Project Gutenberg's Harper's Young People, October 3, 1882, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Harper's Young People, October 3, 1882

An Illustrated Weekly

Author: Various

Release Date: May 31, 2019 [EBook #59639]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S YOUNG PEOPLE, OCT 3, 1882 ***

Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| vol. iii.—no. 153. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, October 3, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

"ALL ABOARD!"

"ALL ABOARD!"

Any one who had come down the St. Gothard to the village of Andermatt, just at daybreak one cold winter morning in 1799, would have seen a very curious sight. All night long the village folks had been busy packing up and carrying away in carts or on horse and mule back whatever they could most easily remove. The first gleam of dawn saw the hindmost fugitives slinking away into the passes of the northern hills, looking fearfully back every now and then at the towering crest of the St. Gothard, as if expecting the whole mountain to fall upon them at once, or to send forth a torrent of fire that would sweep them all away.

The danger from which they were flying was not long behind them. Scarcely had the sun peered above the surrounding hill-tops when the great white slope of the St. Gothard seemed to grow[Pg 770] black all at once, like a white cloth swarmed over by flies. Instantly the whole mountain-side was alive with bear-skin caps, and glittering bayonets, and prancing horses, and bright epaulets, and rumbling wheels, and shining cannon.

Down they came, still downward, thousands upon thousands—tall sallow grenadiers in long overcoats of gray frieze, sharp-faced, narrow-eyed Cossacks with long lances in their hands, black-capped gunners, glittering hussars, blue-nosed, shivering staff officers—and high above all, fluttering gayly in the keen morning breeze, the bullet-torn standard that bore the imperial ensign of Russia.

At sight of the deserted village there was a murmur of satisfaction among the Russian soldiers; for it was now forty-eight hours since any of them had touched a morsel of food, and they were all as hungry as wolves.

"These mountain goats have run away at the very sound of our coming," said a big grenadier; "but so long as they've left some food behind them, it's all right."

"Isn't this the place where they said the famous cheese was made?" suggested a gaunt, red-bearded Cossack.

"Sure enough!" cried one of his comrades, joyfully. "Hey, brothers! won't we have a good feed when we get down there!"

A good feed they certainly did have, a few minutes later. Scarcely had the foremost battalion entered the village when a shout of "Cheese! cheese!" from the front drew every one in that direction. The little shop into which the starving men had rushed was hardly big enough to hold twenty of them at a time; but Russian soldiers, after a two days' fast, are not the men to be over ceremonious. In a trice the plank front of the store was beaten in and torn down, the shining yellow blocks which made such a tempting show were tossed into the street by hundreds, and there began such a feast as Andermatt had not seen, for many a year, even upon a market-day.

But just as they were at the busiest, munching and gnawing away like so many rats, a few dropping shots in front, followed by the roll of a full volley, made them all spring up and seize their arms.

"Infantry, form!" roared an officer, galloping in among them. "Skirmishers, advance! Forward! march!"

And now the work began in earnest. The French had covered their retreat by filling the wood beyond the village with sharp-shooters, and as the Russians moved on, the pine-clumps around them seemed alive with crackling musketry and quick puffs of white smoke, while the gray coats of fallen soldiers dotted the snow on every side.

But presently up came three or four light guns at a hard trot, and sent a shower of grape-shot rattling into the thickets, stirring the crouching marksmen from their covert like rabbits. On pressed the Russians; back fell the French; when suddenly a deep, hoarse roar was heard above all the din of the firing, and right in front of the charging Russians, as they broke from the wood, yawned a chasm as deep and narrow as if made by the cut of a sword. A quaint old bridge of moss-grown stone spanned the gulf, over which the last of the French soldiers were just filing at a run.

No time to lose, evidently. Forward sprang the Russians with a loud hurrah, when suddenly there came a report, sharp as a thunder-clap, while the whole air was filled with smoke and dust and whizzing masses of stone. The bridge had been blown up, leaving an impassable gulf between the two armies; and a taunting laugh from the French, accompanied by a volley of musketry, answered the yell of rage that broke from their pursuers.

What was to be done? Unless they could reach the enemy with the bayonet, the superior numbers of the Russians would avail them nothing; and if they stayed where they were they would be shot down like sparrows.

"This won't do, lads," cried a tall, handsome man in a rich gold-laced uniform, turning to the Cossacks who stood around him. "Follow me."

All obeyed without a word, for the speaker was no other than Prince Bagration, one of the best generals in the Russian army. Creeping round behind the thickets, that the enemy might not see what they were about, they came out again upon the river about half a mile higher up, at a point where the edge of the precipice, though quite bare and rocky on their side of the gap, was thickly wooded on the other.

"If we had three or four of those trees over here," said the Prince, "they'd bridge this gap for us famously. But how are we to get at them?"

"Twist the officers' sashes into a rope, your Highness," suggested a Cossack beside him, "knot a stone in the end of it, fling it across so as to catch in one of the branches, and send somebody over on it. I once robbed a house that way myself at home in Russia."

"Did you?" said the General, with a broad grin. "Well, then, you shall make up for it by being the first man to cross. Off with your sashes, gentlemen."

The impromptu rope was soon twisted, the stone knotted in it, and flung so dexterously across the chasm that it caught in the fork of a tree at the first cast. The daring Cossack, with a sapper's axe slung round his neck, swung himself nimbly over the fearful gulf, and went to work upon the trees with such vigor that it was not long before three of them lay right across the gap, bridging it completely.

Then the Prince and his men, stirred to frenzy by the increasing uproar of the battle below, scrambled like mad-men across the perilous bridge, and rushing up the heights beyond, commenced firing down upon the French on the other side. Confounded by this unexpected attack, the enemy broke and fled, and the fight was won.

"Well done, my children," said Marshal Suvoroff, as he passed along the Russian lines after the battle, with a glow of honest admiration on his rough old face—"well done, indeed! You have given those French dogs a lesson, and shown them that Russian bayonets have points."

"If you're satisfied with us, father, that's all we want," replied a grim old grenadier, with a face criss-crossed with scars, like a railway map; "but, after all, we might well fight stoutly when we'd just had such a big meal of that good cheese."

"Cheese, eh? Where did you get it?"

"In the village yonder. We ate a whole shopful in passing through. I've got a bit left yet, if your Excellency would like to taste."

And opening his pouch, the veteran displayed to the old General's astounded eyes a half-gnawed piece of yellow soap.

A roar of laughter, which even the presence of the Commander-in-Chief could not restrain, broke from the staff officers around, and for many a day after the "good cheese" of Andermatt was their standing joke.

If you drop a lump of sugar into a cupful of tea, or stir the tea about with a spoon, there will be little bubbles, floating on the surface. Watch these bubbles, and you will see that they soon slide off and gather along the edge of the cup. Boys in the first class in philosophy know what that means. It is the attraction of the cup. It is larger than the bubbles, and, as they are free to move about on the tea, they are attracted or pulled toward the sides of the cup.

If you lift the tea-cup, you find it is heavy. The great earth, that is millions of times larger than the cup, pulls[Pg 771] it downward. We call it weight. We say the cup is pulled down by the attraction of gravitation.

Out of doors you can see the sun. It too has an attraction for the cup and for the whole round world and all it contains. It is bigger than our earth, and is pulling it toward itself. So strong is this attraction for the sun that everything that is lying loose on the earth would fly away if it were not that the world is so much nearer, and is attracting it the other way at the same time. There are some things that really start to go to the sun every day, but very fortunately they soon come back again.

Then there is the moon. She too is trying to pull everything toward herself. Poor Mrs. Moon! She is in an unfortunate position. She is pulled away toward the sun, and at the same time the earth attracts her this way. She wants to fly away and tumble into the sun, and she feels a great desire to fall down upon the world. She can't go both ways at once, so she contents herself with flying round the world once every day, and keeping us company in our journey round the sun.

The moon has her revenge on the earth. It pulls hard on the world all the time, and some of the things on the surface, that, like the bubbles in the tea-cup, are free to move, try every day to jump up to the moon. There is the air and all the water in the sea. They can move about, and whenever the moon passes overhead they move up as if to meet it. They can't go far, but they make a good start, and never seem tired of trying. If we could go up in a balloon to the top of the air we would probably find the air at one place piled up in a heap, as if it wanted to fly away to the moon if the earth would only give it a chance.

