The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of Domestic Manners and Sentiments in England During the , by Thomas Wright This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: A History of Domestic Manners and Sentiments in England During the Middle Ages Author: Thomas Wright Illustrator: Frederick William Fairholt Release Date: April 25, 2019 [EBook #59351] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENGLAND DURING THE MIDDLE AGES *** Produced by MWS, Wayne Hammond and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

i

ii

iii

LONDON:

PRINTED BY JAMES S. VIRTUE,

CITY ROAD.

v

vi

vii

vi

vii

Dear Lady Londesborough,

The object of the following pages is to supply what appeared to be a want in our popular literature. We have histories of England, and histories of the Middle Ages, but none of them give us a sufficient picture of the domestic manners and sentiments of our forefathers at different periods, a knowledge of which, I need hardly insist, is necessary to enable us to appreciate rightly the motives with which people acted, and the spirit which guided them. The subject, too, must have an interest for many classes of readers, who will be glad to learn something of the manners of former days, if it were only to see the contrast with those of our own time, and to discover in them the origin of many of the characteristics of modern society. Copious and valuable books have been published in our language on the history of costume, on that of domestic architecture, on military antiquities, on the history of religious rites and ceremonies, and on other kindred subjects, which enable the artist to clothe his personages correctly; but these would form, after all, but the disjointed skeleton of a picture, without that further, and perhaps more important, sort of information which is furnished in the following pages, and which will enable him to give life to his composition. I have not attempted to compose a very learned or very elaborate book. The subject is an immensely wide one as regards the materials, during a large portion of the period which I include; and to treat it completely would require the close study of the whole mass of the mediæval literature of Western Europe, edited or inedited, and of the whole mass of the monuments of mediæval art. But my aim has been to bring together a sufficient viii number of plain facts, in a popular form, to enable the general reader to form a correct view of English manners and sentiments in the middle ages, and I can venture to claim for my book at least the merit of being the result of original research. It is not a compilation from writers who have written on the subject before.

There are at least two ways of arranging a work like this. I might have taken each particular division of the subject, one after the other, and traced it separately through the period of history which this volume embraces; or the whole subject might be divided into historical periods, in each of which all the different phases of social history for that period are included. Each of these plans has its advantages and defects. In the first, the reader would perhaps obtain a clearer notion of the history of any particular division of the subject, as of the history of the table and of diet, or of games and amusements, or the like, but at the same time it would have required a certain effort of comparison and study to arrive at a clear view of the general question at a particular period. The second furnishes this general view, but entails a certain amount of what might almost be called repetition. I have chosen the latter plan, because I think this repetition will be found to be only apparent, and it seems to me the best arrangement for a popular book.

The division of periods, too, is, on the whole, natural, and not arbitrary. During the Anglo-Saxon period, the social system, however developed or modified from time to time, was strictly that of our own Anglo-Saxon forefathers, and was the undoubted groundwork of our own. The Norman conquest brought in foreign social manners and sentiments totally different from those of the Anglo-Saxons, which for a time predominated, but became gradually incorporated with the Anglo-Saxon manners and spirit, until, towards the end of the twelfth century, they formed the English of the middle ages. The Anglo-Norman period, therefore, may be considered as an age of transition—it may perhaps be described as that of the struggle between the spirit of Anglo-Saxon society and feudalism. The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries may be considered in regard to society as the English middle ages—the age of feudalism in its English form—and therefore hold properly the ix largest space in this volume. The fifteenth century forms again a distinct period in the history of society—it was that of the decline and breaking up of feudalism, the close of the middle ages. At the Reformation, we come to a new transition period—the transition from mediæval to modern society. This, for several reasons, I regard rather as a conclusion, than as an integral part, of the history contained in the following pages, and I therefore give only a light sketch of it, noticing some of its prominent characteristics. The materials, at this late period, become so extensive, and so full of interest, that its history admits of several divisions, each of which is sufficient for an important book, and I leave them to future researches. One period, that of the English Commonwealth, is perhaps of greater interest to us at the present time than any other, because it was that which totally overthrew the traditions of the middle ages, and inaugurated English society as it now exists. I know that the history of society at that period has been studied most profoundly by a friend who is, in all respects, far more capable of treating it than myself, Mr. Hepworth Dixon, and from whom I trust we may look forward to a work on the subject, which will be a most valuable addition to the historical literature of our time. Knowing that he has been working on this interesting subject, I have treated this period very slightly. I should be sorry to let my weeds grow upon his flowers.

A portion of the matter contained in this volume has already appeared in a series of papers in the Art-Journal, but this portion has not only been carefully revised and partly re-written, but so much addition has been made, that I believe that more than half the present volume is entirely new, and the whole may fairly be considered as a new book. I ought to add that one chapter, that on mediæval cookery (chapter xvi.) and the brief notices of the history of the horse in the middle ages, first appeared in papers, contributed by the author to the London Review. It must be stated, too, that the illustrations to my chapter on mediæval minstrelsies were originally engraved for a series of papers on the minstrels, by the Rev. E. L. Cutts, published in the Art-Journal, and that I have to thank that gentleman for the ready willingness with which he has allowed me to use them. x

In conclusion, dear Lady Londesborough, I need hardly say that the study of the histories of the people (instead of that of their rulers) has always been a favourite study with me; and that in these researches on mediæval social manners and history, I have always received the warm sympathy and encouragement of the late Lord Londesborough and of your Ladyship. In his Lordship I have lost a respected and valued friend, to whose learned appreciation of the subject of mediæval manners and mediæval art I could always have recourse with trust and satisfaction, with whom I have often conversed on the subjects treated of in the present volume, and whose extensive and invaluable collection of objects of art of the mediæval period, and of that of the renaissance, furnished a never-ending source of information and pleasure. It is therefore with feelings of great personal gratification that I profit by your kind permission to dedicate this volume to your Ladyship.

14, Sydney Street, Brompton, London,

November 10, 1861.

xi

| Anglo-Saxon Period. | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Introductory—the Anglo-Saxons before their conversion—general arrangement of a Saxon house | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| In-door life among the Anglo-Saxons—the hall and its hospitality—the Saxon meal—provisions and cookery—after-dinner occupations—drunken brawls | 18 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The chamber and its furniture—beds and bed-rooms—infancy and childhood among the Anglo-Saxons—character and manners of the Anglo-Saxon ladies—their cruelty to their servants—their amusements—the garden; love of the Anglo-Saxons for flowers—Anglo-Saxon punishments—almsgiving | 40 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Out-of-door amusements of the Anglo-Saxons—hunting and hawking—horses and carriages—travelling—money-dealings | 63 |

| Anglo-Norman Period. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The early Norman period—luxuriousness of the Normans—advance in domestic architecture—the kitchen and the hall—provisions and cookery—bees—the dairy—meal-times and divisions of the day—furniture—the faldestol—chairs and other seats | 80 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Norman hall—social sentiments under the Anglo-Normans—domestic amusements—candles and lanterns—furniture—beds—out-of-door recreations—hunting—archery—convivial intercourse and hospitality—travelling—punishments—the stocks—a Norman school—education | 98 |

| The English Middle Ages. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Early English houses—their general form and distribution | 120 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The old English hall—the kitchen, and its circumstances—the dinner-table—minstrelsy | 141 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The minstrel—his position under the Anglo-Saxons—the Norman trouvere, menestrel, and jougleur—their condition—Rutebeuf—different musical instruments in use among the minstrels—the Beverley minstrels | 175 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Amusements after dinner—gambling—the game of chess—its history—dice—tables—draughts | 194 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Domestic amusements after dinner—the chamber and its furniture—pet animals—occupations and manners of the ladies—supper—candles, lamps, and lanterns | 226 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

