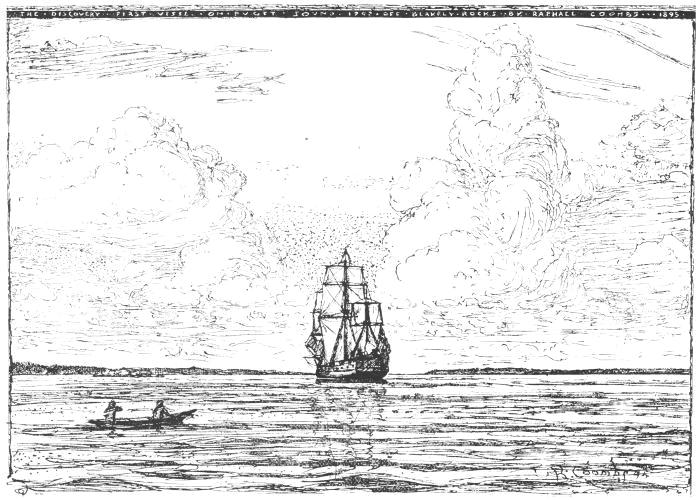

· THE · DISCOVERY · FIRST · VISIT · ON · PUGET · SOUND · 1792 · OFF · BLAKELY · ROCKS ·· BY · RAPHAEL · COOMBS ··· 1895 ·

VANCOUVER’S SHIP DISCOVEROR.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Siwash, by J. A. Costello

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: The Siwash

Their Life Legends and Tales, Puget Sound and Pacfic Northwest

Author: J. A. Costello

Release Date: May 24, 2019 [EBook #59592]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SIWASH ***

Produced by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

· THE · DISCOVERY · FIRST · VISIT · ON · PUGET · SOUND · 1792 · OFF · BLAKELY · ROCKS ·· BY · RAPHAEL · COOMBS ··· 1895 ·

VANCOUVER’S SHIP DISCOVEROR.

THE SIWASH

THEIR

LIFE LEGENDS AND TALES

PUGET SOUND AND PACIFIC NORTHWEST

FULLY ILLUSTRATED

BY J. A. COSTELLO

SEATTLE

The Calvert Company

716 FRONT STREET

1895

Copyright, 1895, by

J. A. COSTELLO

and

SAMUEL F. COOMBS

The excuse for this book is that it is the first attempt to depict the life or ethnology of the maze of Indian tribes on Puget Sound, and it is believed, will be found not wholly uninteresting. It has been the aim to attain as nearly the facts in every instance as possible which in any way lead to a proper understanding of the natives of the country as they were found by the first whites to arrive. Mika mam-ook mika tum-tum de-late wa-wa. Ko-pet mika ip-soot halo mika tum-tum ko-pa o-coke. De-late wa-wa mika tum-tum, nan-ich Sahg-a-lie Tyee; my heart speaks truthful and I hide nothing I know concerning the things of which I speak. My talk is truthful as God sees me.

From the old pioneer and the more intelligent native have all the material facts been drawn, and as these opportunities will not endure for many years longer it is the belief and hope that this work will find an enduring place in the home and public libraries.

For material aid in the compilation of the historical and pictorial matter of this work the author is indebted to Samuel F. Coombs, one of the few pioneers who has a genuine interest in the preservation of the life and habits and traditions of the aboriginees; H. A. Smith, of Smith’s cove; Rev. Myron Eels for valuable information and assistance, touching the Skokomish Indians; Edward Morse, son of Eldridge Morse, than whom, probably none have a truer insight into the mysteries of early Indian life on the Sound; E. H. Brown, and to W. S. Phillips, F. Leather and Raphael Coombs, artists.

Seattle, December 14, 1895.

