Project Gutenberg's Harper's Young People, September 19, 1882, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Harper's Young People, September 19, 1882

An Illustrated Weekly

Author: Various

Release Date: May 29, 2019 [EBook #59628]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S YOUNG PEOPLE ***

Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| vol. iii.—No. 151. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, September 19, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

Long and long ago, before you or I were born, in the year 1799 in fact, a man by the name of Ossip Schumachoff threw away a golden opportunity. Having undertaken an expedition up to the Arctic Ocean in search of ivory, he started from home with his wife on a reindeer sledge, and was so far successful in his undertaking that he discovered on the banks of the river Lena a certain block of ice that would have set all the naturalists in the world in commotion if he had but known it. This block[Pg 738] of ice was of untold value, for it contained the body of an enormous tusked animal in a perfect state of preservation.

Owing to the impenetrable masses of ice surrounding the mammoth, Ossip did not at that time succeed in reaching it; but returning to the same spot some two years later, he found that the ice had so far melted that a portion of the huge creature was exposed to the air.

And yet Chief Ossip was no nearer to his prize than he had been at first. It is true the Ice King smilingly placed it in his grasp, but a mightier power, Superstition, stepping in with her rod of iron, bade him touch it if he dared.

All the old men of his tribe shook their heads discouragingly. All the old women told direful tales of what had happened long years before, how a certain Tungusian chief, having seen just such a monster as this, had immediately fallen ill and died, with all his family.

And as good luck—or bad—would have it, Ossip Schumachoff too began to feel ill, so he slowly went back to his home again to dream by day and night for three years more of that magnificent pair of tusks going to waste up there in the North.

At last he could stand it no longer. Making another expedition to the Lena, he found the monster now entirely melted out of the ice, and slipped down upon a sand-bank; but this time he sawed off the magnificent pair of tusks, and sold them for fifty good Russian rubles.

It was not until two years later, in 1806, that the naturalist and traveller Adams heard of the affair in Jakutsk. In June of the same year he travelled thither to rescue what was still to be saved. Schumachoff accompanied him, together with ten Tunguses.

They found the animal on the right bank of the Lena, near the Arctic Ocean, on a small peninsula called Tamud, but it was by this time in a bad condition. Polar bears, wolves, and foxes had eaten the flesh, and the people of that desolate region had fed their dogs upon it, although of the skeleton itself only one fore-foot was missing.

You may think how the eyes of the naturalist sparkled when they fell upon this colossal ruin. A mammoth, you know, is what is called the elephant of the ages before the Flood. It has long, long ago disappeared from the living world, so long, indeed, that it would be hard telling, perhaps, just how many thousands of years the mammoth of which I have been writing had lain hidden away in his icy bed.

Judging by this most perfect specimen ever discovered by man, the mammoth had the greatest likeness to the elephants of the present day, especially to those of India.

The naturalist was able to discover that his specimen was a male. Its head weighed four hundred pounds. It had a long black mane, the hair measuring at least a foot and a half, and its whole body was covered with a thick coating of reddish wool five inches in length. The tail and the trunk were gone, but the eyes were still preserved; so also was the brain. Professor Adams had no difficulty in stripping off three-quarters of the skin, though this was found to be so heavy that when he attempted to take it away it required fully ten men to carry it.

The hairs which the polar bears and other beasts of prey had trodden into the damp ground were collected, and amounted to some thirty pounds. Specimens of these were afterward shown in almost all the museums of Europe.

The lucky naturalist, having no fear of death like poor old Ossip, had everything carefully packed together and carried up the Lena, then across the country for more than four thousand miles, to the distant city of St. Petersburg, where the skin and skeleton form to-day the most valuable specimen of its famous museum. He also brought home some of the flesh, which, in spite of its age, was still fresh enough to be eaten, and the St. Petersburg Academicians and other gentlemen tasted this remarkable roast. The Academy gave the naturalist eight thousand rubles for his travelling expenses, besides a professorship in Moscow.

And this is the story of the great mammoth discovery that caused so much excitement in all the scientific circles of Europe. But how this ancient elephant strayed in the first place into so uncongenial a climate as that within the arctic circle, or what he could have found to eat when there, remains, I think, a mystery to the present day.

There are many theories advanced, but who can tell which one of them all is right?

We read that the tribes who live in the northern parts of Siberia, upon the thawing of the ice in summer, are constantly finding some immense skull, with its strongly bowed tusks in a perfect state of preservation, or some other skeleton remains (of the same animal apparently), with the red flesh still clinging to them.

And indeed these discoveries seem to have been long a source of revenue to the poor wandering people of the north. As early as 1707 a certain gentleman named Isbeaud Ides, who made a journey to China as ambassador to that distant country, declared that the Tunguse carried on a considerable business with the tusks discovered from time to time in the melting ice.

He further says that the animal known to us as the mammoth was called mammont by the wild tribes of Siberia, and that they believed it to be living still somewhere deep down in the ground, burrowing in the mud in the neighborhood of the river. According to their theory, if in the course of its dark wandering the animal by any possibility struck upon the sand, it immediately sank therein and died. So, too, it was inevitably lost when it came into the air of the upper world upon a bank of the river, because it could bear neither air nor light.

But this was only a theory of ignorant people—one to make the wise men of the earth smile in scorn—and still the question remains unanswered, I think, how it is that the bones and remains of a tropical animal are found in such numbers throughout the region of ice and snow.

A bright, burning summer day on the border of the Sahara Desert; the huge bare cliffs of the El Kantarah Pass hanging like a cloud on the northern horizon; a quivering film of intense heat along the line where the rich blue of the cloudless sky met the hot, lifeless, brassy yellow of the desert; and in the foreground a group of Arabs, encamped beside a tiny stream, in the shade of the clustering palms that overhung it.

Some were munching handfuls of parched corn, others were lying fast asleep, while one dried-up old scarecrow with one eye, and a head like a worn-out scrubbing-brush, was droning out some interminable Eastern legend.

The story did not appear to get on very fast, however, which was not surprising, inasmuch as the whole of it, from beginning to end (if it ever had any), was pretty much in this style:

"Now when the Prince Selim (may his name be honored forever!) came up to the gate of the palace—a gate higher than the dome of the Kaabah [holy place] at Mecca, and built all of marble whiter than the whitest milk—lo! there stood before it a giant, mighty and exceeding terrible. Then was the Prince of Gulistan sore amazed, and said, 'Never since I, Selim, son of Mahmoud, son of Sayid, son of Ali, first wore a yataghan [sabre] have I beheld such a monster as this!'"

And so on for another half-hour, keeping poor Prince Selim waiting at the gate of the palace.

But on a sudden an exclamation of astonishment broke from one of the group, and all eyes were turned to stare at a spectacle quite as wonderful to them as any of the marvels to which they had just been listening.

Sauntering leisurely over the burning plain, as composedly[Pg 739] as if he were lounging along the boulevards of Paris or St. Petersburg, instead of traversing one of the most dangerous spots in the whole north of Africa, was a solitary man, coming slowly toward them. True, he wore the white mantle and huge many-folded turban of the East, but he was none the less a European, as his fair complexion, well-trimmed beard, and jauntily cut pants sufficiently showed.

Instantly the universal listlessness changed to bustle and excitement. The sleepers woke up, the lunch party forsook their dates and corn, the story-teller and his hearers started to their feet together, and all alike hurried forward to meet their strange visitor.

But to their unbounded amazement the strange visitor took no notice of them whatever beyond a slight bow and the usual "Peace be with you!" spoken in good Arabic, though with an unmistakably French accent. Stepping into the shade of the palms, he bent down to the stream, took a long draught of the cool clear water, and then seating himself upon the bank, took off his turban, and began to fan his hot face with a fallen palm leaf, as if wishing to show his coolness in a double sense.

The Arabs were completely taken aback. They had seen men look pale, and try to run away from them; and they had seen men look fierce, and rush at them pistol in hand; but a man who paid no attention to them at all, and who hardly seemed to know whether they were there or not, was a thing which they had never seen before, and they did not know what to make of it. In fact, like most men of their class, the moment they encountered a man whom they could not frighten, they at once began to be frightened themselves.

