Project Gutenberg's Harper's Round Table, September 8, 1896, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Harper's Round Table, September 8, 1896 Author: Various Release Date: April 1, 2019 [EBook #59184] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S ROUND TABLE *** Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 880. | two dollars a year. |

Some weeks were spent at Greenway Court, and George slipped back into the same life he had led for so long in the autumn. Instead, however, of reading in the evenings, Lord Fairfax and himself spent the time in studying rude maps of the region to be explored, and talking over the labors of the coming summer. The Earl told George that William Fairfax had heard of the proposed expedition, and was so anxious to go as George's assistant that his father was disposed to gratify him if it could be arranged.

"But I shall not communicate with him until I have talked with you, George," said the Earl; "for William, although a hardy youngster, and with some knowledge of surveying, is still but a lad, and there might be serious business in hand. However, this season's surveys are not to be far from here, so that if you care for his company I see no reason why he should not go."

"I should be very glad to have him," replied George, blushing a little. "I did a very unhandsome thing to William Fairfax while we were at Mount Vernon at Christmas, and he was so manful about it that I think more of him than ever, and I believe he would be an excellent helper."

"An unhandsome thing?" repeated the Earl, in a tone of inquiry.

"Knocked him sprawling, sir, in my brother's house. My brother was very much offended with me, and I was ashamed of myself."

"But you are good friends now?"

"Better than ever, sir, for William behaved as well as I behaved ill, and if he is willing to come with me I shall be glad to have him."

"I shall send an express, then, to Belvoir, and William will be here in a few days. And now I have something else to propose to you. My man Lance is very anxious to see the new country, although he has not directly asked my permission to go; but the poor fellow has served me so faithfully that I feel like indulging him. Only a lettered man, my dear George, can stand with cheerfulness this solitude month after month and year after year as I do, and although Lance is a man of great natural intelligence, he[Pg 1086] never read a book through in his life, so that his time is often heavy on his hands. I think a few months of mountaineering would be a godsend to him in his lonely life up here, and I make no doubt at all that you would be glad to have him with you."

"Glad, sir! I would be more glad than I can say. But what is to become of you without Lance?"

"I can get on tolerably well without him for a time," replied the Earl, smiling. And the unspoken thought in his mind was, "And I shall feel sure that there is a watchful and responsible person in company with the two youngsters I shall send out."

"And Billy, of course, will go with me," said George, meditatively. "Why, my lord, it will be a pleasure-jaunt."

"Get all the happiness you can out of it, George; I have no fear that you will neglect your work."

Within two weeks from that day William Fairfax had arrived and the party was ready to start. It was then the 1st of April, and not much field-work could be done until May. But Lord Fairfax found it impossible to hold in his young protégés. As for Lance, he was the most eager of the lot to get away. Cut off from association with his own class, nothing but his devotion to Lord Fairfax made the isolated life at Greenway Court endurable to him; and this prospect of variety in his routine, where, to a certain degree, he could resume his campaigning habits, was a fascinating change to him.

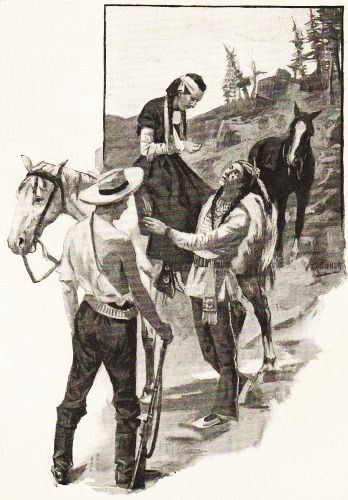

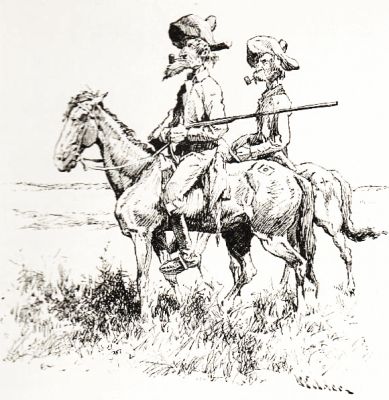

The Earl, with a smile and a sigh at the loss of George and William's cheerful company and Lance's faithful attendance, saw them set forth at sunrise on an April morning. George, mounted on the new half-bred horse that Lord Fairfax had given him, rode side by side with William Fairfax, who was equally well mounted. He carried the most precious of his surveying instruments, and two little books, closely printed, which the Earl had given him the night before. One was a miniature copy of Shakespeare's plays, and the other a small volume of Addison's works.

Behind them, on one of the stout cobs commonly used by the outriders on Lord Fairfax's journey to lower Virginia, rode Lance.

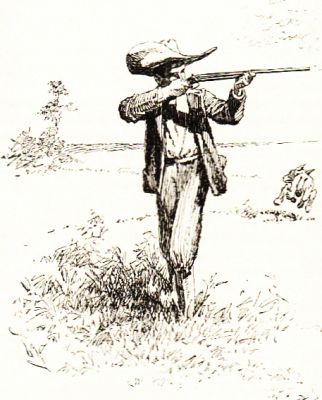

The old soldier was beaming with delight. He neither knew nor cared anything about surveying, but he was off for what he called a campaign, in company with two youths full of life and fire, and it made him feel like a colt. He had charge of the commissary, and a led-horse was loaded with the tent, the blankets, and such provisions as they could carry, although they expected their guns and fishing-rods to supply their appetites. Behind them all rode Billy on an old cart-horse. Billy was very miserable. He had no taste for campaigning, and preferred the fare of a well-stocked kitchen to such as one could get out of woods and streams. George had been so disgusted with Billy's want of enterprise and devotion to the kitchen rations that he had sternly threatened to leave the boy behind, at which Billy had howled vociferously, and had got George's promise not to leave him. Nevertheless, a domestic life suited Billy much better than an adventurous one.

What a merry party they were when they set off! Lord Fairfax stood on the porch watching them as long as they were in sight, and when, on reaching a little knoll, both boys turned and waved their hats at him, he felt a very lonely old man, and went sadly into the quiet house.

The party travelled on over fairly good mountain roads all that day, and at night made their first camp. They were within striking distance of a good tavern, but it was not in boy nature to seek comfort and civilization when camping out was possible.

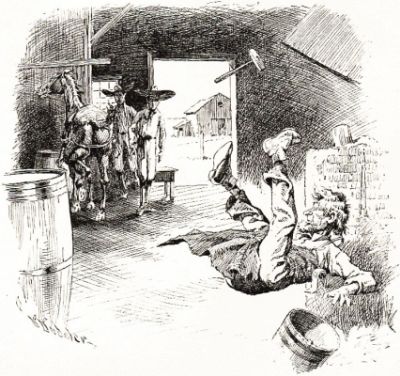

George realized the treasure he had in Lance when, in an inconceivably short time, the tent was set up and supper was being prepared. The horses were taken care of by George and William, who got from a lonely settler's clearing a feed of corn for them. Meanwhile, with a kettle, a pan, and a gridiron, Lance had prepared a supper fit for a king, so the hungry boys declared. Billy had actually been made to go to work, and to move when he was spoken to. The first thing he was told to do by Lance was to make a fire. Billy was about to take his time to consider the proposition, when Lance, who was used to military obedience, instantly drew a ramrod from one of the guns, and gave Billy a smart thwack across his knuckles with it. Billy swelled with wrath. Lance he esteemed to be a "po' white," and, as such, by no means authorized to make him stir.

"Look a-heah, man," said Billy, loftily, "you 'ain' got no business a-hittin' Marse George's nigger."

"I haven't, eh?" was Lance's rejoinder, giving Billy another whack, "Do you make that fire, you rapscallion, or you get no supper. And make it quick, d'ye hear? Oh, I wish I had had you in the Low Countries, under my old drill-sergeant! You would have got what Paddy gave the drum!"

Billy, thus admonished, concluded it would be better to mind, and although he felt sure that "Marse George" would give him his supper, yet he was not at present in high favor with that young gentleman, and did not want to take any risks in the matter. However, he did not really exert himself, until Lance said, severely: "I have a great mind to ask Mr. Washington to send you back to Greenway Court. It is not too far."

At that Billy suddenly became very industrious. Now George, on the other side of the tent currying his horse, heard the whole affair, and when they were called to supper he threw out a hint that his servitor might be sent back, which threat then and forever after acted on Billy like a galvanic battery.