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I | |

| A bit of history | 1 |

| Chapter II | |

| Fifty-four forty or fight | 4 |

| Chapter III | |

| Pioneers of the forties | 6 |

| Chapter IV | |

| Siwash characteristics | 10 |

| Chapter V | |

| The Flathead group | 13 |

| Chapter VI | |

| The Chinook la lang | 15 |

| Chapter VII | |

| Traditions of Vancouver’s appearance | 17 |

| Chapter VIII | |

| The Old-Man-House tribe | 19 |

| Chapter IX | |

| The Twana or Skokomish tribe | 33 |

| Chapter X | |

| Do-Ka-Batl, a great spirit | 46 |

| Chapter XI | |

| Their game of sing-gamble | 51 |

| Chapter XII | |

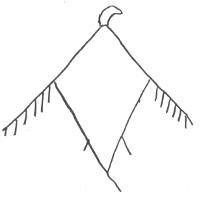

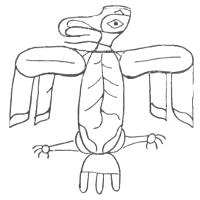

| [vi]Twana Thunderbird | 53 |

| Chapter XIII | |

| Superstition their religion | 57 |

| Chapter XIV | |

| Their daily existence | 62 |

| Chapter XV | |

| Legend of the first frog | 69 |

| Chapter XVI | |

| Another man in the moon | 71 |

| Chapter XVII | |

| S’Beow and his grandmother | 72 |

| Chapter XVIII | |

| The demon Skana | 74 |

| Chapter XIX | |

| The fall of Snoqualm | 75 |

| Chapter XX | |

| Legend of the Stick-pan | 77 |

| Chapter XXI | |

| The magic blanket | 79 |

| Chapter XXII | |

| Legend of Flathead origin | 81 |

| Chapter XXIII | |

| Legend of the first flood | 82 |

| Chapter XXIV | |

| Origin of the sun and moon | 83 |

| Chapter XXV | |

| Skobia the skunk | 84 |

| Chapter XXVI | |

| The extinct Shilshoh tribe | 86 |

| Chapter XXVII | |

| [vii]Quinaiults and Quillayutes | 90 |

| Chapter XXVIII | |

| Tradition of a great Indian battle | 99 |

| Chapter XXIX | |

| Sealth and allied tribes | 102 |

| Chapter XXX | |

| The Makah tribe | 115 |

| Chapter XXXI | |

| Footprints of unknown travelers | 122 |

| Chapter XXXII | |

| Some neighborly tribes | 124 |

| Chapter XXXIII | |

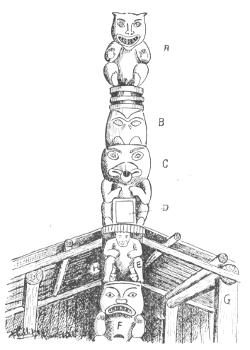

| Totemism and superstitions | 132 |

| Chapter XXXIV | |

| Mythology and native history | 139 |

| Chapter XXXV | |

| Yalth and the butterfly | 142 |

| Chapter XXXVI | |

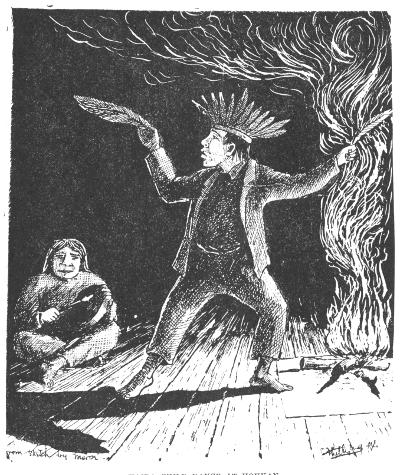

| Potlatch and Devil dance | 145 |

| Chapter XXXVII | |

| The T’Klinkits and Aleuts | 148 |

| Chapter XXXVIII | |

| The Indian and the south wind | 156 |

| Chapter XXXIX | |

| Pleasure and profit in the marsh | 159 |

| Chapter XL | |

| Indians in the hop fields | 162 |

| Chapter XLI | |

| Legend of the crucifixion | 166 |

| Chapter XLII | |

| Romance in real life | 168 |

| Vancouver’s ship (frontispiece) | PAGE |

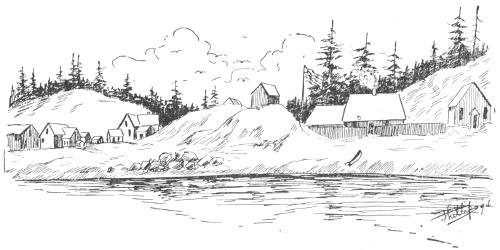

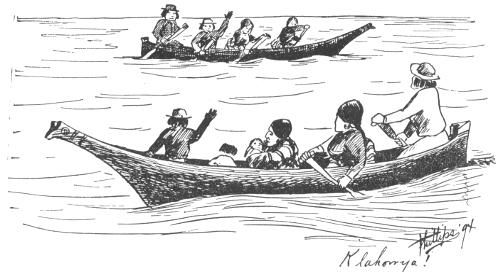

| On the Sound | 3 |

| Sunlight on the water | 9 |

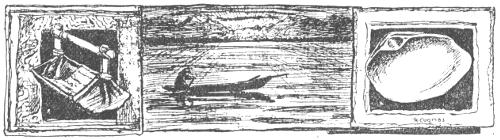

| Typical Siwash face | 10 |

| A Klootchman | 11 |

| La Belle Klootchman | 12 |

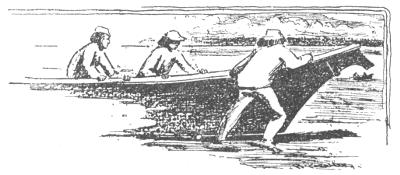

| Launching | 16 |

| Paddling | 18 |

| All that’s left of Old-Man-House | 20 |

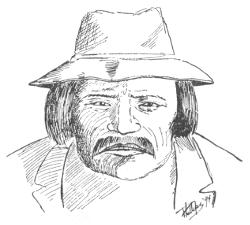

| Wm. Deshaw | 22 |

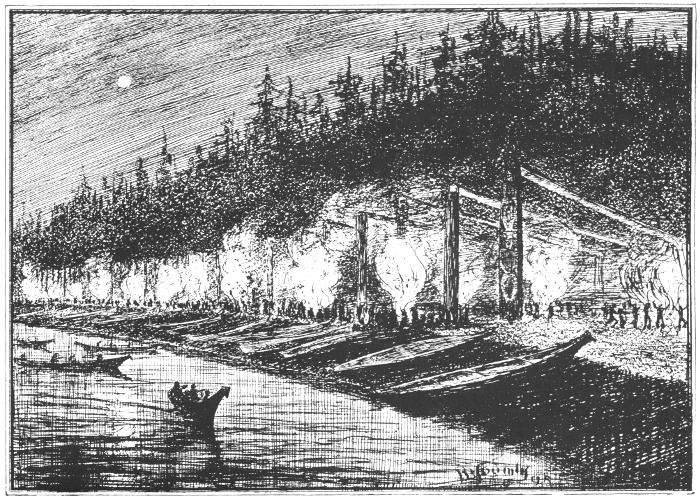

| Grand potlatch | 25 |

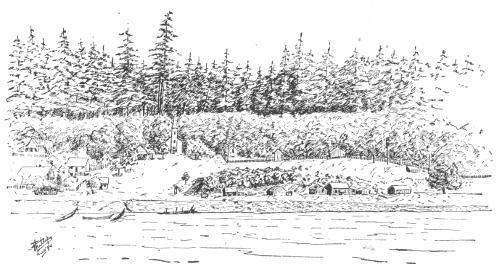

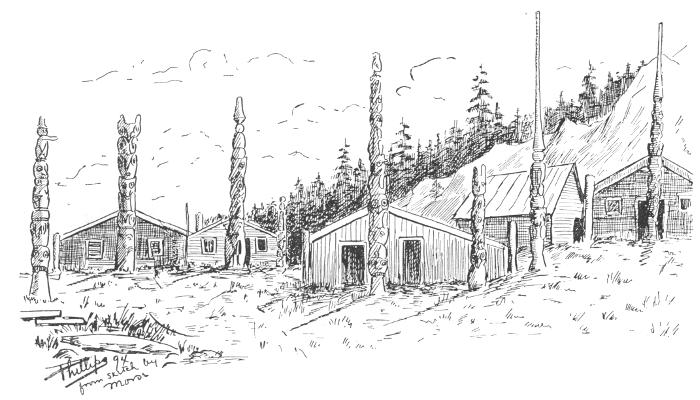

| Old-Man-House village | 28 |

| Digging clams | 32 |

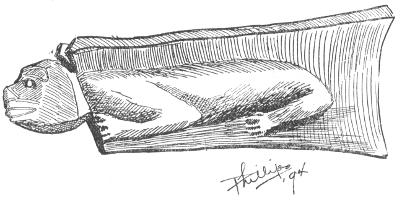

| Guardian spirit Totem | 41 |

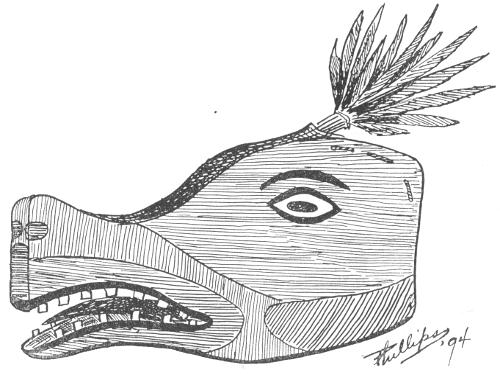

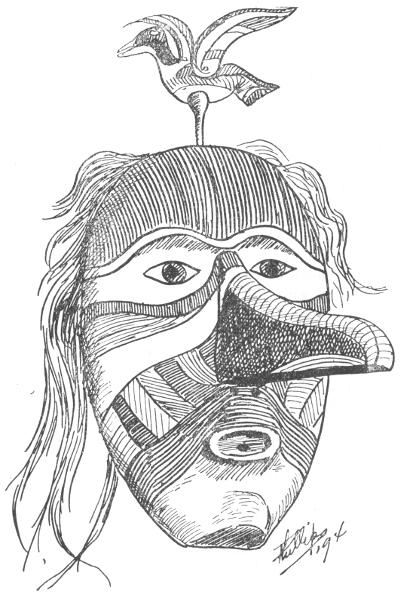

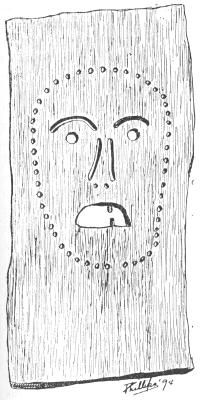

| Wolf mask | 42 |

| Wolf mask | 44 |

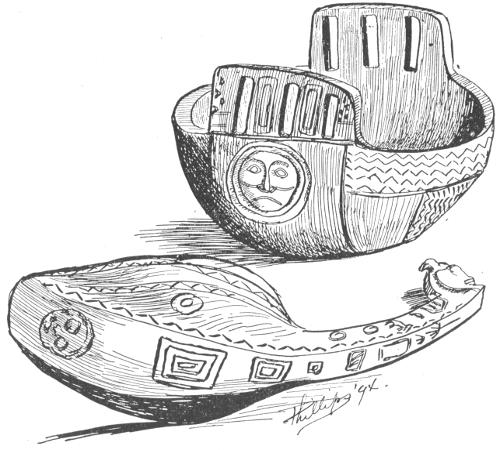

| Bowl and spoon, by Twana Indians | 47 |

| Vignette of Chief Seattle | 50 |

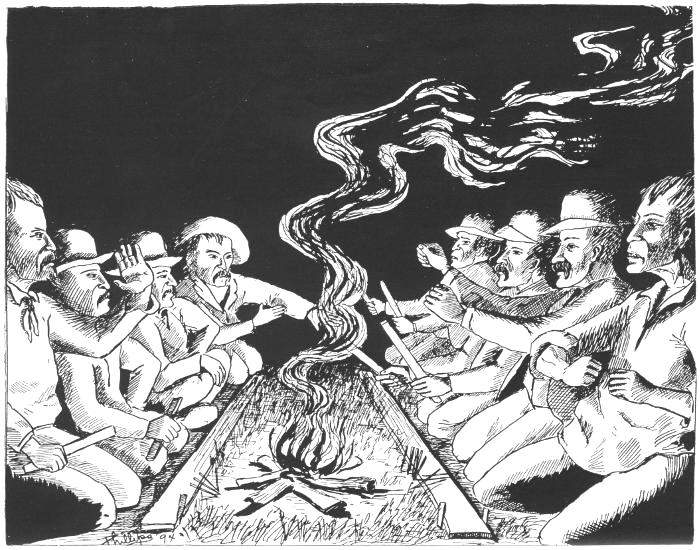

| Night around the sing-gamble | 53 |

| The Twana Thunderbird mask | 54 |

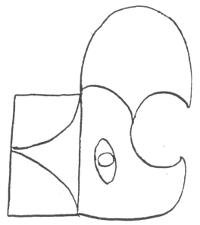

| Box made of slate, carving | 56 |

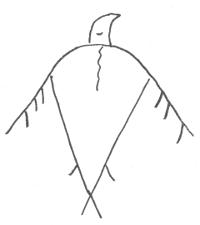

| Thunderbird, Dakotah Indians | 58 |

| Ojibwa, flying Thunderbird | 59 |

| Haida Thunderbird head | 60 |

| Ojibwa Thunderer | 61 |

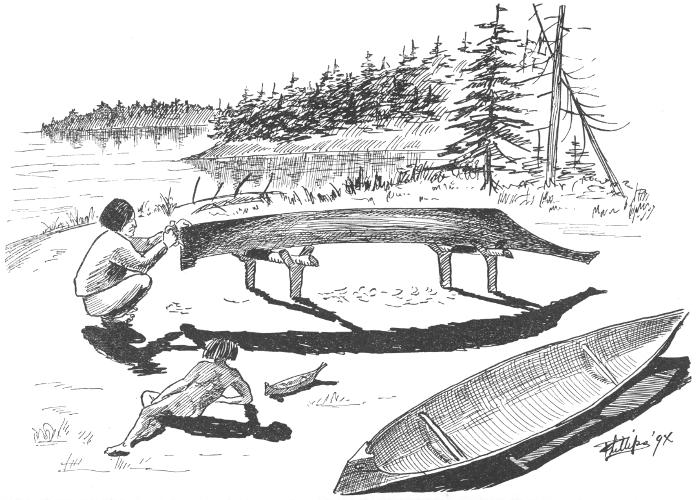

| Building Siwash canim | 63 |

| Symbolic drawing | 68 |

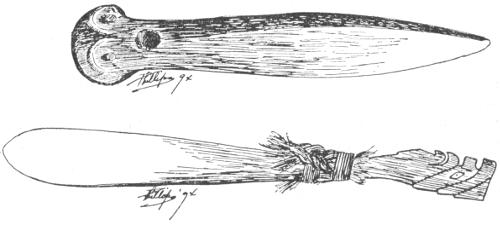

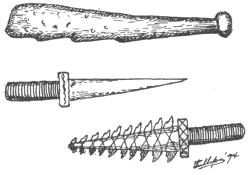

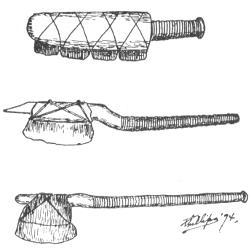

| Indian implements | 76 |

| Face mask of Twanas | 83 |

| Charm mask | 84 |

| Stone and copper war clubs | 85 |

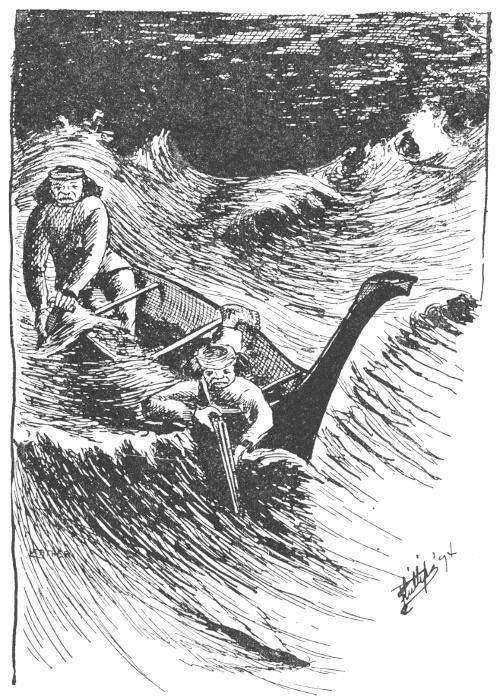

| Quinaiults hunting the hair seal | 97 |

| [x]Copper and iron daggers | 99 |

| Twana war clubs | 100 |

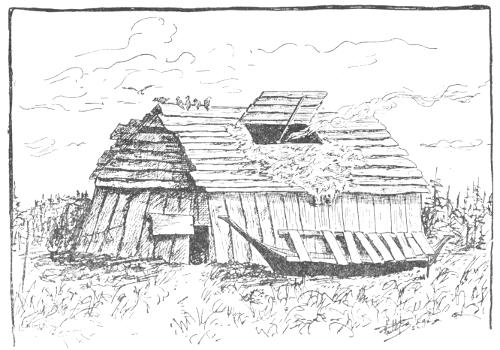

| A Quinaiult hut | 101 |

| Chief Sealth | 102 |

| Oldest house in King county | 110 |

| Duke of York | 112 |

| East Indian carving | 113 |

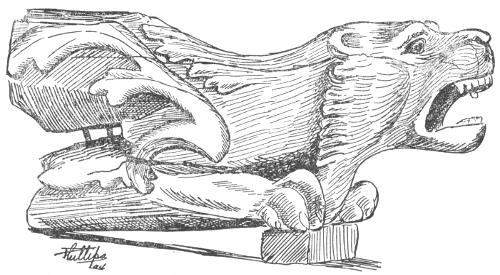

| Canoe head Totem | 114 |

| Totem column, northern Indian | 126 |

| The bear mother | 129 |

| Haida child dance at Houkan | 130 |

| Haida Thundermask | 133 |

| Skamson the Thunderer | 137 |

| Corner of Houkan village | 138 |

| Haida grave-yard | 140 |

| Mrs. Schooltka | 143 |

| Silver and copper ornaments | 144 |

| Quinaiult tribesman | 147 |

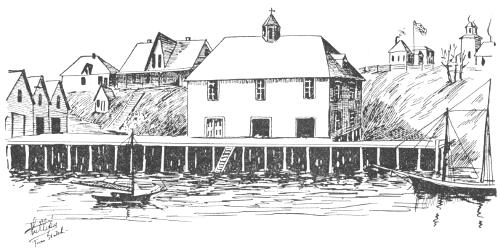

| Yakutat Alaska | 149 |

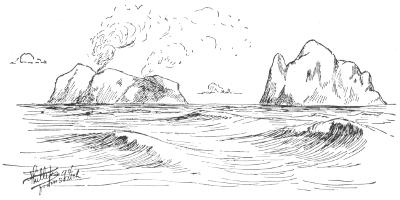

| Volcano of Boguslof | 151 |

| Kodiak Alaska | 153 |

| “Kla-how-ya” | 157 |

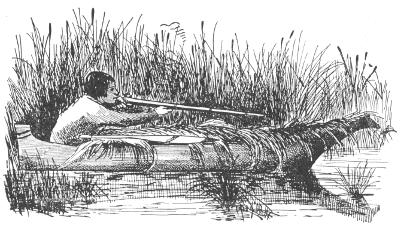

| Spearing the hair seal | 158 |

| Indian duck hunting | 160 |

| Klootchman gathering rushes | 161 |

| An educated Indian | 163 |

| Stone hatchets | 164 |

| Sea otter lookout | 165 |

| Beaver marsh | 167 |

Early explorations of the Northwest coast now embraced in the limits of the state of Washington came after the discovery and occupation of the coast further south. Unlike the Mexican and California conquests it was devoid of wild and extravagant fact or fancy. There is found in the old annals no mention of barbaric splendor, no great empires or extensive cities, no magnificent spoils to be carried away.

The Spaniards first laid claim to the island of Vancouver in 1774. During the war of the Revolution, when England was occupied with her rebellious subjects on the Atlantic sea board, Perez Heceta and other Spanish navigators, explored and took possession, in the name of their sovereign, of the largest island on the Pacific coast.

What is now the straits of Juan de Fuca, or at that time Anian, had been explored by trading vessels from Spanish settlements along the Mexican coast, and doubtless by navigators of other nationalities, but it was not until near the close of the eighteenth century that the Northwest coast became disputed territory between Spaniards, English, Russians and Americans. In 1688, Martinez and Haro were dispatched by the government to the Pacific Northwest, to guard their newly claimed possessions, and here in the following year, Martinez seized a couple of English craft and immediately embroiled his parental country in a serious dispute with Great Britain. This was the initial movement in that spirited competition between the two rival nations which only ended when the Spaniards finally succumbed to British diplomacy and betook themselves to their southern possessions.