At length the chief, seeming to think himself bound to set an example of courage to his followers, walked right up to the stranger, while the rest approached more cautiously, very much as a man approaches a strange dog which may spring up and bite him at any moment.

"Peace be with thee, my brother!" said the chief, in a voice not quite so steady as it might have been.

"With thee be peace, oh, sheik [chief] of the children of the desert!" replied the unknown.

"What seeks the Frank [European] chief among the warriors of the tribe of Ben-Asyr?"

"I am a magician," answered the stranger, quietly.

The Arabs looked at each other with undisguised trepidation. A magician among them, and a Frank magician at that! Who could tell what he might do to them? For every Arab had heard the fame of the mighty sorcerers who could make wagons run without horses, ships go without sails, messages fly along a wire through the air swifter than an arrow, little scraps of paper serve as money, and other scraps of paper, no bigger than a true believer's turban, show the whereabouts of all the wells, rivers, hills, and caravan tracks, over an area of thousands of miles. Evidently this unknown gentleman was not a man to be trifled with.

"I am a magician," repeated the mysterious guest, before any one could speak in reply, "and I have come to see if in the tribe of Ben-Asyr there be another magician like myself, and to try my power against his."

This challenge was followed by a gloomy and universal silence. But suddenly a cunning twinkle showed itself in the chief's small rat-like eye. Perhaps this strange man was only boasting in order to frighten them. At any rate, it might be worth while to see what he was made of, and how much he could really do. So the chief made a very polite bow, and said:

"We are far from the tents of our tribe, and none of our great magicians are with us; but let the wise man of the Franks show us his power, that we may behold it, and honor him as he deserves."

"That will I do willingly," answered the stranger, with a readiness which rather disconcerted the worthy chief. "Look all of you upon this coin"—and he held out a silver franc—"which I have marked with a circle, as ye see. Thinkest thou, O sheik of the Ben-Asyr, that thou canst hold it too firmly for me to take it away?"

"With the blessing of Heaven and of the Prophet, I can," replied the chief, confidently.

"Let us try, then," said the stranger, pressing the coin into the Arab's extended hand, which instantly closed upon it as if meaning never to let it go again.

"Presto! pass!" shouted the magician, in a high, shrill voice; and the chief, opening his hand, found to his unfeigned dismay that it was empty.

Amid the general silence and bewilderment, the stranger pointed to a huge overripe date that lay rotting on the ground at some distance, which one of the Arabs instantly handed to him. One stroke of a knife laid it open, and out tumbled the marked coin.

There was a visible movement of surprise among the Arabs, and even the chief himself looked not a little discomfited.

"For a warrior of the desert, thou art easily conquered," said the Frenchman, jeeringly; "but it is no wonder that ill fortune should come upon the tribe of Ben-Asyr, when their chief himself, a follower of the Prophet, carries with him the liquor which the Prophet forbade."

"What mean you?" cried the chief, fiercely.

"This," answered the other, as, thrusting his hand into the sheik's wallet, he held forth to the horrified eyes of the band a small flask of unmistakable French wine.

"Dog of a Frank!" roared the sheik, losing all patience, "do you dare to try your magical tricks upon a true believer? Take that!"

He snatched a pistol from his girdle, and aimed it full at the conjurer's face; but it only flashed in the pan, and as he dashed it furiously to the ground, his unmoved opponent laughed disdainfully.

"Do you think, then, that I am to be hurt by mortal weapons? Try it again, if you will; or rather let me load a pistol for you, and you shall see whether I am bullet-proof or no."

He drew a second pistol from the girdle of the sheik, who was too much astounded to object, and loaded it before the eyes of the whole band, marking the ball with his knife just before dropping it into the barrel.

"Fire!" cried he, putting the weapon into the sheik's hand.

The chief fired, and for a moment the smoke hid everything. When it cleared, the stranger, with a mocking smile on his face, was seen to let fall the marked bullet from his mouth into his hand, and hold it up for every one to look at.

The dark faces of the Arabs turned perfectly green with terror; but before anybody had time to say a word a loud shout was heard from behind, and up dashed three mounted French officers with a score of light horsemen.

Instantly the Arabs took to their heels with a howl of dismay, never waiting to see whether the new-comers were real men, or phantoms called up by the terrible magician. The spot was deserted in a moment, and far out on the plain might be seen a confused whirl of arms, limbs, and white mantles flying along like dust driven by the wind.

"Really, M. Houdin, you must be more careful," cried the French Colonel, excitedly. "To think of your venturing alone among all those cut-throats! What a fright you've given us!"

"And somebody else too, seemingly," said Robert Houdin—for it was indeed the famous sleight-of-hand artist—glancing slyly at the flying Arabs. "When I first came upon them I knew it was no use running, so I decided to face it out, and scare them a little instead. The next time you make a raid through these parts, Colonel, take a few conjurers with you; they'll be worth a whole battalion of infantry, take my word for it."

A beautiful day in summer,

At Bath, beside the sea,

Where a bevy of careless children

Were as gay as gay could be.

Some with their spades so tiny

Were turning over the sand,

Some were merrily racing

With the surf that dashed on the strand.

And others, bold and daring,

Plunged into the deep green wave,

At the touch of the grim old ocean

They felt so blithe and brave.

Laughing, leaping, and diving,

The sturdy, frolicsome crew

Had never a thought of danger

Under the sky's soft blue.

And nobody noticed Harry,

A dear little five-year-old,

With just a glimmer of sunshine

Tinting his curls of gold.

Till, after the rest, as swiftly

As a flash the darling went;

And a cry of sudden terror

The giddy gladness rent.

The billows have caught the baby,

They are bearing him far away;

Alas for Harry's mother

And her empty arms this day!

Some one has darted to save him,

Forth from an awe-struck throng,

A fearless heart to the rescue,

Steady and true and strong.

Buffeting surge and breaker,

Straight through the curdling foam,

On through the angry waters,

She is toiling to bring him home.

Only a child, with girlhood's

Clear light in her candid eyes;

Only a girl, but a woman

In her glory of sacrifice.

On the shore they watch and listen,

Spell-bound in a dumb despair.

Ah! hark to the shout of triumph,

That ends in a thankful prayer.

Edith has saved wee Harry.

'Twas a noble deed was done,

At Bath, that day, by the ocean,

In the light of the summer sun.

Author of "The Moral Pirates," "The Cruise of the 'Ghost,'" etc., etc.

The early morning visitor was not a bear. He was a very welcome visitor, for as soon as he made himself visible he was seen to be the missing canoeist. Charley was very wet and cold, but he was soon furnished with dry clothes and a blanket, and warmed with a cup of hot coffee made with the help of Harry's spirit-lamp; and as he lay on the bank and waited for daylight, he told the story of his midnight run down the rapid.

When the boys were crossing the river above the rapid Charley's canoe was close behind Joe's. The latter ran on a rock, and in order to avoid her Charley was compelled to pass below the rock. In so doing he found himself in great danger of running on another rock, and in his effort to avoid this he drifted still farther down the river. Before he was aware of his danger he was caught by the current at the head of the rapid. He had just time to turn his canoe so as to head her down stream, and to buckle his life-belt around him. In another second he was rushing down the rapid at a rate that, in view of the darkness, was really frightful.

It was useless to attempt to guide the canoe. Charley could see so little in advance of him that he could not choose his channel nor avoid any rock that might lie in his path. He therefore sat still, trusting that the current would carry him into the deepest channel, and keep him clear of the rocks. The rapid seemed to be a very long one, but the Midnight ran it without taking in a drop of water or striking a single rock.

As soon as quiet water was reached, Charley paddled to the shore, intending to make his canoe fast and to sleep quietly in her until morning. He was in high spirits at having successfully run a rapid in the dark, and he paddled so carelessly that just as he was within a yard of the shore the canoe ran upon a sunken log, spilled her captain into the water, and then, floated off in the darkness, and disappeared.

