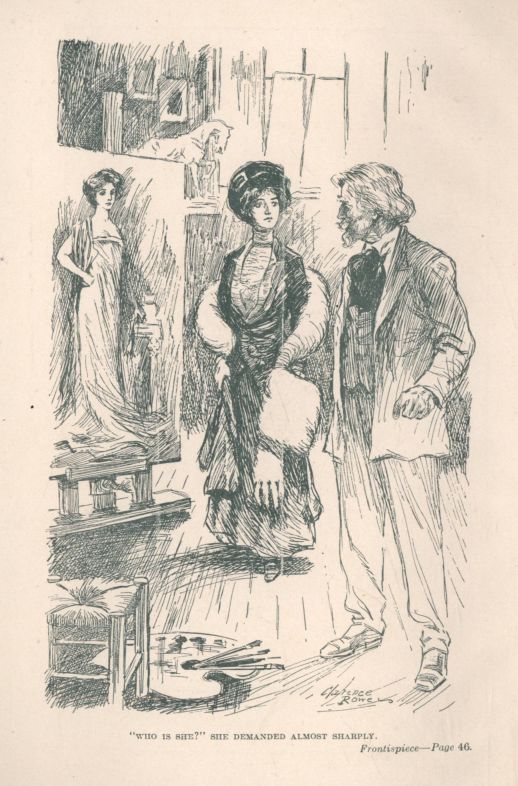

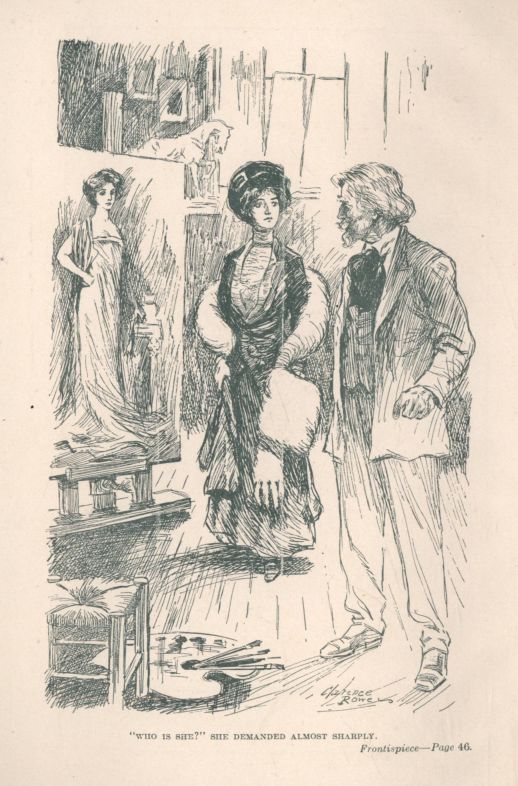

"WHO IS SHE?" SHE DEMANDED ALMOST SHARPLY. Frontispiece—Page 46.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Redeemed, by Mrs. George Sheldon Downs This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Redeemed Author: Mrs. George Sheldon Downs Illustrator: Clarence Rowe Release Date: April 14, 2019 [EBook #59277] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REDEEMED *** Produced by Al Haines

"WHO IS SHE?" SHE DEMANDED ALMOST SHARPLY. Frontispiece—Page 46.

BY

Mrs. GEORGE SHELDON DOWNS

AUTHOR OF

"Gertrude Elliott's Crucible," "Step by Step,"

"Katherine's Sheaves," etc.

Illustrations by

CLARENCE ROWE

M. A. DONOHUE & COMPANY

CHICAGO NEW YORK

Copyright, 1910 and 1911

By VICKERY & HILL PUB. CO.

Copyright, 1911

By G. W. DILLINGHAM COMPANY

Redeemed

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I A WIFE REPUDIATED

II THE FINAL RUPTURE

III A BACKWARD GLANCE

IV A YOUNG WIFE'S BRAVE STRUGGLES

V FLUCTUATING EXPERIENCES

VI AN OLD TEMPTATION REVIVED

VII SERIOUS DOMESTIC COMPLICATIONS

VIII HELEN PLANS HER FUTURE

IX AFTER TEN YEARS

X A BRIEF RETROSPECT

XI A SEALED BOOK REOPENED

XII THE SOUBRETTE

XIII A TRYING INTERVIEW

XIV "LOVE THY NEIGHBOR"

XV A STARTLING APPARITION

XVI SACKCLOTH AND ASHES

XVII AS WHEAT IS SIFTED

XVIII LOVING SERVICE

XIX JOHN HUNGERFORD BEGINS LIFE ANEW

XX FIVE YEARS LATER

XXI SOME INTERESTING REVELATIONS

XXII A HAPPY REUNION

XXIII A FINAL RENUNCIATION

XXIV A MASTERPIECE

ILLUSTRATIONS

"Who is she?" she demanded almost sharply . . . Frontispiece

"To begin with, and not to mince matters, I want some money"

She found herself face to face with John Hungerford

"The stranger was—my father"

[Transcriber's note: The last three illustrations were missing from the source book]

REDEEMED

Two lives that once part are as ships that divide,

When, moment on moment, there rushes between

The one and the other a sea—

Ah, never can fall from the days that have been

A gleam on the years that shall be.

BULWER LYTTON.

"Very well, John; I have nothing more to say. You can commence proceedings as soon as you choose. I shall not contest them."

The speaker was a slight, graceful woman of perhaps thirty-five years. Her figure was a little above the medium stature, and symmetrical, almost perfect, in its proportions. Her beautiful, refined face and proudly poised, shapely head were crowned with a wealth of soft brown hair, in which there was a glint of red, and which lay in bright profusion above her white forehead, in charming contrast with the delicate fairness of her skin, which, at the present moment, was absolutely colorless.

Drawn to her full height, she was standing opposite her companion, her large, expressive gray eyes, in which pity and scorn struggled for supremacy, lifted to his in a direct, unflinching gaze which bespoke the strength of purpose and straightforward character of one who possessed the courage of her convictions; while, in her rich-toned voice, as well as in her crisp, decisive sentences, there was a note of finality which plainly indicated that she had taken her stand regarding the matter under discussion, and would abide by it.

"What! Am I to understand that you do not intend to contest proceedings for a divorce, Helen?"

Surprise and an unmistakable intonation of eagerness pervaded John Hungerford's tones as he spoke, while, at the same time, he searched his wife's face with a curious, almost startled, look.

At a casual glance the man impressed one as possessing an unusually attractive personality.

He had a fine, athletic figure—tall, broad-shouldered, well-proportioned—which, together with an almost military bearing, gave him a distinguished air, that instantly attracted attention wherever he went. A clear olive complexion, dark-brown eyes and hair, handsomely molded features, and a luminous smile, that revealed white, perfect teeth, completed the tout ensemble that had made havoc with not a few susceptible hearts, even before he had finally bestowed his coveted affections upon beautiful Helen Appleton, whom later he had made his wife. But upon closer acquaintance one could not fail to detect disappointing lines in his face, and corresponding flaws in his character—a shifty eye, a weak mouth and chin, an indolent, ease-loving temperament, that would shirk every responsibility, and an insatiable desire for personal entertainment, that betrayed excessive selfishness and a lack of principle.

"No," the woman coldly replied to her husband's exclamation of astonishment, "I have no intention of opposing any action that you may see fit to take to annul our union, provided——"

She paused abruptly, a sudden alertness in her manner and tone.

"Well?" he questioned impatiently, and with a frown which betokened intolerance of opposition.

"Provided you do not attempt to take Dorothy from me, or to compromise me in any way in your efforts to free yourself."

The man shrugged his broad shoulders and arched his fine eyebrows.

"I am not sighing for publicity for either you or myself, Helen," he observed. "I simply wish to get the matter settled as quickly and quietly as possible. As for Dorothy, however——"

"There can be no question about Dorothy; she is to be relinquished absolutely to me," Helen Hungerford interposed, with sharp decision.

