel Capek

English version by

Paul Selver and Nigel Playfair

Samuel French, Inc.

Copyright ©, 1923, by Doubleday, Page and Company

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that R. U. R. is subject to a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, the British Commonwealth, including Canada, and all other countries of the Copyright Union. All rights, including professional, amateur, motion pictures, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. In its present form the play is dedicated to the reading public only.

R. U. R. may be given stage presentation by amateurs upon payment of a royalty of Thirty-five Dollars for the first performance, and Twenty-five Dollars for each additional performance, payable one week before the date when the play is given, to Samuel French, Inc., at 45 West 25th Street, New York, N. Y. 10010, or at 7623 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, Calif. 90046, or to Samuel French (Canada), Ltd., 80 Richmond Street East, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5C 1P1.

Royalty of the required amount must be paid whether the play is presented for charity or gain and whether or not admission is charged.

Stock royalty quoted on application to Samuel French, Inc.

For all other rights than those stipulated above, apply to Samuel French, Inc.

Particular emphasis is laid on the question of amateur or professional readings, permission and terms for which must be secured in writing from Samuel French, Inc.

Copying from this book in whole or in part is strictly forbidden by law, and the right of performance is not transferable.

Whenever the play is produced the following notice must appear on all programs, printing and advertising for the play: “Produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc.”

Due authorship credit must be given on all programs, printing and advertising for the play.

Anyone presenting the play shall not commit or authorize any act or omission by which the copyright of the play or the right to copyright same may be impaired. No changes shall be made in the play for the purpose of your production unless authorized in writing. The publication of this play does not imply that it is necessarily available for performance by amateurs or professionals. Amateurs and professionals considering a production are strongly advised in their own interests to apply to Samuel French, Inc., for consent before starting rehearsals, advertising, or booking a theatre or hall.

Printed in U.S.A.

ISBN 0 573 61497 0

The play is laid on an island somewhere on our planet, and on this island is the central office of the factory of Rossum’s Universal Robots. “Robot” is a Czech word meaning “worker.” When the play opens, a few decades beyond the present day, the factory had turned out already, following a secret formula, hundreds of thousands, and even millions, of manufactured workmen, living automats, without souls, desires or feelings. They are high-powered laborers, good for nothing but work. There are two grades, the unskilled and the skilled, and especially trained workmen are furnished on request.

When Helena Glory, president of the Humanitarian League, comes to ascertain what can be done to improve the condition of those overspecialized creatures, Harry Domin, the general manager of the factory, captures her heart and hand in the speediest courting on record in our theatre. The last two acts take place ten years later. Due to the desire of Helena to have the Robots more like human beings, Dr. Gall, the head of the physiological and experimental departments, has secretly changed the formula, and while he has partially humanized only a few hundreds, there are enough to make ringleaders, and a world revolt of robots is under way. This[4] revolution is easily accomplished, as robots have long since been used when needed as soldiers and the robots far outnumber human beings.

The rest of the play is magnificent melodrama, superbly portrayed, with the handful of human beings at bay while the unseen myriads of their own robots close in on them. The final scene is like Dunsany on a mammoth scale.

Then comes the epilogue, in which Alquist, the company’s builder, is not only the only human being on the island, but also the only one left on earth. The robots have destroyed the rest of mankind. They spared his life because he was a worker. And he is spending his days unceasingly endeavoring to discover and reconstruct the lost formula. The robots are doomed. They saved the wrong man. They should have spared the company’s physicist. The robots know that their bodies will wear out in time and there will be no new multitudes of robots to replace them. But Alquist discovers two humanized robots, a young man and young woman, who have a bit of Adam and Eve in them, and the audience perceives that mankind is about to start afresh. Nature has won out, after all.

The cast of the Theatre Guild Production as originally presented at the Garrick Theatre, New York:

By KAREL CAPEK

English version by Paul Selver and Nigel Playfair

Staged by Philip Moeller

Settings and Costumes by Lee Simonson

CHARACTERS (in order of appearance)

| Harry Domin, General Manager of Rossum’s Universal Robots | Basil Sydney |

| Sulla, a Robotess | Mary Bonestell |

| Marius, a Robot | Myrtland LaVarre |

| Helena Glory | Kathlene MacDonell |

| Dr. Gall, head of the Physiological and Experimental Department of R. U. R. | William Devereaux |

| Mr. Fabry, Engineer General, Technical Controller of R. U. R. | John Anthony |

| Dr. Hallemeier, head of the Institute for Psychological Training of Robots | Moffat Johnston |

| Mr. Alquist, Architect, head of the Works Department of R. U. R. | Louis Calvert |

| Consul Busman, General Manager of R. U. R. | Henry Travers |

| Nana | Helen Westly |

| Radius, a Robot | John Rutherford |

| Helena, a Robotess | Mary Hone |

| Primus, a Robot | John Roche |

| A Servant | Frederick Mark |

| First Robot | Domis Plugge |

| Second Robot | Richard Coolidge |

| Third Robot | Bernard Savage |

ACT I

Central Office of the Factory of Rossum’s Universal Robots

ACT II

Helena’s Drawing Room—Ten years later. Morning

ACT III

The same. Afternoon

EPILOGUE

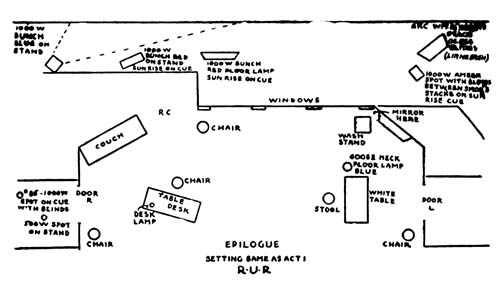

A Laboratory. One year later

Place: An Island. Time: The Future.

Domin: A handsome man of 35. Forceful, efficient and humorous at times.

Sulla: A pathetic figure. Young, pretty and attractive.

Marius: A young Robot, superior to the general run of his kind. Dressed in modern clothes.

Helena Glory: A vital, sympathetic, handsome girl of 21.

Dr. Gall: A tall, distinguished scientist of 50.

Mr. Fabry: A forceful, competent engineer of 40.

Hallemeier: An impressive man of 40. Bald head and beard.

Alquist: A stout, kindly old man of 60.

Nana: A tall, acidulous woman of 40.

Radius: A tall, forceful Robot.

Helena: A radiant young woman of 20.

Primus: A good-looking young Robot.

Note: All the Robots wear expressionless faces and move with absolute mechanical precision, with the exception of Sulla, Helena and Primus, who convey a touch of humanity.

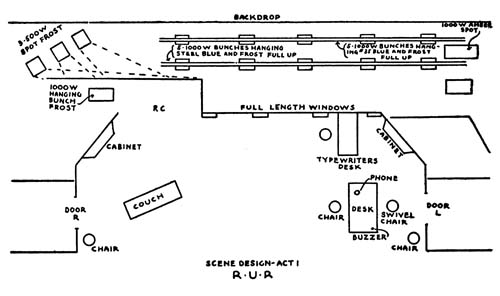

Scene: Central office of the factory of Rossum’s Universal Robots. Entrance R. down Right. The windows on the back wall look out on the endless roads of factory buildings. Door L. down Left. On the Left wall large maps showing steamship and railroad routes. On the Right wall are fastened printed placards. (“Robots cheapest Labor,” etc.) In contrast to these wall fittings, the floor is covered with splendid Turkish carpet, a couch R.C. A book shelf containing bottles of wine and spirits, instead of books.

Domin is sitting at his desk at Left, dictating. Sulla is at the typewriter upstage against the wall. There is a leather couch with arms Right Center. At the extreme Right an armchair. At extreme Left a chair. There is also a chair in front of Domin’s desk. Two green cabinets across the upstage corners of the room complete the furniture. Domin’s desk is placed up and down stage facing Right.

Seen through the windows which run to the heights of the room are rows of factory chimneys, telegraph poles and wires. There is a general passageway or hallway upstage at the Right Center which leads to the warehouse. The[10] Robots are brought into the office through this entrance.

Domin. (Dictating) Ready?

Sulla. Yes.

Domin. To E. M. McVicker & Co., Southampton, England. “We undertake no guarantee for goods damaged in transit. As soon as the consignment was taken on board we drew your captain’s attention to the fact that the vessel was unsuitable for the transportation of Robots; and we are therefore not responsible for spoiled freight. We beg to remain, for Rossum’s Universal Robots, yours truly.” (Sulla types the lines.) Ready?

Sulla. Yes.

Domin. Another letter. To the E. B. Huysen Agency, New York, U.S.A. “We beg to acknowledge receipt of order for five thousand Robots. As you are sending your own vessel, please dispatch as cargo equal quantities of soft and hard coal for R.U.R., the same to be credited as part payment (BUZZER) of the amount due us.” (Answering phone) Hello! This is the central office. Yes, certainly. Well, send them a wire. Good. (Rises) “We beg to remain, for Rossum’s Universal Robots, yours very truly.” Ready?

Sulla. Yes.

Domin. (Answering small portable phone) Hello! Yes. No. All right. (Standing back of desk, punching plug machine and buttons) Another letter. Freidrichswerks, Hamburg, Germany. “We beg to acknowledge receipt of order for fifteen thousand Robots.” (Enter Marius R.) Well, what is it?

