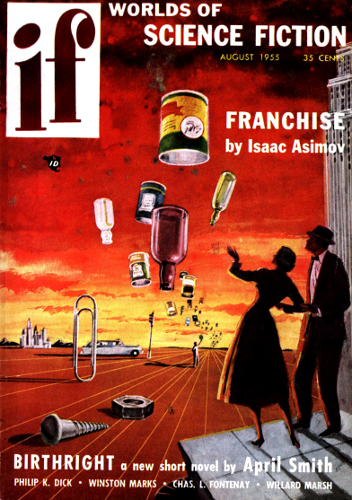

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Birthright, by April Smith This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Birthright Author: April Smith Release Date: April 21, 2019 [EBook #59329] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BIRTHRIGHT *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Why was Cyril Kirk, highest man in his

class, assigned to such an enigmatic place

as Nemar? Of what value was it—if anything?

No one could tell him the answer. He

wouldn't have believed them....

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, August 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Cyril Kirk's first sight of the planet from the spaceship did nothing to abate the anger seething within him. He stared at it in disgust, glad there were no other passengers left to witness his arrival.

All during the long trip, he had felt their curious stares and excited whispers everywhere he passed, and he had felt a small wave of relief whenever a large batch of them had been unloaded on some planet along the way. None of them had come this far—which was hardly surprising, he thought; the last of them had been taken off two-thirds of the way to Nemar. He was very glad to see them go, though by that time they had stopped making their cautious, deferential attempts to draw him into conversation and elicit some clue about his mission and destination.

He had let them wonder. He knew that his aloofness was being taken as snobbishness, but he was past caring. They all recognized that he was a Planetary Administrator by the blazing gold insignia on the dark uniform, insignia calling for awe and respect all over the galaxy. They guessed that this was his first appointment, but the thing that really aroused their curiosity was the bitter, angry look that went with what they considered his arrogant reserve.

Since polite efforts at conversation by the braver or more confident among the company were met with icy monosyllables that cut off further attempts, they were left with a wide range of controversy. Some of them held, though they had never actually seen a Planetary Administrator before in the flesh, that all PA's were like this. They argued that the long, grueling years of study, the ascetic, disciplined life from childhood, and the constant pressure of competition, knowing that only a small percentage would finally make the grade, made them kind of inhuman by the time they finished. Besides, they were near-geniuses or they wouldn't have been selected in the first place—and everybody knows geniuses are sort of peculiar.

One of the bolder and more beautiful girls on board had been argued into making a carefully planned attempt to draw information out of him, and bets had been placed on the results. She was eager enough to try her hand at this rich prize, and her self-confidence was justified by a long trail of broken hearts in high places, but the attempt came to nothing. Kirk was aware of her efforts and aware that in another mood he would have appreciated her charm, but he felt too sick and miserable to respond.

Remembering her piquant, laughing face later in his cabin, Kirk thought morosely of the long train of girls he had known in the past. Many of them had been lovely—a fledgling PA was considered a highly desirable date, even though the chances were always that he wouldn't make it in the end. But Kirk had always been filled with an iron determination that he was going to make it in the end, and this meant no distractions. If he began to feel he might get really emotionally entangled with a girl, he stopped seeing her at once. He saw them seldom enough, anyway. The regulations of the PA Institute gave him a fair amount of free time, but the study requirements made the apparent freedom meaningless.

How hard he'd worked for the day he'd be wearing this uniform, he thought bitterly. How proud and happy he'd thought he'd feel wearing it! And now, instead, here he was, practically hiding in his cabin, hoping nobody would discover the name of his destination and guess the reason for the humiliated rage that was still coursing through him.

He'd gone over the interview with Carlin Ross a hundred times since the trip started, and he wasn't any nearer to making sense out of it than when he began....

He'd entered Ross's office for the interview in which he would be awarded his post, full of confidence and pride. The final examination results posted in the main lobby were headed by his name. He knew that, because of his good record and general popularity, he had been watched with special interest by the teachers and staff for some time; and he looked forward to being awarded a particularly desirable planet, in spite of its being his first post.

Technical ability and sound training in administration had long ago been decided upon as more important than practical experience, as mankind began to sicken of the bungling of political appointees. The far-flung planets that had been colonized or held an intelligent, humanoid population were so numerous that even an experienced Planetary Administrator could know very little about each one. Only someone brought up on a planet could have a detailed knowledge of it, and it was a basic premise of the Galactic Union that governors with a common upbringing and training on Terra were necessary to keep the varied parts of the empire from splitting off and becoming alienated from the rest.

Ross was one of the half-dozen men in the top echelon governing the galaxy and its warring components. His official title was Galactic Coordinator, and one of his minor duties was the supervision of the Institute of Training for Planetary Administration, which had been home to Kirk for so long. Although he was the Institute's official head, he was too busy to be seen in its halls more than rarely, but Kirk had had several brief talks with him and one long one. He had the feeling that Ross had a special interest in him, and this had added to his anticipation on the fatal day.

As he entered the room, Ross looked up, his blue eyes friendly and alert in the weathered, tanned face. "Hello, Kirk," he said. As always, the simple warmth of his smile threw Kirk off guard. It had never failed to surprise him the few times he had seen Ross. In this place of dedicated, serious men, of military crispness of speech, of stiffly erect carriage, Ross's relaxed body and quiet, open expression seemed startlingly out of place. Except for the alertness and intelligence of the eyes, he looked like a country farmer who had wandered in by mistake. Kirk, and his friends, had more than once wondered how such an anomaly had risen to the high position of Galactic Coordinator.

However, if his manner left you puzzled, it also made you feel surprisingly comfortable, and Kirk had felt relaxed and happy as Ross motioned him to a chair. Nothing prepared him for the shock that was to come.

He remembered the apparent casualness with which Ross had spoken. "I'm sending you to Nemar."

For a moment Kirk felt blank. The name did not register. His private speculations had centered on the question of whether he would be sent to a thriving, pleasant, habitable planet or to one of those whose bleak surface contained some newly discovered, highly valuable mineral and whose struggling colonists lived under pressurized domes. Either type could have held the chance to work up to the galactic eminence and power he had set his heart on. He had been over and over the list of planets that were due to receive new PA's (there was a rotational system of five years, with an additional five years made optional), and he had a private list of those which, as the star graduate of his class, he hoped he might draw. Nemar was not among them.

His face stayed blank for a minute as he searched his memory for the name, and as vague bits of information filtered through to him, his eyes widened in disbelief. "But, sir—" He fumbled for words. "That's on the very edge of the galaxy."

Ross's voice was quiet. "Yes, it's a long way."

"But there's nothing on it!"

Ross sounded a little amused. "There are some very nice people on it—the natives are of the same species as we are, though they look a little different. That means the air is breathable without aids. It's quite a pleasant planet."

"That's not what I mean, sir. I mean there's nothing of any value—no minerals, no artifacts, no valuable plant or animal products." He searched his memory for what little he could remember about Nemar from classes. He recalled that the planet had been discovered only forty years ago by a Survey ship that had gone off course far toward the outer rim of the galaxy. It had been incorporated into the Galactic Union because it was considered dangerous to leave any inhabited planet free of control; but it had not been considered a valuable addition. It was far off the established trade routes, and seemed to contain nothing worth the expense of transporting it. "The culture is very primitive, isn't it?" Kirk asked, half thinking aloud.

"It is so considered," Ross answered.

The reply struck Kirk as odd. A sudden hope filled him. Maybe something new had been discovered about the place, possibly something that only Ross and a few of the top command knew about. He threw a sharp glance at Ross's face, but it told him nothing. "I don't remember too much about the place from class," he ventured.

