Project Gutenberg's Harper's Young People, October 10, 1882, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Harper's Young People, October 10, 1882

An Illustrated Weekly

Author: Various

Release Date: May 31, 2019 [EBook #59644]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S YOUNG PEOPLE ***

Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| A VERY NEW COW. |

| CLIMBING PLANTS. |

| PLAYING CIRCUS. |

| CHILDREN'S CHURCH. |

| BITS OF ADVICE. |

| THE CRUISE OF THE CANOE CLUB. |

| THE STEAMBOAT.—ROBERT FULTON. |

| THE MAGIC SACK. |

| "THEIR GIRL." |

| OUR POST-OFFICE BOX. |

| vol. iii.—no. 154. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday October 10, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

"Father," exclaimed Katy Chittenden, the moment the buggy stopped in front of the gate, "Bun Gates and Rube Hollenhouser were here this morning just after you went away, and they said all our cows were in Mr. Gates's pasture lot."

Deacon Chittenden and his wife and his son William were all in the buggy, and the seat did not look uncomfortably full either. All three of them answered Katy in the same breath, with,

"How did they get in?"

"Oh, I don't know. They didn't say. Rube didn't say anything. It was Bun. He wanted me to tell you."

"It's all that new cow's doings," groaned her father, and the news seemed to make him slow in getting out of the buggy.

"Bun Gates and Rube Hollenhouser are the roughest pair of fellows," began William, but his father checked him.

"They drive my cows for me half the time, William. They drove 'em up to the lot this morning. I'd never have trusted you with that new cow."

It was a serious matter, and it had been on Katy Chittenden's mind all the morning. She had formed an extraordinary idea concerning the "new cow" for which her father had paid so much. So costly a creature, with such horns, and so dreadfully brindled, and that kicked the milk-pail at least three feet, was to be regarded with awe.

Dinner was hardly over before the Deacon solemnly remarked: "William, put on your apron. I will put on mine. You take the axe and I will carry the maul and some nails. We must fix that fence."

The day was warm, and it was a good walk, over the bridge, along past the wagon shop, and away up the hill road to the bars that let down into the pasture lot. It was only twenty yards from these to the bars that led into Mr. Gates's lot, and Mr. Hollenhouser pastured his cows there also.

The bars were all up, and the fence looked all right as far as they could see.

"We must follow it up," said the Deacon. "The break is further on."

It was a large, roomy pasture, and so was that of Mr. Gates at the side of it, but it was because they were both very long, for they were not very wide. They reached up and over the hill, away to the cross-roads on the upper level, so that there was a great deal of fence between them.

It was good fence, too, and in perfect order, but for all that, before they reached the top of the slope, William suddenly exclaimed:

"Father, there are Mr. Gates's cows in our lot. Both of them."

"I declare! So they are. And there are both of Mr. Hollenhouser's beyond them. There must be a bad gap somewhere."

"Wonder where our cows are?"

"It's a wonder. I haven't seen one of them, and that new cow—"

He stopped there, as if he did not wish to say anything against her just then; but the mystery was getting deeper. There was no hole in the fence, nor any sign of his own cattle until they had nearly reached the cross-roads at the upper end of the pasture.

"There they are, father. All three of 'em. In the corner."

"Yes, my son. I see them. But how did they get there? They're in Mr. Gates's lot."

"Guess he or Mr. Hollenhouser's been up here and fixed the fence before we got home. Rube and Bun would have told them, sure."

"Of course they would. I never thought of that. I should have asked them about it before we came. I can't understand it exactly now."

There certainly was a mystery about it, and one that only Rube and Bun could have explained.

Early that morning the Deacon had roused himself out of bed, so as not to miss Rube and Bun when they let out their cows. He would not have trusted his new cow with any other boys in that neighborhood. They were up good and early too, and were just fairly out in the road, with two cows apiece, when Deacon Chittenden came along, and Bun's first remark was,

"That's his new cow. Hasn't she got a pair of horns, though!"

"She's a brindle. Wonder if she's a good milker?"

However that might be, they were quickly informed that she was an animal of uncommon value, and that they could have the privilege of driving her that morning.

"All right," said Bun. "She'll go right along with ours. We'll turn her into the lot for you."

The Deacon explained that he had a trip to make which would keep him away until dinner-time, and hurried away.

The new cow must have kept an eye on him, for she behaved very well until he was out of sight. Even a cow might feel more orderly for looking at Deacon Chittenden. This one, moreover, might have done very well after he disappeared, and gone along under good influences, if it had not been for Watch Hollenhouser.

That dog was always doing more than anybody asked of him. The other cows were so well used to having him bark at them, from their own yard gates down to the bridge over the creek, that if he had not been there they would have missed him.

It was all a matter of course, therefore, with Rube's cows and Bun's and the old two of Deacon Chittenden's; but Watch was as new to the new cow as she was to him.

The distance to the creek was made in safety, a rod or so at a time, and then the little drove had all its seven noses in the water at once. It was only for a moment, indeed, and it was a good deal a matter of custom. All the cows of Prome Centre preferred to take a drink and wade across in warm weather. The creek was very wide there, and so it was very shallow, and half the teams from both ways drove right through.

The six cows that were used to it were quickly on their way over, and Watch had already crossed the bridge, and stood now on the opposite shore waiting for them, with his bark in full operation.

"Rube," suddenly exclaimed Bun, "there goes the Deacon's new cow!"

"Yes, sir, and she's heading right up stream."

"You stand here, Rube, and pelt her if she tries to come ashore on this side. I'll run for old Harms's boat and head her off. The water's too cold yet for wading."

Bun Gates could do a thing about as quickly as some people could say they were going to do it, and in half a minute more he was shoving an old narrow-built punt of a boat after the slow but very wrong-headed wading of the new cow. She had the whole length of the creek before her when she started, but now Bun Gates and his boat were ahead of her in no time, and Bun's troubles were just ahead of him.

The cow seemed determined to dodge past that boat. The water ran very fast, and it was so shallow that even the punt ran aground every two minutes. It was by no means easy to push a boat in a swift current and drive a new cow at the same time.

"Run right against her," shouted Rube. "She'll have to turn then."

Bun did so, and the cow did turn down stream. It looked as if the battle were half won, but the water was nearly three feet deep a little below. Right there the cow slipped and floundered, and the punt received so sudden a shove at one end from her, just as Bun gave it a sharp push at the other end, that it also "turned." It turned so nearly over that the best thing Bun could do was to jump. After that he did not care so much whether he was in the boat or out of it, but he could drive the cow better. He had a good deal of driving to do, but he got her out at last on the right side of the creek.

"Is the water cold?" asked Rube.

"Awful cold. But I guess I'll keep that cow warm the rest of the way to the pasture."

He pulled the boat ashore, and then Rube helped him, and so did Watch, but it looked as if an unruly temper was spreading from Deacon Chittenden's costly brindle all around among the other cows.

They did very well, but it was harder work than common, especially for Watch, until they got within a few rods of the two sets of bars of the pasture lots.

"Rube," said Bun, "I'll run ahead and let down the Deacon's bars and ours. Don't you let that new cow get away from you."

The bars were down in a twinkling, and beyond them were acres and acres of tempting green grass. Surely no cow in her senses would prefer the dusty road to all that hill-side of breakfast.

Still, it might have occurred to Rube and Bun that cows could have preferences. Their own, indeed, had always marched on into the right lot without a blunder, and so had the Deacon's old ones. Even the new cow might now have been rightly guided if it had not been for her disturbed state of mind. So might all the rest but for the "worry" they were in. As it was, however, Watch had no sooner made his last dash at the head of the brindle than she made her last rush at him, and when she was met by Bun Gates and a long stick, she wheeled sharply to the right. There was the open gap before her. All the bars were down, and on she went into Mr. Gates's pasture at a gallop that was full of angry head-shaking. Both of Deacon Chittenden's orderly and sedate old cows followed as if she had called them.

"There they go!" shouted Rube. "Run in, Bun, and drive 'em out."

It would have been better if he had attended only to his other cattle, for Watch saw at once how badly things were going, and charged upon his old acquaintances in the road as if the confusion were driving him crazy.