As it is not convenient for us to go up to the top of the air, we will go down to the beach to see how the water behaves when the moon goes by. No matter what time of the day or night you go to the sea-shore, you will find the water either rising up toward the moon or falling back again. It never seems to be discouraged, but as soon as it fails it starts again. You can not see it move, but if you put a stone at the edge of the water, and wait an hour or two, you will find the stone has been covered by the water or is left quite high and dry. It seems as if the whole of the great sea was forever slowly rising or falling, up and down, with a slow and solemn motion.

Any boy who lives by the shore knows that this is the tide. He knows that all his fun depends on this regular rising and falling of the tide. At high tide the fishing is good. At low tide the flats are bare, and the boys can dig clams or watch the long-legged plovers wading about in the shallow water. This curious rising and falling of the tide is caused by the attraction of the moon. The sun also helps, but in a lesser degree. How and why it all happens would take a long time to explain. We do not care for that just now, as the strange effects of the tides upon the land are more interesting.

I have already told you something of the way in which the sea and the waves are at work cutting out, tearing down, or building up the dry land on which we live. Perhaps you remember the stories of the walking beaches and the fight between the rivers and the sand-bars? We can now see what the moon has to do with this business.

The tide is like a wave. It is not very high, but wonderfully wide. It is so broad that a single tide-wave will reach half round the world. Out at sea it is impossible to tell whether it is high or low tide at any time. Near the shore the tides behave in a curious and often wonderful manner, and we can walk along the beaches and see how they work. One of the best places to do this is the vicinity of New York city.

South of this city is the harbor. Still farther south, past the Narrows, is the beautiful bay called New York Bay. Sandy Hook at the south and Coney Island at the north mark the broad entrance to this bay from the Atlantic Ocean. The Hudson River, that stretches far back into the country, runs along the west side of the city. On the east is the narrow and crooked arm of the sea called the East River. You know all this, and it may seem a trifle like a school-book, but your books never told you of half the wonders of this familiar place. The East River opens into Long Island Sound, and the Sound opens into the Atlantic at the farther end of Long Island. Thus it is possible for ships to start from New York and go to sea by the way of the harbor and bay, past Sandy Hook, or they may sail up the East River into the Sound, and reach the sea at Block Island, more than a hundred miles to the east of Sandy Hook.

In the same way the tide coming in from the sea may reach New York by the way of Long Island Sound and the East River, or by the way of Sandy Hook and the bay. Suppose it is low tide off Block Island, at the east end of Long Island (you should look on your map for all this). The tide begins to rise, and enters the Sound. In two hours the wave reaches Sand's Point, and begins to enter the East River. Now happens a curious thing. The Sound grows narrower, and the river is narrower still, and as all the water has to pass at the same time, it rises higher and runs faster. At Block Island the tide rises only two feet. At Hallet's Point, near the city, it rises more than seven feet. The quiet peaceful tide at Block Island becomes here a swiftly flowing stream that surges with foam and fury between the rough rocky banks, and making many a dangerous eddy and whirl-pool. It is no wonder the sailors used to call this place Hell Gate.

Let us look at this place a moment. The East River is open to the sea at each end. It is not like a real river, flowing down hill, and with a current constantly flowing in one direction. It has no current of its own, and were it not for the tides that surge backward and forward through the place twice every day, its waters would be dull and stagnant as any of the quiet lagoons behind the beaches that we have been studying. You can guess what would happen then. The place would soon fill up with mud and sand. Oysters and shell-fish would make it their home; sea-weeds and mosses would cover the bottom, and before long the river would be filled up, and Hell Gate would be closed. This wild turmoil of water just here, this swift-flowing current, keeps the place clear. The tides scour out the river-bed, and help keep it clean for the ships. There are more vessels passing through Hell Gate in a year than at any other place on this continent. If it were closed, our commerce would be sadly injured. Millions of dollars have been spent to make the channel clear, but it is the moon that keeps this great water gate open.

The same tide that first appears off Block Island, and travels through the Sound, also travels along the southern shore of Long Island, and reaches Sandy Hook. As the water grows more shallow, the tide piles up higher, and at Sandy Hook it is more than four feet high. It sweeps on into the bay, and past the Narrows into the harbor, growing higher at every step. It rushes past the Battery, and into the East River, and now it is a swift and powerful current. It rushes onward along both sides of Blackwell's Island, and at Hell Gate the two tides meet. This only increases the war and turmoil of the waters. One tide seems to be piled upon another, and the currents become more furious. In a very little while one or the other gives way. The current turns, and rushes as swiftly the other way. All this strange performance is the work of the moon and the sun.

Everywhere on the sea-coast all round the world the moon lends a hand to help the sea carve out the land. At Sandy Hook it also holds the key of the bay, and keeps the harbor open, that ships may pass out and come in. Were it not for the moon, Sandy Hook would creep[Pg 772] slowly out over the shallow waters until it nearly reached Coney Island. The friendly tide comes sweeping in from the sea, and spreads far and wide over the bay. It fills miles and miles of bays and rivers with water, and then when the moon passes on, and the water can follow her no farther, it turns in a mighty flood, and scours and sweeps out all the channels. The outflowing tide is a big broom to brush away the sand and mud, and keep the front door of our port open to all the ships of the world. Did not the sea every day try to reach after the moon, perhaps there would be no tides. Were the tides to stop, our grand front gate would soon be shut, and our convenient back way into the Sound would be closed. It is in this way a great and wise Creator has commanded even the moon to lend a hand in controlling the sea and the land.

Oh, mamma, I've heard such charming news

From the Bobolink down in the lane;

He knows many beautiful stories,

And promised to meet me again.

He told me about this rich Golden-Rod,

And whence came its glowing hue;

And I'm sure the bright little gossip

Wouldn't care if I should tell you.

He says when dear little Titania

Was proclaimed the fairies' Queen,

There was such a splendid banquet

As never before was seen,

And Titania's gorgeous costly robe,

All puffed with fold on fold,

Was made of a sunset tissue

Of shining dazzling gold.

The Knight of the Topaz Helmet

Was chosen to dance with her,

And he tore her beautiful court train

With the point of his diamond spur.

The wonderful exquisite fragment

Fluttered about in the breeze,

Now lighting the spears of the bending grass,

Now floating among the trees,

Till 'twas caught by the old head gardener,

Who gazed at it long, and said;

"This, fugitive flying sunbeam

Has put something new in my head,

"And our royal lady's accident

Has strangely given a hint,

And furnished me just what I longed for—

An idea of shape, and a tint

"For the flower that must be ready,

As soon as the dancing is done,

To present to our lovely sovereign

In token of fealty won.

"I'll take its form from the flashing plume

Of the Knight who threw in my way

This fleecy fluttering fragment,

So delicate, dainty, and gay.

"And if she accepts the token,

And prints with her gracious hand

The mystical sign upon it

That shows it from Fairy-land,

"I'll blow its seed to the outer world,

And scatter them over the sod,

And christen my feathery favorite

Queen Titania's Golden-Rod."

Author of "The Moral Pirates," "The Cruise of the 'Ghost,'" etc., etc.

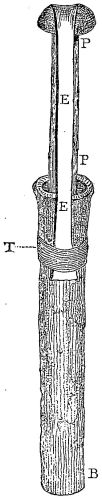

There is no place more unfit for a sudden and unexpected bath than the lock of a canal. The sides and the gates are perpendicular and smooth, and present nothing to which a person in the water can cling. Charley had no difficulty in supporting himself by throwing one arm over the stern of Harry's canoe, but had he been alone in the lock he would have been in a very unpleasant position.

As soon as the gates were opened the boys paddled out of the lock, and went ashore to devise a plan for raising the sunken canoe. Of course it was necessary that some one should dive and bring up the painter, so that the canoe could be dragged out of the lock; but as canal-boats were constantly passing, it was a full hour before any attempt at diving could be made. There were half a dozen small French boys playing near the lock, and Charley, who was by no means anxious to do any unnecessary diving, hired them to get the canoe ashore, which they managed to do easily. It was then found that nearly everything except the spars had floated out of her, and the rest of the morning was spent in searching for the missing articles in the muddy bottom of the canal. Most of them were recovered, but Charley's spare clothes, which were in an India-rubber bag, could not be found.