Charley had no difficulty in getting ashore, but he was wet to the skin, and his dry clothes and all his property, except his paddle, had gone on a cruise without him. There was nothing for him to do but to make his way back along the bank to the other boys. This proved to be a tiresome task. The woods were very thick, and full of underbrush and fallen trunks. Charley was terribly scratched, and his clothes badly torn, as he slowly forced his way through the bushes and among the trees. He was[Pg 741] beginning to think that he would never reach the boys, when he fortunately heard their voices as they whispered together.

When morning dawned, the canoeists, feeling extremely cramped and stiff, cast their canoes loose, and started down the river, intending, if possible, to find Charley's canoe, and then go ashore for breakfast and a good long sleep. The rapid had been run so easily by Charley in the night that they rightly imagined they would find no difficulty in running it by daylight. Tom took Charley in the Twilight, and the fleet, with Harry leading the way, passed through the rapid without accident. The boys could not but wonder how Charley had escaped the rocks in the darkness, for the rapid, which was much the roughest and swiftest they had yet seen, seemed to be full of rocks.

Not very far below the rapid the missing canoe was discovered aground in an eddy. She was uninjured; and as there was a sandy beach and plenty of shade near at hand, the boys went ashore, made their breakfast, and lying down on their rubber blankets, slept until the afternoon.

RUNNING THE RAPID.

RUNNING THE RAPID.

It was time for dinner when the tired canoeists awoke, and by the time they had finished their meal and were once more afloat it was nearly three o'clock. They ran three more rapids without any trouble. Their canoes frequently struck on sunken rocks; but as they were loaded so as to draw more water aft than they did forward, they usually struck aft of midships, and did not swing around broadside to the current. When a canoe struck in this way, her captain unjointed his paddle, and taking a blade in each hand, generally succeeded in lifting her clear of the rock by pushing with both blades against the bottom of the river. In the next rapid Joe's canoe ran so high on a rock that was in the full force of the current that he could not get her afloat without getting out of her. He succeeded in getting into her again, however, without difficulty, by bringing her alongside of the rock on which he was standing, although he had to step in very quickly, as the current swept her away the moment he ceased to hold her.

In running these rapids the canoes were kept at a safe distance apart, so that when one ran aground, the one following her had time to steer clear of her. At Charley's suggestion, the painter of each canoe was rove through the stern-post instead of the stem-post. By keeping the end of the painter in his hand the canoeist whose canoe ran aground could jump out and feel sure that the canoe could not run away from him, and that he could not turn her broadside to the stream by hauling on the painter, as would have been the case had the painter been rove through the stem-post.

"I want to see that Sherbrooke postmaster!" exclaimed Joe, after running what was the seventh rapid, counting from the dam at Magog. "He said there were only one or two little rapids in this river. Why, there isn't anything but rapids in it."

"There's something else just ahead of us worse than rapids," said Charley. "Look at that smoke."

Just a little distance below the fleet the river was completely hidden by a dense cloud of smoke that rested on the water, and rose like a heavy fog-bank above the tops of the highest trees. It was caused by a fire in the woods—probably the very fire which the boys had started on the previous night. How far down the river the smoke extended, and whether any one could breathe while in it, were questions of great importance to the canoeists.

The fleet stopped just before reaching the smoke, and the boys backed water gently with their paddles while they discussed what they had better do. It was of no use to go ashore with the hope of finding how far the smoke extended, for it would have been as difficult to breathe on shore as on the water.

"There's one good thing about it," said Charley; "the smoke blows right across the river, so the chances are that it does not extend very far down stream."

"We can't hear the noise of any rapid," said Harry, "and that's another good thing. There can't be a rapid of any consequence within the next quarter of a mile."

"Then I'll tell you what I'll do, with the Commodore's permission," continued Charley. "There is no use in staying here all day, for that smoke may last for any length of time. I'll tie a wet handkerchief around my mouth and nose, and take the chances of paddling through the smoke. It isn't as thick close to the water as it looks to be, and I haven't the least doubt that I can run through it all right."

"But suppose you get choked with smoke, or get into a dangerous rapid?" suggested Tom.

"There isn't any rapid near us, or we would hear it, and I don't think the smoke will hurt me while I breathe through a wet handkerchief. At any rate, I'd rather try it than sit here and wait for the smoke to disappear."

It was decided, after farther discussion, that Charley should attempt to paddle through the smoke if he really wished to do so; and that he should blow a whistle if he got through all right, and thought that the other boys could safely follow his example. Paddling a little way up stream, so as to have room to get up his fastest rate of speed before reaching the smoke, Charley started on his hazardous trip. He disappeared in the smoke, with his canoe rushing along at a tremendous rate, and in a few seconds his comrades heard him calling to them to come on without fear.

They followed Charley's example in covering their mouths and noses with wet handkerchiefs, and in paddling at the top of their speed. They were agreeably surprised to find that the belt of smoke was only a few yards wide, and that almost before they had begun to find any difficulty in breathing they emerged into pure air and sunlight.

"It was a risky business for you, Charley," said Harry, "for the smoke might have covered the river for the next quarter of a mile."

"But then it didn't, you see," replied Charley. "How cheap we should have felt if we had waited till morning for the smoke to blow away, and then found that we could have run through it as easily as we have done!"

"Still I say it was risky."

"Well, admitting that it was, what then? We can't go canoeing unless we are ready to take risks occasionally. If nobody is ever to take a risk, there ought not to be any canoes, or ships, or railroads."

"That Sherbrooke postmaster isn't afraid to take risks," observed Joe. "If he keeps on telling canoeists that there are no rapids in this river, some of these days he'll have an accident with a large canoeist and a heavy paddle. We've run seven rapids already, and have another one ahead of us. If we ever get to Sherbrooke, I think it will be our duty to consider whether that postmaster ought to be allowed to live any longer."

Just before sunset the fleet reached Magog Lake—a placid sheet of water about four miles long, with three or four houses scattered along its eastern shore. At one of these houses eggs, milk, butter, bread, a chicken, and a raspberry pie were bought, and the boys went into camp near the lower end of the lake. After a magnificent supper they went to bed rather proud of their achievements during the last day and night.

The next day the canoeists started in the cool of the morning, and as soon as they left the lake found themselves at the head of their eighth rapid. All that day they paddled down the river, running rapids every little while, jumping overboard when their canoes ran aground and refused to float, and occasionally slipping on the smooth rocky bottom of the stream and sitting down violently in the water. Once they came to a dam, over which the canoes had to be lowered, and on the brink of which Joe slipped and slid with awful swiftness into the pool below, from which he escaped with no other injury than torn trousers and wet clothes.

"That postmaster said there were no dams in the Magog, didn't he?" asked Joe as he prepared to get into his canoe. "Well, I hope he hasn't any family."

"Why, what about his family?" demanded Tom.

"Nothing; only I'm going to try to get him to come down the Magog in a canoe, so he can see what a nice run it is. I suppose his body will be found some time, unless the bears get at him."

"That's all rubbish, Joe," said Charley. "We wouldn't have had half the fun we've had if there hadn't been any rapids in the river. We're none the worse for getting a little wet."

"We might have had less fun, but then I'd have had more trousers if it hadn't been for that dam. I like fun as well as anybody, but I can't land at Sherbrooke with these trousers."

"I see Sherbrooke now," exclaimed Harry; "so you'd better change your clothes while you have a chance."

Sherbrooke was coming rapidly into sight as the fleet paddled down the stream, and in the course of half an hour the boys landed in the village, near a dam which converted the swift Magog into a lazy little pond. While his comrades drew the canoes out of the water and made them ready to be carted to the St. Francis, Harry went to engage a cart. He soon returned with a big wagon large enough to take two canoes at once; and it was not long before the fleet was resting in the shade on the bank of the St. Francis, and surrounded by a crowd of inquisitive men, boys, and girls.

It was difficult to convince the men that the canoes had actually come from Lake Memphremagog by the river, and the boys were made very proud of their success in running rapids which the men declared could only be run in skiffs during a freshet. Without an exception all the men agreed that there were rapids in the St. Francis which were really impassable, and that it would be foolish for the boys to think of descending that river. After making careful inquiries, and convincing themselves that the men were in earnest, the canoeists retired some distance from the crowd and held a council.

"The question is," said Harry, "shall we try the St. Francis after what we have heard? The youngest officer present will give his opinion first. What do you say, Joe?"