George and William thought, as they sat by the fire in the woods eating their rude but palatable supper, that they were the luckiest creatures in the world. They were exhilarated rather than fatigued by their day's work. A roaring fire cast a red glare among the rocks and trees, and warmed the keen cold air of the spring night in the mountains. Within their tent were piles of cedar boughs for beds, and blankets to cover them.

William Fairfax had never heard any of Lance's interesting stories, although George had told him of them. When supper was over, and the boys had an hour before turning in, George induced Lance to tell of some of his adventures in the wars of the Spanish Succession. They were deeply interesting, for Lance was a daring character, and had seen many strange vicissitudes. Billy and Rattler, who were not very much interested in the proceedings, dropped asleep early, and George, throwing a blanket over Billy, let him lie and snore before the fire until it was time to take to the tent. After a while Lance said:

"It was the Duke of Marlborough's way to have all the lights out early; and I think, Mr. Washington, if we want to make an early start, we had better turn in now."

George and William, nothing loath, betook themselves to their beds of boughs within the tent. Lance preferred to lie just in the doorway, the flap being left up for air. The boys noticed that he very carefully took off his shoes and washed his feet in a pail of ice-cold water brought from a spring near by.

"Why do you do that, Lance?" asked George, who thought it rather severe treatment.

"Because that's the way to keep your feet in order, sir, and to keep from taking cold in a campaign; and I recommend you and Mr. Fairfax to try it for a regular thing," answered Lance.

Within two days they reached the point where they must leave their horses and really begin their work. They struck now into a wilderness, full of the most sublime scenery, and with a purity of air and a wild beauty of its own that would appeal to the most sluggish imagination. George had found William Fairfax to be a first-rate camping companion, and he proved to be an equally good assistant in surveying. George was not only an accurate but a very rapid surveyor, and William was equal to every demand made upon him. Although they carried their guns along when at work, they shot but little game, leaving that to Lance, and the trapping of birds and small animals to Billy, who was always willing to forage for his dinner. They met a few Indians occasionally. Many of the Indians had never seen surveying instruments, and thought them to be something miraculous.

Lance was a genius in the way of making a camp comfortable. Although all of his experiences had been under entirely different circumstances, in an old and settled country with a flat surface, he was practical enough to transmute his knowledge to suit other conditions. He made no pretence of assisting in the field-work, but when George and William would come back to camp in the evenings, after a long day's tramp on the mountains, Lance would always be ready with a good supper, a bed of pine or cedar branches, and an endless store of tales of life in other days and other places. In the absence of books, except the two volumes given George by Lord Fairfax, these story-tellings became a great resource to the two young fellows, and were established as a regular thing. Although Lance had been only a private soldier, and was not an educated man, he had natural military talents, and when they would talk about possibilities of war with the French upon the frontier, which was then looked upon as inevitable, Lance clearly foresaw what actually happened years afterwards. The military instinct was always active in George, and it developed marvellously. For recreation he and Lance devised many campaigns against the French and Indians, and proved, on paper at least, how easy it would be to capture every French fort and block-house from the Alleghanies to the Great Lakes. George had a provincial's enthusiastic confidence in regular troops, and was amazed to find Lance insisting that their usefulness in a campaign in the wilderness was doubtful.

"I tell you, Mr. Washington, I have seen a little of the Indian fighting, and you give a few of those red devils fire-locks, with a handful of French to direct them, and there is not a General in England who would know how to fight them. And the worst of it is that the English despise the Indians, and you could not make an Englishman believe that he could not lick two Frenchmen until he has been licked. An English General would want roads and bridges and an artillery train and a dozen other things that these savages never heard of, while all they want is a fire-lock and a tree, and they can pick off their man every time."

"Then do you think the English will not be able to hold this part of the country?" asked George.

"With the militia—yes, sir. Your provincial troops know how to fight Indians, and can get through a wilderness without making a highway like a Roman road. But mark my words, Mr. Washington, many a brave fellow has got to lay down his life before the English learn how to fight in the woods."

These prophetic words came back vividly to George before many years had passed.

The summer came on apace. Never had George seen anything more beautiful than the outburst of tree and leaf and flower among these lonely peaks. The out-door life agreed with him perfectly, as it did with William Fairfax. They worked hard all the week, always leaving camp before sunrise, and generally not returning until after sunset. Lance always had a good fire and a capital supper waiting for them. He fashioned rude but comfortable seats and tables out of logs, and his impromptu out-door kitchen was a model of neatness and order. He was an accomplished launderer, but, after instructing Billy in the art of washing and drying clothes, turned that branch of their housekeeping over to this young person, who worked steadily, if unwillingly. On rainy days the boys remained in their tent, with two large tarpaulins thrown over it to keep out the water. George then wrote in his journal and read one of his precious books, William reading the other. On Sundays they took turns in the morning, after the work of the camp was over, in reading the service of the Church of England to a congregation composed of Lance, Billy, and Rattler—the two latter generally going to sleep in the first five minutes.

Besides his regular work and having an eye to military operations in that region, George and William both had an opportunity to study the animals and birds the forests and mountains harbored. For the first time they had a chance of closely watching the beaver, and admiring this great engineer among beasts. They were lost in admiration at the dam constructed by him, which the most scientific engineering could not surpass. The brown bear, a good-natured creature that was always frightened at the sight of a human being, was common to them, and deer enough to keep their larder supplied were found. Lance was a skilful fisherman, and the mountain trout was on their daily bill of fare. Tho only thing they feared was the snakes, but as they always wore long and stout boots, they escaped being bitten while at their work, and Lance and Billy kept a close watch on the camp, examining the tent and ground every night before they slept. It was so cold at night, however, that they were in but little danger from reptiles then, for no matter how warm the day, by nightfall a fire was pleasant.

And so days became weeks, and weeks became months. George had begun his work with a fierce disappointment gnawing at his heart, and thought he should never live to see the day when he would not regret that he was not in the navy. But at sixteen, with health and work, despair cannot long abide. Before he knew it the pain grew less, and insensibly he found himself becoming happier. But this was not accomplished by sitting down and brooding over his troubles; it was done by hard work, by a powerful will, and the fixed determination to make the best of things. Before the summer was over he could think, without a pang, of that cruel blow he had received the day after he reached Ferry Farm.

Lord Fairfax thought he had not given George too much time when he named the 1st of October as the date the party would probably return to Greenway Court. But on a glorious day in early September, when Lord Fairfax came in from riding over his principality in land, he saw a young figure that he well knew speeding down the road to meet him, and recognized George. The boy was much grown, and gave full promise of the six feet three that he attained in his manhood. His figure was admirably developed, his fair complexion bronzed, and his bright, expressive eyes were brilliant with health and spirits.

Lord Fairfax's pale and worn face lighted up with pleasure, and he dismounted on seeing George. Arm in arm the two walked up to the great, quaint house—the man, old before his time, and never losing the sad and wearied look that showed he had not found life all roses, and the splendid youth glowing with health and hope and brightness. Lord Fairfax asked many questions about the work, and George was equally full of questions about lowland affairs. Of these Lord Fairfax knew little, but he told George there were a number of letters for him in a desk in the library. George was all eagerness to get them, as he knew he should find letters from his mother and Betty and his brother Laurence.

As they neared the house they passed within view of the kitchen. Billy had not been off his horse's back half an hour, but he was already seated in the kitchen door, and between his knees was a huge kettle, in which were some bacon and beans. In one hand he held a tremendous hoe-cake, which he shared with Rattler, who was sitting on his haunches, with an expression of profound satisfaction very like that which irradiated Billy's dusky features. Neither George nor Lord Fairfax could forbear laughing, and Billy grinned appreciatively at them.

But on reading his letters a little later in the library George's face lost its merry smile. His mother and Betty were quite well only ten days before—which was late news for that day—but his little playmate Mildred, at Mount Vernon, was fading fast. One of Madam Washington's letters, dated about three weeks before, said:

"I have just come from a visit of eight days to Mount Vernon; your brother and sister are fairly well, although Laurence will never be of a robust constitution. But the little girl, I see, is not to be spared us long. She is now nearly three years old—older than any of Laurence's other children have lived to be—but there is a blight upon this dear little innocent, and I doubt whether she will not be a flower in God's garden by Christmas-time—greatly to her profit, but to the everlasting grief of her sorrowing parents."