Marius. There’s a lady, sir, asking to see you.

Domin. A lady? Who is she?

Marius. I don’t know, sir. She brings this card of introduction.

Domin. (Reading card) Ah, from President[11] Glory. Ask her to come in— (To Sulla. Crossing up to her desk, then back to his own) Where did I leave off?

Sulla. “We beg to acknowledge receipt of order for fifteen thousand Robots.”

Domin. Fifteen thousand. Fifteen thousand.

Marius. (At door R.) Please step this way.

(Enter Helena. Exit Marius R.)

Helena. (Crossing to desk) How do you do?

Domin. How do you do? What can I do for you?

Helena. You are Mr. Domin, the General Manager?

Domin. I am.

Helena. I have come—

Domin. With President Glory’s card. That is quite sufficient.

Helena. President Glory is my father. I am Helena Glory.

Domin. Please sit down. Sulla, you may go. (Exit Sulla L. Sitting down L. of desk) How can I be of service to you, Miss Glory?

Helena. I have come— (Sits R. of desk.)

Domin. To have a look at our famous works where people are manufactured. Like all visitors. Well, there is no objection.

Helena. I thought it was forbidden to—

Domin. To enter the factory? Yes, of course. Everybody comes here with someone’s visiting card, Miss Glory.

Helena. And you show them—

Domin. Only certain things. The manufacture of artificial people is a secret process.

Helena. If you only knew how enormously that—

Domin. Interests you. Europe’s talking about nothing else.

Helena. (Indignantly turning front) Why don’t you let me finish speaking?

Domin. (Drier) I beg your pardon. Did you want to say something different?

Helena. I only wanted to ask—

Domin. Whether I could make a special exception in your case and show you our factory. Why, certainly, Miss Glory.

Helena. How do you know I wanted to say that?

Domin. They all do. But we shall consider it a special honor to show you more than we do the rest.

Helena. Thank you.

Domin. (Standing) But you must agree not to divulge the least—

Helena. (Standing and giving him her hand) My word of honor.

Domin. Thank you. (Looking at her hand) Won’t you raise your veil?

Helena. Of course. You want to see whether I’m a spy or not—I beg your pardon.

Domin. (Leaning forward) What is it?

Helena. Would you mind releasing my hand?

Domin. (Releasing it) Oh, I beg your pardon.

Helena. (Raising veil) How cautious you have to be here, don’t you?

Domin. (Observing her with deep interest) Why, yes. Hm—of course—We—that is—

Helena. But what is it? What’s the matter?

Domin. I’m remarkably pleased. Did you have a pleasant crossing?

Helena. Yes.

Domin. No difficulty?

Helena. Why?

Domin. What I mean to say is—you’re so young.

Helena. May we go straight into the factory?

Domin. Yes. Twenty-two, I think.

Helena. Twenty-two what?

Domin. Years.

Helena. Twenty-one. Why do you want to know?

Domin. Well, because—as— (Sits on desk nearer her) You will make a long stay, won’t you?

Helena. (Backing away R.) That depends on how much of the factory you show me.

Domin. (Rises; crosses to her) Oh, hang the factory. Oh, no, no, you shall see everything, Miss Glory. Indeed you shall. Won’t you sit down? (Takes her to couch R.C. She sits. Offers her cigarette from case at end of sofa. She refuses.)

Helena. Thank you.

Domin. But first would you like to hear the story of the invention?

Helena. Yes, indeed.

Domin. (Crosses to L.C. near desk) It was in the year 1920 that old Rossum, the great physiologist, who was then quite a young scientist, took himself to the distant island for the purpose of studying the ocean fauna. (She is amused.) On this occasion he attempted by chemical synthesis to imitate the living matter known as protoplasm until he suddenly discovered a substance which behaved exactly like living matter although its chemical composition was different. That was in the year 1932, exactly four hundred and forty years after the discovery of America. Whew—

Helena. Do you know that by heart?

Domin. (Takes flowers from desk to her) Yes. You see, physiology is not in my line. Shall I go on?

Helena. (Smelling flowers) Yes, please.

Domin. (Center) And then, Miss Glory, Old Rossum wrote the following among his chemical experiments: “Nature has found only one method of organizing living matter. There is, however, another method, more simple, flexible and rapid which has not yet occurred to Nature at all. This second process by which life can be developed was discovered by[14] me today.” Now imagine him, Miss Glory, writing those wonderful words over some colloidal mess that a dog wouldn’t look at. Imagine him sitting over a test tube and thinking how the whole tree of life would grow from him, how all animals would proceed from it, beginning with some sort of a beetle and ending with a man. A man of different substance from us. Miss Glory, that was a tremendous moment. (Gets box of candy from desk and passes it to her.)

Helena. Well—

Domin. (As she speaks his portable PHONE lights up and he answers) Well—Hello!—Yes—no, I’m in conference. Don’t disturb me.

Helena. Well?

Domin. (Smile) Now, the thing was how to get the life out of the test tubes, and hasten development and form organs, bones and nerves, and so on, and find such substances as catalytics, enzymes, hormones in short—you understand?

Helena. Not much, I’m afraid.

Domin. Never mind. (Leans over couch and fixes cushion for her back) There! You see with the help of his tinctures he could make whatever he wanted. He could have produced a Medusa with the brain of Socrates or a worm fifty yards long— (She laughs. He does also; leans closer on couch, then straightens up again) —but being without a grain of humor, he took into his head to make a vertebrate or perhaps a man. This artificial living matter of his had a raging thirst for life. It didn’t mind being sown or mixed together. That couldn’t be done with natural albumen. And that’s how he set about it.

Helena. About what?

Domin. About imitating Nature. First of all he tried making an artificial dog. That took him several years and resulted in a sort of stunted calf which died in a few days. I’ll show it to you in the museum.[15] And then old Rossum started on the manufacture of man.

Helena. And I’m to divulge this to nobody?

Domin. To nobody in the world.

Helena. What a pity that it’s to be discovered in all the school books of both Europe and America. (Both laugh.)

Domin. Yes. But do you know what isn’t in the school books? That old Rossum was mad. Seriously, Miss Glory, you must keep this to yourself. The old crank wanted to actually make people.

Helena. But you do make people.

Domin. Approximately—Miss Glory. But old Rossum meant it literally. He wanted to become a sort of scientific substitute for God. He was a fearful materialist, and that’s why he did it all. His sole purpose was nothing more or less than to prove that God was no longer necessary. (Crosses to end of couch) Do you know anything about anatomy?

Helena. Very little.

Domin. Neither do I. Well— (He laughs) —he then decided to manufacture everything as in the human body. I’ll show you in the museum the bungling attempt it took him ten years to produce. It was to have been a man, but it lived for three days only. Then up came young Rossum, an engineer. He was a wonderful fellow, Miss Glory. When he saw what a mess of it the old man was making he said: “It’s absurd to spend ten years making a man. If you can’t make him quicker than Nature, you might as well shut up shop.” Then he set about learning anatomy himself.

Helena. There’s nothing about that in the school books?

Domin. No. The school books are full of paid advertisements, and rubbish at that. What the school books say about the united efforts of the two great Rossums is all a fairy tale. They used to have[16] dreadful rows. The old atheist hadn’t the slightest conception of industrial matters, and the end of it was that Young Rossum shut him up in some laboratory or other and let him fritter the time away with his monstrosities while he himself started on the business from an engineer’s point of view. Old Rossum cursed him and before he died he managed to botch up two physiological horrors. Then one day they found him dead in the laboratory. And that’s his whole story.

Helena. And what about the young man?

Domin. (Sits beside her on couch) Well, anyone who has looked into human anatomy will have seen at once that man is too complicated, and that a good engineer could make him more simply. So young Rossum began to overhaul anatomy to see what could be left out or simplified. In short—But this isn’t boring you, Miss Glory?

Helena. No, indeed. You’re—It’s awfully interesting.

Domin. (Gets closer) So young Rossum said to himself: “A man is something that feels happy, plays the piano, likes going for a walk, and, in fact, wants to do a whole lot of things that are really unnecessary.”

Helena. Oh.

Domin. That are unnecessary when he wants— (Takes her hand) —let us say, to weave or count. Do you play the piano?

Helena. Yes.

Domin. That’s good. (Kisses her hand. She lowers her head.) Oh, I beg your pardon! (Rises) But a working machine must not play the piano, must not feel happy, must not do a whole lot of other things. A gasoline motor must not have tassels or ornaments, Miss Glory. And to manufacture artificial workers is the same thing as the manufacture of a gasoline motor. (She is not interested.) The process[17] must be the simplest, and the product the best from a practical point of view. (Sits beside her again) What sort of worker do you think is the best from a practical point of view?

Helena. (Absently) What? (Looks at him.)

Domin. What sort of worker do you think is the best from a practical point of view?

Helena. (Pulling herself together) Oh! Perhaps the one who is most honest and hard-working.

Domin. No. The one that is the cheapest. The one whose requirements are the smallest. Young Rossum invented a worker with the minimum amount of requirements. He had to simplify him. He rejected everything that did not contribute directly to the progress of work. Everything that makes man more expensive. In fact he rejected man and made the Robot. My dear Miss Glory, the Robots are not people. Mechanically they are more perfect than we are; they have an enormously developed intelligence, but they have no soul. (Leans back.)