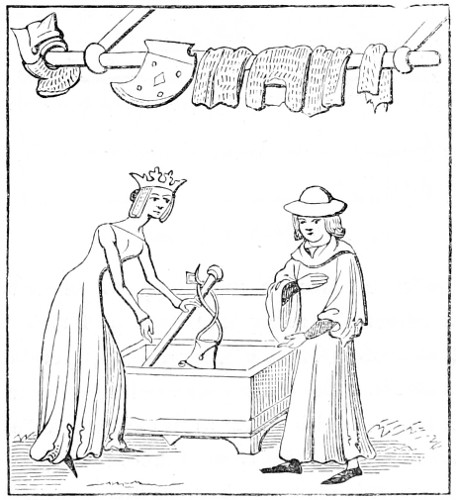

| The bed and its furniture—the toilette; bathing—chests and coffers in the chamber—the hutch—uses of rings—composition of the family—freedom of manners—social sentiments, and domestic relations | 256xiii |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Occupations out of doors—the pleasure-garden—the love of flowers, and the fashion of making garlands—formalities of the promenade—gardening in the middle ages | 283 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Amusements—performing bears—hawking and hunting—riding—carriages—travelling—inns and taverns—hospitality | 304 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Education—literary men and scribes—punishments; the stocks; the gallows | 338 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Old English cookery—history of “gourmandise”—English cookery of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries—bills of fare—great feasts | 347 |

| The Fifteenth Century. | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Slow progress of society in the fifteenth century—enlargement of the houses—the hall and its furniture—arrangement of the table for meals—absence of cleanliness—manners at table—the parlour | 359 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| In-door life and conversation—pet animals—the dance—rere-suppers—illustrations from the “Nancy” tapestry | 379 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The chamber and its furniture and uses—beds—hutches and coffers—the toilette; mirrors | 399xiv |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| State of society—the female character—greediness in eating—character of the mediæval servants—daily occupations in the household: spinning and weaving; painting—the garden and its uses—games out of doors; hawking, etc.—travelling, and more frequent use of carriages—taverns; frequented by women—education and literary occupations; spectacles | 415 |

| England after the Reformation. | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Changes in English domestic manners during the period between the reformation and the commonwealth—the country gentleman’s house—its hall—the fireplace and fire—utensils—cookery—usual hours for meals—breakfast—dinner, and its forms and customs—the banquet—custom of drinking healths | 441 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Household furniture—the parlour—the chamber | 471 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Occupations of the ladies—games and enjoyments—roughness of English sports at this period—the hot-houses, or baths—the ordinaries—domestic pets—treatment of children—methods of locomotion—conclusion | 4821 |

Much has been written at different times on the costume and some other circumstances connected with the condition of our forefathers in past times, but no one has undertaken with much success to treat generally of the domestic manners of the middle ages. The history of domestic manners, indeed, is a subject, the materials of which are exceedingly varied, widely scattered, and not easily brought together; they, of course, vary in character with the periods to which they relate, and at certain periods are much rarer than at others. But the interest of the subject must be felt by every one who appreciates art; for what avails our knowledge of costume unless we know the manners, the mode of living, the houses, the furniture, the utensils, of those whom we have learnt how to clothe? and, without this latter knowledge, history itself can be but imperfectly understood.

In England, as in most other countries of western Europe, at the period of the middle ages when we first become intimately acquainted with them, the manners and customs of their inhabitants were a mixture of those of the barbarian settlers themselves, and of those which they found among the conquered Romans; the latter prevailing to a greater or less extent, according to the peculiar circumstances of the country. 2 This was certainly the case in England among our Saxon forefathers; and it becomes a matter of interest to ascertain what were really the types which belonged to the Saxon race, and to distinguish them from those which they derived from the Roman inhabitants of our island.

We have only one record of the manners of the Saxons before they settled in Britain, and that is neither perfect, nor altogether unaltered—it is the romance of Beowulf, a poem in pure Anglo-Saxon, which contains internal marks of having been composed before the people who spoke that language had quitted their settlements on the Continent. Yet we can hardly peruse it without suspecting that some of its portraitures are descriptive rather of what was seen in England than of what existed in the north of Germany. Thus we might almost imagine that the “street variegated with stones” (stræt wœs stân-fáh), along which the hero Beowulf and his followers proceeded from the shore to the royal residence of Hrothgar, was a picture of a Roman road as found in Britain.

It came into the mind of Hrothgar, we are told, that he would cause to be built a house, “a great mead-hall,” which was to be his chief palace, or metropolis. The hall-gate, we are informed, rose aloft, “high and curved with pinnacles” (heáh and horn-geáp). It is elsewhere described as a “lofty house;” the hall was high; it was “fast within and without, with iron bonds, forged cunningly;” it appears that there were steps to it, and the roof is described as being variegated with gold; the walls were covered with tapestry (web æfter wagum), which also was “variegated with gold,” and presented to the view “many a wondrous sight to every one that looketh upon such.” The walls appear to have been of wood; we are repeatedly told that the roof was carved and lofty; the floor is described as being variegated (probably a tesselated pavement); and the seats were benches arranged round it, with the exception of Hrothgar’s chair or throne. In the vicinity of the hall stood the chambers or bowers, in which there were beds (bed æfter búrum).

These few epithets and allusions, scattered through the poem, give us a tolerable notion of what the house of a Saxon chieftain must have been in the country from whence our ancestors came, as well as afterwards in 3 that where they finally settled. The romantic story is taken up more with imaginary combats with monsters, than with domestic scenes, but it contains a few incidents of private life. The hall of king Hrothgar was visited by a monster named Grendel, who came at night to prey upon its inhabitants; and it was Beowulf’s mission to free them from this nocturnal scourge. By direction of the primeval coast-guards, he and his men proceeded by the “street” already mentioned to the hall of Hrothgar, at the entrance to which they laid aside their armour and left their weapons. Beowulf found the chief and his followers drinking their ale and mead, and made known the object of his journey. “Then,” says the poem, “there was for the sons of the Geats (Beowulf and his followers), altogether, a bench cleared in the beer-hall; there the bold of spirit, free from quarrel, went to sit; the thane observed his office, he that in his hand bare the twisted ale-cup; he poured the bright sweet liquor; meanwhile the poet sang serene in Heorot (the name of Hrothgar’s palace), there was joy of heroes.” Thus the company passed their time, listening to the bard, boasting of their exploits, and telling their stories, until Wealtheow, Hrothgar’s queen, entered and “greeted the men in the hall.” She now served the liquor, offering the cup first to her husband, and then to the rest of the guests, after which she seated herself by Hrothgar, and the festivities continued till it was time to retire to bed. Beowulf and his followers were left to sleep in the hall—“the wine-hall, the treasure-house of men, variegated with vessels” (fættum fáhne). Grendel came in the night, and after a dreadful combat received his death-wound from Beowulf. The noise in the hall was great; “a fearful terror fell on the North Danes, on each of those who from the walls heard the outcry.” These were the watchmen stationed on the wall forming the chieftain’s palace, that enclosed the whole mass of buildings (of wealle).

As far as we can judge by the description given in the poem, Hrothgar and his household in their bowers or bed-chambers had heard little of the tumult, but they went early in the morning to the hall to rejoice in Beowulf’s victory. There was great feasting again in the hall that day, and Beowulf and his followers were rewarded with rich gifts. After 4 dinner the minstrel again took up the harp, and sang some of the favourite histories of their tribe. “The lay was sung, the song of the gleeman, the joke rose again, the noise from the benches grew loud, cup-bearers gave the wine from wondrous vessels.” Then the queen, “under a golden crown,” again served the cup to Hrothgar and Beowulf. She afterwards went as before to her seat, and “there was the costliest of feasts, the men drank wine,” until bed-time arrived a second time. While their leader appears to have been accommodated with a chamber, Beowulf’s men again occupied the hall. “They bared the bench-planks; it was spread all over with beds and bolsters; at their heads they set their war-rims, the bright shield-wood; there, on the bench, might easily be seen, above the warrior, his helmet lofty in war, the ringed mail-shirt, and the solid shield; it was their custom ever to be ready for war, both in house and in field.”

Grendel had a mother (it was the primitive form of the legend of the devil and his dam), and this second night she came unexpectedly to avenge her son, and slew one of Hrothgar’s favourite counsellors and nobles, who must therefore have also slept in the hall. Beowulf and his warriors next day went in search of this new marauder, and succeeded in destroying her, after which exploit they returned to their own home laden with rich presents.

These sketches of early manners, slight as they may be, are invaluable to us, in the absence of all other documentary record during several ages, until after the Anglo-Saxons had been converted to Christianity. During this long period we have, however, one source of invaluable information, though of a restricted kind—the barrows or graves of our primeval forefathers, which contain almost every description of article that they used when alive. In that solitary document, the poem of Beowulf, we are told of the arms which the Saxons used, of the dresses in which they were clad; of the rings, and bracelets, and ornaments, of which they were proud; of the “solid cup, the valuable drinking-vessel,” from which they quaffed the mead, or the vases from which they poured it; but we can obtain no notions of the form or character of these articles. From the graves, on the contrary, we obtain a perfect knowledge of the form 5 and design of all these various articles, without deriving any knowledge as to the manner in which they were used. The subject now becomes a more extensive one; and in the Anglo-Saxon barrows in England, we find a mixture, in these articles, of Anglo-Saxon and Roman, which furnishes a remarkable illustration of the mixture of the races. We are all perfectly well acquainted with Roman types; and in the few examples which can be here given of articles found in early Anglo-Saxon barrows, I shall only introduce such as will enable us to judge what classes of the subsequent mediæval types were really derived from pure Saxon or Teutonic originals.