This was the second time that the unfortunate Midnight had foundered, and Charley was thoroughly convinced of the necessity of providing some means of keeping her afloat in case of capsizing. It was impossible for him to put water-tight compartments in her, such as the Sunshine and the Dawn possessed, but he resolved to buy a dozen beef bladders at the next town, and after blowing them up, to pack them in the bow and stern of his canoe. Tom, whose "Rice Lake" canoe was also without water-tight compartments, agreed to adopt Charley's plan, and thus avoid running the risk of an accident that might result in the loss of the canoe and cargo.

When the fleet finally got under way again there was a nice breeze from the south, which sent the canoes along at the rate of four or five miles an hour. Chambly, the northern end of the canal, was reached before four o'clock, the boys having lunched on bread and water while in the canoes in order not to lose time by going ashore. They passed safely through the three great locks at Chambly; and entering the little lake formed by the expansion of the river, and known as Chambly Basin, they skirted its northern shore until they reached the ruins of Chambly Castle.

More than one hundred and fifty years ago the Frenchmen built the great square fort, with round towers at each angle, which is now called Chambly Castle. At that time the only direct way of communication between the settlements on the St. Lawrence and those in the valleys of the Hudson and the Mohawk was up the Richelieu River, Lake Champlain, and Lake George. It was this route that Burgoyne followed when he began the campaign that ended so disastrously for him at Saratoga, and it was at Chambly Castle that he formally took command of his army. The castle was placed just at the foot of the rapids, on a broad, level space, where Indians used to assemble in large numbers to trade with the French. Its high stone walls, while they could easily have been knocked to pieces by cannon, were a complete protection against the arrows and rifles of the savages, and could have withstood a long siege by any English force not provided with artillery. In the old days when the castle was garrisoned by gay young French officers, and parties of beautiful ladies came up from Montreal to attend the officers' balls, and the gray old walls echoed to music, and brilliant lights flashed through the windows, the Indians encamped outside the gates must have thought it the most magnificent and brilliant place in the whole world. Now there is nothing left of it but the four walls and the crumbling towers. The iron bolts on which the great castle gate once swung are still imbedded in the stone, but nothing else remains inside the castle except grassy mounds, and the wild vines that climb wherever they can find an angle or a stone to cling to.

The canoeists made their camp where the Indians had so often camped before them, and after supper they rambled through the castle and climbed to the top of one of the towers. They had never heard of its existence, and were as surprised as they were delighted to find so romantic a ruin.

"I haven't the least doubt that the place is full of ghosts," said Charley, as the boys were getting into the canoes for the night.

"Do you really believe in ghosts?" asked Tom, in his matter-of-fact way.

"Why," replied Charley, "when you think of what must have happened inside of that old castle and outside of it when the Indians tortured their prisoners, there can't help but be ghosts here."

"I don't care, provided there are no mosquitoes," said Joe. "Ghosts don't bite, and don't sing in a fellow's ears."

Any one who has camped near a rapid knows how strangely the running water sounds in the stillness of the night. Joe, who, although there were no mosquitoes to trouble him, could not fall asleep, was sure that he heard men's voices talking in a low tone, and two or three times raised himself up in his canoe to see if there were any persons in sight. He became convinced after a while that the sounds which disturbed him were made by the water, but, nevertheless, they had made him rather nervous. Though he had professed not to be afraid of ghosts, he did not like to think about them, but he could not keep them out of his mind. Once, when he looked out of his canoe toward the castle, he was startled to find it brilliantly lighted up. The light was streaming from the case-mates, loop-holes, and windows, and it was some moments before he comprehended that it was nothing more ghostly than moonlight.

Toward midnight Joe fell asleep, but he slept uneasily. He woke up suddenly to find a dark object with two fiery eyes seated on the deck of his canoe, and apparently watching him. He sprang up, with a cry of terror, which awakened his comrades. The strange object rushed[Pg 774] away from the canoe, and stopping near the gate of the castle, seemed to be waiting to see what the boys would do.

By this time Joe had recovered his senses, and knew that his strange visitor was a wild animal. The boys took their pistols. Tom, who was the best shot, fired at the animal. He did not hit it, but as Tom advanced slowly toward it the creature went into the castle.

"It's a wild-cat," cried Charley. "I saw it as it crossed that patch of moonlight. Come on, boys, and we'll have a hunt."

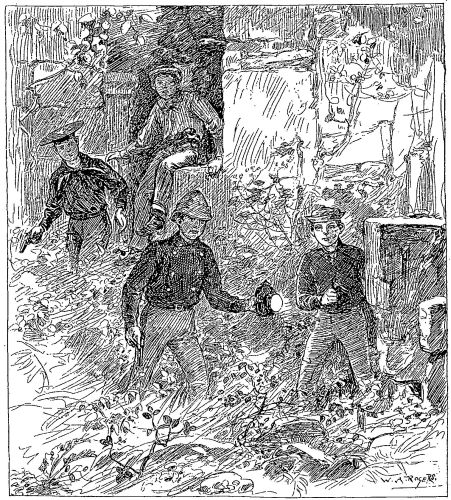

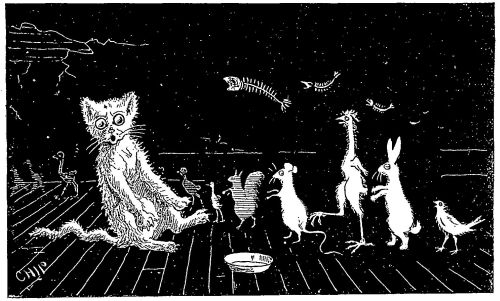

HUNTING FOR A WILD-CAT IN CHAMBLY CASTLE.

HUNTING FOR A WILD-CAT IN CHAMBLY CASTLE.

With their pistols ready for instant service, the canoeists rushed into the castle. The wild-cat was seated on a pile of stones in what was once the court-yard, and did not show any signs of fear. Three or four pistol-shots, however, induced it to spring down from its perch and run across the court-yard. The boys followed it eagerly, plunging into a thick growth of tall weeds, and shouting at the top of their lungs. Suddenly the animal vanished; and though Tom fancied that he saw it crouching in the shadow of the wall, and fired at it, as he supposed, he soon found that he was firing at a piece of old stove-pipe that had probably been brought to the place by a picnic party.

Giving up the hunt with reluctance, the canoeists returned to their canoes; at least three of them did, but Joe was not with them. They called to him, but received no answer, and becoming anxious about him, went back to the castle and shouted his name loudly, but without success.

"It's very strange," exclaimed Charley. "He was close behind me when we chased the wild-cat into those weeds."

"Has anybody seen him since?" asked Harry.

Nobody had seen him.

"Then," said Harry, "the wild-cat has carried him off or killed him."

"Nonsense!" exclaimed Charley; "a wild-cat isn't a tiger, and couldn't carry off a small baby. Joe must be trying to play a trick on us."

"Let's go back, and pay no attention to him," suggested Tom. "I don't like such tricks."

"There's no trick about it," said Harry. "Joe isn't that kind of fellow. Something has happened to him, and we've got to look for him until we find him."

"Harry's right," said Charley. "Go and get the lantern out of my canoe, won't you, Tom? I've got matches in my pocket."

When the lantern was lit a careful search was made all over the court-yard. Harry was greatly frightened, for he was afraid that Joe might have been accidentally shot while the boys were shooting at the wild-cat, and he remembered that in his excitement he had fired his pistol in a very reckless way. It was horrible to think that he might have shot poor Joe; worse even than thinking that the wild-cat might have seized him.

The court-yard had been thoroughly searched without finding the least trace of Joe, and the boys were becoming more and more alarmed, when Charley, whose ears were particularly sharp, cried, "Hush! I hear something." They all listened intently, and heard a voice faintly calling "Help!" They knew at once that it was Joe's voice, but they could not imagine where he was. They shouted in reply to him, and Charley, seizing the lantern, carefully pushed aside the tall weeds, and presently found himself at the mouth of a well.

"Are you there, Joe?" he cried, lying down on the ground, with his head over the mouth of the well.

"I believe I am," replied Joe. "I'm ready to come out, though, if you fellows will help me."

The boys gave a great shout of triumph.