"You appear to be very insistent upon that point," retorted her companion, with sneering emphasis and an unpleasant lifting of his upper lip that just revealed the tips of his gleaming teeth.

"I certainly am; that my child remains with me is a foregone conclusion," was the spirited reply.

"The judge may decree differently——"

"You will not dare suggest it," returned the wife, in a coldly quiet tone, but with a dangerous gleam in her eyes. "No judge would render so unrighteous a decree if I were to tell my story, which I certainly should do if driven to it. I have assented to your demand for this separation, but before I sign any papers to ratify the agreement you will legally surrender all claim to, or authority over, Dorothy."

"Indeed! Aren't you assuming a good deal of authority for yourself, Helen? You appear to forget that Dorothy is my child as well as yours—that I love her——"

"Love her!" Exceeding bitterness vibrated in the mother's voice. "How have you shown your love for her? However, it is useless to discuss that point. I have given you my ultimatum—upon no other condition will I consent to this divorce," she concluded, with an air of finality there was no mistaking.

"I swear I will not do it!" John Hungerford burst forth, with sudden anger.

An interval of silence followed, during which each was apparently absorbed in troubled thought.

"Possibly it will make no difference whether you do or do not accede to my terms," Mrs. Hungerford resumed, after a moment, "for it has occurred to me that there is already a law regulating the guardianship of minors, giving the child a voice in the matter; and, Dorothy being old enough to choose her own guardian, there can be little doubt regarding what her choice would be."

"You are surely very sanguine," sneered her husband.

"And why should I not be?" demanded the woman, in a low but intense tone. "What have you to offer her? What have you ever done for her, or to gain her confidence and respect, that could induce her to trust her future with you? How do you imagine she will regard this last humiliation to which you are subjecting her and her mother?"

John Hungerford flushed a conscious crimson as these pertinent questions fell from the lips of his outraged wife. His glance wavered guiltily, then fell before the clear, accusing look in her eyes.

"Oh, doubtless you have her well trained in the rôle she is to play," he sullenly observed, after an interval of awkward silence, during which he struggled to recover his customary self-assurance. "You have always indulged her lightest whim, and so have tied her securely to your apron strings, which, it goes without saying, has weakened my hold upon her."

His companion made no reply to this acrid fling, but stood in an attitude of quiet dignity, awaiting any further suggestions he might have to offer.

But, having gained his main point—her consent to a legal separation—the man was anxious to close the interview and escape from a situation that was becoming exceedingly uncomfortable for him. At the same time, he found it no easy matter to bring the interview to a close and take final leave of the wife whom he was repudiating.

"Well, Helen," he finally observed, assuming a masterful tone to cover his increasing embarrassment, "I may have more to say regarding Dorothy, later on—we will not discuss the matter further at present. Now, I am going—unless you have something else you wish to say to me."

Helen Hungerford shivered slightly at these last words, and grew marble white.

Then she suddenly moved a step or two nearer to him, and lifted her beautiful face to him, a solemn light in her large gray eyes.

"Yes, I have something else I would like to say to you, John," she said, her voice growing tremulous for the first time during their interview. "This separation is, as you know, of your own seeking, not mine. A so-called divorce, though sanctioned a thousand times by misnamed law, means nothing to me. When I married you I pledged myself to you until death should part us, and I would have held fast to my vows until my latest breath. I may have made mistakes during the years we have lived together, but you well know that whenever I have taken a stand against your wishes it has always been for conscience's sake. I have honestly tried to be a faithful wife—a true helpmeet, and a wise mother. I have freely given you the very best there was in me to give. Now, at your decree, we are to part. I make no contest—I hurl no reproaches—I simply submit. But I have one last plea to make: I beg of you not to ruin your future in the way you are contemplating—you know what I mean—for life is worthless without an honored name, without the respect of your fellow men, and, above all, without self-respect. You have rare talent—talent that would lift you high upon the ladder of fame and success, if you would cease to live an aimless, barren existence. For your own sake, I pray you will not longer pervert it. That is all. Good-by, John; I hear Dorothy coming, and you may have something you would like to say before you go."

She slipped quietly between the portières near which she had been standing, and was gone as a door opened to admit a bright, winsome lassie of about fifteen years.

Dorothy Hungerford strongly resembled her mother. She was formed like her; she had the same pure complexion, the same large, clear gray eyes and wealth of reddish-brown hair, which hung in a massive braid—like a rope of plaited satin—between her shoulders, and was tied at the end with a great bow of blue ribbon.

The girl paused abruptly upon the threshold, and flushed a startled crimson as her glance fell upon her father.

"Where—is mamma?" she inquired, in evident confusion.

"Your mother has just gone to her room," the man replied, his brows contracting with a frown of pain as he met his daughter's beautiful but clouded eyes. "Come in, Dorothy," he added, throwing a touch of brightness into his tones; "I wish to have a little talk with you."

The maiden reluctantly obeyed, moving forward a few paces into the room and gravely searching her father's face as she did so.

"I suppose you know that I am going away, Dorothy? Your mother has told you—ahem!—of the—the change I—we are contemplating?" John Hungerford inquiringly observed, but with unmistakable embarrassment.

"Yes, sir," said Dorothy, with an air of painful constraint.

"How would you like to come with me, dear? You have a perfect right to choose with whom you will live for the future."

"I choose to live with my mother!" And there was now no constraint accompanying the girl's positive reply.

The man's right hand clenched spasmodically; then his dark eyes blazed with sudden anger.

"Ha! Evidently your mother has been coaching you upon the subject," he sharply retorted.

"Mamma hasn't said a word to me about—about that part of the—the plan," Dorothy faltered.

"Then you mean me to understand that, of your own free will, you prefer to remain with your mother altogether?"

Dorothy nodded her drooping head in assent, not possessing sufficient courage to voice her attitude.

"Pray tell me what is your objection to living with me—at least for a portion of each year?"

The child did not immediately answer. The situation was an exceedingly trying one, and she appeared to be turning her father's proposition over in her mind.

At length she lifted her head, and her eyes met his in a clear, direct gaze.

"Where are you going to live?" she questioned, with significant emphasis.

Her companion shrank before her look and words as if he had been sharply smitten.

"That is not the question just at present," he said, quickly recovering himself. "I asked what objection you have to living with me. Don't you love me at all?"

Again Dorothy's head fell, and, pulling the massive braid of her ruddy hair over her shoulder, she stood nervously toying with it in silence.

"Dorothy, I wish you to answer me," her father persisted, greatly irritated by her attitude toward him, and growing reckless of consequences in his obstinate determination to force her to give him a definite answer.

But Dorothy was not devoid of obstinacy herself. She pouted irresolutely a moment; then, tossing her braid back into its place, stood erect, and faced her father squarely.

"Why are you going away—why will you not live here with mamma?"

Again the man flushed hotly. He was guiltily conscious that she knew well enough why.

"I—we are not congenial, and it is better that we live apart," he faltered, as he shifted uncomfortably from one foot to the other. Then, becoming suddenly furious in view of being thus arraigned by his own child, he thundered: "Now I command you to give me your reason for refusing to live with me during some portion of each year! I know," he went on, more temperately, "that you love your mother, and I would not wish to take you from her altogether; but I am your father—I certainly have some claim upon you, and it is natural that I should desire to keep you with me some of the time. Now, tell me at once your objections to the plan," he concluded sternly.

The interview had been a severe strain upon the delicately organized and proud-spirited girl, and she had found great difficulty in preserving her self-control up to this point; but now his tone and manner were like spark to powder.

"Because—— Oh, because I think you are just horrid! I used to think you such a gentleman, and I was proud of you; but now you have shamed me so! No, I don't love you, and I wouldn't go to live with you and—and that dreadful woman for anything!" she recklessly threw back at him.

For a minute John Hungerford stood speechless, staring blankly at his child, his face and lips colorless and drawn. Her words had stabbed him cruelly.

"Dorothy, you are impertinent!" he said severely, when he could command his voice.

She caught her breath sharply; she bit her lips fiercely, her white teeth leaving deep imprints upon them; then passion swept all before it.