Ross rose, and with his incongruously quick, lazy grace strode to the filing cabinet along the wall, pulling out documents and pamphlets. He plumped them in a pile in front of Kirk. "Most of the factual information we have is in these. You can try the library, too, but I doubt if you'll find anything more." He added a book to the pile. "This covers their language. You'll have two months of intensive instruction in it before you go. You were always good in your language structure courses, so I doubt that you'll have any trouble with it. You'll have another two weeks to learn the stuff in these documents, and two more weeks to rest or do whatever you like before you leave." He resumed his chair. "You're luckier than some of the others. The boy who got Proserpine will have a stack of books up to there to absorb." He gestured toward the ceiling.

At the mention of Proserpine, Kirk's brown eyes darkened. Proserpine had been recently discovered, too, but that was all it had in common with Nemar. Its inhospitable surface held vast amounts of a highly valuable fuel ore, and it had been one of the places on his list. He wondered who was going there, his insides suddenly twisting with envy. He tried to keep his voice even. "I don't understand why I'm being sent to Nemar." He searched for words. After all, he couldn't exactly mention his graduating first and his record. "Is there something I don't know about? Has something valuable been discovered that hasn't been publicized, or—" He waited hopefully.

Ross's answer was flat. "No, there's nothing there that can be transported that's worth transporting."

Kirk felt despair surging through him, then suddenly changing to sharp anger. "I've worked hard. I have a good record. Why are you giving me this—this lemon? Why don't you give it to whoever graduated lowest, or better still to some older PA who bungled things somewhere, but not quite enough to be retired!" His face was burning with rage. Somewhere inside he felt shocked at himself for speaking to a Coordinator this way; at the same time he felt a violent urge to carry it farther and sock Ross in the nose. His body was shaking....

Remembering the scene now as he watched Nemar swing closer, Kirk felt the anger again, time hadn't dimmed it at all. Ross must have perceived his fury, but he had shown no signs of it. Looking as friendly as ever, he had told him mildly that he did not consider Nemar a "lemon", that he had excellent reasons for sending him there, but he preferred not to tell him what they were. He wanted him to discover them for himself after he arrived. The rest of the interview had concerned itself mainly with practical information, most of which Kirk had scarcely heard through his fog of emotion.

His endless speculations since then had gotten him nowhere. He had dredged out of his memory every incident that might reveal some trait for which he was being discreetly given a back seat. He recalled a roommate who had said he was going to become a living machine if he kept it up, and no machine had the right to have jurisdiction over people. But Jere had flunked out along the way, like most candidates who had an attitude like that. He went over the time he had been called to Ross's office and gently rebuked for working men under him on a project too hard. "I don't ask anything from them I don't ask of myself," he had protested.

"I know," Ross had answered, "and I respect that. But you work that hard from choice." Then he had nodded in dismissal.

Kirk had puzzled over these and other incidents, searching for a clue, but found nothing. All his probing in a more optimistic direction led to blind alleys also. The documents on Nemar, all the information he could dig up, confirmed Ross's statement that the planet held nothing of commercial value.

The planet, to judge by what he had read, was a pleasant place, apparently very pretty, with heavy vegetation and a warm, temperate climate, and the natives were hospitable and friendly. But all this held very little comfort for him and did little to assuage the sense of angry humiliation that had made him seek isolation from the other passengers.

He could see the planet more clearly now as the ship began to angle into an orbit, preparatory to sending out the smaller landing ship which would take him down. Hastily he reviewed in his mind once more the few facts he knew about the place, and shaped his tongue to the unfamiliar sounds of the native language. He fought down the feeling of humiliation, and straightened his shoulders. After all, to these people, he would be the most important person on the planet. If he was to be a big frog in a small puddle, he was still supreme administrator here, and he had no intention of letting them know his arrival signified a disgrace to him.

From the airlock of the landing ship, Kirk looked out on a cleared plain. In the foreground a group of natives were gathered to greet him, and a scattering of dark uniforms among them indicated the officials who would make up the Terran part of his staff. As the natives approached him, he noted the green-gold hair and the slightly greenish tinge to their skin, for which his studies had prepared him.

Nothing in his studies, however, had prepared him for the extraordinary grace and beauty of these people.

They were dressed, men and women alike, in a simple fold of bright-colored cloth circling their body from the waist and reaching a third of the way to their knees. Kirk noted, with a slight sense of shock, that the women wore nothing above the waist except for a strand of woven reeds, interlaced with shells and flowers, which fell loosely to their breasts. In these brief and primitive garments, the natives bore themselves with such imperious grace and assurance that for a moment Kirk felt as if his role had been abruptly reversed—as if instead of being the powerful representative of a great civilization to a backward people, he were the humble primitive waiting for their acceptance.

One of the older natives stepped forward from the rest, his palm outstretched, shoulder high, in greeting. "Welcome to Nemar," he said, his glance steady and gracious on Kirk's face.

Kirk recognized the words of the native language with surprise. The clear, musical quality of the native's speech made his own words, harsh and grating by comparison, sound like a different language, as he replied. "Thank you. I am very happy to be here."

As he spoke, he realized that the lie had for a moment felt almost like truth. For a moment he wondered if the planet's apparent primitiveness was deceptive and if its simplicity concealed a highly developed culture. But even as the hope surged through him, he remembered Ross's clear and definite statement to the contrary. Besides, there would be no point in keeping a thing like that secret from the rest of the galaxy, even if it could be done. Such a culture, moreover, would certainly have things of value to trade.

As these thoughts coursed through his mind, one of the Terrans stepped forward from the crowd. The insignia on his uniform were the same as his own, and he realized, with a surge of curiosity, that this must be his predecessor.

The man reached forward to shake his hand. "Hello. The name's Jerwyn." His tanned face was open and friendly, and reminded Kirk curiously of someone; he couldn't remember who. "Glad to see you."

I'll bet you are, Kirk thought: your gain, my loss. "Greetings from Terra," he replied, somewhat stiffly. "Cyril Kirk." He tried to keep his vague disapproval of Jerwyn's breezy informality out of his voice. It was hard to realize this man was also a Planetary Administrator. He seemed to have lost completely the look of authority that was the lifelong mark of the PA graduate.

After the various introductions and a short period of conversation, Kirk found himself seated beside Jerwyn in the small ground vehicle which was to take him to his headquarters. Jerwyn immediately resumed the standard Galactic-Terran language, which he had dropped during the introductions. "As soon as I show you around a bit, I'll be off on the landing ship you came in. I wonder how Terra will seem after all this time."

"Five years is a long time," Kirk ventured.

"Ten."

Kirk stared at him in astonishment. "You took the optional five years! Why in heaven would anyone—" He broke off suddenly. The question might be one Jerwyn would not care to answer. He threw him a speculative glance, wondering why he had been sent here and whether he, too, was bitter. Maybe a poor record, or something in his past he didn't care to go back to...? That didn't fit in his own case—but then there was no knowing what did fit in his own case. Jerwyn had an alert, perceptive look that indicated considerable intelligence, but still he somehow looked inadequate. Some quality an Administrator should have was lacking ... dignity? drive?

Jerwyn's voice interrupted his thoughts. "Beautiful, isn't it?"

The groundcar had left the plain and was entering a heavily wooded section. For the first time, Kirk took a good look at his surroundings. Some of the trees and plants were very like those he had seen in parks at home. Still, there was a definitely alien feel to it all. The trees were low and wide and had peculiar contours, different from those of trees on Terra, and their flowering foliage came in odd sizes and colors. The sky wasn't quite the blue he was used to, and the shapes of the clouds were different. He noticed for the first time a heady, pungent perfume carried on the breeze, that was both pleasant and stimulating. It came, perhaps, from the wide-petaled flowers in oddly shimmering colors that clustered thickly everywhere.