Captain Cook, the English navigator, who later fell a victim to the savage inhabitants of the Sandwich islands, was sent over by his government a few years after the Spanish occupation of the island, to discover, if possible a northwest passage which should unite the widely separated waters of the Atlantic[2] and Pacific. Cook perpetuated the memory of this voyage by giving names to a number of capes and promontories, chief of which is Cape Flattery. At that time the waters of Fuca strait, Puget Sound and lands adjoining had not been christened by those names by which they are now known.

English navigators explored and gave names to Queen Charlotte islands and the surrounding waters soon after the occupation of the larger island of Vancouver, but they appear not to have visited the waters of the Georgian gulf until some years afterwards.

Numbers of navigators sent out by English companies visited the Northwest coast prior to the voyage of Captain Cook in 1785, and he, in succeeding years by many others who followed close upon his heels, giving names to and exploring channels and passages on the west side of Vancouver island. Among the latter navigators who visited the country from 1785 to the close of the Eighteenth century were Captain Portlock in the ship King George, the ship Queen Charlotte, Captain Dixon, the latter naming the Queen Charlotte islands, Dixon strait, etc. Then there was the Imperial Eagle, Captain Barclay, who sailed into the waters of Barclay sound, since which they have perpetuated the name of the worthy captain. Captain Barclay sailed into the mouth of Fuca straits and sent a boat out on a short exploring expedition. He then passed on south of Cape Flattery, where he had the misfortune to lose a boat’s crew at the hands of the savages. Captain Meares came the following summer, visited Clayoquot sound, gave the name to Fuca straits, christened Tatoosh island, and sailed along the coast southward to Shoalwater and Deception bays, and on to Cape Lookout, and thence retraced his steps to Barclay sound. While here an exploring party of twelve men under First Officer Duffin were attacked by the Indians and beat a hasty retreat to the ship, after being severely wounded. The vessel soon after returned to Nootka sound, where the ship Iphigenia, Captain Douglas, and the sloop Washington had arrived, followed soon after by the Columbia, Captain Kendrick, from Boston. A new vessel had been built at Nootka during that year, and was christened Northwest America, which sailed soon afterwards, accompanied by the Iphigenia and Felice.

Captain Gray, of the Washington, wintered on the west coast of Vancouver island in 1788, and the following year circumnavigated the island, explored the west coast of Queen Charlotte island and called it Washington island. He had, also, during this winter, a residence at Clayognut harbor. Captain Gray built a fortification, and launched a small vessel, which he sent to Queen Charlotte island, previous to his sailing for the Atlantic coast. George Vancouver did not come till 1792.

Soon afterwards Gray took command of the Columbia, sailed away for Boston and returned on a second voyage, and entered and named the Columbia river.

Captains Lewis and Clark explored the interior of Washington territory during Jefferson’s presidency and settlements were made by the Hudsons Bay company in 1828. The renowned Whitman came in the 30’s to the Walla Walla country and Americans began to settle in 1845 on this side, then a part of the Oregon territory.

The name Puget Sound, as given by Vancouver, the British navigator, in 1792 extended only to the waters south of Point Defiance, near Tacoma. The waters north of this point were named Hood’s canal, Admiralty inlet, Possession sound, Rosario straits, Gulf of Georgia, etc.

The name Puget Sound afterwards was applied to all the waters included in the American possessions south of British Columbia.

The Greek pilot Juan de Fuca is supposed to be the first man who ever sailed into these placid waters. He thought he had at last found the “Northwest Passage,” but finding that such was not the case, he took possession of the country in the name of the king of Spain and then made his way back to Mexico. The straits of Fuca are about 12 miles in width and 100 miles long from its beginning to where it is lost in the many bays and fjiords and waters that surround the numerous islands at its head. There is perhaps no body of water that is as secure for the navigator as the straits of Juan de Fuca, there being no rocks or shoals in it. These northern waters are filled with numerous islands and the character of the country is almost the same from the 47th to the 60th parallel.

Oregon was the name given to the country west of the Rocky mountains and thought to extend to 54 degrees 40 minutes north. England also claimed the entire territory. In 1827 a treaty of joint occupation was formed, terminated in 1846 by the United States and it seemed for a time likely to embroil the two countries in war. A compromise was however effected fixing the international boundary at the 49th parallel, and through the good offices of the German Emperor, the beautiful San Juan islands were at last given to the American government. It had been said in the English parliament, by Sir Robert Peel: “England knows her rights and dares maintain them;” while Wentworth, of Illinois, in a speech before congress in January, 1844 said: “I think it our duty to speak freely and candidly and let England know that she can never have an inch of the country claimed as a part of the United States.” Such is in brief the history of Washington prior to the actual occupation and settlement along in the latter 40’s and the early 50’s. Of these we shall speak more fully.

Many yet living within her borders and enjoying the benefits of mature and full-fledged statehood remember the time when Washington was an almost unexplored wilderness, silent and tomblike as the Sphinx. The first faint echoes of civilization were heard only along the shorelines of its inland sea, or along the water course of its debouching rivers. The vast and wealth-laden interior was unknown, the inner secrets of the Dark Continent today being perhaps better known than was the heart of this then northwestern territory. Ships of sail on occasional voyages ploughed the waters of the placid Sound, distributing here and there along the deeply wooded shore lines a pioneer with his family and rude effects, while the less majestic, though none the less important white-winged “Prairie” schooner, via the Willamette and the Rocky Mountain passes brought his neighbor, perhaps of Yankeedom, to keep him company in the wilderness. Suffering from the agonies of long sea voyages, or racked with the ills and tribulations of long overland journeys across burning sands and rocky passes, they pitched their rude habitations here in the primeval wilds to become neighbors of the dusky red man for many years while waiting for the population which should follow in their wake.

