The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Parowan Bonanza, by B. M. Bower This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Parowan Bonanza Author: B. M. Bower Release Date: April 1, 2019 [EBook #59179] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PAROWAN BONANZA *** Produced by David T. Jones, Al Haines & the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Hopeful Bill Dale | 3 |

| II | Music Hath Charms | 16 |

| III | Luella Announces | 29 |

| IV | Good, Lively Prospect | 41 |

| V | Strangers in Camp | 50 |

| VI | Bill Grows Sentimental | 65 |

| VII | What Drives Prospectors Crazy | 74 |

| VIII | "Monte Cristo Would Enjoy This!" | 86 |

| IX | A "Hint" from Doris | 96 |

| X | "We're Rich, Bill, Dear" | 108 |

| XI | Mr. Rayfield Gives Advice | 119 |

| XII | A Man Shouldn't Mix Business with Love | 130 |

| XIII | Bill Learns About Women from 'er | 146 |

| XIV | Baker Cole | 159 |

| XV | "Mary's Going to Have a Home!" | 171 |

| XVI | So Bill Goes Back | 180 |

| XVII | Bill Gives the Public Mind a Lift | 191 |

| XVIII | The Yarn Al Freeman Told | 205 |

| XIX | "There'll Be More to Come of It" | 219 |

| XX | Luella Entertains | 229 |

| XXI | Bill and the Tame Bandits | 240 |

| XXII | Bill Buys Parowan | 255 |

| XXIII | Bill is Back Where He Started | 260 |

| XXIV | The Town That Was | 282 |

| XXV | Hopeless Bill Dale | 291 |

| XXVI | Bill Acquires a Cook | 295 |

To those who do not know the desert, the word usually conjures a picture of hot, waterless wastes of sand made desolate by sparse, withered gray sage more depressing than no growth at all; blighted by rattlesnakes and scorpions and the bleached bones of men from which lean coyotes go skulking away in the brazen heat that comes with the dawn; a place where men go mad with thirst and die horribly, babbling the while of mountain brooks and the cool blur of lakes shining blue in the distance, painted treacherously there by the desert mirage.

Sometimes the desert is like that in certain places and at certain seasons of the year, but the men who know it best forgive the desert its trespasses, and love it for its magnificent distances, always beautiful, always changing their panorama of lights and shadows on uptilted mesas[4] and deep, gray-green valleys. Such men yield to the thrall of desert sorcery that paints wonderful, translucent tints of blue, violet and purple on all the mountains there against the sky. They love the desert nights when the stars come down in friendly fashion to gaze tranquilly upon them as they sit beside their camp fires and smoke and dream, and see rapturous visions of great wealth born of that mental mirage which is but another bit of desert enchantment.

Bill Dale was such a man. Hopeful Bill, men called him, with the corners of their mouths tipped down. Bill loved the desert, loved to wander over it with his two burros waddling under full packs of grub and mining tools and dynamite. He loved to pry and peck into some mineral outcropping in a far canyon where no prospector had been before him. And though he sometimes cursed the heat and the wind and brackish water, where he expected a clear, cold spring, he loved the desert, nevertheless, and called it home.

Men jibed at his unquenchable optimism and mistook the man behind his twinkling eyes for a rainbow chaser, mirage-mad in a mild way. For even in Nevada, where the hills have made many a man a millionaire, they laugh at the seeker and call failure after him until he has found what he seeks. Then they want his friendship and a share[5] in his good fortune; and this merely because Nevada is peopled—very thinly—with human beings and not by gods or saints.

Occasionally, when Bill Dale came to town for fresh supplies and mail, some one would wonder why a great, strapping fellow like Hopeful didn't go to work. Perhaps that was because Hopeful carried a safety razor in his pack, and had the knack of looking well-groomed on a pint of water, a clean shirt, an aluminum comb and six inches of mirror. Your orthodox prospector (at least in fiction) promises himself a bath and a clean shave when he strikes it rich, and frequently is made to forego the luxury for years.

Men liked Hopeful Bill, but they thought he was a shiftless cuss who would never amount to anything, since he had taken to the burro trail. A few remembered that Hopeful's father had been unlucky in a boom when Hopeful was just a kid. They thought it was a bad thing to have the legend of a gold mine in the family. Personally they called him a good scout,—and that was because they could borrow money from him, if he had any, and need not fear the embarrassment of being asked to repay it. They could tell their private troubles to Bill and be sure that he would never betray the confidence. But it never occurred to any man that knew him that Hopeful Bill Dale[6] might now and then need money, or sympathy, or some one besides his menagerie to tell his troubles to.

It was the menagerie that belittled Hopeful Bill Dale in the eyes of his fellows. Commonplace souls they were, their brains dust-dry in that cranny where imagination should flourish. They could not see why any grown man should carry a green parrot and a great, gray, desert turtle around with him wherever he went. They were willing to concede the harmlessness of the fuzzy-faced Airedale, since any man is entitled to own a dog if he wants one. But they could not understand a man who would call a dog Hezekiah; which was not a dog's name at all. The mournful, hairy-chopped Hezekiah was therefore a walking proof of Hopeful Bill Dale's eccentricity. And as all the world knows, a man must be rich before he dare be different from his fellows.

Of course, they argued in Goldfield, any grown man that would keep a turtle on a string—tied firmly through a hole bored in the tail of its shell—might be expected to call it Sister Mitchell and claim that it had a good Methodist face. Who ever heard of a turtle having a face? And there was the parrot, that cooed lovingly against Bill's cheek and made little kissing sounds with its beak,—the same beak that had taken a chunk out of a[7] stranger's hand, swearing volubly at her victim afterward. Even if Goldfield could overlook the parrot, there was its name to damn Hopeful Bill Dale finally and completely. Couldn't call it Polly, which is the natural, normal name for a parrot! No, he had to name the thing Luella. Add to that Bill's burros, that answered gravely to the names Wise One and Angelface. Could any man know these things and still take Bill Dale seriously?

Goldfield shook its head—behind Bill's back—and said he was a nice, likable fellow, but—a little bit "off" in some ways.

So there you have him, according to the estimate of his acquaintances: A great, good-natured, fine-looking man in his early thirties; a man always ready to listen to a tale of woe or to put his hand in his pocket and give of what he had, nor question the worthiness of the cause; but a man who seemed content to wander through the hills prospecting, when he might have made a success of some business more certain of yielding a good living—and mediocrity; a man with a queer kink somewhere in his make-up that prevented his taking life seriously.

Prospectors were usually men who, having failed, through age or other cause, to make good at anything else, took to burrowing in the hills[8] and pecking at rocks and dreaming. If the habit fixed itself upon them they became plain desert rats, crack-brained and useless for any other vocation. Hopeful Bill Dale was too young, too vigorous to have the name "desert rat" laid upon him,—yet. But it was tacitly agreed that he was in a fair way to become a desert rat, if he did not pull up short and turn his mind to something else. The purposeless life he was leading would "get" him in a few more years, they prophesied sagely.

One day in spring Bill Dale walked behind his burros into Goldfield and outfitted for a long trip. Had any one examined closely Bill's pack loads, he would have guessed that Hopeful Bill had a camp established somewhere in the wilderness and was in for all the grub his two burros and a borrowed one could carry.

The storekeeper knew, as he weighed out sugar, rice, beans, dried fruit (prunes, raisins and apricots mostly), that Bill was buying with a careful regard for the maximum nourishment coupled with the minimum weight. For instance, Bill bought five pounds of black tea, though he loved coffee with true American fervor. Rolled oats he also bought,—a twenty-five pound sack. There was a great deal of nourishment in rolled oats, properly cooked. And when Bill called for[9] two large cans of beef extract, the storekeeper looked at him knowingly.

"Goin' to develop something you've struck, hey?" he guessed with unconscious presumption.

"Going to stay till the grub's low, anyway," Bill drawled imperturbably. "Hazing burros over the trail is going to be hot work, from now on until fall. It's cooler in the hills. I'm taking out a rented burro that will come back alone. I figure this grubstake ought to run me until cool weather."

"Got a pretty good claim?" Storekeepers in mining towns are likely to be inquisitive.

"Can't say as I have," Bill grinned. "Open for engagements with old Dame Fortune, though. Kinda hoping, too, that she don't send her daughter, instead, to make a date with me."

"Her daughter?" The storekeeper was one of those who had desert dust in the folds of his brain. "Who's she?"

Bill looked at him soberly, rolling a smoke with fingers smoother and better kept than prospectors usually could show.