This letter made George feel as if he would like that very moment to have his horse saddled and to start for Mount Vernon. But he felt that with the great interests[Pg 1088] with which he had been trusted by Lord Fairfax it would not be right to go without giving an account of his work. He was sitting sadly enough at the library table, reading his mother's letter, when Lord Fairfax entered.

"You have bad news, George," said he, after one glance at the boy's troubled face.

"Very bad, sir," replied George, sadly. "My brother's only living child, a dear little girl, is very ill, I am afraid. My mother writes me she is fading fast. My poor brother and sister love her so much—she is the only child that has been spared to them. Three others have all died before they were a year old."

"Then you want to go to Mount Vernon as soon as possible?" said the Earl, reading the unspoken wish in George's heart.

"Oh, sir, I do want to go; but I think I ought to stay here for some days, to show you what I have done."

"One night will be enough, if you will leave your surveys and papers with me; and perhaps I may myself go down to Mount Vernon later on, when the little one is either better on earth or eternally well in heaven."

George looked at him with eloquent eyes.

"If you will be so kind as to let me go, I will come back just as soon—" George stopped; he could say no more.

Although just come from a long journey, so vigorous and robust was George that he began at once exhibiting his surveys and papers. They were astonishingly clear, both in statement and in execution; and Lord Fairfax saw that he had no common surveyor, but a truly great and comprehensive mind in his young protégé. George asked that William Fairfax might be sent for; and when he came, told Lord Fairfax how helpful William had been to him.

"And you did not have a single falling out while you were together?" asked Lord Fairfax, with a faint smile. At which both boys answered at the same time, "No, sir!"—William with a laugh and George with a deep blush.

All that day, and until twelve o'clock that night, George and Lord Fairfax worked on the surveys, and at midnight Lord Fairfax understood everything as well as if a week had been spent in explaining it to him.

When daylight came next morning George was up and dressed, his horse and Billy's saddled and before the door, with Lord Fairfax, Lance, and William Fairfax to bid him good-by.

"Good-by, my lord," said George. "I hope we shall soon meet at Mount Vernon, and that the little girl may get well, after all. Good-by, William and Lance. You have been the best of messmates; and if my work should be satisfactory, it will be due as much to you as to me."

Three days' hard travel brought him to Mount Vernon on a warm September day. As he neared the house his heart sank at the desolate air of the place. The doors and windows were all open, and the negroes with solemn faces stood about and talked in subdued tones. George rode rapidly up to the house, and, dismounting, walked in. Uncle Manuel, the venerable old butler, met him at the door, and answered the anxious inquiry in George's eyes.

"De little missis, she k'yarn lars' long. She on de way to de bosom o' de Lamb, w'har tecks keer o' little chillen," he said, solemnly.

George understood only too well. He went up stairs to the nursery. The child, white and scarcely breathing, her yellow curls damp on her forehead, lay in her black mammy's arms. The father and mother, clasped in each other's arms, watched with agonized eyes as the little life ebbed away. The old mammy was singing softly a negro hymn as she gently rocked the dying child:

"'De little lambs in Jesus' breas'

He hol' 'em d'yar and giv' 'em res';

He teck 'em by dee little hands,

An' lead 'em th'u' de pleasant lands.'"

As George stood by her, with tears running down his face, the old mammy spoke to the child. "Honey," said she, "heah Marse George. Doan' you know Marse George, dat use ter ride you on he shoulder, an' make de funny little rabbits on de wall by candle-light?"

The child opened her eyes, and a look of recognition came into them. George knelt down by her. She tried to put her little arms around his neck, and he gently placed them there. The mother and father knelt by her too.

"My darling," said the mother, trembling, "don't you know papa and mamma too?"

The little girl smiled, and whispered, "Yes—papa and mamma and Uncle George and my own dear mammy."

The next moment her eyes closed. Presently George asked, brokenly,

"Is she asleep?"

"Yes," calmly answered the devoted old black woman, straightening out the little body, "she 'sleep heah, but she gwi' wake up in heaben, wid her little han' in Jesus Chris's; an' He goin' teck keer of her twell we all gits d'yar. An' po' ole black mammy will see her honey chile oncet mo'."

George Moore from New York was visiting his cousin Frank up in New England, and was being shown Frank's pet birds.

"I had a time catching that oriole," said Frank. "The nest was on the end of a slender limb of the big elm back of the barn. The oriole is the smartest bird we have, when it comes to house-building, always putting his hanging nest where even a squirrel is afraid to venture. I got Jonah, one of father's hired help, to hold the longest ladder we have under the nest while I climbed to the top of it. Even then I could barely reach the birds, and had hardly put my hand on a young one when Jonah, who was puffing and blowing with the strain of holding the heavy ladder, and me on the top round, nearly lost his balance, so I grabbed my bird, shinning down in a hurry, I tell you. The one in the last cage is a bluebird. I took him out of a hollow in an old apple-tree over there," and he pointed out to George a fine old orchard.

The following morning the cousins were up at break of day. On their way down stairs Frank said: "Father only allows me to keep wild birds in cages on condition I take good care of them. It's my first work in the morning. Come and see what I do."

The birds were wide awake, and did not seem at all afraid of their young master as he quietly withdrew the trays on the bottoms of the cages, refilling them with sand from a handy barrel. Then fresh water was supplied to each one, and they all took a drink, throwing their heads back after each sip. From a covered tin the boy filled the linnet's seed-cup, first blowing out the empty shells. To the others he gave soft food.

"They are soft-billed birds, and must have soft food," he explained, "They are now fixed for the day," said Frank; "and by the time breakfast is ready you'll hear some music."

After the birds came the ducks, chickens, and pigs, all receiving careful attention, George going the rounds, and laughing to see how the different creatures expressed their satisfaction for the meal.

Their own breakfast was now announced by a loud toot from the horn. The pure country air together with the early rising had given George a fine appetite as he sat down to the plentiful meal spread before him, and for a time neither of the youngsters had a word to say.

The clatter of the knives and forks seemed to excite Frank's pets, for the bluebird, seconded by the oriole and linnet, gave them a sweet concert.

Uncle John replied, when his young guest expressed his pleasure and surprise on hearing their fine notes: "My son has always been fond of the wild birds, wanting, when he was younger, to make a collection of their eggs. I could not allow it, as it is cruel to rob nests, but I knew the birds, both young and old, have numerous enemies. Snakes, hawks, owls, and other vermin every year kill so many of[Pg 1089] them that it's only by the sharpest lookout the old birds escape at all, while the younger are devoured as soon as found. Therefore I consented to his having these birds in the house, taking one young one from a nest of four varieties of birds he fancied. These little captives, who, if they have not their liberty, are safe and well cared for here, and besides, being taken so young with only their pin-feathers on, they do not know what freedom means as trapped old birds would do."

Breakfast over, the boys started on an excursion to Black Pond, half a mile away, a stretch of water sparkling under the sun's rays like a sheet of silver.

The route led through a winding lane. In one of the fields by the side of it, surrounded by a higher fence than usual, the city boy noticed a very large black and white cow, as he thought, and was in the act of vaulting the rail to examine her closer, when Frank caught him by the leg.

"Thunderation! Don't you know a bull when you see him?" he shouted. "He is dangerous, and I don't dare to go in that pasture, though I'm sure there is a bobolink's nest in it that I want to see."

George felt ashamed of himself at such a mistake, and determined he would not show his ignorance of the country again. By this time the boys were within a hundred yards of the pond. Frank proposed a race to see who would get there first. George was ready for anything. Away they started, running side by side till three-quarters of the distance was passed. Here George took the lead, holding it to the water's edge. Frank opened his eyes, for there was not a boy in F—— his equal in a foot-race.

"How did you do it?" he cried, excitedly.

George's eyes sparkled as he answered, "One has got to know how to use his legs to play good baseball."

Birds were numerous now, and Frank told their names, with something of their habits, to his companion as they watched them. "Look at that fellow with a gray body, in the thicket. It's a cat-bird, a good singer, and mimic besides. There are a lot of their nests about here. Black-snakes eat the young ones. They can climb bushes too. Two weeks ago on this very spot I noticed one of these beauties flying excitedly in and out of the alders. I thought something was up, and crept softly into the thicket. Sure enough, twined around a limb within a foot of a nest filled with young cat-birds was the biggest blacksnake I ever saw, over four feet long, and his body was as thick as my wrist. Luckily I had a stout stick with me. He tried to get away, but I settled his snakeship with a whack as he reached the ground."