The storm of bark he raised was enough to have made any cow nervous at any time, and those four were already "so worried." Well, in ever so few seconds Mr. Hollenhouser's cows and Mr. Gates's, all four of them, were scampering up the hill-side in Deacon Chittenden's lot. All Bun Gates could do over there beyond the partition fence only served to make the Deacon's new prize and the two others scatter in three different directions.

"What'll we do now?" shouted Rube.

"Put up the bars and go home," responded Bun, at the top of his voice. "I want to get some breakfast, and dry myself. We'll swap grass with Deacon Chittenden to-day."

That seemed fair; but after they had been to breakfast it looked like a duty to leave word at Deacon Chittenden's where his cows were, and Bun Gates did it. Rube did not see but what the news was told correctly, and so Katy Chittenden's forenoon was just spoiled for her, and her father and brother spent their afternoon looking for a gap that was not in the pasture fence.

Even when the Deacon on his way home stopped to ask Mr. Gates about it, all he learned was that Bun had complained that the new cow drove him all around the creek in a boat, and upset him.

"But that does not account for her being in your lot."

"Yes," said Mr. Gates; "a cow that would do that would take down a fence and let the other cows through, and then put it up after them."

It was a great mystery, and when Rube and Bun came along from school that afternoon there was Katy Chittenden at the gate, and Bill Chittenden was in the yard, and the Deacon was on the stoop, and Mrs. Chittenden was at the window.

"Katy," asked Bun, "did you tell your father what I told you?"

"Yes; and he and William have been up there all the afternoon mending the pasture."

"Audubon," exclaimed the Deacon, "how did those cows get mixed?"

"No, sir," said Bun; "the cows ain't mixed, it's the lots."

"How did they get in?"

"Through the bars. It's all that new cow. She tipped me into the creek, and Watch Hollenhouser can't but just bark; but we can get 'em all right when we go for 'em."

The Deacon looked puzzled even after that explanation, and so did Katy and the rest; but it was soon made plain to them, and, after all, as Rube Hollenhouser remarked, "It's only trading grass for one day."

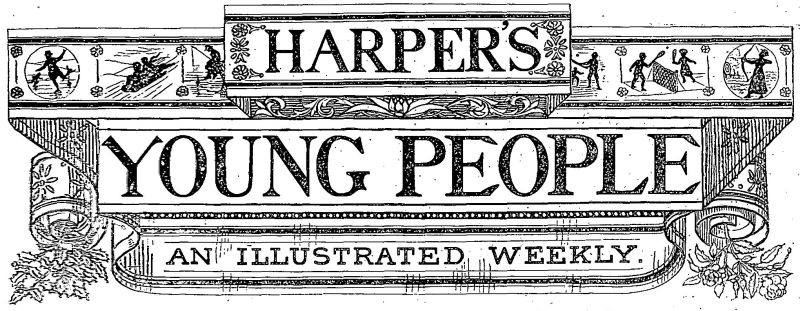

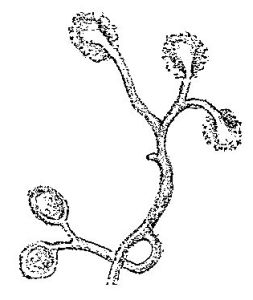

Fig. 1.—The Bean. First Leaves in different Stages.

Fig. 1.—The Bean. First Leaves in different Stages.

Have you never wondered, when you looked at a tangle of grape-vine or morning-glory stems, how they came to twist themselves together so? Perhaps you had some sort of a notion that they got tangled up as a bunch of silk or a skein of worsted lying loose might do. Examine any vine which you can find growing near you, and see how different the tangle is from a snarl of thread, there is a regular twist, the branches coiling in the same direction. In some plants the turn is from right to left, in others from left to right.

There must, of course, be some reason for this, and we can best find it out by taking a young plant, a seedling, and watching what it does from the start.

It would be very natural to think that plants moved only as stones do, because something pulled or pushed them; but this would not be a true conclusion. Every plant that we know much about is firmly fastened by its root in the ground; the movements of its leaves and flowers seem only caused by the blowing of the wind or the beating of the rain. But though plants are anchored fast to the earth, they are all the while moving as they grow.

Fig. 2.—Movement of Root of Black Bean.

Fig. 2.—Movement of Root of Black Bean.Take some seed—beans will do—and after soaking them, plant them in the ground about two inches deep. In a week or ten days you will see the earth cracked all about. This is not because the growing plant acts like a wedge and splits the earth open, but because in growing the first little leaves move round and round, boring their way out of the ground very much as a corkscrew works its way into a cork. The first leaves of most plants—a bean, for instance—do not come straight up out of the seed; but when the seed coat bursts from the swelling of the inner part a little arch projects, which raises itself up. This arch is the stem, and after a while the leaves are pulled out of the sheath, and the arch widens out, and finally straightens up. You have often seen a man who had a heavy weight to lift bow himself over and receive the weight, and then lift it by straightening himself, as the stem does to lift the leaves (Fig. 1, first leaves). The root burrows into the earth in very much the same way as the stem revolves, by going around and around as it grows (Fig. 2). Take a morning-glory vine, and let it lie without any wire or trellis to catch hold of. After a while you will find the stems and tendrils coiled round each other in a tight twist (Fig. 3); you could not begin to twist them so tightly yourself without breaking the stem.

Fig. 3.—Morning-Glories.

Fig. 3.—Morning-Glories.

The tips of all growing plants, like the first leaves that pierce the ground, move around; they are forever weaving their magic circles in the air; they take many hours sometimes to make a single turn, but they are as regular as the hands of a clock, and never forget and go backward. I have been watching some wistaria branches lately, and have been very much interested to see the new shoots, as they grew rapidly in the soft warm air, taking a slow turn around the wire placed to support them very much as you might wrap your arm about a swing rope to take a better hold. If there is a post or a wire near, you do not have to give your vines the twist they need to climb; they do their own twisting as they grow, and always in this quiet, deliberate way.

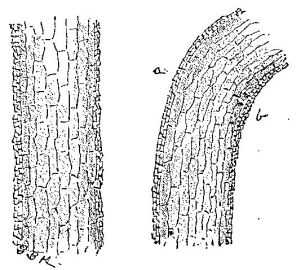

Fig. 4.—Virginia Creeper.

Fig. 4.—Virginia Creeper.

You have no doubt noticed that a Virginia creeper does not need a wire to climb by; it grows beautifully up any wall which has little unevennesses. Now look, if you can get hold of a new shoot, what the creeper has to help it along. It sends out tendrils that branch into many ends, and each one of these ends swells and becomes a sort of sticky pad, which glues itself to the wall (Fig. 4). These little pads, when they find no wall to fasten themselves upon, remain small, and finally wither away. Those on the vine in Fig. 4, which was trailing from a[Pg 788] vine, are so, some small and some quite gone; but look at the pads in Fig. 5, which were detached from a painted board, and see how they look through the microscope. Very much like a boy's India rubber sucker, are not they? Some of these have the paint from the board still sticking fast on them. Others are all sparkling with the dried mucilage, which makes them look as if they had been sprinkled with sugar.

These little many-armed suckers give the plant a firm hold, while its head waves around until it touches some surface again, and again the pads lay hold for another upward stretch.

Fig. 5.—Pads through the Microscope.

Fig. 5.—Pads through the Microscope.

There must be some curious arrangement by which plants, that can not feel and will as animals do, can move. They have no brains to think with, no nerves to feel with; it is strange to believe that they really do move with a reason. Mr. Darwin has examined the subject so closely that he has taken nearly six hundred good-sized pages to tell all he has found out about it. His ways of finding out are many. One method is this: he takes a small stiff bristle and glues it on the growing part of a shoot. By watching this shoot and comparing it with other shoots which had no bristle attached, he could not detect any difference in the movements. Above the little branch with the bristle attached he placed a piece of glass that had been smoked, so that the bristle, as it moved with the movement of the tip, would travel over the glass. He did not need to stand by and watch the branch; he could go away and attend to anything he chose, and when he came back there on the glass was a history of the travels the shoot had made, written by itself. He managed to hang up a sprouting bean or pea so that the root recorded its own movements in the same way. There were other ways which he used, all of them being ingenious, and requiring the greatest attention to get a correct map of their movements. He found that every plant in growing moved around as well as upward, but that some moved far more than others; the ones that grew tall and slender and needed support would send out shoots that swayed round in bigger and bigger circles until they could reach something to sustain themselves by, or else they would fall in helpless heaps on the ground.