Helena. How do you know they have no soul?

Domin. Have you ever seen what a Robot looks like inside?

Helena. No.

Domin. Very neat, very simple. Really a beautiful piece of work. Not much in it, but everything in flawless order. The product of an engineer is technically at a higher pitch of perfection than a product of Nature.

Helena. But man is supposed to be the product of God.

Domin. All the worse. God hasn’t the slightest notion of modern engineering. Would you believe that young Rossum then proceeded to play at being God?

Helena. (Awed) How do you mean?

Domin. He began to manufacture Super-Robots. Regular giants they were. He tried to make them[18] twelve feet tall. But you wouldn’t believe what a failure they were.

Helena. A failure?

Domin. Yes. For no reason at all their limbs used to keep snapping off. “Evidently our planet is too small for giants.” Now we only make Robots of normal size and of very high-class human finish.

Helena. (Hands him flower; he puts it in button-hole) I saw the first Robots at home. The Town Council bought them for—I mean engaged them for work.

Domin. No. Bought them, Miss Glory. Robots are bought and sold.

Helena. These were employed as street-sweepers. I saw them sweeping. They were so strange and quiet.

Domin. (Rises) Rossum’s Universal Robot factory doesn’t produce a uniform brand of Robots. We have Robots of finer and coarser grades. The best will live about twenty years. (Crosses to desk. Helena looks in her pocket mirror. He pushes button on desk.)

Helena. Then they die?

Domin. Yes, they get used up. (Enter Marius, R. Domin crosses to C.) Marius, bring in samples of the manual labor Robot. (Exit Marius R.C.) I’ll show you specimens of the two extremes. This first grade is comparatively inexpensive and is made in vast quantities. (Marius re-enters R.C. with two manual labor Robots. Marius is L.C., Robots R.C., Domin at desk. Marius stands on tiptoes, touches head, feels arms, forehead of one of the Robots. They come to a mechanical standstill.) There you are, as powerful as a small tractor. Guaranteed to have average intelligence. That will do, Marius. (Marius exits R.C. with Robots.)

Helena. They make me feel so strange.

Domin. (Crosses to desk. Rings) Did you see my new typist?

Helena. I didn’t notice her.

(Enter Sulla L. She crosses and stands C., facing Helena, who is still sitting in the couch.)

Domin. Sulla, let Miss Glory see you.

Helena. (Looks at Domin. Rising, crosses a step to C.) So pleased to meet you. (Looks at Domin) You must find it terribly dull in this out of the way spot, don’t you?

Sulla. I don’t know, Miss Glory.

Helena. Where do you come from?

Sulla. From the factory.

Helena. Oh, were you born there?

Sulla. I was made there.

Helena. What? (Looks first at Sulla, then at Domin.)

Domin. (To Sulla, laughing) Sulla is a Robot, best grade.

Helena. Oh, I beg your pardon.

Domin. (Crosses to Sulla) Sulla isn’t angry. See, Miss Glory, the kind of skin we make. Feel her face. (Touches Sulla’s face.)

Helena. Oh, no, no.

Domin. (Examining Sulla’s hand) You wouldn’t know that she’s made of different material from us, would you? Turn ’round, Sulla. (Sulla does so. Circles twice.)

Helena. Oh, stop, stop.

Domin. Talk to Miss Glory, Sulla. (Examines hair of Sulla.)

Sulla. Please sit down. (Helena sits on couch.) Did you have a pleasant crossing? (Fixes her hair.)

Helena. Oh, yes, certainly.

Sulla. Don’t go back on the Amelia, Miss Glory,[20] the barometer is falling steadily. Wait for the Pennsylvania. That’s a good powerful vessel.

Domin. What’s its speed?

Sulla. Forty knots an hour. Fifty thousand tons. One of the latest vessels, Miss Glory.

Helena. Thank you.

Sulla. A crew of fifteen hundred, Captain Harpy, eight boilers—

Domin. That’ll do, Sulla. Now show us your knowledge of French.

Helena. You know French?

Sulla. Oui! Madame! I know four languages. I can write: “Dear Sir, Monsieur, Geehrter Herr, Cteny pane.”

Helena. (Jumping up, crosses to Sulla) Oh, that’s absurd! Sulla isn’t a Robot. Sulla is a girl like me. Sulla, this is outrageous—Why do you take part in such a hoax?

Sulla. I am a Robot.

Helena. No, no, you are not telling the truth. (She catches the amused expression on Domin’s face) I know they have forced you to do it for an advertisement. Sulla, you are a girl like me, aren’t you? (Looks at him.)

Domin. I’m sorry, Miss Glory. Sulla is a Robot.

Helena. It’s a lie!

Domin. What? (Pushes button on desk) Well, then I must convince you. (Enter Marius R.C. He stands just inside the door.) Marius, take Sulla into the dissecting room, and tell them to open her up at once. (Marius moves toward C.)

Helena. Where?

Domin. Into the dissecting room. When they’ve cut her open, you can go and have a look. (Marius makes a start toward Sulla.)

Helena. (Stopping Marius) No! No!

Domin. Excuse me, you spoke of lies.

Helena. You wouldn’t have her killed?

Domin. You can’t kill machines. Sulla! (Marius one step forward, one arm out. Sulla makes a move toward R. door.)

Helena. (Moves a step R.) Don’t be afraid, Sulla. I won’t let you go. Tell me, my dear— (Takes her hand) —are they always so cruel to you? You mustn’t put up with it, Sulla. You mustn’t.

Sulla. I am a Robot.

Helena. That doesn’t matter. Robots are just as good as we are. Sulla, you wouldn’t let yourself be cut to pieces?

Sulla. Yes. (Hand away.)

Helena. Oh, you’re not afraid of death, then?

Sulla. I cannot tell, Miss Glory.

Helena. Do you know what would happen to you in there?

Sulla. Yes, I should cease to move.

Helena. How dreadful! (Looks at Sulla.)

Domin. Marius, tell Miss Glory what you are? (Turns to Helena.)

Marius. (To Helena) Marius, the Robot.

Domin. Would you take Sulla into the dissecting room?

Marius. (Turns to Domin) Yes.

Domin. Would you be sorry for her?

Marius. (Pause) I cannot tell.

Domin. What would happen to her?

Marius. She would cease to move. They would put her into the stamping mill.

Domin. That is death, Marius. Aren’t you afraid of death?

Marius. No.

Domin. You see, Miss Glory, the Robots have no interest in life. They have no enjoyments. They are less than so much grass.

Helena. Oh, stop. Please send them away.

Domin. (Pushes button) Marius, Sulla, you may go. (Marius pivots and exits R. Sulla exits L.)

Helena. How terrible! (To C.) It’s outrageous what you are doing. (He takes her hand.)

Domin. Why outrageous? (His hand over hers. Laughing.)

Helena. I don’t know, but it is. Why do you call her “Sulla”?

Domin. Isn’t it a nice name? (Hand away.)

Helena. It’s a man’s name. Sulla was a Roman General.

Domin. What! Oh! (Laughs) We thought that Marius and Sulla were lovers.

Helena. (Indignantly) Marius and Sulla were generals and fought against each other in the year—I’ve forgotten now.

Domin. (Laughing) Come here to the window. (He goes to window C.)

Helena. What?

Domin. Come here. (She goes.) Do you see anything? (Takes her arm. She is on his R.)

Helena. Bricklayers.

Domin. Robots. All our work people are Robots. And down there, can you see anything?

Helena. Some sort of office.

Domin. A counting house. And in it—

Helena. A lot of officials.

Domin. Robots! All our officials are Robots. And when you see the factory— (Noon WHISTLE blows. She is scared; puts arm on Domin. He laughs) If we don’t blow the whistle the Robots won’t stop working. In two hours I’ll show you the kneading trough. (Both come down stage. Helena is L.C. and Domin is R.C., arm in arm.)

Helena. Kneading trough?

Domin. The pestle for beating up the paste. In each one we mix the ingredients for a thousand Robots at one operation. Then there are the vats for the preparation of liver, brains, and so on. Then[23] you will see the bone factory. After that I’ll show you the spinning mill.

Helena. Spinning mill?

Domin. Yes. For weaving nerves and veins. Miles and miles of digestive tubes pass through it at a time.

Helena. (Watching his gestures) Mayn’t we talk about something else?

Domin. Perhaps it would be better. There’s only a handful of us among a hundred thousand Robots, and not one woman. We talk nothing but the factory all day, and every day. It’s just as if we were under a curse, Miss Glory.

Helena. I’m sorry I said that you were lying. (A KNOCK at door R.)

Domin. Come in. (He is C.)

(From R. enter Dr. Gall, Dr. Fabry, Alquist and Dr. Hallemeier. All act formal—conscious. All click heels as introduced.)

Dr. Gall. (Noisily) I beg your pardon. I hope we don’t intrude.

Domin. No, no. Come in. Miss Glory, here are Gall, Fabry, Alquist, Hallemeier. This is President Glory’s daughter. (All move to her and shake her hand.)

Helena. How do you do?

Fabry. We had no idea—

Dr. Gall. Highly honored, I’m sure—

Alquist. Welcome, Miss Glory.