"I know it—I feel impertinent! I feel awful wicked, as if I could do something dreadful!" she cried shrilly and quivering from head to foot from mingled anger and grief. "You have broken mamma's heart, and it breaks mine, too, to see her looking so crushed and getting so white and thin. And now you are going to put this open disgrace upon her—upon us both—just because you are tired of her and think you like some one else better. I do love my mother—she is the dearest mother in the world, and I'm glad you're going. I—I don't care if I never——"

Her voice broke sharply, at this point, into something very like a shriek. She had wrought herself up to a frenzy of excitement, and now, with great sobs shaking her slight form like a reed, she turned abruptly away, and dashed wildly out of the room, slamming the door violently behind her.

John Hungerford was stricken with astonishment and dismay by the foregoing outburst of passion from his child. As a rule, she had ever been gentle and tractable, rarely defying his authority, and never before had he seen her manifest such temper as she had just given way to. He had always believed that she loved him, although he had long been conscious of a growing barrier between them—that she invariably sought her mother's companionship when she was in the house, and held aloof from him. But he had been so absorbed in his own pursuits that he had not given much serious thought to the matter; consequently it had now come like a bolt from a clear sky, when she had openly declared that she did not love him, while he was at no loss for words to complete the scathing, unfinished sentence to which she had given utterance just before she had fled from his presence.

It had taken him unawares, and, indifferent as he had become to his responsibilities as a husband and father; determined as he was to cut loose from them to gratify his pleasure-loving and vacillating disposition, his heart was now bruised and lacerated, his proud spirit humiliated as it never before had been, by Dorothy's passionate arraignment and bitter repudiation of him.

His wife, greatly to his surprise, had received him with her accustomed courtesy, had quietly acceded to his wishes when he informed her that he contemplated seeking a divorce, and had calmly told him that she had no intention of contesting his application for a legal separation. He had not believed he would be able to secure his freedom so easily, and secretly congratulated himself that the matter had been so quickly adjusted, and had terminated without a scene, even though he had been not a little chagrined by his wife's dignified bearing and a certain conscious superiority throughout the interview; also by the absence of all excitement or sentiment, except as, now and then, a flash of scorn or pity for him leaped from her eyes or rang in her tones.

But it had been quite another thing to have Dorothy, whom he had always fondly loved, in his selfish way, so openly denounce him for his faithlessness to her mother, and impeach him for the humiliation to which he was about to subject them both. As his anger subsided, as he began to realize something of what it meant, he was cut to the quick, and a sickening sense of loss and desolation suddenly swept over him, causing his throat to swell with painful tension and his eyes to sting with a rush of hot tears.

His only child—his pet and little playmate for fifteen years—had practically told him that she would not care if she never saw him again. It seemed almost as if she had suddenly died and were lost to him forever. He wondered if he ever would see her again, hear her fresh young voice calling "papa," or feel her soft lips caressing his cheek.

He stood for several minutes staring miserably at the door through which she had disappeared, a long, quivering sigh heaving his broad chest. Then his eyes swept the familiar, tastefully arranged room, which showed the graceful touch of his wife's deft hands in every detail, and finally rested upon the great bow of blue ribbon which had become loosened from Dorothy's hair and fallen to the floor almost at his feet.

He stooped, picked it up, and thrust it into his bosom; then mechanically took his hat, and quietly left the house.

But, as the outer door closed behind him, and the latch clicked sharply into its socket, there shot through all his nerves a thrill of keen pain which for many years repeated itself whenever the same sound fell upon his ears.

There seemed to be an ominous knell of finality in it, and, mingling with it, a sinister jeer at his supreme folly in thus turning his back forever upon this attractive, though comparatively simple, home, with its atmosphere of purity and sweet, refining influences; in discarding the beautiful and loyal woman whom he had once believed he adored; in abandoning and forfeiting the affection and respect of a lovely daughter, who also gave promise of becoming, in the near future, a brilliant and cultured woman, and—for what?

More than an hour elapsed after Dorothy fled from her father's presence before she could control herself sufficiently to seek her mother, who also had been fighting a mighty battle in the solitude of her own room. Even then the girl's eyes were red and swollen from excessive weeping; neither had she been able to overcome wholly the grief-laden sobs which, for the time, had utterly prostrated her.

"Mamma, he has told me, and—he has gone," she faltered, almost on the verge of breaking down again, as she threw herself upon her knees by her mother's side and searched with anxious eyes the white, set face of the deserted wife.

"Yes, dear; I heard him go."

"Do you think it will be forever?"

"That is what a divorce—a legal separation—means, Dorothy."

The girl dropped her head upon her mother's shoulder, with a moan of pain, and Helen slipped a compassionate arm around the trembling form.

"Mamma," Dorothy began again, after a few moments of silence.

"Well, dear?"

"I think it is awful—what he is doing; but don't you think that we—you and I—can be happy again, by and by, just by ourselves?"

"I am sure we can, dearest," was the brave response, as Helen Hungerford drew her daughter closer to her in a loving embrace.

Dorothy seized her mother's hand and kissed it passionately, two great, burning tears dropping upon it as she did so.

"He asked me to go with him—to live with him some of the time," she presently resumed.

"And you told him——" breathed Helen, almost inaudibly.

"I was very disrespectful, mamma," confessed the girl humbly; "but I couldn't help it when I thought what it all meant. I said I wouldn't live with him for anything—I almost told him that I wouldn't care if I never saw him again. Where will he go now? What will he do? Will—he marry that woman?" she concluded, her voice growing hard and tense again.

Her mother's lips grew blue and pinched with the effort she made to stifle a cry of agony at the shameful suggestion. But she finally forced herself to reply, with some semblance of composure:

"I do not know, Dorothy, and we will try not to worry over anything that he may do. However, when he secures the necessary decree from the court he will have the legal right to do as he pleases."

"The legal right," repeated Dorothy reflectively.

"Yes, the law will give him the right to marry again if he wishes to do so."

"What an abominable law! And what a shameful thing for any man to want to do, when he already has a family! What will people think of us if he does?" queried the girl, with a shiver of repulsion.

"My dear, ask rather what people will think of him," said her mother tenderly, as she laid her lips in a gentle caress against the child's forehead.

"Of course, I know that nice people will not respect him; but I can't help feeling that the shame of it will touch us, too," opposed sensitive Dorothy.

"No, dear; what he has done, or may do, cannot harm either you or me in the estimation of our real friends," replied Helen, throwing a note of cheer she was far from feeling into her tones. "It can only bring condemnation upon himself, and you are not to feel any sense of degradation because of your father's wrongdoing. We are simply the innocent victims of circumstances over which we have no control; and, Dorrie, you and I will so live that all who know us will be compelled to respect us for ourselves."

Dorothy heaved a deep sigh of relief as her mother concluded, and her somber eyes brightened perceptibly. She sat silently thinking for f several minutes; then a cloud again darkened her face.

"Mamma," she began hesitatingly, "you said the law would give p—him the right to do as he pleases—to marry that woman. Can you do as you please? Could you——"

"Oh, hush, Dorothy!" gasped the tortured wife, in a shocked tone, and laying an icy hand over the girl's lips. "When I married your father," she went on more calmly after a little, "I promised to be true to him while we both lived, and you must never think of anything like that for me—never—never! He may choose another, but I—— Oh, God, my burden is heavier than I can bear!"

Helen Hungerford buried her agonized face in her hands, cowering and shrinking from the repulsive suggestion as if she had been smitten with a lash.

Dorothy was shocked by the effect of her thoughtless question. She had never seen her mother so unnerved before.

"Oh, mamma, don't!" she cried wildly. "I love you dearly—dearly—I did not mean to hurt you so, and I hate him for making you so wretched—for putting this dreadful disgrace upon us both. I will never forgive him—I never want to see him again. I know it is wicked to hate, but I can't help it—I don't care! I do—I do——"

These incoherent utterances ended in a piercing shriek as the overwrought girl threw herself prone upon the floor at her mother's feet, in a violent paroxysm of hysteria.