Fig. 6.—Diagram of Straight and Curved Stems.

Fig. 6.—Diagram of Straight and Curved Stems.Mr. Darwin was not a man to be satisfied with finding that a thing is so. He never rested until he found just how it came about. I do not mean to say that he was the only man who studied these things, for there were many others who did; but he wrote about what he had studied in such a clear and simple and interesting way that anybody could understand him, and so people who don't pretend to be very wise in such matters read Mr. Darwin's account and nobody's else, and are apt to forget, though he is always careful to mention their names and what they have done, that any one else deserves any of the credit.

By closely studying the little cells of which the leaf or stem is made up, he found that when, for any reason, a plant needed to turn in a certain direction, the water in the stem rushed from the inner to the outer part of the curve, making the cells on the inner side of the stem a little smaller and those on the outer a little larger than usual. After a while the stretching of the outer cells makes them grow and stay larger (see in the figure how it must be, Fig. 6), and so the curve remains. You can not straighten a stem curved in this way without breaking it.

Every movement of stems and leaves comes from the movement of the water that fills their cells. But besides the water, there is something else just as important, and that is the sun. The water is only a servant, which obeys the light as its master. Many flowers turn their bright faces always to the light. They follow the sun as he moves through the heavens all the day long from his rising to his setting. This comes from the effect the sun has on the water in the stem, and not because the flower is beginning to "take notice," as the baby's bright eyes do of a lamp when it is moved about a room, though it does remind one of it.

The movement of climbing plants is only one of many curious movements that are made by stems and roots and leaves and flowers, though the cause is the same in all cases.

The circus came through our town three weeks ago, and me and Tom McGinnis went to it. We didn't go together, for I went with father, and Tom helped the circus men water the horses, and they let him in for nothing. Father said that circuses were dreadfully demoralizing, unless they were mixed with wild animals, and that the reason why he took me to this particular circus was that there were elephants in it, and the elephant is a Scripture animal, Jimmy, and it can not help but improve your mind to see him. I agreed with father. If my mind had to be improved, I thought going to the circus would be a good way to do it.

We had just an elegant time. I rode on the elephant, but it wasn't much fun, for they wouldn't let me drive him. The trapeze was better than anything else, though the Central African Chariot Races and the Queen of the Arena, who rode on one foot, were gorgeous. The trapeze performances were done by the Patagonian Brothers, and you'd think every minute they were going to break their necks. Father said it was a most revolting sight and do sit down and keep still Jimmy or I can't see what's going on. I think father had a pretty good time, and improved his mind a good deal, for he was just as nice as he could be, and gave me a whole pint of pea-nuts.

Mr. Travers says that the Patagonian Brothers live on their trapezes, and never come down to the ground except when a performance is going to begin. They hook their legs around it at night, and sleep hanging with their heads down, just like the bats, and they take their meals and study their lessons sitting on the bar, without anything to lean against. I don't believe it; for how could they get their food brought up to them? and it's ridiculous to suppose that they have to study lessons. It grieves me very much to say so, but I am beginning to think that Mr. Travers doesn't always tell the truth. What did he mean by telling Sue the other night that he loved cats, and that her cat was perfectly beautiful, and then when she went into the other room he slung the cat out of the window, clear over into the asparagus bed, and said get out you brute? We can not be too careful about always telling the truth, and never doing anything wrong.

Tom and I talked about the circus all the next day, and we agreed we'd have a circus of our own, and travel all over the country, and make heaps of money. We said we wouldn't let any of the other boys belong to it, but we would do everything ourselves, except the elephants. So we began to practice in Mr. McGinnis's barn every afternoon after school. I was the Queen of the Arena, and dressed up in one of Sue's skirts, and won't she be mad when she finds that I cut the bottom off of it!—only I certainly meant to get her a new one with the very first money I made. I wore an old umbrella under the skirt, which made it stick out beautifully, and I know I should have looked splendid standing on Mr. McGinnis's old horse, only he was so slippery that I couldn't stand on him without falling off and sticking all the umbrella ribs into me.

Tom and I were the Madagascar Brothers, and we were going to do everything that the Patagonian Brothers did. We practiced standing on each other's head hours at a time, and I did it pretty well, only Tom he slipped once when he was standing on my head, and sat down on it so hard that I don't much believe that my hair will ever grow any more.

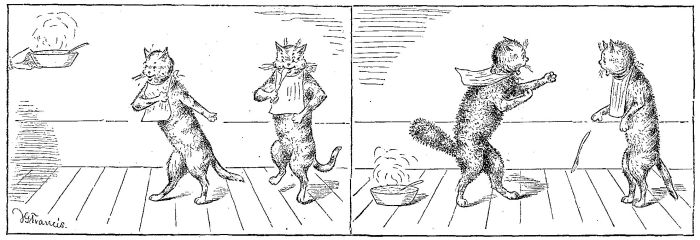

THE TRAPEZE PERFORMANCE.

THE TRAPEZE PERFORMANCE.

The barn floor was most too hard to practice on, so last Saturday Tom said we'd go into the parlor, where there was a soft carpet, and we'd put some pillows on the floor besides. All Tom's folks had gone out, and there wasn't anybody in the house except the girl in the kitchen. So we went into the parlor, and put about a dozen pillows and a feather-bed on the floor. It was elegant fun turning somersaults backward from the top of the table; but I say it ought to be spelled summersets, though Sue says the other way is right.

We tried balancing things on our feet while we laid on our backs on the floor. Tom balanced the musical box for ever so long before it fell; but I don't think it was hurt much, for nothing except two or three little wheels were smashed. And I balanced the water pitcher, and I shouldn't have broken it if Tom hadn't spoken to me at the wrong minute.

We were getting tired, when I thought how nice it would be to do the trapeze performance on the chandeliers. There was one in the front parlor and one in the back parlor, and I meant to swing on one of them, and let go and catch the other. I swung beautifully on the front-parlor chandelier, when, just as I was going to let go of it, down it came with an awful crash, and that parlor was just filled with broken glass, and the gas began to smell dreadfully.

As it was about supper-time, and Tom's folks were expected home, I thought I would say good-by to Tom, and not practice any more that day. So we shut the parlor doors, and I went home, wondering what would become of Tom, and whether I had done altogether right in practicing with him in his parlor. There was an awful smell of gas in the house that night, and when Mr. McGinnis opened the parlor door he found what was the matter. He found the cat too. She was lying on the floor, just as dead as she could be.

I'm going to see Mr. McGinnis to-day and tell him I broke the chandelier. I suppose he will tell father, and then I shall wish that everybody had never been born; but I did break that chandelier, though I didn't mean to, and I've got to tell about it.

The church-bells for service are ringing,

The parents gone forth on their way,

And here on the door-step are sitting

Three golden-haired children at play.

The darlings, untiring and restless,

Are still for the service too small;

But yet they would fain be as pious

As parents and uncles and all.

So each from a hymn-book is singing—

'Tis held upside down, it is true;

Their sweet roguish voices are ringing

As if every number they knew.

But what they are singing they know not;

Each sings in a different tone.

Sing on, little children; your voices

Will reach to the Heavenly Throne;

For yonder your angels are standing,

Who sing to the Father of all;

He loves best the sound of His praises

From children, though ever so small.

Sing on! How the birds in the garden

Are vying with you in your song,

As, hopping among the young branches,

They twitter on all the day long!

Sing on! For in faith ye are singing,

And that is enough in God's sight:

A heart like the dove's, pure and guileless,

Wings early to heaven its flight.

Sing ever! We elders sing also;

We read, and the words understand;

Yet oft, too, alas! we are holding

Our books upside down in the hand.

Sing ever! We sing, as is fitting,

From notes written carefully down;

But ah! from the strife of the brethren

How often has harmony flown!

Sing on! From our lofty cathedrals

What melodies glorious we hear!

What are they?—a sweet childish lisping,

A breath in the Mighty One's ear.

"I wouldn't mind being left to take care of the little ones," said Fannie the other day, "if they would only mind me. But when mamma is away they think they may do as they please, and they behave like little witches."

"Mollie manages the nursery splendidly," said Kittie; "the children are quite angelic under her, but I have not her magic. I seem to stir up the naughtiness, and the more I tell them to be good, the worse they act."