"I think I've had rapids and dams enough," replied Joe; "and I'd rather try some river where we can sail. I vote against the St. Francis."

"What do you say, Tom?"

"I'll do anything the rest of you like; but I think we'd better give the St. Francis up."

"Now, Charley, how do you vote?"

"For going down the St. Francis. I don't believe these men know much about the river, or anything about canoes. Let's stick to our original plan."

"There are two votes against the St. Francis, and one for it," said Harry. "I don't want to make a tie, so I'll vote with the majority. Boys, we won't go down the St. Francis, but we'll go to the hotel, stay there over Sunday, and decide where we will cruise next."

"All right," said Joe, going to his canoe, and taking a paddle blade in his hand.

"What in the world are you going to take that paddle to the hotel for?" asked Harry.

"I'm going to see the postmaster who said there were no rapids in the Magog or the St. Francis; that's all," replied Joe. "I've a painful duty to perform, and I'm going to perform it."

It was a bright breezy day, clear sunshine after rain, and every one was full of energy. All the pleasure-seekers had gone off, some riding, some driving, and several walking parties had been made up.

Two boys on the end of the piazza were discussing a proposed excursion, while the sister of one, a slight, bright-eyed girl of twelve, stood silently listening to their plans.

"We can go and take our luncheon with us just as well as not," said Tom, the elder of the two.

"But it will be an awful climb, and you don't know the path," replied Stanton. "Besides, Cassie can't go so far."

"Leave her at home, then; girls are no good anyway," said Tom, rudely; then remembering himself, he added, "I beg your pardon, Miss Cassie, I didn't mean exactly that, but you know girls always give out on an expedition of this sort."

"Just you try me," said Cassie, not in the least put out, for she was accustomed to boys.

"Well," said Tom, reluctantly, "I suppose we must. But you will be fagged out in less than no time, and then you'll want one of us to go home with you."

"If I do I'll promise not to go again all summer. What are you looking for, Stanton?"

"My axe, to blaze the trees; you don't want to be lost, do you?"

"No, of course I don't. Then you will take me? Good. I'll go after the basket, and my pressing-book for ferns. Shall I get anything to read?"

"No. Who wants to read in the woods? There's always lots to do."

Cassie thought differently, and slipped a little thin volume beside the bread and cake and fruit which the housekeeper gave her.

The boys meanwhile had whittled three fresh sticks, and attached their knives and drinking cups. Their object was to explore a certain fastness of the woods which had no road through it, and to reach a mountain-top, the crags of which had seemed to look with scorn upon them all summer.

Tom was very much vexed that Cassie had heard their desire and shared it, and he was not disposed to be at all gallant. Stanton, being fond of his sister, was more concerned lest she should be, as he phrased it, "fagged out." So for a while their walk was a silent one.

Cassie did not care. She was not one of the pouting sort who shrug their shoulders and get huffy. She knew she was strong, and she hadn't time to waste on little humors and moods, and then she had so much to do. There was her collection of butterflies, her pressed flowers and ferns, her acorn work and her pine cones, frames to make for her sketches, and, besides all this, she was crocheting "Tam o' Shanters" for the boys.

Their path first led them through pasture-lands and stubble, over fences and stone walls. Then they plunged into the thicket, which was dense and brambly, and very rough every way. And now Stanton's axe became of use. "For you know we will want to get home again," he said, as he gave a vigorous cut here and there on each prominent tree, "and this is the way hunters always do."

As he spoke he struck what appeared to be a decayed trunk, when instantly out flew a swarm of angry bees. A ringing laugh from his companions was soon followed by an ominous silence, for all found themselves surrounded by the disturbed insects. Cassie, thinking discretion the better part of valor, hurried away with her dress over her head, but the boys had a hard fight to get off; as it was, both were stung, and had to apply mud poultices. This did not increase their good-nature, and the sun was now adding to their discomfort.

Cassie began a little song, but the way was so steep, and the rocks so precipitous and slippery with pine-needles and moss, that her notes died away for want of breath. She was getting very tired, when Stanton complained of hunger, and Tom espied a brook; so they all concluded to make a halt, and refresh themselves. After the rest and luncheon, with many a draught of the delicious spring water, on they again toiled; and now they seemed to have overcome the worst troubles of the way. The under-growth which had been so dense decreased; broad patches of huckleberry bushes offered their fruit; velvety mosses and nodding ferns made the way beautiful; and here and there through the trees came glimpses of the mountains stretching away in the blue distance. On the top of the crags which lay before them was an old leafless tree which had been scathed by lightning. Up this the boys proposed to climb, and fasten a little flag they had with them; so, hurrying on, they left Cassie to more slowly overtake them.

The spot was so pretty that Cassie lingered, picking a leaf here and there, and listening to the soft whisper of the breeze. Suddenly a crash as of a falling bough arrested her attention; then a cry of alarm, succeeded by as sudden a silence. Hurrying forward, she found Tom bending over Stanton, who was lying all in a heap at the foot of the tree.

"What is it—a fall? Is he dead?" she cried.

Tom turned his white face to her, utterly speechless.

"Get water—quick! But oh, look here!—he is bleeding!—he is cut!"

"Yes, he fell with the axe in his hand. The limb must have been rotten; it gave way," said Tom at last.

"But he will bleed to death, don't you see? What can we do?"

"What, indeed?" muttered Tom, still with a dazed look in his eyes.

The blood, warm and of a bright red, was gushing from the hand. It looked as if an artery had been severed. Cassie's heart sank as she saw Stanton white and immovable, and Tom transfixed with horror. She essayed to stanch the flow with her handkerchief, but it was useless. How could she let her darling brother die for want of help? Then a sudden inspiration came. She had heard of the tourniquet which surgeons use when amputation is necessary. She made Tom grasp Stanton's wrist, while she unbuttoned her cambric skirt and tore it into strips; with these she bandaged the boy's arm, tightening the knot by twisting a stick within it until there could be no longer any circulation between the hand and arm. Then she held it up and watched the success of her plan. Tom helped her as well as he could, but in a benumbed sort of way. He seemed to be in a dream, and the sight of the blood sickened him.

"Now go for water—quick!—quick!" said Cassie, taking her brother's head in her lap, and gently fanning him.

Tom obeyed. It seemed an age to Cassie before he returned, but her whole mind was absorbed in watching the wound. Already it had stopped that rapid flow, she was sure.

And now there was a change in Stanton's face—a little quiver of the lips and nostrils, a sigh, a shudder, and—oh, joy!—the boy opened his eyes and asked, "What is the matter?—where am I?"

"You have hurt yourself, dear. Lie still," whispered Cassie; "please keep still."

"But what is this? why am I all tied up? I can't use my arm."

"You have fallen, and been cut by the axe," explained Cassie, glad to have him conscious, but fearful lest any movement should start the bleeding again. "Do you think you are hurt anywhere else?"

"I don't know. I guess I am only bruised."

Tom now brought the two drinking cups full of water, and after his head was bathed, Stanton tried to get up and walk. But he was faint from loss of blood, and stiff and sore.

"It's no use; you'll not be able to go home," said Cassie.

"But what on earth will I do? I can't stay here."

"We'll have to rig up an ambulance," said Tom, now a little more self-possessed.

"You can not do that," answered Stanton, feebly, glad to again lay his head in his sister's lap.

"Sha'n't I take you on my back?"

"No; even if you were able to carry him all the long distance, he could not endure it. See how faint he is," Cassie whispered. "Besides, I am so afraid the cut may start again. Leave us both here, Tom, and go home as fast[Pg 744] as you can; they will find some method for getting him back."

"And let you be all alone with him perhaps half the night? Suppose—suppose—" He could not say the words, but his anxious glance at the pale face and ghastly spots of blood betrayed his fear.

"It can not be helped. I see no other way."

"Aren't you afraid?"

Cassie smiled a little as she said: "Yes, I am. But there's no help for it."

"Wouldn't you rather go, and have me stay?"

"No, indeed; I could not leave Stanton. Only be as quick as you can, and tell them not to forget anything. Mother will think of everything, though, if you don't frighten her. Be sure and break the news gently."