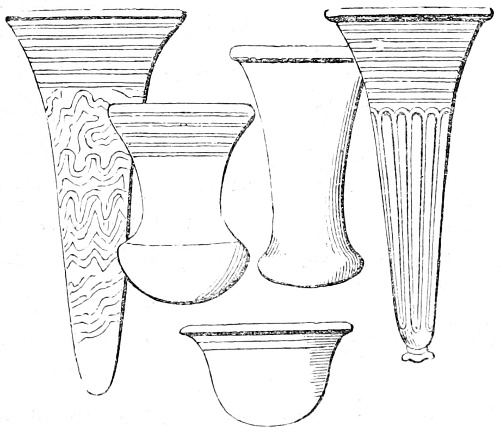

No. 1. Anglo-Saxon Drinking Glasses.

It is curious enough that the poet who composed the romance of Beowulf enumerates among the treasures in the ancient barrow, guarded by the dragon who was finally slain by his hero, “the dear, or precious drinking-cup” (dryncfæt deóre). Drinking-cups are frequently found in the Saxon barrows or graves in England. A group, representing the more usual forms, is given in our cut, No. 1, found chiefly in barrows in Kent, and preserved in the collections of lord Londesborough and Mr. Rolfe, the latter of which is now in the possession of Mr. Mayer, of Liverpool. The example to the left no doubt represents the “twisted” pattern, so often mentioned in Beowulf, and evidently the favourite 6 ornament among the early Saxons. All these cups are of glass; they are so formed that it is evident they could not stand upright, so that it was necessary to empty them at a draught. This characteristic of the old drinking-cups is said to have given rise to the modern name of tumblers.

No. 2. Germano-Saxon Drinking Glasses.

That these glass drinking-cups—or, if we like to use the term, these glasses—were implements peculiar to the Germanic race to which the Saxons belonged, and not derived from the Romans, we have corroborative evidence in discoveries made on the Continent. I will only take examples from some graves of the same early period, discovered at Selzen, in Rhenish Hesse, an interesting account of which was published at Maintz, in 1848, by the brothers W. and L. Lindenschmit. In these graves several drinking-cups were found, also of glass, and resembling in character the two middle figures in our cut, No. 1. Three specimens are given in the cut No. 2. In our cut, No. 5, (see page 8), is one of the cup-shaped glasses, also found in these Hessian graves, which closely resembles that given in the cut No. 1. None of the cups of the champagne-glass form, like those found in England, occur in these foreign barrows.

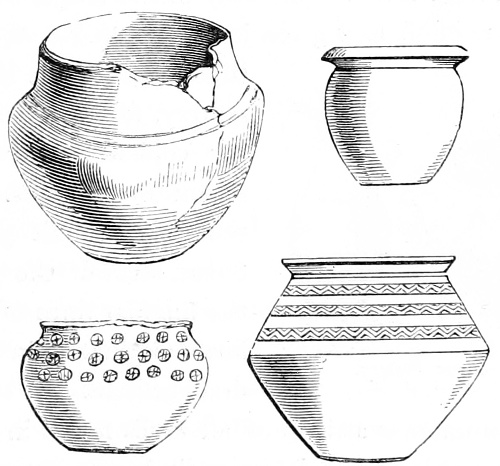

No. 3. Anglo-Saxon Pottery.

No. 4. Germano-Saxon Pottery.

We shall find also that the pottery of the later Anglo-Saxon period presented a mixture of forms, partly derived from those which had belonged to the Saxon race in their primitive condition, and partly copied or imitated from those of the Romans. In fact, in our Anglo-Saxon graves we find much purely Roman pottery intermingled with earthen vessels of Saxon manufacture; and this is also the case in Germany. As Roman forms are known to every one, we need only give the pure Saxon types. Our cut, No. 3, represents five examples, and will give a sufficient notion of their general character. The two to the left were taken, with a large 7 quantity more, of similar character, from a Saxon cemetery at Kingston, near Derby; the vessel in the middle, and the upper one to the right, are from Kent; and the lower one to the right is also from the cemetery at Kingston. Several of these were usually considered as types of ancient British pottery, until their real character was recently demonstrated, and it is corroborated by the discovery of similar pottery in what I will term 8 the Germano-Saxon graves. Four examples from the cemetery at Selzen, are given in the cut No. 4. We have here not only the rude-formed vessels with lumps on the side, but also the characteristic ornament of crosses in circles. The next cut, No. 5, represents two earthen vessels of another description, found in the graves at Selzen. The one to the right is evidently the prototype of our modern pitcher. I am informed there is, in the Museum at Dover, a specimen of pottery of this shape, taken from an Anglo-Saxon barrow in that neighbourhood; and Mr. Roach Smith took fragments of another from an Anglo-Saxon tumulus near the same place. The other variation of the pitcher here given is remarkable, not on account of similar specimens having been found, as far as I know, in graves in England, but because vessels of a similar form are found rather commonly in the Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts. One of these is given in the group No. 6, which represents three types of the later Anglo-Saxon pottery, selected from a large number copied by Strutt from Anglo-Saxon manuscripts. The figure to the left, in this group, is a later Saxon form of the pitcher; perhaps the singular form of the handle may have originated in an error of the draughtsman.

No. 5. Germano-Saxon Pottery and Glass. |

No. 6. Anglo-Saxon Pottery. |

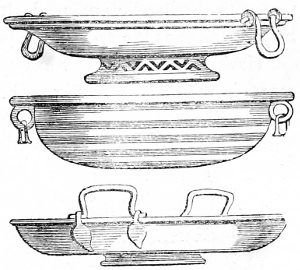

No. 7. Anglo-Saxon Bowls. |

No. 8. Anglo-Saxon Buckets. |

Among the numerous articles of all kinds found in the early Anglo-Saxon graves, are bowls of metal (generally bronze or copper), often very thickly gilt, and of elegant forms; they are, perhaps, borrowed from the Romans. Three examples are given in the cut No. 7, all found in Kent. They were probably intended for the service of the table. Another class 9 of utensils found rather commonly in the Anglo-Saxon barrows are buckets. The first of those represented in our cut, No. 8, was found in a Saxon barrow near Marlborough, in Wiltshire; the other was found on the Chatham lines. As far as my own experience goes, I believe these buckets are usually found with male skeletons, and from this circumstance, and the fact of their being usually ornamented, I am inclined to think they served some purposes connected with the festivities of the hall; probably they were used to carry the ale or mead. The Anglo-Saxon translation of the Book of Judges (ch. vii. ver. 20), rendered hydrias confregissent by to-bræcon tha bucas, “they broke the buckets.” A common name for this implement, which was properly buc, was æscen, which signified literally a vessel made of ash, the favourite wood of the Anglo-Saxons. Our cut, No. 9, represents a bucket of wood with very delicately-formed bronze hoops and handle, found in a barrow in Bourne Park, near Canterbury. The wood was entirely decayed; but the hoops and handle are in the collection of lord Londesborough. Such buckets have, also, been found under similar circumstances on the Continent. The close resemblance between the weapons and other instruments found in the English barrows and in those at Selzen, may be illustrated by a comparison of the two axes represented in the cut, No. 10. The upper one was found at Selzen; the lower one is in the Museum of Mr. Rolfe, and was obtained from a barrow in the Isle of Thanet. The same similarity is observed between the knives, which is the more remarkable, as the later Anglo-Saxon knives were quite of a 10 different form. The example, cut No. 11, taken from a grave at Selzen, is the only instance I know of a knife of this early period of Saxon history with the handle preserved; it has been beautifully enamelled. This may be taken as the type of the primitive Anglo-Saxon knife.

No. 9. Anglo-Saxon Bucket. |

No. 10. Anglo-Saxon Axes. |

Having given these few examples of the general forms of the implements in use among the Saxons before their conversion to Christianity, as much to illustrate their manners as described by Beowulf, as to show what classes of types were originally Saxon, we will proceed to treat of their domestic manners as we learn them from the more numerous and more definite documents of a later period. We shall find it convenient to consider the subject separately as it regards in-door life and out-door life, and it will be proper first that we should form some definite notion of an Anglo-Saxon house.

No. 11. Germano-Saxon Knife.