Now, Fannie and Kittie and other worried elder sisters, let me tell you the trouble with your management. When you can find the key to a problem in arithmetic, the rest is easy work.

I think I can whisper in your ear the name of a certain key to your home problem, when the small brothers and sisters say, as they sometimes do, "You are not my mamma, you are only Fannie; I want to make a noise, and you must not bother me."

The key is a word of four letters—tact. It is a golden key, and is warranted to fit any lock. You can not get along very well in life without it. I am very sure that Mollie possesses this shining key.

You remember what a time you had with Willie, who was determined to have Rosie's French doll as the passenger in his train of cars. Those cars rush around the parlor at so rapid a rate that everything must get out of their way or be crushed. Rosie was in great distress lest her pet's head should be broken, but Willie shouted, blew his whistle, and started his train just as usual. You snatched the doll away, and put her in the closet, high out of reach of both children, saying, "When you two can play without quarrelling, you shall have the doll again, and not until then." Of course Willie stamped his feet, and Rosie screamed, and there was a tempest.

You might have managed your little folks, had you only known how, so that they would have been as obedient as well-trained soldiers, and as peaceable as two doves in a nest.

I would have said, in your place: "Oh, Willie, what a nice train of cars you have there, and what a good conductor you are! Is Cécile your passenger? Oh no, I see she is not dressed for a journey. She has on an evening dress. Here is Laura"—producing an older and less important doll—"and she really needs a change of air. I'll slip on her Ulster in a second, and she will be all ready. She's pining for the country. Here, Rosie, you may take care of Cécile."

Both children would have been satisfied had you spoken to them in this way, and the hour would not have been spoiled by crying and fretting.

In managing little ones, when you are not possessed of any real authority, you must use a great deal of judgment. Humor the children by entering into their plays. They "make believe" a great deal. You must "make believe" too.

Many wee people can be led along by gentle words and merry looks, when they can not be driven without very great trouble. If Susie has a handsome book which you fear she will spoil, do not hurt her self-respect by taking it suddenly from her, but bring a scrap-book, and divert her attention to that. Then she will resign the other very pleasantly.

Elder sisters and brothers should never be above coaxing the little ones.

Author of "The Moral Pirates," "The Cruise of the 'Ghost,'" etc., etc.

It was an easy matter to help Joe out of the old well. He had fallen into it while running after the wild-cat, but a heap of decayed leaves at the bottom broke the fall, and saved him from any serious injury. Nevertheless, he must have been a little stunned at first, for he made no outcry for some time, and it was his first call for help that was heard by Charley.

The boys returned to their canoes, and as it was not yet midnight, prepared to resume the sleep from which they had been so unceremoniously awakened. They had little fear that the wild-cat would pay them another visit, for it had undoubtedly been badly frightened. Still, it was not pleasant to think that there was a wild beast within a few rods of them, and the thought kept the canoeists awake for a long time.

The wild-cat did not pay them a second visit, and when they awoke the next morning they were half inclined to think that their night's adventure had been only a dream. There were, however, the marks made by its claws on the varnished deck of Joe's canoe, and Joe's clothing was torn and stained by his fall. With the daylight they became very courageous, and decided that they had never been in[Pg 791] the least afraid of the animal. The so-called wild-cat of Canada, which is really a lynx, is, however, a fierce and vicious animal, and is sometimes more than a match for an unarmed man.

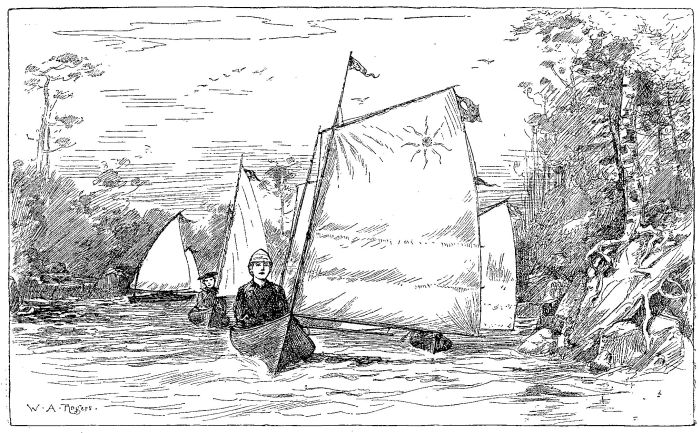

There was a strong west wind blowing when the fleet started, and Chambly Basin was covered with white-caps. As the canoes were sailing in the trough of the sea, they took in considerable water while skirting the east shore of the Basin, but once in the narrow river, they found the water perfectly smooth. This day the fleet made better progress than on any previous day. Nothing could be more delightful than the scenery, and the quaint little French towns along the river, every one of which was named after some saint, were very interesting. The boys landed at one of them, and got their dinner at a little tavern where no one spoke English, and where Charley, who had studied French at Annapolis, won the admiration of his comrades by the success with which he ordered the dinner.

SAILING DOWN THE RICHELIEU RIVER.

SAILING DOWN THE RICHELIEU RIVER.

With the exception of the hour spent at dinner, the canoeists sailed, from six o'clock in the morning until seven at night, at the rate of nearly six miles an hour. The clocks of Sorel, the town at the mouth of the Richelieu, were striking six as the canoes glided into the broad St. Lawrence, and steered for a group of islands distant about a mile from the south shore. It was while crossing the St. Lawrence that they first made the acquaintance of screw-steamers, and learned how dangerous they are to the careless canoeist. A big steamship, on her way to Montreal, came up the river so noiselessly that the boys did not notice her until they heard her hoarse whistle warning them to keep out of her way. A paddle-wheel steamer can be heard while she is a long way off, but screw-steamers glide along so stealthily that the English canoeists, who constantly meet them on the Mersey, the Clyde, and the lower Thames, have nicknamed them "sudden death."

Cramped and tired were the canoeists when they reached the nearest island and went ashore to prepare a camp, but they were proud of having sailed sixty miles in one day. As they sat around the fire after supper, Harry said:

"Boys, we've had experience enough by this time to test our different rigs. Let's talk about them a little."

"All right," said Joe. "I want it understood, however, that my lateen is by all odds the best rig in the fleet."

"Charley," remarked Tom, "you said the other day that you liked Joe's rig better than any other. Do you think so still?"

"Of course I do," answered Charley. "Joe's sails set flatter than any lug-sail; he can set them and take them in quicker than we can handle ours, and as they are triangular he has the most of his canvas at the foot of the sail instead of at the head. But they're going to spill him before the cruise is over, or I'm mistaken."

"In what way?" asked Joe.

"You are going to get yourself into a scrape some day by trying to take in your sail when you are running before a stiff breeze. If you try to get the sail down without coming up into the wind it will get overboard, and either you will lose it or it will capsize you; you tried it yesterday when a squall came up, and you very nearly came to grief."

"But you can say the same about any other rig," exclaimed Joe.

"Of course you can't very well get any sail down while the wind is in it; but Tom can take in his sharpie-sail without much danger even when he's running directly before the wind, and Harry and I can let go our halyards and get our lugs down, after a fashion, if it is necessary. Still, your lateen is the best cruising rig I've ever seen, though for racing Harry's big, square-headed balance-lug is better."

"You may say what you will," said Tom, "but give me my sharpie-sails. They set as flat as a board, and I can handle them easily enough to suit me."

"The trouble with your rig," said Charley, "is that you have a mast nearly fifteen feet high. Now, when Joe takes in his mainsail, he has only two feet of mast left standing."

"How do you like your own rig?" asked Harry.

"Oh, it is good enough. I'm not sure that it isn't better than either yours or Tom's; but it certainly isn't as handy as Joe's lateen."

"Now that you've settled that I've the best rig," said Joe, "you'd better admit that I've the best canoe, and then turn in for the night. After the work we've done to-day, and the fun we had last night, I'm sleepy."

"Do you call sitting still in a canoe hard work?" inquired Tom.

"Is falling down a well your idea of fun?" asked Harry.

"It's too soon," said Charley, "to decide who has the best canoe. We'll find that out by the time the cruise is over."