"Are you hurt?" asked Charley, eagerly.

"I don't think I am; but I think somebody will be if I have to stay here much longer."

It was evident that Joe was not seriously hurt, although he had fallen into the well while rushing recklessly after the wild-cat. Tom and Harry ran to the canoes, and returned with all four of the canoe painters. Tying one of them to the lantern, Charley lowered it down, and was able to get a glimpse of Joe. The well was about twenty feet deep, and perfectly dry, and Joe was standing, with his hands in his pockets, leaning against the side of the well, and apparently entirely unhurt, in spite of his fall.

Author of "Toby Tyler," "Tim and Tip," "Mr. Stubbs's Brother," etc.

"She had on a dress that was silk all over it, an' it was almost as much as you could do to see her hands for the lace an' fringe an' ribbons. She was a good deal handsomer than them wax images in Smith & Jones's store, an' when she bought a paper of pins of me she give five cents, without waitin' for the change."

"Wot's five cents when jest as likely as not she had as much as five dollars in her pocket?" said Johnny Davis, the newsboy, who was sometimes spoken of, and to, by his proper name, but more often as "Water-melon Davis," because of his enormous appetite for the watery fruit.

Johnny spoke almost contemptuously of that which Katy Morrison, the "black-pin girl," considered a piece of good fortune, and if he did not actually turn his nose up in disdain, it was because nature had already so elevated that rather prominent feature of his face that it was impossible for him to get it any higher.

"Well"—and Jimmy Green, Johnny's partner in business, as well as particular friend of Katy's, spoke very slowly, as was customary with him—"five cents ain't to be sneezed at when a feller's only expectin' to get one, an' if Katy could get enough of 'em she'd make three, four dollars a day."

"How I wish I could!" said Katy, enviously, as with her stock of pins in her lap she sat on the door-step of an unoccupied store, her chin resting on one hand as she rattled the pennies in her pocket with the other. "If I could make that much, I'd buy me a whole dress, an' real shoes without any holes in 'em, an'—an'—an' I'd buy a pair of bracelets, that's what I'd do."

"Bracelets!" sneered Johnny, as he folded the paper that was undoubtedly fated to remain on his hands as stale goods from his morning's stock. "It makes me feel almost like gettin' mad, Katy, to hear you talk about buyin' bracelets, when you can get a pair of boxin'-gloves down to Levy's for as much as you'd pay for bracelets."

"Well, I don't know 'bout that," said Jimmy, as he rubbed his chin reflectively. "P'r'aps they'd do her more good than the gloves would, 'cause, you see, Katy don't know nothin' 'bout boxin'."

"Then she oughter learn," was the very decided response from Master Davis. "Girls could box as well as fellers if they'd get somebody to show 'em how."

"But I don't want to learn, an' I do want the bracelets," said Katy, thinking that possibly she had the right to say how this prospective money of hers should be spent. "That's all you boys think about, how you can hurt each other, an' you don't care what you wear nor how you look. I'd like to wear dresses that wasn't all torn, an' I'd like to look the way girls do what have mothers, an' don't have to live in such a old house as we do, an' pay 'most all our money for what Mother Brown calls board an'[Pg 775] lodgin'. Then when I want bracelets, you tell me to get boxin'-gloves."

"Well, if you don't want 'em, don't get 'em," said Johnny, philosophically, and looking much as if he fully understood how difficult it is to persuade girls as to just what they really need. "Buy the bracelets, an' then you'll look fine, won't you? sellin' pins fur a cent a paper with a big pair of gold bracelets slippin' down over yer hands every time you try to shy a stick at a dog."

"I never throwed a stick at a dog in my life," said Katy, indignantly; and then she added, quickly, "'cept once, when Dutch Pete cheated me outer two herrin's, an' I hit his dog to get even with him."

"I tell you what it is, fellers," said Jimmy, who had been making mental calculations based upon this argument he had unwittingly started, until he believed he understood it better than either of his companions did: "neither one of you hain't got the money to buy either the bracelets or the gloves, so wot's the use of makin' a fuss over it? When I get a paper stand of my own, I'm goin' to buy Katy everything she wants, an' I ain't goin' to let her sell pins, neither."

"Ain't you kinder tired talkin' 'bout that stand, Jimmy? We've heard 'bout it ever since you an' I was pardners, an' you hain't got no nearer to it now than to owe Mother Brown five cents on last week's board."

Johnny said this in a reproving tone, but it is very probable that he did it more to hide his confusion, caused by his partner's first remark, than for any other purpose, for he was usually careful not to hurt Jimmy's feelings.

"I'll have it jest the same," was the calm reply, and then Jimmy relapsed into another fit of chin rubbing, from which he did not arouse himself until one of his friends in the same line of business rushed up with the startling intelligence that there had been "a big accident on the railroad, an' papers are jest goin' to fly to-night."

It was not until quite a late hour in the afternoon that the three friends, who boarded in the same house, met again after their interview was broken in upon by the news of a probable activity in the newspaper business, and when they did meet both the boys were in the highest possible state of excitement.

The prediction that papers would "fly" had been verified, and more than one of Mother Brown's boarders had been made happy. Particularly was this happiness apparent in Jimmy's case. Even while the rush of trade was at its height he had been thinking of what Katy had said about wearing a dress that was not torn, and as his profits accumulated he conceived a plan so brilliant that he could hardly wait to meet Katy before he explained it.

The stores had been closed, and Katy, finding no customers for her pins, was walking slowly toward the not very cheerful place where Mrs. Brown kept a boarding-house for those children of the streets who have no idea of what home is, save as they see it from the outside, peering curiously in at those more fortunate ones who have a father, mother, home, and everything which goes to make up happiness and content.

She had walked nearly down town—for, as may be imagined, Mrs. Brown's house was not in the most pleasant portion of New York—and she was just beginning to wonder where her friends were, when she saw them coming toward her, looking quite as important and a great deal more satisfied than the most prosperous merchant on the street.

"Say, Katy," shouted Jimmy, while he was yet some distance away, his secret having grown so overpowering in the last few moments that he could hardly keep it until he saw the girl, "I've made a dollar 'n' forty-one cents, an' what d'yer s'pose I'm goin' to do with it?"

"Goin' to start your stand?" and Katy seemed quite as much pleased by the good fortune as Jimmy was.

"NO, SIR; I'M GOIN' TO BUY YOU A NEW DRESS."

"NO, SIR; I'M GOIN' TO BUY YOU A NEW DRESS."

"No, sir! I'm goin' to buy you a new dress, after I pay Mother Brown, an' give Tom Brady the cent I owe him. That'll leave me a dollar 'n' thirty-five cents, an' you shall have the best one we can find in the city. I shouldn't wonder if we'd have money enough to get the bracelets too," he added, in the tone of one who is certain, but prefers to let the matter remain in pleasing doubt for a time.

"Oh, Jimmy," cried Katy, in delight, for the thoughts of what she might have if she only had the money had made her very nearly unhappy during the remainder of that afternoon, when trade had been dull, "are you goin' to spend that money for me?"

"Every cent," was the decided reply, as the money was rattled to give greater emphasis to the words.

"But you mustn't, Jimmy," said Katy, as she began to understand that her friend needed it quite as much as she did. "You can get your stand with that, an' I can wear this dress as well as not."

"But I'm goin' to buy the dress, an' the bracelets, an' a lot of things," was the reply, in a tone that admitted of no argument.

"An' ef he hain't got enough, I can put out the balance," said Johnny, speaking thus tardily because there had been a great struggle in his mind as to whether or no he would not be doing Katy a greater favor by buying the boxing-gloves for her.

Never since Katy Morrison could remember had she worn a dress that was made of new material. Even before her mother had died, leaving her to the anything but tender care of Mrs. Brown, her dresses had been made of old ones, and now the mere idea of having one without a hole in it seemed almost too good to be true.

She did make another protest against her friends spending their money for her, though she admitted that if the pin market remained in its present overstocked condition she could never hope to buy one from her earnings; but Jimmy had made up his mind, after much rubbing of his chin, and nothing she could have said would have caused him to change it. He and Johnny discussed the question of what color the dress should be—that it was to be of silk was understood, and Katy hardly knew how to contain her joy, so impossible had such a thing seemed a few hours before.