"Yes, it's beautiful," he agreed, "but—" The feeling of despair and frustration welled up in him again. The warmth he sensed in Jerwyn made him suddenly long to blurt out the whole story. He controlled himself with difficulty, as he turned toward him. "It's pretty enough. It might make a good vacation resort if it weren't on the edge of nowhere." His pent-up emotion exploded as he spoke. "But five years in this hole! I'd feel a hell of a lot better if I were looking at some rocky, barren landscape with some mines on it—with something of value on it—with a name somebody'd heard of, where you could hope to get somewhere. I don't want to waste five years here!" He paused for breath, staring angrily at the lush landscape. "And for that matter, life on one of those planets where you live under domes, with a sealed-in atmosphere, is probably a lot more civilized and convenient than in this primitive jungle."

Jerwyn nodded slowly, an unspoken compassion in his face. "I know how you're feeling." He paused. "And it does seem pretty primitive here at first—no automatic precipitrons for cleaning your clothes, natural foods instead of synthetics, no aircars, no automatic dispensers for food or drinks or clothes; none of a hundred things you take for granted till you don't have them. But you get used to it. There are things to make up—" He broke off as the car began to descend into a valley. "Look!" His voice held an odd tone of affection. "There's your new home."

Kirk gazed downward at the settlement nested in the valley below them. He fished in his pocket for a magnascope to bring the view nearer and stared curiously, as the lens adjusted to the distance. He picked out groups of buildings, low units of some coarse, natural material, widely spaced. This was the largest city on the planet, he knew, but it seemed to be little more than a village. It was undoubtedly primitive—very primitive. Remembering the magnificent high buildings of Terra, he was filled with sudden homesickness for the speeding sidewalks crowded with people, the skylanes humming with aircars.

Turning the magnascope here and there, he kept his gaze trained on the town beneath him, studying it now in more detail. Slowly, some of his depression began to leave him, and he felt a strange sense of warmth begin to take its place. He stepped up the power of the glass till he could see the inhabitants walking in the streets. Like the natives who had met him at the landing ship, they walked with a beautiful, easy grace, a sumptuous ease that seemed somehow almost a rebuke of his own stiffly correct military posture. They gave an impression of combined leisure and vitality.

Gradually, as he watched, an odd feeling of nostalgia began to stir in him, an old, childish longing. He remembered suddenly a dream he had had years ago, in which he had run laughing through green meadows with a lovely girl. He had fought against waking from it and returning to his desk piled high with books and his ascetically furnished room.

He blinked his eyes and put down the magnascope. "Rather attractive, in a way," he said grudgingly to Jerwyn. He settled back slowly into his seat.

"Just the same," he added, annoyed at himself for his sentimental lapse, "how have you managed to stand it all this time? I still can't figure how I came to get it in the neck like this." Abruptly, he plunged into the words he had been holding back, telling the whole story of his confusion to Jerwyn.

He rationalized to himself that perhaps Jerwyn could help him solve the mystery. At least he might tell him how he himself came to be sent to Nemar, without his having to ask directly; and this might give him a clue.

"I've been over the whole business a million times, trying to figure it out," he concluded. "Somebody with pull must have had it in for me. But who? And why? I never had any real run-ins with Ross. In fact, I'd always thought he liked me." He scowled. "Of course, he gives practically everybody that impression. Maybe he's just a professional glad-hander, though he certainly doesn't seem like it." He shook his head. "Maybe that's the secret of his success; I never could figure out how he got where he is. He certainly doesn't seem typical of the command. Oh, he's brilliant enough, but there's a quality about him I'd almost call—weak, I guess. Unsuitable for his post, anyway. He treats the janitor the same as—"

Kirk stopped abruptly. He suddenly had the answer to the question that had been nagging at the edge of his mind: it was Ross that Jerwyn reminded him of.

Trying to cover up his confusion, he went on rapidly, hoping Jerwyn would not notice. "Anyway, whatever his reasons were, he's played me a dirty trick, and if there's ever any way I can pay him back for it, I'll do it. I'll have five years to think about it. Me! The fair-haired boy of the Institute! On my way to the top!" His face flushed with resentment. "Sent to sweat out five years in this Godforsaken place with a bunch of savages hardly evolved out of the jungle!" He passed his hand over his forehead, wiping off sweat, feeling the full force of his pent-up anguish and rage flood through him.

Jerwyn spoke very quickly. "I felt pretty much the same way when I was sent here. But I feel differently now. I could try to explain. But I don't think it's a good idea. I don't think anyone could have explained to me. This is a place you've got to live in; you can't be told about it." He shifted in his seat as a small group of buildings came into view. "As for Ross—well, he was responsible for my being sent here, too, and I spent some time when I first came, thinking of ways to cut his body in little pieces and throw them in a garbage pulverizer—but I wouldn't waste my time if I were you. I know now he had his reasons." As he spoke the car pulled to a stop. "Well, here we are. This is where you'll be living and working."

Jerwyn stayed with Kirk while he was shown through various buildings. He found most of the office buildings full of bright murals and little watered patios, but lacking the simplest devices for working efficiency. He was introduced to various officials, Terran and Nemarian. Some of the latter, to his surprise, were women—a rare phenomenon for a primitive planet, he remembered from his classes.

By the time the touring was over and he had said goodbye to Jerwyn, he was too tired to do more than glance briefly at the quarters to which he was shown. Left alone in his rooms, he took a quick, awkward bath, too weary to feel more than a brief annoyance at the lack of automatic buttons for temperature controls, soaping, and drying, and fell exhausted on the low bed.

For a moment, as he woke, Kirk could not remember where he was. Drowsiness mingled with a sense of eeriness at the sound of long bird-calls unlike any on Terra and the unfamiliar rustling of leaves; the rays from the late afternoon sun seemed too crimson.

Then, as sleep fell from his eyes, he remembered. He glanced at the window above his bed from which the orange light filtered into the room and saw it was completely open to the outside air. Something would have to done about that, he thought grimly, or he'd never be able to sleep with an easy mind. There were always people, sooner or later, who hated you if you had power; or if they didn't hate you, they at least wanted you out of commission for one reason or another.

He sat up to take a better look at the room he had been too tired to investigate before. There were mats of woven reeds, and low carved chests, and flowers; the walls were clean and glimmering, and bare except for a single picture of two young native children. He got up and walked over to look at it more closely. A boy of about seven was holding his arm out to a girl, slightly younger, to help her on to the low, swaying branch on which he was sitting. The picture was full of sunshine and green leaves and happiness, and you could feel the trusting softness of her arms reaching up to him. An odd picture, Kirk thought. The children looked childlike enough, but the emotions looked adult.

As he looked at it, he heard a soft, swishing sound in the next room, and stiffened. There was no lock on the door, he noticed. Well, it was time to get up, anyway. He dressed hurriedly, trying to remember the layout of his rooms. Except for the bathroom, he recalled only one other room, a sort of arbored porch, one side completely open to the air, with a low table and some cooking equipment at one end.

As he opened the door, a faint whisk of something made of reeds went out of sight. A primitive broom, he thought, with a faint sense of relief. Some servant was tidying the house. He opened the door further—and stared.

A native girl was standing before him. She was extraordinarily lovely. The gold-green hair of her race rippled and flowed in waves over her bare back and shoulders down to the circlet of vermilion cloth girdling her thighs. The band of small shells that circled her throat was netted with wide orange and red flowers that half-hid, half-disclosed the firm naked breasts. The light brown, gold-flecked eyes beneath the gold-green eyebrows were soft; so was the tender mouth, rose-colored against the flawless skin, with its undertones of faint green. Her body, too, looked soft and yielding, but was borne with imperious grace that somehow dignified even the broom held loosely now in one delicate hand.

Kirk stared at this vision of beauty, taken by surprise, and found himself caught up in sudden desire. She was like something out of a dream. He tried to get hold of himself.

You're just not used to half-nude women, he told himself. You're used to girls in uniforms, crisp, businesslike uniforms. A wild suspicion caught at the edge of his mind. He didn't know anything about this planet, really—except that there was something he didn't know. Maybe they made a practice of diverting their rulers with beautiful women. She certainly didn't look like a servant. He smiled at the thought that came to him: this servant was the first indication of the luxury befitting a Planetary Administrator. The thought enabled him to gain control of himself again. He regained a semblance of his customary reserved look.