The island where the boys camped during their first night on the St. Lawrence was situated at the head of Lake St. Peter. This lake is simply an expansion of the St. Lawrence, and though it is thirty miles long, and about ten miles wide at its widest part, it is so shallow that steamboats can only pass through it by following an artificial channel dredged out by the government at a vast expense. Its shores are lined with a thick growth of reeds, which extend in many places fully a mile into the lake, and are absolutely impassable, except where streams flowing into the lake have kept channels open through the reeds.

On leaving the island in the morning the canoeists paddled down the lake, for there was not a breath of wind. The sun was intensely hot, and the heat reflected from the surface of the water and the varnished decks of the canoes assisted in making the boys feel as if they were roasting before a fire. Toward noon the heat became really intolerable, and the Commodore gave the order to paddle over to the north shore in search of shade.

It was disappointing to find instead of a shady shore an impenetrable barrier of reeds. After resting a little while in the canoes, the boys started to skirt the reeds, in hope of finding an opening; and the sun, apparently taking pity on them, went under a cloud, so that they paddled a mile or two in comparative comfort.

The friendly cloud was followed before long by a mass of thick black clouds coming up from the south. Soon the thunder was heard in the distance, and it dawned upon the tired boys that they were about to have a thunder-storm without any opportunity of obtaining shelter.

They paddled steadily on, looking in vain for a path through the reeds, and making up their minds to a good wetting. They found, however, that the rain did not come alone. With it came a fierce gust of wind, which quickly raised white-caps on the lake. Instead of dying out as soon as the rain fell, the wind blew harder and harder, and in the course of half an hour there was a heavy sea running.

The wind and sea coming from the south, while the canoes were steering east, placed the boys in a very dangerous position. The seas struck the canoes on the side and broke over them, and in spite of the aprons, which to some extent protected the cockpits of all except the Twilight, the water found its way below. It was soon no longer possible to continue in the trough of the sea, and the canoes were compelled to turn their bows to the wind and sea, the boys paddling just sufficiently to keep themselves from drifting back into the reeds.

The Sunshine and the Midnight behaved admirably, taking very little water over their decks. The Twilight "slapped" heavily, and threw showers of spray over herself, while the Dawn showed a tendency to dive bodily[Pg 792] into the seas, and several times the whole of her forward of the cockpit was under the water.

"What had we better do?" asked Harry, who, although Commodore, had the good sense always to consult Charley in matters of seamanship.

"It's going to blow hard, and we can't sit here and paddle against it all day without getting exhausted."

"But how are we going to help ourselves?" continued Harry.

"Your canoe and mine," replied Charley, "can live out the gale well enough under sail. If we set our main-sails close-reefed, and keep the canoes close to the wind, we shall be all right. It's the two other canoes that I'm troubled about."

"My canoe suits me well enough," said Joe, "so long as she keeps on the top of the water, but she seems to have made up her mind to dive under it."

"Mine would be all right if I could stop paddling long enough to bail her out, but I can't," remarked Tom. "She's nearly half full of water now."

"We can't leave the other fellows," said Harry, "so what's the use of our talking about getting sail on our canoes?"

"It's just possible that Tom's canoe would live under sail," resumed Charley; "but it's certain that Joe's won't. What do you think about those reeds, Tom? Can you get your canoe into them?"

"Of course I can, and that's what we'd better all do," exclaimed Tom. "The reeds will break the force of the seas, and we can stay among them till the wind goes down."

"Suppose you try it," suggested Charley, "and let us see how far you can get into the reeds? I think they're going to help us out of a very bad scrape."

Tom did not dare to turn his canoe around, so he backed water, and went at the reeds stern first. They parted readily, and his canoe penetrated without much difficulty some half-dozen yards into the reeds, where the water was almost quiet. Unfortunately he shipped one heavy sea just as he entered the reeds, which filled his canoe so full that another such sea would certainly have sunk her, had she not been provided with the bladders bought at Chambly.

Joe followed Tom's example, but the Dawn perversely stuck in the reeds just as she was entering them, and sea after sea broke over her before Joe could drive her far enough into the reeds to be protected by them.

Joe and Tom were now perfectly safe, though miserably wet; but as the rain had ceased, there was nothing to prevent them from getting dry clothes out of their water-proof bags, and putting them on as soon as they could bail the water out of their canoes. Harry and Charley, seeing their comrades in safety, made haste to get up sail, and to stand out into the lake, partly because they did not want to run the risk of being swamped when entering the reeds, and partly because they wanted the excitement of sailing in a gale of wind.

When the masts were stepped, the sails hoisted, and the sheets trimmed, the two canoes, sailing close to the wind, began to creep away from the reeds. They behaved wonderfully well. The boys had to watch them closely, and to lean out to windward from time to time to hold them right side up. The rudders were occasionally thrown out of the water, but the boys took the precaution to steer with their paddles. The excitement of sailing was so great that Charley and Harry forgot all about the time, and sailed on for hours. Suddenly they discovered that it was three o'clock, that they had had no lunch, and that the two canoeists who had sought refuge in the reeds had absolutely nothing to eat with them. Filled with pity, they resolved to return to them without a moment's delay. It was then that it occurred to them that in order to sail back they must turn their canoes around, bringing them while so doing in the trough of the sea. Could they possibly do this without being swamped? The question was a serious one, for they were fully four miles from the shore, and the wind and sea were as high as ever.

"BESIEGED."

"BESIEGED."

Robert Fulton, the inventor of steamboats, was born on a farm in Pennsylvania. His parents were Irish Protestants—a strong, laborious race. Robert was a delicate, handsome boy, with a fine forehead and brilliant eyes. Almost as a child he became a mechanic, inventing machines and lingering around workshops. He was thought dull at school, and made slow progress in the usual studies. But he was always inventing.

One day, when Robert was about nine years old, he came late to school, and when his teacher reproved him, produced a new lead-pencil which he had been making while playing truant. The boys were all anxious to have one of Fulton's pencils—they were better than any they had seen. In his school days he made rockets to celebrate the Fourth of July, and in 1778, in the midst of the war, set them off in his native town. About this time he made an air-gun and a boat moved by wheels. He had a strong taste for drawing. His mother, who was now a widow and poor, wanted his help.

Fulton was only seventeen, but he went up to Philadelphia, made money, became acquainted with Dr. Franklin, and when he was twenty-one came back to his mother with his earnings, and bought her a farm. Here she lived happily for some years, watching and enjoying the rising prosperity of her son. The deed by which Fulton at twenty-one gave the farm to his mother is still preserved.

There are persons living who might have seen the first steamboat that sailed on the Hudson. Many remember when the famous De Witt Clinton and North America were thought the wonders of navigation; when they sailed over the tranquil river at the rate of sixteen miles an hour, and left behind them thick clouds of black smoke that hung over the landscape for miles. The North America was long the pride of the river navigation, the swiftest vessel in the world. The Hudson has always been the favorite scene of steam navigation and enterprise. It is the birth-place of the steamboat.

Here, in 1807, Robert Fulton, on board of the Clermont, his first vessel, sailed in a day and a half from New York to Albany. He stopped for a few hours at Clermont, and then in four more finished his voyage. It was the signal for an entire change in the whole art of navigation. From that time the steamboat has been slowly advancing, its size has increased to immense proportions, its engines have become animated giants, and Fulton's little vessel of one hundred and sixty tons is converted into the Furnessia, the Alaska, and the Great Eastern.

Fulton, a fair, delicate, thoughtful young man, had gone to England, to France, had become acquainted with many eminent inventors, and had already planned a steamboat. He was the first to make one successful. He came back to New York, and, aided by his friend Livingston, in 1806 began to build his boat. It was only a small vessel, rudely built; in it he placed an engine made by James Watt, the English inventor; the paddle-wheels he planned himself, and the imperfect machinery. It seems now a very easy thing to build a steamboat, but it was then thought impossible. Men called the boat Fulton's Folly. Hardly any one supposed that a new era in navigation was about to begin, and that Fulton's machine would at last cover the world with its discoveries. At last the boat was finished.

The fires were lighted, the boilers hissed, the crank turned, the wheels began to move, and the Clermont made its way, at about five miles an hour, from Charles Brown's dock-yard on the East River to Jersey City. Once she stopped, and men cried, "There, it has failed!" But it was only because Fulton was anxious to alter some part of his machine. The great voyage was successful. The steamer reached Jersey City, and Fulton's victory was won.