"Mean to tell me you never met Miss Fortune yet?" His lips were serious; as for his eyes, one never could tell. His eyes always had a twinkle. "She can sure keep a man guessing," he added. "I like her mother better, myself."[10]

"Oh. Er—he-he! Pretty good," testified the storekeeper dubiously. Something queer about a fellow that springs things you never heard of before, he was thinking. The storekeeper liked best the familiar jokes he had heard all his life. He didn't have to think out their meaning.

"Hey! Cut that out! Bill! Take a look at that!" A voice outside called imperiously, and Bill swung toward the door.

"What is it, Luella?"

"Take a look at that! Git a move on!"

In the doorway Bill stopped. Luella was walking pigeon-toed up and down the back of Wise One, where she usually perched while Bill traveled the desert. Three half-grown boys were crowding close, trying to reach the string of Sister Mitchell, who had crawled under the store steps. The string was fastened to the crotch of Wise One's pack saddle, and Wise One was circling slowly, keeping his heels toward the enemy. Luella's tail was spread fanwise, showing the red which even Nature seems to recognize as a danger signal. Her eyes were yellow flames, her neck feathers were ruffled. By all these signs Luella was not to be trifled with.

"Cut that out! Hez! Here, Hez! Where the hell is that dog? Hezekiah! Bill! Come alive, come alive!" Up and down, up and down, one[11] foot lifted over the other, her eyes on the giggling boys, Luella expostulated and swore.

Bill stepped outside, throwing away the burnt stub of a match. The three boys looked at him and fled, though Bill was not half so dangerous as Luella or Wise One, either of which would have sent them yelping in another minute.

"Hez! Here, Hez! Where the hell's that dog?" Luella called again impatiently and wheeled, stepping up relievedly upon Bill's outstretched finger. "Lord, what a world!" she muttered pensively, and subsided under Bill's caressing hand.

Bill dragged Sister Mitchell from under the steps and swung her, head down, to the porch. He sat down beside her, his knees drawn up, Luella perched upon one of them.

"Add two cartons of Durham, will you?" Bill called over his shoulder to the storekeeper and turned back to his perturbed pets.

Sister Mitchell thrust forth a cautious head and craned a skinny neck, looking for fresh alarms. Luella tilted her head and eyed the turtle speculatively. "Cut that out!" she commanded harshly, and Sister Mitchell drew in her head timorously before she realized that it was only parrot talk and not to be taken seriously.

The storekeeper asked Bill a question which ne[12]cessitated Bill's personal examination of two brands of bacon; wherefore, he placed Luella on the porch beside Sister Mitchell and went inside to finish making up his load of supplies. When he emerged with a sack of flour on his shoulder and three sides of bacon under one arm, Luella was riding up the platform on Sister Mitchell's back and telling her to "git a move on." At the other end of the porch a small audience stood laughing at the performance.

"What'll you take for that parrot, Hopeful?" a man asked, grinning.

"Same price you ask for your oldest kid," Bill retorted, and returned for another load from the store.

"Make that strike yet?" another called, as Bill came out with his arms full.

"You bet! Solid ledge of gold, Jim. Knock it off in chunks with a single-jack and gadget. Bring you a hunk next trip in—if I can think of it."

"Hate to hang by the heels till you do," Jim retorted.

"Hate to have you," Bill agreed placidly, stepping over Luella and her mount that he might deposit his load on the edge of the porch.

"What yuh got out there, anyway?" Jim persisted curiously. "You aren't packing all that[13] grub out in the desert just to eat in the shade of a Joshuway tree. What yuh got?"

"Hopes." Bill bent and slid a sack from his shoulder to the pile of supplies. "Outcropping of lively looking rock, Jim. Good indications. I'm hoping it'll turn out something, maybe, when I get into it a ways."

"Get an assay on it?" Jim's curiosity was fading perceptibly. The same old story: lively looking rock, indications; desert rats all came in with that elusive encouragement.

"Trace of silver, two dollars in gold," Hopeful Bill replied. "I'm hoping it'll run into higher values when I hit the contact."

"What contact you got?" Jim's tone was plainly disparaging. "You can't bank too strong on values at contact, Bill."

"Well, this looks pretty fair," Bill argued mildly. "A showing of quartzite,—if it's in place; which I'm digging to find out. Nothing lost but a little sweat and powder, if I don't hit it. I can eat as cheaply in the hills as I can here. Cheaper." From under his dusty hat brim he sent a glance toward the restaurant across the street. "And I know it's clean. I like to have eat a fly, this noon."

"Why didn't you try the Waffle Parlor? They've got screens."[14]

"My own cooking suits me just fine," Bill returned amiably.

"All right, if you like that kinda life," Jim carped. "I should think you'd want to get into something, Bill. You aren't any has-been——"

"Nope, I'm a never-was," Bill retorted shamelessly. "And a going-to-be," he added with naïve assurance. "You mark that down in your book, Jim. Some day you're going to brag about knowing Bill Dale. Some day your tone's going to be hearty and your hand'll be out when you see me coming. You guys will all of you be saying you knew me when."

The group bent backward to let the laughs out full and free. Into the midst of their mirth Luella came scrabbling with her pigeon-toed walk, her tail spread wide and her throat ruffled.

"You cut that out!" she shrieked angrily. "Hez! Here, Hez! Where the hell's that dog? Git outa here! Git a move on."

Bill grabbed her before she succeeded in shedding blood.

"Luella doesn't like the tone of that applause," he observed, holding her close to his chest while he smoothed her ruffled feathers. "Luella's a sensitive bird, and she stands up for her folks."

With three loaded burros nipping along before him, the whiskered Hezekiah slouching at[15] his heels, and Luella and Sister Mitchell riding serenely the pack of Wise One, Bill left the town and struck off up the hill by a trail he knew that would cut off a great elbow of the highway, which was dusty and rutted with the passing of great, heavy ore wagons and automobiles loaded with fortune-hunters and camp equipment. At the crest of the long slope the burros stopped to breathe, and Bill turned and stood gazing back at the camp whose first fever was already cooling a bit, leaving the restless ones a bit bored and eager for some new strike in a fresh district, with the whooping boom times that must inevitably follow.

"Laugh, darn you!" Bill figuratively addressed Jim and his companions down there in the town. "You're bone from your necks up, or you'd see plumb through my talk—and be on my trail like ants after a leaky syrup can. Go ahead and laugh, and call me a fool behind my back! You won't take the notion to follow me, anyway."

"Lord, what a world!" chuckled Luella, scrambling for fresh foothold on the canvas pack as Wise One started on with a lurch.

"You're dead right, old girl," Bill agreed; and went on, grinning at something hidden in his thoughts.

Just before sundown, while Bill and his burros and Hezekiah were plodding down the highway toward the sporadic camp called Cuprite, a big touring car came roaring up behind and passed Hopeful Bill in a smothering cloud of yellow dust. Bill observed that it was loaded with luggage and stared after it with that aimless interest which the empty desert breeds in men. A coyote on a hilltop, a strange track in the trail, human beings traveling that way,—it matters little what trivial thing breaks the monotony of plodding through desert country.

Bill could remember when this same road was peopled with men rushing here and there after elusive fortune. Good men and bad, honest men and thieves, the dust never settled to lie long upon the yellow trail. That last two years had made a difference. The tide was fast ebbing, and men were rushing elsewhere in search of the millions they coveted.

"Get a move on!" Bill called to Wise One, at[17] the head of the pack train, with the strange burro tied behind at a sufficient length of rope to protect him from Wise One's heels, which were likely to lift unexpectedly. Luella repeated the command three times without stopping, and the burros shuffled a bit faster in the lowering dust cloud kicked up by the speeding car.

Farther on, Wise One stopped short, backing up from an object in the trail. Bill went forward to investigate, and lifted from the ground a black leather case such as musicians use to hold band instruments. Bill undid the catches and looked in upon a shining, silver object with a gold-lined, bell-shaped mouth and many flat discs all up and down its length. He gazed up the road, already veiled with the purplish haze that comes to the desert before dusk, when the sun has dipped behind a mountain. The car was gone, hidden completely from sight by a low ridge.

"They'll be back," Bill observed tranquilly, and tied the case securely upon the pack of Angelface. "They're bound to miss a thing like that. Anyway, I'll probably run across 'em somewhere."

"Hate to hang till yuh do," remarked Luella, who had evidently been adding to her repertoire in Goldfield while no one thought she was taking heed; which is the way of parrots the world over.[18]

"I don't know about that, now," Bill grinned. "Anyway, if it was mine, I know I'd miss it. I always did want to play a horn."