She was a sensitively organized child, proud as a young princess, and possessed of a high sense of honor; and grief over the threatened break in the family, together with fear of the opprobrium which she believed it would entail upon her idolized mother, as well as upon herself, had been preying upon her mind for several weeks; and now the climax had come, the cloud had burst, and, with the strenuous excitement and experiences of the day, had resulted in this nervous collapse.

Hours elapsed before Helen succeeded in soothing her into any degree of calmness, and when at last she fell into a deep sleep, from utter exhaustion, the forsaken wife found something very like hatred surging within her own heart toward the faithless man who had ruthlessly wrecked their happiness.

"Neither will I forgive him for imposing this lifelong sorrow and taint upon my child," she secretly vowed as she sat through the long, lonely hours of the night, and watched beside the couch of her daughter.

In due time, she received formal announcement that her husband had secured his divorce, and that she also was free, by the decree of the court; and, following close upon this verdict, came the news that John Hungerford, the artist, had gone abroad again to resume his studies in Paris.

It was significant, too, at least to Helen, that the same papers stating this fact also mentioned that the Wells Opera Company, which had just finished a most successful season in San Francisco, was booked for a long engagement, with Madam Marie Duncan as leading soprano, in the same city; the opening performance was set for a date in the near future.

Helen Gregory Appleton was the only child of cultured people, who, possessing a moderate fortune, had spared no pains or expense to give their daughter a thorough education, with the privilege of cultivating whatever accomplishments she preferred, or talent that she possessed.

Helen was an exceptionally bright girl, and, having conscientiously improved her opportunities, she had graduated from high school at the age of seventeen, and from a popular finishing school at twenty, a beautiful and accomplished young woman, the joy and pride of her devoted parents, who anticipated for her not only a brilliant social career, but also an auspicious settlement in life.

Her only hobby throughout her school life had been music, of which, from childhood, she had been passionately fond. "I don't care for drawing or painting," she affirmed, "so I will stick to music, and try to do one thing well." And with no thought of ever making it a profession, but simply for love of it, she had labored tirelessly to acquire proficiency in this accomplishment, with the result that she not only excelled as a pianist, but was also a pleasing vocalist—attainments which, later in life, were destined to bring her rich returns for her faithful study.

It was during her last year in school that she had met John Hungerford, a graduate of Yale College, and a promising young man, possessing great personal attractions. He was bright, cheerful, and witty, always looking for the humorous side of life; while, being of an easy-going temperament, he avoided everything like friction in his intercourse with others, which made him a very harmonious and much-sought-after companion. Naturally courteous, genial, and quick at repartee, enthusiastically devoted to athletic sports, ever ready to lead in a frolic and to entertain lavishly, he was generally voted an "all-around jolly good fellow." Hence he had early become a prime favorite with his class, and also with the faculty, and remained such throughout his course.

He was not a brilliant scholar, however, and barely succeeded in winning his degree at the end of his four years' term. He did not love study; he lacked application and tenacity of purpose, except in sports, or such things as contributed to his personal entertainment. At the same time, he had too much pride to permit him to fail to secure his diploma, and he managed to win out; but with just as little work and worry as possible.

The only direction in which he had ever shown a tendency to excel was in art, the love of which he had inherited from his paternal grandfather, who, in his day, had won some renown, both abroad and in his own country, as a landscape painter; and from early boyhood "John Hungerford, Second"—his namesake—had shown unmistakable talent in the same direction.

Possessing a small fortune, which had fallen to him from this same relative, the young man had given scarcely a serious thought to his future.

Life had always been a bright gala day to him; money was easy, friends were plenty, and, with perfect health, what more could he ask of the years to come? And when questioned regarding what business or profession he purposed to follow, on leaving college, he would reply, with his usual irresponsible manner: "It will be time enough to decide that matter later on. I propose to see something of the world, and have some fun, before settling down to the humdrum affairs of life."

Once the formality of their introduction was over, John had proceeded forthwith to fall desperately in love with beautiful Helen Appleton, and, as she reciprocated his affection, an early engagement had followed. Six months later they were married, and sailed for Europe, with the intention of making an extensive tour abroad.

Helen's parents had not sanctioned this hurried union without experiencing much anxiety and doubt regarding the wisdom of giving their idolized daughter to one whom they had known for so short a time. But young Hungerford's credentials had appeared to be unquestionable, his character above reproach, his personality most winning, and his means ample; thus there had seemed no reasonable objection to the marriage.

The young man's wooing had been so eager, and Helen so enamored of her handsome lover, who swept before him every argument or obstacle calculated to retard the wedding with such plausible insistence, that the important event had been consummated almost before they could realize what it might mean to them all when the excitement and glamour had worn away.

Frequent letters came to them from the travelers, filled with loving messages, with enthusiastic descriptions of their sight-seeing, and expressions of perfect happiness in each other; and the fond father and mother, though lonely without their dear one, comforted themselves with assurances that all was well with her, and they would soon have her back with them again.

After spending a year in travel and sight-seeing, the young couple drifted back to Paris, from which point they intended, after John had made another round of the wonderful art galleries, which had enthralled him upon their previous visit, to proceed directly home. But the artist element in him became more and more awakened, as, day after day, he studied the world-renowned treasures all about him, until he suddenly conceived the idea of making art his profession and life work; whereupon, he impulsively registered himself for a course in oils, under a popular artist and teacher, Monsieur Jacques by name.

Helen would have preferred to return to her parents, for she yearned for familiar scenes, and particularly for her mother at this time; but she yielded her will to her husband's, and they made a pretty home for themselves in an attractive suburb of Paris, where, a little later, there came to the young wife, in her exile—for such it almost seemed to her—a great joy.

A little daughter, the Dorothy of our opening chapter, was born to John and Helen Hungerford a few weeks after the anniversary of their marriage; and, being still deeply in love with each other, it seemed to them as if their cup of happiness was filled to the brim.

Shortly afterward, however, with only a few days between the two sad events, cable messages brought the heartbreaking tidings that Helen's father and mother had both been taken from her, and the blow, for the time, seemed likely to crush her.

John, in his sympathy for his wife, was for immediately throwing up his work, and taking her directly home; but Helen, more practical and less impulsive than her husband, reasoned that there was nothing to be gained by such a rash move, while much would have to be sacrificed in forfeiting his course of lessons, which had been paid for in advance; while she feared that such an interruption would greatly abate his enthusiasm, if it did not wholly discourage him from the task of perfecting himself in his studies.

She knew that her father's lawyer, who had been his adviser for many years, was amply qualified to settle Mr. Appleton's business; and, having unbounded confidence in him, she felt that whatever would be required of her could be done as well by correspondence as by her personal presence. Consequently it was decided best to remain where they were until John should become well grounded in his profession, and able to get on without a teacher.

But when Mr. Appleton's affairs were settled it was learned that the scant sum of five thousand dollars was all that his daughter would inherit from his estate. This unlooked-for misfortune was a great surprise to the young husband and wife; a bitter disappointment, also, particularly to John Hungerford, who had imagined, when he married her, that Helen would inherit quite a fortune from her father, who, it was generally believed, had amassed a handsome property.

Helen very wisely decided that the five thousand dollars must be put aside for Dorothy's future education, and she directed the lawyer to invest the money for the child, as his best judgment dictated, and allow the interest to accumulate until they returned to America.

Three years slipped swiftly by after this, and during this time John, who seemed really to love his work, gave promise of attaining proficiency, if not fame, in his profession. At least, Monsieur Jacques, who appeared to take a deep interest in his student's progress, encouraged him to believe he could achieve something worth while in the future, provided he applied himself diligently to that end.

Helen, though chastened and still grieving sorely over the loss of her parents, was happy and content to live very quietly, keeping only one servant, and herself acting the part of nurse for Dorothy. Before her marriage she had supposed John to be the possessor of considerable wealth, and this belief had been confirmed during their first year abroad by his lavish expenditure. He had spared no expense to contribute to her pleasure, had showered expensive gifts upon her, and gratified every whim of his own. But when her father's estate had been settled he had betrayed deep disappointment and no little anxiety in view of the small amount coming to Helen; and it had finally come out that his own fortune had been a very moderate one, the greater portion of which had been consumed during their extravagant honeymoon.