Soon the Hudson began to abound with Fulton's steamboats, the wonders of the world. There was the famous Paragon, a vessel of the enormous size of three hundred tons. One built for the Czar was called the Emperor of Russia. A ferry-boat ran from New York to Jersey City. In the midst of the war with England Fulton built the first war steamer. It was two thousand tons burden, a fine shot-proof vessel, and sailed at the rate of three miles an hour as far as Sandy Hook. Its size seemed immense, its power irresistible, and it was told with alarm in London that Fulton and New York had produced the most dangerous of warlike machines. America now abounded in steamboats, but they were only slowly adopted in Europe. London, Carlyle relates, was long without them.

The fair, pale, delicate inventor did not live long to enjoy his success. His lungs were always weak. He was always at work. His patents were infringed, and his invention only involved him in endless lawsuits. At last he caught cold crossing the Hudson on a chill February day, and died 1815, a good son, an inventor who has been useful to every one. He has founded nations, and opened the distant seas to trade.

Yes, boys, real Simon-pure "magic." Just such tricks as you have seen the "magician" do; just such tricks as some of you may have seen your humble servant do. Many of these you can do yourselves—when you know how; others require more practice than you ought to give to such nonsense, and others again are too expensive. But there are some that any boy—or girl, for that matter—can do with little rehearsing and at slight expense. The magic sack trick, which I had the honor of introducing to America in 1873, is as clever as it is simple.

A muslin sack large enough to contain a boy of fourteen is handed out for examination, and after the audience are satisfied that the seams are not only secure and perfect, but that its only opening is at the mouth, the performer's assistant gets inside. The sack is gathered over his head, and the mouth tied fast with a silk handkerchief, and then with a tape, the knots of the latter being not only sealed in any way that seems best to the audience, but the ends, which are left long, given to some one to hold.

A screen is now placed between the audience and the boy in the sack, the ends of the tape passing either over the top of the screen or through holes in its side.

It would seem impossible for the person thus securely enveloped to get out of the sack without cutting or untying the tape and handkerchief; and yet, O mystery of mysteries! in a few seconds the screen is thrown open, and the late occupant of the sack walks out, while the sack is found still tied up, the knots not tampered with, and the seals unbroken.

Surprising as this appears, there are needed but three requisites for its successful accomplishment: first, an assistant upon whose secrecy and faithfulness the young conjurer can rely, for he will require his help in very many tricks; second, two sacks, exactly alike, made of very light material, so that they will fold into small compass; and third, unlimited impudence, assurance, or whatever you may be pleased to call it.

When about to exhibit the trick, the performer comes forward, holding a silk handkerchief in one hand, and sack No. 1 in the other. The assistant, who is to be tied up, has the duplicate, or sack No. 2, concealed about him, say, inside his vest, or in some such suitable place.

As soon as he gets fairly into No. 1, he whips out the duplicate, and puts the mouth of it inside the mouth of No. 1. The exhibitor, who is fumbling about as if to gather No. 1 over the assistant's head, seizes No. 2, and drawing out about nine inches of it, at once wraps the silk handkerchief over the two so as to cover the point where they meet.[Pg 795] This he does deliberately, as an appearance of haste would give rise to suspicion among the audience. As it is now impossible for any one to distinguish between the parts of the two sacks, the exhibitor turns to his audience with the remark: "I have now tied up the mouth of the sack in such a way as to make it next to impossible for the young man to get out. But to make assurance doubly sure, I should like one of the audience to tie it again; this time with a piece of tape." As he says this, he produces the tape and ties it once around the part between the handkerchief and the mouth of No. 2. The person selected from the audience then draws the knots tight, seals them, and retains the ends of the tape in his hand.

When the screen is placed in position—for home exhibition a clothes-horse with a sheet over it makes an excellent substitute for a screen—the assistant gently pulls on the mouth of No. 1, which is readily drawn out from under the handkerchief, and steps out, leaving the tape and handkerchief still closely wound around No. 2. It takes but a second to fold up No. 1, conceal it, and then to walk out from behind the screen to receive the applause of the audience.

This brief, but I trust clear, description can give but little idea of the effect produced by this really surprising trick. I first saw it exhibited by a performer calling himself Le Duc, at Stockholm, Sweden, some twenty-five years ago, and at that time, though I knew considerable about magic, I was completely mystified.

Author of "Toby Tyler," "Tim and Tip," "Mr. Stubbs's Brother," etc.

Business, so far as Johnny and Jimmy were concerned, was almost entirely neglected for two weeks after Katy was carried to the hospital. If they sold any papers, it was only sufficient to pay Mother Brown for their board, and nearly all their time was spent in remaining where they could look at the gloomy walls of the building in which Katy yet remained.

Some of their friends in the newspaper business had attempted to make sport of them for spending so much of their time simply looking at the walls of a hospital; but the light in Johnny's eyes had warned them to stop, and Jimmy had said, quietly, "We stay round here 'cause it would make Katy feel good if she knew it."

Fully repaid for the long hours of watching by the knowledge that their being there would please their friend if she could know it, the two remained day after day, and far into each night, until the time came when they were actually startled by the news that in another week, if nothing happened to her, Katy would leave the hospital.

This good news came to them so suddenly that they were almost as stupefied as they had been when the accident happened; but when they did fully realize all the happiness contained in that announcement, they gave vent to their joy in such extravagant antics that the old porter, who chanced to see them, declared it to be his solemn belief that they were "a couple of ijuts."

"Now what'll we do to show Katy how glad we are?" asked Johnny, when, breathless from the severe exercise, they seated themselves on the curb-stone to talk the matter over. "We've got to do somethin', you know, an' what shall it be?"

Jimmy rubbed his chin vigorously, as if to call forth his most brilliant ideas, and after an unusually long pause, replied, "I'll tell you jest what we'll do: we'll scurry 'round an' get money enough to buy her one of the stunnin'est dresses we can find, an' we'll carry it up to her the day before she comes out."

It certainly seemed as if that idea was an inspiration, and Johnny was so anxious to carry it into execution that he urged his friend along, on the way down town to purchase a stock of papers, at the most furious rate of speed.

They were not just certain how much money would be required to carry out their plan, but when they had gotten together a fund of two dollars and sixty cents, they were certain they could purchase almost any dress that was displayed in the shop windows, and have enough left not only to buy bracelets, but anything else in the jewelry line that they might chance to fancy.

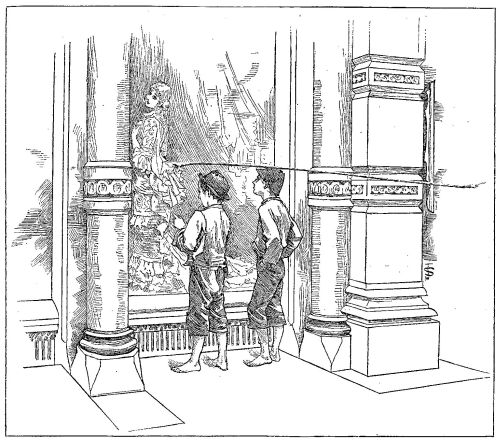

THE BOYS TRYING TO SELECT A DRESS FOR KATY.

THE BOYS TRYING TO SELECT A DRESS FOR KATY.

During one entire forenoon they went from one to another of the largest stores in the city, peering in at the windows at the ready-made dresses displayed, and not quite able to make up their minds which to choose. The greater number of the garments appeared to be too large, while none of them were quite bright enough in colors to suit them exactly.

"I'll tell you what it is," said Jimmy, after he had rubbed his chin harder than usual in front of a delicate party dress of pink and white silk with an enormous train, and had decided that it was not brilliant enough in color to please them, "we'd better go to Bob Spratt's mother, an' get her to come out with us to buy it. She'd know best what Katy'd like."

"I'm afraid that's what we'll have to do," said Johnny, with a sigh, fully convinced of the hopelessness of their succeeding unaided in their task. "I don't see how folks get along that have to buy more'n one dress a year; it must take 'em 'bout all their time pickin' 'em out."

"I s'pose they get kinder used to it, an' know jest what they want," said Jimmy, with an air of wisdom; and then, with just a shade of envy toward those particularly fortunate people who know exactly what to purchase, the newspaper merchant walked resolutely away from the party-dress which he was convinced was not beautiful enough for Katy to wear while selling pins on the street.