George wanted to see a blacksnake.

This wish was soon gratified, for as they passed some granite bowlders a snake, which was sunning himself on a bit of sand near by, made for the rocks. The boys grabbed stones, throwing them at him and killing him before he could gain cover.

"The birds will thank us for that," said Frank. "I've no doubt this scamp has devoured a good many of them this summer."

The boys then made a regular hunt through the alders, finding many nests, mostly with young ones in them, as it was the first of July, the experienced country lad discovering most of them, as he knew where to look for the nest of each variety, whether on a high or low tree, or on a bush or on the ground. Still George had the pleasure of running onto two or three nests himself. One was the cat-bird of Frank's story. The young ones had flown, but an old one soon appeared, scolding and flying close to the boys' heads.

"Look sharp, George, the little ones can't be far off, I know by the way the bird acts," exclaimed Frank.

THE LITTLE CHAP COULD FLY, HOWEVER, AND REFUSED TO BE

CAUGHT.

THE LITTLE CHAP COULD FLY, HOWEVER, AND REFUSED TO BE

CAUGHT.

True enough, after a short and exciting search George[Pg 1090] spied one on top of a bush. He knew it was a young bird by its short tail. Creeping cautiously up, the boy made a dash for him. The little chap could fly, however, and refused to be caught, hiding himself so cleverly that though the hunters looked for half an hour, they did not see him again.

Along with the cat-bird the brown thrasher and wood-thrush rear their young. A nest of the former was discovered in the fork of a bush near the ground. The mother was on it, allowing George to almost put his hand on her before she flew, to alight close by, making a curious clocking noise. The nest contained four little ones not over a day old. The cousins admired them, but took care not to handle the naked babies or disturb their home. Frank took a small book from his pocket and wrote something in it.

"What's that for?" asked George.

"Oh, I'm putting down the date of their birth. I like to know when the different birds hatch or lay their eggs. To-night I shall transfer this note into a book full of them. You shall see it if you like."

They spent the morning and many other mornings searching the fields and woods, peeking into bird homes, and learning a good deal about them, and George, before his departure, began to love the happy days spent in this fascinating way.

Their afternoons were passed on the surface of Black Pond catching pickerel or gathering lily-pads, and giving the youngsters great sport.

George found his vacation ended all too quickly, but gladly promised to come again the next summer, inviting his cousin to his city home for the Christmas holidays.

As he boarded the cars he said to Frank, "I forgot to mention it before, but in New York there are lots of stores that sell all kinds of birds from South America, England, and everywhere, so when you are with me 'we'll take them all in.'"

This promise was so alluring to Frank that he replied, "Look for me the day before Christmas, for I'm coming, even if I have to walk all the way."

hen Elizabeth first went into the room she could see nothing. The window-blinds were tightly closed, and the lack of sunlight out of doors made it doubly dark within. She had no thought of fear, however, as she stood motionless for a moment on the inner side of the forbidden door. The dark had never any terrors for Elizabeth, and her one feeling was that of elation that her curiosity was at last to be gratified.

What great secret was she at last to discover in this mysterious chamber?

Gradually her eyes became accustomed to the dim twilight. She found her way to one of the windows and opened the slats of the shutters, letting in the cool damp air, and relieving the close, musty atmosphere of the unused room. Then she looked about her and exclaimed aloud with admiration.

It was, beyond doubt, the prettiest room in her aunt's house.

A dainty dressing-table stood between the windows, and the little bed in the corner was hung with white drapery, now fast yellowing with age. The wall was covered with an exquisite paper of delicate tints, and soft rugs lay on the floor. In the corner was a pretty desk, with a sheet of paper lying on it, and a pen, evidently thrown down in haste. Everything in the room had the appearance of having been untouched since the former owner left it, and was covered with a thick coating of dust.

On the dressing-table was a pile of unopened letters. Elizabeth looked at them, and found that all but two of them were addressed in the same hand to "Miss Herrick, No. — South Fourth Street, Philadelphia." There were seven altogether; and the remaining two bore the name of her father, Mr. Edward Herrick.

How did they get to this room? And how very strange that neither her father nor her aunt had opened them. The seals had not been touched.

Very soon Elizabeth made another discovery more startling still. Near one of the windows stood an easel such as artists use for their work, and on it was a canvas, its back turned toward the room. Elizabeth dearly loved pictures, and she carefully lifted this one down and, turning it toward the light, looked at it. It was an unfinished portrait of her aunt Caroline.

The child surveyed it for some minutes, and then replaced it on the easel as she had found it. What could it all mean? Who had once lived in this mysterious apartment? It could not have been her father, for she had frequently been in the room that was formerly his. She had never heard of any one else in the family. She must certainly ask her aunts if they had ever used any rooms but those they now occupied.

And then she heard Marie calling her. She waited until the maid's voice sounded quite far away, and then Elizabeth closed the window and left the fascinating chamber, carefully locking the door behind her.

Then she answered Marie's renewed calls, and submitted to having her shoes changed, her mind absorbed with the startling revelations which this rainy afternoon had brought about.

Miss Herrick was extremely fond of having company to dinner, and there were but few evenings in the week when she and her sister did not either entertain in their own house or dine out. On those rare occasions when they were at home alone Elizabeth came to the table. Otherwise she had supper by herself and went early to bed.

To-night she was to dine with her aunts, and she intended to question them as closely as possible. It would be difficult, for Aunt Caroline always told her when she became too pressing that children should be seen and not heard, and other maxims to the same effect, but Elizabeth made up her mind that this time she should not be daunted. Her aunts must give her some satisfaction.

There was another matter also which she had on her mind, and which must be discussed this evening.

The soup was barely served before she began.

"I wish you would tell me something about this house, Aunt Caroline. Have you always lived here?"

"Always. I fancied that you knew that, Elizabeth. Your great-great-grandfather built the house, and it has been occupied ever since by succeeding generations of Herricks."

"And have you always had the room you have now?"

"Certainly not. It was your grandmother's during her lifetime."

"And what room did you have?"

"Really, Elizabeth, your questions are most tiresome! I had the one next to yours."

"Always?"

"Always."

"Aunt Rebecca, which one did you have?" continued Elizabeth, turning toward the other end of the table.

"I have had my present room ever since I emerged from the nursery, Elizabeth; the place where I think you should still be."

"Aunt Caroline, did you ever have any brothers and sisters but my father and Aunt Rebecca?"

Elizabeth's eyes were fixed upon Miss Herrick's face as she asked this question. She could not fail to see the wave of color which swept over the usually pale cheeks, and that her aunt's hand shook as she laid down her fork.

"You have been told all of the family history that it is desirable for you to know, Elizabeth. I have one brother, your father, and I have one sister, your aunt Rebecca. Further than this I decline to tell you."

Elizabeth still looked at her, and Miss Herrick moved uneasily. Those dark eyes were so penetrating.

"Aunt Caroline, is there a skeleton in your closet?"

Miss Herrick did not reply, and her sister came to the rescue.

"What on earth do you mean, Elizabeth? Where did you get hold of that expression?"

"I read it in a book, and I thought it meant a real skeleton, all bones and ugly skull, standing up in the people's closet—the people in the book, I mean. I asked Miss Rice, and she said it was a family secret, something not at all pleasant, and most families had them. It seems a very strange thing to call a secret. But I was wondering if our family had one. Is there a skeleton in our closet?"

"Do be quiet, Elizabeth, and do not discuss family affairs before the servants. It is bad form."

"Oh!" said Elizabeth. "Very well. I will wait until another time; but I should like to know some time. There is something else I want to talk about, and if you don't mind, Aunt Caroline, I should like to now. You see, I don't have much chance to ask you things."

"You certainly make the most of every opportunity," returned her aunt. "What is it now?"

"It is about the Bradys."

"And who are the Bradys?"

"The poor family who live in the back street."

"I know nothing about them."

"No, I know you don't, Aunt Caroline, and that is why I want to tell you. They are very poor."

"Indeed!"

"And sometimes I am afraid that they are very hungry."

"Indeed!" said Miss Herrick again. "They had better come here for the cold scraps—that is, if they are deserving. How do you happen to know about them?"