This startling revelation set Helen to thinking very seriously. She realized that the limited sum remaining to them would have to be carefully husbanded, or they would soon reach the end of their resources. John's studies were expensive, and it might be some time yet before he could expect to realize from his profession an income that could be depended upon, while, never yet having denied himself anything he wanted, he had no practical idea of economy.

At length he sold a few small pictures, which, with some help in touching up from monsieur, were very creditable to him. But instead of being elated that his work was beginning to attract attention and be appreciated, he was greatly chagrined at the prices he received for them, and allowed himself to become somewhat discouraged in view of these small returns; and, during his fourth year, it became evident that his interest was waning, and he was growing weary of his work.

He had never been a systematic worker, much to the annoyance of his teacher, who was rigidly methodical and painstaking in every detail. John would begin a subject which gave promise of being above the ordinary, and work well upon it for a while; but after a little it would pall upon his fancy, and be set aside to try something else, while Monsieur Jacques would look on with grave disapproval, and often sharply criticize such desultory efforts. This, of course, caused strained relations between teacher and student, and conditions drifted from bad to worse, until he began to absent himself from the studio; at first for only a day in the week; then, as time went on, he grew more and more irregular, and sometimes several days would elapse during which he would do nothing at his easel, while no one seemed to know where, or with whom, he was spending his time.

Monsieur Jacques was very forbearing. He knew the young man possessed rare talent, if not real genius; he believed there was the promise of a great artist in him, and he was ambitious to have him make his mark in the world. He was puzzled by his peculiar moods and behavior, and strove in various ways to arouse his waning enthusiasm. He knew nothing of his circumstances, except that he had a lovely wife and child, of whom he appeared to be very fond and proud, and he believed him to be possessed of ample means, for he spent money freely upon himself and his fellow students, with whom he was exceedingly popular; hence he was wholly unable to account for his growing indifference and indolence, unless there were some secret, subtle influence that was leading him astray—beguiling him from his high calling.

Two years more passed thus, and still he had made no practical advancement. He worked by fits and starts, but rarely completed and sold anything, even though everything he attempted was, as far as developed, alive with brilliant possibilities.

Helen had also realized, during this time, that something was very wrong with her husband. He was often away from home during the evening, and had little to say when she questioned him regarding his absence; sometimes he told her he had been at the theater with the boys, or he had been bowling at the club, or having a game of whist at the studio.

She was very patient; she believed in him thoroughly, and not a suspicion arose in her loyal heart that he would tell her a falsehood to conceal any wrongdoing on his part.

But one night he did not return at all; at least, it was early morning before he came in, and, not wishing to disturb his wife, he threw himself, half dressed, upon the couch in the library, where Helen found him, in a deep sleep, when she came downstairs in the morning. She appeared relieved on seeing him, and stood for a minute or two curiously searching his face, noting how weary and haggard he looked after his night of evident dissipation, while the odor of wine was plainly perceptible in his heavy breathing.

Her heart was very sore, but she was careful not to wake him, for she felt he needed to sleep, and she presently moved away from him, gathering up the light overcoat he had worn the previous evening, and which he had heedlessly thrown in a heap upon a chair on removing it. She gently shook out the wrinkles, preparatory to putting the garment away in its place, when something bright, hanging from an inner pocket, caught her eye.

With the color fading from her face, she drew it forth and gazed at it as one dazed.

It was a long, silken, rose-hued glove, that exhaled a faint odor of attar of roses as it slipped from its hiding place. It was almost new, yet the shape of the small hand that had worn it was plainly discernible, while on one of the rounded finger tips there was a slight stain, like a drop of wine.

To whom did the dainty thing belong? How had it come into her husband's possession? Had it been lost by some one returning from a ball, or the opera, and simply been found by him? Or had it some more significant connection with the late hours and carousal of the previous night and of many other nights?

A hundred questions and cruel suspicions flashed thick and fast through her mind and stung her to the quick, as she recalled the many evenings he had spent away from her of late, and his evasive replies whenever she had questioned him regarding his whereabouts.

She shivered as she stood there, almost breathless, with that creepy, slippery thing that seemed almost alive, and a silent, mocking witness to some tantalizing mystery, in her hand.

What should she do about it? Should she wake John, show him what she had found, and demand an explanation from him? Or would it be wiser to return the glove to its place of concealment, say nothing, and bide her time for further developments?

She had never been a dissembler. As a girl, she was artless and confiding, winning and keeping friends by her innate sincerity. As a wife, she had been absolutely loyal and trustful—never before having entertained the slightest doubt of her husband's faithfulness to her. Could she now begin to lead a double life, begin to be suspicious of John, to institute a system of espionage upon his actions and pursuits, and thus create an ever-increasing barrier between them? The thought was utterly repulsive to her, and yet it might perhaps be as well not to force, for a time, at least, a situation which perchance would ere long be unfolded to her without friction or estrangement.

She glanced from the rose-hued thing in her hand to the sleeper on the couch, stood thoughtfully studying his face for a moment; then she silently slipped the glove into the pocket where she had found it, dropped the coat back in a heap upon the chair, and stole noiselessly from the room.

Another year slipped by, with no change for the better in the domestic conditions of the Hungerfords. When he felt like it, John would work at his easel; when he did not, he would dawdle his time away at his club, or about town, with companions whom, Helen began to realize, were of no advantage to him, to say the least. Meantime, his money was fast melting away, and there seemed to be no prospect of a reliable income from his art.

Helen became more and more anxious regarding their future, and often implored her husband to finish some of his pictures, try to get them hung at different exhibitions, and in this way perhaps find a market for them.

He was never really unkind to her, though often irritable; yet he was far from being the devoted husband he had been during the first three or four years of their married life. He would often make fair promises to do better, and perhaps work well for a while; then, his interest flagging again, he would drop back into his indolent ways, and go on as before.

One morning, just as he was leaving the house, John informed his wife that he was going, with several other artists, to visit a noted château a few miles out of Paris, where there was a wonderful collection of paintings, comprising several schools of art, some of the oldest and best masters being represented; and the owner of these treasures, the Duc de Mouvel, had kindly given them permission to examine them and take notes at their leisure. It was a rare opportunity, he told her, and she was not to be anxious about him if he did not reach home until late in the evening.

Helen was quite elated by this information; it seemed to indicate that John still loved his art, and she hoped that his enthusiasm would be newly aroused by this opportunity to study such priceless pictures, and he would resume his work with fresh zeal upon his return.

She was very happy during the day, refreshing herself with these sanguine hopes, and did not even feel troubled that John did not come back at all that night. The owner of the château had probably extended his hospitality, and given the students another day to study his pictures, she thought.

The third day dawned, and still her husband had not returned; neither had he sent her any message explaining his protracted absence.

Unable longer to endure the suspense, Helen went in town, to the studio, hoping that Monsieur Jacques might be able to give her some information regarding the expedition to the Château de Mouvel.

But her heart sank the moment she came into the artist's presence.

He greeted her most cordially, but searched her face curiously; then gravely inquired:

"And where is Monsieur Hungerford, madame? I hope not ill? For a week now his brushes they have been lying idle."

"A week!" repeated Helen, with an inward shock of dismay. "Then, Monsieur Jacques, you know nothing about the excursion to the château of le Duc de Mouvel?"

"Excursion to the galleries of le Duc de Mouvel!" exclaimed the artist, astonished. "But surely I know nothing of such a visit—no, madame."

Helen explained more at length, and mentioned the names of some of those whom John had said were to be of the party.

Her companion's brow contracted in a frown of mingled sorrow and displeasure.

"I know nothing of it," he reiterated; "and the persons madame has named are dilettante—they are 'no good,' as you say in America. They waste time—they have a love for wine, women, and frolic; and it is regrettable that monsieur finds pleasure in their company."