"Aw, cut it out!" Luella advised him shrewishly. "Git a move on!" Which pertinent retort may possibly explain why Hopeful Bill Dale looked upon the parrot as a real companion. He swore that the bird understood what he said and conversed intelligently, so far as her vocabulary permitted. And her vocabulary, while simple, seemed sufficient for her needs.

Instead of turning aside to a certain spring and camping there for the night, Bill camped near the road where he could not miss seeing and being seen, if any came that way. It was quite a tramp to the spring, so he took a couple of desert water bags and mounted Wise One, leaving the other two burros to follow, and trusting his supplies to the care of Hezekiah and the parrot.

He was not approached that night, nor the next day. Cars passed him, it is true, hurrying through dust clouds from either direction; but never the automobile that had lost the horn. So Bill arrived, in the course of time, at his camp, richer—or poorer, according to viewpoint—by one band instrument of doubtful name and unknown possibilities.

In spring the desert is beautiful. Bill loved[19] the desert flowers, vivid pinks and blues and yellows, dainty of form, sweet as honeycomb. He loved the desert lights, as delicately vivid as were the flowers growing out of the sandy soil, shyly snuggled against some stiff, scraggy bush. Cottontails romped through the sage in the afterglow that lingers long in that high altitude, and Bill let them go unmolested, and gave Hezekiah a lecture. He did not believe in killing just because one can, and there was meat in camp already. From the juniper bushes above the spring the quail were calling. "Shut-that-door! Shut-that-door!"—or so Bill and Luella interpreted the call. Farther up on the hillside, doves were crying mournfully. And Bill knew that higher, on the very top of the butte, mountain sheep, deer and antelope were hiding their bandy-legged young away from the prowling coyotes and "link cats" that were less conscientious than Bill when the chance came for a killing.

Yet this was the desert, against which men rail. There was no mistaking. Out there stood a barrel cactus, almost within reach of a gaunt yucca whose awkward, spiny limbs were rigidly upheld like bloated arms,—colloquially called Joshua trees because they seemed always to be imploring the sun. Down in the valley a dry lake lay baked yellow, hard as cement, with dust devils[20] whirling dizzily down its bald length when Bill looked that way. On the map you will see that valley. It is officially known as the Amargosa Desert. And over the ridge which wore a mystic veil of blended violet and amethyst, Death Valley lay crouched low amongst the hills. The maps call that amethyst and violet pile the Funeral Mountains; and away to the east, Bill could see the faint blue line of Skull Mountains and the Specter Range standing bold behind the Skeleton Hills; proof enough that this was the desert, since it bore the sinister names given it by those who knew too little and dared too much.

It could be cruel,—but not crueller than the cities. It could be lonely, though not so lonely as a multitude. The air was clean and sweet and of that heady quality that only altitude can give. Bill squatted on his heels by his camp fire, just about four thousand feet above sea level,—higher than that above the floor of Death Valley, whose rim he could see, whose poison springs he knew, whose terrible breath he had drawn into his nostrils.

From now on the geography will remain closed and you must take my word for it. And when I tell you that the great, blunt-topped butte behind him was Parowan Peak, don't look for it on the map; you'll never find it. It's a great, wild[21] country, a beautiful, savage country, and if you don't love it you will fear it greatly. And fear it is that rouses the sleeping devil of the desert and sets the bones of men bleaching under the arid sky.

Hopeful Bill Dale knew the desert, and loved it, and made friends with it. He plucked a bright red "Indian paintbrush" from beside a rock and held it up to Luella, watching him cock-eyed from her crude perch of juniper laid across two forked sticks driven into the sand. Luella took the flower in one claw, looked it over and dropped it disdainfully.

"Aw, cut it out! Let's eat," she suggested.

"You're on," Bill replied amiably, turning fried potatoes out of the frying pan. "Come and get it, old girl."

Luella was not a flying bird, except under stress of great emotion. Now she leaned head downward, her beak closing upon a knob where a small branch had been lopped off the stick. Turning like an acrobat, she went down with the aid of beak and claws, and pigeon-toed over to Bill's crude table, crawled upon a convenient rock and waited solemnly for her first helping of fried potato, which she ate daintily, holding it in one claw.

"I've got a surprise for you, old girl," Bill began, when the edge of their hunger had dulled[22] a bit. "That horn we picked up in the road,—it's mine now, by right of discovery. You saw how I stuck to the Goldfield road and made an extra day's journey of the trip, just in case that car came back, hunting for the horn. Lord knows where they are, by now. So I figure the thing belongs to me. After supper, I'm going to open her up and give you some music."

"Hate to hang till yuh do," Luella observed pessimistically. "Let's eat."

Bill dipped a piece of bread in his coffee and gave it to her, unmoved by her pessimism. "One thing a fellow needs out here alone is distraction," he went on. "You're getting so you know more than I do—leave you to tell it—and you're more human than lots of folks. You've reached the point where I can't seem to teach you anything more, Luella. You could almost hold down a claim alone, except for the cooking and maybe swinging a single-jack. So I figure a little diversion will come in about right."

"You're on," said Luella. "Git a move on."

So that is how Hopeful Bill Dale conceived the idea of becoming a musician, thus making use of the opportunity which Providence—or something not so kind—had thrown in his way. It may seem a trivial thing, but trivial things have a fashion of tripping one's feet in the race for hap[23]piness, or perchance proving to be the one factor that makes success certain. Bill washed his dishes and tidied his camp, and then he opened the instrument case and for the first time removed the shining thing within. Luella, once more back on her perch, watched him distrustfully.

"Luck's own baby boy!" he ejaculated under his breath. "Here's a book goes with it. 'Progressive Method for the Saxophone.' Saxophone, hunh? I always did want to learn one, Luella; believe it or not. Well, let's go."

"Aw, cut it out!" Luella advised him gloomily, but Bill was absorbed in putting together the instrument and in reading certain directions on the first page of the book.

Followed a muttered monologue, accompanied by certain unusual grimaces and gestures.

"'Upper and lower lips slightly over the teeth—chin must be down—lips drawn back as when laughing.' I got that, all right. 'Put the mouthpiece into the mouth a little less than halfway.'" Goggling down at the page, Bill obeyed,—or tried to. When he recovered from that experiment, he read in silence and looked up at Luella puzzled.

"Now if you were human, you could maybe explain to me how a fellow is going to breathe steadily without making use of his nose, mouth, ears or eyes," he hazarded. "Your mouth is[24] full of saxophone to your palate and past it, and you mustn't breathe through your nose, because that looks bad, and your eyes must follow the notes and it's against the rule to puff out your cheeks, which is unbecoming. I figure, Luella, a man's got to curl up his toes and die till he's through playing. Hunh?"

"Git a move on! Come alive, come alive!"

"Oh, well,—" said Bill, and began again.

Nothing happened, save imminent death from strangulation. Bill looked foolishly at the instrument. Once more he placed certain fingers carefully upon certain keys, flattened his lips to a fixed, painful grin, swallowed as much mouthpiece as was possible without choking himself to death, and blew until his eyes popped. Sister Mitchell came slowly forward and stood with her skinny gray neck stretched toward Bill, her melancholy eyes regarding curiously the long silver thing in Bill's tense embrace. Hezekiah came up and squatted on his stump of a tail, his ugly, hairy face tilted sidewise while he stared. Bill's family were always keenly interested in everything that concerned Bill, if it were only a new label on a can of tomatoes.

"Didn't get a rise out of it yet," Bill apologized embarrassedly, "but I will. I've heard fellows warble on these brutes till your heart fair[25] melts in your chest. What they can do, I can do. A little music, evenings, is what this camp needs."

In the dimming light he read the confusing instructions all over again, engulfed the ebony mouthpiece within his carefully grinning mouth, took a deep breath,—and something slipped. A terrific, deep bass note rumbled forth quite unexpectedly, before Bill had fairly begun to blow.

Bill jumped. Sister Mitchell disappeared precipitately into her shell, Luella let out an oath which Bill only used under sudden overwhelming emotion, and Hezekiah gave a howl and streaked it into the desert.

Bill recovered first, and on the whole he was pleased with himself. He had gotten the hang of it by sheer accident, and he sat and made terrible sounds while Luella paced up and down her perch with her tail spread, cursing and imploring by turns.

She wronged Bill if she thought that Bill enjoyed his spasmodic blattings and squeakings. He did not. He winced at every squawk, even while he persisted doggedly in the uproar. Through discord only might he hope to become a master of the melody he craved, wherefore he endured the discord, thankful that no human being was near. It took him all the next day to round[26] up the burros, however, and Sister Mitchell went into retirement in her shell and remained there stubbornly.