"Good afternoon," he said, in the native language.

She smiled and held out her hand.

He hesitated, then held out his own awkwardly. Did one shake hands with one's servants here? He wished he'd asked Jerwyn for more advice about protocol.

She took his hand and pressed it lightly for a moment. "I am Nanae." Her voice was low and musical. "I am going to clean and take care of your house."

She turned and with exquisite precision gestured toward the low table and cooking equipment at the end of the room. "I thought you would be waking soon. I have prepared some jen for you."

Jen? he thought. Oh, yes, a very light stimulant—the local variety of tea. He walked over to the low table and sat down, fighting the impulse to enter into conversation with her. He watched her as she poured the hot liquid into wide cups of polished gourd, her hair radiant about her shoulders. A stab of longing shot through him. The long years of training in the Institute paraded through his mind, the years of strict routine, hard work, ascetic, bare rooms, with women considered playthings that took too much time from needed study; the only beauty was the dream of power among the glittering stars.

Well, he wasn't going to give up and forget the dream, he told himself—and he wasn't going to be led astray by any pretty girls, particularly a maid. Hell, he thought suddenly, maybe Ross is testing me. Maybe he picked the worst planet in the whole damn galaxy to find out if I could do something with it. It's obvious if I can get this place on the trademaps, I can handle anything.

He looked speculatively at the girl as she pushed the cup toward him. He wondered how she came by her job. Did they hold beauty contests here for the honor of being cleaning woman in the PA's household? He realized he was feeling more cheerful. The jen and the soothing quietness of the girl's presence were doing him good. He felt a resurgence of his old energy and ambition that the interview with Ross had quelled for so long.

"Did you work for Jerwyn, too?" he asked. Yes, his voice was just right, courteous, but not too friendly, he thought.

"No, but I knew him." She looked at him with an odd smile. "He became one of our best dancers."

"Dancers!" Kirk stared at her in amazement. He started to open his mouth, then stopped. He'd better not ask any more questions till he'd had a chance to talk to some Terrans. Apparently, Jerwyn had gone native. Maybe it was his way of rebelling against being sent here in the first place—and he'd let himself go so far that he'd skipped his chance of reassignment at the end of the first five years, afraid of the problems of a new post after being a beachcomber for so long. That would account for the curious lack of deference he'd found in all these people. They were friendly enough, but they lacked proper respect for his position. You weren't supposed to be friendly to a PA; you were supposed to be humbly polite. He recalled the respect and awe he'd received on the ship.

As he finished his cup, he realized he was very hungry. He looked around instinctively for food. He had enough synthetics in his bags to do him for awhile, but he might as well make the plunge and start eating the native foods right away. No use coddling himself.

The girl noticed the look. "I didn't prepare food for you because dinner will be served in just a little while. We eat all together, down by the river. You will hear drums to announce when the meal is ready, and you get there by walking to the end of that path." She pointed a delicate finger at a small foot-path winding by a few yards from where he sat.

Coming out of the little forest at the end of the path, Kirk paused to take in the scene. Between him and the river was a wild jumble of men and women, laughing and talking, children running and stumbling over small pet animals, piles of nuts and fruits and hot foods heaped together beside small fires. Some of the people sat on straw mats, but most, simply on the ground. There were neither tables nor chairs. To Kirk it looked like utter confusion.

With a sense of gratitude, he saw a tall, uniformed figure coming up to him, with a brisk, definite stride. The Terran's face was lined and firm, the kind of face Kirk was familiar with. The man with this face would be a man who stood for no nonsense, a man who was a little tough, but also fair and capable. He recognized him as he came closer.

"Hello, sir. I'm Matt Cortland, your second in command," he said brusquely. "I met you this afternoon, but you met so many people then it must have been just a blur of names and faces."

Kirk greeted him, feeling a sense of satisfaction that this man would be his chief assistant. He looked efficient; he should be able to help him learn the ropes and get a program of action started.

"No chairs," Cortland said laconically, as they walked toward the gathering. He chose a soft spot of lavender-tinted moss near a pile of hot food and sat down, cross-legged. Awkwardly, Kirk sat down beside him, folding his legs under him stiffly. "You can be served in your rooms, of course, if you like," Cortland went on, turning to him. "These people are very obliging. Very obliging." He reached for two of the leaf-wrapped, steaming objects, handing one to Kirk. "But you probably have a better chance of influencing them if you eat among them. If they can be influenced." He opened the leaf and bit into the yellow vegetable inside.

Kirk looked dubiously at the object in his hand. He hoped it wouldn't make him sick. Pushing back his sense of disgust, he bit into it carefully. The bland, sweetish flavor filled him with delightful surprise. It was rather like a mixture of sweet potato, carrot, and peach synthetics—but the texture and flavor were new and wonderful. Maybe civilization had lost something good when it gave up natural foods. Though, of course, their preparation was time-wasting and inefficient, he reminded himself; and swallowing synthetics required only a momentary break in your work when you were pressed for time. He looked up and found Cortland watching him.

"Pretty different from the food at home, eh?" He had slipped into the Terran language. "Good food and pretty girls." He gestured toward the graceful, half-nude women scattered along the mossy bank. "Everything for the lotus-eaters."

The phrase meant nothing to Kirk.

One of the girls came over to them with a large gourd full of fruit and nuts, and another on which she heaped hot foods from the piles on the ground as she passed. She placed them on the ground beside the two men.

"Yes, everything for the lotus-eaters," Cortland repeated. "Incidentally, I hope you're not under the impression that that girl is naked from the waist up."

Kirk looked at him questioningly.

"Oh, no. She's completely covered. They have taboos about naked breasts, just like we do." He laughed at Kirk's look of mystification. "You notice those strands of shells or woven reeds they wear around their necks?"

Kirk looked around. They all wore them.

"Well, that signifies they are dressed. If you ever see a native girl without one, she'll be terribly embarrassed." He stuck his hand out toward the bowl of hot food. "After you've been here long enough you'll think they're dressed, too."

He laughed, then looked more serious.

"I've been here a long time, getting nowhere," he said, in a different tone. "There are a lot of things that could be done here. I've spent a lot of time thinking about it. But Jerwyn—" He hesitated. "I hope you intend to make the name of the Galactic Union mean something here."

Kirk nodded, and Cortland went on. "Jerwyn tried when he first came. But after awhile he seemed to just give up. I couldn't do anything without him backing me, I don't have enough authority." He looked grim as he spoke. "And besides that, it takes more than one good man. Oh, the other GU men here are capable enough—" He glanced toward a group of Terrans sitting nearby. "They'll be over in a little while to speak to you, incidentally; I asked them to hold off for a little, while I briefed you a bit—no sense deluging you with new people while you're trying to eat."

"But to get back," he went on, "they're capable enough, or they were once, anyway, but none of them has the drive and brains it takes to push through a project to develop this planet. They've pretty well given up. Some of them like it here and some of them don't, but they've all stopped trying." A look of contempt crossed his face. "They go through the motions of doing some work to earn their salaries, knock off at noon, and spend their time lying around on the beaches with Nemarian girls. I've done what I could to keep a semblance of discipline, but it's uphill work."

Kirk looked at him steadily. "All that's going to be changed."

Cortland smiled. "Good." Their eyes met, with understanding.

"And I'm very happy to have a man of your caliber with me," Kirk said quietly.

Cortland gave him a long look. "Maybe you've got what it takes. Maybe you have." He nodded slowly. "I should have told you I don't entirely blame the men. This planet's a tough nut to crack." His voice was grim.

Kirk felt a vague uneasiness, but his look stayed determined. "We'll crack it."

"We've been here forty years, and we haven't made a dent. They're funny people, these Nemarians. They're really alien. I've been here fifteen years, and I don't understand them any better than when I came."