We can already form some notion of the primeval Saxon mansion from our brief review of the poem of Beowulf; and we shall find that it 11 continued nearly the same down to a late period. The most important part of the building was the hall, on which was bestowed all the ornamentation of which the builders and decorators of that early period were capable. Halls built of stone are alluded to in a religious poem at the beginning of the Exeter book; yet, in the earlier period at least, there can be little doubt that the materials of building were chiefly wood. Around, or near this hall, stood, in separate buildings, the bed-chambers, or bowers (búr), of which the latter name is only now preserved as applied to a summer-house in a garden; but the reader of old English poetry will remember well the common phrase of a bird in bure, a lady in her bower or chamber. These buildings, and the household offices, were all grouped within an inclosure, or outward wall, which, I imagine, was generally of earth, for the Anglo-Saxon word, weall, was applied to an earthen rampart, as well as to masonry. What is termed in the poem of Judith, wealles geát, the gate of the wall, was the entrance through this inclosure or rampart. I am convinced that many of the earth-works, which are often looked upon as ancient camps, are nothing more than the remains of the inclosures of Anglo-Saxon residences.

In Beowulf, the sleeping-rooms of Hrothgar and his court seem to have been so completely detached from the hall, that their inmates did not hear the combat that was going on in the latter building at night. In smaller houses the sleeping-rooms were fewer, or none, until we arrive at the simple room in which the inmates had board and lodging together, with a mere hedge for its inclosure, the prototype of our ordinary cottage and garden. The wall served for a defence against robbers and enemies, while, in times of peace and tranquillity, it was a protection from indiscreet intruders, for the doors of the hall and chambers seem to have been generally left open. Beggars assembled round the door of the wall—the ostium domûs—to wait for alms.

The vocabularies of the Anglo-Saxon period furnish us with the names of most of the parts of the ordinary dwellings. The entrance through the outer wall into the court, the strength of which is alluded to in early writers, was properly the gate (geát). The whole mass inclosed within this wall constituted the burh (burgh), or tun, and the inclosed 12 court itself seems to have been designated as the cafer-tun, or inburh. The wall of the hall, or of the internal buildings in general, was called a wag, or wah, a distinctive word which remained in use till a late period in the English language, and seems to have been lost partly through the similarity of sound.1 The entrance to the hall, or to the other buildings in the interior, was the duru, or door, which was thus distinguished from the gate. Another kind of door mentioned in the vocabularies was a hlid-gata, literally a gate with a lid or cover, which was perhaps, however, a word merely invented to represent the Latin valva, which is given as its equivalent. The door is described in Beowulf as being “fastened with fire-bands” (fyr-bendum fæst, I. 1448), which must mean iron bars.2 Either before the door of the hall, or between the door and the interior apartment, was sometimes a selde, literally a shed, but perhaps we might now call it a portico. The different parts of the architectural structure of the hall enumerated in the vocabularies are stapul, a post or log set in the ground; stipere, a pillar; beam, a beam; ræfter, a rafter; læta, a lath; swer, a column. The columns supported bigels, an arch or vault, or fyrst, the interior of the roof, the ceiling. The hrof, or roof, was called also thecen, or thæcen, a word derived from the verb theccan, to cover; but although this is the original of our modern word thatch, our readers must not suppose that the Anglo-Saxon thæcen meant what we call a thatched roof, for we have the Anglo-Saxon word thæc-tigel, a thatch-tile, as well as hrof-tigel, a roof-tile. There was sometimes one story above the ground-floor, for which the vocabularies give the Latin word solarium, the origin of the later mediæval word, soler; but it is evident that this 13 was not common to Anglo-Saxon houses, and the only name for it was up-flor, an upper floor. It was approached by a stæger, so named from the verb stigan, to ascend, and the origin of our modern word stair. There were windows to the hall, which were probably improvements upon the ruder primitive Saxon buildings, for the only Anglo-Saxon words for a window are eag-thyrl, an eye-hole, and eag-duru, an eye-door.

We have unfortunately no special descriptions of Anglo-Saxon houses, but scattered incidents in the Anglo-Saxon historians show us that this general arrangement of the house lasted down to the latest period of their monarchy. Thus, in the year 755, Cynewulf, king of the West Saxons, was murdered at Merton by the atheling Cyneard. The circumstances of the story are but imperfectly understood, unless we bear in mind the above description of a house. Cynewulf had gone to Merton privately, to visit a lady there, who seems to have been his mistress, and he only took a small party of his followers with him. Cyneard, having received information of this visit, assembled a body of men, entered the inclosure of the house unperceived (as appears by the context), and surrounded the detached chamber (búr) in which was the king with the lady. The king, taken by surprise, rushed to the door (on tha duru eode), and was there slain fighting. The king’s attendants, although certainly within the inclosure of the house, were out of hearing of this sudden fray (they were probably in the hall), but they were roused by the woman’s screams, rushed to the spot, and fought till, overwhelmed by the numbers of their enemies, they also were all slain. The murderers now took possession of the house, and shut the entrance gate of the wall of inclosure, to protect themselves against the body of the king’s followers who had been left at a distance. These, next day, when they heard what had happened, hastened to the spot, attacked the house, and continued fighting around the gate (ymb thá gatu) until they made their way in, and slew all the men who were there. Again, we are told, in the Ramsey Chronicle published by Gale, of a rich man in the Danish period, who was oppressive to his people, and, therefore, suspicious of them. He accordingly had four watchmen every night, chosen alternately from his household, who kept guard at the outside of his hall, evidently for the purpose of 14 preventing his enemies from being admitted into the inclosure by treachery. He lay in his chamber, or bower. One night, the watchmen having drunk more than usual, were unguarded in their speech, and talked together of a plot into which they had entered against the life of their lord. He, happening to be awake, heard their conversation from his chamber, and defeated their project. We see here the chamber of the lord of the mansion so little substantial in its construction that its inmates could hear what was going on out of doors. At a still later period, a Northumbrian noble, whom Hereward visited in his youth, had a building for wild beasts within his house or inclosure. One day a bear broke loose, and immediately made for the chamber or bower of the lady of the household, in which she had taken shelter with her women, and whither, no doubt, the savage animal was attracted by their cries. We gather from the context that this asylum would not have availed them, had not young Hereward slain the bear before it reached them. In fact, the lady’s chamber was still only a detached room, probably with a very weak door, which was not capable of withstanding any force.

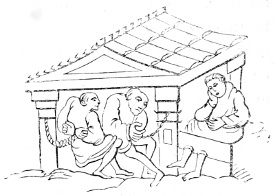

The Harleian Manuscript, No. 603 (in the British Museum), contains several illustrations of Anglo-Saxon domestic architecture, most of which are rather sketchy and indefinite; but there is one picture (fol. 57, vo.) which illustrates, in a very interesting manner, the distribution of the house. Of this, an exact copy is given in the accompanying cut, No. 12.3 The manuscript is, perhaps, as old as the ninth century, and the picture here given illustrates Psalm cxi., in the Vulgate version, the description of the just and righteous chieftain: the beggars are admitted within the inclosure (where the scene is laid), to receive the alms of the lord; and he and his lady are occupied in distributing bread to them, while his servants are bringing out of one of the bowers raiment to clothe the naked. The larger building behind, ending in a sort of round tower 15 with a cupola, is evidently the hall—the stag’s head seems to mark its character. The buildings to the left are chambers or bowers; to the 16 right is the domestic chapel, and the little room attached is perhaps the chamber of the chaplain.

No. 12. Anglo-Saxon Mansion.

It is evidently the intention in this picture to represent the walls of the rooms as being formed, in the lower part, of masonry, with timber walls above, and all the windows are in the timber walls. If we make allowance for want of perspective and proportion in the drawing, it is probable that only a small portion of the elevation was masonry, and that the wooden walls (parietes) were raised above it, as is very commonly the case in old timber-houses still existing. The greater portion of the Saxon houses were certainly of timber; in Alfric’s colloquy, it is the carpenter, or worker in wood (se treo-wyrhta), who builds houses; and the very word to express the operation of building, timbrian, getimbrian, signified literally to construct of timber. We observe in the above representation of a house, that none of the buildings have more than a ground-floor, and this seems to have been a characteristic of the houses of all classes. The Saxon word flór is generally used in the early writers to represent the Latin pavimentum. Thus the “variegated floor” (on fágre flór) of the hall mentioned in Beowulf (l. 1454) was a paved floor, perhaps a tessellated pavement; as the road spoken of in an earlier part of the poem (stræt wæs stán-fáh, the street was stone-variegated, l. 644) describes a paved Roman road. The term upper-floor occurs once or twice, but only I think in translating from foreign Latin writers. The only instance that occurs to my memory of an upper-floor in an Anglo-Saxon house, is the story of Dunstan’s council at Calne in 978, when, according to the Saxon Chronicle, the witan, or council, fell from an upper-floor (of ane úp-floran), while Dunstan himself avoided their fate by supporting himself on a beam (uppon anum beame). The buildings in the above picture are all roofed with tiles of different forms, evidently copied from the older Roman roof-tiles. Perhaps the flatness of these roofs is only to be considered as a proof of the draughtsman’s ignorance of perspective. One of Alfric’s homilies applies the epithet steep to a roof—on tham sticelan hrofe. The hall is not unfrequently described as lofty.