Thereafter, the stars looked down upon a pathetic little desert comedy enacted every night: The pathetic comedy of Bill Dale tying up his burros and his dog and anchoring a gray desert turtle to a rock before he sat down, with a dull-green instruction book before him on the ground, its corners weighted with small rocks, and practiced dolefully and indefatigably upon a silver-plated saxophone. As long as he could see he would sit cross-legged, humped over his notes,—of which he possessed a rudimentary knowledge learned in school. When darkness blurred the staff, Bill would tootle up and down the scale to the accompaniment of vituperous remarks from Luella and an occasional howl from Hez.

Down deep in his heart there was a reason, which he would not divulge to any one, much less Luella. Twenty miles away, in a vine-covered ranch house that looked out upon the desert from under the branches of cool, green cottonwoods, a certain Doris Hunter sang sweet old songs sometimes in the twilight, and played a sketchy, pleasant little accompaniment upon the piano. Bill knew no ecstasy sweeter than sitting in the gloaming, staring dreamily up through the cottonwood[27] branches at the evening star, while Doris sang "Love's Old Sweet Song."

The pathetic note in the little comedy, the note which his outraged menagerie missed altogether, was the fact that Bill would sit for hours, there under the stars, and try to play "Love's Old Sweet Song." And while he tried patiently to make the notes come true, his heart was away over the ridge and down in that little, vine-covered ranch house, worshiping Doris Hunter while she sang.

A dream came to him every night while he played and watched the stars. He dreamed of some day going down to the Hunter ranch, with some perfectly convincing excuse for a visit. He would have the saxophone tied on Wise One, who was more dependable in his habits than Angelface, who was a devil. He would wait until after supper, when Doris would finally settle down on the piano stool. Then he would remember his saxophone and suggest nonchalantly that they try a few little things together. Doris would round her eyes at him, and the dimple would show in her left cheek when she begged him to bring it in.

Then,—Bill's lips would smile in spite of the correct position of the mouth, when he reached that point in his dream—then, after a little talk, and the whole family gathering around to ex[28]claim over the beautiful instrument (which really was beautiful, in cold reality), why, then Bill would suggest something, and Doris would strike a preliminary chord or two, and Bill would follow her voice softly with his music while she sang:

Bill's lips would soften, his eyes would grow luminous and very, very tender. He would forget to play and would stare up into the gemmed purple, and wonder, and dream, and hope.

After a long while, when Luella had tucked her head under her wing, Bill would lay the saxophone carefully in its velvet nest and begin absently to unlace his boots. Doris Hunter—the gold mine he meant to find—had indeed almost found—"Love's Old Sweet Song"—the skill to play while Doris sang; these things mingled indissolubly in his soul while he slept and dreamed, shuttled through his waking mind while he worked.

So this was the real Bill Dale, whom men called Hopeful Bill with their mouths tipped down.

In the beginning of mining booms, accident and freaks of chance are popularly supposed to play the leading rôle. A mule, for instance, played fairy godmother when it let fly its heels and kicked a nub off a ledge of fabulous richness in gold. A man threw a rock at a jack rabbit, and then realized that the rock was heavier than it should be; sought its mates and found a mine. Or a man takes an inadvertent slide down a ledge and lands upon a bonanza.

These things do happen occasionally; and, being ready-made romance, they are seized upon avidly by the teller of tales. So the public comes to believe that chance, and chance alone, discovers the precious minerals and leads men like blind children to the spot; a sort of "Shut-your-eyes-and-open-your-mouth" game played by Fate.

In reality, more mines are found by careful prospecting than are ever given to the world by sheer accident. More and more is science turning prospector, and men go carefully, reading[30] geologic formations, following volcanic breaks and mineral outcroppings. Your desert prospector may eat with his knife and forget to take off his hat in the house, but he can talk you blind on intrusions and sedimentary deposits and the dips, angles and faults of certain mineral formations he knows. Chlorides, "bromides," sulphides,—these things are the shop talk of desert and mountains. Men speak of one another with praise or disparagement, as "knowing rock" or as not knowing rock. And the man who does not know rock is the man who goes about praying for a mule to kick the dirt off a gold outcropping for him.

Bill Dale knew rock. He had spent two years, more or less, prospecting on the southern slope of Parowan, because there was a "break" running across, and because, in the lower end of a wash that had many feeders wrinkled into the mountainside, he had picked up a few pieces of "float" carrying free gold in such quantity that it would mean a real bonanza if he found it "in place," which means in a continuous vein leading to the main body that produced it.

As a bystander he had observed the boom at Goldfield, Tonopah, and at other lesser points. His father had been rich in a boom town for a few weeks. Then he had been a broken, old pauper[31] until he died. Wherefore, Bill Dale did not want a premature boom, nor any boom at all. He wanted to find the ledge or vein that had produced that float, so that he would have something tangible to offer Doris Hunter,—in case he ever found courage enough to offer her anything. He knew that he was liked by the Hunters; but he also knew that as a prospective husband for Doris he was never for one moment seriously considered. Don Hunter, her father, was a stockman. He did not believe much in mines, and he looked askance, from a business viewpoint, at any man who spent good, working days in prospecting the desert. It was the most insidious, the most hopeless form of gambling, according to Don Hunter. He would rather see a man sit down to poker and play for a living than to see him wallowing around like a badger, digging holes in a sidehill looking for wealth.

Bill had done a great deal of pecking and prying, up this wash and that. He believed he knew where the float had come from, but there seemed to be an overburden of soil, probably the result of some beating storm and consequent slide, which had covered the ledge that had at one time been an outcropping. It was slow, tedious work, but Bill was a patient man. Prospectors have to learn patience, or quit the game.[32]

Flaunting desert lilies, dainty blue bells, the deep magenta bloom of the cacti gave way to the tiny pink and pale lavender blossoms that cling close to the arid soil. The sky was brazen with heat, or it turned deep shades of slate as the thunderheads poked over Parowan and rumbled warningly at the desert. Bill worked on through the hot days and practised scales and simple melodies in the evening, and quarreled with Luella and confided to her many things which he would not want repeated.

One sultry evening he brought into camp several pieces of rock and held them where Luella could gaze upon certain telltale, yellow specks. Bill's perspiring face glowed. His eyes were dancing with something akin to mirth.

"We've struck it, old girl! What I've been looking for all this while. Biggest thing yet, from the looks. We're rich, I tell you! Doggone, thundering rich! You watch Parowan go on the map. Biggest thing in the country. If I showed that rock in Goldfield, they'd be down here like flies." He laid the rock down and broke a dry stick across his knee, meaning to start a fire. But he was excited and kept on talking,—now definitely to Luella, now to himself.

"It's the kind of thing I've been hunting. I knew it should be here somewhere. This district[33] is entitled to a big mine. It's got all the earmarks. I've got her traced, now. That rock is in place, or I'm a Chinaman. I tell you, old girl, we're rich! I've got a nugget in my shirt pocket that I didn't show you, for fear you might swallow it."

"Aw, cut it out!" Luella snapped at him. She was a pessimistic bird, as a rule.

Bill burrowed deeper and found more gold. Rock so rich that he could break it up by hand and pan it in the spring, and glean gold enough for another grubstake, more equipment. He was in no great hurry to proclaim his fortune to the world, and he did not mean to show himself in town until his grub was gone. Then he would make a trip, buy more supplies, perhaps hire a man if he could find one whom he could trust. He did not want the harpies to know about Parowan,—yet.

He relieved his inner excitement by talking to Luella, and by tootling on the saxophone and dreaming of Doris Hunter, who did not seem quite so unattainable, now that he had found the mine he had wanted to find and was proving it richer than his most lavish expectations.

With the first discovery he had put up his location notices on three claims, calling them simply Parowan Number One, Parowan Number Two and Parowan Number Three. And in compliment[34] to the girl of his dreams he had located another, called it the Evening Star and signed Doris Hunter's name as the locator. Which is a chivalrous custom observed quite commonly among prospectors.

He did the location work on all four claims, put up the corner and side-line monuments required by law, and then, having eaten most of his supplies, he cached the remainder and started for Goldfield, his mind at ease, his heart singing and his lips wearing an unconscious half-smile all the way.

It was in Goldfield, while Bill was in the recorder's office, that the news leaked out where it shouldn't. Luella, like others of her sex, began talking, inspired by an audience of four men, one of whom was Jim Lambert, who had betrayed some curiosity over Bill Dale's affairs when Bill was last in town.