So Tom went off, and Cassie fanned her brother while he slept. Then she opened her little book and read a page or two of Longfellow. The afternoon stretched on its weary length; the chirp of crickets and the hum of insects were all that broke the stillness. Stanton moaned in his sleep, and the flush of fever succeeded his first pallor.

The dusk came on, and stars began to twinkle. To Cassie's weary vision the woods became peopled with fantastic forms. She imagined she saw a snake glide stealthily past, and twist itself in and out the brake. A spider made her tremble. The hooting of an owl sent cold shivers down her spine; her limbs were cramped and stiff with sitting so long in one position; and when the men came with lanterns, blankets, brandy, and the village doctor, and carried Stanton to the nearest farm-house, Cassie was glad to throw herself in her mother's arms and have "a good cry."

"That girl's presence of mind saved her brother's life," Tom heard the doctor say next day; and then remembering his own speech of "girls being no good anyway," he began to think he had made a mistake. Stanton soon recovered. The cut, though dangerous, readily healed, and there were no bones broken.

Cassie did not have her surgical ability again tested, but the boys all avowed she was "plucky," and showed their appreciation by various gifts of caramels, popped corn, and green apples.

As for Stanton, he had always loved Cassie, and said she was a sister worth having.

AN AFTERNOON TEA.

AN AFTERNOON TEA.

Did you ever see a humming-bird? If you live in the country, or if you have been in the country during summer, very probably you may have done so, though in our Eastern and Middle States, and, in fact, in any part of the Atlantic States, they are not very abundant. Only one species, the ruby-throat, will you find east of the Mississippi, except that the Mango humming-bird comes over from Cuba into Florida, and then follows a little way further up the coast. But if you have ever seen one, you are not likely to forget it. There is no family of birds which attracts more attention, or which deserves more. Their size and their movements make them really objects of wonder. They are the smallest of all flying things, except insects, and in truth some of them are decidedly smaller than many of the large insects. And then, too, they come and go so like magic as always to astonish those who are not accustomed to watching them.

You see one hovering over a flower, but you can not tell how he hovers, for he moves his wings so rapidly that you can not see them; there he hangs in the air, making all the time a low hum, from which he takes his name, and which is caused by the flapping of his wings. You are looking at him, and all at once he is not there; but you probably did not see him go, for he shot away so quickly that you failed to detect it, and perhaps in another second there he is again, hanging in the same place, over the same flower. That is what a humming-bird does, and it is not strange that they are counted so wonderful,[Pg 745] especially when you add to it all the fact that their colors are almost always very brilliant. Even our own little ruby-throat, which comes so far to the north, flashes like a fiery coal when he brings his red throat to glance in the sunlight.

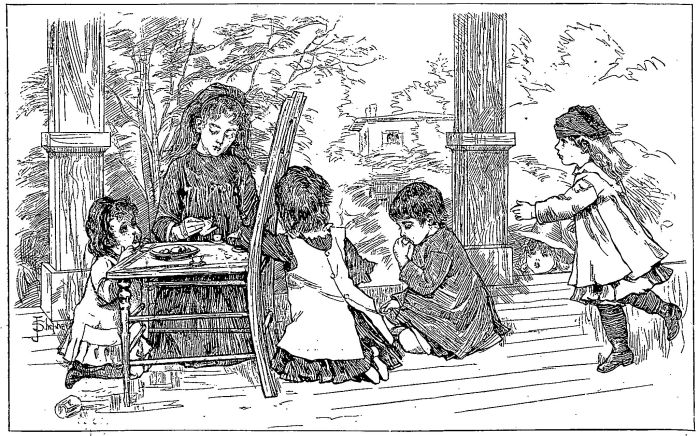

HUMMING-BIRDS AND NEST.

HUMMING-BIRDS AND NEST.

I have said that humming-birds in general are marked with brilliant colors. This is strictly true; but among them all there is scarcely one more gorgeously elegant than the one whose picture you see here, and whose Spanish name I have placed at the head of this account. Perhaps you can not read it in Spanish, but you can in English; it means the gold and emerald tuft or curl; and when I tell you more about him, you will understand the reason for such a name. I do not think the name is a common one; perhaps it is called so only by the people who told it to me; but it struck me as being so beautiful, and fitting the bird so nicely, that I have always loved to remember it. In works on natural history it is called Rhamphomicron microrhynchum. What do you think of that? What a horrid long name to give to such a lovely little fellow! It is as long as the bird himself. I doubt if you can pronounce it. El Bucle (boo'-klay) de Esmeralda y Oro sounds to me like music in comparison with it. Shall I tell you where I first saw him?

It was in a place almost as remarkable as the bird himself. The species is found only on the west coast of South America, and even there you do not see it until you reach the high valleys of the Andes.

I had landed about two weeks before at Truxillo, which is a port in Peru a little more than three hundred miles north of Lima. Look on your map, and find it. You will see that it is about eight degrees south of the equator. The name is Spanish, and you must pronounce it Trooheel'-yo. Does that sound strange to you? It should not; you ought to be taught to pronounce it that way in school. The Spanish x sounds like our letter h. Truxillo was founded by Pizarro nearly three hundred and fifty years ago, in 1535. But we must not stop here; we are looking for El Bucle.

It was the third day after my leaving Truxillo, when I found myself in a deep valley filled with flowers, and over the first flowering bush a humming-bird was hovering. I saw at once not only that he was very beautiful, but that he was different from any one that I had seen. It was my custom there to keep one barrel of my gun prepared especially for humming-birds, that is, loaded with what is called dust-shot, thus enabling me to kill them without tearing their skins, as large shot would do. It was but a minute, and I had my new bird in my hand. The right-hand figure of the two in this plate represents him as I saw him then, excepting that here the colors are not given, but I will describe them to you.

The top of his head and his back—his cap and mantle, so to speak—were of the most exquisite deep dark violet; his throat looked like polished gold, its long scaly feathers appearing to be gilded plates; while his sides and breast shone like emeralds, so bright was their green color. You see that his under surface was thus all emerald and gold—esmeralda y oro—only that his delicate little feet, almost too small to be seen, were so white as to fairly sparkle. At the same time his wings and tail were of a rich purplish-black. Can you imagine anything more elegant? I sat down to admire him, turning him over and over in my hand, and while I was thus engaged I heard a step, and looking up, I saw that one of the native girls from a house just below was coming toward me. I spoke to her, and after the usual salutation I asked her, "Seņorita, como se llama este pajarito hermoso?"—"What do you call this beautiful little bird?"—and then she told me its name, just as I have told it to you. She also told me that the skins were sometimes set to wear as a brooch or buckle, and I did not wonder at it, so very beautiful were the colors.

These figures are of the natural size, and you can judge for yourself how small he is. Even with such a long tail as he has, his entire length is only three and a half inches, thus making him decidedly smaller than our ruby-throated humming-bird. As I went on down the valley I found them in abundance, and I found also that in that valley scarcely any other species was to be seen.

I was constantly watching for their nests, and before very long I saw one, and you have it represented here, with the two birds sitting on its edge. It was a very difficult matter to distinguish the nest, either that one or the others which I afterward saw, for they looked almost precisely like little knots on the bark. I found the first from seeing the bird sitting on it, and having learned how they look, I was able to find others. I climbed up to examine a number of them, and they were really very charmingly built. They were made of fine twigs and mosses, the inside being lined with the soft down from plants, while the outside was covered over with lichens, evidently with the intention of hiding the nest by causing it to look only like a knot or lump on the bark, and it was so neatly done as to require close search before the nest could be found.