While they were talking they had passed through City Hall Park, and as they started to cross the street they were still eagerly discussing the question of color, Johnny being decidedly in favor of red, while Jimmy believed a bright green would be more suitable. Katy was just behind them, taking no part in the conversation, because one color would please her as well as another; the "whole" dress, whatever its shade, was sufficient for her.

So heated had the argument become that neither of the boys noticed, amid the general bustle of the square, the clatter and rush of a horse attached to a light express wagon, nor did they hear the warning cries of the driver until it was close upon them.

Then they had only time to escape being knocked down by the horse. As they jumped suddenly they heard a cry from Katy, another from those on the sidewalk, and they turned just in time to see the poor girl, whose thoughts of a new dress had rendered her careless to everything around her, lying on the pavement, with a great crimson stain, that grew larger and larger, upon her hair.

Before they could reach her a policeman had carried her to the sidewalk, and they were obliged to stand on the outside of a large crowd of curious ones, who always gather at anything unusual as if by magic, while the only being in the world who loved them and whom they loved, was perhaps dying, perhaps dead.

Clutching each other's hands tightly, while the great tears of a sorrow that had almost stupefied them rolled down their cheeks, the two stood there, near the curb-stone,[Pg 776] not knowing what to do or say. They did not even know how long they remained there; but when the ambulance came, and they saw the still, lifeless form of "their girl," as they called her, lifted into the black, ominous-looking wagon, there was such a lump in the throat of each that it seemed as if he could not breathe.

The ambulance started off at full speed, its bell clanging the warning to drivers of other vehicles to clear the way, and without knowing where it was going, or anything save the fact that "their girl" was in it, the two boys ran after it regardless of fatigue or danger.

On and on the precious load was carried, until finally, when it seemed to Jimmy a physical impossibility that he could run any further, the ambulance was stopped before a huge building, which both the boys knew was the hospital.

One more glimpse they had of Katy as she was carried through the gate, and then they waited in painful suspense, as if they expected some word would be sent to them.

It was late in the evening when one of the attendants came out of the building, and found the boys crouching close by the gate. Before he had time to ask them what they were doing there, they overwhelmed him with questions as to the fate of Katy, and when he finally understood who they were inquiring about, he told them that it was impossible to say whether she could recover or not, as her injuries were believed to be very severe.

For several moments the boys stood looking at each other in mute fear, after the man had passed on, and then Johnny said, solemnly,

"Jimmy, did you ever pray the same as the rich folks do?"

"No."

"Let's do it now, an' p'r'aps Katy'll get well."

"Well, let's," replied Jimmy, earnestly, and there, upon the dusty street, two boys whose ragged coats covered true, kindly hearts, prayed, after their fashion, to the God of whom they had but seldom heard, for the life of "their girl."

"BREAD-AND-BUTTER DAYS."—From a Painting by Weedon Grossmith.

"BREAD-AND-BUTTER DAYS."—From a Painting by Weedon Grossmith.

Deep down in a mine in Wardley Colliery, Newcastle, England, there is a brave boy who deserves to be called a hero. In a situation of sudden peril he used precautions which prevented a dreadful explosion, simply by behaving with courage and presence of mind.

He noticed that his lamp flared up, a sure sign of the presence of dangerous gas. Had he hastily rushed away, his light might have burst through the wire gauze which surrounds a miner's lamp, and setting fire to the gas, caused a heart-rending accident.

The lad did nothing so silly. When questioned by the Superintendent as to how he had found out that there was gas in the neighborhood where he was at work, he replied, "Because my lamp flared."

"And what did you do then?" asked the gentleman.

"I took my pricker, and pulled down the wick, but the lamp still flared."

"Well, my boy, and how did you manage then?"

"Why, I put the lamp inside my jacket, and covered it up tight, and the light went out."

Of course, the lamp could not burn without air.

To think of the right thing to do, and then promptly to do it, boys, that is what makes the difference between a common man and a hero.

This little fellow, whose name is not mentioned—Mick, or Ted, or Jack—has in him the making of a grand man, cool, resolute, and clever.

Fortunately there was an overseer near him, who, when, he heard from the lad about his lamp, went bravely through the gas, in total darkness, and set open a door, the closing of which had forced the gas into the main-ways of the mine.

All honor to them both.

Three of us boys—Will Harald, his cousin from the nearest city, who was visiting him, and myself—went down to Deacon Dodd's farm one Friday afternoon, after tea. We found the old gentleman mowing the grass in the front yard.

"Come in, boys; set down on the steps there. Hot, isn't it?" He wiped his forehead vigorously with his red silk handkerchief.

"Deacon," said Will, "we came to ask you for a peck or so of your pound sweets, for our fishing excursion to-morrow."

"Have a drink of cold water? Pound sweets, eh? Well, now, I'm sorry. Won't anything else do you? Fact is, every pound sweet I've got's promised; there wa'n't many this year, and they're a skurse kind, you see. But you can have anything else you can find on the farm, and welcome. The bell-flowers are tiptop—help yourselves."

We thanked him, but didn't care for anything else. We had plenty of other apples ourselves, and had set our minds on having some of the Deacon's great yellow pound sweets. We wandered discontentedly into the orchard without finding anything we wanted, peeped at the big snapping-turtle by the spring, patted the pretty gentle Jersey cow and her half-grown calf, both of which were the pride and delight of the Deacon's heart, and then sat down in the open doorway of the great barn.

"He's a mean old skinflint, I say," said George, the boy from town. Will and I knew he wasn't any such thing, but we were out of humor at having our walk for nothing, and did not take the trouble to argue the matter.

"I don't think he would have missed a peck," I said.

"Wants to sell 'em, I s'pose. Seems to me I'd oblige a few boys even if it was a few cents out of my pocket."

"Let's play a trick on the old codger," said George. "Last summer our teacher wouldn't give us a holiday when we wanted it, so we shut him up in the school till late at night."

"And what came of it?" we inquired, in great interest.

"Oh, well, one or two of us got expelled for awhile, but that just suited us."

This did not sound to me like a very successful issue of the trick, but George went on:

"Let's run off his calf."

"How do you mean?" asked Will.

"Why, lead it clear off, and tie it up somewhere, so he'll think it's lost."

"He thinks about as much of that cow and calf as he does of his children," I said, with some misgivings.

"All the better—he'll be in a jolly sputter over it. We won't hurt anything; just have a little fun on the old fellow. Nobody'll know. Come on."

Somehow I couldn't help feeling that I hated to do anything like playing a trick on the Deacon, for as a general thing he was very good to us boys. But then, on the other hand, it did seem perfectly unreasonable for him to refuse to give us just a few of those apples when we knew he had three times as many as he and all his family put together could eat. Still, I don't think I would have given in if George hadn't urged the matter so. He is one of those fellows who always takes the lead, and the rest of us just follow on. He started off, and Will and I went after him.

We quietly stole round the back of the barn to the lot in which we had seen the cow and calf. No one happened to be about just then. We found a rope, tied it to the calf, and led her into a lane. Soon she got tired of being handled by so many strangers, and I tell you she gave us a lively time. She was a stout, skittish little creature, and we boys had no end of exercise getting her along. She would walk quietly enough for a few steps, and then make a jump forward, which would nearly jerk us off our feet; or she would stop suddenly and turn back, tipping over a boy or two, like enough. At last we put our apple-bag over her head, and she travelled a little easier, but you'd better believe all our hands were sore hanging on to that rope. At last we tied her in a bushy grove about half a mile from the far end of the Deacon's farm.

We had thought it great fun as long as we were all together, but when I was at home alone it didn't seem half so smart to be putting a joke on an old man, and a good kindly old man at that. I woke up several times in the night with the stinging and burning in my hands, and thought what if anything should happen to the calf. Not a word had been said between us as to how it was to be got back again—I don't believe any of us had thought so far ahead as that.

It is dreadful hard work to sleep when you've got anything troublesome on your mind. I tossed about and thought it over just what the Deacon would say when he found the calf was gone; and how Mrs. Dodd would worry. Finally I thought of the piles of doughnuts she had given us boys at one time and another. I got so wretched that I couldn't stand it any longer.

I didn't know how long George intended to keep it hidden, but I made up my mind to get up with the first streak of day, and went to see if I couldn't get the calf back by myself. Then I meant to leave George and Will to bother themselves awhile, wondering what could become of it. It was a long walk, but at last I reached the place, and then I tell you I stood and stared—that calf was gone!