"Bill Dale's outfit. Hello, Luella," Jim greeted.

Luella looked down at him, seemed to recall having seen him before, and began her pigeon-toed march up and down Wise One's spinal column.

"Boy, we've struck it rich!" she began, chuckling in vivid imitation of Hopeful Bill's tone when he was particularly pleased. "Got her[35] traced now. Richest thing in Nevada. Goldfield can't show stuff like this. Tell you, old girl, we're rich! Doggone, thunderin' rich! Can't tell anybody. Don't want a boom. Git a move on! They'd be down here like flies. Hez! Hez'll have a gold collar. Gold perch for you. Luck's turned; luck's patting us on the back." Luella laughed, then, just as Bill laughed.

Jim and his three companions had stood perfectly still, listening. Jim turned his head and looked at the others, who stared back at him inquiringly.

"Inside dope, boy, believe me." Jim plucked the nearest man by the sleeve. "Bill Dale's parrot has give us the real dope on Bill, if you want my opinion. Come on. We'll lay low, and I'll feel Bill out. He's inside—recording claims, I'll bet. Anyway, I've got a claim to record, come to think of it. I'll git all I can outa the recorder. Bill Dale's parrot has tipped Bill's hand. I'll see the recorder."

They went away. Five minutes later, Bill came down the steps to his burros and discovered Luella toeing it up and down, up and down, practising new sets of words.

"Bill Dale's parrot has tipped Bill's hand. I'll see the recor'," she muttered, over and over.

"You damned huzzy," Bill reproved her, when[36] he had got the full significance of her speech. He picked up Wise One's lead rope and went thoughtfully down to the store.

"We'll lay low," Luella continued, bobbing her head as Wise One's empty pack swayed and lurched under her feet. "Come on. We'll lay low. I'll feel Bill out. Bill Dale's parrot has tipped Bill's hand. I'll see the recor-r'——" She worried over the final syllable that defeated her powers of enunciation.

Bill looked back at her speculatively. At the store, the first thing he asked for was a large, pasteboard carton. Having found one which he thought would do, he plucked Luella unceremoniously off her perch and shut her up, with the box lid tied firmly in place with much heavy twine.

"Fellow tried to steal her, last time I was in," he explained good-humoredly. "She's a pet I'd hate to lose. I'll give you a dollar if you'll let me put her away somewhere till I'm ready to leave town."

"Sure! Keep the dollar, though. It ain't any trouble—if you feed her yourself." Bill was a good customer. He bought largely when he did buy, and he never hinted at credit; which was more than could be said of most prospectors.

"Wait! I'll just put the turtle in with her. Then she'll be more at home, and won't try to[37] break out." Bill went out and returned, swinging a headless, footless, tailless mass of gray turtle insouciantly by the string. "Bunch of boys was after Sister Mitchell too, last time," he observed. "I hate to have trouble, and I can't always keep an eye on things in town. Got quite a lot of running around to do."

He carried the turtle to the back of the store, opened the box and slid her in with little ceremony.

"What the hell!" Luella ejaculated, but Bill slipped on the cover and left her in darkness, so that Luella subsided into throaty mutterings. She never talked in the dark, as Bill knew very well.

"How's prospecting?" the storekeeper asked when Bill returned. "Found anything?"

"Well, I've got a dandy prospect," Bill confided, lowering his voice and glancing sidelong toward the door. "I want to do some more digging, though, before I throw up my hat. Just recorded three claims, as I came past the courthouse. I've got to go in on a lead, and I want the work to count as location work. In fact," he further elucidated, "I've recorded what work I've done as location. No use digging for nothing, and even if they don't pan out rich enough to pay now,[38] so far from transportation, there's enough showing of mineral to pay for hanging on awhile."

"Um-hmm." The storekeeper nodded. "Pity all prospectors don't take the pains to make sure uh what they got. They come in here blattin' about their strikes—and want more grub on credit. I used to fall for it. What's your claims? Gold?"

"Showing of gold," Bill told him unhesitatingly. "The formation entitles me to gold, too, so that's what I'm looking for. Here's a piece of rock. Take a look at it."

The storekeeper tilted the specimen to the light and squinted. Bill obligingly lent him a miner's glass, and with his finger pointed to a certain spot on the sample. "Right there—at the edge of that iron stain; there's a speck of color."

"Mh-hmm—yeah—I see it. Well, it's good, live-lookin' rock, Bill. I think you're wise to dig into it." He returned the sample, weighing it in his mind as he held it out.

"I'm keeping quiet about it—to outsiders," Bill said, dropping the rock into his pocket again. "Don't want any stampede. But I do want a couple more burros, and a hundred pounds of powder, and four boxes of Six-X caps, and five hundred feet of fuse. If you can get me all the stuff I need, and get the two extra burros packed[39] and headed down the trail with orders for the fellow to camp and wait till I show up, I'll make it right with you. This town's got big ears and big eyes. And—you can maybe remember why I hate boom stampedes that don't pan out. I'll give you ten per cent. on every dollar's worth of stuff and the cost of the burros you get to—say to Hick's Hot Spring for me, and twenty-five dollars for a good, trusty man that can swing a single-jack and throw a mess of sour-dough bread together."

The storekeeper ruminated.

"Why, I'll do it for nothing, Bill. You're a good customer, and if you do make a strike I guess I won't lose your trade by treating you white. Trade's slidin' into the credit class more'n what I like to see. You're hard cash when you buy. Just give me your order, and I'll fill it. And what's more, I'll keep my damn mouth shut. And glad to accommodate yuh, Bill."

"Say, you're a white man!" Bill looked full at him and grinned appreciation. But he did not confide further in the storekeeper, nevertheless. "Don't let anybody hang around my pets, and don't say who's to own the burros. You buy 'em, and I'll buy 'em from you, same as I do bacon. And be careful, pickin' that man, will yuh? I[40] want one that can swing something besides his tongue."

"I getcha, Bill. How about booze?"

"All right—if he can do without for a month or two at a stretch. I don't pack any jugs into the desert, as you maybe know."

"That's why I asked. Town's full of good men, but they are mostly booze-punishers. Well—how long you expect to be in town?"

"Just until I'm hooked up with what I need."

"Well—I can get yuh out to-morrow, maybe."

"Just in case you happen to run shy,——" Bill wrote a check on a Reno bank and handed it over. "Any balance, either way, we'll straighten up before I leave."

He purloined a handful of withered lettuce leaves and dropped them into the box for Sister Mitchell and Luella, and went out to idle here and there through town and discover, if he could, just how much damage Luella had done to his plans.

Jim Lambert had known Bill Dale since the beginning of the boom that had broken Bill's father,—broken him mentally and financially. Jim was a broker in Goldfield and sold real estate and underwrote fire insurance as a side line. Lately, the side line had become the chief industry, since mines had begun to close down and adventurers were drifting on to later excitements.

Bill did not care much for Jim Lambert. Although he never troubled to explain to himself his indifference that edged close to dislike, he had no definite distrust of the man. Yet Jim Lambert had been active in his father's Myrtle Mine boom and had professed to suffer when the bubble burst. Bill's father had complained vaguely that Jim Lambert was largely responsible for the bursting of the bubble, but Bill had not paid much attention to that talk. He knew his dad too well. His dad always blamed some one for his misfortunes,—some one other than himself. Bill's nature was built of stiffer material. When his plans went[42] wrong, Bill set all his energies to work planning the next move and wasted little thought upon the reason for his last failure; unless, to be sure, in that reason lay his safety in the future. Thus, Bill flatly refused to help his father play the game of find-the-guilty-party. He went to work and earned and saved all he could out of it, and when he had enough to keep him going for five years, he set out deliberately to spend that five years in finding a mine.

Wherefore, Bill never did learn what part, if any, Jim Lambert had played in the failure of the Myrtle Mine. All he knew was that the mine had been attached and sold by its creditors, and his father had come out of it without a dollar. And he knew that he was not going to be caught that way when he had found his mine. He meant to steer clear of those speculating crooks who managed to loot every enterprise they got hold of and still kept out of jail.

Jim Lambert met Bill by accident—or so Bill believed. It was in the Great Northern bar, where Bill was treating himself to a glass of beer and a San Francisco paper in a quiet corner. Both were inexpressibly refreshing after his long exile, but Bill was not too engrossed to keep a quiet eye open for those who came and went, or remained to chat desultorily before the polished bar.[43]

He was waiting for some one to approach him. Some one did, presently, and that one was Jim Lambert. Jim brought his schooner of beer over and sat down opposite Bill, grinning goodfellowship while he wiped his perspiring brow.