The collective house had various names in Anglo-Saxon. It was called hús, a house, a general term for all residences great or small; it 17 was called heal, or hall, because that was the most important part of the building—we still call gentlemen’s seats halls; it was called ham, as being the residence or home of its possessor; and it was called tún, in regard of its inclosure.

The Anglo-Saxons chose for their country-houses a position which commanded a prospect around, because such sites afforded protection at the same time that they enabled the possessor to overlook his own landed possessions. The Ramsey Chronicle, describing the beautiful situation of the mansion at “Schitlingdonia” (Shitlington), in Bedfordshire, tells us that the surrounding country lay spread out like a panorama from the door of the hall—ubi ab ostio aulæ tota fere villa et late patens ager arabilis oculis subjacet intuentis. 18

The introductory observations in the preceding chapter will be sufficient to show that the mode of life, the vessels and utensils, and even the residences of the Anglo-Saxons, were a mixture of those they derived from their own forefathers with those which they borrowed from the Romans, whom they found established in Britain. It is interesting to us to know that we have retained the ordinary forms of pitchers and basins, and, to a certain degree, of drinking vessels, which existed so many centuries ago among our ancestors before they established themselves in this island. The beautiful forms which had been brought from the classic south were not able to supersede national habit. Our modern houses derive more of their form and arrangement from those of our Saxon forefathers than from any other source. We have seen that the original Saxon arrangement of a house was preserved by that people to the last; but it does not follow that they did not sometimes adopt the Roman houses they found standing, although they seem never to have imitated them. I believe Bulwer’s description of the Saxonised Roman house inhabited by Hilda, to be founded in truth. Roman villas, when uncovered at the present day, are sometimes found to have undergone alterations which can only be explained by supposing that they were made when later possessors adapted them to Saxon manners. Such alterations appear to me to be visible in the villa at Hadstock, in Essex, opened by the late lord Braybrooke; in one place the outer wall seems to have been broken through to make a new entrance, and a road of tiles, which was supposed to have been the bottom of a water course, was more probably the paved pathway 19 made by the Saxon possessor. Houses in those times were seldom of long duration; we learn from the domestic anecdotes given in saints’ legends and other writings, that they were very frequently burnt by accidental fires; thus the main part of the house, the timber-work, was destroyed; and as ground was then not valuable, and there was no want of space, it was much easier to build a new house in another spot, and leave the old foundations till they were buried in rubbish and earth, than to clear them away in order to rebuild on the same site. Earth soon accumulated under such circumstances; and this accounts for our finding, even in towns, so much of the remains of the houses of an early period undisturbed at a considerable depth under the present surface of the ground.

It has already been observed that the most important part of the Saxon house was the hall. It was the place where the household (hired) collected round their lord and protector, and where the visitor or stranger was first received,—the scene of hospitality. The householder there held open-house, for the hall was the public apartment, the doors of which were never shut against those who, whether known or unknown, appeared worthy of entrance. The reader of Saxon history will remember the beautiful comparison made by one of king Edwin’s chieftains in the discussion on the reception to be given to the missionary Paulinus. “The present life of man, O king, seems to me, in comparison of that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the hall where you sit at your meal in winter, with your chiefs and attendants, warmed by a fire made in the middle of the hall, whilst storms of rain or snow prevail without; the sparrow, flying in at one door and immediately out at another, whilst he is visible is safe from the wintry storm, but after this short space of fair weather, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, into the dark winter from which he had emerged.” Dining in private was always considered disgraceful, and is mentioned as a blot in a man’s character.

Internally, the walls of the hall were covered with hangings or tapestry, which were called in Anglo-Saxon wah-hrægel, or wah-rift, wall-clothing. These appear sometimes to have been mere plain cloths, 20 but at other times they were richly ornamented, and not unfrequently embroidered with historical subjects. So early as the seventh century, Aldhelm speaks of the hangings or curtains being dyed with purple and other colours, and ornamented with images, and he adds that “if finished of one colour uniform they would not seem beautiful to the eye.” Among the Saxon wills printed by Hickes, we find several bequests of heall wah-riftas, or wall-tapestries for the hall; and it appears that, in some cases, tapestries of a richer and more precious character than those in common use were reserved to be hung up only on extraordinary festivals. There were hooks, or pegs, on the wall, upon which various objects were hung for convenience. In an anecdote told in the contemporary life of Dunstan, he is made to hang his harp against the wall of the room. Arms and armour, more especially, were hung against the wall of the hall. The author of the “Life of Hereward” describes the Saxon insurgents who had taken possession of Ely, as suspending their arms in this manner; and in one of the riddles in the Exeter Book, a war-vest is introduced speaking of itself thus:—

hwilum hongige, Sometimes I hang, hyrstum frœtwed, with ornaments adorned, wlitig on wage, splendid on the wall, þær weras drinceð, where men drink, freolic fyrd-sceorp. a goodly war-vest.

We have no allusion in Anglo-Saxon writers to chimneys, or fireplaces, in our modern acceptation of the term. When necessary, the fire seems to have been made on the floor, in the place most convenient. We find instances in the early saints’ legends where the hall was burnt by incautiously lighting the fire too near the wall. Hence it seems to have been usually placed in the middle, and there can be little doubt that there was an opening, or, as it was called in later times, a louver, in the roof above, for the escape of the smoke. The historian Bede describes a Northumbrian king, in the middle of the seventh century, as having, on his return from hunting, entered the hall with his attendants, and all standing round the fire to warm themselves. A somewhat similar scene, but in more humble life, is represented in the accompanying cut, taken 21 from a manuscript calendar of the beginning of the eleventh century (MS. Cotton. Julius, A. iv.). The material for feeding the fire is wood, which the man to the left is bringing from a heap, while his companion is administering to the fire with a pair of Saxon tongs (tangan). The vocabularies give tange, tongs, and bylig, bellows; and they speak of col, coal (explained by the Latin carbo), and synder, a cinder (scorium). As all these are Saxon words, and not derived from the Latin, we may suppose that they represent things known to the Anglo-Saxon race from an early period; and as charcoal does not produce scorium, or cinder, it is perhaps not going too far to suppose that the Anglo-Saxons were acquainted with the use of mineral coal. We know nothing of any other fire utensils, except that the Anglo-Saxons used a fyr-scofl, or fire-shovel. The place in which the fire was made was the heorth, or hearth.

No. 13. A Party at the Fire.

The furniture of the hall appears to have been very simple, for it consisted chiefly of benches. These had carpets and cushions; the former are often mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon wills. The Anglo-Saxon poems speak of the hall as being “adorned with treasures,” from which we are perhaps justified in believing that it was customary to display there in some manner or other the richer and more ornamental of the household vessels. Perhaps one end of the hall was raised higher than the rest for the lord of the household, like the dais of later times, as Anglo-Saxon writers speak of the heah-setl, or high seat. The table can hardly be considered as furniture, in the ordinary sense of the word: it was literally, according to its Anglo-Saxon name bord, a board that was brought out for the occasion, and placed upon tressels, and taken away as soon as the meal was ended. Among the inedited Latin ænigmata, or riddles, of the Anglo-Saxon writer Tahtwin, who flourished at the beginning of the eighth century, is one on a table, which is curious enough to be given here, from the manuscript in the British Museum (MS. Reg. 12, C. xxiii.). 22 The table, speaking in its own person, says that it is in the habit of feeding people with all sorts of viands; that while so doing it is a quadruped, and is adorned with handsome clothing; that afterwards it is robbed of all it possesses, and when it has been thus robbed it loses its legs:—

In the illuminated manuscripts, wherever dinner scenes are represented, the table is always covered with what is evidently intended for a handsome table-cloth, the myse-hrægel or bord-clath. The grand preparation for dinner was laying the board; and it is from this original character of the table that we derive our ordinary expression of receiving any one “to board and lodging.”