"That's quite a statement."

"They're very appealing. Naive. Childlike. The soul of courtesy—on the surface. But it's deceptive. And you could spend a lifetime trying to find out what's underneath."

A young boy of about twelve came up as he spoke, setting a large gourd full of steaming liquid down beside them with lithe grace, filling smaller cups from it as he did so. Cortland nodded at him, turning again to Kirk as the boy walked away. "Even their children aren't really childlike. Did you see his eyes—makes you damned uncomfortable."

As Kirk started to answer, drum-beats began to fill the air, first softly, then louder. Strange sounds from unfamiliar instruments began to mingle with them, and a clear, high instrument added a melody. The whole effect had an alien, discordant quality for Kirk, but as he listened further he grew intrigued and began to enjoy it; a mood—happy and romantic and energetic, all at once—came through to him from the music.

"The dancing's beginning," Cortland informed him.

Kirk saw young men and women rise by ones and two's and begin swaying and turning their bodies to the music. They all seemed to be doing different things, and yet somehow it made an integrated pattern. To his surprise older people and even young children gradually joined in, and managed not to look inappropriate, although the dance movements were rapid and strenuous.

He noticed a sweet, pungent odor filling his nostrils and realized it came from the steaming bowl beside them. He picked up one of the filled cups and tried it cautiously. It was delightful. He emptied it and poured another.

He felt Cortland's hand on his arm, and looked up to find him grinning at him. "Hey, take it easy with that stuff. That's fermented kara root—the local variety of booze. They can drink quarts of the stuff and be all right; I've never seen one of them really drunk. But you'd better not try it."

Kirk frowned. "Something different in our metabolism? I thought—"

"No, they're quite human," Cortland broke in. "And it's not a matter of immunity. I wondered about it for a long time—and got quite disgracefully drunk a couple of times, keeping up with them, before I figured it out." He sipped at his own cup. "No, the secret of their success is the dancing."

Kirk looked at the light, whirling figures, puzzled.

Cortland smiled at his bewilderment. "It's the exercise. It burns up the alcohol as fast as they drink it. When they're having a real feast, they dance and drink all night, till they collapse from pure exhaustion. They wake up feeling fine—not a sign of a hangover. Of course, tonight they'll only dance for a little while, so they'll only drink a little...."

"Sensible, aren't they?" The voice came out of the air behind them, sardonic, feminine. The language was Terran.

Kirk whirled and peered through the dusk, which was gathering rapidly. He saw a slightly amused pair of brown eyes, brunette hair, and a trim body dressed in chic good taste in expensive Terran clothes.

Cortland stood up. "Mrs. Sherrin ... our new Planetary Administrator, Cyril Kirk."

She lowered herself to the ground, spreading out a small mat under her as she did so. "Jeannette, if you don't mind." She folded her legs under her carefully. "I don't mean to be disrespectful. But there's such a small number of us here, we need to be friends and stick together."

Cortland, who had been looking away for a moment turned to them. "If you'll excuse me, someone wants to talk to me." Kirk nodded.

"Did I meet your husband this afternoon?" he inquired politely, as Cortland strode off.

"No; I'm a widow."

"Oh, I'm sorry," he murmured.

"Don't be. Not for me, I mean. We'd been coming to a parting of the ways for a long time. But let's not talk about that. How do you like the dancing?"

He looked at the firelit figures, whirling in the growing dusk. "I don't know. I'm sort of overwhelmed by everything. It's all so new. I've heard so many confusing things—"

She nodded. "If you manage to make sense out of the Nemarians, you'll make history. It's better not to worry about it too much. Immerse yourself in their gay, happy life."

"What do you mean?"

She gave him a sharp look. "You'll find out what I mean. Didn't Cortland tell you?"

"What are you talking about?"

"Well, you might as well go in cold at that. Form your own conclusions as you go along. No use giving you prejudices before you start. Maybe you're the man who'll cut the Gordian knot. No use telling you it can't be done."

"What can't be done?"

"We'll all be rooting for you." She poured herself a drink and downed it quickly. "Great stuff, this. Makes you forget the petty annoyances of the garden-spot of the galaxy." She poured another. "To Nemar," she said, lifting it. "Now tell me about Terra. What's been happening back home?"

He could get nothing more out of her.

Kirk struggled to control his irritation as the last Nemarian on his list walked in, poised and self-confident, casually unconcerned about his lateness. Something would have to be done about their sloppiness and lack of discipline, but now wasn't the time. It wouldn't do to lose his temper at the first official meeting he called.

First he needed to stir some ambition in them, prod them out of their lethargy.

He looked around at the assembled members of his joint Terran-Nemarian staff. The Terran members were making an attempt to stand stiffly at attention, somewhat awkwardly as though they were out of practice. They threw rather disconcerted looks at his stern, impassive young face. The Nemarians stood casually erect or lounged against the wall.

Once more, he found himself troubled by a faint sense of incongruity. Something about these natives was not primitive. Without saying a word, just by standing and looking at him, they made him feel awkward and insecure.

He straightened his shoulders and tried to make his expression even more stern. He wished he looked older.

A sense of the power of his position overwhelmed him for a moment.

He glanced at the speech he'd prepared, then at the faces before him. Slowly he pushed it aside. Somehow he couldn't use those formal sentences with these people. Diplomatic phrases didn't sound right in Nemarian.

"Good morning," he said abruptly. "I won't waste time on preliminaries." He paused. "I've only been here a day, but so far I've seen very few signs of Terran influence—a more or less obsolete type of ground transportation, a few tools and household conveniences, some art objects. Very little else. I don't fully understand why conditions are so backward here on Nemar when it has been part of the Galactic Union for forty years."

The Terrans in the group stirred uneasily.

"The important thing, however, is that the situation be changed so that Nemar may be given the benefits of galactic culture."

He paused and looked around. The natives were listening courteously and looking slightly bored. The Terrans looked uneasy or embarrassed.

"What prevents this change," he went on, "is the fact that there is nothing of value to export." He leaned forward. "But I don't believe that this or any planet can possess nothing of value. It's simply a matter of finding it. It's a matter of looking into new places, with new techniques, or for new things. If a sufficiently thorough search is made, something will turn up." He tried to ignore the signs of restlessness in his audience.

"I'm going to organize research groups for this purpose immediately. Each of you will head a committee to investigate the possibilities in a particular field—fuels, plants, animal products, etc. You will bring the reports to me, and I will check them and indicate further directions of search."

He continued, outlining his plans in detail, stressing the great advantages to be gained, the wonderful things galactic culture had to offer them—the marvelous machines and labor-saving devices, the rich fabrics and jewels, the vidar entertainments, the whole fabulous technology of a great, advanced civilization. He spoke with enthusiasm, but as he continued, a growing sense of apprehension began to creep into his energetic, determined mood.

Something was wrong with their reactions.

He puzzled over it as he watched them file out of the room after he finished. The voice of one of his younger subordinates drifted back to him from the hall outside: "Made me homesick for good old Terra. I'd give a lot to see a good vidar-show right now...." Cortland pressed his arm lightly as he passed, nodding his approval of the proceedings.

One of the Terrans lingered a moment as the last of the group left. His expression was serious. "I'd like you to know that I'm all for you, sir, and I'm glad to see a man of your stature in the PA's office," he said nervously. "I hope we'll see some changes in the attitude of these Nemarians. I've never liked their attitude." He ran a hand through his sandy-colored hair. "They're funny people, sir. You've only been here a day, and nobody may have warned you yet. They're very courteous, but don't let it fool you. You're going to have trouble with them."

Kirk looked after him as he followed the others out, a sense of confusion and discouragement beginning to settle over him. He wandered slowly into the flowered patio adjoining the office.