"Got baked out, eh? Must be pretty hot in the desert, now."

"Fair," said Bill, and folded the paper for politeness' sake. "Still, it hasn't been so bad. The man that cusses the desert is the man that strikes out into it and thinks he'll hurry up and get it over with. The desert's all right—if you know how to take it."

"I guess you're right. The old-timers don't seem to have much trouble."

"Not unless they're drunk, or have an accident," Bill agreed, and took two slow, satisfying swallows of beer.

"Well, how's she going? Hit that contact yet you were after?" Jim spoke over his beer mug carelessly.

"Not yet. Been doing location work on three claims. Located first and planned to prospect more thoroughly afterwards." He set down the mug and reached into his pocket for the specimen he had shown to the storekeeper. It was not a good sample of his ore; it was, in fact, the[44] "leanest" rock he could find. But he pushed it across the table with an air of subdued pride.

Jim picked it up, testing its weight as he did so. Bill hooked his toes behind his chair legs and leaned forward expectantly, watching Jim Lambert's face. He thought he read there a shade of disappointment, and he leaned back satisfied. Luella, he told himself, did not talk to perfect strangers except when goaded to profanity by teasing. Jim she had seen many times.

"Good, lively-looking rock," Jim said at last, repeating the storekeeper's comment. "Carries gold, doesn't it?"

"You bet! Here, take this glass and look right there at the point of that iron stain. It shows color, there, under the glass. When I get depth on that, it ought to show good values, don't you think?"

"How deep is this?" Jim turned the rock under the glass. "Looks to me like surface rock."

"You're right. That's outcropping. If I had enough of it, I'll bet it would pay, just as she is. Or if it was close to a railroad, even."

Jim did not reply. He was pretending to study the rock; in reality he was studying Bill Dale. Bill's optimism was a byword, to be sure; yet Jim fancied he saw a slight discrepancy between Bill's keen eyes and the easy hopefulness of his words.[45] He missed somewhere the good-natured twinkle and the drawl.

"Well, it's pretty good for surface rock," Jim said, when the silence became noticeable. "Nothing to get excited over, though, do you think?"

"I should say not! It'll have to look better than that before I get excited."

"Well, good luck to yuh, Bill. If you do get something good, let me know. I might be able to turn a deal for you. There's money in this town yet—if you can show something good enough. It's shy, but it's here. I'll be glad to help you out, any way I can."

"Thanks." Bill's drawl was quite apparent now. "I'll sure remember, if I want to turn anything, later on."

Jim looked at his watch and said he must go; a simple expedient for breaking off a conversation that has grown barren of interest, and one that can never be gainsaid. And Bill, having finished his beer to the dregs, went away also, quite satisfied in his mind.

His satisfaction was not so keen as Jim's, however. Had Bill Dale tiptoed to the door of Jim's office, half an hour later, and put his ear to the keyhole, he might have heard himself being talked about.[46]

"He didn't get by, with me," Jim was saying positively. "Not for one minute. He showed me a piece of rock no better than you can pick up on any tailing dump in Goldfield, and claimed that was his best showing. It wasn't good enough to account for what that parrot of his let out. Remember? I jotted it down, first thing. Parrot talk is just parrot talk, but they don't invent nothing. They've got to hear it said before they'll say it. And if you might say Bill Dale was teaching it that stuff for fun, that don't sound reasonable—knowing Bill."

He fumbled for a minute and brought out a little, soiled, red book.

"Now here's what the parrot reeled off, and I'll gamble she got it straight. A man out alone by himself lets go and says what he really thinks. We all know that. Now, the parrot says, 'Boy, we've struck it rich! Got her traced now. Richest thing in Nevada. Goldfield can't show stuff like this. Tell you we're rich. Won't tell anybody—don't want a boom. Git a move on!' (That's something else, run in). 'They'd be down here like flies. Gold perch for you. Luck's turned. Luck's patting us on the back.'"

He looked at his companions and grinned. "Don't tell me that wasn't picked up from Bill Dale's camp talk."[47]

"Maybe he taught the parrot that lingo just to have her spill it in town and start a rush," one tight-faced man said cautiously.

Jim shook his head. "I saw him in the Great Northern—trailed him there. Most generally, when Bill's in town, he takes the parrot around with him, riding on his shoulder. She's a smart bird. Bill's proud of her and likes to show her off. Talks everything, just like a human; everything she hears and takes a notion to, that is. Well, he didn't have her with him to-day. He's left her somewhere. From the saloon he went into the barber shop. He's getting a haircut. Shave too, probably. Never saw him in a barber shop before without that green parrot. My guess is, he's afraid she'll let out something." Jim put the book back in his pocket with a self-satisfied air. Men who live by their wits are usually a bit vain of their shrewdness.

"Well, if you're right, he got scared too late to do any good," chuckled a jovial, round little man with one eye milky from cataract.

"He was just coming into town. Leaving her in the street for five minutes, up there at the courthouse, would look safe enough to anybody. It's just luck we happened along."

"Well, now, how's it to help us?" The tight-faced man had brown eyes that stared intently,[48] as do the near-sighted. He leaned forward, bringing the conference to a point.

Four heads went together, at that, and if Bill had been listening at the keyhole he wouldn't have heard much. They were a careful quartette, and they had worked in harmony through the complexities of several "deals."

Bill saw Jim Lambert again the next day. Jim was in the store, looking boredly impatient to be served. The storekeeper's signal to Bill, of tilted head and lowered eyelid did not pass unobserved. Bill followed him back among the piled boxes of canned goods, and Jim idled over to a pile of overalls and inspected them carefully while he tried to listen.

He did not hear as much as he desired, and much that he did hear was irrelevant. There was something about two burros leaving last night. Then, after some mumbling, he caught the storekeeper's earnest assurance, "—all right when he's sober. Just off a big drunk, so he's good for three months, anyway. Tommy's an old, hard-rock man; all around good guy if he takes a notion to yuh. And I got him cheap for yuh. Three dollars and found."

Jim Lambert could not guess what Tommy this might be, but he was glad to know that Bill was hiring a man by the underground route, and that[49] Tommy liked whisky. Working through the storekeeper meant only one thing; the need of absolute secrecy. Which provided wonderful illumination for a man like Jim Lambert.

Jim moved carelessly back to the front of the store and was giving his order to the clerk when Bill emerged, carrying a spiteful-tongued parrot on one finger. Bill grinned a greeting at Jim.

"Say, 'Hello, Jim,'" he instructed Luella in his coaxing tone.

Luella's reply was just barely printable when the editor's sense of humor is keener than his puritanism. Luella blinked and said, "You damned hussy, git a move on!"

"She's peevish," Bill apologized. "She's getting such a darned nuisance in town I had to shut her up. Now you listen to me, old girl. Back you go in the box, if you don't behave. Be quiet—you know I mean it."

Luella turned and walked up Bill's arm to his shoulder, and leaned forward to click her beak against his neck. "Lord, what a world!" she murmured, and began daintily to eat half a banana which Bill gave her.

Jim Lambert took his few small packages and went out, and Bill saw him no more. Which does not mean that Jim ceased to take an interest in Bill Dale's prosperity and personal affairs.

From beside a camp fire at the springs which Bill Dale had designated as the rendezvous, an undersized, ape-bodied individual rose and goggled up at Bill through thick-lensed spectacles that magnified his eyelids grotesquely.

"Hello," said Bill, looking down at him whimsically. "Is this the outfit the Goldfield Supply Company sent out?"

"An' if ye'll tell me what business it might be uh yoors, I c'd maybe say yis er no to that," the undersized one retorted, raising his voice at the end of the sentence as if it were a question.

"All right, Tommy. You'll do, I reckon. I'm Bill Dale, and if I'm not mistaken you'll be looking to me for your pay."

"An' from the look of ye I'll be earnin' that same," Tommy suggested drily.

Bill lifted Luella and Sister Mitchell off Wise One, and began to unlash the heavy pack, Tommy helping him. The two studied each other with covert interest; Tommy seeking to discover[51] whether Bill Dale would make a good boss, one easy to work for, which, next to the security of his pay, is a laborer's chief consideration. Bill measured Tommy shrewdly as a man who would work—and gossip. A man who could be loyal to the last gasp, but a man who might easily choose to be disloyal. He was a garrulous little Irishman, was Tommy; a man of indeterminate age and of problematic usefulness. But Bill was not inclined to carp. He was content to give Tommy a trial, which was as much as the best man could justly expect.