Mrs. Spratt was found, according to her way of expressing it, at her old established place of business, on the corner of Vesey Street, where she drove a flourishing trade in jackknives, candy, and other such necessary articles.

Never before had either of them doubted Mrs. Spratt's wisdom and superior judgment; but when she boldly declared that a silk dress could not be purchased for two dollars and sixty cents, they began to have suspicions that she was not the wise woman they had always believed her to be. Those suspicions became a certainty when she added that even if they could afford to buy such dresses as they had seen, they would not be suitable for Katy to wear while plying her trade on the street.

It was not until after they had withdrawn to a convenient distance, and there discussed the question of Mrs. Spratt's mental condition for fully ten minutes, that they finally decided to ask her just what she thought would be suitable for a dress for Katy, and within their means.

Even if Mrs. Spratt was not altogether right in her mind, and even if she did have ridiculous ideas regarding color, she spoke just as if she believed what she said when she told the boys that they could buy some pretty, plain material, sufficient for a dress for Katy, for about a dollar and a quarter, while with another dollar they could hire Mrs. Isaacs to make it for them in the latest style.

Several more strictly private consultations between the partners were necessary before they could make up their minds to trust to Mrs. Spratt's taste and honesty in buying the dress, and then they placed the entire matter in her hands, she generously offering to purchase the goods that very afternoon, providing they would care for her stand while she was away.

The boys had plenty of time in which to discuss the matter in all its bearings while Mrs. Spratt was attending to the important business. It was with deep sorrow that they admitted to each other that if the dress was to cost[Pg 796] two dollars and a quarter, it would be almost impossible for them to buy any very large bracelets with the remaining thirty-five cents.

It was a disappointment that caused Jimmy to rub his chin until it was very red; but he bore up under the sorrow like a philosopher, his active mind presenting another plan that seemed quite as brilliant as the first.

"Johnny!" he cried, as he started up suddenly, at great danger of overturning Mrs. Spratt's rather frail "old established place of business."

"Wot?" asked Master Davis, moodily, for the impossibility of buying the bracelets weighed heavily on his mind.

"Why can't we earn a little more money, an' the day Katy comes out of the hospital, take her somewheres for a good time, jest like reg'lar folks do?"

"Cricky!" exclaimed Johnny; and by that expressive word Jimmy knew that he was impressed with the idea.

"I know a feller what carries 'round nuts an' candy on one of the Coney Island boats, an' jest as likely as not he could fix it for us so we could go down for half price. How Katy's eyes would stick out when she got down there! Why, she'd jest roll over in the sand, she'd be so tickled."

"Then good-by dress," said Johnny, feeling actually relieved that he had been able to find some fault with Jimmy's plan, for he was almost jealous of his partner's active brain.

"Well, of course I don't mean that she would really roll over if she had the dress on," said Jimmy, quickly, conscious that he had colored his picture a trifle too high, "but I mean she'd feel good enough to do it."

"When could we find that feller on the steamboat?" asked Johnny, anxious to settle all the details of this very brilliant scheme at once.

"I guess we'd see him if we went down on the pier an' waited till his boat come in."

"Then we'll go jest as soon as Mrs. Spratt comes back."

Johnny was not hindered very long by the absence of the owner of the stand, for in a few moments afterward she returned, flushed and heated by her unusual exertion, but wearing a triumphant look.

"I bought it," she said, as she tried unsuccessfully to fan herself with one of her largest combs, "an' I thought I'd save time by carryin' it right over to Mrs. Isaacs. But I brought a piece to show you what it is like," she added, quickly, as she saw a look of disappointment come over the boys' faces.

The goods was not exactly what they would have chosen, for it seemed much too sober in color, and not "shiny enough," as Jimmy said; but it was a soft, rather thin piece of blue material, which would make a very becoming dress for "their girl."

"I got it for twelve cents a yard," said Mrs. Spratt, in a tone of triumph, "an' I made the man throw in as much as ten inches extra, which will give her a good dress pattern. Then I bought the buttons an' the trimmings for twenty cents more, an' Mrs. Isaacs will find the thread, an' make it for a dollar. It'll be as handsome a dress as you could get anywhere for two dollars an' forty cents, an' a good deal better than Katy ever had before."

Mrs. Isaacs had promised to have the garment ready the day before Katy was to come from the hospital, and this most important business having been attended to, the boys started out in search of their friend the employé on the Coney Island boat.

The steamer which Ikey Moses graced with his presence and particularly valuable services was not at the pier when the boys arrived there; but what did two or three hours of waiting amount to when such an end was to be gained? Absolutely nothing, so they thought, as they loitered around the dock until, two hours later, the steamer arrived.

Ikey was on board, and in particularly good humor, having made twenty cents extra that day on a private speculation in sassafras bark. And being intrusted with his friends' secret, after he had solemnly crossed his throat never to divulge it, he made of the question of getting tickets at half price a very simple matter. In fact, he was quite certain he could get tickets for nothing, and he promised to use all his great influence in their behalf, providing they would pay him ten cents in case he was successful.

As may be imagined, the boys readily agreed to do this, and Johnny even generously promised that in case Ikey succeeded, they would give him all their custom on the passage. This latter consideration was not a weighty one with Master Moses, for, since his employer was the only one who had eatables to sell on the boat, and since he was the only clerk, the boys would be obliged to deal with him or go hungry.

All the details having thus been arranged, it only remained for the boys to work industriously to procure the necessary funds.

Business was not remarkably good during the four days that intervened before Katy's time in the hospital had expired; but they made enough to pay Mother Brown for their board, and then have a cash capital of one dollar on hand.

Ikey had succeeded in getting for them free passes, and they had paid him the amount agreed upon. The dress had been finished, and on the evening before Katy was to leave the hospital they carried it up to be sent in to her, in order, as Jimmy said, "that they might jest knock her eye out before she was stunned by the idea of the excursion."

"Tell her Jim an' John sent it in to her," said the latter, as he handed the bundle to the porter, "an' that we want her to be all ready when we come up here for her at nine o'clock to-morrow mornin'."

"That'll fix her," said Jimmy, triumphantly, as they left the hospital; and during the remainder of that evening they enjoyed in anticipation the royal time they were to have next day when they took "their girl" on her first excursion.

| With gun upon his shoulder, Sir Beetle hunting goes, |

| There is nothing in the larder, for a dreadful wind arose; |

| It blew their cottage over, and the rain began to beat, |

| They couldn't find their overshoes, or anything to eat. |

| But Mrs. Beetle's thankful that after such a storm |

| She has still a silk umbrella, and a fire to keep her warm. |

| Back from the forest we're bringing our sheaves— |

| Armfuls of posies and bright Autumn leaves; |

| Happy are we, though the chill wind may blow, |

| The herald of Winter in garments of snow. |

| Oh, what a host of playmates has little Johnny Grey! |

| He says that Puss and Rover know everything we say; |

| And that the birds and squirrels always understand; |

| So he's talking to the beetle that is crawling on his hand. |

| Mamma must work the long, long day, |

| While I have lessons to learn and say; |

| But Baby Blue Eyes, so bright and gay, |

| Has nothing to do but laugh and play, |

| Till the Sand Man works his wonderful charms, |

| When he goes to sleep in somebody's arms. |

Many of you will be very glad to hear again from Mrs. Richardson, whose work among the poor people at Lincolnton has interested you very much. For the information of new subscribers we will state that this lady has, for several years, been trying to make the lives of the colored people around her brighter and happier.

She began by teaching the children of Uncle Pete, her faithful friend and servant, and once her slave. At present she is giving religious and other instruction to a great many children and young people, and through her self-denying efforts a little chapel has been built, where they worship on Sundays.

The little readers of Young People have assisted Mrs. Richardson by sending books, toys, and cast-off clothing to her for the use of her protégées:

Woodside (near Lincolnton), North Carolina.

My dear young Friends,—I have not written to you very often lately. The Post-office Box is always so full of interesting letters that I felt that it would be an imposition in me to take up space in it very often. Then, too, there has been nothing very interesting to tell you. The chapel is up (not yet finished, but covered), the floor laid, windows in (they look so pretty!), and the pews made; we can use it, though the door and a good deal of work is yet to be done. The chapel stands in a grove of pines and weeping-oaks. The branches of these oaks droop almost to the ground, and are very graceful and pretty, besides making delightful horses for the children to ride. You all, I guess, know just how far to creep up the limb, and then spring to make it go, and ride delightfully among the branches.