It was early in the forties when this onward march of civilization began landing in this country. ’Tis true the fur gatherer was here before them, but they were only transients and saw not, nor cared for the great natural wealth of the country that spread out before them.

In the Sound country, Fort Steilacoom, Port Townsend, Olympia and Seattle and a few down Sound ports became the central points of the sparse settlements which thus early began to spread over the country. The buzz of the saw mill was simultaneous with the first efforts of these early settlers, and in its wake came one of the most potent factors in the development of new countries—the newspaper.

As it was in California, so it was in a great measure in this northwest country, the greed for gold formed the incentive that hastened the early and quick settlement of the Northwest coast. “To Frazer River,” was the watchword from California and the east, and thousands hastened to the unexplored country to find first, disappointment, and secondly, permanent homes. The overflow from the mines added many hundreds to the permanent settlements on the Sound and in the interior and the march of civilization and commerce was greatly augmented.

In 1858, and even at an earlier date, the newspaper became an important factor in the development of the country. On the 12th of March of that year, the first issue of the Puget Sound Herald appeared. The editor thereof, Mr. Charles Prosch, has humorously written of the manner in which he gathered in the $20-gold-pieces from enthusiastic subscribers, and speaks of his reception by the hardy settlers as having been exceedingly gratifying and flattering. At that time but one other newspaper was issued in the territory, that being the Pioneer and Democrat, a partisan journal of bitter proclivities.

Previous to 1845, this magnificent arm of the Pacific ocean—Puget Sound—was used only as a thoroughfare of trade by the Hudsons Bay company, and save the arrival of a few vessels in that company’s service, its placid water was disturbed only by the canoe of the native red man, and the unbroken silence of the tree-clad shores proclaimed the country a wilderness. The posts of the above named company at Cowlitz river and Fort Nisqually were the only evidences of civilization. No extensive explorations had ever been made by the company’s agents, and the Indians confined themselves to the streams and shores of the Sound and so gave no information regarding the country in the interior.

In August 1845 Col. M. T. Simmons, George Wauch and seven others arrived at Budd’s inlet, under the pilotage of Peter Bercier, the first American citizens who ever settled north of the Columbia river. Being pleased with the appearance of the country Col. Simmons returned to the Columbia where he had left his family and in October of the same year moved over accompanied by J. McAllister, D. Kindred, Gabriel Jones, Geo. Bush and families, and J. Ferguson and S. B. Crocket, single men. They at first settled on prairies from one to eight miles back of the present town of Olympia.

They were fifteen days in completing this journey from Cowlitz landing to the Sound, a distance of 60 miles, being compelled to cut a trail through the timbered part of the country.

In the fall of the same year J. R. Jackson located at Aurora.

In 1846 S. S. Ford and J. Borst settled on the Chickeeles river, Packwood and Eaton with their families also joined the American settlers on the Sound the same year and Col. Simmons erected the first American grist mill north of the Columbia river. Previous to this the inhabitants had to subsist on boiled wheat or do their grinding with hand mills.

In 1847 the first house, a log cabin, was built in Olympia and E. Sylvester, Chambers, Brail and Shayer located on the Sound during the same year. The first saw mill was erected at the falls of Deschutes river by Col. Simmons and his friends during the same year. In June 1848 the Rev. Father Richard established the Roman Catholic mission of St. Joseph on Budd’s inlet, one mile and a half below Olympia, and a few more families were added to the settlement of the Sound country that year.

In the year 1849 the brig Orbit from San Francisco put into Budd’s inlet for a load of piles and that was the opening of the lumber trade.

In 1850 the first frame house was put up in Olympia, and during the same year Col. I. N. Eby made a settlement on Whidby island and a number of other improvements and new settlements were made during the year. In 1851 Fort Steilacoom was established by Capt. L. Balch, and Bachelor, Plummer, Pettygrove,[7] Hastings and Wilson, names familiar even at this day around Port Townsend, came in the same year, while Steilacoom City by J. B. Chapman and New York (Alki point) by Mr. Lowe were founded.

From the beginning of the 50’s the settlement of the country became too swift to permit of following the individual pioneers in their brave and daring exploits in hewing homes out of the primeval wilderness. There was no general way of reaching Puget Sound up to this time except by the toilsome trail from the Columbia river, and the necessity of a steamer from San Francisco became the leading topic in the settlements. Capt. A. B. Gove of the ship Pacific took the matter up and agitation, as it always does, soon after had the desired effect.

The report of Wilke’s expedition and the development of the fur trade caused American interests to be directed toward this country. The account of Joe Meek who went overland from Walla Walla and gave such glowing descriptions of the Territory of Oregon had its effect, 1848, as he expressed himself; “this was the finest country that ever a bird flew over.”

The lower house of Congress passed a bill to establish a territorial government for Oregon January 10, 1847, but many difficulties were in the way before it became a law, and the slave question, 1848, had its influence. It was in the middle of August of the last year of President Polk’s administration before the territorial government bill for Oregon became a law and the long journey over the mountains caused much more delay.

Joseph Lane of Indiana was appointed Oregon’s first Governor with Knitzing Pritchett of Pennsylvania as Secretary, W. P. Bryant of Indiana as Chief Justice, F. Turney of Illinois and P. H. Burnett of Oregon as Associate Justices, I. W. R. Bromley of New York as United States Attorney, Joseph L. Meek Marshal and John Adair of Kentucky Collector of the District of Oregon. Turney declining, O. C. Pratt of Ohio was named in his place. Bromley also declined and Amory Holbrook was appointed in his place. The party landed at Oregon City two days before the expiration of Polk’s term of office.

During the fall of 1852 the people of Northern Oregon, now Washington, were loud in their demands for a separate territory and The Columbian, a bright little paper published at Olympia, became a zealous worker in behalf of a separate jurisdiction.

Northern Oregon was at first slow to attract the full tide of emigration, the worn out travelers who had journeyed across the plains were glad to find a resting place in the valleys of the Columbia or Willamette and those people who had homes established in Southern Oregon were always eager to discourage the emigration to the northern territory and often circulated reports condemning the Puget Sound country that caused a degree of enmity to exist between the two sections of the Northwest. The majority of the population being south of[8] the Columbia river had the result of causing the attention of the government to be always directed to that part of the country and every appropriation from Congress was for the benefit of Southern Oregon and for a time the country bordering on Puget Sound was left to take care of itself. That naturally caused the people who had sought homes in that northern part of the country to ask that they be formed into a separate territory.

Not among the least of the trials and dangers which beset the early pioneer, were those which arose by reason of the contact with Indians. The average Siwash was a peaceable being, but the worst danger came from the deceitful and savage northern tribes and east of the mountain clans. From Nootka sound, Queen Charlotte and Vancouver islands, came swarms of the red devils in their nimble canoes and left havoc and destruction among many a pleasant home and settlement. Across the Cascade passes came bands of painted warriors spreading terror and death on every side.

Numbers of the early settlers fell early victims to the atrocities of these bloodthirsty bands, and their names are only remembered by the few survivors whose silver hair and wrinkled features form objects of interest, as they stand upon the pavement, in the pushing throng now crowding our busy thoroughfares. If you will ask Charles Prosch, Hillory Butler, Judge Swan, John Collins, G.A. Meigs and other old patriarchs yet among us, they can recount many a stirring tale of battle and ambush, and name over many an old settler who years ago gave away his life in his efforts to pave the way for the thousands, who, happy in the peaceful present, go about their daily work with scarce a thought of those early times.

Concerning themselves the rightful owners of the soil, the Indians, looked with jealous eye upon the daily encroachment of the whites and regarded with increasing and ominous distrust the oft repeated and oft broken promises held out to them that this land would be purchased under treaties with the government. Then the habits of the Indian was disgusting to the eye of civilization and no language can ever draw the slothful and dirtyness of this people, yet there were many wrongs done them and it was no more than could be expected that they would, true to their nature, do such acts of barbarity as would shock the whites and bring upon the Indian a terrible revenge and that a war for supremacy would only end in his discomfiture.

“Money was plentiful,” remarks one of the early chroniclers of those times, “and I was not a little surprised at the abundance of money in the hands of the people. All but the farmers seemed to carry purses well filled with twenty dollar gold pieces. The farmers had been driven from their homes and impoverished by the Indian wars of 1856, from the effects of which they had not had time to recover; but the men engaged in cutting piles and logging for the mills (and they comprised a large proportion of the whites here) suffered but[9] little from the same cause. The man who owned the building in which I first printed my paper could neither read nor write, but managed to earn thirty dollars a day by hauling piles with three yoke of oxen from the timber to the water. Soldiers received permission from the officers to cut these piles, and earned ten dollars each a day. All lumbermen were paid in like manner.”

The now historic Hudsons Bay company was in early Washington days a power in the wilderness and with the native Indians. Their agents and trappers encroached upon every square mile of wilderness, almost from Hudsons bay to Puget Sound. Their forts occupied the most important places in the developing Northwest, and were viewed with more or less of distrust by American settlers. Fortunately, a friendly and parental government intervened in time, to the great advantage of the pioneers dwelling upon the disputed country. First a ten years’ lease of, and then final purchase of the improvements of the Hudsons Bay company did away forever with the English fur monopoly in Washington territory.

In 1858 the permanent white settlement on Puget Sound numbered, according to one chronologer, 2500. The festive boomer in real estate and the dispenser of town lots and “wildcat” schemes was a being incognito. His sun had not then risen. A single newcomer in those times was an event of neighborhood notoriety. The blowing of an incoming steamer’s whistle was a signal for every resident, male, female, child and Indian to hasten to the landing, the former to peer into the faces of the passengers for friends or relatives, the latter to gape in open-eyed astonishment at the white man’s monster, the steamboat.