Helen sighed; her heart was very heavy.

"Monsieur is one natural artist," the master resumed, bending a compassionate gaze on her white face; "born with talent and the love of art. He has the true eye for color, outline, perspective; the free, steady, skillful hand. He would do great work with the stable mind, but—pardon, madame—he is what, in English, you call—lazy. He will not exercise the necessary application. To make the great artist there must be more, much more, than mere talent, the love of the beautiful, and skillful wielding of the brush; there must be the will to work, work, work. Ah, if madame could but inspire monsieur with ambition—real enthusiasm—to accomplish something, to finish his pictures, he might yet win fame for himself; but the indifference, the indolence, the lack of moral responsibility, and the love of pleasure—ah, it all means failure!"

"But—the Duc de Mouvel—is there such a man? Has he a rare collection?" faltered Helen, thus betraying her suspicion that her husband had deceived her altogether regarding the motive of his absence.

"Yes, my child; I have the great pleasure of acquaintance with le Duc de Mouvel," kindly returned Monsieur Jacques, adding: "He is a great connoisseur in, and a generous patron of, all that is best in art; and if he has extended to your husband and his friends an invitation to view the wonderful pictures in his magnificent château at —— they have been granted a rare honor and privilege."

In her heart, Helen doubted that they had ever been the recipients of such an invitation; she believed it all a fabrication to deceive her and perhaps others. It was a humiliating suspicion; but it forced itself upon her and thrust its venomed sting deep into her soul.

"If there is anything I can do for madame at any time, I trust she will not fail to command me," Monsieur Jacques observed, with gentle courtesy, and breaking in upon the troubled reverie into which she had fallen.

Helen lifted her sad eyes to his.

"I thank you, monsieur," she gratefully returned. "You are—you always have been—most kind and patient." Then, glancing searchingly around the room, the walls of which were covered with beautiful paintings, she inquired: "Are there any of Mr. Hungerford's pictures here?"

"Ah! Madame would like to see some of the work monsieur has been doing of late?" said the artist alertly, and glad to change the subject, for he saw that his proffered kindness had well-nigh robbed her of her composure. "Come this way, if you please, and I will show you," he added, turning to leave the room.

He led her through a passage to a small room in the rear of the one they had just left; and, some one coming to speak to him just then, excusing himself, he left her there to look about at her leisure.

This was evidently John's private workroom; but it was in a very dusty and untidy condition, and Helen was appalled to see the many unfinished subjects which were standing against the walls, in the windows, and even upon chairs. Some were only just begun; others were well under way, and it would have required but little time and effort to have completed them and made them salable.

She moved slowly about the place, pausing here and there to study various things that appealed to her, and at the same time recognizing the unmistakable talent that was apparent in almost every stroke of the brush.

At length she came to a small easel that had been pushed close into a corner. There was a canvas resting on it, with its face turned to the wall, and curiosity prompted her to reverse it to ascertain the subject, when a cry of surprise broke from her lips as she found herself gazing upon the unfinished portrait of a most beautiful woman.

John had never seemed to care to do portraits—they were uninteresting, he had always said—and she had never known of his attempting one before; hence her astonishment.

The figure had been painted full length. It was slight, but perfect in its proportions; the pose exceedingly graceful and natural, the features delicate, the coloring exquisite. The eyes were a deep blue, arch and coquettish in expression; the hair a glossy, waving brown, a few bewitching locks falling softly on the white forehead, beneath a great picture hat. The costume was an evening gown of black spangled net, made décoletté, and with only an elaborate band of jet over the shoulders, the bare neck and beautifully molded arms making an effective contrast against the glittering, coal-black dress.

The girl was standing by a small oval table, one hand resting lightly upon it, the other hanging by her side, and loosely holding a pair of long silken gloves.

Helen's face flooded crimson as her glance fell upon the gloves. Even though they were black, they were startlingly suggestive to her, and her thought instantly reverted to the one, so bright-hued, which she had found in the inner pocket of her husband's overcoat some months previous.

Had she to-day inadvertently stumbled upon the solution of that mystery which had never ceased to rankle, with exceeding bitterness, in her heart from that day to this?

There was still much to be done before the picture would be finished, though it was a good deal further along than most of its companions. Enough had been accomplished, however, to show that there had been no lack of interest on the part of the artist while at work upon it.

Who was she—this blue-eyed, brown-haired siren in glittering black? When and where had the portrait been painted? Had the woman come there, to John's room, for sittings? Or was she some one whom he met often, and had painted from memory? Helen did not believe she could be a model; there was too much about her that hinted at high life, and of habitual association with the fashionable world—possibly of the stage.

She stood a long time before the easel, studying every line of the lovely face until she found that, with all its beauty, there was a suggestion of craftiness and even cruelty in the dark-blue eyes and in the lines about the mouth and sensuous chin.

A step behind her caused Helen to start and turn quickly, to find Monsieur Jacques almost beside her, his eyes fastened intently, and in unmistakable surprise, upon the picture she had discovered.

"Who is she?" she demanded, almost sharply, and voicing the query she had just put to herself.

"Madame, I have never before looked upon the picture—I did not even know that Monsieur Hungerford had attempted a portrait," gravely returned the artist. "It is finely done, however," he added approvingly.

"Has no woman been here for sittings?"

"No, madame; no one except our own models—I am sure not. That is not allowed in my studio without my sanction and supervision," was the reply. "It may be simply a study, original with monsieur; if so, it is very beautiful, and holds great promise," the man concluded, with hearty appreciation.

Helen replaced the portrait as she had found it, somewhat comforted by her companion's assurance and high praise of her husband's effort; then she turned to leave the room.

"I thank you, monsieur, for your courtesy," she said, holding out to him a hand that trembled visibly from inward excitement.

"Pray do not mention it, but come again, my child, whenever I can be of service to you. Au revoir," he responded kindly, as he accompanied her to the door and bowed her out.

Helen went home with a heavy heart. She was well-nigh discouraged with what she had heard and seen. She had long suspected, and she was now beginning to realize, that her husband's chief aim in life was personal entertainment and love of ease; that he was sadly lacking in force of character, practical application, and moral responsibility; caring more about being rated a jolly good fellow by his boon companions than for his duties as a husband and father, or for attaining fame in his profession.

Thus she spent a very unhappy day, haunted continually by that portrait, and brooding anxiously over what the future might hold for them; while, at the same time, she was both indignant and keenly wounded in view of John's improvidence, prodigality, and supreme selfishness, and of his apparent indifference to her peace of mind and the additional burdens he was constantly imposing upon her.

John returned that evening, in a most genial mood. He made light of his protracted absence and of Helen's anxiety on account of it, but offered no apologies for keeping her in suspense for so long. He briefly remarked that the party had concluded to extend their tour, and make more of an outing than they had at first planned. It had evidently been a very enjoyable one, although he did not go into detail at all, and when Helen inquired about the Duc de Mouvel's wonderful collection of paintings, he appeared somewhat confused, but said they were "grand, remarkable, and absolutely priceless!" then suddenly changed the subject.

Helen's suspicion that the party had never been inside the Château de Mouvel was confirmed by his manner; but she was too hurt and proud to question him further, and so did not pursue the subject. She thought it only right, however, to tell him of her visit to Monsieur Jacques, and what the artist had said about his talent, and the flattering possibilities before him, if he would conscientiously devote himself to his work. She referred to his disapproval of his present course, and the company he was keeping; whereupon John became exceedingly angry, in view of her "meddling," as he termed it; said Monsieur Jacques would do better to give more attention to his own affairs, and less to his; then, refusing to discuss the situation further, he abruptly left the room in a very sulky frame of mind.

Helen had debated with herself as to the advisability of telling him of her discovery of the portrait. She did not like to conceal anything from her husband. She felt that every such attempt only served to establish a more formidable barrier between them; but after the experience of to-night she thought it would be wiser not to refer to the matter—at least until later.