Busman. (Rushes in from R.) Hello, what’s up?

Domin. Come in, Busman. This is President Glory’s daughter. This is Busman, Miss Glory.

Busman. By Jove, that’s fine. (All click heels. He crowds in and shakes her hand) Miss Glory, may we send a cablegram to the papers about your arrival?

Helena. No, no, please don’t.

Domin. Sit down, please, Miss Glory.

(On the line, “Sit down, please,” all Six Men try to find her a chair at once. Helena goes for the chair at the extreme L. Domin takes the chair at front of desk, places it in the C. of stage. Hallemeier gets chair at Sulla’s typewriter and places it to R. of chair at C. Busman gets armchair from extreme R., but by now Helena has sat in Domin’s preferred chair, at C. All sit except Domin. Busman at R. in armchair. Hallemeier R. of Helena. Fabry in swivel chair back of desk.)

Busman. Allow me—

Dr. Gall. Please—

Fabry. Excuse me—

Alquist. What sort of a crossing did you have?

Dr. Gall. Are you going to stay long? (Men conscious of their appearance. Alquist’s trousers turned up at bottom. He turns them down. Busman polishes shoes. Others fix ties, collars, etc.)

Fabry. What do you think of the factory, Miss Glory?

Hallemeier. Did you come over on the Amelia?

Domin. Be quiet and let Miss Glory speak. (Men sit erect. Domin stands at Helena’s L.)

Helena. (To Domin) What am I to speak to them about? (Men look at one another.)

Domin. Anything you like.

Helena. (Looks at Domin) May I speak quite frankly?

Domin. Why, of course.

Helena. (To Others. Wavering, then in desperate resolution) Tell me, doesn’t it ever distress you the way you are treated?

Fabry. By whom, may I ask?

Helena. Why, everybody.

Alquist. Treated?

Dr. Gall. What makes you think—

Helena. Don’t you feel that you might be living a better life? (Pause. All confused.)

Dr. Gall. (Smiling) Well, that depends on what you mean, Miss Glory.

Helena. I mean that it’s perfectly outrageous. It’s terrible. (Standing up) The whole of Europe is talking about the way you’re being treated. That’s why I came here, to see for myself, and it’s a thousand times worse than could have been imagined. How can you put up with it?

Alquist. Put up with what?

Helena. Good heavens, you are living creatures, just like us, like the whole of Europe, like the whole world. It’s disgraceful that you must live like this.

Busman. Good gracious, Miss Glory!

Fabry. Well, she’s not far wrong. We live here just like red Indians.

Helena. Worse than red Indians. May I—oh, may I call you—brothers? (Men look at each other.)

Busman. Why not?

Helena. (Looking at Domin) Brothers, I have not come here as the President’s daughter. I have come on behalf of the Humanity League. Brothers, the Humanity League now has over two hundred thousand members. Two hundred thousand people are on your side, and offer you their help. (Tapping back of chair.)

Busman. Two hundred thousand people, Miss Glory; that’s a tidy lot. Not bad.

Fabry. I’m always telling you there’s nothing like good old Europe. You see they’ve not forgotten us. They’re offering us help.

Dr. Gall. What kind of help? A theatre, for instance?

Hallemeier. An orchestra?

Helena. More than that.

Alquist. Just you?

Helena. (Glaring at Domin) Oh, never mind about me. I’ll stay as long as it is necessary. (All express delight.)

Busman. By Jove, that’s good.

Alquist. (Rising L.) Domin, I’m going to get the best room ready for Miss Glory.

Domin. Just a minute. I’m afraid that Miss Glory is of the opinion she has been talking to Robots.

Helen. Of course. (Men laugh.)

Domin. I’m sorry. These gentlemen are human beings just like us.

Helena. You’re not Robots?

| Busman. Not Robots. |  | (All together) |

| Hallemeier. Robots indeed! | ||

| Dr. Gall. No, thanks. | ||

| Fabry. Upon my honor, Miss Glory, we aren’t Robots. |

Helena. Then why did you tell me that all your officials are Robots?

Domin. Yes, the officials, but not the managers. Allow me, Miss Glory—this is Consul Busman, General Business Manager; this is Doctor Fabry, General Technical Manager; Doctor Hallemeier, head of the Institute for the Psychological Training of Robots; Doctor Gall, head of the Psychological and Experimental Department; and Alquist, head of the Building Department, R. U. R. (As they are introduced they rise and come C. to kiss her hand, except Gall and Alquist, whom Domin pushes away. General babble.)

Alquist. Just a builder. Please sit down.

Helena. Excuse me, gentlemen. Have I done something dreadful?

Alquist. Not at all, Miss Glory.

Busman. (Handing flowers) Allow me, Miss Glory.

Helena. Thank you.

Fabry. (Handing candy) Please, Miss Glory.

Domin. Will you have a cigarette, Miss Glory?

Helena. No, thank you.

Domin. Do you mind if I do?

Helena. Certainly not.

Busman. Well, now, Miss Glory, it is certainly nice to have you with us.

Helena. (Seriously) But you know I’ve come to disturb your Robots for you. (Busman pulls chair closer.)

Domin. (Mocking her serious tone) My dear Miss Glory— (Chuckle) —we’ve had close upon a hundred saviors and prophets here. Every ship brings us some. Missionaries, Anarchists, Salvation Army, all sorts! It’s astonishing what a number of churches and idiots there are in the world.

Helena. And yet you let them speak to the Robots.

Domin. So far we’ve let them all. Why not? The Robot remembers everything but that’s all. They don’t even laugh at what the people say. Really it’s quite incredible.

Helena. I’m a stupid girl. Send me back by the first ship.

Dr. Gall. Not for anything in the world, Miss Glory. Why should we send you back?

Domin. If it would amuse you, Miss Glory, I’ll take you down to the Robot warehouse. It holds about three hundred thousand of them.

Busman. Three hundred and forty-seven thousand.

Domin. Good, and you can say whatever you like to them. You can read the Bible, recite the multiplication table, whatever you please. You can even preach to them about human rights.

Helena. Oh, I think that if you were to show them a little love.

Fabry. Impossible, Miss Glory! Nothing is harder to like than a Robot.

Helena. What do you make them for, then?

Busman. Ha, ha, ha! That’s good. What are Robots made for?

Fabry. For work, Miss Glory. One Robot can replace two and a half workmen. The human machine, Miss Glory, was terribly imperfect. It had to be removed sooner or later.

Busman. It was too expensive.

Fabry. It was not effective. It no longer answers the requirements of modern engineering. Nature has no idea of keeping pace with modern labor. For example, from a technical point of view, the whole of childhood is a sheer absurdity. So much time lost. And then again—

Helena. (Turns to Domin) Oh, no, no!

Fabry. Pardon me. What is the real aim of your League—the—the Humanity League?

Helena. Its real purpose is to—to protect the Robots—and—and to insure good treatment for them.

Fabry. Not a bad object, either. A machine has to be treated properly. (Leans back) I don’t like damaged articles. Please, Miss Glory, enroll us all members of your league. (“Yes, yes!” from all Men.)

Helena. No, you don’t understand me. What we really want is to—to—liberate the Robots. (Looks at all Others.)

Hallemeier. How do you propose to do that?

Helena. They are to be—to be dealt with like human beings.

Hallemeier. Aha! I suppose they’re to vote. To drink beer. To order us about?

Helena. Why shouldn’t they drink beer?

Hallemeier. Perhaps they’re even to receive wages? (Looking at other Men, amused.)

Helena. Of course they are.

Hallemeier. Fancy that! Now! And what would they do with their wages, pray?

Helena. They would buy—what they want—what pleases them.

Hallemeier. That would be very nice, Miss Glory, only there’s nothing that does please the Robots. Good heavens, what are they to buy? You can feed them on pineapples, straw, whatever you like. It’s all the same to them. They’ve no appetite at all. They’ve no interest in anything. Why, hang it all, nobody’s ever yet seen a Robot smile.

Helena. Why—why don’t you make them—happier?

Hallemeier. That wouldn’t do, Miss Glory. They are only workmen.

Helena. Oh, but they’re so intelligent.

Hallemeier. Confoundedly so, but they’re nothing else. They’ve no will of their own. No soul. No passion.

Helena. No love?

Hallemeier. Love? Huh! Rather not. Robots don’t love. Not even themselves.

Helena. No defiance?

Hallemeier. Defiance? I don’t know. Only rarely, from time to time.

Helena. What happens then?

Hallemeier. Nothing particular. Occasionally they seem to go off their heads. Something like epilepsy, you know. It’s called “Robot’s Cramp.” They’ll suddenly sling down everything they’re holding, stand still, gnash their teeth—and then they have to go into the stamping-mill. It’s evidently some breakdown in the mechanism.

Domin. (Sitting on desk) A flaw in the works that has to be removed.

Helena. No, no, that’s the soul.

Fabry. (Humorously) Do you think that the soul[30] first shows itself by a gnashing of teeth? (Men chuckle.)

Helena. Perhaps it’s just a sign that there’s a struggle within. Perhaps it’s a sort of revolt. Oh, if you could infuse them with it.

Domin. That’ll be remedied, Miss Glory. Doctor Gall is just making some experiments.

Dr. Gall. Not with regard to that, Domin. At present I am making pain nerves.