The history of the Siwash is tradition, as it is with all aborigines. The early tales of the Norsemen, the Gaul, the Celt, are mere matters of history, perhaps distorted, but withal, history. The lower the order of the race, the lower its mental capacities, the more truth there is in the lore—the tales of its past. The incidents of their lives which collectively become their history, are handed down from father to son, from generation to generation, plain and unembellished. The Siwash, a race to whom instinct is superior to thought, are perhaps the strongest example of a people whose history is least faulty. What grandsire has told to father is retold to son in a language whose vocabulary is so limited as not to permit of changing of the original subject matter. True, the same deficiency of mental power blots out the distant past. Three generations represent the era of their history; beyond that the grandsire’s memory closes; but as the incidents which are here chronicled are within the memory of many natives living at this time, and from whom they were gathered and related without variation it can be truly accepted as authentic. It has been practically accepted as a historic fact that Vancouver first penetrated into Puget Sound with his vessel the Discoveror. Juan de Fuca preceded him on the straits, but to Vancouver belongs the glory of having first penetrated to the upper Sound and pointed out a way for the sturdy pioneers that were to follow him. The first vessel of which the Indians, on the upper Sound at least, had any memory at the time the whites began to flock among them was certainly Vancouver’s.

TYPICAL SIWASH FACE

The Siwash of Puget Sound (a general term applied to males of all the tribes) and the Indians of the entire North Pacific coast, like every native of every country possessing significant features of topography, flora, and most of all[11] climate, is bent to his surroundings. The Siwash is the creature of the circumstances of climate in a very great degree, and he could never escape it—never will till the last of his race is lost in oblivion. His mode of life, the almost continual living in a squatting, cramped position in his canim from generation to generation, shows in his broken, ungraceful proportions today; and it cannot be doubted but that in the humid atmosphere of Puget Sound and the abbreviated territory in which he has lived are to be found the potent factors that have united to make him at this day the essence of ugliness in human mould.

No matter where the Siwash came from, his past is so remote it will never be known.

A favorite way some have and a plausible excuse for saying anything at all, is to speculate on the Asiatic origin of the Indians of this part of America. Captain Maryatt tries to locate the Shoshones, whom he gives very wide latitude and longitude on the Pacific coast, among ruined cities and an extinct civilization and fauna, in distant Tartary; the Hydias are ascribed to Japan; the Kanacka resembles the Japanese, etc. As well assume the Siwash of Puget Sound are descendants of the Dakotahs or of some of the tribes east of the great Father of Waters, because the Thunderbird myth is traced from east to west with slightly varying antecedents and forms from one tribe to another. The Indian origin is a theme for speculation only.

A KLOOTCHMAN

The Siwash is indubitably the result of hundreds of years residence on the forest-fringed shores of his Whulge. He probably could not endure for a generation elsewhere. He is completely moulded to his surroundings and is more nearly able to resist the deleterious results of the superior civilization than 99 out of 100 of the tribes in the broad interior of the American continent. Years and years ago, when the renowned old Chief Sealth was at the head of the allied tribes around Sdze-Sdze-la-lich and Squ-ducks (Seattle and West Seattle, or Elliott bay and Alki point), it is said that his legions numbered not more than 750 or 800 Indians. Who today will say that there is not now nearly that number of Indians almost within the same confines? In the face of the most aggressive development and civilization of the last ten years, robbed of every favorite haunt for hunting and fishing, with paddle wheels never ceasing to disturb the quiet waters of his ancient rivers and bays where the salmon was wont to sport, and with new population that had encroached[12] upon every foot of land where his klootchman might have raised a little patch of potatoes, as she did a score of years ago, he has withstood it all and continues to hold on. No one ever hears of a Siwash dying unless occasionally on the reservations. A papoose dies once in a while during a change from the ordinary modes of life brought about by annual migrations to the hop fields.

LA BELLE KLOOTCHMAN

The Siwash is the very reverse of a Nomad. He is studious only in his stolidity and inactivity. He never travels within the meaning of the word, and there’s probably not a dozen of the full-blooded Indians who have been fifty miles from salt water. It was not infrequent for the plains’ Indians beyond the great coast range of mountains to descend to the sea, but that the Siwash should ascend to and beyond the summit of those lofty and snow-clad hills—never.

Out of his canoe he is a fish out of water, a sloth away from his natural surroundings. He is like a seal on shore, a duck on dry land, ungainly and awkward. He never, probably, was brave, never quarrelsome in that he went out in search of war. Not infrequently he was the object of forays by his kinsmen from the far north or the east. Then he defended himself and family as best he could and got into the brush with all possible haste, where he was as safe from pursuit as if in a citadel. Not in the museums anywhere in the country is there at this time, it is believed, a single genuine implement of war of the early Indians who lived on the shores of Puget Sound. The Atlantic seaboard and the interior were deluged with centuries, it may be said, of savage warfare. One short war, a mere uprising on Puget Sound in early days, and that instigated by natives living beyond the edges of the Puget Sound forest, and all was over. Ever after the Siwash was an indifferent, uncomplaining creature. He drew one or two short annuities and government aid was practically withdrawn, and that, too, after his heritage of woods and waters had been taken from him. But one hears no plaint of disturbed and unmanageable Indians. He is content to live on so long as there is space for his cedar canoe to glide on the water and an open beach whereon he may erect a temporary tent.

The Puget Sound Indians have generally been classified according to the language spoken by them in the Selish family or Flathead group. They were first classified in this way by Albert Gallatin, who was one of the first Americans to interest himself in the ethnology of the North American Indian. The extent of the Selish family was not known by Gallatin, neither did he know the exact locality of the tribe whose name he extended to this great family of tribes. The tribe is stated to have resided upon one of the branches of the Columbia river, which must be either the most southerly branch of Clark’s Fork or the most northerly branch of Lewis river. The former supposition is correct. As employed by Gallatin the family embraced only a single tribe, the Flathead tribe proper. The Atnah, a Selishan tribe was considered by Gallatin to be distinct, and the name Atnah according to him would be eligible as the family name; preference, however, is given to Selish. The few words given by Gallatin in his American Archæology from the Friendly Village near the sources of the Salmon river belong under this family.

Since Gallatin’s time our knowledge of the territorial limits of this great linguistic family has greatly extended. The most southerly tribes are the Tillamooks who extend along the Oregon coast about 50 miles south of the Columbia river. Beginning on the north side of Shoalwater bay, Selishan tribes held the entire northwestern part of Washington, including the whole Puget Sound region except some insignificant spots about Cape Flattery, which were held by the Makah and the Chimakuan tribes. The Selishans also held a large portion of the eastern coast of Vancouver island, while the greater area of their territory lay on the main land opposite and included much of the country tributary to the upper Columbia. They were hemmed in on the south mainly by the Shahaptian tribes. They dwelt as far east as the extreme eastern feeders of the Columbia, and on the southeast their territory extended into Montana.

Within the territory thus indicated there are a great variety of costumes with greater differences in language.

During the early explorations along the Pacific coast the Selishan Indians held the territory along the western coast of Vancouver island as far north as Nootka sound, but since that time the Aht races of the west coast of the island have crowded them to the southward and eastward until now even the Neah bay agency is largely composed of Makah Indians, while the Chimakuans have obtained a strong foothold further south along the coast.

These Selish Indians were subdivided into numerous tribes, each one speaking a language a little different than the rest.

The Semi-ah-moos occupied the region of country nearest the British boundary line, but they were not a large tribe.

Proceeding southward were the Nooksacks, who inhabited the valley of the river of the same name; the Lummies, who lived around Bellingham bay; the Samish Indians, who camped along the banks of the Samish river and around its mouth, while the more important tribes to the south of them were the Skagits, Snoqualmies, Nis-qual-lies and Puyallups. On the west side of the Sound the most important tribes were the Chehalis, Clallam, Cowlitz, Sko-ko-mish or Twanas and Chinook Indians.

The Snoqualmies occupied the valleys of the Snohomish and Snoqualmie rivers from a short distance above the mouth of the Snohomish. The Snohomish Indians proper lived around its mouth. Much of the time the Snoqualmies occupied a large portion of the Still-a-guam-ish and Sky-ko-mish valleys. The tribe known as the Snohomish Indians never extended their territory far above the mouth of the river.

The Puyallups lived along the river of that name and about Commencement bay, while the Nis-qual-lies were most numerous around Olympia and the Stillacoom plains. There were also a number of smaller tribes that have not yet been mentioned who lived for the most part along some portions of the streams or lakes which bear their names. Among them the Duwamish, Samamish, Satsops, Stillacooms, Squaxons, Sumas, Suquamps and Swinomish Indians.

The Makahs around Cape Flattery, as has been stated, were closely related in language with the Indians of Vancouver island and it also appears that the Clallams or the Nus-klai-yums, as they called themselves, were closely connected with them ethnically, but though they show certain affinities for the Nootka dialect there is no doubt but that they belong to the Selish or Flathead stock.

The dialects of the Lummies and Semi-ah-moos have some affinity with the Sanetch dialect of Vancouver island as well as for the Nootka and the Skagit, Samish and Nisqually Indians which strongly approach each other while there are some wide variations among the dialects of some of the intervening tribes.

Of all the languages spoken by the aborigines of the Northwest coast of America the Chinook spoken in various dialects by the tribes around the mouth of the Columbia river is the most intricate. The English vocabulary does not contain words to describe it. To say that it is guttural, clucking, spluttering and the like, is to put it mildly. The Chinook does not appear to have yet discovered the use of tongue and lips in speaking. Like the T’Klinkit of Alaska, their language contains no labials, but the T’Klinkit is music in comparison to it.

There is danger of falling into error concerning the Chinook jargon, by confusing it with the intricate language of a tribe of that name. On the other hand, people are apt to make the mistake of imputing its invention to a few of the Hudsons Bay company’s factors at Astoria.

The Chinook jargon was and is yet employed by the white people in their dealings with the natives, as well as by the natives among themselves. It is spoken all over Washington, Oregon, a portion of Idaho and the whole length of Vancouver island. Like other languages formed for convenience it is in all probability a gradual growth. There seems but little doubt that the rudiments of it first existed among the natives themselves and that the trappers and hunters adopted it and improved upon it to facilitate intercourse with the natives. Slowly it was brought to its present state.