"I met them in the alley," returned Elizabeth, composedly. "There are two very nice girls and four boys. One of them is a bootblack, and another is a newspaper-boy, and Tom is—"

"Heavens!" cried Miss Herrick, in horror. "Where did you pick these people up?" While Miss Rebecca, who was more frivolous, laughed aloud.

"In the alley, I told you," repeated Elizabeth. "I went out the back gate when I was playing in the garden one day, and met them. The alley is so interesting and the girls are so pleasant, though they do have rather dirty faces sometimes. But the boys—"

"Spare us any further details, I beg of you," said her aunt. "Your tastes must be extremely low, Elizabeth."

"Well, I like to have a few people to play with. You know I have only Julius Cæsar, and he won't always play. But I was going to ask you something about the Brady family, Aunt Caroline. Why do we have such lots and lots of money and they none at all?"

"Elizabeth, you are too absurd!"

"But why?"

"I—I don't exactly know. They are of a very different class of life, for one thing. Their ancestors—if they had any—were poor men, I suppose, while ours were rich."

"I don't think that explains it. And I am sure they are terribly hungry half the time. They look so. Tom doesn't—"

"Again I must beg you to stop, Elizabeth. I do not care to hear all this at the dinner table. It quite takes away my appetite."

"I am very sorry, Aunt Caroline. Then I will stop. But I was only going to say, don't you think it would be nicer and evener all round if we were to give them some of our money and a nice house to live in? We could easily do it."

"Bless me, what socialistic notions the child has!" cried her aunt Rebecca. "Encouraging pauperism in this style!"

"What is porprism?" asked Elizabeth, turning quickly.

"Don't ask another question, I beg of you! You have used twenty interrogation points at least since we sat down to dinner."

And then the Misses Herrick began resolutely to talk of something else, and Elizabeth knew no more than she did before, and had by no means settled satisfactorily the affairs of the Brady family.

Clearly, if she wanted to know anything she must find it out for herself, and if she wished to do anything to improve the condition of the Bradys she must take matters into her own hands.

If her father would only come home and explain everything to her! But when he received her letter he would certainly come, and with the thought of this possibility the world grew brighter.

The days went by and Elizabeth paid frequent visits to the closed room. It did not once occur to her that it was not by any means an honorable proceeding for her to slip into her aunt's room as soon as that lady left the house, take the keys, and go to a place which it was evidently intended that she should know nothing about. Elizabeth would have scorned to read some one else's letter, or open bureau drawers, or investigate boxes. But this seemed so different. A room was unlike a bureau drawer or a box, she thought. Surely she had a perfect right to go into any room that she wished in her own home, and find out, if she could, about her own family.

But her repeated visits threw no light on the subject. She could not discover to whom it belonged.

It was not very long before something most exciting and utterly unprecedented occurred in the family. A letter was received from Mrs. Redmond, Elizabeth's aunt in Virginia, stating that Valentine Herrick had trouble with his eyes, and that he was coming North to consult a Philadelphia oculist. Of course his aunt's house would be open to him, and it would also be an opportunity for him to become acquainted with his sister. Mrs. Redmond deplored the necessity for bringing up the children apart from one another, and would be only too glad to have Elizabeth come for a long stay at her house, if Miss Herrick would allow her to return with Valentine.

Now the Misses Herrick were not particularly fond of entertaining visitors. It interfered too seriously with their accustomed pursuits. And above all, to have a boy! Valentine must now be about fourteen years old, and could anything be more objectionable to have in the house than a boy of fourteen?

However, there was nothing to be done but to say that he should come, and so the day was fixed, and the family, from the servants up, were in a flutter of excitement. Elizabeth was truly delighted. It would be a vast improvement to have some one in the house besides her stately aunts, and she had longed many a time to know her brother. She was doubtful about boys in general, but then she did not know any but the Brady boys, who were inclined to be rough. This one would be her own brother, and besides, it would be a change, and variety is always desirable.

It was four o'clock one afternoon when a hansom dashed up to the door. Elizabeth and Julius Cæsar, in the window, saw a tall, strong-looking boy jump out, pay the driver, and run up the steps. There was a resounding ring at the door-bell, a loud boyish voice was heard asking if Miss Herrick lived there, and from that moment the old house in Fourth Street lost its accustomed quiet.

He came into the parlor, and at the same instant Julius Cæsar fled away to the safer precincts of the kitchen. He also disliked boys. Elizabeth remained hidden in the window-seat, overcome with shyness.

Peering out from behind the drapery, which formed a deep recess, she could see that her new brother had bright golden hair of the same odd shade as her own, but his eyes were blue and full of fun, and his mouth seemed very ready for a smile. She thought that she should like him.

Miss Herrick was long in appearing, and Valentine occupied the time in looking around him. Presently he began to whistle as he walked about the room, knocking over a screen and upsetting a vase. At last he reached one of the windows, where he was confronted by a small figure in a white dress, with golden hair and great solemn brown eyes, which were fixed upon his face.

"Holloa!" he exclaimed, his whistle stopping short in the middle of a bar.

There was no reply.

"WHY, I SUPPOSE YOU ARE MY SISTER."

"WHY, I SUPPOSE YOU ARE MY SISTER."

"Why, I suppose you are my sister?"

"Yes, I am Elizabeth."

"Elizabeth! That is a terribly long name for such a short person."

The little girl considered it beneath her dignity to respond to this. Suddenly, however, she remembered her manners.

"How do you do?" she said, rising, and holding out a small right hand.

"How do you do?" replied Valentine, as he took it and shook it warmly.

"I hope you had a pleasant journey?"

"Very pleasant, thank you. My eye, aren't you a funny one! I should think you were Miss Herrick herself."

"I am the youngest Miss Herrick. My aunt will come down soon, I think."

"Oh, I say, come off your perch, do! She is my aunt, too. I shall die if you keep on talking like your great-grandmother. Why, how old are you, little Miss Betsey?"

"I am eleven. Did you ever see my great-grandmother?"

Valentine stared. He had not been in Fourth Street long enough to know that Elizabeth's great-grandmother was a very real personage to her, her name being often quoted by the aunts. The titles of their ancestors were too much reverenced to be used as figures of speech.

"Not that I know of," he said. "And so you are eleven. Just the same age as Marjorie, and she would make two of you."

"Who is Marjorie?"

"My cousin, Marjorie Redmond. Your cousin too, as to that."

"Aren't you older?"

"Well, I should say so! What do you take me for? I am thirteen, almost fourteen."

And then their conversation was interrupted by the advent of Miss Herrick. Valentine had really extremely good manners, and his aunt was favorably impressed with her new nephew, despite the fact that he was precisely the age which she had most dreaded.

After a little conversation she went out in the carriage, and left the children together. She said to herself that she might as well begin at once to make the boy understand that she could not entertain him, and besides, the brother and sister had better become acquainted.

Elizabeth felt a terrible responsibility about the matter. She had an impression that boys never did what girls enjoyed doing; for instance, a boy would never play with a doll. But then Elizabeth did not care much for dolls herself. She had always preferred live animals.

"What shall I do with him?" she sighed to herself.

"I wish I had my wheel here," remarked Valentine, presently. "Do you ride?"

"A bicycle? No, indeed!"

"You ought to see Marjorie go. Why, she rides off on my machine like a breeze, though she is so short compared to me that her feet don't go anywhere near the pedals when they are down. What do you do all day?"

"I have lessons with Miss Rice, my governess, and I go to walk, and play in the garden—"

"Have you got a garden? That is jolly. I have one too, and so has Marjorie; but hers is a great deal better than mine. She spends more time over it, weeding and all that. I say life is too short for weeding, but Marjorie loves to grub."

This unknown Cousin Marjorie must be a very superior person, thought Elizabeth. She appeared to surpass the rest of the world in everything. Elizabeth would put what was to her an important question.

"Is Marjorie pretty?"

"Pretty? Oh, I don't know. I never thought much about it. No, I don't believe Marjorie is pretty. Her hair is too straight, and hangs all in a shag, and she has a turned-up nose. I call her 'Pug' half the time. But she is a jolly one, Marjorie is," said the admiring cousin.

Elizabeth began to feel a strong liking for the new-comer. A boy who was so fond of his cousin, and that cousin a girl, must be very nice, she thought. She did hope that as he was her own brother he would grow to like her a little. And then an idea occurred to her.