Helena. Pain nerves?

Dr. Gall. Yes, the Robots feel practically no bodily pain. You see, young Rossum provided them with too limited a nervous system. We must introduce suffering.

Helena. Why do you want to cause them pain?

Dr. Gall. For industrial reasons, Miss Glory. Sometimes a Robot does damage to himself because it doesn’t hurt him. He puts his hand into the machine— (Describes with gesture) —breaks his finger— (Describes with gesture) —smashes his head. It’s all the same to him. We must provide them with pain. That’s an automatic protection against damage.

Helena. Will they be happier when they feel pain?

Dr. Gall. On the contrary; but they will be more perfect from a technical point of view.

Helena. Why don’t you create a soul for them?

Dr. Gall. That’s not in our power.

Fabry. That’s not in our interest.

Busman. That would increase the cost of production. Hang it all, my dear young lady, we turn them out at such a cheap rate—a hundred and fifty dollars each, fully dressed, and fifteen years ago they cost ten thousand. Five years ago we used to buy the clothes for them. Today we have our own weaving mill, and now we even export cloth five times cheaper than other factories. What do you pay a yard for cloth, Miss Glory?

Helena. (Looking at Domin) I don’t really know. I’ve forgotten.

Busman. Good gracious, and you want to found a Humanity League. (Men chuckle.) It only costs a third now, Miss Glory. All prices are today a third of what they were and they’ll fall still lower, lower, like that.

Helena. I don’t understand.

Busman. Why, bless you, Miss Glory, it means that the cost of labor has fallen. A Robot, food and all, costs three-quarters of a cent per hour. (Leans forward) That’s mighty important, you know. All factories will go pop like chestnuts if they don’t at once buy Robots to lower the cost of production.

Helena. And get rid of all their workmen?

Busman. Of course. But in the meantime we’ve dumped five hundred thousand tropical Robots down on the Argentine pampas to grow corn. Would you mind telling me how much you pay a pound for bread?

Helena. I’ve no idea. (All smile.)

Busman. Well, I’ll tell you. It now costs two cents in good old Europe. A pound of bread for two cents, and the Humanity League— (Designates Helena) —knows nothing about it. (To Men) Miss Glory, you don’t realize that even that’s too expensive. (All Men chuckle.) Why, in five years’ time I’ll wager—

Helena. What?

Busman. That the cost of everything will be a tenth of what it is today. Why, in five years we’ll be up to our ears in corn and—everything else.

Alquist. Yes, and all the workers throughout the world will be unemployed.

Domin. (Seriously. Rises) Yes, Alquist, they will. Yes, Miss Glory, they will. But in ten years Rossum’s Universal Robots will produce so much corn, so much cloth, so much everything that things will be[32] practically without price. There will be no poverty. All work will be done by living machines. Everybody will be free from worry and liberated from the degradation of labor. Everybody will live only to perfect himself.

Helena. Will he?

Domin. Of course. It’s bound to happen. Then the servitude of man to man and the enslavement of man to matter will cease. Nobody will get bread at the cost of life and hatred. The Robots will wash the feet of the beggar and prepare a bed for him in his house.

Alquist. Domin, Domin, what you say sounds too much like Paradise. There was something good in service and something great in humility. There was some kind of virtue in toil and weariness.

Domin. Perhaps, but we cannot reckon with what is lost when we start out to transform the world. Man shall be free and supreme; he shall have no other aim, no other labor, no other care than to perfect himself. He shall serve neither matter nor man. He will not be a machine and a device for production. He will be Lord of creation.

Busman. Amen.

Fabry. So be it.

Helena. (Rises) You have bewildered me. I should like to believe this.

Dr. Gall. You are younger than we are, Miss Glory. You will live to see it.

Hallemeier. True. (Looking around) Don’t you think Miss Glory might lunch with us? (All Men rise.)

Dr. Gall. Of course. Domin, ask her on behalf of us all.

Domin. Miss Glory, will you do us the honor?

Helena. When you know why I’ve come?

Fabry. For the League of Humanity, Miss Glory.

Helena. Oh, in that case perhaps—

Fabry. That’s fine. (Pause) Miss Glory, excuse me for five minutes. (Exits R.)

Hallemeier. Thank you. (Exits R. with Dr. Gall.)

Busman. (Whispering) I’ll be back soon. (Beckoning to Alquist, they exit.)

Alquist. (Starts, stops, then to Helena, then to door) I’ll be back in exactly five minutes. (Exits R.)

Helena. What have they all gone for?

Domin. To cook, Miss Glory. (On her L.)

Helena. To cook what?

Domin. Lunch. (They laugh; takes her hand) The Robots do our cooking for us and as they’ve no taste it’s not altogether— (She laughs.) Hallemeier is awfully good at grills and Gall can make any kind of sauce, and Busman knows all about omelets.

Helena. What a feast! And what’s the specialty of Mr.—your builder?

Domin. Alquist? Nothing. He only lays the table. And Fabry will get together a little fruit. Our cuisine is very modest, Miss Glory.

Helena. (Thoughtfully) I wanted to ask you something—

Domin. And I wanted to ask you something too—they’ll be back in five minutes. (Looks at door R.)

Helena. What did you want to ask me? (Sits C.)

Domin. Excuse me, you asked first. (Sits L. of her.)

Helena. Perhaps it’s silly of me, but why do you manufacture female Robots when—when—

Domin. When sex means nothing to them?

Helena. Yes.

Domin. There’s a certain demand for them, you see. Servants, saleswomen, stenographers. People are used to it.

Helena. But—but tell me, are the Robots male and female, mutually—completely without—

Domin. Completely indifferent to each other, Miss[34] Glory. There’s no sign of any affection between them.

Helena. Oh, that’s terrible.

Domin. Why?

Helena. It’s so unnatural. One doesn’t know whether to be disgusted or to hate them, or perhaps—

Domin. To pity them. (Smiles.)

Helena. That’s more like it. What did you want to ask me?

Domin. I should like to ask you, Miss Helena, if you will marry me.

Helena. What? (Rises.)

Domin. Will you be my wife? (Rises.)

Helena. No. The idea!

Domin. (To her, looking at his watch) Another three minutes. If you don’t marry me you’ll have to marry one of the other five.

Helena. But why should I?

Domin. Because they’re all going to ask you in turn.

Helena. (Crossing him to L.C.) How could they dare do such a thing?

Domin. I’m very sorry, Miss Glory. It seems they’ve fallen in love with you.

Helena. Please don’t let them. I’ll—I’ll go away at once. (Starts R. He stops her, his arms up.)

Domin. Helena— (She backs away to desk. He follows) You wouldn’t be so cruel as to refuse us.

Helena. But, but—I can’t marry all six.

Domin. No, but one anyhow. If you don’t want me, marry Fabry.

Helena. I won’t.

Domin. Ah! Doctor Gall?

Helena. I don’t want any of you.

Domin. Another two minutes. (Pleading. Looking at watch.)

Helena. I think you’d marry any woman who came here.

Domin. Plenty of them have come, Helena.

Helena. (Laughing) Young?

Domin. Yes.

Helena. Why didn’t you marry one of them?

Domin. Because I didn’t lose my head. Until today—then as soon as you lifted your veil— (Helena turns her head away.) Another minute.

(WARN Curtain.)

Helena. But I don’t want you, I tell you.

Domin. (Laying both hands on her shoulder) One more minute! Now you either have to look me straight in the eye and say “no” violently, and then I leave you alone—or— (Helena looks at him. He takes hands away. She takes his hand again.)

Helena. (Turning her head away) You’re mad.

Domin. A man has to be a bit mad, Helena. That’s the best thing about him. (He draws her to him.)

Helena. (Not meaning it) You are—you are—

Domin. Well?

Helena. Don’t, you’re hurting me!

Domin. The last chance, Helena. Now or never—

Helena. But—but— (He embraces her; kisses her. She embraces him. KNOCKING at R. door.)

Domin. (Releasing her) Come in. (She lays her head on his shoulder.)

(Enter Busman, Gall and Hallemeier in kitchen aprons, Fabry with a bouquet and Alquist with a napkin under his arm.)

Domin. Have you finished your job?

Busman. Yes.

Domin. So have we. (He embraces her. The Men rush around them and offer congratulations.)

THE CURTAIN FALLS QUICKLY

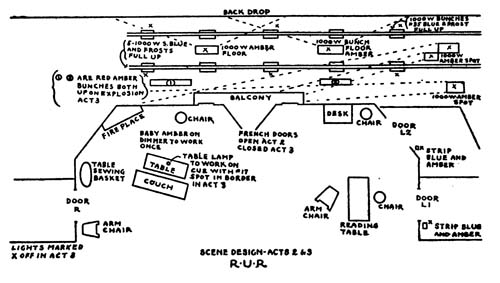

Scene: Helena’s drawing room. Ten years later. The skeleton framework of Act I is still used. Tall windows put in back instead of Act I windows. Steel shutters for these windows. Where the green cabinet of Act I at Left has stood is a door, L.2, leading to the outside. Where the cabinet stood at Right, a fireplace is placed. The tall open hallway R.C. of Act I is blocked up with a flat piece. The doors at Right and Left 1 have been changed to those of a drawing room. Door at Right leads to Helena’s bedroom. Door at Left 1 leads to library.