You have seen from what I have said, even if you have not noticed it yourself, that humming-birds come about flowers of various kinds constantly, and evidently do it for some object. Perhaps you have been told that they get their food from the flowers. Do you know of what that food consists? It was formerly always said that they sucked the honey from the flowers, and that the honey constituted their food, and I have read many accounts in which the attempt was made to show how nicely their bills were fitted to draw up the honey from the bottom of the flower. We know now that this is not so. The humming-bird has nothing to do with the sweet fluid in the flowers, which by-the-way is not honey, though it is often called so; he cares nothing for it. Then why does he come to the flowers, you may ask, if he is not getting something from them. He is getting something; he is getting his food; but that food is insects, and nothing but insects. The sweet fluid of the flowers attracts great numbers of small flies of various sorts; you can scarcely look into any sort of flower without finding more or less of them, and sometimes the flower will be almost black with them. This the humming-bird knows, and he thrusts in his bill, and throwing out his slender sticky tongue, he picks up the flies one by one and swallows them, and that is the way he takes his meals; but the honey is nothing to him. The next time you see a humming-bird, watch him carefully, and remember what it is he is gathering.

Race-ball is a highly interesting game, combining the best points of lacrosse and chevy. The game is played with five men on a side, each armed with a lacrosse bat. The sides congregate in their respective dens, and the captains toss for innings. Let us suppose the captain of C den wins the toss, the D den side then range themselves in a row on the line E, and the first man in on the line F, the latter having a lacrosse ball on his bat, and with this, directly the umpire cries "play," he tears off in the direction of the "Home" A, and the D side give chase, the object of the man in being to drop the ball in his "Home" while part of his foot, at least, is over the "home line"; the object of the others, to deprive him of the ball and take it to their den. If he get home, he waits till all his side get their innings, and then starts again; if not, he is out. Each man home counts one point, and the inning lasts till all are out, when the total is made up, and the other side go in, the highest score, of course, winning. When a man finds he can not get home, he may get the ball back to his den, and then wait his next inning, but without counting anything for his "failed inning." None of the in side may help the man in; one minute is given to the out side to get ready between each man, and three minutes between each inning. The usual rules as to umpires, etc., will hold good, and the man in may not run into his opponents' ground or out of bounds, or he is out, and if he unintentionally run into his own den he counts a "failed inning" as above.

I'm Bartlett myself—R. F., and my partner's name is Guy. Anyhow, he was my partner once, but he isn't now, because we've gone out of business. We've been acquainted ever since we were real little, and always good friends, except once in a while we have a tiff or something.

Last summer there was going to be a big celebration at New Holland. It's called New Holland because our State sent over for lots of Holland people to come and settle, and we'd give 'em land. So they came, and we gave 'em farms, and their town is called New Holland, and it's twelve miles away from Deerville. Deerville is our town.

Well, the Governor was coming, and more'n a dozen brass bands, and militionary companies, and folks from all over everywhere. And they were going to make speeches and sing and eat dinner. And I and Guy we were talking about it under a plum-tree in the garden.

"Cal Pressy says his father's going to have a shanty and sell things out there—gingerbread, and pies, and pea-nuts, and such. And lemonade."

'Twas before this that I and Guy we wanted a good lot of money for something very particular. I don't mind telling you about it now, for 'tain't likely we'll ever get it, and I'd as lieves some other boy'd have the chance as not.

'Twas to buy a pony we wanted it, like those the circus had. The circus men told us that they bought their ponies of a man named David Solomon, who lived in a county that sounded like "Jumpup," down to Texas. And he had one more pony to sell for ten dollars, which was cheap, but we'd have to pay for him to ride on the cars.

The circus man winked a good deal and laughed when we thanked him, and said 'twasn't any trouble at all, and he hoped we'd get the pony.

So that's what we wanted the lot of money for. And as soon as Guy said that about Cal Pressy's father, an idea popped into my head, and I popped it out of my mouth:

"Let's we have a shanty too."

Guy stopped to think a minute.

"Well, say we do," said he, when the minute was up; "if the folks'll let us, which maybe they won't."

But I said they would; for I knew my father always likes to have me do business on my own hook, because he says it learns a chap to think for himself; and mother's bound to say "yes" if father does; and Mrs. Arnold always says, "Do as Mrs. Bartlett tells you"; and of course Mr. Arnold wouldn't fly in the faces and eyes of all three of 'em, and he's a little man anyway.

So it turned out just the way I said this time, though they chaffed us some, and father and Mr. Arnold made a good deal of talk about the new firm. But I and Guy we didn't care.

We counted up our bank money, and I had five dollars and four cents and Guy had three dollars and seventy-nine cents. But his father lent him one and a quarter to make him even partner, and Guy gave his note.

So that made ten, and ten dollars'll buy quite a lot of things. And the women-folks they said they'd make the pies and gingerbread and cake for nothing, but we must buy the flour, and so forth. So we did. The and-so-forth cost a good deal more'n the flour.

So we had six left—six dollars—and we bought candy with it, and nuts, and twelve lemons, and some sugar. And we divided up so's if it came to eating we wouldn't get more'n belonged to us. And we painted a sign with black paint:

It looked real nice. And Captain Tilley said he'd lend us his camping-out tent if we'd be careful of it, and we said we would.

So that's all until we came to go. We went the night before with the express wagon and Duke, because our old Duke he's pretty slow, and we wanted to be there before the procession did in the morning.

Well, we got to New Holland, and we were going to set up our tent 'long-side of the Capitol—that's their meeting-house and school-house and town-house all in a bunch. And I and Guy we were going to set up and get ready to sell things, when along comes a man, and says he, big as life,

"Got a license?"

"No, sir," said we.

"Then you can't sell here," said he.

"Why not?" said I.

"My father's name is Mr. Arnold," said Guy, redding up, "and he keeps a store."

"I don't care ef he keeps a dozen stores," said the man.

Come to find out, that man had bought the right, if that's what you call it, of a mile square, with the Capitol in the middle, and folks had to give him money or they couldn't sell there.

"How much is a license?" said I.

"Five dollars," said he.

"Will you trust us?" said Guy, bold as brass.

"No," said the man, "I won't."

Well, sir, we didn't know what to do, and all that gingerbread and pies and things just waiting to spoil. And we stood and thought.

"Let's we go half a mile back on the Deerville road," said Guy, in a minute, throwing up his hat, with a hooray, "and then the procession'll go by us, and maybe the folks'll buy something."

"Good!" said I.

So we found out how far half a mile was, and we went a little more, so's to pitch right on the top of a long hill. And we hitched old Duke out to grass. And after a while we laid down in the tent, and said 'twas fun. But I thought, for my part, I'd rather be to home.

In the night I dreamed I was in swimming, and the water was awful cold. And pretty soon I woke up, and there I was two inches deep in water, and 'twas raining like sixty. So I woke up Guy, and we felt round and found that the things to sell weren't getting wet; and then we sat down on a board, and the next thing I remember of 'twas morning, and the sun was shining, and I and Guy we laid there in the tent wet as water.

So we got up and combed each other's hair with our fingers, and then we ate a pie between us, and then we put out our sign. It was streaked some because it got rained on, but you could read it close to. Then we spread our pies an' things out on a board, and began to roll our lemons the way I'd seen mother do to make the juice come out easy. We rolled 'em slow, and before they were all done, after a long while, we heard music, away off and faint, but coming nearer every minute, the big drums and little drums and bugles and horns all pounding and tooting away at "The Star-spangled Banner."

Oh, it was grand! I and Guy we ran out to the road. We couldn't see the procession so far away, because everything was so misty after the rain; but we could hear it coming nearer and nearer, and we wondered if our folks would come first, or last, or where. It did seem as if we hadn't seen our mothers for a month of Sundays.

So we stood and cracked our feet together once in a while and waited. And all of a sudden we heard a thundering racket a good deal nearer than the procession—a dreadful rattling and humping and thumping, and somebody away behind singing out "Whoa!"

"It's Mr. Pressy's old roan!" yelled Guy, all on fire in a minute. "He's running away with the gingerbread 'n' stuff, I do believe."

Then we heard a screech—a regular ear-splitter. And a girl ran out of a little Hollander house across the road and down a ways. And she put her hands over her eyes,[Pg 748] and tumbled right on her knees, and screeched and screeched. And it all happened in a heap, though you have to tell it one to time; so about as soon as we saw Mr. Pressy's old roan and the woman we saw two little Hollander babies, with their yellow hair braided in wispy pigtails, and white dresses on, playing right square in the middle of the road.