The hall was peculiarly the place for eating—and for drinking. The Anglo-Saxons had three meals in the day,—the breaking of their fast (breakfast), at the third hour of the day, which answered to nine o’clock in the morning, according to our reckoning; the ge-reordung (repast), or nón-mete (noon-meat) or dinner, which is stated to have been held at the canonical hour of noon, or three o’clock in the afternoon; and the æfen-gereord (evening repast), æfen-gyfl (evening food), æfen-mete (evening meat), æfen-thenung (evening refreshment), or supper, the hour of which is uncertain. It is probable, from many circumstances, that the latter was a meal not originally in use among our Saxon forefathers: perhaps their only meal at an earlier period was the dinner, which was always their principal repast; and we may, perhaps, consider noon as midday, and not as meaning the canonical hour.

As I have observed before, the table, from the royal hall down to the most humble of those who could afford it, was not refused to strangers. When they came to the hall-door, the guests were required to leave their arms in the care of a porter or attendant, and then, whether known or 23 not, they took their place at the tables. One of the laws of king Cnut directs, that if, in the meantime, any one took the weapon thus deposited, and did hurt with it, the owner should be compelled to clear himself of suspicion of being cognisant of the use to be made of his arms when he laid them down. History affords us several remarkable instances of the facility of approach even to the tables of kings during the Saxon period. It was this circumstance that led to the murder of king Edmund in 946. On St. Augustin’s day, the king was dining at his manor of Pucklechurch, in Gloucestershire; a bandit named Leofa, whom the king had banished for his crimes, and who had returned without leave from exile, had the effrontery to place himself at the royal table, by the side of one of the principal nobles of the court; the king alone recognised him, rose from his seat to expel him from the hall, and received his death-wound in the struggle. In the eleventh century, when Hereward went in disguise as a spy to the court of a Cornish chieftain, he entered the hall while they were feasting, took his place among the guests, and was but slightly questioned as to who he was and whence he came.

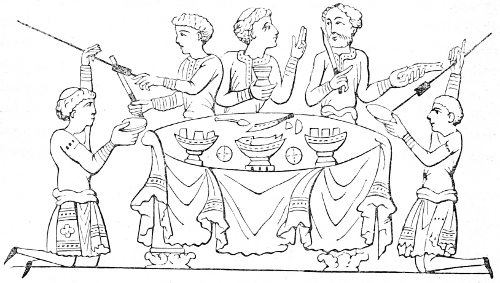

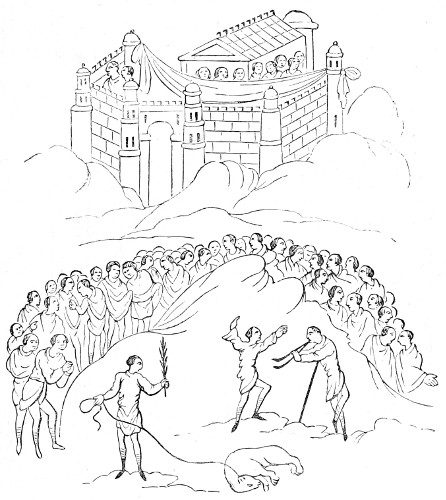

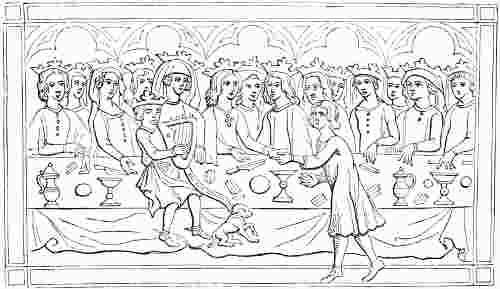

No. 14. An Anglo-Saxon Dinner-Party Pledging.

In the early illuminated manuscripts, dinner scenes are by no means uncommon. The cut, No. 14 (taken from Alfric’s version of Genesis, 24 MS. Cotton. Claudius, B. iv., fol. 36, vo), represents Abraham’s feast on the birth of his child. The guests are sitting at an ordinary long hall table, ladies and gentlemen being mixed together without any apparent special arrangement. This manuscript is probably of the beginning of the eleventh century. The cut, No. 15, represents another dinner scene, from a manuscript probably of the tenth century (Tiberius, C. vi., fol. 5, vo), and presents several peculiarities. The party here is a very small one, and they sit at a round table. The attendants seem to be serving them, in a very remarkable manner, with roast meats, which they bring to table on the spits (spitu) as they were roasted. Another festive scene is represented in the cut, No. 16, taken from a manuscript of the Psychomachia of the poet Prudentius (MS. Cotton. Cleopatra, C. viii., fol. 15, ro). The table is again a round one, at which Luxury and her companions are seated at supper (seo Galnes æt hyre æfen-ge-reordum sitt).

No. 15. Anglo-Saxons at Dinner.

It will be observed that in these pictures, the tables are tolerably well covered with vessels of different kinds, with the exception of plates. There are one or two dishes of different sizes in fig. 14, intended, no doubt, for holding bread and other articles; it was probably an utensil borrowed from the Romans, as the Saxon name disc was evidently taken from the 25 Latin discus. It is not easy to identify the forms of vessels given in these pictures with the words which are found in the Anglo-Saxon language, in which the general term for a vessel is fæt, a vat; crocca, a pot or pitcher, no doubt of earthenware, is preserved in the modern English word crockery; and bolla, a bowl, orc, a basin, bledu and mele, each answering to the Latin patera, læfel and ceac, a pitcher or urn, hnæp, a cup (identical in name with the hanap of a later period), flaxe, a flask, are all pure Anglo-Saxon words. Many of the forms represented in the manuscripts are recognised at once as identical with those which are found in the earlier Anglo-Saxon graves. In the vocabularies, the Latin word amphora is translated by crocca, a crock; and lagena by æscen, which means a vessel made of ash wood, and was, in all probability, identical with the small wooden buckets so often found in the early Saxon graves. In a document preserved in Heming’s chartulary of Canterbury, mention is made of “an æscen, which is otherwise called a back-bucket” (æscen the is othre namon hrygilebuc gecleopad, Heming, p. 393), which strongly confirms 26 the opinion I have adopted as to the purpose of the bucket found in the graves.

No. 16. A Supper Party.

The food of the Anglo-Saxons appears to have been in general rather simple in character, although we hear now and then of great feasts, probably consisting more in the quantity of provisions than in any great variety or refinement in gastronomy. Bread formed the staple, which the Anglo-Saxons appear to have eaten in great quantities, with milk, and butter, and cheese. A domestic was termed a man’s hlaf-ætan, or loaf-eater. There is a curious passage in one of Alfric’s homilies, that on the life of St. Benedict, where, speaking of the use of oil in Italy, the Anglo-Saxon writer observes, “they eat oil in that country with their food as we do butter.” Vegetables (wyrtan) formed a considerable portion of the food of our forefathers at this period; beans (beana) are mentioned as articles of food, but I remember no mention of the eating of peas (pisan) in Anglo-Saxon writers. A variety of circumstances show that there was a great consumption of fish, as well as of poultry. Of flesh meat, bacon (spic) was the most abundant, for the extensive oak forests nourished innumerable droves of swine. Much of their other meat was salted, and the place in which the salt meat was kept was called, on account of the great preponderance of the bacon, a spic-hus, or bacon-house; in latter times, for the same reason, named the larder. The practice of eating so much salt meat explains why boiling seems to have been the prevailing mode of cooking it. In the manuscript of Alfric’s translation of Genesis, already mentioned, we have a figure of a boiling vessel (No. 17), which is placed over the fire on a tripod. This vessel was called a pan (panna—one Saxon writer mentions isen panna, an iron pan) or a kettle (cytel). It is very curious to observe how many of our trivial expressions at the present day are derived from very ancient customs; thus, for example, we speak of “a kettle of fish,” though what we now term a kettle would hardly serve for this branch of cookery. In another picture (No. 18) we have a similar boiling vessel, placed similarly on a tripod, while the cook is using a very singular utensil to stir the contents. Bede speaks of a goose being taken down from a wall to be boiled. It seems probable that in earlier times among the Anglo-Saxons, and perhaps at a 27 later period, in the case of large feasts, the cooking was done out of doors. The only words in the Anglo-Saxon language for cook and kitchen, are cóc and cycene, taken from the Latin coquus and coquina, which seems to show that they only improved their rude manner of living in this respect after they had become acquainted with the Romans. Besides boiled meats, they certainly had roast, or broiled, which they called bræde, meat which had been spread or displayed to the fire. The vocabularies explain the Latin coctus by “boiled or baked” (gesoden, gebacen). They also fried meat, which was then called hyrstyng, and the vessel in which it was fried was called hyrsting-panne, a frying-pan. Broth, also (broth), was much in use.