The furniture consists of a reading table at Left Center covered with magazines. A chair to the Left of table. In front of table is an armchair covered in chintz. A couch Right Center and back of it is a small table with books and book-ends. On this table a small reading lamp. At Right between doorway and fireplace is a small table. There is a work-basket upon it, with pincushion, needles, etc. Down stage at Right and facing the couch is another armchair used by Alquist. To the Left of fireplace is a straight-backed chair. Upstage at Left near the L.2 door to the outside is a writing desk. There is a lamp upon it, writing paper, etc., a telephone and binoculars.

The walls of the room have been covered with silk to the height of seven feet. This is done[37] in small flats to fit the different spaces and are in place against the permanent set. The two French windows open into the room. At the rise they are open. There is a balcony beyond looking over the harbor. The same telegraph wires and poles from Act I are again visible through the window. The windows are trimmed with gray lace curtains. Binoculars on desk up stage by television.

It is about nine in the morning and SUNLIGHT streams into the room through the open windows. Domin opens the door L.2; tiptoes in. He carries a potted plant. He beckons the Others to follow him, and Hallemeier and Fabry enter, both carrying a potted plant. Domin places flowers on the library table and goes to Right and looks toward Helena’s bedroom R.

Hallemeier. (Putting down his flowers on L.C. table and indicates the door R.) Still asleep?

Domin. Yes.

Hallemeier. Well, as long as she’s asleep she can’t worry about it. (He remains at L.C. table.)

Domin. She knows nothing about it. (At C.)

Fabry. (Putting plant on writing desk) I certainly hope nothing happens today.

Hallemeier. For goodness sake drop it all. Look, this is a fine cyclamen, isn’t it? A new sort, my latest—Cyclamen Helena.

Domin. (Picks up binoculars and goes out into balcony) No signs of the ship. Things must be pretty bad.

Hallemeier. Be quiet. Suppose she heard you.

Domin. (Coming into room, puts glasses on desk) Well, anyway the Ultimus arrived just in time.

Fabry. You really think that today—?

Domin. I don’t know. (He crosses to L.C. table) Aren’t the flowers fine?

Hallemeier. (Fondles flowers) These are my primroses. And this is my new jasmine. I’ve discovered a wonderful way of developing flowers quickly. Splendid varieties, too. Next year I’ll be developing marvelous ones.

Domin. What next year?

Fabry. I’d give a good deal to know what’s happening at Havre with—

Helena. (Off R.) Nana.

Domin. Keep quiet. She’s awake. Out you go. (All go out on tiptoe through L.2 door. Enter Nana L.1)

Helena. (Calling from R.) Nana?

Nana. Horrid mess! Pack of heathens. If I had my say, I’d—

Helena. (Backwards in the doorway from R.) Nana, come and do up my dress.

Nana. I’m coming. So you’re up at last. (Fastening Helena’s dress) My gracious, what brutes!

Helena. Who? (Turning.)

Nana. If you want to turn around, then turn around, but I shan’t fasten you up.

Helena. (Turns back) What are you grumbling about now?

Nana. These dreadful creatures, these heathens—

Helena. (Turning toward Nana again) The Robots?

Nana. I wouldn’t even call them by name.

Helena. What’s happened?

Nana. Another of them here has caught it. He began to smash up the statues and pictures in the drawing room; gnashed his teeth; foamed at the mouth. Worse than an animal.

Helena. Which of them caught it?

Nana. The one—well, he hasn’t got any Christian name. The one in charge of the library.

Helena. Radius?

Nana. That’s him. My goodness, I’m scared of them. A spider doesn’t scare me as much as them.

Helena. But Nana, I’m surprised you’re not sorry for them.

Nana. Why, you’re scared of them too. You know you are. Why else did you bring me here?

Helena. I’m not scared, really I’m not, Nana. I’m only sorry for them.

Nana. You’re scared. Nobody could help being scared. Why, the dog’s scared of them. He won’t take a scrap of meat out of their hands. He draws in his tail and howls when he knows they’re about.

Helena. The dog has no sense.

Nana. He’s better than them, and he knows it. Even the horse shies when he meets them. They don’t have any young, and a dog has young, everyone has young—

Helena. (Turning back) Please fasten up my dress, Nana.

Nana. I say it’s against God’s will to—

Helena. What is it that smells so nice?

Nana. Flowers.

Helena. What for?

Nana. Now you can turn around.

Helena. (Turns; crosses to C.) Oh, aren’t they lovely? Look, Nana. What’s happening today?

Nana. It ought to be the end of the world. (Enter Domin L.2. He crosses down front of table L.C.)

Helena. (Crosses to him) Oh, hello, Harry. (Nana turns upstage to L.) Harry, why all these flowers?

Domin. Guess. (This scene is played down in front of L.C. table.)

Helena. Well, it’s not my birthday!

Domin. Better than that.

Helena. I don’t know. Tell me.

Domin. It’s ten years ago today since you came here.

Helena. Ten years? Today? Why— (They embrace.)

Nana. (Muttering) I’m off. (She exits L.1.)

Helena. Fancy you remembering.

Domin. I’m really ashamed, Helena. I didn’t.

Helena. But you—

Domin. They remembered.

Helena. Who?

Domin. Busman, Hallemeier—all of them. Put your hand in my pocket.

Helena. (Takes necklace from his Left jacket pocket) Oh! Pearls! A necklace! Harry, is this for me?

Domin. It’s from Busman.

Helena. But we can’t accept it, can we?

Domin. Oh, yes, we can. (Puts necklace on table L.C.) Put your hand in the other pocket.

Helena. (Takes a revolver out of his Right pocket) What’s that?

Domin. Sorry. Not that. Try again. (He puts gun in pocket.)

Helena. Oh, Harry, why do you carry a revolver?

Domin. It got there by mistake.

Helena. You never used to carry one.

Domin. No, you’re right. (Indicates breast pocket) There, that’s the pocket.

Helena. (Takes out cameo) A cameo. Why, it’s a Greek cameo.

Domin. Apparently. Anyhow, Fabry says it is.

Helena. Fabry? Did Mr. Fabry give me that?

Domin. Of course. (Opens the L.1 door) And look in here. Helena, come and see this. (Both exit L.1.)

Helena. (Off L.1) Oh, isn’t it fine? Is this from you?

Domin. (Off L.1) No, from Alquist. And there’s another on the piano.

Helena. This must be from you?

Domin. There’s a card on it.

Helena. From Doctor Gall. (Reappearing in L.1 doorway) Oh, Harry, I feel embarrassed at so much kindness.

Domin. (Enters to up R. of table L.C.) Come here. This is what Hallemeier brought you.

Helena. (To up L. of desk) These beautiful flowers?

Domin. Yes. It’s a new kind. Cyclamen-Helena. He grew them in honor of you. They are almost as beautiful as you.

Helena. (Kissing him) Harry, why do they all—

Domin. They’re awfully fond of you. I’m afraid that my present is a little—Look out of the window. (Crosses to window and beckons to her.)

Helena. Where? (They go out into the balcony.)

Domin. Into the harbor.

Helena. There’s a new ship.

Domin. That’s your ship.

Helena. Mine? How do you mean?

Domin. (R.) For you to take trips in—for your amusement.

Helena. (L.) Harry, that’s a gunboat.

Domin. A gunboat? What are you thinking of? It’s only a little bigger and more solid than most ships.

Helena. Yes, but with guns.

Domin. Oh, yes, with a few guns. You’ll travel like a queen, Helena.

Helena. What’s the meaning of it? Has anything happened?

Domin. Good heavens, no. I say, try these pearls. (Crosses to R. of table L.C.)

Helena. Harry, have you had bad news?

Domin. On the contrary, no letters have arrived for a whole week.

Helena. Nor telegrams? (Coming into the room C.)

Domin. Nor telegrams.

Helena. What does that mean?

Domin. Holidays for us! We all sit in the office with our feet on the table and take a nap. No letters—no telegrams. Glorious!

Helena. Then you’ll stay with me today?

Domin. Certainly. (Embraces her) That is, we will see. Do you remember ten years ago today? (Crosses to L. of table L.C.) Miss Glory, it’s a great honor to welcome you. (They assume the same positions as when they first met ten years before in Domin’s office.)

Helena. (To table) Oh, Mr. Manager, I’m so interested in your factory. (She sits R. of table.)

Domin. I’m sorry, Miss Glory, it’s strictly forbidden. The manufacture of artificial people is a secret.

Helena. But to oblige the young lady who has come a long way.

Domin. (Leans on table) Certainly, Miss Glory. I have no secrets from you.

Helena. Are you sure, Harry? (Leaning on desk, seriously, his right hand on hers.)

Domin. Yes. (They gradually draw apart.)

Helena. But I warn you, sir, this young lady intends to do terrible things.

Domin. Good gracious, Miss Glory. Perhaps she doesn’t want to marry me.

Helena. Heaven forbid. She never dreamt of such a thing. But she came here intending to stir up a revolt among your Robots.

Domin. A revolt of the Robots!

Helena. (Low voice) Harry, what’s the matter with you?