The reaction of the Nemarian officials was the strangest. They had shown no open opposition. On the other hand, there had certainly been no cheering. Their attitude had been one of courteous interest, plus some quality he couldn't quite define. He searched for the right word ... something almost like compassion, as if they were humoring a child's enthusiasm for a naive, impractical project.

He sat down by a clump of blue-green flowers. Maybe he was just nervous because of his inexperience, he thought. He'd had plenty of practice experience (supervised, of course), but it was a different matter managing an isolated planet, completely on his own. And he'd had the bad luck to come after a guy who'd apparently let discipline go to pieces. Maybe it was just the newness of the whole thing. Maybe—

But he knew better.

He had given them a good, efficient, well-organized plan of action. They should have been impressed—impressed and respectful. They should have been grateful he was plunging so enthusiastically into an effort to improve their situation. They should have been excited and hopeful.

There was something strange here, something he didn't understand.

He knew so little about Nemar.

The Terrans in the group had not reacted as they should have, either, he thought. Some of them had shown the sort of reaction he expected, but most of them had remained quiet, too quiet, with a peculiar, tolerant look. As if they knew something he didn't.

There was something disturbing about their whole manner. They were respectful and deferential, but not quite respectful enough. Their attitude was just a shade too casual. Something was wrong.

They even looked different, somehow, from the usual Terran on space duty. The dedicated look was gone and a softness had crept in.

Somehow, the planet had infected them.

The clear-eyed old Nemarian he'd been talking to had just turned away when she came up.

"Good evening. How do you like bird's eggs a la Nemar?" Jeannette pointed to the shells beside him.

"Hello. They're very good." He motioned her to sit down.

"The youngsters here gather them out of the trees. They make a sport of it." She reached for one from the pile near them and tapped it open. "Sentimental creatures—they always leave one or two so the mother bird won't be unhappy."

Kirk was trying to draw his eyes away from the young Nemarian mother in the group near him who was complacently nursing her baby in full view of everyone. Jeannette stared in the direction of his look.

"Oh, you'll get used to that soon enough."

He wondered if he would. They made a rather touching picture, though, he realized through his embarrassment. There was a lot of tenderness in the woman's gestures.

"They spoil their children rotten."

Kirk looked surprised. "The ones I've seen have been very courteous."

She shrugged. "Oh, they're polite enough. But just try and make them do something they don't want to! They're completely undisciplined—they're fed when they please, they sleep when they please, they do whatever they like. They have schools for them, but it's completely up to the children whether they want to go or not. The parents haven't a thing to say about it. No one ever lays a hand to them, no matter what they do."

"I haven't noticed any quarreling," he said, surprised at his own observation. It was true. He hadn't seen a sign of it, even between the children themselves, though they made enough noise yelling and romping.

"Oh, those tactics fit them perfectly for this society," she said indifferently. "The adults here are just like the children. Nobody ever does any work."

"But that's impossible. The food, the houses, the—"

"Well, I suppose I exaggerated. They do things they don't like once in awhile, if they want the end product enough. But mostly, if they can't make a big game of it, they don't do it. Tomorrow's nut-gathering day," she added irrelevantly.

"Nut-gathering day?"

"Yes. Everybody frolics off into the hills to pick nuts. Like a picnic. That's what I mean—if they didn't consider it a pleasure outing, the nuts could hit them on the head, and they'd never bother to pick them up." She cocked her head at him. "Want to go?"

"Go where? Nut-gathering, you mean?" He laughed. "No, thanks."

"Thought you might like to study the natives in their day-to-day activities, get the real local flavor. You might learn something, at that. Though I guess you'd have a rough time climbing the trees."

"I've had an hour a day at gymnastics for the past three years."

"Yes, you look in good shape." Her glance swept over him approvingly. "But gymnastics and those trees are two different things. The edible nuts grow on the tall trees, not the short ones, and they sway in the wind. The young men do most of the climbing. They're pretty wonderful physical specimens, I'll say that." She glanced at one of them near by, who was whispering in the ear of a Nemarian girl.

Kirk felt oddly annoyed. They were magnificent physical specimens, he thought. But then so were the women and children. He realized that he hadn't seen a sickly or weak-looking native since he arrived. Even the old people kept their magnificent posture, and managed to make age seem a matter of gathering wisdom instead of collecting infirmities. Weren't they ever sick, he wondered.

"The girls are lovely, too," he reminded her.

"Yes, but try to get near one of them," she flashed back. "They prefer their own." Her eyes narrowed. "They're pleasant people, but they're not pleasant to live with. It gets on your nerves after awhile."

"Why didn't you leave, Jeannette?"

"On the spaceship you came on?"

"Yes. There may not be another for five years."

"That's the big question," she said slowly. "I'm not sure I know the answer. I half intended to leave on the ship when it came. But when it came down to it, I didn't leave." She stared ahead of her. "Something about the place gets you. Maybe it's the life. Maybe you get used to lying around in the sun, and you feel kind of frightened at returning to all the hustle and bustle of Terra. And then, you keep waiting, hoping that—"

"Hoping what?"

For a moment, she looked defenseless and a little hurt. Then the cynical smile came back. "You don't even know what you're hoping for, really," she said lightly.

He knew she was evading him.

He lay in bed later, wondering what Jeannette could have meant, what could account for that brief hurt look.

She was an attractive girl, he thought idly. He wondered why he felt nothing for her, when the native girl aroused in him such an unreasonable longing. It would be a good deal more convenient to fall for Jeannette.

He couldn't afford to get mixed up with his maid.

Remembering her, he suddenly felt his body trembling.

All right, he told himself, so she's an ignorant, backward native on a planet nobody ever heard of. Practically a savage. And even here, she's just a maid, a cleaning woman. Nobody a Planetary Administrator could think about getting mixed up with. But how do they turn them out like that?

How do they turn them out like that, he thought—every movement fluid, every position graceful, every gesture exquisite? How does this nonentity of a planet turn out a girl with the kind of walk the video-stars back home practice and work years to approach? With a voice with that indescribable music and precision? With a flawless skin, radiant hair, a serenity and self-confidence that would make the greatest beauties on Terra envious? With a quiet, careless pride that made him, the new ruler of her planet, awkward and insecure in the presence of his own servant?

Jeannette had been jealous, he realized suddenly. She was jealous of these girls, of their grace, of their radiance. Her cynicism covered a bitter envy.

For a long time he lay there, trying to sleep, haunted by Nanae's luminous eyes.

He started working the next morning.

There was no use putting it off, he thought. Nemar seemed to act like a drug, gradually depriving you of your drive and ambition. He wasn't going to give it a chance to let its poison seep into him.

He flung himself into his duties as Planetary Administrator with a grim determination. He struggled to organize the affairs of the planet on a more efficient basis. He introduced new methods and techniques. He worked tirelessly, relentlessly, hardly noticing their passage as one day followed another. And every moment he could spare, he devoted to the project for finding something of value to export.

He was going to put this planet on the map. He didn't know how yet, but he was going to do it.

He was going to turn his misfortune into a triumph.

Every hint of a possibility was followed up with eagerness. Every lead, every clue, was the subject of exhaustive study and investigation. His days were a succession of guarded hopes and disappointments, of surges of optimism and long stretches of discouragement. He pushed his wearied body into greater and greater efforts, working unflaggingly through the day and most of the night, spurred by the anger that still burned in him.

The natives, he knew, looked at the light burning late into the night and thought he was a little crazy. He gave up eating with them. It was too easy, there by the river, to drift into staying later and later, drinking their hot wine, chatting, watching the dancing. It was too hard to resist the temptation of midnight swimming later with the young men and women at the nearby beach, with revels and bonfires on the lavender sands afterward.

At the end of two weeks, he sat on his bed, taking stock of what he had accomplished.

It was very little.

And he was very tired.