No. 17. A Saxon Kettle. |

No. 18. A Saxon Cook. |

In the curious colloquy of Alfric (a dialogue made to teach the Anglo-Saxon youth the Latin names for different articles), three professions are mentioned as requisite to furnish the table: first, the salter, who stored the store-rooms (cleafan) and cellars (hedderne), and without whom they could not have butter (butere)—they always used salt butter—or cheese (cyse); next, the baker, without whose handiwork, we are told, every table would seem empty; and lastly, the cook. The work of the latter appears not at this time to have been very elaborate. “If you expel me from your society,” he says, “you will be obliged to eat your 28 vegetables green, and your flesh-meat raw, nor can you have any fat broth.” “We care not,” is the reply, “for we can ourselves cook our provisions, and spread them on the table.” Instead of grounding his defence on the difficulties of his profession, the cook represents that in this case, instead of having anybody to wait upon them, they would be obliged to be their own servants. It may be observed, as indicating the general prevalence of boiling food, that in the above account of the cook, the Latin word coquere is rendered by the Anglo-Saxon seothan, to boil.4 Our words cook and kitchen are the Anglo-Saxon cóc and cycene, and have no connection with the French cuisine.

We may form some idea of the proportions in the consumption of different kinds of provisions among our Saxon forefathers, by the quantities given on certain occasions to the monasteries. Thus, according to the Saxon Chronicle, the occupier of an estate belonging to the abbey of Medeshamstede (Peterborough) in 852, was to furnish yearly sixty loads of wood for firing, twelve of coal (græfa), six of fagots, two tuns of pure ale, two beasts fit for slaughter, six hundred loaves, and ten measures of Welsh ale.

No. 19. Anglo-Saxons at Table.

It will be observed in the dinner scenes given above, that the guests 29 are helping themselves with their hands. Forks were totally unknown to the Anglo-Saxons for the purpose of carrying the food to the mouth, and it does not appear that every one at table was furnished with a knife. In the cut, No. 19 (taken from MS. Harl. No. 603, fol. 12, ro.), a party at table are eating without forks or knives. It will be observed here, as in the other pictures of this kind, that the Anglo-Saxon bread (hlaf) is in the form of round cakes, much like the Roman loaves in the pictures at Pompeii, and not unlike our cross-buns at Easter, which are no doubt derived from our Saxon forefathers. Another party at dinner without knives or forks is represented in the cut No. 20, taken from the same manuscript (fol. 51, vo.). The tables here are without table-cloths. The use of the fingers in eating explains to us why it was considered necessary to wash the hands before and after the meal.

No. 20. Anglo-Saxons at Table.

The knife (cnif), as represented in the Saxon illuminations, has a peculiar form, quite different from that of the earlier knife found in the graves, but resembling rather closely the form of the modern razor. Several of these Saxon knives have been found, and one of them, dug up in London, and now in the interesting museum collected by Mr. Roach Smith, is represented in the accompanying cut, No. 21.5 The blade, of 30 steel (style), which is the only part preserved, has been inlaid with bronze.

When the repast was concluded, and the hands of the guests washed, the tables appear to have been withdrawn from the hall, and the party commenced drinking. From the earliest times, this was the occupation of the after part of the day, when no warlike expedition or pressing business hindered it. The lord and his chief guests sat at the high seat, while the others sat round on benches. An old chronicler, speaking of a Saxon dinner party, says, “after dinner they went to their cups, to which the English were very much accustomed.”6 This was the case even with the clergy, as we learn from many of the ecclesiastical laws. In the Ramsey History printed by Gale, we are told of a Saxon bishop who invited a Dane to his house in order to obtain some land from him, and to drive a better bargain, he determined to make him drunk. He therefore pressed him to stay to dinner, and “when they had all eaten enough, the tables were taken away, and they passed the rest of the day, till evening, drinking. He who held the office of cup-bearer, managed that the Dane’s turn at the cup came round oftener than the others, as the bishop had directed him.” We know by the story of Dunstan and king Eadwy, that it was considered a great mark of disrespect to the guests, even in a king, to leave the drinking early after dinner.

No. 21. An Anglo-Saxon Knife.

Our cut, No. 22, taken from the Anglo-Saxon calendar already mentioned (MS. Cotton. Julius, A. vi.), represents a party sitting at the heah-setl, the high seat, or dais, drinking after dinner. It is the lord of the household and his chief friends, as is shown by their attendant guard 31 of honour. The cup-bearer, who is serving them, has a napkin in his hand. The seat is furnished with cushions, and the three persons seated on it appear to have large napkins or cloths spread over their knees. Similar cloths are evidently represented in our cut No. 16. Whether these are the setl-hrœgel, or seat-cloths, mentioned in some of the Anglo-Saxon wills, is uncertain.

No. 22. An Anglo-Saxon Drinking Party.

It will be observed that the greater part of the drinking-cups bear a resemblance in form to those of the more ancient period which we find in Anglo-Saxon graves, and of which some examples have been given in the preceding chapter. We cannot tell whether those seen in the pictures be intended for glass or other material; but it is certain that the Anglo-Saxons were ostentatious of drinking-cups and other vessels made of the precious metals. Sharon Turner, in his History of the Anglo-Saxons, has collected together a number of instances of such valuable vessels. In one will, three silver cups are bequeathed; in another, four cups, two of which were of the value of four pounds; in another, four silver cups, a cup with a fringed edge, a wooden cup variegated with gold, a wooden knobbed cup, and two very handsome drinking-cups (smicere scencing-cuppan). Other similar documents mention a golden cup, with a golden dish; a gold cup of immense weight; a dish adorned with gold, and another with Grecian workmanship (probably brought from Byzantium). A lady bequeathed a golden cup weighing four marks and a half. Mention of silver cups, silver basins, &c., is of frequent 32 occurrence. In 833, a king gave his gilt cup, engraved outside with vine-dressers fighting dragons, which he called his cross-bowl, because it had a cross marked within it, and it had four angles projecting, also like a cross. These cups were given frequently as marks of affection and remembrance. The lady Ethelgiva presented to the abbey of Ramsey, among other things, “two silver cups, for the use of the brethren in the refectory, in order that, while drink is served in them to the brethren at their repast, my memory may be more firmly imprinted on their hearts.”7 It is a curious proof of the value of such vessels, that in the pictures of warlike expeditions, where two or three articles are heaped together as a kind of symbolical representation of the value of the spoils, vessels of the table and drinking-cups and drinking-horns are generally included. Our cut, No. 23, represents one of these groups (taken from the Cottonian Manuscript, Claudius, C. viii.); it contains a crown, a bracelet or ring, two drinking-horns, a jug, and two other vessels. The drinking-horn was in common use among the Anglo-Saxons. It is seen on the table or in the hands of the drinkers in more than one of our cuts. In the will of one Saxon lady, two buffalo-horns are mentioned; three horns worked with gold and silver are mentioned in one inventory; and we find four horns enumerated among the effects of a monastic house. The Mercian king Witlaf, with somewhat of the sentiment of the lady Ethelgiva, gave to the abbey of Croyland the horn of his table, “that the elder monks may drink from it on festivals, and in their benedictions remember sometimes the soul of the donor.”

No. 23. Articles of Value.

The liquors drunk by the Saxons were chiefly ale and mead; the immense quantity of honey that was then produced in this country, as we learn from Domesday-book and other records, shows us how great must 33 have been the consumption of the latter article. Welsh ale is especially spoken of. Wine was also in use, though it was an expensive article, and was in a great measure restricted to persons above the common rank. According to Alfric’s Colloquy, the merchant brought from foreign countries wine and oil; and when the scholar is asked why he does not drink wine, he says he is not rich enough to buy it, “and wine is not the drink of children or fools, but of elders and wise men.” There were, however, vineyards in England in the times of the Saxons, and wine was made from them; but they were probably rare, and chiefly attached to the monastic establishments. William of Malmesbury speaks of a vineyard attached to his monastery, which was first planted at the beginning of the eleventh century by a Greek monk who settled there, and who spent all his time in cultivating it.

In their drinking, the Anglo-Saxons had various festive ceremonies, one of which is made known to us by the popular story of the lady Rowena and the British king. When the ale or wine was first served, the drinkers pledged each other, with certain phrases of wishing health, not much unlike the mode in which we still take wine with each other at table, or as people of the less refined classes continue to drink the first glass to the health of the company; but among the Saxons the ceremony was accompanied with a kiss. In our cut, No. 14, the party appear to be pledging each other.

No. 24. Drinking and Minstrelsy.

No. 25. An Anglo-Saxon Fithelere.