She could ask Valentine all the questions she wished, and probably he would not mind. She could tell him of her trials about the Brady family, and of her hopes of their father's return. She could even consult him in regard to the skeleton in the Herrick family closet.

She was glad he had come.

"Now, look, Bluebird. See how wise the little rough-coat is. Up! Big chief! March!"

Elk accompanied his commands with expressive actions. He waved his hands upwards, threw out his chest, and strutted off along the river-bank. The young bear he was training stood up on his hind legs and comically repeated his movements.

Bluebird clapped her slender brown hands in delighted applause.

Elk gave a short, pleased laugh. He regarded his accomplished pet affectionately. "That's enough for to-night," he said, patting the brown head. "Bluebird," he added, glancing over towards the Cheyenne village among the straggly trees a few rods back from the river, "let's go see what Yellow Stripe's boy is saying to Much Tongue."

A white lad, whom Elk and his sister recognized as the son of a cavalry officer stationed at the adjacent fort, had just ridden up to the Indian camp, and was leaning across a rifle on his knees, talking to Harlow, the interpreter, called by the Cheyennes Much Tongue.

Elk and Bluebird had attended school on the reservation since their people had surrendered to the military authorities, and they understood the white man's language.

The sun was just setting. Its long last rays cast reflections across the prairie like gigantic finger-marks. It was late August, and some good-sized rabbits were abroad amongst the sage-brush at that hour. Alan stopped to fire at them now and then.

Elk and Bluebird, watching his receding figure, saw him dismount and creep cautiously along the ground for some distance once before firing. Afterwards he spent several minutes apparently searching amongst the bushes. Then he remounted his horse and rode on home.

"He's lost whatever he shot at," remarked Elk.

He and Bluebird were hunting the bear, whom they had forgotten for a moment, and who, it seemed, had run away. He was not very large; his body might easily be concealed in the high sage. They whistled and called for him.

"Here he comes," Bluebird said at length.

The bushes rustled in a line towards them, and presently they saw the little fellow. He seemed to be struggling with difficulty to reach them. They could hear him pant.

Elk sprang quickly to him. He fell on his knees beside the bear, uttering a cry.

"Oh, Bluebird, he is hurt!"

The cub's breast was covered with blood. His pink tongue lolled out of his month. He ceased his efforts to walk when Elk reached him. He sank down in a helpless heap, and looked imploringly up into his master's face.

Elk hastily parted the thick fur to discover the wound. He gave another sharp cry.

"Oh, Bluebird, my little dear one is dying! He is shot! He is shot!"

A moment later the bear fell over lifeless.

Elk flung himself upon his face in a passion of tears.

Bluebird took the bear's head between her hands and blew into his face. But he was past any aid in her power.

"Poor little thing!" she murmured, patting it gently down; "the white boy did not know who you were!"

Elk suddenly sprang to his feet. He looked across the dusky prairie to Fort Strong, where lights were beginning to twinkle, and shook his fist.

"Mean coward!" he shouted, menacingly. "I'll pay you back for this! You think because you belong to the strong white tribe that you can do whatever you choose! But I'll tell you that when a Cheyenne's heart gets bad he can find a way to revenge himself!"

"Oh, Elk, don't!" Bluebird laid her hand on her brother's arm. She looked entreatingly into his face, distorted with grief and anger. "I'm sure Yellow Stripe's boy didn't know he was your pet," she said.

"Didn't know? Didn't care!" retorted Elk.

He dropped upon his knees, and drawing the knife from the leather sheath hanging from his belt, began to dig at the darkening earth.

"I'm going to bury him," he said, in a short, hard voice.

Bluebird took out her knife and proceeded to help him.

They dug away without talking. Elk's anger grew as he worked, as if the dark silence about him was filled with a host of malicious whispering spirits.

"Lone Dog is right," he broke out, bitterly, after a few[Pg 1094] minutes. "These white people are never really our friends. They conquer us because they are rich and powerful. Then they keep us down like dogs. I'd rather we'd all been captured by the Sioux and killed outright."

"Oh, Elk, think what you're saying!" Bluebird remonstrated. "You know the soldier chiefs treat us kindly. Remember how often we used to be cold and starved in the old life, and how we lived in fear day and night of enemies, and think of the food and blankets and quiet homes we have here! And, Elk," she added, somewhat shyly, "it is good to have learned the things they have taught us. The white people's way of acting towards each other is wiser for happiness and peace of the heart than ours. We have learned that it is better not to seek revenge, haven't we, Elk?"

Elk's fierce cut at the ground expressed his mental determination to sever himself from all such opinions.

"You always talk that way, Bluebird!" he cried, irately. "But no one except a mean coward will overlook an injury, Lone Dog says."

"Oh, Elk, don't listen to the hard sour things Lone Dog says!" Bluebird beseeched.

The boy made no reply. The grave being large enough, he quietly laid the bear in it, refilled the hole, and led the way home.

"Ride away from the angry tongue which meddles in a stranger's quarrel, for the fawn with the bit ear shall recover, but if by evil counsel he is made to turn furiously on the wolf he shall surely be torn in pieces."

"Yes, mother, that is why I say I wish Elk would not talk with Lone Dog. He is the angry tongue that is always trying to stir up the boys to do mischief."

Bluebird's voice was seriously troubled. She scraped away thoughtfully at the fresh hide of a buffalo that she and her mother, Ready Proverb, were getting ready to tan.

"Lone Dog is like the lame coyote since he was put in the guard-house for stealing," observed Ready Proverb. "He will not rest until his whole band has felt the snare which caught him."

"Elk's heart is so bad over the bear's death, and he has been in Lone Dog's tepee all morning," said Bluebird.

"Elk is the grandson of my father Wise Eye," the mother responded, placidly; "he will detect the hidden iron that scorched the hide of the branded bull! He will not suffer to be led by Lone Dog, who is the dirt of the tribe! Elk shall avenge his wrongs himself in due season! He shall be the powerful warrior of the Cheyennes! He shall count his coups, and they shall be as many as the hairs on his head! He shall lie in peace at night on a bed made of scalps of his enemies!"

"Mother doesn't understand," Bluebird thought, sadly.

She suffered the intense pain the children of a people in a state of transition from savagery to Christianity must suffer in the realization that their parents have failed to grasp the new truths already embraced by their more teachable minds.

Ready Proverb, however, according to her light, was a good mother. She was proud and fond of her children.

"Elk," she presently remarked, "ate very little breakfast, and when a boy's stomach is empty his heart trails on the ground. You better go dig some turnips for his dinner. Ho always likes turnips."

Bluebird cleaned her knife in the earth and slipped it into its beaded sheath, and started at once after the wild turnips. They grew profusely among the cottonwoods half a mile below the camp.

Bluebird had nearly reached the spot when a strange noise attracted her attention. Looking around she found that it came from a large old tin kerosene can standing a short ways off. She walked towards it curiously.

All of a sudden Elk flew out from behind a tree.

"Don't touch that!" he cried, warningly.

Bluebird started in surprise at finding him so near. She glanced cautiously into the open can. She recoiled from it with a horrified look.

"What are you going to do with those rattlesnakes, Elk?" she exclaimed.

"Something." A dark flush spread over the boy's face. He looked sullen and jaded.

Bluebird forgot her consternation in a flood of compassion for her unhappy-looking brother.

"I've come to dig turnips. You'll like them for dinner, won't you?" she said, pleasantly.

"I don't want any dinner," he answered.

"But you ate hardly a mouthful of breakfast."

"I ate enough," returned Elk. "I'm not going to eat so much hereafter. We reservation Cheyennes overfeed with three meals a day. The braves grow fat and flabby. They cry like children when they're hurt." He colored shamedly, remembering how he had wept for the bear. He gave the can a shake. The snakes hissed, and his eye flashed sharply. "I'm through living the soft life of a white man," he added. "I'm a Cheyenne!"

In moving, the light sleeve of his calico shirt slipped up and revealed to Bluebird his arm covered with horrible gashes. Elk had been torturing himself to test his endurance, after the dreadful old tribal custom. Bluebird was convinced that he was acting under Lone Dog's advice. A dread of what her brother might be led to do next by the bad man formed like a layer of ice on her heart.