I hunted and hunted all about there, but it was no use. The faces of Will and George grew as blank as my own as I told them, and we joined the fishing party of a dozen or so boys with a heavy sinking at our hearts, and many doubts as to what might be the outcome of our clever joke on the old Deacon.

Early in the afternoon we saw a spring-wagon working its way along under the willows where we were fishing. Two men were in it, one of whom, a stumpy, freckle-faced Irishman, I recognized as Deacon Dodd's new hired man. The other was a neighbor of ours, and it was not until he had beckoned George and Will and myself a little apart from the other boys that I remembered all of a sudden, with a great addition to the weight on my mind, that he was the deputy-sheriff.

"Yis, sor, thim's the very b'ys," said the Irishman, with a very positive nod of his head at us.

The deputy-sheriff looked puzzled.

"Why, my man," he said, "you don't mean it's these boys you're after?"

"It's jist these same I'm maning—the very wans me own eyes saw shtalin' away the Daacon's calf."

At this we burst out laughing, and gave the deputy-sheriff an account of our frolic of the night before. Mike listened unmoved, simply asking, as we finished:

"But wheriver is the Daacon's baste, thin?"

This we could not answer. The deputy-sheriff whispered with the Irishman, seeming to intercede for us; but Mike only answered, doggedly:

"The Daacon was called away suddint lasht night, and only mesilf to see to things. Them b'ys had the calf—wheriver is the calf?"

His stubborn faithfulness was not to be shaken, and the deputy-sheriff gave up.

"Well, boys, seeing he's so set, I guess you'd better just jump in and go along with me—being such a valuable animal, you see. Of course it won't amount to anything, mere matter of form; only a little talk before Squire Granger."

We were a crest-fallen three as we mounted that spring-wagon, dimly realizing that, spite of the deputy-sheriff's politeness, the plain English of all this was that we were under arrest, and on our way to a magistrate's office. Our worst fears all the morning had been of our being called upon to pay the price of a choice specimen of blooded stock, but an indefinite train of horrible possibilities now seemed to open out before our imaginations.

How our cheeks burned as we found ourselves before the country justice, and perceived the crowd drawn by the excitement of a preliminary examination, and heard the astonishment and horror expressed that we should be the criminals. How our shame and confusion increased as the other members of the picnic, whom we had devoutly hoped would not allow their day's sport to be shortened by our leaving the party so early, quietly filed in, and added their gaze to the others'.

The justice seemed somewhat embarrassed himself. There did not seem to be much of a case, but what little there was was dead against us. The only thing about it was Mike's unwavering testimony to having seen us in the lane driving away the calf. This we could not deny, and all our protestations of its being only a joke were thrown into confusion by his stubbornly repeated question:

"Thin, wheriver is the Daacon's baste?"

The thing began to look less and less like a joke to us as we found it impossible to bring any witnesses for the defense. The justice and the deputy-sheriff whispered solemnly together.

All at once there was a stir in court. Deacon Dodd elbowed his way into our neighborhood, and as he looked us over, his genial face expanded into a laugh that shook the very rafters.

"Well, boys, have you had enough fun?"

We had nothing to say. The justice seemed cheered by the entrance into the case of something lively, and asked the Deacon if he had any evidence to offer. We, the prisoners, were not encouraged, feeling very sure his testimony could not be in our favor. The justice had some trouble in getting things sobered down enough to swear the Deacon properly, but when this was accomplished he was allowed to give his account in his own way, which went something like this:

"Yes, your honor, I felt bad when the boys wanted them pound sweets, for I always do take to giving to boys—used to be a boy myself, you know, and it don't seem so very long ago neither, 'though I don't pretend to be as young as I was once. Well, when I got into my little tool-room in the barn to hang up my scythe, and sat there to cool off a bit, being as the evening was warmish, and them poor chaps, after having tired themselves all out trying to find something nice in the orchard, and couldn't, come to take a rest at the barn door, and says they, 'The Deacon's an old skinflint, and wants to put every cent he can in his pocket.' Likewise wishing every apple on his place would rot and such like—I say, Squire, I could hardly forbear just getting up and going out to them boys and saying, 'Boys, just you go 'n' get every pound sweet on that tree—don't you leave one.' But, you see, my wife, Mis' Dodd, had told me how she'd been and promised every individual one of them pound sweets to the hospital; for them poor souls lying there sick found it hard to get anything real relishing, and liked 'em baked. So I couldn't help myself, seeing she'd passed her word for a charity, and would 'a felt hard at me, naturally, if I'd gone back on her.

"But when the boys thought they'd like a little fun with the Jersey calf, I knew they wouldn't do the pretty creatur' any hurt, for I heard 'em saying how they knew I set great store by her. The evening was getting cooler then, so I just took a walk along behind the hedge, they being on t'other side.—You did have a time with her, didn't you, boys?"

What a roar went up from that roomful of listeners!

"'Twas tough; yes, I could see that, a regular tussle to get her along. I'd 'a helped you, for she follows me like a lamb, only I was afraid 'twould spoil your fun if I took hold too. So I just kept along till you tied her up safe and comfortable—"

Here Mike broke in, in total disregard of the proprieties of a court-room:

"But, Daacon, wheriver's the baste now? Be the howly poker she's clane gone off the farrum!"

"She's in the northeast corner pasture. I'd been calculating to put her there, to be more in the shade, and the boys gave me just so much help with her, you see. After I'd put her there and got home, I found a letter from my son Isaac, telling how he was sick, and wanted to see me and his mother, Mis' Dodd. So I just hitched up, and without waiting to see Mike, me and her started off to drive over there—better than four miles 'tis—and the calf slipped my mind till I just now got back, and heard tell how Mike here was making a bother with the boys. That's all, your honor."

His honor, I knew, had been dreadfully worried at not having been able to give more dignity to the court, and he now opened his mouth, I suppose to dismiss the proceedings in proper form, but the Deacon gave him no chance at all. I am not prepared to say that we three are not legally under arrest to this day.

"Better go back to your fishing now, boys," he said. "Too bad to have your day broke up so; but Mike meant well, you know."

"Three cheers for Mike!" shouted some one, intent on pushing the fun as far as possible.

"Three cheers for Deacon Dodd!" came next, and when they had been given with a will by the merry crowd, a cry arose:

"Three cheers for the half-grown calf!"

Before they had died away, Mike turned with a most meaning look at us three boys, exclaiming:

"Ivery wan of 'em."

And they gave us a tiger.

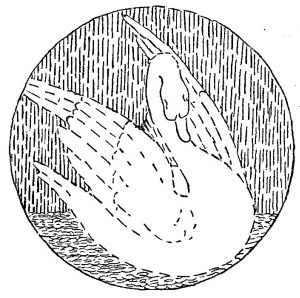

Mark very exactly on some thin white material of a polished surface and fine quality outlines of the pincushion and the design. The best way to do this is to make a very careful tracing of the design, and transfer it by means of transfer-paper. Any carelessness in following the design loses all the style it may possess. This done, outline the swan and all the markings of the wing feathers, eyes, etc., with simple stitching in a gray silk so pale as to appear white until contrasted with the brilliant white cloth. Work the part representing water in simple horizontal lines of chain stitch, as shown in the design, with silk of light blue across the lower end of the circle. Work the rest of the background in darning stitch perpendicularly from the top of the circle to the water in a rich deep blue silk, being very careful not to interfere with the outline of the swan or of the water.

Cut two pieces of card-board exactly the size and shape of the circle. Mount the embroidery upon one of them, and cover the other with blue satin. Baste the two circles thus covered together back to back, having laid carefully between them three little circles of flannel a very little smaller than the outer circles. Then overhand the two edges of the pincushion very carefully together.

Entering Rome by what was anciently called the Flaminian Gate, but is now the Porta del Popolo, or People's Gate, the stranger finds himself in a large, beautiful open place called the People's Square. It lies at the foot of the Pincian Hill, called by the ancient Romans, in the language of the time, the Hill of Gardens. If it deserved this name in those days, it does not deserve it less now. The most beautiful gardens in Rome, laid out with lovely flower beds, commodious carriage drives, and shady walks, are on its summit. A military band plays there in the afternoons, and it is the favorite resort of the rank and fashion of modern Rome, from the King downward.