If Tommy had received any hint of the probable value of Bill's claims, he gave no sign of knowing. Until he slept he sat cross-legged by the fire and stared into the flames through his thick-lensed glasses, and regaled Bill with choice anecdotes culled from his past,—that endless, obvious odyssey of the common laborer whose world is bounded by his "job." His voice was a soft, complaining monotone saturated with the eternal vague question. Never did his inflection fall to a period. At a distance which would blur the words of his speech, his voice would inevitably give one the impression that Tommy was asking one reproachful question after another, with never a statement to relieve the endless inquiry.

Bill was amused, but he was also convinced that[52] Tommy would presently become a bore. He was interested to note that Luella preserved a dignified silence all through the evening. One yellow eye on the latest recruit, she sat humped upon the crotch of a packsaddle with her green feathers ruffled moodily, still sulking over her incarceration with Sister Mitchell.

At Parowan, whither they arrived one sultry afternoon with a smell of rain in the air, Tommy went to work like an old hand on the desert. Bill watched him unobtrusively and decided that the storekeeper had shown pretty good judgment. While they were unpacking the burros, Tommy cocked an eye at the sullen clouds that tore themselves on Parowan Peak only to mend immediately and crowd lower down the slope, and began gathering heavy rocks which he piled in a row on the lower edge of Bill's tent, and to test the guy ropes and drive the pegs deeper.

"She's a cloud-burst comin', er I never seen wan," he observed complainingly, when he was again lugging the supplies into the tent. "Them taties c'd stay outside, but watter will cause the bacon t' mold, Mr. Dale. An' beans is never the same, wancet they've been wrinkled wit' rain watter an' dried agin. I dunno, but that's been my experience wit' grub. I'd git it all under cover, if it was mine, Mr. Dale."[53]

"Does look bad, for a fact," Bill admitted. "I was going up to the workings; but I reckon we'd better make camp snug. Now, Hez, what'll happen if you bust a lung? What's on your fool mind?"

Hez appeared to have a good deal on his mind. Presently his excitement was explained by four loaded burros laboring up the draw, followed by three men who hurried the animals up the uneven slope. Bill frowned when he saw them, wondering if they had followed him.

But the men were strangers to him. If they came from Goldfield, he thought, they must have hurried,—because Bill himself had made the trip in record time. He nodded as they came up, and sent the impolite Hezekiah into the tent with his hindquarters drooping guiltily. Two of the men had the look of mining engineers (for your desert dwellers learn to judge a man's profession by the way he dresses and carries himself on the desert). The third, who evidently had charge of the burros, had "desert rat" written all over him.

"Spring up here still workin', mister?" the burro driver asked in a flat voice raised shrilly by way of attaining some volume. "Used to be a spring up here."

"The spring is still there," Bill replied neutrally.[54]

A pleasant, short man came forward, smiling and holding out his hand, never doubting his welcome.

"Glad to see you, sir. My name is Rayfield; Walter B. Rayfield. My partner, here, is John S. Emmett, a mining expert of whom you may have heard, if you're the mining man you look to be. Working for the government, making a report of the gold, silver and copper possibilities of Nevada. I examine the country for gold and silver, and Emmett, here, takes care of the copper report. We've been allotted what is called the Furnace Creek quadrangle. We're working the northern part first, so as to have cooler weather for the Death Valley neighborhood."

"Glad to meet you." Bill's handshake was cordial, with a certain reticence behind it. Happy-go-lucky as he seemed, Bill Dale was slow in choosing his friends, while acquaintances never got below the surface of his mind. "My name is Dale; Bill for short, Hopeful Bill for sarcasm. You're just ahead of a big storm, by the looks, Mr. Rayfield."

"Yes, it does look like rain." Mr. Rayfield glanced at the heavy clouds that were now hiding the peak. "We expect to camp here for a while, if the spring is all right. Glad to have a neighbor. Most of the time we have to put up with our own[55] company. Well, Al, suppose you find a place for camp. You'll have to hustle, my man, if we're to get our tents up before it rains."

"You've a nice little camp here," the man introduced as Emmett observed, his hard brown eyes taking in the surroundings appraisingly. It's certainly a great view you have here. We saw your tent from miles away, down there."

"You came from Vegas way, then," Bill stated calmly. From that direction only could they see his camp from any distance; the Goldfield trail twisted around the mountain.

"We started from Las Vegas. We've been out some time, though. Came down Forty Mile Canyon to the main road and followed that as far as we could." He pulled a pipe from his pocket and began filling it in leisurely fashion from a leather pouch while his gaze traveled sophisticatedly over the surrounding hills.

"Prospecting, I suppose?" His eyes came back to Bill's face. His tone had the casual note of one who wishes to be civil.

"Yes, a little," Bill replied guardedly. Even to research men he did not feel like telling all he knew. "She's a hard country to prospect in, though. Too much overburden. But I like the formation here. Seems to me there's a chance[56] here to run on to something, if a fellow keeps right after it."

"I see already why they call you Hopeful Bill," Mr. Emmett grinned over his pipe. "I don't think it's sarcasm, though." He gave another professional glance at the rough outcroppings near them. "Looks pretty fair, but my specialty is copper. Doesn't seem very promising for that—but one never can tell. You're looking for gold, I take it. That's more in Rayfield's line."

"I'm looking for anything I can find," Bill corrected lazily. "Anything from gold to diamonds; just so there's money in it."

The fitful breeze died suddenly to an ominous, stifling calm. The copper expert glanced up at the slatey mass moving up from the west and went to help the others set up the tent before the storm broke.

"Want any help?" Bill called after him. But Mr. Emmett shook his head, waved a hand and went on.

Tommy, who had retreated into the tent as the party drew near, pushed his head through the opening and goggled at the group fifty yards away. They were spreading a wall tent, preparing to make camp in the lee of a rocky ledge. Tommy wiped the tobacco stain from his lips[57] with the back of his hand and glanced sidelong up at Bill.

"That's Al Freeman they got wit' 'em," he drawled in his complaining, questioning way. "An' how he c'd git wit' 'em I dunno, fer I left him in Goldfield—I did—and him owin' me tin dollars and denying all knowledge of that same. He's a liar an' a t'ief, Mr. Dale, an' them that trusts him is like t' find their t'roats cut some marrnin' an' their pockets turned out.

"How he got to Las Vegas t' join up with these fellers I dunno—fer he was in Goldfield whin I left, and there can't be two of 'im—an' the devil wit' his hands full a'ready just wit' wan of 'im. I'd tip off them gov-ment men, Mr. Dale, I sure would. He's worse ner a rattler in camp, an' he's the kind that'll lie wit' 'is ears open an' then run an' make bad use o' what he hears, Mr. Dale. He's a durrty claim-robber fer wan t'ing, an' if yuh've got annything here wort' robbin', Mr. Dale, yuh'd best set yer tent over it whilst Al Freeman's on the mountain. It's the Gawd's trut' I tellin' yuh—an' yuh better slip them experts the word—though how he got wit' 'em I dunno, fer I left him in Goldfield; I did that!"

"That's mighty queer," Bill assented dubiously. "If you're sure of that, we'll step lightly till we know the bunch better. Keep your eye on[58] him, Tommy, until I find out more about it. They won't get that tent up in time to save a wetting; I can see that right now."

The man Tommy said was Al had unpacked one burro, but it was certain they would not have time to make themselves even passably comfortable. Even now the tent they were erecting was bellying like a balloon in a sudden blast of wind, and while they struggled with it pegs and guy ropes snapped loose. The short man, whose name was Rayfield, evidently made a suggestion. All three looked toward Bill's camp. Then, as the earth quivered under a deafening crash of thunder, Al hurriedly tied the burros to a couple of stunted junipers, wadded the tent hastily into an ungainly bundle and thrust it between two rocks.

Heads down against the wind, holding their hats on with both hands, they came running. Bill opened the tent flaps and held it against the wind until the strangers and Tommy were inside. Then he double-tied the flaps and turned, grinning hospitably. His twelve-by-fourteen tent was more than comfortably full now, what with the piles of supplies, Bill's stove and table and bed, and the five men. But it was a shelter, set shrewdly against just such an emergency as this[59] storm. It faced away from the wind, and a ledge protected it from the full force of the gale.

Thunder, lightning, wind—then an abrupt silence, a holding of the breath. Tommy, crouched down in his corner, his shoulder held carefully away from the canvas wall, stared owl-like through his thick glasses.

"She's comin'," he mumbled dolefully.

She came. All the water in the clouds seemed to have been dumped unceremoniously upon the tent. A fine mist beat through the roof and sides until warp and woof became saturated, and shrunk to a waterproof texture that sent the water running off in streams.