John evidently did some thinking on his own part that night, for he was more like his former self when he appeared at breakfast the next morning, and proceeded directly to the studio on leaving the house. He did better for a couple of months afterward, manifested more interest in his work, and finished a couple of pictures, which, through the influence of Monsieur Jacques, were hung at an exhibition and sold at fair prices, greatly to Helen's joy.

But instead of being inspired to even greater effort by this success, John seemed content to rest upon his honors, and soon began to lapse again into his former indolent ways, apparently indifferent to the fact that his money was almost gone, and poverty staring himself and his family in the face.

Long before this, Helen had given up her maid, had practiced economy in every possible way, and denied herself many things which she had always regarded as necessary to her comfort. But the more she gave up, the more John appeared to expect her to give up; the harder she worked, the less he seemed to think he was obliged to do himself. Thus, with her domestic duties, her sewing, and the care of Dorothy, every moment of the day, from the hour of rising until she retired at night, the young wife was heavily burdened with toilsome and unaccustomed duties.

It was a bitter experience for this delicately nurtured girl, but no word of repining ever escaped her lips. She had pledged herself to John "for better or worse," and, despite the unremitting strain upon her courage, patience, and strength, despite her increasing disappointment in and constantly waning respect for her husband, she had no thought but to loyally abide by her choice, and share his lot, whatever it might be.

The day came, however, when John himself awoke to the fact that he had about reached the end of his rope—when he was startled to find that less than two hundred dollars remained to his credit in the bank, and poverty treading close upon his heels. He knew he could no longer go on in this desultory way; something radical must be done, and done at once. He was tired of his art; he was tired of facing, day after day, Monsieur Jacques' grave yet well-deserved disapproval; while, for some reason, he had become weary of Paris, and, one morning, to Helen's great joy—for she believed it the best course to pursue—he suddenly announced his intention to return to the United States.

They sublet their house, and were fortunate in selling their furniture, just as it stood, to the new tenant, thus realizing sufficient funds, with what money they already possessed, to comfortably defray all expenses back to San Francisco, which had been their former home, and to which Helen had firmly insisted upon returning, although John had voiced a decided preference for New York.

"No, I am going home—to my friends," she reiterated, but with her throat swelling painfully as she thought she would find no father and mother there to greet her. "I have lived in exile long enough; I need—I am hungry to see familiar faces."

"But——" John began, with a rising flush.

"Yes, I know, we are going back poor," said his wife, reading his thought as he hesitated; "but my real friends will not think any the less of me for that, and they will be a comfort to me. Besides, all the furniture of my old home is stored there, and it will be useful to us in beginning life again."

During the voyage Helen seemed happier than she had been for months. The freedom from household cares and drudgery was a great boon to her, and the rest, salt air, and change of food were doing her good; while the anticipation of once more being among familiar scenes and faces was cheering, even exhilarating, to her.

To Dorothy the ocean was a great marvel and delight, and it was a pleasant sight to see the beautiful mother and her attractive little daughter pacing the deck together, enjoying the novelty of their surroundings, watching the white-capped waves, or the foaming trail in the wake of the huge vessel, their bright faces and happy laughter attracting the attention of many an appreciative observer.

John, on the contrary, was listless and moody, spending his time mostly in reading, smoking, and sleeping in his steamer chair, apparently taking little interest in anything that was going on about him, or giving much thought to what was before him at his journey's end.

One morning Helen came on deck with two or three recent magazines, which a chance acquaintance had loaned her. She handed two of them to her husband, and, tucking herself snugly into her own chair, proceeded to look over the other, with Dorothy standing beside her to see the pictures.

By and by the child ran away to play, and Helen became interested in a story. A half hour passed, and she had become deeply interested in the tale she was reading, when she was startled by a smothered exclamation from John.

She glanced at him, to find him gazing intently at a picture in one of the magazines she had given him. The man's face was all aglow with admiration and pleased surprise, and she noted that the hand which held the periodical trembled from some inward emotion.

Wondering what could have moved him so, yet feeling unaccountably reluctant to question him, she appeared not to notice his excitement, and composedly went on with her reading. Presently he arose, saying he was going aft for a smoke, and left her alone; but, to her great disappointment, taking the magazine with him.

Later in the day, on going to their stateroom, however, she found it in his berth, tucked under his pillow!

Eagerly seizing it, she began to search it through, when suddenly, on turning a leaf, a great shock went quivering through her, for there on the page before her was the picture of a woman, the exact counterpart of the half-finished portrait she had seen in John's work-room during her visit to Monsieur Jacques.

Like a flash, her eyes dropped to the name beneath it.

"Marie Duncan, with the Wells Opera Company, now in Australia," was what she read.

On the opposite page was a brief account of the troupe and the musical comedy, which, during the past season, had had an unprecedented run in Paris, and was now making a great hit in Melbourne, Miss Duncan, the star, literally taking the public by storm.

"Well, that mystery is finally solved! And doubtless she was the owner of that pink glove, also," mused Helen, her lips curling with fine scorn, as she studied the fascinating face before her. "Thank fortune," she presently added, with a sigh of thankfulness, as she closed the book and replaced it under the pillow, "she is away in Australia, and we are every day increasing the distance between us."

She kept her own counsel, however, and gave no sign of the discovery she had made.

The day preceding their landing in New York, Helen asked her husband what plans he had made for their future, how he expected to provide for their support upon reaching San Francisco.

"Oh, I don't know!" he replied, somewhat irritably. "Possibly I may ask Uncle Nathan to give me a position in his office."

"And give up your art, John!" exclaimed Helen, in a voice of dismay, adding: "You are better fitted for that than for anything else."

"But I shall have to do something to get a start. You know, it takes money to live while one is painting pictures," he moodily returned.

"But it would not take very long to finish up some of them—the best ones; and I feel sure they would sell readily," said his wife.

"The best ones would require the help of a good teacher, or an expert artist, to complete," her husband curtly replied.

Helen sighed regretfully over the time which had been so wantonly wasted in Paris, and during which, under the skillful supervision of Monsieur Jacques, he might have finished much of his work, and at the same time perfected himself upon many important points. She preserved a thoughtful silence for several moments; then gravely inquired:

"Do you suppose, John, that, with another year of study, with some good teacher, you could finish and dispose of the various subjects you have begun?"

"Possibly I might," he briefly observed, but there was very little enthusiasm in his tone or manner.

"Do you feel in the mood? Have you any ambition for honest, painstaking effort—for hard work, John, to attempt this under a first-class artist?" Helen persisted.

The man began to grow restive; he could never bear to be pinned down to committing himself to anything, or to yield a point.

"You have no idea, Helen, what a grind it is to sit before an easel day after day, and wield a brush," he said, in an injured tone, and with a frown of annoyance.

"Everything is a grind unless you put your heart into your work—unless one is governed by principle and a sense of moral responsibility," said Helen gravely.

"Is that the way you have baked and brewed, washed dishes and made beds the past year?" queried her husband, with a covert sneer.

"I certainly never baked and brewed, or washed dishes, solely from love of the work," she quietly but significantly replied, as her glance rested upon her wrist, where a faint scar was visible—the fading reminder of a serious burn sustained when she first began her unaccustomed duties as cook and maid of all work.

John observed it also, then quickly looked away, as he remembered that she had never murmured or neglected a single duty on account of it.

"But where is the money for a teacher coming from?" he inquired, after a moment, and referring to Helen's unanswered question regarding his unfinished work.

"You know Dorothy's money has been accumulating all these years," she began in reply. "The interest now amounts to upward of fifteen hundred dollars, and I will consent to use it for this purpose, if you will agree to do your level best to make your unfinished pictures marketable during the coming year."

Her husband flushed hotly—not because he experienced either gratitude or a sense of shame in view of becoming dependent upon his wife's bounty, but because it angered him to have conditions made for him.

He appeared to be utterly devoid of ambition for his future, and Helen's suggestion possessed no real attraction for him. Painting had become a bore—the last thing he had really taken any interest in having been the portrait his wife had discovered in his studio just previous to the sailing of its original for Australia.