I know you will be glad to know that the school has gone on regularly and well since it first began. The scholars have all improved very much; those who were learning their letters last summer are now using Second Readers. A great number of them are reading in the Testament—very poor reading in many cases, spelling many words, but still we find, with the explanations we give them as we go on, that going through the Gospels they understand a great deal of it. We feel that it must do them good. When they came they did not know anything of prayer; only three knew "Now I lay me." Now they all know that and the Lord's Prayer, almost all the Creed, and the Ten Commandments.

Did I write you—no, I know I have not, for it was only a few weeks ago—that some kind, very kind, persons sent me an organ? I wish they could know and see the pleasure it gives us all. The scholars seem so delighted to sing that last Sunday we let them try chanting a psalm we had been reading, and they learned it very quickly. Then we tried the Creed and the Lord's Prayer to a tune in the choral service; that they did beautifully, all of them, even the tiny children, and all of them (over sixty) singing as with one voice, they naturally made a swell on the Amen that was truly beautiful. They were so happy singing these things over and over with the hymns they know, saying always, "Please, ma'am, one time more!" "Abide with me" they sing very well. "Jerusalem the Golden" is a great favorite too. When we thought we must stop, they begged so just to sing everything over once more that we did it, and found when we came home that we had been three hours at Sunday-school and singing. Two boys, or men, carry the little organ up there, and back again when we are done. We hope to have the door and lock this week.

I would like very much to have a few primers, and also some readers and copy-books and pencils; there are many of them so anxious to learn to write. A few slates were sent—most of them broken a good deal in coming—but their copies and writing get rubbed out, so they do not get on very well with them.

Oh, I do so wish you could be here and see how happy they are in Sunday-school, and in the singing after! My husband says they won't be any happier in paradise than they were last Sunday afternoon. Their black faces were filled with ecstasy, and we were almost as happy, seeing them so delighted. There are three children to be baptized next Sunday, when we will have service and a sermon after Sunday-school.

I find they are counting the weeks already to Christmas. There are some little ones and babies the mothers have to bring, so we shall have to give them something. Presents for seventy! We will do all we can, but can not make a tree for so many unless we have help. Remember, in sending, that things you would not care for will delight them. Clothes you would think worn out will please them, and make them warm and comfortable; ribbons, etc., too much soiled for you to use will please them as well as new; shawls, no matter if old and faded, anything warm, will be of great service; quilt patches, needles, and thread—in fact, anything and everything will be of use in making a tree for them. They all are very, very fond of candy.

One lady will give me some paper to help make cornucopias; that is all the help I know of yet for Christmas. Christmas is yet a long time off to you young people, but when one grows older the weeks just fly away, and Christmas always comes before we get ready for it. We are going to begin the 1st of November practicing the carols for Christmas, and hope they will all have as happy a day as they did last year.

With a heart full of love to you all for the help you have so kindly given me before, and hoping, as the years roll on, I may see some of your dear faces, I am, now and always, gratefully and truly your friend,

Mrs. Richardson.

What does the brook say, flashing its feet

Under the lilies' blue brimming bowls,

Brightening the shades with its tender song,

Cheering all drooping and sorrowful souls?

It says not, "Be merry," but deep in the wood

Rings back, "Little maiden, be good, be good."

What does the wind say, pushing slow sails

Over the great troubled path of the sea;

Whirling the mill on the breezy height,

Shaking the fruit from the orchard tree?

It breathes not "Be happy," but sings loud and long,

"O bright little maiden, be strong, be strong."

What says the river, gliding along

To its home on far-off Ocean's breast;

Fretted by rushes, hindered by bars,

Ever weary, but singing of rest?

It says not, "Be bright," but in whisperings grave,

"Dear little maiden, be patient, be brave."

What do the stars say, keeping their watch

Over the slumbers the long lone night,

Never closing their bonnie bright eyes,

Though great storms blind them, and tempests fright?

They say not, "Be splendid," but write on the blue,

In clear silver letters, "Maiden, be true."

What a rainy time we have had, to be sure, children! I thought about my little correspondents as the floods fell day after day, and I wondered how those who have long, long walks to school contrived to get there when the bridges were down, and the great trees were torn up by the roots, and the paths, usually dry, were all covered with water.

Some years ago a friend of mine, waking up one morning, was saluted by her cook with the news that the kitchen floor was so wet that she could not prepare the breakfast. The water came over the poor woman's rubber shoes. My friend thought she could manage to boil a cup of coffee and make toast by the fire in the parlor; but later in the day Joe and Frank, her sons, found it great fun to march about the wet kitchen on stilts. They made the fire in the range, and, under Mary's directions, produced omelet, broiled steak, and other things, so that the family did not starve during the rainy day.

If any of you have met with adventures during the freshet, I shall expect to hear all about them.

Lincoln, Nebraska.

School begins next week, and I would like to tell you about my first vacation. In June I went to Indiana to visit my cousins. When I came home I crossed the Mississippi and Missouri rivers for the fourteenth time. In two weeks papa and mamma and I started for Denver. We left Lincoln at noon, and the next morning I saw the mountains for the first time. How strange to see snow in July! We spent a few days in Denver, and then such a wild ride as we had through the mountains to Georgetown, where I can't tell you half of the fun I had. I fed the fish, and had a lovely row on Green Lake. I went one-third of a mile into the Colorado Mine in a little car, then down a shaft 250 feet, in a bucket with a miner, to see the men at work; but I did not buy a mine like the other little "tenderfoot" I read about in Harper's. But it was the most fun to ride on a burro. There were ten children and seven burros, and we had a fine ride on the mountain, and then had our pictures taken. The cutest picture was a burro with four children on his back.

We went to Central over a queer railroad that runs almost up to the town at the foot of the mountain, then makes a loop and runs back a mile on the side of the mountain over the tops of the houses, then turns again and runs into the town—oh, ever so high up! And we went to the Bobtail Mine, and into the mill where they crush the ore and wash the gold out of it. It was very interesting. I had a nice play with a little new friend, Ethel S., whose papa owns lots of mines.

And now I must tell you about our going up Pike's Peak. We left Manitou at seven in the morning on horses, and such a wild, beautiful ride I never had before. We had to go on a narrow path just wide enough for a horse to go, very carefully winding around the mountain-side, and we could hardly ever see to the top, and not to the bottom, it was so far down. The bright little creek that came splashing down through the rocks made the sweetest music that mamma ever heard. The flowers, too, were very bright. When we were near the top, papa let me pass him, and I was the first to get there. Then we had coffee made from the snow-bank near the house. But the going down! So tired we were, we were fit to fall.

And now I am too tired to tell you about the Garden of the Gods, the Cave of the Winds, and the Denver Exposition. I am eight years old.

Joy W.

P. S.—It is twelve miles to the top of Pike's Peak.

I really felt, little Joy, as I read your letter, that some time or other I too must climb those great mountains, and venture into those mines, and maybe even ride on a burro, as, you did. But very likely the burro would not care about carrying even a lady like me, unless, perhaps, I could find the little fellow that had four on his back at once. And what would become of the Post-office Box while I was climbing the steep mountains? For the present I suppose I must be content to view the snow-clad peaks through your bright eyes. Thanks, dear child, for the lovely pressed flowers so prettily arranged.

"Oh, mamma, see how it is raining!" said little Lottie; "and it looks so dark, too, all around, that I fear it will keep on all the afternoon."

"And then we can't go for the new kid gloves you promised us," chimed in Helen. "Won't that be too bad?"

And the two little sisters—Helen, eleven years of age, and Lottie, nine—were quite disposed to pout and feel very ill-humored at the prospect of a rainy Saturday afternoon, and the consequent postponement of their anticipated walk for the purpose of purchasing two pairs of new kid gloves.

Mamma smiled at them. "Now, little folks, although you take so much pleasure in having and wearing kid gloves, I am sure you do not often think how many nice and careful operations these gloves have to go through, and how many hands are employed in their manufacture, before they can be put in the stores for sale. If you will sit down contentedly by me, with your cork-work or knitting, I will tell you, while I sew, much that is interesting about kid gloves, so that we can make this disappointment of a rainy afternoon as instructive and profitable as possible.