The tiredness was familiar. It was just like school all over again, he thought, the same long exhausting hours of driving oneself relentlessly. He wondered when he'd be able to relax. He didn't dare relax now. When he had a lead, a definite hope of some kind, he could begin to let up. But not till then. It would be too easy to give up and let go altogether, go the way Jerwyn had gone.

He was beginning to understand why Jerwyn had given up.

He was beginning to understand a lot of things—the odd, cryptic remarks he had heard about the natives when he first arrived, the mixed admiration and exasperation they seemed to arouse.

He remembered a man named Gandhi from ancient Indian history.

The Nemarians could have given Gandhi lessons.

Working with them was like working with an invisible wall of resistance that weakened here and strengthened there, gave in unexpectedly at one place and resisted implacably at another.

At times his plans were praised; then they were put into effect with an efficiency that astonished him. At other times they were criticized, in a casual, friendly manner that enraged him. Then they were not put into effect at all. When he insisted on obedience, the natives reacted with an attitude of patient tolerance, and did nothing. Most of the time, his orders were received indifferently and carried out with an agonizing slowness.

He pushed and prodded them. He reasoned with them. He shouted at them.

He reaped nothing but frustration.

They didn't hate him. He knew that. He had never seen a trace of malice in their expressions. People smiled at him when he passed, and children came up to tug at his hand and ask him to come to visit their house. There was none of the stony hatred here he knew existed in many places for the all-powerful Galactic Union.

They simply seemed to lack all appreciation of the importance of his position.

Yet they knew, he thought. They knew he had what amounted to almost unlimited power over their planet. They knew a space-fleet that had burned life off the face of entire planets lay at his disposal. They knew he could crush any rebellion instantly.

But, of course, they weren't rebelling, he thought. They weren't even openly uncooperative. There it was again: they weren't even unfriendly; they deluged him with constant invitations.

They knew of his power, but they acted as if it didn't exist.

And he wasn't sure they weren't going to win with him, as they had with Jerwyn. The Galactic Union did not look with approval on any call for aid except in a military crisis; such a request was in effect an affidavit of failure. Besides, he didn't want to complain. He didn't want to set himself against them. He was working for them, not just for himself.

He sighed and began to get ready for bed.

Primitive people had always fought progress and change. They had always clung to old, outworn methods. But there was more to it than that, he thought. Primitive people were usually full of superstitious fear of change, but the Nemarians were not afraid. You couldn't think of them as fearful. They knew the danger—they knew the strength and power that faced them—but they were not afraid. They didn't even "handle with care".

Where did their courage come from?

Or was it just blind stupidity, he thought, a refusal to look facts in the face, to admit that they were the helpless, backward subjects of an immensely more powerful and more advanced civilization?

He pulled off a shoe absently, and he thought of all the documents and reports he had read about Nemar. Ross had given them to him, and he had searched in them for a clue to help him understand why Ross was sending him here. He had read and reread them, and they had told him little more than Ross himself about Nemar.

There was something peculiar about all those documents, he thought, something odd about the way they were written. They described an undeveloped planet without valuable resources or any kind of technology, in no way out of the ordinary. But between the lines was something that said this planet was out of the ordinary, in spite of the apparent facts. There was the unavoidable feeling that something was left unsaid.

What were they trying to hide? Why hadn't they let him know what he was in for?

Terrans had been coming for forty years. In forty years, they must have learned something. They must have found out something about what made these people the way they were, and about how to deal with them. There should have been warnings and suggestions and at least, if nothing else, descriptions of methods that had been tried and failed. It should all have been there, out in the open; it should have been down in black and white: this is the situation, so far as we know it; these are the problems.

Instead, there had been only routine description, and veiled hints and allusions.

He hadn't been here long, he thought. There was a lot to learn here yet. The other Terrans, the ones who had been here a long time, knew something he didn't know. He could tell from their faces, from their attitude toward him. Cortland didn't know, or he would have told him, and some of the others didn't either, but most of them did. They knew something, but whether it was pleasant or unpleasant knowledge, he couldn't tell. Whatever it was, it affected them. They neglected their work, and they had a different look from the Terrans back home.

Jerwyn had known, and he hadn't told him. He'd said he'd have to live here to find out.

He lay down and stretched out wearily on the bed.

Well, the answers here exist, he thought. Somehow, when he had all the pieces, the jigsaw would have to fit together and make a coherent picture.

Maybe he was looking in the wrong direction.

But he didn't know where to look.

He thought of the day he had just been through, remembering incident after incident when he had had all he could do to keep his temper under control. Annoyance welled up in him again, as he recalled the series of frustrations, the useless arguments.

His mind was still revolving in an upheaval of confusion and anger as he fell asleep.

It was barely past dawn when he awoke. He tried to fall asleep again and failed. Giving up, he dressed and wandered into the other room and the garden beyond. He felt the early morning coolness slipping over his shoulders like a garment, and a sense of the futility of all his struggling filled him. He felt a sudden longing to rest, bask in the sun, live as the natives did in sunny, amiable unconcern.

He stiffened, annoyed at himself. That would mean giving up everything he had worked so hard for all his life, ending up as a lazy failure. He felt a surge of anger inside him toward something he could hardly name.

As he stood there, he saw two Nemarian children, a boy and a girl about five years old, emerge from the trees and begin to pick the shimmering flowers in the garden. Irritation rose hotly in him. He knew that it was out of proportion, built out of a hundred frustrating incidents, but he found he didn't want to control it. He wanted to lash out at somebody.

"Stop stealing my flowers!" he yelled. He was surprised at the harshness of his own voice.

The children did not start fearfully or run, as he expected. They turned and stared at him in an unconcerned manner. "You can't steal flowers," the boy said matter-of-factly. "They don't belong to anybody." He looked at Kirk questioningly. "You didn't plant them, did you?"

Kirk stared at him, speechless.

The boy went on, his tone slightly indignant. "Anyway, it's very rude of you to speak to us like that!"

"They are quite right," an angry voice cut in. Kirk whirled around to find Nanae standing beside him, a basket in her hand. Her hair, radiant in the sunlight, was caught back from her face with a green ribbon, and the brown, gold-flecked eyes, for once, were not soft, but sparkling with anger. "These are my sister's children," she said icily. "They help me gather flowers for your table. Do you think just because they are young you have the right to treat them without respect?"

Staring at her angry face, Kirk felt his own anger ebbing. Into his mind a forgotten incident flashed back from his childhood. Through a door left ajar in a neighboring apartment he had seen a ripe purple fruit imported from a newly discovered planet, and had taken it, curious to find out what unsynthetic food might taste like. He had been discovered, and angrily whipped and locked in his room. He remembered wiping away the tears, alone in his room, smarting with humiliation, and vowing he would show them, he would show them all; he would grow up to be so powerful he could have anything he wanted, and everybody would be afraid of him.

He looked now at Nanae, who had put an arm around each of the children, cradling them to her. His anger left him completely. Remembering the hurt child he had once been, he found himself longing for the touch of softness and kindness that had never come to him, wishing that even now for a moment he could take the children's place—lay his head against her breast, and feel her fold him in and brush her hand through his hair. He felt something melting inside of him. He could feel the lines of his face softening as he looked at them.

The words stuck, but he forced them out. "I'm sorry."

"It's all right," said the boy.

Leaning down, Kirk put an arm tentatively around each of the children, half-surprised at himself for the gesture. As he felt their small bodies relax against his, it seemed as though some deep inner tension began to flow out of him. He straightened up to find Nanae's glance on him surprisingly warm, almost tender. The approval in her eyes filled him with an unfamiliar kind of happiness.

"You mean Ross spent five years here!" Kirk stared in amazement at Cortland, sitting beside him.

The older officer turned toward him, shifting his position on the grassy ledge to which they had climbed for a look at the surrounding countryside. "Yes, that's right. Ross was straight out of the Institute then, had an A-1 record, and this place had just been discovered. They thought then it might have all sorts of valuable minerals and things. It seemed like a great chance." He shrugged. "As it turned out, of course, there was nothing, but nobody could have known then."