When Lewis and Clark reached the coast in 1806, the jargon seems to have already assumed a fixed shape. It was extensively quoted by those explorers. But no English or French words of which it now contains so many, seem to have been added after the expedition sent out by John Jacob Astor reached the coast. The words of the original jargon have been modified to a large extent however. They have been so changed as to eliminate much of the harsh guttural unpronounceable native crackling, thus forming a speech far more suitable to all. In the same manner, some of the English sounds such as “f” and “r,” which are so troublesome to the native were either dropped or changed to “p” and “l,” and all unnecessary grammatical forms have been eradicated. Even the Chinook jargon is not without its dialects. There are many words used at Victoria that are not used at Seattle or at the mouth of the Columbia. This fact may be accounted for in various ways, but chiefly by the introduction of foreign words. Thus an Indian sees some object that is unfamiliar to him and asks to know the name of it. The trader tells him a name and with him it continues to be the name of the article ever afterward. For example: bread, is always biscuit; whisky is paih-water, or in some localities, paih-chuck; a cat is expressed as a puss-puss, an American is a Boston-man, and a Britisher a King-George-man. However, in different localities the things may be named quite differently.

Mr. Gibbs, formerly of the British boundary commission, has stated that the number of Chinook words were about five hundred. After analyzing the language carefully he classified the words into the various languages from which they originated and came to the following conclusion as to the number of words derived from each: Chinook and Clatsop, 200 words; Chinook having analogies with other languages, 21 words; interjections common to several, 8 words; Nootka, including dialects, 24 words; Chehalis, 32, and Nisqually 7 words; Klikitat and Yakima, 2 words; Cree, 2 words; Chippeway, 1 word; Wasco, 4 words; Calapooya, 4 words; by direct onomatopoeia, 6 words; derivation unknown, 18 words; French, 90 words; Canadian, 4 words; English, 67 words.

There are many people who think the Chinook jargon to be the invention of McLaughlin, the Hudsons Bay company’s factor at Astoria, but the foregoing facts cited by Mr. Gibbs would seem to indicate that nothing could be further from the truth. There is no doubt however, that the great fur company assisted it in its development and aided in its spread but even then, American settlers and traders contributed more than the Hudsons Bay company ever did. It is a remarkable fact that such old Indians as came in contact with the Hudsons Bay company only, could not speak Chinook while the younger class who came in contact with the settlers and traders could all speak it.

It is already on record that Chiefs Sealth and Hettie Kanim belonged to the former class who never learned to speak Chinook.

Jacobs, Big John, William Kitsap and others were among the leading or head men of the tribes on the upper Sound when the whites came. They were given christian names by the early settlers and before their deaths commanded the respect of the whites, who not only learned their simple tongue, but were often regaled with the traditions and history of their tribes. From these men were gleaned the account of the arrival on the upper Sound of the first ship. Before any of these existing Indians were born, so their fathers had imparted to them, during the early part of a “warm sun” (summer time) just after sunset while the Indians were in camp at Beans point, near what are now known as Blakeley rocks, the camp was thrown into great excitement and they ran about the beach uttering exclamations of wonder and astonishment. There upon the bosom of the placid Sound was the first white man’s ship with wings outspread. Never had Indian eyes looked upon anything so wonderful. “Uch-i-dah uch-i-dah” wonderful, wonderful. “Ik-tch-o-coke; Ik-tch-o-coke!” what is that, what is that. Then the astonished natives took to the woods, fearing the greatest evil and disaster as they heard for the first time the noise of firing cannon. The more superstitious conceived it a message from the Great Spirit and were filled with the greatest alarm. Old Chief Kitsap was there and the brave old fellow stood his ground and by his demeanor allayed the fears of the more timorous, as well as by pronouncing it a big canoe. It is believed that Kitsap had, on some of his migrations to the lower Sound waters and straits, come in contact with some of the earlier Spanish cruisers. This was the belief of the older Indians at the time of the first white occupation of this country. Both Kitsap and old Chief Sealth had made voyages at that time as far north as what is now Victoria harbor.

The next day following the appearance of the strange visitors, old Kitsap with a few of his sub-chiefs were persuaded to go on board the vessel and were filled with unbounded astonishment at what they saw. It was with an evident relish and much interest that the old Indians above named related through the interpreter Alfred, the story of the visit aboard the first ship, as it was related[18] to them by their fathers and grandsires. Iron, metal goods, knives, forks, chains, firearms and hard bread and other goods were brought out for their inspection. They were offered the hard bread and molasses to eat. The Indians called the latter Ta-gum, which in Chinook means pitch, but after persuasion tasted it and were well pleased and partook of both bread and molasses. Old Kitsap soon made himself at home on board the vessel and the strange white creatures that flitted about her decks were, after the first visit or two, without fear for the sturdy old native. The Indian account, meager as it is, tallies well with Vancouver’s record of the same when, for instance, he says it was on the 16th of May, 1792, that he anchored off an island which they named Bainbridge and near a ledge of rocks they called Blakeley rocks.

The Indians’ account of Vancouver’s movements while anchored off and in view of what is now Seattle harbor or Elliott bay, corresponds with his own. Kitsap piloted Vancouver up the Sound to what is now Olympia. While on this cruise with row-boats they visited the celebrated Old-Man-House at North bay, an Indian rendesvous already mentioned. After an exploring expedition of ten or twelve days up the Sound, old Chief Kitsap as pilot went with Vancouver on a cruise down inside the Whidby island channel to Bellingham bay. Vancouver’s ship remained at anchor nearly two moons at Blakeley rocks and the Indians secured of him the first instruments made of iron with which they executed fine carving, after the fashion of the totem posts at the Old-Man-House.

The history of the Old-Man-House (or as the Indians called it Tsu-Suc-Cub) if fully known would unfold a story as interesting as romance. At this late day its time and surroundings are so shrouded in the mists of the past that but only a glimpse can be had. Its habitats like itself have long years since withered and returned to dust. Probably the best and most authentic account of its history and purpose is the story told by Indian Williams, or as the Indians called him, Sub-Qualth, about 80 or 85 years old at that time, and long since joined to his fathers. Old Williams told his story through an intelligent interpreter also of the Old-Man-House reservation, whose name had been christianized to that of H. S. Alfred.

In the Tsu-Suc-Cub lived eight great chiefs and their people. Space in the big house was allotted to each chief and his people and this was religiously consecrated to them and never encroached upon by others. To old Chief Sealth was given the position of honor; Chief Kitsap came next, Sealth’s aged father ranked third, and Tsu-lu-Cub came fourth. These four Sub Qualth remembered and they represented one-half of the Tsu-Suc-Cub. The next four Sub Qualth did not remember but his father, who was a cousin of Chief Sealth had told him their names. There was Bec-kl-lus, Ste-ach-e-cum, Oc-ub, and Lach-e-ma-sub. These were petty chieftains with subordinate tribes and authority and each had a carved totem supposed to properly delineate and perpetuate the deeds of valor of himself and people.

In 1859 there were many of these carved posts remaining and yet standing in fairly good preservation with the big logs still resting on them 16 to 20 feet above the ground. Three of them remained in position in 1870, but during the next fifteen years all were torn down, or falling from decay, were carried off and lost to the historian.

The posts in the front were about 25 feet apart, making the length of the structure over 1,000 feet frontage with the width of the main room fully 60 feet inside. The big corner post was of cedar, as were all of them for that matter, and was of immense size, showing that the tree from which it was cut must have been seven feet through. Clear and distinctly cut on the front of the big[20] totem stood out first and foremost the big Thunderbird in the proportions in which it had fixed itself in the minds of the particular tribe. On the same totem was carved the full sized figure of a man with bow and arrows, representing the old Chief Kitsap, the most noted chief for great strength and prowess on the Sound, save possibly old Sealth.

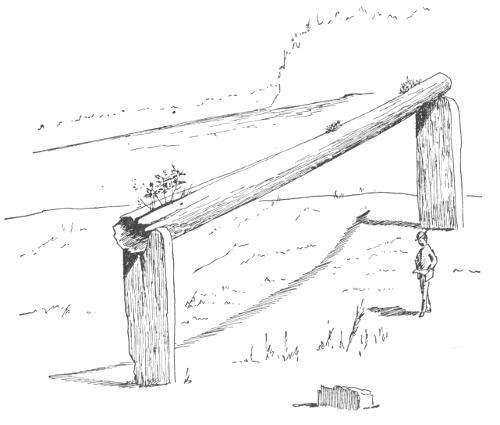

ALL THAT’S LEFT OF OLD-MAN-HOUSE

What a home it must have been. Although the family residing there was large, yet never a resident of Washington lived in a home more spacious. It covered the length and breadth of sandy beach like a king’s palace that it was. Three hundred and eighty-four or ninety-four yards, as Wm. Deshaw remembered, did it stretch away up and down the beach of the narrow Agate passage. Twenty yards or more in breadth it extended back to the edge of the little bluff where its long timbers rested as on a footstool, and high enough for the tallest Indian brave.

The outlines of the old pile are still readily traceable along the ground although it has been nearly thirty years since the Indians gave it up as a place of abode and took to constructing little huts and lean-tos along the beach and on the gentle slopes above. The attractive relic of the old structure and the one that lends the best idea of the old building’s original shape, is one of the log[21] rafters still resting in position on two immense uprights just as it did in the days when the allied tribes hoisted its great weight into the air. It is a cedar log 63 feet long, 12 inches in diameter at the smaller end and probably 23 or 24 inches at the larger end. The uprights, to lend color to the great proportions the old building must have attained, are of immense cedar trees that must have been four feet through. The one nearer the water is 12 feet high and the other fully eight feet. The big timbers were first split asunder and the inside hollowed out and hewn away until a piece probably 10 or 12 inches thick had been left to form the upright. They have been hoisted into position with the convex or bark side turned to face the interior of the house and tamped into the ground until they became solidly set and able to support the great weight that was put on above. Back of the row of uprights that stood at the rear and furthest from the beach, extended another row of stringers or girders to the bank, supporting also a roof, and this greatly enlarged the area of the building. Up and down the beach are numberless posts and foundation blocks of the old house and all in a good state of preservation, as is the single big rafter and two uprights yet in position. These latter are only worn and rotted where they came in contact once with the other or where they enter at the surface of the ground.

An alder bush, a salal bush, and a weed or two have found a foothold in an old wind crack of the rafter and now add to its quaint and picturesque appearance. All else has been torn down or fallen down by the lapse of time and has either floated off with the tide or been burned up in their earthen fires.

Five hundred, six hundred, and as high as seven hundred Indians lived in the big palace here at one time. They lived here long after the white people came among them. The site had been their great village for probably hundreds of years before. Successive chiefs have sat in council here and great war dances and night orgies held through generations of time under the chiefs of the Sealth.