"Elk," she begged, tremulously, "please come home to dinner. I'm sure you've courage enough. I don't think it's weak for a brave to cry when he loses a thing he loves. If you'll eat something perhaps you'll feel differently."

Elk shook his head resolutely.

He did not return until evening. During the afternoon Bluebird's anxious eyes spied him riding along the trail skirting the Bad Lands, making for the town across the river beyond the fort. She felt certain that he had made the long circuit to avoid attention. She wondered why he was leading his second pony.

When Elk returned home he did not have the second pony. He had bartered it for an old rifle and some cartridges. He supposed the weapon was concealed beneath his blanket, but Bluebird, beading a moccasin beside the tepee door, observed it as he passed in. She said nothing about it, but the circumstances added to the weight of her anxiety over Elk's strange actions.

The next day was Wednesday. Elk had not relaxed his gloomy silence since the bear's death. He scarcely spoke to any one; he sulked off by himself.

Bluebird had an errand at the trader's this morning. She was crossing the prairie to the fort when, glancing over to the west where the hills lay, she saw Elk disappearing into the cañon beside Flat Butte. She looked after the lonely figure with a sigh.

She was kept waiting at the post trader's for quite a long time before the clerk could wait upon her. At length, while she was selecting her beads, Alan Jervis and an officer came sauntering down the long store past where she stood.

Alan carried a quirt, and he had the cruel little steel wheels which the white chiefs used to make their horses go fast attached to his boot heels. Bluebird understood that he was dressed for riding. She heard him say to the officer:

"Father said I might come out to the camp for a few days, and I'm going now in about an hour. I know the way, and Harlow has told me of a short-cut the Indians take through a cañon in the hills."

"Past Flat Butte, isn't it?" inquired the officer. "That route is considerably shorter than around the hills, but it's a bad bit of travelling through the cañon. You must look out for the fissures in the ground: the sage completely covers some of them, and you're liable to fall into one and break your neck."

"Harlow warned me," replied Alan.

The two passed on, leaving Bluebird in a strange tumult of troubled thoughts. She began all at once to connect Elk's trip to the Bad Lands that morning with Alan's intended journey through the desolate, rarely travelled cañon.

Elk's sworn purpose to revenge the bear's death, his conversations with Lone Dog, his self-torture to prove his[Pg 1095] hardiness, the grewsome can of rattlesnakes, the rifle—all these things came before her mind in an ominous jumble.

What did they all mean? What was Elk about to do?

Bluebird forgot her beads. She hurried out of the store through the rear exit, which opened onto the prairie. She started at a rapid pace across the stretch to the hills. She had no idea what she was going to do other than that she must find Elk, and in some way, even at the risk of her life, prevent an attempt on the white boy. Oh, Elk must not hurt him! Elk, when he was his right-minded self, saw, as she did, that revenge was low and cowardly, and did not mean manliness, as they had been led to believe in the old days.

Moreover, she knew that Elk would be summarily dealt with by the fort authorities if he should molest Alan. If he could not escape them by running away he would be put in prison. The white people hanged men for killing others. It was by such stern laws against wrongdoers that they kept their state of peace.

Bluebird's heart quaked and her steps went faster. It was a sunny morning. She grew very hot. The perspiration poured off her face. She flung away her blanket without stopping. Now and then she glanced hurriedly back to see if Alan was coming. She had just reached the mouth of the cañon when she saw him. She was very tired by now, but she summoned what remained of her strength, and started up the narrow pass with fresh vigor.

Alan was not many minutes behind her.

Elk stopped his pony just outside the Cheyenne village to watch Alan's horse going across the open space from the fort to the hills. He had returned from the cañon by a roundabout way, and had escaped Bluebird's observation.

"He'll soon be there," he thought. An irrepressible shudder went through him. He could not see the rider at that distance, but the sun shone on the white horse, and he knew it was Alan's.

As he watched it the memory of a game of marbles he once had played with Alan came involuntarily to his mind. Yellow Stripe's boy had played generously. After the game he had presented Elk with a large bag of marbles. He was a brave white boy. Elk always had liked him until he had killed the bear.

Elk looked after the white speck irresolutely.

"Windfoot might get there even now before his slow horse," he was thinking. His heart beat hard; his body leaned unconsciously forward towards Alan.

Impelled by a sweep of changed feelings, he suddenly raised his quirt to start up his pony, when a dark hand fell with deaden force upon his arm.

Lone Dog's evil face looked up at him. "I've put the paint sticks and a looking-glass in the twisted tree," he whispered.

Elk looked at him undecidedly a moment. Then he heavily replied, "Very good," and turned his horse slowly in among the tepees under the cotton woods.

Lone Dog smiled satisfiedly as he limped home.

Elk dismounted at his home and went in. Presently he came out with the rifle he had got the day before. He carried it cautiously concealed. The young Cheyennes were not allowed to have fire-arms.

He glanced about a moment for his mother. Then he told himself he was glad she was away from home. Reservation life certainly had the effect of making a brave weak-hearted in an enterprise. He felt a moisture about his eyes as he remounted his pony and rode on among the trees down the river to a desolate spot some distance below the camp.

Three-quarters of an hour later he emerged from the trees quite changed in appearance. He had painted yellow lines like sunrays from the corners of his eyes and mouth; on each cheek he had painted a grotesque red spot. He had braided a defiant scalp-lock on the top of his head. He was, in fact, preparing to join a band of hostiles in the north that Lone Dog had directed him to.

It would not be safe, Lone Dog had told him, to remain any longer in the vicinity of Fort Strong. Besides, it was time that he was going on the war-path and making a name for himself.

He tried to grunt "Huh!" in the savage, manly manner he had heard the warriors do. Somehow it sounded rather weak. He did not dare look round towards home as he rode rapidly off for the Bad Lands. Reservation life certainly turned men into children!

Elk had almost reached the hills when, far down to the south of him, he saw something emerge from the hills close beside Flat Butte.

His keen-sighted eyes peered sharply. It was a boy leading a horse—a white horse. And something was on the horse's back.

Elk stopped his pony and looked excitedly. Could it be possible that Alan had escaped, after all? What would Lone Dog think if he knew how relievedly Elk's heart was beating?

Why was Yellow Stripe's boy walking? The pack on the white horse was a brilliant blue. It looked familiar.

Elk, with a strange presentiment of what had happened, whipped up his pony and started wildly towards the party. He rode like a wild man to reach them. Alan stopped the horse and waited when he saw him coming.

Bluebird, her head and right arm swathed in bandages torn from Alan's shirt, sat upon the horse. She looked towards Elk. The cruel scratches on her face protruded beyond the cloths. Her eyes showed intense suffering.

Alan began explaining how, riding up the cañon, he had found Bluebird in a cut in the ground, clinging to a root of sage-brush to keep herself from falling to the bottom.

Elk scarcely heard him. He sprang off at Bluebird's side; his face had grown suddenly sharp and thin with terror.

"DID ANYTHING BITE YOU, BLUEBIRD?" HE SAID, HOARSELY.

"DID ANYTHING BITE YOU, BLUEBIRD?" HE SAID, HOARSELY.

"Did anything bite you, Bluebird?" he said, hoarsely. "Do you feel yourself swelling anywhere?" His sister's soft eyes poured a flood of sorrow into his upturned face.

"No, Elk; I caught hold of a root and held on, and the snakes could not get at me," she said, in Cheyenne. A shudder went over her. "I could hear them rattling beneath me, but the brush was between us."

"I'm certain Bluebird's fall saved my life," Alan was saying, earnestly. "The bottom of that pit was fairly alive with rattlers, and my horse would have crushed right down into them, and then we'd both have been done for. Somebody had covered the hole with dry brush and rubbish and put loose earth over it. Nobody would have guessed it was a hole. Bluebird says she was running right across it. I think it must have been intended for a bear trap. Do you know there are bears about? I saw one Monday evening, and fired at it, but missed it."

Bluebird shot a swift, meaning glance into Elk's eyes. "The white boy saved my life, Elk," she said. "I couldn't have held on with one hand a moment longer. My right arm broke when I fell, I think, and I couldn't use it. But, dear Elk"—she tried to lean towards him as she added rapidly, in Cheyenne—"it's all right that only I am hurt. I went to the cañon to save Yellow Stripe's boy—and you."