"They know now," Kirk said shortly. He sat looking over the valleys beneath them, silent for a moment. It was discouraging to learn Ross had been here and had not turned up anything: Ross was capable, whatever else he might be, and it would take luck as well as work to succeed where he had failed. And his luck didn't seem to be working out too well, he thought, unhappily.

But this might throw some new light on why he'd been sent here. Maybe Ross's reason for sending the Institute's star pupil had been one he could never have guessed at the time—a gesture of sentimentality. Maybe he wanted to help these people with whom he had spent his first years as an Administrator. Maybe he wanted to make up for his own failure to help lift their living standards.

He turned toward the other man. "Cortland, you say you've done a lot of traveling here. How about the rest of the planet? Are any of the other villages more advanced; are the people any different?"

Cortland laughed shortly. "Thinking of hiring yourself a new native staff? Your impatience about worn out bucking this one? Can't say I blame you, but it's no go. All these villages are the same. One outfit's as bad as the next. Oh, they go in for different things—one will go all out for sculptures, one will be great on weaving, and another one maybe will grow a special kind of fruit. But the people are all alike—all equally charming and equally impossible. All sweet and friendly on the surface and stubborn as mules underneath. All acting like they know something they're not talking about, like they've got some secret hidden behind those clear, guileless eyes of theirs, some source of strength that makes them able to tell us to go to hell—figuratively, of course—when they don't like our orders." He leaned forward, intently. "I'd give a lot to find out what makes them tick." A look of insecurity, almost of anxiety filled his eyes.

A sudden gust of wind blew a flurry of leaves against Kirk's face. He brushed them away, feeling chilled.

Cortland blinked his eyes, and his face resumed its customary firm look. "But to get back to your question—this village here is supposed to be a center of government. When the Nemarians have to decide on anything that affects the whole planet, the Council in this village does it. The Council has nothing to do with the Galactic Union set-up, of course. It's strictly local, was here before GU discovered this place. You probably studied up on it before you came here."

Kirk nodded. Every planet with an indigenous population had its own political set-up. It was GU policy not to interfere with them, unless their interests clashed in some way.

Cortland went on. "Anyone who likes being in on that sort of thing packs up and emigrates to this village. I don't know whether you've noticed, but these people are pretty casual about moving from one town to another. Anyway, when your would-be politician gets here, the people take him in and watch him awhile, and then, if they like him all right, he's put on the Council. What a system! The truth is, most of the Nemarians consider political work something of a nuisance and would just as soon somebody else did it. They don't care for power the way we do. They look on it as just a heavy responsibility and a burden."

Kirk shifted his leg uncomfortably, feeling a bit self-conscious.

"By the way," Cortland added casually, "how are you getting on with that girl?"

"What girl?"

"That beautiful creature who keeps house for you."

"Nanae?"

"Yes, Nanae. The beauty of the village, the girl who cooks breakfast for you, the head of the Council—"

"What did you say? What was that about the Council?"

"She's head of the Council. Didn't you know?"

"How can she be? She's a maid, she—"

"They don't have maids here. She's being neighborly. And they have sort of a "power corrupts" philosophy here. If you're in a position of authority, you're sort of expected to go out and do humble tasks for people once in awhile, so you won't get to feeling above them. These people like to keep everyone on the same low—"

"But head of the Council!" Kirk broke in. "She's just a young girl!"

"So what? You're just a young man."

"But—"

"Sorry for the levity. But they let women do everything here. They've got equality of the sexes, old man. They—"

"We'd better be starting back," Kirk broke in. He rose to his feet.

He walked silently down the hill beside Cortland, his head whirling.

When they reached the village, he left Cortland as quickly as he could and hurried in the direction of his house, incoherent thoughts tumbling over each other in his mind. His face burned as he remembered his condescension, the way he had fought his desire for her by holding her off with curt remarks, indicating with raised eyebrows that he wished no personal conversation. He thought of the occasional glint of amusement he had seen breaking through her serene courtesy.

Why had she kept coming, he wondered.

He saw, with a start, that he was nearly to his house, and he realized he had been hoping Nanae would be there. He had to talk to her, though he had no idea what he would say. As he drew closer, he saw a flicker of motion inside the porch.

He walked forward quietly, and then stood a moment watching her, silently. She had her back to him and was sweeping, as she had been that first time he saw her. Her thighs were wrapped in soft, violet cloth, and a cascade of violet flowers jeweled the lovely hair which rippled and swirled down her back and shoulders. Not a wasted motion, he thought, not a gesture that isn't beautiful. He wondered why he had ever felt sweeping a floor was a menial task. She moved like a great dancer.

She turned as he watched and saw him. "Hello." She smiled, and he felt himself tremble a little.

"I just heard about you—about your being head of the Council," he blurted out. "I want to apologize; I didn't know, I—"

"What difference does it make?" She looked genuinely puzzled.

"I thought you were a maid, a ... a sort of person who waits on other people, on Terra," he tried to explain. "I didn't know you were just doing this to be kind. I've been very rude. I—I hardly know what to say...."

Her eyes widened. "Do you treat people who clean your houses on Terra one way and officials another? You are funny, you Terrans."

"Yes, I guess we are funny." He searched for words. "This is the first time I've really talked to you, isn't it?"

She smiled. "We've just been people in the same room." She spoke gently. "I've seen you were unhappy and confused under that proud manner. I wanted to help, but you weren't ready to let anyone help."

"Why did you keep coming?" He waited anxiously for her answer.

"I liked you." Her glance was half-tender and a little amused. "And I knew you wanted me here, even though you tried not to show it." She paused. "There was another reason, too."

"What was it?"

"You know Marlin Ross lived here once?" He nodded. "Well, there was a note from him on the spaceship you came on. It was addressed to my father, asking him to take care of you. He and Ross were good friends. But my father is dead now, and so the letter was given to me."

"And so you've been taking care of me."

"Yes."

"But I'm sure he didn't mean it literally—taking care of my house and fixing my food and—"

"No, of course not. He just meant to take care of you, give you what you needed. But you needed this. You needed to be waited on a little."

"I guess I did." He could find nothing adequate to say. "Thank you."

There was a moment of silence.

She put aside the broom, which was still poised in one hand. "Let me make you some jen. You look tired."

"Thank you." Kirk sat down, with a deep sigh, and leaned back, watching her precise, exquisite movements, as she prepared the hot liquid. He found himself longing to touch her, to reach out and feel the soft, supple flesh, the rippling hair. The sight of her beautiful, firm breasts moving as she worked tortured him. The low necklace that signified they were covered didn't work very well for him, he thought. The flowers twined into it kept falling aside as she bent and turned, tantalizing him more. He pulled his eyes away, and forced himself to think of other things.

She had been very kind, he realized.

She hadn't made him feel like a fool.

He stood waiting for the last of the staff to assemble, letting the feel of triumph course through his body. He felt heady, exultant, a little drunk with joy. This was his moment. This made it all worth while—the long hours, the sleepless nights, the relentless work, the struggle. They would see. They would see he hadn't been driving himself and them for nothing.

He stared down for a moment at the piece of ore which he had brought to show them. It contained unpolished zenites.

Nemar possessed zenites, the fabulous gems valued all over the galaxy for their shimmering, glowing beauty of changing color. Infinitely more precious and rare than diamonds, they served often as a galactic medium of exchange, where weight was important. A handful of them could be worth the whole cargo of a trading ship.

He was not surprised that no one had found the ore deposits before. They were the products of immense and peculiar pressures and no appreciable amount of the ore was ever found except very deep underground. He was very glad now he had specialized in geology and mineralogy instead of social structure and alien psychology. Otherwise, the geologic reports he had received of the area would have seemed perfectly routine and ordinary. The nagging feeling that there was something a little unusual about the soil analysis would never have come into consciousness as a definite, tremulous hunch.