Great banks of crushed and broken and roasted clam shells that whiten the beach and cover the bottom of the sea as with a porcelain lining far out into deep water, attest this better than could have musty scroll or parchment. The entire sea beach extending back onto the high ground is but a bed of decayed clam shells, and even as high up as the Indian farmer’s little garden, soil had to be carted in and put upon it, in which the seed germs could take hold and grow. Below it was a bed of lime-like earth, the offal and remains of many thousands of Indian feasts.

Besides the vast amount of crumbled shell mounds there are other and smaller mounds about the site that look as if they might have served the purpose of an elevated fire place. The whole area is overgrown with a thick carpet of short sand grass which even now makes it a most inviting place for[22] campers or picnic parties. Beyond the few things mentioned above there is nothing to remind one now of the interesting past hereabouts.

An interesting character still resides, 1895, at the Old-Man-House reservation. He is William Deshaw, whom the tides of time cast upon the beach at Agate point, Kitsap county, 27 years ago.

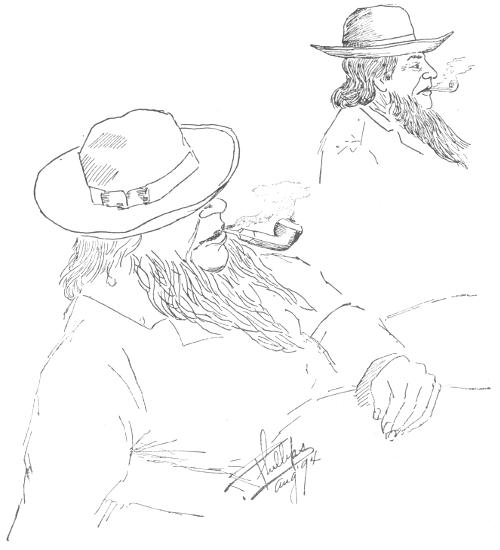

WILLIAM DESHAW, THE PIONEER AND INTIMATE FRIEND OF CHIEF SEALTH

From a Life Sketch

Deshaw, a rank copper-head to this day, is part of the flotsam and jetsam that came into the Sound along with the early tide of emigration. He was born in Galveston, Texas, in 1834, and was part of the early drift of Arizona, New Mexico and California. He went into the Sacramento valley a year before the[23] others struck the coast and true to his nature of moving out on the flood tides soon left there and came this way. He has been shot full of arrow holes, and has among numerous other trophies five Indian scalps in his trunk of his own taking. That he ever remained here so long is entirely due to the climate. Let the rains of one long winter on Puget Sound percolate down a man’s back and he seldom gets away after that. He takes to it, as it were, like the moss on the roof, and becomes a fixture of the location. And so it was with the old Texan. He drifted in here for a stay of a month or two and he is here yet. He soon got mixed up with the natives, became a squaw man and never after that could he pull himself away. And why should he leave? He had wedded into the royal house of Sealth; wedded a princess, a grand-daughter of the chief of the allied tribes of the Duwamish, Samamish, Squamish, etc., and probably forgot about his old-time habit of drifting. Mrs. Deshaw, nee Princess Mary Sealth, has been dead these many years, and now lies buried in the little reservation churchyard on the hill across the narrow strip of tide water. There are, however, two fine looking girls and some boys left of the union, and in their society the old man is happy and contented. Speaking of the little “God’s acre” on the hill near the reservation church reminds us very vividly that within its sacred precincts rests almost all that there is of the races and tribes of Sealth. Eighteen new mounds have been added during the past year. Yet a little while and there will not be a solitary individual left alive to remind those of to-day that such a people ever lived. Father Time has wrought some rapid changes with the allied tribes since the whites came among them. The evil and contaminating influences that have ever followed civilization into the dominion of the simple natives, coupled in this case with their severe and taxing superstitions, have combined to quickly wipe them out of existence.

So quickly have the changes been wrought that whole families have disappeared almost in the night-time. A Siwash with a wife and eight or ten apparently healthy children might wake up to-morrow to find himself a widower without family. Men there are now at the Old-Man-House who have buried their third wife and living with the fourth. Klootchmen were pointed out who have married five different times and only the fifth man living. Chief of Police Jimmy Sealth is the fourth husband of his present wife, who is not over 30 years of age. She lost her first, second and third husbands successively, and with the first one buried seven children. The record of the second and third marriages was not given. Jimmy Sealth, no relation of the old chief, who besides being chief of police, was sheriff, prosecuting attorney, judge and general factotum on the reservation, has been married two or three times and buried two children by his first wife. In one little family plot in the reservation churchyard 23 graves were counted side by side. The dead are not alone buried[24] side by side—they are piled in one on top of another in many cases, although there is a waste of wilderness on every side of the burying ground.

Disease has fallen with a heavy hand upon the allied tribes, but even in the memory of the first white man superstition has done almost as much in the labor of thinning out the population. Graves there are at the Old-Man-House that have been wet with the blood of human sacrifice within the memory of their great Ta-mahn-a-wis, William Deshaw. One man there is on the Old-Man-House reservation who has slain 11 children in the practice of their Skal-lal-a-toot, or hoodooism, and whose blood saturated the tomb of their hy-as-tyees.

Such in a few words is the rather sympathetic story of a people who hereabouts were the first in the land. A people whose Ta-mahn-a-wis men, or great medicine men, foretold the coming of the white people days and days before the Indians themselves saw the ships of Vancouver sailing from out the heavy cloud banks and high up in the air, for from such a source did the three ships appear to the simple natives as told now in some of their traditions. The Old-Man-House, or Port Madison Indian reservation lies about 15 miles northwest of Seattle and not far from the Port Madison mills, one of the big lumber camps of Puget Sound, now idle and almost tenantless, a result as much probably of extensive litigation as anything else. It is a mill town owned exclusively by the mill company, which furnishes all the employment of the place to its 300 or 400 inhabitants when the mill is busy. Now that there is nothing to do in the mill there is no occasion for remaining there and the mill men with their families have moved elsewhere and the rows of pretty whitewashed cottages are empty and voiceless.

The mill property is situated in a pretty little bight of the Sound, once a favorite nook of the Indians, hid away from view until one is right upon it. It is located nearly at the northernmost end of Bainbridge island, and the mill town at one time besides supporting a considerable mill population, was the county seat of Kitsap county. But during a few years past, however, the most officious and omnipresent individual over there was the court’s officer, who held the keys to the mill and looked after the property for the court pending final adjudication of the case on behalf of all litigants.

The Indian reservation lies about three miles distant from the mill and separated from it by Agate passage, a narrow thread of water 900 feet across at half tide.

The way over to the reservation is nothing more than a narrow trail hewn out of the woods a few feet up from the beach, and was apparently first cut by the men who strung the old Puget Sound telegraph and cable company’s wire to the lower Sound.

GRAND POTLATCH—OLD-MAN-HOUSE.

At the extreme limit of Bainbridge island is Agate point and directly across,[25] the reservation. On the point is the old trading store of William Deshaw, first started in the early sixties, and has been a trading store ever since. Deshaw has been left in undisturbed possession ever since and there he is to-day, probably his only accumulation being his now motherless but happy family of half-breed boys and girls. Every nook and corner hereabouts appears remindful of the musty past, everything is interesting to look upon or ruminate over. Deshaw’s old trading store is a museum of antiquities, and its restless, gray-haired and slippered proprietor is the one living specimen and most interesting of all there is on exhibition. Sixty years old, yet he is apparently as full of vitality as he ever was. There is just as much fire in his small gray eyes and as much of a spring in the step as there was when he was taking the scalp-locks of the bloodthirsty Comanche and Apaches.

The old gentleman hearing our approach one Wednesday morning came shambling out onto his front porch and was soon in the midst of an interesting talk on the Indians with whom for so long he has been associated. Although the better part of his life he has spent among the tribes that first held possession of the wooded shores of the Sound here, he is by no means an Indian lover, especially of the renegade set which now has possession of Old-Man-House village. He has without doubt during the last 25 years talked twice as much Chinook and pure Siwash as English yet he uses the strongest expletives of the English tongue in speaking of his present Indian neighbors. “Lo, the poor Indian,” finds no sympathy in his breast. He thinks it a great pity that 14,800 acres of land should be kept exclusively for a few shiftless and unworthy Indians to live upon it to the exclusion of the white people, and so it appears. They have had these lands for generations yet there is just the narrowest border of clearing along the waters that bears any resemblance to cultivation, and that for the most part is due to the labor of a few white men rather than to the Indians.

“They never would work,” says Deshaw, “and never will. Kindness is wasted upon them; every kind act done them is returned with an injury.”

Probably the otherwise kind-hearted old man would not talk so but for the fact that the old Indians, those who gave allegiance to old Chief Sealth, have all been crowded out and either dead or driven away and become lost in other tribes by renegade Indians. These last are “cultus” people, who have been run out of and off other reservations and becoming wanderers and veritable Indian tramps have at last found a stopping place at Old-Man-House.

Deshaw says there are about 60 inhabitants on the reservation, big, little, old, young and indifferent, but the agent would probably give a larger number. Of these, he counts but six that are truly men of the allied tribes, once ruled by old Chief Sealth. These men are Big John, now chief, Charley Shafton, Charley Uk-a-ton, Charley Ke-ok-uk, one of the two honest Indians on the reservation,[26] according to Deshaw, George Thle-wah and Jacob Huston, one of the old-time Indians, but a slave. None of these are of the family or descendants of the old chief though the families of Big John and Jacob have always been considered among the nobility of the allied tribes. Not even all the six Indians mentioned are good Indians, for Deshaw reckons but five on the reservation who care for a home or make any effort toward providing for their necessities in the way the white men have taught them. They prefer to keep to their old customs and superstitions; would rather troll for salmon and send their klootchmen to dig for clams than plant potatoes or milk a cow. Two or three years without the watchful care of the government and the very few whites who take interest enough to look after them, and they would drift back into a barbarism as deep as that of 50 years ago. The government pays a man to reside upon the reservation in the capacity of Indian farmer to see to it that the men with families and homes do something toward raising gardens and gather the fruit that ripens in the little orchards. The Indian agent proper does not reside there but anon visits the spot in his official capacity. That personage lives at Tulalip, Lummi, Old-Man-House reservation, Muk-il-shoot and one other. The present Indian farmer, J. Y. Roe, and his wife, have been upon the reservation a little over a year and are full of sympathy for the wards they watch over. They have done much to improve the situation on the reservation and give up all their time and a portion of the small pittance they receive, $50 a month, to do the work. Among the improvements in the village on the reservation the farmer has accomplished is the building of a new court house or town hall and “skookum” house, and a number of other things in the way of improvements to the small gardens and orchards.