John Hungerford had never performed a day's manual labor in his life, and even though he had said he might ask his uncle for a position on his arrival in San Francisco, he had no relish for the prospect of buckling down to a humdrum routine of duties in Nathan Young's flourishing manufactory.

He sat chewing the cud of sullen discontent for some time, while considering the situation, and finally gave Helen a half-hearted promise to stick to his art, under a teacher, for another year. But his consent had been so reluctantly given, his manner was so indifferent, Helen felt that she had received very little encouragement to warrant that the future would show any better results than the past, and the outlook seemed rather dark to her.

Upon their arrival in San Francisco, the Hungerfords took a small apartment in a quiet but good location, where Helen felt she could ask her friends, and they would not hesitate to come to see her.

This she tastefully fitted up with some of the simplest of her old-home furniture, which her father's lifelong friend and lawyer had carefully stored for her against her return. The more expensive pieces, with some massive, valuable silver, and choice bric-a-brac that Mr. Appleton had purchased to embellish the beautiful new residence which he had built a few years previous to his death—these extravagances having really been the beginning of his undoing—she sold, thus realizing several hundred dollars, which would go far, with careful management, toward tiding over the interval during which John was working to turn his paintings into money.

As yet Dorothy had never attended school, Helen having systematically taught her at home; but the child was bright and quick to learn, and was fully up to the standard with, if not in advance of, girls of her own age. She could speak French like a Parisian, and her mother had also given her excellent training in music.

Helen, thus far, had been very wise in her management of Dorothy. Profiting by the mistakes which she realized her own indulgent parents had made in rearing herself, as well as by the faults she had detected in her husband's character, she had determined that her daughter should not suffer in the future, along the same lines, for lack of careful discipline. At the same time, she by no means made her government irksome; indeed, it never seemed to the child that she was being governed, for the companionship between them was so close and tender that she fell naturally into her mother's way of thinking, and seldom rebelled against her authority, even though she was by no means devoid of spirit or a mind of her own.

Now, however, feeling that Dorothy needed a wider horizon, with different environment and training, as she pursued her education, her mother decided to put her into the public school.

This would relieve Helen of much care, and also give her more time to take up a systematic course of piano and voice culture, which she had determined to do, with the view of turning her talent for music to some practical purpose, at least until her husband was better equipped to provide suitably for his family.

She had been cordially received on her return by most of her old friends, even though she had made no secret of the change in her circumstances. She had been a great favorite before her marriage, and her family highly respected; hence her reverses did not now appear to affect her social standing, at least among those who knew her best.

Very grateful and happy in view of this proof of real friendship, Helen was encouraged to quietly seek pupils in music, and easily secured a class of ten, which were all she felt she could do justice to with her domestic duties and other cares.

She felt very independent and not a little proud of the money thus earned, while she found it a great help in meeting the many expenses of her household.

During the first year after their return from abroad, John also worked well. He liked his teacher—a German, who had studied many years in Italy—who spoke in high praise of his talent, as well as of the thoroughness of the instruction he had received from Monsieur Jacques, all of which was apparent in his beautiful but unfinished work, he said.

Although Herr Von Meyer was not permanently located in San Francisco, his work had become popular, and he had quite a large following as students. He might almost have been called an itinerant artist, for he had traveled extensively in the United States and Canada, stopping for a longer or shorter time, as his fancy dictated, in numerous places, painting and sketching American life and scenery. He was now planning to return to his own country at the end of another year, to again take up work in his own studio in Berlin.

It was, therefore, a rare opportunity for John to have found so talented a teacher just at this time; and, under his supervision, he completed and disposed of a goodly number of his paintings. Some of these were so well appreciated that he received orders to duplicate them, and the future looked promising.

This success so elated and encouraged him that at the end of a year he concluded he was now competent to do business for himself without further assistance or instruction. Accordingly, he hired some rooms, furnished them attractively, and launched out upon an independent career with something like real enthusiasm.

For a time all went well; more pictures were painted and sold, bringing good prices; while, after the departure of Herr Von Meyer, students began to flock to him. Young Hungerford, the artist, was beginning to be talked about in society and at the various clubs; he was also much sought after and admired in fashionable circles; his studio became a favorite resort for people interested in art, and here John shone a bright particular star.

Helen became happy in proportion to her husband's advancement; she grew radiant with health; the lines of care and worry all faded out of her face; she was like a light-hearted girl, and John told her she was prettier than ever.

It was almost too good to be true, she sometimes said to herself, as she remembered the sad conditions that had prevailed while they were in Paris. But she would not allow herself to dwell upon those unhappy experiences; the present was full of hope and promise, and she firmly believed that her husband's fame and fortune were assured.

Had John Hungerford possessed "the stable mind," as Monsieur Jacques once expressed it, all must have gone well; if he had been less egotistical, selfish, and vain, more persevering and practical; had he not been naturally so indolent—"lazy," to quote his former teacher again—and pleasure-loving, he might have risen rapidly, and maintained his position.

But, as time wore on, and the novelty of his popularity and prosperity began to pall upon him; as the demands upon his patience became greater, and the supervision of students required more concentration and attention to detail; as the filling of increasing orders for his own work made it necessary to stick closer to his easel, day after day, life began to seem "a grind" again.

He grew discontented, irritable, restless. He lost patience with his students, and became indifferent to his duty to them, until they began to be disaffected, and dropped away from him. He neglected orders until his patrons became angry and withdrew them, and finally, becoming dissatisfied with his own work, he dropped back into his old habit of starting subject after subject, only to set them aside to try something else, rarely completing anything; all of which tended toward the ruin of his once prosperous business, as well as his reputation as an artist.

All this came about so gradually that, for a long time, no one save Helen suspected how matters were going. She begged him to wake up and renew his efforts, both for her sake and Dorothy's, as well as for his own; and she encouraged him in every possible way. But nothing that she could say or do served to arouse him from the mental and moral lethargy that possessed and grew upon him.

Fortunately, in spite of their recent prosperity, Helen had retained her pupils in music, more because of her love for the work than because she felt the need of money, as at first. Thus, when her husband's income began to fall off, she dropped, little by little, into the way of sharing the household expenses from her own earnings, and so assumed burdens which he should have borne himself.

As month succeeded month, things continued to grow worse, until rumors of the truth got afloat, and his friends and patrons began to show their disapproval of his downward course, and even to shun his society.

Yet these significant omens did not serve to arouse him. On the contrary, his indifference and indolence increased, and his old love for wandering returned; his studio would frequently be closed for days, sometimes for weeks, at a time, and only his boon companions knew where he could be found.

Helen regarded these evidences of deterioration with a sinking heart, yet tried to be patient. She did not complain, even when their funds ran very low, but cheerfully supplied the needs of the family, and bravely tried to fortify herself with the hope that John could not long remain oblivious to his responsibilities, and would eventually retrieve himself.

During all this time she had been making splendid progress in her own musical training—especially in the cultivation of her voice. She had often given her services in behalf of charitable entertainments, and not infrequently assisted her friends to entertain by singing a charming group of songs at parties and receptions; thus she had gained for herself the reputation of being a most pleasing vocalist.

Recently these same friends, who sympathized with her domestic trials, and, recognizing her financial difficulties, had arranged for several musical functions, asking her to superintend them, and had paid her liberally for her services.

This new departure seemed to Helen like the pointing of Providence to a more promising future, by making her entirely independent of her husband, and it would also enable her to give Dorothy advantages which she could never hope—judging from present indications—to receive from her father. Accordingly, she immediately issued attractive cards, advertising to provide musical entertainment for clubs, receptions, or social functions of any kind.

It was somewhat late in the season when she conceived this project, and she secured only a limited number of engagements; but as she gained fresh laurels and had delighted her patrons in every instance, she believed she had paved the way for a good business by the following fall.

During the month of May of this year John began to talk of going out of town for the summer.

"We cannot afford it," Helen objected. "My pupils will leave me in June, and will not return to me until September, and we must not spend the money it would cost for such an outing."

"But you need a change, as well as I, and—and some of—of Dorothy's money would be well spent in giving us all a good vacation," her husband argued.