Like much else in Rome, the history of the Pincian Gardens is sad and terrible. The great Mistress of the World, if she was at times rich in virtues, was just as often famed for terrible crimes. These gardens belonged at one time to the famous epicure Lucullus. This man, possessor of enormous wealth, loved good dinners much, but hated the trouble of ordering them as heartily as many a fine lady of the present day. To save himself this trouble, then, he had a number of dining-halls in his house, each arranged in a different manner. His steward was so well trained that he knew to a nicety, on receiving the order as to which hall the supper was to be served in, how it was to be arranged, and what degree of splendor it was to be of. The banquets of Lucullus became proverbial for luxury. It is even told of him that being very fond of a certain sort of eel he had a pond made for them in this garden. Their favorite food being human flesh, the legend tells us that he occasionally ordered a slave to be thrown in to them, to help to make them fat and savory for his table.

After the death of Lucullus, these gardens passed into the hands of a certain patrician named Valerius Asiaticus. This was during the reign of the Emperor Claudius. The Emperor's wicked wife Messalina coveted them for herself, so she got up a false accusation against poor Asiaticus, who seems, on the whole, to have been a very worthy man. But his innocence did not save him. He was condemned to death, and his property given to Messalina. The wretched woman's triumph did not last long, however. Claudius was told of her wicked life, and she was killed by his command on the very place she had obtained for herself by such a horrid crime. Word was brought to the Emperor while he was sitting at table that his wicked wife was dead. He made no reply, and went on quietly eating his supper. They were a queer people, those old heathen Romans.

To return to the People's Square. In the centre is a tall obelisk brought from the Temple of the Sun in Egypt during the reign of Augustus. It was thousands of years old, perhaps, before Rome was built. A beautiful fourfold fountain at its base spouts clear sparkling water from the mouths of four antique lions of basalt. It is the most picturesque square in Rome.

At the left-hand side of the Porta del Popolo, as you enter, stands the ancient Church of St. Mary's of the People, concerning the building of which the following story is told:

When the bloody and cruel Emperor Nero, who had wantonly killed so many people during his short reign, was killed in his turn, he was so execrated by the people that none could be found to give him burial. Then his nurse Eclaga, who still went on loving him, as some gentle souls will do, in spite of his dreadful crimes, buried him, with the help of two other women, compassionate like herself, in a tomb at the foot of the Hill of Gardens. On this tomb, for many years, a wreath of fresh flowers was found every morning, no one knowing who had placed it there. So they watched one night, and just before break of day discovered this poor faithful old woman bringing this loving offering to the memory of him whom she remembered only as the innocent babe she had nursed in her arms.

As time went on, these offerings ceased. Eclaga was dead and gone, and with her had passed away every loving remembrance of the wretched man who was buried at the foot of the Pincian Hill. Horror and loathing were the only sentiments his memory inspired. By-and-by nothing marked the spot where his body lay but a gigantic walnut-tree which had grown out of his grave. It was so large that it overshadowed all the place and covered it with gloom.

This gloom was still further increased by an innumerable quantity of large crows that had taken up their abode in this tree. They darkened the air all around by their flight. The people inhabiting the neighborhood had no rest by night or by day by reason of their hideous, unearthly croaking. Every means tried to drive them away proved vain. They kept their abode on the tree above Nero's tomb, and defied all earthly power to assail them.

Then a great fear fell on all the people, for they thought that it was not with natural crows they had to do, but with demons who were keeping watch over the grave of the wicked Emperor. Then, as there was no help in man, they prayed to God.

Now Paschal the First, who was Bishop of Rome at that time, and a good and holy man, had a strange dream one night. In this dream it was revealed to him that no earthly power could drive away the demon crows, which, if not exorcised, would soon overpower the whole of Rome. The only way to do this effectually was to go forth at early morning, at the head of all his clergy, singing psalms and hymns and praying fervently. Then they were to cut down the tree, and take it out by the roots to the very last fibre of it, and build a church on the spot where it had stood.

Full of joy at this revelation, Paschal summoned his clergy, and told them of his dream. Then he went, as he had been directed, at their head in procession through the city, singing psalms and hymns. Arrived at the spot, they knelt down and prayed fervently. Then they commenced to hew down the tree, the supposed demons all the while uttering wild and unearthly croakings. After the tree was cut down, and every root of it taken up, the crows flew away with a terrible noise.

A beautiful church was then built on the spot; and as the funds for its erection were entirely collected and given by the common people, it received the name of St. Mary's of the People. There are some beautiful marbles in it, and many fine old paintings, some of them by the most famous of the old masters.

Oh, such a bunch of posies!

We found them on our way,

And gathered them for Robin,

Who lies abed all day.

"You'll soon be well, dear laddie,"

The posies sweet will say.

Oh dear, but he's queer, this wonderful snail,

O'er the whole wide world he may travel and sail;

But where'er he may go on the longest track,

He carries his house on his funny back.

What wonder, then, that he likes to roam,

When the comical fellow is always at home.

Wilt thou listen, Jesus dear,

To the prayer that I would say;

Thou didst promise Thou wouldst hear

When the little children pray.

I would like, dear Lord, to be

Patient, gentle, good, and mild,

Ever growing more like Thee,

And as Thou wert when a child.

Just about this time, dears, your mammas are very busy in looking at the fall fashions. They wish to dress their girls and boys so neatly and comfortably that they shall have no temptation to think too much about their clothes. And then, too, they want you to wear pretty things, because children should look bright and beautiful, just as flowers and birds do.

If you choose, you may ask them to make your own new costumes like some of these pictures. We think, too, the little women who write to the Post-office Box about their doll families, and who have so much on their minds in the way of caring for the Lady Bettys, and Miss Lucys, and Mabels, and Isabels, whom they so dearly love, will be glad to see some dainty fall fashions for dolls. The little girls in the picture are very graceful and sweet.

I wonder if I can help you a little in dressing these same dollies. There are two tall girls nearly in the middle. The one on the right we will call Alice. Her dress is of fine soft cashmere of an olive tint. She has a wide sash of satin a little darker than her gown. Her friend Florence has on a petticoat of Indian red, which is a peculiarly rich dark shade. If mamma will give you a few bits of velvet or velveteen for this petticoat, and also for the shoulder cape, Miss Florence will look very charming. Her over-dress may be of fawn-colored silk.

Shall we call the two little ladies on Alice's right Dotty and Dimple? Dimple has her face this way, and Dotty's is turned aside. We will dress Dimple in lavender and heliotrope, and Dotty shall be a cunning little maiden in two shades of brown.

Now for the others. Don't you wish we could see little Marjorie's blue eyes and rosy cheeks? But we can only guess at them. Our artist has shown us that she knows how to stand up straight, and the way she holds her head is delightful. She is wearing, as you see, a pretty gray check, and she is a very good match for her little sister in that stylish cadet blue, and her cousin Willie in his jaunty suit.

When you shall have succeeded in dressing some of your pets like these pictures, you may write and tell me all about the fun you had in cutting out the clothes and making them fit. Be sure you write about how you contrived the little bonnets and hats. Perhaps you will be trying your skill at dressing dolls for a fair this winter, or in making Christmas presents, and these illustrations may give you some new ideas.

The boys must not feel that they are left out of this pleasure. They may draw these little figures on bits of paper, and then color them beautifully with their paints. Or, if they do so very carefully indeed, they may color the figures as they stand.

Foochow, China.

I was very glad to see my letter printed in one of the February papers. I do not expect to learn to write Chinese, but I learn to talk a little from the servants. Our Amah talks "pidgin English." This is the way she talks, "Amy just now have got too muchee rain, no can go walkee."

I have a doll that can say Papa and Mamma, but my mamma does not let me play with it, as it is wax. There are a great many roaches here, and one bit a piece of my dolly's cheek out when it was put away in the wardrobe.

Our only pet is a small cat, which is very lazy, and does nothing but eat and sleep. Sometimes we dress her up in doll's clothes as a baby. We have a very nice aquarium with gold-fish, shrimp, and one other kind of fish in it. The gold-fish have double tails. In the fall we hope to get the aquarium nicely filled with plants and things.