Elk had a sudden conviction that the teachings of reservation life had not made his sister weak-hearted, at all events. There was an appeal in her tones that he did not attempt to resist. She was offering her own sufferings in atonement for Alan's fault. Elk did not let her sacrifice go for nothing. He took a step towards Alan, and extended his hand.

"Hough!" he cried, in a firm hearty voice, which begged forgiveness and pledged his own friendship.

Elk gave Alan his pony to carry him home. He took charge of Bluebird on the horse.

Lone Dog came limping a way out to meet them as they neared the village. His sinister eyes inquired of Elk how his villanously counselled scheme happened to miscarry.

Elk feigned not to see him. He passed him by with a high countenance. His momentary apostleship to the disturbers of the youths of the village was over, never to return. Bluebird saw that Ready Proverb was right. Now that the black veil of revengeful passion had swept by and his right vision was restored to him, the grandson of Wise Eye was not indeed to be led by the dirt of the tribe!

A "LITTLE MOTHER."

A "LITTLE MOTHER."

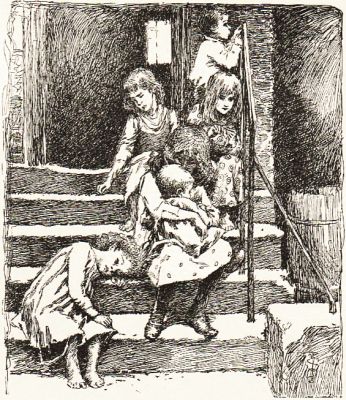

The first thing most of the New York children learn is how to mind the baby. Even a small boy soon learns how to "hush" a child in his arms, and almost all the small girls are good little mothers. The babies on our block are the most beloved little people you ever saw. There are a great many of them, and they tumble around on the sidewalks so that we have to walk very carefully; but somewhere near there is generally to be found a little girl who loves that baby with all her heart, and the more trouble the baby is the more she seems to love it. The little girl in a rich man's family may love her little sister very dearly, but the baby can't be quite so dear to her as it is to the little girl who must save every penny for car fares, so that on the hot days she can take the baby to the dock, where the air is cooler.

"My knee hurts awfully," said one little girl to me. "I just have to hop around on one foot when I am carrying the baby"; and she looked very much surprised when I said, "But you must not carry the baby while you are sick."

All through the summer months the children are kept down on the street so that they can have the fresh air. The baby is generally in his carriage, but the two-year-old child runs about, and he must be carefully watched, for there is danger of his falling under the horses' feet. Sometimes the little mother is careless and one of the youngsters is lost. Then there is a great excitement till the lost child is found at the station-house, usually busy making friends with the policemen.

By the time a girl is eight years old she has not only learned how to take good care of the baby, but she has generally learned also to run on errands, and to buy groceries, and even meat, and she can be trusted with the keys. One often sees a little girl five or six years old playing on the street while her mother is out, and holding in her hand a big bunch of keys, so that, if necessary, any of the family can get into the house. The children in all parts of the city, whether they are Italian or German or American, learn these same things.

Many of the children bring with them from Europe ways that seem very odd to us, but they soon learn from the other children the New York customs. The most marked differences are connected with the differences in the religion of their parents. Some of the children say very funny things. One little Polish Hebrew child named Rachel, while she was in the country, helped to chase an old hen and her brood until several of the chickens were killed. After they had been buried, Rachel said, "I dassent go over there; that's a Christian burying-ground." No one could find out how she knew that the chicken was a Christian and not a Jew.

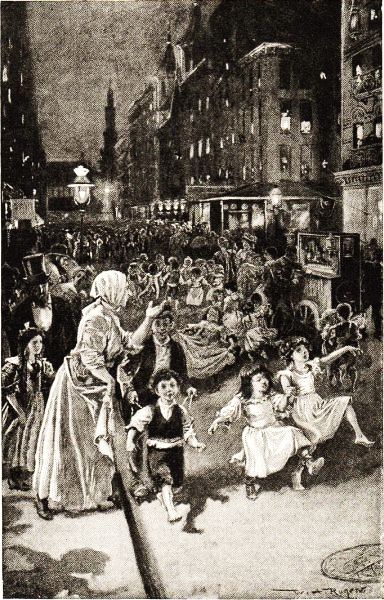

JUST THE SAME KIND OF CHILDREN WE FIND EVERYWHERE.

JUST THE SAME KIND OF CHILDREN WE FIND EVERYWHERE.

The children play a great many ring-around games in the evenings. The German children sing "Liebe Mary, dreh dich herum," and other German songs; and all over the city they sing, "Lazy Mary, will you get up?" and "All around the mulberry bush," and "I came to see Miss Jinny Ann Jones, and how is she to-day?" They play tag and hide-and-seek, and, sitting on the door-steps, they play a buttermilk game, where no one may laugh, and a great many other games. In some parts of the city the boys and girls play with one another, as they do in the country, but in other neighborhoods the girls play alone. They are fond of dancing, and the Italian man with his piano is often surrounded by fifty or a hundred little girls in the middle of the street, waltzing gracefully, and making for the passers-by a very pretty picture. In the evenings they are generally allowed to stay down on the street until nine o'clock; but that is the hour when careful mothers see that their younger girls are all at home, though the older girls are often allowed to stay out until ten o'clock. The girls go to school until they are thirteen or fourteen, and they study with eagerness, and worry over their lessons. In New York it seems to be an especially great calamity to be kept at home for even one day, and the little girls give the doctors much trouble by not telling when they have sore throats or feel sick, for fear that they will be told that they must not go to school. At half past three they come home carrying great bundles of books, and you wonder how they have time to play or to do any house-work. But Saturdays are very busy days, and they learn to scrub and to clean the house, and somehow they learn to wash, so that little girls of twelve years[Pg 1097] of age often show me dresses that they have washed and ironed themselves. They don't know so much about sewing, but most of them learn to crochet lace, and they have little crocheting schools in the summer, where they teach one another. They sit in "the yard" or in front of the house, and sometimes each girl brings a penny and they have a party. They have more pennies than country children, I am sorry to say, for they buy too many candies and cakes. They teach one another all the songs that they know, and sometimes one girl tells a story or reads to the others. When the mother knows how to sew well she generally teaches her daughters, but many of the mothers do not know much about sewing. There are sewing-classes in the public schools, but these classes are so large that the children generally seem to learn only how to sew badly.

They want to know how to sew, and nothing makes a lady so popular with school-girls as to tell them that they can have a sewing-class at her house. Then if after the sewing there can be stories and singing and games, the girls are sure to have a fine time. They save their pennies to buy the cloth on which they work. I have seen many a mother much pleased with the tiny stitches her daughter has learned to make. A blue cheese-cloth duster, neatly hemmed, makes a nice present from the youngest ones to their mothers, while the older girls make clothes for themselves or for the children at home.

In the house where I live there are a good many young women who are fond of teaching, and they have friends who come and help with the sewing-classes, so that we have seven sets of school-girls every week. They give themselves names like the Rosebuds, the Sunshine Club, the Butterflies, the Rainbow Club, and the Bluebells. There are many other girls that we know who are waiting anxiously for their chance to come, and the mothers beg us to let their daughters join the sewing-clubs. We have cooking-classes a few times a week when our cook can let us have the kitchen, and these are liked the best of all. The girls have the fun of eating what they have cooked, and they have a jolly time even while they are washing dishes. The older girls who go to work like the cooking-classes, too, and some of them, when they get home early on Saturday afternoons, make biscuit and cookies and apple-sauce for supper. One girl made cookies for the callers who came to her house on New-Year's day, and they liked them better than cake.

The girls enjoy the cooking more than sewing, because they are tired after their day's work. The younger working-girls want mostly to talk together and laugh and sing and dance. Sometimes we are very sorry for the fifteen-year-old girls, they look so young, and they work very hard, but most of them are quite light-hearted, after all. The little cash-girls often tell us what fun they have, and even the flower and feather girls and the girls in the box-factories and in the candy-factories enjoy so much being with one another that they forget all about their troubles. At the noon hour they sing and tell one another stories. They bring their lunches from home or they send a girl out to buy the lunch, and some of these are the girls who make their noonday meal of cream-cakes and pickles. They like to read the same books that girls read everywhere, but sometimes they do not understand how other lives can be so different from theirs, how other girls can have their own rooms all to themselves, and can have all the nice things that come to girls who have never lived in small rooms, with nineteen other families in the same house.