"She's a cloud-burst—I said she'd be a cloud-burst!" Tommy muttered again in melancholy triumph.

"You didn't get here any too soon," Bill observed cheerfully. "It would be pretty tough, climbing through this. You're lucky."

"We certainly are!" Mr. Rayfield's voice was raised almost to a shout, to carry above the storm. "Wouldn't want to be caught out in this!"

They sat and listened to it,—the boom and crash of the thunder, the vivid flashes that lightened blindingly the gloom of the tent, the roar of the falling water.[60]

"She's a tough one, all right!" Bill rose and pried open the flaps with his fingers, and put an eye to the crack. "Now I know how old Noah felt when he shut the door of the ark. Nothing in sight but water—good Lord!"

Something sagged against the tent, beat upon the taut canvas. A voice was raised shrilly, frantically.

"Bill! Oh, Bill! Let me in!"

Bill's face had whitened at the first sound. His fingers clawed at the stiff, canvas knots that held the flaps shut. His hands, reaching out to loosen the outside fastenings, touched other fingers that tore nervously at the soaked knots. Bill was hampered by those other fingers, as a swimmer is hampered by the frenzied clutchings of a drowning man. But he managed the two lower fastenings and was beginning on the upper when the person outside stooped and ducked in past Bill's knees.

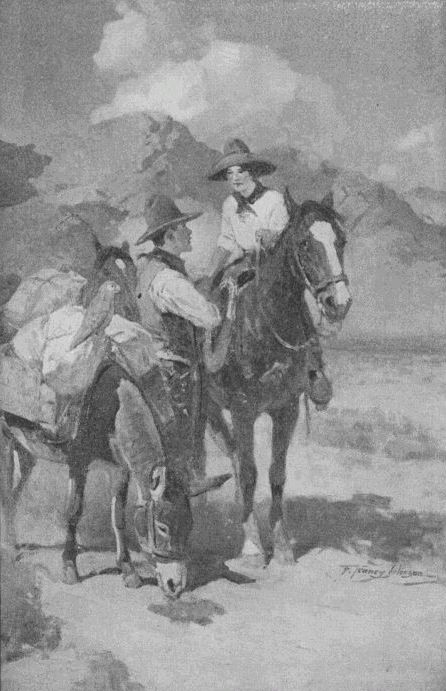

"Doris—— Miss Hunter! What——"

"Oh, it's perfectly awful! I thought I'd never make it, Bill. I couldn't make the horses face it, so I tied them down the gulch and came on afoot. I could see your tent when it lightened—I'm just soaked! It's the worst storm this year."

She was talking in gasping little rushes of words, talking because she must have some emo[61]tional outlet. Her hat had gone in the wind, and she wiped the water from her face with quick, impatient brushes of her palms outward from her nose. Her hair was wet as a drowned woman's, and as lank about her face and shoulders. She wore a khaki riding skirt and a striped cotton blouse that clung to her shoulders and arms like wet paper. Her high-laced boots squelched soppily when she moved. Had she been pulled from a river she could not have been wetter.

"Tommy, start a fire in the stove; you're the closest," Bill commanded. "Miss Hunter, let me introduce some other storm birds—only they were luckier than you were. They beat it in. This is Mr. Rayfield, and Mr. Emmett—both government experts making an examination of the country for mineral. That's Al Freeman over there; working for them" (Mr. Rayfield looked surprised) "and Tommy, over there by the stove, is going to work for me. Get over there in the corner and dry out. It'll be hot in a minute. You must be chilled."

The men moved back to leave clear passage to the stove, and she hurried toward it, nodding to them shyly as she went. Mr. Rayfield smiled upon her benignantly and drew a box from under the table for her to sit on.

"Take off those wet boots, Miss Hunter, and[62] put your feet in the oven," he commanded, in the same tone which he might have used to his own daughter. "A cup of coffee will take the chill out of your bones. My, my! I've heard that it could rain pitchforks in this country, but nobody mentioned raining angels!" His own hearty laugh robbed the remark of any offensive familiarity, as he picked a blanket off the bunk—disturbing Mr. Emmett and Al Freeman to do so—and laid it matter-of-factly upon her shoulders.

"Here, let me unlace your boots. Tommy, get the coffee pot working." Bill knelt and reverently lifted her small, booted foot to his knee. "Mr. Emmett, if you'll pass that war-bag over here, I'll dig up some dry socks. And if you'll remember to hold out your arms, Miss Hunter, so you won't fall in outa sight, I'll lend you a pair of my boots. Or maybe we could tie a loop under your arms and hitch you somehow. Anyway, we'll fix you up comfortably as we can.

Miss Hunter laughed, which was exactly what Bill had intended that she should do. If every little happy nerve in his big body tingled while he unlaced her boots, that was his own business and none of his neighbors'. He did not mean to have Doris Hunter experience one moment's embarrassment if he could help it.

With a fine tact for which Bill was silently[63] grateful, the two government men resumed their casual talk of the storm and of the desert,—the small talk of the region which is useful for filling in the awkward spots in strange situations. Tommy busied himself with a ham, a few cans and the coffee pot, and said not a word. Al Freeman, over by the door, made himself as inconspicuous as possible,—perhaps for reasons which Tommy could guess.

Bill casually turned his back upon Miss Hunter and the stove and stood there with his hands in his pockets and his legs slightly apart, throwing a sentence now and then into the talk of the others.

Thus hidden away in the corner, ignored for the time being, Doris Hunter pulled the blanket tighter around her slim person, and fumbled within its shelter. She was a sensible girl, and she had lived all of her twenty years on the edge of the desert, and knew nothing much about cads and crooks. So presently her khaki skirt was spread over her knees to dry, and she was holding the blanket open to dry the rest of her. And not a man of the five noticed the skirt, or paid any attention to her whatever.

But when Tommy said supper was ready, Bill moved from his position as screen, and pulled up a box to hold the girl's plate and cup so that she[64] could eat without moving away from the stove. It was casually done; so casually that it would not have cost a nun the quiver of an eyelash. Certainly Miss Hunter felt no confusion, for presently she was chatting quite as composedly as if she were at home with her family around her.

It rapidly grew dark, the lightning coming at more infrequent intervals as the downpour continued. Bill found a lantern, lighted it and hung it on a wire hook from the ridgepole, where it swayed to the spasmodic shuddering of the tent. Miss Hunter turned and turned her skirt, and Bill watched her boots that they did not dry too quickly. There seemed nothing unusual in this foregathering, which was but one more incident of the wilderness.

"Bill, you haven't asked me if I were lost or just going somewhere," Miss Hunter accused suddenly, setting down her cup which she had twice emptied of coffee. "You ought to be ashamed of yourself. Any one else would have asked me that before I got the water out of my eyes."

"Well—are you lost, or just going somewhere?" Bill inquired obediently. "I've known this young lady a good long while," he added to the others, glad of the opportunity. "She rides the range right alongside her dad, and can sling a pack or rope a critter better than lots of men that draw wages for doing it. She couldn't get lost to save her neck. Looking for cow brutes or horses, Miss Hunter?"

"Neither one. And don't call me Miss when I've been Doris all my life. These gentlemen don't demand the starch in your speech, and I know it. Dad sent me over to see if you'd come and help him out for awhile. He's going to run[66] the water by a tunnel through that little ridge back of the corrals, and water the lower meadow directly from the spring. It will save at least an inch" (she referred to a miner's inch of water, which is a cubic measurement) "that's lost now in seepage as it's carried around the hill.

"He's been sort of looking for you over to the ranch. But you didn't show up, so he sent me over to see if you'd drive the tunnel for him. He thinks your cautious disposition will make the blasting safe for the cattle, I reckon. Anyway, that's what I came for, and the storm did the rest. I guess the horses will be all right, but if they ever get loose they'll beat it for home—and that will worry the folks. I brought old Rambler with my camp outfit, and of course I rode Little Dorrit."

"My, my, if some of the young ladies back in Washington could hear you talk so calmly of traveling the desert alone with your own camp outfit!" Mr. Rayfield pursed his lips and then smiled at her. Mr. Rayfield was disfigured somewhat by a milky film over one eye, but for all that his face was a pleasant one that made friends for him easily.

"If you folks can make out with a candle," said Bill, "I'll take the lantern and go see about[67] the horses. I can bring them up closer to camp, maybe——"

"You'll do nothing of the kind, Bill Dale. Don't you suppose I made sure they would stay tied? Or do you think I like to take a chance on being set afoot? I was, once. That was a plenty, thank you. You stay right where you are."