It is very hot here in the summer, but there is a large island, called Sharp Peak, in the China Sea, thirty miles from here, where the missionaries have houses, and go to spend part of the time. There is a very nice beach, and the bathing is very good. We went down for two weeks in June, and had a nice time. My brothers and I found some pretty shells. Please tell me if the lady whom you heard talk about China has ever been in Foochow. I have 568 stamps in my album now.

Amy C. J.

Your cat is very accommodating to be willing to wear doll's clothes to please you. Ask mamma to let you play with your wax doll, and then she will not be in danger of making a dinner for roaches or rats. I think the lady I spoke of when replying to your former letter has been in Foochow.

Boston, Massachusetts.

All the young people will be writing about their vacations, I suppose, and so I will write about mine. The most interesting part will be, I think, about my visit to Nantucket. Nantucket is a very old town. The houses are all built away from the sea, so when one is walking through the streets one has no view of the water at all. The very old houses all have on their roofs what are called "Lookouts." These are small railed platforms for the people to stand in and look out for the whaling vessels. When one came in sight, whoever was on the lookout gave the signal, and then great preparations were commenced—cooking mostly, I guess, for they didn't illuminate and send up fire-works in those days.

A splendid view of the town of Nantucket is obtained from the Unitarian church tower. In this tower is a very old bell, with a cross on two of its sides, and a Latin inscription under each cross. This bell was originally intended to form one of twelve chimes in an ancient Catholic church in Spain, but it was stolen, and after changing hands several times, it was landed in Nantucket.

Whoever goes to Nantucket must be sure and visit the Old Mill, which is a great curiosity. There is only one other like it in America. The curious part about it is that it is so old, and it never has been changed since it was first built, many, many years ago. The town-crier is another ancient institution, and with his bell and tin fish-horn he goes about the streets crying out all the news. When they wish to have an auction in Nantucket, everybody who has anything to sell carries it to the corner of some designated street, and there the things are auctioned off. We did not have time to go over to Siasconsett, but I mean to if I ever go to Nantucket again. The next time I write I will tell you about Plymouth. Good-by.

A. B.

Well, you have made me feel a strong desire to go to quaint old Nantucket. Don't you think the good home cooking must have tasted very delicious to hungry sailors who had been used to sea fare during long and tedious voyages? And how happy must dear little girls have been when, climbing to the lookout, they saw in the distance their fathers' ships coming in! How they must have hurried down to tell mother, and what a joyful troop must have been at the wharf to welcome the bronzed and bearded man when once more he set foot on his native land!

Brick Church, New Jersey.

I am eleven years of age, and have been receiving Harper's Young People as a present for nearly two years. I think it is one of the nicest Christmas presents I ever had given to me, and I enjoy the stories, puzzles, and Post-office Box very much. As school opened last Monday, I thought I would wind up my holidays by sending you fifty cents of my own for Young People's Cot, and hope it may help a little to do some poor sick child good.

I had a real good time during vacation, and among other things, my brothers and sisters and I (there are six of us all—steps and stairs, mamma says) made a collection of caterpillars, putting them in boxes with covers of glass, so that we could watch them. We fed them with cabbage leaves and turnip-tops. Did you know some caterpillars were cannibals? We caught some very pretty green ones with black stripes and yellow horns, and they soon attached themselves to the side of the box by two threads, and after a day or so their skins came off, and they turned into cocoons. It was just after they hung themselves up that the other caterpillars attacked them, and kept them company until they had eaten them all up. Wasn't it awful?

We have lots of butterflies now, but I scarcely[Pg 783] think so much of them since I know how they behaved in their youth. But my uncle Jim says they are regenerated, and I suppose that takes the bad out.

Hoping, dear Postmistress, that you had a pleasant time this summer. I am your little friend,

Effie W. R.

You were well employed in watching the caterpillars. That is the best way to study natural history, not depending on books only, but taking notice for yourself of the ways and habits of insects and birds.

Shelton, Nebraska.

I thought that I must write to you because all the other little girls and boys do. I take Harper's Young People and The Pansy, and like them both. I have a pet pig, and I call her Peggy. She is an orphan; I raised her on a bottle. I once had a pet kitty. I would put a shawl around her and rock her, and she would go to sleep. Papa has a horse that I can ride. I can ride sideways on a gallop without a saddle. My home is on a farm with my papa and mamma, and I am their only child. We had a hail-storm here in July which destroyed the wheat for many miles around. I attended the Grand Army Reunion at Grand Island, Nebraska.

Louie L.

Take care that the horse does not run away with you one of these merry days when you are riding without a saddle.

Detroit, Michigan.

I thought I would write and tell you about my baby brother; he is seven months old. I have a pet hen and a little kitten. My brother had a little rabbit a short time ago, but it ran away and got lost. I like Harper's Young People; we have had it every week since it came out, but I would like it better if you would write more about girls.

Clara B. K.

If you will look carefully over the last few numbers, Clara, you will find some very pretty stories and poems which are about girls. And we have some very delightful things all ready for our bright girls this autumn.

Greenwich, Connecticut.

I thought I would tell you about some historical reminiscences for which this place is noted. Not quite a mile out of the village is the place where brave General Putnam rode down what is now called "Put's Hill," and escaped from the British soldiers under General Tryon; and General Putnam's old stone house is still standing here, and is occupied.

We have no pets, but papa has a very valuable bull-terrier named Leo, which is so very gentle that my dear little sister Helen, who is only five years old, has only to speak to him to make him drop a bone, no matter how choice it may be. He never attempts to growl at us when he is eating, as some dogs do. We got him as a pup, when he was two weeks old, and as he was so young, he was sent back to his mother until he was six weeks old. Then we have two of the nicest, gentlest horses that ever were; their names are Charlie and Fannie. We have had them ten years, and we can do anything with them. They are unhitched in the main part of the stable, and they are allowed to go where they will, but they always go in the right stalls. There are four stalls, two day stalls and two night stalls. I have a collection of picture cards, and my brother Gershom and I have a splendid album of stamps. We have quite a large family—twelve in all—and necessarily never lack company.

I should think that the Postmistress would be very busy with all the letters from young people. I am my parents' sixth child and second son, and I am fourteen years old.

Fred L. S.

Fort Concho, Texas.

My papa is an officer in the army. We live at Fort Concho. I take Harper's Young People, and get the St. Nicholas from our post library. I suppose you have heard of the great flood we had here. I went to the river every day with papa, and saw a great many things floating down the stream. Mamma saw a big rat on a small piece of wood sailing along, and looking quite comical. I saw hundreds of sheep and pieces of furniture and a piano leg rushing on. But all that did not make me feel so bad as the little girl who lost her mamma and sister. She stood on the bank and saw them float away on the house roof. They were brought back dead.

If you publish this, I will write again, and tell you about my good times pecan-nutting and Indian-pony-riding, etc. I am ten years old.

Ruth W. P.

It was, indeed, heart-rending for that poor little girl to see her dear mother and sister carried to death before her eyes. I hope you will write again, little Ruth.

We are very glad to see that the interest of our dear little readers in Young People's Cot does not decline. The letters which we publish in connection with the treasurer's report show that the children are learning how pleasant it is to work for others.

Contributions received for Young People's Cot, in Holy Innocent's Ward, St. Mary's Free Hospital for Children, 407 West Thirty-fourth Street:

L. Benedict, Jun., New York, $5; Charles, David, Ernest, Wilfred, and Robert Bliss, Kent, Iowa, $5; proceeds of a fair held by Ned and Lulu Rawson, Port Richmond, S. I., $1.77; from Harry, Clarence, Todie, James, and little Florrie, in memoriam of their dear uncle, $1; Susie and Robbie Orton, Darlington, Wis., $4.50: Fannie, Emma, Eddie, Mamie, and Bessie Pearson, $1; "The Willing Workers," Minnie and Mattie Lloyd and Daisy Mason, L'Anse, Mich., $5.25; Fanny G., 6c.; Ernest L. Scott, Kinsman, Ohio, $1; Roy, Aileen, Dicky, and George Guppy, Oakland, Cal., $1; fines for using words "horrid" and "awful," 27c.; Richard P. Appleton, Boonton, N. J., 25c.; total, $26.10; amount previously acknowledged, $1232.05; grand total, September 12, $1258.15.