The Anglo-Saxon potations were accompanied with various kinds of amusements. One of these was telling stories, and recounting the exploits of themselves or of their friends. Another was singing their national poetry, to which the Saxons were much attached. In the less elevated class, where professed minstrels were not retained, each guest was minstrel in his turn. Cædmon, as his story is related by Bede, became a poet through the emulation thus excited. One of the ecclesiastical canons enacted under king Edgar enjoins “that no priest be a minstrel at the ale (ealu-scóp), nor in any wise act the gleeman (gliwige), with himself or with other men.” In the account of the murder of king Ethelbert in Herefordshire, by the treachery of Offa’s wicked queen (A.D. 792), we are told that the royal party, after dinner, “spent the 34 whole day with music and dancing in great glee.” The cut, No. 24 (taken from the Harl. MS., No. 603), is a perfect illustration of this incident of Saxon story. The cup-bearer is serving the guest with wine from a vessel which is evidently a Saxon imitation of the Roman amphora; it is perhaps the Anglo-Saxon sester or sæster; a word, no doubt, taken from the Latin sextarius, and carrying with it, in general, the notion of a certain measure. In Saxon translations from the Latin, amphora is often rendered by sester. We have here a choice party of minstrels and gleemen. Two are occupied with the harp, which appears, from a comparison of Beowulf with the later writers, to have been the national instrument. It is not clear from the picture whether the two men are playing both on the same harp, or whether one is merely holding the instrument for the other. Another is perhaps intended to represent the Anglo-Saxon fithelere, playing on the fithele (the modern English words fiddler and fiddle); but his instrument appears rather to be the cittern, which was played with the fingers, not with the bow. Another representation of this performer, from the same manuscript, is given in the cut No. 25, where the instrument is better defined. The other two minstrels, in No. 24, are playing on the horn, or on the Saxon pip, or pipe. The two dancers are evidently a man and a woman, and another lady to the extreme right 35 seems preparing to join in the same exercise. We know little of the Anglo-Saxon mode of dancing, but to judge by the words used to express this amusement, hoppan (to hop), saltian and stellan (to leap), and tumbian (to tumble), it must have been accompanied with violent movements. Our cut No. 26 (from the Cottonian MS., Cleopatra, C. viii. fol. 16, vo), represents another party of minstrels, one of whom, a female, is dancing, while the other two are playing on a kind of cithara and on the Roman double flute. The Anglo-Saxon names for the different kinds of musicians most frequently spoken of were hearpere, the harper; bymere, the trumpeter; pipere, the player on the pipe or flute; fithelere, the fiddler; and horn-blawere, the horn-blower. The gligman, or gleeman, was the same who, at a later period, was called, in Latin, joculator, and, in French, a jougleur; and another performer, called truth, is interpreted as a stage player, but was probably some performer akin to the gleeman. The harp seems to have stood in the highest rank, or, at least, in the highest popularity, of musical instruments; it was termed poetically the gleó-beam, or the glee-wood.

No. 26. Anglo-Saxon Minstrels.

Although it was considered a very fashionable accomplishment among the Anglo-Saxons to be a good singer of verses and a good player on the harp, yet the professed minstrel, who went about to every sort of joyous 36 assemblage, from the festive hall to the village wake, was a person not esteemed respectable. He was beneath consideration in any other light than as affording amusement, and as such he was admitted everywhere, without examination. It was for this reason that Alfred, and subsequently Athelstan, found such easy access in this garb to the camps of their enemies; and it appears to have been a common disguise for such purposes. The group given in the last cut (No. 26) are intended to represent the persons characterised in the text (of Prudentius) by the Latin word ganeones (vagabonds, ribalds), which is there glossed by the Saxon term gleemen (ganeonum, gliwig-manna). Besides music and dancing, they seem to have performed a variety of tricks and jokes, to while away the tediousness of a Saxon afternoon, or excite the coarse mirth of the peasant. That such performers, resembling in many respects the Norman jougleur, were usually employed by Anglo-Saxons of wealth and rank, is evident from various allusions to them. Gaimar has preserved a curious Saxon story of the murder of king Edward by his stepmother (A.D. 978), in which the queen is represented as having in her service a dwarf minstrel, who is employed to draw the young king alone to her house. According to the Anglo-Norman relator of this story, the dwarf was skilled in various modes of dancing and tumbling, characterised by words of which we can hardly now point out the exact distinction, “and could play many other games.”

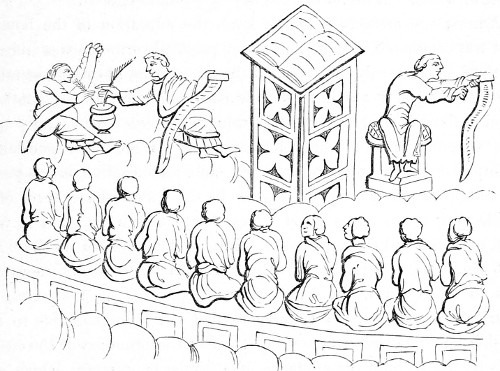

In a Saxon manuscript in the British Museum (MS. Cotton. Tiberius, C. vi.), among the minstrels attendant on king David (represented in our cut, No. 27), we see a gleeman, who is throwing up and catching knives and balls, a common performance of the later Norman jougleurs, as well as of our modern mountebanks. Some of the tricks and gestures of these performers were of the coarsest description, such as could be only tolerated in a rude state of society. An example will be found in a story told by William of Malmesbury of wandering minstrels, whom he had seen 37 performing at a festival at that monastery when he was a child, and which we can hardly venture to give even under the veil of the original Latin. A poem in the Exeter manuscript describes the wandering character of the Saxon minstrels. He tells us:—

swa scriþende Thus roving gesceapum hweorfað with their lays go gleo-men gumena the gleemen of men geond grunda fela, over many lands, þearfe secgað, state their wants, þonc-word sprecaþ, utter words of thank, simle suð oþþe norð always south or north, sumne gemetað they find one gydda gleawne, knowing in songs, geofum unhneawne. who is liberal of gifts. 38

No. 27. Anglo-Saxon Minstrels and Gleeman.

We are not to suppose that our Anglo-Saxon forefathers remained at table, merely drinking and listening. On the contrary, the performance of the minstrels appears to have been only introduced at intervals, between which the guests talked, joked, propounded and answered riddles, boasted of their own exploits, disparaged those of others, and, as the liquor took effect, became noisy and quarrelsome. The moral poems often allude to the quarrels and slaughters in which feasts ended. One of these poems, enumerating the various endowments of men, says:— sum bið wrœd tæfle; one is expert at dice; sum bið gewittig one is witty æt win-þege, at wine-bibbing, beor-hyrde god. a good beer-drinker. A “Monitory Poem,” in the same collection, thus describes the manners of the guests in hall:— þonne monige beoð but many are mæþel-hergendra, lovers of social converse, wlonce wig-smiþas, haughty warriors, win-burgum in, in pleasant cities, sittaþ æt symble they sit at the feast, soð-gied wrecað, tales recount, wordum wrixlað, in words converse, witan fundiað strive to know hwylc æsc-stede who the battle place, inne in ræcede within the house, mid werum wunige; will with men abide; þonne win hweteð then wine wets beornes breost-sefan, the man’s breast-passions, breahtme stigeð suddenly rises cirm on corþre, clamour in the company, cwide-scral letaþ an outcry they send forth missenlice. various. In a poem on the various fortunes of men, and the different ways in which they come by death, we are told:— sumum meces ecg from one the sword’s edge on meodu-bence, on the mead-bench, yrrum ealo-wosan, angry with ale, ealdor oþþringeð, life shall expel, were win-sadum. a wine-sated man. 39 And in the metrical legend of St. Juliana, the evil one boasts:— sume ic larum geteah, some I by wiles have drawn, te geflite fremede, to strife prepared, þæt hy færinga that they suddenly eald-afþoncan old grudges edniwedan, have renewed, beore druncne; drunken with beer; ic him byrlade I to them poured wreht of wege, discord from the cup, þæt hi in win-sale so that they in the social hall þurh sweord-gripe through gripe of sword sawle forletan the soul let forth of flæsc-homan. from the body.

There were other amusements for the long evenings besides those which belonged especially to the hall, for every day was not a feast-day. The hall was then left to the household retainers and their occupations. But we must now leave this part of the domestic establishment. The ladies appear not to have remained at table long after dinner—it was somewhat as in modern times—they proceeded to their own special part of the house—the chamber—and thither it will be my duty to accompany them in the next chapter. I have described all the ordinary scenes that took place in the Anglo-Saxon hall. 40