The reservation forms a large body of land which ends in a beautiful peninsula between Squim bay and the narrows. The site of the reservation village which is also the site of the famous Old-Man-House, fronts the water on the south in a gentle slope, covered with half grown evergreens and the narrowest border of cleared lands set to orchards, flower gardens and vegetables. The most conspicuous figure of the village is the Catholic church, a perfect little model in its way, and as white and gleaming in the sun as a snowy peak. It will bear the utmost scrutiny for it is just the same in or out, far or near. By far the most interesting thing to be found there at this day is the relic of the Old-Man-House, which can just be made out from the porch of the old trading store on the opposite side of the bay. It is down close to the water’s edge and about midway in the little clearing. But how can one be expected to glean anything from its past and old associations without the presence of the big Tah-mahn-a-wis man along. So Mr. Deshaw shambled away after his big, rusty key, locks up his store and goes off for a whole day with us, perfectly unconcerned as to the propriety of good business methods.

At the waters’s edge on the reservation side of the narrows lives the Indian farmer, a sub-agent, and his spouse, a very easy-going, plodding, pleasant natured old couple. Old-Man-House is usually as serene and quiet as a Sabbath day, in fact every day is a Sunday in this respect.

There is a school, but no business, no nothing but what would prove to a white person a monotonous and unbearable existence. There is one irregular and vagrant looking street connecting with a little beaten trail that leads to the cemetery on the hill. Here is the populous part of the village. We lead the way into the inclosure and through the windings between the thickly made mounds, a large portion of which have a little emblem of the crucifixion raised above them. The old Texan with us has known, in their day, most of the Indians who are sleeping the last quiet sleep here and hesitates not to indicate who were the cultus and who were the good Indians. “That fellow,” he would say, “was as big a rascal as ever lived,” or of another, “he was a good Indian and a hard worker.” Directly he leads the way up near the north side of the inclosure where a large marble monument marks the resting place of some big tyee. There are a dozen small mounds in the same little plot and ranged on either side of it, but the only inscription is on the big monument and it reads:

SEATTLE

Chief of the Suquamps and allied tribes

Died June 7, 1866

The firm friend of the whites, and for him

the city of Seattle was named by

its founders

On the reverse is inscribed the following:

Baptismal name, Noah Sealth. Age probably

80 years.

That is the only bit of history there is about or on the monument. The little plot is not enclosed, and the weeds have full possession. The dozen or more graves in the same plot are of the family of the old chief, but the Texan fails now to call them by name. He however takes exception to the inscription as being incorrect, and in part superfluous. He objects to the name Sealth or Seattle, but says the Indian pronunciation was as near Se-at-tlee as the English language can reproduce it. The word Sealth, says Deshaw, was the translation of the old settlers who lived on Elliott bay. The old chief himself spoke the name for him a thousand times or more as given above, as did the people of the Old-Man-House. The Indians never knew the old chief by the name of Noah, that word being used probably but once, and that at the time of his baptism into the Catholic faith.

There are graves of other old-time chiefs in the little churchyard, the most[28] conspicuous one being that of Alex. George, whose little monument is surrounded by twenty-two other graves, all enclosed in a neat white-washed picket fence. They are all of the immediate family of the dead chieftain.

On the way back to the village we stop and inspect the garden and orchard of the boss gardener of the Indians, John Kettle. Besides himself and wife, he has about a score of dogs of every hair and color, which set up a perfect pandemonium as we approach. Kettle is one of the old slaves, a Clayoquot sound, or West coast Indian, who was sold to a chief of the allied tribes when a boy by some other tribe who had captured him and brought him into the Sound country. Kettle seemed pleased at the interest shown his garden and orchard and said he had 160 acres of fine land, and some day would be a rich Indian.

THE OLD-MAN-HOUSE VILLAGE AS IT APPEARS TO-DAY

Kettle when brought into the allied tribes’ camp could not speak a word of their language nor could they understand him. He was almost starved. The old chief who bought him was with the family eating from a big kettle of roasted or boiled clams. When Siwash and Chinook failed, the old chief motioned to his slave to eat clams. John didn’t wait for a second bidding, and soon finished the kettle of clams. Then another kettle filled with the bivalves was prepared for him. John had heard the Indians speak the word kettle several times when dipping into the pot and he took the word to mean clams. So John began to call out as best he could,“kettle, kettle.” “Umph,” cried the old chief in Siwash, “he wants more clams. I have it, that will be his name, John Kettle,” and from that day to this the new slave was called John Kettle. The fellow is not over 35 years old, but his wife, who has been married five or six times and had a cultus husband every time, and who has been beaten all[29] through her life, looks as if she might be John Kettle’s grandmother instead of his spouse.

The first “Boston” house built on the reservation is still standing and occupied by one of the chief men of the village. It was built entirely at the expense of William Deshaw as his first free offering towards a reform in the mode of life of the Old-Man-House Indians. This was a reform very much desired by the government at that time, but towards the accomplishment of which it did very little according to Mr. Deshaw.

The Old-Man-House agency was, according to this authority, very much of a sinecure to the early agents, a half dozen of whom he thinks, probably never set foot on the agency. Deshaw for several years acted as a sub-agent for these appointees and virtually had the say in everything at Old-Man-House or that concerned the allied tribes. He got to be such a trusted lieutenant that he would be intrusted with large sums of money to spend for the Indians and at one time had $18,000 which the government gave him and with which he bought supplies in Portland. This was during the incumbency of the late George D. Hill of Seattle as Indian agent. Hillory Butler of Seattle was another agent for whom Mr. Deshaw looked after things at Old-Man-House.

The first great duty with which the government charged Mr. Deshaw was the breaking up of the Old-Man-House and the isolation of the 600 or 800 Indians in separate households with the idea of inculcating civilized ideas of living. It was a hard task and one fraught with many disappointments before it was accomplished. The Indians were a curious lot. To-day they were your friends; to-morrow they were ready to plug you full of lead from an old Hudsons bay company’s musket. Finally he got one or two to make the first attempts at separate residence and by degrees got them all out of the building and ruined it from further inhabitancy. But in almost every instance the Indians wanted the work all done by the sub-agent and refused to lend a hand themselves.

Old Chief Sealth was a great power at Old-Man-House and lived for several years after Mr. Deshaw went among them. He became very friendly with the sub-agent and accepted his advice in everything and tried to make his people live up to the orders of the great father at Washington City. According to Deshaw, the old chief was greatly reverenced and to as great degree feared by the Indians. Sealth gave all the assistance in his power to Deshaw in an effort to break up the heathenish practices of the Ta-mahn a-wis men and destroy the superstition of their scal-al-a-toots, but these evils were never eradicated and to this day, but for the ridicule cast upon them by the whites, thy would still practice them openly.

The habit of burying their dead in trees and elevated places was in vogue long after Deshaw went among them, but was never done openly or with the[30] consent of the old chief. Even the baneful practice of slaying the dead chief’s horse or dog and his slaves on the grave was religiously carried out for several years after Deshaw’s appearance whenever the Indians could do it with safety.

Deshaw tells of one prominent Indian now living on the reservation, Huston, who was a slave at that time and who was with his klootchman and his little daughter doomed to suffer death on the grave of their master, Chief Ska-ga-ti-quis. Huston got wind of what the Indians were about to attempt and, with his klootchman and 12-year-old girl, slipped away in a canoe to the other side of the narrows and took refuge in Deshaw’s trading store. Seventeen big and brawny bucks with Hudsons bay company muskets followed the refugees over and stormed the store. They rushed in clamorous and gesticulating and swinging their guns, and demanded their prisoners, saying they were going to kill them over Ska-ga-ti-quis’ grave. The prisoners were hid away in a little side building. Deshaw began parleying with the blood-thirsty fellows and directly several of them carelessly lay their guns on the counter. Deshaw, without attracting attention, moved up close to them and quickly pulled the guns over and allowed them to fall on the floor back of the counter. Almost at the same time old Chief Sealth, who had heard of the trouble at the store, quickly got into a canoe, paddled across and went rushing into the store. The old chief possessed a powerful voice and herculean strength.

“Whoo, whoo, do I hear; what do I hear,” he cried several tunes upon his entry, but the Indians began falling back and said never a word. Then the old chief’s little grand-daughter, one of Mr. Deshaw’s daughters, yet living, went up to the old gray head and in her Indian and childish way said, “Grandpa, they are going to kill the Hustons over Ska-ga-ti-quis’ grave.”

Then, “whoo, whoo,” puffed the old chief, and grabbing up a musket, prepared to slay every Indian in sight, but the Indians knew the old fellow’s temper too well and shot out of the doorway in a twinkling, and went pell-mell into the water and scrambled into their canoes. The old chief rushing after them grabbed up a big cedar rail, after dropping the gun (it was entirely too light for him), and tried to reach them with that, but they got away and across back to the village. The old chief kept right after them, and once on his own side called the whole village together and made the people a speech.

He could be heard distinctly on the opposite side of the channel haranguing them on the evil of killing their slaves.

“Mr. Deshaw, the big white medicine, did not want it done, Governor Stevens did not want it, Colonel Simmons did not want it, and the great chief at Washington City did not want it, and it must stop.” Such was the speech, as now remembered and translated by one of those most interested in the occurrence. The speech seemed to have a good effect, at least for the time. Guards were placed over the Hustons, and they remained out of sight for a week or more,[31] and no attempt was again made to take and kill them in so barbarous a way.

Until quite recently several very aged Siwash resided at the Old-Man-House reservation. There was Jacob, aged about 75 years, a grandson of the old Chief Kitsap; old man Williams, aged about 85; William Kitsap, grandson Of old Chief Kitsap, and H. S. Alfred, both educated Indians. Old William’s daughter married a Kitsap county pioneer who as the years went by grew rich and prominent and his half-breed progeny promise to become honorary and intelligent members of society.