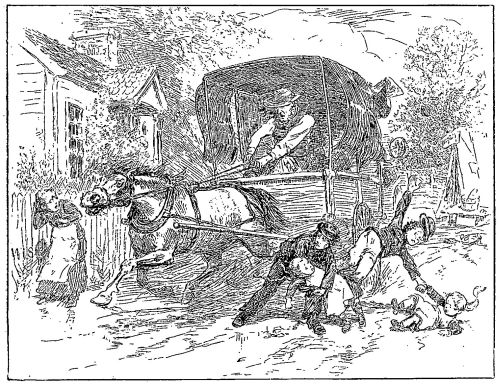

"IT WAS ALL IN A MINUTE."

"IT WAS ALL IN A MINUTE."

It seems to me as if I looked at Guy a long, long time, and Guy looked at me. And I thought about my mother, and my dog Ponto, and that we hadn't rolled all of the lemons; and then I felt as if something gave me a push. And it was all in a minute, and I and Guy we ran. And Guy was a little first, and he grabbed the nearest one, and I grabbed the other, and felt the horse right over me. And I jumped sideways, and threw the little Hollander, and something hit me.

So that's all I knew till I heard a roar in my ears that grew louder and louder, and pretty soon I knew 'twas folks talking, and I opened my eyes, and there I was in a little low room, with two funny brass candlesticks on the mantel-shelf; and my mother was there, and Guy, and Mrs. Arnold, and father, and Mr. Arnold, and Dr. Henry. They looked funny to me, and there was a queer smell in the room, and my head was tied up with a wet rag; the wet was what smelled so funny.

"Hullo!" said I, first thing.

"Oh, my boy!" said my mother, and then she began to cry like a good one.

"Pulse is pretty well," said the doctor, feeling of my wrist.

Then I looked at Guy, and Guy looked at me, and we both began to laugh.

"All right," said Dr. Henry, rubbing his glasses up; "he's all right, Mrs. Bartlett."

And so I was, only dizzy a little, and headachy where the hub of one of Mr. Pressy's wagon wheels had hit me.

Well, when we went out of the little Hollander house, there was the Governor's carriage stopped right in front, only I and Guy we didn't know 'twas the Governor's then. And the whole procession had stopped; and when we went out, you never heard such a cheer as the folks gave, just as if we'd done something big. They swung their hats—and the Governor did too—and hurrahed like all possessed for "Bartlett & Arnold." Because, you see, that Hollander woman she told the Commissioner what the fuss was all about, and he got up on a wagon and told it in English to the crowd, and the ones that could hear told the ones that couldn't, and my mother said when it came to her she thought she must faint. But she didn't; she wouldn't be so foolish.

So the folks cheered, and laughed a little, when they looked at our sign. And something swelled up big and hard in my throat, till I almost cried; but not because I was sorry. Guy almost did too. And my mother kept tight hold of my hand, and choked, and said:

"Now you'll come with me, Roy; I can't leave you here again."

Mrs. Arnold said so too. But I and Guy we said we'd got to sell our things, because we couldn't afford to lose ten dollars, could we? And there was the pony, too.

So we went over to the tent, and our mothers with us. And it seems as if everybody understood, for they came in and bought things until we had more than fifteen dollars, and not a gingerbread or anything left.

So then we said we'd go. And I suppose you won't believe that the Governor sung out "let the little young gentlemen ride with me, if you please, madam."

So we did; we rode with the Governor. And he talked to us, and looked just the same as other folks, only not so handsome as some. We sat side of him at dinner, too, because he said for us to; and after dinner some of the folks put us in their speeches. And I hope we didn't feel too stuck up about it, though my father he said 'twas enough to turn any boy's head.

So we made something out of it after all; and Guy said, what a good thing it was we didn't have a license, and had to go back just to where the babies would be in the road, or else they'd have been run over. And most all of Mr. Pressy's gingerbread and things bounced out along the way, so he didn't have much to sell; but he whipped the horse to pay for it. And that man that wouldn't let us have any license stood around all day and looked as if he thought somebody ought to give him a dollar. And we is satisfied, I and Guy are, because we made quite a lot besides what we ate, and the babies didn't get run over to boot. But don't you believe that the Hollander woman shook the two poor little chaps up like a breeze because they got their frocks muddy. That's what the folks said, anyhow, and it's just like what some women would do, I think.

'Tisn't likely we'll ever get the pony the way I said at first, because the circus man didn't tell us the town where Mr. David Solomon lives, and we don't know. And I don't know as I ought to tell this story, because it's about myself so much; but maybe you needn't print my name to it, and then folks won't know it's me.

Six little goslings without any shoes,

But to make them the shoemaker has to refuse;

For he has no last that will fit their queer feet,

And in great disappointment they'll have to retreat.

And now, Baby Curlyhead, what shall we do

With six little goslings without any shoe?

We take their soft down to make Baby a bed

On which he can pillow his soft little head.

It's very naughty of the bees

My little boy to scare and tease,

And eat his bread and honey up;

They can breakfast out of a buttercup.

See the jolly, jolly baker,

He who makes the cakes so nice;

How he kneads them, kneads them, kneads them,

Out of sugar, flour, and spice.

To the oven then he takes them,

In the great hot oven bakes them,

Thinking all the time, it may be,

Of my cunning little baby,

Who will eat the sugar-cakes

That the jolly baker makes.

Awake, awake, my baby,

The morning sun is up

And waiting for my baby

To find a buttercup.

Buttercups and daisies

Are growing all around,

And here are baby's little shoes

To caper o'er the ground.

Soon he'll bring me pretty flowers

Gathered in the morning hours.

Golden-rod and asters;

Pears and purple grapes,

Just the prettiest colors,

And the finest shapes.

Through the dear old orchard,

Down the dear old lane,

After fruit and flowers

They will go with Jane.

First, a kiss from Kittie

Through the meadow gate.

"Hurry, sister Elsie,

We will be too late."

This from Master Freddie,

Who would hate to miss

Golden pears and apples

Just to get a kiss.

Do not fear, the flowers

And the fruit will wait

Till a little maiden

Kisses through the gate.

"Woodlawn," Jenkintown, Pennsylvania.

Dear Young Folks,—You have read so often in your charming paper of the wonderful intelligence and strange fancies of animals that I am tempted to write you of a "Happy Family" in which we are all greatly interested.

About four weeks ago I went down to the stable and found a mother cat and three little ones on a bed of straw in a half-hogshead. A few days later another cat had three snowy little kittens in the same place. They were the prettiest creatures you ever saw, and the happy mammas seemed to enjoy my admiration of their babies.

The next morning, on visiting my pets, the cats were away, and to my astonishment I found a speckled hen sitting on four of the kittens. I drove her off, but she went most unwillingly. The next day she was there again, and the next, but two of the kittens had been carried out on the floor, and as I was afraid the cats would hide them, I removed the two families, putting them on some straw behind their former home. In a few moments the hen found them, and has never left them day or night except for her food. The little ones are growing finely; they creep under and around her, play with her feathers, and do the funniest things imaginable, all of which I am sure she enjoys.

It is a strange and beautiful sight—the two mothers, the six babies, and the demure old hen making herself as large as possible, often spreading her wings to accommodate one of the old cats.

A friend said to me, "I wish you would write this out for publication, but I fear you will not be believed; I should have doubted the story myself." So I have written a mere outline of the pretty scenes enacted down in the stable entry of my country house; no day has repeated itself, and as I write, the foster-mother, nurse, friend of the family, or whatever she may be called, is faithfully brooding over her charge, crooning low, as if to a brood of little sleepy chicks.

I wonder how all this will end? When the children go out into the world to seek their fortunes, will their devoted nurse stay with the "old folks"? I know not. But this I know: that the fate of barn-yard fowls shall not be hers. She shall be marked with our approval, and shall live out all her days in her own way, and according to her "own sweet will."

Hoping I have won your interest in my little family, I am very truly yours,

F. T. C.

The Postmistress thanks you in behalf of all the children for this very entertaining account of your pets.

Paris, France.