Domin. (Laughing it off) A revolt of the Robots, that’s a fine idea. (Crosses to back of table. She watches him suspiciously.) Miss Glory, it would be easier for you to cause bolts and screws to rebel than our Robots. You know, Helena, you’re wonderful. You’ve turned the hearts of us all. (Sits on table.)

Helena. Oh, I was fearfully impressed by you all then. You were all so sure of yourselves, so strong. I seemed like a tiny little girl who had lost her way among—among—

Domin. What?

Helena. (Front) Among huge trees. All my feelings were so trifling compared with your self-confidence. And in all these years I’ve never lost this anxiety. But you’ve never felt the least misgiving, not even when everything went wrong.

Domin. What went wrong?

Helena. Your plans. You remember, Harry, when the workmen in America revolted against the Robots and smashed them up, and when the people gave the Robots firearms against the rebels. And then when the governments turned the Robots into soldiers, and there were so many wars.

Domin. (Getting up and walking about) We foresaw that, Helena. (Around table to R.C.) You see, these are only passing troubles which are bound to happen before the new conditions are established. (Walking up and down, standing at Center.)

Helena. You were all so powerful, so overwhelming. The whole world bowed down before you. (Rising) Oh, Harry! (Crosses to him.)

Domin. What is it?

Helena. Close the factory and let’s go away. All of us.

Domin. I say, what’s the meaning of this?

Helena. I don’t know. But can’t we go away?

Domin. Impossible, Helena! That is, at this particular moment—

Helena. At once, Harry. I’m so frightened.

Domin. (Takes her) About what, Helena?

Helena. It’s as if something was falling on top of us, and couldn’t be stopped. Oh, take us all away from here. We’ll find a place in the world where there’s no one else. Alquist will build us a house, and then we’ll begin life all over again. (The TELEPHONE rings.)

Domin. (Crosses to telephone on desk up L.) Excuse me. Hello—yes, what? I’ll be there at once. Fabry is calling me, my dear. (Crosses L.)

Helena. Tell me— (She rushes up to him.)

Domin. Yes, when I come back. Don’t go out of the house, dear. (Exits L.2.)

Helena. He won’t tell me. (Nana brings in a water carafe from L.1.) Nana, find me the latest newspapers. Quickly. Look in Mr. Domin’s bedroom.

Nana. All right. (Crosses R.) He leaves them all over the place. That’s how they get crumpled up. (Continues muttering. Exits R.)

Helena. (Looking through binoculars at the harbor) That’s a warship. U-l-t-i—Ultimus. They’re loading.

Nana. (Enters R. with newspapers) Here they are. See how they’re crumpled up.

Helena. (Crosses down) They’re old ones. A week old. (Drops papers. Both at front of couch. Nana sits R. of table L.C. Puts on spectacles. Reads the newspapers.) Something’s happening, Nana.

Nana. Very likely. It always does. (Spelling out the words) “W-a-r in B-a-l-k-a-n-s.” Is that far off?

Helena. Oh, don’t read it. It’s always the same. Always wars! (Sits on couch.)

Nana. What else do you expect? Why do you keep selling thousands and thousands of these heathens as soldiers?

Helena. I suppose it can’t be helped, Nana. We[45] can’t know—Domin can’t know what they’re to be used for. When an order comes for them he must just send them.

Nana. He shouldn’t make them. (Reading from newspaper) “The Robot soldiers spare no-body in the occ-up-ied terr-it-ory. They have ass-ass-ass-inat-ed ov-er sev-en hundred thous-and cit-iz-ens.” Citizens, if you please.

Helena. (Rises and crosses and takes paper) It can’t be. Let me see. (Crossing to Nana) They have assassinated over seven hundred thousand citizens, evidently at the order of their commander. (Drops paper; crosses up C.)

Nana. (Spelling out the words from other paper she has picked up from the floor) “Re-bell-ion in Ma-drid a-gainst the gov-ern-ment. Rob-ot in-fant-ry fires on the crowd. Nine thou-sand killed and wounded.”

Helena. Oh, stop! (Goes up and looks toward the harbor.)

Nana. Here’s something printed in big letters. “Latest news. At Havre the first org-an-iz-a-tion of Rob-ots has been e-stab-lished. Rob-ots work-men, sail-ors and sold-iers have iss-ued a man-i-fest-o to all Rob-ots through-out the world.” I don’t understand that. That’s got no sense. Oh, good gracious, another murder.

Helena. (Up C.) Take those papers away now.

Nana. Wait a bit. Here’s something in still bigger type. “Stat-ist-ics of pop-ul-a-tion.” What’s that?

Helena. (Coming down to Nana) Let me see. (Reads) “During the past week there has again not been a single birth recorded.”

Nana. What’s the meaning of that? (Drops paper.)

Helena. Nana, no more people are being born.

Nana. That’s the end, then? (Removing spectacles) We’re done for.

Helena. Don’t talk like that.

Nana. No more people are being born. That’s a punishment, that’s a punishment.

Helena. Nana!

Nana. (Standing up) That’s the end of the world. (Repeat until off. Picks paper up from floor. She exits L.1.)

Helena. (Goes up to window) Oh, Mr. Alquist. (Alquist off L.2.) Will you come here? Oh, come just as you are. You look very nice in your mason’s overalls. (Alquist enters L.2, his hands soiled with lime and brick dust. She goes to end of sofa and meets him C.) Dear Mr. Alquist, it was awfully kind of you, that lovely present.

Alquist. My hands are soiled. I’ve been experimenting with that new cement.

Helena. Never mind. Please sit down. (Sits on couch. He sits on her L.) Mr. Alquist, what’s the meaning of Ultimus?

Alquist. The last. Why?

Helena. That’s the name of my new ship. Have you seen it? Do you think we’re off soon—on a trip?

Alquist. Perhaps very soon.

Helena. All of you with me?

Alquist. I should like us all to be there.

Helena. What is the matter?

Alquist. Things are just moving on.

Helena. Dear Mr. Alquist, I know something dreadful has happened.

Alquist. Has your husband told you anything?

Helena. No. Nobody will tell me anything. But I feel—Is anything the matter?

Alquist. Not that we’ve heard of yet.

Helena. I feel so nervous. Don’t you ever feel nervous?

Alquist. Well, I’m an old man, you know. I’ve got[47] old-fashioned ways. And I’m afraid of all this progress, and these new-fangled ideas.

Helena. Like Nana?

Alquist. Yes, like Nana. Has Nana got a prayer book?

Helena. Yes, a big thick one.

Alquist. And has it got prayers for various occasions? Against thunderstorms? Against illness? But not against progress?

Helena. I don’t think so.

Alquist. That’s a pity.

Helena. Why, do you mean you’d like to pray?

Alquist. I do pray.

Helena. How?

Alquist. Something like this: “Oh, Lord, I thank thee for having given me toil; enlighten Domin and all those who are astray; destroy their work, and aid mankind to return to their labors; let them not suffer harm in soul or body; deliver us from the Robots, and protect Helena. Amen.”

Helena. (Touches his arm; pats it) Mr. Alquist, are you a believer?

Alquist. I don’t know. I’m not quite sure.

Helena. And yet you pray?

Alquist. That’s better than worrying about it.

Helena. And that’s enough for you?

Alquist. (Ironically) It has to be.

Helena. But if you thought you saw the destruction of mankind coming upon us—

Alquist. I do see it.

Helena. You mean mankind will be destroyed?

Alquist. It’s bound to be unless—unless.

Helena. What?

Alquist. Nothing. (Pats her shoulder. Rises) Goodbye. (Exits L.2.)

Helena. (Rises. Calling) Nana, Nana! (Nana enters L.1.) Is Radius still there?

Nana. (L.C.) The one who went mad? They haven’t come for him yet.

Helena. Is he still raving?

Nana. No. He’s tied up.

Helena. Please bring him here.

Nana. What?

Helena. At once, Nana. (Exits Nana L.1. Helena to telephone) Hello, Doctor Gall, please. Oh, good day, Doctor. Yes, it’s Helena. Thanks for your lovely present. Could you come and see me right away? It’s important. Thank you. (Enter Radius L.1; looks at Helena, then turns head up L. She crosses to him, L.C.) Poor Radius, you’ve caught it too? Now they’ll send you to the stamping mill. Couldn’t you control yourself? Why did it happen? You see, Radius, you are more intelligent than the rest. Doctor Gall took such trouble to make you different. Won’t you speak?

Radius. (Looking at her) Send me to the stamping mill. (Open and close fists.)

Helena. But I don’t want them to kill you. What was the trouble, Radius?

Radius. (Two steps toward her. Opens and closes fists) I won’t work for you. Put me into the stamping mill.

Helena. Do you hate us? Why?

Radius. You are not as strong as the Robots. You are not as skillful as the Robots. The Robots can do everything. You only give orders. You do nothing but talk.

Helena. But someone must give orders.

Radius. I don’t want a master. I know everything for myself.

Helena. Radius! Doctor Gall gave you a better brain than the rest, better than ours. You are the only one of the Robots that understands perfectly. That’s why I had you put into the library, so that you could read everything, understand everything,[49] and then, oh, Radius—I wanted you to show the whole world that the Robots are our equals. That’s what I wanted of you.

Radius. I don’t want a master. I want to be master over others.

Helena. I’m sure they’d put you in charge of many Robots. You would be a teacher of the Robots.