My auntie, living in Washington, sends Young People to me. I like it very much. I can hardly wait a week for it to come, because the continued stories all leave off in such interesting places. All the little boys and girls who write letters tell about their pets. I have not any. I have neither brother nor sister. I am eleven years old. I go to a French college, where there are twelve hundred boys. It is a government school, and we wear a uniform. Blue pantaloons with red stripes up the side, a jacket and vest with brass buttons, and a little cap trimmed with gold tape. The name of my school is College Rollin. Each boy has his own room. We go to bed at eight o'clock, and get up at six. Papa comes for me Saturday evening at seven o'clock. I spend Sunday at home, and return to the college at nine in the evening.

I am taking my vacation now. I went with my uncle to the sea-shore at Dieppe. There is a very old fort there, and also old churches about falling to pieces. I went to Dinan, and saw a large fortification. I went to St. Malo, and then to Granville. Both of these places are on the sea-shore, and both have old forts and churches which interest visitors. I gathered some pretty shells and pebbles. I had a very nice time playing in the sand. I also went to the Isle of Jersey, which belongs to England. We went to take a drive, and I saw some large caves.

I am now staying in the country by the side of a little lake, and in about five minutes' walk you are in the woods. I have a little boat in which I sail on the lake. I have a friend who has a donkey. I go nearly every day to ride with him.

This is the first letter I have written to Young People. I hope it is not too long to be published. My auntie is very much interested in the Post-office Box.

Harry J. B.

Your letter pleased me very much, Harry, for it was almost as easy to read as print, so very carefully had you formed each character. Your uniform is a very pretty one. I hope all the boys who wear it behave always like little gentlemen. I am glad you had so pleasant a vacation.

Beechland, Kentucky.

I have been wishing to write to you for some time, but as my oldest brother had written, mamma said it would be better for me to wait awhile. Friday was my birthday; I was seven years old. Brother is almost nine, and we have a fat little brother just five. Our baby sister is almost two years old, and she is so cute and sweet! We all like the paper very much indeed, and think the pictures beautiful. We have an aunt eight years old, two little cousins, and brother Willie and myself who take it, so we have a nice time talking about the pieces when we are all together. Our papa has a new hay-press. We love to watch them bale the hay. I think we boys who live in the country have fine times, there is so much to see and to do, and we have so much nice fruit. Mamma says it would be better to live in the city in winter, so that we could go to school. As it is, she teaches us at home. There are so many of us to play together that we do not care much for pets. Our dog Tip is one year old now. He was named for Tip in Young People. He is a real smart dog, although he is so small. He wants to go with us wherever we go, but mamma wants him to stay at home, so now whenever the "Jersey" is hitched up he hides himself under the back seat so that we will not notice him. We have a great many things I would love to tell you about, but I have not time now. My little brother Charlie will want to write before long.

Luddie M. B.

Brooklyn, New York.

I am a little girl eleven years old, and have taken Harper's Young People from the first number. I am just recovering from a severe attack of diphtheria, which has left me with both limbs paralyzed. I have a little sister five years old, and her name is Mamie. We have no pets except a little canary-bird whose name is Dickey; he is the sweetest little fellow you ever saw. If you wake him up in the night he will get very angry, and spread out his wings, and open his mouth wide at you. Has the dear Postmistress ever read the "Elsie Series"? I have, and think they are very interesting. Good-by, dear Young People.

Jessie S.

I hope, dear Jessie, that you will in time recover your strength, and be able to walk again. I hope that Young People helps to amuse you and pass the time that might be weary without it.

Huntington, Long Island.

I am ten years old, and have taken Harper's Young People ever since the first number came out. I have every one except No. 142, and that papa left in the ferry-boat. In winter we live in Brooklyn, but in summer we come to my grandpa's farm. It is very pleasant here; it is thirty-six miles from Brooklyn. I have two sisters and one brother, all younger than myself. One of my sisters is a baby, and I am her godmother. She is so cunning! We had four squirrels, but my brother's and baby sister's died, and I gave mine to brother, so that I have no pets now. We have four cats. The largest one is Solomon Isaac Moses Levy Marcus Antonio, the next is Lizzie, the next is Fannie Smith, and the fourth is Jumbo Peter.

Aimee H.

Did you not have a headache, dear, after giving Puss No. 1 that remarkable name? I hope you do not forget to set every day the very best example you can to the little one whose godmother you are.

Hood River, Oregon.

I have never seen a letter in the Post-office Box from this place, so I thought I would write. I have taken Harper's Young People since November, and like to read it very much. We are spending our vacation here, but our home is in Portland, Oregon. We are only about fifteen miles from Mount Hood, and we can also see Mount Adams very plainly from here. Most of our trees are pine, but there are a great many oaks too. We have lots of fun swinging on their long branches. My brother and another man killed a rattlesnake with six rattles the other day. We eat out-of-doors, in a dining-room made of small pine-trees and boughs. We have a horse whose name is Silly. There are five girls in our family and two boys. My baby brother is three months old, and we think he is the dearest baby in the world. He laughs right out loud sometimes. I have been trying to learn something else besides what I find in my books at school, but all that I have yet learned to do well is to darn stockings and make biscuits.

Dora D. E.

If you can make good biscuits, light and sweet, and darn stockings well, you are quite a little housekeeper already.

Gallipolis, Ohio.

I have not been taking Young People very long. But my father bought a few copies when he was at Richmond, Virginia, about two or three months ago, and I liked them so much that he gave me a subscription for a birthday present. I have not many pets, but my grandmother, who lives next door to us, has a fountain about eighteen feet round, and she has some gold-fish. They are the largest that were ever seen in this city. They are about ten or twelve inches long, and they will jump out of the water for something to eat if you hold it in your fingers. They have two little ones, which appeared in the spring. At first they were quite dark, very nearly black, and then they turned a pale yellow on their sides, and finally became a golden color. The four fish came all the way from Cincinnati in a quart bucket, and now you could not get one of them into a bucket so small. They lived all through the cold winter, and many and many a morning the thermometer was down below zero, and the fountain was frozen over. They would not eat our food through the winter, and they must have lived on insects or on air.

Edward S. A., Jun.

Silverton, Colorado.

As I have not seen a letter from the Gem of the Rockies, as our pretty town is called, I thought I would write one. While I am writing,[Pg 751] it is snowing quite hard, this last day of August. When I got up this morning, as soon as the fog had disappeared, the mountains looked beautiful. I have a nice pair of snow-shoes all ready for winter. It is great fun snow-shoeing for my sister and I. I have a big sister, who is helping me to make clothes for my doll. Her name is Saidie. I am a little girl eleven years old. I am always so delighted when I see papa coming home with my Harper's. Much love to the dear Postmistress.

Florence F.

Snow in August, Florence! No wonder you need snow-shoes for winter at that rate.

The apples, O! the apples, O!

See they come tumbling

Down below.

Climb the ladder,

And shake the tree!

One for baby,

And one for me,

And one for Dick,

Who climbs the tree

And shakes the apples,

And that makes three.

The apples, O! the apples, O!

Into the basket

See them go.

Pippins and Baldwins

All in a row;

One for baby,

And one for me,

And one for Dick,

Who climbs the tree

And shakes the apples,

And that makes three.

There are some amusing features connected with the process of making the very useful article we call indigo. You all know that it is a plant. The leaves, which are green, are first placed under heavy pressure, and then steeped from ten to fifteen hours in immense vats, so large that they contain 2000 cubic feet of water. In very hot weather this water swells until the surface becomes a frothing liquid, and should a match be applied, it would cause a loud report, and the flames would leap from vat to vat, like the will-o'-wisp flitting over marshes. These vats are filled from immense reservoirs, into which the water has been previously pumped. They have a time-keeper, who is called "gunta-paree"; he watches the process closely, and at the proper moment lets the steeped liquor run into another vessel, called the beating vat. And now comes the funniest part of it. They put a gang of coolies into the vats, each one having a long stick with a disk at the end. The coolies immediately plant themselves in two rows, facing each other; then they commence throwing up the liquor, which, meeting in mid-air, the two jets fall confusedly together. This they continue until the excitement grows intense. Such a screeching and yelling, with splashing of water and beating of sticks, until their naked bodies fairly glisten with the blue liquor. Oh, how they twist and contort themselves, until they look like imps or queer blue demons!