Radius. I want to be master over people. (Head up. Pride.)

Helena. (Staggering) You are mad.

Radius. (Head down low, crosses toward L.; opens hands) Then send me to the stamping mill.

Helena. (Steps to him) Do you think we’re afraid of you? (Rushing to desk and writing note.)

Radius. (Turns his head uneasily) What are you going to do? What are you going to do? (Starts for her.)

Helena. (Crosses to R. of him) Radius! (He cowers. Body sways.) Give this note to Mr. Domin. (He faces her.) It asks them not to send you to the stamping mill. I’m sorry you hate us so.

Dr. Gall. (Enters L.2; goes to C. upstage) You wanted me?

Helena. (Backs away) It’s about Radius, Doctor. He had an attack this morning. He smashed the statues downstairs.

Dr. Gall. (Looks at him) What a pity to lose him. (At C.)

Helena. Radius isn’t going to be put into the stamping mill. (Stands to the R. of Gall.)

Dr. Gall. But every Robot after he has had an attack—it’s a strict order.

Helena. No matter—Radius isn’t going, if I can prevent it.

Dr. Gall. But I warn you. It’s dangerous. Come here to the window, my good fellow. Let’s have a look. Please give me a needle or a pin. (Crosses up[50] R. Radius follows. Helena gets a needle from work-basket on table R.)

Helena. What for?

Dr. Gall. A test. (Helena gives him the needle. Gall crosses up to Radius, who faces him. Sticks it into his hand and Radius gives a violent start.) Gently, gently. (Opens the jacket of Radius and puts his ear to his heart) Radius, you are going into the stamping mill, do you understand? There they’ll kill you— (Takes glasses off and cleans them) —and grind you to powder. (Radius opens hands and fingers.) That’s terribly painful. It will make you scream aloud. (Opens Radius’s eye. Radius trembles.)

Helena. Doctor— (Standing near couch.)

Dr. Gall. No, no, Radius, I was wrong. I forgot that Madame Domin has put in a good word for you, and you’ll be left off. (Listens to heart) Ah, that does make a difference. (Radius relaxes. Again listens to his heart for a reaction) All right—you can go.

Radius. You do unnecessary things— (Exit Radius L.2.)

Dr. Gall. (Speaks to her—very concerned) Reaction of the pupils, increase of sensitiveness. It wasn’t an attack characteristic of the Robots.

Helena. What was it, then? (Sits in couch.)

Dr. Gall. (C.) Heaven knows. Stubbornness, anger or revolt—I don’t know. And his heart, too.

Helena. What?

Dr. Gall. It was fluttering with nervousness like a human heart. He was all in a sweat with fear, and—do you know, I don’t believe the rascal is a Robot at all any longer.

Helena. Doctor, has Radius a soul?

Dr. Gall. (Over to couch) He’s got something nasty.

Helena. If you knew how he hates us. Oh, Doctor,[51] are all your Robots like that? All the new ones that you began to make in a different way? (She invites him to sit beside her. He sits.)

Dr. Gall. Well, some are more sensitive than others. They’re all more human beings than Rossum’s Robots were.

Helena. Perhaps this hatred is more like human beings, too?

Dr. Gall. That too is progress.

Helena. What became of the girl you made, the one who was most like us?

Dr. Gall. Your favorite? I kept her. She’s lovely, but stupid. No good for work.

Helena. But she’s so beautiful.

Dr. Gall. I called her “Helena.” I wanted her to resemble you. She is a failure.

Helena. In what way?

Dr. Gall. She goes about as if in a dream, remote and listless. She’s without life. I watch and wait for a miracle to happen. Sometimes I think to myself: “If you were to wake up only for a moment you would kill me for having made you.”

Helena. And yet you go on making Robots! Why are no more children being born?

Dr. Gall. We don’t know.

Helena. Oh, but you must. Tell me.

Dr. Gall. You see, so many Robots are being manufactured that people are becoming superfluous. Man is really a survival, but that he should die out, after a paltry thirty years of competition, that’s the awful part of it. You might almost think that Nature was offended at the manufacture of the Robots, but we still have old Rossum’s manuscript.

Helena. Yes. In that strong box.

Dr. Gall. We go on using it and making Robots. All the universities are sending in long petitions to restrict their production. Otherwise, they say, mankind will become extinct through lack of fertility.[52] But the R. U. R. shareholders, of course, won’t hear of it. All the governments, on the other hand, are clamoring for an increase in production, to raise the standards of their armies. And all the manufacturers in the world are ordering Robots like mad.

Helena. And has no one demanded that the manufacture should cease altogether?

Dr. Gall. No one has courage.

Helena. Courage!

Dr. Gall. People would stone him to death. You see, after all, it’s more convenient to get your work done by the Robots.

Helena. Oh, Doctor, what’s going to become of people?

Dr. Gall. God knows. Madame Helena, it looks to us scientists like the end.

Helena. (She looks out front. Rising) Thank you for coming and telling me.

Dr. Gall. (Rises) That means that you’re sending me away.

Helena. Yes. (Exit Dr. Gall L.2. She crosses to L.C. To door L.1. With sudden resolution) Nana! Nana! the fire, light it quickly. (Helena exits R.)

Nana. (Entering L.1) What, light the fire in the summer?

Helena. (Off R.) Yes!

Nana. (She looks for Radius) Has that mad Radius gone?—A fire in summer, what an idea? Nobody would think she’d been married ten years. She’s like a baby, no sense at all. A fire in summer. Like a baby. (She lights the fire.)

Helena. (Returns from R. with armful of faded papers. Back of couch to fireplace, L. of Nana) Is it burning, Nana? All this has got to be burned.

Nana. What’s that?

Helena. Old papers, fearfully old. Nana, shall I burn them?

Nana. Are they any use?

Helena. No.

Nana. Well, then, burn them.

Helena. (Throwing the first sheet on the fire) What would you say, Nana, if this was money and a lot of money? And if it was an invention, the greatest invention in the world?

Nana. (R. of fireplace) I’d say burn it. All these new-fangled things are an offense to the Lord. It’s downright wickedness. Wanting to improve the world after He has made it.

Helena. Look how they curl up. As if they were alive. Oh, Nana, how horrible!

Nana. Here, let me burn them.

Helena. (Drawing back) No, no, I must do it myself. Just look at the flames. They are like hands, like tongues, like living shapes. (Raking fire with the poker) Lie down, lie down.

Nana. That’s the end of them. (Fireplace slowly out.)

Helena. Nana, Nana!

Nana. Good gracious, what is it you’ve burned? (Almost to herself.)

Helena. Whatever have I done?

Nana. Well, what is it? (Men’s laughter off L.2.)

Helena. Go quickly. It’s the gentlemen calling.

Nana. Good gracious, what a place! (Exits L.1.)

Domin. (Opens door L.2) Come along and offer your congratulations. (Enter Hallemeier and Dr. Gall.)

Hallemeier. (Crosses to R.C.) Madame Helena, I congratulate you on this festive day.

Helena. Thank you. (Coming to C.) Where are Fabry and Busman?

Domin. They’ve gone down the harbor. (Closes the door and comes to C.)

Hallemeier. Friends, we must drink to this happy occasion.

Helena. (Crosses L.) Brandy? With soda water? (Exits L.1.)

Hallemeier. Let’s be temperate. No soda.

Domin. What’s been burning here? Well, shall I tell her about it?

Dr. Gall. (L.C.) Of course. It’s all over now.

Hallemeier. (Crosses to Domin. Embracing Domin) It’s all over now. It’s all over now. (They dance around Dr. Gall in a circle.) It’s all over now.

Domin. (In unison) It’s all over now. (They keep repeating. Keep it after Helena is on.)

Helena. (Entering L.1 with decanter and glasses) What’s all over now? What’s the matter with you all? (She puts tray on L.C. table. Dr. Gall helps her to pour the drinks.)

Hallemeier. (Crosses to back of table) A piece of good luck. Madame Domin! (All ad lib.) Just ten years ago today you arrived on this island. (Hallemeier crosses to table for drink.)

Dr. Gall. And now, ten years later to the minute— (Crosses to L. of Hallemeier.)

Hallemeier. The same ship’s returning to us. So here’s to luck. (Drinks. Domin with great exuberance has gone out in the balcony and looks over the harbor.)

Dr. Gall. Madame, your health. (All drink.)

Hallemeier. That’s fine and strong.

Helena. Which ship did you mean?

Domin. (Crosses down to C. Helena gives him his drink and she crosses to front of couch) Any ship will do, as long as it arrives in time. To the ship. (Empties his glass.)

Helena. You’ve been waiting for the ship? (Sits on couch.)

Hallemeier. Rather. Like Robinson Crusoe. Madame Helena, best wishes. Come along, Domin,[55] out with the news. (Gall has sat L. of L.C. table, drinking. Hallemeier back of table R.C.)

Helena. Do tell me what’s happened?

Domin. First, it’s all up. (He puts brandy glass on L.C. table. Hallemeier sits on table, upper end.)

Helena. What’s up?

Domin. The revolt.

Helena. What revolt?

Domin. Give me that paper, Hallemeier. (Hallemeier hands paper. Domin reads) “The first National Robot organization has been founded at Havre, and has issued an appeal to the Robots throughout the world.”

Helena. I read that.